The History Teacher’s

Magazine

Volume I.

Number 9.

PHILADELPHIA, MAY, 1910.

$1.00 a year

15 cents a copy

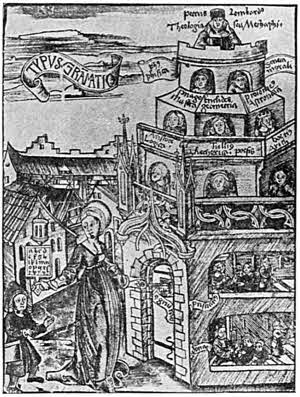

“TOWER OF KNOWLEDGE.”

Reproduced from the “Margarita Philosophica” (1504). From the copy in the library

of Mr. George A. Plimpton, New York City. (See page 202)

Published monthly, except July and August, by McKinley Publishing Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

Copyright, 1910, McKinley Publishing Co.

Entered as second-class matter, October 26, 1909, at the Post-office at Philadelphia, Pa., under Act of March 3, 1879.

[190]

W. & A. K. Johnston’s Classical Maps

7 MAPS In the Series

Roman World

Ancient World

Ancient Italy

Ancient Greece

Ancient Asia Minor

Ancient Gaul

Caesar De Bello Gallico

Mediterranean

COUNTRIES (Outline)

Send for special booklet of Historical Maps of all kinds.

A. J. NYSTROM & CO.,

Sole U. S. Agents Chicago

Western History in Its Many Aspects

MISSISSIPPI VALLEY

AND LOCAL HISTORY IN PARTICULAR

—THE AMERICAN INDIANS—

Books on the above subjects supplied promptly by

THE TORCH PRESS BOOK SHOP

Catalogs on Application. Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Hart’s Essentials in

American History

By ALBERT BUSHNELL HART, LL. D., Professor of History

Harvard University

$1.50

The purpose of this volume is to present an adequate

description of all essential things in the

upbuilding of the country, and to supplement

this by good illustrations and maps. Political geography,

being the background of all historical knowledge,

is made a special topic, while the development of government,

foreign relations, the diplomatic adjustment

of controversies, and social and economic conditions,

have been duly emphasized. All sections of the Union,

North, East, South, West, and Far West, receive fair

treatment. Much attention is paid to the causes and

results of our various wars, but only the most significant

battles and campaigns have been described. The

book aims to make distinct the character and public

services of some great Americans, brief accounts of

whose lives are given in special sections of the text.

Towards the end a chapter sums up the services of

America to mankind.

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

NEW YORK CINCINNATI CHICAGO BOSTON

You will favor advertisers and publishers by mentioning this magazine in answering advertisements.

CONTENTS.

| Page. |

| FRESHMAN HISTORY COURSE AT YALE, by Edward L. Durfee | 193 |

| WRITINGS OF WILLIAM PENN | 194 |

| HISTORY IN THE SUMMER SCHOOLS | 195 |

| HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS, 1909-1910 | 198 |

| THE TOWER OF KNOWLEDGE, by Prof. Paul Monroe | 202 |

| RECENT HISTORY, by John Haynes, Ph.D. | 202 |

| ANNOUNCEMENTS | 203 |

| EUROPEAN HISTORY IN THE SECONDARY SCHOOL, by D. C. Knowlton, Ph.D. | 204 |

| ANCIENT HISTORY IN THE SECONDARY SCHOOL, by William Fairley, Ph.D. | 205 |

| AMERICAN HISTORY IN THE SECONDARY SCHOOL, by A. M. Wolfson, Ph.D. | 206 |

| ENGLISH HISTORY IN THE SECONDARY SCHOOL, by C. B. Newton | 207 |

| REPORTS FROM THE HISTORICAL FIELD, W. H. Cushing, Editor | 208 |

| Louisiana High School Rally; History Teaching in London; Newark Examination; Indiana Association; Annual

Meeting of the North Central Association; Missouri Association; Spring Meeting of the New England Association. |

| CORRESPONDENCE | 211 |

| College Catalogue Requirements in History; The Topical Method. |

[191]

The

History Teacher’s

Magazine

Published monthly, except July and August,

at 5805 Germantown Avenue,

Philadelphia, Pa., by

McKINLEY PUBLISHING CO.

A. E. McKINLEY, Proprietor.

SUBSCRIPTION PRICE. One dollar a

year; single copies, 15 cents each.

POSTAGE PREPAID in United States and

Mexico; for Canada, 20 cents additional

should be added to the subscription price,

and to other foreign countries in the Postal

Union, 30 cents additional.

CHANGE OF ADDRESS. Both the old and

the new address must be given when a

change of address is ordered.

ADVERTISING RATES furnished upon

application.

EDITORS

Managing Editor, Albert E. McKinley,

Ph.D.

History in the College and the School, Arthur

C. Howland, Ph.D., Assistant Professor

of European History, University of

Pennsylvania.

The Training of the History Teacher, Norman

M. Trenholme, Professor of the

Teaching of History, School of Education,

University of Missouri.

Source Methods of Teaching History, Fred

Morrow Fling, Professor of European

History, University of Nebraska.

Reports from the History Field, Walter H.

Cushing, Secretary, New England History

Teachers’ Association, South Framingham,

Mass.

Current History, John Haynes, Ph.D., Dorchester

High School, Boston, Mass.

American History in Secondary Schools,

Arthur M. Wolfson, Ph.D., DeWitt Clinton

High School, New York.

The Teaching of Civics in the Secondary

School, Albert H. Sanford, State Normal

School, La Crosse, Wis.

European History in Secondary Schools,

Daniel C. Knowlton, Ph.D., Barringer

High School, Newark, N. J.

English History in Secondary Schools, C. B.

Newton, Lawrenceville School, Lawrenceville,

N. J.

Ancient History in Secondary Schools, William

Fairley, Ph.D., Commercial High

School, Brooklyn, N. Y.

History in the Grades, Armand J. Gerson,

Supervising Principal, Robert Morris Public

School, Philadelphia, Pa.

CORRESPONDING EDITORS.

Henry Johnson, Teachers’ College, Columbia

University, New York.

Mabel Hill, Normal School, Lowell, Mass.

George H. Gaston, Wendell Phillips High

School, Chicago, Ill.

James F. Willard, University of Colorado,

Boulder, Col.

H. W. Edwards, High School, Berkeley, Cal.

Walter L. Fleming, Louisiana State University,

Baton Rouge, La.

Mary Shannon Smith, Meredith College,

Raleigh, N. C.

HAZEN’S EUROPE SINCE 1815

By CHARLES D. HAZEN, Professor in Smith College

(American Historical Series.) xxvi + 830 pp. 8vo. [Ready in May.]

The aim has been to make the narrative so interesting in style as

to attract the student, without sacrificing accuracy or proportion.

For the sake of impressiveness it has been necessary to concentrate

attention upon a relatively small number of topics, but it is

hoped that no important step in the development of modern Europe has

been slighted. English history has been interwoven with continental

history, and colonial development has received careful treatment. Great

pains have been taken to make the bibliographical apparatus really useful

to the undergraduate.

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

34 West 33d Street, NEW YORK 376 Wabash Avenue, CHICAGO

Atkinson-Mentzer Historical Maps

A series of 16 maps to accompany United States History, 40 x 45 inches in size, lithographed

in seven colors on cloth, surfaced both sides with coated paper, complete with iron

standard, per set, $16.00 net. Sent on approval.

TWO NOTABLE OPINIONS

We regard the “Atkinson-Mentzer Historical

Maps” as superior, and should recommend schools

purchasing new maps to purchase this set in preference

to others.

Max Farrand,

Department of History, Leland Stanford Junior University.

I shall have a set ordered for the use of our

classes, and I shall be glad to recommend them, as

yours are the best maps of the kind that have been

brought to my attention.

N. M. Trenholme,

Head Department of History, University of Missouri.

ATKINSON, MENTZER & GROVER, Publishers

BOSTON NEW YORK

CHICAGO DALLAS

A Source History of

the United States

By Caldwell and Persinger. Full cloth. 500

pages. Price, $1.25. By Howard Walter Caldwell,

Professor of American History, University of Nebraska,

and Clark Edmund Persinger, Associate Professor of

American History, University of Nebraska.

Containing Introduction and Table of Contents. The

material is divided into four chapters, as follows:

Chap. I. The Making of Colonial America, 1492-1763

Chap. II. The Revolution and Independence, 1763-1786

Chap. III. The Making of a Democratic Nation, 1784-1841

Chap. IV. Slavery and The Sectional Struggle, 1841-1877

Complete single copies for reference or for libraries

will be forwarded by express paid on receipt of the

stated price of $1.25.

Correspondence in reference to introductory supplies

is respectfully solicited and will have our prompt attention.

A full descriptive list of Source History books

and leaflets forwarded on application.

AINSWORTH & COMPANY

378-388 Wabash Avenue, Chicago, Ill.

The College Entrance

Examination Board

has used McKINLEY OUTLINE MAPS in connection

with its questions upon historical

geography in eight out of the last nine years.

Many Colleges

use these maps in their entrance examinations.

All Preparatory Teachers and Students

of History should be familiar with them.

Samples cheerfully furnished

McKINLEY PUBLISHING CO., Philadelphia

You will favor advertisers and publishers

by mentioning this magazine in answering

advertisements.

Translations and

Reprints

Original source material for ancient,

medieval and modern history in

pamphlet or bound form. Pamphlets

cost from 10 to 25 cents.

SYLLABUSES

H. V. AMES: American Colonial History.

(Revised and enlarged edition,

1908) $1.00

D. C. MUNRO and G. SELLERY:

Syllabus of Medieval History, 395

to 1500 (1909) $1.00

In two parts: Pt. I, by Prof.

Munro, Syllabus of Medieval History,

395 to 1300. Pt. II, by

Prof. Sellery, Syllabus of Later

Medieval History, 1300 to 1500.

Parts published separately.

W. E. LINGELBACH: Syllabus of

the History of the Nineteenth Century 60 cents

Combined Source Book of the Renaissance.

M. WHITCOMB $1.50

State Documents on Federal Relations.

H. V. AMES $1.75

Published by Department of History,

University of Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia, and by Longmans,

Green & Co.

[192]

A NEW SCHOOL HISTORY

A History of the United States

By S. E. FORMAN, PH.D., Author of “Advanced Civics,” etc.

Ready in May, 1910, and published by The Century Co.

◖ Teachers of American history, who are looking for the best text-book for their classes, are

invited to examine this new work of Dr. Forman’s. They will find that it excels:

1 In the method of unfolding the story of OUR COUNTRY’S

GROWTH

The pupils have before them the story of an ever-growing

nation, and step by step they follow its upbuilding

from small beginnings to its present great proportions.

2 In the special prominence given to the progress of THE

WESTWARD MOVEMENT

The story of the marvelous growth of the Middle West,

and of the States further West, is told, it is believed,

with greater fullness than in any previous school history.

The student will see that the greatness of our

history is due as much to the Western States as to

those on the Atlantic seaboard.

3 In the treatment of THE BIOGRAPHICAL ELEMENT

The great leaders of our country stand out as real and

interesting personalities, because the author writes their

lives into the main body of the text.

4 In the account given of our COMMERCIAL, INDUSTRIAL

AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Throughout the book frequent surveys are made of

American civilization as it existed at successive stages,

and in these surveys the pupil learns how we have

passed from the simple life of the seventeenth century

to the complex life of to-day.

5 In the material provided for THE TEACHERS’ ASSISTANCE

At the end of the chapters are carefully framed questions

on the text, with review questions that keep constantly

in mind the points that have been gone over,

and with topics for special reading and special references.

In the appendix are comprehensive outlines and

analytical reviews.

6 In the fullness and richness of ITS MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

Entirely new maps have been made for the book, and

the illustrations have been selected from authentic

sources. Many of the pictures are illustrative of Western

life in the early days.

7 In the CLEARNESS AND INTEREST OF ITS STYLE

No student can fail to be attracted by the manner in

which the story is told. The style is simple—sometimes

almost colloquial—but never undignified. Every paragraph

in the book is interesting.

More than 400 pages, strongly bound in half leather. Price, $1.00 net.

Superintendents, teachers, and others interested are invited to send for further particulars.

THE CENTURY CO. Union Square, New York

Outline of English History

Based on Cheyney’s “History of England”—Just Published.

By Norman Maclaren Trenholme, Professor of History in the University of Missouri. Price, 50 cents.

Syllabus for the History of Western Europe

Based on Robinson’s “Introduction to the History of Western Europe.” By Norman Maclaren Trenholme.

Part I.—THE MIDDLE AGES 45 cents

Part II.—THE MODERN AGE 45 cents

These outlines are arranged to give the student a clear grasp of the course and the connection of events

in the periods covered. The topics are carefully outlined; useful reference books are listed, and review

questions which will stimulate the students’ power of orderly thought are included.

Outlines and Studies

To Accompany MYER’S ANCIENT HISTORY 40 cents

To Accompany MYER’S GENERAL HISTORY 40 cents

To Accompany MYER’S MEDIÆVAL AND MODERN HISTORY 35 cents

By Florence E. Leadbetter, Teacher of History in the Roxbury High School, Boston.

The purpose of these outlines is to train pupils to work independently and to study with definite aim.

For the teacher they furnish a text for the introduction to the study of the different periods and for the student

they furnish a frame-work upon which to build his study.

GINN AND COMPANY, 29 Beacon Street, Boston

You will favor advertisers and publishers by mentioning this magazine in answering advertisements.

[193]

The History Teacher’s Magazine

Volume I.

Number 9.

PHILADELPHIA, MAY, 1910.

$1.00 a year

15 cents a copy

Freshman History Course at Yale

The scope and character of the elementary history course

at Yale[1] is determined by a twofold necessity: first, that of

giving a general survey of the main facts of historical development

from the fall of the Roman Empire to modern times

which shall be valuable in itself and profitable to the student,

even though he were to pursue his historical studies no further;

and second, that of providing a course which will fit

into the general scheme of the history curriculum, and serve

as an introduction to the more advanced courses which follow

it. According to the present arrangement, the fields of English

and American History are reserved for succeeding years,

and as a result, the Freshman course is limited to the study

of Continental European History, from 375 A.D. to 1870

or thereabouts.

Although I follow current local usage in speaking of this

course as “Freshman History,” the name is not strictly appropriate;

it is open to Sophomores, and even to upper classmen

under certain limitations and restrictions. The name by

which it is known in the catalogue, History A 1, better expresses

the fact that it is the introductory course which is a

necessary preliminary to all the other history work. As a

matter of fact, the popular name is not seriously in error,

for over four-fifths of the students pursuing it are Freshmen.

The amount of time allotted to the study of the different

epochs is pretty evenly distributed. Beginning with a summary

view of the Roman Empire and an analysis of the

causes of its decline, the work of the first twelve weeks covers

rather thoroughly the history of the Middle Ages to 1250

A.D.; the Renaissance, Reformation, and Religious Wars occupy

the next third of the year; and the spring term has to

suffice for the period from Louis XIV to the Congress of

Vienna. At that point, the course practically ends, for the

events of the nineteenth century are sketched very briefly,

partly because time is lacking, but more particularly for the

reason that a later and more advanced course treats that

period in detail.

Experience has convinced the instructors that any course,

particularly an introductory one, which deals in specious

generalizations and vague trends of development to the exclusion

of a thorough drill in concrete facts will, of necessity,

be a failure; and so the methods of instruction are designed,

first of all, to secure an accurate knowledge of events,—to

make the student master the fundamental data upon which

any real comprehension of a great movement as a whole

must be based. Of course, this is equivalent to saying that

we do not consider the lecture method adapted to the immaturity

of first year students,—even the mixture of lecture and

quiz recitations seems to offer too many temptations to irregularity

and slovenliness. Consequently, each of our three

exercises per week is devoted to a thorough test of the student’s

industry by oral questioning and, at frequent intervals,

by short written papers. The fact that the class is

divided into small divisions, averaging only twenty men in

each, makes the desired end comparatively easy of attainment.

In the matter of text-books, three or four are used, chosen

for their supplementary excellencies, and with the additional

object in view of developing in the student an elementary

power of comparison and synthesis,—an ability to select

facts from different sources and mould them into some sort

of orderly cohesion for presentation in the recitation. The

proof that he has done this is sought, not only in the recitation,

but by inspection of his note-book, in which he is

required to keep a condensed but carefully arranged digest

of the facts gleaned from the various books.

As regards original sources, an experience lasting for a

period of six years has forced upon the unwilling minds of

the instructors the conviction that contemporary material,

as a part of the required reading, cannot be used to advantage

in a general course, so broad in scope as the one we are

considering. The experiment was a thorough one and long

continued,—in fact, the feeling that we ought to find a

profitable method of using sources lingered long after the

proof had been forced upon us that we could not, and it has

produced no change in the general opinion that such work

is of the utmost value where time is available to pursue it

properly. But in this particular instance, that was precisely

what we could not do, at least not without entirely changing

the character of the course and modifying its relation to the

rest of the curriculum. Source collections are therefore no

longer among the required text-books, but are relegated to

the domain of collateral reading.

Unity and cohesion among the different instructors and

the various text-books is obtained by the use of a syllabus,

blocked off into lessons, each containing in addition to an

outline and the necessary assignments in the text-books,

further references for reading in the larger standard histories

and biographies. Nor is historical geography neglected,

for each student must fill in with colors the successive maps

of an outline atlas.

Casual mention of collateral reading has already been

made, but there now remains to be described the method

by which it is enforced and directed,—a method which, I

think, is unique and which, judged by its results, would

seem to be the most valuable feature of the course. In the

fall term, which is by far the hardest, owing to the Freshman’s

unfamiliarity with college methods of work and the

difficult character of the text-books used, little is done in

this direction other than to introduce him to the library,

to point out to him the section in which the books are to

be found that are especially reserved for this course, and

to require him to do a fair amount of collateral reading

upon some specific subject, a clear outline of which he must

insert in his note book. But in the winter and spring terms

a much more systematic and thorough drill is undertaken,

a brief description of which follows:

Some time in January or February a topic is assigned

to each student, comparatively restricted in its scope, chosen

from the field of medieval history up to and including the[194]

Renaissance. Within two or three days, at a definitely appointed

time, he meets his instructor in a conference lasting

from twenty minutes to half an hour, and submits a list of

books, magazine articles, essays, etc., which contain material

bearing upon his subject. This list is to be as complete

as the student can make it, and the first object of the conference

is to discover if he has exhausted the possibilities

of the library,—to find out whether he knows how to use the

various catalogues, the more ordinary aids such as Poole’s

Index, the A. L. A. Index to General Literature, etc., and

whether he is familiar with the location of the reference

shelves and the stacks accessible to him. Satisfied upon

these points, the instructor selects from the list presented

(and perhaps amended) a number of chapters, articles, or

books, as the case may require, from which the student is to

extract and collect in the form of notes material for an

essay on his particular subject. The remaining portion of

the conference period is occupied with describing and explaining

to the student just how these notes are to be

taken.

The method of note taking is the most important matter

in connection with this first piece of work, for here, probably

for the first time in his life, the student is introduced to

this particular application of the card index and filing system.

It is required that each note be taken upon a separate

card, that each card shall have a head line appropriate for

filing purposes, and that there be an accurate volume and

page reference to the book from which each bit of information

was taken. Emphasis is also put upon the fact that

all the reading should be done and all the notes completed

before the essay is begun, and that the essay should be

written solely from the notes, without further reference to

the books; for experience has shown that this is the best

way of proving to the student himself whether his notes have

been well or poorly taken.

It may be urged that twenty or thirty minutes will not

suffice for thorough instruction in such a variety of matters;

it certainly would be impossible if it were not for the fact

that the whole process is simplified by providing each student

in advance with a pamphlet which, besides explaining

briefly all these points, contains also a condensed guide to

the library. With the aid of this, the work of the instructor

is reduced to the task of ascertaining by well-directed questions

just what the student has done, and what he would do

if he were confronted with certain problems which are sure

to arise. And of course, each man is encouraged to consult

the instructor informally at any time in connection with

puzzling points that may crop up.

As before, a definite time limit is set for this part of the

work, and at a second meeting, both the notes and the essay

are handed in; and in addition, directions are at that time

given for the construction of a formal bibliography. This

differs from the preliminary book list which was submitted

at the beginning of the work in the following points: in the

first place, each book is to be properly and formally listed

on a separate card; secondly, reference must be made on

each card, not only to the pages which deal with the student’s

particular topic, but to those where further bibliographical

lists are to be found; again, he is at this time

introduced to and taught to use the principal historical

bibliographies, and required to enter on cards those which

give lists of books on his subject, with an exact reference

to the pages where these lists are to be found, without, however,

copying any titles from these lists; and lastly, he must

make an elementary classification of all his cards by dividing

them into three groups,—bibliographies, sources and secondary

works.

In the spring term the process is repeated with each

student, certain modifications being introduced, however,

which constitute steps in advance and prevent the men from

viewing the second piece of work as a monotonous repetition

of the first. For instance, the subject is chosen from the

modern period; while the notes and essay are done in the

same manner, a longer time is allowed, and, on the basis of

a sharp criticism of his first theme, much improvement in

these respects is expected; and the character of the bibliography

is entirely changed.

The primary object of the first bibliography, it will be

noticed, was to teach the student how to find all the books

on his subject, how to use the library, catalogues, bibliographies,

etc. In the case of the second, we endeavor to teach

him how to find the best books; in other words, we require a

selected and critical bibliography, and insist that no book

be entered unless its card bears a statement of its comparative

value by some recognized authority. To secure such

statements the student must, of course, in addition to using

the usual bibliographies critically and selectively, search for

book reviews in the various reputable magazines, historical

and otherwise. As an additional incentive, a prize, named

for the Hon. Andrew D. White, is awarded to the author of

the best piece of work.

This system was evolved from tentative experiments lasting

three years, and has now been in operation, in its present

form, for three more; and it seems to be the opinion of

competent judges that it is an unqualified success. In the

first place, it teaches the student a great deal, not only about

particular phases of European history, but more especially

about methods of work which will stand him in good stead in

all his future courses; and while it demands much of him,

the requirements are all so carefully graded and the work so

progressive in character that at no time is he overwhelmed

by the amount suddenly thrust upon him. And another

feature that deserves emphasis is the care taken to prevent

each man from slighting any part of the process; during the

time he is at work on his two themes he must meet his

instructor in no less than five personal consultations which

punctuate at carefully chosen times the various stages of the

work.

The obvious difficulty that the system demands too much

of the instructor is met by the fact that the History Department,

as well as the whole Faculty, have shown their appreciation

of the results obtained by lightening the ordinary

work of teaching to an extent that permits the teacher to

carry this extra burden without undue effort.

THE WRITINGS OF WILLIAM PENN.

An interesting announcement has been made by Albert

Cook Myers, of Moylan, Pa., concerning a plan for the publication

of the complete works of William Penn. It is noteworthy

that there is no edition of Penn’s works which is

nearly complete. The fullest edition, that of 1726, is difficult

to obtain. The later editions of 1771, 1782 and 1823

contain but a small portion of his works. Yet even the

first edition contains but twenty per cent. of the works

which were published during Penn’s lifetime. Of the eleven

hundred known letters of Penn only one hundred and

twenty-five have ever been printed. The aim of Mr. Myers

is to obtain a guarantee from members of the Society of

Friends and others of a fund amounting to $18,000, which

will be sufficient to defray the expense incident to making

such a collection. A committee of the Historical Society

of Pennsylvania has been appointed to co-operate with Mr.

Myers in this publication. The committee includes Hon.

Samuel W. Pennypacker, William Brooke Rawle, Charlemagne

Tower, John Bach McMaster, Isaac Sharpless, William

I. Hull, and William Penn-Gaskell Hall. Persons

willing to assist in this work either by the contribution of

funds or by the loaning of manuscripts are requested to

correspond with Mr. Myers.

[195]

History in the Summer Schools, 1910

EDITOR’S NOTE.—In the April number of the Magazine appeared

descriptions of the summer courses in history at University of

Arkansas, Cornell University, University of Chicago, University

of Illinois, Indiana University, University of Kansas, Ohio University,

University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania State College,

Summer School of the South, University of West Virginia, and

University of Wisconsin.

University of California.

Berkeley, Cal.

SUMMER SESSION, 1910.

1. European Background of American History. By Professor

J. N. Bowman.

2. The Teaching of History. By Professor J. N. Bowman.

3. United States History, 1815-1850. By Professor E. D.

Adams.

4. British Official and Parliamentary Opinion on the

American Civil War. By Professor E. D. Adams.

5. England from the Revolt of the American Colonies to the

Constitutional Crisis of 1909-1910. A study of Organic and

Social changes. By Mr. Edward Porritt.

University of Colorado.

SUMMER SCHOOL, 1910.

1. Medieval Institutions. Professor Willard.

A detailed study of the organization of certain of the more important

medieval institutions. Special emphasis will be placed

upon the formation and organization of the medieval church, the

monastic orders, feudalism and the Holy Roman Empire. The

course is designed to supplement a knowledge of medieval political

history by a more careful study of institutional life.

2. The Revolution and Constitution, 1750-1800. Professor

Risley.

From the Albany plan of union to the completion of the organization

of the government under the Constitution; the period preceding

the Revolution as preparation for separation; the Revolution;

the confederation and the constitution. Special stress will

be placed on the formation of the constitution.

3. Methods or Presenting History in Secondary Schools.

Professor Risley.

This is a lecture course intended for teachers and involves a

consideration of teachers’ preparation, model lessons, emphasis,

definiteness, point of view, various aids as outlines, maps, illustrative

material, etc., with suggestions as to syllabus and a review

of leading texts.

Note.—Course 1 and 2 may be taken with graduate credit upon

the recommendation of the professors.

Columbia University.

New York City.

SUMMER SESSION, JULY 6 TO AUGUST 17, 1910.

HISTORY.

sA1. Europe in the Middle Ages; the Chief Political, Economic

and Intellectual Achievements. Lectures, reading, and

discussion. Three points. Dr. Hayes.

sA2. Modern and Contemporary European History. Lectures,

reading, and discussion. Three points. Dr. Hayes.

This course is designed as an introduction to current national

and international problems. The principal topics will be monarchy

by divine right and the old régime in Europe, the intellectual

achievements of the eighteenth century, the French Revolution

with reference to political and economic changes, the work of

Napoleon in reforming France and in re-shaping the map of Europe,

the Industrial Revolution, the development of Italian and German

unity, the third French Republic, the rise of Russia, modern social

problems, and European imperialism in Africa and the Orient. The

text-book will be Robinson and Beard, “The Development of Modern

Europe.”

s356. Seminar. English History During the Industrial

Revolution. 2 points. Professor Shotwell.

This course is designed primarily for students taking s156. It

will furnish an introduction into the extensive collections of sources

on the economic and industrial history of England available in

both the University and the Astor libraries. The course will include

as well some practical investigation of the working out of the

Industrial Revolution in America.

s156. The Social and Industrial History of Modern Europe.

Lectures, readings, and discussions. Two points. Professor Shotwell.

This course is mainly concerned with the Industrial Revolution

and the rise of democracy during the nineteenth century.

s13-14b. American History; Political History of the United

States from 1815 to 1889. Recitations, written tests, reports and

occasional lectures. Two points. Professor Bassett.

The course begins at the point at which foreign affairs cease to

predominate, and deals with the important phases of internal history.

s162b. American History, from 1815 to 1837. Lectures, reports,

examination of original materials, and familiarity with the larger

secondary sources. Two points. Professor Bassett.

The course will deal with the decay of the Virginia hegemony

and the rise and supremacy of Jacksonian democracy.

s115-116b. Ancient History: Roman Politics. Two points.

Professor Abbott.

A research course identical with Latin s155-156.

Harvard University.

Cambridge, Mass.

SUMMER SCHOOL, JULY 9 TO AUGUST 18, 1910.

Brief Announcement.

GOVERNMENT

*S1. Civil Government; the United States, Great Britain,

Germany, France, and Switzerland. Lectures, conferences, and

thesis. Five times a week. Dr. Arthur N. Holcombe.

HISTORY.

*S2. Ancient History for Teachers. Lectures, reports, reading,

and examination of illustrative material. Five times a week, 9-10

and 11-12 a.m. Assistant Professor William S. Ferguson.

*S4. History of England from 1689 to the Present. Lectures,

discussions, and written reports. Five times a week. Professor

William MacDonald, of Brown University.

*S5. American History from the Beginnings of English Colonization

to 1783. Lectures, discussions, and written reports. Five

times a week. Professor William MacDonald, of Brown University.

Courses for Advanced Students.

*S25. Historical Bibliography. Two hours, once a week. Professor

Charles H. Haskins.

This course is open only to college graduates.

*S20i. Research in Greek and Roman History. Asst. Professor

William S. Ferguson.

*S20c. Research in Medieval History. Professor Charles H.

Haskins.

*S20d. Research in Modern European or Asiatic History.

Professor Archibald Cary Coolidge.

*S20e. Research in American History. Professor William

MacDonald, of Brown University.

State University of Iowa.

Iowa City, Iowa.

SUMMER SESSION, JUNE 20 TO JULY 30, 1910.

History.

Professor Wilcox.

I. Europe in the Nineteenth Century. Five hours.

An outline study of European history from the fall of Napoleon

Bonaparte to the close of the nineteenth century. Professor Wilcox.

Daily, except Saturday, at 10.00.

II. American Historical Biography. Five hours.

Lectures on the personal element in American history. A critical

study of the public careers of some of the principal American

leaders. Professor Wilcox. Daily, except Saturday, at 1.30.

[196]

III. Public Lectures. One hour.

1. The danger of democracy.

2. The educated American girl.

3. What is an education in Iowa in 1910?

4. The eastern question and the western question.

5. The triumph of American diplomacy.

Saturday, at 9.

IV. Graduate Work. An opportunity will be given for graduate

students to do individual research work in preparation for advanced

degrees. Special appointments and conferences with each

candidate, either in European or American history, will be made

upon request.

Political Economy.

III. Economic History of the United States. Five hours. A

general course designed to supplement courses in political and constitutional

history and to serve as a background for the study of

economic and social questions. Assistant Professor Peirce. Daily,

except Saturday, at 9.00.

Political Science.

Professor Shambaugh.

I. Modern Government. Five hours. A study of leading European

governments in comparison with the government of the United

States. Daily, except Saturday, at 9.

II. Iowa History and Politics. Five hours. A course of lectures

with library reading on the history and government of Iowa.

Daily, except Saturday, at 7.

III. Research in Iowa History. Two to four hours. In this

course work along the lines of Iowa history will be outlined and

directed for students who have already taken a course in Iowa

history.

Louisiana State University.

Baton Rouge, La.

SUMMER SCHOOL, JUNE 6 TO AUGUST 5, 1910.

1. The Civilization of the Greeks and Romans.

2. American History. Based entirely upon the study of

sources.

3. History of Louisiana. An advanced course, in which the

French authorities and the sources are used.

4. The Teaching of History in High Schools. A course of

four hours a week of lectures and discussion, and two hours a week

of observation and practice in the University Demonstration High

School.

5. The Government of Louisiana. A study of the constitutional

history of the State, and of the present State Government.

6. The Principles of Constitutional Government.

7. The Teaching of Civics in Schools.

8. Principles of Economics.

9. Elements of Sociology.

The work in History and Political Science will be given by four

instructors. The summer term lasts nine weeks, and a subject

taken six hours a week for the nine weeks is equivalent to the regular

course of three hours a week for one of the regular terms.

It is the purpose of the Departments of History, Political Science,

and Economics to give first term work at one summer school and

second term work in the next one, in addition to certain courses

planned especially for teachers.

University of Michigan.

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

SUMMER SESSION, JULY 5 TO AUGUST 26, 1910.

HISTORY.

1. General History of England. From the Restoration to the

Eve of the American Revolution. This course, treating briefly the

chief features of the Restoration and the Revolution of 1688, aims

to deal in more detail with the Revolution Settlement and the

events which followed. Considerable emphasis will be laid upon

the two characteristic features of the period: the Great Wars,

with the resulting expansion of England, and the development of

cabinet and party government. Two hours credit. Room 5, T. H.,

M, T, W, Th, at 2. Professor Cross.

2. General History of England. From the Norman Conquest

to the accession of Henry VII. This course deals with the political

institutions and the constitutional development of England. Attention

is paid to bibliography. Two hours credit. Room 7, T. H.,

M, T, Th, F, at 1. Mr. Bacon.

3. A History of Europe From 814 to 1300. This course deals

in outline with the Roman Papacy, the revival of the Roman

Empire on a German basis, the conflict of the investiture, the

Hohenstaufen policy in Germany and Italy, the Crusades, growth

of the French Monarchy, the Intellectual Life, and Feudal Institutions.

Two hours credit. Room 7, T. H., M, T, Th, F, at 3. Mr.

Bacon.

4. The History of Civil War and Reconstruction. The causes

and nature of secession are considered; the conduct of the war is

sketched; the constitutional, political and social conditions resulting

from the struggle are examined in detail. Two hours credit.

Room 2, T. H., M, T, W, F, at 8. Assistant Professor Bretz.

5. The Constitutional History of the United States, as

Affected by Judicial Decisions. The course will deal with the

history of the process by which the original conceptions of the

meaning of the constitution has been changed by court decisions.

Two hours credit. Room 2, T. H., M, T, W, F, at 11. Assistant

Professor Corwin.

Graduate Work.

6. Seminary in American History.—This course is intended to

offer training in the investigation of historical problems and practice

in the handling of original material. Open only to graduates

and to seniors receiving special permission. The field of work will

be in the history of the Westward Movement. Two hours credit.

East Seminary Room. T and Th, 2 to 4. Assistant Professor

Bretz.

University of Missouri.

Columbia, Missouri.

SUMMER SESSION, 1910.

HISTORY.

Professor N. M. Trenholme; Dr. F. F. Stephens.

For Undergraduates.

1b. Modern History. With especial reference to the later or

strictly modern portion of the period. This course will deal with

the history of western Europe from the age of the Renaissance and

Reformation to the present time. It is especially designed for

teachers of medieval and modern history and as introductory to the

English, American, and more advanced modern history courses in

the University. Five times a week; (3). Dr. Stephens.

[A. 53; 8:00-9:00.]

2. English History and Government. A course dealing with

the political, social, and governmental history of England. The

earlier or medieval portion of English History will be covered somewhat

rapidly, and the attention of the class directed to such topics

as the formation of parliamentary government, social and economic

changes and advances, and the evolution of popular government.

Five times a week; (3). Professor Trenholme. [A. 53; 10:30-11:30.]

3. American History. A general course on the exploration and

settlement of North America, the French and English colonies,

the American Revolution, and the United States. Five times a

week; (3). Dr. Stephens. [A. 54; 9:00-10:00.]

5b. Ancient History. With especial reference to the later or

Roman period. This course will cover the political, social and

institutional aspects of the history of the ancient world from the

rise of Roman power in Italy to the conquest of Western Europe

by the Germans. It is especially designed for teachers, and will be

conducted as a discussion and recitation course with a small

amount of required written work. Five times a week; (3). Professor

Trenholme. [A. 53; 9:00-10:00.]

Primarily for Graduates.

35b. Advanced United States History. A study of selected

topics in United States History. Lectures, discussion, and reports

by the class. Twice a week; (2). Dr. Stephens. [A. 53; 10:30-11:30.]

36. Research Studies in European Culture. An advanced

course of pro-seminar character, open to students who are qualified

to pursue graduate work. The subject of study for this summer

will be Dante and his times from the historical viewpoint. The

work will be conducted by means of lectures and reports based on

extensive reading in sources and secondary literature. Students

are recommended to purchase Snell’s Handbook to Dante for reference.

Twice a week; (2). Professor Trenholme. [A. 53; 11:30-12:30,

Tu. Th.]

[197]

University of Nebraska.

Lincoln, Neb.

SUMMER SESSION (EIGHT WEEKS), 1910.

AMERICAN HISTORY.

The following courses are intended to meet the needs of three

classes of students: (1) teachers of history in Nebraska high

schools who may wish to enlarge or perfect their knowledge of the

subject they are teaching; (2) undergraduate students desiring to

make extra credits towards the Bachelor’s degree; (3) graduate

students seeking advanced degrees through summer session work.

2. Revolutionary Period, 1764-1783. British “change of colonial

policy” after 1763; the Stamp act, Townshend acts, Tea act,

and Intolerable acts; revolution, independence, alliance, confederation;

war and peace. Open to all. Five hours attendance; three

hours preparation. Three hours credit. Associate Professor Persinger.

9. Territorial Expansion. European rivalries in colonial

America; territorial making of original union; diplomacy, politics

and geography of the various acquisitions; government and administration

of dependencies. Open to advanced students. Five hours

attendance; three hours preparation. Three hours credit. Associate

Professor Persinger.

6. The New Nation, 1877-1910. Industrial problems: tariff,

banking, money, transportation, immigration, trusts, labor and

conservation; reforms: Granger movement, Farmers’ Alliance, anti-monopoly;

politics: White supremacy in South; reorganization;

rise of third parties; expansion into tropics and its problems:

Cuba, Porto Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines. Open to graduates

and advanced students; three hours attendance; ten hours per week

preparation; two hours credit. Professors Caldwell and Persinger.

New York University.

New York City.

SUMMER SCHOOL, JULY 6 TO AUGUST 16, 1910.

Professor Marshall Stewart Brown; Professor W. K. Boyd

(Trinity College).

HISTORY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE.

S1. Political and Constitutional History of the United

States. Thirty hours. Professor Brown.

S2. American Civil Government. Thirty hours. Professor

Brown.

S3. History of the Middle Ages. Thirty hours. Professor

Boyd (Trinity College).

S4. Secession, the Confederacy and Reconstruction. Thirty

hours. Professor Boyd.

SG1. The American Colonies. Thirty hours. Professor Boyd.

SG2. Seminar in American Colonial History. Thirty hours.

Professor Brown.

Northwestern University.

Evanston, Illinois.

SUMMER SCHOOL, JUNE 27 TO AUGUST 6, 1910.

HISTORY.

Dr. Pooley.

(Not more than three of the following courses will be given.)

General Course in American History, 1783-1860. Some attention

will be given to the methods of presenting this subject in

secondary schools. Credit, two semester hours.

General Course in Medieval History. Special attention to

social, economic, and intellectual life. Credit, two semester hours.

Ancient History. This will be a course in either Greek or

Roman History, as the class may elect. Credit, two semester

hours.

Medieval History. A course covering the period between the

break-up of the Roman Empire to the Reformation. Credit, two

semester hours.

Ohio State University.

Columbus, Ohio.

SUMMER SESSION, JUNE 20 TO AUGUST 12.

HISTORY.

Professor Knight.

101. American Political History. Three credit hours. Prerequisite:

a thorough high-school course in American History and

Civics. Daily, 10.30.

A study of the period from 1600 to 1776, based upon Thwaites’

“The Colonies,” and Hart’s “Formation of the Union.”

For Advanced Undergraduates and Graduates.

112. The Slavery Struggle and Its Results, 1854-1900. Three

credit hours. Prerequisite: at least one full year of collegiate

work in American History.

This course will be devoted to a study of the divergence of the

North and South, and the rise and fall of political parties as influenced

by slavery; the relation of slavery to the Civil War; the

results of the struggle as traced in the reconstruction of the

Southern States; and the readjustment of society and the States

to the new status of the negro. Daily, 8.30.

For Graduates.

205. The Administrations of Pierce and Buchanan. Two

credit hours. Hour to be arranged. Lectures and student research.

Students intending to take this course must first consult with the

instructor.

Assistant Professor Perkins.

102. Modern European History, from 1500 A.D. Three credit

hours. Text-book: “Robinson’s History of Western Europe.”

Daily, 8.30.

A thorough course covering the whole period, but with especial

emphasis on the Protestant Revolt, the French Revolutionary and

Napoleonic Era, and the Nineteenth Century. Extensive outside

reading will be required.

105. The History of Greece. Preceded by a brief sketch of

the ancient empires of the East. Three credit hours. Daily, 7.30.

An advanced course conducted by means of lectures, discussions,

and assigned readings, designed especially for high school teachers

of history.

Primarily for Graduates.

203. Seminary in Modern History. One or two credit hours.

Time to be arranged.

Assistant Professor Shepard.

101. Constitutional Government. Three credit hours. Prerequisite:

American History 101, European History 101, or a substitute

acceptable to the department. Daily, 7.30.

State University of Oklahoma.

Norman, Okla.

SUMMER SCHOOL, 1910.

HISTORY.

1. American History and Government. Required of all who

take the B.A. Degree. By Associate Professor Gittinger.

2. Political and Constitutional History of United States

from Jackson to the Present Time. Professor Buchanan.

3. Medieval Europe. An introductory survey of the period from

barbarian invasions to the end of the fifteenth century. Text and

readings. By Associate Professor Floyd.

4. Modern Europe. An introductory survey of the period from

the end of the fifteenth century to the present time. Associate

Professor Floyd.

5. A Course in English History. Associate Professor

Gittinger.

Syracuse University.

Syracuse, N. Y.

SUMMER SCHOOL, JULY 5 TO AUGUST 16, 1910.

HISTORY.

Professor Gilbert G. Benjamin, Ph.D.

A. Ancient History. A general course in Ancient History.

This course is preparatory to a study of history. It aims to show

the continuity of history, and will lay especial stress on the contribution

of the Ancients to our modern cultural development. Not

only will the political and dynastic changes be studied, but the

economic and the social life of the various peoples will be outlined.

West’s “Ancient History” will be used as an outline. Lectures,

readings and manual.

By especial arrangement with the instructor extra credit may

be given. University credit, two semester hours. Five hours a

week.

B. Medieval History. A preparatory course in the institutional

development of the Middle Ages, from about 395 A.D. to the

German Reformation. The rise and growth of the Christian church;

the feudal state and a general study of the rise of modern nations.

[198]

Students will be expected to prepare papers upon some topic to

be assigned by the instructor. Robinson’s “History of Western

Europe” and Robinson’s “Readings” will be used as manuals.

University credit, two semester hours. Five hours a week.

C. American History. A lecture course with assigned readings

on American history from 1765-1860. A great deal of reading in

the sources will be demanded. Special stress will be laid upon

the economic and constitutional development of the American

people.

University credit, two semester hours. Five hours a week.

D. Method in History and Principles of Historical Research

and Criticism. A course in Methods of teaching history especially

adapted for teachers in secondary schools. It will also deal with

scientific criticism of historical documents.

This course will not be offered unless at least five students are

registered. Students will be expected to prepare papers on the

teaching of History, and topics will be assigned for historical criticism.

For the work in criticism. Langlois and Seignobos’ “Introduction

to the Study of History” will be used, and students contemplating

entering the course should prepare themselves with a copy of

this manual. University credit, two semester hours. Five hours a

week.

University of Texas.

Austin, Texas.

UNIVERSITY SUMMER SCHOOLS, JUNE 18 TO AUGUST 4, 1910.

COLLEGE OF ARTS.

HISTORY.

1f. History of Greece. Five hours a week throughout the term.

A general survey of Greek History. Text-book to be announced

later. Dr. Duncalf.

1w. History of Rome to the Death of Julius Caesar. Five

hours a week throughout the term. A general survey of the period.

Text-book, Abbott’s “History of Rome.” Dr. Duncalf.

2w. The Feudal Age, 814-1300. Five hours a week throughout

the term. Mr. Hamilton.

3f. Europe During the Period of the Reformation and the

Religious Wars, 1500-1648. Five hours a week throughout the

term. Adjunct Professor Barker.

13f. A. The Causes of the French Revolution. Five hours a

week throughout the term. Adjunct Professor Barker.

4s. Imperial England, 1688-1910. Five hours a week throughout

the term. Dr. Ramsdell.

5f. European Expansion in America, 1492-1775. Five hours a

week throughout the term. Professor Garrison.

7. A. Southwestern History. Five hours a week throughout

the term.

In 1910 this course will be occupied with a study of the diplomatic

relations of the Republic of Texas with the United States.

The materials used will be the diplomatic correspondence between

the two countries, together with various related sources in the

libraries of the University and the State. Credit will vary from

one-third to one full course according to the amount of work

accomplished by the student. Professor Garrison.

SUMMER NORMAL SCHOOL.

History, General. Five times a week throughout the term.

Dr. Ramsdell and Mr. Hamilton.

History of Texas. Five times a week during the second half

of the term.

This course will be based on Pennybacker’s “History of Texas.”

The student should read Bolton and Barker’s source-book, “With

the Makers of Texas,” for realistic and vivid pictures of the life

in Texas during all the periods of her romantic history, and familiarize

himself with the history of the United States from 1800

to 1845. Principal Littlejohn.

History of the United States. Five times a week during the

second half of the term. Superintendent McCallum.

University of Washington.

Seattle, Washington.

SUMMER SCHOOL, 1910.

HISTORY.

Professors Meany, Richardson and McMahon.

1. England Under the Tudors and Stuarts. The history of

England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries, with special

reference to the social and political conditions which led to the

foundation of the Tudor absolutism; and to the development of

the religious, political and constitutional issues which culminated

in the Puritan Revolution and the Political Revolution of 1688-9.

Lectures and supplementary reading. Five hours per week at 10.

Two credits. Professor Richardson.

2. The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era. An advanced

course. Among the principal topics considered are the following.

The material conditions out of which, in France, the Revolution

emerged, and the nature of the new ideals which inspired

it; contemporary conditions in the European states system which

facilitated the extension of the revolution over Europe; the epoch

of international wars, with special reference to its effect on France,

Europe, and the liberal movements of the Nineteenth century; the

career of Napoleon. Lectures and supplementary reading. Five

hours per week at 11.00. Two credits. Professor Richardson.

3. History of the United States from the Close of the War

of 1812 to the End of Jackson’s Presidency. In this course the

relation between economic, social and political forces are considered;

and the Constitutional history of the period is studied as the

outgrowth of economic and social conditions in the physiographic

provinces that made up the United States. Lectures and assigned

reading. Five hours per week at 8.00. Two credits. Professor

McMahon.

4. Civil War and Reconstruction. A study of the political and

constitutional phases of the civil war and the problems of statecraft

involved in a realignment of National powers and a readjustment

of the political forces between 1865 and 1876. Lectures and

assigned readings. Five hours per week at 9.00. Two credits.

Professor McMahon.

Professor Meany gives 13 popular lectures on “The History of

the Northwest.”

Historical Publications, 1909-1910

The following list contains references to

the principal publications of American publishers

issued between April 15, 1909, and

April 15, 1910. In addition to new text-books

and books for class reference, it contains

general works upon history and

biography. No attempt has been made to

include in it the publications of historical

societies or works peculiarly of local interest.

The works of foreign publishers are

not included. If the list proves helpful to

history teachers similar lists will be printed

each year.

Books on Method.

Committee of Eight. Report to the American

Historical Association, upon the

Teaching of History in Elementary

Schools. Charles Scribner’s Sons. 50

cents.

Keatinge, M. W. Studies in the Teaching

of History. The Macmillan Co. $1.50

net.

Text-books.

Callender, G. S. Selections from the

Economic History of the United States,

1765-1860. Ginn & Co. $2.75.

Caldwell, H. W., and Persinger, C. E. A

Source History of the United States from

Discovery (1492) to End of Reconstruction

(1877). Ainsworth & Co. (Chicago).

$1.25.

Chambers, A. M. A Constitutional History

of England. The Macmillan Co. $1.40.

Channing, Edward, and Ginn, Susan J. Elements

of United States History. The

Macmillan Co. (In press.)

Channing, Edward, and Ginn, Susan J. A

Short History of the United States for

School Use. The Macmillan Co. $1.00

net. [For 7th and 8th grades.]

Davis, William Stearns. An Outline History

of the Roman Empire. The Macmillan

Co.

Dickson, Marguerite Stockman. American

History for Grammar Schools. The Macmillan

Co. (In press.)

Forman, S. E. School History of the

United States. The Century Co. $1.00.

Gerson, Oscar. History Primer. Hinds,

Noble and Eldredge.

Gerson, Oscar. Our Colonial History.

Hinds, Noble & Eldredge.

Harding, Samuel B. Essentials in Medieval

History. American Book Co. $1.00.

Hix, Melvin. History for Fifth Grades.

Hinds, Noble & Eldredge.

[199]

James, James Alton, and Sanford, Albert

Hart. American History. Charles

Scribner’s Sons.

Mace, William H. A Primary History.

Stories of Heroism. Rand, McNally &

Co.

Montgomery, D. H. Leading Facts of

American History. Revised. Ginn & Co.

Morris, Charles. School History of the

United States. J. B. Lippincott Co.

Renouf, V. A. Outlines of General History.

The Macmillan Co. $1.30 net.

Robinson, J. H., and Beard, C. A. Readings

in Modern European History. Vol. II.

Ginn & Co.

Stearns. A Primer of Hebrew History.

Eaton & Mains (N. Y.). 40 cents net.

Southworth, G. V. D. First Book in American

History. D. Appleton & Co.

Supplementary Reading for Elementary

Schools.

Bevan, Thomas. Stories from British History

(B. C. 54—A. D. 1485). Little,

Brown & Co. 50 cents.

Bruce, H. Addington. The Romance of

American Expansion. Moffat, Yard & Co.

Coe, Fanny E. The First Book of Stories

for the Story-Teller. Houghton, Mifflin

Co. 80 cents net.

Cox, John H. Knighthood in Germ and

Flower. Little, Brown & Co. $1.00 net.

(In press.)

Otis, James. Richard of Jamestown: A

Story of the Virginia Colony. American

Book Co. 35 cents.

Elson, H. W. A Child’s Guide to American

History. Baker & Taylor Co. $1.25 net.

Hancock, Mary S. Children of History:

Early Times. Little, Brown & Co. 50

cents.

Hancock, Mary S. Children of History:

Later Times. Little, Brown & Co. 50

cents.

Harding. Samuel B. The Story of England.

Scott, Foresman & Co.

Hill, Frederic Stanhope. The Romance of

the American Navy. G. B. Putnam’s

Sons.

Hill, F. T. On the Trail of Washington:

A Narrative History of Washington’s

Boyhood and Manhood. D. Appleton &

Co. $1.50 net.

Historical Stories of the Ancient World and

the Middle Ages: Retold from St. Nicholas.

6 vols. Century Co.

Jenks, T. When America Won Liberty.

Crowell & Co. $1.25.

Josselyn, Freeman M., and Talbot, L. Raymond,

eds. Elementary Reader of French

History. 30 cents.

Little People Everywhere: Fritz in Germany;

Gerda in Sweden; Boris in Russia;

Betty in Canada. Little, Brown & Co.

60 cents each.

Lucia, R. Stories of American Discoverers

for Little Americans. American Book

Co. 40 cents.

Moores, William Elliott. The Life of

Abraham Lincoln, for Boys and Girls.

Houghton, Mifflin Co. 60 cents net.

Oxley, J. M. With Fife and Drum at

Louisburg. Little, Brown & Co. $1.00

net. (In press.)

Smith. Mary P. W. Boys and Girls of ’77.

Little, Brown & Co. $1.25.

Stephens, K. Stories from Old Chronicles.

Edited with introductions to the stories.

Sturgis & Walton. $1.50.

Stevenson, B. E. A Child’s Guide to Biography.

Baker and Taylor (N. Y.) $1.25

net.

Stevenson, Augusta. Children’s Classics in

Dramatic Form. Houghton, Mifflin Co.

Book II, $0.35 net; Book III, $0.40 net.

Tappan, Eva March. Heroes of European

History. Houghton, Mifflin Co.

Tappan, Eva March. Old Ballads in Prose.

Houghton, Mifflin Co. 40 cents net.

Tappan, Eva March. The Story of the

Greek People. Houghton, Mifflin Co.

$1.50.

Washington’s Birthday: Its History, Observance,

etc. Edited by R. H. Schauffler.

Moffat, Yard & Co. $1.00 net.

Government.

Beard, Charles A. Readings in American

Government and Politics. The Macmillan

Co. $1.90.

Bowker, Richard Rogers. Copyright: Its

History and Law. Houghton, Mifflin Co.

(Ready May. 1910.)

Commission Plan of Municipal Government:

Selected Articles Compiled by E. C. Robbins.

H. W. Wilson Co. (Minneapolis).

Dodd, W. F. The Government of the District

of Columbia. J. Byrne & Co. (Washington,

D. C.). $1.50.

Dodd, Walter F. Modern Constitutions. 2

vols. University of Chicago Press. $5.00

net.

Fuld, L. F. Police Administration: A

Study of Police Organization in the

United States and Abroad. G. P. Putnam’s

Sons. $3.00 net.

Fuller, H. B. The Speakers of the House.

Little, Brown & Co. $2.00 net.

Hughes, E. H. The Teaching of Citizenship.

W. A. Wilde Co. (Boston). $1.25.

Jenks, Jeremiah W. Principles of Politics,

from the Viewpoint of the American Citizen.

The Macmillan Co. $1.50 net.

Marriott, C. How Americans Are Governed

in Nation, State and City. Harper Brothers.

$1.25.

Reinsch, Paul S. Readings on American

Federal Government. Ginn & Co. $2.75.

Thomas, W. I. Source Book for Social

Origins. University of Chicago Press.

$4.50.

United States—General.

Abel, A. H. History of Events Resulting in

Indian Consolidation West of the Mississippi.

Government Printing Office

(Wash.).

Allen, Gardner W. Our Naval War With

France. Houghton, Mifflin Co. $1.50 net.

American Foreign Policy. By “A Diplomatist.”

Houghton, Mifflin Co. $1.25 net.

Avery, E. M. A History of the United

States and Its People. Vol. VI. Burrows

Bros. (Cleveland. O.).

Brooks, U. R. Butler and His Cavalry in

the War of Secession. 1861-1865. The

State Co. (Columbia. S. C.).

Bruce, H. Addington. Daniel Boone and the

Wilderness Road. The Macmillan Co.

(In press.)

Buchanan, James. The Works of. Edited by

John Bassett Moore. Vol. VII, VIII. IX,

X. J. B. Lippincott Co.

Campbell, T. J. Pioneer Priests of North

America. 1642-1710. Vol. II.

Canby, G., and Balderston, L. The Evolution

of the American Flag. Ferris &

Leach (Philadelphia). $1.00 net.

Carpenter, E. J. Roger Williams. The

Grafton Press (N. Y.), $2.00 net.

Carr, C. E., Stephen A. Douglas. A. C.

McClurg. $2.00 net.

Carter, Charles F. When Railroads Were

New. Henry Holt & Co. $2.00 net.

Carter, Clarence E. Great Britain and the

Illinois Country, 1763-1774. American

Historical Association (Wash., D. C.).

$1.50.

Chadwick, F. E. The Relations of the

United States and Spain: Diplomacy.

Chas. Scribner’s Sons. $4.00 net.

Chinese Question in the United States,

Bibliography of the. Compiled by R. E.

Cowan and B. Dunlap. A. M. Robertson

(San Francisco). $1.40 net.

Clay, T. H. Henry Clay. Jacobs & Co.

(Philadelphia.) $1.25 net.

Cockshott, Winnifred. The Pilgrim Fathers.

Their Church and Colony. G. P.

Putnam’s Sons, $2.50 net.

Coman, Katherine. Industrial History of

the United States (revised edition).

The Macmillan Co. (ready summer of

1910).

Connelley, William Elsey. Quantrill and the

Border Wars. The Torch Press (Cedar

Rapids, Ia.). $3.50.

Cornish, Vaughan. The Panama Canal and

Its Makers. Little, Brown & Co. $1.50

net.

Davis, J. Travels of Four Years and a Half

in the United States of America During

1798, 1799, 1800, and 1801 and 1802.

Henry Holt & Co. $2.50 net.

Documentary History of American Industrial

Society. Edited by John R. Commons,

Ulrich B. Phillips, Eugene A. Gilmore,

Helen L. Sumner and John B. Andrews.

10 vols. The Arthur H. Clark

Co. (Cleveland, O.). The set, $50.00 net.

(Vols. I to IV issued to April, 1910).

Documents of the States of the United

States. 1809-1904. The Carnegie Institution

of Washington.

Dodge, John. Narrative of his Captivity at

Detroit. With introduction by Clarence

Monroe Burton. The Torch Press (Cedar

Rapids, Ia.) $5.00.

Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the

War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. The

Torch Press (Cedar Rapids, Ia.) $10.00

net.

Eggleston, George Cary. The History of the

Confederate War. Its Causes and Its

Conduct. A Narrative and Critical History.

2 vols. Sturgis and Walton Co.

(N. Y.). $4.00 net.

Elliott, Edward G. The Biographical Story

of the Constitution. G. P. Putnam’s

Sons.

Esquemeling, J. The Buccaneers of America.

E. P. Dutton. $4.00 net.

Everhart, E. A Handbook of United States

Public Documents. H. W. Wilson Co.

(Minneapolis).

Ewing, E. W. R. History and Law of the

Hayes-Tilden Contest before the Electoral

Commission. Cobden Publishing Co.

(Wash., D. C.).

Faust, Albert Bernhardt. The German Element

in the United States. 2 vols.

Houghton, Mifflin Co. $7.50 net.

Fee, M. H. A Woman’s Impressions of the

Philippines. A. C. McClurg & Co. $1.75

net.

Fite, Emerson David. Social and Industrial

Conditions in the North During the Civil

War. The Macmillan Co. $2.00 net.

Flom, George T. A History of Norwegian

Immigration from Earliest Times to 1848.

The Torch Press (Cedar Rapids. Ia.).

$2.00.

Fow, John H. The True Story of the

American Flag. W. J. Campbell (Phila.).

$1.75.

Gilder, R. W. Lincoln the Leader. Houghton,

Mifflin Co. $1.00.

Griffin, Grace Gardner. Writings on American

History, 1907. The Macmillan Co.

$2.50.

Griffin, Grace G. Writings on American

History, 1908. The Macmillan Co. (In

press).

Gummere, Amelia Mott. Witchcraft and

Quakerism: A Study in Social History.

Biddle Press (Phila.), $1.00.

Hall, Alfred B. Panama and the Canal.

Newson & Co. (N. Y.). 60 cents.

Hanks, Charles Stedman. Our Plymouth

Forefathers: The Real Founders of Our

Republic. Dana Estes (Boston). $1.50.

[200]

Harding, S. B. Select Orations Illustrating

American Political History. The Macmillan

Co.

Hart, A. B., and others. Decisive Battles of

America. Harper & Brothers. $1.50.

Haskell, Frank A. The Battle of Gettysburg.

Wisconsin History Commission.

Hayes, John Russell. Old Meeting Houses.

Biddle Press (Phila.). $1.00.

Haynes, G. H. Charles Sumner. G. W.

Jacobs & Co. (Phila.). $1.25 net.

Hitchcock, Ethan Allen. Fifty Years in

Camp and Field. Diary edited by W. A.

Cruffut. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Hulbert, Archer Butler. Index to the Crown

Collection of Photographs of American

Maps. Only 25 copies printed. The

Arthur H. Clark Co. (Cleveland, O.).

$5.00 net.

Janvier, T. A. Henry Hudson. Harper &

Brothers. 75 cents net.

Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789.

Edited by W. C. Ford. Vols. XIII,

XIV and XV. Government Printing

Office (Wash.). $1.00 each.

Koerner, Gustave. Memoirs of. 1809-1896.

Edited by Thomas J. McCormack. 2 vols.

The Torch Press (Cedar Rapids, Ia.).

$10.00 net.

Learned, Marion Dexter. Abraham Lincoln.

An American Migration. W. J. Campbell

(Phila.). $3.00 net.

Leupp, F. E. The Indian and His Problem.

Chas. Scribner’s Sons. $2.00 net.

Lipps, Oscar H. The Navajos. The Torch

Press (Cedar Rapids. Ia.) $1.00.

Lyell’s Travels in North America in the

Years 1841-2. Edited by J. P. Cushing.

C.E. Merrill Co. 30 cents.

McChesney, Nathan W. Abraham Lincoln:

The Tribute of a Century, 1809-1909.

A. C. McClurg & Co. $2.75 net.

Macdonough, Rodney. Life of Commodore

Thomas Macdonough. Fort Hill Press

(Boston). $2.00.

McLaughlin, James. My Friend the Indian.

Houghton, Mifflin Co. $2.50 net.

McMaster, John Bach. A History of the

People of the United States, Vol. VII.

D. Appleton & Co. $2.50 net.

Mathews, Lois K. The Expansion of New

England. Houghton, Mifflin Co. $2.50

net.

Mathews, John Mabry. Legislative and Judicial

History of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Johns Hopkins Press (Balt.).

Myers, G. History of the Great American

Fortunes. Vol. II. Great Fortunes from

Railroads. Kerr & Co. (Chicago).

Newton, Joseph Fort. Lincoln and Herndon.

Including the Correspondence Between

Herndon and Theodore Parker. The

Torch Press (Cedar Rapids, Ia.). In

preparation.

Northmen in America. (Vol. II of Islandica.)

Cornell University Library (Ithaca,

N. Y.).

Noyes, Alexander Dana. Forty Years of

American Finance. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

$1.50 net.

Paullin, Charles Oscar. Commodore John

Rodgers. 1773-1838. A Biography. The

Arthur H. Clark Co. (Cleveland, O.). $4.00

net.

Paxson, Frederic L. The Last American

Frontier. The Macmillan Co. $1.50 net.

Phillips, I. N. Lincoln. McClurg & Co.

(Chicago). $1.00.

Polk, James K., The Diary of. Edited by

M. M. Quaife. 4 vols. A. C. McClurg &

Co. $20.00 net. (In press.)

Population Growth, a Century of: From the

First Census of the United States to the

Twelfth, 1790-1900. Department of Commerce

and Labor (Wash.)

Putnam, George Haven. Abraham Lincoln.

The People’s Leader in the Struggle for

National Existence. G. P. Putnam’s

Sons. $1.25 net.

Rankin, George A. An American Transportation

System. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

$1.50.

Ray, P. Orman. The Repeal of the Missouri

Compromise. The Arthur H. Clark

Co. (Cleveland, O.). $3.50 net.

Sanborn, F. B. Recollections of Seventy

Years. 2 vols. The Gorham Press (Boston).

Seal of the United States, The History of.

Government Printing Office (Wash.).

Simonds, William E. A History of American

Literature. Houghton, Mifflin Co.

Sonneck, O. G. T. Report on The Star-Spangled

Banner, Hail Columbia, America,

Yankee Doodle. Government Printing

Office (Wash.). 85 cents.

Spears, J. R. The Story of the American

Merchant Marine. The Macmillan Co.

$1.50 net.

Speer, E. Lincoln, Lee, Grant and Other

Biographical Addresses. Neale Publishing

Co. $2.00 net.

Steele, M. F. American Campaigns. 2 vols.

War Department, Washington.

Sumner, E. A. Abraham Lincoln. Tandy-Thomas

Co. (N. Y.). 25 cents.

Sutcliffe, A. C. Robert Fulton and the Clermont.

Century Co. $1.25 net.

Thorpe, Francis Newton. The Statesmanship

of Andrew Jackson as Told in His

Writings and Speeches. Tandy-Thomas

Co. (N. Y.). $2.50.

Warren, Charles. History of the Harvard

Law School and of Early Legal Conditions

in America. 3 vols. Lewis Publishing

Co.

Weir, Hugh C. The Conquest of the Isthmus.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons. $2.00 net.

Worcester, Dean C. The Philippine Islands

and Their People. The Macmillan Co.

United States—Local.

Alexander, De Alva Stanwood. A Political

History of the State of New York. Vol.

III (1862-1884). Henry Holt & Co. $2.50

net.

Ambler, Charles H. Sectionalism in Virginia.

University of Chicago Press. (In

press.)

Boggess, Arthur Clinton. The Settlement of

Illinois. 1778-1830. Chicago Historical

Society.

Bruce, Philip Alexander. The Institutional

History of Virginia in the Seventeenth

Century. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Canal Enlargement in New York State, and

Related Papers. Buffalo Historical Society

Publications. Vol. XIII.

Channing, Edward, and Lansing, Marion

Florence. The Story of the Great Lakes.

The Macmillan Co. $1.50 net.

Crawford, Mary C. Old Boston Days and

Ways. Little, Brown & Co. $2.50 net.

Crawford, Mary C. Romantic Days in Old

Boston. Little, Brown & Co. $2.50 net.

Crockett, Walter Hill. A History of Lake

Champlain: The Record of Three Centuries.

1609-1909. II. J. Shanley & Co.

(Burlington, Vt.).

Drake, Samuel Adams. New England

Legends and Folk Lore. Little, Brown &

Co. $1.50 net. (In press.)

Enoch, C. R. The Great Pacific Coast.

Chas. Scribner’s Sons. $4.00 net.

Griffis, William Elliot. The Story of New

Netherland. Houghton, Mifflin Co. $1.25

net.

Hamilton, Peter J. Colonial Mobile. Revised

and enlarged. Houghton, Mifflin Co.

$3.50 net.

Hart, Albert Bushnell. The Southern

South. D. Appleton & Co. $1.50 net.

Hichborn, L. Story of the Session of the

California Legislature of 1909. F. Hichborn

(Santa Clara, Cal.). $1.25.

Historical Guide to the City of New York.

Compiled by F. B. Kelley, F. A. Stokes

Co. $1.50 net.

Illinois Historical Collections: Governors’

Letter-Books, 1818-1834. Vol. IV. Illinois