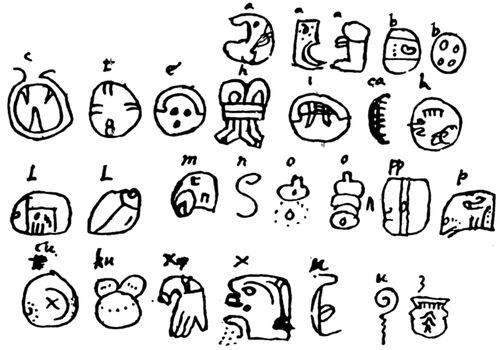

Fig. 1.—Landa’s Alphabet; after a photograph from the original manuscript.

Title: A Primer of Mayan Hieroglyphics

Author: Daniel G. Brinton

Release date: July 19, 2018 [eBook #57540]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Julia Miller, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

In the following pages I have endeavored with the greatest brevity to supply the learner with the elements necessary for a study of the native hieroglyphic writing of Central America. The material is already so ample that in many directions I have been obliged to refer to it, rather than to summarize it. This will explain various omissions which may be noted by advanced scholars; but they will not, I believe, diminish the usefulness of the work as an elementary treatise.

In conclusion I would express my thanks to the officers of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, and of the Peabody Museum of Archæology, Cambridge, for various facilities they have obligingly furnished me.

| I. Introductory. | |||

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | General Character of Mayan Hieroglyphics, | 9 | |

| 2. | The Mayan Manuscripts or “Codices,” | 11 | |

| 3. | Theories of Interpretation. “Alphabets” and “Keys,” | 13 | |

| II. The Mathematical Elements. | |||

| 1. | The Codices as Time-counts, | 18 | |

| 2. | The Mayan Numeral System, | 19 | |

| 3. | Numerical and Allied Signs, | 19 | |

| 4. | The Rhetorical and Symbolic Use of Numbers, | 24 | |

| 5. | The Mayan Methods of Counting Time, | 25 | |

| 6. | The Calculations in the Codices, | 29 | |

| 7. | Rules for Tracing the Tonalamatl, or Ritual Calendar, | 31 | |

| 8. | The Codices as Astronomical Treatises, | 32 | |

| 9. | Astronomical Knowledge of the Ancient Mayas, | 34 | |

| III. The Pictorial Elements. | |||

| 1. | The Religion of the Ancient Mayas, | 37 | |

| Itzamna—Cuculcan—Kin ich—Other Gods—The Cardinal Points—The Good Gods—The Gods of Evil—The Conflict of the Gods. | |||

| 2. | The Cosmogony of the Mayas, | 46 | |

| 3. | The Cosmical Conceptions of the Mayas, | 47 | |

| 4. | Pictorial Representations of Divinities, | 50 | |

| Representations of Itzamna—Of Cuculcan—Of Kin ich—Of Xaman Ek, the Pole Star—Of the Planet Venus—Of Ghanan, God of Growth—Of the Serpent Goddess—of Xmucane—Of Ah puch, God of Death—Of the God of War—Of Ek-Ahau and other Black Gods. | |||

| 5. | The Maya Priesthood, | 68 | |

| 6. | Fanciful Analogies, | 69 | |

| 7. | Total Number of Representations, | 70 | |

| 8. | Figures of Quadrupeds, | 71 | |

| 9. | Figures of Birds, | 72 | |

| 10. | Figures of Reptiles, | 74 | |

| 11. | Occupations and Ceremonies, | 76 | |

| viIV. The Graphic Elements. | |||

| 1. | The Direction in which the Glyphs are to be Read, | 78 | |

| 2. | Composition of the Glyphs, | 81 | |

| 3. | The Proper Method of Studying Glyphs, | 81 | |

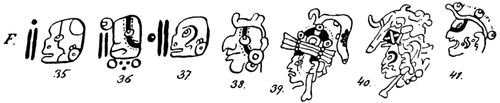

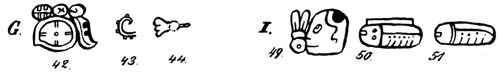

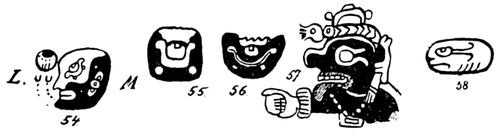

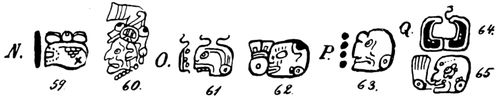

| 4. | An Analysis of Various Graphic Elements, | 82 | |

| The Hand—The Eye and Similar Figures—The “Spectacles”—The Ear—Crescentic Signs—Sun and Moon Signs—Supposed Variations of the Sun Sign—The Knife Signs—The “Fish and Oyster” Sign—The Sacred Food Offerings—The Ben ik and Other Signs—The Drum Signs—The Yax and Other Feather Signs—The Cross-hatched Signs—Some Linear Signs and Dots—Linear Prefixes—The “Cloud-balls” and the “Cork-screw Curl”—Signs for Union—The “Tree of Life”—The “Machete” and Similar Signs—Supposed Bird Signs—The “Crotalean Curve”—Objects Held in the Hand—The Aspersorium, the Atlatl and the Mimosa—The “Constellation Band”—The Signs for the Cardinal Points—The Directive Signs—The “Cuceb.” | |||

| 5. | The Hieroglyphs of the Days, | 109 | |

| 6. | The Hieroglyphs of the Months, | 116 | |

| 7. | The Hieroglyphs of the Deities, | 121 | |

| V. Specimens of Texts. | |||

| 1. | The God of Time Brings in the Dead Year. Dresden Codex, | 127 | |

| 2. | Sacrifice at the Close of a Year. Dresden Codex, | 128 | |

| 3. | End of One and Beginning of Another Time Period. Cortesian Codex, | 129 | |

| 4. | The God of Growth and the God of Death. Cortesian Codex, | 131 | |

| 5. | Auguries from the North Star. Cortesian Codex, | 131 | |

| 6. | Itzamna, the Serpent Goddess, and Kin ich. Dresden Codex, | 132 | |

| 7. | The Gods of Death, of the Sun, and of War. Dresden Codex, | 132 | |

| 8. | Cuculcan Makes New Fire. Codex Troano, | 133 | |

| 9. | The Gods of Death, of Growth, and of the North Star. Dresden Codex, | 133 | |

| 10. | The God of Growth, of the Sun, and of the East. Dresden Codex, | 134 | |

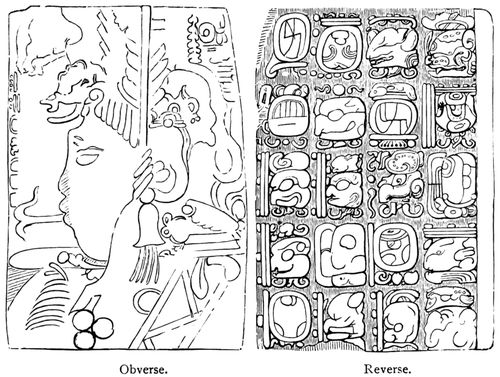

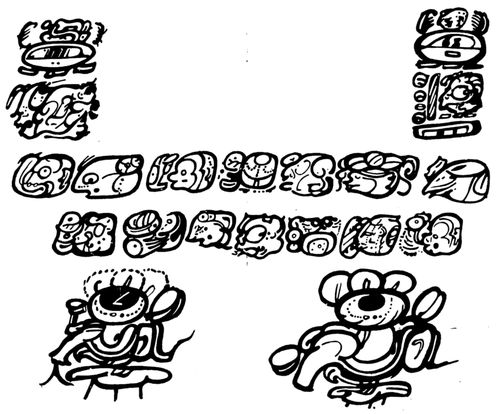

| 11. | An Inscription from Kabah, | 135 | |

| 12. | Linear Inscription from Yucatan, | 136 | |

| 13. | The “Initial Series” from the Tablet of the Cross, Palenque, | 137 | |

| 14. | Inscription on the “Tapir Tablet,” Chiapas, | 138 | |

| 15. | Inscription on a Tablet from Toniná, Chiapas, | 139 | |

| 16. | Inscription on an Amulet from Ococingo, Chiapas, | 139 | |

| 17. | Inscription on a Vase from a Quiche Tomb, Guatemala, | 140 | |

The explorations among the ruined cities of Central America undertaken of late years by various individuals and institutions in the United States and Europe, and the important collections of casts, tracings and photographs from those sites now on view in many of the great museums of the world, are sure to stimulate inquiry into the meaning of the hieroglyphs which constitute so striking a feature on these monuments.

Within the last decade decided advances have been made toward an interpretation of this curious writing; but the results of such studies are widely scattered and not readily accessible to American students. For these reasons I propose, in the present essay, to sum up briefly what seem to me to be the most solid gains in this direction; and to add from my own studies additional suggestions toward the decipherment of these unique records of aboriginal American civilization.

One and the same hieroglyphic system is found on remains from Yucatan, Tabasco, Chiapas, Guatemala, and Western Honduras; in other words, in all Central American regions occupied 10at the Conquest by tribes of the Mayan linguistic stock.[1] It has not been shown to prevail among the Huastecan branch of that stock, which occupied the valley of the river Panuco, north of Vera Cruz; and, on the other hand, it has not been discovered among the remains of any tribe not of Mayan affinities. The Mexican manuscripts offer, indeed, a valuable ancillary study. They present analogies and reveal the early form of many conventionalized figures; but to take them as interpreters of Mayan graphography, as many have done, is a fatal error of method. In general character and appearance the Mayan is markedly different from the Mexican writing, presenting a much more developed style and method.

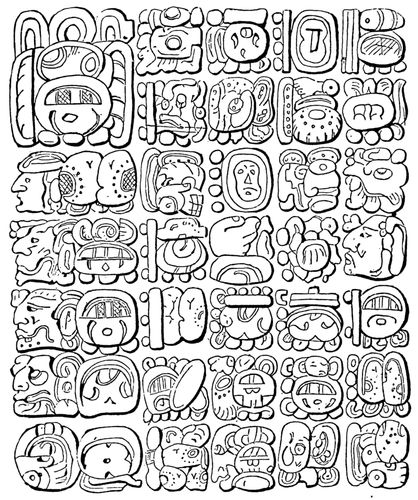

Although the graphic elements preserved in the manuscripts and on the monuments vary considerably among themselves, these divergencies are not so great but that a primitive identity of elements is demonstrable in them all. The characters engraved on stone or wood, or painted on paper or pottery, differ only as we might expect from the variation in the material or the period, and in the skill or fancy of the artist.

The simple elements of the writing are not exceedingly numerous. There seems an endless variety in the glyphs or characters; but this is because they are composite in formation, made up of a number of radicals, variously arranged; as with the twenty-six letters of our alphabet we form thousands of words of diverse significations. If we positively knew the meaning or meanings (for, like words, they often have several different meanings) of a hundred or so of these simple elements, none of the inscriptions could conceal any longer from us the general tenor of its contents.[2]

11It will readily be understood that the composite characters may be indefinitely numerous. Mr. Holden found that in all the monuments portrayed in Stephen’s Travels in Central America there are about fifteen hundred;[3] and Mr. Maudslay has informed me that according to his estimate there are in the Dresden Codex about seven hundred.

Each separate group of characters is called a “glyph,” or, by the French writers, a “katun,” the latter a Maya word applied to objects arranged in rows, as soldiers, letters, years, cycles, etc. As the glyphs often have rounded outlines, like the cross-section of a pebble, the Mayan script has been sometimes called “calculiform writing” (Latin, calculus, a pebble).

The hieroglyphic writing is preserved to us on two classes of remains—painted on sheets of native paper, about ten inches wide and of any desired length, which were inscribed on both sides and folded in the manner of a screen; and engraved or painted on stone, wood, pottery, or plaster.[4]

Of the former only four examples remain, none of them perfect. They have all been published with great care, some of them in several editions. They are usually spoken of as “codices” under the following names: the Codex Troanus and the Codex Cortesianus, probably parts of the same book, the original of which is at Madrid; the Codex Peresianus, which is in Paris; and the Codex Dresdensis, in Dresden. The two former and the two latter resemble each other more closely than they do either member of the other pair. There are reasons to believe that the two first mentioned were written in central Yucatan, and the 12last two in or near Tabasco.[5] This district and that of Chiapas, adjacent to it on the south, was occupied at the time of the Conquest by the Tzental-Zotzil branch of the Mayan stock, who spoke a dialect very close to the pure Maya of Yucatan; they were the descendants of the builders of the imposing cities of Palenque, Ococingo, Toniná and others, and we know that their culture, mythology, and ritual were almost identical with those of the Mayas. I shall treat of them, therefore, as practically one people.

Although Lord Kingsborough had included the Dresden Codex in his huge work on “Mexican Antiquities,” and the Codex Troanus had been published with close fidelity by the French government in 1869, it cannot be said that the serious study of the Mayan hieroglyphs dates earlier than the faithful edition of the Dresden Codex, issued in 1880 under the supervision of Dr. E. W. Förstemann, librarian-in-chief of the Royal Library of Saxony.

The most important studies of the codices have been published in Germany. Besides the excellent writings of Dr. Förstemann himself, those by Dr. P. Schellhas and Dr. E. Seler, of Berlin, are of great utility and will be frequently referred to in these pages. In France, Professor Leon de Rosny, the competent editor of the Codex Peresianus, the Count de Charencey, and M. A. Pousse, whose early death was a severe loss to this branch of research, deserve especial mention. In England no one has paid much attention to it but Mr. Alfred P. Maudslay, whose investigations have yielded valuable results, forerunners of others of the first importance. The earlier speculations of Bollaert are wholly fanciful. In our own country, the mathematical portions of the essays of Professor Cyrus 13Thomas are worthy of the highest praise; and useful suggestions can be found in Charles Rau’s article on the inscriptions of Palenque, and in Edward S. Holden’s paper on Central American picture-writing.[6]

The theories which have been advanced as to the method of interpreting the Mayan hieroglyphs may be divided into those which regard them as ideographic, as phonetic, or as mixed. The German writers, Förstemann, Schellhas, and Seler, have maintained that they are mainly or wholly ideographic; the French school, headed by the Abbé Brasseur, de Rosny, and de Charencey, have regarded them as largely phonetic, in which they have been followed in the United States by Professor Cyrus Thomas, Dr. Cresson, Dr. Le Plongeon, and others.

The intermediate position, which I have defended, is that while chiefly ideographic, they are occasionally phonetic, in the same manner as are confessedly the Aztec picture-writings. In these we constantly meet with delineations of objects which are not to be understood as conveying the idea of the object itself, but merely as representing the sound of its name, either in whole or in part; just as in our familiar “rebus writing,” or in the “chanting arms” of European heraldry. I have applied to this the term “ikonomatic writing,” and have explained it so fully, as 14it is found in the Mexican manuscripts, in my “Essays of an Americanist,” that I need not enter upon it further in this connection, but would refer the reader to what I have there written.[7]

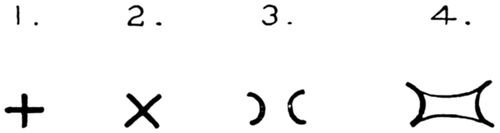

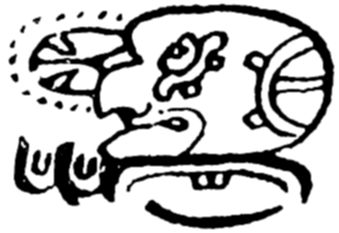

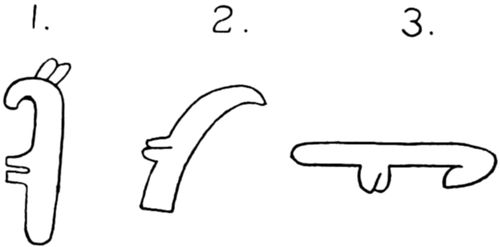

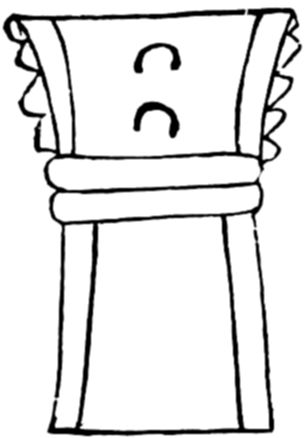

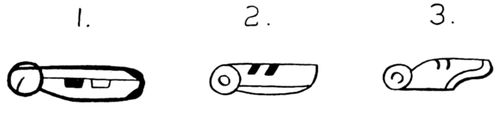

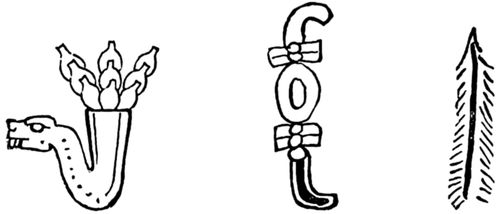

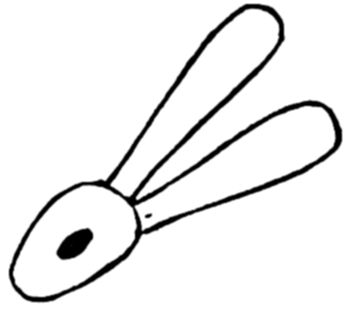

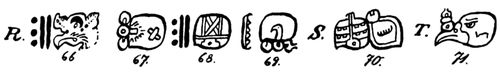

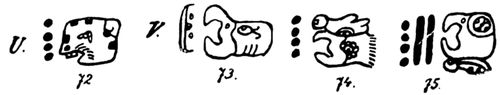

The attempt to frame a real alphabet, by means of which the hieroglyphs could be read phonetically, has been made by various writers.

The first is that preserved in the work of Bishop Landa. It has failed to be of much use to modern investigators, but it has peculiar value as evidence of two facts; first, that a native scribe was able to give a written character for an unfamiliar sound, one without meaning, like that of the letters of the Spanish alphabet; and, secondly, that the characters he employed for this purpose were those used in the native manuscripts. This is proof that some sort of phonetic writing was not unknown.[8]

This alphabet was extended by the Abbé Brasseur, and especially by de Rosny, who, in 1883, defined twenty-nine 15letters, with numerous variants from the Codices and inscriptions.[9]

Two years later, Dr. A. Le Plongeon published an “Ancient Maya Hieratic Alphabet according to Mural Inscriptions,” containing twenty-three letters, with variants. This he applied to the translating of certain inscriptions, but added nothing to corroborate the correctness of the interpretations. Each sign, he believed, stood for a definite letter.[10]

Fig. 1.—Landa’s Alphabet; after a photograph from the original manuscript.

Another student who devoted several years to an attempt to reduce the hieroglyphs to an alphabetic form was the late Dr. Hilborne T. Cresson. His theory was that the glyphs stood for the names of pictures worn down to a single phonetic element, 16alphabetic or syllabic. This element he conceived was consonantal, to be read with any vowel, either prefixed or suffixed; and the consonant was permutable with any of its class, as a lingual, palatal, etc. On this basis he submitted, shortly before his death in 1894, to the American Association for the Advancement of Science several translations from the Codex Troano. Previous to this, in 1892, he had announced his method in the journal “Science,” and claimed that he had worked it out ten years before.[11]

An alphabet of twenty-seven characters, with variants, which the author considered in every way complete, was published in 1888, by F. A. de la Rochefoucauld.[12] By means of it he offered a volume of interlinear translations from the inscriptions and codices! They are in the highest degree fanciful, and can have little interest other than as a warning against the intellectual aberrations to which students of these ancient mysteries seem peculiarly prone.

In 1892 Professor Cyrus Thomas, of the Bureau of Ethnology, announced with considerable emphasis that he had discovered the “key” to the Mayan hieroglyphs; and in July, 1893, published a detailed description and applications of it.[13] In theory, it is the same as Dr. Cresson’s, that is, that the elements of the glyphs were employed as true phonetic elements, or letters. In the article referred to he gives the characters for the following letters of the Maya alphabet: b, c, c’, dz, ch, h, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, pp, t, th, tz, x, v, z; also for a large number of syllabic sounds which he claimed to have recognized. With such an 17apparatus, if it had any value, one would expect to reach prompt and important results; but, aside from the doubtful character of many of his analyses, the fact that this “key” has wholly failed to add any tangible, valuable addition to our knowledge of the inscriptions is enough to show its uselessness; and the same may be said of all the attempts mentioned.

A slight inspection of the Maya manuscripts and of almost any of the inscriptions will satisfy the observer that they are made up of three classes of objects or elements:—

1. Arithmetical signs, numerals, and numerical computations,

2. Pictures or figures of men, animals, or fantastic beings, of ceremonies or transactions, and of objects of art or utility; and,

3. Simple or composite characters, plainly intended for graphic elements according to some system for the preservation of knowledge.

I shall refer to these as, (1) the Mathematical Elements, (2) the Pictorial Elements, and (3) the Graphic Elements of the Mayan hieroglyphic writing.

In another work I have explained the numeral system in vogue among the ancient Mayas, as well as the etymology of the terms they employed.[14] It will be sufficient, therefore, to say here that their system was vigesimal, proceeding by multiples of twenty up to very large sums. In the same work I have quoted from original sources the information that the fives up to fifteen were represented by single straight lines and the intermediate numbers by dots. This has also been discovered independently by several students of the manuscripts.

The frequency and prominence of these elementary numerals in nearly every relic of Mayan writing, whether on paper, stone, or pottery, constitute a striking feature of such remains, and forcibly suggest that by far the majority of them have one and the same purpose, that is, counting; and when we find with almost equal frequency the signs for days and months associated with these numerals, we become certain that in these records we have before us time-counts—some sort of ephemerides or almanacs. This is true of all the Codices, and of nine out of ten of the inscriptions. Here, therefore, is a first and most important step gained toward the solution of the puzzle before us.

But did this incessant time-counting refer to the past or to the future? Was it history or was it prophecy? Or, passing beyond this world, was it astronomy? Was it mythology or ritual, the epochs and the eons of the gods? Perhaps the disposition, sequence, and values of the numbers themselves, once comprehended, will answer these vital questions.

Unfortunately, the old writers, either Spanish or native, tell us little about Maya mathematics. They say the computation ran thus:—

| 20 units | = one kal, 20. |

| 20 kal | = one bak, 400. |

| 20 bak | = one pic, 8000. |

| 20 pic | = one calab, 160,000. |

| 20 calab | = one kinchil or tzotzceh, 3,200,000. |

| 20 kinchil | = one alau, 64,000,000. |

The Tzental system was the same, though the terms differed somewhat: 20 units = one tab (cord or net-ful); 20 tabs = one bac; 20 bacs = one bac-baquetic (bundle of bacs); 20 bac-baquetics = one mam (grandfather); 20 mams = one mechun (grandmother); 20 mechuns = one mucul mam (great-grandfather), 64,000,000.[15]

No doubt in the numerical notation there were special signs for each of these higher unities; but neither Bishop Landa nor the native writers who composed the singular “Books of Chilan Balam” have handed them down. Modern sagacity, however, has repaired ancient negligence, and we can, almost to a certainty, restore the numerical notation of the aboriginal arithmeticians.

The scholar who has worked most successfully in this field is Dr. Förstemann, the editor of the Codex of Dresden, and I shall introduce a condensed statement of his results, referring the student to his own writings for their demonstration.

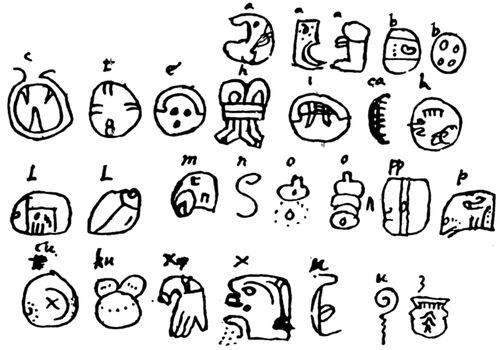

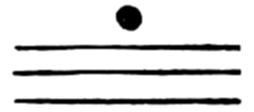

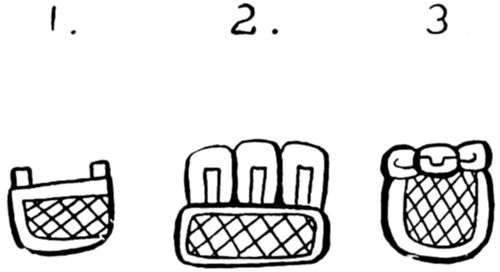

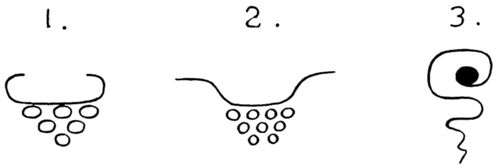

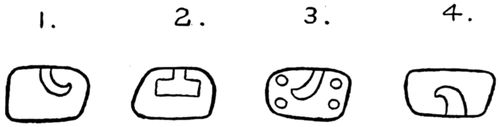

The first important discovery of Dr. Förstemann in this direction was that of the sign for the naught or cipher, 0. It is given in Fig. 2.[16] It has a number of variants, some ornamental in design. Next, he discovered the system of notation of high 20numbers. This is not like ours, but resembles that in use in the arithmetic of ancient Babylonia and some parts of China. The numerals are arranged in columns, to be read from below upward, the value of each unit of a given number being that power of 20 which corresponds to the line on which it stands counted from the bottom. This will be readily understood from the following example:—

| Maya numerals. | Simple values. | Composite values. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

8 | (1 = 204, | = | 160,000; | hence, | 8 × | 160,000) = | 1,280,000 |

|

11 | (1 = 203, | = | 8,000; | hence, | 11 × | 8,000) = | 88,000 |

|

8 | (1 = 202, | = | 400; | hence, | 8 × | 400) = | 3,200 |

|

7 | (1 = 20, | = | 20; | hence, | 7 × | 20) = | 140 |

|

0 | (1 = 1, | = | 1; | hence, | 0 × | 1) = | 0 |

| Total | 1,377,340 | |||||||

This would be according to the regular system of the Maya numeration as given above; but in applying it to the calculations of the native astronomer who wrote the Dresden Manuscript, Dr. Förstemann discovered a notable peculiarity which may extend over all that class of literature. In the third line from the bottom, where in accordance with the above rule the unit is valued at 20 × 20 = 400, its actual value is 20 × 18 = 360.

It immediately suggested itself to him that in time-counts this irregular value was assigned in order that the series might be brought into relation to the old solar year of 360 days, composed of 18 months of 20 days each, in the native calendar.

This correction being made, the above table would read:—

| 8 | (1 = | 7200 | × 20 = | 144,000) | = | 1,152,000 |

| 11 | (1 = | 360 | × 20 = | 7,200) | = | 79,200 |

| 8 | (1 = | 20 | × 18 = | 360) | = | 2,880 |

| 7 | (1 = | 20) | = | 140 | ||

| 0 | (1 = | 1) | = | 0 | ||

| 1,234,220 |

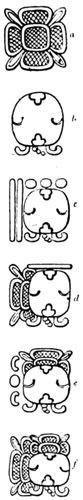

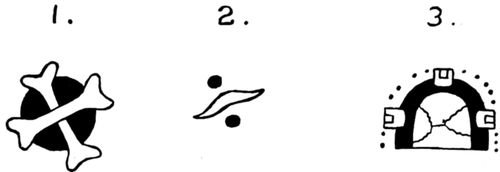

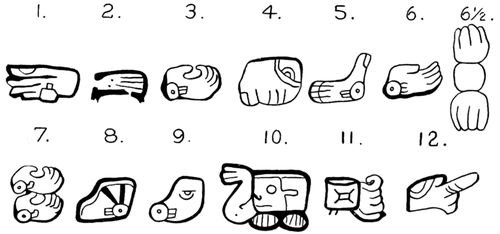

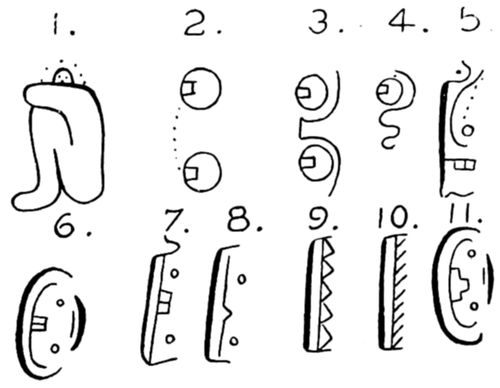

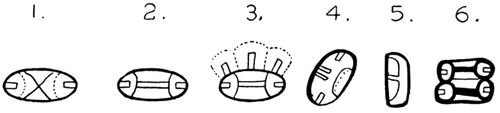

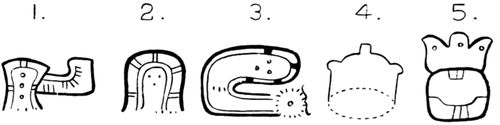

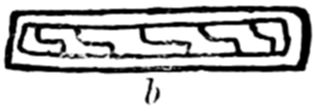

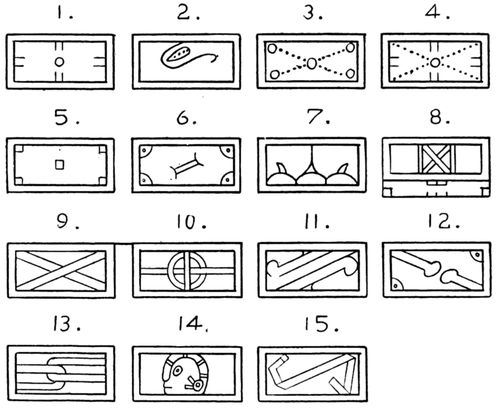

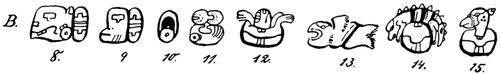

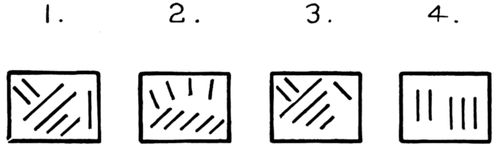

Fig. 3.—Maya Numerals.

An examination of the mural inscriptions showed that on them also the same plan for the expression of high numbers had been employed, and Dr. Förstemann was enabled to interpret with accuracy the computations on the monuments from Copan, Quirigua, and Palenque; developing incidentally the remarkable fact that the inscriptions of Copan contain as a rule higher numbers and are therefore presumably of later date than those of Palenque. The highest is that on “Stela N,” as catalogued by Mr. Maudslay, which ascends to 1,414,800 days, or 3930 years of 360 days.[17]

The next step was the identification of the graphic signs for the higher unities, 20, 360, and 7200,—corresponding to the native kal, bak, and pic.

That generally used for 20 was identified by several students. It is shown in Fig. 3, No. 3; another also employed under certain circumstances for 20 is shown Fig. 3, No. 2. This was identified independently, first by Pousse, later by Seler.[18] No. 4 is perhaps a variant of it.

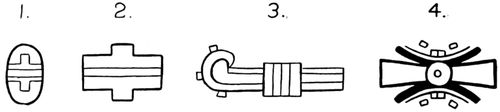

The signs for the bak, 360, and the pic, 7200, are not so certainly established, but Dr. Förstemann has given cogent reasons for recognizing them respectively in the two shown Fig. 4, Nos. 6 and 7.

22Higher signs than these in the direct numerical scale have not yet been ascertained; but such plausible reasons have been advanced by Dr. Förstemann for assigning calendar values to certain other signs that they should be added in this description of the numerals.

The first is that shown in Fig. 4, No. 8. It represents the katunic cycle of 52 years of 365 days each, = 18,980 days. The second is No. 9. This is taken to be the sign of the ahau katun, 24 years of 365 days, = 8760 days. The third is No. 10. This corresponds to one-third of an ahau katun, = 2920 days. The fourth, shown No. 11, is an old cycle of 20 years of 360 days, = 7200. No. 12 means an old katunic cycle of 52 years of 360 days, = 18,720 days, and No. 13 an old year of 360 days.[19]

Fig. 4.—Calendar Signs.

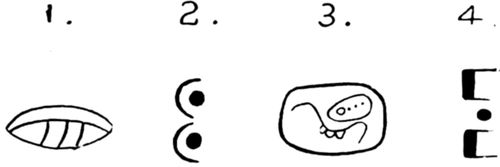

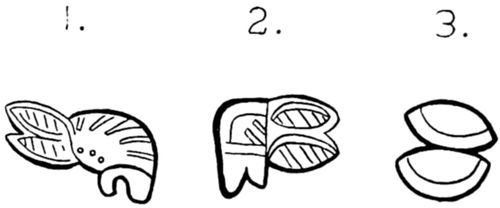

There are also a series of other signs evidently connected with the numerals, the precise value of which is yet undetermined. One of these is a small right or oblique cross, or sometimes two 23arcs abutting against each other, connected or not. It is usually by the side of a single dot or unit, or between two such. In certain places, it seems to be a multiplier with the value 20; in others, it would indicate a change or alternation in the series presented of days or years. (See Fig. 5, Nos. 1–4.)

Fig. 5.—Numeral Signs.

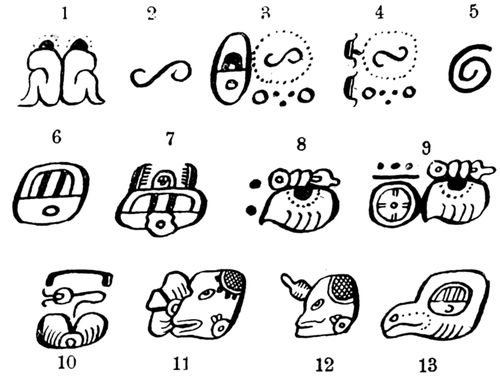

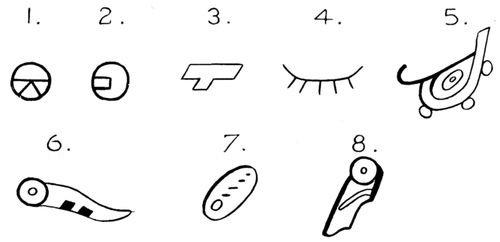

Fig. 6.—The “Cosmic Sign” and its Combinations.

Of somewhat similar value are the calendar signs  , Fig. 4,

Nos. 2, 3, 4, like an S placed lengthwise.

This is also understood to be a sign of

alternation or change of series of years or

cycles.

, Fig. 4,

Nos. 2, 3, 4, like an S placed lengthwise.

This is also understood to be a sign of

alternation or change of series of years or

cycles.

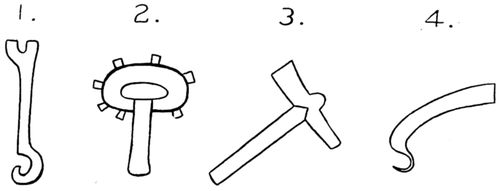

Of an opposite sense is the sign No. 5, the spiral, and also the sign No. 1, both of which are held to represent union.

This list exhausts the mathematical signs so far as they have been ascertained with probability. Those for high numbers brought forward by Brasseur,[20] have no evidence in their favor.

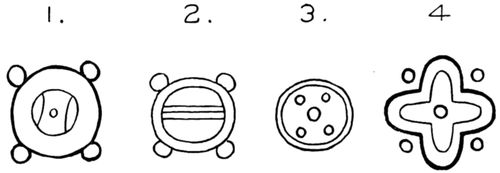

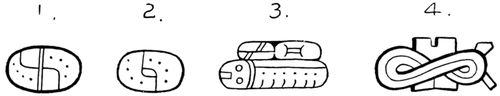

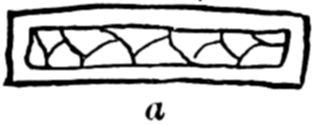

Mr. Maudslay has offered reasons for

believing that the character in Fig. 6, a,

stands for the numeral 20 in a certain

class of mural inscriptions.[21] He further

24points out that the character b is not unfrequently united with

a, and that it (b) almost alone of the mural glyphs is found

with a double set of numerals attached to it as in c. One or

both these sets of numerals are at times replaced by the sign a,

giving the composites d, e, and f. It is thus evident that a has

some numerical or calendar meaning. As a character itself, it

is the “cosmic sign,” conveying the idea of the world or universe

as a whole, as is seen by the examples to which Mr.

Maudslay refers, from various Codices. The cross-hatching

upon it means, as I shall show later, “strong, mighty,” and is

merely a superlative. It may very well mean 20, as that is the

number conveying completeness or perfection in this mythology.[22]

That it appears on what Mr. Maudslay calls the

“Initial Series” of glyphs (which I consider terminals), is explained

by the nature of the computations they preserve.

Another combination, belonging most likely to a similar class,

is the following  where the “cosmic sign” is united

as a superfix to the pax and the flint. It has usually been explained

as a “phallic emblem,” and by Thomas as “tortillas.”[23]

where the “cosmic sign” is united

as a superfix to the pax and the flint. It has usually been explained

as a “phallic emblem,” and by Thomas as “tortillas.”[23]

In the old Maya language we find that certain numbers were used in a rhetorical sense, and this explains their appearance in some non-mathematical portions of the Codices and inscriptions. The two most commonly employed were 9 and 13. These conveyed the ideas of indefinite greatness, of superlative excellence, 25of infinity, etc. A very lucky man was a “nine-souled man;” that which had existed forever was “thirteen generations old,” etc. The “demon with thirteen powers” was still prominent in Tzental mythology in the time of Nuñez de la Vega. Other numerals occasionally employed in a symbolic sense were 3, 4, and 7.[24]

All these occur in the Codices as prefixes in relations where they are not to be construed in their arithmetical values, but in those assigned them by the usages of the language or the customs of religious symbolism. Thus, “twenty,” owing to the vigesimal method of numeration, conveyed the associated ideas of completeness and perfection; and as the month of 20 days was divided into four equal parts of 5 days each, by which markets, etc., were assigned, these numbers also stood independently for other concepts than those of computation.

Having ascertained the characters for the numerals, and having learned that these records are mainly time-counts, the next question which arises is: How did the Mayas count time?

About this we have considerable information from the works of the Spanish writers, Landa, Aguilar, Cogolludo, Pio Perez, etc., which has been supplemented by the researches of modern authors.

The Maya system was a complicated one, based on several 26originally distinct methods, which it was the duty and the aim of the astronomer-priests to bring into unison,—and the effort to accomplish this will chiefly explain their elaborate computations.

Undoubtedly their earliest time-count was that common to primitive tribes everywhere—a measurement of the solar year by lunations or “moons.” The exact lunar month is 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes, 3 seconds; but primitive peoples usually estimate it at 28 days, and allow 13 months to the solar year, as do yet many North Asiatic peoples, and as probably did the early Aryans;[25] or, they estimate the “moon” at 30 days, and allow 12 moons to the year. There are good grounds for believing that the Mayan tribes were at one time divided in custom about this, some using one, some the other method. At the time of the Conquest they had undoubtedly reached a knowledge of the length of the year as 365 days; and there is considerable probability that some of them at least made the correction arranged for in our bissextile or leap year.[26]

This is all familiar enough and would create no difficulty in deciphering these aboriginal almanacs; but a disturbing element enters. The real time-count by which they adjusted the important events of their lives, and which is most prominent in their records, had nothing to do with the motions of the sun, or 27the moon, or any other natural phenomenon. It was based on purely mythical relations supposed to exist between man and nature. As the number 20 (fingers and toes) completes the man, and as all the directions, that is, potencies, of the visible and invisible worlds were held to be 13, these two numbers, 13 and 20, formed the basis of an astrological and ritual calendar, by which auspicious and inauspicious days were assigned, future events foretold, the major feasts and festivals of religious worship dictated, and the like.

This singular time-count of 20 × 13 = 260 days was adopted with slight variations by every semi-civilized nation of Mexico and Central America, and even the names of the 20 days are practically of the same meaning in all these languages.[27] It constituted the tonalamatl of the Nahuas, the “Book of Days,” used in divination.

This sacred period was subdivided into four equal parts of 65 days each, each of which was assigned to the rule of a special planet or star, and to a particular cardinal point with attendant divinities; and each was marked with a color of its own, white, black, red, or blue.

Each “month” of 20 days was subdivided into four periods of five days each, again each having its own divinity, assignment, etc.

But the importance to us of the tonalamatl is that its computations underlay the measurement of long periods of time, the less and greater cycles. These were estimated by the methods of the sacred year, in groups of 13, 20, 24, 52, 104, 260 years, etc. These irregular numbers had to be brought into unison with the lunar and solar years, with the vigesimal system of counting by 20 and its multiples, and with the observed motions of the planets, who were divinities controlling the ritual divisions of time.

To devise a mathematical method of equalities and differences 28by which these conflicting numbers could be placed in harmonious relations, subsumed under common measures, and the ceremonies and forecasts which they controlled assigned by uniform laws—this is the arithmetical problem which fills the pages of the Mayan Codices, and in parts or at length is spread over the surface of the inscribed monuments and painted vases. We need not search for the facts of history, the names of mighty kings, or the dates of conquests. We shall not find them. Chronometry we shall find, but not chronicles; astronomy with astrological aims; rituals, but no records. Pre-Columbian history will not be reconstructed from them. This will be a disappointment to many; but it is the conclusion toward which tend all the soundest investigations of recent years.

Let us recapitulate the numbers which the Maya mathematician had to deal with and adjust under some scheme of uniformity:—

| 1. | The “week” of 13 days, | 13. |

| 2. | The “month” of 20 days, | 20. |

| 3. | Its division into four parts (called tzuc), each, | 5. |

| 4. | The complete tonalamatl, 13 × 20 days, | 260. |

| 5. | Its divisions into four parts, each, | 65. |

| 6. | The solar year, counted as 18 months of 20 days each, | 360. |

| 7. | The solar year, counted as 12 months of 30 days each, | 360. |

| 8. | The solar year, counted as 13 lunar months of 28 days each, | 364. |

| 9. | The solar year, counted as 28 weeks of 13 days each, | 364. |

| 10. | The true solar year, days, | 365. |

| 11. | The bissextile year (?), | 366. |

| 12. | The apparent revolution of Venus (Noh-ek, the Great Star), days, | 584. |

| 13. | The apparent revolution of Mercury (?), days, | 115. |

| 14. | The apparent revolution of Mars (?), days, | 780. |

| 15. | The kin katun, or day-cycle of years, | 13. |

| 16. | The older cycle of years, | 20. |

| 17. | The newer cycle of years, | 24. |

| 18. | The katun cycle of years, | 52. |

| 19. | The double cycle of years, | 104. |

| 20. | The great cycle of years, | 260. |

The Codices contain numerous calculations intended to bring these various quantities into definite relations as aliquot parts of some arithmetical whole, which might be taken as a general unit. The scribes appear to have begun by establishing a period of 14,040 days. This equals 39 years of 360 days each, and also 54 years of 260 days each, together, of course, with the divisors of these numbers, 13, 18, 20, 65, etc. Then followed the determination of the period of 18,980 days, = 73 tonalamatl, = 52 solar years, so prominent in the calendar and ritual of the Nahuas.

This number, however, could not be adjusted to the cycle of the ahau katun, which was 24 years of 365 days each;[28] nor to the ceremonially prominent revolution of “the Great Star,” Venus, which coincides with the Earth’s revolutions in 2920 days, or eight solar years. To bring these into accord with the tonalamatl required a period of 104 solar years, or 37,960 days; and to adjust under one number the katuns, the ahau katuns, the revolutions of Venus, the solar year, and the tonalamatl, three times that number of days are required, that is, 113,880, = 312 years.

This period had still to be brought into relation to the old year of 360 days, and this requires the estimation of a term covering 1,366,560 days, or 3744 years; and this extended era we find expressed in the Dresden Codex, page 24, in the following simple notation, the interpretation of which into our system of calculation, according to the method above explained, I add to the right.

30This long period allowed all their important time-measures to be dealt with as aliquot parts of one whole, and would seem to be sufficient for the purposes they had in view. The credit of establishing it from their ancient writings is exclusively due to Dr. Förstemann, whose demonstrations of it appear to be conclusive.[29]

|

9 (unit = | 144,000) = | 1,296,000 |

|

9 (unit = | 7,200) = | 64,800 |

|

16 (unit = | 360) = | 5,760 |

|

0 (unit = | 20) = | 0 |

|

0 (unit = | 1) = | 0 |

| Total, | 1,366,560 |

This acute observer has, however, discovered some reasons to suppose that the native priests occasionally contemplated a much more extended era; some of their calculations seem to require an era which embraced 12,299,040 days, that is, 33,696 years![30]

No doubt each of these periods of time had its appropriate name in the technical language of the Maya astronomers, and also its corresponding sign or character in their writing. None of them has been recorded by the Spanish writers; but from the analogy of the Nahuatl script and language, and from certain indications in the Maya writings, we may surmise that some of these technical terms were from one of the radicals meaning “to tie, or fasten together,” and that the corresponding signs would 31either directly, that is, pictorially; or ikonomatically, that is, by similarity of sound, express this idea.

Proceeding on the first of these suppositions, Dr. Förstemann has suggested that the character, Fig. 4, No. 8, signifies the period of 52 years, the Nahuatl xiuhmolpilli, “the tying together of the years,” represented in the Aztec pictographs by a bundle of faggots tied with cords. The Maya figure is explained as the day-sign imix, representing the first day of the calendar, and, by a kind of synecdoche, the whole calendar, with a superfix.

That the computations of the tonalamatl underlie most of the numerals in the Codices is shown by the rules for reading them, formulated by Pousse with reference to the red and black numerical signs. These rules are as follows:—[31]

1. If to a red number be added the black number immediately following it, the total less 13 (or its multiples, when the total is above 13) equals the next following red number.

2. When the red and black numbers are written alternately on the same line, they are to be read from left to right; when written one above the other, they are to be read from below upward; when in two vertical columns, they are to be read passing from one column to the other, beginning with the first black number on the left, passing to the first black number on the right, returning to the second black number on the left, and so on.

Sequences of this kind are governed by the following rules:—

1. In any of the above systems the beginning is always marked by one or more columns of days surmounted by a number.

2. This number is always the same as that which ends the series, and both are written in red.

3. The sum of the numbers written in black, multiplied by the number of days with different names represented by the 32hieroglyphs attached, always equals 260, that is, the number of days in the tonalamatl.

The above rules enable the student to recognize the relations of the different parts of the Codices. They prove, for instance, that the pages are not to be read from top to bottom, but that the separate parts or chapters are to be read in many instances from left to right in the section of the page in which they begin, without respect to the folds of the MSS.; and that evidently in reading these “books” they were unfolded and spread out. A good example of this is in Cod. Dresden, pages 4–10, on which one chapter covers all the upper thirds of the seven pages.

A careful examination of Dr. Förstemann’s remarkable studies, as well as a number of other considerations drawn from the Codices themselves, have persuaded me that the general purpose of the Codices and the greater inscriptions, as those of Palenque, have been misunderstood and underrated by most writers. In one of his latest papers[32] Professor Cyrus Thomas says of the Codices: “These records are to a large extent only religious calendars;” and Dr. Seler has expressed his distrust in Dr. Förstemann’s opinions as to their astronomic contents. My own conviction is that they will prove to be much more astronomical than even the latter believes; that they are primarily and essentially records of the motions of the heavenly bodies; and that both figures and characters are to be interpreted as referring in the first instance to the sun and moon, the planets, and those constellations which are most prominent in the nightly sky in the latitude of Yucatan.

This conclusion is entirely in accordance with the results of the most recent research in neighboring fields of American culture. The profound studies of the Mexican Calendar undertaken by Mrs. Zelia Nuttall have vindicated for it a truly surprising accuracy 33which could have come only from prolonged and accurately registered observations of the relative apparent motions of the celestial bodies.[33] We may be sure that the Mayas were not behind the Nahuas in this; and in the grotesque figures and strange groupings which illustrate the pages of their books we should look for pictorial representations of astronomic events.

Of course, as everywhere else, with this serious astronomic lore were associated notions of astrology, dates for fixing rites and ceremonies, mythical narratives, cosmogonical traditions and liturgies, incantations and prescriptions for religious functions. But through this maze of superstition I believe we can thread our way if we hold on to the clue which astronomy can furnish us. In the present work, however, I do not pretend to more than prepare the soil for such a labor.

A proof of the correctness of this opinion and also an admirable example of the success with which Dr. Förstemann has prosecuted his analysis of the astronomical meaning of the Codices is offered by his explanation of the 24th page of the Dresden Codex, laid before the International Congress of Americanists, in 1894.

He showed that it was intended to bring the time covered in five revolutions of Venus into relation to the solar years and the ceremonial years, or tonalamatl, of 260 days; also to set forth the relations between the revolutions of the Moon and of Mercury; further, to divide the year of Venus into four unequal parts, assigned respectively to the four cardinal points and to four divinities; and, finally, to designate to which divinities each of the five Venus-years under consideration should be dedicated.

This illustrates at once the great advance his method has made in the interpretation of the Codices, and the intimate relations we find in them between astronomy and mythology.

34Such a theory of the Mayan books which we have at hand is world-wide distant from that of Thomas and Seler. Take, for example, the series of figures, Cod. Cort., pp. 14a, 15a, 16a.[34] Förstemann and myself would consider them to represent the position of certain celestial bodies before the summer solstice (indicated by the turtle on p. 7); while Thomas says of them, “It may safely be assumed that these figures refer to the Maya process of making bread!!”[35]

Our information from European sources as to the astronomical knowledge possessed by the Mayas is slight.

That they looked with especial reverence to the planet Venus is evident from the various names they applied to it. These were: Noh Ek, “the Great Star” or “the Right-hand Star;” Chac Ek, “the Strong Star” (or “the Red Star”); Zaztal Ek, “the Brilliant Star;” Ah-Zahcab, “the Controller or Companion of the Dawn;”[36] and Xux Ek, “the Bee or Wasp Star,” for reasons which will be considered later. In the Tzental dialect it was called Canan Chulchan, “the Guardian of the Sky,” and Mucul Canan, “the Great Guardian.”

The North Star was well known as Xaman Ek (xaman, north, ek, star), and also as Chimal Ek, “the Shield Star,” or “Star on the Shield.”[37] It was spoken of as “the Guide of the Merchants” (Dicc. de Motul), and therefore was probably one of their special divinities.

The historian Landa states that the Mayas measured the passage 35of time at night by observations of the Pleiades and Orion.[38] The name of the former in their language is Tzab, a word which also means the rattles of the rattlesnake. In the opinion of Dr. Förstemann,[39] their position in the heavens decided the beginning of the year (or, perhaps, cycle, as with the Nahuas), and they were represented in the hieroglyphs by the moan sign (to be explained on a later page).

Certain stars of the constellation Gemini were defined, and named Ac, or Ac Ek, “the Tortoise Stars,” from an imagined similarity of outline to that of the tortoise.[40] This may explain the not infrequent occurrence of the picture of that animal in the Codices, and its representations in stone at Copan and elsewhere.

The terms for a comet in Maya were Budz Ek, “Smoking Star,” and Ikomne, “Breathing or Blowing,” as it was supposed to blow forth its fiery train; in Tzental it was Tza Ec, “Star Dust.” Shooting stars were Chamal Dzutan, “Magicians’ Pipes,” as they were regarded as the fire-tubes of certain powerful enchanters.

The stars in Orion were known as Mehen Ek, “the Sons,” doubtless referring to some astronomical myth.

The Milky Way was spoken of under two different names, both of obscure application, Tamacaz and Ah Poou. Another meaning of the former word is “madness, insanity;” and the latter term was also applied to a youth who had just attained the age of puberty.[41] Perhaps the connection of the word lies in the ceremonies of initiation practiced by many tribes when a youth reached this age, and which, by fasting and the administration of 36toxic herbs, often led to temporary mania; and the deity of the Milky Way may have presided over these rites.

The moon in opposition was referred to as u nupptanba, from nupp, opposed, opposite. When in conjunction, the expression was hunbalan u, “the rope of the moon,” or, “the moon roped.” When it was in eclipse, it was chibil u, “the moon bitten,” the popular story being that it was bitten by a kind of ant called xulab. An eclipse of the sun was also chibil kin, “the sun bitten;” but more frequently the phrase was tupul u uich kin, or, tupan u uich kin, “the eye of the day is covered over,” or, “shut up.” It is useful to record such expressions, as they sometimes suggested the graphic representations of the occurrences.[42]

To understand the pictorial portions of the inscriptions some acquaintance with the native mythology is indispensable.

The religion of the Mayas was a polytheism, but the principal deities were few in number, as is expressly stated by Father Francisco Hernandez, the earliest missionary to Yucatan (1517);[43] and these, according to the explicit assertion of Father Lizana, were the same as those worshipped by the Tzentals of Tabasco and Chiapas.[44] Both these statements are confirmed by a comparison of the existing remains, and they greatly facilitate a comprehension of the Codices and epigraphy.

The spirit of this religion was dualistic, the gods of life and light, of the sun and day, of birth and food, of the fertilizing showers and the cultivated fields, being placed in contrast to those of misfortune and pain, of famine and pestilence, of blight and night, darkness and death. Back of them all, indeed the source of them all, was Hunab Ku, “the One Divine;” but of him no statue and no picture was made, for he was incorporeal and invisible.[45]

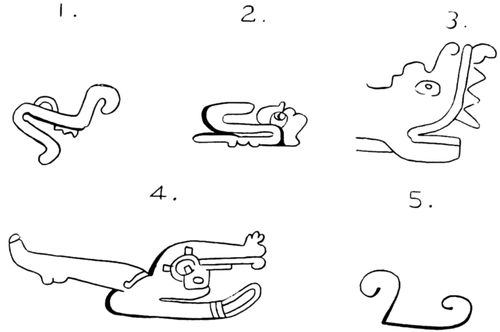

Itzamna.—Chief of the beneficent gods was Itzamna. He was the personification of the East, the rising sun, with all its manifold mythical associations. His name means “the dew or 38moisture of the morning,” and he was the spirit of the early mists and showers. He was said to have come in his magic skiff from the East, across the waters, and therefore he presided over that quarter of the world and the days and years assigned to it.

For similar reasons he received the name Lakin chan, “the Serpent of the East,” under which he seems to have been popularly known. As light is synonymous with both life and knowledge, he was said to have been the creator of men, animals, and plants, and was the founder of the culture of the Mayas. He was the first priest of their religion, and invented writing and books; he gave the names to the various localities in Yucatan, and divided the land among the people; as a physician he was famous, knowing not only the magic herbs, but possessing the power of healing by touch, whence his name Kabil, “the skilful hand,” under which he was worshipped in Chichen Itza. For his wisdom he was spoken of as Yax coc ah-mut, “the royal or noble master of knowledge.”

Cuculcan.—In some sense a contrast, in others a completion of the mythical concepts embodied in Itzamna, was Cuculcan or Cocol chan, “the feathered or winged serpent.”[46] He also was a hero-god, a deity of culture and of kindliness. He was traditionally the founder of the great cities of Chichen Itza, and Mayapan; was active in framing laws and introducing the calendar, at the head of which some Maya tribes placed his name; was skilled in leechcraft, and was spoken of as the god of chills and fevers.

As Itzamna was identified with the East, so was Cuculcan with the West. Thence he was said to have come, and thither returned.[47] In the Tzental calendars he was connected with the 39seventh day (moxic, Maya, manik); hence he is mystically associated with that number. He corresponds to the Gukumatz of the Quiche mythology, a name which has the same signification.

In the myth he is described as clothed in a long robe and wearing sandals, and, what is noteworthy, having a beard. In the calendars of the Tzentals he was painted “in the likeness of a man and a snake,” and the “masters” explained this as “the snake with feathers, which moves in the waters,” that is, the heavenly waters, the clouds and the rains; for which reason Bishop Nuñez de la Vega, to whom we owe this information, identified him with the Mexican Mixcoatl, “the cloud serpent;”[48] whereas Bishop Landa was of opinion that he was the Mexican Quetzalcoatl.

Kin ich.—As Itzamna was thus connected with the rising, morning sun, and Cuculcan with the afternoon and setting sun, so the sun in the meridian was distinguished from both of them. As a divinity, it bore the name Kin ich, “the eye or face of the day.” The sacrifices to it were made at the height of noontide, when it was believed that the deity descended in the shape of the red macaw (the Ara macao), known as Kak mo, “the bird of fire,” from the color of its plumage, and consumed the offering. Such ceremonies were performed especially in times of great sickness, general mortality, the destruction of the crops through locusts, and other public calamities. It seems probable from the accounts that Kin ich was a much less prominent divinity in the popular mind than either of the other two solar deities, and his attributes were occasionally assigned to Itzamna, 40as we find the combination Kin ich ahau Itzamna among the names of divinities.

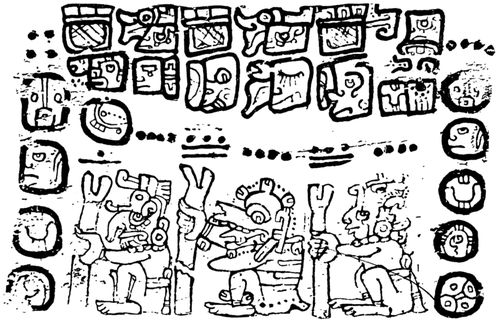

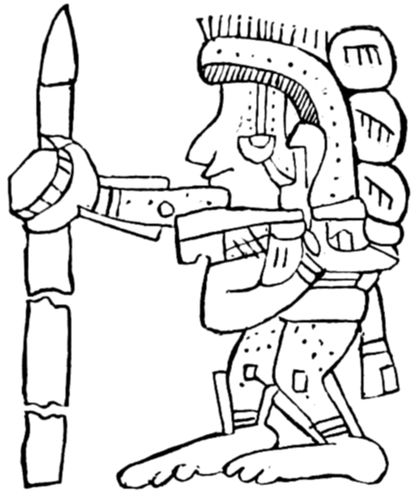

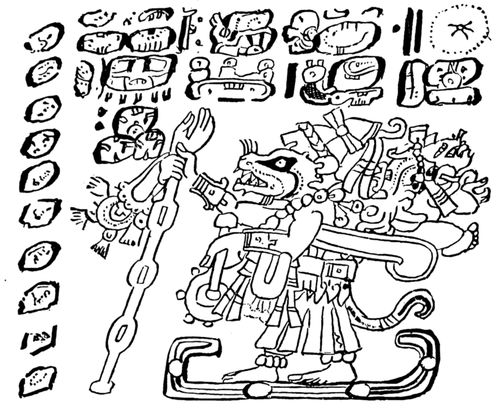

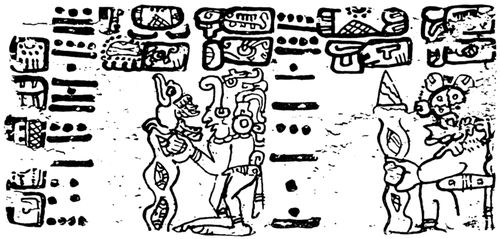

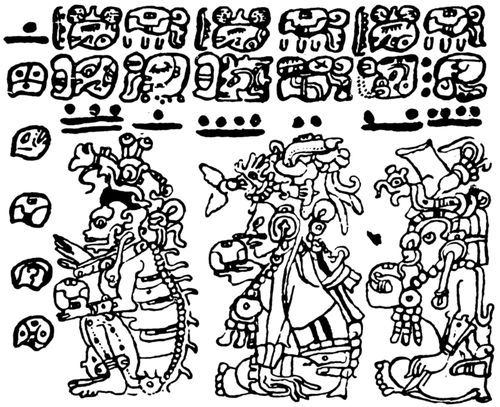

Fig. 7.—The Beneficent Gods draw from their Stores. (Photographed from the Cortesian Codex.)

Other Gods.—To Itzamna was assigned as consort Ix Chel, “the rainbow,” also known as Ix Kan Leom, “the spider-web” (which catches the dew of the morning). She was goddess of medicine and of childbirth, and her children were the Bacabs, or Chacs (giants),[49] four mighty brethren, who were the gods of the four cardinal points, of the winds which blow from them, of the rains these bring, of the thunder and the lightning, and consequently of agriculture, the harvests, and the food supply. Their position in the ritual was of the first importance. To each were assigned a particular color and a certain year and day in the calendar. To Hobnil, “the hollow one” or “the belly,” were given the south, the color yellow, and the day and years kan, 41the first of the calendar series, and so on. The red Bacab was to the east, the white to the north, and the black, whose name was Hozan Ek, “the Disembowelled,” to the west.[50]

The Cardinal Points.—Much attention has been directed to these divinities as representing the worship of the cardinal points and to the colors, days, cycles, and elements mythically associated with them. Uniform results have not been obtained, as the authorities differ, as probably did also the customs of various localities.[51] Pio Perez assigns kan to the east, muluc to the north, ix to the west, and cauac to the south. The arrangement based on Landa’s statements would be as follows:—

| Cardinal point. | Bacab. | Days. | Colors. | Elements. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South, | Hobnil (the Belly), | Kan, | Yellow, | Air. |

| East, | Canzicnal (Serpent Being), | Muluc, | Red, | Fire. |

| North, | Zaczini (White Being), | Ix, | White, | Water. |

| West, | Hozan ek (the Disembowelled Black one), | Cauac, | Black, | Earth. |

On the other hand, it should be noted that the names of the winds in Maya distinctly assign the color white to the east, thus:—

| East wind, | zac ik, “white wind.” |

| Northeast wind, | zac xaman ik, “white north wind.” |

| Southeast wind, | zac nohol ik, “white south wind.” |

The solution of these difficulties must be left for future investigation.

The Good Gods.—Divinities of a beneficent character were Yum Chac, “Lord of Waters or Rains;” Yum Kaax, “Lord of the Harvest Fields;” Cum Ahau, “Lord of the Vase,” that is, 42of the rains, who is described in the Dic. Motul as “Lucifer, Chief of the Devils” and is probably a name of Itzamna; Zuhuy Kak, “Virgin Fire,” patroness of infants; Zuhuy Dzip, “The Virgin of Dressed Animals,” a hunting goddess; Ix Tabai, “Goddess of the Ropes or Snares,” also a hunting goddess as well as the patroness of those who hanged themselves; Ah Kak Nech, “He Who Looks after the Cooking Fire,” Ah Ppua, “the Master of Dew,” and Ah Dziz, “The Master of Cold,” divinities of the fishermen.

To this list should be added Acan, “the God of the Intoxicating Mead,” the national beverage, that being its name; Ek Chua, “the Black Companion,” god of the cacao planters and the merchants, as these used the cacao beans as a medium of exchange; Ix Tub Tun, “she who spits out Precious Stones,” goddess of the workers in jade and amethysts; Cit Bolon Tun, “the Nine (i. e., numberless) Precious Stones,” a god of medicine; Xoc Bitum, the God of Singing, and Ah Kin Xoc or Ppiz Lim Tec, the God of Poetry (xoc, to sing or recite); Ix Chebel Yax, the first inventress of painting and of colored designs on woven stuffs (chebel, to paint, and a paint-brush).

A minor deity was Tel Cuzaan, “the swallow-legged,” a divinity of the island of Cozumel (“Swallow Island”).

On a lofty pyramid, where is now the city of Valladolid, Yucatan, was worshipped Ah zakik ual, “Lord of the East Wind.” His idol was of pottery in the shape of a vase, moulded in front into an ugly face. In it they burned copal and other gums. His festival was celebrated every fourth year with sham battles.[52] Probably this was a representation of Itzamna as lord of the cardinal point.

The “Island of Women,” Isla de Mugeres, on the east coast, was so named because the first explorers found there the statues of four female divinities, to whom altars and temples were dedicated.[53] 43They were Ix-chel, Ix-chebel-yax, Ix-hun-yé, and Ix-hun-yeta. The first two have already been mentioned. The last two seem to have been goddesses connected with the moonrise and sunrise, as the dictionaries give as the meaning of yé, “to show one’s self, to appear;” as in the phrases yethaz y ahalcab, “at the appearance of the dawn;” yethaz u hokol u, “at moonrise;” yet hokol kin, “at sunrise.”

Prominent among mythical beings were the dwarfs, known as ppuz, “bent over;” ac uinic, “turtle men;” tzapa uinic, “shortened men;” and pputum, “small of body.” They are sometimes represented in the carvings, an interesting example being in the Peabody Museum. A legend concerning such brownies was that before the last destruction of the world the whole human race degenerated into like diminutive beings, which prompted the gods to destroy it.[54] One class of these little creatures, called acat, were said to become transformed into flowers.

As I have shown elsewhere,[55] many similar superstitions survive in the folk-lore of Yucatan and Tabasco to-day. But it is not safe to look at such survivals as part of genuine ancient mythology. For instance, the goddess Ix-nuc, or Xnuc, said by Brasseur to have been goddess of the mountains, by Seler, goddess of the earth, and by Schellhas, goddess of water, is in fact not a member of the Maya Pantheon. The name means simply “old woman,” and was first mentioned by an anonymous modern writer in the Registro Yucateco.

The Gods of Evil.—In contrast to the beneficent deities were those who presided over war, disease, death, and the underworld. Distinctively war gods were Uac Lom Chaam, “He 44whose teeth are six lances,” worshipped anciently at Ti-ho, the present Mérida; Ahulane, “The Archer,” painted holding an arrow, whose shrine was on the island of Cozumel; Pakoc (from paakal, to frighten) and Hex Chun Chan, “The dangerous one,” divinities of the Itzaes; Kak u pacat, “Fire (is) his face,” who is said to have carried in battle a shield of fire; Ah Chuy Kak, “He who works in fire,” that is, for destruction; Ah Cun Can, “The serpent charmer,” also worshipped at Ti-Ho; Hun Pic Tok, “He of 8000 lances,” who had a temple at Chichen Itza.

Chief of all these evil beings was the God of Death. His name is preserved in the first account we have of Yucatecan mythology, that by Father Hernandez, and, according to Father Lara, it was the same among the Tzentals, Maya, Ah-puch, Tzental, Pucugh. These words mean “the Undoer,” or “Spoiler,” apparently a euphemism to avoid pronouncing a name of evil omen.[56] In modern Maya he is plain Yum cimil, “lord of death.” He was painted as a skeleton with bare skull, and was then called Chamay Bac, or Zac Chamay Bac, “white teeth and bones.”[57]

The spirit (pixan) after death was supposed to go to the Underworld, which was called Mitna, or Metna where presided the god Xibilba or Xabalba, sometimes called Hun Ahau, “the One lord,” for to his realm must all come at last.[58] Another name for this Hades was tancucula (perhaps tan kukul, “before the gods,” i. e., where one is judged), which is given by the Dicc. Motul as an “ancient word” (vocablo antiguo). The happy souls then passed to a realm of joy, where they spent 45their time under the great green tree Yaxche, while those who were condemned sank down to a place of cold and hunger.

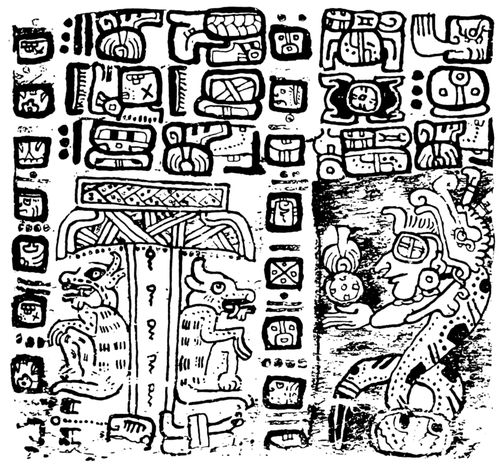

The Conflict of the Gods.—Between these two classes of deities—those who make for good and those who make for evil in the life of man—there is, both in the myths and in the picture writings, an eternal conflict.

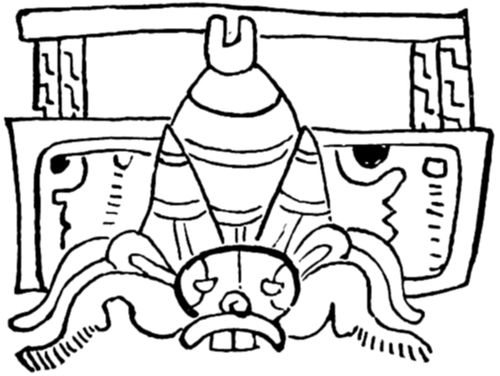

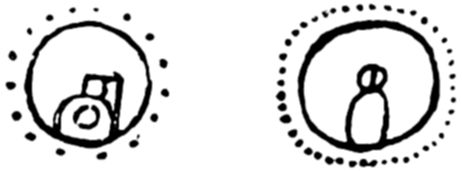

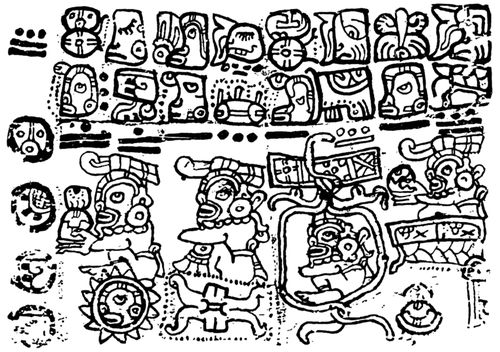

Fig. 8.—The gods of Life and of Growth plant the tree. Death breaks it in twain. (Photographed from the Cortesian Codex.)

In the Codex Troano, as Dr. Seler remarks, “The god of death appears as the inevitable foil of the god of light and heaven. In whatever action the latter is depicted, the god of death is imitating it, but in such a manner that with him all turns to nought and emptiness. Where the light-god holds the string, in the hands of the death-god it is torn asunder; where the former offers incense, the latter carries the sign of ‘fire’ wherewith to consume it; where the former presents the sign kan, food, the latter lifts an empty vase bearing the signs of drought and death.”

We know practically nothing of the cosmogony of the Mayas; but it is instructive in connection with their calendar system to find that, like the Nahuas, they believed in Epochs of the Universe, at the close of each of which there was a general destruction of both gods and men. The early writer, Aguilar, says that he learned from the native books themselves that they recorded three such periodical cataclysms. The first was called Mayacimil, “general death;” the second, Oc na kuchil, “the ravens enter the houses,” that is, the inhabitants were all dead; and the third, Hun yecil, a universal deluge, a term which the Dicc. Motul seems to explain by mentioning a tradition that the water was so high “that its surface was within the distance of one stalk of maguey from the sky!” Another term for this catastrophe was bulcabal, haycabal or haycabil (destruccion, asolamiento y diluvio general con que fué destruido y asolado el mundo. Dicc. Motul).

This would make the present the fourth age of the world (not the fifth, as the Nahuas believed); and this corresponds to the prophecies contained in the “Books of Chilan Balam,” which I have quoted in another work. The scene of the creation of man, the “terrestrial Paradise,” was known as hun anhil, and the name of the first man was Anum, both apparently from the verb anhel, to stand erect.

Many of the high calculations of the priests must have been for the purpose of discovering the length of the present epoch and how soon the world would end. They seem to have thought this would take place when all their various time-measures would merge together into a common unity, which each could divide without remainder.[59]

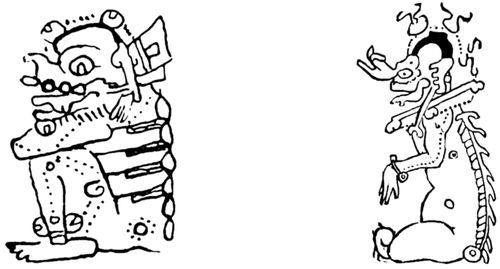

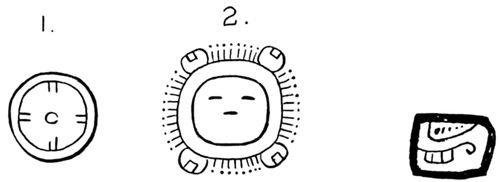

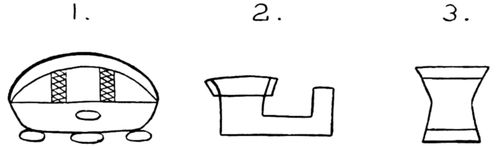

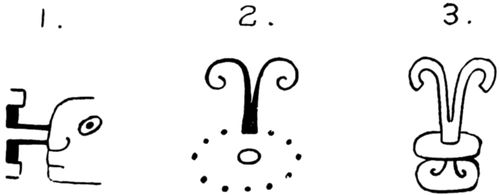

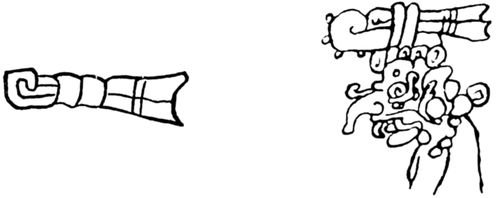

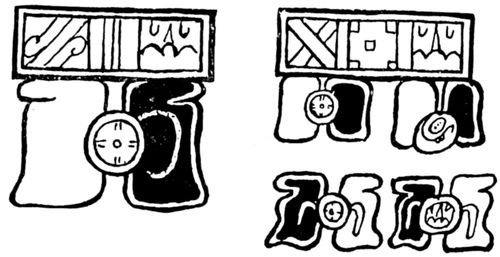

The cosmical conceptions of the ancient Mayas have not hitherto been understood; but by a study of existing documents I believe they can be correctly explained in outline.

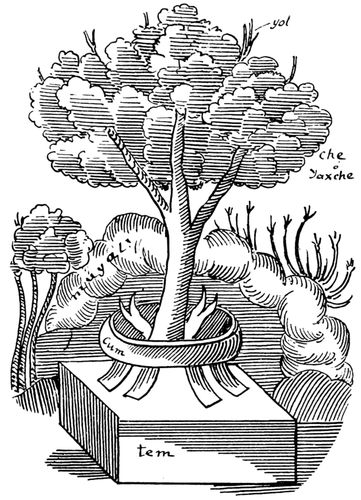

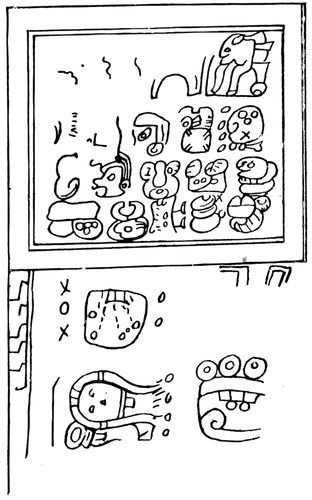

Fig. 9.—The Universe. (From the Chilan Balam of Mani.)

One of these is the central design in the Chilan Balam, or Sacred Book, of Mani (Fig. 9). It was copied by Father Cogolludo in 1640, and inserted in his History of Yucatan, with a totally false interpretation which the natives designedly gave him.

48The lettering in the above figure is by the late Dr. C. H. Berendt, and was obtained by him from other books of Chilan Balam, and native sources. In Cogolludo’s work, this design is surrounded by thirteen heads which signify the thirteen ahau katuns, or greater cycles of years, as I have explained elsewhere.[60] The number thirteen in American mythology symbolizes the thirteen possible directions of space.[61] The border, therefore, expresses the totality of Space and Time; and the design itself symbolizes Life within Space and Time. This is shown as follows: At the bottom of the field lies a cubical block, which represents the earth, always conceived of this shape in Mayan mythology.[62] It bears, however, not the lettering, lum, the Earth, as we might expect, but, significantly, tem, the Altar. The Earth is the great altar of the Gods, and the offering upon it is Life.

Above the earth-cube, supported on four legs which rest upon the four quarters of the mundane plane, is the celestial vase, cum, which contains the heavenly waters, the rains and showers, on which depends the life of vegetation, and therefore that of the animal world as well. Above it hang the heavy rain clouds, muyal, ready to fill it; within it grows the yax che, the Tree of Life, spreading its branches far upward, on their extremities the flowers or fruit of life, the soul or immortal principle of man, called ol or yol.[63]

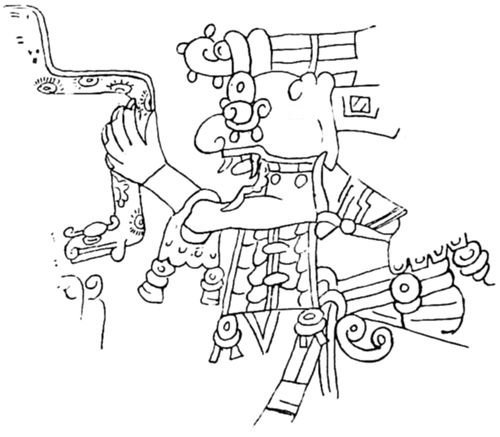

Turning now to the central design of what has been called the “Tableau of the Bacabs,” in the Codex Cortesianus, Fig. 10, we can readily see in the light of the above explanation that its 49lesson is the same. The design is surrounded by the signs of the twenty days, beyond which the field (not shown in this cut) is apportioned to the four cardinal points and the deities and time-cycles connected with them.

Fig. 10.—Our First Parents. (From the Cortesian Codex.)

Again it is Life within Space and Time which the artist presents. The earth is not represented; but we readily recognize in conventionalized form the great Tree of Life, across it the celestial Vase, and above it the cloud-masses. On the right sits Cuculcan, on the left Xmucane, the divine pair called in the Popol Vuh “the Creator and the Former, Grandfather and Grandmother 50of the race, who give Life, who give Reproduction.”[64] In his right hand Cuculcan holds three glyphs, each containing the sign of Life, ik. Xmucane has before her one with the sign of union (sexual); above it, one containing the life-sign (product of union); and these are surmounted by the head of a fish, symbolizing the fructifying and motherly waters.

The total extension of the field in these designs resembles the glyph a in Fig. 6. It is found in both Mayan and Mexican MSS.,[65] and expresses the conception these peoples had of the Universe. Hence I give it the name of the “cosmic sign.”

Turning to the Codices and the monuments with the above mythological lore in one’s memory, it seems to me there is no difficulty in identifying most of the pictures presented by them. That this has not been accomplished heretofore, I attribute to the neglect of the myths by previous writers, and a persistent desire to discover in the mythology of the Mayas, not the divinities which they themselves worshipped, but those of some other nation, as the Nahuas, Quiches, Zapotecs, or Pueblo dwellers.[66] I shall pay small attention to such analogies, as the Mayas had a religion of their own, and it is that which I wish to define. We may turn first to the—

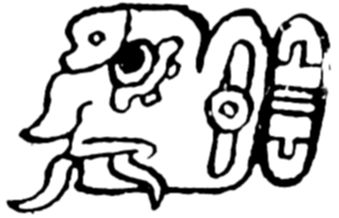

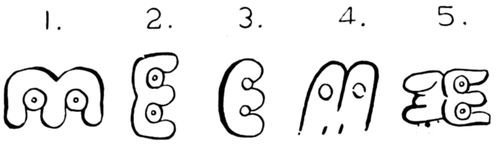

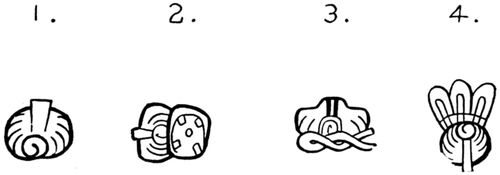

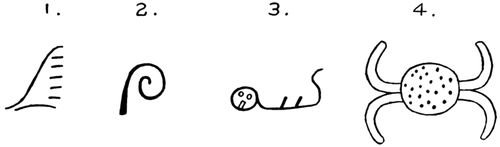

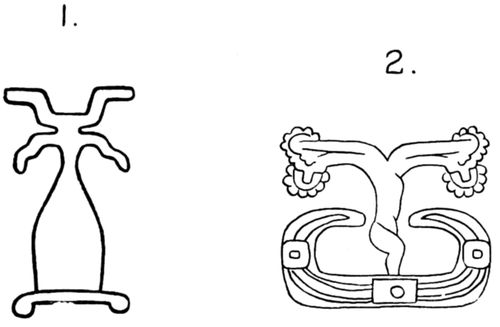

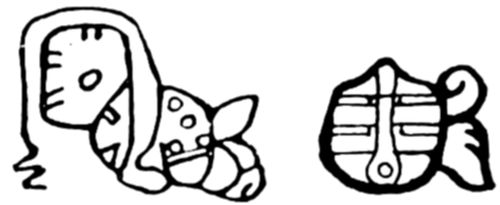

Fig. 11.—Monogram of Itzamna.

Representations of Itzamna.—I have no hesitation in identifying Itzamna with the “god B,” as catalogued by Dr. Schellhas in his excellent study of the divinities of the Codices,[67] and which he believes to be Cuculcan, while the Abbé Brasseur, followed by Dr. Seler, argue, that it is a “Tlaloc” or Chac, i. e., a rain god.[68] He is extremely prominent in the Codices, being painted in the Dresden Codex alone not less than 130 times, and in the others about 70 times. No other deity has half so many representations, and we may well believe, therefore, that he was the Jove of their Pantheon.

This at once suggests Itzamna; but a phrase of the historian Cogolludo leaves no doubt about it. The “god B” is associated with the signs of the east, and his especial and invariable characteristic are two long, serpent-like teeth, which project from his mouth, one in front, the other to the side and backward.[69] These traits enable us to identify “B” with Lakin Chan, “the serpent of the east,” who was portrayed “with strangely deformed teeth,” and this was unquestionably but another name for Itzamna, the god of the east.[70]

Fig. 12.—Itzamna: from the Codex Troano.

Fig. 13.—Itzamna: from the Inscription of Kabah.

An abundance of evidence may be adduced to confirm this opinion. This deity is represented in close relations with the serpent, holding it in his hand, sitting upon it, even swallowed by it, or emerging from its throat. As a “medicine man” he carries the “medicine bag,” and the wand or baton, called in Maya caluac, “the perforated stick,”[71] surmounted with a hand, hinting at his name above given, Kabil, the Skilful Hand. He is often in a boat, to recall his advent over the eastern sea, and he is frequently associated with the showers, as was Itzamna, who said of himself, itz en muyal, itz en caan, “I am what trickles from the clouds, from the sky.” As the rising sun which dispels the darkness, or else as the physician who heals disease, he is portrayed sitting on the head of the owl, the bird of night and sickness; and as the giver of 53life he is associated with the emblem of the snail, typical of birth.

He himself is never connected with the symbols of death or misfortune, but always with those of life and light. The lance and tomahawk which he often carries are to drive away the spirits of evil.

Besides the above peculiarities, he is portrayed as an elderly man, his nose is long and curved downward, his eye is always the “ornamented eye,” which in the Maya Codices indicates a divinity. He is associated with all four quarters of the globe, for the East defines the cardinal points; and what is especially interesting, it is he who is connected with the Maya “Tree of Life,” the celebrated symbol of the cross, found on so many ancient monuments of this people and which has excited so much comment. This I shall consider later.

Fig. 14.—Itzamna: from the Dresden Codex.

Fig. 15.—Mask of Itzamna (?).

We know from the mythology that Itzamna, like most deities, was multiform, appearing in various incarnations. In the ceremonies this was represented by masks; with this in mind I class as merely one of the forms or epiphanies of Itzamna that figure 54in the Codices described by Dr. Schellhas as a separate deity, “the god with the ornamental nose,” whom he catalogues as “god K.” I am led to this conclusion by a careful study of all the pictographs in which this deity appears; they all seem to show that it is Itzamna wearing a mask to indicate some one manifestation of his power (see especially Cod. Dresden., pp. 7, 12, 25, 26, and 34, 65, and 67, where Itzamna is carrying the mask on his head). That there is a particular monogram for this character merely indicates that it was a separate mythological manifestation, not a different deity.

A remarkable and constant feature in the representations of Itzamna is his nose. Thomas calls it “elephantine,” but, as Waldeck and Seler have shown, it is undoubtedly intended to imitate the snout of the tapir.[72]

When we remember that this animal was sacred to Votan, who played the same part in Chiapas that Itzamna did in Yucatan, dividing and naming the land, etc.; and that the interesting slate tablets from Chiapas, in the National Museum of Mexico, portray the sacred tapir in intimate connection with the symbol of the hand,[73] that associated with Itzamna,—we are led to identify the two mythical personages as one and the same. According to Bishop Landa the tapir was not found in Yucatan except on the western shore near the bay of Campeche,[74] which shows 55that the myth of the tapir god was imported from Tzental territory.

It may be asked why the tapir, a dull animal, loving swamps and dark recesses of the forests, should have been chosen to represent a divinity of light. I reply, that it arose from the “ikonomatic” method of writing. The word for tapir in Maya is tzimin, in Tzental tzemen, and from the similarity of this sound to i-tzam-na the animal came to be selected as his symbol. No such sacredness attached to the brute among the Quiches, for in their tongue the allusive sound did not exist, the tapir being called tixl. This rebus also confirms the identity of Itzamna with the tapir-nosed deity of the Codices.[75]

The annual festival to Itzamna was called Pocam, “the cleansing.” On that occasion the priests, arrayed in all their insignia, assembled in the house of their prince. First, they invoked Itzamna as the founder of their order and burned to him incense with fire newly made from the friction of sticks. Next they spread out upon a table covered with green leaves the sacred books, and asperged their pages with water drawn from a spring of which no woman had ever tasted. This was the ceremonial “cleansing.” Then the chief priest arose and declared the prognostics for the coming year as written in the holy records.[76]

We may well believe that the Dresden Codex, pages 29–43, which are entirely taken up with the deeds and ceremonies of Itzamna, was one of the books spread out on this solemn occasion.

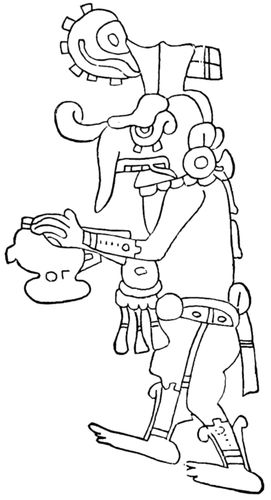

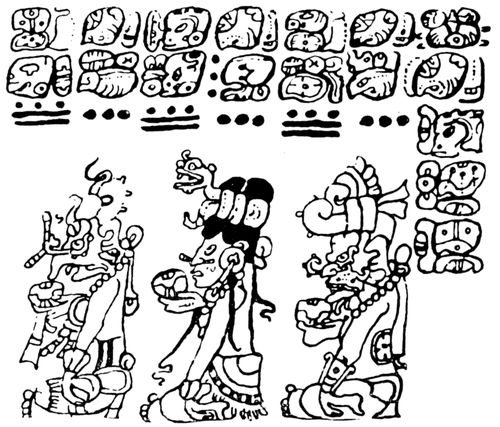

Representations of Cuculcan.—As I believe the reasons above given are sufficient to establish the identity of the “god B,” 56of Dr. Schellhas’ catalogue, with Itzamna, so I think his “god D” is Cuculcan.[77] He himself believes it to be a “night god,” or a “moon god,” while Dr. Seler considers it to portray Itzamna.

Fig. 16.—Monogram of Cuculcan.

Fig. 17.—Cuculcan, with owl head-dress.

The characteristics of this divinity are: A face of an old man, with sunken mouth and toothless jaws, except one tooth in the lower jaw, which, in the Tro. and Cortes. Codices, is exaggerated as a distinctive sign; he has the “ornamented eye” peculiar to deities; and to his forehead is attached, or over it hangs, an affix, which generally bears the sign akbal, which means “darkness,” because he is the setting or night sun; for which reason his head-dress is often the horns of the eared owl. He is clearly a beneficent deity, and is never associated with symbols of misfortune or death. Indeed, he is at times evidently a god of birth, being accompanied with the symbol of the snail, above explained, and is sometimes associated with women apparently as an obstetrician. He is connected with serpent emblems, and holds in his hand a sacred rattle formed of the rattles of the rattlesnake.

All these traits coincide with the myths of Cuculcan; but when we perceive that he, and he alone of all the deities, is 57occasionally depicted with a beard under his chin, just as Cuculcan wore in the legend, the identification becomes complete.[78]

The most striking of his representations, and that which is most distinctive of his identity with the “green-feathered serpent,” is the picture which extends over pp. 4 and 5, middle, of the Dresden Codex. Here he is seen with face emerging from the mouth of the great, green-feathered snake-dragon, indicative of his own personality, his hieroglyph immediately above his head.[79]

Representations of Kin ich.—As has already been observed, the sun at noon, conceived as a divinity, did not occupy a prominent place in Maya mythology; and this is also the case in the pictorial designs.

Fig. 18.—Monogram of Kin ich.

There is no doubt as to his representation. It is accompanied by the well-known ideogram of the sun scattered over his body and represented above him. It will be seen on a later page.

He is richly arrayed with large ear-rings and a characteristic, prominent nose decoration. He has the “ornamented eye” and a full head dress. (God “G” of Schellhas.)

Proceeding now to consider other divinities of the beneficent class, I begin with—

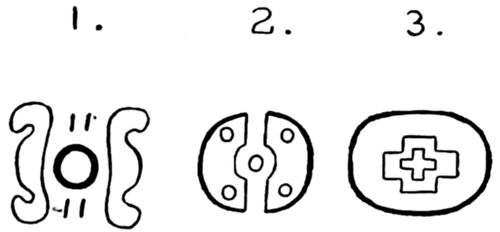

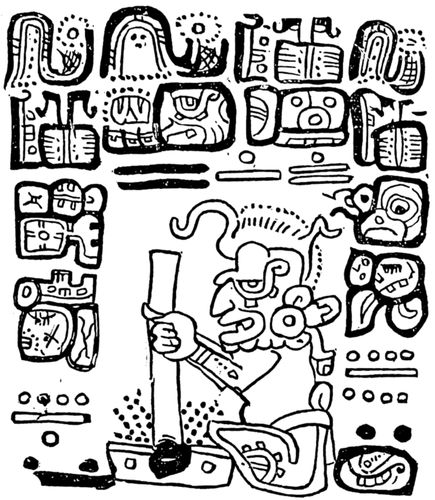

Representations of Xaman Ek, the Pole Star.—This is the “god C, of the ornamented face,” of Dr. Schellhas’ list, who suggests its identity with the pole star. The very characteristic face recurs extremely frequently, especially in Codices Troano, Cortesianus, and Peresianus. We have evidently to do with an important divinity, and, as Dr. Schellhas says, “one of the 58most remarkable and difficult figures in the manuscripts.” That it is the personification of a star he argues, (1) from the ring of rays with which it is surrounded, Cod. Cort., p. 10; (2) from its appearance in the “constellation band;” (3) from its surmounting in certain pictures the “tree of life;” and that it is the North Star is shown by its presence in the hieroglyph of that quarter and its association with the sign for north.

There is another, and, to me, decisive argument, which at once confirms Dr. Schellhas’ opinion, and explains why the north star is represented by this peculiar, decorated face.

The term for “north” in Maya is xaman, whence xaman ek, north star. The only other word in the language which at all resembles this is xamach, the flat, decorated plate or dish (Nahuatl, comalli) on which tortillas, etc., are served. In the rebus-writing the decorations on the rim of this dish were conventionally transferred to the face of the deity, so as to distinguish it by recalling the familiar utensil. For a similar reason it is also called “the shield star,” chimal ek (like chimal ik, north wind); but as this is a foreign word (from the Nahuatl, chimalli, shield), it was doubtless later and local. I shall refer to this peculiar edging or border as the “pottery decoration,” and we shall find it elsewhere.

That the figure is associated at times with all four quarters of the world, and also with the supreme number 13 (see above, p. 24), are not at all against the identification, as Dr. Schellhas seems to think, but in favor of it; for at night, all four directions are recognized by the position of the pole; and its immovable relation to the other celestial bodies seems to indicate that it belongs above the highest.

The North Star is especially spoken of as “the guide of merchants.” Its representation is associated with symbols of peace and plenty (removing the contents of a tall vase, C. Cortes., p. 40; seated under a canopy, ibid., p. 29). In front of his forehead is attached a small vase, the contents of which are trickling into his mouth (?).

Fig. 19.—The North Star God.

He is especially prominent in the earlier pages of the Cod. Peres., where his presence seems to have been practically overlooked by previous writers; and it is true that the drawings are nearly erased. Close inspection will show, however, that he is portrayed on both sides of the long column of figures which runs up the middle of page 3. On the left, he is seated on the “Tree of Life,” as in Cod. Troanus, p. 17, a (which is growing from the vase of the rains, precisely as in Cod. Tro., 14, b, where the star-god is sailing in the vase itself). On the right of the column he is shown in the darkness of night (on a black background), holding in his hand the kan symbol of fortune and food. A similar contrast is on page 7, where on the right of the column he is seen above the fish, and on the left, in the dark, again with the kan symbol. On the intermediate page he is seated opposite the figure of Kin ich Ahau, which is head downward, signifying that when the sun is absent the pole star rules the sky.

Fig. 20.—The Bee god. (Codex Troano.)

Representations of the Planet Venus.—In view of the prominent part which the Venus-year plays in the calculations of the Codices, it has surprised students that no pictorial figures of this bright star appear on their pages. On this point I have some suggestions to make.

In one part of the Codex Troano (pp. 1*–10*) there are a great many—nearly fifty—pictures of an insect resembling a bee in descending flight. These pages have been explained by Thomas as relating to apiculture and the festivals of the bee-keepers, and by Seler, who rejects that rendering, as referring generally to the descent of deities to receive offerings. Direction downward is indicated not only by the position of the insect, but by the accompanying hieroglyph, 60which reads caban, the first syllable of which, cab, means “downward.” My suggestion is that in this bee-like insect we have an ikonomatic allusion to the Evening Star, which, as I have already stated, was sometimes called xux ek, “the bee or wasp star.”[80]

Not only is the picture phonetically appropriate, and the “sign” consistent, but that a deity is referred to is shown by three anthropomorphic pictures of the bee (two on p. 4* and one on p. 5*). Furthermore, the “sign” or monogram of the bee deity (Fig. 20) appears on the so-called “title pages” of the Cod. Tro. and Cod. Cortes., adjacent to that of the north star, indicating that another stellar deity is represented.