Title: Ulysses of Ithaca

Author: Karl Friedrich Becker

Homer

Translator: George P. Upton

Release date: June 13, 2019 [eBook #59750]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D A Alexander, Stephen Hutcheson, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by the Library of Congress)

MERCURY DESCENDING TO EARTH

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Karl Friedrich Becker

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Author of “Musical Memories,” “Standard Operas,” etc.

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1912

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1912

Published September, 1912

THE · PLIMPTON · PRESS

[W · D · O]

NORWOOD · MASS · U · S · A

Many years ago Karl Friedrich Becker wrote a series of romances of the ancient world for German boys and girls, of which “Ulysses” and “Achilles” in the present series of “Life Stories for Young People” form an important part. They became great favorites in their day and still preserve their interest, so that in a sense they may be called classics. The masterly manner in which the author has presented the old gods and heroes from the human point of view and the atmosphere of the old days of mythology, as well as the thrill of the adventurous narrative and the deep human interest of the story, should commend them also to American boys and girls. None of the ancient stories is more entrancing than that of Ulysses and the vicissitudes he had to endure in his effort to return to Ithaca after the Trojan war, and of the patience, sweetness, and faithfulness of Penelope, as she waited year after year for the return of her lord, while her life was made wretched by the unwelcome and often brutal solicitations of her numerous suitors, as well as of her final happiness when Ulysses returned and wreaked deserved vengeance upon her persecutors. Incidentally also the reader will enjoy the charming descriptions of his adventures with Calypso and the beautiful Nausicaa, his escape from the monstrous Cyclops, the fascinating Circe, and his thrilling experiences in passing Scylla and Charybdis. It is a story replete with interest, delightfully told.

G. P. U.

Chicago, July, 1912

World-renowned Troy had fallen. After a siege of ten long years the united forces of the Greeks had sacked and burned the city. The princes, having thus satisfied their thirst for revenge, now longed for home, and putting to sea with their ships, soon sailed away with their companions. Some reached home in safety, others were tossed to and fro upon stormy seas, wandered about for years, and never succeeded in reaching their native land. Agamemnon, the bravest of the surviving heroes, met a still more terrible fate. Joyfully he had gazed once more upon his ancestral home, and thanking the gods for his safe return, hastened impetuously to the arms of his beloved spouse Clytemnestra, not knowing that the faithless one had wed another during his absence. The false one received him with feigned tenderness and presented him with a refreshing draught; he disrobed, drank with deep emotion from the old familiar goblet, and stretched his weary limbs luxuriously upon the soft cushions. Alas! while the unsuspecting hero slept, the despoiler of his fortune and his spouse suddenly fell upon him with a sword and slew him.

How different is the story of the noble Penelope, the beautiful wife of Ulysses! He was king of the isle of Ithaca, off the western coast of Greece, and had been drawn into the war against Troy. Ever since her husband had set sail, a number of the young princes of Ithaca and the neighboring islands had beset her with proposals for her hand. She was young and beautiful and had great wealth in sheep and cattle, goats and swine, so that whoever wed her might hope, by taking Ulysses’ place as chief of the island, to rule over the minor princes. This was a tempting prospect and the young men used every means in their power to persuade the beautiful queen to return to her father’s house as a widow, so that they might formally demand her hand according to ancient custom. Ulysses, they said, would never return. But it was not easy for the suitors to banish the image of her beloved husband from the heart of this devoted wife. She could not so lightly break the tie in which she had found her youthful happiness. He will surely return, she thought, and though she wept day and night for fear and longing, this hope cheered her anxious soul. Year after year passed and still the war went on. At last news reached Ithaca that Troy had fallen and the heroes were returning. Fresh hope now filled the heart of the faithful wife, but another year passed, and still another, and no ship brought back her lord.

Penelope talked with every stranger who came to Ithaca and asked for news of the hero. His companions were said to have returned long ago—Nestor to Pylos, Menelaus to Sparta; no one knew what had become of Ulysses or whether he was dead or living. For nine years longer the poor woman nursed her grief, until nineteen years had passed since she had seen her lord. He had left her with a nursling, now grown into a handsome lad, who was her only consolation, but much too impotent to cope with the presumptuous rabble, which became each year more insistent and at length hit upon a cruel means of forcing the poor lady to return to her father’s house. They leagued themselves with the princes of the neighborhood, over a hundred in number, and agreed that they would all assemble each morning at Ulysses’ palace, there to consume the produce of his herds and granaries and to drink his wines, until his heir, Telemachus, for fear of becoming impoverished, should be compelled to thrust his faithful mother from the door and thus force her into another marriage. Thenceforth the great halls of Ulysses’ palace were filled from morning till night with these uninvited guests, who compelled the king’s servants to do their bidding. They took what they wanted and mocked the owners with loud shouts and laughter. The herds were diminishing perceptibly, the abundance of grain and wine disappearing, and there was no one able to check the robbers. Penelope sat in her upper chamber at her loom and wept; Telemachus was derided whenever he showed himself among the insolent crowd.

A god had brought this woe upon Ulysses’ house. Poseidon, ruler of the sea, was angry at the hero, who had sorely offended him. Therefore he drove him from south to north and from east to west upon the broad seas, dashed his ships to pieces, killed his companions, and forced him through whirlpools and canyons to strange peoples. And now, while his insolent neighbors were consuming his substance, he was held a prisoner upon a lonely island far from home, where reigned Calypso, a daughter of the gods. She desired him for her husband, but Ulysses brooded continually upon his dear country, his wife, and son. He went daily to the shore, and seated himself mournfully by the surf, wishing for nothing more ardently than that he might see the smoke ascending from his own hearth before he died.

The gods in high Olympus were touched, especially his friend Athene. One day, when they were all assembled in their vast halls and the unfriendly Poseidon happened to be absent among the Ethiopians, Athene seized the opportunity to relate the story of the sad plight of Ulysses and Penelope to father Jupiter. The king of the gods was filled with compassion and gladly granted his daughter’s request that she might be permitted to visit Telemachus in disguise, to breathe courage into his soul, and that Hermes should be sent to the isle of Ogygia to transmit the command of the gods to Calypso to release immediately her prisoner. Athene straightway prepared for the journey. She bound her golden sandals upon her feet, took her mighty lance in her hand, and descending like the wind upon Ithaca, stood suddenly before Telemachus’ lofty gateway, in the guise of Mentor, the Taphian king. Here she saw with amazement the wild company of wanton suitors feasting and drinking, gambling and shouting, and the servants of Telemachus waiting upon them, carving the meat, washing the tables, and pouring wine and mixing it with water after the ancient custom. Among them, taking no part in their revels, sat Telemachus, with a heavy heart. He no sooner saw the stranger at the gate than he went to meet him, gave him his hand, and, greeting him kindly, took his lance. He then conducted the unknown guest into the dwelling, but not among the revellers, so that his meal should not be disturbed by their riotous behavior. The stranger was placed upon a dais, with a footstool under his feet. Telemachus seated himself beside him, and at a sign a servant immediately brought a golden ewer and a silver basin, bathed their hands, and placed a polished table before them. The stewardess brought bread and meat, while a lusty servant poured the wine.

Not until the stranger had been refreshed with food and drink did Telemachus ask his name and the object of his journey. “I am Mentor, the son of Alcimus, and rule the Taphians,” said the disguised goddess. “I have come hither on my way to Temesa, in a ship which lies at anchor in the bay, and as Ulysses and I are old friends, I wished in passing to pay thee a visit.”

Thereupon Telemachus told the story of his wrongs to his guest. The goddess listened attentively, just as though she had not known it all before. She advised him to adopt a manly attitude in public assemblage, boldly to forbid the suitors the house, and, above all, to set out for Sparta and Pylos, where lived the valiant heroes Nestor and Menelaus, Ulysses’ companions in the siege of Troy. There he might learn where they had parted from his father and where he was now most likely to be found; “for a divine inspiration tells me that he is not dead,” added Mentor. “He is indeed far away, shipwrecked and held by cruel captors, but thou shalt certainly see him again if thou wilt follow my advice.”

The youth began to love and revere his father’s old friend. In accordance with the ancient rites of hospitality, he offered him a gift at his departure, which was declined on the plea of haste. He promised to come again on his return voyage, however, when he would take the gift with him. Upon this, he disappeared suddenly like a bird, and for the first time Telemachus suspected that he had been entertaining a divinity. He pondered all that the stranger had said, and determined to follow the divine counsel. He began at once to protest against the suitors’ demeanor, and they, never having seen him appear so manly before, were astonished at his boldness. Antinous and Eurymachus, however, the most insolent among them all, mocked at his words and soon had them all laughing at him. They spent the evening in song and dance, and when night came dispersed as usual to their own dwellings.

Telemachus also went to his sleeping chamber, accompanied by his faithful old nurse, Euryclea, carrying a flaming torch before him. He threw off his soft flowing garment and tossed it to the old dame who, folding it carefully, hung it on the wooden peg by his bed. Telemachus threw himself upon his couch and wrapped himself in the woollen covers. The old dame retired, barring the doors.

As soon as morning dawned Telemachus sprang from his couch, dressed himself, laced his sandals, and girded on his sword. Thus apparelled, the stately youth sallied forth. He sent out heralds to summon the populace to assemble, and when the crowd had gathered in close ranks, he went among them bearing his lance and accompanied by two swift-footed dogs. Then to the amazement of all, Telemachus stepped forth, caused the heralds to bring him the sceptre, as a sign that he wished to speak, and began as follows: “I have called you, people of Ithaca, because the deep distress of my house impels me. My father, as you know, is far away, perhaps forever lost to me. I am forced to endure every day a swarm of unmannerly guests intrenching themselves in my house, who pretend to court my mother, while they maliciously consume my substance and will soon make a beggar of the king’s son. Unhappy one! I need a man such as Ulysses was to purge my house of this plague. Therefore I pray you to resent the wrong. Be ashamed before your neighbors and fear the vengeance of the gods. Did my good father ever intentionally offend you, and am I not already unhappy enough in losing him?”

At these words tears overcame him and he dashed the sceptre to the ground. Pity and compassion seized upon the assemblage. All were silent except the most determined of the suitors, Antinous, who answered insolently: “Bold-tongued youth, what sayest thou? Wouldst thou make us hateful in the eyes of the people? Who but thyself is to blame for thy troubles? Why dost thou not send away thy mother and why does she not go willingly? Has she not mocked us with subterfuges and kept us in suspense for more than three years? Did she not say: ‘Delay the wedding until I shall have finished weaving the shroud for my old father-in-law, Laertes, that the women may not censure me if the old man, who in life possessed such riches, should be carried out unclothed’? And what did the crafty lady do? She wove day after day, but the garment was never finished, and at length we learned the secret from one of her women. By lamp-light she undid the work of the day. Then we compelled her to finish it, and now we demand that she shall keep her promise. Thou must immediately command her to return to her father’s house and take for her husband whoever pleases her or one whom her father shall select for her. If thou doest this, none of us will molest thee further; but we shall not retire until she has chosen a bridegroom from among the Achaians.”

Telemachus spurned the proposal with righteous indignation. Once more he besought the suitors to spare his house and threatened them with the vengeance of the gods. But they only mocked at him and everyone who took his part. He then proposed that a ship should be fitted out, so that he might sail to Pylos and Sparta to seek his father, and if in a year’s time he should have heard nothing of him, he promised that his mother should wed with whom she would.

This proposal was received with scorn, and the assembly broke up. Sadly Telemachus wandered down to the sea, bathed his hands in the dark waters, and prayed to the goddess who had appeared to him the day before. Behold, as he stood there alone, Mentor, his father’s old friend, came toward him. He also had been amongst the people and had heard with anger the defiant language of the suitors. Indeed he had arisen to speak for Telemachus, but their mocking cries prevented him; and now he reappeared, as Telemachus believed, to assist him in carrying out his plans.

Mentor, or rather Athene, encouraged him, urged him not to delay the journey, and even offered to supply a ship and crew. Telemachus went straight home, confided his plan to his old nurse Euryclea, and ordered her to provide wine in jars, meal in skins, and whatever else was needful for the voyage. The tender-hearted old dame wept bitterly when she saw the delicate youth prepare to start on such a long and dangerous journey. She begged him a thousand times to give it up and await his father’s arrival at home. He was manfully resolute, however, and the nurse was obliged to promise to keep his departure a secret—not even to tell his mother until she should have missed him.

Athene, in Mentor’s shape, was meanwhile employed in hiring a ship and oarsmen, so that by evening everything was in readiness. When the suitors had retired and everyone was asleep, Mentor took Telemachus secretly away. The youths carried the provisions down to the ship, raised the mast, and bound it fast with ropes. Then the rowers came aboard and loosed the ship from shore. Athene had seated herself by the side of Telemachus. The oars splashed gayly on the quiet surface of the sea. The silent night encompassed them, and only the twinkling stars illumined with a faint light the dark waters through which the vessel was being swiftly propelled.

At sunrise the travellers saw Pylos before them, a little town on the western coast of Peloponnesus, or the present peninsula of Morea. It was the home of the venerable Nestor, who lived amongst his subjects like a father with his children. His descendants were numerous and all the people reverenced his opinion, and loved him for his kindness and benignity, and the recital of his adventures whiled away many an hour for the eager youths who hung upon his words.

On the morning when Telemachus and his companions were nearing Pylos, Nestor had summoned his people to the shore to offer up a great sacrifice to Poseidon. These thousands of festive people, ranged in nine columns each composed of five hundred men, made a wonderful picture. Each column had contributed nine bulls which, having been offered up, were now smouldering on the altars, while the people were feasting upon the residue.

Athene and young Telemachus disembarked, and, leaving the ship in the care of the rowers, set out on foot toward the scene of festivity. The divine guide encouraged the timid youth to address the old man boldly and instructed him what to say and how to conduct himself.

Scarcely had the men of Pylos caught sight of them when a group of youths hastened forward to welcome them, holding out their hands in friendly greeting, according to the hospitable custom of ancient times. Pisistratus, Nestor’s youngest son, was the most cordial of them all. He took both strangers by the hand and led them to soft seats upon sheepskins beside his father and his brother, Thrasymedes, bringing meat and wine to refresh the weary guests. He then filled a golden goblet, quaffed it in Athene’s honor, and spoke to her as follows: “Dear guest, join us, I pray thee, in our joyful sacrifice; it is offered to Poseidon, ruler of the sea. Pour out this wine to the mighty god and pray to him for our welfare! No man can do without the gods! And when thou hast offered sacrifice and drunk of the wine, then give thy friend the goblet that he also may pray for us. Thou art the older, therefore I have offered the cup first to thee.”

Athene was pleased with these modest and courteous words. She took the cup, poured a few drops on the ground, and prayed: “Hear me, Poseidon; deign to prosper every good work which we shall undertake. Crown Nestor and his sons with honor and graciously reward the men of Pylos for the holy sacrifice which they have offered before thee to-day. And graciously prosper my friend and me in the enterprise which has brought us hither!” Thus she prayed, and while still speaking, by reason of her divine power, she secretly granted the prayer. Then Telemachus received the cup from her hand and drank, also offering sacrifice and prayer for the feasting people.

Not until the guests had partaken of food did the venerable Nestor consider it proper to inquire the name and business of the strangers. Telemachus told him the object of their journey and conjured the old man to tell him all he knew about his noble father, urging him not to conceal anything, however terrible, that would give him certainty as to his fate. Then Nestor began, with the garrulity of old age, to relate the adventures of the heroes and the story of his own return. But Telemachus could draw no comfort from these tales, for what he most wished to learn was what Nestor knew no better than himself. The old man advised him to go to Menelaus at Sparta, who of all the heroes had been longest on the way, and having only lately reached home, would certainly be able to give him news of Ulysses’ fate. Mentor approved of this proposal, and the journey to Sparta was determined upon. As by this time night was beginning to fall, the goddess reminded her young friend that it was time to set out. The sons of Nestor filled the cups once more and the customary offerings were made to Poseidon and the immortal gods. Then Mentor and Telemachus arose to go down to their vessel.

“The gods forbid!” cried Nestor, when he saw them about to depart. “Shall my guests spend the day with me and go away to pass the night in a musty vessel, as though I were a poor man, who had no cloaks nor warm covers in my house? No, my friends, I have plenty of soft cushions and fine garments, and the son of my old friend Ulysses shall not thus depart so long as I live! And even when I am gone, there will always be sons to pay honor to the stranger within my gates.”

“Well said,” answered Mentor. “Telemachus must accept thy hospitality. Let him go with thee to lodge in thy palace, but I must hasten to the shore to pass the night with the young sailors and look after their welfare. Very early in the morning I must pay a visit to the valiant Cauconians to settle an old debt. In the meanwhile do thou send Telemachus with thy sons to Sparta and provide him with a chariot and fleet horses for the journey.”

With these words Mentor turned and in the shape of an eagle swung himself up into the air. All were amazed, but Nestor immediately recognized the goddess; for he knew how many times in the past she had aided Ulysses. “Take courage,” he said to Telemachus, “for thou seest that the gods are with thee. And thou, divine Athene, have mercy upon us all and crown us with fame and renown! Behold! I vow to thee each year a bull, broad of forehead and without blemish, which has never been under the yoke.”

The people dispersed, and Nestor returned to his dwelling with his sons and their guest. On their arrival wine was again offered up and drunk, and then Pisistratus conducted Telemachus to a couch beside his own in the pillared hall. The other sons, being married, had their quarters in the interior of the house.

As soon as morning dawned the sons and their venerable father arose and assembled on the stone seats before the portal to discuss the proposed journey. Nestor presently sent some of his sons to select the offering which he had promised Athene. One was sent to the vessel to fetch all of Telemachus’ rowers except two, another to order a goldsmith to gild the horns of the victim, a third to command the shepherd to seek out and bring up an ox of the promised quality, and another finally to notify the maidens to prepare a banquet.

It was not long before the goldsmith appeared, also the rowers, and the shepherd soon brought the desired animal. When the goldsmith had finished gilding the horns of the ox, two of the sons led it into the circle. Nestor, having sprinkled himself with water, cut off the animal’s forelock and cast it with prayer on the flaming altar, strewing consecrated barley upon the ground. And now the mighty Thrasymedes advanced and struck a heavy blow with a sharp axe, which sundered the tendons of the animal’s neck and it fell stunned to the ground. Perseus caught the gushing blood in a vessel, while Pisistratus completed the slaughter of the victim. The others now came up to carve the beef. They cut off the shanks, wrapped them well in strips of fat, and laid them on the altar fire to send up delicious odors to the goddess, sprinkled wine upon and roasted the other pieces for the offering, turning them upon spits. Other youths cut up the remainder and roasted it carefully for the feast.

When all was prepared Telemachus appeared in the midst of the company beautiful as a god. He had bathed, anointed himself with oil, and wrapped himself in a rich mantle. The company sat down in a circle to enjoy the magnificent feast, and when they had eaten their fill, Nestor reminded his sons that it was time to depart. They quickly harnessed two horses to a chariot, while a servant stowed away bread, wine, and meat for the journey. Telemachus took his place on the seat with Pisistratus beside him holding the reins and whip. They travelled rapidly all day and at eve reached Pheræ, the dwelling of the good Diodes, who hospitably entertained them. On the second day they arrived at the castle of Menelaus in Lacedæmon, having recognized his dominions by the broad fields of wheat. Pisistratus drew up his prancing steeds before the gateway of the castle, and the two strangers sprang hurriedly out.

They heard sounds of revelry within. The voice of a singer was accompanied by the sweet tones of a stringed instrument, and through the open gateway they saw a crowd of guests in the centre of which two dancers were moving in time to the music. This was a great day in Menelaus’ palace. The old hero was celebrating the marriage of two of his children. There was so much noise and confusion within that the clatter of the chariot had not been noticed. A servant by chance saw the strangers at the gate. “Two strange youths of kingly mien are without. Shall I unharness their horses,” he asked, “or shall I bid them drive on to seek hospitality elsewhere?”

“What!” cried Menelaus angrily, “how canst thou ask such childish questions. Have we not ourselves received many gifts and been kindly entertained amongst strangers? Go quickly, take out the horses, and bring the men in to the feast!”

The servant obeyed, and Telemachus and Pisistratus were conducted into the hall. They were astonished at the splendor of the palace, for Menelaus had returned with great possessions. Maid servants conducted them to the bath, and when they had anointed themselves, they donned their tunics and cloaks and took their places on raised seats beside the host. Servants appeared at once with small tables and food. One poured water over their hands from a golden ewer into a silver basin, while another brought wine, meat, and bread. “Now eat and drink with us,” cried Menelaus; “afterward shall you tell me who you are, for I perceive that ye are no common men.” With these words he placed a fine fat piece of roast, his own special portion, upon their plates, and the youths found it a delicious morsel.

Menelaus gazed at them intently. He remarked with satisfaction that they were astonished at the magnificence of his hall and of the utensils, and he saw how they called each other’s attention secretly to new objects. This induced him to speak of his travels, of the perils to which he had been exposed for eight years after the Trojan war, and of the persons he had met who had presented him with the costly objects by which he was now surrounded. In his recital he often referred to the hardships of the Trojan war, while the mention of the ignominious death of his brother, Agamemnon, caused him to shed bitter tears. “But,” he continued, “I would bear all this with patience if only I might have kept my friend, dearer to me than all the rest, the noble Ulysses, with whom I have shared good and evil days! Or if I but knew that he was safe and could have him near me! I would endow him with a city that we might live side by side and commune with each other daily until death should part us. But the gods alone know whether he is alive or dead. Perhaps his old father, his chaste wife, and his son Telemachus are even now mourning him as dead!”

Telemachus hid his tears behind his cloak. Menelaus saw this and was uncertain whether to question him or to leave him to his grief. Just then his spouse, the once beautiful Helen, entered the hall accompanied by her maidens, one of whom brought her a chair, another carried the soft woollen carpet for her feet, a third her silver work basket. She seated herself near the strangers, observed them attentively, and then said to her husband: “Hast thou inquired the names of our guests? I should say that two people were never more alike than this youth is unto the noble Ulysses.”

“Indeed it is true,” answered the hero. “He has the hands, the feet, the eyes, and hair of Ulysses. And just now while I was speaking of our old friend, the hot tears sprang from the youth’s lids and he hid his face in the folds of his purple mantle.”

“Thou art quite right, Menelaus, godlike ruler,” interrupted Pisistratus. “This is truly the son of Ulysses, but he is a modest youth and did not wish to make himself known at once with boastful speech. My father, Nestor, hath sent me with him thither that thou mightest give him tidings of his noble father and advice, for he is sore beset at home and there is none among the people to rise up and avert disaster from him.”

Menelaus would now have rejoiced over the youth had not sad memories of his lost friend overwhelmed him. He wept, Helen also, and Telemachus still sobbed, while young Pisistratus was much moved. For a while they gave themselves up to their grief until Menelaus proposed that they should talk the matter over on the morrow and should now banish these sorrowful thoughts and return to the feast. This sensible advice was approved by all. A servant at once laved the hands of the guests, and they began once more to eat and drink. Helen, who was an adept at various arts, secretly poured a magic powder into the wine. It was a wonderful spice given her by an Egyptian princess, which had the property of deadening every discomfort or sorrow and cheering the soul, even though a father and mother, brother or sister, or even one’s own son had been killed before one’s eyes. They all drank of it and became gay. Helen told many amusing tales of the craftiness of Ulysses which she had herself experienced. For while she was still in Ilium he had come into the city in disguise to spy out the plans of the Trojans. No one recognized him, and only to Helen did he discover himself and confide the plans of the Greeks. Menelaus also told how they had been concealed within the wooden horse and would scarcely have withstood Helen’s call had Ulysses not restrained them. While the evening was thus being passed in confidential talk, Helen had a couch prepared in the hall with cushions and soft covers for the guests and a herald conducted them thither with a torch. Menelaus and his spouse, however, slept in the interior of the palace.

Not until morning did the host ask his guests their business. Telemachus told him the story of the insolent suitors, and begged Menelaus for some news of his father. “Ah!” cried the hero when he had heard the tale, “it shall be as though the doe had left her young in the lion’s cave and had gone away to graze upon the hills. When the lion returns and finds the strange brood, he destroys them. Thus will Ulysses return to his house and make a terrible end of those trespassers! Could they but see him in the majesty of his power as he once threw Philomelides in Lesbos, then truly they would have little stomach for courting. But, dear youth, as thou hast asked me, I will tell thee what the old prophet Proteus in Egypt once told me of him. On my return voyage angry gods detained me for twenty days on an island at the mouth of the Nile, for I had carelessly forgotten to make the customary offering of atonement. Our food was nearly gone, my companions lost courage, and I should perhaps have perished with them had a goddess not taken pity on me. Idothea, the lovely daughter of Proteus, looked upon us with compassion, and once when I had wandered far from the others, she came and spoke to me. Then I told her my plight, and begged her to tell me some means of gaining the favor of the heavenly powers to discern which of the gods was hindering my journey and how I might reach home through the endless leagues of ocean.

“‘Gladly, oh stranger,’ said she, ‘will I tell thee of an unfailing means. Thou knowest that my father, the old sea god, Proteus, is omniscient, and if thou canst surprise him by some cunning scheme he might easily tell thee all that thou wishest to know.’ ‘Good,’ said I; ‘but tell me what means I can employ to ensnare him.’ ‘Listen,’ answered the goddess; ‘every day when the sun is at the zenith the god rises from the sea, and comes on shore to sleep in the cool grottoes. With him come also the seals to sun themselves upon the shore. Therefore, if thou wouldst approach him unseen thou must conceal thyself in the skin of a seal and take thy place amongst the others. I will help thee. Come here early to-morrow morning with three picked companions, and I will furnish you all with glossy skins. When my father comes up, the first thing he does is to count his seals as a shepherd counts his sheep; then he lies down amongst them. As soon as thou seest that he has fallen asleep it is time to use force. You must all seize him and hold him fast, not letting go, no matter how he struggles to free himself. He will use all his arts of transformation to get away, now as fire, now as water, and now as some rapacious animal. But ye must not cease to contend with him until he shall have reassumed his proper form. Then loose the bonds, and let him tell thee what thou wishest to know.’

“As soon as Idothea had said this she disappeared into the depths of the sea. I went to my ship and spent the night in anxious vigil, and in the morning I picked out three men of proven strength and bravery to accompany me in this wonderful adventure. We went to the appointed place, and behold! the nymph kept her word. She arose out of the sea with four fresh sealskins, enveloped us each in one of them, and showed us where to lie down. Friends, you cannot imagine our plight. The oily smell of the skins would certainly have overcome us had not Idothea rubbed sweet-smelling ambrosia upon them to smother the horrible odors. Thus unpleasantly masquerading we passed the whole morning, until at last, in the heat of the noonday, the troop of seals rose out of the water, and after them came the gray god of the sea. He looked about, examined and counted his seals, ourselves with the rest, and then laid himself down in their midst. Very soon we sprang up with loud cries and held him down with all our strength. Everything transpired as his daughter had warned us. He suddenly transformed himself into a lion to frighten us, but we were not to be thus outwitted and only held the tighter. Then he became a panther, then a dragon, and finally, a bristly boar. While we thought we were grasping the bristles he tried to escape us as water, and scarcely had we dammed up the water when he rose into the air in the form of a tree. At last the old magician became weary of these changes, resumed his true shape, and said: ‘Son of Atreus, what mortal has discovered to thee the art of holding me—and what dost thou want of me?’

“I told him my perplexities. He bade me return to Egypt and there propitiate the offended gods with rich offerings. He promised that my return voyage should be successful. I asked one last question of the god: What had become of my friends, and had they all reached home safely? He then began a long story which caused me to weep bitter tears. He spoke of Ajax and his sad fate. He told me of my dear brother Agamemnon’s horrible death. My heart was broken; I no longer wished to live. But the venerable god comforted me and commanded me to hasten home to avenge this wrong. Finally I asked the fate of my dear friend Ulysses and whether he still lived. Proteus answered: ‘Ulysses lives, but is held a prisoner far from here on an island, by the nymph Calypso. He weeps tears of home-sickness and longing, and would gladly intrust himself to the unknown waters, but he has no ship and no men, and the nymph who loves him will never let him go.’ Thus Proteus prophesied to me, then suddenly sank into the sea. I followed Proteus’ commands and arrived safely at home. Now thou knowest all that I can tell thee. Remain thou with me for a while, then I will send thee home with worthy gifts,—three splendid horses and a cunningly carved chariot,—and in addition I will present thee with a beautiful goblet in which thou canst make offerings to the gods, so that thou shalt always remember me.”

Telemachus declined the invitation, for he could not desert his companions whom he had left in Pylos, anxiously awaiting his return. In the morning the king had prepared for the two youths a bountiful farewell repast of freshly killed goats and lambs. Telemachus would scarcely have enjoyed this early meal if he had known what the wicked suitors at home were preparing for him. They learned with deep concern that Telemachus had really had the courage to undertake the journey. Who could tell but he might return with help from Nestor or Menelaus and put them all to death? Until now no one had given the boy credit for much courage, but now—was it not as though the father’s spirit had been awakened in the son? Antinous, the most insolent of them all, cried: “No! we must not allow the youth to defy us! He must be crushed before he can harm us. Give me a ship and man it with twenty brave warriors. I will row out to meet him and waylay him in the straits between Ithaca and Samos. If I meet him he will never see this house again alive, and then all will be ours.”

All applauded the wicked Antinous and conferred as to how they might most surely destroy the youth, and when all was arranged the ship rowed away to the appointed place to await Telemachus. Medon the herald had overheard the plot, and hastened to acquaint Penelope with the sad news. Her heart was already heavy with anxiety, and at this fresh misfortune her knees began to tremble and she sank unconscious on the threshold of her chamber. Her maidens wept over her, and at last tears sprang to the eyes of the beautiful queen. She moaned aloud and could not compose herself. At first she thought of sending for her father-in-law, Laertes; but the old man was as powerless as she. Then she considered other succor, but all was useless. At last to her oppressed heart came the comforting inspiration of calling upon a god for protection. She prayed fervently to Athene, and when she had finished she felt renewed strength and composure. She sank down upon her couch in a deep sleep.

Athene heard her prayer, and desiring not to leave the good lady comfortless, sent her a pleasant dream. Penelope’s sister appeared to the sleeper, and asked the cause of her grief. Penelope was comforted in telling her woes, and the dream figure put courage into her soul with the consoling words: “Be comforted, sister, and pluck these cowardly fears from thy heart. Thy son will return. He has a guide and companion such as many a one might wish for. Pallas Athene herself is with him, and she has compassion on him and on thee and has also sent me to tell thee this.” Penelope wished to ask other things, but the dream figure vanished. She then awoke, was comforted, and no longer bemoaned the fate of the two loved ones whom she had thought were lost.

Athene was busy preparing Ulysses’ return. Hermes, messenger of the gods, bound on the golden sandals which enabled him to soar like a bird through the air, took up his magic serpent staff with which he could both kill and restore people to life, and flew swiftly away across the sea. He soon stood upon Calypso’s distant island, enchanted with the lovely dwelling so charmingly nestling among the trees. Singing birds had made their nests in the dark recesses of the foliage, and the entrance to the grotto was framed in vines from which hung bunches of purple grapes. Round about stretched rich meadows intersected by gleaming brooks, and many-colored flowers peeped out of the rich verdure.

Hermes paused to admire the lovely spot, then entered the grotto to seek Ulysses. The poor fellow who could find no peace of mind in this beautiful isle, and who was vexed by the advances of the goddess, used to go down every day and seat himself beside the surf to gaze out over the dark waters in the direction in which his beloved fatherland lay. The nymph, however, sat at her loom weaving herself a garment with a golden shuttle and singing gayly at her work. She recognized Hermes at once and was surprised to see him. He delivered to her the strict command of Jupiter to release Ulysses, as the gods had determined upon his return. This frightened the goddess, and she began to complain of the jealousy and cruelty of the gods. She promised to obey, however, through fear of the anger and vengeance of Jupiter.

In the meanwhile Hermes had been hospitably entertained, for even the gods regale one another, though they do not eat mortal food. Their food is called ambrosia and they drink a divine liquid which the poets call nectar. After feasting, Hermes repeated the message and left the island.

When Calypso had spent her grief in a flood of tears she went out to seek Ulysses. She found him sitting pensively on the shore. “My dear friend,” she said, “thou must not pass thy life here in melancholy and grieving. I will have compassion on thee and let thee go. But thou must build a craft for thyself. Go to the forest, select trees, cut and trim them with the axe which I shall give thee, and fashion for thyself a strong raft. I can give thee no rowers, but I will plentifully provide thee with food, drink, and clothes, and will give thee a gentle wind to bear thee out into the sea. If the gods are willing thou shalt soon reach thy dear native land in safety.”

Ulysses sprang up. Her words gave him a thrill of joyful surprise. He could scarcely believe his good fortune. “Swear to me,” he cried hastily, “that thou speakest the truth and art not contriving fresh affliction for me!” The goddess smiled, and to please him swore the most terrible oath of the gods, by the earth, the heavens, and the river Styx, and now at last the hero believed her.

The following morning he hastened into the forest, and after four days of incessant labor his raft was finished and furnished with mast, rudder, and yard-arms. Calypso supplied the sail and filled the raft with skins and baskets of sweet water, wine, and delicious food, and on the fifth day she accompanied him to the beach and he joyfully embarked. A gentle breeze filled his sail and he steered boldly across the boundless waters, guided by the sun by day and the stars by night. He journeyed swiftly for seventeen days, happy in the thought that he was approaching nearer to his beloved wife and native land. But lo, on the eighteenth day, when in sight of the island of Corfu, Poseidon caught sight of the bold man and his anger blazed up anew. “Aha!” said he, “the gods have doubtless taken him under their protection while I have been away, but in spite of this he shall suffer disaster and sorrow enough before he reach the land which is appointed for his refuge.”

The angry words had scarcely been spoken before dark clouds began to gather at his bidding. He dipped his trident into the sea and it was disturbed to its depths. Then he called upon the winds to come out of their caves and strive together, and dark night descended upon the waters. Ulysses trembled. He was alone upon the broad ocean. Land had disappeared, and as far as the eye could see there were only the dark waves which rose in their might, then dashed upon him, carrying him first heavenwards, then down into the depths of an abyss. Clinging desperately to his raft, he was tossed to and fro. A terrific blast swept away mast and sail and then came a great wave, like a mountain, which broke over the raft and submerged it. Ulysses lost his hold, but when he arose he saw it floating near him and managed to climb upon it, thus escaping certain death. But the storm still raged and there seemed no hope of rescue.

However, he was destined to be saved. Leucothea, the sea goddess, discovered him in the midst of the angry waves and took pity on him. She swung herself up out of the sea on to the raft and seated herself. “Poor man,” said she, “thou must surely have sorely offended Poseidon, but he shall not destroy thee. Thou shalt be cast on the shores of Scheria. Take this girdle and tie it about thee; then cast off thy heavy garments, leave thy float, and save thyself by swimming. The girdle will bear thee safely to the shore, but when thou art once there, do not fail to throw it behind thee into the sea.”

With these words she disappeared in the waters. Ulysses was still in doubt, for he feared the vision was a malicious deception of Poseidon’s. He would not leave the raft so long as it held together, but he kept the girdle to try its power in case of need.

He did not have long to wait, for a sudden shower of water dashed the raft in pieces. The logs separated and the poor sailor fell between them into the sea. It was now life or death. He swam toward the largest piece of the raft, caught hold of it, and swung himself astride the log like a horseman, holding fast by his knees. Riding thus, he drew off his heavy tunic and threw it into the sea, tied on the girdle, and sprang confidently into the water to try his luck. As he was struggling in the water Poseidon saw him and said: “This time thou mayst escape death, but I hope that thou wilt not soon forget the horrors of this day.”

Poseidon departed and by degrees the wild waves subsided. The terrible storm had lasted two days and two nights, and in all this time poor Ulysses had had nothing to eat or drink. He kept on swimming, sustained by the divine girdle. He was again filled with hope and joy when he saw the waves subsiding and the rocky coast of Scheria (or Corfu) close before him. But he was not yet safe, for the surf kept dashing him back from the steep walls of rock. This was worse than his battle with the waves; and with torn hands he was obliged to swim nearly around the island before he could find a landing place.

At length he came to a spot where a little island stream flowed into the sea. The beach was low and it was protected from the winds. Ulysses took courage, and praying to the divinity of the stream he said: “Hear me, oh ruler, whoever thou art, and take pity on me! Thou seest I have escaped Poseidon’s wrath, and now I put myself under thy protection.”

The river god heard him, and Ulysses soon sank upon his knees on the green grass and kissed the blessed earth. But now his strength was spent and he sank into a state of deep unconsciousness. Voice and breath left him; he was utterly exhausted.

As soon as he recovered himself he gratefully remembered Leucothea and her command. He arose, unbound the wet girdle, and with averted face cast it into the sea. Then fearfully and timidly he began to explore the island. Night was approaching and no one was to be seen. Naked as he was, where should he find shelter? It was damp and cold on the beach, and in the wood which he saw before him there might be savage animals. Still he walked on toward it and discovered a few wild olive trees whose thick boughs made a welcome shelter against sun, rain, and wind. On the ground lay a great mass of dry leaves which he heaped together and then crept under, his body hidden by the foliage. A deep sleep fell upon him in his bed of leaves, and for a time his hardships were forgotten.

Scheria was inhabited by a peaceful people, who cared more for commerce and navigation than for agriculture and the chase. They had built a town near the harbor, and had dockyards where busy workmen were to be seen building ships. Order, morality, and prosperity reigned and the people were ruled by gentle King Alcinous who had a magnificent palace in the city, where the nobles gathered daily to offer sacrifice and to feast with their king.

While the weary Ulysses was sleeping his friend Athene was planning a means of making him acquainted with the foremost people of the island. The king had a young and pretty daughter named Nausicaa, who was dreaming sweetly one morning when Athene appeared in her dreams in the form of one of her youthful companions and began to scold her. “Lazy girl! when wilt thou think of washing the fine garments which are lying soiled about the house? Thou wilt soon be a bride, and what if thy garments are not in order? Arise quickly! Let thy father provide thee with a cart and donkeys to take us to the washing place. I will go with thee, and we will take our maidens and wash and dry so that father and mother shall be delighted with our industry.”

Nausicaa, upon awaking, determined to obey the admonition. She begged her father for the cart and, when it was ready, filled it with the soiled garments. Her mother provided victuals and a skin of wine, and when all was ready the pretty washer maiden seated herself on the cart, took up the reins and whip, and drove out of the city, followed by her companions. The washing place was beside a clear stream whose waters filled little canals and basins which had been excavated for the purpose. The clothes were thrown into one of these basins, the maidens undressed and sprang into the water, where they trod the garments with their feet. After being thus cleansed the clothes were spread out to dry on a beach of clean pebbles by the side of the stream.

The maidens then bathed, anointed themselves with oil, and opened the baskets and wine skin to enjoy an out-of-door breakfast. Next they seated themselves in a circle. Nausicaa began to sing and the maidens to dance and amuse themselves playing ball. When they had had enough of the games they gathered up the garments, folded them neatly, and packed them away in the cart, harnessed the donkeys, and made ready to depart. Before she mounted, the sportive Nausicaa threw the ball once more toward one of her companions. But it fell into the river far away, making the frolicsome girls clap their hands and shriek with laughter, which awoke the echoes along the shore. And behold Athene had so arranged that these gay sounds should awaken the snoring Ulysses. He raised himself, listening, rubbing his eyes and brushing the leaves from his hair and beard.

“Those are human voices,” he thought; “but alas, what kind of people may they be? Perchance rough barbarians who will not understand my language and know nothing of the gods or of hospitality. But stay—are they not the voices of laughing maidens? I will come out and take a look at them.”

He crawled out of the thicket, shook off the dry leaves, and as he was stark naked, broke off a thick bough with which to cover himself. Thus he appeared like some wild forest monster. The maidens, who saw him coming from a distance, were afraid, cried out, and ran away. But Nausicaa was an intrepid girl, and Athene secretly encouraged her. She stood still and quietly waited for the man to approach.

He came nearer, but did not presume to embrace her knees after the manner of a petitioner, but made plea at a respectful distance. “Humbly I approach thee, goddess or virgin, for I know not who thou art,” said he. “Thy stature and thy splendid form tell me that if a goddess thou must be Artemis. Art thou a mortal maiden, then are thy parents and thy brethren fortunate; for truly their hearts must leap within them to see thee in the dance. But happier than all others I count the man from whose hands thy father shall accept the suitor’s gifts and who shall take thee to his house, a bride. Truly I have never seen a human creature so like a slender palm tree. Yesterday I was cast by the sea upon this coast. I know it not, and no one here knows me. I do not presume, noble maiden, to embrace thy knees, but I beg thee have compassion on me; for after unspeakable trials thou art the first person whom I have met. Show me the city where the men of this land live, and give me some rags to cover myself. May the gods reward thee a thousand times. May they give thee all that thy heart desires, a husband, a house, and blessed harmony of life. For certainly nothing is so desirable as that husband and wife shall live in peace and united in tender love.”

This speech pleased pretty Nausicaa and she pitied the stranger. She told him her name and all about her father and mother and promised him hospitality. Then she recalled her maidens, commanded them to conduct the guest to the bath and to refresh him with food and drink. But the man was too fearsome a sight. One pushed forward the other until they at last plucked up heart and led Ulysses to the river. Nausicaa sent him some of the freshly washed clothes and the remains of their oil. The maidens placed all these things beside the stream and withdrew while Ulysses made his toilet.

The bath was very necessary, for he was covered with mud from head to foot, but after it he was like one new born. Graced with the new garments he appeared in renewed youth amongst the maidens, who were astonished at his glowing countenance. He seemed to have grown taller and handsomer. His matted hair now fell in shining ringlets over his forehead and neck, and his whole appearance gave such an impression of nobility and charm that Nausicaa could not help a secret wish that he might remain in Scheria and take her to wife.

The maidens placed before him what was left of the food and wine, and truly the poor man had fasted long enough. When he had eaten the company prepared to return. Nausicaa mounted her cart, and the maidens followed her on foot. As long as the road led through the fields Ulysses accompanied them, but when they neared the city Nausicaa bade him wait in a poplar grove until she should reach home; then he was to follow and appear at her father’s house.

Thus she wished to avoid gossip so that no one might say: “Ah, see what a stately stranger Nausicaa has picked out for herself. She wishes him for her husband. She can really not wait until she is wooed. Of course it is better to choose a stranger, for the noble youths among our own people are certainly not good enough for her.” “No, stranger, not thus shall they speak,” she added, blushing. “I have myself often found fault with girls who have been seen with a man without the knowledge of their parents and before the nuptials were celebrated.”

Nausicaa gave Ulysses one more direction. When he entered the royal hall he was first to embrace the knees of the queen and to make his plea for protection to her. If she favored him then he might hope to see his home again. Not until then was he to approach the king.

Ulysses carefully noted all these directions and remained in the grove until he was sure the maidens had arrived at their destination. Meanwhile he prayed to his protector, Athene, that she might grant that he find pity and favor with the men of this unknown people.

The sun had set and darkness had fallen when the hero set out for the city of the Phæacians. As soon as he came near the first houses, his friend Athene met him disguised as a young girl returning with a pitcher of water from the well.

“Daughter, canst thou show me the way to the palace of Alcinous, thy king?” Ulysses addressed her. “I am come from a distant country and am a stranger here.”

“Very willingly, good father, will I show thee the house,” answered the friendly girl. “The king lives very near my father. Come with me and I will guide thee that thou needst not inquire of another. People are not overfriendly to strangers here.”

Ulysses thanked the maiden and followed her unseen by anyone. He was astonished at the great market place and harbor, the large ships and high walls. When they had been walking for a while the girl stopped and said: “See, good father, here is the king’s house. Thou wilt find the princes at their meal. Walk boldly in and fear nothing, for a bold front is always successful. But I must tell thee one thing more. When thou enterest thou shalt go straight to the queen, Arete. She is very wise and is honored far and wide above all women. The king also reverences her and she rules everything, judging even the men’s quarrels with wisdom. She is greeted everywhere by old and young like a goddess. If she is gracious to thee, then mayest thou hope to return to thy native land.”

With these words Athene left him, and Ulysses went into the courtyard of the castle and paused in amazement on the threshold of the house. Everything that he saw was very beautiful. The walls looked like bronze, the doorway like silver, and the ring on the gate was of gold. At the back of the open hall were rows of seats disposed against the walls, on which sat the nobles at the banquet. Beside them stood beautifully clothed youths holding torches to light the feast. Fifty maidens served in the palace, some of them grinding grain on the handmills, others embroidering or spinning; for the women of the Phæacians were as famous for their wonderful weaving as the men were as navigators.

When the hero entered the king’s hall it was already late and the company was about to break up. The guests were standing with their goblets in their hands ready to drink a last offering to Hermes. Just then they saw a stranger cross the hall and kneel before the queen. All listened attentively to what he was about to say. He clasped Arete’s knees, as was the custom of supplicants, and spoke: “O Arete, daughter of the immortal hero Rhexenor, I embrace thy knees and the king’s, thy husband’s, and all the guests. I am a man overwhelmed with misfortune. May the gods prosper thee and give thee long life and to thy children great honor and wealth! Only help me to return to my home, for it is many years since I have seen my people.”

With these words he arose and seated himself in the ashes beside the hearth, as was customary for one asking help. At first the spectators were dumb with surprise, but in a few moments an old man broke the silence. “Alcinous,” he said, “thou must not allow a stranger to sit amongst the ashes. Come, lead him to a couch and let the heralds mix wine for him as an offering to Jupiter, and let the servants bring the stranger food.”

The king immediately arose, took Ulysses by the hand, and led him to a seat beside his own. What a contrast to the previous evening when the poor man, deprived of his clothes, dripping and exhausted by his struggle with the waves, had staggered on land and raked together a bed of leaves in which to warm himself. Now he was luxuriously feasting, by torchlight, in a magnificent hall.

“Come,” cried the king to the herald, “mix another bowl of wine and fill the cups of the guests that we may drink once more to Jupiter, the protector of those seeking aid.”

The herald did the king’s bidding and all poured the libation to Jupiter on the ground, then drank off the remainder, and arose from their seats. The king commanded them to come again the following day to discuss how they might assist the stranger to return to his home, unless—this had just occurred to him—he might be a god in disguise who took pleasure in mingling with mortals.

Ulysses modestly denied this flattering suggestion. “No, indeed,” said he, “I am the most miserable and unfortunate of men. But now let me eat a little more, for unhappy as I am, hunger is stronger than my sorrows, and an empty stomach gives a mortal no peace. But to-morrow, noble lords, ye shall do to me even as the king hath said and send me home, since for many years I have been consumed with longing for my wife and home.”

The princes listened to the stranger with respect, for his speech and noble mien betrayed the man of intellect and ability. When the guests had gone, Ulysses was left alone with the king and queen. Servants removed the remains of the feast, and now the queen, who had remained silent before the men, began to question her guest. She had been watching him, half in admiration and half with distrust, for she recognized the garments which he wore, having woven them herself. “I must ask thee,” said she, “who thou art and whence thou comest. Who gave thee these garments? Thou sayest that thou comest to us from across the sea.”

“Ah, Queen,” answered Ulysses, “it is too long a story to tell thee all my history. Far out in the sea lies the isle Ogygia, where lives the beautiful and powerful goddess Calypso. A frightful storm which destroyed my ship cast me on that shore, and for seven years the lovely goddess held me captive there. She promised me immortal youth if I would abide with her and be her husband, but she could not persuade me. At last she changed her mind and only twenty days ago released me, gave me rich gifts and a successful voyage until I came in sight of the blue hills of this isle. Then Poseidon’s wrath overtook me, and a terrible storm broke up my ship. Naked, I managed by constant swimming to reach these shores. Last night I passed miserably in a thicket, but a sweet sleep held me fast bound for nearly twenty hours. I did not awaken until afternoon; then I heard voices, and saw thy daughter and her maidens not far away. I approached her in my distress, and behold, I found a sensible and noble-minded maiden. She refreshed me with food and wine, bathed and anointed me, and gave me these garments; then bade me come hither.”

“All that is very good,” said Alcinous, “but the naughty girl has neglected a part of her duty. She should have brought thee straight to us, and she was here long before thou camest.”

“She did indeed offer to conduct me hither,” said the hero, “but I did not consider it fitting and did not wish thee to misjudge me. Therefore I remained modestly behind, for we men are very suspicious creatures.”

“I am not so hasty in my judgments,” interrupted Alcinous. “However, all things should be done in order, and I perceive that thou art an excellent man. If such a one as thou should request my daughter’s hand, I would gladly take him for a son-in-law. If thou wilt remain here I will give thee houses and lands, but Jupiter would not wish that I should force thee to stay with us. No, if thou so desirest I will despatch thee to-morrow on thy way. Our rowers shall take thee safely back to thy home, however far away it may be.”

“O Father Jupiter,” cried Ulysses at these words, “let all come to pass as this noble man hath said.”

And now the queen commanded the maids to prepare a bed with soft cushions and fine covers for the stranger in the hall. They went out with torches, and when all was in readiness called the stranger to his well-earned rest.

At daybreak King Alcinous and his guest arose. They went to the market place and seated themselves upon two hewn stones, such as were ranged about for the princes when they were gathered together for conference. No one had yet arrived, but Athene, disguised as a herald, was already going from house to house inviting the chiefs to a counsel. They appeared in groups and occupied the seats, while the populace crowded about to catch a glimpse of the stranger. He stood among them like a god, for Athene had made him seem taller and his glances fierier, that he might awaken admiration and love in the Phæacians. When they had all come together the king began to speak.

“Hear me,” he said, “ye noble lords of Phæacia! This stranger here—I know not whether he comes to us from the east or from the west—implores us to speed him on his way. Let us quickly settle the matter, for never has anyone come to me with a plea which has not been granted. Then arise, youths, and assemble twenty-two of your number, launch a stanch ship, and provide all that is necessary for the voyage. Then come to my palace and I will set food and drink before you. And ye, princes, grant me another favor. Follow me to my stately hall that we may once more entertain the stranger worthily. And that song may not be lacking for our friend, call the divine singer Demodocus.”

The company separated to carry out the king’s commands, and when all was ready they repaired to the palace, which was filled with guests. Alcinous caused twelve sheep, eight swine, and two oxen to be brought from his stables, which the youths began to prepare, while the herald returned with the minstrel who was to entertain the guests.

He was blind, but his mind was stored with splendid tales which he could recite most eloquently, accompanying himself upon the harp. The herald led him gently by the arm into the midst of the company, where he placed a chair for him near a pillar. He then hung the harp upon a nail and guided the blind man’s hand to the place. Next he placed a table before him with meat, brought the bread basket, mixed the wine for him, and waited upon the other guests likewise. As soon as the company had satisfied their appetites, the minstrel took down his harp and began to prelude; then his song rang out like unto distant cries of battle and clang of swords and thundering of hoofs. He sang of the heroic deeds of the Trojan war, and the song found an echo deep in the hearts of his Greek hearers. Then the lines changed, and he celebrated the prowess of two heroes whose fame outshone all others—Achilles and Ulysses.

It was like a sword-thrust to our hero. His heart was torn with memories. He pulled his mantle over his head and hid his face, that the Phæacians might not see his tears. Alcinous, who sat beside him, heard his sobs and at the minstrel’s next pause tactfully said: “Friends, I think we have had enough of feasting and song. Let us go forth and practise some games, that our guest may see and admire the skill of our people.”

The company at once arose and followed the king, the blind minstrel being guided by a faithful servant. The market place was full of life. The nobles seated themselves, the people stood round about, and the youths who were to show their skill in wrestling, boxing, running, and throwing entered the great arena.

First there was a race between three sons of the king, Laodamas, Halius, and Clytonæus, which was won by the latter. Then came the wrestlers, the strongest of whom was Euryalus. Next came jumping, then disk throwing, and at last boxing. In this dangerous sport the handsome Laodamas was the victor.

“Listen, friends,” cried the bold young man; “let us inquire if our guest be not skilled in games. Truly he has a noble figure. See his powerful chest, his thighs, his arms, and his strong neck. His build proclaims the man of skill, and he is in the prime of his powers.” “It is a good idea! Go and challenge him,” answered Euryalus, the wrestler.

Laodamas followed the behest, but Ulysses declined. “Ah,” said he, “my misfortunes are nearer to my heart than feats of strength, and my only thought is of how I may quickly reach home. Ye do not know all that I have suffered.”

“Very good, my friend,” mocked the hasty Euryalus; “one can see that thou art not an expert. No warrior art thou, but perchance an agent on a merchant vessel, who ships the goods and reckons up the profits.”

“That was an unseemly speech,” answered the noble Ulysses. “Truly the gods have distributed their gifts in various ways. Many a man of insignificant stature is distinguished for his intellect, while perhaps another with a godlike form is poor in good sense. Thus it is with thee. Thou art beautiful to look upon, but hast little wit. Truly, wert thou not so young a fool, thou hadst angered me with thine impertinent speech. No, believe me, I am no novice at boxing. I have measured myself with the bravest before calamity bowed me down; for I have suffered all that a man can, on the field of battle as well as in storms at sea. But even so, I will not leave thy challenge unanswered. Give me the disk.”

He took the heaviest of the metal plates, swung it by the strap a few times—in a circle, and then cast it high in the air, so that it fell far beyond the marks of the other throwers. One of the spectators ran forward and put a stake in the place where the disk lay, and when he returned he cried aloud: “Hail to thee, stranger. In this contest thou mayest be sure none shall equal thee.”

“See if ye can throw as far, ye youths,” cried Ulysses. “And if anyone is anxious to contend with me, either in boxing, wrestling, or in running, let him come. Phæacians, I am ready! Come who will, excepting Laodamas. He is my host, and it were unseemly to challenge him who hath fed and sheltered me. But I will not refuse any of the others, and truly I need not fear. I am expert in all feats of strength, but in spanning the bow I still have to find my master. Amongst a crowd of the enemy I can single out my man, and my arrow will lay him low. But one man excelled me when we lay before Troy, Philoctetes; but amongst all the rest I was the foremost. With the lance I aimed better than another with the arrow. In running, one of you could perhaps outdo me; for the stormy sea and long fasts have much weakened me.”

The Phæacians all were silent. Not one dared challenge the hero. Then the king began to speak. “Worthy stranger, we believe thy words, for thou dost not speak through love of boasting, but because the youth has bitterly offended thee. Listen to me, that thou mayest yet speak well of us at home. In boxing and wrestling we do not excel, but Jupiter has granted us to be fleet in the race above all peoples and masters upon the sea. We also love much feasting, harping, and the dance, beautiful garments and warm baths. Come then, ye who are skilled in the dance, show yourselves, that the stranger may tell of your art. Let some one fetch Demodocus’ harp.”

The young dancers took their places and began the dance with measured steps and wondrous leapings, while Ulysses admired their flying feet. The strains of the harp formed a lovely accompaniment to the movements of the dancers, and the old minstrel soon struck up a comic song which compelled the listeners to break into shouts of laughter. When the choral dance had lasted a while, Laodamas and Halius danced alone, to the admiration of all. One threw a ball almost to the clouds, and the other, leaping, caught it ere his foot had touched the earth. Ulysses was delighted with the agility and grace of the youths and paid them compliments which delighted their father’s heart. And as he had determined to dismiss the stranger royally, he proposed to the assembly that each of the twelve chiefs of the Phæacians should make the guest a present of gold, together with a fine embroidered robe. The impertinent Euryalus was obliged to beg the guest’s pardon and to offer him a propitiatory gift.

All agreed to the king’s proposal, and the youth brought a brazen sword with a silver hilt and scabbard of ivory as his offering. He approached Ulysses abashed, and with eyes cast down addressed him. “Be not angry, oh stranger. Let the winds scatter the offensive words which I have spoken. May the gods grant thee a speedy return to thy house and thy people, after thy long wanderings.”

“My dear fellow,” answered Ulysses, “mayest thou also enjoy the favor of the gods. And mayest thou never regret the gift which thou hast offered me.” He hung the sword over his shoulder, and all irritation was forgotten.

In the meanwhile evening had descended. Servants brought the gifts to the market place, and they were carried into the palace. There also the princes gathered, taking their usual places in the hall. Alcinous requested the queen to have a warm bath prepared for their guest, while he selected the gifts which he intended to present to him.

A great kettle of water was brought, the maids piled up wood and kindled a fire under it, while the queen herself brought in the costly presents and packed them deftly away in a chest, which Ulysses bound and tied with a cunning knot taught him by the powerful Circe. He then went out to the bath, luxuriating in the steaming tub. When he had dried himself, the maids anointed him with oil, and draped him with a magnificent tunic and cloak. Just as he was about to reënter the festal hall he felt soft hands upon his arm. It was the lovely Nausicaa, whom he had not seen since the previous day. She had learned of the preparations for his departure, and her heart desired to look once more upon the splendid man who had approached her with such dignity the day before. So she stole down the stairs and awaited him at the door. He came, a noble virility shining from his countenance, his bearing breathing dignity and power.

“Hail to thee, oh guest,” she whispered. “When thou art again in thine home, think sometimes of the girl in Scheria to whom thou once didst owe thy life.” She looked down and could scarcely keep back the tears.

The stranger answered: “If the gods will but grant me a safe return I shall remember thee and praise thy name like a goddess’ each day, for thou hast saved my life, gentle maiden.”

Nausicaa went sorrowfully back to her chamber, while Ulysses entered the hall and took his seat. The servants brought roasted meat and began to fill the goblets of the guests from great pitchers of milk. A herald guided the venerable minstrel to his place. Ulysses beckoned to the herald, then cut a fat morsel from the piece of meat before him, saying: “Take this to Demodocus. Poor though I am, I should like to do him honor, for one should always respect the minstrels. The muse herself has taught them and showers her favors upon them.” Demodocus accepted the gift with pleasure.

When all had appeased their hunger, Ulysses turned again to the minstrel and begged him, as he knew all the adventures of the Trojan war, to sing the one of the wooden horse with which Ulysses had deceived the Trojans. So the man sang the curious tale, never dreaming that the hero whose cunning he was celebrating was at his side. During the recital the hero often sighed and wiped away a tear. Alcinous noticed his emotion and again tactfully bade the singer pause, saying: “Our guest has been listening in tears; a deep sorrow seems to gnaw at his heart. Let the singer be silent, then, that all may be joyful. The stranger who cometh to us with confidence must be dear to us as a brother. And now tell us, friend, without evasion, what we would know of thee. Speak! What is thy name, who are thy parents, and where thy native land? For this we must know, if we would guide thee thither, which we shall gladly do, although an ancient oracle has warned us that jealous Poseidon will sometime sink our ship on its return from such a voyage. Tell us, too, where thou hast been and of the people thou hast met. Tell us all this and also why thou weepest while the minstrel sings of Troy.”

The company sat in silent expectation, gazing intently at the stranger, who began as follows: “The land of the Phæacians is indeed a delightful land, and I know no greater pleasure than to sit in the banquet hall, while heralds move from table to table filling the cups, and the minstrel sings splendid songs of the heroic deeds of brave men. For harp and voice are the ornaments of the feast. But ye ask me for my unhappy history. Where shall I begin the tale, for the immortal gods have heaped much misery upon me? Let my name come first, that ye may know me and keep me in remembrance. I am Ulysses, son of Laertes, well known to men through many exploits.”

The Phæacians were transfixed with astonishment, and the old minstrel bemoaned the loss of his eyesight that he was unable to see the man whose heroic deeds he had so often sung. He, the most famous among all the Trojan warriors, had eaten and drunk with them, and was now going to tell them of all the wonderful deeds which he had done and the hardships he had suffered.

“Yes, I am Ulysses,” continued the hero. “The sunny isle of Ithaca is my home. I will not speak of the unhappy war. When it was ended I turned with my comrades to Ismarus, the city of the Ciconians, destroyed it, slew the fleeing men, while we divided the women and other booty amongst us. I now counselled that we should hasten from the place, but my foolish comrades did not obey me. As long as they had enough plunder, wine, sheep, and goats, they caroused upon the shore and thus brought the first misfortune upon us.

“The conquered Ciconians summoned their allies in the interior, who responded in great numbers, fell upon us, and horribly revenged themselves. The fierce battle at the ships began early in the morning. At first we defied the overwhelming numbers of the enemy, but as the sun set we were obliged to give way. Each of my ships lost six men, and it was only with difficulty that I escaped in swift boats with the others. Happy in our escape we sailed toward the west, keeping near to the coast of Greece. Then a terrible storm arose, breaking the masts and tearing the sails. With difficulty we put to shore to mend them, and on the third morning when we set out with renewed hope, a fresh storm descended upon us from the heights of Malea and drove us far out into the open sea.

“For nine days we drifted before the awful north wind, and on the tenth day were driven on the coast of the lotus-eaters. They are an amiable people and most fortunate, for they possess a fruit called the lotus, which is their daily food and is sweeter than honey. Whoever eats of it forgets his home and desires to remain there forever. We landed to take on fresh water and the lotus did not fail in its effects. I had to drive my companions back to the ships, bind them with ropes, and throw them under the rowers’ benches, and if I had not put off again quickly, not a single man would have followed me.

“We now rowed out again over the boundless sea and landed on a wooded island near the coast of Sicily, which was uninhabited except by countless herds of goats roaming the lowlands. They were without fear, so that we had easy hunting, and provided ourselves plentifully with game. When we had refreshed ourselves with food and sleep I was anxious to row across to the next island, which seemed to be very large and fruitful. We could hear voices there and see cattle climbing about the hills. It is the home of the giant race of Cyclops, a savage people who know nothing of agriculture, have no laws, nor fear gods nor men. I said to my companions: ‘Remain here with your ships. I will row across in mine with twelve picked companions and examine the land.’ I embarked, taking with me a large skin of excellent wine, for I divined that I might fall in with savage people who could not be won by reason or fair words, and therefore I furnished myself with this sweet, beguiling drink.

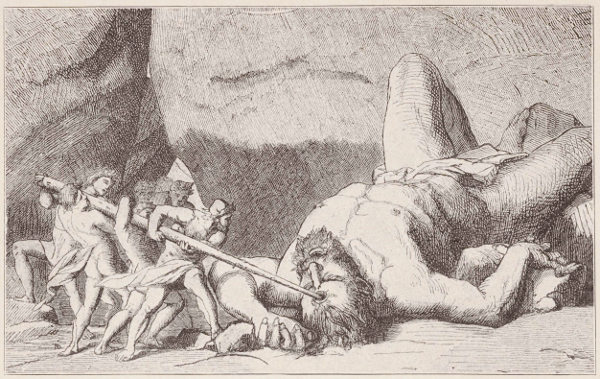

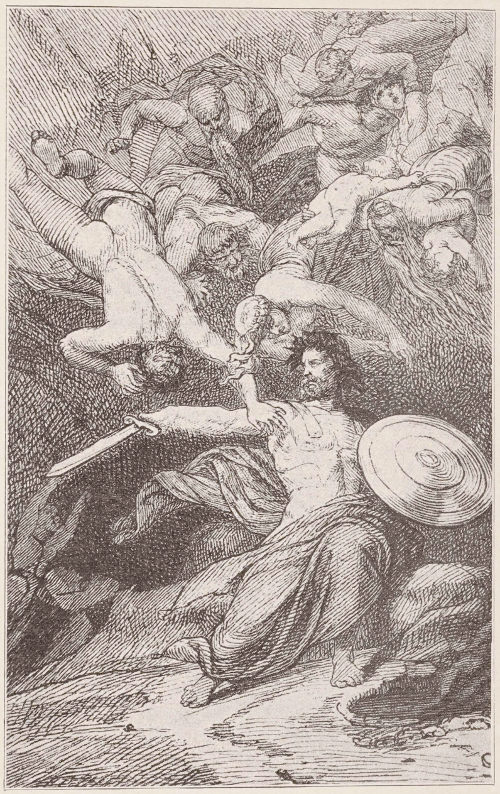

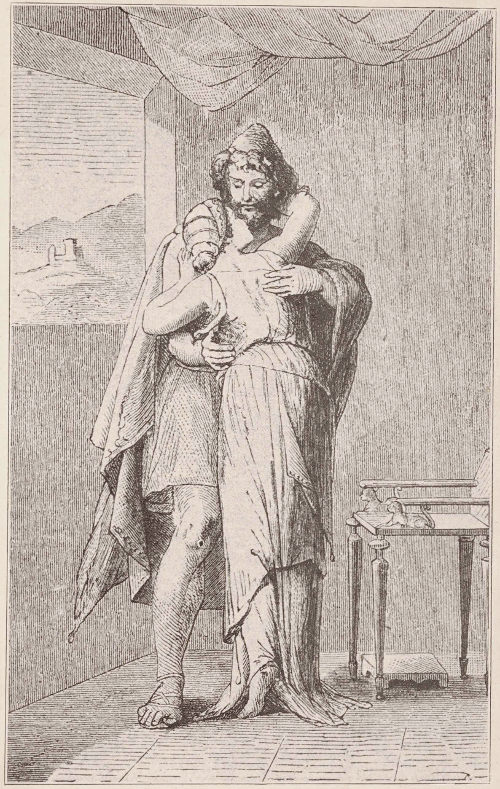

“On our arrival I carefully concealed my vessel in a hidden cave and landed with my people and my wine skin. Not far away I saw a tremendous cave in the rock surrounded by a wall of great stones and shaded by a row of gigantic firs and oaks. It was the dwelling of the most terrible of the giants, where he spent the night with his goats and sheep; for the care of his flocks was his sole occupation. He was the son of Poseidon and his name was Polyphemus. Like all the Cyclops, he had a single but horrible eye in the middle of his forehead. His arms were powerful enough to move rocks, and he could sling granite blocks through the air like pebbles. He wandered about alone among the mountains, none of the other Cyclops holding intercourse with him. He was savage and delighted only in mischief and destructiveness.