Title: A Military Dictionary and Gazetteer

Author: Thomas Wilhelm

Release date: May 20, 2019 [eBook #59563]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this e-text, and is placed in the public domain.

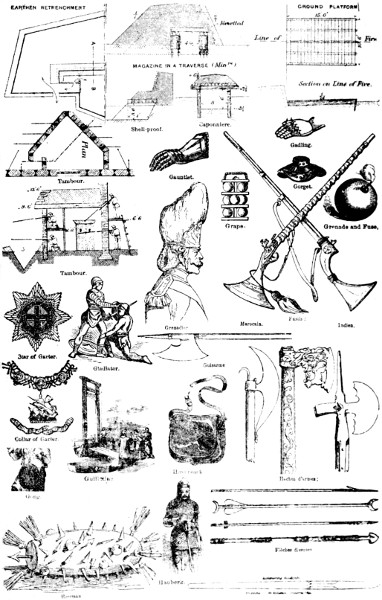

COMPRISING

ANCIENT AND MODERN MILITARY TECHNICAL TERMS, HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS

OF ALL NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS, AS WELL AS ANCIENT WARLIKE

TRIBES; ALSO NOTICES OF BATTLES FROM THE EARLIEST PERIOD

TO THE PRESENT TIME, WITH A CONCISE EXPLANATION OF

TERMS USED IN HERALDRY AND THE OFFICES THEREOF.

THE WORK ALSO GIVES VALUABLE GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION.

COMPILED FROM THE BEST AUTHORITIES OF ALL NATIONS.

WITH AN APPENDIX CONTAINING THE ARTICLES OF WAR, Etc.

BY

THOMAS WILHELM,

CAPTAIN EIGHTH INFANTRY.

REVISED EDITION.

PHILADELPHIA:

L. R. HAMERSLY & CO.

1881.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1880, by

THOMAS WILHELM, U.S.A.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

TO

BREVET MAJOR-GENERAL AUGUST V. KAUTZ,

COLONEL EIGHTH REGIMENT OF INFANTRY, U.S.A.,

BY WHOSE SUGGESTIONS, ENCOURAGEMENT, AND AID THE WORK WAS UNDERTAKEN, PERSEVERED IN, AND COMPLETED,

THIS COMPILATION

IS, WITH RESPECT AND GRATITUDE, DEDICATED

BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT,

THE COMPILER.

[4]

It is with no small degree of relief that the compiler of this work now turns from a self-imposed task, involving some years of the closest application, to write a brief preface, not as a necessity, but in justice to the work and the numerous friends who have taken the warmest interest in its progress and final completion.

It is inevitable that in the vast amount of patient and persistent labor in a work of this kind, extending to 1386 pages, and containing 17,257 distinct articles, there should be a few errors, oversights, and inconsistencies, notwithstanding all the vigilance to the contrary.

Condensation has been accomplished where it was possible to do so, and repetition avoided to a great extent by reference, where further information was contained in other articles of this book.

The contributions to the Regimental Library, which afforded the opportunity for this compilation, of standard foreign works, were of infinite value, and many thanks are tendered for them.

To G. & C. Merriam, Publishers, for the use of Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary; J. B. Lippincott & Co., Publishers, Philadelphia; D. Van Nostrand, Publisher, New York; Maj. William A. Marye, Ordnance Department, U.S.A.; Maj. W. S. Worth, Eighth Infantry, U.S.A.; Maj. D. T. Wells, Eighth Infantry, U.S.A.; Lieut. F. A. Whitney, Adjutant Eighth Infantry, U.S.A.; Lieut. C. A. L. Totten, Fourth Artillery, U.S.A.; Lieut. C. M. Baily, Quartermaster Eighth Infantry, U.S.A.; and Lieut. G. P. Scriven, Third Artillery, U.S.A., the compiler is indebted for courteous assistance in the preparation of this volume.

October, 1879.

[5]

In submitting this volume to the public it is deemed proper to say that the design of the work is to bring together into one series, and in as compact a form as possible for ready reference, such information as the student of the science and art of war, persons interested in the local or reserve forces, libraries, as well as the editors of the daily press, should possess. In short, it is believed that the work will be useful to individuals of all ranks and conditions.

The compiler has labored under some disadvantages in obtaining the necessary information for this volume, and much is due to the encouragement and assistance received from accomplished and eminent officers, through which he was enabled to undertake the revision of the first issue of this work with greater assurance; and among the officers referred to, Lieut. William R. Quinan, of the Fourth Artillery, U.S.A., deserves especially to be mentioned. It may not be out of place here to state that the compiler takes no credit to himself beyond the labor contributed in the several years of research, and bringing forward to date the matter requiring it, with such changes as the advance of time and improvements demand.

As it was thought best to make this work purely military, all naval references which appeared in the first edition have been eliminated.

May, 1881.

[6]

[8]

Misfortune will certainly fall upon the land where the wealth of the tax-gatherer or the greedy gambler in stocks stands, in public estimation, above the uniform of the brave man who sacrifices his life, health, or fortune in the defense of his country.

Officers should feel a conviction that resignation, bravery, and faithful attention to duty are virtues without which no glory is possible, no army is respectable, and that firmness amid reverses is more honorable than enthusiasm in success.

It is not well to create a too great contempt for the enemy, lest the morale of the soldier should be shaken if he encounter an obstinate resistance.

It would seem to be easy to convince brave men that death comes more surely to those who fly in disorder than to those who remain together and present a firm front to the enemy, or who rally promptly when their lines have been for the instant broken.

Courage should be recompensed and honored, the different grades in rank respected, and discipline should exist in the sentiments and convictions rather than in external forms only.—Jomini.

An army without discipline is but a mob in uniform, more dangerous to itself than to its enemy. Should any one from ignorance not perceive the immense advantages that arise from a good discipline, it will be sufficient to observe the alterations that have happened in Europe since the year 1700.—Saxe.

If the first duty of a state is its own security, the second is the security of neighboring states whose existence is necessary for its own preservation.—Jomini’s “Life of Napoleon.”

A good general, a well-organized system, good instruction, and severe discipline, aided by effective establishments, will always make good troops, independently of the cause for which they fight. At the same time, a love of country, a spirit of enthusiasm, a sense of national honor, will operate upon young soldiers with advantage.

The officer who obeys, whatever may be the nature or extent of his command, will always stand excused executing implicitly the orders which have been given to him.

Every means should be taken to attach the soldier to his colors. This is best accomplished by showing consideration and respect to the old soldier.

The first qualification of a soldier is fortitude under fatigue and privation. Courage is only the second; hardship, poverty, and want are the best schools for a soldier.

Troops, whether halted, or encamped, or on the march, should be always in favorable position, possessing the essentials required for a field of battle.

Some men are so physically and morally constituted as to see everything through a highly-colored medium. They raise up a picture in the mind on every slight occasion, and give to every trivial occurrence a dramatic interest. But whatever knowledge, or talent, or courage, or other good qualities such men may possess, nature has not formed them for the command of armies or the direction of great military operations.—Napoleon’s “Maxims of War.”

[9]

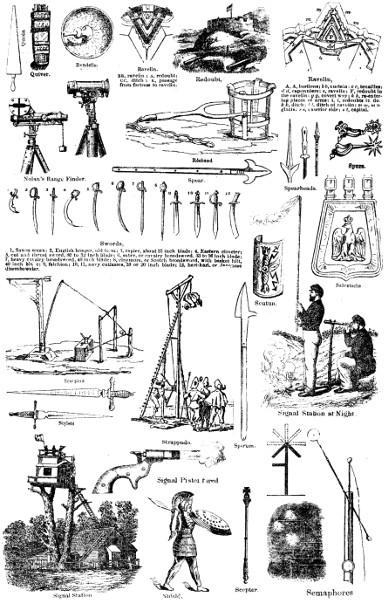

MILITARY DICTIONARY.

Aachen. See Aix-la-Chapelle.

Aar. A river in Switzerland, flows into the Rhine opposite and near Waldshut, in Aargau. Prince Charles, while crossing the river, August 17, 1799, was repulsed by the French generals Ney and Heudelet.

Aarau. A city in Switzerland. Peace was here declared, July 18, 1712, ending the war between the cantons Zurich and Berne on one side, and Luzerne, Uri, Schuyz, Unterwalden, and Zug on the other.

Abad (Abadides). A line of Moorish kings who reigned in Seville from 1026 to 1090.

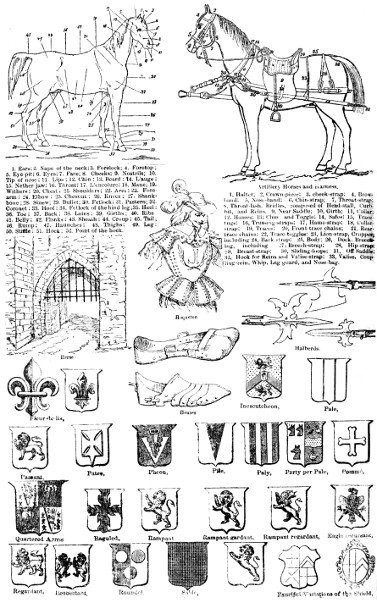

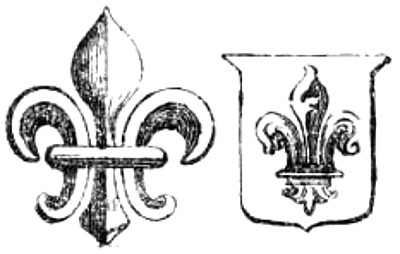

Abaisse. In heraldry, when the fesse or any other armorial figure is depressed, or situated below the centre of the shield, it is said to be abaisse (“lowered”).

Abandon. In a military sense, used in the relinquishment of a military post, district, or station, or the breaking up of a military establishment. To abandon any fort, post, guard, arms, ammunition, or colors without good cause is punishable.

Abase, To. An old word signifying to lower a flag. Abaisser is in use in the French marine, and both may be derived from the still older abeigh, to cast down, to humble.

Abatement. In heraldry, is a mark placed over a portion of the paternal coat of arms, indicating some base or ungentlemanly act on the part of the bearer.

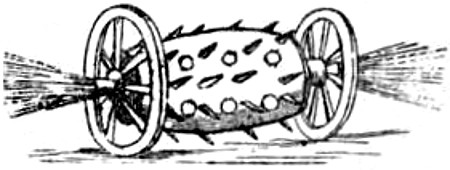

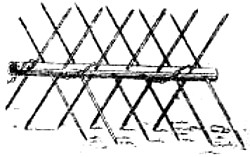

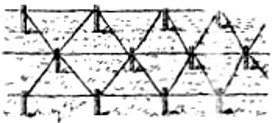

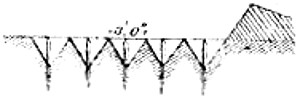

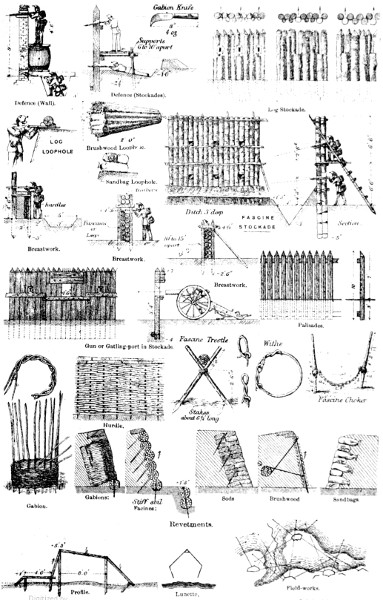

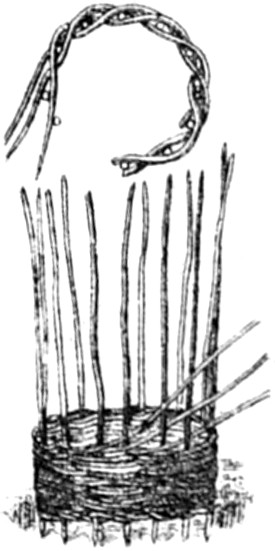

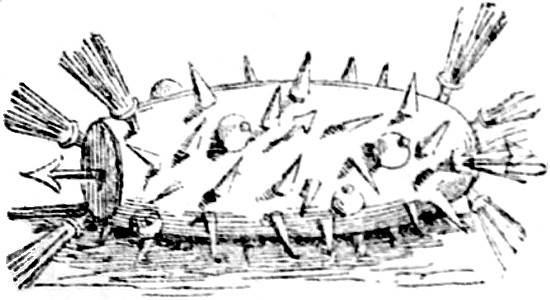

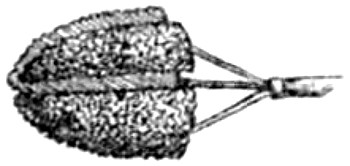

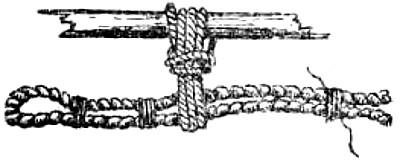

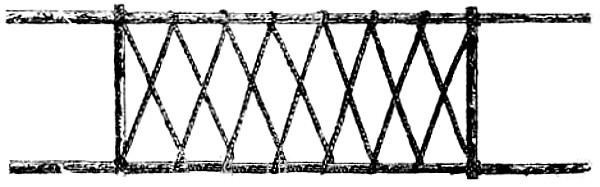

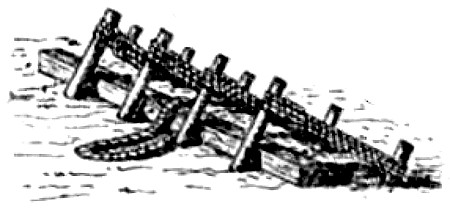

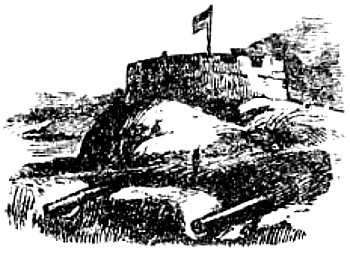

Abatis, or Abattis. A means of defense formed by cutting off the smaller branches of trees felled in the direction from which the enemy may be expected. The ends of the larger branches are sharpened and the butts of the limbs or trees fastened by crochet picket, or by imbedding in the earth, so that they cannot be easily removed. Abatis is generally used in parts of a ditch or intrenchment to delay the enemy under fire.

Abblast. See Arbalest.

Abblaster. See Arbalist.

Abdivtes. A piratical people descended from the Saracens, who lived south of Mount Ida (Psilorati), in the island of Crete (Candia), where they established themselves in 825.

Abduction (Fr.). Diminution; diminishing the front of a line or column by breaking off a division, subdivision, or files, in order to avoid some obstacle.

Abencerrages. A Moorish tribe which occupied the kingdom of Granada. Granada was disturbed by incessant quarrels between this tribe and the Zegris from 1480 to 1492. They were finally extinguished by Abou-Abdoullah, or Boabdil, the last Moorish king of Granada, and the same who was dethroned by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492.

Abensburg. A small town of Bavaria, on the Abens, 18 miles southwest of Ratisbon. Here Napoleon defeated the Austrians, April 20, 1809.

Aberconway, or Conway. A maritime city of the Gauls in England, fortified by William the Conqueror, and taken by Cromwell in 1645.

Abet. In a military sense it is a grave crime to aid or abet in mutiny or sedition, or excite resistance against lawful orders.

Abgersate. Fortress of the Osrhoene, in Mesopotamia. The Persians took it by assault in the year 534.

Abii. A Scythian tribe which inhabited the shores of the Jaxartes, to the northeast of Sogdiana. They were vanquished by Alexander the Great.

Abipones. A tribe of Indians living in the Argentine Confederation, who were formerly numerous and powerful, but are now reduced to a small number.

Able-bodied. In a military sense applies to one who is physically competent as a soldier.

Ablecti. Ancient military term applied to a select body of men taken from the extraordinarii of the Roman army to serve as a body-guard to the commanding general or the consul. The guard consisted of 40 mounted and 160 dismounted men.

Abo. A Russian city and seaport, on the Aurajoki near its entrance into the Gulf of Bothnia. It formerly belonged to Sweden, but was taken with the whole of Finland by the Russians in the war begun by Sweden in 1741. By a treaty of peace concluded hero in 1743 the conquered possessions were restored to Sweden. They were ceded to Russia in 1809.

[10]

Abolla. A warm kind of military garment, lined or doubled, worn by both Greeks and Romans.

Abou-girgeh. A city of Upper Egypt where the French defeated the Egyptians in 1799.

Aboukir (anc. Canopus). A village of Egypt on a promontory at the western extremity of the bay of the same name, 15 miles northeast of Alexandria. In the bay Nelson defeated the French fleet, August 1, 1798. This engagement, which resulted in a loss to the French of 11 line-of-battle ships, is known as the “battle of the Nile.” In 1801 a British expedition under Sir Ralph Abercromby landed at Aboukir, and captured the place after an obstinate and sanguinary conflict with the French (March 8). Here also a Turkish army of 15,000 men was defeated by 5000 French under Bonaparte, July 25, 1799.

Aboumand. Village of Upper Egypt, near the river Nile, where the French fought the Arabs in 1799.

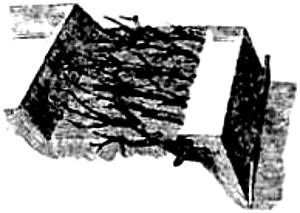

About. A technical word to express the movement by which a body of troops or artillery carriages change front.

Abraham, Heights of. Near Quebec, Lower Canada. In the memorable engagement which took place here September 13, 1759, the French under Gen. Montcalm were defeated by the English under Gen. Wolfe, who was killed in the moment of victory.

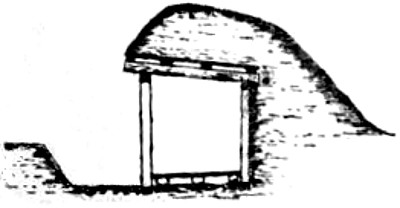

Abri (Fr.). Shelter, cover, concealment; arm-sheds in a camp secure from rain, dust, etc.; place of security from the effect of shot, shells, or attack.

Absence, Leave of. The permission which officers of the army obtain to absent themselves from duty. In the U. S. service an officer is entitled to 30 days’ leave in each year on full pay. This time he may permit to accumulate for a period not exceeding 4 years. An officer, however, may enjoy 5 months’ continuous leave on full pay, provided the fifth month of such leave is wholly distinct from the four-year period within and for which the 4 months’ absence with full pay was enjoyed. An officer on leave over this time is entitled to half-pay only.

Absent. A term used in military returns in accounting for the deficiency of any given number of officers or soldiers, and is usually distinguished under two heads, viz.: Absent with leave, such as officers with permission, or enlisted men on furlough. Absent without leave; men who desert are sometimes reported absent without leave, to bring their crimes under cognizance of regimental, garrison, or field-officers’ courts; thus, under mitigating circumstances, trial by general court-martial is avoided. Absence without leave entails forfeiture of pay during such absence, unless it is excused as unavoidable. An officer absent without leave for three months may be dropped from the rolls of the army by the President, and is not eligible to reappointment.

Absolute Force of Gunpowder. Is measured by the pressure it exerts on its environment when it exactly fills the space in which it is fired. Various attempts have been made to determine this force experimentally with widely different results. Robins estimated the pressure on the square inch at 1000 atmospheres, Hutton at 1800, and Count Rumford as high as 100,000 atmospheres. While Rodman, by experiments upon strong cast-iron shells, verified the accuracy of Rumford’s formulas, he found that his estimate of the force was greatly in error. According to Rodman the pressure is approximately 14,000 atmospheres. Dr. Woodbridge, another American philosopher and inventor, has shown that, fired in small quantities, the force of gunpowder does not exceed 6200 atmospheres. This agrees closely with the conclusion arrived at by the English “Committee on Explosives,” 1875, who found that even in large guns the force did not exceed 42 tons.

Absorokas. A tribe of North American Indians. See Crows.

Absterdam Projectile. See Projectile.

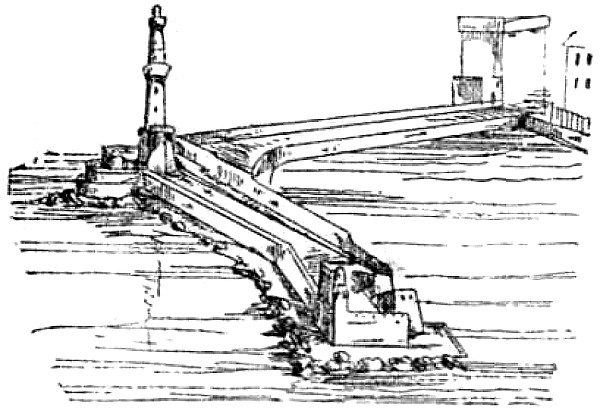

Abydus. An ancient city of Mysia on the Hellespont nearly opposite Sestus on the European shore. Near this town Xerxes placed the bridge of boats by which his troops were conveyed across the channel to the town of Sestus, 480 B.C.

Abyssinia. A country of Eastern Africa, forming an elevated table-land and containing many fertile valleys. Theodore II., the king of this country, having maltreated and imprisoned some English subjects, an expedition under Lord Napier was sent against him from Bombay in 1867. On April 14, 1868, the mountain fortress of Magdala was stormed and taken with but little trouble, and Theodore was found dead on the hill, having killed himself. The country is at present governed by Emperor John of Ethiopia, who was crowned in 1872.

Academies, Military. See Military Academies.

Accelerator. A cannon in which several charges are successively fired to give an increasing velocity to the projectile while moving in the bore. See Multi-charge Gun.

Accessible. Easy of access or approach. A place or fort is said to be accessible when it can be approached with a hostile force by land or sea.

Accintus. A word in ancient times signifying the complete accoutrements of a soldier.

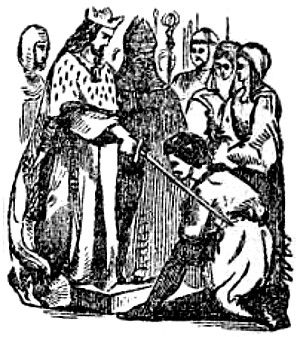

Accolade. The ceremonious act of conferring knighthood in ancient times. It consisted of an embrace and gentle blow with the sword on the shoulder of the person on whom the honor of knighthood was being conferred.

Accord. The conditions under which a fortress or command of troops is surrendered.

Accoutre. To furnish with accoutrements.

[11]

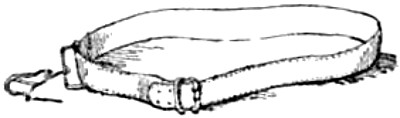

Accoutrements. Dress, equipage, trappings. Specifically, the equipments of a soldier, except arms and clothing.

Accused. In a military sense, the designation of one who is arraigned before a military court.

Acerræ (now Acera). A city in the kingdom of Naples, taken and burned by Hannibal in 216 B.C. In 90 B.C. the Romans defeated under its walls the allied rebels commanded by Papius.

Acerræ. A city of the Gauls, taken by Marcellus in 222 B.C.

Achæan League. A confederacy which existed from very early times among the twelve states of the province of Achaia, in the north of the Peloponnesus. It was broken up after the death of Alexander the Great, but was set on foot again by some of the original cities, 280 B.C., the epoch of its rise into great historical importance; for from this time it gained strength, and finally spread over the whole Peloponnesus, though not without much opposition, principally on the part of Lacedæmon. It was finally dissolved by the Romans, on the event of the capture of Corinth by Mummius, 147 B.C. The two most celebrated leaders of this league were Aratus, the principal instrument of its early aggrandizement, and Philopœmen, the contemporary and rival, in military reputation, of Scipio and Hannibal.

Achern. A city in the grand duchy of Baden, on the river Acher. Near this place a monument marks the spot where Marshal Turenne was killed by a random shot in 1675.

Acheron. A small stream in ancient Bruttium. In 330 B.C., Alexander, king of Epirus, was killed while crossing it.

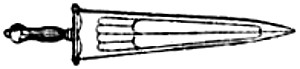

Acinaces. A short sword used by the Persians.

Aclides. In Roman antiquity, a kind of missile weapon with a thong fixed to it whereby it might be drawn back again.

Acoluthi. In military antiquity, was a title given in the Grecian empire to the captain or commander of the body-guards appointed for the security of the emperor’s palace.

Aconite. A poisonous plant. Several ancient races poisoned their arrows with an extract from this plant.

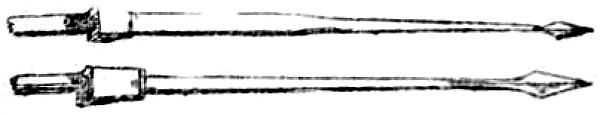

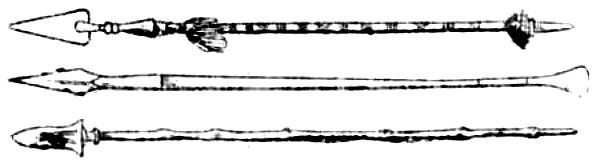

Acontium. In Grecian antiquity, a kind of dart or javelin resembling the Roman spiculum.

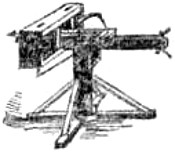

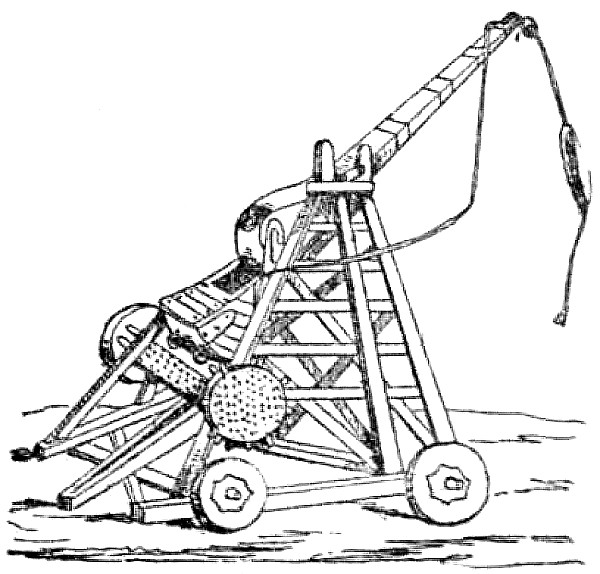

Acquereaux (Fr.). A machine of war, which was used in the Middle Ages to throw stones.

Acqui. A walled town of the Sardinian states on the river Bormida in the division of Alessandria. It was taken by the Spaniards in 1745, retaken by the Piedmontese in 1746; it was dismantled by the French, who defeated the Austrians and Piedmontese here in 1794.

Acquit. To release or set free from an obligation, accusation, guilt, censure, suspicion, or whatever devolves upon a person as a charge or duty; as, the court acquits the accused. This word has also the reflexive signification of “to bear, or conduct one’s self;” as, the soldier acquitted himself well in battle.

Acquittance Roll. In the British service, a roll containing the names of the men of each troop or company or regiment, showing the debts and credits, with the signature of each man, and certificate of the officer commanding it.

Acre, or St. Jean d’Acre. A seaport town of Palestine (in ancient times the celebrated city of Ptolemais), which was the scene of many sieges. It was last stormed and taken by the British in 1840. Acre was gallantly defended by Djezzar Pacha against Bonaparte in July, 1798, till relieved by Sir Smith, who resisted twelve attempts by the French, between March 16 and May 20, 1799.

Acre, or Acre-fight. An old duel fought by warriors between the frontiers of England and Scotland, with sword and lance. This dueling was also called camp-fight.

Acrobalistes (Fr.). A name given by the ancients to warlike races, such as the Parthians and Armenians, who shot arrows from a long distance.

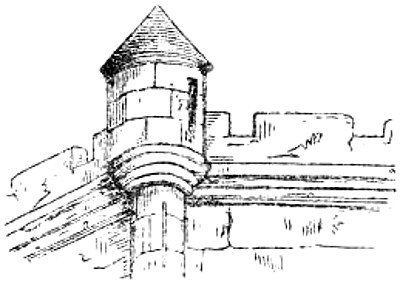

Acropolis. In ancient Greece, the name given to the citadel or fortress of a city, usually built on the summit of a hill. The most celebrated was that of Athens, remains of which still exist.

Acs. A village in Hungary on the right bank of the Danube, noted as the scene of several battles in the Hungarian revolution, that of August 3, 1849, being the most important.

Acting Assistant Surgeons. See Surgeons, Acting Assistant.

Action. An engagement between two armies, or bodies of troops. The word is likewise used to signify some memorable act done by an officer, soldier, detachment, or party.

Actium (now Azio). A town of ancient Greece in Arcanania, near the entrance of the Ambracian Gulf. It became famous for the great naval engagement fought near here in 31 B.C. between Octavius and Antony, in which the former was victorious.

Active Service. Duty against an enemy; operations in his presence. Or in the present day it denotes serving on full pay, on the active list, in contradistinction to those who are virtually retired, and placed on the retired list.

Activity. In a military sense, denotes attention, labor, diligence, and study.

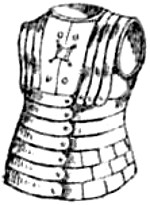

Acto, or Acton. A kind of defensive tunic, made of quilted leather or other strong material, formerly worn under the outer dress and even under a coat of mail.

Act of Grace. In Great Britain, an act of Parliament for a general and free pardon to deserters from the service and others.

Actuarius. A name given by the Romans[12] to officers charged with the supplying of provisions to troops.

Adacted. Applies to stakes, or piles, driven into the earth by large malls shod with iron, as in securing ramparts or pontons.

Adda. A stream in Italy. The Romans defeated the Gauls on its banks in 223 B.C.

Addiscombe Seminary. An institution near Croydon, Surrey, England, for the education of young gentlemen intended for the military service of the East India Company; closed in 1861.

Aden. A free port on the southwest corner of Arabia. It was captured by England in 1839, and is now used as a coal depot for Indian steamers.

Aderbaidjan (Fr.). A mountainous province of Persia, celebrated for raising the finest horses in the province for army purposes.

Adige (anc. Athesis). A river in Northern Italy formed by numberless streamlets from the Helvetian Alps. In 563 the Romans defeated the Goths and Franks on its banks. Gen. Massena crossed it in 1806.

Adis. A city in Africa. Xantippe, chief of the Carthaginians, defeated under its walls the Romans commanded by Regulus.

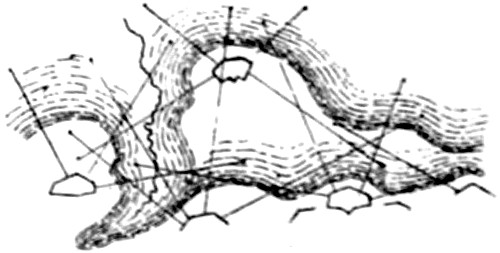

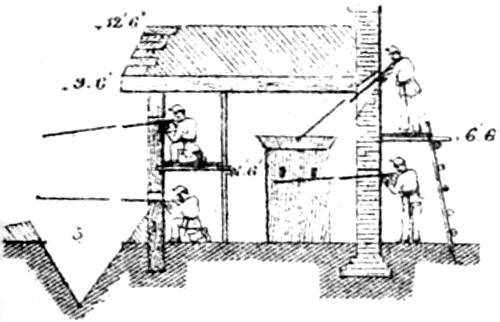

Adit. A passage under ground by which miners approach the part they intend to sap.

Adjeighur. A fortress in Bundelcund, which was captured in 1809 by a force under the command of Col. Gabriel Martindell.

Adjourn. To suspend business for a time, as from one day to another; said of military courts. Adjournment without day (sine die), indefinite postponement.

Adjutant (from adjuvo, “to help”). A regimental staff-officer with the rank of lieutenant, appointed by the regimental commander to assist him in the execution of all the details of the regiment or post. He is the channel of official communication. It is his duty to attend daily on the commanding officer for orders or instructions of any kind that are to be issued to the command, and promulgate the same in writing after making a complete record thereof. He has charge of the books, files, and men of the headquarters; keeps the rosters; parades and inspects all escorts, guards, and other armed parties previous to their proceeding on duty. He should be competent to instruct a regiment in every part of the field exercise, should understand the internal economy of his corps, and should notice every irregularity or deviation from the established rules or regulations. He should, of course, be an officer of experience, and should be selected with reference to special fitness, as so much depends upon his manner and thoughtfulness in the exercise of the various and important duties imposed upon him. Unexceptionable deportment is especially becoming to the adjutant.

Adjutant-General. An officer of distinction selected to assist the general of an army in all his operations. The principal staff-officer of the U. S. army. The principal staff-officers of generals of lower rank are called assistant adjutant-generals.

Adjutant-General’s Department. In the United States, consists of 1 adjutant-general with the rank of brigadier-general; 2 assistant adjutant-generals, colonels; 4 lieutenant-colonels, and 10 majors; also about 400 enlisted clerks and messengers. The officers are generally on duty with general officers who command corps, divisions, departments, etc. “They shall also perform the duties of inspectors when circumstances require it.” The lowest grades must be selected from the captains of the army.

Administration. Conduct, management; in military affairs, the execution of the duties of an office.

Administration, Council of. A board of officers periodically assembled at a post for the administration of certain business.

Admissions. In a military sense, the judge-advocate is authorized when he sees proper to admit what a prisoner expects to prove by absent witnesses.

Adobe (Sp.). An unburnt brick, dried in the sun, made from earth of a loamy character, containing about two-thirds fine sand mixed intimately with one-third or less of clayey dust or fine sand.

Adour. A river in the southwest of France, which Lord Wellington, after driving the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte across the Pyrenees, passed in the face of all opposition, on the 26th of February, 1814.

Adrana. A river in Germany, at present called Eder. Germanicus defeated the Germans on its bank in 15.

Adrianople. A Turkish city named after the Emperor Adrian; unsuccessfully besieged by the Goths in the 4th century; the army of Murad I. took the city in 1361; unconditionally surrendered to the Russians in August, 1829; peace was declared in this city between Russia and Turkey, September 14, 1829, and the city relinquished to the Turks.

Adrumetum, or Hadrumetum. An ancient African city, now in ruins, situated on the Mediterranean, southeast from Carthage. The Moors took this city from the Romans in 549, but it was retaken soon after by a priest named Paul.

Advance. Before in place, or beforehand in time; used for advanced; as, advance-guard, or that before the main guard or body of an army; to move forward.

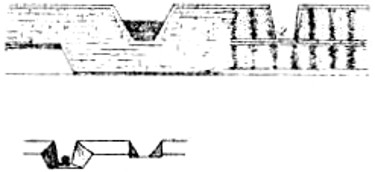

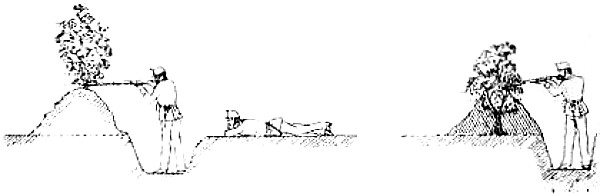

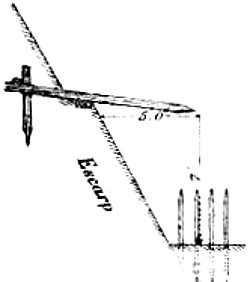

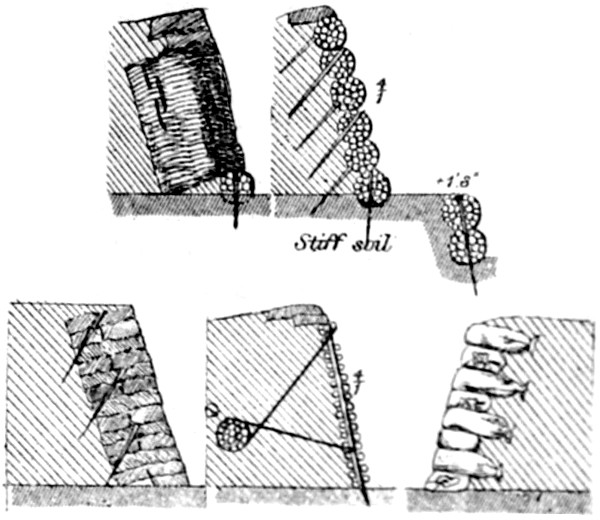

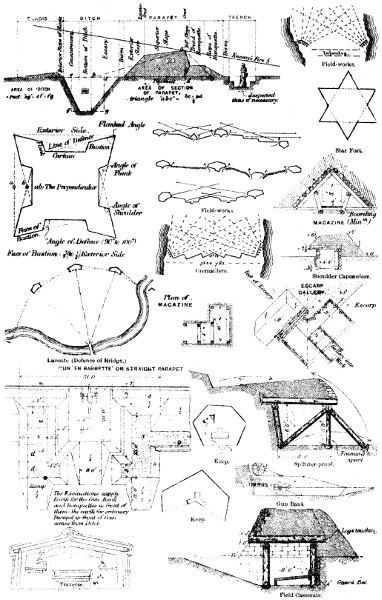

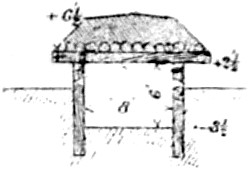

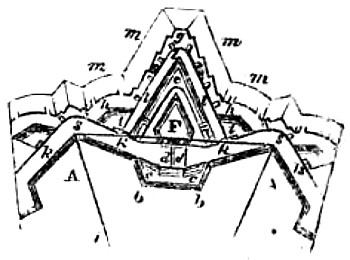

Advanced Covered Way. Is a terre plein on the exterior of the advanced ditch, similar to the first covered way.

Advanced Ditch. Is an excavation beyond the glacis of the enceinte, having its surface on the prolongation of that slope, that an enemy may find no shelter when in the ditch.

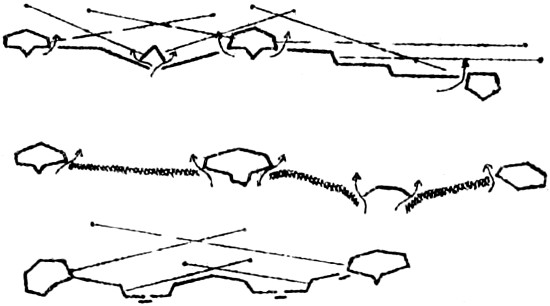

Advanced Guard. A detachment of troops which precedes the march of the main body.

[13]

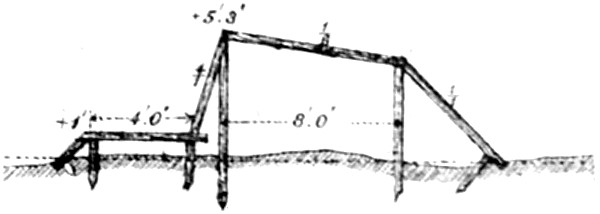

Advanced Guard Equipage. See Pontons.

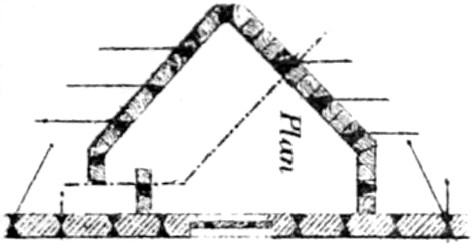

Advanced Lunettes. Works resembling bastions or ravelins, having faces or flanks. They are formed upon or beyond the glacis.

Advanced Works. Are such as are constructed beyond the covered way and glacis, but within range of the musketry of the main works.

Advancement. In a military sense, signifies honor, promotion, or preferment in the army, regiment, or company.

Advantage Ground. That ground which affords the greatest facility for annoyance or resistance.

Adversary. Generally applied to an enemy, but strictly an opponent in single combat.

Advising to Desert. Punishable with death or otherwise, as a court-martial may direct. See Appendix, Articles of War, 51.

Advocate, Judge-. See Judge-Advocate.

Adynati. Ancient name for invalid soldiers receiving pension from the public treasury.

Ægide (Æges). A name, according to Homer, for a protecting covering wound around the left arm in the absence of a shield; used by Jupiter, Minerva, and Apollo.

Ægolethron (Gr.). A plant. This word means goat and death. It was believed by the ancients that this plant would kill goats only, if eaten by them. Xenophon reports that the soldiers of the army of the “Ten Thousand” tasted of some honey prepared from this plant which caused them to be affected with hallucinations.

Ægospotamos (“Stream of the Goat”). A small river flowing into the Hellespont, in the Thracian Chersonese; is famous for the defeat of the Athenian fleet by the Lacedæmonians under Lysander, which put an end to the Peloponnesian war, and to the predominance of Athens in Greece, 405 B.C.

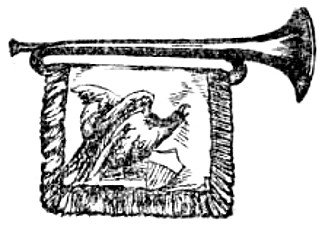

Æneatores. In military antiquity, the musicians in an army, including those who sounded the trumpets, horns, etc.

Ærarium Militare. In Roman antiquity, the war treasury of Rome, founded by Augustus; in addition to other revenues, the one-hundredth part of all merchandise sold in Rome was paid into it.

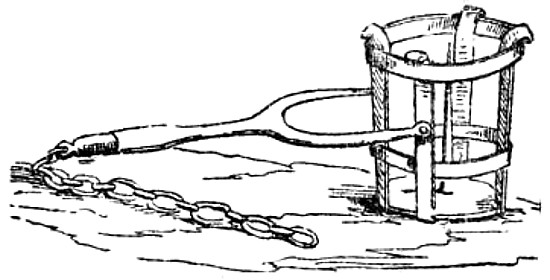

Æro. A basket used by the Roman soldiers to carry earth in to construct fortifications.

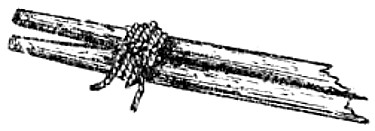

Ærumnula. A wooden pole or fork, introduced among the Romans by Consul Marius. Each soldier was provided with one of these poles, which had attached thereto a saw, hatchet, a sack of wheat, and baggage; and he was compelled to carry it on a march.

Affair. An action or engagement, not of sufficient magnitude to be termed a battle.

Affamer (Fr.). To besiege a place so closely as to starve the garrison and inhabitants.

Affidavit. In military law is an oath duly subscribed before any person authorized to administer it. In the U. S. service, in the absence of a civil officer any commissioned officer is empowered to administer an oath.

Afforciament. An old term for a fortress or stronghold.

Afghanistan. A large country in Central Asia, at war with England 1838, and 1878-79.

Afrancesados (Sp.). Name given to the Spaniards who upheld the oath of allegiance to king Joseph Bonaparte; also called Josephins (in the Peninsular war).

Aga. Rank of an officer in the Turkish army; the same as a general with us.

Age. In a military sense, a young man must be 14 years old before he can become an officer in the English army, or be entered as a cadet at Woolwich, in the English military academy. For admission to the military academy at West Point, U. S., the age is from 17 to 22 years. Men are enlisted for soldiers at from 17 to 45 in the English army, and in the U. S. army at from 18 to 35. Officers in the U. S. army may be retired, at the discretion of the President, at 62 years of age.

Agema (Gr.). In the ancient military art, a kind of soldiery, chiefly in the Macedonian army. The word is Greek, and denotes vehemence, to express the strength and eagerness of this corps.

Agen. Principal place of the department Lot-et-Garonne, France, on the right bank of the river Garonne, which has a city of the same name, and was the scene of many battles.

Agency. A certain proportion of money which is ordered to be subtracted from the pay and allowances of the British army, for transacting the business of the several regiments comprising it.

Agent, Army. A person in the civil department of the British army, between the paymaster-general and the paymaster of the regiment, through whom every regimental concern of a pecuniary nature is transacted.

Agger. In ancient military writings, denotes the middle part of a military road raised into a ridge, with a gentle slope on each side to make a drain for the water, and keep the way dry; it is also used for a military road. Agger also denotes a work or fortification, used both for the defense and attack of towns, camps, etc., termed among the moderns, lines. Agger is also used for a bank or wall erected against the sea or some great river to confine or keep it within bounds, and called by modern writers, dam, sea-wall.

Agiades. In the Turkish armies are a kind of pioneers, or rather field engineers, employed in fortifying the camp, etc.

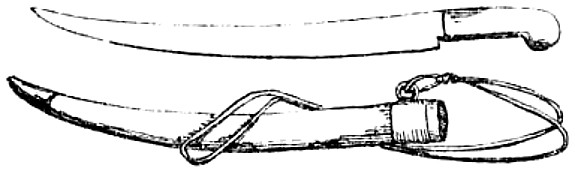

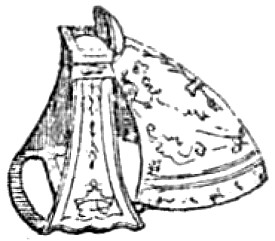

Agiem-clich. A very crooked sabre, rounded near the point; an arm much in use in Persia and Turkey.

Agincourt, or Azincourt. A village of France, celebrated for a great battle fought[14] near it in 1415, wherein Henry V. of England defeated the French.

Agmen. Roman name for an army on the march.

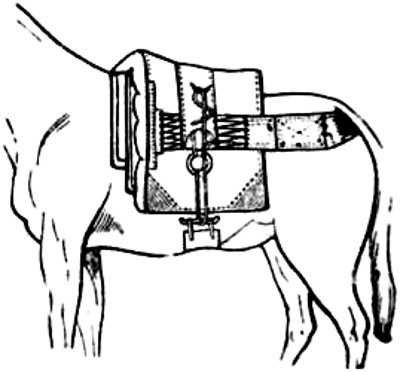

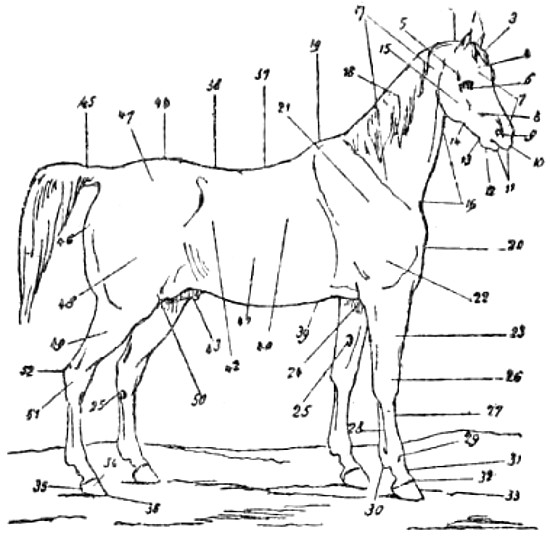

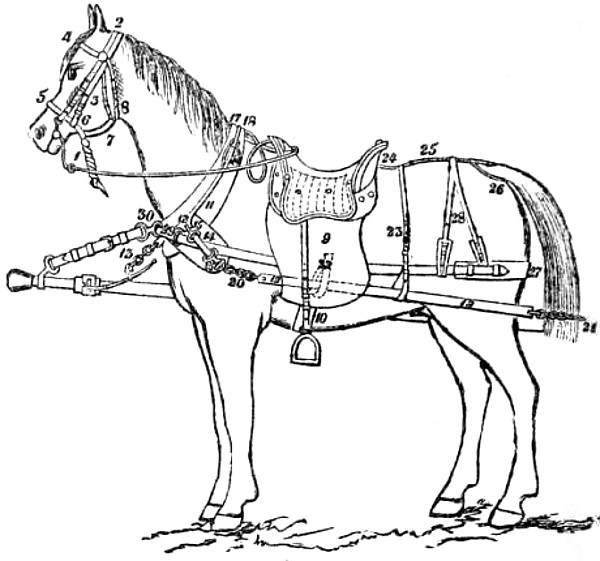

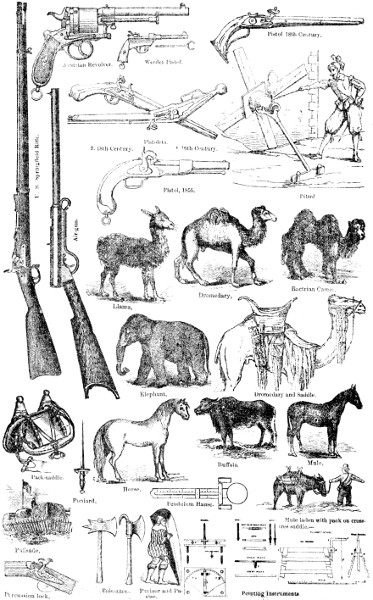

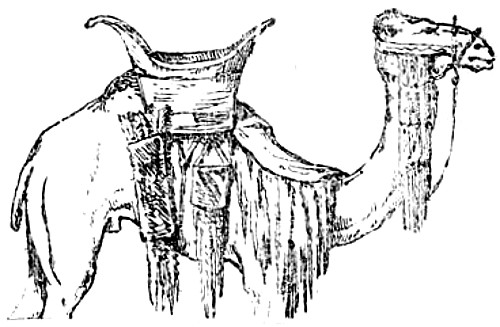

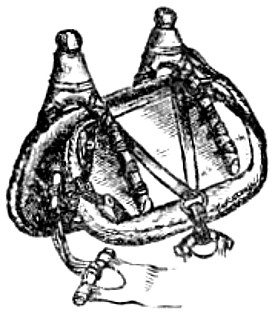

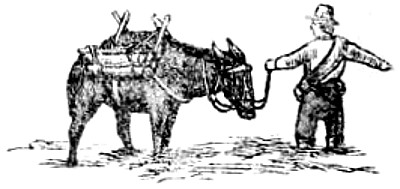

Agminalis. Name given by the ancients to a horse which carried baggage, equipments, etc., on its back; now termed pack-horse.

Agnadello. Village in the duchy of Milan, on a canal between the rivers Adda and Serio, celebrated by the victory of Louis XII., king of France, over the Venetian and Papal troops in 1509, and by a battle between Prince Eugene and the Duke of Vendôme in 1705.

Agrigente (now Girgenti). City in Sicily, situated on the Mediterranean; sacked by the Carthaginians under Amilcar in 400 B.C., and taken twice by the Romans in 262 and 210 B.C.

Aguebelle. City in the province of Maurienne, in Savoy. The French and Spaniards defeated the troops of the Duke of Savoy in 1742.

Aguerri (Fr.). A term applied to an officer or soldier experienced in war.

Agustina. See Saragossa, Maid of.

Ahmednuggur. A strong fortress in the Deccan, 30 miles from Poonah, which was formerly in the possession of Scindia, but fell to the British arms during the campaign conducted by Gen. Wellesley.

Aidan (Prince). See Scotland.

Aid-de-camp. An officer selected by a general to carry orders; also to represent him in correspondence and in directing movements.

Aid-major (Fr.). The adjutant of a regiment.

Aigremore. A term used by the artificer in the laboratory, to express the charcoal in a state fitted for the making of powder.

Aiguille (Fr.). An instrument used by engineers to pierce a rock for the lodgment of powder, as in a mine, or to mine a rock, so as to excavate and make roads.

Aiguillettes. A decoration, consisting of bullion cords and loops, which was formerly worn on the right shoulder of general officers, and is now confined to the officers of household cavalry; also worn in the U. S. army by officers of the adjutant-general’s department, aids-de-camp, and adjutants of regiments.

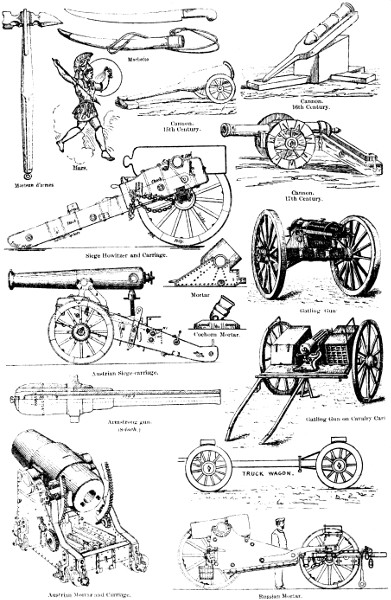

Aiguillon. A city in France; while in the possession of the English in 1345, it was besieged by the Duke of Normandy, son of Philip de Valois. According to some authors, cannons were used on this occasion for the first time in France.

Aile (Fr.). A wing or flank of an army or fortification.

Ailettes (Fr.). Literally “little wings,” were appendages to the armor worn behind or at the side of the shoulders by knights in the 13th century. They were made of leather covered with cloth, and fastened by silk laces. They are supposed to have been worn as a defense to the shoulders in war.

Aim. The act of bringing a musket, piece of ordnance, or any other missive weapon, to its proper line of direction with the object intended to be struck.

Aim-frontlet. A piece of wood hollowed out to fit the middle of a gun, to make it of an equal height with the breech; formerly made use of by the gunners, to level and direct their pieces.

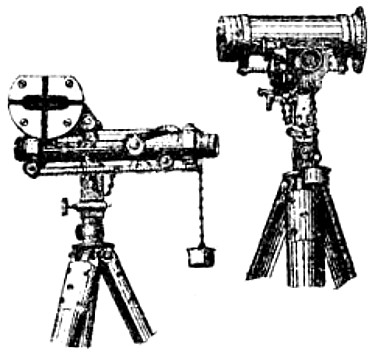

Aiming Drill. A military exercise to teach men to aim fire-arms. Great importance is justly attached to this preliminary step in target practice.

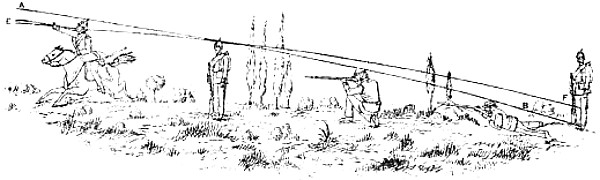

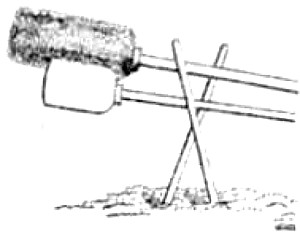

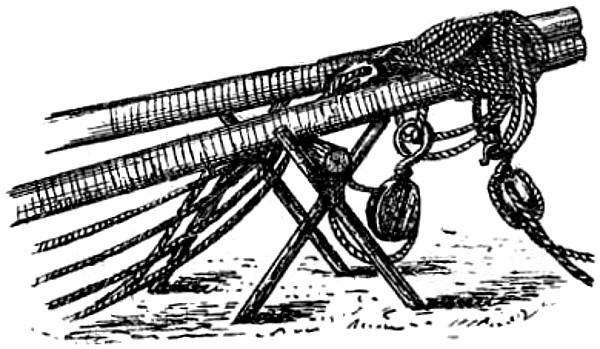

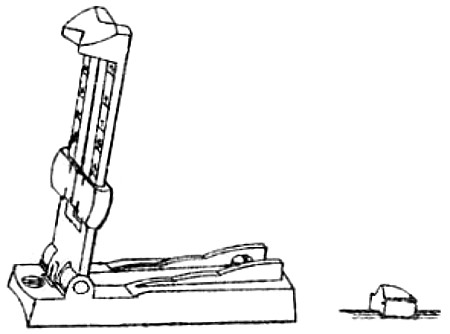

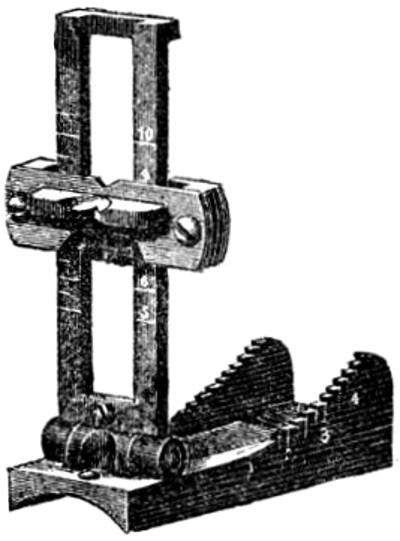

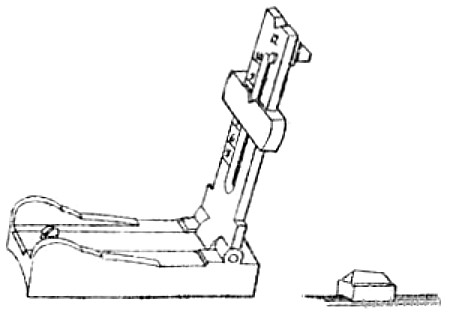

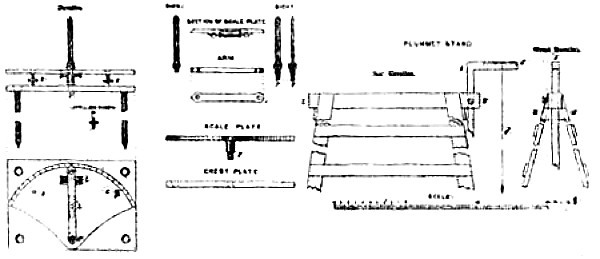

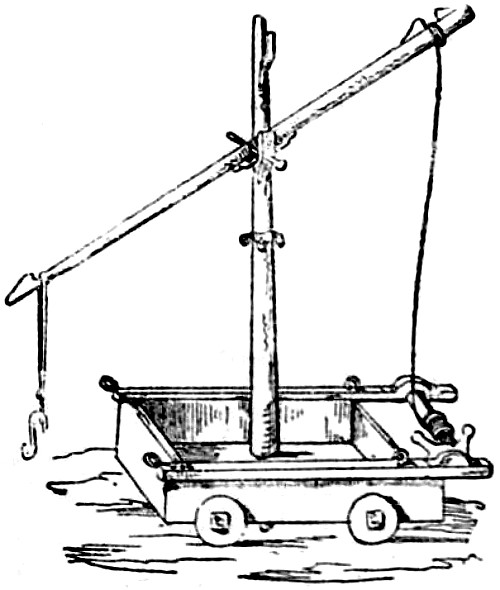

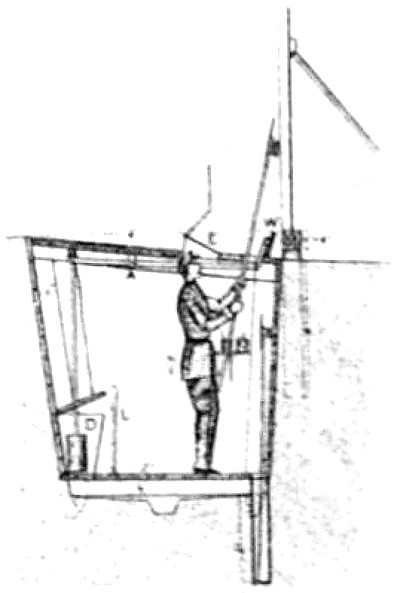

Aiming-stand. An instrument used in teaching the theory of aiming with a musket. It usually consists of a tripod with a device mounted upon it, which holds the gun and allows it to be pointed in any direction.

Ainadin. Name of a field near Damas in Syria, celebrated by a battle on July 25, 633, in which Khaled, chief of the Saracens, defeated Verdan, a general of the Roman army. Verdan lost 50,000 men and was decapitated.

Ain-Beda (Africa). An engagement at this place between the French and Arabs in October, 1833.

Ain Taguin. “Spot of the little desert,” in the province of Algiers; here the Duke d’Aumale surprised and dispersed the troops of Abd-el-Kader.

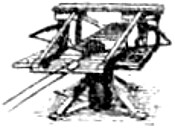

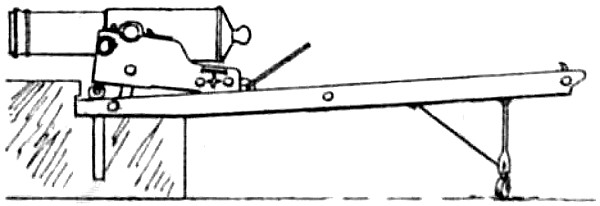

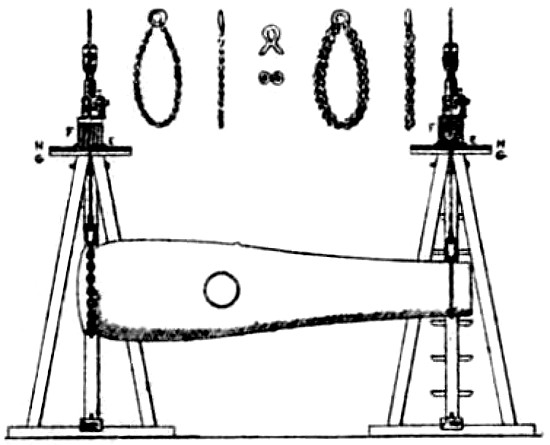

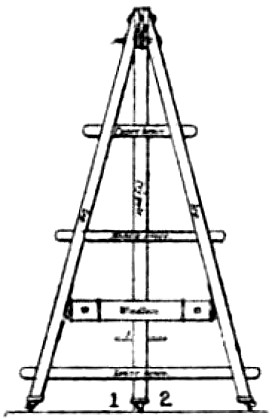

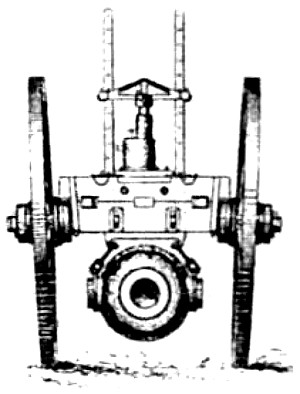

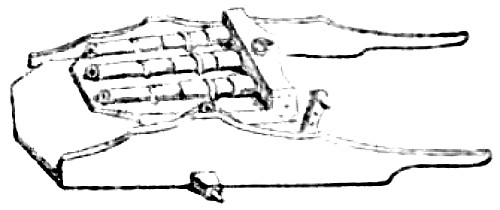

Air-cylinder. A pneumatic buffer used in America to absorb the recoil of large guns. For 10-inch guns, one cylinder is used; for the 15-inch, two. They are placed between the chassis rails, to which they are firmly secured by diagonal braces. A piston traversing the cylinder is attached to the rear transom of the top carriage. When the gun recoils the piston-head is drawn backwards in the cylinder, and the recoil is absorbed by the compression of the air behind it. Small holes in the piston-head allow the air to slowly escape while the gun is brought to rest. The hydraulic buffer largely used abroad operates in the same way, water being used in place of air.

Air, Resistance of. The resistance which the air offers to a projectile in motion. See Projectiles, Theory of.

Aire. A military position on the Adour, in the south of France, where the French were defeated by the English under Lord Hill, on March 2, 1814.

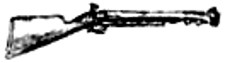

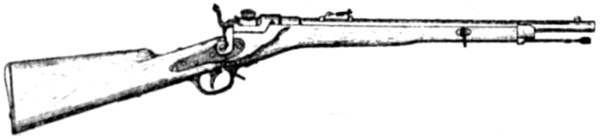

Air-gun. An instrument resembling a musket, used to discharge bullets by the elastic force of compressed air.

Aix. A small island on the coast of France between the Isle of Oleron and the continent. It is 12 miles northwest of Rochefort, and 11 miles from Rochelle. On it are workshops for military convicts.

Aix-la-Chapelle (Ger. Aachen). A district in the Prussian province of the Lower Rhine. Here Charlemagne was born in 742, and died in 814. The city was taken by the French in 1792; retaken by the Austrians in 1793; by the French 1794; reverted to[15] Prussia 1814. Congress held by the sovereigns of Austria, Russia, and Prussia, assisted by ministers from England and France, at Aix-la-Chapelle, and convention signed October 9, 1818.

Akerman (Bessarabia). After being several times taken it was ceded to Russia, 1812. Here the celebrated treaty between Russia and Turkey was concluded in 1826.

Aketon. Another name for a portion of armor, used in the feudal times, called the gambeson (which see).

Akhalzikh (Armenia). Near here Prince Paskiewitch defeated the Turks Aug. 24, and gained the city, Aug. 28, 1828.

Akindschi. A sort of Turkish cavalry, employed during the war between the Turks and the German emperors.

Aklat. A small town in Asiatic Turkey, taken by Eddin in 1228, and by the Turks in the 14th century.

Akmerjid. A city in the Crimea; an ancient residence of the khan of Tartary; taken by the Russians in 1771.

Akoulis. A city in Armenia, often pillaged by the Persians and Turks; taken in 1752 by the Persian general Azad-Khan, by whom the majority of the inhabitants were put to the sword.

Akrebah. At this place, about the year 630, Khaled, general of the Mussulman troops, fought the army of a new prophet named Mosseilamah, who perished in the combat.

Ala. According to Latin authors, this word signifies the wing of an army, i.e., the flanks, on which were placed troops furnished by the allied nations; also sometimes used to designate a brigade of cavalry occupying the same position in battle.

Alabama. One of the Southern States of the American confederacy, is bounded on the north by Tennessee, east by Georgia, south by Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, and west by Mississippi. The celebrated exploring expedition of De Soto in 1541 is believed to have been the first visit of the white man to the wilds of Alabama. In the beginning of the 18th century the French built a fort on Mobile Bay, but the city of that name was not commenced till nine years later (1711). In 1763, the entire French possessions east of the Mississippi (except New Orleans) fell into the hands of the English. Alabama was incorporated first with Georgia, afterwards, in 1802, with the Mississippi Territory; but finally, in 1819, it became an independent member of the great American confederacy. In 1813 and 1814 the Creek Indians waged war on the settlers and massacred nearly 400 whites who had taken refuge at Fort Mimms, on the Alabama River. They were, however, soon reduced to subjection by Gen. Jackson, and after their defeat at Horseshoe Bend, March, 1814, the greater portion of their territory was taken from them, and they were subsequently removed to the Indian Territory. On the outbreak of the civil war in 1861, the temporary capital of the Confederate States was established at Montgomery, Ala., but it was soon afterwards removed to Richmond, Va.

Alabanda (Bour Dogan, or Arab Hissar). A city in Asia Minor; destroyed by Labienus, a Roman general, in 38 B.C.

Alacays. Name given by the ancients to a kind of soldiery, and afterwards to servants following an army.

Alage. A mounted guard of the Byzantine emperors, doing duty in the palace of Constantinople, and defending, in case of danger, the person of the emperor.

Alaibeg. A Turkish commander of regiments of levied troops.

Alamo, Fort, or The Alamo. A celebrated fort in Bexar County, near San Antonio, Texas, where a small garrison of Texans bravely resisted a body of Mexicans ten times their number, and perished to a man, March 6, 1836. This spot has hence been called the Thermopylæ of Texas, and “Remember the Alamo!” was used as the battle-cry of the Texans in their war of independence.

Alanda. Name of a legion formed by Julius Cæsar from the best warriors of the Gauls.

Aland Isles (Gulf of Bothnia). Taken from Sweden by Russia, 1809. See Bomarsund.

Alani. A Tartar race; invaded Parthia, 75; were subdued by the Visigoths, 452, and eventually incorporated with them.

Alarcos (Central Spain). Here the Spaniards under Alfonso IX., king of Castile, were totally defeated by the Moors, July 19, 1195.

Alares. Name given by the Romans to troops which were placed on the wings of an army; these troops were generally furnished by allies.

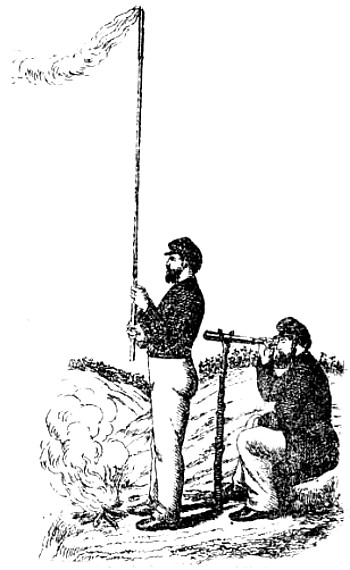

Alarm. A sudden apprehension of being attacked by surprise, or the notice of such attack being actually made. It is generally signified by the discharge of fire-arms, the beat of a drum, etc.

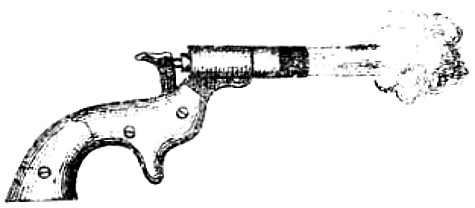

Alarm Gun. A gun fired to give an alarm.

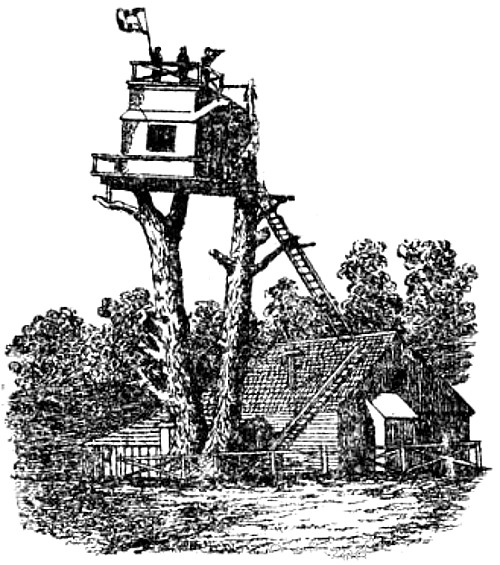

Alarm Post. In the field, is the ground appointed by the quartermaster-general for each regiment to march to, in case of an alarm. In a garrison, it is the place allotted by the governor for the troops to assemble on any sudden alarm.

Alaska. A large territory forming the northwest part of North America, which was purchased by the United States from Russia in 1867, and was annexed as a county to Washington Territory in 1872. The native inhabitants are Esquimaux, Indians, and Aleuts, with a few persons of Russian descent.

Alba de Tormes. A city in Spain, where the French defeated the Spaniards in 1809.

Albana. A city in ancient Albania, situated on the coast of the Caspian Sea; a wall was constructed to the west of the city for[16] the purpose of staying the progress of the Scythians, by Darius I., or by Chosrois.

Albania. A province in European Turkey, formerly part of the ancient Epirus, a scene of many battles; a revolt in Albania was suppressed in 1843.

Albanians, or Albaniers. The inhabitants of the Turkish territory of Albania, are a very brave and active race, and furnish the best warriors for the Turkish army.

Albans, St. (Hertfordshire, Eng.). Near the Roman Verulam; first battle of St. Albans took place in May, 1455, between the Houses of Lancaster and York, wherein the former were defeated, and King Henry VI. taken prisoner; second battle took place in February, 1461, wherein Queen Margaret totally defeated the Yorkists and rescued the king.

Albe. A city in Naples, situated near the Lake Celano; in ancient times it was an important city in Samnium.

Albeck. A village in Würtemberg where 25,000 Austrians, under the command of Gen. Mack, were defeated by 6000 French in 1805.

Alberche. A river of Spain, which joins the Tagus near Talavera de la Reyna, where, in 1809, a severe battle was fought between the French army and the allied British and Spanish troops, in which the former were defeated.

Albe-Royale. A city in Lower Hungary, which sustained several sieges.

Albesia. In antiquity, a kind of shield, otherwise called decumana.

Albi. A city in the department of Tarn, France; pillaged by the Saracens in 730, and taken by Pepin in 765.

Albigenses. A sect of heretics, who were in existence during the 12th and 13th centuries, and inhabited Albi, France; fought many battles; went to Spain in 1238, where they were slowly exterminated.

Albuera. A small village near the river Guadiana, in Spain, where the French army under Marshal Soult was defeated by the British and Spanish forces under Marshal, afterwards Lord, Beresford, March 16, 1811.

Albufera (Spain, East Central). A lagoon, near which the French marshal Suchet (afterwards Duke of Albufera), defeated the Spaniards under Blake, January 4, 1812; this led to his capture of Valencia, January 9.

Alcacsbas (Portugal). A treaty was concluded here between Alfonso V. of Portugal and Ferdinand and Isabella of Castile.

Alcantara. A creek near Lisbon, on the banks of which a battle was fought between the Spaniards under Alva and the Portuguese under Antonio de Crato (prior of the Maltese order).

Alcantara, Order of. Knights of a Spanish military order, who gained a great name during the wars with the Moors.

Alcassar, or Alcacar. A fortified city in Morocco, situated between Ceuta and Tangier; the narrowest point of the Strait of Gibraltar. The Portuguese seized this city in 1468.

Alcazar-Quiver. A city near Fez, Northwest Africa, where the Moors totally defeated the Portuguese, whose gallant king, Sebastian, was slain August 4, 1578.

Alcmaer. A city in Holland; besieged by the Spaniards in 1573 without success; here the British and Russians were defeated by the French in 1799.

Aldenhofen. A village of the Prussian Rhenish province, where the French, under Gen. Miranda, were defeated by Archduke Charles, March 1, 1793; the Austrians were defeated March 18, 1793.

Aldershott, Camp. A moor near Farnham, about 35 miles from London. In April, 1854, the War Office, having obtained a grant of £100,000, purchased 4000 acres of land for a permanent camp for 20,000 men; additional land was purchased in 1856. The camp is used as an army school of instructions.

Aldionaire (Aldionarius). A sort of equerry, who in the army was kept at the expense of his master. Under Charlemagne, the aldionaires were of an inferior rank.

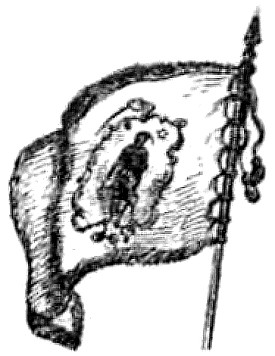

Alem. Imperial standard of the Turkish empire.

Alemanni (or all men, i.e., men of all nations, hence Allemannen, German). A body of Suevi, who took this name; were defeated by Caracalla, 214. After several repulses they invaded the empire under Aurelian; they were subdued in three battles, 270. They were again vanquished by Julian, 356-57. They were defeated by Clovis at Tolbiac (or Zulpich), 496. The Suabians are their descendants.

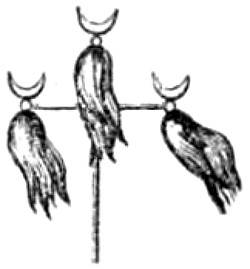

Alemdar. An official who carries the green banner of Mahomet (Mohammed), when the sultan assists in ceremonies of solemnity.

Alençon (Northern France). Gave title to a count and duke. Martel, count of Anjou, seized this city, which was retaken by William the Conqueror in 1048. It was the scene of many battles.

Aleppo (Northern Syria). A large town named Berœa Seleucus Nicator about 299 B.C. It was taken by the Turks in 638; by Saladin, 1193, and sacked by Timur, 1400. Its depopulation by the plague has been frequent; 60,000 persons were computed to have perished by it in 1797; and many in the year 1827. On October 16, 1850, the Mohammedans attacked the Christians, burning nearly everything. Three churches were destroyed; five others plundered, and thousands of persons slain. The total loss of property amounted to about a million pounds sterling; no interference was attempted by the pasha.

Aleria. An important city in Corsica, at the mouth of the river Tavignano; was taken in 259 B.C. by the Romans under Consul Cornelius.

Alert. Watchful; vigilant; active in vigilance;[17] upon the watch; guarding against surprise or danger.

Alesia, or Alisia. Now called Alise-Sainte-Reine, a city in the department of Cote-d’Or. This city was besieged and taken by the Romans in 52 B.C.; it was one of the greatest events of Cæsar’s war in Gaul.

Alessandria. A city of Piedmont, built in 1168, under the name of Cæsarea by the Milanese and Cremonese, to defend the Tanaro against the emperor, and named after Pope Alexander III. It has been frequently besieged and taken. The French took it in 1796, but were driven out July 21, 1799. They recovered it after the battle of Marengo, in 1800, and held it until 1814, when the strong fortifications erected by Napoleon were destroyed. They have been restored since June, 1856.

Alet, or Aleth. A small city in the department of Ande, France; was taken by the Protestants in 1573.

Aleut. An inhabitant of the Aleutian Islands. These people differ both from the Indians of the neighboring continent and the Esquimaux farther north. They are expert hunters of the seal and other animals. They are industrious and peaceful, but addicted to drunkenness.

Aleutian Islands. A number of islands stretching from the peninsula of Alaska in North America to Kamtschatka in Asia. The greater number belong to the territory of Alaska.

Alfere, or Alferez. Standard-bearer; ensign; cornet. The old English term for ensign; it was in use in England till the civil wars of Charles I.

Alford (Northern Scotland), Battle of. Gen. Baillie, with a large body of Covenanters, was defeated by the Marquis of Montrose, July 2, 1645.

Alfuro. A city in Navarre, Spain. The British proceeded against the city in 1378, the garrison being absent; they found the women ranged on the ramparts disposed to defend the place. Capt. Tivet, commander of the English forces, would not attack the brave women, but retreated and did not molest the place.

Algebra. A peculiar kind of mathematical analysis allied to arithmetic and geometry.

Algidus. A mountain-range in Latium, Italy, where Cincinnatus defeated the Æqui in 458 B.C.

Algiers (now Algeria, Northwest Africa). Part of the ancient Mauritania, which was conquered by the Romans, 46 B.C.; by the Vandals, 439; recovered for the empire by Belisarius, 534, and subdued by the Arabs about 690. The city of Algiers was bombarded a number of times, and finally taken by the French in 1830. Algeria at present belongs to France.

Algonkins, or Alogonquins. One of the two great families of Indians who formerly peopled the country east of the Mississippi. The Chippewas are at present the most numerous race descended from this stock.

Alhama. A city in Spain, in the province of Granada. It was a most important fortress when the Moors ruled Granada, and its capture by the Christians in 1482 was the most decisive step in the reduction of their power.

Alhambra. The ancient fortress and residence of the Moorish monarchs of Granada; founded by Mohammed I. of Granada about 1253; surrendered to the Christians in November, 1491.

Ali Bey. Colonel of Turkish cavalry; also the rank of a district commander.

Alibi (Lat. “elsewhere”). An alibi is the best defense in law if a man is innocent; but if it turns out to be untrue, it is conclusive against those who resort to it.

Alicante. A fortified city and seaport in Spain, where the French defeated the Spaniards in a naval battle, April 1, 1688.

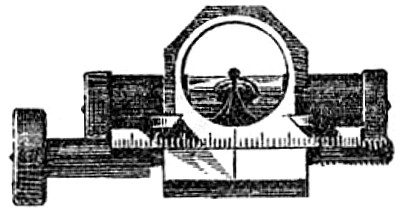

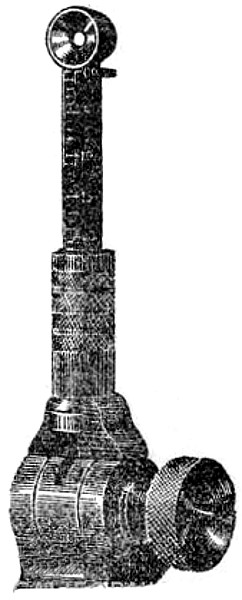

Alidade. The movable arm or rule carrying the sights of an angle-measuring instrument.

Alien. In law, implies a person born in a foreign country, in contradistinction to a natural born or naturalized person.

Alife (Alifa). A city in the kingdom of Naples, where Fabius defeated the Samnites in 307 B.C.

Alighur. See Allyghur.

Align. To form in line as troops; to lay out the ground-plan, as of a road.

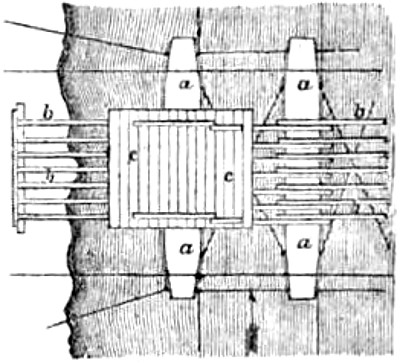

Alignment. A formation in straight lines, for instance, the alignment of a battalion means the situation of a body of men when drawn up in line. The alignment of a camp signifies the relative position of the tents, etc., so as to form a straight line from given points.

Aliwal. A village on the banks of the Sutlej, contiguous to the Punjab, where a British division, commanded by Maj.-Gen. Sir Henry Smith, on the 29th of January, 1846, encountered and defeated a superior body of Sikhs.

Aljubarrota (Portugal). Here John I. of Portugal defeated John I. of Castile, and secured his country’s independence, August 14, 1385.

Alkmaer. See Bergen-op-Zoom.

Allahabad (Northwest Hindostan). The holy city of the Indian Mohammedans, situated at the junction of the rivers Jumna and Ganges; founded by Akbar, in 1583; incorporated with the British possessions in 1803. During the Indian mutiny several Sepoy regiments rose and massacred their officers, June 4, 1857; Col. Neil marched promptly from Benares and suppressed the insurrection. In November, 1861, Lord Canning made this the capital of the northwest provinces.

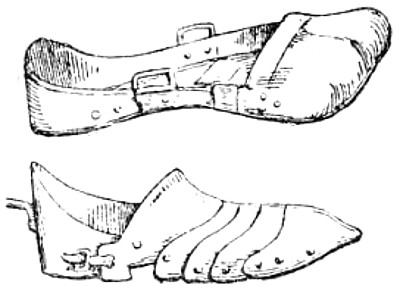

Allecrete. Light armor used by both cavalry and infantry in the 16th century, especially by the Swiss. It consisted of a breastplate and gussets, often reaching to the middle of the thigh, and sometimes below the knees.

Allecti Milites. A name given by the[18] Romans to a body of men who were drafted for military service.

Allegiance. In law, implies the obedience which is due to the laws. Oath of Allegiance is that taken by an alien, by which he adopts America and renounces the authority of a foreign government. It is also applied to the oath taken by officers and soldiers in pledge of their fidelity to the state.

Allegiant. Loyal; faithful to the laws.

Allia (Italy). A small river flowing into the Tiber, where Brennus and the Gauls defeated the Romans, July 16, 390 B.C. The Gauls sacked Rome and committed so much injury that the day was thereafter held to be unlucky (nefas), and no public business was permitted to be done on its anniversary.

Alliage (Fr.). A term used by the French to denote the composition of metals used for the fabrication of cannon, mortars, etc.

Alliance. In a military sense, signifies a treaty entered into by sovereign states for their mutual safety and defense. In this sense alliances may be divided into such as are offensive, where the contracting parties oblige themselves jointly to attack some other power; and into such as are defensive, whereby the contracting powers bind themselves to stand by and defend one another, in case of being attacked by any other power. Alliances are variously distinguished according to their object, the parties in them, etc. Hence we read of equal, unequal, triple, quadruple, grand, offensive, defensive alliances, etc.

Alligati. A name given by the Romans to prisoners of war and their captors. A chain was attached to the right wrist of the prisoner and the left wrist of the warrior who captured him.

Allobroges. A powerful race in ancient Gaul; inhabited a part of Savoy; vanquished by Fabius Maximus, 126 B.C.

Allocutio. An oration addressed by a Roman general to his soldiers, to animate them to fight, to appease sedition, or to keep them to their duty.

Allodial. Independent; not feudal. The Allodii of the Romans were bodies of men embodied on any emergency, in a manner similar to our volunteer associations.

Allonge. A pass or thrust with a rapier or small sword, frequently contracted into lunge; also a long rein used in the exercising of horses.

Allowance. A sum paid periodically for services rendered. The French use the word traitment in this sense. The allowances of an officer are distinct from his pay proper, and are applicable to a variety of circumstances.

Alloy. Is a composition by fusion of two or more metals. The alloy most used for gun-making is bronze (which see).

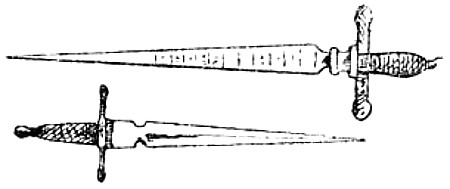

Allumelle. A thin and slender sword which was used in the Middle Ages, to pierce the weak parts or joints of armor.

Ally. In a military sense, implies any nation united to another,—under a treaty either offensive or defensive, or both.

Allyghur. A strong fortress on the northwest of India, which was captured, after a desperate conflict, by Lord Lake, in 1803. The French commander-in-chief, Gen. Perron, surrendered himself after the siege.

Alma. A river in the Crimea, near which was fought a great battle on September 20, 1854, between the Russian and Anglo-French armies; the Russians were defeated with great loss.

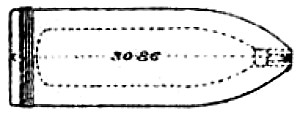

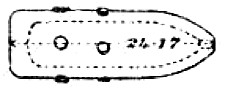

Almadie. A kind of military canoe or small vessel, about 24 feet long, made of the bark of a tree, and used by the negroes of Africa. Almadie is also the name of a long boat used at Calcutta, often from 80 to 100 feet long, and generally 6 or 7 broad; they are rowed with from 10 to 30 oars.

Alman-rivets, Almain-rivets, or Almayne-rivets. A sort of light armor derived from Germany, characterized by overlapping plates which were arranged to slide on rivets, by means of which flexibility and ease of movement were promoted.

Almaraz, Bridge of. In Spain, which on the 18th of May, 1812, was captured by Lord Hill, when he defeated a large French corps d’armée, which was one of the most brilliant actions of the Peninsular war.

Almeida. A strong fortress of Portugal, in the province of Beira. The capture of it by the Duke of Wellington, in 1811, after it had fallen into the hands of the French, was deemed a very brilliant exploit.

Almenara, or Almanara. City in Spain, in the province of Lerida, where, in 1710, Gen. Stanhope, with 4 regiments of dragoons and 20 companies of grenadiers, defeated a Spanish corps, composed of 4 battalions and 19 escadrons.

Almeria. City and seaport in Andalusia, Spain; captured from the Moors in 1147, by the united troops of Alfonso VII., king of Castile, Garcias, king of Navarre, and Raymond, count of Barcelona.

Almexial, Battle of. Between the Spaniards and Portuguese in 1663. The Portuguese were commanded by Sanctius Manuel, count of Vilaflor, and the celebrated Count Frederick von Schomberg, the latter being the veritable hero of the day. The Portuguese gained a great victory; the Spanish army was commanded by Don Juan of Austria, son of Philip IV.

Almissa (Dalminium). City in Dalmatia, Austria; it was the ancient capital of Dalmatia, but was ruined by Scipio Nasica in 156 B.C.

Almogavares. See Catalans.

Almohades. Mohammedan partisans, followers of El-Mehedi in Africa, about 1120. They subdued Morocco, 1145; entered Spain and took Seville, Cordova, and Granada, 1146-56; ruled Spain until 1232, and Africa until 1278.

Almonacid-de-Zorita. A town in the province of Guadalaxara, Spain, where the French defeated the Spaniards in 1809.

[19]

Almora. City in Bengal, which the English captured in 1815, and still hold.

Almoravides. Mohammedan partisans in Africa, rose about 1050; entered Spain by invitation, 1086; were overcome by the Almohades in 1147.

Alney. An island in the Severn, Gloucestershire, England. Here a combat is asserted to have taken place between Edmund Ironside and Canute the Great, in the sight of their armies. The latter was wounded, and proposed a division of the kingdom, the south part falling to Edmund. Edmund was murdered at Oxford shortly after, it is said, by Aedric Streon, and Canute obtained possession of the whole kingdom, 1016.

Alnwick (Sax. Elnwix). On the river Alne in Northumberland, England, was given at the Conquest to Ivo de Vesco. It has belonged to the Percies since 1310. Malcolm, king of Scotland, besieged Alnwick in 1093, where he and his sons were killed. It was taken by David I. in 1136, and attacked in 1174, by William the Lion, who was defeated and taken prisoner. It was owned by King John in 1215, and by the Scots in 1448. Since 1854 the castle has been repaired and enlarged with great taste and at unsparing expense.

Alost. A city in Belgium, captured and dismantled by Turenne in 1667, then abandoned to the allies after the battle of Ramillies, in 1706.

Alps. European mountains. Those between France and Italy were passed by Hannibal, 218 B.C.; by the Romans, 154 B.C., and by Napoleon I., May, 1800.

Alsace. See Elsass.

Altenheim. A village on the banks of the Rhine, grand duchy of Baden, where the French under Count de Lorges fought the Imperials, July 30, 1675, neither side being victorious; the French army retreated after the death of Turenne.

Altenkirchen. A town in the Prussian Rhine province, where several battles were fought during the war of the Republic, in one of which Gen. Marceau was killed, while protecting the retreat of Gen. Jourdan, September 20, 1796.

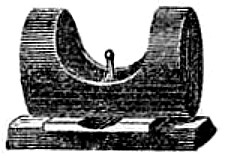

Altiscope. A device which enables a person to see an object in spite of intervening obstacles. In gunnery it is used to point a piece without exposing the person of the gunner. The simplest form consists of a small mirror set in the line of the sights, which reflects the sights and the object aimed at to the eye of the gunner. This form of reflecting sight is used with the Moncrieff counterpoise carriage, and has been recently proposed by Col. Laidley (U. S. Ordnance Corps) for small-arms.

Altitude. Height, or distance from the ground, measured upwards, and may be both accessible and inaccessible. Altitude of a shot or shell, is the perpendicular height of the vortex of the curve in which it moves above the horizon. Altitude of the eye, in perspective is a right line let fall from the eye, perpendicular to the geometrical plane.

Alumbagh. A palace with other buildings near Lucknow, Oude, India, taken from the rebels and heroically defended by the British under Sir James Outram, during the mutiny, September, 1857. He defeated an attack of 30,000 Sepoys on January 12, 1858, and of 20,000 on February 21.

Aluminium Bronze. An alloy of copper and aluminium, having great strength and hardness. See Ordnance, Metals for.

Alure. An old term for the gutter or drain along a battlement or parapet wall.

Alveda. An ancient city in Spain, where a battle was fought between Ramire I., king of the Austurias, and the Moors under the famous Abdolrahman, or Abd-el-Rahm; according to Spanish history, the Moors lost 60,000 men.

Amantea, or Amantia. City and seaport in Naples; sustained a siege against the French in 1806. It is believed that this city is the ancient Nepetum.

Amazons. Female warriors. Tribes, either real or imaginary, belonging to Africa and Asia, among which the custom prevailed for the females to go to war; preparing themselves for that purpose by destroying the right breast, in order to use the bow with greater ease. According to Greek tradition, an Amazon tribe invaded Africa, and was repulsed by Theseus, who afterwards married their queen. Hence all female warriors have been called Amazons.

Amberg. A town in Bavaria, where the French were defeated by the Austrians in 1796.

Ambit. The compass or circuit of any work or place, as of a fortification or encampment, etc.

Ambition. In a military sense, signifies a desire of greater posts or honors. Every person in the army or navy ought to have a spirit of emulation to arrive at the very summit of the profession by his personal merit.

Amblef. Ancient residence of the kings of France on the river of the same name, in Germany. Here Charles Martel defeated Chilperic II. and Rangenfroi, mayor of the Neustrians, 716.

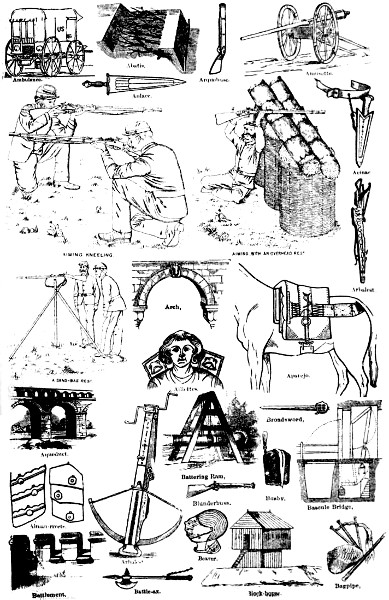

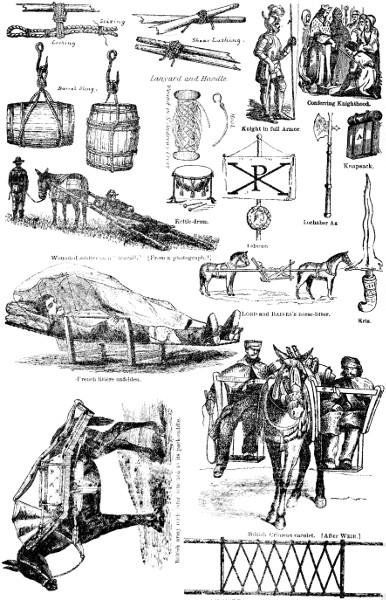

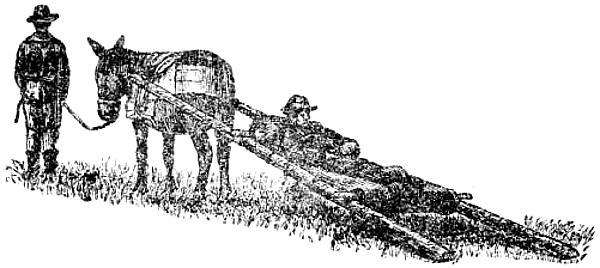

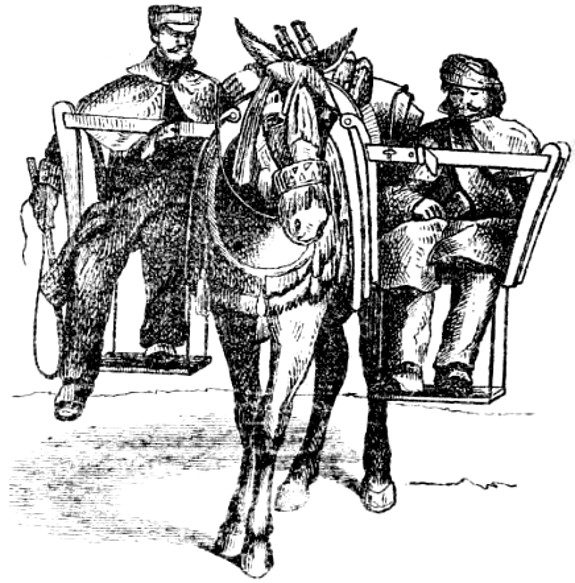

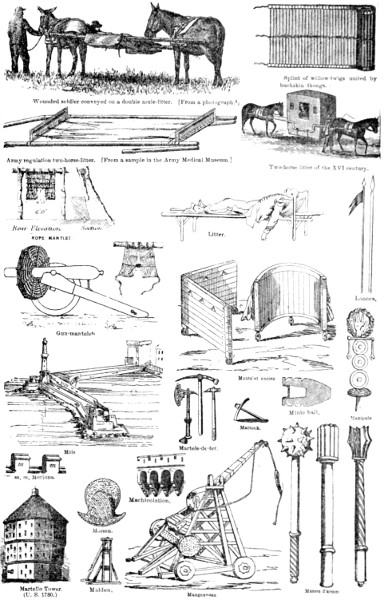

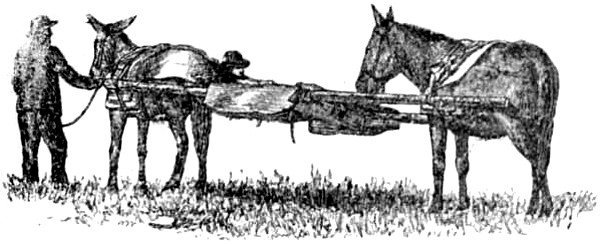

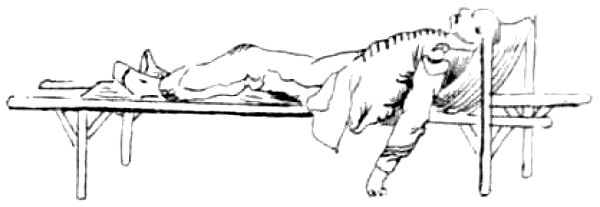

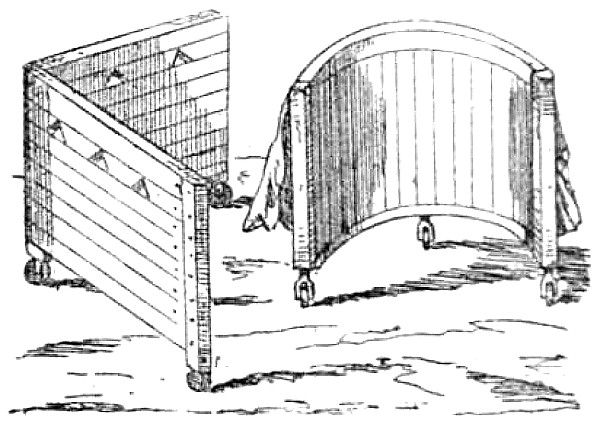

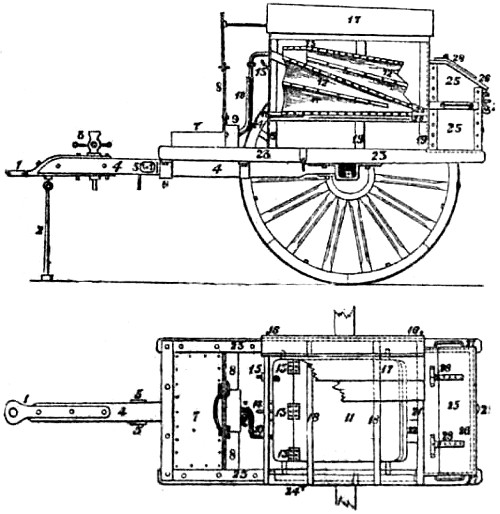

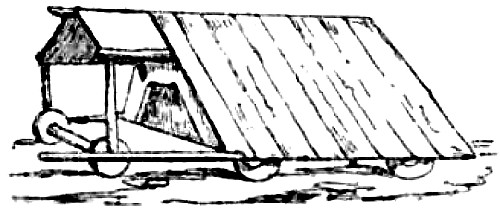

Ambulances. Are flying hospitals, so organized that they can follow an army in all its movements, and are intended to succor the wounded as soon as possible; a two- or four-wheeled vehicle for conveying the wounded from the field; called also an ambulance-cart.

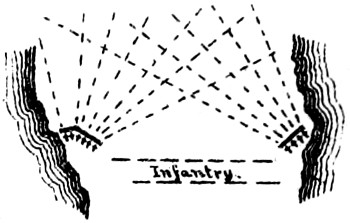

Ambuscade. A snare set for an enemy either to surprise him when marching without precaution, or to draw him on by different stratagems to attack him with a superior force.

Ambush. A place of concealment where an enemy may be surprised by a sudden attack.

Ame. A French term, similar in its import to the word chamber, as applied to cannon, etc.

Amende Honorable (Fr.). In the old[20] armies, of France, signified an apology for some injury done to another, or satisfaction given for an offense committed against the rules of honor or military etiquette, and was also applied to an infamous kind of punishment inflicted upon traitors, parricides, or sacrilegious persons, in the following manner: The offender being delivered into the hands of the hangman, his shirt stripped off, a rope put about his neck, and a taper in his hand; then he was led into the court, where he begged pardon of God, the court, and his country. Sometimes the punishment ended there; but sometimes it was only a prelude to death, or banishment to the galleys. It prevails yet in some parts of Europe.

Amenebourg. A place in Hanover which was captured from the English by the French in 1762.

Amentatæ. A sort of lance used by the Romans, which had a leathern strap attached to the centre of it.

Amentum. A leathern strap used by the Romans, Greeks, and Galicians, to throw lances. It was fastened around the second and third fingers, a knot was tied on it, which at the throwing of the lance loosened itself.

America. One of the great divisions of the earth’s surface, so called from Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine navigator, who visited South America in 1499. It is composed of two vast peninsulas called North and South America, extending in a continuous line 9000 miles, connected by the Isthmus of Panama or Darien, which is only 28 miles wide at its narrowest part. The physical features of this large continent are on a most gigantic scale, comprising the greatest lakes, rivers, valleys, etc., in the world; and its discovery, which may be said to have doubled the habitable globe, is an event so grand and interesting that nothing parallel to it can be expected to occur again in the history of mankind. Upon its discovery, in the latter half of the 15th century, colonists, settlers, warriors, statesmen, and adventurers of all nations began to flock to its shores, until after a lapse of nearly four centuries of wars, struggles, civilization, progress, and amalgamation of the more powerful races, and weakness and decay of the effete, it ranks in wealth and enlightenment as the first of the great divisions of the earth. Of the different races, governments, etc., occupying its area, it is not necessary here to speak; events of importance in their histories will be found under appropriate headings in this work.

Ames Gun. The rifled guns made by Mr. Horatio Ames, of Falls Village, Conn., are made of wrought iron on the built-up principle. See Ordnance, Construction of.

Amiens. A city in Picardy (Northern France). It was taken by the Spaniards March 11, and retaken by the French September 25, 1587. The preliminary articles of the peace between Great Britain, Holland, France, and Spain were signed in London by Lord Hawkesbury and M. Otto, on the part of England and France, October 1, 1801, and the definitive treaty was subscribed at Amiens, March 27, 1802, by the Marquis of Cornwallis for England, Joseph Bonaparte for France, Azara for Spain, and Schimmelpennick for Holland. War was declared in 1803.

Amisus. A city in the ancient kingdom of Pontus, fortified by Mithridates, and captured by Lucullus in 71 B.C.

Ammedera. An ancient city in Africa, where the rebel Gildon was defeated by Stilicho in 398.

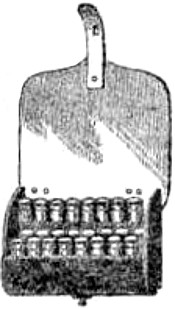

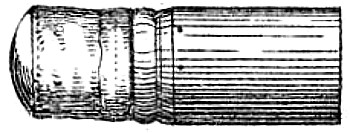

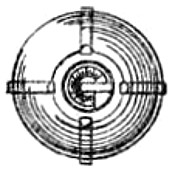

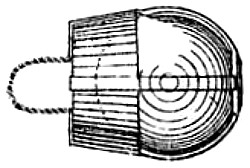

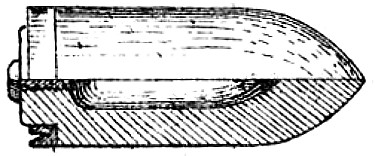

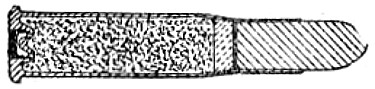

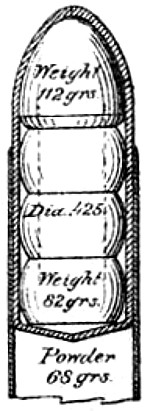

Ammunition. Is a term which comprehends gunpowder, and all the various projectiles and pyrotechnical composition and stores used in the service. See Ordnance, Ammunition for.

Ammunition Bread. That which is for the supply of armies and garrisons.

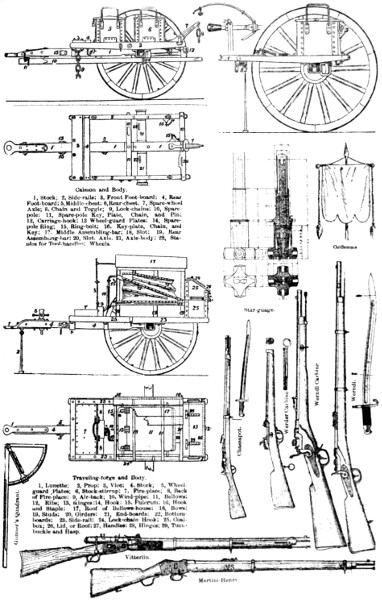

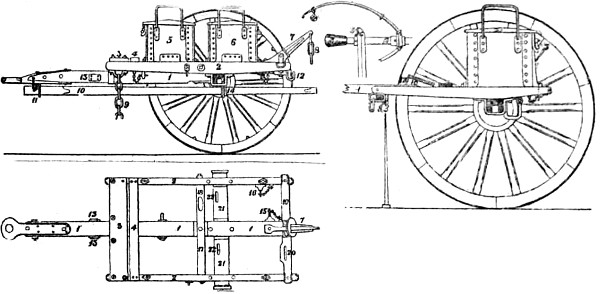

Ammunition-chest. See Ordnance for Caisson.

Ammunition Shoes. Those made for soldiers and sailors in the British service are so called, and particularly for use by those frequenting the magazine, being soft and free from metal.

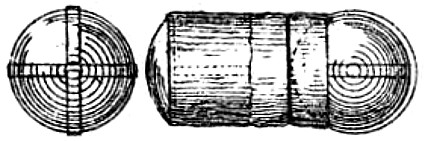

Ammunition, Stand of. The projectile, cartridge, and sabot connected together.

Amnesty. An act by which two belligerent powers at variance agree to bury past differences in oblivion; forgiveness of past offenses.

Amnias. A stream in Asia near which the army of Nicomedes, king of Bithynia, was defeated by the troops of Mithridates in 92 B.C.

Amorce (Fr.). An old military word for fine-grained powder, such as was sometimes used for the priming of great guns, mortars, or howitzers; as also for small-arms, on account of its rapid inflammation. A port-fire or quick-match.

Amorcer (Fr.). To prime; to decoy, to make a feint in order to deceive the enemy and draw him into a snare; to bait, lure, allure.

Amorcoir (Fr.). An instrument used to prime a musket; also for a small copper box in which were placed the percussion-caps.

Amoy. A town and port in China, which was taken by the troops under Sir Hugh Gough, assisted by a naval force, in August, 1841.

Ampfing. A village in Bavaria, where Louis, king of Bavaria, defeated Frederick of Austria in 1322; here Gen. Moreau was attacked by a superior force of Austrians in 1800, and accomplished his celebrated retreat.

Amphea. A city of Messenia, captured by the Lacedæmonians in 743 B.C.

Amphec. A city in Palestine where the Philistines defeated the Israelites in the year 1100 B.C.

Amphictyonic Council. A celebrated congress of deputies of twelve confederated tribes of ancient Greece, which met twice every year. The objects of this council were to insure mutual protection and forbearance[21] among the tribes, and for the protection of the temple of Delphi.

Amphipolis (now Emboli). A city situated on the Strymon in Macedonia; was besieged in 422 B.C., by the Athenians, where Cleon their chief was killed. Philip of Macedon captured the city in 363.

Amplitude. In gunnery, is the range of shot, or the horizontal right line, which measures the distance which it has run.

Ampoulette (Fr.). A wooden cylinder which contains the fuze of hollow projectiles.

Amsterdam. The capital of Holland. It was occupied by the French general Pichegru on January 19, 1795, and by the Prussians in 1813.

Amstetten. A village on the highway between Ems and Vienna, where the Russians were defeated by the French under Murat, November 5, 1805.

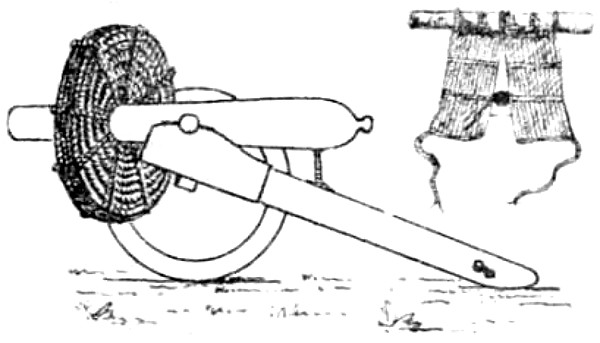

Amusette (Fr.). A brass gun, of 5 feet, carrying a half-pound leaden ball, loaded at the breech; invented by the celebrated Marshal Saxe. It is no longer used.

Amyclæ. An ancient town of Laconia, on the right bank of the Eurotas, famous as one of the most celebrated cities of the Peloponnesus in the heroic age. It is said to have been the abode of Castor and Pollux. This town was conquered by the Spartans about 775 B.C.

Anabash. In antiquity, were expeditious couriers, who carried dispatches of great importance in the Roman wars.

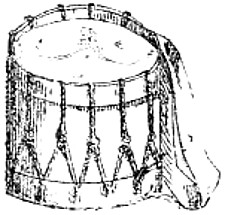

Anacara. A sort of drum used by the Oriental cavalry.

Anacleticum. In the ancient art of war, a particular blast of the trumpet, whereby the fearful and flying soldiers were rallied to the combat.

Anah. A city in Asiatic Turkey, which was captured and devastated in 1807 by the Wahabites, who were a warlike Mohammedan reforming sect.

Anam, or Annam, Empire of. Also called Cochin China, an empire in Southeastern Asia, which became involved in a war with France (1858-62), concluded by a treaty by which the emperor of Anam ceded the provinces of Cochin China, Saigon, Bienhoa, and Mytho to France. Subsequently three other provinces were annexed to France in 1867.

Anapa. A city in Circassia which was fortified by the Turks in 1784; stormed and taken by the Russians in 1791.

Anarchy. Want of government; the state of society where there is no law or supreme power, or where the laws are not efficient, and individuals do what they please with impunity; political confusion; hence, confusion in general.

Anatha. A fort on an island of the Euphrates; taken by Julian the Apostate in 363.

Anatolia, Nadoli, or Natolia. The modern name of Asia Minor, a peninsula in the most western territory of Asia, extending northward from the Mediterranean to the Euxine, or Black Sea, and eastward from the Grecian Archipelago to the banks of the Euphrates. It is a part of the Turkish dominions, and was in ancient times the seat of powerful kingdoms and famous cities.

Anazarba, or Anazarbus. A city in Asia Minor, where the Christians were defeated by the Saracens in 1130.

Anazehs. Nomadic Arabs, who infested the desert extending from Damas to Bagdad; they often laid under contribution the caravans on the way to Mecca.

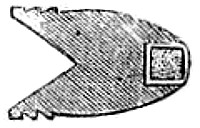

Ancile. In antiquity, a kind of shield, which fell, as was pretended, from heaven, in the reign of Numa Pompilius; at which time, likewise, a voice was heard declaring that Rome would be mistress of the world as long as she should preserve this holy buckler.

Ancona. An ancient Roman port on the Adriatic. In 1790 it was taken by the French; but was retaken by the Austrians in 1799. It was occupied by the French in 1832; evacuated in 1838; after an insurrection it was bombarded and captured by the Austrians, June 18, 1849. The Marches (comprising this city) rebelled against the papal government in September, 1800. Lamoriciere, the papal general, fled to Ancona after his defeat at Castelfidardo, but was compelled to surrender himself, the city and the garrison, on September 28. The king of Sardinia entered soon after.

Ancyra. A town in ancient Galatia, now Angora, or Engour, Asia Minor. Near this city, on July 28, 1402, Timur, or Tamerlane, defeated after a three days’ battle and took prisoner the sultan Bajazet, and is said to have conveyed him to Samarcand in a cage.

Andabatæ. In military antiquity, a kind of gladiators who fought hoodwinked, having a kind of helmet that covered the eyes and face. They fought mounted on horseback, or on chariots.

Andaman Islands. A group of small islands in the Bay of Bengal, which has been used by Great Britain as a penal colony for Hindoos. The Earl of Mayo, governor-general of India, was assassinated here by a convict, February 8, 1872.

Anderlecht. A town near Brussels, in Belgium, where the French under Gen. Dumouriez defeated the Austrians, November 13, 1792.

Andernach. A city in Rhenish Prussia; near here the emperor Charles I. was totally defeated by Louis of Saxony, on October 8, 876.

Andersonville. A post-village of Sumter Co., Ga., about 65 miles south-southwest of Macon. Here was located a Confederate military prison in which Union soldiers were confined during the civil war. So severe was the treatment which they received here (nearly 13,000 having died), that a general feeling of horror was excited against the superintendent, Capt. Henry Wirz; and after the close of the war he was tried for inhuman treatment of the prisoners, found[22] guilty, and executed November, 1865. The place is now the site of a national cemetery.

Andrew, St., or The Thistle, Order of. A nominally military order of knighthood in Scotland. The principal ensign of this order is a gold collar, composed of thistles interlinked with amulets of gold, having pendent thereto the image of St. Andrew with his cross and the motto, Nemo me impune lacessit.

Andrew, St., Knights of. Is also a nominal military order instituted by Peter III. of Muscovy in 1698.

Andrussov, Peace of. This peace was ratified (January 30, 1667) between Russia and Poland for 13 years, with mutual concessions, although the latter power had been generally victorious.

Anelace, or Anlace. A kind of knife or dagger worn at the girdle by civilians till about the end of the 15th century.

Anemometer, or Wind-gauge. An instrument wherewith to measure the direction and velocity of wind under its varying forces,—used in the Signal service.

Aneroid Barometer. A pocket instrument indicating variations in atmospheric pressure. Used in military surveys to obtain the height of mountains. It consists of a circular metallic box, hermetically sealed, from which the air has been extracted. The play of the thin, metallic cover under atmospheric pressure, is made to operate a hand pointing to a scale on the dial-face.

Angaria. According to ancient military writers, means a guard of soldiers posted in any place for the security of it. Angaria, in civil law, implies a service by compulsion; as, furnishing horses and carriages for conveying corn and other stores for the army.

Angeliaphori. Reconnoitring parties of the Grecian army.

Angel-shot. A kind of chain-shot. See Chain-shot.

Angers. Principal city of the department of Maine-et-Loire, France. It was sacked by the Normans during the 9th century; taken and retaken several times by the Bretons, English, and French.

Anghiari. A city of Tuscany, where the Florentines under Berardino Ubaldini were defeated by the Milanese general Torello, in 1425, and in 1440 the Florentine general Orsini defeated the Milanese general Piccinino.

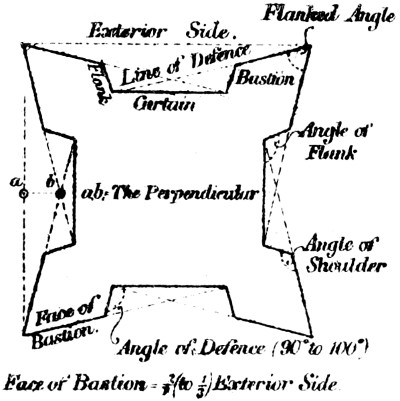

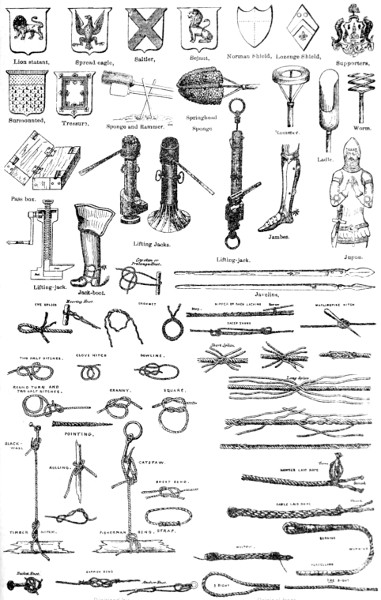

Angle. In geometry, is the inclination of two lines meeting one another in a point, or the portion of space lying between two lines, or between two or more surfaces meeting in a common point called the vertex. Angles are of various kinds according to the lines or sides which form them. Those most frequently referred to in fortification and gunnery are:

Angle, Diminished, is that formed by the exterior side and the line of defense.

Angle, Flanked, or Salient, is the projecting angle formed by the two faces of a bastion.

Angle, Interior Flanking, is that which is formed by the meeting of the line of defense and the curtain.

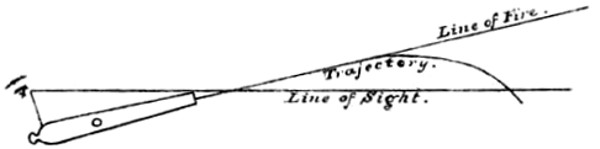

Angle of Arrival. The angle of arrival is the angle which the tangent to the trajectory at the crest of the parapet makes with the horizon.

Angle of Departure, or Angle of Projection, is the angle which the tangent makes with the horizontal at the muzzle.

Angle of Elevation, or Angle of Fire, in gunnery, is that which the axis of the barrel makes with the horizontal line.

Angle of Fall, in gunnery, is the angle made at the point of fall by the tangent to the trajectory with a horizontal line in the plane of fire.

Angle of Fire, in gunnery, is the angle included between the line of fire and horizon; on account of the balloting of the projectile, the angle of fire is not always equal to the angle of departure, or projection.

Angle of Incidence is that which the line of direction of a ray of light, ball from a gun, etc., makes at the point where it first touches the body it strikes against, with a line drawn perpendicularly to the surface of that body.