The Ingoldsby Legends

MORRISON AND GIBB, EDINBURGH,

PRINTERS TO HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE.

[Pg iv]

REV. RICHARD HARRIS BARHAM.

(Thomas Ingoldsby.)

[Pg v]

The

Ingoldsby Legends

OR

Mirth and Marvels

By

THOMAS INGOLDSBY

Esquire

WITH EIGHTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS BY

CRUIKSHANK, LEECH, ETC.

AND PORTRAIT

LONDON AND NEW YORK

FREDERICK WARNE AND CO.

1889

[Pg vii]

CONTENTS.

| PAGE |

| MEMOIR, |

xi |

| PREFACE, |

xxi |

| |

| |

| FIRST SERIES. |

| |

| THE SPECTRE OF TAPPINGTON, |

5 |

| THE NURSE'S STORY—THE HAND OF GLORY, |

29 |

| PATTY MORGAN THE MILKMAID'S STORY—"LOOK AT THE CLOCK," |

35 |

| GREY DOLPHIN, |

41 |

| THE GHOST, |

59 |

| THE CYNOTAPH, |

69 |

| MRS. BOTHERBY'S STORY—THE LEECH OF FOLKESTONE, |

74 |

| LEGEND OF HAMILTON TIGHE, |

99 |

| THE WITCHES' FROLIC, |

104 |

| SINGULAR PASSAGE IN THE LIFE OF THE LATE HENRY HARRIS, D.D., |

118 |

| THE JACKDAW OF RHEIMS, |

139 |

| A LAY OF ST. DUNSTAN, |

145 |

| A LAY OF ST. GENGULPHUS, |

153 |

| A LAY OF ST. ODILLE, |

162 |

| A LAY OF ST. NICHOLAS, |

168 |

| THE LADY ROHESIA, |

178 |

| THE TRAGEDY, |

185 |

| MR. BARNEY MAGUIRE'S ACCOUNT OF THE CORONATION, |

188 |

| THE "MONSTRE" BALLOON, |

191 |

| HON. MR. SUCKLETHUMBKIN'S STORY—THE EXECUTION, |

194 |

| SOME ACCOUNT OF A NEW PLAY, |

198 |

| ACT I. |

201 |

| ACT II. |

202 |

| ACT III. |

203 |

| ACT IV. |

203 |

| ACT V. |

204 |

| MR. PETERS'S STORY—THE BAGMAN'S DOG, |

205 |

| APPENDIX, |

218 |

| |

| |

| SECOND SERIES. |

| |

| THE BLACK MOUSQUETAIRE, |

224 |

| SIR RUPERT THE FEARLESS, |

244 |

| THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, |

252 |

| THE AUTO-DA-FÉ, |

264 |

| [Pg viii]

THE INGOLDSBY PENANCE, |

282 |

| NETLEY ABBEY, |

293 |

| FRAGMENT, |

297 |

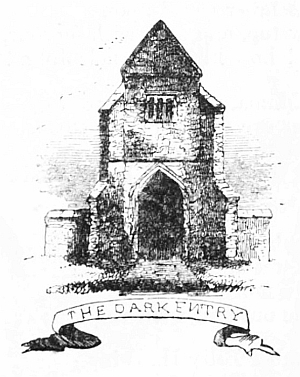

| NELL COOK, |

299 |

| NURSERY REMINISCENCES, |

306 |

| AUNT FANNY, |

308 |

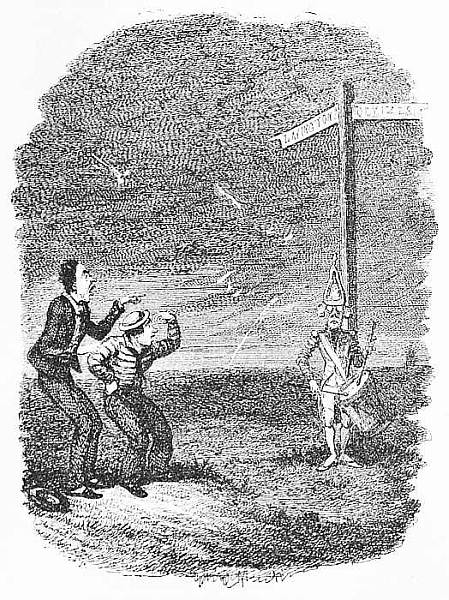

| MISADVENTURES AT MARGATE, |

314 |

| THE SMUGGLER'S LEAP, |

318 |

| BLOUDIE JACKE OF SHREWSBERRIE, |

323 |

| THE BABES IN THE WOOD, |

334 |

| THE DEAD DRUMMER, |

339 |

| A ROW IN AN OMNIBUS (BOX), |

351 |

| THE LAY OF ST. CUTHBERT, |

355 |

| THE LAY OF ST. ALOYS, |

368 |

| THE LAY OF THE OLD WOMAN CLOTHED IN GREY, |

377 |

| RAISING THE DEVIL, |

393 |

| THE LAY OF ST. MEDARD, |

394 |

| |

| |

| THIRD SERIES. |

| |

| THE LORD OF THOULOUSE, |

405 |

| THE WEDDING-DAY; OR, THE BUCCANEER'S CURSE, |

418 |

| THE BLASPHEMER'S WARNING, |

432 |

| THE BROTHERS OF BIRCHINGTON, |

449 |

| THE KNIGHT AND THE LADY, |

460 |

| THE HOUSE-WARMING, |

469 |

| THE FORLORN ONE, |

483 |

| JERRY JARVIS'S WIG, |

483 |

| UNSOPHISTICATED WISHES, |

501 |

| HERMANN; OR, THE BROKEN SPEAR, |

503 |

| HINTS FOR AN HISTORICAL PLAY, |

505 |

| MARIE MIGNOT, |

507 |

| THE TRUANTS, |

508 |

| THE POPLAR, |

512 |

| MY LETTERS, |

512 |

| NEW-MADE HONOUR, |

515 |

| THE CONFESSION, |

516 |

| EPIGRAM, |

517 |

| SONG, |

517 |

| EPIGRAM, |

518 |

| SONG, |

518 |

| AS I LAYE A-THYNKYNGE, |

519 |

| |

| |

| |

| Transcriber's notes |

a |

[Pg ix]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE |

| REV. RICHARD HARRIS BARHAM (Thomas Ingoldsby), |

Frontispiece |

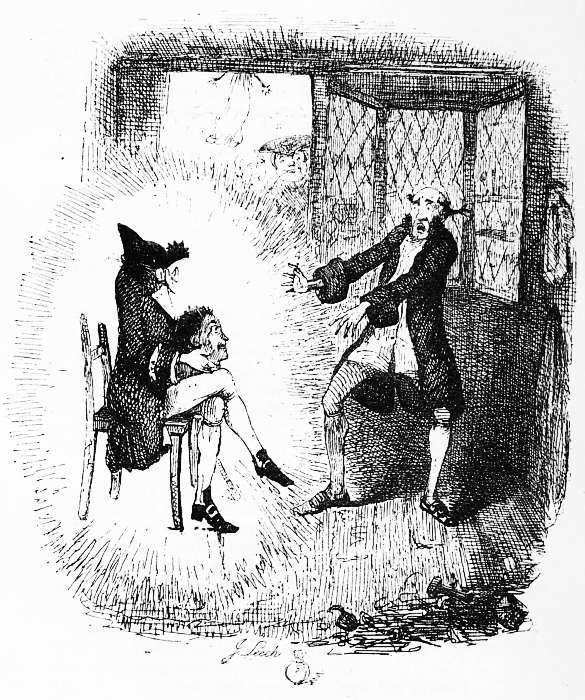

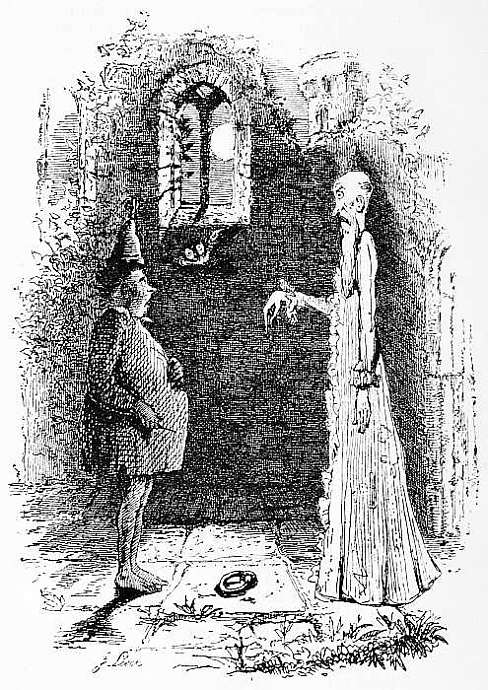

| THE SPECTRE OF TAPPINGTON, |

4 |

| THE GHOST, |

66 |

| HAMILTON TIGHE, |

102 |

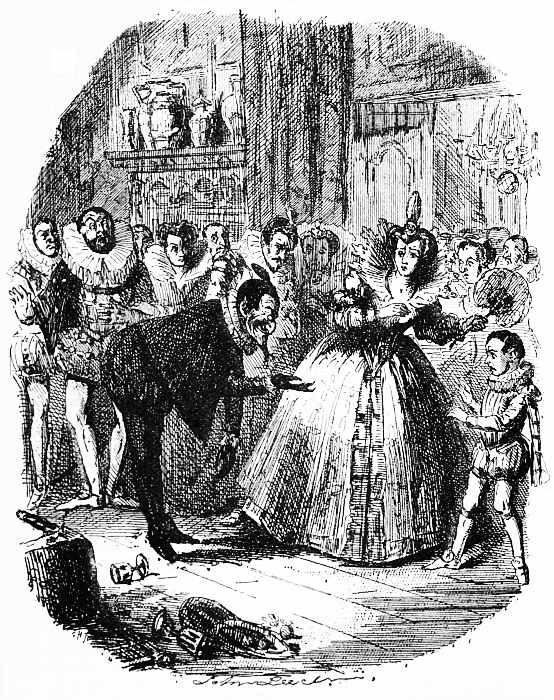

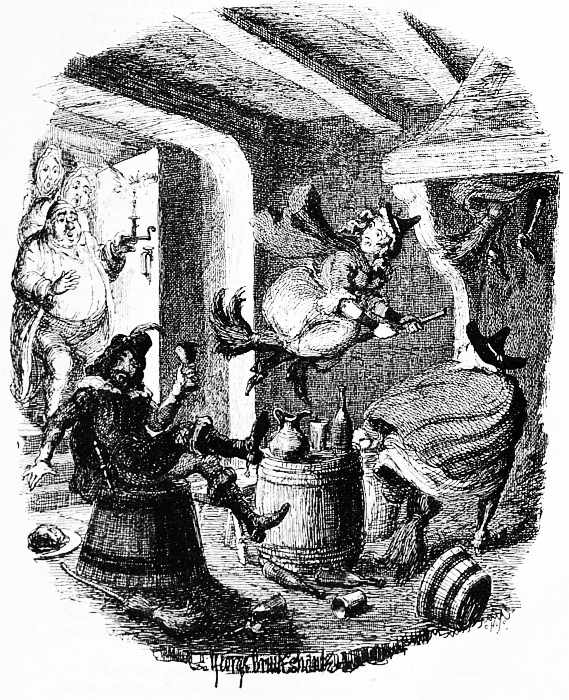

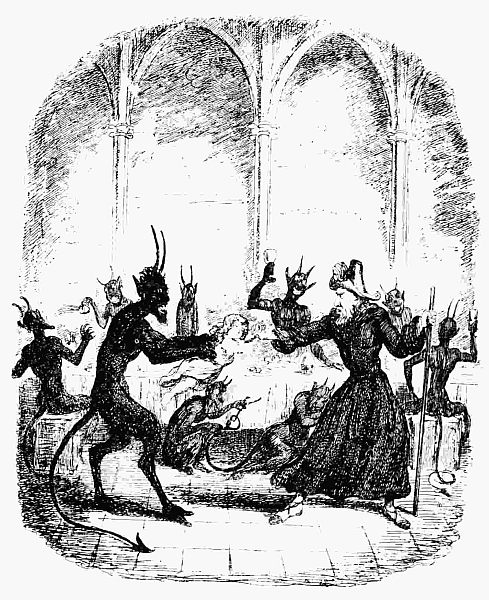

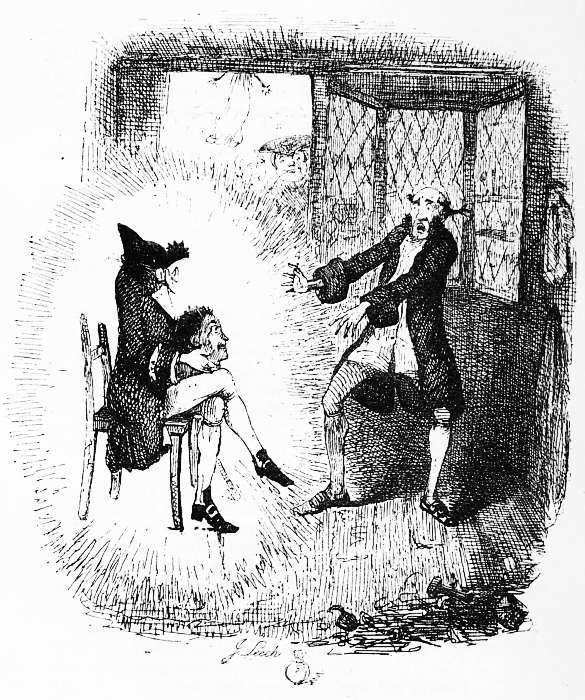

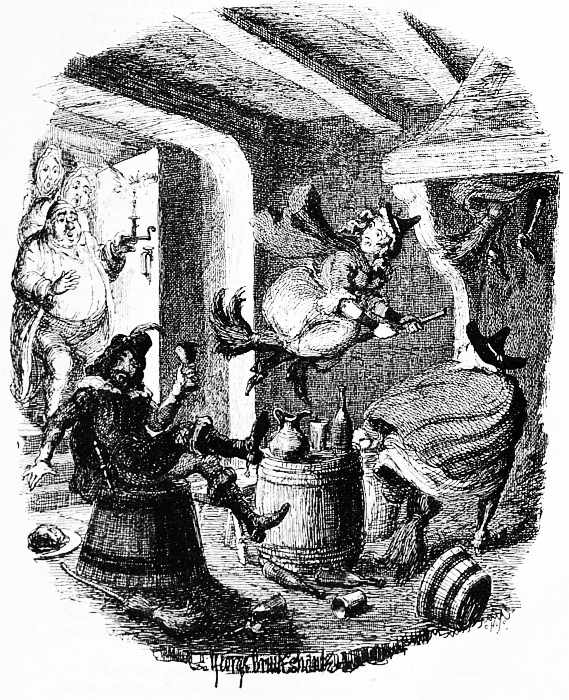

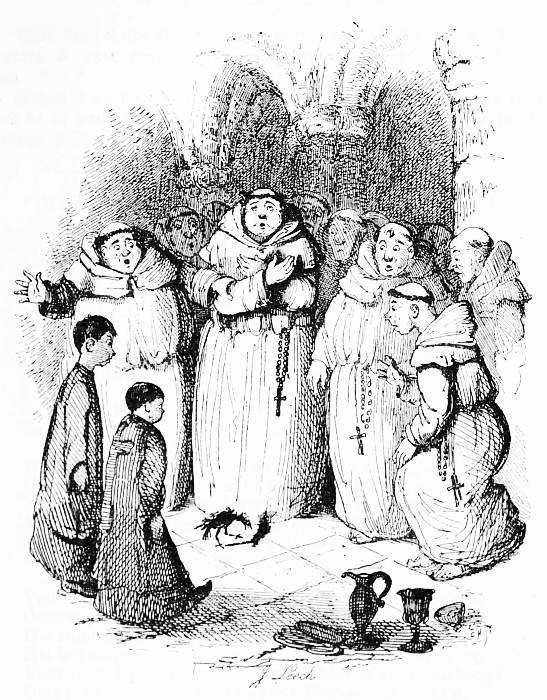

| GRANDFATHER'S STORY; OR, THE WITCHES' FROLIC, |

113 |

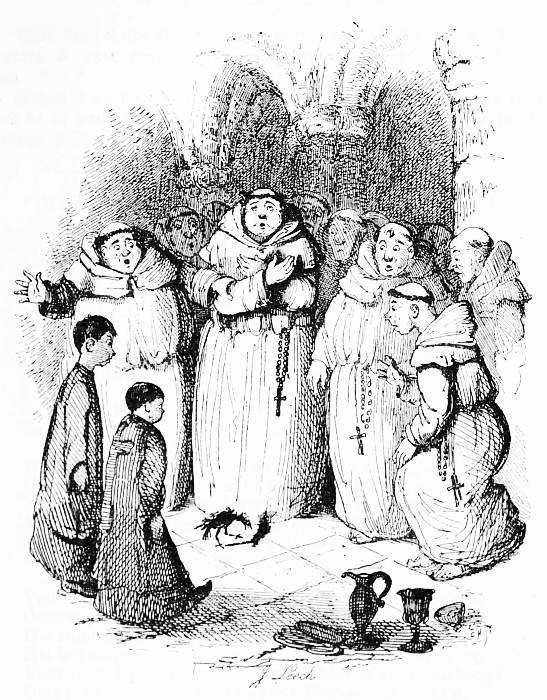

| THE JACKDAW OF RHEIMS, |

143 |

| A LAY OF ST. NICHOLAS, |

175 |

| THE BLACK MOUSQUETAIRE, |

241 |

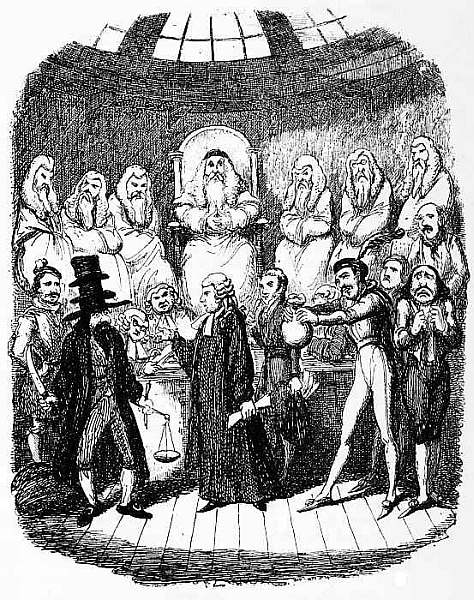

| THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, |

260 |

| THE AUTO-DA-FÉ, |

277 |

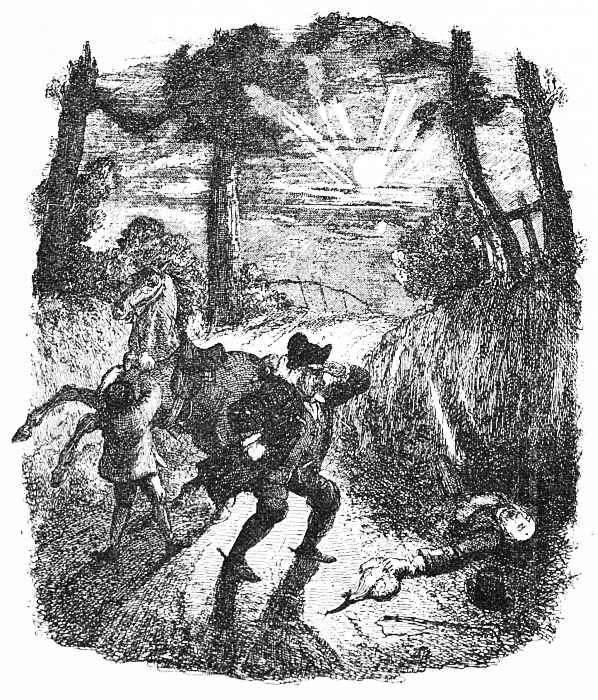

| THE DEAD DRUMMER, |

343 |

| THE LAY OF ST. CUTHBERT, |

362 |

| A LEGEND OF DOVER, |

381 |

| LEGEND OF ST. MEDARD, |

399 |

| THE LORD OF THOULOUSE, |

413 |

| THE BUCCANEER'S CURSE, |

428 |

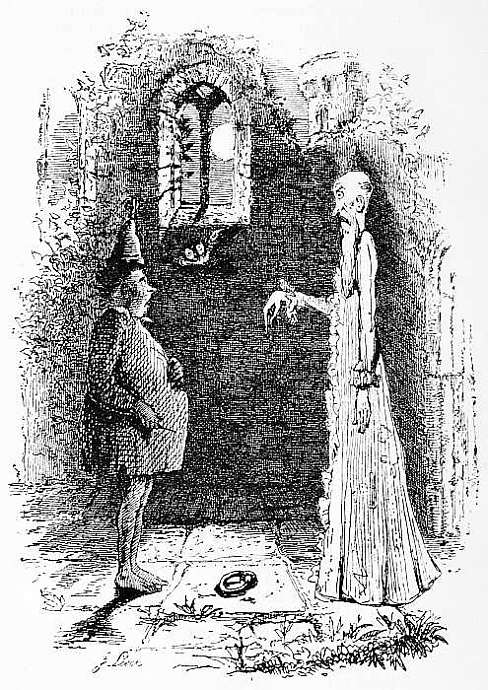

| THE KNIGHT AND THE LADY, |

467 |

| THE HOUSE-WARMING, |

479 |

| JERRY JARVIS'S WIG, |

497 |

[Pg xi]

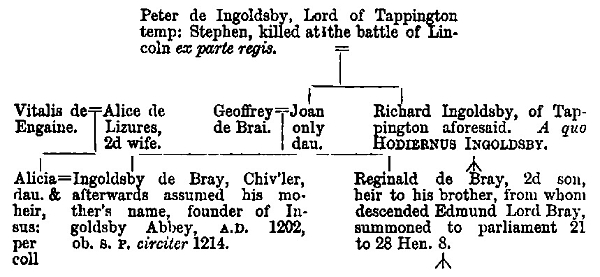

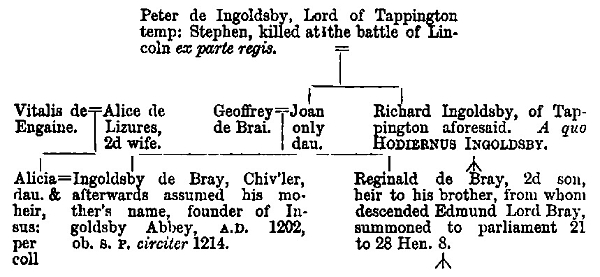

Richard Harris Barham, the "Thomas Ingoldsby" of literature, was born

at Canterbury, December 6th, 1788. His family had long been residents

in the archiepiscopal city, and had estates in Kent. He (Barham) used

to trace his descent from a knight who came over to England with

William the Conqueror, and whose son, Reginald Fitzurse, was one of the

assassins of Thomas à Becket. After the deed Fitzurse fled to Ireland,

and there changed his name to MacMahon, which has the same meaning.

His brother Robert, who succeeded to the English estates, changed his

patronymic to de Berham, converted in process of time into Barham.

Richard Barham was only between five and six years old when his father

died, leaving him heir to a small estate in Kent. A portion of it

consisted of a manor called Tappington Wood, often alluded to in the

Ingoldsby Legends.

Richard was sent to St. Paul's School, and it was on his road thither,

in 1802, that he met with an accident that endangered his life. The

horses of the Dover mail, in which he was travelling, took fright and

galloped off furiously: the boy put his right hand out of the window

to open the door, when at that moment the coach upset; his hand was

caught under it, and it was dragged along on a rough road and seriously

mutilated. The surgeons, believing he would die, did not amputate the

limb; and through the tender care of the headmaster's wife (he had been

sent on to school) he recovered.

At school Barham formed some friendships which lasted his life: one

of these school friends was afterwards his publisher, Mr. Bentley;

Dr. Roberts, who attended him in his last illness, was another. He

remained captain of St. Paul's School for two years, and when nineteen

was entered as a Gentleman Commoner at Brasennose

[Pg xii]

College. Here he

was speedily elected a member of a first-class university club,—the

Phœnix Common Room,—where he became acquainted with Lord George

Grenville, Cecil Tattersall, and Theodore Hook, a friend of his

after-life.

A specimen of his youthful humour has been preserved in an answer he

made to his tutor, Mr. Hodson, when reproved by him for the late hours

he kept and his absence from chapel. "The fact is, sir," said Barham,

"you are too late for me." "Too late!" repeated the tutor. "Yes, sir; I

cannot sit up till seven in the morning. I am a man of regular habits;

and unless I get to bed by four or five at latest, I am really fit for

nothing the next day." The habit that he had acquired of sitting up

late continued during his life, and he believed that he wrote best at

night.

His original intention had been to study for the Bar, but a very severe

though short illness brought serious thoughts to the young man, and he

determined to enter the Church, his mind having also been painfully

impressed by the suicide of a young college friend; consequently he

took Holy Orders, and obtained the curacy of Ashford, in Kent, from

whence he was transferred to Westwell, a parish a few miles distant

from his first one.

In 1814, when he had attained the age of twenty-six, Barham married

Caroline, third daughter of Captain Smart of the Royal Engineers, a

very charming young lady; and shortly afterwards he was presented to

the living of Snargate, and accepted also the curacy of Warehorn. Both

these parishes were situated in Romney Marsh, at the distance of only

two miles from each other. The young clergyman took up his abode at

Warehorn, a place then noted as a haunt of smugglers.

A second accident, by the upsetting of a gig, caused Mr. Barham a

fracture of the leg, and it was during the seclusion entailed by this

misfortune that he produced his first literary effort, a novel called

Baldwin, for which he received £20; it issued from the Minerva Press,

and was unsuccessful. He had scarcely recovered from this accident

when the illness of one of his children took him to London, for the

purpose of consulting Abernethy. Here he chanced to meet a friend,

who was about to post a letter to invite a young clergyman to come up

and become a candidate for a vacant Minor Canonry at St. Paul's. It

suddenly struck him that the place might suit Mr. Barham, and they at

once agreed that he should stand for it. He resigned at once his curacy

and living, stood for the Canonship, and was elected. Thus in 1821 he

exchanged Romney Marsh, its dulness

[Pg xiii]

and smugglers, for a residence in

London and the society of a highly intellectual circle.

We will give here the testimony of a dear friend of the poet's, as

to his character, at this time. "My first acquaintance with Mr.

Barham," writes the Rev. John Hughes, "dated from his election into

the body of Minor Canons of St. Paul's, of which Cathedral my late

father was then a Residentiary. Mr. Barham had married early in life,

and in every respect enviably. His previous career as a graduate of

Brasennose College had thrown him much into contact with several

gifted and accomplished men, upon whom a shred of Reginald Heber's

mantle, and a smack and savour of the 'Whippiad,' had descended in the

way of corporate inheritance, and his quick talents had mended the

lesson. It was soon evident to the Dean and Chapter, and to my father

in particular, that their new subordinate combined superior powers of

conversation with most decorous and gentlemanly tact and attention to

all points connected with his duties."

In 1824, Mr. Barham was appointed a priest in ordinary of the King's

Chapel Royal, and was shortly afterwards presented with the incumbency

of St. Mary Magdalene and St. Gregory-by-St. Paul. Mr. Barham was not

an eloquent preacher, because he disapproved of all oratorical display

in the pulpit, but he was an excellent parish priest, ever watchful

over his flock, and delighting in doing good.

In 1825 a series of domestic sorrows fell on the Minor Canon. His

dearly-loved eldest daughter died; her loss was followed at intervals

by that of four of his other children, to all of whom he was devotedly

attached. How deeply the gentle-hearted clergyman felt these severe

afflictions, some touching lines in Blackwood's Magazine of that date

testify, though he bore them with Christian resignation. "The best

substitute for stoicism which a man of keen and sensitive feelings

finds it possible to adopt, is to think a little less of his own

sorrows, and more of those of others; and this," writes Mr. Hughes, "I

believe to have been Barham's secret for bearing with equanimity the

loss of more than one

Who ne'er gave him pain till they died.

He strove to be happy in making others so, especially those more

congenial spirits who more directly shared in his affections.... Here

it may not be amiss to notice one trait of character connected with

the appointment which he held as chaplain to the Vintners'

[Pg xiv]

Company.

Part of his duty in this capacity was to perform divine service at

an almshouse in the vicinity of town, tenanted by certain widows of

decayed members of the corporation. The old ladies quarrelled sadly,

and Barham was in the habit of devoting one extra morning a week to a

pastoral visitation of these poor isolated old women, for charity and

decency's sake, and acted as arbiter and referee in their ridiculous

feuds, with as much gravity as it was in his nature to assume on such

an occasion." There was surely no small degree of self-denial in a man

of such talent devoting his valuable time to such an office.

The expenses of an increasing family made Mr. Barham once more attempt

literary work—this time successfully; and he contributed light

articles in rapid succession to Blackwood, John Bull, and The

Globe. He also assisted in the completion of Gorton's Biographical

Dictionary. "Cousin Nicholas" appeared in Blackwood in 1878. It owed

its publication to Mrs. Hughes, the mother of John Hughes, Esq.,—from

whose account of Barham we have just quoted,—a most remarkable and

highly-gifted woman, the friend and correspondent of Scott, Southey,

etc. The MS. was in an unfinished state, having been laid by for some

years, when Barham submitted it to this lady. So highly did she think

of it, and so aware was she of the author's sensitive doubts, that she

sent it off at once to Mr. Blackwood, who was greatly pleased with

it, and at once inserted it in his magazine. The first Barham knew of

the Blackwood. He was thus compelled to finish it, and worked up the

catastrophe with great skill. Nor was this the only benefit he derived

from this gifted friend. It was to her he was indebted for much of the

material of the poems that have made his fame as a writer, though this

was to come afterwards.

In 1831, Sidney Smith was appointed one of the Canons of St. Paul's,

and thus two of our famous wits became intimate. On October 2, 1831,

Sidney Smith read himself in as Residentiary at St. Paul's. He told

Barham that he had once nearly offended Sam Rogers by recommending him,

when he sat for his picture, to be drawn saying his prayers—with his

face in his hat.

Mr. Barham was by no means an ardent politician, and he never used

his pastoral influence on either side. For himself, he was a staunch

Conservative, and never failed, in spite of any personal inconvenience,

himself to record his vote. He told one amusing anecdote about an

election. As he was landing from the steamer at Gravesend, where his

vote was to be taken, it was raining heavily,

[Pg xv]

and the passengers

landing from the boat naturally put up their umbrellas. Partisans of

both candidates lined the pier, watching eagerly to see what colours

the arrivals wore. Barham, remembering a dead cat that had been thrown

at him on a previous occasion, wore none; nevertheless he was detected.

He heard the Tory partisans cry out, "Here comes one on our side."

"You be blowed," said a voter in sky-blue ribbons, "I say he's our'n."

"Be blowed yourself," was the reply; "don't you see the gemman's got a

silk umbrella?"

In 1837 appeared the famous "Ingoldsby Legends" in Blackwood.

Of their production Mr. Hughes thus writes: "In my mother's

presentation copy of the Ingoldsby Legends, written in Barham's own

hand, occurs the following distich,—

To Mrs. Hughes, who made me do 'em,

Quod placeo est—si placeo—tuum.

The fact is that my mother, to whom Lockhart has alluded as a frequent

correspondent of Scott and Southey, and who inherited a family stock of

strange tales and legends, suggested the subject of 'Hamilton Tighe'

to Barham. The original ghost story, in the circumstances of which he

made some slight alteration, was said to have occurred in the family

of Mr. Pye, the poet laureate, a neighbour and brother magistrate of

my maternal grandfather, Mr. W., and the date of it was supposed to

be connected with the taking of Vigo. This legend, which appeared in

Bentley's Miscellany, was the first in the series, and is, as an

illustration of his peculiar style, worth better criticism than my own.

Suffice it to state that which my friend Miss Mitford can confirm, that

the simple recitation of 'Hamilton Tighe' has actually made persons

start and turn pale, and complain of nervous excitement. 'Patty Morgan

the Milkmaid's Story' and the 'Dead Drummer' were transmitted also

to him through the same medium,—the former having been recounted

to us by Lady Eleanor Butler, as a whimsical Welsh legend which had

diverted her much; the latter by Sir Walter Scott, who, having better

means than most men of ascertaining facts and names, believed in their

authenticity. I think, but am not certain, that the 'Hand of Glory'

was suggested by a conversation at our house on the subject of country

superstition. Of the source of the remaining legends I am ignorant,

save that the basis of some of them was furnished by an old Popish book

in the library of Sion College, from which, as from other sources,

Barham was wont to gratify his love

[Pg xvi]

of heraldry and antiquarianism....

The Ingoldsby Legends were the occasional relief of a suppressed

plethora of native fun.

"Many of these effusions were written while waiting for a cup of tea,

a railroad train, or an unpunctual acquaintance, on some stray cover

of a letter in his pocket-book; one in particular served to relieve

the tedium of a hot walk up Richmond Hill. It was rather a piece of

luck if he found time to joint together the disjecti membra poetæ

in a fair copy; and before the favoured few had done laughing at some

rhymes which had never entered a man's head before, the zealous Bentley

had popped the whole into type. After all, the imputed instances of

inadvertence (for no one who knew him would style it irreverence)

chiefly occur in that part of the series in which his purpose, to my

knowledge, was to quiz that spirit of flirtation with the Scarlet Lady

of Babylon, which had of late assumed a pretty marked shape; and it was

difficult to prosecute this end without confounding the Scriptural St.

Peter with the Dagon of the Vatican."

We give these extracts from a letter written by Mr. John Hughes, of

Donnington Priory, to Mr. Ainsworth, believing that the reprinted

report of a personal friend will be more interesting than a condensed

account of it. Mr. Hughes himself was a ripe scholar and a wit. He

published poetical pleasantries, under the name of "Mr. Butler of

Brasen-nose," in Blackwood and Ainsworth's Magazine, and was the

father of Mr. Thomas Hughes, the author of Tom Brown's Schooldays.

"As regards the 'Dead Drummer,' the story was attested in a

contemporary pamphlet, called A Narrative of the Life, Confession,

and Dying Speech of Jarvis Matchan, which was signed by the Rev. J.

Nicholson, who attended him as minister, and by another witness. The

murder was not committed on Salisbury Plain, but near Alconbury in

Huntingdonshire, and the culprit was hanged in chains at Huntingdon,

August 2nd, 1786, for the wilful murder of Benjamin Jones, a drummer

boy in the 48th Regiment of Foot, on August 19, 1780. Matchan's escape

to sea, and the subsequent vision on Salisbury Plain, which wrung

from him his confession, are given with great minuteness, and are as

marvellous as any in the poem."

"Nell Cook," "Grey Dolphin," "The Ghost," and "The Smuggler's Leap"

are Kentish legends, well known, though of course much embellished by

the poet. "The Old Woman clothed in Grey" was taken from the story of

a ghost that haunted an old rectory near Cambridge, whose custom it

was to stroll about the house at mid-night, with a bag of money in

her hand, which she offered to

[Pg xvii]

whomever she met; but no one was brave

enough to take it from her.

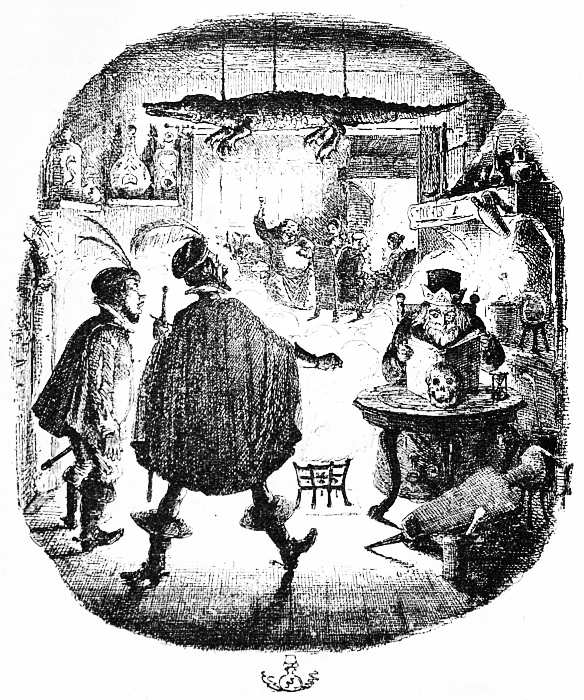

The foundation of most of the legends on subjects of Popish

superstition may be found in the Monkish Chronicles which the

library at Sion College contains. He tells us that the "Jackdaw of

Rheims"—one, by the way, of his most popular legends—was a version of

an old Roman Catholic legend "picked up" out of a High Dutch author.

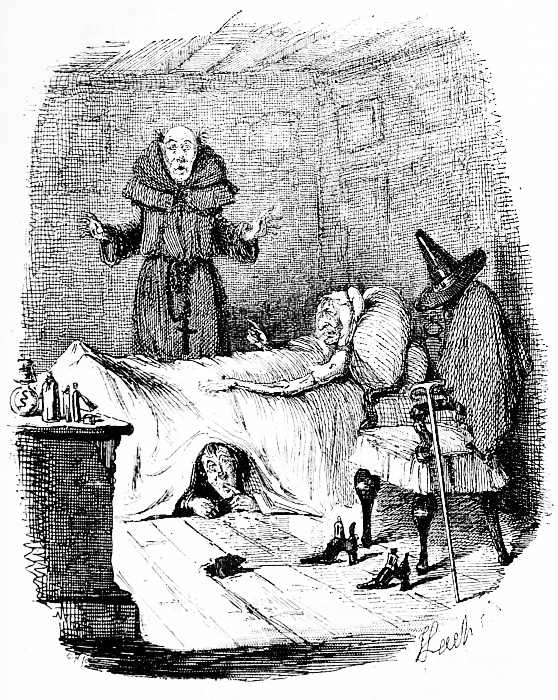

The strange details contained in "The Singular Passage in the Life of

the late Dr. Harris" were communicated to Mr. Barham by a young lady

on her sick-bed, who fully believed all she told him, and even urged

the arrest of the young man, to whose arts she believed herself to be

a victim. She retained the delusion as long as she lived. The story

appeared first in Blackwood.

In 1839, Sidney Smith placed a Residentiary house, in Amen Corner, at

the disposal of Mr. Barham, and the family moved into it in September.

This dwelling dated from the erection of the Cathedral itself, and,

having been long unoccupied, had become the stronghold of legions of

rats, which had first to be destroyed before the family could settle in

it.

In 1840, Mr. Barham succeeded, in course of rotation, to the Presidency

of Sion College, which was held for one year only by the London

incumbents in rotation.

The death of Theodore Hook, his life-long friend, occurred in 1841,

and Mr. Barham was deeply affected by it. "One of the last parties at

which Hook was present" (Mr. Barham's son tells us in his "Memoirs" of

his father) "was at Amen Corner" (Barham's house). He was unusually

late, and dinner was served before he made his appearance; Mr. Barham

apologized for having sat down without him, observing that he had quite

given him up, and supposed that the weather had deterred him.

"Oh," replied the former, "I had determined to come—weather or no."

The friends met only once more after that evening.

Within a year after taking up his abode at Amen Corner, a far heavier

sorrow had fallen on Mr. Barham. His youngest son, a boy of great

promise and precocious talent, died. His second son had died of cholera

in 1832. This last blow fell heavily on the father. His elastic spirits

had rebounded from the previous ones, but this loss was never fully

recovered by him. The death of Hook, coming soon after, depressed him

still more.

[Pg xviii]

In 1842, Mr. Barham was appointed to the Divinity Readership of St.

Paul's, and was permitted to exchange the living he held for the more

valuable one of St. Faith; the duties of which were, also, less onerous

than those of the parish in which he had worked for twenty years.

His parishioners felt the separation from their excellent pastor

deeply, and no doubt their feelings were shared by him who had so long

been their guide and sympathetic friend. Mrs. Barham was also greatly

loved, and had rendered good service in the management of the school,

and visiting the poor; a testimonial was presented to both by their

grateful people, in the shape of a handsome silver salver.

His new living being contiguous to his old one, Mr. Barham did not

change his residence, in which, in fact, he was permitted to live for

the remainder of his life. But he was always delighted when a little

leisure enabled him to go into the country and to the seaside, or to

his native Kent to find legends; but such excursions were few and brief

for the hardly worked clergyman.

Mr. Barham was one of the first members of the Archæological

Association, instituted for the purpose of making trips to places where

antiquarian research could be carried on; he had always possessed a

great taste for, and much knowledge of, antiquarian subjects. He was

also an excellent Shakspearian scholar, and could supply the context

to any quotation made from the plays, and mention the play, act,

and generally the scene from which it came. He was therefore deeply

interested in the formation of the Garrick Club, of which he wrote

the words of a glee song at the opening dinner (the music was by Mr.

Hawes),—

Let poets of superior parts

Consign to deathless fame

The larceny of the Knave of Hearts,

Who spoiled his Royal Dame.

Alack! my timid muse would quail

Before such thievish cubs,

But plumes a joyous wing to hail

Thy birth, fair Queen of Clubs.

On October 28, 1844, Her Majesty the Queen visited the city to open

the Royal Exchange. Mr. Barham, his wife and daughters, had accepted

an invitation from a friend to witness the procession, and, standing

at an open window, he remarked that the cutting east wind then blowing

would cost many of the spectators their lives.

[Pg xix]

The speech seemed in

his own case prophetic. In the course of the evening he was attacked

by a violent fit of coughing, and his old friend and schoolfellow Dr.

Roberts was called in. The poet rallied from this attack, but fresh

ones succeeded it, and at length his articulation became impeded. He

was advised to leave London for Bath, rest being absolutely necessary;

but a meeting of the Archæological Association induced him to hurry

back to town to attend it, and then other business pressed on him, and

another attack followed. His son relates a little incident that shows

Barham had begun to realize the serious nature of his illness. He had

been for many years on the Committee of the Garrick Club, and by the

rules of the society the names of the Committee were placed in a ballot

box and six withdrawn, by chance, on St. George's day, which was the

anniversary of the birth and death of Shakspeare. The first name drawn

out that year was Barham's; but he was unanimously re-elected. When

he was told of the circumstance, he said: It had been well to have

accepted the omen, and filled up his place at once. In fact he never

entered the Club again.

Mrs. Barham had also been ill; therefore he and she went together in

the following May to Clifton, for change of air and rest; but unhappily

they had only been a few hours in their lodgings before Mrs. Barham

was taken dangerously ill, and unable to attend to her husband. Their

eldest daughter soon joined them, and a slight amendment enabled her

to bring them back to their home; but the expedition proved to have

been a fatal one. Here Dr. Roberts, and the great surgeon Coulson, did

all that was possible to save the life of the beloved poet. But they

knew that their skill was vain, and their patient readily divined the

truth that he was dying. He learned the certainty of the approaching

end with perfect calmness and cheerfulness, only disturbed by anxiety

about his wife, who was still extremely ill. He arranged his worldly

affairs; received the Holy Communion with his household; and waited

for the certain result of his malady with patience and resolution. His

last lines, "As I lay a-thinking," referring chiefly to the death of

his youngest son, were written, his son tells us, just before he left

Clifton; he now desired that they might be sent to Mr. Bentley for

publication.

He died on the 17th of June 1845. His life as a clergyman had been most

useful and beneficial to his parishioners; his poems have cheered many

a weary spirit, and been a source of much innocent household mirth.

[Pg xx]

The Ingoldsby Legends are not only remarkable for their humour; they

are equally to be praised for their wonderful versification. That he

was a perfect master of the language who could thus use every variety

of stanza, and find rhymes for the most extraordinary, even technical

words, no one can doubt; there are no harsh lines or imperfect rhymes

in the Legends, and the wit and mirth are charmingly blended at times

with touching pathos. The poet's antiquarian knowledge gives much

effect, also, to his tales, and there is never anything in his most

comic relations that would be unworthy the pen of a gentleman and a

cultured scholar. England has cause to be proud of such a writer as

"Thomas Ingoldsby," otherwise Richard Harris Barham.

[Pg xxi]

TO RICHARD BENTLEY, ESQ.

My dear Sir,

I should have replied sooner to your letter, but that the last

three days in January are, as you are aware, always dedicated, at

the Hall, to an especial battue, and the old house is full of shooting-jackets,

shot-belts, and "double Joes." Even the women wear

percussion caps, and your favourite (?) Rover, who, you may

remember, examined the calves of your legs with such suspicious

curiosity at Christmas, is as pheasant-mad as if he were a biped,

instead of being a genuine four-legged scion of the Blenheim breed.

I have managed, however, to avail myself of a lucid interval in the

general hallucination, (how the rain did come down on Monday!)

and as you tell me the excellent friend whom you are in the habit

of styling "a Generous and Enlightened Public" has emptied your

shelves of the first edition, and "asks for more," why, I agree with

you, it would be a want of respect to that very respectable personification,

when furnishing him with a farther supply, not to endeavour

at least to amend my faults, which are few, and your own, which

are more numerous. I have, therefore, gone to work con amore,

supplying occasionally on my own part a deficient note, or elucidatory

stanza, and on yours knocking out, without remorse, your

superfluous i's, and now and then eviscerating your colon.

My duty to our illustrious friend thus performed, I have a crow

to pluck with him,—Why will he persist—as you tell me he does

persist—in calling me by all sorts of names but those to which I

am entitled by birth and baptism—my "Sponsorial and Patronymic

appellations," as Dr. Pangloss has it?—Mrs. Malaprop complains, and

with justice, of an "assault upon her parts of speech:" but to attack

one's very existence—to deny that one is a person in esse, and

[Pg xxii]

scarcely to admit that one may be a person in posse, is tenfold

cruelty;—"it is pressing to death, whipping, and hanging!"—let me

entreat all such likewise to remember, that as Shakspeare beautifully

expresses himself elsewhere—I give his words as quoted by a very

worthy Baronet in a neighbouring county, when protesting against a

defamatory placard at a general election—

"Who steals my purse steals stuff!—

'Twas mine—'tisn't his—nor nobody else's!

But he who runs away with my Good Name,

Robs me of what does not do him any good,

And makes me deuced poor!!"[1]

In order utterly to squabash and demolish every gainsayer, I had

thought, at one time, of asking my old and esteemed friend, Richard

Lane, to crush them at once with his magic pencil, and to transmit my

features to posterity, where all his works are sure to be "delivered

according to the direction;" but somehow the noble-looking profiles

which he has recently executed of the Kemble family put me a little out

of conceit with my own, while the

[Pg xxiii]

undisguised amusement which my "Mephistopheles Eyebrow," as he termed

it, afforded him, in the "full face," induced me to lay aside the

design. Besides, my dear Sir, since, as has well been observed, "there

never was a married man yet who had not somebody remarkably like him

walking about town," it is a thousand to one but my lineaments might,

after all, out of sheer perverseness be ascribed to anybody rather

than to the real owner. I have therefore sent you, instead thereof, a

very fair sketch of Tappington, taken from the Folkestone road (I tore

it last night out of Julia Simpkinson's album); get Gilks to make a

woodcut of it. And now, if any miscreant (I use the word only in its

primary and "Pickwickian" sense of "Unbeliever,") ventures to throw any

further doubt upon the matter, why, as Jack Cade's friend says in the

play, "There are the chimneys in my father's house, and the bricks are

alive at this day to testify it!"

"Why, very well then—we hope here be truths!"

Heaven be with you, my dear Sir!—I was getting a little excited;

but you, who are mild as the milk that dews the soft whisker of the

new-weaned kitten, will forgive me when, wiping away the nascent

moisture from my brow, I "pull in," and subscribe myself,

Yours quite as much as his own,

THOMAS INGOLDSBY.

Tappington Everard,

Feb. 2nd, 1843

[Pg 1]

THE INGOLDSBY LEGENDS.

FIRST SERIES.

[Pg 4]

THE SPECTRE OF TAPPINGTON.

[Pg 5]

The Ingoldsby Legends.

"It is very odd, though; what can have become of them?" said Charles

Seaforth, as he peeped under the valance of an old-fashioned

bedstead, in an old-fashioned apartment of a still more old-fashioned

manor-house; "'tis confoundedly odd, and I can't make it out at all.

Why, Barney, where are they?—and where the d—l are you?"

No answer was returned to this appeal; and the lieutenant, who was, in

the main, a reasonable person,—at least as reasonable a person as any

young gentleman of twenty-two in "the service" can fairly be expected

to be,—cooled when he reflected that his servant could scarcely reply

extempore to a summons which it was impossible he should hear.

An application to the bell was the considerate result; and the

footsteps of as tight a lad as ever put pipe-clay to belt sounded along

the gallery.

"Come in!" said his master.—An ineffectual attempt upon the door

reminded Mr. Seaforth that he had locked himself in.—"By Heaven! this

is the oddest thing of all," said he, as he turned the key and admitted

Mr. Maguire into his dormitory.

"Barney, where are my pantaloons?"

"Is it the breeches?" asked the valet, casting an inquiring eye round

the apartment;—"is it the breeches, sir?"

"Yes; what have you done with them?"

"Sure then your honour had them on when you went to bed, and it's

hereabout they'll be, I'll be bail;" and Barney lifted a fashionable

tunic from a cane-backed arm-chair, proceeding in his examination.

But the search was vain: there was the tunic aforesaid,—there was a

smart-looking kerseymere waistcoat; but the most important article of

all in a gentleman's wardrobe was still wanting.

[Pg 6]

"Where can they be?" asked the master, with a strong accent on the

auxiliary verb.

"Sorrow a know I knows," said the man.

"It must have been the devil, then, after all, who has been here and

carried them off!" cried Seaforth, staring full into Barney's face.

Mr. Maguire was not devoid of the superstition of his countrymen, still

he looked as if he did not quite subscribe to the sequitur.

His master read incredulity in his countenance. "Why, I tell you,

Barney, I put them there, on that arm-chair, when I got into bed; and,

by Heaven! I distinctly saw the ghost of the old fellow they told me

of, come in at midnight, put on my pantaloons, and walk away with them."

"May be so," was the cautious reply.

"I thought, of course, it was a dream; but then,—where the d—l are

the breeches?"

The question was more easily asked than answered. Barney renewed his

search, while the lieutenant folded his arms, and, leaning against the

toilet, sunk into a reverie.

"After all, it must be some trick of my laughter-loving cousins," said

Seaforth.

"Ah! then, the ladies!" chimed in Mr. Maguire, though the observation

was not addressed to him; "and will it be Miss Caroline, or Miss Fanny,

that's stole your honour's things?"

"I hardly know what to think of it," pursued the bereaved lieutenant,

still speaking in soliloquy, with his eye resting dubiously on the

chamber-door. "I locked myself in, that's certain; and—but there must

be some other entrance to the room—pooh! I remember—the private

staircase; how could I be such a fool?" and he crossed the chamber to

where a low oaken doorcase was dimly visible in a distant corner. He

paused before it. Nothing now interfered to screen it from observation;

but it bore tokens of having been at some earlier period concealed by

tapestry, remains of which yet clothed the walls on either side the

portal.

"This way they must have come," said Seaforth; "I wish with all my

heart I had caught them!"

"Och! the kittens!" sighed Mr. Barney Maguire.

But the mystery was yet as far from being solved as before. True, there

was the "other door;" but then that, too, on examination, was even

more firmly secured than the one which opened on the gallery,—two

heavy bolts on the inside effectually prevented any

[Pg 7]

coup de main on

the lieutenant's bivouac from that quarter. He was more puzzled than

ever; nor did the minutest inspection of the walls and floor throw any

light upon the subject! one thing only was clear,—the breeches were

gone! "It is very singular," said the lieutenant.

Tappington (generally called Tapton) Everard is an antiquated but

commodious manor-house in the eastern division of the county of Kent. A

former proprietor had been High-sheriff in the days of Elizabeth, and

many a dark and dismal tradition was yet extant of the licentiousness

of his life, and the enormity of his offences. The Glen, which the

keeper's daughter was seen to enter, but never known to quit, still

frowns darkly as of yore; while an ineradicable bloodstain on the oaken

stair yet bids defiance to the united energies of soap and sand. But it

is with one particular apartment that a deed of more especial atrocity

is said to be connected. A stranger guest—so runs the legend—arrived

unexpectedly at the mansion of the "Bad Sir Giles." They met in

apparent friendship; but the ill-concealed scowl on their master's brow

told the domestics that the visit was not a welcome one; the banquet,

however, was not spared; the wine-cup circulated freely,—too freely,

perhaps,—for sounds of discord at length reached the ears of even the

excluded serving-men as they were doing their best to imitate their

betters in the lower hall. Alarmed, some of them ventured to approach

the parlour; one, an old and favoured retainer of the house, went so

far as to break in upon his master's privacy. Sir Giles, already high

in oath, fiercely enjoined his absence, and he retired; not, however,

before he had distinctly heard from the stranger's lips a menace that

"There was that within his pocket which could disprove the knight's

right to issue that or any other command within the walls of Tapton."

The intrusion, though momentary, seemed to have produced a beneficial

effect; the voices of the disputants fell, and the conversation was

carried on thenceforth in a more subdued tone, till, as evening closed

in, the domestics, when summoned to attend with lights, found not only

cordiality restored, but that a still deeper carouse was meditated.

Fresh stoups, and from the choicest bins, were produced; nor was it

till at a late, or rather early hour, that the revellers sought their

chambers.

The one allotted to the stranger occupied the first floor of the

eastern angle of the building, and had once been the favourite

[Pg 8]

apartment of Sir Giles himself. Scandal ascribed this preference to the

facility which a private staircase,communicating with the grounds, had

afforded him, in the old knight's time, of following his wicked courses

unchecked by parental observation; a consideration which ceased to be

of weight when the death of his father left him uncontrolled master

of his estate and actions. From that period Sir Giles had established

himself in what were called the "state apartments;" and the "oaken

chamber" was rarely tenanted, save on occasions of extraordinary

festivity, or when the yule log drew an unusually large accession of

guests around the Christmas hearth.

On this eventful night it was prepared for the unknown visitor, who

sought his couch heated and inflamed from his midnight orgies, and

in the morning was found in his bed a swollen and blackened corpse.

No marks of violence appeared upon the body; but the livid hue of

the lips, and certain dark-coloured spots visible on the skin,

aroused suspicions which those who entertained them were too timid to

express. Apoplexy, induced by the excesses of the preceding night, Sir

Giles's confidential leech pronounced to be the cause of his sudden

dissolution; the body was buried in peace; and though some shook their

heads as they witnessed the haste with which the funeral rites were

hurried on, none ventured to murmur. Other events arose to distract the

attention of the retainers; men's minds became occupied by the stirring

politics of the day, while the near approach of that formidable

armada, so vainly arrogating to itself a title which the very elements

joined with human valour to disprove, soon interfered to weaken, if

not obliterate, all remembrance of the nameless stranger who had died

within the walls of Tapton Everard.

Years rolled on: the "Bad Sir Giles" had himself long since gone to his

account, the last, as it was believed, of his immediate line; though

a few of the older tenants were sometimes heard to speak of an elder

brother, who had disappeared in early life, and never inherited the

estate. Rumours, too, of his having left a son in foreign lands were at

one time rife; but they died away, nothing occurring to support them:

the property passed unchallenged to a collateral branch of the family,

and the secret, if secret there were, was buried in Denton churchyard,

in the lonely grave of the mysterious stranger. One circumstance

alone occurred, after a long-intervening period, to revive the memory

of these transactions. Some workmen employed in grubbing an old

plantation, for the purpose of raising on its site a modern shrubbery,

dug up, in the

[Pg 9]

execution of their task, the mildewed remnants of what

seemed to have been once a garment. On more minute inspection, enough

remained of silken slashes and a coarse embroidery to identify the

relics as having once formed part of a pair of trunk hose; while a few

papers which fell from them, altogether illegible from damp and age,

were by the unlearned rustics conveyed to the then owner of the estate.

Whether the squire was more successful in deciphering them was never

known; he certainly never alluded to their contents; and little would

have been thought of the matter but for the inconvenient memory of one

old woman, who declared she heard her grandfather say that when the

"stranger guest" was poisoned, though all the rest of his clothes were

there, his breeches, the supposed repository of the supposed documents,

could never be found. The master of Tapton Everard smiled when he heard

Dame Jones's hint of deeds which might impeach the validity of his own

title in favour of some unknown descendant of some unknown heir; and

the story was rarely alluded to, save by one or two miracle-mongers,

who had heard that others had seen the ghost of old Sir Giles, in his

night-cap, issue from the postern, enter the adjoining copse, and wring

his shadowy hands in agony, as he seemed to search vainly for something

hidden among the evergreens. The stranger's death-room had, of course,

been occasionally haunted from the time of his decease; but the periods

of visitation had latterly become very rare,—even Mrs. Botherby, the

housekeeper, being forced to admit that, during her long sojourn at the

manor, she had never "met with anything worse than herself;" though, as

the old lady afterwards added upon more mature reflection, "I must say

I think I saw the devil once."

Such was the legend attached to Tapton Everard, and such the story

which the lively Caroline Ingoldsby detailed to her equally mercurial

cousin Charles Seaforth, lieutenant in the Hon. East India Company's

second regiment of Bombay Fencibles, as arm-in-arm they promenaded a

gallery decked with some dozen grim-looking ancestral portraits, and,

among others, with that of the redoubted Sir Giles himself. The gallant

commander had that very morning paid his first visit to the house of

his maternal uncle, after an absence of several years passed with his

regiment on the arid plains of Hindostan, whence he was now returned on

a three years' furlough. He had gone out a boy,—he returned a man; but

the impression made upon his youthful fancy by his favourite cousin

[Pg 10]

remained unimpaired, and to Tapton he directed his steps, even before

he sought the home of his widowed mother,—comforting himself in this

breach of filial decorum by the reflection that, as the manor was so

little out of his way, it would be unkind to pass, as it were, the door

of his relatives without just looking in for a few hours.

But he found his uncle as hospitable and his cousin more charming

than ever; and the looks of one, and the requests of the other, soon

precluded the possibility of refusing to lengthen the "few hours" into

a few days, though the house was at the moment full of visitors.

The Peterses were there from Ramsgate; and Mr, Mrs., and the two Miss

Simpkinsons, from Bath, had come to pass a month with the family;

and Tom Ingoldsby had brought down his college friend the Honourable

Augustus Sucklethumbkin, with his groom and pointers, to take a

fortnight's shooting. And then there was Mrs. Ogleton, the rich young

widow, with her large black eyes, who, people did say, was setting

her cap at the young squire, though Mrs. Botherby did not believe

it; and, above all, there was Mademoiselle Pauline, her femme de

chambre, who "mon-Dieu'd" everything and everybody, and cried "Quel

horreur!" at Mrs. Botherby's cap. In short, to use the last-named and

much-respected lady's own expression, the house was "choke-full" to the

very attics,—all, save the "oaken chamber," which, as the lieutenant

expressed a most magnanimous disregard of ghosts, was forthwith

appropriated to his particular accommodation. Mr. Maguire meanwhile

was fain to share the apartment of Oliver Dobbs, the squire's own man:

a jocular proposal of joint occupancy having been first indignantly

rejected by "Mademoiselle," though preferred with the "laste taste in

life" of Mr. Barney's most insinuating brogue.

"Come, Charles, the urn is absolutely getting cold; your breakfast will

be quite spoiled: what can have made you so idle?" Such was the morning

salutation of Miss Ingoldsby to the militaire as he entered the

breakfast-room half an hour after the latest of the party.

"A pretty gentleman, truly, to make an appointment with," chimed

in Miss Frances. "What is become of our ramble to the rocks before

breakfast?"

"Oh! the young men never think of keeping a promise now," said Mrs.

Peters, a little ferret-faced woman with underdone eyes.

[Pg 11]

"When I was a young man," said Mr. Peters, "I remember I always made a

point of—"

"Pray how long ago was that? asked Mr. Simpkinson from Bath.

"Why, sir, when I married Mrs. Peters, I was—let me see—I was—"

"Do pray hold your tongue, P., and eat your breakfast!" interrupted his

better half, who had a mortal horror of chronological references; "it's

very rude to tease people with your family affairs."

The lieutenant had by this time taken his seat in silence,—a

good-humoured nod, and a glance, half-smiling, half-inquisitive, being

the extent of his salutation. Smitten as he was, and in the immediate

presence of her who had made so large a hole in his heart, his manner

was evidently distrait, which the fair Caroline in her secret soul

attributed to his being solely occupied by her agrémens,—how would

she have bridled had she known that they only shared his meditations

with a pair of breeches!

Charles drank his coffee and spiked some half-dozen eggs, darting

occasionally a penetrating glance at the ladies, in hope of detecting

the supposed waggery by the evidence of some furtive smile or conscious

look. But in vain; not a dimple moved indicative of roguery, nor did

the slightest elevation of eyebrow rise confirmative of his suspicions.

Hints and insinuations passed unheeded,—more particular inquiries were

out of the question:—the subject was unapproachable.

In the meantime, "patent cords" were just the thing for a morning's

ride; and, breakfast ended, away cantered the party over the downs,

till, every faculty absorbed by the beauties, animate and inanimate,

which surrounded him, Lieutenant Seaforth of the Bombay Fencibles

bestowed no more thought upon his breeches than if he had been born on

the top of Ben Lomond.

Another night had passed away; the sun rose brilliantly, forming with

his level beams a splendid rainbow in the far-off west, whither the

heavy cloud, which for the last two hours had been pouring its waters

on the earth, was now flying before him.

"Ah! then, and it's little good it'll be the claning of ye,"

apostrophised Mr. Barney Maguire, as he deposited, in front of his

master's toilet, a pair of "bran-new" jockey boots, one of Hoby's

primest fits, which the lieutenant had purchased in his way through

[Pg 12]

town. On that very morning had they come for the first time under the

valet's depuriating hand, so little soiled, indeed, from the turfy ride

of the preceding day, that a less scrupulous domestic might, perhaps,

have considered the application of "Warren's Matchless," or oxalic

acid, altogether superfluous. Not so Barney: with the nicest care had

he removed the slightest impurity from each polished surface, and there

they stood, rejoicing in their sable radiance. No wonder a pang shot

across Mr. Maguire's breast, as he thought on the work now cut out for

them, so different from the light labours of the day before; no wonder

he murmured with a sigh, as the scarce-dried window-panes disclosed

a road now inch-deep in mud, "Ah! then, it's little good the claning

of ye!"—for well had he learned in the hall below that eight miles

of a stiff clay soil lay between the manor and Bolsover Abbey, whose

picturesque ruins,

"Like ancient Rome, majestic in decay,"

the party had determined to explore. The master had already commenced

dressing, and the man was fitting straps upon a light pair of

crane-necked spurs, when his hand was arrested by the old question,

"Barney, where are the breeches?"

They were nowhere to be found!

Mr. Seaforth descended that morning, whip in hand, and equipped in

a handsome green riding-frock, but no "breeches and boots to match"

were there: loose jean trowsers, surmounting a pair of diminutive

Wellingtons, embraced, somewhat incongruously, his nether man, vice

the "patent cords," returned, like yesterday's pantaloons, absent

without leave. The "top-boots" had a holiday.

"A fine morning after the rain," said Mr. Simpkinson from Bath.

"Just the thing for the 'ops," said Mr. Peters. "I remember when I was

a boy—"

"Do hold your tongue, P.," said Mrs. Peters,—advice which that

exemplary matron was in the constant habit of administering to "her

P.," as she called him, whenever he prepared to vent his reminiscences.

Her precise reason for this it would be difficult to determine, unless,

indeed, the story be true which a little bird had whispered into Mrs.

Botherby's ear,—Mr. Peters, though now a wealthy man, had received a

liberal education at a charity-school, and was apt to recur to the days

of his muffin-cap and leathers. As

[Pg 13]

usual, he took his wife's hint in good part, and "paused in his reply."

"A glorious day for the ruins!" said young Ingoldsby. "But, Charles,

what the deuce are you about?—you don't mean to ride through our lanes

in such toggery as that?"

"Lassy me!" said Miss Julia Simpkinson, "won't you be very wet?"

"You had better take Tom's cab," quoth the squire.

But this proposition was at once overruled; Mrs. Ogleton had already

nailed the cab, a vehicle of all others the best adapted for a snug

flirtation.

"Or drive Miss Julia in the phaeton?" No; that was the post of Mr.

Peters, who, indifferent as an equestrian, had acquired some fame as

a whip while travelling through the midland counties for the firm of

Bagshaw, Snivelby, and Ghrimes.

"Thank you, I shall ride with my cousins," said Charles, with as much

nonchalance as he could assume,—and he did so; Mr. Ingoldsby, Mrs.

Peters, Mr. Simpkinson from Bath, and his eldest daughter with her

album, following in the family coach. The gentleman-commoner "voted

the affair d—d slow," and declined the party altogether in favour

of the gamekeeper and a cigar. "There was 'no fun' in looking at old

houses!" Mrs. Simpkinson preferred a short séjour in the still-room

with Mrs. Botherby, who had promised to initiate her in that grand

arcanum, the transmutation of gooseberry jam into Guava jelly.

"Did you ever see an old abbey before, Mr. Peters?"

"Yes, miss, a French one; we have got one at Ramsgate; he teaches the

Miss Joneses to parley-voo, and is turned of sixty."

Miss Simpkinson closed her album with an air of ineffable disdain.

Mr. Simpkinson from Bath was a professed antiquary, and one of the

first water; he was master of Gwillim's Heraldry, and Milles's History

of the Crusades; knew every plate in the Monasticon; had written an

essay on the origin and dignity of the office of overseer, and settled

the date of a Queen Anne's farthing. An influential member of the

Antiquarian Society, to whose "Beauties of Bagnigge Wells" he had

been a liberal subscriber, procured him a seat at the board of that

learned body, since which happy epoch Sylvanus Urban had not a more

indefatigable correspondent. His inaugural essay on the President's

cocked hat was considered a miracle of erudition: and his account of

the earliest application of gilding to

[Pg 14]

gingerbread, a masterpiece of

antiquarian research. His eldest daughter was of a kindred spirit: if

her father's mantle had not fallen upon her, it was only because he had

not thrown it off himself; she had caught hold of its tail, however,

while it yet hung upon his honoured shoulders. To souls so congenial,

what a sight was the magnificent ruin of Bolsover! its broken arches,

its mouldering pinnacles, and the airy tracery of its half-demolished

windows. The party were in raptures; Mr. Simpkinson began to meditate

an essay, and his daughter an ode: even Seaforth, as he gazed on

these lonely relics of the olden time, was betrayed into a momentary

forgetfulness of his love and losses; the widow's eye-glass turned from

her cicisbeo's whiskers to the mantling ivy: Mrs. Peters wiped her

spectacles; and "her P." supposed the central tower "had once been the

county jail." The squire was a philosopher, and had been there often

before, so he ordered out the cold tongue and chickens.

"Bolsover Priory," said Mr. Simpkinson, with the air of a

connoisseur,—"Bolsover Priory was founded in the reign of Henry the

Sixth, about the beginning of the eleventh century. Hugh de Bolsover

had accompanied that monarch to the Holy Land, in the expedition

undertaken by way of penance for the murder of his young nephews in

the Tower. Upon the dissolution of the monasteries, the veteran was

enfeoffed in the lands and manor, to which he gave his own name of

Bowlsover, or Bee-owls-over (by corruption Bolsover),—a Bee in chief,

over three Owls, all proper, being the armorial ensigns borne by this

distinguished crusader at the siege of Acre."

"Ah! that was Sir Sidney Smith," said Mr. Peters; "I've heard tell of

him, and all about Mrs. Partington, and—"

"P., be quiet, and don't expose yourself!" sharply interrupted his

lady. P. was silenced, and betook himself to the bottled stout.

"These lands," continued the antiquary, "were held in grand serjeantry

by the presentation of three white owls and a pot of honey—"

"Lassy me! how nice!" said Miss Julia. Mr. Peters licked his lips.

"Pray give me leave, my dear—owls and honey, whenever the king should

come a rat-catching into this part of the country."

"Rat-catching!" ejaculated the squire, pausing abruptly in the

mastication of a drumstick.

"To be sure, my dear sir: don't you remember that rats once came under

the forest laws—a minor species of venison? 'Rats and

[Pg 15]

mice, and such

small deer,' eh?—Shakspear, you know. Our ancestors ate rats ("The

nasty fellows!" shuddered Miss Julia in a parenthesis); and owls, you

know, are capital mousers—"

"I've seen a howl," said Mr. Peters; "there's one in the Sohological

Gardens,—a little hook-nosed chap in a wig,—only its feathers and—"

Poor P. was destined never to finish a speech.

"Do be quiet!" cried the authoritative voice, and the would-be

naturalist shrank into his shell, like a snail in the "Sohological

Gardens."

"You should read Blount's 'Jocular Tenures,' Mr. Ingoldsby," pursued

Simpkinson. "A learned man was Blount! Why, sir, his Royal Highness the

Duke of York once paid a silver horse-shoe to Lord Ferrers—"

"I've heard of him," broke in the incorrigible Peters; "he was hanged

at the Old Bailey in a silk rope for shooting Dr. Johnson."

The antiquary vouchsafed no notice of the interruption; but,

taking a pinch of snuff, continued his harangue.

"A silver horse-shoe, sir, which is due from every scion of royalty

who rides across one of his manors; and if you look into the penny

county histories, now publishing by an eminent friend of mine, you

will find that Langhale in Co. Norf. was held by one Baldwin per

saltum, sufflatum, et pettum; that is, he was to come every Christmas

into Westminster Hall, there to take a leap, cry hem! and—"

"Mr. Simpkinson, a glass of sherry?" cried Tom Ingoldsby, hastily.

"Not any, thank you, sir. This Baldwin, surnamed Le—"

"Mrs. Ogleton challenges you, sir; she insists upon it," said Tom,

still more rapidly; at the same time filling a glass, and forcing it on

the sçavant, who, thus arrested in the very crisis of his narrative,

received and swallowed the potation as if it had been physic.

"What on earth has Miss Simpkinson discovered there?" continued Tom;

"something of interest. See how fast she is writing."

The diversion was effectual: every one looked towards Miss Simpkinson,

who, far too ethereal for "creature comforts," was seated apart on

the dilapidated remains of an altar-tomb, committing eagerly to paper

something that had strongly impressed her: the air,—the eye "in a fine

frenzy rolling,"—all betokened that the divine afflatus was come.

Her father rose, and stole silently towards her.

"What an old boar!" muttered young Ingoldsby; alluding,

[Pg 16]

perhaps, to a

slice of brawn which he had just begun to operate upon, but which, from

the celerity with which it disappeared, did not seem so very difficult

of mastication.

But what had become of Seaforth and his fair Caroline all this while?

Why, it so happened that they had been simultaneously stricken with

the picturesque appearance of one of those high and pointed arches,

which that eminent antiquary, Mr. Horseley Curties, has described in

his "Ancient Records" as "a Gothic window of the Saxon order;"—and

then the ivy clustered so thickly and so beautifully on the other

side, that they went round to look at that;—and then their proximity

deprived it of half its effect, and so they walked across to a little

knoll, a hundred yards off, and in crossing a small ravine, they came

to what in Ireland they call "a bad step," and Charles had to carry his

cousin over it;—and then, when they had to come back, she would not

give him the trouble again for the world, so they followed a better but

more circuitous route, and there were hedges and ditches in the way,

and stiles to get over, and gates to get through; so that an hour or

more had elapsed before they were able to rejoin the party.

"Lassy me!" said Miss Julia Simpkinson, "how long you have been gone!"

And so they had. The remark was a very just as well as a very natural

one. They were gone a long while, and a nice cosey chat they had; and

what do you think it was all about, my dear miss?

"O, lassy me! love, no doubt, and the moon, and eyes, and nightingales,

and—"

Stay, stay, my sweet young lady; do not let the fervour of your

feelings run away with you! I do not pretend to say, indeed, that one

or more of these pretty subjects might not have been introduced; but

the most important and leading topic of the conference was—Lieutenant

Seaforth's breeches.

"Caroline," said Charles, "I have had some very odd dreams since I have

been at Tappington."

"Dreams, have you?" smiled the young lady, arching her taper neck like

a swan in pluming. "Dreams, have you?"

"Ay, dreams,—or dream, perhaps, I should say; for, though repeated, it

was still the same. And what do you imagine was its subject?"

"It is impossible for me to divine," said the tongue;—"I have

not the least difficulty in guessing," said the eye, as plainly as ever

eye spoke.

[Pg 17]

"I dreamt—of your great grandfather!"

There was a change in the glance—"My great grandfather?"

"Yes, the old Sir Giles, or Sir John, you told me about the other day:

he walked into my bedroom in his short cloak of murrey-coloured velvet,

his long rapier, and his Raleigh-looking hat and feather, just as the

picture represents him: but with one exception."

"And what was that?"

"Why, his lower extremities, which were visible, were—those of a

skeleton."

"Well."

"Well, after taking a turn or two about the room, and looking round him

with a wistful air, he came to the bed's foot, stared at me in a manner

impossible to describe,—and then he—he laid hold of my pantaloons;

whipped his long bony legs into them in a twinkling; and strutting up

to the glass, seemed to view himself in it with great complacency. I

tried to speak, but in vain. The effort, however, seemed to excite

his attention; for, wheeling about, he showed me the grimmest-looking

death's head you can well imagine, and with an indescribable grin

strutted out of the room."

"Absurd! Charles. How can you talk such nonsense?"

"But, Caroline,—the breeches are really gone."

On the following morning, contrary to his usual custom, Seaforth was

the first person in the breakfast parlour. As no one else was present,

he did precisely what nine young men out of ten so situated would have

done; he walked up to the mantel-piece, established himself upon the

rug, and subducting his coat-tails one under each arm, turned towards

the fire that portion of the human frame which it is considered equally

indecorous to present to a friend or an enemy. A serious, not to say

anxious, expression was visible upon his good-humoured countenance, and

his mouth was fast buttoning itself up for an incipient whistle, when

little Flo, a tiny spaniel of the Blenheim breed,—the pet object of

Miss Julia Simpkinson's affections,—bounced out from beneath a sofa,

and began to bark at—his pantaloons.

They were cleverly "built," of a light grey mixture, a broad stripe

of the most vivid scarlet traversing each seam in a perpendicular

direction from hip to ankle,—in short, the regimental costume of the

Royal Bombay Fencibles. The animal, educated in the country, had never

seen such a pair of breeches in her life—Omne ignotum pro magnifico!

The scarlet streak, inflamed as it was by the

[Pg 18]

reflection of the fire,

seemed to act on Flora's nerves as the same colour does on those

of bulls and turkeys; she advanced at the pas de charge, and her

vociferation, like her amazement, was unbounded. A sound kick from the

disgusted officer changed its character, and induced a retreat at the

very moment when the mistress of the pugnacious quadruped entered to

the rescue.

"Lassy me! Flo! what is the matter?" cried the sympathising lady,

with a scrutinising glance levelled at the gentleman.

It might as well have lighted on a feather bed.—His air of

imperturbable unconsciousness defied examination; and as he would not,

and Flora could not expound, that injured individual was compelled to

pocket up her wrongs. Others of the household soon dropped in, and

clustered round the board dedicated to the most sociable of meals;

the urn was paraded "hissing hot," and the cups which "cheer, but not

inebriate," steamed redolent of hyson and pekoe; muffins and marmalade,

newspapers and Finnon haddies, left little room for observation on

the character of Charles's warlike "turn-out." At length a look from

Caroline, followed by a smile that nearly ripened to a titter, caused

him to turn abruptly and address his neighbour. It was Miss Simpkinson,

who, deeply engaged in sipping her tea and turning over her album,

seemed, like a female Chrononotonthologos, "immersed in cogibundity of

cogitation." An interrogatory on the subject of her studies drew from

her the confession that she was at that moment employed in putting

the finishing touches to a poem inspired by the romantic shades of

Bolsover. The entreaties of the company were of course urgent. Mr.

Peters, "who liked verses," was especially persevering, and Sappho at

length compliant. After a preparatory hem! and a glance at the mirror

to ascertain that her look was sufficiently sentimental, the poetess

began:—

"There is a calm, a holy feeling,

Vulgar minds can never know,

O'er the bosom softly stealing,—

Chasten'd grief, delicious woe!

Oh! how sweet at eve regaining

Yon lone tower's sequester'd shade—

Sadly mute and uncomplaining—"

—Yow!—yeough!—yeough!—yow!—yow! yelled a hapless sufferer from

beneath the table.—It was an unlucky hour for quadrupeds; and if

"every dog will have his day," he could not have selected a more

unpropitious one than this. Mrs. Ogleton, too,

[Pg 19]

had a pet,—a favourite

pug,—whose squab figure, black muzzle, and tortuosity of tail, that

curled like a head of celery in a salad-bowl, bespoke his Dutch

extraction. Yow! yow! yow! continued the brute,—a chorus in which Flo

instantly joined. Sooth to say, pug had more reason to express his

dissatisfaction than was given him by the muse of Simpkinson; the other

only barked for company. Scarcely had the poetess got through her first

stanza, when Tom Ingoldsby, in the enthusiasm of the moment, became so

lost in the material world, that, in his abstraction, he unwarily laid

his hand on the cock of the urn. Quivering with emotion, he gave it

such an unlucky twist, that the full stream of its scalding contents

descended on the gingerbread hide of the unlucky Cupid.—The confusion

was complete;—the whole economy of the table disarranged;—the company

broke up in most admired disorder;—and "Vulgar minds will never know"

anything more of Miss Simpkinson's ode till they peruse it in some

forthcoming Annual.

Seaforth profited by the confusion to take the delinquent who had

caused this "stramash" by the arm, and to lead him to the lawn, where

he had a word or two for his private ear. The conference between the

young gentlemen was neither brief in its duration nor unimportant in

its result. The subject was what the lawyers call tripartite, embracing

the information that Charles Seaforth was over head and ears in love

with Tom Ingoldsby's sister; secondly, that the lady had referred

him to "papa" for his sanction; thirdly and lastly, his nightly

visitations, and consequent bereavement. At the two first items Tom

smiled auspiciously; at the last he burst out into an absolute "guffaw."

"Steal your breeches!—Miss Bailey over again, by Jove," shouted

Ingoldsby. "But a gentleman, you say,—and Sir Giles too.—I am not

sure, Charles, whether I ought not to call you out for aspersing the

honour of the family."

"Laugh as you will, Tom,—be as incredulous as you please. One fact is

incontestible,—the breeches are gone! Look here—I am reduced to my

regimentals; and if these go, to-morrow I must borrow of you!"

Rochefoucault says, there is something in the misfortunes of our very

best friends that does not displease us;—assuredly we can, most of

us, laugh at their petty inconveniences, till called upon to supply

them. Tom composed his features on the instant, and replied with more

gravity, as well as with an expletive, which, if my Lord Mayor had been

within hearing, might have cost him five shillings.

[Pg 20]

"There is something very queer in this, after all. The clothes, you

say, have positively disappeared. Somebody is playing you a trick;

and, ten to one, your servant has a hand in it. By the way, I heard

something yesterday of his kicking up a bobbery in the kitchen, and

seeing a ghost, or something of that kind, himself. Depend upon it,

Barney is in the plot."

It now struck the lieutenant at once, that the usually buoyant spirits

of his attendant had of late been materially sobered down, his

loquacity obviously circumscribed, and that he, the said lieutenant,

had actually rung his bell three several times that very morning before

he could procure his attendance. Mr. Maguire was forthwith summoned,

and underwent a close examination. The "bobbery" was easily explained.

Mr. Oliver Dobbs had hinted his disapprobation of a flirtation carrying

on between the gentleman from Munster and the lady from the Rue St.

Honoré. Mademoiselle had boxed Mr. Maguire's ears, and Mr. Maguire had

pulled Mademoiselle upon his knee, and the lady had not cried Mon

Dieu! And Mr. Oliver Dobbs said it was very wrong; and Mrs. Botherby

said it was "scandalous," and what ought not to be done in any moral

kitchen; and Mr. Maguire had got hold of the Honourable Augustus

Suckle-thumbkin's powder-flask, and had put large pinches of the best

double Dartford into Mr. Dobbs's tobacco-box;—and Mr. Dobbs's pipe had

exploded, and set fire to Mrs. Botherby's Sunday cap;—and Mr. Maguire

had put it out with the slop-basin, "barring the wig;"—and then they

were all so "cantankerous," that Barney had gone to take a walk in the

garden; and then—then Mr. Barney had seen a ghost!!

"A what? you blockhead!" asked Tom Ingoldsby.

"Sure then, and it's meself will tell your honour the rights of it,"

said the ghost-seer. "Meself and Miss Pauline, sir,—or Miss Pauline

and meself, for the ladies comes first anyhow,—we got tired of the

hobstroppylous skrimmaging among the ould servants, that didn't know a

joke when they seen one: and we went out to look at the comet,—that's

the rory-bory-alehouse, they calls him in this country,—and we walked

upon the lawn,—and divil of any alehouse there was there at all;

and Miss Pauline said it was because of the shrubbery maybe, and why

wouldn't we see it better beyonst the trees?—and so we went to the

trees, but sorrow a comet did meself see there, barring a big ghost

instead of it."

"A ghost? And what sort of a ghost, Barney?"

"Och, then, divil a lie I'll tell your honour. A tall ould gentleman

[Pg 21]

he was, all in white, with a shovel on the shoulder of him, and a

big torch in his fist,—though what he wanted with that it's meself

can't tell, for his eyes were like gig-lamps, let alone the moon

and the comet, which wasn't there at all;—and 'Barney,' says he to

me,—'cause why he knew me,—'Barney,' says he, 'what is it you're

doing with the colleen there, Barney?'—Divil a word did I say.

Miss Pauline screeched, and cried murther in French, and ran off with

herself; and of course meself was in a mighty hurry after the lady,

and had no time to stop palavering with him any way; so I dispersed at

once, and the ghost vanished in a flame of fire!"

Mr. Maguire's account was received with avowed incredulity by both

gentlemen; but Barney stuck to his text with unflinching pertinacity.

A reference to Mademoiselle was suggested, but abandoned, as neither

party had a taste for delicate investigations.

"I'll tell you what, Seaforth," said Ingoldsby, after Barney had

received his dismissal, "that there is a trick here, is evident; and

Barney's vision may possibly be a part of it. Whether he is most knave

or fool, you best know. At all events, I will sit up with you to-night,

and see if I can convert my ancestor into a visiting acquaintance.

Meanwhile your finger on your lip!"

"'Twas now the very witching time of night,

When churchyards yawn, and graves give up their dead."

Gladly would I grace my tale with decent horror, and therefore I do

beseech the "gentle reader" to believe, that if all the succedanea to

this mysterious narrative are not in strict keeping, he will ascribe

it only to the disgraceful innovations of modern degeneracy upon the

sober and dignified habits of our ancestors. I can introduce him, it is

true, into an old and high-roofed chamber, its walls covered on three

sides with black oak wainscotting, adorned with carvings of fruit and

flowers long anterior to those of Grinling Gibbons; the fourth side is

clothed with a curious remnant of dingy tapestry, once elucidatory of

some Scriptural history, but of which not even Mrs. Botherby could

determine. Mr. Simpkinson, who had examined it carefully, inclined

to believe the principal figure to be either Bathsheba, or Daniel in

the lions' den; while Tom Ingoldsby decided in favour of the King of

Bashan. All, however, was conjecture, tradition being silent on the

subject.—A lofty arched portal led into, and a little arched portal

led out of, this apartment; they were opposite each other, and each

possessed the security of massy

[Pg 22]

bolts on its interior. The bedstead,

too, was not one of yesterday, but manifestly coeval with days ere

Seddons was, and when a good four-post "article" was deemed worthy

of being a royal bequest. The bed itself, with all the appurtenances

of palliasse, mattresses, etc., was of far later date, and looked

most incongruously comfortable; the casements, too, with their little

diamond-shaped panes and iron binding, had given way to the modern

heterodoxy of the sash-window. Nor was this all that conspired to ruin

the costume, and render the room a meet haunt for such "mixed spirits"

only as could condescend to don at the same time an Elizabethan doublet

and Bond Street inexpressibles.

With their green morocco slippers on a modern fender, in front of

a disgracefully modern grate, sat two young gentlemen, clad in

"shawl-pattern" dressing gowns and black silk stocks, much at variance

with the high cane-backed chairs which supported them. A bunch of

abomination, called a cigar, reeked in the left-hand corner of the

mouth of one, and in the right-hand corner of the mouth of the

other;—an arrangement happily adapted for the escape of the noxious

fumes up the chimney, without that unmerciful "funking" each other,

which a less scientific disposition of the weed would have induced.

A small pembroke table filled up the intervening space between them,