HENRY MAYHEW.

[From a Daguerreotype by Beard.]

Title: London Labour and the London Poor, Vol. 1

Author: Henry Mayhew

Release date: November 19, 2017 [eBook #55998]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Henry Flower, Jonathan Ingram, Suzanne Lybarger,

the booksmiths at eBookForge and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

In the html version of this eBook, images with blue borders are linked to higher-resolution versions of the illustrations.

A Cyclopædia of the Condition and Earnings

OF

THOSE THAT WILL WORK

THOSE THAT CANNOT WORK, AND

THOSE THAT WILL NOT WORK

BY

HENRY MAYHEW

THE LONDON STREET-FOLK

COMPRISING

STREET SELLERS · STREET BUYERS · STREET FINDERS

STREET PERFORMERS · STREET ARTIZANS · STREET LABOURERS

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

VOLUME ONE

| First edition | 1851 |

| (Volume One only and parts of Volumes Two and Three) | |

| Enlarged edition (Four volumes) | 1861-62 |

| New impression | 1865 |

THE STREET-FOLK.

| PAGE | |

| Wandering Tribes in General | 1 |

| Wandering Tribes in the Country | 2 |

| The London Street-Folk | 3 |

| Costermongers | 4 |

| Street Sellers of Fish | 61 |

| Street Sellers of Fruit and Vegetables | 79 |

| Stationary Street Sellers of Fish, Fruit, and Vegetables | 97 |

| The Street Irish | 104 |

| Street Sellers of Game, Poultry, Rabbits, Butter, Cheese, and Eggs | 120 |

| Street Sellers of Trees, Shrubs, Flowers, Roots, Seeds, and Branches | 131 |

| Street Sellers of Green Stuff | 145 |

| Street Sellers of Eatables and Drinkables | 158 |

| Street Sellers of Stationery, Literature, and the Fine Arts | 213 |

| Street Sellers of Manufactured Articles | 323 |

| The Women Street Sellers | 457 |

| The Children Street Sellers | 468 |

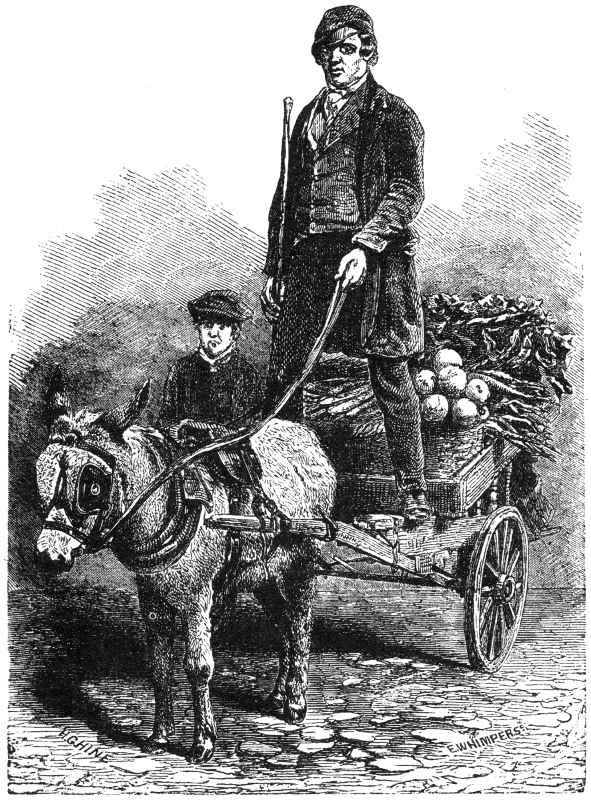

| London Costermonger | Page 13 |

| The Coster Girl | „ 37 |

| The Oyster Stall | „ 49 |

| The Orange Mart (Duke’s Place) | „ 73 |

| The Irish Street-Seller | „ 97 |

| The Wall-Flower Girl | „ 127 |

| The Groundsell Man | „ 147 |

| The Baked Potato Man | „ 167 |

| The Coffee Stall | To face page 184 |

| Coster Boy and Girl “Tossing the Pieman” | „ 196 |

| Doctor Bokanky, the Street-Herbalist | „ 206 |

| The Long Song Seller | „ 222 |

| Illustrations of Street Art, No. I. | „ 224 |

| „ „ No. II. | „ 238 |

| The Hindoo Tract Seller | „ 242 |

| The “Kitchen,” Fox Court | „ 251 |

| Illustrations of Street Art, No. III. | „ 278 |

| The Book Auctioneer | „ 296 |

| The Street-Seller of Nutmeg-Graters | „ 330 |

| The Street-Seller of Dog-Collars | „ 360 |

| The Street-Seller of Crockeryware | „ 366 |

| The Blind Boot-Lace Seller | „ 406 |

| The Street-Seller of Grease-Removing Composition | „ 428 |

| The Lucifer-Match Girl | „ 432 |

| The Street-Seller of Walking-Sticks | „ 438 |

| The Street-Seller of Rhubarb and Spice | „ 452 |

| The Street-Seller of Combs | „ 458 |

| Portrait of Mr. Mayhew | To face the Title Page |

The present volume is the first of an intended series, which it is hoped will form, when complete, a cyclopædia of the industry, the want, and the vice of the great Metropolis.

It is believed that the book is curious for many reasons:

It surely may be considered curious as being the first attempt to publish the history of a people, from the lips of the people themselves—giving a literal description of their labour, their earnings, their trials, and their sufferings, in their own “unvarnished” language; and to pourtray the condition of their homes and their families by personal observation of the places, and direct communion with the individuals.

It may be considered curious also as being the first commission of inquiry into the state of the people, undertaken by a private individual, and the first “blue book” ever published in twopenny numbers.

It is curious, moreover, as supplying information concerning a large body of persons, of whom the public had less knowledge than of the most distant tribes of the earth—the government population returns not even numbering them among the inhabitants of the kingdom; and as adducing facts so extraordinary, that the traveller in the undiscovered country of the poor must, like Bruce, until his stories are corroborated by after investigators, be content to lie under the imputation of telling such tales, as travellers are generally supposed to delight in.

Be the faults of the present volume what they may, assuredly they are rather short-comings than exaggerations, for in every instance the author and his coadjutors have sought to understate, and most assuredly never to exceed the truth. For the omissions, the author would merely remind the reader of the entire novelty of the task—there being no other similar work in the language by which to guide or check his inquiries. When the following leaves are turned over, and the two or three pages of information derived from books contrasted with the hundreds of pages of facts obtained by positive observation and investigation, surely some allowance will be made for the details which may still be left for others to supply. Within the last two years some thousands of the humbler classes of society must have been seen and visited with the especial view of noticing their condition and learning their histories; and it is but right that the truthfulness of the poor generally should be made known; for though checks have been usually adopted, the people have been mostly found to be astonishingly correct in their statements,—so much so indeed, that the attempts at deception are certainly the exceptions rather than the rule. Those persons who, from an ignorance of the simplicity of the honest poor, might be inclined to think otherwise, have, in order[iv] to be convinced of the justice of the above remarks, only to consult the details given in the present volume, and to perceive the extraordinary agreement in the statements of all the vast number of individuals who have been seen at different times, and who cannot possibly have been supposed to have been acting in concert.

The larger statistics, such as those of the quantities of fish and fruit, &c., sold in London, have been collected from tradesmen connected with the several markets, or from the wholesale merchants belonging to the trade specified—gentlemen to whose courtesy and co-operation I am indebted for much valuable information, and whose names, were I at liberty to publish them, would be an indisputable guarantee for the facts advanced. The other statistics have been obtained in the same manner—the best authorities having been invariably consulted on the subject treated of.

It is right that I should make special mention of the assistance I have received in the compilation of the present volume from Mr. Henry Wood and Mr. Richard Knight (late of the City Mission), gentlemen who have been engaged with me from nearly the commencement of my inquiries, and to whose hearty co-operation both myself and the public are indebted for a large increase of knowledge. Mr. Wood, indeed, has contributed so large a proportion of the contents of the present volume that he may fairly be considered as one of its authors.

The subject of the Street-Folk will still require another volume, in order to complete it in that comprehensive manner in which I am desirous of executing the modern history of this and every other portion of the people. There still remain—the Street-Buyers, the Street-Finders, the Street-Performers, the Street-Artizans, and the Street-Labourers, to be done, among the several classes of street-people; and the Street Jews, the Street Italians and Foreigners, and the Street Mechanics, to be treated of as varieties of the order. The present volume refers more particularly to the Street-Sellers, and includes special accounts of the Costermongers and the Patterers (the two broadly-marked varieties of street tradesmen), the Street Irish, the Female Street-Sellers, and the Children Street-Sellers of the metropolis.

My earnest hope is that the book may serve to give the rich a more intimate knowledge of the sufferings, and the frequent heroism under those sufferings, of the poor—that it may teach those who are beyond temptation to look with charity on the frailties of their less fortunate brethren—and cause those who are in “high places,” and those of whom much is expected, to bestir themselves to improve the condition of a class of people whose misery, ignorance, and vice, amidst all the immense wealth and great knowledge of “the first city in the world,” is, to say the very least, a national disgrace to us.

Of the thousand millions of human beings that are said to constitute the population of the entire globe, there are—socially, morally, and perhaps even physically considered—but two distinct and broadly marked races, viz., the wanderers and the settlers—the vagabond and the citizen—the nomadic and the civilized tribes. Between these two extremes, however, ethnologists recognize a mediate variety, partaking of the attributes of both. There is not only the race of hunters and manufacturers—those who live by shooting and fishing, and those who live by producing—but, say they, there are also the herdsmen, or those who live by tending and feeding, what they consume.

Each of these classes has its peculiar and distinctive physical as well as moral characteristics. “There are in mankind,” says Dr. Pritchard, “three principal varieties in the form of the head and other physical characters. Among the rudest tribes of men—the hunters and savage inhabitants of forests, dependent for their supply of food on the accidental produce of the soil and the chase—a form of head is prevalent which is mostly distinguished by the term “prognathous,” indicating a prolongation or extension forward of the jaws. A second shape of the head belongs principally to such races as wander with their herds and flocks over vast plains; these nations have broad lozenge-shaped faces (owing to the great development of the cheek bones), and pyramidal skulls. The most civilized races, on the other hand—those who live by the arts of cultivated life,—have a shape of the head which differs from both of those above mentioned. The characteristic form of the skull among these nations may be termed oval or elliptical.”

These three forms of head, however, clearly admit of being reduced to two broadly-marked varieties, according as the bones of the face or those of the skull are more highly developed. A greater relative development of the jaws and cheek bones, says the author of the “Natural History of Man,” indicates a more ample extension of the organs subservient to sensation and the animal faculties. Such a configuration is adapted to the wandering tribes; whereas, the greater relative development of the bones of the skull—indicating as it does a greater expansion of the brain, and consequently of the intellectual faculties—is especially adapted to the civilized races or settlers, who depend mainly on their knowledge of the powers and properties of things for the necessaries and comforts of life.

Moreover it would appear, that not only are all races divisible into wanderers and settlers, but that each civilized or settled tribe has generally some wandering horde intermingled with, and in a measure preying upon, it.

According to Dr. Andrew Smith, who has recently made extensive observations in South Africa, almost every tribe of people who have submitted themselves to social laws, recognizing the rights of property and reciprocal social duties, and thus acquiring wealth and forming themselves into a respectable caste, are surrounded by hordes of vagabonds and outcasts from their own community. Such are the Bushmen and Sonquas of the Hottentot race—the term “sonqua” meaning literally pauper. But a similar condition in society produces similar results in regard to other races; and the Kafirs have their Bushmen as well as the Hottentots—these are called Fingoes—a word signifying wanderers, beggars, or outcasts. The Lappes seem to have borne a somewhat similar relation to the Finns; that is to say, they appear to have been a wild and predatory tribe who sought the desert like the Arabian Bedouins, while the Finns cultivated the soil like the industrious Fellahs.

But a phenomenon still more deserving of[2] notice, is the difference of speech between the Bushmen and the Hottentots. The people of some hordes, Dr. Andrew Smith assures us, vary their speech designedly, and adopt new words, with the intent of rendering their ideas unintelligible to all but the members of their own community. For this last custom a peculiar name exists, which is called “cuze-cat.” This is considered as greatly advantageous in assisting concealment of their designs.

Here, then, we have a series of facts of the utmost social importance. (1) There are two distinct races of men, viz.:—the wandering and the civilized tribes; (2) to each of these tribes a different form of head is peculiar, the wandering races being remarkable for the development of the bones of the face, as the jaws, cheek-bones, &c., and the civilized for the development of those of the head; (3) to each civilized tribe there is generally a wandering horde attached; (4) such wandering hordes have frequently a different language from the more civilized portion of the community, and that adopted with the intent of concealing their designs and exploits from them.

It is curious that no one has as yet applied the above facts to the explanation of certain anomalies in the present state of society among ourselves. That we, like the Kafirs, Fellahs, and Finns, are surrounded by wandering hordes—the “Sonquas” and the “Fingoes” of this country—paupers, beggars, and outcasts, possessing nothing but what they acquire by depredation from the industrious, provident, and civilized portion of the community;—that the heads of these nomades are remarkable for the greater development of the jaws and cheekbones rather than those of the head;—and that they have a secret language of their own—an English “cuze-cat” or “slang” as it is called—for the concealment of their designs: these are points of coincidence so striking that, when placed before the mind, make us marvel that the analogy should have remained thus long unnoticed.

The resemblance once discovered, however, becomes of great service in enabling us to use the moral characteristics of the nomade races of other countries, as a means of comprehending the more readily those of the vagabonds and outcasts of our own. Let us therefore, before entering upon the subject in hand, briefly run over the distinctive, moral, and intellectual features of the wandering tribes in general.

The nomad then is distinguished from the civilized man by his repugnance to regular and continuous labour—by his want of providence in laying up a store for the future—by his inability to perceive consequences ever so slightly removed from immediate apprehension—by his passion for stupefying herbs and roots, and, when possible, for intoxicating fermented liquors—by his extraordinary powers of enduring privation—by his comparative insensibility to pain—by an immoderate love of gaming, frequently risking his own personal liberty upon a single cast—by his love of libidinous dances—by the pleasure he experiences in witnessing the suffering of sentient creatures—by his delight in warfare and all perilous sports—by his desire for vengeance—by the looseness of his notions as to property—by the absence of chastity among his women, and his disregard of female honour—and lastly, by his vague sense of religion—his rude idea of a Creator, and utter absence of all appreciation of the mercy of the Divine Spirit.

Strange to say, despite its privations, its dangers, and its hardships, those who have once adopted the savage and wandering mode of life, rarely abandon it. There are countless examples of white men adopting all the usages of the Indian hunter, but there is scarcely one example of the Indian hunter or trapper adopting the steady and regular habits of civilized life; indeed, the various missionaries who have visited nomade races have found their labours utterly unavailing, so long as a wandering life continued, and have succeeded in bestowing the elements of civilization, only on those compelled by circumstances to adopt a settled habitation.

The nomadic races of England are of many distinct kinds—from the habitual vagrant—half-beggar, half-thief—sleeping in barns, tents, and casual wards—to the mechanic on tramp, obtaining his bed and supper from the trade societies in the different towns, on his way to seek work. Between these two extremes there are several mediate varieties—consisting of pedlars, showmen, harvest-men, and all that large class who live by either selling, showing, or doing something through the country. These are, so to speak, the rural nomads—not confining their wanderings to any one particular locality, but ranging often from one end of the land to the other. Besides these, there are the urban and suburban wanderers, or those who follow some itinerant occupation in and round about the large towns. Such are, in the metropolis more particularly, the pickpockets—the beggars—the prostitutes—the street-sellers—the street-performers—the cabmen—the coachmen—the watermen—the sailors and such like. In each of these classes—according as they partake more or less of the purely vagabond, doing nothing whatsoever for their living, but moving from place to place preying upon the earnings of the more industrious portion of the community, so will the attributes of the nomade tribes be found to be more or less marked in them. Whether it be that in the mere act of wandering, there is a greater determination of blood to the surface of the body, and consequently a less quantity sent to the brain, the muscles being thus nourished at the expense of the mind, I leave physiologists to say. But certainly be the physical cause what it may, we must all allow that in each of the classes above-mentioned, there is[3] a greater development of the animal than of the intellectual or moral nature of man, and that they are all more or less distinguished for their high cheek-bones and protruding jaws—for their use of a slang language—for their lax ideas of property—for their general improvidence—their repugnance to continuous labour—their disregard of female honour—their love of cruelty—their pugnacity—and their utter want of religion.

Those who obtain their living in the streets of the metropolis are a very large and varied class; indeed, the means resorted to in order “to pick up a crust,” as the people call it, in the public thoroughfares (and such in many instances it literally is,) are so multifarious that the mind is long baffled in its attempts to reduce them to scientific order or classification.

It would appear, however, that the street-people may be all arranged under six distinct genera or kinds.

These are severally:

The first of these divisions—the Street-Sellers—includes many varieties; viz.—

1. The Street-sellers of Fish, &c.—“wet,” “dry,” and shell-fish—and poultry, game, and cheese.

2. The Street-sellers of Vegetables, fruit (both “green” and “dry”), flowers, trees, shrubs, seeds, and roots, and “green stuff” (as water-cresses, chickweed and grun’sel, and turf).

3. The Street-sellers of Eatables and Drinkables,—including the vendors of fried fish, hot eels, pickled whelks, sheep’s trotters, ham sandwiches, peas’-soup, hot green peas, penny pies, plum “duff,” meat-puddings, baked potatoes, spice-cakes, muffins and crumpets, Chelsea buns, sweetmeats, brandy-balls, cough drops, and cat and dog’s meat—such constituting the principal eatables sold in the street; while under the head of street-drinkables may be specified tea and coffee, ginger-beer, lemonade, hot wine, new milk from the cow, asses milk, curds and whey, and occasionally water.

4. The Street-sellers of Stationery, Literature, and the Fine Arts—among whom are comprised the flying stationers, or standing and running patterers; the long-song-sellers; the wall-song-sellers (or “pinners-up,” as they are technically termed); the ballad sellers; the vendors of play-bills, second editions of newspapers, back numbers of periodicals and old books, almanacks, pocket books, memorandum books, note paper, sealing-wax, pens, pencils, stenographic cards, valentines, engravings, manuscript music, images, and gelatine poetry cards.

5. The Street-sellers of Manufactured Articles, which class comprises a large number of individuals, as, (a) the vendors of chemical articles of manufacture—viz., blacking, lucifers, corn-salves, grease-removing compositions, plating-balls, poison for rats, crackers, detonating-balls, and cigar-lights. (b) The vendors of metal articles of manufacture—razors and pen-knives, tea-trays, dog-collars, and key-rings, hardware, bird-cages, small coins, medals, jewellery, tin-ware, tools, card-counters, red-herring-toasters, trivets, gridirons, and Dutch ovens. (c) The vendors of china and stone articles of manufacture—as cups and saucers, jugs, vases, chimney ornaments, and stone fruit. (d) The vendors of linen, cotton, and silken articles of manufacture—as sheeting, table-covers, cotton, tapes and thread, boot and stay-laces, haberdashery, pretended smuggled goods, shirt-buttons, etc., etc.; and (e) the vendors of miscellaneous articles of manufacture—as cigars, pipes, and snuff-boxes, spectacles, combs, “lots,” rhubarb, sponges, wash-leather, paper-hangings, dolls, Bristol toys, sawdust, and pin-cushions.

6. The Street-sellers of Second-hand Articles, of whom there are again four separate classes; as (a) those who sell old metal articles—viz. old knives and forks, keys, tin-ware, tools, and marine stores generally; (b) those who sell old linen articles—as old sheeting for towels; (c) those who sell old glass and crockery—including bottles, old pans and pitchers, old looking glasses, &c.; and (d) those who sell old miscellaneous articles—as old shoes, old clothes, old saucepan lids, &c., &c.

7. The Street-sellers of Live Animals—including the dealers in dogs, squirrels, birds, gold and silver fish, and tortoises.

8. The Street-sellers of Mineral Productions and Curiosities—as red and white sand, silver sand, coals, coke, salt, spar ornaments, and shells.

These, so far as my experience goes, exhaust the whole class of street-sellers, and they appear to constitute nearly three-fourths of the entire number of individuals obtaining a subsistence in the streets of London.

The next class are the Street-Buyers, under which denomination come the purchasers of hareskins, old clothes, old umbrellas, bottles, glass, broken metal, rags, waste paper, and dripping.

After these we have the Street-Finders, or those who, as I said before, literally “pick up” their living in the public thoroughfares. They are the “pure” pickers, or those who live by gathering dogs’-dung; the cigar-end finders, or “hard-ups,” as they are called, who collect the refuse pieces of smoked cigars from the gutters, and having dried them, sell them as tobacco to the very poor; the dredgermen or coal-finders; the mud-larks, the bone-grubbers; and the sewer-hunters.

Under the fourth division, or that of the Street-Performers, Artists, and Showmen, are likewise many distinct callings.

1. The Street-Performers, who admit of being classified into (a) mountebanks—or those who enact puppet-shows, as Punch and Judy, the fan[4]toccini, and the Chinese shades. (b) The street-performers of feats of strength and dexterity—as “acrobats” or posturers, “equilibrists” or balancers, stiff and bending tumblers, jugglers, conjurors, sword-swallowers, “salamanders” or fire-eaters, swordsmen, etc. (c) The street-performers with trained animals—as dancing dogs, performing monkeys, trained birds and mice, cats and hares, sapient pigs, dancing bears, and tame camels. (d) The street-actors—as clowns, “Billy Barlows,” “Jim Crows,” and others.

2. The Street Showmen, including shows of (a) extraordinary persons—as giants, dwarfs, Albinoes, spotted boys, and pig-faced ladies. (b) Extraordinary animals—as alligators, calves, horses and pigs with six legs or two heads, industrious fleas, and happy families. (c) Philosophic instruments—as the microscope, telescope, thaumascope. (d) Measuring-machines—as weighing, lifting, measuring, and striking machines; and (e) miscellaneous shows—such as peep-shows, glass ships, mechanical figures, wax-work shows, pugilistic shows, and fortune-telling apparatus.

3. The Street-Artists—as black profile-cutters, blind paper-cutters, “screevers” or draughtsmen in coloured chalks on the pavement, writers without hands, and readers without eyes.

4. The Street Dancers—as street Scotch girls, sailors, slack and tight rope dancers, dancers on stilts, and comic dancers.

5. The Street Musicians—as the street bands (English and German), players of the guitar, harp, bagpipes, hurdy-gurdy, dulcimer, musical bells, cornet, tom-tom, &c.

6. The Street Singers, as the singers of glees, ballads, comic songs, nigger melodies, psalms, serenaders, reciters, and improvisatori.

7. The Proprietors of Street Games, as swings, highflyers, roundabouts, puff-and-darts, rifle shooting, down the dolly, spin-’em-rounds, prick the garter, thimble-rig, etc.

Then comes the Fifth Division of the Street-Folk, viz., the Street-Artizans, or Working Pedlars;

These may be severally arranged into three distinct groups—(1) Those who make things in the streets; (2) Those who mend things in the streets; and (3) Those who make things at home and sell them in the streets.

1. Of those who make things in the streets there are the following varieties: (a) the metal workers—such as toasting-fork makers, pin makers, engravers, tobacco-stopper makers. (b) The textile-workers—stocking-weavers, cabbage-net makers, night-cap knitters, doll-dress knitters. (c) The miscellaneous workers,—the wooden spoon makers, the leather brace and garter makers, the printers, and the glass-blowers.

2. Those who mend things in the streets, consist of broken china and glass menders, clock menders, umbrella menders, kettle menders, chair menders, grease removers, hat cleaners, razor and knife grinders, glaziers, travelling bell hangers, and knife cleaners.

3. Those who make things at home and sell them in the streets, are (a) the wood workers—as the makers of clothes-pegs, clothes-props, skewers, needle-cases, foot-stools and clothes-horses, chairs and tables, tea-caddies, writing-desks, drawers, work-boxes, dressing-cases, pails and tubs. (b) The trunk, hat, and bonnet-box makers, and the cane and rush basket makers. (c) The toy makers—such as Chinese roarers, children’s windmills, flying birds and fishes, feathered cocks, black velvet cats and sweeps, paper houses, cardboard carriages, little copper pans and kettles, tiny tin fireplaces, children’s watches, Dutch dolls, buy-a-brooms, and gutta-percha heads. (d) The apparel makers—viz., the makers of women’s caps, boys and men’s cloth caps, night-caps, straw bonnets, children’s dresses, watch-pockets, bonnet shapes, silk bonnets, and gaiters. (e) The metal workers,—as the makers of fire-guards, bird-cages, the wire workers. (f) The miscellaneous workers—or makers of ornaments for stoves, chimney ornaments, artificial flowers in pots and in nose-gays, plaster-of-Paris night-shades, brooms, brushes, mats, rugs, hearthstones, firewood, rush matting, and hassocks.

Of the last division, or Street-Labourers, there are four classes:

1. The Cleansers—such as scavengers, nightmen, flushermen, chimney-sweeps, dustmen, crossing-sweepers, “street-orderlies,” labourers to sweeping-machines and to watering-carts.

2. The Lighters and Waterers—or the turncocks and the lamplighters.

3. The Street-Advertisers—viz., the bill-stickers, bill-deliverers, boardmen, men to advertising vans, and wall and pavement stencillers.

4. The Street-Servants—as horse holders, link-men, coach-hirers, street-porters, shoe-blacks.

The number of costermongers,—that it is to say, of those street-sellers attending the London “green” and “fish markets,”—appears to be, from the best data at my command, now 30,000 men, women, and children. The census of 1841 gives only 2,045 “hawkers, hucksters, and pedlars,” in the metropolis, and no costermongers or street-sellers, or street-performers at all. This number is absurdly small, and its absurdity is accounted for by the fact that not one in twenty of the costermongers, or of the people with whom they lodged, troubled themselves to fill up the census returns—the majority of them being unable to read and write, and others distrustful of the purpose for which the returns were wanted.

The costermongering class extends itself yearly; and it is computed that for the last five years it has increased considerably faster than the general metropolitan population. This increase is derived partly from all the children of costermongers following the father’s trade, but chiefly from working men, such as the servants of greengrocers or of innkeepers, when out of[5] employ, “taking to a coster’s barrow” for a livelihood; and the same being done by mechanics and labourers out of work. At the time of the famine in Ireland, it is calculated, that the number of Irish obtaining a living in the London streets must have been at least doubled.

The great discrepancy between the government returns and the accounts of the costermongers themselves, concerning the number of people obtaining a living by the sale of fish, fruit, and vegetables, in the streets of London, caused me to institute an inquiry at the several metropolitan markets concerning the number of street-sellers attending them: the following is the result:

During the summer months and fruit season, the average number of costermongers attending Covent-garden market is about 2,500 per market-day. In the strawberry season there are nearly double as many, there being, at that time, a large number of Jews who come to buy; during that period, on a Saturday morning, from the commencement to the close of the market, as many as 4,000 costers have been reckoned purchasing at Covent-garden. Through the winter season, however, the number of costermongers does not exceed upon the average 1,000 per market morning. About one-tenth of the fruit and vegetables of the least expensive kind sold at this market is purchased by the costers. Some of the better class of costers, who have their regular customers, are very particular as to the quality of the articles they buy; but others are not so particular; so long as they can get things cheap, I am informed, they do not care much about the quality. The Irish more especially look out for damaged articles, which they buy at a low price. One of my informants told me that the costers were the best customers to the growers, inasmuch as when the market is flagging on account of the weather, they (the costers) wait and make their purchases. On other occasions, such as fine mornings, the costers purchase as early as others. There is no trust given to them—to use the words of one of my informants, they are such slippery customers; here to-day and gone to-morrow.

At Leadenhall market, during the winter months, there are from 70 to 100 costermongers general attendants; but during the summer not much more than one-half that number make their appearance. Their purchases consist of warren-rabbits, poultry, and game, of which about one-eighth of the whole amount brought to this market is bought by them. When the market is slack, and during the summer, when there is “no great call” for game, etc., the costers attending Leadenhall-market turn their hand to crockery, fruit, and fish.

The costermongers frequenting Spitalfields-market average all the year through from 700 to 1,000 each market-day. They come from all parts, as far as Edmonton, Edgeware, and Tottenham; Highgate, Hampstead, and even from Greenwich and Lewisham. Full one-third of the produce of this market is purchased by them.

The number of costermongers attending the Borough-market is about 250 during the fruit season, after which time they decrease to about 200 per market morning. About one-sixth of the produce that comes into this market is purchased by the costermongers. One gentleman informed me, that the salesmen might shut up their shops were it not for these men. “In fact,” said another, “I don’t know what would become of the fruit without them.”

The costers at Billingsgate-market, daily, number from 3,000 to 4,000 in winter, and about 2,500 in summer. A leading salesman told me that he would rather have an order from a costermonger than a fishmonger; for the one paid ready money, while the other required credit. The same gentleman assured me, that the costermongers bought excellent fish, and that very largely. They themselves aver that they purchase half the fish brought to Billingsgate—some fish trades being entirely in their hands. I ascertained, however, from the authorities at Billingsgate, and from experienced salesmen, that of the quantity of fish conveyed to that great mart, the costermongers bought one-third; another third was sent into the country; and another disposed of to the fishmongers, and to such hotel-keepers, or other large purchasers, as resorted to Billingsgate.

The salesmen at the several markets all agreed in stating that no trust was given to the costermongers. “Trust them!” exclaimed one, “O, certainly, as far as I can see them.”

Now, adding the above figures together, we have the subjoined sum for the gross number of

| Billingsgate-market | 3,500 |

| Covent-garden | 4,000 |

| Spitalfields | 1,000 |

| Borough | 250 |

| Leadenhall | 100 |

| 8,850 |

Besides these, I am credibly informed, that it may be assumed there are full 1,000 men who are unable to attend market, owing to the dissipation of the previous night; another 1,000 are absent owing to their having “stock on hand,” and so requiring no fresh purchases; and further, it may be estimated that there are at least 2,000 boys in London at work for costers, at half profits, and who consequently have no occasion to visit the markets. Hence, putting these numbers together, we arrive at the conclusion that there are in London upwards of 13,000 street-sellers, dealing in fish, fruit, vegetables, game, and poultry alone. To be on the safe side, however, let us assume the number of London costermongers to be 12,000, and that one-half of these are married and have two children (which from all accounts appears to be about the proportion); and then we have 30,000 for the[6] sum total of men, women, and children dependent on “costermongering” for their subsistence.

Large as this number may seem, still I am satisfied it is rather within than beyond the truth. In order to convince myself of its accuracy, I caused it to be checked in several ways. In the first place, a survey was made as to the number of stalls in the streets of London—forty-six miles of the principal thoroughfares were travelled over, and an account taken of the “standings.” Thus it was found that there were upon an average upwards of fourteen stalls to the mile, of which five-sixths were fish and fruit-stalls. Now, according to the Metropolitan Police Returns, there are 2,000 miles of street throughout London, and calculating that the stalls through the whole of the metropolis run upon an average only four to the mile, we shall thus find that there are 8,000 stalls altogether in London; of these we may reckon that at least 6,000 are fish and fruit-stalls. I am informed, on the best authority, that twice as many costers “go rounds” as have standings; hence we come to the conclusion that there are 18,000 itinerant and stationary street-sellers of fish, vegetables, and fruit, in the metropolis; and reckoning the same proportion of wives and children as before, we have thus 45,000 men, women, and children, obtaining a living in this manner. Further, “to make assurance doubly sure,” the street-markets throughout London were severally visited, and the number of street-sellers at each taken down on the spot. These gave a grand total of 3,801, of which number two-thirds were dealers in fish, fruit, and vegetables; and reckoning that twice as many costers again were on their rounds, we thus make the total number of London costermongers to be 11,403, or calculating men, women, and children, 28,506. It would appear, therefore, that if we estimate the gross number of individuals subsisting on the sale of fish, fruit, and vegetables, in the streets of London, at between twenty-five and thirty thousand, we shall not be very wide of the truth.

But, great as is this number, still the costermongers are only a portion of the street-folk. Besides these, there are, as we have seen, many other large classes obtaining their livelihood in the streets. The street musicians, for instance, are said to number 1,000, and the old clothesmen the same. There are supposed to be at the least 500 sellers of water-cresses; 200 coffee-stalls; 300 cats-meat men; 250 ballad-singers; 200 play-bill sellers; from 800 to 1,000 bone-grubbers and mud-larks; 1,000 crossing-sweepers; another thousand chimney-sweeps, and the same number of turncocks and lamp-lighters; all of whom, together with the street-performers and showmen, tinkers, chair, umbrella, and clock-menders, sellers of bonnet-boxes, toys, stationery, songs, last dying-speeches, tubs, pails, mats, crockery, blacking, lucifers, corn-salves, clothes-pegs, brooms, sweetmeats, razors, dog-collars, dogs, birds, coals, sand,—scavengers, dustmen, and others, make up, it may be fairly assumed, full thirty thousand adults, so that, reckoning men, women, and children, we may truly say that there are upwards of fifty thousand individuals, or about a fortieth-part of the entire population of the metropolis getting their living in the streets.

Now of all modes of obtaining subsistence, that of street-selling is the most precarious. Continued wet weather deprives those who depend for their bread upon the number of people frequenting the public thoroughfares of all means of living; and it is painful to think of the hundreds belonging to this class in the metropolis who are reduced to starvation by three or four days successive rain. Moreover, in the winter, the street-sellers of fruit and vegetables are cut off from the ordinary means of gaining their livelihood, and, consequently, they have to suffer the greatest privations at a time when the severity of the season demands the greatest amount of physical comforts. To expect that the increased earnings of the summer should be put aside as a provision against the deficiencies of the winter, is to expect that a precarious occupation should beget provident habits, which is against the nature of things, for it is always in those callings which are the most uncertain, that the greatest amount of improvidence and intemperance are found to exist. It is not the well-fed man, be it observed, but the starving one that is in danger of surfeiting himself.

Moreover, when the religious, moral, and intellectual degradation of the great majority of these fifty thousand people is impressed upon us, it becomes positively appalling to contemplate the vast amount of vice, ignorance and want, existing in these days in the very heart of our land. The public have but to read the following plain unvarnished account of the habits, amusements, dealings, education, politics, and religion of the London costermongers in the nineteenth century, and then to say whether they think it safe—even if it be thought fit—to allow men, women, and children to continue in such a state.

Among the street-folk there are many distinct characters of people—people differing as widely from each in tastes, habits, thoughts and creed, as one nation from another. Of these the costermongers form by far the largest and certainly the mostly broadly marked class. They appear to be a distinct race—perhaps, originally, of Irish extraction—seldom associating with any other of the street-folks, and being all known to each other. The “patterers,” or the men who cry the last dying-speeches, &c. in the street, and those who help off their wares by long harrangues in the public thoroughfares, are again a separate class. These, to use their own term, are “the aristocracy of the street-sellers,” despising the costers for[7] their ignorance, and boasting that they live by their intellect. The public, they say, do not expect to receive from them an equivalent for their money—they pay to hear them talk. Compared with the costermongers, the patterers are generally an educated class, and among them are some classical scholars, one clergyman, and many sons of gentlemen. They appear to be the counterparts of the old mountebanks or street-doctors. As a body they seem far less improvable than the costers, being more “knowing” and less impulsive. The street-performers differ again from those; these appear to possess many of the characteristics of the lower class of actors, viz., a strong desire to excite admiration, an indisposition to pursue any settled occupation, a love of the tap-room, though more for the society and display than for the drink connected with it, a great fondness for finery and predilection for the performance of dexterous or dangerous feats. Then there are the street mechanics, or artizans—quiet, melancholy, struggling men, who, unable to find any regular employment at their own trade, have made up a few things, and taken to hawk them in the streets, as the last shift of independence. Another distinct class of street-folk are the blind people (mostly musicians in a rude way), who, after the loss of their eyesight, have sought to keep themselves from the workhouse by some little excuse for alms-seeking. These, so far as my experience goes, appear to be a far more deserving class than is usually supposed—their affliction, in most cases, seems to have chastened them and to have given a peculiar religious cast to their thoughts.

Such are the several varieties of street-folk, intellectually considered—looked at in a national point of view, they likewise include many distinct people. Among them are to be found the Irish fruit-sellers; the Jew clothesmen; the Italian organ boys, French singing women, the German brass bands, the Dutch buy-a-broom girls, the Highland bagpipe players, and the Indian crossing-sweepers—all of whom I here shall treat of in due order.

The costermongering class or order has also its many varieties. These appear to be in the following proportions:—One-half of the entire class are costermongers proper, that is to say, the calling with them is hereditary, and perhaps has been so for many generations; while the other half is composed of three-eighths Irish, and one-eighth mechanics, tradesmen, and Jews.

Under the term “costermonger” is here included only such “street-sellers” as deal in fish, fruit, and vegetables, purchasing their goods at the wholesale “green” and fish markets. Of these some carry on their business at the same stationary stall or “standing” in the street, while others go on “rounds.” The itinerant costermongers, as contradistinguished from the stationary street-fishmongers and greengrocers, have in many instances regular rounds, which they go daily, and which extend from two to ten miles. The longest are those which embrace a suburban part; the shortest are through streets thickly peopled by the poor, where duly to “work” a single street consumes, in some instances, an hour. There are also “chance” rounds. Men “working” these carry their wares to any part in which they hope to find customers. The costermongers, moreover, diversify their labours by occasionally going on a country round, travelling on these excursions, in all directions, from thirty to ninety and even a hundred miles from the metropolis. Some, again, confine their callings chiefly to the neighbouring races and fairs.

Of all the characteristics attending these diversities of traders, I shall treat severally. I may here premise, that the regular or “thorough-bred costermongers,” repudiate the numerous persons who sell only nuts or oranges in the streets, whether at a fixed stall, or any given locality, or who hawk them through the thoroughfares or parks. They repudiate also a number of Jews, who confine their street-trading to the sale of “coker-nuts” on Sundays, vended from large barrows. Nor do they rank with themselves the individuals who sell tea and coffee in the streets, or such condiments as peas-soup, sweetmeats, spice-cakes, and the like; those articles not being purchased at the markets. I often heard all such classes called “the illegitimates.”

“From the numbers of mechanics,” said one smart costermonger to me, “that I know of in my own district, I should say there’s now more than 1,000 costers in London that were once mechanics or labourers. They are driven to it as a last resource, when they can’t get work at their trade. They don’t do well, at least four out of five, or three out of four don’t. They’re not up to the dodges of the business. They go to market with fear, and don’t know how to venture a bargain if one offers. They’re inferior salesmen too, and if they have fish left that won’t keep, it’s a dead loss to them, for they aren’t up to the trick of selling it cheap at a distance where the coster ain’t known; or of quitting it to another, for candle-light sale, cheap, to the Irish or to the ‘lushingtons,’ that haven’t a proper taste for fish. Some of these poor fellows lose every penny. They’re mostly middle-aged when they begin costering. They’ll generally commence with oranges or herrings. We pity them. We say, ‘Poor fellows! they’ll find it out by-and-bye.’ It’s awful to see some poor women, too, trying to pick up a living in the streets by selling nuts or oranges. It’s awful to see them, for they can’t set about it right; besides that, there’s too many before they start. They don’t find a living, it’s only another way of starving.”

The earliest record of London cries is, according to Mr. Charles Knight, in Lydgate’s poem of “London Lyckpeny,” which is as old as the days of Henry V., or about 430[8] years back. Among Lydgate’s cries are enumerated “Strawberries ripe and cherries in the rise;” the rise being a twig to which the cherries were tied, as at present. Lydgate, however, only indicates costermongers, but does not mention them by name.

It is not my intention, as my inquiries are directed to the present condition of the costermongers, to dwell on this part of the question, but some historical notice of so numerous a body is indispensable. I shall confine myself therefore to show from the elder dramatists, how the costermongers flourished in the days of Elizabeth and James I.

“Virtue,” says Shakespeare, “is of so little regard in these coster-monger times, that true valour is turned bear-herd.” Costermonger times are as old as any trading times of which our history tells; indeed, the stationary costermonger of our own day is a legitimate descendant of the tradesmen of the olden time, who stood by their shops with their open casements, loudly inviting buyers by praises of their wares, and by direct questions of “What d’ye buy? What d’ye lack?”

Ben Jonson makes his Morose, who hated all noises, and sought for a silent wife, enter “upon divers treaties with the fish-wives and orange-women,” to moderate their clamour; but Morose, above all other noisy people, “cannot endure a costard-monger; he swoons if he hear one.”

In Ford’s “Sun’s Darling” I find the following: “Upon my life he means to turn costermonger, and is projecting how to forestall the market. I shall cry pippins rarely.”

In Beaumont and Fletcher’s “Scornful Lady” is the following:

Dr. Johnson, gives the derivation of costard-monger (the orthography he uses), as derived from the sale of apples or costards, “round and bulky like the head;” and he cites Burton as an authority: “Many country vicars,” writes Burton, “are driven to shifts, and if our great patrons hold us to such conditions, they will make us costard-mongers, graziers, or sell ale.”

“The costard-monger,” says Mr. Charles Knight, in his “London,” “was originally an apple-seller, whence his name, and, from the mention of him in the old dramatists, he appears to have been frequently an Irishman.”

In Ireland the word “costermonger” is almost unknown.

A brief account of the cries once prevalent among the street-sellers will show somewhat significantly the change in the diet or regalements of those who purchase their food in the street. Some of the articles are not vended in the public thoroughfares now, while others are still sold, but in different forms.

“Hot sheep’s feet,” for instance, were cried in the streets in the time of Henry V.; they are now sold cold, at the doors of the lower-priced theatres, and at the larger public-houses. Among the street cries, the following were common prior to the wars of the Roses: “Ribs of beef,”—“Hot peascod,”—and “Pepper and saffron.” These certainly indicate a different street diet from that of the present time.

The following are more modern, running from Elizabeth’s days down to our own. “Pippins,” and, in the times of Charles II., and subsequently, oranges were sometimes cried as “Orange pips,”—“Fair lemons and oranges; oranges and citrons,”—“New Wall-fleet oysters,” [“fresh” fish was formerly cried as “new,”]—“New-river water,” [I may here mention that water-carriers still ply their trade in parts of Hampstead,]—“Rosemary and lavender,”—“Small coals,” [a cry rendered almost poetical by the character, career, and pitiful end, through a practical joke, of Tom Britton, the “small-coal man,”]—“Pretty pins, pretty women,”—“Lilly-white vinegar,”—“Hot wardens” (pears)—“Hot codlings,”—and lastly the greasy-looking beverage which Charles Lamb’s experience of London at early morning satisfied him was of all preparations the most grateful to the stomach of the then existing climbing-boys—viz., “Sa-loop.” I may state, for the information of my younger readers, that saloop (spelt also “salep” and “salop”) was prepared, as a powder, from the root of the Orchis mascula, or Red-handed Orchis, a plant which grows luxuriantly in our meadows and pastures, flowering in the spring, though never cultivated to any extent in this country; that required for the purposes of commerce was imported from India. The saloop-stalls were superseded by the modern coffee-stalls.

There were many other cries, now obsolete, but what I have cited were the most common.

Political economy teaches us that, between the two great classes of producers and consumers, stand the distributors—or dealers—saving time, trouble, and inconvenience to, the one in disposing of, and to the other in purchasing, their commodities.

But the distributor was not always a part and parcel of the economical arrangements of the State. In olden times, the producer and consumer were brought into immediate contact, at markets and fairs, holden at certain intervals. The inconvenience of this mode of operation, however, was soon felt; and the pedlar, or wandering distributor, sprang up as a means of carrying the commodities to those who were unable to attend the public markets at the appointed time. Still the pedlar or wandering distributor was not without his disadvantages. He only came at certain periods, and commodities were occasionally required in the interim. Hence the shopkeeper, or stationary distributor, was called into existence, so that the consumer might obtain any commodity of the producer at[9] any time he pleased. Hence we see that the pedlar is the primitive tradesman, and that the one is contradistinguished from the other by the fact, that the pedlar carries the goods to the consumer, whereas, in the case of the shopkeeper, the consumer goes after the goods. In country districts, remote from towns and villages, the pedlar is not yet wholly superseded; “but a dealer who has a fixed abode, and fixed customers, is so much more to be depended on,” says Mr. Stewart Mill, “that consumers prefer resorting to him if he is conveniently accessible, and dealers, therefore, find their advantage in establishing themselves in every locality where there are sufficient customers near at hand to afford them a remuneration.” Hence the pedlar is now chiefly confined to the poorer districts, and is consequently distinguished from the stationary tradesman by the character and means of his customers, as well as by the amount of capital and extent of his dealings. The shopkeeper supplies principally the noblemen and gentry with the necessaries and luxuries of life, but the pedlar or hawker is the purveyor in general to the poor. He brings the greengrocery, the fruit, the fish, the water-cresses, the shrimps, the pies and puddings, the sweetmeats, the pine-apples, the stationery, the linendrapery, and the jewellery, such as it is, to the very door of the working classes; indeed, the poor man’s food and clothing are mainly supplied to him in this manner. Hence the class of travelling tradesmen are important, not only as forming a large portion of the poor themselves, but as being the persons through whom the working people obtain a considerable part of their provisions and raiment.

But the itinerant tradesman or street-seller is still further distinguished from the regular fixed dealer—the stallkeeper from the shopkeeper—the street-wareman from the warehouseman, by the arts they respectively employ to attract custom. The street-seller cries his goods aloud at the head of his barrow; the enterprising tradesman distributes bills at the door of his shop. The one appeals to the ear, the other to the eye. The cutting costermonger has a drum and two boys to excite attention to his stock; the spirited shopkeeper has a column of advertisements in the morning newspapers. They are but different means of attaining the same end.

The street sellers are to be seen in the greatest numbers at the London street markets on a Saturday night. Here, and in the shops immediately adjoining, the working-classes generally purchase their Sunday’s dinner; and after pay-time on Saturday night, or early on Sunday morning, the crowd in the New-cut, and the Brill in particular, is almost impassable. Indeed, the scene in these parts has more of the character of a fair than a market. There are hundreds of stalls, and every stall has its one or two lights; either it is illuminated by the intense white light of the new self-generating gas-lamp, or else it is brightened up by the red smoky flame of the old-fashioned grease lamp. One man shows off his yellow haddock with a candle stuck in a bundle of firewood; his neighbour makes a candlestick of a huge turnip, and the tallow gutters over its sides; whilst the boy shouting “Eight a penny, stunning pears!” has rolled his dip in a thick coat of brown paper, that flares away with the candle. Some stalls are crimson with the fire shining through the holes beneath the baked chestnut stove; others have handsome octohedral lamps, while a few have a candle shining through a sieve: these, with the sparkling ground-glass globes of the tea-dealers’ shops, and the butchers’ gaslights streaming and fluttering in the wind, like flags of flame, pour forth such a flood of light, that at a distance the atmosphere immediately above the spot is as lurid as if the street were on fire.

The pavement and the road are crowded with purchasers and street-sellers. The housewife in her thick shawl, with the market-basket on her arm, walks slowly on, stopping now to look at the stall of caps, and now to cheapen a bunch of greens. Little boys, holding three or four onions in their hand, creep between the people, wriggling their way through every interstice, and asking for custom in whining tones, as if seeking charity. Then the tumult of the thousand different cries of the eager dealers, all shouting at the top of their voices, at one and the same time, is almost bewildering. “So-old again,” roars one. “Chestnuts all ’ot, a penny a score,” bawls another. “An ’aypenny a skin, blacking,” squeaks a boy. “Buy, buy, buy, buy, buy—bu-u-uy!” cries the butcher. “Half-quire of paper for a penny,” bellows the street stationer. “An ’aypenny a lot ing-uns.” “Twopence a pound grapes.” “Three a penny Yarmouth bloaters.” “Who’ll buy a bonnet for fourpence?” “Pick ’em out cheap here! three pair for a halfpenny, bootlaces.” “Now’s your time! beautiful whelks, a penny a lot.” “Here’s ha’p’orths,” shouts the perambulating confectioner. “Come and look at ’em! here’s toasters!” bellows one with a Yarmouth bloater stuck on a toasting-fork. “Penny a lot, fine russets,” calls the apple woman: and so the Babel goes on.

One man stands with his red-edged mats hanging over his back and chest, like a herald’s coat; and the girl with her basket of walnuts lifts her brown-stained fingers to her mouth, as she screams, “Fine warnuts! sixteen a penny, fine war-r-nuts.” A bootmaker, to “ensure custom,” has illuminated his shop-front with a line of gas, and in its full glare stands a blind beggar, his eyes turned up so as to show only “the whites,” and mumbling some begging rhymes, that are drowned in the shrill notes of the bamboo-flute-player next to him. The boy’s sharp cry, the woman’s cracked voice, the gruff, hoarse shout of the man, are all mingled together. Sometimes an Irish[10]man is heard with his “fine ating apples;” or else the jingling music of an unseen organ breaks out, as the trio of street singers rest between the verses.

Then the sights, as you elbow your way through the crowd, are equally multifarious. Here is a stall glittering with new tin saucepans; there another, bright with its blue and yellow crockery, and sparkling with white glass. Now you come to a row of old shoes arranged along the pavement; now to a stand of gaudy tea-trays; then to a shop with red handkerchiefs and blue checked shirts, fluttering backwards and forwards, and a counter built up outside on the kerb, behind which are boys beseeching custom. At the door of a tea-shop, with its hundred white globes of light, stands a man delivering bills, thanking the public for past favours, and “defying competition.” Here, alongside the road, are some half-dozen headless tailors’ dummies, dressed in Chesterfields and fustian jackets, each labelled, “Look at the prices,” or “Observe the quality.” After this is a butcher’s shop, crimson and white with meat piled up to the first-floor, in front of which the butcher himself, in his blue coat, walks up and down, sharpening his knife on the steel that hangs to his waist. A little further on stands the clean family, begging; the father with his head down as if in shame, and a box of lucifers held forth in his hand—the boys in newly-washed pinafores, and the tidily got-up mother with a child at her breast. This stall is green and white with bunches of turnips—that red with apples, the next yellow with onions, and another purple with pickling cabbages. One minute you pass a man with an umbrella turned inside up and full of prints; the next, you hear one with a peepshow of Mazeppa, and Paul Jones the pirate, describing the pictures to the boys looking in at the little round windows. Then is heard the sharp snap of the percussion-cap from the crowd of lads firing at the target for nuts; and the moment afterwards, you see either a black man half-clad in white, and shivering in the cold with tracts in his hand, or else you hear the sounds of music from “Frazier’s Circus,” on the other side of the road, and the man outside the door of the penny concert, beseeching you to “Be in time—be in time!” as Mr. Somebody is just about to sing his favourite song of the “Knife Grinder.” Such, indeed, is the riot, the struggle, and the scramble for a living, that the confusion and uproar of the New-cut on Saturday night have a bewildering and saddening effect upon the thoughtful mind.

Each salesman tries his utmost to sell his wares, tempting the passers-by with his bargains. The boy with his stock of herbs offers “a double ’andful of fine parsley for a penny;” the man with the donkey-cart filled with turnips has three lads to shout for him to their utmost, with their “Ho! ho! hi-i-i! What do you think of this here? A penny a bunch—hurrah for free trade! Here’s your turnips!” Until it is seen and heard, we have no sense of the scramble that is going on throughout London for a living. The same scene takes place at the Brill—the same in Leather-lane—the same in Tottenham-court-road—the same in Whitecross-street; go to whatever corner of the metropolis you please, either on a Saturday night or a Sunday morning, and there is the same shouting and the same struggling to get the penny profit out of the poor man’s Sunday’s dinner.

Since the above description was written, the New Cut has lost much of its noisy and brilliant glory. In consequence of a New Police regulation, “stands” or “pitches” have been forbidden, and each coster, on a market night, is now obliged, under pain of the lock-up house, to carry his tray, or keep moving with his barrow. The gay stalls have been replaced by deal boards, some sodden with wet fish, others stained purple with blackberries, or brown with walnut-peel; and the bright lamps are almost totally superseded by the dim, guttering candle. Even if the pole under the tray or “shallow” is seen resting on the ground, the policeman on duty is obliged to interfere.

The mob of purchasers has diminished one-half; and instead of the road being filled with customers and trucks, the pavement and kerb-stones are scarcely crowded.

Nearly every poor man’s market does its Sunday trade. For a few hours on the Sabbath morning, the noise, bustle, and scramble of the Saturday night are repeated, and but for this opportunity many a poor family would pass a dinnerless Sunday. The system of paying the mechanic late on the Saturday night—and more particularly of paying a man his wages in a public-house—when he is tired with his day’s work, lures him to the tavern, and there the hours fly quickly enough beside the warm tap-room fire, so that by the time the wife comes for her husband’s wages, she finds a large portion of them gone in drink, and the streets half cleared, so that the Sunday market is the only chance of getting the Sunday’s dinner.

Of all these Sunday-morning markets, the Brill, perhaps, furnishes the busiest scene; so that it may be taken as a type of the whole.

The streets in the neighbourhood are quiet and empty. The shops are closed with their different-coloured shutters, and the people round about are dressed in the shiney cloth of the holiday suit. There are no “cabs,” and but few omnibuses to disturb the rest, and men walk in the road as safely as on the footpath.

As you enter the Brill the market sounds are scarcely heard. But at each step the low hum grows gradually into the noisy shouting, until at last the different cries become distinct, and the hubbub, din, and confusion of a thousand voices bellowing at once again fill the air. The road and footpath are crowded, as on the over-night; the men are standing in groups, smoking and talking; whilst the women run[11] to and fro, some with the white round turnips showing out of their filled aprons, others with cabbages under their arms, and a piece of red meat dangling from their hands. Only a few of the shops are closed, but the butcher’s and the coal-shed are filled with customers, and from the door of the shut-up baker’s, the women come streaming forth with bags of flour in their hands, while men sally from the halfpenny barber’s smoothing their clean-shaved chins. Walnuts, blacking, apples, onions, braces, combs, turnips, herrings, pens, and corn-plaster, are all bellowed out at the same time. Labourers and mechanics, still unshorn and undressed, hang about with their hands in their pockets, some with their pet terriers under their arms. The pavement is green with the refuse leaves of vegetables, and round a cabbage-barrow the women stand turning over the bunches, as the man shouts, “Where you like, only a penny.” Boys are running home with the breakfast herring held in a piece of paper, and the side-pocket of the apple-man’s stuff coat hangs down with the weight of the halfpence stored within it. Presently the tolling of the neighbouring church bells breaks forth. Then the bustle doubles itself, the cries grow louder, the confusion greater. Women run about and push their way through the throng, scolding the saunterers, for in half an hour the market will close. In a little time the butcher puts up his shutters, and leaves the door still open; the policemen in their clean gloves come round and drive the street-sellers before them, and as the clock strikes eleven the market finishes, and the Sunday’s rest begins.

The following is a list of the street-markets, and the number of costers usually attending:—

| New-cut, Lambeth | 300 |

| Lambeth-walk | 104 |

| Walworth-road | 22 |

| Camberwell | 15 |

| Newington | 45 |

| Kent-street, Borough | 38 |

| Bermondsey | 107 |

| Union-street, Borough | 29 |

| Great Suffolk-street | 46 |

| Blackfriars-road | 58 |

| 764 |

| Brill and Chapel-st., Somers’ Town | 300 |

| Camden Town | 50 |

| Hampstead-rd. and Tottenham-ct.-rd. | 333 |

| St. George’s Market, Oxford-street | 177 |

| Marylebone | 37 |

| Edgeware-road | 78 |

| Crawford-street | 145 |

| Knightsbridge | 46 |

| Pimlico | 32 |

| Tothill-st. & Broadway, Westminster | 119 |

| Drury-lane | 22 |

| Clare-street | 139 |

| Exmouth-street and Aylesbury-street, Clerkenwell | 142 |

| Leather-lane | 150 |

| St. John’s-street | 47 |

| Old-street (St. Luke’s) | 46 |

| Whitecross-street, Cripplegate | 150 |

| Islington | 79 |

| City-road | 49 |

| Shoreditch | 100 |

| Bethnal-green | 100 |

| Whitechapel | 258 |

| Mile End | 105 |

| Commercial-rd. (East) | 114 |

| Limehouse | 88 |

| Ratcliffe Highway | 122 |

| Rosemary-lane | 119 |

| 3147 |

We find, from the foregoing list of markets, held in the various thoroughfares of the metropolis, that there are 10 on the Surrey side and 27 on the Middlesex side of the Thames. The total number of hucksters attending these markets is 3,911, giving an average of 105 to each market.

I find it impossible to separate these two headings; for the habits of the costermonger are not domestic. His busy life is past in the markets or the streets, and as his leisure is devoted to the beer-shop, the dancing-room, or the theatre, we must look for his habits to his demeanour at those places. Home has few attractions to a man whose life is a street-life. Even those who are influenced by family ties and affections, prefer to “home”—indeed that word is rarely mentioned among them—the conversation, warmth, and merriment of the beer-shop, where they can take their ease among their “mates.” Excitement or amusement are indispensable to uneducated men. Of beer-shops resorted to by costermongers, and principally supported by them, it is computed that there are 400 in London.

Those who meet first in the beer-shop talk over the state of trade and of the markets, while the later comers enter at once into what may be styled the serious business of the evening—amusement.

Business topics are discussed in a most peculiar style. One man takes the pipe from his mouth and says, “Bill made a doogheno hit this morning.” “Jem,” says another, to a man just entering, “you’ll stand a top o’ reeb?” “On,” answers Jem, “I’ve had a trosseno tol, and have been doing dab.” For an explanation of what may be obscure in this dialogue, I must refer my readers to my remarks concerning the language of the class. If any strangers are present, the conversation is still further clothed in slang, so as to be unintelligible even to the partially initiated. The evident puzzlement of any listener is of course gratifying to the costermonger’s vanity, for he feels that he possesses a knowledge peculiarly his own.

Among the in-door amusements of the costermonger is card-playing, at which many of them are adepts. The usual games are all-fours, all-fives, cribbage, and put. Whist is known to a few, but is never played, being considered dull and slow. Of short whist they have not heard; “but,” said one, whom I questioned on the subject, “if it’s come into fashion, it’ll soon be among us.” The play is usually for beer, but the game is rendered exciting by bets both among the players and the lookers-on. “I’ll back Jem for a yanepatine,” says one. “Jack for a gen,” cries another. A penny is the lowest sum laid, and five shillings generally the highest, but a shilling is not often exceeded. “We play fair among ourselves,” said a costermonger to me—“aye, fairer than the aristocrats—but we’ll take in anybody else.” Where it is known that the landlord will not supply cards, “a sporting coster” carries a pack or two with him. The cards played with have rarely been stamped;[12] they are generally dirty, and sometimes almost illegible, from long handling and spilled beer. Some men will sit patiently for hours at these games, and they watch the dealing round of the dingy cards intently, and without the attempt—common among politer gamesters—to appear indifferent, though they bear their losses well. In a full room of card-players, the groups are all shrouded in tobacco-smoke, and from them are heard constant sounds—according to the games they are engaged in—of “I’m low, and Ped’s high.” “Tip and me’s game.” “Fifteen four and a flush of five.” I may remark it is curious that costermongers, who can neither read nor write, and who have no knowledge of the multiplication table, are skilful in all the intricacies and calculations of cribbage. There is not much quarrelling over the cards, unless strangers play with them, and then the costermongers all take part one with another, fairly or unfairly.

It has been said that there is a close resemblance between many of the characteristics of a very high class, socially, and a very low class. Those who remember the disclosures on a trial a few years back, as to how men of rank and wealth passed their leisure in card-playing—many of their lives being one continued leisure—can judge how far the analogy holds when the card-passion of the costermongers is described.

“Shove-halfpenny” is another game played by them; so is “Three up.” Three halfpennies are thrown up, and when they fall all “heads” or all “tails,” it is a mark; and the man who gets the greatest number of marks out of a given amount—three, or five, or more—wins. “Three-up” is played fairly among the costermongers; but is most frequently resorted to when strangers are present to “make a pitch,”—which is, in plain words, to cheat any stranger who is rash enough to bet upon them. “This is the way, sir,” said an adept to me; “bless you, I can make them fall as I please. If I’m playing with Jo, and a stranger bets with Jo, why, of course, I make Jo win.” This adept illustrated his skill to me by throwing up three halfpennies, and, five times out of six, they fell upon the floor, whether he threw them nearly to the ceiling or merely to his shoulder, all heads or all tails. The halfpence were the proper current coins—indeed, they were my own; and the result is gained by a peculiar position of the coins on the fingers, and a peculiar jerk in the throwing. There was an amusing manifestation of the pride of art in the way in which my obliging informant displayed his skill.

“Skittles” is another favourite amusement, and the costermongers class themselves among the best players in London. The game is always for beer, but betting goes on.

A fondness for “sparring” and “boxing” lingers among the rude members of some classes of the working men, such as the tanners. With the great majority of the costermongers this fondness is still as dominant as it was among the “higher classes,” when boxers were the pets of princes and nobles. The sparring among the costers is not for money, but for beer and “a lark”—a convenient word covering much mischief. Two out of every ten landlords, whose houses are patronised by these lovers of “the art of self-defence,” supply gloves. Some charge 2d. a night for their use; others only 1d. The sparring seldom continues long, sometimes not above a quarter of an hour; for the costermongers, though excited for a while, weary of sports in which they cannot personally participate, and in the beer-shops only two spar at a time, though fifty or sixty may be present. The shortness of the duration of this pastime may be one reason why it seldom leads to quarrelling. The stake is usually a “top of reeb,” and the winner is the man who gives the first “noser;” a bloody nose however is required to show that the blow was veritably a noser. The costermongers boast of their skill in pugilism as well as at skittles. “We are all handy with our fists,” said one man, “and are matches, aye, and more than matches, for anybody but reg’lar boxers. We’ve stuck to the ring, too, and gone reg’lar to the fights, more than any other men.”

“Twopenny-hops” are much resorted to by the costermongers, men and women, boys and girls. At these dances decorum is sometimes, but not often, violated. “The women,” I was told by one man, “doesn’t show their necks as I’ve seen the ladies do in them there pictures of high life in the shop-winders, or on the stage. Their Sunday gowns, which is their dancing gowns, ain’t made that way.” At these “hops” the clog-hornpipe is often danced, and sometimes a collection is made to ensure the performance of a first-rate professor of that dance; sometimes, and more frequently, it is volunteered gratuitously. The other dances are jigs, “flash jigs”—hornpipes in fetters—a dance rendered popular by the success of the acted “Jack Sheppard”—polkas, and country-dances, the last-mentioned being generally demanded by the women. Waltzes are as yet unknown to them. Sometimes they do the “pipe-dance.” For this a number of tobacco-pipes, about a dozen, are laid close together on the floor, and the dancer places the toe of his boot between the different pipes, keeping time with the music. Two of the pipes are arranged as a cross, and the toe has to be inserted between each of the angles, without breaking them. The numbers present at these “hops” vary from 30 to 100 of both sexes, their ages being from 14 to 45, and the female sex being slightly predominant as to the proportion of those in attendance. At these “hops” there is nothing of the leisurely style of dancing—half a glide and half a skip—but vigorous, laborious capering. The hours are from half-past eight to twelve, sometimes to one or two in the morning, and never later than two, as the costermongers are early risers. There is sometimes a good deal of drinking; some of the young girls being often pressed to drink, and frequently yielding to the temptation. From 1l. to 7l. is spent in drink at a hop; the youngest men or lads present spend the most, especially in that act of costermonger [15] politeness—“treating the gals.” The music is always a fiddle, sometimes with the addition of a harp and a cornopean. The band is provided by the costermongers, to whom the assembly is confined; but during the present and the last year, when the costers’ earnings have been less than the average, the landlord has provided the harp, whenever that instrument has added to the charms of the fiddle. Of one use to which these “hops” are put I have given an account, under the head of “Marriage.”

THE LONDON COSTERMONGER.

“Here Pertaters! Kearots and Turnups! Fine Brockello-o-o!”

[From a Daguerreotype by Beard.]

The other amusements of this class of the community are the theatre and the penny concert, and their visits are almost entirely confined to the galleries of the theatres on the Surrey-side—the Surrey, the Victoria, the Bower Saloon, and (but less frequently) Astley’s. Three times a week is an average attendance at theatres and dances by the more prosperous costermongers. The most intelligent man I met with among them gave me the following account. He classes himself with the many, but his tastes are really those of an educated man:—“Love and murder suits us best, sir; but within these few years I think there’s a great deal more liking for deep tragedies among us. They set men a thinking; but then we all consider them too long. Of Hamlet we can make neither end nor side; and nine out of ten of us—ay, far more than that—would like it to be confined to the ghost scenes, and the funeral, and the killing off at the last. Macbeth would be better liked, if it was only the witches and the fighting. The high words in a tragedy we call jaw-breakers, and say we can’t tumble to that barrikin. We always stay to the last, because we’ve paid for it all, or very few costers would see a tragedy out if any money was returned to those leaving after two or three acts. We are fond of music. Nigger music was very much liked among us, but it’s stale now. Flash songs are liked, and sailors’ songs, and patriotic songs. Most costers—indeed, I can’t call to mind an exception—listen very quietly to songs that they don’t in the least understand. We have among us translations of the patriotic French songs. ‘Mourir pour la patrie’ is very popular, and so is the ‘Marseillaise.’ A song to take hold of us must have a good chorus.” “They like something, sir, that is worth hearing,” said one of my informants, “such as the ‘Soldier’s Dream,’ ‘The Dream of Napoleon,’ or ‘I ’ad a dream—an ’appy dream.’”

The songs in ridicule of Marshal Haynau, and in laudation of Barclay and Perkin’s draymen, were and are very popular among the costers; but none are more popular than Paul Jones—“A noble commander, Paul Jones was his name.” Among them the chorus of “Britons never shall be slaves,” is often rendered “Britons always shall be slaves.” The most popular of all songs with the class, however, is “Duck-legged Dick,” of which I give the first verse.