![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: The Inns of Court

Author: Cecil Headlam

Illustrator: Gordon Home

Release date: July 6, 2017 [eBook #55062]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

THE INNS OF COURT

|

List of Illustrations Index: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, Y. (etext transcriber's note) |

Uniform with this Volume

WESTMINSTER ABBEY

PAINTED BY JOHN FULLEYLOVE, R.I. DESCRIBED BY MRS. A. MURRAY SMITH

CONTAINING 21 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR. SQ. DEMY 8VO., CLOTH, GILT TOP PRICE 7/6 NET (POST FREE, PRICE 7/11)

“In general appearance, in wealth of illustration, and in trustworthy letterpress, it is a charming book.”—Guardian.

THE TOWER OF

LONDON

PAINTED BY JOHN FULLEYLOVE, R.I. DESCRIBED BY ARTHUR POYSER

CONTAINING 20 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR. SQ. DEMY 8VO., CLOTH, GILT TOP PRICE 7/6 NET (POST FREE, PRICE 7/11)

“Perhaps one of the best books of modern times on the great fortification.... The fine paintings by Mr. John Fulleylove give added charm to the book.”—Globe.

A. & C. Black. Soho Square. London, W.

| AGENTS | |

| AMERICA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK |

| AUSTRALASIA | OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 205 Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE |

| CANADA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. 27 Richmond Street West, TORONTO |

| INDIA | MACMILLAN & COMPANY, LTD. Macmillan Building, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA |

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_001_sml.jpg)

OLD HALL AND OLD SQUARE FROM THE TOWER OF THE NEW HALL, LINCOLN’S INN

On the left is the Old Hall, dating from the reign of Edward VI. (circa 1555), and the scene of the Chancery case of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce in ‘Bleak House.’ Beyond the Hall are the red roofs of Old Square, and in the distance the domes of the Central Criminal Court and St. Paul’s, the latter appearing over a portion of the buildings of the Record Office.

PAINTED

BY·GORDON·HOME

DESCRIBED

BY·CECIL·HEADLAM

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1909

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| Origin of the Inns | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Knights Templars | 27 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Temple Church | 44 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Middle Temple | 54 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Inner Temple | 86 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Lincoln’s Inn and the Devil’s Own | 106 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Gray’s Inn | 135 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Inns of Chancery | 165 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Serjeants and Serjeants’ Inns | 186 |

| 1. | Old Hall and Old Square from the Tower of the New Hall, Lincoln’s Inn | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| 2. | Middle Temple Lane | 6 |

| 3. | Interior of the Middle Temple Hall | 20 |

| 4. | Lamb Building from Pump Court, Temple | 34 |

| 5. | Interior of the Temple Church | 46 |

| 6. | The East End of the Temple Church and the Master’s House | 56 |

| 7. | The Middle Temple Gatehouse in Fleet Street | 66 |

| 8. | Fountain Court and Middle Temple Hall | 74 |

| 9. | Middle Temple Library | 84 |

| 10. | Hall and Library, Inner Temple | 94 |

| 11. | No. 5, King’s Bench Walk, Inner Temple | 102 |

| 12. | Old Square, Lincoln’s Inn | 112 |

| 13. | The New Gateway and Hall of Lincoln’s Inn | 118 |

| 14. | Stone Buildings, Lincoln’s Inn, from the Gardens | 128 |

| 15. | A Doorway in South Square, Gray’s Inn | 144 |

| 16. | Gray’s Inn Square | 154 |

| 17. | The Gabled Houses outside Staple Inn, Holborn | 164 |

| 18. | Staple Inn Hall and Courtyard | 172 |

| 19. | The Great Hall of the Royal Courts of Justice | 176 |

| 20. | Clifford’s Inn | 184 |

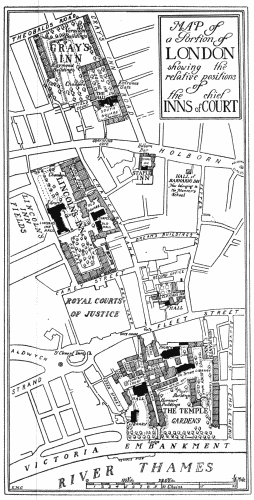

| Sketch-plan at end of volume. | ||

The features of every ancient City are marked with the wrinkles and the scars of Time. The narrow lanes, the winding streets, the huddled houses, the blind alleys form, as it were, the furrows upon her aged countenance. They contribute enormously to the charm and beauty of her riper years, for they point to a life rich in experience and varied reminiscences. But, like other wrinkles, they have their drawbacks. As the bottle-neck of Bond Street, which blocks the traffic half the season, is the direct topographical result of the river which once flowed thereabouts, so the boundary of the property of the Knights Templars, marked by the Inner and Middle Temple Gateways, imposes the southern limit of Fleet Street, opposite to Street’s Gothic pile of Law Courts and to Chancery Lane. Hence the narrowness of that famous street, and{2} the consequent congestion of traffic on the main route to the City. Then come the Beauty Doctors, who smooth out the old wrinkles, and broaden the ancient, narrow lines, which Time has cut so deeply on the face of the Town. The old landmarks are removed, and Wren’s gateways and buildings must disappear in order that broad, straight paths be driven right to the sanctuary of Business.

And yet the old influences and the effects of historic movements and historic events persist, and will persist. It may seem far-fetched to say that everyone whose business or pleasure takes him to Fleet Street is directly subject to the influence of the Crusades. Yet it is so. But for those strange wars of mingled religious enthusiasm and commercial aggression, there would have been no Templars, and had there been no Templars, the whole nomenclature and topographical arrangement of this part of London would have been different; for the Societies of Lawyers, who succeeded to their property, succeeded, of course, to the boundaries of the messuages, as to the Round Church of the Knights Templars.

Of the Temple, and the Templars, and their successors, we shall deal more at length in their proper places. It will be convenient first to consider what{3} these Societies of Lawyers were and are, how they arose, and why they settled in the particular vicinity wherein they have chosen to set their ‘dusty purlieus.’

William the Conqueror had established the Law Courts in his Palace. The great officers of State and the Barons were the Judges of this King’s Court—Aula Regis—which developed into three distinct divisions: King’s Bench and Common Pleas, under a Chief Justice, and Exchequer, where a Chief Baron presided to try all causes relating to the royal revenue. It was the business of a Norman King to ride about the country settling the affairs of the realm, which was his estate, and administering justice. The great Court of Justice, therefore, naturally accompanied the King in all his progresses, and suitors were obliged to follow and to find him, travelling for that purpose from all parts of the country to London, to Exeter, or to York.

It was a system that was found ‘cumbersome, painful, and chargeable to the people,’ as Stow[1] puts it, and one of the provisions of Magna Charta accordingly enacted that the Court of Common Pleas should no longer follow the King, but be{4} held in some determined place. The place determined was Westminster. The Court was held, though not at first, in the famous Hall, which William Rufus had erected and Richard II. rebuilt.

It was to be expected that the fixing of the Courts would be followed by the settlement of ‘Students in the Law and the Ministers of each Court,’[2] as Dugdale has it, somewhere near at hand. Advocates had been drawn at first from the ranks of the clergy. This was natural enough, seeing that they formed the only educated class of the day. Nullus clericus nisi causidicus, the historian complains. It was equally natural that in the course of time objection should be taken to the spectacle of the professors of Christianity wrangling at the Bar, and monopolizing the power born of legal knowledge. Dugdale notes the first instance of an attempt to check their presence in the Courts as occurring at the beginning of the reign of Henry III. The clergy were at length excluded from practising in the Civil Courts, and a privileged class of lay Lawyers came into existence. Edward I. specially appointed the Justices of the Court of Common Pleas to ‘ordain from every County certain Attorneys and Lawyers of the{5} best and most apt for their learning and skill, who might do service to his Court and People, and who alone should follow his Court and transact affairs therein.’

And at this date, or shortly after it, we may assume that ‘students in the University of the Laws’[3] began to congregate in Hostels, or Inns, of Court, in order to study as ‘apprentices’ in the Guild of Law. For, as at Oxford or Cambridge, an Inn, or Hostel of residence, was the natural necessary requirement of such students when they began to come in numbers to sit at the feet of their teachers, the Masters of Law. The earliest mention of an Inn for housing apprentices of the Law occurs in 1344, in a demise from the Lady Clifford of the house near Fleet Street, called Clifford’s Inn, to the apprenticiis de banco, the lawyers belonging to the Court of Common Pleas. And Thavie’s Inn was similarly leased from one John Thavie, ‘a worthy citizen and armourer,’ of London, who died in 1348. In such hostels, leased to the senior members, voluntary associations, or guilds of teachers and learners of law would congregate, and gradually evolve their own regulations and customs.{6}

Other references occur to the ‘apprentices in hostels’ during this same reign (Edward III.). And from about this date the four Inns of Court—Gray’s Inn, Lincoln’s Inn, and the Inner and Middle Temple—‘which are almost coincident in antiquity, similar in constitution, and identical in purpose,’[4] begin to emerge from the mists of the past.

It is noticeable that all the Inns of Court and Chancery cluster about the borders of the City Ward called Faringdon Without, and were once placed, as old Sir John Fortescue observed, ‘in the suburbs, out of the noise and turmoil of the City.’

The Lawyers were thus conveniently placed between the seat of judicature at Westminster and the centre of business in the City of London, and secured the advantage of ‘ready access to the one and plenty of provisions in the other.’ In the wall which bounds the Temple Gardens upon the modern Embankment of the Thames is set a stone which marks the western boundary of the Liberty of the City and the spot where Queen Victoria received the City Sword (1900); the old Bar of the City, which took its name from the Temple, and{7}

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_003_sml.jpg)

MIDDLE TEMPLE LANE

The overhanging buildings just inside Sir Christopher Wren’s Gateway in Fleet Street (see p. 67).

Holborn Bar, marked the limit farther north. It is to be remembered that this famous Temple Bar did not mark the boundary of the City proper, but only of the later extension known as the Liberty of the City, and the Temple buildings within the Bar were yet without the narrower boundary of the City.

Temple Bar consisted originally of a post, rails, and chain. Next, a house of timber was erected across the street, with a narrow gateway and entry on the south side under the house.[5] This was superseded about 1670 by the stone gate-house, designed by Christopher Wren, which was the scene of so many historic pageants when Lord Mayors have received their Sovereigns, and presented to them the keys of the City. It was here, notably, that the Lord Mayor delivered the City sword to good Queen Bess when she rode to St. Paul’s to return thanks for the victory over the Spanish Armada. Hereon, as upon London Bridge, the heads of famous criminals or rebels were stuck to warn the passers-by; and in the pillory here stood Titus Oates and Daniel de Foe—the latter for publishing his scandalous and seditious pamphlet, ‘The Shortest Way with the Dissenters.’ The{8} citizens, however, pelted De Foe, not with rotten eggs, but with flowers. This noble gate-house was removed when the Strand was widened and the new Law Courts erected. It was rebuilt at Meux Park, Waltham Cross, and its original site is marked by a column surmounted by a griffin, representing the City arms (1880).

It would appear that the Lawyers in choosing sites just outside the City boundaries for the Inns of their University were further influenced by the ordinance of Henry III. (1234), which enjoined the Mayor and Sheriffs to see to it that ‘no man should set up Schools of Law within the City.’ The object of this prohibition is a matter of dispute; Stubbs, for instance, maintaining that it applied to Canon Law, and others[6] that only Civil Law was intended, the object being to confine the clergy to the Theology and Canon Law, which seemed more properly their province.

By the middle of the fourteenth century, then, we find the students of what we may call a London University of National Law established in their Inns or Hostels, which clustered about the boundaries of the City, from Holborn to Chancery Lane, from{9} Fleet Street to the River. The Schools of Law, of which this University was composed, were distinctively English, and the University itself developed upon the peculiarly English lines of a College system, closely similar to that of Oxford and Cambridge. The Inns of Court and Chancery were the Colleges of Lawyers in the London University of Jurisprudence.

Here dwelt, and here were trained for the Courts those guilds or fraternities of Lawyers, according to a scheme of oral and practical education which they gradually evolved. Trade Guilds were the basis of medieval social life, and medieval Universities were, in fact, nothing more nor less than Guilds of Study.[7] The four Inns of Court survive to-day as instances of the old Guilds of Law in London, and the lawyers, in their relations with the Courts, the public and solicitors, seem to represent still a highly organized Trade Union.

The Inns of Court, then, have always exhibited, and still retain, the salient features of a University based upon the procedure of the medieval Guild. Just as, in other Universities, no one was allowed to teach until he had served an apprenticeship of terms, and, having been duly approved by the{10} Masters of their Art, had received his degree or diploma of teaching; just as no butcher or tailor was allowed to ply his trade until he had qualified himself and had been duly approved by the Masters of his Guild, so in the Masters of these Guilds of Law was vested the monopoly of granting the legal degree, or call to practise at the Bar, to apprentices who had served a stipulated term of study and passed the ordeal of certain oral and practical preparation. And as though to emphasize beyond dispute the Collegiate nature of these Societies, we find that each one of them made haste to provide itself with buildings and surroundings, which still present to us, in the midst of the dirt and turmoil of busy London, something of the charm and seclusion and self-sufficiency of an Oxford College, with its Hall and Chapel, its residential buildings, its Library, and grassy quadrangles, and its Gateway to insure its privacy.

The same system of discipline, of celibate life, of a common Hall, of residence in community, and of compulsory attendance at the services of the Church, which marked the ordinary life of a medieval University, was repeated at the Inns of Court.

And the kind of Collegiate Order into which{11} they shaped themselves was also shown by the several grades existing within the Societies themselves. The word ‘barrister’ itself perpetuates the ancient discipline of the Inns, where the dais of the governing body, or Benchers, corresponding to the High Table of an Oxford College, was separated by a bar from the profane crowd of the Hall. The Halls of the Inns were not only the scenes of that business of eating and drinking, the ‘dinners’ to which so much attention was devoted, and by which the students ‘eat their way to the Bench,’ but also the centres of the social life and educational system of these Guilds.

Dugdale gives at length the degrees of Tables in the Halls of the Inns—the Benchers’ Tables, the tables of the Utter Barristers, the tables of the Inner-Bar, and the Clerks’ Commons, and, without the screen, the Yeoman’s Table for Benchers’ Clerks.

The Utter- or Outer Barristers ranked next to the Benchers. They were the advanced students who, after they had attained a certain standing, were called from the body of the Hall to the first place outside the bar for the purpose of taking part in the moots or public debates on points of law. The Inner Barristers assembled near the centre of the Hall.{12}

‘For the space of seven years or thereabouts,’ says Stow, ‘they frequent readings, meetings, boltinges, and other learned exercises, whereby growing ripe in the knowledge of the lawes, and approved withal to be of honest conversation, they are either by the general consent of the Benchers or Readers, being of the most auncient, grave and iudiciall men of everie Inn of the Court, or by the special priviledge of the present Reader there, selected and called to the degree of Utter Barristers, and so enabled to be Common Counsellors, and to practise the law, both in their Chambers, and at the Barres.’

Readers, to help the younger students, were chosen from the Utter Barristers. From the Utter Barristers, too, were chosen by the Benchers ‘the chiefest and best learned’ to increase the number of the Bench and to be Readers there also. After this ‘second reading’ the young Barrister was named an Apprentice at the Law, and might be advanced at the pleasure of the Prince, as Stow says, to the place of Serjeant, ‘and from the number of Serjeants also the void places of Judges are likewise ordinarily filled.’ ‘From thenceforth they hold not any roome in those Innes of Court, being translated to the Serjeants’ Innes, where none{13} but the Serjeants and Judges do converse’ (Stow, i., pp. 78, 79).

Upon the Benchers, or Ancients, devolved the government of the Inn, and from their number a treasurer was chosen annually.

Readings and Mootings would seem to have been the chief forms of legal training provided by the Societies, and they may be said roughly to represent the theoretical and practical side of their system of education. As to Readings, the procedure in general was as follows: Every year the Benchers chose two Readers, who entered upon their duties to the accompaniment of the most elaborate ceremonial and feasting. Then upon certain solemn occasions it was the duty of one of them to deliver a lecture upon some statute rich in nice points of law. The Reader would first explain the whole matter at large, and after summing up the various arguments bearing on the case, would deliver his opinion. The Utter Barristers then discussed with him the points that had been raised, after which some of the Judges and Serjeants present gave their opinions in turn.[8]

I have referred to the feasting that attended the appointment of the Readers. We have seen that{14} medieval Universities were Guilds of Learning, scholastic fraternities of masters or students, who framed rules and exacted compliance with certain tests of skill, precisely in the same way as did the masters and apprentices of ordinary manual trades. It was a universal feature of the Guilds, whether of manual crafts or of Learning, that the newly-elected Master was expected to entertain the Fraternity to which he had been admitted, or in which he had just been raised to the full honours of Mastership. And just as at Oxford, Cambridge, or Paris, a Master was obliged to give a feast, or even some more sumptuous form of hospitality, such as a tilt or tourney, upon the attainment of his degree, so at the Inns of Court the newly-appointed Reader was obliged by custom to entertain the Benchers and Barristers in Hall. It was the general experience everywhere that such entertainments tended to increase in splendour and costliness, and to be a severe tax upon the resources of the new Masters, and a check, consequently, upon the number of aspirants. So here the excessive charges attending Readers’ feasts led to a decrease in the Readers, which was regarded as tending to ‘an utter overthrow to the learning and study of the Law,’ and the Justices{15} of both Benches accordingly issued an order insisting upon their observance, and at the same time regulating the amount that a Reader might expend upon ‘diet in the Hall.’

Moots were a kind of rehearsal of real trials at the Bar. They were cases argued in Hall by the Utter and Inner Barristers before the Benchers.

When the horn had blown to dinner, says Dugdale, a paper containing notice of the Case which was to be argued after dinner was laid upon the salt. Then, after dinner, in open Hall, the mock-trial began. An Inner Barrister advanced to the table, and there propounded in Law-French—an exceedingly hybrid lingo—some kind of action on behalf of an imaginary client. Another Inner Barrister replied in defence of the fictitious defendant, and the Reader and Benchers gave their opinions in turn.

As in other Universities, other subjects besides Law were included in the educational curriculum.

‘Upon festival days,’ says Fortescue, who wrote in the seventeenth century, ‘after the offices of the Church are over, they employ themselves in the study of sacred and profane history; here everything which is good and virtuous is to be learned, all vice is discouraged and banished. So{16} that knights, barons, and the greatest nobility of the kingdom often place their children in those Inns of Court, to form their manners, and to preserve them from the contagion of vice.’

As time went on, in fact, the Inns of Court gradually changed their character, and became a kind of aristocratic University, where many of the leading men in politics and literature received a general training and education.

And whilst Oxford and Cambridge, essentially more democratic, drew their students chiefly from the yeoman and artisan class, the Inns of Court became the fashionable colleges for young noblemen and gentlemen.

Throughout the Renaissance, indeed, the Inns of Court men were the leaders of Society, and the Gentlemen of the Long Robe laid down the law, not only upon questions of politics, but upon points of taste, of dress, and of art.

In the reign of Henry VI. the four Inns of Court contained each 200 persons, and the ten Inns of Chancery 100 each. The expense of maintaining the students there was so great that ‘the sons of gentlemen do only study the Law in these hostels.’

‘There is scarce an eminent lawyer who is not a gentleman by birth and fortune,’ says Fortescue;{17} ‘consequently they have a greater regard for their character and honour.’

And John Ferne, a student of the Inner Temple, wrote,[9] in 1586, especially commending the wisdom of the regulation that none should be admitted to the Houses of Court except he were a gentleman of blood, since ‘nobleness of blood, joyned with virtue, compteth the person as most meet to the enterprizing of any publick service.’

Shortly after the accession of James I., a royal mandate denied admission to a House of Court to anyone that was ‘not a gentleman by descent.’

‘The younger sort,’ says Stow (1603), ‘are either gentlemen, or the sons of gentlemen, or of other most welthie persons.’

It is one of the almost unvarying features of a Guild that a fixed period of apprenticeship must be served before admission to be a Master. The term of apprenticeship in the Inns of Court has varied with each Society, and in different epochs.

In June, 1596, the period of probation which must be spent by a student in attending preliminary exercises in the Inns, before graduating in Law, was limited by an ordinance of the Judges and{18} Benchers to seven years. Before that date the ‘exercises’ necessary for ‘a call to the Bar’ occupied eight years, during which twelve grand moots must be attended in one of the Inns of Chancery, and twenty petty moots in term time before the Readers of one of the greater Societies.

But in 1617, in a ‘Parliament’ of the Benchers of the Inner Temple, it was ordained that ‘no man shall be called to the Bar before he has been full eight years of the House.’ Nor was lapse of time to be considered sufficient without proportionate acquisition of learning. Only ‘painful and sufficient students’ were to be called, who had ‘frequented and argued grand and petty moots in the Inns of Chancery, and brought in moots and argued clerks’ common cases within this House.’ A proviso against outside influence was added by the injunction that ‘anyone who procured letters from any great person to the Treasurer or Benchers in order to be called to the Bar, should forever be disqualified from receiving that degree within that House.’

In the seventeenth century, however, ‘readings’ and ‘mootings’ alike fell into desuetude, and official instruction practically disappeared. The Inns became merely formal institutions, residence{19} within the walls of which, indicated by the eating of dinners, was alone necessary for admittance to the Bar. The loss of the Law was the gain of Letters. A new class of students, educated in literature and politics, and highly born, were bred up to take their place in the direction of affairs and the criticism of writers.

‘When the “readings” with their odds and ends of law-French and Latin went out into the darkness of oblivion, polite literature stepped into their place. “Wood’s Institutes” and “Finch’s Law” shared a divided reign with Beaumont and Fletcher, Butler and Dryden, Congreve and Aphra Behn. The “pert Templar” became a critic of belles lettres, and foremost among the wits, whereas his predecessors had been simply regarded by the outer world as a race that knew or cared for little else save black-letter tomes and musty precedents. Polite literature ultimately came to clothe the very forms of law with an elegance of diction not dreamed of in the philosophy of the older jurists, and thus deprived an arduous study of one of its most repellent features.’[10]

Another cause which greatly contributed to the brilliant record of the Inns as homes of Literature{20} and the Drama, as well as of the Law, was the rule which, up till quite a few years ago, compelled Irish Law-students to keep a certain number of terms in London prior to ‘call’ at the King’s Inn, Dublin. Daniel O’Connell, at Lincoln’s Inn, Curran, Flood, Grattan, the orators; Tom Moore, the poet, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the dramatist, at the Temple, are among the later ‘Wild Irishmen’ who owed something to the London Inns in accordance with this rule, and rewarded the Metropolis with their eloquence and wit.

In modern times the need of general regulations as to qualification by the keeping of terms and of examinations as a guarantee of competency has been recognized.

After over 200 years of survival as an obsolete office, Readerships have been revived again to perform their proper functions. ‘A council of eight Benchers, representing all the Inns of Court, was appointed to frame lectures “open to the members of each society,” and five Readerships were established in several branches of legal science (1852). Attendance at these lectures was made compulsory, unless the candidate preferred submitting to an examination in Roman and English Law and Constitutional History. Three years{21}

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_004_sml.jpg)

INTERIOR OF THE MIDDLE TEMPLE HALL

The date of its erection (1570) is in the stained-glass window on the right. In this Hall Queen Elizabeth may have danced with Sir Christopher Hatton, and here Shakespeare’s ‘Twelfth Night’ was first performed (see pp. 75-78).

later, a Royal Commission advised the establishment of a preliminary and final examination for all Bar students, together with the formation of a Law University with power to confer degrees in Law. The suggestions of the Commission were only partially acted upon, and then not till 1870, when Lord Chancellor Westbury succeeded in getting a preliminary examination in Latin and English subjects adopted and the final examination made obligatory.’[11]

And it is pleasant to note, too, that about the same time (1875) the custom of the ancient mootings, so useful for promoting ready address and sound knowledge of the Law among the aspirants to the Bar, was revived at Gray’s Inn.

The discipline which the Inns of Court enforced upon their students corresponded in general to that exercised by an Oxford or Cambridge College.

Fines and ‘putting out of Commons’ were the usual forms of punishment, though the power of imprisoning ‘gentlemen of the House’ for wilful misdemeanour and disobedience ‘was sometimes exercised by the Masters of the Bench.’[12]

Attendance at Divine Service was insisted upon,{22} and the wearing of long beards forbidden. A beard of over three weeks’ growth was subject to a fine of 20s. A student’s gown and a round cap must be worn in Hall and in Church, and gentlemen of these Societies were forbidden to go into the City in boots and spurs, or into Hall with any weapon except daggers. They were forbidden to keep Hawkes, or to ill-treat the Butlers. They were not allowed to play shove-groat. In the reign of Elizabeth, by an order of the Judges for all the Inns of Court, the wearing of a sword or buckler, of a beard above a fortnight’s growth, or of great hose, great ruffs, any silk or fur, was equally forbidden, and no Fellow of these Societies was allowed to go into the City or suburbs ‘otherwise than in his gown according to the ancient usage of the gentlemen of the Inns of Court,’ upon penalty of expulsion for the third transgression. The wearing of gowns of a sad colour was enjoined by Philip and Mary, and long hair, or curled, was forbidden as surely as white doublets and velvet. These are echoes of the ordinary sumptuary laws of the period.

‘There is both in the Inns of Court and the Inns of Chancery,’ says Fortescue, ‘a sort of an Academy or Gymnasium fit for persons of their station, where{23} they learn singing and all kinds of music, dancing and Revels.’ These forms of recreation constituted, indeed, the lighter side of the educational and social life of the Inns.

All-Hallowe’en, Candlemas, and Ascension Day, were the grand days for ‘dancing, revelling, and musick,’ when, before the Judges and Benchers seated at the upper end of the Hall, the Utter Barristers and Inner Barristers performed ‘a solemn revel,’ which was followed by a post-revel, when ‘some of the Gentlemen of the Inner-Barr do present the House with dancing.’[13] On occasions of more particular festivity, even so great dignitaries as the Lord-Chancellor, the Justices, Serjeants, and Benchers, would dance round the coal fire which blazed beneath the louvre in the centre of the Hall, whilst the verses of the Song of the House rang out in rousing chorus, like the song of the Mallard of All Souls, at Oxford.

Dugdale gives the order of the Christmas ceremonies in delightful detail: ‘At night, before supper, are revels and dancing, and so also after supper, during the twelve daies of Christmas. The antientest Master of the Revels is after dinner and supper to sing a carol or song, and command other{24} gentlemen then there present to sing with him and the company.’ On Christmas Day ‘Service in the Church ended, the gentlemen presently repair into the Hall, to breakfast with Brawn, Mustard and Malmsey,’ and so forth. The good-fellowship and the long evenings of Christmastide had natural issue in the production of plays and masques in these Halls, by students who have always been in close touch with the drama. It is not surprising, therefore, that one of Shakespeare’s plays was written for Twelfth Night, and first produced by the students of Law, at the Temple, for this merry and convivial season (see Chapter IV.).

On St. Stephen’s Day the Lord of Misrule was abroad, and at dinner and afterwards games and pageants were performed about the fire that burned in the centre of the Hall, and whence the smoke escaped through the open chimney in the roof. For instance: ‘Then cometh in the Master of the Game apparelled in green velvet, and the Ranger of the Forest also, in a green suit of satten, bearing in his hand a green bow and divers arrows, with either of them a hunting horn about their necks; blowing together three blasts of Venery, they pace round about the fire three times.’ They make obeisance to the Lord Chancellor, and then ‘a{25} Huntsman cometh into the Hall, with a Fox and a Purse-net, with a Cat, both bound at the end of a staff, and with them nine or ten couple of Hounds. And the Fox and Cat are by the Hounds set upon, and killed beneath the fire’ (Dugdale).

The Post Revels, we are told, were ‘performed by the better sort of the young gentlemen of the Societies, with Galliards, Corrantoes, or else with Stage-plays.’ Masques were frequently performed by the members of the Inns, and Sir Christopher Hatton first obtained Queen Elizabeth’s favour by his appearance in a masque prepared by the lawyers.

Besides the solemnities of Christmas and Readers’ Feasts, the Antique Masques and Revelries, as Wynne in his ‘Eunomus’ observes (ii., p. 253), ‘introduced upon extraordinary occasions, as to the grandeur of the preparations, the dignity of the performers and of the spectators, at which our Kings and Queens have condescended to be so often present, seem to have exceeded every public exhibition of the kind.’

One famous masque was presented by the four Inns of Court to Charles I. and Henrietta (1633), which cost some £24,000. So pleased were the King and Queen with ‘the noble bravery of it,’ and the answer implied in it to Prynne’s ‘Histrio Mastix,’{26} that they returned the compliment by inviting 120 gentlemen of the Inns of Court to the masque at Whitehall on Shrove Tuesday.

If these and other old customs have fallen into abeyance, the traditional spirit of sociability is far from being dead, and on ‘Grand Nights’ their old habit of hospitality is gratefully revived by the Inns of Court in favour of famous men, who are honoured as their guests.{27}

About the year 1118 certain noblemen, horsemen, religiously bent, bound themselves by vow in the hands of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, ‘to serve Christ after the manner of Regular Canons in chastity and obedience, and to renounce their owne proper willes for ever.’

The Order was founded by a Burgundian Knight who had mightily distinguished himself at the capture of Jerusalem. Hugh de Paganis was his name. Only seven of his comrades joined the Brotherhood at first.

Their first profession was to safeguard pilgrims on their way to visit the Holy Sepulchre, and to keep the highways safe from thieves. A rule and a white habit were granted to this pilgrims’ police by Pope Honorius II. Crosses of red cloth were afterwards added to their white upper garments, and earned them the familiar title of the Red-Cross{28} Knights. And for their first banner they adopted the Beaucéant, the upper part of which was black, signifying, it is said, death to their enemies; the lower part white, symbolizing love for their friends.

Their services were rewarded and their efforts encouraged by Baldwin, King of Jerusalem, who granted them quarters in his palace, within the sacred enclosure of the Temple on Mount Moriah.

Hence they came to be known as the Knights of the Temple, or Knights Templars. For Baldwin’s Palace was formed partly of a building erected by the Emperor Justinian, partly of a mosque built by the Caliph Omar, upon the site of Solomon’s Temple.

The Order increased rapidly in popularity. It spread over Europe and the East, accumulating property and privileges. It was most highly organized, and at its head was a Grand Master, who resided at first in Jerusalem. A visit paid by the Founder, Paganis, to Henry I. in Normandy led to the establishment of settlements in England. Cambridge, Canterbury, Warwick, and Dover are mentioned amongst others by Stow. Temples, ‘built after the form of the Temple near to the Sepulchre at Jerusalem,’ were erected in many of the chief towns{29} in England. And this circular shape of church, modelled upon the Holy Sepulchre in accordance with a prevailing love of imitating the holy places at Jerusalem, as, for instance, the Stations of the Cross, was the design adopted for the Templars’ London Churches. The date of their first settlement in London is not certain, but about the middle of the twelfth century they are said to have established themselves in Chancery Lane, between Southampton Buildings and Holborn Bars. Their property, which was afterwards to be known as the Old Temple, embraced part of the site of what is now Lincoln’s Inn. The foundations of a round church were discovered in 1595 near the site of the present Southampton Buildings.

But it was not long before they moved to a pleasanter site, to the ‘most elegant spot in the Metropolis,’ as Charles Lamb declared. For, about the year 1180, the Templars acquired a large meadow sloping down to the broad River Thames, on the south side of Fleet Street, and stretching from Whitefriars on the east to Essex Street on the west. Here they built themselves a lordly dwelling-place and a splendid Church, again a round Church upon the same sacred model, part of which still stands. Across the way lay their{30} recreation ground. For the site of the modern Law Courts—that Gothic pile which we can never wholly see, and in which Street just failed to design a truly complete, effective, and absolute building, and failed entirely to produce a building practically suited for its purpose—was known then as Fitchett’s Field. The scene of the labours of the Lawyers, who have succeeded to their inheritance, was once the tilting-ground of the Knights Templars.

Five years later, in 1185, in the presence of Henry II. and all his Court, the dedication of the Round Church of the ‘New Temple’ took place. The ceremony was performed by Heraclius, Patriarch of Jerusalem.

The surroundings of the ‘New Temple,’ when Henry graced it upon this occasion with his royal presence, were extraordinarily different even from the aspect they wore a century later.

Fleet Street itself was not yet in existence. Its neighbourhood was a mere marsh, and Fleet Ditch, at the bottom of Ludgate Hill, was spanned by no bridge. The two highways to the City, when the Templars first settled at this spot, were first and foremost the River, and, secondly, by land, the old Roman Way through Newgate, up Holborn Hill{31} to Holborn Bars, striking southwards from St. Mary-le-Strand, past the Roman Bath, to the River. But seventy years later a new main route to the City was constructed, which passed by the boundary of the Templars’ plot. For the marshes were drained, a bridge was thrown across the Fleet, and the ‘Street of Fleetbrigge’ came into existence.

The grandeur of the ceremony of dedication and the splendour of the Templars’ Church itself indicate clearly enough the importance of the ‘New Temple’ as the headquarters of the Order in England, and also the waxing wealth and power of the Order itself.

For these ‘fellow-soldiers of Christ,’ as they termed themselves, ‘poor and of the Temple of Solomon,’ had bound themselves to a vow of poverty, but they soon changed their allegiance to Mammon. The heraldic sign of the Winged Horse, which is now the well-known badge of the Inner Temple, and meets the eye at every turn as we pass through the narrow lanes and devious courts of which their property is composed, recalls and typifies the changing purposes of the ancient Templars and their successors. For the old crest of the Templars was a horse carrying two men, which probably was intended to suggest their profession{32} of helping Christian pilgrims upon their road, but in which some saw an emblem of humiliation and of a vow to poverty so strict that they could afford but one horse for two knights. Whatever its significance, the badge was changed with changing circumstances. The two riders were converted into two wings, and the horse transformed into a Pegasus—Pegasus argent on a field azure—upon the occasion of some Christmas Revels and pageantry held at the Inner Temple in honour of Lord Robert Dudley, 1563, when it appears that this emblem, typical of the soaring ambitions of the new Society, was adopted by that Inn. The Middle Temple appropriated another badge, which the Templars had assumed in the thirteenth century. This was the sign of the Agnus Dei, the Holy Lamb, with the banner and nimbus, which figures so prominently upon the buildings of this Inn. These heraldic signs of Winged Horse and Holy Lamb should be encouraging to the young litigant, who, in his first experience of the Law, may be led to expect ‘justice without guile and law without delay’ from these legal fraternities, supposing that, in the words of the witty skit,

The Order of Templars followed the almost invariable practice of such Institutions in accumulating treasure at the expense of the devout, and they succeeded more strikingly than most. By the beginning of the fourteenth century they had long abandoned all pretence to the performance of their original duties, but had at least earned the reputation of being exceedingly wealthy. The Treasury, indeed, of these devotees of Poverty was a prominent feature of their House, and they seem to have acted as Bankers, to whom the charge of money and jewels was entrusted in those troublous times.

Here King John stored his Royal Treasury; here he often lodged, seeking refuge from his Barons; and here he passed the night before he signed the Great Charter at Runnymede. Henry III. followed his example in endowing the Temple with manors and privileges, whilst from his guardian, Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent, whom he had imprisoned in the Tower, he extracted all the Treasure that careful nobleman had committed to the custody of the Master of the Temple.

Hither came King Edward I., and under pretence of seeing his mother’s jewels there laid up, this royal burglar broke open the coffers of certain{34} persons who had likewise lodged their money here, and took away to the value of a thousand pounds.

Of the Templars’ Treasure House nothing now remains, but the Treasurer survives, one of the chief officials of the Inn, whose duties correspond roughly to those of a Bursar of an Oxford College.

The laying up of treasure upon earth is always apt to provoke the predatory instinct, even in the breast of a Chancellor of the Exchequer, and to the motive of greed was added, in the case of the Templars, the unanswerable charge that they had done nothing for many years to redeem their vows to succour Jerusalem or protect pilgrims. They were also accused, not without reason, of indulging in odious vices, and of being a masonic society devoted to the propagation of some heresy. The rival fraternity of military Knights, the Order of St. John, who had settled themselves in the rural seclusion of Clerkenwell, envied them. The Pope himself turned against them. Philip le Bel, who seems to have been the leading spirit in a general attack, dealt cruelly with the Order in France, causing the chief Members of it to be put to death. In England Edward II. contented himself with confiscating their possessions. The Order was abolished (1312), and, by decree of the Pope,{35}

confirmed by the Council of Vienne, all their property was granted to the Knights Hospitallers, the rival Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Edward, however, at first ignored their claims. He granted that part of the Templars’ domain which was not within the City boundaries, and which is now represented by the Outer Temple, to Walter de Stapleton, Bishop of Exeter. It was thenceforth known indifferently as Stapleton Inn, Exeter Inn, or the Outer Temple. It passed by purchase to Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Essex House was then erected, which, with its gardens, covered the site now occupied by Essex Court, Devereux Court, and Essex Street, and the buildings that abut upon the Strand.

The Gate at the end of Essex Street, with the staircase to the water, is the only portion of the old building that survives. The Outer Temple was never occupied by any College or Society of Lawyers. But the history of the portion of the Templars’ property which lay within the liberties of the City, indicated by Temple Bar, was destined to be very different. This property was granted by Edward II. to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. On his rebellion the estate reverted to the Crown, and was granted, in 1322, to Aymer de Valence,{36} Earl of Pembroke. He died without issue, and Edward bestowed the property upon his new favourite, Hugh le Despencer, upon whose attainder it passed again to the Crown. At length the claim of the Knights Hospitallers was admitted. For in 1324 Edward II. assigned to them ‘all the lands of the Templars,’ except, of course, some nineteen-twentieths which King and Pope ‘touched’ in transference. The King finally made to them an absolute grant of the whole Temple, apart from the Outer Temple, in consideration of £100 contributed for the wars.

What happened next it is impossible, owing to lack of documentary evidence, with certainty to say. This absence of evidence is partly due, no doubt, to the behaviour of Wat Tyler’s men in 1381, as quoted by Stow. For they not only sacked and burned John of Gaunt’s noble palace, the neighbouring Savoy, but also ‘destroyed and plucked down the houses and lodgings of the Temple, and took out of the Church the books and records that were in Hutches of the apprentices of the law, carried them into the streets and burnt them.’ And later records must have disappeared in other ways, notably in the fire of 1678. Be that as it may, the fact with which{37} everybody is familiar is that the Temple property passed into the occupancy, and finally into the possession, of two Societies of Lawyers, who existed, and still exist, on terms of absolute equality, neither taking precedence of the other, and both sharing equally the Round Church of the Knights Templars. These two Societies or Inns are called after the property of the Knights within the boundaries of the City, which they divided between them—the Inner and the Middle Temple.

Now, the first discoverable mention of the Temple as an abode of lawyers occurs in Chaucer’s ‘Prologue to the Canterbury Tales’ (c. 1387). Geoffrey Chaucer himself, a fond tradition would have us believe, dwelt for a while in these Courts, and was a student of the Inner Temple. Be that as it may, he tells us

Here, then, we have a clear indication of a Society of Masters dwelling in the Temple, whilst{38} Walsingham’s account of Wat Tyler’s rebellion refers to apprentices of the Law there. But there is nothing to indicate the existence of the two Inns till about the middle of the fifteenth century, when we find references to them in the Paston Letters (1440 ff.), and in the Black Book of Lincoln’s Inn (1466 ff.). This does not, of course, prove that there was only one Inn before. Such, however, is the traditional account. ‘In spite of the damage done by the rebels under Wat Tyler,’ says Dugdale, ‘the number of students so increased that at length they divided themselves in two bodies—the Society of the Inner and the Society of the Middle Temple.’ Those who believe this maintain that when, in course of natural development—rapid expansion apparently following the rebels’ onslaught—the original Society had attained an unwieldy bulk and outgrown the capacity of the Old Hall, a split was made. Two distinct and divided Societies, upon a footing of absolute equality, took the place of the parent body. A new Hall was built, but equal rights in the Old Church and the contiguous property were maintained.

This form of propagation by subdivision is common enough, of course, in the vegetable and insect world, but it seems highly improbable in the{39} case of a learned body. It is to me an incredible dichotomy. And it is not necessary to stretch one’s credulity so far. There are indications—faint, it is true, but still indications—of the existence of two Societies of Lawyers settled here on two parcels of land that once belonged to the Knights Templars, and dating from almost the earliest days after Edward’s confiscation.

For, according to Dugdale, who repeats a tradition which is probably correct, the Knights Hospitallers leased the property soon after they had acquired it to ‘divers apprentices of the Law that came from Thavie’s Inn in Holborn’ at an annual rental of £10. This must have been before 1348. For in that year died John Thavye, who bequeathed this Inn to his wife, and described it in his will as one ‘in which certain apprentices of the Law used to reside’ (solebant). But there is also evidence of another and earlier settlement of lawyers on this property. Some lawyers, it is recorded, ‘made a composition with the Earl of Lancaster for a lodging in the Temple, and so came thither and have continued ever since.’[14] The Earl of Lancaster, as we have seen above, held the Temple c. 1315-1322.{40}

Here, then, we have indications of two Societies of Lawyers settling in the Temple. The first body, holding from the Earl of Lancaster, may reasonably be supposed to have had their grant confirmed by the owners who succeeded him. The Society of the Middle Temple must be considered the successors of those tenants. And this Society Mr. Pitt Lewis, K.C.,[15] has traced to a former home in St. George’s Inn, a students’ hostel mentioned by Stow.

The second body, migrating from Thavye’s Inn, obtained a lease of the part not occupied by the former, at an annual rental of £10, as Dugdale states. And from them are descended the Inner Templars of to-day.

From the time when the Order of the Knights Hospitallers was dissolved, till 1608, these two Societies held these two separate parcels of land direct of the Crown by lease, paying two separate rents. Then they discovered that James I. was beginning to negotiate a sale of the freehold.

The present of a ‘stately cup of pure gold, filled with gold pieces,’ presented by the two Societies, converted the Scholar-Monarch. On August 13, 1608, he granted a Charter to the Treasurers and{41} Benchers of the Inner and Middle Temple, conferring upon them the freehold of the Temple, together with the Church, ‘for the hospitation and education of the Professors and Students of the Laws of this Realm,’ subject to a rent charge of £10, payable by each of the two Societies. In 1673 these rents were extinguished by purchase by the two Societies.

This patent of James I. is the only existing formal document concerning the relations between the Crown and the Inns, though it would be strange indeed if no other grant or patent ever existed. It is preserved in the Church in a chest kept beneath the Communion Table, which can only be opened by the keys held by the two Treasurers. The importance of the patent is, for the purpose of our investigation, that it is based almost certainly upon documents that have disappeared, but which reached back to the original conveyance, and it shows that there were two separate parcels, exacting two separate rents. Moreover, it provided that each Society should continue to pay a rental of £10. Now, if these two Societies represented a division of the one parent body which had come from Thavye’s Inn and held the whole Inner and Middle Temple at a{42} rent of £10, it is hardly conceivable that when this supposed division took place, each Society should have continued to pay the whole rent. The first thing they would have divided, after dividing themselves, would surely have been that rent of £10.[16]

That the theory of a division having taken place early caused much wonderment is shown by a report that was rife in the seventeenth century. This ‘report’ was to the effect that the division arose from the sides taken by the Lawyers in the Wars of the Roses. Those wars, however, took place after the date when there is evidence of the existence of the two Societies. The ‘report’ represents an attempt to explain the existence of the two Societies when their origin was already forgotten, and was perhaps suggested by the fact that it was in the Temple Gardens that Shakespeare placed the famous incident that led to the Wars of the Roses:

In 1732, in order to put an end to many questions of property, an elaborate deed of partition was agreed to by the two Inns, and forms the final authority upon what belongs to each.{44}

It is natural to turn from this story of the Templars to the Round Church in the Temple, which is their chief memorial. We leave the roar and rattle of Fleet Street, and pass through the low Gateway of the Inner Temple into the narrow lane which leads us between the gross modern buildings, called after Oliver Goldsmith and Dr. Johnson, to the west end of the Church—the west end, which is formed by the round building which we have already mentioned.

The Gate-House beneath which we have passed is in itself a building of no ordinary interest. It is, as we now see it, a modern (1905) version of an old timber and rough-cast house, with projecting upper stories, pleasantly contrasting with the Palladian splendour of the adjoining Bank. It was built ‘over and beside the gateway and the lane’ in 1610 by one John Bennett, and was perhaps designed{45} by Inigo Jones. The room on the first floor was, there is every reason to suppose, used by the Prince of Wales as his Council Chamber for the Duchy of Cornwall. It contains some fine Jacobean and Georgian panelling, an admirable eighteenth-century staircase, and an elaborate and beautiful Jacobean plaster ceiling, with the initials, motto, and feathers of Prince Henry, who died 1612.

This is No. 17, Fleet Street. No. 16, to the west of it, with the sign of the Pope’s Head, was the shop of Bernard Lintot, who published Pope’s ‘Homer,’ and later of Jacob Robinson, the bookseller and publisher, with whom Edmund Burke lodged when ‘eating his dinners’ as a student of the Middle Temple.

The Gate-House escaped the Fire of London, and, having been restored, is now preserved to the public use by the London County Council.[17] It forms an appropriate introduction to those narrow lanes and quiet Courts and that lovely Church, whose pavements once resounded with the tread of the mail-clad champions of Christendom, and echo now with the softer footfall of bewigged, begowned{46} Limbs of the Law. Dull and prosaic must he be indeed who cannot here feel the thrill of imagination which stirred the soul of Tom Pinch as he wandered through these Courts:

‘Every echo of his footsteps sounded to him like a sound from the old walls and pavements, wanting language to relate the histories of the dim, dismal rooms; to tell him what lost documents were decaying in forgotten corners of the shut-up cellars, from whose lattices such mouldy sighs came breathing forth as he went past; to whisper of dark bins of rare old wine, bricked up in vaults among the old foundations of the Halls; or mutter in a lower tone yet darker legends of the cross-legged knights, whose marble effigies were in the Church’ (‘Martin Chuzzlewit’).

The Round part of the Church of the Knights Templars, which we now see lying below us, is one of the very few instances of Norman work left in London—the only instance, save the superb fragments of St. Bartholomew’s Church and the splendid whole of the Tower of London. It was dedicated, as we have seen, in 1185 to St. Mary by Heraclius, Patriarch of Jerusalem. This fact was recorded on a stone over the door, engraved in the time of Elizabeth, and said by Stow to be an{47}

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_006_sml.jpg)

INTERIOR OF THE TEMPLE CHURCH

A Round Church of the Order of Knights Templars (dedicated in 1185). The oblong nave is seen through the pillars of polished Purbeck marble (1240).

accurate copy of an older one. It also proclaimed an Indulgence of sixty days to annual visitors, the earliest known example, I believe, of this particular form of taxation. The Church was again dedicated in 1240. The rectangular portion of the Church, the Eastern portion added to the Western Round, was now probably reconstructed, supplanting a former chancel or choir, just at the period when the new Pointed style had ousted the round Norman.

The circular type of church is not peculiar to the Order of Templars, as we have seen, or even to the Christians, but the choice of it was due in this case to the practice of imitating the architecture, as the topography, of the Holy Places at Jerusalem. In England, Round Churches occur at Ludlow and Cambridge (1101), built before the Knights of the Temple were established. St. Sepulchre at Northampton is possibly a Templar Church, but the Round Church at Little Maplestead in Essex belongs to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and was built by the Knights Hospitallers.

The Temple Church escaped the Fire of London as by a miracle, for the flames came as near as the Master’s House at the East End. It escaped the{48} fire of 1678, when the old Chapel[18] of St. Anne, once perhaps the scene of the initiation of the Knights Templars, lying at the junction of Round and Rectangle, was destroyed by gunpowder to save the church. But it could not escape the destroying hands of the nineteenth-century Goths. For here, between 1824 and 1840, the great Gothic Revivalists indulged in one of their most ineffable and ineffaceable triumphs of intemperate enthusiasm. The Round part of the Church was almost rebuilt, and the old carvings were supplanted by inferior modern work. The conical roof was added; the horrid battlements banished. The old marble columns were removed and replaced by new ones, to obtain which the old Purbeck quarries were reopened. This marble{49} takes an extraordinarily high polish, and presents a surface so clean and lustrous as to be almost shocking in its contrast to our dingy London atmosphere, and buildings begrimed with dirt and soot.

The many brasses, which Camden praised, have disappeared; the rich collection of tablets and monuments and inscribed gravestones that once pleased the eye of Pepys, and formed a feast of heraldic ornament, has been dispersed, and found sanctuary in the tiny Churchyard without, on the north side of the Church, or in the Triforium. The floor of the Church was, at the same time, wisely lowered to its original level, and covered with a pavement of tiles designed after the pattern of the remains of old ones found there, or in the Chapter House of Westminster.

A continuous stone bench, or sedile, which runs round the base of the walls was added at this period, together with the delightful arcade above it, with grotesque and other heads in the spandrels. The wheel window—a lovely thing—was uncovered and filled with stained glass, and the windows in the circular aisle of the Round have since been filled by Mr. Charles Winston with stained glass which is good, but the colour of which it is absurd to compare, as Mr. Baylis does, with the blues and{50} rubies of the glass of the best period. It is to be hoped that the remaining windows will not be filled with coloured glass, as Mr. Baylis[19] suggests, for the interior of the Round is too dark already.

The result of all this Gothic reconstruction is that, save for the old rough stones in the exterior Round walls, and some of the ornate semicircular arches, the Templars’ Church exists no more. The grandeur, beauty, and historical interest of their building can be gathered now from old engravings only; the monuments of many famous men, in judicial robes and with shields rich in heraldry, a representative gallery of unbroken centuries, which once crowded its floors, must be judged by broken and scattered fragments. What we have is a reconstruction such as the Restorers chose to give us—that is, a light and very pleasing Early English interior, fitted into a Round Norman exterior, beneath the remaining arcade of round arches and windows.[20]

If the enthusiasm of the Restorers, however, led them to destroy so that we can never forgive them for having taken from us original work for the sake of indulging their own fancy, yet it is evident{51} that there was much for them legitimately to undo. There were plaster and stucco, and dividing gallery and whitewashed ceiling, and all the usual horrors of the eighteenth century, to be got rid of. The graves and monuments were historically interesting, but they crowded the little church unbearably. And at least the Restorers have given us beautiful work of their own, and a seemly and beautiful sanctuary worthy of the place.

The Round is entered by a western door—a massive oaken door superbly hung upon enormous hinges, quite modern. It closes beneath a semicircular arch enriched by deeply-recessed columns with foliated capitals of the transitional Norman style, though all this work, like the Gothic Porch which contains it, is modern restoration. The scene as we enter the Church is one of striking singularity. Near at hand is the arcaded sedile about the walls of the Round, and through six clustered columns of great elegance, made of polished Purbeck marble, which support the dome, we catch a glimpse of the polished marble columns in the Choir, the lancet windows in the North and South walls, and the three stained windows of the East End, beneath which the gilded Reredos glitters. And through the painted windows of the{52} Round itself the light strikes upon a wonderful series of monumental recumbent figures, some of which are made of this flashing Purbeck marble too. It is a strange, unforgettable sight, that summons up unbidden the vision of the Red-Cross Knights, to the tread of whose mailed feet these pavements rang, when, beneath their baucéant banners, they gathered here to the Dedication of their Temple.

These monuments, though re-arranged and restored indeed by Richardson, 1840, are still of great interest. Nine only out of eleven formerly mentioned remain. Two groups of four each lie beneath the Dome, with the ninth close by the South wall, balancing a stone coffin near the North. Two of them belong to the twelfth century and seven to the thirteenth, and these silent figures wear the armour of that period—the chain mail and long surcoats, the early goad spurs, the long shields and swords, the belts, and mufflers of mail.

The Monuments in the Temple Church have been frequently described, by Stow and Weever, for instance, by Dugdale,[21] and by Gough.[22] The tradition that they represent ‘ancient British{53} Kings,’ or even necessarily Templars, has been long exploded. The theory that every figure whose legs are crossed in effigy belonged to that Order has been consigned to the limbo of vulgar errors. But five of these effigies are mentioned by Stow as being of armed Knights ‘lying cross-legged as men vowed to the Holy Land, against the infidels and unbelieving Jews.’ And it is very probable that cross-legs did indicate those who had either undertaken a Crusade or vowed themselves to the Holy Land. At any rate, I know no evidence to show that this was not the symbolism by which the medieval mason in England and Ireland chose to indicate the Crusader.

None of these remarkable monuments can with certainty be identified. Of those now grouped upon the South side Stow says: ‘The first of the crosse-legged was W. Marshall, the elder Earl of Pembroke, who died 1219; Wil. Marshall, his son, the second, and Gilbert Marshall, his brother, also Earl of Pembroke, slayne in a tournament at Hertford, besides Ware,’ in 1241. And this may or may not be so. The fourth is nameless; the fifth, near the wall, is possibly that of Sir Robert Rosse, who, according to Stow, was buried here.{54}

Of the group upon the North side, only that of the cross-legged knight in a coat of mail and a round helmet flattened on top, whose head rests on a cushion, and whose long, pointed shield is charged with an escarbuncle on a diapered field, can with any probability be named. For these are the arms of Mandeville (de Magnavilla)—‘quarterly, or and gules, an escarbuncle, sable’—and this monument of Sussex marble gives us the first example of arms upon a sepulchral figure in England.[23] It is supposed to be the effigy of Geoffrey Mandeville, whom Stephen made first Earl of Essex, and Matilda Constable of the Tower. A ferocious and turbulent knight, he received an arrow-wound at last in an attack upon Burwell Castle, and was carried off by the Templars to die. But, as he died under sentence of excommunication, it is said that they hung his body in a lead coffin upon a tree in the Old Temple Orchard, until absolution had been obtained for him from the Pope. Then they brought him to the new Temple and buried him there (1182).

The Choir, or rectangular part of the Church, of which the nave is broader than the aisles, but of {55}the same height, is a beautiful example of the Early English style, and is lighted by five lancet triplet windows. By the Restorers the old panelling and the beautiful seventeenth-century Reredos were removed. Tiers of deplorable pews, deplorably arranged, and a very feeble Gothic Reredos[24] were substituted. The roof, supported by the Purbeck marble clustered columns that culminate in richly-moulded capitals, was painted with shields and mottoes in painstaking imitation of the thirteenth century. The windows at the East End were filled with very inferior modern stained glass, none of it of the least interest, poor in colour and wretchedly ignorant in design—ignorant, that is, of the rules which guided the art of the medieval glazier.

A bust of the ‘Judicious’ Hooker, Master of the Temple Church, and author of the ‘Ecclesiastical Polity,’ the grave of Selden near the South-West corner of the Choir, and above it a mural tablet to his memory, are the monuments of known men most worthy of attention. The fine fourteenth-century sepulchral effigy near the double piscina of Purbeck marble is supposed to be that of Silvester de Everden, Bishop of Carlisle.

The Organ, frequently reconstructed and finally renewed by Forster and Andrews, 1882, has been{56} famous for generations. It was originally built by Bernard Schmidt. Dr. Blow and Purcell, his pupil, played upon it in competition with that built by Harris. The decision of this Battle of the Organs was referred to the famous, or infamous, Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys, who was a good musician, and in this matter, at least, seems to have proved himself a good Judge.

The Triforium[25] is reached by a small Norman door in the North-West corner of the oblong. A winding staircase leads to the Penitential Cell—4 feet long, by 2 feet 6 inches wide—where many of the Knights were confined. To the Triforium many tablets and monuments (e.g., of Plowden), once in the Church below, have been removed.

Among the epitaphs in brass, quoted at length by Dugdale, is one in memory of John White:

The Templars’ Church was equally divided between the two Societies of Lawyers from ‘East to West, the North Aisle to the Middle, the South{57}

to the Inner Temple.’ This fact, with many others, clearly indicates the basis of perfect equality upon which the two Societies were agreed to stand, and on which, in spite of subsequent claims to precedence on the part of both, declared groundless by judicial authority, they will henceforth continue. As to the Round, it appears to have been used by both Societies in common, largely as a place of business, like the Parvis of St. Paul’s, where lawyers congregated, and contracts were concluded. Butler refers to this custom in his ‘Hudibras’:

Joint property of the two Societies, also, is that exquisite example of Georgian domestic architecture, the Master’s House (1764). This perfect model of a Gentleman’s Town-House owes its great charm almost entirely to its beautiful proportions, and to the appropriate material of good red brick and stone of which it is built. It is a thousand pities that blue slates have been allowed to supplant the good red tiles that should form the roof. The House itself is the successor of one{58} which was erected (1700) after the Great Fire.[26] The original Lodge is said to have been upon the site of the present Garden, directly in line with the east end of the Church. In the vaults beneath this Garden many Benchers of both Inns have been laid to rest.

In this Lodge, then, dwells the Master of the Temple Church.

‘There are certain buildings,’ says Camden, ‘on the east part of the Churchyard, in part whereof he hath his lodgings, and the rest he letteth out to students. His dyet he hath in either House, at the upper end of the Bencher’s Table, except in the time of reading, it then being the Reader’s place. Besides the Master, there is a Reader, who readeth Divine Service each morning and evening, for which he hath his salary from the Master.’

A Custos of the Church had been appointed by the Knights Hospitallers, but after the Dissolution of the Monasteries the presentation of the office was reserved to the Crown. The Church is not within the Bishop’s jurisdiction. On appointment by the Crown, the Master is admitted forthwith without any institution or induction. But the Master of the Temple Church is Master of nothing{59} else. When, in the reign of James I., Dr. Micklethwaite laid claim to wider authority, the Benchers of both Temples succeeded in proving to the Attorney-General that his jurisdiction was confined to his Church.

Masters of real eminence have been few. By far the greatest was the learned Dr. John Hooker, appointed by Elizabeth, who resigned in 1591. Dr. John Gauden, who claimed to have written the ‘Eikon Basilike,’ was Master of the Temple before he became Bishop of Exeter and Worcester. And in our own day Canon Ainger added to the charm of a singularly attractive personality the accomplishments of a scholar who devoted much of his time to the works of another devout lover of the Temple—Charles Lamb.

The Church was once connected with the Old Hall by Cloisters, communicating with the Chapel of St. Thomas that once stood outside the north door of it, and with the Refectory of the Priests, a room with groined arches and corbels at the west end of the present Inner Temple Hall, which still survives (see p. 48). Later on, Chambers were built over the Cloisters, and the Church itself was almost stifled by the shops and chambers that were allowed to cluster about it, along the South Wall,{60} and even over the Porch. Beneath the shelter of these Cloisters the Students of the Law were wont to walk, in order to ‘bolt’ or discuss points of law, whilst ‘all sorts of witnesses Plied in the Temple under trees.’

The Fire of 1678 burnt down the old Cloisters and other buildings at the south-west extremity of the Church. The present Cloisters at that angle, designed by Wren, were rebuilt in 1681, as a Tablet proudly proclaims.

The Cloister Court is completed by Lamb Building, which, though apparently within the bounds of the Inner Temple, belongs (by purchase) to the Middle Temple, and is named from the badge of that Inn, the Agnus Dei, which figures over the characteristic entrance of this delightful Jacobean building, and has now given its title to the whole Court. Here lived that brilliant Oriental Scholar, Sir William Jones, sharing chambers with the eccentric author of ‘Sandford and Merton,’ Thomas Day. And it was to the attics of these buildings, where Pen and Warrington dwelt, that Major Pendennis groped his way through the fog, piloted, as he might be to-day, ‘by a civil personage with a badge and white apron through some dark alleys and under various{61} melancholy archways into courts each more dismal than the other.’[27]

The consecrated nature of their tenement resulted in certain inconveniences to the Lawyers. On the one hand, the Temple was a place of Sanctuary, and its character suffered accordingly. Debtors, criminals, and dissolute persons flocked to it as a refuge, so that it became necessary to issue orders of Council (1614) that the Inns should be searched for strangers at regular intervals, whilst, with the vain view of reserving the precincts for none but lawyers, it was ordained that ‘no gentleman foreigner or discontinuer’ should lodge therein, so that the Inns might not be converted into ‘taverns’ (diversoria). On the other hand, the benevolence of the Benchers was taxed by many unnatural or unfortunate parents, who used the Temple as a crèche, and left their babies at its doors. The records give many instances of payments made towards the support of such infants, who were frequently given the ‘place-name’ of Temple.

I have quoted from Thackeray a phrase not so over-complimentary to the surroundings of Lamb Building.{62}

But now, before passing on to the story of the Halls of these renowned Societies, and the Chambers which have harboured so many famous men, I must quote, as an introduction, the passage in which the novelist makes amends, and nobly sums up the spirit of the life men lead there, and the atmosphere of strenuous work and literary tradition which lightens those ‘dismal courts’ and ‘bricky towers.’

‘Nevertheless, those venerable Inns which have the “Lamb and Flag” and the “Winged Horse” for their ensigns have attractions for persons who inhabit them, and a share of rough comforts and freedom, which men always remember with pleasure. I don’t know whether the student of law permits himself the refreshment of enthusiasm, or indulges in poetical reminiscences as he passes by historical chambers, and says, “Yonder Eldon lived; upon this site Coke mused upon Lyttelton; here Chitty toiled; here Barnwell and Alderson joined in their famous labours; here Byles composed his great work upon bills, and Smith compiled his immortal leading cases; here Gustavus still toils with Solomon to aid him.” But the man of letters can’t but love the place which has been inhabited by so many of his brethren or peopled by their{63} creations, as real to us at this day as the authors whose children they were; and Sir Roger de Coverley walking in the Temple Gardens, and discoursing with Mr. Spectator about the beauties in hoops and patches who are sauntering over the grass, is just as lively a figure to me as old Samuel Johnson rolling through the fog with the Scotch Gentleman at his heels, on their way to Dr. Goldsmith’s chambers in Brick Court, or Harry Fielding, with inked ruffles and a wet towel round his head, dashing off articles at midnight for the Covent Garden Journal, while the printer’s boy is asleep in the passage.’[28]

The passage I have quoted from Thackeray at the end of the last chapter shadows forth eloquently enough something of the feeling of respect and awe which the young barrister—and even those who are not young barristers—may naturally feel for the precincts within which the great English Lawyers lived and worked—the Inns of Court, where the splendid fabric of English Law was gradually built up, ‘not without dust and heat.’

But for most laymen the Temple and its sister Inns have other and perhaps more obvious charms. For as we pass by unexpected avenues into ‘the magnificent ample squares and classic green recesses’ of the Temple, they seem to be bathed in the rich afterglow of suns that have set, the light which never was on sea or land, shed by the glorious associations connected with some of the greatest names in English literature. Here, we remember, by fond tradition Geoffrey Chaucer is{65} reputed to have lived. Here Oliver Goldsmith worked and died, and here his mortal remains were laid to rest. Here, within hail of his beloved Fleet Street, Dr. Johnson dwelt, and Blackstone wrote his famous ‘Commentaries.’ Here the gentle Elia was born. Hither possibly came Shakespeare to superintend the production of ‘Twelfth Night.’ Here, in the Inner Temple Hall, was acted the first English tragedy, ‘Gorboduc; or Ferrex and Porrex,’ a bloodthirsty play, by Thomas Sackville, Lord High Treasurer of England, and Thomas Norton, both members of the Inner Temple. And hither, to witness these or other performances, came the Virgin Queen.

The main entrance to the Middle Temple is the gateway from Fleet Street, scene of many a bonfire lit of yore by Inns of Court men on occasions of public rejoicing.[29] This characteristic building, of red brick and Portland stone, with a classical pediment, was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, and built, as an inscription records, in 1684. An old iron gas-lamp hangs above the arch, beneath the sign of the Middle Temple Lamb.

Wren’s noble gate-house replaced a Tudor building, erected, according to tradition, by Sir Amias{66} Paulet, who, being forbidden—so Cavendish[30] tells the story—to leave London without license by Cardinal Wolsey, ‘lodged in this Gate-house, which he re-edified and sumptuously beautified on the outside with the Cardinal’s Arms, Hat, Cognisance, Badges, and other devices, in a glorious manner,’ to appease him. The fact seems to be that this old Gateway was built in the ordinary way when one Sir Amisius Pawlett was Treasurer.[31]

Adjoining this Gateway is Child’s Bank, where King Charles himself once banked, and Nell Gwynne and Prince Rupert, whose jewels were disposed of in a lottery by the firm. Part of this building covers the site of the famous Devil’s Tavern, which boasted the sign of St. Dunstan—patron of the Church so near at hand—tweaking the devil’s nose. Here Ben Jonson drank the floods of Canary that inspired his plays; hither to the sanded floor of the Apollo club-room came those boon companions of his who desired to be ‘sealed of the tribe of Ben,’ and here, in after-years, Dr. Johnson loved to foregather, and Swift with Addison, Steele with Bickerstaff.

Immediately within the Gateway, on the left, is{67}

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_008_sml.jpg)

THE MIDDLE TEMPLE GATEHOUSE IN FLEET STREET

It stands on the south side close to the site of Temple Bar, was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, and built in 1684.