Cover art

Title: The Last Three Soldiers

Author: W. H. Shelton

Illustrator: B. West Clinedinst

Release date: March 3, 2018 [eBook #56671]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

"'THERE THEY ARE! SEE? BY THE END OF THE HOUSE!'

EXCLAIMED PHILIP." (See page 98.)

BY

WILLIAM HENRY SHELTON

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1897

Copyright, 1896, 1897, by

THE CENTURY CO.

THE DEVINNE PRESS.

WITH AN APOLOGY TO THE LITTLE SISTER

THAT THE PLOT IS NOT MORE BLOOD-CURDLING AND

HARROWING, THIS STORY OF WHAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED TO HIS YOUNG

FRIENDS GUSSIE AND GENIE DEMAREST

BY THE AUTHOR

145 WEST FIFTY-FIFTH STREET,

NEW YORK, September 4, 1897

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

II The Old Man of the Mountain

III The Mountain of the Twentieth Red Pin

VII In which the Three Soldiers Make a Remarkable Resolution

IX The Plateau Receives a Name

XI In which the Soldiers Make a Map

XII How the Bear Disgraced Himself

XIII How the Bear Distinguished Himself

XIV Which Gives a Nearer View of the Neighbor Called "Shifless"

XVI Which Shows that a Mishap is Not Always a Misfortune

XVII How the Postmaster Saw a Ghost

XVIII Knowledge from Above

XX The Stained-glass Windows and the Prismatic Fowls

XXI A Scrap of Paper

XXII The Deserted House

XXIII Starvation

XXIV The Rescue

XXV Conclusion

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"'There They Are! See? By the End of the House!' Exclaimed Philip" . . . . . . Frontispiece

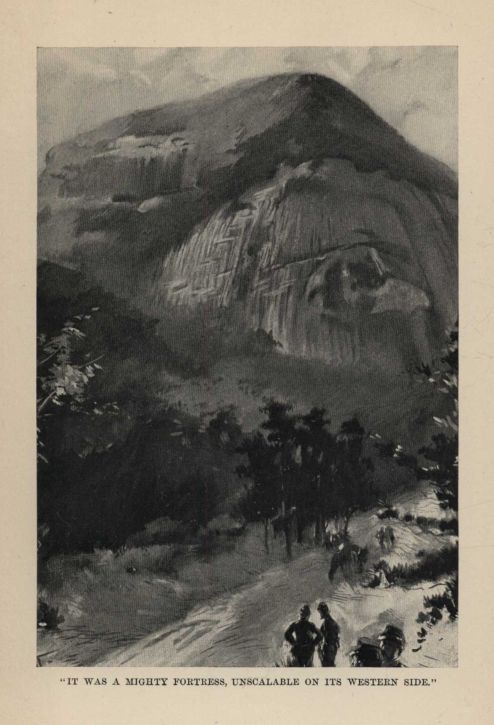

"It was a Mighty Fortress, Unscalable on its Western Side"

Andy Tells the Story of the Old Man of the Mountain

"Corporal Bromley Took Position with a Red Flag having a Large White Square in the Center"

"Poor Philip, Left Alone, Burst into Tears"

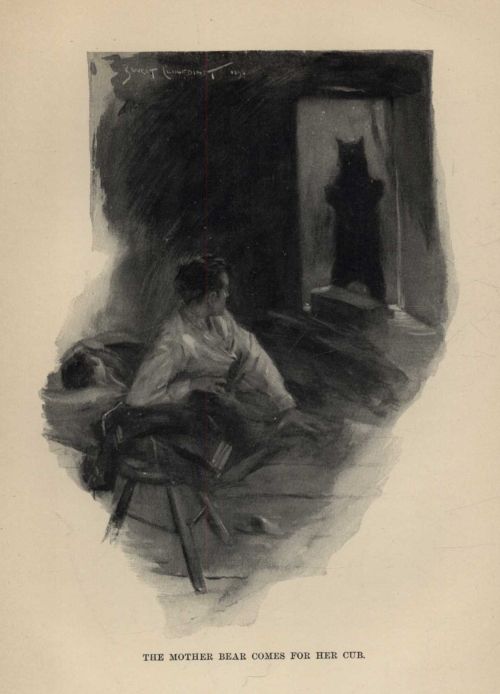

The Mother Bear Comes for her Cub

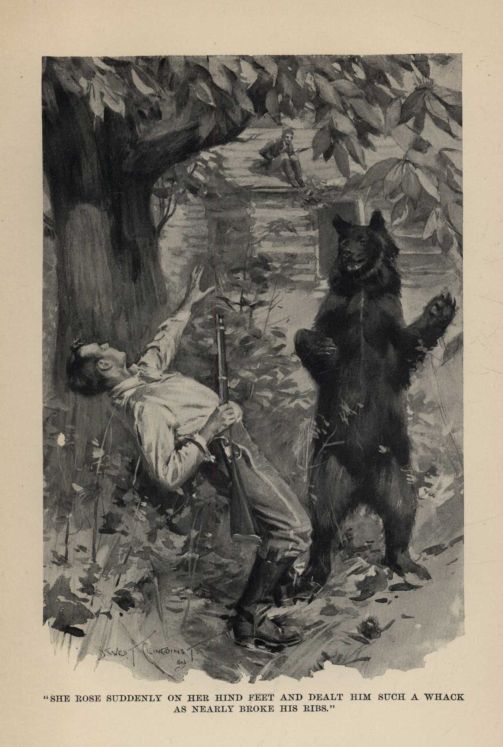

"She Rose Suddenly on her Hind Feet and Dealt Him such a Whack as Nearly Broke his Ribs"

"The Fowls Hung about the Door"

"Philip Made Up the Most Marvelous Stories, which were Recited before the Fire"

"The Cask was Overturned so that the Yellow Pieces Poured Out upon the Floor"

"They Drove Him Off with Sticks and Stones"

Making a Hundred-dollar Caster

Philip on the Edge of the Precipice

"Philip could See the Hole in the Snow, through which He Knew He must have Fallen"

"Rushing Out from under the Trees, They Saw a Huge Balloon Sweeping over their Heads"

"Beyond the Illumination of his Torch He Saw Two Gleaming Eyes"

Exploring the Cave of the Bats

"He was Down on his Hands and Knees upon the Turf"

The Grave of the Old Man of the Mountain

"He Could Only Cry Out, 'Fred! Fred! Here They Come!'"

"They Looked Hardly Less Comical than Before"

If Andy Zachary, the guide, had not mysteriously disappeared from his home within the month which followed the events of the night of the 2d of July in the year 1864, sooner or later the postmaster in the Cove on one side and the people in the valley on the other must have learned of the presence of the little colony on the summit of the great rock.

On that particular night the cavalcade had come silently and secretly over the mountains by an unfrequented trail from the last station on Upper Bald, which towered above the Sandy River country. The troopers had followed the guide in single file along the ridges and down the stony trails, and now, when they emerged on the open Cove road for the first time, Andy fell back to the captain's side, in his butternut suit and mangy fur cap, with his long rifle slung behind his broad, square shoulders.

For that night his will was law above that of the captain; and before the three pack-mules at the end of the train had come out on the road, the head of the column had turned up a washout to the left, which presently brought the whole outfit into the shelter of a grove of pines alongside a deserted log cabin. It was just a trifle past midnight by the captain's watch, and the full moon which hung above the ridge to the west would light the Cove face of old Whiteside for yet an hour; and during the darkness which must follow in the small hours of the morning there would be ample time to steal through the sleeping settlement and find a lodgment high up on the mountain which was the objective of the expedition.

The troopers dismounted, and some lay down on the ground by the horses, while two kindled a fire in the stone chimney of the cabin and made coffee for the others. Corporal Bromley leaned a bundle of red-and-white flags against the door-post, and after turning aside with Lieutenant Coleman and Philip Welton to inspect their supplies on the pack-mules, the three joined the captain and the guide in the shadow of that end of the cabin which looked toward the singular mountain standing boldly between the Cove and the valley beyond. That it was a mighty fortress, unscalable on its western side, could be seen at a glance. The broad moonlight fell full on a huge boulder, whose mighty top, a thousand feet above the Cove, was fringed with a tall forest growth that looked in the distance like stunted berry-bushes, and whose rounded granite side was streaked with black storm-stains where the rains of centuries had coursed down. The moonlight picked out white spots underneath the huge folds which here and there belted the rock and protected its under face from the storms. These were the spots which the rills dribbled over and the torrents jumped clear of to meet their old tracks on the bulging rock below. It looked for all the world as if the smoke from huge fires had been curling against the mountain for ages, so black were the broad upward streaks and so white in the moon's light were the surrounding faces of the rock. Phil was the first to speak.

"IT WAS A MIGHTY FORTRESS, UNSCALABLE ON ITS WESTERN SIDE."

"It must have been a giant that rolled it there," he said with a sigh of relief, and looking up at Andy, the guide.

"Well, now, youngster," said Andy, "you'd 'low so if you was round these parts in the springtime, when the sun loosens the big icicles hangin' on them black ledges, an' leaves 'em fall thunderin' into the Cove bottom."

The Cove post-office, whose long white roof crowned a knoll nearly in the center of a small tract within the mountain walls, Andy said, was at such times a great resort of the mountaineers, who came that they might watch the movement of the avalanches of snow and ice.

Because of its wonderful formation this mountain was of abundant interest to all during their brief halt, but it was examined most carefully by the three young soldiers who were to be stationed on its crest. Philip Welton was the youngest of the three, only just past seventeen, and it was well known to his officers that if he had not been an orphan, without parents to object, he would never have been permitted to enlist even as a drummer-boy in the 2d Ohio, or in any capacity in any other command. The lad was of a gentle, affectionate nature, sensitive and refined, but his opportunities for education had been limited to the winter schools and the books he had read behind the flour-sacks in his uncle's mill. Some said his uncle was glad to be rid of him when he went away to the war. Like his friend and protector, Bromley, he had served with the colors on many a hard-fought field, and now the two had just been detached from their regiment and assigned to duty under the command of Frederick Henry Coleman, a second lieutenant whose regiment was the 12th United States Cavalry.

George Bromley, although the oldest of the three, was not yet twenty at the time he had enlisted at the beginning of the war, and he had left college in his junior year to enter the army.

Lieutenant Coleman had graduated from West Point the summer before, the very youngest member of his class. Although the three were mere boys at the time of their enlistment, each had entered the service through the strongest motives of patriotism, and each followed the fortunes of the national arms with an interest which showed itself in accordance with his personal character.

At that time General Sherman's army was engaged in that series of battles which began at Marietta, Georgia, and, including the capture of Pine and Lost Mountains, was soon to end in the victory at Kenesaw. The army of General Sherman was steadily advancing its lines in spite of the most heroic resistance of General Johnston, and every new position gained was fortified by lines of log breastworks, sometimes thrown up in an hour after the regiments had stacked arms. These hastily constructed works, extending ten and twelve miles across the thickly wooded country, were nowhere less than four feet high, with an opening under the top log for musketry, and out in front the tree-tops were thrown into a tangled mass, almost impossible for an attacking army to pass. These peculiar and original tactics of General Sherman enabled him to hold his front with a thin line of men, while the bulk of his troops were sent around one flank or the other to turn the enemy out of his works and so gain a new position.

This was the sort of service Corporal Bromley and Philip Welton had been engaged in during the early part of the campaign; and when they remembered the long rains and the deep mud through which the soldiers marched, and the wagon-trains foundered and stuck fast, they were not sorry to be mounted on good horses and riding over hard roads.

Now that the moon had set, the troopers mounted again and moved quietly along the stony road, Andy Zachary, the guide, riding with the captain at the head of the column. The deep silence of the forest was on every hand, broken only by the clicking of iron shoes and the occasional foaming and plunging of a mountain stream down some laurel-choked gorge. The road wound and turned about, fording branches, mounting hills, and dipping down into hollows for an hour, until open fields began to appear bristling with girdled trees, and then the wooded side of the huge granite mountain shot up, towering over the left of the column. Soon thereafter the forest gave way to open country, and as the road swept round the base of the mountain it became a broad and sandy highway, so that when the horses trotted out there was only a light jangling of equipments,—sabers clicking on spurred heels, and the jingling of steel bits,—and when the pace was checked to a walk in passing some dark cabin only the creaking of the saddles was heard.

So it was that the troopers stole silently through the valley of Cashiers, with the solemn mountain-peaks standing like blind sentinels above the sparse settlement. Occasionally a drowsy house-dog roused himself to bark, and his fellow gave back an answering echo across the bushy fields; but no one of the sleepers awoke under the patchwork quilts of many colors, and the long rifles hung undisturbed over the cabin doors. Then the troopers exulted in their cleverness, and laughed softly in their beards, while the night winds blew over the roofs of the dark cabins as they passed.

After they were clear of the sandy road in the settlement, it was a long way up the mountain-side, and the iron shoes of the scrambling horses clicked on many a rolling stone, and some sleepy heads caught forty winks as they climbed and climbed. The cabins disappeared, and the fences, and the plow-steers in the hill pastures rattled their copper bells from below as the troop got higher; and so it was lonesome enough on the shaggy mountain, and every trace of the habitation of man had disappeared long before they reached the rickety old bridge which spanned the deep gorge.

Andy said that this bridge was the only possible way by which the top of the mountain could be reached, and that it had been built a great many years ago by a crazy old man who once lived on the mountain, but who was long since dead. It was still too dark to examine its condition. It could be seen that the near-by poles of the old railing had rotted away and fallen into the black chasm below. More than half of the bridge was swallowed up in the shadows of the foliage on the other bank. Away down in the throat of the gorge, where tall forest-trees grew and stretched their topmost limbs in vain to reach the level of the grass and flowers on the fields above them, a tinkling stream fell over the rocks with a far-away sound like the chinking of silver coins in a vault. The silence above and the murmur of the water below in the thick darkness were enough to make the stoutest hearts quail at the thought of crossing over by the best of bridges, so the captain prudently decided to wait for daylight; and as the distance they had gained above the settlement made the spot a safe encampment for a day, he ordered the troopers to unsaddle.

After feeding the tired horses from the sacks of oats carried in front of the saddles, the men lay down on the ground and were soon sleeping soundly under the tall pines which grew above the bridge-head.

The captain and Andy lingered by the bridgehead, and the three boy-soldiers who were to be left behind next day, long as the march had been, felt no inclination for sleep. They were too much interested in watching for the first light by which they could examine this important approach to their temporary station.

"I should like to know something more of the crazy old man who built this crazy old bridge," said Philip, appealing to Lieutenant Coleman. "Why not ask the guide to tell us?"

Andy was by no means loath to tell the story so far as he knew it, which was plain enough to be seen by the deliberate way in which he seated himself on a rock. Andy's audience reclined about him on the dry pine-needles.

Mountaineers are not given to wasting their words, and by the extreme deliberation of the guide's preparations it was sufficiently evident that something important was coming.

"Thirty years back," said Andy, taking off his coonskin cap, and looking into it as if he read there the beginning of his story, "and for that matter down to five year ago, there was a man by the name of Jo-siah Woodring lived all by himself in a log cabin about half-way up this mountain, and just out o' sight of the trail we-all come up to-night. He owned right smart of timber-land and clearin', and made a crap o' corn every year, besides raisin' 'taters and cabbage and enions in his garden patch. He had a copper still hid away somewhere among the rocks, where he turned his corn crap into whisky; and when Jo-siah needed anything in the line of store goods he hooked up his steer and went off, sometimes to Walhalla and sometimes clean up to Asheville.

"Now about a year after Jo-siah settled on his clearin', about the time he might have been twenty or thereabouts, when he come back from one of those same merchandisin' trips, instid of one steer he had a yoke, and along with him there was a little man a good thirty year older 'n Jo-siah, an' him walkin' a considerable piece behind the cart when they come through the settlement, same as if the two wa'n't travelin' together. The stranger was a dark-complected man, so the old folks say, and went just a trifle lame as he walked; and as for his clothes, he was a heap smarter dressed than the mountain folks. Not that he looked to care for his dress, for he didn't, not he; but through the dust of the road, which was white on him, hit was plain that he wore the best of store cloth.

"As the cart was plumb empty, hit would seem that the little man fetched nothing along with him besides the clothes on his hack, and such other toggery as he may have stowed away in the cowskin knapsack they do say he staggered under. If he had any treasure, he must 'a' toted hit in his big pockets, which, hit is claimed by some folks now livin', was stuffed out like warts on an apple-tree, and made him look as misshapen as he was small.

"Now, whether anybody heard the chinkin' o' gold or not (which I'm bettin' free they didn't), hit looked bad for Jo-siah that this partic'lar stranger should disappear in his company, for he was never seen ag'in in the settlement, or anywhere else, by any human for a good two year after the night he come trudgin' along behind the cart. Hit was nat'ral enough that the neighbor folks in time began to suspicion that Jo-siah had murdered the man for his money, and all the more when he made bold to show some foreign-lookin' gold pieces of which nobody knowed the vally.

"They say how feelin' run consid'ble high in the settlement that year, but hit was only surmisin' like, for there was no evidence that would hold water afore a jury of any crime havin' been committed; and hit all ended in the valley folks avoidin' Jo-siah like his other name was Cain—and that sort o' treatment 'peared to suit him mighty well. Leastways, he went on with his plowin' and sowin' and stillin' his crap, and whistled at the neglect of his neighbors, who never came to the clearin' any more, and in that very year he built this bridge, with or without the help of the other one.

"When the bridge was first seen, hit was stained by the weather, and moss had come to grow on the poles, and rotten leaves filled the chinks of the slab floor as if hit had never been new, and no one cared to ask any questions of Jo-siah, who kept his own counsel and seemed to live more alone than ever. The bridge was only another mystery connected with the life of this man that everybody shunned, and nobody suspicioned that hit had anything to do with the disappearance of the other one, who was counted for dead.

"Now when day comes," said Andy, "you-all will see for yourselves that there is no timber on the other side o' this here gully tall enough to make string-pieces for a bridge of this length, and so the two string-pieces must have been cut on this side so as to fall across the chasm pretty much where they were wanted. Well, that was how it was; and the story goes that the man who first saw the bridge reported, judging by the stumps, that the right-hand timber had been cut six months or more before the other one, which might have been just about the time Jo-siah brought the stranger home with him, and would easily account for his disappearance onto the summit of the mountain, for of course you understand he was not dead, and Jo-siah the Silent had no stain of blood on his conscience.

"The mountain folks, however, thought different at that time, and looked cross-eyed at the painted cart drawed by the two slick critters on hits way to the low country. They was quick to take notice, too, when Jo-siah come back, that the cart carried more kegs than what hit had taken away, besides some mysterious-lookin' boxes and packages. Now this havin' continued endurin' several half-yearly trips, hit was the settled idee in the valley that Jo-siah was a-furnishin' of his cabin at a gait clear ahead of the insolence like of drivin' two steers to his cart when honest mountain folks couldn't afford but one. Hit was suspicioned, moreover, that he was a-doin' this with the ill-got gold of the old man he had murdered, and the gals shrugged their shoulders as he passed, for no one of the gals as knew his goin's-on would set a foot in his cabin. It leaked out some way that Jo-siah had been investin' in books, which was the amazin' and crownin' extravagance of all, for hit was knowed that he could scarcely read a line of print or much more 'n write his own name.

ANDY TELLS THE STORY OF THE OLD MAN OF THE MOUNTAIN.

"These unjust suspicions of murder and robbery against an innocent man continued to rankle in the minds of the valley folks for more than two years, until a most surprisin' event took place on the mountain, to the great disappointment and annoyance of those gossips who had been loudest in their charges against Jo-siah Woodring. Hit happened that two bear-hunters from the settlement found themselves belated in the neighborhood of this very bridge one September night, and, bein' worn out with the chase, they sat down to rest in the shadow of an old chestnut, where they soon fell asleep. They awoke just before mid-night, and were about to start on down the mountain when they heard footsteps coming up the trail, and presently, dark as the night was, they saw a man with a keg on his shoulder a-walkin' toward the bridge. The man was Jo-siah; and after restin' his burden on a stump and wipin' the sweat from his forehead, he shouldered hit again and tramped on over the bridge.

"The hunters were bold men and well armed, and, having had a good rest, they followed the man at a safe distance until he came to the ledge of rocks which you-all will view for yourselves by sun-up, and there he was met by a man with a ladder, who stood out on the rocks above. The hunters noticed that the stranger was a small man, and just then the moon came out from behind a cloud, and they knew him for the little old man who was supposed to have been murdered.

"When the hunters told what they'd seen on the mountain, you may believe," said Andy, "there was right smart excitement in Cashiers, and some disappointment to find that Jo-siah was neither a murderer nor a robber. They went on hating him all the same for driving two steers to his cart and for having deceived them so long about the man on the mountain, and then they started the story that he was feedin' his prisoner on whisky, and that it was only a slow murder, after all. After that, one day, when Jo-siah had gone away to market, half a dozen of the valley men, with the two hunters to guide them, went up the mountain for the purpose of liberating that poor prisoner o' Jo-siah's.

"They carried a ladder along, and when they had climbed up the ledge they found a little log shelter not fit for a sheep-hovel; and as for the prisoner, he kept out of their way, for it was a pretty big place, with plenty of trees and rocks to hide among. Well, as the years went on, Jo-siah brought back less and less of suspicious packages in his cart when he came up from the low country; but it was known that he still went up the mountain on certain dark nights with a keg on his shoulder. The strange old man himself was seen at a distance from time to time, but at last his existence on the mountain came to be a settled fact, and the people ceased to worry about him.

"Well, five years ago, as I said," continued Andy, "Jo-siah took sick with a fever, and come down into the settlement to see the doctor; and he was that bad that the doctor had to go back with him to drive the cattle. He rallied after that so as to be about again, and even out at night; but three months from the time he took the fever he died. The doctor was with him at the time, and the night before he breathed his last he told the doctor that the little man on the mountain was dead. After the funeral another party went up to the top of the mountain, and, sure enough, there was the grave, just outside of the miserable shelter he had lived in so long; and it looks like he did, sure enough, drink himself to death, for there was no sign about the hovel that he ever cooked or ate ordinary food.

"The strangest thing about the whole strange business," said Andy, getting on to his feet, "is that there was nothing in Jo-siah's poor cabin worth carrying away; and if the old man didn't build this here bridge with his own hands thirty year ago, hit stands to reason that he helped Jo-siah."

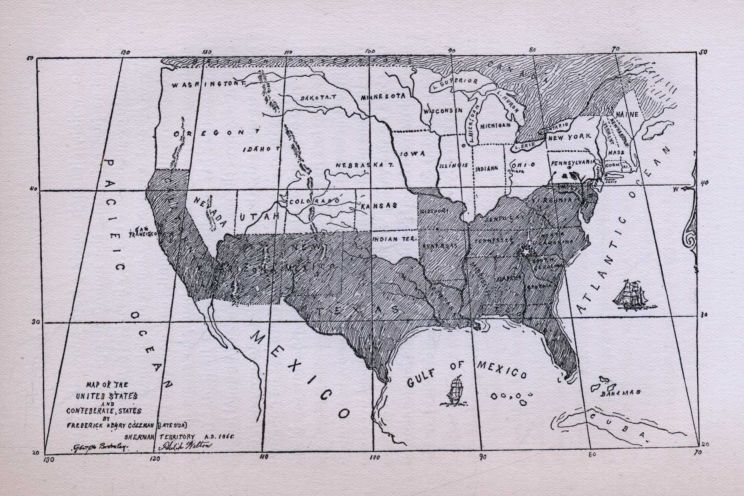

A fortnight before the events described in the opening chapter of this story, the topographical officer attached to General Sherman's headquarters might have been seen leaning over a table in his tent, busily engaged in sticking red-headed pins into a great map of the Cumberland and Blue Ridge Mountains. The pins made an irregular line, beginning at Chattanooga, and extending through Tennessee and North Carolina at no great distance from the Georgia border. Altogether there were just twenty of these pins, and each pin pierced the top of a mountain whose position and altitude were laid down on the map. After this officer, who was a lieutenant-colonel, had spent half the night, by the light of guttering candles, in arranging and rearranging his pins, he sent in the morning for the adjutant of a regiment of loyal mountaineers. Beginning with the first pin outside of Chattanooga, he requested the presence of a mountaineer who lived in the neighborhood of that particular peak. When the man reported, the colonel questioned him about the accessibility of the mountain under the first pin, its distance from that under the second pin, and whether each peak was plainly visible from the other. The colonel's questions, which were put to the soldier in the shade of the fly outside the tent where the map lay, brought out much useful information, and much more that was of no use whatever, because half the questions were intended to mislead the soldier and conceal the colonel's purpose. Sometimes he changed a pin after the soldier went away; and at the end of three days of interviewing and shifting the positions of his pins, the twentieth red head was firmly fixed above the point laid down on the map as Whiteside Mountain. Still a little farther along a blue-headed pin was set up, and then the work of the topographical officer of the rank of lieutenant-colonel was done.

These pins represented a chain of signal-stations, nineteen of which the captain of cavalry, with Andy Zachary to guide him, had now established one after the other, with as much secrecy as the lieutenant-colonel had employed in selecting the positions. And now the gray dawn was coming on the side of the twentieth mountain as Andy finished his story. In fact, as the last word fell from his lips a lusty cock tied on one of the pack-saddles set up a shrill crow to welcome the coming day. Although tall pines grew thick about the bridge-head where the troopers were still sleeping, it was light enough to see that only low bushes and gnarled chestnuts grew on the other bank. The noisy branch kept up its ceaseless churning and splashing among the rocks far down in the throat of the black gorge, and the great height and surprising length of its single span made the crazy old bridge look more treacherous than ever. It swayed and trembled with the weight of the captain by the time he had advanced three steps from the bank, so that he came back shaking his head in alarm. By this time the men were afoot, and Andy asked for an ax, which at the first stroke he buried to its head in the rotten string-piece.

"Just what I feared," said the captain. "Do you think I am going to trust my men on that rotten structure?"

Andy said nothing in reply as he kicked off with his boot a huge growth of toadstools, together with the bark and six inches of rotten wood from the opposite side of the log. Then he struck it again with the head of the ax such a blow that the old sticks of the railing and great sections of bark fell in a shower upon the tree-tops below. The guide saw only consternation in the faces of the men as he looked around, but there was a smile on his own.

"Hit may be old," said Andy, throwing down the ax, "but there is six inches of tough heart into that log, and I'd trust hit with a yoke o' cattle." With that he strode across to the other side, and coming back jounced his whole weight on the center, with only the effect of rattling another shower of bark and dry fungi into the gorge.

"Bring me one of the pack-mules," cried Andy; and presently, when the poor brute arrived at the head of the old causeway, it settled back on its stubborn legs and refused to advance. At this the guide tied a grain-sack over the animal's eyes and led him safely across. Lieutenant Coleman led over the second mule by the same device, and Bromley the third. By this time it was broad daylight, and the captain detailed three men to help in the unpacking. These he sent over one at a time, so that after himself Philip was the last to cross.

Beyond was an open field where blue and yellow flowers grew in the long, wiry grass, which was wet with the dew. This grass grew up through a thick mat of dead stalks, which was the withered growth of many years. Under the trees and bushes the leaves had rotted in the rain where they had fallen, or in the hollows where they had been tossed by the wandering winds. There was not a sign of a trail, nor a girdled tree, nor a trace of fire, nor any evidence that the foot of man had ever trodden there. The little party seemed to have come into an unknown country, and after crossing the open field they continued climbing up a gentle ascent, winding around rocks and scraggly old chestnut-trees, until they arrived under the ledge which supported the upper plateau. This was found to extend from the boulder face on the Cove side across to a mass of shelving rocks on the Cashiers valley front, and was from thirty to fifty feet in height, of a perpendicular and bulging fold in the smooth granite. After a short exploration a place was found where the ledge was broken by a shelf or platform twenty feet from the ground; and just here, in the leaves and grass below, lay the rotted fragments of a ladder which had doubtless been used by the old man of the mountain himself.

Meanwhile Andy, with the help of the detail, was cutting and notching the timber for ladders, the captain and the three young soldiers of the station made a breakfast, standing, from their haversacks and canteens, and looked about them over the wild country at their feet, and off at the blue peaks which rose above and around the valley of Cashiers, and then at the ridges in the opposite direction, drawn like huge furrows across the western horizon, showing fainter and fainter in color until the blue of the land was lost in the blue of the sky.

The men worked with a will, so that by ten o'clock the main ladder, which was just a chestnut stick deeply notched on the outer side, was firmly set in the ground against the face of the cliff. The landing-shelf was found to extend into a natural crevice, so that the short upper ladder was set to face the bridge, and so as to be entirely concealed from the view of any one approaching from below.

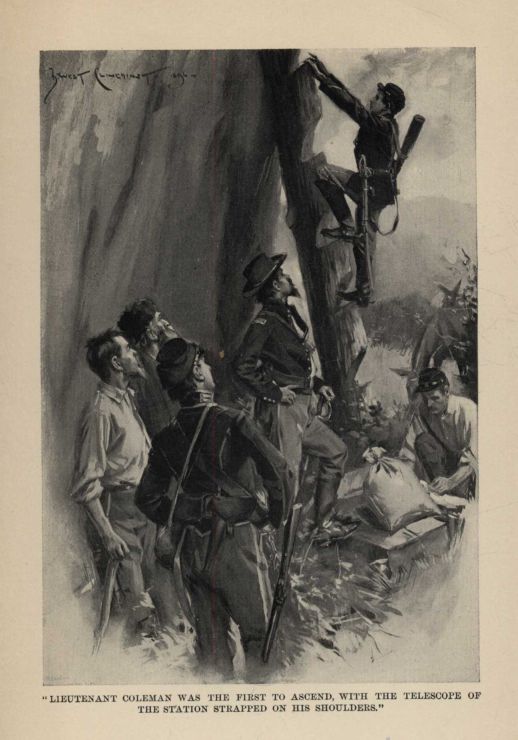

When everything was in readiness, Lieutenant Coleman was the first to ascend, with the powerful telescope of the station strapped on his shoulders; and the others quickly followed, except the three troopers who remained behind to unpack the mules and bring up the rations and outfit for the camp.

"LIEUTENANT COLEMAN WAS THE FIRST TO ASCEND,

WITH THE TELESCOPE OF THE STATION STRAPPED ON HIS SHOULDERS."

At the point where they landed there was little to be seen of the top of the mountain beyond a few stunted chestnuts which clung to the rocks and were dwarfed and twisted by the wind; and nearly as many dead blue limbs lay about in the thin grass as there were live green ones forked against the sky. There was the suggestion of a path bearing away to the left, and following this they came to a series of steps in the rocks, partly natural and partly artificial, which brought them on to a higher level where an extended plateau was spread out before them. On the western border they saw the line of trees overhanging the Cove side—the same that had looked like berry-bushes the night before from the cabin where they had halted for the moon to go down. From this point the crest of the Upper Bald was in plain view across the Cove, but, anxious as they were to open communication with the other mountain, the flags had not yet come up, and there was nothing left for them to do but continue their exploration. It was observed, however, that the trees overhanging the Cove would conceal the flagging operations from any one who might live on the slopes of the mountains in that direction, and, moreover, that by going a short distance along the ridge to the right a fine backing of dark trees would be behind the signal-men. Philip would have scampered off to explore and discover things for himself, but the captain restrained him and directed that the party should keep together. Andy carried his long rifle, and Philip and Bromley had brought up their carbines, so that they were prepared for any game they might meet, even though it were to dispute progress with a bear or panther. Since they had come up the ladders the region was all quite new to Andy, and he no longer pretended to guide them.

Back from the last ridge the ground sloped to a lower level, much of which was bare of trees and so protected from the wind that a rich soil had been made by the accumulation and decay of the leaves. At other points there were waving grass and clumps of trees, which latter shut off the view as they advanced, and opened up new vistas as they passed beyond them. It could be seen in the distance, however, that the southern end of the plateau was closed in by a ledge parallel to and not unlike that which they had already scaled, except that it was much more formidable in height.

There was a stream of clear, cold water that was found to come from a great bubbling spring. It broke out of the base of this southern ledge, and after flowing for some distance diagonally across the plateau tumbled over the rocks on the Cashiers valley side and disappeared among the trees.

After inspecting this new ledge, which was clearly an impassable barrier in that direction, and as effectually guarded the plateau on that side as the precipices which formed its other boundaries, the captain and his party turned back along the stream of water, for a plentiful supply of water was more to be prized than anything they could possibly discover on the mountain.

"There is one thing," said Andy, as they walked along the left bank of the stream, "that you-all can depend on. Risin' in the spring as hit does, that branch will flow on just the same, summer or winter."

"Probably," said Lieutenant Coleman; "but then, you know, we are not concerned about next winter."

A little farther on a rose-bush overhung the bank, and at the next turn they found a grape-vine trailing its green fruit across a rude trellis, which was clearly artificial. A few steps more and they came to a foot-log flattened on the top; and, although it tottered under them, they crossed to the other side, and coming around a clump of chinkapin-bushes, they found themselves at the door of a poor hut of logs, whose broken roof was open to the rain and sun. The neglected fireplace was choked with leaves, and weeds and bushes grew out of the cracks in the rotting floor; and, surely enough, in one dry corner stood the very brown keg that Josiah Woodring had brought up the mountain. In the midst of the dilapidation and the rotting wood about it, it was rather surprising that the cask should be as sound as if it were new, and the conclusion was that it had been preserved by what it originally contained.

Just then there was a cry from Philip, who had gone to the rear of the hovel; and he was found by the others leaning over the grave of the old man of the mountain, and staring at the thick oak headboard, which bore on the side next the cabin these words:

ONE WHO WISHES TO BE FORGOTTEN.

The letters were incised deep in the hard wood, and seemed to have been cut with a pocket-knife. It was evident from the amount of patient labor expended on the letters that the work had been done by the unhappy old man himself, perhaps years before he died. Of course it had been set up by Josiah, who must have laid him in his last resting-place.

"That looks like Jo-siah was no liar, any more than he was a murderer and robber," said Andy; "and if the little man could live up here twenty-five years, I reckon you young fellers can get along two months."

A spot for camp was selected a few rods up the stream from the poor old cabin and grave. This was at a considerable distance from the ridge where the station was to be, but it had two advantages to balance that one inconvenience. In the first place, it was near the water, and then no smoke from the cook-fire would ever be seen in the valley below. Accordingly, the stores were ordered to be brought to this point, and Corporal Bromley hurried away to the head of the ladders to detain such articles as would be needed at the station on the ridge. Below the ledge the mules could be seen quietly browsing the grass, and, to the annoyance of Lieutenant Coleman, a blue haze was softly enveloping the distant mountains, as in a day in Indian summer, so that it was no longer possible to think of communicating with the next station, which was ten miles away.

That being the case, the afternoon was spent in pitching the tents and making the general arrangements of the camp. Owing to the difficulty of transportation, but the barest necessaries of camp life were provided by the government; and, notwithstanding his rank, Lieutenant Coleman had only an "A" tent, and Bromley and Philip two pieces of shelter-tent and two rubber ponchos. It was quickly decided by the two soldiers to use their pieces of tent to mend the roof of the hut of the old man of the mountain, and to store the rations as well as to make their own quarters therein. From the Commissary Department their supplies for sixty days consisted precisely of four 50-pound boxes of hard bread, 67 pounds 8 ounces bacon, 103 pounds salt beef, 27 pounds white beans, 27 pounds dry peas, 18 pounds rice, 12 pounds roasted and ground coffee, 8 ounces tea, 27 pounds light-brown sugar, 7 quarts vinegar, 21 pounds 4 ounces adamantine candles, 7 pounds 4 ounces bar soap, 6 pounds 12 ounces table-salt, and 8 ounces pepper. The medical chest consisted of 1 quart of commissary whisky and 4 ounces of quinine. Besides the flags and telescope for use on the station, their only tools were an ax and a hatchet. On ordinary stations it was the rule to furnish lumber for building platforms or towers, but here they were provided with only a coil of wire and ten pounds of nails, and if platforms were necessary to get above the surrounding trees they must rely upon such timber as they could get, and upon the ax to cut away obstructions. Fortunately for this particular station, they could occupy a commanding ridge and send their messages from the ground.

Philip had by some means secured a garrison flag, which was no part of the regular equipment; and through Andy they had come into possession of a dozen live chickens and a bag of corn to feed them. On the afternoon before the departure of the troopers, the captain, who had now established the last of the line of stations, confided to Lieutenant Coleman his final directions and cautions. He asked Andy to point out Chestnut Knob, which was the mountain of the blue pin, and whose bald top was in full view to the right of Rock Mountain, and not more than eight miles away in a southeasterly direction, and, as Andy said, just on the border of the low country in South Carolina. This was the mountain, the captain informed Lieutenant Coleman, from which in due time, if everything went well in regard to a certain military movement, he would receive important messages to flag back along the line.

What this movement was to be was still an official secret at headquarters, and Lieutenant Coleman would be informed by flag of the time when he would be required to be on the lookout for a communication from the mountain of the blue pin. At the close of his directions, the captain, standing very stiff on his heels and holding his cap in his hand, made a little speech to Lieutenant Coleman, in which he complimented him for his loyalty and patriotic devotion to the flag, and reminded him that in assigning him to the last station the commanding general had thereby shown that he reposed especial confidence in the courage, honor, and integrity of Lieutenant Frederick Henry Coleman of the 12th Cavalry, and in the intelligence and obedience of the young men who were associated with him. This speech, delivered just as the shadows were deepening on the lonely mountain-top, touched the hearts of the three boys who were so soon to be left alone, and was not a whit the less impressive because Andy plucked off his coonskin cap and cried, in his homely enthusiasm, that "them was his sentiments to the letter!"

It was understood that there should be no signaling by night, and no lights had been provided for that purpose; so that, there being nothing to detain them on the plateau, they decided to accompany the captain and Andy back to the bridge and see the last of the escort as it went down the mountain.

Two of the troopers, contrary to orders, had during the day been as far as the deserted cabin of Josiah Woodring, and one of these beckoned Philip aside and told him where he would find a sack of potatoes some one had hidden away on the other side of the gorge, which, with much disgust, he described as the only booty they had found worth bringing away.

So great is the love of adventure among the young that there was not one of the troopers but envied his three comrades who were to be left behind on the mountain; but it was a friendly rivalry, and, in view of the possibilities of wild game, they insisted upon leaving the half of their cartridges, which were gladly accepted by Philip and Bromley.

The moon was obscured by thick clouds, and an hour before midnight the horses were saddled, and with some serious, but more jocular, words of parting, the troopers started on the march down the mountain, most of them hampered by an additional animal to lead. The captain remained to press the hand of each of the three young soldiers, and when at last he rode away and they turned to cross the frail old bridge, whose unprotected sides could scarcely be distinguished in the darkness, they began to realize that they were indeed left to their own resources, and to feel a trifle lonely, as you may imagine.

Before leaving that side of the gorge, however, Corporal Bromley had shouldered their precious cartridges, which had been collected in a bag, and on the other side Philip secured the sack of potatoes; and thus laden they trudged away across the open field and among the rocks and bushes, guided by the occasional glimpses they had of the cliff fringed with trees against the leaden sky. It was of the first importance that the cartridges should be kept dry, and to that end they hurried along at a pace which scattered them among the rocks and left but little opportunity for conversation. Lieutenant Coleman was in advance, with Philip's carbine on his arm; next came Corporal Bromley, with the cartridges; and a hundred yards behind, Philip was stumbling along with the sack of potatoes on his shoulder. They had advanced in this order until the head of the straggling column was scarcely more than a stone's throw from the cliff, when a small brown object, moving in the leaves about the foot of the ladder, tittered a low growl and then disappeared into the deeper shadow of the rock. At the same moment the rain began to fall, and Corporal Bromley stepped one side to throw his bag of cartridges into the open trunk of a hollow chestnut. While he was thus engaged, with the double purpose of freeing his hands and securing the cartridges from the possibility of getting wet, his carbine lying on the ground where he had hastily thrown it, Lieutenant Coleman fired at random at the point where he had indistinctly seen the moving object. The darkness had increased with the rain, and as the report of the carbine broke the quiet of the mountain a shadowy ball of fur scampered by him, scattering the leaves and gravel in its flight. The mysterious object passed close to Bromley as he was groping about for his weapon, and the next moment there was a cry from Philip, who had been thrown to the ground and his potatoes scattered over the hillside.

"Whatever it was," said Philip, when he presently came up laughing at his mishap, "I don't believe it eats potatoes, and I will gather them up in the morning."

As it was too dark for hunting, and the cartridges were in a safe place, Lieutenant Coleman and Corporal Bromley slung their carbines and followed Philip, who was the first to find the foot of the ladder.

It was not so dark but that they made their way safely to the camp, and, weary with the labors of the day, they were soon fast asleep in their blankets, unmindful of the rain which beat on the "A" tent and on the patched roof of the cabin of the old man of the mountain.

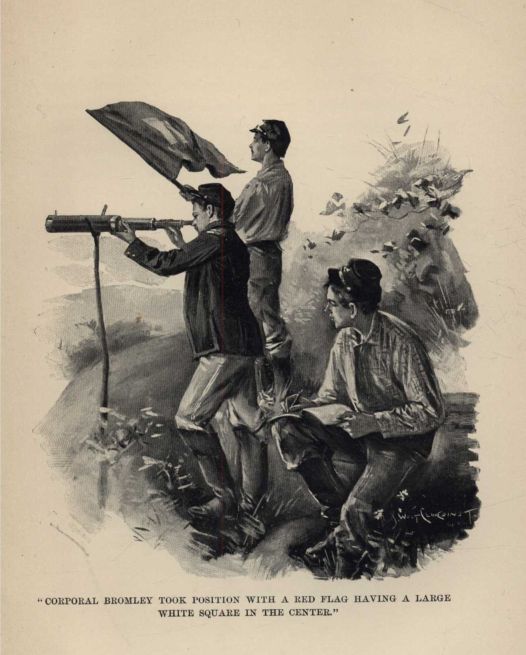

On the morning of July 4 the sun rose in a cloudless sky above the mountains, and the atmosphere was so clear that the most remote objects were unusually distinct. The conditions were so favorable for signaling that, after a hurried breakfast, the three soldiers hastened to the point on the ridge which they had selected for a station. Corporal Bromley took position with a red flag having a large white square in the center, and this he waved slowly from right to left, while Lieutenant Coleman adjusted his spy-glass, resting it upon a crotched limb which he had driven into the ground; and at his left Philip sat with a note-book and pencil in hand, ready to take down the letters as Lieutenant Coleman called them off. There are but three motions used in signaling. When the flag from an upright position is dipped to the right, it signifies 1; to the left, 2; and forward, 3. The last motion is used only to indicate that the end of the word is reached. Twenty-six combinations of the figures 1 and 2 stand for the letters of the alphabet.

"CORPORAL BROMLEY TOOK POSITION WITH A RED FLAG

HAVING A LARGE WHITE SQUARE IN THE CENTER."

It is not an easy task to learn to send messages by these combinations of the figures 1 and 2, and it is harder still to read the flags miles away through the telescope. The three soldiers had had much practice, however, and could read the funny wigwag motions like print. If any two boys care to learn the code, they can telegraph to each other from hill to hill, or from farm to farm, as well as George and Philip. You will see that the vowels and the letters most used are made with the fewest motions—as, one dip of the flag to the left (2) for I, and one to the right (1) for T. Z is four motions to the right (1111); and here is the alphabet as used in the signal-service:

A, 11, O, 12,

B, 1221, P, 2121,

C, 212, Q, 2122,

D, 111, R, 122,

E, 21, S, 121,

F, 1112, T, 1,

G, 1122, U, 221,

H, 211, V, 2111,

I, 2, W, 2212,

J, 2211, X, 1211,

K, 1212, Y, 222,

L, 112, Z, 1111,

M, 2112, &, 2222,

N, 22, ing, 1121,

tion, 2221.

When the flag stops at an upright position, it means the end of a letter—as, twice to the right and stop (11) means A; one dip forward (3) indicates the end of a word; 33, the end of a sentence; 333, the end of a message. Thus 11-11-11-3 means "All right; we understand over here; go ahead"; and 11-11-11-333 means "Stop signaling." Then 212-212-212-3 means "Repeat; we don't understand what you are signaling"; while 12-12-12-3 means "We have made an error, and if you will watch we will give the message to you correctly."

Now, if Lieutenant Coleman wanted to say to another signal-officer "Send one man," the sentence would read in figures, "121, 21, 22, 111, 3, 12, 22, 21, 3, 2112, 11, 22, 33." But in time of war the signalmen of the enemy could read such messages, and so each party makes a cipher code of its own, more or less difficult; and the code is often changed. So if Lieutenant Coleman's cipher code was simply to use for each letter sent the fourth letter later in the alphabet, his figures would have been quite different, and the letters they stood for would have read:

W-i-r-h s-r-i q-e-r. S-e-n-d o-n-e m-a-n.

So, after fifteen minutes of waiting, during which time the flag in Corporal Bromley's hand made a great rustling and flapping in the wind, moving from side to side, Lieutenant Coleman got his glass on the other flag, ten miles away, and found it was waving 11-11-11-3—"All right." Corporal Bromley then sent back the same signal, and sat down on the bank to rest. What Lieutenant Coleman saw at that distance was a little patch of red dancing about on the object-glass of his telescope; he could not see even the man who waved it, or the trees behind him. Promptly at Bromley's signal "All right," the little object came to a rest; and when it presently began again, Lieutenant Coleman called off the letters, which Philip repeated as he entered them in the book. For an hour and a half the messages continued repeating all the mass of figures which had come over the line during the last three days.

When the mountain of the nineteenth red pin had said its say as any parrot might have done, for it was absolutely ignorant of the meaning of the figures it received and passed on (for the reason that it had no officer with the cipher), Lieutenant Coleman took from his pocket a slip of paper on which he had already arranged his return message to Chattanooga. When this had been despatched, the lieutenant took the note-book from Philip, and went away to his tent to cipher out the meaning of the still meaningless letters.

They were sufficiently eager to get the latest news, for they knew that the army they had just left had been advancing its works and fighting daily since the twenty-second day of June for the possession of Kenesaw Mountain. The despatches were translated in the order in which they came, so that it was a good half-hour before Lieutenant Coleman appeared with a radiant face to say that General Sherman had taken possession of Kenesaw Mountain on the day before. "And that is not all," he cried, holding up his hand to restrain any premature outburst of enthusiasm. "Listen to this! 'The "Alabama" was sunk by the United States steamer "Kearsarge" on the nineteenth day of June, three miles outside the harbor of Cherbourg, on the coast of France.'"

Corporal Bromley was not a demonstrative man, yet the blood rushed to his face, and there was a glittering light in his eyes which told how deeply the news touched him; but Philip, on the contrary, was wild with delight, and danced and cheered and turned somersaults on the grass.

"What a pity," cried Philip, "that the boys on the next mountain should be left in ignorance of these victories when we could so easily send them the news without using the cipher—and this the Fourth of July, too!"

That form of communication, however, was strictly forbidden by the severe rules of the service, and it was the fate of Number 19 to remain in the dark, like all the other stations on the line, except the first and tenth and their own, which alone were in charge of commissioned officers who held the secret of the cipher.

The news of the destruction of the "Alabama," which had been the terror of the National merchant-vessels for two years, was of the highest importance, and would cause great rejoicing throughout the North. Although the battle with the "Kearsarge" had taken place on June 19, it must be borne in mind that this period was before the permanent laying of the Atlantic cable, and European news was seven and eight days in crossing the ocean by the foreign steamers, and might be three days late before it started for this side, in case of an event which had happened three days before the sailing of the steamer. After several unsuccessful attempts, a cable had been laid between Europe and America in 1858, three years before the beginning of the great war, and had broken a few weeks after some words of congratulation had passed between Queen Victoria and President Buchanan. Some people even believed that the messages had been invented by the cable company, and that telegraphic communication had never been established at all along the bed of the ocean. At all events, news came by steamer in war-times, and so it happened that these soldiers, who had been three days in the wilderness, heard with great joy on July 4 of the sinking of the "Alabama," which happened on the coast of France on June 19.

The garrison flag was raised on a pole over the "A" tent, and the day was given up to enjoyment, which ended in supping on a roast fowl, with such garnishings as their limited larder would furnish. On this occasion Lieutenant Coleman waived his rank so far as to preside at the head of the table,—which was a cracker-box,—and after the feast they walked together to the station and sat on the rocks in the moonlight to discuss the military situation.

If General Grant had met with some rebuffs in his recent operations against Petersburg in Virginia, he was steadily closing his iron grasp on that city and Richmond; and not one of these intensely patriotic young men for a moment doubted the final outcome. Philip and Lieutenant Coleman had been much depressed by the recent disaster, and the news of the morning greatly raised their spirits. If Bromley was less excitable than his companions, the impressions he received were more enduring; but, on the other hand, he would be slower to recover from a great disappointment.

"The reins are in a firm hand at last," said Lieutenant Coleman, referring to the control then recently assumed by General Grant, "and now everything is bound to go forward. With Grant and Sheridan at Richmond, Farragut thundering on the coast, the 'Alabama' at the bottom of the sea, and Uncle Billy forcing his lines nearer and nearer to Atlanta, we are making brave progress. I believe, boys, the end is in sight."

"Amen!" said Corporal Bromley.

"Hurrah!" cried Philip.

"You boys," continued Lieutenant Coleman, "have enlisted for three years, while I have been educated to the profession of arms; but if this rebellion is not soon put down I shall be ashamed of my profession and leave it for some more respectable calling."

So they continued to talk until late into the night, cheered by the good news they had heard, and very hopeful of the future.

The following day was foggy, and Philip went down the ladder to bring up the potatoes, which he had quite forgotten in the excitement of the day before. Bromley, too, paid a visit to the tree where he had thrown in the cartridges; but the opening where he had cast in the sack was so far from the ground that it would be necessary to use the ax to recover it, and as he could find no drier or safer storehouse for the extra ammunition, he was content to leave it there for the present. Lieutenant Coleman busied himself in writing up the station journal in a blank-book provided for that purpose.

When Philip found his potatoes, which had been scattered on the ground where he had been thrown down in the darkness by the mysterious little animal, he was at first disposed to leave them, for they were so old and shrunken and small that he began to think the troopers had been playing a joke on him. But when he looked again, and saw the small sprouts peeping out of the eyes, a new idea came to him, and he gathered them carefully up in the sack. He bethought himself of the rich earth in the warm hollow of the plateau, where the sun lay all day, and where vegetation was only smothered by the coating of dead leaves; and he saw the delightful possibility of having new potatoes, of his own raising, before they were relieved from duty on the mountain. What better amusement could they find in the long summer days, after the morning messages were exchanged on the station, than to cultivate a small garden? If he had had the seeds of flowers, he might have thrown away the wilted potatoes; but next to the cultivation of flowers came the fruits of the earth, and if his plantation never yielded anything, it would be a pleasure to watch the vines grow. Lieutenant Coleman readily gave his consent; and, after raking off the carpet of leaves with a forked stick, the soft, rich soil lay exposed to the sun, so deep and mellow that a piece of green wood, flattened at the end like a wedge, was sufficient to stir the earth and make it ready for planting. Philip cut the potatoes into small pieces, as he had seen the farmers do, and with the help of the others, who became quite interested in the work, the last piece was buried in the ground before sundown.

On the following morning the flags announced that, in a cavalry raid around Petersburg, General Wilson had destroyed sixty miles of railroad, and that forty days would be required to repair the damage done to the Danville and Richmond road. During the next three days there was no news worth recording, and the fever of gardening having taken possession of Philip, he planted some of the corn they had brought up for the chickens, and a row each of the peas and beans from their army rations.

The 10th of July was Sunday, the first since they had been left alone on the mountain; and Lieutenant Coleman required his subordinates to clean up about the camp, and at nine o'clock he put on his sword and inspected quarters like any company commander. After this ceremony, Philip read a psalm or two from his prayer-book, and Corporal Bromley turned over the pages of the Blue Book, which was the Revised Army Regulations of 1863. These two works constituted their limited library.

There was a dearth of news in the week that followed, and what little came was depressing to these enthusiastic young men, to whom the temporary inactivity of the army which they had just left was insupportable.

On Monday morning, however, came the cheering news that General Sherman's army was again in motion, and had completed the crossing of the Chattahoochee River the evening before.

On the 19th they learned that General Sherman had established his lines within five miles of Atlanta, and that the Confederate general Johnston had been relieved by General Hood.

The messages by flag were received every day, when the weather was favorable, between the hours of nine and ten in the morning; and now that the campaign had reopened with such promise of continued activity, the days, and even the nights, dragged, so feverish was the desire of the soldiers to hear more. They wandered about the mountain-top and discussed the military situation; but, if anything more than another tended to soothe their nerves, it was the sight of their garden, in which the corn and potatoes were so far advanced that each day seemed to add visibly to their growth.

On the morning of the 21st they learned that Hood had assaulted that flank of the intrenched line which was commanded by General Hooker, and that in so doing the enemy had been three times gallantly repulsed. The new Confederate general was less prudent than the old one, and they chuckled to think of the miles of log breastworks they knew so well, at which he was hurling his troops. General Sherman was their military idol, and they knew how well satisfied he would be with this change in the tactics of the enemy.

By this time it had become their habit to remain near the station while Lieutenant Coleman figured out the messages, each of which he read aloud as soon as he comprehended its meaning.

On Saturday morning, July 23, while Corporal Bromley leaned stolidly on his flagstaff, and Philip walked about impatiently, Lieutenant Coleman jumped up and read from the paper he held in his hand:

"Hood attacked again yesterday. Repulsed with a loss of seven thousand killed and wounded."

With no thought of the horrible meaning of these formidable figures to the widows and orphans of the men who had fallen in this gallant charge, Philip and Bromley cheered and cheered again, while the lieutenant sat down to decipher the next message. When he had mastered it the paper fell from his hands. He was speechless for the moment.

"What is it?" said Philip, turning pale with the certainty of bad news.

"General McPherson is killed," said Lieutenant Coleman.

Now, so strangely are the passions of men wrought up in the time of war that these three hot-headed young partizans were quick to shed tears over the death of one man, though the destruction of a great host of their enemies had filled their hearts only with a fierce delight.

During the Sunday which followed there was a feeling of gloomy foreboding on the mountain, and under it a fierce desire to hear what should come next.

On Monday morning, July 25, the sun rose in a cloudless sky, bathing the trees and all the distant peaks with cheerful light, while at the altitude of the station his almost vertical rays were comfortable to feel in the cool breeze which blew across the plateau. Lieutenant Coleman glanced frequently at the face of his watch, and the instant the hands stood at nine Philip began waving the flag. There was no response from the other mountain for so long a time that Corporal Bromley came to his relief, and the red flag with a white center continued to beat the air with a rushing and fluttering sound which was painful in the silence and suspense of waiting.

When at last the little flag appeared on the object-glass of the telescope, it spelled but seven words and then disappeared. Philip uttered an exclamation of surprise at the brevity of the message, while Bromley wiped the perspiration from his forehead and waited where he stood.

In another minute Lieutenant Coleman had translated the seven words, but even in that brief time Corporal Bromley, whose eyes were fixed on his face, detected the deathly pallor which spread over his features. The young officer looked with a hopeless stare at his corporal, and without uttering a word extended his hand with the scrap of paper on which he had written the seven words of the message.

Bromley took it, while Philip ran eagerly forward and looked tremblingly over his comrade's shoulder.

The seven words of the message read:

"General Sherman was killed yesterday before Atlanta."

Lieutenant Coleman, although stunned by the news conveyed by the seven words of the message, as soon as he could reopen communication with the other mountain, telegraphed back to Lieutenant Swann, in command of the tenth station:

"Is there no mistake in flagging General Sherman's death?"

It was late in the afternoon when the return message came, which read as follows:

"None. I have taken the same precaution to telegraph back to the station at Chattanooga.

"LIEUTENANT JAMES SWANN, U.S.A."

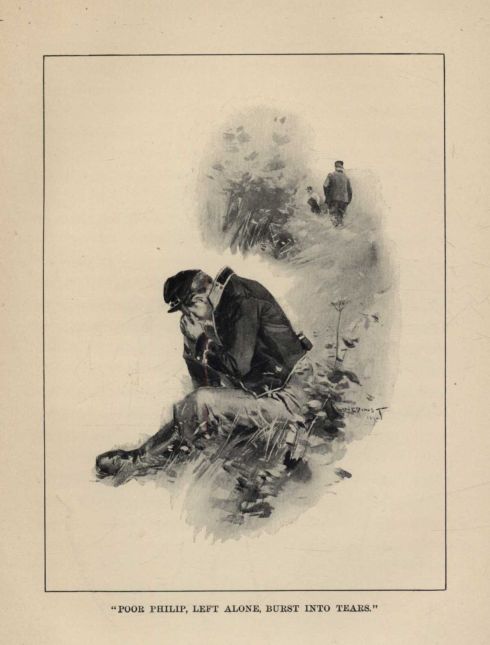

After this, and the terrible strain of waiting, Lieutenant Coleman and Corporal Bromley walked away in different directions on the mountain-top; and poor Philip, left alone, sat down on the ground and burst into tears over the death of his favorite general. He saw nothing but gloom and disaster in the future. What would the old army do without its brilliant leader?

"POOR PHILIP, LEFT ALONE, BURST INTO TEARS."

And, sure enough, on the following morning came the news that the heretofore victorious army was falling back across the Chattahoochee; and another despatch confirmed the death of General Sherman, who had been riding along his lines with a single orderly when he was shot through the heart by a sharp-shooter of the enemy.

Every morning after that the three soldiers went up to the station at the appointed hour, expecting only bad news, and, without fail, only bad news came. They learned that the baffled army in and about Marietta was being reorganized by General Thomas; but the ray of hope was quenched in their hearts a few days later, when the news came that General Grant had met with overwhelming disaster before Richmond, and, like McClellan before him, was fighting his way back to his base of supplies at City Point.

One day—it was August 6—there came a message from the chief signal-office at Chattanooga directing them to remain at their posts, at all hazards, until further orders; and, close upon this, a report that General Grant's army was rapidly concentrating on Washington by way of the Potomac River.

They had no doubt that the swift columns of Lee were already in motion overland toward the National capital, and they were not likely to be many days behind the Federal army in concentrating at that point. Rumors of foreign intervention followed quick on the heels of this disheartening news, and on August 10 came a despatch which, being interpreted, read: "Yesterday, after a forced march of incredible rapidity, Longstreet's corps crossed the Upper Potomac near the Chain Bridge, and captured two forts to the north of Rock Creek Church. At daylight on August 9, after tearing up a section of the Baltimore and Ohio's tracks, a column of cavalry under Fitzhugh Lee captured a train-load of the government archives, bound for Philadelphia."

Thus on the very day when General Sherman was bombarding the city of Atlanta, and when everything was going well with the National cause elsewhere, these misguided young men were brought to the verge of despair by some mysterious agency which was cunningly falsifying the daily despatches. Nothing more melancholy can be conceived than the entries made at this time by Lieutenant Coleman in the station diary.

Returning to the entry of July 26, which was the day following that on which they had received information of the death of General Sherman, the unhappy officer writes:

"My men are intensely patriotic, and the despatch came to each of us like a personal blow. Its effect on my two men was an interesting study of character. Corporal Bromley is a Harvard man, having executive ability as well as education far above his humble rank, who entered the service of his country at the first call to arms without a thought for his personal advantage. He is a man of high courage, and if he has a fault, it is a too outspoken intolerance of the failures of his superiors. Private Welton is of a naturally refined and sensitive nature, and at first he seemed wholly cowed and broken in spirit. Bromley, on the other hand, as he strode away from the station, showed a countenance livid with rage.

"After supper, for we take our meals apart, I invited the men to my tent, and we sat out in the moonlight to discuss the probable situation. We talked of the overwhelming news until late in the evening, and then sat for a time in silence in the shadow of the chestnut-trees, looking out at the dazzling whiteness of the mountain-top before retiring, each to his individual sorrow."

In the entry for August 6, after commenting somewhat bitterly on the report of the defeat of the Army of the Potomac, Lieutenant Coleman says, with reference to the despatch from the chief signal-officer of the same date:

"The situation at this station is such, owing to our ignorance of the sentiment of the mountaineers and the hazard of visiting them in uniform, that I find a grave difficulty confronting me, which must be provided for at once. Our guide to this point has returned to Tennessee with the cavalry escort, and I have now reason deeply to regret that he was not required to put us in communication with some trustworthy Union men. The issue of commissary stores is reduced from this date to half-rations, and we shall begin at once to eke out our daily portion by such edibles as we can find on the mountain. Huckleberries are abundant in the field above the bridge, and the men are already counting on the wild mandrakes.

"August 8. Nothing cheering to brighten the gloom of continued defeat and disaster. The necessity of procuring everything edible within our reach keeps my men busy and affords them something to think of besides the disasters to the National armies. Welton discovered to-day four fresh-laid eggs, snugly hidden in a nest of leaves, under a clump of chestnut sprouts, interwoven with dry grasses, three of which he brought in."

These entries referring to trivial things are interesting as showing the temper of the men, and how they employed their time at this critical period.

On August 18 came a despatch that the Army of Northern Virginia was entering Washington without material opposition. Lieutenant Coleman, in a portion of his diary for this date, says:

"After a prolonged state of anger, during which he has commented bitterly on the conduct of affairs at Washington, Corporal Bromley has settled into a morose and irritable mood, in which no additional disaster disturbs him in the slightest degree. With his fine perceptions and well-trained mind, the natural result of a liberal education, I have found him heretofore a most interesting companion in hours off duty. My situation is made doubly intolerable by his present condition."

At 9:30 A.M. of August 20, 1864, came the last despatches that were received by the three soldiers on Whiteside Mountain.

"Hold on for immediate relief. Peace declared. Confederate States are to retain Washington."

The effect of this last message upon the young men who received it is fully set forth in the diary of the following day, and no later account could afford so vivid a picture of the remarkable events recorded by Lieutenant Coleman:

"August 21, 1864. The messages of yesterday were flagged with the usual precision, and we have no reason to doubt their accuracy. Indeed, what has happened was expected by us so confidently that the despatches as translated by me were received in silence by my men and without any evidence of excitement or surprise. I myself felt a sense of relief that the inevitable and disgraceful end had come.

*******

"Last evening was a memorable occasion to the three men on this mountain. We are no longer separated by any difference in rank, having mutually agreed to waive all such conditions. In presence of such agreement, I, Frederick Henry Coleman, Second Lieutenant in the 12th Regiment of Cavalry of the military forces of the United States (formerly so called), have this day, August 21, 1864, written my resignation and sealed and addressed it to the Adjutant-General, wherever he may be. I am fully aware that, until the document is forwarded to its destination, only some power outside myself can terminate my official connection with the army, and that my personal act operates only to divest me of rank in the estimation of my companions in exile.

"After our supper last night we walked across the field in front of our quarters and around to the point where the northern end of the plateau joins the rocky face of the mountain. The sun had already set behind the opposite ridge, and the gathering shadows among the rocks and under the trees added a further color of melancholy to our gloomy and foreboding thoughts.

"I am forced to admit that I have not been the dominant spirit in the resolution at which we have arrived. George Bromley had several times asserted that he would never return to a disgraced and divided country. At the time I had regarded his words as only the irresponsible expression of excitement and passion.

"As we stood together on the hill last night, Bromley reverted to this subject, speaking with unusual calmness and deliberation. 'For my part,' said he, pausing to give force to his decision, 'I never desire to set foot in the United States again. I suppose I am as well equipped for the life of a hermit as any other man; and I am sure that my temper is not favorable to meeting my countrymen, who are my countrymen no longer, and facing the humiliation and disgrace of this defeat. I have no near relatives and no personal attachments to compensate for what I regard as the sacrifice of a return and a tacit acceptance of the new order of things. I came into the army fresh from a college course which marked the close of my youth; and shall I return in disgrace, without a profession or ambition, to begin a new career in the shadow of this overwhelming disaster? I bind no one to my resolution,' he continued in clear, cold tones; 'all I ask is that you leave me the old flag, and I will set up a country of my own on this mountain-top, whose natural defenses will enable me to keep away all disturbers of my isolation.'

"I was deeply impressed with his words, and the more so because of the absence of all passion in his manner. I had respected him for his attainments; I now felt that I loved the man for his unselfish, consuming love of country. Strange to say, I, too, was without ties of kindred. My best friends in the old army had fallen in battle for the cause that was lost. On the night when we sat together exulting over the double victory of the capture of Kenesaw Mountain and the sinking of the 'Alabama,' I had expressed a determination to renounce my chosen profession in a certain event. That event had taken place. Under the magnetic influence of Bromley, what had only been a threat before became a bitter impulse and then a fierce resolve.

"Taking his hand and looking steadily into his calm eyes, I said: 'I am an officer of the United States army, but I will promise you this: until I am ordered to do so, I will never leave this place.'

"Philip Welton had been a silent listener to this strange conversation. His more sentimental nature was melted to tears, and in a few words he signified his resolution to join his fate with ours.

"We walked back across the mountain-top in the white light of the full moon, silently as we had come. After the resolve we had made, I began already to experience a sense of relief from the shame I felt at the failure of our numerous armies. The old government had fallen from its proud position among the nations of the earth. The flag we loved had been trampled under foot and despoiled of its stars—of how many we knew not. Our path lay through the plantation of young corn, whose broad, glistening leaves brushed our faces and filled the air with the sweet fragrance of the juicy stalks. The planting seemed to have been an inspiration which alone would make it possible for us to survive the first winter."

The morning after the three soldiers had pledged themselves to a life of exile, like the (otherwise) practical young persons they were, they proceeded resolutely to take stock of the provisions they had on hand and to consider the means of adding to their food-supply. They had already been nearly two months in camp, which was the period for which their rations had been issued; but, what with the generous measure of the government and the small game they had brought down with their carbines, nearly half of the original supply remained on storage in the hut of the old man of the mountain. It is true that there was but one box left of the hard bread; but the salt beef, which had been covered with brine in the cask found in the corner of the cabin, had scarcely been touched. A few strips of the bacon still hung from the rafters. Of the peas and beans, only a few scattering seeds lay here and there on the floor. The precious salt formed but a small pile by itself, but there was still a brave supply of coffee and sugar, and the best part of the original package of rice. In another month they would have green corn and potatoes of their own growing, and they already had eggs, as, fortunately, they had killed none of their hens.

The tract of ground on the mountain was a half-hundred acres in extent, with an abundance of wood and water, protected on the borders by trees and bushes, and accessible only by the wooden ladder by which they themselves had come up the ledge. Their camp was in the center of the tract, where the smoke of their fires would never be seen from the valleys. Overhanging the boulder face of the mountain, just back of the ridge they had used for a signal-station, was a clump of black oaks, through which something like an old trail led down to a narrow tongue of land caught on a shelf of granite, which was dark with a tall growth of pines, and the earth beneath was covered with a thick, gray carpet of needles, clean and springy to the feet. Along the southern cliff, and to the west of the spring which welled out from under the rock, was a curtain of dogwoods and birches, and elsewhere the timber was chestnut. At some points the trees of the latter variety were old and gnarled, and clung to the rocks by fantastic twisted roots like the claws of great birds, and at others they grew in thrifty young groves, three and four lusty trunks springing from the sides of a decayed stump.

They were certainly in the heart of the Confederacy, but the plateau was theirs by the right of possession, and over this, come what might, they were determined that the old flag with its thirty-five stars should continue to float. They at least would stubbornly refuse to acknowledge that there had been any change in the number of States.

Owing to the danger of being seen, they agreed together that no one should go down the ladder during the day. They were satisfied that they had not been seen since they had occupied the mountain. They had no reason to believe that any human being had crossed the bridge since the night the captain and his troopers had ridden away into the darkness; but still the bridge remained, the only menace to their safety, and, with the military instinct of a small army retreating in an enemy's country, they determined to destroy that means of reaching them.

Accordingly, when night came, Lieutenant Coleman and George Bromley, leaving Philip asleep in the hut, armed themselves with the ax and the two carbines, and took their way across the lower field to the deep gorge. They had not been there since the night they parted with the captain and Andy, the guide. It was very still in this secluded place—even stiller, they thought, for the ceaseless tinkling of the branch in the bottom of the gorge. They had grown quite used to the stillness and solitude of nature in that upper wilderness. Enough of moonlight fell through the branches overhead so that they could see the forms of the trees that grew in the gorge; and the moon itself was so low in the west that its rays slanted under the bridge and touched with a ghostly light the dead top of a great basswood which forked its giant limbs upward like beckoning arms. Then there was one ray of light that lanced its way to the very heart of the gorge, and touched a tiny patch of sparkling water alongside a shining rock.

They had the smallest ends of the string-pieces to deal with, as the trees had fallen from the other side. Bromley wielded the ax, which fell at first with a muffled sound in the rotten log, and then, as he reached the tougher heart, rang out clear and sharp, and echoed back from down the gorge. Presently he felt a weakening in the old stick, and, stepping back, he wiped his forehead on the sleeve of his jacket. The stillness which followed the blows of the ax was almost startling; and the night wind which was rising on the mountain sounded like the rushing of wings in the tops of the pines on the opposite bank.