Title: The Fleets at War

Author: Archibald Hurd

Release date: March 3, 2017 [eBook #54275]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’ Notes at the end of this text.

The Daily Telegraph

WAR BOOKS

The Daily Telegraph

WAR BOOKS

CLOTH 1/- NET.

VOL. I. (3rd Enormous Edition.)

HOW THE WAR BEGAN

By W. L. COURTNEY, LL.D., and J. M. KENNEDY

Is Britain’s justification before the Bar of History.

VOL. II.

THE FLEETS AT WAR

By ARCHIBALD HURD,

The key book to the understanding of the NAVAL situation

VOL. III.

THE CAMPAIGN OF SEDAN

By GEORGE HOOPER

The key book to the MILITARY situation.

VOL. IV.

THE CAMPAIGN ROUND LIEGE

¶ Describes in wonderful detail the heroic defence of Liege, and shows how the gallant army of Belgium has upset and altered the whole plan of advance as devised by the Kaiser and his War Council.

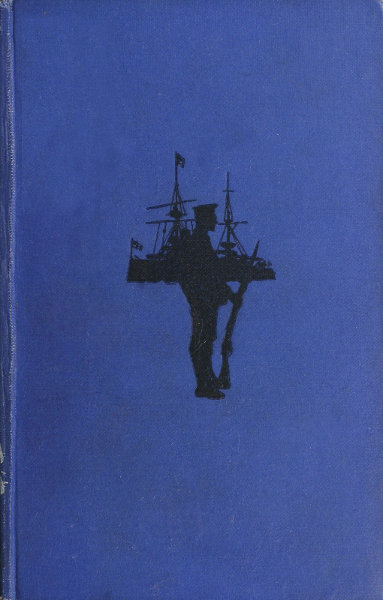

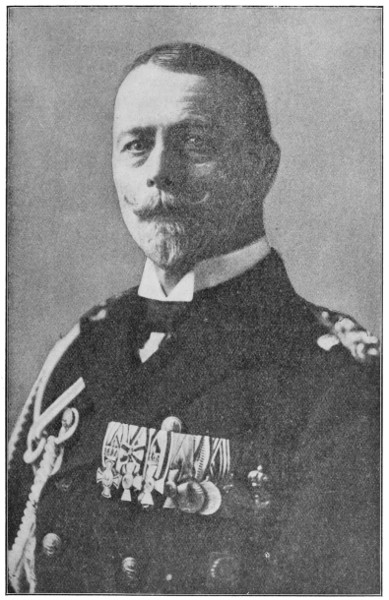

Photo: Speaight, Ltd.

ADMIRAL SIR JOHN JELLICOE.

Supreme Admiral, British Home Fleet.

THE FLEETS AT

WAR

BY

ARCHIBALD HURD

Author of “Command of the Sea,” “Naval Efficiency,”

“German Sea Power: Its Rise, Progress, and Economic

Basis” (part author), etc.

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXIV

It is hoped that this volume will prove of permanent value as presenting a conspectus of the great navies engaged in war when hostilities opened, and in particular of the events of singular significance in the naval contest between Great Britain and Germany which occurred in the years immediately preceding the war.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Mr. H. C. Bywater for valuable assistance in preparing this volume.

A. H.

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction—The Opening Phase | 9 | |

| I. | THE RELATIVE STANDING OF THE BRITISH AND GERMAN FLEETS | 49 |

| II. | THE BRITISH NAVY | 54 |

| III. | THE GERMAN NAVY | 101 |

| IV. | ADMIRAL JELLICOE | 131 |

| V. | OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE BRITISH NAVY | 137 |

| VI. | THE COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF OF THE GERMAN FLEET | 141 |

| VII. | OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE FOREIGN NAVIES | 147 |

| VIII. | GERMAN NAVAL BASES | 151 |

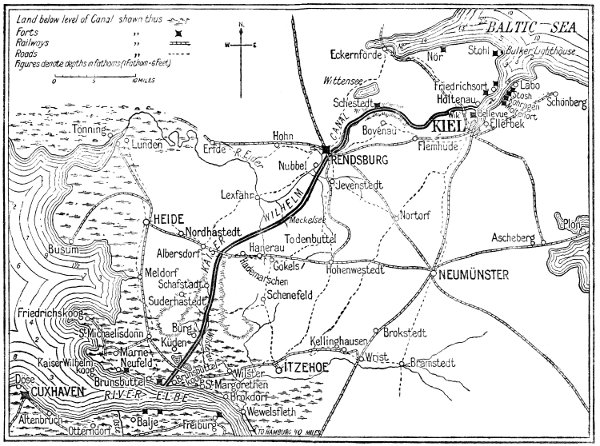

| IX. | THE KIEL CANAL | 161 |

| X. | THE GREAT FLEETS ENGAGED: TABULAR STATEMENT | 168 |

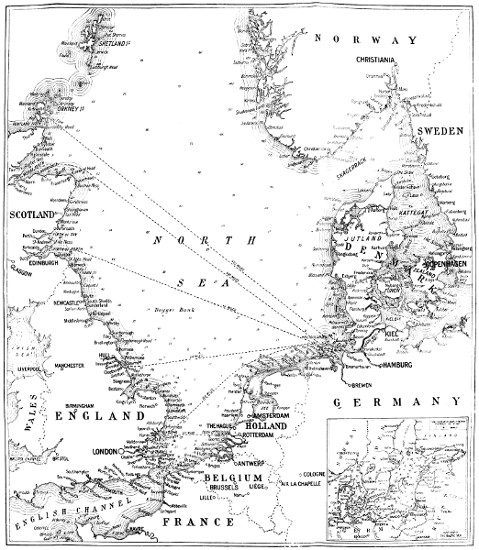

Large map (550 kB).

[9]

The declaration of war against Germany, followed as it was by similar action against Austria-Hungary, was preceded by a sequence of events so remarkable in their character that if any British writer had made any such forecast in times of peace he would have been written down as a romantic optimist.

Owing to a series of fortunate circumstances, the British Fleet—our main line of defence and offence—was fully mobilised for war on the morning before the day—August 4th at 11 p.m.—when war was declared by this country, and we were enabled to enter upon the supreme contest in our history with a sense of confidence which was communicated to all the peoples of the British Empire. This feeling of assurance and courage furnished the best possible augury for the future.

Within a fortnight of diplomatic relations being broken off with Germany, and less than a[10] week after Austria-Hungary by her acts had declared her community of interest with her ally, the British Navy, without firing a gun or sending a single torpedo hissing through the water, had achieved four victories.

These successes were due to the influence of sea-power. Confidence in the Navy, its ships and men, and a belief in the competency of Mr. Winston Churchill and Prince Louis of Battenberg and the other Sea Lords, and the War Staff, steadied the nerve of the nation when it received the first shock. Apparently the crisis developed so swiftly that there was no time for effective co-operation between the German spies. All the mischievous stories of British reverses which were[11] clumsily put in circulation in the early period of hostilities were tracked down; for once truth was nearly as swift as rumour, though the latter was the result of an elaborately organised scheme for throwing the British people off their mental balance. It was conjectured that if a feeling of panic could be created in this country, a frightened nation would bring pressure to bear on the naval and military authorities and our strategic plans ashore and afloat would be interfered with. A democracy in a state of panic cannot make war. The carefully-laid scheme miscarried. Never was a nation more self-possessed. It had faith in its Fleet.

In the history of sea power, there is nothing comparable with the strangulation of German oversea shipping in all the seas of the world. It followed almost instantly on the declaration of war. There were over 2,000 German steamers, of nearly 5,000,000 tons gross, afloat when hostilities opened. The German sailing ships—mostly of small size—numbered 2,700. These vessels were distributed over the seas far and wide. Some—scores of them, in fact—were captured, others ran for neutral ports, the sailings of others were cancelled, and the heart of the German mercantile navy suddenly stopped beating. What must have been the feelings of Herr Ballin and the other pioneers as they contemplated the ruin, at least temporary ruin, of years of splendid enterprise? The strategical advantages enjoyed by England in a war against Germany, lying as she does like a bunker across Germany’s approach to the oversea world, had never been[12] understood by the mass of Germans, nor by their statesmen. Shipowners had some conception of what would happen, but even they did not anticipate that in less than a week the great engine of commercial activity oversea would be brought to a standstill.

By its prompt action on the eve of war in instituting a system of Government insurance of war risks, Mr. Asquith’s administration checked any indication of panic among those responsible for our sea affairs. The maintenance of our oversea commerce on the outbreak of hostilities had been the subject of enquiry by a sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence. When war was inevitable, the Government produced this report, and relying on our sea power, immediately carried into effect the far-reaching and statesmanlike recommendations which had been made, for the State itself bearing 80 per cent. of the cost of insurance of hull and cargoes due to capture by the enemies. Thus at the moment of severest strain—the outbreak of war—traders recognised that in carrying on their normal trading operations overseas they had behind them the wholehearted support of the British Government, the power of a supreme fleet, and the guarantee of all the accumulated wealth of the richest country in the world. None of the dismal forebodings which had been indulged in during peace were realised. Traders were convinced by the drastic action of the Government and by the ubiquitous pressure of British sea power on all the trade routes that, though some losses might be suffered owing to the action of[13] German cruisers and converted merchantmen, the danger was of so restricted a character and had been so admirably covered by the Government’s insurance scheme that they could “carry on” in calm courage and thus contribute to the success of British arms. Navies and armies must accept defeat if they have not behind them a civil population freed from fear of starvation.

Even more remarkable, perhaps, than either of these victories of British sea power was the safe transportation to the Continent of the Expeditionary Force as detailed for foreign service. Within a fortnight of the declaration of war, while we had suffered from no threat of invasion or even of such raids on the coast as had been considered probable incidents in the early stage of war, the spearhead of the British Army had been thrust into the Continent of Europe.

It is often the obvious which passes without recognition. The official intelligence that the Expeditionary Force had reached the Continent fired the imagination of Englishmen, and they felt no little pride that at so early a stage in the war the British Army—the only long-service army in the world—should have been able to take its stand beside the devoted defenders of France and Belgium.

It is, of course, obvious that the army of an island kingdom cannot leave its base except it receive a guarantee of safe transport from the Navy. The British Army, whether it fights in India, in Egypt, or in South Africa, must always be carried on the back of the British Navy.[14] If during the years of peaceful dalliance and fearful anticipation it had been suggested that, in face of an unconquered German fleet, we could throw an immense body of men on the Continent, and complete the operation within ten days or so from the declaration of war, the statement would have been regarded as a gross exaggeration. This was the amazing achievement. It reflected credit on the military machinery; but let it not be forgotten that all the labours of the General Staff at the War Office would have been of no avail unless, on the day before the declaration of war, the whole mobilised Navy had been able to take the sea in defence of British interests afloat.

We do well not to ignore these obvious facts, because they are fundamental. The Navy must always be the lifeline of the Expeditionary Force, ensuring to it reinforcements, stores, and everything necessary to enable it to carry out its high purpose. That the Admiralty, with the approval of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, felt itself justified in giving the military authorities a certificate of safe transport before the command of the sea had been secured indicated high confidence that when the German fleet did come forth to accept battle the issue would be in no doubt, though victory might have to be purchased at a high price.

Nor was this all. Thanks to the ubiquitous operations of the British Navy, the Government was able to move two divisions of troops from India, and to accept all the offers of military aid which were immediately made by the Dominions.[15] It was realised in a flash by all the scattered people of the Empire that the Fleet, with its tentacles in every sea, maintains the Empire in unity: when “the earth was full of anger,” the seas were full of British ships of war.

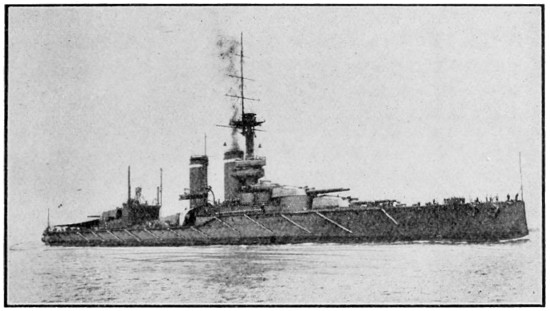

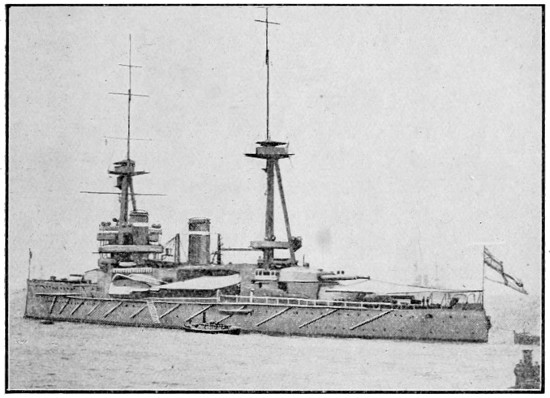

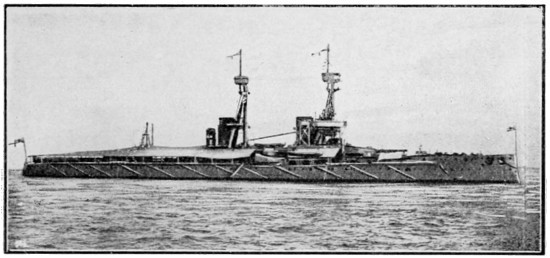

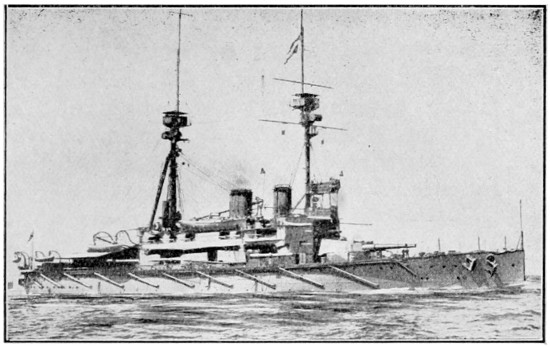

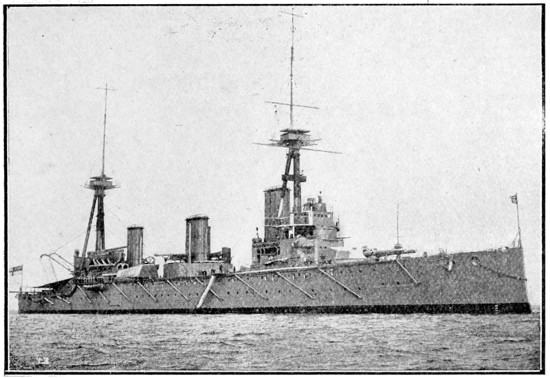

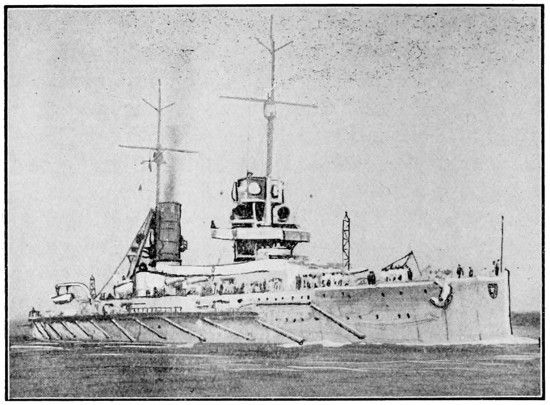

H.M.S. King George V. Photo: Cribb, Southsea.

KING GEORGE V CLASS.

KING GEORGE V, CENTURION, AUDACIOUS, AJAX.

Displacement: 23,000 tons.

Speed: 22 knots; Guns: 10 13·5in., 16 4in.; Torpedo tubes: 5.

| Astern fire: | Broadside: | Ahead fire: |

|---|---|---|

| 4 13·5in. | 10 13·5in. | 4 13·5in. |

It was in these circumstances that the war opened. Every incident tended to remind the people of the British Isles and the subjects of the King who live in the far-flung Dominions and those who reside in the scattered Crown Colonies and Dependencies of the essential truth contained in the phrases which had come so trippingly to the lips in days of peace. Men recognised that the statement of our dependence upon the sea as set forth in the Articles of War was a declaration of policy which we had done well not to ignore:

“It is upon the Navy that, under the good Providence of God, the wealth, prosperity and peace of these islands and of the Empire do mainly depend.”

How true these words rang when, in defence of our honour, we had to take up the gage thrown down by the Power which claimed supremacy as a military Power and aspired to primacy as a naval Power. Those who turned to Mr. Arnold White’s admirable monograph on “The Navy and Its Story,” must admit that this writer, in picturesque phrase, had set forth fundamental facts:

“Since the first mariner risked his life in a canoe and travelled coastwise for his[16] pleasure or his business, Britain has acquired half the seaborne traffic of the world. She relies on her Navy to fill the grocer’s shop, to bring flour and corn to our great cities and to keep any possible enemy at a distance. So successfully has the British Navy done its work that many generations of Englishmen have grown up without hearing the sound of a gun fired in anger. Every other nation in Europe has heard the tramp of foreign soldiery in the lifetime of men still living and felt the pain and shame of invasion.

“Five times in the history of England the British Navy has stood between the would-be master of Europe and the attainment of his ambition. Charlemagne, Charles V., Philip II. of Spain, Louis XIV. of France, and Napoleon—all aspired to universal dominion. Each of these Sovereigns in turn was checked in his soaring plans by British sea power.”

When the British peoples awoke to the fact that they owed it to themselves and their past to join in humbling another tyrant, they gained confidence in the task which confronted them from the glorious record of the past achievements of those who, relying upon command of the sea, had crushed in the dust the mightiest rulers that had ever tried to impose their yoke on humanity.

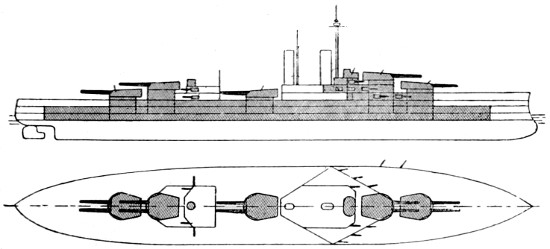

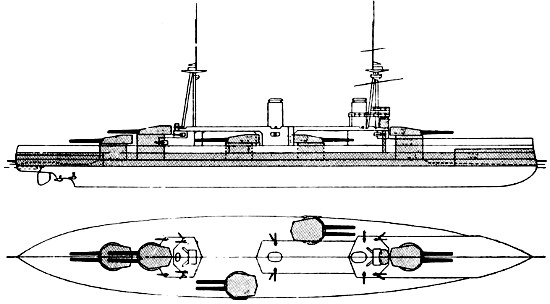

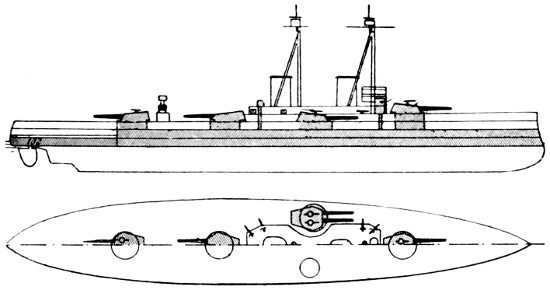

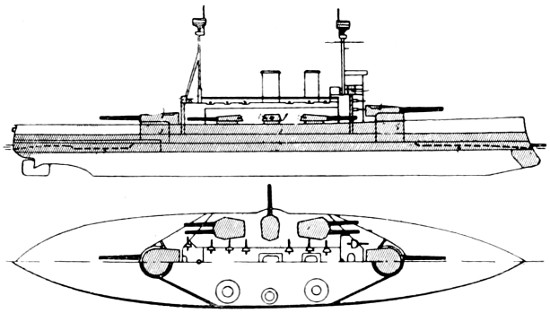

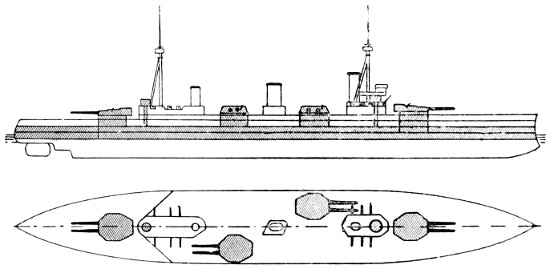

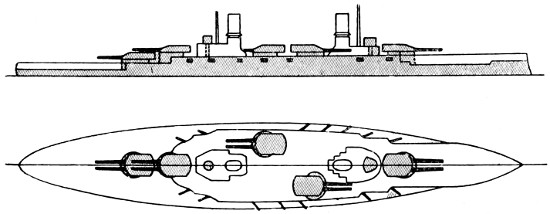

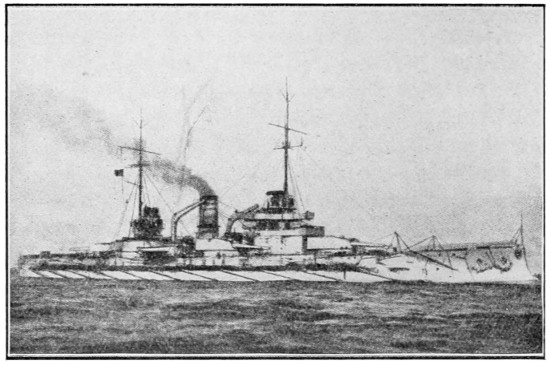

H.M.S. Orion. Photo: Sport & General.

ORION CLASS.

ORION, CONQUEROR, MONARCH, THUNDERER.

Displacement: 22,500 tons.

Speed: 22 knots; Guns: 10 13·5in., 16 4in.; Torpedo tubes: 3.

| Astern fire: | Broadside: | Ahead fire: |

|---|---|---|

| 4 13·5in. | 10 13·5in. | 4 13·5in. |

In a spirit of calmness, patience and courage the British people took up the task which their[17] sense of honour forced upon them all unwillingly. Glancing back over the record of naval progress during the earlier years of the twentieth century we cannot fail to recognise that, in spite of many cross currents and eddies of public opinion, fate had been preparing the British peoples, all unconsciously, for the arbitrament of a war on the issue of which would depend all the interests, tangible and intangible, of the four hundred and forty million subjects of the King—their freedom, their rights to self government, their world-wide trade, and that atmosphere which distinguishes the British Empire from every other empire which has ever existed. In the years of peace men had often asked themselves whether a new crisis would produce the men of destiny to defend the traditions we had inherited from our forefathers. While peace still reigned, they little realised that the men of destiny were quietly, but persistently, working out our salvation. When the hour struck England was fully prepared, confident in her sea power, to take up the gage in defence of all the democracies of the world against the tyrant Power which sought to impose the iron caste of militarism and materialism upon nations that had outgrown mediæval conditions.

If we would realise the bearing of British naval policy in the years which preceded the outbreak of war, we shall do well to cast aside all party bias and personal animosities and study the sequence of events after the manner of the historian who collates the material to his hand, analyses it without fear or favour, and sets down[18] his conclusions in all faithfulness. Pursuing this course we are carried back to the year 1897. Since the German Emperor had ascended the throne in 1888, he had endeavoured to communicate to his subjects the essential truths as to the influence of sea power upon history which he had read in Admiral Mahan’s early books. His educational campaign was a failure. In spite of all the efforts of Admiral von Hollmann, the Minister of Marine, the Reichstag refused to vote increased supplies to the Navy. At last, when he had been finally repulsed, first by the Budget Committee and then by the Reichstag itself, Admiral von Hollmann retired admitting defeat. The Emperor found a successor in a naval officer who, then unknown, was in a few years to change radically the opinion of Germans on the value of a fleet. Born on March 19th, 1849, at Custrin, and the son of a judge, Alfred Tirpitz became a naval cadet in 1865, and was afterwards at the Naval Academy from 1874 to 1876. He subsequently devoted much attention to the torpedo branch of the service, and was mainly responsible for the torpedo organisation and the tactical use of torpedoes in the German Navy—a work which British officers regard with admiration.[1] Subsequently he became Inspector of her Torpedo Service, and was the first Flotilla Chief of the Torpedo Flotillas. Later he was appointed Chief of the Staff at the naval station[19] in the Baltic and of the Supreme Command of the German Fleet. During these earlier years of his sea career, Admiral Tirpitz made several long voyages. He is regarded as an eminent tactician, and is the author of the rules for German naval tactics as now in use in the Navy. In 1895 he was promoted to the rank of Rear-Admiral, and became Vice-Admiral in 1899. In 1896 and 1897 he commanded the cruiser squadron in East Asia, and immediately after became Secretary of State of the Imperial Navy Office. In the following year he was made a Minister of State and Naval Secretary, and in 1901 received the hereditary rank of nobility, entitling him to the use of the honorific prefix “Von.”

[1] German Sea Power: Its Rise, Progress and Economic Basis, by Archibald Hurd and Henry Castle (London: John Murray 1913).

With the advent of this sailor-statesman to the Marineamt, the whole course of German naval policy changed, and in 1898 the first German Navy Act was passed authorising a navy on a standard which far exceeded anything hitherto attained. It provided for the following ships:

| THE BATTLE FLEET | ||

| 19 | battleships (2 as material reserve). | |

| 8 | armoured coast defence vessels. | |

| 6 | large cruisers. | |

| 16 | small cruisers. | |

| FOREIGN SERVICE FLEET[20] | ||

| Large Cruisers | ||

| For East Africa | 2 | |

| For Central and South America | 1 | |

| Material reserve | 3 | |

| Total | 6 | |

| Small Cruisers | ||

| For East Asia | 3 | |

| For Central and South America | 3 | |

| For East Africa | 2 | |

| For the South Seas | 2 | |

| Material reserve | 4 | |

| Total | 14 | |

| 1 | Station ship. | |

This dramatic departure in German naval policy aroused hardly a ripple of interest in England. Then occurred the South African War, the seizure of the “Bundesrat,” and other incidents which were utilised by the German Emperor, the Marine Minister, and the official Press Bureau, with its wide extending agencies for inflaming public opinion throughout the German Empire against the British Navy. The ground having been well prepared, in 1900 the naval measure of[21] 1898, which was to have covered a period of six years, was superseded by another Navy Act, practically doubling the establishment of ships and men. This is not the time, nor does space permit, to trace the evolution of German naval policy during subsequent years or to analyse the successive Navy Acts which were passed as political circumstances favoured further expansion. The story—and it is a fascinating narrative in the light of after events—may be read elsewhere. The fact to be noted is that the British peoples generally viewed the early indications of German naval policy without suspicion or distrust. Most men found it impossible to believe that any Power could hope to challenge the naval supremacy which had been won at such great sacrifice at the Battle of Trafalgar, and which the British people had continued to enjoy virtually without challenge throughout the nineteenth century.

Happily, the hour when preparations had to be made, if made at all, to maintain in face of any rivalry our sea command, produced the man. In the autumn of 1901 Lord Selborne, then First Lord of the Admiralty, paid a special visit to Malta to discuss the naval situation with a naval officer with whose name not a thousand people in the British Isles were then familiar. Sir John Fisher had, as recently as 1899, taken over the command of the Mediterranean Squadron; he had already made a great name in the service as a man of original thought and great courage, possessing a genius for naval politics and naval administration. He had represented the British[22] Navy at the Hague Peace Conference, but he might have walked from end to end of London, and not a dozen people would have recognised him. In the following March, thanks to Lord Selborne, he became Second Sea Lord, and a naval revolution was inaugurated. Elsewhere I have recapitulated the remarkable Navy of the renaissance of British sea power.[2]

[2] Fortnightly Review, September, 1914.

First, attention was devoted to the personnel. New schemes of training for officers and men and for the Naval Reserve were introduced. A new force—the Royal Fleet Reserve—was established, consisting of naval seamen and other ratings who had served afloat for five years or more; a Volunteer Naval Reserve was initiated; steps were taken to revise the administration of the naval establishments ashore, and to reduce the proportion of officers and men engaged in peace duties, freeing them for service in ships afloat. On the anniversary of Trafalgar in 1904, after a short period in command at Portsmouth in order to supervise personally the reforms in training and manning policy already introduced, Sir John Fisher—Lord Fisher as he is now known—returned to the Admiralty as First Sea Lord. Instantly, with the support of Lord Selborne and Mr. Balfour, then Prime Minister, to whom all honour is due, the new Board proceeded to carry into effect vast correlated schemes for the redistribution of the fleets at sea and the more rapid mobilisation of ships in reserve, the reorganisation of the Admiralty, and the re-adjustment of our[23] world naval policy to the new conditions in accordance with a plan of action which the new First Sea Lord had prepared months in advance.

Our principal sea frontier has been the Mediterranean. It was necessary to change it, and the operation had to be carried out without causing undue alarm to our neighbours—at that time we had no particular friends, though the foundations of the Entente were already being laid. Without asking your leave from Parliament, the great administrative engine, to which Lord Fisher supplied fuel, proceeded to carry out the most gigantic task to which any Governmental Department ever put its hand. Overseas squadrons which had no strategic purpose were disestablished; unimportant dockyards were reduced to cadres; ships too weak to fight and too slow to run away were recalled; a whole fleet of old ships, which were eating up money and adding nothing to our strength, were scrapped; the vessels in reserve were provided with nucleus crews. With a single eye to the end in view—victory in the main strategical theatres—conservative influences which strove to impede reform were beaten down. With the officers and men taken out of the weak ships, and others who were wrenched from comfortable employment ashore, a great fleet on our new frontier was organised.

In the preamble to the German Navy Act of 1900 it had been stated:

“It is not absolutely necessary that the German Battle Fleet should be as strong as that of the greatest naval Power, for a great[24] naval Power will not, as a rule, be in a position to concentrate all its striking force against us. But even if it should succeed in meeting us with considerable superiority of strength, the defeat of a strong German Fleet would so substantially weaken the enemy that, in spite of the victory he might have obtained, his own position in the world would no longer be secured by an adequate fleet.”

Lord Fisher had not studied the progress of the German naval movement without realising that in this passage was to be found the secret of the strategic plan which the German naval authorities had formed. With the instinct of a great strategist, he reorganised the whole world-wide machinery of the British Navy, in order to suit the new circumstances then developing.

The war in the Far East had shown that changes were necessary in the design of British ships of all classes. The First Sea Lord insisted that the matter should have immediate attention, and a powerful committee of naval officers, shipbuilders, and scientists began its sittings at the Admiralty. The moment its report was available, Parliament was asked for authority to lay down groups of ships of new types, of which the “Dreadnought” was the most famous. In the preceding six years, sixteen battleships had been laid down for Great Britain, while Germany had begun thirteen; our sea power, as computed in modern ships of the line, had already begun to shrink. Secretly and rapidly, four units of the new type—the “Dreadnought,”[25] with her swift sisters, the “Indomitable,” “Inflexible,” and “Invincible”—were rushed to completion. No battleship building abroad carried more than four big guns; the “Dreadnought” had ten big guns, and her swift consorts eight.[3] Thus was the work of rebuilding the British Fleet initiated. Destroyers of a new type were placed in hand, and redoubled progress was made in the construction of submarines, which Lord Fisher was the first to realise were essential to this country, and were capable of immense development as offensive engines of warfare. We gained a lead of eighteen months over other Powers by the determined policy adopted.

[3] It is officially admitted by the United States Navy Department that it had prepared plans for a ship similar in armament to the Dreadnought in 1904, and was awaiting the approval of Congress before beginning construction. American officers had come to the same conclusions as to the inevitable tendency of battleship design as the British Admiralty.

Owing to the delay imposed by the necessity of obtaining the consent of Congress, the United States lost the advantage; in the exercise of its powers, the British Admiralty acted directly the designs of the new ships were ready.

Just as the task of rebuilding the Fleet had been initiated, a change of Government occurred, and there was reason to fear that the stupendous task of reorganising and re-creating the bases of our naval power would be delayed, if not abandoned. In Lord Fisher the nation had, fortunately, a man of iron will. Though Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, above all things[26] desirous of arresting the rivalry in naval armaments, was Prime Minister, and Lord Tweedmouth was First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Fisher, supported by his colleagues on the Board, insisted on essentials. Delays occurred in German shipbuilding, and the Admiralty agreed that British shipbuilding could be delayed. In 1906, 1907, and 1908 only eight Dreadnoughts were begun. Subsequent events tend to show that this policy was a political mistake, though we eventually obtained more powerful ships by the delay. Germany was encouraged to believe that under a Liberal Administration she could overtake us. Between 1906 and 1908 inclusive we laid down eight large ships of the Dreadnought type; and Germany laid down nine, and began to accelerate her programme of 1909.

Then occurred a momentous change in British affairs. Lord Tweedmouth, after the famous incident of the German Emperor’s letter, retired from office (1908), and his place was taken by Mr. Reginald McKenna, who was to show that a rigid regard for economy was not incompatible with a high standard of patriotism. In association with the Sea Lords, he surveyed the naval situation. In the following March occurred the naval crisis. Germany had accelerated her construction, and our sea power was in peril. The whole Board of Admiralty determined that there was no room for compromise. Mr. McKenna, it is now no secret, found arrayed against him a large section of the Cabinet when he put forward the stupendous programme of 1909, making provision for eight Dreadnoughts, six protected[27] cruisers, twenty destroyers, and a number of submarines. The naval crisis was accompanied by a Cabinet crisis, in spite of the fact that Sir Edward Grey, as Foreign Secretary, gave the naval authorities his full support. Unknown to the nation, the Admiralty resigned, and for a time the Navy had no superior authority. This dramatic act won the day. The Cabinet was converted; the necessity for prompt, energetic action was proved. The most in the way of compromise to which the Board would agree was a postponement in announcing the construction of four of the eight armoured ships. But from the first there was no doubt that, unless there was a sudden change in German policy, the whole octette would be built. When the programme was presented to the House of Commons, the Prime Minister and Sir Edward Grey gave to Mr. McKenna their wholehearted support; either the Government had to be driven from office, or the Liberal Party had to agree to the immense commitment represented in the Navy Estimates. The programme was agreed to.

This, however, is only half the story. Neither the Government nor the Admiralty was in a position to tell the country that, though all the ships were not to be laid down at once, they would all be laid down in regular rotation, in order that they might be ready in ample time to meet the situation which was developing. Perhaps it was well in the circumstances that this fact was not revealed. Public opinion became active. The whole patriotic sentiment of the country was roused, and the jingle was heard on a thousand[28] platforms, “We want eight and we won’t wait.” The Admiralty, which had already determined upon its policy, remained silent and refused to hasten the construction of the ships. Quietly, but firmly, the Board resisted pressure, realising that it, and it only, was in possession of all the facts. Secrecy is the basis of peace as well as war strategy. The naval authorities were unable to defend themselves by announcing that they were on the eve of obtaining a powerful weapon which could not be ready for the ships if they were laid down at once. By waiting the Navy was to gain the most powerful gun in the world.

In order to keep pace with progress in Germany, it was necessary to lay down two of the eight ships in July, and be satisfied with the 12-inch guns (projectile of 850 lbs.) for these units. The construction of the other six vessels was postponed in order that they might receive the new 13·5-inch gun, with a projectile of about 1,400 lbs. Two of the Dreadnoughts were began at Portsmouth and Devonport Dockyards in the following November, and the contracts for the remaining four were not placed until the spring, for the simple reason that the delivery of the new guns and mountings and their equipment could not be secured for the vessels, even if their hulls were started without a moment’s delay. Thus we obtained six battleships which are still unique; in no other Navy is so powerful a gun to be found to-day as the British 13·5-inch weapon. In 1910 and in 1911 Mr. McKenna again fought for national safety, and he won the essential provision for the Fleet. He risked his all in defence of our sea[29] power. He was probably during those years of struggle the most unpopular Minister the Liberal Party ever had. What has been the sequel of his tenacity and courage and patriotism? What has been gained owing to the bold front which Lord Fisher presented, as First Sea Lord, supported by his colleagues? Sixteen of the eighteen battleships and battle-cruisers of the Dreadnought type, the fifteen protected cruisers, and the sixty destroyers, with a group of submarines, which the Board over which Mr. McKenna presided secured, constituted the spearhead of the British Fleet when the crisis came and war had to be declared against Germany in defence of our plighted word.

With the addition of one more chapter, this story of the renaissance of British sea power is complete. In the autumn of 1911, over seven years after Lord Fisher had begun to shake the Navy into renewed life, encouraged Sir Percy Scott in his gunnery reforms, and brought to the Board the splendid intellect of Sir John Jellicoe, Mr. Winston Churchill replaced Mr. McKenna as First Lord. Thus the youngest statesman of the English-speaking world realised his ambition. Lord Fisher, under the age clause, had already been compelled to vacate his seat on the Board, retiring with a peerage, and his successor, Sir Arthur Wilson, was also on the eve of retirement. Mr. McKenna had to be freed to take over the Welsh Church Bill and to place his legal mind at the service of the country at the Home Office. He had done his work and done it well. Mr. Winston Churchill proved the ideal man to put[30] the finishing touches to the great task which had been initiated during Lord Selborne’s period of office. Perhaps the keynote of his administration is to be found in the attention which he devoted to the organisation of the War Staff, the elements of which had been created by former Boards, and the readjustment of the pay of officers and men. No service is efficient for war in which there exists a rankling feeling of injustice. The rates of pay of officers and men were revised and increased; facilities were opened up for men of the lower deck to reach commissioned rank. About 20,000 officers and men were added to the active service of the Fleet. At the same time with the ships provided by former Boards, the organisation of the ships in Home waters was placed on a higher standard of efficiency, particular attention being devoted to the organisation of the older ships so as to keep them efficient for war. The Naval Air Service was established, and its development pressed forward with all speed. Thus the work of reform and the task of changing the front of the British Navy had been brought to completion, or virtual completion, at the moment when Germany, by a concatenation of circumstances, was forced into a position where she had to fight the greatest of sea Powers, or admit the defeat of all her ambitions.

A study of the sequence of events which immediately preceded the outbreak of hostilities is hardly less interesting than the earlier and dramatic incidents which enabled us to face the supreme crisis in our history with a measure[31] of assured confidence. On March 17th, 1914, Mr. Winston Churchill spoke in the House of Commons on the Navy Estimates. It is common knowledge that he had just fought a stern battle in the Cabinet for adequate supplies, and it was assumed at the time, from various incidents, that he had been compelled to submit to some measure of retrenchment. He received, however, Cabinet authority to ask Parliament for the largest sum ever devoted to naval defence—£51,500,000. In the course of his speech on these Estimates he made the announcement that there would be no naval manœuvres in 1914. He stated:

“We have decided to substitute this year for the grand manœuvres—not, of course, for the numberless exercises the Fleet is always carrying out—a general mobilisation of the Third Fleet.[4] We are calling up the whole of the Royal Fleet Reserve for a period of eleven days, and those who come up for that period will be excused training next year, and will receive £1 bounty in addition to their regular pay.

“We have had a most admirable response. 10,170 men, seamen, and others, and 1,409 marines, are required to man the ships of the Third Fleet. We have already, in the few days our circular has been out, received replies from 10,334 men volunteers, and from 3,321 marines. I think that reflects great credit on the spirit of the Reserve[32] generally, and also reflects credit upon the employers, who must have greatly facilitated this operation all over the country. I hereby extend to them the thanks of the Admiralty.

“This test is one of the most important that could possibly be made, and it is really surprising to me that it has never been undertaken before. The cost, including the bounty of £1, will be about £50,000. Having no grand manœuvres yields a saving of £230,000, so there is a net saving on the substitution of £180,000.”

[4] The Third Fleet consists of the oldest ships of the Navy maintained in peace with skeleton crews.

It was hardly surprising in the circumstances that many persons thought the Admiralty was bent merely upon economy. If the naval authorities had had foreknowledge of the course of events they could not, in fact, have adopted a wiser course. From March onwards, week by week down to the middle of July, the elaborate and complicated drafting arrangements were examined and readjusted. Then, after the assassinations at Sarajevo and on the eve of the final developments on the Continent, which were to make war inevitable, the test mobilisation was carried out. The principal ships passed before the King off the Nab Lightship, a column of seaplanes and aeroplanes circling high above the ships, and then disappeared in the Channel to carry out what were believed to be peace exercises, but were, in fact, to prove the manœuvres preliminary to war. Later in the same week, the vessels of the Patrol Flotillas were engaged in testing a new scheme for sealing this narrow exit to the North Sea.

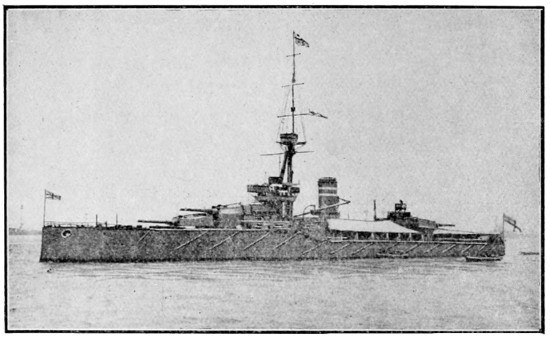

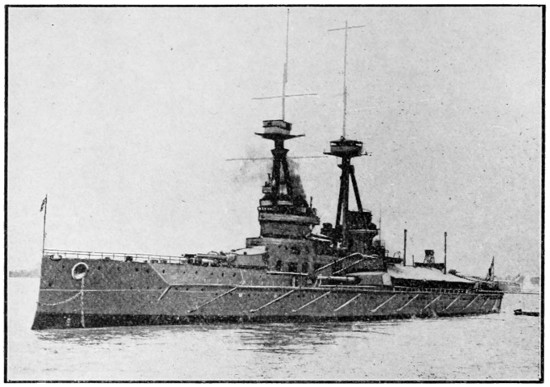

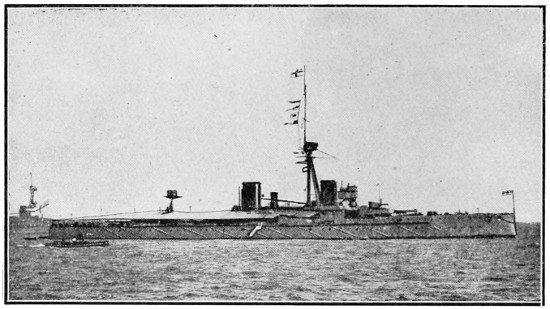

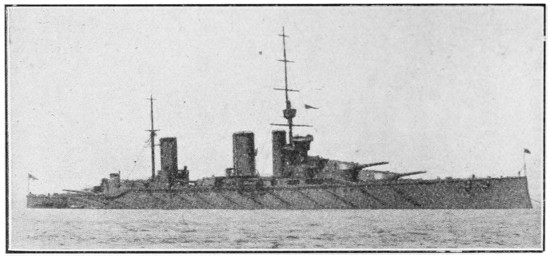

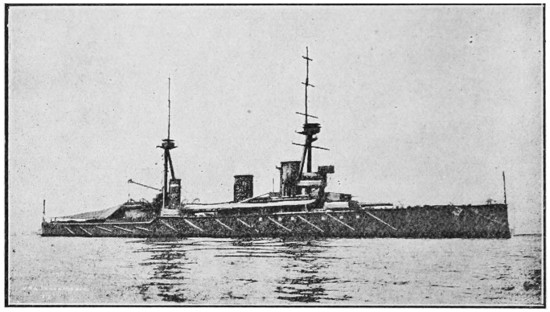

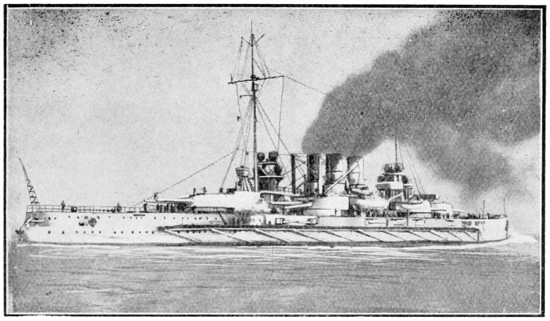

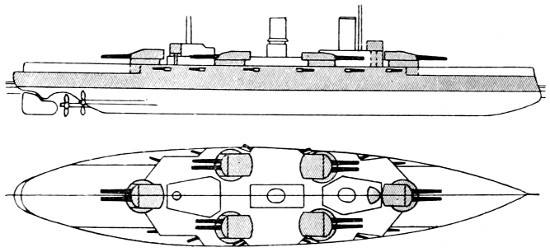

H.M.S. Neptune. Photo: Sport & General.

NEPTUNE CLASS.

COLOSSUS, NEPTUNE, HERCULES (slight differences).

Displacement: 19,200 to 20,000 tons.

Speed: 22 knots; Guns: 10 12in., 16 4in.; Torpedo tubes: 3.

| Astern fire: | Broadside: | Ahead fire: |

|---|---|---|

| 8 12in. | 10 12in. | 6 12in. |

[33]

A week afterwards the thunderbolt fell; the crisis found the First and Second Fleets ready in all respects for war, and, after additional reserves had been called out on Sunday, August 2nd, the Admiralty was able to give the nation a certificate that by 4 a.m. the following morning the British Navy had been raised from a peace footing to a war footing, and was fully mobilised.

Immediately the curtain fell, hiding from view the movements of all British men-of-war, not only in the main strategical theatre, but in the outer seas. Two battleships, which had just been completed for Turkey by those whom Mr. G. H. Perris had denounced only a short time before in his pamphlet as the “War Traders,” were taken over by the Admiralty, proving valuable accessions to our naval strength. Two swift destroyer-leaders were also compulsorily purchased from Chile, the appointment of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe as supreme British Admiral of the Home Fleets was announced, and all the preliminaries to the great war drama on the sea were completed without delay, confusion, or panic. The nation will remember in gratitude the courage and decision exhibited by Mr. Churchill in the hour of supreme crisis. He proved himself a statesman.

This is not the place to relate the story of the renaissance of British military power. The virtue of the measures adopted by Lord Haldane as Secretary for War lay in the fact that he did homage to the essential principle which must underlie all schemes of defence by an island kingdom, which is the nerve centre of a maritime[34] Empire. As in Opposition he had been foremost in advertising our dependence upon the sea, so in office, as Minister responsible for the Army, he based all his schemes on the assumption that the British Army is the projectile of a supreme fleet, to be hurled oversea as soon as the naval authority is able to give guarantee of safe passage. It was in the light of this essential truth that the Expeditionary Force was organised, and the Volunteers converted into the Territorial Army. Mistakes were, no doubt, made; no man who avoids them can ever expect to do anything. But at practically no additional expense, and without, therefore, withdrawing a penny from the necessary provision of the fleet, Lord Haldane initiated and completed military schemes, the value of which became apparent when we were confronted with the necessity of entering upon a contest with two of the great military powers of Europe, which possessed fleets of such a standing that they could offer challenge to our supremacy afloat.

The survey of British naval policy in the years immediately preceding the war would be incomplete were no reference made to the fact, of which we were insistently reminded when hostilities opened, that sea power, even more than military power, must stand defeated from the very outset, unless it is supplemented by economic power. In the past the weakness of all democracies when faced by war has been apparent. However great the power on the sea, however formidable the military arm ashore, the real strength of a people lies in itself. It must be ready on the instant to organise[35] every department of life on a war basis. Armed forces which have not behind them a resolute community are robbed of more than half their power. A feeling of panic is always apt to infect a democracy, and then under the palsy of fear the tendency is for pressure to be brought to bear on the supreme naval and military authorities, with the result that strategic plans, matured in peace, become confused and ineffective. An illustration of the influence of the fears of the civil population upon war policy was furnished during the Spanish-American War. Under the pressure of nervous public opinion, the Naval Board was compelled to depart from the sound strategy of concentration upon the main objective, and to dissipate no little of the power at its command in order to provide some measure of local protection for various coast towns. Fortunately, British naval policy had been developed on lines which minimised this peril, and our economic resources had been surveyed, and adequate preparations made to afford to our sea power every possible economic support. As to the first, fear of invasion or raids, the coast and port guard ships, with little more than skeleton crews, had been abolished; in their place patrol flotillas of destroyers and submarines had been created to keep an efficient and active watch and ward along the sea frontier which the enemy at our door might threaten. This provision was supplemented by the mobilisation of all our national resources, under the direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence. When Mr. Balfour founded this body he builded[36] better than he knew. When war came not only were the main fleets not tied to our shores, but every department of State had before it a complete plan of the duty which it had to perform in order to give that national support to the fleet, without which it could not hope to achieve victory.

During the years which immediately preceded war the Committee of Imperial Defence was quietly at work co-ordinating the naval and military arms, and laying the foundation of a wide-spreading organisation. On July 25th, 1912, Mr. Asquith, in a speech in the House of Commons, gave the nation some conception of the character of one aspect of the work which was then being quietly performed by this small body, unrecognised by our Constitution, and regarded, as it had been since its birth, with no little suspicion and distrust. Mr. Asquith related that the Committee of Imperial Defence had appointed what was styled “a sub-committee for the co-ordination of departmental action at the outbreak of war.” Describing this particular work of the Committee of Imperial Defence, Mr. Asquith added:

“This sub-committee, which is composed of the principal officials of the various Departments of State, has, after many months of continuous labour, compiled a War-Book. We call it a War-Book—and it is a book which definitely assigns to each Department—not merely the War Office and the Admiralty, but the Home Office,[37] the Board of Trade, and every Department of the State—its responsibility for action under every head of war policy. The Departments themselves, in pursuance of the instructions given by the War-Book, have drafted all the proclamations, Orders in Council, letters, telegrams, notices, and so forth, which can be foreseen. Every possible provision has been made to avoid delay in setting in force the machinery in the unhappy event of war taking place. It has been thought necessary to make this Committee permanent, in order that these war arrangements may be constantly kept up to date.”

What happened in the last days of July, 1914? During the period of strained relations, the War-Book was opened, and every official in every State Department concerned—eleven in all—had before him a precise statement of exactly what contribution he had to make in mobilising the State as an economic factor for war. Proclamations, Orders in Council, letters, and telegrams flowed forth throughout the British Isles, and to the uttermost parts of the Empire, in accordance with the pre-arranged plan which had been so assiduously elaborated. Hardly had the Navy been mobilised, the Army Reserves called out to complete the regular Army, and the Territorials embodied, than the nation realised that, without confusion, it had itself been placed upon a war footing. The creation of the British War-Book must be acclaimed as a monument to the[38] perspicacity of Mr. Asquith and the Ministers who assisted him on the Committee of Defence, and to the splendid labours of the Secretary of the Committee, Captain Maurice Hankey, C.B., and the small staff associated with him. This organisation, which owed so much to the “staff mind” of its former secretary, Rear-Admiral Sir Charles Ottley, imposed upon the nation a charge of only about £5,000 a year, which was returned increased by a thousandfold when the crisis came, and the United Kingdom, existing under the most artificial conditions owing to its dependence on the sea for food and raw materials, was prepared, for the first time in its history, to offer to its fleets and armies the wholehearted and organised support of the richest nation in the world.

When the curtain fell upon the seas, the nation had the assurance that everything which foresight could suggest had been done to make secure our essential supremacy. The newspapers preserved a discreet silence as the Home Fleets took up their stations in the main strategical area. They were convinced, by irrefutable evidence, that adequate power had been concentrated in this theatre to enable the North Sea to be sealed, thus confining the main operations of the naval war to one of the smallest water areas in the world.

Those who study the conspectus of British sea power at the moment when the fog of war hid from view all that was occurring in distant waters would miss the real significance of the picture which British sea power presented at this[39] dramatic moment if they failed to recognise the means by which the British Navy was able to impose an iron grip upon the great highways which are the life blood of British commerce. When war occurred the British sea power was predominant in all the outer seas in contrast with every other Power engaged in hostilities. At every point the British fleet was supreme in contrast with every other Power now engaged in hostilities. Austria and Italy were hardly represented outside the Mediterranean; Germany had only one armoured ship and two small cruisers in the Mediterranean and a few small cruisers in the Atlantic; in the Pacific, though she had the largest squadron of any Continental Power, the Admiralty regarded our forces as being at least twice as strong. This balance of strength was maintained in accordance with the terms of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

From the moment of the ultimatum all the Empire was at war. At a hundred and one points of naval and military importance a state of war existed. Wherever the British flag was flying—and it flies over about one quarter of the habitable globe—officers and men of the sea and land services stood awaiting the development of events.

What precise orders were issued by the Admiralty cannot be revealed, but telegrams which were received during the early days of hostilities indicated that at all the great junctions of the Empire sections of the British Navy had been concentrated, and their commanding officers[40] directed to omit no measure necessary to maintain the lifeline of the Empire.

Under the scheme of concentration which for ten years previously had been the outstanding feature, not only of British naval policy, but of the naval policy of all the Great Powers of Europe, the number of ships in distant seas had been reduced, but the fighting value of the British units was higher than ever before. The character of the British naval representation outside home waters when war began may be appreciated from the following official statement of the composition of the squadrons which were held on the leash by the Admiralty, awaiting the development of events:

MEDITERRANEAN FLEET.

Battle Cruiser Squadron.—Inflexible (Flag), Indefatigable, Indomitable.

Armoured Cruiser Squadron.—Defence (Flag), Black Prince, Duke of Edinburgh, Warrior.

Cruisers.—Chatham, Dublin, Gloucester, Weymouth.

Attached Ships.—Hussar, Imogene.

Destroyer Flotilla.—Blenheim (Depot Ship), Basilisk, Beagle, Bulldog, Foxhound, Grampus, Grasshopper, Harpy, Mosquito, Pincher, Racoon, Rattlesnake, Renard, Savage, Scorpion, Scourge, Wolverine.

Submarines.—B 9, B 10, B 11.

[41]

Torpedo Boats.—Nos. 044, 045, 046, 063, 064, 070.

GIBRALTAR.

Submarines.—B 6, B 7, B 8.

Torpedo Boats.—83, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96.

EASTERN FLEET.

East Indies Squadron.—Battleship Swiftsure (Flag), cruisers Dartmouth, Fox; sloops Alert, Espiègle, Odin, Sphinx.

China Squadron.—Battleship Triumph; armoured cruisers Minotaur (Flag), Hampshire; cruisers Newcastle, Yarmouth; gunboats, etc., Alacrity, Bramble, Britomart, Cadmus, Clio, Thistle.

New Zealand Division.—Cruisers Philomel, Psyche, Pyramus, Torch.

ATTACHED TO CHINA SQUADRON.

Destroyers.—Chelmer, Colne, Fame, Jed, Kennet, Ribble, Usk, Welland.

Submarines.—C 36, C 37, C 38.

Torpedo Boats.—Nos. 035, 036, 037, 038.

River Gunboats.—Kinsha, Moorhen, Nightingale, Robin, Sandpiper, Snipe, Teal, Woodcock, Woodlark, Widgeon.

[42]

AUSTRALIAN FLEET.

Battle Cruisers.—Australia (Flag.)

Cruisers.—Encounter, Melbourne, Sydney.

Destroyers.—Parramatta, Warrego, Yarra.

Submarines.—AE 1, AE 2.

CAPE OF GOOD HOPE.

Cruisers.—Hyacinth (Flag), Pegasus, Astræa.

WEST COAST OF AFRICA.

Gunboat.—Dwarf.

S.E. COAST OF AMERICA.

Cruiser.—Glasgow.

WEST COAST OF AMERICA.

Sloops.—Algerine, Shearwater.

WEST ATLANTIC.

Armoured Cruisers.—Suffolk, Berwick, Essex, Lancaster; cruiser Bristol.

This narrative of the opening phases of the war between six of the great fleets of the world would be incomplete were no reference made to the conditions of the German Fleet. A month[43] before the final cleavage between the two nations, Kiel had kept high festival in honour of the British Navy. At the invitation of the German Government, Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender had taken some of the finest battleships of the British Navy into this German port. During the Regatta Week official Germany entertained the officers and men with the utmost hospitality, and, for a time, the Emperor had his flag, the flag of an honorary admiral of the British Navy, flying from the mainmast of one of the latest “Dreadnoughts,” the “King George V.,” and was in technical command of this important section of the Home Fleet. Luncheons, dinners, and receptions filled the days over which the yacht racing extended, and when Sir George Warrender steamed out of Kiel to meet at a rendezvous at sea the British squadron, under Rear-Admiral Sir David Beatty, which had been visiting the Baltic ports of Russia, and the other squadrons which had been entertained by the peoples of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, every indication encouraged the belief that peace was more completely assured than at any time during this century.

The Kiel festivities at an end, the High Sea Fleet, reinforced by a number of reserve ships, put to sea for its summer cruise in Norwegian waters. The Emperor, in the Royal Yacht “Hohenzollern,” also left for the coast of Norway. These were the conditions when the bolt fell. Can it be doubted that, when in after years and in full knowledge, the history of the war is written, it will be concluded that Germany, in[44] giving her support to Austria-Hungary, had no thought that this would involve her use of her fleet against the greatest sea Power of the world? With much labour, and at great sacrifice, she had created a formidable diplomatic weapon to be brandished in the eyes of a timid and commercially-minded people—and such she believed the British people to be; but it was not a fleet of sufficient standing to face the greatest sea Power with confidence.

The war occurred at an unpropitious moment not only for Germany, but for her ally, Austria-Hungary, so far as sea power was concerned. This country had, it is true, almost completed her first programme of four “Dreadnoughts,” but her navy was still deficient in cruisers—possessing six only—as well as in torpedo craft. In combination Austria-Hungary and Italy could have faced the naval forces of France and Great Britain in the Mediterranean, but in isolation the former’s position was from the first well-nigh hopeless, and her ships retired to Pola at the outbreak of the war.

The French fleet was in good condition to take the seas. Under the spur furnished by German acts and German words it had been strengthened in ships and men, its administration ashore remodelled, and its fleets at sea reorganised. The Republican Government had confided the supreme command of its battle forces to one of the most conspicuously able sailors of the period, Admiral Boué du Lapeyrère, and could enter on the war in its naval aspects with confidence and courage.

[45]

Russia was not so fortunate. She had only comparatively recently taken serious steps to replace the fleet she lost in the war with Japan. A ship-building project, known as the “Minor Programme,” was being carried out, but so far none of the vessels it comprised had become available for service. When war occurred, four “Dreadnoughts,” which were begun as far back as 1909, were not yet ready, and seven others were on the stocks, but not yet launched. Eight small cruisers laid down under the “Minor Programme” were building, two of them in a German yard, and the remainder in Russia, and there was besides a large flotilla of torpedo craft under construction. With all these vessels in commission, the Russian Navy would have become once more a factor to be reckoned with. As it happened, Russia faced the war practically without any considerable sea power.

When hostilities had begun, a dramatic incident reminded the world that Japan, the ally of Great Britain in the Far East, was not viewing the course of events unconcerned. On Monday, August 16th, it was announced that the Japanese Government had delivered an ultimatum to Germany in the following terms:

“We consider it highly important and necessary in the present situation to take measures to remove the causes of all disturbance of peace in the Far East, and to safeguard general interests as contemplated in the Agreement of Alliance between Japan and Great Britain.

[46]

“In order to secure firm and enduring peace in Eastern Asia, the establishment of which is the aim of the said Agreement, the Imperial Japanese Government sincerely believes it to be its duty to give advice to the Imperial German Government to carry out the following two propositions:

“The Imperial Japanese Government announces at the same time that in the event of its not receiving by noon on August 23rd an answer from the Imperial German Government signifying unconditional acceptance of the above advices offered by the Imperial Japanese Government, Japan will be compelled to take such action as it may deem necessary to meet the situation.”

When Germany was confronted with heavy odds, Japan remembered the events following the war of 1894-5, when this Power,[47] having joined in robbing her of the spoil of her victory over China, herself entered into possession of Kiao Chau, as the price for the lives of two murdered missionaries.

Thus, at the touch of German arrogance, four great sea Powers of the world arrayed themselves against her—the British, French, and Russian fleets in European waters, and the great navy of Japan in the Pacific.

In this wise did the struggle for the command of the sea open. Germany reaped as she had sown. Since 1898 she had boasted how she would challenge the greatest sea Power. When the day and hour came it was not the British fleet only, but the navies of France, Russia, and Japan which confronted her. By her words and acts she had alienated the sympathies of every nation except her ally, Austria-Hungary. The war began with her fleets and squadrons sheltering behind the forts of her naval bases, and with a few cruisers in the Atlantic being hunted by an overpowering force of British and French ships. Such was the fruit of her diplomacy and her forward naval policy; her shipping suffered instant strangulation; her colonies were divorced from the Motherland, and she was confronted with the approaching ruin of that world-politic which had been her pride and inspiration.

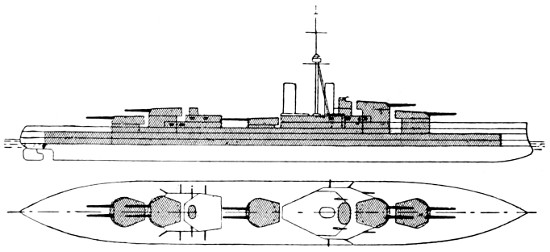

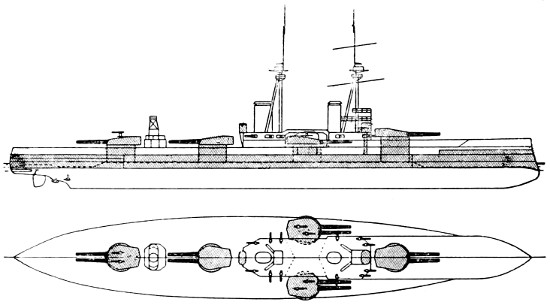

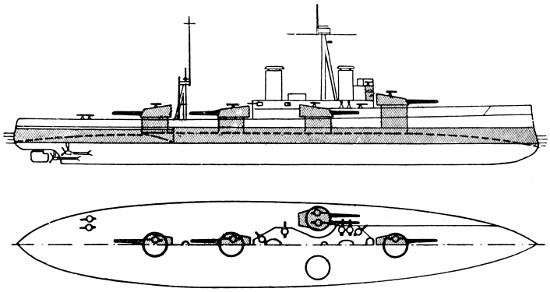

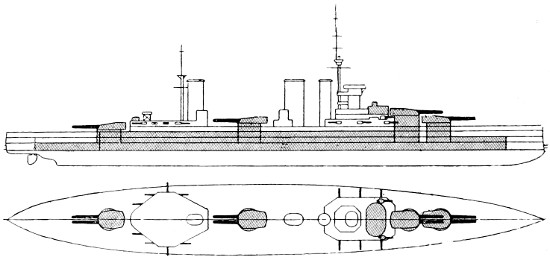

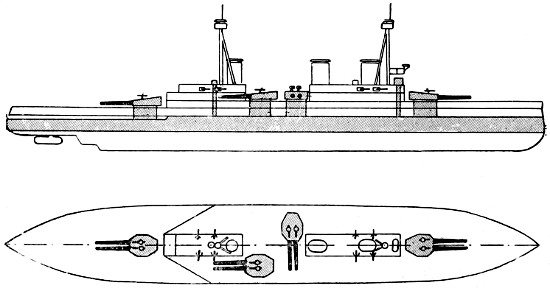

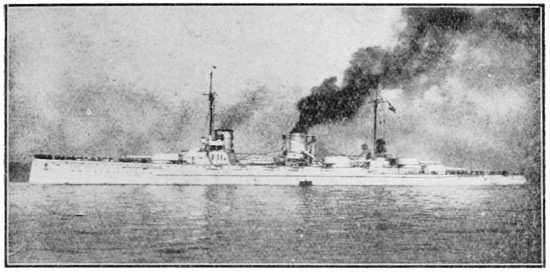

H.M.S. Vanguard. Photo: Sport & General.

VANGUARD CLASS.

ST. VINCENT, VANGUARD, COLLINGWOOD.

Displacement: 19,250 tons.

Speed: 22 knots; Guns: 10 12in., 18 4in.; Torpedo tubes: 3.

| Astern fire: | Broadside: | Ahead fire: |

|---|---|---|

| 6 12in. | 8 12in. | 6 12in. |

[49]

The relative strength of the British and German navies at the moment when war was declared is of historical interest.

The appended particulars have been prepared from “Fighting Ships, 1914,” and brought up-to-date by the inclusion of the two Turkish battleships and the two Chilian destroyer leaders, which were purchased on the outbreak of hostilities by the British Government.

British Navy.

| Super-Dreadnought battleships | 11 | ||

| Super-Dreadnought battle-cruisers | 3 | ||

| 14 | |||

| Dreadnought battleships | 13 | ||

| Dreadnought battle-cruisers | 5 | ||

| 18 | |||

| Total of ships of Dreadnought era: (Three more super-Dreadnoughts near completion, and due to commission late in 1914.) |

32 | ||

| Pre-Dreadnoughts:[50] | |||

| Powerful ships all completed between 1905 and 1908 | 8 | ||

| Older and less powerful ships completed between 1895 and 1904 | 30 | ||

| 38 | |||

| Total battleships | 70 | ||

| Armoured Cruisers: | |||

| Big, heavily-armed ships completed between 1905 and 1908 | 9 | ||

| “County” class, slower and less powerful, completed between 1903 and 1905 | 15 | ||

| “Drake” and “Cressy” class, bigger and better, but slightly older ships, completed between 1901 and 1903 | 10 | ||

| Total armoured cruisers | 34 | ||

| Cruisers: | |||

| Big protected cruisers, “Diadem” class, 21 knots, 6in. guns (1889-1902) | 6 | ||

| Older and smaller (1890-1892) | 9 | ||

| 15 | |||

| Fast Light Cruisers: | |||

| “Arethusa” class, 3,500 tons, 30 knots, burning oil, completed 1914 | 8 | ||

| “Town” class, 5,400 to 4,800 tons, 25 knots (1910-1914) | 15 | ||

| 25-knot ships, round about 300 tons (1903-1907)[51] | 15 | ||

| 30 | |||

| 20-knot ships, 2,100 to 5,400 tons (1896-1900) | 16 | ||

| 19-knot ships, 5,600 tons (1895-1896) | 9 | ||

| Older ships, 2,500 to 4,300 tons, 16·5 to 19·5 knots (1890-1893) | 9 | ||

| Total protected cruisers | 87 | ||

| Destroyers, 36 to 251⁄2 knots (1893-1914) | 227 | ||

| Torpedo-boats, 26 to 20 knots (1885-1908) | 109 | ||

| Submarines, from 1,000 to 200 tons, speed from 20 to 11·5 knots surface, 12 to 7 knots submerged (1904-1913) | 75 | ||

| Minelayers | 7 | ||

| Repair Ships | 3 | ||

It need hardly be added that a number of these vessels—including the two Pre-Dreadnought battleships “Swiftsure” and “Triumph” and groups of cruisers, destroyers, and submarines—were on duty in the outer seas when war opened.

[52]

German Fleet.

| Super-Dreadnoughts (3 building) | None | ||

| Dreadnought battleships | 13 | ||

| Dreadnought battle-cruisers | 5 | ||

| 18 | |||

| (Three other battleships are due to commission in 1914.) | |||

| Pre-Dreadnought battleships (1891-1908) | 22 | ||

| Old coast defence battleships (1889-1893) | 8 | ||

| Armoured cruisers (1897-1909) 8,900 to 15,500 tons, 24·5 to 19 knots | 9 | ||

| Big protected cruisers (1892-1910), 6,000 tons, 19 knots | 6 | ||

| 24-knot cruisers (1904-1913), 3,000 to 5,000 tons | 25 | ||

| 31 | |||

| (Most of these ships have belt armour as thick as that of the British “County” class of armoured cruisers.) | |||

| Small cruisers, 21 knots (1893-1910) | 12 | ||

| Destroyers (1889-1913), 34 to 26 knots | 152 | ||

| Torpedo-boats (1887-1898), 26 to 22 knots | 45 | ||

| Submarines, about equal to British in size and speed | 30 to 40 | ||

| Minelayers | 2 | ||

[53]

All the German Navy, except one battle-cruiser, two armoured cruisers, and a few light cruisers, were concentrated in the North Sea and Baltic when war occurred.

[54]

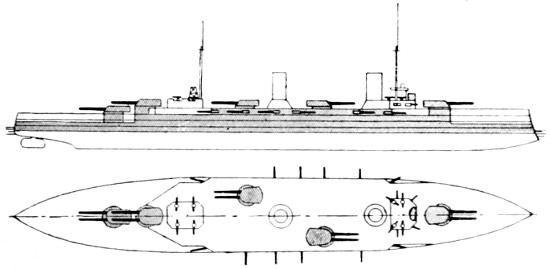

These fine ships are the very latest additions to the British battle-fleet. The displacement is 25,000 tons, but with a full supply of coal, ammunition, and stores on board the actual figure is nearly 27,000 tons. The length over all is 645 ft., the maximum breadth is 891⁄2 ft., and under normal conditions the ship draws 28 ft. of water. Parsons’ turbines, designed for 29,000 h.p., give a speed of 21 knots, which was exceeded by over one knot on trial. An extremely powerful armament is carried. It consists of ten 13·5-in. and twelve 6-in. guns, with some small quick-firers on high-angle mountings for use against aircraft.

The big guns, mounted in twin turrets, are all on the centre line, and can thus be trained[55] on either broadside, while four train ahead and the same number astern. Ten of the 6-in. guns are disposed in an upper-deck battery forward, the remaining two in casemates right at the stern. This disposition was adopted owing to the fact that torpedo attacks are usually delivered from ahead, and it is necessary, therefore, that as many quick-firing guns as possible can be trained on the approaching boats before they are able to discharge their torpedoes.

Armour protection is very complete in this class. On the waterline there is a 12-in. belt, with 10-in. armour rising above this as far as the upper deck. The belt thins to 6-in. forward and aft, but the extreme ends of the ship are unarmoured. On the turrets there is 12-in. armour, with 6-in. plating over the secondary battery. Four 21-in. submerged torpedo tubes are fitted. The fuel supply is well over 3,000 tons. The complement of these ships totals more than 1,000 officers and men. They each cost over £2,000,000 to complete.

This battleship, although she was only launched in January, 1913, has had a very chequered career. Originally laid down as the Rio de Janeiro for the Brazilian Government at Elswick, she was purchased before completion by Turkey, and was on the point of leaving for Turkish waters under the name of Osman I.,[56] when she was taken over by the British Admiralty on the outbreak of war with Germany. Turkey is understood to have made a protest, but the transfer is an accomplished fact, and this fine vessel has already passed into our battle fleet. She is quite unique in design. The displacement is 27,500 tons, length 632 ft., and the designed speed, which was made on trial, 22 knots.

Her main armament consists of no fewer than fourteen 12-in. guns, mounted in seven double turrets on the centre-line, an arrangement which permits all fourteen weapons to be fired on either broadside. In the secondary battery are mounted twenty 6-in. quick-firing guns, and the tale of weapons is completed by sixteen small quick-firers and three torpedo tubes. The ship is armoured with 9-in. plates amidships, tapering to 6 in. and 4 in. at the ends. Armour of the same thickness (9-in.) protects the 12-in. turrets, and there is 6-in. plating over the secondary guns. The maximum coal capacity is 3,500 tons. A complement of 1,100 officers and men is required to work this huge vessel, which cost nearly £2,700,000 to build and equip.

This vessel was laid down at Barrow for the Turkish Government, and named Reshadieh, but was taken over by the British Admiralty on the outbreak of war with Germany. Launched in September, 1913, she displaces 23,000 tons,[57] is 525 ft. long, and has turbines of 31,000 h.p., which are expected to give a speed of 21 knots. In general her design corresponds to that of the Iron Duke class. The armament consists of ten 13·5-in., sixteen 6-in., and four 12-pounder guns, with five submerged torpedo tubes.

The five double turrets in which the big guns are mounted are on the centre-line, thus allowing all ten weapons to be used on each broadside. Armour protection is very complete, the main belt being 12 in., the turrets 12 in., and the secondary battery 5 in. thick. Her coal capacity is 2,100 tons. The complement is 900 officers and men. The price paid for this ship has not yet been made public.

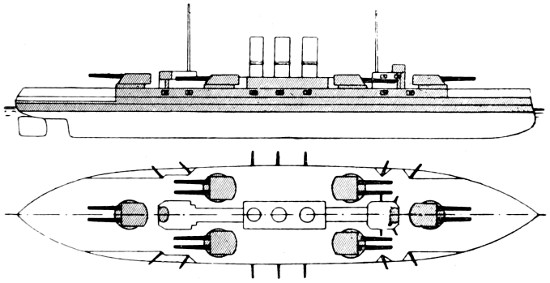

These fine vessels are among the most powerful of our super-Dreadnought battleships. The displacement is nominally 23,000 tons, but when in service, with maximum fuel, stores, &c., on board, they displace about 25,000 tons. They are 596 ft. in length, with a beam of 89 ft., and their turbines of 27,000 h.p. drive them at a speed of 211⁄2 knots. The armament consists of ten 13·5-in. and sixteen 4-in. guns, with three submerged torpedo tubes.

[58]

All the big guns, which are mounted in pairs in turrets on the centre line, can fire on either broadside. Protection is afforded by a 12-in. armour belt amidships, with thinner plating above and at the ends. The turrets are of 11-in. armour. The secondary battery of 4-in. quick-firers is practically unprotected. A maximum fuel supply of 2,700 tons can be carried. The complement is 900 officers and men. Each of these ships cost more than £1,900,000 to build and equip.

Super-Dreadnoughts of 22,500 tons displacement and 545 ft. in length. The Orion class, to which these ships belong, inaugurated the “super-Dreadnought” era by reason of the super-calibre guns with which they are armed. They are propelled by Parsons’ turbines of 27,000 h.p. at a speed of 21 knots, but did considerably better than this on the trial runs. The main armament comprises ten 13·5-in. breech-loading guns, firing a 1,250 lb. projectile at the rate of two per minute.

These guns are mounted in five twin turrets on the centre line of the vessel, and all of them can be trained on either broadside. Sixteen[59] 4-in. quick-firers are mounted for use against torpedo craft, and there are three 21-in. submerged torpedo tubes. The armour belt is 12-in. thick amidships, the turrets 11-in. Some of the smaller guns are protected by 4-in. armour. Coal and oil to the amount of 2,700 tons can be carried. The complement of these ships is 900 officers and men. They cost complete nearly £2,000,000.

These are Dreadnought battleships of 20,000 tons displacement. They are 510 ft. in length, and have Parsons’ turbines of 25,000 h.p., which give them a speed of 21 knots. The main battery consists of ten 12-in. guns, 50 calibres (i.e., 50 ft.) long, mounted in five twin turrets. Two of these turrets are in echelon amidships, the remaining three being on the centre line, an arrangement that permits all ten guns to come into action on either broadside through a limited arc.

In the class to which these ships belong the super-posed turret appeared for the first time in the British Navy. Sixteen 4-in. quick-firers and three submerged torpedo tubes complete[60] the armament. There is an 11-in. armour belt on the waterline, similar protection being given to the big guns. The fuel capacity is 2,700 tons. The complement numbers over 800 officers and men. These vessels cost about £1,700,000 apiece to complete.

These are Dreadnought battleships with a displacement of 19,250 tons. They are 500 ft. long, and have Parsons’ turbines of 24,500 h.p., which give them a top speed of 21 knots. Their main battery comprises ten 12-in. guns of powerful type, mounted in five twin turrets, the disposition of which allows eight guns to be used on either beam. They also carry eighteen 4-in. quick-firers, some mounted on top of the turrets, and others in the superstructure. There are three submerged torpedo tubes.

The waterline is protected by armour barely 10-in. thick, this being also the thickness of the turret armour. Coal and oil to the amount of 2,700 tons can be carried. The complement of these battleships numbers rather more than 800 officers and men. They cost about £1,700,000 to build and complete.

[61]

These ships are some of our earliest Dreadnoughts. Their displacement is 18,900 tons, length 490 ft. Parsons’ turbines of 23,000 h.p. propel them at a maximum speed of 21 knots, which they can maintain for several hours without difficulty. Ten 12-in. guns form the primary armament, which is mounted in five twin turrets, so disposed as to allow eight guns to fire on the broadside. They carry, further, sixteen 4-in. quick-firing guns to repel attack by torpedo craft, and there are three torpedo tubes below water.

On the waterline and the big-gun positions there is 11-in. armour. The maximum supply of coal and oil is 2,700 tons. The complement is 800 officers and men. These battleships cost about £1,700,000 to build and complete.

This famous battleship was laid down at Portsmouth in October, 1905, and completed by December, 1906, and thus established a record for speedy construction. She was designed by a[62] committee of experts to meet the requirements of modern naval tactics, and with various modifications the main principles she embodied have since been almost universally adopted. She displaces 17,900 tons, and is 520 ft. long. Parsons’ turbines of 23,000 h.p. give her a speed of 21 knots. She was the first battleship ever fitted with turbine machinery.

The armament consists of ten 12-in. guns, mounted in five twin turrets, which are so placed as to give a broadside fire of eight and an axial fire of six guns. For keeping off torpedo craft a battery of twenty-four 12-pounder quick-firers is provided. There are five submerged torpedo tubes. Waterline and vitals are protected by 11-in. armour, as also are the gun turrets. The ship has a great amount of internal protection against mine or torpedo explosion. She can carry 2,700 tons of coal. The complement numbers about 800 officers and men. This battleship cost upwards of £1,800,000 to build and equip.

These battleships are sometimes called semi-Dreadnoughts, because they approximate to the Dreadnought type in tonnage and armament. The displacement is 16,500 tons, length 410 ft., and engines of 16,750 h.p., giving a speed of over 18 knots. Each of these vessels is armed with[63] four 12-in. and ten 9·2-in. breech-loading guns, all mounted in armoured turrets. The four 12-in. and eight of the 9·2-in. guns are in twin turrets, the other two 9·2-in. being in single turrets. The disposition of the armament is such that four 12-in. and five 9·2-in. can fire on each broadside. An outstanding defect is the smallness of the double 9·2-in. turrets, which hardly give elbow room to the crews and do not allow full advantage to be taken of the extraordinary rapidity with which the 9·2-in. piece can be worked when there is plenty of space.

On the whole, however, these ships are extremely powerful units. For driving off torpedo craft there are twenty-four 12-pounder quick-firers mounted in the superstructure. Five torpedo tubes are fitted. Armour protection consists of a 12-in. belt amidships, and there is similar plating on the 12-in. turrets, the smaller turrets having 8-in. armour. The fuel capacity is 2,500 tons. Each battleship carries 750 officers and men and cost £1,650,000 to build and complete.

This is the largest battle cruiser in the British Navy. She was built at Clydebank, and was approaching completion at the outbreak of war. The displacement is 28,000 tons, length 660 ft.,[64] and Parsons’ turbines of 100,000 h.p. give a speed of at least 28 knots. Her armament comprises eight 13·5-in., twelve 6-in., and some smaller guns, with three torpedo tubes. The big guns are in double turrets on the centre-line, and all can be fired on either broadside. The 6-in. guns are mounted in an armoured battery.

For a battle cruiser this ship is heavily armoured. She has a belt at least 10 in. thick amidships, and the turrets are of equal thickness. She can store as much as 4,000 tons of coal and oil. The complement is about 1,100 officers and men. In appearance the “Tiger” is quite unlike other British battle cruisers. She has three equal-sized funnels and only one mast. Her total cost is understood to be not less than £2,200,000.

These battle cruisers displace 27,000 tons, are 660 ft. in length, and 881⁄2 ft. broad. They have turbines of about 70,000 h.p., which enable them to steam at 28 knots, though this speed has been greatly exceeded in service. The main armament consists of ten 13·5-in. guns, discharging a projectile of 1,400 lb. weight, at the rate of two rounds per minute.

H.M.S. Bellerophon. Photo: Symonds & Co.

BELLEROPHON CLASS.

BELLEROPHON, TEMERAIRE, SUPERB.

Displacement: 18,000 tons.

Speed: 22 knots; Guns: 10 12in., 16 4in.; Torpedo tubes: 3.

| Astern fire: | Broadside: | Ahead fire: |

|---|---|---|

| 6 12in. | 8 12in. | 6 12in. |

[65]

These weapons are mounted in four double turrets on the centre-line, and can thus be fired on either broadside. Sixteen 4-in. quick-firers are carried for repelling torpedo attack. There are also two submerged torpedo tubes. The main armour belt is about 9 in. thick, with 10-in. plating on the turrets. The full fuel capacity is 3,000 tons, and the complement numbers 980 officers and men. These ships averaged £2,085,000 to build and complete.

These vessels displace about 19,000 tons. They are 555 ft. in length, 80 ft. broad, and are designed for a speed of 25 knots, which was much exceeded during trials. The main armament consists of eight 12-in. guns, mounted in four double turrets, two being placed fore and aft, and two diagonally amidships, thus permitting all eight guns to be discharged on either broadside.

In addition there are sixteen 4-in. quick-firers mounted in the superstructure, and two submerged torpedo tubes. A 7-in. armour belt protects the waterline, the same thickness being on the turrets. The fuel capacity is 2,500 tons, including oil. A complement of 790 officers and men is carried. These ships cost about £1,500,000 each to build and complete.

[66]

The Invincible class were the first battle-cruisers to be built. The type is a cruiser edition of the Dreadnought, combining great offensive qualities with high speed. The displacement is 17,250 tons, length 530 ft., and the turbines of 41,000 h.p. are designed for a speed of 25 knots. In service, however, these vessels have steamed at more than 28 knots. They are armed with eight 12-in guns, mounted in four double turrets, one turret being placed at each end and the other two en echelon amidships.

This system enables all eight weapons to be fired on either broadside through a very limited arc. Sixteen 4-in. guns are mounted for repelling torpedo attack. The waterline and vital parts are protected by 7-in. armour, this being also the thickness of the turret plates. Coal to the amount of 2,500 tons can be carried. The complement is 780 officers and men. These vessels each cost over £1,700,000 to build and equip.

[67]

The King Edward class is considered to be the finest homogeneous group of pre-Dreadnought battleships in the world. The displacement is 16,350 tons, length 425 ft., and engines of 18,000 h.p. give a speed of over 19 knots. The armament consists of four 12-in., four 9·2-in., ten 6-in., twelve 12-pounder, and twelve 3-pounder guns, with four torpedo tubes.

All eight big guns are mounted in armoured turrets, the 6-in. weapons being in a box battery. Broadside fire is from four 12-in., two 9·2-in., and five 6-in. guns. A 9-in. armour belt protects vital parts. On the main turrets there is 12-in. plating, and the smaller guns also have good protection. The maximum coal supply is 2,200 tons. A complement of 820 officers and men is carried. These ships each cost about £1,450,000 to build and equip.

[68]

These battleships were built for the Chilian Government, but both were purchased by Great Britain before they were completed. The displacement is 11,980 tons, length 436 ft., and engines of 12,500 h.p. give a speed of 20 knots. For their size the armament of these vessels is most formidable. It comprises four 10-in., fourteen 7·5-in., and fourteen 14-pounder guns, with two torpedo tubes. The 10-in. weapons are in two twin turrets, the 7·5-in. guns being in an armoured battery.

The waterline and vital parts are protected by 7-in. of armour, which is increased to 10-in. on the turrets and there is 6-in. plating over the secondary battery. The coal supply is 2,000 tons. A complement of 700 officers and men is carried. The ships each cost £845,000 to build and complete. In all but very calm weather they lose much of their fighting value owing to the nearness of the 7·5-in. battery to the water, a position which makes it impossible to work these guns in a seaway. In other respects, too, the type is considered inferior to standard British design.

H.M.S. Dreadnought. Photo: Sport & General.

DREADNOUGHT.

Displacement: 17,900 tons.

Speed: 22 knots; Guns: 10 12in., 24 12pdrs.; Torpedo tubes: 5.

| Astern fire: | Broadside: | Ahead fire: |

|---|---|---|

| 6 12in. | 8 12in. | 6 12in. |

[69]

These are vessels of 14,000 tons displacement, 405 ft. in length, with engines of 18,000 h.p., and a speed of 20 knots. Their armament consists of four 12-in., twelve 6-in., and ten 12-pounder guns, with four submerged torpedo tubes. The 12-in. guns are in turrets, the 6-in. in casemates. Broadside fire is from four 12-in. and six 6-in. guns.

The class to which these ships belong was designed with a view to speed, to gain which sacrifices were necessary. Hence the armour protection is very light, the thickness of the belt being only 7-in. on the waterline. The turrets are of the same moderate thickness. The maximum fuel capacity is 2,000 tons. A complement of 750 officers and men is carried. The average cost was £1,000,000 to build and complete.

[70]