The ROMAN EMPIRE

in the time of

Constantine the Great

Title: Europe in the Middle Ages

Author: Ierne L. Plunket

Release date: March 10, 2017 [eBook #54334]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Clarity, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

EUROPE

IN THE MIDDLE AGES

BY

IERNE L. PLUNKET

M.A. Oxon.

AUTHOR OF ‘THE FALL OF THE OLD ORDER’, ‘ISABEL OF CASTILE’, ETC.

OXFORD

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

1922

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen

New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town

Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai

HUMPHREY MILFORD

Publisher to the University

Printed in England

The history of Mediaeval Europe is so vast a subject that the attempt to deal with it in a small compass must entail either severe compression or what may appear at first sight reckless omission.

The path of compression has been trodden many times, as in J. H. Robinson’s Introduction to the History of Western Europe, or in such series as the ‘Periods of European History’ published by Messrs. Rivingtons for students, or text-books of European History published by the Clarendon Press and Messrs. Methuen.

To the authors of all these I should like to express my indebtedness both for facts and perspective, as to Mr. H. W. Davis for his admirable summary of the mediaeval outlook in the Home University Library series; but in spite of so many authorities covering the same ground, I venture to claim for the present book a pioneer path of ‘omission’; it may be reckless but yet, I believe, justifiable.

It has been my object not so much to supply students with facts as to make Mediaeval Europe live, for the many who, knowing nothing of her history, would like to know a little, in the lives of her principal heroes and villains, as well as in the tendencies of her classes, and in the beliefs and prejudices of her thinkers. This task I have found even more difficult than I had expected, for limits of space have insisted on the omission of many events and names I would have wished to include. These I have sacrificed to the hope of creating reality and arousing interest, and if I have in any way succeeded I should like to pay my thanks first of all to Mr. Henry Osborn Taylor for his two volumes of The Mediaeval Mind that have been my chief inspiration, and then to the many authors whose names and books I give elsewhere, and whose researches have enabled me to tell my tale.

IERNE L. PLUNKET.

| I. | The Greatness of Rome | 1 |

| II. | The Decline of Rome | 9 |

| III. | The Dawn of Christianity | 21 |

| IV. | Constantine the Great | 27 |

| V. | The Invasions of the Barbarians | 37 |

| VI. | The Rise of the Franks | 54 |

| VII. | Mahomet | 66 |

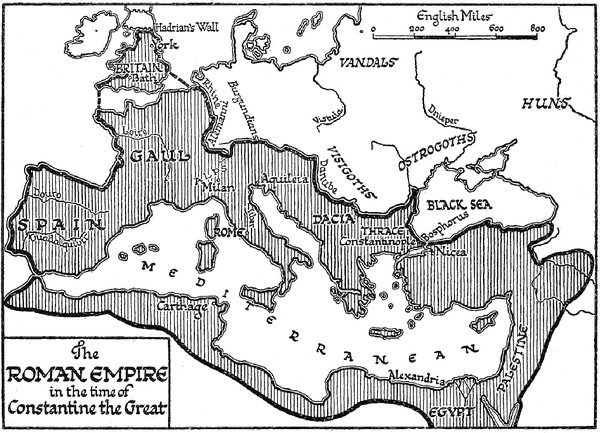

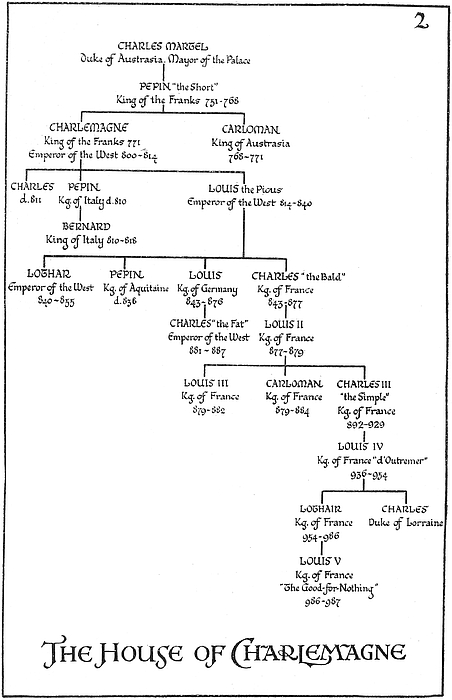

| VIII. | Charlemagne | 79 |

| IX. | The Invasions of the Northmen | 101 |

| X. | Feudalism and Monasticism | 117 |

| XI. | The Investiture Question | 130 |

| XII. | The Early Crusades | 143 |

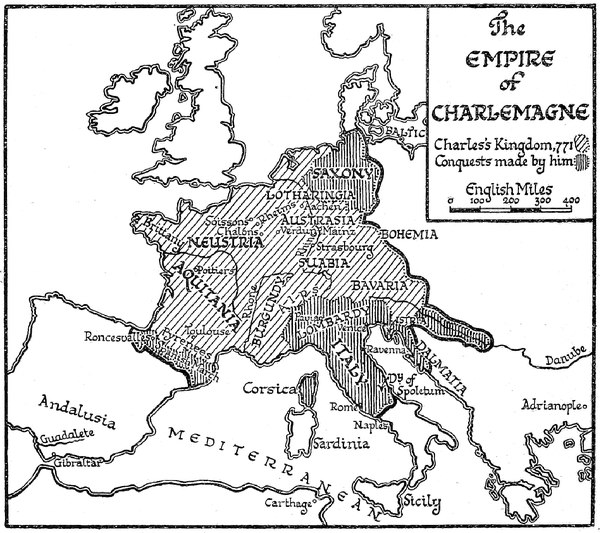

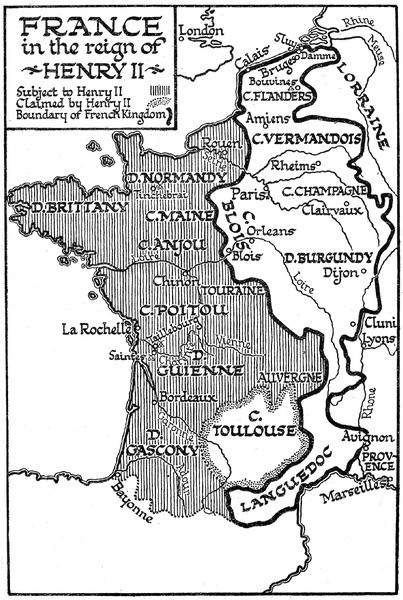

| XIII. | The Making of France | 159 |

| XIV. | Empire and Papacy | 176 |

| XV. | Learning and Ecclesiastical Organization in the Middle Ages | 196 |

| XVI. | The Faith of the Middle Ages | 207 |

| XVII. | France under Two Strong Kings | 223 |

| XVIII. | The Hundred Years’ War | 236 |

| XIX. | Spain in the Middle Ages | 259 |

| XX. | Central and Northern Europe in the Later Middle Ages | 276vii |

| XXI. | Italy in the Later Middle Ages | 297 |

| XXII. | Part I: The Fall of the Greek Empire | 327 |

| Part II: Voyage and Discovery | 337 | |

| XXIII. | The Renaissance | 346 |

| Some Authorities on Mediaeval History | 365 | |

| Chronological Summary, 476–1494 | 368 | |

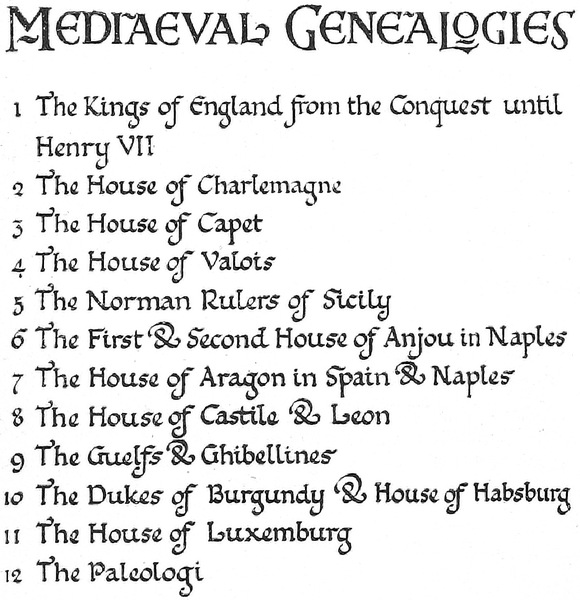

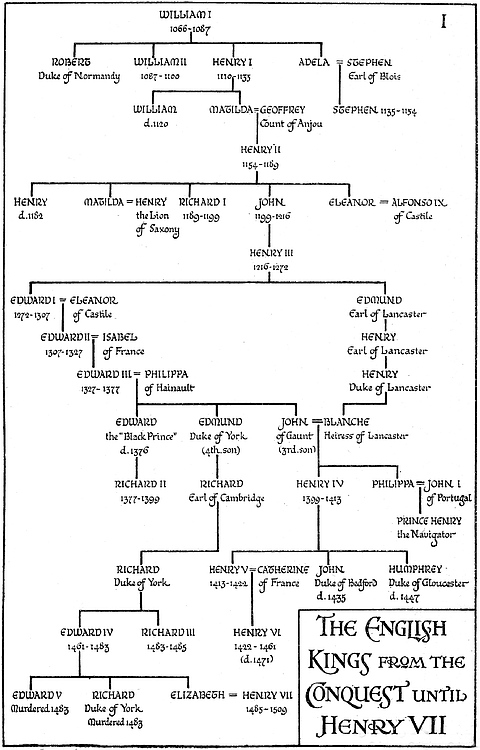

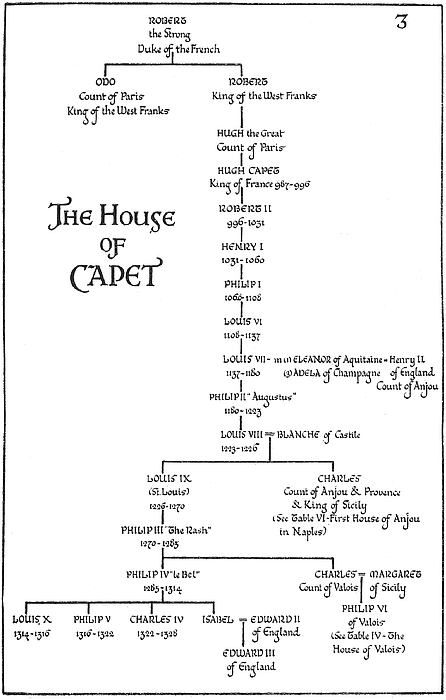

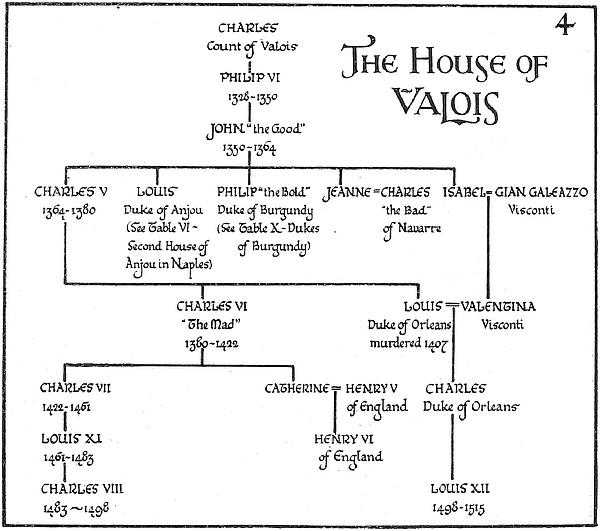

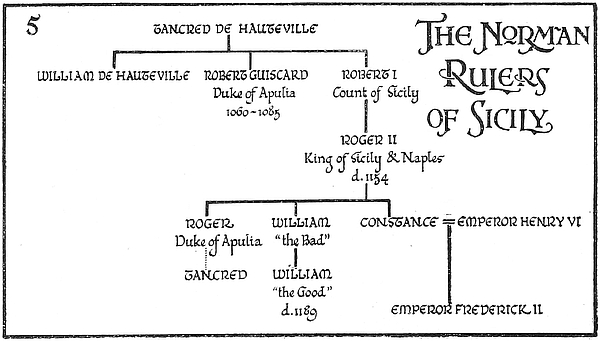

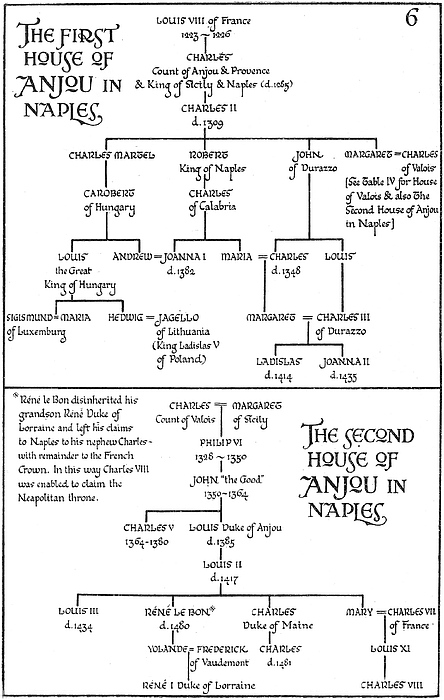

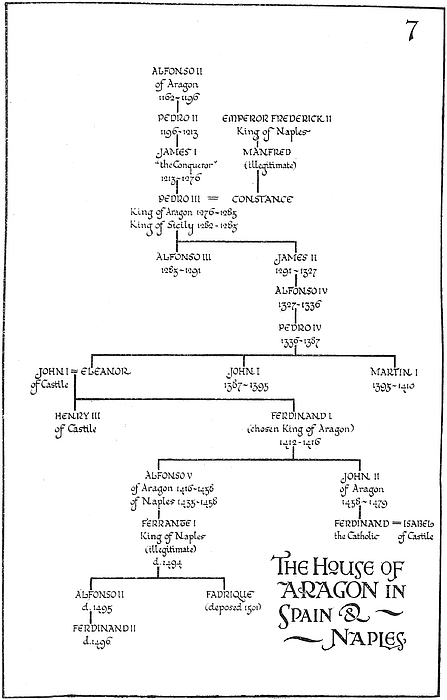

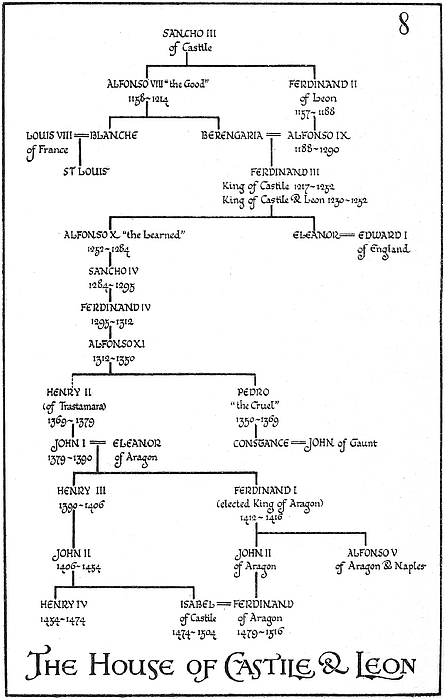

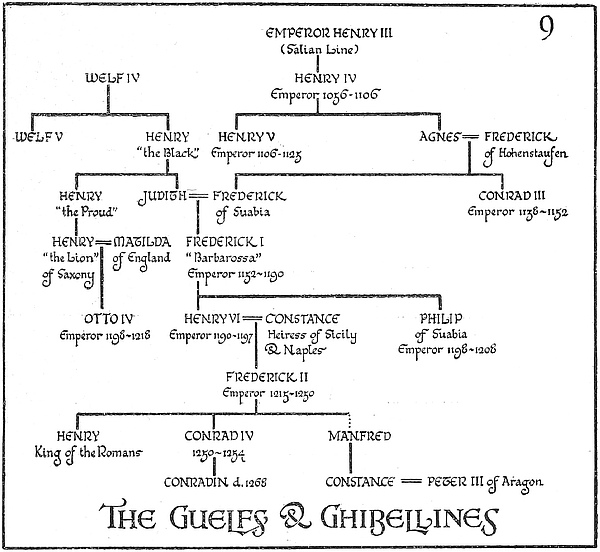

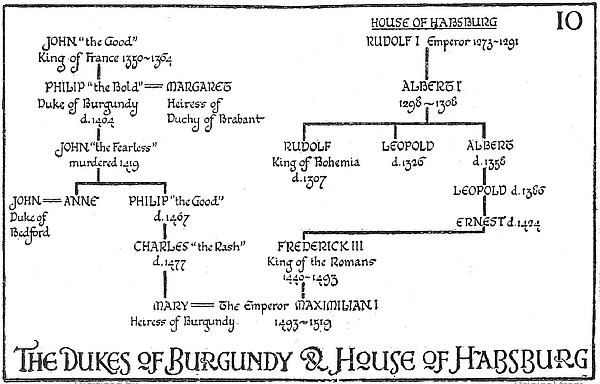

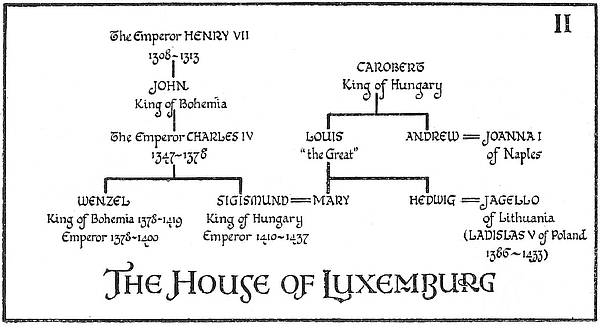

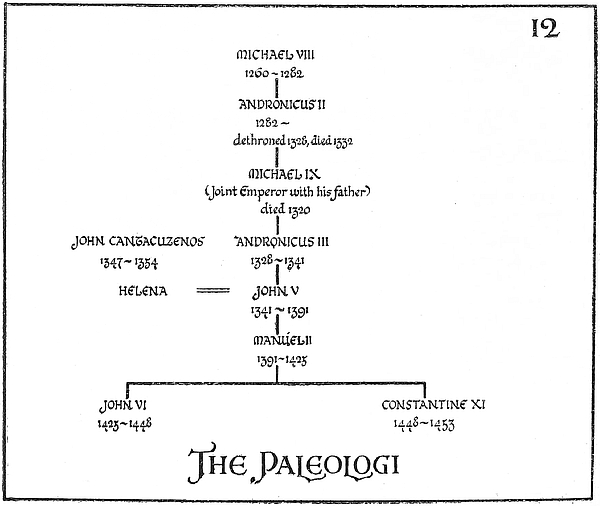

| Mediaeval Genealogies | 375 | |

| Index | 385 |

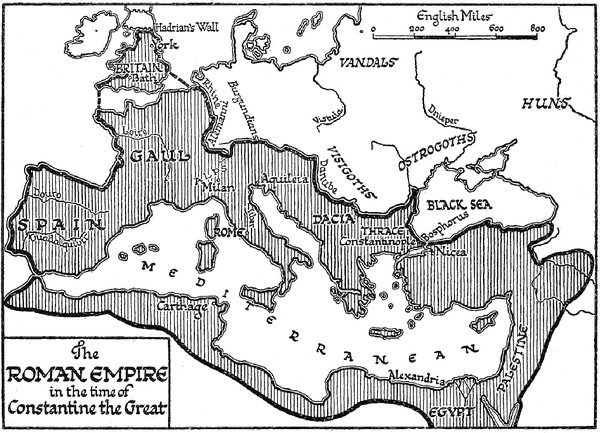

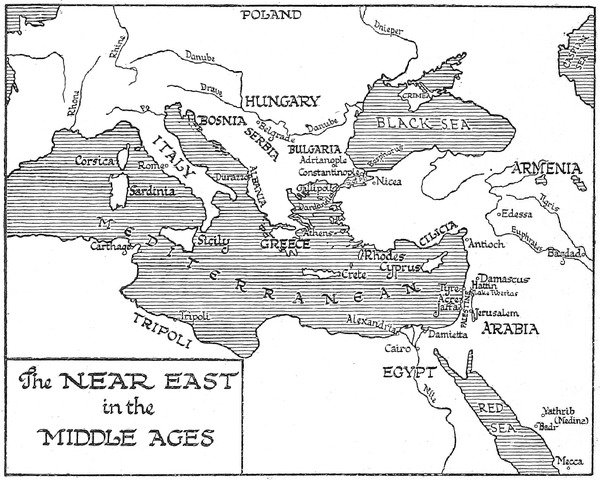

| The Roman Empire in the Time of Constantine the Great | 28 |

| The Empire of Charlemagne | 80 |

| France in the Reign of Henry II | 161 |

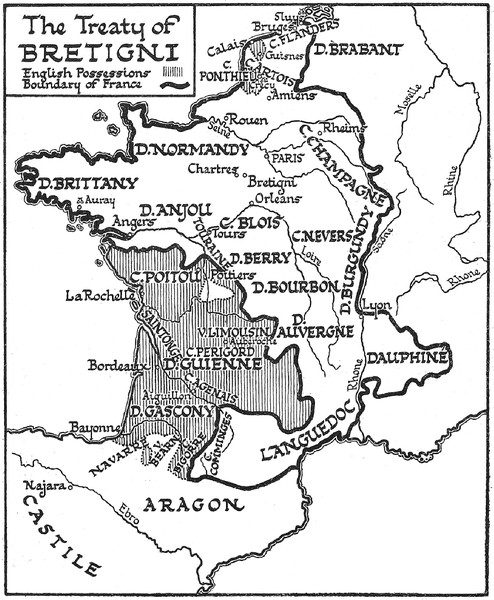

| The Treaty of Bretigni | 246 |

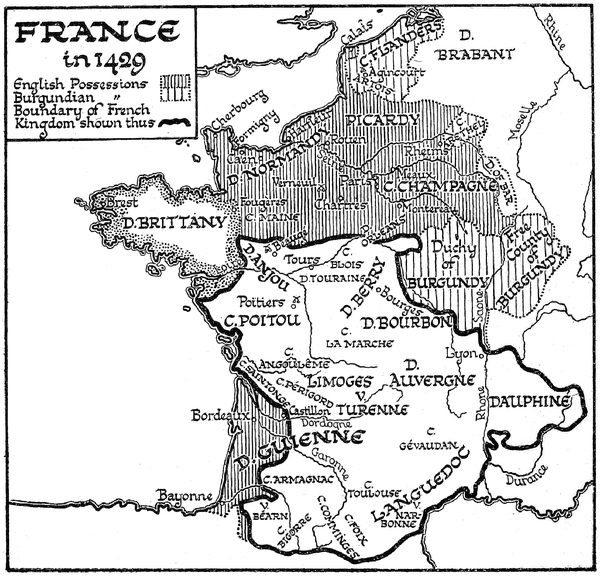

| France in 1429 | 254 |

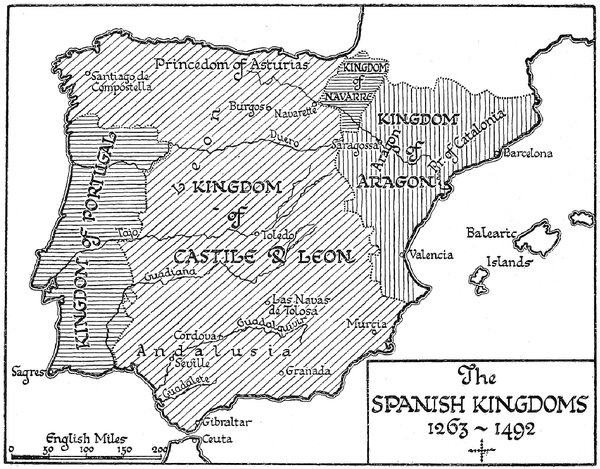

| The Spanish Kingdoms, 1263–1492 | 260 |

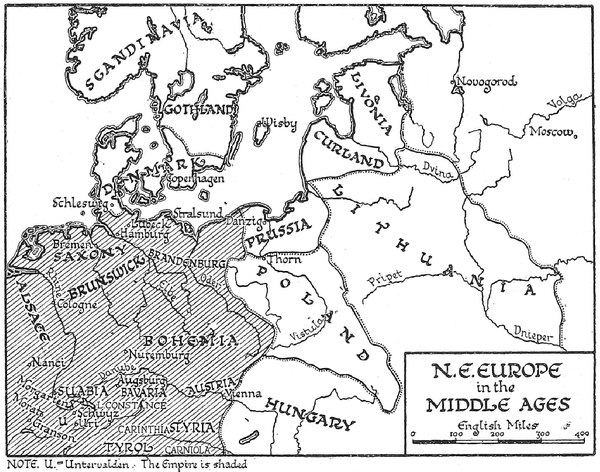

| North-East Europe in the Middle Ages | 287 |

| Italy in the Later Middle Ages | 298 |

| The Near East in the Middle Ages | 328 |

‘Ave, Roma Immortalis!’, ‘Hail, Immortal Rome!’ This cry, breaking from the lips of a race that had carried the imperial eagles from the northern shores of Europe to Asia and Africa, was no mere patriotic catchword. It was the expression of a belief that, though humanity must die and personal ambitions fade away, yet Rome herself was eternal and unconquerable, and what was wrought in her name would outlast the ages.

In the modern world it is sometimes necessary to remind people of their citizenship, but the Roman never forgot the greatness of his inheritance. When St. Paul, bound with thongs and condemned to be scourged, declared, ‘I am Roman born,’ the Captain of the Guard, who had only gained his citizenship by paying a large sum of money, was afraid of the prisoner on whom he had laid hands without a trial.

To be a Roman, however apparently poor and defenceless, was to walk the earth protected by a shield that none might set aside save at great peril. Not to be a Roman, however rich and of high standing, was to pass in Roman eyes as a ‘barbarian’, a creature of altogether inferior quality and repute.

‘Be it thine, O Roman,’ says Virgil, the greatest of Latin poets, ‘to govern the nations with thy imperial rule’: and such indeed was felt by Romans to be the destiny of their race.

Stretching on the west through Spain and Gaul to the Atlantic, that vast ‘Sea of Darkness’ beyond which according to popular belief the earth dropped suddenly into nothingness, the outposts of the Empire in the east looked across the plains of Mesopotamia towards Persia and the kingdoms of central Asia. Babylon ‘the Wondrous’, Syria, and Palestine with its2 turbulent Jewish population, Egypt, the Kingdom of the Pharaohs long ere Romulus the City-builder slew his brother, Carthage, the Queen of Mediterranean commerce, all were now Roman provinces, their lustre dimmed by a glory greater than they had ever known.

The Mediterranean, once the battle-ground of rival Powers, had become an imperial lake, the high road of the grain ships that sailed perpetually from Spain and Egypt to feed the central market of the world; for Rome, like England to-day, was quite unable to satisfy her population from home cornfields. The fleets that brought the necessaries of life convoyed also shiploads of oriental luxuries, silks, jewels, and perfumes, transported from Ceylon and India in trading-sloops to the shores of the Red Sea, and thence by caravans of camels to the port of Alexandria.

Other trade routes than the Mediterranean were the vast network of roads that, like the threads of a spider’s web, kept every part of the Empire, however remote, in touch with the centre from which their common fate was spun. At intervals of six miles were ‘post-houses’, provided each with forty or more horses, that imperial messengers, speeding to or from the capital with important news, might dismount and mount again at the different stages, hastening on their way with undiminished speed.

How firm and well made were their roads we know to-day, when, after the lapse of nearly nineteen centuries of traffic, we use and praise them still. They hold in their strong foundations one secret of their maker’s greatness, that the Roman brought to his handiwork the thoroughness inspired by a vision not merely of something that should last a few years or even his lifetime, but that should endure like the city he believed eternal.

It was the boast of Augustus, 27 B.C.–A.D. 14, the first of the Roman Emperors, that he had found his capital built of brick and had left it marble; and his tradition as an architect passed to his successors. There are few parts of what was once the Roman Empire that possess no trace to-day of massive aqueduct or Forum, of public baths or stately colonnades. In Rome itself, the Colosseum, the scene of many a martyr’s death and gladiator’s3 struggle; elsewhere, as at Nîmes in southern France, a provincial amphitheatre; the aqueduct of Segovia in Spain, the baths in England that have made and named a town; the walls that mark the outposts of empire—all are the witnesses of a genius that dared to plan greatly, nor spared expense or labour in carrying out its designs.

Those who have visited the Border Country between England and Scotland know the Emperor Hadrian’s wall, twenty feet high by seven feet broad, constructed to keep out the fierce Picts and Scots from this the most northern of his possessions. Those of the enemy that scaled the top would find themselves faced by a ditch and further wall, bristling with spears; while the legions flashed their summons for reinforcements from guardhouse to guardhouse along the seventy miles of massive barrier. All that human labour could do had made the position impregnable.

A scheme of fortifications was also attempted in central Europe along the lines of the Rhine and Danube. These rivers provided the third of the imperial trade routes, and it is well to remember them in this connexion, for their importance as highways lasted right through Roman and mediaeval into modern times. Railways have altered the face of Europe: they have cut through her waste places and turned them into thriving centres of industry: they have looped up her mines and ports and tunnelled her mountains: there is hardly a corner of any land where they have not penetrated; and the change they have made is so vast that it is often difficult to imagine the world before their invention. In Roman times, in neighbourhoods where the sea was remote and road traffic slow and inconvenient, there only remained the earliest of all means of transport, the rivers. The Rhine and Danube, one flowing north-west, the other south-east, both neither too swift nor too sluggish for navigation, were the natural main high roads of central Europe: they were also an obvious barrier between the Empire and barbarian tribes.

To connect the Rhine and Danube at their sources by a massive wall, to establish forts with strong garrisons at every point where these rivers could be easily forded, such were the precautions by which wise Emperors planned to shut in Rome’s4 civilization, and to keep out all who would lay violent hands upon it.

The Emperor Augustus left a warning to his successors that they should be content with these natural boundaries, lest in pushing forward to increase their territory they should in reality weaken their position. It is easy to agree with his views centuries afterwards, when we know that the defences of the Empire, pushed ever forward, snapped at the finish like an elastic band; but the average Roman of imperial days believed his nation equal to any strain.

It was a boast of the army that ‘Roman banners never retreat’. If then a tribe of barbarians were to succeed in fording the Danube and in surprising some outpost fort, the legions sent to punish them would clamour not merely to exact vengeance and return home, but to conquer and add the territory to the Empire. In the case of swamps or forest land the clamour might be checked; but where there was pasturage or good agricultural soil, it would be almost irresistible. Emigrants from crowded Italy would demand leave to form a colony, traders would hasten in their footsteps, and soon another responsibility of land and lives, perhaps with no natural protection of river, sea, or mountains, would be added to Rome’s burden of government. Such was the fertile province of Dacia, north of the Danube, a notable gain in territory, but yet a future source of weakness.

At the head of the Empire stood the Emperor, ‘Caesar Augustus’, the commander-in-chief of the army, the supreme authority in the state, the fountain of justice, a god before whose altar every loyal Roman must burn incense and bow the knee in reverence.

It was a great change from the old days, when Rome was a republic, and her Senate, or council of leading citizens, had been responsible to the rest of the people for their good or bad government. The historian Tacitus, looking back from imperial days with a sigh of regret, says that in that happy age man could speak what was in his mind without fear of his neighbours, and draws the contrast with his own time when the Emperor’s spies wormed their way into house and tavern, paid to betray5 those about them to prison or death for some chance word or incautious action. Yet Rome by her conquests had brought on herself the tyranny of the Empire.

It is comparatively easy to rule a small city well, where fraud and self-seeking can be quickly detected; but when Rome began to extend her boundaries and to employ more people in the work of government, unscrupulous politicians appeared. These built up private fortunes during their term of office: they became senators, and the Senate ceased to represent the will of the people and began to govern in the interests of a small group of wealthy men. Members of their families became governors of provinces, first in Italy, and then as conquests continued, across the mountains in Gaul and Spain, and beyond the seas in Egypt and Asia Minor. Except in name, senators and governors ceased to be simple citizens and lived as princes, with officials and servants ready to carry out their slightest wish.

Perhaps it may seem odd that the Roman people, once so fond of liberty that they had driven into exile the kings who oppressed them, should afterwards let themselves be bullied or neglected by a hundred petty tyrants; but in truth the people had changed even more than the class of ‘patricians’ to whom they found themselves in bondage.

No longer pure Roman or Latin, but through conquest and intermarriage of every race from the stalwart Teuton to the supple Oriental or swarthy Egyptian, few amongst the men and women crowding the streets of Rome remembered or reverenced the traditions of her early days. Rome stood for military glory, luxury, culture, at her best for even-handed justice, but no longer for an ideal of liberty. If national pride was satisfied, and adequate food and amusement provided, the Roman populace was content to be ruled from above and to hail rival senators as masters, according to the extent of their promises and success. A failure to fulfil such promises, resulting in a lost campaign or a dearth of corn, would throw the military tyrant of the moment from his pedestal, but only to set up another in his place.

It was an easy transition from the rule of a corrupt Senate to6 that of an autocrat. ‘Better one tyrant than many’ was the attitude of mind of the average citizen towards Octavius Caesar, when under the title of Augustus he gathered to himself the supreme command over army and state and so became the first of the Emperors. Had he been a tactless man and shouted his triumph to the Seven Hills he would probably have fallen a victim to an assassin’s knife; but he skilfully disguised his authority and posed as being only the first magistrate of the state.

Under his guiding hand the Senate was reformed, and its outward dignity rather increased than shorn. Augustus could issue his own ‘edicts’ or commands independently of the Senate’s consent; but he more frequently preferred to lay his measures before it, and to let them reach the public as a senatorial decree. In this he ran no risk, for the senators, impressive figures in the eyes of the ordinary citizen, were really puppets of his creation. At any minute he could cast them away.

His fellow magistrates were equally at his mercy, for in his hands alone rested the supreme military command, the imperium, from which the title of imperator, or ‘emperor’, was derived. At first he accepted the office only for ten years, but at the end of that time, resigning it to a submissive Senate, he received it again amid shouts of popular joy. The tyranny of Augustus had proved a blessing.

Instead of corps of troops raised here and there in different provinces by governors at war with one another, and thus divided in their allegiance, there had begun to develop a disciplined army, whose ‘legions’ were enrolled, paid, and dismissed in the name of the all-powerful Caesar, and who therefore obeyed his commands rather than those of their immediate captains.

The same system of centring all authority in one absolute ruler was followed in the civil government. Governors of provinces, once petty rulers, became merely servants of the state. Caesar sent them from Rome: he appointed the officials under them: he paid them their salaries: and to him they must give an7 account of their stewardship. ‘If thou let this man go thou art not Caesar’s friend.’ Such was the threat that induced Pontius Pilate, Governor of Judea in the reign of Tiberius, to condemn to death a man he knew to be innocent of crime.

This is but one of many stories that show the dread of the Emperor’s name in Rome’s far-distant provinces. Governors, military commanders, judges, tax-collectors, all the vast army of officials who bore the responsibility of government on their shoulders, had an ultimate appeal from their decisions to Caesar, and were exalted by his smile or trembled at his frown.

It is not a modern notion of good government, this complete power vested in one man, but Rome nearly two thousand years ago was content that a master should rule her, so long as he would guarantee prosperity and peace at home. This under the early Caesars was at least secured.

Two fleets patrolled the Mediterranean, but their vigilance was not needed, save for an occasional brush with pirates. Naught but storms disturbed her waters. The legions on the frontiers, whether in Syria or Egypt, or along the Rhine and Danube, kept the barbarians at bay until Romans ceased to think of war as a trade to which every man might one day be called. It was a profession left to the few, the ‘many’ content to pay the taxes required by the state and to devote themselves to a civilian’s life.

To one would fall the management of a large estate, another would stand for election to a government office, a third would become a lawyer or a judge. Others would keep shops or taverns or work as hired labourers, while below these again would be the class of slaves, whether prisoners of war sold in the market-place or citizens deprived of their freedom for crime or debt.

In Rome itself was a large population, living in uncomfortable lodging-houses very like the slum tenements of a modern city. Some of the inhabitants would be engaged in casual labour, some idle; but when the Empire was at its zenith lavish gifts of corn from the government stood between this otherwise destitute population and starvation. It crowded the streets to see Caesar pass, threw flowers on his chariot, and hailed him8 as Emperor and God, and in return he bestowed on it food and amusements.

The huge amphitheatres of Rome and her provinces were built to satisfy the public desire for pageantry and sport; and, because life was held cheap, and for all his boasted civilization the Roman was often a savage at heart, he would spend his holidays watching the despised sect of Christians thrown to the lions, or hired gladiators fall in mortal struggle. ‘We, about to die, salute thee.’ With these words the victims of an emperor’s lust of bloodshed bent the knee before the imperial throne, and at Caesar’s nod passed to slay or be slain. The emperor’s sceptre did not bring mercy, but order, justice, and prosperity above the ordinary standard of the age.

The years of Rome’s greatness seemed to her sons an age of gold, but even at the height of her prosperity there were traces of the evils that brought about her downfall. An autocracy, that is, the rule of one man, might be a perfect form of government were the autocrat not a man but a god, thus combining superhuman goodness and understanding with absolute power. Unfortunately, Roman emperors were representatives of human nature in all its phases. Some, like Augustus, were great rulers; others, though good men, incompetent in the management of public affairs; whilst not a few led evil lives and regarded their office as a means of gratifying their own desires.

The Emperor Nero (54–68), for instance, was cruel and profligate, guilty of the murder of his half-brother, mother, and wife, and also of the deaths of numberless senators and citizens whose wealth he coveted. Because he was an absolute ruler his corrupt officials were able to bribe and oppress his subjects as they wished until he was fortunately assassinated. He was the last of his line, the famous House of Julius to which Augustus had belonged, and the period that followed his death was known as ‘the year of the four Emperors’, because during that time no less than four rivals claimed and struggled for the coveted honour.

Nominally, the right of election lay with the Senate, but the final champion, Vespasian (69–79), was not even a Roman nor an aristocrat, but a soldier from the provinces. He had climbed the ladder of fame by sheer endurance and his power of managing others, and his accession was a triumph not for the Senate but the legions who had supported him and who now learned their10 power. Henceforward it would be the soldier with his naked sword who could make and unmake emperors, and especially the Praetorian Guard whose right it was to maintain order in Rome.

The gradual recognition of this idea had a disastrous effect on the government of the Empire. Too often the successful general of a campaign on the frontier would remember Vespasian and become obsessed with the thought that he also might be a Caesar. Led by ambition he would hold out to his legions hopes of the rewards they would receive were he crowned in Rome, and some sort of bargain would be struck, lowering the tone of the army by corrupting its loyalty and making its soldiers insolent and grasping.

The Senate attempted to deal with this difficulty of the succession by passing a law that every Emperor should, during his lifetime, name his successor, and that the latter should at once be hailed as Caesar, take a secondary share in the government, and have his effigy printed on coins. In this way he would become known to the whole Roman world, and when the Emperor died would at once be acknowledged in his place. Thus the Romans hoped to establish the theory that England expresses to-day in the phrase ‘The King never dies’.

Though to a certain extent successful in their efforts to avoid civil war, they failed to arrest other evils that were undermining the prosperity of the government. One of these was the imperial expenditure. It was only natural that the Emperor should assume a magnificence and liberality in excess of his wealthiest subjects, but in addition he found it necessary to buy the allegiance of the Praetorian Guard and to keep the Roman populace satisfied in its demands for free corn and expensive amusements.

The standard of luxury had grown, and Romans no longer admired, except in books, the simple life of their forefathers. Instead the fashionable ideal was that of the East they had enslaved, and the Emperor was gradually shut off from the mass of his subjects by a host of court officials who thronged his antechambers and exacted heavy bribes for admission. In this unhealthy atmosphere suspicion and plots grew apace like weeds,11 and money dripped through the imperial fingers as through a sieve, now into the pockets of one favourite, now of another.

‘I have lost a day,’ was said by the Emperor Titus (A.D. 79–81), whenever twenty-four hours had passed without his having made some valuable present to those about him. His courtiers were ready to fall on their knees and hail him for his liberality as ‘Darling of the human race’; but he only reigned for two years. Had he lived to exhaust his treasury it is probable that the greedy throng would have passed a different verdict.

Extravagance is as catching as the plague, and the Roman aristocracy did not fail to copy the imperial example. Just as the Emperor was surrounded by a court, so every noble of importance had his following of ‘clients’ who would wait submissively on his doorstep in the morning and attend him when he walked abroad to the Forum or the Public Baths. Some would be idle gentlemen, the penniless younger sons of noble houses, others professional poets ready to write flattering verses to order, others again famous gladiators whose long death-roll of victims had made them as popular in Rome as a champion tennis-player or footballer in England to-day. All were united in the one hope of gaining something from their patron, perhaps a gift of money, or his influence to secure them a coveted office, at the least an invitation to a banquet or feast.

The class of senators to which most of these aristocrats belonged had grown steadily richer as the years of empire increased, building up immense landed properties something like the feudal estates of a later date. These ‘villas’, as they were called, were miniature kingdoms over which their owners had secured absolute power. Their affairs were administered by an agent, probably a favoured slave who had gained his freedom, assisted by a small army of officials. The principal subjects of the landlord would be the small proprietors of farms who paid a rent or did various services in return for their houses, while below these again would be a larger number of actual slaves, employed as household servants, bakers, shoe-makers, shepherds, &c.

The most striking thing about the Roman ‘villa’ was that it was absolutely self-contained. All that was needed for the life12 of its inhabitants, whether food or clothing, could be grown and manufactured on the estate. The crimes that were committed there would be judged by the master or his agent, and from the former’s decision there would be little hope of appeal. Where the proprietor was harsh or selfish, miserable indeed was the condition of those condemned to live on his ‘villa’.

The income of the average senator in the fourth century A.D. was about £60,000, a very large sum when money was not as plentiful as it is to-day. Aurelius Symmachus, a young senator typical of this time, possessed no less than fifteen country seats, besides large estates in different parts of Italy and three town houses in Rome or her suburbs. It was his object to become Praetor of Rome, one of the highest offices in the city; and in order to gain popularity he and his father organized public games that cost them some £90,000. Lions and crocodiles were fetched from Africa, dogs from Scotland, a special breed of horses from Spain; while captured warriors were brought from Germany, whom he destined to fight with one another in the arena.

The life of this young senator, according to his letters, was controlled by purely selfish considerations. He did not want the praetorship in order to be of use to the Empire, but merely that the Empire might crown his career with a coveted honour. The same narrow outlook and lack of public spirit was common to the majority of the other men and women of his class, and so great was their blindness that they could not even see that they were undermining Rome’s power, far less avail to save her.

More fatal even than the corruption of the aristocracy was the decline of the middle classes, usually called the backbone of a nation’s greatness. ‘The name of Roman citizen,’ says a native of Marseilles in the fifth century, ‘formerly so highly valued and even bought with a great price, is now ... shunned, nay it is regarded with abomination.’

This change from the days of St. Paul may be traced back long before the time when Symmachus wasted his patrimony in bringing crocodiles from Africa and horses from Spain. Its cause was the gradual but constant increase of taxation required to13 fill the imperial treasury, and the unequal scale according to which such taxation was levied.

Rome’s main source of revenue was an impost on land, and ought by rights to have been exacted from the senatorial class that owned the majority of the large estates. Unfortunately, it was left to the local municipal councils, the curias, to collect this tax, and if it fell short of the amount required from the locality by the imperial treasury, the curiales, or class compelled as a duty to attend the councils, were held responsible for the deficit.

Here was a problem for Roman citizens of medium wealth, members of their curia by birth, quite unable to divest themselves of this more than doubtful honour, and conscious that their sons at eighteen must also accept the dignity and put their shoulders to the burden. It was one thing to assess the chief landlords of the neighbourhood at a sum that matched their revenues, it was another to obtain the money from them. In England to-day the man who refuses to pay his taxes is punished; in imperial Rome it was the tax-collector.

Possessed of money and influence, it was not hard for a senator to outwit mere curiales, either by obtaining an exemption from the Emperor, or by bribing the occasional inspectors sent by the central government to condone his refusal to pay. The imperial court set an example of corruption, and those who could imitate this example did so.

The curiales, faced by ruin, sought relief in various ways. Those with most wealth tried to raise themselves to senatorial rank: others, unable to achieve this, yet conscious that they must obtain the money required at all costs, demanded the heaviest taxes from those who could not resist them, so that the phrase spread abroad, ‘So many curiales just so many robbers.’

Less important members of the middle classes, unable to pay their share of taxation or to force others to do so instead, tried in every way to divest themselves of an honour grown intolerable, and the legislation of the later Empire shows their efforts to escape out of the net in which the government tried to hold them enmeshed. Some sought the protection of the nearest landowners,14 and joined the dependants of their ‘villas’: others, though forbidden by law, entered the army: while others again sold themselves into slavery, since a master’s self-interest would at least secure them food and clothing.

More desperate and adventurous spirits saw in brigandage a means both of livelihood and of revenge. Joining themselves to bands of criminals and escaped slaves, they infested the high roads, waylaid and robbed travellers, and carried off their spoils to mountain fastnesses. Thus, through fraud or violence, the ranks of the curiales diminished, and taxation fell with still heavier pressure on those who remained to support its burdens.

This evil state of affairs was intensified by the widespread system of slavery that, besides its bad influence on the character of both master and slave, had other economic defects. When forced labour and free work side by side, the former will nearly always drive the latter out of the market, because it can be provided more cheaply. A master need not pay his slaves wages; he can make them work as many hours as he chooses, and lodge and feed them just as he pleases. From his point of view it is more convenient to employ men who cannot leave his service however much they dislike the work and conditions. For these reasons business and trade tended to fall into the hands of wealthy slave-owners who could undersell the employers of free labour, and as the number of slaves increased the number of free workmen grew less.

In Rome, and the large towns also, free labourers who remained were corrupted like men and women of a higher rank by the general extravagance and love of pleasure. They did not agitate so much for a reform of taxation or the abolition of slavery, but for larger supplies of free corn and more frequent public games and spectacles.

An extravagant court, a corrupt government, slavery, class selfishness, these were some of the principal causes of Rome’s decline; but in recording them it must be remembered that the taint was only gradual, like some corroding acid eating away good metal. Not all curiales, in spite of popular assertions, were robbers, not every taxpayer on the verge of starvation,15 not every dependant of a ‘villa’ cowed and miserable. In many houses masters would free or help their slaves, slaves be found ready to die for their masters. The canker lay in the indifference of individual Roman citizens to evils that did not touch them personally, in the refusal to cure with radical reform even those that did, in the foolish confidence of the majority in the glory of the past as a safeguard for the present. ‘Faith in Rome killed all faith in a wider future for humanity.’

This lack of vision has ruined many an empire and kingdom, and Rome only half-opened her eyes even when the despised barbarians who were to expose her weakness were already knocking at the imperial gates.

‘Barbarian’, we have noticed, was the epithet used by the Roman of the early Empire to describe and condemn the person not fortunate enough to share his citizenship.

At this time the most formidable of the barbarians were the German tribes who inhabited large stretches of forest and mountain land to the north of the Danube and east of the Rhine—a tall, powerfully built race for the most part with ruddy hair and fierce blue eyes, whose business was warfare, and the occupation of their leisure hours the chase or gambling.

In his book, the Germania, Tacitus, a famous Roman historian of the first century, describes these Teutons, and besides drawing attention to their primitive customs and lack of culture, he made copy of their simplicity to lash the vices of his own countrymen.

The Germans, he said, did not live in walled towns but in straggling villages standing amid fields. These were either shared as common pasturage or tilled in allotments, parcelled out annually amongst the inhabitants. A number of villages would form a pagus or canton, a number of pagi a civitas or state. At the head of the state was more usually a king, but sometimes only a number of important chiefs, or dukes, who would be treated with the utmost reverence.

It was their place to preside over the small councils that dealt with the less important affairs of the state, and to lay before the16 larger meeting of the tribe measures that seemed to require public discussion. Lying round their camp fire in the moonlight the younger men would listen to the advice of the more experienced and clash their weapons as a sign of approval when some suggestion pleased them.

At the councils were chosen the principes, or magistrates, whose duty it was to administer justice in the various cantons and villages. Tribal law was very primitive in comparison with the Roman code that required highly trained lawyers to interpret it. Had a man betrayed his fellow villagers to their enemies, let him be hung from the nearest tree that all might learn the fitting reward of treachery. Had he turned coward and fled from the battle, let him be buried in a morass out of sight beneath a hurdle, that such shame should be quickly forgotten. Had he in a rage or by accident slain or injured a neighbour, let him pay a fine in compensation, half to his victim’s nearest relations, half to the state. If the decision did not satisfy those concerned, the family of the injured person could itself exact vengeance, but since it would probably meet with opposition in so doing, more bloodshed would almost certainly result, and a feud, like the later Corsican vendetta, be handed down from generation to generation.

Such a state of unrest had no horror for the German tribesman. From his earliest days he looked forward to the moment when, receiving from his kinsmen the gift of a shield and sword, he might leave boyhood behind him and assume a man’s responsibilities and dangers. With his comrades he would at once hasten to offer his services to some great leader of his tribe, and as a member of the latter’s comitatus, or following, go joyfully out to battle.

Like the Spartan of old he went with the cry ringing in his ears, ‘With your shield or on your shield!’

‘It is a disgrace’, says Tacitus, ‘for the chief to be surpassed in battle ... and it is an infamy and a reproach for life to have survived the chief and returned from the field.’

This statement explains the reckless daring with which the scattered groups of Germans would fling themselves time after17 time against the disciplined Roman phalanxes. The women shared the hardihood of the race, bringing and receiving as wedding-gifts not ornaments or beautiful clothes but a warrior’s horse, a lance, or sword.

‘Lest a woman should think herself to stand apart from aspirations after noble deeds and from the perils of war, she is reminded by the ceremony that inaugurates marriage that she is her husband’s partner in toil and danger, destined to suffer and die with him alike both in peace and war.’

Chaste, industrious, devoted to the interests of husband and children, yet so patriotic that, watching the battle, she would urge them rather to perish than retreat, the barbarian woman struck Tacitus as a living reproach to the many faithless, idle, pleasure-seeking wives and mothers of Rome in his own day. The German tribes might be uncouth, their armies without discipline, even their nobles ignorant of culture, but they were brave, hospitable, and loyal. Above all they held a distinction between right and wrong: they did not ‘laugh at vice’.

It is probable that in the days of Tacitus his views were received throughout the Roman Empire with an amused shrug of the shoulders, for to many the Germans were merely good fighters, whose giant build added considerably to the glory of a triumphal procession, when they walked sullenly in their shackles behind the Victor’s car. With the passing of the years into centuries, however, intercourse changed this attitude, and much of the contempt on one side and hatred on the other vanished.

Germans captured in childhood were brought up in Roman households and grew invaluable to their masters: numbers were freed and remained as citizens in the land of their captivity. The tribes along the borders became more civilized: they exchanged raw produce or furs in the nearest Roman markets for luxuries and comforts, and as their hatred of Rome disappeared admiration took its place. Something of the greatness of the Empire touched their imagination: they realized for the first time the possibilities of peace under an ordered government; and whole tribes offered their allegiance to a power that knew not only how to conquer but to rule.

18 Emperors, nothing loath, gathered these new forces under their standards as auxiliaries or allies (foederati), and Franks from Flanders, at the imperial bidding, drove back fellow barbarians from the left bank of the Rhine; while fair-haired Alemanni and Saxons fell in Caesar’s service on the plains of Mesopotamia or on the arid sands of Africa. From auxiliary forces to the ranks of the regular army was an easy stage, the more so as the Roman legions were every year in greater need of recruits as the boundaries of the Empire spread.

It is at first sight surprising to find that the military profession was unpopular when we recall that it rested in the hands of the legions to make or dispossess their rulers; but such opportunities of acquiring bribes and plunder did not often fall to the lot of the ordinary soldier, while the disadvantages of his career were many.

A very small proportion of the army was kept in the large towns of the south, save in Rome that had its own Praetorian Guards: the majority of the legions defended the Rhine and Danube frontiers, or still worse were quartered in cold and foggy Britain, shut up in fortress outposts like York or Chester. English regiments to-day think little of service in far-distant countries like Egypt or India, indeed men are often glad to have the experience of seeing other lands; but the Roman soldier as he said farewell to his Italian village knew in his heart that it had practically passed out of his life. The shortest period of military service was sixteen years, the longest twenty-five; and when we remember that, owing to the slow and difficult means of transport, leave was impossible we see the Roman legionary was little more than the serf of his government, bound to spend all the best years of his life defending less warlike countrymen.

Moving with his family from outpost to outpost, the memories of his old home would grow blurred, and the legion to which he belonged would occupy the chief place in his thoughts. As he grew older his sons, bred in the atmosphere of war, would enlist in their turn, and so the military profession would tend to become a caste, handed down from father to son.

19 The soldier could have little sympathy with fellow citizens whose interests he did not share, but would despise them because they did not know how to use arms. The civilians, on their side, would think the soldier rough and ignorant, and forget how much they were dependent on his protection for their trade and pleasure. Instead of trying to bridge this gulf, the government, in their terror of losing taxpayers, widened it by refusing to let curiales enlist. At the same time they filled up the gaps in the legions with corps of Franks, Germans, or Goths; because they were good fighting material, and others of their tribe had proved brave and loyal.

In the same way, when land in Italy fell out of cultivation, the Emperor would send numbers of barbarians as coloni or settlers to till the fields and build themselves homes. At first they might be looked on with suspicion by their neighbours, but gradually they would intermarry and their sons adopt Roman habits, until in time their descendants would sit in municipal councils, and even rise to become Praetors or Consuls.

When it is said that the Roman Empire fell because of the inroads of barbarians, the impression sometimes left on people’s minds is that hordes of uncivilized tribes, filled with contempt for Rome’s luxury and corruption, suddenly swept across the Alps in the fifth century, laying waste the whole of North Italy. This is far from the truth. The peaceful invasion of the Empire by barbarians, whether as slaves, traders, soldiers, or colonists, was a continuous movement from early imperial days. There is no doubt that, as it increased, it weakened the Roman power of resistance to the actually hostile raids along the frontiers that began in the second and third centuries and culminated in the collapse of the imperial government in the West in the fifth. An army partly composed of half-civilized barbarian troops could not prove so trustworthy as the well-disciplined and seasoned Romans of an earlier age; for the foreign element was liable in some gust of passion to join forces with those of its own blood against its oath of allegiance.

As to the main cause of the raids, it was rather love of Rome’s wealth than a sturdy contempt of luxury that led these barbarians20 to assault the dreaded legions. Had it been mere love of fighting, the Alemanni would as soon have slain their Saxon neighbours as the imperial troops; but nowhere save in Spain, or southern Gaul, or on the plains of Italy could they hope to find opulent cities or herds of cattle. Plunder was their earliest rallying cry; but in the third century the pressure of other tribes on their flank forced them to redouble in self-defence efforts begun for very different reasons.

This movement of the barbarians has been called ‘the Wandering of the Nations’. Gradually but surely, like a stream released from some mountain cavern, Goths from the North and Huns and Vandals from the East descended in irresistible numbers on southern Germany, driving the tribes who were already in possession there up against the barriers, first of the Danube and then of the Alps and Rhine.

Italy and Gaul ceased to be merely a paradise for looters, but were sought by barbarians, who had learned something of Rome’s civilization, as a refuge from other barbarians who trod women and children underfoot, leaving a track wherever their cruel hordes passed red with blood and fire. With their coming, Europe passed from the brightness of Rome into the ‘Dark Ages’.

When Augustus became Emperor of Rome, Jesus Christ was not yet born. With the exception of the Jews, who believed in the one Almighty ‘Jehovah’, most of the races within the boundaries of the Empire worshipped a number of gods; and these, according to popular tales, were no better than the men and women who burned incense at their altars, but differed from them only in being immortal, and because they could yield to their passions and desires with greater success.

The Roman god ‘Juppiter’, who was the same as the Greek ‘Zeus’, was often described as ‘King of gods and men’; but far from proving himself an impartial judge and ruler, the legends in which he appears show him cruel, faithless, and revengeful. ‘Juno’, the Greek ‘Hera’, ‘Queen of Heaven’, was jealous and implacable in her wrath, as the ‘much-enduring’ hero, Ulysses, found when time after time her spite drove him from his homeward course from Troy. ‘Mercury’, the messenger of the gods, was merely a cunning thief.

Most of the thoughtful Greeks and Romans, it is true, came to regard the old mythology as a series of tales invented by their primitive ancestors to explain mysterious facts of nature like fire, thunder, earthquakes. Because, however, this form of worship had played so great a part in national history, patriotism dictated that it should not be forgotten entirely; and therefore emperors were raised to the number of the gods; and citizens of Rome, whether they believed in their hearts or no, continued to burn incense before the altars of Juppiter, Juno, or Augustus in token of their loyalty to the Empire.

The human race has found it almost impossible to believe in22 nothing, for man is always seeking theories to explain his higher nature and why it is he recognizes so early the difference between right and wrong. Far back in the third and fourth centuries before Christ, Greek philosophers had discussed the problem of the human soul, and some of them had laid down rules for leading the best life possible.

Epicurus taught that since our present life is the only one, man must make it his object to gain the greatest amount of pleasure that he can. Of course this doctrine gave an opening to people who wished to live only for themselves; but Epicurus himself had been simple, almost ascetic in his habits, and had clearly stated that although pleasure was his object, yet ‘we can not live pleasantly without living wisely, nobly, and righteously’. The self-indulgent man will defeat his own ends by ruining his health and character until he closes his days not in pleasure but in misery.

Another Greek philosopher was Zeno, whose followers were called ‘Stoics’ from the stoa or porch of the house in Athens in which he taught his first disciples. Zeno believed that man’s fortune was settled by destiny, and that he could only find true happiness by hardening himself until he grew indifferent to his fate. Death, pain, loss of friends, defeated ambitions, all these the Stoic must face without yielding to fear, grief, or passion. Brutus, the leader of the conspirators who slew Julius Caesar, was a Stoic, and Shakespeare in his tragedy shows the self-control that Brutus exerted when he learned that his wife Portia whom he loved had killed herself.

The teaching of Epicurus and Zeno did something during the Roman Empire to provide ideals after which men could strive, but neither could hold out hopes of a happiness without end or blemish. The ‘Hades’ of the old mythology was no heaven but a world of shades beyond the river Styx, gloomy alike for good and bad. At the gates stood the three-headed monster Cerberus, ready to prevent souls from escaping once more to light and sunshine.

Paganism was thus a sad religion for all who thought of the future: and this is one of the reasons why the tidings of23 Christianity were received so joyfully. When St. Paul went to Athens he found an altar set up to ‘the unknown God’, showing that men and women were out of sympathy with their old beliefs and seeking an answer to their doubts and questions. He tried to tell the Greeks that the Christ he preached was the God they sought; but those who heard him ridiculed the idea that a Jewish peasant who had suffered the shameful death of the cross could possibly be divine.

The earliest followers of Christianity were not as a rule cultured people like the Athenians, but those who were poor and ignorant. To them Christ’s message was one of brotherhood and love overriding all differences between classes and nations. Yet it did not merely attract because it promised immortality and happiness; it also set up a definite standard of right and wrong. The Jewish religion had laid down the Ten Commandments as the rule of life, but the Jews had never tried to persuade other nations to obey them—rather they had jealously guarded their beliefs from the Gentiles. The Christians on the other hand had received the direct command ‘to go into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature’; and even the slave, when he felt within himself the certainty of his new faith, would be sure to talk about it to others in his household. In time the strange story would reach the ears of his master and mistress, and they would begin to wonder if what this fellow believed so earnestly could possibly be true.

In a brutal age, when the world was largely ruled by physical force, Christianity made a special appeal to women and to the higher type of men who hated violence. One argument in its favour amongst the observant was the life led by the early Christians—their gentleness, their meekness, and their constancy. It is one thing to suffer an insult through cowardice, quite another to bear it patiently and yet be brave enough to face torture and death rather than surrender convictions. Christian martyrs taught the world that their faith had nothing in it mean or spiritless.

Perhaps it may seem strange that men and women whose conduct was so quiet and inoffensive should meet with persecution24 at all. Christ had told His disciples to ‘render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s’, and the strength of Christianity lay not in rebellion to the civil government but in submission. This is true, yet the Christian who paid his taxes and took care to avoid breaking the laws of his province would find it hard all the same to live at peace with pagan fellow citizens. Like the Jew he could not pretend to worship gods whom he considered idols: he could not offer incense at the altars of Juppiter and Augustus: he could not go to a pagan feast and pour out a libation of wine to some deity, nor hang laurel branches sacred to the nymph Daphne over his door on occasions of public rejoicing.

Such neglect of ordinary customs made him an object of suspicion and dislike amongst neighbours who did not share his faith. A hint was given here and there by mischief makers, and confirmed with nods and whisperings, that his quietness was only a cloak for evil practices in secret; and this grew into a rumour throughout the Empire that the murder of newborn babies was part of the Christian rites.

Had the Christians proved more pliant the imperial government might have cleared their name from such imputations and given them protection, but it also distrusted their refusal to share in public worship. Lax themselves, the emperors were ready to permit the god of the Jews or Christians a place amongst their own deities; and they could not understand the attitude of mind that objected to a like toleration of Juppiter or Juno. The commandment ‘Thou shalt have none other gods but me’ found no place in their faith, and they therefore accused the Christians and Jews of want of patriotism, and used them as scapegoats for the popular fury when occasion required.

In the reign of Nero a tremendous fire broke out in Rome that reduced more than half the city to ruins. The Emperor, who was already unpopular because of his cruelty and extravagance, fearing that he would be held responsible for the calamity, declared hastily that he had evidence that the fire was planned by Christians; and so the first serious persecution of the new faith began.

Here is part of an account given by Tacitus, whose history of the German tribes we have already noticed:

‘He, Nero, inflicted the most exquisite tortures on those men who under the vulgar appellation of Christians were already branded with deserved infamy.... They died in torments, and their torments were embittered by insult and derision. Some were nailed on crosses; others sewn up in the skins of wild beasts and exposed to the fury of dogs; others again, smeared over with combustible materials, were used as torches to illuminate the darkness of the night. The gardens of Nero were destined for this melancholy spectacle, which was accompanied with a horse race and honoured with the presence of the Emperor.’

Tacitus was himself a pagan and hostile to the Christians, yet he admits that this cruelty aroused sympathy. Nevertheless the persecutions continued under different emperors, some of them, unlike Nero, wise rulers and good men.

‘These people’, wrote the Spanish Emperor Trajan (98–117), referring to the Christians, ‘should not be searched for, but if they are informed against and convicted they should be punished.’

Marcus Aurelius (161–180) declared that those who acknowledged that they were Christians should be beaten to death; and during his reign men and women were tortured and killed on account of their faith in every part of the Empire. The test required by the magistrates was nearly always the same, that the accused must offer wine and incense before the statue of the Emperor and revile the name of Christ.

The motive that inspired these later emperors was not Nero’s innate love of cruelty or desire of finding a scapegoat, but genuine fear of a sect that grew steadily in numbers and wealth, and that threatened to interfere with the ordinary worship of the temples, so bound up with the national life.

In the reign of Trajan the Governor of Bithynia wrote to the Emperor complaining that on account of the spread of Christian teaching little money was now spent in buying sacrificial beasts. ‘Nor’, he added, ‘are cities alone permeated by the contagion of this superstition, but villages and country parts as well.’

Emperors and magistrates were at first confident that, if only26 they were severe enough in their punishments, the new religion could be crushed out of existence. Instead it was the imperial government that collapsed while Christianity conquered Europe.

Very early in the history of Christianity the Apostles had found it necessary to introduce some form of government into the Church; and later, as the faith spread from country to country, there arose in each province men who from their goodness, influence, or learning, were chosen by their fellow Christians to control the religious affairs of the neighbourhood. These were called ‘Episcopi’, or bishops, from the Latin word Episcopus, ‘an overseer’. Tradition claims that Peter was the first bishop of the Church in Rome, and that during the reign of Nero he was crucified for loyalty to the Christ he had formerly denied.

To help the bishops a number of ‘presbyters’ or ‘priests’ were appointed, and below these again ‘deacons’ who should undertake the less responsible work. The first deacons had been employed in distributing the alms of the wealthier members of the congregation amongst the poor; and though in early days the sums received were not large, yet as men of every rank accepted Christianity regardless of scorn or danger and made offerings of their goods, the revenues of the Church began to grow. The bishops also became persons of importance in the world around them.

In time emperors and magistrates whose predecessors had believed in persecution came to recognize that it was not an advantage to the government, even a danger, and instead they began to consult and honour the men who were so much trusted by their fellow citizens. At last, in the fourth century, there succeeded to the throne an emperor who looked on Christianity not with hatred or dread, but with friendly eyes as a more valuable ally than the paganism of his fathers. This was the Emperor Constantine the Great.

Constantine the Great was born at a time when the Empire was divided up between different emperors. His father, Constantius Chlorus, ruled over Spain, Gaul, and Britain; and when he died at York in A.D. 306, Constantine his eldest son succeeded to the government of these provinces. The new Emperor, who was thirty-two years old, had been bred in the school of war. He was handsome, brave, and capable, and knew how to make himself popular with the legions under his command without losing his dignity or letting them become undisciplined.

When he had reigned a few years he quarrelled with his brother-in-law Maxentius who was Emperor at Rome, and determined to cross the Alps and drive him from his throne. The task was difficult; for the Roman army, consisting of picked Praetorian Guards, and regiments of Sicilians, Moors, and Carthaginians, was quite four times as large as the invading forces. Yet Constantine, once he had made his decision, did not hesitate. He knew his rival had little military experience, and that the corruption and luxury of the Roman court had not increased either his energy or valour.

It is said also that Constantine believed that the God of the Christians was on his side, for as he prepared for a battle on the plains of Italy against vastly superior forces, he saw before him in the sky a shining cross and underneath the words ‘By this conquer!’ At once he gave orders that his legions should place on their shields the sign of the cross, and with this same sign as his banner he advanced to the attack. It was completely successful, the Roman army fled in confusion, Maxentius was28 slain, and Constantine entered the capital almost unopposed. The arch in Rome that bears his name celebrates this triumph.

Constantine was now Emperor of the whole of Western Europe, and some years later, after a furious struggle with Licinius the Emperor of the East, he succeeded in uniting all the provinces of the Empire under his rule.

The ROMAN EMPIRE

in the time of

Constantine the Great

This was a joyful day for Christians, for though Constantine was not actually baptized until just before his death, yet, throughout his reign, he showed his sympathy with the Christian religion and did all in his power to help those who professed it. He used his influence to prevent gladiatorial shows, abolished the horrible punishment of crucifixion, and made it easier than ever before for slaves to free themselves. When he could, he avoided pagan rites, though as Emperor he still retained the office of Pontifex Maximus, or ‘High Priest’, and attended services in the temples.

His mother, the Empress Helena, to whom he was devoted, was a Christian; and one of the old legends describes her29 pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and how she found and brought back with her some wood from the cross on which Christ had been crucified.

Soon after Constantine conquered Rome he published the famous ‘Edict of Milan’ that allowed liberty of worship to all inhabitants of the Empire, whether pagans, Jews, or Christians. The latter were no longer to be treated as criminals but as citizens with full civil rights, while the places of worship and lands that had been taken from them were to be restored.

Later, as Constantine’s interest in the Christians deepened, he departed from this impartial attitude and showed them special favours, confiscating some of the treasures of the temples and giving them to the Church, as well as handing over to it sums of money out of the public revenues. He also tried to free the clergy from taxation, and allowed bishops to interfere with the civil law courts.

Many of these measures were unwise. For one thing, Christianity when it was persecuted or placed on a level with other religions only attracted those who really believed in Christ’s teaching. When it received material advantages, on the other hand, the ambitious at once saw a way to royal favour and their own success by professing the new beliefs. A false element was thus introduced into the Church.

For another thing, few even of the sincere Christians could be trusted not to abuse their privileges. The fourth century did not understand toleration; and those who had suffered persecution were quite ready as a rule to use compulsion in their turn towards men and women who disagreed with them, whether pagans or those of their own faith. Quite early in its history the Church was torn by disputes, since much of its teaching had been handed down by ‘tradition’, or word of mouth, and this led to disagreement as to what Christ had really said or meant by many of his words. At length the Church decided that it would gather the principal doctrines of the ‘Catholic’ or ‘universal’ faith into a form of belief that men could learn and recite. Thus the ‘Apostles’ Creed’ came into existence.

In spite of this definition of the faith controversy continued.30 At the beginning of the fourth century a dispute as to the exact relationship of God the Father to God the Son in the doctrine of the Trinity broke out between Arius, a presbyter of the Church in Egypt, and the Bishop of Alexandria, the latter declaring that Arius had denied the divinity of Christ. Partisans defended either side, and the quarrel grew so embittered that an appeal was made to the Emperor to give his decision.

Constantine was reluctant to interfere. ‘They demand my judgement,’ he said, ‘who myself expect the judgement of Christ. What audacity of madness!’ When he found, however, that some steps must be taken if there was to be any order in the Church at all, he summoned a Council to meet at Nicea and consider the question, and thither came bishops and clergy from all parts of the Christian world. The meetings were prolonged and stormy; but the eloquence of a young Egyptian deacon called Athanasius decided the case against Arius; and the latter, refusing to submit to the decrees of the Council, was proclaimed a heretic, or outlaw. The orthodox Catholics, that is, the majority of bishops who were present, then drew up a new creed to express their exact views, and this took its name from the Council, and was called the ‘Nicene Creed’. In a revised form it is still recited in all the Catholic churches of Christendom.

Arius, though defeated at the Council, succeeded in winning the Emperor over to his views, and Constantine tried to persuade the Catholics to receive him back into the Church. When this suggestion met with refusal the Emperor, who now believed that he had a right to settle ecclesiastical matters, was so angry that he tried to install Arius in one of the churches of his new city of Constantinople by force of arms. The orthodox bishop promptly closed and barred the gates, and riots ensued that were only ended by the death of Arius himself.

The schism, however, continued, and it may be claimed that its bitterness had a considerable influence in deciding the future of Europe by raising barriers between races that might otherwise have become friends. Arianism, like orthodox Catholicism, was full of the missionary spirit, and from its priests the half-civilized tribes of Goths and Vandals learned the new faith.31 A Gothic bishop was present at the Council of Nicea, while another, Ulfilas, who had studied Latin, Greek, and Hebrew at Constantinople, afterwards translated a great part of the Bible into his own tongue. This is the first-known missionary Bible; and, though the original has disappeared, a copy made about a century later is in a museum at Upsala, written in Gothic characters in silver and gold on purple vellum.

The Goths regarded their Bible with deep awe, and carried it with them on their wanderings, consulting it before they went into battle. Like the Vandals, who had also been converted by the Arians, they considered themselves true Christians; but the orthodox Catholics disliked them as heretics almost more than the pagans.

Constantine himself imbibed the spirit of fanaticism; and when he became the champion of Arius, persecuted Athanasius, who had been made Bishop of Alexandria, and compelled him to go into exile. Athanasius went to Rome, where it is said that he was at first ridiculed because he was accompanied by two Egyptian monks in hoods and cowls. Western Europe had heard little as yet of monasticism, though the Eastern Church had adopted it for some time.

To the early Christians with their high ideals the world around them seemed a wicked place, in which it was difficult for them to lead a Christ-like life. They thought that by withdrawing from an atmosphere of brutality and material pleasure, and by giving themselves up to fasting and prayer, they would be able more easily to fix their minds on God and so fit themselves for Heaven. Sometimes they would go to desert places and live as hermits in caves, perhaps without talking to a living person for months or even years. Others who could not face such loneliness would join a community of monks, dwelling together under special rules of discipline. At fixed hours of the day and night they would recite the services of the Church, and in between whiles they would work or pray and study the Scriptures.

Many of the austerities they practised sound to us absurd, for it is hard to feel in sympathy with a Simon Stylites who spent the best days of his manhood crouched on a high pillar at the32 mercy of sun, wind, and rain, until his limbs stiffened and withered away. Yet the hermits and monks were an arresting witness to Christianity in an age that had not fully realized what Christ’s teaching meant. ‘He that will serve me let him take up his cross and follow me.’ This ideal of sacrifice was brought home for the first time to hundreds of thoughtless men and women when they saw some one whom they knew give up his worldly prospects and the joy of a home and children in order to lead a life of perpetual discomfort until death should come to him as a blessing not a curse. The majority of the leading clergy in the early Church, the ‘Fathers of the Church’, as they are usually called, were monks.

Two of them, St. Gregory and St. Basil, studied together at the University of Athens in the fourth century. St. Basil founded a community of monks in Asia Minor, where his reputation for holiness soon drew together a large number of disciples. He did not try to win them by fair words or the promise of ease and comfort, for his monks were allowed little to eat and spent their days in prayer and manual labour of the hardest kind. The Arians, who hated St. Basil as an orthodox Catholic, once threatened that they would confiscate his belongings, torture him, and put him to death. ‘My sole wealth is a ragged cloak and some books,’ replied the hermit calmly. ‘My days on earth are but a pilgrimage, and my body is so feeble that it will expire at the first torment. Death will be a relief.’ It came when he was only fifty, but not at the hands of his enemies, for he died exhausted by the penances and privations of his customary life. He left many letters and theological works that throw light on the religious questions of his day.

St. Gregory had lived for a time with St. Basil and his monks in Asia Minor but was not strong enough to submit to the same harsh discipline. Indeed he declared that but for the kindness of St. Basil’s mother he would have died of starvation. Afterwards he returned home and was ordained a priest. He was a gentler type of man than St. Basil, a poet of no little merit and an eloquent preacher.

Yet another of the Catholic ‘Fathers of the Church’ was33 St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan. He was elected to this see against his own will by the people of the town, who respected him because he was strong and fearless. St. Ambrose did not hesitate to use the wealth of the Church, even melting down some of the altar-vessels, to ransom Christians who had been carried away captive during one of the barbarian invasions. ‘The Church,’ he declared, ‘possesses gold and silver not to hoard, but to spend on the welfare and happiness of men.’

The impetuosity and vigour that made him a born leader he also employed to express his intolerance of those who disagreed with him. When some Christians in Milan burned a Jewish synagogue and the Emperor Theodosius ordered them to rebuild it, St. Ambrose advised them not to do so. ‘I myself,’ he said, ‘would have burned the synagogue.... What has been done is but a trifling retaliation for acts of plunder and destruction committed by Jews and heretics against the Catholics.’ This was not the spirit of the Founder of Christianity: it was too often the spirit of the mediaeval Church.

A man of even greater influence than St. Ambrose of Milan was St. Jerome, a monk of the fifth century, who is chiefly remembered to-day because of his Latin translation of the Bible, ‘the Vulgate’ as it is called, that is still the recognized edition of the Roman Catholic Church.

St. Jerome was born in Italy, but in his extreme asceticism he followed the practices of the Eastern rather than the Western Church. As a youth he had led a wild life, but, suddenly repenting, he disappeared to live as a hermit in the desert, starving and mortifying himself. So strongly did he believe that this was the only road to Heaven that when he went to Rome he preached continually in favour of celibacy, urging men and women not to marry, as if marriage had been a sin. He was afraid that if they became happy and contented in their home life they would forget God.

Many of the leading families, and especially their women, came under St. Jerome’s influence, but such exaggerated views could never be really popular and, instead of being chosen Bishop of Rome as he had expected, he was forced, by the34 many enemies he had aroused, to leave the town, and returned once more to the desert. Of his sincerity there can be little doubt, but his outlook on life was warped because, like so many good and earnest contemporary Christians, he believed that human nature and this earth were entirely bad and that only by the suppression of any enjoyment in them could the soul obtain salvation.

Several centuries were to pass before St. Francis of Assisi taught his fellow men the beauty and value of what is human.

Constantinople (the Polis or city of Constantine) had been a Greek colony under the name of Byzantium long before Rome existed. Built on the headland of the Golden Horn, its walls were lapped by an inland sea whose depth and smoothness made a splendid harbour from the rougher waters of the Mediterranean. Almost impregnable in its fortifications, it frowned on Asia across the narrow straits of the Hellespont and completely commanded the entrance to the Black Sea, with its rich ports, markets then as now for the corn and grain of southern Russia.

Constantine, when he decided that Byzantium should be his capital, was well aware of these advantages. He had been born in the Balkans, had spent a great part of his life as a soldier in Asia, had assumed the imperial crown in Britain, and ruled Gaul for his first kingdom. This medley of experience left little place in his heart for Italy, and the name of Rome had no power to stir his blood. Rome to him was a corrupt town in one of the outlying limbs of his Empire: it had no harbour nor special military value on land, while the Alps were a barrier preventing news from passing quickly to and fro. Byzantium, on the other hand, near the mouth of the Danube, was easy of access and yet could be rendered almost impregnable to his foes. It had the great military advantage also of serving as an admirable head-quarters for keeping watch over the northern frontier and an outlook towards the East.

The walls of the original town could not embrace the Emperor’s ambitions, and he himself, wand in hand, designed the boundaries. His court, following him, gasped with dismay. ‘It is enough,’ they urged; ‘no imperial city was ever so great35 before.’ ‘I shall go on,’ replied Constantine, ‘until he, the invisible guide who marches before me, thinks fit to stop.’

Not until the seven hills outside Byzantium were enclosed within his circuit was the Emperor satisfied; and then the great work of building began, and the white marble of Forum and Baths, of Palaces and Colonnades, arose to adorn the Constantinople that has ever since this time played so large a part in the history of Europe. In the new market-place, just beyond the original walls, was placed the ‘Golden Milestone’, a marble column within a small temple, bearing the proud inscription that here was the ‘central point of the world’. Inside were statues of Constantine and Queen Helena his mother, while Rome herself and the cities of Greece were robbed of their masterpieces of sculpture to embellish the buildings of the new capital.

In May A.D. 330 Constantinople was solemnly consecrated, and the Empire kept high festival in honour of an event that few of the revellers recognized would alter the whole course of her destiny. The new capital, through her splendid strategic position, was to preserve the imperial throne with one short lapse for more than a thousand years, but this advantage was obtained at the expense of Rome, and the complete severance of the interests of the Empire in the East and West.

The Romans had never loved the Greeks, even when they most admired their art and subtle intellect, and now in the fourth century this persistent distrust was intensified when Greece usurped the glory that had been her conqueror’s. In the absence of an Emperor and of the many high officials who had gone to swell the triumph of his new court, Rome set up another idol. The symbols of material glory might vanish, but the Christian faith had supplied men with fresh ideals through the teaching of the Apostles and their representatives, the Bishops.

Roman bishops claimed that the gift of grace they received at their consecration had been passed down to them by the successive laying-on of hands from St. Peter himself. ‘Thou art Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church ... and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.’36 These words of Christ seemed to grant to his apostle complete authority over the souls of men; and Christians at Rome began to ask if the power of St. Peter to ‘bind and loose’ had not been handed down to his successors? If so Il Papa, that is, ‘their father’, the Pope, was undoubtedly the first bishop in Christendom, for on no other apostle had Christ bestowed a like authority.

It must not be imagined that this reasoning came like a flash of inspiration or was willingly received by all Christians. Many generations of Popes, from the days of St. Peter onwards, were regarded merely as Bishops of Rome, that is, as ‘overseers’ of the Church in the chief city of the Empire. They were loved and esteemed by their flock not on account of special divine authority but because they stood neither for self-interest nor for faction, but for principles of justice, mercy, and brotherhood.

Had a Roman been robbed by a fellow citizen, were there a plague or famine, was the city threatened by enemies without her walls, it was to her bishop Rome turned, demanding help and protection. Afterwards it was only natural that the one power that could and did afford these things when Emperors and Senators were far away should in time take the Emperor’s place, and that the Pope should appear to Rome, and gradually as we shall see to Western Europe, God’s very viceroy on earth.

To the Church in Greece, Egypt, and Asia Minor he never assumed this halo of glory. Byzantium, the great Constantinople, was the pivot on which the eastern world turned, and the Bishop of Rome with his tradition of St. Peter made no authoritative appeal. Thus far back in the fourth century the cleft had already opened between the Churches of the East and West that was to widen into a veritable chasm.

Constantine ‘the Great’ died in 337, and if greatness be measured by achievement he well deserves his title. Where men of higher genius and originality had failed he had succeeded, beating down with calm perseverance every object that threatened his ambitions, until at last the Christian ruler of a united empire, feared and respected by subjects and enemies alike, he passed to his rest.

Instead of endeavouring to maintain a united empire, Constantine in his will divided up his dominions between three sons and two nephews. Before thirty years were over, however, a series of murders and civil wars had exterminated his family; and two brothers, Valentian and Valens, men of humble birth but capable soldiers, were elected as joint emperors. Valens ruled at Constantinople, his brother at Milan; and it was during this reign that the Empire received one of the worst blows that had ever befallen her.

We have already mentioned the Goths, a race of barbarians half-civilized by Roman influence and converted to Christianity by followers of Arius. One of their tribes, the Visigoths, had settled in large numbers in the country to the north of the Danube. On the whole their relations with the Empire were friendly, and it was hardly their fault that the peace was finally broken, but rather of a strange Tartar race the Huns, that, massing in the plains of Asia, had suddenly swept over Europe. Here is a description given of the Huns by a Gothic writer: ‘Men with faces that can scarcely be called faces, rather shapeless black collops of flesh with tiny points instead of eyes: little in stature but lithe and active, skilful in riding, broad-shouldered, hiding under a barely human form the ferocity of a wild beast.’

Tradition says that these monsters, mounted on their shaggy ponies, rode women and children under foot and feasted on human flesh. Whether this be true or no, their name became a terror to the civilized world, and after a few encounters with them the Visigoths crowded on the edge of the Danube and implored the Emperor to allow them to shelter behind the line of Roman forts.