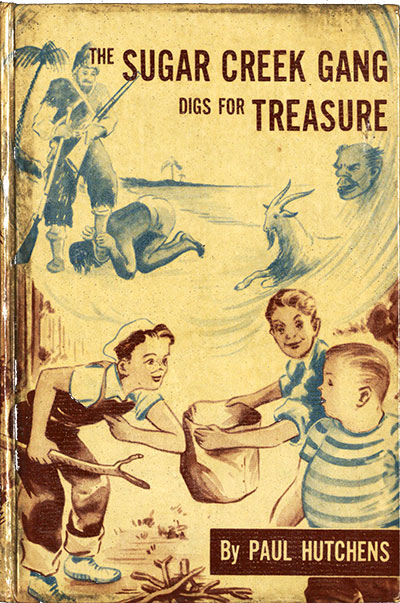

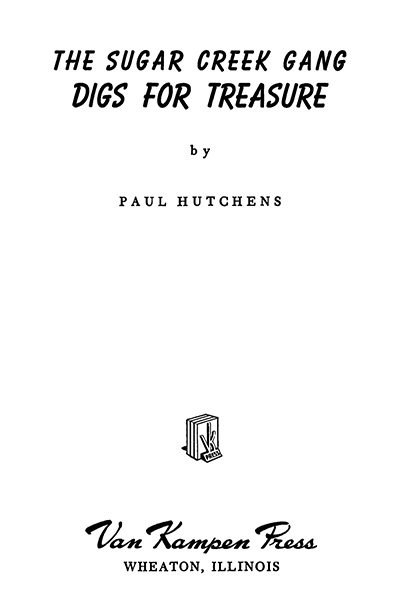

Title: The Sugar Creek Gang Digs for Treasure

Author: Paul Hutchens

Release date: February 12, 2018 [eBook #56553]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE SUGAR CREEK GANG

DIGS FOR TREASURE

by

PAUL HUTCHENS

Van Kampen Press

WHEATON, ILLINOIS

The Sugar Creek Gang Digs for Treasure

Copyright, 1948, by

Paul Hutchens

All rights in this book are reserved. No part may be reproduced in any manner without the permission in writing from the author, except brief quotations used in connection with a review in a magazine or newspaper.

Printed in the United States of America

I WAS sitting right that minute in a big white rowboat that was docked at the end of the pier which ran far out into the water of the lake. From where I was sitting, in the stern of the boat, I could see the two brown tents where the rest of the Sugar Creek Gang was supposed to be taking a short afternoon nap—which was one of the rules about camp life none of us liked very well, but which was good for us on account of we always had more pep for the rest of the day and didn’t get too tired before night.

I’d already had my afternoon nap, and had sneaked out of the tent and come to the dock where I was right that minute, to just sit there and imagine things such as whether there would be anything very exciting to see if some of the gang could explore that great big tree-covered island away out across the water, about a mile away.

Whew! it certainly was hot out here close to the water with the sunlight pouring itself on me from above and also shining up at me from below, on account of the lake was like a great big blue mirror that caught sunlight and reflected it right up under my straw hat, making my hot freckled face even hotter than it was. Because it was the style for the people to get tanned almost all over, I didn’t mind the heat as much as I might have.

It seemed to be getting hotter every minute though—the kind of day we sometimes had back home at Sugar Creek just before some big thunderheads came sneaking up and surprised us with a fierce storm. It was also a perfect day for a sunbath. What on earth made people want to get brown all over for anyway? I thought. Then I looked down at my freckled brownish arm, and was disgusted at myself, on account of instead of getting a nice tan like Circus, the acrobatic member of our gang, I4 always got sunburned and freckled and my upper arm looked like a piece of raw steak instead of a nice piece of brown fried chicken.... Thinking that, reminded me that I was hungry and I wished it was suppertime.

It certainly was a quiet camp, I thought, as I looked at the two tents, where the rest of the gang was supposed to be sleeping. I just couldn’t imagine anybody sleeping that long—anyway, not any boy—unless he was at home and it was morning and time to get up and do the chores.

Just that second I heard a sound of footsteps from up the shore, and looking up I saw a smallish boy with brownish curly hair coming toward me along the path that runs all along the shore line. I knew right away it was Little Jim, my almost best friend, and the grandest little guy that ever lived. I knew it was Little Jim not only ’cause he carried his ash stick with him, which was about as long as a man’s cane, but because of the shuffling way he walked. I noticed he was stopping every now and then to stoop over and look at some kind of wild flower, then he’d write something down in a book he was carrying which I knew was a wild flower Guide Book.

He certainly was an interesting little guy, I thought. I guess he hadn’t seen me, ’cause I could hear him talking to himself which is what he had a habit of doing when he was alone and there was something kinda nice about it that made me like him even better than ever. I think that little guy does more honest-to-goodness thinking than any of the rest of the gang, certainly more than Dragonfly, the pop-eyed member of our gang, who is spindle-legged and slim and whose nose turns south at the end; or Poetry, the barrel-shaped member who reads all the books he can get his hands on and who knows one hundred poems by heart and is always quoting poems; and also more than Big Jim, the leader of our gang who is the oldest and who has maybe seventeen smallish strands of fuzz on his upper lip which one day will be a mustache.

5 I ducked my head down below the dock so Little Jim couldn’t see me, and listened, still wondering “What on earth!”

Little Jim stopped right beside the path that leads from the dock to the Indian kitchen which was close by the two brown tents, stooped down and said, “Hm! Wild Strawberry....” He leafed through the book he was carrying and with his eversharp pencil wrote something down. Then he looked around him and, seeing a Balm of Gilead tree right close to the dock with a five-leafed ivy on it, went straight to the tree and with his magnifying glass, began to study the ivy.

I didn’t know I was going to call out to him and interrupt his thoughts, which my mother had taught me not to do, when a person is thinking hard, on account of anybody doesn’t like to have somebody interrupt his thoughts.

“Hi, Little Jim!” I said from the stern of the boat where I was.

Say, that little guy acted as cool as a cucumber. He just looked slowly around in different directions, including up and down, then his bluish eyes looked absent-mindedly into mine, and for some reason I had the kindest, warmest feeling toward him. His face wasn’t tanned like the rest of the gang’s either, but was what people called “fair”; his smallish nose was straight, his little chin was pear-shaped, and his darkish eyebrows were straight across, his smallish ears were like they sometimes were—lopped over a little on account of that is the way he nearly always wears his straw hat.

When he saw me sitting there in the boat, he grinned and said, “I’ll bet I’ll get a hundred in nature study in school next fall. I’ve found forty-one different kinds of wild flowers.”

I wasn’t interested in the study of plants at all, right that minute, but in some kind of an adventure instead, so I said to Little Jim, “I wonder if there are any different kinds of flowers over there on that island, where Robinson Crusoe had his adventures.”

6 Little Jim looked at me without seeing me, I thought, then he grinned and said, “Robinson Crusoe never saw that island.”

“Oh yes, he did! He’s looking at it right this very minute and wishing he could explore it and find a treasure or something,” meaning I was wishing I was Robinson Crusoe myself.

Just that second a strange voice piped up from behind some sumac on the other side of the Balm of Gilead tree and said, “You can’t be a Robinson Crusoe and land on a tropical island without having a shipwreck first, and who wants to have a wreck?”

I knew right away it was Poetry, even before I saw his barrel-shaped body shuffle out from behind the sumac and I saw his fat face, and his pompadour hair and his heavy eye brows that grew straight across the top of his nose, like he had just one big longish eyebrow instead of two like most people have.

“You are a wreck,” I called to him, and didn’t mean it, but we always liked to have word fights, which we didn’t mean and always liked each other better all the time.

“I’ll leave you guys to fight it out,” Little Jim said to us. “I’ve got to find nine more kinds of wild flowers,” and with that, that little chipmunk of a guy shuffled on up the shore swinging his stick around and stooping over to study some new kind of flower he spied every now and then.

And that’s how Poetry and I got our heads together to plan a game of Robinson Crusoe, not knowing we were going to run into one of the strangest adventures we’d had in our whole lives.

“See here,” Poetry said, grunting himself down and sliding down off the side of the dock and into the boat where I was, “if we play Robinson Crusoe, we’ll have to have one other person to go along with us.”

“But there were only two of them,” I said, “—Robinson Crusoe himself and his man Friday, the colored boy who became7 his slave, and whom Crusoe saved from being eaten by the cannibals, and who, after he was saved, did nearly all Crusoe’s work for him.”

“All right,” Poetry said, “I’ll be Crusoe, and you be his Man Friday.”

“I will not,” I said. “I’m already Crusoe. I thought of it first, and I’m already him.”

Poetry and I frowned at each other, almost half mad for a minute until his fat face brightened up and he said, “All right, you be Crusoe, and I’ll be one of the cannibals getting ready to eat your man Friday, and you come along and rescue him.”

“But if you’re going to be a cannibal, I’ll have to shoot you, and then you’ll be dead,” I said.

That spoiled that plan for a jiffy, until Poetry’s bright mind thought of something else, which was, “didn’t Robinson Crusoe have a pet goat on the island with him?”

“Sure,” I said, and Poetry said, “All right, after you shoot me, I’ll be the goat.”

Well that settled that, but which one of the gang should be the colored slave, whom Robinson Crusoe saved on a Friday and whom he named his Man Friday, we couldn’t decide right that minute.

It was Poetry who thought of a way to help us decide which other one of the gang to take along with us.

“Big Jim is out,” I said, “’cause he’s too big and would want to be the leader himself, and Robinson Crusoe has to be that.”

“And Circus is out, too,” Poetry said, on account of he’s almost as big as Big Jim.

“Then there’s only Little Jim, Dragonfly and Little Tom Till left,” I said, and Poetry said, “Maybe not a one of them’ll be willing to be your Man Friday.”

We didn’t have time to talk about it any further, ’cause right that second Dragonfly came moseying out toward us from his tent, his spindling legs swinging awkwardly and his crooked8 nose and dragonfly-like eyes making him look just like a ridiculous Friday afternoon, I thought.

“He’s the man I want,” I said. “We three have had lots of exciting adventures together, and he’ll be perfect.”

“But he can’t keep quiet when there’s a mystery. He always sneezes just when we don’t want him to.”

Right that second, Dragonfly reached the pier and let the bottoms of his bare feet go ker-plop, ker-plop, ker-plop on the smooth boards, getting closer with every “ker-plop.”

When he spied Poetry and me in the boat at the end, he stopped like he had been shot at, and looked down at us and said with an accusing voice, “You guys going on a boat ride? I’m going along!”

I started to say, “Sure, we want you,” thinking how when we got over to the island, we could make a slave out of him as easy as pie.

But Poetry beat me to it by saying, “There’s only one more of the gang going with us, and it might not be you.”

Dragonfly plopped himself down on the edge of the dock, swung one foot out to the gunwale of the boat, caught it with his toes, pulled it toward him, swished himself in and sat down in the seat behind Poetry. “If anybody goes, I go, or I’ll scream and tell the rest of the gang, and nobody’ll get to go.”

I looked at Poetry and he looked at me and our eyes said to each other, “Now what?”

“Are you willing to be eaten by a cannibal?” I asked, and he got a puzzled look in his eyes. “There’re cannibals over there on that island—one, anyway—a great big fat barrel-shaped one that—”

Poetry’s fist shot forward and socked me in my ribs, which didn’t have any fat on them, and I grunted and stopped talking at the same time. “We’re going to play Robinson Crusoe,” Poetry said, “and whoever goes’ll have to be willing to do everything I say—I mean everything Bill says.”

9 “Please,” Dragonfly said. “I’ll do anything.”

Well that was a promise, but Poetry wasn’t satisfied. He pretended he wanted Tom Till to go along, on account of he liked Tom a lot and thought he’d make a better Man Friday than Dragonfly.

“We’ll try you out,” Poetry said, and caught hold of the dock with his hands and climbed out of the boat, all of us following him.

“We’ll have to initiate you,” Poetry explained, as we all swished along together. “We can’t take anybody on a treasure hunt who can’t keep quiet when he’s told to, and who can’t take orders without saying ‘WHY?’”

“Why?” Dragonfly wanted to know, and grinned, but Poetry said with a very serious face, “It isn’t funny,” and we went on.

“What’re you going to do?” Dragonfly wanted to know, as we started to march him along with us up the shore to the place where we were going to initiate him. I didn’t know myself where we were going to do it, but Poetry seemed to know exactly what to do and where to go and why, so I acted like I knew too, Poetry making me stop to pick up a great big empty gallon can that had had prunes in it, the gang having to eat prunes for breakfast nearly every morning on our camping trip.

“What’s that for?” Dragonfly wanted to know, and Poetry said, “That’s to cook our dinner in.”

“You mean—you mean—me!”

“You!” Poetry said, “Or you can’t be Bill’s Man Friday.”

“But I get saved, don’t I?” Dragonfly said with a worried voice.

“Sure, just as soon as I get shot,” Poetry explained.

“And then you turn into a goat,” I said to Poetry, as he panted along beside us, “and right away you eat the prune can!”

With that, Poetry smacked his lips like he had just finished10 eating a delicious tin can. Then he leaned over and groaned like it had given him a stomach-ache.

Right that second, I decided to try Dragonfly’s obedience, so I said, “All right, Friday, take the can you’re going to be cooked in and fill it half full of lake water!”

There was a quick scowl on Dragonfly’s face, which said, “I don’t want to do it.” He shrugged his scrawny shoulders lifted his eyebrows and the palms of his hands at the same time, and said, “I’m a poor heathen; I can’t even understand English; I don’t want to fill any old prune can with water.”

With that, I scowled, and said to Poetry in a fierce voice, “That settles that! He can’t take orders. Let’s send him home!”

Boy, did Dragonfly ever come to life in a hurry. “All right, all right,” he whined, “give me the can!” He grabbed it out of my hand, made a dive toward the lake which was still close by us, dipped the can in and came back with it filled clear to the top with nice clean water.

“Here, Crusoe,” he puffed. “Your Man Friday is your humble slave.” He extended the can toward me.

“Carry it yourself!” I said.

And then, all of a sudden, Dragonfly set it down on the ground where some of it splashed over the top onto Poetry’s shoes, and Dragonfly got a stubborn look on his face and said, “I think the cannibal ought to carry it. I’m not even Friday yet—not till the cannibal gets killed.”

Well, he was right, so Poetry looked at me, and I at him, and he picked up the can, and we went on till we came to the boathouse, which if you’ve read “The Sugar Creek Gang Goes North,” you already know about.

It was going to be fun initiating Dragonfly—just how much fun I didn’t know—and I certainly didn’t know what a mystery we were going to run into in less than fifteen minutes of the next half hour.

In only a little while we came to Santa’s boathouse, Santa11 as you maybe know being the barrel-shaped owner of the property where we had pitched our tents. He also owned a lot of other lakeshore property up here in this part of the Paul Bunyan country. Everybody called him Santa ’cause he was round like all the different Santa Clauses we’d seen and was always laughing.

Santa himself with his big laughing voice called to us when he saw us coming and said, “Well, well, if it isn’t Bill Collins, Dragonfly and Poetry,” Santa being a smart man, knowing that if there’s anything a boy likes to hear better than anything else, it’s somebody calling him by his name.

“Hi,” we all answered him, Poetry setting the prune can of water down with a savage sigh like it was too heavy to stand and hold.

Santa was standing beside his boathouse door, with a hammer in one hand and a handsaw in the other.

“Where to, with that can of water?” he asked us, and Dragonfly said, “We’re going to pour the water in a big hole up there on the hill and make a new lake.”

Santa grinned at all of us with a mischievous twinkle in his bluish eyes, knowing Dragonfly hadn’t told any lie but was only doing what most boys do most all the time anyway—playing “Make-believe.”

“May we look inside your boathouse a minute?” Poetry asked, and Santa said, “Certainly, go right in,” which we did, and looked around a little.

Poetry acted very mysterious, like he was thinking about something very important, while he frowned with his fat forehead, and looked at different things such as the cot in the farther end, the shavings and sawdust on the floor, and the carpenter’s tools above the work bench—which were chisels, screwdrivers, saws, planes and also hammers and nails; also Poetry examined the different kinds of boards made out of beautifully grained wood.

“You boys like to hold this saw and hammer a minute?”12 Santa asked us, and handed a hammer to me and a saw handle to Dragonfly, which we took, not knowing why.

“That’s the hammer and that’s the saw the kidnapper used the night he was building the gravehouse in the Indian cemetery,” Santa said, and I looked and felt puzzled, till he explained, saying, “The police found them the night you boys caught him.”

“But—how did they get there?” I asked, but Poetry answered me by saying, “Don’t you remember, Bill Collins, that we found this boathouse door wide open that night, with the latch hanging? The kidnapper stole ’em.”

I looked at the hammer in my hand, and remembered, and tried to realize that the hammer handle I had in my hand right that minute was the same one that, one night last week, had been in the wicked hand of a very fierce man who had used it in an Indian cemetery to help him build a gravehouse. Also, the saw in Poetry’s hand was the one the man had used to saw pieces of lumber into the right lengths.

“And here,” Santa said, lifting a piece of canvas from something in the corner, “is the little, nearly-finished gravehouse. The lumber was stolen from here also. The police brought it out this morning. They’ve taken fingerprints from the saw and hammer.”

“Why on earth did he want to build an Indian gravehouse?” I asked, looking at the pretty little house that looked like a longish chicken coop, like we have at home at Sugar Creek, only twice as long, almost. Dragonfly spoke up then and said, “He maybe was going to bury the little Ostberg girl there.”

But Poetry shook his head, “I think he was going to bury the ransom money there, where nobody in the world would guess to look.”

Well, we had to get going with our game of Robinson Crusoe, which we did, all of us feeling fine to think that last week we had had a chance to catch the kidnapper, even though the ransom money was still missing.

BUT say, it was a queer feeling I had in my mind as we left the boathouse and went up the narrow, hardly-ever-used road to the top of the hill and followed that road through a forest of jack pine and along the edge of the little clearing. I was remembering what exciting things happened here the very first night we’d come up North on our camping trip. Poetry was remembering it too, ’cause he said in a ghost-like voice so as to try to make the atmosphere of Dragonfly’s initiation seem even more mysterious to him, “Right here, at this sandy place in the road, is where the car was stuck in the sand, and right over here behind these bushes is where Bill and I were crouching half scared to death, watching him.”

“Yeah,” I said, “and he had the little Ostberg girl he’d kidnapped right in the back seat of the car all the time and we didn’t know it for sure.”

“How’d he get his car unstuck?” Dragonfly wanted to know, even though the whole Sugar Creek Gang had probably been told it a dozen times, every time Poetry and I had told it to them. So I said to Dragonfly, “Well, his wheels were spinning and spinning in the sand and he couldn’t make his car go forward, but it would rock forth and back, so he got out and let the air out of his back tires till they were almost half flat. That made them wider and increased traction, and then when he climbed back into his car and stepped on the gas, why he pulled out of the sand and went lickety-sizzle right on up this road.”

“You going to initiate me here?” Dragonfly wanted to know, and I started to say, “Yes,” but Poetry said, “No, a little farther up, where we found the little girl herself.”

We walked along, in the terribly sultry afternoon weather. Pretty soon we turned off to the side of the road and came out14 into a little clearing that was surrounded by tall pine trees. I was remembering how right here Poetry and I had heard the little girl gasping out half-smothered cries and with our flashlights shining right on her, we’d found her lying wrapped up in an Indian blanket.

“She was lying right here,” Poetry said, “—right here where we’re going to initiate you.” Poetry’s ordinarily duck-like voice changed to a sound like a growling bear’s voice as he talked and sounded very fierce. There really wasn’t anything to worry about, though, ’cause we knew the police had caught the kidnapper and he was in jail somewhere, and the pretty little golden-haired Ostberg girl was safe and sound with her parents again back in St. Paul.

“But they never did find the ransom money,” Poetry said, which was the truth, “and nobody knows where it is. But whoever finds it gets a thousand dollar reward—a whole thousand dollars!”

“You think maybe it’s buried somewhere?” Dragonfly asked with a serious face.

“Sure,” Poetry said. “We’re going to play Robinson Crusoe and Treasure Island both at once. First we save our Man Friday from the cannibals, and then we quit playing Robinson Crusoe and change to Treasure Island.”

Well, it was good imagination and lots of fun, and I was already imagining myself to be Robinson Crusoe on an island, living all by myself. In fact, I sometimes have more fun when I imagine myself to be somebody else than when I am just plain red-haired fiery-tempered, freckled-faced Bill Collins, living back at Sugar Creek.

It was fun the way Poetry and I initiated Dragonfly into our secret gang—anyway, fun for Poetry and me. This is the way we did it....

I hid myself out of sight behind some low fir trees with a stick in my hand for a gun, and Poetry stood Dragonfly up15 against a tree and tied him with a piece of string he carried in his pocket.

“Now, don’t you dare break that string!” Poetry told him. “You’re going to be cooked and eaten in a few minutes! You can pretend to try to get loose, but don’t you dare do it!”

I stood there hiding behind my fir trees getting ready to shoot with my imaginary gun, just in time to save Dragonfly from being cooked. Dragonfly looked half crazy standing there tied to the tree and with a grin on his face, watching Poetry stack a little stack of sticks in one place for our imaginary fire. We wouldn’t start a real fire on account of it would have been absolutely crazy to start one, nobody with any sense starting a fire in a forest on account of there might be a terrible forest fire and thousands of beautiful trees would be burned, and lots of wild animals, and maybe homes and cottages of people, and even people themselves.

A jiffy after the stack of sticks was ready, Poetry set the big prune can on top, then he turned to Dragonfly and started to untie him.

“Groan!” Poetry said to him. “Act like you’re scared to death! Yell! Do something!”

Dragonfly didn’t make a very scared black man. “There’s nothing to be afraid of,” he said; and there wasn’t, I thought—but all of a sudden there was, ’cause the very second Poetry had Dragonfly cut loose and was dragging him toward the imaginary fire, Dragonfly making it hard for him by struggling and hanging back and making his body limp so Poetry had to almost carry him, and just as I peered through the branches of my hideout and pointed my stick at Poetry and was getting ready to yell, “BANG! BANG!” a couple of times, and then rush in and rescue Dragonfly, there was a crashing noise in the underbrush behind me, and footsteps running and then a terribly loud explosion that sounded like the shot of a revolver or some kind of a gun which almost16 scared the living daylights out of me, and also out of the poor black boy and the cannibal that was getting ready to eat him.

Say, when I heard that shot behind me, I jumped almost out of my skin, I was so startled and frightened. Poetry and poor little pop-eyed Dragonfly acted like they were scared even worse than I was.

When you’re all of a sudden scared like that, you don’t know what to say or think. Things sort of swim in your head and your heart beats fiercely for a minute. Maybe we wouldn’t have been quite so frightened if we hadn’t had so many important things happen to us already on our camping trip, such as finding a little kidnapped girl in this very spot the very first night we’d been up here, and then the next night catching the kidnapper himself in a spooky Indian cemetery.

I was prepared to expect almost anything when I heard that explosion and the crashing in the underbrush; and then I could hardly believe my astonished eyes when I saw right behind and beside Dragonfly and Poetry a little puff of bluish gray smoke and about seventeen pieces of shredded paper, and knew that some body had thrown a firecracker right into the middle of our excitement.

“It’s a firecracker!” Dragonfly yelled at us, and then I had an entirely new kind of scare when I saw a little yellow flame of fire where the explosion had been, and saw some of the dry pine needles leap into flames and the flames start to spread fast.

I knew it must have been one of the gang who’d maybe had some firecrackers left over from the fourth of July at Sugar Creek. Quicker even than I can write it for you, I dashed into the center of things, grabbed up our prune can and in less than a jiffy had the fire out, and then a jiffy later, I heard a scuffling behind me and a grunting and puffing; and looking around quick, the empty prune can in my hands, I was just in time to see Circus, our acrobat, scramble out of Poetry’s fat hands, and in less than another jiffy,17 go shinning up a tree, where he perched himself on a limb and looked down at us, grinning like a monkey.

I was mad at him for breaking up our game of make-believe, and for shooting off a firecracker in the forest where it might start a terrible fire. So I yelled up at him and said, “You crazy goof! Don’t you know it’s terribly dry around here and you might burn up the whole Chippewa forest!”

“I was trying to help you kill a fat cannibal,” Circus said. He had a hurt expression in his voice and on his face, as he added, “Please don’t tell Barry I was such a dumb-bell,”—Barry being our camp director.

I forgave Circus right away when I saw he was really trying to join in with our fun and just hadn’t used his head, not thinking of the danger of forest fires at all.

“You shouldn’t even be carrying matches, to light a firecracker with,” Poetry said up at him.

“Every camper ought to have a waterproof matchbook with matches in it,” Circus said. “I read it in a book, telling what to take along on a camping trip. Besides,” Circus said down to us, “we can’t play Robinson Crusoe without having to eat food, and how are we going to eat without a fire?” I knew then that he’d guessed what game we were playing and had decided to go along.

“We don’t need you,” I said. “We need only my Man Friday, and a cannibal that gets killed—”

“And turns into a goat,” Poetry cut in and said.

“Only one goat would be terribly lonesome,” Circus said. “I think I ought to go along. I’d be willing to be another goat.”

Well, we had to get Dragonfly’s initiation finished, so I took charge of things and said, “All right, Poetry, you’re dead! Lie down over there by that tree. And you, Dragonfly, get down on your knees in front of me and put your head clear down to the ground.”

“Why?” Dragonfly wanted to know, and I said, “Keep still. My Man Friday doesn’t ask ‘Why?’”

18 Dragonfly looked worried a little, but did as I said, and bowed his head low in front of me, with his face almost touching the ground.

“Now,” I said, “Take hold of my right foot and set it on the top of your neck—NO” I yelled down at him, “Don’t ask ‘why!’ JUST DO IT!” which Dragonfly did.

“And now, my left foot,” I ordered.

“That’s what the blackboy did in Robinson Crusoe, so Crusoe would know he thanked him for saving his life from the terrible cannibals, and that he would be willing to be his slave forever,” I said to Dragonfly. “Do you solemnly promise to do everything I say, from now on and forevermore?” I asked, and when Dragonfly started to say, “I do,” but got only as far as “I—” when he started to make a funny little sniffling noise. His right hand let loose of my foot, and he grabbed his nose and went into a tailspin kind of a sneeze, as he ducked his neck out of the way of my foot and rolled over and said, “I’m allergic to your foot,” which the dead cannibal on the ground thought was funny and snickered, but I saw a little bluish flower down there with pretty yellowish stamens in its center, and I knew why Dragonfly had sneezed.

My Man Friday, in rolling over, tumbled ker-smack into the cannibal and the two of them forgot they were in a game and started a friendly scuffle, just as Circus slid down the tree, joined in with them, and all of a sudden Dragonfly’s initiation was over. He was my Man Friday, and from now on he had to do everything I said.

Up to now, it was only a game we’d been playing, but a jiffy later Circus rolled over and over, clear out of reach of the rest of us, and scrambled up into a sitting position and said to us excitedly, “Hey Gang! Look! I’ve found something—here at the foot of the tree. It’s a letter of some kind!”

I stared at an old envelope in Circus’s hands, and remembered that right here where we were was exactly where we’d found the19 kidnapped girl and that the police hadn’t been able to find the ransom money, and that the captured kidnapper hadn’t told them where it was. In fact, he had absolutely refused to tell them. We’d read it in the newspapers.

Boy oh boy, when I saw that envelope in Circus’s hands, I imagined all kinds of things, such as it being a ransom note or maybe it had a map in it and would tell us where we could find the money and everything! Boy oh boy, oh boy, oh boy!...

WELL, when you have a mysterious sealed envelope in your hand, which you’ve just found under some pine needles at the base of a tree out in the middle of a forest, and when you’re playing a game about finding buried treasure, all of a sudden you sort of wake up and realize that your game has come to life and that you’re in for an honest-to-goodness mystery that will be a thousand times more interesting and exciting than the imaginary game you’ve been playing.

We decided to keep our new names, though, which we did, although we had an argument about it first. I was still Robinson Crusoe, and Dragonfly was my Man Friday. Circus and Poetry wanted us to call them the cannibals, but Dragonfly wouldn’t. “I don’t want to have to worry about being eaten up every minute. You’ve got to turn into goats right away. Besides, one cannibal’s already been shot and is supposed to be dead.”

“You’d make a good goat yourself,” Circus said to me,—“a Billy goat, ’cause your name’s Bill.”

But it wasn’t any time to argue, when there was a mysterious envelope right in the middle of our huddle where we were on the ground at the base of the tree where Circus had found it, so Poetry said, “All right, I’ll be the goat, if you let me open the envelope.”

“And I’ll be the other goat,” Circus said, “if you’ll let me read it.”

“Let me read it,” Dragonfly said to me. “Goats can’t read anyway.”

“You can’t either,” I said. “You’re a black man that doesn’t know anything about civilization and you don’t know how to read.”

So it was I who got to open the soiled brownish envelope, which I did with excited fingers, and then we all let out four disappointed21 groans, for would you believe it? there wasn’t a single thing written on the folded white paper on the inside—not one single thing. It was only a piece of typewriter paper.

Well that was that. We all sank down on the ground in different directions and felt like the bottom had dropped out of our new mystery world. I looked at Friday and he at me, and the fat goat started chewing his cud, while our acrobatic goat rolled over on his back, pulled his knees up to his chin, and groaned, then he rolled over on his side and, my Man Friday lying right there right then, got his side rolled onto, which started a scuffle, making my Man Friday angry. All of a sudden he remembered something about the story of Robinson Crusoe. He grunted and said, while he twisted and tried to get out from under the goat, “Listen, you—when Robinson Crusoe and his Man Friday got hungry, they killed and ate one of the goats, and if you don’t behave yourself like a good goat, we’ll—”

But Circus was as mischievous as anything and said, while he rolled himself back toward Dragonfly again and laid his head on his side, “Isn’t your name Friday?”

Dragonfly grunted and said, “Sure,” and Circus answered, “All right. I’m sleepy, and there’s nothing better than taking a nap on Friday,” which he pretended to do, shutting his eyes and started in snoring as loud as he could, which sounded like a goat with the asthma.

That reminded Poetry of something funny he’d read somewhere, and it was about two fleas who were supposed to have lived on the island with Robinson Crusoe and his Man Friday. Both of these fleas had been chewing away on Crusoe and were getting tired of him and wanted a change, so pretty soon one of them called to the other and said, “So long, kid, I’ll be seeing you on Friday.”

I just barely giggled at Poetry’s story ’cause my mind was working hard on the new mystery, thinking about the blank piece of paper and why it was blank, and why was the envelope sealed, and who had dropped it here, and when, and why?

22 So I stood up and walked like Robinson Crusoe might have walked, in a little circle around the tree, looking up at the limb where Circus had been perched, and then at the ground, and at Poetry, my fat goat, who right then unscrambled himself from the rest of the inhabitants of our imaginary island, and followed me around, sniffling at my hand, like a hungry goat that wanted to eat the letter I had.

Abruptly Poetry stopped and said to me, “Sh!” which means to keep still, which I did, and he said, “Look, here’s a sign of some kind.”

I looked, but didn’t see anything except a small twig about four or five feet tall that was broken off, and had been left with the top hanging.

My Man Friday and the acrobatic goat were still scuffling under the tree, and didn’t seem interested in what we were doing. “What kind of a sign?” I asked Poetry, knowing that he was one of our gang who was more interested in woodcraft than most of the gang and was always looking for signs and trails and things.

“See here,” he said to me, “this is a little birch twig, and somebody’s broken it part way off and left it hanging.”

“What of it?” I said, remembering that back home at Sugar Creek I’d done that myself to a chokecherry twig or a willow, and it hadn’t meant a thing.

“But look which way the top points!” Poetry said mysteriously. “That means it’s a signal on a trail. It means for us to go in the direction the top of the broken twig points, and after awhile we’ll find another broken twig, and whichever way it points we’re to go that way.”

Say, did my disappointed mind ever come to quick life! Although I still doubted it might mean anything. Right away, we called the other goat and my Man Friday and let them in on our secret, and we all swished along, pretending to be scouts, going23 straight in the direction the broken twig pointed, all of us looking for another twig farther on.

We walked about twenty yards through the dense growth before we found another broken twig hanging, but sure enough we did find one, and this time it was a broken oak twig, and was bent in the opposite direction we’d come from, which meant the trail went straight on. Then we did get excited, ’cause we knew we were on somebody’s trail.

My Man Friday was awful dumb for one who was supposed to be used to outdoor life, though, ’cause he wanted to finish breaking off the top of the oak twig and also cut off the bottom and make a stick out of it to carry, and to take home with us back to Sugar Creek when we finished our vacation. “For a souvenir,” he whined complainingly, when we wouldn’t let him and made him fold up his pocket knife and put it back into his pocket again.

“That’s the sign post on our trail,” Poetry explained. “We have to leave it there so we can follow the trail back to where we started from, or might get lost,” which I thought was good sense and said so.

We scurried along, getting more and more interested and excited as we found one broken twig after another. Sometimes they were pointing straight ahead, and sometimes at an angle. Once we found a twig broken clear off and lying flat on the ground, at a right angle from the direction we’d been traveling, so we turned in the direction it pointed, and hurried along.

Once when Poetry was studying very carefully the direction a new broken twig was pointing, he gasped and said, “Hey, Gang! Look!”

We scrambled to him like a flock of little fluffy chickens making a dive toward a mother hen when she clucks for them to hurry to her and eat a bug or a fat worm or something.

“See here,” Poetry said, “—here’s where our trail branches off in two directions—one to the right and the other to the left.”24 And sure enough, he was right, for only a few feet apart were two broken twigs, one an oak, and the other a chokecherry, the chokecherry pointing to the right and the oak to the left.

“Which way do we go for the buried treasure?” Poetry asked me, and I didn’t know what to answer.

Then Poetry let out a gasp and said, “Hey, this one pointing to the right looks like it’s fresher than the other. We certainly are getting the breaks.”

We all studied the two broken twigs, and I knew that Poetry was right. The one pointing to the right looked a lot fresher break than the one pointing to the left. Why, it might even have been made today! I thought. And for some reason, not being able to tell for sure just how long it had been since somebody had been right here making the trail, I got a very peculiar and half-scared feeling all up and down my spine.

“I wish Big Jim was here,” my Man Friday said. I wished the same thing, but instead of saying it, I said bravely, “Who wants Big J—” and stopped like I had been shot at and hit, as I heard a sound from somewhere that was like a high-pitched trembling woman’s voice calling for help. It also sounded a little bit like a screech owl’s voice that wails along Sugar Creek at night back home.

“’Tsa loon,” Circus said, and was crazy enough to let out a long, loud wail that trembled and sounded more like a loon than a loon’s wail does.

I looked at my Man Friday and at my fat goat to see what they thought it was. Right away before I could read their thoughts, there was another trembling high-pitched voice which answered Circus. The second I heard it, I thought it didn’t sound like a loon but like an actual person calling and crying and terribly scared.

You can’t hear a thing like that out in the middle of the Chippewa Forest where there are Indians and different kinds of wild animals and not feel like I felt, which was almost half scared to death for a minute, although I knew there weren’t any bears25 or lions, but maybe only deer and polecats and coons and possums and maybe mink.

“It’s NOT a loon,” I whispered huskily, and felt my knees get weak and I wanted to plop down on the ground and rest. I also wanted to run.

Then the call came again not more than a hundred feet ahead of us, and as quick as I had been scared, I wasn’t again, for this time it did sound exactly like a loon.

In a jiffy we all felt better and said so to each other. The newest broken twig right beside us was pointing in the direction the sound came from, so we decided there was probably a lake right close by which is where loons nearly always are—out on some lake somewhere swimming along like ducks, and diving and also screaming bloody murder to their mates.

We all swished along, being very careful to look at the broken twigs so we’d remember what they looked like when we got ready to come back, which we planned we’d do after awhile.

My fat goat and I were walking together ahead of my Man Friday and my acrobatic goat. We dodged out way around fallen tree trunks and old stumps and around wild rose bushes and also wild raspberry patches and chokecherries, and still there wasn’t any lake anywhere.

It certainly was a queer feeling we had though, as we dodged along, talking about our mystery and wondering where we were going, and how soon we would get there.

“’Tsfunny how come Circus found that envelope back there with only a blank piece of white paper in it,” I said. “Do you s’pose the kidnapper dropped it when he left the little Ostberg girl there?”

“I suppose—why sure, he did,” Poetry said.

“How come the police didn’t find it there then, when they searched the place last week for clues. If it’d been there then, wouldn’t they have found it?” I asked those two questions as fast26 as I could ’cause that envelope in my pocket seemed like it was hot and would burn a hole in my shirt any minute.

Poetry’s fat forehead frowned. He was as struck as I was, over the mystery.

All our minds were as blank as the blank letter and not a one of us could think of anything that would make it make sense, so we went on, following our trail of broken twigs. It was fun what we were doing, and we didn’t feel very scared ’cause we knew the kidnapper was in jail. In fact, we were all thrilled with the most interesting excitement we’d had in a long time, ’cause for some reason we were sure we might find something terribly interesting at the end of the trail—if we ever came to it—not knowing that we’d not only find something very interesting but would bump into an experience even more exciting and thrilling than the ones we’d already had on our camping trip—and one that was just as dangerous.

Right that second we came to a hill. I looked ahead and spied a wide expanse of pretty blue water down below us. Between us and the lake, on the hillside, was a log cabin with a chimney running up and down the side next to us, and a big log door. We all had seen it at once I guess, ’cause we all stopped and dropped down behind some underbrush or something and most of us said, “Sh!” at the same time.

We lay there for what seemed like a terribly long time before any of us did anything except listen to ourselves breathe. I was also listening to my heart beat. But not a one of us was as scared as we would have been if we hadn’t known that the kidnapper was all nicely locked up in jail and nobody needed to be afraid of him at all. I guess I never had such a wonderful feeling in my life for a long time as I did right that minute, ’cause I realized we’d followed the trail like real scouts and we’d actually run onto the kidnapper’s hideout, and we might find the ransom money. Boy oh boy, oh boy, oh boy!

Why all we’d have to do would be to go up to that crazy27 old-fashioned looking old house, push open a door or climb in through a window and look around until we found it, I thought. It was certainly the craziest looking weathered old house, and it looked like nobody had lived in it for years and years. The windows had old green blinds hanging at crooked angles, some of the stones had fallen off the top of the chimney, and the doorstep was broken down and looked rotten. I could tell from where I was that there hadn’t been anybody going into that door for a long time on account of there was a spider web spun from the doorpost next to the old white knob, to one of the up-and-down logs in the middle of the door.

“Let’s go in and investigate.”

“Let’s n-n-n-n-not,” my Man Friday said, and I scowled at him and said fiercely, “Slave, we’re going in!”

EVEN though there was a spider web across the door, which meant that nobody had gone in or out of the door for a long time, still that didn’t mean there might not be anybody inside, ’cause there might be another door on the side next to the lake.

Poetry and I made my Man Friday and the acrobatic goat stay where they were while we circled the cabin, looking for any other door and any signs of anybody living there. The only door we found was one that led from the cabin out onto a screened front porch, but the porch was closed-in with no doors going outside, on account of there was a big ravine just below the front of the house and between it and the lake. So we knew that if anybody wanted to go in and out of the house he would have to use the one and only door or else go through a window.

We circled back to Dragonfly and Circus, where we all lay down on some tall grass behind a row of shrubbery, which somebody years ago had set out there, when maybe a family of people had lived there. It had probably been someone’s summer cabin, I thought—somebody who lived in St. Paul or Minneapolis, or somewhere, and had built the cabin up here. I noticed that there was a cement pavement running all around the back side of the cabin, which was set up against the almost cliff-like hill. Also there was a very long stone stairway beginning about twenty feet from the old spider-web-covered door and running around the edge of the ravine, making a sort of semi-circle down to the lake to where there was a very old dock, which the waves of the lake in stormy weather, or else the ice in the winter, had broken down, and nobody had fixed it.

We waited in our hiding place for maybe about ten minutes, listening and watching before we decided nobody was inside, and before we decided to look in the windows and later go inside, ourselves. We didn’t think about it being trespassing, on account29 of there was an old abandoned house back at Sugar Creek which our gang always went into anytime we wanted to, and nobody thought anything about it, because that old cabin back home belonged to a very old long-whiskered old man whom everybody knows as Old Man Paddler, and anything that belonged to him seemed to belong to us, too, he being a very special friend of anybody who was lucky enough to be a boy.

Anyway, we, all of us, were pretty soon peeking in through the windows, trying to see what we could see, but it was pretty dark inside, so we knew if we wanted to see more we had to find some way to get in.

Right that second I decided to see if my Man Friday was my Man Friday or not, so I said, “O.K., Friday, go up and knock at that door.”

Say, Dragonfly got the scaredest look on his face. As you maybe know, if you’ve read some of the other Sugar Creek Gang stories, Dragonfly’s mother believed in ghosts, and good luck happening to you if you find a four-leaf clover or a horseshoe, so Dragonfly believed it too, most boys believing and doing what their parents believe and do.

Dragonfly not only had a scared look on his face but also a stubborn one, when he said, “I won’t!”

He refused to budge an inch, and so in a very fierce voice I commanded Poetry and Circus, “O.K., cannibals, eat him up!”

“They’re NOT cannibals!” Dragonfly whined. “They’re goats, and goats only eat tin cans and shirts and ivies and things like that!”

“What’s the difference?” the fat goat said, and started head-first for Dragonfly.

But we couldn’t afford to waste any time that way, so Poetry, being maybe the bravest one of us, went up to the door, while we held our breath, I knowing that there wasn’t anybody inside but wondering if there was, and if there was, who was it, and was he30 dangerous, and what would happen if there was a fierce man in there or something.

First Poetry brushed away the spider web, then he knocked on the door.

Nobody answered the knock so he knocked again and called, “Hello! Anybody home?”

He waited and so did we, but there wasn’t any answer, so he turned the knob, twisting it this way and that, and the door didn’t open. He turned around to us and said, “It’s locked.”

Well, I had it in the back of my mind that the ransom money might be in that cabin and that we ought to go in and look, as I told you, not thinking that it was trespassing on somebody’s property to go in without permission.

We found a window on one side of the cabin right next to the hill, which on that side of the house was kinda like a cliff, and that window, when we tried it, was unlocked.

“You go in through the window and unlock the door from the inside and let us in,” I said to my acrobatic goat, and he said, “It’s private property.”

Right that second I felt a drop of rain on my face and that’s what saved the day and made it all right for us to go inside. We all must have been so interested in following the trail of broken twigs and in our game of Robinson Crusoe that we hadn’t noticed the lowering sky and the big thunderheads that had been creeping up, for only about a few jiffies after that first drop of rain splashed onto my freckled face, there was a rumble of thunder, then another, and right away it started to rain.

We could have ducked under some trees for protection, but it was that kind of rain that sometimes comes when it seems like the sky has burst open and water just drives down in blinding sheets, which it started to do.

“It’s raining pitchforks and nigger babies!” Circus yelled above the roar of the wind in the trees. He quick shoved up the window31 and scrambled in, with all of us scrambling in after him and slamming the window down behind us.

The rain was coming down so hard that it made a terrible roaring noise on the shingled roof, reminding me of storms just like that back at Sugar Creek when I was in the haymow of our barn. If there was anything I liked to hear better than almost anything else, it was rain on a shingled roof. Sometimes when I was in the upstairs of our house, I would open the attic door on purpose just to hear the friendly noise the rain made.

It was pretty dark inside the old cabin on account of the walls were stained with a dark stain of some kind, maybe to protect the wood, like some north woods cabins are. It was also dark on account of the sky outside was almost black with terribly heavy rain clouds. I noticed that the window we’d climbed in was the kitchen window and that there was a table with an oil cloth, with a few soiled dishes on one side next to the wall. Also there was a white enameled sink and an old-fashioned pitcher pump like the one we have outdoors at our house at Sugar Creek.

The main room where the fireplace was, was in the center of the cabin and was so dark you could hardly see anything clearly, but I did see two big colored pictures on the back wall of the porch at the front. I hurried out there, just to get a look at the storm, storms being one of the most interesting sights in the world, and they make a boy feel very queer inside, like maybe he isn’t very important and also make him feel like he needs the One Who made the world in the first place, to sort of look after him, which is the way I felt right that minute.

I noticed that there was a sheer drop of maybe fifteen feet right straight down into the ravine and remembered that if anybody wanted to get out of the cabin by a door, he’d have to use the only one there was which was the one that had been locked when Poetry had tried the knob.

On the front porch where I was, were two or three whiskey bottles, I noticed, and one with the stopper still in it, was half32 full, standing on a two-by-four ledge running across the front.

I could see better out here, although the terribly dark clouds in the sky, and also the big pine trees all around with their branches shading the cabin, made it almost dark even on the porch, but I did see two big colored pictures on the back wall of the porch advertising whiskey, and with important looking people drinking or getting ready to. Circus was standing with me right then, and I looked at him out of the corner of my eye, remembering how his pop used to be a drunkard before he had become a Christian, but had been saved just by repenting of his sins and trusting the Lord Jesus to save him. Say, Circus was looking fiercely at those pictures, and I noticed he had his fists doubled up, like he wished he could sock somebody or something terribly hard. I was glad right that minute that Little Tom Till wasn’t there, on account of his daddy was still a drunkard and a mean man.

I left Circus standing looking fiercely at those whiskey pictures, and looked out at the lake which was one of the prettiest sights I ever saw, with the waves being whipped into big white caps, and blowing and making a noise which, mixed up with the noise on our roof, was very pretty to my ears.

We didn’t even bother to look around inside the cabin for a while—anyway, I didn’t. Away out on the farther side of the lake there was a patch of sunlight and the water was all different shades of green and yellow. Right away there was a terrific roar, as a blinding flash of lightning lit up the whole porch, and then it did rain, and the wind blew harder and whipped the canvas curtains on the porch; and the pine trees between us and the lake acted like they were going to bend and break. Six white birch trees that grew in a cluster down beside the old outdoor stone stairway that led in the semi-circle from the cabin down to the broken-down dock, swayed and twisted and acted like they were going wild and might be broken off and blown away any minute.

“Hey! Look!” Poetry said. “There are little moving mountains out there on the lake!”

33 I looked, and sure enough that was what it did look like. The wind had changed its direction and was blowing parallel with the shore, instead of toward it, and other high waves were trying to go at right angles to the ones that were coming toward the shore. It was a terribly pretty sight.

All of a sudden while I was standing there, and feeling a little bit scared on account of the noise and the wind and the rain, I got to thinking about my folks back home, and was lonesome as well as scared; and also I was thinking that my parents had taught me that all the wonderful and terrible things in nature had been made and were being taken care of by the same God that had made growing boys, and that He loved everybody and was kind and had loved people so much that He had sent His only Son into this very pretty world, to die for all of us and to save us from our sins. My parents believed that, and had taught it to me; and nearly every time I thought about God, it was with a kind of friendly feeling in my heart, knowing that He loved not only all the millions of people in the world but also me—all by myself—red-haired, fiery-tempered, freckle-faced Bill Collins, who was always getting into trouble, or a fight, or doing something impulsive and needing somebody to help me to get out of trouble. Without knowing I was thinking outloud, I did what I sometimes do when I’m all by myself and have that very friendly feeling toward God. I said, “Thank You, dear Saviour, for dying for me.... You’re an awful wonderful God to make such a pretty storm.”

I didn’t know Dragonfly was standing there beside me, until he spoke up all of a sudden and said, “You oughtn’t to swear like that. It’s wrong to swear,” which all the gang knew it was, and none of us did it, Little Jim especially not being able to stand to even hear it without getting a hurt heart.

“I didn’t swear,” I said to Dragonfly. “I was just talking to God.”

“You what?”

34 “I was just telling Him it was an awful pretty storm.”

“You mean—you mean you aren’t afraid to talk to Him?”

Imagine that little guy saying that! But then, he hadn’t been a Christian very long and didn’t seem to understand that praying and talking to God are the same thing, and everybody ought to do it, and if your sins have been washed away, then there isn’t anything to be afraid of.

I was aroused from what I’d been thinking, by my acrobatic goat calling to us from back in the cabin saying, “Hey, Gang! Aren’t we going to explore this old shell and see if we can find the ransom money?”

That sort of brought me back from where for a few minutes my mind had been.

I took another quick look at the little moving mountains on the lake and pretty soon we were all inside where Circus had been all the time looking around to see what he could find. But it was too dark to see anything very clearly, and we didn’t have any flashlight. I looked on a high mantel above the fireplace to see if there was any kerosene lamp, but there wasn’t. There wasn’t any furniture in the main room except a table, three small chairs and one great big old-fashioned Morris chair like one my pop always sat in at home in our living room. It had a fierce-looking tiger head with a wide-open mouth on the end of each arm, which gave me an eery feeling when I saw them, which I did right away, when Circus lit one of the matches he had with him.

“Here’s a candle, out here on the kitchen table,” Dragonfly said, and brought it in to where we were. It certainly was the darkest cabin on the inside I ever saw. The walls were almost black, and the stone arch at the top of the fireplace was black with smoke where the fireplace had probably smoked when it had a fire in it. There was only about an inch of the candle left.

Circus lit it while Poetry held it, and we followed Poetry all around wherever he went. The noise of the storm and the dark35 cabin made it seem like we were having a strange adventure in the middle of the night.

There were spider webs on nearly everything, and dust on the floor, and it looked like nobody had lived here for an awful long time, maybe years and years. Besides the front porch there were just the three rooms—the kitchen with the sink and pitcher pump, the main room with the fireplace and a smallish bedroom which had a curtain hanging between it and the main room. In the bedroom was a rollaway bed all folded up and rolled against a wall.

Even though the broken twig trail had led us here, still we couldn’t find a thing that looked like anything the ransom money might have been hidden in.

So since the rain was still pouring down, we decided to call a meeting and talk things over. We pulled the three stiff-backed chairs up to the table in the center of the main room, and also the big chair, which I turned sidewise, and I sat on one of the wooden arms. Poetry set the short flickering candle in a saucer in the center of the table, and I, being supposed to be the leader, called the meeting to order, just like Big Jim does when the gang is all present. It felt good to be the leader, even though I knew I wasn’t—and Poetry would have made a better one.

We talked all at once, and also one at a time part of the time, and not one of us had any good ideas as to what to do, except when the storm was over to follow our trail of broken twigs back to where the girl had been found and from there to the road and back to camp.

I looked at Poetry’s fat face and at Dragonfly’s large eyes and his crooked nose and at Circus’s monkey-looking face, and we all looked at each other.

All of a sudden Poetry’s forehead puckered and he lifted his head and sniffed two or three times like he was smelling something strange, and said, “You guys smell anything funny, like—kinda like a dead chicken or something?”

36 I sniffed a couple of times, and we all did, and as plain as the nose on my face I did smell something—something dead. I’d smell that smell many a time back along Sugar Creek when there was a dead rabbit or something that the buzzards were circling around up in the sky, or had swooped down on it and were eating it.

Dragonfly’s dragonfly-like eyes looked startled, and I knew that if I could have seen mine in a mirror, they’d have looked just as startled.

“It smells like a dead possum carcass that didn’t get buried,” Circus said, he especially knowing what they smell like on account of his pop catches many possums and sells the fur. Sometimes on a hunting trip when he catches a possum, he skins it before going on, and leaves the carcass in the woods or in a field.

It was probably a dead animal of some kind, we decided, and went right on with our meeting, talking over everything from the beginning up to where we were right that minute—the kidnapping, the found girl, the police which had come that night and the plaster-of-Paris cast they’d made of the kidnapper’s tire tracks, and the kidnapper himself which we’d caught in the Indian cemetery, which you know all about maybe, if you’ve read the other stories called “Sugar Creek Gang Goes North” and “Adventure in an Indian Cemetery”....

“Yes,” Poetry said, “but what about the envelope with the blank piece of typewriter paper in it?”

There wasn’t any sense in talking about that again, ’cause we’d already decided it had maybe been left there by the kidnapper who had planned to write a note on it and had gotten scared, and left it, planning to come back later, maybe, or something. Anyway, anything we’d said about it didn’t make sense, so why bring it up again? I thought.

“That’s OUT,” I said. “I’m keeping it for a souvenir.” I had it in my shirt pocket and for fun pulled it out and opened it and turned it over and over in my hands to show them that it was37 as white as a Sugar Creek pasture field after a heavy snowfall.

But say, all of a sudden as I spread it out, Poetry let out an excited gasp, and exclaimed, “Hey! Look! There’s something written on it!”

I could hardly believe my eyes, but there it was as plain as day, something that looked like writing—scratches and longish straight and crooked lines, and down at the bottom a crazy drawing of some kind.

YOU can imagine how we felt when we looked at that crazy, almost illegible drawing on that paper, which, when we’d found it, had been without even one pencil mark on it, and now as plain as day there was something on it—only it wasn’t drawn with a pencil or ink or crayon but looked kinda like what is called a “water mark” which you can see on different kinds of expensive writing paper.

All of us leaned closer, and I held it as close to the smoking and flickering candle as I could, so we could see it better, when Poetry gasped again and said, “Hey! It’s getting plainer. Look!”

And Poetry was right. Right in front of our eyes as I held the crazy looking lines close to the candle, the different lines began to be clearer, although they still looked like water marks.

Dragonfly turned as white as a sheet, with his eyes almost bulging out of his head. “There’s a-a-a- ghost in here!” He whispered the words in such a ghost-like voice that it seemed like there might be one.

For a jiffy I was as weak as a cat, and my hands holding the paper were trembly so, I nearly dropped it. In fact, as quick as a flash, Poetry grabbed my hand that had the paper in it and pulled it away from the candle or it might have touched it and caught fire.

Whatever was going on, didn’t make sense. My brain sort of whirled and I sniffed again and thought of something dead, and then of the writing that was on the paper and hadn’t been before, and about Dragonfly’s idea that there was a ghost in the old cabin, and I wished I was outside in the rain running lickety-sizzle for camp, and getting there right away.

But it was Poetry who solved the problem for us by saying, “It’s invisible ink, I’ll bet you. Its being in Bill’s pocket next to his body made it warm, and now the heat from the candle is bringing out what was written on it.”

39 It took only a jiffy to decide Poetry was right, and as we all looked at that crazy drawing, we knew we’d found a map of some kind, and that if we could understand it, and follow it, we would find the kidnapper’s ransom money.

Poetry took out his pencil and because the lines weren’t any too plain in some places, he started to trace them, then he gasped and whistled and said, “Hey, it’s a map of some kind!”

When he got through tracing it, we saw that it was a map of the territory up here, with the different places named, such as the Indian cemetery, the firewarden’s cabin, the boathouse, two summer resorts, and the different roads and lanes running from one to another, also the names of the different lakes on one of which we had our camp.

We all crowded around the table, looking over Poetry’s shoulders, and feeling mysterious and also a little bit scared, but not much ’cause I was remembering that the kidnapper was locked up in jail, and couldn’t get out.

“What’s that ‘X’ there in the middle for?” my Man Friday wanted to know, and Poetry said, “That’s where we initiated you,” and there was a mischievous grin in his duck-like voice.

“WHAT?” I said, beginning to get a let-down feeling.

Dragonfly burst out with a savage sigh, and said, “I might have known there wasn’t any mystery. You made that map yourself.” And was thinking the same sad thing, and said so, but Poetry shushed us and said, “Don’t be funny; that’s where Bill and I found the little Ostberg girl.”

“Yeah,” Dragonfly said, “but that’s also where Robinson Crusoe stepped on my neck!”

“Oh, all right,” Poetry said, “That’s a dirty place on your neck which needs washing.” But Dragonfly didn’t think it was funny, which maybe it wasn’t very.

Just above the X a little distance, we noticed there was a big V, a drawing of a broken twig, and a line pointing toward the cabin where we were right that minute. Also there was a line running from the top of the other arm of the V off in another40 direction and kept on going until it came to a drawing that looked like a smallish mound; and lying across it was a straight short line that made me think of a walking stick or something.

It didn’t make sense until I noticed that Poetry’s pencil had missed tracing part of it, so I said, “Here, give me your pencil. There’s a little square on the end of this straight line.”

I made the square, and then noticed there was a small circle at the opposite end of the straight line, so I traced that, and the whole map was done.

It was Circus who guessed the meaning of the square and the circle I’d just made at the opposite ends of the straight line. “Look!” he said, “it’s a shovel or a spade! That circle is the top of the handle, and the square is the blade,” and we knew he was right.

And that meant, as plain as the nose on Dragonfly’s face, that if we left this house and went back to where our trail had branched off, and followed the broken twigs in that other direction, we’d come to a place where the money was buried.

Boy oh boy, oh boy! I felt so good I wanted to scream.

It was just like being in a dream, which you know isn’t a dream, and are glad it isn’t—only in dreams you always wake up, which maybe I’d do in just another excited minute.

“Is this a dream or not?” I asked my fat goat, and he said, “I don’t know, but I know how I can find out for you,” and I said, “How?” and he said, “I’ll pinch you to see if there is any pain, and if there is, it isn’t, and if there isn’t, it is.” He was trying to be funny and not being, ’cause right that second he pinched me and it hurt just like it always does when he pinches me, only worse.

“Hey—ouch!” I said, and right away I pinched him so he could find out for himself that the map wasn’t any dream, and neither was my hard pinch on his fat arm.

The rain was still roaring on the roof, sounding like a fast train roaring past the depot at Sugar Creek. We all sat looking at each other with queer expressions on our faces and mixed-up41 thoughts in our minds. I was smelling the dead something or other. The odor seemed to come from the direction of the kitchen on account of it was on the side of the cottage next to the steep hillside, which was as steep almost as a cliff, and right above its one window I noticed there was a stubby pine tree growing out of the hill, its branches extending over the roof.

Because the rain wasn’t falling on the window, I opened it and looked out and noticed that water was streaming down the hill like there was a little river up there and was pouring itself down onto the cement walk and rippling around the outside of the cabin. I thought for a jiffy how smart the owners of the cabin had been to put that cement walk there, so the water that swished down the hillside could run away and not pour into the cabin.

It was while I was at the window that I noticed there was an old rusty wire stretched across from the stubby pine tree toward the cabin. I yelled to the rest of the gang to come and look, which they did.

“’Tsa telephone wire,” Dragonfly said, and Poetry, squeezing in between Dragonfly and me and looking up at the wire, said, “I’ll bet it’s a radio aerial!” Poetry’s voice got excited right away and he turned back into the kitchen and said, “There might be a radio around here somewhere.”

With that he started looking for one, with all of us helping him, going from the kitchen where we were, to the main room where the fireplace was, and through the hanging curtains into the bedroom, which had the rollaway bed in it, all folded up against the wall; then we hunted through the screened porch, and looked under some old canvases on the porch floor, but there wasn’t any radio anywhere.

“There’s got to be one,” Circus said. “That’s an aerial, I’m sure.”

Poetry spoke up and said, “If it is, let’s look for the place where it comes into the cabin,” which we did, and which we42 found. It was through the top of a window in the bedroom. But that didn’t clear up our problem even a tiny bit, on account of there was only a piece of twisted wire hanging down from the curtain pole and it wasn’t fastened to anything.

Well that was that. Besides what’d we want to know whether there was a radio for? “Who cares?” I said, feeling I was the leader, and wishing Poetry wouldn’t insist on following out all his ideas.

“Goof!” he said to me, which was what he was always calling me, but I shushed him, and said, “Keep still, Goat! Who’s the head of this treasure hunt?”

He puckered his fat forehead at me, and half yelled above the roar of the rain on the roof, “If there’s a radio, it means somebody’s been living here just lately.”

“And if there isn’t, then what?”

It was Dragonfly who saw the edge of a newspaper sticking out of the crack between the folded-up mattress of the rollaway bed which was standing in the corner. He quick pulled it out and opened it, and we looked at the date, and it was just a week old. In fact, it was dated the day before we’d caught the kidnapper, so we were pretty sure he’d been here at that same time.

Well, the rain on the roof was getting less noisy, and we knew that pretty soon we’d have to be starting for camp. We wouldn’t dare try to follow the trail of broken twigs to the place where we thought the money was buried, because we had orders to be back at camp an hour before supper time, to help with the camp chores. That night we were all going to have a very special campfire service, with Eagle Eye, an honest-to-goodness Chippewa Indian, telling us a blood curdling story of some kind—a real live Indian story.

“Let’s get going,” I said to the rest of us—“just the minute it stops raining.”

“Do we go out the door or the window?” my Man Friday43 wanted to know, and I took a look at the only door, saw that it was nailed shut, tighter than anything.

I grunted and groaned and pulled at the knob, and then gave up and said, “Looks like we’ll use the window.”

It was still raining pretty hard, and I had the feeling I wanted to go out and take a last look at the lake. I’d been thinking also if this cabin was fixed up a little and the underbrush and stuff between it and the lake and a battered down old clock, was cleared away, and if the walls were painted a light color, it might make a pretty nice cabin for anybody to rent and spend a summer vacation in, like a lot of people in America do do. On the wall of the porch I noticed a smallish mirror which was dusty and needed to be wiped off before I could see myself. I stopped just a second to see what I looked like, like I sometimes do at home, especially just before I make a dash to our dinner table—and sometimes get stopped before I can sit down—and have to go back and finish washing my face and combing my hair before I get to take even one bite of Mom’s swell fried chicken.

I certainly didn’t look much like the pictures I’d seen of Robinson Crusoe. Instead of looking like a shipwrecked person with home-made clothes, I looked just like an ordinary “wreck” without any ship. My red hair was mussed up like everything, my freckled face was dirty and my two large front teeth still looked too big for my face, which would have to grow a lot more before it was big enough to fit my teeth. I was glad my teeth were already as big as they would ever get—which is why lots of boys and girls look funny when they’re just my size, Mom says. Our teeth grow in as large as they’ll ever be, and our faces just sorta take their time.

“You’re an ugly ‘mut,’” I said to myself, and then turned and looked out over the lake again. Anyway, I was growing a little bit, and I had awfully good health and nearly always felt wonderful most of the time.

While I was looking out at the pretty lake, some of the44 same feeling I’d had before came bubbling up inside of me. For a minute I wished Little Jim had been with us,—in fact, I wished he had been standing right beside me with the stick in his hand which he always carries with him wherever he goes, almost ... I was feeling good inside ’cause the gang was still letting me be Robinson Crusoe and were taking most of my orders. Sometimes, I said to myself, I’d like to be a leader of a whole lot of people, who would do whatever I wanted them to. I might be a general in an army, or a Governor or something—only I wanted to be a doctor, too, and help people to get well. Also I wanted to help save people from their troubles, and from being too poor, like Circus’s folks, and I wished I could take all the whiskey there was in the world and dump it out into a lake, only I wouldn’t want the perch and northern pike or walleyes or the pretty blue gills or bass or sunfish to have to drink any of it, but maybe I wouldn’t care if some of the bullheads did.

While I was standing there, thinking about that pretty lake, and knowing that Little Jim, the best Christian in the gang, would say something about the Bible if he was there, I remembered part of a Bible story that had happened out on a stormy, rolling lake just like this one. Then I remembered that in the story of Robinson Crusoe there had been a Bible and that he had taught his ignorant Man Friday a lot of things out of it and Friday had become a Christian himself. My pop used to read Robinson Crusoe to Mom and me at home many a night in the winter—Pop reading good stories to us instead of whatever there was on the radio that wouldn’t be good for a boy to hear, and my folks having to make me turn it off. Pop always picked a story to read that was very interesting to a red-haired boy and would be what Mom called “good mental furniture”—whatever that was, or is.

All of the gang nearly always carried New Testaments in our pockets, so, remembering Robinson Crusoe had had a Bible, I took out my New Testament and stood with my back to the rest of the cabin, still looking at the lake. I felt terribly good inside,45 with that little brown leather Testament in my hands. I was glad the One Who is the main character in it was a Friend of mine and that He liked boys.

“It was swell of You to help us find the little Ostberg girl,” I said to Him, “and also to catch the kidnapper, and it’s an awful pretty lake and sky and ...”

Right then I was interrupted by music coming from back in the cabin somewhere, some people’s voices singing a song I knew and that we sometimes sang in church back at Sugar Creek, and it was:

I guessed quick that one of my goats or else my Man Friday had actually found a radio in the cabin and had turned it on. I swished around, dashed back inside and through the hanging curtains into the bedroom where I’d left them, when what to my wondering eyes should appear but the rollaway bed opened out and there, sitting on the side of it, my two goats and my Man Friday and a little portable radio, which I knew was the kind that had its own battery and its own inbuilt aerial. It was sitting on my fat goat’s lap, and was playing like a house afire that very pretty church hymn:

A jiffy after I got there, the music stopped and a voice broke in and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, we interrupt this program to make a very important announcement. There is a new angle regarding the ransom money still missing in the Ostberg kidnapping case. Little Marie’s father, a religious man, has just announced that the amount represented a sum he had been saving for the past several years to build a memorial hospital in the heart of the mission field of Cuba. In St. Paul, the suspect, caught last week at Bemidji by a gang of boys on vacation, still denies knowing anything about the ransom money; claims he never received it. Police46 are now working on the supposition that there may have been another party to the crime. Residents of northern Minnesota are warned to be on the lookout for a man bearing the following description: He is believed to be of German descent, a farmer by occupation, about thirty-seven years of age, six feet two inches tall, weighs one hundred eighty seven pounds, stoop-shouldered, dark complexion, red hair, partly bald, bulgy steel-blue eyes, bushy eyebrows that meet in the center, hook-nose....”