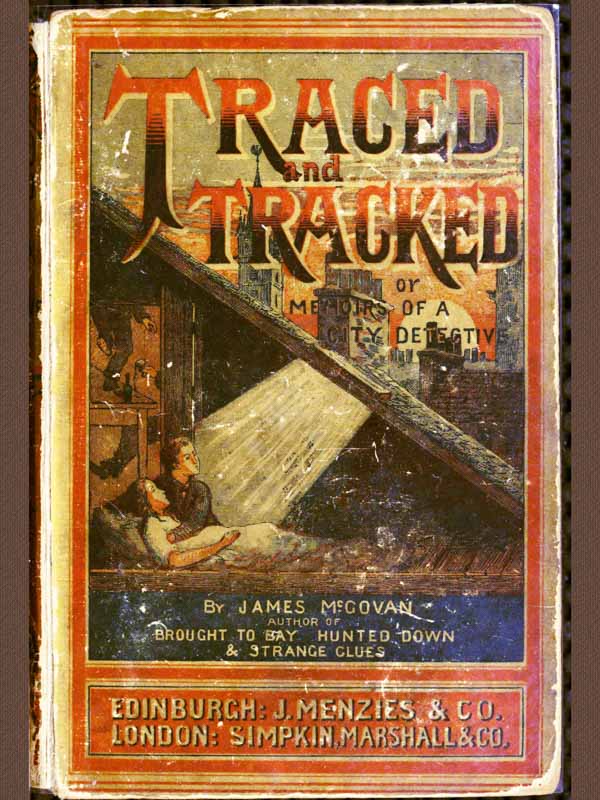

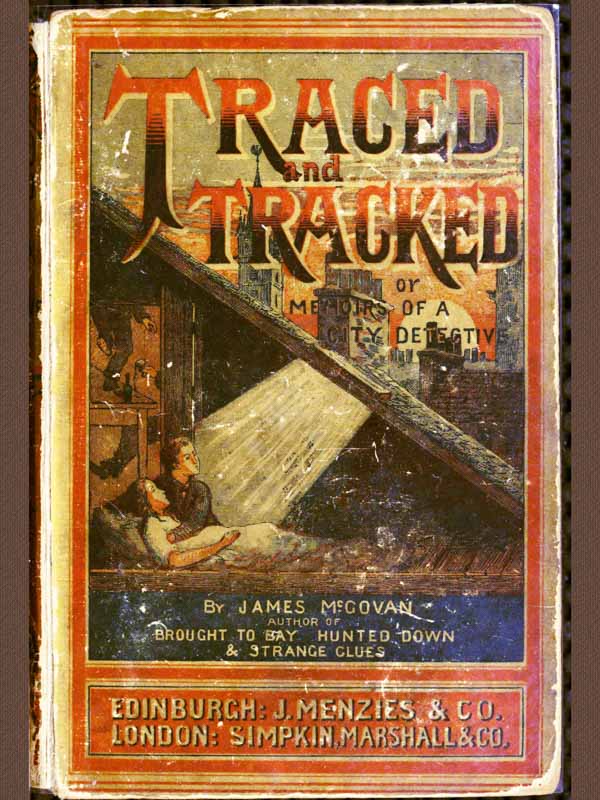

Title: Traced and Tracked; Or, Memoirs of a City Detective

Author: James M'Govan

Release date: January 17, 2019 [eBook #58711]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel, RichardW, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The above are uniform in size and price with “TRACED AND TRACKED,” and the four works form the complete set of McGovan’s Detective Experiences.

The gratifying success of my former experiences—25,000 copies having already been sold, and the demand steadily continuing—has induced me to put forth another volume. In doing so, I have again to thank numerous correspondents, as well as the reviewers of the public press, for their warm expressions of appreciation and approval. I have also to notice a graceful compliment from Berlin, in the translation of my works into German, by H. Ernst Duby; and another from Geneva, in the translation of a selection of my sketches into French, by the Countess Agènor de Gasparin.

A severe and unexpected attack of hæmorrhage of the lungs has prevented me revising about a third of the present volume. I trust, therefore, that any trifling slips or errors will be excused on that account.

In conclusion, I would remind readers and reviewers of the words of Handel, when he was complimented by an Irish nobleman on having amused the citizens of Dublin with his Messiah. “Amuse dem?” he warmly replied; “I do not vant to amuse dem only; I vant to make dem petter.”

JAMES McGOVAN.

EDINBURGH, October 1884.

I have alluded to the fact that many criminals affect a particular line of business, and show a certain style in their work which often points unerringly to the doer when all other clues are wanting. A glance over any record of convictions will convey a good idea of how much reliance we are led to place upon this curious fact. One man’s list will show a string of pocket-picking cases, or attempts in that line, and it will be rare, indeed, to find in that record a case of robbery with violence, housebreaking, or any crime necessitating great daring or strength. Another shows nothing but deeds of brute strength or bull-dog ferocity, and to find in his record of prev. con. a case of delicate pocket-picking would make any one of experience open his eyes wide indeed. The style of the work is even a surer guide than the particular line, as the variety there is unlimited as it is marked. This is all very well; and often I have been complimented on my astuteness in thus making very simple and natural deductions leading to convictions. But the pleasure ceases to be unmixed when the criminal is as cunning as the detective, and works upon that knowledge. To show how a detective may be deceived in working on this—one of his surest modes of tracing a criminal—I give the present case.

Dave Larkins was a Yorkshire thief, who had drifted northwards by some chance and landed in Edinburgh. Street robbery was his line, and, as he was a professional pedestrian, or racing man, he was not caught, I should say, once in twenty cases. The list of his previous convictions in Manchester, Liverpool, Preston, and other places showed with unvarying monotony the same crime and the same style of working. He would go up to some gentleman on the street and make an excuse for addressing him, snatch at his watch, and run for it. More often the victim was a lady with a reticule or purse in her hand, and then no preliminary speaking was indulged in. He made the snatch, and ran like the wind, and the whole was done so quickly that the astounded victim seldom retained the slightest recollection of his appearance.

Yet Dave’s appearance was striking enough. He was a wiry man of medium height, with strongly-marked features, red hair, and a stumpy little turned up nose, the round point of which was always red as a cherry with bad whisky, except at those rare intervals when he was “in training” for some foot race which it was to his advantage to win.

Then his dress had notable points. He generally wore a knitted jersey in place of a waistcoat, and he had a grey felt hat covered with grease spots, for which he had such a peculiar affection that he never changed it for a new one. Under these circumstances it may be thought that a conviction would have been easily got against Dave. But Dave was “Yorkshire,” as I have indicated, and about as smart and cunning in arranging an alibi as any I ever met. No doubt his racing powers helped him in that, but his native cunning did more.

There is a popular impression that a Yorkshire man will hold his own in cunning against all the world, but I have here to record that Dave met his match in a Scotchman who had nothing like Dave’s reputation for smartness, and who was so stupid-looking that few could have conceived him capable of the task. This man was known in racing circles—for he was a pedestrian too—as Jake Mackay, but more generally received the nickname of “The Gander.”

Why he had been so named I cannot tell—perhaps because some one had discovered that there was nothing of the goose about him. Your stupid-looking man, who is not stupid but supremely sharp-witted, has an infinite advantage over those who carry a needle eye like Dave Larkins, and have cunning printed on every line about their lips and eyes.

The Gander was not a professional thief, though he was often in the company of thieves. He had been in the army, and had a pension, which he eked out by odd jobs, such as bill-posting and acting as “super.” in the theatres. He was a thorough rascal at heart, and would have cheated his own grandfather had opportunity served, and had there been a shilling or two to gain by it.

These two men became acquainted at a pedestrian meeting at Glasgow, and when Dave Larkins came to Edinburgh they became rather close companions. The Gander had the advantage of local knowledge, and could get at all the men who backed pedestrians, and then told them to win or lose according to the way the money was staked. A racing tournament was arranged about that time in which both of them were entered for one of the shorter races, in which great speed, rather than endurance, was called for. In that particular race they had the result entirely in their own hands, though, if fairly put to it, Dave Larkins, or “Yorky” as he was named, could easily have come in first. The other men entered having no chance, these two proceeded to arrange matters to their mutual advantage—that is, had they been honest men, the advantage would have been mutual, for they agreed to divide the stakes whatever the result. But in these matters there is always a great deal more at stake than the money prize offered to the winner. The art of betting and counterbetting would task the brain of a mathematician to reduce its subtleties to a form intelligible to the ordinary mind; and the supreme thought of each of the rogues, after closing hands on the above agreement, was how he could best benefit himself at the expense of the other. What the private arrangements of The Gander were does not appear, except that he had arranged to come in first, though the betting was all in favour of Yorky; but just before they entered the dressing tent, a patron of the sports—I will not call him a gentleman—took Yorky aside and said—

“How is this race to go? Have you any money on it to force you to win?”

Yorky, having already arranged to lose, modestly hinted that, for a substantial consideration, he would be willing to come in second.

“Second? whew! then who’d be first?” said the patron, not looking greatly pleased with the proposal. “The Gander would walk off with the stakes. He’d be sure to come in first. Could you not let Birrel get to the front?”

“It might be managed,” said Yorky, with a significant wink.

“Then manage it;” and the price of the “management” was thrust into his hand in bank notes, and the matter settled.

Yorky counted the money, and ran up in his mind all that The Gander had on the race, and decided that the old soldier would promptly refuse to lose the race in favour of Birrel. The money was not enough to stand halving, so Yorky decided to keep it all, and also to “pot” a little more by the new turn things had taken. He therefore passed the word to a boon companion to put all his spare money on Birrel, and then took his place among the competitors dressing for the race. The start was made, and, as all had expected, Yorky and The Gander gradually drew together, and then moved out to the front. Birrel at the last round was a very bad third, while the other runners were nowhere, and evidently only remaining on the track in the faint hope of some unforeseen accident taking place to give one of them the chance of a place. They had not long to wait. Yorky, running at his swiftest, and apparently in splendid form, about three yards in front of The Gander, instead of slackening his speed as he had arranged, suddenly reeled and fell to the ground right in front of his companion. The result may be guessed. The Gander was on the obstruction before he knew, and sprawling in a half-stunned condition a yard in front of Yorky’s body, while Birrel, amid a yell from the spectators, drew up and shot ahead. The yell roused The Gander, and he feebly scrambled to his feet, and made a desperate effort for the first place, but all in vain, for Birrel touched the tape before him, and he was second in everything but swearing. To the surprise of all, Yorky did not rise to his feet, and remained to all appearance insensible for five minutes after he had been tenderly carried to the dressing tent. Of course there was a protest of the most vigorous description to the referee by The Gander, who not only found that he had laid his money the wrong way, and disappointed numerous friends who had followed his advice, but was not even to have the meagre satisfaction of sharing the first prize. But under the impression that Yorky had simply over-exerted himself, and fainted on the course, the referee, who possibly had money on the result, refused to listen to the appeal, and Birrel got the prize. The Gander denounced Yorky with great vehemence, but was met with the most solemn protestations of innocence. He then put on his clothes and left the tent in a bad temper, but in leaving the grounds was accorded a “reception” which did not tend to soothe his feelings. A dozen or so of his friends, who had received his private “tip” as to the way the race was to go, gathered round the supposed traitor, and, before the police could interfere, had him beaten almost to a jelly. The poor Gander was removed in a cab to the Infirmary to have his wounds dressed, while the elated and successful Yorky went to enjoy himself with his ill-gotten gains.

When the two met again, The Gander appeared to have recovered his temper, and listened to Yorky’s explanations of the mishap on the course as pleasantly as if he believed them, which was very far from being the case. Then Yorky so far unbent as to spend some of his money in drinks for The Gander, and was foolish enough to believe that he had cheated the stupid-looking Scotchman very nicely, and that he would hear no more of the matter.

The races had taken place during the New Year holidays, and while the pantomimes were running at the theatres. In one of these The Gander was engaged as a “super.,” and it was known to him that the treasurer was in the habit of leaving the theatre for his home, at the foot of Broughton Street, late every night, carrying under his arm or in his hand a tin box resembling a cash-box. This box contained nothing but metal checks, which the treasurer counted at his home. All the money drawn at the doors remained in possession of the manager. Had Yorky not been an unusually cunning man it is probable that The Gander would have manipulated him direct, but as it was, he was forced to confide in another. A loafing acquaintance of Yorky’s seemed a suitable tool, and he was engaged and primed accordingly. Bob Slogger had himself an old grudge against Yorky, so, on the whole, perhaps a better choice could not have been made.

The opportunity came when Bob and Yorky were drinking together one afternoon, when the former incidentally remarked that they were doing immense business at the theatre, and making piles of money. Yorky only grunted in reply. It seemed hard that any one but him should be making money, and he did not like the subject.

“I got it out of The Gander that the treasurer can hardly carry the money home some nights,” continued Slogger, repeating his lesson. “He lives at the foot of Broughton, and carries it there in a tin box every night about half-past eleven. I could do with that boxful of silver on a Saturday night.”

“Ah! Saturday night? is there most in it then?” observed Yorky, suddenly rousing into deep interest.

“Of course there is;” and Slogger at once gave the reasons, and repeated all that The Gander had said regarding the appearance of the treasurer, his hour of going home, and the dark and deserted appearance of the streets at that lonely locality. Yorky snapped at the bait, but did not abandon his usual caution. He said nothing to his informant of his intentions, and much of The Gander’s after proceedings had to be founded on mere acute inferences. The spot to be chosen for the attack he guessed at by one of Yorky’s questions, and the night most likely to be selected for the attempt was Saturday, for, of course, when the robbery was to be done, it might as well be for a big sum as a little one. He made sure of this last point, however, by trying hard to get Yorky to engage to meet him that night after business, but failed, as Yorky gruffly indicated that he was engaged.

So far all had succeeded to The Gander’s satisfaction. It only remained for him to give the finishing stroke. He got a sheet of note-paper, of a kind used in the theatre, and penned the following note to me:—

“If McGovan will watch at the west end of Barony Street between eleven and twelve o’clock on Saturday night, he will see a gent attacked and robbed by a desperate thief who can run like Deerfoot. The gent always carries a tin box, and, as it’s supposed to be full of money, it’s the box that will be grabbed at. There had better be more than one at the catching, or he’s sure to get off.”

There was no signature, and at first I was inclined to believe the thing a hoax, or worse—a plot to draw me away from some spot where I was likely to be more useful, but in the end I decided to act on the advice.

I had no idea that the gent described was the worthy treasurer of the theatre, and I suppose The Gander had purposely remained silent on that point lest I should warn the gentleman threatened, and so spoil the little plot.

I was down at Barony Street before eleven o’clock. I took the west end, and planted McSweeny under shelter at the east. It was a dark night, and scarcely any one passed me at my lonely lurking-place. I was so suspicious of a hoax that I was positively surprised when a gentleman appeared at the other end of the street carrying the tin box in his hand, and whistling away as cheerily as if there were no such thing as street robbers in existence. He had scarcely appeared in sight when another man turned the corner walking rapidly in his wake, and looking hastily round to make sure that they were alone in the short street.

The distance between the two rapidly diminished, and then, looking anxiously along behind them, I had the satisfaction of seeing McSweeny’s head cautiously appear from his hiding-place at the other end of the street. I had scarcely noted the fact when the footpad was on his victim, making a dash from behind at the treasurer, tripping him up, and at the same moment wrenching the tin box from his grasp.

None but an expert thief could have done the thing so swiftly. The moment the box was in his possession the thief caught sight of me making a dash towards him, and turned and flew towards the end of the street by which he had entered. He flew so fast that his feet seemed scarcely to touch the ground. McSweeny had emerged from his hiding-place at the first outcry, and appeared directly in front of the flying man with his great, strong arms extended for a bear’s hug; but the flying man, unable to check his pace, yet unwilling to be taken, merely raised the tin box of tokens and dashed it full in McSweeny’s face, flattening my chum’s little nose with his face, and laying him on his back on the snowy pavement as neatly as if he had been tugged back by the hair. I paid no attention to McSweeny, but flew on in the wake of the thief; but when I turned the corner of the street into Broughton he had vanished, I knew not in what direction. I turned back, after a run up the brae, and found McSweeny sitting up on the pavement and tenderly feeling the place where his nose had been.

“Oh, you thickhead!” was my only remark, as I passed on to speak to the robbed man.

“Thick, is it?” he dolefully returned. “Faix, it’s a great deal thinner than it was a minit ago.”

“And you let him off, money and all,” I added, in deep disgust.

“Begorra, if you’d felt the weight of the money, like me, you’d wish it far enough away,” he returned, busy with his handkerchief; “a steam hammer’s nothing to it.”

“I am happy to say that there was no money in the box,” said the robbed man, who was little the worse of his fall. “Nothing but a number of metal tokens used as checks at the theatre.”

“Tokens?” groaned McSweeny, clenching his fists. “I’d like to give him some more.”

A few words of explanation followed, which considerably relieved my concern over the loss of the thief; and then the robbed man accompanied us to the Central to report the case, and get a look at the handwriting of the note sent us in warning. He readily recognised the note-paper as of a kind used in the theatre, but could make nothing of the handwriting. However, the fact that the warning had come from some one employed in the theatre was a clue of a kind, and with the promise to give us every help in following it out, he took leave.

Meantime, Yorky had gone with his plunder no farther than a lighted stair at the foot of Broughton Street, which had stood conveniently open when he dashed round the corner of Barony Street. There he quickly wrenched off the lid, plunged his hand into the box to empty big handfuls of silver and gold into his pockets, and found instead only lead. The fact that he was alone draws a veil over the scene which followed. I have no doubt that his words flowed rapidly over his immediate disappointment, and his disgust may be inferred from the fact that he left the box and tokens entire in a corner of the stair. But a deeper rage was to come. Yorky remembered that the first information had come from The Gander, and the fact that we had been in waiting for him, and dummies or tokens substituted for the money the treasurer had been said to carry, seemed to the quick-witted Yorky to point to a plot to trap him. If he could bring that plot home to The Gander he resolved to put a knife in him. I have stated, however, that Nature had favoured The Gander with a look of dense stupidity, and, though Yorky took the first opportunity of seeking his society, and suspiciously sounding him on the subject, he made nothing of it. Bob Slogger he could not get at, for he was already in our hands for a separate offence.

The suspicious manner and queer questions of Yorky alarmed The Gander quite as much as the failure of his plot disappointed him.

“If I don’t have him laid by the heels soon he’ll shove a knife into me,” was his acute thought, which shows how sharp-witted folks can read each other through every fence of face and words.

I took Yorky on the Monday, and we kept him for a day or two on suspicion, but, as the street had been dark and we had but a momentary glimpse of him, he had to be let off for want of evidence. Meantime, The Gander’s wits had been at work on a plot which, I must confess, was quite worthy of the object.

When Yorky was set at liberty he was greeted by The Gander, who, with many demonstrations of satisfaction, and to celebrate the occasion, proposed that they should adjourn to Yorky’s den in the Canongate and there consume a bottle of brandy at The Gander’s expense. No proposal could have been more welcome. Yorky had a weakness for drink at all times, but when some one else paid for that drink it was to him perfect nectar. They had the garret all to themselves, as Yorky’s wife, in anticipation of a long sentence on her husband, had fled to her native clime. The drinking began, and from the first Yorky managed to appropriate the lion’s share. He was not easily affected by drink, but his ideas were getting a little cloudy by the time the brandy was finished, and readily assented to The Gander’s proposal to go for more. Into this second supply The Gander poured a strong dose of laudanum, and, as Yorky swallowed the whole, he was soon insensible. The Gander and he were of about a height and build, but, of course, in appearance and features they were not at all alike. As soon as it was quite certain that Yorky had succumbed, his amiable friend stripped him and tumbled him into bed. He then exchanged his own shabby and paste-spotted clothing for Yorky’s trousers, jersey, and pilot jacket. Then, taking from his own pocket a short-haired red wig which he had got from some of the theatricals, he drew it over his scalp, and then with a little rouge did up the point of his nose to resemble the fiery organ of the slumbering thief. Having fastened about his throat the red cotton handkerchief used by Yorky as a scarf, and topped the whole with the greasy and battered grey felt hat, The Gander softly left the den, locking the door after him and taking the key with him. It was between three and four o’clock in the afternoon, but not nearly dark. The Gander got down to Leith Street in his strange disguise, and when near the foot, at that part where Low Calton branches off towards Leith Wynd, he stopped a suitable gentleman and asked the time by the clock. Quite unsuspicious in the broad daylight, the gentleman took out his watch, and in a moment it had changed hands. The grasp had been made at it with such force by The Gander, that the gold Albert attached to the watch was snapped, and half of it left dangling at the owner’s button-hole.

The moment the grasp was made, The Gander ran like the wind, and got clear away by Low Calton and the Back Canongate, and never halted till he landed breathless but triumphant at the bedside of the sleeping Yorky. His first business was to resume his own clothing, clean the paint from his nose, and take the wig from his head. Then he took the watch, with the fragment of gold chain still attached, and thrust it as far as his arm could reach in under the mattress on which lay the virtuous form of the sleeping Yorky. This done, he pocketed the red wig, laid Yorky’s clothes at the bedside beside his muddy boots, in some confusion, as if they had been taken off somewhat hurriedly, and then left the house, with the pleasing consciousness of having done all he could to help Fate to do the right thing to a great rascal.

While this was being done, the robbed man had made his way to the Central Office to report his loss. He had got a full view of the robber’s face and dress—or at least imagined he had—and went over the details with such minuteness and fidelity that I turned to some one and said in surprise—

“Surely it can’t be Yorky at his old games already, and he was only let out this morning? It’s just his style.”

I then went over one or two of Yorky’s peculiar features, to all of which the gentleman so eagerly responded in the affirmative that I thought it could do no harm at least to look for Yorky, with a view to bringing him face to face with the victim. I should have found him at once if I had gone to his den, but that was the very last place I thought he would go near when in danger of being taken. I therefore went over all his haunts, but in vain. No one had seen him, and several told me of the flight of his wife, which gave me the idea that Yorky, finding himself “on the rocks,” and deserted, had committed the robbery with great audacity, and then left the city for good with the proceeds in the wake of his partner. It was quite late at night when I thought of his garret in the Canongate. I believe it was McSweeny’s suggestion that I should go there—at least he always insists that it was, and possibly he is right, for the way in which Yorky had grinned at his damaged face had made my chum certain that the hands which inflicted the injuries were before him, and McSweeny was now eager for revenge.

There was no answer but snores to our knock, so we opened the door and entered.

“How sound the divil sleeps,” said McSweeny, with a sceptical grin, as he struck a light. “Sure a fox himself couldn’t do it better.”

Yorky refused to wake with a word, and even when violently shaken by both of us only half opened his eyes, and uttered some sleepy imprecations. At length, getting impatient, McSweeny lifted a dish containing water and emptied it over Yorky’s face, which startled him into a wakefulness and some vigorous protests.

“What do you want now?” he growled at last, when he was able to recognise us.

“I want to know where you were at half-past three o’clock to-day?” was my significant reply. “On with your things and trudge. You’ve got drunk too soon—you’ve overdone it. Man, see, there’s the slush off your boots all over the floor.”

“I haven’t been across the door since morning,” he solemnly protested, on which McSweeny somewhat savagely remarked that “we believed him every word.”

While McSweeny was helping him to put on his clothes, and replying to his protests, I made a search through the room, and finally drew out from under the mattress the stolen watch and fragment of gold chain.

Yorky stared as it was held up before his eyes, and became very sober indeed.

“I never saw that in my life before; somebody must have put it there,” he cried, with the most vigorous swearing, all of which we listened to with great merriment and marked derision.

“I thought we should sober you before long,” I said to him, as I fastened his wrist to my own. “We’ll see what the owner of the watch says to it.”

The owner of the watch had a great deal to say, all of which astonished Yorky beyond description. The watch and fragment of chain he identified at a glance, and Yorky as well. He swore most positively that Yorky was the man who attacked him—he had had too good a view of the rascal’s features and dress to have a moment’s doubt on the matter. Yorky, as he listened to it, was a picture to behold. He scratched his head in the most solemn manner imaginable, and muttered to himself—

“I was very tight, but I never yet did anything in drink that I couldn’t remember when sober. I can’t make it out at all; but I know I’m as innocent as a lamb.”

A grin ran round the room as he uttered the words, and, after a word with the superintendent, the “lamb” was led off to the cells. He was next day remitted to the High Court of Justiciary. I strongly advised him to plead guilty, but the wilful man would have his own way, and took the opposite course.

Then the Fiscal pointed out that Yorky had been often convicted of the same crime, and produced a list of these, and demanded the heaviest penalty. The judge promptly responded to the appeal by sentencing Yorky to fourteen years’ penal servitude. As he was being removed, a voice among the audience behind exclaimed—

“Ah, Yorky, what a time it’ll be before you can make me lose another race!”

The voice came from The Gander. So elated was that worthy over the success of his scheme that he took to boasting of the feat, and giving details to his companions, and thus the story eventually reached my ears. Shortly after, when taking The Gander for helping himself to a bank-note out of a coat pocket in one of the actors’ dressing-rooms, I twitted him about depriving the sporting world of such a treasure as Yorky. He denied the whole, but with a twinkle of superlative cunning and delight in his eyes.

“I never before believed it possible to overreach a Yorkshire man,” I suggestively remarked.

“A Yorkshire man?” cried The Gander, with great contempt; “if he’d been twenty Yorkshire men rolled into one, I could have done him.”

I think he spoke the truth.

The boy whose name I have put at the head of this paper was looked upon as a timid simpleton, perfectly under the power of the two men to whom his fate was linked. If Billy had been a dog they could not have looked upon him with more indifference—he was so small, and thin, and insignificant, and above all so quiet and submissive, that they felt that they could have crushed him at any moment with a mere finger’s weight.

Rodie McKendrick, the first of his masters, was a big fellow with an arm like a giant, whose standing boast was that it never needed more than one drive of his fist to knock the strongest man down. Rodie was a housebreaker, who filled up his spare time by counterfeit coining and “smashing,” or passing, the same. The other, his companion and partner, Joss Brown by name, I can best describe as a comical fiend—that is, he always did the most cruel acts with a grin or a smile, joking away all the while about the wriggles or agony of his victim, as if it was the best fun in the world to him. Joss, I believe, fairly delighted in the sufferings of others, and would have reached the height of happiness had he been appointed chief torturer in an inquisition. He was an insignificant-looking wretch, but an extraordinarily swift runner. These two had settled in Glasgow, for the benefit of that city, and Billy Sloan was their spaniel and slave. There was another spaniel and slave in the person of Kate, Billy’s sister, but as she was in bad health she did not count for much. The two children had been left to Rodie by their mother, a Manchester shop-lifter, whom he had brought to Scotland with him, and managed to hurry out of the world shortly after.

They were not his own children, therefore, and that fact encouraged him to deal with them as he pleased. Kate was ten, and Billy nearly nine, and both were small and weakly, so Rodie’s treatment of them was not the kindest in the world. Kate’s ill health had arisen from that treatment. She had bungled in the passing of some pewter florins made by Rodie and Joss, and not only nearly got captured—which could have been forgiven—but had almost got these two worthies into trouble as well. It was a narrow escape, and Rodie thought best to impress it on her memory by first knocking her down with one tap of his big fist, and then kicking her ribs till she fainted. Billy crouched in a corner, clasping his hands, and looking on pale as death, and with his eyes fixed steadily on Rodie’s face. Joss, who was looking on in exuberant delight, noticed the peculiar look, and said—

“Look at the other whelp; he looks as if he could bite, if he’d only teeth in his head.”

“Oh, him? Poh!” grunted Rodie in supreme contempt, as he rested from his task; but Joss could not resist the temptation, and reproved Billy’s look by sinking his nails into the boy’s ear, and then shaking him about till Billy thought that either the ear or the head must come off.

Joss made jokes all the while, and then went back to his supper and his whisky-drinking with fresh zest. Billy crouched in the corner, watching the slow breathing of his senseless sister till he saw that Rodie and Joss were considerably mollified by eating and drinking. Then he crept forward and lifted Kate from the floor, and bore her into a little closet off the room, in which they both slept. Kate moaned a little on being moved, but it took an hour’s persistent efforts on Billy’s part to bring her back to consciousness, and then he was almost sorry he had restored her, for she suffered dreadful agony where Rodie’s iron-toed boots had been at work.

It is possible that some of her ribs were broken,—the dreadful pains and the after-effects all point to that conclusion,—but, though the whole night was spent in sleepless agony by Kate, she was forced to rise next day and attend to her two masters. Kate was the housewife; and though Billy would willingly have undertaken her duties for a time, the comical fiend Joss would not allow it, and insisted, with many jokes, on pulling her out of bed by the ear, with his nails, as usual, and then goading her on to every task which his ingenious brain could suggest as likely to aggravate her trouble.

The children had no idea of resenting this treatment, or of running away, or of anything but their own utter dependence upon these men; and they longed with all the strength of their young minds for the happy moment which should see Rodie and Joss either senseless with drink or out of the house. It happened, however, that the men were alarmed at their narrow escape of the day before, and had decided to keep out of sight for a day or two; so the children had a weary time of agony and secret tears. At night, when clasped in each other’s arms in the hole under the slates which was their sleeping place, they sympathised and communed, and mingled their bitter tears; but Kate’s dreadful sufferings did not abate much. As weeks passed away she grew shadowy and pale, and a bad cough afflicted her incessantly, so much so that Joss was often compelled to rise out of bed in the night-time and sink his nails into her ears, or stick a long pin into her arm, or wrench a handful of hair out of her head by the roots to induce her to desist, and give him some chance of enjoying his much-needed repose. And the jokes he showered on her and Billy on these occasions would have filled a book. One day both men were providentially out of the house, and Kate, sitting by the fire with her face looking strangely pinched, and her eyes big and shiny, while Billy cooked the dinner by her directions, pressed her hand on her breast, and said to the boy—

“Oh, Billy, is there nothing that would take away this awful pain?”

Billy stopped his stirring at the pot and reflected. His knowledge was exceedingly limited, and his ideas did not come fast at any time; but after a little his face brightened, and he said briefly—

“Yes—I know—medicine.”

“Are you sure?”

Billy scratched his head. He wasn’t sure, but he thought so.

“Then where could we get some?” was Kate’s next query.

They both knew of the chemists’ shops, but to go to them required money. At length they remembered of some one in the rookery getting medicine and doctor’s advice at the dispensary, and, setting the dinner aside, they decided to slip out of the house, and see what could be done at that blessing to the ailing poor. When they got to the place, and their turn came, Kate went in with great trepidation before a couple of doctors and some students, and explained that she was troubled with a cough and pains in her breast and side. Dozens more were waiting, so there was little time to spare upon each.

“What brought it on?” the doctor asked when he had hastily sounded her lungs. “Caught cold, I suppose?”

Kate blushed and nodded. She did not care to reveal all she had suffered at the hands and feet of Rodie, or she would have told the doctor that far from having caught cold she had caught it very hot indeed. A bottle of medicine was quickly put up and labelled, and Kate was free to depart.

Billy was in high spirits, and danced and pranced all the way home, quite sure that the magic elixir which was to banish all pain from Kate’s poor breast was in the bottle she carried. When they got home they found to their great relief that the house was still empty, and after Kate had taken a spoonful of the medicine they hid the bottle away under their bed, lest the comical fiend should jokingly throw it out at the window. The medicine thus applied for and taken in stealth had the effect of soothing the pain somewhat and easing the cough, but it did not stop the decay of Kate’s lungs. She got weaker and thinner, till at last even the comical fiend confessed his ingenuity and skill in forcing her out of bed quite exhausted and at fault. Kate spent most of her time in bed in the hole under the slates, while Billy became housewife and nurse combined. Strange thoughts came into her head, and half of the time she was in a hazy dream, through which she saw little but Billy’s eager face as he tended, and nursed, and soothed, and consoled, and tried every device for keeping the comical fiend out of the hole. One morning, while Rodie and Joss were still snoring in bed, Kate was more wide awake than she had seemed for a long time, and startled Billy, as she had often done of late, with one of her odd questions—

“Wouldn’t it be nice, Billy, if I was to fall asleep, and sleep on and never wake?”

Billy stared at her and tried to realise the thought.

“It wouldn’t be nice for me,” he said at last, “for I couldn’t get speaking to you. You’d be the same as dead.”

“Well, what becomes of folks when they’re dead?” pursued Kate. “I heard a man say once that there’s another world they go to, all bright and beautiful, where there’s no pain. I’d like to be there, if there’s such a place.”

Billy didn’t think there was such a place—at least, he had never heard of it, and anyhow he did not wish Kate to die. His heart gave a great pang as he thought for the first time of what it would be to be left in the world—alone—without Kate, and he choked and gulped and would have cried, if it had not been that he did not wish to excite or alarm her.

“But, Billy, I sometimes in my dreams see a hole in the ground, with a light shining through from the other side,” persisted Kate. “I see it often, and always want to go into it.”

“There ain’t no such hole,” said Billy, sturdily and determinedly.

“There may be if I die and am put in the ground,” said Kate, wearily. “Sometimes I’m so tired that I can hardly wake up again. But, Billy, how would I find the road to the other place if I should fall asleep and not wake again? I’ve heard it’s not easy found, and I think it’s only a place for good folks, and we’re not that, you know.”

“That’s true,” said Billy, “so you needn’t bother your head about going to that place; you’re better beside me. You’d never find it; I know you wouldn’t.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” said Kate, with dreadful earnestness. “I’m afraid I’ll be left wandering about in the dark at the other side. I’ve heard that there’s a man with a light shining out of his head walking about ready to take folks’ hands and guide them, but he’s a kind of an angel, and would never look at me. Isn’t it a pity that Rodie kicked so hard? That’s what has done it all. And now I’m always sinking. I often catch myself up when I’ve sunk about half-way through the world, and grip on to your hand just to keep myself here, but if I get much weaker I’ll not be able to do that.”

Billy clenched his teeth and hands, and said—

“Yes, Rodie did it all. He called me a dog the other day, and maybe I am, for I feel like biting him. Yes, I’ll bite him some day, when I’m big enough.”

“Could you not help me, Billy?” said Kate, after a long silence. “I’m afraid to go there without knowing something of the road. Couldn’t you get some one to tell me how to do when I get through the hole?”

“I tell you there ain’t no such hole; and don’t you speak about it, for I do-o-o-n’t like it,” sobbed Billy, almost in anger; “but if there was, I’d be willing glad to go into it to find the road for you,” he added, more lovingly, as he noted the distressed look which gathered on her pinched face. “Maybe you need a new kind of medicine. I’ll ask them to-day when I’m at the dispensary.”

Billy did ask, and in such a way that the doctor’s attention was roused, and he whispered a few words to one of the students, who put on his hat and kindly told Billy that he was going home with him. The student was a tall man, and had difficulty in getting into the hole where Kate lay, but when he did, and looked into her pinched face and brilliant eyes, and listened to her quick, gasping breath, he merely gave his head a slight shake, and knelt down by the bedside to take her thin hand tenderly in his own. He had been very merry and chatty with Billy on the way, but now he was grave and solemn, and scarcely spoke a word.

“Will she be better soon?” asked Billy at last, when the silence had almost sickened him.

The student looked down on the white features of the sick girl, and said softly—

“Yes—very soon.”

There was another painful silence, and then Kate dropped off into slumber, with her hand resting trustfully in that of the student. Then the gentleman softly disengaged his hand, and motioned Billy out of the hole.

“Where’s your father or mother?” he gravely asked, for the room was empty.

“Not got any—mother’s dead,” said Billy. “Rodie looks after us,” and his hands and teeth clenched, as they generally did now when Rodie was in his thoughts, or at his tongue’s end.

“Then I should like to see Rodie for a minute,” said the student with the same pitying look in his eyes, which Billy could not understand at all. “Could you find him now?”

No, no, Billy could not do that; and did not know when Rodie would be at home, or where he was likely to be found. The student looked round the miserable hovel, and sighed and shook his head, and then left. He had ordered no medicine, he had said nothing about Kate, except that she was to be better very soon, yet Billy felt a vague uneasiness and distrust. The house seemed oppressively quiet, and Kate’s slumber unusually deep. What if she should sleep on and never wake?

Billy crept into the hole again, and sat down on the floor beside the bed to listen intently to every breath Kate drew, holding her hand softly the while to make sure that she did not slip away from him as she slept.

“Oh, if Rodie had only kicked me instead!” he thought for the hundredth time. “A boy is more able to stand kicks, and Rodie’s so strong—he’d kick anybody right through the world, whether there was a hole or not.”

Late in the afternoon Rodie and the comical fiend came in boisterous and gleeful to dinner. They had been unusually successful in passing some bad florins, and had invested some of the proceeds in drink, part of which they had brought home with them to make a night of it, and laughed consumedly over the manner in which they had cheated one of their victims.

Billy served them passively, and then, unable to taste food himself, he crept quietly back to watch Kate. The comical fiend made some splendid jokes, having Billy for their subject, but for once Billy was undisturbed, for he did not hear them. He sat on the floor holding Kate’s hand, and sometimes he put his other arm softly round her neck, lest his hold should not be strong enough to keep her by him.

The men got very noisy and uproarious; Rodie banged the table with tumblers and the bottle, and shouted and stamped his feet, and then the comical fiend, at his own request, favoured the company with several songs.

One smash rather louder than the rest caused Kate to start and open her eyes. She looked up in Billy’s face steadily for some moments without moving, and the expression was so strange that in alarm he cried—

“Kate, Kate! don’t you know me?”

There was no immediate answer. There was in the slates immediately above them a single pane of glass, which gave light to the closet, and that pane now showed a deep red square of the crimson sky. Kate’s eyes wandered to the pane, and became fixed for some moments.

“What’s—that?” she whispered at last, with a strange trembling eagerness.

“It’s only the winder,” answered Billy, a little scared.

“No, it isn’t; it’s the hole you go through into the other world,” said Kate joyfully. “Billy, dear, I can’t stay any longer. I’m going through!”

Billy threw both his arms around her slight form, and rained his tears upon her face. At the same moment there was a chorus of gleeful shouts and table-smashing like thunder in the adjoining room. It was the comical fiend applauding his own song. Kate continued to gaze steadily at the crimson pane in the roof with a smile brightening on her face.

“I wish—oh, I wish there had been somebody to tell me what to do at the other side,” she said at last in a whisper so low that Billy could scarce catch it. “But maybe somebody will hold out a hand to me. I’ll keep feeling about for it. It’s growing darker. Am I going through? and is the light only at the door?”

“No, its almost night, and Rodie’s lit the candle,” said Billy. “Do you hear me, Kate? You’re awful dreamy and queer—I’m saying it’s almost night.”

“Night! night!” feebly and hazily breathed Kate. “Good-night.”

Her lips stood still, and her eyes, though fixed on the crimson pane, were strange and big and unearthly. Billy stared at them in awe, and then moved a hand quickly before them to break the steady stare and draw it to himself. There was no response. Her eyes remained fixed on the pane.

“Kate! Kate!” he cried in a scream of alarm.

A slight spasm—almost shaping into a smile—crossed the pinched features; the eyes gazed unwinkingly at the pane—the breath came and went in long-drawn sighs—paused—came again—then paused for ever. Kate had slipped through to another world, where her feeble and groping hand would surely be gently taken by a Guide who Himself knew all suffering and temptation and weakness that can afflict frail humanity, and who will surely be as pitiful to the benighted savages of our land as of any other.

Billy screamed and wept, and threw himself on the still form; and at length even the comical fiend, who had got up on the table to execute a flourishing hornpipe, became annoyed and got down to put a stop to the unseemly disturbance. Rodie, too, who became stupid and sullen with drink just as his partner became lively, roused himself sufficiently to stagger across the room towards the hole, vowing that if he could only trust himself to the support of one foot he would use the other in stopping Billy’s howling.

“Kate stares up, and won’t move or speak to me,” cried Billy in gasps, as soon as he was conscious of the nails of the comical fiend almost meeting in his ear.

“Maybe she’s croaked at last,” suggested Rodie. “See if she breathes.”

Joss hopped in, and soon answered in a gleeful negative.

“It’s a good job,” said Rodie, “for she’d never have been of any more use.”

“Three cheers for her death!” cried the comical fiend, and as there was nobody to laugh at his joke, Rodie being too sullen, Joss laughed the required quantity for a dozen people himself.

Rodie tried to kick Billy, but, finding himself unable to stand on one leg, he contented himself with some horrible threats, and then they went back comfortably to their drinking. Billy cried and cried—softly, so that the men should not hear him—with his arms round the still form, till he fell asleep, and there they lay all night, the living and the dead. Next day Rodie and Joss put all their implements and money out of sight, and sent word to the poorhouse, and a medical inspector came and glanced at the wasted body, and asked a few questions, and signed a paper, which Billy took to the undertaker, who brought a coffin the next day, and placed Kate’s form in it, and then asked if they wished it screwed down. Rodie and Joss were too drunk to reply, but Billy, never tired of looking at the wide open eyes, and fancying they were looking at him, said he should like it kept open as long as possible.

The funeral took place the day after, and there was only one mourner to follow the coffin to the grave—Billy himself, in his ragged jacket and bare feet. The only mournings he had to put on were the tears which flowed down his cheeks all the way. Even when the coffin was hid in the ground, and the earth tumbled in, and the turf spread over the top, he could not put off his mournings, or leave the place chatting gaily about business matters, as is the custom at funerals. He still seemed to see Kate’s open eyes shining up at him through earth and turf, and he had a firm idea that she could still hear him speak, though herself unable to reply. He loitered long after the gravediggers were gone, and stuck a little twig in the ground so that he should know the spot again, and then, when no one was near to see, he lay down on the grass and whispered to Kate through the openings in the turf. He had but two thoughts to reiterate—the regret that Rodie had not kicked him out of the world instead of Kate, and the wish that he might live to “bite Rodie” for what he had done to Kate. Whenever Billy was in trouble after that he came to the graveyard to whisper his griefs to Kate through the turf. He told her of all his adventures and the tortures of the comical fiend and the kicks of Rodie; and though he got no reply, he felt quite certain that he had Kate’s sympathy in every word he uttered. Billy’s was not a large mind, or a very acute one, but when an idea did get fairly in, it stuck there firmly. When Kate had been some months in the grave, Rodie and Joss prepared a lot of florins—their most successful effort in base coining—and informed Billy that they were going through to Edinburgh to attend the Musselburgh Races, on business, and that he was to accompany them, and have the honour of carrying their luggage—an old leather valise containing the base florins. Joss and Rodie, for prudential reasons, went by different trains, and Billy, though he accompanied Rodie, had strict orders to sit at the other end of the carriage, and take no more notice of Rodie than of any stranger.

It chanced, however, that by the time the train drew up at the Waverley Station platform, that particular carriage was empty of all but Billy and Rodie, and the base coiner had no sooner glanced along the platform than he uttered an oath and drew in his head with surprising quickness.

“Do you see that ugly brute standing over there, near the cabman with the white hat?” he observed to Billy.

“That ugly brute” was I, the writer of these experiences, on the look out for any of my “bairns” who might be drawn thither by the race meeting, and Billy quickly signified that he did see me.

“Well, keep clear of him, or we’re done for. That’s McGovan, and he’s a perfect bloodhound,” and Rodie cursed the bloodhound with great heartiness. “If he gets his teeth on us, we’ll feel the bite, I tell ye.”

“Ah!” it was all Billy said, and it was uttered with a start, for Rodie’s words had suggested a strange idea to him.

“Yes, if he gets us at it it’ll mean twenty years to us if it means a day,” continued Rodie, still wasting a deal of breath on me. “Now you get out first, and go straight to the place I told ye of, while I jink him and get round by the other.”

Billy obeyed, and was soon lost in the crowd, while Rodie—who mistakenly believed that his face was as familiar to me as mine was to him—cut round by another outlet, and escaped to the appointed rendezvous.

Meantime Billy had only gone far enough with the crowd to get behind one of the waiting cabs, whence he watched Rodie leave the station. Then he crept out of his hiding-place, and walked back to the spot where I stood, and touched me lightly on the arm.

“I’m Rodie’s boy,” he said, while I stared at him in astonishment. “I’ve come from Glasgow with him, and we’re to go ‘smashing’ at the races to-morrow. Would it be twenty years to him if you caught us at it?”

“What Rodie do you mean?” I asked at length. “Is his other name McKendrick?”

“That’s it; and Joss Brown is with him,” said Billy with animation. “He says you’re a bloodhound, and can bite. Twenty years would be a good bite, wouldn’t it?”

“Ah, I see, he has injured you, and you want to pay him back,” I said, not admiring Billy much, though his treachery was to bring grist to my mill.

“He kicked Kate, my sister, and she died, and I’ve told her often since then that I would bite him for it, and now I’ve got the chance I must keep my word.”

I took Billy into one of the waiting-rooms and drew from him his story. Billy told the story much better than I could put it down though I were to spend months on the task. He showed me also the piles of base florins put up in screws ready for use, and offered them to me. But while he had been telling the story I had been studying the position. I had perfect faith in Billy’s truthfulness. The tears he shed over the narrative of Kate’s death would have convinced the most sceptical. I therefore explained to him that in order to secure Rodie the full strength of a good bite it was necessary that I should take him and Joss in the act, and if possible with the supply of base coin in their possession. To that end I arranged to see the three next day at the race-course, and explained to Billy how he was to act when he got from me the required signal.

I had the idea that Billy was densely stupid—almost idiotic—and that therefore the scheme would be sure to be bungled, but in this I misjudged the boy sadly. If Billy had been the most acute of trained detectives he could not have gone through his part with more coolness or precision. When I had my men ready and dropped my handkerchief, Billy quickly wriggled himself out of a crowd and hastily thrust the valise containing the reserve of base florins into the hands of Rodie, who hid the same under his jacket and looked nervously round. The comical fiend helped him. They had not long to look. We were on them like bloodhounds the next moment. Joss was easily managed, but Rodie fought hard, and struggled, and kicked, and finally threw away the valise of base coin in the direction of Billy, with a shout to him to pick it up and run. Billy looked at him, but never moved.

“You kicked Kate, and she died. It’s Billy’s Bite,” he calmly answered, when Rodie worked himself black in the face, and the comical fiend nearly choked himself with hastily concocted jokes.

The two got due reward in the shape of fifteen and twenty years respectively, but Billy was sent to the Industrial School, and is now an honest working man.

The case of the tailor, Peter Anderson, who was beaten to death near the Royal Terrace, on the Calton Hill, may not yet be quite forgotten by some, but, as the after-results are not so well known, it will bear repeating.

Some working men, hurrying along a little before six in the morning, found Anderson’s body in a very steep path on the hill, and in a short time a stretcher was got and it was conveyed to the Head Office. The first thing I noticed when I saw the body was that one of the trousers’ pockets was half-turned out, as if with a violent wrench, or a hand too full of money to get easily out again; and from this sprang another discovery—that the waistcoat button-hole in which the link of his albert had evidently been constantly worn was wrenched clean through. There was no watch or chain visible, and the trousers’ pockets were empty, so the first deduction was clear—the man had been robbed.

Robbery, indeed, appeared to me, at this stage of the case, to have been the prime cause of the outrage, and an examination of the body confirmed the idea. The neck was not broken, but there were marks of a strangulating arm about the neck, and the injuries about the head were quite sufficient to cause death. These seemed to indicate that two persons had been engaged in the crime, as is common in garroting cases—one to strangle and the other to rob and beat—and made me more hopeful of tracking the doers. On examining the spot at which the body had been found, I found traces of a violent struggle, and also a couple of folded papers, which proved to be unreceipted accounts headed “Peter Anderson, tailor and clothier,” with the address of his place of business. These might have given us a clue to his identity had such been needed, but his wife had been at the Office reporting his absence only an hour before his body was brought in, and we had only to turn to her description of his person and clothing to confirm our suspicion.

Anderson, on the fatal night on which he disappeared, had unexpectedly drawn an account of some £10 or £12 from a customer, and in the joy of receiving the money had invited the man to an adjoining public-house to drink “a jorum,” and one round followed another until poor Peter Anderson’s head was fitter for his pillow than for guiding his feet. On entering the public-house—which was a very busy one, not far from the Calton Hill—Anderson, I found, had gone up to the bar, and before all the loungers or hangers-on pulled a handful of notes, and silver, and gold from his trousers’ pocket, saying to his companion—

“What will you have?”

Afterwards, when they got into talk, they adjourned to a private box at the back; but it was there I thought that the mischief had been done. Anderson had a gold albert across his breast, and might be believed to have a watch at the end of it; but the chain, after all, might have been only plated, and the watch a pinchbeck thing, to a thief not worth taking; but the reckless display of a handful of notes, gold, and silver, if genuine criminals chanced to see it, was a temptation and revelation too powerful to be resisted. The man who carried money in that fashion was likely to have more in his pockets, and a gold watch at least. If he got drunk, or was likely to get drunk, he would be worth waiting and watching for; so, at least, I thought the intending criminals would reason, never dreaming of course of the plan ending in determined resistance and red-handed murder. Your garroter is generally a big coward, and will never risk his skin or his liberty with a sober man if he can get one comfortably muddled with drink.

There was no time to elaborate theories or schemes of capture. A gold watch and chain valued at about £30, and £14 in money, were gone. A rare prize was afloat among the sharks, and I surmised that the circumstance would be difficult to hide. The thief and the honest man are alike in one failing—they find it difficult to conceal success. It prints itself in their faces; in the quantity of drink they consume; in the tread of their feet; the triumphant leer at the baffled or sniffing detective, and in their reckless indulgence in gaudy articles of flash dress. I went down to the Cowgate and Canongate at once, strolling into every likely place, and nipping up quite a host of my “bairns.” I thought I had got the right men indeed when I found two known as “The Crab Apple” and “Coskey” flush of money and muddled with drink, but a day’s investigation proved that they owed their good fortune to a stupid swell who had got into their clutches over in the New Town. Coskey, indeed, strongly declared that he did not believe the Anderson affair had been managed by a professional criminal at all.

“If it had been done by any of us I’d have heard on it,” was his frank remark to me.

I was pretty sure that Coskey spoke the truth, for in his nervous anxiety to escape Calcraft’s toilet he had actually confessed to me all the particulars of the New Town robbery by which his own pockets had been filled, and which afterwards led to a seven years’ retirement from the scene of his labours.

The hint thus received prepared me for making the worst slip of all I had made in the case. I went to Anderson’s widow to get the number of the watch, and some description by which it might be identified. She could not tell me the number or the maker’s name; she could only say that it had a white dial and black figures, but declared that she would know it out of a thousand by a deep “clour” or indentation on the back of the case.

“I was there when it got the mark,” she said, “and I could never be mistaken if the watch was put before me. A thief might alter the number, but nobody could take out that mark, for we tried it, and the watchmaker could do nothing for it. My man was working hard one day with the watch on, when a customer called to be measured. The waistcoat he wore wasn’t a very bonny one, and he whipped it off in a hurry, forgetting about the watch, which was tugged out, and came bang against the handle of one of his irons. The watch was never a bit the worse, but the case had aye the mark on it—just there,” and the widow, to illustrate her statement, showed me a spot on the back of my own watch, and then so minutely explained the line of the indentation, its length and its depth, that I felt sure that if it came in my way I should be able to identify it as readily as by a number.

This would have been all very well if her information had there ended, but it didn’t.

“You are hunting away among thieves and jail birds for the man that did it,” she bitterly remarked, “but I think I could put my hand on him without any detective to help me.”

“You suspect some one, then?” I exclaimed, with a new interest.

“Suspect? I wish I was as sure of anything,” she answered, with great emphasis. “The brute threatened to do it.”

“What brute?”

“Just John Burge, the man who was working to him as journeyman two months ago.”

“Indeed. Did they quarrel?”

“A drunken passionate wretch that nobody would have any thing to do wi’,” vehemently continued the widow, waxing hotter in her words with every word she had uttered, “but just because they had been apprentices together Peter took pity on him and gave him work. They were aye quarrelling, but one day it got worse than usual, and I thought my man would have killed him. It was quite a simple thing began it—an argument as to which is the first day in summer—but in the end they were near fighting, and after Peter had near choked him, Burge swore that he would have his life for it—that he would watch him night and day, and then knock the ‘sowl oot o’ him in some dark corner, before he knew where he was.’ That was after the master and the laddies had thrown him out at the door and down the stair; and for some days I wouldn’t let Peter cross the door. But he only laughed at me after a bit, and said that Burge’s ‘bark was waur than his bite,’ and went about just as usual. And all the time the wicked, ungrateful wretch was watching for a chance to take his life.”

“Why did you not tell us of this quarrel at first?” I asked, after a pause.

“Because I thought you detectives were so sharp and clever that you would have Burge in your grips before night, without a word from me; but you’re not nearly so clever as you’re called.”

“But he never actually attacked your husband?” I quietly interposed, knowing that wives are apt to take exceedingly exaggerated views of their husband’s wrongs or rights.

“Oh, but he did, though. He came up once, not long after the quarrel, and said he had not got all the money due to him, and tried to murder Peter with the cutting shears.”

“Murder him? How could he murder him with shears?” I asked, with marked scepticism.

“Well, I didn’t wait to see; but ran in and gripped him by the arms till my man took the shears from him. The creatur’ had no more strength than a sparry, though he’s as tall as you.”

“No more strength than a sparrow?” That incidental revelation staggered me. It seemed to me quite impossible that a weak man could have been the murderer of Anderson, unless, indeed, he had had an accomplice, and that was unlikely with a man seeking mere revenge. For a moment I was inclined to think it possible that Burge might have tracked his victim to the hill and accomplished the revenge, and that afterwards, when he had fled the spot, some of the “ghosts” haunting the hill might have stripped the dead or dying man of his valuables; but several circumstances led me to reject the supposition—wisely, too, as it appeared in the end. Burge, the widow told me, was a tall man, with a white, “potty” face, and a little, red, snub-nose, and always wore a black frock coat and dress hat. I took down the name of the street in which he lived—for I could get no number—and turned in that direction. In about fifteen minutes I had reached, not the street, but the crossing leading to it, when I met full in the face a man answering his description, and having the unmistakable tailor’s “nick” in his back.

“That should be Burge,” was my mental conclusion, though I had never seen him before. “If he’s not, he is at least a tailor, and may know him,” and then I stopped him with the words—

“Do you know a tailor called John Burge who lives here-about?”

“That’s me,” he said, with sudden animation, taking the pipe from his mouth, and evidently expecting a call at his trade, “who wants me?”

“I do.”

“Oh,” and he looked me all over, evidently wondering how I looked so unlike the trade.

There was a queer pause, and then I said—

“My name’s McGovan, and I want you to go with me as far as the Police Office, about that affair on the Calton Hill.”

A wonderful change took place in his face the moment I uttered the words—a change which, but for the grave nature of the case, would have been actually comical; his “potty” white cheeks became red, and his red snub-nose as suddenly became white.

“Well, do you know, that’s curious!” he at length gasped; “but I was just coming up to the Office now, in case I should be suspected of having a hand in it. I had a quarrel with Anderson, and said some strong things, I’ve no doubt, in my passion, but of course I never meant them.”

I listened in silence; but my mental comment, I remember, was, “A very likely story!”

“I was coming up to say what I can prove—that I was at the other end of the town that night, and home and in my bed by a quarter to eleven,” he desperately added, rightly interpreting my silence.

I became more interested at the mention of the exact hour; for I had ascertained beyond doubt that Anderson had not left the public-house and parted with his friend till eleven o’clock struck. He had, in fact, been “warned out,” along with a number of bar-loafers, at shutting-up time.

“Did any one see you at home at that hour?” I asked, after cautioning him.

“Yes, the wife and bairns.”

“Imphm.”

“You think that’s not good evidence; but I have more; I was in a public-house with some friends till half-past ten; they can swear to that; and they went nearly all the road home with me,” he continued with growing excitement. “Do I look like a murderer? My God! I could swear on a Bible that such a thing was never in my mind. Don’t look so horrible and solemn, man, but say you believe me!”

I couldn’t say that, for I believed the whole a fabrication got up in a moment of desperation; and little more was spoken on either side till we reached the Head Office, where he repeated the same story to the Fiscal, and was locked up. I fully expected that I should easily tear his story to pieces by taking his so-called witnesses one by one, but I was mistaken. His wife and children, for example, the least reliable of his witnesses in the eyes of the law, became the strongest, for when I called and saw them they were in perfect ignorance both of Burge’s arrest and the fact that he expected to be suspected.

They distinctly remembered their father being home “earlier” on that Friday night, and the wife added that it was more than she had expected, for by being in bed so early Burge had been able to rise early on the following morning and finish some work on the Saturday which she had fully expected would be “disappointed.” Then the men with whom he had been drinking and playing dominoes up to half-past ten were emphatic in their statements, which tallied almost to a minute with those of Burge. Burge had not been particularly flush of money after that date, but, on the contrary, had pleaded so hard for payment of the work done on the Saturday that the man was glad to compromise matters and get rid of him by part payment in shape of half-a-crown. The evidence, as was afterwards remarked, was not the best—a few drinkers in a public-house, whose ideas of time and place might be readily believed to be hazy, and the interested wife and children of the suspected man; but in the absence of condemning facts it sufficed, and after a brief detention Burge was set at liberty.

About that time, among the batch of suspected persons in our keeping was a man named Daniel O’Doyle. How he came to be suspected I forget, but I believe it was through having a deal of silver and some sovereigns in the pockets of his ragged trousers when he was brought to the Office as a “drunk and disorderly.” O’Doyle gave a false name, too, when he came to his senses; but then it was too late, for a badly-written letter from some one in Ireland had been found in his pocket when he was brought in. He was a powerfully-built man, and in his infuriated state it took four men to get him to the Office. He could give no very satisfactory account of how he came by the money in his possession. He had been harvesting, he said, but did not know the name of the place or its geographical position, except that it was east of Edinburgh “a long way,” and he was going back to Ireland with his earnings, but chanced to take a drop too much and half-murder a man in Leith Walk, and so got into our hands. On the day after his capture and that of his remand O’Doyle was “in the horrors,” and at night during a troubled sleep was heard by a man in the same cell to mutter something about “Starr Road,” and having “hidden it safe there.” This brief and unintelligible snatch was repeated to me next morning, but, stupid as it now appears to me, I could make nothing of it. I knew that there was no such place as “Starr Road” in Edinburgh, and said so; and as for him having hidden something, that was nothing for a wandering shearer, and might, after all, be only his reaping hook or bundle of lively linen. O’Doyle was accordingly tried for assault, and sentenced to thirty days’ imprisonment, at the expiry of which he was set at liberty and at once disappeared. My impression now is that O’Doyle was never seriously suspected of having had a hand in the Calton Hill affair, but that, being in our keeping about the time, he came in for his share of suspicion among dozens more perfectly innocent. If he had had bank-notes about him it might have been different, for I have found that there is a strong feeling against these and in favour of gold among the untutored Irish, which induces them to get rid of them almost as soon as they chance to receive them.

So the months passed away and no discovery was made; we got our due share of abuse from the public; and the affair promised to remain as dark and mysterious as the Slater murder in the Queen’s Park. But for the incident I am now coming to, I believe the crime would have been still unsolved.

About two years after, I chanced to be among a crowd at a political hustings in Parliament Square, at which I remember Adam Black came in for a great deal of howling and abuse. I was there, of course, on business, fully expecting to nip up some of my diligent “family” at work among the pockets of the excited voters; but no game could have been further from my thoughts than that which I had the good fortune to bag. I was moving about on the outskirts of the crowd, when a face came within the line of my vision which was familiar yet puzzling. The man had a healthy prosperous look, and nodded smilingly to me, more as a superior than an inferior in position.

“Don’t you remember me?—John Burge; I was in the Anderson murder, you mind; the Calton Hill affair;” and then I smiled too and shook the proffered hand.

“How are you getting on now?”

“Oh, first rate—doing well for myself,” was the bright and pleased-looking answer. “Yon affair was a lesson to me; turned teetot. when I came out, and have never broke it since. It’s the best way.”

It seemed so, to look at him. The “potty” look was gone from his face; his cheeks had a healthy colour, and his nose had lost its rosiness. His dress too was better. The glossy, well-ironed dress hat was replaced by one shining as if fresh from the maker, and the threadbare frock coat by one of smooth, firm broadcloth. He was getting stouter, too, and his broad, white waistcoat showed a pretentious expanse of gold chain. He chatted away for some time, evidently a little vain of the change in his circumstances, and at length drew out a handsome gold watch, making, as his excuse for referring to it, the remark—

“Ah, it’s getting late; I can’t stay any longer.”

My eye fell upon the watch, as it had evidently been intended that it should, and almost with the first glance I noticed a deep nick in the edge of the case, at the back. Possibly the man’s own words had taken my mind back to the lost watch of the murdered tailor and its description, but certainly the moment I saw the mark on the case I put out my hand with affected carelessness, as he was slipping it back to his pocket, saying—

“That’s a nice watch; let’s have a look at it.”

It was tendered at once, and I found it to have a white china dial and black figures. At last I came back to the nick and scrutinised it closely.

“You’ve given it a bash there,” I remarked, after a pause.

“No, that was done when I got it.”

“Bought it lately?”

“Oh, no; a long time ago.”

“Who from?”

“From one of the men working under me; I got it a great bargain,” he answered with animation. “It’s a chronometer, and belonged to an uncle of his, but it was out of order—had lain in the bottom of a sea chest till some of the works were rusty—and so I got it cheap.”

“Imphm. There has been some lying in the bargain anyhow,” I said, after another look at the watch, “for it is an ordinary English lever, not a chronometer. Is the man with you yet?”

“No; but, good gracious! you don’t mean to say that there’s anything wrong about the watch? It’s not—not a stolen one?”

“I don’t know, but there was one exactly like this stolen that time that Anderson was killed.”

In one swift flash of alarm, his face, before so rosy, became as white as the waistcoat covering his breast.

Then he slowly examined the watch with a trembling hand, and finally stammered out—

“I remember it, and this is not unlike it. But that’s nothing—hundreds of watches are as like as peas.”

I differed with him there, and finally got him to go with me to the Office, at which he was detained, while I went in search of Anderson’s widow to see what she would say about the watch.

If I had an opinion at all about the case at this stage, it was that the watch taken was not that of the murdered man. I could scarcely otherwise account for Burge’s demeanour. He appeared so surprised and innocent, whereas a man thus detected in the act of wearing such a thing, knowing its terrible history, could scarcely have helped betraying his guilt.

My fear, then, as I made my way to the house of Anderson’s widow, was that she, woman like, would no sooner see the mark on the case than she would hastily declare it to be the missing watch. To avoid as far as possible a miscarriage of justice, I left the watch at the Office, carefully mixed up with a dozen or two more then in our keeping, one or two of which resembled it in appearance. I found the widow easily enough, and took her to the Office with me, saying simply that we had a number of watches which she might look at, with the possibility of finding that of her husband. The watches were laid out before her in a row, faces upward, and she slowly went over them with her eye, touching none till she came to that taken from Burge. Then she paused, and there was a moment’s breathless stillness in the room.

“This ane’s awfu’ like it,” she said, and, lifting the watch, she turned it, and beamed out in delight as she recognised the sharp nick on the back of the case. “Yes, it’s it! Look at the mark I told you about.”

She pointed out other trifling particulars confirming the identity, but practically the whole depended on exactly what had first drawn my attention to the watch—the nick on the case. Now dozens of watches might have such a mark upon them, and it was necessary to have a much more reliable proof before we could hope for a conviction against Burge on such a charge.

I had thought of this all the way to and from the widow’s house. She knew neither the number of the watch nor the maker’s name, but with something like hopefulness I found that she knew the name of the watchmaker in Glasgow who had sold it to her husband, and another in Edinburgh who had cleaned it. I went through to Glasgow the same day with the watch in my pocket, found the seller, and by referring to his books discovered the number of the watch sold to Anderson, which, I was electrified to find, was identical with that on the gold lever I carried. The name of the maker and description of the watch also tallied perfectly; and the dealer emphatically announced himself ready to swear to the identity in any court of justice. My next business was to visit the man who had cleaned the watch for Anderson in Edinburgh. I was less hopeful of him, and hence had left him to the last, and therefore was not disappointed to find that he had no record of the number or maker’s name. On examining the watch through his working glass, however, he declared that he recognised it perfectly as that which he had cleaned for Anderson by one of the screws, which had half of its head broken off, and thus had caused him more trouble than usual in fitting up the watch after cleaning.

“I would have put a new one in rather than bother with it,” he said, “but I had not one beside me that would fit it, and as I was pressed for time, I made the old one do. It was my own doing, too, for I broke the top in taking the watch down.”

I was now convinced, almost against my will, that the watch was really that taken from Anderson; my next step was to test Burge’s statement as to how it came into his possession. If that broke down, his fate was sealed.

When I again appeared before Burge he was eager to learn what had transpired, and appeared unable to understand why he should still be detained; all which I now set down as accomplished hypocrisy. It seemed to me that he had lied from the first, and I was almost angry with myself for having given so much weight to his innocent looks and apparent surprise.