GIBBON

Title: The historians' history of the world in twenty-five volumes, volume 07

the history of the later Roman Empire

Editor: Henry Smith Williams

Release date: March 26, 2019 [eBook #59134]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

GIBBON

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME VII—THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1904

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

New York, U. S. A.

THE HISTORY OF THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE

BASED CHIEFLY UPON THE FOLLOWING AUTHORITIES

AGATHIAS, AMMIANUS, AUGUSTAN HISTORY, J. B. BURY, HENRY FYNES CLINTON,

GEORGIUS CEDRENUS, ANNA COMNENA, DION CASSIUS, MICHAEL DUCAS,

EINHARD (EGINHARD), EUTROPIUS, GEORGE FINLAY, HEINRICH

GELZER, EDWARD GIBBON, FRIEDRICH WILHELM

BENJAMIN VON GIESEBRECHT,

FERDINAND GREGOROVIUS, G. F. HERTZBERG, THOMAS HODGKIN, JORDANES

(JORNANDES), JOANNES MALALAS, PROCOPIUS, L. VON RANKE,

STRABO, TACITUS, VELLEIUS, GEORG WEBER,

JOANNES ZONARAS, ZOSIMUS

TOGETHER WITH

A SURVEY OF THE HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE AGES

BY

JAMES T. SHOTWELL

WITH ADDITIONAL CITATIONS FROM

SIGURD ABEL, JOHANN CHRISTOPH ADELUNG, AGOBARD, ANASTASIUS, ANNALES

FULDENSES, ANNALES METTENSES, BARONIUS, FRIEDRICH BLUHME, HENRY

BRADLEY, HERMANN BROSIEN, JAMES BRYCE, CODEX CAROLINUS,

CASSIODORUS, CHRONICLE OF MOISSIAC, ROBERT COMYN,

CORIPPUS, C. DU F. DU CANGE, S. A. DUNHAM,

JEAN VICTOR DURUY, ERCHANBERTUS,

EVAGRIUS OF EPIPHANEIA,

ERNST WILHELM FÖRSTEMANN, FREDEGARIUS SCHOLASTICUS, E. A. FREEMAN,

GABRIEL H. GAILLARD, GEORGIUS MONACHUS, HEINRICH GERDES, AUGUST

FRIEDRICH GFÖRER, GREGORY OF TOURS, JACOB GRIMM, ALBERT

GUELDENPENNING, HENRY HALLAM, JOSEPH VON HAMMER-PURGSTALL,

JEAN BARTHÉLEMY HAURÉAU, KARL

JOSEPH VON HEFELE, ISIDORUS HISPALENSIS,

HENRY H. HOWORTH,

JOHN OF EPHESUS, JULIAN, LAMBERT VON HERSFELD (or ASCHAFFENBURG), ERNEST

LAVISSE AND ALFRED RAMBAUD, CHARLES LECOINTE, LEO DIACONUS,

CHARLTON T. LEWIS, MARIE PAULINE DE LÉZARDIÈRE, LIBANIUS,

JULIUS LIPPERT, MALCHUS PHILADELPHUS, WILHELM

MARTENS, HENRI MARTIN, WOLFGANG MENZEL,

J. F. MICHAUD, MONK OF ST. GAUL, DAVID

MÜLLER, FRIEDRICH MÜLLER,

NICEPHORUS PATRIARCHA, NICETAS ACOMINATUS, OELSNER, GEORGIUS PACHYMERES,

R. PALLMANN, PANEGYRICI VETERES, PAULUS DIACONUS, WALTER C. PERRY,

PETRUS PATRIARCHUS, GEORGIUS PHRANZES, PROSPER AQUITANICUS,

PTOLEMY, HERMANN VON REICHENAU, E. ROBERT ROESLER,

SALVIANUS OF MARSEILLES, F. J. SAULCY, K. SCHENK,

F. C. SCHLOSSER, LUDWIG SCHMIDT,

J. Y. SHEPPARD,

C. SOLLIUS APOLLINARIS SIDONIUS, JAMES SIME, M. E. THALHEIMER, THEOPHANES,

THEOPHYLACTUS SIMOCATTA, THIETMAR OF MERSEBURG, GEOFFREY DE

VILLE-HARDOUIN, WALAFRIED STRABUS, WIPO, JOHANN

G. A. WIRTH, J. K. ZEUS

| VOLUME VII | |

| PAGE | |

| BOOK I. THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE IN THE EAST | |

| Introductory Essay. A Survey of the History of the Middle Ages. By James T. Shotwell, Ph.D. | xiii |

| History in Outline of the Later Roman Empire in the East | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Reign of Arcadius (395-408 A.D.) | 25 |

| A comparison of the two empires, 25. Greatness of Constantinople, 28. The East and the West, 30. Alaric’s revolt, 30. Eutropius the Eunuch, 33. Tribigild the Ostrogoth; the fall of Eutropius, 35. St. John Chrysostom, 39. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Reign of Theodosius the Younger to the Elevation of Justinian (408-527 A.D.) | 42 |

| The Huns, 45. Ammianus Marcellinus describes the Huns, 47. Attila, king of the Huns, 48. The diplomacy of Attila, 54. Attempt to assassinate Attila, 58. Successors of Theodosius, 60. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

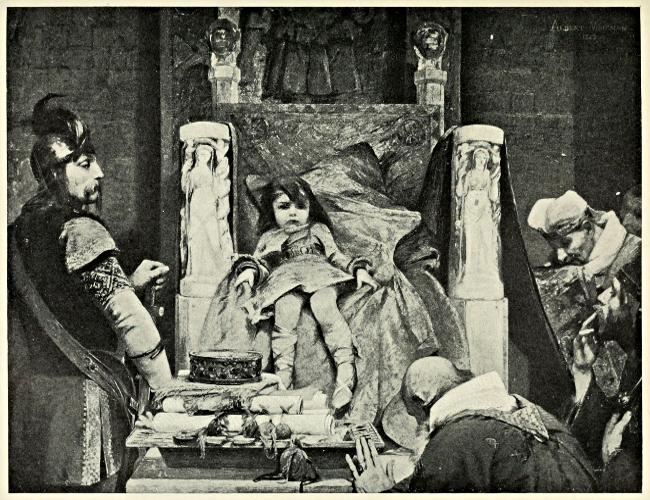

| Justinian and Theodora (525-548 A.D.) | 66 |

| The factions of the Circus, 69. Avarice and profession of Justinian, 74. The building of St. Sophia, 79. Other buildings of Justinian, 81. Fortifications, 82. Suppression of the schools, 85. Extinction of the Roman consulship, 87. The Vandalic War, 87. Belisarius, 89. Belisarius enters Carthage, 92. Triumph and meekness of Belisarius, 96. Solomon’s wars with the Moors, 98. Military tactics under Justinian, 100. Decadence of the soldiery, 103. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Later Years of Justinian’s Reign (535-565 A.D.) | 106 |

| Byzantium rids Rome of the Goths, 106. Finlay’s estimate of Belisarius, 109. The Goths renew the war, 110. Belisarius in Rome, 111. Gibbon’s estimate of Belisarius and his times, 113. Barbaric inroads, 114. Slavic incursions, 116. Turks and Avars, 119. Relations of the Roman Empire with Persia, 121. The revolt in Africa, 124. Invasion of the Cotrigur Huns, 127. End of Belisarius, 129. Death of Justinian, 130. Justinian as a legislator, 131. Bury’s estimate of Justinian, 136. | |

| [viii]CHAPTER V | |

| Reign of Justin II to Heraclius (565-629 A.D.) | 137 |

| Reign of Tiberius, 140. The Emperor Maurice, 142. The Persian War, 143. The Avars, 147. State of the Roman armies, 150. Rebellion against Maurice, 151. Phocas emperor, 153. Heraclius emperor, 155. Heraclius plans to remove the capital to Carthage, 158. The awakening of Heraclius, 159. Triumph of Heraclius, 162. The siege of Constantinople, 164. Third expedition of Heraclius, 165. Battle of Nineveh, 166. The end of Chosroes, 167. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Heraclius and his Successors (610-717 A.D.) | 170 |

| The provinces under Heraclius, 173. Barriers against the Northern barbarians, 176. Religious activities of Heraclius, 177. Wars with the Mohammedans, 179. The reign of Constans II, 182. Religious feuds, 183. The growing danger from the Saracens, 184. Reign of Constantine IV, 186. Saracen wars and siege of Constantinople, 187. Justinian II, 189. The government of Leontius, 192. Justinian recovers the throne, 193. Anarchy, 194. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Leo the Isaurian to Joannes Zimisces (717-969 A.D.) | 197 |

| Leo (III) the Isaurian, 201. The siege of Constantinople, 202. Revolt against Leo, 205. The Iconoclasts, 207. Iconoclasm after Leo, 209. The reign of Constantine (V) Copronymus, 210. Government of Copronymus; the Saracen wars, 211. Wars with Bulgaria, 212. Council of 754, 214. Leo IV and Constantine VI, 215. The empress Irene, 216. Irene and iconoclasm, 217. End of Byzantine authority at Rome, 219. Nicephorus and Michael I, 220. Leo the Armenian, 221. The Amorian dynasty (820-867 A.D.): Michael II, 222. Theophilus, 222. Theodora and Michael the Drunkard, 223. The Basilian or Macedonian dynasty (867-1057 A.D.): Basil, 225. Leo (VI) the Philosopher, 228. Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, 228. Romanus Lecapenus, 229. Romanus II, 230. Nicephorus Phocas, 231. The wars of Nicephorus, 231. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Glory and Decline of the Empire (969-1204 A.D.) | 235 |

| The Russian war, 237. War with the Saracens, 241. The apex of glory, 242. Basil II and his successors, 243. Separation of Greek and Latin churches, 250. The Comneni, 251. Romanus in the field, 253. Captivity of the emperor, 255. The sons of Constantine XI and Nicephorus III, 257. Anna Comnena’s history, 259. Troubles of Alexius, 259. The Norman invasion, 260. Joannes (II) Comnenus (Calo-Joannes), 263. Manuel I, 264. The adventures of Andronicus, 266. Alexius II, 269. Andronicus I emperor, 270. Gibbon’s review of the emperors, 271. Isaac (II) Angelus, 273. Intervention of the crusaders, 273. The capture of Constantinople, 275. Second capture, and sack of the city, 278. | |

| [ix]CHAPTER IX | |

| The Latin Empire (1204-1261 A.D.) | 282 |

| The election of an emperor, 283. Baldwin crowned, 284. Division of the territory, 285. The pope acknowledged, 286. Fate of the royal fugitives, 287. Baldwin quarrels with Boniface, 288. Other conquests, 290. The Bulgarian War, 291. Defeat of the Latins, 292. The fate of Baldwin, 295. Henry of Hainault, 296. Pierre de Courtenai and Robert of Namur, 298. Jean de Brienne, 299. Baldwin II, 300. The crown of thorns, 300. Progress of the Greeks, 301. Constantinople recovered by the Greeks, 302. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Restoration of the Greek Empire (1204-1391 A.D.) | 304 |

| Theodore (I) Lascaris and Joannes Vatatzes, 304. Theodore (II) Lascaris and Joannes (IV) Lascaris, 305. Michael (VIII) Palæologus, 305. Michael Palæologus crowned emperor, 307. Return and rule of the Greek emperor, 308. The provinces of the empire, 311. Andronicus II, 317. The Catalan Grand Company, 320. The duchy of Athens, 322. Walter de Brienne and Cephisus, 322. Andronicus II to the restoration of the Palæologi, 323. The crusade of the fourteenth century, 329. The empire tributary to the Turks, 330. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Manuel II to the Fall of Constantinople (1391-1453 A.D.) | 331 |

| Manuel II, 331. Reign of Joannes VII, 336. Brief union of the Greek and Roman churches, 337. Reign of Constantine XIII, 338. War with Muhammed, 340. Church dissensions, 341. Preparations for defence, 342. The siege begins, 344. The final assault, 349. The sack of Constantinople, 352. End of the Comneni and Palæologi, 356. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 359 |

| BOOK II. THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE IN THE WEST | |

| Introduction | 361 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Odoacer to the Triumph of Narses (476-568 A.D.) | 377 |

| The rise of Theodoric, 380. The Goths move upon Italy, 383. Theodoric the Great, 385. Theodoric and the Church, 389. The fate of Boethius and Symmachus, 391. The troubles of Amalasuntha, 394. Justinian intervenes, 396. Witiges king of the Goths, 399. Belisarius and the siege of Rome, 399. Sufferings of the Romans, 402. The pope deposed, 403. A three months’ truce, 404. Last efforts of the Goths, 405. Jealousy of the Roman generals, 406. A Frankish invasion, 407. The test of Belisarius’ fidelity, 409. The rise of Totila, 410. Belisarius again in[x] Italy, 412. Second siege of Rome, 413. Totila captures Rome, 415. Belisarius remantles the deserted city, 416. Totila again takes Rome, 417. Narses returns to Italy, 418. Battle of Taginæ and death of Totila, 419. Progress of Narses, 420. Interference of the Franks, 422. Battle of Capua, or the Vulturnus, 423. End of Gothic sway, 424. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Lombard Invasion to Liutprand’s Death (568-744 A.D.) | 426 |

| Early history of the Lombards, 426. Their wanderings from the Elbe to the Danube, 427. The Lombards in the region of the Danube, 429. Wars with the Gepids, 431. Alboin annihilates the Gepid power, 433. Alboin plans to invade Italy, 434. The end of Narses, 435. The Lombards enter Italy, 436. The end of Alboin, 437. Extent of Lombard sway, 440. The reign and wooing of Authari, 442. Lombard government and law, 443. The decay of Rome, 444. The Lombard kings, 445. Decline of the Lombard kingdom, 446. Reign of Liutprand, 447. Liutprand and Martel, 448. Liutprand and the Italian powers, 449. Liutprand, the pope, and Constantinople, 450. Peace with Rome, 454. Hodgkin’s estimate of Liutprand, 455. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Franks to the Time of Charles Martel (55 B.C.-732 A.D.) | 457 |

| First conflicts with Rome, 460. Franks in the Roman army, 462. Early kings and the Salic Laws, 463. The reign of Clovis, 466. Clovis turns Christian, 469. Successors of Clovis to Pepin, 477. The rise of Pepin, 481. Pepin of Heristal, 482. The career of Charles Martel, 488. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Charles Martel to Charlemagne (732-768 A.D.) | 497 |

| The Saracens repelled, 498. The affairs of Rome, 499. The pope calls to Charles, 500. Carloman and Pepin the Short, 502. Pepin sole ruler, 504. Secularisation, 506. The anointing of Pepin, 507. Lombard affairs, 509. The pope visits Pepin, 511. Pepin invades Italy, 513. Second war with the Lombards, 513. Desiderius made Lombard king, 515. Pepin and the Aquitanians, 516. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

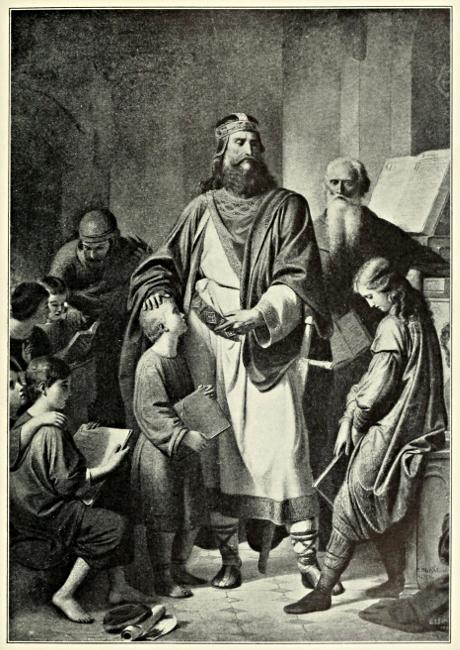

| Charlemagne (768-814 A.D.) | 520 |

| His biography, by a contemporary, 520. The Italian War, 523. The Saxon War, 524. The pass of Roncesvalles, 525. Third visit to Italy, 526. Bavarian War with Tassilo, 526. Wars in the North and with the Avars, 527. Danish War, 528. Glory of Charlemagne, 528. His family, 530. His personal look and habits, 532. His imperial title, 535. His death, 535. His will and testament, 537. Giesebrecht on Charles the Great, 539. The final subjugation of the Saxons, 543. The imperial coronation, 544. Administration and reforms of Charles, 546. Last years of Charles, 552. The legendary Charlemagne, 554. The Monk of St. Gall’s story, 554. Sheppard’s summary of the legends, 555. | |

| [xi]CHAPTER VI | |

| Charlemagne’s Successors to the Treaty of Verdun (814-843 A.D.) | 557 |

| Louis le Débonnaire, or Pious, 557. Humiliation of Louis, 560. Louis returns to power, 561. Last years of Louis, 563. Quarrels of his successors, 565. Charles the Bald and Ludwig the German unite, 566. Lothair brought to terms, 569. Oppression of the Saxon freemen, 570. The Treaty of Verdun, 571. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Birth of German Nationality (843-936 A.D.) | 574 |

| The reign of Ludwig the German, 575. War with the Slavonic tribes, 576. Ludwig turns against Charles the Bald, 577. The end of Lothair, 578. Ludwig and Charles divide Lothair’s possessions, 580. Last years of Ludwig the German, 580. The sons of Ludwig the German; Charles the Fat, 582. Ludwig the Younger, 583. Ravages of the Northmen, 586. Charles the Fat, 587. Arnulf, 589. Arnulf enters Italy, 591. The Babenberg feud, 593. The Hungarian invasions, 594. Conrad I, 595. Reign of Henry (I) the Fowler, 598. The unification of the empire, 599. Wars against outer enemies, 601. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

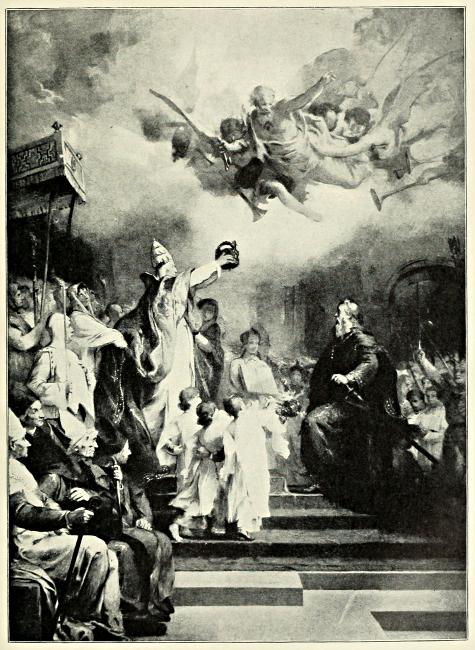

| Otto the Great and his Successors (936-1024 A.D.) | 608 |

| The coronation of Otto I, 608. The overthrow of the Stem duchies, 609. The tenth-century renaissance, 610. The strengthening of the marks, 613. Victory over the Magyars and Wends, 613. The revival of the Roman Empire, 614. The imperial coronation, 615. Wars in Italy against Byzantium, 617. Comparison of Henry the Fowler and Otto with Charlemagne, 618. The unforeseen evils of Otto’s reign, 620. Otto II, 621. Otto in France and Italy, 622. Quelling of the Slavs, 622. Otto III, 623. Otto III makes and unmakes popes, 624. Henry (II) the Saint, 626. Henry’s policy, 627. Relation of Italy to the empire at death of Henry II, 628. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Franconian, or Salian Dynasty (1024-1125 A.D.) | 630 |

| A national assembly, 631. Conrad II increases his power, 633. Conrad in Italy and Germany, 635. The accession of Henry III, 638. Henry’s efforts for peace, 639. The papacy subordinated to Henry, 640. The truce of God, 644. Sorrows of Henry’s last years, 645. Henry IV, 646. Quarrel between Henry IV and Gregory VII, 648. “Going to Canossa”: a contemporary account, 650. Henry’s struggle to regain power, 653. Henry and Conrad, 654. End of Henry IV, 655. Henry V and the war of investitures, 656. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 660 |

Written Specially for the Present Work

By JAMES T. SHOTWELL, Ph.D.

Of Columbia University

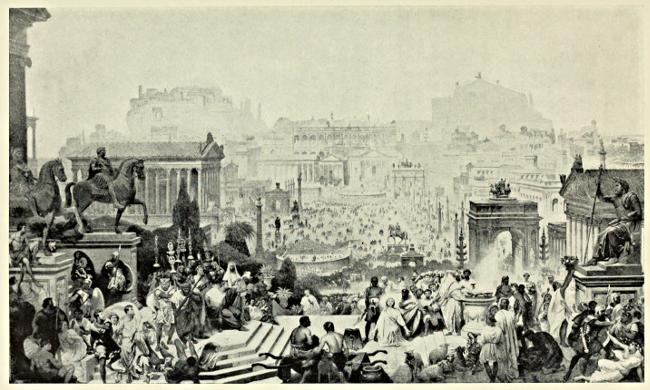

The fifth century is, in a way, the beginning of the history of Europe. Until the hordes of Goths, Vandals, and Franks came out from the fastnesses beyond the Rhine and Danube and played their part upon the cleared arena of the empire itself, the history of the world was antique. The history of the later empire is still a part of the continuous but shifting history of the Mediterranean peoples. The civilisation which the legions of Constantine protected was not the product of Rome, it was the work of an antiquity which even then stretched farther back, three times farther, than all the distance which separates his time from ours. The empire was all antiquity, fused into a gigantic unit, and protected by the legions drawn from every quarter of the world, from Spain to Syria. As it grew old its roots sank deeper into the past. When it had taken all that Greece had to offer in art and literature, the tongue of Greece gave free access to the philosophy of the orient, and as its pantheon filled with all the gods of the world, its thought became the reflex of that of the Hellenised east. If Rome conquered the ancient world, it was made captive in return. The last pagan god to shine upon the standards of the legions was Mithras, the Sun-god of the Persians, while Isis shared with Jupiter the temple on the Capitol. This world entrenched behind the bulwarks that stretched from Solway to Nineveh, brooding upon its past, was quickened with but one new thought,—and that was an un-Roman one,—the strange, unworldly, Christian faith. The peoples that had become subjects of Rome were now to own a high allegiance to one whom it had condemned as a Jewish criminal; on the verge of its own destruction the empire became Christian. It is the fashion to decry the evil influences of the environment of early Christianity, but it was the best that human history has ever afforded. How would it have fared with Christian doctrine if it had had to do with German barbarians instead of with Greek philosophers, who could fit the new truths into accordance with the teachings of their own antiquity, and Roman administrators who could forge from the[xiv] molten enthusiasm of the wandering evangelists, the splendid structure of Catholicism. Before the storm burst which was to test the utility of all the antique civilisation, the church was already stronger than its protectors. And so, at the close, the empire stood for two things, antiquity and Christianity.

In structure, too, the government and society were no longer Roman in anything but name. The administration of the empire had become a Persian absolutism, and its society was verging towards oriental caste. If the art, philosophy, and science of the ancients could be preserved only by such conditions, it was well that they should pass away. The empire in ceasing to be Roman had taken up the worst as well as the best of the past, and as it grew respectable under Stoic or Christian teaching, it grew indifferent to the high impulses of patriotism, cold and formal outwardly, wearying inwardly of its burden.

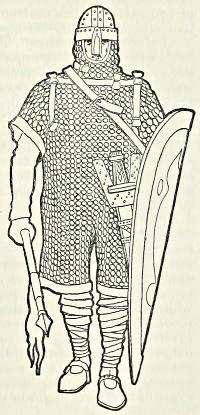

The northern frontiers of this empire did not prove to be an unbroken barrier to the Germans, however, and for two centuries before the sack of Rome, they had been crossing, individually or in tribes, into the peaceful stretches of the civilised world. Their tribal wars at home made all the more alluring the attractions of the empire. For a long time the Roman armies kept these barbarians from anything resembling conquest, but even the vanquished who survived defeat found a home in Roman villas or among the federated troops. The fifth century merely brought to light what had been long preparing, and it took but few invaders to accomplish the final overthrow. The success of these last invasions has imposed an exaggeration of their extent upon historians. They were not true wanderings of nations, but rather incursions of adventurers. The barbarians we call by the name of Goths were a mixture of many nations, while the army of Clovis was hardly more than a single Roman legion. Yet the important fact is that the invasions of the fifth century were successful, and with them the new age begins.

There were two movements which brought about the overthrow of the Roman Empire; one among the barbarians, the other within the empire itself. The Huns were pressing from the east upon the German peoples, whom long civil wars had weakened to such a degree that they must yield or flee. Just as the strength of the Roman frontier was to be tested, whether it could hold back the combined impulsion of Teuton and Hun, the West Goth within the empire struck at its heart. The capture of Rome by Alaric did not end the empire; it does not seem to have created the universal consternation with which we now associate it. Poets and orators still spoke of Rome as the eternal city, and Alaric’s successor, Ataulf, sought the service of that state which he felt unable to destroy. But the sack of Rome was not the worst of the injuries inflicted by Alaric; it was one of the slightest. A disaster had been wrought before he reached the walls of Rome for which all the zeal of Ataulf could not atone. For, so the story runs, Stilicho the last heroic defender of the old empire called in the garrisons from along the frontiers to stay the Gothic advance. The incursions of Alaric within the confines of Italy opened the way to the hesitating but still eager barbarians along the Rhine. The storm bursts at once; the Germans are across the Rhine before Alaric can reach Rome. Instead of their German forests, they have the vineyards of the Moselle and the olive orchards of Aquitaine. The proud nobles in Gaul, unaccustomed to war or peril, can but stand by and watch while their villas lend their plunder to the raiders. After all, the storm,—this one at least,—soon passes. The Suabians and the Vandals cross the Pyrenees and the West Goths come up from Italy, with the varnish of culture upon them, to repress their lawless cousins, and drive them[xv] into the fastnesses of Leon or across to Africa. Fifteen years after the invasion, the poet Ausonius is again singing of the vine-clad hills of the Moselle, and their rich vintage. Gaul has been only partly changed. The noble Sidonius Apollinaris dines with the king Theodoric and is genially interested in his Burgundian neighbours who have settled in the eastern part. By the middle of the century, unaided by the shadow emperors in Italy, this mixture of peoples, conscious of the value of their present advantages, unite to defeat the invading Huns at the battle of Châlons. But another and more barbarous people is now taking possession of the North. The Franks are almost as different from the Visigoths as the Iroquois from the Norman Crusaders. Continually recruited from the forests of the lower Rhine, they do not cut themselves off from their ancient home and lose themselves in the midst of civilisation; they first break the Roman state north of the Loire and then crowd down the Visigoths towards Spain. By the year 500 Gaul has become Frankland, and the Franks have become Catholic Christians. Add to these facts the Saxon conquest of England, the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy, and the overthrow of the empire in the West, and we have a survey of part of the transformation which the fifth century wrought in Western Europe. With it we enter upon the Middle Ages.

Such is our introduction to the new page of history. Behind us are now the fading glories of old Rome; the antique society is outwardly supplanted by the youthful and untutored vigour of the Teutonic peoples. But the numbers of the invaders is comparatively few and the world they conquered large in extent, and it had been romanising for four hundred years. The antique element still persisted; in the East it retained its sovereignty for another thousand years, in the West it compromised with the Teutonic element in the creation of a Roman Empire on a German basis, which was to last until the day of Napoleon, and in the recognition of the authority of the Roman hierarchy. The Church and the Empire, these two institutions of which we hear most in the Middle Ages, were both of them Roman, but both owed their political exaltation to the German Carolingian kings. It was Boniface the Saxon, that “proconsul of the Papacy,” who bound the Germans to the Roman See; but Pepin lent his strong aid, and Charlemagne doubly sealed the compact.

The coronation of the great king of the Franks as emperor of the Romans forecasts a line of history that was not followed, however, in the way he had in mind. The union of Teuton and Roman, or better, of Teuton and antiquity, was not destined to proceed so simply and so peacefully. Instead of an early revival of the great past, the world went down into the dark age, and was forced to struggle for many centuries slowly upward towards the day when it could again appreciate the antiquity it had forgotten. In other words the Middle Ages intervened to divide the renaissance of Charlemagne from that which culminated in Erasmus. How can we explain this phenomenon? What is its significance? It is essential that we face these questions if we would understand in the slightest the history of Europe. And yet as we examine the phenomenon itself we may find some reconstruction of our own ideas of it will be necessary.

Let us now turn to the Middle Ages. We shall find something of novelty in the act, for in all the world’s history there is no other period which ordinarily excites in us so little interest as this. Looking back across the[xvi] centuries from the heights of Modern Times, we have been taught to train our eyes upon the far but splendid table-lands of Rome, and to ignore the space that intervenes, as though it were nothing but a dreary blank between the two great epochs of our history. Dark Ages and Middle Ages are to most of us almost synonymous terms,—a thousand years filled with a confusion, with no other sign of life than the clash of battle or the chanting of hymns, a gruesome and unnatural world, dominated by either martial or monastic ideals, and void of almost everything we care for or seek after to-day.

It is strange that such a perspective has persisted so long, when it requires but the slightest analysis of the facts to prove its utter falsity. The merest glance along the centuries reveals the fact that this stretch of a thousand years is no level plain, no monotonous repetition of unprogressive generations, but is varying in character and progressive in all the deeper and more essential elements of civilisation; in short, is as marked by all the signs of evolution as any such sweep of years in all the world’s history. Yet the mistake in perspective was made a long time ago; it is a heritage of the Renaissance. When men looked back from the attainments of the sixteenth century to the ancient world which so fascinated them, they forgot that the very elevation upon which they stood had been built by the patient work of their own ancestors, and that the enlightenment which they had attained, the culture of the Renaissance itself, would have been impossible but for the stern effort of those who had laid the foundations of our society upon Teutonic and Christian basis in the so-called Middle Ages. The error of the men of the Renaissance has passed into history and lived there, clothed with all the rhetoric of the modern literatures, and upheld with all the fire of religious controversy. How could there be anything worth considering in an age that on the one hand was void of a feeling for antique ideas and could not write the periods of Cicero, and on the other hand was dominated by a religious system which has not satisfied all classes of our modern world? But if we condemn the Middle Ages on these grounds, we are turning aside from the up-building of the Europe of to-day, because its æsthetic and religious ideals were not as varied or as radical as ours. And for this we are asked to pass by that brilliant twelfth century which gave us universities, politics, the dawn of science, a high philosophy, civic life, and national consciousness, or the thirteenth century that gave us parliaments. Is there nothing in all this teeming life but the gropings of superstition? It is clear that as we look into it, the error of the Renaissance grows more absurd. Our perspective should rather be that of a long slope of the ascending centuries, rising steadily but slowly from the time of the invasions till the full modern period.

Let us look at the details. The break-up of the Roman world which resulted in the first planting of the modern nations, did not cause that vast calamity which we call the Dark Age. The invasion of the Teutons and the infusion of their vigour into the effete society of southern Europe was not a fatal blow to civilisation. Rude as they were when first they crossed the frontiers of the empire, the German peoples, and especially their leaders, gave promise that almost in their own day whatever was of permanent value in the Roman world should be re-incorporated into the new society. This series of recoveries had to be repeated with every new people, but it finally seemed about to culminate in the wider renaissance of Charlemagne. By the year 800 it looked as though Europe were already on the clear path to modern times. But just as the young Teutonic civilisation reached the light, a second wave of invasion came dashing over it. The Vikings, whom Charlemagne’s aged eyes may have watched stealing past the hills of Calais, not only swept the[xvii] northern seas, but harried Frankland from the Rhine to the Rhone, until progress was at a standstill and the only thought of the ninth century was that of defence. Then the Hungarians came raiding up the Danube valley, and the Slavs pressed in upon the North. Along the coasts of the Mediterranean the Moorish corsairs were stifling the weak commerce of Italian towns, and landing they attacked such ports as Pisa and even sacked a part of Rome. The nascent civilisation of the Teutons was forced to meet a danger such as would call for all the legions of Augustus. No wonder the weak Caroline kings sank under the burden and the war lords of the different tribes grew stronger as the nerveless state fell defenceless before the second great migration, or maintained but partial safety in the natural strongholds of the land.

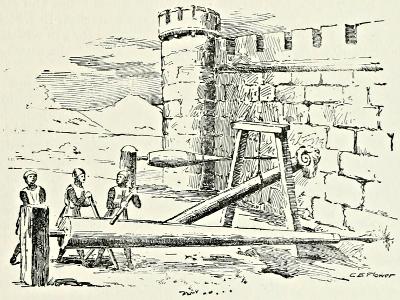

In such a situation self-defence became a system. The palisade upon some central hill, the hedge and thicket in the plain, or the ditch in the morass, became the shelter and the centre of life for every neighbourhood that stood in the track of the new barbarians. The owner of the fastness led his neighbours and his tenants to battle; they gave him their labour for his protection, the palisades grew into stone walls and the “little camps” (castella) became the feudal castles. Those grim, battlemented towers, that rise up before us out of the dark age, were the signs of hope for the centuries that followed. Society was saved, but it was transformed. The protection of a time of danger became oppression in a time of safety, and the feudal tyranny fastened upon Europe with a strength that cities and kings could only moderate but not destroy.

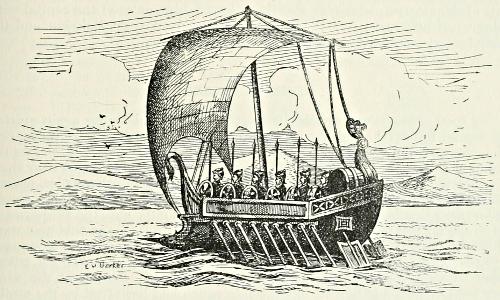

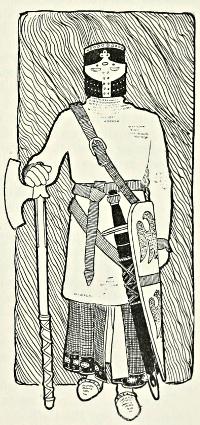

From the tenth century to the present, however, the history of Europe is that of one continuous evolution, slow, discouraging at times, with many tragedies to record and many humiliations to be lived down. But all in all, no century from that to this has ended without some signal achievement in one line or another, in England, in France, in Italy, or in Germany. By the middle of the tenth century the first unyielding steps had been taken when the Saxon kings of Germany began to build their walled towns along the upper Elbe, and to plant the German colonists along the eastern frontiers, as Rome had long before shielded the northern frontiers of civilisation. By the end of the century the Magyars have settled in the middle Danube, under a king at once Christian and saint, and the greatest king of the Danes is champion of Christendom. In another fifty years the restless Normans are off on their conquests again, but now they carry with them to England and to Italy the invigorating touch of a youthful race who are in the front of their time, and not its enemies.

This new movement of the old Viking stock did good rather than harm in its own day, but it has done immeasurable harm to history. For writers and readers alike have turned at this point from the solid story of progress to follow the banners of these wandering knights, to live in the unreal world of chivalry at the hour when the whole society of Europe was forming itself into the nations of to-day, when the renaissance of commerce was building cities along all the highways of Europe, and the schools were crowded with the students of law and philosophy. From such a broad field of vital interests we are turned aside to follow the trail of some brutal noble who wins useless victories that decide nothing, or besieges cities to no discoverable purpose, and leaves a transient princedom for the spoil of his neighbours. These are the common paths of history through the Middle Ages, and what wonder if they are barren, in the track of such men.

But the age of chivalry was also the age of the universities. Turn from the knight-errant to the wandering scholar if we would find the true key to[xviii] the age, but still must leave it in the realm of romance. Few have ever guessed that the true Renaissance was not in the Florence of Lorenzo nor the Rome of Nicholas V, but rather in that earlier century when the great jurists of Bologna restored for all future time the code of Justinian. The greatest heritage of Rome was not its literature nor its philosophy, but its law. The best principles that had been evolved in all the ancient world, on justice, the rights of man, and property,—whose security is the basis of all progress,—all these invaluable truths were brought to light again through the revival of the Roman law, and incorporated again by mediæval legists into the structure of society two centuries before the literary Renaissance of the Italian cities. The crowds of students who flocked to Bologna to study law, and who formed their guild or university on so strange a basis, mark the dawn of modern times fully as well as the academy at Florence or the foundation of a Vatican library. Already the science of politics was revived and the problems of government given practical and scientific test.

Then came the gigantic tragedy of the Hundred Years’ War, retarding for more than a century that growth of industry and commerce upon which even the political structure rests. But while English and French alike are laying waste the fairest provinces of France, the University of Paris is able to dictate the policy of the universal church and for a generation to reduce the greatest absolutism of the age, that of the papacy, to the restrictions of parliamentary government. The Council of Constance was in session in the year of the battle of Agincourt. And, meanwhile, there is another development, far more important than the battles of the Black Prince or the marches of Du Guesclin. Commerce thrives along the shores of Italy, and in spite of their countless feuds and petty wars, the cities of Tuscany and Lombardy grow ready for the great artistic awakening. The story of the Middle Ages, like that of our own times, comes less from the camp fire than from the city square. And even there, how much is omitted! The caravans that line the rude bazaar could never reach it but for the suppression of the robbers by the way, largely the work of royalty. The wealth of the people is the opportunity for culture, but without the security of law and order, neither the one nor the other can be attained. In the last analysis, therefore, the protection of society while it developed is the great political theme of the Middle Ages. And now it is time to confess that we have touched upon but one half of that theme. It was not alone feudalism that saved Europe, nor royalty alone that gave it form. Besides the castle there was another asylum of refuge, the church. However loath men have been in recent years to confess it, the mediæval church was a gigantic factor in the preservation and furthering of our civilisation.

The church was the only potent state in Europe for centuries,—an institution vastly different from our idea of it to-day. It was not only the religious monitor and the guardian of the salvation of mankind, it took up the duty of governing when the Roman Empire was gone. It helped to preserve the best things of antiquity; for when the barbarians were led to destroy what was of no use to them, it was the church, as Rashdall says, that widened the sphere of utility. It, more than the sword of Charlemagne tamed the barbarian Germans, and through its codes of penance with punishments almost as severe as the laws of Draco, it curbed the instincts of savagery, and taught our ancestors the ethics of Moses while promising them the salvation of Christ. It assumed much of the administration of justice in a lawless age, gave an inviolate asylum to the persecuted, and took in hand the education of the people. Its monks were not only the pioneer farmers in the fastnesses[xix] of the wilderness, but their entertainment of travellers made commerce possible. Its parish church furnished a nursery for democracy in the gatherings at the church door for counsel and deliberation. It opened to the sons of peasants a career that promised equality with the haughtiest seigneur, or even the dictation over kings. There was hardly a detail of daily life which did not come under the cognisance or control of the church,—questions of marriage and legitimacy, wills, oaths, even warfare, came under its surveillance.

But in depicting this wonderful system which so dominated Europe in the early Middle Ages, when kings were but shadows or military dictators over uncertain realms, we must be careful not to give too much of an air of religiosity to the whole Middle Age. The men of the Middle Ages did not all live in a cowl. Symonds in his brilliant history of the Renaissance in Italy likens the whole mediæval attitude to that of St. Bernard, the greatest of its ascetics. St. Bernard would walk by the blue waters of Lake Geneva intent only upon his rosary and prayer. Across the lake gleam the snows of Mont Blanc,—a sight no traveller forgets when once he has seen it; but the saint, with his cowl drawn over his eyes, sees only his own sin and the vision of the last judgment. So, says Symonds, humanity walked along its way, a careful pilgrim unheeding the beauty or delight of the world around. Now this is very striking, but is it true? First of all, the Middle Ages, as ordinarily reckoned, include a stretch of ten centuries. We have already seen how unlike these centuries were, how they differed from each other as much as any centuries before or since. The nineteenth is hardly more different from the eighteenth than the twelfth was different from the eleventh. So much for the universalisation as we go up and down the centuries; it can hardly apply to all. Some gave us the Chansons des Gestes, the Song of Roland, the legends of Charlemagne and his paladins. Others gave us the delicious lyrics of the minnesingers and troubadours, of Walter von der Vogelweide and Bertran de Born. And as for their variety, we must again recall that the same century that gave us St. Francis of Assisi—that jongleur of God—and the Divine Comedy, gave us also Magna Charta and representative government.

But even if we concede that the monks dominated mediæval society as Symonds paints it, we must not imagine that they were all St. Bernards. Few indeed—the sainted few—were alone able to abstract themselves so completely from this life as to be unconscious of their surroundings. The successive reforms, Clugny, Carthusians, Cistercians, beginning in poverty and ending in wealth and worldly influence, show what sort of men wore the cowl. The monks were not all alike; some were worldly, some were religious, some were scholars, and some were merely indolent. The monastery was a home for the scholar, a refuge for the disconsolate, and an asylum for the disgraced. And a monk might often be a man whose sensibilities, instead of being dull, were more sharply awake than our own to-day. His faith kindled an imagination that brought the next world down into his daily life, and one who is in communion with eternity is an unconscious poet as well as a devotee. Dante’s great poem is just the essence of a thousand years of such visions. Those phases of the Middle Ages farthest removed from our times and our habits of thought are not necessarily sombre. They are gilded with the most alluring light that ever brightened humanity—the hope and vision of immortality.

It has seemed necessary to say this much at least about the ecclesiasticism of the Middle Ages so that we may get a new or at least a more sympathetic[xx] point of view as we study its details. Humanity was not in a comatose condition for a thousand years, to wake up one fine day and discover itself again in a Renaissance. Such an idea gives false conceptions of both the Middle Ages and that slow change by which men acquired new interests,—the Renaissance.

What then was the Italian Renaissance? What was its significance and its result? First of all no new birth of the human spirit, as we have been commonly taught, could come after that wonderful twelfth and busy thirteenth centuries. It would sound strange to the wandering jongleur or the vagabond student, whose satirical and jovial songs of the twelfth century we still sing in our student societies, to be told that he had no joy in the world, no insight into its varying moods, no temperament capable of the comprehension of beauty. If any man ever “discovered himself,” surely that keen-witted, freedom-loving scholar, the goliard, was the man, and yet between him and the fall of Constantinople, that commonest date for the Renaissance, there are two hundred years or more. A little study of preceding centuries shows a world brimming with life and great with the promise of modern times. Lawyers were governing in the name of kings; universities were growing in numbers and influence. It has been said, and perhaps it is not far wrong, that there were three great powers in Europe in the Middle Ages—the Church, the Empire, and the University of Paris. And not all the men at the universities of Paris or Oxford or Bologna were busy counting how many angels could dance on the point of a needle, as we are apt to think when we read Lord Bacon’s denunciation of the scholastics. If half of them,—and that is a generous estimate,—were busied over theology, not all that half were examining it for their religious edification. Their interests were scientific. In a way they were scientists,—scientists of the world to come,—not of this transient life. They were analysing theology with about the same attitude of mind as that of the physicist of to-day in spite of all that has been said against their method. When one examines a world which he cannot yet reach, or a providence whose ways are not as the ways of man, he naturally will accept the authority of those whom he believes to be inspired, if he is to make even a little headway into the great unknown. The scholastics stretched the meaning of the word inspired, and accepted authority too easily. But they faced their problem with what seems something like a scientific spirit even if they had not yet attained a scientific method. And I may add in passing that to my mind the greatest tragedy of the human intellect is just here,—in this story of the abused scholastics. Starting out confident that all God’s ways can be comprehended and reduced to definite data, relying in calm security upon the power of the human intellect to comprehend the ways of Divine governance, they were forced point by point, through irreconcilable conclusions and inexplicable points of controversy, to admit that this doctrine and that, this fact and that one, lie outside the realms of reason and must be accepted on faith. Baffled in its vast endeavour to build up a science of things divine the reason of man turned from the task and grappled with the closer problems of the present world. If the work of the scholastics was futile, as so many claim, it was a grand futility that reaches to tragedy. But out of its very futility grew the science of to-day.

And now with all this intellectual activity of which scholasticism is only a part, where did the so-called Renaissance come in? By the year 1300 the problem of the scholastics was finished. In the works of Thomas Aquinas lay codified and systematised the whole positive product of their work. Not[xxi] until after that was their work empty and frivolous, but when scholasticism turned back upon itself, even the genius of the great Duns Scotus but discovered more and more its futility. Men of culture began to find it distasteful; they did not care to study law,—the other main interest. It was time for a new element in the intellectual realm. The need was no sooner felt than supplied. The study of the antique pagan world afforded scholars and men of leisure the desired change. The discovery of this antique world was not a new process; but the features that had been ignored before, the art and literature of the pagan world, now absorbed all attention. The “humanities” gradually crowded their way into university curricula, especially in Germany and England, and from the sixteenth century to the present day the humanities have been the dominant study at the universities. Looking over the era of the Renaissance, we commonly begin it in the fourteenth century, just where our previous sketch of the other intellectual conditions stopped. The age of Petrarch was its dawn. France and England, where most progress had been made before, were now to be absorbed in the barbarism of international and civil wars; and so the last stage of that long Renaissance which we call the Middle Ages became the task and the glory of Italy.

It may seem at first as if, in exalting the achievements of the Middle Ages, we have undervalued the work of the humanists. It would not be in accord with the attempted scientific judicial attitude which it is now our ambition to attain, if this charge were to be admitted. We must give full credit to the influence of that new knowledge, that new criterion, and especially to that new and healthy criticism which came with the Italian Renaissance. Its work in the world was absolutely necessary if modern society was to take up properly its heritage of all those splendid ages which adorned the Parthenon and made the Forum the centre of the world. All the intellectual energy which had gone into antique society must be made over into our own. But after all, the roots of our society are Teutonic and Christian even more than they are Roman or antique. We must learn to date our modern times not merely from the literary revival which witnessed the recovery of a long-lost pagan past; but from the real and splendid youth of Europe when it grappled with the earnest problems of law and order and put between itself and the Viking days the barriers of the national state,—king and people guarding the highways of the world for the protection of the caravans that made the cities. It is as essential for us to watch those boats that ascended the Rhone and the Rhine, and the merchants whose tents were pitched at the fairs of Champagne, as it is to know who discovered the proper derivation of agnus.

The period upon which we are now entering presents peculiar difficulties for the historian. The body politic under consideration is in some respects unique. Historians are not even agreed as to the name by which it should properly be designated. It is an empire having its capital at Constantinople; an empire not come suddenly into being in the year 395, at which point, for the sake of convenience, we are now taking up this history; but which is in reality nothing more or less than the continuation of that Roman Empire in the East, the affairs of which we left with the death of Theodosius. That emperor, as we have seen, held sway over an undivided Roman commonwealth. On his death the power that he had wielded passed to his two sons, one of whom nominally held sway in the East, the other in the West. The affairs of the Western division of the empire under Honorius and his successors have claimed our attention up to the time of the final overthrow of Rome in the year 476. We are now returning to follow the fortunes of Arcadius, the other heir of Theodosius, and his successors.

But whether this Eastern principality should properly be spoken of as the Later Roman Empire, or as the Eastern, Byzantine, or Greek Empire, is, as has been suggested, a moot point among historians. The difficulty is perhaps met to the best advantage if we disregard the controversial aspects of the question and make free use of each and all of these names; indeed, in so doing, convenience joins hands with logicality. The empire of Arcadius and his immediate successors was certainly entitled to be called the Roman Empire quite as fully as, for example, were the dominions of Diocletian and Constantine. There was no sudden breach of continuity, no thought of entrance upon a new epoch with the accession of Arcadius. It was no new thing that power was divided, and that there should be two capitals, one in the East and one in the West. On the contrary, as we have seen, there had been not merely a twofold but a fourfold division of power most of the time since the day of Diocletian. No contemporary could have predicted that after the death of Theodosius the Roman dominions in the East and in the West would never again be firmly united under a single head. Nor indeed is it quite true that the division was complete and permanent; for, as we shall see, there were to be rulers like Justinian and Zeno who had a[2] dominating influence over the Western territories, and who regarded themselves as masters of the entire Roman domain. And even when the division became complete and permanent, as it scarcely did before the time of Charlemagne, it could still be fairly held that the Roman Empire continued to exist with its sole capital at Constantinople, whither Constantine had transferred the seat of power, regardless of the fact that the Western dominion had been severed from the empire. The fact that this Western dominion included the city of Rome itself, which had given its name to the empire, and hence seemed indissoluble from it, is the chief reason for the seeming incongruity of applying the term Later Roman Empire to the dominion of the East.

It must not be overlooked, however, that there were other reasons for withholding the unqualified title of Roman Empire from the Eastern dominions. The chief of these is that the court of Constantinople departed very radically from the traditions of the West, taking on oriental manners and customs, and, what is most remarkable, gradually relinquishing the Latin speech and substituting for it the language of Greece. We have seen in our studies of earlier Roman history the marked tendency to the Hellenisation of Rome through the introduction of Greek culture from the time when the Roman Republic effected the final overthrow of Greece. It will be recalled that some of the most important histories of Rome, notably those of Polybius and Appian and Dionysius and Dion Cassius, were written in Greek. The emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote his Meditations in the same language. But this merely represented the tendency of the learned world. There was no propensity to substitute Greek for Latin as the language of everyday life so long as the seat of empire remained in the West. Now, however, as has been intimated, this strange substitution was effected; the writers of this Later Roman Empire in the East looked exclusively to classical Greece for their models, and in due course the language of court and of common people alike came to be Greek also, somewhat modified from the ancient idiom with the sweep of time, but in its essentials the same language which was spoken at Athens in the time of Pericles. Obviously there is a certain propriety in this use of the term Greek Empire as applied to a principality whose territory included the ancient realms of Athens, and whose customs and habits and speech thus preserved the traditions of ancient Hellas.

The use of the terms Eastern Empire and Byzantine Empire requires no elucidation, having an obvious propriety. As has been said, we shall find it convenient here to employ one or another of the four terms indiscriminately; giving preference perhaps, if a choice must be made, to the simplest and most non-committal form, Eastern Empire.

By whatever name designated, the principality whose fortunes we are to follow will hold our interest throughout a period of more than a thousand years, from the death of Theodosius in 395 to the final overthrow of Constantinople in 1456. This period is almost exactly coincident with the epoch pretty generally designated by historians as the Middle Ages, and usually estimated as a time of intellectual decadence.

As a general proposition this estimate is doubtless just. It must be born in mind, however, that the characterisation applies with far less force to the conditions of the Eastern Empire than to the conditions of Western Europe. The age of Justinian was certainly not a dark age in any proper acceptance of that term. If no subsequent period quite equalled this in brilliancy, yet there were epochs when the Eastern Empire showed something of its old-time vitality. Indeed, there was an almost incessant[3] intellectual output which served at least to sustain reminiscences of ancient culture, though it could not hope to rival the golden ages of the past. In point of fact, the chief defect of the literature of the time was that it did attempt to rival the classical literature. We have just pointed out that the later Byzantine Empire was essentially Greek in language and thought. Unfortunately the writers of the time failed to realise that in a thousand years of normal development the language—always a plastic, mobile thing, never a fixed structure—changes, grows, evolves.

Instead of contenting themselves with the use of the language with which they were familiar in everyday speech as the medium of their written thoughts, they insisted on harking back to the earlier classical period, consciously modelling their phraseology and style upon authors who had lived and died a thousand years earlier. No great art was ever produced by such conscious imitation. Great art is essentially spontaneous, never consciously imitative; the epoch-making works are done in the vernacular by artists whose first thought is to give expression to their spontaneous feelings and emotions, unhampered by tradition. It was thus that Homer, Sophocles, Euripides, Herodotus, and Aristophanes wrote; and if Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Livy, and Tacitus were more conscious craftsmen, somewhat in the same measure were they less great as artists.

But the Byzantine writers were rather to be compared with the Alexandrians of the age of the Ptolemies. They were far more scientific than their predecessors and proportionately less artistic. As grammarians they analysed and criticised the language, insisting on the retention of those chance forms of speech which the masters of the earlier day had used spontaneously. The critical spirit of the grammarian found its counterpart everywhere in the prevalence of the analytical rather than the synthetic cast of thought. As the masters of the past were the models, so were their stores of knowledge the chief sources on which to draw. What Aristotle had said must be considered the last word as regards physical knowledge. What the classical poets and historians had written must needs be copied, analysed, and praised as the final expression of human thought. Men who under different auspices and in a different atmosphere might perhaps have produced original works of some significance, contented themselves with elaborating anthologies, compiling dictionaries and encyclopædias, and epitomising chronicles of world history from the ancient sources. It is equally characteristic of the time that writers who did attempt creative work found prose romance the most congenial medium for the expression of their ideals. Even this measure of creative enthusiasm chiefly marked the earliest period of the Byzantine era and was stifled by the conservatism of the later epoch.

But if the reminiscent culture of the Byzantine Empire failed to produce an Herodotus, a Thucydides, or a Livy, it gave to the world, nevertheless, a line of historians and chronologists of the humbler class, beginning with Procopius the secretary of Justinian’s general, Belisarius, and ending with Ducas, Phrantzes, Laonicus Chalcocondyles, and Critobulus, the depicters of the final overthrow of Constantinople, who have left us a tolerably complete record of almost the entire life of the Eastern Empire. A list of these historians—numbering about half a hundred names—has been given in our general bibliography of Rome in Volume VI.

Here we shall add only a very brief résumé of the subject, naming the more important authors. For the later period of the undivided Roman Empire and the earlier Byzantine epoch we have, among others, the following works: the history of the war with Attila, bringing the story of the empire to the year 474, by Priscus, a Thracian, and the continuation of his history to the year 480 by Malchus of Philadelphia; the important history of Zosimus, which we have had occasion to quote in an earlier volume; and, most important of all, the historical works of Procopius of Cæsarea in Palestine. The last-named author was, as already mentioned, the secretary of Justinian’s famous general, Belisarius. He accompanied that general on many of his campaigns and apparently was associated with him on very intimate terms. This association, together with the character of his writings, has caused Procopius to be spoken of rather generally in later times as the Polybius of the Eastern Empire,—a compliment not altogether unmerited.

His works are by far the most important of the Byzantine histories, partly because of their intrinsic merit and partly because of the character of the epoch with which they deal. The more pretentious of his works has two books on the Persian War, two on the war with the Vandals, and four on the Gothic war. Curiously enough, another work ascribed to Procopius, and now generally admitted to be his, deals with the lives of Justinian and Theodora and to some extent with that of Belisarius himself, in a very different manner from that employed in the other history just mentioned. This so-called secret history was apparently intended for publication after the author’s death; it therefore gives vent to the expression of what are probably the true sentiments of the author, showing up the character of his patrons in a very different and much less complimentary light from that in which they are depicted in the earlier work. As an illustration of the difference between the diplomatic and the candid depiction of events this discrepancy of accounts coming from the same pen is of the highest interest. The moral for the historian—vividly illustrative of Sainte-Beuve’s famous saying that history is a tradition agreed upon—need hardly be emphasised.

Among the later Byzantine historians the names of John Zonaras, of Nicetas Acominatus, of Nicephorus Gregoras, occur as depicters of the events of somewhat comprehensive periods; Agathias, Simocatta, Epiphaneia, Anna Comnena, and George Phrantzes as biographers or writers on more limited epochs. Of these Anna Comnena in particular is noteworthy because her life of her father Alexius I has been spoken of as the only really artistic historical production of the period. It is popularly known as having supplied Sir Walter Scott with the subject and some of the materials for his last romance, Count Robert of Paris. But most noteworthy of all is the fact that this is the first important historical production, so far as is known, that ever came from the pen of a female writer.

The list of chronologies or epitomes of world history includes the Chronicon Paschale, and the works of Georgius Syncellus, Malalas, Cedrenus, Michael Glycas, and Constantine Manasses. In some respects more important than any of these were the collections of excerpts from ancient authors which were made by Stobæus, by Photius, and by Suidas. These have preserved many fragments of the writings of historians of antiquity that would otherwise have been altogether lost. A very noteworthy collection of excerpts, comprising in the aggregate a comprehensive history of the world made up from the writings of the Greek historians, forms one portion of the encyclopædia which the emperor Constantine (VII) Porphyrogenitus—himself a writer of[5] some distinction—caused to be compiled in the tenth century. This work contained extracts, often very extensive, from the writings of most of the Greek classical historians. It was apparently very popular in the Middle Ages, and has been supposed to be responsible for the loss of many of the works from which it made excerpts. Unfortunately, the encyclopædia itself has come down to us only in fragments; but, even so, it gives us excerpts from such writers as Polybius, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Diodorus, Nicholas of Damascus, Appian, and Dion Cassius, and of numerous Byzantine histories that are not otherwise preserved.

Taken together, even the extant portions of the Byzantine histories make up a very bulky literature. Being produced in this relatively recent time, a correspondingly large proportion of it has been preserved. Not, indeed, that many of the original manuscripts of the Byzantine historians have come down to us, but they appear to have been copied very extensively by the monks of western Europe, who found in them an interest which the classical writings often failed to arouse. The very fact that so many of these writings epitomise ancient history furnishes, perhaps, the explanation of this popularity. In the day when the reproduction of books was so laborious a process, condensation was naturally a merit that appealed to the bookmaker. Hence, as has been suggested, the epitome was often made to do service for the more elaborate original work, which latter was allowed to drop altogether out of view. But the modern world has not looked upon the Byzantine writings with the same interest. For the most part they had never been translated into modern European languages, and the original texts have been collated, edited, and printed in comparatively recent times.

On the other hand, these writings were almost the first to be subjected to the critical analysis of the historian, working with what we speak of as the modern spirit. Tillemont began the laborious process of reconstructing in detail the chronology of later Roman history, with the aid of these materials, and the work was taken up a little later by Edward Gibbon, and carried to completion in what is incontestably the greatest historical work of modern times,—if not, indeed, the greatest of any age,—The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. In this work, Gibbon not only set an epochal standard for future historians, but he so exhaustively covered the ground as to leave almost nothing for a successor in the same field. His work is the more remarkable because it was produced at a time when the general tendency was to accept the writings of the ancients in a much less critical spirit than that to which they have been more recently subjected. Gibbon, however, vaulted at once to the critical heights. Indeed, he went a step beyond most critics of more recent generations, in that he insisted on applying to the traditions and superstitions of all ancient nations the same critical standards. Most of Gibbon’s contemporaries and a large proportion of his successors, until very recent times, while looking askance at the traditions of Greece and Rome, have wished to adjudge Hebrew traditions by a different standard. It has been a curious illustration of the illogicality of even critical minds, that the very critics who have inveighed against the credulity of the ages which could accept the myths of Greece and Rome as historical, should have inveighed also against the mind which had the breadth of view to see that all ancient myths and traditions must be weighed in the same historical balance. Only in our own day have considerable numbers of critics attained the plane of historical impartiality which Gibbon had reached a century and a quarter ago, but in most other regards his example found a readier following.

The Roman Empire, permanently divided at the death of Theodosius (395) into an eastern and a western section does not, nevertheless, lose its unity as an organisation. The period of disintegration has set in, and the extinction of the western section in 476 is an event in this disintegration rather than the “fall” of an empire. It was not until 800, the year of Charlemagne’s accession, that there were really two empires, and that the term “Eastern Empire” may properly be applied. But for convenience we call the history of Arcadius and his successors that of the Eastern Roman Empire.

A.D.

395 Arcadius, co-regent, and elder son of Theodosius, continues to reign at Constantinople. The Huns ravage Asia Minor, and the Visigoths, under Alaric, rise in Mœsia and Thrace. At the death of Rufinus, the eunuch Eutropius becomes chief adviser of the emperor, supported by Gainas.

398 Alaric becomes governor of Eastern Illyricum.

399 Death of Eutropius.

401 Death of Gainas. The emperor comes entirely under the influence of his dissolute wife, Eudoxia.

408 Theodosius II succeeds his father. He is but seven years of age and is controlled by his sister Pulcheria. Alaric moves upon Rome.

410 Death of Alaric.

421 Theodosius marries Athenais (Eudocia). War breaks out with Persia.

425 Organisation of the University of Constantinople.

438 Publication of the Theodosian Code.

439 Genseric takes Carthage.

441 War with Persia. War with the Huns and Vandals continues.

442 Invasion of Thrace and Macedonia by Attila.

447 Peace of Anatolius made with the Huns.

450 Death of Theodosius. Marcian is raised to the throne by Pulcheria, whom he marries. He makes a wise ruler and resists payment of tribute to the Huns.

457 The Theodosian dynasty comes to an end with Marcian. The choice of the emperor rests with the army, and the general Aspar brings about the election of Leo I, a native of Thrace.

465 Great fire at Constantinople.

468 With the co-operation of Anthemius, Leo plans a great expedition against Genseric in Africa, but it fails through treachery of Aspar, who is executed, 469.

474 Leo I dies, leaving empire to his grandson Leo II. The latter dies the same year and Zeno, his father, reigns, but Basiliscus at once drives him out and rules for twenty months, when Zeno recovers the throne.

476 With the resignation of Romulus Augustulus the western division is definitely detached from the empire.

478-481 The Ostrogoths invade the Balkan peninsula.

483 Promulgation of the Henoticon.

488 Zeno induces Theodoric and the Ostrogoths to leave Illyricum and attack Rome.

491 At death of Zeno, Anastasius I is proclaimed emperor, through influence of the empress Ariadne, who marries him.

491-496 The Isaurian War instigated by the supporters of Longinus results favourably for Anastasius.

499 The Bulgarians invade Thrace.

502-505 Unsuccessful war with Persians, who take several provinces.

507 The “Long Wall” of Thrace is built to keep out the Goths.

514 Revolt of Vitalianus.

518 Death of Anastasius; Justin I, an illiterate Illyrian peasant, obtains the emperorship through the army. With him the empire enters on a new era. He prepares his nephew Justinian to succeed him..

527 Justinian created augustus.

528 Justin dies; Justinian I, “the great,” sole monarch. He is the chief figure of his time. His wife is the empress Theodora. He begins active warfare at once against the Arians, Jews, and pagans. Belisarius appointed commander-in-chief in the East.

529 First edition of the Justinian Code published.

530 Belisarius defeats the Persians at Dara.

531 Chosroes ascends the Persian throne.

532 Peace made with Persia. Insurrections break out in Constantinople. St. Sophia burned. Belisarius quells the riots.

533 Belisarius begins a campaign against the Vandals in Africa. The Pandects published.

534 Belisarius captures the Vandal king Gelimer and destroys his kingdom, and for this is made sole consul.

535-540 Belisarius in Italy and Sicily against the Ostrogoths. He makes himself master of Rome and other cities.

540 Recall of Belisarius. Persian invasion of Syria.

542 Repulse of the Persians. Belisarius degraded by Theodora on his return from the campaign. The great plague.

543 Totila, king of the Goths, captures Naples.

544 Belisarius proceeds to Italy against Totila.

545 Five years’ peace with Persia. Totila besieges Rome. Belisarius has not sufficient forces to resist him.

546 Capture of Rome by Totila.

547 Romans recover Rome.

548 Totila retakes Rome. Belisarius returns to Constantinople. Death of Theodora. Conspiracy against Justinian.

549 The imperial armies occupy the lands of the Lazi.

550 Slavonians and Huns invade the empire.

551 Battle of Sinigaglia. The Goths lose Sicily.

552 The eunuch Narses arrives in Italy as commander-in-chief. Recovers Rome. Defeat and death of Totila.

553 End of the Ostrogothic War.

554-557 Terrible earthquakes visit Constantinople and other cities.

558 Belisarius repels the invading Huns under Zabergan.

562 Fifty years’ peace with Persia. Narses continues his victorious career in Italy.

565 Death of Justinian.

565 Justin II succeeds Justinian I. He determines to change Justinian’s unpopular system and refuses payment to an embassy of Avars, which is the cause of serious depredations in the provinces.

567 The Gepid kingdom overthrown by Lombards and Avars.

568 Lombard invasion of Italy.

571 Birth of Mohammed.

572 War breaks out with the Persians. They make several important conquests, and

574 Justin, realising his inability to govern, makes Tiberius, the captain of the guard, cæsar.

575 Peace with Persia.

576 Battle of Melitene. The Romans reach the Caspian Sea.

578 Justin dies. Tiberius emperor.

581 The imperial army led by Maurice defeats the Persians at Constantina.

582 Maurice elected emperor. Death of Tiberius.

584 Treaty with the Avars, whose depredations have become very serious.

586 Roman victory at Solachon.

589 Persian victory at Martyropolis. Slavonic colonies begin to settle in the Peloponnesus.

590 Maurice crowns his son Theodosius at Easter. Rebellion of Vaharan of Persia, who deposes Hormisdas or Hormuz.

591 Maurice puts Chosroes II on the Persian throne. He proceeds against the Avar invasion of Thrace.

602 Rebellion in the army. Phocas, the centurion, made emperor. Maurice put to death.

603 War with Persia breaks out.

604 Treaty of peace with the Avars.

606-608 Disastrous invasion of Asia Minor by the Persians. They advance to Chalcedon.

609 Revolts in Africa and Alexandria.

610 Heraclius, son of the governor of Africa, accomplishes the overthrow and death of Phocas.

614 The Persian War continues. Damascus captured.

615 Jerusalem taken by the Persians.

616 Persian invasion of Egypt.

617 Occupation of Chalcedon by the Persians. Heraclius contemplates moving to Carthage.

620 Peace made with Avars who have attempted to seize the emperor.

622 Heraclius takes command in person of the Persian War.

622-628 The war is vigorously conducted. Campaigns in Cappadocia, Pontus, Armenia, Cilicia, and Assyria, ending 628 with treaty of peace with Siroes.

629 Heraclius restores the holy cross to Jerusalem.

632 Death of Mohammed.

633 The Mohammedan conquests begin. The imperial cities fall before them in the following order: Bosra (634), Damascus (635), Emesa, Heliopolis, Antioch, Chalcis, Berœa, Edessa (636), Jerusalem (637).

638 Constantine, the king’s son, fails in an attempt to recover Syria. Mesopotamia lost to the Mohammedans.

639 Amru invades Egypt.

641 Death of Heraclius. Death of Constantine III, after three months’ reign. Another son of Heraclius, by Martina, Heracleonas, whom Heraclius appointed to reign conjointly with Constantine, reigns alone for five months and then is banished. His brother David is appointed emperor under the name of Tiberius. His fate is unknown. Constans II, son of Constantine, becomes emperor. Alexandria taken by the Mohammedans.

647 Mohammedans drive the Romans out of Africa.

648 The Type of Constans published.

649 Mohammedans invade Cyprus.

650 They take Aradus.

652 Armenia falls into their hands.

654 They capture Rhodes.

655 They defeat Constans in the great naval battle off Mount Phœnix in Lycia. Pope Martin is banished to the Chersonesus.

658 Campaign of Constans against the Slavs. Peace made with the Mohammedans.

661 Constans leaves Constantinople and spends winter at Athens.

662-663 Great Mohammedan invasion of Asia Minor.

663 Constans in Rome.

668 Mohammedans advance to Chalcedon and hold Amorium for a short time. Assassination of Constans at Syracuse. His son Constantine (IV) Pogonatus succeeds.

669 Mohammedans invade Sicily and carry off 180,000 prisoners from Africa.

670 Foundation of Kairwan, near Carthage.

673-677 Mohammedans besiege Constantinople. The Romans use the newly invented Greek fire against them.

678 Peace concluded with the Mohammedans.

679 Bulgarian War and foundation of the Bulgarian kingdom.

681 Constantine deprives his brothers Heraclius and Tiberius of the imperial title. The troops of the Orient had demanded that they, too, should receive the crown, and thus the Trinity in heaven might be represented on earth.

685 Justinian II succeeds his father. The caliph and emperor make peace.

687 Transference of the Mardaites from Lebanon to Thrace and Asia Minor.

689-690 Successful expedition of Justinian against the Bulgarians and Slavs. The Greeks are forced to emigrate from Cyprus; two hundred thousand Slavs transported to Asia Minor.

692 Battle of Sebastopolis. Symbatius revolts. Mohammedan subjection of Armenia.

695 In consequence of his cruelties the general Leontius deposes Justinian, cuts off his nose, and banishes him to the Chersonesus. Leontius emperor.

697 Revolt of Lazica. Great Mohammedan invasion of Asia Minor. Hassan proceeds against Africa with success. Carthage taken.

698 The Mohammedans retake Carthage. Leontius dethroned. Aspimar becomes emperor as Tiberius III. The Mohammedans continue to ravage the empire.

705 Justinian II, now named Rhinotmetus, from his nasal mutilation, recovers the throne.

709 Tyana falls before the Mohammedans in their ravages on the Bosporus.

710 Great cruelty shown to Ravenna and the Chersonesus by the emperor.

711 Justinian overthrown by Bardanes, who becomes emperor under the name of Philippicus. In his reign the Mohammedans invade Spain (711) and the Bulgarians ravage Thrace (712). The Mohammedans take Antioch in Pisidia.

713 Philippicus dethroned and his eyes put out. Artemius his secretary is raised to the emperorship as Anastasius II. He tries honestly to bring about reforms, and sends an embassy to Damascus to arrange a peace with the Mohammedans.

715 The army determines to depose Anastasius, and chooses an obscure person, Theodosius III, who unwillingly assumes the purple.

716 The Mohammedans again invade Asia Minor and besiege Amorium. Leo III the Isaurian relieves the town, makes a truce with the besiegers, and is proclaimed emperor by the army.

717 Mohammedans besiege Pergamus. They begin the siege of Constantinople, which is raised the following year.

726 The dispute over image-worship arises. Publication of the first iconoclastic decree. The great iconoclastic schism begins, immersing the empire in many calamities and revolts, leading to the final separation of the Greek and Latin churches.

The Mohammedans invade Cappadocia.

727-728 Revolts in Italy and Greece.

734 Mohammedan invasion of Asia Minor.

739 Battle of Acronum.

740 Constantine (V) Copronymus succeeds his father.

742 Defeat of the rebel Artavasdes, who has obtained possession of Constantinople.

744-747 The Great Plague devastates the empire.

746 Mohammedan invasion of Cyprus.

750 Fall of the Omayyad dynasty. Two rival Saracen powers are formed. Ravenna taken by the Lombards.

751 Capture of Melitene and Theodosipolis by Constantine.

753 Invasion of Italy by Pepin. Council of Constantinople favours iconoclasm.

755 Invasion of Thrace by the Bulgarians. Pepin continues invasion of Italy.

757 The Bulgarians driven back to their own territory with great slaughter.

760-765 Constantine invades Bulgaria. Victory of Anchialus, 762.

766 Wreck of the Roman fleet at the mouth of the Danube. Edicts against image-worship extended and vigorously enforced.

773-774 Campaigns against the Bulgarians. Victory of Lithosoria. Peace made with the Bulgarian monarch, which Constantine breaks.

775 Leo IV, son of Constantine, succeeds him. He is a zealous iconoclast. He marries the empress Irene.

778 Successful campaign against the Bulgarians.

780 Capture of Semaluos by Harun-ar-Rashid. Death of Leo. Irene becomes regent for the ten-year-old Constantine VI.

781 Revolt of Elpidius in Sicily.

782 The Mohammedans under Harun-ar-Rashid invade Asia Minor.

787 Council of Nicæa sanctions image-worship.

788 The Bulgarians gain a victory at the Strymon.

789 The Arabs invade Rumania.

790 Constantine assumes control of the government. Irene is unwilling to relinquish power and a struggle between the two begins.

791 The emperor conducts a campaign against the Bulgarians.

792 A conspiracy formed against Constantine by his uncles is suppressed and severely punished. Irene’s dignity restored. Second campaign against the Bulgarians.

795 Constantine divorces his wife Maria and marries Theodota.

796 Third Bulgarian campaign of Constantine.

797 Irene, taking advantage of Constantine’s unpopularity on account of his treatment of Maria, imprisons him and has his eyes put out. She now reigns alone. Conspiracy to place one of Constantine V’s sons on the throne.

798 Peace made with the Mohammedans.