Title: Harper's Young People, June 13, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: October 16, 2018 [eBook #58110]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—no. 137. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, June 13, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

THE DOGS HOLDING THE LYNX AT BAY.

THE DOGS HOLDING THE LYNX AT BAY.

Captain Banner, of the Yellowbird Ranch, sat upon a flat hot rock, half-way up a certain California hill-side, eating his luncheon. A few feet from the Captain stood tethered his good horse Huckleberry, who had no luncheon. No more had the three stout mongrel dogs who commonly ran along with Captain Banner, when the straying off of some of his cattle forced him to spend the day in getting at their whereabouts.

The dogs sat composedly on their haunches, two of them staring down into the ravine below, and the other one, Poncho, with his tongue out, watching every mouthful that the Captain took with much interest. But his master was in anything but a good-humor. He had ridden since early daylight, and not a single horned runaway had been sighted. No wonder he was discouraged.

"Upon my word," he said to the group of dogs, tossing a bit of cheese into Poncho's jaws, "you're a pretty set of brutes, I must say! Stringing along all day after Huckleberry's heels, and no more good at keeping a herd together or recovering it than—than greyhounds. Now if any one of you had the least— My good gracious!" he exclaimed, breaking off, "what is up?"

Before he had time for another syllable, away went the three dogs, heels over head, down the hill, and into the ravine, leaping and barking like mad creatures. One of them had suddenly caught a scent on the breeze; a second later espied with his keen eye a large tawny animal stealthily crossing the dried-up rivulet below. The trio were on full jump after it at once, like four-legged tornadoes. It seemed to be springing and dashing ahead of them like a beast resolved to get away at any price.[Pg 514] Captain Banner threw himself on Huckleberry, and clattered down after the dogs and it.

The dogs gained ground. "After him, Poncho!" shouted the Captain, wondering very much what "him" might stand for. All at once he heard a violent snarl and a loud yelp of pain. Poncho, the black dog, was on his back, struggling to regain his footing. Plainly the foe had bestowed a rousing whack with his paw upon the nearest pursuer, as a caution to come no closer. The chase, too, was slackened. The Captain came plunging along on his horse just in time to see a curious picture.

Rising up from the furze a few yards beyond was another flat rock. Upon that rock, with a thick thorn bush to defend him in the rear, half crouched, half stood, a great California lynx, all muscle, pluck, and grit, and seemingly full of fight from the end of his nose to the tip of his thick tail. The three dogs, including Poncho, leaped and bounded furiously around the rock, and barked with all their might and main; but they warily kept quite out of the reach of a dazzling set of teeth and enormous claws all displayed for action. The lynx remained compressed into the smallest possible space, growling and sputtering, and apparently contriving to look at each one of the three dogs at once. There was no doubt about it; he was clearly master of the field.

"Shame on you!" cried Captain Banner; "and three of you, too! At him, Turco; catch him by the throat, Poncho," he continued calling, while he prepared his lasso. But though, inspired by these encouragements, Turco, Poncho, and Red Jacket bayed and leaped up and about the lynx as if they would part company with their stout legs entirely, the great cat raised his thick paw and sputtered so savagely that all three beat a prudent retreat.

"Steady, Huckleberry!" came the Captain's voice. The lasso was thrown. Unluckily Huckleberry was nervous in such close relations to a lynx. He whined and started, and not the lynx, but poor Poncho, was successfully encircled by the flying noose, and rolled over, howling dismally and half choked. Nevertheless, this episode changed the current of the battle. The lynx realized that his enemy on horseback was more dangerous than the dogs. He sprang up and bounded away amongst the brush. The two free dogs tore after, and Captain Banner, hastily rescuing the gasping Poncho, spurred on too, coming up to the next battle-ground just when as close a rough-and-tumble fight as ever one could behold was under way.

The lynx had been overtaken. Turco had thrown himself upon him and pulled him down, while Red Jacket also sprang to his companion's help. But theirs was by no means the victory. The ground sloped considerably. The lynx grappled with his antagonists, and dragged them with him in his fall. The attacked and the attackers rolled down the ravine, an undistinguishable mass of legs and bodies, howling, spitting, snarling, and making the hair and fur fly to a degree that completely took away the Captain's breath, and made him wonder in what sort of condition the coveted skin would be when the struggle was over.

At one moment the lynx was under—now the dogs. Here leaped one of them, torn and bleeding, while his brother gladiator was dragged further along into the thicket, tugging to disengage himself from the gripping muscles that were rending and strangling him. But Poncho, comparatively fresh for a new onset, rushed up, and turned the tide of the fray. He fell upon the lynx like a small-sized tiger. Turco was freed, and the lynx, shaking off Poncho, gave a furious bound directly toward the Captain and Huckleberry (it was hard to say which was the more excited by this time), who were charging along well on the left. The lasso fell true at this second cast, though it had been an extremely hasty throw. The cord fell full over the furious creature's neck. It was taut in a second. The lynx struggled and gurgled, but it was too late.

Keeping off Poncho and Turco with his whip, the Captain finished up the enemy with the noose, and saved what was uninjured of his fine coat. Its late owner measured some four feet as he lay stiff and still upon the earth, so that the Captain as he rode back up the hill-side did not feel that his time and the chase had been lost. Poncho, Turco, and Red Jacket probably had their own private doubts about the matter, for one had lost an ear, another had suffered a cruel gash in his shoulder, and all of the trio were badly disfigured by scratches, bruises, and bites, and limped along rather dolefully.

The lynx's skin adorned Captain Banner's wall for weeks after, until it went with him up to San Pedro, and was converted into a goodly number of hard dollars.

Oh, the red roses, the pretty red roses,

That come with the June-time so fragrant and fair—

The sweet crimson roses that bud and that blossom

So joyously out in the soft summer air!

Under the hedges and over the hedges,

Out in the meadows, and down in the lane,

Blushing and blooming and clinging and nestling,

Grow the sweet roses again and again.

Beautiful, are they? But I have some fairer,

And, oh, so much sweeter! Look yonder, and see

The cluster of rose-buds, than none e'er grew rosier—

The freshest and daintiest of rose-buds for me.

The little white sun-bonnets—go, peep beneath them;

Mark the bright faces, where through the glad day

The breezes and sunbeams lay kisses in plenty,

And dimples and smiles chase each other in play.

Three little maidens so dainty and rosy,

Three little sun-bonnets all in a row,

Six little hands that are merrily twining

Crimson-red wreaths where the June roses grow.

Oh, how they welcome the bright smiling weather,

My little rose-buds that blossom for me!

And I tumble them out in the sunshine together,

And help them grow sweet as June roses should be.

Boys never have such splendid times anywhere as they do at their grandfathers'. How some fellows get along the way they have to without any grandfathers or grandmothers I never could make out. Just fancy having no grandfather to go and see Christmas and Thanksgiving and summer vacations! The fact is, a boy without any grandfather can't begin to have half a good time.

Fathers and mothers are all very well, but, you see, as mother explained the last time father had to whip us, they feel a responsibility. Now, grandfathers and grandmothers haven't any such responsibility. They can just give themselves up to being good-natured, and let a fellow have a good time. If he turns out bad, you see, it ain't their fault, and they don't have to worry about not having done their duty by him.

My grandfather lived just out of Blackridge, on a large farm. There was an academy at Blackridge, and so mother sent me to live there for a while and go to school; and Uncle Jerry's two boys, Ham and Mow (right names Hamilton and Mowbray), lived there all the time, and Uncle Jerry and Aunt Anna too, and we had just the best fun that ever any boys did have: I don't mean Uncle Jerry and Aunt Anna; they didn't go in for fun, you know. Uncle Jerry kept a store in the village, and Aunt Anna staid in the kitchen with grandma.

We always had to behave ourselves, and never thought of doing things without leave, for grandpa was not one of the kind to be disobeyed; besides, we loved him too well for that. But he was always ready to let us have a good time, and said that he liked to see boys enjoy themselves when they did it in the right way.

Besides Ham and Mow, there were the Davis boys, about five miles off, who went to the academy too; and once a week or so we spent the day with them, or they came to spend it with us. Real good fellows, both of them; and I think we liked the visit to them best, there were such lots of things to do there. Mr. Davis, you see, was what grandpa called "a progressive man"—I used to wonder what that meant, and say it over to myself whenever I saw him—and he wanted Frank and George to understand everything that was going on; and he used to get them all the improving boys' books that came out, and they had a tool chest, and a printing-press, and all kinds of drawing things, and the greatest lot of scrap-books; and they collected stamps and coins, and taught us how; and we used to make things when we went there, and Mr. Davis always gave a prize for the best.

Mr. Davis's right name was "Hon. Charles M. Davis." I saw it on his letters when the boys brought them from the Post-office, and they were very proud of their father's name. He had been to Congress, people said, and I used to wonder if this was as far off as the Cape of Good Hope.

Mrs. Davis used to train round (I don't mean that she acted bad) in a real handsome dress mornings, and she smiled at us pleasantly, and said that she liked boys, and hoped we wouldn't make her head quite split (Ham guessed there must be a big crack in it somewhere); and then she went off, and we didn't see her again until dinner-time.

I used to get 'most sick then, because Mrs. Davis said she thought boys could never have too much to eat; and she kept piling things on our plates, and it wouldn't be polite to leave them; and I was the littlest, and it really seemed as if I couldn't hold them all. Aunt Anna always said that "visiting didn't agree with Phil"; but I went all the same.

This was the way we got there: grandpa would let us have a horse when it wasn't too busy a day on the farm, and we all took turns in riding him. It was prime fun, and gave each of us just about enough walking. There was the one-mile mill, and Heckles's pasture, and the brook, and old Mrs. Junkett's little red house, and lots of places, where the boy that was on got off, and the next one took his turn; and we never quarrelled about it, and always came back feeling just about as good as when we started.

One morning in July we set off, expecting to have just the grandest kind of a time. Mr. Davis had got the boys something new from the city, and they wouldn't tell us what it was until we came. It was Saturday, of course, and most amazingly hot. Kitty (that was the horse) did not care about going very fast, and she crawled along with us, turn and turn, till we got about a mile from Mr. Davis's.

"A hornets' nest!" shouted Mow, who had walked on ahead of Kitty. "Come on, boys!"

"Stop," said Ham; "let's tie Kitty safely first."

So we led her to the shade of some trees on the edge of a piece of woods, where she would be safe from the hornets, and tied her fast; then off we went, full tilt, after Mow. He was staring up into a hollow tree, where we could just see the hornets' nest, looking like a brown-paper parcel full of holes—and a big fat one it was.

"There's millions in it," said he, as we came up; but he didn't mean money, only hornets.

This pleased us very much; not that we were exactly fond of hornets, but it made it more exciting. No matter what a boy is doing, he always has to go for a hornets' nest when he sees it; and we never thought about being warm or anything else, but just to send those hornets flying. We could see a few of them crawling in and out, and hanging round their paper house, and we meant to give them a hint that they'd been living in that hollow tree about long enough.

The tree was quite low, and we got long sticks and went at them. We had a lively time of it. The hornets came swarming out at us like ten thousand red-hot locomotives, burning us everywhere at once, for they stung us like fun; and we ran for dear life, and then came back and hacked away at them, our faces blazing with heat, and perspiration oozing from every pore. We took off our jackets at the beginning of the fray, or there would not have been much of them left, for the hornets were as mad as they could be, and so were we.

We kept it up for hours, never thinking how hot we were, or that it was time to be hungry, and we got that nest pretty well demolished. When the hornets were nearly gone, and there wasn't much of the nest to be seen, three tired boys limped off rather lamely to Kitty's cool bower, and throwing themselves down on the ground, fell fast asleep.

When they awoke, each looked at the other in great amazement. Ham's upper lip was puffed 'way out, and one eye closed; Mow's nose looked like a large pink potato: while as for me, the hornets seemed to have attacked every feature I had. The lengthening shadows warned us that it was supper-time, and with a puzzled feeling about our visit at the Davises', we turned our highly ornamented faces homeward.

"What has happened?" cried grandma, as we came within sight of the family gathered on the porch. "Do look at these boys!"

Of course every one looked at us; and as soon as they had settled what was the matter, they made us look ten times worse than ever by daubing our faces with mud.

We were rather afraid of punishment, at least by being sent supperless to bed; and I think we never loved grandma so much as when, calling us into the kitchen, she gave us one of the best suppers we ever had in our lives.

All that was ever said to us was said by grandpa the next morning, with a comical twist of his eye. "Boys, when you want another hornets' nest, you needn't go quite so far after it. There's a splendid one over the northeast end of the barn."

The Davises had a man with a wonderful magic lantern that day.

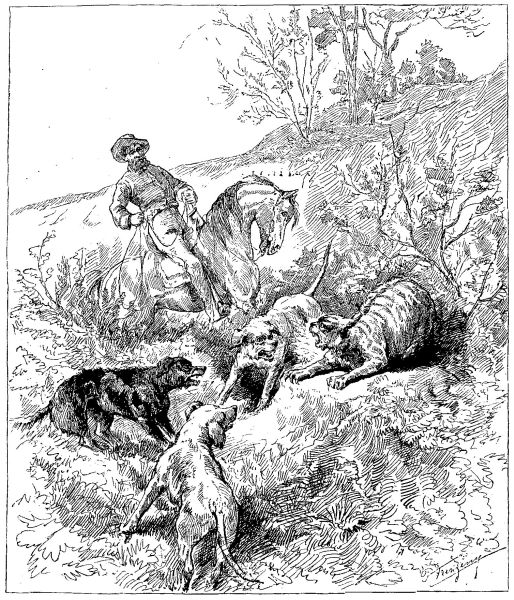

Some one has probably imagined that this curious floating animal looks like a Portuguese war vessel, and on that account has given to the innocent and defenseless creature a name which seems to us very inappropriate. We will not be dismayed, however, by a forbidding name, for the graceful animal is not in the least warlike. I hope you may all have the pleasure some day of seeing one floating over the sea like a fairy vessel, not minding the winds or the storms. You will be delighted with its beauty, and you will wonder how so frail a bark can withstand the waves.

When we examine it we shall find it to be a transparent pear-shaped bladder, about nine inches long, throwing off like a soap-bubble bright blue colors tinged with green and crimson. On top of the bladder there is a wavy rumpled crest of delicate pink. This may perhaps act as a sail.

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR.

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR.

From one end of the bottom hangs a large bunch of curious-looking, bright-colored threads, and bags, and coiled tentacles which trail after it. You will see these streamers in the picture, and you may be surprised to[Pg 516] learn that they are separate animals, forming a little colony, and floated by the same bladder. Still, they are not entirely distinct; they have various uses, and each contributes its share to the good of the colony. Some produce eggs, some do the swimming, some do the eating, and others are provided with lasso cells to procure food.

In such colonies of animals as this, the food which is taken by one individual helps to nourish all the others. This is accomplished by the circulation of fluids throughout the whole colony carrying nourishment to each one.

In animals that are more highly developed we shall find these offices performed by special parts of the same body. These different portions of the body, which are set apart to perform certain duties, are called organs. Thus we speak of the eye as the organ of sight, the ear as the organ of hearing, etc.

The tentacles of the Portuguese man-of-war are more than twenty feet long, yet they may be drawn up to within an inch of the bladder. It is exceedingly interesting to watch them as they are drawn up and then let down again. They are furnished with lasso cells, which not only wound the prey, but sting bathers or any persons who come in contact with them. Even after death the tentacles produce irritation when they are touched.

These beautiful creatures are found in tropical seas. They are abundant in the Gulf of Mexico, and they are often carried by the Gulf Stream into Northern waters. Occasionally they drift upon our own shore. Do you think you would recognize one floating on the ocean when you had not expected to see it? If you should ever have one in your possession, do not fail to dry it or keep it in alcohol, for although its delicate beauty can not be preserved, it will still be interesting to those who have never seen living ones.

One might suppose these animals were fond of society, since they float together in large companies, which have been fancifully called fleets. Travellers sometimes speak of meeting with them in great numbers, studding the surface of the ocean, and composed of both large and small animals, probably the young ones out sailing with their parents.

Shall I tell you a true story of a Portuguese man-of-war which was run down and captured by an American vessel?

Not many years ago a party of summer visitors on the quaint island of Martha's Vineyard, wishing to go to Gay Head, hired for the purpose a little steam-tug, and started one morning in fine spirits. Gay Head, I should tell you, is a promontory at the southwestern extremity of the island, remarkable for the curious manner in which the layer's of different-colored clays are deposited, making it look gay indeed. If you should see it, you would think it had been properly named. For quite a distance out at sea we may detect the distinct layers of black and white clays, with bright red and many soft shades of gray and yellow clay placed one above another, and all slanting from the top of the cliff at one side to the bottom of the other side.

The merry little party on board the steam-tug were enjoying the quiet waters and picturesque shores of Vineyard Sound, when a shrill cry from the children, "Portuguese man-of-war!" brought the whole party to that side of the boat in time to see the curious animal gliding past. It seemed to move very fast, but that was a deception caused by the rapid motion of the boat in the opposite direction.

Some of the party had a desire to catch the little thing floating so gallantly on the great waters, and as the Captain was easily persuaded, after a little delay the steamboat was turned about in its course, and started in pursuit. Does it not strike you as an uneven race? The eager company of men, women, and children, and the Captain too, and the pilot, with the steam-engine at their bidding, all intent upon overtaking the Portuguese man-of-war! So it appeared to some of those who were present, and the capture seemed rather an ignominious one. One little girl wondered how they had the heart to catch such a beautiful thing.

The little tug looked large and awkward as it came up beside the graceful creature gliding over the waves without the slightest effort. It seemed especially clumsy, as it had to back several times and make a fresh attempt to get within reach of the animal without swamping it.

The water was so clear that the whole length of the tentacles could be seen, and all on board were filled with admiration for the elegant form and delicate colors of the creature whose fate was sealed.

There was at least one on board who wished it was possible to warn it of its peril, and to suggest sinking in the water as its only means of escape. But it seemed to scorn the thought of danger, and floated proudly on right into the scoop-net that awaited it.

It was a moment of great excitement. The Portuguese man-of-war was lifted carefully on board, and placed in a pail of sea-water, where each one had an opportunity to examine it. The movement of its tentacles was curious. At times some of them were drawn up so as scarcely to be seen, then those were let down suddenly, and others drawn up; sometimes they were all lowered to the bottom of the pail, and were curled and twisted in a peculiar manner.

In lifting it from the water the tentacles hung so far over the edge of the boat as to leave no doubt about their being fully twenty feet in length. A gentleman lifted them into the pail with the handle of a broom. He must have touched the lasso cells in some way, for, notwithstanding his precaution, his hand was badly stung; the swelling extended the whole length of his arm, and it soon became very painful. The company examined some of the lasso cells with a microscope, and they were surprised that such fine white threads could cause so much pain.

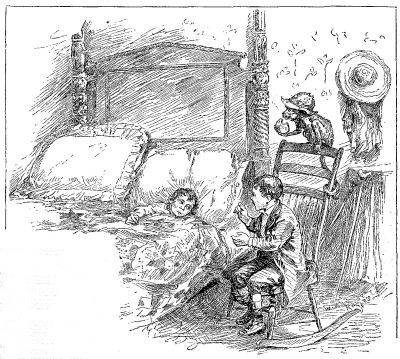

Toby was thoroughly surprised, when he awoke, to find that it was morning, and that his slumber had been as sweet as if nothing had happened. He dressed himself as quickly as possible, and ran down-stairs. Uncle Daniel told him the doctor had just left, after saying he thought Abner would recover.

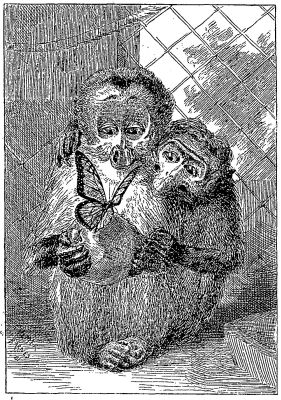

It was a sad visit that Toby paid Mr. Stubbs's brother that morning. The tears came into his eyes when he thought of poor Abner, until he was obliged to leave the monkey to himself, after having tied him so that he could take a short run out-of-doors.

Then he visited the ponies in the stable, and when he returned to the house he found all his partners in the circus enterprise, as well as several other boys, waiting to hear an account of the accident.

Dr. Abbott had reported that Abner had been injured; but as he had not given any particulars, the villagers were in a state of anxious uncertainty regarding the accident.

After Toby had told them all he knew about the matter, and had allowed them to see the monkey and the ponies, which some of them seemed to regard as of more importance than the injured boy, Bob asked:

"Well, now, what about our circus?"

"Why, we can't do anything on that till Abner gets well," said Toby, as if surprised that the matter should even be spoken about.

"Why not? He wasn't goin' to do any of the ridin', an' now's the time for us to go ahead, while we can remember what they did at the show yesterday. It don't make any difference 'bout our circus if he did get hurt;" and Bob looked around at the others as if asking whether they agreed with him or not.

"I think we ought to wait till he gets better," said Joe, "'cause he was goin' in with us, an' it don't seem fair to have the show when he's so sick."

"That's foolish," said Ben, with a sneer. "If he hadn't come up to the pasture the other day you wouldn't have thought anything 'bout him, an' he'd been out to the poor-farm, where he belongs now."

"If he hadn't come up there," said Toby, "I'd never known how lonesome he was, an' I'd gone right on havin' a good time without ever once thinkin' of him. An' if he hadn't come up there, perhaps he wouldn't have got hurt, an' it seems almost as if I'd done it to him, 'cause I took him to the circus."

"Don't make a fool of yourself, Toby Tyler!" and Ben Cushing spoke almost angrily. "You act awful silly 'bout that feller, an' father says he's only a pauper anyway."

"It wouldn't make any difference if he was, 'cause he's a poor lonesome cripple; but he ain't a pauper, for old Ben's goin' to take care of him, an' he pays Uncle Dan'l for lettin' him stay here."

This news was indeed surprising to the boys, and as they fully realized that Abner was under the protection of a "circus man," he rose considerably in their estimation.

They were anxious to know all about the matter, and when Toby had told them all he could, they looked at the case in such an entirely different light that Ben Cushing even offered to go out in the field, where he could be seen from the windows of the room in which Abner lay, and go through his entire acrobatic performance, in the hope the sight might do the invalid some good. Leander Leighton also offered to come twice each day and play "Yankee Doodle," with one finger, on the accordion, in order to soothe him.

But Toby thought it best to decline both these generous offers; he was glad they had been made, but would have been much better pleased if they had come while it was still believed Abner's only home was the poor-house.

When the boys went away, Toby pleaded so hard that Aunt Olive consented to his sitting in the chamber where Abner lay, with the agreement that he should make no noise; and there he remained nearly all the day, as still as any mouse, watching the pale face on which death seemed already to have set its imprint.

Each day for two weeks Toby remained on watch, leaving the room only when it was necessary, and he was at last rewarded by hearing Abner call him by name.

"MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER WAS BROUGHT IN."

"MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER WAS BROUGHT IN."

After that, Aunt Olive allowed the two boys to talk a little, and a few days later Mr. Stubbs's brother was brought in to pay his respects to the invalid.

Many times during Abner's illness had the boys been up to learn how he was getting on, and had tried to persuade Toby to commence again the preparations for the circus; but he had steadily refused to proceed further in the matter until Abner could at least play the part of spectator.

Uncle Daniel had had several letters from Ben inquiring about Abner's condition; and as each one contained money, some of which had been sent by the skeleton and his wife to "Toby Tyler's friend," the sick boy had wanted for nothing. Ben had also written that he had gained the consent of the proprietors of the circus to have the ponies driven for Abner's benefit, and had sent a dainty little carriage and harness so that he could ride out as soon as he was able.

Chandler Merrill had grown tired of waiting for his pony, and had taken him from the pasture, while Reddy had long since returned the blind horse to its owner.

But during all these five weeks the work of getting ready for the circus had gone slowly but steadily on. Leander had become so expert a musician on the accordion that he could play "Yankee Doodle" with all his fingers, "Old Hundred" with two, and was fast mastering the intricacies of "Old Dog Tray."

As to Ben Cushing, it would be hard to say exactly how much progress he had made, the reports differed so. He claimed to be able to turn hand-springs around the largest circus ring that was ever made, and to stand on his head for a week; but some of the boys who were not partners in the enterprise flatly contradicted this, and declared that they could do as many feats in the acrobatic line as he could.

Joe Robinson had practiced howling until Reddy insisted that there was little or no difference between him and the fiercest and strongest-lunged hyena that ever walked. Bob could sing the two songs his sister had taught him, and had written out twelve copies of them in order to have a good stock to sell from; but Leander predicted that he would not be able to dispose of many, because one was the "Suwanee River," and the other "A Poor Wayfaring Man," the words of which any boy could get by consulting an old music-book.

Reddy had made a remarkably large whip, which he could snap once out of every three attempts, and not hit himself on the head more than once out of five.

Thus the circus project was as promising as ever, and Abner, as well as the other partners, had urged Toby to take hold of it again; but he had made no promises until the day came when Abner was able to sit up, and Dr. Abbott said that he could go out for a ride in another week if he still continued to improve.

Then it was that Toby told his partners he would meet them on the first day Abner went out for a ride, and tell them when he would take up the circus work again, which made every one more anxious than ever to see the poor-farm boy out-of-doors.

From the time when the tiny little carriage and the two sets of harness glistening with silver had come, Toby had been anxious for a drive with the ponies; but he had resolutely refused to use them until Abner could go with him, although Uncle Daniel had told him he could try them whenever he wished. He had waited for his other pleasures until Abner could join him, and he insisted on waiting for this one. One day, when Aunt Olive spoke to him about it, he said:

"If I was sick, an' had such a team sent to me, I'd feel kinder bad to have some other boy using it, an' so I'm goin' to let Abner be the first one to go out with the ponies."

It was hard not even to get into the little carriage that was so carefully covered with a white cloth in the stable; but he resisted the temptation, and when at last the day did come that Aunt Olive and Uncle Daniel helped the sick boy down-stairs, and lifted him into the prettiest little pony-carriage ever seen in Guilford, Toby felt amply rewarded for his self-denial.

They drove all over the town, stopping now and then to speak with some of their friends, or to answer questions as to Abner's health. When it was nearly time to return home, Toby turned the ponies' heads toward the pasture, where he knew his partners were waiting for him according to agreement.

"We'll go on with the circus now," he said to Abner, "for I can take you with me in this team, an' you can stay in it all the time we're practicin', so's it'll be 'most as good as if you could do something toward it yourself."

Abner was quietly happy; the tender, thoughtful care that had been bestowed upon him since his mishap had been such as, in his mind at least, repaid him for all the pain.

"I hope you will have it," he said, earnestly, "for even if I can't be with you all the time, I won't feel as if I was keepin' you from it."

Then he put his hand in a loving way on Toby's cheek, and the "boss of the circus" felt fully repaid for having waited for his pleasure.

At the pasture all the partners were gathered, for Toby had promised to tell them when he would begin operations; and as he drove the ponies up to the bars, he shouted:

"Abner an' me will be up here about nine o'clock to-morrow mornin', an' we'll bring Mr. Stubbs's brother with us."

There was a mighty shout, and Ben Cushing stood on his head when this announcement was made, and then Toby and Abner drove home as quickly as their ponies could scamper.

Carniola, in the western part of Austria, and fronting on the Adriatic Sea, is a region remarkable chiefly for its subterranean streams and immense caverns and abysses. It is very mountainous, being traversed by spurs of the Alps, and covers an area of 3857 square miles. Its inhabitants are a hardy, thrifty race, engaged in the cultivation of wine, timber, maize, and millet.

Of all the wonders of nature to be met with in this country the one most deserving of notice is the lake of Zirknitz. This lake takes its name from a small market-town with a population of 1500, and situated about thirty miles northeast of Trieste, the principal sea-port city of Austria.

Lake Zirknitz lies in a deep valley surrounded by beautiful hills. It is a fair sheet of water, six miles long and three miles broad, and teeming with fishes and water-fowl. The monotony of this large expanse of water is relieved by five small islands, on one of which is the village of Ottok. These islands are favorite resorts for picnic parties. The bottom of the lake is formed of limestone rock, and is full of clefts and fissures. During prolonged dry weather the waters pass into these caverns, carrying their finny inhabitants with them. The church bells give warning when the first sign of the sinking of the lake is observed, and the people hasten to make the most of the fishing while there is yet time.

When the water has entirely disappeared, a crop of luxuriant herbage takes its place, affording pasture for the cattle of the neighboring farmers, who are thus enabled to reap where before they went a-fishing. With the recurrence of heavy rains the lake gushes forth from its under-ground retreat, rises speedily to its normal level, and resumes its ordinary appearance.

Until a comparatively recent time the causes of the periodical disappearance of the lake were involved in mystery, and people were content to accept as a fact that which they could not explain. In later years, however, scientific men have devoted many years of their lives to the task of exploring these under-ground recesses, and with the happiest results.

Although the subterranean geography of this region has been, to the present, only sketched out, still enough has been discovered to satisfy them that many of the under-ground passages extend to long distances, and it has been conclusively proven that the waters of the Zirknitz Lake at the periods of their recession flow through under-ground channels into the river Unz, which further on joins the river Save, a tributary of the Danube.

It had been an eventful morning in the attic. There were six of us—three of the Guernsey cousins and three of ourselves. Fanny Guernsey and our Ned had been reading Robinson Crusoe and the Swiss Family Robinson, and so we had all suffered a most horrible shipwreck, and had finally been cast upon a desert island. The ship was an ancient cradle, into which we were packed like sardines, and which, owing to Ned's vigorous efforts at "the wheel," lurched around the attic in a fearful way, and finally tumbled us all out in a heap upon an old-fashioned braided rug in a corner. We found ourselves too dense a population for "the island," and so Jamie Guernsey and I paddled off to the wreck, and got aboard. Then all at once a change passed over the wreck, and we (Jem and I) were Mr. and Mrs. Noah, urging our sons and daughters to hurry into the ark, and be saved. They at once saw that they were huddled upon the highest peak of a mountain, and must soon be drowned, so in they clambered, bringing two dolls with them to make out eight souls, and again we went sailing over the floods. It was Ned who first thought of our little oversight in forgetting to take animals into the ark.

"What on earth are we to do?" he cried.

"There isn't any earth. It's all water," said Fanny.

"Well, when we do get on earth, what are we to do for meat and milk and wool—and—and—"

"Oh, it's all up, and we might as well stop being Noah and his wife," said Jem to me, impatiently. "What's an ark without the animals? And there isn't room for a mouse."

"Oh, Jem, you and the girls get on the chest," said the fertile Ned, "and we'll be pirates, and swoop down on you."

"I don't want to be swooped down upon," said Jem, unreconciled.

"Oh, it's fun. Come on, Phil!" And upon that we were tumbled out, and Ned and Phil leaped into the cr—cruiser with such a piratical mien, and turned so fiercely upon us, that we were glad—Fanny and Jessie and I—to clamber up on the old chest for refuge. Then the cruiser, with a black neck-tie flying from a cane mast, bore down upon us so hotly that Jem was forced to come to our defense, and manfully he fought, too. Poor Jessie shrank into a little heap, and screamed. Fanny, her eyes flashing, and her tumbled, shining hair full of dried thoroughwort leaves from a great bunch hanging close above her, was struggling desperately with Ned, who, instead of carrying her off in his arms, as a true pirate should do, was pulling her aboard his cruiser by one foot, while with a crutch that used to be our grandfather's I was pushing her off—not Fanny, but the cruiser, I mean—into deep water. I was succeeding finely, when Phil kicked the foot of the crutch aside as I was throwing my whole weight upon the top, and in a trice I had rolled into the hold of the pirate ship.

This was too much for Jamie, who seized the mast of the cruiser, with a cry of "Down with the black flag!" and dealt Phil a blow upon the back that added another voice to the general chorus of shrieks.

In the midst of the uproar we heard a soft voice from the extreme end of the attic, calling,

"Children! children!"

One by one we ceased our outcries, and listened.

"Children"—what a soft thread of a voice it was that came out of the darkness!—"children—Ned, Fanny, Phil, Jessie, Bessie, Jem—come here."

We all looked at each other, until Ned rose bravely and started for the voice, the rest of us creeping after him. Midway we stopped, and the voice called,

"Come, children, come."

There was no mistake now; it was the portrait. We huddled together, but drew nearer and nearer, for there was enchantment in the voice, and as it grew upon us in the dim light there was enchantment in the face and figure also.

"LITTLE GRANDMOTHER."

"LITTLE GRANDMOTHER."

It was the portrait we were all familiar with, and which we called the "Little Grandmother." It was the portrait of our mother's grandmother, taken at the age of sixteen, and which had always hung in the library until the last holidays, when Phil had by mischance let a missile from his new toy gun fly in the direction of the portrait. It made an ugly hole in the canvas among the dark curls of our pretty Little Grandmother. It was considered a family calamity, but until it could be sent to a reliable restorer of pictures, it was set up on an old dresser at the end of the attic. It had had a piece of green baize thrown over it, which was removed, and now lay on the dresser beside it. Had she taken off the veil herself?

"Children," she continued, looking right on up among the rafters, as if she were talking to herself instead of to us, "you never heard me speak before, and you will never hear me speak again; so open your ears. Phil"—Phil started and began to quake—"I am sure I hold no personal grudge against you for that unlucky shot that mutilated my poor head in this way, but your general conduct is a distress to me. A boy of twelve should begin to show his knightly qualities, if ever he hopes to bear the grand old name of gentleman. Gentleman, indeed! to shoot his great-grandmother, with scarcely a pang of regret, and trip his girl cousin, and witness her fall with a laugh! Gentleman, indeed! And, Ned, you are scarcely a whit behind. You are brave, in a sense, but the bravery that attacks weakness, and shouts over its own triumphs, is a spurious bravery. A fine Sir Galahad or Sir Philip Sidney you would make! There is as crying need of brave and courtly men now as in the days of Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, but where are they? The dear maidens must hope in vain for protection from evil men and evil beasts if 'the boy is father to the man.' Jamie, you are not as strong and as full of action as Ned and Phil, but you are a true knight, and perhaps one of these days you can say,

"'My strength is as the strength of ten

Because my heart is pure.'

"You have nothing to fear, Sir Jamie."

By this time Fanny, Jessie, and I had sunk in a little heap on the floor. How pretty she looked, this girl grandmother! Her dark curls clung so daintily around her olive face, and the dark eyes shone out from the shaded brow with such a clear, honest light. We fancied we could see the red lips move, and the creamy white dress, with its bit of a waist and short puffy sleeves, tremble with the beating of her heart. Our own almost ceased to beat when she resumed.

"Fanny, Bessie, Jessie, you are dear girls, though I fear you are going to lack nobility and dignity of character; but what can be expected of girls that are taught French instead of their catechism, and the waltz in place of the minuet! Really, girls, I never screamed in my life—not even when a shell from a man-of-war burst in front of our house; and I must say I never witnessed such a romp as this among boys and girls in all the eighty-five years that I lived."

Eighty-five years! We looked from our Little Grandmother to each other in astonishment, and then the voice went on:

"But girls are not as they used to be, and perhaps they can not be. The world is growing weaker and wiser, and you have more already in your little noddles than I ever learned from books. I did not mean to scold you, my dears, but I have often wished to give you a bit of advice, and I have never had so fine an opportunity as this. If[Pg 520] the great-grandsons of Mary Angela Bascombe are knightly men, brave, tender, and true, and her great-granddaughters are ladies, indeed, gracious, gentle, loyal, and loving, she will be grateful for the happy misfortune that sent her to the attic."

There was a long silence. Then Fanny drew a long breath, and each one of us immediately did the same. Ned, always the leader, stepped forward a little, and said, "Little Grandmother, we mean, you know, to be all right—but—but—"

"And we'll do our best after this; indeed we will," added Jamie.

"That's so," put in Phil, rather awkwardly.

"We love, you, Little Grandmother!" burst out Fanny—clasping her hands—in a little ecstasy, while Jessie and I murmured something in chorus about wishing to be like her; but there was no response from the portrait to anything that we said.

We had not noticed that the dim light was fading from the attic, and the portrait losing its outlines, until the sound of a bell below recalled us to outward things. Then, clutching each other as we went, we passed down the attic stairs and through the halls, and gathered in a very quiet knot in the tea-room. One by one the family gathered there also, and the seats around the long table were quietly filled.

"What is the matter with you youngsters?" said my father, scanning our faces keenly. "You are as mute as mice, and look as if you had seen your grandmother's ghost."

"We—we have," said Fanny, with a hysterical laugh, that ended in a sob; and at that Jessie and I put our napkins to our faces and began to sob too, while the boys looked at each other and smiled in a sickly sort of way.

"What does this mean, Ned?" said my father, laying down his napkin; and my mother nearly shivered a cup and saucer, she set it down so suddenly.

"Why, the—the portrait, you know, up in the attic—the Little Grandmother—has been talking to us, and we don't just know what it means," said Ned, making a strong effort to overcome his tremor.

"Talking to you! What did it say?" my father demanded again.

Here Phil came to the rescue, and said, sturdily, if not defiantly, "She said we were no gentlemen, sir."

"Gentlemen, indeed!" echoed Cousin Rob, in a sweet falsetto voice, from the end of the table; whereupon Ned, Phil, and Jamie rose in their seats, nearly overturning their chairs. Fanny and Jessie caught each other around the neck, and sobbed a short sob, with a little shriek at the end of it, and I fled crying to my mother.

It was a very trying scene. My father lost all patience, and my mother was in real distress, and as five or six were talking at the same moment, the matter became more and more hopeless, until Ned, who had gone over to speak to Rob at the end of the table, set up a clear, ringing, healthy laugh that silenced us all, and turned the force of my father's wrath full in that direction.

"Ned, we want no more of this nonsense. If this is one of your offensive practical jokes, explain at once."

"It's not mine—it's Rob's," cried Ned.

"Well, Robert?" said my father, trying to control himself.

"I beg your pardon, Uncle James," said Robert. "I am wholly to blame, but I did not anticipate such a scene as this. Aunt Fanny sent me to the store-room at the end of the attic about an hour ago for some corn for the children to pop after tea. I went up by the back attic stairs. There was fun, I can assure you, in the main attic. I never heard such a Babel. I went to the little open window that was made to let light through from the store-room into the main attic, and saw that you had set the portrait on the old dresser on the other side, and so covered the window; but through that ugly hole that Phil made in the Little Grandmother's head I could see that Ned and Phil were making terrible havoc with the girls, while Jamie was trying to defend them. When I saw poor Bessie go under, I thought it time to interfere, and began calling to them. Then the funny fact of talking through the Little Grandmother's head grew upon me, and I assumed the falsetto voice that you heard a few minutes ago. I was the falsetto in the college quintette club, and so became an expert in the use of it. I found that the youngsters really thought the Little Grandmother was calling them, and so I improved the golden opportunity. I'm afraid I didn't lecture in character. I beg the Little Grandmother's pardon if I did not, but I think I managed to make a few timely suggestions to Ned and Phil; and I saw and heard one thing that I shall never, never forget. It was Fanny, when she clasped her hands like this; and gushed: 'I love you, Little Grandmother.'"

Here all the children, who had returned to their normal state of mind, fell into fits of laughter, and were joined by the mollified father and relieved mother.

All the children, except Fanny. She cried with vexation, and did not promise to forgive "Brother Rob" until he had promised to forget.

And this is the story of the Little Grandmother.

"Uncle Horace, do, please, come out here and look. It is just too funny. When papa was here last summer he left a pair of old boots, and this spring some one threw them out on the pile of rails behind the barn. I was around there a few minutes ago, and I found that two little birds had gone into one of the boots and built a nest there. I looked in, and I saw the nest and three eggs. Do come out and tell me what birds they are. Just now one of them scolded at me very much because he thought I went too close to the boot."

"I think I can tell you before going what the bird is, for there is only one which would fairly be apt to adopt the boot as a place for housekeeping. The birds are probably wrens, Bennie, but we will go and see."

As we were passing around toward the rear of the barn I heard, sure enough, the song of a wren from the branches of a cherry-tree which we passed, and when we reached the "boot," out flew the mate of the songster, and without going further than the nearest fence post, she stopped and began to scold us at a furious rate.

"That is just the way she went on before, Uncle Horace. What a spiteful little thing she is!"

"Oh no, not spiteful, Bennie; she is only standing up for her rights. She evidently thinks that the boot belongs to her, and that we have no business here."

"But is it not queer that they should take such a place for their nest? An old boot!"

"No, it is not queer, Ben; it is precisely the sort of thing you might expect. When you mentioned the place of the nest, I felt at once tolerably sure that a pair of wrens must be the builders, for they seem to have a special fancy for odd places. When we go into the house again I will show you Mr. Audubon's plate of this species, and you will see that he represents them as having built their nest in an old torn hat which had been hung on a branch of a tree. I saw a wren's nest once in a pickle jar, and at another time a pair had taken possession of a tomato can which some boys had hung on a fence stake and used as a mark for shooting till it was full of shot-holes. They often go into empty boxes, and it is curious how much work they will do in filling up a box when it is too large for their little nest. I recollect one case where a pair of wrens took a fancy to a soap box which was more than a foot long, and rather than leave any part of it vacant they actually worked away till they had piled grass, etc., into it clear down to the very hole by which they entered, and there they built their nest right down close to the entrance. These were all American wrens; but here is a beautiful drawing of another species never seen in this country."

"Oh, Uncle Horace, what a cunning little fellow, one up above and one looking out of that hole in the nest! You say he never comes to this country; where does he live, then?"

"That drawing represents the common wren of England and of France, Bennie. In fact, the bird is found in most parts of southern and western Europe, and is just as familiar in its habit of coming about houses there as our wren is here. They all of them seem to like the idea of being where people are, and yet they are timid and retiring little things after all. The genus to which they belong is called in the books Troglodytes, which you must pronounce in four syllables, not three. It sounds like a harsh name for such a delicate bird; it means a dweller in caves."

"Why, Uncle Horace, you did not say anything about their living in caves."

"No, I did not, Bennie, nor do I think they ever go into caves. Still, the name is a very correct one, as applying to their habits. If you will carefully watch this pair out here behind the barn, you will see for yourself. There is no nook or corner about there which you will not see them prying into."

"Here comes one of them now, Uncle Horace, out through the stone fence. He is going to scold us for being here to watch him. You need not mind it, little fellow; we shall not hurt you. But what makes him keep his tail held up so straight? Some of the time he almost lays it over on his back."

"I was about to call your attention to that very thing. That is one of their singular peculiarities. All of this tribe of the wrens have that curious habit. By 'this tribe,' I mean those species which so much resemble the common wren of Europe or the house wren of America, for there are others which are quite distinct from them, and which do not carry their tails in that manner. Look at the drawing, and you will see that the bird on the top of the nest has his tail raised, though scarcely so remarkably as our friend here on the fence, but still it is enough to show his tendency. Now we have here, in our Northern and Eastern States especially, another species which commonly comes to us only in the winter instead of being here, as this bird is, during the summer. Though he lives more in the woods, and does not very often come about houses, yet they are very similar to the house wren, and you would notice them at once because of this habit of carrying the tail erect; and it would be the same with the wood wren, and also with the queer little fellows who live in the marshes, the marsh wrens."

"And then are there others which are not like them—not what you call of the same 'tribe'?"

"Yes, in our Southern States, and even no further south than Delaware, we find a species decidedly larger than our house wren, and having no resemblance to it as far as familiarity with men and houses is concerned. It is the great Carolina wren, and from seeing this species now before us you would scarcely imagine that to be a wren at all. He lives in the woods, he carries his tail as a robin or a bluebird does, and his song is not like the few trilling and twittering notes of the house wren. He pours out a flood of music that is similar to that of a thrush; you can scarcely believe when you see him that so much power of notes can come from a body so small."

"I see in this drawing, Uncle Horace, that the European species makes a nest with only a hole in the side. I have seen a robin's nest, and several swallows' nests, and sparrows' nests, and they were all open on the top, like a cup; they were not covered."

"No, that is very true, Ben. That is the way in which the greater number of birds build. But many of the wrens have the propensity to arch their nests over. The one in the drawing is represented correctly. They always seem determined to have an arch, even if it is not needed—if there is an arch there already. One pair, I recollect, built their nest inside a small gourd shell. The top of the shell arched over so close that the back of the bird as she sat in the nest almost touched the shell, but she had not been contented without having an arch of her own, and she had actually made one no thicker than fine paper. It seemed to me that it was only one layer of fine fibres, hair, grass etc. But there it was, an arch, and she was doubtless contented."

"What did you mean by the marsh wrens being queer little fellows?"

"They are queer fellows, sure enough. Queer in their nests, queer in their song, queer in the places they choose for their homes. They are of two species, quite closely resembling each other, and yet one will never live where the water is fresh, and the other will live only where it is fresh. The first is seen only on the salt-marshes, and yet its habits are almost the same as those of the fresh-water bird. They build nests almost alike, and yet they never put them in similar places. In going across a salt-marsh you often see a tuft of the tall coarse grasses, of which the stems have been woven and bound together into a sort of column, and then in their top, two or three feet from the ground, is a large coarse ball of long leaves and fibres, of the size of a child's head. This is the nest of a marsh wren. Now you may cross the fresh-water marshes all day long, and you will see no such thing, and yet you will see numbers of the short-billed marsh wrens, and you will pass many of their nests, and the nests will look almost exactly like those perched up in the tops of the salt-water grasses, but you will not see them unless you know where to look. Why? Because instead of being away up on the grasses, they are placed at the roots. Can you tell why they differ so in their nest-building? I can not. Each nest, of either species, is a coarse ball, as already mentioned,[Pg 523] with a round hole on the side, and inside is the real nest, a beautifully smooth and comfortable place for the bird and her young."

"Is the nest like this one in the drawing? This has a hole in the side."

"Somewhat like it, but it is built commonly of coarser materials. I mentioned also that the marsh wrens of either the salt or fresh water species were peculiar in their notes, for you can scarcely call it a song. It is a series of short sounds, seeming almost like the bubbling of air through water—somewhat like the noise which your feet make in stepping on the marshy ground, and yet it has a musical effect which is very pleasant."

Almost every one has read of Ezekiel Green and his flying machine, and a great many boys and men have been quite sure that they could manufacture wings which would enable them to fly.

As long ago as the reign of James IV. of Scotland an Italian who pretended to be able to change common metals into gold, and who wasted a great deal of the King's money in this way, but all to no purpose, "took in hand to fly with wings" as far as France, and to be there before the King's ambassadors, who travelled in the ordinary way. He had a pair of wings made of feathers, and when these had been fastened upon him he flew off the wall of Stirling Castle, but only to fall heavily to the ground, and break his thigh-bone.

The abbot of Tarryland (for so he had been created by the credulous King) declared that the blame of this failure should be laid upon the fact that there were hen feathers in the wings, and that hens are more inclined to the barn-yard than the skies—a very ingenious way of defending himself; but it could not quiet the twinges in his broken limb.

Another experiment, which was made three hundred years later, was more successful. It was tried on a convict from the galleys, whose life was not thought too valuable to risk, and when ready for flight he must have been an object capable of frightening all the birds of the air. He was "surrounded with whirls of feathers, curiously interlaced, and extending gradually at suitable distances in a horizontal direction from his feet to his neck." When first launched from a height of seventy feet, his feelings could not have been enviable, and the great mass of spectators watched him in almost breathless silence. But instead of falling, he went down slowly, and landed on his feet, with no inconvenience except a feeling of sea-sickness.

Nothing seems to have come of it, as men are not flying through the air yet; but the Flying Ship may possibly have led to the balloon. This strange scheme made quite a sensation in the year 1709, and the first account of it was written in Portuguese. It was invented by a Brazilian priest, who wanted the King of Portugal to adopt it.

In an ancient document purporting to be an address made to this monarch we read: "Father Bartholomew Laurent says that he has found out an Invention, by the Help of which one may more speedily travel through the Air than any other Way either by Sea or Land, so that one may go 200 Miles in 24 Hours; send Orders and Conclusions of Councils to Generals, in a manner, as soon as they are determined in private Cabinets; which will be so much the more Advantageous to your Majesty, as your Dominions lie far remote from one another, and which for want of Councils cannot be maintained nor augmented in Revenues and Extent.

"Merchants may have their Merchandize, and send Letters and Packets more conveniently. Places besieged may be Supply'd with Necessaries and Succours. Moreover, we may transport out of such Places what we please, and the Enemy cannot hinder it."

This remarkable ship was made as nearly in the form of a bird as possible; the tail (not quite true to nature) being the stern, and the head the figure-head of the vessel. At the bottom were two queerly shaped wings "to keep the ship upright"; at the top, the sails, which rounded over like the body of the bird; the light body of the ship was scalloped at both ends, and in the cavity of each was a pair of bellows, to be blown when there was no wind; and there were globes of heaven and earth, two load-stones, and "a good number of large amber beads fastened in an iron wire net, which, by a secret operation, would help to keep the ship aloft."

The strange vehicle was supposed to accommodate ten or eleven men "besides the artist," and this last personage, "by the help of the celestial globe, a sea map and compass, takes the height of the sun, thereby to find out the spot of land over which they are on the globe of the earth." It was a very funny affair, but quite ingenious, considering how little the laws of gravitation, and many other things connected with the art of flying, were then understood; yet no such object has been seen making its way through the air, and a flying ship would be very apt to find itself on the ground or in the water.

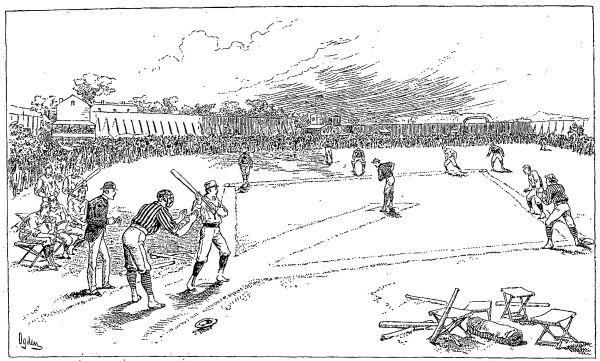

A GAME OF BASE-BALL AT THE POLO GROUNDS, NEW YORK CITY,

ON DECORATION-DAY—YALE VS. PRINCETON.

A GAME OF BASE-BALL AT THE POLO GROUNDS, NEW YORK CITY,

ON DECORATION-DAY—YALE VS. PRINCETON.

Base-ball has long been recognized as the national game of this country, and if any one has any idea that cricket or lawn tennis or lacrosse is likely to put it into the background, that person should have been one of the twelve thousand persons who witnessed the great game between Princeton and Yale Colleges on Decoration-day.

If the play might have been better, the weather could not, and the enthusiasm and enjoyment of the immense crowd of spectators knew no bounds. Almost every one was decorated either with the blue of Yale or the orange of Princeton, for, as every boy who lives in the neighborhood of New York knows, the population of that great city and the neighboring cities, towns, and villages is divided into two parties, which are as enthusiastic about their favorite colleges as Republicans and Democrats are for their candidates at a Presidential election. "Are you Yale or Princeton?" one boy asks of another, and then, if the two boys prove to be of different parties, there follows a long argument about the merits of the two colleges, and however strong may be the facts brought forward, it always ends by one of the boys being convinced—that the other does not know much about foot-ball or base-ball, as the case may be, anyhow.

The rules of base-ball are very long and elaborate, and moreover, they are frequently altered. If we were to print them all, they would occupy at least six times as much space as this article. That being the case, we will not print them, and even if we did, very few of our readers would care to read them, for every American boy knows the principal rules, even though he may not be able to pass an examination in the whole code. Nor shall we attempt to describe the game as we have done with other less-known games. Like the Constitution, base-ball is one of the institutions of the country, but it has an advantage over that important document in the fact that the citizens of this country have mastered the art and science of base-ball (or think they have) long before they know anything about the Constitution. And so we will not describe or attempt to teach it, and if any of our young readers think that we are not treating them fairly by keeping back the[Pg 524] valuable information with which, if the editor would allow it, we could fill the paper, we shall be much obliged if those young gentlemen will send their names and addresses to this office, when we will endeavor to refer them to some good authority on the subject.

Everybody knows by this time that in the great college game played on Decoration-day Yale beat Princeton easily. The fact is, the Princeton men were sadly wanting in sharp fielding, and fielding is the real science of the game. Your good fielder is always on the move. No matter where the ball may be, it will be in-field in a few seconds, and neither basemen nor short-stop must be caught napping.

Each man must be ready to support his fellow, and he must not think that because the ball does not come in his particular part of the field he need not trouble himself about it. Every player plays not for himself alone, but for his side, and it is in the perfect working together of the whole nine that the highest art of ball-playing consists. The basemen have their regular positions, but it must be remembered that the game is where the ball is, and that the fielder who can best reach the ball is the one who should field it.

One of the most important positions is that of short-stop. He is a kind of Jack-of-all-trades. He must be able to do the work of any of the in-fielders, to occupy a baseman's place when that person is fielding a ball, to "back up" the basemen, so as to cover any swift or widely thrown balls which they may be unable to reach, and to back up the pitcher, and so save him extra work in fielding balls returned to him by the catcher. The most eminent positions in a nine are, of course, those of pitcher and catcher, but the short-stop may have just as much enjoyment out of his part, and may do his side as much service as the more prominent players of the "battery."

It is not every one that can be a catcher. Like poets and wicket-keepers at cricket, the catcher is "born, not made." Because there is a catcher on every nine, it does not follow that every ninth man is one of these much-valued creatures whose excellence is due to instinct rather than to education. It is by no means the case that every person who writes verse is a poet, nor that every cricketer who stands behind the wicket is a wicket-keeper. A man may catch, but he is not therefore a catcher. If he has not a hand that acts directly with the eye, and an eye that sees almost before it has time to look—above all, if he shrinks from the swiftly darting ball, or winces as the bat is swung within a very few inches of his head—he will not make a catcher.

The kind of courage required for this position is very peculiar. It is not necessarily the sort of courage that would lead a man to jump into a mill-race to save another from drowning, nor is it especially the calm bravery that carries a soldier up to the ramparts behind which the enemy and perhaps death are lurking. But it is an admirable quality, and the chances are that the man who can control his nerves in the hazardous position of a base-ball catcher would not be found wanting when the time arrived for the exercise of his courage under even more trying circumstances.

The great Duke of Wellington said, as he watched the Eton boys playing cricket, "It was here that the battle of Waterloo was won," and though Waterloo is in Belgium and Eton in England, there was much truth in what the great commander said. The qualities which cricket brings out and educates (and it is fully as much so with base-ball) are qualities that make a man or boy courageous, quick to act in emergency, and loyal. These are the three qualities that are most desired in a soldier, and especially in one who is set over others.

When the American boy shall have become a man, and shall be placed in a position to test himself to see what kind of stuff he is made of, and finds that his courage, his resolution, his faithfulness, do not fail him, he may look back upon those happy afternoons spent on the base-ball field, and think how valuable an education he was working out for himself when he thought he was merely "having a good time."

The Postmistress thinks that every little reader will be interested in the letter from Alberto Dal M., who tells about a visit to Naples. She is very much pleased to hear from little travellers as well as from little stay-at-homes. The poem entitled "A Pansy Show" is the first attempt of the youthful writer. Our Post-office Box is quite sparkling this lovely summer day, with its letters, rhymes, and bits of information. Let nobody fail to read the amusing description of the wedding outfit of a Hindoo bride under the head of C. Y. P. R. U. After a long silence, we are pleased to receive another letter from Mrs. Richardson, of Woodside. We have not forgotten Uncle Pete and his Ida, nor the little school among the pines.

Venice, Italy.

This time I will tell the readers of Young People about my visit to Naples. From our rooms I could see the lovely bay, and in the distance the island of Capri, where there is a beautiful grotto. One morning at seven o'clock I started for Vesuvius in a carriage that had three horses for the mountain roads, and arrived at the Observatory at about half past eleven. I would like to have gone up by the railroad to the crater, but it was considered too dangerous, as there had been an accident a short time before my visit. I went into the Observatory, where visitors are not usually admitted. There I saw many electric wires, one of which showed when Vesuvius was throwing out stones. Even the slightest movement of the mountain could be felt by this wire, which without it would be unnoticed; another showed in which direction the movement was, whether east, west, north, or south; and still another told when the temperature changed.

There were many specimens of the different minerals thrown from Vesuvius. Some were crystallized sulphur, some iron, some salt, and some magnesia. Some of the lava when broken contained in the centre a white substance which had the form of a flower, another piece looked like a butterfly, and there were also some long white sticks which resembled macaroni. I saw the instruments with which they take up the hot lava; one was a kind of shovel, another a long pair of pincers. All that I saw here interested me very much. The view from the Observatory was magnificent. In the distance one could see the whole city of Naples, and the mountain looked like a desert of burnt wood. The lava which had been thrown out from different eruptions covered the ground everywhere, and was in some places heaped up very high in many curious forms. Some of the lava was gray, some red, and some brown. I picked up several pieces to carry home, also a few flowers which I found growing among the lava.

A few days after, I went to visit the ruined city of Pompeii. After passing through one of the old gates of the city, I went into a small museum, where I saw a few petrifactions and other things, but most of the curiosities are at Naples, in the National Museum. The streets of Pompeii are very narrow, paved with large blocks of stone, and I could see the ruts made by the wagons before the city was destroyed. I went into what was once a barber's shop, where there was still a block of marble which had been used as a seat. I saw a shelf there, and was told that a razor, a comb, and pomade were found on it. In a baker's shop I saw an oven where loaves of bread had been found. The houses were but one story high, and each house opened into a court, from which it received its light, as the rooms had no windows. Some of the frescoes on the walls were still fresh.

Alberto Dal M.

Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.

I began to take your paper last May, and like it very much. I often read the letters in Our Post-office Box, and have often thought I would like to write one. I have a little bird named Dicky, and he is very tame. When I call him he will come to me, and often when I am writing he will fly down and perch on my pen. I leave his cage door open all the time, and he goes out and in when he likes. The other day he was sick, and we thought he was going to die, but he got well again the next day. I have a little baby brother a week and three days old. This is my first letter to Young People.

Victor F.

Germantown, Pennsylvania.

I am staying in Germantown with my aunt, and am having a lovely time; and as I have not seen many letters from here, I thought I would write and tell you about our place. We have a good many chickens, six horses, and a very pretty pet cat. His name is Pursius, but we call him Persie for a short name. He climbs up from our back shed to the window-sill, and cries until we open the window and let him in. Does not the Postmistress think him a smart cat, I wonder? He does a good many more cute things, but it would make my letter too long to tell them all. I do not go to school, but study at home. I took lessons of a French mademoiselle in the winter, and can talk a little in French. My favorite stories in Young People are "The Dolls' Dressmaker," "Toby Tyler," "Tim and Tip," and "Phil's Fairies." I forgot to say that the woods are only five minutes' walk from the house, and the apple-trees are all in bloom, and I often take my little basket over to the woods and gather it full of apple blossoms and dogwood flowers. My papa gave me a pretty little watch on my last birthday.

Margaret J.

Three children sat in a row on a fence;

They knew not what to do;

They were tired of playing their old games,

And wished for something new.

They looked around with discontent,

'Till they saw the pansy bed,

Where each bright blossom, in purple and gold,

Was nodding its royal head.

Then one of the children cried aloud:

"Let's have a pansy show;

We can dress the flowers and make them look

Just like people, you know."

They gathered the velvet pansies,

And when dressed in green and white.

They were placed in groups on the smooth green grass—

It was truly a fairy sight.

They charged five pins admission

To see the wonderful flowers;

In this way they made great profits,

And spent many pleasant hours.

In summer you will see the pansies,

On their faces an eager glow,

Waiting to be picked by the children,

And placed in the flower show.

Myra A. Scott.

Cleveland, Ohio.

Newmarket, Tennessee.

A kind uncle, away off in New Jersey, sends me Harper's Young People. Unless you have been a little country girl ten years old, like me, you can not imagine what pleasure it gives me, or how eagerly I run to meet brother Bertram when he brings the mail on Thursdays. Bertie, who is twelve years old, goes to school, while I have to stay at home and help to take care of a baby brother and sister (twins) so sweet and cunning that I wish you could see them. The little boy is named after grandpa, and the girl after uncle Jesse B., by adding an i to Jesse. Papa told me I must not use many capital I's if I wrote you a letter; but how else can I tell you that I ride six miles on horseback once a week, to take a music lesson, on a dear old horse (we call her Kate) so faithful and true that I am sure Toby Tyler and the boys would be delighted to have her in their circus, but I can't spare her? Papa is a farmer, and we make pets of colts and calves and lambs and pigs, but I do not give as much attention to them as I do to books and the babies. I have a little sister Dora, four years old, who came running in one evening and said, "Mamma, the gipperwills are singing, and it is time to go barefooted." She had been told that when the whippoorwills sing there is no danger of catching cold. My home is on a high location, overlooking a beautiful valley—a landscape that never fails to please all who look upon it. Here, if I can not go to school. I try to learn, and be happy and busy and helpful to mamma.

Gertrude Elizabeth W.

What fun it must be to take care of twins! Do they look very much alike, and how old are they? You ought to have said more about them, dear. Although you can not attend school, you are learning a great many pleasant things at home, as your letter shows. The I's are not too numerous. I shall think of Bertie carrying Young People home from the office on Thursdays, and fancy my little correspondent flying down the garden walk to meet him as he stops at the gate.

Springfield, Kentucky.

My home is in Springfield. I have been wanting to write a letter for the Young People since I first took it, which was last January, but I was timid about doing it. My papa gave the paper to me as a New-Year's gift, and I have had more than a dollar and a half's worth of pleasure from it already. I have seen so much about "Toby Tyler" in the letters, but have never seen anything about him in the numbers, and my mamma reads everything in them to me; so please tell me where to find him. I am seven and a half years old; have never been to school, but am taught at home; will start in a week or two. I am the only child, and mamma says she will be too lonely without me; but I tell her she must let me learn and be a smart little girl. I have a lot of pets: a beautiful Esquimau dog just one year younger than I, a canary-bird, and a lot of the prettiest little chickens; but my kitten has run away, or has been killed. He was such a pet, because he was so smart, and performed so many tricks. I am going to have a pony as soon as I learn to ride. I have the money, given to me by my uncle; he gave me one hundred dollars six months ago, and I loaned it to papa at ten per cent. interest. I have written 'most too long a letter, but please publish it if you can.

Carrie S.

The story of "Toby Tyler" was begun in No. 58, Vol. II., of Harper's Young People. The same Toby is the hero of "Mr. Stubbs's Brother"; but if you are very anxious to read all the adventures of a little boy who was once so foolish as to run away from his kind uncle Daniel and travel with a circus, you must send for Toby Tyler, which the Messrs. Harper publish in a very pretty little book by itself. The price is $1. I hope you will enjoy school, and surprise mamma by learning very fast. When the pony is bought, you must write again, and tell me his name, and all about your charming rides.

Woodside (near Lincolnton), North Carolina.

My dear "Young People,"—It has been quite a while since I have written a letter to you all. I had books and papers enough, thanks to your kind help, and so I have not had any need to call upon your generosity again. Our school, you will be glad to know, still keeps on in a very encouraging way. I had only a few dollars sent for the building, and had almost despaired of ever getting one, when one day I received a letter from a very kind gentleman, who wrote that if we were willing to give the land to the diocese, and build a chapel, he could raise us money to do it. You may be sure we were only too glad to do so, and he did his part very soon. We have the building framed, all the lumber is ready, and the carpenter promises that he will soon have it done. We have the windows, sent by the same kind gentleman, of colored and ground glass, and the rector in Lincolnton will give our school one service each month. The people have no preaching now except from preachers of their own race, who are often very ignorant men. We hope this will be a great help in educating the children and their parents, and making them good and happy. I will tell you about it when church begins. Your friend,

Mrs. Richardson.

Kau, Hawaii, Sandwich Islands.

I like "Toby Tyler" and "Talking Leaves" the best of all the stories. I have a pet rooster; his name is Whitehead, because when little he had a white spot on the top of his head. He is so tame that my little sister can take him by the tail and drive him all around the yard like a dog, and he will not try to get away; and when we have a bunch of bananas on the veranda hanging up over the railing, he will fly up on the railing and pull the bananas off the bunch, and drop them down for the hens that are on the ground below him. I have a handsome parrot; he is yellow, green, blue, red, and black. His name is Dandy, but he calls himself Polly.