Title: The History of Christianity

Author: John S. C. Abbott

Release date: May 1, 2019 [eBook #59400]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

This book has illustrated drop-caps at the start of each chapter. These illustrations may adversely affect the pronunciation of the word with screen-readers or not display properly in some handheld devices.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and have been accumulated in a table at the end of the text.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book and are identified in the text by a dotted underline and may be seen in a tool-tip by hovering the mouse over the underline.

F. T. Stuart Eng. Boston

I am yours very truly

John S. C. Abbott.

THE

HISTORY

OF

CHRISTIANITY:

CONSISTING OF THE

LIFE AND TEACHINGS OF JESUS OF NAZARETH;

THE

ADVENTURES OF PAUL AND THE APOSTLES;

AND

The Most Interesting Events in the Progress of Christianity,

FROM THE EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE PRESENT TIME.

BY

JOHN S. C. ABBOTT,

AUTHOR OF “THE MOTHER AT HOME,” “LIFE OF NAPOLEON,” “LIFE OF FREDERIC THE GREAT,” ETC.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY B. B. RUSSELL, 55 CORNHILL.

PHILADELPHIA: QUAKER-CITY PUBLISHING-HOUSE.

SAN FRANCISCO: A. L. BANCROFT &

CO.

DETROIT,

MICH.: R. D. S. TYLER.

1872.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872,

By B. B. RUSSELL,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Boston:

Stereotyped and Printed by Rand, Avery, & Co.

TO THE MEMBERS OF

The Second Congregational Church and Society

IN FAIR HAVEN, CONNECTICUT,

This Volume

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

BY THEIR FRIEND AND PASTOR,

JOHN S. C. ABBOTT.

THE author of this volume has for many years, at intervals, been engaged in its preparation. It has long seemed to him very desirable that a brief, comprehensive, and readable narrative of the origin of Christianity, and of its struggles and triumphs, should be prepared, adapted to the masses of the people. There are many ecclesiastical histories written by men of genius and erudition. They are, however, read by few, excepting professional theologians. The writer is not aware that there is any popular history of the extraordinary events involved in the progress of Christianity which can lure the attention of men, even of Christians, whose minds are engrossed by the agitations of busy life.

And yet there is no theme more full of sublime, exciting, and instructive interest. All the heroism which the annals of chivalry record pale into insignificance in presence of the heroism with which the battles of the cross have been fought, and with which Christians, in devotion to the interests of humanity, have met, undaunted, the most terrible doom.

The task is so difficult wisely to select and to compress within a few hundred pages the momentous events connected with Christianity during nearly nineteen centuries, that more than once the writer has been tempted to lay aside his pen in despair. Should this book fail to accomplish the purpose which he prayerfully seeks to attain, he hopes that some one else may be incited to make the attempt who will be more successful.

In writing the life of Jesus, the author has accepted the narratives of the evangelists as authentic and reliable, and has endeavored to give a faithful, and, so far as possible, a chronological account of what Jesus said and did, as he would write of any other distinguished personage. The same principle has guided him in tracing out the career of Paul and the apostles.

It has not been the object of the writer to urge any new views, or to discuss controverted questions of church polity or theology. This is a history of facts, not a philosophical or theological discussion of the principles which these facts may involve. No one, however, can read this narrative without the conviction that the religion of Jesus, notwithstanding the occasional perversions of human depravity or credulity, has remained essentially one and the same during all the centuries. We need no additional revelation. The gospel of Christ is “the power of God and the wisdom of God.” In its propagation lies the only hope of the world. Its universal acceptance will usher in such a day of glory as this world has never witnessed since the flowers of Eden wilted.

JOHN S. C. ABBOTT.

FAIR HAVEN, CONN.

THE BIRTH, CHILDHOOD, AND EARLY MINISTRY, OF JESUS.

The Roman Empire.—Moral Influence of Jesus.—John.—The Annunciation.—The Birth of Jesus.—Visit of the Magi.—Wrath of Herod.—Flight to Egypt.—Return to Nazareth.—Jesus in the Temple.—John the Baptist.—The Temptation.—The First Disciples.—The First Miracle.—Visit to Jerusalem.—Nicodemus.—The Woman of Samaria.—Healing of the Nobleman’s Son.—Visit to Capernaum.—Peter and Andrew called.—James and John called.—The Demoniac healed.—Tour through Galilee.

TOUR THROUGH GALILEE.

The Horns of Hattin.—The Sermon on the Mount.—Jesus goes to Capernaum.—The Miraculous Draught of Fishes.—Healing the Leper; the Paralytic.—Associates with Publicans and Sinners.—The Feast of the Passover.—The Cripple at the Pool.—The Equality of the Son with the Father.—Healing the Withered Hand.—Anger of the Pharisees.—The Twelve Apostles chosen.—Inquiry of John the Baptist.—Jesus dines with a Pharisee.—The Anointment.—Journey through Galilee.—Stilling the Tempest.—The Demoniacs and the Swine.—The Daughter of Jairus.—Restores Sight to the Blind.—Address to his Disciples.

THE TEACHINGS OF JESUS, AND MIRACLES OF HEALING.

Infamy of Herod.—Jesus in the Desert.—Feeds the Five Thousand.—Walks on the Sea.—Preaches to the People.—Visits Tyre and Sidon.—The Syro-Phœnician Woman.—Cures all Manner of Diseases.—Feeds the Four Thousand.—Restores Sight to a Blind Man.—Conversation with Peter.—The Transfiguration.—Cure of the Lunatic.—Dispute of the Apostles.—Law of Forgiveness.—Visits Jerusalem.—Plot to seize Jesus.—The Adulteress.—Jesus the Son of God.—The Blind Man.—Parable of the Good Shepherd.—Raising of Lazarus.

LAST LABORS, AND FAREWELL TO HIS DISCIPLES.

Journey to Jerusalem.—Mission of the Seventy.—Jesus teaches his Disciples to pray.—Lament over Jerusalem.—Return to Galilee.—The Second Coming of Christ.—Dangers of the Rich.—Promise to his Disciples.—Foretells his Death.—Zacchæus.—Mary anoints Jesus.—Enters Jerusalem.—Drives the Traffickers from the Temple.—The Pharisees try to entrap him.—The Destruction of Jerusalem, and the Second Coming.—Judas agrees to betray Jesus.—The Last Supper.—The Prayer of Jesus.

ARREST, TRIAL, AND CRUCIFIXION.

Anguish of Jesus.—His Prayers in the Garden.—The Arrest.—Peter’s Recklessness.—Flight of the Apostles.—Jesus led to Annas; to Caiaphas.—Jesus affirms that he is the Messiah.—Frivolous Accusations.—Peter denies his Lord.—Jesus is conducted to Pilate.—The Examination.—Scourging the Innocent.—Insults and Mockery.—Rage of the Chief Priests and Scribes.—Embarrassment of Pilate.—He surrenders Jesus to his Enemies.—The Crucifixion.—The Resurrection.—Repeated Appearance to his Disciples.

THE CONVERSION AND MINISTRY OF SAUL OF TARSUS.

The Baptism of the Holy Ghost.—Boldness of the Apostles.—Anger of the Rulers.—Martyrdom of Stephen.—Baptism of the Eunuch.—Saul’s Journey to Damascus.—His Conversion.—The Disciples fear him.—His Escape from the City.—Saul in Jerusalem.—His Commission to the Gentiles.—The Conversion of Cornelius.—The Vision of Peter.—Persecution of the Disciples.—Imprisonment of Peter.—Saul and Barnabas in Antioch.—Punishment of Elymas.—Missionary Tour.—Incidents and Results.

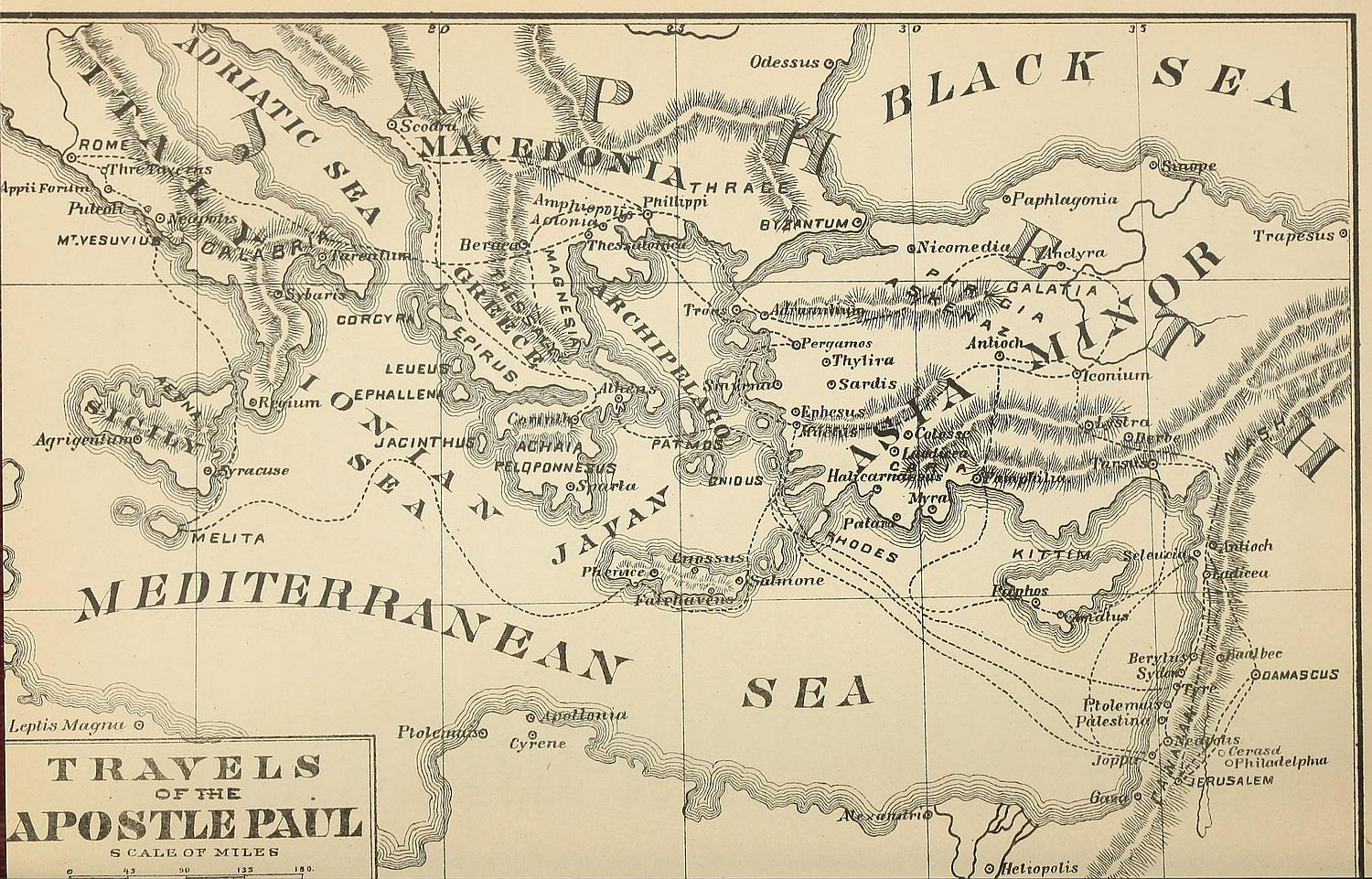

MISSIONARY ADVENTURES.

The First Controversy.—Views of the Two Parties.—Council at Jerusalem.—Results of Council.—The Letter.—Vacillation of Peter.—Rebuked by Paul.—The Missionary Excursion of Paul and Barnabas.—They traverse the Island of Cyprus.—Land on the Coast of Asia Minor.—Mark returns to Syria.—Results of this Tour.—Paul and Silas set out on a Second Tour through Asia Minor.—Cross the Hellespont.—Introduction of Christianity to Europe.—Heroism of Paul at Philippi.—Tour through Macedonia and Greece.—Character of Paul’s Preaching.—Peter’s Description of the Final Conflagration.—False Charges.—Paul in Athens; in Corinth.—Return to Jerusalem.

THE CAPTIVE IN CHAINS.

The Third Missionary Tour.—Paul at Ephesus.—The Great Tumult.—The Voyage to Greece.—Return to Asia Minor and to Jerusalem.—His Reception at Jerusalem.—His Arrest, and the Riot.—Speech to the Mob.—Paul imprisoned.—Danger of Assassination.—Transferred to Cæsarea.—His Defence before Festus and Agrippa.—The Appeal to Cæsar.—The Voyage to Rome.—The Shipwreck.—Continued Captivity.

THE FIRST PERSECUTION.

The Population of Rome.—The Reign of Tiberius Cæsar.—His Character and Death.—The Proposal to deify Jesus.—Caligula.—His Crimes, and the Earthly Retribution.—Nero and his Career.—His Crimes and Death.—The Spirit of the Gospel.—Sufferings of the Christians.—Testimony of Tacitus.—Testimony of Chrysostom.—Panic in Rome.—The Sins and Sorrows of weary Centuries.—Noble Sentiments of the Bishop of Rome.

ROMAN EMPERORS, GOOD AND BAD.

Character of the Roman Army.—Conspiracy of Otho.—Death of Galba.—Vitellius Emperor.—Revolt of the Jews, and Destruction of Jerusalem.—Reign of Vespasian.—Character of Titus; of Domitian.—Religion of Pagan Rome.—Nerva.—Anecdotes of St. John.—Exploits of Trajan.—Letter of Pliny.—Letter of Trajan.

MARTYRDOM.

The Martyrdom of Ignatius.—Death of Trajan.—Succession of Adrian.—Infidel Assaults.—Celsus.—The Apology of Quadrat.—The Martyrdom of Symphorose and her Sons.—Character and Death of Adrian.—Antoninus.—Conversion of Justin Martyr.—His Apology.—Marcus Aurelius.—Hostility of the Populace.—The Martyrdom of Polycarp.

PAGAN ROME.

Infamy of Commodus.—His Death.—The Reign of Pertinax.—The Mob of Soldiers.—Death of Pertinax.—Julian purchases the Crown.—Rival Claimants.—Severus.—Persecutions.—Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicitas.—The Reign of Caracalla.—Fiendlike Atrocities.—Elagabalus, Priest of the Sun.—Death by the Mob.—Alexander and his Mother.—Contrast between Paganism and Christianity.—The Sin of Unbelief.

SIN AND MISERY.

Maximin the Goth.—Brutal Assassination of Alexander.—Merciless Proscription.—Revolt of the Army on the Danube.—Rage of Maximin.—His March upon Rome.—Consternation in the Capital.—Assassination of Maximin.—Successors to the Throne.—Popular Suffrage unavailing.—Persecution under Decius.—Individual Cases.—Extent of the Roman Empire.—Extent of the Persecution.—Heroism of the Christians.

INVASION, CIVIL WAR, AND UNRELENTING PERSECUTION.

Æmilianus and Valerian.—Barbaric Hordes.—Slavery and its Retribution.—Awful Fate of Valerian.—Ruin of the Roman Empire.—Zenobia and her Captivity.—The Slave Diocletian becomes Emperor.—His Reign, Abdication, Death.—Division of the Empire.—Terrible Persecution.—The Glory of Christianity.—Characteristics of the First Three Centuries.—Abasement of Rome.

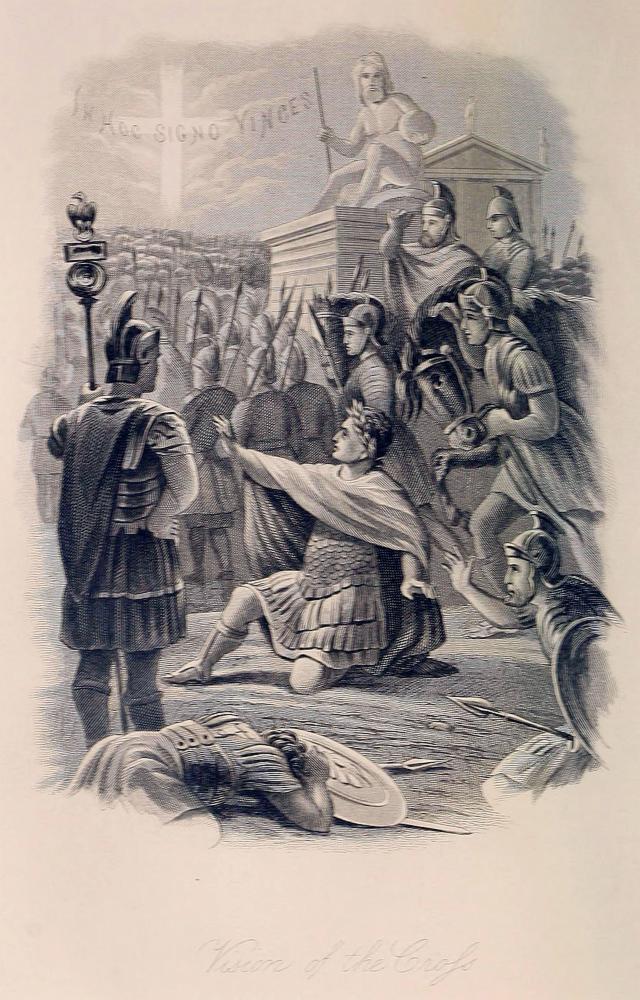

CONSTANTINE.—THE BANNER OF THE CROSS UNFURLED.

Helena, the Christian Empress.—Constantine, her Son, favors the Christians.—Crumbling of the Empire.—Constantine the Christian, and Maxentius the Pagan.—Vision of Constantine.—The Unfurled Cross.—Christianity favored by the Court.—Licinius defends the Christians.—Writings of Eusebius.—Apostasy of Licinius.—Cruel Persecution.

THE CONVERSION OF CONSTANTINE.

The Arian Controversy.—Sanguinary Conflict between Paganism and Christianity.—Founding of Constantinople.—The Council of Nice.—Its Decision.—Duplicity of some of the Arians.—The Nicene Creed.—Tragic Scene in the Life of Constantine.—His Penitence and true Conversion.—His Baptism, and Reception into the Church.—Charles V.—The Emperor Napoleon I.

JULIAN THE APOSTATE.

The Devotion of Constantine to Christianity.—Constantius and the Barbarians.—Conspiracy of Magnentius.—The Decisive Battle.—Decay of Rome.—Fearful Retribution.—Noble Sentiments of the Bishop of Alexandria.—Death of Constantius.—Gallus and Julian.—Julian enthroned.—His Apostasy.—His Warfare against Christianity.—Unavailing Attempt to rebuild Jerusalem.—Persecution.—His Expedition to the East, and Painful Death.

THE IMMEDIATE SUCCESSORS OF JULIAN.

Anecdote.—Accession of Jovian.—His Character.—Christianity reinstated.—Death of Jovian.—Recall of Athanasius.—Wide Condemnation of Arianism.—Heroism of Jovian.—Valentinian and Valens.—Valentinian enthroned.—Valens in the East.—Barbarian Irruptions.—Reign of Theodosius.—Aspect of the Barbarians.—Rome captured by Alaric.—Character of Alaric.—His Death and Burial.—Remarkable Statement of Adolphus.—Attila the Hun.—Valentinian III.—Acadius.—Eloquence of Chrysostom.—His Banishment and Death.—Rise of Monasticism.

THE FIFTH CENTURY.

Christianity the only Possible Religion.—Adventures of Placidia.—Her Marriage with Adolphus the Goth.—Scenes of Violence and Crime.—Attila the Hun.—Nuptials of Idaho.—Eudoxia and her Fate.—Triumph of Odoacer the Goth.—Character of the Roman Nobles.—Conquests of Theodoric.—John Chrysostom.—The Origin of Monasticism.—Augustine.—His Dissipation, Conversion, and Christian Career.

CENTURIES OF WAR AND WOE.

Convulsions of the Sixth Century.—Corruption of the Church.—The Rise of Monasteries.—Rivalry between Rome and Constantinople.—Mohammed and his Career.—His Personal Appearance.—His System of Religion.—His Death.—Military Expeditions of the Moslems.—The Threatened Conquest of Europe.—Capture of Alexandria.—Burning of the Library.—Rise of the Feudal System.—Charlemagne.—Barbarian Antagonism to Christianity.

THE DARK AGES.

The Anticipated Second Coming of Christ.—State of the World in the Tenth Century.—Enduring Architecture.—Power of the Papacy.—Vitality of the Christian Religion.—The Pope and the Patriarch.—Intolerance of Hildebrand.—Humiliation of the Emperor Henry IV.—Farewell Letter of Monomaque.—The Crusades.—Vladimir of Russia.—His Introduction of Christianity to his Realms.—Marriage with the Christian Princess Anne.—Extirpation of Paganism.—The Baptism.—The Spiritual Conversion of Vladimir.

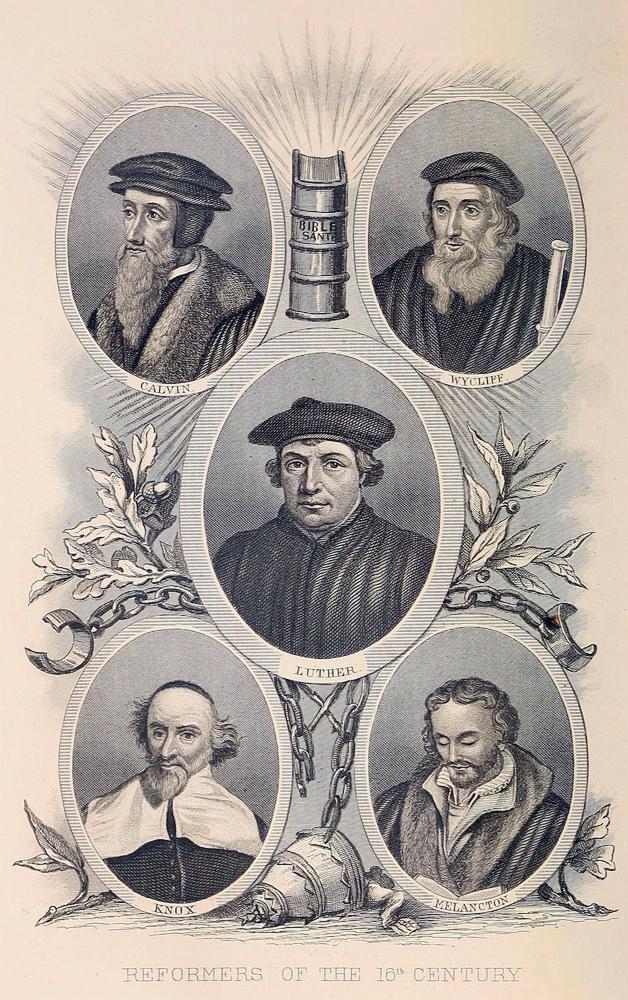

THE REFORMATION.

Two Aspects of Catholicism.—Jubilee at Rome.—Infamy of Philip of France.—Banditti Bishops.—Sale of Indulgences.—Tetzel the Peddler.—The Rise of Protestantism.—Luther and the Diet at Worms.—Intolerance of Charles V.—Civil War and its Reverses.—Perfidy of Charles V.—Coalition against the Protestants.—Abdication and Death.

THE MASSACRE OF ST. BARTHOLOMEW.

Principles of the two Parties.—Ferdinand’s Appeal to the Pope.—The Celibacy of the Clergy.—Maximilian.—His Protection of the Protestants.—The Reformation in France.—Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre.—Proposed Marriage of Henry of Navarre and Marguerite of France.—Perfidy of Catharine de Medici.—The Nuptials.—The Massacre of St. Bartholomew.—Details of its Horrors.—Indignation of Protestant Europe.—Death of Charles IX.

THE CHURCH IN MODERN TIMES.

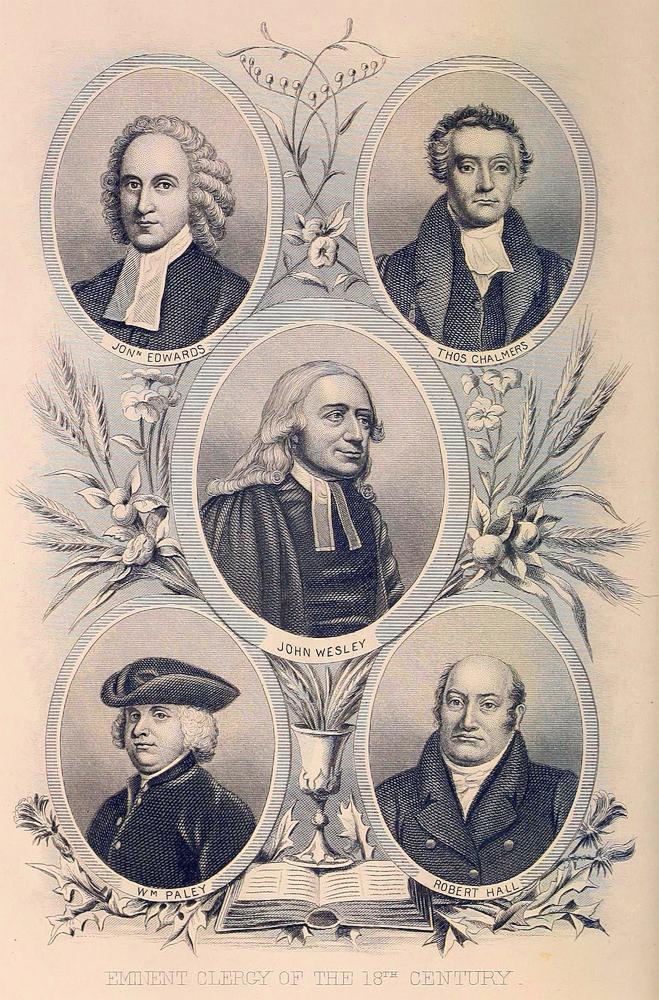

Character of Henry III.—Assassination of the Duke of Guise.—Cruel Edicts of Louis XIV.—Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.—Sufferings of Protestants.—Important Question.—Thomas Chalmers.—Experiment at St. John.—His Labors and Death.—Jonathan Edwards.—His Resolutions.—His Marriage.—His Trials.—His Death.—John Wesley.—His Conversion.—George Whitefield.—First Methodist Conference.—Death of Wesley.—Robert Hall.—His Character and Death.—William Paley.—His Works and Death.—The Sabbath.—Power of the Gospel.—Socrates.—Scene on the Prairie.—The Bible.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS, AND MAPS.

HISTORY OF CHRISTIANITY.

The Roman Empire.—Moral Influence of Jesus.—John.—The Annunciation.—The Birth of Jesus.—Visit of the Magi.—Wrath of Herod.—Flight to Egypt.—Return to Nazareth.—Jesus in the Temple.—John the Baptist.—The Temptation.—The First Disciples.—The First Miracle.—Visit to Jerusalem.—Nicodemus.—The Woman of Samaria.—Healing of the Nobleman’s Son.—Visit to Capernaum.—Peter and Andrew called.—James and John called.—The Demoniac healed.—Tour through Galilee.

O one now takes much interest in the history of the world before the coming of Christ. The old dynasties of Babylon, Media, Assyria, are but dim spectres lost in the remoteness of the long-forgotten past. Though the Christian lingers with solemn pleasure over the faintly-revealed scenes of patriarchal life, still he feels but little personal interest in the gorgeous empires which rise and disappear before him in those remote times, in spectral vision, like the genii of an Arabian tale.

Thebes, Palmyra, Nineveh,—palatial mansions once lined their streets, and pride and opulence thronged their dwellings: but their ruins have faded away, their rocky sepulchres are swept clean by the winds of centuries; and none but a few antiquarians now care to know of their prosperity or adversity, of their pristine grandeur or their present decay.

All this is changed since the coming of Christ. Eighteen centuries ago a babe was born in the stable of an inn, in the Roman province of Judæa. The life of that babe has stamped a new impress upon the history of the world. When the child Jesus was born, all the then known nations of the earth were in subjection to one government,—that of Rome.

The Atlantic Ocean was an unexplored sea, whose depths no mariner ever ventured to penetrate. The Indies had but a shadowy and almost fabulous existence. Rumor said, that over the wild, unexplored wastes of interior Asia, fierce tribes wandered, sweeping to and fro, like demons of darkness; and marvellous stories were told of their monstrous aspect and fiendlike ferocity.

The Mediterranean Sea, then the largest body of water really known upon the globe, was but a Roman lake. It was the central portion of the Roman Empire. Around its shores were clustered the thronged provinces and the majestic cities which gave Rome celebrity above all previous dynasties, and which invested the empire of the Cæsars with fame that no modern kingdom, empire, or republic, has been able to eclipse.

A few years before the birth of Christ, Julius Cæsar perished in the senate-chamber at Rome, pierced by the daggers of Brutus and other assassins. At the great victory of Pharsalia, Cæsar had struck down his only rival Pompey, and had concentrated the power of the world in his single hand. His nephew Octavius, the second Cæsar, surnamed Augustus, or the August, was, at the time Jesus was born, the monarch of the world. Notwithstanding a few nominal restraints, he was an absolute sovereign, without any constitutional checks. It is not too much to say, that his power was unlimited. He could do what he pleased with the property, the liberty, and the lives of every man, woman, and child of more than three hundred millions composing the Roman Empire. Such power no mortal had ever swayed before. Such power no mortal will ever sway again.

Fortunately for humanity, Octavius Cæsar was, in the main, a good man. He merited the epithet of August. Though many of the vices of paganism soiled his character, still, in accordance with the dim light of those dark days, he endeavored to wield his immense power in promotion of the welfare of his people.

Little did this Roman emperor imagine, as he sat enthroned in his gorgeous palace upon the Capitoline Hill, that a babe slumbering in a manger at Bethlehem, an obscure hamlet in the remote province of Syria, and whose infant wailings perhaps blended with the bleating of the goat or the lowing of the kine, was to establish an empire, before which all the power of the Cæsars was to dwindle into insignificance.

But so it was. Jesus, the babe of Bethlehem, has become, beyond all others, whether philosophers, warriors, or kings, the most conspicuous being who ever trod this globe. Before the name of Jesus of Nazareth all others fade away. Uneducated, he has introduced principles which have overthrown the proudest systems of ancient philosophy. By the utterance of a few words, all of which can be written on half a dozen pages, he has demolished all the pagan systems which pride and passion and power had then enthroned. The Roman gods and goddesses—Jupiter, Juno, Venus, Bacchus, Diana—have fled before the approach of the religion of Jesus, as fabled spectres vanish before the dawn.

Jesus, the “Son of man” and the “Son of God,” has introduced a system of religion so comprehensive, that it is adapted to every conceivable situation in life; so simple, that the most unlearned, and even children, can comprehend it.

This babe of Bethlehem, whose words were so few, whose brief life was so soon ended, and whose sacrificial death upon the cross was so wonderful, though dead, still lives and reigns in this world,—a monarch more influential than any other, or all other sovereigns upon the globe. His empire has advanced majestically, with ever-increasing power, down the path of eighteen centuries; and few will doubt that it is destined to take possession of the whole world.

The Cæsars have perished, and their palaces are in ruins. The empire of Charlemagne has risen, like one of those gorgeous clouds we often admire, brilliant with the radiance of the setting sun; and, like that cloud, it has vanished forever. Charles V. has marshalled the armies of Europe around his throne, and has almost rivalled the Cæsars in the majesty of his sway; and, like a dream, the vision of his universal empire has fled.

But the kingdom of Jesus has survived all these wrecks of empires. Without a palace or a court, without a bayonet or a sabre, without any emoluments of rank or wealth or power offered by Jesus to his subjects, his kingdom has advanced steadily, resistlessly, increasing in strength every hour, crushing all opposition, triumphing over all time’s changes; so that, at the present moment, the kingdom of Jesus is a stronger kingdom, more potent in all the elements of influence over the human heart, than all the other governments of the earth.

There is not a man upon this globe who would now lay down his life from love for any one of the numerous monarchs of Rome; but there are millions who would go joyfully to the dungeon or the stake from love for that Jesus who commenced his earthly career in the manger of a country inn, whose whole life was but a scene of poverty and suffering, and who finally perished upon the cross in the endurance of a cruel death with malefactors.

As this child, from the period of whose birth time itself is now dated, was passing through the season of infancy and childhood, naval fleets swept the Mediterranean Sea, and Roman legions trampled bloodily over subjugated provinces. There were conflagrations of cities, ravages of fields, fierce battles, slaughter, misery, death. Nearly all these events are now forgotten; but the name of Jesus of Nazareth grows more lustrous as the ages roll on.

The events which preceded the birth of Jesus cannot be better described than in the language of the inspired writers:—

“There was in the days of Herod, the king of Judæa, a certain priest named Zacharias, of the course of Abia; and his wife was of the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elisabeth. And they were both righteous before God, walking in all the commandments and ordinances of the Lord blameless. And they had no child, because Elisabeth was barren; and they both were now well stricken in years. And it came to pass, that while he executed the priest’s office before God in the order of his course, according to the custom of the priest’s office, his lot was to burn incense when he went into the temple of the Lord; and the whole multitude of the people were praying without at the time of incense.

“And there appeared unto him an angel of the Lord, standing on the right side of the altar of incense. And, when Zacharias saw him, he was troubled, and fear fell upon him. But the angel said unto him, Fear not, Zacharias: for thy prayer is heard; and thy wife Elisabeth shall bear thee a son, and thou shalt call his name John. And thou shalt have joy and gladness, and many shall rejoice at his birth. For he shall be great in the sight of the Lord, and shall drink neither wine nor strong drink; and he shall be filled with the Holy Ghost even from his mother’s womb. And many of the children of Israel shall he turn to the Lord their God. And he shall go before him in the spirit and power of Elias, to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the disobedient to the wisdom of the just; to make ready a people prepared for the Lord.

“And Zacharias said unto the angel, Whereby shall I know this? for I am an old man, and my wife well stricken in years.

“And the angel, answering, said unto him, I am Gabriel, that stand in the presence of God, and am sent to speak unto thee, and to show thee these glad tidings. And, behold, thou shalt be dumb, and not able to speak, until the day that these things shall be performed, because thou believest not my words, which shall be fulfilled in their season.

“And the people waited for Zacharias, and marvelled that he tarried so long in the temple. And, when he came out, he could not speak unto them. And they perceived that he had seen a vision in the temple; for he beckoned unto them, and remained speechless. And it came to pass, that, as soon as the days of his ministration were accomplished, he departed to his own house. And, after those days, his wife Elisabeth conceived, and hid herself five months, saying, Thus hath the Lord dealt with me in the days wherein he looked on me to take away my reproach among men.

“And in the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favored; the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women. And, when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. And the angel said unto her,

“Fear not, Mary; for thou hast found favor with God. And, behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son; and thou shalt call his name JESUS. He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David; and he shall reign over the house of Jacob forever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end.

“Then said Mary unto the angel, How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?

“And the angel answered and said unto her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore, also, that holy thing that shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God. And, behold, thy cousin Elisabeth, she hath also conceived a son in her old age; and this is the sixth month with her who was called barren. For with God nothing shall be impossible.

“And Mary said, Behold the handmaid of the Lord: be it unto me according to thy word. And the angel departed from her.”1

Elisabeth was at that time residing in what was called the “hill-country” of Judæa, several miles south of Jerusalem. Mary was in Galilee, the extreme northern part of Palestine. “And Mary arose in those days, and went into the hill-country with haste, into a city of Juda; and entered into the house of Zacharias, and saluted Elisabeth. And it came to pass, that, when Elisabeth heard the salutation of Mary, the babe leaped in her womb; and Elisabeth was filled with the Holy Ghost; and she spake out with a loud voice, and said,

“Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. And whence is this to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me? for, lo! as soon as the voice of thy salutation sounded in mine ears, the babe leaped in my womb for joy. And blessed is she that believed; for there shall be a performance of those things which were told her from the Lord.

“And Mary said, My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour. For he hath regarded the low estate of his handmaiden; for, behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is his name. And his mercy is on them that fear him from generation to generation. He hath showed strength with his arms; he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree. He hath filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he hath sent empty away. He hath holpen his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy; as he spake to our fathers, to Abraham, and to his seed forever.”

“Now, the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When as his mother Mary was espoused to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost. Then Joseph her husband, being a just man, and not willing to make her a public example, was minded to put her away privily. But, while he thought on these things, behold, the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream, saying, Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife; for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost. And she shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his name JESUS; for he shall save his people from their sins.

“Now, all this was done that it might be fulfilled which was spoken of the Lord by the prophet, saying, Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel; which, being interpreted, is God with us.2

“Then Joseph, being raised from sleep, did as the angel of the Lord had bidden him, and took unto him his wife; and knew her not till she had brought forth her first-born son.”

Mary, upon her visit to Elisabeth, remained with her about three months, and then returned to Nazareth. Upon the birth of John, he was taken on the eighth day to be circumcised. His father, who still remained dumb, wrote that he should be called John. To the surprise of his friends, speech was then restored to him. These remarkable events were extensively noised abroad. “And all they that heard them laid them up in their hearts, saying, What manner of child shall this be?”

In the year of Rome 450, the Emperor Cæsar Augustus ordered a general census of the population of Palestine to be taken, that he might, with exactitude, know the resources of the province. The Jewish custom had long been, that a man should be registered in his birthplace instead of that of his residence. During the months of January and February of that year, all the narrow pathways of Judæa were crowded by cavalcades of those who were seeking their native places to be registered according to this decree.

Among these lowly pilgrims there were two, Joseph and Mary, from the obscure village of Nazareth. Toiling along through the ravines of Galilee, over the plains of Samaria, and across the hill-country of Judæa, they continued their journey, until, at the end of the fourth day, they entered the little village of Bethlehem, about five miles south of Jerusalem.

So many travellers had entered the village before them, that there was no room left in the inn. Perhaps even the stable might have been refused, had not the woman’s condition appealed to the heart of the inn-keeper. But there she and her husband found a place to rest.

Outside of the village stretched the plains, where, hundreds of years before, David watched his father’s flocks. On the same hill-slopes shepherds tended their sheep still. It was apparently a serene and cloudless night. Suddenly there appeared in the heavens, descending from amidst the stars, the form of an angel. The simple-minded shepherds gazed upon the wonderful spectacle with alarm. The angel, radiant with heaven’s light, addressed them, saying,—

“Fear not; for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day, in the city of David, a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you: Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling-clothes, lying in a manger.”

As these words were uttered, the babe was born; and immediately there appeared a vast multitude of the heavenly host,—the retinue which had accompanied the celestial visitant from heaven to earth. Such a band never before met mortal eyes. With simultaneous voice they sang, while the melody floated over the silent hills, “Glory to God in the highest; and on earth peace, good-will toward men.”

The voice of prophecy had announced, ages before, that the long-expected Messiah should be born in Bethlehem. Seven hundred years had passed since the prophet Micah wrote,—

“And thou Bethlehem, in the land of Juda, art not the least among the princes of Juda; for out of thee shall come a Governor that shall rule my people Israel.”3

The angels disappeared, and the heavenly depths resumed their accustomed calm. But the scene and the words sank deep into the hearts of the shepherds, who believed without questioning this wonderful announcement. The time foretold by the prophets—had it truly come? Was the long watching of the true-hearted Jew really at an end?

Making haste in the eagerness of their hope, the shepherds went to Bethlehem, and found Mary, Joseph, and the babe lying in the manger. Having this corroboration of the angels’ words, they told to all whom they met the marvellous scene which they had witnessed. All wondered; for it was not thus that they had expected the Messiah to come. But Mary, the mother, kept all these things, and pondered them in her heart.

Although the birth of Jesus was thus heralded by a choir of angels, it seems not to have been universally recognized that the Messiah had come. The evidence is abundant, from passages taken from both Roman and Jewish writers, that there was a general expectation at the time, throughout the East, that some one was soon to be born in Judæa who would rule the world. The ideas prevailing respecting the nature of his reign were extremely vague. Tacitus, Suetonius, Zoroaster, all allude to this coming man, whose advent had been so minutely foretold in the sacred writings of the Jews.

The Persian priests, or Magi, were among the most learned men of those times. Whatever of science then was known was inseparably blended with religion. Astrology and astronomy were kindred studies. The Persian Magi were surprised by the appearance of a star, or meteor, of wonderful brilliancy. They interpreted it as a sign that the long-expected Messiah was born. As they approached the meteor, it moved before them. A deputation of their number was appointed to follow it. It led them to Judæa. They then began eagerly to inquire where the child was born. Herod the king heard these strange tidings. He trembled from fear that this prophetically-announced Messiah would assume kingly power, and eject him from his throne. In great anxiety he sent for the most approved interpreters of the Bible, and inquired of them if the prophets had announced the place in which the Messiah should be born. They replied that the place was Bethlehem, citing in proof the prediction of the prophet Micah. Herod, having determined to take the life of the child, called the Magi before him, and directed them to go immediately to Bethlehem, and, as soon as they had found the young child, to report to him, saying that he wished to worship him also.

The meteor, which had led them from the plains of Persia, and which had perhaps, for a time, vanished, re-appeared, and went before them till it came and stood over where the young child was. After paying the divine babe the tribute of their homage and adoration, instead of returning to Herod with the information, admonished by God, they departed by an unfrequented route to their own country.

The infamous king, thus baffled, in his rage sent officers to put to death all the children in the city of Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years of age and under. He supposed that in that number the infant Jesus would surely be included. But Joseph, warned by God in a dream, escaped by night with Mary and the babe into Egypt, about forty miles south of Bethlehem. There the holy family remained for several months, until the wretched Herod died, devoured by a terrible disease. But, as his son Archelaus ascended the throne vacated by Herod, Joseph did not deem it safe to return to Judæa, but, by a circuitous route, found his way back to the obscure hamlet of Nazareth, buried among the mountains of Galilee. Here, we are informed, “the child grew, and waxed strong in spirit, filled with wisdom; and the grace of God was upon him.”

Before the flight into Egypt, all the ceremonies enjoined by the Mosaic law upon the birth of a child of Jewish parents were strictly observed. At the presentation of the babe in the temple, the aged Simeon, then the officiating priest, recognized him as the long-looked-for Messiah. Anna too, the prophetess, gave thanks to the Lord for him.

After these scenes, a veil is dropped over the child-life of Jesus. It is lifted but once, when, at the age of twelve, the child attended his parents to Jerusalem. Being separated from Joseph and Mary in the crowd, they sought anxiously for him, and found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, hearing them, and asking them questions. All who heard the questions and the answers of the child were amazed at his wisdom. To the tender reproof of his mother, he answered as though the meaning of his life were just beginning to dawn upon him: “How is it that ye sought me? Wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?”

His parents did not understand him; but he returned with them to Nazareth. Here among the hills of Galilee, in a village so obscure that its name is not mentioned in the Old Testament, the youthful years of Jesus passed unnoticed away until he had attained the age of thirty. According to the Jewish law, a man could not take upon himself priestly duties until he was thirty years old. Not until then was he considered to have obtained that maturity of character which would warrant him in assuming the office of a teacher, or which would enable him to realize the sacredness of the priestly calling. No record of these years is given us, save that contained in the declaration, “And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favor with God and man.”

John the Baptist, forerunner of Jesus, seems to have passed through very different youthful discipline from that of Him whom he was to herald. Jesus spent his childhood and early manhood, so far as we are informed, in the seclusion of that domestic life which is common to man. Nurtured in its sweet simplicity, he learned from experience the trials and cares of humanity in its lowliest condition.

John, forsaking these tranquil scenes of domestic life, fled into the desert, and, in the most dreary solitudes, prepared for his momentous ministry. The last of the prophets, “greater was not born of women than he.” The place he chose for his preparation was one of desolate grandeur. The borders of the desert reached the barren, verdureless banks of the Dead Sea. All signs of life were lost in a region apparently cursed by the frown of God. The heavy waters of the lake lay motionless, and the mountains of Moab rose beyond in their severe and rugged sublimity.

Yet here John dwelt, that he might ponder the meaning of the Scripture prophecies, so as to be able to expound them with power when the time should come for him to address the people. Here he was impressed with the enormity of sin against God, and the hopelessness of the sinner, unless a higher power came to his rescue. Here God revealed to his soul the doctrine of repentance and remission of sins through faith in an atoning Saviour,—“the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world,”—the Lamb so often slain in symbolic sacrifice, but now to appear and suffer in his own sacred person.

When the time of preparation was completed, the word of God came to John, summoning him to his work. Emerging from his life of solitude, he traversed all the country round about Jordan, crying out in trumpet-tones, which collected thousands to listen to him, “Repent ye; for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” The new prophet, humble in his own soul, as the truly great always are, disclaimed all title to the Messiahship, declaring that One was coming mightier than he, the latchet of whose shoes he was unworthy to unloose. When the multitude, impressed by his figure, his character, and his words, inquired of him, “Art thou the Christ?” he replied emphatically, “I am not.”—“Art thou Elias, then?” was the continued query. The reply was equally emphatic, “No.”—“Who art thou, then?” they further inquired. He replied, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord; make his paths straight.”

A leathern girdle encircled the loins of this wonderful man. His frugal fare consisted of locusts and wild honey. John stood by the River Jordan, baptizing those who presented themselves for the rite. Jesus, then about thirty years of age, appeared among them. Since his twelfth year, no act of his had been recorded. But now, according to the Jewish idea of maturity, he was prepared to enter upon his ministry. John doubtless had not seen him for many years. Probably he had never known that he was the Christ. But, when that pure and holy One came to be baptized, the eyes of the prophet were opened, and he hesitated, saying, “I have need to be baptized of thee; and comest thou to me?” But Jesus commands, and John performs the rite. Then the faithful prophet is rewarded by seeing the heavens opened, and the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and lighting upon the brow of Jesus. A voice at the same time was heard from the serene skies, exclaiming in clear utterance, “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”

Then John was filled with fulness of assured joy, as he says, “I knew him not;” meaning, of course, that, before the performance of the rite, he had not known Jesus as the Messiah. The following day, John pointed out Jesus to two of his disciples as the “Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world.”

Soon after this came the period of our Lord’s temptation, over which our hearts are moved with wonder and tender compassion. Son of God as he was in his spiritual nature, in the humiliation of his earthly mission he had also become Son of man. Sinless from his birth, the taint of evil had never touched his pure soul. Yet a higher nature than even this was necessary before he could redeem the people from their sins. There was needed in his human nature a knowledge of the power of evil, which could only be obtained through suffering its temptations.

How else could he truly sympathize with and succor those who are tempted? Oh holy mystery of the temptation of the Son of God!—a mystery so sacred and unfathomable, that we can only bow our hearts in adoration, knowing that we have now a high priest who can be touched with the feeling of our infirmities,—one who “was in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin.”

It is impossible to ascertain with certainty the chronology of our Saviour’s movements. But, following that which is generally most approved, we infer that Jesus returned from the temptation in the wilderness to Nazareth, where he sojourned for a short time. John had publicly announced Jesus to be the Messiah, in the words, “Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world!” Jesus was thus declared to be the atoning Lamb, which for so many centuries had been represented by the sacrifices offered under the law.

Among the crowd who had flocked to the wilderness to hear the impassioned preaching of John there were two fishermen, who became convinced that Jesus was the long-promised Christ. The first of these, Andrew, hastened to inform his brother Simon Peter that he had found the Messiah. These two were apparently our Saviour’s first disciples. Probably their views of the nature of his mission were exceedingly vague. They, however, attached themselves to his person, and followed him. Jesus received them kindly, but without any parade. At the first glance he seems to have comprehended the marked character of Simon Peter; for he addressed him in language in some degree prophetic of his future career: “Thou art Simon, the son of Jona: thou shalt be called Cephas; which is, by interpretation, a stone.” Cephas was the Syriac for Peter.

Jesus.

BOSTON: B. B. RUSSELL.

The next day two others attached themselves to Jesus,—Philip and Nathanael. Then, as now, the moment one became a disciple of Jesus, he was anxious to lead others to him. Philip, who had accepted the invitation of Christ to follow him, sought out one of his friends, Nathanael, and said to him, “We have found him of whom Moses in the law, and the prophets, did write, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.” Nathanael was a little doubtful whether the son of the carpenter Joseph, from the obscure hamlet of Nazareth, could be the heaven-commissioned Messiah for whose advent the pious Jews had been praying during weary centuries. Incredulously he inquired, “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” The laconic reply of Philip was, “Come and see.”

It appears that Nathanael was a man remarkable for his upright and noble character. As Jesus saw him approaching, he said to those around him, “Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!” Nathanael, overhearing the remark, inquired of him, “Whence knowest thou me?” The reply of Jesus, “Before that Philip called thee, when thou wast under the fig-tree, I saw thee,”—thus alluding to some secret event which Nathanael was sure no mortal could know,—convinced him of the supernatural powers of Jesus; and he exclaimed in fulness of faith, “Rabbi, thou art the Son of God; thou art the King of Israel!”

The reply of Jesus was a distinct avowal of his Messiahship: “Because I said unto thee, I saw thee under the fig-tree, believest thou? Thou shalt see greater things than these. Hereafter ye shall see heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of man.”

Jesus, strengthened, not exhausted, by his temptation in the wilderness, returned to Nazareth. In the mystery of his double nature as Son of God and Son of man, the mission of his life seems now to have been fully revealed to him. He then commenced preaching his gospel of penitence for sin, faith in him as a Saviour, and a holy life.

Not with words of denunciation did he open his ministry. Tenderly he bore with the doubts and questionings, which led many to hesitate to acknowledge him as the long-looked-for Messiah. Sympathy and healing for body and soul were the first messages of our Lord. The hard, stern outlines of the Jewish law were softened, yes, glorified, by the spiritual meaning infused into them by Jesus. Sent to preach the gospel to the poor, and to bind up the broken-hearted, he addressed the desponding in words of encouragement and cheer, while he did not abate one iota of the integrity and authority of the law.

A few miles north of Nazareth, slumbering among the hills of Galilee, was the little village of Cana. A marriage was celebrated there on the third day after the return of Jesus from the wilderness. He was invited to the wedding, with his mother and the disciples who had accompanied him to Nazareth. The fame of Jesus was rapidly extending, and the knowledge of his expected presence probably drew an unexpected number to the wedding. Consequently, the wine, simple juice of the grape, usually provided on such occasions, was found to be insufficient. The mother of Jesus informed him with some solicitude that the wine was falling short. It would appear that he had anticipated this; for his reply, “What have I to do with thee? mine hour is not yet come,” may be interpreted, “It is not necessary for you, mother, to be anxious about this: the time for me to interpose is not yet come.” That time soon came,—probably when the wine was entirely exhausted. The anxious, care-taking mother understood this to mean that he would, at the proper time, provide for the emergency; for she went to the servants, and requested them to do whatever Jesus should ask of them.

In the court-yard there were six stone firkins, or jars, about two-thirds the size of an ordinary barrel, containing about thirty gallons each. Jesus ordered the servants to fill them with water. Surprised, but unhesitatingly they obeyed. He then directed them to draw from those firkins, and present first to the governor of the feast. To their amazement, pure wine filled their goblets,—wine which the governor of the feast declared to be of remarkable excellence. This was the first miracle which is recorded of our Saviour. There is no evidence that there was the slightest intoxicating quality in this pure beverage thus prepared for the wedding-guests.

Soon after this, Jesus went to Capernaum, a thriving seaport town upon the western shores of the Lake of Galilee, about twelve miles north-east of Nazareth. His mother, his brothers,—who did not accept his Messiahship,—and his disciples,—we know not how many in number,—accompanied him. We have no record of his doings during the few days that he remained there. As the feast of the Passover was at hand, Jesus went up to Jerusalem, there to inaugurate his ministry in the midst of the thousands whom the sacred festival would summon to the metropolis. A few of his disciples accompanied him. Their journey was undoubtedly made on foot, a distance of about a hundred miles.

Upon their arrival, Jesus directed his steps immediately to the temple, probably then the most imposing structure in the world. The sight which met his view as he entered the outer court-yard of the temple with his humble Galilean followers excited his indignation. The sacred edifice had been perverted to the most shameful purposes of traffic. The booths of the traders lined its walls. The bleating of sheep and the lowing of oxen resounded through its enclosures. The litter of the stable covered its tessellated floors, and the tables of money-changers stood by the side of the magnificent marble pillars. The din of traffic filled that edifice which was erected for the worship of God.

Jesus, in the simple garb of a Galilean peasant, and without any badge of authority, enters this tumultuous throng. Picking up from the floor a few of the twigs, or rushes, he bound them together; and, with voice and gesture of authority whose supernatural power no man could resist, “he drove them all out of the temple, and the sheep and the oxen; and poured out the changers’ money, and overthrew the tables; and said unto them that sold doves, Take these things hence: make not my Father’s house a house of merchandise.”

No one ventured any resistance. The temple was cleared of its abominations. There must have been a more than human presence in the eye and voice of this Galilean peasant, to enable him thus, in the proud metropolis of Judæa, to drive the traffickers from all nations in a panic before him, while invested with no governmental power, and his only weapon consisting of a handful of rushes; for this seems to be the proper meaning of the words translated “a whip of small cords.”

The temple being thus cleared, some of the people ventured to ask of him by what authority he performed such an act. His extraordinary reply was, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” There is no evidence that there was any thing in the voice or gesture of Jesus upon this occasion which implied that he did not refer to the material temple whose massive grandeur rose around them. It is certain that his interrogators so understood him: for they replied, “Forty and six years was this temple in building; and wilt thou rear it up in three days?”

The evangelist John adds, “But he spake of the temple of his body.” We have no intimation that Jesus attempted to rectify the error into which they had fallen. And it is difficult to assign any satisfactory reason why he should have left them to ponder his dark saying. Human frailty is often bewildered in the attempt to explicate infinite wisdom.

Probably the fame of Jesus had already reached Jerusalem. His wonderful achievement, in thus cleansing the temple, must have excited universal astonishment. Many were inclined to attach themselves to him as a great prophet. There was at that time residing in Jerusalem a man of much moral worth, by the name of Nicodemus. He was rich, was in the highest circles of society, a teacher of the Jewish law, and a member of the Sanhedrim, the supreme council of the nation.

He sought an interview with Jesus at night, that he might enjoy uninterrupted conversation, or, as is more probable, because he had not sufficient moral courage to go to him openly. In the following words he announced to Jesus his full conviction of his prophetic character: “Rabbi, we know that thou art a teacher come from God; for no man can do these miracles that thou doest except God be with him.”

Jesus did not wait for any questions to be asked. With apparent abruptness, and without any exchange of salutations, he said solemnly, as if rebuking the assumption that he, the Lamb of God, had come to the world merely as a teacher, “Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.”

Nicodemus ought to have understood this language. The “new birth” was no new term, framed now for the first time. The proselytes from heathenism, having been received into the Jewish fold by circumcision and baptism, in token of the renewal of their hearts, were said to be “born again.” Jesus, adopting this perfectly intelligible language, informed Nicodemus that it was not by intellectual conviction merely that one became a member of the Messiah’s kingdom, but by such a renovation of soul, that one might be said to be born again,—old things having passed away, and all things having become new. Nicodemus, who perhaps, in pharisaic pride, imagined that he had attained the highest stage of the religious life, was probably a little irritated in being told that he needed this change of heart to gain admission to the kingdom of God; and, in his irritation, allowed himself in a very stupid cavil. “How can a man,” said he, “be born when he is old? Can he enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born?”

Jesus, ever calm, did not heed the cavil, but simply reiterated his declaration, that no man could become a member of the kingdom of God, unless, renewed in the spirit of his mind, he thus became a partaker of the divine nature. Nicodemus probably assumed that he, as a Jew, would be entitled by right of birth to membership in the kingdom of the Messiah. When a Gentile became a proselyte to the Jewish religion, by the rite of baptism he promised to renounce idolatry, to worship the true God, and to live in conformity with the divine law. The external rite gradually began to assume undue importance. Our Saviour, in announcing to Nicodemus the doctrine that a spiritual regeneration was needful, of which the application of water in baptism was merely the emblem, said, “Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh is flesh,”—is corrupt: “that which is born of the Spirit is spirit,”—is pure. “Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again.”

And then, in reply to queries which he foresaw were rising in the mind of Nicodemus, he continued: “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.” This sublime truth is thus enunciated without any attempt at explanation. Why is one man led by the Holy Spirit to the Saviour, while another, certainly no less deserving, is not? This question has been asked through all the ages, but never answered. Where is the Christian who has not often said,—

“Why was I made to hear thy voice,

And enter while there’s room,

When thousands make a wretched choice,

And rather starve than come?”

Infinitely momentous as are these truths, they are the most simple truths in nature. Nothing can be more obvious to an observing and reflective man than that a thorough renovation of spirit is essential to prepare mankind for the society of spotless angels and for the worship of heaven. This is one of the most simple and rudimental of moral truths. And when Nicodemus, with the spirit of cavil still lingering in his mind, allowed himself to say, “How can these things be?” Jesus gently rebuked him, saying, “Art thou a master of Israel, and knowest not these things? If I have told you earthly things,”—the simplest truths of religion, obvious to every thoughtful man,—“and ye believe not, how shall ye believe if I tell you of heavenly things?”—the sublime truths which can only be known by direct revelation.

Jesus then proceeds from the simple doctrine of regeneration to the sublimer theme of an atoning Saviour,—a theme the most wonderful which the mind of man or angel can contemplate. There cannot be found in all the volumes of earth a passage so full of meaning, in import so stupendous, as the few words which then came from the Saviour’s lips. It was the distinct and emphatic announcement of the plan of salvation devised by a loving Father in giving his Son to die upon the cross, in making atonement for the sins of the world.

“No man hath ascended up to heaven but he that came down from heaven; even the Son of man, which is in heaven. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up; that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life. For God so loved the world, that he gave his only-begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through him might be saved. He that believeth on him is not condemned; but he that believeth not is condemned already, because he hath not believed in the name of the only-begotten Son of God. And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil. For every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved; but he that doeth truth cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest that they are wrought in God.”

It does not appear that even this enunciation from the lips of Jesus, of the sublime doctrines of regeneration and atonement, produced any immediate result upon the heart of Nicodemus. That they produced a deep impression upon his mind cannot be doubted. Not long after, when there was intense commotion in Jerusalem in consequence of the teachings of Jesus, Nicodemus summoned sufficient moral courage to speak one word in his defence. “Doth our law,” said he, “judge any man before it hear him and know what he doeth?” But he seems to have been effectually silenced by the stem rebuff, “Art thou also of Galilee?” We hear no more of this timid man, until after the lapse of three years, when Jesus had perished upon the cross, Nicodemus brought to Joseph of Arimathea some spices to embalm the body. This, also, he probably did secretly and by night. How contemptible does such a character appear—one too cowardly to live according to its own convictions of duty—when contrasted with such men as Abraham, Noah, Daniel, and Paul! And yet there is many a Nicodemus in almost every village in our land.

Soon after this, Jesus left Jerusalem, and went into the rural districts of Judæa, where he preached his gospel, and his disciples baptized, and by this rite received to the general Church such as became converts. John the Baptist was then preaching to large assemblies in Samaria, in a place called Ænon, about twenty miles west of the River Jordan, and about sixty miles north from Jerusalem. This place, though among the hills, was well watered with springs and streams, and thus well adapted for the vast numbers who gathered to hear this renowned preacher.

Jesus and his disciples were in Judæa, in the vicinity of Jerusalem, probably about forty miles south of John. Some of the zealous disciples of John became annoyed in hearing that larger crowds were flocking to Jesus than to him; that Jesus was making many converts, and that his disciples were actually baptizing more than were the disciples of John. But the illustrious prophet did not share in their feelings of envy. In words worthy of his noble character he replied,—

“Ye yourselves bear me witness that I said I am not the Christ, but that I am sent before him. He must increase; but I must decrease. He that cometh from above is above all; for he whom God hath sent speaketh the words of God. The Father loveth the Son, and hath given all things into his hand. He that believeth on the Son hath everlasting life; and he that believeth not the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God abideth on him.”

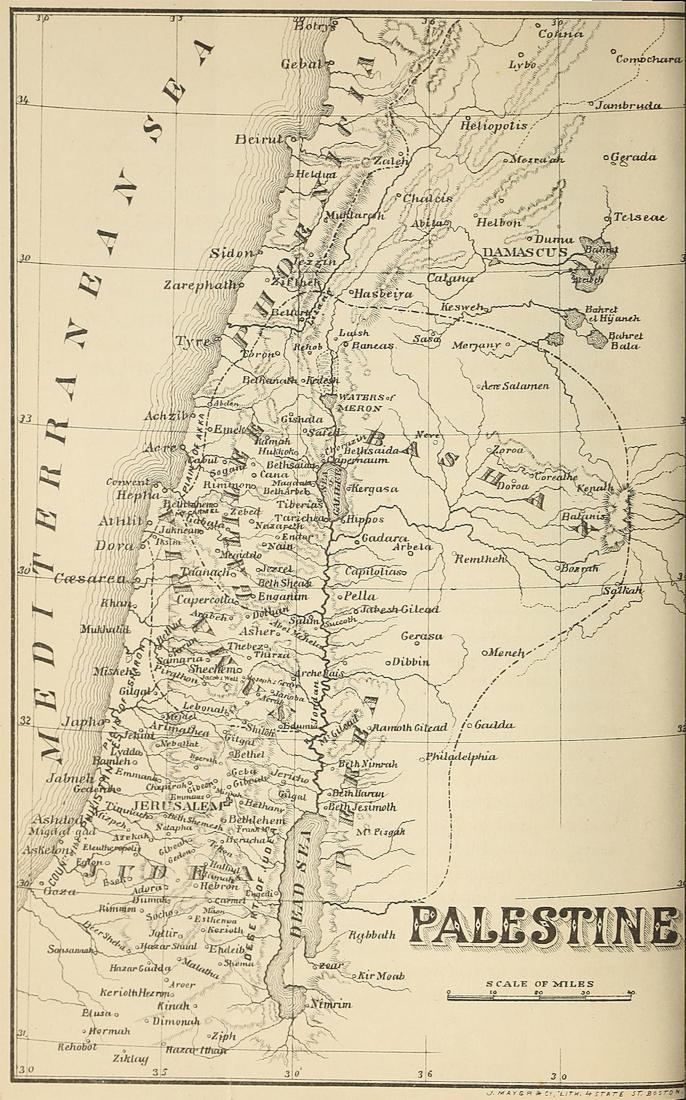

PALESTINE

Jesus, being informed of the spirit of rivalry which existed on the part of John’s disciples, decided to withdraw from that region, and return to Galilee. His direct route led through the central district of Samaria. There was a bitter feud between the inhabitants of Judæa and Samaria, so that there was but little social intercourse or traffic between them. The road led first over barren plains as far as Bethel; then traversed a region of undulating hills smiling with verdure, till it became lost in a winding mountain-pass quite densely wooded. On the third day of the journey, Jesus, toiling on foot beneath the scorching sun of Syria, reached Sychar, in the heart of Samaria. About a mile and a half from the village, at the foot of Mount Gerizim, there was a celebrated well, which the patriarch Jacob had dug several centuries before. Jesus sat down by the well to rest, while his disciples, who accompanied him, went into the village to purchase some food. While seated there alone, a Samaritan woman came to draw water. Jesus said to her, “Give me to drink.” His dress and language indicated that he was a Jew.

The woman replied, “How is it that thou, being a Jew, askest drink of me, which am a woman of Samaria?”

“If thou knewest,” said Jesus, “the gift of God, and who it is that saith to thee, Give me to drink, thou wouldest have asked of him, and he would have given thee living water.”

To this enigmatical reply, which evidently aroused the attention of the woman, she rejoined, “Thou hast nothing to draw with, and the well is deep. From whence, then, hast thou that living water? Art thou greater than our father Jacob, which gave us the well, and drank thereof himself, and his children and his cattle?”

Again Jesus replied in enigmatical language, “Whosoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again: but whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life.”

The woman, bewildered, and with excited curiosity, said, “Sir, give me this water, that I thirst not, neither come hither to draw.”

“Go, call thy husband,” said Jesus, “and come hither.”

The woman, conscience-smitten, and somewhat alarmed by the mysterious nature of the conversation, answered, “I have no husband.”

The startling response of Jesus was, “Thou hast well said, I have no husband: for thou hast had five husbands; and he whom thou now hast is not thy husband. In that saidst thou truly.”

The woman, alarmed, and anxious to withdraw the conversation from her own sins and personal duty, sought, as half-awakened sinners have ever endeavored to do from that day to this, to change the theme into a theological discussion.

“Sir,” she said, “I perceive that thou art a prophet. Our fathers worshipped in this mountain; and ye say that in Jerusalem is the place where men ought to worship.”

This question was a standing controversy between the Jews and the Samaritans. “Believe me,” Jesus replied, “the hour cometh when ye shall neither in this mountain, nor yet at Jerusalem, worship the Father. Ye worship ye know not what: we know what we worship; for salvation is of the Jews. But the hour cometh, and now is, when the true worshippers shall worship the Father in spirit and in truth; for the Father seeketh such to worship him. God is a Spirit; and they that worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth.”

The Samaritans rejected the prophets, and received only the five books of Moses. Jesus therefore announced that the Jewish, not the Samaritan faith, was the true religion; while at the same time he declared that external forms were important only as they promoted and indicated holiness of heart.

The woman replied, “I know that Messias cometh, which is called Christ. When he is come, he will tell us all things.”

Her astonishment must have been great when Jesus rejoined, “I that speak unto thee am he.”

The conversation was here interrupted by the return of the disciples who had gone into the village. Though surprised in seeing Jesus engaged in earnest conversation with the Samaritan woman, they asked him no questions upon the subject; but the woman, so agitated that she forgot to take her water-pot with her, hurried back to the village, saying to her friends, in language somewhat exaggerated, “Come see a man which told me all things that ever I did. Is not this the Christ?”

Quite a crowd of Samaritans were soon gathered around the well. In the mean time, the disciples besought Jesus to partake of the refreshments which they had brought from the village. His remarkable reply was,—

“I have meat to eat that ye know not of. My meat” (the great object of my life) “is to do the will of Him that sent me, and to finish his work. Say not ye, There are yet four months, and then cometh harvest? Behold, I say unto you, Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest. And he that reapeth receiveth wages, and gathereth fruit unto life eternal, that both he that soweth and he that reapeth may rejoice together. And herein is that saying true, One soweth, and another reapeth. I sent you to reap that whereon ye bestowed no labor: other men labored, and ye have entered into their labors.”

It is probable that Jesus went from the well into the village or city of Sychar; for he continued in that region for two days, preaching the glad tidings of the kingdom of God. The result was, that many more believed, and said unto the woman, “Now we believe, not because of thy saying; for we have heard him ourselves, and know that this is indeed the Christ, the Saviour of the world.”

Continuing his journey, Jesus proceeded still northward to Galilee. The fame of his words and of his works was spreading far and wide. As he travelled, he entered the synagogues of the villages, and preached his gospel probably to large crowds. Popularity accompanied his steps; for, we are informed by the sacred historian, “he taught in their synagogues, being glorified of all.”

Upon reaching the province of Galilee, he repaired to Cana, where his first miracle was performed. His name was now upon all lips; and, wherever he appeared, crowds were attracted. About twelve miles north-east from Cana, upon the shores of the Lake of Galilee, was the city of Capernaum. A nobleman there, of high official rank, had a son dangerously sick. Hearing of the arrival of Jesus in Cana, and fully convinced of his miraculous powers, he hastened to him, and entreated him to come down and heal his son. Immediately upon the application of the nobleman, appreciating the faith he thus exhibited, he said, “Go thy way: thy son liveth.” Apparently untroubled with any incredulity, the nobleman set out on his return. Meeting servants by the way, they informed him that his son was recovering. Upon inquiry, he learned that his convalescence commenced apparently at the very moment in which Jesus assured him of his safety. In consequence of this second miracle in Galilee, the nobleman and all his family became disciples of Jesus.

From Cana, Jesus went to the home of his childhood and youth, in Nazareth, which was but a few miles south of Cana. It is probable that his reputed father, Joseph, was dead, as we have no subsequent allusion to him; and that there was no home in Nazareth to welcome the wanderer. Upon the sabbath day, according to his custom, he repaired to the synagogue. Taking the Bible, he opened to the sixty-first chapter of Isaiah, and read those prophetic words of the promised Messiah which had been written nearly seven hundred years before:—

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord hath anointed me to preach good tidings unto the meek: he hath sent me to bind up the broken-hearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound; to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord.”

He closed the book, returned it to the officiating minister, and sat down upon the raised seat from which it was customary for the Jewish speakers to address the audience. The eyes of all were fastened upon him.

“This day,” said Jesus, “is this scripture fulfilled in your ears.” It was universally understood that this passage from the prophet referred to the Messiah. Thus he solemnly announced to his astonished fellow-citizens of Nazareth that he was the Son of God, whose coming the pious Jews had, through so many centuries, been expecting. It is evident that the tidings of his career were already creating great excitement in Nazareth.

“All bare witness,” writes the inspired historian, “and wondered at the gracious words which proceeded out of his mouth. And they said, Is not this Joseph’s son?

“And he said unto them, Ye will surely say unto me this proverb, Physician, heal thyself: whatsoever we have heard done in Capernaum, do also here in thy country. And he said, Verily I say unto you, No prophet is accepted in his own country. But I tell you of a truth, many widows were in Israel in the days of Elias, when the heaven was shut up three years and six months, when great famine was throughout all the land; but unto none of them was Elias sent, save unto Sarepta, a city of Sidon” (a Gentile city), “unto a woman that was a widow” (a Gentile woman). “And many lepers were in Israel in the time of Eliseus the prophet; and none of them was cleansed saving Naaman the Syrian.”

This declaration, that God regarded Gentiles as well as Jews with his parental favor, roused their indignation. The inspired historian records, “And all they in the synagogue, when they heard these things, were filled with wrath, and rose up, and thrust him out of the city, and led him unto the brow of the hill whereon their city was built, that they might cast him down headlong; but he, passing through the midst of them, went his way.”

It is not known whether a miracle was performed at this time to disarm the mob, or whether the infuriated populace were overawed by the natural dignity of his demeanor, and by the sacredness which began to be attached to his person as the reputed Messiah. It was a case similar to that which occurred when he cleansed the temple.

Jesus, upon this occasion, took his text from the Bible, and commented upon it. The text and a few of his remarks have been alone transmitted to us. There is a rocky cliff which extends for some distance along the hill on which Nazareth is built, which is still thirty or forty feet high, notwithstanding the accumulated débris of eighteen centuries, which was undoubtedly the scene of this transaction.

John the Baptist was now cast into prison. His work as the forerunner of Christ was accomplished. Eight months of our Lord’s ministry had passed away. On the eastern shore of the Dead Sea there was an immense fortress called Machærus. Built on a crag, surrounded by gloomy ravines, and strengthened by the most formidable works of military enginery then known, it was deemed impregnable. Here the despot Herod had shut up John the Baptist as a prisoner. Weary months rolled away as the impetuous spirit of the prophet beat unavailingly against the bars of his prison. Though a prophet, the whole mystery of the Messiah’s kingdom had not been revealed to him. With great solicitude, apparently with many doubts and fears, he watched the career of Jesus, so inexplicable to human wisdom.

Jesus, rejected with insult and outrage by the people of Nazareth, repaired to Capernaum, on the shores of the lake. This body of water, so renowned in the life of Jesus, is the only sea referred to in the gospel history. It is alike called the “Sea of Galilee,” the “Sea of Tiberias,” and “Lake Gennesaret.” In Capernaum he took up his residence for a time, “preaching the gospel of the kingdom of God;” that is, preaching the glad tidings of full and free remission of sins through faith in him as the Messiah, and his coming kingdom. “The time,” said he, predicted by the prophets, “is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand. Repent ye, and believe the gospel.”4

Walking one day on the shores of the lake, he met Simon Peter and his brother Andrew, engaged in their occupation as fishermen. It will be remembered that they had met Jesus before, at the time of his baptism by John, and had become convinced that he was the Messiah. On some of his journeyings they had accompanied him. But they had not, as yet, permanently attached themselves to his person. He said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.” Their unwavering faith in him is manifest from the fact, that leaving their boat and their net, and their earthly all, in their humble garb of fishermen they followed him.

Continuing the walk along the water’s edge, they met two other young fishermen, also brothers, James and John. They were sitting upon the shore with their father Zebedee, mending their net. Jesus called them also to follow him; which they promptly did, leaving their father behind them. Jesus had selected them to be preachers of his gospel; and they were to be with him, that, listening to his addresses, they might learn the doctrines which they were to preach.

Accompanied by these four disciples, Jesus returned into the city of Capernaum; and probably the next day, it being the sabbath, he entered the synagogue, and addressed the people. We have no record of his address. Mark simply informs us that he “taught; and they were astonished at his doctrine; for he taught them as one that had authority, and not as the scribes.”5 Luke says, “His word was with power.”6

Among the crowd assembled there was a man possessed of a devil. He startled the whole assembly by shouting out, “Let us alone! What have we to do with thee, thou Jesus of Nazareth? Art thou come to destroy us? I know thee whom thou art, the Holy One of God.”

“Accepting, with whatever mystery the whole subject of demoniac possession is clothed, the simple account of the evangelists, it does appear most wonderful,—the quick intelligence, the wild alarm, the terror-stricken faith, that then pervaded the demon world, as if all the spirits of hell who had been suffered to make human bodies their habitation grew pale at the very presence of Jesus, and could not but cry out in the extremity of their despair.”7

Jesus turned his mild, commanding eye upon the demoniac, and calmly said, “Hold thy peace, and come out of him.” The foul spirit threw the man to the ground, tore him with convulsions, and, uttering a loud, inarticulate, fiendlike cry, departed. The man rose to his feet, serene and happy, conversing with his friends in his right mind. All were seized with amazement. The strange tidings ran through the streets of the city. The fame of such marvels spread rapidly far and wide. “What new thing is this?” was the general exclamation; “for with authority he commandeth the unclean spirits, and they do obey him.”

The mother of Simon Peter’s wife was taken sick with a violent fever. Jesus, being informed of it, visited her bedside, took her gently by the hand, and rebuked the fever. The disease, as obedient to his command as was the foul spirit, immediately left the sufferer. The cure was instantaneous and complete. She arose from her couch, and returned at once to her household duties.

It is difficult to imagine the excitement which these events must have produced. Upon the evening of that memorable day, the region around the house was thronged with the multitude, bringing unto him all that were sick with divers diseases. “And he laid his hands on every one of them, and healed them. And devils also came out of many, crying out, and saying, Thou art Christ, the Son of God. And he, rebuking them, suffered them not to speak; for they knew that he was Christ.”8

It is impossible for us to comprehend the nature of the union of God and man in the person of Jesus. The sacred historian, in announcing that God “was made flesh and dwelt among us,” makes no attempt to solve this mystery. But it seems that Jesus, though possessed of these miraculous powers, was so exhausted by the labors and excitements of the day, that, long before the dawn of the morning, he rose from his bed, and, leaving the slumbering city behind him, retired to a solitary place, where, fanned by the cool breeze of the mountain and of the lake, he spent long hours in prayer.

Peter and his companions, when they rose in the morning, missed Jesus. It was not until after a considerable search that he was found in his retreat. They informed him of the great excitement which pervaded the city, and that the people were looking for him in all directions. But Jesus, instead of returning to Capernaum to receive the adulation which awaited him there, said, “Let us go into the next towns, that I may preach there also. I must preach the kingdom of God to other cities; for therefore came I forth.”