Title: Notes on the New Testament, Explanatory and Practical: Revelation

Author: Albert Barnes

Editor: Robert Frew

Release date: July 30, 2017 [eBook #55228]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Hulse, Colin Bell, CCEL and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation, including Greek accents, have been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words and abbreviations may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and have been accumulated in a table at the end of the text.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes are not identified in the text, but have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book.

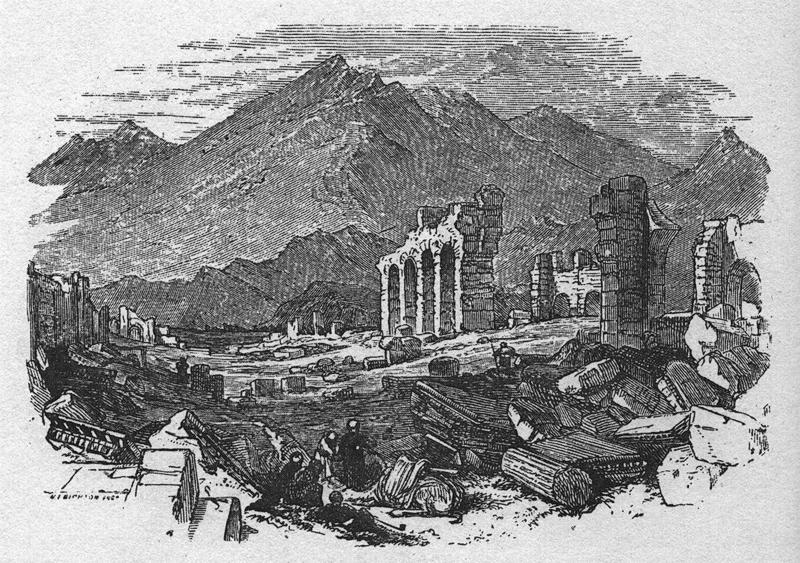

Drawn by S. BoughEngraved by T. Flemming

PATMOS.

THE PORT OF SCALA & TOWN OF PATINO

NOTES

ON THE

New Testament

EXPLANATORY AND PRACTICAL

BY

ALBERT BARNES

Enlarged Type Edition

EDITED BY

ROBERT FREW, D.D.

WITH NUMEROUS ADDITIONAL NOTES AND

A SERIES OF ENGRAVINGS

REVELATION

BAKER BOOK HOUSE

Grand Rapids 6, Michigan

1951

Editor’s Preface:—

Author’s qualifications for Apocalyptic exposition—Author’s plan in preparing his Commentary, affords assurance of his sobriety as an interpreter, and rebukes the scorn of hostile critics—Peculiarities of this edition.

Importance of the question regarding—Protestant theory of Apocalyptic interpretation stands or falls with it—Rival schemes, nature and origin of—Advocates on both sides—Views of Dr. Davidson and Professor Stuart.

Arguments in favour of Year-day Theory.

1. Concurrent Testimony of Protestant Interpreters—Objection of Dr. Davidson—Reply—Use which the Reformers made of the Apocalypse—Views of Walter Brute—Views of Luther.

2. Symbolical Character of the Predictions in Daniel and the Apocalypse—Laws of symbolic propriety—Dr. Maitland’s famous objection, that a day is no symbol for a year—General principles on which Year-day view rests—Ground occupied by Mede—Principle of Bush and Faber—True basis—View of Birks and Elliott.

3. Indications of the Year-day Principle in Scripture—The case of the spies in the book of Numbers—Ezekiel’s typical siege—Objection of Professor Stuart—Professor Bush’s reply—Objection of Bishop Horsley—Objections from Isaiah, ch. xx. 2, 3—Daniel’s seventy weeks—Diverse views of opponents—Outlines of Discussion.

4. Exigency of Passages in which Prophetic Times occur—Saracenic woe in Rev. ix. 5‒10—Turkish woe in Rev. ix. 15—The forty-two months of the Gentiles in ch. xi. 2—The times of the two witnesses in ch. xi. 3‒11—The times of the woman in the wilderness, in ch. xii. 6‒14—Forty-two months of the Beast, in ch. xiii. 5—Danielic periods—Objections alleged, novelty of the Year-day principle.

Author’s Introduction:—Sect. I. The Writer of the Book of Revelation.—Sect. II. The Time of Writing the Apocalypse.—Sect. III. The Place where the Book was written.—Sect. IV. The Nature and Design of the Book.—Sect. V. The Plan of the Apocalypse.

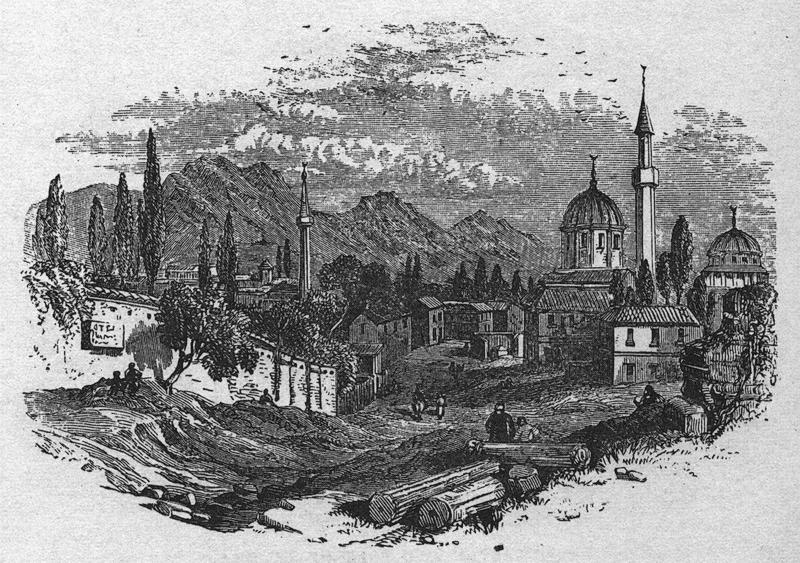

Patmos—the Port of Scala, and Town of Patino.

The Site of Ephesus, from the Theatre.

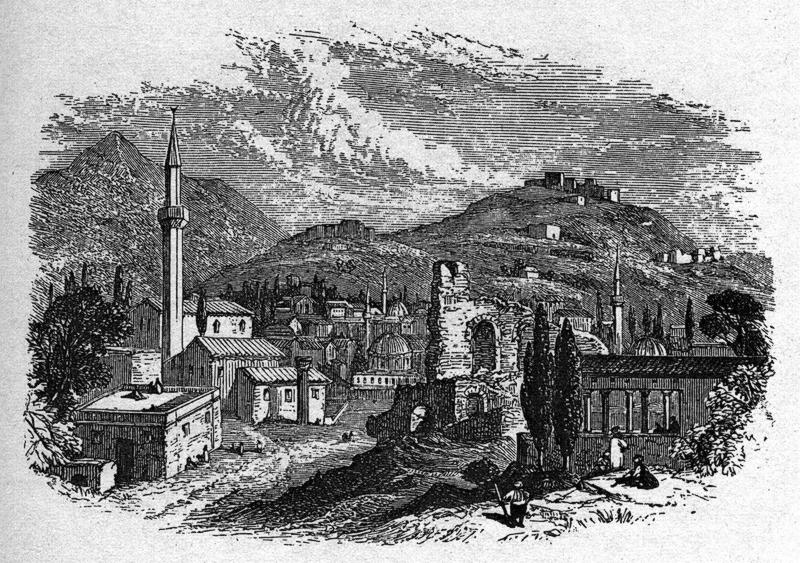

The Castle and Port of Smyrna.

Ruins of the Church of St. John, Pergamos.

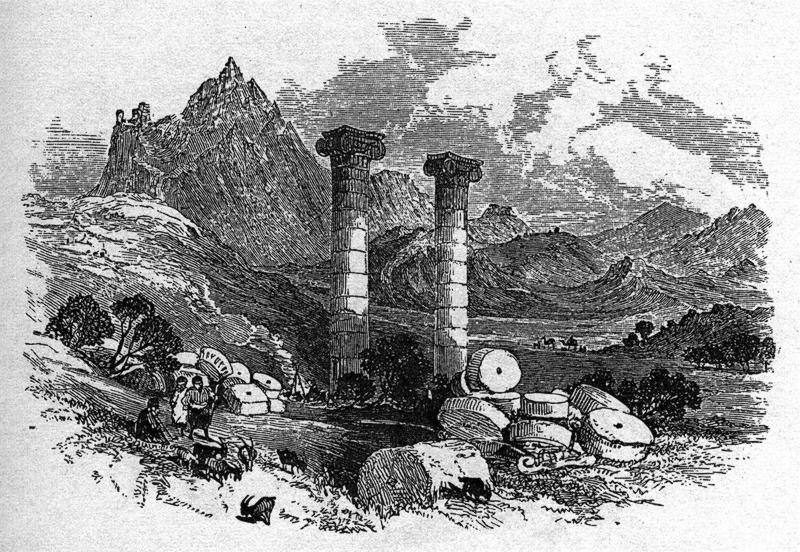

Sardis—Remains of Ancient Temple, &c.

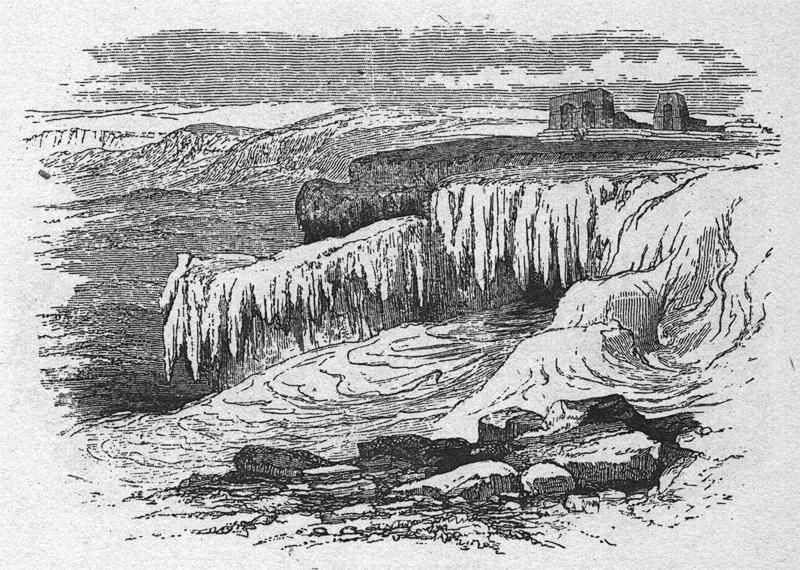

Petrified Cascades at Hierapolis.

Map of N. Italy, 4to—Scene of the Third Trumpet and Third Vial.

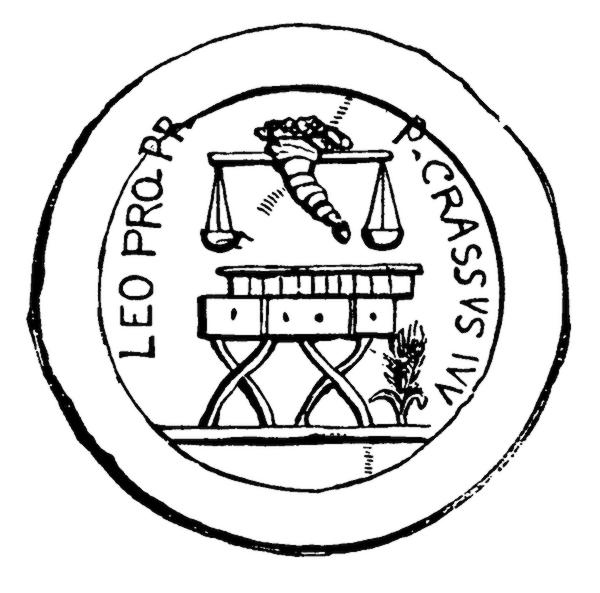

Engravings Printed in the Text.

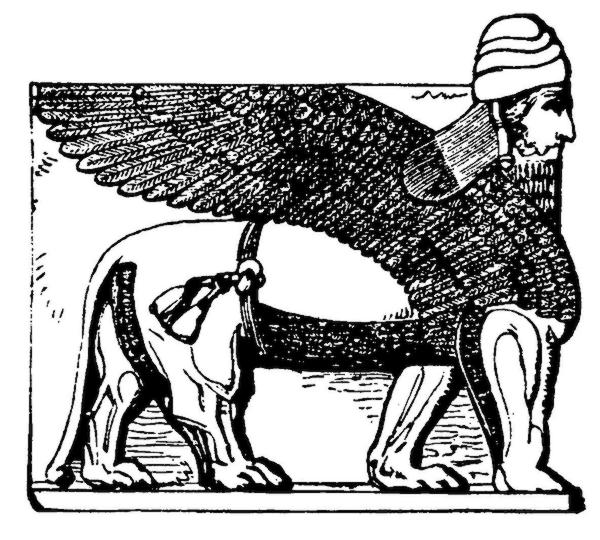

Human-headed Winged Lion; from the Nineveh Sculptures.

Eagle-headed Winged Lion; from the Nineveh Sculptures.

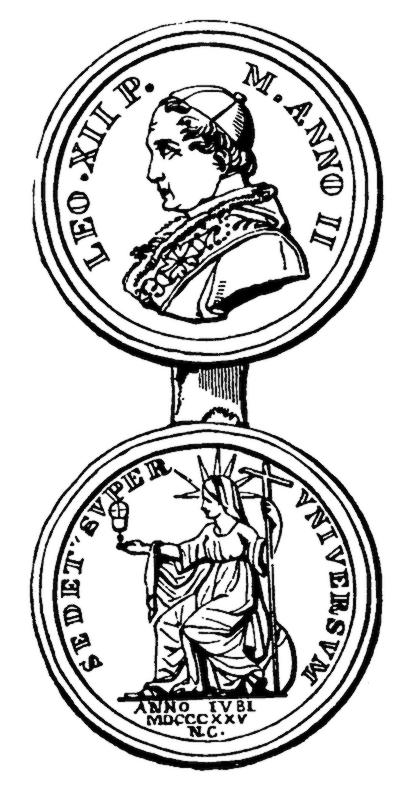

Medal of the Emperor Nerva wearing Crown.

Medal of the Emperor Valentinian wearing Diadem.

Symbolic Bas-reliefs from a Roman Triumphal Arch.

Symbolical Locust, according to Elliott.

Standard-bearer of a Turkish Pasha.

When I began the preparation of these “Notes” on the New Testament, now more than twenty years ago, I did not design to extend the work beyond the Gospels, and contemplated only simple and brief explanations of that portion of the New Testament, for the use of Sunday-school teachers and Bible classes. The work originated in the belief that Notes of that character were greatly needed, and that the older commentaries, having been written for a different purpose, and being, on account of their size and expense, beyond the reach of most teachers of Sunday-schools, did not meet the demand which had grown up from the establishment of such schools. These Notes, contrary to my original plan and expectation, have been extended to eleven volumes, and embrace the whole of the New Testament.

Having, at the time when these Notes were commenced, as I have ever had since, the charge of a large congregation, I had no leisure that I could properly devote to these studies, except the early hours of the morning; and I adopted the resolution—a resolution which has since been invariably adhered to—to cease writing precisely at nine o’clock in the morning. The habit of writing in this manner, once formed, was easily continued; and having been thus continued, I find myself at the end of the New Testament. Perhaps this personal allusion would not be proper, except to show that I have not intended, in these literary labours, to infringe on the proper duties of the pastoral office, or to take time for these pursuits on which there was a claim for other purposes. This allusion may perhaps also be of use to my younger brethren in the ministry, by showing them that much may be accomplished by the habit of early rising, and by a diligent use of the early morning hours. In my own case, these Notes on the New Testament, and also the Notes on the books of Isaiah, Job, and Daniel, extending in all to sixteen volumes, have all been written before nine o’clock in the morning, and are the fruit of the habit of rising between four and five o’clock. I do not know that by this practice I have neglected any duty which I should otherwise have performed; and on the score of health, and, I may add, of profit in the contemplation of a portion of divine truth at the beginning of each day, the habit has been of inestimable advantage to me.

It was not my original intention to prepare Notes on the book of Revelation, nor did I entertain the design of doing it until I came up to it in the regular course of my studies. Having written on all the other portions of the New Testament, there remained only this book to complete an entire commentary on this part of the Bible. That I have endeavoured to explain the book at all is to be traced to the habit which I had formed of spending the early hours of the day in the study of the sacred Scriptures. That habit, continued, has carried me forward until I have reached the end of the New Testament.

It may be of some use to those who peruse this volume, and it is proper in itself, that I should make a brief statement of the manner in which I have prepared these Notes, and of the method of interpretation on which I have proceeded; for the result which has been reached has not been the effect of any preconceived theory or plan, and if in the result I coincide in any degree with the common method of interpreting the volume, the fact may be regarded as the testimony of another witness—however unimportant the testimony may be in itself—to the correctness of that method of interpretation.

Up to the time of commencing the exposition of this book, I had no theory in my own mind as to its meaning. I may add, that I had a prevailing belief that it could not be explained, and that all attempts to explain it must be visionary and futile. With the exception of the work of the Rev. George Croly,1 which I read more than twenty years ago, and which I had never desired to read again, I had perused no commentary on this book until that of Professor Stuart was published, in 1845. In my regular reading of the Bible in the family and in private, I had perused the book often. I read it, as I suppose most others do, from a sense of duty, yet admiring the beauty of its imagery, the sublimity of its descriptions, and its high poetic character; and though to me wholly unintelligible in the main, finding so many striking detached passages that were intelligible and practical in their nature, as to make it on the whole attractive and profitable, but with no definitely formed idea as to its meaning as a whole, and with a vague general feeling that all the interpretations which had been proposed were wild, fanciful, and visionary.

In this state of things, the utmost that I contemplated when I began to write on it, was to explain, as well as I could, the meaning of the language and the symbols, without attempting to apply the explanation to the events of past history, or to inquire what is to occur hereafter. I supposed that I might venture to do this without encountering the danger of adding another vain attempt to explain a book so full of mysteries, or of propounding a theory of interpretation to be set aside, perhaps, by the next person that should prepare a commentary on the book.

Beginning with this aim, I found myself soon insensibly inquiring whether, in the events which succeeded the time when the book was written, there were not historical facts of which the emblems employed would be natural and proper symbols, on the supposition that it was the divine intention, in disclosing these visions, to refer to them; and whether, therefore, there might not be a natural and proper application of the symbols to these events. In this way I examined the language used in reference to the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth seals, with no anticipation or plan in examining one as to what would be disclosed under the next seal, and in this way also I examined ultimately the whole book: proceeding step by step in ascertaining the meaning of each word and symbol as it occurred, but with no theoretic anticipation as to what was to follow. To my own surprise I found, chiefly in Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a series of events recorded, such as seemed to me to correspond, to a great extent, with the series of symbols found in the Apocalypse. The symbols were such as it might be supposed would be used, on the supposition that they were intended to refer to these events; and the language of Mr. Gibbon was often such as he would have used, on the supposition that he had designed to prepare a commentary on the symbols employed by John. It was such, in fact, that if it had been found in a Christian writer, professedly writing a commentary on the book of Revelation, it would have been regarded by infidels as a designed attempt to force history to utter a language that should conform to a predetermined theory in expounding a book full of symbols. So remarkable have these coincidences appeared to me in the course of this exposition, that it has almost seemed as if he had designed to write a commentary on some portions of this book; and I have found it difficult to doubt that that distinguished historian was raised up by an overruling Providence to make a record of those events which would ever afterwards be regarded as an impartial and unprejudiced statement of the evidences of the fulfilment of prophecy. The historian of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire had no belief in the divine origin of Christianity, but he brought to the performance of his work learning and talent such as few Christian scholars have possessed. He is always patient in his investigations; learned and scholar-like in his references; comprehensive in his groupings, and sufficiently minute in his details; unbiassed in his statements of facts, and usually cool and candid in his estimates of the causes of the events which he records; and, excepting his philosophical speculations, and his sneers at everything, he has probably written the most candid and impartial history of the times that succeeded the introduction of Christianity that the world possesses; and even after all that has been written since his time, his work contains the best ecclesiastical history that is to be found. Whatever use of it can be made in explaining and confirming the prophecies, will be regarded by the world as impartial and fair; for it was a result which he least of all contemplated, that he would ever be regarded as an expounder of the prophecies in the Bible, or be referred to as vindicating their truth.

It was in this manner that these Notes on the Book of Revelation assumed the form in which they are now given to the world; and it surprises me—and, under this view of the matter, may occasion some surprise to my readers—to find how nearly the views coincide with those taken by the great body of Protestant interpreters. And perhaps this fact may be regarded as furnishing some evidence that, after all the obscurity attending it, there is a natural and obvious interpretation of which the book is susceptible. Whatever may be the value or the correctness of the views expressed in this volume, the work is the result of no previously-formed theory. That it will be satisfactory to all, I have no reason to expect; that it may be useful to some, I would hope; that it may be regarded by many as only adding another vain and futile effort to explain a book which defies all attempts to elucidate its meaning, I have too much reason, judging from the labours of those who have gone before me, to fear. But as it is, I commit it to the judgment of a candid Christian public, and to the blessing of Him who alone can make any attempt to explain his Word a means of diffusing the knowledge of truth.

I cannot conceal the fact that I dismiss it, and send it forth to the world, as the last volume on the New Testament, with deep emotion. After more than twenty years of study on the New Testament, I am reminded that I am no longer a young man; and that, as I close this work, so all my work on earth must at no distant period be ended. I am sensible that he incurs no slight responsibility who publishes a commentary on the Bible; and I especially feel this now in view of the fact—so unexpected to me when I began these labours—that I have been permitted in our own country to send forth more than two hundred and fifty thousand volumes of commentary on the New Testament, and that probably a greater number has been published abroad. That there are many imperfections in these Notes no one can feel more sensibly than I do; but the views which I have expressed are those which seem to me to be in accordance with the Bible, and I send the last volume forth with the deep conviction that these volumes contain the truth as God has revealed it, and as he will bless it to the extension of his church in the world. I have no apprehension that the sentiments which I have expressed will corrupt the morals, or destroy the peace, or ruin the souls of those who may read these volumes; and I trust that they may do something to diffuse abroad a correct knowledge of that blessed gospel on which the interests of the church, the welfare of our country, and the happiness of the world depend. In language which I substantially used in publishing the revised edition of the volumes of the Gospels (Preface to the Seventeenth Edition, 1840), I can now say, “I cannot be insensible to the fact that, in the form in which these volumes now go forth to the public, I may continue, though dead, to speak to the living; and that the work may be exerting an influence on immortal minds when I am in the eternal world. I need not say that, while I am sensitive to this consideration, I earnestly desire it. There are no sentiments in these volumes which I wish to alter; none that I do not believe to be truths that will abide the investigations of the great day; none of which I am ashamed. That I may be in error, I know; that a better work than this might be prepared by a more gifted mind, and a purer heart, I know. But the truths here set forth are, I am persuaded, those which are destined to abide, and to be the means of saving millions of souls, and ultimately of converting this whole world to God. That these volumes may have a part in this great work is my earnest prayer; and with many thanks to the public for their favours, and to God, the great source of all blessing, I send them forth, committing them to His care, and leaving them to live or die, to be remembered or forgotten, to be used by the present generation and the next, or to be superseded by other works, as shall be in accordance with his will, and as he shall see to be for his glory.”

ALBERT BARNES.

Washington Square, Philadelphia,

March 26, 1851.

The works which I have had most constantly before me, and from which I have derived most aid in the preparation of these Notes, are the following. They are enumerated here, as some of them are frequently quoted, to save the necessity of a frequent reference to the Editions in the Notes:—

A Commentary on the Apocalypse. By Moses Stuart, Professor of Sacred Literature in the Theological Seminary at Andover, Mass. Andover, 1845.

Horæ Apocalypticæ; or, a Commentary on the Apocalypse, Critical and Historical. By the Rev. E. B. Elliott, A.M., late Vicar of Tuxford, and Fellow of Trinity College. Third Edition. London, 1847.

The Works of Nathaniel Lardner, D.D. In ten volumes. London, 1829.

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. By Edward Gibbon, Esq. Fifth American, from the last London edition. Complete in four volumes. New York, J. and J. Harper, 1829.

History of Europe. By Archibald Alison, F.R.S.E. New York, Harper Brothers, 1843.

An Exposition of the Apocalypse. By David N. Lord. Harpers, 1847.

Hyponoia; or, Thoughts on a Spiritual Understanding of the Apocalypse, a Book of Revelation. New York, Leavitt, Trow, and Co., 1844.

The Family Expositor. By Philip Doddridge, D.D. London, 1831.

Ἀνάκρισις Apocalypsios Joannis Apostoli, etc. Auctore Campegio Vitringa, Theol. et Hist. Professore. Amsterdam, 1629.

Kurtzgefasstes exegetisches Handbuch zum Neuen Testament. Von Dr. W. M. L. De Wette. Leipzig, 1847.

Rosenmüller, Scholia in Novum Testamentum.

Dissertations on the Opening of the Sealed Book. Montreal, 1848.

Two New Arguments in Vindication of the Genuineness and Authenticity of the Revelation of St. John. By John Collyer Knight. London, 1842.

The Seventh Vial: being an Exposition of the Apocalypse, and in particular of the pouring out of the Seventh Vial, with special reference to the present Revolution in Europe. London, 1848.

Die Offenbarung des Heiligen Joannes. Von G. W. Hengstenberg. Berlin, 1850.

The Works of the Rev. Andrew Fuller. Newhaven, 1825.

Novum Testamentum. Editio Koppiana, 1821.

Dissertation on the Prophecies. By Thomas Newton, D.D. London, 1832.

The Apocalypse of St. John. By the Rev. George Croly, A.M. Philadelphia, 1827.

The Signs of the Times, as denoted by the fulfilment of Historical Predictions, from the Babylonian Captivity to the present time. By Alexander Keith, D.D. Eighth Edition. Edinburgh, 1847.

Christ’s Second Coming: will it be Pre-millennial? By the Rev. David Brown, A.M., St. James’s Free Church, Glasgow. New York, 1851.

Apocalyptical Key. An extraordinary Discourse on the Rise and Fall of the Papacy. By Robert Fleming, V.D.M. New York, American Protestant Society.

A Treatise on the Millennium. By George Bush, A.M. New York, 1832.

A Key to the Book of Revelation. By James M’Donald, minister of the Presbyterian Church, Jamaica, L. I. Second Edition. New London, 1848.

Das Alte und Neue Morgenland. Rosenmüller. Leipzig, 1820.

The Season and Time; or, an Exposition of the Prophecies which relate to the two periods subsequent to the 1200 years now recently expired, being the time of the Seventh Trumpet, &c. By W. Ettrick, A.M. London, 1816.

Einleitung in das Neue Testament. Von Johann Gottfried Eichhorn. Leipzig, 1811.

For a very full view of the history of the interpretation of the Apocalypse, and of the works that have been written on it, the reader is referred to Elliott’s Horæ Apocalypticæ, vol. iv. pp. 307‒487, and Prof. Stuart, vol. i. pp. 450‒475. See, for a condensed view, Editor’s Preface.

YEAR-DAY PRINCIPLE.

Professor Bush, in the Hierophant for January, 1845, at the close of a review of Barnes on the Hebrews, thus wrote:—“We sincerely hope Mr. Barnes may be enabled to accomplish his plan to its very ultimatum, and furnish a commentary of equal merit on the remaining books of the New Testament; with the exception, however, of the Apocalypse, to which, we think, his rigid Calvinian austerity of reason is not so well adapted; and which, we presume to think, would fare better under our own reputed fanciful and allegorical pen.”2 The indefatigable author has lived to accomplish his plan, and has ventured to include within it the mysterious prophecy, for the elucidation of which the reviewer imagined the severe character of his mind disqualified him. Many will think the supposed disqualification a foremost requisite in an Apocalyptic commentator, inasmuch as the Apocalypse has been too long interpreted on fanciful and allegorical principles; and it is now “high time for principle to take the place of fancy, for exegetical proof to thrust out assumption.”3 The advocates of what has been called the Protestant Historic Scheme of Interpretation, have been supposed peculiarly liable to delusions of this nature. It is, therefore, gratifying to find that this new defender of that scheme has been distinguished by a “Calvinian austerity of reason,” which may help to preserve both him and his readers from being in like manner led astray, and at the same time secure a more respectful tone from critics who have espoused opposite views. Bush, who has himself so ably defended the Protestant scheme on the other side of the Atlantic, now that he finds Barnes on the same ground, will think that the spirit of severe logic and searching inquiry which he has brought with him to the contest, render him all the more valuable an associate. In examining the former volumes of Mr. Barnes, we found it was no part of his system of interpretation to admit typical and mystical senses where the literal one could at all be adopted. We had to complain that his tendency was too strong in the opposite direction.4

The plan which the author tells us he adopted in preparing his commentary, is a singular illustration of his judgment and caution; and therefore affords another assurance of his sobriety as an interpreter of the symbols of John. Up to the time of commencing the exposition of this book, he tells us he had no theory in his mind as to its meaning. The utmost he contemplated, when he began, was to explain the meaning of its language and symbols, without attempting to apply that explanation to historical events. But, to his own surprise, he found a series of events, recorded chiefly in Gibbon, such as seemed to correspond, to a great extent, with the series of symbols found in the Apocalypse. Farther examination exhibited this correspondence still more strikingly; and the result was, that his views ultimately took the shape of those given by the great body of Protestant interpreters. He therefore justly claims to be another and independent witness in favour of the common interpretation.5 These statements, while they cannot but increase the reader’s confidence in the guide who now offers to lead him through the mazes of the Apocalypse, ought also to mitigate the scorn with which some have affected to regard all expositions of this school—speaking of them as “hariolations” and “surmises,” which set the reader “afloat upon a boundless ocean of conjecture and fancy, without rudder or compass.”6 It is easy to say such things, and they are therefore too often said by the followers of Eichhorn and Stuart; but accurate inquiry into the non-Protestant scheme will speedily convince anyone that the hariolations do by no means all belong to one side. We venture to say, that nothing so much deserving the name occurs in the whole series of Protestant expositions, as the absurd and unfounded guesses of the last-named writer regarding the witnesses in chap. xi., and the explanation of chap. xvii. 8, by an unfounded heathen rumour regarding the reappearance of Nero after he had been slain.7

With this edition of the Notes on the Book of Revelation we have not found it expedient to present any accompanying or supplementary notes. The author’s text has been carefully revised, and many errors which had crept both into the American and English editions have been corrected. On certain points we could have wished a little more fulness. The important question of the date of the book; the history of apocalyptic interpretation; and the principles of prophetic interpretation, particularly as regards designations of time, are matters lying at the very foundation of just views of the Apocalypse. The first of these points has, indeed, a page or two allotted to it in the “Introduction,” and is also incidentally noticed in the commentary; the second is less or more touched on in the exposition of difficult passages; but the last is almost entirely overlooked, on the ground that the author intends a full discussion of the subject in his forthcoming volume on Daniel. We somewhat regret this, because of the importance of the Year-day principle itself, and because every reader of the Notes on the Book of Revelation may not possess, or have immediately at hand, those on Daniel. We have no doubt that the author’s defence of this part of the Protestant citadel will prove one of the most able that has yet been given. It will, beyond a doubt, avoid the errors of those who have weakened the argument by insisting on points which, at best, are uncertain; and place the theory on a basis sufficiently broad to admit of rational and hopeful maintaining of it, in spite of numerous learned and able assaults. In the meantime, that our edition may not be without something, however brief and imperfect, on a point which on all hands is allowed to be fundamental, we purpose to devote the following pages to an examination of the Year-day principle.

The importance of the question on which we now enter can scarcely be overestimated. If the prophetic periods of Daniel and John; if the famous 1260 days, the time, times, and the dividing of time, are to be understood literally, and explained of the limited term of three and a half years, during the days of Nero and Antiochus Epiphanes, or days yet to come, towards the consummation and era of the second advent,8 then clearly the ideas that have been long current among Protestants are untenable. There is no figuration of Papal Rome, in the Apocalypse or in Daniel, existing through long and dreary ages, wearing out the saints of the Most High. There are no witnesses during that period of gloom ever and anon lifting up their testimony against the grand apostasy. There is no cheering assurance, derived from an infallible oracle, that the Papal system is doomed, that its days are numbered, and must now be drawing to a close. All the arguments against this “mystery of iniquity,” derived from Daniel and John, must be abandoned; and Protestants must, with shame, retire from a field so long and so successfully occupied by them, whilst the Romanists triumph in their overthrow. “If,” says Bush in his animadversions on Stuart, “your hypothesis be correct, not only has nearly the whole Christian world been led astray for ages by a mere ignis fatuus of false hermeneutics, but the church is at once cut loose from every chronological mooring, and set adrift in the open sea, without the vestige of a beacon, lighthouse, or star, by which to determine her bearings or distances from the desired millennial haven to which she was tending. She is deprived of the means of taking a single celestial observation, and has no possible data for ascertaining, in the remotest degree, how far she is yet floating from the Ararat of promise. Upon your theory the Christian world has no distinct intimation given it as to the date of the downfall of the Roman despotism, civil or ecclesiastical, of Mahometanism, or of Paganism; no clue to the time of the conversion of the Jews or of the introduction of the millennium. On all these points the church is shut up to a blank and dreary uncertainty, which, though it may not extinguish, will tend greatly to diminish the ardour of her present zeal in the conversion of the world.”9 Strange, indeed, it must be regarded, that while the Old Testament church was cheered by her chronological promises or predictions, marking her progress as she floated down the stream of time, and indicating, at any stage of it, how far she was yet distant from the happy times of deliverance that awaited her, everything of this kind should be systematically excluded from the sublime predictions of the New Dispensation. Strange, too, that the grand symbols of Daniel and John—that their glorious predictions, confessedly allowed to reach onwards to the consummation of all things, should embrace a brief chapter in the lives of such men as Nero or Antiochus, and give no notice of that gigantic apostasy which for ages has cast its dark shadow over Christendom, and no comfort to a sorrowing church walking amid the gloom. Yet if the Protestant exposition of Daniel and the Apocalypse has proceeded on false principles, the sooner a return is made to the right path the better, however humbling may be the confession of error, and grieving the loss of imagined advantage in our controversy with Rome. Truth is great, and must prevail. None of her friends would assail even the worst cause with weapons she did not approve.

On both sides of this question, the importance of which has been set forth in the preceding paragraph, we find men of the very highest character for learning and skill in biblical science. “On one side Maitland and Burgh are the most able; on the other Faber, Elliott, and Birks. In America the indefatigable Stuart has taken up the same ground as the former, and has met with a formidable antagonist in Bush.” To the first class—the literal day class, namely—must now be added the name of the author who has thus specified the chief combatants—Dr. Davidson of the Lancashire Independent College. He has taken up the subject in the third volume of his Introduction to the New Testament, and discussed it with all the learning and ability which his high position among English critics might have led us to anticipate. “Si Pergama dextra defendi possent, etiam hoc defensa fuissent.” We think we can discern in his able defence some symptoms of progress in the controversy. The line which Dr. Davidson pursues is essentially different in many respects from that of Professor Stuart. The American professor insists on many points which the English divine seems to have abandoned.10

Everything like dogmatism in the discussion of a question so circumstanced is of course to be carefully avoided. There are difficulties on both sides, of which no satisfactory solution has as yet been given. Our aim shall be to ascertain, if possible, on which side the greater amount of truth lies. While avowing a decided leaning to the Year-day theory, we shall endeavour to do justice to the arguments of its opponents, and shall frankly allow it whenever the arguments of its supporters seem to us weak or dubious.

First, then, it must be allowed that the concurrent testimony of the great mass of Protestant interpreters, the nearly unanimous voice of the Protestant church, furnishes a prestige in favour of the Year-day principle. If it do not supply an argument it creates a favourable feeling, which is worthy of a better name than “prejudice.” It is a prepossession, but a prepossession founded on perfectly just ground, namely, that wherever men of learning and research, as well as Christian people at large, have long and tenaciously held any particular view, there must be something in that view that has a better foundation than its assailants are willing to allow. This is certainly very different from “calling up the names of illustrious dead, as the infallible expounders of the Bible;” and from “giving our language the semblance of assuming that, to differ from current opinions, is to disown Protestantism and favour Romanism.” That there is something in this presumptive argument, which we seek to build on Protestant opinion, is obvious from the anxiety that is manifested to make out that the principle or theory in question has, in reality, no connection with the reformers and the Protestant cause. “The statement,” it is said, “that certain applications of the Apocalypse caused or promoted the Reformation is wholly incorrect. It is absolutely false. A spiritual apprehension of the simple gospel, accompanied with the power of the Spirit, led these illustrious men to separate from the Romish church. And then it should be remembered, by those who write like Bush of the reformers and the ‘Protestant’ interpretation, that not one of the reformers understood a day in prophecy to mean a year. To talk of the reformers, therefore, in connection with this so-called ‘Protestant’ notion, is worse than trifling. It conveys a false impression.”11 Two questions are involved here:—How far the reformers made use of the Apocalypse in their controversy with Papists? and whether the Year-day principle may be regarded as a “Protestant” notion? The fact is, in regard to the first question, that the Waldenses and Wickliffites, previous to the Reformation, drew their weapons from the Apocalypse; and if we do not present references or quotations to prove it, it is just because the matter seems too plain to admit of any doubt. One testimony shall suffice, namely, that of Walter Brute, A.D. 1391. According to Foxe, the martyrologist, he was “a layman, and learned and brought up in the University of Oxford, being there a graduate.” He was accused of saying, among sundry other things, that the Pope is Antichrist, and a seducer of the people. Being called to answer, he put in, first, certain more brief “exhibits;” then another declaration, more ample, explaining and setting forth the grounds of his opinion. His defence was grounded very mainly on the Apocalyptic prophecy. For he at once bases his justification on the fact, as demonstrable, of the pope answering alike to the chief of the false Christs, prophesied of by Christ as to come in his name; to the man of sin, prophesied of by St. Paul; and to both the first beast and beast with the two lamb-like horns, in the Apocalypse; the city of Papal Rome, also answering similarly to the Apocalyptic Babylon.12 Indeed, we may learn much as to how far the Apocalypse had, even in these times, come to be used against the Church of Rome, from the fears of the Papists themselves, which prompted the fifth council of Lateran authoritatively to prohibit all writing or preaching on the subject of Antichrist, and all speculation regarding the time of the expected evils—“Tempus quoque prefixum futurorum malorum vel Antichristi adventum, aut certum diem judicii predicare vel asserere nequaquan presumant.”13 As to the reformers, properly so called, they appear in the field next, using the same weapons with increasing skill and energy, as the two great prophecies whence they were drawn came to be better understood. The pages of Milner, D’Aubigné, or other historians of the period, abound with evidence; and Mr. Barnes has collected part of it under chap. x. 6, to which the reader is referred. Luther and his German associates seem to have drawn more upon Daniel, while in Switzerland and England the Apocalypse, for the most part, was appealed to. We might multiply proofs, were it necessary, from the writings of Leo Juda, Bullinger, Latimer, Bale, Foxe, &c. It is enough to refer to the very copious extracts given in the last volume of the Horæ Apocalypticæ.14 As to the other question, namely, whether the Year-day principle can be regarded as a “Protestant” notion, opportunity will be found for the consideration of it when we come to consider the objection against that principle, drawn from its alleged novelty. Meantime we shall only remark, that while Luther certainly had arrived at no definite conclusions regarding the Apocalyptic designations of time, his mind nevertheless was in search of some principle by which he should be enabled to extend the times beyond the literal sense. Nor need it in any way surprise us, that definite ideas on this subject should only have been obtained when the notion became settled and prevalent that the Popedom was the Apocalyptic Antichrist, and the interpretation of the times on a scale suited to the duration of that system became, in consequence, imperative.

2. The next consideration we advance is, the symbolical character of most of the predictions in which the disputed designations of time occur. In Daniel and the Apocalypse, things pictured to the eye are the signs or representations of a hidden sense intended to be conveyed by them. Now, it seems reasonable to conclude, that in this symbolic or picture writing the times should be hidden under some veil, as well as the associated events. Nay, one would imagine that these were just the very things that specially required concealment, in accordance with the design of the predictions, especially such as relate to the future deliverance and glory of the church; which is, that the saints should understand as much as may sustain their hope, yet in a way of diligence, watchfulness, and prayer. It is said, indeed, that symbolical times are not essential to this partial concealment. It may be so, yet they are doubtless fitted to serve this purpose; and there cannot but appear a manifest impropriety in associating symbolical events with literal or natural times. Why the veil in the one case and not in the other? Is not this system of mixing the symbolic and the literal fitted to mislead? and, according to the theory of Maitland and others, has it not, in point of fact, led astray the greater part of the Protestant world? Is it wonderful, that when times are found “imbedded in symbols,” a symbolical character should have been attached to them too. Let it be observed also, that in cases of what has been called miniature symbolization, as where an empire is represented by a man or a beast, long periods, such as might very well be attributed to an empire, or to any great political or ecclesiastical system, could not, in consistency with symbolical propriety, have been expressed otherwise than we find them. On the supposition that long periods were designed to be expressed, they must necessarily have been symbolized by shorter ones. “Nothing is more obvious than that the prophets have frequently, under divine prompting, adopted the system of hieroglyphic representation, in which a single man represents a community, or a wild beast an extended empire. Consequently, since the mystic exhibition of the community or empire is in miniature, symbolical propriety requires that the associated chronological periods should be exhibited in miniature also. The intrinsic fitness of such a mode of presentation is self-evident. In predicating of a nation a long term of 400 or even 4000 years, there is nothing revolting to verisimilitude or decorum; but to assign such a period to the actings of a symbolical man or animal would be a grievous outrage on all the proprieties of the prophetic style. The character of the adjuncts should evidently correspond with those of the principal, or the whole picture is at once marred by the most palpable incongruity.”15 It appears, then, in regard to dates occurring in passages where this principle of miniature symbolization is adopted, there is a strong presumption in favour of the Year-day theory, or some theory suitably extending the times.

Dr. Maitland has attempted to dislodge his antagonists from this intrenchment. His argument is subtle, and must have been deemed triumphant, for it is repeated and praised as a master-stroke by almost every subsequent writer on the same side. Allowing even that symbols of time might be expected in symbolic predictions, along with symbols of events, he denies that a day can in any way be regarded as the symbol of a year. It is not, he argues, a symbol at all. We give the argument in his own words, premising only that the advocates of the Year-day principle, as we shall by and by see, appeal to Ezek. iv. 4‒9 in proof of it:—“When you speak of the beasts I know what you mean, for you admit that Daniel saw certain beasts; but when you speak of ‘the days,’ I know not what days you refer to, for your system admits of no days: you take, if I may so speak, the word ‘goat’ to mean the thing ‘goat,’ and the thing goat to represent the thing ‘king;’ but you take the word ‘day’ not to represent the thing ‘day,’ but at once to represent the thing year. And this is precisely the point which distinguishes this case from that of Ezekiel’s, which has been so often brought forward as parallel to it. The whole matter lies in this, that the one is a case of representing, the other of interpreting. A goat, not the word goat, represented a king; a day, that is the word day, is interpreted to mean a year.”16 The pith of the argument seems to lie in this, that while, in Daniel, kingdoms are represented by certain visible symbols—beasts, namely—there is no visible symbol of a year. We may interpret a day of a year, but we cannot say a day symbolizes a year. The objector appears to have been met, in the first instance, by the alleged difficulty of symbolizing times in a visible way; but the case of Pharaoh and his officers was at once appealed to, in whose dreams three years are represented by three branches and three baskets; and seven years by seven kine, and seven ears of corn.17 A writer in the Investigator rejoined, that large numbers, such as the 1260 or 2300, could not easily be represented in the same way; a statement which seems so very simple and obvious, that we cannot but wonder it should have elicited such a burst of indignation as this: “What! shall it be affirmed that he who called up a vision in which seven kine symbolized seven years, could not employ visible and equally intelligible representations of 1260 years? This were to limit the power of the Almighty, by arrogantly assuming, that though he presented a few years by outward pictures to the eye, He could not, with equal facility, and like intelligibleness to men, have painted a much larger number by external emblems. We refer the writer in the Investigator to Rev. xiv. 1, and ask him how the apostle John knew there were exactly 144,000. On his principle that large number could not have been presented to the eye. How then did he know that there were 144,000?”18 Does the critic mean that John must have come to the knowledge of it by picture representation? Is he sure of this? The number is the same, and the company is the same as in chap. vii. 4, and there we read, “And I heard the number of them which were sealed, and there were sealed an hundred and forty and four thousand of all the tribes of the children of Israel.” The question is by no means one regarding what God could do, but one regarding merely the powers and capabilities of symbolic language; and we do not feel ourselves at all guilty of any unwarrantable “daring,” when we aver that large numbers could not be visibly represented like small ones. The real solution of the difficulty which the objection presents, seems to us to have been given by Birks, in his First Elements of Prophecy. “The beasts were conceptions visually suggested to the eye of the prophet, and nothing more; and the days, in like manner, were conceptions suggested by the words of the vision to his ear. The only difference is in the sense by which the mental image is conveyed; for it is plain that a day, when used as a symbol, must be mentioned, and could not appear visibly to the eye.”19 But whatever may be thought of this, and of the preceding observations, we have still our appeal to the matter of fact. If it be the fact, that in Scripture a day does represent a year, we have no concern about speculations regarding modes of representing. The only question is, What is the Bible mode? and to that question we shall very shortly apply ourselves.

Meanwhile, we would remark, ere leaving this part of the subject, that although we affirm that wherever we find the principle of miniature symbolization of events, there we have a strong presumption in favour of the times, if such there be, being also expressed on a miniature scale, yet we do not exalt this into a principle embracing the entire case. We shall endeavour to ascertain here, what such general principle is. It need not be disguised that the ground of it has been shifted more than once during the progress of discussion. Mede himself seems to have occupied ground by far too wide; and few or none now choose to defend the Year-day principle on the platform chosen by him who has been erroneously regarded as its originator. He maintained that, “alike in Daniel, and, for aught he knew, in all the other prophets, times of things prophesied, expressed by days, are to be understood of years.” But prophecies can be quoted almost without number in which the predicted times must be understood literally; and against this position, somewhat doubtingly and casually assumed by an illustrious interpreter, the artillery of Stuart and Maitland would be most successful, if any were found so foolish as to intrench themselves within it. Professor Stuart, however, chooses to write as if it were an essential part of the Year-day theory. He fights with a man of straw, and expends his logic and his ridicule alike in vain. He asks in triumph, If the 120 years, predicted as the period that should elapse before the flood, must be extended into a respite for the ante-diluvians of 43,200 years? and if the predicted bondage of Abraham’s posterity in Egypt, for 400 years, must be extended into 144,000 years? if the seven years of plenty, and seven of famine to Egypt, must mean 2520 years of each? if Israel’s forty years’ wilderness-wanderings are to last 14,400 years?20 No, truly! and yet the times in Daniel and John may be symbolical times notwithstanding. By Bush and Faber, the principle is much narrowed. The ground assumed is that of miniature symbolization. This covers a large part of the field within which the Year-day theory is applied; still, it must be allowed, that both in Daniel and the Apocalypse, there are passages where the times are construed symbolically, or according to the longer reckoning, without being associated with symbols of events. Of this kind is Daniel’s famous prophecy of the seventy weeks. What, then, is the true principle or basis of the Year-day theory? We are disposed to reply, as we find Mr. Barnes in one place has done, that it is the manner of the symbolical books of Daniel and John, to express times on the scale of a day for a year; and that in regard to those places, if such there be, where the times are literal, the circumstances of the case, or some expressions in the text, prevent the possibility of mistake, and leave the principle untouched. The circumstances of the case, for example, forbid us to explain Dan. iv. 32 in accordance with the principle of a day for a year. “According to this, Nebuchadnezzar must have been mad and eat grass 2520 years.”21 The limited life of man renders any such extension of times here positively absurd. So also with the other case, so much insisted on by the Day-day theorists, of Daniel fasting three weeks.22 “Surely no one will contend that Daniel fasted twenty-one years.” No, but not to mention that this is not a prophecy at all, the circumstances of the case forbid it; and besides, in this place, we have the addition of יָמִים (weeks of days), “inserted expressly to bar any such interpretation as would assign to it, as its first sense, the meaning of years.”23 It would, therefore, be most unwise24 to argue from these exceptive passages, where there can be no danger of mistakes, against the application of the Year-day principle to the great leading prophecies in Daniel and John, regarding the glorious epochs of the church, and the times especially of the consummation. Nor can anyone rationally contend, that because these prophets have adopted this style of a day for a year, in predictions of the character above specified—predictions which form the chief part of their writings—that they are in no single instance to depart from that style—that they are never to lay aside the symbolic and assume the natural. Birks and Elliott, it may be noticed finally, find, in those passages where the Year-day theory is applicable, a purpose of temporary concealment; it being “the express design of God, that the church should be kept in the constant expectation of Christ’s advent,” and that, “yet as the time of the consummation drew near, there should be evidence of it sufficiently clear to each faithful inquirer.” “This,” adds the latter writer, “sets aside, from its very nature, the objections that have been drawn from sundry prophetic periods, known to be literally expressed, in prophecies where no such temporary concealment was intended.”25

3. Having seen that the symbolical character of the predictions in which the disputed times for the most part occur, affords a strong presumption, amounting as nearly as possible to proof, in favour of some such principle as that involved in the Year-day theory, we inquire next whether there be any indications of such principle in Scripture?

The case of the spies in the book of Numbers26 has been appealed to by nearly all writers on the Year-day side, and by some of them with no little confidence. “They returned from searching the land after forty days.... After the number of the days in which ye searched the land, even forty days, each day for a year, shall ye bear your iniquities, even forty years, and ye shall know my breach of promise.” We confess, however, that if this passage were the only one of its kind, we should not be disposed to build much on it. It has been too much pressed; and many will find it difficult to see anything typical or mystical in it. It cannot be proved that the spies were types of the whole nation, or that the days were meant to represent years. Dr. Davidson seems to give the true account of the passage when he says, “It is a simple historical prophecy, in which God ordained that as the spies had wandered forty days, so the Israelites should wander forty years in the wilderness because of their sins.”27 Taken in connection with other passages, however, it may serve to show that the “Year-day scale” readily occurs in Scripture, when another might as easily have been adopted. The very fact of the punishment of Israel in this case being on the precise scale of a year for a day, seems to indicate something of this kind.

Ezekiel’s typical siege presents a much stronger case. We give the passage at length. Ezekiel having been commanded to portray the city of Jerusalem on a tile, and conduct a symbolic siege against it, is further enjoined—“Lie thou also upon thy left side, and lay the iniquity of the house of Israel upon it: according to the number of the days that thou shalt lie upon it thou shalt bear their iniquity. For I have laid upon thee the years of their iniquity, according to the number of the days, three hundred and ninety days: so shalt thou bear the iniquity of the house of Israel. And when thou hast accomplished them, lie again on thy right side, and thou shalt bear the iniquity of the house of Judah forty days: I have appointed thee each day for a year.”28 Ezekiel was ordered to assume this painful position that he might be a sign or symbol of the sufferings of the Jewish nation; and the number of days during which he lay prostrate was declared to symbolize the years of their punishment. Here, then, we have a plain precedent showing that in symbolical representations days stand for years. The argument is equally valid whether we suppose the symbolical actions represented things past or things future. The principle is the same. The probability is, that at the time of the representation a few years of the 390 had yet to run; and the design was to show that Jerusalem should be destroyed, and the inhabitants led away captive into Babylon. It is not our province, however, to enter into any exposition of the prophecy. The grand objection made to the argument from this passage is, that in it the symbolic significancy of the days “is expressly stated at the outset.”29 “It is expressly stated that God had appointed a day for a year, whereas in Daniel and John no such information is given.”30 But what if there had not been an “express statement” of the principle? That omission, we imagine, would have been eagerly laid hold on as an evidence that no such principle was contained in it. The “express statement,” then, so far from being an argument against using this passage as a precedent, is in reality a strong argument in favour of so doing. Can anything be more unreasonable than to object to the passages furnishing a clue or key for certain difficulties elsewhere, that they are plain and express? Nothing, we apprehend, unless to object next that the passages for which a key is sought are not plain and express. We had thought that it belonged to the very nature of key-passages that they should be plain, and to the very nature of the passages for which the key was needed, that they should not be plain. The demand that there shall be the express statement in these latter which belongs to the former, is just to demand that there shall be no mystery about the times at all,—that they shall be revealed with perfect clearness, and that no wisdom and diligence be called for in evolving a principle and applying it to special cases. Bush’s reply to Stuart on this point is, we think, triumphant. “The obvious reply to all this (the want of express statement in Daniel and the Apocalypse) is, that the instances now adduced are to be considered as merely giving us a clue to a general principle of interpretation. Here are two or three striking examples of predictions constructed on the plan of miniature symbolic representation in which the involved periods of time are reduced to a scale proportioned to that of the events themselves. What, then, more natural or legitimate, than that, when we meet with other prophecies constructed on precisely the same principle, we should interpret their chronological periods by the same rule? Instead of yielding to a demand to adduce authority for this mode of interpretation, I feel at liberty to demand the authority for departing from it. Manente ratione manet lex is an apothegm which is surely applicable here if anywhere. You repeatedly, in the course of your pages, appeal to the oracles of common sense, as the grand arbiter in deciding upon the principles of hermeneutics. I make my appeal to the same authority in the present case. I demand, in the name of common sense, a reason why the symbolical prophecies of Daniel and John should not be interpreted on the same principle with other prophecies of the same class. But however loud and urgent my demand on this head, I expect nothing else than that hill and dale will re-echo it, even to the ‘crack of doom,’ before a satisfactory response from your pages falls on my ear. All the answer I obtain is the following:—‘Instead of being aided by an appeal to Ezekiel iv. 5, 6, we find that a principle is recognized there which makes directly against the interpretation we are calling in question. The express exception as to the usual modes of reckoning goes directly to show, that the general rule would necessitate a different interpretation.’ I may possibly be over sanguine, but I cannot well resist the belief, that the reader will perceive that that which you regard as the exception, is in fact the rule.”31

Dr. Maitland’s famous objection, that in Ezekiel the case is one of representing, whereas in Daniel and the Apocalypse it is one of interpreting, has already been met in a previous part of this Preface. The objection of Bishop Horsley is not very grave—namely, that because the day of temptation in the wilderness was forty years, and one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day, we might as well conclude that a day is forty years or a thousand years, as that it represents but one year. So might we, indeed, if a number of passages could be produced in which a day has such significancy, and another set of passages could be produced to which the first set furnish a key that seems exactly to answer. In the meantime, we must recognize the difference between what is merely figurative language, and therefore loose and shifting, and the language of symbol.

But the case of Isaiah32 has been supposed to neutralize any argument built upon that of Ezekiel: “The Lord spake by Isaiah, go and loose the sackcloth from off thy loins, and put off thy shoe from thy foot. And he did so, walking naked and barefoot. And the Lord said, Like as my servant Isaiah hath walked naked and barefoot three years, for a sign and wonder upon Egypt and upon Ethiopia, so shall the king of Assyria lead away the Egyptians prisoners.” Now, it is argued that here “three years correspond to three years, not three days to three years. It is arbitrary to suppose with Lowth that the original reading was three days, or to supply three days, with Vitringa. The text must stand as it is.”33 But the interpretation of Lowth and Vitringa is not the only mode in which we may escape from the difficulty, as this learned writer seems to hint. We are not shut up to conjectural emendations. The “three years” in the third verse may be connected with what follows, as well as with what goes before; then the verse will run, “Like as my servant Isaiah hath walked naked and barefoot; a three years’ sign and wonder,” which relieves us entirely from the supposition that Isaiah walked three years barefoot, and, by consequence, from the objection that is founded on it. All that is intimated is, that in some way or other (the passage does not say how) the prophet was a three years’ sign—a sign, that is, of a calamity that would last during that time, or commence from that time. In proof of the justice of this arrangement, it may be noticed that the Masoretic interpunction throws the three years into the second clause; that the Septuagint gives both solutions, by repeating τρία ἔτη;34 and that in a period of such alarm, when Ashdod was taken and the Assyrian pressing on them, it is not likely the symbolical representation would be continued so long. Indeed, this opinion seems to meet with little or no countenance.35 The opinion that seems generally to prevail is, that Isaiah indicated the three years’ captivity either by exhibiting himself in the manner described in the text for three days, which would intimate three years, or by appearing in this manner once only, and at the same time verbally declaring his design in so doing.

We come next to what is confessedly a main pillar of the Year-day theory, the prophecy of the seventy weeks in Daniel.36 “Seventy weeks are determined upon thy people, and upon thy holy city, to finish the transgression, and to make an end of sins, and to make reconciliation for iniquity, and to bring in everlasting righteousness, and to seal up the vision and prophecy, and to anoint the most holy. Know therefore and understand, that from the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem, unto Messiah the prince, &c.” Now, the all but universal agreement that this prophecy was fulfilled in a period of 490 years, usually reckoned from the 7th of Artaxerxes, and extending to A.D. 33, the year in which Christ died, seems at once to settle the question regarding the mode of computation. There are, indeed, those37 who maintain that this prediction has yet to be fulfilled, and they profess to look for its fulfilment in seventy weeks of days; but the number holding this opinion is exceedingly small. The great mass of writers, even of those who contend for literal times, reject it as quite untenable. This mode of cutting the knot, however, indicates the difficulty that is felt by some “Day-dayists” in reconciling the passage with their theory, and their dissatisfaction with the more usual method of reconciliation. That method adopts a new rendering. The words, it is said, ought to be translated seventy sevens; and these are assumed to be sevens of years, because in the early part of the chapter Daniel had been meditating on Jeremiah’s prophecy regarding the seventy years’ captivity. By thus understanding the sevens at once of years, without the intervention of symbolic days or weeks, the argument for the Year-day principle, it will be seen, is entirely destroyed.

It would be difficult and tedious to trace the course of discussion fully to which the passage has given rise. A very general outline must suffice. It had been maintained by some who contended for “sevens of years,” that the word translated weeks (שָׁבֻעִים shabuim) was the regular masculine plural of שֶׁבַע (sheba), seven, and ought, therefore, to be translated sevens.38 But שָׁבֻעִים (shabuim), as was alleged in reply, “is not the normal plural of the Hebrew term for seven.” The normal plural is שִׁבְעִים (shibim); but that is the term for seventy, and cannot mean sevens.39 It seems now admitted on all hands, that both שָׁבֻעִים (shabuim) and the feminine form שָׁבֻעוֹת (shabpuoth) are plural forms of שָׁבוּעַ (shabua), which, according to the etymology of the word, signifies a hebdomad or septemized period.40 The only question that remains, therefore, regards the use of the word. What is its use? So that after much controversy, the matter stands very much as Mede left it. “The question,” says he, “lies not in the etymology, but in the use, wherein שָׁבוּעַ (shabua) always signifies sevens of days, and never sevens of years. Wheresoever it is absolutely put, it means of days; it is nowhere thus used of years.”41 Besides the places in Daniel, the word occurs absolutely elsewhere, in some one or other of its forms, eleven times, and in every one of these cases with the sense of weeks of days.42 It is true that if we except the places in Daniel, there is no instance in Scripture where the masculine plural שָׁבֻעִים (shabuim) is used to denote weeks. The word elsewhere used for that purpose is uniformly שָׁבֻעוֹת (shabpuoth) in the feminine. But we confess ourselves at a loss to understand why so much should be made of this. The word which Daniel uses is confessedly the masculine plural43 of the same word, which in the singular is translated “week,” and in the feminine plural “weeks;” and although there are instances in various languages of the masculine and feminine plurals having different significations, yet, in the absence of anything like proof that such is the case here, we must be guided by the use of the word in its other forms throughout the Scripture, when we come to interpret the peculiar form that occurs in Daniel. What good reason can be given for departing from the analogy of the other forms? This, it must be confessed, is entirely on the side of the Year-day principle; and the objection resolves itself into nothing more than this, that it is a peculiar form of the word which Daniel uses.

As to what is said of the qualifying word יָמִים, yamim (days), twice occurring in chap. x. 2, 3,44 in connection with שָׁבֻעִים (shabuim), giving the literal sense three weeks, days, or three weeks as to days, we cannot see that it furnishes any grave objection to our argument. It seems rather to strengthen it. For here we have two places in which the word in question, and the form of it in question, are declared to mean weeks of days. Does not this intimate that such is the ordinary and primary sense? Are we not as much entitled to draw this conclusion, as other parties to conclude that the qualifying word is added because the usual sense is sevens of years? Let us only suppose that the qualifying word had been years instead of days (sevens as to years), would it not very readily have been said in that case, Here is a plain declaration that sevens of years are to be understood; and certainly the places where no qualifying word occurs must be ruled by this? Gesenius supposes the addition of יָמִים (days) is merely pleonastic; but if any other reason must be found for it, that of Bush seems as satisfactory as any, which regards it as an intimation that the primary sense is the only admissible one in the circumstances.

4. We entitle our next head of evidence, Exigency of the passages in which the prophetic times occur. The very best plan of arriving at the truth in the question, whether the shorter or longer reckoning be the right one, is to test both by application to the disputed passages. Try the two keys, and see which best suits the lock. One section of the literal dayists have here, however, a great advantage over their opponents, inasmuch as their plan of placing the Apocalyptic fulfilments entirely in the future (with the exception, on the part of some of them, of the epistles to the seven churches), relieves them from every embarrassment that might arise from any specific historical application. Of course it is impossible to argue with men of this school, that their literal times do not answer to their historical events, for historical events they have none, and we cannot prove that their ideal fulfilments may not be realized.

To discuss fully this part of our subject, however, would require a volume embracing an exposition of nearly all the more important passages in Daniel and the Apocalypse. We intend only to offer a few passing remarks on one or two of these, referring such as wish to prosecute the subject, to the “Notes” in this volume.

Let us take first the Saracenic woe.45 We say not, in the meantime, that the interpretation which has given rise to this name is necessarily the right one. We merely wish to institute a comparison between it and another interpretation, which proceeds on the principle of the shorter dates. If the reader will turn to our author’s exposition, and attentively study it, he will, we think, be disposed to acquiesce in the justice of his closing remark, that, on the supposition that it was the design of John to symbolize these events (the Arabian conquests), the symbol has been chosen which of all others is best adapted to the end. Moreover, it will be seen that the Arabian history, according to the requirements of the passage, on the Year-day principle, furnishes a period of five months, or 150 years of intense stinging oppression, and immediately thereafter exhibits a gradual decline in power, along with a disinclination to persecute. Now what have we to oppose to this view on the part of those who advocate literal times? We turn to Professor Stuart. He tells us he can find no event in history that, with any good degree of probability, will correspond to a period of 150 years. “And,” adds he, “if we count five literal months, we are still involved in the same difficulty. Hence the tropical use of the expression five months, seems to be most probable and facile.” His conclusion is that “the meaning must be a short period.” We cannot think that this “tropical use” is very “probable;” it is however abundantly “facile;” and we know not how to argue with those who, when events will not correspond with their literal times, immediately take refuge in tropes. When Professor Stuart can find events that suit, his times are literal, as we shall immediately see; when he cannot find such events, his times are tropical. But a principle so “facile,” however it may suit his convenience, is not fitted to guide us in an inquiry into the prophetic periods. “The proper laws of interpretation,” our author has justly observed in his exposition of the place, “demand that one or the other of these periods should be found, either that of five months literally, or that of a hundred and fifty years.”

Take next the Turkish woe.46 We refer the reader again to the author’s exposition, that he may see how “the hour, day, month, and year” of this prediction—that is, the 391 years, and a 12th or 24th of a year—find their fulfilment in the history of the Turkish empire. But on the supposition that the times are literal, what events can be fixed on as occupying this period of little more than a year? or how, in transactions so great, should a single hour be mentioned? These questions are evaded by assigning a new sense to the clause εἰς τὴν ὥραν καὶ ἡμέραν, &c. It is said to mean only, “that at the destined hour, and destined day, and destined month, and destined year,” the calamity should happen; that is to say, it should occur simply at the appointed time. We venture to say that such a periphrasis for an idea so simple has no parallel elsewhere. For the criticism of the passage, we refer to Barnes and Elliott, who have successfully contended that the words completely reject this sense. The latter appeals also to the parallel passage in Dan. xii. 7, where “for a time, times, and half a time” is universally understood of the aggregate period of three years and a half.47

The forty-two months of the Gentiles is another and remarkable Apocalyptic period.48 If we do not, with our author, apply the passage in which this notation of time occurs, to the trampling down of the church by the Papacy during her long and oppressive reign of 1260 years, but seek an explanation from those who deny the Year-day principle, shall we find events that will better answer on the principle of literal times? Let us try. Professor Stuart, in this place, abandons the idea he sometimes resorts to, of supposing the periods “figurative modes of expressing a short time.” He thinks a “literal and definite period” is here meant; and he even condescends, in spite of all his hatred of historical comments, on historical events answering to this definite period. “It is certain,” says he, “that the invasion of the Romans lasted just about the length of the period named until Jerusalem was taken.” And again, in his Excursus on Designations of Time, he says that in the spring of A.D. 67, Vespasian was sent by Nero to subdue Palestine; and that on the 10th of August, A.D. 70, Jerusalem was taken and destroyed by Titus. Thus he makes out the literal period of forty-two months or three and a half years. He is, however, compelled to admit that the war actually began some time before Vespasian’s mission. But allowing all this to be correct, there was, as Mr. Barnes remarks, “no precise period of three years and a half, in respect to which the language here used would be applicable to the literal Jerusalem. Judea was held in subjection, and trodden down by the Romans for centuries, and never, in fact, gained its independence.” It is trodden down still. And yet we are told, in a laboured article written on purpose to set aside the Year-day principle, that there can scarcely be a doubt that the period in question (the forty-two months) is designed to mark the time during which the conquest of Palestine and of the Holy City was going on.

In close connection with this prediction, we have the times of the two witnesses.49 They were to “prophesy a thousand two hundred and threescore days, clothed in sackcloth.” Again, we think the longer reckoning meets the requirements of the passage, and is consistent with the historical events offered in explanation. During all the dark period of Papal rule, there has been a competent number of witnesses testifying in favour of the truth. The reader will find ample details in the exposition within. Let us turn now to the exposition offered by the great chief of the Literal-day theorists. His theory requires him to find the witnesses in Jerusalem immediately previous to its fall. But where the witnesses in Jerusalem prophesying during three and a half literal years? History is quite silent in regard to any such parties; nay more, the accounts which we have of the period render it exceedingly improbable that any such parties could have existed in Jerusalem at that time. The Christians, warned by their Master, had fled to Pella, and thereby escaped the calamity in which their unbelieving countrymen were overwhelmed. Yet, in the absence of history, and in spite of history, suppositions are made to stand in its place. We are told that some of the faithful and zealous teachers of Christianity would certainly remain in spite of their Lord’s warning. These, it is supposed next, would be slain by the Zealots, who would, notwithstanding, be unable to destroy Christianity. The truth should ever have a resurrection. We offer no further remark on this, than that if pure imaginations are to be alleged, where history fails, there can be no difficulty in meeting the requirements of any theory, inasmuch as inventions are much more “facile” than facts. But the exposure of the dead bodies of the witnesses is supposed to be perfectly fatal to the Year-day principle in this passage. “What now,” it is asked, “if we should insist on interpreting this (the three days and a half of exposure) as meaning three and a half years? It would bring out an absurdity; for a single month in the climate of Palestine would in one way or another destroy any dead body, not to speak of its being devoured.” Doubtless this is an absurdity; but it is an absurdity obtained by subjecting a symbolical passage to a very singular process, in which one part of the symbol is explained, and then read along with the unexplained part. But explain both parts of the passage, the lying exposed, as well as the days, and then we have no incongruous sense, but an intimation, that for three and a half years the witnesses should be silenced, and be treated with great indignity, as if unworthy of Christian burial. Or if the question be regarding symbolical propriety, let the symbolical representation stand as it is—both parts unexplained; and what inconsistency is there in supposing dead bodies exposed for three and a half days in the climate of Palestine? If we choose to proceed on a principle like this, we may make as many absurdities as there are passages in the Apocalypse.

Next in order, we have the times of the woman in the wilderness,50 the thousand two hundred and threescore days, or time, times, and half a time, during which she was protected and nourished by God. Once more we refer to the author’s exposition of this passage for a defence of the Protestant interpretation, which explains it of the preservation of the church in a state of comparative obscurity during the long period of Papal oppression. But on the principle of literal days, that is, “if the period of the woman’s sojourn be only three years and six months, the preparation must be either quite disproportionate to the event, or the steps of the preparation will be crowded into the narrowest compass. The spiritual deliverance, the dejection of Satan, the renewed persecution, the protection, the flood, its absorption by the friendly earth, and the persevering rage of the dragon, will all be crushed into the space of two or three years. Surely nothing but the most distinct revelation could make us receive such an exposition of the true reference of so glorious a prophecy.”51 It is difficult, indeed, to conceive that a prophecy of this nature should find its fulfilment in any three and a half years of the church’s history; and our difficulties certainly are not diminished, when we come to consider the special interpretations that are constructed on this principle. We are told that the woman is the Jewish Theocratic church. But that church never dwelt 1260 days in the wilderness, nor can any historical event be alleged in illustration of such a view that does not bear its refutation on the face of it. The Christians who fled to Pella, will the reader believe it, are, for the sake of a theory, made to stand for the church, symbolized by the woman; and their protection, during the continuance of the Jewish war, is the woman’s wilderness sojourn. The flight is the flight of the woman, or Jewish Theocratic church, in the first instance. But the Jewish church, to answer the necessities of the case, is at once transformed into the Christian; and finally, a comparatively small body of Christians in the neighbourhood of Jerusalem is elevated into the dignity of the church, to the exclusion of the numerous societies of Christians existing elsewhere. These are the assumptions set forth in antagonism to the Protestant view; set forth, too, not as modest guesses, but as certain verities, to reject which, brings down on us the charge of ignorance of history, and of exegetical science.

Our limits forbid us to speak of the forty-two months of the beast,52 or of the periods in Daniel. Of the beast, it is manifest, that it is a power of no brief duration; but one which, existing through a long previous period, appears again at the great final battle immediately previous to the millennium, and is then destroyed. Great care is taken, in the chapter which describes the closing struggle, to identify the beast which was then slain with that which had previously appeared on the stage.53 As to the view which explains the beast of Nero, and the times of the three and a half years of his persecution, it is certainly enough to observe, that it requires the aid of a heathen hariolation to make it out, and may, therefore, be dismissed without argument. Of the periods in Daniel, particularly those in the seventh and twelfth chapters,54 we can only say that the mode of authoritatively asserting that the reference is to Antiochus Epiphanes, and then ridiculing the idea of any one man living through 1260 years,55 is a mode which must be abandoned by such as would secure a favourable reception for their views. We believe the sublime predictions of Daniel and John are occupied with far higher subjects—subjects of infinitely more concern to the church and the world than the history of the two tyrants, Antiochus and Nero.