Title: The Young Train Dispatcher

Author: Burton Egbert Stevenson

Illustrator: A. P. Button

Release date: September 25, 2017 [eBook #55624]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

THE YOUNG TRAIN DISPATCHER

The Works of

Burton E. Stevenson

The Boys’ Story of the Railroad Series

| The Young Section-Hand | $1.75 |

| The Young Train Dispatcher | 1.75 |

| The Young Train Master | 1.75 |

| The Young Apprentice | 1.75 |

Other Works

| The Spell of Holland | $3.75 |

| The Quest for the Rose of Sharon | 1.65 |

THE PAGE COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

|

||

|

The Boys’ Story of the Railroad Series THE

|

|

|

||

Copyright, 1907

By The Page Company

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

All rights reserved

Made in U. S. A.

PRINTED BY C. H. SIMONDS COMPANY

BOSTON, MASS., U.S.A.

[Translation of Morse Code: in appreciation of their assistance and kindly interest]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The New Position | 1 |

| II. | A Rescue | 12 |

| III. | A New Friend | 22 |

| IV. | The Young Operators | 33 |

| V. | "Flag Number Two!" | 43 |

| VI. | A Private Line | 54 |

| VII. | The Call to Duty | 67 |

| VIII. | An Old Enemy | 88 |

| IX. | An Unwelcome Guest | 98 |

| X. | A Professional Friendship | 107 |

| XI. | The President’s Special | 116 |

| XII. | Placing the Blame | 127 |

| XIII. | Probing the Mystery | 138 |

| XIV. | To the Rescue | 150 |

| XV. | Light in Dark Places | 160 |

| XVI. | All’s Well That Ends Well | 171 |

| XVII. | Allan Entertains a Visitor | 185 |

| XVIII. | Facing the Lion | 200 |

| XIX. | The First Lesson | 211 |

| XX. | What Delayed Extra West | 221 |

| XXI. | A Call for Aid | 237 |

| XXII. | The Treasure Chest | 248 |

| XXIII. | "Hands Up!" | 260 |

| XXIV. | Jed Hopkins, Phœnix | 270 |

| XXV. | How the Plot Was Laid | 281 |

| XXVI.« viii » | The Pursuit | 292 |

| XXVII. | A Gruesome Find | 303 |

| XXVIII. | Jed Starts for Home | 313 |

| XXIX. | The Young Train Dispatcher | 326 |

| PAGE |

|

“Hurled itself on across the waiting-room and through the outer door to safety” (See page 271) |

Frontispiece |

“‘Look out!’ he cried, and seizing him by the arm, dragged him sharply backwards” |

21 |

“Snatched up the fusee, and fairly hurled himself down the track” |

56 |

“In the next instant, the tall figure had been flung violently into the room” |

153 |

“The afternoon passed happily” |

200 |

“‘It b’longs t’ th’ mine company,’ said Nolan” |

291 |

THE

YOUNG TRAIN DISPATCHER

THE NEW POSITION

Stretching from the Atlantic seaboard on the east to the Mississippi River on the west, lies the great P. & O. Railroad, comprising, all told, some four thousand miles of track. Look at it on the map and you will see how it twists and turns and sends off numberless little branches; for a railroad is like a river and always seeks the easiest path—the path, that is, where the grades are least and the passes in the mountains lowest.

Once upon a time, a Czar of Russia, asked by his ministers to indicate the route for a railroad from St. Petersburg to Moscow, placed a ruler on the map before him and drew a straight line between those cities, a line which his engineers were forced to follow; but that is the only road in the world constructed in so wasteful a fashion.

That portion of the P. & O. system which lies within the boundaries of the Buckeye State is known as the Ohio division, and the headquarters are at the little town of Wadsworth, which happens, by a fortunate chance of geographical position, to be almost exactly midway between the ends of the division. A hundred miles to the east is Parkersburg, where the road enters the State; a hundred miles to the southwest is Cincinnati, where it gathers itself for its flight across the prairies of Southern Indiana and Illinois; and it is from this central point that all trains are dispatched and all orders for the division issued.

Here, also, are the great division shops, where a thousand men work night and day to repair the damage caused by ever-recurring accidents and to make good the constant deterioration of cars and engines through ordinary wear and tear. It is here that the pay-roll for the division is made out; hither all complaints and inquiries are sent; and here all reports of business are prepared.

In a word, this is the brain. The miles and miles of track stretching east and west and south, branching here and there to tap some near-by territory, are merely so many tentacles, useful only for conveying food, in the shape of passengers and freight, to the great, insatiable maw. In fact, the system resembles nothing so much as a gigantic cuttle-fish. The resemblance is more than superficial, for, like the cuttle-fish, it possesses the faculty of "darting « 3 » rapidly backward" when attacked, and is prone to eject great quantities of a “black, ink-like fluid,”—which is, indeed, ink itself—to confuse and baffle its pursuers.

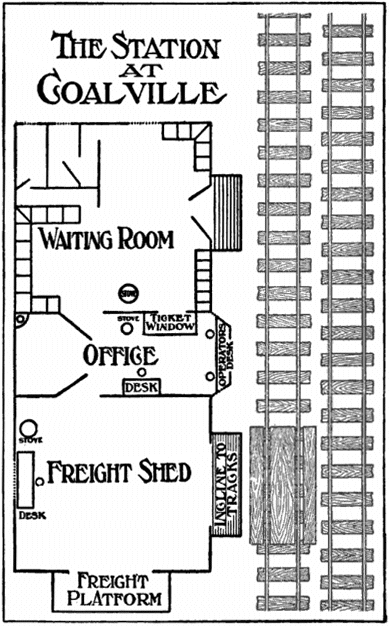

The headquarters offices are on the second floor of a dingy, rectangular building, the lower floor of which serves as the station for the town. It is surrounded by broad cement walks, always gritty and black with cinders, and the atmosphere about it reeks with the fumes of gas and sulphur from the constantly passing engines. The air is full of soot, which settles gently and continually upon the passers-by; and there is a never-ceasing din of engines “popping off,” of whistles, bells, and the rumble and crash of cars as the fussy yard engines shunt them back and forth over the switches and kick them into this siding and that as the trains are made up. It is not a locality where any one, fond of quiet and cleanliness and pure air, would choose to linger, and yet, in all the town of Wadsworth, there is no busier place.

First of all, there are the passengers for the various trains, who, having no choice in the matter, hurry in and hurry out, or sit uncomfortably in the dingy waiting-rooms, growing gradually dingy themselves, and glancing at each other furtively, as though fearing to discern or to disclose a smut. Then, strange as it may seem, there are always a number of hangers-on about the place—idlers for whom the railroad seems to possess a curious and « 4 » irresistible fascination, who spend hour after hour lounging on the platform, watching the trains arrive and depart—a phenomenon observable not at Wadsworth only, but throughout this broad land at every city, town, or hamlet through which a railroad passes.

Across one end of the building is the baggage-room, and at the other is the depot restaurant, dingy as the rest notwithstanding the valiant and unceasing efforts made to keep it clean. The sandwiches and pies and pallid cakes are protected from the contamination of the atmosphere by glass covers which are polished until they shine again; the counter, running the whole length of the room, is eroded by much scrubbing as stones sometimes are, and preserves a semblance of whiteness even amid these surroundings. Behind it against the wall stand bottles of olives, pickles, and various relishes and condiments, which have been there for years and years, and will be there always—for who has time for food of that sort at a railway restaurant? Indeed, it would seem that they must have been purchased, in the first place, for ornament rather than for use.

At one end of the counter is a glass case containing a few boxes of stogies and cheap cigars, and at intervals along its length rise polished nickel standards bearing fans at the top, which are set in motion by a mechanism wound up every morning like a clock; but the motion is so slow, the fans revolve « 5 » with such calm and passionless deliberation, that they rather add to the drowsy atmosphere of the place, and the flies alight upon them and rub the jam from their whiskers and the molasses from their legs, and then go quietly to sleep without a thought of danger.

How often has this present writer sat before that counter in admiring contemplation of the presiding genius of the place as he sliced up a boiled ham for sandwiches. He was a master of the art; those slices were of more than paper thinness. It was his peculiar glory and distinction to be able to get more sandwiches out of a ham than any other mere mortal had ever been able to do, and he was proud of it as was Napoleon of the campaign of Austerlitz.

The greater part of the custom of the depot restaurant was derived from “transients;” from passengers, that is, who, unable to afford the extravagance of the diner, are compelled to bolt their food in the five minutes during which their train changes engines, and driven by necessity, must eat here or nowhere. And they usually got a meal of surprising goodness; so good, in fact, that there were and still are many men who willingly plough their way daily through smoke and cinders, and sit on the high, uncomfortable stools before the counter, in order to enjoy regularly the entertainment which the restaurant offers—a striking instance of the triumph of mind over environment.

These, then, are the activities which mark the lower floor of the building; those of the upper floor are much more varied and interesting, for it is there, as has been said, that the division offices are located. A constant stream of men pours up and down the long, steep flight of stairs which leads to them. Conductors and engineers must report there and register before they take out a train and as soon as they bring one in; trainmen of all grades climb the stair to see what orders have been posted on the bulletin-board and to compare their watches with the big, electrically adjusted clock which keeps the official time for the division.

Others ascend unwillingly, with downcast countenances, summoned for a session “on the carpet,” when trainmaster or superintendent is probing some accident, disobedience of orders, or dereliction of duty. Still others, in search of employment, are constantly seeking the same officials, standing nervously before them, cap in hand, and relating, more or less truthfully, the story of their last job and why they left it;—so that the procession up and down the stair never ceases.

The upper floor is not quite so dingy as the lower. It is newer, for one thing, its paint and varnish are fresher, and it is kept cleaner. But it is entirely inadequate to the needs of the business which is done there; for here are the offices of the division engineer, the division passenger and freight agents, the timekeeper, the division superintendent, the « 7 » trainmaster—and dominating them all, the dispatchers’ office, whence come the orders which govern the movements of every train. Near by is a lounging-room for trainmen, where they can loiter and swap yarns, while waiting to be called for duty. It is a popular place, because if one only talks loud enough one can be overheard in the dispatchers’ office across the hall.

So the men gather there and express their opinions of the dispatchers at the top of the voice—opinions, which, however they may differ in minor details, are always the reverse of complimentary. For the dispatchers are the drivers; they crack the whip over the heads of the trainmen by means of terse and peremptory telegraphic orders, which there is no answering, and which no one dares disobey; and the driver, however well-meaning, is seldom popular with the driven.

Such is the station and division headquarters at Wadsworth: unworthy alike as the one and the other. The whole effect of the building is of an indescribable, sordid dinginess; it is a striking example of that type of railroad economy which forbids the expenditure of money for the comfort and convenience of its patrons and employees—a type which, happily, is fast passing away.

On a certain bright spring morning—bright, that is, until one passed beneath the cloud of smoke which hung perpetually above the yards at Wadsworth—a « 8 » boy of about eighteen joined the procession which was toiling up the stair to the division offices, and, after hesitating an instant at the foot, as though to nerve himself for an ordeal which he dreaded, mounted resolutely step after step. As he pushed open the swinging-door at the top, the clamour of half a dozen telegraph instruments greeted his ears. He glanced through the open window of the dispatchers’ office as he passed it, pushed his way through a group of men gathered before the bulletin-board, and, after an instant’s hesitation, turned into an open doorway just beyond.

There were two men in the room, seated on either side of a great desk which stood between the windows looking down over the yards. They glanced up at the sound of his step, and one of them sprang to his feet with a quick exclamation of welcome.

“Why, how are you, Allan!” he cried, holding out his hand. “I’m mighty glad to see you. So you’re ready to report for duty, are you?”

“Yes, sir,” answered the boy, smiling into the genial gray eyes, and returning the warm handclasp, “I’m all right again.”

“You’re a little pale yet, and a little thin,” said the trainmaster, looking him over critically; “but that won’t last long. George,” he added, turning to his companion, “this is Allan West, who saved the pay-car from that gang of wreckers last Christmas Eve.”

“Is it?” and the chief-dispatcher held out his hand and shook the boy’s heartily. “I’m glad to know you. Mr. Schofield has told us the story of that night until we know it by heart. All the boys will be glad to meet you.”

The boy blushed with pleasure.

“Thank you,” he said.

“Allan’s to take a job here as office-boy,” added Mr. Schofield. “When will you be ready to go to work?”

“Right away, sir.”

“That’s good. I was hoping you’d say that, for there’s a lot of work piled up. The other boy was promoted just the other day, and I’ve been holding the place open. That will be your desk there in the corner, and your principal business for the present will be to see that each official here gets promptly the correspondence addressed to him. That basketful of letters yonder has to be sorted out and delivered. In this tray on my desk I put the messages I want delivered at once. Understand?”

“Yes, sir,” answered Allan, and immediately took possession of the pack of envelopes lying in the tray.

He sat down at his desk, with a little glow of pride that it was really his, and sorted the letters. Three were addressed to the master mechanic, three to the company’s freight agent, two to the yardmaster, and five or six more to other officials. As « 10 » soon as he got them sorted, he put on his hat and started to deliver them.

The trainmaster watched him as he left the office, and then smiled across at the chief-dispatcher.

“Bright boy that,” he commented. “Did you notice—he didn’t ask a single question; just went ahead and did as he was told—and he didn’t have to be told twice, either.”

The chief dispatcher nodded.

“Yes,” he said; “he’ll be a valuable boy to have about.”

“He’s already proved his value to this road,” added Mr. Schofield, and turned back to his work.

No one familiar with Allan West’s history will dispute the justice of the remark. It was just a year before that the boy had secured a place on the road as section-hand—a year fraught with adventure, which had culminated in his saving the pay-car, carrying the men’s Christmas money, from falling into the hands of a gang of desperate wreckers. The lives of a dozen men would have been sacrificed had the attempt succeeded. That it did not succeed was due to the ready wit with which the boy had managed to defeat the plan laid by the wreckers, and to the sheer grit which had carried him through a situation of appalling danger. He had barely escaped with his life; he had spent slow weeks recovering from the all-but-fatal bullet-wound he had received there. It was during this period of convalescence, spent at the little cottage « 11 » of Jack Welsh, the foreman under whom he had worked on section, that the trainmaster had come to him with the offer of a position in his office—a position not important in itself, but opening the way to promotion, whenever that promotion should be deserved. Allan had accepted the offer joyfully—how joyfully those who have read the story of his adventures in “The Young Section-Hand” will remember—and at last he was ready to begin his new duties, where yet other adventures awaited him.

A RESCUE

With the packet of envelopes in his hand, Allan descended the stair and came out upon the grimy platform. Just across the yards lay the low, dark, brick building which was the freight office, and he made his way toward it over the tangle of tracks and switches, where the freight-trains were being “made up” to be sent east or west. After some inquiry, he found the freight agent gazing ruefully at a barrel of oil which had just been smashed to pieces by a too vigorous freight-handler. Allan gave him the letters addressed to him and hurried away to deliver the others.

Farther down the yards was the office of the yardmaster, a little, square, frame building, standing like an island amid the ocean of tracks which surrounded it. Here was kept the record of every car which entered or left the yards—the road it belonged to, its number, whence it came, whither it went, by what train, at what hour. This dingy little building was one link in that great chain of offices which enables every road in the country to keep track of the cars it is using, to know where « 13 » they are, what progress they are making, and what service they are performing.

Every one who has seen a freight-train has noticed that it is almost always composed of cars belonging to many different roads, and must have wondered how these cars were kept accounted for. Every road would prefer to use only its own cars, and to keep them on its own system, but this is impossible. A car of sugar, for instance, sent from New York to Denver, must pass over at least two different lines. It can go from New York to Chicago over the New York Central, and from Chicago to Denver over the Santa Fé. Now, if the car belonging to the New York Central in which the sugar was loaded at New York be stopped at Chicago, the sugar must be reloaded into another car belonging to the Santa Fé, a long and expensive process to which neither the shipper nor the road would agree.

To avoid this loading and unloading, freight in car-load lots is always sent through to its destination without change, no matter how many roads the car must traverse, and when it reaches its destination and is emptied, it is usually held until it can be loaded again before it is sent back whence it came. When the traffic is not evenly balanced,—when there is more freight, that is, being sent one way than another,—the “empties” must be hauled back, and as “empties” produce no revenue, this is a dead expense which cuts deeply into the « 14 » earnings. The roads which use a car must pay the road which owns it a fee of fifty cents for every day they keep it in their possession, whether loaded or empty; hence the road holding it tries to keep it moving, and when business is slack and it is not needed, gets it back to its owner as quickly as possible. If it is damaged in an accident on a strange road, it must be repaired before it is returned to its owner; if it is totally destroyed, it must be paid for.

It is the duty of the conductor of every freight-train, as soon as he reaches a terminal, to mail to the superintendent of car service at headquarters, a report giving the initial and number of every car in his train, its contents, destination, and the hour of its departure from one terminal and arrival at another. These reports, as they come in from day to day, are entered in ledgers and enable the superintendent of car service to note the progress of every car, and to determine the per diem due its owner. These accounts are balanced every month.

The books at headquarters are always, of necessity, at least three days behind, since the conductors’ reports must come in from distant parts of the road; but reports so old as that are of small service in tracing a car, so it is the duty of the employees of the yardmaster’s office to keep a daily record of the movement of cars, which shall be up-to-date and instantly available. Every train which enters « 15 » the yards is met by a yard-clerk, book in hand, who makes a note of the number and name of every car as it passes him. The men who do this gain an amazing facility, and as the cars rush past, jot down numbers and initials as unconcernedly as though they had all the time in the world at their disposal. Allan had observed this more than once, and had often wondered how it was possible for a man to write down accurately the number of a car which had flashed past so rapidly that he himself was not able to distinguish it.

There was a train coming in at the moment, and Allan paused to watch the accountant with his note-book; then he went on to the office to leave the two letters addressed to John Marney, the yardmaster, a genial Irishman with bronzed face and beard tinged with gray, who knew the yards and the intricacies of “making up” better than most people know the alphabet. Allan knew him well, for many an evening had he spent in the little shanty, where conductors and brakemen assembled, listening to tales of the road—tales grave and gay, of comedy and tragedy—yes, even of ghosts! If I stopped to tell a tenth of them, this book would never be. finished!

“How are ye, Allan?” the yardmaster greeted him, as he opened the door. “So ye’ve got a new job?”

“Yes, sir; official mail-carrier,” and he handed him the letters.

“Hum,” grunted Marney; “this road never was over-liberal. You’re beginnin’ at th’ bottom, fer sure!”

“Just where I ought to begin! I’ve got to learn the ropes before I can begin to climb.”

“Well, it won’t take ye long, my boy; I know that,” said Marney, his eyes twinkling. “You’ll soon begin t’ climb, all right; they can’t kape ye down!”

“I fully expect to be superintendent some day,” said Allan, laughing.

“Of course ye will!” cried the other. “I don’t doubt it—not fer a minute. Yes—an’ I’ll live t’ see it! I’ll be right here where I’ve allers been; an ye mustn’t fergit old Jack Marney, me boy.”

“I won’t,” Allan promised, still laughing. “I’ll always speak to you, if I happen to think of it.”

“Let me give you one piece of advice,” went on Marney, with sudden earnestness. "You’ll be knockin around these yards more or less now, all th’ time, an’ if ye want t’ live t’ be suprintindint, you’ve got t’ kape your eyes open. Now moind this: when you’re crossin’ th’ yards, niver think of anything but gittin’ acrost; niver step on a track without lookin’ both ways t’ see if anything’s comin; an’ if anything is comin’ an’ you’re at all doubtful of bein’ able t’ git acrost ahead of it at an ordinary walk, don’t try. Give it th’ right o’ way. I’ve been workin’ in these yards goin’ on forty year, an’ I’ve managed t’ kape all my arms « 17 » an’ legs with me by allers rememberin’ that rule. Th’ boys used t’ laugh at me, but them that started in when I did are ayther sleepin’ in th’ cimitery, or limpin’ around on one leg, or eatin’ with one hand. A railroad yard is about th’ nearest approach to a human slaughter-house there is on this earth. Don’t you be one o’ th’ victims."

“I’ll certainly try not to,” Allan assured him, and went out with a livelier sense of the dangers of the yard than he had ever had before; and, indeed, the yardmaster had not overstated them, though the crushing and maiming and killing which went on there were due in no small degree to the carelessness and foolhardiness of the men, who grew familiar with danger and contemptuous of it from looking it every day in the face, and took chances which sooner or later ended in disaster.

The person Allan had next to find was the master-mechanic, whose office was a square, one-storied building behind the great shops which closed in the lower end of the yards. He knew the shops thoroughly, for he had been through them more than once under Jack Welsh’s guidance, and had spent many of his spare moments there, for there was a tremendous fascination about the intricate and mammoth machinery which filled them, almost human in its intelligence, and with which so many remarkable things were accomplished.

So on he went, past the great roundhouse where « 18 » stood the mighty engines groomed ready for the race, or being rubbed down by the grimed and sweaty hostlers after a hundred-mile run; past the little shanty with “21” in big figures on its door—headquarters of Section Twenty-One, and receptacle for hand-car and tools,—the hand-car which he had pumped along the track so many times, the tools with which his hands had grown familiar. The door of the “long-shop” lay just beyond, and he entered it, for the shortest path to the master-mechanic’s office lay through the shops; and Allan knew that he would probably find the official he was seeking somewhere among them, inspecting some piece of machinery, or overseeing some important bit of work.

The “long-shop,” so named from its peculiar shape, very long and narrow, is devoted wholly to repairing and rebuilding engines. Such small complaints as leaking valves and broken springs and castings may be repaired in the roundhouse, as the family medicine-chest avails for minor ailments; but for more serious injuries the engines must be taken to the experts in the long shop, and placed on one of the operating-tables there, and taken apart and put together and made fit for service again. When the injuries are too severe—when, in other words, it would cost more to rebuild the engine than the engine is worth—it is shoved along a rusty track back of the shop into the cemetery called the “bone-yard,” and there eventually dismantled, « 19 » knocked to pieces, and sold for “scrap.” That is the sordid fate, which, sooner or later, overtakes the proudest and swiftest empress of the rail.

In the long-shop, four or five engines are always jacked up undergoing repairs; each of them has a special gang of men attached to it, under a foreman whose sole business it is to see that that engine gets back into active service in the shortest possible time.

To the inexperienced eye, the shop was a perfect maze of machinery. Great cranes ran overhead, with chains and claws dangling; shafting whirred and belts rattled; along the walls were workbenches, variously equipped; at the farther end were a number of drills, and beyond them a great grindstone which whirred and whirred and threw out a shower of sparks incessantly, under the guidance of its presiding genius, a little, gray-haired man, whose duty it was to sharpen all the tools brought to him. There was a constant stream of men to and from the grindstone, which, in consequence, was a sort of centre for all the gossip of the shops. Once the grindstone had burst, and had carried the little man with it through the side of the shop, riding a great fragment much as Prince Feroze-shah rode his enchanted horse; and though there was no peg which he could turn to assure a safe landing, he did land safely, and next day superintended the installation of a new stone, from which the sparks were soon flying as merrily as ever.

And even if the visitor was not confused by this tangle of machinery, he was sure to be confounded by the noise, toward which every man in the shop contributed his quota. The noise!—it is difficult to give an adequate idea of that merciless and never-ceasing din. Chains clanked, drills squeaked, but over and above it all was the banging and hammering of the riveters, and, as a sort of undertone, the clangour from the boiler-shop, connected with the long-shop by an open arch. The work of the riveters never paused nor slackened, and the onlooker was struck with wonder and amazement that a human being could endure ten hours of such labour!

Allan, closing behind him the little door by which he had entered, looked around for the tall form of the master-mechanic. But that official was nowhere in sight, so the boy walked slowly on, glancing to right and left between the engines, anxious not to miss him. At last, near the farthest engine, he thought that he perceived him, and drew near. As he did so, he saw that an important operation was going forward. A boiler was being lowered to its place on its frame. A gang of men were guiding it into position, as the overhead crane slowly lowered it, manipulated by a lever in the hands of a young fellow whose eyes were glued upon the signalling hand which the foreman raised to him.

“Easy!” the foreman shouted, his voice all but inaudible in the din. “Easy!” and the boiler was lowered so slowly that its movement was scarcely perceptible.

There was a pause, a quick intaking of breath, a straining of muscles—

“Now!” yelled the foreman, and with a quick movement the young fellow threw over the lever and let the boiler drop gently, exactly in place.

The men drew a deep breath of relief, and stood erect, hands on hips, straightening the strained muscles of their backs.

There was something marvellous in the ease and certainty with which the crane had handled the great weight, responsive to the pressure of a finger, and Allan ran his eyes admiringly along the heavy chains, up to the massive and perfectly balanced arm—

Then his heart gave a sudden leap of terror. He sprang forward toward the young fellow who stood leaning against the lever.

“Look out!” he cried, and seizing him by the arm, dragged him sharply backwards.

The next instant there was a resounding crash, which echoed above the din of the shop like a cannon-shot above the rattle of musketry, and a great block smashed the standing-board beside the lever to pieces.

A NEW FRIEND

The crash was followed by an instant’s silence, as every man dropped his work and stood with strained attention to see what had happened; then the young fellow whose arm Allan still held turned toward him with a quick gesture.

“Why,” he cried, “you—you saved my life!”

“Yes,” said Allan; “I saw the block coming. It was lucky I happened to be looking at it.”

“Lucky!” echoed the other, visibly shaken by his narrow escape, and he glanced at the splintered board where he had been standing. “I should say so! Imagine what I’d have looked like about this time, if you hadn’t dragged me out of the way!”

The other men rushed up, stared, exclaimed, and began to devise explanations of how the accident had occurred. No one could tell certainly, but it was pretty generally agreed that the sudden rebound from the strain, as the boiler fell into place, had in some way loosened the block, thrown it away from its tackle, and hurled it to the floor below.

But neither Allan nor his companion paid much attention to these explanations. For the moment, « 23 » they were more interested in each other than in anything else. A sudden comradeship, born in the first glance they exchanged, had arisen between them; a mutual feeling that they would like to know each other—a prevision of friendship.

“My name is Anderson,” the boy was saying, his hand outstretched; “my first name is James—but my friends call me Jim.”

“And my name is Allan West,” responded Allan, clasping the proffered hand in a warm grip.

“Oho!” cried Jim, with a start of surprise, “so you’re Allan West! Well, I’ve always wanted to know you, but I never thought you’d introduce yourself like this!”

“Always wanted to know me?” repeated Allan in bewilderment. “How could that be?”

“Hero-worship, my boy!” explained Jim, grinning at Allan’s blush. “Do you suppose there’s a man on this road who hasn’t heard of your exploits? And to hero-worship there is now added a lively sense of gratitude, since you arrived just in time to save me from being converted into a grease-spot. But there—the rest will keep for another time. Where do you live?”

“At Jack Welsh’s house,” answered Allan; “just back of the yards yonder.”

“All right, my friend,” said Jim. “I’ll take the liberty of paying you a call before very long. I only hope you’ll be at home.”

“I surely will, if you’ll let me know when to « 24 » look for you,” answered Allan, heartily. “But I’ve got some letters here for the master-mechanic—I mustn’t waste any more time.”

“Well!” said Jim, smiling, “I don’t think you’ve been exactly wasting your time—though of course there might be a difference of opinion about that. But there he comes now,” and he nodded toward the tall figure of the master-mechanic, who had heard of the accident and was hastening to investigate it.

Allan handed him his letters, which he thrust absently into his pocket, as he listened with bent head to the foreman’s account of the mishap. Allan did not wait to hear it, but, conscious that the errand was taking longer than it should, hurried on to deliver the other letters. This was accomplished in a very few minutes, and he was soon back again at his desk in the trainmaster’s office.

He spent the next half-hour in sorting the mail which had accumulated there. The trainmaster was busy dictating letters to his stenographer, wading through the mass of correspondence before him with a rapidity born of long experience. Allan never ceased to be astonished at the vast quantity of mail which poured in and out of the office—letters upon every conceivable subject connected with the operation of the road—reports of all sorts, inquiries, complaints, requisitions—all of which had to be carefully attended to if the business of the road was to move smoothly.

There was no end to it. Every train brought a big batch of correspondence, which it was his duty to receive, delivering at the same time to the baggage-master other packets addressed to employees at various points along the road. The road took care of its own mail in this manner, without asking the aid of Uncle Sam, and so escaped a charge for postage which would have made a serious hole in the earnings.

As soon as he had received the mail, Allan would hasten up-stairs to his desk to sort it. Always about him, echoing through the office, rose the clatter of the telegraph instruments. The trainmaster had one at his elbow, the chief-dispatcher another, and in the dispatchers’ office next door three or four more were constantly chattering. It reminded Allan of nothing so much as a chorus of blackbirds.

Often Mr. Schofield would pause in the midst of dictating a letter, open his key and engage in conversation with some one out on the line. And Allan realized that, after all, the pile of letters, huge as it was, represented only a small portion of the road’s business—that by far the greater part of it was transacted by wire. And he determined to master the secrets of telegraphy at the earliest possible moment. It was plainly to be seen that that way, and that way only, lay promotion.

He was still pondering this idea when, the day’s work over, he left the office and made his way toward the little house perched high on an embankment « 26 » back of the yards, where he had lived ever since he had come to Wadsworth, a year before, in search of work. Big-hearted Jack Welsh had not only given him work, but had offered him a home—and a real home the boy found it. He had grown as dear to Mary Welsh’s heart as was her own little girl, Mamie, who had just attained the proud age of seven and was starting to school.

Allan found her now, waiting for him at the gate, and she escorted him proudly up the path and into the house.

“Well, an’ how d’ you like your new job?” Mary asked, as they sat down to supper.

“First rate,” Allan answered, and described in detail how he had spent the day.

Mary sniffed contemptuously when he had finished.

“I don’t call that sech a foine job,” she said. “Why, anybody could do that! A boy loike you deserves somethin’ better! An’ after what ye did fer th’ road, too!”

“But don’t you see,” Allan protested, “it isn’t so much the job itself, as the chance it gives me. I’m at the bottom of the ladder, it’s true, just as John Marney said; but there is a ladder, and a tall one, and if I stay at the bottom it’s my own fault.”

Jack nodded from across the table.

“Right you are,” he agreed. “And you’ll git ahead, never fear!”

“I’m going to try,” said Allan, and as soon as « 27 » supper was over, he left the house and hastened uptown to the Public Library, where he asked for a book on telegraphy. He was just leaving the building with the coveted volume under his arm, when somebody clapped him on the shoulder, and he turned to find Jim Anderson at his side.

“I say,” cried the latter, “this is luck! Where you going?”

“I was just starting for home,” said Allan.

“I’ll go with you,” said Jim, promptly wheeling into step beside him and locking arms. “That is, if you don’t mind.”

“Mind!” cried Allan. “You know I’m glad to have you.”

“All right then,” said Jim, laughing. “That’s a great load off my mind. What’s that book you’re hugging so lovingly?”

“It’s a book on telegraphy,” and Allan showed him the title.

“Going to study it?”

“Yes; it didn’t take me long to find out that to amount to anything in the offices, one has to understand what all that chatter is about.”

“Right you are,” assented Jim, “but you’ll find it mighty hard work learning it from a book. It’ll be a good deal like learning to eat without any food to practise on. Have you got an instrument?”

“No. But of course I’ll get one.”

“Look here!” cried Jim, excitedly, struck by a sudden idea; "I have it! My brother Bob has « 28 » two instruments stored away in the attic, batteries and everything. He’s the operator at Belpre now, and hasn’t any more use for them than a dog has for two tails. He’ll be glad to let us have them—glad to know that his lazy brother’s improving his spare time. Why can’t we rig up a line from your house to mine, and learn together? I’m pretty sure I can get some old wire down at the shops for almost nothing."

“That’s a great idea,” said Allan, admiringly; “if we can only carry it out. Where do you live? Is it very far?”

“Well, it’s quite a way; but I think we can manage it,” said Jim. “Suppose we look over the ground.”

“All right; only wait till I take this book home; I live just over yonder,” and a moment later they were at the gate. “Won’t you come in?”

“No, not this time; it’ll soon be dark and we’ll have to step out pretty lively.”

“I won’t be but a minute,” said Allan; and he wasn’t.

The two started up through the yards together, arm in arm. Jim’s house was, as he had said, “quite a way;” in fact, it was nearly a mile away, straight out the railroad-track. The house was a large brick, which stood very near the track, so near, indeed, that one corner had been cut away to permit the railroad to get by. The house had been built there nearly a century before by some wealthy « 29 » farmer who had never heard of a railroad, and never dreamed that his property would one day be wanted for a right of way. But the day came when the railroad’s surveyors ran their line of stakes out from the town, along the river-bank, and up to the very door of the house itself. Condemnation proceedings were begun, the railroad secured the strip of land it wanted, and tore down the corner of the house which stood upon it. Whereupon the owner had walled up the opening and rented what remained of the building to such families as had nerves strong enough to ignore the roar and rumble of the trains, passing so near that they seemed hurling themselves through the very house itself.

Allan knew it well. He had passed it many and many a time while he was working on section. Indeed, it was this old house, when he learned its history, which made him realize for the first time, how young, how very modern the railroad was. Looking at it—at its massive track, its enduring roadway carried on great fills and mighty bridges—it seemed as old, as venerable, as the rugged hills which frowned down upon the valley; it seemed that it must have been there from the dawn of time, that it was the product of a force greater than any now known to man. And yet, really, it had been in existence scarce half a century. Many men were living who had seen the first rail laid, who had welcomed the arrival of the first train, and who still recalled with mellow and tender memory « 30 » the days of the stage-coach—a mode of travel which, seen through the prism of the years, quite eclipsed this new fashion in romance, in comfort, and in good-fellowship.

This leviathan of steel and oak had grown like the beanstalk of Jack the Giant-killer—had spread and spread with incredible rapidity, until it reached, not from earth to heaven, but from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from the Lakes to the Gulf. It had brought San Francisco as near Boston as was Philadelphia in the days of the post rider. The four days’ stage journey from New York to Boston it covered in four hours. It had bound together into a concrete whole a country so vast that it equals in area the whole of Europe. And all this in little more than fifty years! Verily, there are modern labours of Hercules beside which the ancient ones seem mere child’s play!

“It’s a long stretch,” said Allan, looking back, through the gathering darkness, along the way that they had come. “It must be nearly a mile from here to the station.”

“Just about,” agreed Jim. “But I know Tom Mickey, the head lineman, pretty well, and I believe that I can get him to let us string our wire on the company’s poles. You see there’s three or four empty places on the cross-bars.”

“Oh, if we can do that,” said Allan, “it will be easy enough. Do you suppose he will let us?”

“I’m sure he will,” asserted Jim, with a good « 31 » deal more positiveness than he really felt. “I’ll see Mickey in the morning—I’ll start early so I’ll have time before the whistle blows.”

“It seems to me that you’re doing it all, and that I’m not doing anything,” said Allan. “You must let me furnish the wire, anyway.”

“We’ll see about it,” said Jim. “Won’t you come in and see my mother?” he added, a little shyly.

“It’s pretty late,” said Allan. “Do you think I’d better?”

“Yes,” Jim replied. “She—she asked me to bring you, the first chance I had.”

“What for?” asked Allan, looking at him in surprise.

“No matter,” said Jim. “Come on,” and he opened the door and led him into the house.

They crossed a hall, and beside a table in the room beyond, Allan saw a woman seated. She was bending over some sewing in her lap, but she looked up at the sound of their entrance, and as the beams of the lamp fell upon her face, Allan saw how it lighted with love and happiness. And his heart gave a sudden throb of misery, for it was with that selfsame light in her eyes that his mother had welcomed him in the old days.

“Mother,” Jim was saying, “this is Allan West.”

She rose with a little cry of pleasure, letting her « 32 » sewing fall unheeded to the floor, and held out her hands to him.

“So this is Allan West!” she said, in a voice soft and sweet and gentle. “This is the boy who saved my boy’s life!”

“It was nothing,” stammered Allan, turning crimson. “You see, I just happened to be there—”

“Nothing! I wonder if your mother would think it nothing if some one had saved you for her!”

A sudden mist came before Allan’s eyes; his lips trembled. And the woman before him, looking at him with loving, searching eyes, understood.

“Dear boy!” she said, and Allan found himself clasped close against her heart.

THE YOUNG OPERATORS

Tom Mickey, chief lineman of the Ohio division of the P. & O., was, like most other human beings, subject to fluctuations of temper; only, with Tom, the extremes were much farther apart than usual. This was due, perhaps, to his mixed ancestry, for his father, a volatile Irishman, had married a phlegmatic German woman, proprietress of a railroad boarding-house, where Mickey found a safe and comfortable haven, with no more arduous work to do than to throw out occasionally some objectionable customer—and Mickey never considered that as work, but as recreation pure and simple. It was into this haven that Tom was born; there he grew up, alternating between the chronic high spirits of his father and the chronic low ones of his mother, and being, on the whole, healthy and well-fed and contented.

He had entered the service of the road while yet a mere boy, preferring to go to work rather than to school, which was the only alternative offered him; and he soon became an expert lineman, running « 34 » up and down the poles as agile as a monkey and dancing out along the wires in a way that earned him more than one thrashing from his boss. Advancing years had tempered this foolhardiness, but had only served to accentuate the eccentric side of his character. He would be, one day, buoyant as a lark and obliging to an almost preposterous degree, and the next day, ready to snap off the head of anybody who addressed him, and barely civil to his superior officers.

These vagaries got him into hot water sometimes; and more than once he was “on the carpet” before the superintendent; but the greatest punishment ever meted out to him was a short vacation without pay. The road really could not afford to do without him, for Tom Mickey was the best lineman in the middle west. The tangle of wires which were an integral part of the system was to him an open book, to be read at a glance. Was any wire in trouble, he would mount his tricycle, a sort of miniature hand-car, spin out along the track, and in a surprisingly short time the trouble was remedied and the wire in working order. Tom was a jewel—in the rough, it is true, and not without a flaw—but a jewel just the same.

Luckily he was in one of his buoyant moods when Jim Anderson approached him on the morning following his conversation with Allan. Perhaps it is only right to say that this was not wholly luck, for Jim had reconnoitred thoroughly beforehand, « 35 » and had not ventured to approach the lineman until assured by one of his helpers that he was in a genial humour.

Mickey was just loading up his tricycle with wire and insulators, preparatory to a trip out along the line, when Jim accosted him.

“Mr. Mickey,” he began, “another fellow named Allan West and myself want to rig up a little telegraph line from my house, out near the two bridges, to his, just back of the yards here, and we were wondering if you would let us string our wire on the company’s poles. There seem to be some vacant places, and of course we’d be mighty careful not to interfere with the other wires.”

He stopped, eying Mickey anxiously, but that worthy went on with his work as though he had not heard. He was puffing vigorously at a short clay pipe, and with a certain viciousness that made Jim wonder if he had approached him at the wrong moment, after all.

“What ’d ye say th’ other kid’s name is?” Mickey asked, after what seemed an age to the waiting boy.

“Allan West.”

“Is that th’ kid that Jack Welsh took t’ raise?”

“Yes; he lives with the Welshes. He worked in Welsh’s section-gang last year—took Dan Nolan’s place, you know.”

“Yes—I moind,” said Mickey, and went on smoking.

“How does it happen,” he demanded at last, “that he wants t’ learn t’ be a operator?”

“He’s got a job in th’ trainmaster’s office,” Jim explained. “He wants to learn the business.”

Mickey nodded, and knocking out his pipe against his boot-heel, deliberately filled it again, lighted it, and turned back to his work. Finally the tricycle was loaded and he pushed it out on the main line, ready for his trip. Jim followed him anxiously. He watched Mickey take his seat on the queer-looking machine, spit on his hands and grasp the lever; then he turned away disappointed. That line was not going to be possible, after all.

“Wait a minute,” called Mickey. “What th’ blazes are ye in such a hurry about? Do ye see that wire up there—th’ outside wire on th’ lowest cross-arm?”

“Yes,” nodded Jim, following the direction of the pointed finger.

“Well, that’s a dead one. We don’t use it no more, an’ I’m a-goin’ t’ take it down afore long. Ye kin use it, if ye want to, till then—mebbe it’ll be a month ’r two afore I git around to it.”

“Oh, thank you, Mr. Mickey,” cried Jim, his face beaming. “That will be fine. We’re a thousand times obliged—”

But the lineman cut him short with a curt nod, bent to the lever, and rattled away over the switches, out of the yards.

Jim hurried on to his place in the long-shop, getting « 37 » there just as the whistle blew, and went about his accustomed work, but he kept an eye out for Allan, who, he knew, would be coming through before long in search of the master-mechanic. Allan, you may be sure, did not neglect the chance to say good-morning to his new friend, and listened with sparkling eyes while Jim poured out the story of his success with Mickey.

“And now,” he concluded, “all we’ll have to do is to run a wire into our house from the pole just in front of it, and then run another across the yards here to your house. We can do it in a couple of evenings.”

“And we’ll have it for a month, anyway,” added Allan.

“A month! We’ll have it as long as we want it. That was just Mickey’s way. He didn’t want to seem to be too tender-hearted. He’ll never touch the wire as long as we’re using it. I’ll get some old wire to make the connections with, and fix up the batteries.”

“All right,” agreed Allan, and went on his way.

The work of stringing the wires was begun that very evening; the batteries were overhauled and filled with dilute sulphuric acid, and the keys and sounders were tested and found to be in good shape. Three evenings later, one of the instruments was clicking on the table in Allan’s room, and Jim was bending over the other one in his room a mile away. « 38 » Only, alas, the clicks were wild and irregular and without meaning.

But that did not last long. The book on telegraphy helped them; Allan himself, in the dispatchers’ office, had ample opportunity to observe how the system worked, and each of the boys copied out the Morse alphabet and set himself to learn it, practising on his key at every spare moment.

They found that telegraphic messages are transmitted by the use of three independent characters: short signals, or dots; long signals, or dashes; and dividing intervals or spaces between adjacent signals. Thus, a dot followed by a dash represents the letter a; a dash followed by three dots represents the letter b, while two dots, space, dot, represents the letter c, and so through the alphabet, which, according to the Morse code, is written like this: a, .-; b, -...; c, .. .; d, -..; e, .; and so on. Longer spaces or pauses divide the words, and longer dashes are also used in representing some of the letters.

The dots and dashes are made by means of a key which opens and closes the electric circuit, and causes the sounders of all the other instruments connected with the wire to vibrate responsively. When an operator desires to send the letter a, he depresses his key for a short interval, then releases it, and, after an interval equally brief, depresses it again, holding it down three times as long before releasing it. All the other sounders repeat this dot « 39 » and dash, and the listening operators recognize the letter a. Every word must be spelled out in this manner, letter by letter.

As may well be believed, the boys found the sending and receiving of even the shortest words difficult and painful enough at first, but in a surprisingly short time certain combinations of sounds began to stand out, as it were, among their surroundings. The two combinations which first became familiar were - .... . and .- -. -.., representing respectively “the” and “and.” Following this, came the curious combination of sounds, ..—.., which represents the period, one of the most difficult the learner has to master. Other combinations followed, until most of the shorter words began to assume the same individuality when heard over the wire that they have when seen by the eye. It was no longer necessary to listen to them letter by letter; the ear grasped them as a whole, just as the eye grasps the written word without separating it into the letters which compose it.

But even then, Allan still found the clicking of the instruments in the office an unsolvable riddle. This was due largely to the system of abbreviation which railroad operators use, a sort of telegraphic shorthand incomprehensible to the ordinary operator; but the sending was in most cases so rapid that even if the words had been spelled out in full the boy would have had great difficulty in following them. Train-dispatchers, it may be said in passing, « 40 » have no time to waste; their messages are terse and to the point, and are sent like a flash. And woe to the operator who has to break in with the . .. . .. which means “repeat!” The dispatchers themselves, of course, are capable of taking the hottest ball or the wildest that ever came over the wires. Indeed, most of them can and do work the key with one hand while they eat their lunch with the other; and the call or signal for his office will instantly awaken him from a sleep which a cannon-shot would not disturb. Telegraphy, in a word, develops a sort of sixth sense, and the experienced operator receives or sends a message as readily as he talks or reads or writes. It is second nature.

It was about this time that one of the old dispatchers resigned to seek his fortune in the West, and a new one made his début in a manner that Allan did not soon forget. He was a slender young fellow, with curly blond hair, and he came on duty at three o’clock in the afternoon, just when the rush of business is heaviest. The induction of a new dispatcher is something of a ceremony, for the welfare of the road rests in his hands for eight hours of every day, and everybody about the offices is always anxious to see just what stuff the newcomer is made of. So on this occasion, most of the division officials managed to have some business in the dispatchers’ office at the moment the new man came on.

He glanced over the train-sheet, while the man « 41 » he was relieving explained to him briefly the position of trains and what orders were outstanding. His sounder began to click an instant later, and he leaned over, opened his key, and gave the signal, .. .., which showed that he was ready to receive the message. Then, as the message started in a sputter which evidenced the excited haste of the man who was sending it, he turned away, took off his coat, and hung it up, deliberately removed his cuffs, and lighted a cigar. Then he sat down at his desk, and picked up a pen. Something very like a sigh of relief ran around the office. But the pen did not suit him. He tried it, made a wry face, and looked inquiringly at the other dispatcher.

“The pens are over yonder in that drawer,” said that worthy, with assumed indifference, and went on sending a message he had just started.

The newcomer arose, went to the drawer, opened it, and selected a pen with leisurely care. Allan watched him, his heart in his mouth. He could see that the chief-dispatcher was frowning and that the trainmaster looked very stern. He knew that neither of these officials would tolerate any “fooling,” when the welfare of the road was in question. But at last the newcomer was in his seat again. He reached forward and opened his key, and every one waited for the . .. . .., which would ask that the message, a long and involved one, be repeated. But instead, a curt “Cut it short,” flew over the line, followed by an order so terse, so admirable, so « 42 » clean-cut, that the trainmaster turned away with a sudden relaxation of countenance.

“He’ll do,” he murmured, as he got out a match and lighted his forgotten cigar. “He’ll do.”

And, indeed, at a later day, Allan saw the same dispatcher receive and answer two messages simultaneously. But these were merely the trimmings of the profession. They savoured of sleight of hand, and had little to do with the real business of train-dispatching.

So Allan did not despair. Every evening, he and Jim laboured at their keys. First, Allan would send an item, perhaps, from the evening paper, and Jim would receive it. Then he would send it back, and Allan would write it out, as his sounder clicked along, and compare his copy with the original, to detect any errors. At first, errors were the rule; but as time went on, they became more and more infrequent; and at the end of two months, both the boys had acquired a very fair facility in sending and receiving. Indeed, one evening, after an unusually satisfactory bout, Jim was moved to a little self-approval.

“I think we’re both pretty good,” he clicked out. “Let’s apply for a job as operator.”

“Not yet,” Allan answered. “This line hasn’t done all it can for us yet.”

Nor for the road, he might have added, could he have foreseen the events of the next twenty-four hours.

“FLAG NUMBER TWO!”

The snow was falling steadily, a late spring snow, but as heavy as any of the winter. It had started in the early morning as sleet, which clung to everything it touched with a vise-like grip. Then, the wind veering to the north had turned the sleet to snow, soggy, tenacious, and swirling fast and faster, until now, as night closed in, nearly six inches had fallen.

It was a bad night for railroading, and the instruments in the office clicked incessantly as the dispatchers laboured, with tense faces, to keep their trains straight. The wires were working badly under the burden of snow and sleet; some were crossed, some were down, and the instruments slurred the dots and dashes which rattled over them in a way that brought a line of worry between the eyes of the men upon whom rested so great a responsibility.

As for the less experienced operators along the line, they were—to use the expressive phrase usually applied to them—“up in the air.” They « 44 » knew that a single mistake might cost the lives of a score of people, and yet how were mistakes to be avoided when the instruments, instead of their usual clear-cut enunciation, stuttered and stammered and chattered meaninglessly. It was one of those crises which grow worse with each passing moment; when nerves, strained to snapping, finally give way; when brains, aching with anxiety, suddenly refuse to work; when, in a word, there is a break in the system to which even the smallest cog is necessary.

So it was that the trainmaster, having swallowed his supper hastily, had hurried back to the office, and stood now peering out into the night, chewing nervously the end of a cigar which he had forgotten to light, and listening to the instruments clattering wildly on the tables behind him. Although there were two of them, and their clatter never ceased, he followed without difficulty the story which each was telling, for he had risen to his present position after long years at the key.

Allan West had also hurried back to the office as soon as he had eaten his supper. It seemed to him that disaster was in the air; besides, he might be needed to carry a message, or for some other service, and he wanted to be on hand. It had been a hard day, for he had toiled back and forth across the slippery yards a score of times, but he forgot his fatigue as he sat there and listened to the crazy instruments and realized the tremendous odds against which the dispatchers were fighting.

For the trains must be moved, and as nearly on time as human effort could do it. There is no stopping a railroad because of unfavourable weather. The movement of trains ceases only when an accident breaks the road in two or wreckage blocks the track, and then only until arrangements can be made to détour them past the place where the accident has occurred. When this cannot be done, a train is run to the spot from either side, and passengers, mail, and baggage transferred.

And then the passengers get a fleeting and soon-forgotten glimpse of how the road is struggling to set things right again. For as they hurry past the place, they see a gang of men—a hundred, perhaps—toiling like the veriest galley-slaves to repair the damage; they see a huge derrick grappling with wrecked cars and engines and swinging them out of the way; they see locomotives puffing and hauling, and in command of it all, two or three haggard and dirt-begrimed men whom no one would recognize as the well-dressed and well-groomed gentlemen who fill the positions of superintendent, trainmaster, and superintendent of maintenance of way. All this the passengers pause a moment to contemplate, as one looks at a play at the theatre; then they hasten on and forget all about it. As for the labourers, they do not even raise their heads. It is no play for them, but deadly earnest. They have been toiling in just that fashion « 46 » for hours and hours; they will keep doggedly at it until the road is open.

To-night a dozen passengers in the luxuriantly appointed Pullmans of the east-bound flyer were fuming and fretting because their train was ten minutes late. They complained to the conductor; they expressed their opinion of the road at length and in terms the most uncomplimentary. They vowed one and all that never again would they travel by this route. Not that the delay really made any difference to any of them; but average human nature seems to be so constituted that it is most deeply annoyed by trifles. And the conductor reassured them, talked confidently of making up the lost time, did his best to keep them cheerful and contented, joked and laughed and seemed to be thinking about anything rather than the storm which swirled and howled outside. Only for an instant, as he passed from one coach to another, and found himself alone, did the careless smile leave his lips. His face lined with anxiety as he glanced out through the door of the vestibule at the driving snow, and he shook his head. Then he resumed his jaunty air and passed on into the next coach.

Every profession has its ethics—some citadel, some point of honour, which must be defended to the death. The physician may not refuse a call for aid, may not hesitate to risk his own life in the work of saving others—that is the implied agreement he makes with humanity when he accepts his « 47 » diploma. The captain may not leave his ship until the last passenger has done so; his life is negligible and worthless in comparison with that of any passenger on board; if his passengers cannot be saved, he must go down with them; to think of his own life at such a time is to confess himself a coward and a traitor to a noble calling. The conductor of a passenger-train occupies much the same position. He is responsible for his train and his passengers; never must he seem worried, or admit that there is any danger; he must front death with a smile on his lips, and when the crash comes, his first duty is to the men and women entrusted to his charge. And what a glorious commentary it is on human nature that so few, brought face to face with that duty, seek to evade it!

Back in the dispatchers’ office, the situation grew worse and worse. The dispatcher in charge of the east end had lost a freight-train. He supposed that it was somewhere between two stations, but it was long overdue, and the conviction began to be forced upon him that it had somehow got past a station unnoticed and unreported, in the snow and storm. The operator swore it hadn’t; swore that he had not slept a second; swore that he had kept a sharp lookout for the train, and hazarded the opinion that it had run off the track somewhere. The dispatcher retorted that when he wanted his opinion he would ask for it; and in the meantime that section « 48 » of track was closed until the missing train could be found.

A missing train! The words send a shiver through the bravest. Somewhere, out yonder in the storm, it is careening along the rails; its crew is confident that its passage has been noted by the operator at the last station, and that the dispatcher will keep clear the track ahead. They do not suspect their peril; they do not know that another train may be speeding toward them, and that, in a few minutes, there will be a roar, a crash, the shriek of escaping steam, and then the cruel tongues of flame licking around the wrecked cars. So the fireman bends to his task, the engineer stares absently out into the night, his hand on the throttle, the front brakeman dozes upon the fireman’s box, and back in the caboose, the conductor and hind-end brakeman engage in a social game of seven-up—

In safety, this time; for the dispatcher is one who knows his business and takes no chances. Proceeding on the theory that the train has got past, he keeps the track clear and holds up the road’s traffic until the missing train can be found. Which, of course, is as soon as it reaches the next station—for on that end of the road, every operator, knowing what is wrong, has his eyes wide open. A mighty sigh of relief goes up as it is reported; traffic starts again with a rush. And the next day, « 49 » the operator who swore so positively that the train had not got past was hunting another job.

The dispatcher in charge of the west end was doing his best to keep the track clear for Number Two, the east-bound flyer, the premier train of the road, with right of way over everything; but there was no telling what any train would do on such a night, and the flyer had already been held ten minutes at Vienna because a freight-train had stuck on the hill east of there and had to double over. The dispatcher set his teeth and vowed that there should be no more delay if he had to hold every other train on the division until the flyer passed. But freight conductors have a persuasive way with them, and when Lew Johnson reported from Lyndon at 8.40 that his train was made up, engine steaming finely, and that he could make Wadsworth easily in half an hour, the dispatcher yielded and told him to come ahead.

But Johnson had exaggerated a little, for his wife was sick and he was anxious to get home to her; the engine was not steaming so well, after all, the flues got to leaking, and when the train finally coasted down the grade into the yards at Wadsworth, the flyer was only ten minutes behind. Still, a miss is as good as a mile, and the dispatcher heaved a sigh of relief, as he looked out from the window and saw the freight pull into the yards. He stood staring a moment longer, then sprang to his key and began calling Musselman.

The trainmaster swung around sharply.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“An extra west has just pulled out of the yards,” gasped the dispatcher. “It had orders to start as soon as Number Two pulled in. The engineer must have thought that freight was the flyer,” and he kept on calling Musselman.

In a moment came the tick-tick, tick-tick, which told that the operator at Musselman had heard the call.

“Flag Number Two!” commanded the dispatcher, “and hold till arrival extra west.”

There was an instant’s suspense; then the reply came ticking slowly in:

“Number Two just passed. Was just going to report her.”

The dispatcher leaned back in his chair, his face livid, and stared mutely at the trainmaster.

“There’s no night office between here and Musselman,” he said, hoarsely. “There’ll be a head-end inside of ten minutes.”

Allan had listened with white face. He shut his eyes for an instant and fancied he could see the passenger and freight rushing toward each other through the night. Then, suddenly, he sprang erect.

“Do you know the number of that outside wire on the lower cross-arm?” he asked the trainmaster.

“Yes—fifteen—”

“Can you cut it in?”

“Of course—but what—”

“No matter—do it!” cried Allan, and sat down at the key, while the trainmaster went mechanically to the switchboard and pushed the proper plug into place.

“J—J—J!” Allan called. “J—J—J!”

Would Jim hear? Was he within call of his instrument? Perhaps he was in some other part of the house; perhaps he was not at home at all. Even if he were, how would he be able—

Then, suddenly, the circuit was broken, and as Allan held down his key, there came the welcome tick-tick, tick-tick, which told that Jim had answered.

“Flag Number Two!”

Allan’s hand was trembling so that he could scarcely control the key.

“R—R,” clamoured Jim. “Repeat—repeat!”

Small wonder that he doubted he had heard correctly!

“Flag Number Two—quick—collision!”

This time Allan controlled the trembling of his hand and sent the message clearly.

“O. K.,” flashed back the answer, and Jim was gone, forgetting in his agitation to close his key.

“Who is it?” demanded Mr. Schofield, who had listened to this interchange with strained attention.

“It’s Jim Anderson,” Allan explained. “He lives in that house right by the track about a mile « 52 » west of here. He and I rigged up a private line—Mr. Mickey let us use that old wire. Perhaps he’ll be in time.”

“Perhaps—perhaps,” agreed the trainmaster; but he did not permit himself to hope. The chance was too slender. How was the boy to flag the train? How could he make the engineer see him through that driving snow? It was absurd to suppose it could be done.

“I think we’d better order out the wrecking-train,” he said, to the chief-dispatcher. “Call up a couple of doctors, too; we’ll probably need them; and tell the hospital to have its ambulance at the station here before we get back. As for that fool who made the mistake—”

He stopped abruptly. For, in the driving snow, the mistake was not so surprising, after all—the flyer was running ten minutes late, and the freight had come in exactly on her time—two facts with which the crew of the extra west could not have been familiar.

“Perhaps he’s paid for it with his life by now,” added the trainmaster, after a moment, and started toward the telephone to order the wrecking-train got ready.

Then, suddenly, he stopped, rigid with expectancy, for the instrument on the table in front of Allan had begun to sound.

“A—A,” it called. “A—A.”

“Tick-tick, tick-tick,” Allan answered, instantly.

“I have Number Two, also extra west stopped here,” came the message. “What shall they do?”

“I guess I’ll have to turn this over to you, sir,” said Allan, looking at Mr. Schofield, his eyes bright with emotion. “Don’t send too fast,” he added, with a little, unsteady laugh, as the trainmaster took the key. “Neither Jim nor I is very expert, you know.”

A PRIVATE LINE

The conductor of Number Two, having consoled and encouraged his passengers to the best of his ability, went forward into the smoker and sat down in a corner seat to sort his tickets and make up his report. From time to time, he glanced out the window, and though the driving snow shut off any glimpse of the landscape, he could tell, by a sort of instinct, just where the train was. He knew the rattle of every switch, the position of every light. The quick rattle of a target told him that the train had passed Harper’s. He recognized the clatter of the switches at Roxabel as the train swept over them; then, from the peculiar echo, he knew that it had entered a cut and that Musselman was near. Then the train struck another cut, whirred over a bridge, and began to coast down a long grade, while the shrill blast of the whistle sounded faintly through the storm, and he knew that they were approaching Wadsworth. The lights of the city would have been visible upon the right but for the swirling snow. There was a sharp repeated roar « 55 » as the train shot over the two iron bridges at the city’s boundary—and then there came a shock which shook the train from end to end, and sent the parcels flying from the wall-racks.

Instantly the conductor swung up his feet and braced himself against the seat in front of him. He knew that that sudden setting of the brakes meant danger ahead, and he wanted to be prepared for the crash which might follow. It is a trick which every trainman knows and which every passenger should know. The passengers who are injured in a collision are usually those who were sitting carelessly balanced on the edge of their seats, and who, when the crash came, were hurled about the car, with the inevitable result of broken bones. To trainmen and experienced travellers, the unmistakable shock which tells of brakes suddenly applied is always a signal to brace themselves against the more violent one which may follow in a moment. Often this simple precaution means all the difference between life and death.

But in this case, the train came shrieking to a stop without any shock more violent than the first, and the conductor hastened out to investigate. He found the engineer and fireman standing in front of the engine, staring at a fusee burning red in the darkness, and questioning a young fellow who stood near by.

“What is it?” demanded the conductor, hurrying up.

“This here youngster says he had orders t’ flag th’ train,” answered the engineer.

“Orders from whom?” asked the conductor sharply, turning to the boy.

“Orders from—”

The boy stopped and turned red.

“Well, go on. Who gave the orders?”

“A chum of mine,” burst out the boy desperately. “He works in the trainmaster’s office. He wired me a minute ago to flag Number Two and be quick about it. I just had time to get that fusee lighted when you whistled for the crossing.”

The conductor frowned. The whole affair savoured of a boyish prank.

“And do you mean to say,” he demanded, sternly, “that because another boy told you to, you stopped this train—”

He paused, his mouth open, and listened, hand to ear. Then he stooped, snatched up the fusee, and fairly hurled himself down the track, waving the blazing torch above his head. And an instant later, his companions caught the sound of an engine pounding up the grade toward them.

The red light disappeared through the snow; then two sharp whistles testified that the signal had been seen; and a moment later, a great mogul of a freight-engine loomed through the darkness and came grinding to a stop not thirty feet away.

Her engineer swung himself to the ground and came running forward.

“What’s all this?” he demanded; and then he saw the headlight of the other engine, almost obscured by the snow which encrusted it, and turned livid under his coat of tan. “What train’s that?”

“That’s Number Two,” answered the conductor, who had returned with the smoking fusee still in his hand.

“Number Two!” echoed the engineer, and a cold sweat broke out across his forehead. “Nonsense! I saw Number Two pull into the yards ten minutes ago!”

“No you didn’t,” retorted the conductor, grimly, “for there’s Number Two back there.”

The engineer passed his hand before his eyes and stared, scarce able to understand. Then his face hardened and his lips tightened.

“There must have been a freight ahead of you,” he said. “It came in just on your time.”

“We’re ten minutes late—and getting later every minute,” the conductor added, and stamped impatiently.

Just then the conductor of the freight came hurrying up. The engineer turned to him with a little sardonic laugh.

“Well, Pete,” he said, “I guess this is our last run over this road.”

The conductor’s face turned ghastly white.

“Wha-what do you mean?” he stammered.

The engineer answered with a wave of the hand toward the headlight glaring down at them.

“That’s Number Two,” he said.

“Number Two!” echoed the conductor, blankly. “But then—why weren’t we smashed to kindling wood?”

“Blamed if I know,” answered the engineer, turning to clamber back on his engine. “And I don’t much care. I reckon we’re done, anyway.”

And they were, for a railroad never forgives or overlooks a mistake so serious as this.

Jim Anderson came out of the house a moment later with an order from the trainmaster for the freight to back into the yards, and the flyer to follow.

Only the driving storm had kept the passengers on the flyer from coming out to inquire what the matter was; and when the conductor swung himself on board again, he was greeted with a volley of questions. What was the trouble? What had happened?

“Trouble?” he repeated, with a stare of surprise. “There wasn’t any. We had to stop for orders, that was all.”

“You stopped pretty sudden, it seems to me,” growled one old traveller.

“The engineer didn’t see the stop signal till he was right on it,” answered the conductor, blandly.

“Snow so thick, you know.”

And the passengers returned to their seats satisfied, and none of them ever knew how narrow their escape had been—for it is the policy of all railroads « 59 » that the passengers are never to know of mistakes and dangers, if the knowledge can by any means be kept from them.

However, the employees in the yards at Wadsworth had realized the mistake almost as soon as the dispatchers had—and there was quite a crowd waiting to greet the trains—a crowd which even yet did not understand how a terrible accident had been averted. It was not until the conductor of the flyer stepped off upon the platform and told the story in a few words, with voice carefully lowered lest some outsider should hear him, that they did understand; and even then, it was not as clear as it might have been until Tom Mickey came along and told how he had permitted the boys to use the old wire.

As for the engineer of the freight, he dropped off his engine the moment it stopped, and hurried away to his home without even pausing to remove his overalls. Six hours later, he was boarding a train on the N. & W., to seek a job in the south. The conductor remained for the inquiry and tried to brazen it through, but the evidence showed that, instead of staying out in the storm to watch for the arrival of Number Two and give the engineer the signal to go ahead, he had told the latter to start as soon as the passenger pulled in, and had ensconced himself in his berth in the caboose and gone comfortably to sleep. So he, too, was informed « 60 » that the P. & O. no longer required his services.