Title: William Morris to Whistler

Author: Walter Crane

Release date: January 13, 2017 [eBook #53954]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Crown 8vo, 6s. net each

With 200 Illustrations

With 157 Illustrations

With 165 Illustrations

Medium 8vo. 10s. 6d. net

PAPERS THEORETICAL, PRACTICAL,

CRITICAL

With Title-page, End-papers, and Cover

designed by the Author, and

numerous Illustrations

LONDON: G. BELL AND SONS, LTD.

LONDON: G BELL & SONS LTD

YORK HOUSE PORTUGAL ST W.C.

1911

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

OF the collected papers and addresses which form this book, the opening one upon William Morris was composed of an address to the Art Workers' Guild, an article which appeared in "The Progressive Review," at the instance of Mr. J. A. Hobson, and a longer illustrated article written for "The Century Magazine," and now reprinted with the illustrations by permission of Messrs. Charles Scribner's Sons, to whom my thanks are due.

"The Socialist Ideal as a New Inspiration in Art" was written for "The International Review," when it appeared under the editorship of Dr. Rudolph Broda, as the English edition of "Documents du Progrès."

"The English Revival in Decorative Art" appeared in the "Fortnightly Review," and I have to thank Mr. W. L. Courtney for allowing me to reprint it. It has some additions.

"Notes on Early Italian Gesso Work," was written for Messrs. George Newnes's Magazine of the Fine Arts with the illustrations, and I am obliged to them for leave to use both again.

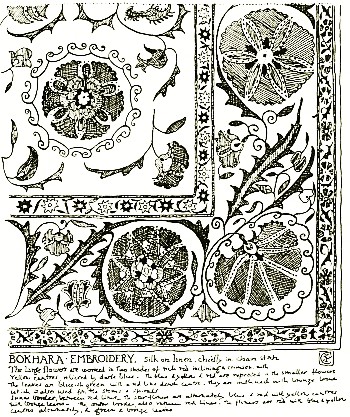

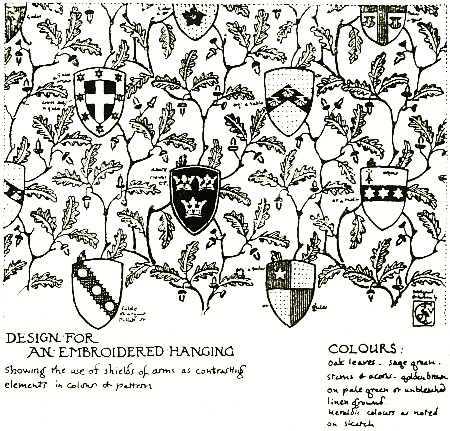

"Notes on Colour Embroidery and its Treatment" was written at Mrs. Christie's request for [pg vi] "Embroidery," which she edited, and I have Messrs. Pearsall's authority to include it here.

"The Apotheosis of 'The Butterfly'" was a review written for "The Evening News," and I thank the editor for letting me print it again. It appears now, however, with a different title, and considerable additions.

"A Short Survey of the Art of the Century" appeared in a journal, the name of which has escaped me, but it has been largely rewritten and added to since.

For the rest, "Modern Aspects of Life and the Sense of Beauty" was originally addressed as the opening of a debate at the Pioneer Club, in which my late friend Lewis F. Day was my opponent, and my chief supporter was Mr. J. Ramsay Macdonald, M.P.

"Art and the Commonweal" was an address to the Students of Art at Armstrong College, Newcastle-on-Tyne, and the paper "On Some of the Arts allied to Architecture" was given before the Architectural Association. That "On the Study and Practice of Art" was delivered in Manchester before the Art School Committee and City authorities, and the "Notes on Animals in Art" to the Art Workers' Guild in London.

Kensington,

September 1911.

(TN: These corrections have been applied.)

IF it is agreed that art, after all, may be summed up as the expression of character, it follows that the more we realize an artist's personality the clearer understanding we shall get of his work. So remarkable a personality as that of William Morris must have left many distinct, and at the same time different, impressions upon the minds of those who knew him, or enjoyed his friendship in life.

It is difficult to realize that fifteen years have passed away since he left us; but from the dark and blurred background of changing years his character and work define themselves, and his position and influence take their true place, while his memory, like some masterly portrait, remains clear and vivid in our minds—re-presented as it were in the severe but refined draughtsmanship of time.

With so distinct and massive an individuality it was strange to hear him say, as I once did, that of the six different personalities he recognized within himself at different times he often wondered which was the real William Morris! Those who knew him, however, were aware of many different sides, and we know that the "idle dreamer of an [pg 4] empty day" was also the enthusiastic artist and craftsman, and could become the man of passionate action on occasion, or the shrewd man of business, or the keen politician also, as well as the quiet observer of nature and life. Even the somewhat Johnsonian absoluteness and emphasis of expression which characterized him generally, would occasionally give way to an open-to-conviction manner, when tackled by a sincere and straightforward questioner.

But Morris was above and before all else a poet—a practical poet, if one may use such a term—and this explains the whole of his work. Not that personally he at all answered to the popular conventional idea of a poet, rather the reverse, and he was anything but a sentimentalist. He hated both the introspective and the rhetorical school, and he never posed. He loved romance and was steeped in mediaeval lore, but it was a real living world to him, and the glimpses he gives us are those of an actual spectator. It is not archaeology, it is life, quite as vivid to him, perhaps more so than that of the present day. He loved nature, he loved beautiful detail, he loved pattern, he loved colour—"red and blue" he used to say in his full-blooded way. His patterns are decorative poems in terms of form and colour. His poems and romances are decorative patterns in forms of speech and rhyme. His dream world and his ideal world were like one [pg 5] of his own tapestries—a green field starred with vivid flowers upon which moved the noble and beautiful figures of his romantic imagination, as distinct in type and colour as heraldic charges. Textile design interested him profoundly and occupied him greatly, and one may trace its influence, I think, throughout his work—even in his Kelmscott Press borders. One might almost say that he had a textile imagination, his poems and romances seem to be woven in the loom of his mind, and to enfold the reader like a magic web.

But though he cast his conceptions in the forms and dress of a past age, he took his inspiration straight from nature and life. His poems are full of English landscapes, and through the woods of his romances one might come upon a reach of the silvery Thames at any moment. The river he loved winds through the whole of his delightful Socialistic Utopia in "News from Nowhere."

As a craftsman and an artist working with assistants and in the course of his business he was brought face to face with the modern conditions of labour and manufacture, and was forced to think about the political economy of art. Accepting the economic teaching of John Ruskin, he went much further and gave his allegiance to the banner of Socialism, under which, however, he founded his own school and had his own following, and conducted his own newspaper. From the dream [pg 6] world of romance, and from the sequestered garden of design, he plunged into the thick of the fight for human freedom, in which, he held, was involved the very existence of art.

Ever and anon he returned to his sanctuary—his workshop—to fashion some new thing of beauty, in verse or craftsmanship, in which we see the results of his labour in so many directions.

He certainly seemed to have possessed a larger and fuller measure of vitality and energy than most men—perhaps such extra vitality is the distinction of genius—but the very strenuousness of his nature probably shortened the duration of his life. There were never any half-measures with him, but everything he took up, he went into seriously, nay, passionately, with the whole force of his being. His power of concentration (the secret of great workers) was enormous, and was spent from time to time in a multitude of ways, but whether in the eager search for decorative beauty, his care for the preservation of ancient buildings, in the delight of ancient saga, story, or romance, or in the battle for the welfare of mankind, like one of his own chieftains and heroes, he always made his presence felt, and as the practical pioneer and the master-craftsman in the revival of English design and handicraft his memory will always be held in honour.

His death marked an epoch both in art and in social and economic thought. The press notices [pg 7] and appreciations that have appeared from time to time for the most part have dwelt upon his work as a poet and an artist and craftsman, and have but lightly passed over his connection with Socialism and advanced thought.

But, even apart from prejudice, a hundred will note the beauty and splendour of the flower to one who will notice the leaf and the stem, or the roots and the soil from which the tree springs.

Yet the greatness of a man must be measured by the number of spheres in which he is distinguished—the width of his range and appeal to his fellows.

In the different branches of his work William Morris commanded the admiration, or, what is equally a tribute to his force, excited the opposition—of as many different sections of specialists.

As a poet he appealed to poets by reason of many distinct qualities. He united pre-Raphaelite vividness (as in "The Haystack in the Floods"), with a dream-like, wistful sweetness and charm of flowing narrative, woven in a kind of rich mediaeval tapestry of verse, and steeped with the very essence of legendary romance as in "The Earthly Paradise"; or with the heroic spirit of earlier time, as in "Sigurd the Volsung," while all these qualities are combined in his later prose romances.

His architectural and archaeological knowledge again was complete enough for the architect and the antiquary.

His classical and historical lore won him the respect of scholars.

His equipment as a designer and craftsman, based upon his architectural knowledge and training enabled him to exercise an extraordinary influence over all the arts of design, and gave him his place as leader of our latter-day English revival of handicraft—a position perhaps in which he is widest known.

In all these capacities the strength and beauty of William Morris's work has been freely acknowledged by his brother craftsmen, as well as by a very large public.

There was, however, still another direction in which his vigour and personal weight were thrown with all the ardour of an exceptionally ardent nature, wherein the importance and significance of his work is as yet but partially apprehended—I mean his work in the cause of Socialism, in which he might severally be regarded as an economist, a public lecturer, a propagandist, a controversialist.

No doubt many even of the most emphatic admirers of William Morris's work as an artist, a poet, and a decorator have been unable to follow him in this direction, while others have deplored, or even denounced, his self-sacrificing enthusiasm. There seems to have been insuperable difficulty to some minds in realizing that the man who wrote "The Earthly Paradise" should have lent [pg 9] a hand to try to bring it about, when once the new hope had dawned upon him.

There is no greater mistake than to think of William Morris as a sentimentalist, who, having built himself a dream-house of art and poetry, sighs over the turmoil of the world, and calls himself a Socialist because factory chimneys obtrude themselves upon his view.

It seems to have escaped those who have inclined to such an opinion that a man, in Emerson's phrase, "can only obey his own polarity." His life must gravitate necessarily towards its centre. The accident that he should have reached economics and politics through poetry and art, so far from disqualifying a man to be heard, only establishes his claim to bring a cultivated mind and imaginative force to bear upon the hard facts of nature and science.

The practice of his art, his position as an employer of labour, his intensely practical knowledge of certain handicrafts, all these things brought him face to face with the great Labour question; and the fact that he was an artist and a poet, a man of imagination and feeling as well as intellect, gave him exceptional advantages in solving it—at least theoretically. His practical nature and sincerity moved him to join hands with men who offered a practical programme, or at least who opened up possibilities of action towards bringing about a new social system.

His own personal view of a society based upon an entire change of economic system is most attractively and picturesquely described in "News from Nowhere, some Chapters of a Utopian Romance." He called it Utopian, but, in his view, and granting the conditions, it was a perfectly practical Utopia. He even gave an account (through the mouth of a survivor of the old order) of the probable course of events which might lead up to such a change. The book was written as a sort of counterblast to Edward Bellamy's "Looking Backward," which on its appearance was very widely read on both sides of the water, and there seemed at the time some danger of the picture there given of a socialized state being accepted as the only possible one. It may be partly answerable for an impression in some quarters that a Socialist system must necessarily be mechanical. But the society described in "Looking Backward" is, after all, only a little more developed along the present lines of American social life—a sublimation of the universal supply of average citizen wants by mechanical means, with the mainspring of the machine altered from individual profit to collective interest. This book, most ingeniously thought out as it was, did its work, no doubt, and appealed with remarkable force to minds of a certain construction and bias, and it is only just to Bellamy to say that he claimed no finality for it.

But "News from Nowhere" may be considered—apart from the underlying principle, common to both, of the collective welfare as the determining constructive factor of the social system—as its complete antithesis.

According to Bellamy, it is apparently the city life that is the only one likely to be worth anything, and it is to the organization of production and distribution of things contributing to the supposed necessities and comforts of inhabitants of cities that the reader's thoughts are directed.

With Morris the country life is obviously the most important, the ideal life. Groups of houses, not too large to be neighbourly, each with a common guest-hall, with large proportions of gardens and woodland, take the place of crowded towns. Thus London, as we know it, disappears.

What is this but building upon the ascertained scientific facts of our day, that the inhabitants of large cities tend to deteriorate in physique, and would die out were it not for the constant infusion of new blood from the country districts?

Work is still a hard necessity in "Looking Backward," a thing to be got rid of as soon as possible, so citizens, after serving the community as clerks, waiters, or what not, until the age of forty-five, are exempt.

With Morris, work gives the zest to life, and all labour has its own touch of art—even the dustman can indulge in it in the form of rich embroidery [pg 12] upon his coat. The bogey of labour is thus routed by its own pleasurable exercise, with ample leisure, and delight in external beauty in both art and nature.

As regards the woman's question, it never, in his Utopia, appears to be asked. He evidently himself thought that with the disappearance of the commercial competitive struggle for existence and what he termed "artificial famine" caused by monopoly of the means of existence, the claim of women to compete with men in the scramble for a living would not exist. There would be no necessity for either men or women to sell themselves, since in a truly co-operative commonwealth each one would find some congenial sphere of work.

In fact, as Morris once said, "settle the economic question and you settle all other questions. It is the Aaron's rod which swallows up the rest."

I gather that while he thought both men and women should be economically free, and therefore socially and politically free, and free to choose their occupation, he by no means wished to ignore or obliterate sex distinctions, and all those subtle and fine feelings which arise from it, which really form the warp and weft of the courtesies and relationships of life.

Now, whatever criticisms might be offered, or whatever objections might be raised, such a conception [pg 13] of a possible social order, such a view of life upon a new economic basis as is painted in this delightful book, is surely, before all things, remarkably wholesome, human, and sane, and pleasurable. If wholesome, human, sane, and pleasurable lives are not possible to the greater part of humanity under existing institutions, so much the worse for those institutions. Humanity has generally proved itself better than its institutions, and man is chiefly distinguished above other animals by his power to modify his conditions. Life, at least, means growth and change, and human evolution shows us a gradual progression—a gradual triumph of higher organization and intelligence over lower, checked by the inexorable action of natural laws, which demand reparation for breaches of moral and social law, and continually probe the foundations of society. Man has become what he is through his capacity for co-operative social action. The particular forms of social organization are the crystallization of this capacity. They are but shells to be cast away when they retard growth or progress, and it is then that the living organism, collective or individual, seeks out or slowly forms a new home.

As to the construction and colour of such a new house for reorganized society and regenerated life, William Morris has left us in no doubt as to his own ideas and ideals. It may seem strange that a man who might be said to have been steeped in [pg 14] mediaeval lore,1 and whose delight seemed to be in a beautifully imagined world of romance peopled with heroic figures, should yet be able to turn from that dream world with a clear and penetrating gaze upon the movements of his own time, and to have thrown himself with all the strength of his nature into the seething social and industrial battle of modern England. That the "idle singer of an empty day" should voice the claims and hopes of Labour, stand up for the rights of free speech in Trafalgar Square, and speak from a wagon in Hyde Park, may have surprised those who only knew him upon one side, but to those who fully apprehended the reality, ardour, and sincerity of his nature, such action was but its logical outcome and complement, and assuredly it redounds to the honour of the artist, the scholar, and the poet whose loss we still feel, that he was also a man.

Few men seemed to drink so full a measure of life as William Morris, and, indeed, he frankly admitted in his last days that he had enjoyed his life. I have heard him say that he only knew what it was to be alive. He could not conceive of death, and the thought of it did not trouble him.

I first met William Morris in 1870, at a dinner [pg 15] at the house of the late Earl of Carlisle, a man of keen artistic sympathies and considerable artistic ability, notably in water-colour landscapes. He was an enthusiast for the work of Morris and Burne-Jones, and had just built his house at Palace Green from the designs of Mr. Philip Webb, and Morris and Company had decorated it. Morris, I remember, had just returned from a [pg 16] visit to Iceland, and could hardly talk of anything else. It seemed to have laid so strong a hold upon his imagination; and no doubt its literary fruits were the translations of the Icelandic sagas he produced with Professor Magnússon, and also the heroic poem of "Sigurd the Volsung." He never, indeed, seemed to lose the impressions of that Icelandic visit, and was ever ready to talk of his experiences there—the primitive life of the people, the long pony rides, the strange, stony deserts, the remote mountains, the geysers and the suggestions of volcanic force everywhere, and the romance-haunted coasts.

I well remember, too, the impression produced by the first volume of "The Earthly Paradise," which had appeared, I think, shortly before the time of which I speak: the rich and fluent verse, with its simple, direct, Old World diction; the distinct vision, the romantic charm, the sense of external beauty everywhere, with a touch of wistfulness. The voice was the voice of a poet, but the eye was the eye of an artist and a craftsman.

It was not so long before that the fame began to spread of the little brotherhood of artists who gathered together at the Red House, Bexley Heath, built by Mr. Philip Webb, it was said, in an orchard without cutting down a single tree. Dante Gabriel Rossetti was the centre of the group, the leading spirit, and he had absorbed the spirit of the pre-Raphaelite movement and centralized [pg 17] it both in painting and verse. But others co-operated at first, such as his master, Ford Madox Brown, and Mr. Arthur Hughes, until the committee of artists narrowed down, and became a firm, establishing workshops in one of the old-fashioned houses on the east side of Queen Square, Bloomsbury, a retired place, closed by a garden to through traffic at the northern end. Here Messrs. Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co. (which included a very notable man, Mr. Philip Webb, the architect) began their practical protest against prevailing modes and methods of domestic decoration and furniture, which had fallen since the great exhibition of 1851 chiefly under the influence of the Second Empire taste in upholstery, which was the antithesis of the new English movement. This latter represented in the main a revival of the mediaeval spirit (not the letter) in design; a return to simplicity, to sincerity; to good materials and sound workmanship; to rich and suggestive surface decoration, and simple constructive forms.

The simple, black-framed, old English Buckinghamshire elbow-chair, with its rush-bottomed seat, was substituted for the wavy-backed and curly-legged stuffed chair of the period, with its French polish and concealed, and often very unreliable, construction. Bordered Eastern rugs, and fringed Axminster carpets, on plain or stained boards, or India matting, took the place of the stuffy planned carpet; rich, or simple, flat patterns acknowledged [pg 18] the wall, and expressed the proportions of the room, instead of trying to hide both under bunches of sketchy roses and vertical stripes; while, instead of the big plate-glass mirror, with ormolu frame, which had long reigned over the cold white marble mantel-piece, small bevelled glasses were inserted in the panelling of the high wood mantel-shelf, or hung over it in convex circular form. Slender black wood or light brass curtain rods, [pg 19] and curtains to match the coverings, or carry out the colour of the room, displaced the heavy mahogany and ormolu battering-rams, with their fringed and festooned upholstery, which had hitherto overshadowed the window of the so-called comfortable classes. Plain white or green paint for interior wood-work drove graining and marbling to the public-house; blue and white Nankin, Delft, or Grès de Flandres routed Dresden and [pg 20] Sèvres from the cabinet; plain oaken boards and trestles were preferred before the heavy mahogany telescopic British dining-table of the mid-nineteenth century; and the deep, high-backed, canopied settle with loose cushions ousted the castored and padded couch from the fireside.

Such were the principal ways, as to outward form, in which the new artistic movement made itself felt in domestic decoration. Beginning with the houses of a comparatively limited circle, mostly artists, the taste rapidly spread, and in a few years Morrisian patterns and furniture became the vogue. Cheap imitation on all sides set in, and commercial and fantastic persons, perceiving the set of the current, floated themselves upon it, tricked themselves out like jackdaws with peacocks' feathers, and called it "the aesthetic movement." The usual excesses were indulged in by excitable persons, and the inner meaning of the movement was temporarily lost sight of under a cloud of travesty and ridicule, until, like a shuttlecock, the idea had been sufficiently played with and tossed about by society and the big public, it was thrown aside, like a child's toy, for some new catch-word. These things were, however, but the ripples or falling leaves upon the surface of the stream, and had but little to do with its sources or its depth, though they might serve as indications of the strength of the current.

The art of Morris and those associated with [pg 21] him was really but the outward and visible sign of a great movement of protest and reaction against the commercial and conventional conceptions and standards of life and art which had obtained so strong a hold in the industrial nineteenth century.

Essentially Gothic and romantic and free in spirit as opposed to the authoritative and classical, its leader was emphatically and even passionately Gothic in his conception of art and ideals of life.

The inspiration of his poetry was no less mediaeval than the spirit of his designs, and it was united with a strong love of nature and an ardent love of beauty.

One knows but little of William Morris's progenitors. His name suggests Welsh origin, though his birthplace was Walthamstow. Born 24th March 1834, one of a well-to-do family, it was a fortunate circumstance that he was never cramped by poverty in the development of his aims. Escaping the ecclesiastical influence of Oxford and a Church career, his prophets being rather John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle, he approached the study and practice of art from the architectural side under one of our principal English Gothic revivalists, George Edmund Street, although he at one time entertained the idea of becoming a painter, and the very interesting picture of "Guinevere" which was shown at one of the Arts and Crafts Exhibitions makes one regret he did not do more [pg 22] in this way. Few men had a better understanding of the nature of Gothic architecture, and a wider knowledge of the historic buildings of his own country, than William Morris, and there can be no doubt that this grasp of the true root and stem of the art was of enormous advantage when he came to turn his attention to the various subsidiary arts and handicrafts comprehended under decorative design. The thoroughness of his methods of [pg 23] work and workmanlike practicality were no less remarkable than his amazing energy and capacity for work.

In one of his earlier papers he said that it appeared to be the object with most people to get rid of, or out of, the necessity of work, but for his part he only wanted to find time for more work, or (as it might be put) to live in order to work, rather than to work in order to live.

While as a decorative designer he was, of course, interested in all methods, materials, and artistic expression, he concentrated himself generally upon one particular kind at a time, as in the course of his study and practice he mastered the difficulties and technical conditions of each.

At one time it was dyeing, upon which he held strong views as to the superiority, permanency, and beauty of vegetable dyes over the mineral and aniline dyes, so much used in ordinary commerce, and his practice in this craft, and the charm of his tints, did much to check the taste for the vivid but fugitive colours of coal-tar.

His way was to tackle the thing with his own hands, and so he worked at the vat, like the practical man that he was in these matters. An old friend tells the story of his calling at the works one day and, on inquiring for the master, hearing a strong, cheery voice call out from some inner den, "I'm dyeing, I'm dyeing, I'm dyeing!" and the well-known robust figure of the craftsman presently appeared in his blue shirt-sleeves, his hands stained blue from the vat where he had been at work.

At another time it was weaving that absorbed him, and the study of dyeing naturally led him to textiles, and, indeed, was probably undertaken with the view of reviving their manufacture in new forms, and from rugs and carpets he conceived the idea of reviving Arras tapestry. I remember [pg 25] the man who claimed to have taught Morris to work on the high-warp loom. His name was Wentworth Buller. He was an enthusiast for Persian art, and he had travelled in that country and found out the secret of the weaving of the fine Persian carpets, discovering, I believe, that they were made of goats' hair. He made some attempt to revive this method in England, but from one cause or another was not successful. William Morris, when he had learned the craft of tapestry weaving himself, set about teaching others, and trained two youths, one of whom (Mr. Dearle) is now chief at the Merton Abbey Works, who became exceedingly skilful at the work, executing the large and elaborate design of Sir Edward [pg 26] Burne-Jones (The Adoration of the Magi), which was first worked for the chapel of his own and Morris's college (Exeter College) at Oxford.

In this tapestry, as was his wont, Morris enriched the design with a foreground of flowers, through which the Magi approach with their gifts the group of the Virgin and Child, with St. Joseph.

In fact, the designs of William Morris are so associated with and so often form part of the work of others or only appear in some conditioned material form, that little or no idea of his individual work, or of his wide influence, could be gathered from any existing autograph work of his. That he was a facile designer of floral ornament his numerous beautiful wall-papers and textile hangings prove, but he always considered that the finished and final form of a particular design, complete in the material for which it was intended, was the only one to be looked at, and always objected to showing preliminary sketches and working drawings. He was a keen judge and examiner of work, and fastidious, and as he did not mind taking trouble himself he expected it from those who worked for him. His artistic influence was really due to the way he supervised work under his control, carried out by many different craftsmen under his eye, and not so much by his own actual handiwork.

In any estimate of William Morris's power and influence as an artist, this should always be borne [pg 27] in mind. He always described himself as an artist working with assistants, which is distinct from the manufacturer who simply directs a business from the business point of view. Nothing went out of the works at Queen Square, or, later, at Merton Abbey, without his sanction from the artistic point of view.

The wave of taste which he had done so much to create certainly brought prosperity to the firm, and larger premises had to be taken; so Morris and Company emerged from the seclusion of Queen Square and opened a large shop in Oxford [pg 28] Street, and set up extensive works at Merton Abbey—a most charming and picturesque group of workshops, surrounded by trees and kitchen gardens, on the banks of the river Wandle in Surrey, not far from Wimbledon. The tapestry and carpet looms which were first set up at Kelmscott House, on the Upper Mall at Hammersmith,2 were moved to Merton, where also the dyeing and painted glass-work were carried on.

This latter art had long been an important part of the work of the firm. In early days designs were supplied by Ford Madox Brown and D. G. Rossetti, but later they were entirely from the hands of Morris's closest friend, Edward Burne-Jones; that is to say, the figure-work. Floral and subsidiary design were frequently added by William Morris, as was also the leading of the cartoons. The results of their co-operation in this way have been the many fine windows scattered over the land, chiefly at Oxford and Cambridge, where the Christ Church window and those at Jesus College may be named, while the churches of Birmingham [pg 29] have been enriched by many splendid examples, more particularly at St. Philip's. Their glass has also found place in the United States, in Richardson's famous church at Boston, and at the late Miss Catherine Wolfe's house, Vinland, Newport.

An exquisite autograph work of William Morris's is the copy of "The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám," which he wrote out and illuminated with his own hand, though even to this work Burne-Jones contributed a miniature, and Mr. Fairfax Murray worked out other designs in some of the borders. This beautiful work was exhibited at the first Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1888. It is in the possession of Lady Burne-Jones, and by her special permission I am enabled to give some reproductions of four of the pages here.

It is so beautiful that one wonders the artist was not induced to do more work of the kind; but there is only known to be one or two other manuscripts partially completed by him. Certainly his love for mediaeval illuminated MSS. was intense and his knowledge great, and his collection of choice and rare works of this kind probably unique. The same might be said of his collection of early printed books, which was wonderfully rich with wood-cuts of the best time and from the most notable presses of Germany, Flanders, Italy, and France.

Alike for those who for today prepare

And those that after a tomorrow stare

A muezzin from the Tower of Darkness cries

Fools, your reward is neither here nor there

25

Why, all the saints and sages who discussed

Of the Two Worlds so learnedly, are thrust

Like foolish prophets forth, their words to scorn

Are scattered, and their mouths are stopt with dust

26

O come with old Khayyam, and leave the wise

To talk; one thing is certain, that Life flies;

One thing is certain, and the rest is lies

The flower that once has blown for ever dies

27

Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and saint, and heard great argument

FROM MORRIS'S MS. OF OMAR KHAYYÁM.

About it and about, and evermore

Came out by the same door as in I went.

28

With them the seed of Wisdom did I sow,

And with my own hand laboured it to grow:

And this was all the harvest that I reaped—

I came like water, and like wind I go.

29

Into this Universe, and why not knowing

Nor whence, like water willy-nilly flowing

And out of it as wind along the waste

I know not whither, willy-nilly blowing

30

What without asking hither hurried whence

And without asking whither hurried hence

Another, and another cup to drown

The memory of this impertinence!

FROM MORRIS'S MS. OF OMAR KHAYYÁM.

My thread-bare penitence apieces tore.

71

And much as wine has played the infidel,

And robbed me of my robe of honour—well,

I often wonder what the vintners buy

One half so precious as the goods they sell.

72

Alas, that Spring should vanish with the rose,

That Youth's sweet-scented manuscript should close

The Nightingale that in the branches sang,

Ah whence, and whither flown again, who knows!

73

Ah, Love! could thou and I with Fate conspire

To grasp this sorry scheme of things entire,

Would we not shatter it to bits, and then

Remould it nearer to the heart's desire?

FROM MORRIS'S MS. OF OMAR KHAYYÁM.

Ah Moon of my delight who knowest no wane,

The Moon of Heaven is rising once again;

How oft hereafter rising shall she look

Through this same garden after me—in vain.

75

And when Thyself with shining foot shall pass

Among the guests star-scattered on the grass,

And in thy joyous errand reach the spot

Where I made one—turn down an empty glass!

TAMAM SHUD

FROM MORRIS'S MS. OF OMAR KHAYYÁM.

This brings us to William Morris's next and, as it proved, last development in art—the revival of the craft of the printer, and its pursuit as an art.

I recall the time when the project was first discussed. It was in the autumn of 1889. It was the year of an Art Congress at Edinburgh, following the initial one at Liverpool the preceding year, held under the auspices of the National Association for the Advancement of Art. Some of us afterwards went over to Glasgow to lecture; and a small group, of which Morris was one, found themselves at the Central Station Hotel together. It was here that William Morris spoke of his new scheme, his mind being evidently centred upon it. Mr. Emery Walker (who has supplied me with the photographs which illustrate this article) was there, and he became his constant and faithful helper in all the technicalities of the printer's craft; Mr. Cobden-Sanderson also was of the party; he may be said to have introduced a new epoch in book-binding, and his name was often associated with Morris as binder of some of his books.

Morris took up the craft of printing with characteristic thoroughness. He began at the beginning and went into the paper question, informing himself as to the best materials and methods, and learning to make a sheet of paper himself. The Kelmscott Press paper is made by hand, of fine white linen rags only, and is not touched with chemicals. It has the toughness and something [pg 35] of the quality of fine Whatman or O.W. drawing-paper.

When he set to work to design his types he obtained enlarged photographs of some of the finest specimens of both Gothic and Roman type from the books of the early printers, chiefly of Bale and Venice. He studied and compared these, and as the result of his analysis designed two or three different kinds of type for his press, beginning with the "Golden" type, which might be described as Roman type under Gothic influence, and developing the more frankly Gothic forms known as the "Troy" and the "Chaucer" types. He also used Roman capitals founded upon the best forms of the early Italian printers.

Morris was wont to say that he considered the glory of the Roman alphabet was in its capitals, but the glory of the Gothic alphabet was in its lower-case letters.

He was asked why he did not use types after the style of the lettering in some of his title-pages, but he said this would not be reasonable, as the lettering of the titles was specially designed to fit into the given spaces, and could not be used as movable type.

The initial letters are Gothic in feeling, and form agreeably bold quantities in black and white in relation to the close and rich matter of the type, which is still further relieved occasionally by floral sprays in bold open line upon the inner margins, [pg 36] while when woodcut pictures are used they were led up to by rich borderings.

The margins of the title and opening chapter which faced it are occupied by richly designed broad borders of floral arabesques upon black grounds, the lettering of the title forming an essential part of the ornamental effect, and often placed upon a mat or net of lighter, more open arabesque, in contrast to the heavy quantities of the solid border.

The Kelmscott Chaucer is the monumental work of Morris's Press, and the border designs, made specially for this volume, surpass in richness and sumptuousness all his others, and fitly frame the woodcuts after the designs of Sir Edward Burne-Jones.

The arabesque borders and initial letters of the Kelmscott books were all drawn by Morris himself, the engraving on wood was mostly done by Mr. W. H. Hooper—almost the only first-rate facsimile engraver on wood left—and a good artist and craftsman besides. Mr. Arthur Leverett engraved the designs to the "The Glittering Plain," which were my contribution to the Kelmscott Press, but I believe Mr. Hooper did all the other work, while Mr. Fairfax Murray and Mr. Catteson Smith drafted the Burne-Jones designs upon the wood.

It was not, perhaps, generally known, at least before the appearance of Miss May Morris's fine [pg 37] edition of her father's works, published by Messrs. Longman, that many years before the Kelmscott Press was thought of an illustrated edition of "The Earthly Paradise" was in contemplation, and not only were many designs made by Burne-Jones, but a set of them was actually engraved by Morris himself upon wood for the "Cupid and Psyche," though they were never issued to the public.

I have spoken of the movement in art represented by William Morris and his colleagues as really part of a great movement of protest—a crusade against the purely commercial, industrial, and material tendencies of the day.

This protest culminated with William Morris when he espoused the cause of Socialism.

Now some have tried to minimize the Socialism of William Morris, but it was, in the circumstances of his time, the logical and natural outcome of his ideas and opinions, and is in direct relation with his artistic theories and practice.

For a thorough understanding of the conditions of modern manufacture and industrial production, of the ordinary influences which govern the producers of marketable commodities, of wares offered in the name of art, of the condition of worker, and the pressure of competition, he was in a particularly advantageous position.

So far from being a sentimentalist who was content melodiously and pensively to regret that [pg 38] things were not otherwise, he was driven by contact with the life around him to his economic conclusions. As he said himself, it was art led him to Socialism, not economics, though he confirmed his convictions by economic study.

As an artist, no doubt at first he saw the uglification of the world going on, and the vast industrial and commercial machine grinding the joy and the leisure out of human life as regarded the great mass of humanity. But as an employer he was brought into direct relation with the worker as well as the market and the public, and he became fully convinced that the modern system of production for profit and the world-market, however inevitable as a stage in economic and social evolution, was not only most detrimental to a healthy and spontaneous development of art and to conditions of labour, but that it would be bound, ultimately, by the natural working of economic laws, to devour itself.

Never cramped by poverty in his experiments and in his endeavours to realize his ideals, singularly favoured by fortune in all his undertakings, he could have had no personal reasons on these scores for protesting against the economic and social tendencies and characteristics of his own time. He hated what is called modern civilization and all its works from the first, with a whole heart, and made no secret of it. For all that, he was a shrewd and keen man in his dealings with the world. If he set [pg 39] its fashions and habits at defiance, and persisted in producing his work to please himself, it was not his fault that his countrymen eagerly sought them and paid lavishly for their possession. A common reproach hurled at Morris has been that he produced costly works for the rich while he professed Socialism. This kind of thing, however, it may be remarked, is not said by those friendly to Socialism, or anxious for the consistency of its advocates—quite the contrary. Such objectors appear to ignore, or to be ignorant of, the fact that according to the quality of the production must be its cost; and that the cheapness of the cheapest things of modern manufacture is generally at the cost of the cheapening of human labour and life, which is a costly kind of cheapness after all.

If anyone cares for good work, a good price must be paid. Under existing conditions possession of such work is only possible to those who can pay the price, but this seems to work out rather as part of an indictment against the present system of production, which Socialists wish to alter.

If a wealthy man were to divest himself of his property and distribute it, he would not bring Socialism any nearer, and his self-sacrifice would hardly benefit the poor at large (except, perhaps, a few individuals), but under the working of the present system his wealth would ultimately enrich the rich—would gravitate to those who had, and not to [pg 40] those who had not. The object of Socialism is to win justice, not charity.

A true commonwealth can only be established by a change of feeling, and by the will of the people, deliberately, in the common interest, declaring for common and collective possession of the means of life and of wealth, as against individual property and monopoly. Since the wealth of a country is only produced by common and collective effort, and even the most individual of individualists is dependent for every necessary, comfort, or luxury of life upon the labour of untold crowds of workers, there is no inherent unreasonableness in such a view, or in the advocacy of such a system, which might be proved to be as beneficial, in the higher sense, for the rich as for the poor, as of course it would abolish both. It is quite possible to cling to the contrary opinion, but it should be fully understood that Socialism does not mean "dividing up," and that a man is not necessarily not a Socialist who does not sell all that he has to give to the poor. "A poor widow is gathering nettles to stew for her dinner. A perfumed seigneur lounging in the œil de bœuf hath an alchemy whereby he can extract from her every third nettle and call it rent." Thus wrote Carlyle. Men like William Morris would make such alchemy impracticable; but no man can change a social (or unsocial) system by himself, however willing; nor can anyone, however gifted or farseeing, [pg 41] get beyond the conditions of his time, or afford to ignore them in the daily conduct of life, although at the same time his life and expressed opinions may all the while count as factors in the evolution by which a new form of society comes about.

Thus much seems due to the memory of a man like William Morris, who was frequently taunted with not doing, as a Socialist, things that, as a Socialist, he did not at all believe in; things, for which, too, one knows perfectly well, his censors, if he had done them, would have been the first to denounce him for a fool.

At all events, it is certain that William Morris spent some of the best years of his life, he gave his time, his voice, his thought, his pen, and much money to put Socialism before his countrymen. This can never be gainsaid. Those who have been accustomed to regard him from this point of view as a dangerous revolutionary might be referred to the writings of John Ball, and Sir Thomas More, his predecessors in England's history, who upheld the claims of labour and simple life, against waste, want, and luxury. Indeed, it might be contended that it was a conservative clinging to the really solid foundations of a happy human life which made Morris a Socialist as much as artistic conviction and study of modern economics. The enormous light which has been recently thrown by historic research upon mediaeval life and conditions [pg 42] of labour, upon the craft guilds, and the position of the craftsman in the Middle Ages—light to which Morris himself in no small degree contributed—must also be counted as a factor in the formation of his opinions.

But whether accounted conservative or revolutionary in social economics and political opinion, there can be no doubt of William Morris's conservatism in another field, important enough in its bearings upon modern life, national and historic sentiment, and education—I mean the protection of Ancient Buildings. He was one of the founders of the society having that object, and remained to the last one of the most energetic members of the committee, and in such important work his architectural knowledge was of course of the greatest value. At a time when, owing to the action of a multitude of causes, the historic buildings of the past are in constant danger, not only from the ravages of time, weather, and neglect, but also, and even to a greater extent, from the zeal of the "restorer," the importance of the work which Morris did with his society—the work which that society carries on—can hardly be overestimated.

The pressure of commercial competition and the struggle for life in our cities—the mere necessity for more room for traffic—the dead weight of vested interest, the market value of a site, the claims of convenience, fashion, ecclesiastical or otherwise, or [pg 43] sometimes sheer utilitarianism, entirely oblivious of the social value of historic associations of architectural beauty—all are apt to be arrayed at one time or another, or even, perhaps, all combined, against the preservation of an ancient building if it happens to stand in their way.

The variety, too, of the cases in which the difference of the artistic conditions which govern the art and craft of building in the past and in the present is another element which often prevents the defenders and destroyers from meeting on the same plane. It is the old tragic conflict between old and new, but enormously complicated, and with the forces of destruction and innovation tremendously increased.

William Morris was a singularly sane and what is called a "level-headed" man. He had the vehemence, on occasion, of a strong nature and powerful physique. He cared greatly for his convictions. Art and life were real to him, and his love of beauty was a passion. His artistic and poetic vision was clear and intense—all the more so, perhaps, for being exclusive on some points. The directness of his nature, as of his speech, might have seemed singularly unmodern to some who prefer to wrap their meaning with many envelopes. He might occasionally have seemed brusque, and even rough; but so does the north wind when it encounters obstacles. Men are judged by the touchstones of personal sympathy [pg 44] or antipathy; but whether attracted or repelled in such a presence, no one could come away without an impression that he had met a man of strong character and personal force, whether he realized any individual preconception of the poet, the artist, and the craftsman, or not.

He was certainly all these, yet those who only knew him through his works would have but a partial and incomplete idea of his many-sided nature, his practicality, personal force, sense of humour,3 and all those side-lights which personal acquaintance throws upon the character of a man like William Morris.

1: At the same time, it must be remembered, his knowledge of mediaeval life, the craft guilds, and the condition of the labourer in England in the fifteenth century, helped him in his economic studies and his Socialist propaganda.

2: Here Morris lived when in London and his press was set up close by at Sussex House, opposite to which is the Doves Bindery of Mr. Cobden-Sanderson. Much of Morris's time was spent at Kelmscott, near Lechlade, Gloucestershire, a delightful old manor house close to the Thames stream. This house was formerly held by D. G. Rossetti conjointly with Morris. At Hammersmith the room outside the house, after the carpet looms went to Merton, was used as the meeting room of the Hammersmith Socialist Society.

3: It is noteworthy that one who excluded humour from his own work, whether literary, or artistic, had a keen appreciation of it in the work of others. Few who only knew Morris through his poems, romances, and designs would imagine that among his most favourite books were "Huckleberry Finn," by Mark Twain, and "Uncle Remus." I have often heard him recall passages of the first-named book with immense enjoyment of the fun. He was, besides, always an admirer of Dickens.

THE sense of beauty, like the enchanted princess in the wood, seems liable, both in communities and individuals, to periods of hypnotism. These periods of slumber or suspended animation, are not, however, free from distorted dreams, having a certain tyrannical compulsion which causes those under their influence blindly to accept arbitrary ideas and cast-iron customs as if they were parts of the irreversible order of nature—until the hour of the awakening comes and the household gods of wood and stone, so ignorantly worshipped, are cast from their pedestals.

Such a period of apathetic slumber and of awakening in the arts we have been passing through in England during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and since, side by side with analogous movements in the political and social world.

As regards domestic architecture, the streets of London will illustrate the successive waves of taste or fashion which the past and present century have seen, from the quasi-classical, represented in the Peloponnesus of Regent's Park, to the eclectic Queen Anne-ism of the aesthetic village at Turnham Green; or the more recent developments which have followed newer ideas of town-planning, the modern hotel such as the Savoy or the Piccadilly, or the New Aero Club in Pall Mall, the modern store, such as Selfridge's. Contrast such examples of what one might call our new Imperial Renascence style with the types of simple cottage dwellings in the Garden City at Letchworth, or in the Hampstead garden suburb, and elsewhere; or these again with the larger country mansions some of our best architects are raising in the land. These extremes, with all the various modifications of the outward aspect of the English home—degrees indicating the arc of architectural fashion, as it were—imply a series of corresponding transformations of interiors with all their modern complexities of furniture and decorations.

But the wheat of artistic thought and invention is a good deal encumbered with chaff—the chaff of commerce and of fashion—and it needs some pains to find the real vital germs. To trace the genesis of our English revival we must go back to the days of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and although none of that famous group were decorative [pg 49] designers in the strict sense—unless we except D. G. Rossetti—yet by their resolute and enthusiastic return to the direct symbolism, frank naturalism, and poetic or romantic sentiment of mediaeval art, with the power of modern analysis superadded, and the more profound intellectual study of both nature and art, which the severity of their practice demanded, and last, but not least, their intense love of detail, turned the attention to other branches of design than painting. The very marked character of their pictures, standing out with almost startling effect from among the works of the older Academic School, demanded at least a special architecture in the frames of their pictures, and this led to the practice of painters designing their own frames, at least those who were concerned for unity and decorative effect. Mr. Holman Hunt, for instance, I believe always designed his own frames, as well as some of the ornamental accessories of his pictures—such as the pot for the basil in his "Isabella." D. G. Rossetti the poet-painter, and perhaps the central and inspiring luminary of the remarkable group, evidently cared greatly for decorative effect, and bestowed the utmost pains upon tributary detail, designing the frames to his pictures, the cover and lining for his own poems, and various title-pages. Many of his pictures, too, are remarkable for their beauty and richness of accessory details which give a distinct decorative charm to his work, closely associated [pg 50] as they are with its motive and poetic purpose.

The researches of Henry Shaw, and his fine works upon art of the middle ages, first published in the "Forties" by Pickering, and printed by the Chiswick Press, no doubt had their share in directing the attention of artists to the beauty and intention bestowed upon every accessory of daily life in mediaeval times.

Above all influences from the literary side, however, must be placed the work of John Ruskin, an enormously vitalizing and still living force, powerful to awaken thought, and by its kindling enthusiasm to stir the dormant sense of beauty in the minds that come under the spell of his eloquence, which always turns the eyes to some new or unregarded or forgotten beauty in nature or in art. The secret of his powers as a writer on art lies no doubt in the fact that he approached the whole question from the fundamental architectural side, and saw clearly the close connection of artistic development with social life. The whole drift of his teaching is towards sincerity and Gothic freedom in the arts, and is a strong protest against Academic convention and classical coldness.

Among architects, men like Pugin and William Burges, enthusiasts in the Gothic revival, gave a great deal of care and thought to decorative detail and the design of furniture and accessories. The [pg 51] latter, in the quaint house which he built for himself in Melbury Road, showed a true Gothic spirit of inventiveness and whimsicality applied to things of everyday use as well as the mural decorator's instinct for symbolism. Since their day Mr. Norman Shaw may almost be said to have carried all before him, and has quite created a type of later Victorian architecture, and his advice is still sought in the design of various buildings and street improvements of modern London. His work, beautiful, well proportioned, and decorative as it often is, however, has not the peculiar character and reserve of the work of Mr. Philip Webb, and the latter is a decorative designer, especially of animals, of remarkable originality and power. His work in architecture and other designs is generally seen in association with that of William Morris in decoration.

The impulse towards Greek and Roman forms in furniture and decoration, which had held sway with designers since the French Revolution, appeared to be dead. The elegant lines and limbs of quasi-classical couches and chairs on which our grandfathers and grandmothers reclined—the former in high coat-collars and the latter in short waists—had grown gouty and clumsy, in the hands of Victorian upholsterers. The carved scrolls and garlands had lost even the attenuated grace they once possessed and a certain feeling for naturalism creeping in made matters worse, and utterly deranged [pg 52] the ornamental design of the period. An illustrated catalogue of the exhibition of 1851 will sufficiently indicate the monstrosities in furniture and decoration which were supposed to be artistic. The last stage of decomposition had been reached, and a period of, perhaps, unexampled hideousness in furniture, dress, and decoration set in which lasted the life of the second empire, and fitly perished with it. Relics of this period I believe are still to be discovered in the cold shade of remote drawing-rooms, and "apartments to let," which take the form of big looking-glasses, and machine-lace curtains, and where the furniture is afflicted with curvature of the spine, and dreary lumps of bronze and ormolu repose on marble slabs at every opportunity, where monstrosities of every kind are encouraged under glass shades, while every species of design-debauchery is indulged in upon carpets, curtains, chintzes and wall-papers, and where the antimacassar is made to cover a multitude of sins. When such ideas of decoration prevailed, having their origin or prototypes, in the vapid splendours of imperial saloons, and had to be reduced to the scale of the ordinary citizen's house and pocket, the thing became absurd as well as hideous. Besides, the cheap curly legs of the uneasy chairs and couches came off, and the stuffed seats, with a specious show of padded comfort, were delusions and snares. Long ago the old English house-place with its big chimney-corner had given way to the [pg 53] bourgeois arrangement of dining and drawing-room—even down to the smallest slated hut with a Doric portico. The parlour had become a kind of sanctuary veiled in machine-lace, where the lightness of the curtains was compensated for by the massiveness of their poles, and where Berlin wool-work and bead mats flourished exceedingly.

Enter to such an interior a plain unvarnished rush-bottomed chair from Buckinghamshire, sound in wind and limb—"C'est impossible!" And yet the rush-bottomed chair and the printed cotton of frank design and colour from an unpretending and somewhat inaccessible house in Queen Square may be said to have routed the false ideals, vulgar smartness and stuffiness in domestic furniture and decoration—at least wherever refinement and feeling have been exercised at all.

"Lost in the contemplation of palaces we have forgotten to look about us for a chair," wrote Mr. Charles L. Eastlake in an article which appeared in "The Cornhill Magazine" some time in the "sixties," or early "seventies." The same writer (afterwards Keeper of the National Gallery) brought out "Hints on Household Taste" shortly afterwards, and he, too, was "on the side of the angels" of sense and fitness in these things. The "chair" at any rate was now discovered, if only a rush-bottomed one.

Nowadays it might perhaps be said that the [pg 54] chair gets more contemplation and attention than the palace, as since then the influence of our old English eighteenth-century furniture designers has been restored, and Chippendale, Sheraton, and Hepplewhite are again held in honour in our interiors, and to judge from the innumerable specimens offered in their name by our furniture dealers the industry of these famous designers must have been prodigious!

The first practical steps towards actually producing things combining use and beauty and thus enabling people so minded to deck their homes after the older and simpler English manner was taken by William Morris and his associates, who founded the house in Queen Square afore-mentioned. Appealing at first only to a limited circle of friends mostly engaged in the arts, the new ideas began to get abroad, the new designs were eagerly seized upon. Morris and Company had to extend their operations, and soon no home with any claim to decorative charm was felt to be complete without its vine and fig-tree so to speak—from Queen Square; and before long a typical Morris room was given to the British Public to dine in at the South Kensington (now the Victoria and Albert) Museum.

The great advantage and charm of the Morrisian method is that it lends itself to either simplicity or to splendour. You might be almost plain enough to please Thoreau, with a rush-bottomed chair, [pg 55] piece of matting, and oaken trestle-table; or you might have gold and lustre (the choice ware of William de Morgan) gleaming from the sideboard, and jewelled light in your windows, and walls hung with rich arras tapestry.

Of course, a host of imitators appeared, and manufacturers and upholsterers were quick to adapt the more superficial characteristics, watering down the character a good deal for the average taste—that is, the timid taste of the person who has not made up his mind, which may be described as the "wonder-what-so-and-so-will-think-of-it" state—but its effects upon the older ideas of house decoration were definite. Plain painting displaced graining and marbling, frankly but freely conventionalized patterns routed the imitative and nosegay kinds. Leaded and stained glass filled the places which were wont to be filled with the blank despair of ground glass. The white marble mantelpiece turned pale before rich hangings and deep-toned wall-papers, and was dismantled and sent to the churchyard.

These were some of the most marked effects of the adoption of the new, or a return to older and sounder ideas in domestic decoration.

The quiet influence of the superb collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the opportunities of study, open to all, of the most beautiful specimens of mediaeval, renascence, and oriental design and craftsmanship of all kinds must not be forgotten—an [pg 56] influence which cannot be rated as of too much importance and value, and which has been probably of more far-reaching influence in its effect on designers and craftsman than the more direct efforts of the Art Department to reach them through its school system. By means of this, as is well known, it was sought to improve the taste and culture of artisans by putting within their reach courses of study and exercises in drawing and design, the results of which, it was hoped, carried back into the practice of their various trades and handicrafts, would make them better craftsmen because better draughtsmen. Now, if we were to ask why on the whole the system has not been so fruitful of result in this direction we should find ourselves plunged at once into the deep waters of economic conditions, of the relations of employer and employed, of hours, of wages, of commercial competition, trade unions, and, in fact, should bring the whole Labour question about our ears.

Of course the whole scheme of the schools of design was based upon the idea of improvement downwards, and like many modern improvements, or reforms, its contrivers sought to make the tree of art flourish and put forth new leaves without attending to the nourishment of the roots or touching the soil. But the drawing-board and the workshop-bench are after all two very different things, and it is by no means certain that proficiency at one would necessarily produce a corresponding [pg 57] improvement at the other, except indeed, it be on the principle that if a man acquires one language it will be easier for him to learn others. But at this point another consideration comes in. You get your student seated at his drawing-board, you set him to represent at the point of his pencil or chalk certain objects, casts, for instance, and encourage him to portray their appearance with all relief of light and shade, dwelling solely on the necessity of his attaining a certain degree of purely pictorial skill, which in itself is really of no practical use to a designer of ornament intended to be worked out in some other material such as a textile, wood, or metal. In fact, the development of pictorial skill has a strong tendency to lead the student to devote himself entirely to pictorial work, and hitherto there have been plenty of other inducements, such as the chance of larger monetary reward and social position. If he is not ultimately drawn into the already overcrowded ranks of the picture producers, he is too likely to carry back into his own particular craft a certain love of pictorial treatment and effect which may really be injurious to his sense of fitness in adapting design and material. This indeed is what evidently has happened as the result of much so-called art-education, and we are only now slowly awakening to the conception that art is not necessarily the painting of pictures, but that the most refined artistic feeling may be put into every work of man's hand, and that each [pg 58] after its kind gives more delight and becomes more and more beautiful in proportion as it follows the laws of its own existence—when a design is in perfect harmony with its material, and one does not feel one would want it reproduced in any other way.

It is next to impossible to get this unity of design and material unless the craftsman fashions the thing he designs, or unless the designer thoroughly understands the conditions and allows them to determine the character of his design, which he can hardly do unless he is in close and constant touch with the craftsman. Now the industrial conditions under which the great mass of things are produced, which have gradually been developed in the interests of trade rather than of art have tended to separate the designer and craftsman more and more and to subdivide their functions. Our enterprising manufacturers are quick enough to adopt or adapt an idea, and some will pay liberally for it, but they do not always realize that it does not follow because one good thing is produced in a limited quantity that therefore it must be much better if a cheap imitation of it can be produced by the thousand—but then we no longer produce for use but for profit. Demand and supply—"thou shalt have no other gods but these," says the trader in effect; although the demand in these days may be as artificial as the supply.

The Nemesis of trade pursues the invention [pg 59] of the artist, as the steamers on the river on boat-race day pursue, almost as if they would run down, the slender craft of the oarsmen straining every nerve for victory. It is a suggestive spectacle. Someone's brain and hand must set to work—must give the initiative before the steam-engine can be set going. But how many brains and hands, nay lives, has it devoured since our industrial epoch began?

Up to about 1880 artists working independently in decoration were few and far between, mostly isolated units, and their work was often absorbed by various manufacturing firms. About that time, in response to a feeling for more fellowship and opportunity for interchange of ideas on the various branches of their own craft, a few workers in decorative design were gathered together under the roof of the late Mr. Lewis F. Day on a certain January evening known as hurricane Tuesday and a small society was formed for the discussion of various problems in decorative design and kindred topics; meeting in rotation at the houses or studios of the members. The society had a happy if obscure life for several years, and was ultimately absorbed into a larger society of designers, architects, and craftsmen called "The Art Workers' Guild," which met once a month with much the same objects—fellowship and interchange of ideas and papers and demonstrations in various arts and crafts. In fact, since artists more or less concerned [pg 60] with decoration had increased, owing to the revived activity and demand arising for design of all kinds the feeling grew stronger among men of very different proclivities for some common ground of meeting. A desire among artists of different crafts to know something of the technicalities of other crafts made itself felt, and the result has been the rapid and continual growth of the Guild which now includes, beside the principal designers in decoration, painters, architects, sculptors, wood-carvers, metal-workers, engravers, and representatives of various other crafts.

A junior Art Workers' Guild has also been established in connection with the older body, and there are besides two Societies of Designers in London, while in the provinces there is the Northern Art Workers' Guild at Manchester and various local Arts and Crafts societies all over the country.

We have, of course, our Royal Academy, or as it ought to be called, Royal Guild of Painters in Oil, always with us; but its use of the term "Arts" applies only (and almost exclusively so) to painting, sculpture, architecture, and engraving, and while absorbing gifted artists from time to time, often after they have done their best work, it has never, as a body, shown any wide or comprehensive conception of art, although it has done a certain amount of educational work, chiefly through its valuable exhibitions of old masters [pg 61] and its lectures and teaching in the schools, which are free, and where famous artists act as visitors. Its influence in the main it is to be feared has been to encourage an enormous overproduction of pictures every year, and to foster in the popular mind the impression that there was no art in England before Sir Joshua Reynolds, and none of any consequence since, outside the easel picture.

The magnificently arranged and deeply interesting "Town-planning Exhibition," held last year in connection with the International Congress on that subject, however, was a new departure and most welcome as an example of what might be done by the Royal Academy under the influence of wider conceptions of art.

Nevertheless, the work of such fine decorative artists as Albert Moore, Alfred Gilbert, Harry Bates has been introduced to the public through the Royal Academy, these two last-named being members; and once upon a time even a picture by Sir E. Burne-Jones appeared there.

Many gifted artists have strengthened the institution since these passed away. The names of Watts and Leighton will always shed lustre and distinction upon it, but of course the Academy necessarily depends for its continued vitality upon new blood. The advantages of membership are generally too strong a temptation to our rising artists to encourage the formation of anything like an English "secession," though [pg 62] according to our British ideas of the wholesomeness of competition or, let us say emulation, a strong body of independent artists might have a good effect all round.

I have often wondered that no attempt has been made by the Royal Academy to give a lead in the arrangement and hanging of an exhibition. With the fine rooms at their disposal it would be possible to make their great annual show of pictures far more striking and attractive by some kind of classification or sympathetic grouping. The best system, of course, would be to group the works of each artist together. This, however, would take up more wall space and lead to more exclusions than at present; but, still the plan might be tried of placing all the portraits together, and, say, the subject pictures according to scale, and the landscapes, arranging them in separate rooms. Sculpture and architecture, and water colours and engravings are already given separate rooms, so that it would only be extending a principle already adopted. The effect of the whole exhibition would be much finer, I venture to think, and also less fatiguing, and there would probably be less chance of pictures being falsified or injured by juxtaposition with unsympathetic neighbours. Surely some advance is possible on eighteenth-century ideas of hanging, or the old days of Somerset House? I respectfully commend the above suggestion to their consideration.

While mentioning names we must not forget (although I have hitherto dwelt rather on the Gothic side of the English revival) such distinguished designers as the late Alfred Stevens and his able followers Godfrey Sykes and Moody. These artists drew their inspiration largely from the work of the Italian Renascence, and it is a testimony to their remarkable powers—especially of the first-named—that they should have achieved such distinction on the lines of so marked a style, and one which, as it appears to me, had already reached its maturity in the country of its birth, unlike Gothic design, which might almost be said to have been arrested in its development by the advent of the Renascence.

Another influence upon modern decorative art cannot be left out of account, and that is the Japanese influence. The extraordinary decorative daring, and intimate naturalism; the frank or delicate colouration, the freshness, as of newly gathered flowers of many of their inventions and combinations: the wonderful vivacity and truth of the designs of such a master as Hokusai, for instance—these and the whole disclosure of the history of their art (which, however, was entirely derived from and inspired by the still finer art of the Chinese), from the early, highly wrought, religious and symbolic designs, up to the vigorous freedom and naturalism of the later time, together [pg 64] with their extraordinary precision of technique, inevitably took the artistic world by storm. Its immediate effects, much as we may be indebted to such a source, cannot be set down altogether to the good so far as we can trace them in contemporary European art; but perhaps on the whole there is no more definitely marked streak of influence than this of the Japanese. In French art it was at one time more palpable still. In fact it might almost be said to have taken entire possession of French decorative art, or a large part of it; or rather, it is Japanese translated into French with that ease and chic for which our lively neighbours are remarkable.

Whistler, by the way, who must be numbered with the decorators, showed unmistakably in his work the results of a close study of Japanese art. His methods of composition, his arrangements of tones of colour declare how he had absorbed it, and applied it to different methods and subjects, in fact, his work shows most of the qualities of much Japanese art, except precision of drawing, although his earlier etchings have this quality.

In modern decoration, the most obvious and superficial qualities of Japanese art have generally been seized upon, and its general effect has been to loosen the restraining and architectonic sense of balance and fitness, and a definite ordered plan of construction, which are essential in the finest types of design. On the whole, the effects of the discovery [pg 65] of Japanese art on the modern artistic mind, may be likened to a sudden and unexpected access of fortune to an impoverished man. It is certain to disorganize if not demoralize him. The sudden contact with a fresh and vigorous art, alive with potent tradition, yet intimate with the subtler forms and changes of nature, and in the full possession and mastery of its own technique—the sudden contact of such an art with the highly artificial and eclectic art of a complex and effete civilization must be more or less of the nature of a shock. Shocks are said to be good for sound constitutions, but their effect on the unsound are as likely as not to be fatal.

While fully acknowledging the brilliancy of Japanese art, however, one feels how enormously they were indebted to the art of China, and the greater dignity and impressiveness of the latter becomes more and more apparent on comparison. Both in graphic characterization of birds and animals and flowers and splendour of ornament, the Chinese both preceded and excelled the Japanese. There were recently some striking demonstrations of this at the British Museum, when Mr. Laurence Binyon arranged a series of most remarkable ancient Chinese paintings on silk side by side with Japanese work.

The opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, owing to the enterprise of Sir Coutts Lindsay, was the means of bringing the decorative school in [pg 66] English painting to the front, and did much towards directing public attention in that direction.