Title: Life in the Shifting Dunes

Author: Laurence B. White

Release date: April 18, 2017 [eBook #54566]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, MFR and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

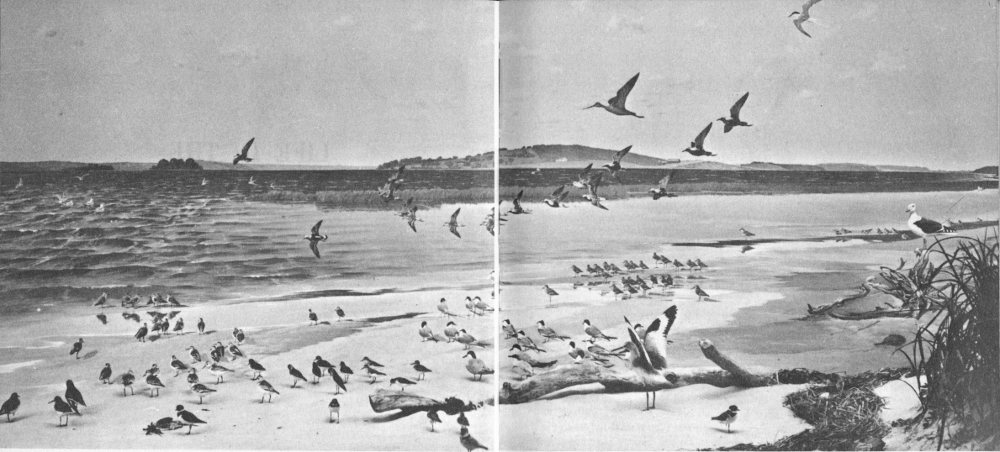

Crane’s Beach Diorama, Museum of Science

A popular field guide to the natural history of Castle Neck, Ipswich, Massachusetts, with attention to the unusual ecological relationships peculiar to such an area

BY LAURENCE B. WHITE, JR.

Museum of Science, Boston

Illustrated by HENRY B. KANE

A PUBLICATION OF THE MUSEUM OF SCIENCE, BOSTON

Copyright, 1960,

by the Museum of Science, Boston

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the publishers.

Library of Congress Card Number: 60-8980

Printed in the United States of America by

The Murray Printing Company

Forge Village, Massachusetts

This popular field guide to Castle Neck, Ipswich, Massachusetts, was the inspiration of Mr. Cornelius Crane, who has summered there since boyhood. Two years ago, Mr. Crane asked us if we would be willing to undertake a survey of this typical dune area if funds were made available for the study. We were delighted to cooperate in the project, and our Education Department undertook it with real enthusiasm.

Some preliminary work was done in 1957, but during July, August, and part of September, 1958, Laurence B. White, Jr., of our Education staff, and Geoffrey Moran, his assistant, moved to Castle Neck. It is Larry who has compiled this field guide.

Larry has been associated with our Museum since his Junior High School days, when his consuming interest in natural history made him an almost daily visitor, and later a valued Education Department volunteer. Now, after his graduation from the University of New Hampshire, where he majored in Biology and Education, he has joined our permanent staff. I recount this only to point out that this study was undertaken by a born and bred New England naturalist who enjoyed every minute of his work on it.

Finding a little cottage on the side of a marsh on the road to Little Neck, Larry and Jeff took it over as their combined summer residence and laboratory, and spent the July and August weeks in Thoreau-like exploration of the beach and dunes, the swamps and woodlands of Castle Neck. Their personal relationship with the living things on the Neck is feelingly reflected in this guide: sympathy with the heroic struggle for survival on the dunes; admiration for the hardihood of the little-admired Poison Ivy; amusement with the odd ways of the Common Barnacle, which “goes through life standing on its head and kicking food into its mouth with its feet”; and exasperation with the mischievous practice of noisy Crows, who delight in wrecking an Owl’s daytime sleep.

It is perhaps because of this perceptive quality of understanding that Larry’s report of the survey has readily adapted into a popular field guide, directing the curious into a fascinating exploration of the “heap o’ living” going on under our very noses and all but ignored by most of us. This guide is not intended as an exhaustive research work or a listing of all the living things to be found on Castle Neck. Rather, it purposely addresses itself to natural history readily observable by visitors with sharp eyes and reasonable patience. When a rarity is included like the Ipswich Sparrow, it is only to indicate that such unusual thrills await the discoverer—occasionally!

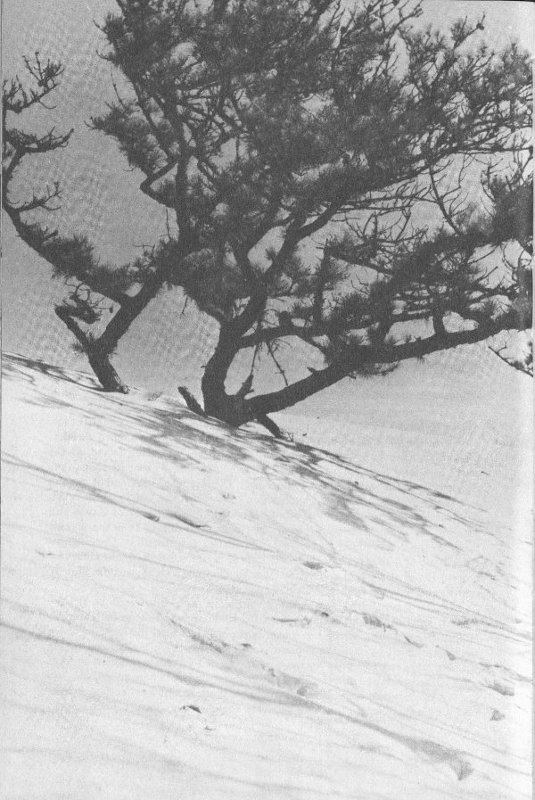

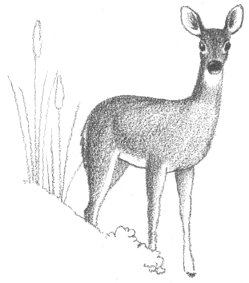

Deer Tracks in the Sand.

While this guide serves as a reminder to those engaged in the study of ecology that this is a rich area for serious investigation, the amateur naturalist or the casual beach visitor, primarily on hand to sun, swim, or picnic, may use it to make his stop on the Neck more meaningful. Knowing, for instance, that Hog Island is a drumlin (a pile of debris deposited in the Great Ice Age) adds enormous interest to the surroundings. Larry’s guide is compiled with the understanding eye and heart of an able and enthusiastic young naturalist. It invites you to look over his shoulder as he investigates his finds, and tempts you to further exploration on your own.

The analysis of the infinitely complex relationships of living animals and plants to their environment, and to one another, is a relatively new science. People with a strong desire to know more about the great sea of life surrounding them have a real opportunity to contribute valuable observations to ecological knowledge. You may very well be one of these!

Bradford Washburn

Director

Museum of Science

Boston, Massachusetts

The author is first and foremost indebted to Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Crane for their unfailing interest in the preparation of this field guide, and to members of the Museum staff who collaborated to edit and produce it. Among these were Norman D. Harris, Director of Education, Gilbert E. Merrill and Chan Waldron of the Education Department, Miss Caroline Harrison, Director of Public Relations, and Mrs. Christina Lopes and Mrs. Margaret Jordan of her department. Invaluable also in preparation of the manuscript was the careful final editing of Miss Helen Phillips, Houghton Mifflin Company.

Especially is the author grateful to the following for advice and comment on various chapters: Clifford S. Chater, Assistant Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Waltham Field Station; Dr. Norman A. Preble, Mammalogist, Northeastern University; J. Phillip Schafer, Geologist, U. S. Geological Survey; Colonel E. S. Clark, Curator of Marine Life, Peabody Museum of Salem, and Dr. Stuart K. Harris, Department of Botany, Boston University.

L.B.W.

Surprising as it may seem, there was a time when many of our most beautiful beaches, the Castle Neck area included, were far inland from the edge of the sea. This was about a million and a half years ago, when the sea was at a lower level than it is today. In fact, a great many changes have helped to form the beaches we see and enjoy now. Of them all, the one brought about by the Ice Age was probably the most influential. It was some 30,000 or 40,000 years ago that New England was overwhelmed by the final advance of a great continental ice sheet. It came from the northwest, and as it inched its way toward the ocean it pushed chunks of rock and great quantities of soil along with it. The rock was continually breaking up as it was shoved forward under the ice.

This last glacier covered New England for thousands of years. When it melted, all the debris it had been moving along like a giant bulldozer was left deposited irregularly over the land, some debris perhaps a hundred miles from original location. In addition, the water from the melting ice swept finer sands and gravels along, depositing them over land areas and in lakes and bays.

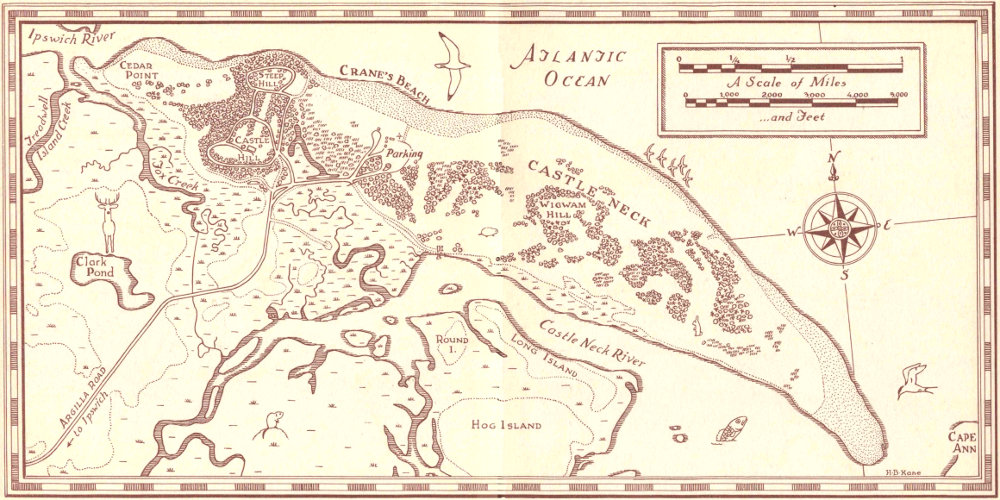

In some places, streamlined hills of debris had been built up under the ice. Later, as the ice melted, they became exposed. They were shaped like the bowl of an inverted spoon, and we call them “drumlins.” Hog Island, to the south of Castle Neck, is a perfectly preserved example. From its shape it is easy to tell which way the ice was moving. The steeply sloping end of its long axis is toward the northwest, the direction from which the last ice sheet came. All drumlins are not so easily spotted. About a mile southeast of Castle Hill you will see a hill that looks like an enormous sand dune. It is the highest point on the Neck, about eighty feet, and it, too, is a drumlin. Once it protruded out of a shallow bay that had formed as the ice melted. Modified by the erosion of the waves and veneered with windblown sand, this drumlin by now has quite lost its characteristic shape.

In the general Boston area many drumlins were uncovered as the ice melted; some of them are such well-known landmarks as Beacon Hill, Bunker Hill, or Breed’s Hill. Along the coast, as the sea level rose, the drumlins there were surrounded by water and became islands. On the sides exposed to the sea they were eroded by the waves, and the eroded materials collected to form spits. Other sands and gravels carried by longshore currents were added, and, by-and-by, in some cases these sand spits connected one drumlin to another. It was just such a modification of three separate drumlins that formed Castle Neck.

While the Neck was thus taking shape, the glacial debris and outwash sands that had been deposited in New Hampshire and at the mouth of the Merrimack River were being picked up and carried southward by the prevailing currents. Finally this material was wave-tossed onto the newly created beach at Castle Neck, some of it being lifted and carried farther inland. In this way, except for a few protected spots behind the drumlins, the entire area became blanketed with sand. The shape of the Beach as we see it is the result of this ever-continuing modification, the work of wind and waves.

It was on the protected back side of the drumlins that plants first took hold. Since the drumlins were formed from fertile soil scraped from rich inland areas and carried here by the ice, the same kinds of plants sprang up on them—Aspens, Pines, Gray Birches, shrubs, and grasses—as we often see today taking over some abandoned farmland. As these early plants died, the soil was further enriched to stimulate even more and different plant life. In fact, at one time much of the dune area was a fertile spot, abounding with all sorts of plants and animals. In certain places on the Neck today, very fertile soil can be found just a few feet under the sand, evidence that here was once a rich farmland.

The broad flat areas of sand on the Beach were very susceptible to the whims of the wind. Now and then, as the wind eroded the sand particles from one place, and blew them to another, it piled them up against the base of some beach plant. Collecting here, the sand began to form a gentle slope with a sharp drop-off downwind. Continuation of this action sometimes built up a huge mound, which we call a dune.

This process of erosion and deposition still goes on. Usually you can tell the general direction of the prevailing wind by observing which way it builds the gentle slope as it piles the sand into ripples or mounds.

If you should mark a dune’s position today and return in several years, you might find that the dune had moved several yards from its original position. Dunes move slowly downwind, such movement being termed “migration.” With a normal dune, during windy periods the sand is blown up its gentle slope and dropped over its crest, whence it slides down the lee side. In this way the dune migrates with the wind.

Eventually, of course, the dunes might migrate the entire length of the Neck and again be blown into the sea, which would carry the sands farther south, mayhap to become part of Coffin and Wingaersheek Beaches. In fact, we might expect the eventual removal of the entire Neck if sand wasn’t constantly being added from similar erosion going on farther north. Obviously there is a very delicate balance here, adding and subtracting sand. The future of Castle Neck is entirely dependent upon the sand supply from the north. Too little may eventually diminish Crane’s Beach; while an increase could create 3 an even larger and more beautiful Neck. Actually, it is impossible to predict the future of a beach, at the mercy, as it is, of changes in any of the several factors controlling its form—sand supply, waves, currents, and position of sea level. Anyway, what has been so long taking shape will not be altered drastically overnight. As a matter of fact, if you really wish to know the future of Crane’s Beach, you will have to be patient. Another million and a half years will probably tell the story!

These small, faceted pebbles found in the dunes have been blasted by the windblown sand. They show the powerful abrasive action of the wind. Most of those you will find here were faceted just after they had been deposited by retreating glacial ice. A migrating dune or a blowout in the sand has left them uncovered.

Large rocks occasionally found in the dunes are called “erratics.” In this world of tiny particles they appear very much out of place, but they were carried here by the glacier a million years ago. They have been uncovered by the migration of some dune.

Occasionally lightning strikes the sand, fusing it into a little tube or ball of glass. These fulgurites have been found here but are very rare and a real “discovery.”

The original soil deposited by the glacier may be seen by digging into the sand at the drumlin. Such rocky soil is quite surprising to people who think the beach is nothing but a big “sand pile.”

Examine a handful of sand. You will find that it consists of light-colored particles (mostly Quartz) and of black particles. Under a microscope many of these dark particles look like little gems. They are actually a deep red and are true Garnets. Large Garnets are used as gem stones, small ones for sandpaper—further proof of the abrasive ability of windblown sand.

In your handful of sand you may find particles that are neither Quartz nor Garnet. Minerals such as Feldspar, Biotite, Mica, Magnetite, Hornblende, and others can be identified by the geologist and are a clue to the original type of rock over which the glacier moved.

These are hard-packed balls of twigs and grasses. Loose vegetable matter is very light and may be blown along by the wind for many miles. As it goes it adds other vegetation to itself, until packed into a very tight, hard ball. It may also get its start in the water by being whirled into a tiny ball; and later it is thrown onto the beach, to begin rolling along. A most curious souvenir!

The face of the land is a storybook waiting to be read. The following books will help you piece together some of the story:

Living things cover the face of the earth from the torrid sands of the desert to the cold wastes of the Arctic, and every variation in environment develops a closely knit community of plants and animals. They are the ones best adapted to living where they do, or they may have been the first to arrive there, filling all available homesites and monopolizing the food and water supply to create a “closed” community. In each environment, a delicate balance is established between its various residents and between them and their surroundings. The study of all these interrelationships is called “ecology.”

Beginning with the environment, we have seen in our brief look at the origins of Castle Neck how drastically an area can be altered as conditions change on the earth’s surface. Environment is affected in other ways, too. Man’s activity can change it almost overnight as a bulldozer clears land for a housing development, a dam alters the flow or course of a river, or careless disposal of a cigarette or campfire lays waste to acres of woodland. Or, as in the slow development of a forest, the growth of the trees themselves can change the environment, the maturity of one species whose seedlings require sunlight contributing to the growth of those better adapted to shade. If you should watch an old abandoned pasture over a period of many years, you could see environment gradually altered. First there are the mosses and grasses that create a fertile soil. Then come the Poplars and shrubs. As these grow they offer shade where Pines and, finally, the broad-leaved trees can flourish. This change in vegetation will also bring about a change in the resident animal communities.

When parts of Castle Neck were rich farmland, specialized forms of life which thrive in that type of environment were abundant there. We have only to look at Castle Hill, just a few hundred yards from the dunes, or at some of the swamps that dot the Neck to see how different are the inhabitants from those of the dunes. On the Hill live the Oaks, Maples, Jumping Mice, Raccoons, and Toads, plants and animals that would be misfits indeed—if they could live at all—in the world of moving sand. Maples and Oaks, relics of the time when the dune area was fertile, may still be found dying and being buried over by drifting sand. Now it is a different community of plants and animals living here. The continually shifting sand and the scarcity of water limit the variety of life found, but each dune dweller is specially adapted to this homesite, and no matter how lush, green, and more attractive a neighboring meadow may look to us, many of these specialized organisms could not survive there at all.

It has taken millions of years for the long, slow process of evolution to develop specific adaptations that suit dune dwellers to their environment. There are variations between individuals in every form of life. Mostly these are normal inherited variations, such as height or color. But sometimes sudden variations, called “mutations,” occur through accidental changes in the genes controlling inheritance. These are new characteristics not found in other members of the same species. If the mutation is advantageous it may be passed on, and it is in this way that new life forms slowly develop. If the mutation allows a species to live more easily in its environment, it may displace some older form, which may then be unable to compete successfully for food, water, or shelter.

Indeed, all life is engaged in a constant struggle for survival; it is those individuals and species best able to adapt to the changing conditions of their environment that endure. Think of the whole series of crises faced by any living thing in its lifetime, then of these crises being met and overcome in the seemingly inhospitable environment of the dunes. In the beginning, our dune dweller must be born, a difficult enough task without interference from unkind surroundings; it must feed itself, here in an area where meals would certainly seem at a premium; it must grow, oftentimes shedding its skin in the process; it must live not only in the summer’s heat but, if its life span is that long, in the winter’s cold; it must endure long periods of drought, flood, wind, and storm; and most important of all, it must survive long enough to reproduce its kind, or else it has missed its goal. But such is the wonder of nature’s specializations that our dune dwellers can usually meet these normal crises. Their adaptability and rate of reproduction safely insure the future of their kind, and their overpopulation, if left to nature, is delicately controlled by available food and shelter and their predators.

Exploring the dunes and making the acquaintance of the inhabitants, you can see this environmental community meshing its lives together, and you can observe the fine degree of adaptation developed by each life form. You may find an occasional Apple tree growing out of the sand, rooted in a more fertile soil below, a reminder of the time when that bit of the Neck was a rich farmland. The roots of the Beach Plum also reach down to the water table, and it is thus able to grow out of the sand, although its seedlings cannot take root in the sand. Most of all, you will have an opportunity to note many special animal and plant peculiarities the dune dwellers have developed to suit their particular environment.

Walking through the dunes, you will frequently notice a small hole in the sand. Poke a blade of grass into it and you will find the hole quite deep. As a matter of fact, it may extend down two feet. This hole is made by the Sand 7 Dune Wolf Spider (Lycosa pikei) to provide a home where the female may raise her young. Wolf Spiders are a species that elsewhere carry their young on the back and hunt down their food wolf fashion, not even taking time to construct a web. On the exposed dunes, the Sand Dune Wolf Spider protects its young in this hole far beneath the ground.

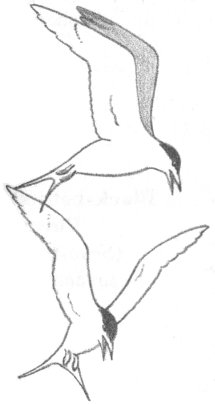

Dozens of Common Terns are to be found nesting at the southern tip of the Neck. Long ago, the Common Tern began laying its eggs on the bare sand, and made no nest at all. Each egg is sand-colored, with speckles resembling pebbles. Only a patient search will locate a Tern nest on the Beach, and then, unless you are cautious, the discovery may come after you have accidentally stepped on the eggs.

Bayberries have a hard wax covering that makes them seem quite unpalatable to us, compared to the more succulent berries found away from the dunes. Yet here the Crows, Tree Swallows, and Myrtle Warblers are Bayberry-eaters. The Myrtle Warbler in particular derives most of its winter diet from Bayberries. In fact, its name comes from the scientific classification of the Bayberry, which is in the Wax Myrtle Family.

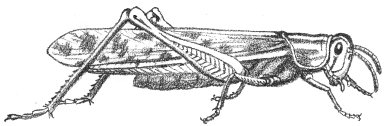

The sand offers few places of retreat and few for hiding. It is not surprising, then, that many of the living things here have a sand-colored protective coloration. There is a large Grasshopper, or Locust, commonly found on the Beach. Its dull, gray, speckled wing-covers make it practically invisible when at rest. But the underwings, used for flight, are a striking orange with black bands. When discovered, the Locust flies up, confusing its attacker with this bright flash of color and a loud whirring noise. Unlike most insects, this Locust eats the thick-skinned, dry Beach Grass.

Any plant that is adjusted to living in a region where there is a decided lack of water is called a “xerophyte.” There are many different ways in which plants have adapted their structure and way of life to the dune environment. For instance, to reduce water evaporation they may have a very small leaf, to 8 offer less surface area to the sun; or smaller and more numerous stomata than other plants (“Stomata” are tiny openings through which plants exchange gasses. A pair of guard cells surround them and control the size of their opening); or a very thick cuticle (waxy protective covering found on many plants); or their sap may be changed chemically. Xerophytes may also be very fleshy, like the cactus, to give more storage space for water. Their roots may drive very deep into the ground to reach the water table, or they may be shallow and spread out over a wide area to cover more surface. Their leaves may grow in closely packed bundles to reduce further the surface area, or they may be very thorny and prickly as a protection in exposed surroundings.

Here are just a few common examples of xerophytes and other plant adaptations to be found at Crane’s Beach.

Beach Grass (Ammophila breviligulata) is a true xerophyte and has many sand-dwelling characteristics. Its grasslike blade is rolled in at the sides, oftentimes becoming a tube, in order to reduce the surface area. As you will probably discover, it has a pointed tip that can prick a finger and, as you may well imagine, acts as a deterrent to those who would eat or walk through it. Its underground stems, in true xerophyte fashion, extend over a large area in an attempt to gather all possible water, and these dense root-mats serve to anchor the dunes and prevent their migration.

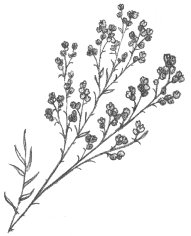

The Woolly Hudsonia (Hudsonia tomentosa) carpets the dunes, preferring its place in full sun to more shaded spots. The tiny leaves are awl-shaped and press very tightly against the stem, as though trying to hold in as much water as possible. Hudsonia is covered with a velvet-like down, which is less susceptible to evaporation than a smooth, large surface would be.

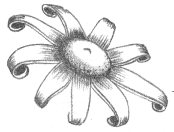

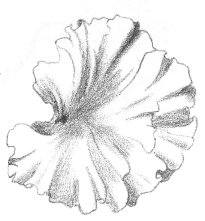

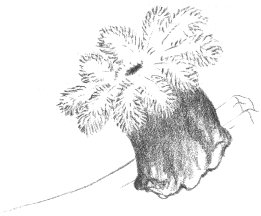

Since mushrooms generally require plenty of water, you would not expect to find them at the beach. Several species, however, may be discovered here. The most readily identifiable is the Earth Star (Geaster hygrometricus), which resembles a Puff Ball but differs in having the outer layer of the skin divided into tough, star-shaped segments. During the dry seasons, this star is drawn up around the ball by its contraction, thus protecting it against further desiccation. In wet weather, the ball swells and holds the star against the ground to allow for water absorption. The “roots” of the Earth Star are shallow, so the plant may readily be dislodged. The wind easily blows it across the dunes, spreading the spores over a wide area.

There is something new to be known about every animal and plant. Now it’s up to you! Careful observation will allow you to discover many other examples of special adaptation to life in the shifting dunes, and the next chapters will introduce you to some of the more common of the living things inhabiting this strange sand-world. And if you wish to read more about ecology, try these books:

Plants add embellishment to the earth. For thousands of years people have valued them for their elegance and their usefulness. They may rate no more than a passing glance in fields and woods, but at the beach they stand out boldly, for here they seem almost out of place.

We have already become acquainted with some strange beach-dwelling plants; now let us examine more closely a few of the most common species.

The flower-like shape of this common mushroom always amazes its discoverer. The basal star is actually a protective coat that covers the ball during dry spells. Its scientific name, Geaster, means “earth star.” Hygrometricus means “water-measuring,” and refers to the opening and closing of the star.

Beach Grass is the most common xerophyte here. It forms dense mats everywhere, and once it gains footing, spreads at a remarkable rate. When windy weather bends the blade it sometimes scribes circles in the sand. If these are deeper on one side or incomplete, they help determine the direction of the prevailing wind. Beach Grass can be extremely uncomfortable to bare legs—so beware!

Because of the great variety of leaf shapes and sizes, it is usually desirable to have the flower for conclusive identification of seashore plants. As an aid, the following species are listed by color.

This very attractive flower is seldom found at any distance from water’s edge. Usually it grows in the moist sand of fresh-water pools, just above water level. On close examination you will find the leaves quite hairy, almost downy. The flowers are mounted at the tips of long stalks. They appear early in the spring, about May, and blooming is over by June.

This is one of the most common beach plants, and is seldom found away from salty soil. It grows in the salt marshes and on the beach, starting its flowering in June and continuing throughout the summer.

Anyone who has seen a garden pea will recognize the Beach Pea, which is similar to but smaller than its cousin. The purple flowers are seen from May throughout the summer, and the peas are found in late summer. These peas are edible, though not particularly delicious. You will notice that Beach Pea stems are angular in cross section—a further clue to identification.

Pinweed is a plant of sandy soils. Often it is found growing alone on a patch of barren sand. It flowers throughout July and August. Its stem is so very woody and tough that it may easily be mistaken for a tiny, stunted tree.

The Sea Lavender goes by a great variety of names: “Beach Heather” and “Marsh Rosemary” are the most common. It is not a true dune dweller, for it is more often found in marshy spots; but it is a typical seaside plant. Its flowers are delicately fragrant. Amazingly enough, you may find Sea Lavender completely submerged in salt water during periods of high tide.

The Hudsonia is sometimes called a “False Heather” and surely reminds one of the moors. It is found in dense mats on the dunes, and when in bloom covers the sand with a bright yellow carpet. The flowers are borne in May and June and open only in sunlight. Any attempt to uproot the plant will merely break it off at the base, for the roots are extremely long and spread over many square yards.

You don’t need to see its flowers to identify Dusty Miller. Its heavy “wool” coat makes identification easy by feel alone. The flowers form dense clusters during July and August.

Everyone is familiar with Goldenrod, but few realize that there are more than a hundred species, some of them very specific as to where they live. The Seaside Goldenrod is the only common species found on beaches or in marshes with salty soil.

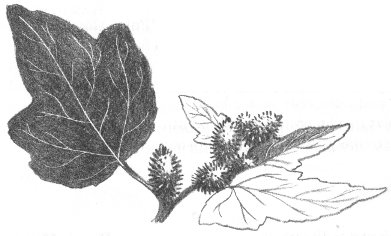

The heads of this weedy plant, like those of the Burdock, are covered with curved spines easily attaching to the fur or clothing of passers-by. The burrs come late in the summer, during August or September.

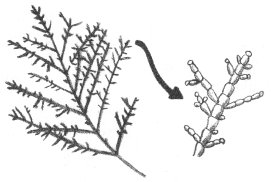

Glasswort, a plant of the salt marsh, requires quantities of salt water. It is easily identified by its leafless stem, which looks like a string of sausages. In autumn these succulent stems turn a bright red, adding an attractive flash of color to the dying plants around them. Glasswort stems take in great quantities of salt, which you will taste if you chew one.

The shrubs and trees found on the dunes are those that grow well in sunlight and can subsist on a small amount of water.

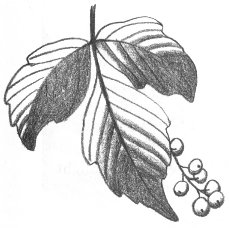

No doubt the Bayberry is familiar to you. Wax from its berries has long been used to make candles, and you may wish to take some berries home to try your hand at this. Boiling them will cause the wax to float on the water. Dip a piece of string (wick) to collect it.

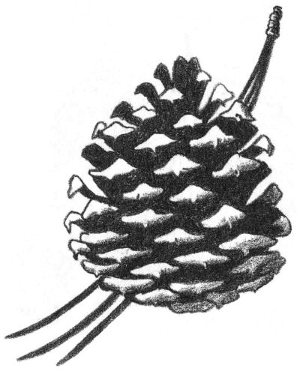

Sweet Gale (Myrica gale) very closely resembles Bayberry but has tiny pine-cone-like fruits instead of white berries. It is very common in the swampy areas on the beach.

This “typical” sea-beach shrub is well known. Its fruit has long been used for “Beach Plum preserve,” a New England favorite. The plums may be collected in late summer. Beach Plum is reasonably common on the back side of Crane’s Beach, high on the dunes. It is often twisted and gnarled from exposure to the winds.

One must admire Poison Ivy. It apparently can live anywhere and survive anything. Beware—for it occurs in patches on the beach. It is very poisonous to the touch, and the best course is to wash thoroughly with a strong soap if you come into contact with it. Some of the worst cases of ivy poisoning may originate at the beach just because people don’t expect to find it here.

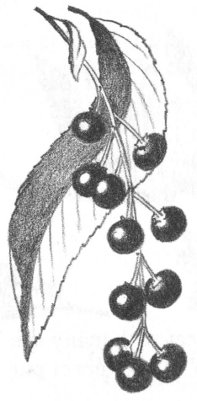

Cherries are usually considered lovers of rich soils, but this member of the family is quite common on the dunes. It is always contorted here, and frequently diseased, but still it survives. Generally it is found with large swellings on the branches caused by the black cherry knot fungus, since it is highly susceptible to this infection. The cherries are edible, and you may or may not enjoy them. Try one and see.

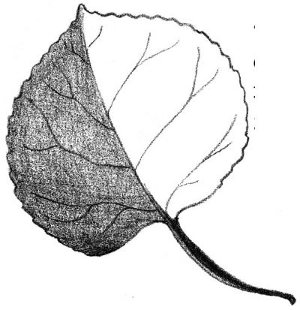

The Aspen thrives in sunlight and dry soil. It grows and dies quickly. It is called a “Quaking” Aspen because its flattened leaf stems allow its leaves to shake even in the gentlest breeze. It is often called a Poplar tree, or just “Popple.”

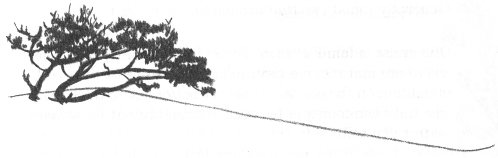

This picturesque pine grows well in sterile soil. It is small, gnarled, contorted, and of little commercial value. It serves a twofold purpose here—anchoring the soil and supplying seeds for a great variety of birds and animals.

These are the most common plants of the dunes and beach. Any careful search will disclose many others not described. You will have to consult one of the reference books listed below for their identification.

To aid you further in your investigation, we attach a list of other plants that may be found occasionally at the beach or in the swamps.

| Flower Color | Name | Habitat |

|---|---|---|

| White | Sundew | Swamps |

| Meadowsweet (shrub) | Swamps | |

| Canada Mayflower | Woods | |

| Garlic Mustard | Woods | |

| Wild Sarsaparilla | Woods | |

| Indian Pipe | Woods | |

| Wintergreen | Woods | |

| Starflower | Woods | |

| Dodder | Woods | |

| Bedstraw | Woods | |

| Pokeweed | Fields | |

| Chickweed | Fields | |

| Yellow | Sweet Flag | Swamps |

| Jewelweed | Swamps | |

| St.-John’s-wort | Swamps | |

| Yellow Loosestrife | Swamps | |

| Silvery Cinquefoil | Woods | |

| Wood Sorrel | Woods | |

| Mustards (several) | Fields | |

| Leafy Spurge | Fields | |

| Cyprus Spurge | Fields | |

| Evening Primrose | Fields | |

| Common Mullein | Fields | |

| Butter-and-Eggs | Fields | |

| Reddish | Seaside Knotwood | Sand |

| Steeplebush (shrub) | Swamp | |

| Sheep Sorrel | Fields | |

| Soapwort | Fields | |

| Coast Blite | Marsh | |

| Roses (several) | Various | |

| Purple | Purple Loosestrife | Swamps |

| American Cranberry | Swamps | |

| Common Milkweed | Fields | |

| Canada Thistle | Fields | |

| Seaside Gerardia | Marshes | |

| Blue | Blue Flag | Swamps |

| Violets (several) | Swamps | |

| Forget-me-not | Swamps | |

| Skullcap | Swamps | |

| Bittersweet Nightshade | Swamps | |

| Monkey Flower | Swamps | |

| Asters (many species) | Woods | |

| Bluets | Fields | |

| Blue Curls | Fields | |

| Brown or Green | Common Cat-tail | Swamps |

| Narrow-leaved Cat-tail | Swamps | |

| Curled Dock | Fields | |

| Halberd-leaved Orache | Marshes | |

| Sea Blite | Marshes | |

Everyone likes to be a beachcomber! And each passing tide exposes the secrets of the sea to those interested enough to take a closer look. Suppose that we examine this world which is revealed to us twice daily.

The sea holds many strange plants that have taken on fantastic sizes and shapes because of their underwater environment. In spite of their size, these plants are usually among the most primitive—a simple sheet of cells. Such plants are called algae and are subdivided according to their colors.

The bladders are filled with air, and children like to squeeze them to hear their pop. These bladders cause the plant to float upright, thus keeping all its sides in contact with water.

When dried by the sun, this plant makes an interesting and lasting souvenir, for it turns a lustrous black.

The kelps of the Pacific grow several hundred feet in length, making them the largest of the algae and among the very largest plants.

All kelps have a rootlike structure called a “holdfast” to serve as an anchor. Often tiny sea creatures dwell in among the holdfast. Why not take a look?

In Asia this kelp is farmed for food called agar. An extract of the plant, agar-agar, is used in the laboratory as a culture medium for bacteria and other disease-producing organisms.

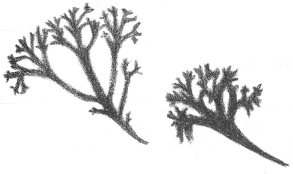

This is a very simple seaweed that reproduces itself by fragmentation, each fragment growing into a new plant. Two common kinds are found at Crane’s Beach:

Ulva lactuca, which is the broad green “leaf”; Ulva lanceolata, which is in thinner, more ribbon-like strips.

Here is a very common tidal plant that has commercial value. It is called “Dulse” on the Boston markets, and a very delicious pudding is prepared from it (seamoss farine). Why not take some home and try it?

Sometimes called “Mermaid’s Hair,” these tiny plants are very common on the beach. There are many kinds of Polysiphonias, but a microscopic study is usually necessary to tell them apart.

These plants have the amazing ability of concentrating lime from the sea water and depositing it on their fronds, thus acquiring a stony, coral-like appearance.

Animals, in a kaleidoscope of unbelievable sizes, shapes, and colors, abound here at the margin of the sea. Specializations range from the single-celled body of the zooplankton to the multicellular body of the Seals and the occasional Porpoise.

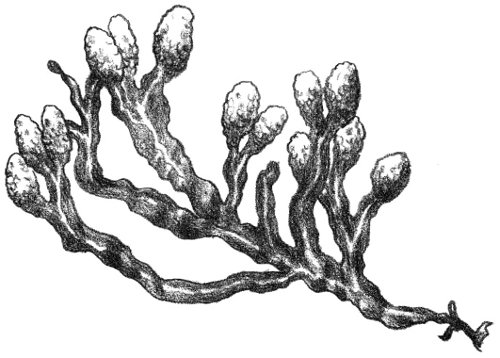

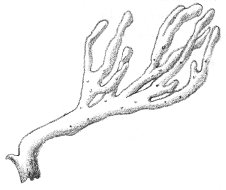

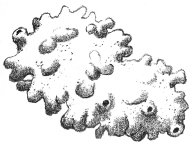

The most common sponge on Crane’s Beach is the Finger Sponge. Even a small piece may be identified by the holes on its surface, through which the animal filtered water. The strange appearance of this sponge has given it the repulsive name of “Dead Men’s Fingers.”

Only the most searching eye will discover this sponge, because it so closely resembles a dull uninteresting rock or pile of bread crumbs. When it has been freshly broken, it has a vile odor—a good clue to identification.

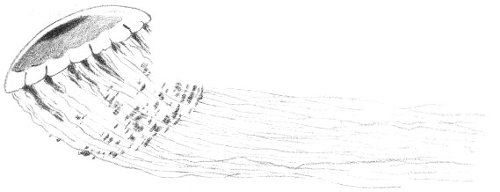

The tentacles dangling down from the underside of this jellyfish are covered with tiny stinging cells, which in this species do not penetrate human skin.

This jellyfish occasionally grows up to eight feet in diameter, with tentacles a hundred or more feet long. The stinging cells can painfully wound a swimmer, but you may examine a small jellyfish safely by placing your hand on the smooth dorsal surface and turning it over.

The “petals” of the Sea Anemone’s flower-like head are actually tentacles covered with stinging cells and used to stun its food. Generally found in the water at tide level, the Sea Anemone moves by walking on its single, base-like foot.

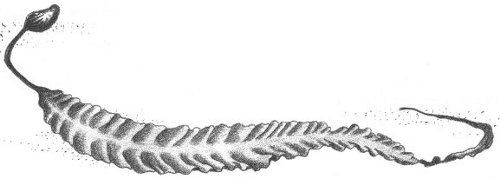

This is the best-known worm on the beach because of its desirability as fish bait. During the day it lives in its burrow in the sand, wandering forth at night and swimming about in the water, where it becomes easy prey for gulls and fishes. The skin is brilliantly iridescent in the sunlight.

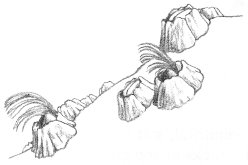

This animal goes through life standing on its head and kicking food into its mouth with its feet! When it is submerged in sea water you can see its shell doors open and its feather-like feet sweep the water for microscopic food organisms. The limy shell first suggests a relationship with the clam, but body structure shows it to be a closer relative of the crab.

These tiny tide-pool creatures look for all the world like the larger edible shrimp served in local restaurants. Actually, these miniature two-inch-long shrimps are edible also, and quite enjoyable if you have the time and patience to collect enough for a meal.

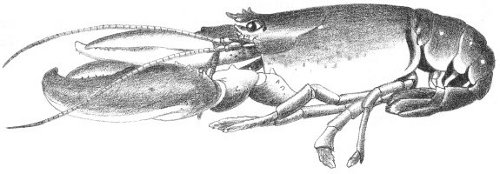

Bits and pieces of Lobster are frequently found on the beach, but seldom the entire animal. The Lobster inhabits deeper water and finds its way to shore only after losing a battle with one of its enemies. A favorable dining size is one or two pounds; however, Lobsters do attain weights up to forty pounds.

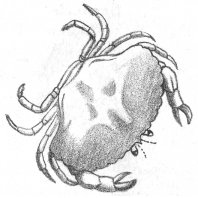

The three very common True Crabs of Crane’s Beach may be found in one search of the tidal pools. They are:

Rock Crab (Cancer irroratus): A brick-red shell, somewhat granulated, with a black and yellowish undersurface.

Jonah Crab (Cancer borealis): Similar in color to the above, but its shell has a more sculptured surface.

Green Crab (Carcinides maenas): A greenish-colored shell. The last pair of legs end in sharp points, rather than being flattened like paddles.

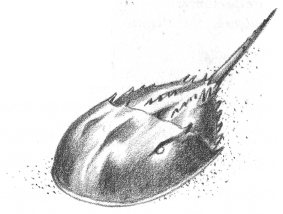

The Horseshoe is not a Crab at all, but is more closely related to the spiders, mites, and scorpions. In spite of its relations, the Horseshoe is a harmless creature whose only protection is its hard shell. Therefore it may be examined freely—a strange “living fossil” that has survived 400,000,000 years of evolution with very little change.

Even without pearls, our Oyster is worth many thousands of dollars a year to shellfish dealers because of its delicious flesh. Its tropical relatives are the pearl producers.

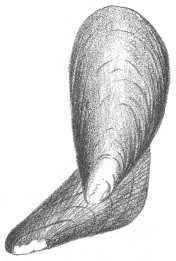

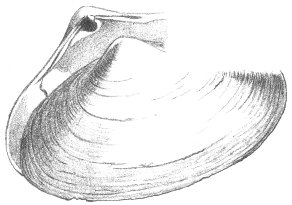

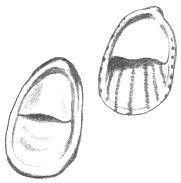

Living mussels are always found attached to rocks or pieces of wood by tiny threads of their own making. Two common mussels are:

Edible Mussel (Mytilus edulis): Smooth, velvety-blue shell identifies it. The animal within is edible and quite delicious. It is commonly utilized as food in Europe but less so here, where we have, and seem to prefer, the Oyster.

Ribbed Mussel (Modiolus demissus plicatulus): Similar to the above but with many distinct ribs radiating on the surface. The Ribbed Mussel is not considered edible. While not poisonous, it is most unpalatable.

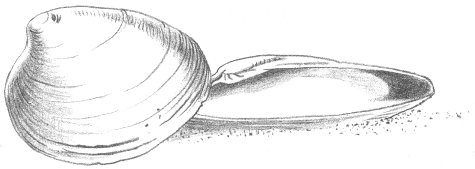

Also called “Quahog,” “Little Neck,” “Round Clam,” or “Cherrystone,” the Hardshell Clam is another highly prized seafood.

These clams are found just a foot or so under the sand, and their empty shells are common on the beaches. This is the Softshell Clam, which we enjoy steamed, baked, or fried, as well as in New England’s famous clambakes and clam chowders.

This is the largest clam on the Atlantic seaboard, growing up to about seven inches in length. It is edible, and just one or two make a large chowder. The shell makes a fine ashtray and an unusual and useful souvenir.

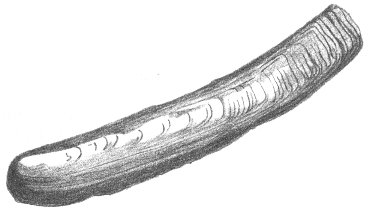

The Razor has a very large foot, with which it can often dig faster than the hand trying to discover it. Although delicious, the Razor Clam is seldom seen on the markets because it is so difficult to capture.

Several species are found at Crane’s Beach:

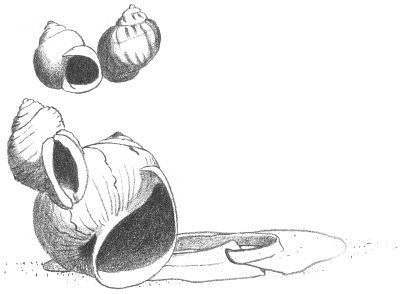

Periwinkles (Littorina): These have a wrinkled shell about the size of a thumbnail. Because they are able to withstand long periods without water, Periwinkles are often found high on a beach.

Rock Purple (Thais lapillus): Has a rough, white shell coming to a point at the top. This snail secretes a purplish dye that was used by the American Indians and the ancient Phoenicians to produce their “royal purple” dyes.

Moon Snail (Polinices heros): Large white shell with almost round shape. The Moon Snail lays its eggs in a sand “collar,” which is frequently discovered on the beach in its dry state.

This animal protects its bare underside by attaching itself to a handy rock with its suction-cup foot. Often there are enough of them to give the rock a warted appearance.

The Starfish seems to like Oysters as well as we do, and it opens them by sheer strength. Oystermen used to tear Starfish apart to destroy them, until they discovered that each arm has the ability to regenerate and become a whole starfish!

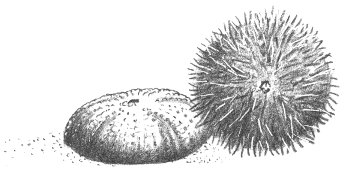

Here is a creature with a scientific name much too long for its size. Indeed, the name is said to be the longest in animal nomenclature. The Sea Urchin is a living fossil with four times as many extinct cousins as living ones.

This is an animal of deeper water and so the bather seldom sees a live, heavily spined specimen. We find the dry, spineless shells on the beach. Wrap them carefully if you wish to take them home, because they are most fragile.

The waters off Crane’s Beach abound with many dramatic fishes such as Cod, Mackerel, Flounder, and Sand Sharks; but we are concerned only with the common tidal fishes that are regularly washed onto the shore.

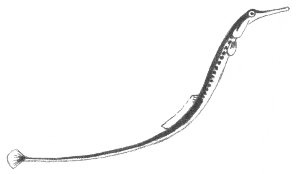

One look at a Pipefish will convince you that it must be related to the Seahorse. It spawns late in the spring, the female laying her eggs in the pouch on the stomach of the male. The male carries these eggs kangaroo-fashion, until they hatch during the summer.

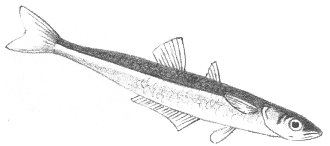

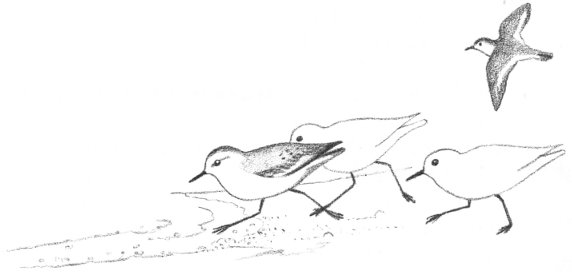

These fish are also an important food item for the Gulls and Terns. Silversides run in schools of a hundred or more, which can be located by the flocks of birds gathered round overhead.

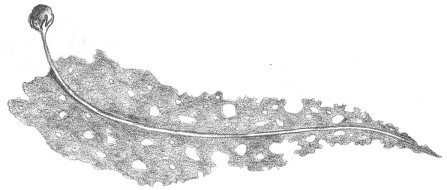

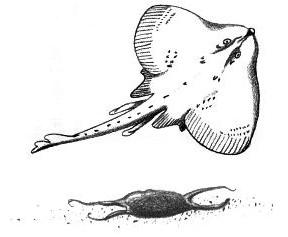

These are harmless fish resembling the dangerous Rays of the tropics, except for their habits. The egg cases of the Skate are rectangular, black, horny envelopes. They are commonly found on the beach, where they are called “mermaids’ purses.” If you find a fresh one and open it, you may discover a miniature Skate inside.

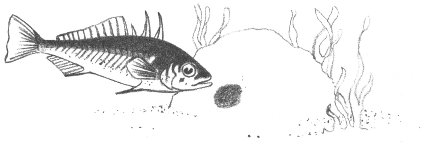

The “Chub,” well known to fishermen, can live for a day covered only with a layer of damp seaweed. It does us a real service by feeding on the mosquito larvae in brackish water.

During the early summer months, the Stickleback builds a barrel-shaped nest, held together with gelatinous threads. After the eggs have been deposited, the male guards the nest with amazing vigor, considering his size.

Thriving abundantly off the beach, the Sand Lance is an important item in the diet of shore birds.

Thus begins our day of beachcombing. Every animal and plant of the sea has a tale to tell and some of the most exciting of all are found in this ribbon-like strip of water in the tidal wash.

For your further investigation, here is a list of reference books:

The insect world populating the dense grass jungles and sand-dune deserts at Castle Neck is generally unfamiliar to the human towering above, yet its principal characters may readily be observed by the keen eye, or, better, the keen eye aided by a simple magnifying glass.

Insects are identified by the presence of six legs. Insect-like animals may be found with more than six legs. Let’s look at these first.

Ticks are quite common at the beach, but only the tourist who ventures into the woods will encounter them. From the tip of a blade of grass they hook on to a warm-blooded animal passing by. In removing a Tick some care is necessary so that the tiny head will not remain embedded in the victim. Ticks can usually be persuaded to let go if touched with a lighted cigarette or daubed with rubbing alcohol.

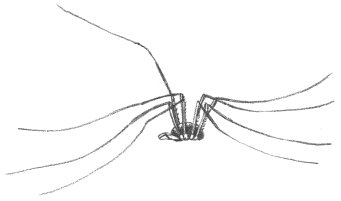

Better known as “Daddy-long-legs,” these creatures resemble Spiders, but are not very closely related to them. They are perfectly harmless and cannot bite. Most of them feed on plant juices or dead insects.

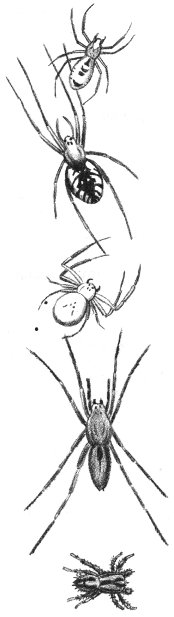

Many spiders are to be found on Crane’s Beach. Most are small, harmless, and difficult to identify. However, some of the general groups may be readily recognized:

Sheet-web Spiders (Linyphiidae): A small spider, usually less than a quarter of an inch long. Its sheetlike web identifies it.

Orb-weaving Spiders (Argiopidae): All of these spiders build their webs like a wheel with radiating spokes. The Orange-and-Black Garden Spider (Miranda aurantia), a large species infesting grassy places in the fall, is typical of the group.

Crab Spiders (Thomisidae): The Crab Spiders do not construct webs, but their crablike shape and the fact that they walk sidewise will identify them.

Wolf Spiders (Lycosidae): This spider hunts its prey instead of building a web and waiting for its meal to happen along. Wolf Spiders are often large and quite hairy. The holes you find in the sand dunes are nurseries constructed by the female Sand Dune Wolf Spider (Lycosa pikei).

Jumping Spiders (Attidae): “Jumpers” have a rather fat body that is heavily covered with hair. They too hunt their prey, often jumping several inches to capture it.

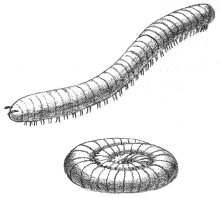

The Sow Bug, commonly called the “Pill Bug,” is usually found hiding under a damp log. It is completely innocuous and will often roll into a ball when disturbed.

The Centipede is usually found hidden in a moist place. It feeds on insects killed by a poison injected through its jaw. Although Centipedes occasionally bite a finger, their poison is so weak that the bite can be ignored.

The Millipede is found in much the same habitat as the Centipede, under a board or rock or inside a rotten stump. It is harmless, and lives for the most part on decaying plants.

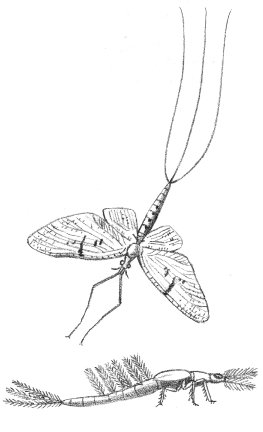

These insects have long, soft bodies and two long “tails.” The first stage in the Mayfly’s life is spent under water in one of the several swampy pools behind the main beach. Early in the spring it changes into the winged adult that is unable to eat. This adult lays its eggs and dies soon afterwards.

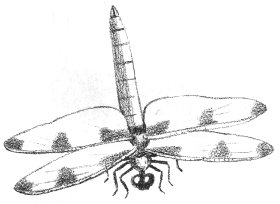

Dragonflies are often called “Devil’s Darning Needles,” but they are perfectly harmless. They frequent wet areas, where they feed on other insects—particularly mosquitoes!

Aside from their smaller, more delicate appearance, these insects look like the Dragonflies. They are found in the same places and have similar habits.

Most Grasshoppers are strong fliers and are easily frightened into flight. The males may be heard singing during the day—a rasping noise produced by drawing the hind leg across the veins on the wing.

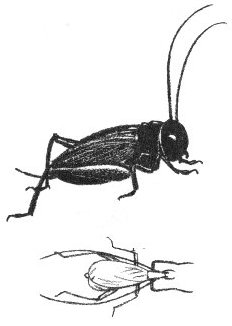

The commonest Cricket here is the Black Field Cricket (Acheta assimilis). The “singing” of the Cricket is produced by the male as he rubs his wings together. Of particular interest is the Snowy Tree Cricket (Oecanthus niveus), which chirps rhythmically. By counting the chirps in one minute and subtracting forty, then dividing this total by four and adding your new sum to fifty, you will have a rough estimate of the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit.

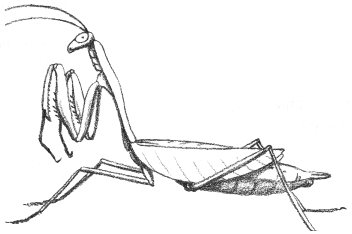

Mantids were once rare in New England but in recent years seem to have been extending their range northward and are now quite common even in the grassy beach area. They are said to be the only insects that can look over their shoulders.

The Earwig hides by day, coming out at night to feed on plant material. Since it does not bite with its pincers, it can be handled freely. Other species are occasionally found. The Seaside Earwig (Anisolabis maritima) is the largest New England earwig. It has more than twenty-four segments to its antennae, whereas the European has no more than fifteen.

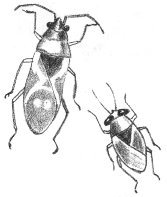

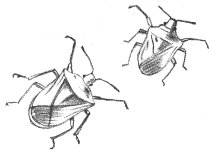

In common parlance, the term “bug” is usually applied to all insects. Actually the following group is the only one scientifically recognized as “bugs.” In all of them, half of the forewing is thickened and leather-like, and all of the mouth parts are designed to pierce their food.

The most common member of this group is the Red-and-Black Milkweed Bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus), which feeds exclusively on Milkweed. A small insect (Geocoris) also belongs to this group. It has a hammer-shaped head and may be found beneath dried seaweed.

There are many kinds of Stink Bugs, so named because of the disagreeable odor they emit when crushed. Some are brightly colored and are commonly found on the fleshy dune plants.

The Woolly Aphid is found only on Alder and Maple trees and may be recognized by its downy appearance. Although it feeds on the tree, it is never common enough to do any damage. The wool is a secretion of wax protecting the insect.

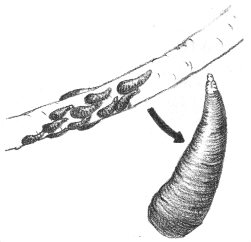

You must look very carefully to discover one of these insects. The young Scales have legs and move about during the month of June. Then they settle down, lose their legs, and secrete a wax shell over their bodies. These Scales are extremely common at the beach, but only the careful observer is likely to see them.

In spite of its delicate shape, when caught the Lacewing emits an odor which has earned it the name “Stink Fly.” Its eggs are laid singly on long stalks because the young, called “aphid lions,” are cannibalistic.

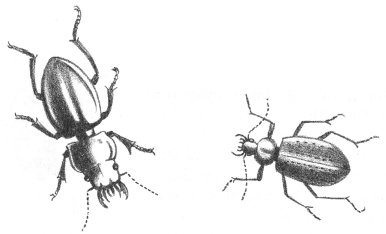

The Carrion Beetles lay their eggs on a dead animal, which they bury as a food reserve for their young. This habit has given them the common name of “Burying Beetles.”

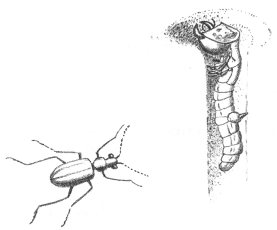

The legs of the Ground Beetle are designed for quick movement. These beetles are mostly active by night. They are beneficial because they eat other insects.

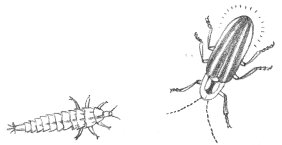

The adult feeds savagely on other insects, killing them with powerful jaws—which can also nip your finger. The larvae are called “doodlebugs” and live in upright burrows in the sand, allowing their jaws to extend above ground to capture unsuspecting prey.

Click Beetles are so named because of the resounding “click” they make when snapping up into the air after being overturned. The adults are strict vegetarians, so look for them on plants.

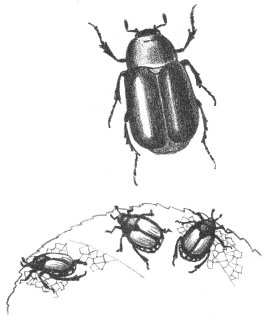

There are more than 1400 species in this group in the United States and more than 30,000 in the world. Two of the most common at the beach are:

May Beetle (Phyllophaga fusca): A large cylindrical brown body. Also called “June Bug,” in May and June it is frequently discovered at night flying to a light.

Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica): The head and forebody are metallic green; the wings are copper color. Introduced from the Orient about fifty years ago, these beetles do great damage to many kinds of plants.

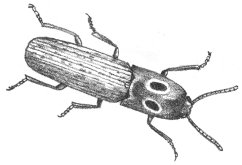

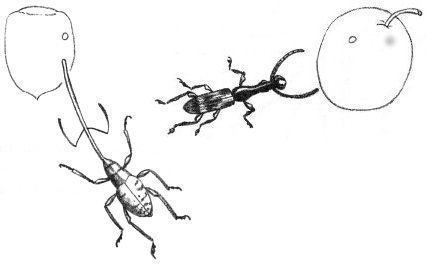

These are very common beetles on the dunes. Their long snout is used to drill into seeds and plant tissues. None of our species do great harm, but they have some unpleasant relatives—the Plum Curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar) and the Cotton Boll Weevil (Anthonomus grandis).

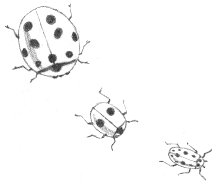

Many kinds of “Ladybug” or “Ladybird” Beetles can be found at the beach. Some feed on plants and others on small insects. The insect-eating varieties are extremely valuable.

The Firefly’s light is produced by the chemical reaction of a substance called luciferin. It is an almost perfect “cold” light, with practically no heat loss. The light is used to attract the opposite sex during mating. The larva of this beetle is the “glowworm.”

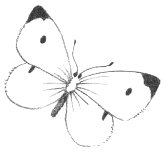

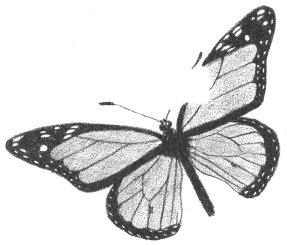

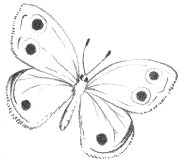

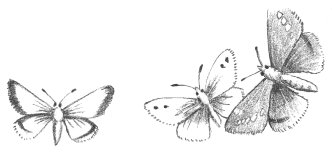

Butterflies may be identified by their threadlike antennae, which are club-shaped at the end; Moths usually have feathered antennae.

The Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio ajax), with yellow and black wings, is the largest butterfly at the beach, and, indeed, the largest butterfly in America. In midsummer you may find one fluttering about flowering plants.

These butterflies are common wherever there is an open area such as the dunes. In other parts of the United States the caterpillars destroy great amounts of alfalfa and cabbage.

The Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is our most common species. Because of its bitter taste the birds won’t eat it.

Nymphs are found from sea level to the mountain peaks. Look for them in the Pitch Pine woods behind the beach.

The Skippers look much like Moths. Their crazy, zigzag flight helps identify them.

Two species occur in our area:

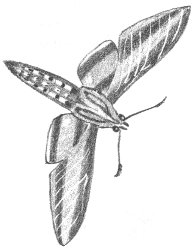

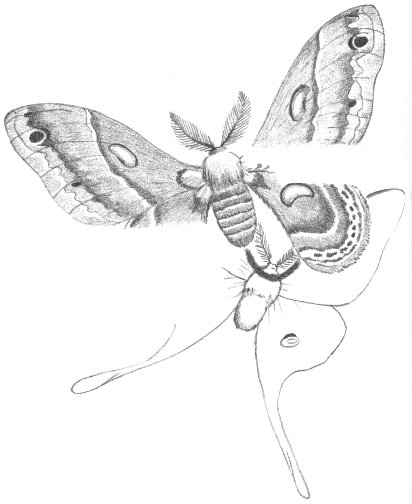

Cecropia Moth (Samia cecropia): It is the largest moth in our area, having varying colors of brown and yellow.

Luna Moth (Tropaea luna): New England’s most beautiful moth, the Luna is pale green, with a brown leading edge on the forewing and a long tail-like extension from the hind wing.

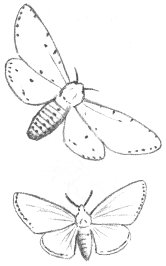

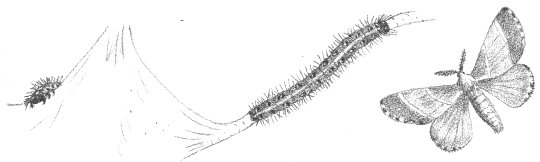

The larvae of these moths are the well-known “Woolly Bear” caterpillars that are covered with a dense coat of rusty-red and black hairs. They are not beneficial. Two common examples are:

Salt-marsh Caterpillar (Estigmene acrea): This caterpillar is covered with rose-colored hair. It feeds on practically every type of leaf in the fall.

Webworm (Hyphantria cunea): It covers the ground for several feet with its silky web. In large numbers, Webworms can denude a tree in short order. Periodic outbreaks of these “Soldier Worms” are common at the beach.

The adult is less readily recognized than is the web home of these caterpillars. In the spring, the webs may be found on most of the Black Cherry trees in the area.

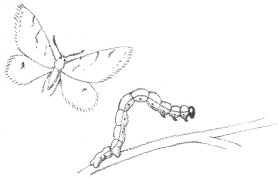

The caterpillars of these moths are the famous “Inch-worms” which move along by arching the body to bring the tail up to the head, then throwing the head out as if measuring the inches with the body.

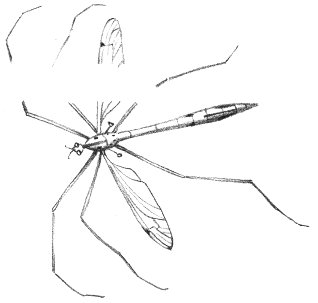

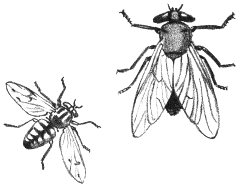

Flies differ from other insects in having only two wings (one pair). The second pair has degenerated into a tiny club-shaped structure that aids the Fly in keeping its balance.

Also called “No-see-ums” and “Sand Flies,” these tiny blood-sucking Flies are altogether too common at the beach. So small that they can pass through window screening, they are best discouraged with a liberal dose of insect repellent.

Crane Flies are associated with the wet, swampy areas behind the beach. In spite of their mosquito-like shape, they can’t bite.

The galls appear as unnatural swellings on plant stems or leaves. Each species of these flies has a specific-shaped gall, made on a specific type of plant, and at a specific place on the plant.

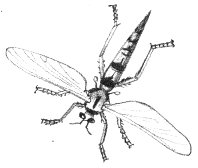

Robber Flies do not bother human beings but they attack other insects, often larger than themselves, in mid-air.

The Syrphids are constantly found among flowers and so are called “Flower Flies.” They are nearly as important as bees in pollination. All are harmless to us.

Only female Mosquitoes bite. They must have one meal of blood before they can lay eggs. We have eighteen species of Mosquitoes in our area.

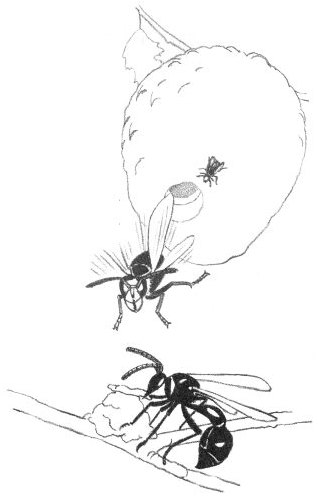

Ants are social insects, and our species is found in large or small colonies everywhere. Ants are also the most common insect. Two readily recognized types are:

Carpenter Ant (Camponotus herculeanus pennsylvanicus): A large black ant that is found burrowing in damp wood. The labyrinth-like tunnels in rotten wood will aid you in finding a colony.

Mound Ant (Formica exsectoides): Produce the well-known “ant hills,” which may be six inches to a foot in diameter.

Bald-faced Hornet (Vespula maculata): This is a black wasp with white markings. The distinctive nest is made of paper manufactured from wood pulp gathered by the insect from dead trees or old fence posts. At the end of the season, it may be as much as a foot or two in diameter. The only safe time to collect these nests is during the winter months!

Potter Wasp (Eumenes fraternus): The Potter Wasp constructs a “clay pot” on branches of trees, particularly Red Cedar, which it fills with paralyzed caterpillars as food for its young.

Bumblebees (Bombus, species): Bumblebees are common visitors to flowers. Their heavy body seems much too bulky for flight. The bee makes its nest in old mouse nests on the ground and a careful search for such nests will generally result in discovery of a Bumblebee’s home.

Honey Bee (Apis mellifera): The well-known Honey Bee was brought to this country from Europe. It has now become a common “wild” bee as well as a domesticated species. You may find some wild-bee colonies in hollow trees, particularly on Castle Hill.

Insects are everywhere and it is easy to collect them. Practically no expense is required to produce a very beautiful collection. Some of the seaside insects are most unusual and not available elsewhere, so it would be well to start your collection right here. Some references that will help you are:

Mammals are defined simply as warm-blooded animals that have hair and nourish their young on milk. They are considered the highest form of Earth life. They are common everywhere, but their secretive habits make observation difficult. You may consider yourself quite fortunate if you see even one or two of the mammals living on Castle Neck during a single visit here.

In this chapter lengths given are measurements from the nose to tip of the tail.

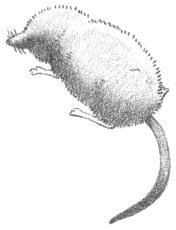

This little mammal is a creature of damp areas and is generally associated with damp forests. It makes burrows just under the surface of the ground. It is the only poisonous mammal in the United States and uses its venom to stun and kill its prey. However, the only result of a nip on your finger will be considerable swelling. Because of its insect-eating habit the Shrew is a most beneficial animal.

This is the most common shrew on the Neck. It is found roving about the salt marshes in search of insects. It hunts during the day as well as at night, generally keeping concealed under a grassy cover.

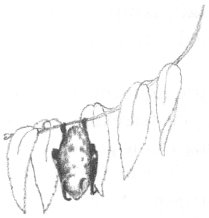

Everyone can identify Bats. Their fingers are extended and joined with a leathery membrane. Their ears are large to aid in catching the echo of their voice as it is reflected from obstacles. They are most frequently seen at twilight when they flitter over the dunes in quest of the many insects abounding there. Bats have tremendous value because they eat such insect pests as mosquitoes and flies.

We have five major kinds of Bats. They are not easily identified in flight.

and

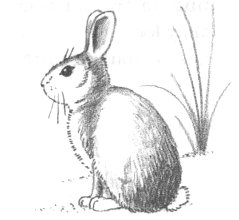

While the New England Cottontail is named for our area, it does extend its range southward to mid-Alabama. It may be separated from other species of Cottontails by a narrow black spot between the ears. It is very common on the Neck. These rabbits stay hidden most of the day, venturing forth at night or early in the morning. Because their diet is exclusively vegetable matter, we do not consider them beneficial.

The Gray Squirrel easily adapts itself to any environment. The large treetop nests constructed of leaves are made by this squirrel. A brood of two to six young is raised once or twice each spring.

This little squirrel will often be heard before it is seen, scolding its terrestrial enemies with a loud clatter from a perch high in a protective tree. In late spring its yearly brood of four or five is raised in a nest of shredded bark built high in a tree.

The Chipmunk is a squirrel that keeps to the ground and seldom climbs trees except to collect nuts. It packs the nuts in two large cheek pouches, and when these are full they look like a very bad case of mumps. The Chipmunk’s nest is found underground.

The Woodchuck has many common names; “Chuck,” “Marmot,” or “Ground Hog” are the ones used in our area. “Chucks” live in deep burrows underground and there is always a great mound of earth in front of their opening. Frequently the “Chuck” is seen standing upright on its hind feet surveying its territory from the top of this mound. The same tunnel probably has several other more concealed openings which are used as escape hatches. The Woodchuck hibernates far below the ground during the winter months, and in the northern United States never comes out on February 2, “Ground Hog Day.”

The Muskrat is an aquatic mammal and is always found in association with water. It is very common in the marshy areas of the beach and may frequently be seen swimming about in such spots. The Muskrat’s fur has become specialized for its aquatic existence and is water-proofed with a heavy layer of oil. Muskrats feed extensively on the marsh plants. In late fall they construct large dome-shaped homes that protrude above the water.

These mice are common all over the Neck. They are nocturnal and may be discovered in the daytime hiding under boards that have washed onto the shore, or they may be found in the wooded areas behind the main beach. Their small nests are constructed out of fur and grass and are located in depressions in the ground, frequently under a board or log. When the original owners vacate these nests they are often taken over by Bumblebees, Centipedes, Earwigs, and other secretive creatures.

The Meadow Mouse is by far the most common mammal of Castle Neck. Its burrows may be seen just under the grass in all areas having ground cover. It feeds on many of the trees in the area, chewing the bark around the base. This girdling will eventually kill the tree. While this habit makes Meadow Mice undesirable, they fortunately prefer the smaller herbaceous plants when they are available. Although common, Meadow Mice are seldom seen because their days are spent running through their burrows. These may extend over an area of many square yards.

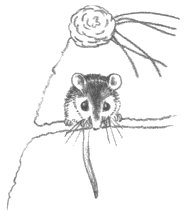

Occasionally when one is walking in the grassy fields, a Jumping Mouse will suddenly bound away in leaps averaging three or four feet. If it is really frightened, these leaps may carry the mouse as far as ten feet. In the United States the Jumping Mouse is much more closely related to the Porcupine than to true mice. Un-mouse-like, it hibernates in an underground nest during the winter months. Jumping Mice eat both insects and plants.

Only the most fortunate observer will see a Fox, which is most secretive and truly sly in its habits. It digs burrows and produces four to nine young during April. The Fox has been known to adapt its habits to changes humans have made in its environment, and it is most beneficial because it eats thousands of mice annually.

Raccoons are creatures of the night and seldom venture forth in the daylight. They are expert climbers, spending many hours high in a lofty perch, and if pursued they usually seek refuge in a tree or swamp. They feed on frogs, fish, eggs, insects, nuts, corn, and shellfish, which they rinse carefully. The shellfish they skillfully remove from their shells, and often small piles of shells are the only clue to a Raccoon’s presence.

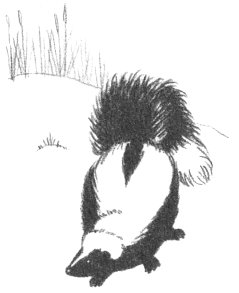

The Skunk is an inoffensive creature that tries hard to avoid people. Even when confronted, it is generally good-natured, relying on its presence to discourage investigation and employing its powerful scent only if pressed. Skunks usually live in holes not far from water. These holes have generally been taken over from another mammal by “squatter’s rights.” From four to seven youngsters are born in late April and they follow their mother about faithfully wherever she goes.

The Mink is extremely rare on the Neck and a careful and thorough search is required to locate one. They are associated with water and feed on shellfish and other aquatic creatures. They are best known for their fur, a favorite for coats. Fortunately, Mink are not common enough on the Neck to warrant commercial trapping.

The Weasel is a vicious, bloodthirsty animal that often kills just for the sport of it. Most of its victims are mice and insects, so its murderous instincts really benefit us. Weasels hunt at all hours of the day or night and all year round. Specimens in our area will occasionally turn pure white in winter and become an “Ermine.”

The White-tailed Deer is certainly the most obvious mammal on the Neck and is readily seen if one will take a short stroll in the wooded area behind the main beach or farther out on the Neck. There are probably close to one hundred deer here, a number approaching overpopulation. They feed mostly on grasses and the more succulent plants. Usually deer produce twins in early summer (June). The fawns are light tan and spotted with white. Deer may be seen readily in early evening when they come into the open fields to browse. They seem to have become quite accustomed to human observers and will frequently be as interested in you as you are in them.

Occasionally Whales, Seals, and Porpoises are sighted off the beach. These are true aquatic mammals. We have only listed the mammals regularly found living on the Neck. To see all of them is a summer’s project, and to study their life histories is equally exciting and challenging.

A few books to help you are:

More than any other form of nature, birds invite the notice of the casual naturalist. Their specializations, their plumage, and their song all serve as attractive bait for our attention.

It is not surprising, then, that more books have been written about birds than any other life form, and that many of these have been directed especially to the layman.

Although more than 150 species of birds may appear during the course of a year at Crane’s Beach, only a small number will be described here in any detail. Many of these will be summer birds that regularly nest on Castle Neck.

The common and scientific names of the birds listed below are in accordance with the nomenclature in the latest edition (5th) of the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-list (1957).

This is the familiar “Sea Gull,” one of many species so called. Its value as a beach scavenger and “garbage collector” has earned it protection by the federal government. While preferring the rocky coasts of Maine for nesting, the Herring Gull is by far the most familiar, if not the most common bird found at Crane’s Beach.

This beautiful gull, like its common cousin, is a scavenger. It is larger and more antagonistic than the Herring Gull and will often steal its food. In Maine, where both breed, the Great Black-back frequently feeds on the Herring Gull’s eggs or nestlings.

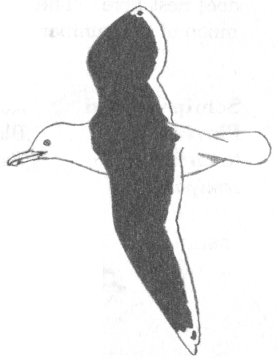

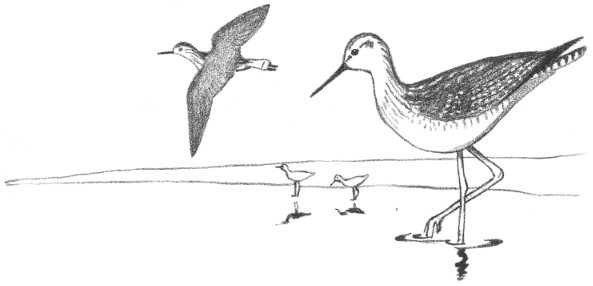

These delightful, graceful birds are again nesting at the tip of the Neck. Their nest has been described earlier (page 7). Under government protection, their numbers have been increasing rapidly. Keep a sharp watch and you may spot an Arctic or Roseate Tern, both very similar to the Common. It is entertaining to watch the Tern fish. It hovers against the wind in one spot just off shore—then suddenly drops into the water, only to reappear again in a moment with some morsel of food. Repeated again and again, this performance becomes a real show which even the most uninterested sun bather cannot ignore.

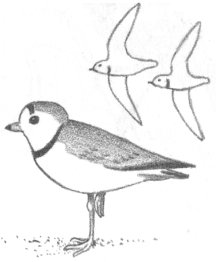

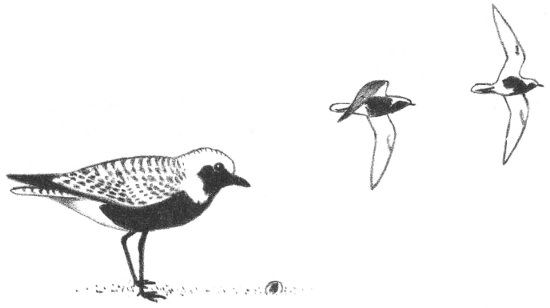

This rather rare shorebird so perfectly matches the dry sand on which it hunts that it is often completely invisible until it moves. If the sparsely lined nest is discovered, the parents go into a “broken wing” act to draw attention to themselves and away from their eggs or young. The four light buff eggs marked with black are laid in May.

Although rare, the Piping Plover has been described in detail because it does nest here. The following five birds are very common on the Neck during much of the summer but do not nest on New England beaches.

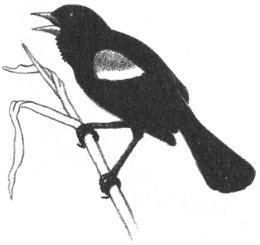

The male Redwing is familiar to everyone. His beautiful black plumage with red shoulder bars allows a rapid identification. He is usually seen flitting about over a marsh attempting to attract the attention of some admiring female. The nest is built in a shrub on the marsh in late May or June. Ordinarily it is well concealed, and often the only indication of its existence is the loud scolding of the anxious parents when intruders approach.

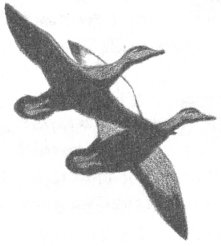

This heavily hunted waterfowl continues to breed even in well-populated areas. Its nest is found here on the edges of the many fresh-water pools that dot the Neck in association with the swamps. About nine white or buff-colored eggs are produced in May. After nesting, these ducks may still be seen feeding on submerged plants. They obtain their meal in a crazy “dabbling” fashion, standing on their heads so that only the tail protrudes above the surface.

Although most active at night, these herons may be seen throughout the day resting or feeding. They wade about in both the fresh and salt marshes in search of fish or crustaceans, which they seize with their long bills. This heron nests only rarely, if ever, on the Neck now, but thirty years ago great rookeries were found here. These birds are still to be found on the Neck in fair numbers even though man’s invasion of the area has reduced its desirability as a nesting place.

During the summer this handsome bird of prey is a familiar sight soaring close to the ground over all large marshy areas. In flight it holds its wings at an angle over its back, rather than parallel to the ground as do most hawks. It mates for life, bringing forth a brood of young once each summer. The nest is quite un-hawk-like, located on the ground and constructed of tall grasses. The Marsh Hawk leaves the area and migrates southward sometime in early September.

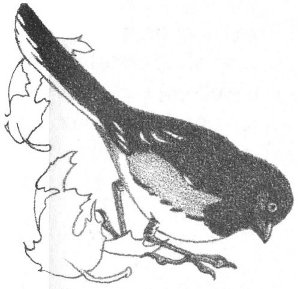

Towhees are more often heard than seen. Their loud scratching noise in the underbrush frequently frightens hikers. If disturbed, they will run on the ground to a place of safety. Their song is very distinctive and has been said to sound like “Drink your tea” with the tea ending extended, or “You and meeeee.” The Towhee generally breeds twice every summer, building its nest in a small shrub or on the ground. This nest is usually as difficult to discover as the bird itself.

Usually seen winging low over water, the Tree Swallow serves to clean the air of water-loving insects. These swallows appear on the Neck in great numbers during the fall, when the scarcity of insects changes their diet to Bayberries. Tree Swallows are among the last birds to migrate in the fall and always the first to return the following spring. Their nests are occasionally discovered in a hollow tree during May or June, but these little birds will readily accept a bird house in lieu of a hollow tree.

Infrequently, one sees a Hawk being attacked in flight by a much smaller bird. This little ball of courage is likely to be the Kingbird. Because of its swiftness in flight, the Kingbird is an able fly catcher and feeds on flies regularly. It builds a nest on the Neck, usually high in a tree, affording it a good lookout post. Watch for this nest in June.

The Thrasher, and its cousin the Catbird, are both common summer residents and nest on Castle Neck. The Thrasher’s loud song, often mimicking other birds, is distinctive because every phrase occurs in pairs. When the nest is approached, the song changes into a series of short clucking noises, with an occasional hiss scolding the intruder. Persistent investigation may uncover the well-constructed nest on the ground. Look for this nest containing four brown-marked blue eggs during late May or June.

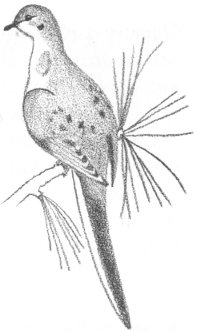

This lovely, delicate dove occurs in every state of the Union. The waste areas on the Neck are especially suited to it because its main foodstuff is Pitch Pine seeds, weeds, and grasses. The Mourning Dove’s nest, placed in a Pitch Pine, is so carelessly made that it is apt to be mistaken for an old nest which is falling apart. Why it doesn’t do just this during the nesting season is a marvel. This beautiful dove is sometimes mistaken for its extinct cousin the Passenger Pigeon.

In recent years this colorful hawk has become quite a city dweller, having little fear of humans. During May, four or five eggs are laid in a deserted Woodpecker’s hole or any convenient cavity. As one would guess from its size, the Sparrow Hawk feeds mainly on insects and seldom on a mouse or sparrow. It is often seen hovering over a field in search of prey or just surveying its feeding territory from a high vantage point.

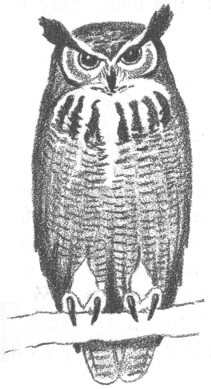

One or two of these magnificent birds can generally be found on any thorough search of the Neck. They hunt the Neck by night, taking a great toll of mice and other small animals. The Great Horned Owl nests earlier than any other New England bird, usually in February or March. So early, in fact, it occasionally returns from a hunt to find its nest and eggs covered with snow. A Great Horned can often be located during the day by following the sound of a noisy flock of Crows. These birds spend hours screaming and scolding Owls whenever they find one sleeping during the day.

On first discovery, this warbler is likely to be identified as an escaped canary. Indeed, it is oftentimes called the “Wild Canary.” It has a very charming, persistent song, which it sings during most of the day. It builds a tiny nest lined with down in the fork of a shrub. Unfortunately, the Yellow Warbler arrives late in the spring and leaves us early in the fall.

A very familiar bird on Castle Neck, the Yellowthroat constantly makes its presence known by a bright “witchity-witchity” song, sounding as though it is asking “What-cha-see?” Its nest is built on or close to the ground and is a rather bulky affair, much larger than seems necessary for so small a bird. As with most of the warblers, the Yellowthroat’s diet consists entirely of insects—a characteristic that makes it a most valuable guest.

A few tourists visit the beach during the winter. It is generally considered to be a “dead” time of year. Yet the birds abound here, and many may be found only during the cold months. Five examples are:

All summer long the Loon lives in the quiet of some hidden northern lake, but in the winter it moves out into the ocean. The winter seas are cold and savage, and yet the Loon takes them in stride. It is a powerful swimmer and can dive easily and deeply. The voice of the Loon, heard only in summer, is very distinctive; the loud, “crazy” laughing call is responsible for the saying “As crazy as a loon.”

The Horned Grebe spends most of its time on the water, frequently even sleeping there. It has also learned to preen itself in water by rolling over on its side. Grebes swim and dive actively, catching many small fish and crustaceans. When frightened into flight they will run many yards across the surface of the water before finally hurtling into the air.

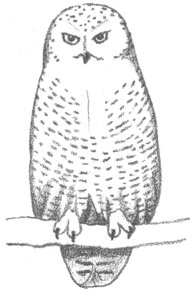

The Snowy is a day-flying owl and therefore may be seen perched high on a sand dune looking around for mice. Its home is in the Arctic tundra, where it feeds on Lemmings. When these are scarce during the winter, the Snowy migrates southward to new feeding grounds. Because it is not used to humans, you can often get quite close to this owl before it will be frightened into flight.

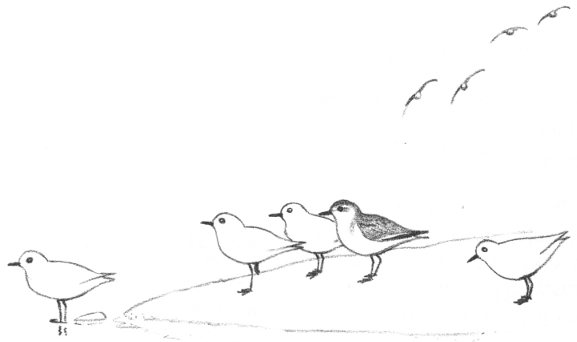

From its breeding grounds in the Arctic, this large sparrow-like bird comes to Crane’s Beach only in the winter. It is at home during the hardest, most severe snowstorms. One may stand on the verge of frostbite and watch large flocks of Snow Buntings flitting about, whistling in a cheerful tinkling song. Look for them among the dunes or marshes, where they feed on the grass and weed seeds.

The Ipswich Sparrow is an occasional visitor to Ipswich. It was isolated years ago on desolate Sable Island off the coast of Nova Scotia. It breeds only on Sable Island, but its winter migrations cause it to wander along the Atlantic Coast. It was first reported in 1868 from the dunes on Castle Hill, hence its name Ipswich Sparrow. When observed, this bird is most often found among the debris left at high tide on the upper beach. It is quick to fly when disturbed and, upon landing, will run for several yards to lose itself in the Beach Grass.

It is obvious that this chapter serves only to introduce you to the great variety of bird life awaiting the interested naturalist. To continue your study, consider the purchase of a good binocular and one or all of the books listed below.

Here are sixty of the most common birds you can expect to find at Castle Neck:

For your added interest the following personal check list of 179 specimens discussed in this field guide allows for recording where and when you make your own discoveries at Castle Neck.

As a matter of convenience, animals are arranged by chapter and broad groupings.

Use the Field Note pages for additional observations.

Date seen Locality