Title: Bygone Scotland: Historical and Social

Author: David Maxwell

Release date: February 26, 2017 [eBook #54245]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by ellinora and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

For a country of comparatively small extent, and with a large proportion of its soil in moor and mountain, histories of Scotland have been numerous and well-nigh exhaustive. The present work is not a chronicle of events in order and detail, but a series of pictures from the earlier history, expanding into fuller narratives of the more striking events in later times. And it includes portions of contemporaneous English history; for the history of Scotland can only be fully understood through that of its larger and more powerful neighbour.

The growth of a people out of semi-barbarism and tribal diversity, to civilization and national autonomy, is ever an interesting study. This growth in Scotland included many elements. The Roman occupation of Southern Britain banded together for defence and aggression the northern tribes. For centuries after the Roman evacuation the old British race held the south-western shires, up to the Clyde; the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria extended to the Frith of Forth; there were Norse settlements on the eastern coast, in Orkney, and the Hebrides. Of the various races out of which the Scottish nation was formed, the Picts were the most numerous; but the Scots—a kindred race, wanderers from Ireland—were the more active and aggressive—came to assume the general government, and gave their name to the whole country north of the Solway and the Tweed.

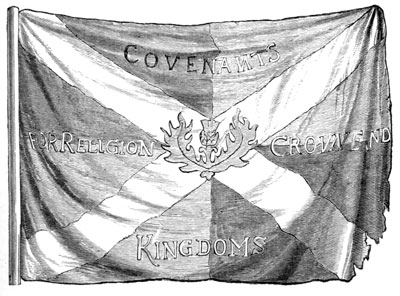

It is interesting to trace how, in unsettled times, the burghs developed into little, distinct communities, largely self-governed. And the religious element in Scotland has been a powerful factor in shaping the character of the people and of the national institutions; the conflict of the Covenant was the epic in Scottish history. The rebellion of 1745, as the last specially Scottish incident in British history, is properly the closing chapter in Bygone Scotland.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The Roman Conquest of Britain | 1 |

| Britain as a Roman Province | 12 |

| The Anglo-Saxons in Britain | 18 |

| The Rise of the Scottish Nation | 26 |

| The Danish Invasions of Britain | 38 |

| The last Two Saxon Kings of England | 48 |

| How Scotland became a Free Nation | 63 |

| Scotland in the Two Hundred Years after Bannockburn | 73 |

| The Older Scottish Literature | 80 |

| The Reformation in England and Scotland | 85 |

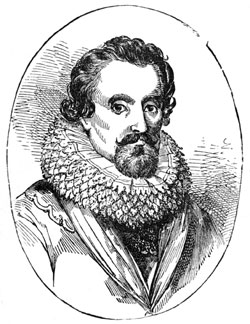

| The Rival Queens, Mary and Elizabeth | 102 |

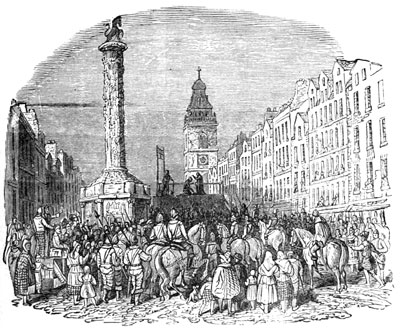

| Old Edinburgh | 111 |

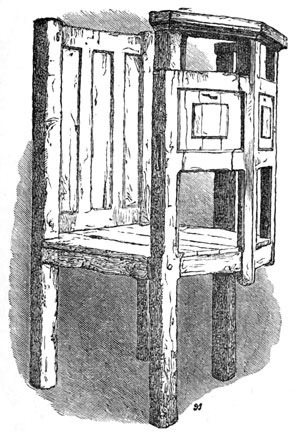

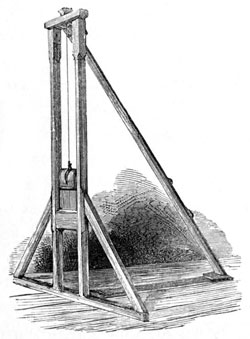

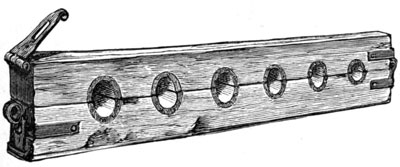

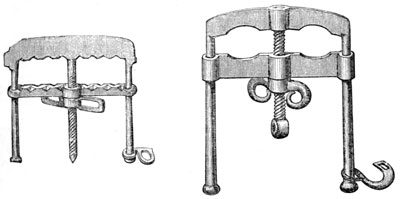

| Offences and their Punishment in the Sixteenth Century | 134 |

| Old Aberdeen | 152 |

| Witchcraft in Scotland | 160 |

| Holy-Wells in Scotland | 166 |

| Scottish Marriage Customs | 172 |

| Scotland under Charles the First | 178 |

| Scotland under Cromwell | 199 |

| Scotland under Charles the Second | 211 |

| Scotland under James the Second | 236 |

| The Revolution of 1688 | 252 |

| The Massacre of Glencoe | 264 |

| The Union of Scotland and England | 270 |

| The Jacobite Risings of 1715 | 279 |

| The Rebellion of 1745 | 289 |

We cannot tell—it is highly improbable that we ever shall know—from whence came the original inhabitants of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland. Men living on the sea-coasts of the great quadrant of continental land which fronts these islands, would, when the art of navigation got beyond the raft and canoe, venture to cross the narrow seas, and form insular settlements. It is indeed possible that, before that subsidence of the land of Western Europe which separated our islands from the mainland and from each other, was effected by the slow but ever-acting forces of geology, men were living on the banks of ancient rivers which are now represented by the Clyde, the Thames, and the Shannon.

The authentic history of Britain dates from the 2Roman invasion; before this event all is myth and legend. Half a century before the commencement of our era, Julius Cæsar, whilst consolidating in strong and durable Roman fashion his conquest of Gaul, was informed by certain merchants of the country that on the other side of the narrow sea which bounded them on the north, there was a fertile land called Britain, or the land of tin. With his legions, in the trireme galleys of the period, Cæsar crossed the narrow sea, and, so far as he went, he conquered the land.

The inhabitants were in a rude condition of life; semi-barbarous perhaps, but certainly the peoples of Fingal and Ossian in the north, and of Caractacus and Boadicea in the south, had advanced far beyond simple savagery. Climatic and geographical influences had moulded into a robust, if a fierce and stubborn type, the common materials of humanity. The ancient Britons had, in their ideas of government, advanced beyond mere clan chieftainship. Their annals, in stone cairns and the songs of bards, commemorated bygone battles and deeds of warrior renown. They had a religion with its trained priesthood—it was not a religion of 3sweetness and light, but of ferocity and gloom, of human sacrifices, and mystical rites. Its temples and altars were clusters of huge stones, arranged in forest glades on some astronomical principles. The Druidic faith was one of the many offshoots of ignorant barbarism, in which the celestial orbs and the forces in terrestrial nature—lightning and tempest—life and fire—were deified. Its priesthood was a close order, holding in their mystical gripe the minds and lives of the people. It has been said that the ancient Britons were such firm believers in a future state, that they would even lend each other money, to be repaid in the spiritual world. Their language was a dialect of the Gaelic—the language spoken in more ancient times over the greater portion of Western Europe.

The Roman invasion under Julius was little more than a raid. He marched his legions as far inland as the Thames, and again retired to the coast; he left Britain without forming a Roman settlement, and for nearly a hundred years the island remained free, and did a considerable maritime trade with Gaul and Scandinavia. In A.D. 43, the fourth Roman emperor, Claudius, with a large army, invaded 4Britain. The native tribes, although generally inimical to the Romans, had no concerted action amongst themselves, were often, indeed, at war with each other; and thus the disciplined soldiers of Rome had a comparatively easy task, although they had many fierce encounters with native bravery and hardihood. One British chief, Caractacus, held out the longest. He was the King of the Silurians, the dwellers in South Wales and its neighbourhood. For several years he withstood the masters of the world, but was ultimately defeated in battle, and he and his family were sent prisoners to Rome.

On the eastern coast, in what is now Suffolk and Norfolk, was a tribe called the Icenians. This tribe, under Boadicea, the widow of one of its kings, made, in the absence of the Roman governor, Suetonius, raids upon London, Colchester, and other Roman towns. When Suetonius returned, he defeated Boadicea in a battle near London. She killed herself rather than submit. Agricola succeeded Suetonius as governor, and he pushed the Roman Conquest northwards to a line between the Firths of Forth and Clyde. Beyond this line the Romans never made permanent conquests. Along this line 5Agricola built a chain of forts as a defence of the Roman province against incursions from the northern tribes, and as a base of operations in attempting farther conquests. In a campaign in the year 84, he was opposed by a native force under a chief called Galgacus. A battle was fought amongst the Grampian Hills, near Blairgowrie, with a hardly-won victory to Agricola. It was such a victory as decided him to make the Tay the northern boundary of Roman occupation. But Roman fleets sailed round the northern shores,—planting the Imperial Standard on Orkney,—and returned, having proved that Britain was an island.

The northern portion of the island, beyond the line of forts, was then called Caledonia; border fighting was the rule, and the “barbarians from the hills” made frequent raids into the Romanized lowlands. Indeed, not only had the Romans to build a wall connecting the forts of Agricola, but also, as a second line of defence, one between the Tyne and the Solway Firth. The two walls prove the determination of the Romans to maintain their British conquests, and also at what a high rate they estimated the native resistance.

In 208, Severus had to re-conquer the country 6between the walls, restoring that of Agricola, and he carried the Roman eagles to the farthest points north which they ever reached. The remains of Roman roads through Strathearn to Perth, and thence through Forfar, the Mearns, and Aberdeen to the Moray Firth, belong to this period; and they represent attempts to subdue the whole island. Dion, the Roman historian, ascribes the failure of this attempt to the death of Severus at York, in 211. He describes the Caledonians as painting on their skins the forms of animals; of being lightly armed; making rapid dashes in battle; of having no king, only their tribal chieftains. In 305, Constantius defeated the tribes between the walls; they are called in the Roman records, “Caledonians and other Picts;” the latter name being then used for the first time, and as being the more generic appellation. In 360, the Scots are named for the first time. They and the Picts made a descent upon the Roman province, and this is spoken of in terms which imply that they had previously passed the southern wall.

For about 366 years the Romans held sway in Britain; if we think of it, for as long a period as elapsed between Henry the Eighth’s publishing 7his treatise in defence of the seven Romish sacraments, and the jubilee of Queen Victoria. The conquest of an inferior by a superior race is generally fraught with progressive issues to the conquered people. In the roads and architecture, the laws and the civic institutions of the country, the Romans left lasting memorials of their British rule. Towns rose and flourished; marshes were drained; the land was cultivated; low-lying coast lands were, by embankments, protected from the sea; trade advanced; Christianity and Roman literature were introduced.

As a constituent portion of the empire, Britain occupies a place in Roman history. A Roman commander in Britain, Albinus, had himself nominated emperor. He carried an army into Gaul, but was there beaten and slain in a battle with the rival emperor, Severus. Severus himself died at York, then called Eboracum; and, in 273, Constantine, since styled The Great, was born in that city, his mother, Helena, being British. Constantius, the father of Constantine, had a long struggle for the possession of Britain with Carausius, a Belgian-born Roman general, who, in 286, rebelled against the authority of the empire. The usurper formed a navy, with which 8he for eight years prevented Roman troops from landing on our shores, but he lost his life through treachery, and once more the imperial eagles floated over Britain. For a time Britain might be said to be the head-quarters of the empire. Residing principally at York, Constantius gave his commands to Gaul and Spain, to Italy itself, to Syria and Greece. It was in Britain that on the death of his father, in 306, Constantine was proclaimed emperor. He was the first Christian emperor, and all the emperors who succeeded him professed Christianity, except Julian, who, returning to the old gods, was called The Apostate; but Julian was really a wiser ruler and a better man than many of those who called themselves Christian. The new religion became the official faith of the empire. Not much is known with certainty of the early British church, but there are said to have been archbishops in the three chief cities, London, York, and Caerleon.

The grand old Latin language, containing in its literature the garnered up thoughts and attainments of centuries, spread its refining influences wherever the Roman camp was pitched. Latin was the official language in Roman Britain, and it would be known and probably spoken by the 9well-to-do Britons in the towns. But it never amalgamated with the old Celtic-Welsh of the common people. Celtic, although in many respects a well-constructed language, is not a pliant one—is not adapted for readily intermingling with other tongues. It has in its various dialects, which have through the succeeding centuries maintained their existence in Wales, in Ireland, and in the Highlands of Scotland, kept itself altogether apart from the English language; and it has given comparatively few of its words to the modern tongue.

In the third century the Roman empire was in its decline, and hastening to its fall. Constantine transferred the seat of government to Byzantium, and that city was thenceforth named from him, Constantinople; and then the Roman power was divided—there were eastern emperors and western emperors. In the Patriarch of the Greek Church residing in Constantinople and the Pope of the Catholic Church in Rome, we have that division perpetuated to this day.

The Romans had never been able to conquer more than small portions of the great country in Central Europe which lies north of the Danube and east of the Rhine, which we now call 10Germany. One Teutonic chief called Arminius, afterwards styled The Deliverer, destroyed a whole Roman invading army. Towards the end of the fourth century the Teutonic nations began to press into the Roman empire, and one by one the provinces were wrested from it by these incursions. The Romans hired one tribe against another; but stage by stage the empire shrank in its dimensions, until it came to be within the frontiers of Italy; and still the barbarians pressed in.

On the 24th day of August, 410, the evening sun was gilding the roof of the venerable Capitol, and peace and serenity seemed to hover over the eternal city. But at midnight the Gothic trumpets sounded as the blasts of doom. No devoted Horatius now kept bridge and gate as in the brave days of old. Alaric, “the curse of God,” stormed the city, to burn and slay and inflict all the horrors of assault; but sparing Christian churches, monks and nuns. It is said that forty thousand slaves in the city rose against their masters.

From the spreading of the Teutonic tribes, new nations were formed in Western Europe. The Franks pressed into Northern Gaul. Their 11name remains in Franconia, and in that portion of Gaul called France. In Italy, Spain, and Acquitaine, the Goths and other Teutonic peoples mingled with the Romans. From the Latin language, corrupted and mixed up with other tongues, arose the Italian, Spanish, Provençal, and French languages, all, from the name of Rome, called the Romance languages. The eastern empire still went on; in the sixth century it recovered for a time Italy and Africa. Its people called themselves Romans, but were not so much Roman as Greek. After a lengthened decline, its last fragments were destroyed by the Turks, who took Constantinople in 1453.

It was fortunate for Britain that it came under the rule of Rome, not in the time of the Republic, when the conquered peoples were ruined by spoliation and enslavement; nor yet in the earlier years of the empire, a time of conflict and unsettlement, but after the death of the infamous Caligula, when Claudius had assumed the purple. At the beginning of the second century the Roman Empire was, under Trajan, at its culminating point of magnitude and power. Trajan was succeeded by Hadrian, whose governmental solicitude was shown in continuous journeying over his vast empire; and by the general construction of border fortification, of which the wall in Britain, linking the Tyne with the Solway Firth, is an example. Antoninus followed Hadrian, and of him it has been said: “With such diligence did he rule the subject peoples that he cared for every man of them, equally as for his own nation; all the provinces flourished under him.” His reign was tranquil, 13and his fine personal qualities obtained for him the title of Pius. Of course for Britain it was the rough rule of military conquest; but it prevented tribal conflicts, secured order, and encouraged material development; corn was exported, the potter’s wheel was at work, there was tin-mining in Cornwall, and lead-mining in Northumberland and Somerset; iron was smelted in the Forest of Dean.

But distance from the seat of government, as well as its murky skies, and wintry severity—no vines, no olive or orange trees in its fields—made Britain an undesirable land for Roman colonisation; it was held chiefly as a military outpost of the empire.

Whilst the more intimate Roman rule in South Britain gave there its civilizing institutions, its Latin tongue, its arts, laws, and literature, and in the fourth century Christianity, these results became less emphasized northwards—hardly reaching to the wall of Hadrian. The country between the walls remained in the possession of heathen semi-barbarians, scarcely more civilized or trained in the arts of civil government than were the Celtic tribes of the north. There were no Roman towns, and very few remains of Roman 14villas have been found, beyond York: remains of roads and camps, of altars and sepulchral monuments are found. To the south of York, Britain was a Roman settlement; north of York it was a military occupation.

In spite of its roads, its towns, and its mines, Britain was still, at the close of the Roman rule, a wild, half-reclaimed country; forest and wasteland, marsh and fen occupied the larger portion of its surface. The wolf was still a terror to the shepherd; beavers built their dams in the marshy streams of Holderness.

Unarmed, and without any military training, feeling themselves weak and helpless in the presence of the dominant race, the Britons of the province were yet sufficiently patriotic, to give negative help at least to the Pictish tribes who were ever making incursions into the district between the walls, and even at times penetrating into the heart of the province. One of these inroads in the reign of Valentinian all but tore Britain from the empire: an able general, Theodosius, found southern Britain itself in the hands of the invaders; but he succeeded in driving them back to their mountains, winning back for Rome the land as far as the wall of Agricola, and the 15district between the walls was constituted a fifth British province, named after the Emperor, Valentia.

And whilst the Pictish clans were thus making wild dashes over the walls, the sea-board of the province was harrassed by marauders from the sea. Irish pirates called Scots, or “wanderers,” harried the western shores; whilst on the eastern and southern coast, from the Wash to the Isle of Wight, a stretch of coast which came to be called the Saxon Shore, Saxon war-keels were making sudden raids for plunder, and for kidnapping men, women, and children, to be sold into slavery. They also intercepted Roman galleys in the Channel, which were engaged in commerce, or on imperial business. In the year 364, a combined fleet of Saxon vessels for a time held the Channel.

And now the Romanized British towns began to shew their lack of faith in imperial protection, by strengthening themselves by walls. A special Roman commander was appointed, charged with the defence of the Saxon shore. The shore was dotted by strong forts, garrisoned by a legion of ten thousand men. The thick forests which lined the coast to the westward of Southampton water 16were considered sufficient guards against invasion in that quarter. As long as the Romans remained in Britain they were able to repel the attacks of their barbarous assailants. But when the fated hour came—when Rome in her death-struggle with the Teutonic hordes, whose gripe was at her throat in every one of her dominions in western Europe, and even in Italy itself, had to recall her troops from Britain—then the encircling foes closed in upon their prey.

In withdrawing, in 410, his troops from Britain, the Emperor Honorius, grandson of the general Theodosius we have mentioned, told the people in a letter to provide for their own government and defence. We may imagine how ill prepared, after ten generations of servitude, the Romanized Britons were for such an emergency. But they had fortified towns with their municipal institutions, and under the general sway of Rome they had lost their tribal distinctions, and become a more united people; and not in any one of the Romanized lands which became a prey to the barbarians did these encounter so prolonged and so energetic a resistance as in Britain. For some thirty years after the Roman evacuation of the province, it held out or maintained a fluctuating 17struggle with its enemies. The Scoto-Irish bucaneers were not only continuing their raids upon the western coast, but they planted settlements in Argyle to the north of Agricola’s wall, and in Galloway—between the two walls. And the Picts were ever making incursions from the north. The policy was tried of hiring barbarian against barbarian. The Picts were the nearest and most persistent danger; and the marauders from over the North Sea,—Saxons, Angles, and Jutes, were, if not hired as mercenaries, permitted to hold a footing in the land, as a defence against Pictish invasion. About 450, three keels filled with Jutes, under two brothers, Hengist and Horsa, with a white horse as their cognisance, came by invitation from their own home—which is from them called Jutland—and landed on the Isle of Thanet on the eastern Kentish shore, making this their base for further conquests.

The Teutonic nations from mid-Europe which, in their various tribes, conquered Italy, Spain, and Gaul, had had previous intercourse with the empire. Many had become Christians, and in their conquests they did not destroy. Their kings ruled the invaded lands, and their chiefs seized large portions of soil; but they adopted the provincial Latin tongues, and the general government was by Roman law. The clergy were mostly Romans, and they retained considerable power and estates. Thus the Goths, Visigoths, and Vandals did not become the peoples of the countries which they overran. The Teutonic element was absorbed into the national elements, largely resembling what afterwards took place in England, under the Norman Conquest.

But it was very different in Britain. Its Teutonic invaders—Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, had lived outside the influence of the empire; and indeed we know very little about them before 19they came to Britain. With the landing of Ella, in 477, Anglo-Saxon history may be said to begin. They were still heathens, and they knew nothing, and they cared nothing for the arts, the laws, or the language of Rome. Their object was not merely rule and authority over the Romanized Britons, but their destruction, and the entire occupation of the land. As they conquered, they killed the Britons or made them slaves, or drove them into Cornwall and Wales in the west, and into Caledonia in the north. They came over the North Sea in families, and thus propagated largely as an unmixed Anglo-Saxon race. But doubtless there were many more men than women in their bands, and there would be marriages with native women. Thus strains of British and Roman blood were left in the new occupants of what came to be England, and the lowlands of Scotland. The Anglo-Saxon tribes in Britain thus became a nation with its own language and laws, manners and customs. From the name of one tribe—the Angles—the southern and larger portion of the island came to be called England. English is the common language of Britain, and of its many off-shoots scattered over the habitable globe.

20Kent—the nearest British land to the continent—bore the first brunt of Anglo-Saxon, as it had done of Roman, conquest. Then came Sussex (South Saxon). But the third settlement, that of Wessex (West Saxon), was a far larger one; taking in at least seven shires. It began in Hampshire, under Cedric, and his son Cynric—then styled Ealdermen—and gradually extended over all south-western Britain, and stretching northwards over Oxford and Buckingham shires. This was the era assigned to the legendary British King Arthur, fighting strongly for his native soil and his Christian faith, against the heathen invaders.

Another, the fourth Saxon kingdom, was that of Essex. And then there were three Anglian kingdoms—East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia. East Anglia comprised Suffolk (South-folk), Norfolk (North-folk), and Lincolnshire. Northumbria included the country north of the Humber, as far as the Frith of Forth. That portion of Northumbria now known as Yorkshire was then called Deira, with York, then named Eboracum, its chief town; the portion north of the Tees was named Bernicia. The kingdom of Mercia, that is, of the March, had its western 21frontier to Wales, being thus the midlands of England.

And besides South Wales, including Cornwall, Devonshire, and the greater portion of Somersetshire, the old race still held a large district to the north of Wales, called Strathclyde, taking in Galloway and other districts in the south-east of what is now Scotland; together with Cumberland, Westmoreland, and Lancashire, down to the river Dee, and the city of Chester; they, even to the end of the sixth century, held portions of west Yorkshire, including Leeds.

The Anglo-Saxon occupation having thus at the close of the sixth century resolved itself into seven independent governments, is hence called the Heptarchy. But the division was not a lasting one. The conquerors, although a kindred race—with one understood language—and one old Scandinavian faith, were far from being a homogeneous people. They had tribal proclivities, and were generally at war with each other—“battles of kites and crows,” Milton wrote. At times one king was powerful, or of such personal superiority to his neighbours, that he assumed a suzerainty over them, and was called a Bretwalda. But the Anglo-Saxon kings were not autocrats; 22they had to consult their Witans—their council of “witty or wise ones.” And there was in society the elements of what came to be feudalism. The King had his Thanes, or Earls; and these had their churls, who, holding lands under their lords, were expected to follow him in the wars. And there was slavery; men were made slaves who committed crimes, or were taken prisoners in war.

The seventh century witnessed in Anglo-Saxon Britain the conversion from the old Norse belief in Odin, Thor, and Fries to the Christian faith. Not from their British slaves, nor from the independent British of Wales and Strathclyde, did the new faith reach them. In 597, Pope Gregory sent Augustine and a number of other monks to preach Christianity in England. The most powerful ruler in Britain at this time was the Kentish king, Ethelbert; he was Bretwalda, exercising some authority over all the kings south of the Humber; and he had married a Frankish wife who was a Christian. The King received the missionaries kindly; and they preached to him and his chief men through interpreters. In a short time the King and a number of his people were baptized. Augustine made Canterbury his 23headquarters, and it has ever since been the chief See of the Anglican Church.

In 635, Oswald, King of Northumbria, routed a British Strathclyde army, largely shattering this kingdom of the older race; it was as much as the Welsh could do to hold the country west of the Severn.

In this seventh century, Devon and the whole of Somersetshire became English. Oswald was now Bretwalda, and Northumbria, in the struggles for supremacy of the Saxon kingdoms, was for a generation the foremost power. It also became Christian, but more from the labours of Scottish missionaries from Iona, than from the successors of Augustine.

In early life, Oswald, during an exile amongst the Scots, had visited Iona, and there became acquainted with Christianity. On his return he founded a monastery on Lindisfarne, thence called Holy Isle; a Scottish Bishop, Aidan, he placed at its head; a succeeding Bishop, Cuthbert, was the most famous of the saints of Northern England. And the Christianity which came to Scotland from Ireland through Columba, himself a Dalriadan Scot, differed in many ways from that which had come from Rome. 24Not only did they differ in ritual, in dates of festivals, and in the shape of the monkish tonsure, but in what was of more political importance—ecclesiastical discipline and organization. The Church of Augustine implied dioceses, bishops in gradation of rank and authority, culminating in the Bishop of Rome as the head of the Church. The Church of Columba was a network of monasteries, a missionary church full of the zeal of conversion, but wanting in the power of organization. And thus there was conflict between the two churches, and this conflict was an important factor in the political history of the times. Ultimately the policy of Rome prevailed. The country was divided into dioceses, the loose system of the mission-station sending out priests to preach and baptize as their enthusiasm led them, gave place to the parish system with its regular incumbency, and settled order.

In the beginning of the ninth century the strife for headship over the others, which had been long waged by the kings of the stronger kingdoms, was terminated by the Northumbrian Thanes owning Egbert, King of Wessex, as their over-lord. Egbert defeated the Britons in 25Cornwall, brought Mercia under his rule, and united all the territories south of the Tweed. The Kings of Wessex were henceforth, so far as Anglo-Saxon rivals were concerned, Kings of England.

In the second century, Ptolemy, the Egyptian astronomer, composed the first geography of the world, illustrated by maps. He would probably get his information about Britain—which was still called Albion—from Roman officers. What is now England, is shown with fair accuracy; but north of the Wear and the Solway it is difficult to identify names, or even the prominent features of the country; and the configuration of the land stretches east and west, instead of north and south.

The Celts were not indigenous to Britain. It is hardly possible to trace in any—in the very earliest peoples, of whom history or archæology can speak—the first occupants of any one spot on the earth. Science is ever pushing back, and still farther back, the era of man’s first appearance as fully developed man upon the globe. And in his families, his tribes, and his nations, man has ever been a migrant. Impelled by the necessities of life, or by his love of adventure or of conquest, 27he has changed his hunting and grazing grounds, made tracks through forests, sought out passes between mountains; and the great, all-encompassing sea has ever been a fascination; the sound of its waves a siren-song inciting him to make them a pathway to new lands beyond his horizon. Before the Celtic Britons dwelt in this island in the northern seas, which they have helped to a great name, there were tribes here who had not yet learned the uses of the metals, whose spear-heads and arrow-tips were flints, their axes and hammers of stone. But the Celts were of that great Aryan race, tribes of which, spreading westwards over Europe, had carried with them so much of the older civilization of Persia, that they never degenerated into savagedom. The Britons were probably in pre-Roman times the only distinctive people upon the island.

How came the Celts to Britain? Probably colonies from Old Gaul first took possession of the portions of Britain nearer to their own country; and gradually spreading northwards, came in time to be scattered over what is now England and Wales, and the Lowlands of Scotland. Ireland being in sight of Britain from both Wigton and Cantyre, adventurers would 28cross the North Channel, and become the founders of the Irish nation.

The Picts—a Latin name for the first northern tribes whom the Romans distinguished from the Britons—called themselves Cruithne. Their earliest settlements in and near Britain appear to have been in the Orkneys, the north-east of Ireland, and the north of Scotland. They must then have made considerable advancement in the art of navigation. At the time of the Roman invasion, the southern Britons called the dwellers in the northern part of the island Cavill daoin, or “people of the woods,”—and thus the Romans named the district Caledonia. It has been surmised that the Picts of ancient Caledonia were a colony of Celtic-Germans; for such offshoots from the parent race occupied portions of central Europe. There was the same element of Druidism; but the Druids in Caledonia declined in influence and authority at an earlier date than did their brethren in Wales and South Britain. The bards took their place in preserving and handing down—orally and in verse—the traditions of their tribes—the heroism and virtues, the loves and adventures, of their ancestors. It may be noted that whilst in this early poetry the spirits of 29the dead are frequently introduced, and the powers of nature—sun, moon, and stars, the wind, the thunder, and the sea—are personified, there is no mythology,—no deities are called in to aid the heroes in battling with their foes.

By the end of the Roman occupation, the Caledonian Picts had spread down east and central Scotland as far as Fife. And there are Pictish traces in Galloway on the west coast; probably a migration from Ireland. After the Romans left, the Picts, in their southern raids, so often crossed and made use of Hadrian’s wall, that the Romanized-Britons came to call it the Pictish wall. Their language was a dialect of Celtic, afterwards coalescing with, or being absorbed in, the Gaelic of the Scots, and which came to be the common tongue in the Highlands and western isles; but it was never a spoken tongue in the Scottish Lowlands.

The Scots are first found historically in Ireland; and they were there in such numbers and influence, that one of the names of Ireland from the sixth to the twelfth century was Scotia. Irish traditions represent the Scotti as “Milesians from Spain;” Milesia was said to be the name of the leader of the colonizing expedition. But 30their Celtic name of Gael sounds akin to Gaul. Their history in Ireland forms an important factor in the annals of that country. Those of the Irish people who considered themselves the descendants of the earlier colonists of the island never came heartily to recognise as fellow-countrymen,—although these had been for many generations natives of the land,—the descendants of those who settled at a later date. On the other hand—and similarly keeping up old race hatreds and lines of demarcation—the descendants of the later settlers looked upon themselves as a superior race, and never heartily called themselves Irishmen. This restricted and mock patriotism, aggravated by religious differences, has almost made of the Irish people two nations.

The Scotti must have made considerable settlements in North Britain in the second or third century, or they would not have been in a position to join the Picts in attacks upon the Roman province in the fourth century. When we come to enquire who were the peoples associated with the Christian missionary Columba in the latter half of the sixth century, we find that the districts bordering the east coast down to the Firth of Forth, and the central Highlands, 31with the chief fort at Inverness, were peopled by Picts; and that Scots were in Argyle and the Isles as far north as Iona. Their settlement around the shores of Loch Linnhe—the arm of the sea at the entrance to which Oban now stands—became in time a little kingdom called Dalriada, which gradually shook off the over-lordship of the Scotic kings in Ireland, and maintained itself against the Picts on its northern and eastern borders. A British king ruled in Strathclyde, which included the south-west of Scotland up to the Clyde; and, bordering on Strathclyde, Anglo-Saxon Northumbria included the east of Scotland up to the Forth. Up to this time the Celts in North Britain had left no written history behind them; indicating that they were less civilized than their Welsh and Irish kin. It is in the annals of Beda and other Anglo-Saxon writers that we find anything like trustworthy history after the departure of the Romans. The Romanized Britons got Christianity from their rulers, but subjection to the Bishop of Rome was not transmitted with the faith. The British bishops, at their meeting under St. Augustine’s oak, declined to submit to the missionary from Rome.

32It is usually said that Scotland gave Patrick to Ireland. It was a strange kind of giving. Shortly after the Roman exodus, amongst a number of Britons taken captive by a Scotti-Irish raid on the banks of the Clyde, was a young lad of sixteen, who was sent as a slave to tend sheep and cattle in Antrim. The people round him were idolators; but in the solitude of the pastures he nursed the Christian faith of his childhood, and burned with the zeal of a young apostle for the conversion of the land. For ten years he remained in captivity, then he made his escape, and after many wanderings, reached his old home. Ordained a priest, and in time a bishop, he set manfully to realize in Ireland the dream of his youth, and he had abundant success. He founded churches, seminaries, and monasteries; the new faith spread like wildfire over the land.

And a century later, in 563, thirty-three years before the Roman mission of Augustine, Ireland sent over Columba to Britain. He, with twelve companion monks, founded on the little isle of Iona a monastery, which became the centre of Christianity in North Britain. The Scotti who had settled in the neighbouring islands, and on the nearest mainland, were already Christians. 33But Columba visited and converted the Pictish King Bruda, and founded a number of churches and monasteries. Than Iona there is no spot of greater historical interest in the United Kingdom; but none of the ecclesiastical ruins found there date from Columba. The first buildings were of wood, but the original foundations in Skye and Tiree were his work. Columba was also a warrior, taking a strong part in several campaigns in Ireland, as a liegeman of the Scotic King. The disciples of Columba were called Culdees, meaning, from their monastic life, “sequestered persons.” The Pictish bard Ossian is said, when blind and in old age, to have met and conversed with one of these Culdees. After ten years of prosperous rule in Iona, Columba contributed to start into greater unity and more vigorous life the Scotic settlement of Dalriada. He consecrated a young chieftain, Aedhan, as king; and Aedhan drove the Bernicians from the debatable land south of the head-waters of the Forth, and formed a league of Scots and Strathclyde Britons against Northumbria itself. But the league was, in 603, defeated by the Northumbrian King Ethelfrith in a great battle. The Scots were thrown back 34into their Highland fastnesses, and Beda says, writing a hundred years later, “From that day to this no Scot King has dared to come into battle with the English folk.” Ethelfrith, by another victory over the Welsh at Chester, in 611, and further successes up to Carlisle, divided by a great gap the Kingdom of Strathclyde from North Wales, and it became tributary to Northumbria. On the decline of Northumbria, in the eighth century, Strathclyde re-asserted its independence; and, in a restricted sense, its extent, more nearly answered to its name, “The Valley of the Clyde.” With Galloway, it continued under its own rulers, until, in the tenth century, it was connected with the Kingdom of Scone by the election to its throne—if it could afford a throne—of Donald, brother of Constantine II., King of Scots.

The Picts whom Columba converted appear to have been then consolidated under one monarch, Brude; his rule was from Inverness to Iona on the west; on the north to the Orkneys—probably including Aberdeen; its southern boundary is undefined. Of succeeding kings to Brude, there is a list of names; but little is known of the men themselves until, in 731, we come to Angus Mac-Fergus. 35In reprisal for the capture of his son by Selvach, King of the Dalriad Scots, he attacked Argyle, and reduced the whole western highlands. The Strathclyde Britons were assailed by a brother of Angus, in 756, and their chief town, Alclyde, destroyed. In the beginning of the ninth century, the seat of the Pictish government appears to have migrated from Inverness into Perthshire,—Scone becoming its political capital.

The history of the Dalriadan Scots, although interwoven with that of the Picts, and meeting at many points with the histories of the Britons of Strathclyde, and the Angles of Northumbria, is yet misty and legendary. True, there is a list of kings, and their stalwart portraits hang in the great hall of Holyrood; so extensive is this list, that if they had reigned for anything like an average period, it would carry the history back to about three hundred years B.C.

We find something like a trustworthy beginning in Fergus, the son of Earac, in 503. From this date for upwards of two hundred years, down to Selvach, who was conquered by the Pictish King Angus Mac-Fergus, there is from the Irish Annals, and the Church History 36of Beda, a reasonable certainty. After this there is another century of hazy legend. If, as seems probable, Dalriada continued through the latter seventy years of the eighth, and the first half of the ninth century, under Pictish rule, it is not easy to see how, in the middle of the ninth century, Kenneth Mac-Alpine, called in the Irish Annals a king of the Picts, founded, as there is no doubt he did, a line of Scottish monarchs on the throne of Scone. One hypothesis is, that Kenneth was the son of a Pictish king by a Scottish mother, and by the Pictish law, the mother’s nationality determined that of the children. Whatever the circumstances of the case, the accession of Kenneth Mac-Alpine represents an era in Scottish history. There was thenceforth such a complete union of Scots and Picts, that as separate races they lost all distinctiveness. But it certainly appears that, both by numerical superiority and historical prestige, the country should have been Pictland, rather than Scotland.

The kingdom of Kenneth included central Scotland from sea to sea, Argyle and the Isles, Perthshire, Fife, Angus, and the Mearns. Lothian was still Northumbrian. The Vale of the Clyde, 37Ayr, Dumfries, and Galloway, were under a British king at Dumbarton. There were several independent chieftains in Moray and Mar; and Orkney and the northern and north-western fringes of the country, were dominated by Norsemen.

In the first quarter of the ninth century, invaders from lands farther north than Jutland—hence called Norsemen—played broadly the same parts in Britain as the Angles and Saxons had played three hundred years previously. These Norsemen, in their war galleys, prowled over the Northern Seas, plundering the coasts, and making first incursions and then settlements in Muscovy, Britain, and Gaul. They discovered and colonised Iceland. Many centuries before Columbus, they had sailed along the coast of North America, and even attempted settlements thereon. On the northern coast of France, Normandy, under its powerful dukes, had become almost an independent state.

In their English invasions they are commonly called Danes, but in their own homes they formed three kingdoms, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Probably the invaders of England were mainly Danes. They were still “heathens,” i.e., of the old Scandinavian faith; and they held 39the Christian faith in supreme detestation. They were daring, fierce, and cruel; but still people of a kindred race, speaking dialects of the same Teutonic tongue; and when they settled in the land and became Christians, their language and manners differed so little from those of the Anglo-Saxons, that they did not remain a separate nation, as the Anglo-Saxons did from the British. It was more as if another Teuton tribe had come over and become joint occupants of the land. But, to begin with, they came as plunderers, taking their booty home. They ravaged Berkshire, Hampshire, and Surrey, destroying churches and monasteries. They invaded and took possession of East Anglia. They penetrated into Mercia; at Peterborough they burned the minster, slaying the abbot and his monks. They made extensive settlements in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

In 876, the Danes invaded Wessex, of which Alfred—one of the grandest names in old English history—was then King. Alfred had to fight the invaders both on sea and land. In and about Exeter there were several engagements, resulting in the Danes agreeing to leave Alfred’s territories. Two years later they broke truce, 40made a sudden incursion to Chippenham, and became for a time masters of the west country. This is the time assigned to the neatherd-cottage negligence of Alfred, in allowing the cakes to burn in baking, whilst sheltering amongst the wood and morasses of Somersetshire. After a time he organised a sufficient army to meet, fight with, and beat the Danes—they gave him oaths and hostages against further disturbance, and their King Guthrum—thence called Athelstan—with thirty of his chief followers were baptized. But the Danes now held East Anglia, Northumbria, and large portions of Essex and Mercia,—indeed more than one-half of what is now England. Alfred being in peace during the latter years of his reign, devoted himself to works of governmental utility, he made a digest of the laws, and saw that justice was impartially administered; and he was the father of the English navy. His mind was cultured with the best learning of the times, and he made Anglo-Saxon translations of the Psalms, of Æsop’s Fables, and of Bede’s Church History.

In the first year of the tenth century, Alfred’s son, Edward (styled the Elder, so as not to confuse him with later Edwards), began a reign of 41twenty-five years. He was a strong king; through all his reign he had conflicts with the Danes, who had settled in the north and east of England; always beating them, and then having to quell fresh insurrections. And he made himself Over-King of the Scots and Welsh; so he was the first Anglo-Saxon king who became lord of nearly all Britain. Wessex, Kent, and Sussex he had inherited, Wales, Strathclyde, and Scotland acknowledged him as Suzerain. His son, Athelstan, succeeded him in 925; and the King of England now held such a high place among the rulers of Western Europe, that several of his sisters married foreign kings and princes. In 937 a great battle was fought in the North, when a combination of Scots under Constantine, and Danes and Irish under Anlaf, were defeated with much slaughter by Athelstan. It is called by the old chroniclers the Battle of Brunanburg, but the locality is uncertain. Constantine and Anlaf escaped; but Constantine’s son was killed, as, says the old chronicler, were “five Danish Kings and seven Jarls.”

Athelstan died in 941. Two of his brothers, and one brother’s son occupied the throne successively during the next eighteen years. 42Then, in 959, Edgar, a grandson of Alfred, then only sixteen years of age, was by the Witan made King. He was called The Peaceable; during his reign of sixteen years, no foe, foreign or domestic, vexed the land. Northumbria, extending as far north as the Forth, with Edwinsburh its border fortress—garrisoned by Danes and Anglo-Saxons—having long been a trouble to the Kings of Wessex, Edgar divided the earldom. He made Oswulf Earl of the country beyond the Tees—including the present county of Northumberland; and Osla, Earl of Deira, where the Danes had ruled, with York for his chief town; but the Danes were allowed to live peaceably under their own laws. And Edgar granted Lothian, containing the counties of Linlithgow, Edinburgh, and Haddington, to Kenneth, King of Scots, to be held under himself. And thus Lothian was ever after held by the Scottish Kings, and its English speech became the official language of Scotland. With Strathclyde, west of the Solway, under a Scottish prince, the map of the Kingdom of Scotland was now broadly traced out.

Edgar commuted the annual Welsh tribute to 300 wolves’ heads. He appointed standard 43weights and measures, maintained an efficient fleet, and was altogether a fine example of a man who—although of small stature and mean presence—by vigour of mind and will, ruled ably and well in rude times. He was really Basileus,—lord-paramount of all Britain. After his coronation at Bath, which was not before he had reigned thirteen years—he sailed with his fleet round the western coasts. Coming to Chester, it is related that eight Kings, viz.: Kenneth of Scotland, Malcolm of Cumberland, Maccus of the Western Isles, and five Welsh princes did homage to him. They are said to have rowed him in a boat on the Dee—he steering—from the palace of Chester to the minster of St. John, where there was solemn service; and then they returned in like manner.

But these halcyon days for England of peace and settled government ended with Edgar. He died in 975, leaving two sons—Edward by a first wife—Ethelred by a second. Edward succeeded, but reigned only four years, being assassinated at the instigation of his step-mother, who desired the crown for her son. Edward was in consequence styled The Martyr. Ethelred was named The Unready. He was weak, cowardly, 44and thoroughly bad; his long reign of thirty-eight years, was one duration of wretchedness and confusion. He had hardly begun to reign when the foreign Danes began to be troublesome, and this time it was a farther stage of invasion: they meant not plunder or partial settlement, but conquest!

In the first quarter of this tenth century, the Northmen had taken possession of a large district on the north of France. Their leader, Rolf Ganger, became a Christian—or at least was baptized as such,—married the daughter of Charles the Simple, King of the West Franks, and was, as Duke of Normandy, confirmed in his possessions—a territory on either side of the Seine, with Rouen for its capital. And after this, the Danes and other Northmen, in their expeditions against England, had assistance from their kinsfolk in Normandy.

Ethelred tried first to bribe the Danes to leave him in peace; and for the money for this purpose he levied the first direct tax imposed upon the English nation. It was called Dane-gild, and amounted to twelve pence on each hide of land, excepting lands held by the clergy. But the idea was a vain one, for whilst the tax was 45vexatious, the pirate-ships still swarmed along the English shores. In 1001, the Danes, under King Sweyn, attacked Exeter, but were repulsed by the citizens. Then—beating an English army—they ravaged Devon, Dorset, Hants., and the Isle of Wight; loading their ships with the spoils. Next year Ethelred gave them money; but finding this of no use, he devised the mad and wicked scheme of ordering a general massacre of the Danes residing in England. On St. Bryce’s Day this massacre, to a large extent, took place; it included aged persons, women, and children. Gunhild, a sister of Sweyn’s, was one of the victims. Burning for revenge, Sweyn again invaded England. Exeter he now took and plundered, and again marched eastwards through the southern shires. He was generally successful, for there was treason and incompetency amongst the English leaders; and the unpopularity of Ethelred was a down-drag on the English cause. Year after year, Sweyn’s fleets appeared on the fated coasts, and the Danes marched farther and farther inwards. Through East Anglia they went into the heart of England, burning Oxford and Northampton.

In August, 1013, Sweyn sailed up the Humber 46and Trent to Gainsborough. Here he had submission made to him of the Earl of Northumbria, and of the towns of Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham, Stamford, and Derby. He then marched to Bath, where the western Thanes submitted to him, and then London submitted. Ethelred and his queen fled to Normandy, Emma, the Queen, being the Duke’s sister, and Danish Sweyn was virtually King of England. But he did not long enjoy his conquest; early in 1014 he died at Gainsborough.

Canute, the son of Sweyn, was a man of strong will, and he had already achieved warrior renown: but he had a severe struggle before he secured his father’s conquests. First, after Sweyn’s death, the Witan, after extorting promises that he would now govern rightly, recalled King Ethelred. Receiving better support, and his son Edmund, named Ironside, being an able commander, he defeated Canute, who had to take to his ships. Then Ethelred died, and Canute returned. There was much fighting,—London being twice unsuccessfully assaulted by the Danes,—and then the rival princes, Edmund and Canute, had a conference on a little island in the Severn. They agreed to a division of the kingdom,—the Saxon district to be south,—and the Danish 47district to be north of the Thames. A few weeks after the treaty, Edmund died, and although he left a young son Edward, Canute became sole monarch. For twenty-four years,—1017 to 1041,—England was under Danish rule. Canute married Emma, the widow of King Ethelred, and he further tried to win over his English subjects by sending home all Danish soldiers, except a bodyguard of 3000 men. Besides England, he ruled over the three Scandinavian kingdoms in the north, and is said to have exacted homage from Malcolm, King of Scotland, and his two under-kings. He was the first Danish King who professed Christianity. He introduced the faith into Denmark, and himself made a pilgrimage to Rome. He reigned nineteen years, dying in 1036.

After Canute’s death, the Witan divided England into two portions. The counties north of the Thames, including London, were assigned to Harold, a son of Canute by his first wife; and the district south of the river to Hardicanute, his son by Emma. Harold died in 1039, and Hardicanute became sole King. He died two years later, and before he was buried, his half-brother Edward, the son of Ethelred and Emma, and thus a descendant of Alfred, was chosen King.

A notable personage, Earl Godwin, was the chief influence in this reversion to the old race. Who was Earl Godwin? In 1020, Canute, having come to trust his English subjects, and wishing to mix the two nations in the administration of affairs, created Godwin Earl of the West Saxons. He was an able administrator, an eloquent speaker, of high courage, and these qualities generally exerted for the freedom and independence of his country; and he came to have the greatest personal influence of any man in England. Little is known with certainty of his birth, but he married Gytha, the sister of Ulf, a Danish Earl, who had married a sister of Canute, and whose son, Sweyne, became after the death of Hardicanute, King of Denmark. Godwin had several children, all of whom occupy conspicuous places in the history of this eleventh century; the second son, Harold, being the last of the Saxon Kings of England.

Earl Godwin became the King’s chief minister, 49and the King married his daughter Edith. The King lived an ascetical, monkish life, and they had no children. Edward had been born in England, but on the deposition of his father Ethelred, his mother Emma took him to the court of her brother Robert, Duke of Normandy; and he had lived there through the reigns of Canute and Harold, coming back to England with Hardicanute. He was thus thoroughly Norman-French in his speech and his manners,—very fond of his young cousin, Duke William, and he now gathered French people about him, and promoted them to office and estate. The French language and fashions prevailed at Edward’s court; and in this language lawyers began to write deeds, and the clergy to preach sermons. These foreign modes, so different from the English, gave great displeasure to the old nobles; and Earl Godwin—although three of his sons had been advanced to earldoms—rebelled against the King’s authority. After some fighting, the Earl’s army deserted him at Dover, and he had to seek refuge in Flanders. His daughter, the queen, was deprived of her lands, and sent to a nunnery of which the King’s sister was abbess.

At the outbreak of the revolt, Edward asked 50aid from William; the aid was not required, but William, then twenty-three years of age, came, with a retinue of knights to his cousin’s court. They were hospitably entertained, and it is said that the King promised to bequeath his crown to William.

Things did not go on well during Godwin’s absence, so when, in 1052, he and his sons appeared with a fleet in the Channel, there was an under-current of mutiny in the King’s ships under their French commanders. “Should Englishmen fight with and slay Englishmen, that outlandish folks might profit thereby?” So the King had to take Godwin back into his honours and estates: but he died next year, leaving to Harold his titles, and his place as foremost man in England.

And now the dangers of a disputed succession loomed over England. The Witan advised Edward to send for Edward, the son of Edmund Ironside, then an exile in Hungary. Edward came with his family—a son Edgar, and three daughters: but he died shortly after his arrival. About this time Harold was shipwrecked on the Norman coast; William kept him prisoner for some time, and under circumstances of fraud and 51chicanery, an oath was extorted from him to favour William’s pretensions to the English throne. Edward died on 5th January, 1046, at the age of 65. He was buried next day in Westminster Abbey, which he had built. There, in the centre of the magnificent pile, is his shrine, for, about a century after his death, he was canonised, and awarded the title of Confessor.

And now, who was to be chosen King of England? For a choice had to be made. Edgar the Atheling was quite young, and was hardly English—having been born and brought up in a foreign land; so, in these unsettled times, he was not thought of. The Witan were obliged to do what had never previously been done in English history, and has never been done since (except partially, in the case of calling William of Orange to reign jointly with his wife Mary),—to choose a King not of the blood royal.

But it was not a difficult choice. Amongst the nobles of England, one man, Harold, stood foremost, both in strength of position and in personal qualifications. He had now for years been the chief administrator—a born ruler of men—energetic yet prudent—valiant without ferocity; and he had been the later recommendation of 52Edward as his successor. So, on the very day of Edward’s burial, Harold was crowned in the same Abbey, King of England.

Harold’s troubles began almost from the day of his coronation. William sent demands for the crown; Edward had promised it to him, the King’s nearest of kin, and Harold had sworn over concealed relics, to help him to it. It was replied that the crown was not disposable by Edward; all he could do was to recommend a successor to the Witan; and this he had done in favour of Harold: Edward’s kinship to William was on the maternal side, not on that of the blood-royal of England: and as to Harold’s oath, it was extorted by force and fraud, and was entirely nil in that it pledged Harold to do what he had no right to do,—the diversion of the crown from the will of the English people. William stormed and threatened, and, in building ships and organising troops, made active preparations for the invasion of England.

Harold set about preparations for the defence of his kingdom. He spent the summer in the south, getting ready a fleet and army. He had to wait too long for William; provisions falling short in the beginning of September, he had 53to disband the most of his troops. And meantime another foe, and this one of his own house, was intriguing against him—his brother Tostig. Harold had given Tostig the earldom of Northumberland; but he reigned so badly that the people rose and expelled him,—Harold sanctioning the expulsion. Tostig now went to Harold Hardrada, the King of Norway, and induced him to invade England. A fleet was sent up the Humber; York was captured, and there Harold Hardrada was proclaimed King. But English Harold—hastily getting an army together, met the invaders at Stamford Bridge; and there, on September 25th, a fierce battle was fought,—ending in victory for England; the Norwegian King and the traitorous Tostig both being slain.

But in meeting the Norwegian invasion, the Anglo-Saxons lost England. Four days later, William, with a banner consecrated by the Pope, landed near Pevensey in Sussex. Harold was seated at a banquet in York when the evil news reached him. And now, the last in a life of turmoil, Harold began his march through England; collecting on his way what troops he could, he reached the hill Senlac, nine miles from Hastings, on the 13th of October. Here he 54marshalled his army—nearly all on foot—and next day the Normans attacked him. It was a well-contested fight; but discipline and knighthood prevailed. The setting sun witnessed a routed English army, its leader slain, and the Norman William, conqueror of England.

The eleventh century, so momentous in English history, was also an important one in the history of Scotland. The Norse energy and ability to rule shewed itself in the Earls of Orkney, who dominated the Hebrides, and Ross, Moray, Sutherland, and Caithness. About 1010, Earl Sigurd married the daughter of King Malcolm II. In 1014, Sigurd went over to Ireland, to aid the Danish kings there against Brian Boru. In a battle at Clontarf, the Danes were defeated—Sigurd being slain—and the Celtic dynasty was restored. Sigurd’s territories were divided amongst two sons by a former marriage, and an infant son, Thurfinn, by Malcolm’s daughter; to the last was assigned the earldom of Caithness. In 1018—taking advantage of the distracted state of England in this, the first year of Canute’s reign—Malcolm invaded upper Northumbria; by a victory at Carham, near Coldstream on the 55Tweed, the Lothians were brought more under his rule. But after Canute’s return from his pilgrimage to Rome, he invaded Scotland, and received the submission of Malcolm and two under-kings, Mælbæthe and Jehmarc.

Malcolm II. was succeeded by his grandson Duncan,—a daughter’s son by a secular abbot of Dunkeld. Duncan’s right was disputed by his cousin Thurfirm, who was now Earl of Orkney. Duncan went north to check the advance of his kinsman, and was defeated near the Pentland Firth. But an invasion of Danes under King Sweyn on the coast of Fife, and which was probably made in aid of Thurfirm, was defeated by Macbeth, an able general of Duncan’s, and who, it is said, was also a grandson of Malcolm’s, by another daughter. Duncan was probably—as in Shakespeare’s great drama—killed by Macbeth. Certainly, to the exclusion of Duncan’s two sons, Malcolm and Donaldbane, Macbeth seized the crown. He reigned seventeen years—1040 to 1057—being contemporary with the Confessor,—a glowing description of whom, posing as a saint with miraculous powers of healing, occurs in Shakespeare’s play. When, on the return of Earl Godwin from exile, there was a general exodus of 56the Normans, whom Edward had placed in high positions, many of them went to Scotland, and were well received by Macbeth. He appears historically, in spite of our great poet’s portraiture of him, to have been an able monarch; and he might be said to represent Celtic supremacy in Scotland, as against the tendency to subvert it by Anglo-Saxon alliances. Duncan had married the daughter of Siward, Earl of Northumbria, and Macbeth had to resist the attacks of Siward on behalf of his grandson Malcolm. Malcolm spent his boyhood in Cumbria, and his youth at the court of the Confessor. He appealed to Edward for help to gain his father’s throne, and by an English army under Siward, and Macduff, the powerful Thane of Fife, and Tostig, the son of Earl Godwin, Macbeth was overthrown and slain.

Malcolm III., named Canmore—“big-head”—reigned thirty-five years, 1058 to 1093. The Norman victory at Hastings brought to the Scottish court, then at Dunfermline, a number of English refugees—these were a leaven of higher culture and refinement amongst the rude thanes and chieftains, and tended to further the advance of civilization, of letters and the arts of life, throughout 57the northern kingdom. And numbers of Normans also came and took service under Malcolm—and thus it came about that not only in England, but in Scotland also, most of the noble families have in them a strain of Norman blood.

Amongst the refugees were Edgar Atheling and his sisters, grand-children of Edmund Ironside. Malcolm married Margaret, the eldest sister; she was a noble woman, learned, pious, and charitable, doted upon by her husband, and ever influencing his fierce nature for good. Thus connected by birth with the heir of the old race of English Kings, Malcolm invaded Northumberland on behalf of Edgar; but William was too strong for him, and in turn invaded Scotland. William marched as far north as Abernethy, where he forced Malcolm to do him homage. William never really subjugated Northumbria north of the Tyne, but built Newcastle as a border fortress. After the death of William in 1087, Malcolm made other invasions of Northumbria, and to consolidate the possession of Lothian, he removed the seat of government to Edinburgh. In 1093, he made a desperate attempt to gain the counties of Northumberland and Cumberland; but, whilst besieging the 58border fortress of Alnwick, he was attacked, defeated, and killed by a Norman army.

The marriage of Henry, the youngest son of the Conqueror, with Matilda, daughter of Malcolm, and niece of Edgar Atheling, united the Norman and the older English royal lines. Henry’s son William was, in 1120, drowned in “The White Ship,” and his only other child, Maud, was thus the rightful heir to the throne. But the proud Norman barons had not been used to female rule; so, after Henry’s death, in 1135, Stephen, a son of the Conqueror’s daughter Adela, was made King.

David I., youngest son of Malcolm Canmore, succeeding his two elder brothers, was at this time King of Scotland, and he took up the cause of his niece Maud. In 1138 he invaded Northumberland, penetrating into Yorkshire. At Northallerton he was met and defeated in a battle called “Of the Standard.” It is said that he was gaining the day, when an English soldier cut off the head of one of the slain, placed it on a spear, and called out that it was the head of the King of Scots, thus causing a panic in the Scottish army which the King, riding amongst it without his helmet, vainly tried to overcome. After peace, David was allowed to retain Northumberland and 59Durham, excepting the fortresses of Newcastle and Bamborough. He was so good a king that after his death, in 1153, he was canonised.

David was succeeded by his twelve years old grandson, Malcolm. He was, from his gentle disposition, called The Maiden. He was greatly attached to the English King, Henry II., accompanying him to France as a volunteer in his army. Malcolm’s Scottish subjects were afraid of the influence of the older sovereign. Homage rendered by the Scottish kings for their possessions in England, was always liable to be construed into national homage; and it was notified that Malcolm had gone beyond mere homage, and had absolutely resigned these possessions. So Malcolm had a strong message from Scotland, asking him to return; this he did, was again in favour with his people, but died in 1165, being then only twenty-four years old.

He was succeeded by his brother William. He was called The Lion because he used as his armorial bearing a red lion—rampant—that is in heraldry, standing upon its hind legs; and this has ever since been the heraldric cognizance of Scottish royalty. In 1174, for the recovery of his ancestral possessions in Northumberland, William 60invaded England. One day riding in a mist with a slender retinue, he came upon a body of four hundred English horse. At first he thought that this was a portion of his own army; seeing his mistake he fought boldly, but was overpowered and made prisoner. He was taken to Northampton and conducted into King Henry’s presence, with his feet tied together under his horse’s belly. Now Henry had just been to Canterbury doing penance at the tomb of the murdered Thomas à Becket; he had walked barefoot through the city, prostrated himself on the pavement before the shrine, passed the whole night in the church, and in the morning had himself scourged by the priests with knotted cords. And now, as a token that his penance had reconciled him to heaven, and obtained the saint’s forgiveness, here was his enemy, the King of Scots, delivered into his hands.

Henry shewed no generosity towards his captive. He demanded to have homage paid him as Lord Paramount of Scotland. In his prison, first at Richmond, and then at Falaise in Normandy, William’s spirit was so far broken that he acceded to Henry’s demands, and the Scottish parliament, to obtain the release of their 61king, ratified a dishonourable treaty. At York the required homage was publicly paid; and for fifteen years it continued in full force. But in 1189, Henry’s son, Richard, the Lion-hearted, on the eve of his crusade to the Holy Land,—desirous to place his home affairs in safety during his absence, renounced the claim of general homage extorted from William,—reserving only such homage as was anciently rendered by Malcolm Canmore.

And in almost unbroken peace between the two countries for upwards of a century, the generous conduct of Richard bore good fruit. Then a course of accidents, which nearly extinguished the Scottish royal family, gave an English monarch the opportunity for reviving old pretensions to supremacy, and was thus the cause of renewed wars and national animosities.

William died in 1214, and was succeeded by his son, Alexander III. He reigned thirty-five years, and being of good parts, and with considerable force of character, did much for the progress of Scotland in the arts of civilization. He was succeeded in 1249 by his son, Alexander III., then only eight years of age. He married the daughter of Henry III., but the children of 62the marriage died young. The chief trouble of his reign was from Norwegian invasions, but in 1263 Alexander defeated Haco, King of Norway, at Largs, at the mouth of the Firth of Clyde. By this victory Scotland obtained possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. Alexander was accidentally killed in 1263; riding too near the edge of a cliff on the Fifeshire coast, near Kinghorn, in the dusk of the evening, his horse stumbled and threw him over the cliff.

We are not attempting to present a detailed history of Scotland: such a history has both a general and a national value, and there has been no lack of writers of ability to give to it their best of thought and of research. But as having been a supreme crisis in this history, and as having placed Scotland high on the list of free nations, we give a brief summary of events at the end of the thirteenth and beginning of the fourteenth century.

The English King, Edward the First, who has been called the greatest of the Plantagenets, was led to undertake the conquest of Scotland. He found that insurgent spirits amongst his own subjects therein found refuge, and that France—the natural enemy of England—was generally in alliance with Scotland. His designs on Scotland had three separate phases. First: King Alexander the Third of Scotland having died without immediate issue, the crown devolved upon his grand-daughter, Margaret, daughter of 64Eric, King of Norway. The young princess is called in history the Maid of Norway. Edward proposed a marriage between her and his own eldest son, also named Edward. A treaty for this marriage was entered into. It was one of the might-have-beens of history; had it taken place, and been fruitful, the union of the crowns might have been anticipated by over three centuries, and the after-histories of the two countries very different. But on her voyage to take possession of her crown, Margaret sickened; she landed at Orkney, and there died, September, 1290.

Then there were various claimants to the crown, the rights of the claimants dating back several generations. All having their partizans, and anarchy and conflict appearing imminent, it was agreed that Edward should be arbitrator. He here saw an opening for the revival of what might now have been thought the obsolete claim of the English sovereign to be recognised as Lord Paramount of Scotland. Two of the candidates, Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale, and John Baliol, Lord of Galloway, were found to be nearer in blood to the throne than all the others. Both of them traced their descent from daughters of David, Earl of Huntingdon, brother 65of King William, called The Lion. Edward gave his decision in favour of Baliol, as being descended from the elder daughter; but he declared that the crown was to be held under him as feudal superior; and Baliol did homage to Edward as to his lord sovereign, and was summoned as a peer to the English Parliament.

EDWARD I.

Edward soon shewed that his claim was not to be a merely formal one; he demanded the 66surrender of three important Scottish fortresses. Baliol would himself have submitted to this arrogant demand, but at the instigation of the nobles he sent a refusal, and a formal renunciation of his vassalage. In a war which in 1294 broke out between France and England, Scotland allied itself with France. Then Edward assembled a powerful army and invaded Scotland. He gained a victory near Dunbar, and made a triumphant march through the Lowlands. The country was divided within itself; the powerful Bruce faction was arrayed against that of Baliol. Baliol made a cringing submission to Edward; and Bruce sued for the nominal throne, as tributary sovereign of Scotland. “Think’st thou I am to conquer a kingdom for thee?” was Edward’s stern reply; and he forthwith took measures to make evident his purpose of keeping Scotland to himself. He appointed an English nobleman his viceroy, garrisoned the fortresses with English troops, and removed to London the regalia and the official records of the Kingdom, and also the legendary stone upon which the Scottish Kings had sat on their coronation. It was the very nadir in the cycle of Scottish history.

Then came revolts, with varied measures of 67success. A notable hero, Sir William Wallace, whose name yet lives in Scottish hearts as the very incarnation of patriotism and courage, took the leadership in an all but successful insurrection. But the larger, better appointed, and better disciplined armies of Edward again placed Scotland under his iron heel. Brave Wallace was, through treachery, taken prisoner, carried up to London, and tried for treason at Westminster Hall. “I never could be a traitor to Edward, for I was never his subject,” was Wallace’s defence: the English judges condemned him to a traitor’s death. With the indignities customary in these semi-barbarous times, he was executed on Tower Hill, 23rd August, 1305.

Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, a grandson of the Bruce who was Baliol’s rival for the Crown, had been one of Wallace’s ablest lieutenants. He had a fine person, was brave and strong, was moreover prudent and skilful, fitted to be a leader of men, both in the council and on the battle-field. He had the faults of his times—could be passionate, and in his passion cruel and relentless. He now aimed at the sovereignty, and within a year of the death of Wallace, had himself, with a miniature court and slender following, crowned 68King at Scone. When Edward heard of this he was exceedingly wroth, and would himself again go into Scotland and stamp out all the embers of rebellion. In 1307, he did accompany an army through Cumberland, to within three miles of the Scottish border. But ruthless and determined in spirit, he was now old and feeble in body, and

He was stricken by mortal sickness and died, 6th July, 1307. Before he died he made his son promise to carry his unburied corpse with the army until Scotland was again fully conquered. The Second Edward did not carry out that savage injunction, but had his father buried in Westminster Abbey, where his tomb styles him, with greater truth than is found in many monumental inscriptions, “The hammer of Scotland.”

For years Bruce was little other than a guerilla chief, sometimes even a fugitive, hiding in highland fastnesses, or in the Western Isles. He was under the pope’s excommunication, for that in a quarrel within the walls of a consecrated church in Dumfries he had slain Sir John Comyn, who had also certain hereditary claims to the throne. But he was possessed of wonderful perseverance. 69Edward II. had, by the withdrawal of his father’s great army of invasion, encouraged the Scottish hopes of independence. In different parts of the country there were partial insurrections against English rule and English garrisons. In March, 1313, by a sudden coup, Edinburgh Castle was taken. Gradually the greater number of the Scottish nobles, with their retainers, declared for Bruce. By the early spring of 1314, all the important towns except Stirling had passed out of English possession; and it was to be given up unless relieved before midsummer.

Such a state of things would not have come about in the days of the elder Edward, before he would have been with an army in Scotland, to drive back the tide of insurrection. Now, instigated by his counsellors to save Stirling, Edward the Second assembled one of the largest armies which had ever been under the command of an English King. One hundred thousand men are said to have crossed the Scottish border, the flower of English chivalry—the best trained archers in the world—soldiers from France, Welsh and Irish, a mighty host. Bruce with all his efforts could not bring into the field more than one disciplined soldier for every three such in the 70enemy’s ranks; but there were many loose camp-followers, half-armed and undisciplined, who, if their only aim was plunder, could yet harass and cut off stragglers of an army on the march. Bruce himself was a consummate general, possessing the entire confidence of his men; he had the choice of his ground, and he had as lieutenants his brave brother Edward, his nephew Randolph, and his faithful follower Lord James Douglas, all commanding men with whom they had in previous hard fights stood shoulder to shoulder and achieved victory.