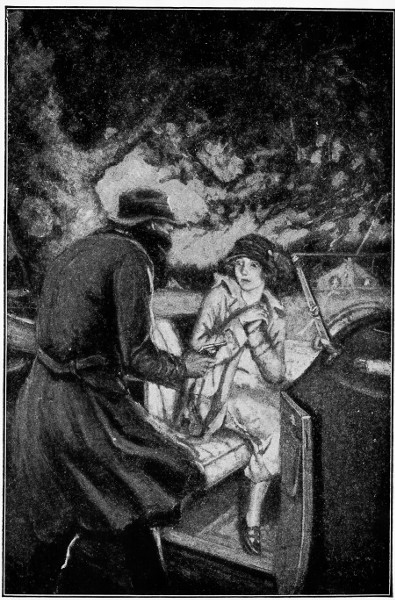

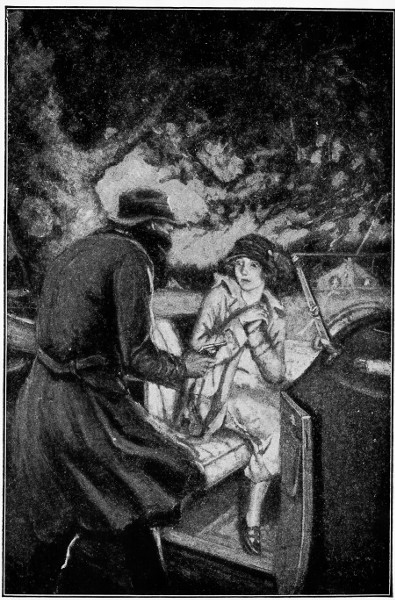

“Give me that key!”

Title: The Meredith Mystery

Author: Natalie Sumner Lincoln

Release date: January 2, 2019 [eBook #58597]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

E-text prepared by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/meredithmystery00nata |

“Give me that key!”

| I | THE TEMPTATION |

| II | THE SCENTED HANDKERCHIEF |

| III | A QUESTION OF COLOR |

| IV | RUFFLES |

| V | THE INQUEST |

| VI | TESTIMONY |

| VII | SUSPICION |

| VIII | THE PLEDGE |

| IX | TWO PIECES OF STRING |

| X | THE SOLITARY INITIAL |

| XI | THE HAND ON THE COUNTERPANE |

| XII | MURDER |

| XIII | PRELIMINARY SKIRMISHING |

| XIV | THE DUPLICATE KEY |

| XV | AT THE FORK OF THE ROAD |

| XVI | A CRY IN THE NIGHT |

| XVII | UNDER LOCK AND KEY |

| XVIII | THE POLICE WARRANT |

| XIX | OUT OF THE MAZE |

Anne Meredith looked at her mother, appalled. “Marry David Curtis!” she exclaimed. “Marry a man I have seen not more than a dozen times. Are you mad?”

“No, but your uncle is,” bitterly. “God knows what has prompted this sudden philanthropy,” hesitating for a word. “This sudden desire to, as he expresses it, ‘square accounts’ with the past by insisting that you marry David Curtis or be disinherited.”

“Disinherited—?”

“Just so”—her mother’s gesture was expressive. “Having brought you up as his heiress, he now demands that you carry out his wishes.”

“And if I refuse—?”

“We are to leave the house at once.”

Anne stared at her mother. “It is too melodramatic for belief,” she said, and laughed a trifle unsteadily. “This is the twentieth century—women are not bought and paid for. I,” with a proud lift of her head, “I can work.”

“And starve—” Mrs. Meredith shrugged her shapely shoulders.

Anne colored hotly at her mother’s tone. “There is always work to be found—honest work,” she contended stubbornly.

“For trained workers,” Mrs. Meredith supplemented.

“I can study stenography—typewriting,” Anne persisted.

“And what are we to live on in the meantime?” with biting irony. “The savings from your allowance?”

Again the carmine dyed Anne’s pale cheeks. “My allowance,” she echoed. “It has kept me in clothes and a little spending money. But you, mother, you had father’s life insurance—”

“My investments have not turned out well,” Mrs. Meredith looked away from her daughter. “Frankly, Anne, I haven’t a penny to my name.”

Anne regarded her blankly. “But your bank account at Riggs’—”

“Is overdrawn!” Walking swiftly over to her desk she took a letter from one of the pigeonholes. “Here is the notification—see for yourself.” She tossed the paper into Anne’s lap. “If you refuse to accede to your uncle’s wishes, we leave this house beggars.”

Beggars! The word beat its meaning into Anne Meredith’s brain with cruel intensity. Brought up in luxury, with every wish gratified, could it be that want stared her in the face? Her gaze wandered about the cozy boudoir, and she took in its dainty furnishings, bespeaking wealth and good taste, with clearer vision than ever before. With a swift, half unconscious movement she covered her eyes with her fingers and found the lids wet with tears.

Rising abruptly she walked over to the window and, parting the curtain, looked outside across the well-kept lawn. The giant elms on the place gained an added beauty in the moonlight. From where she stood she glimpsed the Cathedral, resembling, in the mellow glow from hidden arc lights, a fairy palace perched high upon a nearby hill, and far in the distance the twinkling lights of Washington, the City Beautiful. It was a view of which she had never tired since coming to her ancestral home when a tiny child.

The historic mansion, set in its ten acres, from which it derived its name, had been built by a Virginia gentleman over one hundred years before. He had occupied it with lavish hospitality until his death, after which his widow, a gracious stately dame with the manner and elegance of the veille cour, had led Washington society for many years. The wits, beaux, and beauties of the early nineteenth century, the chief executives, as they came and went, the diplomats and American statesmen, together with every foreigner of distinction who visited the capital city had been welcomed there, and as one Washingtonian whispered to another:

“A passport viséd by St. Peter would not be more eagerly sought by some of us than admission to these dear old doors.”

The prestige which clung to beautiful Ten Acres was one of the reasons which had induced John Meredith to purchase his brother’s share in it and, as his fortune grew with the years, to renovate the colonial mansion and make it one of the show places within the District of Columbia. With the exception of a wing added to increase its size, he had left the quaint rooms and corridors untouched in their old-time simplicity.

From her chair by her desk Mrs. Marshall Meredith watched her daughter in silent speculation. A woman of the world, entirely worldly, she had seen to it that Anne, her only child, had been provided with the best of education in a convent in Canada. Upon Anne’s graduation a year before, she had prevailed upon her brother-in-law, John Meredith, to give her a trip abroad before she made her debut.

John Meredith’s pride in his pretty niece had intensified with her success in society, and once again Ten Acres had become the center of social life. Diplomats, high government officials, and residential society sought eagerly for invitations to the banker’s lavish entertainments, and Mrs. Meredith’s pet ambition—a titled son-in-law—seemed nearer attainment.

Like a bolt from the blue had come Meredith’s extraordinary interest in David Curtis, a patient at Walter Reed General Hospital, his invitation for a week-end visit to Ten Acres, and now his ultimatum that his niece marry David Curtis within a week or leave his house forever.

Mrs. Meredith’s outlook on life was shaken to its foundations. Her frayed nerves snapped under the continued silence and she rose as Anne turned back from the window and advanced to the center of the room. She looked very girlish in her pretty dressing gown which she had donned just before her mother sent for her to come to their boudoir, and her chestnut hair, her greatest glory, was still dressed as she had worn it that evening at dinner. Her mother switched on another electric light and under its direct rays Anne’s unnatural pallor was intensified.

“It is cruel of Uncle John to force such a marriage,” she declared.

“You will agree to it?” The question shot from Mrs. Meredith. Anne shook her head. “But think of the alternative—”

“There may be but the one alternative.” Anne had some difficulty in speaking and her voice was little more than a whisper. “Suppose—suppose there was an unsurmountable obstacle—”

“An obstacle—of what kind?”

“A—a previous marriage—”

“Good God!” Mrs. Meredith stepped back and clutched a chair for support. “You don’t mean—Anne—!”

“That I might be already married?” Anne’s soft voice added flame to her mother’s fury. Stepping forward she gazed sternly at her daughter.

“No; it is not possible,” she declared. “I know every incident in your life. The good Sisters kept a strict watch, and you have never been away from my chaperonage since you left the convent. You cannot avoid your uncle’s wishes with such a palpable lie.” In her relief she laughed. “Anne, you frightened me, silly child.”

“And what are your feelings compared to mine?” Anne raised miserable, agonized eyes and gazed straight at her mother. “Uncle John demands that I marry David Curtis, and you, mother, are playing into his hands for this most unnatural marriage—”

“Unnatural—?”

“Yes. You both wish me to marry a stranger—a blind man.”

“Say, rather, a hero blinded in the late War.”

“Cloak it in any language,” Anne’s gesture of despair was eloquent. “Oh, mother, I cannot marry him.”

“Cease this folly, Anne, and pull yourself together,” Mrs. Meredith’s voice was low and earnest. “I have been to your uncle this evening, and he has agreed that this marriage with David Curtis is to be a marriage of convenience only; and yet, ungrateful girl that you are, you forget all that I have dared for your sake.”

Anne recoiled. “For me?” she said bitterly. “Oh, no. You love luxury, wealth, power, and by sacrificing me you can attain your desires. You wish to force me to marry this blind man—to make a mockery of the marriage vows by assuring me that the ceremony is all that is required of me. Do you think God smiles on such vows?”

Her mother stepped to her side and seized the girl’s hand. It was marvelous how her long, slender fingers could compress the tender flesh. Anne uttered a cry of pain, then threw back her head and met her mother’s furious glance with an amount of resolution which amazed her.

“I am more than six years old,” she said quietly. “And I am subservient to your will only because you are my mother and I am not yet of age. If I must do this abominable thing, let it be done immediately.”

Mrs. Meredith dropped her hand. The passion died out of her face and the smooth, handsome mask covered it as before.

“I am glad that you have recovered your senses,” she said in a calmer voice. “Your uncle has retired for the night, not feeling well, but Sam Hollister is waiting in the library to learn your decision.”

Anne shrank back. “Sam knows—” she gasped.

“Certainly; he has been your uncle’s confidential lawyer for many years,” replied Mrs. Meredith. “Sam was present this evening when your uncle disclosed his wishes to me regarding your marriage.”

“And why was I not present also?” demanded Anne, stepping forward as her mother walked toward the hall door.

“Because John has a horror of hysterics,” she stated. “He has often told you that he never married because he dreads a tyranny of tears,” and going outside she shut the door with a firm hand.

Anne stared at the closed door for a full minute, then walked unsteadily over to the couch and threw herself face downward among the sofa pillows. Not until then did her clenched hands relax.

“Uncle John, how could you? How could you?” she gasped and her voice choked on a sob.

The grandfather clock in the big entrance hall to Ten Acres was chiming eleven when Mrs. Meredith pulled aside the portières in front of the library door and crossed its threshold. At her almost noiseless entrance a man standing with his back to the huge stone fireplace, which stretched across one end of the large room, glanced up and made a hasty step forward. With characteristic directness Mrs. Meredith answered his inquisitive look.

“Anne has consented to marry David Curtis,” she announced and stopped abruptly, her hasty speech checked by Sam Hollister’s upraised hand.

“Doctor Curtis is here,” he said, and indicated a lounging chair upon their right.

Mrs. Meredith faced David Curtis as he rose and bowed. In the brief silence she scanned him from head to foot. What she saw was a tall, well-set-up man, broad-shouldered and with an unmistakable air of breeding. Ill health had set its mark on his face, which was pale and furrowed beyond his years, but the features were fine, the forehead broad, and the sightless eyes a deep blue under their long lashes.

The lawyer broke the pause. “Doctor Curtis has just informed me that he cannot accede to Mr. Meredith’s wishes regarding a marriage with your daughter,” he said. “He will tell you his reasons.”

Mrs. Meredith’s face paled with anger. Hollister, watching her, felt a glow of reluctant admiration as he saw her instantly regain her self-control.

“Your reasons, Doctor Curtis?” she asked suavely. “Pray keep your seat. I will sit on the sofa by Mr. Hollister.”

David Curtis, with the instinct of location given to the blind, turned so as to face the sofa.

“Your daughter, madam,” he began, “is a young and charming girl, with life before her. I”—he hesitated, choosing his words carefully—“I have to start life afresh, handicapped with blindness. Before the War I had gained some reputation as a surgeon, now I can no longer practice my profession. Until I learn some occupation open to the blind, I cannot support myself, much less a wife.”

“But my brother-in-law proposes settling twenty-five thousand dollars a year each upon you and Anne after your marriage,” she interposed swiftly. “It is—” she hesitated and glanced at Hollister. “Have you told him?”

Hollister bowed gravely. “It is to be a marriage in name only,” he stated. “You can live abroad if you wish, Curtis. Meredith only stipulates that this place, Ten Acres, is to be occupied after his death for two or three months every year by you both, and never sold.”

“And Mr. Meredith’s reasons for wishing this marriage to take place?” demanded Curtis. “What are they?”

Hollister shook his head. “I do not know them,” he admitted. “John told me to tell both Anne and you that he would state his reasons immediately after the marriage ceremony. I have known John Meredith,” the lawyer added, “for nearly fifteen years, and I know that he always keeps his word.”

Curtis’ sensitive fingers played a noiseless tattoo on the chair arm. “It is too great an injustice to Miss Meredith,” he objected.

“But the alternative is far more unjust,” broke in Mrs. Meredith. “My brother-in-law has announced that if this marriage does not take place, he will disinherit Anne. She has never been taught any useful profession; she is delicate in health—her lungs,” her voice quivered with feeling. “If this marriage does not take place Anne will be a homeless pauper. Upon you, doctor, rests the decision.”

She was clever, this woman. She instinctively seized Curtis where he was vulnerable; she appealed to his kindly heart and the human interest which was part of his profession.

The seconds ticked themselves into minutes before Curtis spoke.

“Very well, I will go through with the ceremony,” he said, and Mrs. Meredith had difficulty in restraining an exclamation. Hollister read rightly the relief in her eyes and smiled. He had no love for the handsome widow. She rose at once.

“You will not regret your decision, Doctor Curtis,” she said, and turned to Hollister. “Will you tell John?”

“If he is awake, yes; if not, the news will keep until to-morrow.” Hollister concealed a yawn. “Good night, Mrs. Meredith,” as she walked toward the entrance. Curtis’ mumbled “good night” was almost lost in her clear echo of their words as she disappeared through the portières.

“Coming upstairs, Curtis?” asked Hollister, pausing on his way out of the library. “Can I help you to your room?”

“Thanks, no. I’ve learned to find my way about fairly well,” answered Curtis. “I’ll stay down and smoke for a bit longer.”

“All right, see you in the morning,” and Hollister departed, after first pausing to pick up several magazines.

In spite of his statement that he was fairly familiar with his surroundings, it took Curtis some moments to locate the smoking stand and a box of matches. While lighting his cigar he was conscious of the sound of voices in the hall, which grew louder in volume and then died away. He had resumed his old seat and his cigar was drawing nicely when a hand was laid on his shoulder.

“Sorry to startle you,” remarked the newcomer. “I am Gerald Armstrong.”

“Yes, I recognize your voice,” Curtis started to rise, but his companion, one of the week-end house guests at Ten Acres, pressed him back in his chair.

“I only stopped for a word.” Armstrong hesitated as if in doubt. “I’ve just learned of—that you and Anne Meredith are to be married.”

“Yes,” answered Curtis as the pause lengthened. “Yes?”

“You are going through with the ceremony?”

Curtis turned his head and looked up with sightless eyes in Armstrong’s face.

“Certainly. May I ask what affair it is of yours?”

“None,” hastily. “But you don’t know Anne—”

“I do.”

“Oh, yes, you know that she is the only daughter of Mrs. Marshall Meredith and the niece and reputed heiress of John Meredith, millionaire banker,” Armstrong’s usually pleasant voice was harsh and discordant. “As to the girl herself—you are marrying Anne, sight unseen.”

With a bound Curtis was on his feet and Armstrong winced under the grip of his fingers about his throat.

“Stand still!” The command was issued between clenched teeth. “I won’t hurt you, you fool!” Shifting his grip Curtis ran his sensitive fingers over Armstrong’s face and brow. He released him with such suddenness that Armstrong, who had stood passive more from surprise than any other motive, staggered back. “Go to bed!”

Armstrong hesitated; then without further word, whirled around and sped from the library.

Curtis did not resume his seat. Instead he paced up and down the library, dexterously avoiding the furniture, for over an hour. At last, utterly exhausted, he dropped into a chair near the doorway. His brain felt on fire as he reviewed the events of the evening. He had promised to marry a girl unknown to him three days before. He would marry her “sight unseen.” God! To be blind! Fate had reserved a sorry jest for him. What could be the motive behind John Meredith’s sudden friendliness for him, his invitation to spend a week at Ten Acres, and now his demand that he and Anne Meredith go through a “marriage of convenience”?

And he had weakly consented to the plan! Curtis rubbed a feverish hand across his aching forehead. Forever cut off from practicing his beloved profession, with poverty staring him in the face, handicapped by blindness, it was a sore temptation to be offered twenty-five thousand dollars a year to go through a mere ceremony. But he had steadfastly refused until Mrs. Meredith had pointed out to him that Anne would thereby lose a fortune.

Anne—his face softened at the thought of her. Could it be that she had sung her way into his heart? The evening of his arrival he had spent listening enthralled to her glorious voice. Her infectious laugh, the few times that she had addressed him, lingered in his memory.

With a sigh he arose, picked up his cane and felt his way out into the hall. He had cultivated a retentive memory and his always acute hearing had aided him in making his way about. He had grown both sure-footed and more sure of himself as his general health improved. At John Meredith’s suggestion he had spent a good part of a day familiarizing himself with the architectural arrangements of the old mansion until he felt that he could find his way about without great difficulty.

Curtis was halfway up the circular staircase to the first bedroom floor when he heard the faint closing of a door, then came the sound of dragging footsteps. As Curtis approached the head of the staircase the footsteps, with longer intervals between, dragged themselves closer to him. He had reached the top step when a soft thud broke the stillness. Curtis paused in uncertainty. He remembered that the wide hall ran the depth of the house, with bedrooms and corridors opening from it. From which side had proceeded the noise?

Slowly, cautiously, he turned to his right and moved with some speed down the hall. The next second his outflung hands saved him from falling face downward as he tripped over an inert body.

Considerably shaken, Curtis pulled himself up on his knees and bent over the man on the floor. His hand sought the latter’s wrist. He could feel no pulse. Bending closer he pressed his ear against the man’s chest—no heartbeat!

Curtis’ hand crept upward to the man’s throat and then was withdrawn with lightning speed. He touched his sticky fingers with the tip of his tongue, then sniffed at them—blood. An instant later he had located the jagged wound by sense of touch. Taking out his handkerchief he wiped his hands, then bending down ran his fingers over the man’s face, feature by feature, over his mustache and carefully trimmed beard, over the scarred ear. The man before him was his host, the owner of Ten Acres, John Meredith.

With every sense alert Curtis rose slowly, his head bent in a listening attitude. The silence remained unbroken. Apparently he and John Meredith, lying dead at his feet, were alone in the hall.

Fully a minute passed before David Curtis moved. Stooping down, he groped about for his cane. It had rolled a slight distance away and it took him some few seconds to find it. Possession of the cane brought a sense of security; it was something to lean on, something to use to defend himself.... He paused and listened attentively. No sound disturbed the quiet of the night. Taking out his repeater he pressed the spring—a quarter past two. He had remained downstairs in the library far later than he had realized.

How to arouse the sleeping household and tell them of the tragedy enacted at their very doors? In groping for his cane he had lost his sense of direction. He took a step forward and paused in thought. Sam Hollister! He was the man to go to, but how could he reach Hollister without running the risk of disturbing the women of the household? Suppose he rapped on the wrong door?

To be eternally in the dark! Curtis raised his hand in a gesture eloquent of despair; then with an effort pulled himself together. Falling over a dead man, and that man his host, was enough to shake the stoutest nerves of a person possessing all his faculties—but to a blind man! Curtis was conscious that the hand holding his cane was not quite steady as he felt his way down the hall in search of his bedroom. The soft chimes of the grandfather clock in the hall below brought not only a violent start on his part in their train but an idea. The house telephone in his bedroom! John Meredith, that very afternoon, had taught him how to manipulate the mechanism of the instrument.

Quickening his pace Curtis moved down the corridor and turned a corner. If he could only be positive that he was going in the right direction and not away from his room. His outstretched hand passed from the wall to woodwork—a door. He felt about and found the knob. No string such as he had instructed the Filipino servant, detailed to valet him, to tie to his door as a means of identification in case he had to go to his room unaccompanied by a servant or friend, was hanging from it.

With an impatient ejaculation, low spoken, Curtis walked forward, taking care to step always on the heavy creepers with which the halls were carpeted. He had passed several doors when his hand, raised higher than usual, encountered an electric light fixture. The heat of the bulb proved that the light was still turned on, it also restored Curtis’ sense of direction as recollection returned of having been told by Fernando, the Filipino, that an electric fixture was near his room. A second more and he again paused before a door. Cautiously his fingers moved over the polished surface of the mahogany toward the door knob and closed over a piece of dangling twine.

With a sigh of utter thankfulness Curtis pushed open the door, which was standing slightly ajar, and entered the room. The house telephone should be in a small alcove to the left of the doorway—ah, he was right—the instrument was there. What was it John Meredith had told him—his room number was No. 1; that of the suite of rooms occupied by Mrs. Meredith and her daughter Anne, No. 2; his own bedroom call No. 3; that occupied by Gerald Armstrong, No. 4. Lucile Hull, Anne’s cousin and another guest over the week-end, was No. 5—no, five was the number of Sam Hollister’s bedroom in the west wing. But was it? Curtis paused in uncertainty. He did not like the idea of awakening Lucille Hull at nearly three o’clock in the morning. He was quite positive that to tell her John Meredith lay dead in the hall would send her into violent hysterics. It was no news to impart to a woman.

Suddenly Curtis’ hand on the telephone instrument clenched and his body grew rigid. A sixth sense, which tells of another’s presence, warned him that he was not alone. It was a large bedroom with windows opening upon a balcony which circled the old mansion, two closets, and a mirrored door which led to a dressing room beyond and a shower bath.

From the direction of the windows came a sigh, then the sound of some one rising stiffly from the floor, and a chair rasped against another piece of furniture as it was dragged forward with some force.

Moving always in darkness it had not occurred to Curtis to switch on the electric light when first entering the room. But why had not his appearance alarmed the intruder? He had made no especial effort to enter noiselessly. It must be that the room was unlighted. There was one way of solving the problem. Curtis opened his mouth, but the challenge, “Who’s there?” remained unspoken, checked by the unmistakable soft swish of silken garments. The intruder was a woman.

What was a woman doing in his bedroom? His bedroom, but suppose it wasn’t his bedroom? Suppose he had walked into some woman’s room by mistake and he was the intruder? The thought made him break out in a cold perspiration. No, it could not be. It was his bedroom; the string tied to the door knob proved that.

A sudden movement behind him caused Curtis to turn his head and the sound of a light footfall gave warning of the woman’s approach. As she passed the alcove something was tossed against Curtis’ extended hand, and then she slipped out of the room. Curtis instinctively stooped and picked up the object. As he smoothed out the small square of fine linen he started, then held it up to his nose—only to remove it in haste. Chloroform was a singular scent to find on a woman’s handkerchief.

The door of his bedroom had been left ajar and through the opening came a woman’s voice.

“Good gracious, the hall is in darkness!” Mrs. Meredith’s tones were unmistakable. “Anne, how you startled me!” in rising crescendo. “Come to bed, child; the fuse is probably burned out.” A door was shut with some vigor, then silence.

Curtis slipped the handkerchief inside his coat pocket and once again turned to the house telephone. His nervous fingers spun the dial around to the fifth hole and he pressed the button. He must chance it that Hollister’s call number was five. Three times he pushed the button, each with a stronger pressure, before a sleepy “hello” came over the wires.

“Hollister?” he called into the mouthpiece, keeping his voice low.

“Yes—what is it?”

“Thank the Lord!” The exclamation was fervid. He had secured help at last without creating a scene. “This is Curtis speaking. John Meredith is lying in the hall, dead.”

“What? My God!” Hollister’s shocked tones rang out loudly in the little receiver. “Are you crazy?”

“No. He’s there— I stumbled over his body. Yes—front hall. Bring matches—the lights are out.”

Curtis was standing in the doorway of his room as Hollister, in his pajamas, ran toward him down the hall, an electric torch in one hand and a bath robe in the other.

“Have you rung for the servants, Curtis?” he asked, keeping his voice lowered.

“No. I couldn’t recall their room numbers or find a bell.”

Hollister brushed by him into the bedroom, switched on the light, and, pausing only long enough to get the servants’ quarters on the house telephone and order a half-awake butler to come there at once, he bolted into the hall again.

“Where is John?” he demanded.

“Lying near the head of the staircase—” Not stopping for further words Curtis caught the lawyer’s arm and, guided by Hollister, hurried with him down the hall.

At sight of the figure on the floor Hollister stopped abruptly. Loosening Curtis’ grasp, he thrust the electric torch into his hand, then dropped on one knee and looked long and earnestly at his dead friend.

“You are sure he is beyond aid?” he stammered.

“Absolutely. He died before I reached him.”

Hollister crossed himself. “John—John!” His voice broke and covering his face with his hands he remained upon his knees for fully a minute. When he rose his forehead was beaded with tiny drops of moisture.

“Go and hurry the servants, Curtis. Oh, I forgot—you can’t see.” It was not often that the quick-witted lawyer was shaken out of his calm. “We must get John back into his bedroom.”

“You cannot remove the body until the coroner comes,” interposed Curtis.

“But, man, the place is all blood—it’s a ghastly sight!”

“I imagine it is,” replied Curtis curtly. “The coroner must be sent for at once.”

“Very well, I’ll attend to that. You stay here and keep the servants from making a scene; we can’t alarm the women.” Hollister stopped long enough to put on his bath robe. “I’ll telephone from my room—there’s an outside extension phone there; then I’ll put on some clothes before I come back,” and he sped away.

Herman, the butler, heralded his approach with an exclamation of horror.

“Keep quiet!” Curtis’ stern tones carried command and Herman pulled himself together. “Go and see what is the matter with the electric lights in this corridor; then come back. Make as little noise as possible,” he added by way of caution and the alarmed butler nodded in understanding.

At sound of the servant’s receding footsteps Curtis dropped on one knee and ran his hand over John Meredith. A startled exclamation escaped him. He had left the body lying partly on one side as he had found it; now John Meredith was stretched at full length upon his back. Could Hollister have been so foolish as to turn him over? Only the coroner had the right to move a dead body.

As Curtis drew back his hand preparatory to rising, he touched a strand of hair caught around a button on the jacket of Meredith’s pajamas.

“If I could only see!” The exclamation escaped him unwittingly. He hesitated a brief second, then deftly unwound a few hairs and placed them inside his leather wallet just as Herman stopped by his side.

“There weren’t nothing the matter with the lights,” he said, in an aggrieved tone. “They was just turned off. My, don’t the master look awful! You oughter be thankful, sir, that you can’t see ’im.”

Hollister’s return saved any reply on Curtis’ part, and the servant stepped back respectfully to make room for him.

“Coroner Penfield is coming right out,” the lawyer announced. “Also Dr. Leonard McLane, Meredith’s family physician. I thought it best to have him here when we break the news to Mrs. Meredith and Anne, not to mention Miss Hull—she’s a bundle of nerves.”

His thoughts elsewhere, Curtis failed to remark the change in Hollister’s voice at mention of Lucile Hull’s name.

“Did you notify the police?” he asked.

“The police? Certainly not.” Hollister stared at his companion. “We don’t need the police, Curtis. Say, are you ill?” noticing for the first time the blind surgeon’s pallor.

“I’m beginning to feel a bit faint.” Curtis pushed his hair off his forehead and unloosened his collar.

“Here, Herman, nip into my room and get the flask out of my bureau drawer,” directed Hollister. “Hurry!”

As the servant hastened on his errand Hollister half guided, half pushed Curtis to a hall chair and propped him in it. Not pausing to dilute the fiery liqueur, he snatched the flask from the breathless servant and tilted it against Curtis’ lips.

“Take a good swallow,” he advised, keeping his voice low. “There, you look better already,” as the fiery stimulant brought a touch of color to Curtis’ cheeks. “Rest a bit, then I’ll let Herman take you to your room and help you undress. You haven’t been to bed?”

“No. I was on my way to my room when I tripped over Meredith’s body.” Curtis spoke with an effort, the sensation of deadly faintness had not entirely vanished, in spite of the stimulant. He had no means of knowing that Hollister was watching him with uneasy suspicion. “I stayed down in the library until around two o’clock or a little after.”

“Ah, then you don’t know the exact hour you found poor Meredith,” Hollister spoke half to himself, but Curtis caught the words.

“It was a quarter past two by my repeater,” he answered.

“A quarter past two—and you did not call me until three o’clock,” exclaimed Hollister. “How was it that you let so long a time elapse?”

“Because I did not know which was your room,” explained Curtis, speaking slowly so that Hollister could not fail to understand. “I thought it best to call you on the house telephone, and it took me quite a time to find my way back to my bedroom. The moment I got there I telephoned to you—”

“The moment you got there,” repeated Hollister. “The moment you got to your bedroom, do you mean?”

“Yes. I identified it by the string on the door knob. You found me standing in my doorway when you came down the hall.”

Hollister stared at him, his eyes big with wonder. “Was it from that room you telephoned to me?” he asked.

“Yes,” with growing impatience. “I have already told you that I called you on the house ’phone in my bedroom.”

“But, my dear fellow, that wasn’t your bedroom.”

Curtis half rose. “That wasn’t my bedroom,” he gasped. “Then whose was it?”

“John Meredith’s bedroom—good Heavens!” as Curtis collapsed. “Help, Herman. Doctor Curtis has fainted.”

Coroner Penfield waited with untiring patience for Inspector Mitchell to complete his examination before signing to the undertaker’s assistants, who stood grouped at the further end of the hall, to remove the body. In utter silence the men came forward with their stretcher, and all that was mortal of John Meredith was tenderly lifted and carried to a spare bedroom. As the bearers passed Mrs. Meredith’s boudoir door it opened and Anne Meredith stepped across the threshold.

Dressed in her white pegnoir and the unnatural pallor of her cheeks enhanced by the deep shadows under her eyes, she appeared, in the uncompromising glare of the early morning sunlight, like a wraith, and the men halted involuntarily. Before any one could stop her, Anne stepped to the side of the stretcher and drew back the sheet. A shudder shook her at sight of the bloodstains. With a self-control little short of marvelous in one so young she mastered her emotion and laid her hand, with caressing tenderness, against the cold cheek.

“Poor Uncle John!” she murmured. Her hand slipped downward across the broad chest. There was an instant’s pause, then stooping over, she kissed him as some one touched her on the shoulder.

“Anne,” her mother’s voice sounded coldly in her ear. “Come away, at once.”

Under cover of the sheet Anne plucked at a button on the jacket, then with a single sweep of her arm she tossed the sheet over the dead man’s face.

“Pardon me,” she stammered as Coroner Penfield walked over to the stretcher. “Uncle John was very dear to me,” her voice ended in a sob. “I—I—had to see him—to—to—convince myself that this awful thing had really happened. Oh, merciful God—”

Her mother’s firm grasp on her arm checked her inclination to hysterics.

“Come.” There was no mistaking the power of the imperious command. With a grave inclination of her head to Coroner Penfield and Inspector Mitchell, who had stood a silent spectator of the little scene, she led her daughter inside the boudoir and closed the door. Not until Anne was in her own bedroom did Mrs. Meredith release her hold upon her arm.

“I trust your morbid curiosity is satisfied,” she said, making no effort to conceal her deep displeasure.

Anne walked over to her bureau and, turning her back upon her mother, opened a small silver bonbon box and in feverish haste slipped several hairs, which she had held tightly clenched between the fingers of her left hand, under the peppermints which the box contained.

“I am quite satisfied, mother,” her voice shook pitifully. “Would you mind sending Susanne to me. I—I will lie down for awhile.”

“An excellent plan.” Mrs. Meredith turned back to the door connecting Anne’s bedroom with the boudoir. “Doctor McLane expressly ordered us to remain in our rooms until Coroner Penfield sent for us. Have you—” she paused—“have you seen Lucille?”

“No.” Anne looked around quickly. “Has she been told about Uncle John?”

“She was still asleep when I went to her room half an hour ago, and I thought it best not to awaken her.” Mrs. Meredith laid her hand on the knob of the door, preparatory to closing it behind her. “I will go there shortly. Try and rest, Anne; a little rose water might make your eyes less red,” and with this parting shot, her mother retreated.

Crossing the boudoir Mrs. Meredith hastened into her bedroom. The suite of rooms which she and her daughter occupied were the prettiest in the old mansion, overlooking the well-kept grounds and lovely elm trees, but she did not pause to contemplate her surroundings, although the large bedroom and its handsome mahogany furniture were worthy a second look.

“Susanne,” she called. “Order my breakfast at once, then go to Miss Anne.”

“Oui, madame” The Frenchwoman emerged in haste from the closet where she had been rearranging Mrs. Meredith’s dinner gowns. She smiled shrewdly as she went below stairs. “You give orders as if you were already mistress here,” she muttered, below her breath. “But wait, madame, but wait.” And with a shrug of her pretty shoulders Susanne hastened to find the chef.

Mrs. Meredith regarded herself attentively in the long cheval glass, added a touch of rouge, then rubbed it off vigorously. Pale cheeks were not amiss after the tragedy of the night. Powder, delicately applied, removed all traces of sleeplessness, and finally satisfied with her appearance, she left her bedroom. The old mansion had but two stories, with rambling corridors and unexpected niches and alcoves. The wide attic was lighted by dormer windows and a deep cellar extended under the entire building.

The large drawing-room, library, billiard room and dining-room were on the first floor, the servants’ quarters in a wing over the kitchen and three large pantries, and the ten masters’ rooms took up all the space on the second floor. A second wing, added at the time John Meredith had had electricity and plumbing installed, furnished three additional bedrooms and baths and were reserved for bachelor guests. The ground floor of this wing made a commodious garage.

As Mrs. Meredith walked down the broad corridor she noted two detectives loitering by the head of the circular staircase and frowned heavily. Her pause in front of the door leading to the bedroom occupied by Lucille Hull was brief. She knew, from her earlier visit that morning, that her cousin had neglected to lock the door upon retiring the night before. Without the formality of knocking she turned the knob and entered. The dark green Holland shades were drawn and in the semidarkness Mrs. Meredith failed to see a pair of bright eyes watching her approach. By the time Mrs. Meredith reached the bedside, Lucille was in deep slumber, judging by her closed eyes and regular breathing.

Lucille’s good looks were not due to cosmetics, Mrs. Meredith conceded to herself as she stood looking down at her. Even in the darkened room the girl’s regular features and beautiful auburn hair which, flying loose, partly covered the pillow, made an attractive picture. Mrs. Meredith laid a cool hand on the girl’s exposed arm, and gave it a gentle shake.

“Lucille,” she called softly. “Wake up.”

Slowly the handsome eyes opened. Her first glance at the older woman became a stare.

“Good gracious, Cousin Belle, you!” she exclaimed. “And fully dressed. Am I very late? Have I slept the clock around?”

“On the contrary it is very early; only six o’clock.” Mrs. Meredith’s somewhat metallic voice was carefully lowered. “I have distressing news—”

Lucille raised herself upon her elbow, her eyes large with fear.

“What is it? Father—? Oh, Cousin Belle, don’t keep me in suspense.”

“Hush, calm yourself! My news has nothing to do with your immediate family.” Mrs. Meredith was not to be hurried. “Turn up that bed light, Lucille; I cannot talk in the dark.”

Bending sideways the girl pushed the button of the reading lamp. Its adjusted shade threw the light over the bed, but her face remained in shadow. “Go on,” she urged. “Go on!”

“Your Cousin John has—has—committed suicide.”

With a convulsive bound the girl swung herself out of bed.

“W-what?” she stammered. “W-what are you saying? Cousin John a suicide?”

“Yes.”

She stared at Mrs. Meredith for a full second. “Did he kill himself?” she asked, in little above a whisper.

Mrs. Meredith nodded. “His dead body was found in the hall near the staircase early this morning,” she said. “It has shocked me unutterably.”

“Cousin John dead! I cannot believe it. It is dreadful.” Lucille spoke as one stunned. She covered her eyes with her hand in an attitude of prayer, then rose and walked over to the windows and raised the shades until the bedroom was flooded with light.

“And Anne?” she questioned. “Has Anne been told?”

“Yes.” Lucille, still with her back to her cousin, felt that the keen eyes watching her were boring a hole through her head. “Doctor McLane broke the news to Anne after he had spoken to me. I fear she is inclined to be hysterical.”

“Poor Anne!” Lucille whirled around with sudden feverish energy. “I will dress at once and go to her.”

“Not just now, she is lying down and absolute quiet is what she needs,” Mrs. Meredith’s manner, which had thawed at sight of the girl’s emotion, stiffened. “If you will come to the dining room, breakfast will be served shortly.”

“Breakfast!” Lucille shuddered. “I don’t feel as if I could ever eat a mouthful again. Oh, Cousin Belle, how can you be so—so callous?”

“So what—” Mrs. Meredith stopped on her way to the door, and under the steady regard of her fine dark eyes Lucille’s burst of temper waned.

“So calm,” she replied hastily. “I wish that I had your self-control.”

A faint ironical smile crossed Mrs. Meredith’s pale face. “Self-control will come when you cease smoking,” she remarked dryly, pointing to an empty cigarette package and a filled ash tray by the bed. “And, you doubtless recall your discussion, only yesterday, with Cousin John on the subject of keeping early hours.”

Lucille flushed. “Cousin John was absurdly puritanical,” she protested. “We—ah—” she hesitated. “How has Cousin John’s death affected his plans for that extraordinary marriage? Surely, Anne won’t be forced to wed that blind surgeon. Doctor Curtis?”

“Our thoughts have not gone beyond the moment,” replied Mrs. Meredith. “We can think of nothing but John’s tragic death; all else is secondary. We must adjust ourselves,” she paused. “Hurry, Lucille, and join me in the dining room.”

Lucille dressed with absolute disregard of detail, a novel experience, as her personal appearance usually was a consideration which loomed large on her horizon, and generally consumed a good part of two hours of every morning. Loving luxury, the idol of an indulgent father, she had spent twenty-six indolent years, petted by men and gossiped about by women. She had made her debut into Washington society upon her eighteenth birthday and, in spite of the many predictions of her approaching engagement to this man and that, one season had followed another and she still remained unmarried.

Her father, Julian Hull, by courtesy a colonel, was a first cousin of John Meredith, and at one time a business associate. But unlike Colonel Hull, John Meredith had early deserted the stock-brokerage field and devoted his financial interests and his business ability to banking. He had climbed rapidly in his chosen profession, and finally attained the presidency of one of the oldest banks in the District of Columbia, a position which he had held until, upon advice of Doctor McLane, he had resigned owing to ill health. The brokerage firm of Hull and Armstrong had likewise prospered and, upon the death of its junior member, his son, Gerald Armstrong, had been taken into partnership, a partnership which, rumor predicted, would culminate in his marriage to Lucille.

Lucille and her father were frequent week-end visitors at Ten Acres, and Lucille was often called upon to act as hostess at dinners and dances when Mrs. Marshall Meredith was not present. John Meredith’s affection for his niece, Anne, and his cousin’s daughter had appeared to be about equally divided until Anne graduated from her convent school and came, as he expressed it, to make her home permanently with her uncle. Her half-shy, wholly charming manner, her old-world courtesy and consideration for others, and her delicate, almost ethereal beauty had made instant appeal, and John Meredith had been outspoken in his affectionate admiration. His marked preference for Anne had brought no appreciable alteration in the friendship between the cousins, and, in spite of the eight years difference in their ages, she and Lucille were inseparable companions.

It had been Meredith’s custom to have guests every week-end from January to June and from June to January at Ten Acres. He never wearied of improving the stately old mansion and its surrounding land and enjoyed having others share its beauty. Anne’s nineteenth birthday anniversary two days before had proved the occasion for much jollification, but the house party, to the surprise of Mrs. Meredith, had only included Lucille Hull, Sam Hollister and Gerald Armstrong. The arrival of David Curtis just in time to be present at the birthday dinner had aroused only a temporary interest in the blind surgeon and a feeling of pity, tinged with admiration on Anne’s part, for Curtis’ plucky acceptance of the fate meted out to him. What had occasioned surprise was Meredith’s absorption in his blind guest the night of the dinner and the following day; then had come his interview with his sister-in-law and the peremptory statement of his wishes respecting a marriage between Anne and David Curtis. In every way it had proved an eventful Sunday, ending with John Meredith’s suicide.

Lucille checked her rapid walk down the corridor only to collide with some vigor with David Curtis as she turned the corner leading from her bedroom into the main hallway.

“Oh, ah—excuse me!” she gasped, as he put out a steadying hand. “Let me pick up your cane,” and before he could stop her she had stooped to get it.

“Thank you,” he said, as she put the cane back in his hand. “It was awkward of me to drop it. I hope that I did not startle you, Miss Hull?”

Lucille looked at him queerly for a moment, “Miss Hull,” she repeated. “Why not Anne Meredith?”

“No. Miss Hull,” his smile was very engaging; and again she noted the deep blue of his sightless eyes.

“You are very quick to guess identities, Doctor Curtis,” she remarked. “Are you coming downstairs?”

“Not just now. Coroner Penfield is waiting for me,” he added by way of explanation.

“Then I will see you later,” and with a quick bow Lucille hurried toward the staircase.

As Curtis stood listening to her light footfall he heard some one approaching from the servants’ wing of the house.

“That you, Fernando?” he questioned.

“Yes, sir,” and the Filipino boy bowed respectfully. “I ver’ late. Please pardon. This way, sir,” and he touched Curtis’ arm to indicate the direction.

“Just a moment,” Curtis lowered his voice. “What color is Miss Hull’s hair?”

“Mees Hull,” Fernando paused in thought. “She got what you call red hair.”

Curtis tucked his cane under his arm and took out his wallet. Opening it he carefully drew out several hairs.

“What color are these, Fernando?” he asked. “Look carefully.”

Fernando bent over and then glanced up, a mild surprise at the question in his sharp black eyes.

“These, honorable sir,” he said slowly, “these are white hairs.”

As David Curtis crossed the threshold of the door of John Meredith’s bedroom Doctor Leonard McLane sprang forward with a low ejaculation.

“Dave! It’s you—really you,” he exclaimed. “Penfield said a Doctor Curtis was here, but it did not dawn on me that it was you.” He looked closely at his old friend and his expression of eager welcome gave place to one of compassion. His handclasp tightened. “I’m—”

“Leonard McLane,” Curtis’ tired face lightened. “I recognized your voice when you first spoke.”

“The same keen ears.” McLane pulled forward a chair, and helped his blind companion into it. “I recollect your memory tests; they were almost uncanny—”

“Freakish, is a better word,” broke in Curtis, and a short sigh, which McLane caught, completed his sentence. “My early training is standing me in good stead, for which,” his smile was whimsical, “praise be!” A movement to his right caused him to cease speaking as Coroner Penfield stepped into the room.

“You are acquainted, gentlemen?” he asked, observing McLane’s hand resting on his friend’s shoulder.

“Well, rather!” McLane smiled broadly. “We were pals at McGill Institute in Canada and graduated in the same class. I came here and Doctor Curtis went to Boston.”

“Where I remained until I went overseas with the Canadian forces at the outbreak of the World War,” added Curtis. “I saw service with them until we entered the War and then joined an American medical unit. I was blinded in the Argonne.” He stopped for a moment, then asked, “Am I speaking to Coroner Penfield?”

“I beg pardon, I thought that you two had met,” ejaculated McLane, as Penfield shook Curtis’ extended hand.

“I know Doctor Curtis by reputation,” the latter said. “It is a pleasure to meet you, even in such a ghastly business as this,” and he wrung Curtis’ hand hard before releasing it.

“It is a ghastly business,” agreed McLane gravely. “A most shocking affair.”

His words were echoed by Sam Hollister who, at that instant, came into the room followed by Inspector Mitchell.

“Meredith’s suicide has fairly stunned me,” he added, as the men grouped themselves about Curtis, who occupied the only chair in that part of the room. “It is incomprehensible, astounding. A man in the best of health—”

“Hold on!” Coroner Penfield held up his hand. “Let me do the questioning, Hollister.” He turned to McLane. “You were Mr. Meredith’s family physician, were you not?”

“Yes; for the past five years.”

“Was he in good health?”

“He had made an excellent recovery from a nervous breakdown,” explained McLane. “Yes, I should say that he was, until last night, enjoying normal health.”

“Why until last night?” questioned Hollister, and Penfield frowned at the interruption.

“Last night—he died,” replied McLane dryly, and would have added more, but Penfield again cut in on the conversation.

“Can you place the exact time at which you found Meredith, Doctor Curtis?” he asked, turning to the surgeon.

“A quarter past two this morning,” answered Curtis. “Meredith was dead when I tripped over his body.” He paused. “I should say, however, that he died only a few minutes before my arrival.”

“How do you know that?” demanded Hollister, and McLane glanced at the little lawyer in some surprise; his manner was far from courteous.

“By the warmth of his body and its limp condition.” Curtis spoke quietly, his sightless eyes turned toward Hollister. “Besides, I heard Meredith coming down the corridor as I came up the staircase.”

“Did he walk briskly?” asked Hollister before Inspector Mitchell could speak.

Curtis shook his head. “He appeared to drag one foot after the other; then I heard a soft thud—”

“Probably staggered along the hall and fell,” broke in Mitchell.

“But where was he going?” persisted Hollister, not deterred by Coroner Penfield’s irritation at his continuous questions.

“We have not yet found an answer to that question,” replied Mitchell.

“He was probably on his way to summon help,” suggested McLane.

“But he had the house telephone right here at hand,” objected Hollister.

“If he regretted his rash act and wished immediate aid he did not have to leave his room and crawl down the hall to find it.” He looked belligerently at the others. “Why didn’t John cry out? That would have been the quickest way to have awakened us.”

“A man with such a gash in his throat would not have breath enough to shout,” McLane pointed out.

“He could not have lived ten minutes after—”

“Inflicting it,” supplemented Hollister. “Then it is all the more extraordinary that he left his bedroom and tried to go down this winding corridor.”

Coroner Penfield and Inspector Mitchell exchanged glances.

“Mr. Hollister,” the latter asked, “when did you last see Meredith?”

“On my way to bed,” responded the lawyer. “I looked in for a moment. It was just after I left you in the library,” he turned to Curtis; “about eleven-twenty, I suppose.”

“And where was Meredith?” asked Mitchell patiently.

“Here in his room, reading in bed, as was his custom.” Hollister twisted the ends of his waxed mustache until they pointed upward.

“And did he appear in his usual health or did he evince any, eh, morbid tendencies?” Mitchell hesitated over his words, but Hollister’s reply was instant.

“He seemed to be his usual self except that he showed unusual excitement over the—” with a side-long glance at Curtis—“arrangements for the marriage of his niece, Anne, to Doctor Curtis.”

Curtis lifted his head. “Ah, then you told him the result of our conversation?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And did it appear satisfactory to him?”

“Yes.” Hollister paused before adding: “John insisted upon my drawing up the prenuptial settlements so that he might sign the agreement before I left.”

“Oh, so he signed some legal papers, did he?” Mitchell looked keenly at the lawyer and then at Curtis; the latter’s expression puzzled him, and he put his next question without removing his gaze from the blind surgeon. “Can you let me see the papers?”

Hollister shook his head. “I haven’t them,” he answered. “I left the papers lying on the bed by John Meredith.”

With one accord the Coroner, Inspector Mitchell and Leonard McLane wheeled around and stared at the carved four-post mahogany bedstead which occupied one side of the large room. It was evident that the bed had been slept in; the pillows were tumbled about and the bedclothes turned back in disorder. A dressing gown lay on the floor not far from the bed. No papers of any kind were on the bed, but on the right side an ominous red stain had spread a zigzag course from the under sheet to the carpet.

Curtis broke the long pause. “I take it the papers are not on the bed now, judging from your silence,” he said. “Was any one, beside yourself, Hollister, aware that Meredith had drawn up this, what did you call it—”

“Prenuptial agreement,” interposed Hollister.

“The witnesses knew—”

“And who were the witnesses?” asked Mitchell, notebook in hand.

“Miss Lucille Hull and Gerald Armstrong.” Hollister glanced keenly about the bedroom and moved as if to cross to a mahogany secretary which stood near one of the windows. “Perhaps they are in Meredith’s secretary—”

“Just a moment, Mr. Hollister,” Coroner Penfield held out a detaining hand. “Nothing is to be touched in this room. Inspector Mitchell and I will conduct a thorough search later on. In the meantime have you any notes, any memorandum of the agreement signed by Meredith last night which you could give us?”

Hollister nodded. “I made a rough copy, and if I remember correctly I stuffed it in the pocket of my dinner jacket. I’ll get it,” and he started for the door, only to be halted at the threshold by a question from Coroner Penfield.

“After the signing of the agreement were you the first to leave Mr. Meredith, or did the witnesses go first?” he asked.

Hollister thought a moment. “Gerald Armstrong left immediately,” he said. “Miss Hull and I started to go at the same time, but Meredith called her back.”

“I see,” Penfield paused, then looked up. “All right, Mr. Hollister, if you will get that paper for me, I’ll be much obliged.” As Hollister disappeared through the doorway, he turned to Mitchell. “Inspector, will you look up Miss Hull and Mr. Armstrong and tell them that I wish to see them within the next half hour.”

“Do you wish to see them together?” questioned Mitchell, stopping halfway to the door.

“No, one at a time,” and Mitchell hurried away as Fernando, the Filipino, upon the point of entering, stepped back to allow him to pass from the room.

“If you please, sir,” said the latter, reappearing and bowing low to McLane. “Doctor Pen is wanted on the telephone.”

McLane, knowing Fernando’s habit of clipping names, smiled. “It’s you he wants, Penfield,” he explained, and as the coroner went out of the bedroom, followed by Fernando, he closed the hall door and turned to Curtis.

“The years drop away, Dave,” he drew up a chair as he spoke. “It seems only yesterday that we were together in Montreal.”

quoted Curtis, and his voice held a depth of pathos which touched McLane. “I’ve heard with delight, Leonard, of your success and of your happy marriage.”

“My wife is—well,” McLane laughed, a trifle embarrassed. “You must meet her and then you’ll know for yourself how dear she is. Why haven’t you let me know you were in Washington, Dave?”

“I intended to do so to-day anyway, even if this tragedy had not happened,” explained Curtis. “John Meredith yesterday promised to run me in to see you this morning.”

McLane eyed him closely. “I had no idea you were an intimate friend of John Meredith’s.”

“I wasn’t,” broke in Curtis. “I only met him ten days ago at Walter Reed—”

“What?”

Curtis nodded. “Just so,” he exclaimed. “I saw Meredith again on Monday and he very kindly insisted that I come over here last Friday evening, and spend the week with him.”

McLane glanced at his watch, then turned again to his companion. “Is it really true,” he spoke with some hesitation, “really true that you are to marry Anne Meredith?”

Again Curtis nodded his head. “It is as wild as an Arabian Nights’ romance,” he said somberly. “John Meredith appealed to the latent dare-devil spirit that still lingers with me by such an extraordinary proposition.”

“Exactly what was the proposition?” questioned McLane.

“Meredith wished me to marry his niece, Anne, and declared that after the ceremony I need never meet her again except for a few months each year at Ten Acres,” replied Curtis. “He agreed to settle twenty-five thousand dollars a year on us individually.”

“A very tidy sum,” interposed McLane.

“And mental degradation!” The words came almost in a whisper. “Meredith tempted me more than he knew. To be handicapped with blindness and poverty, and then to be offered a chance to get away, to have some means of subsistence for the life remaining to me—on the other hand, the humiliation of taking such a means of rescue. God!” He shaded his face with his hand.

McLane leaned over and patted him on the shoulder. “I understand,” he said softly. “You agreed to Meredith’s proposal—”

“Only after I had been told by the girl’s mother that Meredith would otherwise disinherit his niece and that thus she would be left penniless,” answered Curtis. “Then I consented to go through with the ceremony.”

“One for Anne and two for herself,” McLane muttered, too low for Curtis to catch the words, then raised his voice. “Take it from me, Dave, Mrs. Marshall Meredith is Satan in petticoats.”

Curtis laughed mirthlessly. “It would seem so,” he agreed. “Think of it, man, was there ever so mad a scheme? A bride, and one that I have never laid eyes on. I wonder if she be ugly as Hecate or with the temper of Xanthippe.”

“Neither, I assure you,” replied McLane warmly. “Anne Meredith could not do a mean or dishonorable act. Convent bred, she is at times painfully shy, but she has plenty of character. And,” McLane wound up, “she is very beautiful.”

Curtis passed a nervous hand across his sightless eyes. “What you say makes our marriage appear even more unsuitable; in fact, a mockery. I am a derelict—human flotsam—whereas Anne Meredith is at the threshold of life with the world before her.”

McLane stood up and looked down at his companion. “Blindness with you will not be a handicap,” he said stoutly. “I know your capabilities, Dave; your generous heart and splendid courage. I am not afraid of the future for either you or Anne,” and as Curtis opened his lips to speak, he asked: “But tell me, what inspired Meredith’s wish that you and Anne should marry?”

Curtis rose also and stood leaning on his cane. “Good knows, I don’t,” he said. “I have absolutely no idea why he wished the marriage to take place, or why he selected me—a blind man and a stranger—to be the bridegroom.”

McLane stared at him in incredulity. “Most extraordinary!” he ejaculated finally. “Has no one any inkling of the reason?”

“Sam Hollister said last night that Meredith would tell us after the marriage ceremony,” answered Curtis. “But now he is dead.”

“Another mystery!” McLane drew a long breath. “Upon my word, Dave, you have two very pretty problems on your hands.”

Curtis swung closer to his side. “You think that the two are linked together?” he asked. “Meredith’s sudden determined wish for this marriage and then his death—”

McLane hesitated. “It’s impossible to say at this stage of the investigation,” he admitted. “And it is early to surmise.” His voice trailed off as he stopped to glance about the bedroom. Curtis’ hand on his shoulder brought his attention back to the blind surgeon.

“Describe the room, Leonard,” he suggested. “Everything, just as it stands now.”

“I judge the room’s about fifteen by twenty-two feet,” McLane began. “There are four windows opening on a balcony, two facing the east and two the north. Two closet doors, one ajar, and another door leads to the bathroom.”

“And the furniture,” prompted Curtis, as McLane stopped speaking.

“The four-post bedstead, a bed table, with reading lamp and smoking set on it; a highboy and a bureau with toilet silver.” Curtis was listening with close attention to every detail. “Meredith’s desk-secretary is near the east window, and there is a table with books and magazines upon it and another reading lamp near the bathroom door.”

“What about chairs?”

“Three; one a large tufted lounging chair near the north window; a chair by the desk, and, eh,” bending his head to peer around—

“One by the bed,” supplemented Curtis. “It is overturned.”

McLane glanced at him in astonishment. “It is,” he admitted. “But I can only see the legs of the chair from where we are standing. How did you know the chair was there and lying on the floor?”

“Intuition perhaps, or only a good guess,” Curtis smiled oddly. “On which side of the bed is it? On the side Meredith climbed out?”

“No, on the far side.” Curtis nodded his head thoughtfully as he stepped forward.

“Which way is the bed?” he asked. For answer McLane led him to it.

With touch deft as a woman’s, Curtis passed his hands over the pillows and the bolster, leaving them undisturbed; then his hands traveled across the sheet, hovered for a second on the edges of the bloodstain and followed its course over the side of the bed and from the valance to the carpet.

As he dropped on one knee and ran his fingers along the carpet the hall door opened and Coroner Penfield entered. He halted abruptly at sight of David Curtis creeping across the floor, his long sensitive fingers playing up and down the carpet, and glanced questioningly at McLane. Before the latter could explain Curtis broke the silence.

“Meredith must have either fallen or stooped over here,” he said. “Oh, I forgot,” his smile was a bit twisted. “You can see this and deduct it for yourself.”

“But we can’t,” cut in Penfield quickly. “What makes you think Meredith stopped there? It is not on the way to the door.”

“Because of the amount of blood on this spot.” Curtis raised his head. “See for yourself.”

“But we can’t see the blood,” exclaimed McLane. “The carpet is red.”

“So!” Curtis paused as Penfield bent down and felt the spot indicated by the blind surgeon.

“You are right,” he exclaimed. “The carpet has been saturated with blood. What was Meredith doing in this corner of the room? There are no stains on the mahogany wainscoting,” he added, as Curtis turned to his left and ran his hands over the wall, “nor on the paper.”

“It is quite possible that Meredith lost his sense of direction,” suggested Curtis, rising. “He was probably frightfully weak from loss of blood. It is remarkable that he got as far as he did with such a wound. Is the bed to my left?”

“Yes, this way.” Penfield, as interested as McLane, followed Curtis back to the four-poster. “Inspector Mitchell followed my instructions, and nothing has been touched in this bedroom.”

“You are quite certain that no one has entered since your arrival?” asked Curtis.

“Positive. Mitchell stationed a detective outside the door and another on the balcony on which these windows open,” with a jerk of his hand in their direction. “Well, what the—”

The coroner’s voice failed him as Curtis, who had approached the bed from its other side, dexterously avoiding, as he did so, the overturned chair, lifted the tossed-back sheet, blanket and counterpane and disclosed a parrot. The bird, its brilliant plumage sadly tumbled, lay inert upon its side, its eyes closed.

“Good Lord! Ruffles!” exclaimed McLane. “Is he dead?”

Curtis picked up the parrot and examined it. “There’s a heartbeat; pretty feeble, but the bird’s alive.” Suddenly he raised the bird and sniffed at its beak, then bent over and put his head down where the parrot had lain.

“Why in the world didn’t the parrot get out from under the bedclothes before it was smothered,” exclaimed Penfield. “I’ve always understood that parrots were nearly human.”

“Ruffles is,” declared McLane. “I can tell you many stories of his sagacity. Meredith was devoted to the bird. He never tired of hearing him talk—he said that Ruffles took the place of wife and watchdog.”

“Watchdog?” Curtis raised his head. “Um!” He held up the parrot. “Carry him over to the window, Leonard; the fresh air may revive him. He has been chloroformed.”

“Well, I’ll be d—mned!” ejaculated a voice behind them and Inspector Mitchell, who had returned a few minutes before, went with McLane to the window and carried the parrot’s stand to him. McLane laid Ruffles on the flooring under the perch and refilled the water cup, sprinkling some of its contents on the bird, and then pulled back the curtains so that the air blew slightly upon it.

Curtis wiped his fingers on his handkerchief and turned to Coroner Penfield.

“Where have you taken Meredith’s body?” he asked.

“To the empty bedroom next to this,” answered Penfield. “We will hold an autopsy there within the hour. McLane will aid me. Would you care to be present, Doctor Curtis?”

“Yes, if I may.” Curtis moved over to the window. “How is the parrot, Leonard?”

“Coming out of his stupor,” Mitchell answered for McLane, who had gone into the bathroom. “There, Ruffles, drink a little water.” He held the cup up to the bird. “Have you called the inquest, Doctor Penfield?”

“Yes; it will be held this afternoon,” answered the coroner. “Will that suit your plans, Mitchell?”

“Sure!” Mitchell set the parrot on its perch and placed a steadying hand on its back as the beadlike black eyes regarded him with an unwinking stare. “Will the inquest be here or at the morgue?”

“I haven’t quite decided.” Penfield stroked his chin thoughtfully. “But I have fully decided that Meredith’s death is not a case of suicide, but of murder.”

McLane, reentering the bedroom, stopped as if shot and gazed in horror at the coroner. Curtis replaced the handkerchief in his pocket and changed his cane to his right hand.

“May I ask what has led you to that conclusion. Doctor Penfield?”

Penfield hesitated and looked behind him to make certain that the hall door was closed, then lowered his voice to a confidential pitch as the men gathered about him.

“For one thing,” he began, “the absence of any weapon. Had Meredith killed himself the weapon would have been in this bedroom or in the hall. It is a case of murder.”

A hoarse croak from the parrot cut the silence and turning they looked at the bird. Ruffles leered drunkenly at them, before he spoke with startling clearness:

“Anne—I’ve caught you—you devil!”

The opening and closing of doors and the murmur of distant voices came fitfully to David Curtis as he sat near the window of his bedroom, his head propped against his hand and his sightless eyes turned toward the view over the hills to the National Capital. He had sat in that position for fully an hour trying to reduce his chaotic thoughts to order. Out of the turmoil one idea remained uppermost—John Meredith had undoubtedly been murdered. Who had committed so dastardly a crime? Would the answer be forthcoming at the inquest?

Contrary to custom, Coroner Penfield had decided to hold the inquest at Ten Acres instead of having it meet in the District of Columbia Morgue, and he had specified three o’clock that afternoon—it must be close to the hour. Curtis touched his repeater—a quarter past three. The inquest must have started. Curtis reached for his cane and then laid it down.

Coroner Penfield had said that he would be sent for when his presence was required.

Curtis had eaten both his breakfast and luncheon in solitary grandeur in the small morning room upstairs, waited on by Fernando who had been told by Mrs. Meredith to act as his valet. During the morning he had requested an interview with Anne, but a message had come from Mrs. Meredith stating that the girl was completely unstrung by the shocking death of her uncle and could see no one.

That the entire household was thrown out of its usually well-ordered existence was evidenced by the confusion among the servants. It had required all Mrs. Meredith’s combative personality to check the incipient panic and keep them at their work. The servants represented a number of nationalities. Jules, the chef, and his sister, Susanne, Mrs. Meredith’s maid, had come from France before the outbreak of the World War; Gretchen, the chambermaid, was a new acquisition, having arrived from Holland only the previous fall; Fernando and his twin brother, Damason, had been in John Meredith’s employ from the time he brought them with him from the Philippine Islands eight years before. But in point of service Herman claimed seniority, having served first as office boy and then been taken into Meredith’s bachelor household as valet and later as butler.

Curtis had judged somewhat of the excitement prevailing below stairs by Fernando’s unusual talkativeness, except on one point—he became totally uncommunicative when the subject of string was broached.

“You tell me you say last night, ‘Fernando, hang string on my door so I find bedroom,’” he had repeated. “But please, Mister Doctor, you no tell me that,” with polite insistence. “Always I do what you say. I good boy.”

“Yes, yes, I know,” a touch of impatience had crept into Curtis’ quiet voice. “How was it that a string was tied to the knob of Mr. Meredith’s bedroom door and thereby led me to believe that it was my bedroom?”

“I dunno,” Fernando clipped his words with such vigor that his lips made a hissing sound. “Please, Mister Doctor, I dunno,” and with that Curtis had, perforce, to be satisfied.

Curtis stirred uneasily in his chair. He would have given much for an interview with Anne before the inquest. As it was he was going further into the affair blindfolded. His lips curled in a bitter smile—a blind man blindfolded! Did Anne wish to go on with the marriage ceremony arranged for her by her uncle? Was he to consider himself engaged to her? He had been given no key to the situation—no inkling even whether he was expected to remain as a guest at Ten Acres, or to leave immediately after the inquest.

Mrs. Meredith had left him severely alone, but he had been informed by Fernando that his fellow guests had gone their several ways into town but would return in time to appear at the inquest. Leonard McLane had hurried away also at the conclusion of the autopsy, first having extracted a promise from Curtis that he would make him a visit of at least a week’s duration should he decide to leave Ten Acres.

A discreet knock on the door brought back Curtis’ wandering thoughts with a jump.

“Please, Mister Doctor, you are wanted downstairs,” announced Fernando, and stepping forward he offered his arm to Curtis.

The coroner’s jury to a man gazed with curiosity at the blind surgeon as Fernando guided him to the chair reserved for the witnesses. Upon consultation with Mrs. Meredith and Sam Hollister it had been decided to hold the inquest in the library and Coroner Penfield had lost no time in summoning his jurymen, while the servants, under Mrs. Meredith’s direction, had arranged tables and chairs and made of the attractive living room a place in which to conduct a preliminary investigation. The general public had been excluded, but Coroner Penfield had seen to it that a large table and chairs had been set aside for representatives of the press who had early put in an appearance on the scene.

Doctor Mayo, the deputy coroner, who had been busy jotting down the details of the opening of the inquest, laid aside his fountain pen and, picking up a Bible, stepped forward and administered the oath—“to tell the truth and nothing but the truth”—to Curtis. As the latter resumed his seat and Mayo went back to his table, Coroner Penfield stepped forward.

“Your full name, occupation, and place of residence, doctor?” he asked.

“David Curtis, surgeon, of Boston,” he answered concisely. “I graduated from McGill Institute in 1906. I am,” he added, “thirty-eight years of age. I was blinded in the Argonne offensive when serving with American troops.”

“And when did you return to this country?” questioned the coroner.

“About eight months ago.” Curtis paused, then added: “I was pretty well shot up, and have been in first one hospital and then another in France, and was not in shape to return until recently. I came to Walter Reed Hospital a month ago for treatment, hoping my general health would benefit thereby.”

“And when did you meet John Meredith?”

“He called upon me ten days ago.”

“Had you never met previous to that time?”

“Never.”

“And what was the occasion of the call?”

“Mr. Meredith said that a mutual friend, Arthur Reed, had written him that I was at the hospital and requested him to look me up,” explained Curtis. “Mr. Meredith took me out in his car a number of times and then asked me to spend this week at Ten Acres.”

“I see!” Penfield disentangled the string of his eyeglasses, which had slipped off his nose. “Had you met any member of this household before you came here on Friday?”

“No; they were all strangers to me.”

“Doctor Curtis,” Penfield referred to his notes, “were you the first to find John Meredith?”

“I was.”

“Describe the circumstances.”

Curtis cleared his throat. “As I was coming up the staircase I heard footsteps approaching and then a soft thud. I could not place the sound and went ahead up the staircase and down the corridor; the next second I had fallen over Meredith’s body.” He hesitated. “I could find no evidence of life.”

“And how did you learn that it was John Meredith who lay before you?” questioned Penfield.

“Since my blindness my fingers have been my eyes,” replied Curtis. “Meredith bumped his head against a door yesterday and asked me to see if he had injured himself. On investigating the slight abrasion, I ran my fingers over his head and face, and noticed his Van Dyke beard and that the top of his right ear was missing. This aided me in establishing the identity of the dead man.”

Penfield regarded Curtis for a moment before putting another question.

“What did you do next?” he inquired.

“I found my way into a bedroom and called up Mr. Sam Hollister, a fellow guest, on the house telephone and told him of my discovery,” answered Curtis. “He came at once.”

As Curtis ceased speaking the foreman of the jury leaned forward and, with a deprecatory look at Penfield, asked:

“Was the hall lighted, Doctor Curtis?”

Curtis’ hesitation was hardly perceptible. “I could not see,” he said simply, and the foreman, intent on the scene, flushed; he had forgotten, in his interest, that he was addressing a blind man. “But on feeling my way along the hall to the bedroom, my hand came in contact with an electric fixture. As the bulb was hot I concluded the corridor was lighted.”

Penfield paused to make an entry on his pad. “Did you hear any one moving about, doctor? Did any noise disturb you as you examined Mr. Meredith?”

Curtis shook his head. “No, I could detect no sound of any kind,” he answered. “As far as I could judge I was alone in the hall with the dead man.”

“In what position did you find the body, doctor?” asked Penfield.

“Meredith had evidently fallen forward, for he lay partly turned upon his right side, his face pressed against the carpet,” replied Curtis. “His head was almost touching the banisters which guard that side of the staircase.”

Coroner Penfield glanced about the library and saw a vacant chair near the huge open fireplace.

“That is all just now, Doctor Curtis,” he said. “Suppose you sit over here; it will be more convenient if I should want you again.” And stepping forward he walked with Curtis to the vacant chair. Returning once more to his place at the head of the big table around which were seated the jurymen, he summoned Herman, the butler, to the stand.

Herman’s perturbed state of mind was evidenced in his slowness of speech and dullness of comprehension. It required the united efforts of Penfield and the deputy coroner to administer the oath and to drag from him his age, full name and length of service with John Meredith.

“He was a kind master,” Herman stated. “Not but what he had his flare-ups and his rages like any other gentleman what has a big household. But mostly he was right ca’m.”

“And did Mr. Meredith have one of his rages recently?” asked Penfield.