Title: Children of Wild Australia

Author: Herbert Pitts

Release date: October 14, 2018 [eBook #58098]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

CHILDREN OF WILD AUSTRALIA

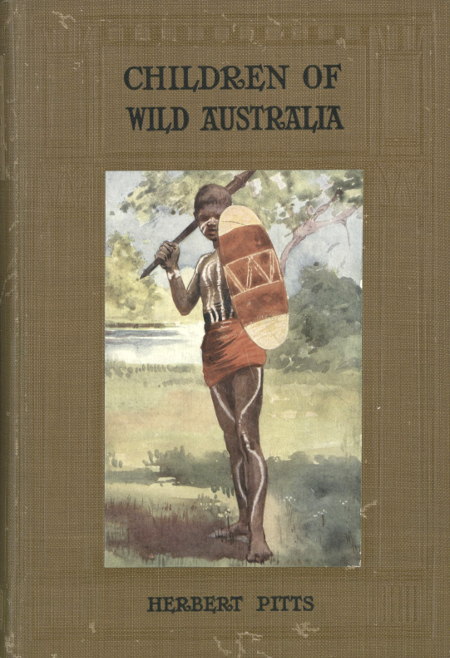

BOY SPEARING FISH

BY

HERBERT PITTS

AUTHOR OF

"THE AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL AND THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH"

WITH EIGHT COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

OLIPHANT, ANDERSON & FERRIER

PRINTED BY

TURNBULL AND SPEARS,

EDINBURGH

TO

DEAR LITTLE MARY

THIS LITTLE BOOK

ABOUT

THE LITTLE BLACK BOYS AND GIRLS

OF A FAR-OFF LAND

IS DEDICATED BY

HER FATHER

My Dear Boys and Girls,

All the time I have been writing this little book I have been wishing I could gather you all around me and take you with me to some of the places in faraway Australia where I myself have seen the little black children at their play. You would understand so much better all I have tried to say.

It is a bright sunny land where those children live, but in many ways a far less pleasant land to live in than our own. The country often grows very parched and bare, the grass dies, the rivers begin to dry up, and the poor little children of the wilderness have great difficulty in getting food. Then perhaps a great storm comes and a great quantity of rain falls. The rivers fill up and the grass begins to grow again, but myriads of flies follow and they get into the children's eyes and perhaps blind some of them, and the mosquitoes come and bite them and give them fevers sometimes.

Yet though much of the land is wilderness—bare, sandy plains—beautiful flowers bloom there after the rains. Lovely hibiscus, the giant scarlet pea, and thousands of delicate white and yellow [Pg 8]everlastings are there for the eyes to feast upon, but the loveliest flowers of all are frequently the love and tenderness and unselfishness which bloom in the children's hearts.

I have left Australia now and settled down again in the old homeland, but the memories of the eight years I spent among the dear little children out there are still very delightful ones, and they, more than anything I have read, have helped me to write this little book for you.

Your Sincere friend,

HERBERT PITTS

Douglas, I.O.M., 1914

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Introductory Letter | 7 | |

| I. | Introductory | 11 |

| II. | Piccaninnies | 17 |

| III. | "Great-great-greatest-grandfather" | 23 |

| IV. | Blackfellows' "Homes" | 26 |

| V. | Education | 31 |

| VI. | Weapons, etc., which Children learn to make and use | 35 |

| VII. | How Food is Caught and Cooked | 40 |

| VIII. | Corrobborees, or Native Dances | 44 |

| IX. | Magic and Sorcery | 47 |

| X. | Some Strange Ways of Disposing of the Dead | 56 |

| XI. | Some Stories which are told to Children | 60 |

| XII. | More Stories told to Children | 65 |

| XIII. | Religion | 68 |

| XIV. | Yarrabah | 72 |

| XV. | Trubanaman Creek | 79 |

| XVI. | Some Aboriginal Saints and Heroes | 85 |

| XVII. | The Chocolate Box | 89 |

| Boy spearing Fish | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Hunting Parrots and Cockatoos | 12 |

| Aboriginal Children and Native Hut | 28 |

| Learning to use the Boomerang | 42 |

| Youth in War Paint | 52 |

| Girls' Class at Yarrabah School | 73 |

| Bathing off Jetty at Yarrabah | 78 |

| The first School at Mitchell River | 84 |

CHILDREN OF

WILD AUSTRALIA

This little book is all about the children of wild Australia—where they came from, how they live, the weapons they fight with, their strange ideas and peculiar customs. But first of all you ought to know something of the country in which they live, whence and how they first came to it, and what we mean by "wild Australia" to-day, for it is not all "wild"—very, very far from that.

Australia is a very big country, nearly as large again as India, and no less than sixty times the size of England without Wales. Nearly half of it lies within the tropics so that in summer it is extremely hot. There are fewer white people than there are in London, in fact less than five millions in all and more than a third of these live in the five big cities which you will find around the coast, and about a third more in smaller towns not so very far from the sea. The further you travel from the coast the more scattered does the white population become, till some hundred[Pg 12] miles inland or more you reach the sheep and cattle country where the homes of the white men are twenty or even more miles apart. Further back still lies a vast, and, as far as whites are concerned, almost unpeopled region into which, however, the squatter is constantly pushing in search of new pastures for his flocks and herds, and into which the prospector goes further and further on the look-out for gold. This country we call in Australia "the Never-Never Land," and it is this which is wild Australia to-day. It lies mostly in the North and runs right up to the great central desert. It is there that the aboriginals, or black people, are found. The actual number of these black people cannot be exactly ascertained, but there are probably not more than 100,000 of them left to-day.

Much of wild Australia is made up of vast treeless plains and huge tracts of spinifex (a coarse native grass) and sand. Sometimes in the North-west one travels miles and miles without seeing a tree except on the river banks, but in Queensland there is sometimes dense and almost impenetrable jungle, and mighty, towering trees, with many beautiful flowering shrubs. All alike is called "bush," which is the general term in Australia for all that is not town.

The animals of wild Australia are most interesting and numerous. Several kinds of kangaroo (from the giant "old man," five feet or more in height, to the tiny little kangaroo mice no larger than our own mice at home), make their home there, and emus may often[Pg 13] be seen running across the plains. Gorgeous parrots and many varieties of cockatoos are found in great numbers, snakes are numerous, whilst the rivers and water-holes teem with fish. Wild dogs, or dingos, too, are very numerous.

HUNTING PARROTS AND COCKATOOS

For hundreds and hundreds of years the aborigines had this vast country to themselves, for though Spaniards, like Torres and De Quiros, and Dutchmen, like Tasman and Dirk Hartog, had visited their shores, and an Englishman named William Dampier had even landed in the North West in 1688, it was not till exactly a hundred years afterwards that white men first came to make their homes in their land.

The aborigines are a Dravidian people, and, some think, of the same parent stock as ourselves. Thousands of years ago, long, long before our remote ancestors had learned how to build houses, make pottery, till the soil, or domesticate any animal except the dog—long years, in fact, before history began, the aboriginals left their primitive home on the hills of the Deccan and drifting southward in their bark canoes landed at last on the northern and western shores of the great island continent. There they found an earlier people with darker skins than their own and curly hair, very much like the Papuans and Melanesians of to-day, and they drove them further and further southwards before them just as our own English forefathers, coming to this land, drove an earlier people before them into the mountain [Pg 14]fastnesses of Wales and Cumberland and into Cornwall. Some time afterwards came a series of earthquakes and other disturbances which cut Tasmania away from the mainland, and there till 1878 that early Papuan people survived.

As the blacks grew more numerous they began to form tribes, and to divide the country up among themselves. Thus each tribe had its own hunting-ground to which it must keep and on which no other tribe must come and settle. But at length the white men came and they recognized no such law. They settled down and began to build their own homes upon the black men's hunting-grounds and to bring in their sheep and cattle and turn them loose on the plains. The blacks did not at all like the white man's coming, and sometimes did all they could to prevent their settling down. They speared their sheep and cattle for food, they burned down their houses, they threw their spears at the men themselves, and did all they could to drive them back to sea. Sometimes hundreds of them would surround a new settler's home, and murder all the whites they could see. We must not blame the blacks. They were only doing what we should do ourselves if some invader came and settled in our country and tried to drive us back. But the white men were not to be driven back. They armed themselves and made open war upon the black people and I am afraid did many things of which we are all now thoroughly ashamed. For a few years the struggle between the two races[Pg 15] went on and at length the blacks had to own themselves beaten, and so Australia passed into the white man's hands.

The blacks to-day may be divided into three classes:—

1. The Mialls, or wild blacks, still living their own natural life in their great hunting-grounds in the North, just as they lived before the white men came. It is chiefly about these that this little book will tell.

2. The station-blacks, living on the sheep and cattle stations and helping the squatters on their "runs." They are fed and clothed in return for their work, and are given a new blanket every year. The men and boys ride about the run looking after the sheep, bring them in at shearing time and help with the shearing. The women and girls learn to do housework and make themselves useful in many ways. They seem very happy and comfortable and are usually well treated and well cared for by their masters. Once or twice a year, perhaps, they are given a "pink-eye," or holiday, and then away they go into the wild bush with their boomerangs and their spears, or perhaps visit some neighbouring camp further up or down the river's bank. Their houses are just "humpies," made of a few boughs, plastered over with clay or mud, with perhaps a piece or two of corrugated iron put up on the weather side. In this class, too, we ought to include those blacks, some hundreds, alas! in number, who spend their time "loafing about"[Pg 16] the mining camps and the coastal towns of the North, living as best they can, guilty often of crime, learning to drink, and swear, and gamble, and often making themselves a thorough nuisance to all around. More wretched, degraded beings it would not be possible to see—such a contrast to the fine, manly wild-blacks. The pity and the shame of it all is that it is the white man who has made them what they are.

3. The mission-blacks, that is the blacks on the mission stations such as Yarrabah, Mitchell River, and Beagle Bay. These will have some chapters to themselves later on and you will, I hope, be much interested in them. There are not very many of them, perhaps not more than six or seven hundred in all, but new mission stations are being started and so we may well hope that their number will soon increase. There are some splendid Christians among them, some of them quite an example to ourselves. Of those you shall hear more fully by and by.

As you read this little book your heart will be stirred sometimes with strange feelings that you cannot quite understand. Those strange feelings will be nothing less than the expression of your own brotherhood with them. Their skins may be "black" (though they are not really black at all), and their lives may be wild; but they have human hearts beating within them just as we have, and immortal souls, like ours, for which Christ died. Never forget this as you are reading. It is so easy to forget—to claim brotherhood with those who are wiser and greater than [Pg 17]ourselves, and to forget that just that same brotherhood unites us one by one with the countless thousands who make up what we call the wild and primitive peoples of the world.

People in wild Australia very seldom talk about babies. They call them by a much longer name, and one not nearly so easy to spell, piccaninnies. But whatever name we call them by—babies or piccaninnies—the little black children are perfectly delightful, as all children are.

I shall never forget the first little Australian piccaninny I ever saw. It was not more than a few hours old, and so fat and jolly, with a little twinkle in its eye as much as to say, "I know all about you and you needn't come and look at me." Of course I expected to see a dear little shiny black baby as black as coal, but very much to my surprise it wasn't black at all. It was a very beautiful golden-brown, but as the mother said to me, "him soon come along black piccaninny all right." Under his eyes and on his arms and on other parts of his body were little jet black lines, and these gradually widened and spread till in a few weeks time he was a very deep chocolate colour, for though we call them "the blacks" the[Pg 18] people of wild Australia are not really black but deep chocolate.

I am very sorry to tell you that many of the little piccaninnies who are born in Australia, especially if they happen to be girls, are not allowed to live at all. Perhaps the last little baby is still quite young and unable to help itself at all and so still needs all it's mother's care. Or perhaps there hasn't been any rain for many, many months and the grass has all withered and the water-holes have very nearly dried up, and there is very, very little food for anyone and the natives are beginning to think that it is never going to rain any more. In either of these cases the little baby is almost certain to be killed almost as soon as it is born, and perhaps, so scarce has food become, it may even be eaten by its parents and other members of the tribe.

There is another reason why babies are sometimes killed and eaten, and to us it seems a very horrible one indeed. Perhaps it is fat and healthy and there is some other and older child in the tribe who is weakly and thin. The natives will then sometimes kill the healthy baby and feed the weakly child on tiny portions of its flesh. It seems, as I said just now, very awful and very horrible, but the idea is this, that the strength and vigour of the younger child will be imparted to the weaker one.

It is the father who always decides whether the baby shall live or die. If it is allowed to live you must not imagine that it will be in any way neglected[Pg 19] or ill-treated. Quite the opposite is true. There is no country in the world where babies and older children are spoiled quite so much as they are in wild Australia. They are never corrected or chastised by either father or mother, and they do just exactly as they like. Sometimes, perhaps, when father and mother are both away their maternal grandmother may happen to give them a good smack in the same way and on the same part as is usual in civilized countries, but this is certainly the only form of punishment they ever receive. They are everyone's idol and everyone's playthings, and yet they are never kissed, because no Australian aboriginal knows how to kiss. If a mother wants to show her love for her little one she will place her lips to his and then blow through them, and this is the nearest to kissing she ever gets. But baby crows with delight whenever mother does this.

Australian mothers never carry their piccaninnies in their arms as British mothers do, neither of course do they have any fine perambulators or mail-carts to push them out in. The most usual way of carrying them when they are quite tiny is in a bag of opossum skin or plant fibre slung on the mother's back. At night baby will very likely be put to sleep in a cradle made of a piece of bent bark perhaps sown up at the ends and covered with an opossum skin or a few green leaves. This is generally called a pitchi. As soon, however, as baby is able to hold on it seems to prefer to sit astride its mother's shoulder or hip and hang on by her hair.

Names are usually given according to the order of birth, but on the sheep stations the babies usually receive a white child's name. "Tommies" and "Maries" are of course almost as frequent as they are here at home, but some babies get very fine names indeed, and some three or four. In the wild parts, however, it would be considered unlucky to name a child before it could walk. It is often called simply "child" or "girl" until then. The name, when it is given, often depends on something that happened at the time of its birth. A baby was once named "kangaroo rat" because one of these little animals ran through the mia-mia (house or home) a few minutes after it was born. Another was called "fire and water" because at the time of his birth the mia had caught fire and the fire had been put out with water. There is a similar custom among the Bedouins to-day, which has been in existence ever since the days of Jacob. You can see an instance of it in Genesis XXX. 10, 11. "Zilpah, Leah's maid, bare Jacob a son. And Leah said, A troop cometh: and she called his name Gad (i.e. a troop or company.)" Is it not strange that we should find this old Hebrew custom still in use in wild Australia?

But the name which is first given is frequently changed. Most boys and girls are given a new name altogether as soon as they are regarded as grown-up, i.e. about the age of fourteen. Again, should someone die who happens to have the same name, the child's will at once be changed, for the aboriginals, for[Pg 21] reasons which will be explained in a later chapter, never mention the names of their dead. Sometimes, again, as a sign of very special friendship two black people will exchange names.

There is one very curious custom among the blacks the "why" and "wherefore" no one has ever been quite able to explain. One of the things that would strike you most if you could look into the face of an aboriginal would be the great width of the nose. It sometimes extends almost across the face. It looks, if I may put it that way, almost as though it had been put on hot and before it had properly cooled had been accidentally sat upon. The reason is that when babies are quite tiny their mothers flatten their noses, but why they do this I cannot say. Probably a very broad nose is part of their idea of beauty.

It is always pretty to watch children at their play. You will remember how our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, like all child lovers, would often stand in the market place and watch the children playing. Sometimes they played weddings, sometimes funerals, and He once drew a lesson for the Jews from the conduct of those disagreeable and sulky children who would not join in. So it is a very pretty sight to see the little children of wild Australia playing. Like all other children they are very fond of games and grow very excited over them. Little girls may sometimes be seen sitting down and playing with little wooden dolls which a kind uncle or grandfather has made for them, whilst boys and girls alike will often play "Cat's[Pg 22] Cradle" for quite a long time, and very wonderful and elaborate are the figures some of them contrive. Yet, like most other children, they like noisier games best. A kind of football is very popular, and they will often play it for hours at a time. Some one chosen to begin the game will take a ball of fibre or opossum or kangaroo skin and kick it into the air. The others all rush to get it and the one who secures it kicks it again with his instep. They get very excited over it and their fathers and big brothers sometimes get very excited too and come and join in, and the shouts and laughter grow until the very rocks begin to echo back their merriment.

At another time they will play "hide and seek" just as white children do, or a sort of "I spy." Another time perhaps a mock kangaroo hunt will engage them. One of them will be kangaroo and the others will hunt him. For a long time he will elude them, but at last he has to own himself captured and allow the hunters to dispatch him with their tiny spears. So, in one way or another, the merry days roll on until childhood's days are done and the education of the young savage, of which you will learn in a later chapter, begins to be taken in hand.

Often when the writer has watched the little black children at their play that beautiful promise in the prophets has come into his mind, "the streets of the city shall be full of boys and girls playing in the streets thereof." The prophet was thinking of the New Jerusalem and its happiness, and a great longing has[Pg 23] come into the writer's mind for more men and women and children, too, to realize their duty to these forgotten children of the wild, and to take their part in bringing them into that heavenly city. Perhaps all those who read this little book will try what they can do.

Every little black piccaninny as soon as it is old enough to understand is told by its mother what sort of a spirit it has inside it, for the blackfellows all believe that their spirits have lived before and came in the very beginning out of some animal or plant. So some children have "kangaroo spirits," some "eagle spirits," some "emu spirits," and some, perhaps, the "spirit of the rain."

The mothers know exactly what kind of spirit each baby has. If it came to her in the kangaroo country then it has a kangaroo spirit and so on. In some parts it doesn't matter a bit what kind of a spirit father or mother may have. Father may have an emu spirit, mother an eagle hawk's, but if the baby came in the snakes' country it will have a snake's spirit.

Sometimes on the rocks in wild Australia you may see a rough picture of a kangaroo drawn by some native artist in coloured clays. It is a picture of the great-great-greatest-grandfather of the kangaroo men and so also, of course, of any little child who has a kangaroo spirit, because when he grows up he will belong to the kangaroo men. The story which he will be told about his great-great-greatest-grandfather will be something like this:—

"Ever so many moons ago" (for the blackfellows count all time by moons), "a great big kangaroo came up out of the earth at such and such a place and wandered about for a long time. After this he changed himself into a man and then he amused himself making spirits. Of course as he was a kangaroo man he could only make kangaroo spirits. These kangaroo spirits did not at all like having no bodies, so as they had none of their own they began to look about for other bodies to go into. (You will remember how in the Gospel story the spirits who were cast out of the poor demoniacs of Gadara were unhappy at the prospect of having no bodies, and so asked to go into the swine.) So some went into kangaroos and some into little black children who happened to come in their country. Then one day great-great-greatest-grandfather called them all together—all the kangaroos and all the little children with kangaroo spirits—and told them that they all alike had kangaroo spirits and so were really brothers and must never eat or harm one another. And so to-day all the children[Pg 25] with kangaroo spirits are taught to call the kangaroo their brother, and they will never eat or harm a kangaroo, and as you all know a kangaroo will never eat them."

If they have emu spirits they will never eat emu and so on.

The children are not told these stories by word of mouth as I have told you, but they are taught chiefly by means of corrobborees, or native dances, which you will read about later on.

The proper name of the animal or plant whose spirit they are said to have is their Totem, and every man, woman, and child in wild Australia belongs to some totem group and calls its totem its brother. You will hear more about these totems later on.

When I saw a black man, as I did sometimes, who wouldn't eat iguana I knew at once that he belonged to the iguana totem group and had an iguana spirit; and, of course, his great-great-greatest-grandfather was not a kangaroo but an iguana.

Now that you have learnt in this chapter something of what the little black children of wild Australia are taught about where they came from and the sort of spirits which they have you will, I hope, want to do something to help to teach them the truth—that God made them all and that not the spirit of an animal or plant but a beautiful bright spirit fresh from God's own hand has been given them all, and that all have the same kind of spirit and those spirits when they leave the body will not wander about the earth again[Pg 26] looking for some other body, but will "return to God Who gave them." They, just as much as we, are meant to live and enjoy God now and be happy with Him for ever hereafter.

[1] I owe this title and something of the contents of the chapter to Mrs Aeneas Gunn's very interesting book for children, "Little Black Princess."

One of the first things of which a little child takes notice is its home. The pictures on the wall, the pretty things all around, the flowers in the garden are a source of ever-increasing delight to its growing consciousness. The older it grows the more it comes to know and love its home. Some of those who read this book will, perhaps, have very beautiful homes richly decked with all that art and money can supply, others will have smaller and plainer ones, but the children of wild Australia have scarcely anything that can be called a home at all.

A blackfellows' camp will consist of a number of the plainest and rudest huts that one can either imagine or describe. Sometimes there is not even a hut, but they live entirely in the open air on the bank of some creek or stream with merely a breakwind of boughs to keep off the wind and rain. During bad weather they will all huddle together as close to the breakwind as they can, whilst their limbs shake and their teeth chatter with cold.

More often, however, something in the way of a hut is made. A few pieces of stick, which will easily bend, will be driven into the ground, covered with sheets of bark and a few boughs and perhaps plastered over with mud. Sometimes, where kangaroos are plentiful, some dried skins will be used instead of bark and boughs. There will, of course, be nothing in the way of chairs or tables, a few skins and a pitchi or two will probably be the only furniture, but a miscellaneous assortment of odds and ends will lie around. Some eight or nine souls may claim the hut as home.

These huts are arranged according to a fixed plan. Some will face in one direction, some in another. Thus a man's hut must never face in the same direction as that of his mother-in-law and certain other of his relatives.

A native camp always has a most untidy appearance. All kinds of things are left lying about, but as the black people are very honest nothing is ever stolen. They will give their things away freely but they will never think of taking what is not their own. Most of their time is spent out of doors. They only use their huts in wet and windy weather or when the nights are cold. Their food is always cooked and eaten outside, and bones and all kinds of remnants are littered about everywhere, but as they usually have several dogs these things do not remain for long. How thankful you and I ought to be for our homes and our home comforts, however plain and humble those homes may be!

If food is becoming scarce the people will often leave their camp altogether and migrate further up the river where it is more plentiful, for their camps, you must remember, are nearly always built upon a river's bank. Sometimes there may have been heavy rain in one part of their country and very little in another. Then they will move to where grass and game are more plentiful. We expect our food to be brought to our home, but the blacks take their homes to their food. Sometimes after a death, too, they will desert their settlement and encamp elsewhere. The dead man may have been a very troublesome person to get on with when alive, and they think if they bury him near his old camp and then move away themselves his ghost will not know where to find them and they will be rid of him altogether. This frequent moving of their homes is in many ways a very good thing. If they stayed too long in one place their huts would soon become very insanitary and diseases would begin to work havoc among them.

In the camp the old man's word is law. They even decide what food may be eaten and what must be left alone. They manage to forbid all the more delicate morsels to all the younger members of the tribe and so secure the best of everything for themselves. Women and girls are of little account among them. They are in fact but the "hewers of wood and drawers of water" for the men, and their life is one of terrible and never-ending drudgery. The little girls, of course, do not have to work, but they are[Pg 29] seldom made such pets of as are the little boys. At fourteen they are girls no longer and their life of drudgery begins.

ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND NATIVE HUT

Where, as on the mission stations, the Gospel is preached to this poor people it brings new joy and hope to the women. There is no other hope for them, nothing else that saves them from the slavery in which they are compelled to live. On the mission stations are real homes, houses like our own, into which love has entered and where woman is no longer slave or chattel, but a queen. Each family on these settlements has its own little holding fenced and cleared in which fruit, flowers, and vegetables and, perhaps, rice and maize are grown. The cottages are patterns of neatness both without and within, so tremendous is the difference the religion of Jesus Christ makes to this poor degraded people. If we had more missionaries we should have many more such homes and many more of the black women would enter into the meaning of those words in the twentieth chapter of St John—"The disciples went away again to their own home" and found the Resurrection light shining there in all its beauty.

Perhaps nothing would give us so good an idea of the position of women and girls among this people as to take our place in a native camp on the morning of some aboriginal girl's wedding day. The poor little bride, she will probably not be more than about fourteen, will have been told that her husband has come to fetch her. She has very likely never seen[Pg 30] him before, although she was engaged to him as soon as she was born, and he will probably be much older than she. She will cry a good deal and say she does not want to go, but she knows very well that by the laws of her tribe she must do so. Her father, expecting rebellion, will be standing by her side with a spear and a heavy club in his hand. The moment she attempts to resist her capture (for it is really nothing less) a blow from the spear will remind her she must go. If she tries, as she probably will, to run away the heavy club will fell her to the ground. Her husband may then begin to show his authority. He will seize her by her hair and drag her off in the the direction of his mia. She will very likely make her teeth meet in the calf of his leg, but it will be no good. She will only receive a kick from his bare foot in return. Arrived at her new home she has to cook her husband a dinner and then sit quietly by his side while he eats it. When he has finished she may have what is left, although he, not improbably, has been throwing pieces to the dogs all the time.

Such are the marriage ceremonies in wild Australia.

There are no schools in wild Australia, yet it must not be thought that the children receive no education. On the contrary their education begins at a very early age and is continued well into manhood and womanhood. Up to the age of seven or eight boys and girls play together and remain under their mother's care, but a separation then takes place and schooldays, if we may call them by that name, begin. The boys leave the society of the girls and sleep in the bachelor's camp. They begin to accompany their fathers on long tramps abroad. They are taught the names and qualities of the different plants and animals which they see, and the laws and legends of their tribe. Lessons of reverence and obedience to their elders are instilled into their young minds, and they have impressed upon them that they must never attempt to set up their own will against the superior will of the tribe. They are taught to use their eyes, and to take note of the footprints of the different animals and birds, and eventually to track them to their haunts. In this art of tracking many of them become wonderfully skilled. They will often say how long it is since a certain track was made, and in the case of a human foot-mark will often tell whose it is. They will say whether the traveller was a man or a woman,[Pg 32] and in some cases have been known to say, quite correctly, that the man was knock-kneed or slightly lame. Trackers employed by the police have often traced a man's footsteps over stony and rocky ground, being able to tell, from the displacing of a stone here and there, that the man whom they were seeking had passed that way. On one occasion a clergyman was travelling in the bush when he was met by an aboriginal boy who told him that a man had gone along that way earlier in the day, had been thrown from his horse about five miles further on but had not been hurt very much because he had got up after a few minutes and had gone after his horse; the man, however, was slightly lame, and the horse had cast a shoe. The same evening the clergyman met the man in question and found that the native's account of what happened was correct in every detail. He had gained his information entirely from careful observation of the tracks.

So wonderfully is this power of seeing trained that every object is most carefully noted as it is passed. The foot-marks of an emu or kangaroo on their way to water, the head of a wild turkey standing above the grass some two hundreds yards away, will be pointed out to the purblind white man who has never learned to see. If one of the lessons of life is to use the eyes the aboriginal teacher teaches his lessons well.

The children of wild Australia are taught to use their ears. They will start up at the first faint stirring of the leaves which tells that a storm of wind will[Pg 33] soon be down upon them or that an opossum or parrot is awakening in the tree. Their ears, too, will notice the slight rustling of the grass and the stealthy footsteps on the ground which tell that some enemy is near. It takes long and careful training to bring the power of hearing to such perfection as this.

They are taught to use their hands and to make and use the weapons, etc., of which you will read in the next chapter. What wonderful natural history lessons, too, theirs must be. The habits of all the various animals are learned out in the wild, and numerous stories about them are told. The traditions of all the places they come to are carefully narrated by the older men, and in this way a faithful adherence to the rules and customs of the tribe is ensured. Wonderful are the tales of their old ancestors which will be narrated around the camp fires at night, whilst in the day time excursions to some of the sacred spots, whose legends were told over night, may be made. So in one way or another a remarkable reverence for antiquity—for the dim and shadowy (though, to the aboriginal, very real) heroes of the "alcheringa," or distant dream age in which these old heroes lived, and for the aged will be instilled and the children grow up in ways of reverence and obedience which are often sadly lacking in more favoured lands.

Sometimes the growing lad at about the age of twelve or thirteen will be sent away to school, that is he will go to stay with some neighbouring friendly tribe whose old men will carefully complete the[Pg 34] education which his father and the men of his own tribe began.

But lessons are taught not only by word of mouth but by means of sacred rites which the young lad at about the age of fourteen is allowed to witness for the first time. In these sacred performances the deeds of some doughty ancestor are portrayed, and the boy as he gazes upon them, and listens to the answers given to the questions he is allowed to ask, learns more and more of the rules and traditions of his tribe. No women and children are ever allowed to be present at these solemnities. The tribal secrets which they depict may be known only to the men. A woman or girl who dared to venture near or pry into them would have her eyes put out or be killed at once by the men.

Before the young lad can be allowed to attend he needs to be solemnly initiated into his tribe. He is taken away into the bush and there undergoes a kind of savage Confirmation. A front tooth is knocked out, and the body is gashed with sharp stones. In some tribes a new gash is given as each new secret is imparted. Into the wounds thus made ashes or the down of the eagle hawk are rubbed to make the wound heal. The actual result is a raised scar which lasts on through life.

Sometimes what is called a Fire Ceremony is also performed to test the power of endurance of those who are henceforth to be regarded as men. A large fire is lighted and then the hot embers are strewn[Pg 35] on the ground. Over these a few green boughs are placed and the boys are made to lie down upon them until permission is given them by their elders to rise. The boughs, of course, keep them from being actually burned, but the heat of the fire is very great and they are often nearly suffocated with the smoke. Should the faintest cry escape one of them or should they fail to lie perfectly still they would be regarded as weak and effeminate and unworthy to be "made men," and their admission into the full privileges of the tribe would be delayed. These fire ceremonies are a very severe test of their power of endurance. The native lad will suffer a great deal rather than be thought soft and womanish, and there are few who fail to stand the severe test which is here demanded of them.

The people of wild Australia are still in what is called "the stone age," which means that all their tools and weapons are made of wood or stone. Those on the sheep stations and near the towns are, however, learning to use tin and iron, but it is not natural for them to do so.

The first tool they learn to use is a little digging[Pg 36] stick. Almost as soon as they are able to run alone one of these little instruments will be put into their hands and they will be shown how to use it. With these they learn very quickly how to dig for grubs and edible roots, and as they get a little older they may be seen making little "humpies" of sand. But the most wonderful of all their weapons is the boomerang. No other people in the world is known to use it though some have thought that it was once in use among the very ancient Egyptians. There is a very interesting theory as to the origin of the boomerang. Some children, it is said, were playing one day with the leaf of a white gum tree. As the leaves of this tree fall to the ground they go round and round, and if thrown forward with a quick jerk they make a curve and come back. An old man was watching them playing, and to please them he made a model of the leaf in wood. This was improved upon from time to time until it developed into the boomerang.

Boomerangs are of two kinds—war-boomerangs and toy-boomerangs or boomerangs proper. The first kind are rather larger and usually less curved than the others, but do not return when thrown. They are often about thirty inches long and have a sharp cutting edge. They are made entirely of wood, the branches of the iron-bark or she-oak tree being preferred. The necessary cutting and shaping has to be done entirely with sharp flints or diorite, the only tools except stone axes, which the natives in their wild state employ. They naturally take a very long[Pg 37] time to make, but, when made, are very deadly weapons. They can be thrown as far as a hundred and fifty yards, and even at that distance will inflict a very severe wound. When thrown from a distance of sixty yards they have been known to pass almost through a man's body.

Boomerangs proper are usually about twenty-four inches long, but there are seldom two of exactly the same size and pattern. They are rather more curved on the under than on the upper side. A man or boy who wants to throw one of them first examines it very carefully and then takes equally careful notice of the direction of the wind. He then throws it straight forward giving it a very sharp twist as he throws. At first it will keep fairly close to the ground, then after it has gone a certain distance it will turn over and at the same time rise in the air. Completing its outward flight, and perhaps hitting the object at which it was aimed, it turns over again and comes back to within a few feet of the man who threw it. Boys may often be seen practising for hours at a time with their little toy boomerangs, and by the time they are men many of them have become very proficient in throwing them.

A skilful thrower can do almost anything he likes with his boomerang. A native has been seen to knock a stone off the top of a post fifty yards away, but very few of them are quite as clever as this. None the less it would be rather dangerous for an unwary spectator to watch a party of native men and boys[Pg 38] throwing their boomerangs. An enemy or a hunted animal hiding behind a tree would be quite safe from a spear or bullet but could easily be taken in the rear and seriously injured by one of these extraordinary weapons when thrown by a skilful thrower. Kangaroos and emus find it almost impossible to avoid them whilst they work the most amazing havoc among a number of ducks or cockatoos just rising from water, or even among a flock of parrots on the wing. Many a supper has an aboriginal boy brought home with the aid of his trusty boomerang.

In Western Australia most of the aboriginals use a smaller and lighter boomerang than those in use in the other parts of the continent. This is called a kylie or kaila, and is very leaf-like. It will also fly further than the heavier weapon.

Next to the boomerang or kylie the weapons in most frequent use are spears. These, too, are very remarkable and vary much in length and character. Some are quite small and can be used without difficulty by a child. Some are as much as fifteen feet long. The simplest form of spear is no more than a pointed stick, but the wild blacks seldom content themselves with these. Often a groove is cut in one or both sides of the spear, and pieces of flint are inserted in the groove and fastened with native gum. More frequently deep barbs are cut at the sides and these will inflict a very ugly and painful wound, especially when, as is often the case, they have been previously dipped in the juice of some poison plant. The most elaborate spears are[Pg 39] those with stone heads. These heads are often beautifully made and are securely fastened to the spear with twine or gum. Where there are white men glass is often used instead, the glass being chipped into shape in a perfectly wonderful way with tools of flint. The patience displayed in their manufacture is admirable indeed. When the telegraph line was first erected in wild Australia the natives caused endless trouble to the Government by knocking off the glass or porcelain insulators and using them for spear heads.

Spears are sometimes thrown with the hand, but perhaps more frequently by means of a special instrument called a meero or wommera. This is a flat piece of wood about twenty-four inches long, with a tooth made of very hard white wood fastened to its head in such a way that when the wommerah is handled the tooth is towards the man who is holding it. This tooth fits into a hole at the end of the spear. Spears thrown with the wommerah will travel further and with much greater force than those thrown with the hand.

As a protection against an enemy's spear the aborigines usually provide themselves with a wooden shield or woonda. These are usually about thirty-three inches long and six inches wide and have a handle cut in the back. They are cut out of one solid block; and have grooved ridges on the front. The hollow parts between the ridges are frequently painted white with a kind of pipe-clay and the ridges are stained red. Why they are marked in this way and why the grooves are cut at all no one seems to know. The native men[Pg 40] are extraordinarily quick in the use of these shields, and will sometimes ward off with their aid a very large number of spears thrown at them in rapid succession. It is very important that boys should become proficient in making and using all these things as in after days their food-supply and even their lives may depend upon their proficiency.

While the men and boys are hard at work making these different implements the women and girls very likely busy themselves manufacturing bags and baskets. The baskets are made of thin twigs and the bags with string spun from the fibre of a coarse grass called spinifex, or perhaps from animal fur. In them they contrive to carry all their worldly goods as they travel from camp to camp, and occasionally baby also is safely stowed away in the same receptacle.

In very few parts of wild Australia can the black people count on a regular supply of food. Sometimes there is no rain for months, and consequently the grass disappears, water dries up, and many of the animals die. In these times of drought the conditions of the people are pitiable indeed.

The chief articles of diet besides seeds and roots are fish of various kinds—kangaroo, emu, lizards,[Pg 41] snake, wild turkey or bustard, parrots and cockatoos, insects and grubs. Vermin, too, are sometimes eaten, and clay is occasionally indulged in as dessert.

There are many ways of catching fish. The commonest method is by means of a spear. A native boy may often be seen standing on a rock in the middle of a pool, or by the water's edge, with a spear in his hand, his eyes intently fixed upon the water. As soon as a fish comes near down goes the spear and it is seldom that he fails to land his prey. In some parts rough canoes of bark are made and the fishing will be done from these. Sometimes the fish are poisoned by pouring the juices from some poison plant into the water but this method is not very often employed.

Their method of catching crayfish is not one that you and I would care to employ. They will walk about in the water and allow the fish to fasten on their toes, but so extraordinarily quick are they that they will stoop down and crush the creature's claws with their own fingers before it has had time to nip.

Even more varied than their ways of fishing are their methods of catching birds. A black boy may sometimes be seen stretched naked and motionless on a bare rock with a piece of fish in his fingers. When a bird comes to sample the fish he will with his disengaged hand, catch it by the leg. Parrots and cockatoos are often caught by means of the boomerang, but the native will sometimes employ quite another method. He will get into a tree at night, tie himself to a branch, and take with him a big stick. As the birds fly past[Pg 42] him he will lash out with his stick and bring large numbers of them to the ground. Emus are far too powerful to be caught in any of these ways. They are usually taken in nets as they come in the early morning to water. A number of natives will hide themselves in bushes or behind rocks and when the emus have gathered at the water-hole will steal out almost noiselessly (for emus are very timid birds and easily startled) and stretch large nets on three sides of a square behind them. The birds on returning from the pool walk straight into the nets and are easily speared.

Kangaroos are sometimes captured in the same way, but more frequently they are killed with spears. A native has been known to walk very many miles stalking a kangaroo. A case is even on record where a man spent three days in capturing one. When the kangaroo ran he ran, when it stood he stood, when it slept he slept, and so on till at last he was enabled to creep up sufficiently closely to dispatch it with his spear.

The way in which his food is cooked when he has caught it depends upon how hungry the aboriginal is. If he is very hungry indeed he may pull it to pieces with his teeth and his fingers there and then and eat it raw. If not quite so hungry but still impatient for his meal, the fish, or whatever it is, will be thrown upon the fire and eaten as soon as it is warmed through. The most elaborate way of all is to wrap the fish in a piece of paper bark with a few aromatic leaves, tie the ends carefully with native twine, and allow it[Pg 43] to cook slowly underneath the camp fire. A fish cooked in this way is most delicate and tasty, and would probably tempt the palate of a white man as much as it does the blacks.

LEARNING TO USE THE BOOMERANG

The natives always roast their food. They never touch anything boiled. But not even an aboriginal can cook his dinner unless he has first made a fire. There is nothing of the nature of matches among this people. When they want to make a fire they will take a piece of soft wood, place it on the ground and hold it in position with their feet. Another stick is then taken, pressed down upon the first piece, and made to rotate quickly upon it. Perhaps a few very dry leaves are placed near the place where one stick touches the other and as soon as the friction has caused the light dust to smoulder a gentle blow with the breath will cause the leaves to burst into flame. At other times two shields or kylies will be rubbed together until the dust catches fire. As these are rather wearisome methods of kindling flame, a fire once lighted is seldom allowed to go out. When camp is moved the women may be seen carrying pieces of smouldering charcoal in their hands. The movement through the air causes these to keep alight, and as soon as the new camping ground is reached all that needs to be done is to place them on the ground, pile a few dry leaves and sticks over them, and in a very few seconds a cheerful fire is blazing merrily. So expert are the women in keeping these fire-sticks alight that a party of[Pg 44] them will travel all day without allowing a single one to go out.

Among the special delights of an aboriginal boy or girl is the memory of the first corrobboree he was ever allowed to see. These corrobborees are very elaborate and curious native dances nearly always performed at night. The women and children are allowed to witness them but only the men actually take part. The black men who live on or near the stations often speak of these as "Debbil-debbil dances," as they are supposed to have some relation to the evil spirits, or "debbil-debbils," of whom the blacks are so terribly afraid.

It takes a long while to dress the men up for these dances. Often they are first pricked all over with sharp stones to make the blood flow, and this blood is then smeared all over their faces and bodies. Little tufts of white cockatoo or eagle hawk down are then stuck all over them, the blood being used as gum. If the doings of some mythical emu ancestor are to be celebrated in the dance only men belonging to the emu totem group will be allowed to perform. An enormous head-dress of down and feathers will next be made and put on, and large anklets of fresh green leaves will complete the array.

A large space will be specially prepared as the ceremonial ground. In front of this huge fires will usually be lighted, and either in front of these, or at the sides, a number of women and older girls will be seated with kangaroo skins drawn tightly across their knees. On these skins they beat with sticks or with their hands, making a noise similar to that which would be made by a number of kettle-drums. All the time the dancing is going on the women keep up a weird, monotonous chant, often beginning on a high key and dying down almost to a whisper. It is not very musical to our ears but the effect is often very strange and wonderful. It sometimes sounds as though a number of singers were gradually coming towards one from afar, then standing still awhile, then turning round and going back again.

One of the performers will come out upon the stage, go through a few curious antics which he calls a dance, then retire whilst another takes his place. After a while, perhaps, all will come on together and the fun for a time will be very fast and furious. The blacks are all so very serious about it, but any white people who happened to be looking on would find it very difficult to restrain their laughter. It would not do to laugh though, as the "debbil-debbils" would be very angry and might revenge themselves upon the blacks before long. After they have been dancing for some time the men present a very curious sight. The perspiration which has been pouring down their faces and bodies has disarranged their[Pg 46] paint and feathers and their head-dresses have got very much awry. Perhaps, too, they have grown almost dizzy with excitement, so that they certainly look more ludicrous than impressive.

They greatly enjoy these corrobborees and get wildly excited about them, but to us they would appear very monotonous and wearisome. To them, too, they are very full of meaning and they are one of the chief ways in which the young people are taught the legends of their tribes. Sometimes very useful moral lessons are taught by their means. An old man will very likely sit in the centre of a group of boys and carefully explain to them the meaning of all they see. They frequently last for hours, and some of them even require three or four nights if they are to be properly performed, so that the blackfellows spend a very great deal of time in preparing for and performing them.

Some of these corrobborees no women and young children are allowed to see. When this is the case a peculiar piece of sacred stone with a hole in the end, through which a string is fastened, is swung round and round by one of the men. As it is swung it makes a loud booming sound. This instrument is called a Bullroarer, and is looked upon as a very sacred thing. The women and girls are taught that the noise it makes is the voice of the evil spirit to whom it is sacred, warning them to hurry away and not dare to look at the sacred ceremonies which are about to be performed. If any of them disregarded the warning their eyes[Pg 47] would certainly be put out, and they might even be put to death.

When a friendly tribe, or group of natives, is visiting another tribe they will often be entertained by a corrobboree. On such an occasion the most difficult and elaborate of all their dances will most probably be performed. The next night the visitors will provide the entertainment.

Though there is very little idea of religion among the people, as you will see in later chapters, yet these dances have something of a religious character about them. They keep alive the old tribal legends, and the blacks most firmly believe that the spirits of their old ancestors are pleased when corrobborees are properly performed. On the other hand they are grievously offended if anything is done carelessly and without proper thought.

The blacks are great believers in magic and sorcery. Some of these beliefs are quite harmless and merely help to keep them amused, but others prove a terrible curse to them, as they can seldom rid themselves of the idea that another blackfellow somewhere is working them harm by means of sorcery, and they often die from fear.

The magical ceremonies of the aboriginals are of three kinds:—

1. Those by which they think they can control the weather.

2. Those by which they endeavour to secure an abundant supply of food.

3. Those by which they cause sickness and death—the use of "pointing sticks" and bones.

We will speak of each of these in order.

The commonest and most universal of all their magical ceremonies by which they hope to control the weather is that of making rain. Every group of natives has its "rain-makers," but the methods they employ are not everywhere the same. In North-western Australia the rain-maker usually goes away by himself to the top of some hill. He wears a very elaborate and wonderful head-dress of white down with a tuft of cockatoo feathers, and holds a wommera, or spear-thrower, in his hand. He squats for some time on the ground, singing aloud a very monotonous chant or incantation. Then, after a time, he rises to a stooping position, goes on singing, and as he does so moves his wommera backwards and forwards very rapidly, makes his whole body quiver and sway, and turns his head violently from side to side. Gradually his movements become more and more rapid, and by the time he has finished he is probably too dizzy to stand. If he were asked what the ceremonies meant he would most likely be unable to say more than that he was doing just what his great-great[Pg 49] greatest-grandfather did when he first made rain. Only men belonging to the "rain totem" are supposed to possess this power of making rain. Should rain fall after he has finished he, of course, takes all the credit for it and is a very important personage for a time. If it should fail to rain, as not infrequently happens, he will put it down to the fact that some other blackfellow, probably in some other tribe, has been using some powerful hostile magic to prevent his from taking effect. If he should happen to meet that other blackfellow there would probably be a very bad quarter of an hour for somebody!

Sometimes the rain-maker contents himself with a very much simpler ceremony. He goes to some sacred pool, sings a charm over it, then takes some of the water into his mouth and spits it out in all directions.

In the New Norcia district when the rain-makers wanted rain they used to pluck hair from their thighs and armpits and after singing a charm over it blow it in the direction from which they wanted the rain to come. If on the other hand they wished to prevent rain they would light pieces of sandalwood and beat the ground hard and dry with the burning brands. The idea was that this drying and burning of the soil would soon cause all the land to become hardened and dried by the sun. In fact their entire belief in this "sympathetic magic" as it is called is based upon the notion, perfectly true in a way, that "like produces like," and that for them to initiate either the actions of their ancestors who first produced such[Pg 50] and such a thing will have the same effect as then, or that the doing of something (such as causing water to fall) in a small way will cause the same result to happen on a very much larger scale.

In some parts of Western Australia when cooler weather is desired a magician will light huge fires and then sit beside them wrapped in a number of skins and blankets pretending to be very cold. His teeth will chatter and his whole body shake as though from severe cold, and he is fully persuaded that colder weather will follow in a few days.

In the second class of magical ceremonies are included all those which have for their purpose the ensuring of a plentiful supply of food. The people of wild Australia have no knowledge of those natural laws and forces, much less of that over-ruling Hand controlling them, by which their food supply is assured. They think that everything is due to magic, and therefore the performance of these magical ceremonies occupies a very large amount of their time. You have seen already that every tribe consists of a number of "totem groups" as they are called, and it is to these totem groups that the whole tribe looks to maintain the supply of their particular animals or plant. If the kangaroo men do their duty there will be plenty of kangaroos, but if they should become careless and slothful and begin to think of their own ease and comfort instead of the well-being of the tribe then the kangaroos will become fewer and fewer and perhaps disappear. These kangaroo ceremonies, as we may[Pg 51] call them, are usually performed at some rock or stone specially sacred to this particular animal and believed by the natives to have imprisoned within it, or at any rate in its near neighbourhood, a number of kangaroo spirits who are only awaiting the due performance of the ancient ceremonies to set them free from their prison and again go forth and become once more embodied. The men gather round the rock or stone, freely bleed themselves, and then smear the rock or stone with their blood. As they are "of one blood" with their totem it is, they think, kangaroo blood which is being poured out, and as "the blood is the life" they feel quite sure that it will enable the weak and feeble kangaroo spirits to become quite strong again. Then they arrange themselves in a kind of half-circle and "sing" their charm. No magical ceremonies are ever performed without "singing."

The "cockatoo" ceremonies, by which the natives hope to increase the number of cockatoos are much simpler, but to a white man who might happen to be in the near neighbourhood would prove a very thorough nuisance. A rough image of a white cockatoo will be made, and the man will imitate its harsh and piercing cry all night. When his voice fails, as it does at last from sheer exhaustion, his son will take up the cry till the father is able to begin again.

But of all the forms of magic or sorcery the most terrible is that of "bone-pointing" and "singing-dead."

A man desirous of doing his neighbour some harm[Pg 52] will provide himself with one of these sticks or bones, go off by himself into some lonely part of the bush, place the bone or stick in the ground, crouch over it and then mutter or "sing" into it some horrible curse. Perhaps he will sing some such awful curse as this over and over again:—

Then he will go back to the camp leaving the bone in the ground. Later he will return and bring the bone nearer to the camp. Then some evening, after it has grown dark, he will creep quietly up to the man whom he wants to injure and secretly point the bone at him. The magic will, he believes, pass at once from the bone to his victim, who soon afterwards will without any apparent cause sicken and die unless some bullya, or medicine man, can remove the curse. The bone is then taken away and hidden, for should it be found out that he had "pointed" it he would be killed at once.

YOUTH IN WAR PAINT

All the blackfellows, men, women, and children alike are horribly afraid of these pointing-bones, and believe fully in their awful power, and anyone who believes that one of them has been pointed at him is almost certain to die. Men in the full vigour of[Pg 53] early manhood and middle life have wasted away, just as though they had been stricken with consumption, because they could not rid themselves of the belief that this horrible magic had entered them. A man coming from the Alice Springs to the Tennant Creek caught a slight cold, but the natives at the latter place told him that some men belonging to a tribe about twelve miles away had taken his heart out by means of one of these pointing sticks. He believed their story, and though there was absolutely nothing the matter with him but a cold, simply laid himself down and wasted away. Probably several hundreds of men, women, and children die in wild Australia every year from fear of these awful bones and sticks alone. All sickness and death is ascribed to magic.

The only person who is believed able to remove this evil magic is the "bullya," or medicine man. These medicine men are believed to have had mysterious stones placed in their bodies by certain spirits. It is the possession of these stones that gives them their power to counteract evil magic. Lest these stones should dissolve they have to be very careful never to eat or drink anything hot. You could probably never tempt one of them to take a cup of hot tea. Should he do so all his powers as a doctor would be gone. Medicine men, however, are not called in for simpler ailments, though these too are attributed to magic. A common remedy for head-ache is to wear tightly round the forehead a belt of woman's hair. This is believed to have the power of driving out the magic.[Pg 54] Another frequent but much nastier medicine is several blows on the head with a heavy waddy. It is wonderful how few doses are required! Should a man be suffering from back-ache, or stomach-ache, he will lie down on the ground with the painful part of his body uppermost, and his friends and relations will jump on him one at a time till the "magic" goes.

One day a man came home from a long journey through the bush. Soon afterwards he was attacked by rheumatism and severe lameness. The medicine men told him that one of his enemies had seen his tracks and had put some sharp flints into his footmarks. His friends searched the track, found the flints, and removed them. Almost immediately the rheumatism and lameness left him and he was completely cured.

On another occasion a medicine man was called in to see a blackfellow who was lying very nearly at death's door. He said that some men in another tribe had charmed away his spirit but it hadn't gone very far and he could fetch it back. He at once ran after it and caught it just in time, so he said, and brought it back in his rug. He then threw himself across the sick man, pressed the rug over his stomach, made a few "passes" somewhat after the manner of a conjurer and so restored the spirit. The sick man speedily recovered.

These medicine men are not guilty of any trickery. They believe in their powers as thoroughly as the best European doctors believe in theirs. They are never paid for their services, but, of course, they expect to[Pg 55] be looked up to by the other members of the tribe and to be spared all labour and unpleasantness. They also expect the chief delicacies to be reserved for them, and that others should, as far as possible, do their bidding. No one would willingly offend a medicine man. His control of magic is much too dangerous a weapon to be used against them, far more deadly in its effects than spear or boomerang. He can put a curse in even more easily than he can get it out, and if he puts it in who is there to take it away? So you can see on the whole the medicine man has rather an easy time of it, but as no one wills it otherwise all are satisfied.

What a boon a few medical missions would prove in wild Australia—a few earnest Christian men and women who would go and heal the bodily diseases of the black people, and by their faithful teaching destroy this awful curse of belief in magic! How glad we all ought to be that wherever missions have been started, a hospital has been one of the first buildings to be erected. At Yarrabah, at Mitchell River and at the Roper River, all of which you will learn more fully about later on, the missionaries are devoting much time and thought to healing the sick, just as our Blessed Lord did when He was here among men. Soon after the missionaries have settled in a new home the sick from all around will come flocking in to have their needs attended to, and often stay in the settlement long after they are cured to learn the wonderful new message those missionaries have[Pg 56] brought about the Great Healer and all His Power and Love.

When a death has occurred in a blackfellow's camp, strange scenes are often witnessed. Perhaps just before it took place the dying man or woman would be brought out of the mia where he or she was lying and placed on a rug or blanket in the open air. The mia would then be pulled down to prevent the spirit remaining within it and thus becoming an annoyance and perhaps a source of danger to the survivors.

After death has actually occurred the mourners paint themselves all over with pipe-clay, or wilgi, rub huge quantities of clay and mud into their hair, and sit around the corpse making a most hideous wailing. They rock themselves to and fro for hours, keeping up the mourning cry all the time, but every now and again the women will relieve the monotony by a series of loud piercing shrieks.

The bodies of very young children sometimes remain unburied for some considerable time. The mothers will carry them about with them wherever they go in the hope that the spirit, seeing their grief and so young a body, will be full of pity and return.

With this exception dead bodies are usually disposed of within a few hours of death. The commonest method is burial, but bodies are sometimes burned, sometimes eaten, and not infrequently placed in trees, the bones being afterwards raked down and buried.

Graves are usually shallow, but the bodies are sometimes buried in a sitting position, sometimes standing. In Western Australia the hands, and at times the feet, are tied together in order to prevent the ghost from moving about and doing mischief. Among some tribes the right thumb is cut off before burial so that the dead man may be unable to use a spear. In other tribes a spear and a boomerang will be placed in the grave as the dead man may require them in the beautiful sky country to which his spirit will go. On one of the North-West Australian sheep stations a dead man who had been an inveterate smoker had his pipe and a stick of tobacco placed by his side. Very often a hole is left in the grave to enable the spirit if it wishes to do so to go in and out. In some places the grave is covered with boughs. In other places a hut will be built over it in the hope that the ghost will thus be kept within bounds and will refrain from wandering about and annoying the living. The ground around the grave will be swept clean with boughs and occasionally watched for footmarks. After the burial the camp will as a rule be moved.

When bodies are cremated a huge pile of dry grass and boughs is first prepared. Above this a platform,[Pg 58] also of boughs, is built, and the body placed upon it and covered with more boughs. A fire-stick is then applied by one of the nearest female relatives.

The most curious of all aboriginal methods of disposing of a dead body is that which is usually called "tree-burial." This is probably done in the hope of speedy re-incarnation, but when it becomes evident, say after a year has passed, that the spirit does not intend to return the bones are raked down with a piece of bark and placed in a cave and there buried. In the Kimberley district of Western Australia there are numbers of these burial caves. The arm-bone, however, is not buried with the rest. It is solemnly laid aside, wrapped in paper bark, and often elaborately decorated with feathers. When everything is in readiness preparations are made for bringing it into the camp with great ceremony. The bone is first placed in a hollow tree while some of the men go off in search of game which they bring into the camp and solemnly offer to the dead man's nearest male relatives. Next day the bone itself will be brought in and placed on the ground. All at once bow reverently towards it, the women meanwhile maintaining a loud wailing. It is then given to one of the dead man's female relatives who places it in her hut until it is required for the final ceremonies some days afterwards. These final ceremonies begin with a corrobboree, and the bone is then snatched by one of the men from the woman who has charge of it and taken to another of the men who breaks it with an axe. As soon as the[Pg 59] blow of the axe is heard the women flee, shrieking, to their camp and re-commence their wailing. The broken bone is then buried and the mourning ceremonies for the dead man are at an end.

The most revolting of all methods of disposing of dead bodies is that of eating them. This, however, you will be glad to learn is not very often employed. Sometimes it is pure cannibalism that makes them do so. Mothers have been known to join in a meal upon the bodies of their own children. Usually only the bodies of the famous dead, great warriors for instance, or of enemies killed in battle are thus disposed of. In some tribes it is looked upon as the most honourable form of burial. The reasons for this custom you will understand better when you have read carefully the chapter on Religion.

There is one very curious custom connected with mourning which I am sure you will be interested in hearing about, and the reason for which you will also come to understand when you have read a few more chapters. So far as I know it is not practised among any other people. Until the period of mourning is at an end the nearest female relatives of the dead man are placed under a rule of silence, and are not allowed to utter a single word. Perhaps for as long a time as two years they are only allowed to make use of "gesture language." Any attempt to speak on their part would at once be visited with heavy punishment perhaps even with death itself. It sometimes happens if there have been several deaths in a tribe[Pg 60] that all the women are under this ban, and it very seldom occurs that all are allowed to speak.

In this chapter and the next you shall hear some of the stories which the little children of wild Australia are told about the earth, the origin of man, the sun, the moon, and the stars, and about how sin and death came into this world of men. These tales fall very far short of those beautiful stories which have come down to us in the early chapters of Genesis, but the blackfellows all believe them to be strictly true. Often when they are seated around the camp fire on some bright star-lit night when the light from the fire will be shining brightly on their eager, dusky faces these old, old tales will be told again as only an old black can tell them.

They believe the earth to be flat and to stand out of the water on four huge lofty pillars, like very big tree trunks, and some think that above the sky, which they believe to be a solid dome arching over the earth, is a beautiful sky country where Baiame lives and the spirits. This Baiame is a god who is specially concerned in the ceremonies of making men, and is pleased when those ceremonies are properly performed. This sky country is much more beautiful and much better[Pg 61] watered than their own, and there are great numbers of kangaroo and game so that blackfellows who go there are never hungry and always have plenty of fun.

The road to it is the milky way which is made up of the spirits of the dead.

In many tribes the sun is regarded as a woman because among the blackfellows it is a woman's work to make fire. Here is one of the most remarkable of all the "sun stories" which the old blackfellows tell the children.

In olden days before there was any sun the birds and beasts were always quarrelling and playing tricks upon one another. A kind of crane called the courtenie, or native companion, was at the bottom of nearly all the mischief. In those days the emus lived in the clouds and had very long wings. They often looked down upon the earth and were particularly interested in the courtenies as they danced. One day an emu came down to earth and told them how much she would like to dance too. But the courtenies only laughed, and one of the oldest ones among them told the emu she could never dance while she had such long wings. Then all folded their wings and appeared to be wingless. The poor simple emu at once allowed her wings to be cut quite short, but no sooner had she done so than those wicked courtenies unfolded their beautiful wings and flew away. Then the kookaburra—or laughing jackass—burst into a loud laugh to think that the emu could be so silly. Later on the emu had a big[Pg 62] brood. A native companion saw her coming and at once hid all her chicks except one. "You poor silly emu," she said, "why don't you kill all your chicks except one? They'll wear you out with worry if you don't. Where do you think I should be if I went about with a family like that? You'll break down from over-work if you let them all live." So the silly emu destroyed her brood. Then the native companion gave a peculiar cry and out from their hiding-place came all her chicks one after the other. When the emu saw them she flew into a great rage and attacked that native companion and twisted her neck so badly that in future she was only able to utter two harsh notes.

Next season the emu was sitting on her eggs when the courtenie came along and pretended to be very friendly. This was more than that poor tormented emu could stand and she made a rush at the courtenie. But the courtenie leaped over the emu's back and broke all her eggs except one. Maddened with rage the emu made for her again, but she was not nearly agile enough, and met with no better success than before. The courtenie took the one remaining egg and sent it flying to the sky. At once a wonderful thing happened. The whole earth was flooded with brilliant and beautiful light. The egg had struck a huge pile of wood which a being named Ngoudenout, who lived in the sky, had been collecting for a very long time and set it on fire. The birds were so frightened by the beautiful light that they made up[Pg 63] their quarrel there and then and have lived happily ever after, but ever since then the courtenies have had twisted necks and only two harsh notes, and emus have had very short wings and have never laid more than one egg. Ngoudenout saw what a good thing it would be for the world to have the sun, and so ever since then he has lit the fire again every day. Of course when it is first lighted it doesn't give very much heat, and as it dies down towards night the world begins to get cold again. Ngoudenout spends the night collecting more wood for next day.

There are numerous other stories about the sun, but this one is sufficient to enable you to see the kind of beliefs the people of wild Australia have on these matters. Now listen to one which will show you how some of them account for the phases of the moon and for the stars.

Far away in the East is a beautiful country where numbers of moons live, a very big mob of moons, whole tribes in fact. These moons are very silly fellows. They will wander about at night alone, although a great big giant lives in the sky who as soon as he sees them cuts big pieces off and makes stars of them. Some of the moons get away before he can cut much off, but sometimes he cuts them nearly all up and hardly any moon is left at all.

"Why don't stars come out in the day-time?" a young child will ask and will receive this answer:—

"The stars are all very afraid of the sun. If he finds them out in the day-time he gets very angry[Pg 64] and burns them all. So they never come out till he has gone down under the earth. Sometimes, though, a little star will come and see if he has gone, but most of them wait in their country till he is really down."