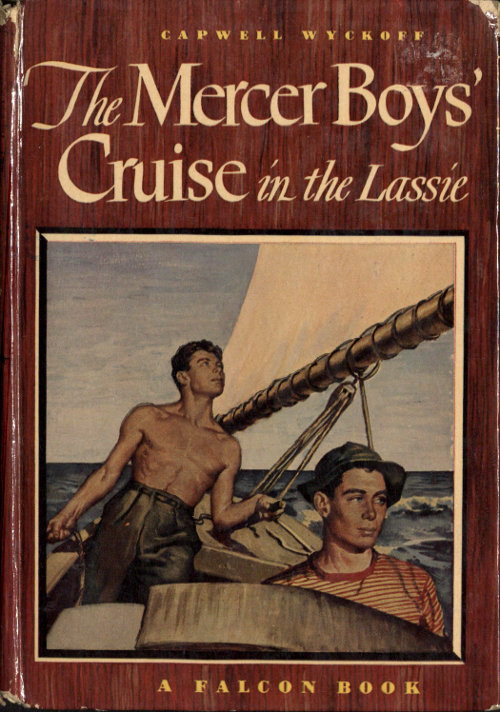

Title: The Mercer Boys' Cruise in the Lassie

Author: Capwell Wyckoff

Release date: August 11, 2017 [eBook #55335]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

FALCON BOOKS

When Don and Jim Mercer and their buddy Terry Mackson set out in their sloop, Lassie, for a visit to Mystery Island, they were in search of adventure and fun. But they quickly found they were getting more than they bargained for—real danger, a skirmish with marine bandits, and a fight for their lives. This is a thrilling adventure story of three modern boys—with action and excitement on every page.

Other titles in The Mercer Boys’ Series

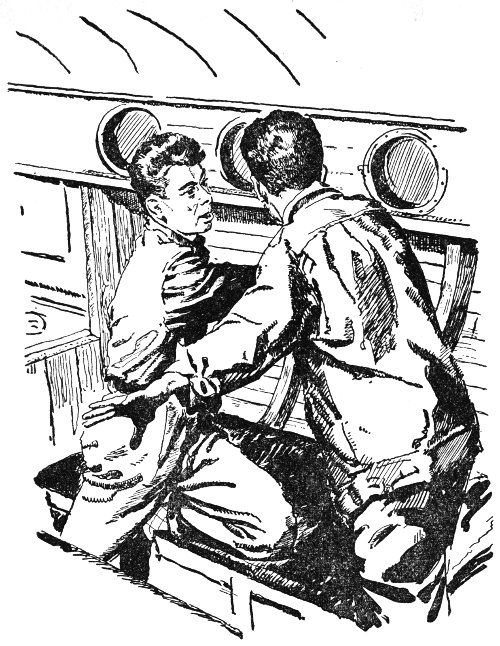

Don joined Jim at the porthole.

By CAPWELL WYCKOFF

THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK

Falcon Books

are published by THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

2231 West 110th Street · Cleveland 2 · Ohio

W 4

COPYRIGHT 1948 BY THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

“Hooray! That finishes it!”

Don Mercer straightened up from the marine motor over which he had been bending and gave a whoop to express his feelings. At the same time a browned face, topped off by a wind-blown mass of brown hair, looked down at him from the companionway of their sloop, the Lassie.

“What’s up?” Jim Mercer grinned. “Are you getting old and talking to yourself, Don?”

His older brother returned the grin from the bottom of the tiny cabin of the sloop. “Not so you could notice it. But I’ve got the engine hooked up, and now we can start our summer cruise, as soon as I see if she works.” He mopped his forehead. “Boy, that was some job. Lucky thing I learned something about marine engines down at Stillwell last year.”

Jim slipped one foot over the edge of the companionway and dropped into the hold, joining his brother beside the engine. “It surely was. Every connection hooked up?”

“Everything. I thought there was a little leak in that exhaust pipe, the one we had brazed over at Tarrytown, but it’s all right. I had a little trouble hooking up the switch wires, because I had never seen just this type of motor before, but I got it at last. How does it look to you, kid?”

Jim bent down to look at the motor. The two Mercer boys were much alike in every way, and were devoted to each other. Their father owned a large lumber business in the Maine woods, and the boys had never wanted anything in their young lives, but as they were fine, healthy boys, their comparative wealth had never spoiled them. Don was the older of the two, being seventeen, and Jim was one year his junior. Both of them were well built physically, with fine gray eyes, sandy hair, an abundance of freckles, and good-humored grins. They had graduated from the Bridgewater High School the year before.

Besides the two boys there was one sister, Margy, aged fifteen, and their mother. They had grown up in Bridgewater and were well known and liked in the town. Mr. Mercer believed in keeping his boys interested in wholesome things, and during their early years they had had one or two cat-boats. On the first week of the summer, however, the boys were surprised and delighted to find a fine 30-foot sloop riding gently at anchor in the creek which ran through their own back yard. Their father, who had done considerable cruising in his younger days, taught them how to handle the larger-sized boat, and had given them permission to go for a cruise down the Maine coast that summer.

For the last week Don, who was mechanically inclined, had been hooking up the motor. He had always been interested in motors and had studied them carefully while spending a week at the house of an uncle. He had learned more than he had thought. The motor had been in the boat at the time Mr. Mercer purchased it, but the connections had not been fitted. Late on this July afternoon Don had succeeded in finishing it.

Jim straightened up from his inspection of the motor. “Looks all right to me,” he declared. “Although I don’t know as much about them as you do. But before we crow, I guess we had better give it a spin and see if it works.”

“OK,” agreed Don. “Go up and push the starting lever over a couple of notches, while I spin the flywheel, will you?”

Jim skipped up the four steps that led to the deck, and bending down beside the tiller, grasped the lever. Don gave the flywheel a vigorous turn, and a slight chug answered him. He gave it a second spin, it coughed, chugged and began to turn over. Jim moved the lever a notch, slowly.

The engine broke into a regular, steady run, and a thin streak of smoke issued from the exhaust pipe above the water line. Don’s cheerful face appeared above the rim of the companionway.

“Jeepers, it works!” he exulted.

Jim nodded. “It sure does. Nice work, old man. Want to let it run?”

“Yes, let it go for awhile. It needs a little breaking in; I notice it’s stiff in spots.” He climbed up alongside his brother and wiped his moist brow. “Wow, that was quite a job while it lasted.”

“I’ll bet it was. Nothing to stop us from taking our cruise, now.”

“You are right there. But the question is: who are we going to take along with us? Dad wants us to take at least one other fellow. He thinks just the two of us won’t be enough. I’ve thought of most of the fellows round here, but either they have summer jobs or they are away. Who do you think we ought to take?”

“What time is it?” Jim asked, casually.

Don looked at his watch. “Half past three. What has that to do with who we’ll take on a cruise with us?”

“Maybe a whole lot!” Jim answered mysteriously. “Want to take a walk?”

“Where to?”

“Oh, nowhere in particular. Just up to where the highway touches the Lane.”

“Sure, I’ll go. I can’t see what you’re driving at, but I’ll go along.”

They stepped into the dock, walked the long stretch that made up their back yard, passed the house and walked out to the shady street on which their home stood, a street appropriately called the Lane. They walked slowly down it, making plans concerning provisioning the sloop for the cruise, which they expected to begin on the following day. About half a mile from the house the Lane ran into the State highway, and here Jim said he wanted to sit on a stone wall. So they sat down and continued to talk for a time.

Don finally became restless. “Let’s go to town and get some of the things we need,” he suggested. “No use sitting here all day.”

But Jim was not ready to go yet. He was looking down the road, to where a single car was coming toward them. It was a battered old rattletrap of a car, with sad-looking mudguards, no top, and doubtful looking tires on it. The wheels, which were the least bit crooked, made weird movements as it came toward them.

“Wait a minute,” Jim said. “I want to see who’s in this car.”

The driver of the car was a red-headed boy of seventeen, tanned by the sun and endowed with a multitude of freckles. Two laughing gray eyes peered from his long face. He looked Scotch. He was whistling as he drove the battered old car, and his sandy hair, decidedly red in the sun, stood up almost straight. There was no glass in the windshield of his car, and now and then he pretended to wipe the missing glass, greatly to the amusement of as many of the Bridgewater inhabitants as chanced to be on the road.

“Why do you want to see who the driver is?” Don began, impatiently. “You don’t——”

He broke off as Jim waved to the driver, and the driver waved back and brought his bounding car to a halt beside them. Don gasped.

“Why ‘Chucklehead’ Mackson!” he cried, while Jim grinned.

Terry Mackson, known as chucklehead, from his habit of bobbing his auburn head when laughing, ignored him completely. He carefully adjusted one soiled glove on his hand and asked Jim gravely: “Pardon me, old fellow, but could you by any chance direct me to the residence of the Mercers?”

“I think I could, if you give me time enough to think,” Jim grinned.

“Then please do so, without unnecessary loss of time,” Terry drawled. That was as far as he got. With a whoop the Mercer brothers piled into the car and thumped him on the back.

Terry Mackson had gone to grammar school with the boys, but had moved to a distant town, where he had worked hard on a farm for his old father. The boys had always admired him for his cheerful kindliness and respected him for his fine self-sacrificing nature. He had worked without complaint for a mean old father, who had even begrudged him his brief time in grammar school. Recently his father had died, and Terry had been living somewhat more happily with his mother and one sister.

When Terry was out of breath, and the old car had jounced dangerously, the boys stopped to catch their breath.

“How in the world did you get here?” Don asked.

“Jim wrote me to come down for a summer cruise,” Terry explained, as he started his car. “Didn’t you know it?”

“He didn’t know a thing about it,” Jim declared, sinking into the back seat. “We were looking for someone to take on our cruise with us, and I heard from Bill Bennet that you were living in Berrymore, so I didn’t say a thing to Don, but wrote to you. Thought I’d put one over on him.”

“And you certainly did that,” Don nodded. “But that’s OK. I’d rather it be Terry than anyone else.”

“Many thanks,” the newcomer murmured.

“How is everything at home?” Jim asked.

“Very well, thanks. We’re getting in nice shape. Mother said it was high time I had a vacation, when I read her your letter. Oh, I beg your pardon!”

“What’s the matter?” both boys asked.

“I’ve been guilty of a grave social error. I want you to meet my trusted chariot, my car. Boys, this is my intimate friend ‘Jumpiter.’”

To make it seem real, he drove the car over a bump, and the car bounced like a thing alive. Both boys acknowledged the introduction gravely.

“Happy to meet you, Jumpiter,” Don said.

“Me too,” Jim added. Terry made it rattle furiously, and vigorously wiped the imaginary windshield.

Mrs. Mercer made Terry feel right at home, and then the boys took him down to see the Lassie. To Terry it was quite a treat, for his life had been spent in working hard, far from any of the pleasures of life. He was delighted with the trim little ship, and the boys led him down the companionway.

Inside, there was plenty of room to move around without being cramped. There were four bunks built along the side of the hull, a tiny sink with running water, a refrigerator, a small stove and two compact closets for knives and forks and linen. Toward the bow it became narrow, and before the mast a small storage room took up the waste space. The engine was in the stern, under the steps that led down into the cabin. The center of the cabin was taken up with the centerboard, which the boys told Terry was an extra keel weighing two hundred and fifty pounds.

“That’s in addition to the regular keel,” Don explained. “There is about two tons of lead in the keel, but it isn’t enough when the canvas is spread. When we’re sailing under full sail, without reefs, we have to let the centerboard down. The 250 pounds makes just enough weight to balance the weight of the sails and keeps us from capsizing. When we come up the creek, or when we are using motor power, we don’t use the centerboard.”

The boys spent the rest of the afternoon running down to the village and getting supplies. Terry insisted on using his car for the work, so they bought food from the grocery stores and loaded several gallons of gasoline. With Terry’s car they were able to run right down to the sloop and carry the supplies aboard.

“There!” exclaimed Jim, finally. “We’re all set to go.”

The boys went up to supper, where Terry saw Mr. Mercer again. While they were eating they discussed plans and Mr. Mercer gave them a word of warning.

“There has been quite a little trouble lately with a gang of marine bandits,” the lumber man said. “They’ve been working up and down the coast, robbing boats and boathouses, and no one has been able to catch them. They steal all kinds of ship materials that they can lay their hands on. People think they store it all somewhere and then go down to Boston or other seaports where they sell it to dishonest ship chandlers. Nowadays a good many people are going in for sailing, and the ship chandlers have quite a business. I suppose people buy things where they can get them cheapest, and so there is quite a trade in it. I want you boys to keep your eyes wide open.”

“We certainly will,” Jim said. “You mean that they may try to take things off the Lassie?”

“Yes, you’ll have to be careful.”

“I’d like to run those fellows down,” Don declared.

After supper they went down to close up the sloop. The sails were tied down firmly and the portholes closed. After making an inspection Don pulled the top of the companionway closed, and snapped the lock.

“There,” he said, with satisfaction. “I don’t think anybody will get aboard the Lassie tonight. Nor any other night, if we can help it.”

After they had locked up the sloop the boys took Terry around town, showing him the sights, and then they returned to the house, where they pored over a map of the Atlantic coast. Since they would naturally keep inshore in a boat as small as the sloop was, the boys paid particular attention to channel markings. Then, bidding the family good night, they left the house and went down the yard to the little shack that the boys always slept in.

A few years ago, during one of their summer vacations, the boys had built a small two-room house at the end of the yard, near the boathouse and the dock. There was plenty of room for all of them in the house, but they had thought that when they had company during the summer it would be a little more convenient for their mother if they had a small place of their own down in the yard; so their parents had allowed them to build the bungalow. Whenever company came they took them to the cottage and they slept there, going to the main house for their meals. The arrangement had been handy in many ways, and had taught the boys to be self-reliant, as they had to keep things clean and attend to their own beds and the daily airing of their blankets. Just outside their cottage they had built a workbench, with a tool shed at the end of it, and on clear days they worked out there, making small things for the house and their boats. Jim had made the stand for the ship’s clock and other small pieces.

It was to this cottage that they now took Terry, and he was delighted with the cozy little place. The boys had wired it for electric lights, and on a back porch, protected from intrusion by lattice work, they had installed a shower bath and a small sink. The front room of the cottage was taken up with a table, some chairs, lockers, and a few boxes, and the walls were covered with pictures of boats and the teams at school. It was a typical boy’s room. The back room was given over to sleeping, and three cots occupied most of the floor space. In the glow of a ship’s lantern, now made over into an electric lamp, the boys undressed and prepared for bed.

“I won’t be a bit sorry for these blankets,” Terry decided, as he crawled into his cot.

“No, it gets quite cold here at night, no matter how warm the days may be,” Don said, as he settled down on his cot.

They talked for a few minutes and then, saying good night, dropped off to sleep. That is, the two Mercer boys did. They were so used to the place that they wasted no time lying in bed thinking, and they were usually so active in the daytime that they dropped into a healthy sleep as soon as they went to bed. But everything was new to Terry, and he lay there thinking about it.

He had been used to a life of constant work, and the prospect of this vacation, spent with boys like the Mercer brothers, held a fascination to him. His mother had been right when she said that he needed a vacation, and as things at home were in much better circumstances than they ever had been before, Terry felt justified in going away. So he lay there, staring out of the window over his head, seeing the black outline of the boathouse, and beyond it the mast and rigging of the sloop, moving gently with the motion of the tide.

Finally, Terry dozed off, enjoying to the last the cool wind that brushed over his brown face, and the slight and refreshing tang of the salt air. How long he had been asleep he did not know, but suddenly he awoke. He sat up, leaning on one elbow and listened. The brothers were asleep, as he could tell from their deep and regular breathing, and the boy was at a loss to know what had awakened him. He listened keenly, thinking that some sound, usual to the place, but new to him, had awakened him, but as a few minutes went by and he heard nothing, he lay down again.

Then a sound reached his ears, a thin, screaming sound as though someone was pulling nails out of a board. Wondering what it could be, Terry looked in the direction from which the sound had come.

Terry’s eyes were good, and he could make out the boathouse perfectly even in the darkness. At first he could see nothing, but as he continued to watch, a shadow detached itself from the corner of the boathouse and went around the side. Terry tossed aside his blanket, stepped over to Don and shook him, at the same time placing his hand over the boy’s mouth. Don sat up quietly, pushing Terry’s hand away.

When Terry had whispered his message to Don they woke up Jim, and standing at the window, the three boys looked toward the boathouse. While looking they were hastily dressing, tossing on a few clothes and pulling on rubber boots.

“I don’t see anybody,” Don whispered.

“He went around the side,” Terry answered. “Is there a window there?”

“Yes, there is. Are you ready, Jim?”

“Sure thing. Let’s go.”

They cautiously opened the back door, crossed the yard, and arrived at the front of the boathouse, where they paused for a moment to listen. Inside, they could hear someone walking around.

“Somebody in there, all right,” nodded Jim. “Shall we rush ’em?”

“Yes. We’ll catch them in a trap. Come on, kids.”

With that Don stepped around the corner of the boathouse. There was a small stick lying on the ground, and the boy stepped on it, causing it to break with a loud, snapping sound. Realizing that caution was now useless Don called out:

“Who is there?”

From the shadows beside the boathouse a man stepped into view. He darted to the window of the boathouse and called out: “Beat it, Barney, the kids is coming!”

Don dashed forward, clutching at the man, who was tall and thin, but the man twisted savagely and got away. At the same time Terry and Jim ran to the window, but they were too late. A small man leaped nimbly over the sill and joined his companion in flight.

“After them!” shouted Don, as they heard the men thrashing their way through the tangled undergrowth. All three boys joined in the chase, following the men with ease by the sound of their headlong progress. The chase led them to the edge of their own creek, where the men jumped into a small boat and pushed away from the shore.

“The dinghy!” gasped Jim.

The Mercer boys turned and ran to where the sloop was anchored, and Terry followed them. Riding gently on the waters of the creek, attached to the Lassie by a rope, was a new dinghy. Into this rowboat the boys piled, Don and Jim seizing the oars.

“Cast off, Terry,” Don called.

Terry slipped the rope from the deck of the sloop and the brothers began to pull toward the other boat, which was drifting aimlessly along the creek. Both men seemed to be in the back of their boat, bending over something. Just as the boys got within hailing distance one of the men whirled his arm, there was a flash of a spark, and a small motor began to hum.

“I knew it!” Don groaned. “He’s got an outboard motor.”

One of the men seized the tiller and the other boat ran rapidly down the creek, leaving the rowboat with the boys in it far behind. Although they knew it was useless they followed, reaching the broad expanse of the ocean. But once in the open water they lost track entirely of the other boat and its occupants.

“It’s no use,” Jim declared. “We haven’t a chance to find them.”

“I’m sorry to say that you’re right,” Don agreed. “I don’t even hear the sound of their motor. More than likely they shut it off and rowed up some creek, to throw us off. Well, there is nothing to do but to go back, I guess.”

They turned the dinghy, which bobbed like a cork in the ocean waves, and headed back for the creek.

“Do you suppose they were the marine bandits your father mentioned at supper?” asked Terry.

“I wouldn’t wonder,” Don replied. “But we’ll see when we get back to the boathouse. I hope it all didn’t wake the family up.”

But it had. When they finally tied the dinghy up to the sloop they found Mr. Mercer standing at the dock, anxiously watching for them.

“Hello,” he hailed. “What’s going on down there?”

Don briefly related the events of the last few minutes and then led the way to the boathouse. Using a key, which he had in his pocket, Don led them into the boathouse.

It was a neat little building, with various grades of wood stacked along the walls, a work bench in one corner, and some extra canvas piled on racks. A small rowboat lay bottom up in the center of the floor. They examined the window, to find that several wooden bars had been pried out and the sash raised.

“Is there anything missing?” Mr. Mercer asked. “There doesn’t seem to be.”

But Jim shook his head sadly. “Sorry to say that there is, Dad. That swell ship’s clock that you bought me down in Boston is missing. It was over there on the bench, and I was making a new case for it. I guess those guys were the marine bandits, all right.”

As the clock which Jim had lost was a very valuable one, they wasted no time in reporting the circumstances to the police. Early in the morning the boys were up, and spent the time immediately after breakfast in loading last minute articles on the sloop. Don found that the lock on the companionway had been tampered with.

“Somebody tried to get in here,” he said, showing the others the lock, which was slightly twisted. “But I guess they found it too much of a job.”

After they had reported the entire matter to the chief of police, who promised to have the waterfront searched for the thieves, the boys ran down in Terry’s car to the local drugstore and bought a case of cokes. When they had loaded it on the boat, and final instructions had been half-jokingly given them by Mr. and Mrs. Mercer, the boys were prepared to go.

Don went below, bending over the engine, while Jim sat at the tiller, his fingers on the starting switch. Terry, feeling useless as a sailor, sat in the cockpit, watching the proceedings. Jim nodded to him.

“Cast off the painter, will you, Terry?”

Terry looked helplessly around. “When did a painter get aboard?” he asked.

Jim laughed. “The painter is that rope at the bow,” he explained. “Throw it to Dad.”

Terry took the painter and tossed it to Mr. Mercer, who caught it and placed it on the ground. Don turned the flywheel and the motor began to churn. Slowly, Jim advanced the spark, pushing the tiller from him. Like some graceful bird the Lassie turned in the creek, her nose pointing toward the ocean.

The boys waved goodbye to Mr. and Mrs. Mercer and Margy and the sloop headed out to the mouth of the creek. As it cleared the banks at the mouth of the channel it struck the small ocean waves, bounding and dipping like a thing alive. The little ship seemed glad to get out on its own element. The boys were fairly launched on their cruise.

“Well, we’re off,” exclaimed Don, coming up the ladder and stepping into the little cockpit.

“Off on a nice start,” Jim nodded, watching a buoy about half a mile ahead of him.

“This is swell,” Terry struck in, his eyes dancing.

The wind was blowing a lively little breeze, and the Lassie rose and fell with the action of the waves. It was a bright, clear day, and they could see for miles over the tossing, tumbling Atlantic. On the port side they could see the long coast of Maine stretching along before them.

“Just think,” sighed Don. “Nothing to do but sail for a month or more.”

“It surely is great,” Terry agreed. “I hope in that month you’ll teach me something about sailing. I feel awfully ignorant.”

“You needn’t,” Jim told him. “We’re not any too good, ourselves. We’ve been used to sailing cat-boats around, but this is the first time we’ve had an opportunity to handle this boat in any kind of weather. I think we’ll all learn things together.”

After they had sailed down the coast for five miles Don said to Jim: “How about putting on sail?”

Jim considered the sky. “I guess we can. But we’ll have to take two reefs in it. With a small gale like this, we can’t risk putting on full canvas.”

“No, you’re right. Teach Terry how to hold the tiller, while I shut the motor off.”

“All you have to do,” Jim told Terry, while Don turned the motor off, “is simply to drive the bow straight toward that buoy. See the buoy? Now, hold the tiller loose in your hand. Just as soon as the bow moves away from pointing straight at the buoy, move the tiller the least little way in either direction. No, not so far over. That’s it, just a fraction. Now you have it.”

While Terry held the tiller somewhat gingerly, secretly as proud as a prince, the Mercer boys sprang to the sails, and began to untie the straps that held down the spread of canvas on the boom. When this was finished they jumped to the halyards and pulled the canvas up the mast, the wooden rings slipping with a clattering sound. While Don held the halyard ropes Jim tied the sail down at the second reef. Then, pulling up the jib sail, the boys walked back over the heaving cabin roof.

“All right, Terry my friend,” said Don. “You can let me have the tiller now. I have to guide the mainsail and jib from the tiller. Let down the centerboard, Jim.”

Terry surrendered the tiller. “Here you are,” he announced, with dignity. “Any time you want your boat tillered straight, call for Mr. Mackson!”

Under the spread of canvas the Lassie sped along before the wind, the sails cracking with a stinging, invigorating sound, the mast creaking and the pulleys straining and squealing occasionally. The sloop was heeled far over on her port side, and the water boiled furiously over the rail, much to the wonder of Terry, who was perched far up on the starboard side.

“Gosh, this boat leans far over,” he observed. “Doesn’t it ever go all the way over?”

Jim winked at Don. “Well, once in a while. I think the most times it ever capsized was three times.”

“Three times!” repeated Terry, aghast. “In how many cruises?”

“Oh, all in one cruise,” Jim replied.

Terry’s eyes narrowed. “Look here! If the boat went over a good-sized derrick would have to come out here and right it. And if I remember correctly, this is the first time you have ever been out for any length of time in this boat.”

Jim opened his eyes in surprise. “That’s so! It must have been some other boat!”

“I think you mean you fell out of bed three times on one cruise,” Terry retorted.

Jim was the cook, and on the little galley stove he prepared an excellent meal at noontime. Rather than bother with the sails while eating, the boys had taken the canvas in, and were at present simply drifting idly with the tide. A few miles down the coast they could see the Midland Amusement beach, and Don proposed that they go there for a swim in the afternoon.

After the meal was over they cruised under motor power to the beach and, locking the companionway door, went ashore in the dinghy. They hired a bathhouse and soon emerged onto the beach in their trunks. From a long dock they dived into the water, amusing themselves for fully an hour in the sparkling water. Then, as the afternoon sun showed signs of going down rapidly, they dressed and climbed into the dinghy, pushing out from the shore.

“Hey, look!” exclaimed Terry. “There is someone on our boat.”

The boys stopped rowing and looked toward the sloop. A small rowboat was tied to the stern, and two men were walking around in the cockpit, peering down into the cabin through the portholes in the companionway.

“Wonder what they have in mind?” Jim said.

“Let’s get out there and see,” advised Don. Accordingly, they rowed with all their strength, until they were alongside.

The men had seen them coming, and one of them, a stocky individual with an unpleasant face, stepped to the side and smiled at them. Although the boys did not like the looks of either of them, they were polite and open in their manner.

“How d’you do?” the stocky individual hailed. “This your boat?”

“Yes, it is,” said Don, stepping on deck. The others followed, and Jim tied the dinghy to the stern.

“Thought likely it was,” the leader of the two went on. “Nice boat.”

“It surely is,” Don agreed, waiting. He felt sure that the man wanted him to open the companionway slide, and he had no intention of doing so. The shorter of the two men was standing back of him, evidently waiting.

“You—you don’t want to sell it, do you?” the leader asked.

Don shook his head. “No, it isn’t for sale. I don’t think you would have any trouble in having one like it built, though.”

“I couldn’t wait for one to be built,” the heavy man murmured. He turned to his companion. “Come on, Frank, time we were getting along. Thanks for letting us look it over, boys.”

“You are welcome,” Don replied. The men entered their boat and pulled rapidly for the shore.

“I don’t know that we could help letting them look at it,” Jim remarked.

“We couldn’t,” Don agreed, sliding back the hatch. “I wonder who those guys were? They must have come aboard while we were getting dressed.”

“Maybe they belong to the marine gang, and were looking us over,” Terry suggested.

“You may be right,” Don replied. “We’ll have to keep our eyes open for them in the future.”

After supper the boys continued the cruise, sailing for a time and then, as darkness came down, using the motor. Jim put on the lights and Terry asked concerning them.

“The green one is the starboard light,” Jim said. “The port is the red one. The danger side of a ship is the port side; the watch has to be keenest there. The easiest way to remember which is which is to think that port wine is red, and then you can always remember that the port light is the red one.”

Two miles off shore, on a lonely section of the coast, the boys lowered the anchor and prepared to spend the night. Terry, who had looked forward eagerly to his first night on the water and his first sleep in a bunk, was disappointed to find that they intended to sleep on deck.

“You can sleep inside, if you want to,” Don told him. “Only, I think you’ll like it better sleeping out on deck, under the stars. If we have stormy weather—and I think we are going to, because the barometer is going down—you’ll sleep indoors quite enough. But suit yourself.”

Terry decided that he would sleep on deck, and they accordingly carried the blankets out on deck and spread them out. As it was too early to go to sleep yet, they talked for a time of general subjects.

“Suppose a storm, like a fog, comes up in the night?” Terry asked.

“Well, we can go close to shore, or anchor out, but if we anchor out, we’ll have to toll the bell all night. If anyone feels particularly like sitting up all night and pulling on the rope, they are perfectly welcome to do so.”

“Count me out,” Terry decided. “We might use Jim, however.”

“How is that?” Jim asked, suspiciously.

“When you give that little imitation of a snore that you do, your mouth half opens and shuts,” Terry explained. “I was just thinking that we might hitch the rope up to your front tooth and have it tolled all night without anyone having to sit up or keep awake!”

“I see. Well, look here. When you are lying under the bell, don’t you ever yawn!”

“And why not?”

“Because we’ll never find it again, and we’ll have to hang you to the mast and shake you back and forth every time we have a fog,” said Jim, soberly.

“Meaning that I’ll swallow the bell, I suppose?”

“Something like that.”

The boys turned in around ten o’clock, thoroughly tired out. Before Don put out the light he looked at the barometer.

“Going down,” he muttered. “Doesn’t look any too good for the morning.”

The last thing that Terry remembered was lying on the gently heaving deck, looking up at a multitude of soft glowing stars. Then a deep sleep fell upon him.

Terry Mackson was dreaming. He dreamed that he was sitting on a bench and that Jim was hurling buckets of water over him. The bench was heaving up and down and the water continued to pour over him. The part that made him angry was the fact that he couldn’t seem to get up. And now, to make matters much worse, someone, he couldn’t see who it was, was shaking him.

He woke up with a start, to find Jim bent over him shaking him roughly, and shouting something in his ear. Jim was saying, “Get up, it’s raining,” and Terry, struggling to his feet, found that Jim was putting things mildly. The rain was coming down in sheets, and Don was heaving the bedding down the companionway. Terry took a brief look before going below.

The millions of stars that he had looked at earlier in the evening had all disappeared, and only a dense, heavy gray sky hovered over the sloop now. The waves, which had been so gentle, now reared angry heads alongside the little craft, and the deck was soaked with the spray. The world had turned completely upside down in the farm boy’s eyes.

“Go on down,” Don shouted. Terry obeyed, but Don ran forward and examined the anchor cable. When he came back downstairs, he was wringing wet. He slipped the companionway shut and Jim closed and bolted the portholes.

“The anchor is holding all right,” Don reported. “I think we can weather it.” He slipped out of his pajamas and vigorously rubbed himself down with a rough towel. “Well, we’ll sleep indoors, like Terry wanted us to, sooner than we expected.”

“I never saw a storm come up so fast,” declared Terry.

“I’ll bet you didn’t see it at all,” Jim retorted, rubbing down. “Judging by the way I had to shake you, you didn’t see much of anything.”

In the light of the electric lamp the boys changed into dry night clothes, and sat on the edge of the bunks talking. The experience was slightly weird to Terry, but the Mercer boys did not seem to mind it. The sloop tossed madly, causing dishes to clatter inside the cupboard and other things to rattle and clink all over the boat. The fog bell clashed and clanged with each roll of the boat, and the electric lamp oscillated continually. Each time the sloop slid down a wave it pulled with a jerk on the anchor cable. To Terry, as he looked around, it seemed like being boxed in a trunk, at the mercy of the waves that slapped overhead.

“Well,” yawned Don, at last. “No use sitting up any longer, I suppose. We’ll see how things look in the morning. Do you feel all right, Terry?”

“Sure I do. Why?”

“I was just thinking that if you are going to get seasick at all, you’ll get that way tonight,” grinned Don, as he put out the lamp.

“Thanks for your cheerful thoughts,” grumbled Terry, as Jim snickered.

Terry was the first to awake in the morning, and he lay for a moment looking around the interior of the Lassie. The storm had evidently not subsided, for the floor continued to heave and sink, and the continual clinking and bumping went on. The portholes were still wet and a faint trickle of water ran out from the bottom of the engine. Outside, he could hear the whistle of the wind and the slap of the waves, and now and then a particularly big one ran across the deck. The brothers were still asleep.

At seven-thirty they woke up together and the three boys got dressed. Getting breakfast was no easy job, and Jim was hard put to it, especially in the matter of making coffee. Don, clad in oilskins, went on deck and examined the anchor cable, which he found to be bearing the strain very well. It was decided that they would cruise along with the storm during the morning and see what they thought best to do later in the day.

On the side of the centerboard casing, which came up from the floor of the cabin, dividing it somewhat, a board on hinges served as a table. This board, when raised, made a good substitute for a regular table, and on this Jim placed the eggs, bacon and coffee. The meal was a gay one because the food slipped back and forth with the rolling of the sloop. On one occasion, just as Terry was about to spear a piece of egg, his plate slipped downhill to the other side of the board, where Don was eating.

“Would you mind giving me back my plate?” Terry asked.

A particularly violent roll dumped the remaining egg from his plate and spread it dismally all over the board. Don pushed the plate back to him gravely.

“How about my breakfast, too?” Terry asked.

“Oh, do you want that too? You only asked for your plate, you know.”

All three boys pitched into the job of washing plates and then they pulled in the anchor and continued the cruise. Terry, outfitted in a coat of oilskins, enjoyed the rough sailing much more than the smooth. The little ship dipped joyously down into the troughs, plunging its nose beneath the waves and flinging them right and left in a smother of foam. Then, riding magnificently up the side of a gray green monster, it rushed with speed down the watery hill, to bury its nose in another small mountain. Quantities of water rushed across the deck, soaking them in spite of their oilskins, but as the weather was warm, the boys did not mind it. At times Terry was allowed to hold on to the tiller, a job that amounted to something, and he found it vastly different from the easy job it had been on the day before, when the water had been smooth.

They brought a portable radio on deck and listened to it throughout most of the morning, but the static was very bad and they finally gave up. After several unsuccessful attempts at playing a losing game of gin rummy against the wind, the boys decided it was easier just to watch the sea and the dark clouds as they scudded across the sky.

Another meal was eaten under conditions similar to those of the breakfast, and the sail continued. The day was dark and the sky threatening, and Don thought seriously of running inshore and tying up at a dock until the blow was over. Late in the afternoon they decided to swim.

“Want to go in for a real swim?” Jim asked Terry.

Terry looked toward the shore. “Where is a beach?” he asked.

“Jim doesn’t mean at a beach,” Don supplied. “He means to go swimming from the boat. Like to try it?”

“With the waves running like that?” Terry demanded.

“Sure thing. It will be the best swim you ever had.”

Terry was not sure, but as the Mercer boys got into their trunks he slowly followed, secretly appalled at the size of the waves that broke against the side of the sloop. Don was first to go over. Poised for an instant on the cabin roof, he suddenly launched out into a splendid curving dive. Right into the heart of a wave he went, to reappear some yards away, puffing.

“Oh, boy!” he called. “Get in, it’s great.”

Jim followed his brother, and Terry, whose swimming had been confined to quiet water all his life, hesitated for a few minutes before he made his plunge. Then, standing on the stern, he shot himself forward into a smother of gray-green water, instantly shooting below a small, churning mountain. An instant later he came to the surface, bobbing up and down on the waves.

Don swam to him. “How do you like it, kid?”

“It’s great stuff,” Terry gasped. “There certainly is plenty of room to swim in!”

Under these conditions the boys only swam for fifteen minutes, keeping close to the sloop. When they were once more clad in dry clothes they felt invigorated and healthy as they never had before. Supper, consisting of beans and potatoes and some peaches, tasted very good to them.

As evening came on the sea became rougher and rougher, and the brothers agreed to anchor somewhere in port for the night. They were now out of sight of the mainland, and Jim proposed that they run back to the coast. But Don, who was looking intently across the starboard bow, called his attention to a long low black mass just visible above the waves.

“Isn’t that Mystery Island?” Don asked.

Jim looked and then went down the companionway steps, to unfold the marine map and look at it closely. Presently his head appeared above the combing.

“That’s it, all right. Not thinking of anchoring near there, are you?”

Don nodded. “Yes, I am. It is a whole lot nearer the boat than the main shore is. I don’t see why we can’t run in and heave to.”

“The place hasn’t got a very good reputation, Don!”

“Nonsense, Jim. Most of the tales you hear about Mystery Island are false to begin with, and besides, I’m not afraid of a lot of old legends. I guess we can find a good cove there to anchor in until this storm blows over. Spin the motor, will you?”

Jim spun the flywheel and the Lassie, under Don’s guiding hand at the tiller, turned her nose to the low island in the distance. Terry turned to Don.

“What is all this business about Mystery Island, skipper?”

“Oh, just a collection of idle stories, mostly. It was supposed to have been the hiding place for pirates once, and for smugglers later on. I guess most of it is all foolishness, but people around this part of the country have a habit of saying, ‘Keep away from Mystery Island.’ Personally, I don’t believe there is a thing the matter with the place at all.”

It took them less than an hour to reach Mystery Island, and they found a fine cove to anchor in. It was now too dark to see the island clearly or to make out any details of it. After sitting around and talking over old school days for some time, the boys turned in and went to sleep.

A loose pan rattled around the top of the sink, annoying Jim as he tried to sleep. Finally, completely disgusted, he got up and captured the utensil, placing it firmly in a small closet.

“Should have done that in the first place,” he murmured, moving about in the darkness.

The rolling of the sea had abated somewhat, and Jim looked out of an open porthole. Close to them lay the black island, and Jim wondered idly what secrets it did contain. Then, uttering an exclamation, he looked intently out of the porthole.

Don stirred uneasily in his bunk. “Coming to bed, Jim?” he inquired.

“Sometime, yes. But come here, Don.”

Terry, awakened by the whispering, joined Don and Jim at the porthole and looked toward the island. On a sort of bluff, fronting the cove, a lantern was flickering in the breeze. Although they could not see clearly, they could nevertheless make out the outline of a man back of the lantern.

“Somebody standing there and looking us over,” Jim whispered.

“Wonder who he is?” Don asked.

“Mighty strange that he should come out on the shore on a night like this to look at the sloop,” muttered Terry.

For two or three minutes longer the man stood perfectly still, evidently looking toward the sloop, although the boys could not make out his face. Then, swinging the light as he walked, the mysterious watcher passed along the bluff and out of sight.

“There goes our reception committee,” chuckled Don.

“All I hope is that it is the right kind of a reception committee,” grumbled Jim. Don sought his blankets. “I guess it’s OK. Maybe they don’t have many boats stop here, and the sight is a novelty. Well, we won’t worry over it. I’m dead tired.”

When the boys woke up in the morning they found that most of the storm had subsided, but the day was anything but fair. The sky was gray and overcast, and the sea rose and fell in short, choppy billows. The wind, however, had gone down altogether, and that made a big difference.

Before dressing the three boys stepped out on deck and dove overboard into the stinging water that tumbled alongside the sloop. After this invigorating swim they enjoyed a wholesome breakfast, eaten out on the deck under the leaden sky.

“Sure does seem good to eat without having your plate run up and down hill every second,” Terry affirmed.

“It seems good to get out of the heat of the cabin,” Don said.

Jim showed a perspiring face above the companionway. “That goes for everybody but the cook,” he observed. “I will admit, though, that getting breakfast today has been easier than it was before.”

They ate slowly, not being pressed in any way for time. “Looks like an idle day,” Don ventured.

“I agree with you there,” his brother answered. “Until it clears up we won’t want to sail on, and so it looks as though today might be a trifle dull. But we’ll get through it somehow.”

“There will be plenty to do.” Don looked off toward the island, to where the top of a long house showed through the trees. “I know what I’m going to do. See that house?”

“I see it,” Terry replied. “Thinking of renting it for the summer?”

“No,” Don retorted. “But I saw smoke coming from a chimney on it this morning, and I’m going up there. They may have some fresh eggs, and if so, we want them. I’ll row over in the dinghy and take a trip to the house.”

“How about that man we saw last night with the lantern?” asked Jim.

“What about him?”

“I just didn’t like the looks of things, that is all. I’m wondering why anyone should take the trouble to come out on a bluff at three o’clock or thereabouts in the morning and look at us so long. It doesn’t look right to me.”

“Maybe it was someone that couldn’t sleep, and decided to go out for a morning stroll,” grinned Terry.

“With a lantern in his hand?”

“Well, believe me, I’d hate to go wandering around that black island at night without a light of some kind with me!”

“Oh, there is no doubt about that. But I feel that he came down to look at us, and I don’t think there was any good in it all, either.”

“Nuts, Jim,” Don broke in. “You’re letting your imagination run away with you. Just as soon as I help you clean up, I’m going ashore.”

They all cleaned up ship after breakfast. A large amount of bilge water had crept in under the floor during the storm, and as the boys had no pump aboard, they were forced to dip it out by the bucket. Terry scooped the water up in a pail down below, passed the pail up the ladder to Don, who passed it to Jim in the stern. From there Jim emptied it overboard. This task took them the better part of an hour, and when it was over Don announced: “I’m going ashore now.”

Jim was airing out the blankets and Terry decided that he would write to his mother and sister, so Don stepped down into the dinghy alone. Grasping the oars he called up to them, “See you later,” and rowed toward Mystery Island.

He found that it was a hard pull. The waves were choppy and troublesome, and the dinghy climbed and slipped backward. It took all his strength to keep it going forward, and the distance to the shore seemed long because of the energy necessary to reach it. After a half-hour’s row Don beached the dinghy on the sand at Mystery Island.

He pulled the boat far up on the sand, to make sure that the tide, creeping in, would not carry it away while he was gone. He stood for a moment and looked around him. He was in a sheltered cove, ringed around with trees and thick undergrowth, with a shelving sandy beach running down to the water. If any of the stories about pirates and smugglers were true, he reflected, this island was just the place for such things. It was a black, silent sort of a place, well named Mystery Island. Although Don had laughed at Jim’s fears he admitted to himself that he did not feel altogether comfortable. There was a brooding sense of mystery over the place, an air of evil watchfulness that he did not like.

Quite sharply he pulled himself together, realizing that he was allowing the wrong impressions to play upon his mind. “You’ll never get anywhere that way, Donald my son,” he murmured. To fortify himself, he began to whistle as he found the path through the woods.

The path was well beaten and he wondered who used it so much. Obviously someone lived on the island most of the year, possibly all year around, though Don could not imagine anyone living on the bleak waste in the wintertime. He wondered why there was no boat to be seen, since the inhabitants must have a boat. It would be impossible otherwise to get across to the mainland for supplies, and no one could live for any length of time on the place without renewing supplies from time to time. Possibly the boat was on the other side of the island. He knew that it would have to be a good-sized boat, too, for no rowboat or small power boat would do. But as the map had showed the island to be a large-sized one, he wondered why the people who lived at the house kept a boat on the far side of the island, especially as there was such a perfectly good harbor on this side.

He followed the path through a dense growth of trees and small shrubbery, finding that it had been worn down by many feet. The ground had been worn down hard and there was no sign of cluttering grass. Admitting that a rather large family lived in the house just ahead, he wondered why they went so often to the beach as to keep in perfect order a path through the undergrowth.

The path dipped slightly and then wound up a small hill, and at length he saw before him the low house. Before going any further he stopped to study it. It was old, built of boards that looked rough and weatherbeaten, and if it had ever had a coat of paint on it, the fact was not evident now. One crooked chimney stood unsteadily at the back. The windows of the upper floor had all been broken and were boarded up, but those on the ground floor were, for the most part, whole. The glass was dirty and the frames warped and bent. Don walked nearer, looking closely for signs of life about the place.

The front door was boarded up, and he saw at once that he could not get in there. A rotting front porch sprawled across the width of the house, and one corner of the roof was falling down. Don took a path around the house, looking closely to see if anyone was around, but there was no sign of movement in the place. But he felt sure that someone lived in the place, for a thin line of smoke drifted upward from the crooked chimney.

The back yard of the house was an overgrown plot, with a few rotting outhouses standing near the dense woods that pressed close to the place. Don stepped on the low porch and knocked gently. While he waited, he turned once more and looked around him. It struck him that there was not a sign of a chicken about the property, and he felt that his journey for eggs would be useless.

“Nothing like trying, though,” he thought, and knocked again. There was no response, and he was inclined to think that there was no one at home. But just then the tempting odor of bacon assailed his nose.

“Surely there is someone at home,” he decided. “No one would leave the house and allow bacon to fry on the stove. I wonder why they——”

He heard a bolt rattle on the inside of the door and it slowly opened. At first the interior of the place seemed so dark that he could not make out the person of the one who had opened the door. Then he saw that it was an old woman, with a severe face and untidy white hair.

“What do you want?” she asked, somewhat harshly.

“Pardon me,” Don said politely, “but I’d like to know if you have any eggs for sale? I just came from a boat which we have anchored in the cove, and I thought that you might have some eggs you could sell us.”

The woman nodded slowly. “Oh, eggs, certainly! Step in, young man, and I’ll wrap you up some.”

She stepped back from the doorway and Don entered. He found himself in a kitchen, which was furnished with a rickety table, three chairs, a couch and a sink and stove. The bacon that he had smelled was still sending forth a fascinating odor from the back of the iron stove.

While the old woman stepped out of the room to get the eggs Don noticed that although it was broad daylight all of the shades had been pulled down, creating a semi-gloom which he thought quite unnecessary. Three doors opened from the kitchen into other rooms, he also noticed. It seemed to him that the old lady was gone an unnecessary length of time, when she returned, but without any package.

“They are in the next room, young man,” she said, going to the stove. “Pick out as many as you want of ’em.” With her thumb she pointed to one of the doors which opened from the kitchen.

Wondering a bit, Don pushed the door open and stepped into a large room, which had evidently at one time been the dining room of the house. It too was almost dark, and a big table took up the center. He looked around but saw no eggs. He turned to the door again.

“Where are—” he began, but got no further. The door back of him went shut with a bang, and he heard a bolt shot. He tried the knob, to find that he was locked in and a prisoner.

It was with something of a start that Don realized that he was caught in a trap. He shook the door furiously, but it was firmly bolted, and his efforts were entirely in vain. Stepping off, he sent a heavy kick against it.

The old woman shuffled over to the door. “Here!” she shrilled. “You quit that! It’s no use of you tryin’ to git yourself out.”

“What am I in here for?” cried Don.

“Don’t ask me. Ask the Boss,” she replied.

“Who is the boss?”

A chuckle came from the other side of the door. “Soon you’ll find out. He’ll be in to see you before very long.”

Seeing that a display of temper would get him nowhere Don gave up his attempt to break the door and fell to examining the room with care. The windows had been boarded on the inside, and he gave up any thought of trying to pry loose any of the boards without the necessary tools. There was only one door in the room beside the one he had entered by, and he soon found that this door was as firmly locked as the other one. The walls, cold and wet to his touch, gave him no hope, for they were firm enough. Finally, he gave it all up in disgust.

“Nothing doing anyway,” he muttered. “I wonder what the heck the game is?”

He did not have long to wonder. Fifteen minutes after he had entered the room he heard a key rattle in the lock on the opposite door. Evidently the lock was quite rusted, for it took a few minutes for the other to unlock it, but at length the task was completed, and the door opened.

Two men entered the room, and at sight of them Don felt a shock of recognition. One of them was the stocky individual who had offered to buy their boat the day before, and the other was the smaller man who had been called Frank. Both of them were smoking cigars and seemed pleased with something.

“How do you do, young man?” nodded the older of the two.

“What is the idea of locking me in here?” Don demanded.

The man called Frank laughed and turned to the other. “He’s a very inquiring sort of a kid, isn’t he, Benito?”

“I certainly am,” retorted Don. “I’d like to know what you mean by locking me in here.”

“Well, to tell you the truth,” answered Benito, “we don’t know ourselves yet. We saw you anchor last night and we just waited for you to walk into our trap. We haven’t decided what we’re going to make out of it yet.”

“I see,” nodded the boy. “But you’re sure you are going to make something out of it, aren’t you?”

“To be sure. Frank, be kind enough to hand me the boy’s wallet.”

Don eyed Frank and clenched his fist. “He’s liable to see a whole collection of stars before he sees that wallet,” he said, determinedly. Frank hesitated and looked at the other man.

Benito’s manner changed instantly from the friendly to the business-like, and he frowned in an ugly manner. “Look here, kid, none of that. You hand over your wallet or we’ll just put you to sleep and take it. Don’t think we let you walk in here for nothing. Come on now, hurry up.”

Boiling with anger, Don handed over his wallet. He realized that resistance, under the circumstances, was absolutely useless. Benito took the wallet and glanced through its contents.

“Hum,” he commented. “Fifty dollars in cash and your name is Mercer. Is your father the lumber man?”

“Yes, he is, and he will make things hot for you, if you don’t let me out of here,” Don promised.

Frank raised his eyebrows and looked significantly at Benito. “That means big money, Boss.”

Don laughed outright. “I think you’ll have to go a long way to make any big money on it,” he said.

But Benito shook his head easily. “Oh, no, we won’t. Your father will be willing to pay a heavy price for your safe return, my boy. So we’ll just keep you here until he does come across with a neat little day’s pay. All you have to do is write a letter to your father, telling him where you are, or about where you are, and asking him for a sum I will name for you. That will be your end of the game.”

Don grinned. “That’s all I have to do, huh?”

“Yes, that’s all.”

“Well, that’s just twice as much as I intend to do. I won’t write a line for you, and you can do what you like about it.”

Benito jerked the cigar from his lips. “You’ll do just as we tell you!”

“I’ll not write one single line,” Don came back, steadily.

They glared at each other for a moment, Benito inwardly raging, Don angry but perfectly calm. Then Benito smiled evilly.

“So that’s the way you feel about it, is it? Well, I don’t think you’ll feel just that way after you haven’t eaten for a few days. You’ll change your tune by that time.”

Don’s thoughts flew to Jim and Terry aboard the sloop, but as though the man could read his thought he said: “You needn’t think your friends on the boat can help you any. We’re going out there as soon as it gets dark and take that little ship for our own. Then we’ll put those two boys in here with you, for company.”

“You wouldn’t dare touch that boat!” Don gasped.

“No? You just watch and see. Come along, Frank. This young man wants to be alone to think, I can see that. Pretty soon he’ll want something to eat, too, but he won’t get it. Maybe then he’ll be able to listen to reason.”

Don smiled coolly. “They say the emptier your stomach is, the clearer you can think. I think you are both a fine pair of scoundrels now, so I don’t know what I’ll think you are when I get hungry!”

“Be careful of that tongue of yours, young man!” snapped Benito.

“As long as I won’t be able to use it for eating, I’ve got to use it for something,” Don retorted.

“The healthiest thing for you to do would be to keep it quiet,” the man warned as they left the room, taking Don’s wallet with them.

“Well, here’s a pretty mess!” thought Don, as soon as he was left alone. “I’m not a bit afraid as far as my own safety goes, but I don’t want those fellows to get hold of the Lassie. I’ve got to get out of here.”

He now went to work in deadly earnest to seek a difficult job’s solution. A few minutes’ work on the two doors with his pocket knife showed him that all hope in that direction was at an end. Then he once more examined the boarded windows, to find that it would take him hours to remove one board. That would do only as a last resort. From the windows he walked around the darkened room, examining walls and floor.

Near one of the windows he found a straight, pointed iron rod which was screwed to the wall. He decided that it had formerly held a bird cage, and as it was loosely held in place he soon pulled it out. It would act as a lever or some kind of a tool, and he decided to keep it to use. If he found that he was to be kept a prisoner for a long time this weapon might come in handy as a lever for prying loose the window boards. Meanwhile, he continued to roam around.

The men and the old woman had an appetizing meal in the next room, for he could still smell the bacon, and he heard them sit down and talk. He decided that he was to be kept next to the kitchen purposely, so that each meal might undermine his resolution as some particular smell of cooking food assailed him.

“They’ll never get me to write a letter to Dad,” he told himself, doggedly.

He was beginning to feel hungry, for he had a healthy appetite, but he pulled his belt tighter and resolved to fight it out. He began to examine the floor more carefully, knowing that darkness would necessarily limit his range of effort. Inch by inch he went over the rough boards, and at the far end of the room he made a discovery.

A stove had stood in a corner at some time and under it a section of the floor had been cut away, probably to allow the ashes to drop into the cellar of the old house. The boards had been replaced later, but he could see just where they joined to the rest of the floor, and there was space enough to insert his improvised lever under the end of the first board. Carefully he pried the first board loose and took it out.

To his surprise he found that he could put his arm through the hole and feel only the cold, damp air of the cellar beneath. A second board was soon taken out, and the opening was much bigger, though not large enough to admit his whole body. He went to work rapidly on the third board.

This was not nearly so easy. While he was working he could hear the old woman moving around the kitchen, washing dishes and humming to herself in a high, cracked tone. The men had gone to another part of the house and all, with the exception of the woman in the kitchen, was silent. Once he heard her approach his door and listen, and he became very quiet, scarcely daring to breathe. But she went away again and he continued his work.

At last the third board came up and the hole was large enough to permit him to go through. He lay on his stomach, peering down into the dark void, sickened by the rank, foul odor which rose in force to his nose. But he was unable to make out a thing in the dark hole, as he had not brought any matches with him from the sloop.

“Nothing to do but take a chance at it,” he decided. “Anything is better than staying here.”

He lowered himself over the hole, dropping his legs down slowly, until his body hung over the black pit. Down and down he went, until he hung by his finger tips. He had hoped to feel something beneath his feet, but there was nothing, so, with a prayer for his safety, he let go, and shot down into the inky blackness of the mysterious cellar.

After Don left the sloop Jim busied himself in straightening up the little ship, talking to Terry as the latter wrote his letter home. When the sloop was in first class order Jim sat idly in the cockpit, watching the ocean and the shore alternately. After a time, wearying of doing nothing, he got out a book on navigation, and began to study it.

In this manner an hour went by, and it was Terry who called his attention to the fact that Don had been gone a long time. Jim put the book down and looked toward the shore.

“That’s so, he has,” he replied. “He should be back by now. From the looks of things, that house isn’t ten minutes’ walk from the shore.”

They waited around for another hour, and at the end of that time they were really worried. Jim was for going ashore at once, but Terry proved to have better sense.

“I wouldn’t do it,” he urged. “It may be that someone has captured Don and is just waiting to have one of us walk right into their trap. But if Don doesn’t come back by nightfall we’ll have to do something, that’s sure.”

“If Don doesn’t show up by nightfall we’ll swim ashore and hunt him up ourselves,” Jim decided.

“Sure. It isn’t a pleasant outlook in any way, because, beside having to swim ashore, we’ll be forced to find our way around that island in the dark. What in the world do you suppose could have happened to him?”

“I haven’t any idea, but I keep thinking of that man with the lantern. There isn’t any doubt that something has happened to him, or he would at least let us know somehow that he was all right. I hate to sit here and wait.”

Waiting, Jim found, was the hardest part of all. They spent a miserable afternoon just sitting there, eagerly watching the dinghy on the shore. But no one came to move it and it lay there on its side. Both of the boys had the sensation of being watched.

“I just feel it,” Jim said, as they discussed it. “I’ll bet you someone is hiding there in that dense undergrowth, just watching us. After all, I think it would be useless to go ashore at this point. As soon as it gets dark we’ll pull up anchor, drop down the shore a way, and I’ll go ashore.”

“I’m going with you,” declared Terry, promptly.

But Jim shook his head firmly. “Nothing doing, Terry. Somebody has got to guard the Lassie. What would happen to us if the ship was taken? If the worst comes to the worst you’ll have to sail to the main shore and get help. I mean if I should fail to show up.”

“I don’t know how to sail it alone,” Terry objected.

Jim leaped to his feet. “Then I’ll show you right now. We’ve got to prepare for an emergency. There isn’t much to learn.”

For the next half hour Jim showed Terry how to start the engine, and how to control it from the tiller. When he had finished a slight dusk was beginning to steal over the water, and the boys impatiently awaited the time for action. Both of them went through the motions of eating, though neither was at all hungry. Slowly, almost painfully, the darkness crept over the sea.

When it had grown so dark that they could not see the shore Jim went into action. “We’ll have to hoist the sail and move down the shore,” he said, walking forward. “And we’ve got to be careful about it, too. The night is pretty still, and they’ll hear the creaking of the blocks on shore if we don’t take care. First, I’ll lash down the tiller.”

This having been accomplished, Jim instructed Terry in the method of hauling the mainsail up. On opposite sides of the mast they pulled the halyards, until the sail, still with the two reefs in it, was spread against the black sky. When the jib had been placed in position Jim took the tiller, and under a gentle breeze the Lassie began to sail quietly down the coast.

In fifteen minutes Jim was satisfied, and he and Terry quickly lowered the sails and trimmed them, lashing them fast to the boom. Then Jim went below and changed into an old shirt and a pair of trousers, reappearing on deck a few minutes later. Although they could not see the shore, they knew that it lay off their bow.

“If I don’t show up by noontime tomorrow,” Jim said, as he dangled his feet over the stern, “don’t wait around any longer. Sail across to the mainland and get help. You may find it a bit hard to sail the sloop alone, but it can be done. Simply give any other boat a wide berth and you won’t run into ’em. Keep your eyes open all night, either for my return or for some enemy. I hate to go away and leave you alone all night.”

Terry grasped his hand. “I hate to think of you wandering around all night alone on the island. Good luck, kid.”

“Thanks. See you later.”

Noiselessly, Jim slid over the side and into the water, disappearing from Terry’s view as he sank under the waves. In a second he reappeared and struck out vigorously for the shore. Both Terry and the boat were lost to his view as he forged his way through the water that was as black as the sky.

It was not long before Jim struck bottom, and he stood upon his feet. The island was just ahead of him, and he pushed his way steadily through the water, his upward progress steady, until he stood upon the shore of the dark island. Then, after pausing to listen for a time, he walked up the sand and entered the woods.

He was at a complete loss as to which way to turn, but judging that the house lay north, he walked in that direction. His clothing was dripping wet, but as the night was hot, he did not mind it. He found that he was at the bottom of a hill, and at first decided not to climb it, but realizing that he could see any light on the island from a hilltop, he resolved to go on. So he pushed his way forward through the undergrowth, feeling his way with infinite care, and at length stood on the top of the hill.

As soon as he had looked around with care, he was glad that he had come. For, although he could not make out the details of the island, he could see below him, distant by a half mile, the light from a house. It was indistinct, but he knew that it was flooding out of a window on a ground floor room.

“That’s the place,” Jim decided, and hastened down the other side of the hill, guiding himself by the light as it came to him through the trees. When he reached the ground level, however, he could not see it any more, and he was compelled to trust to a general sense of direction. But he had fixed it firmly in his mind, and in less than an hour’s painful toil through the black woods he arrived at last at the front of the house.

Somewhere inside Don must be, perhaps a prisoner, perhaps even hurt. The light still shone from the single window, which was a front one just off the main section of the house, in a wing, and there were no shutters or shades over it. The long, rambling porch ran under it.

Stealing silently over the rank grass that choked the front yard of the house Jim cautiously approached the beam of light. He had hoped to stand on the ground and look in, preferring to trust the firm earth rather than the boards of the porch, but he found that in order to see in at all he would be compelled to mount the rickety steps. So he went to the short flight, stepping quietly up them, and tiptoed across the rotting porch. Coming to the window, he carefully thrust his head forward and looked into the room.

Benito and Frank were seated in the room, before an open fireplace, in which a wood fire snapped and smoked. The house was wet and cold, and the men had made the fire earlier in the evening. Benito was smoking, and the smaller man was chewing on a piece of straw, staring into the fire. A corner of the window glass had been broken and Jim could hear perfectly everything that was said.

Frank was speaking when Jim, after having looked around the room for a trace of Don, turned his full attention to the men. Scarcely daring to breathe, Jim listened breathlessly.

“Marcy says the boys moved the boat about a half mile down the shore,” the little man was saying.

Benito nodded, blowing a ring of smoke toward the ceiling. “They must have suspected that we’d be out after them before long. They won’t dare to go away from the island while we have the brother, and they will be on the lookout. Soon as Marcy comes back we’ll go after the other two.”

Jim felt his blood chill as the facts of the case came to him. The men had Don and were coming to take Terry and himself prisoner. They even knew where the Lassie was anchored. For the moment he was at his wit’s end, unable to decide whether to go back and warn Terry to sail away, or stay and try to save Don. He was trying to figure out just what their object was when Frank unconsciously helped him.

“You figure it’ll be worth while to take in all three of them?” he asked.

Benito nodded. “I don’t know a thing about that third fellow,” he admitted. “But I do know that Mr. Mercer will pay plenty to get his boys back home. Meanwhile we’ll grab the sloop, give it a new coat of paint, and realize a pretty little penny from it. By the time the new owner finds out how we got it, we’ll be out of the country and safe.”

Jim’s eyes flashed fire, he clenched his teeth, and for a moment he had the impulse to smash his way through the window and hurl himself upon the two men. Realizing how rash and foolish such a move would be he controlled himself and waited, still uncertain as to what to do. He was tormented by the thought that he must decide wisely, for the wrong move might ruin everything. He wondered if Don was safe, and he was overjoyed to hear Frank’s next remark.

“We’ve got the older Mercer boy safe enough. Like enough he’ll soon get hungry and write that note to his father.”

“Oh, of course. It’s merely a matter of time. I judge that the boy is used to eating regularly and plenty, and I don’t think he’ll hold out long.”

“How are we going to get the other two?” Frank asked.

Benito looked at his watch. “Just as soon as Marcy gets back we’ll take the power boat and go out after them. We’ll muffle the oars and sneak up on ’em. I suppose they’ll be awake but it won’t take us long to overcome them. We’ll tow their sloop up the creek and take good care of it.”

Jim was beginning to wonder uneasily where Marcy might be, but Frank’s next remark reassured him. “Marcy’s taking a look in on young Mercer, ain’t he?”

“Yep. Just seeing if he is fixed for the night. The boy’s been very quiet, and I was just wondering——”

At that moment rapid footsteps sounded in a hall outside of the room in which Benito and Frank sat, causing the two men to look in alarm at each other. Jim strained forward to see what was to happen next.

A door opened hurriedly, and a rough-looking man with a week’s growth of beard burst into the room. Benito sprang to his feet.

“What is it, Marcy?” he snapped.

“That kid is gone!” the man gasped. “Pulled up some boards out of the floor and dropped into the cellar. We got to get him, or he’ll find the——”

“Never mind,” shouted Benito. “You go down the hole after him. Frank and I will look around the grounds. That kid must not get away. What’s that?”

“That” was an accident of serious nature. Jim had forgotten the porch he had been standing on, and he had pressed too near the house. The boards at that point were rotten, and with a crash that sounded like the explosion of a cannon they went through.

At the sound caused by Jim’s fall through the rotted boards the three men paused for an instant in stunned surprise. But it was only a brief second. Suspecting that some enemy had been spying on them the men made haste to pursue.

Marcy, upon the repeated demand of Benito, went back down the hall to capture Don, but the chief and Frank rushed to the window. Jim’s right leg had plunged into the hole as far as his knee, and he was at first frantic, believing that he could not get out in time, but realizing that losing his head would not help him, he calmed himself and pulled more easily. His leg came out of the hole just as Benito and Frank sighted him from the window.

“It’s one of those kids!” shouted Benito. “Get him!”

The door was several yards from the window and to that circumstance Jim owed the start that he got. He sprinted across the shaking porch and jumped to the ground just as the two men opened the door back of him. They gave chase, running swiftly, but Jim had just enough of a start to enable him to outdistance them. But as the country around the old house was new to him, and he believed that the men knew it perfectly, he thought that it would only be a matter of minutes before they took him captive.

It was useless to keep on running. Benito was too heavy to run well, but with Frank it was a different story. The little man was fast, and Jim could hear him gaining inch by inch, beating through the undergrowth like some evil bloodhound. The boy determined to find some spot and hide, trusting to luck to keep from being found, and as he ran, he kept his eyes open for some shelter.

It was almost useless in such darkness, but at last, after ducking back and forth and doubling on his tracks several times he saw before him a dense tangle which had been created by two trees falling together, forming an arch over which a screen of vines had grown. Close in under one of the trunks he ran, worming his body in under the mass of vines. Then, smothering his heavy breathing as best as he could, he waited to see what would happen.

Frank had been several yards back of him, crashing his way recklessly through the bushes, but now the noise stopped abruptly. Either the little man knew where he was hiding, or he was at a total loss. Jim’s groping hand encountered a fairly hard stick of wood and he grasped it firmly. If they found him, he could at least put up a fight, he decided. A sudden dash, while plying vigorously about him with the stick, might earn his liberty for him. Determined on this point, he waited tensely.

But a moment later it was evident that Frank was lost. Benito joined him and the little man growled profanely.

“He ain’t far off,” Frank said. “All of a sudden I heard him quit running. He’s hiding right around here in the bushes, I tell you.”

“Then we’ll root him out,” answered Benito. “I wish we’d brought a flashlight, but it’s too late now.”

They began to beat around in the thicket, and Jim was in an agony of suspense as they approached his hiding place. Once they saw it he was lost, for they would surely investigate so promising a place. But they had halted just far enough away to keep them from reaching his place of concealment, and after a half-hour’s search they gave it up.

“It’s no use,” decided the leader. “He got away somewhere, but he won’t get off of the island. Now, we’d better not waste any more time fooling. We’ve got to get under way and capture that other kid out on the boat.”

“Going out after him now, eh?”

“Oh, sure! They wouldn’t have left that boat unguarded, and I guess that one boy is on board. We’ve got to go out there and take the boat away from him. We had better get started before this other kid swims out there and warns him.”

With that they moved away, leaving Jim with a relieved mind, but with another problem confronting him. He knew that he must get back and warn Terry of the coming danger; in fact, if he could get back before the men got out to the boat he and the red-headed boy could sail out to sea. The question now was to find his way back to the house, from there to the hill, and then swim back to the boat. Carefully, he worked his way free of the vines and stood out in the woods, looking for his path.