THE BRITISH NAVY

IN BATTLE

BY

ARTHUR H. POLLEN

ILLUSTRATED

Garden City New York

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1919

Title: The British Navy in Battle

Author: Arthur Joseph Hungerford Pollen

Release date: March 26, 2017 [eBook #54441]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

BY

ARTHUR H. POLLEN

ILLUSTRATED

Garden City New York

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1919

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF

TRANSLATION INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES,

INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Greeting. By Way of Dedication | 3 |

| II. | A Retrospect | 11 |

| The First Crisis | 14 | |

| The Second Crisis | 20 | |

| The Third Crisis | 22 | |

| The Fourth Crisis | 25 | |

| The New Era | 28 | |

| III. | Sea Fallacies: A Plea for First Principles | 33 |

| IV. | Some Root Doctrines | 48 |

| V. | Elements of Sea Force | 61 |

| VI. | The Actions | 79 |

| VII. | Naval Gunnery, Weapons and Technique | 93 |

| Fire Control | 96 | |

| The Torpedo in Battle | 103 | |

| VIII. | The Action that Never Was Fought | 108 |

| IX. | The Destruction of Koenigsberg | 119 |

| The First Attempt | 126 | |

| Success | 134 | |

| A Problem in Control | 142 | |

| X. | Capture of H. I. G. M. S. Emden | 152 |

| XI. | The Career of Von Spee. I | 165 |

| Coronel | 172 | |

| XII. | Battle of the Falkland Islands. I: | |

| The Career of Von Spee II | 180 | |

| A. Preliminary Movements | 182 | |

| XIII. | Battle of the Falkland Islands. II: | |

| B. Action with the Armoured Cruisers | 191 | |

| XIV. | Battle of the Falkland Islands. III:vi | |

| C. Action with the Light Cruisers | 201 | |

| D. Action with the Enemy Transports | 210 | |

| XV. | Battle of the Falkland Islands. IV: | |

| Strategy—Tactics—Gunnery | 213 | |

| British Strategy | 215 | |

| The Tactics of the Battle | 219 | |

| A Point in Naval Ethics | 230 | |

| XVI. | The Heligoland Affair | 232 |

| The North Sea | 240 | |

| XVII. | The Action Off the Dogger Bank. I | 245 |

| XVIII. | The Dogger Bank. II | 251 |

| XIX. | The Battle of Jutland: | |

| I. North Sea Strategies | 267 | |

| XX. | The Battle of Jutland (continued): | |

| II. The Urgency of a Decision | 283 | |

| XXI. | The Battle of Jutland (continued): | |

| III. The Distribution of Forces | 294 | |

| XXII. | The Battle of Jutland (continued): | |

| IV. The Second Phase | 307 | |

| XXIII. | The Battle of Jutland (continued): | |

| V. The Three Objectives | 315 | |

| The Tactical Plans: | ||

| Admiral Scheer’s Tactics | 317 | |

| Sir David Beatty’s Tactics | 324 | |

| Sir John Jellicoe’s Tactics | 326 | |

| XXIV. | The Battle of Jutland (continued): | |

| VI. The Course of the Action | 330 | |

| The German Retreat | 333 | |

| The Night Actions and the Events of June 1 | 335 | |

| XXV. | Zeebrügge and Ostend | 341 |

| Strategical Object | 342 | |

| Sir Roger Keyes’s Tactics | 345 | |

| Attack on the Mole | 352 | |

| Moral Effect | 353 | |

| PAGE | ||

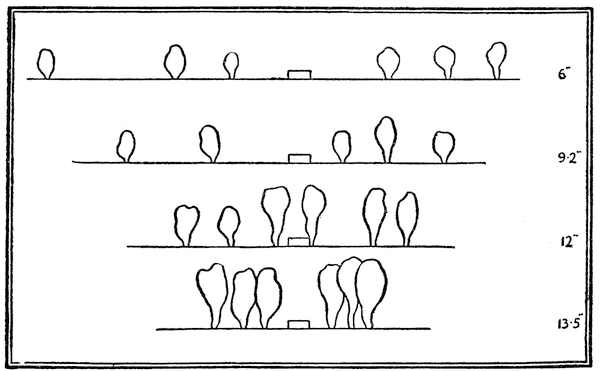

| Big guns more accurate at long range, because more regular | 94 | |

| Big guns need less accurate range-finding, because the danger space is greater | 95 | |

| Range-finding by bracket | 97 | |

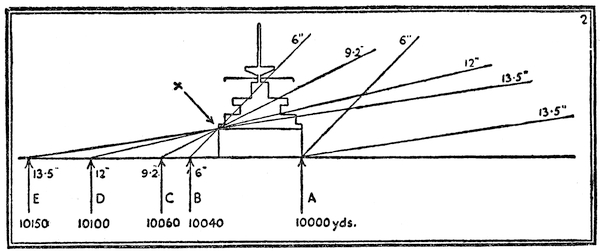

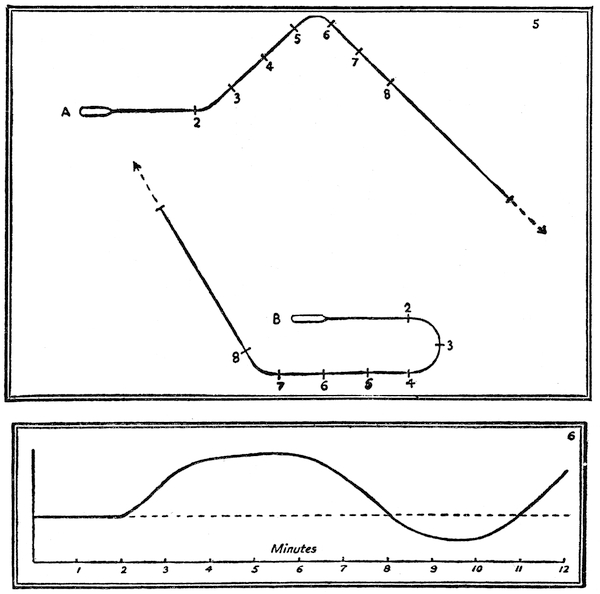

| The crux of sea fighting, changes of course and speed produce an irregularly changing range | 98 | |

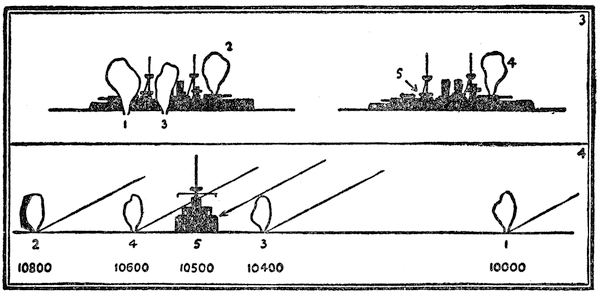

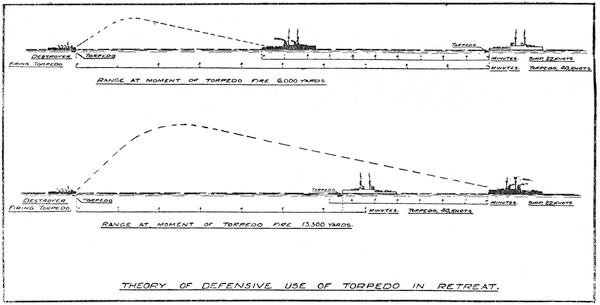

| In this sketch the black silhouette shows the position at the moment the torpedo is fired; the white silhouette the position the ship has reached when the torpedo meets it | 107 | |

| Plan of Sydney and Emden in action | 158 | |

| Plan of the action between the British battle-cruisers and the German armoured cruisers | 199 | |

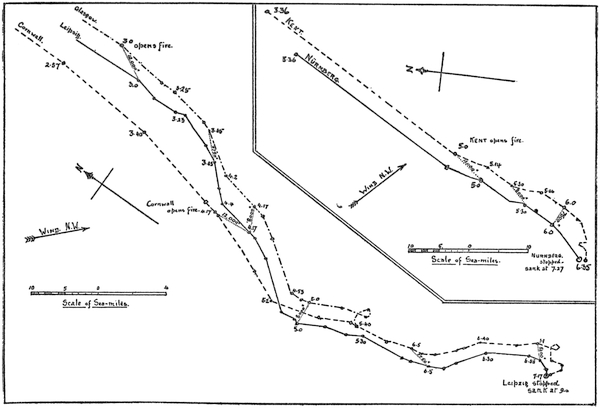

| Plan of action between Kent and Nürnberg, and of that between Cornwall and Glasgow and Leipzig | 207 | |

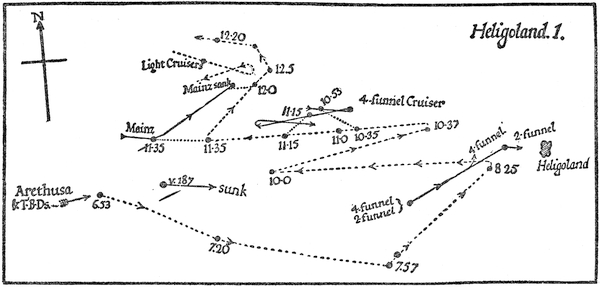

| The action off Heligoland up to the intervention of Commodore Goodenough’s Light Cruiser Squadron | 235 | |

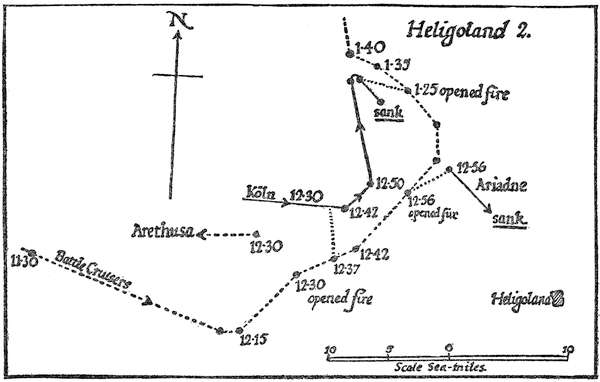

| The action off Heligoland. The course of the battle-cruisers | 239 | |

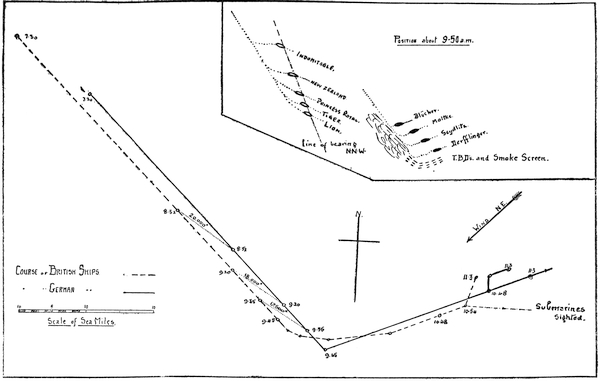

| The Dogger Bank Affair. Diagram to illustrate the character of the engagement up to the disablement of Lion | 249 | |

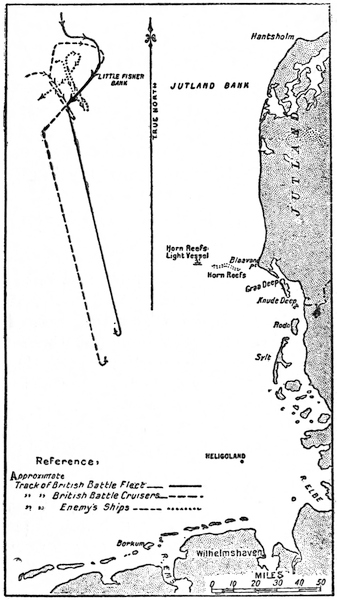

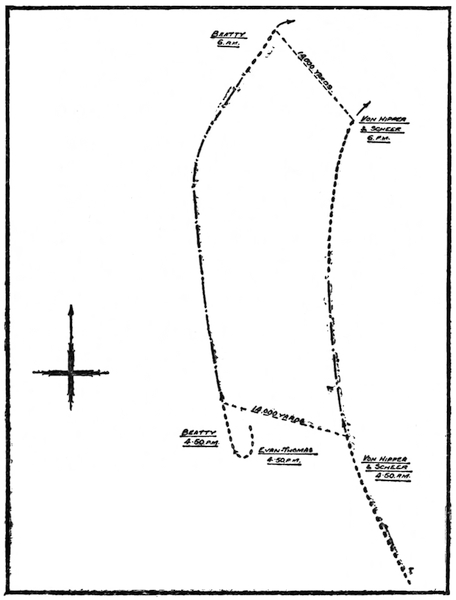

| The official plan of the Battle of Jutland. Noteviii that the course of the Grand Fleet is not shown to be “astern” of the battle-cruisers, but parallel to their track | 295 | |

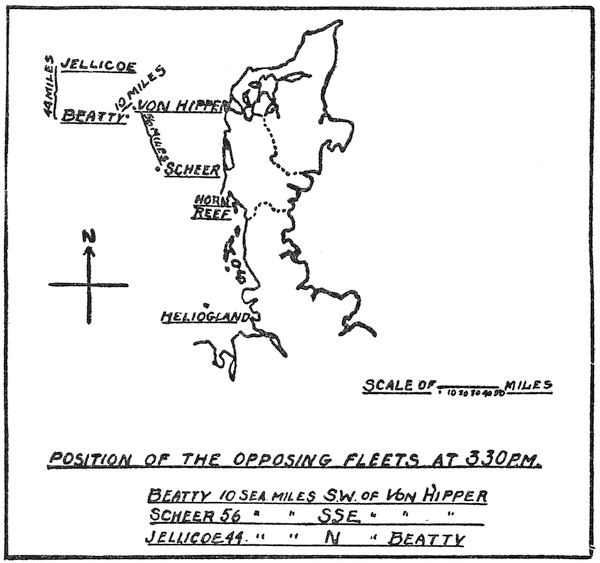

| Position of the opposing fleets at 3:30 P.M. | 298 | |

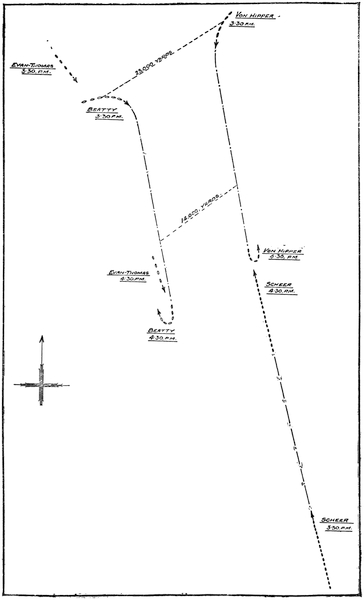

| The first phase; from Von Hipper’s coming into view, until his juncture with Admiral Scheer | 301 | |

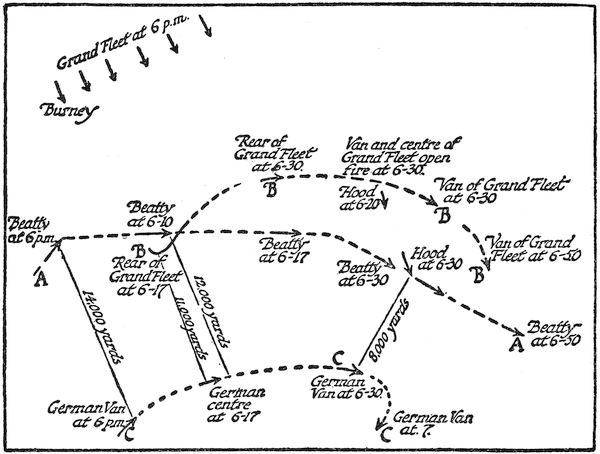

| The second phase; Beatty engages the combined German Fleet, and draws it toward the Grand Fleet | 309 | |

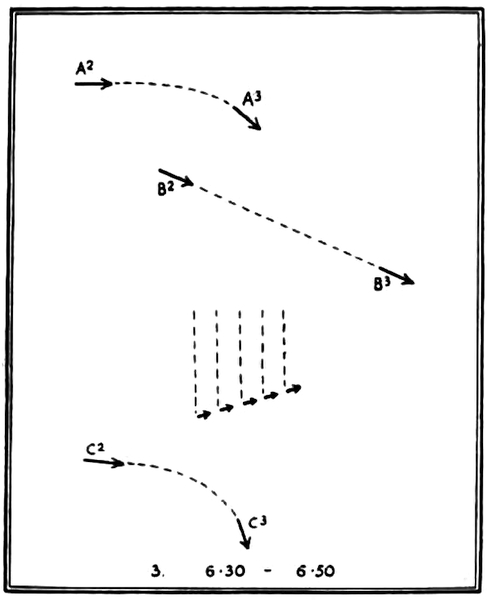

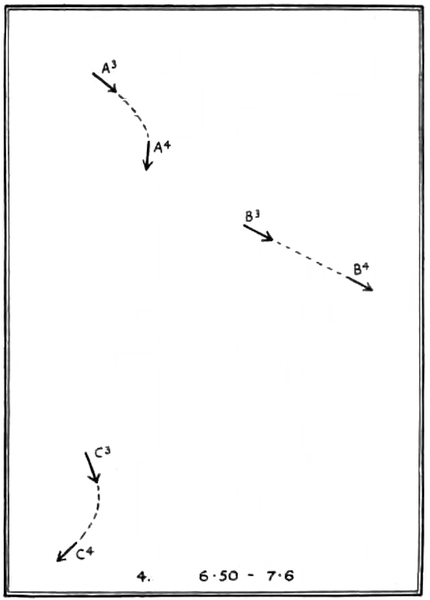

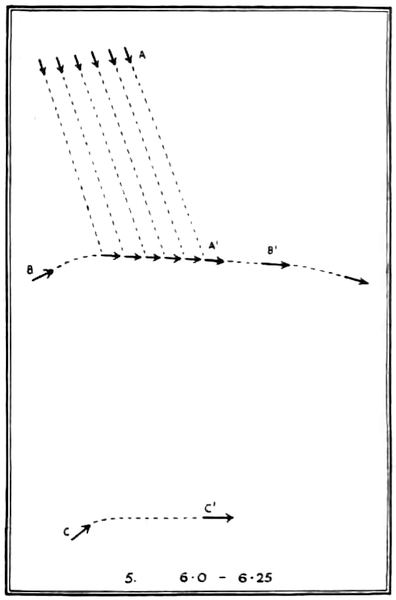

| Sketch plan of the action from 6 P.M. when the Grand Fleet prepared to deploy, till 6:50 when Admiral Scheer delivered his first massed torpedo attack | 332 | |

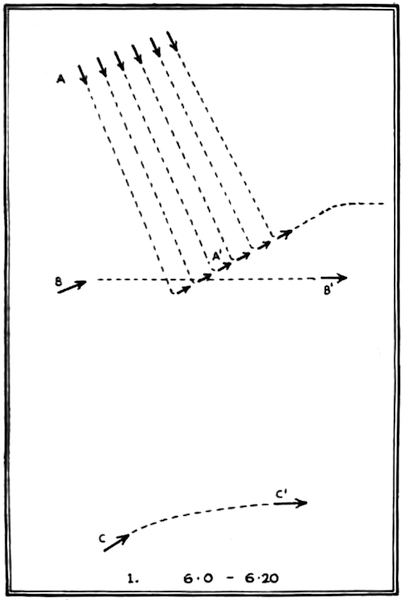

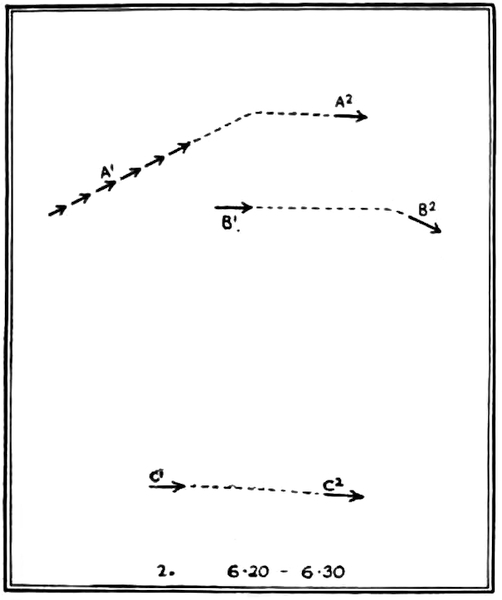

| Jutland Diagrams. Third phase | at end of book | |

Xmas, 1915.

To the Admirals, Captains, Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Naval Reserve:

To the men of the merchant service and the landsmen who have volunteered for work afloat:

To all who are serving or fighting for their country at sea:

To all naval officers who are serving—much against their will—on land:

Greetings, good wishes and gratitude from all landsmen.

We do not wish you a Merry Christmas, for to none of us, neither to you at sea nor to us on land, can Christmas be a merry season now. Nor, amid so much misery and sorrow, does it seem, at first sight, reasonable to carry the conventional phrase further and wish you a Happy New Year. But happiness is a different thing from merriment. In the strictest sense of the word you are happy in your great task, and we doubly and trebly happy in the security that your great duties, so finely discharged, confer. So, after all it is a Happy New Year that we wish you.

If you could have your wish, you of the Grand Fleet—4well, we can guess what it would be. It is that the war would so shape itself as to force the enemy fleet out, and make it put its past work and its once high hopes to the test against the power which you command and use with all the skill your long vigil and faithful service have made so singly yours to-day. And in one sense—and for your sakes, because your glory would be somehow lessened if it did not happen—we too could wish that this could happen. But we wish it only because you do. Although you do not grumble, though we hear no fretful word, we realize how wearing and how wearying your ceaseless watch must be. It is a watchfulness that could not be what it is, unless you hoped, and indeed more than hoped, expected that the enemy must early or late prove your readiness to meet him, either seeking you, or letting you find him, in a High Seas fight of ship to ship and man to man. We, like you, look forward to such a time with no misgiving as to the result, though, unlike you, we dread the price in noble lives and gallant ships that even an overwhelming victory may cost.

Your hopes and expectation for this dreadful, but glorious, end to all your work do not date from August, eighteen months ago. When as little boys you went to the Britannia, you went drawn there by the magic of the sea. It was not the sea that carries the argosies of fabled wealth; it was not the sea of yachts and pleasure boats. It was the sea that had been ruled so proudly by your fathers that drew you. And you, as the youngest of the race, went to it as the heirs to a stern and noble heritage. So, almost from the nursery have you been vowed to a life of hardship and of self-denial, of peril and of poverty—a fitting apprenticeship for those who were destined to bear themselves so nobly in the day of strain and battle. To the mission confided5 to you in boyhood you have been true in youth and true in manhood. So that when war came it was not war that surprised you, but you that surprised war.

When the war came, you from the beginning did your work as simply, as skilfully, and as easily as you had always done it. Not one of you ever met the enemy, however inferior the force you might be in, but you fought him resolutely and to the end. Twice and only twice was he engaged to no purpose. Pegasus, disabled and outraged, fell nobly, and the valiant Cradock faced overwhelming odds because duty pointed to fighting. Should the certainty of death stand between him and that which England expects of every seaman? There could only be one answer. In no other case has an enemy ship sought action with a British ship. In every other case the enemy has been forced to fight, and made to fly. It was so from the first. When two small cruisers penetrated the waters of Heligoland with a flotilla of destroyers, the enemy kept his High Seas Fleet, his fast cruisers, and his well-gunned armoured ships in the ignoble safety of his harbours and his canal. He left, to his shame, his small cruisers to fight their battle alone. Tyrwhitt and Blount might, and should, have been the objects of overwhelming attack. But the Germans were not to be drawn into battle. The ascendancy that you gained in the first three weeks of war you have maintained ever since. Three times under the cover of darkness or of fog, the greater, faster units of the German force have—in a frenzy of fearful daring—ventured to cross or enter the sea that once was known as the German Ocean. Three times they have known no alternative but precipitate flight to the place from which they came.

Not once has a single merchant ship bound for England been stopped or taken by an enemy ship in home waters.6 But fifty-six out of eight thousand were overtaken in distant seas. It has been yours to shepherd and protect the vast armies we have sent out from England, and so completely have you done it that not a single transport or supply ship has been impeded between this country and France. From the first there has not been, nor can there now ever be, the slightest threat or the remotest danger of these islands being invaded. Indeed, so utter and complete has been your work that the phrase “Command of the Sea” has a new meaning. The sea holds no danger for us. Allied to other great land powers, we find ourselves able and compelled to become a great land power also. The army of four millions is thus not the least of your creations.

So thorough is your work that Britain stands to-day on a pinnacle of power unsurpassed by any nation at any time.

Has the completeness of your work been impaired by the ravages of the submarine? Its gift of invisibility has seemed to some so mystic a thing that its powers become magnified. Because it clearly sometimes might strike a deadly blow, it was thought that it always could so strike, till madness was piled upon madness, and it seemed as if the very laws of force had been upset, and ships and guns things obsolete and of no use. But you have always known—and we at last are learning—that this is idle talk, and that as things were and as they are, so must they always be; and that sea-power rests as it always has, and as it always will, with the largest fleet of the strongest ships, and with big guns well directed and truly aimed.

It did not take you long to learn the trick of the submarine in war, and had things been ordered differently, you might have learned much of what you know in the years of peace. But you learned its tricks so well that it7 has failed completely to hurt the Navy or the Army which the Navy carries over the sea, and has found its only success in attacking unarmed merchant ships. These are only unarmed because the people of Christendom had never realized that any of its component nations could turn to barbarism, piracy, and even murder in war. It would have been so easy, had this utter lapse into devilry been expected, to have armed every merchant ship—and then where would the submarine have been? But even with the merchantmen unarmed, the submarine success has been greatly thwarted by your splendid ingenuity and resource, your sleepless guard, your ceaseless activity, and the buccaneers of a new brutality have been made to pay a bloody toll.

Take it for all in all, never in the history of war has organized force accomplished its purpose at so small a cost in unpreventable loss, or with such utter thoroughness, or in face of such unanticipated difficulties.

It was inevitable that there should be some failures. Not every opportunity has been seized, nor every chance of victory pushed to the utmost. Who can doubt that there are a hundred points of detail in which your material, the methods open to you, the plans which tied you, might have been more ample, better adapted to their purpose, more closely and wisely considered? For when so much had changed, the details of naval war had to differ greatly from the anticipation. In the long years of peace—that seem so infinitely far behind us now—you had for a generation and a half been administered by a department almost entirely civilian in its spirit and authority. It was a control that had to make some errors in policy, in provision, in selection. But your skill counter-balanced bad policy when it could; your resources supplied the defects of material;8 too few of you were of anything but the highest merit for many errors of selection to be possible.

And the nation understood you very little. Your countrymen, it is true, paid you the lip service of admitting that you alone stood between the nation and defeat if war should come. But war seemed so unreal and remote to them, that it was only a few that took the trouble to ask what more you needed for war than you already had.

And you were so absorbed in the grinding toil of your daily work to be articulate in criticism; too occupied in trying to get the right result with indifferent means—because the right means cost too much and could not be given to you—to strive for better treatment; too wholly wedded to your task to be angry that your task was not made more easy for you. Hence you took civilian domination, civilian ignorance, and civilian indifference to the things that matter, all for granted, and submitted to them dumbly and humbly, as you submitted silent and unprotesting to your other hardships; you were resigned to this being so; and were resigned without resentment. If, then, the plans were sometimes wrong, if you and your force were at other times cruelly misused, if the methods available to you were often inadequate, it was not your fault—unless, indeed, it be a fault to be too loyal and too proud to make complaint.

If we took little trouble to understand you, we took still less to pay and praise you. There is surely no other profession in the world which combines so hard a life, such great responsibilities, such pitiful remuneration. But small as the pay is, we seize eagerly every chance to lessen it. If we waste our money, we do not waste it on you. But we fully expect you to spend your money in our service. The naval officer’s pay is calculated to meet his expenses9 in time of peace. Now a very large proportion of the pay of cadets, midshipmen, sub-lieutenants, and lieutenants necessarily goes in uniform and clothes. The life of a uniform can be measured by the sea work done by the wearer. Sea work in war is—what shall we say?—three to six times what it is in peace. But we do nothing to help young officers to meet these very ugly attacks on their very exiguous pay. We do not even distribute the prize money that the Fleet has earned.

Some day, when this war is won, it may be realized that it has been won because there is a great deal more water than land upon the world, and because the British Fleet commands the use of all the water, and the enemy the use of only a tiny fraction of all the land. If France can endure, and if Russia can “come again”; if Great Britain has the time to raise the armies that will turn the scale; if the Allies can draw upon the world for the metal and food that make victory—and waiting for victory—possible; if the effort to shatter European civilization and to rob the Western world of its Christian tradition fails, it is because our enemies counted upon a war in which England would not fight. Some day, then, we shall see what we and all the world owe to you.

We may then be tempted to be generous and pay you perhaps a living wage for your work, and not cut it down to a half or a third if there is no ship in which to employ you. And if you lose your health and strength in the nation’s service, we may pay you a pension proportionate to the value of your work, and the dangers and responsibilities that you have shouldered, and to the strenuous, self-sacrificing lives that you have led, for our sakes. We may do more. We may see to it that honours are given to you in something like the same proportion that they are given,10 say, to civilians and to the Army. We may do more still. We may realize that to get the best work out of you, you must be ordered and governed and organized by yourselves.

But then again we may do nothing of the kind. We may continue to treat you as we have always treated you; and if we do, there is at any rate this bright side to it. You will continue to serve us as you have always served us, working for nothing, content so you are allowed to remain the pattern and mirror of chivalry and knightly service, and to wear “the iron fetters” of duty as your noblest decoration.

August, 1918.

In looking back over the last four years, the sharpest outlines in the retrospect are the ups and downs of hopes and fears. Indeed, so acutely must everyone bear these alternations in mind, that to remark on them is almost to incur the guilt of commonplace. For they illustrate the tritest of all the axioms of war. It is human to err—and every error has to be paid for. If the greatest general is he who makes the fewest mistakes, then the making of some mistakes must be common to all generals. The rises and reversals of fortune on all the fronts are of necessity the indices of right or wrong strategy. These transformations have been far more numerous on land than at sea, and locally have in many instances been seemingly final. Thus to take a few of many examples, Serbia, Montenegro, and Russia are almost completely eliminated as factors; our effort in the Dardanelles had to be acknowledged as a complete failure. But at no stage was any victory or defeat of so overwhelming and wholesale a nature as to promise an immediate decision. The retreat from Mons, Gallipoli, Neuve Chapelle, Hulloch, Kut—the British Army could stand all of these, and much more. France never seemed to be beaten, whatever the strain. Even after the defection of Russia, a German victory seemed impossible on land. Never once did either side see defeat, immediate and final, threatened. A right12 calculation of all the forces engaged may have shown a discerning few where the final preponderance lay. The point is that, despite extraordinary and numerous vicissitudes, there never was a moment when the land war seemed settled once and for all.

This has not been the case at sea. The transformations here have been fewer; but they have been extreme. For two and a half years the sea-power of the Allies appeared both so overwhelmingly established and so abjectly accepted by the enemy, that it seemed incredible that this condition could ever alter materially. Yet between the months of February and May, 1917, the change was so abrupt and so terrific that for a period it seemed as if the enemy had established a form of superiority which must, at a date that was not doubtful, be absolutely fatal to the alliance. And again, in six months’ time, the situation was transformed, so that sea-power, on which the only hope of Allied victory has ever rested was once more assured.

Thus, after the most anxious year in our history, we came back to where we started. This nation, France, Italy, and America no less, we have all returned to that absolute and unwavering confidence in the navy as the chief anchor of all Allied hopes. Not that the navy had ever failed to justify that confidence in the past. There was no task to which any ship was ever set that had not been tackled in that heroic spirit of self-sacrifice which we have been taught to expect from our officers and men; there had never been a recorded case of a single ship declining action with the enemy. There were scores of cases in which a smaller and weaker British force had attacked a larger and stronger German. Ships had been mined, torpedoed, sunk in battle, and the men on board had gone13 to their death smiling, calm, and unperturbed. If heroism, goodwill, a blind passion for duty could have won the war, if devotion and zeal in training, patient submission to discipline, a fiery spirit of enterprise could have won—then we never should have had a single disappointment at sea. The traditions of the past, the noble character of the seamen of to-day—we hoped for a great deal, nor ever was our hope disappointed. And when the time of danger came, when our tonnage was slipping away at more than six million tons a year, so that it was literally possible to calculate how long the country could endure before surrender, it never occurred to the most panic-stricken to blame the navy for our danger. The nation saw quite clearly where the fault lay, and the Government, sensitive to the popular feeling, at last took the right course.

But it was a course that should have been taken long before. For, though the purposes for which sea-power exists seemed perfectly secure and never in danger at all till little more than a year ago, yet there had been a series of unaccountable miscarriages of sea-power. Battles were fought in which the finest ships in the world, armed with the best and heaviest guns, commanded by officers of unrivalled skill and resolution, and manned by officers and crews perfectly trained, and acting in battle with just the same swift, calm exactitude that they had shown in drill—and yet the enemy was not sunk and victory was not won. Though, seemingly, we possessed overwhelming numbers, the enemy seemed to be able to flout us, first in one place and then in another, and we seemed powerless to strike back. Almost since the war began we kept running into disappointments which our belief in and knowledge of the navy convinced us were gratuitous disappointments.14 A rapid survey of the chief events since August, 1914, will illustrate what I mean.

The opening of the war at sea was in every respect auspicious for the Allies. By what looked like a happy accident, the British Navy had just been mobilized on an unprecedented scale. It was actually in process of returning to its normal establishment when the international crisis became acute, and, by a dramatic stroke, it was kept at war strength and the main fleet sent to its war stations before the British ultimatum was despatched to Berlin. The effect was instantaneous. Within a week transports were carrying British troops into France and trade was continuing its normal course, exactly as if there were no German Navy in existence. The German sea service actually went out of existence. Before a month was over a small squadron of battle-cruisers raided the Bight between Heligoland and the German harbours, sank there small cruisers and half-a-dozen destroyers, challenged the High Seas Fleet to battle, and came away without the enemy having attempted to use his capital ships to defend his small craft or to pick up the glove so audaciously thrown down. The mere mobilization of the British Fleet seemed to have paralyzed the enemy, and it looked as if our ability to control sea communications was not only surprisingly complete, but promised to be enduring. The nation’s confidence in the Navy had been absolute from the beginning, and it seemed as if that confidence could not be shaken.

Before another two months had passed we had run into one of those crises which were to recur not once, but again and again. During September an accumulation of errors15 came to light. The enormity of the political and naval blunder which had allowed Goeben and Breslau to slip through our fingers in the Mediterranean, and so bring Turkey into the war against us, at last become patent. There was no blockade. There were the raids which Emden and Karlsruhe were making on our trade in the Indian Ocean and between the Atlantic and the Caribbean. The enemy’s submarines had sunk some of our cruisers—three in succession on a single day and in the same area. Then rumours gained ground that the Grand Fleet, driven from its anchorages by submarines, was fugitive, hiding now in one remote loch, now in another, and losing one of its greatest units in its flight. For a moment it looked as if the old warnings, that surface craft were impotent against under-water craft, had suddenly been proved true. Von Spee, with a powerful pair of armoured cruisers, was known to be at large. As a final insult, German battle-cruisers crossed the North Sea, and battered and ravaged the defenceless inhabitants of a small seaport town on the east coast. Something was evidently wrong. But nobody seemed to know quite what it was.

The crisis was met by a typical expedient. We are a nation of hero-worshippers and proverbially loyal to our favourites long after they have lost any title to our favour. In the concert-room, in the cricket-field, on the stage, in Parliament—in every phase of life—it is the old and tried friend in whom we confide, even if we have conveniently to overlook the fact that he has not only been tried, but convicted. This blind loyalty is, perhaps, amiable as a weakness, and almost peculiar to this nation. But we have another which is neither amiable nor peculiar. We hate having our complacency disturbed by being proved to be wrong and, rather than acknowledge our fault, are16 easily persuaded that the cause of our misfortune is some hidden and malign influence. And so in October, 1914, the explanation of things being wrong at sea was suddenly found to be quite simple. It was that the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty was of German birth. With the evil eye gone the spell would be removed. And so a most accomplished officer retired, and Lord Fisher, now almost a mythological hero, took his place.

Within very few weeks the scene suffered

Von Spee was left but a month in which to enjoy his triumph over Cradock; Emden was defeated and captured by Sydney; Karlsruhe vanished as by enchantment from the sea; and Von Hipper’s battle-cruisers, going once too often near the British coast, had been driven in ignominious flight across the North Sea and paid for their temerity by the loss of Blücher. Three months of the Fisher-Churchill régime had seemingly put the Navy on a pinnacle that even the most sanguine—and the most ignorant—had hardly dared to hope for in the early days. The spectacle, in August, of the transports plying between France and England, as securely as the motor-buses between Fleet Street and the Fulham Road, had been a tremendous proof of confidence in sea-power. The unaccepted challenge at Heligoland had told a tale. The British fleet had indeed seemed unchallengeable. But the justification of our confidence was, after all, based only on the fact that the enemy had not disputed it. It was a negative triumph. But the capture of Emden, the obliteration of Von Spee, the uncamouflaged flight of Von17 Hipper, here were things positive, proofs of power in action, the meaning of which was patent to the simplest. No man in his senses could pretend that our troubles in October had not been attributed to their right origin, nor that the right remedy for them had been found and applied.

There was but one cloud on the horizon. The submarine—despite the loss of Hogue, Cressy, Aboukir, Hawk, Hermes, and Niger, and the disturbing rumours that the fleet’s bases were insecure—had been a failure as an agent for the attrition of our main sea forces. The loss of Formidable, that clouded the opening of the year, had not restored its prestige. But Von Tirpitz had made an ominous threat. The submarine might have failed against naval ships. It certainly would not fail, he said, against trading ships. He gave the world fair warning that at the right moment an under-water blockade of the British Isles would be proclaimed; then woe to all belligerents or neutrals that ventured into those death-doomed waters. The naval writers were not very greatly alarmed. For four months, after all, trading ships—turned into transports—had used the narrow waters of the Channel as if the submarines were no threat at all. Yet, on pre-war reasoning, it was precisely in narrow waters crowded with traffic that under-water war should have been of greatest effect. These transports and these narrow waters were the ideal victims and the ideal field, and coast and harbour defence and the prevention of invasion, by common consent, the obvious and indeed the supreme functions the submarine would be called upon to discharge. From a military point of view the landing of British troops in France was but the first stage towards an invasion of Germany and, from a naval point of view, it looked as if to defend the French18 ports from being entered by British ships was just as clearly the first objective of the German submarine as the defence of any German port. Now six months of war had shown that, if they had tried to stop the transports, the submarines had been thwarted. Means and methods had evidently been found of preventing their attack or parrying it when made. Was it not obvious that it could be no more than a question of extending these methods to merchant shipping at large to turn the greater threat to futility? It was this reasoning that, in January and February, made it easy for the writers to stem any tendency of the public to panic, and when, towards the end of February, the First Lord addressed Parliament on the subject, and dealt with the conscienceless threat of piracy with a placid and defiant confidence, all were justified in thinking that the naval critics had been right.

And so the beginning of the submarine campaign, though somewhat disconcerting, caused no wide alarm. An initial success was expected. It would take time to build the destroyers and the convoying craft on the scale that was called for, and so to organize the trade that the attack must be narrowed to protected focal points. And as absolute secrecy was maintained, both as to our actual defensive methods and as to our preparations for the future, there was neither the occasion nor the material for questioning whether the serene contentment of Whitehall was rightly founded.

Meantime, as we have seen, success had justified the solution of the October crisis. The attempt to probe deeper and to get at the cause of things was a thankless task. Those who could see beneath the surface could not fail to note in December and January that, while an exuberant optimism had become the mark of the British19 attitude towards the war at sea, a movement curiously parallel to it was going forward in Germany. The shifts to which the Grand Fleet had been put by the defenceless state of its harbours, though rigidly excluded from the British Press, has been triumphantly exploited in the German. Hence, when the enemy’s only oversea squadron was annihilated by Sir Doveton Sturdee, his Press responded with an outcry on the cowardice of the British Fleet that, while glad to overwhelm an inferior force abroad, dared not show itself in the North Sea. And, as if to prove the charge, Whitby and the Hartlepools were forthwith bombarded by a force we were unable to bring to action while returning from this exploit. The enemy naval writers surpassed themselves after this. And it looked so certain that the German Higher Command might itself become hypnotized by such talk that, before the New Year, it seemed prudent to note these phenomena and warn the public that we might be challenged to action after all, of the kind of action the enemy would dare us to, and what the problems were that such an action would present. And in particular it seemed advisable to state explicitly that much less must be expected from naval guns in battle than those had hoped, whose notions were founded upon battle practice. A battle-cruiser manœuvring at twenty-eight knots—instead of a canvas screen towed at six—mines scattered by a squadron in retreat, a line of retreat that would draw the pursuers into minefields set to trap them; the attacks on the pursuing squadrons by flotillas of destroyers, firing long-range torpedoes—these new elements would upset, it was said, all experiences of peace gunnery, because in peace practices it is impossible to provide a target of the speed which enemy ships would have in action, and because there had been no practice20 while executing the manœuvres which torpedo attack would make compulsory in battle.

Within a fortnight the action of the Dogger Bank was fought and Von Hipper’s battle-cruisers were subjected to the fire of Sir David Beatty’s Fleet from nine o’clock until twelve, without one being sunk or so damaged as to lose speed. The enemy’s tactics included attacks by submarine and destroyer which had imposed the manœuvres as anticipated—and the best of gunnery had failed. But Blücher had been sunk; the enemy had run away; so the warning fell on deaf ears; the lesson of the battle was misread. Optimism reigned supreme.

Within a month a naval adventure of a new kind was embarked upon, based on the theory that if only you had naval guns enough, any fort against which they were directed must be pulverized as were the forts of Liège, Namur, Maubeuge, and Antwerp. The simplest comprehension of the principles of naval gunnery would have shown the theory to be fallacious. It originated in the fertile brain of the lay Chief of the Admiralty, and though it would seem as if his naval advisers felt the theory to be wrong, none of them, in the absence of a competent and independent gunnery staff, could say why. And so the essentially military operation of forcing the passage of the Dardanelles was undertaken as if it were a purely naval operation, with the result that, just as naval success had never been conceivable, so now the failure of the ships made military success impossible also.

It was thus we came to our second naval crisis. The first we had solved by putting Lord Fisher into Prince Louis’s place. The lesson of the second seemed to be21 that there was only one mistake that could be made with the navy and that was for the Government to ask it to do anything. Mr. Churchill, as King Stork, had taken the initiative. Lord Fisher, the naval superman, had not been able to save us. It was clear that lay interference with the navy was wrong—equally clear that it would be wiser to leave the initiative to the enemy. And so a new régime began.

But, in reality, the lessons of the first crisis and the second crisis were the same. To suppose that a civilian First Lord is bound to be mischievous if he is energetic, and certain to be harmless if, in administering the navy as an instrument of war, he is a cipher, were errors just as great as to suppose that a seaman with a long, loyal, and brilliant record in the public service had put an evil enchantment over the whole British Navy because, fifty years before, he had been born a subject of a Power with which till now we had never been at war. Things went wrong in October, 1914, for precisely the same reasons that they went wrong in February, March, and April, 1915. The German battle-cruisers escaped at Heligoland for exactly the same reasons that the attempt to take the Dardanelles forts by naval artillery was futile. We had prepared for war and gone into war with no clear doctrine as to what war meant, because we lacked the organism that could have produced the doctrine in peace time, prepared and trained the Navy to a common understanding of it, and supplied it with plans and equipped it with means for their execution. What was needed in October, 1914, was not a new First Sea Lord, but a Higher Command charged only with the study of the principles and the direction of fighting.

But in May, 1915, this truth was not recognized. And22 in the next year which passed, all efforts to make this truth understood were without effect. And so the submarine campaign went on till it spent itself in October and revived again in the following March, when it was stopped by the threat of American intervention. The enemy, thwarted in the only form of sea activity that promised him great results, found himself suddenly threatened on land and humiliated at sea, and to restore his waning prestige, ventured out with his forces, was brought to battle—and escaped practically unhurt.

The controversies to which the battle of Jutland gave rise will be in everyone’s recollection. Another of the many indecisive battles with which history is full had been fought, and the critics established themselves in two camps. One side was for facing risks and sinking the enemy at any cost. The other would have it that so long as the British Fleet was unconquered it was invincible, and that the distinction between “invincible” and “victorious” could be neglected. After all, as Mr. Churchill told us, while our fleet was crushing the life breath out of Germany, the German Navy could carry on no corresponding attack on us; and when the other camp denounced this doctrine of tame defence, he retorted that victory was not unnecessary but that the torpedo had made it impossible.

Yet, within two months of the battle of Jutland, the submarine campaign had begun again, and, at the time of Mr. Churchill’s rejoinder, the world was losing shipping at the rate of three million tons a year! As there never had been the least dispute that to mine the submarine into German harbours was the best, if not the only, antidote, never the least doubt that it was only the German Fleet23 that prevented this operation from being carried out it seemed strange that an ex-First Lord of the Admiralty should be telling the world first, that the German Fleet in its home bases delivered no attack on us and therefore need not be defeated! And, secondly, as if to clinch the matter and silence any doubts as to the cogency of his argument, we were to make the best of it because victory was impossible.

This utter confusion of mind was typical of the public attitude. If a man who had been First Lord at the most critical period of our history had understood events so little, could the man in the street know any better?

Once more the root principles of war were urged on public notice. But it was already too late. Jutland, whether a victory, or something far less than a victory, had at any rate left the public in the comfortable assurance that the ability of the British Fleet was virtually unimpaired to preserve the flow of provisions, raw material, and manufactures into Allied harbours and to maintain our military communications. But soon after the third year of the war began, a change came over the scene. The highest level that the submarine campaign had reached in the past was regained, and then surpassed month by month. Gradually it came to be seen that the thing might become critical—and this though the campaign was not ruthless. Yet it was carried out on a larger scale and with bolder methods which the possession of a larger fleet of submarines made possible. The element of surprise in the thing was not that the Germans had renewed the attempt—for it was clear from the terms of surrender to America that they would renew it at their own time. The surprise was in its success. The public, still trusting to the attitude of mind induced by the critics and by the authorities in 1915,24 had taken it for granted that the two previous campaigns had stopped in December, 1915, and in March, 1916, because of the efficiency of our counter-measures. The revelation of the autumn of 1916 was that these counter-measures had failed.

It was this that brought about the third naval crisis of the war. Once more the old wrong remedy was tried. The Government and the public had learned nothing from the revelation that we had gone to war on the doctrine that the Fleet need not, and ought not, to fight the enemy, and were apparently unconcerned at discovering that it could not fight with success. And so, still not realizing the root cause of all our trouble, once more a remedy was sought by changing the chief naval adviser to the Government.

But on this occasion it was not only the chief that was replaced, as had happened when Lord Fisher succeeded Prince Louis of Battenberg, and when Sir Henry Jackson succeeded Lord Fisher. When Admiral Jellicoe came to Whitehall several colleagues accompanied him from the Grand Fleet. There was nothing approaching to a complete change of personnel, but the infusion of new blood was considerable. But this notwithstanding, the menace from the submarine grew, when ruthlessness was adopted as a method, until the rate of loss by April had doubled, trebled, and quadrupled that of the previous year. All the world then saw that, with shipping vanishing at the rate of more than a million tons a month, the period during which the Allies could maintain the fight against the Central Powers must be strictly limited.

Thus, without having lost a battle at sea—but because we had failed to win one—a complete reverse in the naval situation was brought about. Instead of enjoying the25 complete command Mr. Churchill had spoken of, we were counting the months before surrender might be inevitable. During the ten weeks leading up to the culminating losses of April, a final effort was made to make the public and the Government realize that failure of the Admiralty to protect the sea-borne commerce of a seagirt people was due less to the Government’s reliance on advisers ill-equipped for their task, than that the task itself was beyond human performance, so long as the Higher Command of the Navy was wrongly constituted for its task. It was, of course, an old warning vainly urged on successive Governments year after year in peace time, and month after month during the war. Evidences of inadequate preparation of imperfect plans, of a wrong theory of command, of action founded on wrong doctrine but endorsed by authority, had all been numerous during the previous two and a half years.

But where reason and argument had been powerless to prevail, the logic of facts gained the victory. At last, in the fourth naval crisis of the war, it was realized that changes in personnel at Whitehall were not sufficient, that changes of system were necessary. Before the end of May the machinery of administration was reorganized and a new Higher Command developed, largely on the long resisted staff principle.

Thus, after repeated failures—not of the Fleet but of its directing minds in London—a complete revolution was effected in the command of the most important of all the fighting forces in the war, viz., the British Navy. It was actually brought about because criticism had shown that the old régime had first failed to anticipate and then to thwart a new kind of attack on sea communications—26just as it had failed to anticipate the conditions of surface war. It was at last realized that two kinds of naval war could go on together, one almost independent of the other. A Power might command the surface of the sea against the surface force of an enemy, and do so more absolutely than had ever happened before, and yet see that command brought, for its main purposes, almost to nothing by a new naval force, from which, though naval ships could defend themselves, they seemingly could not defend the carrying and travelling ships, upon which the life of the nation and the continuance of its military effort on land depended. The revolution of May saved the situation. At last the principle of convoy, vainly urged on the old régime, was adopted, and within six months the rate at which ships were being lost was practically halved. In twelve months it had been reduced by sixty per cent.

But the departure made in the summer of 1917, though radical as to principle, was less than half-hearted as to persons. Many of the men identified with all our previous failures and responsible for the methods and plans that have led to them, were retained in full authority. The mere adoption of the staff principle did indeed bring about an effect so singular and striking as completely to transform all Allied prospects. In April, defeat seemed to be a matter of a few months only. By October it had become clear that the submarine could not by itself assure a German victory. If such extraordinary consequences could follow—exactly as it was predicted they must—from a change in system which all experience of war had proved to be essential, why, it may be asked, was the adoption of the staff principle so bitterly opposed? Partly, no doubt, because of the natural conservatism of men who have grown old and attained to high rank in a service to which they have27 given their lives in all devotion and sincerity. The singularity of the sailor’s training and experience tends to make the naval profession both isolated and exclusive. And that its daily life is based upon the strictest discipline, that gives absolute power to the captain of a ship because it is necessary to hold him absolutely responsible, inevitably grafts upon this exclusiveness a respect for seniority which gives to its action in every field the indisputable finality bred of the quarter-deck habit. Thus, there was no place in Admiralty organization for the independent and expert work of junior men, because no authority could attach to their counsel. It is of the essence of the staff principle that special knowledge, sound, impartial, trained judgment, grasp of principle and proved powers of constructive imagination, are higher titles to dictatorship in policy than the character and experience called for in the discharge of executive command. But to a service not bred to seeing all questions of policy first investigated, analyzed, and, finally, defined by a staff which necessarily will consist more of younger than of older men, the suggestion that the higher ranks should accept the guiding coöperation of their juniors seemed altogether anarchical. The long resistance to the establishment of a Higher Command based on rational principles may be set down to these two elements of human psychology.

That successive Governments failed to break down this conservatism must, I think, be explained by their fear of the hold which men of great professional reputation had upon the public mind and public affections. It was notable, for example, that when our original troubles came to us at the first crisis, the Government, instead of seeking the help of the youngest and most accomplished of our admirals and captains, chose as chief advisers the oldest28 and least in touch with our modern conditions. It was, perhaps, the same fear of public opinion that delayed the completion of the 1917 reforms until the beginning of the next year. But, with all its defects and its limitations, the solution sought of the fourth sea crisis had made the history of the past twelve months the most hopeful of any since the war began.

The period divides itself into two unequal portions. Between June and January, 1918, was seen the slowly growing mastery of the submarine. The rate of loss was halved and the methods by which this result was achieved were applied as widely as possible. But in the next six or eight months no improvement in the position corresponding to that which followed in the first period was obtained. The explanation is simple enough. The old autocratic régime had not understood the nature of the new war any better than the nature of the old. It had from the first, under successive chief naval advisers, repudiated convoy as though it were a pestilent heresy. In June, 1917, the very men who, as absolutist advisers, had taken this attitude, were compelled to sanction the hated thing itself. It yielded exactly the results claimed for it, but no more. It was in its nature so simple and so obvious that it did not take long to get it into working order. It was the best form of defence. But defence is the weakest form of war. The stronger form, the offensive, needed planning and long preparations. In the nature of things these could not take effect either in six months or in twelve. Nor is it likely that, while the old personnel was suffered to remain at Whitehall, those engaged on the plans and charged with the preparations for this were able to work with the expedition29 which the situation called for. For the first six months after the revolution, then, little occurred to prove its efficiency, except the fruits of the policy which instructed opinion had forced on Whitehall. But these, so far as the final issue of the war was concerned, were surely sufficient. For the losses by submarines were brought below the danger point.

It was not until the revolution made its next step forward by the changes in personnel announced in January that marked progress was shown in the other fields of naval war. The late autumn had been marked, as it was fully expected, once the submarine was thwarted, by various efforts on the part of the enemy to assert himself by other means at sea. A Lerwick convoy, very inadequately protected, was raided by fast and powerful enemy cruisers, and many ships sunk in circumstances of extraordinary barbarity. The destroyers protecting them sacrificed themselves with fruitless gallantry. There were ravages on the coast as well. Both things pointed to salient weaknesses in the naval position. At the time of the third naval crisis at the end of 1916, it had been pointed out that the repeated evidences of our inability to hold the enemy in the Narrow Seas ought not to be allowed to pass uncensured or unremedied. But the fatal habit of refusing to recognize that an old favourite had failed prevented any reform for a year. It was not until Sir Roger Keyes was appointed to the Dover Command and a new atmosphere was created that remarkable departures in new policy were inaugurated. This policy took two forms. First, there was the establishment of a mine barrage from coast to coast across the Channel, and simultaneously with this, North Sea minefields stretching, one from Norwegian territorial waters almost to the Scottish foreshore,30 and another in the Kattegat, to intercept such German U-boats as base their activities upon the enemy’s Baltic force. Two great minefields on such a scale as this are works of time. Nor can their effect upon the submarine campaign be expected to be seen until they are very near completion; but then the effect may possibly be immediate and overwhelming.

Principally to facilitate the creation and maintenance of the barrages, a second new departure in policy was the organization of attacks on the German bases in Flanders. Of these Zeebrügge was infinitely the more important, because it is from here that the deep water canal runs to the docks and wharves of Bruges some miles inland. The value of Zeebrügge, robbed of the facilities for equipment and reparation which the Bruges docks afford, is little indeed. It is little more than an anchorage and a refuge. To close Zeebrügge to the enemy called for an operation as daring and as intricate as was ever attempted. Success depended upon so many factors, of which the right weather was the least certain, that it was no wonder that the expedition started again and again without attempting the blow it set out to strike. Its final complete success at Zeebrügge was a veritable triumph of perfect planning and organization and command. It came at a critical moment in the campaign. A month before the enemy, by his great attack at St. Quentin, had achieved by far the greatest land victory of the war. He had followed this up by further attacks, and seemed to add to endless resources in men a ruthless determination to employ them for victory. The British and French were driven to the defensive. Not to be beaten, not to yield too much ground, to exact the highest price for what was yielded, this was not a very glorious rôle when the triumphs on the Somme and in Flanders of31 1916 and 1917 were remembered. It cannot be questioned that the originality, the audacity, and the success of Vice-Admiral Keyes’ attacks on Zeebrügge and Ostend, gave to all the Allies just that encouragement which a dashing initiative alone can give. It broke the monotony of being always passive.

But the new minefields, the barrages, the sealing of Zeebrügge, these were far from being the only fruits of the changes at Whitehall. A sortie by Breslau and Goeben from the Dardanelles, which ended in the sinking of a couple of German monitors and the loss of a light German cruiser on a minefield, directed attention sharply to the situation in the Middle Sea. There was a manifest peril that the Russian Fleet might fall into German hands and make a junction with the Austrian Fleet at Pola. Further, the losses of the Allies by submarines in this sea had for long been unduly heavy. A visit of the First Lord to the Mediterranean did much to put these things right. First steps were taken in reorganizing the command and, before the changes had advanced very far, an astounding exploit by two officers of the Italian Navy resulted in the destruction of two Austrian Dreadnoughts, and relieved the Allies of any grave danger in this quarter.

Meantime, it had become known that a powerful American squadron had joined the Grand Fleet, that our gallant and accomplished Allies had adopted British signals and British ways, and had become in every respect perfectly amalgamated with the force they had so greatly strengthened. And though little was said about it in the Press, it was evident enough that the moral of the Lerwick convoy had been learned, nor was there the least doubt that the Grand Fleet, under the command of Sir David Beatty, had become an instrument of war infinitely more flexible and32 efficient than it had ever been. His plans and battle orders took every contingency into council so far as human foresight made possible. At Jutland, at the Dogger Bank, and in the Heligoland Bight, Admiral Beatty had shown his power to animate a fleet by his own fighting spirit and to combine a unity of action with the independent initiative of his admirals, simply because he had inspired all of them with a common doctrine of fighting. Under such auspices there could be little doubt that our main forces in northern waters were ready for battle with a completeness and an elasticity that left nothing to chance.

But if we are to look for the chief fruit of last year’s revolution, we shall not find it in the reorganized Grand Fleet, nor in the new initiative and aggression in the Narrow Seas, for the ultimate results of which we still have to wait. If the enemy despairs both of victory on land or of such success as will give him a compromise peace, if he is faced by disintegration at home and, driven to a desperate stroke, sends out his Fleet to fight, we shall then see, but perhaps not till then, what the changes of last year have brought about in our fighting forces. Meantime, the success of the great reforms can be measured quite definitely. In the months of May and June over half a million American soldiers were landed in France, sixty per cent. of whom were carried in British ships. No one in his senses in May or June last year would have thought this possible.

Looked at largely, then, last year’s revolution at Whitehall is in all ways the most astonishing and the most satisfactory naval event of the last four years. It is the most satisfactory event, because its results have been so nearly what was foretold and because it only needs for the work to be completed for all the lessons of the war to be rightly applied.

What do we mean by “sea-power” and “command of the sea”? What really is a navy and how does it gain these things? How come navies into existence? Of what constituents, human and material, are they composed? How are the human elements taught, trained, commanded, and led? How are the ships grouped and distributed, and the weapons fought in war?

To the countrymen of Nelson, and to those of his great interpreter, Mahan, these might at first sight seem very superfluous questions, for they, almost of natural instinct, should understand that strange but overwhelming force that has made them. To the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to the Empires that owe allegiance to the British Crown, to the United States of America, sea-power is at once their origin and the fundamental essential of their continued free and independent existence. And it is their predominant races that have produced the world’s greatest sea fighters and sea writers. It is to the British Fleet that the world owes its promise of safety from German diabolism bred of autocracy. It is to sea-power that America must look if she is to finish the work the Allies have begun. With so great a stake in the sea, Great Britain and America should have fathomed its mysteries.

But, despite the fighters and the writers, the sea in a great measure has kept its secret hidden. In every age the truth has been the possession of but a few. Countries34 for a time have followed the light, and have then, as it were, been suddenly struck blind, and the fall of empires has followed the loss of vision. The world explains the British Empire of to-day, and the great American nation which has sprung from it, by a happy congenital talent for colonizing waste places, for self-government, for assimilating and making friends with the unprogressive peoples, by giving them a better government than they had before. And certainly without such gifts the British races could not have overspread so large a portion of the earth. But the world is apt to forget that there were other empires sprung from other European peoples—Portuguese, French, Spanish, and Dutch—each at some time larger in wealth, area, or population, than that which owed allegiance to the British Crown. In each case it was the power of their navies that gave each country these great possessions. Of some of these empires only insignificant traces remain to-day. They have been merged in the British Empire or have become independent. And the merging or the freeing has always followed from war at sea. It is the British sailors, and not the British colonists, that have made the British Empire. It is not because the settlers in New England were better fighters or had more talent for self-government, but because Holland had the weaker navy, that the city which must shortly be the greatest in the world is named after the ancient capital of Northern England, and not after Amsterdam. It was not England’s half-hearted fight on land, but her failure to preserve an unquestionable command of the sea that secured the extraordinary success of Washington and Hamilton’s military plans.

To all these truths we have long paid lip service. Years ago it passed into a commonplace that should ever national35 existence be threatened by an outside force, it would be on the sea that we should have to rely for defence. With so tremendous an issue at stake, why was our knowledge so vague, why has our curiosity to know the truth been so feeble? Perhaps it is that communities that are very rich and very comfortable are slow to believe that danger can hang over them. In the catechism used to teach Catholic children the elements of their religion, the death that awaits every mortal, the instant judgment before the throne of God, the awful alternatives, Heaven or Hell, that depend on the issue, are spoken of as the “Four Last Things.” Their title has been flippantly explained by the admitted fact that they are the very last things that most people ever think of. So has it been with America and England in the matter of war. The threat seemed too far off to be a common and universal concern. It could be left to the governments. So long as we voted all the money that was asked for officially, we had done our share. And, if statesmen told us that our naval force was large enough, and that it was in a state of high efficiency, and ready for war, we felt no obligation to ask what war meant, in what efficiency consisted, or how its existence could be either presumed or proved. We had no incentive to master the thing for ourselves. We were not challenged to inquire whether in fact the semblance of sea-power corresponded with its reality. The fact that it was on sea-power that we relied for defence against invasion should, of course, have quickened our vigilance. It, in fact, deadened it. For we had never refused a pound the Admiralty had asked for. We took the sufficiency of the Navy for granted and, with the buffer of the fleet between ourselves and ruin, the threat of ruin seemed all the more remote.

A minority, no doubt, was uneasy and did inquire. But36 they found their path crossed by difficulties almost insuperable. The literature of sea-power was based entirely upon the history of the great sea wars of a dim past. Mahan, it is true, had so elucidated the broad doctrines of sea strategy that it seemed as if he who ran might read. But lucid and convincing as is his analysis, urbane and judicial as is his style, Mahan’s work could not make the bulk of his readers adepts in naval doctrine. The fact seems to be that the fabled mysteries of the sea make every truth concerning it elusive, difficult for any one but a sailor to grasp. The difficulties were hardly lessened by Mahan’s chief work having dealt completely with the past. The most important of the world’s sea wars may be said to begin with the Armada and to end in 1815. In these two and one quarter centuries the implements of naval warfare changed hardly at all. Broadly speaking, from the days of Howard of Effingham to those of Fulton and Watt, man used three-masted ships and muzzle-loading cannon. Hence the history of the Great Age deals very little with the technique of war.

To the lay reader, therefore, the study of sea-power, based upon these ancient campaigns, seemed not only the pursuit of a subject vague and elusive in itself, but one that becomes doubly unreal through the successive revolutions of modern times. It was like studying the politics of an extinct community told in records of a dead language. The incendiary shell, armour to keep the shell out, steam that made ships completely dirigible in the sense that they could with great rapidity be turned to any chosen course, these alone had, by the middle of the last century, completely revolutionized the tactical employment of sea force. Steam, which made a ship easier to aim than a gun, gave birth to ramming; and naval thought was hypnotized by37 this fallacy for nearly two generations. By the end of the century the whole art had again been changed, first by the development of the monster cannon, and next, a far more important invention, the mountings that made first light, and then heavy, guns so flexible in use that they could be aimed in a moderate sea way. These and the invention of the fish torpedo and the high speed boat for carrying it—that in the twilight of dawn and eve would make it practically invisible—brought about fresh changes that altered not only the tactics of battle, but those of blockade and of many other naval operations.

But, great and surprising as were the changes and developments in naval weapons and the material in the last half of the nineteenth century, they were completely eclipsed by the number and nature of the advances made in the first decade and a half of the twentieth. If, to the ordinary reader, the lessons of the past seemed of doubtful value in the light of what steam, the explosive shell, the torpedo, and the heavy gun had effected, what was to be said in the light of the kaleidoscope of novelties sprung upon the world after the latest of all the naval wars? For between 1906 and 1914 there came a succession of naval sensations so startling as to make clear and connected thinking appear a visionary hope.

First we heard that naval guns, that until 1904 had nowhere been fired at a greater range than two miles, were actually being used in practice—and used with success—at distances of ten, twelve, and fourteen thousand yards. It was not only that guns were increasing their range, they were growing monstrously in size and still more monstrously in the numbers put into each individual ship, so that the ships grew faster than the guns themselves, until the capital ship of to-day is more than double the displacement38 of that of ten years ago. And with size came speed, not only the speed that would follow naturally from the increase in length, but the further speed that was got by a more compact and lighter form of prime mover. Ten years ago the highest action pace a fleet of capital ships would have been, perhaps, seventeen knots. Now whole squadrons can do twenty-five per cent. better. And with the battle-cruiser we have now a capital ship carrying the biggest guns there are, that can take them into action literally twice as fast as a twelve-inch gun could be carried into battle twelve years ago. Thus with range increased out of all imagination, and vastly greater speed, the tactics of battle were obviously in the melting pot.

But these were far from being the only revolutionary elements. There followed in quick succession a new torpedo that ran with almost perfect accuracy for five or six miles and carried an explosive charge three or four times larger than anything previously known. It had seemed but yesterday that a mile was the torpedo’s almost outside range. Then, at the beginning of the decade of which I speak, the submarine had a low speed on the surface, and half of that below it, with a very limited area of manœuvre in which it could work. It seemed little more, many thought, than an ingenious toy capable, perhaps, of an occasional deadly surprise if an enemy’s fleet should come too near a harbour, but seemingly not destined to influence the grand tactics of war. But in an incredibly short time the submarine became a submersible ocean cruiser, with three times the radius of a pre-Dreadnought battleship, with a far higher surface speed, and able to carry guns of such power that they could sink a merchant ship with half-a-dozen rounds at four miles. In this, even the dullest could see something more than a change in naval tactics.39 Might not the whole nature of naval war be changed? For the long range torpedo that could be used in action, at a range equal to that at which the greatest guns could be expected to hit; the submarine that, completely hidden, could bring the torpedo to such short range that hits would be a certainty, the invisible boat that could evade the closest surface cordon and, almost undisturbed, hunt and destroy merchantmen on the trade routes—that, but for the submarine, would have been completely protected by the command won by the predominant fleet—wonderful as these new things were, they were far from exhausting the new developments of under-water war. Great ingenuity had been shown not only in developing very powerful mines, but in devising means of laying them by the fastest ships, so that not only could these deadly traps be set by merchantmen disguised as neutrals, but by fast cruisers whose speed could at any time enable them to evade the patrols. And, finally, it was equally obvious that the submarine could become a mine layer also. There was, then, literally no spot in the ocean that might not at any moment be mined.

Add to all this, that while wireless introduced an almost instant means of sending orders to or getting news from such distant spots that space was annihilated, airships and aeroplanes—with some, as many thought, with a decisive capacity for attacking fleets in harbour—seemed to make scouting possible over unthought of areas. Can we blame the landsman who set himself patiently to learn the rudiments of the naval art if, after a painful study of the past, he found himself so bemused by the changes of the present as to wonder if a single accepted dogma could survive the high-explosive bombardment of to-day’s inventions? It almost looked as if nothing could be learned40 from the past and less, if possible, be foretold about the future. If the understanding of sea-power in the days of old had been the possession of but a few, it seemed that to-day it must be denied to all.

It is, therefore, not surprising that extraordinary misunderstandings were—and are—prevalent. Only one truth seemed to survive—the supremacy of the capital ship. But this, too, became an error, because it excluded other truths. To the vast bulk of laymen the word “navy” suggested no more than a panorama of great super-Dreadnought battleships. From time to time naval reviews had been held, and the illustrated papers had shown these great vessels, long vistas of them, anchored in perfectly kept lines, with light cruisers and destroyers fading away into the distance. Both in the pictures and in the descriptions all emphasis was laid upon the ships. And in this the current official naval thought of the day was reflected. If any one wished to compare the British Fleet with the German or the German with the American, he confined himself to enumerating their respective totals in Dreadnoughts, and let it go at that. His mental picture of a fleet was thus a perspective of vast mastodons armed with guns of fabulous reach and still more fabulous power, gifted, some of them, with speed that could outstrip the fastest liner, and encased, at least in part, in almost impenetrable armour.

He would know generally, of course, that such things as cruisers, destroyers, and submarines not only existed, but were indeed necessary. He would know vaguely that cruisers were useful for cruising, and destroyers for their eponymous duties—though he would have been sorely puzzled if he had been asked to say exactly what the cruising was for, or what the destroyers were intended to destroy.41 He would have heard of the mystic properties of torpedoes, and of mines, and of certain weird possibilities that lay before the combination of the torpedo with the submarine. Similarly, if one challenged him, he would admit, of course, that guns could only be formidable if they hit, and that fleets could only succeed in battle if their officers and crews were properly trained and skilfully led. But these were things that could not be tabulated or scheduled. They did not figure in Naval Annuals, nor in Admiralty statements. They were stumbling blocks to the layman’s desire to be satisfied—and he took it for granted that they were all right, and was content to measure naval strength by the number of the biggest ships, and so rate the navies of the world by what they possessed in these colossal units only. Thus, he would always put Great Britain first, and recently Germany second, with the United States, Japan, and France taking the third place in succession, as their annual programmes of construction were announced. And just as he thought of navies in terms of battleships, so he thought of naval war in terms of great sea battles. A reaction was inevitable.

Four years have now passed since Germany struck her felon blow at the Christian tradition the nations have been struggling to maintain—and so far there has been no Trafalgar. The German Fleet, hidden behind its defences, is still integral and afloat, and though the British Fleet has again and again come out, its battleships have got into action but once, and then for a few minutes only. For four years, therefore, the two greatest battle fleets in the world seem to have been doing nothing; and to be doing nothing now! And so, if you ask the average layman for a broad opinion on sea-power to-day, he will tell you that battle fleets are useless. For a year or more he has heard42 little of any work at sea except of the work of the submarine. To him, therefore, it seemed manifest that the torpedo has superseded the gun and the submarine the battleship. His opinions, in other words, have swung full cycle. Was he right before and is he wrong now, or was his first view an error and has he at last, under the stern teachings of war, attained the truth?

He was wrong then and he is wrong now. It was an error to think of sea-power only in terms of battleships. It is a still greater error to suppose that sea-power can exist in any useful form unless based on battleships in overwhelming strength. It is true that the German submarines did for a period so threaten the world’s shipping as to make it possible that the overwhelming military resources of the Allies might never be brought to bear against the full strength of the German line in France. It is also true that they have added years to the duration of the war, millions and millions to its cost, and have brought us to straits that are hard to bear. They were truly Germany’s most powerful defence, the only useful form of sea force for her. But it is, nevertheless, quite impossible that the submarine can give to Germany any of the direct advantages which the command of the sea confers.

These simple truths will come home convincingly to us if we suppose for a minute that, at the only encounter in which the battle fleets met, it had been the German Fleet that was victorious. Had Scheer and Von Hipper met Beatty and Jellicoe in a fair, well-fought-out action, and sunk or captured the greater part of the British Fleet so that but a crippled remnant could struggle back to harbour—as little left of the mighty British armada as survived of Villeneuve’s and Gravina’s forces after Trafalgar—would it ever have been necessary for Germany to have challenged43 the forbearance of the world by reckless and piratical attacks on peaceful shipping? Quite obviously not. For with her battle-cruisers patrolling unchallenged in the Channel, the North Sea, and the Atlantic, with all her destroyers and light cruisers working under their protection, no British merchantman could have cleared or entered any British port, no neutral could have passed the blockading lines. British submarines might, indeed, have held up German shipping—but we should have lost the use of merchant shipping ourselves. Our armies would have been cut off from their overseas base, our fighting Allies would have been robbed of the food and material now reaching them from North and South America and the British Dominions, and the civil population of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, would have been threatened by immediate invasion or by not very far distant famine. And this is so because command of the sea is conditioned by a superior battleship strength, and can only be exercised by surface craft which cannot be driven off the sea.

Let us look at this question again from another angle. It is probable that Germany possessed, during the summer of 1917, some two hundred submarines at least. She may have possessed more. These submarines were, for many months, sinking on an average of from twenty to twenty-four British ships a week, and perhaps rather more than half as many Allied and neutral ships as well. It was, of course, a very formidable loss. But of every seventeen ships that went into the danger zone, sixteen did actually escape. How many would have escaped if Germany could have maintained a fleet of fifty surface ships—light cruisers, armed merchantmen, swift destroyers—in these waters? Supposing trade ships were to put to sea and try44 to get past such a cordon just as they risk passing the submarines, how many could possibly escape? What would be the toll each surface ship would take—one a fortnight? One a week? One a day?

These are all ridiculous questions, because, could such a cordon be maintained, no ship bound for Great Britain would put to sea at all. It would not be sixteen escaping to one captured; the whole seventeen would so certainly be doomed that they all would stay in port. So much the war has certainly taught us. When, on August 4, 1914, the British Government declared war on Germany, the sailing of every German ship the world over was then and there stopped. A hundred that were at sea could not be warned and were captured. Those that escaped capture made German or neutral ports. But the order not to sail did not wait upon results. The stoppage of the German merchant service was automatic and instantaneous. It would have been raving insanity to have risked encounter with a navy that held the surface command.

Three months later the situation was locally reversed in South American waters. Von Spee, with two very powerful armoured cruisers and three light fast vessels, encountered a very inferior British force under Admiral Cradock off Coronel, and defeated it decisively. Von Spee’s victory meant that in the Southern Atlantic there was no force capable of opposing him. Instantly every South American port was closed. No one knew where Von Spee might turn up next. Not a captain dared clear for England. Even in South Africa General Botha’s hands were tied. A section of the Transvaal and Orange Colony Dutch had risen in rebellion, and had made common cause with the Germans in South West Africa. With Von Spee at large there was no saying what help he would bring to45 the enemy, and the risk that communications with the mother country might be cut, was a real one. For four weeks the South African Government was paralyzed.

Then followed the most brilliant piece of sea strategy in the war. Two battle-cruisers were sent secretly and at top speed to the Falkland Islands. They reached Port Stanley on December 7, and on the next morning at eight o’clock, Von Spee, in obedience to some inexplicable instinct, brought the whole of his forces to attack the islands. It was the most extraordinary coincidence in the history of war. It was as if a man had been told that a sixty-pound salmon had been seen in a certain river, had thrown a fly at random, and had got a bite and landed him with his first cast. The verdict of Coronel was reversed. Four out of five German ships were sunk. The Dresden escaped, but only to hide herself in the fjords of Patagonia. Germany’s brief spell of sea command in the South Atlantic had ended as dramatically as it began. And within twenty-four hours the laden ships of Chile and the Argentine had put to sea, the underwriters had dropped their premiums to the pre-war rate, and the arrangements for the invasion of South West Africa had begun.