Title: Danny again

further adventures of "Danny the Detective"

Author: Vera C. Barclay

Release date: February 28, 2018 [eBook #56658]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

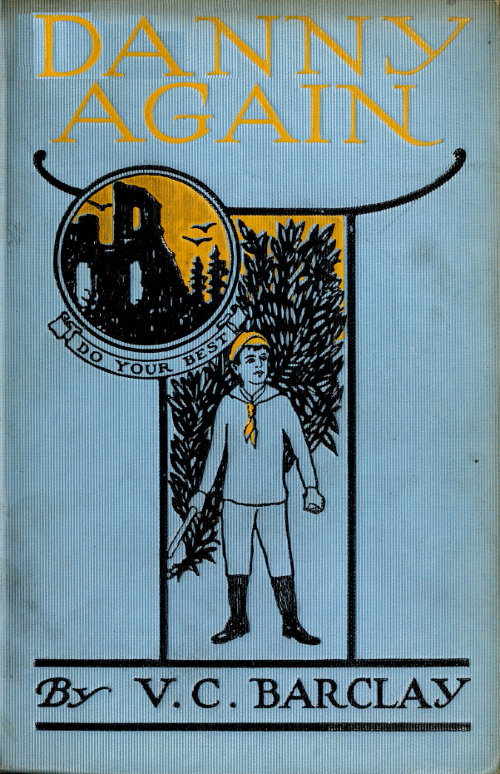

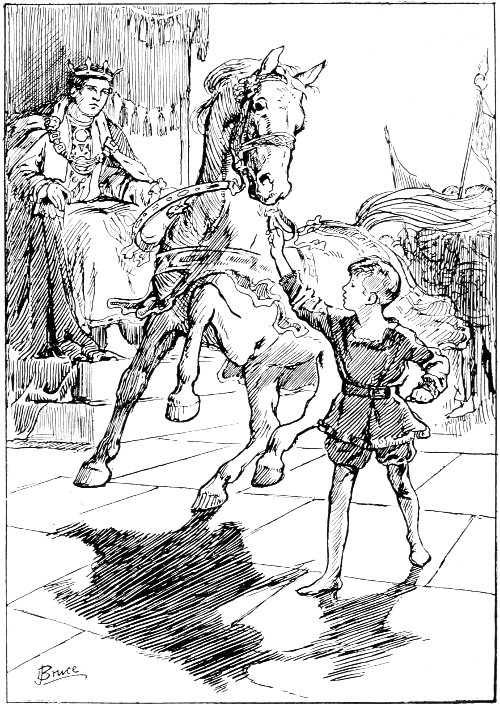

“And then—then he saw the terrible sight; a horse and sleigh was standing across the run”

FURTHER ADVENTURES OF

“DANNY THE DETECTIVE”

BY

VERA C. BARCLAY

Illustrated

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

1920

Dedicated

TO

THE “CARDINAL’S OWN” WOLF CUBS

WHO HEARD THESE STORIES BEFORE THEY EVER CAME TO BE WRITTEN DOWN

*Reprinted from The Wolf Cub by kind permission of Messrs. Pearson.

It all began the morning after a Zepp raid. The village of Dutton had had a very narrow escape. Six bombs had been dropped in the night, but not a single person had been hurt. One sad thing had happened, however, and Danny Moor was the first one to make it known in the village, and the first one to decide how the damage should be put right. The Huns had dropped a bomb thirty yards from the little grey church, and a great piece of metal had smashed to fragments a beautiful stained-glass window. Danny was sad, for the Cubs loved that window very much. It represented the shepherds at Bethlehem on the first Christmas morning, and the Cubs had discovered to their delight that the Child Christ in His Mother’s arms had His two fingers raised, as if in the Cub salute! So they looked upon the little chapel where the window was as their special corner of the church, and it was there that the monthly church parade took place. Now, the window lay in splinters of shimmering glass upon the floor, and the morning sun streamed through a jagged hole where before used to be the little figure of the Holy Child, smiling down upon the Cubs. But as Danny stood looking sadly at the blue sky through the hole, a bright idea came to him, and he made a vow that before long a new window should be put up in the place of the broken one, and that he and the Cubs would pay for it.

After school that morning he got the other Sixers and Seconds to come and hold a special council in the corner of his garden, and then he told them the sad news. “But I’ve vowed we’ll put up a new window,” he said; “will you help?” They all agreed at once, and Fred Codding, practical as usual, began to count the cost. “It’ll cost an awful lot,” he said, “I should think nearly a pound.” “Oh!” said the others. “Well,” continued Fred, “there’s eighteen of us; say we each gave sixpence, that would be 9s. Then my six has got 2s. we saved up for buying a bat—we’ll give that.” “Eleven bob,” said Danny, “good.” “I say,” said Freckles, “what about asking Mr. Fox to give that 5s. the squire gave him for our picnic next Saturday?” “Good idea,” said one of the others, “that’s sixteen bob. I bet we can raise four more somehow.”

So directly school was over that afternoon they dashed down to their chaplain to tell him the splendid good turn they were going to do. He was very pleased. But he said he thought £1 would not do it. He looked up the cost of stained-glass windows in a big book. “I’m afraid it will be £20,” he said. The Cubs did not gasp nor show what they felt.

“All right, sir,” said Danny. “We’ll get £20, somehow—won’t we, boys?—’cos we’ve promised to.”

They were rather silent as they walked home. And yet they felt sure something would turn up to enable them to keep their promise. As they parted they promised each other to think out a good idea, and never to give up till they had earned enough money for the window.

. . . . . . . .

The next day Danny had a bright idea. It was this: that the Pack should start wastepaper collecting. “I’ve been doing sums all the morning,” said Danny, “and I’ve found out that we could get £20 in seven months if we worked hard. Of course it would take all our Saturdays.”

“I suppose you are going round with your baby’s pram,” said Freckles. Danny punched his head for him, and then explained proudly that the Scoutmaster had promised the use of the trek cart. At that the Pack gave a howl of delight, and the waste-paper scheme was passed unanimously by the council. The £20 began to seem more possible now; and the Pack meant to do its best.

. . . . . . . .

It was a month later that something happened which set Danny’s detective’s heart beating fast with hope and excitement. The Pack had been slaving hard at waste paper, and had already collected and sold £3 worth. Danny, tired with the day’s work, was leaning against his garden gate in the cool of the evening when his old friend, the village policeman, sauntered up.

“Hello, Danny the Detective,” he said, “come and have a look at my old sow—she’s got a litter of ten little ’uns, born this morning.” Danny loved baby pigs, and so he went with Mr. Bates at once. But as soon as Mr. Bates had him in his own yard, and out of earshot of other people, he forgot about the pigs, and turned to Danny with a solemn look on his face. “I want a conversation with you, private-like,” he said. “I’m going to tell you something, if you’ll promise never to speak a word to any other folks about it.” “I promise on my honour as a Wolf Cub,” said Danny. “Go ahead, guv’nor.” “Well,” said Mr. Bates, “you done good work with them German spies last autumn. You’ve got a proper detective’s brain, you have. I want you just to keep your eyes on Mr. Bulky, him what goes round tuning up the rich folks’ pianers. I don’t say as how I have anything at all against him at present, but I don’t like the looks of him. Don’t you say a word, but just you keep your eyes open, and poke about, careful-like, round his place, and let me know if you find out something. I’m afraid to say anything at the police station, for fear he finds out he’s being watched. So I says to myself, ‘I’ll put Danny the Detective on his tracks.’”

Mr. Bulky was a man with a fat, pale face and shifty little eyes. He bicycled about all over the neighbourhood with a small black bag, and tuned the pianos in the big houses. When he was not out tuning pianos he would always be found either playing pieces by Mendelssohn in his front parlour, or attending to his famous prize fowls. These he was very proud of, and would often travel to distant parts of the country with a hen in a basket to exhibit her at some poultry show. He even went to the Continent, sometimes, to buy poultry and pigeons. No one in Dutton liked him. He had lived there only about five years. His sister, a very stout person, called Miss Bulky, kept house for him. He had a large cottage on the outskirts of Dutton. And now Mr. Bates, the policeman, suspected him, and had put Danny on his track! Danny, of course, was delighted. For one thing, it was an honour to have a policeman ask his help like that. But most of all he was pleased because he had begun to thirst for another adventure, and he was afraid, having had such a glorious one before, it could never be his luck to have another. “Poke about his place careful-like,” the policeman had said. But Danny found it no easy job. If you crept up at the back of the house, all the horrid hens in the long runs began cackling (like the geese on the Capitol), and if you went up by the front, a beastly mongrel suddenly leapt out of his kennel with a yell, and made a row like several dog fights. This brought Miss Bulky out of the house, looking as fearsome as “Mrs. Bung,” of the Happy Family Cards.

So Danny had to content himself with making sketches of Mr. Bulky’s footmarks and bicycle tracks, and taking notes as to what time he went out and what time he came in.

. . . . . . . .

It was a glorious Saturday in June. A team of Cubs had worked hard all the morning and collected more sacks of waste paper than usual. They had also made a more than usually ghastly mess with it in Pack headquarters. And they had, I am sorry to say, played “trench warfare” and “bayonet charges” with last week’s load. They were just going home, at 1 o’clock, to get dinner and a wash, before starting out for a long-promised expedition to the river, when Mr. Fox, the Cubmaster, arrived on the scene. “My word,” he said, “what a frightful mess! It’s a pity you’ve done that, because the paper has all to be sorted and packed this afternoon, ready to be called for very early on Monday morning. I had hoped you would have got on with it this morning. Now I’m afraid I shall have to tell off three boys for the job this afternoon.”

“But, sir, we are going to the river this afternoon,” they said.

“Yes,” said Mr. Fox, “that’s just why it was a pity you were such little asses as to upset the sacks already packed, and not have got on with to-day’s sorting. Three boys must stay behind and do the work, and when they have done, they can follow on.”

Someone murmured something sulky about its not being fair. Someone else said he would do it to-morrow. “No,” said Mr. Fox, “to-morrow’s Sunday, remember.” “Who’s got to stay, sir?” asked Danny, thinking how cool the river would be this afternoon, and how nice tea in the old punt would be after a swim.

Mr. Fox looked at the team. “Well,” he said, “judging by the filthy condition of your face, young Danny, I should think you’d done a lot of rolling about in the ‘trenches’ yourself. You might have known better, being a Sixer. You must be one. Then this Second, here, is the next dirtiest; you’ve had your play, so it’s only fair you should have the clearing up. And Ginger hasn’t had a fatigue for a long time! I shall expect the waste paper properly packed, and all the newspaper sorted from it and tied in bundles, and this hut quite clean and ready for Sunday.”

In a chastened mood the team went home to dinner. They knew Mr. Fox was in the right, so there was nothing to grumble about.

At 2 o’clock the Pack went off, towels round necks, and a cheery whistle to keep everyone in step. Three sorrowful Cubs watched them go, and then turned into the hut to face a hot and dirty job.

Thicker and thicker flew the dust. “Talk about germs,” said Danny; “it’s all very well to teach us hygiene, and then ask us to swallow germs by the pound.”

“Waste paper!” said Ginger, “I call it just dust-bins.”

“There are more sacks than usual this week,” said Danny.

“Yes,” replied Philip, the Second of the Blacks. “We got one from old Bulky’s. They won’t generally give us any paper, but we saw his servant carrying it down to the rubbish heap. She said she had orders to burn every scrap herself. But we got her to give it to us.”

“Oh,” said Danny, thoughtfully.

“I vote we don’t open any of those sacks,” said Ginger. “Mr. Fox won’t ever know they weren’t sorted. It would save heaps of time.”

“It wouldn’t be fair,” said Danny. “He’s trusted us to do it—we must do it properly. Besides, we get more money if it’s properly sorted, and we want that twenty quid for the window.” And so an argument began. Everybody was hot when it started, but they got hotter and hotter. Ginger said he would not do a stroke of work unless Danny agreed not to sort the sacks that were not open. Philip was so offensive that Danny had to smack his head for him. And so it happened that these two young slackers departed for home and tea, and Danny found himself faced with the entire job alone. At first he thought he would chuck it up and go home, too. Then he decided not to “give in to himself.” And finally he remembered that every minute he worked he was serving the Holy Child, by earning money for the window, and he began to take a delight in getting as hot as possible, and almost relished the mouthfuls of dust he had to swallow. He battled with the sacks with the ardour of a Crusader fighting for the great cause, and suffered the discomfort in the spirit of a martyr. And when he came to the last sack, he was truly rewarded.

. . . . . . . .

It was long past tea time, for sorting the paper unaided was a long job. But Danny was determined he would not leave the hut until he had completely finished the job, and got the place swept clean and the room arranged for Sunday. It would be a surprise for the boys and Mr. Fox to-morrow morning, for he knew the Pack would not be coming back to headquarters that evening, but would dismiss in the village and go straight home. He was nearly tired out by the time he got to the last sack. Untying the string, he emptied the dusty contents on the floor, and picked out the newspaper, waste paper, and cardboard. He was about to shovel back the waste paper when his eyes fell on a scrap of a torn letter covered with curious writing that was certainly not English; the very characters were different. Picking it up, he looked at it carefully. Yes, they were the same funny characters as those on many of the letters that had been found in the possession of the German spies he had caught last autumn. “A German letter!” he said, “in one of our sacks! Of course ... Philip said they had got a sack from old Bulky. This is a clue; or rather it will be a strong piece of evidence if I can find the whole letter.” Eagerly he bent down and began searching about in the pile of waste paper. But it was at that moment that he heard the outer gate click and steps coming along the path. Glancing through the window, he saw to his dismay that it was the very last person in the world he wanted to see just then. It was Mr. Bulky!

When Danny saw Mr. Bulky coming down the path, he thought quick as lightning, and decided what to do, at once. Stepping out of the door, he slammed it after him, so that it locked itself. (The key was in his pocket.) Then he pretended he was off home, and, putting on his cap, began walking down the path towards Mr. Bulky.

“Evening, sir,” he said as he passed. “Hullo, boy,” said Mr. Bulky. “Why did you come to my house this morning and take away my waste paper? I told you I would not give it to you. You must give me back my sack at once. Do you hear?” He scowled angrily.

“I am sorry, sir,” said Danny. “I am afraid I can’t, this evening. I shall have to get leave from our Cubmaster. I am sure he will say yes, and I will bring it back to you on Monday morning.”

“No,” said the man, “you shall give it to me now.”

He walked towards the door and tried to open it. Whilst his back was turned, Danny took the key from his pocket and flung it into a patch of young potato plants.

“Give me the key,” said the man, turning round.

“I haven’t got it on me,” said Danny.

“Little liar,” said the man, and turned out Danny’s pockets. Then he swore hard, and gave Danny’s ear a nasty twist. “I promise to bring you back the sack on Monday,” said Danny. “Very well,” growled Mr. Bulky, and he walked out of the gate. Danny followed him out, and then ran down the road in the opposite direction till he was out of sight round the corner. Then he got through a gap in the hedge and ran back under cover of it. When he had made sure that Mr. Bulky was well on his way home he got back into the garden and found the key. It was after six, and he still had a long job before him, so he went back to tea.

. . . . . . . .

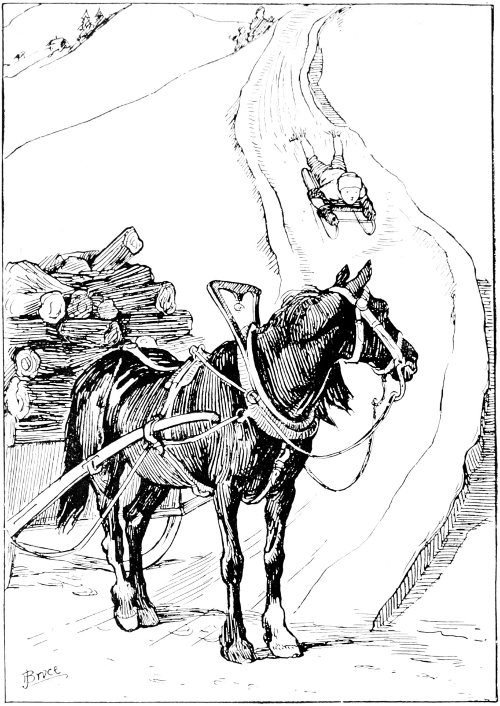

It was past seven when Danny once more set to work. Taking up every scrap of paper he examined it carefully. Before long he had found another scrap covered with the same writing. He put it in a box with the first. It was a slow job, but gradually he found more and more pieces. They fitted together like a jig-saw puzzle. Luckily they were only written on one side.

“I know what I’ll do,” said Danny to himself, “I’ll stick them on a sheet of white paper, and then when I have them all it will make a complete letter, and I can take it to Mr. Bates, as evidence against old Bulky.”

It was getting dark, so he lit the lamp and drew the curtains across the window. Going into the Sixers’ room he took the paste pot off Mr. Fox’s desk, and also a sheet of foolscap paper. Then, squatting on the ground by the sack of paper, he laid all the precious pieces out, fitting them together. Another half-hour’s search had revealed the rest of the scraps, and with a wriggle of delight Danny added the last piece. It made a long letter—nearly the size of the foolscap sheet. It was dated and signed, and Danny felt sure it was in German. Taking the paste brush, he pasted them all down, making a very neat job of it.

“Now I must clear up,” he said to himself as he knelt up admiring his work. “It must be jolly late.”

“His eyes met a pair of watching eyes fixed on him through the crack of the curtains”

He glanced up at the curtained windows to see if any light showed through the cracks, or if it was quite dark, and his heart seemed to stop, and then go on at a furious pace. His eyes had met full a pair of watching eyes fixed on him through the cracks of the curtains. The glimpse he had caught of the eyes and white face filled him with fear—but he was a born Scout, a true wolf of the jungle. He dropped his eyes again immediately to the letter, and pretended he had seen nothing. Not by a tremor did he give away that he knew he was being watched. Taking up the letter he fixed his eyes on it as if he were trying to read it, and while his heart beat like a hammer against his sides he thought quickly what he must do.

The man was Mr. Bulky, of course. He had come back to try and break into the hut, and seeing the light had looked through the window. He had watched Danny paste his letter on the paper. He had seen the complete letter. He knew exactly what Danny was up to. Why was he waiting there so quietly? He was waiting for Danny to come out, with the precious letter on him. He would then kidnap him, and take away the letter, and keep him a prisoner, so that he could not give any information to the police. What on earth should he do? The one thing he must be careful about was not to let the man suspect he had seen him. And so, making a very great effort, he managed to compose himself completely, not allowing his hand so much as to tremble, and even managing to raise a cheerful whistle. He folded the letter and put it in the back pocket of his shorts, and then set to work clearing up. This gave him time to think. He shovelled back the paper into the sack. He went into the Sixers’ room and tidied that. He came back and swept the floor. He dared not look at the window, but he felt that the watching eyes were fixed upon him, like those of a tiger crouching in the darkness ready to spring on its prey.

As he worked he thought and thought. The man was guarding the door, and there was no hope of getting out of any of the windows, for he could see them all. In the little inner room there were no windows, it was lighted by a skylight. Of course it would be possible to climb up through this on to the roof, and then drop on to the ground; but the ground was covered with new gravel, and the man would be certain to hear; also there was no way out of the garden except by the gate guarded by Mr. Bulky, for it would be impossible to get over the high fence without making a noise.

The tidying up of the room was finished. If he stayed there much longer the man would begin to suspect that he had been seen. Besides it was getting very late.

Suddenly an intense feeling of horror came over Danny. He was like a rat in a trap. The moments were slipping by; those silent eyes were watching; before long something must happen, and he was too far from any house to be heard if he shouted for help. His heart began to sink, and then, suddenly, just as if his Guardian Angel had whispered in his ear, a splendid idea came to him, which quickly unfolded itself into a scheme by which he felt sure he would be able to escape, himself, and take the spy prisoner, as well.

But if his plan was to succeed it was most important that he should know if Mr. Bulky was alone, or if he had an accomplice. Also, exactly where he was. Going into the Sixers’ room Danny took his boots off, then climbing on to the top of the bookcase, softly opened the skylight, and drew himself up on to the roof. Creeping along the tiles as silently as a cat, he peered down through the darkness. There, sure enough, stood Mr. Bulky, exactly outside the door of the hut. He was alone.

Creeping softly back, Danny let himself down through the skylight once more. Whistling loudly, he went into the big room, just to show that he was there, and, taking up the spare bundles of newspapers, pretended to be putting them away in the other room. This he did simply to put the man off his guard, if he was still watching through the crack in the curtains. Then, while the spy imagined he was packing away the papers in the Sixers’ room, he began to make his arrangements for capturing Mr. Bulky.

First of all he took the two trek cart ropes, and making them into coils slipped them round his arm. Then from the week-end camp cupboard he took the large travelling rug belonging to Mr. Fox. It was heavy and cumbersome, and climbing out of the skylight with it was no easy job, but somehow Danny managed to do it and to get along the roof until once more he was exactly over the head of Mr. Bulky.

The great moment had come. If only the spy did not chance to look up all would be well. Balancing himself carefully, Danny stood up and opened wide the folds of the heavy rug. Then with great care he flung it completely over the figure of the man below, at the same time jumping down himself straight on to the smothered head of the terrified Mr. Bulky, and knocking him down like a ninepin. Hopelessly tangled in the rug, Mr. Bulky’s struggles were of no avail. Danny, kneeling on his chest, quickly wound one of the ropes about his feet, and secured it with a clove-hitch. The other rope he wound round and round the unhappy man’s body and arms, finishing up with a bow-line round his neck, so that his struggles only made matters worse for him. The language of Mr. Bulky was probably very strong, but fortunately his mouth was so full of rug that Danny did not understand a word.

As he stood there in the semi-darkness, Danny could not help laughing. Mr. Bulky looked so exactly like a chrysalis; he curled about just as they do when you hold them in your warm hand, or poke them with your finger. But what to do with the chrysalis was more than he could decide. At last an idea struck him: he would cart him off to the police station in the trek cart!

With some difficulty he managed to put together the cart, and then with much hauling and pushing, and the help of a strong plank, he managed to hoist the bundle that was Mr. Bulky into the cart. Then, whistling a cheerful tune, he trundled it down the road towards Mr. Bates’s house.

Mr. Bates was just helping Mrs. Bates wash up when Danny knocked at his door. He came out in his shirt-sleeves, a large carving fork in his hand. “Hello, Danny,” he said, “what brings you here so late?”

“I have come,” said Danny with a tone of high importance in his voice, “to deliver into your hands a document, written in German, and found in the possession of Mr. Bulky.”

The constable gasped.

“Here it is,” said Danny, handing him the letter.

Mr. Bates examined it carefully. “That’s German, sure enough,” he said, trying to read it aloud, and only succeeding in making a series of noises very much like his old sow. Danny laughed. “Well,” said Mr. Bates, “how did you get this? Old Bulky don’t know you’ve got it, do ’e?”

“Yes,” said Danny, “he knows I have got it. And what’s more, he knows I have brought it to you.”

Mr. Bates said something strong. “That’s done it,” he added. “He’ll be gone away to London by now, and no more shall we see of him. Couldn’t you have managed to let me know quicker?”

Danny was chuckling to himself.

“I knew you’d be disappointed when I told you, so I’ve brought you something in the trek cart to cheer you up.”

Mr. Bates grunted. He did not sound very grateful.

“Come and see,” said Danny. Mr. Bates walked up to the trek cart and looked at the bundle. He gave it a poke with his carving fork, whereupon the bundle emitted a yell of pain and a torrent of German abuse. Mr. Bates, frightened out of his wits, was half across his little garden in one bound.

“What is it?” he asked, wiping the perspiration from his brow.

“Only Mr. Bulky,” said Danny, doubled up with laughter. “You’ve hurt him, I’m afraid, with your fork.”

Mr. Bates, still half afraid of the uncanny bundle in the trek cart, drew near, somewhat gingerly. Then, as the situation dawned on him, he gave vent to a roar of laughter like a bull. He laughed so much that he had to sit down on a seat. At last he got up and went over to the trek cart.

“I think we had better take this ’ere German sausage to the police station, just as it is,” he said. “I don’t fancy opening it myself.”

So together Danny and Mr. Bates trundled the cart the two miles into the little country town, and made over its contents to the inspector who also laughed.

And Danny went home that night feeling that he had done a good day’s work.

. . . . . . . .

The cheque he received for his good work more than paid for the new window in the Cubs’ chapel; and by Danny’s special request an Angel was put into the picture by the artist, because Danny was quite sure it was his Guardian Angel who had whispered to him the suggestion how he could escape, when he had given up hope.

It was to be a particularly jolly Christmas in Danny’s home this year, for his soldier uncle was going to be there, and two or three little cousins. His mother had made some big plum puddings; the house was decorated with holly and mistletoe; and, to put the final touch of perfection, it was snowing, and the boys would be able to make a snow man on Christmas afternoon. Danny was very happy—all seemed perfect. But on the morning of Christmas Eve a letter came by post that altered things. The letter was from Danny’s Uncle Bill. It was a sad letter. It told how Bill and his wife, who had looked forward to a happy Christmas, would have a dull and sad one. Their son, expected home from Germany, could not get leave. They had both been so ill with influenza that Bill had not been able to work, and was therefore terribly hard up; and his wife had been unable to go out and buy anything to make Christmas jolly.

Bill was a woodcutter, and lived in a little tiny old cottage on the edge of a wood, about five miles from Danny’s home. As Danny listened to his mother reading the letter aloud a thought came into his mind. At first he tried to send it away, and not to see it, but a voice within him said, “You’re a Cub, and when good ideas come to you, you ought not to tell them to go away. It is giving in to yourself. If you are selfish, you will not enjoy your Christmas.” So Danny let the thought come back, and presently he told it to his mother.

“Mother,” he said, “will you pack up some nice things in a basket? Then I will start off after breakfast, and walk over to poor Uncle Bill’s. And I’ll decorate up all their house with holly, and go and do shopping for Aunt Bridget, and then I’ll spend Christmas with them, and try and cheer them up and make them forget they’re disappointed ’cos Ted hasn’t come home.”

Danny’s mother was surprised. “You’re a good boy to think of it,” she said. “But have you forgotten the Cubs’ party on Christmas evening?”

“No,” said Danny, “I haven’t forgotten it.” He stuck his hands in his pockets and whistled, to pretend he didn’t mind at all about missing the Christmas party, where all his fellow Cubs would be enjoying themselves. “I’ll be sorry to miss Uncle Jim,” he said. “Tell him so, mother, won’t you? And keep me a bit of plum pudding. But I must go and cheer up poor Uncle Bill.”

And so half an hour later he started off to tramp the long five miles, a kit-bag full of good things slung over his shoulder. The snowflakes fell soft and white, and the feeling of Christmas was in the air. And Danny was very happy—far happier than he had expected to be this Christmas.

. . . . . . . .

As he tramped along the snowy roads he was thinking of the strange story of Uncle Bill, and the bad luck that had seemed to follow him.

Bill’s father had been a man who owned a good deal of property, and a very clever man too, able to earn much money. But from boyhood he had been a miser. His one thought had been to earn gold and then store it away in secret, and count it up and gloat over it; but never spend more than he possibly could help, and never, never give any away. And so he brought up his children in rags, and often they had to go hungry and barefoot. He sold his property, to get more gold, and lived in a miserable little house by a wood. At last his three boys, tired of this wretched life, ran away from home and went to sea. Two of them were drowned, and Bill found himself the only remaining member of his family, with the exception of his sister, Danny’s mother, who had married and left home.

When Bill was twenty-one he received a message saying that his father was dead, and that all the gold he had amassed during his life would now belong to his son. So, feeling he was a very rich man, he married a nice girl from the little Irish seaport where he was staying, and returned home as quickly as possible. But when he reached his native village he learnt the bad news that the miser had died without leaving any will, and had hidden his gold so well that no one could find it. All that poor Bill inherited was a little old cottage and a woodcutter’s ax.

There was nothing for it but to make the best of a bad job, and settle down in the little house and become a woodcutter. And so Bill and his young wife did their best to make a comfortable home of the old place; but it was a hard life, and it was difficult always to be contented when they knew that somewhere thousands of golden sovereigns lay hidden that should have belonged to them. One son was born to them, and now he was nineteen, and had been fighting in France for the last year.

. . . . . . . .

It had been a long tramp, but at last Danny found himself in the wood on the borders of which was Uncle Bill’s cottage. There was plenty of lovely holly covered with berries in this wood; and up in an oak tree Danny saw some mistletoe. So, putting down his bundle and taking out his knife, he climbed the tree and cut down a great bunch of it, and then filled his arms with holly. He looked like the very spirit of Christmas as he stood in the doorway of Uncle Bill’s house, the snow thick on him, his red muffler making a bright patch of colour, his arms full of holly and mistletoe, and a great bulging kit-bag, slung across his back.

The little room of the cottage looked dull and dismal. Only a tiny fire burned feebly in the great open fireplace. Bill and his wife, looking pale and ill, sat one each side, in silence. But Danny’s appearance seemed to work a miracle. He had brought the spirit of youth to the house. Before long they were all laughing. He and Uncle Bill were putting up holly above the pictures, and hanging the mistletoe in the chimney-corner. And Bridget was unpacking the kit-bag. Before long Danny had been out and chopped some logs, so that a fire was roaring and crackling up the chimney, and sending sparks flying like fire-fairies.

“This is something like Christmas,” said Uncle Bill, as they sat down to a good dinner from what Danny had brought, though the plum pudding and mince pies were being kept for Christmas Day.

After dinner Danny started off for the village to buy the things Aunt Bridget needed. By the time he had finished his shopping and was starting back again for the woodcutter’s, the sun had set, in a glory of red, beyond the snowy trees, and blue dusk was quickly closing in.

. . . . . . . .

As Danny passed the last house in the village he was surprised to see a figure standing in the garden. He had noticed this house before, as he passed, and had seen that it stood empty, the windows shuttered, the doors locked, and everything deserted. Coming nearer, he looked curiously at the figure. It was that of a very, very old man, thin and bent, with a long white beard, and long white hair. He was shaking his head and talking to himself in a most sorrowful voice.

“A sorry thing, a sorry thing,” he was saying, “to be gone eighty year old and never a corner to lay your head on Christmas Eve.”

Danny stopped, filled with pity for the aged man.

“Hullo, grandad!” he said, “is there anything I can do for you?”

The old man shook his head mournfully. “Nay, nay,” he said, “I be eighty year old, and I’ve walked nine mile to spend Christmas with me gran’son, and now I come to his house and find it empty. I haven’t got nowhere to lay me head this night, and not a penny to pay for a lodging. It’s dying of cold I’ll be, a-lying in a ditch all night.” And he took out a big red handkerchief from his pocket and began to wipe his eyes.

It was too sad to think of this! Somehow a happy Christmas must be provided for this old man, so pathetically like Father Christmas himself! Danny knew the charitable spirit that Uncle Bill always showed, and the warm, generous heart of his Irish aunt, and so he felt sure they would welcome this poor old stranger.

“Come home with me, grandad,” he said, “you’ll find a roaring log fire, and an armchair in the chimney corner, and to-morrow you shall eat Christmas pudding.”

The old man looked almost dazed with surprise. He peered closer at Danny. “Is it a Christmas fairy you are, out of the wood?” he said in a whisper.

This was splendid, to be taken for a fairy! “Yes,” said Danny, laughing; and taking the aged man’s cold, gnarled old hand, he led him through the wood to his uncle’s house.

“Shure,” cried his aunt as she opened the door. “I do believe he’s afther bringing us Faither Christmas himself.”

Danny soon explained, and Bill and Bridget gave the old stranger a warm welcome. “They do say,” exclaimed Bridget, “that if you welcome a stranger on Christmas Eve, he may be an Angel.”

“’Tain’t no Angel as I be,” said the old man, shaking his head. And then he laughed, and he had little, twinkling eyes. “If there be an Angel about, ’tis yourself, or the boy here.”

Every one was hungry that night, and supper was a cheery meal. But after supper came the time Danny longed for. The lamp was put out (to save the oil), and the bright, dancing firelight glowed in the quaint little room, with its crooked beams and uneven floor. In the deep chimney-corner, one on each side, sat Bill and Bridget, and enthroned in the large armchair before the fire sat the ancient stranger, puffing contentedly at a long clay pipe. Danny was curled up on the rabbit-skin rug. “Now,” he said, his eyes dancing with expectation, “now for stories.”

So, to the accompaniment of crackles from the logs, Bill recounted many a strange and thrilling yarn of his sailor days. At last he was silent.

“Grandad,” said Danny, turning to the ancient stranger, “will you tell us a story? A mysterious one. I’m sure there were fairies and hobgoblins when you were a boy, long, long ago. Or, do you know a ghost story?”

The old man nodded his head. “Yes,” he said, “there were fairies, sure enough, when I was a boy. But I was not a good enough boy to see them. But a hobgoblin I did see, once. ’Twas on just such a night as this—Christmas Eve, with snow on the ground,—and ’twas but a stone’s throw from this very house.”

This was splendid! Danny turned round and fixed his eyes on the old man’s face. “Tell us, tell us,” he whispered.

. . . . . . . .

“I was born in this here village,” he said, “and here I married a lass. And here my son was born. And ’twas on his first Christmas he fell ill of the croup. Very near death he was, and my wife begged me to run fast as I could to fetch the doctor. The shortest way was through this here wood, and though I was afeared something terrible of the little people as might come after me in the dark, still for love of the boy I came this way.

“’Twas moonlight, and, as I reached the end of the wood, just about outside of this house, I breathed again with relief. But too soon—for when I got to the Druids’ Oak (you know it, for sure—that big old oak, the last of the wood), I saw a hobgoblin.”

The old man made an impressive pause.

Danny was gazing at him, round-eyed. “What was it like?” he said.

“’Twas dressed all in a black cloak, with a hood over its head, and it had a great bag on its back. It was up in the Druids’ Oak, and just before I got to it, it dropped to the ground, light as a feather, and ran quickly into the shadows. I was half mad with fear, and, calling on the saints to protect me, I ran and never stopped till I reached the doctor’s house. That story is true, by all that’s holy. I swear ’tis true.”

“How big was the hobgoblin?” asked Danny.

“Near as big as you,” said the old man. “I thought they was smaller, so it frightened me the more.

“I told the story to one and another in the village, and some laughed at me, but one or two, very solemn-like, told me they had seen that hobgoblin, too. They said that ’twas very lucky to see it, but one must not talk of it to any man. One man told me that the next day he went by daylight past the same tree, and in the snow found a gold piece, which was just what he was sorely needing. He was sure ’twas the hobgoblin had put it there for him. And sure enough, my baby was cured from croup from that time.”

“Do you think the hobgoblin still lives in the oak?” asked Danny, “and still comes out on Christmas Eve.”

“Yes,” said the ancient stranger, “hobgoblins live for five hundred years. This one is still in the oak as likely as not. And they used to say he always comes out on Christmas Eve.”

“Oh,” cried Danny. “I wish I could see him! Perhaps he would bring luck to Uncle Bill.”

The great log fire was beginning to burn low. The ancient stranger was beginning to nod. The church clock struck ten through the stillness of the clear night, while the earth slept beneath its counterpane of snow.

“Time to turn in,” said Bill. He took the aged stranger and led him to the little room that would have been Danny’s, but which Danny had insisted should be given to the stranger, saying he could sleep very well on the rabbit-skin rug before the fire.

“I think I shall go and look for the hobgoblin,” said Danny.

“’Tis foolishness you are talking, child,” said Bridget. “There do be no hobgoblins in this country. If you must be afther getting good luck for me and your oncle, go to midnight Mass and pray for us! ’Tis more likely ye will get what ye do be wantin’ there than from hobgoblins.”

. . . . . . . .

But when all was still and the stranger was snoring, and the line of yellow light under Bill and Bridget’s door had vanished, Danny got softly up from the skin before the fire, and put on his cap and coat and muffler, took down a lantern from the wall, and put a box of matches in his pocket. Then he unbarred the door, and let himself out into the snowy night. A few minutes later he was standing in the shadows, gazing with awe and expectation at the Druids’ Oak, where it stood, gnarled and ancient, in the moonlight.

For some time he stood there watching, but it was very cold, and he grew impatient. Walking with silent steps over the snow, he went up to the tree, and laid his hand on the rough, knobbly trunk. The night was perfectly still, the moon shone steady and white, and at that moment the church clock struck eleven, slowly and clearly. Danny shuddered. This was the hour for ghosts and hobgoblins to prowl. The next hour—twelve to one o’clock—would be the holy hour, when we remember the birth of the Divine Babe.

The last stroke of eleven had scarcely died away when there was a scraping, scrabbling sound from the very heart of the oak, seemingly coming from beneath Danny’s hand. He started, and his heart seemed to miss a beat, and then race on. Something within him seemed to say “Run, run,” and his legs almost obeyed, but his will was stronger than his instinct, and remembering that he was a Cub and must not give in to himself, he stood his ground, only drawing a little into the shadow. He watched the tree intently—was he at last to see a hobgoblin?

Something black moved in the stumpy branches, at the top of the thick, low trunk. Then with a hoot, a great owl floated out, on soft, silent wings, and flew swiftly away into the shadows.

Danny breathed hard. For a while he did not move; then, giving way once more to his impatience, he went up to the tree.

It was curious that the scraping sound should have seemed to come from the very heart of the trunk; it must be a hollow tree, he told himself. Then that was where the hobgoblin lived. Perhaps he had changed himself into an owl, and flown away on his midnight adventures! An idea suddenly struck Danny. He would climb the tree, and see if it was possible to get down into its hollow inside. He would then find the home of the hobgoblin, and perhaps the mysterious door into fairy-land! He lit his lantern and hooked it on a branch; then climbed up by the knots which seemed to form little steps.

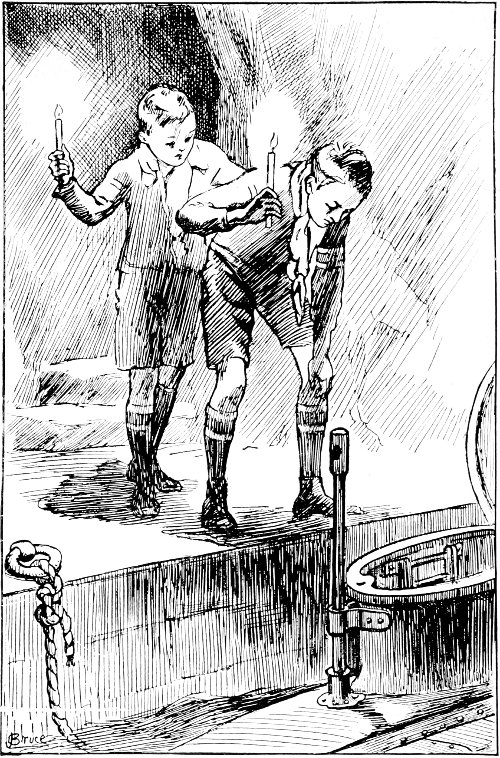

Yes, sure enough the tree was hollow. There was a hole down into its inside just big enough for a boy to squeeze through. Danny tied a piece of string to his lantern, and let it down through the hole. Carefully he lowered it until at last it rested on the ground. Then he peered down. To his amazement he found that a little ladder led down the inside of the tree!

Without a moment’s hesitation he descended the ladder. The tree was like a tiny round room inside, and in the floor at his feet was a hole with a little, narrow staircase leading down.

Danny pinched himself. Was he dreaming? No, he was certainly awake. Could this really be the way into fairy-land? He had only half believed in the hobgoblin all the time. But now he began to think it must really all be true.

Taking up his lantern, he carefully descended the steps, one by one—there were ten of them—and found himself in a little kind of grotto. The walls were of earth and full of gnarled tree roots. The grotto was empty, except for a rough wooden chest that looked as if it had been made by someone who was not a very good carpenter.

With trembling hands Danny raised the lid and looked in. A number of large leather bags were ranged, side by side, at the bottom, and among them was a stout leather book. Breathing hard, Danny lifted out one of the bags. It was very heavy. He placed it on the floor and it chinked. Then he untied the string, and put his hand in. It was a fistful of glittering coins that he drew forth!

Suddenly it all flashed into his mind. The miser and his hidden money—this must have been his hiding-place! Where the hobgoblin came in he did not know or care. All that mattered was that he had found the hidden treasure that belonged to Uncle Bill, and would make him a rich man. One by one Danny lifted out the leather bags. “There must be thousands of pounds there,” he told himself. The sovereigns were funny looking ones, with the head of Queen Victoria when quite young on them.

Last of all he took out the fat, leather book. Then, very carefully, he managed to hoist one bag after another up the tree, and dump it down on the snow. At last he climbed down himself.

Very softly he carried his treasure into the cottage. Looking for somewhere to put the bags, an idea struck him and he hung them in a row on the nails in the high mantelshelf, over the great open hearth. How pleased Uncle Bill would be: what a wonderful Christmas surprise!

And with that thought it struck Danny how good it was of God to have let him find the missing money for his uncle. He glanced at the clock. A quarter to twelve it said. Aunt Bridget had said he should go to midnight Mass and pray for their luck to come back. Now he could do better than that, he could go and thank God for having given it back!

Putting on his cap once more, he hurried out along the snowy path, and turned into the warm, lighted church. Never had he thanked God so fervently for anything. But soon he forgot all about the money, in the wonderful sense of Christmas morning, and the new realization of the Little Christ born to be the Brother and the Saviour of men.

Very sleepily he stumbled home, and curled up on the rug before the red glow of smouldering logs.

. . . . . . . .

“How soundly he sleeps,” said Uncle Bill, the next morning as he lighted the lamp and bent over Danny. Bridget laughed, and shook him by the shoulders. Danny opened his eyes and sat up. His first thought was to look up at the mantelpiece. Yes, there hung the bags.

“Thank God,” he said, “I was afraid it was a dream.”

Bill and Bridget looked up too. “What are they?” said Bill, a puzzled expression on his face, “plum puddings?”

Danny laughed. “No, no,” he said. “Look!”

He unhooked a bag, and shook out the shining contents on to the rabbit skin rug. The sovereigns gleamed and glinted in the lamplight. Bill and Bridget stood speechless. Then Danny explained all that had happened.

At last they examined the book.

It was inscribed at the beginning with the miser’s name, in a little crabbed handwriting. And there were entries made every Christmas Eve, beginning with Christmas, 1830. Each Christmas there was a larger sum to record, until at last in 1898 was entered £3,100.

“And it’s all yours, uncle,” said Danny, smacking Bill on the back.

Bill’s heart was too full to speak, at first; but Bridget had plenty to say—all that they would do with it—all that this would mean for the boy’s future and their old age.

. . . . . . . .

The stranger joined them at breakfast.

“Didn’t I tell you he was Father Christmas or a Holy Angel?” said Bridget. “See what he has brought us.”

“Nay, ’tis the lad,” said the ancient stranger. “I said ’e was a fairy. Or, maybe, ’twas the hobgoblin—he always brings luck; and the owl who flew out of the tree was him, as likely as not.”

Bill was a pious man, not given to belief in such things.

“No,” he said, “’twas the Holy Child, bringing us a Christmas gift, for love of the boy here, who was willing to give up his happy Christmas at home to come and cheer up his poor old uncle.”

“And to give his bed to an old, lonely stranger,” added the old man.

Danny flushed. “No, no,” he said, “it wasn’t for my sake. But I do think uncle is right about it being a Christmas present. I went to midnight Mass to thank for it.” Aunt Bridget kissed him for the twentieth time, and Bill cleared his throat, which seemed rather husky.

“But what about the hobgoblin, really?” said Danny. “Grandad, here, swears he saw him; and you see it was true about the Druids’ Oak being a wonderful tree.”

Bill went to a big press in the corner of the room.

“I think I know who the hobgoblin was. Come here, son,” he added.

Danny went to him, and behind the door of the cupboard Uncle Bill arrayed him in an old black cloak and hood. “Now, hang a bag over your shoulder, and hurry across the room, bent-up like, and see if grandad don’t think he’s seeing his hobgoblin again,” he said.

Danny obeyed, and the old man started up. “’Tis him, ’tis him!” he said, “the very same.”

They all laughed.

“My father,” said Bill, “was a very small, thin, little old man, not much bigger than Danny. ’Twas him you saw, fetching back his money on Christmas Eve to count it, and enter it in his book.”

The old man was nodding his head slowly.

“So, after all I’ve never seen a hobgoblin,” he said. “I’m eighty year old—I shall die afore I get another chance.”

“Never mind, grandad,” said Bridget, “ye’ll be afther seeing the Angels then, so it’ll be all right.”

The glorious day had come at last—the day when Harry and his mother and little sister were to start on their journey to Switzerland. They were going out for the whole winter, and Harry was frightfully excited about it. Fancy being up 7,000 feet in the mountains, and seeing nothing but snow, snow, snow, everywhere! And being able to toboggan and skate and ski all day! And then the journey—to cross the Channel, and then go in a train all day and all night!

The day had come, and Harry was safely in the train on his way to Folkestone. Crossing the Channel was great fun. It was rather rough, and all the old ladies sat tight in red wooden chairs, tucked up in stuffy old rugs. They got greener and greener and looked very unhappy. But Harry and his little sister went up on the top deck and ran about and enjoyed themselves hugely. It was very hard to walk straight, because the ship rolled from one side to the other, and you felt just as a fly on the wall must feel, clinging on with the soles of your feet.

At last the white cliffs of Dover disappeared, and there was nothing to be seen but sea and sky and half a dozen seagulls following the ship. And then a faint line showed on the horizon ahead, and it was the coast of France! Harry and his sister gazed at it, and thought to themselves that it was the first time in their lives they had seen a foreign country.

At last the boat steamed into the harbour at Boulogne. Crowds of funny old French porters came bustling on board. They were dressed in loose blue blouses, and they all talked in French and wrangled with each other and the passengers, as if they were very angry. But they weren’t really—it was only their French way. Harry’s mother managed to get hold of one, and he collected all her bags and suit cases and strapped them together on a long strap, and hung them over his shoulder. Harry thought to himself that he had never seen one man carry so many things before. He barged along through the crowd, shouting most rudely to make people get out of his way. He took all the things to a place called the douane—an awful place full of cross officials, who opened the boxes and pulled things about.

“What awful cheek!” said Harry. But his mother explained it was the Customs.

“A rotten custom, I call it, to pry about in a lady’s private luggage,” said Harry. So his mother explained it was the duty of the Customs officers to see that certain things like food and jewellery and tobacco were not taken into the country without duty being paid on them. When the luggage had all been packed up once again the old French porter, who walked just like a crab, went crawling off with his load to the train. It was a funny train—very high: or, rather, the platform was very low. At last they were all settled in, and in about half an hour they started.

Of course Harry and his sister looked out of the window all the way. It was so exciting to see France. That was before the days of the War, and the little villages were still peaceful and happy, and the rows of stunted willow trees stood along the straight, flat roads for miles and miles, like silent sentinels.

On, on rushed the train. At tea time it was great fun walking along the little wobbly passages to the dining-car. Then again for supper. By that time Harry and his sister were very sleepy. So his mother rang a bell, and a man came along and pressed a button and performed a conjuring trick by which the seats were turned into little white beds, with sheets and blankets and pillows all complete. He did another conjuring trick, and a little bunk was produced from the wall, and Harry found his bed all ready, a few feet above his sister’s.

“When you wake up in the morning we shall be in Switzerland,” said his mother.

They slept beautifully. But every now and then they woke up to find the train still rushing on, on, on, in the darkness. Sometimes it rushed into a station and pulled up. It seemed to Harry that the engine heaved a heavy sigh. Then it started on again. It was nearly six when Harry’s mother woke them up and told them to dress quickly, because soon they would be at Bâle. So they did; and when the train stopped they got out.

They found themselves in a huge station, and it was very cold. Their mother got hold of a porter, and they went along to a big refreshment room, where they had their first Swiss breakfast—coffee and funny little rolls, like half-moons, and honey.

After some time they got into another train, and travelled on until at last, by the afternoon, they had got into the real, snowy part of Switzerland.

Harry had never seen so much snow. But his mother said it would be even more wonderful when they got right up among the mountains to St. Moritz.

At a place called Chur they changed into a funny little train that began slowly plodding up the mountain passes.

Here the snow was wonderful. It lay a yard thick on the mountainside, and was inches thick on the branches of the fir-trees. The train went through many tunnels, and over high, high viaducts; and sometimes the corners were so sharp that you could look out of the window and see the tail of your own train coming round the last curve! The air was so crisp that it seemed to give you new life, and you longed to be out snowballing or doing something active.

The sun went down behind the great white Alps, and the snow began to look a bright bluish purple in the dusk. And before long it was quite dark.

“We shall soon be there, now,” said Harry’s mother.

After stopping at several little stations the train steamed into St. Moritz at last, and everybody got out.

As they stepped out of the station it was like walking into fairy-land. Snow, snow, everywhere—snow roads, with sleighs on them, drawn by horses with jingling bells on their harness. Through the clear, still blue night, shimmered and glittered a thousand little points of light from the many, many windows of all the big hotels, and from the little windows of the chalets, clinging to the hillside, or crowding down on the edge of the great frozen lake. Above, the stars shone larger and brighter than Harry had ever seen them before.

It was freezing hard, but somehow no one seemed to feel cold. Everybody was dressed in woolly garments—white sweaters and coloured mufflers and woolly caps. And everybody seemed to be laughing. Some were pulling toboggans home, others carrying skates, or shouldering their skis. Harry and his little sister began to laugh, too, and ran out on the snow. But soon they fell down, and found out that they must be careful how they walked until they had spiky nails fixed in their boots.

They were to stay in a lovely, big hotel, up the hill. Jumping into an open sleigh, they drove briskly along, gliding smoothly over the snow, their bells making a merry jingle on the frosty air.

That night they slept very soundly, and the next morning they hastened to look out of the window. All was a dazzling white, and the sky was bluer than they had imagined it could be. They dressed quickly in woolly clothes, and put on rubber boots, called “gouties” to stop them slipping; and as soon as they had breakfasted, they went out, and down the little village street.

Tobogganing was the one thing in the world Harry wanted to do. He had already made friends with some very nice boys at the Kulm Hotel, who told him it was the best sport going. So his mother hired a toboggan for him, and he went down to the village run, where he found his friends. They soon showed him how to do it.

The run was like a long curly path, made of hard snow and ice, and very steep. If you wanted to go really fast you took a run, pushed off your toboggan with a final kick, and threw yourself flat on your tummy upon it. As you rushed along you shouted to make everybody clear out of your light.

Harry had a few falls at first, of course, and got a few scrapes and bruises; but every day he would go at it, until, before long, he became the fastest “rider” on the run, and people would clear out of his way pretty quick when they heard him coming.

One day some men he knew at the hotel said he tobogganed so well that they would take him with them on a real, proper toboggan run, all made of ice, called the Dimson Run. Harry was delighted. Tobogganing, here, really was some sport, and rather dangerous too, for the run was very steep, and you went at a tremendous rate. Though he was the youngest rider on the run, he won a silver cup in one of the races!

It was during Harry’s last week at St. Moritz that a great adventure befell him.

His best pal at the Kulm Hotel was his uncle, a very cheery young man, much admired by everyone, for he was the champion of the Cresta Run—the greatest toboggan run in the world. Tobogganing on the Cresta is serious work. Not very many people belong to the Cresta Club, and are allowed to do it. The run is wonderfully made. It is nearly a mile long, and full of dips and twists and turns. It is all made of the smoothest, most shining ice; and the riders, lying face downwards on their heavy, steel toboggans, go down at the speed of an express train. The smallest mistake in leaning the wrong way, or taking a corner too fast, and they would be thrown over the banks, and perhaps killed! To round the corners at such a high speed they have to run round right up on the curved wall of ice, which is made the right shape on purpose. These corners are given different names. The two biggest banks, on a part of the run which looks like a big “S,” are called “Battledore” and “Shuttlecock,” because the rider seems to be thrown across from one bank to the other, rather like a shuttlecock in the game. If they are not very careful, “Battledore” throws them right out over the side, and they fall down about twelve feet into a pile of snow! There are very exciting races on the Cresta. The biggest one is called the Grand National. Crowds and crowds of people come to watch it, and the winner is quite a hero.

When Harry was not tobogganing himself on the smaller runs, his great delight was to come and watch Uncle Hugh practising. He would watch him pass like a flash, his runners making a roaring sound on the ice. Then he would ask the timekeeper how many seconds Uncle Hugh had taken—for each rider is “timed” each time he goes down, to the tenth of a second—and he would run down and tell Uncle Hugh his time (fifty-nine seconds, perhaps), and walk up with him, while an old Italian followed behind, pulling up his “bus” as he called his toboggan.

At last the great day of the Grand National had come. Harry, standing in a huge crowd, watched the different riders tear past. Oh, how he hoped Uncle Hugh would win! The riders had to go down three times. Each time one got to the bottom a man with a megaphone (or speaking trumpet) called out his time. They had all gone down three times, and the great moment came for the winner to be called out. Harry’s heart beat fast. Hooray! It was Uncle Hugh. He felt very proud to be the nephew of the hero; and he rushed down the snowy path to meet him. It was then that he suddenly felt quite sure that if only he were allowed to, he could ride the Cresta!

That evening, in the hotel, he asked Uncle Hugh if he would get leave for him to go down just once. Hugh laughed kindly.

“You’re too young, kid,” he said. “Why you’re only twelve! It’s not very easy, you know. You’d probably have a bad crash and kill yourself.”

Some people standing near had heard. They burst out laughing.

“Do you hear that?” said one of the ladies, “Harry thinks he can ride the Cresta on the strength of his uncle having won the Grand National!”

Everyone laughed, and poor Harry blushed to the roots of his hair. He said nothing, for he knew he could ride the Cresta, if only they would give him the chance, and he determined, inside, that he would manage to go down, somehow, and show them he could.

The next day a small friend of his, Phil, told him something that filled him with delight. The Cresta was closed for that season, for one of the banks was considered too weak, and it would be impossible to rebuild it, for the thaw was beginning to set in. This meant that all the bars would be taken away, and the run left to thaw, and that all the little boys from the village would come and slide about on it, and soon spoil its beautiful, smooth surface. It also meant that there was now nothing to stop any one who liked taking a toboggan, and going down the whole course!

“I’ll tell you a secret, Phil,” said Harry. “To-morrow morning, before any one is up, I am going to go down the Cresta from the top. You can come with me, and we’ll get Dick and Reggie to come too, as witnesses to prove I can do it, and teach those rotters not to laugh.”

Phil was delighted at the prowess of his friend. “What if you get killed?” he said.

“Oh, then it will prove that I couldn’t do it, and they were right!” said Harry.

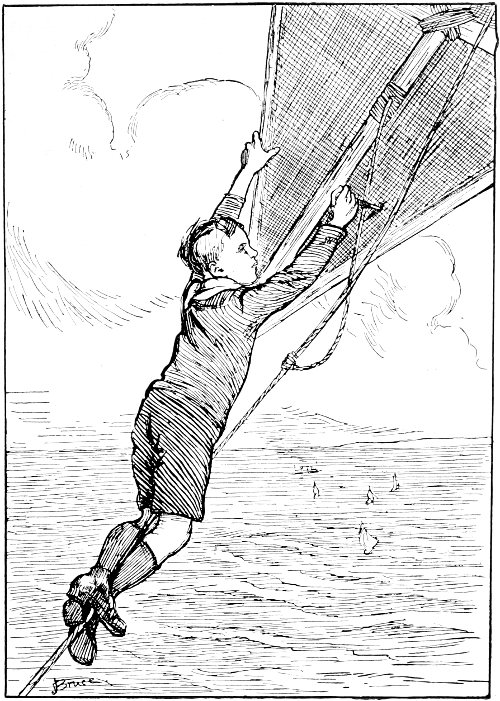

At 8.30 the next morning, just as the sun peeped over the snowy mountains, Harry, with knee and elbow pads, and “rakes” (or spikes) fixed on his toes, crept out, dragging a heavy toboggan. He was followed by his three friends. They walked down by the run first. Every bar had been taken away, it was clear and free.

“Now for it!” said Harry, as he stood at the top, his heart beating fast with excitement. Lying flat on his toboggan, he slid off down the first incline, down towards the steep and sudden dip called “Church Leap.”

At this moment his friends saw a tall figure walking down the path by the run, away by the big corners known as “Battledore” and “Shuttlecock.” In a moment they recognized him by his orange scarf—it was Uncle Hugh! He had stopped, for he had heard the rush of a toboggan on the run. What would he say when he saw it was Harry? But even as they saw him stop, they saw something else that made their blood run cold!

At the place where the run cuts across the road, and is usually guarded by a man with a red flag to keep people from crossing, a wood sleigh suddenly appeared. It advanced slowly and drew up, the horse standing straight across the run. Once a rider has started down the Cresta Run there is no way of stopping—he must rush on at sixty miles an hour! The three boys’ hearts seemed to stop with terror. Hugh was standing still, his eyes fixed on the place.

And what of Harry? Long as this takes to tell, it was all a matter of less than a minute. Harry had rushed in a glorious, thrilling whirl down most of the run—the worst was over. He was now on the long steep straight, and there were only small corners to get round. The cold air seemed to whistle in his face and make his eyes stream, for he was travelling at a very high speed. And then—then he saw the terrible sight. A horse and sleigh was standing across the run!

There were only a few seconds to think what to do as he flew onwards. But Harry did not lose his head. At one glance he had noticed that the horse and not the sleigh was across the run. The driver was round at the back, fixing up a log that had slipped. Lying very flat, and guiding himself straight as an arrow, Harry kept his course, and passed like a flash beneath the horse, between his four great legs! He was safe!

The three boys, watching from the top, threw their caps in the air, and cheered and laughed for joy! Hugh, standing by “Shuttlecock,” his teeth clenched, gave a sigh of relief. “Thank God!” he said. “Thank God! He’s a sporting kid, right enough, and he’s got some wits to have done that—it was his only chance!”

No one at the hotel laughed when they heard the story. Harry was thoroughly scolded, of course. But everyone looked at him with admiration. “Some day he’ll be the champion on the Cresta,” said an old Colonel, who had won the Grand National many years ago.

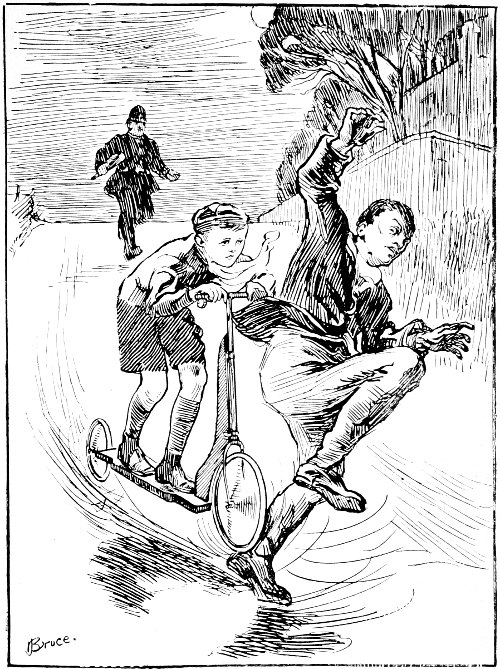

Wolf Cub Pat Shannon awoke with a start, and sat up in bed. He had been far away in the glorious land of dreams, driving a Rolls-Royce motor car. It must have been the happy week he had spent since Christmas, riding on his scooter, that had made him dream this, for his Uncle Patrick had brought him a scooter from London for a Christmas present. It was a real beauty, with solid rubber tires and nice big wheels, and it had cost 7s. 6d.! Pat had learned to get up a tremendous speed upon it.

“Shure, it’s a danger ye are to the pedestrians!” his uncle had said one day, on meeting him rushing down the street of the little Irish town where he lived. Pat had not a notion what a pedestrian was; all he knew was that it made his uncle buy him a real bicycle bell and screw it on the handle of his scooter!

Now he had been suddenly roused from his dreams. He sat up in the darkness and listened. Yes, it was his mother’s voice. She was sitting up, he knew, with baby, who had bronchitis. He was the only man in the house, his father being at the front with his regiment, the Royal Irish Fusiliers. He had wanted to sit up, but his mother had told him to go to bed, and she would call if she wanted help. Now he heard her.

“Pat—Pat—Patrick Michael!” Her voice seemed somehow frightened.

“Yes, mother!” he called, scrambling out of bed. In a moment he was pattering down to the kitchen, barefooted, in his little nightshirt.

“Pat,” said his mother, “Baby’s very ill, he is. He’s after takin’ a sudden turn for the worse. I must have the doctor this minute, or it’s dead he’ll be before morning.”

“Right, mother,” said Pat in a business-like way. “If the doctor is at his house, I’ll have him here in half an hour!”

He ran upstairs again. In three minutes he was back dressed and searching in the back kitchen for his scooter.

“What d’you be after fetchin’, dearie?” said his mother. “Sure, an’ you aren’t goin’ to take out yer scooter this dark night?”

“Yes, mother,” said Pat. “It’s as fast as a motor bike, I can be goin’ on my scooter. I shall be down the hill at the doctor’s house in ten minutes from now.”

Softly he let himself out, and set off down the lonely road. There was a small moon, and he knew every inch of the way.

It was all down hill to the doctor’s house. The road was smooth and quite empty. Pat got up a great speed. It was glorious! The night air rushed past him.

He reached the bottom of the first hill. There was rather a lonely piece of road to go along, here. At the end of it stood a great house, with a high wall round it. The owner of the house had been away from it for many years. Only a very old caretaker lived in it.

People said it was full of treasures and great wealth—jewels and silver plate, priceless china and beautiful pictures. The shutters were always closed, and many were the tales about it.

Pat’s heart beat rather fast as he reached the wall. Great black trees grew in the garden and stretched their branches like great hands over it.

All the stories he had ever heard of ghosts and banshees and the “little people” came into his head. He half wished he hadn’t come. The shadows were so very black, and all was so still. There was no one about, and not the faintest sound to be heard.

“A Cub does not give in to himself.” The words of the Cub Law suddenly came into his head. He felt the little brass badge in his buttonhole, and it gave him courage. With a kick he sent his scooter on, and passed out of the moonlight into the shadow of the trees.

Hullo! what was that sound? A noise of breaking glass and splintering wood, as if someone had jumped through a window—running feet in the garden—a hoarse shout—now a long, shrill blast from a policeman’s whistle—more running behind the wall—then the sound of another policeman running down the road to the help of his comrade!

Pat forgot his fears. Here was a real adventure!

Then, suddenly, just ahead, a dark figure appeared in the moonlight, crouching on the top of the wall. A moment later the policeman had dashed up. Like a tiger springing on his prey, the man leapt down on him, knocking him flat, and then began running down the hill at top speed.

A second policeman had come up, and, seeing the running figure, made after him. But it was a hopeless chase. The man had had a good start, and he was a swift runner. Besides, the policeman was rather fat.

Suddenly a thought flashed into Pat’s mind, and his heart grew big with courage. He would help the policeman in his work—that would be some good turn!

Placing his right foot firmly on his scooter, he kicked off violently with his left. In a moment he was shooting like a flash down the steep hill. It was a dangerous job. He squatted down and balanced carefully. He had never been at such a speed in his life.

In half a minute he had overtaken the policeman. The man, hearing the following footsteps flagging, had reduced his speed a little. Pat’s rubber wheels made no sound on the smooth road. Nearer and nearer he drew to the flying thief. Now he was very near. He set his teeth and steered his scooter straight for the man.

Crash! The scooter and its small rider had hurled themselves against his legs. With a yell of terror and pain the great figure crashed to the ground, Pat on top of it, the scooter flying out into the road. Without a moment’s hesitation he scrambled free of the man’s legs, and sat with all his weight on the furious burglar’s head. The man struggled violently, but one of his arms was caught under him, and Pat was bending the other back in a most painful position. Before long the policeman was up, and had the prisoner handcuffed.

Pat felt as if he were one great bruise all over! Blood was streaming from a cut on his chin, where it had come into violent contact with the burglar’s boot. But his first thought was for baby and the doctor. Picking up his scooter, he did not wait for a word from the policeman, but dashed on down the hill.

Half an hour later Dr. Byrne was up at the cottage in his car, with Pat and his scooter on the seat beside him. Of course the cut on the chin had to be explained. And, when baby was fixed up, it was stitched and bandaged. The next day Dr. Byrne drove his small patient to the Police Court.

“Crash! The scooter and its small rider had hurled themselves against the burglar’s legs”

Ten pounds reward! Why, the very excitement of the adventure would have been enough reward in itself! But, all the same, it’s rather jolly to have £10 of your very own, earned by your own pluck and the help of your scooter!

Eric Stone lived in Westminster with his aunt, for he had no mother or father. He belonged to a Westminster Pack, but he spent all his holidays at his grandfather’s house—a lovely old castle in Wales. Its weather-beaten walls reached out very near to the craggy cliffs, where the sea dashed up, white and foamy. Of course Eric longed for his holidays, and one day it struck him how jolly it would be to take three of the other Cubs with him. So he got leave from his grandfather, Sir David Stone, and then he invited the boys. He did not choose the ones he liked best, but the three chaps who would be likely to have the dullest holiday, and no fun at Christmas. That is how Donald Ford, number six of the Whites, came to have the strange adventure this story is about.

. . . . . . . .

It was Christmas Eve. The four Cubs had decorated the castle with holly and mistletoe. Now they were curled up on the great bearskin rug in the hall, before a blazing log fire. The dark winter afternoon had closed in, but the lamps were not yet lighted. Everything looked very mysterious; the fire-light danced in the dark corners, gleaming on the shining suits of armour and oak-panelled walls.

“Tell us a ghost story,” said one of the Cubs. So Eric told them all the stories he knew about the castle, and the knights who had lived in it hundreds of years ago. “And now,” he said, “I’ll tell you something which is not just a story, but is quite true. Somewhere in this castle there is a secret room. You know in olden days people used to hide in secret rooms, away from their enemies. Well, there’s one here, and it was always kept very secret: only the head of the family knew where it was. It opened by a spring, hidden in the oak panelling. But now nobody knows where it is; the secret has been quite lost for four hundred years, because they found it was very, very unlucky for any one to open the door or go in; it always meant a tragedy, or great shame on the family. I should love to find the room and so would grandfather. Of course it’s all rot about its being unlucky.”

“Oh,” cried the Cubs, “how awfully exciting! Do let’s hunt for it.”

“Yes,” agreed Eric, “we will, to-morrow. There’s one side of the castle we don’t use, because it is unsafe and may fall to ruins any day. The servants say that’s where the secret room is. They wouldn’t go there after dark for anything. In fact they say they hear footsteps there in the night.”

At this moment there were steps in the hall and voices, and Eric’s grandfather came in accompanied by his adopted son, William Mendel, a gloomy-looking man. Sir David Stone was a tall, soldierly looking old man, and devoted to Eric, for Eric’s father (his only son) had been killed in the War. William Mendel was the son of a very old friend of his, who had died when William was quite a boy. Eric and the Cubs disliked “Uncle William,” for he never lost an opportunity of snubbing them. They called him “the Professor” behind his back. He had rather long black hair, and a sullen, yellowish face. He wore large, round spectacles, and stooped badly. He had a nasty habit of peering about him in a suspicious manner.

“Hullo, kiddies!” said old Sir David, “what are you all doing in the dark?”

“I’ve been telling them about the secret room, grandfather,” said Eric; “to-morrow we are going to have a hunt for it.”

Sir David laughed. “All right,” he said, “and a golden sovereign for the one who finds it—that’s a bargain.”

The Cubs were delighted.

But Uncle William was looking very cross. “I shouldn’t have thought you would have wanted to find the secret room, Eric,” he said with a sneer. “You know it is haunted, and brings trouble to whoever finds it.”

Old Sir David turned in surprise. “My dear William,” he said, “you don’t mean to say you believe in that old wives’ tale?”

William Mendel laughed an ugly laugh. “Do you take me for a fool, father?” he said. “I was only trying to frighten the children from going to the left wing of the castle. You know how exceedingly dangerous it is.”

“I don’t believe it’s dangerous,” said Sir David.

“Well, sir,” retorted William, “there will be an accident one day if you let people walk about in those rickety passages.”

Sir David shrugged his shoulders. It was not the first argument he had had with his adopted son about the left wing of the castle.

The Cubs were full of ideas about the secret room, and how to find it and earn the sovereign, as they went to bed that night.

Christmas had passed, one long succession of delights, starting with a most generous Santa Claus and ending with a New Year’s party. Never had the four Cubs had such a Christmas! But during all this time they had forgotten the secret room. It was not until ten days later that the intended search took place. Tired and disappointed, the Cubs had come down to tea, and it was then that Uncle William had made his bright suggestion.

“There’s something more worth hunting for in this neighbourhood than an old secret room,” he said, “and you Cubs are just the people to find it.”

“What’s that, sir?” asked the Cubs, eagerly.

“Why, a German spy!” said Uncle William, with a grin. “And if you catch him I will give you each a golden sovereign—that’s a bargain!” The Cubs were thrilled.

“We’ll go out and look for him first thing to-morrow morning,” said Eric, cheerfully. But his grandfather was looking very grave.

“It is really a very serious matter,” he said, turning to William Mendel. “They say there’s an enemy submarine in the Irish Sea. Another liner was sunk this morning, only a few miles from here. That’s the eighth ship they’ve got near here in the last few weeks. I was speaking to the police, this morning, who say they suspect a base somewhere, at which this boat gets its supply of petrol. Otherwise it could not possibly remain so long in enemy waters. But it must be an extraordinarily clever arrangement, when one considers how well the coast is guarded. I don’t know what can have led them to suspect the spy’s presence in this neighbourhood.”

“No,” said William Mendel, “That’s what struck me. There would seem to be no hiding-place for him. And as to a base for providing a submarine with petrol about these rocky shores—well, that’s out of the question.”

“Quite,” agreed Sir David, “quite.”

But the spy had given the Cubs an object in life—they were hot on his tracks.

. . . . . . . .

Donald Ford, the Cub who had asked Eric to tell them ghost stories on Christmas Eve, had not given up hope of finding the secret room. In fact, while the others were full of the spy, he still thought most of the secret room. He was not a very strong boy, and often, when the others went out in the frosty air, dashing over the bleak, stony hill through a long afternoon, he would choose to stay in, and sit by the log fire, dreaming, or reading tales of the good old days of knights and dragons and tournaments. It was on an afternoon like this that he discovered the old library.

Books lined the walls from floor to ceiling, row upon row. Old brown leather bindings they had, and gold lettering. They smelt very ancient, and were very, very dusty. But Donald loved to take them down, and sit on the floor, looking at their quaint pictures. And it was one day, sitting here in the library, that he made a very wonderful discovery which led to the strange adventure that befell him.

He had found an old book full of pictures of knights and ladies and people going hawking, dressed in curious, old-fashioned clothes. On the fly-leaf of the book was written in a big, childish hand, “Eric Stone, His Booke, 1640.”

Donald turned the old musty pages with interest. So this book had belonged to a boy just about three hundred years ago. As he turned the pages a yellowish paper fluttered from between them, and fell on to the floor. Donald picked it up and examined it. It was covered with writing in the same round hand as there was on the fly-leaf. And this is what he read: