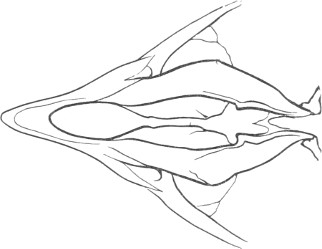

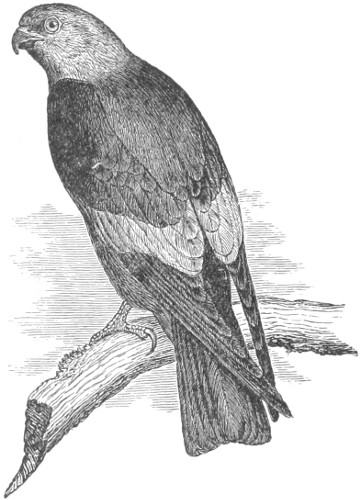

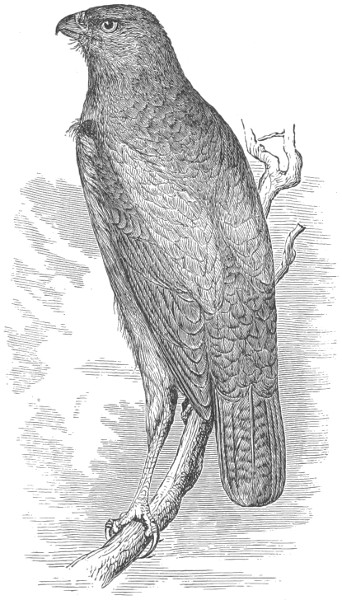

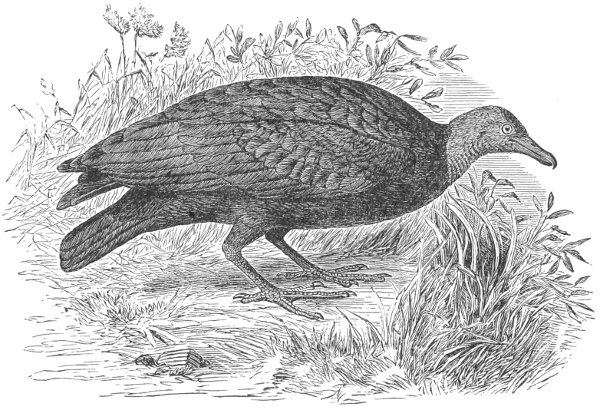

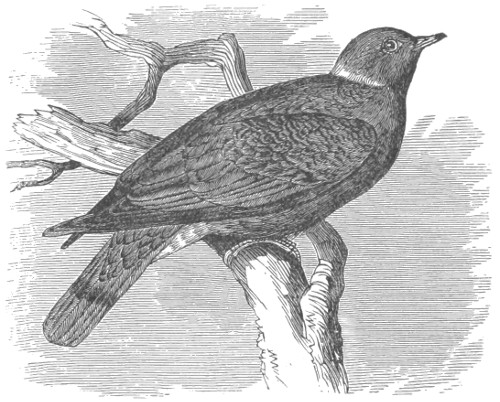

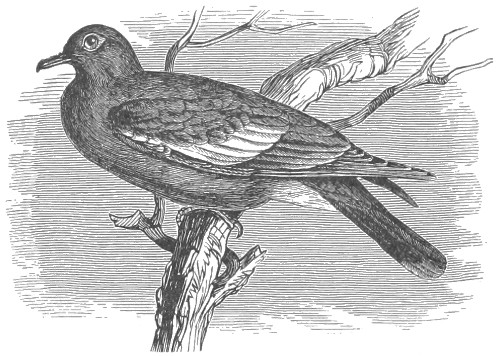

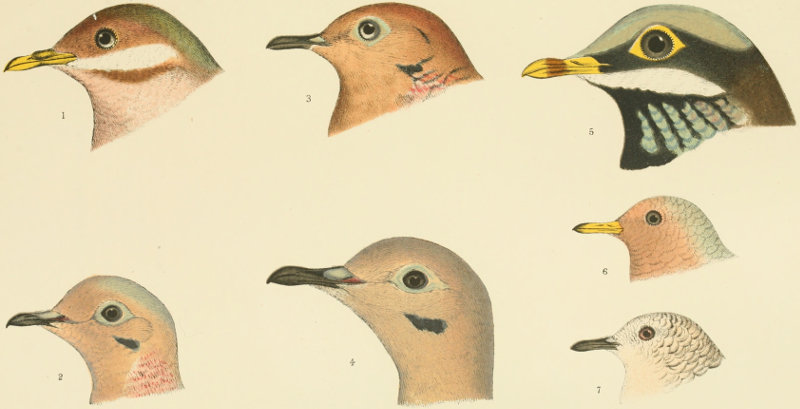

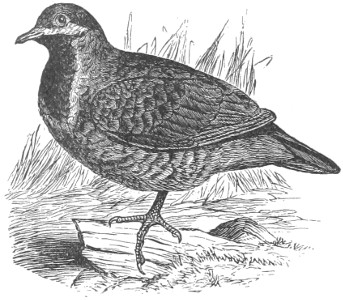

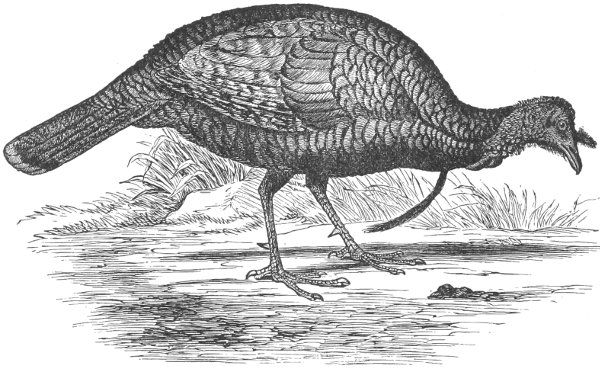

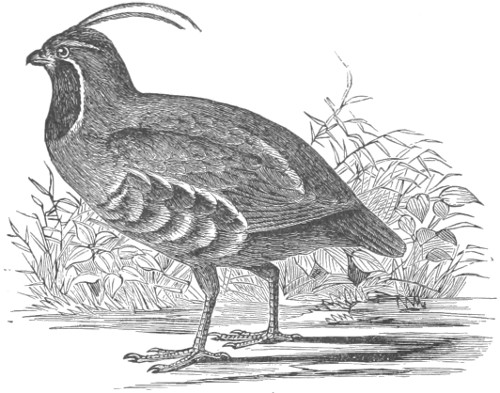

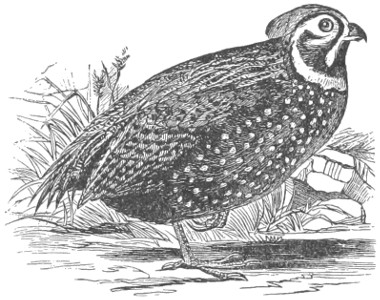

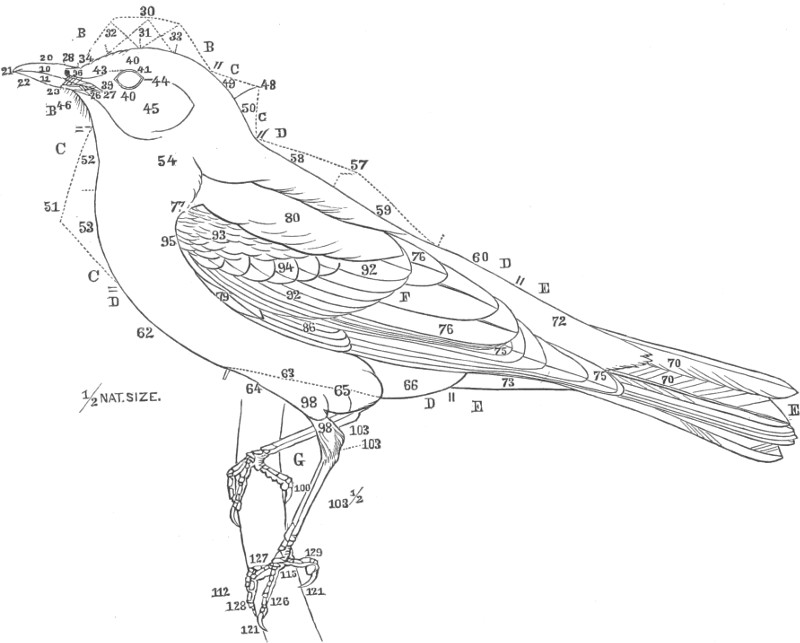

PARAKEET.

(Conurus carolinensis.)

Adult.

Title: A History of North American Birds; Land Birds; Vol. 3 of 3

Author: Spencer Fullerton Baird

T. M. Brewer

Robert Ridgway

Release date: February 15, 2017 [eBook #54169]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Jennifer Linklater, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

PARAKEET.

(Conurus carolinensis.)

Adult.

A HISTORY OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS

LAND BIRDS

ILLUSTRATED BY 64 PLATES AND 593 WOODCUTS

VOLUME III.

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1905

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874,

BY LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY,

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Printers

S. J. Parkhill & Co., Boston, U. S. A.

NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS.

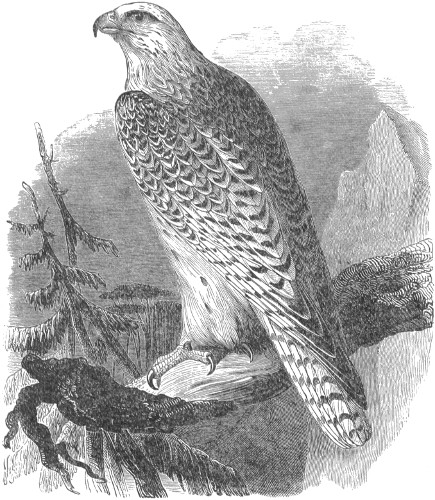

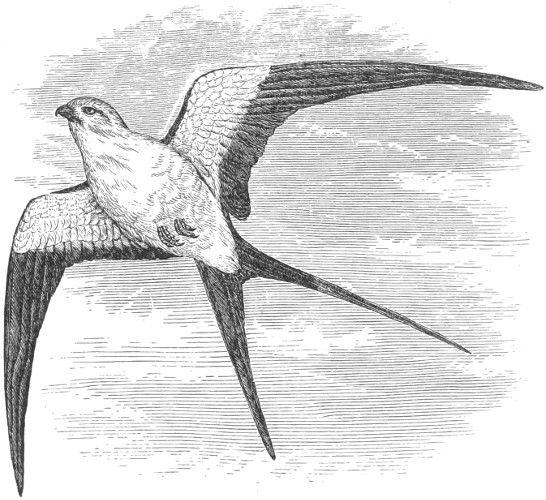

The group of birds usually known as the Raptores, or Rapacious Birds, embraces three well-marked divisions, namely, the Owls, the Hawks, and the Vultures. In former classifications they headed the Class of Birds, being honored with this position in consequence of their powerful organization, large size, and predatory habits. But it being now known that in structure they are less perfectly organized than the Passeres and Strisores, birds generally far more delicate in organization, as well as smaller in size, they occupy a place in the more recent arrangements nearly at the end of the Terrestrial forms.

The complete definition of the order Raptores, and of its subdivisions, requires the enumeration of a great many characters; and that their distinguishing features may be more easily recognized by the student, I give first a brief diagnosis, including their simplest characters, to be followed by a more detailed account hereafter.

Common Characters. Bill hooked, the upper mandible furnished at the base with a soft skin, or “cere,” in which the nostrils are situated. Toes, three before and one behind. Raptores.

Strigidæ. Eyes directed forwards, and surrounded by radiating feathers, which are bounded, except anteriorly, by a circle or rim of differently formed, stiffer feathers. Outer toe reversible. Claws much hooked and very sharp. Legs and toes usually feathered, or, at least, coated with bristles. The Owls.

Falconidæ. Eyes lateral, and not surrounded by radiating feathers. Outer toe not reversible (except in Pandion). Claws usually hooked and sharp, but variable. Head more or less completely feathered. The Hawks.

Cathartidæ. Eyes lateral; whole head naked. Outer toe not reversible; claws slightly curved, blunt. The Vultures.

The preceding characters, though purely artificial, may nevertheless serve to distinguish the three families of Raptores belonging to the North American Ornis; a more scientific diagnosis, embracing a sufficient number of osteological, and accompanying anatomical characters, will be found further on.

The birds of prey—named Accipitres by some authors, and Raptores or Rapaces by others, and very appropriately designated as the Ætomorphæ by Professor Huxley—form one of the most strongly characterized and sharply limited of the higher divisions of the Class of Birds. It is only recently, however, that their place in a systematic classification and the proper number and relation of their subdivisions have been properly understood. Professor Huxley’s views will probably form the basis for a permanent classification, as they certainly point the way to one eminently natural. In his important paper entitled “On the Classification of Birds, and on the Taxonomic Value of the Modifications of certain Cranial Bones observable in that Class,”2 this gentleman has dealt concisely upon the affinities of the order Raptores, and the distinguishing features of its subdivisions. In the following diagnoses the osteological characters are mainly borrowed from Professor Huxley’s work referred to. Nitzsch’s “Pterylography”3 supplies such characters as are afforded by the plumage, most of which confirm the arrangement based upon the osteological structure; while important suggestions have been derived from McGillivray’s “History of British Birds.”4 The Monographs of the Strigidæ and Falconidæ, by Dr. J. J. Kaup,5 contain much valuable information, and were they not disfigured by a very eccentric system of arrangement they would approach nearer to a natural classification of the subfamilies, genera, and subgenera, than any arrangement of the lesser groups which I have yet seen.

The species of this group are spread over the whole world, tropical regions having the greatest variety of forms and number of species. The Strigidæ are cosmopolitan, most of the genera belonging to both continents. The Falconidæ are also found the world over, but each continent has subfamilies peculiar to it. The Cathartidæ are peculiar to America, having analogous representatives in the Old World in the subfamily Vulturinæ belonging to the Falconidæ, The Gypogeranidæ are found only in South Africa, where a single species, Gypogeranus serpentarius (Gmel.), sole representative of the family, is found.

As regards the comparative number of species of this order in the two continents, the Old World is considerably ahead of the New World, which might be expected from its far greater land area. 581 species are given in Gray’s Hand List,6 of which certainly not more than 500, probably not more than 450, are valid species, the others ranking as geographical races, or are synonymous with others; of this number about 350 nominal species are accredited to the Old World. America, however, possesses the greatest variety of forms, and the great bulk of the Old World Raptorial fauna is made up chiefly by a large array of species of a few genera which are represented in America by but one or two, or at most half a dozen, species. The genera Aquila, Spizætus, Accipiter, Haliætus, Falco, Circus, Athene, Strix, and Buteo, are striking examples. As regards the number of peculiar forms, America is considerably ahead.

Char. Eyes directed forward, and surrounded by a radiating system of feathers, which is bounded, except anteriorly, by a ruff of stiff, compactly webbed, differently formed, and somewhat recurved feathers; loral feathers antrorse, long, and dense. Plumage very soft and lax, of a fine downy texture, the feathers destitute of an after-shaft. Oil-gland without the usual circlet of feathers. Outer webs of the quills with the points of the fibres recurved. Feathers on the sides of the forehead frequently elongated into ear-like tufts; tarsus usually, and toes frequently, densely feathered. Ear-opening very large, sometimes covered by a lappet. Œsophagus destitute of a dilated crop; cœca large. Maxillo-palatines thick and spongy, and encroaching upon the intervening valley; basipterygoid processes always present. Outer toe reversible; posterior toe only about half as long as the outer. Posterior margin of the sternum doubly indented; clavicle weak and nearly cylindrical, about equal in length to the sternum. Anterior process of the coracoid projected forward so as to meet the clavicle, beneath the basal process of the scapula. Eggs variable in shape, usually nearly spherical, always immaculate, pure white.

The Owls constitute a very natural and sharply limited family, and though the species vary almost infinitely in the details of their structure, they all seem to fall within the limits of a single subfamily.

They have never yet been satisfactorily classified, and all the arrangements which have been either proposed or adopted are refuted by the facts developed upon a close study into the true relationship of the many genera. The divisions of “Night Owls,” “Day Owls,” “Horned Owls,” etc., are purely artificial. This family is much more homogeneous than that of the Falconidæ, since none of the many genera which I have examined seem to depart in their structure from the model of a single subfamily, though a few of them are somewhat aberrant as regards peculiarities in the detail of external form, or, less often, to a slight extent, in their osteological characters, though I have examined critically only the American and European species; and there may be some Asiatic, African, or Australian genera which depart so far from the normal standard of structure as to necessitate a modification of this view. In the structure of the sternum there is scarcely the least noticeable deviation in any genus7 from the typical form. The appreciable differences appear to be only of generic value, such as a different proportionate length of the coracoid bones and the sternum, and width of the sternum in proportion to its length, or the height of its keel. The crania present a greater range of variation, and, if closely studied, may afford a clew to a more natural arrangement than the one which is here presented. The chief differences in the skulls of different genera consist in the degree of pneumaticity of the bones, in the form of the auricular bones, the comparative length and breadth of the palatines, and very great contrasts in the contour. As a rule, we find that those skulls which have the greatest pneumaticity (e.g. Strix and Otus) are most depressed anteriorly, have the orbital septum thicker, the palatines longer and narrower, and a deeper longitudinal median valley on the superior surface, and vice versa.

The following classification is based chiefly upon external characters; but these are in most instances known to be accompanied by osteological peculiarities, which point to nearly the same arrangement. It is intended merely as an artificial table of the North American genera, and may be subjected to considerable modification in its plan if exotic genera are introduced.8

A. Inner toe equal to the middle in length; inner edge of middle claw pectinated. First quill longer than the third; all the quills with their inner webs entire, or without emargination. Tail emarginated. Feathers of the posterior face of the tarsus recurved, or pointed upwards.

1. Strix. No ear-tufts; bill light-colored; eyes black; tarsus nearly twice as long as middle toe; toes scantily haired. Size medium. Ear-conch nearly as long as the height of the skull, with an anterior operculum for only a portion of its length; symmetrical.

B. Inner toe decidedly or much shorter than the middle; inner edge of middle claw not pectinated. First quill shorter than the third; one to six outer quills with their inner webs emarginated. Tail rounded. Feathers of the posterior face of the tarsus not recurved but pointed downwards.

I. Nostril open, oval, situated in the anterior edge of the cere, which is not inflated.

a. Cere, on top, equal to, or exceeding, the chord of the culmen; much arched. Ear-conch nearly as long as the height of the skull, with the operculum extending its full length; asymmetrical.

2. Otus. One or two outer quills with their inner webs emarginated. With or without ear-tufts. Bill blackish; iris yellow. Size medium.

Ear-tufts well developed; only one quill emarginated … Otus.

Ear-tufts rudimentary; two quills emarginated … Brachyotus.

b. Cere, on top, less than the chord of the culmen; gradually ascending basally, or level (not arched). Ear-conch nearly the height of the skull, with the operculum extending only a part of its full length, or wanting entirely.

† Anterior edge of the ear-conch with an operculum; the two ears asymmetrical.

3. Syrnium. Five to six outer quills with their inner webs emarginated. Top of cere more than half the culmen. Without ear-tufts. Bill yellow; iris yellow or black. Size medium or large.

Six quills emarginated; toes densely feathered, the terminal scutellæ concealed; iris yellow. Size very large … Scotiaptex.

Five quills emarginated; toes scantly feathered, the terminal scutellæ exposed; iris black. Size medium … Syrnium.

4. Nyctale. Two outer quills with inner webs emarginated. Top of cere less than half the culmen, level. Without ear-tufts. Bill yellow or blackish; iris yellow. Size small.

†† Anterior edge of the ear-conch without an operculum. The two ears symmetrical. Tail slightly rounded, only about half as long as the wing.

5. Scops. Two to five quills with inner webs emarginated; second to fifth longest. Bill weak, light-colored. Ear-conch elliptical, about one-third the height of the head, with a slightly elevated fringed anterior margin. Size small; ear-tufts usually well developed, sometimes rudimentary.

6. Bubo. Two to four outer quills with inner webs emarginated; third to fourth longest. Bill robust, black. Ear-conch elliptical, simple, from one third to one half the height of the skull. Size large. Ear-tufts well developed or rudimentary.

Ear-tufts well developed. Two to three outer quills with inner webs emarginated; lower tail-coverts not reaching end of the tail. Toes covered with short feathers, the claws exposed, and bill not concealed by the loral feathers … Bubo.

Ear-tufts rudimentary. Four outer quills with their inner webs emarginated; lower tail-coverts reaching end of the tail. Toes covered with long feathers, which hide the claws, and bill nearly concealed by the loral feathers … Nyctea.

††† Similar to the last, but the tail graduated, nearly equal to the wing.

7. Surnia. Four outer quills with inner webs emarginated. Third quill longest. Bill strong, yellow; ear-conch simple, oval, less than the diameter of the eye. Size medium; no ear-tufts.

II. Nostril, a small circular opening into the surrounding inflated membrane of the cere. Ear-conch small, simple, oval, or nearly round, without an operculum.

First quill shorter than the tenth.

8. Glaucidium. Third to fourth quills longest; four emarginated on inner webs. Tarsus about equal to the middle toe, densely feathered. Tail much more than half the wing, rounded. Bill and iris yellow. Size very small.

9. Micrathene. Fourth quill longest; four emarginated on inner webs. Tarsus a little longer than middle toe, scantily haired. Tail less than half the wing, even. Bill light (greenish ?); iris yellow. Size very small.

First quill longer than sixth.

10. Speotyto. Second to fourth quills longest; three emarginated on inner webs. Tarsus more than twice as long as middle toe, closely feathered in front to the toes, naked behind. Tail less than half the wing, slightly rounded. Bill yellowish; iris yellow. Size small.

In their distribution, the Owls, as a family, are cosmopolitan, and most of the genera are found on both hemispheres. All the northern genera (Nyctea, Surnia, Nyctale, and Scotiaptex), and the majority of their species, are circumpolar. The genus Glaucidium is most largely developed within the tropics, and has numerous species in both hemispheres. Otus brachyotus and Strix flammea are the only two species which are found all over the world,—the former, however, being apparently absent in Australia. Gymnoglaux, Speotyto, Micrathene, and Lophostrix are about the only well-characterized genera peculiar to America. Athene, Ketupa, and Phodilus are peculiar to the Old World. The approximate number of known species (see Gray’s Hand List of Birds, I, 1869) is about two hundred, of which two, as stated, are cosmopolitan; six others (Surnia ulula, Nyctea scandiaca, Glaucidium passerinum, Syrnium cinereum, Otus vulgaris, and Nyctale tengmalmi) are found in both halves of the Northern Hemisphere; of the remainder there are about an equal number peculiar to America and the Old World.

As regards the distribution of the Owls in the Nearctic Realm, a prominent feature is the number of the species (eighteen, not including races) belonging to it, of which six (Micrathene whitneyi, Nyctale acadica, Syrnium nebulosum, S. occidentale, Scops asio, and S. flammeola) are found nowhere else. Speotyto cunicularia and Bubo virginianus are peculiarly American species found both north and south of the equator, but in the two regions represented by different geographical races. Glaucidium ferrugineum and G. infuscatum (var. gnoma) are tropical species which overreach the bounds of the Neotropical Realm,—the former extending into the United States, the latter reaching to, and probably also within, our borders. Of the eighteen North American species, about nine, or one half (Strix flammea var. pratincola, Otus brachyotus, O. vulgaris var. wilsonianus, Syrnium cinereum, Nyctale acadica, Bubo virginianus, and Scops asio, with certainty, and Nyctea scandiaca var. arctica, and Surnia ulula var. hudsonia, in all probability), are found entirely across the continent. Nyctale tengmalmi, var. richardsoni, and Syrnium nebulosum, appear to be peculiar to the eastern portion,—the former to the northern regions, the latter to the southern. Athene cunicularia var. hypugaea, Micrathene whitneyi, Glaucidium passerinum var. californicum, Syrnium occidentale, and Scops flammeola, are exclusively western, all belonging to the southern portion of the Middle Province and Rocky Mountain region, and the adjacent parts of Mexico, excepting the more generally distributed Speotyto cunicularia, var. hypogæa, before mentioned. Anomalies in regard to the distribution of some of the species common to both continents, are the restriction of the American representative of Glaucidium passerinum to the western regions,9 and of Strix flammea to the very southern and maritime portions of the United States, the European representatives of both species being generally distributed throughout that continent. On the other hand, the northwest-coast race of our Scops asio (S. kennicotti) seems to be nearly identical with the Japanese S. semitorques (Schlegel), which is undoubtedly referrible to the same species.

As regards their plumage, the Owls differ most remarkably from the Hawks in the fact that the sexes are invariably colored alike, while from the nest to perfect maturity there are no well-marked progressive stages distinguishing the different ages of a species. The nestling, or downy, plumage, however, of many species, has the intricate pencilling of the adult dress replaced by a simple transverse barring upon the imperfect downy covering. The downy young of Nyctea scandiaca is plain sooty-brown, and that of Strix flammea immaculate white.

In many species the adult dress is characterized by a mottling of various shades of grayish mixed with ochraceous or fulvous, this ornamented by a variable, often very intricate, pencilling of dusky, and more or less mixed with white. As a consequence of the mixed or mottled character of the markings, the plumage of the Owls is, as a rule, difficult to describe.

In the variations of plumage, size, etc., with differences of habitat, there is a wide range, the usually recognized laws10 applying to most of those species which are generally distributed and resident where breeding. Of the eight species common to the Palæarctic and Nearctic Realms, all but one (Otus brachyotus) are modified so as to form representative geographical races on the two continents. In each of these cases the American bird is much darker than the European, the brown areas and markings being not only more extended, but deeper in tint. The difference in this respect is so tangible that an experienced ornithologist can instantly decide to which continent any specimen belongs. Of the two cosmopolitan species one, Otus brachyotus, is identical throughout; the other is modified into geographical races in nearly every well-marked province of its habitat. Thus in the Palæarctic Realm it is typical Strix flammea; in the Nearctic Realm it is var. pratincola; while Tropical America has at least three well-marked geographical races, the species being represented in Middle America by the var. guatemalæ, in South America by var. perlata, and in the West Indies by the var. furcata. The Old World has also numerous representative races, of which we have, however, seen only two, namely, var. javanica (Gm.), of Java, India, and Eastern Africa, and var. delicatula (Gould) of Australia, both of which we unhesitatingly refer to S. flammea.11

On the North American continent the only widely distributed species which do not vary perceptibly with the region are Otus brachyotus and O. vulgaris (var. wilsonianus). Bubo virginianus, Scops asio, and Syrnium nebulosum all bear the impress of special laws in the several regions of their habitat. Starting with the Eastern Province, and tracing either of these three species southward, we find it becoming gradually smaller, the colors deeper and more rufous, and the toes more scantily feathered. Scops asio reaches its minimum of size and maximum depth of color in Florida (var. floridana) and in Mexico (var. enano).

Of the other two I have not seen Florida specimens, but examples of both from other Southern States and the Lower Mississippi Valley region are much more rufous, and—the S. nebulosum especially—smaller, with more naked toes. The latter species is darkest in Eastern Mexico (var. sartori), and most rufescent, and smallest, in Guatemala (var. fulvescens). In the middle region of the United States, Scops asio (var. maccalli) and Bubo virginianus (var. arcticus) are more grayish and more delicately pencilled than from other portions. In the northwest coast region they become larger and much more darkly colored, assuming the clove-brown or sooty tints peculiar to the region. The var. kennicotti represents S. asio in this region, and var. pacificus the B. virginianus. The latter species also extends its range around the Arctic Coast to Labrador, and forms a northern littoral race, the very opposite extreme in color from the nearly albinescent examples of var. arcticus found in the interior of Arctic America.

A very remarkable characteristic of the Owls is the fact that many of the species exist in a sort of dimorphic condition, or that two plumages sufficiently unlike to be of specific importance in other cases belong to one species. It was long thought that these two phases represented two distinct species; afterwards it was maintained that they depended on age, sex, or season, different authors or observers entertaining various opinions on the subject; but it is now generally believed that every individual retains through life the plumage which it first acquires, and that young birds of both forms are often found in the same nest, their parents being either both of one form, or both of the other, or the two styles paired together.12 The normal plumage, in these instances, appears to be grayish, the pattern distinct, the markings sharply defined, and the general appearance much like that of species which do not have the other plumage. The other plumage is a replacing of the grayish tints by a bright lateritious-rufous, the pencillings being at the same time less well defined, and the pattern of the smaller markings often changed. This condition seems to be somewhat analogous to melanism in certain Falconidæ, and appears to be more common in the genera Scops and Glaucidium (in which it affects mainly the tropical species), and occurs also in the European Syrnium aluco. As studied with relation to our North American species, we find it only in Scops asio and Glaucidium ferrugineum. The latter, being strictly tropical in its habitat, is similarly affected throughout its range; but in the former we find that this condition depends much upon the region. Thus neither Dr. Cooper nor I have ever seen a red specimen from the Pacific coast, nor do I find any record of such an occurrence. The normal gray plumage, however, is as common throughout that region as in the Atlantic States. In the New England and Middle States the red plumage seems to be more rare in most places than the gray one, while toward the south the red predominates greatly. Of over twenty specimens obtained in Southern Illinois (Mt. Carmel) in the course of one winter, only one was of the gray plumage; and of the total number of specimens seen and secured at other times during a series of years, we can remember but one other gray one. As a parallel example among mammals, Professor Baird suggests the case of the Red-bellied Squirrels and Foxes of the Southern States, whose relationships to the more grayish northern and western forms appear to be about the same as in the present instance.

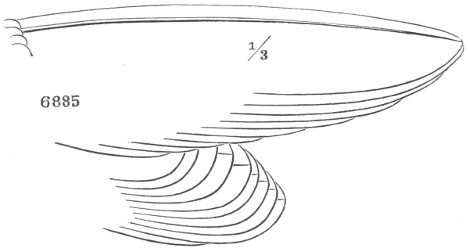

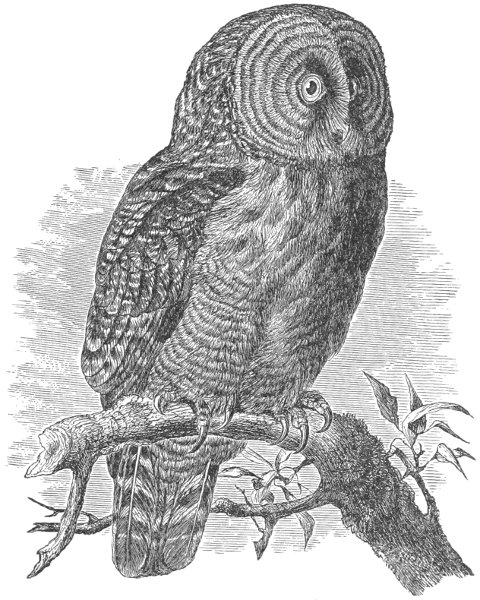

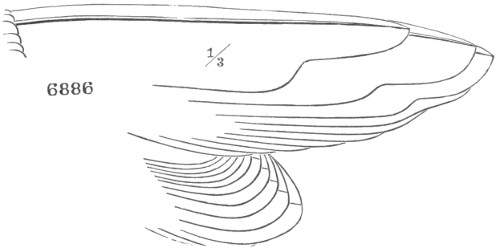

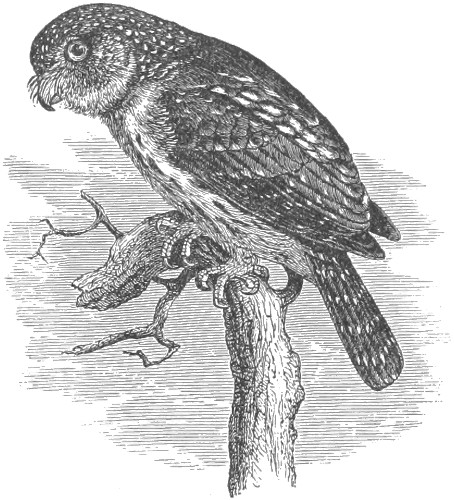

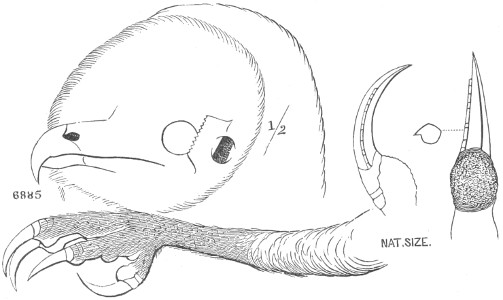

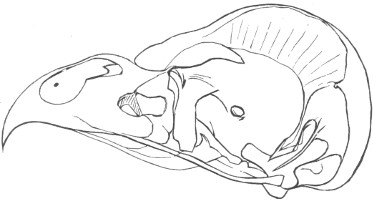

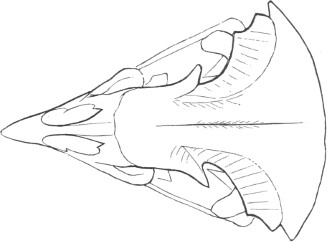

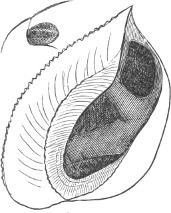

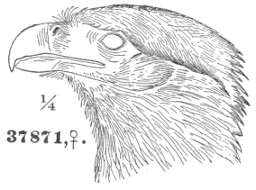

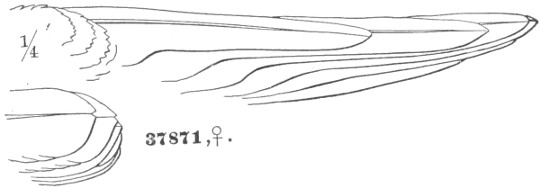

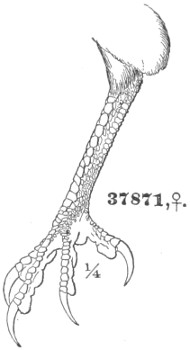

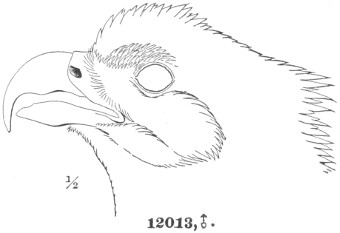

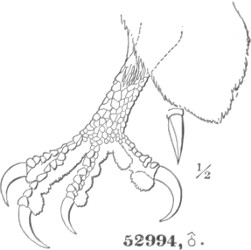

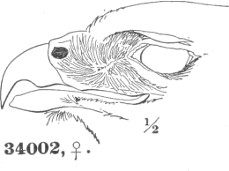

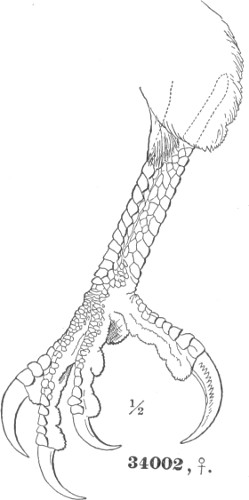

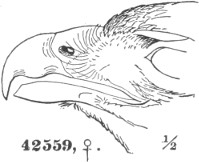

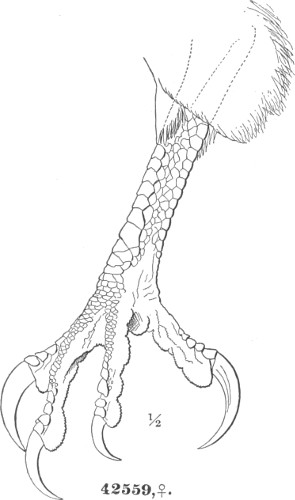

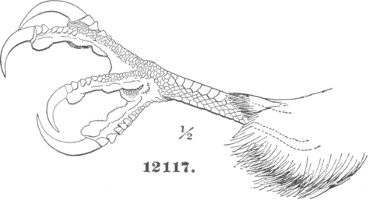

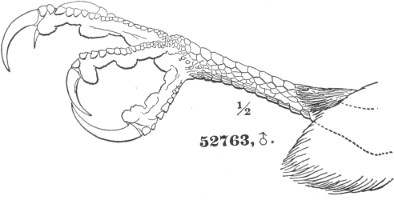

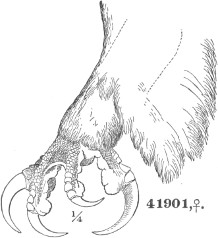

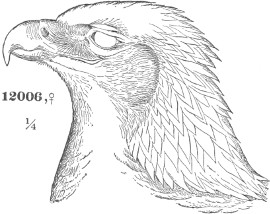

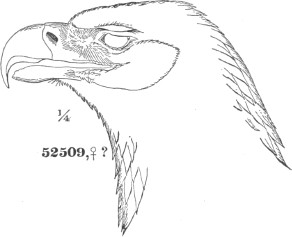

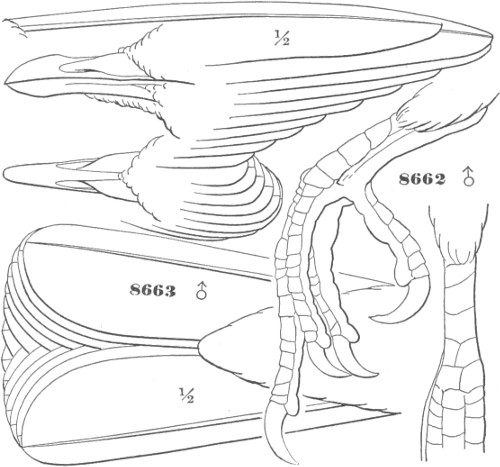

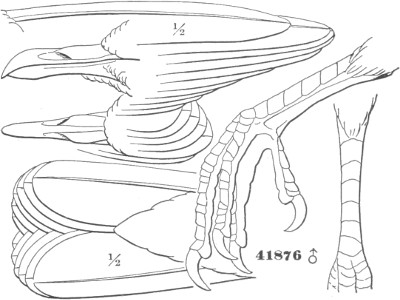

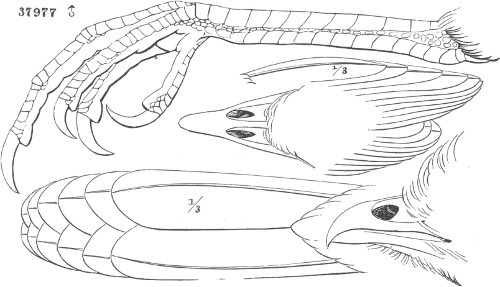

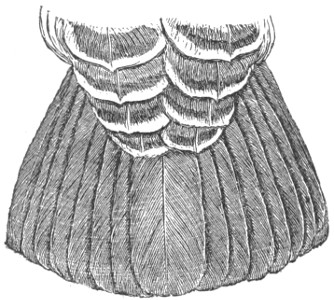

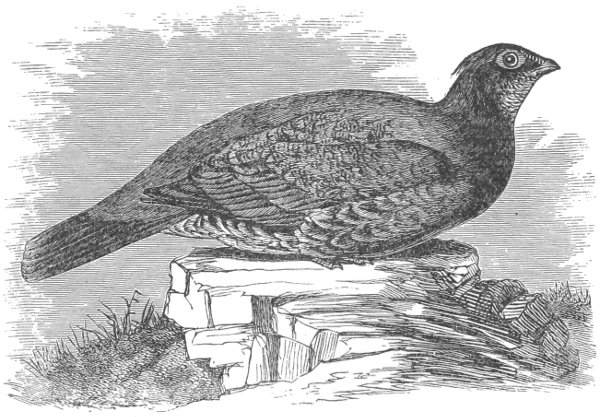

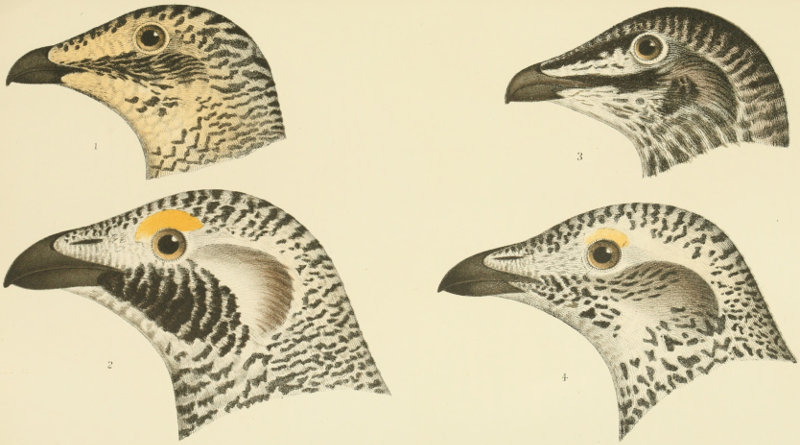

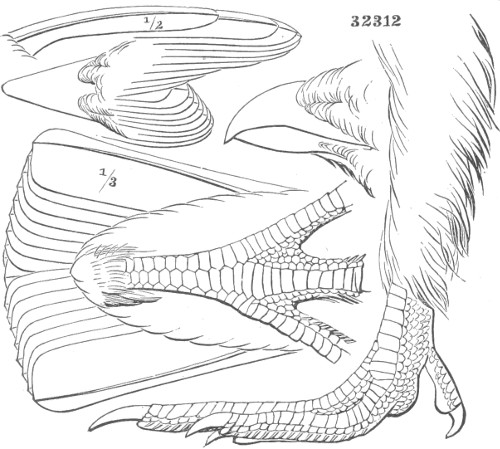

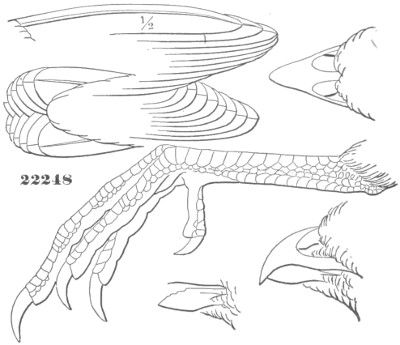

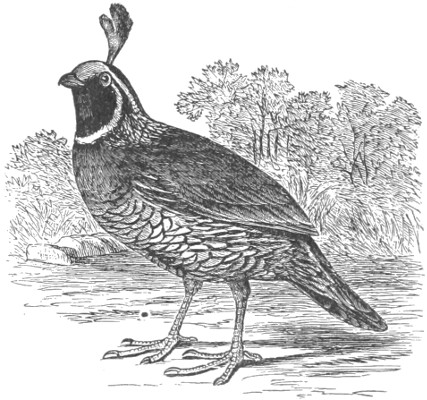

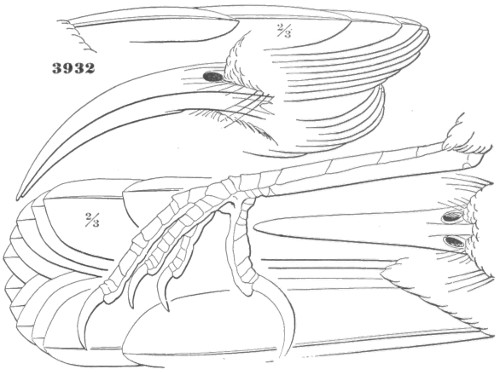

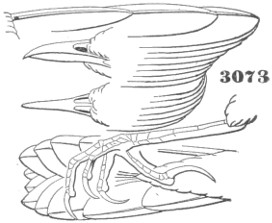

6885 ⅓

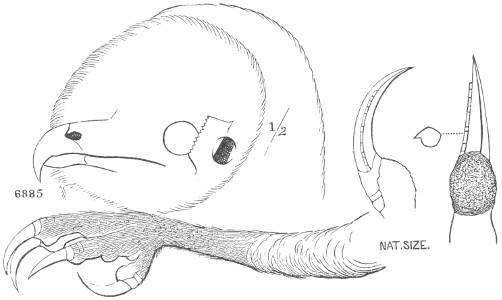

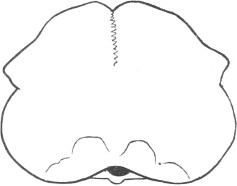

Strix pratincola.

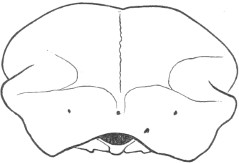

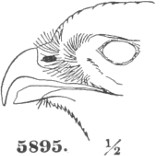

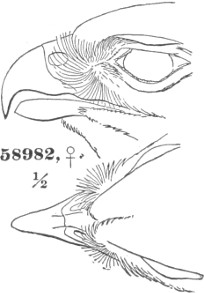

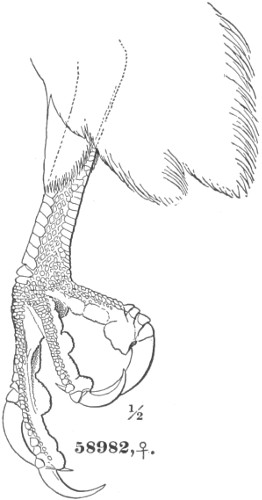

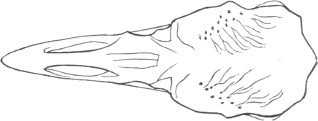

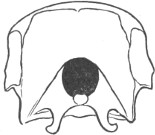

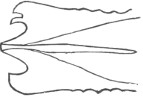

Gen. Char. Size medium. No ear-tufts; facial ruff entirely continuous, very conspicuous. Wing very long, the first or second quill longest, and all without emargination. Tail short, emarginated. Bill elongated, compressed, regularly curved; top of the cere nearly equal to the culmen, straight, and somewhat depressed. Nostril open, oval, nearly horizontal. Eyes very small. Tarsus nearly twice as long as the middle toe, densely clothed with soft short feathers, those on the posterior face inclined upwards; toes scantily bristled; claws extremely sharp and long, the middle one with its inner edge pectinated. Ear-conch nearly as long as the height of the head, with an anterior operculum, which does not extend its full length; the two ears symmetrical?

The species of Strix are distributed over the whole world, though only one of them is cosmopolitan. This is the common Barn Owl (S. flammea), the type of the genus, which is found in nearly every portion of the world, though in different regions it has experienced modifications which constitute geographical races. The other species, of more restricted distribution, are peculiar to the tropical portions of the Old World, chiefly Australia and South Africa.

S. flammea. Face varying from pure white to delicate claret-brown; facial circle varying from pure white, through ochraceous and rufous, to deep black. Upper parts with the feathers ochraceous-yellow basally; this overlaid, more or less continuously, by a grayish wash, usually finely mottled and speckled, with dusky and white. Primaries and tail barred transversely, more or less distinctly, with distant dusky bands, of variable number. Beneath, varying from pure snowy white to tawny rufous, immaculate or speckled. Wing, 10.70–13.50.

Wing, 10.70–12.00; tail, 4.80–5.50; culmen, .75–.80; tarsus, 2.05–2.15; middle toe, 1.25–1.30. Tail with four dark bands, and sometimes a trace of a fifth. Hab. Europe and Mediterranean region of Africa … var. flammea.13

Wing, 12.50–14.00; tail, 5.70–7.50; culmen, .90–1.00; tarsus, 2.55–3.00. Tail with four dark bands, and sometimes a trace of a fifth. Colors lighter than in var. flammea. Hab. Southern North America and Mexico … var. pratincola.

Wing, 11.30–13.00; tail, 5.30–5.90; tarsus, 2.55–2.95. Colors of var. flammea, but more uniform above and more coarsely speckled below. Hab. Central America, from Panama to Guatemala … var. guatemalæ.14

Wing, 11.70–12.00; tail, 4.80–5.20; tarsus, 2.40–2.75. Tail more even, and lighter colored; the dark bars narrower, and more sharply defined. Colors generally paler, and more grayish. Hab. South America (Brazil, etc.) … var. perlata.15

Wing, 12.00–13.50; tail, 5.60–6.00; culmen, .85–.95; tarsus, 2.70–2.85; middle toe, 1.45–1.60. Colors as in var. perlata, but secondaries and tail nearly white, in abrupt contrast to the adjacent parts; tail usually without bars. Hab. West Indies (Cuba and Jamaica, Mus. S. I.) … var. furcata.16

Wing, 11.00; tail, 5.00; culmen, about .85; tarsus, 2.05–2.45; middle toe, 1.30–1.40. Colors of var. pratincola, but less of the ochraceous, with a greater prevalence of the gray mottling. Tail with four dark bands Hab. Australia … var. delicatula.17

Wing, 11.00–11.70; tail, 5.10–5.40; culmen, .85–.90; tarsus, 2.30–2.45; middle toe, 1.35–1.45. Same colors as var. delicatula. Tail with four dark bands (sometimes a trace of a fifth). Hab. India and Eastern Africa … var. javanica.18

Strix pratincola, Bonap. List, 1838, p. 7.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 1844, 31, pl. xiii. f. 28.—Gray, Gen. B., fol. sp. 2.—Cassin, B. Cal. & Tex. 1854, p. 176.—Newb. P. R. Rep. VI, IV, 1857, 76.—Heerm. do. VII, 1857, 34.—Cass. Birds N. Am. 1858, 47.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. (P. A. N. S. Philad. 1866), 13.—Scl. P. Z. S. 1859, 390 (Oaxaca).—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 330 (Texas).—? Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. 1867, 65 (Bahamas). Strix perlata, Gray, List Birds Brit. Mus. 1848, 109 (not S. perlata of Licht. !).—Ib. Hand List, I, 1869, 52.—Kaup, Monog. Strig. Pr. Zoöl. Soc. Lond. IV, 1859, 247. Strix americana, Aud. Synop. 1839, 24.—Brewer, Wilson’s Am. Orn. 1852, 687. Strix flammea, Max. Reise Bras. II, 1820, 265.—Wils. Am. Orn. 1808, pl. l, f. 2.—James, ed. Wilson’s Am. Orn. I, 1831, 111.—Aud. B. Am. 1831, pl. clxxi.—Ib. Orn. Biog. II, 1831, 403.—Spix, Av. Bras. I, 21.—Vig. Zoöl. Jour. III, 438.—Ib. Zoöl. Beech. Voy. p. 16.—Bonap. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. II, 38.—Ib. Isis, 1832, 1140; Consp. Av. p. 55.—Gray, List Birds Brit. Mus. 1844, 54.—Nutt. Man. 1833, 139. Ulula flammea, Jardine, ed. Wilson’s Am. Orn. II, 1832, 264. Strix flammea, var. americana, Coues, Key, 1872, 201.

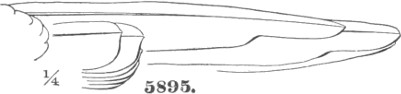

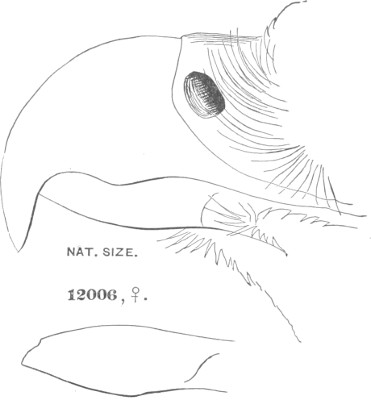

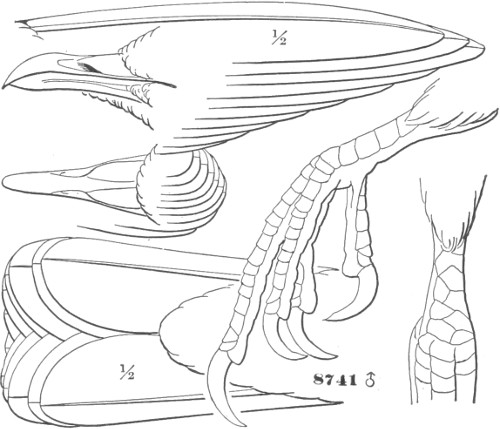

Char. Average plumage. Ground-color of the upper parts bright orange-ochraceous; this overlaid in cloudings, on nearly the whole of the surface, with a delicate mottling of blackish and white; the mottling continuous on the back and inner scapulars, and on the ends of the primaries more faint, while along their edges it is more in the form of fine dusky dots, thickly sprinkled. Each feather of the mottled surface (excepting the secondaries and primaries) has a medial dash of black, enclosing a roundish or cordate spot of white near the end of the feather; on the secondaries and primaries, the mottling is condensed into obsolete transverse bands, which are about four in number on the former and five on the latter; primary coverts deeper orange-rufous than the other portions, the mottling principally at their ends. Tail orange-ochraceous, finely mottled—most densely terminally—with dusky, fading into whitish at the tip, and crossed by about five distinct bands of mottled dusky. Face white, tinged with wine-red; an ante-orbital spot of dark claret-brown, this narrowly surrounding the eye; facial circle, from forehead down to the ears (behind which it is white for an inch or so) soft orange-ochraceous, similar to the ground-color of the upper parts; the lower half (from ears across the throat) deeper ochraceous, the tips of the feathers blackish, the latter sometimes predominating. Lower parts snowy-white, but this more or less overlaid with a tinge of fine orange-ochraceous, lighter than the tint of the upper parts; and, excepting on the jugulum, anal region, and crissum, with numerous minute but distinct specks of black; under surface of wings delicate yellowish-white, the lining sparsely sprinkled with black dots; inner webs of primaries with transverse bars of mottled dusky near their ends.

Extreme plumages. Darkest (No. 6,884, ♂, Tejon Valley, Cal.; “R. S. W.” Dr. Heermann): There is no white whatever on the plumage, the lower parts being continuous light ochraceous; the tibiæ have numerous round spots of blackish. Lightest (No. 6,885, same locality): Face and entire lower parts immaculate snowy-white; facial circle white, with the tips of the feathers orange; the secondaries, primaries, and tail show no bars, their surface being uniformly and finely mottled.

Measurements (♂, 6,884, Tejon Valley, Cal.; Dr. Heermann). Wing, 13.00; tail, 5.70; culmen, .90; tarsus, 2.50; middle toe, 1.25. Wing-formula, 2, 1–3. Among the very numerous specimens in the collection, there is not one marked ♀. The extremes of a large series are as follows: Wing, 12.50–14.00; tail, 5.70–7.50; culmen, .90–1.10; tarsus, 2.55–3.00.

Hab. More southern portions of North America, especially near the sea-coast, from the Middle States southward, and along the southern border to California; whole of Mexico. In Central America appreciably modified into var. guatemalæ. In South America replaced by var. perlata, and in the West Indies by the quite different var. furcata.

Localities: Oaxaca (Scl. P. Z. S. 1859, 390); Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 330); Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 49); ? Bahamas (Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. 1867, 65). Kansas (Snow, List of B. Kansas); Iowa (Allen, Iowa Geol. Report, II, 424).

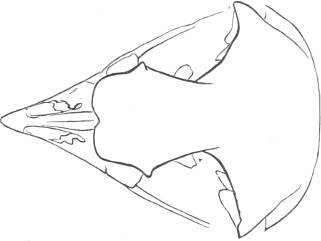

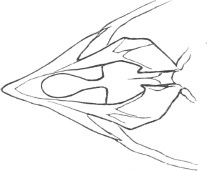

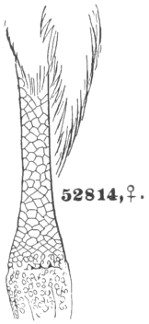

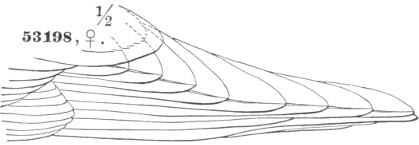

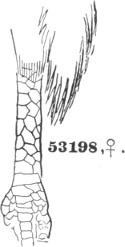

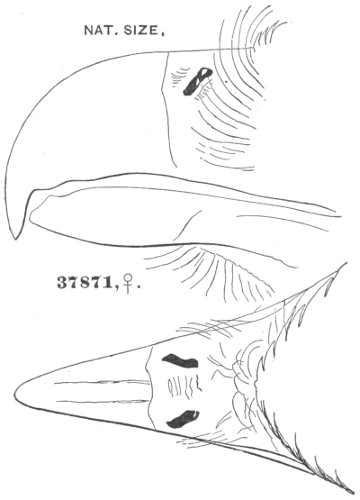

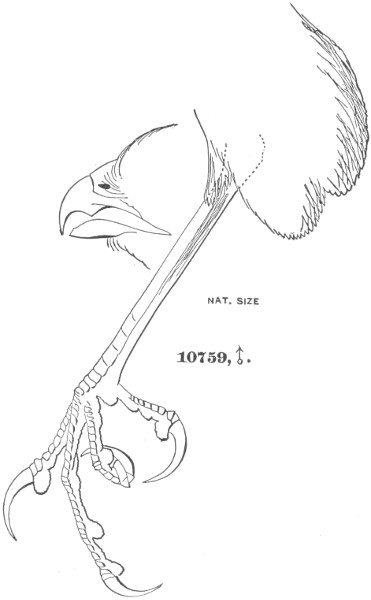

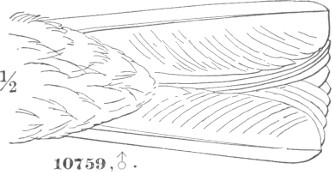

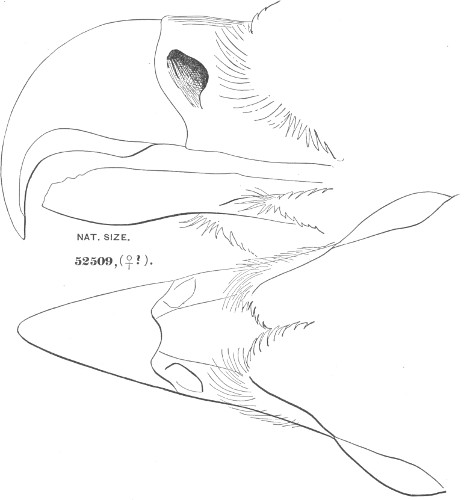

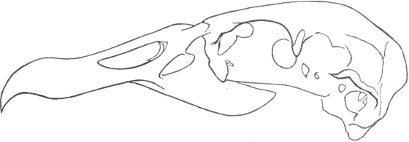

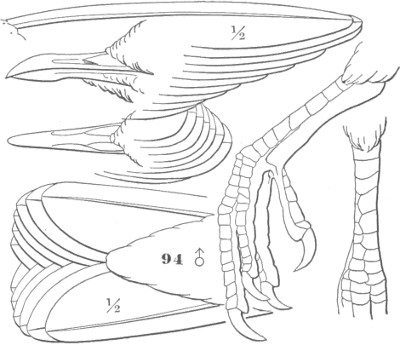

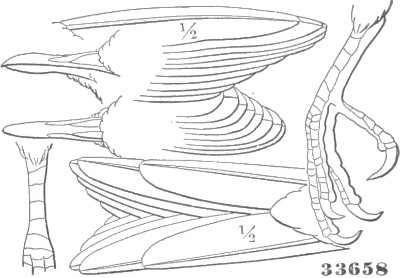

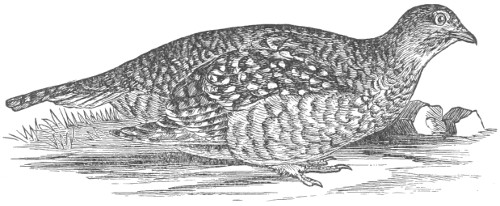

6885 ½ NAT. SIZE.

Strix pratincola.

The variations of plumage noted above appear to be of a purely individual nature, since they do not depend upon the locality; nor, as far as we can learn, to any considerable extent, upon age or sex.

Habits. On the Atlantic coast this bird very rarely occurs north of Pennsylvania. It is given by Mr. Lawrence as very rare in the vicinity of New York, and in three instances, at least, it has been detected in New England. An individual is said, by Rev. J. H. Linsley, to have been taken in 1843, in Stratford, Conn.; another was shot at Sachem’s Head in the same State, October 28, 1865; and a third was killed in May, 1868, near Springfield, Mass.

In the vicinity of Philadelphia the Barn Owl is not very rare, but is more common in spring and autumn than in the summer. Its nests have been found in hollow trees near marshy meadows. Southward it is more or less common as far as South Carolina, where it becomes more abundant, and its range then extends south and west as far as the Pacific. It is quite plentiful in Texas and New Mexico, and is one of the most abundant birds of California. It was not met with by Dr. Woodhouse in the expedition to the Zuñi River, but this may be attributed to the desolate character of the country through which he passed, as it is chiefly found about habitations, and is never met with in wooded or wild regions.

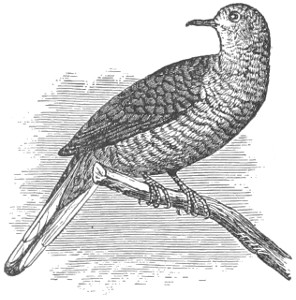

Strix flammea.

Dr. Heermann and Dr. Gambel, who visited California before the present increase in population, speak of its favorite resort as being in the neighborhood of the Missions, and of its nesting under the tiled roofs of the houses. The latter also refers to his finding numbers under one roof, and states that they showed no fear when approached. The propensity of the California bird to drink the sacred oil from the consecrated lamps about the altars of the Missions was frequently referred to by the priests, whenever any allusion was made to this Owl. Dr. Gambel also found it about farm-houses, and occasionally in the prairie valleys, where it obtains an abundance of food, such as mice and other small animals.

Dr. Heermann, in a subsequent visit to the State, mentions it as being a very common bird in all parts of California. They were once quite numerous among the hollow trees in the vicinity of Sacramento, but have gradually disappeared, as their old haunts were one by one destroyed to make way for the gradual development and growth of that city. Dr. Heermann found a large number in the winter, sheltered during the day among the reeds of Suisun Valley. They were still abundant in the old Catholic Missions, where they frequented the ruined walls and towers, and constructed their nests in the crevices and nooks of those once stately buildings, now falling to decay. These ruins were also a shelter for innumerable bats, reptiles, and vermin, which formed an additional attraction to the Owls.

Dr. Cooper speaks of finding this Owl abundant throughout Southern California, especially near the coast, and Dr. Newberry frequently met with it about San Francisco, San Diego, and Monterey, where it was more common than any other species. He met with it on San Pablo Bay, inhabiting holes in the perpendicular cliffs bordering the south shore. It was also found in the Klamath Basin, but not in great numbers.

Mr. J. H. Clark found the Barn Owl nesting, in May, in holes burrowed into the bluff banks of the Rio Frio, in Texas. These burrows were nearly horizontal, with a considerable excavation near the back end, where the eggs were deposited. These were three or four in number, and of a dirty white. The parent bird allowed the eggs to be handled without manifesting any concern. There was no lining or nest whatever. Lieutenant Couch found them common on the Lower Rio Grande, but rare near Monterey, Mexico. They were frequently met with living in the sides of large deep wells.

Dr. Coues speaks of it as a common resident species in Arizona. It was one of the most abundant Owls of the Territory, and was not unfrequently to be observed at midday. On one occasion he found it preying upon Blackbirds, in the middle of a small open reed swamp.

It is not uncommon in the vicinity of Washington, and after the partial destruction of the Smithsonian Building by fire, for one or two years a pair nested in the top of the tower. It is quite probable that the comparative rarity of the species in the Eastern States is owing to their thoughtless destruction, the result of a short-sighted and mistaken prejudice that drives away one of our most useful birds, and one which rarely does any mischief among domesticated birds, but is, on the contrary, most destructive to rats, mice, and other mischievous and injurious vermin.

Mr. Audubon mentions two of these birds which had been kept in confinement in Charleston, S. C., where their cries in the night never failed to attract others of the species. He regards them as altogether crepuscular in habits, and states that when disturbed in broad daylight they always fly in an irregular and bewildered manner. Mr. Audubon also states that so far as his observations go, they feed entirely on small quadrupeds, as he has never found the remains of any feathers or portions of birds in their stomachs or about their nests. In confinement it partakes freely of any kind of flesh.

The Cuban race (var. furcata), also found in other West India islands, is hardly distinguishable from our own bird, and its habits may be presumed to be essentially the same. Mr. Gosse found the breeding-place of the Jamaica Owl at the bottom of a deep limestone pit, in the middle of October; there was one young bird with several eggs. There was not the least vestige of a nest; the bird reposed on a mass of half-digested hair mingled with bones. At a little distance were three eggs, at least six inches apart. On the 12th of the next month he found in the same place the old bird sitting on four eggs, this time placed close together. There was still no nest. The eggs were advanced towards hatching, but in very different degrees, and an egg ready for deposition was found in the oviduct of the old bird.

An egg of this Owl, taken in Louisiana by Dr. Trudeau, measured 1.69 inches in length by 1.38 in breadth. Another, obtained in New Mexico, measures 1.69 by 1.25. Its color is a dirty yellowish-white, its shape an oblong oval, hardly more pointed at the smaller than at the larger end.

An egg from Monterey, California, collected by Dr. Canfield, measures 1.70 inches in length by 1.25 in breadth, of an oblong-oval shape, and nearly equally obtuse at either end. It is of a uniform bluish-white. Another from the Rio Grande is of a soiled or yellowish white, and of the same size and shape.

Char. Size medium. Ear-tufts well developed or rudimentary; head small; eyes small. Cere much arched, its length more than the chord of the culmen. Bill weak, compressed. Only the first, or first and second, outer primary with its inner web emarginated. Tail about half the wing, rounded. Ear-conch very large, gill-like, about as long as the height of the skull, with an anterior operculum, which extends its full length, and bordered posteriorly by a raised membrane; the two ears asymmetrical.

A. Otus, Cuvier. Ear-tufts well developed; outer quill only with inner web emarginated.

Colors blackish-brown and buffy-ochraceous,—the former predominating above, where mottled with whitish; the latter prevailing beneath, and variegated with stripes or bars of dusky. Tail, primaries, and secondaries, transversely barred (obsoletely in O. stygius).

1. O. vulgaris. Ends of primaries normal, broad; toes feathered; face ochraceous.

Dusky of the upper parts in form of longitudinal stripes, contrasting conspicuously with the paler ground-color. Beneath with ochraceous prevalent; the markings in form of longitudinal stripes, with scarcely any transverse bars. Hab. Europe and considerable part of the Old World … var. vulgaris.19

Dusky of the upper parts in form of confused mottling, not contrasting conspicuously with the paler ground-color. Beneath with the ochraceous overlaid by the whitish tips to the feathers; the markings in form of transverse bars, which are broader than the narrow medial streak. Wing, 11.50–12.00; tail, 6.00–6.20; culmen, .65; tarsus, 1.20–1.25; middle toe, 1.15. Wing-formula, 2, 3–4–1. Hab. North America … var. wilsonianus.

2. O. stygius.20 Ends of primaries narrow, that of the first almost falcate; toes entirely naked; face dusky, or with dusky prevailing.

Above blackish-brown, thinly relieved by an irregular sparse spotting of yellowish-white. Beneath with the markings in form of longitudinal stripes, which throw off occasional transverse arms toward the edge of the feathers. Wing, 13.00; tail, 6.80; culmen, .90; tarsus, 1.55; middle toe, 1.50. Wing-formula, 2, 3–4, 1. Hab. South America.

B. Brachyotus, Gould (1837). Similar to Otus, but ear-tufts rudimentary, and the second quill as well as the first with the inner web emarginated.

Colors ochraceous, or white, and clear dark brown, without shadings or middle tints. Beneath with narrow longitudinal dark stripes upon the whitish or ochraceous ground-color; crown and neck longitudinally striped with dark brown and ochraceous.

3. O. brachyotus. Wings and tail nearly equally spotted and banded with ochraceous and dark brown. Tail with about six bands, the ochraceous terminal. Face dingy ochraceous, blackish around the eyes. Wing, about 11.00–13.00; tail, 5.75–6.10; culmen, .60–.65; tarsus, 1.75–1.80; middle toe, 1.20. Hab. Whole world (except Australia?).

Though this genus is cosmopolitan, the species are few in number; two of them (O. vulgaris and O. brachyotus) are common to both North America and Europe, one of them (the latter) found also in nearly every country in the world. Besides these, South Africa has a peculiar species (O. capensis) while Tropical America alone possesses the O. stygius.

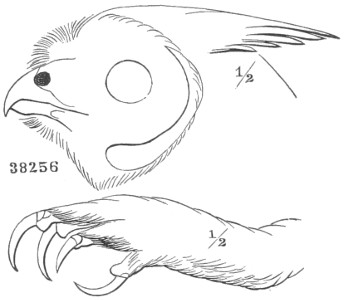

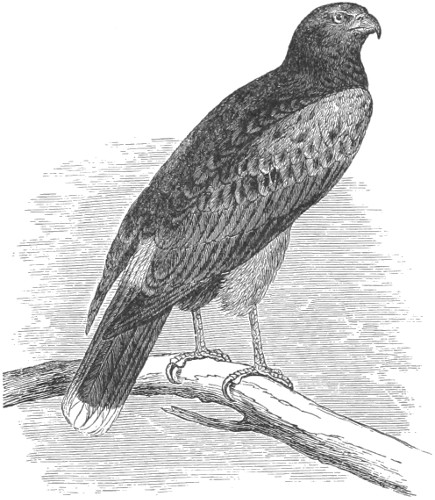

? Strix peregrinator (?), Bart. Trav. 1792, p. 285.—Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. 1854, 196. Asio peregrinator, Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 1855, 207. Otus wilsonianus, Less. Tr. Orn. 1831, 110.—Gray, Gen. fol. sp. 2, 1844.—Ib. List Birds Brit. Mus. p. 105.—Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. 1854, 81.—Ib. Birds N. Am. 1858, 53.—Coop. & Suck. 1860, 155.—Coues, Prod. 1866, 14. Otus americanus, Bonap. List, 1838, p. 7.—Ib. Consp. p. 50.—Wederb. & Tristr. Cont. Orn. 1849, p. 81.—Kaup, Monog. Strig. Cont. Orn. 1852, 113.—Ib. Trans. Zoöl. Soc. IV, 1859, 233.—Max. Cab. Jour. VI, 1858, 25.—Gray, Hand List, I, 1869, No. 540, p. 50. Strix otus, Wils. Am. Orn. 1808, pl. li, f. 1.—Rich. & Sw. F. B. A. II, 72.—Bonap. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. II, 37.—Ib. Isis, 1832, 1140.—Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 572.—Ib. Birds Am. pl. ccclxxxiii.—Peab. Birds, Mass. 88. Ulula otus, Jard. ed. Wils. Am. Orn. I, 1831, 104.—Brewer, ed. Wils. Am. Orn. Synop. p. 687.—Nutt. Man. 130. Otus vulgaris (not of Fleming!), Jardine, ed. Wils. Am. Orn. 1832, II, 278.—Aud. Synop. 1831, 28.—Giraud, Birds Long Island, p. 25. Otus vulgaris, var. wilsonianus (Ridgway), Coues, Key, 1872, 204. Bubo asio, De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 25, pl. xii, f. 25.

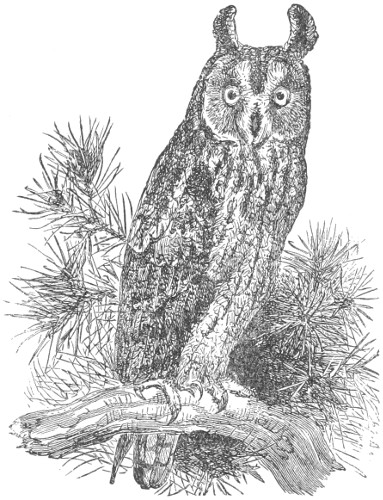

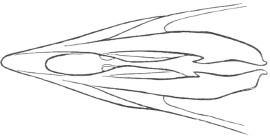

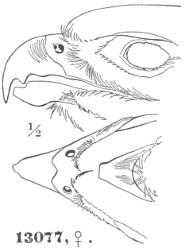

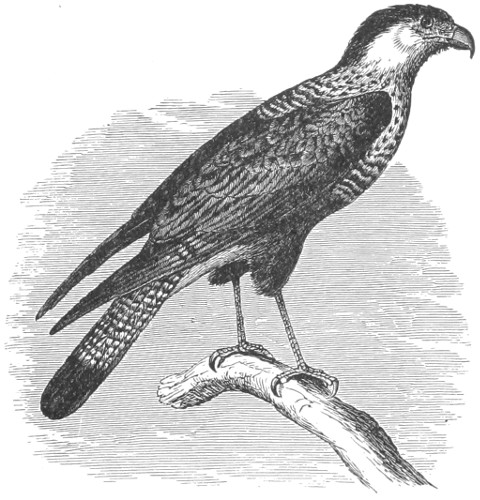

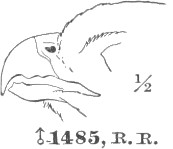

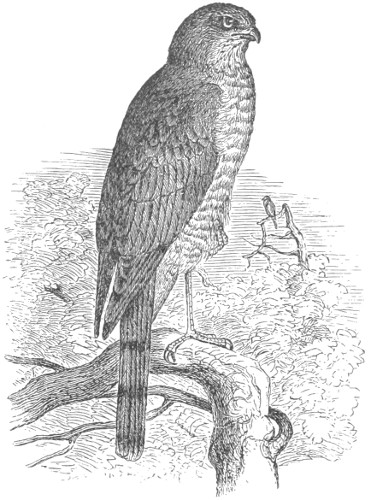

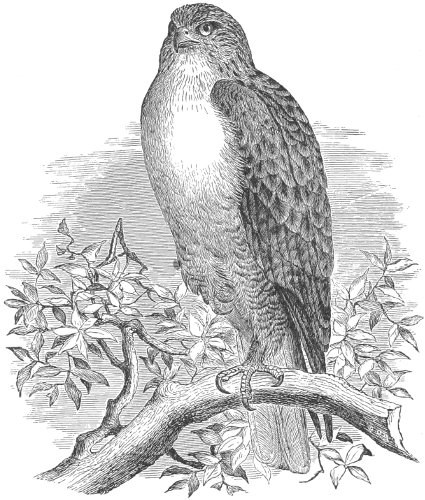

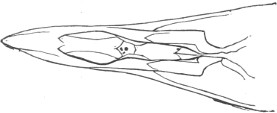

Sp. Char. Adult. Upper surface transversely mottled with blackish-brown and grayish-white, the former predominating, especially on the dorsal region; feathers of the nape and wings (only), ochraceous beneath the surface, lower scapulars with a few obsolete spots of white on lower webs. Primary coverts dusky, with transverse series of dark mottled grayish spots, these becoming somewhat ochraceous basally; ground-color of the primaries grayish, this especially prevalent on the inner quills; the basal third (or less) of all are ochraceous, this decreasing in extent on inner feathers; the grayish tint is everywhere finely mottled transversely with dusky, but the ochraceous is plain; primaries crossed by a series of about seven quadrate blackish-brown spots, these anteriorly about as wide as the intervening yellowish or mottled grayish; the interval between the primary coverts to the first of these spots is about .80 to 1.00 inch on the fourth quill,—the spots on the inner and outer feathers approaching the coverts, or even underlying them; the inner primaries—or, in fact, the general exposed grayish surface—has much narrower bars of dusky. Ground-color of the wings like the back, this growing paler on the outer feathers, and becoming ochraceous basally; the tip approaching whitish; secondaries crossed by nine or ten narrow bands of dusky.

Ear-tufts, with the lateral portion of each web, ochraceous; this becoming white, somewhat variegated with black, toward the end of the inner webs, on which the ochraceous is broadest; medial portion clear, unvariegated black. Forehead and post-auricular disk minutely speckled with blackish and white; facial circle continuous brownish-black, becoming broken into a variegated collar across the throat. “Eyebrows” and lores grayish-white; eye surrounded with blackish, this broadest anteriorly above and below, the posterior half being like the ear-coverts. Face plain ochraceous; chin and upper part of the throat immaculate white. Ground-color below pale ochraceous, the exposed surface of the feathers, however, white; breast with broad longitudinal blotches of clear dark brown, these medial, on the feathers; sides and flanks, each feather with a medial stripe, crossed by as broad, or broader, transverse bars, of blackish-brown; abdomen, tibial plumes, and legs plain ochraceous, becoming nearly white on the lower part of tarsus and on the toes; tibial plumes with a few sagittate marks of brownish; lower tail-coverts each having a medial sagittate mark of dusky, this continuing along the shaft, forking toward the base. Lining of the wing plain pale ochraceous; inner primary coverts blackish-brown, forming a conspicuous spot.

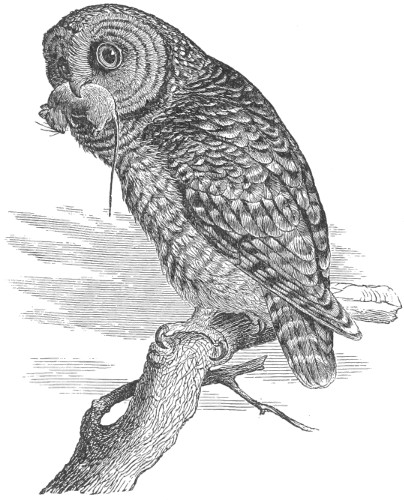

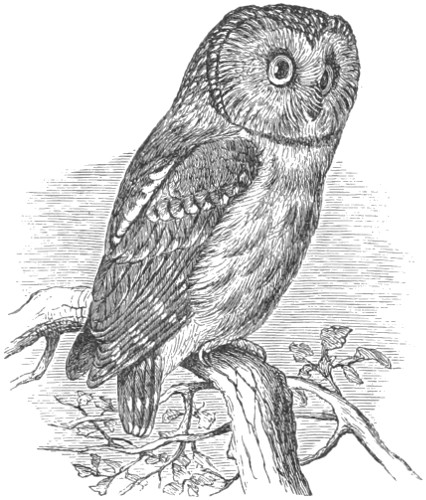

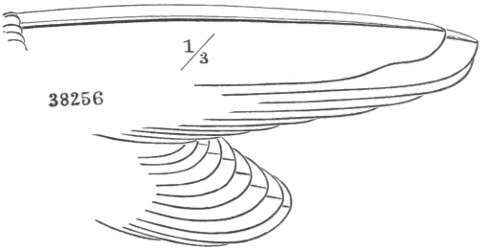

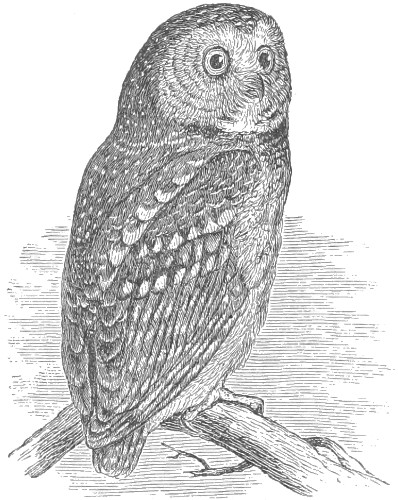

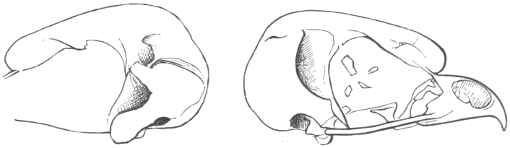

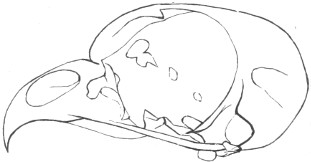

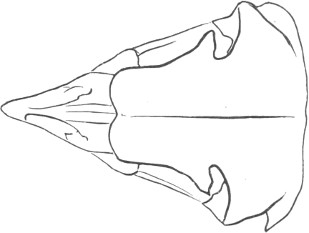

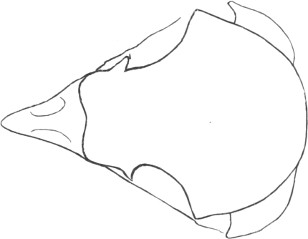

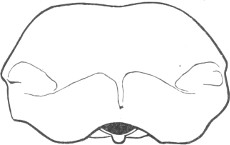

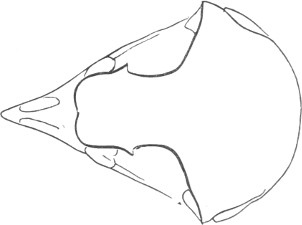

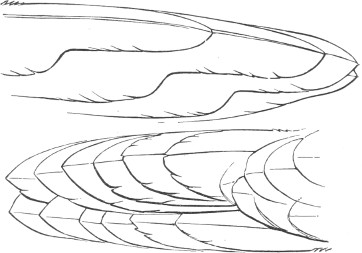

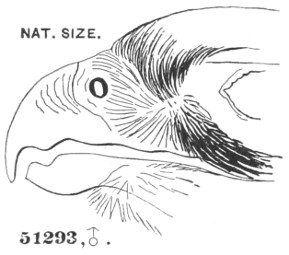

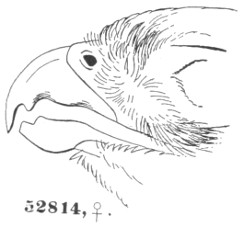

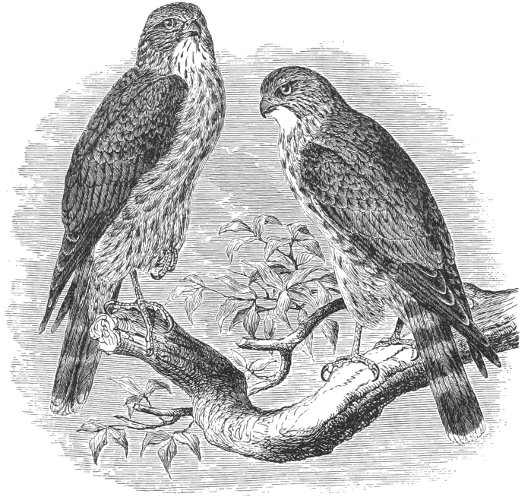

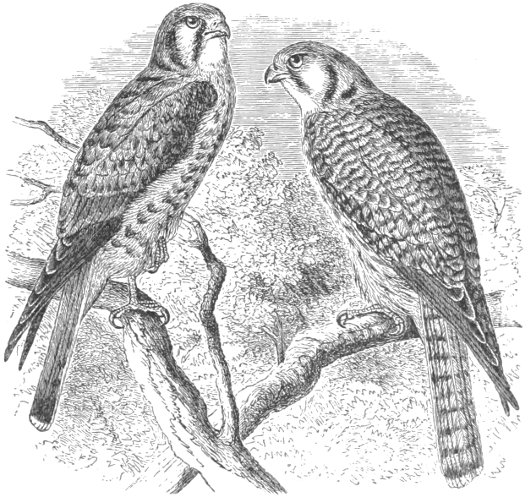

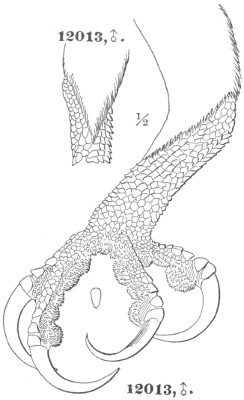

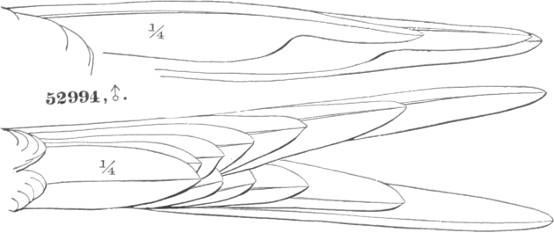

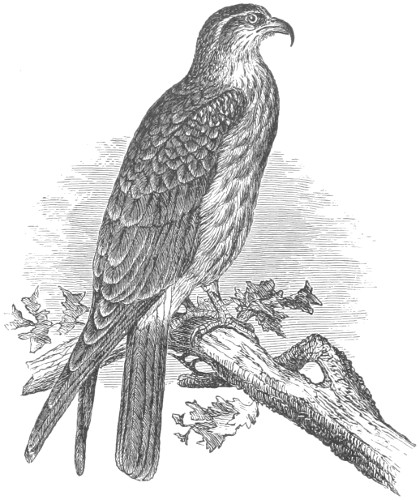

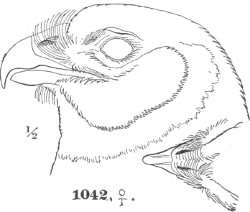

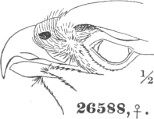

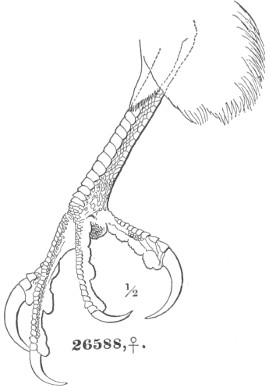

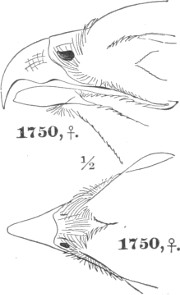

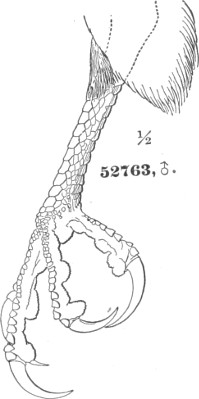

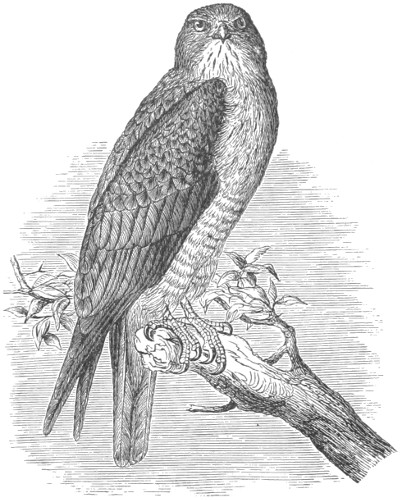

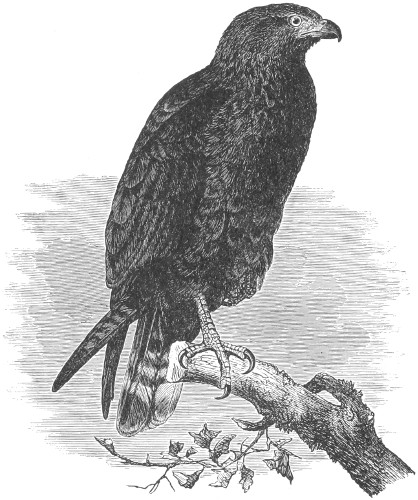

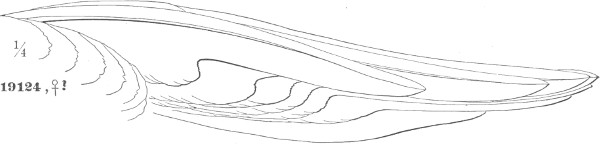

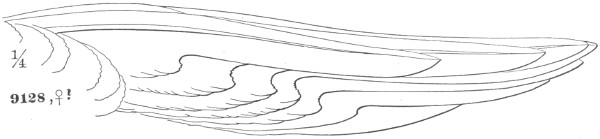

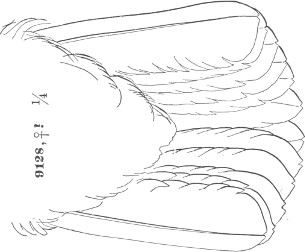

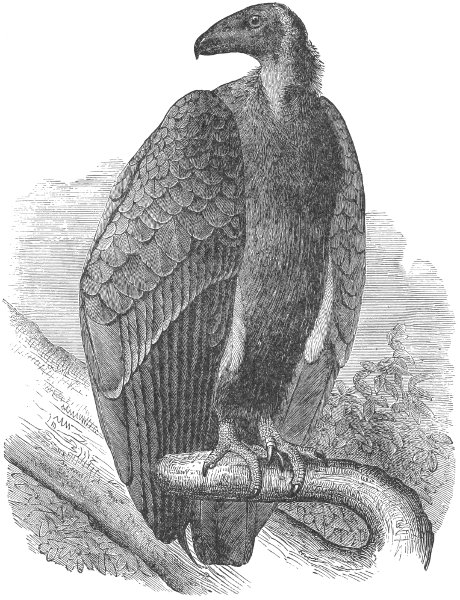

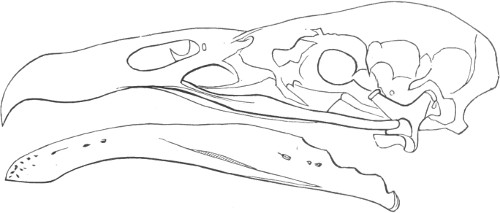

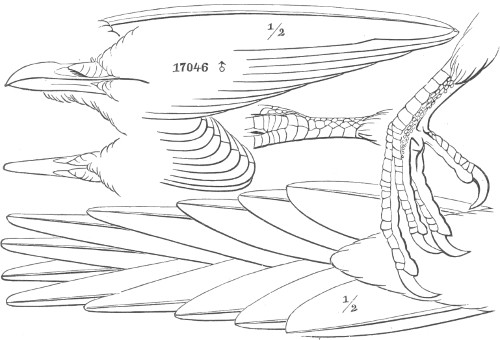

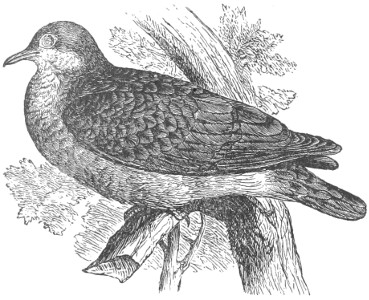

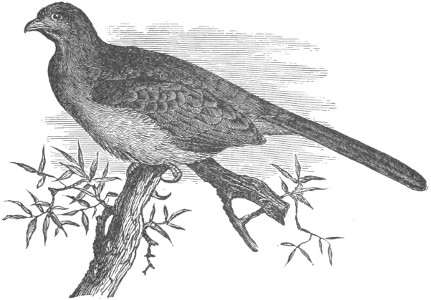

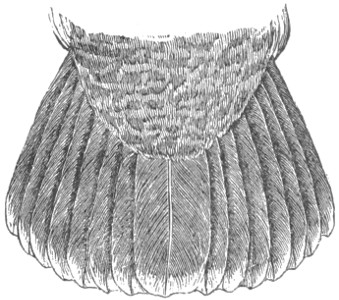

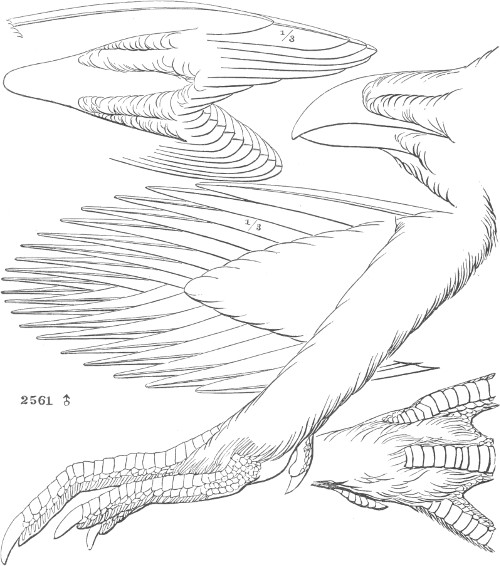

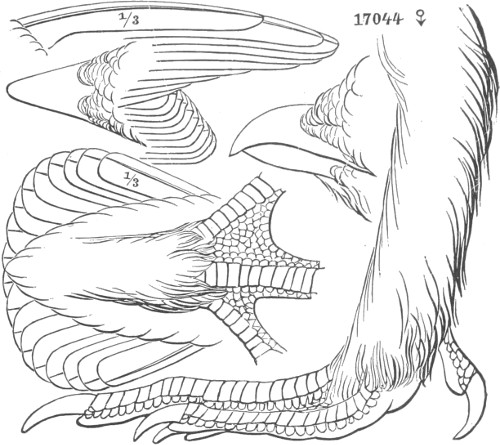

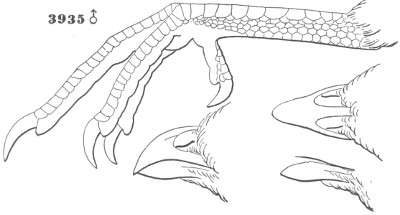

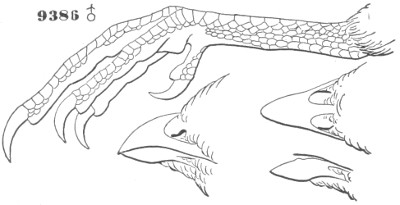

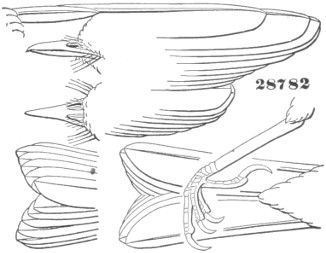

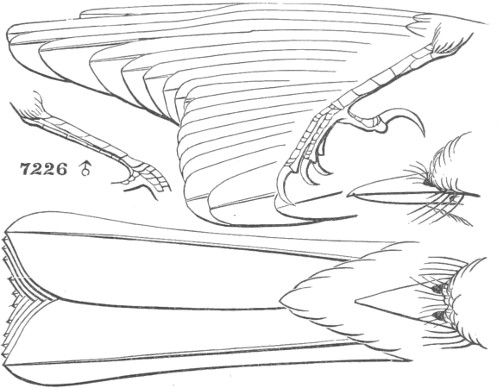

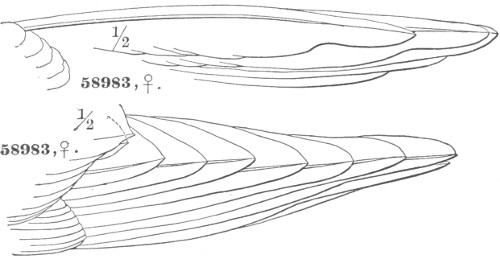

38256 ½ ½

Otus wilsonianus.

♂ (51,227, Carlisle, Penn.; S. F. Baird). Wing formula, 2, 3–1, 4, etc. Wing, 11.50; tail, 6.20; culmen, .65; tarsus, 1.20; middle toe, 1.15.

♀ (2,362, Professor Baird’s collection, Carlisle, Penn.). Wing formula, 2, 3–4–1. Wing, 12.00; tail, 6.00; culmen, .65; tarsus, 1.25; middle toe, 1.15.

Young (49,568, Sacramento, Cal., June 21, 1867; Clarence King, Robert Ridgway). Wings and tail as in the adult; other portions transversely banded with blackish-brown and grayish-white, the latter prevailing anteriorly; eyebrows and loral bristles entirely black; legs white.

Hab. Whole of temperate North America? Tobago? (Jardine).

Localities: Tobago (Jardine, Ann. Mag. 18, 116); Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 50).

The American Long-eared Owl is quite different in coloration from the Otus vulgaris of Europe. In the latter, ochraceous prevails over the whole surface, even above, where the transverse dusky mottling does not approach the uniformity that it does in the American bird; in the European bird, each feather above has a conspicuous medial longitudinal stripe of dark brownish: these markings are found everywhere except on the rump and upper tail-coverts, where the ochraceous is deepest, and transversely clouded with dusky mottling; in the American bird, no longitudinal stripes are visible on the upper surface. The ochraceous of the lower surface is, in the vulgaris, varied only (to any considerable degree) by the sharply defined medial longitudinal stripes to the feathers, the transverse bars being few and inconspicuous; in wilsonianus, white overlies the ochraceous below, and the longitudinal are less conspicuous than the transverse markings; the former on the breast are broader than in vulgaris, in which, also, the ochraceous at the bases of the primaries occupies a greater extent. Comparing these very appreciable differences with the close resemblance of other representative styles of the two continents (differences founded on shade or depth of tints alone), we were almost inclined to recognize in the American Long-eared Owl a specific value to these discrepancies.

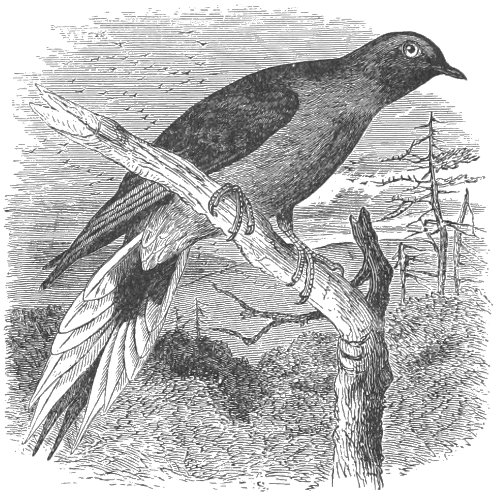

Otus vulgaris.

The Otus stygius, Wagl., of South America and Mexico, is entirely distinct, as will be seen from the foregoing synoptical table.

Habits. This species appears to be one of the most numerous of the Owls of North America, and to be pretty generally distributed. Its strictly nocturnal habits have caused it to be temporarily overlooked in localities where it is now known to be present and not rare. Dr. William Gambel and Dr. Heermann both omit it from their lists of the birds of California, though Dr. J. G. Cooper has since found it quite common. It was once supposed not to breed farther south than New Jersey, but it is now known to be resident in South Carolina and in Arizona, and is probably distributed through all the intervening country. Donald Gunn writes that to his knowledge this solitary bird hunts in the night, both summer and winter, in the Red River region. It there takes possession of the deserted nests of crows, and lays four white eggs. He found it as far as the shores of Hudson’s Bay. Richardson states it to be plentiful in the woods skirting the plains of the Saskatchewan, frequenting the coast of the bay in the summer, and retiring into the interior in the winter. He met with it as high as the 16th parallel of latitude, and believed it to occur as far as the forests extend.

Dr. Cooper met with this species on the banks of the Columbia, east of the Dalles. The region was desolate and barren, and several species of Owls appeared to have been drawn there by the abundance of hares and mice. Dr. Suckley also met with it on a branch of Milk River, in Nebraska. It has likewise been taken in different parts of California, in New Mexico, among the Rocky Mountains, in the valley of the Rio Grande, at Fort Benton, and at Cape Florida, in the last-named place by Mr. Würdemann.

Dr. Cooper found this Owl quite common near San Diego, and in March observed them sitting in pairs in the evergreen oaks, apparently not much troubled by the light. On the 27th of March he found a nest, probably that of a Crow, built in a low evergreen oak, in which a female Owl was sitting on five eggs, then partly hatched. The bird was quite bold, flew round him, snapping her bill at him, and tried to draw him away from the nest; the female imitating the cries of wounded birds with remarkable accuracy, showing a power of voice not supposed to exist in Owls, but more in the manner of a Parrot. He took one of the eggs, and on the 23d of April, on revisiting the nest, he found that the others had hatched. The egg measured 1.60 by 1.36 inches. Dr. Cooper also states that he has found this Owl wandering into the barren treeless deserts east of the Sierra Nevada, where it was frequently to be met with in the autumn, hiding in the thickets along the streams. It also resorts to caves, where any are to be found.

Dr. Kennerly met with this bird in the cañons west of the Aztec Mountains, where they find good places for their nests, which they build, in common with Crows and Hawks, among the precipitous cliffs,—places unapproachable by the wolf and lynx.

On the Atlantic coast the Long-eared Owl occurs in more or less abundance from Nova Scotia to Florida. It is found in the vicinity of Halifax, according to Mr. Downes, and about Calais according to Mr. Boardman, though not abundantly in either region. In Western Maine, and in the rest of New England, it is more common. It has been known to breed at least as far south as Maryland, Mr. W. M. McLean finding it in Rockville. Mr. C. N. Holden, Jr., during his residence at Sherman, in Wyoming Territory, met with a single specimen of this bird. A number of Magpies were in the same bush, but did not seem either to molest or to be afraid of it.

The food of this bird consists chiefly of small quadrupeds, insects, and, to some extent, of small birds of various kinds. Audubon mentions finding the stomach of one stuffed with feathers, hair, and bones.

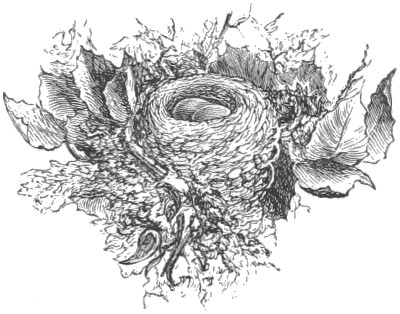

The Long-eared Owl appears to nest for the most part in trees, and also frequently to make use of the nests of other birds, such as Crows, Hawks, or Herons. Occasionally, however, they construct nests for themselves. Audubon speaks of finding such a one near the Juniata River, in Pennsylvania. This was composed of green twigs with the leaflets adhering, and lined with fresh grass and sheep’s wool, but without feathers. Mr. Kennicott sent me from Illinois an egg of this bird, that had been taken from a nest on the ground; and, according to Richardson, in the fur regions it sometimes lays its eggs in that manner, at other times in the deserted nests of other birds, on low bushes. Mr. Hutchins speaks of its depositing them as early as April. Richardson received one found in May; and another nest was observed, in the same neighborhood, which contained three eggs on the 5th of July. Wilson speaks of this Owl as having been abundant in his day in the vicinity of Philadelphia, and of six or seven having been found in a single tree. He also mentions it as there breeding among the branches of tall trees, and in one particular instance as having taken possession of the nest of a Qua Bird (Nyctiardea gardeni), where Wilson found it sitting on four eggs, while one of the Herons had her own nest on the same tree. Audubon states that it usually accommodates itself by making use of the abandoned nests of other birds, whether these are built high or low. It also makes use of the fissures of rocks, or builds on the ground.

As this Owl is known to breed early in April, and as numerous instances are given of their eggs being taken in July, it is probable they have two broods in a season. Mr. J. S. Brandigee, of Berlin, Conn., found a nest early in April, in a hemlock-tree, situated in a thick dark evergreen woods. The nest was flat, made of coarse sticks, and contained four fresh eggs when the parent was shot.

Mr. Ridgway found this Owl to be very abundant in the Sacramento Valley, as well as throughout the Great Basin, in both regions inhabiting dense willow copses near the streams. In the interior it generally lays its eggs in the deserted nests of the Magpie.

The eggs of this Owl, when fresh, are of a brilliant white color, with a slight pinkish tinge, which they preserve even after having been blown, if kept from the light. They are of a rounded-oval shape, and obtuse at either end. They vary considerably in size, measuring from 1.65 to 1.50 inches in length, and from 1.30 to 1.35 inches in breadth. Two eggs, taken from the same nest by Rev. C. M. Jones, have the following measurements: one 1.60 by 1.34 inches, the other 1.50 by 1.30 inches.

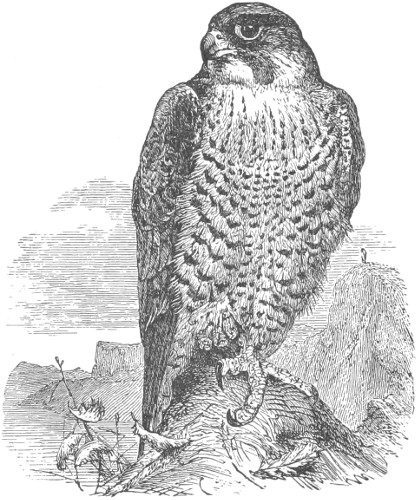

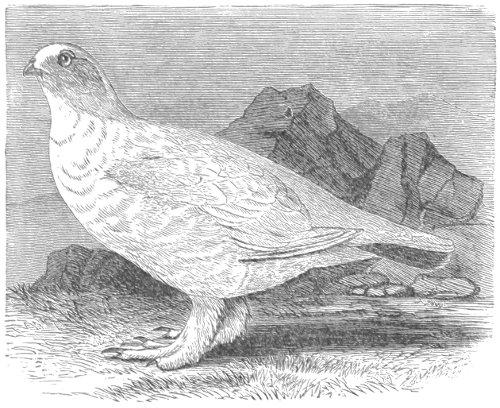

Strix brachyotus, Gmel. Syst. Nat. 289, 1789.—Forst. Phil. Trans. LXII, 384.—Wils. Am. Orn. pl. xxxiii, f. 3.—Aud. Birds Am. pl. ccccxxxii, 1831.—Ib. Orn. Biog. V, 273.—Rich. & Swains. F. B. A. II, 75.—Bonap. Ann. Lyc. N. Y. II, 37.—Thomps. N. H. Vermont, p. 66.—Peab. Birds Mass. p. 89. Ulula brachyotus, James. (Wils.), Am. Orn. I, 106, 1831.—Nutt. Man. 132. Otus brachyotus, (Steph.) Jard. (Wils.), Am. Orn. II, 63, 1832.—Peale, U. S. Expl. Exp. VIII, 75.—Kaup, Monog. Strig. Cont. Orn. 1852, 114.—Ib. Tr. Zoöl. Soc. IV, 1859, 236.—Hudson, P. Z. S. 1870, 799 (habits). Asio brachyotus, Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 259, 1855. Otus brachyotus americanus, Max. Cab. Jour. II, 1858, 27. Brachyotus palustris, Bonap. List. 1838, p. 7.—Ridgw. in Coues, Key, 1872, 204. Otus palustris, (Darw.) De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 28, pl. xii, f. 27, 1844. Brachyotus palustris americanus, Bonap. Consp. Av. p. 51, 1849. Brachyotus cassini, Brewer, Pr. Boston Soc. N. H.—Newb. P. R. Rep’t, VI, IV, 76.—Heerm. do. VII, 34, 1857.—Cassin (in Baird) Birds N. Am. 1858, 54.—Coop. & Suckl. P. R. Rep’t, XII, ii, 155, 1860.—Coues, P. A. N. S. (Prod. Orn. Ariz.) 1866, 14.—Gray, Hand List, I, 51, 1869. Brachyotus galopagoensis, Gould, P. Z. S. 1837, 10. Otus galopagoensis, Darw. Zool. Beag. pt. iii, p. 32, pl. iii.—Gray, Gen. fol. sp. 3; List Birds Brit. Mus. 108.—Bonap. Consp. 51. Asio galopagoensis, Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 1855, 211.

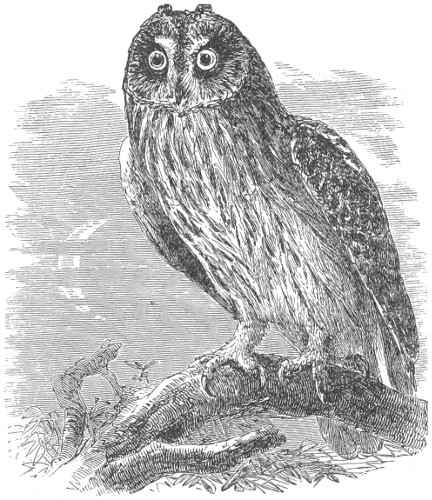

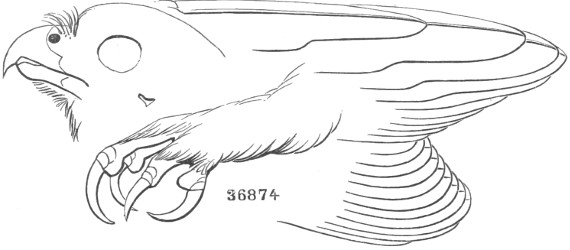

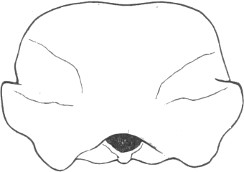

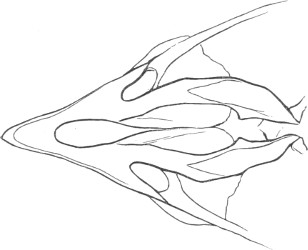

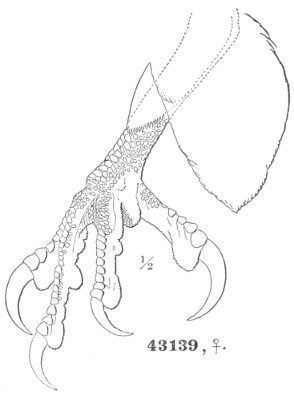

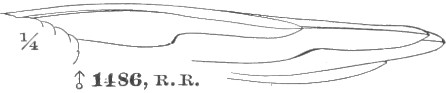

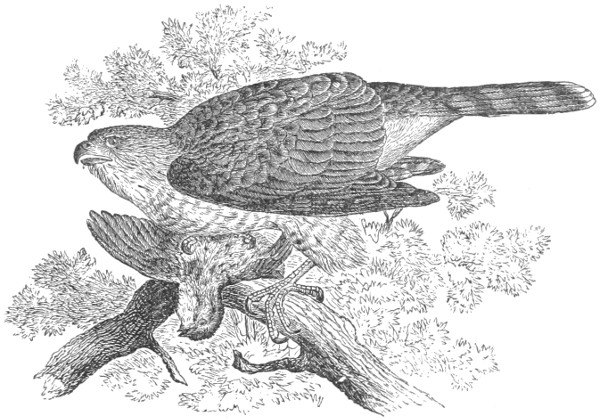

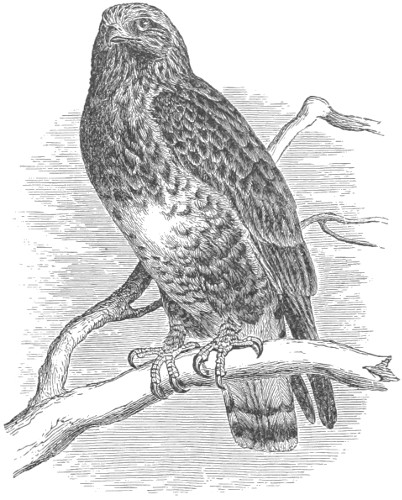

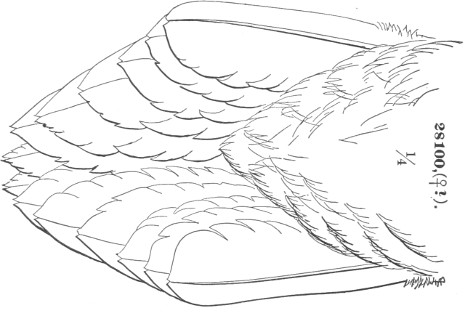

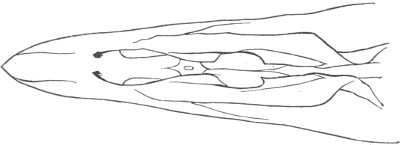

Sp. Char. Adult. Ground-color of the head, neck, back, scapulars, rump, and lower parts, pale ochraceous; each feather (except on the rump) with a medial longitudinal stripe of blackish-brown,—these broadest on the scapulars; on the back, nape, occiput, and jugulum, the two colors about equal; on the lower parts, the stripes grow narrower posteriorly, those on the abdomen and sides being in the form of narrow lines. The flanks, legs, anal region, and lower tail-coverts are always perfectly immaculate; the legs most deeply ochraceous, the lower tail-coverts nearly pure white. The rump has obsolete crescentic marks of brownish. The wings are variegated with the general dusky and ochraceous tints, but the markings are more irregular; the yellowish in form of indentations or confluent spots, approaching the shafts from the edge,—broadest on the outer webs. Secondaries crossed by about five bands of ochraceous, the last terminal; primary coverts plain blackish-brown, with one or two poorly defined transverse series of ochraceous spots on the basal portion. Primaries ochraceous on the basal two-thirds, the terminal portion clear dark brown, the tips (broadly) pale brownish-yellowish, this becoming obsolete on the longest; the dusky extends toward the bases, in three to five irregularly transverse series of quadrate spots on the outer webs, leaving, however, a large basal area of plain ochraceous,—this somewhat more whitish anteriorly. The ground-color of the tail is ochraceous,—this becoming whitish exteriorly and terminally,—crossed by five broad bands (about equalling the ochraceous, but becoming narrower toward outer feathers) of blackish-brown; on the middle feathers, the ochraceous spots enclose smaller, central transverse spots of blackish; the terminal ochraceous band is broadest.

Eyebrows, lores, chin, and throat soiled white, the loral bristles with black shafts; face dingy ochraceous-white, feathers with darker shafts; eye broadly encircled with black. Post-orbital circle minutely speckled with pale ochraceous and blackish, except immediately behind the ear, where for about an inch it is uniform dusky.

Lining of the wing immaculate delicate yellowish-white; terminal half of under primary coverts clear blackish-brown; under surface of primaries plain delicate ochraceous-white; ends, and one or two very broad anterior bands, dusky.

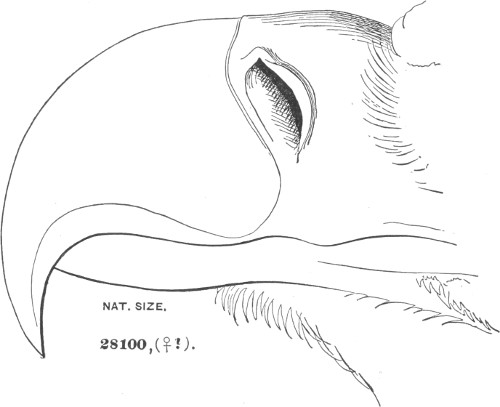

♂ (906, Carlisle, Penn.). Wing-formula, 2–1, 3. Wing, 11.80; tail, 5.80; culmen, .60; tarsus, 1.75; middle toe, 1.20.

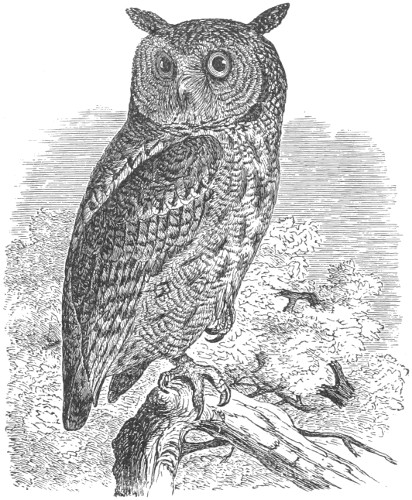

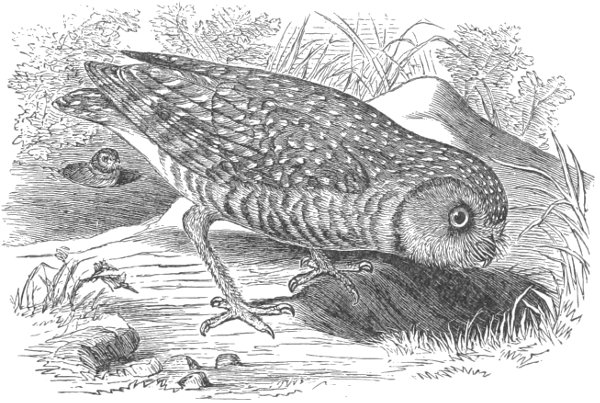

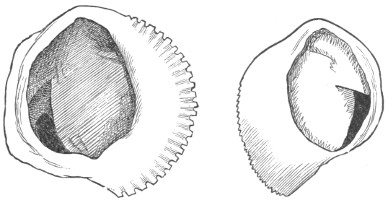

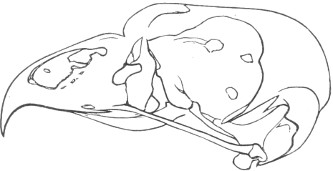

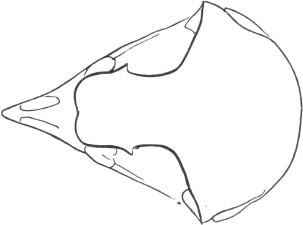

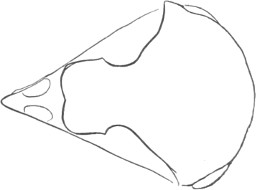

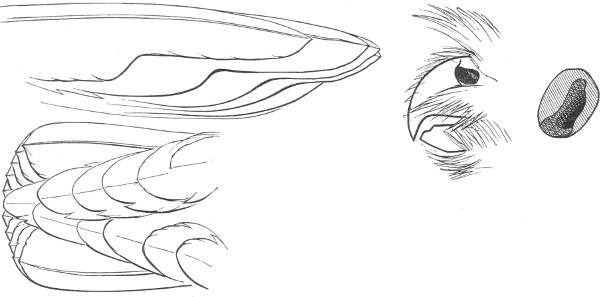

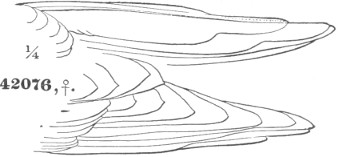

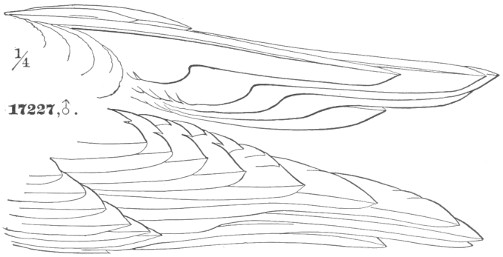

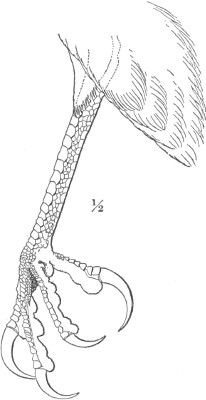

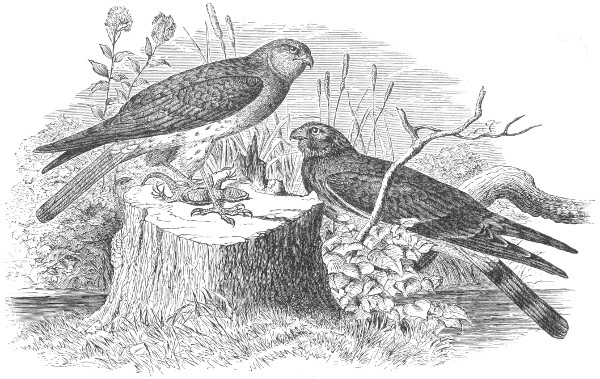

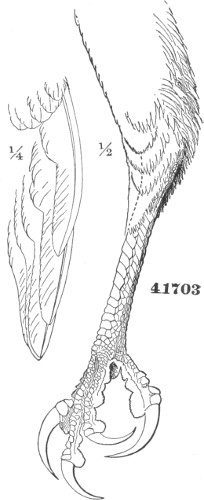

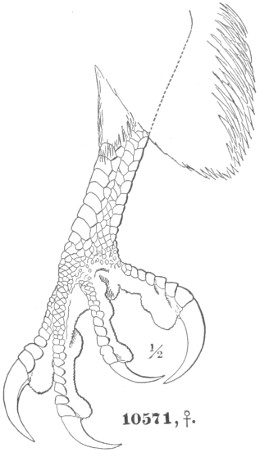

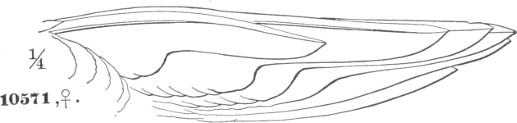

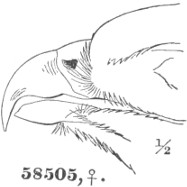

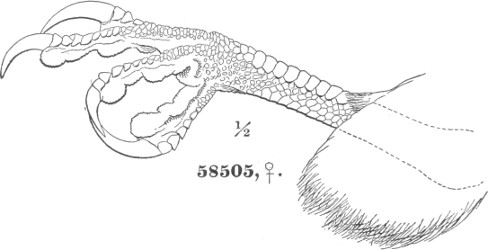

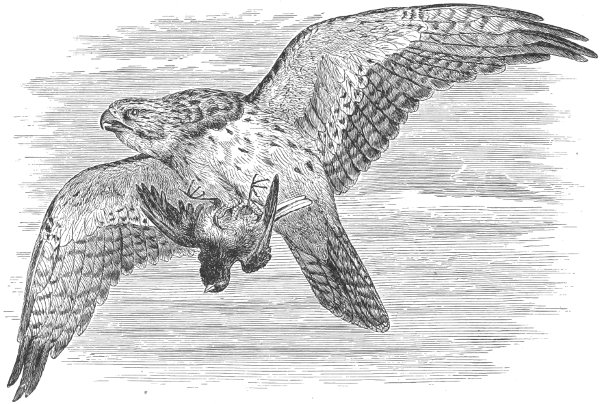

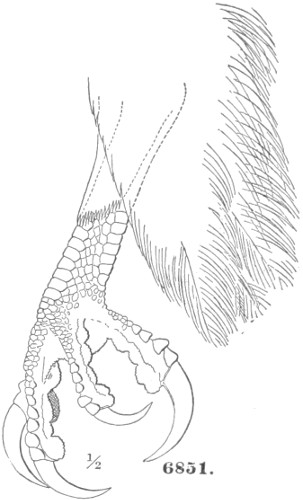

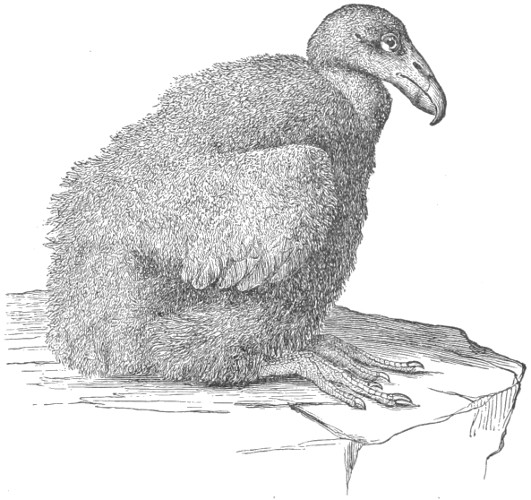

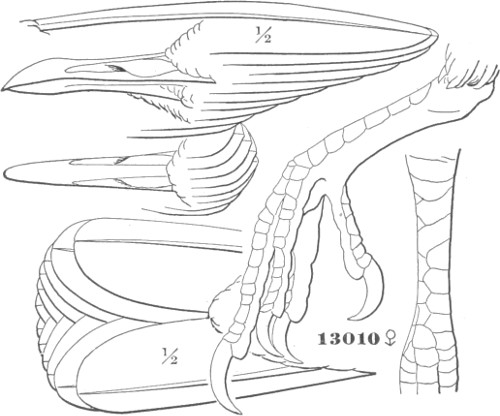

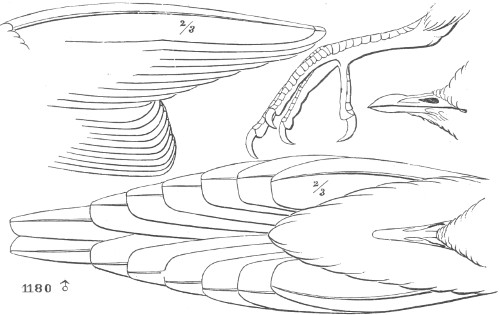

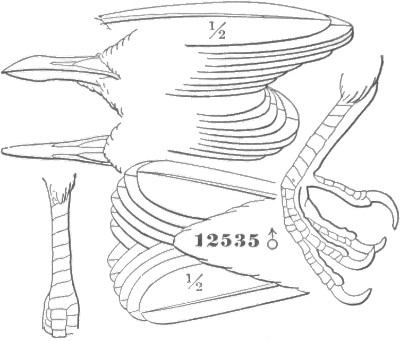

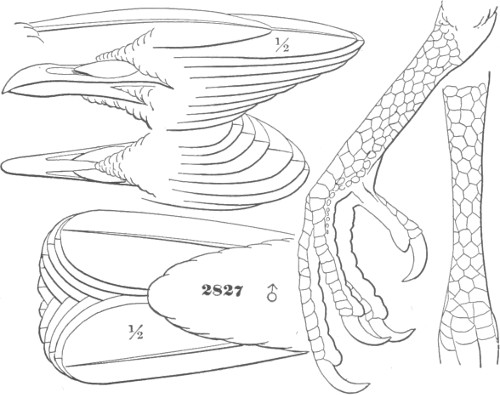

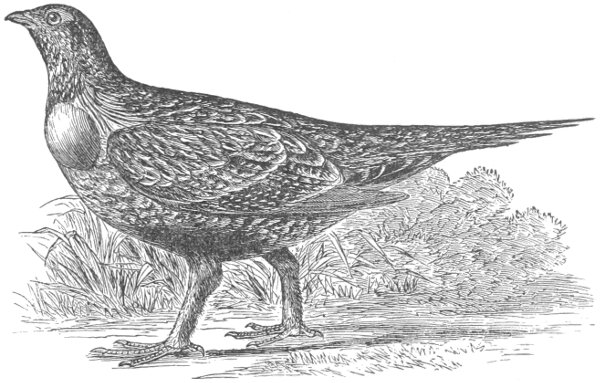

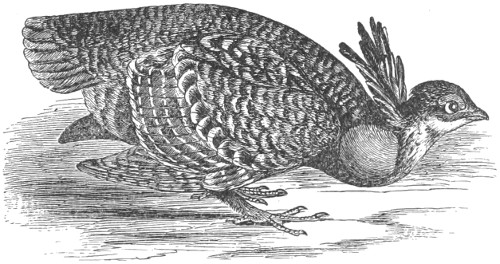

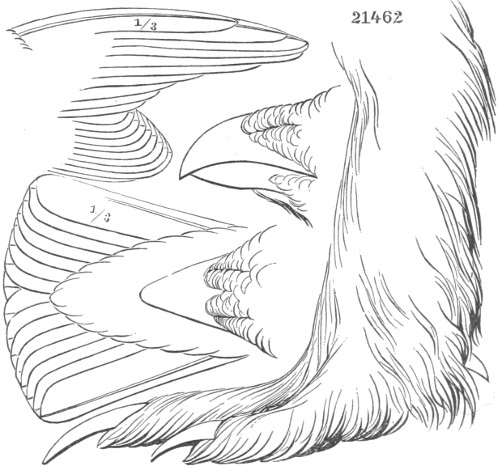

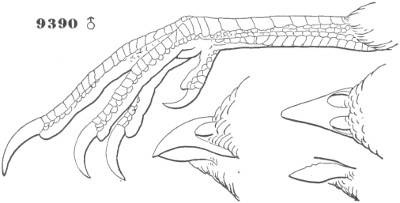

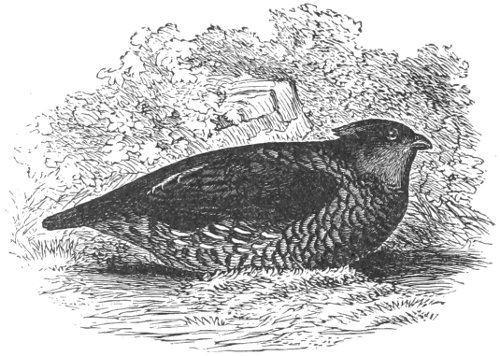

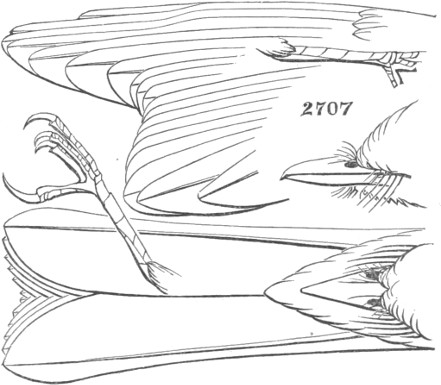

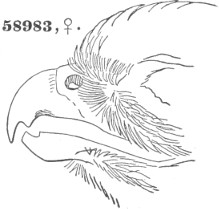

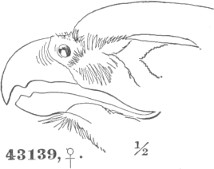

6888 ½ ½

Otus brachyotus.

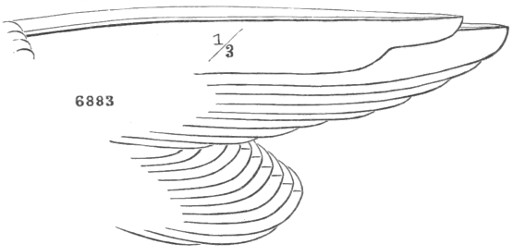

6883 ⅓

Otus brachyotus.

♀ (1,059, Dr. Elliot Coues’s collection, Washington, D. C.). Wing-formula, 2–3–1–4. Wing, 13.00; tail, 6.10; culmen, .65; tarsus, 1.80; middle toe, 1.20.

Hab. Entire continent and adjacent islands of America; also Europe, Asia, Africa, Polynesia, and Sandwich Islands.

Localities: Oaxaca (Scl. P. Z. S. 1859, 390); Cuba (Cab. Journ. III, 465; Gundl. Rept. 1865, 225, west end); Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 50); Brazil (Pelz. Orn. Bras. I, 10); Buenos Ayres (Scl. & Salv. P. Z. S. 1868, 143); Chile (Philippi, Mus. S. I.).

In view of the untangible nature of the differences between the American and European Short-eared Owls (seldom at all appreciable, and when appreciable not constant), we cannot admit a difference even of race between them. In fact, this species seems to be the only one of the Owls common to the two continents in which an American specimen cannot be distinguished from the European. The average plumage of the American representative is a shade or two darker than that of European examples; but the lightest specimens I have seen are several from the Yukon region in Alaska, and one from California (No. 6,888, Suisun Valley).

Not only am I unable to appreciate any tangible differences between European and North American examples, but I fail to detect characters of the least importance whereby these may be distinguished from South American and Sandwich Island specimens (“galopagoensis, Gould,” and “sandwichensis, Blox.”). Only two specimens, among a great many from South America (Paraguay, Buenos Ayres, Brazil, etc.), are at all distinguishable from Northern American. These two (Nos. 13,887 and 13,883, Chile) are somewhat darker than others, but not so dark as No. 16,029, ♀, from Fort Crook, California. A specimen from the Sandwich Islands (No. 13,890) is nearly identical with these Chilean birds, the only observable difference consisting in a more blackish forehead, and in having just noticeable dark shaft-lines on the lower tail-coverts.

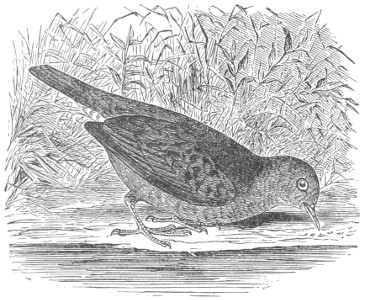

Otus brachyotus.

In the geographical variations of this species it is seen that the average plumage of North American specimens is just appreciably darker than that of European, while tropical specimens have a tendency to be still darker. I know of no bird so widely distributed which varies so little in the different parts of its habitat, unless it be the Cotyle riparia, which, however, is not found so far to the south. The difference, in this case, between the American and European birds, does not correspond at all to that between the two easily distinguished races of Otus vulgaris, Nyctale tengmalmi, Surnia ulula, and Syrnium cinereum.

A specimen from Porto Rico (No. 39,643) is somewhat remarkable on account of the prevalence of the dusky of the upper parts, the unusually few and narrow stripes of the same on the lower parts, the roundish ochraceous spots on the wings, and in having the primaries barred to the base. Should all other specimens from the same region agree in these characters, they might form a diagnosable race. The plumage has an abnormal appearance, however, and I much doubt whether others like it will ever be taken.

Habits. The Short-eared Owl appears to be distributed, in varying frequency, throughout North America, more abundant in the Arctic regions during the summer, and more frequently met with in the United States during the winter months. Richardson met with it throughout the fur countries as far to the north as the 67th parallel. Professor Holböll gives it as a bird of Greenland, and it was met with in considerable abundance by MacFarlane in the Anderson River district. Mr. Murray mentions a specimen received from the wooded district between Hudson’s Bay and Lake Winnipeg. Captain Blakiston met with it on the coast of Hudson’s Bay, and Mr. Bernard Ross on the Mackenzie River.

Mr. Dresser speaks of it as common at times near San Antonio during the winter months, keeping itself in the tall weeds and grass. It is given by Dr. Gundlach as an occasional visitant of Cuba.

Dr. Newberry met with it throughout Oregon and California, and found it especially common in the Klamath Basin. On the level meadow-like prairies of the Upper Pitt River it was seen associating with the Marsh Hawk in considerable numbers. It was generally concealed in the grass, and rose as the party approached. He afterwards met with this bird on the shores of Klamath Lake, and in the Des Chutes Basin, among grass and sage-bushes, in those localities associated with the Burrowing Owl (A. hypogæa). In Washington Territory it was found by Dr. Cooper on the great Spokane Plain, where, as elsewhere, it was commonly found in the long grass during the day. In fall and winter it appeared in large numbers on the low prairies of the coast, but was not gregarious. Though properly nocturnal, it was met with, hunting on cloudy days, flying low over the meadows, in the manner of the Marsh Hawk. He did not meet with it in summer in the Territory.

Dr. Heermann found it abundant in the Suisun and Napa valleys of California, in equal numbers with the Strix pratincola. It sought shelter during the day on the ground among the reeds, and, when startled from its hiding-place, would fly but a few yards and alight again upon the ground. It did not seem wild or shy. He afterwards met with the same species on the desert between the Tejon Pass and the Mohave River, and again saw it on the banks of the latter. Richardson gives it as a summer visitant only in the fur countries, where it arrives as soon as the snow disappears, and departs again in September. A female was killed May 20 with eggs nearly ready for exclusion. The bird was by no means rare, and, as it frequently hunted for its prey in the daytime, was often seen. Its principal haunts appeared to be dense thickets of young pines, or dark and entangled willow-clumps, where it would sit on a low branch, watching assiduously for mice. When disturbed, it would fly low for a short distance, and then hide itself in a bush, from whence it was not easily driven. Its nest was said to be on the ground, in a dry place, and formed of withered grass. Hutchins is quoted as giving the number of its eggs as ten or twelve, and describing them as round. The latter is not correct, and seven appears to be their maximum number.

Mr. Downes speaks of it as very rare in Nova Scotia, but Elliott Cabot gives it as breeding among the islands in the Bay of Fundy, off the coast, where he found several nests. It was not met with by Professor Verrill in Western Maine, but is found in other parts of the State. It is not uncommon in Eastern Massachusetts, where specimens are frequently killed and brought to market for sale, and where it also breeds in favorable localities on the coast. Mr. William Brewster met with it on Muskeget, near Nantucket, where it had been breeding, and where it was evidently a resident, its plumage having become bleached by exposure to the sun, and the reflected light of the white sand of that treeless island. It is not so common in the interior, though Mr. Allen gives it as resident, and rather common, near Springfield. Dr. Wood found it breeding in Connecticut, within a few miles of Hartford.

Dr. Coues gives it as a resident species in South Carolina, and Mr. Allen also mentions it, on the authority of Mr. Boardman, as quite common among the marshes of Florida. Mr. Audubon also speaks of finding it so plentiful in Florida that on one occasion he shot seven in a single morning. They were to be found in the open prairies of that country, rising from the tall grass in a hurried manner, and moving in a zigzag manner, as if suddenly wakened from a sound sleep, and then sailing to some distance in a direct course, and dropping among the thickest herbage. Occasionally the Owl would enter a thicket of tangled palmettoes, where with a cautious approach it could be taken alive. He never found two of these birds close together, but always singly, at distances of from twenty to a hundred yards; and when two or more were started at once, they never flew towards each other.

Mr. Audubon met with a nest of this Owl on one of the mountain ridges in the great pine forest of Pennsylvania, containing four eggs nearly ready to be hatched. They were bluish-white, of an elongated form, and measured 1.50 inches in length and 1.12 in breadth. The nest, made in a slovenly manner with dry grasses, was under a low bush, and covered over with tall grass, through which the bird had made a path. The parent bird betrayed her presence by making a clicking noise with her bill as he passed by; and he nearly put his hand on her before she would move, and then she hopped away, and would not fly, returning to her nest as soon as he left the spot. The pellets disgorged by the Owl, and found near her nest, were found to consist of the bones of small quadrupeds mixed with hair, and the wings of several kinds of coleopterous insects.

This bird was found breeding near the coast of New Jersey by Mr. Krider; and at Hamilton, Canada, on the western shore of Lake Ontario; Mr. McIlwraith speaks of its being more common than any other Owl.

A nest found by Mr. Cabot was in the midst of a dry peaty bog. It was built on the ground, in a very slovenly manner, of small sticks and a few feathers, and presented hardly any excavation. It contained four eggs on the point of being hatched. A young bird the size of a Robin was also found lying dead on a tussock of grass in another similar locality.

The notes of Mr. MacFarlane supply memoranda of twelve nests found by him in the Anderson River country. They were all placed on the ground, in various situations. One was in a small clump of dwarf willows, on the ground, and composed of a few decayed leaves. Another nest was in a very small hole, lined with a little hay and some decayed leaves. This was on a barren plain of some extent, fifty miles east of Fort Anderson, and on the edge of the wooded country. A third was in a clump of Labrador Tea, and was similar to the preceding, except that the nest contained a few feathers. This nest contained seven eggs,—the largest number found, and only in this case. A fourth was in an artificial depression, evidently scratched out by the parent bird. Feathers seem to have been noticed in about half the nests, and in all cases to have been taken by the parent from her own breast. Nearly all the nests were in depressions made for the purpose.

Mr. Dall noticed the Short-eared Owl on the Yukon and at Nulato, and Mr. Bannister observed it at St. Michael’s, where it was a not unfrequent visitor. In his recent Notes on the Avi-fauna of the Aleutian Islands, (Pr. Cal. Academy, 1873,) Dall informs us that it is resident on Unalashka, and that it excavates a hole horizontally for its nesting-place,—usually to a distance of about two feet, the farther end a little the higher. The extremity is lined with dry grass and feathers. As there are no trees in the island, the bird was often seen sitting on the ground, near the mouth of its burrow, even in the daytime. Mr. Ridgway found this bird in winter in California, but never met with it at any season in the interior, where the O. wilsonianus was so abundant.

The eggs of this Owl are of a uniform dull white color, which in the unblown egg is said to have a bluish tinge; they are in form an elliptical ovoid. The eggs obtained by Mr. Cabot measured 1.56 inches in length and 1.25 in breadth. The smallest egg collected by Mr. MacFarlane measured 1.50 by 1.22 inches. The largest taken by Mr. B. R. Ross, at Fort Simpson, measures 1.60 by 1.30 inches; their average measurement is 1.57 by 1.28 inches. An egg of the European bird measures 1.55 by 1.30 inches.

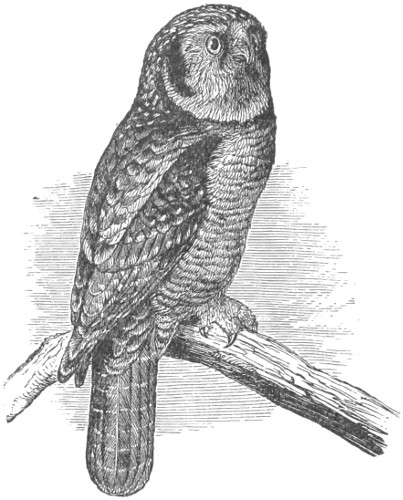

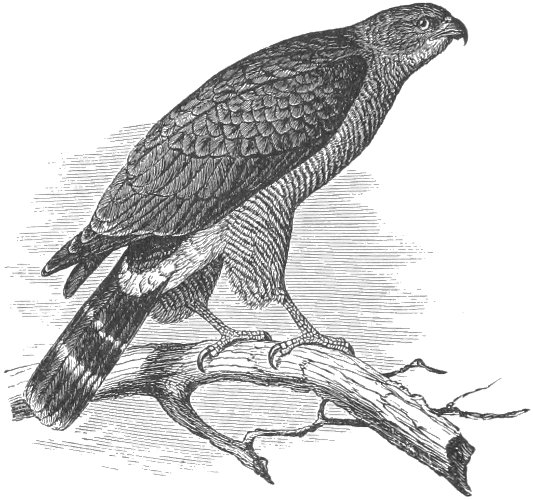

Gen. Char. Size varying from medium to very large. No ear-tufts. Head very large, the eyes comparatively small. Four to six outer primaries with their inner webs sinuated. Tarsi and upper portion, or the whole of the toes, densely clothed with hair-like feathers. Tail considerably more than half as long as the wing, decidedly rounded. Ear-orifice very high, but not so high as the skull, and furnished with an anterior operculum, which does not usually extend along the full length; the two ears asymmetrical. Bill yellow.

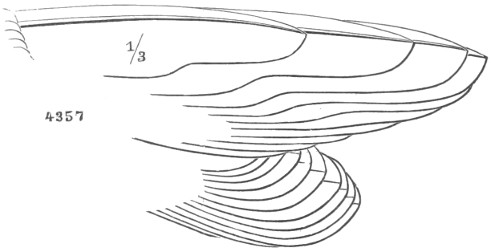

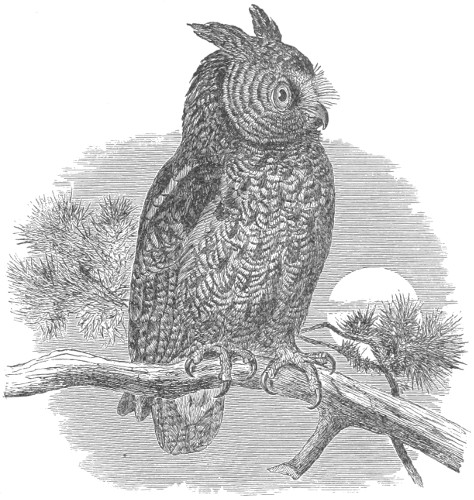

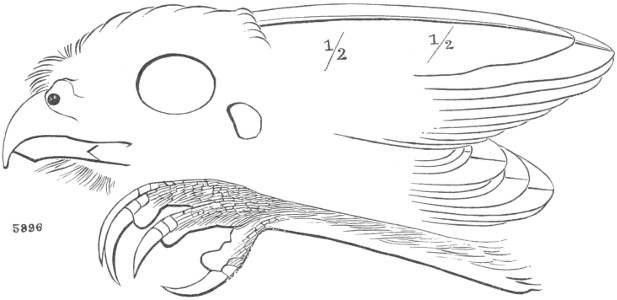

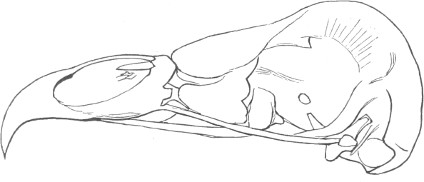

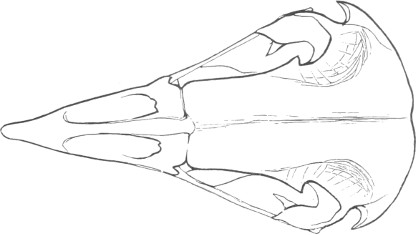

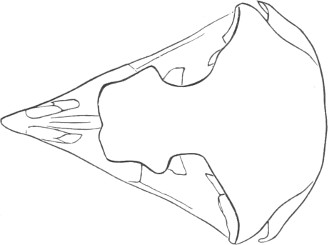

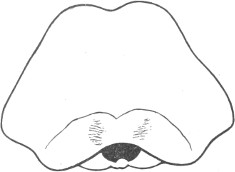

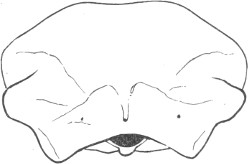

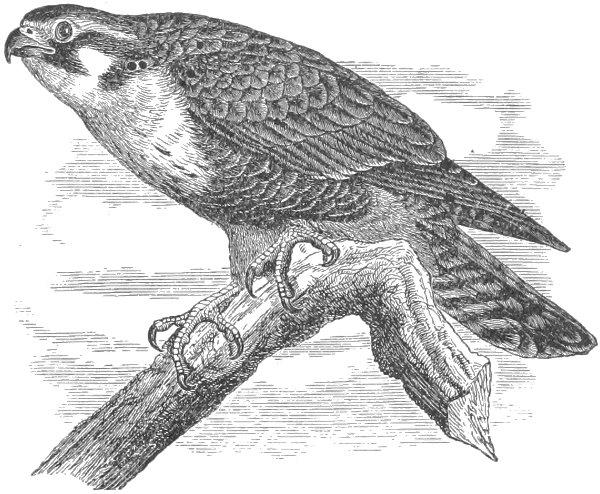

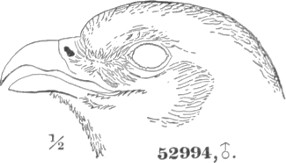

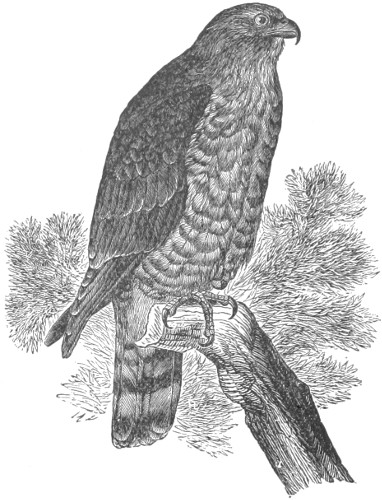

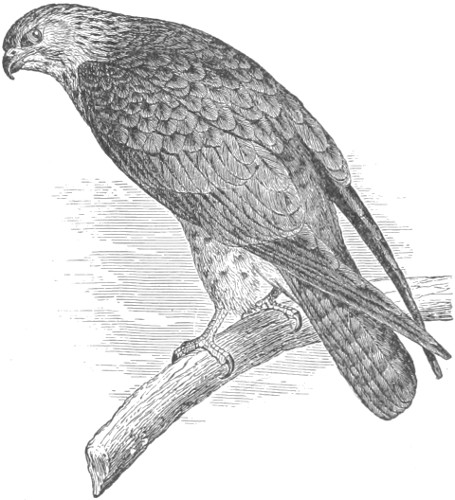

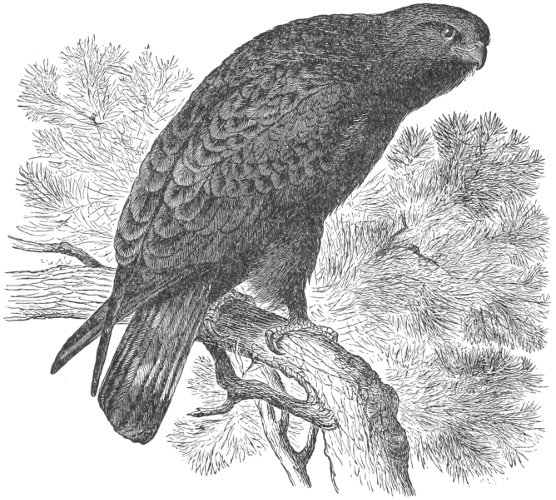

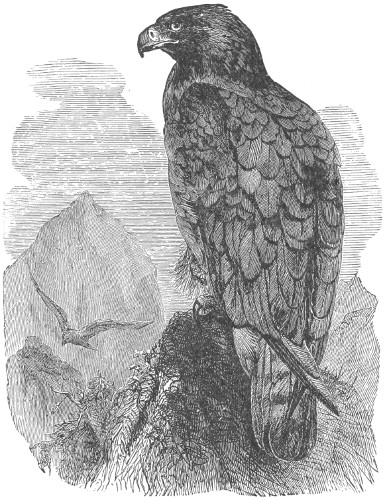

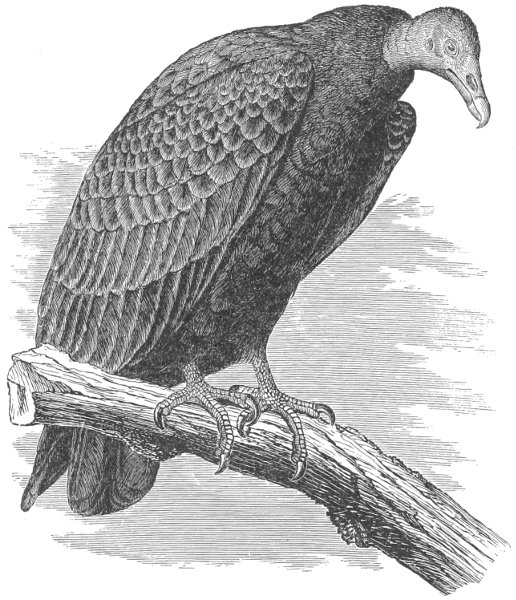

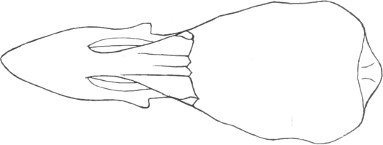

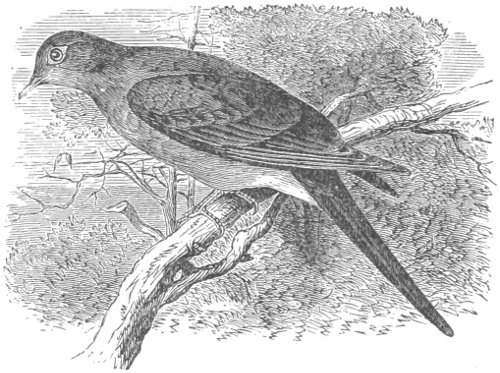

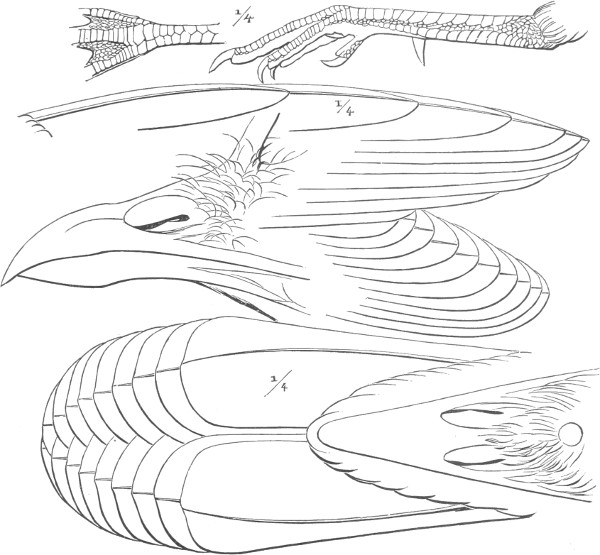

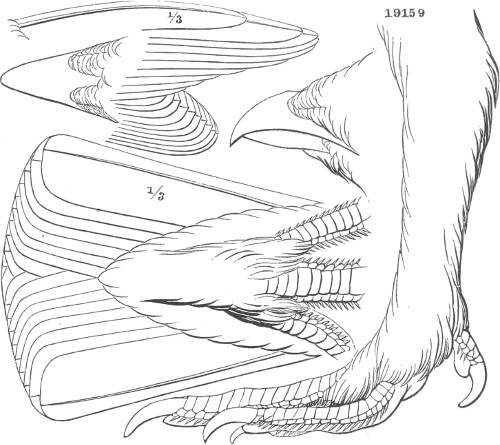

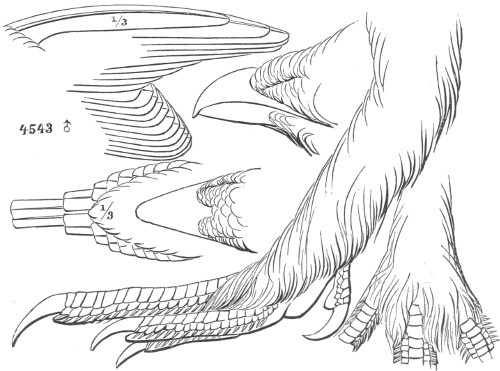

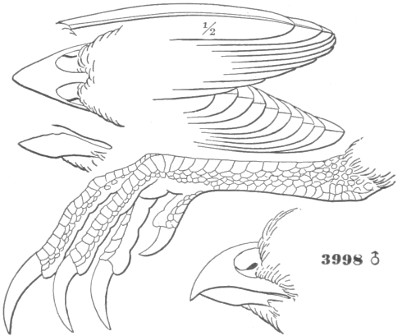

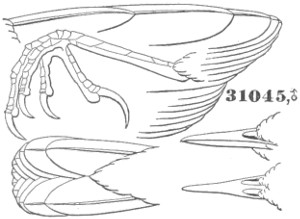

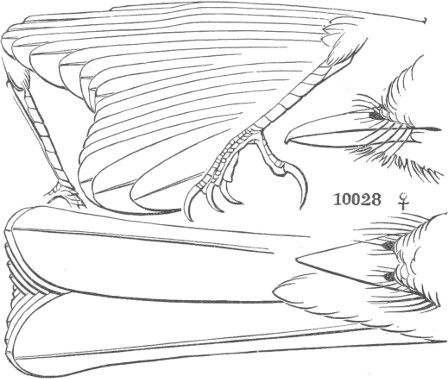

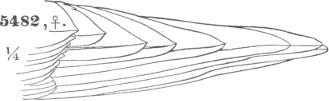

4357 ⅓

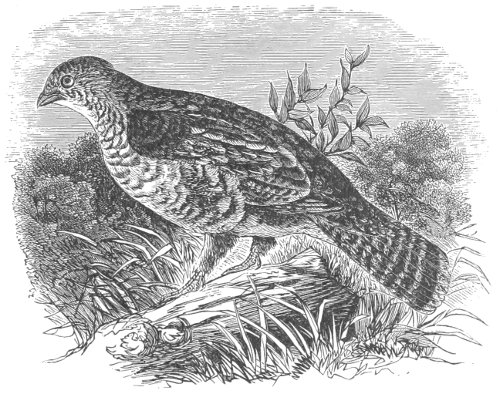

Syrnium nebulosum.

Scotiaptex. Six outer quills with their inner webs emarginated. Toes completely concealed by dense long hair-like feathers. Iris yellow. (Type, S. cinereum.)

Syrnium, Swainson. Five outer quills with their inner webs emarginated. Toes not completely concealed by feathers; sometimes nearly naked; terminal scutellæ always (?) exposed. Iris blackish. (Type, S. aluco.)

The typical species of this genus are confined to the Northern Hemisphere. It is yet doubtful whether the Tropical American species usually referred to this genus really belong here. The genera Ciccaba, Wagl., and Pulsatrix, Kaup, have been instituted to include most of them; but whether these are generically or only subgenerically distinct from the typical species of Syrnium remains to be decided.

Our S. nebulosum and S. occidentale seem to be strictly congeneric with the S. aluca, the type of the subgenus Syrnium, since they agree in the minutest particulars in regard to their external form, and other characters not specific.

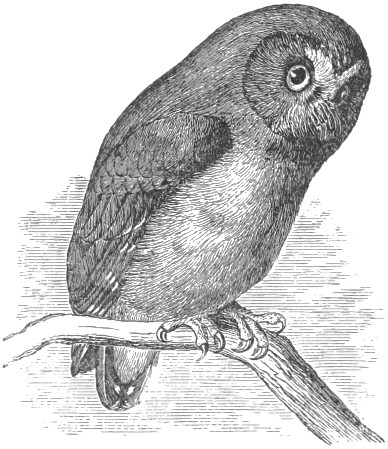

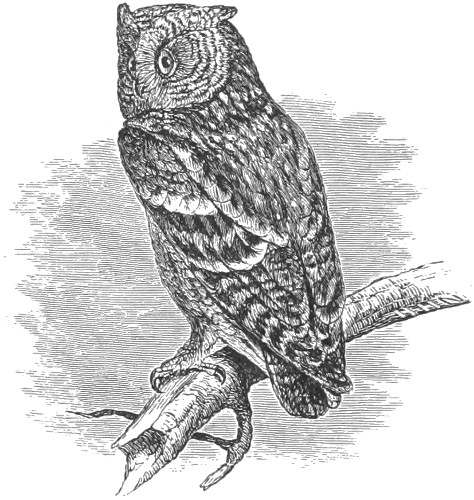

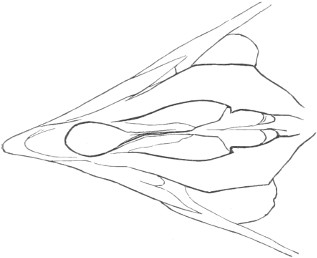

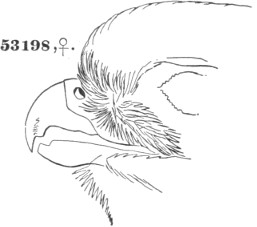

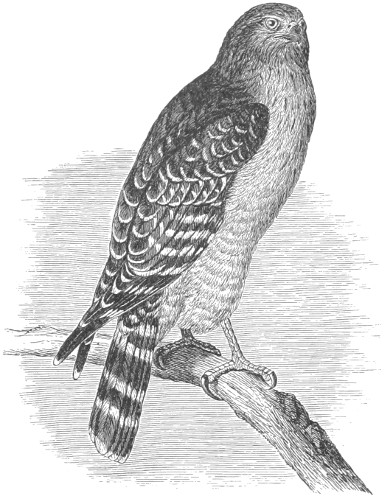

4337 ½ ½

Syrnium nebulosum.

1. S. cinereum. Iris yellow; bill yellow. Dusky grayish-brown and grayish-white, the former prevailing above, the latter predominating beneath. The upper surface with mottlings of a transverse tendency; the lower surface with the markings in the form of ragged longitudinal stripes, which are transformed into transverse bars on the flanks, etc. Face grayish-white, with concentric rings of dusky. Wing, 16.00–18.00; tail, 11.00–12.50.

Dark markings predominating. Hab. Northern portions of the Nearctic Realm … var. cinereum.

Light markings predominating. Hab. Northern portions of the Palæarctic Realm … var. lapponicum.

Common Characters. Liver-brown or umber, variously spotted and barred with whitish or ochraceous. Bill yellow; iris brownish-black.

2. S. nebulosum. Lower parts striped longitudinally. Head and neck with transverse bars.

Colors reddish-umber and ochraceous-white. Face with obscure concentric rings of darker. Wing, 13.00–14.00; tail, 9.00–10.00. Hab. Eastern region of United States … var. nebulosum.

Colors blackish-sepia and clear white. Face without any darker concentric rings. Wing, 14.80; tail, 9.00. Hab. Eastern Mexico (Mirador) … var. sartorii.21

Colors tawny-brown and bright fulvous. Face without darker concentric rings (?). Wing, 12.50, 12.75; tail, 7.30, 8.50. Hab. Guatemala … var. fulvescens.22

3. S. occidentale. Lower parts transversely barred. Head and neck with roundish spots. Wing, 12.00–13.10; tail, 9.00. Hab. Southern California (Fort Tejon, Xantus) and Arizona (Tucson, Nov. 7, Bendire).

Strix cinerea, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 291, 1788.—Lath. Ind. Orn. p. 58, 1790; Syn. I, 134; Supp. I, 45; Gen. Hist. I, 337.—Vieill. Nouv. Dict. Hist. Nat. VII, 23, 1816; Enc. Méth. III, 1289; Ois. Am. Sept. I, 48.—Rich. & Swains. F. B. A. II, pl. xxxi, 1831.—Bonap. Ann. Lyc. N. Y. II, 436; Isis, 1832, p. 1140.—Aud. Birds Am. pl. cccli, 1831; Orn. Biog. IV, 364.—Nutt. Man. p. 128.—Tyzenhauz, Rev. Zoöl. 1851, p. 571. Syrnium cinereum, Aud. Synop. p. 26, 1839.—Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. p. 184, 1854; Birds N. Am. 1858, p. 56.—Brew. (Wils.) Am. Orn. p. 687.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 26, pl. xiii, f. 29, 1844.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 188, 1855.—Newb. P. R. R. Rept. VI, IV, 77, 1857.—Coop. & Suck. P. R. R. Rept. XII, II, 156, 1860.—Kaup, Tr. Zoöl. Soc. IV, 1859, 256.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chicago Acad. I, 1869, 173.—Gray, Hand List, I, 48, 1869.—Maynard, Birds Eastern Mass., 1870, 130.—Scotiaptex cinerea, Swains. Classif. Birds, II, 217, 1837. Syrnium lapponicum, var. cinereum, Coues, Key, 1872, 204. Strix acclamator, Bart. Trans. 285, 1792.

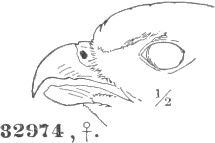

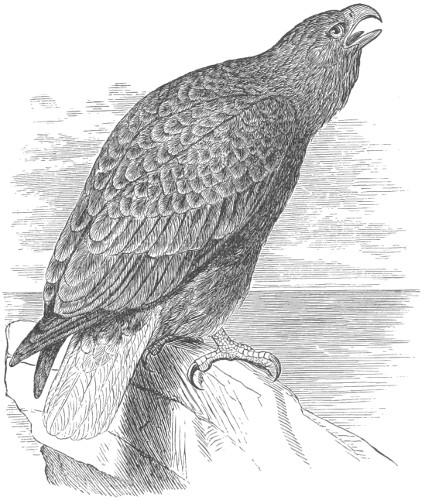

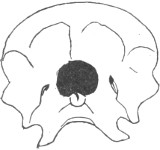

Sp. Char. Adult. Ground-color of the upper surface dark vandyke-brown, but this relieved by a transverse mottling (on the edges of the feathers) of white, the medial portions of the feathers being scarcely variegated, causing an appearance of obsolete longitudinal dark stripes, these most conspicuous on the scapulars and back. The anterior portions above are more regularly barred transversely; the white bars interrupted, however, by the brown medial stripe. On the rump and upper tail-coverts the mottling is more profuse, causing a grayish appearance. On the wing-coverts the outer webs are most variegated by the white mottling. The alula and primary coverts have very obsolete bands of paler; the secondaries are crossed by nine (last terminal, and three concealed by coverts) bands of pale grayish-brown, inclining to white at the borders of the spots; primaries crossed by nine transverse series of quadrate spots of mottled pale brownish-gray on the outer webs, those beyond the emargination obscure,—the terminal crescentic bar distinct, however; upper secondaries and middle tail-feathers with coarse transverse mottling, almost forming bars. Tail with about nine paler bands, these merely marked off by parallel, nearly white bars, enclosing a plain grayish-brown, sometimes slightly mottled space, just perceptibly darker than the ground-color; basally the feathers become profusely mottled, so that the bands are confused; the last band is terminal. Beneath with the ground-color grayish-white, each feather of the neck, breast, and abdomen with a broad, longitudinal ragged stripe of dark brown, like the ground-color of the upper parts; sides, flanks, crissum, and lower tail-coverts with regular transverse narrow bands; legs with finer, more irregular, transverse bars of dusky. “Eyebrows,” lores, and chin grayish-white, a dusky space at anterior angle of the eye; face grayish-white, with distinct concentric semicircles of blackish-brown; facial circle dark brown, becoming white across the foreneck, where it is divided medially by a spot of brownish-black, covering the throat.

♂ (32,306, Moose Factory, Hudson Bay Territory; J. McKenzie). Wing-formula, 4=5, 3, 6–2, 7–8–9, 1. Wing, 16.00; tail, 11.00; culmen, 1.00; tarsus, 2.30; middle toe, 1.50.

♀ (54,358, Nulato, R. Am., April 11, 1868; W. H. Dall). Wing-formula, 4=5, 3, 6–2, 7–8–9, 1. Wing, 18.00; tail, 12.50; culmen, 1.00; tarsus, 2.20; middle toe, 1.70.

Hab. Arctic America (resident in Canada?). In winter extending into northern borders of United States (Massachusetts, Maynard).

The relationship between the Syrnium cinereum and the S. lapponicum is exactly parallel to that between the Otus vulgaris, var. wilsonianus, and var. vulgaris, Surnia ulula, var. hudsonia, and the var. ulula, and Nyctale tengmalmi, var. richardsoni, and the var. tengmalmi. In conformity to the general rule among the species which belong to the two continents, the American race of the present bird is very decidedly darker than the European one, which has the whitish mottling much more prevalent, giving the plumage a lighter and more grayish aspect. The white predominates on the outer webs of the scapulars. On the head and neck the white equals the dusky in extent, while on the lower parts it largely prevails. The longitudinal stripes of the dorsal region are much more conspicuous in lapponicum than in cinereum.

Syrnium cinereum.

A specimen in the Schlütter collection, labelled as from “Nord-Europa,” is not distinguishable from North American examples, and is so very unlike the usual Lapland style that we doubt its being a European specimen at all.