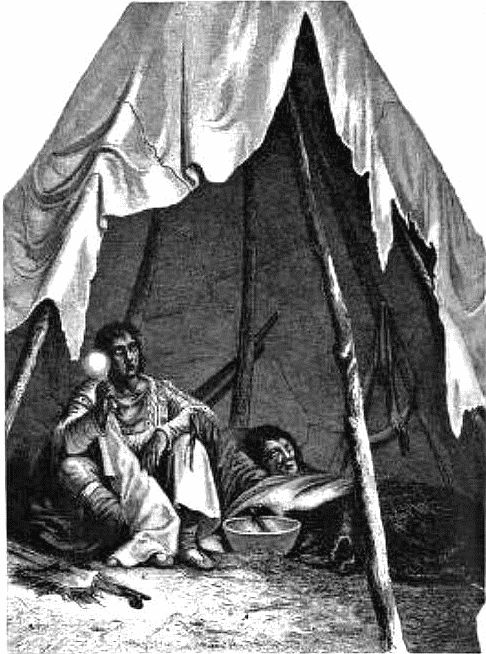

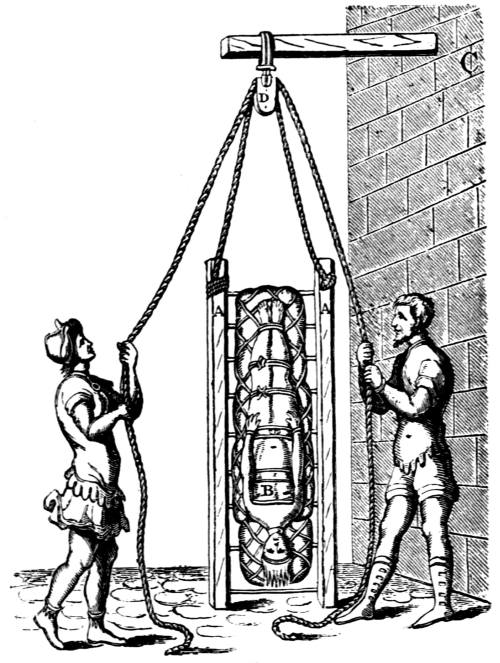

EXPELLING THE DISEASE-DEMON.

[Frontispiece.

Title: The Origin and Growth of the Healing Art

Author: Edward Berdoe

Release date: April 22, 2019 [eBook #59331]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Turgut Dincer, Les Galloway, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/origingrowthofhe00berduoft |

THE HEALING ART.

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

THE BROWNING CYCLOPÆDIA.

A Guide to the Study of the Works of Robert Browning, with copious Explanatory Notes and References on all difficult passages. Second Edition. Pp. xx., 572. Price 10s. 6d.

Some Opinions of the Press.

BROWNING’S MESSAGE TO HIS TIME:

His Religion, Philosophy, and Science. With Portrait and Facsimile Letters. Third Edition. Price 3s. 6d.

[Dilettante Library.]

Opinions of the Press.

“Full of admiration and sympathy.”—Saturday Review.

“Should have a wide circulation; it is interesting and stimulative.”—Literary World.

“We have no hesitation in strongly recommending this little volume to any who desire to understand the moral and mental attitude of Robert Browning.... We are much obliged to Dr. Berdoe for his volume.”—Oxford University Herald.

EXPELLING THE DISEASE-DEMON.

[Frontispiece.

v

A POPULAR HISTORY OF MEDICINE

IN ALL AGES AND COUNTRIES.

BY

EDWARD BERDOE,

Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh; Member of the Royal College of

Surgeons, England; Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, London, etc., etc.

Author of “The Browning Cyclopædia,” etc., etc.

London

SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO.

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

1893

vi

Butler & Tanner,

The Selwood Printing Works,

Frome, and London.

vii

The History of Medicine is a terra incognita to the general reader, and an all but untravelled region to the great majority of medical men. On special occasions, such as First of October Addresses at the opening of the Medical Schools, or the Orations delivered before the various Medical Societies, certain periods of medical history are referred to, and a few of the great names of the founders of medical and surgical science are held up to the admiration of the audience. From time to time excellent monographs on the subject appear in the Lancet and British Medical Journal. But with the exception of these brilliant electric flashes, the History of Medicine is a dark continent to English students who have not made long and tedious researches in our great libraries. For it is a remarkable fact that the History of Medicine has been almost completely neglected by English writers. This cannot be due either to the want of importance or interest of the subject. Next to the history of religion ranks in interest and value that of medicine, and it would not be difficult to show that religion itself cannot be understood in its development and connections without reference to medicine. The priest and the physician are own brothers, and the Healing Art has always played an important part in the development of all the great civilisations. The modern science of Anthropology has placed at the disposal of the historian of medicine a great number of facts which throw light on the medical theories of primitive and savage man. But most of these have hitherto remained uncollected, and are not easily accessible to the general reader.

Although English writers have so strangely neglected this important field of research, the Germans have explored it in the most exhaustive manner. The great works of Sprengel, Haeser, Baas, and Puschmann, amongst many others of the same class, sustain the claim that Germany has created the History of Medicine, whilst the well-known but incompleteviii treatise of Le Clerc shows what a great French writer could do to make this terra incognita interesting.

Not that Englishmen have entirely neglected this branch of literature. Dr. Freind, beginning with Galen’s period, wrote a History of Physic to the Commencement of the Sixteenth Century. Dr. Edward Meryon commenced a History of Medicine, of which Vol. I. only appeared (1861). In special departments Drs. Adams, Greenhill, Aikin, Munk, Wise, Royle, and others have made important contributions to the literature of the subject; but we have nothing to compare with the great German works whose authors we have mentioned above. The encyclopædic work of Dr. Baas has been translated into English by Dr. Handerson of Cleveland, Ohio.

Sprengel’s work is translated into French, and Dr. Puschmann’s admirable volume on Medical Education has been given in English by Mr. Evan Hare.

None of these important and interesting works, valuable as they are to the professional man, are quite suitable for the general reader, who, it seems to the present writer, is entitled in these latter days to be admitted within the inner courts of the temple of Medical History, and to be permitted to trace the progress of the mystery of the Healing Art from its origin with the medicine-man to its present abode in our Medical Schools.

With the exception of an occasional note or brief reference in his text-books of medicine and surgery, the student of medicine has little inducement to direct his attention to the work of the great pioneers of the science he is acquiring.

One consequence of this defect in his education is manifested in the common habit of considering that all the best work of discoverers in the Healing Art has been done in our own times. “History of medicine!” exclaimed a hospital surgeon a few months since. “Why, there was none till forty years ago!” This habit of treating contemptuously the scientific and philosophical work of the past is due to imperfect acquaintance with, or absolute ignorance of, the splendid labours of the men of old time, and can only be remedied by devoting some little study to the records of travellers who have preceded us on the same path we are too apt to think we have constructed for ourselves. Professor Billroth declared, “that the great medical faculties should make it a point of honour to take care that lectures on the history of medicine are not missing in their curricula.” And at several Germanix universities some steps in this direction have been taken. In England, however—so far as I am aware—nothing of the sort has been attempted, and a young man may attain the highest honours of his profession without the ghost of an idea about the long and painful process through which it has become possible for him to acquire his knowledge.

Says Dr. Nathan Davis,1 “A more thorough study of the history of medicine, and in consequence, a greater familiarity with the successive steps or stages in the development of its several branches, would enable us to see more clearly the real relations and value of any new fact, induction, or remedial agent that might be proposed. It would also enable us to avoid a common error of regarding facts, propositions, and remedies presented under new names, as really new, when they had been well known and used long before, but in connection with other names or theories.” He adds that, “The only remedy for these popular and unjust errors is a frequent recurrence to the standard authors of the past generation, or in other words, an honest and thorough study of the history of medicine as a necessary branch of medical education.”

In these times, when no department of science is hidden from the uninitiated, especially when medical subjects and the works of medical men are freely discussed in our great reviews and daily journals, no apology seems necessary for withdrawing the professional veil and admitting the laity behind the scenes of professional work.

Medicine now has no mysteries to conceal from the true student of nature and the scientific inquirer. Her methods and her principles are open to all who care to know them; the only passport she requires is reverence, her only desire to satisfy the yearning to know. In this spirit and for these ends this work has been conceived and given to the world. “The proper study of mankind is man.”

EDWARD BERDOE.

Tynemouth House,

Victoria Park Gate,

London, April 22nd, 1893.

x

Sprengel gives the following Table of the Great Periods in the History of Medicine:—

| I. | Expedition of the Argonauts. | 1273-1263 B.C. | I. | First traces of Greek Medicine. |

| II. | Peloponnesian War. | 432-404 B.C. | II. | Medicine of Hippocrates. |

| III. | Establishment of the | 30 A.D. | III. | School of the Methodists. Christian Religion. |

| IV. | Emigration of the hordes of Barbarians. | 430-530 | IV. | Decadence of the Science. |

| V. | The Crusades. | 1096-1230 | V. | Arabian medicine at its highest point of splendour. |

| VI. | Reformation. | 1517-1530 | VI. | Re-establishment of Greek medicine and anatomy. |

| VII. | Thirty Years War. | 1618-1648 | VII. | Discovery of the circulation of the blood and reform of Van Helmont. |

| VIII. | Reign of Frederick the Great. | 1640-1786 | VIII. | Haller. |

Renouard2 arranges the periods of the growth of the art of medicine as follows:—1st. The Primitive or Instinctive Period, lasting from the earliest recorded treatment to the fall of Troy. 2nd. The Sacred or Mystic Period, lasting till the dispersion of the Pythagorean Society, 500 B.C. 3rd. The Philosophical Period, closing with the foundation of the Alexandrian Library, B.C. 320. 4th. The Anatomical Period, which continued till the death of Galen, A.D. 200.

| Expelling the Disease-Demon | Frontispiece | |

| The Medicine-Dance of the North American Indians | To face p. | 32 |

| Examples of Ancient Surgery | „ | 204 |

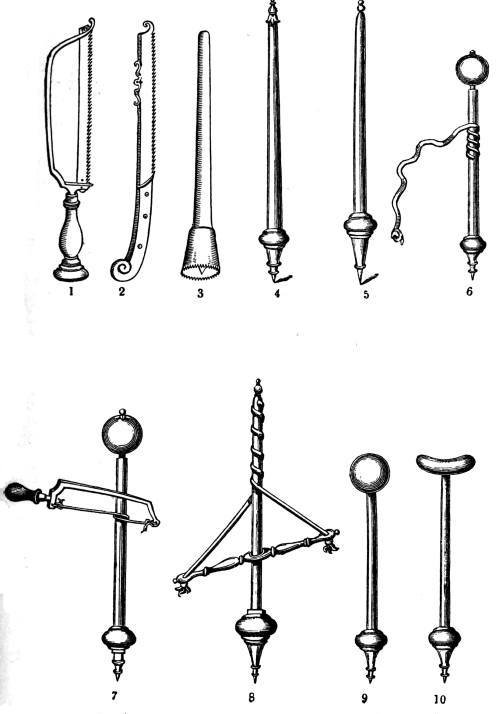

| Ancient Surgical Instruments | „ | 246 |

| Interior of a Doctor’s House | „ | 340 |

xi

| BOOK I. | ||

| THE MEDICINE OF PRIMITIVE MAN. | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Primitive Man a Savage | 3 |

| The Medicine and Surgery of the Lower Animals.—Poisons and Animals.—Observation amongst Savages.—Man in the Glacial Period. | ||

| II. | Animism | 7 |

| Who discovered our Medicines?—Anthropology can assist us to answer the Question.—The Priest and the Medicine-man originally one.—Disease the Work of Magic.—Origin of our Ideas of the Soul and Future Life.—Disease-demons. | ||

| III. | Savage Theories of Disease | 12 |

| Demoniacal.—Witchcraft.—Offended Dead Persons. | ||

| IV. | Magic and Sorcery in the Treatment of Disease | 26 |

| These originated partly in the Desire to cover Ignorance.—Medicine-men.—Sucking out Diseases.—Origin of Exorcism.—Ingenuity of the Priests.—Blowing Disease away.—Beelzebub cast out by Beelzebub.—Menders of Souls.—“Bringing up the Devil.”—Diseases and Medicines.—Fever Puppets.—Amulets.—Totemism and Medicine. | ||

| V. | Primitive Medicine | 33 |

| Bleeding.—Scarification.—Use of Medicinal Herbs amongst the Aborigines of Australia, South America, Africa, etc. | ||

| VI. | Primitive Surgery | 40 |

| Arrest of Bleeding.—The Indian as Surgeon.—Stretchers, Splints, and Flint Instruments.—Ovariotomy.—Brain Surgery.—Massage.—Trepanning.—The Cæsarean Operation.—Inoculation. | ||

| VII. | Universality of the Use of Intoxicants | 46 |

| Egyptian Beer and Brandy.—Mexican Pulque.—Plant-worship.—Union with the Godhead by Alcohol.—Soma.—The Cow-religion.—Caxiri.—Murwa Beer.—Bacchic Rites.—Spiritual Exaltation by Wine. | ||

| VIII. | Customs connected with Pregnancy and Child-bearing | 51 |

| The Couvade, its Prevalence in Savage and Civilized Lands.—Pregnant Women excluded from Kitchens.—The Deities of the Lying-in Chamber. | ||

| BOOK II. | ||

| THE MEDICINE OF THE ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS. | ||

| I. | Egyptian Medicine | 57 |

| Antiquity of Egyptian Civilization.—Surgical Bandaging.—Gods and Goddesses of Medicine.—Medical Specialists.—Egyptians claimed to have discovered the Healing Art.—Medicine largely Theurgic.—Magic and Sorcery forbidden to the Laity.—The Embalmers.—Anatomy.—Therapeutics.—Plants> in use in Ancient Egypt.—Surgery and Chemistry.—Disease-demons.—Medical Papyri.—Great Skill of Egyptian Physicians. xii | ||

| II. | Jewish Medicine | 73 |

| The Jews indebted to Egypt for their Learning.—The only Ancient People who discarded Demonology.—They had no Magic of their own.—Phylacteries.—Circumcision.—Sanitary Laws.—Diseases in the Bible.—The Essenes.—Surgery in the Talmud.—Alexandrian Philosophy.—Jewish Services to Mediæval Medicine.—The Phœnicians. | ||

| III. | The Medicine of Chaldæa, Babylonia, and Assyria | 86 |

| The Ancient Religion of Accadia akin to Shamanism.—Demon Theory of Disease in Chaldæan Medicine.—Chaldæan Magic.—Medical Ignorance of the Babylonians.—Assyrian Disease-demons.—Charms.—Origin of the Sabbath. | ||

| IV. | The Medicine of the Hindus | 96 |

| The Aryans.—Hindu Philosophy.—The Vedas.—The Shastres of Charaka and Susruta.—Code of Menu.—The Brahmans.—Medical Practitioners.—Strabo on the Hindu Philosophers.—Charms.—Buddhism and Medicine.—Jíwaka, Buddha’s Physician.—The Pulse.—Knowledge of Anatomy and Surgery in Ancient Times.—Surgical Instruments.—Decadence of Hindu Medical Science.—Goddesses of Disease.—Origin of Hospitals in India. | ||

| V. | Medicine in China, Tartary, and Japan | 125 |

| Origin of Chinese Culture.—Shamanism.—Disease-demons.—Taoism—Medicine Gods.—Mediums.-Anatomy and Physiology of the Chinese.—Surgery.—No Hospitals in China.—Chinese Medicines.—Filial Piety.—Charms and Sacred Signs.—Medicine in Thibet, Tartary, and Japan. | ||

| VI. | The Medicine of the Parsees | 141 |

| Zoroaster and the Zend-Avesta.—The Heavenly Gift of the Healing Plants.—Ormuzd and Ahriman.—Practice of the Healing Art and its Fees. | ||

| BOOK III. | ||

| GREEK MEDICINE. | ||

| I. | The Medicine of the Greeks before the Time of Hippocrates | 147 |

| Apollo, the God of Medicine.—Cheiron.—Æsculapius.—Artemis.—Dionysus.—Ammon.—Hermes.—Prometheus.—Melampus.—Medicine of Homer.—Temples of Æsculapius.—The Early Ionic Philosophers.—Empedocles.—School of Crotona.—The Pythagoreans.—Grecian Theory of Diseases.—School of Cos.—The Asclepiads.—The Aliptæ. | ||

| II. | The Medicine of Hippocrates and his Period | 172 |

| Hippocrates first delivered Medicine from the Thraldom of Superstition.—Dissection of the Human Body and Rise of Anatomy.—Hippocrates, Father of Medicine and Surgery.—The Law.—Plato. | ||

| III. | Post-Hippocratic Greek Medicine.—The Schools of Medicine | 187 |

| The Dogmatic School.—Praxagoras of Cos.-Aristotle.—The School of Alexandria.—Theophrastus the Botanist.—The great Anatomists, Erasistratus and Hierophilus, and the Schools they founded.—The Empiric School. | ||

| IV. | The Earlier Roman Medicine | 205 |

| Disease-goddesses.—School of the Methodists.—Rufus and Marinus.—Pliny.—Celsus. xiii | ||

| V. | Later Roman Medicine | 227 |

| The Eclectic and Pneumatic Sects.—Galen.—Neo-Platonism.—Oribasius and Ætius.—Influence of Christianity and the Rise of Hospitals.—Paulus Ægineta.—Ancient Surgical Instruments. | ||

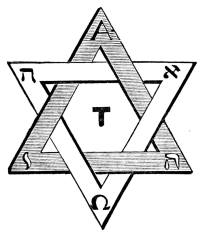

| VI. | Amulets and Charms in Medicine | 247 |

| Universality of the Amulet.—Scarabs.—Beads.—Savage Amulets.—Gnostic and Christian Amulets.—Herbs and Animals as Charms.—Knots.—Precious Stones.—Signatures.—Numbers.—Saliva.—Talismans.—Scripts.—Characts.—Sacred Names.—Stolen Goods. | ||

| BOOK IV. | ||

| CELTIC, TEUTONIC, AND MEDIÆVAL MEDICINE. | ||

| I. | Medicine of the Druids, Teutons, Anglo-Saxons, and Welsh | 269 |

| Origin of the Druid Religion.—Druid Medicine.—Their Magic.—Teutonic Medicine.—Gods of Healing.—Elves.—The Elements.—Anglo-Saxon Leechcraft.—The Leech-book.—Monastic Leechdoms.—Superstitions.—Welsh Medicine.—The Triads.—Welsh Druidism.—The Laws of the Court Physicians.—Welsh Medical Maxims.—Welsh Medical and Surgical Practice and Fees. | ||

| II. | Mohammedan Medicine | 287 |

| Sources of Arabian Learning.—Influence of Greek and Hindu Literature.—The Nestorians.—Baghdad and its Colleges.—The Moors in Spain.—The Mosque Schools.—Arabian Inventions and Services to Literature.—The great Arab Physicians.—Serapion, Rhazes, Ali Abbas, Avicenna, Albucasis, and Averroes. | ||

| III. | Rise of the Monasteries | 300 |

| Alchemy the Parent of Chemistry. | ||

| IV. | Rise of the Universities | 303 |

| School of Montpellier.—Divorce of Medicine from Surgery. | ||

| V. | The School of Salerno | 308 |

| The Monks of Monte Cassino.—Clerical Influence at Salerno.—Charlemagne.—Arabian Medicine gradually supplanted the Græco-Latin Science.—Constantine the Carthaginian.—Archimatthæus.—Trotula.—Anatomy of the Pig.—Pharmacopœias.—The Four Masters.—Roger and Rolando.—The Emperor Frederick. | ||

| VI. | The Thirteenth Century | 319 |

| The Crusades.—Astrology. | ||

| VII. | The Fourteenth Century | 325 |

| Revival of Human Anatomy.—Famous Physicians of the Century.—Domestic Medicine in Chaucer.—Fellowship of the Barbers and Surgeons.—The Black Death.—The Dancing Mania.—Pharmacy. | ||

| VIII. | The Fifteenth Century | 333 |

| Faith-healing.—Charms and Astrology in Medicine.—The Revival of Learning.—The Humanists.—Cabalism and Theology.—The Study of Natural History.—The Sweating Sickness.—Tarantism.—Quarantine.—High Position of Oxford University. | ||

| IX. | Medicine in Ancient Mexico and Peru | 341 |

| Hospitals in Mexico.—Anatomy and Human Sacrifices.—Midwives as Spiritual Mothers.—Circumcision.—Peru.—Discovery of Cinchona Bark. xiv | ||

| BOOK V. | ||

| THE DAWN OF MODERN SCIENTIFIC MEDICINE. | ||

| I. | The Sixteenth Century | 345 |

| The Dawn of Modern Science.—The Reformation of Medicine.—Paracelsus.—The Sceptics.—The Protestantism of Science.—Influenza.—Legal Recognition of Medicine in England.—The Barber-Surgeons.—The Sweating Sickness.—Origin of the Royal College of Physicians of London.—“Merry Andrew.”—Origin of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.—Caius.—Low State of Midwifery.—The Great Continental Anatomists.—Vesalius.—Servetus.—Paré.—Influence of the Reformation.—The Rosicrucians.—Touching for the Evil.—Vivisection of Human Beings.—Origin of Legal Medicine. | ||

| II. | The Seventeenth Century | 377 |

| Bacon and the Inductive Method.—Descartes and Physiology.—Newton.—Boyle and the Royal Society.—The Founders of the Schools of Medical Science.—Sydenham, the English Hippocrates.—Harvey and the Rise of Physiology.—The Microscope in Medicine.—Willis and the Reform of Materia Medica. | ||

| III. | Skatological Medicine and the Reform of Pharmacology | 394 |

| Loathsome Medicines.—Sympathetical Cures.—Weapon Salve.—Superstitions. | ||

| IV. | Baths and Mineral Waters | 400 |

| Miraculous Springs.—The Pool of Bethesda.—Herb-baths. | ||

| V. | Witchcraft and Medicine | 403 |

| Comparative Witchcraft.—Laws against Sorcery.—Magic in Virgil and Horace.—Demonology.—Images of Wax and Clay.—Transference of Disease.—Witchcraft in the Koran.—White Magic and Black.—Coral and the Evil Eye.—“Overlooking” People.—Exorcism in the Catholic Church. | ||

| VI. | Medical Superstitions | 413 |

| Death and the Grave.—Sorcerer’s Ointment.—Teeth-worms.—Disease Transference.—Doctrine of Signatures. | ||

| VII. | The Eighteenth Century | 418 |

| The Sciences accessory to Medicine.—The Great Schools of Medical Theory.—Boerhaave and his System.—Stahl.—Hoffman.—Cullen.—Brown.—Hospitals.—Bichat and the New Era of Anatomy.—Mesmer and Mesmerism.—Surgery.—The Anatomists, Physiologists, and Scientists of the Period.—Inoculation and Vaccination. | ||

| BOOK VI. | ||

| THE AGE OF SCIENCE. | ||

| I. | The Nineteenth Century.—Physical Science Allied to Medicine | 443 |

| Exit the Disease-demon.—Medical Systems again.—Homœopathy.—The Natural Sciences.—Chemistry, Electricity, Physiology, Anatomy, Medicine and Pathology.—Psychiatry.—Surgery.—Ophthalmology. | ||

| II. | Medical Reforms | 464 |

| Discovery of Anæsthetics.—Medical Literature.—Nursing Reform.—History of the Treatment of the Insane. | ||

| III. | The Germ Theory of Disease | 471 |

| The Disease-demon reappears as a Germ.—Phagocytes.—Ptomaines.—Lister’s Antiseptic Surgery.—Sanitary Science or Hygiene.—Bacteriologists.—Faith Cures.—Experimental Physiology and the Latest System of Medicine. | ||

| APPENDIX. | ||

| On Some of the More Important Minerals Used in Medicine | 486 | |

1

3

A POPULAR HISTORY OF MEDICINE.

The Medicine and Surgery of the Lower Animals.—Poisons and Animals.—Observation amongst Savages.—Man in the Glacial Period.

There is abundant proof from natural history that the lower animals submit to medical and surgical treatment, and subject themselves in their necessities to appropriate treatment. Not only do they treat themselves when injured or ill, but they assist each other. Dogs and cats use various natural medicines, chiefly emetics and purgatives, in the shape of grasses and other plants. The fibrous-rooted wheat-grass, Triticum caninum, sometimes called dog’s-wheat, is eaten medicinally by dogs. Probably other species, such as Agrostis caninia, brown bent-grass, are used in like manner.3

Mr. George Jesse describes another kind of “dog-grass,” Cynosurus cristatus, as a natural medicine, both emetic and purgative, which is resorted to by the canine species when suffering from indigestion and other disorders of the stomach. Every druggist’s apprentice knows how remarkably fond cats are of valerian root (Valeriana officinalis). This strong-smelling root acts on these animals as an intoxicant, and they roll over and over the plant with the wildest delight when brought into contact with it. Cats are extravagantly fond of cat-mint (Nepeta cataria). It has a powerful odour, like that of pennyroyal. There is no evidence, however, that these plants have any medicinal properties for which they are used by cats, they are merely enjoyed by them on account of their perfume.

Dr. W. Lauder Lindsay, in his Mind in the Lower Animals, says that the Indian mongoose, poisoned by the snake which it attacks, uses the antidote to be found in the Mimosa octandra.4

4

“Its value both as a cure and as a preventive is said to be well known to it. Whenever in its battles with serpents it receives a wound, it at once retreats, goes in search of the antidote, and having found and devoured it, returns to the charge, and generally carries the day, seeming none the worse for its bite.”5 This, however, is probably a fable of the Hindus.

“A toad, bit or stung by a spider, repeatedly betook itself to a plant of Plantago major (the Greater Plantain), and ate a portion of its leaf, but died after repeated bites of the spider, when the plant had been experimentally removed by man.”6

The medicinal uses of the hellebore were anciently believed to have been discovered by the goat.

“Virgil reports of dittany,” says More, in his Antidote to Atheism, “that the wild goats eat it when they are shot with darts.” The ancients said that the art of bleeding was first taught by the hippopotamus, which thrusts itself against a sharp-pointed reed in the river banks, when it thinks it needs phlebotomy.

If man had not yet learned the medicinal properties of salt, he could discover them by the greedy licking of it by buffaloes, horses, and camels. “On the Mongolian camels,” says Prejevalsky, “salt, in whatever form, acts as an aperient, especially if they have been long without it.” Rats will submit to the gnawing off of a leg when caught in a trap, so that they may escape capture (Jesse). Livingstone says that the chimpanzee, soko, or other anthropoid apes will staunch bleeding wounds by means of their fingers, or of leaves, turf, or grass stuffed into them. Animals treat wounds by licking—a very effectual if tedious method of fomentation or poulticing.

Cornelius Agrippa, in his first book of Occult Philosophy, says that we have learned the use of many remedies from the animals. “The sick magpie puts a bay-leaf into her nest and is recovered. The lion, if he be feverish, is recovered by the eating of an ape. By eating the herb dittany, a wounded stag expels the dart out of its body. Cranes medicine themselves with bulrushes, leopards with wolf’s-bane, boars with ivy; for between such plants and animals there is an occult friendship.”7

Some interesting observations relating to the surgical treatment of wounds by birds were recently brought by M. Fatio before the Physical Society of Geneva. He quotes the case of the snipe, which he has often observed engaged in repairing damages. With its beak and feathers it makes a very creditable dressing, applying plasters to bleeding wounds, and even securing a broken limb by means of a stout ligature. On one occasion he killed a snipe which had on the chest a large dressing com5posed of down taken from other parts of the body, and securely fixed to the wound by the coagulated blood. Twice he has brought home snipe with interwoven feathers strapped on to the site of fracture of one or other limb. The most interesting example was that of a snipe, both of whose legs he had unfortunately broken by a misdirected shot. He recovered the animal only the day following, and he then found that the poor bird had contrived to apply dressings and a sort of splint to both limbs. In carrying out this operation, some feathers had become entangled around the beak, and, not being able to use its claws to get rid of them, it was almost dead from hunger when discovered. In a case recorded by M. Magnin, a snipe, which was observed to fly away with a broken leg, was subsequently found to have forced the fragments into a parallel position, the upper fragment reaching to the knee, and secured them there by means of a strong band of feathers and moss intermingled. The observers were particularly struck by the application of a ligature of a kind of flat-leafed grass wound round the limb in a spiral form, and fixed by means of a sort of glue.

Le Clerc thought that the stories of animals teaching men the use of plants, herbs, etc., meant that men tried them first upon animals before using them for food or medicine. There is no probability of this having been so. If men had observed with Linnæus that horses eat aconite with impunity, and had in consequence eaten it themselves, the result would have been fatal. Birds and herbivorous animals eat belladonna with impunity,8 and it has very little effect on horses and donkeys. Goats, sheep, and horses are said by Dr. Ringer to eat hemlock without ill effects, yet it poisoned Socrates. Henbane has little or no effect on sheep, cows, and pigs. Ipecacuanha does not cause vomiting in rabbits,9 and so on.

Probably from the earliest times man would be led to observe the behaviour of animals when suffering from disease or injury. If he could not learn much from them in the way of medicine, they could teach him many useful arts. In savage man we must seek the beginnings of our civilization, and it is in the lowest tribes and those which have not yet felt the influences of superior races that we must search for the most primitive forms of medical ideas and the earliest theories and treatment of disease.

Sir John Lubbock says:106 “It is a common opinion that savages are, as a general rule, only the miserable remnants of nations once more civilized; but although there are some well-established cases of natural decay, there is no scientific evidence which would justify us in asserting that this applies to savages in general.”

Dr. E. B. Tylor, in his fascinating work on Primitive Culture, says:11 “The thesis which I venture to sustain, within limits, is simply this—that the savage state in some measure represents an early condition of mankind, out of which the higher culture has gradually been developed or evolved by processes still in regular operation as of old, the result showing that, on the whole, progress has far prevailed over relapse. On this proposition the main tendency of human society during its long term of existence has been to pass from a savage to a civilized state. It is mere matter of chronicle that modern civilization is a development of mediæval civilization, which again is a development from civilization of the order represented in Greece, Assyria, or Egypt. Then the higher culture being clearly traced back to what may be called the middle culture, the question which remains is, whether this middle culture may be traced back to the lower culture, that is, to savagery.”

Providing we can find our savage pure and uncontaminated, it matters little where we seek him; north, south, east, or west, he will be practically the same for our purpose.

Dr. Robertson says: “If we suppose two tribes, though placed in the most remote regions of the globe, to live in a climate nearly of the same temperature, to be in the same state of society, and to resemble each other in the degree of their improvement, they must feel the same wants, and exert the same endeavours to supply them.... In every part of the earth the progress of man has been nearly the same, and we can trace him in his career from the rude simplicity of savage life, until he attains the industry, the arts, and the elegance of polished society.”12

Writing of the primitive folk, the Eastern Inoits, Elie Reclus tells us that,13 “shut away from the rest of the world by their barriers of ice, the Esquimaux, more than any other people, have remained outside foreign influences, outside the civilization whose contact shatters and transforms. They have been readily perceived by prehistoric science to offer an intermediate type between man as he is and man as he was in bygone ages. When first visited, they were in the very midst of the stone and bone epoch,14 just as were the Guanches when they were discovered; their iron and steel are recent, almost contemporary importations. The lives of Europeans of the Glacial period cannot have been very different from those led amongst their snow-fields by the Inoits of to-day.”

7

Who discovered our Medicines?—Anthropology can assist us to answer the Question.—The Priest and the Medicine-man originally one.—Disease the Work of Magic.—Origin of our Ideas of the Soul and Future Life.—Disease-demons.

Cardinal Newman, in his sermon on “The World’s Benefactors,” asks, “Who was the first cultivator of corn? Who first tamed and domesticated the animals whose strength we use, and whom we make our food? Or who first discovered the medicinal herbs, which from the earliest times have been our resource against disease? If it was mortal man who thus looked through the vegetable and animal worlds, and discriminated between the useful and the worthless, his name is unknown to the millions whom he has thus benefited.

“It is notorious that those who first suggest the most happy inventions and open a way to the secret stores of nature; those who weary themselves in the search after truth; strike out momentous principles of action; painfully force upon their contemporaries the adoption of beneficial measures; or, again, are the original cause of the chief events in national history,—are commonly supplanted, as regards celebrity and reward, by inferior men. Their works are not called after them, nor the arts and systems which they have given the world. Their schools are usurped by strangers, and their maxims of wisdom circulate among the children of their people, forming perhaps a nation’s character, but not embalming in their own immortality the names of their original authors.”

The reflection is an old one; the son of Sirach said, “And some there be, which have no memorial; who are perished, as though they had never been; and are become as though they had never been born; and their children after them. But these were merciful men, whose righteousness hath not been forgotten” (Ecclesiasticus xliv. 9, 10). Cardinal Newman has framed his question, so far as the healing art is concerned, in a manner to which it is impossible to make a satisfactory answer. No one man first discovered the medicinal herbs; probably the discovery of all the virtues of a single one of them was not the work of any individual. No man8 “looked through the vegetable and animal worlds and discriminated between the useful and the worthless”; all this has been the work of ages, and is the outcome of the experience of thousands of investigators. The medical arts have played so important a part in the development of our civilization, that they constitute a branch of study second to none in utility and interest to those who would know something of the work of the world’s benefactors. Probably at no period in the world’s history have medical men occupied a more honourable or a more prominent position than they do at the present time, and it would almost seem that the rewards which an ignorant or ungrateful civilization denied in the past to medical men are now being bestowed on those who in these latter days have been so fortunate as to inherit the traditions and the acquirements of a forgotten ancestry of truth-seekers and students of the mysteries of nature. As the earliest races of mankind passed by slow degrees from a state of savagery to the primitive civilizations, we must seek for the beginnings of the medical arts in the representatives of the ancient barbarisms which are to be found to-day in the aborigines of Central Africa and the islands of Australasian seas. The intimate connection which exists between the magician, the sorcerer, and the “medicine man” of the present day serves to illustrate how the priest, the magician, and the physician of the past were so frequently combined in a single individual, and to explain how the mysteries of religion were so generally connected with those of medicine.

Professor Tylor has explained how death and all forms of disease were attributed to magic, the essence of which is the belief in the influence of the spirits of dead men. This belief is termed Animism, and Mr. Tylor says: “Animism characterizes tribes very low in the scale of humanity, and thence ascends, deeply modified in its transmission, but from first to last preserving an unbroken continuity, into the midst of high culture. Animism is the groundwork of the philosophy of religion, from that of the savages up to that of civilized men; but although it may at first seem to afford but a meagre and bare definition of a minimum of religion, it will be found practically sufficient; for where the roots are, the branches will generally be produced. The theory of animism divides into two great dogmas, forming parts of one consistent doctrine: first, concerning souls of individual creatures, capable of continued existence after death; second, concerning other spirits, upward to the rank of powerful deities. Spiritual beings are held to affect or control the events of the material world, and man’s life here and hereafter; and it being considered that they hold intercourse with men and receive pleasure or displeasure from human actions, the belief in their existence leads naturally, sooner or later, to active reverence and propitiation.” There is no doubt that the belief in the9 soul and in the existence of the spirits of the departed in another world arose from dreams. When the savage in his sleep held converse, as it seemed to him, with the actual forms of his departed relatives and friends, the most natural thing imaginable would be the belief that these persons actually existed in a spiritual shape in some other world than the material one in which he existed. Those who dreamed most frequently and most vividly, and were able to describe their visions most clearly, would naturally strive to interpret their meaning, and would become, to their grosser and less poetical brethren, more important personages, and be considered as in closer converse with the spiritual world than themselves. Thus, in process of time, the seer, the prophet, and the magician would be evolved.

How did primitive man come by his ideas? When he saw the effects of a power, he could only make guesses at the cause; he could only speak of it by some such terms as he would use concerning a human agent. He saw the effects of fire, and personified the cause. With the Hindus Agni was the giver of light and warmth, and so of the life of plants, of animals, and of men; and so with thunder, lightning, and storm, primitive man looked upon these phenomena as the conflicts of beings higher and more powerful than himself. Thus it was that the ancient people of India formed their conceptions of the storm-gods, the Maruts, i.e. the Smashers. Amongst the Esthonians, as Max Müller tells us,15 prayers were addressed to thunder and rain as late as the seventeenth century. “Dear Thunder, push elsewhere all the thick black clouds. Holy Thunder, guard our seed-field.” (This same thunder-god, Perkuna, says Max Müller, was the god Parganya, who was invoked in India a thousand years before Alexander’s expedition.) We say it rains, it thunders. Primitive folk said the rain-god poured out his buckets, the thunder-god was angry.

What did primitive man think when he observed the germination of seeds; the chick coming out of the egg; the butterfly bursting from the chrysalis; the shadow which everywhere accompanies the man; the shadows of the tree; the leaves which vibrate in the breeze; when he heard the roaring of the wind; the moaning of the storm, and the strange, mysterious echo which, plainly as he heard it, ceased as he approached the mountain-side which he conceived to be its home? He could but believe that all nature was living, like himself; and that, as he could not understand what he saw in the seed, the egg, the chrysalis, or the shadow, so all nature was full of mystery, of a life that he in vain would try to comprehend. Many savages regard their own shadows as one of their two souls,—a soul which is always watching10 their actions, and ready to bear witness against them. How should it be otherwise with them? The shadow is a reality to the savage, and so is the echo. The ship which visits his shores, the watch and the compass, which he sees for the first time, are alive; they move, they must be living!

Mr. Tylor, in his chapter on Animism, in his Primitive Culture, says (vol. ii. pp. 124, 125):—

“As in normal conditions the man’s soul, inhabiting his body, is held to give it life, to think, speak, and act through it, so an adaptation of the self-same principle explains abnormal conditions of body or mind, by considering the new symptoms as due to the operation of a second soul-like being, a strange spirit. The possessed man, tossed and shaken in fever, pained and wrenched as though some live creature were tearing or twisting him within, pining as though it were devouring his vitals day by day, rationally finds a personal spiritual cause for his sufferings. In hideous dreams he may even sometimes see the very ghost or nightmare-fiend that plagues him. Especially when the mysterious, unseen power throws him helpless to the ground, jerks and writhes him in convulsions, makes him leap upon the bystanders with a giant’s strength and a wild beast’s ferocity, impels him, with distorted face and frantic gesture, and voice not his own, nor seemingly even human, to pour forth wild incoherent raving, or with thought and eloquence beyond his sober faculties, to command, to counsel, to foretell—such a one seems to those who watch him, and even to himself, to have become the mere instrument of a spirit which has seized him or entered into him—a possessing demon in whose personality the patient believes so implicitly that he often imagines a personal name for it, which it can declare when it speaks in its own voice and character through his organs of speech; at last, quitting the medium’s spent and jaded body, the intruding spirit departs as it came. This is the savage theory of demoniacal possession and obsession, which has been for ages, and still remains, the dominant theory of disease and inspiration among the lower races. It is obviously based on an animistic interpretation, most genuine and rational in its proper place in man’s intellectual history, of the natural symptoms of the cases. The general doctrine of disease-spirits and oracle-spirits appears to have its earliest, broadest, and most consistent position within the limits of savagery. When we have gained a clear idea of it in this its original home, we shall be able to trace it along from grade to grade of civilization, breaking away piecemeal under the influence of new medical theories, yet sometimes expanding in revival, and, at least, in lingering survival holding its place into the midst of our modern life. The possession-theory is not merely11 known to us by the statements of those who describe diseases in accordance with it. Disease being accounted for by attacks of spirits, it naturally follows that to get rid of these spirits is the proper means of cure. Thus the practices of the exorcist appear side by side with the doctrine of possession, from its first appearance in savagery to its survival in modern civilization; and nothing could display more vividly the conception of a disease or a mental affliction as caused by a personal spiritual being than the proceedings of the exorcist who talks to it, coaxes or threatens it, makes offerings to it, entices or drives it out of the patient’s body, and induces it to take up its abode in some other.”

12

Demoniacal.—Witchcraft.—Offended Dead Persons.

We find amongst savages three chief theories of disease; that it is caused by—

I. The anger of an offended demon.

II. Witchcraft, or

III. Offended dead persons.

Disease and death are set down to the influences of spirits in the Australian-Tasmanian district, where demons are held to have the power of creeping into men’s bodies, to eat up their livers, and sometimes to work the wicked will of a sorcerer by inflicting blows with a club on the back of the victim’s neck.16 The Mantira, a low race of the Malay Peninsula, believe in the theory of disease-spirits in its extreme form; their spirits cause all sorts of ailments. The “Hantu Kalumbahan” causes small-pox; the “Hantu Kamang” brings on inflammation and swelling of the hands and feet; the blood which flows from wounds is due to the “Hantu-pari,” which fastens on the wound and sucks. So many diseases, so many Hantus. If a new malady were to appear amongst the tribes, a new Hantu would be named as its cause.17 When small-pox breaks out amongst these people, they place thorns and brush in the paths to keep the demons away. The Khonds of Orissa try to defend themselves against the goddess of small-pox, Jugah Pensu, in the same way. Among the Dayaks of Borneo, to have been ill is to have been smitten by a spirit; invisible spirits inflict invisible wounds with invisible spears, or they enter bodies and make them mad. Disease-spirits in the Indian Archipelago are conciliated by presents13 and dances. In Polynesia, every sickness is set down to deities which have been offended, or which have been urged to afflict the sufferer by their enemies.18 In New Zealand disease is supposed to be due to a baby, or undeveloped spirit, which is gnawing the patient’s body. Those who endeavour to charm it away persuade it to get upon a flax-stalk and go home. Each part of the body is the particular region of the spirit whose office it is to afflict it.19

The Prairie Indians treat all diseases in the same way, as they must all have been caused by one evil spirit.20

Among the Betschvaria disease may be averted if a painted stone or a crossbar smeared with medicine be set up near the entrance of the residence or approach to a town.21

Amongst the Bodo and Dhimal peoples, when the exorcist is called to a sick man he sets thirteen loaves round him, to represent the gods, one of whom he must have offended; then he prays to the deity, holding a pendulum by a string. The offended god is supposed to cause the pendulum to swing towards his loaf.22

The New Zealanders had a separate demon for each part of the body to cause disease. Tonga caused headache and sickness; Moko-Tiki was responsible for chest pains, and so on.23

The Karens of Burmah and the Zulus both say, “The rainbow is disease. If it rests on a man, something will happen to him.”24 “The rainbow has come to drink wells.” They say, “Look out; some one or other will come violently by an evil death.”

The Tasmanians lay their sick round a corpse on the funeral pile, that the dead may come in the night and take out the devils that cause the diseases.25

The Zulus believe that spirits, when angry, seize a living man’s body and inflict disease and death, and when kindly disposed give health and cattle. In Madagascar, Mr. Tylor tells us, the spirits of the Vazimbas, the aborigines of the island, inflict diseases, and the Malagasy accounts for all sorts of mysterious complaints by the supposition that he has given offence to some Vazimba. The Gold Coast negroes believe that ghosts plague the living and cause sickness. The Dayaks of Borneo think that the souls of men enter the trunks of trees, and the Hindus hold that plants are sometimes the homes of the spirits of the departed. The Santals of Bengal believe that the spirits of the good14 enter into fruit-bearing trees.26 It is but another step to the belief that beneficent medicinal plants are tenanted by good spirits, and poisonous plants by evil spirits. The Malays have a special demon for each kind of disease; one for small-pox, another for swellings, and so on.27

The Dayaks of Borneo acknowledge a supreme God, although, as we have said, they attribute all kinds of diseases and calamities to the malignity of evil spirits. Their system of medicine consists in the application of appropriate charms or the offering of conciliatory sacrifices.28 Yet they are an intelligent and highly capable race, and their steel instruments far surpass European wares in strength and fineness of edge.29

The Javanese, nominally Mahometans, are really believers in the primitive animism of their ancestry. They worship numberless spirits; all their villages have patron saints, to whom is attributed all that happens to the inhabitants, good or bad. Mentik causes the rice disease; Sawan produces convulsions in children; Dengen causes gout and rheumatism.30

The religion of Siam is a corrupted Buddhism; spirits and demons (nats or phees) are worshipped and propitiated. Some of these malignant beings cause children to sicken and die. Talismans are worked into the ornamentation of the houses to avert their evil influence.31

The Rev. J. L. Wilson32 says: “Demoniacal possessions are common, and the feats performed by those who are supposed to be under such influence are certainly not unlike those described in the New Testament. Frantic gestures, convulsions, foaming at the mouth, feats of supernatural strength, furious ravings, bodily lacerations, grinding of teeth, and other things of a similar character, may be witnessed in most of the cases.”

In Finnish mythology, which introduces us to ideas of extreme antiquity, we find the disease-demon theory in all its force.

The Tietajat, “the learned,” and the Noijat, or sorcerers, claimed the power to cure diseases by expelling the demons which caused them, by incantations assisted by drugs; these magicians were the only physicians of the nation. The Tietajat and the Noijat, however, were not magicians of the same class: the former practised “white magic,” or “sacred science”; the latter practised “black magic,” or sorcery. Evil spirits, poisons, and malice were the chief aids to practice in the latter; while Tietajat, by means of learning and the assistance of benevolent supernatural beings, devote themselves to the welfare of the people. The three highest deities of Finnish mythology, Ukko, Wäinä15möinen, and Ilmarinen, corresponded to three superior gods of the Accadian magic collection, Ana, Hea, and Mut-ge. Wäinämöinen was the great spirit of life, the master of favourable spells, conqueror of evil, and sovereign possessor of science. The sweat which dropped from his body was a balm for all diseases. It was he alone who could conquer all the demons. Every disease was itself a demon. The invasion of the disorder was an actual possession. Finnish magic was chiefly medical, being used to cure diseases and wounds.33 The Finns believed diseases to be the daughters of Louhiatar, the demon of diseases. Pleurisy, gout, colic, consumption, leprosy, and the plague were all distinct personages. By the help of conjurations, these might be buried or cooked in a brazen vessel. When the priest made his diagnosis he had to be in a state of divine ecstasy, and then by incantation, assisted by drugs, he proceeded to exorcise the demon. The Finnish incantations belonged to the same family as those of the Accadians. Professor Lenormant translates from the great Epopee of the Kalevala one of the incantations:—

“O malady, disappear into the heavens; pain, rise up to the clouds; inflamed vapour, fly into the air, in order that the wind may take thee away, that the tempest may chase thee to distant regions, where neither sun nor moon give their light, where the warm wind does not inflame the flesh.

“O pain, mount upon the winged steed of stone, and fly to the mountains covered with iron. For he is too robust to be devoured by disease, to be consumed by pains.

“Go, O diseases, to where the virgin of pains has her hearth, where the daughter of Wäinämöinen cooks pains,—go to the hill of pains.

“These are the white dogs, who formerly hurled torments, who groaned in their sufferings.”

Another incantation against the plague was discovered by Ganander, and is given by Lenormant:—

“O scourge, depart; plague, take thy flight, far from the bare flesh.

“I will give thee a horse, with which to escape, whose shoes shall not slide on ice;” and so on.

The Jewish ceremony expelled the scapegoat to the desert; the Accadian banished the disease-demons to the desert of sand; the Finnish magician sent his disease-demons to Lapland.

The goddess Suonetar was the healer and renewer of flesh:—

“She is beautiful, the goddess of veins, Suonetar, the beneficent goddess! She knits the veins wonderfully with her beautiful spindle, her metal distaff, her iron wheel.

16

“Come to me, I invoke thy help; come to me, I call thee. Bring in thy bosom a bundle of flesh, a ball of veins to tie the extremity of the veins.”34

“All diseases are attributed by the Thibetans to the four elements, who are propitiated accordingly in cases of severe illness. The winds are invoked in cases of affections of the breathing; fire in fevers and inflammations; water in dropsy, and diseases whereby the fluids are affected; and the god of earth when solid organs are diseased, as in liver complaints, rheumatism, etc. Propitiatory offerings are made to the deities of these elements, but never sacrifices.”35

Hooker tells of a case of apoplexy which was treated by a Lama, who perched a saddle on a stone, and burning incense before it, scattered rice to the winds, invoking the various mountain peaks in the neighbourhood.

In Hottentot mythology Gaunab is a malevolent ghost, who kills people who die what we call a “natural” death. Unburied men change into this sort of vampire.36

The demoniacal theory of at least one class of disease is found in the Bible, although the New Testament in one passage distinguishes between lunatics and demoniacs. In Matthew iv. 24 we read that they brought to Jesus “those which were possessed with devils, and those which were lunatick.” Epilepsy is evidently the disease described in Mark ix. 17-26, though the symptoms are attributed to possession by a dumb spirit.

Sorcerers and magicians not only use evil words and cast evil glances at the persons whom they wish to afflict, but they endeavour to obtain possession of some article which has belonged to the individual, or something connected more closely with his personality, as parings of the nails or a few of his hairs, and through these he professes to be able to operate more effectually on the object of his malice. It is to this use of portions of the body that ignorant persons, even at the present day, insist that nail-parings, hair-cuttings, and the like, shall be at once destroyed by fire. Such superstitions are found at work all over the world. Mr. Black tells us37 that the servants of the chiefs of the17 South Sea Islanders carefully collect and bury their masters’ spittle in places where sorcerers are not likely to find it. He says also it is believed in the West of Scotland that if a bird used any of the hair of a person’s head in building his nest, the individual would be subject to headaches and become bald. Of course the bird is held to be the embodiment of an evil spirit or witch. Images of persons to be bewitched are sometimes made in wood or wax, in which has been inserted some of the hair of the victim of the enchantment; the image is then buried, and before long some malady attacks the part of the bewitched person corresponding to that in which the hair has been placed in his effigy. Disease-making is a profession in the island of Tanna in the New Hebrides; the sorcerers collect the skins and shells of the fruits eaten by any one who is to be punished, they are then slowly burned, and the victims sicken. Disease-demons are driven away from patients in Alaska by the beating of drums. The size of the drum and the force of the beating are directly proportioned to the gravity of the disease. A headache can be dispelled by the gentle tapping of a toy drum; concussion of the brain would require that the big drum should be thumped till it broke; if that failed to expel the evil spirit, there would be nothing left but to strangle the patient.

The wild natives of Australia are exceedingly superstitious. Sorcery enters into every relation of life, and their great fear is lest they should be injured by the mysterious influence called boyl-ya. The sorcerers have power to enter the bodies of men and slowly consume them; the victim feels the pain as the boyl-ya enters him, and it does not leave him till it is extracted by another sorcerer. While he is sleeping, he may be attacked and bewitched by having pointed at him a leg-bone of a kangaroo, or the sorcerer may steal away his kidney-fat, where the savage believes that his power resides, or he may secretly slay his victim by a blow on the back of his neck. The magician may dispose of his victim by procuring a lock of his hair and roasting it with fat; as it is consumed, so does his victim pine away and die.

Wingo is a superstition which some Australian tribes have, that with a rope of fibre they can partially choke a man, by putting it round his neck at night while he is asleep, without waking him; his enemy then removes his caul-fat from under his short rib, leaving no mark or wound. When the victim awakes he feels no pain or weakness, but sooner or later he feels something break in his inside like a string. He then goes home and dies at once.38

Dr. Watson thus describes the typical medicine-men:—

18

“The Tla-guill-augh, or man of supernatural gifts, is supposed to be capable of throwing his good or bad medicine, without regard to distance, on whom he will, and to kill or cure by magic at his pleasure. These medicine-men are generally beyond the meridian of life; grave, sedate, and shy, with a certain air of cunning, but possessing some skill in the use of herbs and roots, and in the management of injuries and external diseases. The people at large stand in great awe of them, and consult them on every affair of importance.”39

Dr. O. L. Möller, Medical Director-General of the Danish army, describes a certain wise woman near Lögstör, who used in her prescriptions for the sick people who consulted her a charm of willow twigs tied together amongst other mystic things, and whose therapeutics were of a bloodthirsty character, as she would advise her patients to strike the first person they met after returning home, until they drew blood, for that person would be the cause of the disease.40

The fact that ghosts and demons are everywhere believed to cause diseases, and that sorcery is practised more or less by most of the races of man in connection with the causation or cure of disease, has been used as a factor in the argument for the origin of primitive man from a single pair in accordance with the orthodox belief. Dr. Pickering, the ethnologist, says: “Superstitions also appear to be subject to the same laws of progression with communicated knowledge, and the belief in ghosts, evil spirits, and sorcery, current among the ruder East Indian tribes, in Madagascar, and in a great part of Africa, seems to indicate that such ideas may have elsewhere preceded a regular form of mythology.”41

There has long been practised in the West Indies a species of witchcraft called Obeah or Obi, supposed to have been introduced from Africa, and which is in reality an ingenious system of poisoning. Mr. Bowrey, Government chemist in Jamaica, connects Obeah-poisoning with a plant which grows abundantly in Jamaica and other West Indian islands, called the “savannah flower,” or “yellow-flowered nightshade” (Urechites suberecta).42

Mr. Bowrey concludes that there is some truth in the stories told of the poisoning by Obeah-men, and that minute doses, frequently administered, might cause death without suspicion being aroused. The British Medical Journal, June 18th, 1892, has the following interesting notes on Obeah (p. 1296):—

19

“It is difficult to obtain detailed information regarding Obeah practices. They rest largely on the credence given to superstitious practices and vulgar quackery by the uneducated in every country, but there seems little doubt that among them secret poisoning is included. Benjamin Moseley (Medical Tracts, London, 1800) states that Obi had its origin, like many customs among the Africans, from the ancient Egyptians, Ob meaning a demon or magic. Villiers-Stuart (Jamaica Revisited, 1891) says that Obeah in the West African dialects signifies serpent, and that the Obeah-men in Jamaica carry (but in greatest secrecy, for fear of the penal laws) a stick on which is carved a serpent, the emblem being a relic of the serpent worship once universal among mankind, and also that they sacrifice cocks at their religious rites. Moseley gives the following account: ‘Obi, for the purposes of bewitching people or consuming them by lingering illness, is made of grave-dirt, hair, teeth of sharks and other animals, blood, feathers,’ and so on. Mixtures of these are placed in various ways near the person to be bewitched. ‘The victims to this nefarious art in the West Indies among the negroes are numerous. No humanity of the master nor skill in medicine can relieve the poor negro labouring under the influence of Obi. He will surely die, and of a disease that answers no description in nosology. This, when I first went to the colonies, perplexed me. Laws have been made in the West Indies to punish the Obian practice with death, but they have been impotent and nugatory. Laws constructed in the West Indies can never suppress the effect of ideas, the origin of which is in the centre of Africa.’ ‘A negro Obi-man will administer a baleful dose from poisonous herbs, and calculate its mortal effects to an hour, day, week, month, or year.’ The missionaries Waddell (Twenty-nine Years in the West Indies and Central Africa, 1863) and Blyth (Reminiscences of Missionary Life, 1851) confirm this account. They are all agreed that similar practices prevail in West and Central Africa, and that Jamaican Obeah-men use poisons. Mr. Bowrey informs me that he has examined many Obeah charms, and confirms Moseley’s account of them. He thinks, however, that among the negroes the knowledge of poisons has been rapidly dying out, ‘doctor’s medicine’ and the much-advertised patent medicines having largely replaced the drugs of the native practitioners. The belief in Obeah is still, however, almost universal among the black population. According to Sir Spencer St. John (Hayti, or the Black Republic, second edition, London, 1889) secret poisoning is a lucrative occupation in the neighbouring island of Hayti, certain of the people having an intimate knowledge of indigenous poisonous plants and being expert poisoners.”20

How comes it that all the races of man of which we have any accurate information have some belief or other in spirits good or bad, and of some other life than the actual one which they live in their waking hours? The theologian answers it in his own way, the anthropologist in his, and perhaps a simpler one. With the religious aspect of the question we are not here concerned, we have merely to consider the scientific points involved. When the most ignorant savage of the lowest type falls asleep, he is as sure to dream as his more favoured civilized brother. To his companions he appears as though he were dead, he is motionless and apparently unconscious. He awakes and is himself again. What has his spirit or thinking part been doing while his body slept? The man has seen various things and places, has even conversed with friend or foe in his slumbers, has engaged in fights, has taken a journey, has had adventures, and yet his body has not stirred. Naturally enough the explanation most satisfactory is, that his soul has temporarily left his body, and has met other souls in a similar condition. He has seen and conversed with his dead friends or relatives, has been comforted by their presence or alarmed at the visitation. Here, then, we have the anthropologist’s “theory of souls where life, mind, breath, shadow, reflexion, dream, vision, come together and account for one another in some such vague, confused way as satisfies the untaught reasoner.”43

But the savage goes further than this: he has seen his horse, his dog, his canoe, and his spear in his dream, they too must have souls; and thus he invests with a spiritual essence every material object by which he is surrounded. And so we find funeral sacrifices and ceremonies all over the world which testify to this universal belief of primitive man. The ornaments and weapons which are found with the bones of chiefs, the warrior’s horses slain at his burial place, the food and drink and piece of money left with the dead, are intelligible on this theory, and on no other. The savage’s idea of a demon or evil spirit is usually that of a soul of a malevolent dead man. The man was his enemy during life, he remains his enemy after death; or he owed some acknowledgment and reward to a spirit who had helped him, he has neglected to pay his debt, and he has offended the spirit in consequence. In cases of fainting, delirium from fever, hysteria, epilepsy, or insanity, the savage sees the partial absence of the patient’s soul from his body, or the work of a tormenting demon. Demoniacal possession and the ceremonies of exorcism are theories readily explainable by facts with which the an21thropologist is familiar. “The sick Australian will believe that the angry ghost of a dead man has got into him, and is gnawing his liver; in a Patagonian skin hut the wizards may be seen dancing, shouting, and drumming, to drive out the evil demon from a man down with fever.”44

When Prof. Bartram, the anthropologist, was in Burma, his servant was seized with an apopleptic fit. The man’s wife, of course, attributed the misfortune to an angry demon, so she set out for him little heaps of rice, and was heard praying, “Oh, ride him not! Ah, let him go! Grip him not so hard! Thou shalt have rice! Ah, how good that tastes!”

The exorcist may so delude himself that he may believe that he has power to make the demon converse with him. There may be a falsetto voice like that of the mediums of modern civilization issuing from the patient’s mouth, and the exorcist’s questions and commands may be answered, and the evil spirit may consent to leave the sufferer in peace. In nervous or mental disorders, in cases of defective power of assimilating food, such a process may exert a soothing and highly beneficial influence on the patient who is actively co-operating by his faith in his own cure, and so the error both as to the cause of the malady and its treatment is perpetuated.

Primitive folk think that life is indestructible; what is called death is but a change of condition to them; even mites and mosquitos are immortal.45

The Tasmanian, when he suffers from a gnawing disease, believes that he has unwittingly pronounced the name of a dead man, who, thus summoned, has crept into his body, and is consuming his liver. The sick Zulu believes that some dead ancestor he sees in a dream has caused his ailment, wanting to be propitiated with the sacrifice of an ox. The Samoan thinks that the ancestral souls can get into the heads and stomachs of living men, and cause their illness and death. These are examples of human ghosts having become demons.46

In the Samoan group people thought that if a man died bearing ill-will towards any one, he would be likely to return to trouble him, and cause sickness and death, taking up his abode in the sufferer’s head, chest, or stomach. If he died suddenly, they said he had been eaten by the spirit that took him. In the Georgian and Society Islands evil demons cause convulsions and hysterics, or twist the bowels till the sufferers die writhing in agony. Madmen are thought to be entered22 by a god, so they are treated with great respect; idiots are considered to be divinely inspired.47 Many other races believe in the inspiration of mentally feeble or insane persons. Amongst the Dacotas spirits of animals, trees, stones, or deceased persons are believed to enter the patient and cause his disease. The medicine-man recites charms over him, and making a symbolic representation of the intruding spirit in bark, shoots it ceremonially; he sucks over the seat of the pain to draw the spirit out, and fires guns at it as it escapes.

This is just what happened in the West Indies in the time of Columbus. Friar Roman Paul tells of a native sorcerer who pretended to pull the disease from the legs of his patients, blowing it away, and telling it to begone to the mountain or the sea. He would then pretend to extract by sucking some stone or bit of flesh, which he declared had been put into the patient to cause the disease by a deity in punishment for some religious neglect.48 The Patagonians believed that sickness was caused by spirits entering the patient’s body; they considered that an evil demon held possession of the sick man’s body, and their doctors always carried a drum which they struck at the bedside to frighten away the demons which caused the disorder.49 The Zulus and Basutos in Africa teach that ghosts of dead persons are the causes of all diseases. Congo tribes believe also that the souls of the dead cause disease and death amongst men.

The art of medicine in these lands therefore is, for the most part, merely an affair of propitiating some offended and disease-causing spirit. In several parts of Africa mentally deranged persons are worshipped. Madness and idiocy are explained by the phrase, “he has fiends.” The Bodo and Dhimal people of North-east India ascribe all diseases to a deity who torments the patient, and who must be appeased by the sacrifice of a hog. With these people naturally the doctor is a sort of priest. As Mr. Tylor says, “Where the world-wide doctrine of disease-demons has held sway, men’s minds, full of spells and ceremonies, have scarce had room for thought of drugs and regimen.”50

A forest tribe of the Malay Peninsula, called the Original People, are said to have no religion, no idea of any Supreme Being, and no priests; yet their Puyung, who is a sort of general adviser to the tribe, instructs them in sorcery and the doctrine of ghosts and evil spirits. In sickness they use the roots and leaves of trees as medicines. Amongst23 the Tarawan group of the Coral Islands, Pickering says: “Divination or sorcery was also known, and the natives paid worship to the manes or spirits of their departed ancestors.”51 Probably on careful investigation we should find that in these cases the doctrine of ghosts and the worship of spirits has some connection with the causation of disease.

The Malagasy profess a religion which is chiefly fetishism. They believe in the life of the spirit, which they call “the essential part of me,” apart from the body; and they believe that this spirit exists when the body dies. Such “ghosts” they consider can do harm in various ways, especially by causing diseases; consequently they endeavour, as the chief means of cure, to appease the offended ghost. Witchcraft and belief in charms naturally flourish amongst these people.52

Mr. A. W. Howitt says that the Kŭrnai of Gippsland, Australia, believe that a man’s spirit (Yambo) can leave the body during sleep, and hold converse with other disembodied spirits. Another tribe, the Woi-worŭng, call this spirit Mūrŭp, and they suppose it leaves the body in a similar manner, the exact moment of its departure being indicated by the “snoring” of the sleeper. As a theory of the soul, Mr. Howitt says: “It may be said of the aborigines I am now concerned with, and probably of all others, that their dreams are to them as much realities in one sense, as are the actual events of their waking life. It may be said that in this respect they fail to distinguish between the subjective and objective impressions of the brain, and regard both as real events.”53

They believe that these ghosts live upon plants, that they can revisit their old haunts at will, and communicate with the wizards or medicine-men on being summoned by them. A celebrated wizard amongst the Woi-worŭng caught the spirit of a dying man, and brought it back under his ’possum rug, and restored it to the still breathing body just in time to save his life. The ghosts can kill game with spiritually poisoned spears. Even the tomahawk has a spirit, and this belief explains many burial customs. One of the Woi-worŭng people told Mr. Howitt that they buried the weapon with the dead man, “so that he might have it handy.” Other tribes bury with the corpse the amulets and charms used by the deceased during life, in case they may be required in the spirit-world. The Woi-worŭng believe that their wizards could send their deadly magical yark, or rock crystal, against a person they desired to kill, in the form of a small whirlwind. They believe that their wizards “go up” at night to the sky, and obtain such information as24 they require in their profession. They can also bring away the magical apparatus by which some one of another tribe might be injuring the health of a member of his own tribe. It is highly probable that in these Australian beliefs we have the counterparts of those which were everywhere held by primitive man. Good spirits are very little worshipped by savages; they are already well disposed, and need no invocation; it is the bad ones who must be propitiated by an infinite variety of rites and sacrifices. “Thus,” as Professor Keane says, “has demonology everywhere preceded theology.”54

Mr. Edward Palmer, in Notes on Some Australian Tribes, says that the Gulf tribes believe in spirits which live inside the bark of trees, and which come out at night to hold intercourse with the doctors, or “mediums.” These spirits work evil at times. The Kombinegherry tribe are much afraid of an evil-working spirit called Tharragarry, but they are protected by a good spirit, Coomboorah. The Mycoolon people believe in an invisible spear which enters the body, leaving no outward sign of its entry. The victim does not even know that he is hurt; he goes on hunting, and returns home as usual; in the night he becomes ill, delirious, or mad, and dies in the morning. Thimmool is a pointed leg-bone of a man, which, being held over a blackfellow when asleep, causes sickness or death. The Marro is the pinion-bone of a hawk, in which hair of an enemy has been fixed with wax. To work a charm on him a fire circle is made round it. With this charm they can make their enemy sick, or, by prolonging their magic, kill him. When they think they have done harm enough, they place the Marro in water, which removes the charm.55

Mr. H. H. Johnstone says that the tribes on the Lower Congo bury with any one of consequence bales of cloth, plates, beads, knives, and other things required to set the deceased up in the spirit-life on which he has entered. The plates are broken, the beads are crushed, and the knives bent, so as to kill them, that they too may “die,” and go to the spirit-land with their owner.56

This is a valuable confirmation of the doctrine of animism.

As Mr. Herbert Spencer says:57 “It is absurd to suppose that uncivilized man possesses at the outset the idea of ‘natural explanation.’” At a great price has civilized man purchased the power of giving a natural explanation to the phenomena by which he is surrounded. As societies grow, as the arts flourish, as painfully, little by little, his25 experiences accumulate, so does man learn to correct his earlier impressions, and to construct the foundations of science. It is the natural, or it would not be the universal, process for primitive man to explain phenomena by the simplest methods, and these always lead him to his superstitions. It is the only process open to him. The activity which he sees all around him is controlled by the spirits of the dead, and by spirits more or less like those which animate his fellow-men.

Clement of Alexandria says that all superstition arises from the inveterate habit of mankind to make gods like themselves. The deities have like passions with their worshippers, “and some say that plagues, and hailstorms, and tempests, and the like, are wont to take place, not alone in consequence of material disturbance, but also through the anger of demons and bad angels. These can only be appeased by sacrifice and incantations. Yet some of them are easily satisfied, for when animals failed, it sufficed for the magi at Cleone to bleed their own fingers.”58

“The prophetess Diotima, by the Athenians offering sacrifice previous to the pestilence, effected a delay of the plague for ten years.”59

26

These originated partly in the Desire to cover Ignorance.—Medicine-men.—Sucking out Diseases.—Origin of Exorcism.—Ingenuity of the Priests.—Blowing Disease away.—Beelzebub cast out by Beelzebub.—Menders of Souls.—”Bringing up the Devil.“—Diseases and Medicines.—Fever Puppets.—Amulets.—Totemism and Medicine.

Dr. Robertson tells us that the ignorant pretenders to medical skill amongst the North American Indians were compelled to cover their ignorance concerning the structure of the human body, and the causes of its diseases, by imputing the origin of the maladies which they failed to cure to supernatural influences of a baleful sort. They therefore “prescribed or performed a variety of mysterious rites, which they gave out to be of such efficacy as to remove the most dangerous and inveterate malice. The credulity and love of the marvellous natural to uninformed men favoured the deception, and prepared them to be the dupes of those impostors. Among savages, their first physicians are a kind of conjurers, or wizards, who boast that they know what is past, and can foretell what is to come. Thus, superstition, in its earliest form, flowed from the solicitude of man to be delivered from present distress, not from his dread of evils awaiting him in a future life, and was originally ingrafted on medicine, not on religion. One of the first and most intelligent historians of America was struck with this alliance between the art of divination and that of physic among the people of Hispaniola. But this was not peculiar to them. The Alexis, the Piayas, the Autmoins, or whatever was the distinguishing name of the diviners and charmers in other parts of America, were all physicians of their respective tribes, in the same manner as the Buhitos of Hispaniola. As their function led them to apply to the human mind when enfeebled by sickness, and as they found it, in that season of dejection, prone to be alarmed with imaginary fears, or assured with vain hopes, they easily induced it to rely with implicit confidence on the virtue of their spells and the certainty of their predictions.”60

The aborigines of the Amazon have a kind of priests called Pagés,27 like the medicine-men of the North American Indians. They attribute all diseases either to poison or to the charms of some enemy. Of course, diseases caused by magic can only be cured by magic, so these powerful priest-physicians cure their patients by strong blowing and breathing upon them, accompanied by the singing of songs and by incantations. They are believed to have the power to kill enemies, and to afflict with various diseases. As they are much believed in, these pagés are well paid for their services. They are acquainted with the properties of many poisonous plants. One of their poisons most frequently used is terrible in its effects, causing the tongue and throat, as well as the intestines, to putrefy and rot away, leaving the sufferer to linger in torment for several days.61

Amongst many savage tribes their medicine-men pretend to remove diseases by sucking the affected part of the body. They have previously placed bits of bone, stones, etc., in their mouths, and they pretend they have removed them from the patient, and exhibit them as proofs of their success. The Shaman, or wizard-priest of the religion still existing amongst the peoples of Northern Asia, who pretends to have dealings with good and evil spirits, is the successor of the priests of Accad; thus is the Babylonian religion reduced to the level of the heathenism of Mongolia.