Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 13, September 26, 1840

Author: Various

Release date: February 25, 2017 [eBook #54232]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 13. | SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 1840. | Volume I. |

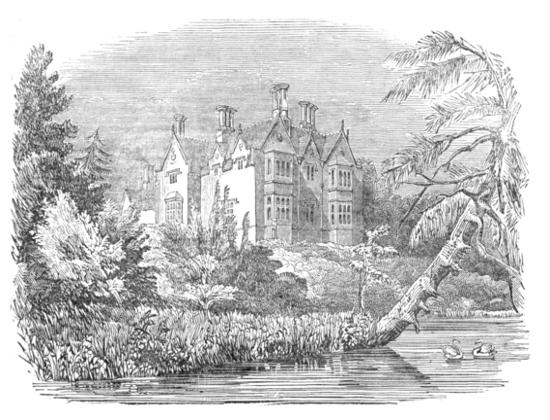

Among the very many beautiful residences of our nobility and gentry, situated within a drive of an hour or two of our metropolis, there is probably not one better worthy of a visit than that which we have chosen to depict as the illustration of our present number—Hollybrook Hall, the seat of Sir George Frederick John Hodson, Bart. It is situated in the county of Wicklow, about a mile beyond the town of Bray, and about eleven miles from Dublin.

To direct public attention to this charming spot is no less our pleasure than our duty, for we feel quite assured that even among the higher classes of our fellow-citizens but a very few know more respecting it than its name and locality, and that it will surprise the vast majority to be told that Hollybrook Hall is no less remarkable for the beauty of the sylvan scenery by which it is surrounded, than as affording in itself the most perfect specimen of the Tudor style of architecture to be found in Ireland.

That Hollybrook is thus little known to the public, is not, however, their fault: excluded from the eye by high and unsightly stone walls on every side by which it might otherwise be seen by the traveller, it is passed without even a glimpse of the bower of beauty, which would attract his attention and excite the desire to obtain a more intimate acquaintance with objects of such interest by a request to its accomplished owner, which we are satisfied would never be denied.

Hollybrook Hall, like Clontarf Castle, of which we have already given some account, is a fine specimen of the many recently erected or rebuilt residences of our nobility and gentry, which we esteem it our duty to notice and to praise. Like that fine structure also, it is an architectural creation of that accomplished artist to whose exquisite taste and correct judgment we are indebted for so many of the most beautiful buildings in the kingdom; and in many of its features and the general arrangement of its parts, it bears a considerable resemblance to that admirably composed edifice. In its ground plan and general outline, however, it is essentially different; and it is, moreover, characterised by a peculiarity which perhaps no other of Mr Morrison’s works exhibits, namely, that it has no mixed character of style, but is in every respect an example of English domestic architecture in the style of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, or, in other words, it uniformly preserves through all its details the character of the Tudor style.

In the choice of this style, as well as in the general composition of the structure, the artist was obviously guided by a judicious desire to adapt the building to the peculiar character of the scenery by which it is surrounded, and the historical associations connected with the locality; and a more happy result than that which he has effected could hardly be imagined. Seated upon a green and sunny terraced bank in the[Pg 98] midst of venerable yew and other evergreens, and immediately above a small artificial lake or pond, which reflects on its surface the dark masses of ancient and magnificent forest trees, which rise on all sides from its banks, and which are only topped by the peaked summits of the greater and lesser Sugar-Loaf Mountains, as seen through vistas, the building and its immediate accompaniments seem of coequal age and designed for each other; and all breathe of seclusion from the cares of the world and a happy domestic repose. It would indeed be impossible to conceive any combinations of architecture and landscape scenery more perfectly harmonious or beautiful of their kind.

Hollybrook Hall is wholly built of mountain granite squared and chiselled, and presents three architectural fronts. That which we have represented in our illustration is the east front, which faces the small lake or pond, and contains the library and drawing-room; but the principal front is that facing the north, on which side the entrance porch is placed. The principal apartments consist of a hall, library, dining and drawing rooms, with the state bed-rooms above them; and of these apartments the hall is the most grand and striking feature, though of inferior size to that of Clontarf Castle. It is thirty-four feet long by twenty feet wide, but has an open porch and vestibule or outer hall, twelve feet six inches wide; and like every other part of the edifice, its details are throughout in the purest style of Tudor architecture. This hall is panelled with oak, and is lighted by one grand stained glass window, eight feet six inches wide, and fourteen feet six inches high. This window, which resembles those of the English ecclesiastical edifices of the fifteenth century, is divided by stone mullions into four days, or compartments, and being beautifully proportioned, affords abundant light to the interior. But the most imposing feature of the hall is its beautiful oak staircase, which, rising from beneath the window, conducts to a gallery which crosses the hall, and communicates with the bed-rooms over the principal apartments. The ceiling is of dark oak, supported by principals which spring from golden corbels, and it is enlivened by golden bosses, which are placed at the various crossings of the rich woodwork, and have a most pleasing effect from the contrasting relief which they give to its pervading dark colour. The cornice, which is equally rich and elegantly proportioned, is surmounted by a gilded crest ornament, which by its lightness and brilliancy attracts the eye, and leads the mind to contemplate the fine proportions and elegance of design which characterises the details of the ceiling in all its parts.

Of the other principal apartments it is only necessary to state that they are equally well proportioned, and have ceilings of great richness and beauty, executed in a bold and masterly style of relief: they are of larger size than the similar rooms of Clontarf Castle, the library being thirty feet by seventeen feet six inches, the dining-room thirty feet by twenty, and the drawing-room thirty-four feet six by twenty. These apartments are lighted by oriel windows, each of which commands a view of some striking beauty in the surrounding scenery. An extensive range of offices and servants’ rooms branches off the Hall on its western side, but these are as yet only partly erected, and further additions are still wanting to carry out the original design of the architect, and give to the edifice as a whole the intricacy and picturesque variety of outline which he intended.

Hollybrook was originally the seat of a highly respectable branch of the Adair family, who, as it is said, though long located in Scotland, are descended from Maurice Fitzgerald, fourth Earl of Kildare. By a marriage with the only daughter of the last proprietor of this family, Forster Adair, Esq., it passed into the possession of Sir Robert Hodson, Bart., descended of an old English family, and father of the present proprietor, who succeeded to the baronetcy and estates on the death of his elder brother the late Sir Robert Adair Hodson, by whom the new structure of Hollybrook Hall was commenced. Sir Robert was a gentleman of refined tastes and intellectual acquirements—a landscape painter of no small merit, and of a poetic mind. The present baronet is, we believe, similarly gifted, and therefore worthy to be the proprietor and resident of a spot of such interest and beauty; but he should raze those odious unsightly walls, which exclude Hollybrook from the eye, and make it an unvisited and almost unknown solitude.

P.

None are so seldom found alone, and are so soon tired of their own company, as those conceited coxcombs who are on the best terms with themselves.

Oh! ye whom business or pleasure shall henceforth lead to the county of Wexford, especially to the baronies of Forth and Bargie, should you see a tall, stout, lazy-looking fellow, with sleepy eyes and huge cocked nose, dragging his feet along as if they were clogs imposed on him by nature to restrain his motion instead of helping him forward, dawdling along the highways, or lounging about a public-house, with a green bag under his arm, beware of him, for that is Tim Callaghan!—fling him a sixpence or shilling if you will, but ask him not for music!

Tim Callaghan seriously assured me “that he sarved seven long years wid as fine a piper as ever put chanther ondher an arm;” and that at the end of that well-spent period he began to enchant the king’s lieges on his own account, master of a splendid set of pipes, and three whole tunes (barring a few odd turns here and there which couldn’t be conquered, and of no consequince), a golden store in his opinion.

“Ah, then, Tim,” said I, when I was perfectly acquainted with himself and his musical merits, “what a pity that with your fine taste and superior set of pipes you did not try to conquer the half dozen at least!”

“Ogh, musha!” quoth Tim, looking sulky and annoyed, “that same quisthen has been put to me by dozens, an’ I hate to hear it! It was only yistherday that another lady axt me that same. ‘Arrah, ma’am,’ ses I, ‘did ye ever play a thune on the pipes in yer life?’ ‘Niver, indeed,’ ses she, lookin’ ashamed ov her ignorance, as she ought. ‘Bekase if ye did,’ ses I agin, ‘ye’d soon say, “bright was yerself, Tim Callaghan, to get over the three thunes dacently, widout axin’ people to do what’s onpossible.”’ An’ now I appail to you, Miss, where’s the use ov bodherin’ people’s brains wid six or seven whin three does my business as well?”

As in duty bound, I admitted that his argument was unanswerable, and thenceforward we were the best friends possible. Grateful for my patience and forbearance, he eternally mangles the three unfortunates for my gratification; and I doubt if I could now relish them with their fair proportions, so accustomed as I have been to Tim’s “short measure!”

After all, Tim Callaghan was a politic fellow; and these three tunes were expressly chosen and learnt to win the ears and suffrages of all denominations of Christian men. Thus, the “Boyne water” is the propitiatory sacrifice at the Protestant’s door, “Patrick’s Day” at that of the Roman Catholic, and when he is not sure of the creed of the party he wishes to conciliate, to suit Quakers, Methodists, Seekers, and Jumpers, “God save the Queen” is the third. For many years he was contented to give these favourite airs in their original purity; but some wicked wight—a gentleman piper, I suspect—has at last persuaded him that his melody would be altogether irresistible if he would introduce some ornamental variations, “such as his own fine taste would suggest;” and poor Tim, unaccustomed to flattery, and wholly unsuspicious of the jest, caught at the bright idea, conquered his natural and acquired laziness, and made an attempt. When he thought he had mastered the difficulties, he did me the honour to select me as judge to pronounce on his melodious acquisitions; and all I shall say anent them is, let the blackest hypochondriac that ever looked wistfully at a marl-hole or his garters, listen to Tim Callaghan’s “varry-a-shins,” and watch his face while performing them, and he will require “both poppy and mandragora to medicine him to sleep,” if sleep he ever will again for laughing!

When Tim arrives at a gentleman’s door, his usual plan is to commence with the suitable serenade, and drone away at that till the few pence he is piping for sends him away content. But if he is detained long, and he sees no great chance of reward or entertainment within doors, he becomes furious, and in his ire he rattles up that one of the three which he supposes most disagreeable and opposite to the politics of the offender. If the party be a Roman Catholic, he will be unpleasantly electrified, and all his antipathies aroused, by “the Boyne water,” performed with unusual spirit; and if a church-goer, he will never recover the shock of “Patrick’s Day,” given with an energy that will render the wound unhealable! If he is asked for any favourite or fashionable air—and you might as well ask Tim Callaghan to repeat a passage of Homer in the original Greek—his civilest reply is, “I haven’t that, but I’ll give yez one as good,” when one of the trio follows of course; and if the impertinent suitor for novelties in[Pg 99] his ignorance persists in demanding more than is to be had, he is angrily cut short, especially if of inferior rank, with “How bad ye are for sortins! Yer masther wud be contint wid what I gave ye, an’ thankful into the bargin!” Thus qualified to please, it is not to be wondered at that he is celebrated through three baronies as “the piper!”

When first I had the pleasure to see and hear Tim Callaghan, it was in the middle of winter, dark and dreary, and in a retired country place, where even the “vile screeching of the wry-necked fife” would have been welcome in lieu of better. Conceive our ecstacy, then, when the inspiring drone of the bagpipe startled our ears into attention and expectation! The very servants were clamorous in expressing their delight, and in beseeching that the piper should be brought into the house and entertained. The petition was granted, the minstrel was led in “nothing loth,” and seated in the hall. Well, Tim’s first essay at the minister’s house was of course “the Boyne,” played very spiritedly and accurately on the whole, with the exception of a few rather essential notes that he omitted as unnecessary and troublesome, or (as the servants supposed) in consequence of the cold of his fingers; and finally they took him to the kitchen, and seated him opposite to a blazing fire. “Now he’ll play in airnest!” cried they, as one and all gathered round him in expectation of music.

Our piper being now in the lower regions, among the inferior gentry, and willing to please all orders and conditions, begins to consider whether he shall repeat the “Boyne,” or commence the all-enlivening “Patrick’s Day.”

“What religion is the sarvints ov?” replied he at length to a little cow-boy gaping with wonder at the grand ornaments of the pipes.

“They are ov all soarts, sur,” whispered Tommy in reply, and reddening all over at the great man’s especial notice.

“Ov all soarts!” mutters Tim significantly; then deciding instantly, with much solemnity of face and strength of arm he squeezed forth the conciliating “God save the King.”

The butler listened awhile with the sapient air of a judge. “You’re a capitial performer, piper!” said he at length patronizingly, and with a hand on each hip; “an’ that’s a fine piece ov Hannibal’s composition! but it is not shutable for all occashins, an’ a livelier air would agree with our timperament betther. Change it to somethin’ new.” And tucking his apron aside, he gallantly took the rosy tips of the housemaid’s fingers and led her out, while the gardener as politely handed forth the cook. The piper looked sullen, and still continued the national anthem as if he knew what he was about, and was determined to play out his tune. The butler’s dignity bristled up.

“Railly,” he observed, and smiled superciliously, “we are very loyal people hereabouts, but at this pertickler moment we don’t want to join in a prayer for our savren’s welfare! Stop that melancholic thing, man! an’ give us one of Jackson’s jigs.”

“Out ov fashin,” quoth Tim sullenly, “but I’ll give yez one as good,” and “Patrick’s Day” set them all in motion for a quarter of an hour.

“Oh, we’re quite tired ov that!” at length lisped the housemaid “do, piper, give us a walse or co-dhreelle. Do you play ‘Tanty-polpitty?’ Jem Sidebottom and I used to dance it beautifully when I lived at Mr A——’s!”

“What does yez call it?” asked Tim rather sneeringly.

“Tanty-polpitty,” replied the damsel, drawing herself up with an air enough to kill a piper!

“Phew!” returned the musician contemptuously, “that’s out ov fashin too; but I’ll give yez one as good;” and the “Boyne” followed, played neither faster nor slower than he had been taught it, which was in right time, and any thing but dancing time, to the no small annoyance of the dancers. Another and another jig and reel was demanded, and to all and each Tim Callaghan replied, “I haven’t that, but I’ll give yez one as good;” and the “King,” the “Boyne,” and the “Day,” followed each other in due succession.

Was there anything more provoking! There stood four active, zealous votaries of Terpsichore, with toes pointed and heads erect, anxiously awaiting a further developement of Tim Callaghan’s powers! There stood the dancers, looking beseechingly at the piper; there sat the piper staring at the dancers, wondering what the deuce they waited for, quite satisfied that they had got all that could reasonably be expected from him.

“An’ have you nothin’ else in yer chanther?” at last angrily demanded the butler.

“E—ah?” drawled Tim Callaghan, as if he did not understand the querist.

The question was repeated in a higher key.

“Arrah, how bad yez are for sortins!” retorted the piper; “yer masther wud be contint wid what I gave yez, an’ thankful into the bargin!”

“By Jupither Amond!” exclaimed he of the white apron, “this beats all the playin’ I ever heerd in my life! Arrah, do ye ever attind the nobility’s concerts?—Ha! ha! ha!”

“’Pon my voracity,” cried the smiling housemaid, “I am greatly afeerd he will get ‘piper’s pay—more kicks than halfpence.’—Ha! ha! ha!”

“An’ good enough for him!” added the gardener; “a fella that has but three half thunes in the world, an’ none ov them right! Arrah, what’s yer name, avie?”

“What’s that to you?” growled the piper.

“Oh, nothin’! Only I thought that you might be ‘the piper that played before Moses.’—Ha! ha! ha!”

sang the cook, as she returned to her avocations. But the butler, as master of the ceremonies, showed his disappointment and displeasure in a summary ejection of the unfortunate minstrel from the comforts of the fire and the house altogether.

Again I had the exquisite delight of hearing Tim Callaghan. It was in another part of our county, and where he was quite a stranger. A lady had assembled a number of young persons to a sea-side dance one evening; but, alas! ere the hour of meeting arrived, she had heard that the fiddler she expected was ill, and could not possibly attend her. What was to be done? Nothing!

When the guests arrived, and the dire news communicated, the gentlemen in spite of themselves looked terrifically glum, as if they anticipated a dull evening; and the bright countenances of the ladies were overcast, though as usual, sweet creatures! they tried to look delightful under all visitations. In this dilemma one of the beaux suddenly recollected that “he had seen a piper coming into the village that evening; and he thought it was probable he would stop for the night at one of the public-houses.” Hope instantly illuminated all faces, and a messenger was forthwith dispatched for the man of music. For my part, whenever I heard a piper mentioned, I knew who was full before me.

“What sort of person is your piper?” asked I of the gentleman that had introduced the subject.

“A tall, stout, rather drowsy-looking fellow,” was the reply.

“Oh!” cried I, “it is the Inimitable!—it is Tim Callaghan!”

I was eagerly asked if he were a good performer; and as I could not venture to reply with any degree of gravity, one other person present, who knew honest Timothy and his ways, with admirable composure answered, “That under the shield of Miss Edgeworth’s mighty name he would decline trumpeting the praises of any one, she having expressly declared in her novel of ‘Ennui,’ that ‘whoever enters thus announced appears to disadvantage;’ and therefore,” said my friend, “we leave Tim Callaghan’s musical merit to speak for itself.” Nothing could be better than this, and the effect Tim produced was corresponding.

While the messenger is away for our piper, I must relate an anecdote of another servant, and a rustic one too, once sent on a similar errand. John’s master had friends spending the evening with him, and he desired his servant to procure a musician for the young folks for love or money. In about half an hour John returned after a fruitless search; and instead of saying in the usual style that “he could not find one,” he flung open the drawing-room door, and announced his unsuccess in the following impromptu,[1] spoken with all due emphasis and discretion—

and then made his bow and retired. The city, by the way, was a village of some half-dozen houses. So much for John, and now for Tim Callaghan.

Presently the identical Tim made his appearance, and was placed in high state at the top of the room, with a degree of attention and respect fully due to his abilities. For my part, the very sight of Tim, and the thought of his consummate[Pg 100] assurance or stupidity in attempting to play for dancing, amused me beyond expression; but I suppressed all symptoms of this, and kept my eyes and ears on the alert in expectation of what was to follow. A bumper of his favourite punch was prepared for him, and while sipping it, I thought he cast a scrutinizing and anxious glance on the company, probably thinking how he should adjust his politics there. But he had little time to pause. A quadrille set was immediately formed, and he was called on to play!—the sapient belles and beaux never dreaming that a modern piper even might not play quadrilles. Never did I find it so difficult to restrain myself from immoderate laughter! There stood the eight elegantes, ringleted, perfumed, white-gloved, and refined; and there sat Tim Callaghan in all his native surly stupidity, dreadfully puzzled, “looking unutterable things,” humming and hawing, and tuning and droning much longer than necessary—not in the least aware of the demand that was to be made on himself or his pipes, but puzzling his brains as to which of his own he should play first.

“A quadrille, piper!—the first of Montague’s!” called out the leading gentleman.

“E—ah!” said Tim Callaghan, opening his sleepy eyes, surprised into some little animation.

“The first of Montague’s set of quadrilles!” repeated the beau.

“Ogh, Mountycute’s is out ov fashin; but I’ll give yez one as good;” and the company being mixed, of whose opinions he could not be sure, the quadrillers were astounded with “God save the King” in most execrable style!

All stared, and most laughed heartily; but what was of more consequence to poor Tim, his arm was fiercely seized, and he was stopt short in the midst of his loyalty by an angry demand “if he could play no quadrilles? Not —— or ——?” and the names of a dozen quadrilles and waltzes were mentioned, that the unfortunate minstrel had never heard of in all his days and travels! In his dire extremity be commenced “the Boyne,” when at the instant some person called the lady of the house. The name seemed a Catholic one—a sudden ray of joy shot through his frame to his fingers’ ends, and from thence to his pipes, and poor “Patrick’s Day” was the result. A kind of jigging quadrille was then danced by the least fastidious and better humoured of the party; the first top couple, superfine exquisites!—the lady an importation from London, and odorous of “Bouquet a-la-Reine,” and the gentleman a perfect “Pelham,” from the aristocratic arch of his brow to his shoe-tie—having retreated to their seats with looks and gestures of horror and disgust, quite unnoticed by Tim Callaghan, who bore himself with all the dignity of a household bard of the olden time, in his element, playing his own favourite tune, and quollity actually dancing to his music! It was a great day for the house of Callaghan!

Well! as there seemed nothing better to be had, “Patrick’s Day” continued in requisition, now as a quadrille, now as a country-dance, by all who preferred motion to sitting still, before and after supper, till at last every one was weary of it, and a general vow was made to drop the “Day” and take the “Boyne,” and endeavour to move it as we best could. By that time, too, our piper seemed most heartily tired of his patron saint, and having quaffed his fourth full-flowing goblet, appeared to be rather inclined for a doze than to renew his melody. But he was roused up by our worthy host, who, good, gay old man! was the very soul of cheerfulness.

“For pity’s sake, piper,” said he, “try to give us something that we can foot it to! I was not in right mood for dancing to-night till now. If you be an Irishman, look at the pretty girl that is to be my partner for the next dance, and perhaps her eyes may inspire even you, you drowsy fellow, with momentary animation, and perform a miracle on your pipes!”

Short as this address was, and gaily as it was uttered, it had no other effect on our piper than administering an additional soporific.

While the old gentleman was speaking, the drowsy god was descending faster and faster on Tim Callaghan. He dozed and was shaken up.

“What does yez want?” growled he at length. “What the d—l does yez want?” looking as if he would say,

“Music! music!” said our host, laughing. “Any sort of music, any sort of noise,” and he left the piper and took his place amongst the dancers.

Tim mechanically fumbled at his pipes, while the gentlemen busied themselves in procuring partners. There was silence for some seconds. “Begin, piper,” called out our host.

“Out ov fashin,” muttered Tim in broken half-finished sentences; “but—I’ll—give—yez—one—as—good——;” and a long, a loud reverberating snore at the instant made good his promise of music almost as harmonious as the sounds elicited from his bagpipe!!

Imagine to yourselves, ye who can, the scene that followed. The salts-bottle and perfumed handkerchief of the exquisites were in instant requisition, as if they felt sensations of fainting! the nervous started as if a pistol went off at their heads, and those who bore the explosion with fortitude joined in a chorus of laughter, increased to pain when it was perceived that the Inimitable, noways disturbed or alarmed, prolonged his repose, and agreeably to the laws of music, and in excellent taste, bringing in his nasal performance as a grand finale to each resounding peal!

“Now,” observed the friend who had answered for me at a critical crisis, “has not Tim Callaghan made his own panegyric? Has not his merit spoken for itself? What a figure our inimitable piper would have cut, had we ushered him in with a flourish of trumpets!”

When the cachinnatory storm had subsided, and when all considered that their unrivalled musician had had enough of slumber, he was once more aroused, to receive his well-earned guerdon, when the following colloquy commenced:—

“Pray, piper, what is your name?” demanded the master of the house, with all the gravity of a magistrate on the bench, and drawing forth his tablets.

“E—ah? Why, Tim Callaghan.”

“Ha! Tim Callaghan (writing), I shall certainly remember Tim Callaghan! I suppose, Tim, you are quite celebrated?”

“E—ah?”

“I suppose you are very well known?”

“Why, those that knowed me wanst, knows me agin,” quoth Tim Callaghan.

“I do believe so! I think I shall know you at all events. Who taught you to play the pipes?”

“One Tim Hartigan, of the county Clare.”

“Had he much trouble in teaching you?”

“He thrubble! I knows nothin’ ov his thrubble, but faix I well remimber me own! There is lumps in my head to this very day, from the onmarciful cracks he used to give it when I wint asthray.”

“Ha! ha! ha! Oh, poor fellow! Well, farewell, Tim Callaghan!—pleasant be your path through life; and may your fame spread through the thirty-two counties of green Erin, till you die surfeited with glory!”

“Faix, I’d rather be surfeited wid a good dinner!” quoth Tim Callaghan, and made his exit.

For a couple of years I quite lost sight of Tim, and I began to fear that he had evanished from the earth altogether “without leaving a copy;” but, lo! this very summer, that “bright particular star” appeared unto us again, with a strapping wife, and a young Timotheus at his heels—a perfect facsimile of its father, nose, sleepy eyes, shovel feet and all; and all subsisting, nay flourishing, on three tunes and their unrivalled “varry-a-shins!”

M. G. R—.

[1] Fact! He composed and spoke the verses as I give them.

The Dead Alive.—In my youth I often saw Glover on the stage: he was a surgeon, and a good writer in the London periodical papers. When he was in Cork, a man was hanged for sheep-stealing, whom Glover smuggled into a field, and by surgical skill restored to life, though the culprit had hung the full time prescribed by law. A few nights after, Glover being on the stage, acting Polonius, the revived sheep-stealer, full of whisky, broke into the pit, and in a loud voice called out to Glover, “Mr Glover, you know you are my second father; you brought me to life, and sure you have to support me now, for I have no money of my own: you have been the means of bringing me back into the world, sir; so, by the piper of Blessington, you are bound to maintain me.” Ophelia never could suppose she had such a brother as this. The sheriff was in the house at the time, but appeared not to hear this appeal; and on the fellow persisting in his outcries, he, through a principle of clemency, slipped out of the theatre. The crowd at length forced the man away, telling him that if the sheriff found him alive, it was his duty to hang him over again!—Recollections of O’Keefe.

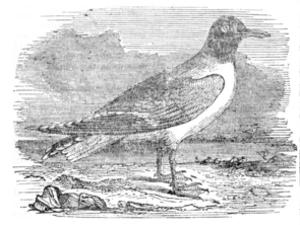

This bird, hitherto known in Great Britain only as an occasional and rare visitant, has now been added to the Fauna of Ireland—one of a pair seen between Shannon Harbour and Shannon Bridge having been shot in the month of May of the present year, by Walter Boyd, Esq. of the 97th regiment, and presented by him to the Natural History Society of Dublin. It has been stuffed by Mr Glennon of Suffolk Street, who continues to gratify the lovers of natural history by a free inspection of it.

The Little Gull was first noticed with certainty as a British bird by Montague, who, in the Supplement to his Ornithological Dictionary, published in 1813, described an immature specimen, the plumage being that of the yearling in transition to its winter garb. The Irish specimen, on the contrary, is invested with its full summer plumage, as described by Temminck. The head and upper portion of the neck are black; the lower portion of the neck and under parts of the body are white, and at first exhibited a rosy tint, which as is usual quickly faded after death; rump and tail white; upper parts pearl grey, the secondaries and quills being tipped with white; legs and toes bright red; bill of a reddish brown, rather than of the deep lake of Temminck, or arterial blood-red of Selby; its length ten inches, or somewhat more than one-half of that of the blackheaded gull (Larus ridibundus), its nearest congener.

Little has been added to the history of this bird as briefly given by Temminck as follows:—“It inhabits the rivers, lakes, and seas of the eastern countries of Europe; is an occasional visitant of Holland and Germany; is common in Russia, Livonia, and Finland; and very rarely wanders to the lakes of Switzerland. It feeds on insects and worms, and breeds in the eastern and southern countries.”

In America the Little Gull was noticed on the northern journey of Sir John Franklin, and it is numbered by Bonaparte amongst the rarer birds of the United States—rendering it probable that the American continent includes also its breeding habitats. To this we may reasonably add—considering the state of plumage of the Irish specimens, the season of their discovery, the inland locality in which they were seen, and the analogy in habits between them and the other blackheaded gulls with which they were associated—a belief and hope that the Little Gull will yet be found to breed on some of the wide expanses of the Shannon, or on the lakes of Roscommon, Leitrim, and Sligo.

To understand the relation of this gull to the other species of the same genus, it is necessary that we should take a rapid survey of the whole family; and happy are we to indulge ourselves in such mental rambling, as many a gladsome reminiscence will be awakened both in our own and in our readers’ minds by the mention of these well-known birds. Few indeed are there who at some period of their lives have not wandered to the sea-side to enjoy the exhilarating influence of the sea breeze, and to revel, perchance, on the rich feast of knowledge which the many strange but admirably formed creatures of the deep must ever present to the inquiring and contemplative mind. To them the sea-mew or gull must be familiar, both in those of the larger species, which are seen heavily winging their way over the waters, or poised in air, wheeling round to approach their surface, and in those of lighter and more aërial form, which, in the words of Wilson, “enliven the prospect by their airy movements—now skimming closely over the watery element, watching the motions of the surges, and now rising into the higher regions, sporting with the winds;” and we may surely add, still in the words of that enthusiastic worshipper of Nature, that “such zealous inquirers must have found themselves amply compensated for all their toil, by observing these neat and clean birds coursing along the rivers and coasts, and by inhaling the invigorating breezes of the ocean, and listening to the soothing murmurs of its billows.” Nor could they fail to notice how admirably the white and grey tints which prevail in the plumage of these birds harmonize with those of air and ocean—a species of adaptation which is manifest in all the works of nature, no colours, however varied, presenting to the eye an incongruous or disagreeable picture, and no sounds, however modified by the throats of a thousand feathered warblers, jarring as discord on the ear. Well may we judge from this that our senses were framed in unison with all created objects, and that the right test of excellence in music, painting, or poetry, is, “that it is natural.”

The genus Larus (Gull) of the early writers included many birds now separated from it—the Skuas, or parasitic gulls; Lestris; the Terns, or sea-swallows; Sterna; and some others—the consequence of increasing knowledge in natural science being the gradual limitation of genera by the use of more precise and restricted characters. All these genera now form part of the family of Laridæ, or gull-like birds—the system of grouping together those genera which exhibit striking analogies in plumage or habits securing the advantages of a natural arrangement, without the danger of that confusion which so often results from loosely defined genera. The tendency is indeed to still further subdivision—the kittiwake (Larus rissa) having been made the type of a new genus, Rissa (Stephens), and the blackheaded gulls classed together as the genus Xema (Boië)—the periodic change of the colour of their heads from the white of winter to the black of summer, their more rapid and tern or swallow-like flight, and their inland habits, forming so many striking and apparently natural marks of distinction. To this genus, if finally admitted, will belong the Little Gull (Xema minuta).

The term Larus is adopted from the Greek, the ancient Latin name as used by Pliny being Gavia. Brisson (1763) applies Larus to some of the larger species, and Gavia to a multitude of others; but there is much confusion in his identifications of species, and the line of separation was not well considered. Modern writers also subdivide the gulls, for the sake of convenience, into two sections—the larger, or those varying from nineteen to twenty-six or more inches in length, the “Goelands” of Temminck; and the smaller, or “Mouettes” of Temminck. But this system of division is imperfect, as it veils the remarkable relation existing between many of the larger and smaller gulls, which should not therefore be separated from each other. This relation was noticed by some of the earlier writers. Willoughby designates under the name Larus cinereus maximus both the herring and the lesser blackbacked gulls; and under that of Larus cinereus minor, the common sea-gull. This kind of relation is indeed strikingly displayed amongst British gulls—as in the greater and lesser blackbacked gulls, the Glaucous and Iceland gulls, the herring and common gulls, and, we may add, the blackheaded and little gulls; and it is very probable that further research will show that it exists still more widely.

From Aristotle or Pliny little can be gleaned of the history of these birds. Aristotle states that the Gaviæ and Mergi lay two or three eggs on the rock—the Gaviæ in summer, the Mergi in the beginning of spring—hatching the eggs, but not building in the manner of other birds. Pliny says that the Gaviæ build on rocks, the Mergi sometimes on trees; from which remark it appears probable that the genus Mergus then included not merely the various divers, but also the cormorants, as was formerly conjectured by Turner. Whilst, therefore, the ancient Latin name of gull, Gavia, has been entirely removed from modern nomenclature, the word Mergus has obtained a signification very limited in comparison to that which it enjoyed among the ancients, being now applied to the Mergansers alone, although for a time restored by Brisson to the Colymbi, which, as possessing the property of diving in its highest perfection, seem most entitled to retain it, whilst the term Merganser might be judiciously applied to the genus now called by some, Mergus, as was done by Aldrovandus, Willoughby, Brisson, and Stephens.

The remarkable differences in the habits of gulls, which form in part the basis of separation, as suggested by Boië in the case of the blackheaded gulls, were early noticed. Old Gesner (1587) says that some gulls dwell about fresh waters, others about the sea; and from Aristotle, that the grey gull seeks lakes and rivers, whilst the white gull inhabits the sea. Every one indeed must have noticed the flocks of gulls which occasionally appear inland, and share with the rooks and other corvidæ the rich repast of grubs which is afforded by the fresh-ploughed land. The common gull (Larus canus) is one of those which indulge in these terrestrial excursions; but the blackheaded gulls (Xema) select even the inland marshes as their breeding-places. The more truly maritime gulls select islands or rocks, on the surface of which they deposit their eggs, as the kittiwake the narrow ledges of precipitous cliffs, the young being reared with safety, where it would seem that the least movement must plunge them from the giddy height into the abyss below. This beautiful illustration of the power of instinct to preserve even the nestling from danger, is admirably displayed on the northern coast of Mayo, where at Downpatrick Head the whole face of the perpendicular limestone cliff is peopled by line above line of gulls, flying, when disturbed by a stone thrown either from mischievous or curious hand, in screaming flocks from their eggs or young, and as quickly settling upon them again, without, as it were, disturbing the equilibrium of either in a place where to move would be to tumble into destruction. The clamour of the kittiwake is indeed so great on such occasions that it has given rise in the Feroe Islands to a proverb, “noisy as the Rita in the rocks.” The eggs of several species of gulls are used as food, being regularly sought for as such on the coast of Devonshire and other maritime places, but those of the blackheaded gulls are considered the best, and often substituted for plover eggs. The flesh of gulls was considered by the ancients unfit for the food of man; not so by the moderns, who, though probably no great admirers of it, have not entirely rejected it. Hence Willoughby tells us (1678) that “the sea-crows (blackheaded gulls) yearly build and breed at Norbury in Staffordshire, in an island in the middle of a great pool, in the grounds of Mr Skrimshew, distant at least 30 miles from the sea. About the beginning of March hither they come; about the end of April they build. They lay three, four, or five eggs of a dirty green colour, spotted with dark brown, two inches long, of an ounce and half weight, blunter at one end. The first down of the young is ash-coloured, and spotted with black. The first feathers on the back, after they are fledged, are black. When the young are almost come to their full growth, those entrusted by the lord of the soil drive them from off the island through the pool, into nets set in the banks to take them. When they have taken them, they feed them with the entrails of beasts; and when they are fat, sell them for fourpence or fivepence a-piece. They take yearly about one thousand two hundred young ones; whence may be computed what profit the lord makes of them. About the end of July they all fly away and leave the island.” And in Feroe, according to Landt (1798), the flesh of the kittiwake is not only eaten, but considered “well-tasted.” As pets, gulls have always on the sea-coast been favourites, Gesner quotes from Oppian, “That gulls are much attached to man—familiarly attend upon him; and, when watching the fishermen, as they draw their nets and divide the spoil, clamorously demand their share.” In our own boyish experience we knew one, poor Tom, which grew up under our care to maturity, and, unrestrained by any artificial means, flew away and returned again as inclination impelled it—recognising and answering our voice even when flying high in air above. But, alas! like too many pets, he fell a sacrifice to the loss of that instinct which would have led him to shun danger. He joined a crowd of water-fowl on a small lake on the Start Bay Sands. His companions, alarmed at the approach of the fowler, flew unharmed away; but poor Tom, with ill-judged confidence, left the water and walked fearlessly toward the enemy of all winged creatures, who could not allow even a gull to escape, and, alas! he was the next moment stretched lifeless on the sand. Here we shall arrest our pen. Perhaps we have dwelt too long on this interesting genus of birds, and yet we would hope that some of our readers may profit by our remarks, and be led to watch with an inquisitive eye the many animated beings which surround them, and thus to read in Nature’s never-tiring, never-exhausted volume, new lessons of wisdom—new proofs of the exalted intelligence which has created every thing perfect and good of its kind.

J. E. P.

TO BE CONTINUED.

Some of Oisin’s expressions might justly shock the piety of St Patrick. But let it be remembered that Oisin is no convert to Christianity; on the contrary, he is opposed to it, principally because it had put an end to his favourite pastimes.

The boasted civilization which Mehemet Ali has introduced into the countries under his sway is entirely superficial, and has no origin whatever in any real improvement or amelioration in the condition or for the benefit of their respective populations; and the reason why a contrary impression has so generally prevailed amongst late travellers is as follows:—When travellers arrive at Alexandria, and more particularly those of name or rank, they immediately fall into the hands of a set of clever persons, some of them consuls, who having either made their fortunes by the Pacha, or having them to make, leave no effort unemployed to impress them with favourable opinions of his government. They are then presented at the Divan, where, instead of a reserved austere-looking Turk, they find a lively animated old man, who converses freely and gaily with them, talks openly of his projects to come, and of his past life, tells them that he is glad to see them, and that the more travellers that pass through Egypt, the better he is pleased; that he wishes every act of his government and institutions to be known and seen, and that the more they are so, the better will he be appreciated. He then turns the conversation to some subject personal to them, for he is always well informed of who and what they are, and what they know, and at last dismisses them with an injunction to visit his establishments with care, and to let him know their opinion of them on their return; and if they happen to be persons of distinction, he offers them a cavass to accompany them on their journey. All this is done in a simple pleasing manner, which can hardly fail to captivate when coming from so remarkable a man. Instructed by the clique, and won by the Pacha, they proceed on their journey to Cairo, where the delusion begun at Alexandria is completed; for travelling through the country is now easy, and comparatively safe to what it was, and establishments of various kinds, such as polytechnic schools, schools of medicine and general instruction, and manufactories, have been formed in Cairo and those parts of the country which are most frequently visited. These are under the direction of foreigners, chiefly Frenchmen, and are open to those who choose to visit them; consequently, as the greater proportion of travellers seek for sights more than instruction, these gentlemen, won at Alexandria, and delighted at the facility of their journey from that place, neither turn to the right nor the left from the beaten track, but, judging of what they do not see by that which is purposely prepared to be shown them, return to Europe, and on grounds such as I have above described, and without looking an inch beneath the surface, proclaim the Pacha the civilizer and regenerator of Egypt. How far such is the case, you will be able to judge from what follows, in which there is no exaggeration. The journey I made extended up to the second cataract on the Nile, throughout Egypt and Nubia, and then through Palestine, the whole of Syria, and the Libanus. I consequently visited very nearly all the countries under the domination of Mehemet Ali, and as I did not allow myself to be influenced at Alexandria, and missed no occasion of informing myself of the state of things whilst on my journey, I may fairly say that I can give an unbiassed opinion as to what is going on in that unhappy part of the world.

In Egypt the whole of the land belongs to the Pacha; besides himself there is no land-proprietor, and he has the absolute monopoly of every thing that is grown in the country. The following is the manner in which it is cultivated:—Portions of land are divided out between the fellahs of a village, according to their numbers; seed, corn, cotton, or other produce, is given to them; this they sow and reap, and of the produce seventy-five per cent. is immediately taken to the Pacha’s depots. The remaining twenty-five per cent. is left them, with, however, the power to take it at a price fixed by the Pacha himself, and then resold to them at a higher rate. This is generally done, and reduces the pittance left them about five per cent. more; from this they are to pay the capitation tax, which is not levied according to the real number of the inhabitants of a village, but according to numbers at which it is rated in the government books; so that in one instance with which I was acquainted, a village originally rated at 200, but reduced by the conscription to 100, and by death or flight to 40, was still obliged to pay the full capitation; and when I went there, 26 of the 40 had been just bastinadoed to extort from them their proportion of the sum claimed. After the capitation comes the tax on the date-trees, raised[Pg 104] from 30 to 60 paras by the Pacha, and that of 200 piasters a-year for permission to use their own water-wheels, without which the lands situated beyond the overflow of the Nile, or too high for it to reach, would be barren. Then comes an infinity of taxes on every article of life, even to the cakes of camels’ dung which the women and children collect and dry for fuel, and which pay 25 per cent. in kind at the gate of Cairo and the other towns. Next to the taxes comes the corvee in the worst form, and in continual action; at any moment the fellahs are liable to be seized for public works, for the transport of the baggage of the troops, or to track the boats of the government or its officers, and this without pay or reference to the state of their crops.

When Mehemet Ali made his famous canal from Alexandria to the Nile, he did it by forcibly marching down 150,000 men from all parts of the country, and obliging them to excavate with their hands, as tools they had not, or perhaps could not be provided. The excavation was completed in three months, but 30,000 men died in the operation. Then comes the curse of the conscription, which is exercised in a most cruel and arbitrary manner, without any sort of rule or law to regulate it. An order is given to the chief of a district to furnish a certain number of men; these he seizes like wild beasts wherever he can find them, without distinction or exemption, the weak as well as the strong, the sick as well as those in health; and as there is no better road to the Pacha’s favour than showing great zeal in this branch of the service, he if possible collects more even than were demanded. These are chained, marched down to the river, and embarked amidst the tears and lamentations of their families, who know that they shall probably never see them again: for change of climate, bad treatment, and above all, despair, cause a mortality in the Pacha’s army beyond belief; mutilation is not now considered an exemption, and the consequence of the system is, that from Assouan, at the first cataract, to Aleppo, you literally speaking never see a young man in a village; and such is the depopulation, that if things continue as they now are for two years more, and the Pacha insists on keeping up his army to its present force, it will be utterly impossible for the crops to be got in, or for any of the operations of agriculture to be carried on.

The whole of this atrocious system is carried into action by the cruelest means—no justice of any sort for the weak, no security for those who are better off: the bastinado and other tortures applied on every occasion, and at the arbitrary will of every servant of the government. In addition to this, the natives of the country are rarely employed—never in offices of trust—and the whole government is entrusted to Turks. In short, the worst features of the Mameluke and Turkish rules are still in active operation; but the method of applying them is much more ingenious, and the boasted civilization of Mehemet Ali amounts to this: that being beyond doubt a man of extraordinary talents, he knows how to bring into play the resources of the country better than his predecessors did, but like them entirely for his own interest, and without any reference to the well-being of the people; and that with the aid of his European instruments he has, if I may say so, applied the screw with a master-hand, and squeezed from the wretches under his sway the very last drop of their blood.

Such is the state of these two countries. Syria is perhaps the worst off of the two: for the Egyptians used to oppression bear it without a struggle: whilst the Syrians, who had been less harshly treated in old times, writhe under and gnaw their chain.—From the Sun newspaper.

Rotation Railway.—This invention aims at effecting a complete revolution in the present mode of railway construction and locomotion. In place of having the ordinary rails and wheeled carriages, two series of wheels are fixed along the whole length of the road at about two yards apart, and at an equal distance from centre to centre of each wheel. These wheels are connected throughout the whole length of the line by bands working in grooved pullies keyed on to the same axle as the wheels, but the axles of one side of the line are not connected with those of the opposite line. The axles of the wheels are raised about one foot from the ground; the top of the wheel, which is proposed to be of 3 feet diameter, will be therefore elevated 2½ feet above the surface. On these wheels is placed a strong framing of timber, having an iron plate fastened on each side in the line of the two series of wheels. A little within this bearing frame, so as just to clear the wheels, is a luggage-box or hold, descending to within a few inches of the ground, in which it is proposed to stow all heavy commodities, for which purpose it is well adapted, opening as it does at either end, and its flooring close to the surface of the ground. At each end of the lower part of the framing of this luggage-box, are fixed horizontal guide or friction wheels, working against the supports of the bearing wheels and pullies, by which arrangement curves will be traversed with little friction, and it will be impossible for the framing to quit the track. The framing of timber will be about 19 feet in length, so that it will rest alternately on six and eight wheels, but never on less than six. On this framing the passenger carriages are erected, which, in its progression forward, it is thought will be kept steady and free from lateral motion by the weight in the luggage-box, assisted by the horizontal guide-wheels. Locomotion is produced by putting the wheels in motion by means of machinery at either end, which would be effected for an immense distance with a moderate power, as there would be very little more friction due to the wheels than that arising from their own weight; and the frame which bears the carriage would not be run on to the bearing-wheels until the whole were in motion, when its weight would act almost after the manner of a fly-wheel, resting as it would on the periphery of the bearing-wheels. It will be perceived that by this plan the bearings of the wheels must be kept perfectly in the direction of the plane of the road, whether inclined or horizontal; otherwise serious concussions would occur. But this would not be the case by the depression of one wheel, or even by its entire removal, as the framing will be constructed sufficiently stiff as not to deflect by having the distance of the bearings doubled. If this plan should be found to answer, it will present facilities of transport never before thought of, as carriages might be continually dispatched without a chance of collision, either by stoppage or from increased speed of the last beyond the preceding. It also promises to remove the present great drawback to railway progression, viz. the being able to surmount but very slight acclivities by locomotive power with any profitable load; but by the rotative system, inclines may be surmounted of almost any steepness without the chance of accident. If a band should break, the action of this railway would not be impeded, as the power being transmitted from either end, rotation would take place throughout its whole length, but the power would not be transmitted from either end past the disjunction. Even should two bands be destroyed at a distance from each other and on the same side of the track, its action would not be destroyed, for although the isolated portion of wheels would be dead, those on the other side of the track would be in action, which, with the horizontal guide-wheels, would move forward the carriage, although, on such portion, at a diminished speed. Instead of an increased outlay being required in the formation of railways on this system, it is estimated that a very considerable saving will be effected, as a single track will be sufficient, with sidings of dead wheels at the termination of the several portions into which a long line would be divided. In crossing valleys, a framing of piles to support the bearing-wheels would be quite sufficient, and the road might be left quite open between each line of wheels, as it would be impossible for the carriage to quit the track, and therefore no necessity for making a solid road for safety sake.—Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal.

Magnanimity.—When the Spanish armies invested Malaga in 1487, when in possession of the Moors, a circumstance occurred in a sortie from the city, indicating a trait of character worth recording. A noble Moor, named Abraher Zenete, fell in with a number of Spanish children who had wandered from their quarters. Without injuring them, he touched them gently with the handle of his lance, saying, “Get ye gone, varlets, to your mothers.” On being rebuked by his comrades, who inquired why he had let them escape so easily, he replied, “Because I saw no beard upon their chins.” An example of magnanimity (says the Curate of Los Palacios) truly wonderful in a heathen, and which might have reflected credit on a Christian hidalgo.—Prescott’s History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, Boston, 1839.

Printed and Published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; M. Bingham, Broad Street, Bristol; Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.