THE ROMANCE

of the

ROMANOFFS

BYJOSEPH McCABE

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1917

Copyright, 1917,

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY. Inc.

PREFACE

The history of Russia has attracted many writers and inspired many volumes during the last twenty years, yet its most romantic and most interesting feature has not been fully appreciated.

Thirteen years ago, when the long struggle of the Russian democrats culminated in a bloody revolution, I had occasion to translate into English an essay written by a learned professor who belonged to what was called “the Russophile School.” It was a silken apology for murder. The Russian soul, the writer said, was oriental, not western. The true line of separation of east and west was, not the great ridge of mountains which raised its inert barrier from the Caspian Sea to the frozen ocean, but the western limit of the land of the Slavs. In their character the Slavs were an eastern race, fitted only for autocratic rule, indifferent to those ideas of democracy and progress which stirred to its muddy depths the life of western Europe. They loved the “Little Father.” They clung, with all the fervour of their mild and peaceful souls, to their old-world Church. They had the placid wisdom of the east, the health that came of living close to mother-earth, the tranquillity of ignorance. Was not the Tsar justified in protecting his people from the feverish illusions which agitated western Europe and America?

Thus, in very graceful and impressive language, wrote the “sound” professors, the clients of the aristocracy, the more learned of the silk-draped priests. The Russia which they interpreted to us, the Russia of the boundless horizon, could not read their works. It was almost wholly illiterate. It could not belie them. Indeed, if one could have interrogated some earth-bound peasant among those hundred and twenty millions, he would have heard with dull astonishment that he had any philosophy of life. His cattle lived by instinct: his path was traced by the priest and the official.

But the American onlooker found one fatal defect in the Russophile theory. These agents of the autocracy contended that the soul of Russia rejected western ideas; yet they were spending millions of roubles every year, they were destroying hundreds of fine-minded men and women every year, they were packing the large jails of Russia until they reeked with typhus and other deadly maladies, in an effort to keep those ideas away from the Russian soul. While Russophile professors were penning their plausible theories of the Russian character, the autocracy which they defended was being shaken by as brave and grim a revolution as any that has upset thrones in modern Europe. Moscow, the shrine of this supposed beautiful docility, was red with the blood of its children. In the jails and police-cells of Russia about 200,000 men and women, boys and girls, quivered under the lash or sank upon fever-beds, and almost as many more dragged out a living death in the melancholy wastes of Siberia. They wanted democracy and progress; and their introduction of those ideas to the peasantry had awakened so ready and fervent a response that it had been necessary to seal their lips with blood.

We looked back along the history of Russia, and we found that the struggle was nearly a century old. The ghastly route to Siberia had been opened eighty years before. Russia had felt the revolutionary wave which swept over Europe during the thirties of the nineteenth century, and the Tsar of those days had fought not less savagely than the rulers of Austria, Spain, and Portugal for his autocracy. Every democratic advance that has since been won in western Europe has provoked a corresponding effort to advance in Russia, and that effort has always been truculently suppressed. Nearly every other country in Europe has had the courage to educate its people and enable them to study its institutions with open mind. Russia remains illiterate to the extent of seventy-five per cent, and its rulers have ever discouraged or restricted education. The autocracy rested, not upon the affection, but upon the ignorance, of its people.

When we regard the whole history of that autocracy we begin to understand the tragedy of Russia. We dimly but surely perceive, in the dawn of European history, that amongst the families which wandered through the forests of Europe none were more democratic than, few were as democratic as, the early Slavs. We find this great family spread over an area so immense that it is further encouraged to cling to democratic, even communistic, life, and avoid the making of princes or kings. We then find the inevitable military chiefs, not born of the Slav people, intruding and creating princedoms: we find an oriental autocracy fastening itself, violently and parasitically, upon the helpless nation: we find the evil example and the tincture of foreign blood continuing the development until Princes of Moscow become Tsars of all the Russias, and convert a title dipped in blood into a title to rule by the grace of God and the affection of the people. And we find that Moscovite dynasty, from which the Romanoffs issued, playing such pranks before high heaven as few dynasties have played, until the old Slav spirit awakens at the call of the world and makes an end of it.

That is the romance of the Romanoffs, of Russia and its rulers, which I propose to tell. This is not a history of Russia, but the history of its autocracy as an episode: of its real origin, its long-drawn brutality, its picturesque corruption, its sordid machinery of government, its selfish determination to keep Russia from the growing light, its terrible final struggle and defeat. To a democratic people there can be no more congenial study than this exposure of the crime and failure of an autocracy. To any who find romance in such behaviour as kings and nobles were permitted to flaunt in the eyes of their people in earlier ages the story of the Romanoffs must be exceptionally attractive.

J. M.

CONTENTS

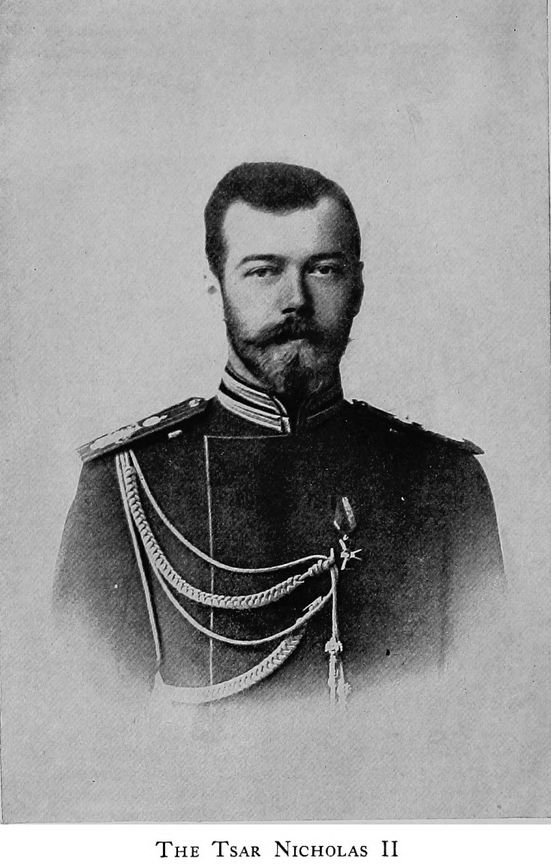

ILLUSTRATIONS

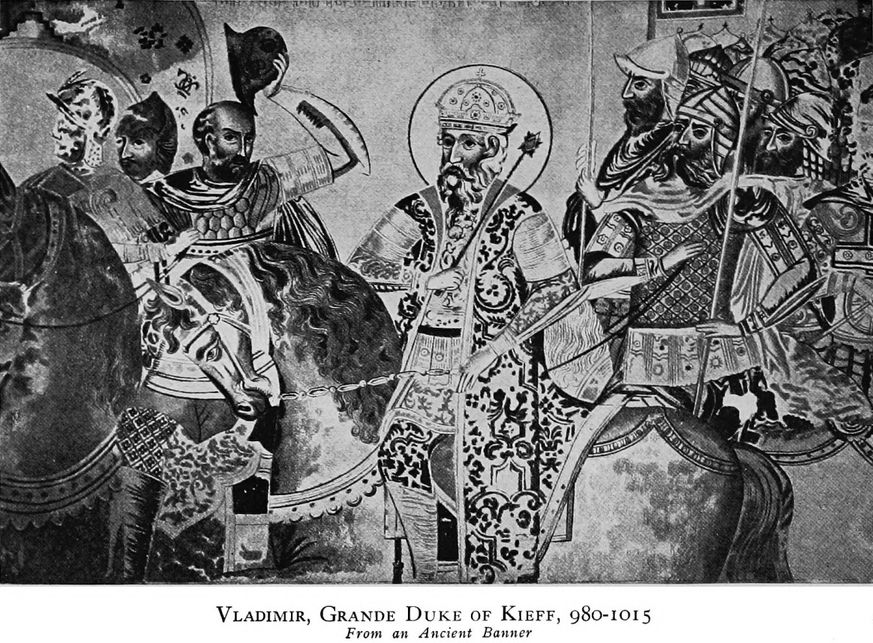

Vladimir, Grande Duke of Kieff, 980-1015 From an Ancient Banner

Costume of Boyars in the Seventeenth Century

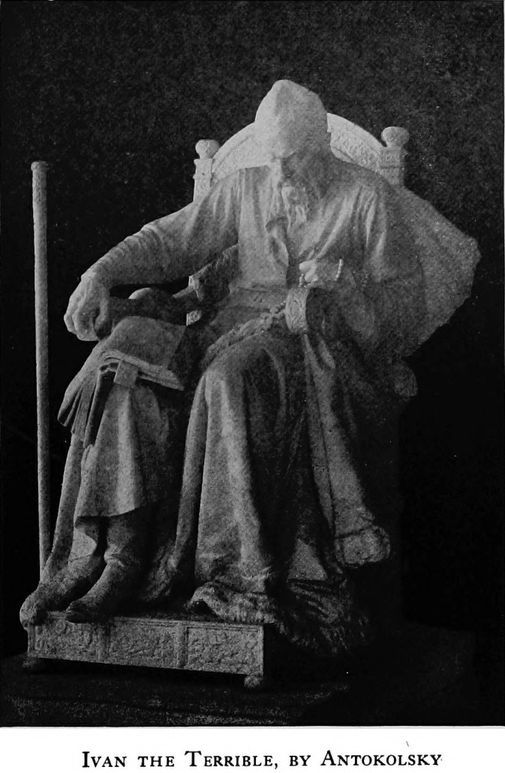

Ivan the Terrible, by Antokolsky

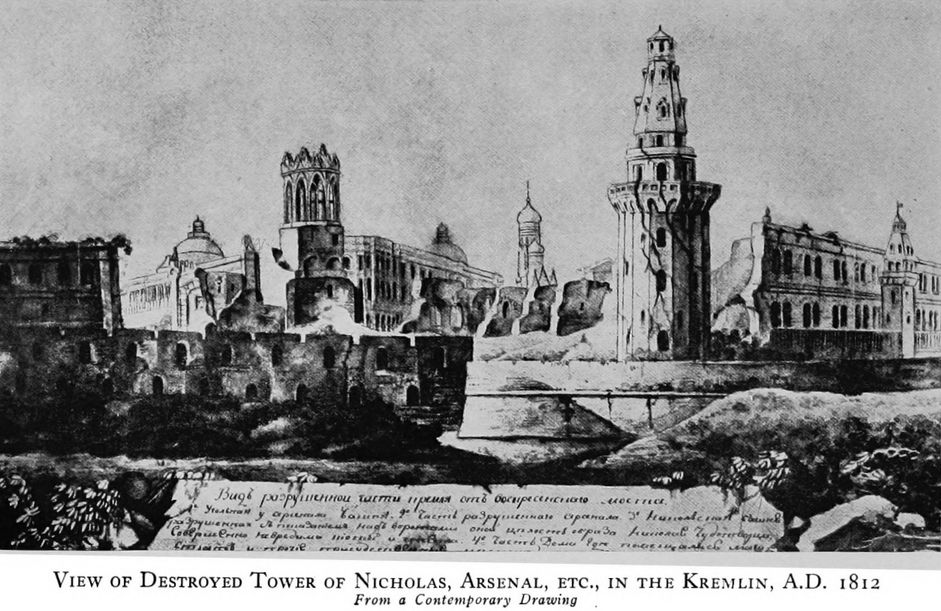

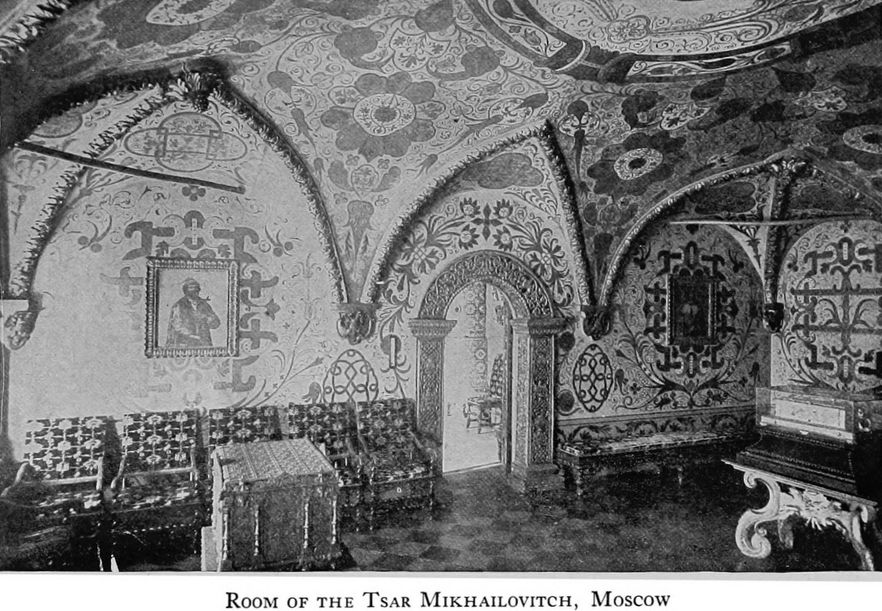

Room of the Tsar Mikhailovitch, Moscow

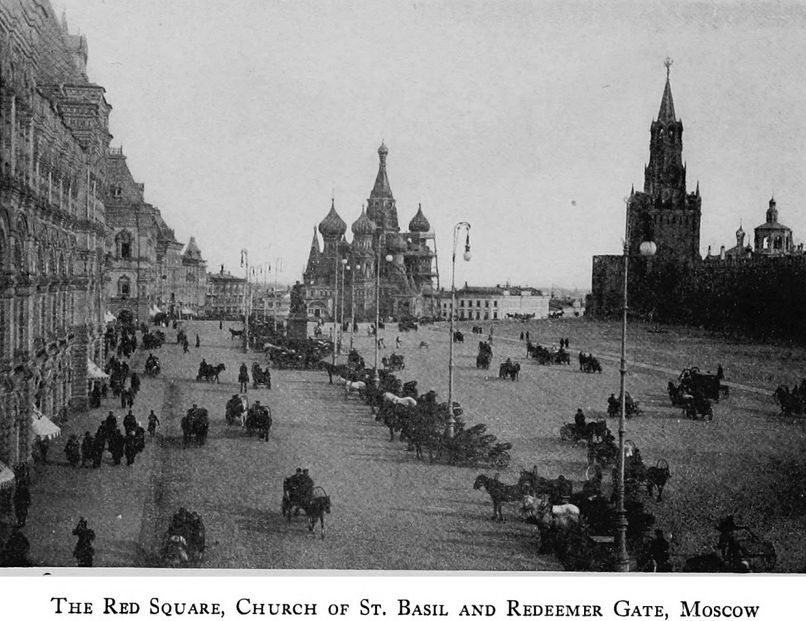

The Red Square, Church of St. Basil and Redeemer Gate, Moscow

Cathedral Erected in Petrograd in Memory of Alexander II

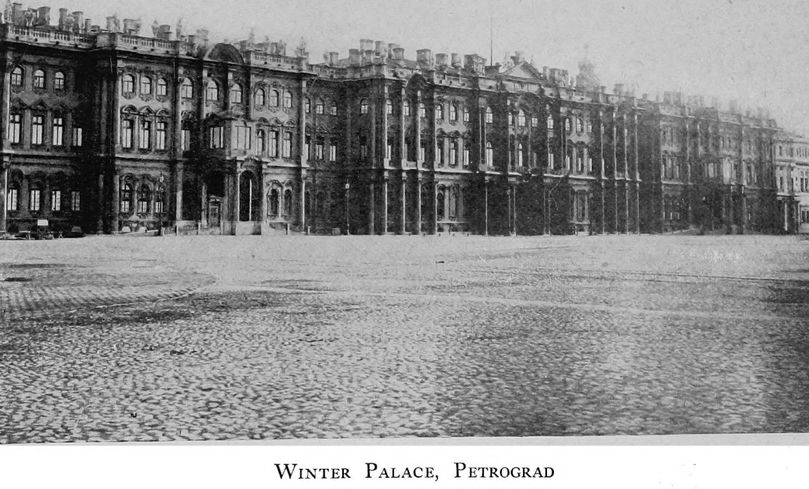

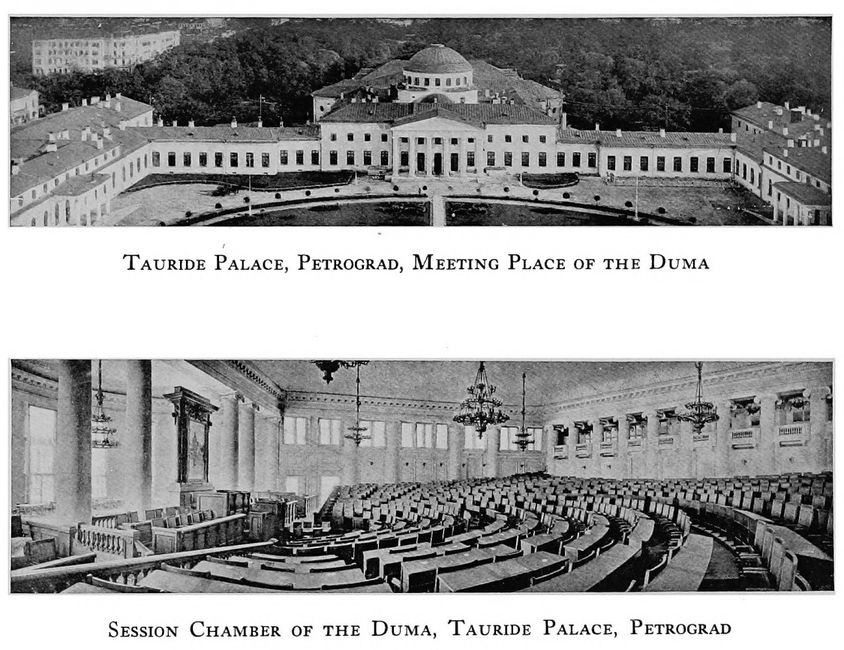

Tauride Palace, Petrograd, Meeting Place of the Duma

Session Chamber of the Duma, Tauride Palace, Petrograd

THE ROMANCE OF THE

ROMANOFFS

CHAPTER I

THE PRIMITIVE DEMOCRACY OF THE SLAV

A little south of the centre of Europe rises the great curve of the Carpathian mountains. The sprawling bulk of this long chain, rising in places until its crown shines with snow and ice, formed a natural barrier to the spread of Roman civilisation. It enfolded and protected the plains of Hungary and the green valley of the Danube, and it seemed to set a limit to every decent ambition. Beyond it men saw a vast and dreary plain filled with wild peoples whom the Romans and Greeks called “Scythians.” It was, in effect, in those days, almost the dividing line of Europe and Asia. One branch of the great European race had gone down into Greece and, becoming civilised, remained there. Another branch had found the blue waters and sunny skies in Italy. A third, the vast horde of the Teutons, was moving heavily and slowly southward in the west.

But about the eastern feet of the Carpathians was a little northern people, the Slavs, which may one day fill the earth’s chronicle when Teuton has followed Greek and Roman into the inevitable tomb of warriors. Where these Slavs came from, and what was their precise kinship to the other northerners and to the Asiatic peoples, we do not confidently know. Some tens of thousands of years before the Christian Era the last spell of the Ice-Age had locked the north of Europe. It seems that a branch of the human family followed the retreating ice-sheet and, in the bracing winds which blew off the frozen regions, shed its weaklings and became the vigorous “northern race.” From this came the successive waves of Greeks and Romans, Goths and Vandals, English and Norman and German. From these northern forests seem also to have come the Slavs, who split at the barrier of the Carpathians into two great streams: Bohemians and Serbs to the west, and Russians (as they were later called) to the east.

We have not much information about this people which settled across the limit of civilisation. To the Romans they were part of the medley of barbarism which got a rude living out of the bleak north. A few later Greek writers had some acquaintance with them, and an early Russian monk, Nestor, gathered their traditions, into a chronicle, and described them as they were before the development of autocracy obliterated their native features. From these sources we learn that the Slavs were singularly democratic for a people at their stage of evolution.

We know to-day the real origin of kingships and princedoms, which was hidden from our fathers by legends of “divine right.” The right of a man to rule his fellows came of his possession of a stronger arm or a wiser head, or a combination of the two: a plausible enough theory until kings began to insist on leaving the power to their sons, whether or no they left them the strong arm and the wise head. As a rule the hunt and the battle gave the strong man his opportunity, and in every other nation at the level of the Slavs we find chiefs, who dispense justice and direct warfare, and exact a reward proportionate to their services.

It is a common and surprised observation of the early writers who notice the Slavs that they had no chiefs. The monk Nestor, who wrote in their midst at the beginning of the twelfth century, says that they had “chiefs,” but would not tolerate “tyranny.” The primitive life of the Slavs had then been modified, as we shall see, but the reports may be reconciled. The Slavs had no hereditary families of chiefs, no rulers of tribes who exacted tribute. Nestor gives a very different character to the various tribes of the Slav family. Being a monk, he is unable to give any of them a good character in their pagan days, but we may make a genial allowance for this natural prejudice. Perhaps some of the tribes, who were in closer touch with the fierce Finns and Scythians, had chiefs. Warfare is the great king-maker. Clearly the primitive and normal condition of a Slav community was exceptionally democratic.

The one definite institution of those early days that is known to us is the village-council; the institution that, being most deeply rooted in the heart of the Slav, has survived all autocracies by divine right and is familiar to-day to the whole world as the Mir. In ancient Slavdom the family was not the basis of the state. It was the state, or there was no state. An enlarged family—for the Slavs were a social and peaceful folk, and the young, founding a new family, clung to the home until it grew too small and some must wander afield—with cousins and children and grand-children, was the unit. The father had patriarchal power in his little colony, and when he departed the next oldest and wisest, a brother generally, took up the mild sway. Such families grew into villages or settlements in a few generations: not too large, for they lived on the land, yet compact, for there were plenty of human wolves east of the Carpathians. The Finns and other Asiatic tribes then filled, or roamed over, the vast area we now call Russia, and their code did not forbid the plunder of peaceful argriculturists. New colonies would be founded near the old and form villages. Out of this grew the Mir, the council in which the heads of the various households met to discuss and decide their common affairs.

No doubt some kind of chairman, some sage elder, would be chosen to preside, but it is clear from later practice and early comment that the council only acted upon a unanimous decision. That form of democracy had inconveniences, and, when Russia begins to have chroniclers, we find that unanimity was often secured, in a struggle, by pitching the minority into the river. That, at all events, was the original Slav custom. In theory even a majority could not tyrannise over a minority, much less a minority over a majority.

There would be frequent calls for these village-councils, as the land, on which most of them worked, was held in common. The head of a family owned only his house and enclosure, and was entitled to the harvest of his own labour. Then there were the rights of hunting in the forest and fishing in the rivers, the constant need to send out new colonies into the eastern wilderness, and especially the need to protect these new colonies from the wandering Asiatics. Flanked by the Carpathians, up which they could not spread, the tribes had to push steadily eastward, and the land was full of Asiatics, for the most part swift and ruthless horsemen. Co-operative defence was as necessary as co-operative counsel. The elders of many neighbouring villages met together in a larger council. There was a rough organisation of villages into a canton or Volost. Again there would probably be a president, and some think that a temporary chief or leader might be appointed in an emergency. But the Slavs had no hereditary rulers, no heads of the various tribes.

It also helped to sustain their democratic and communistic life that they had no priests. When priests later come upon the scene we shall find them very easily becoming the instruments of autocracy. We shall find, as is usual, the autocrat enriching the clergy, and the clergy discovering very impressive legends upon which he may establish his title to rule. In the pagan days of the Slavs there were no priests. The religion was the kind of primitive interpretation of nature which we always find at that level of mental development. The fire of the sun, the roar of the storm, the mysterious fertility of the earth, and the awful solemnity of the forest filled the child-like mind with wonder and dread. These things were felt to have life, a greater life than the puny and limited life of man; and the Slavs learned to bow down to the mighty spirits of the sun and the river and the wind and the earth. In particular they mourned the death of the sun, and celebrated joyously its annual re-birth and restoration to full glory. But they had no priests. The heads of the family or the village performed the invocations and the sacrifices.

We must remember that even in these primitive and patriarchal arrangements there was the germ of autocracy. The eldest male was an autocrat. So absolute was his power that it is said that, when he died, wife and servants and horse had to follow him into the nether world. There seems here to be some confusion between different tribes, and there is evidence that, as among the Teutons, woman was generally respected; although there were ancient marriage-rites which suggest that at one time brides were stolen, and there was some practice of polygamy. However that may have been, the father of the household was an autocrat. We may plead only that he does not seem to have had, as in ancient Rome, power of life and death over his mate.

Such was the Slav people when we first discover them about the feet of the Carpathians. We have next to see how they became the Russian people, and how contact with civilisation and the growth of commerce modified their primitive communism.

The towering masses of the mountains checked the western expansion of the growing tribes. The Danube and the outposts of the Roman Empire—the fathers of the Rumans—shut them from the south. They were, as their number increased, bound to travel eastward, and their pioneers would discover that the central part of this mighty waste of eastern Europe was a particularly fertile region. From the foot of the Carpathians the land spreads in one of the largest plains of the world until it begins to rise toward the Ural mountains. Between the forests and bleak deserts of the north and the arid prairies of the south there are about a hundred and fifty million acres of “black earth,” as rich and fertile as any to be found, and south of these a hundred and fifty million acres of ordinary arable land. At the beginning of the Christian Era this great area would be for the most part forest and morass, chequered by vast spaces of grassy plain, furrowed by broad rivers. The advancing colonies of the Slavs would discover the fertility of the soil and clear the ground for their corn and flax. The rivers gave them abundant fish. The forests swarmed with animals which afforded fur and meat, and the innumerable wild bees gave them stores of honey and wax for the long winters. Timber for the vapour-bath, which the Slav family seems already to have held in affection, lay on every side.

We find the Slavs especially spreading over this fertile heart of Russia about the eighth century of the present era. The land had long been held by the Finns and other Asiatic tribes when, in the third century, the Goths from the north fell upon them and drove them eastward. In the next century began that more formidable invasion from Asia which flung the Finns westward once more, and cast the Teutons upon the crumbling barrier of the Roman Empire. In the seventh century a new semi-civilised race, the Khazars, created an empire in south-eastern Russia, and drove the Asiatic Finns definitely to the north. It was at the close of these great movements that the Slavs moved rapidly over the fertile regions, between the land of the Finns and the southern kingdom of the Khazars, By the end of the eighth century the various Slav tribes had overrun the central part of western Russia.

The chief change which this migration caused in the life of the Slavs was the development of commerce. The great rivers of the land at once became the highways. Fishers as well as tillers of the soil, the Slavs would spread along the river-valleys, and the junctions of the rivers would naturally become the chief stations for what intercourse there was between the scattered villages. It is probable that in those days, when four-fifths of Russia was marsh and forest, the rivers were deeper than they are to-day. In our time they are for the most part shallow throughout the summer. Only in the spring, when the melting snows and rains flush the broad channels, can large boats ascend them; and in the winter their frozen waters make good passage for the sledge. They became the high-roads of the new commonwealth, as the site of the older cities indicates when one glances at the map.

The Slavs had at that time probably little or no commerce. Some exchange, in kind, of fish, fur, honey, or corn might take place, but the resources were much the same for each village. In a short time after the settlement, however, a busy commercial system was inaugurated. Further north than the Finns were the Scandinavians, whose skill in metal-working was early developed. The Slavs traded with them for swords and spears and axes.

To the south, beyond the land of the Khazars, was the chief representative of civilisation in the west, the Byzantine (or Constantinopolitan) Empire. The northern tribes had now shattered Roman civilisation. The solid roads, the ample schools, the courts of law and municipal institutions established by the Romans in southern Europe were in complete decay, and four-fifths of the city of Rome was a charred and desolate wilderness. But the city which Constantine had founded on the Bosphorus, on the site of ancient Byzantium, lay out of the path of most of the barbarians, and the glory of Constantinople penetrated feebly into the distant forests of Russia. Its soldiers give us our first direct knowledge of the Slavs. Its merchants crossed the Black Sea, ascended the rivers of Russia, and spread before the eager eyes of the Slavs the silks and damasks and velvets, the shining metal-work and imitation-jewels, of the great “Tsargrad,” or City of the Emperors. For these the Slavs could offer choice furs, for an enormous variety of fur-clad animals roamed their forests, as well as honey for the table and wax for the myriad tapers of the Byzantine churches.

This busy commerce increased the importance of the settlements at the junction of the rivers. The evenness of the Russian plains, the great depth of soil or clay or glacial rubbish which uniformly covers the level strata below, make stone scarce in the greater part of the country then occupied by the Slavs. The ordinary village was a cluster of rude huts made of timber, with roofs of straw and mud. The towns also were of timber, and the accumulation of merchandise in them for traffic or fairs attracted the Asiatic marauders and increased the need of defence. The Véché, or democratic council of the district, grew in importance. Stockades of timber were erected. The Slavs, preferring peace as an agricultural people always does, were compelled to acquire some skill in the art of war.

Up to this point, the ninth century, the democracy of the Slavs was unaltered. The villagers were still free and independent men, while the peasantry over the rest of Europe were slaves or serfs. They regulated their own affairs in their Mir, recognised no central government, and paid tribute to neither chiefs nor priests. There was plenty of timber to heat their stoves during the long winter, and in the summer the song and dance cheered the leisure from their labours. The plot of corn and the nests of the wild bees fed them; the plot of flax clothed them; and the winter harvest of furs, taken to the nearest town or fair, gave them many a tawdry luxury from the great cities of the south. Even in the towns they had still no money or currency. It was not until long afterwards that they cut disks of leather to serve the purpose of coinage. And even in the largest settlements or towns, such as Novgorod in the north and Kieff in the south, the democratic council, with unanimous decision, ruled their little affairs.

The defect of a primitive democracy of this nature soon became apparent. When the less peaceful neighbours who surrounded them on every side made an attack in force the isolated towns or communities could not defend themselves. The Khazars of the south overspread the nearest Slav districts and virtually enslaved them. The Scandinavian pirates of the Baltic pushed southward from the coast and wrung tribute from them. Either they must establish a compact military organisation, which their loose social texture did not easily permit, or they must hire defenders. They chose the latter course, not knowing, as we do, the ultimate price of engaging military chiefs.

The Scandinavians or Norsemen were as little pacific as any people of Europe, and their large frames and mighty weapons made of them formidable warriors. The Slavs were well acquainted with them. Somehow they had found the way across Russia to Constantinople, where their services were richly paid. From the southern shores of the Baltic they descended the northern rivers, and, crossing short stretches of country from river to river, they sailed down the broad waterways to the Black Sea. In the ninth century the Slavs were familiar with the tall, blue-eyed, blond-haired giants, with heavy spears and formidable axes. The Greeks of the south, who called them Varangians, clothed them in rich armour and made of them a special imperial guard. The Slavs called them Rus, or “sea-farers” (if not “pirates”), a name they seem to have borrowed from the Finns.

This, at least, is what modern scholars make of the ancient legend, given in Nestor, that the men of Rus were foreign warriors invited by the Slavs to come and settle and undertake military service. The story runs that the Slavs of the north, wearied by invasion and pillage, invited these soldiers to defend them and share their goods. Some historians suspect that the legend may be invented by the vanity of the Slavs, who did not care to confess that the northerners had subdued them, but it is not unlikely that they were invited to defend the Slavs as they were invited to defend the Emperors of Constantinople. They had already shown the Slavs that those who did not pay voluntarily might have to pay involuntarily. As the democratic institutions of the Slavs survived most strongly in the city where the Norsemen first settled, Novgorod, it does not seem as if they settled in virtue of conquest. In western Europe the northerners, wherever they settled, established the feudal system, which never existed in Russia.

The story handed down in Russia—as the land of the Slavs soon came to be called—was that three brothers, Rurik, Sineus, and Truvor, answered the call of the Slavs, and, with their kinsmen and followers, settled on the Baltic coast. This is assigned to the year 862. From those seats they cannot have defended, or raised taxes from, much of Russia, but when Sineus and Truvor died Rurik went to settle in Novgorod. That city, about a hundred and twenty miles south of Petrograd, was the chief town in the northern part of the route from north to south. Rurik seems to have built a stone fort overlooking the timber settlement and been content with a kind of tribute for his military services. Novgorod remained until centuries afterwards a jealously democratic community.

The chief Slav town in the south was Kieff, and to this two of the unruly officers of Rurik’s troop, Askold and Dir, led a company of the northerners. As is well known, these northern barbarians, once their barriers were broken down, wandered from end to end of Europe, and even to Carthage and Alexandria, terrifying the natives everywhere with their gigantic frames, their immense axes and swords, their guttural grunts, and their infinite capacity for liquor. The Slavs of Kieff, voluntarily or involuntarily, received the warriors, and a fresh colony of men of Rus was planted. They seem to have infected even some of the Slavs with their piratical spirit, for we read of them leading an expedition down the river and across the Black Sea against Constantinople itself.

The next step was to unite the towns of Novgorod and Kieff, and bring the remainder of the Slavs under the vague lordship of the Norsemen. This was done by Rurik’s brother and successor, Oleg. The Teutonic rule of hereditary succession came in with the northerners, and the men of Novgorod seem to have had no further choice. Oleg assumed command, and he marched his troop against the smaller body of his countrymen in the south. Askold and Dir had, he said, acted without orders, and had usurped a lordship which belonged to his brother. Kieff had no more choice than Novgorod. Oleg found it a finer town than the settlement among the marshes of the north. He set up there his court of brawling, drunken warriors, and gradually induced all the tribes of the Slavs to pay him tribute and furnish soldiers. He was so successful that one year he embarked his men on two thousand boats, led them against the imperial city, and forced the Greeks themselves to add to his treasury.

The land of Rus was in those days not the spacious Russia of our time. It spread little eastward beyond Novgorod and Kieff, and it was bounded by the Khazars to the south and the Finns and Lithuanians to the north. But it was now Russia, a group of Slav tribes dominated by a military caste. It was, however, not yet a nation, certainly not a monarchy. Tax-gathering and defence were the sole duties of the military chief, and as the Slavs had demanded the one they were not unprepared for the other. But the germ of autocracy was now planted in the soil, and the terrible events of the next few centuries would foster its baleful development.

CHAPTER II

THE DESCENT TO AUTOCRACY

It is sometimes said that the Slav people lost its democratic institutions because it was too pacific to defend them. It is true that an agricultural people would tend to be more pacific than hunting tribes like the Asiatics who surrounded them, but the native peacefulness of the Slav has probably been exaggerated. The early Russians seem to have been as much addicted to hunting and fishing as to tilling the soil, and the long winter, when all agricultural work was suspended for six months, would encourage the men to hunt the furry animals which abounded. Certain it is that both the monk Nestor and the Greek Emperor Maurice represent the primitive Slav as far from meek, and the chronicle informs us of constant and even deadly quarrelling.

The truth is that the democracy of the Slavs was too little developed. It was nearer akin to Anarchism than to Socialism, and the mind of the race was not as yet sufficiently advanced to grasp the political exigencies of the new situation. There was no national consciousness, and there could be no national defence and administration, because there was no nation; and a body of disconnected communities, scattered over a wide area, was in those days bound to succumb to marauders.

Russian historians of the official school eagerly point out that the situation plainly called for a monarchic institution, and that the monarchs rendered great service in welding the scattered communities into a nation. That they did unite the people and make the great Russia of to-day is obvious. It is equally obvious that, with rare exceptions, they did this in their own interest, and that in all cases they exacted a reward which made serfs of the independent Slavs, sowed corruption amongst the rising middle class, and laid upon all an intolerable burden.

The period of the Norse warrior-chiefs and their descendants lasted about three centuries, and it fully exposes the fallacy of the monarchic principle. From being military servants the Norsemen rapidly became, as is customary, princes and parasites. As long as they discharged their duty, binding the communities and securing for them the necessary peace against external foes, this departure from the primitive democracy might be regarded as merely a regrettable necessity. But the sheep soon found that the protecting dog was first-cousin of the wolf, The principle of hereditary succession and the practice of providing for all sons and relatives soon led to a worse confusion than ever, and the distracted and weakened country was prepared for a foreign invasion. The long and sanguinary history of the descendants of Rurik may be briefly sketched before we see how the autocratic Mongols beat a path for the autocratic Tsars.

Oleg, who had united the Slav tribes under his ill-defined rule, was murdered in the year 945. To the north of Kieff a tribe known as the Drevlians (“tree-folk”) wandered in the forests and paid a reluctant and uncertain tribute in furs. When Oleg tried to enforce his tax upon these, they captured him and tied him to two young trees in such fashion that, when the bent trees were released, Oleg’s body was torn asunder. Oleg’s widow, Olga, was a handsome Valkyrie of the masterful northern type, and she sent her armies to scatter the thunders of Thor among the wild foresters. It is said that she afterwards visited the Greek capital and was won to the Christian religion. She lives as St. Olga in the calendar of the Russian Church. Her successor involved the Russians in long and terrible wars with Constantinople, to enforce his ambitious claim to Bulgaria, and at his death the fierce feuds and murders of his three sons plunged the country into a condition of bloody anarchy.

From this sordid strife of the shepherds whom the Slavs had hired to protect them there emerged in 972, over the corpses of his brothers, the blond beast St. Vladimir, the founder of Christianity in Russia. To what extent the lusty and lustful Prince Vladimir was, as the priestly chronicles maintain, transformed into a saint during his life we need not stay to consider. He seems to have been converted as superficially as his prototype, the Emperor Constantine. He was married to a beautiful nun who had been torn from a convent during one of the raids upon the Greek Empire, and whom he had taken from his murdered brother; and thousands of concubines relieved the comparative tedium of her companionship. The monastic chronicle tells us, in trite language, that he at length wearied of sin and sought more substantial spiritual aid than the paganism of his fathers could afford. Judaism, Mohammedanism, and Christianity now offered their rival assurances to such a promising penitent, and it is said that Vladimir, with the broad-mindedness of a modern Japanese, sent his servants to inquire into the merits of the three religions. The rich ritual of the Greek Christians at Constantinople prevailed over the more sober practices of the Mohammedans and the less consoling assurances of the religion of the Old Testament, and Vladimir became a Christian and a saint.

But the chronicles also recount that Vladimir, whose principality of Russia was now so important that it could sustain wars with the Greeks, sought a matrimonial alliance with the royal house of Constantinople, and the prosy imagination of our time finds here a safer clue to the development. The Emperors Basil and Constantine replied that the hand of their sister Anne would be bestowed upon the experienced barbarian if he would consent to baptism; and Greek priests, who were apt also to be courtiers, were sent to expound to him the new religion. Vladimir readily consented to pay so small a price for so great an honour and advantage. He threw into the river the idols of the Russian gods—these carven figures had been introduced since the settlement in Russia—and lent his energy and truculence to the extirpation of paganism. His people were driven in troops into the rivers, the Greek priests pronounced over them the sacred formula, and in a very short time the nature-gods of the old Slavs and Norsemen were turned into devils and the cross of Christ glittered above gilded domes in the wooden settlements of the land. Vladimir was so generous to the new clergy that he died in the odour of sanctity.

But the sins of Vladimir’s pagan manhood lived after him. Seven sons, by various legitimate mothers, claimed the succession to his dominions, and there ensued such bloody anarchy as the handsome Teutonic princes, no matter what gods they worshipped, knew how to create. As usual the fitter to survive in such a world—the more lusty and less scrupulous—emerged from the struggle, and Prince Iaroslaf, one of the heroes of early Russian history, reunited the various regions under his rule.

Iaroslaf has been compared, not quite ineptly, to Charlemagne. From Novgorod, which his father had left him, he cut his way to Kieff, and definitely made the southern city the metropolis of the country. Kieff was enriched and adorned with a splendour which, in the mind of the Russians, rivalled that of Constantinople. The southern rivers now bore thousands of Greek artists and architects, musicians and scholars, priests and courtiers, to the new capital of barbarism. Four hundred churches soon shone like gilt mushrooms in the summer sun, and the grateful clergy discovered that a monarchy which rested on a divine foundation in Constantinople could hardly have an inferior basis in Kieff. Iaroslaf, it is true, was not a monarch in title, Russia had no constitution or political organisation. It was still semi-barbaric in culture and judicial procedure. The duel, the ordeal, and the payment of blood-money still flourished, and literacy existed only in the form of feeble lamps here and there in the vast darkness. It must be remembered that Constantinople itself was, with all its splendour of gold and mosaics and jewels and silks, half barbaric in its moral complexion. The most sordid and brutal crimes disgraced its palace-life on the shores of the Sea of Marmora, and the most revolting penalties of vice and crime were publicly inflicted. The discovery by modern apologists that there was a glow-worm here and there does not relieve the terrible gloom of the Dark Ages.

In such an age, amidst so scattered and helpless a people, Iaroslaf needed no kingly title to enable him to act as monarch. To sustain the new splendour of Kieff and his court—his sister and daughters married into the royal families of Poland, Norway, France, and Hungary—a larger tribute from the people was needed, and it was not meekly solicited. Russian historians of the old school have dilated upon the magnificence with which Iaroslaf invested his capital and the measure of prestige which Russia gained in the eyes of the world. They do not point out that this concentration of light at Kieff and the court darkened the life of the Russian people. For the first time we now encounter the odious name for a child of the soil moujik. Foreigners who lightly repeat that name to-day are unaware that it is in origin a term of disdain. It means “mannikin.” The warriors in glittering armour or shining silks who gathered about the court were the prince’s “men.” The vast mass of the people, whose labour ultimately paid for this magnificence, were “mannikins.”

The burden fell most heavily upon the scattered peasantry. Not only were the “legitimate” taxes wrung from them, but the military leaders exacted tribute to support their own splendour and pleasure. The feudal system, which now prevailed over the remainder of Europe, was not introduced. The land was still the possession of the people, and military chiefs remained about the court instead of raising, as they did where stone abounded, massive provincial castles from which they might enslave the peasantry and even defy the ruler. But in their excursions the soldiers behaved as wantonly as feudal barons of the west, and the people sank under the burden. Slavery still flourished in Christendom, and many a Slav found his way to the distant market at Constantinople. Moreover, under the degenerate Greek influence there was introduced the practice of flogging and torture which the rough chivalry of the northerners had hitherto avoided.

To say that the unity of faith, the protection against invaders, and the introduction of art and a small amount of mediocre culture compensate for these evils is an historical mockery. The death of Iaroslaf at once revealed the insecurity and selfishness of the regime he had established. It was followed by two hundred years of civil warfare and murderous confusion. Eighty-three struggles which seem worthy of the name of wars devastated Russia during those two centuries, and over the enfeebled frontiers the waiting tribes repeatedly poured while the guardians of the Russian people slew each other for their petty principalities. Sons, legitimate and illegitimate, abounded in that world of blond warriors, and the successful chief provided for each out of his dominion. Titles were disputed, or the old title of the longer sword was boldly advanced. A dozen large principalities were carved out of the princedom of Iaroslaf, and fragments of these were constantly detached by heredity and restored by war.

It is not my intention to follow the grisly chronicles over this prolonged anarchy and select for admiration the heroic butcheries of some strong-armed soldier. For our purpose it suffices to notice that the mass of the Russian people were, as a rule, the passive and suffering spectators of this brutal pandemonium. During the summers they sowed and gathered their corn and flax, and the long winters occupied them with the making of clothes and the quest of fur. The Mir was still the centre of every village. But a tithe of its produce had now to go to sustain this costly petty monarchy, a tithe to support the whitened monasteries and gold-domed churches, and a tithe to repair the damage when the tornado of civil war or some fierce band of Asiatics had passed over their district. There were, we shall see, provinces of Russia where the larger intelligence of the townsmen saw that the proper thing to do was to form a strong republic, armed in its own defence. These still hated “tyranny” and sustained the old tradition of the race. But the greater part of the Russian people were not sufficiently developed to perceive this, or were too scattered to achieve it, and they sank under the military power they had invited to serve them.

A few pages borrowed from the story of this dark period of anarchy will suffice to explain how Russia was prepared for the later schemes of the Moscovites. Kieff remained “the mother of Russian cities,” and it was natural that, as its princes founded petty princedoms here and there for their descendants, the more ambitious of these should invent a title to the rule of the metropolis itself or found rival cities. One of the chief of these new principalities was Suzdal, on the Volga and the Oka. Here, at the extremity of the Russia of the time, a large dominion was created out of the marshes and forests, and braced by incessant conflicts with the neighbouring Finns. George Dolgoruki, who, after failing to get Kieff, had founded this principality, regarded it as in an especial sense his own creation and possession, and his monarchic sentiment was strengthened.

But the democratic tradition was not wholly obliterated, and the military caste itself—the boyars, or captains of the troops—formed some check upon the will of the prince. George’s successor, therefore, Andrew Bogolyubski, an astute and ambitious man, made a new capital of a small town or village called Vladimir. Andrew possessed the supposed miraculous painting of the face of Christ, which had once been the great treasure of Constantinople, and he professed that this gave him some special measure of divine guidance. He pitched his camp near the village of Vladimir, and shortly afterward the people of Suzdal heard with consternation that he had been divinely directed to convert the little settlement into his capital. Andrew had the great advantage of being extremely pious and generous to the clergy, as nearly every great Russian adventurer has been. The priests warmly supported him, and Vladimir soon grew into a city.

Kieff still had an immeasurably greater splendour, and was in closer touch with Constantinople. Andrew raised a large army and led it south against the metropolis. A three days’ siege was followed by three days of such pillage that Kieff lost forever its supremacy. Even the churches and monasteries were looted, and the golden treasures of both palace and cathedral were carried off to enrich the aspiring city of Vladimir. Flushed with this and other triumphs Andrew then turned his arms against the republic of Novgorod, where the old democratic spirit was best preserved, and, after fierce fighting, compelled it to accept a prince of his own nomination. He extended his rule in other directions, setting a conspicuous example of autocracy and ambition to the Princes of Moscow who would later issue from his blood. But Russia was not yet reduced to the state of servility which Andrew’s design of supremacy required. In 1174 his powerful boyars rebelled and assassinated him, and the oppressed people rose in turn and vented their democratic sentiment in the pillage and slaughter of the rich.

This is but one outstanding figure amidst the host of brutal soldiers or scheming princes who fill the chronicle of the time with blood. It is a wearisome repetition of the same process. A strong or unscrupulous man unites a large part of Russia under his sway, then a group of less strong, but not less ambitious, sons and grandsons fight for the spoil over the helpless bodies of the peasantry. Those who succeed must reward their boyars and the clergy, and the land of Russia passes more and more into the hands of large proprietors and is worked by slaves. “If you want the honey, you must kill the bees,” was the characteristic remark of one of these descendants of Rurik, as he despatched his victims; and the little restraint which their new faith imposed upon them may be gathered from the flippant retort of another princeling, who was accused of breaking an oath solemnly made over a cross: “It was only a little cross.”

There were, as I said, northern parts where the democratic evolution proceeded healthily. Novgorod, a large northern city of a hundred thousand souls, rising in the centre of a beautiful plain fringed by forests, had become a republic with wide territory and three hundred thousand subjects beyond the rude defences of the city. There is a legend that it had rebelled even against Rurik, the first Scandinavian adventurer. It accepted, of its own choice, what had come to be called princes, but it endorsed or rejected them, and curtailed their powers, with a good deal of civic pride and independence. “Come and rule us yourself or else we will choose a prince,” the citizens said to a Grand Prince of Kieff who ordered them to receive his nominee. To another Grand Prince, who would send his son to govern them, a later generation of citizens replied: “Send him—if he has a head to spare.” They had even an independent Church and elected their archbishop. The old democratic Véché, or council of citizens, was the central institution of the city, and the great bell summoned all to the market-square whenever some business of importance called for a decision. The neighbouring republics of Pskoff and Viatka were hardly less faithful to the democratic tradition. While these territories were the farthest from Constantinople, they were nearest to Germany and the Baltic, and they were enriched by the commerce which was then beginning to civilise the northern cities.

Even Novgorod, we saw, felt the heavy hand of Andrew of Vladimir, and the remainder of Russia steadily lost its vitality under the drain of civil war. Upon this distracted and enfeebled population there now fell an autocratic ruler of the most arbitrary character. The year 1237 is, in the chronicles, one of calamities and portents. The fires which so often devoured the timber settlements of the Slavs were more numerous and destructive than ever. Drought and famine made haggard faces over large regions, and from the sky a terrifying eclipse and other portents seemed to mock their prayers for deliverance. As the dreadful year passed a new evil broke upon them. Into the southern principalities poured crowds of fugitives from the east, who told that immense hordes of ferocious and inhuman horsemen were covering the land and completing its desolation. Toward the close of the year the first wave of the Tatars shook the southern frontiers of the Slavs.

Asia had, as well as Europe, its adventurers, and the baleful dream of conquest had lit the imagination of a Tatar chief, Dchingis Khan, amidst the dreary wastes of Siberia. Gathering about him the rough tribes of his race, a swarm of hardy shepherds who knew not what a house, much less a city, was, he led them against the civilisation of the south. His men lived in the saddle, and each was a master in the use of the bow, the sabre, and the lance. Camels and buffaloes bore their (at first) scanty possessions, and they moved with all the speed of devouring nomads. The villages of Manchuria, the tame and placid cities of China, and all the wide spaces of central Asia were successively overrun and forced to pay tribute. From the civilised Chinese the wonderful and profoundly ignorant barbarian quickly learned the art of gathering taxes and enjoying luxury, and he moved further west in a vague design of conquering the earth.

This strange and terrifying horde, a cloud of fiercely yelling centaurs with troops of animals which no Russian had ever seen, first fell upon the southern Russians in 1224. Their method was to press the peasantry into their service and attempt to disarm the towns with hollow assurances of friendship, but, in whatever way the town was taken, there followed a merciless slaughter and a thorough pillage. The Russians, alarmed by the reports of the outlying tribes, sent out a great army to meet the Mongols on the steppes, and were crushingly defeated. The Mongols had, however, retired to Asia, where their dominion was not solidly established, and it was a vaster army, under a new Khan, that appeared in the south of Russia in 1237.

From 1237 to 1240 the Khan Batu led his army of 600,000 men, with appalling destruction, across the various principalities of Russia. Weakened by their feuds, severed by their selfish rivalries, the various provinces fell one by one under the feet of the merciless invaders. Rape, murder, fire, and pillage were the invariable sequels of success. The Russians appealed to the nations of the nearer west to help them to dam this Asiatic flood, but the Latin Christians were not minded to stir themselves for semi-barbarians who did not respect the Pope. When the Khan passed over the prostrate body of Russia and advanced still further, in his determination to conquer an earth of which he knew less than a child in a modern infant-school, the Poles and Hungarians at length spread their barrier of steel across his path. But the check did not now profit Russia. Batu retired upon Russia, built a city, Sarai, on the banks of the Volga (beyond the limits of the principalities), and began a life of organised parasitism upon the unfortunate people. The comparative unity brought about by their Norse defenders had prepared the way for the Khan. The Khan was to prepare the way for the Moscovite.

Again we may ignore the crowded details, the rise and fall and eternal feuds of petty princes, of the Russian chronicle. What matters is that the entire country which was then known as Russia was overspread by a network of tax-gatherers, and the people learned to tremble at the commands of a distant autocrat. At Sarai the Mongols established a court of barbaric magnificence, and this in time declared itself independent of the Tatar Empire in Asia and sought the nourishment of its luxury in Russia. The western sovereignty came to be known throughout Europe as the Golden Horde, and the western nations heard with indifference the cynical extravagance and the occasional brutality with which it treated schismatic Slavs.

No prince could now don his tattered dignity in Russia without the august permission of the semi-civilised ruler on the Volga, and a system was soon evolved which enabled the courtiers and concubines of the Khan to share the good fortune of their lord. In the constant disputes about succession claimants to the various Slav principalities made the perilous journey to Sarai, and the richness of the presents they brought sufficed to illumine the obscurity of their titles. Occasionally a prince whose loyalty to the Mongols was suspected was summoned to Sarai, and not a few who could not pass the humiliating tests left their bones among the Mohammedan Tatars. To those who bent their backs or tendered the cup with servile respect the Khan was gracious. They returned with power to extort the taxes for the Tatars and a large additional sum for themselves. If their people or rival princes were restive, a troop of the dreaded Tatar horse was put at their disposal, and the lash and the sabre cowed every attempt at revolt. The spying and flogging with which the servants of the Khan protected their master’s interests were copied by the Slav-Norse princes. The Byzantine civilisation had itself introduced many devices of autocratic barbarism, for the jails of Constantinople, especially the dungeons of the superb imperial palace, witnessed ghastly tortures and mutilations. The cruelty of the Asiatic completed this machinery of the later Tsars; and the Princes of Moscow were the readiest of all to be the tax-gatherers of the Khan and the pupils of his unscrupulous ministers.

The scattered Slavs had, after the three or four years of terror, returned from the forests to their burned villages and their plundered towns. The gold and silver had gone from their churches: the inmates of their nunneries were the playthings of the Asiatic officers: their democracy was a mockery. Their industry soon healed the torn face of the country, but lands and lives now belonged to the foreign master. One-tenth of all their produce must be paid in taxes, and they might at any time be summoned to do military service. Kieff was in large part a ruin; Suzdal, Moscow, Riazan, and other cities were despoiled. Even Novgorod and Pskoff had, after a bloody resistance, to present their fleece to the shearer.

The miserable condition of the Slavs was further darkened by the behaviour of their Christian neighbours on the west. The Swedes, pleading that the men of Novgorod hindered the conversion to the true faith of the remaining pagans of the north, induced the Pope to declare a holy crusade, with the customary spiritual and temporal advantages, against Russia, and a zealous army advanced against Novgorod. It was shattered, but the Catholic zeal of the west was not extinguished. The Knights of the Sword, the German order which enforced baptism as truculently as the early Mohammedans had enforced the Koran, next appeared on the Russian frontier, and took Pskoff. The Teutonic adventurers were not less formidable in white mantle and red cross than they had been in the dress of the pagan Norsemen, and were hardly less ferocious, but they had to retreat before the stalwart Novgorodians. In the fourteenth century, however, the united Lithuanians and Poles crossed into Russia and added to the miseries of the people. Only half a dozen of the Russian principalities could hold out against the invaders. The Tatars were now in decay, and the red spears of the Lithuanian knights were even seen as far south as the Black Sea.

It is to this demoralisation of the Russians rather than to any direct Tatar influence that we must turn our attention. There was little mingling of Mongol and Slav blood, beyond the occasional marriage of a Tatar princess by some sycophantic prince, and the enslavement of Russian women in the spacious harems of the Asiatics. “Scratch a Russian and you will find a Tatar” is an untruth. Few races in the civilised world are purer in blood than the Russian Slavs. Nor did the Khans modify the Russian culture more than the levying of tribute demanded. With the clergy they were on friendly terms, knowing their power over the ignorant peasants, and they suppressed neither the Mir of the village nor the Véché of the town, as long as it furnished the collective tribute. On the other hand, they entirely broke the original spirit of independence; they organised the country for purposes of extortion, and disorganised it for purposes of self-defence; they helped to convert the brutal and masterful Norseman into a calculating and coldly selfish prince; and they encouraged the subjection of women which the teaching of the Byzantian priests and monks had begun.

CHAPTER III

THE MOSCOVITES BECOME TSARS

The name Moscow has up to the present entered so little into the chronicle that we must retrace our steps and briefly consider its origin. Three successive types of rulers prepared the way for the Romanoff dynasty: the Norsemen, the Tatars, and the Princes of Moscow, or the Moscovites. We have now to see how the third class rose upon the ruins of the Tatar dominion, maintained the evil machinery of subjection which it had constructed, and brought “all the Russias” under a new despotism.

In the year 1147 the Prince of Suzdal, George Dolgoruki, found a village, the site of which is now covered by the opulent Kreml, on the banks of the Moscowa, and is said to have conceived an affection for it. His patronage cannot have extended far, since we find that it remains an obscure village, or small town, for more than a century. It then passed, with a few other towns, to a son of the heroic Alexander Nevski, who (by sharp practice—a fit beginning of the fortune of the Moscovites) enlarged his little principality and bequeathed it to an even less scrupulous brother.

George Danielovitch (1303-25) laid claim to the principality of Tver and took very powerful arguments to enforce his claim, in the shape of handsome presents, to the Mongol court at Sarai. He got his title, a sister of the Khan for wife, and a Mongol army; but he did not get the principality, and the Khan, scenting a larger bargain, summoned both claimants to Sarai. There George ended the argument by having his rival assassinated. He in turn was assassinated, and a terrible feud subsisted for half a century between Moscow and Tver. Ivan, the successor of George, secured another Mongol army to reduce Tver, induced the Khan to remove his rival to another world, and entered upon a series of annexations and purchases which made Moscow the centre of a fairly large dominion, the seat of an archbishop, and a prosperous soil for churches and monasteries; for the piety of all these lords of Moscow was even more conspicuous than their craft and insidious truculence.

This malodorous tradition was sustained by the later princes. There was Simeon the Proud (1341-53) who, at the death of his father Ivan, found the largest bribe for the Mongols and ousted his competitors. At least he held in some check the lawlessness which was bleeding Russia, and it is one of those painful dilemmas of the historian that the valuable service rendered by the crafty Simeon was entirely neglected by his pious and gentle brother and successor, Ivan II. But Dmitri Ivanovitch, the son and successor of Ivan, returned to the sturdy lines of princely tradition. He defied and defeated the Tatars, and in the hour of triumph cried to Russia: “Their hour is past.” But the cry was premature. A rival Russian prince arranged a coalition against Dmitri of the Catholic Lithuanians, and the Mohammedan Tatars, and the great army of Dmitri once more cut to pieces its opponents. In the meantime, however, the famous Tatar general, Timur, had come from Asia and fallen upon the “usurpers” of the Golden Horde. Dmitri unwisely refused the friendship which Timur offered him, and before long the fierce Mongols set flame to the splendid buildings of his capital and littered the streets with the corpses of its children.

Dmitri recovered and handed down a fair principality to his son Vassili (1389-1425), who shrewdly preserved his territory by a friendly alliance with the Tatars on the one hand and a matrimonial alliance with the Lithuanians on the other. His son, Vassili the Blond, was equally submissive to the Tatars and friendly with the Lithuanians. Then, in 1462, there came to the throne Ivan III, the first of the two great makers of imperial Russia.

At the time when Ivan III ascended the throne the principality of Moscow was a small and feeble territory menaced by the Lithuanian empire to the west and the Mongol empire to the east. Most of the other Russian principalities had either won a precarious independence or were subject to Lithuania. The republics of Novgorod and Pskoff alternately lost and recovered their freedom, and wavered between the Lithuanian and the Mongol alliance. Riazan and Tver remained independent and regarded with jealous eyes the growth of Moscow. This was the Russia of the fifteenth century, a mere fragment of the country which bears that name to-day.

Nor was this lack of unity the only reproach which we may bring against the princes who had torn the land in their selfish struggles for supremacy. Round the whitened monasteries and gilded shrines the feuds of the princes had gone on without intermission for so many centuries that the blood ran thin in the veins of Russia. It had neither the vitality nor the organisation required to meet its external foes, and every few years some hostile army scattered the customary desolation over the country. On every side, also, were troops of free lances and brigands, who constantly swooped upon the miserable peasantry. It is the claim of the orthodox historians that the Moscovite princes we have now to describe rescued Russia from this degradation, and we must examine their methods, their motives, and their attainments.

Ivan III is, in the existing portraits, a lean-faced, sombre-looking man, with large melancholy eyes and the patriarchal beard which the Slavs still preserved. These portraits probably accentuate the ostentatious piety of the man, and give us no idea of the cold ferocity which could light his heavy features. It is said that women were known to faint when they met his eye. Certain it is that Ivan united all the craft and calculating cruelty of the degenerate Greeks with professions of humility and peacefulness which provoke our disgust. Conspirators against his terrible rule were burned alive in cages, and the horrible Byzantine practice of cutting out a prisoner’s eyes was more than once employed. Even priests, for whom he affected a humble veneration, were brutally flogged when they departed from the customary subservience of the clergy and took the part of the people. In war he was a coward. All the impulsive and savage bravery of the Norseman had in him degenerated into the mean and shifty hypocrisy of a dishonest huckster.

Ivan ascended the petty throne of Moscow in the year 1462. The city of Moscow was at that time still little more than a large cluster of mud-huts, with a few streets of merchants, about the princely palace and the rich shrines. Ivan looked to his revenues and before long was confronted with the firm refusal of the citizens of Novgorod to pay the tribute he demanded. The Grand Prince proceeded with his habitual craft. Instead of setting out to enforce his demands, he formulated a complaint that the Russian people of Novgorod were oppressed by a wealthy faction, and that this faction contemplated an alliance with the heretics of Poland. We may assume that there was some truth in the charges. Novgorod, still democratic and independent, still proud of the popular parliament on its market-place, was full of factions. In such a city a mutual hostility of rich and poor was inevitable, and Ivan’s agents seem to have encouraged the aggrieved workers to appeal to him against what were represented to be the oligarchs. The wealthier and more powerful faction was led by a woman named Marfa, and may very well have contemplated an alliance with Poland against the ambitions of Moscow.

In 1470 Ivan sent against the city a strong Mongol and Moscovite army, and the ruin which it spread over the lands of Novgorod, as it approached, induced the citizens to compromise. But the Grand Prince wanted more than tribute, and his agents continued to foster the grievances of the popular party and encourage appeals to Moscow. When the time was ripe Ivan wrought the republican spirit of Novgorod to a fury by describing himself, in his official documents, as “sovereign” of that city. The educated citizens saw in this the doom of their liberty, and, acting in the violent mood of the time, they put to death the supporters of Moscow. The story runs that the clergy and boyars of Moscow now gathered round their humane and reluctant ruler, and demanded that he should make war upon Novgorod. Certainly Ivan III did not love the hazards of war, especially as it was still the custom for a Russian prince to lead his troops. But we may measure his humanity by the sequel.

The conscience of the Grand Prince was reconciled by conceiving the campaign as a “holy war” against the allies of the Pope, and a formidable army took the road north. The partial resistance of the distracted republic was overcome, and Ivan set about the extirpation of its spirit of independence. The democratic nobles were transplanted to other soil. The commercial prosperity, which Novgorod had developed in its relations with the cities of north Germany, was systematically destroyed. The stores of merchandise and other treasures were transferred to Moscow. The shadow of the popular council, the Véché, remained—Ivan’s son would complete the work—but a very severe blow had been struck by the Moscovite at what remained of Slav democracy.

The dependent republic of Pskoff submitted to Moscow, and was permitted to retain its institutions. The principality of Viatka was next recovered, from the Tatars, and added to the dominion of Moscow. The victorious troops, indeed, went on to annex a large part of more northern Russia, and the first thin slice of Asiatic territory fell under the rule of the Slav. At a later date the principality of Tver was drawn into the growing empire. Its prince afforded a specious pretext by allying himself with the unholy followers of the Roman Pontiff, the Lithuanians, and religious zeal again edged the swords of the troops.

It will be gathered that the power of the Mongols had now sunk too low to arrest the progress of Moscow. On an earlier page we have seen how Timur had come from Asia and chastised the Khans who had dared to set up an independent sovereignty in Europe. For some reason Timur did not overrun Russia as his predecessor had done. The clerical traditions of Russia attribute the escape to one of the miracles which seem to have been so frequent in that age, but the superior attractions of the new Ottoman Empire in the south, which was then displacing Greece and taking over its treasures, may be regarded as a more satisfactory explanation.

Timur had reduced the strength of the Golden Horde, and the dissensions which followed further enfeebled it. Here was an opportunity after the heart of Ivan III. Dispossessed Tatar princes fled to his court, and he sent them back with their animosities inflamed, while he made the customary presents to the ruling Khan. In 1478 either Ivan or his advisers felt that the time had come to end the Tatar yoke, and Ivan nervously found himself at the head of 150,000 men making for the land of the dreaded Mongol. The issue is one of the most laughable in history. The two large armies encamped in sight of each other for days and dared each other to come on. Priests and officers spurred Ivan to the attack, and his rare fits of confidence, or professions of confidence, alternated with long periods of what we must regard as cowardice. Possibly the intensely superstitious prince thought that one of those miracles of which the clergy spoke so freely would spare him the hazard of war. A miracle, indeed, appeared, and it is difficult for the profane historian to penetrate its mysterious working. Both armies at length, and simultaneously, struck their camps and retreated hastily to their respective homes! The Tatar had sunk as low as the Moscovite.

Ivan’s troops, which did not share the timidity of their high commander, next reduced Bulgaria, and the death of his brothers enabled Ivan to add still further, and with less title, to his dominions. His brother Andrew was, in 1493, accused of the usual perfidy and corresponding with the Polish-Lithuanian kingdom. He was thrown into prison, and there he conveniently died. Ivan summoned his bishops and monks and, as the tears trickled down his gaunt face and grey beard, confessed that he had sinned in sanctioning the cruel treatment of his brother. But he added Andrew’s territory, and that of two other brothers, to his large dominion.

In the following year the lover of peace attacked the joint kingdom of Lithuania and Poland, which had so long afflicted Russia. Ivan had married his daughter to the Polish king, and had strictly stipulated that she should have entire freedom to practise the true religion amongst the adherents of the Pope. In 1494 Ivan found that this agreement was grossly disregarded, and his beloved daughter ran some peril of her soul. Later Russian historians have learned from the daughter’s letters that she had no complaint except against the interested intrigues of Ivan himself. However, a holy war was proclaimed, and a good deal of western Russia was wrested from the Poles and added to the Moscovite dominion.

Such were the methods by which Ivan III doubled the patrimony of his fathers, and accumulated the wealth and power by which his more famous grandson would create the great Russia of the Romanoffs. It remains to see how Ivan organised his dominion, strengthened the autocracy, and raised the culture and splendour of his capital.

Ivan was by nature autocratic. He did not make counsellors of his boyars, as had been the custom, and they were compelled to learn the art of silence in presence of their master. But it was Ivan’s wife who directed this disposition and created a Court in harmony with it. The Turks had taken Constantinople and had driven the remnants of half a dozen rival Greek royal families, and all that remained of Greek culture, into Italy. Amongst the fugitives was the clever and ambitious niece of the last emperor, Sophia Palæologus. The Pope, who saw in this heavy chastisement of the Greek schism a ray of hope of the reunion of Christendom, fathered the homeless princess and sought for her a useful marriage. Ivan accepted her and the Papal dowry. They were married early in his reign (in 1472), and her forceful ambition was behind many of the schemes of conquest we have reviewed. It was especially she and the clergy who forced upon the prince his inglorious campaign against the Tatars.

But we may see her influence especially in the growing splendour and despotism of the Moscovite court. Bred in the sacred palace by the Bosphorus, where there still lingered, until the Turk came, some remains of the most imposing court of the old world, she was made impatient by the thin coat of gilt which covered the Russian barbarism. Accustomed to a city of marble palaces, with walls of mosaic or porphyry, with bronze gates guarded by hundreds of silk-clad servants, and gold and silver vessels so heavy that they had to be lifted on to the tables by mechanical devices, she knew how to use the increasing wealth of her husband’s kingdom. He was now the successor of Constantine and the Roman Emperors. The two-headed eagle, which had been the blatant emblem of Greek vanity, passed with the hand of Sophia to Moscow, and was emblazoned on the banners and plate of the new dynasty. Ivan did not take the title of “Tsar.” His grandson would complete his work.

Sophia invited to her court Greek scholars and Italian architects and engineers, and the splendour of Moscow soon became so famous that its prince corresponded with Popes and Sultans, Kings of Sweden, Denmark, Hungary, and Austria, and even with the Grand Mogul of India. Italy was at that time in the flush of the Renaissance, and much of its colour, and of the less manly art of the Byzantinians, was brought to Moscow. Whatever one may think of the religious quarrel, it can hardly be doubted that the civilisation of Russia would have gained by submission to Rome. The Papacy was then enjoying that period of artistic license which provoked the Reformation, and probably Russia would have joined the Reformers. By its severance from Rome it maintained a barrier against the west, where civilisation was making rapid progress, and prolonged the inferior culture and conservative influence of the late Greek empire. The glory of the new Russia was but a coat of paint upon barbarism.

In the court the oppressive servility and childish pageantry of the Byzantine palace were encouraged. Golden mechanical lions barked before a golden throne, as they had done at Constantinople, and filled the visitor with mingled admiration and disdain. A very numerous guard of nobles, in high white fur caps and long caftans of white satin, with heavy silver axes on their shoulders, protected the sacred person of the monarch, and crowds of courtiers in cloth of gold or bright silk, with costly necklaces round their necks, vied with each other in flattery of speech and humility of demeanour. Yet these glittering aristocrats still carried a spoon in their jewelled girdles, for knives and forks were not yet substituted for fingers at a Russian feast.

The wives of the boyars were not less splendid. The combined influence of Mongol princes and Byzantinian monks had, as I said, lowered the condition of the Slav women. The terem, or women’s quarters of the house, was screened as carefully as the gynecæum had been in ancient Athens or in Constantinople. The Russians had not indeed introduced that later Greek security for the behaviour of their women, the eunuch, and the frailer protection of religion did not prevent disorders; but the women were, as a rule, carefully guarded at home and abroad, while their husbands claimed the free use of slaves and courtesans. In public the wives of the boyars—or, as we may now call them, nobles—presented a curious spectacle. They painted as liberally as the Greeks had done. Thick coats of vivid red and white covered their faces, necks, and even hands; and their eyelashes, and even teeth at times, were dyed. In obedience to the ascetic teaching of the monks great masses of scarlet or gold cloth, silk, satin, and velvet, concealed, or preserved for the admiration of their husbands, the opulent lines of their figures; for a full habit of body was religiously cultivated.

Round this glittering court, with its Gargantuan banquets and its daily intoxication, spread the wooden city of Moscow, whose hundred thousand inhabitants lived, for the most part, in squalor and grossness. Beyond were the broad provinces of Russia which bore the burden of this barbaric splendour. The mass of the people had at an earlier date, we saw, become moujiks, or “mannikins.” Others called them “stinkers.” Now, by one of the most curious freaks of Russian development, they were known as “the Christians”; as if the quintessence of the Christian doctrine, as it was expounded by the Russian priests, was obedience to a lord and master. Their women had the hardest lot; the priests were content to urge the peasant or artisan, who, like his betters, drank heavily, not to beat his wife with a staff shod with iron or one of a dangerous weight. Drink was one of the few luxuries left, for the priests and monks gave fiery warnings against the song and dance and games that had formerly lightened the life of the people. Drinking heavily themselves, they could not, as a rule, rigorously forbid intoxication.

Such was the Russia created by Ivan and his Greek wife, with the aid of the Greek-minded clergy, and bequeathed to their second son Vassili. That prince, zealously educated by his mother, sustained the policy of enlarging and coercing his dominions. The republic of Pskoff had, we saw, retained its democratic forms. Vassili held a court at Novgorod, and thither he summoned the chief men of the neighbouring republic to do homage. Too weak to rebel, yet aware that the monarch sought to swallow the last remnant of the primitive democracy, the citizens appealed eloquently to the sense of honour which the Moscovite might be assumed to have. It was useless, and the republic was dismantled. Amidst the tears of the citizens and the laments of the patriotic poets Vassili removed the great bell to Novgorod and suppressed the Véché or democratic council. The commercial life of Pskoff was ruined, and three hundred docile families from Moscow were substituted for threes hundred who had clung to independence and were now sent into exile.

Riazan was the next victim. The familiar crime of corresponding with heretics—with the Khan of the Crimea—was charged against its prince, and the fertile province was added to the Moscow principality. Vassili recovered territory also from the Tatars and the Lithuanians. Russia expanded rapidly, and the splendour and autocracy of the court proportionately increased. There was now only one court for the innumerable descendants of the earlier princes and boyars, and the sternness of the competition for rewards made the nobles more and more sycophantic. Even less than his father did Vassili ask the counsel of his boyars.

The death of Vassili in 1533 led to a romantic and important interlude. Vassili’s first wife had been thrust into a convent on the ground that she could not furnish an heir to the brilliant throne. Whether or no it is true that she disturbed the solitude of the cloister with the pangs of motherhood, it seems clear that the chief motive for the divorce was that Vassili had fallen in love with the very pretty and capable daughter of a Lithuanian refugee, Helena Glinski. Helena gave birth to two sons, but the eldest was only three years old at the time of his father’s death. The mother vigorously grasped the regency and held power from the furious boyars. Only the Master of Horse, Prince Telepnieff, was allowed to share her despotism, as he shared her affection. The nobles split into factions, and they presently found that the easy-going princess could use the most truculent machinery of despotism. When the heads of a few of them had fallen, they poisoned Helena and her lover, and there followed a sordid scramble for power and plunder.

Now of the two children of Helena one was the boy who would live, even in the history of Russia, as “Ivan the Terrible.” Ingenious historians have found a milder meaning for this epithet, or discovered that Ivan underwent some strange degeneration in his later years. But the boy who was brought up amidst dogs and grooms, who for sheer pleasure cast his dogs from the walls of his palace and watched them writhe, who stabbed his favourite jester for the most trifling fault, is the same Ivan who in later years soaked petitioners in brandy and set fire to them. His impulses were barbaric, and the unhappy features of his education had stimulated rather than curbed them. He was eight years old at the time his mother was murdered, but he was clever, observant, and self-conscious. He saw the boyars plunder the palace, which was now his, and fleece the long-suffering country. He noticed that any servant to whom he became attached was removed or murdered. He read much, and he grew up rapidly in his solitary world.

And during the Christmas festivities of 1543 Ivan, then thirteen years old, summoned his boyars before him and let loose upon them an unexpected storm of reproach. Andrew Chiuski, the most powerful of them, he handed over at once to his groom-attendants—one wonders how far they had inspired this precocious display—and the great noble was soon dispatched. One account runs that by Ivan’s orders he was torn to pieces by the hounds: others say that the grooms acted without orders. Other nobles were banished. The short golden age of the boyars was over. The shadow of a sterner autocracy than ever began to creep over the court.