Title: Organization: How Armies are Formed for War

Author: Hubert Foster

Release date: June 6, 2017 [eBook #54859]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

ORGANIZATION

HOW ARMIES ARE FORMED FOR WAR

BY

COLONEL HUBERT FOSTER

ROYAL ENGINEERS

LONDON

HUGH REES, Ltd.

119 PALL MALL, S.W.

1911

(ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

The Author was led to compile this account of Army Organization owing to his inability to discover any book dealing systematically with that subject. Military writers do, of course, make frequent allusions to Organization, but a previous acquaintance with the subject is generally assumed. One looks in vain for an explicit account, either of the principles underlying organization, or of the development of its forms and methods.

It is true that the word Organization figures in the title of more than one Military treatise, but the subject is handled unsystematically and empirically, so that the ordinary reader is unable to realize the significance of the facts. In some cases the term Organization is interpreted in so wide a sense as to include not only Tactics, Staff Duties, and Administration, but any matters of moment to an army. Thus, in the volume of essays recently published, an author of weight states that “Organization for War means thorough and sound preparation for war in all its branches,” and goes on to say, “the raising of men, their physical and moral improvement ... their education and training ... are the fruits of a sound organization.”

vi In the present work, Organization is taken in a more literal and limited sense. The book would otherwise have tended to become a discussion of every question affecting the efficiency of armies. The intention of the Author is to give in broad outline a general account of Organization for War, and of the psychological principles underlying the exercise of Command, which it is the main purpose of Organization to facilitate.

At the same time the organization discussed is not restricted to that of the British Army, but is that of modern armies in general, as well as of individual armies in particular, that of the British Army being described in greater detail, in Part II.

In Part IV. will be found a sketch of the History of Organization, which should interest any one who, like the Author, is not content with knowing things as they happen to be at present, unless he can trace the steps by which they came to be so.

The subject is intentionally not treated with minuteness of detail. To have made the book a cyclopædia of detailed information about organization would have obscured its purpose. It is hoped that the work may prove useful to the increasing numbers of those who have taken up Military work throughout the Empire, and not uninteresting to general readers, and students of history.

Hubert Foster.

Sydney, June 1910.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v |

| ABBREVIATIONS | xv |

| INTRODUCTION | xvii |

| PART I | |

| WAR ORGANIZATION OF THE PRESENT DAY | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| THE OBJECT OF ORGANIZATION | |

| Command | 3 |

| Definition of Organization | 4 |

| The Chain of Command | 5 |

| Units or Formations of Troops | 6 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE FIGHTING TROOPS | |

| The Arms of the Service | 8 |

| Characteristics of the Arms | 8 |

| 1. Cavalry | 9 |

| 2. Artillery | 12 |

| 3. Engineers | 13 |

| 4. Infantry | 15 |

| CHAPTER IIIviii | |

| ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITS OF EACH ARM | |

| 1. Infantry | 17 |

| 2. Cavalry | 21 |

| 3. Artillery | 23 |

| 4. Engineers | 30 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| NEW VARIETIES OF FIGHTING TROOPS | |

| 1. Mounted Infantry | 32 |

| 2. Mountain Infantry | 33 |

| 3. Mountain Artillery | 34 |

| 4. Machine Guns | 34 |

| 5. Cavalry Pioneers | 35 |

| 6. Cyclists and Motor Cars | 36 |

| 7. Scouts | 37 |

| 8. Field Orderlies | 39 |

| 9. Military Police | 39 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| FORMATIONS OF ALL ARMS | |

| 1. The Division | 42 |

| 2. The Army Corps | 44 |

| 3. Cavalry Corps | 47 |

| 4. The Army as a Unit | 48 |

| The Administrative Services for the above | 51 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE STAFF | |

| Composition of Head-Quarters | 54 |

| The General Staff | 57 |

| The Adjutant-General’s Branch | 59 |

| The Quarter-Master-General’s Branch | 59 |

| Staff of Subordinate Commands | 60 |

| Importance of the Staff | 60 |

| Number of Officers allotted to the Staff | 61 |

| CHAPTER VIIix | |

| WAR ESTABLISHMENTS | |

| Their Object and Utility | 62 |

| States and Returns | 65 |

| Reinforcements | 66 |

| Evils of Improvised Organizations | 68 |

| Importance of Preserving Original Organization | 69 |

| The Ordre de Bataille | 71 |

| Importance of keeping it Secret | 72 |

| Consequent drawbacks of Symmetry in Organization | 72 |

| PART II | |

| BRITISH WAR ORGANIZATION | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE EXPEDITIONARY FORCE | |

| Its Composition | 78 |

| Composition of Subordinate Commands | 80 |

| Strength of the Sub-Commands, and of Whole Force | 83 |

| Strength of Units of each Arm | 85 |

| Composition of their Head-Quarters | 86 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE EXPEDITIONARY FORCE (continued) | |

| ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES | |

| Their Directors | 88 |

| Organization of the Lines of Communication | 90 |

| The Main Services, having Units with the Fighting Troops | 92 |

| 1. Service of Inter-communication | 92 |

| 2. Transport | 97 |

| 3. Supply | 101 |

| 4. The Medical Services | 106 |

| CHAPTER Xx | |

| THE EXPEDITIONARY FORCE (continued) | |

| SERVICES ON THE LINES OF COMMUNICATION | |

| 5. The Veterinary Service | 111 |

| 6. The Ordnance Service | 112 |

| 7. The Railway Services | 115 |

| 8. The Works Service | 116 |

| 9. The Postal Service | 117 |

| 10. The Accounts Department | 118 |

| 11. The Records Branch | 119 |

| 12. Depôts for Personnel | 120 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Territorial Force | 121 |

| The Army of India | 122 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| SPECIAL FEATURES OF BRITISH WAR ORGANIZATION | |

| Their Object and Advantages | 125 |

| PART III | |

| ORGANIZATION OF FOREIGN ARMIES | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| WAR ORGANIZATION OF THE FIGHTING TROOPS | |

| Normal War Organization | 140 |

| Organization of each Army | 141 |

| 1. Germany | 141 |

| 2. France | 145 |

| 3. Russia | 147 |

| 4. Austria-Hungary | 148 |

| 5. Italy | 150 |

| 6. Japan | 151 |

| 7. Switzerland | 152 |

| 8. United States | 154 |

| CHAPTER XIVxi | |

| COMPOSITION OF NATIONAL ARMIES | |

| Armies of First Line | 155 |

| Armies of Second Line | 156 |

| Reserves | 158 |

| War Strengths of the Various Powers | 160 |

| PART IV | |

| HISTORY OF ORGANIZATION | |

| INTRODUCTION | 165 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| ORGANIZATION IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY | |

| Origin of Organization | 167 |

| Earliest Regimental Organization | 171 |

| The early Standing Armies of Europe | 175 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| THE EVOLUTION OF INFANTRY | |

| Early Origins—Pikes—Firearms | 177 |

| Infantry under Maurice of Nassau | 180 |

| Regiments—Brigades—Battalions | 180 |

| Infantry under Gustavus Adolphus | 182 |

| French Infantry in Reign of Louis XIV | 184 |

| Fusiliers—Grenadiers—Light Infantry | 186 |

| CHAPTER XVIIxii | |

| THE EVOLUTION OF CAVALRY | |

| Early Origins | 192 |

| Origin of true Cavalry in the “Reiters” | 193 |

| Cuirassiers—Carbineers—Dragoons | 194 |

| Cavalry under Maurice—under Gustavus—under Cromwell—under Frederick | 195 |

| Light Horse—Hussars—Lancers | 197 |

| Cavalry Brigades—Divisions | 198 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| THE EVOLUTION OF ARTILLERY AND ENGINEERS | |

| The Artillery | 199 |

| Early Origins—the Artillery Train | 200 |

| Battalion Guns—Heavy Guns | 201 |

| Improvement in Artillery Organization under Frederick | 202 |

| Horse Artillery—Batteries formed—Military Drivers | 202 |

| Divisional and Corps Artillery | 203 |

| The Engineers | 204 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| ORGANIZATION IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES | |

| The “New Model” Army | 206 |

| The Armies of the Eighteenth Century | 210 |

| CHAPTER XXxiii | |

| ORGANIZATION IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY | |

| Changes in the Wars following the French Revolution | 215 |

| Divisions—Army Corps | 215 |

| Details of Napoleon’s Organization | 218 |

| Composition and Strength of his Army Corps | 219 |

| Prussian Organization in the Nineteenth Century | 221 |

| Proportion of Cavalry and Guns to Infantry | 223 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| THE EVOLUTION OF THE STAFF AND ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES | |

| 1. The Staff | 225 |

| The General Staff | 228 |

| Napoleon’s Staff | 230 |

| Prussian Staff in 1870 | 231 |

| 2. The Supply and Transport Services | 232 |

| 3. The Medical Organization for War | 234 |

| PART V | |

| MILITARY COMMAND | |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| PRINCIPLES OF COMMAND | |

| Mode of Exercising Command | 239 |

| Instructions—Orders | 242 |

| Limits of Initiative in Staff Officers | 246 |

| CHAPTER XXIIIxiv | |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ARMIES | |

| The Dynamic Crowd | 248 |

| Its Qualities | 250 |

| Its Leaders | 251 |

| Armies Dynamic Crowds | 252 |

| Their Leaders | 252 |

| Will Power—Prestige | 253 |

| APPENDIX A | |

| Origin of Military Terms | 257 |

| APPENDIX B | |

| Remarks on Military Nomenclature | 265 |

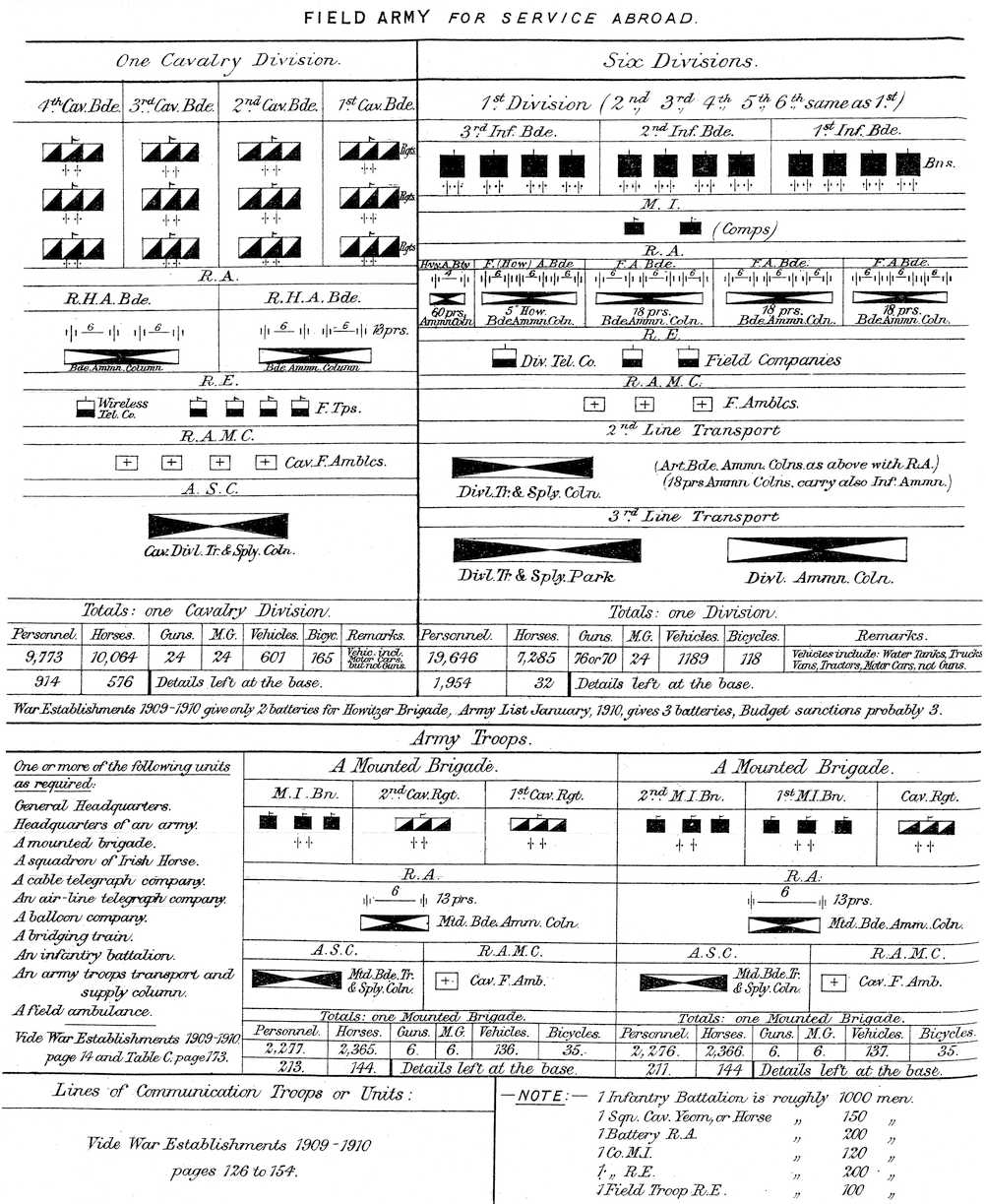

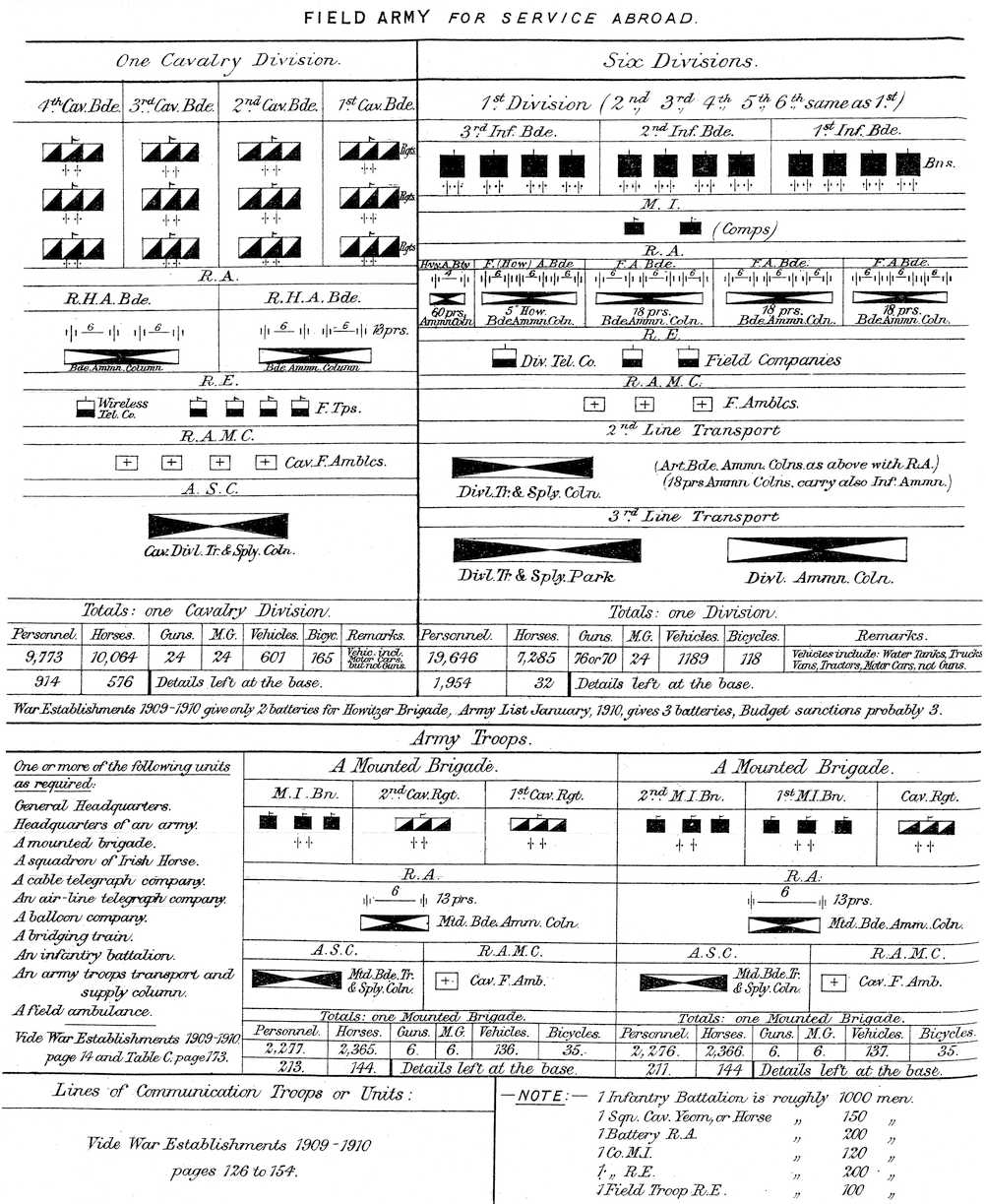

| DIAGRAM OF FIELD ARMY | 136 |

A few abbreviations of familiar military terms have been used. These are:

| A.G. | Adjutant-General. |

| Q.M.G. | Quarter-Master-General. |

| C.-in-C. | Commander-in-Chief. |

| A.D.C. | Aide de Camp. |

| N.C.O. | Non-Commissioned Officer. |

| Q.M.S. | Quarter-Master-Sergeant. |

| A.S.C. | Army Service Corps. |

| R.A.M.C. | Royal Army Medical Corps. |

| T. and S. | Transport and Supply. |

| L. of C. | Lines of Communication. |

The Organization which it is the purport of this work to describe is that of Armies in War. The vast subject of Organization in Peace opens out too wide a field. It is necessarily different in every country, being based on national idiosyncrasies, complicated by political, economic, and topographical conditions. These factors, however dominating in peace, have less influence on organization for war. The general features of War Organization are identical in all modern armies, as they represent the consensus of expert opinion, based on the practice of great leaders, and on the lessons learnt from success and failure in recent wars.

There are, of course, many differences in detail, due to the varying historical development of each army. These really indicate the degree to which the conservative sentiments retarding improvement have been bent to the changes necessitated by progress. The strength of tradition and inertia in armies is enormous. No human institutions—not the Law, not even the Church—so cherish ceremonial and reverence tradition and custom, or remain so long blind to changed conditions. Inxviii military arrangements the very object of their existence often seems obscured by a haze of unessential conventions. Military methods, once suitable, soon pass into mere forms, which it is considered sacrilegious to modify, however useless or even harmful they have become.

Among scores of examples of the extraordinary conservatism of military organization we may remember that England had no transport organized in the army she landed in the Crimea. We find in Germany Army Corps of two Divisions, Divisions of two Brigades, and Brigades of two Regiments, although two is the worst possible number of parts in a unit, according to Clausewitz and common sense. The twentieth century saw Cuirassiers in France, Rifles in most armies, and the “parade step” in Germany. The protean follies of uniform are only now partially disappearing.

The historical portion of this work shows the curious way in which a new form of organization, designed for a definite end, often loses sight of its purpose and reverts to a mere variety of the old type, which then has to put out a new development for the original end. This is the history of the numerous attempts to provide for Light Infantry duties at the front.

The above considerations account for a number of odd survivals in modern armies, and explain many differences in their organization. These, however, are always tending to diminish under the pressure of the hard facts of war, which have little respect for national prejudices and traditions.

A study of the present British war organization,xix described in some detail in Part II., will show that it embodies a large number of the changes suggested by recent wars, and demanded by the trend of modern military thought. The British Army is the latest to be reorganized, and the opportunity has been taken, with no less courage than wisdom, to adopt in every Branch all changes tending to fit it better for the fighting of the immediate future, as far as this can be forecast. When the reorganization is completed it is not too sanguine to believe that the British will be the best organized army of the day.

In the British Field Service Regulations of 1909, Part ii., chap. ii., par. 1, it is stated that the main object of War Organization is to provide the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in the Field with the means of exerting the required influence over the work and action of every individual. This, it is pointed out, will ensure the “combination and unity of effort directed towards a definite object,” on which mainly depends the successful issue of military operations. In other words, the primary object of War Organization is to facilitate Command—that is, to ensure that every man in the force acts promptly in response to the will of the Commander.

A secondary object of War Organization is to facilitate Administration, or the supply of each individual in the Force with all that he requires to make it possible for him not only to live, but to move and fight. If a Force be ill-organized the process of supply will be slow, uncertain, and incomplete, the spirit and health of the men cannot4 fail to suffer, and the efficiency of the Force as a fighting body to be reduced.

Both these objects of Organization—Command and Administration—are, however, really inseparable. The channels through which they act are identical, and the Authority which commands is necessarily responsible for the Administration which enables his Orders to be carried out. Solicitude for the well-being of the soldier is one of the most certain means for obtaining influence over him, and may be called the main lever for exercising Command. Some further consideration of the psychological factors of Command, which are essentially germane to the study of Organization, will be found in Part V. of this work.

The word “Organization”—literally, providing a body with organs—has been more elaborately defined, by Herbert Spencer, as “the bringing of independent bodies into independent relations with each other, so as to form a single organic whole in which they all work together.” He goes on to explain this as follows: “In considering the evolution of living forms we find simple, homogeneous, and non-coherent elements developing into a complex, heterogeneous, and coherent whole, an organism controlled by unity of purpose, and comprising a number of functional parts, which work together in mutual dependence for the common good.” This definition applies closely to the organization of military bodies. The elements are represented by the individual soldiers, the5 functional parts by the units, while in the Army we see the living organism.

Just as in nature no mere assemblage of cells, or even of functional parts, can form a living organism, so no collection of individuals, however efficient—or of small units, however perfect—can in any true sense be called an Army. It might have the appearance of a real military force, but it would only be suited to peace. The means by which it can be made fit for war is Organization, without which it would be little better than an armed mob—inert, or at best irregular and spasmodic in its movements. An ill-organized army is not capable of co-ordinated or of sustained action, owing to the difficulty of either directing its movements or supplying its wants.

It is obvious that a Commander of a Military Force cannot deal personally and directly with all those under his command, but only with a limited number of subordinate commanders. Each of the latter in his turn conveys his will to his own subordinates, and this gradually broadening system, called the Chain of Command, is carried on, till every individual of the Force receives his Orders. These Orders are founded on the original directions of the Commander-in-Chief, with modifications and details added by each lower authority in the chain, so as to suit the special circumstances of his own Command.

This principle combines unity of control with decentralization of command and devolution of6 responsibility. In no other way can ready and effective co-operation of all fractions of the force to a common end be ensured.

The method, generally speaking, of War Organization is to provide the links in the chain of Command by a systematic arrangement, in suitable groups, of the various troops composing the Army. The smallest groups, or Units, are combined in larger ones, and these again are built up into more complex bodies, and so on, until the whole Army is formed in a small number of large bodies, whose Commanders receive direct orders from the Supreme Commander.

For want of a general name for these bodies it is usual to speak of them all as Formations. The term Units, which is often used, properly applies only to the elementary groups. The largest Formations are conveniently styled the Subordinate Commands of the Army.

Each category of Formations forms a step in the pyramid of organization, in which the lowest layer is formed by the Units, the top layer by the Subordinate Commands, and the apex by the Supreme Commander. The Commanders of each Formation, from the largest to the smallest, form the successive links in the chain of Command.

All Formations should have such a strength and composition as to be in the best relation and proportion to each other, and to the larger groups which they help to build up. Every Formation should be formed of at least three subordinate Units.7 This gives the Commander of the whole due importance over his Subordinate Commanders, and ensures his retaining an adequate Command whenever he wishes to detach one of his Units. This would not be the case were there only two Units in the whole, for, if one were detached, the Commander of the whole would be left exercising Command only over the other Unit, already adequately commanded. The Superior Commander would then be superfluous, and harmfully interfering with his subordinate. A Formation with three or more Units can be readily broken up when desired, without affecting the principles of Command, and is therefore more flexible and efficient than one with only two Units. Emphasis is laid on this point by Clausewitz in his classic work “On War.”

It is the purpose of the next few chapters to describe the Units and Formations constituted in modern armies. But, in order to explain the reasons which have dictated their strength and composition, it is necessary first to describe the various kinds of Troops which go to make up an Army, and their respective methods of fighting, and functions in war. Organization exists to facilitate fighting, and cannot be explained without some discussion of Tactics.

Military Forces are of two distinct categories: Fighting Troops, which carry out the actual operations; Administrative Services, whose function is to provide the Fighting Troops with all that they require to keep up their strength and efficiency.

The Fighting Troops consist mainly, as they have for centuries, of what are known as “The Three Arms of the Service”—Cavalry, Artillery, and Infantry. Besides these, however, the introduction of warlike inventions and the increased complexity of modern war have brought into being a fourth Arm—Engineers—as well as varieties of fighting troops for special purposes, which are virtually new Arms, such as Mountain Artillery, Machine Guns, Cyclists, and Mounted Infantry.

The continued existence of the Arms of the Service for centuries is due to a gradual differentiation9 of their mode of fighting, owing to changes in weapons, and progress in the Art of War. Each Arm has its peculiar fighting characteristics and its own sphere of action in war, which will be discussed in this chapter. In the next will be described the organization which each Arm has evolved in order to enable it to carry out its functions in war.

Cavalry has been termed “The Arm of Surprise,” owing to the rapidity with which it can move. This gives it the power to act with little warning, and from an unexpected direction, against the enemy, and thus to take advantage of the fleeting opportunities which occur in war for sudden attack and surprise. It is par excellence the mobile Arm, and the one best adapted for taking the offensive.

Its power of making long and rapid marches enables it also to be thrown far to the front, so as to give to the Army protection from surprise, and to gain the information as to the movements and dispositions of the enemy, without which the Commander will be at a loss in forming his plans.

Cavalry is required too for the effective pursuit of a beaten foe who would elude the slow-moving Infantry. It is also the best Arm to cover a retreat, as it can check the pursuit and then effect a rapid withdrawal before being completely over-powered.

The disadvantage of Cavalry is that it is very dependent on the nature of the country for its action. It is useless in steep, rocky, or marshy ground, or among enclosures, and in woods. Cavalry is also costly to raise, and requires long training for efficiency. It suffers too from great wastage of horses in war, due to unavoidable fatigue, short rations, and bad weather, from which causes horses suffer even more than men.

In the combat, Cavalry acts both by shock and by fire, the latter action being now more developed than of old. Indeed the main difference between the horse-soldiers of the different armies of to-day is whether their training is directed rather to mounted shock-action, or to fire-action dismounted; in the latter case, their rapidity of movement is mainly helpful in getting them to the right place at the right time to use their fire. The ideal Cavalry would be equally capable of shock and fire action, and could be employed either mounted or dismounted, as circumstances and the judgment of the leader might dictate. The British is perhaps the only Cavalry (as General Négrier, Chief of the French General Staff, once said) which is trained to this ideal. The Cavalry of Russia, Japan, and the United States tends rather to action by fire on foot; that of most Continental armies to shock action mounted.

The use of Cavalry in modern war lies less in its action on the battlefield than in the all-important work of reconnoitring the enemy, and protecting its own army—that is, of providing Information and Security. The tendency of the employment of Cavalry in modern war is towards an entire separation of these two duties.

For the first duty, Reconnaissance, Cavalry must try to find out the strength and situation of the enemy’s forces, and the direction in which they are moving. For the second duty, Protection, Cavalry must form a screen along the front of the Army, so as to shelter it from being observed by the enemy’s Cavalry, and to give early notice of the direction of any attack.

These two duties of Cavalry cannot be performed by the same body. To get information Cavalry must be able to break through the enemy’s screen, which can only be effected by beating his Cavalry, and requires concentration of force. Reconnoitring Cavalry will often also have to work round the flanks of the enemy. Both these modes of action must necessarily leave a large portion of the front of its own army uncovered.

On the other hand, protection demands a dispersion of the Cavalry along the whole front of the Army, which is exactly opposed to the concentration generally required for effective reconnaissance.

Again, reconnoitring Cavalry is only concerned with keeping in touch with the enemy, while protective12 Cavalry must remain in touch with its own army.

The distinction between these functions of Reconnaissance and Protection has become recognized of late years, owing to the increased importance of the Strategical direction of the large masses of troops now in the field, which are not easily diverted when once set in motion, and are more than ever dependent on their Lines of Communication. Their Commander needs constant and recent information about the enemy, by which to direct his movements and secure his flanks from attack. Hence has arisen the practice of providing two distinct bodies of Cavalry—the Independent Cavalry, for reconnaissance by independent action at a distance in front of the Army; and the Protective Cavalry, spread over a wide area along the front of the Army so as to form a screen.

In both cases the Cavalry effect the object by sending out squadrons, which furnish patrolling parties. The duty of these is not only to discover the enemy’s movements, but to make such arrangements for transmitting the information gained that it shall reach Head-Quarters with rapidity and certainty.

Artillery is the most powerful and far-reaching of the Arms in its fire effect, but cannot act by shock. It is the only Arm that can strike the others at such a distance that they cannot retaliate, and can injure material objects. Its morale is less liable than that of the other Arms to fail13 in battle, as Artillery is more dependent on the mechanical than the human element for its action. The guns, too—to which the personnel is attached by sentiment and duty—give a definite point to hold to when other troops are falling back. It is on all these grounds a valuable auxiliary to the other Arms.

Artillery, however, is incapable of independent action—it must always be associated with the other Arms, as it is easily avoided or turned, and, when moving, is helpless against attack. It takes up a great deal of space in the column of march, as well as on the battlefield, where it requires advantageous positions to fire from, and cover for its horses and ammunition, both often difficult to find. Artillery is also very dependent on the weather and the nature of the country for its action, as it requires clear air and good light, and an absence of hills and woods, to allow the object and the effect of its fire to be observed. It also needs good roads, and is more obstructed by mud, ice, or snow on the march than are the other Arms.

Engineers, as a body of officers with men, were only introduced towards the end of the eighteenth century, but officers of that name had been employed for centuries on the Staff of Armies, especially at Sieges.

The Engineers are now sometimes styled “The14 Fourth Arm of the Service,” not so much because they are Combatant Troops, armed and trained like Infantry, as because their work on the battlefield is of interesting tactical importance.

The work with which Engineers with an Army in the Field are charged presents great scope and variety. It may be catalogued under the following headings:

Pioneer Work on the march—i.e. making roads and removing obstacles; water supply; bridging of every sort; collecting, making, and using boats and rafts for ferrying.

Field Work on the battlefield—i.e. clearing the communications and field of fire; marking ranges; demolitions; obstacles; special earth-work (ordinary trench-work and gun-pits being made by the troops who use them).

Searchlights in the field.

Inter-communication Work—i.e. use of telegraphs, telephones, wireless, visual signalling, kites, captive balloons.

Aviation by balloon or airship.

Printing and lithography for Orders and Maps.

Engineers are also charged with the following important work on the Lines of Communication:

Construction, repair, maintenance, and working of railways and telegraphs; provisional fortification of posts; camping grounds; formation of workshops15 and depôts of Engineer Stores; hutting and housing troops; providing hospitals, offices, and storehouses; water supply; roads. At sea bases, piers, wharves, and tramways will have to be provided, and perhaps dredging undertaken, and buoys, beacons, and lighthouses kept up. Engineers will also have to run any plant needed, such as that for providing ice for hospitals, cold storage, electric light and power, gas for balloons and lighting.

Engineers are employed in surveying, or mapping the country passed through by the Army, when this is required in the wilder theatres of operations, like the Indian Frontier.

Besides their duties with the Field Army, Engineers are as necessary as ever for the conduct of Sieges, and the defence of Fortresses, in which services they have constantly been employed for centuries.

Infantry, now the principal Arm, has in modern times recovered the place which it held in the armies of the Ancient World, but lost in the Middle Ages when Horsemen were the Men-at-Arms, or the only fighting men worth considering.

Infantry has for three centuries formed the bulk of every army, being the easiest to raise and train, and the cheapest to equip and keep up, as well as the most useful, of all the Arms. On Infantry falls the brunt of the fighting, and the greatest toil in marching, while it endures the hardships of a campaign better than the mounted Arms. It can be used for attack or defence, in close or16 extended order, on any ground, and in any weather. Infantry can fight with its fire, at a distance from the enemy, like Artillery, as well as by shock, at close quarters, like Cavalry.

But Infantry is slow in movement, and without Cavalry cannot ascertain the operations of the enemy, and will therefore be ill-directed in its own; it is helpless in pursuit, and unable either to complete a victory or cover a retreat. The action, too, of Infantry fire is limited to the range of the rifle and the effect of the bullet, so that it finds in Artillery a useful auxiliary, owing to the greater effect of fire from guns, and the distance at which they can act. Hence Infantry is greatly assisted in its fighting by associating it with Cavalry and Artillery, just as Cavalry is aided by association with Artillery. It is essential, therefore, that not only every Army, but every Body of Troops which may have to fight independently, should have a due proportion of all Arms. This is the reason for organizing Armies in the higher Formations, provided with more than one Arm, as contrasted with the Units composed of one Arm only. The latter, however, are the basis of the higher Formations, and their composition and strength must be considered before describing how they are grouped into larger bodies. Therefore the Organization of the Units of each Arm will form the subject of the next chapter.

The formations in which each Arm is independently organized constitute the tactical units of an Army. Their strength and organization are intimately connected with the way in which they are used in fighting, and have varied little since armies first became regularly organized.

The general composition of these Units of each Arm in modern armies will now be described, beginning with Infantry, the principal Arm.

Infantry, as will be seen in the historical portion of this work, used to be of various natures, such as Guards, Grenadiers, Fusiliers, Rifles, and Light Infantry, which still survive, but as names only. Napoleon said he wanted but one sort of Infantry, and that good Infantry. This aspiration may now be realized. All Infantry, however designated, is of one kind only, and works in the same manner in war.

The formations of Infantry are the Company, the Battalion, the Regiment, and the Brigade.

The Company, with its three officers—Captain, Lieutenant, and Ensign—and its Sergeants and Corporals, has been for centuries the foundation stone of the organization of Infantry. Its Chief, the Captain, is the officer with whom the men are most intimately associated, as he is responsible not only for their drill, discipline, and training, but also for their food, clothing, pay, and lodging. The men’s confidence in their Captain is grounded on this responsibility. It is to him that they learn to look for their well-being, comfort, and redress of grievances, as well as for praise or blame. The Captain is thus in daily contact with the men, and learns to know them, and be known by them. His influence with his men, owing to these personal relations, is the keystone of command and discipline, and makes him their natural leader in action.

To avoid repetition, it may be here mentioned that the same remarks apply to the Squadron and Battery Commanders, who, in the Cavalry and Artillery, hold the same position with regard to their men as the Captain does in the Infantry.

The Company is usually divided into Half-Companies, commanded by a Lieutenant, and into four Sections, each under a Sergeant; but the German Company has three Sections under a Lieutenant. The tactical movements of a Company in action are usually carried out by Sections.

The Battalion of 1,000 men is universally recognized as the Tactical Unit of Infantry. Operations are ordered, carried out, and recorded by Battalions. The Battalion is in modern armies provided with transport to carry its ammunition and entrenching tools, as well as its baggage and immediate supply of food, so as to render it independent.

The Battalion is commanded in foreign armies by a Major or his equivalent, but in the British and Russian Services by a Lieutenant-Colonel. The Battalion Commander is assisted by a Staff Officer, styled his Adjutant, and by a small Administrative Staff.

The number of Companies in a Battalion is, in the British Service, eight, with 3 officers and 120 men each, but in other armies four, with 4 or 5 officers and 240 men.

The system of dividing the Battalion into a few large companies was adopted in Prussia during the eighteenth century so as to economize in officers, partly to save expense, partly because of the dearth of men fit for commissions, in the increasing army of that small country. In the huge armies of to-day this system commends itself for the same reasons; while England and the United States have kept to small companies, with their original strength of about 100 men. Owing to the increasing difficulty of exercising control in battle, small companies give advantages as to Command. They also provide any necessary detachments,20 such as outposts and advanced guards, better than large companies, which may have to be broken up for these purposes. The fact, too, cannot be overlooked, that in an army of small companies there are four Captains more per thousand men, which gives a useful reserve of officers.

Two, three, or four Battalions form a Regiment, designated by a number or by a permanent name, territorial or personal. In the Regiment are embodied the honourable traditions which have accrued in history, and the esprit de corps engendered by them. The officers are on one Regimental List for promotion, and so serve continuously in the Regiment. They thereby acquire a camaraderie, professional feeling, and personal intimacy with each other and with their men, of the greatest value in war. In foreign armies, with short service of two years, it is hardly too much to say that the Regimental Officers really constitute the permanent army, through which there flows continuously a stream of recruits, receiving a professional impress from their officers.

The Regiment is in foreign armies commanded by a Colonel (with sometimes a Lieutenant-Colonel), assisted by an Adjutant and a small Administrative Staff. The British Regiment is merely a peace organization never found as a whole in war, and the Battalion, with its Colonel and his Staff, its Colours and band, its traditions, history, and esprit de corps, represents what in foreign armies we find in the21 Regiment. The battalions of the foreign Regiment are merely its tactical units, just as the companies are to the Battalion.

The Brigade is the largest body formed of Infantry only. In the British Service, where there is no Regimental organization in war, the Brigade comprises four battalions. In foreign armies it is composed of two Regiments (comprising six to eight battalions), a faulty organization for Command purposes, as shown in Chapter I.

Brigades are commanded by a Brigadier-General, with a Staff Officer, who is styled in England the Brigade Major.

Cavalry, like Infantry, was once of many different natures—“Light,” “Heavy,” Hussars, Dragoons, Lancers, etc. These names still survive in the armies of Europe, but the regiments so designated now form practically only one sort of Cavalry, and are all trained for identical action in war, although they still bear their historic names and uniforms, and keep up the old rivalry of their corps traditions.

The formations of Cavalry are the Troop, the Squadron, the Regiment, and the Brigade.

The Tactical Unit of Cavalry has since the seventeenth century been the Squadron of about 15022 men. Its strength in different armies now varies between 130 and 180 men.

The Squadron is divided into four Troops, each of which is commanded by a Lieutenant. The Squadron leader is a Major or a Captain. The British Squadron has both these officers, and four Lieutenants.

The Regiment is the permanent and administrative Cavalry Unit, and like the regiment of Infantry, has its special title or number, its own history and esprit de corps, and its band.

The number of Squadrons in a Regiment varies in different armies, there being generally four, but five in the Italian and Japanese, and six in the Austrian and Russian Services. There are three in the British Cavalry at home, but four in the Yeomanry and also in India. The Regiment thus forms a body of from 500 to 900 men, and is commanded by a Colonel, or a Lieutenant-Colonel, with an Adjutant as Staff Officer, besides a small Administrative Staff.

The Brigade is formed in most armies of two Regiments, but in the British, American, and Swiss armies of three—a superior form of organization for Command, as shown in Chapter I., and one probably better suited for the tactics of Cavalry.

The Brigade is commanded by a Brigadier-General, with a Staff Officer (or Brigade Major).

Artillery is of many descriptions, differing in the guns they use, and their functions in war. Only that brought into the field with an army, as distinguished from Siege, Fortress, and Coast Artillery, will be here described. It may be divided into Field Artillery, Heavy Artillery, and Mountain Artillery.

Field Artillery in the most general sense means the Mounted Branch of the Arm, which possesses mobility, so as to accompany the other Arms. Its personnel does not march on foot, so that the guns can move at a pace beyond the walk, when desired. It comprises Field Artillery proper, or that armed with the Field Gun (or Field Howitzer) and Horse Artillery.

Field Guns form the larger portion of all Artillery in the field. They fire mainly shrapnel, or shell containing small round bullets which are very effective against the enemy’s men and horses, but useless against material objects. In foreign armies they have therefore a small amount of shell filled with high explosive, in addition to the shrapnel.

Field Howitzers use high-angle fire, giving a large angle of descent, so that they can search out the enemy’s trenches. They are provided with high-explosive shell in addition to shrapnel, so as to destroy masonry and field works, which the shrapnel of field guns cannot injure.

Both these varieties of Field Artillery have their24 Officers and Sergeants mounted, and carry their men seated on the gun limbers, or on the wagons, so that they can move at a trot.

Horse Artillery is provided for supporting Cavalry in action. It is armed with a lighter nature of field gun, and has its personnel mounted, so as to be very mobile. It can keep up with Cavalry both on the march and in action, and can move at the gallop when required.

This comprises the heaviest guns and howitzers having sufficient mobility to accompany an army in the field. It uses shell filled with a high explosive, as well as a large shrapnel, and is therefore effective against field works and masonry as well as against men and horses. It differs from Field Artillery in having less mobility, but longer range and much greater effect. It generally comes into action at long ranges, and changes its position as little as possible in action. It will be very effective against the enemy’s artillery and field works, and its great range will allow it to bring oblique fire on the vital portions of his line.

Heavy Artillery is manned by the non-mounted Branch, called Garrison Artillery in England, and Foot Artillery abroad. It requires eight-horse teams, and moves only at a walk, the men marching on foot.

Artillery carried on pack animals is used in hilly, enclosed, or rough country, where wheels25 cannot pass. It is the weakest form of Artillery in shell-power, as it is armed with a light gun, which can be carried on a pack mule. A heavier gun can be carried, if formed of two parts, each about 200 lb. weight, or a load for one mule, which can be jointed together for action. The gun carriages, ammunition, and stores are also carried on mules, and the personnel marches on foot, and is provided from the “Foot” (or “Garrison”) Artillery. The slowness of Mountain compared to Field Artillery is compensated in broken country by its ability to take cover, and to come into action in places inaccessible to Field Guns, so that it can support Infantry more closely.

The Tactical Unit of Artillery is the Battery, of 4, 6, or 8 guns, with 1 to 3 Ammunition Wagons to each gun. Field guns and wagons have six-horse teams; Heavy Artillery has eight-horse teams.

In France, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States all Batteries are of 4 guns.

In other armies all Field and Horse Artillery Batteries are of 6 guns, except in Austria, where Horse Artillery has 4-gun Batteries, and in Russia, where Field Batteries have 8 guns.

Heavy Batteries have generally 4 guns, owing to the number of wagons required to carry a sufficient amount of their heavy ammunition.

Mountain Batteries have 4 guns, except in Russia, where they have 8.

26 The Battery in all armies has a strength of from 130 to 200 men and horses. It is divided into Sections of 2 guns with their wagons, commanded by a Lieutenant, and these into Sub-Sections under a Sergeant. The Battery Commander is a Captain, except in the Russian Service, where he is a Lieutenant-Colonel, and in the British Service, where he is a Major, with a Captain as Second-in-Command to take charge of the Ammunition Supply in action. To assist the Battery Commander in action, he has a Staff comprising trumpeters, rangetakers, observers, signallers, mounted orderlies, scouts, and horse-holders. There is also a small Administrative Staff, including artificers for repair of harness and carriages.

Batteries are grouped into larger Units, called in the British Service Brigades. They are commanded by a Lieutenant-Colonel, with an Adjutant, and a Staff for purposes of observation and command, including telephone and signalling detachments, rangetakers, and orderlies. This Unit is called an Abteilung in Germany, a Groupe in France, a Division in Russia and Austria, and a Battalion in Japan and the United States. It comprises as a rule three batteries of Field Guns, or of Howitzers (or two batteries of Horse Artillery), with an Ammunition Column. Heavy Batteries in the British Service are not brigaded, but one, with its own Ammunition Column, forms part of the Artillery of each Division. In foreign armies they are grouped by twos or fours into Battalions.

In foreign armies the above Units of three batteries are grouped by pairs into Artillery Regiments, commanded by a Colonel with a Staff. The Divisional Artillery and the Corps Artillery are respectively formed of one or more Regiments.

Two Artillery Regiments are in some armies grouped into an Artillery Brigade, which forms the Divisional or Corps Artillery, and is commanded by a General with a Staff.

Ammunition Columns form an integral part of the Artillery, but they carry ammunition for Infantry as well as for the guns. They are Fighting Units, because the replenishment of ammunition is a function of the Fighting Troops, and the movements of Ammunition Columns are tactical operations. The Ammunition Columns belonging to Units of Artillery provide the first reserve of ammunition. The second reserve of ammunition is provided by Divisional Ammunition Columns, which in foreign armies form the Divisional Ammunition Park. There is in large armies also an Army Corps Ammunition Park comprising several Columns, and an Army Ammunition Park, behind which are the Ammunition Depôts on the L. of C.

The Ammunition Columns constitute also a reserve to draw on for officers, men, teams, and matériel, to replace the losses of the Batteries. In Manchuria, the men of the Ammunition Columns were, within twelve months, all absorbed by the Batteries.

28 An Ammunition Column comprises about 150 to 200 men and as many horses, with from 20 to 30 ammunition wagons.

In the British Service the organization of the Ammunition Supply is as follows:

The Field Battery and Horse Artillery ammunition wagons carry 176 rounds per gun, those of a Howitzer Battery 88, and of a Heavy Battery 76 rounds per gun.

The Ammunition Column of each Field Artillery Brigade carries 200 rounds per gun for its Brigade. It carries also rifle ammunition (100 rounds per rifle) for one Infantry Brigade. The Horse Artillery Ammunition Column carries a supply of rifle ammunition (100 rounds per rifle) for the Mounted Troops, in addition to gun ammunition at the rate of 220 rounds per gun.

The Ammunition Column of a Howitzer Brigade, and that of a Heavy Battery, which have to carry heavier gun-ammunition, at the rate of 70 and 98 rounds per gun respectively, carry no rifle ammunition.

The Divisional Ammunition Column is divided into 4 Sections, giving three for the three Field Artillery Brigades (carrying 120 rounds per gun), and one Section with ammunition for the Howitzer Brigade (92 rounds per gun) and for the Heavy Battery (80 rounds per gun), and also for a proportion of the guns with the Mounted Troops. Each of the first three Sections carries a reserve of 100 rounds per rifle for one Infantry Brigade. The29 fourth Section, having heavier gun-ammunition to carry, is not burdened with any rifle ammunition.

The number of rounds of ammunition with the Force in the field is as follows:

| Rounds. | |

| Per Field Gun with its two wagons | 176 |

| Brigade Ammunition Column | 200 |

| Divisional Ammunition Column | 120 |

Total with troops, about 500 rounds per Field Gun, and rather more per Horse Artillery Gun. Per Howitzer, or Heavy Gun, about half that per Field Gun. About an equal amount is in Ordnance Store charge on the L. of C. ready to replace what is expended.

| On the man | 150 |

| Regimental Reserve | 100 |

| Brigade Ammunition Column | 100 |

| Divisional Column | 100 |

Ammunition for Machine Guns with Infantry is allotted as follows: With each gun, 3,500 rounds; in Regimental Reserve, 8,000; in Brigade Ammunition Column, 10,000; in Divisional Ammunition Column, 10,000. Guns with Cavalry have the same, except twice as much in Regimental Reserve.

Engineers are allotted to the larger formations of all Arms in the field, to carry out the varied work required with the troops at the front, as described in Chapter II.

In foreign armies they are organized in Companies belonging to the Engineer Battalion of the Army Corps, and one Company is allotted to each Division, and one to the Corps Troops. Its strength is that of the Infantry Company (250 men), under a Captain, with three or four officers. In order that its tools and stores shall accompany it and be at hand for work, each Company has transport allotted to it from the “Train Battalion” of the Army Corps. The Cavalry Division has generally some Engineers, who are mounted or carried on wagons, so as to keep up with the Division.

A reserve of tools and equipment for the Companies is carried by a column of wagons called the Army Corps Engineer Park.

In the British Service there are with each Division two Field Companies of Engineers, each having 156 working sappers, and with the Cavalry Division four Field Troops, each with 40 working sappers, half of whom are mounted, half carried on the tool carts. Thus, if a Cavalry Brigade is detached, it can take with it a Field Troop of Engineers. The drivers and transport are integral portions of the Engineer Troops and Companies.

Telegraph Companies of Engineers are in all armies allotted to each Command for inter-communication31 purposes. Those of the British Service are described later among the Administrative Services, in Chapter IX.

Another Unit of Engineers is the Bridging Train, which supplements the small bridge equipment carried by the Engineer Field Companies. In foreign armies these Trains are manned by Engineers, but horsed by the “Train,” and one is allotted to each Division and Army Corps. In the British Service the Bridging Trains are “Army Troops,” and are not allotted to Divisions.

It was mentioned in Chapter II. that of late years there have been added to modern armies a number of new varieties of troops, which it is not possible to group under the old heads of the Three Arms.

These varieties may be described under the following heads:

A short description of the functions and organization of these troops will now be given.

Mounted Infantry is to-day what Dragoons were when first introduced—that is, Infantry mounted33 only so as to be quickly moved to a point where it is to fight on foot. Mounted Infantry is armed only with the rifle, and is neither trained nor armed for shock action on horseback.

The introduction of Mounted Infantry was advocated long ago by Jomini in his “Art of War” (Vol. ii., chap. viii., sect. 45), but up to now this Arm only exists in the British Service, and there it is only organized in war, when Mounted Infantry Battalions are formed of men from Infantry Battalions trained for the purpose in peace.

British Mounted Infantry is organized in Battalions of 3 Companies with a Machine-Gun Section, Units of identical strength with the Cavalry Regiment, Squadron, and Machine-Gun Section.

Mounted Infantry is employed in two capacities in the British Service:

(a) In the Mounted Brigades, in which it acts with Cavalry, whose shock action it supports by its fire.

(b) As Divisional Mounted Troops, which are used as Advanced Guards and Outposts for protection; as Patrols for reconnaissance; as Escorts for Head-Quarters, Batteries, and Trains; for keeping connection, both with the Cavalry in front and with adjoining Divisions; for internal communication in their own Division.

Infantry Battalions specially trained and equipped for mountain fighting, like the “Alpine Troops” of France and Italy, are kept up in foreign countries, where warfare may, as often in the past, be carried34 on in difficult mountain regions. Switzerland and Austria have Mounted Infantry Battalions formed into Brigades, to which Mountain Batteries are attached. Austria has organized Mountain Transport Squadrons for these Brigades.

The Arm is described under the head of Artillery, in Chapter III. It is provided for mountain fighting in India, France, Austria, Russia, Switzerland, and the United States, and in the “Highlands” Division of the British Territorial Army. In Austria there are Mountain howitzers as well as guns.

Every nation has now introduced Machine Guns as a valuable auxiliary to Cavalry and Infantry. The intention, not as yet fully carried out, is to form a Unit of two Machine Guns in every Cavalry Regiment and in every Battalion (or at least in every Regiment) of Infantry. In the German and some other armies these guns will be taken away from their Units and grouped by sixes into “sections,” which will be virtually independent batteries of machine guns.

In the British Service a Section of two Machine Guns is provided by every Cavalry Regiment and Infantry Battalion. These guns, which fire from tripods, are carried in wagons with four horses in Cavalry Sections, for rapidity of movement, and with two horses in Infantry Sections. The Section is commanded by one of the Lieutenants, with a35 Sergeant, a Corporal, and the necessary drivers. To each gun there are six men, who are of course mounted in the Cavalry Section.

The Germans have adopted the Battery formation. The Mounted Section, for use with the Cavalry Division, consists of 6 guns on four-horsed carriages, with 3 ammunition wagons. The strength is 1 Lieutenant, 130 men, 90 horses. The officer and sergeant are mounted, and the men are carried on the gun carriage. The Foot Section forms an extra Company, the 13th, of each Infantry Regiment. It has 6 guns on two-horsed carriages, with 3 ammunition wagons. The strength is 1 Lieutenant, 83 men, 28 draught horses. The officer and 3 N.C.O.’s are mounted; the men march on foot, and are armed with pistols.

In Japan, there is to be a 6-gun Section to each Infantry Regiment, with a strength of 1 Officer, 1 W.O., 6 N.C.O.’s, 36 men. Guns and ammunition are carried on 30 pack horses. There will be an 8-gun Section to each Cavalry Brigade, with a strength of 3 Officers, 87 men.

In Switzerland a Machine-Gun Battery takes the place of Horse Artillery with Cavalry. It consists of 8 guns, and is carried on pack mules, with its personnel mounted.

In the Austrian Service a few men from each Cavalry Squadron have long been trained to perform Engineers’ duties, such as demolitions and repair of bridges, railways, and telegraphs, and hasty field works. This plan has been adopted to a36 limited extent in the British Cavalry, where a corporal and four men of each Squadron are trained in Pioneer duties. The German Cavalry Regiment has a Bridging equipment of 4 Pontoons, to form small bridges, or rafts, and a Demolition equipment carried in the Pontoon wagons, with men of the Regiment trained to use both.

Cyclist Infantry have been introduced into some armies, to carry Orders and messages. They will relieve Cavalry of part of their orderly, scouting, and patrolling work, as they can move as rapidly as mounted men, as long as the roads are good. Besides these duties it is claimed that Cyclists can also be used for fighting. Being armed as Infantry, but more rapid in movement, they could be used like mounted Infantry, to surprise the enemy with rifle fire from distant and unexpected places, or to seize and hold important tactical points, such as bridges, defiles, and hills, before the Infantry can reach them. As yet, however, it cannot be said that any decision has been arrived at as to the organization, equipment, and sphere of utility of Cyclists, or their employment as fighting troops.

In the British Service it is expected that each Unit will furnish a few Cyclists, and there are bicycles allotted to each Head-Quarters, to every Unit of fighting troops, and to telegraph companies, for inter-communication purposes. The Territorial Army has, besides 12 Cyclists per battalion, ten Cyclist Battalions.

The French, who were the first to form Military37 Cyclists, have a few companies, each of 4 Officers and 175 men.

The Germans provide 19 Cyclists from each Infantry Regiment, 9 from each Artillery Regiment, and 6 from each Cavalry Regiment. The latter will probably be massed as one body in the Cavalry Division, for transmitting intelligence.

Austria has a Volunteer Cyclist Corps for each Army Corps, and two Companies of Cyclists are to be attached to each Cavalry Division for use as fighting troops.

Italy has 24 Cyclists per Infantry Regiment, and two Battalions of Bersaglieri (or Rifles) are organized as Cyclists.

Motor Cars will be much used in war for conveyance of Generals and Staff Officers on the march and in action, as the power of covering the ground rapidly is of great advantage to Command of Troops, enabling what is passing at a distance to be seen, and decisions to be made and communicated without delay.

There will be great scope for Motors in carrying supplies to the troops from railhead, thus rendering the daily supply far more certain, and obviating blocking the roads with long trains of wagons. This system is being organized on the Continent.

Scouts are men whose function is to reconnoitre the ground, or the enemy, without fighting. They are soldiers selected for intelligence, activity, self-38reliance, and powers of observation. (“Infantry Training,” 1905, p. 73.)

Scouts are taken from Infantry Battalions, Cavalry Regiments, or Batteries, and work in the neighbourhood of their own Corps and for its immediate benefit. They move out generally in pairs, so that one man may take back information, if signalling is not possible.

In the British Service the numbers of Scouts are:

Infantry: 1 N.C.O. and 6 men per Company, of whom 1 Sergeant and 16 men per Battalion are First-Class Scouts.

Cavalry: 1 Officer, as Scout Leader, 1 Sergeant, 24 men, per Regiment.

Artillery: One or two “Ground Scouts” in front of the Battery when it is manœuvring. Two “Look-out Men” close to the Battery in action.

German Cavalry has 1 N.C.O. and 2 men per Squadron as Ground Scouts, and 1 Officer per Regiment in charge of them.

In France 12 mounted Ground Scouts, “Eclaireurs de terrain montés d’infanterie,” are to be attached to each Infantry Regiment.

The Russians in Manchuria used volunteers from Infantry Regiments as mounted Scouts, with good results.

Corps of Scouts and Guides have been formed from time to time, as in the American Civil War, and lately in Canada. They cannot, however, be39 said to have any actual existence in organized armies, but will probably be extemporized in war.

Wellington organized in the Peninsula a Corps of Guides and a Mounted Staff Corps, who acted as despatch riders and police. Napoleon had similar corps, and their usefulness is obvious. But it may be doubted if the multiplication of small special corps is not objectionable and wasteful of men and horses. Modern practice tends to allot the carrying of messages and Orders to orderlies furnished at Head-Quarters of Commands, either by Cyclists, by the men of the Cavalry escort, or by the Mounted Police.

The Germans have always had at Head-Quarters a small corps of Feldjägers, or mounted orderlies, for carrying despatches, and have now formed a body of motor-cycle volunteers for this purpose.

In the British Cavalry Division, four men from every squadron are trained as despatch riders, and Officers of the “Motor Reserve,” with their cars, are attached to every Head-Quarters, for carrying Orders and messages.

There is a Courier Corps in the Russian Service, which provides one section of 4 Officers and 6 N.C.O.’s for each Army Corps Head-Quarters. Two sections are allotted to Army Commands.

A body of Police is now a necessity for an Army. They comprise Mounted, as well as Foot40 Police. Their duties are to enforce sanitary regulations, to preserve order, especially in rear of the Army, and to carry out sentences of Courts-Martial. They ensure regularity in allotting billets and enforcing requisitions. They control sutlers and civilians with the Army, protect civil property, prevent marauding, and arrest stragglers, deserters, and spies. During action they will be useful in clearing roads, and maintaining order in rear of the fighting, and later will keep off the ghouls who infest the battlefield to plunder the dead and kill the wounded.

Small detachments of Military Police are in the British Service attached to all Head-Quarters, under the orders of the Assistant-Provost-Marshal. Foot Police will be attached to General Head-Quarters and those of the L. of C.; Mounted Police to all other Head-Quarters; while at Base Head-Quarters there will be both.

The Larger Formations are formed by combining in one body a number of the Smaller Formations composed of Units of each Arm, together with the Administrative Units required for their service. The body thus formed is then provided with Head-Quarters, comprising the Commander and his Staff, and other necessary personnel. The numbers of Units and of Lesser Formations grouped together, and their proportion to each other, are dictated by past experience and a forecast of future fighting requirements.

The bodies thus formed constitute what are called the Subordinate Commands of the Army. They are self-contained, and capable of independent existence and action—existence, because they have the necessary Administrative Services to supply their wants; action, because, having considerable strength, and a proper proportion of all Arms, they can fight for a certain time without support from other bodies of troops.

In this chapter will be discussed these Subordinate Commands and the Administrative Services42 allotted to them. The succeeding chapter will describe their Staff and the composition of their Head-Quarters.

The Division is the basis of the higher organization of Armies in the Field. It may be mainly composed of Infantry or of Cavalry. In the former case it is generally termed simply a Division, in the latter a Cavalry Division. Its Commander is generally a Major-General, and is provided with a Staff, to which the Heads of the Divisional Administrative Services are attached.

Divisions are organized on the following general lines in various armies:

The Infantry Division is formed of two or three Infantry Brigades—that is, of 12, 16, or 18 Battalions. The “two-Brigade” organization, the most common abroad, is inferior to that of the British Army in three Brigades, for the reasons already discussed in the first chapter. The Division is furnished with other Arms to assist the action of the Infantry, and has generally the following:

Cavalry: 1 Regiment, or sometimes only 2 Squadrons.

Artillery: 4 to 12 Batteries, organized in Brigades, and with the Brigades sometimes grouped in Regiments. One or other of these formations has an ammunition column. The larger number of guns is allotted when,43 as in Germany and England, no Army Corps Artillery exists.

Engineers: A Field Company.

Administrative Services: Ammunition Columns; Supply Columns; Field Ambulances; a Field Post Office.

In some armies the Division has also a light Bridging Train; a Field Hospital; a mobile Remount Depôt; a Finance Office; Chaplains.

The Divisional Head-Quarters comprise, besides the Commander and his Staff, a number of Heads of Administrative Services, a Telegraph Company, or “Communication Unit,” Military Police, and the necessary Transport.

The Cavalry Division is formed of two or three Cavalry Brigades—that is, of 16 to 24 Squadrons, in foreign armies. It has also one Brigade of Horse Artillery of 12 guns, with its ammunition column, and generally some Mounted Engineers and a Telegraph Detachment.

The British Cavalry Division has 4 Brigades or 36 Squadrons; 2 Brigades of Horse Artillery—that is, 4 Batteries, or 24 guns; 4 Field Troops of Engineers; and a Wireless Telegraph Company in four sections. It is obvious that by this organization a Brigade can be furnished with all Units it requires for independent action when detached.

Cavalry Divisions are furnished with the following Administrative Units: A Supply Column; Field Ambulances; Field Post Office.

This word is a somewhat misleading translation of the original French term Corps d’Armée, which means one of the bodies of troops forming an army, whereas the English term (which came through the German Armee Korps) might be supposed to mean a Corps which is an army in itself. It is now generally shortened to Corps.

If the Army is very large, there must be an intermediate link in the chain of Command between its Commander and the Divisions, or there would be too many Subordinate Commanders for the Army Commander to direct effectively. This link is provided in the larger armies of the Continent by the Army Corps, formed of two or more Infantry Divisions. A similar grouping of some of the Cavalry Divisions into Cavalry Corps may be occasionally found in war.

Jomini pointed out (“Art de la Guerre,” Vol. ii., chap, vii.), and Clausewitz (“On War,” Book V., chap, v.) endorsed his view, that, for armies up to 100,000 strong, a Divisional organization was best. This strength represents five or six Divisions, and one or two Cavalry Divisions, which may therefore be considered as the maximum number which an army should comprise, if organized in Divisions only.

45 The advantages of the Army Corps organization of armies are that the Supreme Command is facilitated by there being fewer Units to direct, and that a few important Commanders can be better selected than a number. This organization also provides a large independent force, under a Senior Commander, available for any special mission. There were periods in the South African War when the temporary employment of several Divisions for a special purpose would have been more effective had they formed a permanent organization like an Army Corps, with its own Commander and Staff. At the same time it is undoubtedly true that, except when unavoidable, the addition of another step in the gradation of Command is undesirable for many reasons. It is wasteful in Staff; it tends to delay the transmission of Orders; and the large strength of the Army Corps gives their Commanders so much importance as to lead to considerable independence in their action, which may weaken the Supreme Command.

In large armies, however, organization by Army Corps is unavoidable. We therefore naturally find the forces of the great military powers of Europe—Germany, France, Russia, Austria, Italy—organized by Army Corps, while the forces of Turkey, Japan, Great Britain, and the smaller nations of Europe are organized by Divisions only. Switzerland is about to comply with this principle by transforming her present Army Corps into Divisions.

An Army Corps is generally composed, after the German model, of two Divisions, in spite of the ruling of Clausewitz that a division of any Unit into two parts is the worst possible. This is admitted by von der Golz in his “Nation in Arms,” and also by von Schellendorf in his “Duties of the General Staff.” Both agree that an Army Corps should have three Divisions, but think that it would be difficult to alter a system so deeply rooted in Germany. This criticism applies also to the bipartite organization of both Cavalry and Infantry Divisions and Brigades, which exists in most Continental armies. The Austrians have therefore adopted a Corps of three Divisions, and the Germans and French think of adding a Reserve Division to the two forming their Army Corps. To have three Divisions would undoubtedly strengthen the Command of the Corps, and, by reducing the number of Corps, facilitate that of the Army.

Besides the Infantry Divisions, there are other troops in an Army Corps—namely, Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, and Administrative Services.

Corps Cavalry.—The French have a Brigade of Corps Cavalry, the Russians a Division. This is probably a better arrangement for providing “protective Cavalry” than to rely only on the few squadrons of Divisional Cavalry, as in Germany and Austria.

Corps Artillery.—German and Russian Army Corps have no Corps Artillery; other armies have two or more Brigades, organized in Regiments.

47 Heavy Artillery is likely to be allotted to Army Corps or perhaps to Armies, in foreign armies, as it is in England to the Division.

Corps Engineers.—A Company or two, with an Engineer Park of tools and stores, a Bridging Train, and Telegraph Units, form the Corps Engineers.

The Corps Administrative Services comprise in most armies an Ammunition Park, a Supply Park, a Field Bakery, Field Hospitals, and a Remount and Veterinary Depôt.

It has been suggested that the duty of strategic reconnaissance, for which the Cavalry Divisions are organized, might be better performed if these were grouped under one Command; but such a permanent combination of Cavalry Divisions into Corps has only been carried out in Russia, where there is one Cavalry Corps of 2 Divisions (48 squadrons), or 7,000 sabres and 24 guns. The British Cavalry Division, however, of 4 Brigades (36 squadrons and 24 guns) is virtually a Cavalry Corps, except that its internal organization is by Brigades and not by Divisions, and so avoids the evil of bipartite division. An improvised Corps of 2 Divisions has been tried in German manœuvres, and it is expected that in war one or more of them will be formed. They will perhaps be kept in the hands of the Supreme Command for independent action, each Army Commander retaining a Division or two as “Army Cavalry.”

To group 2 or 3 Divisions into a Cavalry Corps under one Command makes it easier and quicker to48 concentrate them and break through the enemy’s screen, as long as all the Divisions are moving in the same direction, and engaged in the same task. But if they are covering a broad front, and acting on separate objectives, it would be a mistake to group them under one Commander, who must necessarily be acting at some distance. In this case, the independence of the Divisional Commanders will conduce to the quick tactical decisions on which success depends.

It would seem sound not to distribute the whole of a large Cavalry force equally among the Divisions, nor the latter equally among the Armies, but to allot according to the capacity of the Commanders, and the importance of the strategical work they have to accomplish. If this be so, there may be something to be said for the French Divisions of unequal strength, some of 2, some of 3 Brigades. But in the opinion of von Bernhardi, the leading exponent of modern Cavalry views, even the usual Continental Division of 3 Brigades is “much too weak,” seeing that the Brigades are of two Regiments. He strongly advocates a three-Regiment Brigade, which is that of the British Service.

The Military Forces of the Great Powers have now grown so large that a further development of organization has become necessary. They are therefore divided in war into separate Armies. Army, in this new sense, does not mean, as it used to, the whole Force, for which, indeed, some other49 word than “Army” is urgently needed. An Army is simply the highest Unit in the organization of a great host in the field.

This division into separate Armies, each forming a definite Unit, with its own Commander and Staff, and numbered from right to left, was first seen in the two great wars carried on by Prussia in 1866 and 1870. Each Army had its own Lines of Communication, and moved and fought independently under its Commander, in obedience to general instructions issued at intervals by Moltke, as Chief of the General Staff, on the authority of the Commander-in-Chief, the King of Prussia.

This system was followed in Manchuria by the Japanese, who had four, and later five, Armies in the field under one Supreme Command. It is now obligatory on all nations putting several hundred thousand men in the field to organize them in separate Armies. In any future war between France and Germany each Power will probably form five such Armies under one Supreme Commander, or “Generalissimo,” as the French (following Jomini) style him. Each Army will have its own sphere of action and Lines of Communication.

The modern organization by Armies differs from that adopted by Napoleon for the invasion of Russia, and in the German campaign which followed in 1813. It is true that, by forming large detachments to the flanks, he divided his enormous forces into what were practically separate Armies; but the main body in the centre was not only by50 far the most important, but was under Napoleon’s own command. In fact he commanded one of the Armies himself, while at the same time directing the whole Force. It is now recognized that this arrangement was far from successful, even under Napoleon, and would be impossible for a lesser man. The Supreme Commander must not himself command one of his Armies. If he were to attempt this, the other Armies would become merely large detachments; plans would tend to be based on the movements of the main body; and the operations of the Armies would lose in scope and independence.

The size of Armies must obviously be limited to the number which one man can command. This, according to Clausewitz, should not exceed 120,000 to 150,000. The total strength depends mainly on the number of Subordinate Commands. Napoleon was of opinion that five were enough for one man to command. Clausewitz laid down eight as the maximum.

In the great hosts of modern nations Armies are not organized in peace, and their composition in war is kept secret, but it is certain that they will not consist of less than three, or of more than six Army Corps (or Divisions, where Army Corps are not used), and most probably of four or five, with two or three Cavalry Divisions.

We have thus traced the development of the Higher Commands, or those of all Arms, from the Division to the Army, and will now consider the Administrative Services and Staff allotted to them.

As indicated at the beginning of the second chapter, a number of Administrative Services are required, to provide the Fighting Troops with all they need to keep up their strength and efficiency. An army cannot act without a service of communication for transmission of Orders; it cannot exist without a supply of food and clothing, fight without ammunition, or move without transport to carry these stores. To maintain its discipline there must be Police, and a department of Military Justice. For reasons of morale, the sick and wounded must be collected and tended, and it is also desirable that its letters should pass with regularity to and from home, and that spiritual ministration should be provided.

These points, with the exception of the Medical Services, were as a rule little considered until the close of the eighteenth century, when Carnot devoted much attention to them while organizing the revolutionary armies in France. Napoleon and Wellington improved them considerably, but they were still very inadequate in England till after the Crimean War.

In modern armies a good system of administration is universally felt to be of the greatest importance. Services are therefore organized to meet the administrative requirements of an army in the field, which may be classed under the following heads:

Inter-communication throughout the Force.

Supply of food, ammunition, and other stores.

Transport by rail and road.

52 Medical and Veterinary aid.

Replacing loss in men or horses.

The above bear directly on the fighting; but there are also certain semi-civil services, which cannot well be dispensed with in war. These deal with the following matters:

Guidance as to Law—military, martial, and international.

Finance, Accounts, the provision and issue of Cash.

Clerical work, in connection with Statistics, Records, invaliding sick and wounded, etc.

Postal Service.

Spiritual ministration.

It is not possible to investigate here the various methods adopted in each foreign army to meet these requirements. The system is generally that the Medical Services are managed by their own Heads, the Communication, or Telegraph, Units are provided by the Engineers, and the other Administrative Services are regulated by officials called “Intendants,” who are attached to Divisional and Army Corps Commands, and have entire responsibility for Supply, Remounts, Stores, and Finance. As to Transport, each Army Corps has a “Train Battalion,” a combatant Unit which provides the Infantry, Cavalry, Engineer, and Medical Units (but not those of Artillery) with the wagons, teams, and drivers they require, and furnishes the Transport Columns for carrying supplies.

53 The personnel of the Medical Services is similarly furnished by the “Army Corps Medical organization,” and the Principal Medical Officers on the Staff of Divisions and Corps administer the Medical Services.

A Director of Medical Services, an Intendant-General, and a Judge-Advocate-General are attached to “General,” as well as to “Army,” Head-Quarters.

As regards the other Services, the Veterinary and Postal Services, and the Chaplains, do not generally form part of any higher Staffs than those of Divisions.

It will be seen that the system is so designed that in the main the business of Administration in detail falls on the Divisional and Army Corps Commands, while the Army Command is left free to concentrate its attention on the enemy.

The principles on which the Administration of an Army in the Field is organized for war as carried on at the present day, can be best understood by a study of the British Administrative Services. The general lines of their organization will be found described in Chapters IX. and X.