Title: The Flower-Fields of Alpine Switzerland: An Appreciation and a Plea

Author: G. Flemwell

Author of introduction, etc.: Henry Correvon

Release date: August 23, 2018 [eBook #57753]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Christian Boissonnas, The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

THE FLOWER-FIELDS OF

ALPINE SWITZERLAND

AN APPRECIATION AND A PLEA

PAINTED AND WRITTEN

BY

G. FLEMWELL

AUTHOR OF “ALPINE FLOWERS AND GARDENS”

WITH TWENTY-SIX REPRODUCTIONS

OF WATER-COLOUR DRAWINGS

London :: ::

HUTCHINSON & CO.

Paternoster Row :: ::

:: 1911

TO

MADEMOISELLE MARTHE DEDIE

AND ALL AT

“LA COMBE,” ROLLE (VAUD)

Last year Mr. G. Flemwell gave us a very beautiful volume upon the Alpine Flora, and it has met with well-deserved success. But the author is not yet satisfied. He thinks to do better, and would now make known other pictures—those of Alpine fields, especially during the spring months.

Springtime in our Alps is certainly the most beautiful moment of the year, and the months of May and June, even to the middle of July, are the most brilliant of all. It is a season which, up to the present, we have rather considered as reserved for us Swiss, who do not much like that which is somewhat irreverently called l’industrie des étrangers, and perhaps we shall not be altogether enchanted to find that the author à la mode is about to draw the veil from our secrets, open the lock-gates of our most sacred joys to the [Pg viii] international flood, and sound the clarion to make known, urbe et orbi, the springtime glory of our fields. With this one little reservation to calm the egotistical anxiety which is in me (Mr. Flemwell, who is my colleague in the Swiss Alpine Club, knows too well our national character not to understand the spirit in which we make certain reservations with regard to this invasion of our mountains by the cosmopolitan crowd), I wish to thank the author, and to compliment him upon this fresh monument which he raises to the glory of our flowers.

He here presents them under a different aspect, and shows us the Alpine field, the meadow, the great green slope as they transform themselves in springtime. He sings of this rebirth with his poet-soul, and presents it in pictures which are so many hymns to the glory of the Creator. And he is justified in this, for nothing in the world is more marvellous than the re-flowering of Alpine fields in May and June. I have seen it in the little vallons of Fully and of Tourtemagne in Valais, in the fields of Anzeindaz and of Taveyannaz (Canton de Vaud), at the summit of the [Pg ix] Gemmi and on the Oberalp in the Grisons; I have seen the flowering spring in the Bernese Oberland and on the Utli (Zurich), in the vallons of Savoie and in those of Dauphiné; I have seen the metamorphosis of the Val de Bagnes and of the Bavarian plain, the transformation of the marvellous valleys of Piémont and of the elevated valley of Aosta. But I have never seen anything more beautiful or more solemn than spring in the Jura Mountains of Vaud and Neuchatel, with their fields of Anemone alpina and narcissiflora, when immense areas disappeared under a deep azure veil of Gentiana verna or of the darker Gentiana Clusii, and when the landscape is animated by myriads of Viola biflora or of Soldanella. In reading what Mr. Flemwell has written, my spirit floats further afield even than this—to the Val del Faene, which reposes near to the Bernina, and I see over again a picture that no painter, not even our author, could render: the snow, in retiring to the heights, gave place to a carpet of violet, blue, lilac, yellow, or bright pink, according as it was composed of either Soldanella pusilla, of long, narrow, pendent bells, which [Pg x] flowered in thousands and millions upon slopes still brown from the rigours of winter, or Gentiana verna, or Primula integrifolia, whose dense masses were covered with their lovely blossoms, or Gagea Liotardi, whose brilliant yellow stars shone on all sides in the sun, or Primula hirsuta. All these separate masses formed together a truly enchanting picture, which remained unadmired by strangers—since these had not yet arrived—and which I was happy and proud to salute under the sky of the Grisons.

Our author seems to have a predilection for the blue flower of Gentiana verna, and I thank him for all he says of my favourite. When, at the age of ten years, I saw it for the first time, carpeting the fields of the Jura in Vaud, my child’s soul was so enthusiastic over it that there were fears I should make myself ill. This impression, which dates from 1864, is still as fresh in my memory as if it were of yesterday. Blue, true blue, is so rare in Nature that Alphonse Karr could cite but five or six flowers that were really so: the Gentian, the Comellina, several Delphiniums, the Cornflower, and the Forget-me-not. [Pg xi] The blue of the Gentian is certainly the most superb and velvety, especially that of Gentiana bavarica. A group of Gentiana verna, brachyphylla, and bavarica which I exhibited at the Temple Show in London in May 1910, and which was a very modest one, it having suffered during the long voyage from Floraire to London, was greatly admired, and did not cease to attract the regard of all flower-lovers. Blue is so scarce, every one said, that it is good to feast one’s eyes upon it when one meets with it!

The practical side of this volume resides in the information it offers to lovers of Alpine flowers in England. One readily believes that, in order to cultivate these mountain plants, big surroundings are necessary: a great collection of rocks, as in the giant Alpine garden of Friar Park. We have proved in our garden of Floraire—where the public is willingly admitted, and which flower-lovers are invited to visit—that mountain plants can be cultivated without rockwork, and that it is even important, if one wishes to give an artistic and natural aspect to the garden, not to be too prodigal of rock and stone. Much verdure is [Pg xii] essential, it is necessary to have a frame for the picture, and that frame can only be obtained by creating the Alpine field. One day at Friar Park, Sir Frank Crisp, the creator of this beautiful alpinum, taking me aside and making me walk around with him, showed me a vast, empty field which stretched away to the north of the Matterhorn, and said: “It is here that I wish to establish a Swiss field to soften the too rocky aspect of the garden and to give it a fitting frame.” And since then I am unable to conceive that there was ever a time when the Alpine garden at Friar Park had not its setting of Alpine fields. There was no idea of making such a thing when the garden was begun; but once the rockwork was finished the rest imposed itself. One needs the flower-filled field, l’alpe en fête, by the side of the grey rocks.

This is why, in our horticultural establishment at Floraire, we make constant efforts to reproduce expanses of Narcissi, Columbines, Gentians, Daphnes, Primulas, etc., grouped in masses as we have seen them in nature, and as Mr. Flemwell gives them in his book.

Herein lies the great utility of this volume, and the reason why it will be consulted with pleasure by gardeners as well as by alpinists and lovers of nature generally.

Henry Correvon.

| PART I | ||

| AN APPRECIATION | ||

| CHAPTER. | Page | |

| I. | Of our Enthusiasm for “Alpines” | 3 |

| II. | Alpine Flower-Fields | 12 |

| III. | The May Fields | 21 |

| IV. | The Vernal Gentian | 35 |

| V. | In Storm and Shine | 48 |

| VI. | The June Meadows | 64 |

| VII. | On Floral Attractiveness and Colour | 86 |

| VIII. | The Rhododendron | 102 |

| IX. | The July Fields | 114 |

| X. | The Autumn Crocus | 134 |

| PART II [Pg xvi] | ||

| A PLEA | ||

| CHAPTER. | Page | |

| XI. | Alpine Fields for England | 149 |

| XII. | Some Ways and Means | 162 |

| L’Envoi | 179 | |

| INDEX | 189 | |

AN APPRECIATION

OF OUR ENTHUSIASM FOR “ALPINES”

“We are here dealing with one of the strongest intellectual impulses of rational beings. Animals, as a rule, trouble themselves but little about anything unless they want either to eat it or to run away from it. Interest in, and wonder at, the works of nature and of the doings of man are products of civilisation, and excite emotions which do not diminish, but increase with increasing knowledge and cultivation. Feed them and they grow; minister to them and they will greatly multiply.”—THE RT. HON. A. J. BALFOUR, in his Address as Lord Rector of St. Andrews University, December 10, 1887.

Some excuse—or rather, some explanation—seems to be needed for daring to present yet another book upon the Alpine Flora of Switzerland. So formidable is the array of such books already, and so persistently do additions appear, that it is not without diffidence that I venture to swell the numbers, and, incidentally, help to fill the new subterranean chamber of the Bodleian.

With the author of “Du Vrai, Du Beau, et Du Bien,” I feel that “Moins la musique fait de bruit et plus elle touche”; I feel that reticence [Pg 4] rather than garrulity is at the base of well-being, and that, if the best interests of the cult of Alpines be studied, any over-production of books upon the subject should be avoided, otherwise we are likely to be face to face with the danger of driving this particular section of the plant-world within that zone of appreciation “over which hangs the veil of familiarity.”

Few acts are more injudicious, more unkind, or more destructive than that of overloading. “The last straw” will break the back of anything, not alone of a camel. One who is mindful of this truth is in an anxious position when he finds himself one of a thousand industrious builders busily bent upon adding straw upon straw to the back of one special subject.

It were a thousand pities if, for want of moderation, Alpines should go the way Sweet Peas are possibly doomed to go—the way of all overridden enthusiasms. Extravagant attention is no new menace to the welfare of that we set out to admire and to cherish, and it were pity of pities if, for lack of seemly restraint, the shy and lovely denizens of the Alps should arrive at that place in our intimacy where they will no longer be generally [Pg 5] regarded with thoughtful respect and intelligent wonder, but will be obliged to retire into the oblivion which so much surrounds those things immediately and continuously under our noses. For, of all plants, they merit to be of our abiding treasures.

But just because we have come to the opinion that Alpines stand in need of less “bush,” it does not necessarily follow that we must be sparing of our attention. There is ample occasion for an extension of honest, balanced intimacy. What we have to fear is an irrational freak-enthusiasm similar to the seventeenth-century craze for Tulips—a craze of which La Bruyère so trenchantly speaks in referring to an acquaintance who was swept off his feet by the monstrous prevailing wave. “God and Nature,” he says, “are not in his thoughts, for they do not go beyond the bulb of his tulip, which he would not sell for a thousand pounds, though he will give it you for nothing when tulips are no longer in fashion, and carnations are all the rage. This rational being, who has a soul and professes some religion, comes home tired and half starved, but very pleased with his day’s work. He has seen some tulips.” Now this was enthusiasm of a degree [Pg 6] and kind which could not possibly endure; reaction was bound to come. Of course, it was an extreme instance of fashion run mad, and one of which Alpines may never perhaps provoke a repetition. Yet we shall do well to see a warning in it.

I think I hear enthusiastic lovers of Alpines protesting that there is no fear whatever of such an eventuality for their gems, because these latter are above all praises and attentions and cannot be overrated. I fancy I hear the enthusiasts explaining that Alpines are not Sweet Peas, or Tulips, or double Show Dahlias; that they occupy a place apart, a place such as is occupied by the hot-house and greenhouse Orchids, a place unique and unassailable. And these protestations may quite possibly prove correct; I only say that, in view of precedents, there lurks a tendency towards the danger named, and that it therefore behoves all those who have the solid welfare of these plants at heart to be on their guard, to discourage mere empty attentions, and to do what is possible to direct enthusiasm into sound, intelligent channels. “An ignorant worship is a poor substitute for a just appreciation.” Aye, but it is often more than this; it is often a dangerous one.

Already the admiration and attention meted out [Pg 7] to Alpines is being spoken of as a fashion, a rage, and a craze; and we know that there is no smoke without fire. Certainly, the same language has been used towards the enthusiasm shown for Orchids. But Orchids have nought to fear from that degree of popularisation which impinges upon vulgarisation. The prices they command and the expense attendant upon their culture afford them important protection—a protection which Alpines do not possess to anything like the same extent.

Of course, the fate in store for Alpines in England is not of so inevitable a nature as that awaiting Japanese gardening; for in this latter “craze” there is an element scarcely present in Alpine gardening. We can more or less fathom the spirit of Alpine gardening and are therefore quite able to construct something that shall be more or less intelligent and true; but can we say as much for ourselves with regard to Japanese gardening? I think not. I think that largely it is, and must remain, a sealed book to us. Japanese gardening, as Miss Du Cane very truly points out in her Preface to “The Flowers and Gardens of Japan,” is “the most complicated form of gardening in the world.” Who in England will master the “seven schools” and absorb all the philosophy [Pg 8] and subtle doctrine which governs them? Who in England will bring himself to see a rock, a pool, a bush as the Japanese gardener sees them, as, indeed, the Japanese people in general see them? The spirit of Japanese gardening is as fundamentally different from the spirit of English gardening as that of Japanese art is from English art. What poor, spiritless results we have when English art assumes the guise of Japanese art! It is imitation limping leagues behind its model. And it is this because it is unthought, unfelt, unrealized.

Strikingly individual, the Japanese outlook is much more impersonal than is ours. Needs must that we be born into the traditions of such a race to comprehend and feel as it does about Nature. A Japanese must have his rocks, streams, trees proportioned to his tea or dwelling house and bearing mystic religious significance. Such particular strictness is the product of ages of upbringing. A few years, a generation or two could not produce in us the reasoned nicety of this phase of appreciation; still less the reading of some book or the visit to some garden built by Japanese hands. The spirit of a race is of far longer weaving; one summer does not make a butterfly;

To us a tiny chalet is quite well placed amid stupendous cliffs and huge, tumbled boulders, and is fit example to follow, if only we are able to do so. In Alpine gardening we feel no need to study the size of our rocks in relation to our summer-house, or place them so that they express some high philosophic or mystic principle. We have no cult beyond Nature’s own cult in this matter. We see, and we are content to see, that Nature has no nice plan and yet is invariably admirable; we see, and we are content to see, that if man, as in Switzerland, chooses to plant his insignificant dwelling in the midst of great, disorderly rocks and crowded acres of brilliant blossoms, it is romantic garden enough and worthy of as close imitation as possible.

With the Japanese, gardening is perhaps more a deeply æsthetic culture than it is the culture of plants. Where we are bald, unemotional, “scientific” gardeners, they will soar high into the clouds of philosophic mysticism. Truer children of the Cosmos than we Western materialists, they walk in their gardens as in some religious rite. We, too, no doubt, are often dreamers; we, too, are often [Pg 10] wont to find in our gardens expression for our searching inner-consciousness; but how different are our methods, how different the spirit we wish to express.

The most, therefore, we can accomplish in Japanese modes of gardening is to ape them; and of this, because of its emptiness, we shall very soon tire. The things which are most enduring are the things honestly felt and thought; for the expression of the true self reaches out nearest to satisfaction. Unless, then, we are apes in more than ancestry, Japanese gardening can have no long life among us. Alpine gardening is far more akin to our natural or hereditary instincts; it holds for us the possibility of an easier and more honest appreciation. And it is just here, in this very fact, where lies much of the danger which may overtake and smother the immense and growing enthusiasm with which Alpines are meeting.

How best, then, to direct and build up this enthusiasm into something substantial, something that shall secure for Alpines a lasting place in our affections? The answer is in another question: What better than a larger, more comprehensive appeal to Alpine nature; what better than a more [Pg 11] thorough translation of Alpine circumstance to our grounds and gardens?

Now, to this end we must look around us in the Alps to find that element in plant-life which we have hitherto neglected; and if we do this, our eyes must undoubtedly alight upon the fields. Hitherto these have been a greatly neglected quantity with us when planning our Alpine gardens, and their possibilities have been almost entirely overlooked in respect of our home-lands. Why should we not make more pronounced attempts to create such meadows, either as befitting adjuncts to our rock works or as embellishments to our parks? I venture to think that such an extension and direction of our enthusiasm would add much sterling popularity to that already acquired by Alpines in our midst, besides doing far greater justice to many of their number. I venture to think, also, that it would add much to the joy and health of home-life. These thoughts, therefore, shall be developed and examined as we push forward with this volume, first of all making a careful study of the fields on the spot, and marking their “moods and tenses.”

ALPINE FLOWER-FIELDS

“If you go to the open field, you shall always be in contact directly with the Nature. You hear how sweetly those innocent birds are singing. You see how beautifully those meadow-flowers are blossoming.... Everything you are observing there is pure and sacred. And you yourselves are unconsciously converted into purity by the Nature.”—YOSHIO MARKINO, My Idealed John Bulless.

Alpine Flower-fields; it is well that we should at once come to some understanding as to the term “Alpine” and what it is here intended to convey, otherwise it will be open to misinterpretation. Purists in the use of words will be nearer to our present meaning than they who have in mind the modern and general acceptation of the words “Alp” and “Alpine.” The authority of custom has confirmed these words in what, really, is faulty usage. “Alp” really means a mountain pasturage, and its original use, traceable for more than a thousand years, relates to any part of a mountain where the cattle can graze. It does [Pg 13] not mean merely the snow-clad summit of some important mountain. Nor does “Alpine” mean that region of a mountain which is above the tree-limit.

Strictly, then, Alpine circumstance is circumstance surrounding the mountain pasturages, whether these latter be known popularly as Alpine or as sub-Alpine. To the popular mind—to-day to a great extent amongst even the Swiss themselves—Alpine heights at once suggest what Mr. E. F. Benson calls “white altitudes”; but that should not be the suggestion conveyed here. For present purposes it should be clearly understood that the term “Alpine pastures” is used in its old, embracive sense, and that sub-Alpine pastures are included and, indeed, predominate.

Of course, we may be obliged to bow occasionally to a custom that has so obliterated original meanings, or we shall risk becoming unintelligible; we may from time to time be obliged to use the word “sub-Alpine” for the lower sphere in Alpine circumstance (although, really and truly, the word should suggest circumstance removed from off the Alps—circumstance purely and simply of the plains). We shall therefore do well to accept the definition of “sub-Alpine” given by [Pg 14] Dr. Percy Groom in the “General Introduction to Ball’s Alpine Guide,”—“the region of coniferous trees.” Yet, at the same time, it must be clearly understood that our use of the term “Alpine” embraces this sub-Alpine region.

It is absolutely necessary to start with this understanding, because, in talking here—or, for that matter, anywhere—of Alpine plants we shall be talking much of sub-Alpine plants. After all, our own gardens warrant this. Our Alpine rockeries are, in point of fact, very largely sub-Alpine with regard to the plants which find a place upon them. As laid down in the present writer’s “Alpine Flowers and Gardens,” it is difficult, if not impossible, to draw any definite line, even for the strictest of Alpine rock-gardening, between Alpines and sub-Alpines. The list would indeed be shorn and abbreviated which would exclude all subjects not found solely above the pine-limit. A ban would have to be placed upon the best of the Gentians, the two Astrantias, the Paradise and the Martagon Lily, to mention nothing of Campanulas, Pinks, Geraniums, Phyteumas, Saxifrages, Hieraciums, and a whole host of other precious and distinctive blossoms. It would never do; our rockworks would be robbed of their best [Pg 15] and brightest. Therefore, because there is much that is Alpine in sub-Alpine vegetation (just as there is much that is sub-Alpine in Alpine vegetation) we must, at any rate for the purposes of this volume, adhere to the etymology of the word “Alpine,” and give the name without a murmur to the middle and lower mountain-fields, in precisely the same spirit in which we give the name to our mixed rockworks in England.

No need for us to travel higher than from 4,000 to 5,000 feet (and we may reasonably descend to some 3,000 or 2,500 feet). No need whatever to scramble to the high summer pastures on peak and col (6,000 to 7,000 feet), where abound “Ye living flowers that skirt the eternal frost”; where, around a pile of stones or signal, solitary Swallow-tail butterflies love to disport themselves; where the sturdy cowherd invokes in song his patron-saint, St. Wendelin; and where the pensive cattle browse and chew the cud for a brief and ideal spell. No need to seek, for instance, the rapid pastures around the summit of Mount Cray, or on the steep col between the Gummfluh and the Rubly, if we are at Château d’Oex; or to toil to the Col de Balme or to the “look-out” on the Arpille, if we are at the Col [Pg 16] de la Forclaz; or to scale the Pas d’Encel or the Col de Coux, if we are at Champéry; or to clamber to the Croix de Javernaz, if we are at Les Plans; or to follow the hot way up to the Col de la Gueulaz, if we are at Finhaut; or to take train to the grazing-grounds on the summit of the Rochers de Naye, if we are at Caux or at Les Avants. We shall find all we desire—as at Randa, Zermatt, Binn, Bérisal, or Evolena—within a saunter of the hotels. Such fields as are above are, for the far greater part, used solely for grazing, and we must stay where most are reserved for hay. Here we shall find the particular flora we require, and shall be able to study it without let or hindrance from “the tooth of the goat” and cow. The only hindrance will be when those strict utilitarians, the haymakers, appear and change our colour-full Eden into a green and park-like domain, with here and there a neglected corner to remind us of what a rich prospect was ours—

Thus, we are to remain in a region comfortably accessible to the average easy-going visitor to the [Pg 17] Alps—the region in which so well-found a place as Lac Champex is situated.

And what a wondrous region it is, this which is of sufficient altitude for Nature to be thrown right out of what, in the plains, is her normal habit; where the Cherry-tree, if planted, blooms only about the middle of June; where the Eglantine is in full splendour in the middle of July and can be gathered well into August; where the blackbird is still piping at the end of July; where the wild Laburnum is in blossom in August; and where quantities of ripe fruit of the wild Currant, Raspberry, and Strawberry may be picked in September.

And Champex, too, what a favoured and beautiful place! I have chosen this particular spot as the “base of operations,” because of its variety in physical aspect, and, consequently, its variety in flowers. This plan I have deemed of more use than to wander from place to place, and I think that, on the whole, it will be fair to the Swiss Alpine field-flora. We can take note from time to time of what is not to be found here; for, of course, Champex does not possess all the varieties of Alpine field-flowers. Lilium croceum, Anemone alpina, Narcissus poeticus, and the Daffodil are, [Pg 18] for instance, notable absentees. The soil is granitic rather than calcareous. Yet, taking all in all, the flora is wonderfully representative; and it certainly is exceptionally rich.

Situated upon what is really a broad, roomy col between the Catogne and that extreme western portion of the Mont Blanc massif containing the Aiguille du Tour and the Pointe d’Orny, Champex, with its sparkling lake and cluster of hotels and châlets, dominates to the south the valleys of Ferret and Entremont, and to the north the valley of the Dranse, thus offering rich, well-watered pasture-slopes of varied aspect and capacity. Whether it be upon the undulating pastures falling away to the Gorges du Durnand, or upon the steeper fields leading down to Praz-de-Fort and Orsières, 1,000 and 2,000 feet below; or whether it be upon the luxuriant, marshy meadows immediately around the lake, or upon the slightly higher, juicy grass-land of the wild and picturesque Val d’Arpette, there is an ever-changing and gorgeous luxury of colour which must be seen to be believed. “The world’s a-flower,” and a-flower without one single trace of sameness. Whichever way we walk, whichever way we gaze, the eye meets with some fresh combination of [Pg 19] tints, some new and arresting congregation of field-flowers.

It is too much, perhaps, to say of any place that it is

But if such eulogy ever were permissible it would be so of Champex and her flower-strewn fields and slopes in May and June and early in July. In any case, we may unquestionably allow ourselves to quote further of Pope’s lines and say that, amid these fields, if anywhere, we are able to

Like Elizabeth of “German Garden” fame, we English love, and justly love, our “world of dandelions and delights.” We find our meadows transcend all others, and, in them—still like Elizabeth—we “forget the very existence of everything but ... the glad blowing of the wind across the joyous fields.” But in this pride there is room, I feel sure, for welcome revelation. I can imagine few things that would more increase delight in a person familiar only with English meadows than to be suddenly set down among the fields of the [Pg 20] Alps in either May, or June, or early July. What would he, or she, then feel about “the glad blowing of the wind across the joyous fields”? It would surely entail a very lively state of ecstasy.

And if only we had at home these grass-lands of Champex! Such hayfields in England would create a furore. Hourly excursions would be run to where they might be found. Lovers of the beautiful would be amazed, then overjoyed, and lost in admiration. Farmers, too, would likewise be amazed—then look askance and rave about “bad farming.” Undoubtedly there would be a war of interests. Upon which side would be the greater righteousness, it is not easy to decide; but presently we shall have occasion to look into the matter more closely. In the meantime, no particular daring is required to predict that, if these meadows came to our parks and gardens, they would come to stay.

THE MAY FIELDS

It is essential that we arrive amid the Alpine fields in May; for we must watch them from the very beginning. To postpone our coming until June would be to miss what is amongst the primest of Alpine experiences: the awakening of the earlier gems in their shy yet trustful legions. Indeed, in June in any ordinary year, we should risk finding several lovely plants gone entirely out of bloom, except perhaps quite sparsely in some belated snow-clogged corner; for, be it [Pg 22] remembered, we shall not be climbing higher than this region: we do not propose to pursue Flora as she ascends to the topmost pasture. As for following the very general rule and coming only in late July, it is quite out of the question. We must come in May; and it should be towards the middle of the month—although the exact date will, of course, be governed by the advanced or retarded state of the season. Speaking generally, however, the 15th is usually neither too early nor too late. It is wiser to be a day or so too early than otherwise, because at this altitude it is remarkable how soon Nature is wide awake when once she has opened her eyes. The earliest floral effects are of the most fleeting in the Alps; and, like most things fleeting in this changeful world, they are of the most lovely. To some it may appear laughable to say that one day is of vast importance; but it is only the truth. Down on the plains things are positively sluggish by comparison (though an artist, wishing to paint them at their best, knows only too well how rapid even are these). As in Greenland, up here, at 4,800 feet, vegetation adapts itself in all practical earnest to the exigencies of shortened seasons. June’s glories are quick in passing; so, alas, are July’s; [Pg 23] but the glories of May, having usually but a brief portion of the month in which to develop, pass, as it were, at breathless speed.

Yes, if ever there is a nervous energy of nature, it is in May in Alpine regions; and it behoves us to be equally quick and timely. For instance, this year (1910) I was struck by the fact that, two weeks after the last vestige of an avalanche had cleared from off a steep slope at the foot of the Breyaz, three or four cows belonging to the hotels were grazing contentedly on rich green grass, and the Crocus and Soldanella had already bloomed and disappeared.

When we quit the plains their face is well set towards June. Spring’s early timidity and delicacy are past; the Primrose, Scilla, Hepatica, Violet, and Wood-Anemone have retired into a diligent obscurity and the fields are already gay with the Orchids and the Globe-Flower. But up here at Champex we find ourselves back with the Crocus, springing fresh and glistening from the brown, snow-soaked sward, and with the as yet scarcely awakened Cowslip. As we climb up from Martigny the slopes grow more and more wintry-looking, and we may perhaps begin to regret leaving the wealth of blushing apple-blossom which dominates [Pg 24] the azure-blue fields of Myosotis below the Gorges du Durnand. And this regret will probably become more keen when we plunge into the forests just below Champex and find them still choked with snow and ice. But we are soon and amply repaid for what at first seems a mad ostracism on our part. One or two brief days, full of intense interest in watching Alpine nature’s unfolding, and all regrets have vanished, and we have quite decided that these May fields are a Paradise wherein, in Meredith’s words, “of all the world you might imagine gods to sit.”

The Crocus is not for long alone in making effective display. The Soldanella soon joins it after a few hours of warm sunshine; in fact, in many favoured corners it is already out when we arrive. And Geum montanum is no laggard; neither are the two Gentians, verna and excisa, nor the yellow-and-white Box-leaved Polygala. By the time the 20th of the month has come the pastures are thickly sown with pristine loveliness, and by the 25th this is at the height of perfection—a height to which nothing in paint or in ink can attain. Flora has touched the fields with her fairy wand and they have responded with amazing alacrity. Turn which way we will, the landscape [Pg 25] is suffused with the freshest of yellow, rose, and blue; and broad, surprising acres of these bewitching hues lie at our very door, coming, as it were,

Our “laundered bosoms” swell with hymns of praise; the plains have receded into Memory’s darker recesses, and we vote these Alpine meadows to a permanent and foremost place in our affections—so much so, indeed, that, with Théophile Gautier, we unhesitatingly declare (though not, be it said, with quite all the musical exaggeration of his poet spirit):

We know, of course, Divinity is not absent on the plains. When the poet says otherwise it is a tuneful licence with which we are merely tolerant. We quite understand that there is a more moderate meaning behind his extravagance. We know, and everybody acquainted with Alpine circumstance knows, that in the Alps there is a very strong and striking sense of the nearer presence of the Divine in nature. There is a superior and indescribable purity, together with a refinement and [Pg 26] restraint which defies what is the utmost prodigality of colour; and, much as we love the divinity of things in the plains, the divinity of those of high altitudes must take a foremost position in our esteem and joy.

Mr. A. F. Mummery has a fine passage touching this subject—a passage that may well be quoted here, for it sums up in admirable fashion all that we ourselves are feeling. “Every step,” he says, “is health, fun, and frolic. The troubles and cares of life, together with the essential vulgarity of a plutocratic society, are left far below—foul miasmas that cling to the lowest bottoms of reeking valleys. Above, in the clear air and searching sunlight, we are afoot with the quiet gods, and men can know each other and themselves for what they are.” “The quiet gods”—yes, indeed! Here, if anywhere, in May and June, is quietness; here at this season these hosts of lovely flowers are indeed “born to blush unseen” and, in Man’s arrogant phrase, to “waste their sweetness on the desert air.”

But what nonsense it is, this assumption that the flowers are wasted if not seen by us! It is not for that reason we should be here: it is not because the flowers would benefit one iota by [Pg 27] our presence. What is it to them whether they have, or have not been seen by Man? “We are what suns and winds and waters make us,” they say; and, in saying thus, they speak but the substantial truth. Their history is one of strenuous self-endeavour; their unique and dazzling loveliness they have attained “alone,” oblivious of Man’s presence in the world. After age-long effort, from which their remarkable happiness and beauty are the primest distillations, Man stumbles upon them in their radiance, declares they are languishing for want of his admiration, and at once commiserates with them upon their lone and wasted lot. What fond presumption! How typically human!

Is there not proof abundant of Nature’s “profuse indifference to mankind?” Why, then, should Man assume that all things are made for him? why, in his small, lordly way, should he say—as he is for ever saying—“The sun, the moon, the stars, have their raison d’être in Me?” In a sense he is right, but not in the arrogant sense he so much presumes. All things help to make him. The sun, moon, and stars are for him, inasmuch as he would not be what he is—he would not, probably, be Man—did they not exist. But neither, then, [Pg 28] would the black-beetle be as it is. Do not let him forget the high claims of the black-beetle.

Let us be humble: let us merge ourselves modestly in the scheme of things. It is not to cheer up the flowers in their “loneliness” that we ought to be with them here in the spring. We ought to be here because of all that the flowers and their loveliness can do for us, in lifting us above “the essential vulgarity of a plutocratic society,” and in revealing us to ourselves and to each other as rarely we are revealed elsewhere. Here with these pastures are health and vigour—vigour that is quiet and restful; here is unpretentiousness more radiant, more glorious, than the most dazzling of pretensions. Here, if we will, we can come and be natural—here, where Man, that “feverish, selfish little clod of ailments and grievances,” as Mr. Bernard Shaw calls him, can be in the fullest sense a man, and be in no wise ashamed of it. For here, in a word, is Nature—unaffected, unconventional, unconscious of herself, yet in the highest degree efficient. The purity of [Pg 29] it all is wonderful. And it is this, with its beneficent power, that we waste.

If spring is reckoned pure below, among “the foul miasmas that cling to the lowest bottoms of reeking valleys,” how much purer must it not be reckoned under Alpine skies! The amelioration is already marked after we have risen a few hundred feet from the plains. Our minds climb with our bodies, both attuning themselves to the increasing purity of our surroundings, until at some 5,000 feet we feel, to use a homely expression, as different as chalk from cheese. And nothing aids more potently in this attunement than do the fields of springtime blossoms.

“Why bloom’st thou so?” asks the poet of these flowers—

The question has been answered, or, at any rate, answered in important part, and far more truthfully than by any blind, patronising remark about “wasted beauty.” Wasted! It is an accusation which the flowers should hurl at us! Wasted? Yes; wasted, in so far as we do not yet take [Pg 30] advantage of the Alpine spring; wasted, in so far as we arrive only in late July or early August!

Nor should our praise be counted amongst surprises. Champex’s fields bear witness to it being no mere idle adulation. On the flat damp grass-land, intersected by sparkling glacier streams, which stretches away to the north of the lake, great and brilliant groups of Caltha palustris (only the common Marsh-Marigold, it is true, but of how much more luscious, brilliant hue than down upon some lowland marsh) lie upon a vast rosy carpet of Primula farinosa, effectively broken here and there by the rich purple tints of Bartsia alpina and the ruddier hues of Pedicularis. And this wondrous wealth of yellow and rose is found again on the extensive sunny slopes to the south of the lake; but here Gentiana verna asserts its bright blue presence amongst the Primula, and the effect is even more astonishingly gay than it is to the north. Like Count Smorltorks “poltics,” it “surprises by himself.”

On these southern slopes, too, are quantities of Micheli’s Daisy, enlivening still more with their glistening whiteness the beautiful colour-scheme. There are also colonies of the two Pinguiculas, [Pg 31] mauve and creamy-white; also of the quaint Alpine Crowfoot and of the yet more quaint, æsthetically tinted Ajuga pyramidalis—the most arresting of the Bugles—and of the demure little Alpine Polygala, varying from blue (the type) through mauve to reddish-pink, even to white. Here, also, is the Sulphur Anemone just unfolding the earliest of its clear citron-coloured blossoms. But to see this Anemone to fullest advantage we must turn to the drier pastures to the east and north of the lake, where it is scattered in endless thousands amongst sheets of Gentiana verna and excisa and a profusion of the yellow Pedicularis (tuberosa), the white Potentilla (rupestris), the golden Geum (montanum), the purple Calamintha (alpina), the canary-yellow Biscutella (lævigata), the rosy-red Saponaria (ocymoides), and many another of the earlier pasture-flowers. And by the side of all this ravishing young life and colour are the still remaining avalanches of piled-up frozen snow—grim reminders of what wild riot winter makes upon these pastures whilst the flowers are sleeping.

Surely, then our praise is not surprising? Surely, nowhere in the Alps in May shall we find anything more admirable or more amazingly colour-full than [Pg 32] are these pasture-slopes and meadows of Lac Champex? In some one or other respect their equal may be found in many favoured places; in many spots we shall find most astonishing displays of other kinds of plants than we have here—of, for instance, the white Anemone alpina and the purple Viola calcarata, as on the slopes of the Chamossaire above Villars-sur-Ollon (though the Viola is in quantity near Champex, in the Val d’Arpette, in June), or of the Pheasant-eye Narcissus, as at Les Avants and Château d’Oex, and the Daffodil, as at Champéry and Saas; but, taking Champex’s floral wealth as a whole, it can have few, if any superiors in point of abundance and colour at this early season. Mindful of what Mr. Reginald Farrer has said of Mont Cenis towards the end of June, we may safely declare that the Viola and Gentian clothed slopes of that district are not the only slopes in the Alps which might be “visible for miles away.”

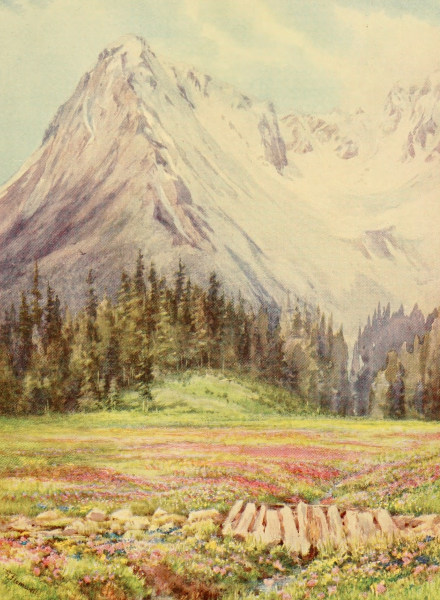

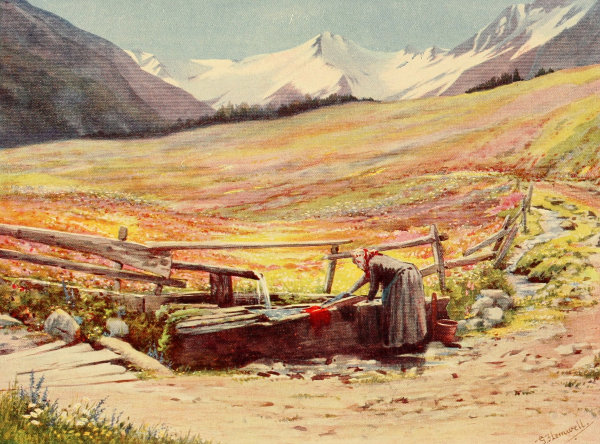

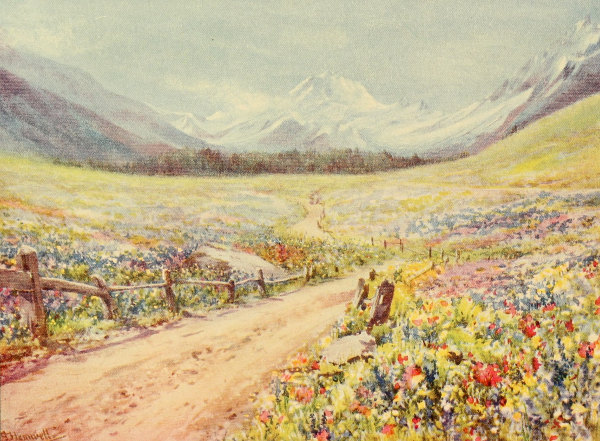

Perhaps some more substantial idea of these fields at this season may be gathered from the pictures facing pages iii and 3; but these transcriptions, though to the uninitiated they may appear reckless with regard to truth, are really far from adequate. Seeing the thing itself must, [Pg 33] in this case, alone bring entire belief and understanding. “Colour, the soul’s bridegroom,” is so abounding, so fresh, light, joyful, and enslaving, that, after all has been said and done to picture it, one sits listless, dejected and despairing over one’s tame and lifeless efforts; one feels that it must be left to speak for itself in its own frank, dreamland language—language at once both elusive and comprehensible. The soul of things is possessed of an eloquent and secret code which is every whit its own; and the soul of these fields is no exception. In spite of Wordsworth, there is, and there must be, “need of a remoter charm”; there is, and there must be, an “interest unborrowed from the eye”; and it is just this vague, appealing “something”—this “something” so real as to transcend what is known as reality—which speaks to us and invades us in the bright and intimate presence of these hosts of Alpine flowers.

In rural parts of England spring is said to have come when a maiden’s foot can cover seven daisies at once on the village green. Why, when spring had come here, on these Alpine meadows, I was putting my foot (albeit of goodlier proportions than a maiden’s) upon at least a score [Pg 34] of Gentians! Whilst painting the study of Sulphur Anemones (facing page 96) about May 20, my feet, camp-stool, and easel were perforce crushing dozens of lovely flowers—flowers which in England would have been fenced about with every sort of reverence. But sacrifice is the mot d’ordre of a live and useful world; worship at any shrine is accompanied by some “hard dealing”; and, sadly as it went against the grain, there was no gentler way in which I could effect my purpose.

Looking at the close-set masses of blossom, it is difficult to realise into what these slopes and fields will develop later on. There seems no room for a crop of hayfield grass. Amid this neat and packed abundance there seems no possible footing for a wealth of greater luxuriance. And yet, in a few weeks’ time, these fields will have so changed as to be scarcely recognisable. What we see at present, despite its ubiquity, is but a moiety of all they can produce. June and July will border upon a plethora of wonders, though they will not perhaps be rivals to the exquisite charm of May.

THE VERNAL GENTIAN

Do you ask what the Alps would be without the Edelweiss? Ask, rather, what they would be without the little Vernal Gentian! Ask what would be the slopes and fields of Alpine Switzerland without this flower of heaven-reflected blue, rather than what the rocks and screes and uncouth places would be without Leontopodium alpinum of bloated and untruthful reputation. Ask what Alpland’s springtide welcome and autumnal salutation would be if shorn of this little plant’s bright azure spontaneity; ask where would be spring’s eager joyfulness, and where the ready hopefulness of autumn. Ask yourself this, [Pg 36] and then the Edelweiss at once falls back into a more becoming perspective with the landscape, into a less faulty pose among the other mountain flowers.

Perhaps it is not very venturesome to think that if the Edelweiss had become extinct, and were now to be found only amid the fastnesses of legend, it would live quite as securely in the hearts of men as it does at present; for its repute rests mostly upon the fabulous. But how different is the case of the earliest of the Gentians! Here is a plant which, despite the romance-breeding nature of its habit, form, and colour, draws little or nothing from legendary sources. Fable has small command where merit is so marked; imagination is outstripped by reality, and there is scarcely room for invention where truth is so arresting, so pronounced.

Gentiana verna flies no false colours. Its flower is a flower, and not for the greater part an assemblage of hoary-haired leaves. It inspires in men no performance of mad gymnastics on the precipice’s brink and brow; it wears, therefore, no halo of unnecessary human sacrifice. It is not a tender token of attachment among lovers. It does not live in myth, nor has it an important [Pg 37] place in folk-lore. In short, it is just its own bright, fascinating self; there is nothing of blatant notoriety about its renown, no suspicion of a succès de scandale such as the Edelweiss can so justly claim.

We may laud the Edelweiss as a symbol of advanced endeavour, but the Gentian is more useful, if not, indeed, worthier, in this respect; for it marks no great extreme and therefore its condition is symbolic of less that is incompatible with consistent human effort. Ruskin has somewhere said that the most glorious repose is that of the chamois panting on its bed of granite, rather than that of the ox chewing the cud in its stall; but, however transcendentally true this may be, the actually glorious position lies midway betwixt the two—the position of the Gentian in relation with, for instance, the positions of the Edelweiss and the Primrose. We are likely to derive inspiration of more abundant practical value from the Gentian than from the Edelweiss, because there is comparatively little about it that is extreme. Though advanced in circumstance it is reasonably situated; it leads, therefore, to no such flagrant inconsistency with facts, no such beating of the drum of romance as, apparently, we find [Pg 38] so necessary in the case of Leontopodium. The Edelweiss is not all it seems; the Gentian is. “Il ne suffit pas d’être, il faut paraître”; and this, certainly, the little Vernal Gentian does. In not one single trait does it belie the high colour of its blossom.

With what curiously different craft do each of these flowers play upon the emotions! With what contrary art does each make its appeal to our regard and adulation! To each we may address Swinburne’s stately lines: to each we may, and do exclaim:

Yet this act of adoration, when it affects the Edelweiss, seems far more an act of idolatry than it does when it affects the Gentian. For on the one hand we have the Edelweiss stirring the imagination to wild, foolhardy flights amid the awesome summer haunts of the eagle and the chamois, when, in simple reality, we could if we would be reposing amongst hundreds of its woolly stars upon some gentle pasture-slope away from the least hint of danger and of scandale; while on the other hand we have the Vernal Gentian calling us [Pg 39] at once in all frankness to accept it as it is—one of the truest and loveliest marvels of the Alps,

To each do we accord, as Mr. Augustine Birrell would say, “a mass of greedy utterances”; to each do we lose our hearts; but only to one do we lose our heads. And that one is the Edelweiss: the plant of leaves which ape a flower; the plant whose flower is as inconspicuous as that of our common Sun Spurge; the plant that would have us forget its abundance on many a pasture, and think of it only as clinging perilously to high-flung cliffs where browse the chamois and where nest the choughs.

The Gentian Family as a whole is possessed of very striking individuality, and for the most part its members arrest more than usual attention. Its name is said to be derived from Gentius, King of Illyria, who is reputed to have first made known its medicinial properties—tonic, emetic, and narcotic. Although it ranges from Behring’s Straits to the Equator and on to the Antipodes, its residence is mainly northern. In New Zealand its chief colour is red; in Europe blue; and of all [Pg 40] its blue European representatives none can eclipse perennial verna’s radiant star.

The Vernal Gentian is no stranger to England, though, as an indigenous plant, it is a stranger to most Englishmen. It is still to be found on wet limestone rocks in Northern England (Teesdale) and also in the north-west of Ireland. Like Gentiana nivalis of the small band of Alpine annuals and tiniest of the blue-starred Gentians, it lingers in the British Isles, a rare, pathetic remnant of past salubrity of climate and condition; and to its homes in England and Ireland, rather than in Switzerland, we should perhaps go to study how to grow it in our gardens more successfully than we do at present. But it is to the Alps that we must turn to find it revelling wealthily in a setting for which it is pre-eminently suited; it is there that its

For, in the Alps, it is an abundant denizen of the pastures in general: both the grazing pastures or “Alps,” and “the artificial modifications of the pastures,” as Mr. Newell Arber calls the meadows.

If we wanted to give this Gentian an English name (and far be it from me to suggest that we [Pg 41] should do any such thing) we should probably have to call it Spring-Felwort; Felwort being an old-time title for Gentiana amarella, an annual herb common to dry pastures and chalk downs in England, and possibly at one time employed by tanners. In the Jura Mountains verna goes by the name of Œil-de-chat, and among the peasants inhabiting the northern side of the Dent du Midi, in the Canton de Valais, I have heard it referred to as Le Bas du Bon Dieu; but, considering the remarkably suggestive character of the plant, the domain of folk-lore seems curiously empty of its presence. This, possibly, is in part due to its amazing abundance, and to the fact that it is to be found from about 1,200 feet to about 10,000 feet, thus causing it to meet with the proverbial fate of things familiar. But, at any rate, its dried flowers, mixed with those of the Rhododendron and the purple Viola, are used in the form of “tea” by the montagnards as an antidote for chills and rheumatism.

The appearance of verna upon the pastures is not confined solely to the early springtime; though this is the season of its greatest wealth, it may be met with quite commonly in the late autumn. Indeed it affects the days which circle round the [Pg 42] whole of winter; and I have found it several times even at Christmas near Arveyes, above Gryon (Vaud), upon steep southward-facing banks where sun and wind combined to chase away the snow. If, then, for no other reason than this, it seems curious that romance has not gathered this Gentian under its wing as it has the Edelweiss.

As for the radiant purity of its five-pointed azure stars, it is perhaps only outshone by that of the Myosotis-like flowers of Eritrichium nanum, King of the Alps; but even this rivalry is doubtful when verna is growing upon a limestone soil, where its blossoms are more brilliant than those produced upon granitic ground.

Blue, however, although it is the superabundant type-colour, is not the invariable hue of its blossoms; indeed, it shows more variety than even many a botanist suspects, and I have found it in all tints from deep French to pale Cambridge blue, from rich red-purple to the palest lilac, and from the faintest yellow-white, through blush-white, to the purest blue-white. I have, too, found it party-coloured, blue-and-white.

These many variations from the type give occasion for suggestive questions that I fain would indicate, because I believe with Mr. Arber that [Pg 43] such variations can only “arise from deep-seated tendencies, which find their expression in the existence of the individual, and the evolution of the race.” For instance, are the mauve and plum-coloured flowers a break-back to the ancestral type; that is to say, was the more primitive verna red? Blue flowers are more highly organised than those of other colours; are, then, all flowers striving to be blue—like Emerson’s grass, “striving to be man?” The French-blue Gentians are of warmer tint than those of Cambridge hue; are they, therefore, the first decided step into this highest of the primary colours: are they the first strikingly victorious effort of the plant to shake off all trammel of red? And white; what of white? I have seen white verna tinged with rose, and white verna of a white altogether free from any tint of grossness—a white so positive as to suggest the utmost frailty arising from degeneracy, if it were not known to be the natural consequence of persistent advance through blue. These are nice points for speculation.

But “let us not rove; let us sit at home with the cause”! Blue for us is the essential colour for this Gentian: we can dispense with all its efforts to be white. Blue, not white, is the hue of promise. [Pg 44] And it is promise we look for at the turn of the year; it is promise we must have after long months of snow. When youthful “chevalier Printemps” hymns us his ancient message; when in penetrating accents of triumph he tells us:

—when, I say, spring thus speaks to us of the rout of winter and the dawn of a wealthier life, it is blue that we look for most upon the frost-stained fields; blue not white—the blue of the type-flowered Gentian, not the white of the Alpine Crowfoot and Crocus.

Whilst writing these lines on the most fascinating spring flower of the Alps, there comes before my mind one spot in particular where it abounds in May—a certain long and rapid grassy slope at Le Planet, above Argentière (Haute-Savoie). Albeit not in Switzerland, Le Planet is only just across the frontier; and, as every one who knows [Pg 45] the district will attest, it is difficult to draw a rigid, formal line where flowers and mountains are so knit in common semblance. Other rich scenes of azure I can recall—as on the swelling slopes of the Jura around the Suchet, or on the fields which mount from Naters towards Bel-Alp; but none forces itself to mind with such persistence as does this slope at Le Planet. And it is because the surrounding circumstance illustrates so well all that I have been saying about this Gentian’s presence in the spring.

The slope in question is not five minutes’ stroll from the hotel. On the plateau itself verna is all but absent, but on this broad and steep incline it congregates in such amazing numbers that, as I think on it, I am sure all I have said of this witching flower is poor and paltry. After all, verbal magniloquence is perhaps out of place, and simplicity is the best translator of such magnificence. All shades of brightest blue are here presented; for, excepting a few pale plum-coloured clusters, the brilliant type-flower is ubiquitous, blending delightfully with the little yellow Violet and with the white, fluffy seedheads of the Coltsfoot.

But what, perhaps, makes this particular slope [Pg 46] so appropriate in point of illustration for this chapter is, that above it towers the mighty Aiguille Verte, decked as in winter with its snows and ice, and in the foreground lies the frozen remains of a great avalanche strewn with fallen rocks and pierced by stricken larch-trees.

Yes; from the lichen, Umbilicaria virginis, the furthest outpost of vegetable life as it clings to the Jungfrau’s awful rocks at an altitude of 13,000 feet, to the yellow Primrose of the woods and meadows of the plains, there is no plant of Alpland that is so precious, so rare in its very abundance as Gentiana verna. Nor is there another Alpine that can make so wide and so certain an appeal. Spread broadcast and alone upon the awakening turf of mountain slope and meadow, it captivates the instant attention of even the merest passer-by. And if amongst its abounding azure there happens, as will often be the case, a vigorous admixture of healthy rose and yellow—the rose of the Mealy or Bird’s-eye Primula, the yellow of the Sulphur Anemone and Marsh Marigold—then this were a scene to “make the pomp of emperors ridiculous”; a scene of subtly true magnificence, of perfectly balanced delight.

See the Vernal Gentian as it lies thus bountifully set, a radiant blue carpet of heavenly intensity, backed majestically by winter’s receding snows on mighty glacier and stupendous peak; note its myriad white-eyed, cœrulean blossoms over which hover with tireless wing its faithful, eager friends, the humming-bird and bee hawk-moths—the very picture of security and peace amid a scene of awful, threatening grandeur. Listen—listen, the while, to the thunder coming from “the vexed paths of the avalanches”; listen to the sound of falling rock and pine, and mark the great air-tossed cloud of powdered snow; listen to the alarm-cry of the speckled mountain-jay, and to the shriek-like warning of the marmot; then tell me if there is any other flower that could so well play the part of hope-inspiring herald to a world as harassed as is that of the Alps in the season that surrounds the winter?

IN STORM AND SHINE

Although Nature is moving apace, and the poet declares he has even “heard the grasses springing underneath the snow”; although one set of flowers is surplanting another in startlingly swift succession, and the first-fruits of the Alpine year are already on the wane, we will take our own time and study this progress with deliberate care and attention. We have seen May smiling; we ought—nay, we are in duty bound—to see her frowning. Like the récluse of Walden, we ought each of us to become a “self-appointed inspector of snowstorms and rainstorms.”

An undoubtedly noble and proper philosophy assures us that there is truth and beauty in no matter what condition, and that they who see [Pg 49] nothing but what is tiresome or hideous in certain estates, draw the overplus of tiresomeness and hideousness from their own selves. “Beauty is truth, and truth is beauty,” says this philosophy; “how, then,” it queries, “can any condition be unbeautiful? Is it not yourselves who are in part lacking in a sense of loveliness, since truth can never really be unbeautiful?”

Now, whatever we think of this as a species of sophistry, it behoves us to look into it with quiet and decent care. An everyday world, deep in its old conventions, will declare that it is certainly straining a point to try thus to make all geese appear as swans. With the exception of the poet minded to verse the innate grandeur of gloom, the entire sublimity of storm, the entrancing mellowness of fog and rain, and the wild joy which comes with a blizzard; or perhaps of the painter minded to achieve in paint what the poet is doing in ink (both of them, most probably, contriving their rhapsodies within the snug seclusion of their rooms)—with the exception of these two privileged persons comfortably absorbed in justifying a bias, an everyday world, voting bad weather a kill-joy and mar-plot, will find happiness only in avoiding and forgetting it.

Be that as it may; be fog, wind, and cloud and driving rain and sleet a luxury in which we should revel—or not; of all places in the world in bad weather, the Alps at springtide and at the altitude at which we are now studying them, are probably among the most interesting and absorbing. Let an everyday world, or as much of it as can, come and judge for itself.

If in our composition we have a grain of love for Nature and for Nature-study, there is a fund of opportunity for exercising it even in cloudland at its gloomiest; and if, as in the present case, we are bent upon studying the flowers and the means for their more adequate reception into our English homelands, then bad weather holds for us an amount of experience such as will aid us materially in our object. “Inclemency” takes so large a share in the nurture of these flowers. By companying with them when steeped in cloud and swept by wind, we catch an important glimpse of the grim and forceful side of their existence which is a prime cause of the superlative loveliness that so impresses us when the sun does shine from out an immaculate azure.

Just as the cheese-mite is a product of the cheese, and has attained its beauty and efficiency because [Pg 51] of the nature of cheese, so are these Alpines the wonderful things they are because of the nature of the conditions with which they have to contend and upon which they have to subsist. It is all very well for us to arrive upon the scene at this late moment in their existence, transplant them to our gardens, and there grow them, maybe, with marked success; it is all very well for us to annex them now to our retinue of chattels, lord it over them, and display them on our rockworks as if it were to us and to our care and trouble that they owe their beauty; but these plants have arrived at what they are without us and our attentions. Our gardens never made them what they are, or gave them one particle of their supreme and striking beauty. Nor are our gardens likely to heighten that beauty in any real way; much more likely is it that we shall arrive at degrading their refinement by bringing it down from the severe purity of the skies to the grosser, easier circumstance of our sheltered soil.

Alpine plants, perhaps because of the extreme conditions with which they have to contend, and therefore because of the extreme measures they have to take in order to defend themselves, seem to be possessed of an efficiency surpassing that [Pg 52] of most other plants. They are what incessant warfare has made of them; they delight in it. Strenuous children of strenuous circumstance, they are self-reliant to a degree, and hold themselves with a winning air of independence. But it is independence begot of strict dependence; they admit as much quite frankly and sanely—an admittal of which man might well make a note in red ink. Nature all over the world is saying, not, “Let me help you to be independent,” but, “You shall and must depend upon me for your independence.” And no living things have better understood this truth than have the Alpines; no living things have acknowledged and mastered this obligation more thoroughly than they. Hence their beauty; hence their serenity and “nerve”; hence their “blended holiness of earth and sky.”

Mark with what consummate efficiency these Alpine field-flowers cope with stern inclemency. Tossed and torn by storms for which the Alps are famous, see how they anchor themselves to Mother Earth! Washed by torrential rains upon the rapid slopes, or parched by the most personal of suns, small wonder that their roots, in many cases, should form by far the greater part of their bulk and stature. They recall to mind that learned [Pg 53] professor who, wishing possibly to postulate something “new,” declared to an unconvinced but amused world that what it saw of a tree was not the tree—the tree was underground.

Whilst painting in the Val d’Arpette in June of this year (1910), I met with a striking instance of the boisterous treatment to which these plants must accustom themselves. The day was radiantly fine (as any one may see from the picture facing page 24), yet suddenly, and without warning, a most violent wind tore through the little valley, sweeping everything loose and insecure before it, upsetting my easel and camp-stool, carrying my Panama hat up on to the snow, and making of the Anemones and Violas a truly sorry sight.

This violence, albeit of a somewhat different nature, reminded me of several experiences I had had of uncommonly powerful eddies of wind, travelling, like some waterspout at sea, slowly, in growling, whirring spirals, over the steep pastures, tearing up the grass and blossoms and carrying them straight and high up into the air; whilst all around—except myself!—remained unmoved and peaceful. I have seen such eddies strike a forest, shaking and swaying the giant pines like saplings, wrenching off dead wood and [Pg 54] many a piece of living branch, and whirling them aloft. Under a glorious sky and amid the solitude and stillness of the Alps, such violence is at least uncanny, if not a little unnerving. One is moved to turn in admiration to the ever-smiling Alpines and ejaculate:

With this as a sample—and a by no means uncommon sample—of what they have to withstand, small wonder that so many of these plants have endowed themselves with such a deep, tenacious grip upon their home! Try with your trowel to dig up an entire root of, for instance, the Alpine Clover (Trifolium alpinum), or the Sulphur Anemone, or the Bearded Campanula, or the tall blue Rampion (Phyteuma betonicifolium), or even so diminutive a plant as Sibbaldia procumbens, or of so modest a one as Plantago alpina, and you will be astounded at the depth to which you must delve. You will find it the same with a hundred other subjects; and, unless you be digging in some loose and gritty soil, most probably your amazement will end in despair, and in destruction to the plant. More likely than not, you will hack [Pg 55] through the main root long before you have unearthed the end of it. If for no other reason than this, then, it is at least unwise to try to uproot these pasture-flowers. Should they be required for the home-garden, it is far wiser and better behaviour to gather seed from them later in the season. Most of them grow admirably from seed thus gathered and sown as soon as possible; most of them develop rapidly and blossom within two years; and with this grand advantage over uprooted plants—they are able to acclimatize themselves from birth to their new conditions and surroundings, their translation being no rude and abrupt transition from one climate to another.

In this and in many other directions, it is when bad weather sweeps the Alps that we can perhaps best learn from Nature what Emerson learnt from her: that “she suffers nothing to remain in her Kingdom which cannot help itself.” And, in learning how these plants help themselves, we are also learning how best we can help them when we remove them to our gardens. Bad weather is the greatest of teachers all the world over. On sunny days we enjoy and admire what is very largely the product of the storms.

Everything, even the worst thing, in its place, [Pg 56] is a good thing. As all sunshine and no storm would make man a nonentity, so would it produce Alpines devoid of their present great ability and comeliness. A thing of complete beauty is a thing of all weathers; and it is a thing of present joy, and of joy for ever, because of much anguish in the past. You and I could see nothing of loveliness if it were not for ugliness; and these Alpines would not be worth looking at were it not for the awful attempts made by Nature to overwhelm them. “A perpetual calm will never make a sailor”; or, as Mr. Dooley says, “Foorce rules the wurruld”—and keeps it peacefully disturbed, bewitchingly “alive.”

And Alpine inclemency possesses an æsthetic value which is as important as it is alluring. Whether “in the smiles or anger of the high air,” these flower-fields are invariably things of beauty; even as the diamond glitters in the gloom, so do these pastures shine throughout the storm. What could be more æsthetically beautiful than the rosy expanses of Mealy Primrose bathed in dense, driving mists, or (as in the picture facing page 16) the regiments of Globe-Flower, standing pale but fascinating, in weather which, were we down on the plains, we should consider “not fit for a dog [Pg 57] to be abroad in”? Or what more winsome than the widespread colonies of Bartsia, Micheli’s Daisy, Pedicularis, Biscutella, and Bell-Gentian (Gentiana verna, unfortunately, is closed when the sun hides itself), lying subdued but colour-full beside the steaming waters of the lake?

Ah! where one of these Alpine lakes is in the landscape, what wonders of Nature’s artistry we may watch when rough winds howl and toss the seething cloud into ever-changing combinations of tint, form, and texture!

A hundred hues of grey fill the vapour-laden air and are mirrored in receptive waters—hues with which the fresh rose of the Primula and the rich, full yellow of the Marsh-Marigold blend with perfect felicity, lending that touch of human appeal which makes the scene ideal.

The forests, too, are never so picturesque as when clouds cling to the pine and larch, softening the tone and carriage of these somewhat formal trees, and breaking up every suggestion of monotony in their reiterated masses. A soft, weird, intimately mysterious beauty reigns over everything. [Pg 58] What matter the winds and the rains if they bring us such expression? By what is regret justified in all this witchery? Regret that the sun no longer shines, inducing the Vernal Gentian to open wide its bright blue eyes? Nay; here, in Alp-land, if nowhere else, does an ultimate philosophy speak possibly of what is actual; here, if nowhere else, bad weather is but a delightful foil to bright and sunny days. Regret! There is no right room for such repining: no sound and balanced reason to moan, as moans, for instance, the Chinese poet:

For in the Alps the lamp of Beauty burns without cessation; and where wondrous flowering pastures border some rough-cut lake, legacy from glaciers long since retired, the lamp burns always brightly.

By writing of inclemency in such full-flavoured tones, I am not trying to make the best of a bad case; I am simply and honestly setting forth the undoubted good there is in what may seem “impossible.” Any one who has lived with these things and has watched them springtime after springtime, [Pg 59] is usually in no way eager to run away, although well aware that the sheltered distractions of the towns are within quite easy reach. One finds no really compensating counterpart in kursaals and shop-windows for an Alpine springtime where flowering pastures kiss “the crystal treasures of the liquid world.” One need not be a poet, one need not be a painter, one need not be a mystic, and one certainly need be no “neurasthenic” to appreciate the figurative sunshine of which spring’s Alpine inclemency is redolent. One has but to be natural—a sanely-simple human being, dismissing the hampering prejudices and conventions born of towns, and allowing the appeal of Nature to come freely into its own. Then oneself is busy a-weaving—a-weaving of cobweb dreams; and the cobwebs are woven of material worthy, substantial, and real. One’s dreams are not of that solid, sordid order, nor of that frail, unhealthy nature so common with dreams arising from unnatural town-life. They are children of completest sanity, and they are in no part begot of ennui. One builds, and one builds for health’s sake; nor does the building know aught of “castles in Spain.” There is no question here of anæmic fancy. All that one dreams is not only possible, but sound, [Pg 60] touching upon realities which control and direct the best of destinies. Compared with town-life, one is in a new world; and it is often astounding to think that town-life is a necessity to which one is obliged to add the important word “imperative.”

And all this may be so even in wet weather. Here, even when clouds hold everything in damp and clinging embrace, we may

And grow rich quite comfortably; for have we not our mackintoshes and goloshes!

The Alps are not ours for climbing purpose only. They are not for us only when winter rules and gives us sports abounding, or when the snows retire to the cradles of the glaciers, and the days of late July and those of August and September grant us the conditions we most seek for long excursions. They are ours also for an intermediate season: a season of the utmost value, though, maybe, not for “sport.” Mr. Frederic Harrison, speaking of “the eternal mountains, vocal with all the most majestic and stirring appeals to the human spirit,” and of the treatment of them by those who think only of “rushing from pass to pass and from peak to peak in order to beat [Pg 61] Tompkins time or establish a new record,” says: “Switzerland might be made one of the most exquisite schools of every sense of beauty, one of the most pathetic schools of spiritual wonder.” And Mr. Harrison is right: this school exists, and is no mere fiction wrought of sentimental thinking. Nor is it ever closed to students—although there be periods when the attendance is lamentably slack. We know that its doors stand wide open in the winter and in the summer; let it be known, and as well known, that they stand equally wide open in the spring. Let it be known, moreover, that in spite sometimes of fickle, fitful weather, it is in the spring, above all other seasons, that this school is “one of the most exquisite schools of every sense of beauty, one of the most pathetic schools of spiritual wonder.”

Then once again,

and we are aware that during the brief period of inclemency a very astonishing change has been taking place in our surroundings under cover of the heavy mists. Nature has been speedily busy, robing the fields in garments fit for June. Before the mists closed down upon us a few days ago insect-life was noticeable mostly by its scarcity. Except for the Orange-Tip and Dingy Skipper butterflies, and for the Skipper-like moth, Euclidia Mi, flitting among the Saponarias, Daisies, and Geums, and for a dainty milk-white spider on the rosy heads of Primula farinosa, there was little of “life” among the flowers. But now the butterflies are legion, a brilliant pea-green spider has joined the white one, and lustrous little beetles—among the most beautiful of Alpine creatures—are either frolicking or basking in the glorious sunshine on the wild Peppermint and other fragrant herbs. As for the flowers themselves, they have more than doubled in kind, if not actually in beauty and in number.

Indeed, there is such transformation in the meadows as makes us rub our eyes and wonder if we have not slept the sleep of Rip van Winkle! The Gentians have all but gone, the Anemone also, and Primula farinosa has become most rare. [Pg 63] In their places stand the Globe-Flower, the Bistort, the Paradise Lily (barely open), the Sylvan Geranium, the blue Centaurea, and the pale yellow Biscutella, while the last blossoms of Anemone sulphurea have been joined by the exquisite blush-tinted heads of Anemone narcissiflora. It is as though some curtain had rolled swiftly up upon another landscape—one which, as we are but human, we must applaud more rapturously than we did the last. For—

And although we still may say we are in dainty May, more than the toe of our best foot is already in gorgeous June.

THE JUNE MEADOWS

“On prête aux riches,” and here is Nature lending yet more wealth to fields that were already so wealthy! It is simply amazing with what doting enthusiasm she pours her floral riches upon the Alps! Many who know only the June fields in England think that we who write of the Swiss fields at this season are either in a chronic state of hysteria, or else do wilfully point our story as if it were a snake story or the story of a tiger-hunt. But, let the fact be known, in writing or speaking upon this subject, the exigencies of the English language oblige us to be temperate; it [Pg 65] is quite impossible to exaggerate. We may use all the adjectives in Webster, yet have we not even then said enough. Acutely conscious of our ineffectual effort, we have, nevertheless, done our best. We could say no more: the rest we must feel, and endeavour that our readers shall feel with us.

Maybe it is with us as it was with Robert Louis Stevenson when he was at Davos in search of a remedy for the malady that afterwards drove him to Samoa and to an early grave upon her mountains—maybe all our “little fishes talk like whales”; but, believe us, whale-talk is the only talk befitting. If Stevenson finds “it is the Alps who are to blame,” we find it is quite as much the fault of the Alpine flora; and if Stevenson found comfort in the fact that he was not alone in being forced to “this yeasty inflation, this stiff and strutting architecture of the sentence,” so also can we.

We English are not the only ones to find ourselves at the ineffectual extreme of language. The German tourist—and he is nowadays more enterprisingly early than are we in visiting the Alps—is equally at a loss, as he stands in wonderment and, with characteristic emphasis, repeatedly [Pg 66] utters the one resounding word “Kolossal!” Even the Englishman loses his habitual reserve, and, if he does not voice his wonderment as loudly as does his Teutonic brother, he is at least amazed in his own insular way. Assuredly, if these flowers themselves could speak, and speak out frankly, they would declare our seemingly over-coloured appreciation a very tame performance; they would vouch that we are a long way from being in the shoes of the proverbial amateur fisherman.