Title: The Chautauquan, Vol. 04, March 1884, No. 6

Author: Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle

Chautauqua Institution

Editor: Theodore L. Flood

Release date: July 17, 2017 [eBook #55133]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

MONTHLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE PROMOTION OF TRUE CULTURE. ORGAN OF THE CHAUTAUQUA LITERARY AND SCIENTIFIC CIRCLE.

Vol. IV. MARCH, 1884. No. 6.

President—Lewis Miller, Akron, Ohio.

Superintendent of Instruction—Rev. J. H. Vincent, D.D., New Haven, Conn.

Counselors—Rev. Lyman Abbott, D.D.; Rev. J. M. Gibson, D.D.; Bishop H. W. Warren, D.D.; Prof. W. C. Wilkinson, D.D.

Office Secretary—Miss Kate F. Kimball, Plainfield, N. J.

General Secretary—Albert M. Martin, Pittsburgh, Pa.

| REQUIRED READING FOR MARCH | |

| Readings from French History | |

| I.—An Outline of French History | 315 |

| II.—The French People | 317 |

| III.—Charlemagne | 317 |

| IV.—The Battle of Crécy and Siege of Calais | 318 |

| V.—Joan of Arc | 319 |

| VI.—Henry of Navarre | 320 |

| VII.—The Court of Louis XIV | 324 |

| VIII.—French Literature | 326 |

| Commercial Law | |

| II.—Notes and Bills | 327 |

| Sunday Readings | |

| [March 2] | 328 |

| [March 9] | 329 |

| [March 16] | 329 |

| [March 23] | 330 |

| [March 30] | 330 |

| Readings in Art | 330 |

| Selections from American Literature | |

| John Lothrop Motley | 333 |

| George Bancroft | 334 |

| William H. Prescott | 335 |

| United States History | 336 |

| Helen’s Tower | 338 |

| Mendelssohn’s Grave and Humboldt’s Home | 339 |

| Flotsam! (1492.) | 341 |

| The Sea as an Aquarium | 341 |

| My Years | 343 |

| Eight Centuries with Walter Scott | 343 |

| Astronomy of the Heavens for March | 346 |

| The Fir Tree | 347 |

| Ardent Spirits | 347 |

| Eccentric Americans | |

| V.—A Methodist Don Quixote | 348 |

| Hyacinth Bulbs | 351 |

| Migrations on Foot | 353 |

| C. L. S. C. Work | 355 |

| Outline of C. L. S. C. Readings | 355 |

| C. L. S. C. ’84 | 355 |

| To the Class of ’85 | 356 |

| Local Circles | 356 |

| Questions and Answers | 362 |

| Chautauqua Normal Course | 364 |

| Editor’s Outlook | 365 |

| Editor’s Note-Book | 368 |

| C. L. S. C. Notes on Required Readings for March | 370 |

| Notes on Required Readings in “The Chautauquan” | 372 |

| Chautauqua Normal Graduates | 374 |

| Errata and Addenda | 375 |

By Rev. J. H. VINCENT, D.D.

From “The People’s Commentary”—and paragraphed.

1. Gallia was the name under which France was designated by the Romans, who knew little of the country till the time of Cæsar, when it was occupied by the Aquitani, Celtæ, and Belgæ.

2. Under Augustus, Gaul was divided into four provinces, which, under subsequent emperors, were dismembered, and subdivided into seventeen.

3. In the fifth century it fell completely under the power of the Visigoths, Burgundians, and Franks.

4. In 486 A. D., Clovis, a chief of the Salian Franks, raised himself to supreme power in the north. His dynasty, known as the Merovingian, ended in the person of Childeric III., who was deposed 752 A. D.

5. The accession of Pepin gave new vigor to the monarchy, which, under his son and successor, Charlemagne,[A] crowned Emperor in the west in 800 (768-814), rose to the rank of the most powerful empire of the west. With him, however, this vast fabric of power crumbled to pieces, and his weak descendants completed the ruin of the Frankish Empire by the dismemberment of its various parts among the younger branches of the Carlovingian family.

6. On the death of Louis V. the Carlovingian dynasty was replaced by that of Hugues, Count of Paris, whose son, Hugues Capet, was elected king by the army, and consecrated at Rheims 987 A. D.

7. At this period the greater part of France was held by almost independent lords. Louis Le Gros (1108-1137) was the first ruler who succeeded in combining the whole under his scepter. He promoted the establishment of the feudal system, abolished serfdom on his own estates, secured corporate rights to the cities under his jurisdiction, gave efficiency to the central authority of the Crown, carried on a war against Henry I., of England; and when the latter allied himself with the Emperor Henry V., of Germany, against France, he brought into the field an army of 200,000 men.

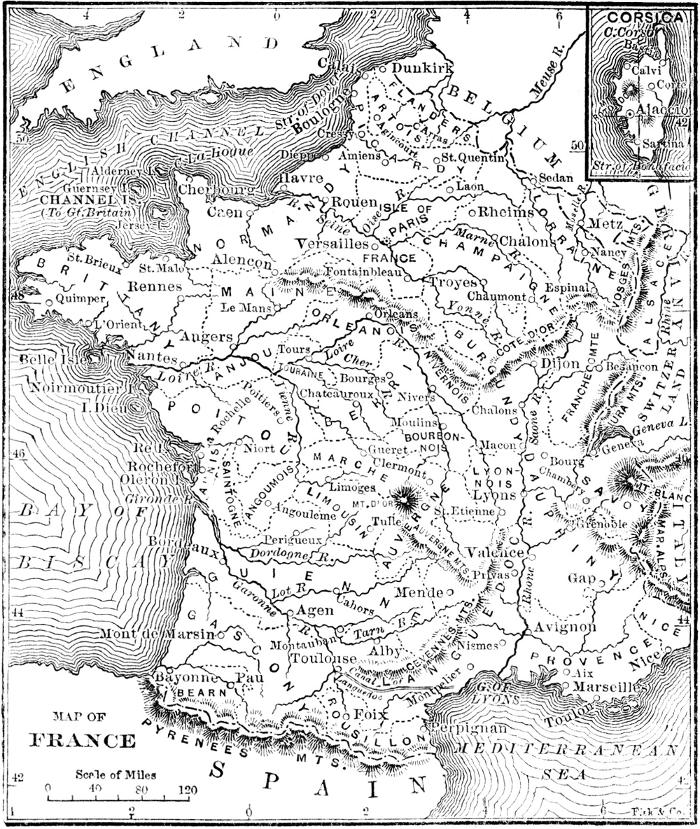

MAP OF FRANCE

8. The Oriflamme is said to have been borne aloft for the first time on this occasion as the national standard.

9. Louis VII. (1137-’80) was almost incessantly engaged in war with Henry II., of England.

10. His son and successor, Philippe Auguste (1180-1223), recovered Normandy, Maine, Touraine, and Poitou from John of England. He took an active personal share in the crusades. Philippe was the first to levy a tax for the maintenance of the standing army.

11. Many noble institutions date their origin from this reign, as the University of Paris, the Louvre, etc.

12. Louis IX. effected many modifications in the fiscal department, and, before his departure for the crusades, secured the rights of the Gallican church by special statute, in order to counteract the constantly increasing assumptions of the Papal power.

13. Philippe IV. (1285-1314), surnamed Le Bel, acquired Navarre, Champagne, and Brie by marriage.

14. Charles IV. (Le Bel, 1321-’28) was the last direct descendant of the Capetian line.

15. Philippe VI., the first of the House of Valois (1328-’50), succeeded in right of the Salic law. His reign, and those of[316] his successors, Jean (1350-’64) and Charles V. (Le Sage, 1364-’80), were disturbed by constant wars with Edward III., of England. Hostilities began in 1339; in 1346 the Battle of Crécy was fought; at the battle of Poitiers (1356) Jean was made captive; and before the final close, after the death of Edward (1377), the state was reduced to bankruptcy.

16. During the regency for the minor, Charles VI. (Le Bien Aime, 1380-1422), the war was renewed with increased vigor on the part of the English nation.

17. The signal victory won by the English at Agincourt in 1415 aided Henry in his attempts upon the throne. But the extraordinary influence exercised over her countrymen by Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans, aided in bringing about a thorough reaction, and, after a period of murder, rapine and anarchy, Charles VII. (Le Victorieux, 1422-’61) was crowned at Rheims.

18. His successor, Louis XI. (1461-’83), succeeded in recovering for the Crown the territories of Maine, Anjou and Provence, while he made himself master of some portions of the territories of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

19. Charles VIII. (1483-’98), by his marriage with Anne of Brittany, secured that powerful state. With him ended the direct male succession of the House of Valois.

20. Louis XII. (1498-1515), Le Père Du Peuple, was the only representative of the Valois-Orleans family; his successor, Francis I. (1547), was of the Valois-Angoulême branch.

21. The defeat of Francis at the battle of Pavia, in 1525, and his subsequent imprisonment at Madrid, threw the affairs of the nation into the greatest disorder.

22. In the reign of Henri II. began the persecutions of the Protestants. Henri III. (1574-’89) was the last of this branch of the Valois. The massacre of St. Bartholomew (1572) was perpetrated under the direction of the Queen-mother, Catherine de’ Medici, and the confederation of the league, at the head of which were the Guises. The wars of the league, which were carried by the latter against the Bourbon branches of the princes of the blood-royal, involved the whole nation in their vortex.

23. The succession of Henri IV., of Navarre (1589-1610), a Bourbon prince, descended from a younger son of St. Louis, allayed the fury of these religious wars, but his recantation of Protestantism in favor of Catholicism disappointed his own party.

24. During the minority of his son, Louis XIII. (1610-’43), Cardinal Richelieu, under the nominal regency of Marie de’ Medici, the Queen-mother, ruled with a firm hand. Cardinal Mazarin, under the regency of the Queen-mother, Anne of Austria, exerted nearly equal power for some time during the minority of Louis XIV. (1643-1715).

25. The wars of the Fronde, the misconduct of the Parliament, and the humbling of the nobility, gave rise to another civil war, but with the assumption of power by young Louis a new era commenced, and till near the close of his long reign the military successes of the French were most brilliant.

26. Louis XV. (1715-’75) succeeded to a heritage whose glory was tarnished, and whose stability was shaken to its very foundations during his reign.

27. The peace of Paris (1763), by which the greater portion of the colonial possessions of France were given up to England, terminated an inglorious war, in which the French had expended 1350 millions of francs.

28. In 1774 Louis XVI., a well-meaning, weak prince, succeeded to the throne. The American war of freedom had disseminated Republican ideas among the lower orders, while the Assembly of the notables had discussed and made known to all classes the incapacity of the government and the wanton prodigality of the court. The nobles and the tiers état were alike clamorous for a meeting of the states; the former wishing to impose new taxes on the nation, and the latter determined to inaugurate a thorough and systematic reform.

29. After much opposition on the part of the king and court, the États Généraux, which had not met since 1614, assembled at Versailles on the 25th of May, 1789. The resistance made by Louis and his advisers to the reasonable demands of the deputies on the 17th of June, 1789, led to the constitution of the National Assembly. The consequence was the outbreak of insurrectionary movements at Paris, where blood was shed on the 12th of July. On the following day the National Guard was convoked; and on the fourteenth the people took possession of the Bastille. The royal princes and all the nobles who could escape, sought safety in flight.

30. The royal family, having attempted in vain to follow their example, tried to conciliate the people by the feigned assumption of Republican sentiment; but on the 5th of October the rabble, followed by numbers of the National Guard, attacked Versailles, and compelled the king and his family to remove to Paris, whither the Assembly also moved.

31. A war with Austria was begun in April, 1792, and the defeat of the French was visited on Louis, who was confined in August with his family in the temple. In December the king was brought to trial. On the 20th of January, 1793, sentence of death was passed on him, and on the following day he was beheaded.

32. Marie Antoinette, the widowed Queen, was guillotined; the Dauphin and his surviving relatives suffered every indignity that malignity could devise. A reign of blood and terror succeeded.

33. The brilliant exploits of the young general, Napoleon Bonaparte, in Italy, turned men’s thoughts to other channels.

34. In 1795 a general amnesty was declared, peace was concluded with Prussia and Spain, and the war was carried on with double vigor against Austria.

35. The revolution had reached a turning point. A Directory was formed to administer the government, which was now conducted in a spirit of order and conciliation.

36. In 1797 Bonaparte and his brother-commanders were omnipotent in Italy. Austria was compelled to give up Belgium, accede to peace on any terms, and recognize the Cis-Alpine republic.

37. Under the pretext of attacking England, a fleet of 400 ships and an army of 36,000 picked men were equipped; their destination proved, however, to be Egypt, whither the Directory sent Bonaparte; but the young general resigned the command to Kleber, landed in France in 1799, and at once succeeded in supplanting the Directory, and securing his own nomination as Consul.

38. In 1800 a new constitution was promulgated, which vested the sole executive power in Bonaparte. Having resumed his military duties, he marched an army over the Alps, attacked the Austrians unawares, and decided the fate of Italy by his victory at Marengo.

39. In 1804, on an appeal of universal suffrage to the nation, Bonaparte was proclaimed Emperor. By his marriage with the archduchess Maria Louisa, daughter of the emperor of Germany, Napoleon seemed to have given to his throne the prestige of birth, which alone it had lacked. The disastrous Russian campaign, in which his noble army was lost amid the rigors of a northern winter, was soon followed by the falling away of his allies and feudatories.

40. Napoleon himself was still victorious wherever he appeared in person, but his generals were beaten in numerous engagements; and the great defeat of Leipsic compelled the French to retreat beyond the Rhine. The Swedes brought reinforcements to swell the ranks of his enemies on the east frontier, while the English pressed on from the west; Paris, in the absence of the emperor, capitulated after a short resistance, March 30, 1814. Napoleon retired to the island of Elba.

41. On the 2d of May, Louis XVIII. (the brother of Louis XVI.) made his entry into Paris.

42. On the 1st of March, 1815, Napoleon left Elba, and landed[317] in France. Crowds followed him; the soldiers flocked around his standard; the Bourbons fled, and he took possession of their lately deserted palaces. The news of his landing spread terror through Europe; and on the 25th of March a treaty of alliance was signed at Vienna between Austria, Russia, Prussia and England, and preparations at once made to put down the movement in his favor, and restore the Bourbon dynasty.

43. At first, the old prestige of success seemed to attend Napoleon; but on the 18th of June he was thoroughly defeated at Waterloo; and, having placed himself under the safeguard of the English, he was sent to the island of St. Helena.

44. In 1821 Napoleon breathed his last at St. Helena; and in 1824 Louis XVIII. died without direct heirs, and his brother, the duc d’Artois, succeeded as Charles X. The same ministerial incapacity, want of good faith, general discontent, and excessive priestly influence characterized his reign, which was abruptly brought to a close by the revolution of 1830, and the election to the throne of Louis Philippe, duke of Orleans, as king, by the will of the people.

45. Louis Philippe having abdicated (February 24, 1848), a republic was proclaimed, under a provisional government. Louis Napoleon was elected president of the Republic in December, 1848, but by the famous coup d’état of December 2, 1851, he violently set aside the Constitution, and assumed dictatorial powers; and a year after was raised, by the almost unanimous voice of the nation, to the dignity of Emperor, as Napoleon III.

46. The result of the appeal made to the nation in 1870, on the plea of securing their sanction for his policy, was not what he had anticipated. The course of events in the short but terrible Franco-German war of 1870-’71, electrified Europe by its unexpected character.

47. On September 2, 1870, Napoleon, with his army of 90,000 men, surrendered at Sedan. With the concurrence of Prussia the French nation next proceeded, by a general election of representatives, to provide for the exigencies of the country.

48. A republic was proclaimed, and the first national assembly met at Bordeaux in February, 1871. After receiving from the provisional government of defense the resignation of the powers confided to them in September, 1870, the Assembly undertook to organize the republican government, and nominated M. Thiers chief of the executive power of the state, with the title of President of the French Republic, but with the condition of responsibility to the National Assembly.

49. The ex-Emperor Napoleon died in 1872, at Chiselhurst, England, where he had resided with his family since his liberation in March, 1871.

50. In 1873 M. Thiers resigned the office of President of the French Republic, and was succeeded by Marshal MacMahon, who resigned in 1879, and was succeeded by M. Grèvy.

From their Celtic ancestry, the Gauls, the French people inherited a certain heedlessness of character, or want of foresight as to consequences. The Romans communicated to them their language; the Franks, a teutonic people, by whom they were captured in the fifth century, gave them a national designation; but to neither the Romans nor Franks were they materially indebted for those qualities which ordinarily stamp the national or individual character. We have therefore to keep in mind that, through all the vicissitudes of modern history, the French people have remained essentially Celtic. With many good qualities—bold, tasteful, quick-witted, ingenious—they have some less to be admired—impulsive, restless, vain, bombastic, fond of display, and, as Cæsar described them, “lovers of novelty.” They have ever boasted of being at the head of civilization; but with all their acknowledged advancement in literature and science, they have at every stage in their political career demonstrated a singular and absolutely pitiable want of common sense.—Chambers’ Miscellany.

From the accession, in 768, of Charlemagne, eldest son of Pepin le Bref may be dated the establishment of clerical power, the rise of chivalry, and the foundation of learning in the Empire of France. He was a man of extraordinary foresight and strength of character, and possessed not only the valor of a hero and the skill of a general, but the calm wisdom of a statesman, and the qualities of a judicious sovereign. Ambitious of conquest as Alexander or Darius, he nevertheless provided as conscientiously for the welfare of his subjects and the advancement of letters, as did Alfred the Great of England about a century afterwards. He founded schools and libraries—convoked national assemblies—revised laws—superintended the administration of justice—encouraged scientific men and professors of the fine arts—and, during a reign of forty-six years, extended his frontiers beyond the Danube, imposed tribute upon the barbarians of the Vistula, made his name a terror to the Saracen tribes, and added Northern Italy to the dependencies of France. Notwithstanding these successes, it appears that the conquest and conversion of the Saxons (a nation of German idolaters, whose territories bordered closely upon his chosen capital of Aix-la-Chapelle) formed the darling enterprise of this powerful monarch. From 770 to 804, his arms were constantly directed against them; and in Wittikind, their heroic leader, he encountered a warrior as fearless, if not as fortunate, as himself. The brave Saxons were, however, no match for one whose triumphs procured him the splendid title of Emperor of the West, and who gathered his daring hosts from dominions which comprised the whole of France, Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, and Prussia, and were only bounded on the east by the Carpathian mountains, and on the west by the Ebro and the ocean. Year after year he wasted their country with fire and sword, overthrew their idols, leveled their temples to the ground, erected fortresses amid the ruins of their villages, and carried away vast numbers of captives to the interior of Gaul. To this forced emigration succeeded a conversion equally unwelcome. Thousands of reluctant Saxons were compelled to subscribe to the ceremony of baptism; their principalities were portioned off among abbots and bishops; and Wittikind did homage to Charlemagne in the Champs-de-Mars.

It was about this period that the Danes and Normans first began to harass the northern coasts of Europe. Confident of their naval strength, they attacked the possessions of Charlemagne with as little hesitation as those of his less formidable neighbor, Egbert of Wessex; descended upon Friesland as boldly as upon Teignmouth or Hengesdown; and even ventured with their galleys into the port of a city of Narbonnese Gaul at a time when the emperor himself was sojourning within its walls. Springing up, as they did, toward the close of so prosperous a reign, these new invaders proved more dangerous than Charlemagne had anticipated. He caused war barks to be stationed at the mouths of his great rivers, and in 808 marched an army to the defense of Friesland. On this occasion, however, he was glad to make terms of peace; and it is said that the increasing power of the Baltic tribes embittered his later days with presentiments of that decay which shortly afterward befell his gigantic empire. From the conclusion of this peace to the date of his death in the year 814, no event of historical importance occurred; and the great emperor was buried at Aix-la-Chapelle, in that famous cathedral of which he was the founder.

The race of Carlovingian kings took their name, and only their name, from this, their magnificent ancestor. Weak of purpose as the descendants of Clovis, and endued, perhaps, with even a less share of animal courage, they suffered their mighty inheritance to be wrested from them, divided, subdivided, pillaged and impoverished. No portion of French history is so disastrous, so unsatisfactory, and so obscure as that which relates to this epoch. Indeed, toward the commencement of the tenth century, an utter blank occurs, and[318] we are left for many years without any record whatever.—A. B. E.

Although Edward III., by supporting with troops and officers, and sometimes even in person, the cause of the countess of Montfort—and Philip of Valois, by assisting in the same way Charles of Blois and Joan of Penthièvre, took a very active, if indirect, share in the war in Brittany, the two kings persisted in not calling themselves at war; and when either of them proceeded to acts of unquestionable hostility, they eluded the consequences of them by hastily concluding truces incessantly violated and as incessantly renewed. They had made use of this expedient in 1340; and they had recourse to it again in 1342, 1343, and 1344. The last of these truces was to have lasted up to 1346; but in the spring of 1345, Edward resolved to put an end to this equivocal position, and to openly recommence war. He announced his intention to Pope Clement IV., to his own lieutenants in Brittany, and to all the cities and corporations of his kingdom. The tragic death of Van Artevelde, however (1345), proved a great loss to the king of England. He was so much affected by it that he required a whole year before he could resume with any confidence his projects of war; and it was not until the 2nd of July, 1346, that he embarked at Southampton, taking with him, beside his son, the prince of Wales, hardly sixteen years of age, an army which comprised, according to Froissart, seven earls, more than thirty-five barons, a great number of knights, four thousand men-at-arms, ten thousand English archers, six thousand Irish and twelve thousand Welsh infantry, in all something more than thirty-two thousand men. By the advice of Godfrey d’Harcourt, he marched his army over Normandy; he took and plundered on his way Harfleur, Cherbourg, Valognes, Carentan, St. Lô, and Caen; then, continuing his march, he occupied Louviers, Vernon, Verneuil, Nantes, Meulan, and Poissy, where he took up his quarters in the old residence of King Robert; and thence his troops advanced and spread themselves as far as Ruel, Neuilly, Boulogne, St. Cloud, Bourg-la-Reine and almost to the gates of Paris, whence could be seen “the fire and smoke from burning villages.” Philip recalled in all haste his troops from Aquitaine, commanded the burgher forces to assemble, and gave them, as he had given all his allies, St. Denis for the rallying point. At sight of so many great lords and all sorts of men of war flocking together from all points the Parisians took fresh courage. “For many a long day there had not been at St. Denis a king of France in arms and fully prepared for battle.”

Edward began to be afraid of having pushed too far forward, and of finding himself endangered in the heart of France, confronted by an army which would soon be stronger than his own. He, accordingly, marched northward, where he flattered himself he would find partisans, counting especially on the help of the Flemings, who, in fulfillment of their promise, had already advanced as far as Béthune to support him. Philip moved with all his army into Picardy in pursuit of the English army, which was in a hurry to reach and cross the Somme, and so continue its march northward.

When Edward, after passing the Somme, had arrived near Crécy, five leagues from Abbeville, in the countship of Ponthieu, which had formed part of his mother Isabel’s dowry, “Halt we here,” said he to his marshals; “I will go no farther till I have seen the enemy; I am on my mother’s rightful inheritance, which was given her on her marriage; I will defend it against mine adversary, Philip of Valois;” and he rested in the open fields, he and all his men, and made his marshals mark well the ground where they would set their battle in array. Philip, on his side, had moved to Abbeville, where all his men came and joined him, and whence he sent out scouts to learn the truth about the English. When he knew that they were resting in the open fields near Crécy and showed that they were awaiting their enemies, the king of France was very joyful, and said that, please God, they should fight him on the morrow [the day after Friday, August 25, 1346].

On Saturday, the 26th of August, after having heard mass, Philip started from Abbeville with all his barons. The battle began with an attack by fifteen thousand Genoese bowmen, who marched forward, and leaped thrice with a great cry; their arrows did little execution, as the strings of their bows had been relaxed by the damp; the English archers now taking their bows from their cases, poured forth a shower of arrows upon this multitude, and soon threw them into confusion; the Genoese falling back upon the French cavalry, were by them cut to pieces, and being allowed no passage, were thus prevented from again forming in the rear; this absurd inhumanity lost the battle, as the young Prince of Wales, taking advantage of the irretrievable disorder, led on his line at once to the charge. “No one can describe or imagine,” says Froissart, “the bad management and disorder of the French army, though their troops were out of number.” Philip was led from the field by John of Hainault, and he rode till he came to the walls of the castle of Broye, where he found the gates shut; ordering the governor to be summoned, when the latter inquired, it being dark, who it was that called at so late an hour, he answered; “Open, open, governor; it is the fortune of France;” and accompanied by five barons only he entered the castle.

Whilst Philip, with all speed, was on the road back to Paris with his army, as disheartened as its king, and more disorderly in retreat than it had been in battle, Edward was hastening, with ardor and intelligence, to reap the fruits of his victory. In the difficult war of conquest he had undertaken, what was clearly of most importance to him was to possess on the coast of France, as near as possible to England, a place which he might make, in his operations by land and sea, a point of arrival and departure, of occupancy, of provisioning, and of secure refuge. Calais exactly fulfilled these conditions. On arriving before the place, September 3rd, 1346, Edward “immediately had built all round it,” says Froissart, “houses and dwelling places of solid carpentry, and arranged in streets, as if he were to remain there for ten or twelve years, for his intention was not to leave it winter or summer, whatever time and whatever trouble he must spend and take. He called this new town Villeneuve la Hardie; and he had therein all things necessary for an army, and more too, as a place appointed for the holding of a market on Wednesday and Saturday; and therein were mercers’ shops and butchers’ shops, and stores for the sale of cloth and bread and all other necessaries. King Edward did not have the city of Calais assaulted by his men, well knowing that he would lose his pains, but said he would starve it out, however long a time it might cost him, if King Philip of France did not come to fight him again, and raise the siege.”

Calais had for its governor John de Vienne, a valiant and faithful Burgundian knight, “the which seeing,” says Froissart, “that the king of England was making every sacrifice to keep up the siege, ordered that all sorts of small folk, who had no provisions, should quit the city without further notice.” The Calaisians endured for eleven months all the sufferings arising from isolation and famine. The King of France made two attempts to relieve them. On the 20th of May, 1347, he assembled his troops at Amiens; but they were not ready to march till about the middle of July, and as long before as the 23rd of June, a French fleet of ten galleys and thirty-five transports had been driven off by the English.

When the people of Calais saw that all hope of a rescue had slipped from them, they held a council, resigned themselves to offer submission to the king of England, rather than die of hunger, and begged their governor, John de Vienne, to enter into negotiations for that purpose with the besiegers. Walter de Manny, instructed by Edward to reply to these overtures, said to John de Vienne, “The king’s intent is that ye put yourselves[319] at his free will to ransom or put to death, such as it shall please him; the people of Calais have caused him so great displeasure, cost him so much money and lost him so many men, that it is not astonishing if that weighs heavily upon him.” In his final answer to the petition of the unfortunate inhabitants, Edward said: “Go, Walter, to them of Calais, and tell the governor that the greatest grace they can find in my sight is that six of the most notable burghers come forth from their town bareheaded, barefooted, with ropes round their necks and with the keys of the town and castle in their hands. With them I will do according to my will and the rest I will receive to mercy.” It is well known how the king would have put to death Eustace de St. Pierre and his companions, and how their lives were spared at the intercession of Queen Philippa.

Eustace, more concerned for the interests of his own town than for those of France, and being more of a Calaisian burgher than a national patriot, showed no hesitation, for all that appears, in serving, as a subject of the king of England, his native city, for which he had shown himself so ready to die. At his death, which happened in 1351, his heirs declared themselves faithful subjects of the king of France, and Edward confiscated away from them the possessions he had restored to their predecessor. Eustace de St. Pierre’s cousin and comrade in devotion to their native town, John d’Aire, would not enter Calais again; his property was confiscated, and his house, the finest, it is said, in the town, was given by King Edward to Queen Philippa, who showed no more hesitation in accepting it than Eustace in serving his new king. Long-lived delicacy of sentiment and conduct was rarer in those rough and rude times than heroic bursts of courage and devotion.

The battle of Crécy and the loss of Calais were reverses from which Philip of Valois never even made a serious attempt to recover; he hastily concluded with Edward a truce, twice renewed, which served only to consolidate the victor’s successes.

On the 6th of January, 1428, at Domremy, a little village in the valley of the Meuse, between Neufchâtel and Vaucouleurs, on the edge of the frontier from Champagne to Lorraine, the young daughter of simple tillers-of-the-soil “of good life and repute, herself a good, simple, gentle girl, no idler, occupied hitherto in sewing or spinning with her mother or driving afield her parent’s sheep and sometimes even, when her father’s turn came round, keeping for him the whole flock of the commune,” was fulfilling her sixteenth year. It was Joan of Arc, whom all her neighbors called Joannette. Her early childhood was passed amidst the pursuits characteristic of a country life; her behavior was irreproachable, and she was robust, active, and intrepid. Her imagination becoming inflamed by the distressed situation of France, she dreamed that she had interviews with St. Margaret, St. Catherine, and St. Michael, who commanded her, in the name of God, to go and raise the siege of Orleans, and conduct Charles to be crowned at Rheims. Accordingly she applied to Robert de Baudricourt, captain of the neighboring town of Vaucouleurs, revealing to him her inspiration, and conjuring him not to neglect the voice of God, which spoke through her. This officer for some time treated her with neglect; but at length, prevailed on by repeated importunities, he sent her to the king at Chinon, to whom, when introduced, she said: “Gentle Dauphin, my name is Joan the Maid, the King of Heaven hath sent me to your assistance; if you please to give me troops, by the grace of God and the force of arms, I will raise the siege of Orleans, and conduct you to be crowned at Rheims, in spite of your enemies.” Her requests were now granted; she was armed cap-a-pie, mounted on horseback, and provided with a suitable retinue. Previous to her attempting any exploit, she wrote a long letter to the young English monarch, commanding him to withdraw his forces from France, and threatening his destruction in case of refusal. She concluded with “hear this advice from God and la Pucelle.”

But, side by side with these friends, she had an adversary in the king’s favorite, George de la Trémoille, an ambitious courtier, jealous of any one who seemed within the range of the king’s good graces, and opposed to a vigorous prosecution of the war, since it hampered him in the policy he wished to keep up toward the duke of Burgundy. To the ill-will of La Trémoille was added that of the majority of courtiers enlisted in the following of the powerful favorite, and that of warriors irritated at the importance acquired at their expense by a rustic and fantastic little adventuress. Here was the source of the enmities and intrigues which stood in the way of all Joan’s demands, rendered her successes more tardy, difficult, and incomplete, and were one day to cost her more dearly still.

At the end of about five weeks the expedition was in readiness. It was a heavy convoy of revictualment protected by a body of ten or twelve thousand men commanded by Marshal de Boussac, and numbering amongst them Xaintrailles and La Hire. The march began on the 27th of April, 1429. Joan had caused the removal of all women of bad character, and had recommended her comrades to confess. She took the communion in the open air, before their eyes; and a company of priests, headed by her chaplain, Pasquerel, led the way whilst chanting sacred hymns. Great was the surprise amongst the men-at-arms. Many had words of mockery on their lips. It was the time when La Hire used to say, “If God were a soldier, he would turn robber.” Nevertheless, respect got the better of habit; the most honorable were really touched; the coarsest considered themselves bound to show restraint. On the 29th of April they arrived before Orleans. But, in consequence of the road they had followed, the Loire was between the army and the town; the expeditionary corps had to be split in two; the troops were obliged to go and feel for the bridge of Blois in order to cross the river; and Joan was vexed and surprised. Dunois, arrived from Orleans in a little boat, urged her to enter the town that same evening. “Are you the bastard of Orleans?” asked she, when he accosted her. “Yes; and I am rejoiced at your coming.” “Was it you who gave counsel for making me come hither by this side of the river and not the direct way, over yonder where Talbot and the English were?” “Yes; such was the opinion of the wisest captains.”

Joan’s first undertaking was against Orleans, which she entered without opposition on the 29th of April, 1429, on horseback, completely armed, preceded by her own banner, and having beside her Dunois, and behind her the captains of the garrison and several of the most distinguished burgesses of Orleans, who had gone out to meet her. The population, one and all, rushed thronging round her, carrying torches, and greeting her arrival “with joy as great as if they had seen God come down amongst them.” With admirable good sense, discovering the superior merits of Dunois, the bastard of Orleans, a celebrated captain, she wisely adhered to his instructions; and by constantly harassing the English, and beating up their intrenchments in various desperate attacks, in all of which she displayed the most heroic courage, Joan in a few weeks compelled the earl of Suffolk and his army to raise the siege, having sustained the loss of six thousand men. The proposal of crowning Charles at Rheims would formerly have appeared like madness, but the Maid of Orleans now insisted on its fulfillment. She accordingly recommenced the campaign on the 10th of June; to complete the deliverance of Orleans an attack was begun upon the neighboring places, Jargeau, Meung, and Beaugency; thousands of the late dispirited subjects of Charles now flocked to his standard, many towns immediately declared for him; and the English, who had suffered in various actions, at that of Jargeau, when the earl of Suffolk was taken prisoner, and at that of Patay, when Sir John Fastolfe fled without striking a blow, seemed now to be totally dispirited. On the 16th[320] of July King Charles entered Rheims, and the ceremony of his coronation was fixed for the morrow.

It was solemn and emotional as are all old national traditions which recur after a forced suspension. Joan rode between Dunois and the archbishop of Rheims, chancellor of France. The air resounded with the Te Deum sung with all their hearts by clergy and crowd. “In God’s name,” said Joan to Dunois, “here is a good people and a devout; when I die, I should much like it to be in these parts.” “Joan,” inquired Dunois, “know you when you will die and in what place?” “I know not,” said she, “for I am at the will of God.” Then she added, “I have accomplished that which my Lord commanded me, to raise the siege of Orleans and have the gentle king crowned. I would like it well if it should please Him to send me back to my father and mother, to keep their sheep and their cattle and do that which was my wont.” “When the said lords,” says the chronicler, an eye-witness, “heard these words of Joan, who, with eyes toward heaven, gave thanks to God, they the more believed that it was somewhat sent from God and not otherwise.”

Historians and even contemporaries have given much discussion to the question whether Joan of Arc, according to her first ideas, had really limited her design to the raising of the siege of Orleans and the coronation of Charles VII. at Rheims. However that may be, when Orleans was relieved and Charles VII. crowned, the situation, posture, and part of Joan underwent a change. She no longer manifested the same confidence in herself and her designs. She no longer exercised over those in whose midst she lived the same authority. She continued to carry on war, but at hap-hazard, sometimes with and sometimes without success, just like La Hire and Dunois; never discouraged, never satisfied, and never looking upon herself as triumphant. After the coronation, her advice was to march at once upon Paris, in order to take up a fixed position in it, as being the political center of the realm of which Rheims was the religious. Nothing of the sort was done. She threw herself into Compiègne, then besieged by the duke of Burgundy. The next day (May 25, 1430), heading a sally upon the enemy, she was repulsed and compelled to retreat after exerting the utmost valor; when, having nearly reached the gate of the town, an English archer pursued her and pulled her from her horse. The joy of the English at this capture was as great as if they had obtained a complete victory. Joan was committed to the care of John of Luxembourg, count of Ligny, from whom the duke of Bedford purchased the captive for ten thousand pounds, and a pension of three hundred pounds a year to the bastard of Vendôme, to whom she surrendered. Joan was now conducted to Rouen, where, loaded with irons, she was thrown into a dungeon, preparatory to appear before a court assembled to judge her.

The trial lasted from the 21st of February to the 30th of May, 1431. The court held forty sittings, mostly in the chapel of the castle, some in Joan’s very prison. On her arrival there, she had been put in an iron cage; afterward she was kept “no longer in the cage, but in a dark room in a tower of the castle, wearing irons upon her feet, fastened by a chain to a large piece of wood, and guarded night and day by four or five soldiers of low grade.” She complained of being thus chained; but the bishop told her that her former attempts at escape demanded this precaution. “It is true,” said Joan, as truthful as heroic, “I did wish and I still wish to escape from prison, as is the right of every prisoner.” At her examination, the bishop required her to take “an oath to tell the truth about everything as to which she should be questioned.” “I know not what you mean to question me about; perchance you may ask me things I would not tell you; touching my revelations, for instance, you might ask me to tell something I have sworn not to tell; thus I should be perjured, which you ought not to desire.” The bishop insisted upon an oath absolute and without condition. “You are too hard on me,” said Joan; “I do not like to take an oath to tell the truth save as to matters which concern the faith.” The bishop called upon her to swear on pain of being held guilty of the things imputed to her. “Go on to something else,” said she. And this was the answer she made to all questions which seemed to her to be a violation of her right to be silent. Wearied and hurt at these imperious demands, she one day said, “I come on God’s business, and I have naught to do here; send me back to God from whom I come.” “Are you sure you are in God’s grace?” asked the bishop. “If I be not,” answered Joan, “please God to bring me to it; and if I be, please God to keep me in it!” The bishop himself remained dumbfounded.

There is no object in following through all its sittings and all its twistings this odious and shameful trial, in which the judges’ prejudiced servility and scientific subtlety were employed for three months to wear out the courage or overreach the understanding of a young girl of nineteen, who refused at one time to lie, and at another to enter into discussion with them, and made no defence beyond holding her tongue or appealing to God who had spoken to her and dictated to her that which she had done. In the end she was condemned for all the crimes of which she had been accused, aggravated by that of heresy, and sentenced to perpetual imprisonment, to be fed during life on bread and water. The English were enraged that she was not condemned to death. “Wait but a little,” said one of the judges, “we shall soon find the means to ensnare her.” And this was effected by a grievous accusation, which, though somewhat countenanced by the Levitical law, has been seldom urged in modern times, the wearing of man’s attire. Joan had been charged with this offense, but she promised not to repeat it. A suit of man’s apparel was designedly placed in her chamber, and her own garments, as some authors say, being removed, she clothed herself in the forbidden garb, and her keepers surprising her in that dress, she was adjudged to death as a relapsed heretic, and was condemned to be burnt in the marketplace at Rouen (1431).

Henry IV. perfectly understood and steadily took the measure of the situation in which he was placed. He was in a great minority throughout the country as well as the army, and he would have to deal with public passions, worked by his foes for their own ends, and with the personal pretensions of his partisans. He made no mistake about these two facts, and he allowed them great weight; but he did not take for the ruling principle of his policy and for his first rule of conduct the plan of alternate concessions to the different parties and of continually humoring personal interests; he set his thoughts higher, upon the general and natural interests of France as he found her and saw her. They resolved themselves, in his eyes, into the following great points: Maintenance of the hereditary rights of monarchy, preponderance of Catholics in the government, peace between Catholics and Protestants, and religious liberty for Protestants. With him these points became the law of his policy and his kingly duty as well as the nation’s right. He proclaimed them the first words that he addressed to the lords and principal personages of state assembled around him. On the 4th of August, 1589, in the camp at St. Cloud, the majority of the princes, dukes, lords, and gentlemen present in the camp expressed their full adhesion to the accession and the manifesto of the king, promising him “service and obedience against rebels and enemies who would usurp the kingdom.” Two notable leaders, the duke of Épernon amongst the Catholics and the duke of La Trémoille amongst the Protestants, refused to join in this adhesion; the former saying that his conscience would not permit him to serve a heretic king, the latter alleging that his conscience forbade him to serve a prince who engaged to protect Catholic idolatry. They withdrew, D’Épernon into Angoumois and Saintonge, taking with him six thousand foot and twelve thousand horse; and La Trémoille[321] into Poitou, with nine battalions of reformers. They had an idea of attempting, both of them, to set up for themselves independent principalities. Three contemporaries, Sully, La Force, and the bastard of Angoulême, bear witness that Henry IV. was deserted by as many Huguenots as Catholics. The French royal army was reduced, it is said, to one half. As a make-weight, Sancy prevailed upon the Swiss, to the number of twelve thousand, and two thousand German auxiliaries, not only to continue in the service of the new king but to wait six months for their pay, as he was at the moment unable to pay them. From the 14th to the 20th of August, in Ile-de-France, in Picardy, in Normandy, in Auvergne, in Champagne, in Burgundy, in Anjou, in Poitou, in Languedoc, in Orleanness, and in Touraine, a great number of towns and districts joined in the determination of the royal army.

As the government of Henry IV. went on growing in strength and extent, the moderate Catholics were beginning, not as yet to make approaches toward him, but to see a glimmering possibility of treating with him, and obtaining from him such concessions as they considered necessary, at the same time that they in their turn made to him such as he might consider sufficient for his party and himself.

Unhappily, the new pope, Gregory XIV., elected on the 5th of December, 1590, was humbly devoted to the Spanish policy, meekly subservient to Philip II.; that is, to the cause of religious persecution and of absolute power, without regard for anything else. The relations of France with the Holy See at once felt the effects of this; Cardinal Gaetani received from Rome all the instructions that the most ardent Leaguers could desire; and he gave his approval to a resolution of the Sorbonne to the effect that Henry de Bourbon, heretic and relapsed, was forever excluded from the crown, whether he became a Catholic or not. Henry IV. had convoked the states-general at Tours for the month of March, and had summoned to that city the archbishops and bishops to form a national council, and to deliberate as to the means of restoring the king to the bosom of the Catholic Church. The legate prohibited this council, declaring, beforehand, the excommunication and deposition of any bishops who should be present at it. The Leaguer parliament of Paris forbade, on pain of death and confiscation, any connection, any correspondence with Henry de Bourbon and his partisans. A solemn procession of the League took place at Paris on the 14th of March, and, a few days afterwards, the union was sworn afresh by all the municipal chiefs of the population. In view of such passionate hostility, Henry IV., a stranger to any sort of illusion, at the same time that he was always full of hope, saw that his successes at Arques were insufficient for him, and that, if he were to occupy the throne in peace, he must win more victories. He recommenced the campaign by the siege of Dreux, one of the towns which it was most important for him to possess, in order to put pressure on Paris and cause her to feel, even at a distance, the perils and evils of war.

On Wednesday, the 14th of March, 1590, the two armies met on the plains of Ivry, a village six leagues from Evreux, on the left bank of the Eure. A battle ensued in which, although the resources of modern warfare were brought into operation, the decisive force consisted, as of old, in the cavalry. It appeared as if Henry IV. must succumb to the superior force of the enemy; further and further backward was his white banner seen to retire, and the great mass appeared as if they designed to follow it. At length Henry cried out that those who did not wish to fight against the enemy might at least turn and see him die, and immediately plunged into the thickest of the battle. It appeared as if the royalist gentry had felt the old martial fire of their ancestry enkindled by these words, and by the glance that accompanied them. Raising one mighty shout to God, they threw themselves upon the enemy, following their king, whose plume was now their banner. In this there might have been some dim principle of religious zeal, but that devotion to personal authority, which is so powerful an element in war and in policy, was wanting. The royalist and religious energy of Henry’s troops conquered the Leaguers. The cavalry was broken, scattered, and swept from the field, and the confused manner of their retreat so puzzled the infantry that they were not able to maintain their ground; the German and French were cut down; the Swiss surrendered. It was a complete victory for Henry IV.

It was not only as able captain and valiant soldier that Henry IV. distinguished himself at Ivry; there the man was conspicuous for the strength of his better feelings, as generous and as affectionate as the king was far-sighted and bold. When the word was given to march from Dreux, Count Schomberg, colonel of the German auxiliaries called Reiters, had asked for the pay of his troops, letting it be understood that they would not fight, if their claims were not satisfied. Henry had replied harshly, “People don’t ask for money on the eve of a battle.” At Ivry, just as the battle was on the point of beginning, he went up to Schomberg: “Colonel,” said he, “I hurt your feelings. This may be the last day of my life. I can’t bear to take away the honor of a brave and honest gentleman like you. Pray forgive me and embrace me.” “Sir,” answered Schomberg, “the other day your majesty wounded me, to-day you kill me.” He gave up the command of the Reiters in order to fight in the king’s own squadron, and was killed in action.

The victory of Ivry had a great effect in France and in Europe, though not immediately, and as regarded the campaign of 1690. The victorious king moved on Paris and made himself master of the little towns in the neighborhood with a view of besieging the capital. The investment became more strict; it was kept up for more than three months, from the end of May to the beginning of September, 1590; and the city was reduced to a severe state of famine, which would have been still more severe if Henry IV. had not several times over permitted the entry of some convoys of provisions and the exit of the old men, the women, the children, in fact, the poorest and weakest part of the population. “Paris must not be a cemetery,” he said: “I do not wish to reign over the dead.” In the meantime, Duke Alexander of Parma, in accordance with express orders from Philip II., went from the Low Countries, with his army, to join Mayenne at Meaux, and threaten Henry IV. with their united forces if he did not retire from the walls of the capital. Henry IV. offered the two dukes battle, if they really wished to put a stop to the investment; but “I am not come so far,” answered the duke of Parma, “to take counsel of my enemy; if my manner of warfare does not please the king of Navarre, let him force me to change it instead of giving me advice that nobody asked him for.” Henry in vain attempted to make the duke of Parma accept battle. The able Italian established himself in a strongly entrenched camp, surprised Lagny and opened to Paris the navigation of the Marne, by which provisions were speedily brought up. Henry decided upon retreating; he dispersed the different divisions of his army into Touraine, Normandy, Picardy, Champagne, Burgundy, and himself took up his quarters at Senlis, at Compiègne, in the towns on the banks of the Oise. The duke of Mayenne arrived on the 18th of September at Paris; the duke of Parma entered it himself with a few officers and left it on the 13th of November, with his army on his way back to the Low Countries, being a little harassed in his retreat by the royal cavalry, but easy, for the moment, as to the fate of Paris and the issue of the war, which continued during the first six months of the year 1591, but languidly and disconnectedly, with successes and reverses see-sawing between the two parties and without any important results.

Then began to appear the consequences of the victory of Ivry and the progress made by Henry IV., in spite of the check he received before Paris and at some other points in the kingdom. Not only did many moderate Catholics make advances[322] to him, struck with his sympathetic ability and his valor, and hoping that he would end by becoming a Catholic, but patriotic wrath was kindling in France against Philip II. and the Spaniards, those fomenters of civil war in the mere interest of foreign ambition.

The League was split up into two parties, the Spanish League and the French League. The committee of Sixteen labored incessantly for the formation and triumph of the Spanish League; and its principal leaders wrote, on the 2nd of September, 1591, a letter to Philip II., offering him the crown of France and pledging their allegiance to him as his subjects: “We can positively assure your Majesty,” they said, “that the wishes of all Catholics are to see your Catholic Majesty holding the scepter of this kingdom and reigning over us, even as we do throw ourselves right willingly into your arms as in to those of our father, or at any rate establishing one of your posterity upon the throne.” These ringleaders of the Spanish League had for their army the blindly fanatical and demagogic populace of Paris, and were, further, supported by 4,000 Spanish troops whom Philip II. had succeeded in getting almost surreptitiously into Paris. They created a council of ten, the sixteenth century’s committee of public safety; they proscribed the policists; they, on the 15th of November, had the president, Brisson, and two councilors of the Leaguer parliament arrested, hanged them to a beam and dragged the corpses to the Place de Grève, where they strung them up to a gibbet with inscriptions setting forth that they were heretics, traitors to the city and enemies of the Catholic princes. Whilst the Spanish League was thus reigning at Paris, the duke of Mayenne was at Laon, preparing to lead his army, consisting partly of Spaniards, to the relief of Rouen, the siege of which Henry IV. was commencing. Being summoned to Paris by messengers who succeeded one another every hour, he arrived there on the 28th of November, 1591, with 2,000 French troops; he armed the guard of burgesses, seized and hanged, in a ground-floor room of the Louvre, four of the chief leaders of the Sixteen, suppressed their committee, reëstablished the parliament in full authority and, finally, restored the security and preponderance of the French League, whilst taking the reins once more into his own hands.

Whilst these two Leagues, the one Spanish and the other French, were conspiring thus persistently, sometimes together and sometimes one against the other, to promote personal ambition and interests, at the same time national instinct, respect for traditional rights, weariness of civil war, and the good sense which is born of long experience, were bringing France more and more over to the cause and name of Henry IV. In all the provinces, throughout all ranks of society, the population non-enrolled amongst the factions were turning their eyes toward him as the only means of putting an end to war at home and abroad, the only pledge of national unity, public prosperity, and even freedom of trade, a hazy idea as yet, but even now prevalent in the great ports of France and in Paris. Would Henry turn Catholic? That was the question asked everywhere, amongst Protestants with anxiety, but with keen desire and not without hope amongst the mass of the population. The rumor ran that, on this point, negotiations were half opened even in the midst of the League itself, even at the court of Spain, even at Rome where Pope Clement VIII., a more moderate man than his predecessor, Gregory XIV., “had no desire,” says Sully, “to foment the troubles of France, and still less that the king of Spain should possibly become its undisputed king, rightly judging that this would be laying open to him the road to the monarchy of Christendom, and, consequently, reducing the Roman pontiffs to the position, if it were his good pleasure, of his mere chaplains” [Œconomies royales, t. ii. p. 106]. Such being the existing state of facts and minds, it was impossible that Henry IV. should not ask himself roundly the same question and feel that he had no time to lose in answering it.

In spite of the breadth and independence of his mind, Henry IV. was sincerely puzzled. He was of those who, far from clinging to a single fact and confining themselves to a single duty, take account of the complication of the facts amidst which they live, and of the variety of the duties which the general situation or their own imposes upon them. Born in the reformed faith, and on the steps of the throne, he was struggling to defend his political rights whilst keeping his religious creed; but his religious creed was not the fruit of very mature or very deep conviction; it was a question of first claims and of honor rather than a matter of conscience; and, on the other hand, the peace of France, her prosperity, perhaps her territorial integrity, were dependent upon the triumph of the political rights of the Béarnese. Even for his brethren in creed his triumph was a benefit secured, for it was an end of persecution and a first step toward liberty. There is no measuring accurately how far ambition, personal interest, a king’s egotism had to do with Henry IV.’s abjuration of his religion; none would deny that those human infirmities were present; but all this does not prevent the conviction that patriotism was uppermost in Henry’s soul, and that the idea of his duty as king toward France, a prey to all the evils of civil and foreign war, was the determining motive of his resolution. It cost him a great deal. On the 26th of April, 1593, he wrote to the grand duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand de Medici, that he had decided to turn Catholic “two months after that the duke of Mayenne should have come to an agreement with him on just and suitable terms;” and, foreseeing the expense that would be occasioned to him by “this great change in his affairs,” he felicitated himself upon knowing that the grand duke was disposed to second his efforts toward a levy of 4000 Swiss and advance a year’s pay for them. On the 28th of April he begged the bishop of Chartres, Nicholas de Thou, to be one of the Catholic prelates whose instructions he would be happy to receive on the 15th of July, and he sent the same invitation to several other prelates. On the 16th of May he declared to his council his resolve to become a convert. This news, everywhere spread abroad, produced a lively burst of national and Bourbonic feeling even where it was scarcely to be expected; at the states-general of the League, especially in the chamber of the noblesse, many members protested “that they would not treat with foreigners, or promote the election of a woman, or give their suffrages to any one unknown to them, and at the choice of his Catholic Majesty of Spain.” At Paris, a part of the clergy, the incumbents of St. Eustache, St. Merri, and St. Sulpice, and even some of the popular preachers, violent Leaguers but lately, and notably Guincestre, boldly preached peace and submission to the king if he turned Catholic. The principal of the French League, in matters of policy and negotiation, and Mayenne’s adviser since 1589, Villeroi, declared “that he would not bide in a place where the laws, the honor of the nation and the independence of the kingdom were held so cheap;” and he left Paris on the 28th of June.

Four months after the conclusion of the treaty of Vervins, on the 13th of September, 1598, Philip II. died at the Escurial, and on the 3rd of April, 1603, a second great royal personage, Queen Elizabeth, disappeared from the scene. She had been, as regards the Protestantism of Europe, what Philip II. had been, as regards Catholicism, a powerful and able patron; but what Philip II. did from fanatical conviction, Elizabeth did from patriotic feeling; she had small faith in Calvinistic doctrines and no liking for Puritanic sects; the Catholic Church, the power of the pope excepted, was more to her mind than the Anglican Church, and her private preferences differed greatly from her public practices. Thus at the beginning of the seventeenth century Henry IV. was the only one remaining of the three great sovereigns who, during the sixteenth, had disputed, as regarded religion and politics, the preponderance in Europe. He had succeeded in all his kingly enterprises; he had become[323] a Catholic in France without ceasing to be the prop of the Protestants in Europe; he had made peace with Spain without embroiling himself with England, Holland and Lutheran Germany. He had shot up, as regarded ability and influence, in the eyes of all Europe. It was just then that he gave the strongest proof of his great judgment and political sagacity; he was not intoxicated with success; he did not abuse his power; he did not aspire to distant conquests or brilliant achievements; he concerned himself chiefly with the establishment of public order in his kingdom and with his people’s prosperity. His well-known saying, “I want all my peasantry to have a fowl in the pot every Sunday,” was a desire worthy of Louis XII. Henry IV. had a sympathetic nature; his grandeur did not lead him to forget the nameless multitudes whose fate depended upon his government. He had, besides, the rich, productive, varied, inquiring mind of one who took an interest not only in the welfare of the French peasantry, but in the progress of the whole French community, progress agricultural, industrial, commercial, scientific, and literary.

On the 6th of January, 1600, Henry IV. gave his ambassador, Brulart de Sillery, powers to conclude at Florence his marriage with Mary de’ Medici, daughter of Francis I. de’ Medici, grand duke of Tuscany, and Joan, archduchess of Austria and niece of the grand duke Ferdinand I. de’ Medici, who had often rendered Henry IV. pecuniary services dearly paid for. As early as the year 1592 there had been something said about this project of alliance; it was resumed and carried out on the 5th of October, 1600, at Florence, with lavish magnificence. Mary embarked at Leghorn on the 17th, with a fleet of seventeen galleys; that of which she was aboard, the General, was all covered over with jewels, inside and out; she arrived at Marseilles on the 3d of November, and at Lyons on the 2nd of December, where she waited till the 9th for the king, who was detained by the war with Savoy. He entered her chamber in the middle of the night, booted and armed, and next day, in the cathedral church of St. John, re-celebrated his marriage, more rich in wealth than it was destined to be in happiness.

Henry IV. seemed to have attained in his public and in his domestic life the pinnacle of earthly fortune and ambition. He was, at one and the same time, Catholic king and the head of the Protestant polity in Europe, accepted by the Catholics as the best, the only possible, king for them in France. He was at peace with all Europe, except one petty prince, the duke of Savoy, Charles Emmanuel I., from whom he demanded back the Marquisate of Saluzzo or a territorial compensation in France itself on the French side of the Alps. After a short campaign, and thanks to Rosny’s ordnance, he obtained what he desired, and by a treaty of January 17, 1601, he added to French territory La Bresse, Le Bugey, the district of Gex and the citadel of Bourg, which still held out after the capture of the town. He was more and more dear to France, to which he had restored peace at home as well as abroad, and industrial, commercial, financial, monumental, and scientific prosperity, until lately unknown. Sully covered the country with roads, bridges, canals, buildings and works of public utility. The conspiracy of his old companion in arms, Gontaut de Biron, proved to him, however, that he was not at the end of his political dangers, and the letters he caused to be issued (September, 1603) for the return of the Jesuits did not save him from the attacks of religious fanaticism.

The queen’s coronation had been proclaimed on the 12th of May, 1610; she was to be crowned next day, the 13th, at St. Denis, and Sunday the 16th had been appointed for her to make her entry into Paris. On Friday, the 14th, the king had an idea of going to the Arsenal to see Sully, who was ill; we have the account of this visit and of the assassination given by Malherbe, at that time attached to the service of Henry IV., in a letter written on the 19th of May, from the reports of eye witnesses, and it is here reproduced, word for word:

“The king set out soon after dinner to go to the Arsenal. He deliberated a long while whether he should go out, and several times said to the queen, ‘My dear, shall I go or not?’ He even went out two or three times and then all on a sudden returned, and said to the queen, ‘My dear, shall I really go?’ and again he had doubts about going or remaining. At last he made up his mind to go, and having kissed the queen several times, bade her adieu. Amongst other things that were remarked he said to her, ‘I shall only go there and back; I shall be here again almost directly.’ When he got to the bottom of the steps where his carriage was waiting for him, M. de Praslin, his captain of the guard, would have attended him, but he said to him, ‘Get you gone; I want nobody; go about your business.’

“Thus, having about him only a few gentlemen and some footmen, he got into his carriage, took his place on the back seat, at the left hand side, and made M. d’Épernon sit at the right. Next to him, by the door, were M. de Montbazon and M. de la Force; and by the door on M. d’Épernon’s side were Marshal de Lavardin and M. de Créqui; on the front seat the marquis of Mirabeau and the first equerry. When he came to the Croix-du-Tiroir he was asked whither it was his pleasure to go; he gave orders to go toward St. Innocent. On arriving at Rue de la Ferronnerie, which is at the end of that of St. Honoré on the way to that of St. Denis, opposite the Salamandre he met a cart which obliged the king’s carriage to go nearer to the ironmonger’s shops, which are on the St. Innocent side, and even to proceed somewhat more slowly, without stopping, however, though somebody, who was in a hurry to get the gossip printed, has written to that effect. Here it was that an abominable assassin, who had posted himself against the nearest shop, which is that with the Cœur couronné percé d’une flèche, darted upon the king and dealt him, one after the other, two blows with a knife in the left side, one, catching him between the arm-pit and the nipple, went upward without doing more than graze; the other catches him between the fifth and sixth ribs, and, taking a downward direction, cuts a large artery of those called venous. The king, by mishap, and as if to further tempt this monster, had his left hand on the shoulder of M. de Montbazon, and with the other was leaning on d’Épernon, to whom he was speaking. He uttered a low cry and made a few movements. M. de Montbazon having asked, ‘What is the matter, sir?’ he answered, ‘It is nothing,’ twice; but the second time so low that there was no making sure. These are the only words he spoke after he was wounded.

“In a moment the carriage turned toward the Louvre. When he was at the steps where he had got into the carriage, which are those of the queen’s rooms, some wine was given him. Of course some one had already run forward to bear the news. Sieur de Cérisy, lieutenant of M. de Praslin’s company, having raised his head, he made a few movements with his eyes, then closed them immediately, without opening them again any more. He was carried up stairs by M. de Montbazon and Count de Curzon en Quercy and laid on the bed in his closet and at two o’clock carried to the bed in his chamber, where he was all the next day and Sunday. Somebody went and gave him holy water. I tell you nothing about the queen’s tears; all that must be imagined. As for the people of Paris, I think they never wept so much as on this occasion.”

On the king’s death—and at the imperious instance of the duke of Épernon, who at once introduced the queen, and said in open session, as he exhibited his sword, “It is as yet in the scabbard, but it will have to leap therefrom unless this moment there be granted to the queen a title which is her due according to the order of nature and of justice”—the Parliament forthwith declared Mary regent of the kingdom. Thanks to Sully’s firm administration, there were, after the ordinary annual expenses were paid, at that time in the vaults of the Bastile, or in securities easily realizable, forty-one million three hundred and forty-five thousand livres, and there was nothing to suggest that extraordinary and urgent expenses would come[324] to curtail this substantial reserve. The army was disbanded and reduced to from twelve to fifteen thousand men, French or Swiss. For a long time past no power in France had, at its accession, possessed so much material strength and so much moral authority.—Guizot.

Louis XIV. ruled everywhere, over his people, over his age, often over Europe; but nowhere did he reign so completely as over his court. Never were the wishes, the defects and the vices of a man so completely a law to other men as to the court of Louis XIV. during the whole period of his long life. When near to him, in the palace of Versailles, men lived and hoped and trembled; everywhere else in France, even at Paris, men vegetated. The existence of the great lords was concentrated in the court, about the person of the king. Scarcely could the most important duties bring them to absent themselves for any time. They returned quickly, with alacrity, with ardor; only poverty or a certain rustic pride kept gentlemen in their provinces. “The court does not make one happy,” says La Bruyère, “it prevents one from being so anywhere else.”

The principle of absolute power, firmly fixed in the young king’s mind, began to pervade his court from the time that he disgraced Fouquet and ceased to dissemble his affection for Mdlle. de La Vallière. She was young, charming and modest. Of all the king’s favorites she alone loved him sincerely. “What a pity he is a king!” she would say. Louis XIV. made her a duchess; but all she cared about was to see him and please him. When Madame de Montespan began to supplant her in the king’s favor, the grief of Madame de La Vallière was so great that she thought she should die of it. Then she turned to God, in penitence and despair; and, later on, it was at her side that Madame de Montespan, in her turn forced to quit the court, went to seek advice and pious consolation. “This soul will be a miracle of grace,” Bossuet had said.

Madame de Montespan was haughty, passionate, “with hair dressed in a thousand ringlets, a majestic beauty to show off to the ambassadors;” she openly paraded the favor she was in, accepting and angling for the graces the king was pleased to do her and hers, having the superintendence of the household of the queen, whom she insulted without disguise, to the extent of wounding the king himself: “Pray consider that she is your mistress,” he said one day to his favorite. The scandal was great; Bossuet attempted the task of stopping it. It was the time of the Jubilee; neither the king nor Madame de Montespan had lost all religious feeling; the wrath of God and the refusal of the sacraments had terrors for them still.

Bossuet had acted in vain, “like a pontiff of the earliest times, with a freedom worthy of the earliest ages and the earliest bishops of the Church,” says St. Simon. He saw the inutility of his efforts; henceforth prudence and courtly behavior put a seal upon his lips. It was the time of the great king’s omnipotence and highest splendor, the time when nobody withstood his wishes. The great Mademoiselle had just attempted to show her independence; tired of not being married, she had made up her mind to a love-match; she did not espouse Lauzun just then, the king broke off the marriage. “I will make you so great,” he said to Lauzun, “that you shall have no cause to regret what I am taking from you; meanwhile, I make you duke and peer and marshal of France.” “Sir,” broke in Lauzun insolently, “you have made so many dukes that it is no longer an honor to be one, and, as for the bâton of marshal of France, your Majesty can give it me when I have earned it by my services.” He was before long sent to Pignerol, where he passed ten years. There he met Fouquet and that mysterious personage called the Iron Mask, whose name has not yet been discovered to a certainty by means of all the most ingenious conjectures. It was only by settling all her property on the duke of Maine after herself that Mademoiselle purchased Lauzun’s release. The king had given his posts to the prince of Marcillac, son of La Rochefoucauld.

Louis XIV. entered benevolently into the affairs of a marshal of France; he paid his debts, and the marshal was his domestic; all the court had come to that; the duties which brought servants in proximity to the king’s person were eagerly sought after by the greatest lords. Bontemps, his chief valet, and Fagon, his physician, as well as his surgeon Maréchal, very excellent men too, were all-powerful amongst the courtiers. Louis XIV. possessed the art of making his slightest favors prized; to hold the candlestick at bed-time (au petit coucher), to appear in the trips to Marly, to play in the king’s own game, such was the ambition of the most distinguished; the possessors of grand historic castles, of fine houses at Paris, crowded together in attics at Versailles, too happy to obtain a lodging in the palace. The whole mind of the greatest personages, his favorites at the head, was set upon devising means of pleasing the king; Madame de Montespan had pictures painted in miniature of all the towns he had taken in Holland; they were made into a book which was worth four thousand pistoles, and of which Racine and Boileau wrote the text; people of tact, like M. de Langlée, paid court to the master through those whom he loved.

All the style of living at court was in accordance with the magnificence of the king and his courtiers; Colbert was beside himself at the sums the queen lavished on play. Madame de Montespan lost and won back four millions in one night at bassette; Mdlle. de Fontanges gave away twenty thousand crowns’ worth of New Year’s gifts. A new power, however, was beginning to appear on the horizon, with such modesty and backwardness that none could as yet discern it, least of all could the king. Madame de Montespan had looked out for some one to take care of and educate her children. She had thought of Madame Scarron; she considered her clever; she was so herself, “in that unique style which was peculiar to the Mortemarts,” said the duke of St. Simon; she was fond of conversation; Madame Scarron had a reputation for being rather a blue-stocking; this the king did not like; Madame de Montespan had her way; Madame Scarron took charge of the children secretly and in an isolated house. She was attentive, careful, sensible. The king was struck with her devotion to the children entrusted to her. “She can love,” he said; “it would be a pleasure to be loved by her.” This expression plainly indicated what was to happen; and Madame de Montespan saw herself supplanted by Madame Scarron. The widow of the deformed poet had bought the estate of Maintenon out of the king’s bounty. He made her take the title. The recollection of Scarron was displeasing to him.

The queen had died on the 30th of July, 1683, piously and gently as she had lived. “This is the first sorrow she ever caused me,” said the king, thus rendering homage, in his superb and unconscious egotism, to the patient virtue of the wife he had put to such cruel trials. Madame de Maintenon was agitated but resolute. “Madame de Montespan has plunged into the deepest devoutness,” she wrote, two months after the queen’s death: “It is quite time she edified us; as for me, I no longer think of retiring.” Her strong common-sense and her far-sighted ambition, far more than her virtue, had secured her against rocks ahead; henceforth she saw the goal, she was close upon it, she moved toward it with an even step. The date has never been ascertained exactly of the king’s private marriage with Madame de Maintenon. It took place probably eighteen months or two years after the queen’s death; the king was forty-seven, Madame de Maintenon fifty. “She had great remains of beauty, bright and sprightly eyes, an incomparable grace,” says St. Simon, who detested her, “an air of ease and yet of restraint and respect, a great deal of cleverness with a speech that was sweet, correct, in good terms and naturally eloquent and brief.”