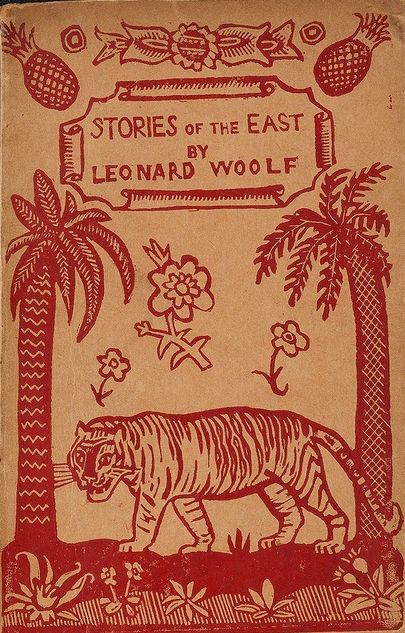

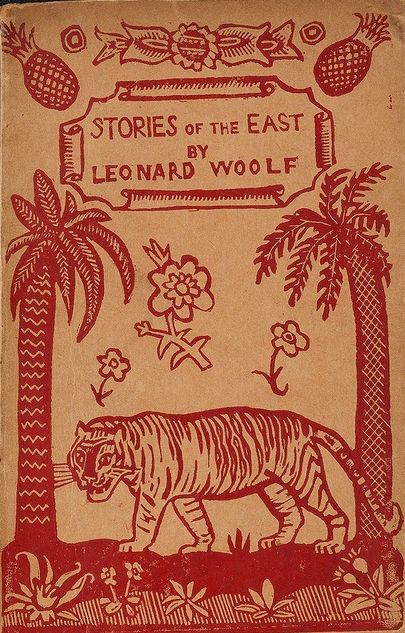

Title: Stories of the East

Author: Leonard Woolf

Illustrator: Dora de Houghton Carrington

Release date: September 6, 2019 [eBook #60239]

Most recently updated: December 9, 2022

Language: English

Credits: Laura Natal Rodrigues at Free Literature (Images

generously made available by Hathi Trust.)

A TALE TOLD BY MOONLIGHT

PEARLS AND SWINE

THE TWO BRAHMANS

Many people did not like Jessop. He had rather a brutal manner sometimes of telling brutal things—the truth, he called it. "They don't like it," he once said to me in a rare moment of confidence. "But why the devil shouldn't they? They pretend these sorts of things, battle, murder, and sudden death, are so real—more real than white kid gloves and omnibuses and rose leaves—and yet when you give them the real thing, they curl up like school girls. It does them good, you know, does them a world of good."

They didn't like it and they didn't altogether like him. He was a sturdy thick set man, very strong, a dark reserved man with black eyebrows which met over his nose. He had knocked about the world a good deal. He appealed to me in many ways; I liked to meet him. He had fished things up out of life, curious grim things, things which may have disgusted but which certainly fascinated as well.

The last time I saw him we were both staying with Alderton, the novelist. Mrs Alderton was away—recruiting after annual childbirth, I think. The other guests were Pemberton, who was recruiting after his annual book of verses, and Smith, Hanson Smith, the critic.

It was a piping hot June day, and we strolled out after dinner in the cool moonlight down the great fields which lead to the river. It was very cool, very beautiful, very romantic lying there on the grass above the river bank, watching the great trees in the moonlight and the silver water slipping along so musically to the sea. We grew silent and sentimental—at least I know I did.

Two figures came slowly along the bank, a young man with his arm round a girl's waist. They passed just under where we were lying without seeing us. We heard the murmur of his words and in the shadow of the trees they stopped and we heard the sound of their kisses.

I heard Pemberton mutter:

A boy and girl if the good fates please

Making love say,

The happier they.

Come up out or the light of the moon

And let them pass as they will, too soon

With the bean flowers boon

And the blackbird's tune

And May and June.

It loosed our tongues and we began to speak—all of us except Jessop—as men seldom speak together, of love. We were sentimental, romantic. We told stories of our first loves. We looked back with regret, with yearning to our youth and to love. We were passionate in our belief in it, love, the great passion, the real thing which had just passed us by so closely in the moonlight.

We talked like that for an hour or so, I suppose, and Jessop never opened his lips. Whenever I looked at him, he was watching the river gliding by and he was growing. At last there was a pause; we were all silent for a minute or two and then Jessop began to speak:

"You talk as if you believed all that: it's queer damned queer. A boy kissing a girl in the moonlight and you call it love and poetry and romance. But you know as well as I do it isn't. It's just a flicker of the body, it will be cold, dead, this time next year."

He had stopped but nobody spoke and then he continued slowly, almost sadly: "We're old men and middle-aged men, aren't we? We've all done that. We remember how we kissed like that in the moonlight or no light at all. It was pleasant; Lord, I'm not denying that—but some of us are married and some of us aren't. We're middle-aged—well, think of your wives, think of—" he stopped again. I looked round. The others were moving uneasily. It was this kind of thing that people didn't like in Jessop. He spoke again.

"It's you novelists who're responsible, you know. You've made a world in which every one is always falling in love—but it's not this world. Here it's the flicker of the body.

"I don't say there isn't such a thing. There is. I've seen it, but it's rare, as rare as—as—a perfect horse, an Arab once said to me. The real thing, it's too queer to be anything but the rarest; it's the queerest thing in the world. Think of it for a moment, chucking out of your mind all this business of kisses and moonlight and marriages. A miserable tailless ape buzzed round through space on this half cold cinder of an earth, a timid bewildered ignorant savage little beast always fighting for bare existence. And suddenly it runs up against another miserable naked tailless ape and immediately everything that it has ever known dies out of its little puddle of a mind, itself, its beastly body, its puny wandering desires, the wretched fight for existence, the whole world. And instead there comes a flame of passion for something in that other naked ape, not for her body or her mind or her soul, but for something beautiful mysterious everlasting—yes that's it the everlasting passion in her which has flamed up in him. He goes buzzing on through space, but he isn't tired or bewildered or ignorant any more; he can see his way now even among the stars.

"And that's love, the love which you novelists scatter about so freely. What does it mean? I don't understand it; it's queer beyond anything I've ever struck. It isn't animal—that's the point—or vegetable or mineral. Not one man in ten thousand feels it and not one woman in twenty thousand. How can they? It's a feeling, a passion immense, steady, enduring. But not one person in twenty thousand ever feels anything at all for more than a second, and then it's only a feeble ripple on the smooth surface of their unconsciousness.

"O yes, we've all been in love. We can all remember the kisses we gave and the kisses given to us in the moonlight. But that's the body. The body's damnably exacting. It wants to kiss and to be kissed at certain times and seasons. It isn't particular however; give it moonlight and young lips and it's soon satisfied. It's only when we don't pay for it that we call it romance and love, and the most we would ever pay is a £5 note.

"But it's not love, not the other, the real, the mysterious thing. That too exists, I've seen it, I tell you, but it's rare, Lord, it's rare. I'm middle-aged. I've seen men, thousands of them, all over the world, known them too, made it my business to know them, it interests me, a hobby like collecting stamps. And I've only known two cases of real love.

"And neither of them had anything to do with kisses and moonlight. Why should they? When it comes, it comes in strange ways and places, like most real things perversely and unreasonably. I suppose scientifically it's all right—it's what the mathematician calls the law of chances.

"I'll tell you about one of them."

There was a man—you may have read his books, so I wont give you his name—though he's dead now—I'll call him Reynolds. He was at Rugby with me and also at Corpus. He was a thin feeble looking chap, very nervous, with a pale face and long pale hands. He was bullied a good deal at school; he was what they call a smug. I knew him rather well; there seemed to me to be something in him somewhere, some power of feeling under the nervousness and shyness. I can't say it ever came out, but he interested me.

I went East and he stayed at home and wrote novels. I read them; very romantic they were too, the usual ideas of men and women and love. But they were clever in many ways, especially psychologically, as it was called. He was a success, he made money.

I used to get letters from him about once in three months, so when he came travelling to the East, it was arranged that he would stay a week with me. I was in Colombo at that time, right in the passenger route. I found him one day on the deck of a P and O just the same as I'd last seen him in Oxford, except for the large sun helmet on his head and the blue glasses on his nose. And when I got him back to the bungalow and began to talk with him on the broad verandah, I found that he was still just the same inside too. The years hadn't touched him anywhere, he hadn't in the ordinary sense lived at all. He had stood aside—do you see what I mean?—from shyness, nervousness, the remembrance and fear of being bullied, and watched other people living. He knew a good deal about how other people think, the little tricks and mannerisms of life and novels, but he didn't know how they felt; I expect he had never felt anything himself, except fear and shyness: he hadn't really ever known a man, and he had certainly never known a woman.

Well, he wanted to see life, to understand it, to feel it. He had travelled 7000 miles to do so. He was very keen to begin, he wanted to see life all round, up and down, inside and out; he told me so as we looked out on the palm trees and the glimpse of the red road beyond and the unending stream of brown men and women upon it.

I began to show him life in the East. I took him to the clubs; the club where they play tennis and gossip, the club where they play Bridge and gossip, the club where they just sit in long chairs and gossip. I introduced him to scores of men who asked him to have a drink, and to scores of women who asked him whether he liked Colombo. He didn't get on with them at all, he said 'No thank you' to the men and 'Yes, very much' to the women. He was shy and felt uncomfortable, out of his element with these fat flanelled merchants, fussy civil servants, and their whining wives and daughters.

In the evening we sat on my verandah and talked. We talked about life and his novels and romance and love even. I liked him, you know; he interested me, there was something in him which had never come out. But he had got hold of life at the wrong end somehow, he couldn't deal with it or the people in it at all. He had the novelist's view, of life and—with all respect to you, Alderton—it doesn't work.

I suppose the devil came into me that evening. Reynolds had talked so much about seeing life that at last I thought: "By Jove, I'll show him a side of life he's never seen before at any rate." I called the servant and told him to fetch two rickshaws.

We bowled along the dusty roads past the lake and into the native quarter. All the smells of the East rose up and hung heavy upon the damp hot air in the narrow streets. I watched Reynolds' face in the moonlight, the scared look which always showed upon it: I very nearly repented and turned back. Even now I'm not sure whether I'm sorry that I didn't. At any rate I didn't, and at last we drew up in front of a low mean looking house standing back a little from the road.

There was one of those queer native wooden doors made in two halves; the top half was open and through it one saw an empty whitewashed room lighted by a lamp fixed in the wall. We went in and I shut the door top and bottom behind us. At the other end were two steps leading up to another room. Suddenly there came the sound of bare feet running and giggles of laughter, and ten or twelve girls, some naked and some half clothed in bright red or bright orange cloths, rushed down the steps upon us. We were surrounded, embraced, caught up in their arms and carried into the next room. We lay upon sofas with them. There was nothing but sofas and an old piano in the room.

They knew me well in the place,—you can imagine what it was—I often went there. Apart from anything else, it interested me. The girls were all Tamils and Sinhalese. It always reminded me somehow of the Arabian Nights; that room when you came into it so bare and empty, and then the sudden rush of laughter, the pale yellow naked women, the brilliant colours of the cloths, the the white teeth, all appearing so suddenly in the doorway up there at the end of the room. And the girls themselves interested me; I used to sit and talk to them for hours in their own language; they didn't as a rule understand English. They used to tell me all about themselves, queer pathetic stories often. They came from villages almost always, little native villages hidden far away among rice fields and coconut trees, and they had drifted somehow into this hovel in the warren of filth and smells which we and our civilization had attracted about us.

Poor Reynolds, he was very uncomfortable at first. He didn't know what to do in the least or where to look. He stammered out yes and no to the few broken English sentences which the girls repeated like parrots to him. They soon got tired of kissing him and came over to me to tell me their little troubles and ask me for advice—all of them that is, except one.

She was called Celestinahami and was astonishingly beautiful. Her skin was the palest of pale gold with a glow in it, very rare in the fair native women. The delicate innocent beauty of a child was in her face; and her eyes, Lord, her eyes immense, deep, dark and melancholy which looked as if they knew and understood and felt everything in the world. She never wore anything coloured, just a white cloth wrapped round her waist with one end thrown over the left shoulder. She carried about her an air of slowness and depth and mystery of silence and of innocence.

She lay full length on the sofa with her chin on, her hands, looking up into Reynolds' face and smiling at him. The white cloth had slipped down and her breasts were bare. She was a Sinhalese, a cultivator's daughter, from a little village up in the hills: her place was in the green rice fields weeding, or in the little compound under the palm trees pounding rice, but she lay on the dirty sofa and asked Reynolds in her soft broken English whether he would have a drink.

It began in him with pity. 'I saw the pity of it, Jessop,' he said to me afterwards, 'the pity of it.' He lost his shyness, he began to talk to her in his gentle cultivated voice; she didn't understand a word, but she looked up at him with her great innocent eyes and smiled at him. He even stroked her hand and her arm. She smiled at him still, and said her few soft clipped English sentences. He looked into her eyes that understood nothing but seemed to understand everything, and then it came out at last; the power to feel, the power that so few have, the flame, the passion, love, the real thing.

It was the real thing, I tell you; I ought to know; he stayed on in my bungalow day after day, and night after night he went down to that hovel among the filth and smells. It wasn't the body, it wasn't kisses and moonlight. He wanted her of course, he wanted her body and soul; but he wanted something else: the same passion, the same fine strong thing that he felt moving in himself. She was everything to him that was beautiful and great and pure, she was what she looked, what he read in the depths of her eyes. And she might have been—why not? She might have been all that and more, there's no reason why such a thing shouldn't happen, shouldn't have happened even. One can believe that still. But the chances are all against it. She was a prostitute in a Colombo brothel, a simple soft little golden-skinned animal with nothing in the depths of the eyes at all. It was the law of chances at work as usual, you know.

It was tragic and it was at the same time wonderfully ridiculous. At times he saw things as they were, the bare truth, the hopelessness of it. And then he was so ignorant of life, fumbling about so curiously with all the little things in it. It was too much for him; he tried to shoot himself with a revolver which he had bought at the Army and Navy Stores before he sailed; but he couldn't because he had forgotten how to put in the cartridges.

Yes, I burst in on him sitting at a table in his room fumbling with the thing. It was one of those rotten old-fashioned things with a piece of steel that snaps down over the chamber to prevent the cartridges falling out. He hadn't discovered how to snap it back in order to get the cartridges in. The man who sold him that revolver, instead of an automatic pistol, as he ought to have done, saved his life.

And then I talked to him seriously. I quoted his own novel to him. It was absurdly romantic, unreal, his novel, but it preached as so many of them do, that you should face facts first and then live your life out to the uttermost. I quoted it to him. Then I told him baldly brutally what the girl was—not a bit what he thouget her, what his passion went out to—a nice simple soft little animal like the bitch at my feet that starved herself if I left her for a day. 'It's the truth,' I said to him, 'as true as that you're really in love, in love with something that doesn't exist behind those great eyes. It's dangerous, damned dangerous because it's real—and that's why it's rare. But it's no good shooting yourself with that thing. You've got to get on board the next P and O, that's what you've got to do. And if you wont do that, why practise what you preach and live your life out, and take the risks.'

He asked me what I meant.

"The risks?" I said. "I can see what they are, and if you do take them, you're taking the worst odds ever offered a man. But there they are. Take the girl and see what you can make of life with her. You can buy her out of that place for fifteen rupees."

I was wrong, I suppose. I ought to have put him in irons and shipped him off next day. But I don't know, really I don't know.

He took the risks any way. We bought her out, it cost twenty rupees. I got them a little house down the coast on the sea shore, a little house surrounded by palm trees. The sea droned away sleepily right under the verandah. It was to be an idyl of the East; he was to live there for ever with her and write novels on the verandah.

And, by God, he was happy—at first. I used to go down there and stay with them pretty often. He taught her English and she taught him Sinhalese. He started to write a novel about the East: it would have been a good novel I think, full of strength and happiness and sun and reality—if it had been finished. But it never was. He began to see the truth, the damned hard unpleasant truths that I had told him that night in the Colombo bungalow. And the cruelty of it was that he still had that rare power to feel, that he still felt. It was the real thing, you see, and the real thing is—didn't I say—immense, steady, enduring. It is; I believe that still. He was in love, but he knew now what she was like. He couldn't speak to her and she couldn't speak to him, she couldn't understand him. He was a civilized cultivated intelligent nervous little man and she—she was an animal, dumb and stupid and beautiful.

I watched it happening, I had foretold it, but I cursed myself for not having stopped it, scores of times. He loved her but she tortured him. People would say, I suppose, that she got on his nerves. It's a good enough description. But the cruellest thing of all was that she had grown to love him, love him like an animal; as a bitch loves her master. Jessop stopped. We waited for him to go on but he didn't. The leaves rustled gently in the breeze; the river murmured softly below us; up in the woods I heard a nightingale singing. "Well, and then?" Alderton asked at last in a rather peevish voice.

"And then? Damn that nightingale!" said Jessop. I wish I hadn't begun this story. It happened so long ago: I thought I had forgotten to feel it, to feel that I was responsible for what happened then. There's another sort of love; it isn't the body and it isn't the flame; it's the love of dogs and women, at any rate of those slow, big-eyed women of the East. It's the love of a slave, the patient, consuming love for a master, for his kicks and his caresses, for his kisses and his blows. That was the sort of love which grew up slowly in Celestinahami for Reynolds. But it wasn't what he wanted, it was that, I expect, more than anything which got on his nerves.

She used to follow him about the bungalow like a dog. He wanted to talk to her about his novel and she only understood how to pound and cook rice. It exasperated him, made him unkind, cruel. And when he looked into her patient, mysterious eyes he saw behind them what he had fallen in love with, what he knew didn't exist. It began to drive him mad.

And she—she of course couldn't even understand what was the matter. She saw that he was unhappy, she thought she had done something wrong. She reasoned like a child that it was because she wasn't like the white ladies whom she used to see in Colombo. So she went and bought stays and white cotton stockings and shoes, and she squeezed herself into them. But the stays and the shoes and stockings didn't do her any good.

It couldn't go on like that. At last I induced Reynolds to go away. He was to continue his travels but he was coming back—he said so over and over again to me and to Celestinahami. Meanwhile she was well provided for; a deed was executed: the house and the coconut trees and the little compound by the sea were to be hers—a generous settlement, a donatio inter vivos, as the lawyers call it—void, eh?—or voidable?—because for an immoral consideration. Lord! I'm nearly forgetting my law, but I believe the law holds that only future consideration of that sort can be immoral. How wise, how just, isn't it? The past cannot be immoral; it's done with, wiped out—but the future? Yes, it's only the future that counts.

So Reynolds wiped out his past and Celestinahami by the help of a dirty Burgher lawyer and a deed of gift and a ticket issued by Thomas Cook and Son for a berth in a P and O bound for Aden. I went on board to see him off and I shook his hand and told him encouragingly that everything would be all right.

I never saw Reynolds again but I saw Celestinahami once. It was at the inquest two days after the Moldavia sailed for Aden. She was lying on a dirty wooden board on trestles in the dingy mud-plastered room behind the court. Yes, I identified her: Celestinahami—I never knew her other name. She lay there in her stays and pink skirt and white stockings and white shoes. They had found her floating in the sea that lapped the foot of the convent garden below the little bungalow—bobbing up and down in her stays and pink skirt and white stockings and shoes.

* * * * *

Jessop stopped. No one spoke for a minute or two. Then Hanson Smith stretched himself, yawned, and got up.

"Battle, murder, and sentimentality," he said. "You're as bad as the rest of them, Jessop. I'd like to hear your other case—but it's too late, I'm off to bed."

I had finished my hundred up—or rather he had—with the Colonel and we strolled into the smoking room for a smoke and a drink rotund the fire before turning in. There were three other men already round the fire and they widened their circle to take us in. I didn't know them, hadn't spoken to them or indeed to anyone except the Colonel in the large gaudy uncomfortably comfortable hotel. I was run down, out of sorts generally, and—like a fool, I thought now—had taken a week off to eat, or rather to read the menus of interminable table d'hôte dinners, to play golf and to walk on the "front" at Torquay.

I had only arrived the day before, but the Colonel (retired) a jolly tubby little man—with white moustaches like two S's lying side by side on the top of his stupid red lips and his kind choleric eyes bulging out on a life which he was quite content never for a moment to understand—made it a point, my dear Sir, to know every new arrival within one hour after he arrived.

We got our drinks and as, rather forgetting that I was in England, I murmured the Eastern formula, I noticed vaguely one of the other three glance at me over his shoulder for a moment. The Colonel stuck out his fat little legs in front of him, turning up his neatly shoed toes before the blaze. Two of the others were talking, talking as men so often do in the comfortable chairs of smoking rooms between ten and eleven at night, earnestly, seriously, of what they call affairs, or politics, or questions. I listened to their fat, full-fed, assured voices in that heavy room which smelt of solidity, safety, horsehair furniture, tobacco smoke, and the faint civilized aroma of whisky and soda. It came as a shock to me in that atmosphere that they were discussing India and the East: it does you know every now and again. Sentimental? Well, I expect one is sentimental about it, having lived there. It doesn't seem to go with solidity and horsehair furniture: the fifteen years come back to one in one moment all in a heap. How one hated it and how one loved it!

I suppose they had started on the Durbar and the King's visit. They had got on to Indian unrest, to our position in India, its duties, responsibilities, to the problem of East and West. They hadn't been there of course, they hadn't even seen the brothel and café chantant at Port Said suddenly open out into that pink and blue desert that leads you through Africa and Asia into the heart of the East. But they knew all about it, they had solved, with their fat voices and in their fat heads, riddles, older than the Sphinx, of peoples remote and ancient and mysterious whom they had never seen and could never understand. One was, I imagine, a stockjobber, plump and comfortable with a greasy forehead and a high colour in his cheeks, smooth shiny brown hair and a carefully grown small moustache: a good dealer in the market; sharp and confident, with a loud voice and shifty eyes. The other was a clergyman: need I say more? Except that he was more of a clergyman even than most clergymen, I mean that he wore tight things—leggings don't they call them? or breeches?—round his calves. I never know what it means: whether they are bishops or rural deans or archdeacons or archimandrites. In any case I mistrust them even more than the black trousers: they seem to close the last door for anything human to get in through the black clothes. The dog collar closes up the armour above, and below, as long as they were trousers, at any rate some whiff of humanity might have eddied up the legs of them and touched bare flesh. But the gaiters button them up finally, irremediably, for ever.

I expect he was an archdeacon: he was saying:

"You can't impose Western civilization upon an Eastern people—I believe I'm right in saying that there are over two hundred millions in our Indian Empire—without a little disturbance. I'm a Liberal you know, I've been a Liberal my whole life—family tradition—though I grieve to say I could not follow Mr. Gladstone on the Home Rule question. It seems to me a good sign, this movement, an awakening among the people. But don't misunderstand me, my dear Sir, I am not making any excuses for the methods of the extremists. Apart from my calling—I have a natural horror of violence. Nothing can condone violence, the taking of human life, it's savagery, terrible, terrible."

"They don't put it down with a strong enough hand," the stock-jobber was saying almost fiercely. "There's too much Liberalism in the East, too much namby-pambyism. It's all right here, of course, but it's not suited to the East. They want a strong hand. After all they owe us something: we aren't going to take all the kicks and leave them all the halfpence. Rule 'em, I say, rule 'em, if you're going to rule 'em. Look after 'em, of course: give 'em schools, if they want education—Schools, hospitals, roads, and railways. Stamp out the plague, fever, famine. But let 'em know you are top dog. That's the way to run an eastern country: I'm a white man, you're black; I'll treat you well, give you courts and justice; but I'm the superior race, I'm master here."

The man who had looked round at me when I said "Here's luck!" was fidgeting about in his chair uneasily. I examined him more carefully. There was no mistaking the cause of his irritation. It was written on his face, the small close-cut white moustache, the smooth firm cheeks with the deep red-and-brown glow on them, the innumerable wrinkles round the eyes, and above all the eyes themselves, that had grown slow and steady and unastonished, watching that inexplicable, meaningless march of life under blazing suns. He had seen it, he knew. "Ah," I thought, "he is beginning to feel his liver. If he would only begin to speak. We might have some fun."

"H'm, h'm," said the archdeacon. "Of course there's something in what you say. Slow and sure. Things may be going too fast, and, as I say, I'm entirely for putting down violence and illegality with a strong hand. And after all, my dear Sir, when you say we're the superior race you imply a duty. Even in secular matters we must spread the light. I believe—devoutly—I am not ashamed to say so—that we are. We're reaching the people there, it's the cause of the unrest, we set them an example. They desire to follow. Surely, surely we should help to guide their feet. I don't speak without a certain knowledge. I take a great interest, I may even say that I play my small part, in the work of one of our great missionary societies. I see our young men, many of them risen from the people, educated often, and highly educated (I venture to think), in Board Schools. I see them go out full of high ideals to live among those poor people. And I see them when they come back and tell me their tales honestly, unostentatiously. It is always the same, a message of hope and comfort. We are getting at the people, by example, by our lives, by our conduct. They respect us."

I heard a sort of groan, and then, quite loud, these strange words:

"Kasimutal Rameswaramvaraiyil terintavan."

"I beg your pardon," said the Archdeacon, turning to the interrupter.

"I beg yours. Tamil, Tamil proverb. Came into my mind. Spoke without thinking. Beg yours."

"Not at all. Very interesting. You've lived in India? Would you mind my asking you for a translation?"

"It means 'he knows everything between Benares and Rameswaram.' Last time I heard it, an old Tamil, seventy or eighty years old, perhaps—he looked a hundred—used it of one of your young men. The young man, by the bye, had been a year and a half in India. D'you understand?"

"Well, I'm not sure I do: I've heard, of course, of Benares, but Rameswaram, I don't seem to remember the name."

I laughed; I could not help it; the little Anglo-Indian looked so fierce. "Ah!" he said, "you don't recollect the name. Well, it's pretty famous out there. Great temple—Hindu—right at the southern tip of India. Benares, you know, is up north. The old Tamil meant that your friend knew everything in India after a year and a half: he didn't, you know, after seventy, after seven thousand years. Perhaps you also don't recollect that the Tamils are Dravidians? They've been there since the beginning of time, before we came, or the Dutch or Portuguese or the Muhammadans, or our cousins, the other Aryans. Uncivilized, black? Perhaps, but, if they're black, after all it's their suns, through thousands of years, that have blackened them. They ought to know, if anyone does: but they don't, they don't pretend to. But you two gentlemen, you seem to know everything between Kasimutal—that's Benares—and Rameswaram, without having seen the sun at all."

"My dear sir," began the Archdeacon pompously, but the jobber interrupted him. He had had a number of whiskies and sodas, and was quite heated. "It's very easy to sneer: it doesn't mean because you've lived a few years in a place..."

"I? Thirty. But they—seven thousand at least."

"I say, it doesn't mean because you've lived thirty years in a place that you know all about it. Ramisram, or whatever the damned place is called, I've never heard of it and don't want to. You do, that's part of your job, I expect. But I read the papers, I've read books too, mind you, about India. I know what's going on. One knows enough—enough—data: East and West and the difference: I can form an opinion—I've a right to it even if I've never heard of Ramis what d'you call it. You've lived there and you can't see the wood for the trees. We see it because we're out of it—see it at a distance."

"Perhaps," said the Archdeacon "there's a little misunderstanding. The discussion—if I may say so—is getting a little heated—unnecessarily, I think. We hold our views. This gentleman has lived in the country. He holds others. I'm sure it would be most interesting to hear them. But I confess I didn't quite gather them from what he said."

The little man was silent: he sat back, his eyes fixed on the ceiling. Then he smiled:

"I won't give you views," he said. "But if you like I'll give you what you call details, things seen, facts. Then you can give me your views on 'em."

They murmured approval.

"Let's see, it's fifteen, seventeen years ago. I had a district then about as big as England. There may have been twenty Europeans in it, counting the missionaries, and twenty million Tamils and Telegus. I expect nineteen millions of the Tamils and Telegus never saw a white man from one year's end to the other, or if they did, they caught a glimpse of me under a sun helmet riding through their village on a fleabitten grey Indian mare. Well, Providence had so designed it that there was a stretch of coast in that district which was a barren wilderness of sand and scrubby thorn jungle—and nothing else—for three hundred miles; no towns, no villages, no water, just sand and trees for three hundred miles. O, and sun, I forgot that, blazing sun. And in the water off the shore at one place there were oysters, millions of them lying and breeding at the bottom, four or five fathoms down. And in the oysters, or some of them, were pearls."

Well, we rule India and the sea, so the sea belongs to us, and the oysters are in the sea and the pearls are in the oysters. Therefore of course the pearls belong to us. But they lie in five fathoms. How to get 'em up, that's the question. You'd think being progressive we'd dredge for them or send down divers in diving dresses. But we don't, not in India. They've been fishing up the oysters and the pearls there ever since the beginning of time, naked brown men diving feet first out of long wooden boats into the blue sea and sweeping the oysters off the bottom of the sea into baskets slung to their sides. They were doing it centuries and centuries before we came, when—as someone said—our ancestors were herding swine on the plains of Norway. The Arabs of the Persian Gulf came down in dhows and fished up pearls which found their way to Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. They still come, and the Tamils and Moormen of the district come, and they fish 'em up in the same way, diving out of long wooden boats shaped and rigged as in Solomon's time, as they were centuries before him and the Queen of Sheba. No difference, you see, except that we—Government I mean—take two-thirds of all the oysters fished up: the other third we give to the diver, Arab or Tamil or Moorman, for his trouble in fishing 'em up.

We used to have a Pearl Fishery about once in three years. It lasted six weeks or two months just between the two monsoons, the only time the sea is calm there. And I had, of course, to go and superintend it, to take Government's share of oysters, to sell them, to keep order, to keep out K. D.'s—that means Known Depredators—and smallpox and cholera. We had what we called a camp, in the wilderness, remember, on the hot sand down there by the sea: it sprang up in a night, a town, a big town of thirty or forty thousand people, a little India, Asia almost, even a bit of Africa. They came from all districts: Tamils, Telegus, fat Chetties, Parsees, Bombay merchants, Sinhalese from Ceylon, the Arabs and their negroes, Somalis probably, who used to be their slaves. It was an immense gamble; everyone bought oysters for the chance of the prizes in them: it would have taken fifty white men to superintend that camp properly; they gave me one, a little boy of twenty-four fresh-cheeked from England, just joined the service. He had views, he had been educated in a Board School, won prizes, scholarships, passed the Civil Service 'Exam'. Yes, he had views; he used to explain them to me when he first arrived. He got some new ones I think before he got out of that camp. You'd say he only saw details, things happen, facts, data. Well, he did that too. He saw men die—he hadn't seen that in his Board School—die of plague or cholera, like flies, all over the place, under the trees, in the boats, outside the little door of his own little hut. And he saw flies, too, millions, billions of them all day long buzzing, crawling over everything, his hands, his little fresh face, his food. And he smelt the smell of millions of decaying oysters all day long and all night long for six weeks. He was sick four or five times a day for six weeks; the smell did that. Insanitary? Yes, very. Why is it allowed? The pearls, you see, the pearls; you must get them out of the oysters as you must get the oysters out of the sea. And the pearls are very often small and embedded in the oyster's body. So you put all the oysters, millions of them, in dug-out canoes in the sun to rot. They rot very well in that sun, and the flies come and lay eggs in them, and maggots come out of the eggs and more flies come out of the maggots; and between them all, the maggots and the sun, the oysters' bodies disappear, leaving the pearls and a little sand at the bottom of the canoe. Unscientific? Yes, perhaps; but after all it's our camp, our fishery—just as it was in Solomon's time? At any rate, you see, it's the East. But whatever it is, and whatever the reason, the result involves flies, millions of them and a smell, a stench—Lord! I can smell it now.

There was one other white man there. He was a planter, so he said, and he had come to "deal in," pearls. He dropped in on us out of a native boat at sunset on the second day. He had a red face and a red nose, he was unhealthily fat for the East: the whites of his eyes were rather blue and rather red; they were also watery. I noticed that his hand shook, and that he first refused and then took a whisky and soda—a bad sign in the East. He wore very dirty white clothes and a vest instead of a shirt; he apparently had no baggage of any sort. But he was a white man, and so he ate with us that night and a good many nights afterwards.

In the second week he had his first attack of D. T. We pulled him through, Robson and I, in the intervals of watching over the oysters. When he hadn't got D. T., he talked: he was a great talker, he also had views. I used to sit in the evenings—they were rare—when the fleet of boats had got in early and the oysters had been divided, in front of my hut and listen to him and Robson settling India and Asia, Africa too probably. We sat there in our long chairs on the sand looking out over the purple sea, towards a sunset like blood shot with gold. Nothing moved or stirred except the flies which were going to sleep in a mustard tree close by; they hung in buzzing dusters, billions of them on the smooth leaves and little twigs; literally it was black with them. It looked as if the whole tree had suddenly broken out all over into some disease of living black currants. Even the sea seemed to move with an effort in the hot, still air; only now and again a little wave would lift itself up very slowly, very wearily, poise itself for a moment, and then fall with a weary little thud on the sand.

I used to watch them, I say, in the hot still air and the smell of dead oysters—it pushed up against your face like something solid—talking, talking in their long chairs, while the sweat stood out in little drops on their foreheads and trickled from time to time down their noses. There wasn't, I suppose, anything wrong with Robson, he was all right at bottom, but he annoyed me, irritated me in that smell. He was too cocksure altogether, of himself, of his School Board education, of life, of his 'views'. He was going to run India on new lines, laid down in some damned Manual of Political Science out of which they learn life in Board Schools and extension lectures. He would run his own life, I daresay, on the same lines, laid down in some other text book or primer. He hadn't seen anything, but he knew exactly what it was all like. There was nothing curious, astonishing, unexpected, in life, he was ready for any emergency. And we were all wrong, all on the wrong tack in dealing with natives! He annoyed me a little, you know, when the thermometer stood at 99, at 6 P.M., but what annoyed me still more was that they—the natives!—were all wrong too. They too had to be taught how to live—and die, too, I gathered.

But his views were interesting, very interesting—especially in the long chairs there under the immense Indian sky, with the camp at our hands—just as it had been in the time of Moses and Abraham—and behind us the jungle for miles, and behind that India, three hundred millions of them listening to the piping voice of a Board School boy, are the inferior race, these three hundred millions—mark race, though there are more races in India than people in Peckham—and we, of course, are superior. They've stopped somehow on the bottom rung of the ladder of which we've very nearly, if not quite, reached the top. They've stopped there hundreds, thousands of years; but it won't take any time to lead 'em up by the hand to our rung. It's to be done like this: by showing them that they're our brothers, inferior brothers; by reason, arguing them out of their superstitions, false beliefs; by education, by science, by example, yes, even he did not forget example, and White, sitting by his side with his red nose and watery eyes, nodded approval. And all this must be done scientifically, logically, systematically: if it were, a Commissioner could revolutionize a province in five years, turn it into a Japanese India, with all the riots as well as all the vakils and students running up the ladder of European civilization to become, I suppose, glorified Board School angels at the top. "But you've none of you got any clear plans out here," he piped, "you never work on any system; you've got no point of view. The result is"—here, I think, he was inspired, by the dead oysters, perhaps—"instead or getting hold of the East, it's the East which gets hold of you."

And White agreed with him, solemnly, at any rate when he was sane and sober. And I couldn't complain of his inexperience. He was rather reticent at first, but afterwards we heard much—too much—of his experiences—one does, when a man gets D. T. He said he was a gentleman, and I believe it was true; he had been to a public school, Cheltenham or Repton. He hadn't, I gathered, succeeded as a gentleman at home, so they sent him to travel in the East. He liked it, it suited him. So he became a planter in Assam. That was fifteen years ago, but he didn't like Assam: the luck was against him—it always was—and he began to roll; and when a man starts rolling in India, well—He had been a clerk in merchants' offices; he had Served in a draper's shop in Calcutta; but the luck was always against him. Then he tramped up and down India, through Ceylon, Burma; he had got at one time or another to the Malay States, and, when he was very bad one day, he talked of cultivating camphor in Java. He had been a sailor on a coasting tramp; he had sold horses (which didn't belong to him) in the Deccan somewhere; he had tramped day after day begging his way for months in native bazaars; he had lived for six months with, and on, a Tamil woman in some little village down in the south. Now he was 'dealing in' pearls. "India's got hold of me," he'd say, "India's got hold of me and the East."

He had views too, very much like Robson's, with additions. 'The strong hand' came in, and 'rule'. We ought to govern India more; we didn't now. Why, he had been in hundreds of places where he was the first Englishman that the people had ever seen. (Lord! think of that!) He talked a great deal about the hidden wealth of India and exploitation. He knew places where there was gold—workable too—only one wanted a little capital—coal probably and iron—and then there was this new stuff, radium. But we weren't go-ahead, progressive, the Government always put difficulties in his way. They made 'the native' their stalking-horse against European enterprise. He would work for the good of the native, he'd treat him firmly but kindly—especially, I thought, the native women, for his teeth were sharp and pointed and there were spaces between each, and there was something about his chin and jaw—you know the type, I expect.

As the fishing went on we had less time to talk. We had to work. The divers go out in the fleet of three hundred or four hundred boats every night and dive until midday. Then they sail back from the pearl banks and bring all their oysters into an immense Government enclosure where the Government share is taken. If the wind is favourable, all the boats get back by 6 P.M. and the work is over at 7. But if the wind starts blowing off shore, the fleet gets scattered and boats drop in one by one all night long. Robson and I had to be in the enclosure as long as there was a boat out, ready to see that, as soon as it did get in, the oysters were brought to the enclosure and Government got its share.

Well, the wind never did blow favourably that year. I sat in that enclosure sometimes for forty-eight hours on end. Robson found managing it rather difficult, so he didn't like to be left there alone. If you get two thousand Arabs, Tamils, Negroes, and Moormen, each with a bag or two of oysters, into an enclosure a hundred and fifty yards by a hundred and fifty yards, and you only have thirty timid native 'subordinates' and twelve native policemen to control them—well, somehow or other he found a difficulty in applying his system of reasoning to them. The first time he tried it, we very nearly had a riot; it arose from a dispute between some Arabs and Tamils over the ownership of three oysters which fell out of a bag. The Arabs didn't understand Tamil and the Tamils didn't understand Arabic, and, when I got down there, fetched by a frightened constable, there were sixty of seventy men fighting with great poles—they had pulled up the fence of the enclosure for weapons—and on the outskirts was Robson running round like a districted hen with a white face and tears in his blue eyes. When we got the combatants separated, they had only killed one Tamil and broken nine or ten heads. Robson was very upset by that dead Tamil, he broke down utterly for a minute or two, I'm afraid.

Then White got his second attack. He was very bad: he wanted to kill himself, but what was worse than that, before killing himself, he wanted to kill other people. I hadn't been to bed for two nights and I knew I should have to sit up another night in that enclosure as the wind was all wrong again. I had given White a bed in my hut: it wasn't good to let him wander in the bazaar. Robson came down with a white face to tell me he had 'gone mad up there again'. I had to knock him down with the butt end of a rifle; he was a big man and I hadn't slept for forty bight hours, and then there were the flies and the smell of those dead oysters.

It sounds unreal, perhaps a nightmare, all this told here to you behind blinds and windows in this—"he sniffed—" in this smell of—of—horsehair furniture and paint and varnish. The curious thing is it didn't seem a nightmare out there. It was too real. Things happened, anything might happen, without shocking or astonishing. One just did one's work, hour after hour, keeping things going in that sun which stung one's bare hands, took the skin off even my face, among the flies add the smell. It wasn't a nightmare, it was just a few thousand Arabs and Indians fishing tip oysters from the bottom of the sea. It wasn't even new, one felt; it was old, old as the Bible, old as Adam, so the Arabs said. One hadn't much time to think, but one felt it and watched it, watched the things happen quietly, unastonished, as men do in the East. One does one's work,—forty eight hours at a stretch doesn't leave one much time or inclination for thinking,—waiting for things to happen. If you can prevent people from killing one another or robbing one another, or burning down the camp, or getting cholera or plague or small-pox, and if one can manage to get one night's sleep in three, one is fairly satisfied; one doesn't much worry about having to knock a mad gentleman from Repton on the head with the butt end of a rifle between-whiles.

I expect that's just what Robson would call 'not getting hold of India but letting India get hold of you.' Well, I said I wouldn't give you views and I won't: I'm giving you facts: what I want, you know, too is to give you the feeling of facts out there. After all that is data for your views, isn't it? Things here feel so different; you seem so far from life, with windows and blinds and curtains always in between, and then nothing ever happens, you never wait for things to happen, never watch things happening here. You are always doing things somehow—Lord knows what they are—according I suppose to systems, views, opinions. But out there you live so near to life, every morning you smell damp earth if you splash too much in your tin bath. And things happen slowly, inexorably by fate, and you—you don't do things, you watch with the three hundred millions. You feel it there in everything, even in the sunrise and sunset, every day, the immensity, inexorableness, mystery of things happening. You feel the whole earth waking up or going to sleep in a great arch of sky; you feel small, not very powerful. But who ever felt the sun set or rise in London or Torquay either? It doesn't: you just turn on or turn off the electric light.

White was very bad that night. When he recovered from being knocked down by the rifle, I had to tie him down to the bed. And then Robson broke down—nerves, you know. I had to go back to the enclosure and I wanted him to stay and look after White in the hut—it wasn't safe to leave him alone even tied down with cord to the camp bed. But this was apparently another emergency to which the manual system did not apply. He couldn't face it alone in the hut with that man tied to the bed. White was certainly not a pretty sight writhing about there, and his face—have you ever seen a man in the last stages of D.T.? I beg pour pardon, I suppose you haven't. It isn't nice, and White was also seeing things, not nice either: not snakes you know as people do in novels when they get D.T., but things which had happened to him, and things which he had done—they weren't nice either—and curious ordinary things distorted in a most unpleasant way. He was very much troubled by snipe: hundreds of them kept on rising out of the bed from beside him with that shrill 'cheep! cheep!' of theirs: he felt their soft little feathered bodies against his bare skin as they fluttered up from under him somewhere and flew out of the window. It threw him into paroxysms of fear, agonies: it made one, I admit, feel chilly round the heart to hear him pray one to stop it.

And Robson was also not a nice sight. I hate seeing a sane man break down with fear, mere abject fear. He just sat down at last on a cane-bottomed chair and cried like a baby. Well, that did him some good, but he wasn't fit to be left alone with White. I had to take White down to the enclosure, and I tied him to a post with coir rope near the table at which I sat there. There was nothing else to do. And Robson came too and sat there at my side through the night watching White, terrified but fascinated.

Can you picture that enclosure to yourself down on the sandy shore with its great fence of rough poles cut in the jungle, lighted by a few flares, torches dipped in cocoanut oil: and the white man tied to a pole raving, writhing in the flickering light which just showed too Robson's white scared little face? And in the intervals of taking over oysters and settling disputes between Arabs and Somalis and Tamils and Moormen, I sat at the table writing a report (which had to go by runner next morning) on a proposal to introduce the teaching of French in 'English schools' in towns. That wasn't a very good report. White gave us the whole history of his life between ten P.M. and four A.M. in the morning. He didn't leave much to the imagination; a parson would have said that in that hour the memory of his sins came upon him—O, I beg your pardon. But really I think they did. I thought I had lived long enough out there to have heard without a shock anything that men can do and do do—especially white men who have 'gone under'. But I hadn't: I couldn't stomach the story of White's life told by himself. It wasn't only that he had robbed and swindled himself through India up and down for fifteen years. That was bad enough, for there wasn't a station where he hadn't swindled and bamboozled his fellow white men. But it was what he had done when he got away 'among the natives'—to men, and women too, away from 'civilization', in the jungle villages and high up in the mountains. God! the cold, civilized, corrupted cruelty of it. I told you, I think, that his teeth were pointed and spaced out in his mouth.

And his remorse was the most horrible thing, tied to that post there, writhing under the flickering light of the flare: the remorse of fear—fear of punishment, of what was coming, of death, of the horrors, real horrors and the phantom horrors of madness.

Often during the night there was nothing to be heard in the enclosure but his screams, curses, hoarse whispers of fear. We seemed alone there in the vast stillness of the sky: only now and then a little splash from the sea down on the shore. And then would come a confused murmur from the sea and a little later perhaps the wailing voice of one man calling to another from boat to boat across the water "Abdulla! Abdulla!" And I would go out on to the shore. There were boats, ten, fifteen, twenty, perhaps, coming in from the banks, sad, mysterious, in the moonlight, gliding in with the little splashing of the great round oars. Except for the slow moving of the oars one would have thought they were full of the dead, there was not a movement on board, until the boats touched the sand. Then the dark shadows, which lay like dead men about the boats, would leap into life—there would rise a sudden din of hoarse voices, shouting, calling, quarrelling. The boats swarmed with shadows running about, gesticulating, staggering under sacks of oysters, dropping one after the other over the boats' sides into the sea. The sea was full of them and soon the shore too, Arabs, negroes, Tamils, bowed under the weight of the sacks. They came up dripping from the sea. They burst with a roar into the enclosure: they flung down their sacks of oysters with a crash. The place was full of swaying struggling forms: of men calling to one another in their different tongues: of the smell of the sea.

And above everything one could hear the screams and prayers of the madman writhing at the post. They gathered about him, stared at him. The light of the flares fell on their dark faces, shining and dripping from the sea. They looked calm, impassive, stern. It shone too on the circle of eyes: one saw the whites of them all round him: they seemed to be judging him, weighing him: calm patient eyes of men who watched unastonished the procession of things. The Tamils' squat black figures nearly naked watched him silently, almost carelessly. The Arabs in their long dirty nightshirts, blackbearded, discussed him earnestly together with their guttural voices. Only an enormous negro, towering up to six feet six at least above the crowd, dressed in sacks and an enormous ulster, with ten copper coffee pots slung over his back and a pipe made of a whole cocoanut with an iron tube stuck in it in his hand, stood smiling mysteriously.

And White thought they weren't real, that they were devils of Hell sent to plague and torture him. He cursed them, whispered at them, howled with fear. I had to explain to them that the Sahib was not well, that the sun had touched him, that they must move away. They understood. They salaamed quietly, and moved away slowly, dignified.

I don't know how many times this didn't happen during the night. But towards morning White began to grow very weak. He moaned perpetually. Then he began to be troubled by the flesh. As dawn showed grey in the east, he was suddenly shaken by convulsions horrible to see. He screamed for someone to bring him a woman, and, as he screamed, his head fell back: he was dead. I cut the cords quickly in a terror of haste, and covered the horror of the face. Robson was sitting in a heap in his chair: he was sobbing, his face in his hands.

At that moment I was told I was wanted on the shore. I went quickly. The sea looked cold and grey under the faint light from the East. A cold little wind just ruffled the surface of the water. A solitary boat stood out black against the sky, just throbbing slowly up and down on the water close in shore. They had a dead Arab on board, he had died suddenly while diving, they wanted my permission to bring the body ashore. Four men waded out to the boat: the corpse was lifted out and placed upon their shoulders. They waded back slowly: the feet of the dead man stuck out, toes pointing up, very stark, over the shoulders of the men in front. The body was laid on the sand. The bearded face of the dead man looked very calm, very dignified in the faint light. An Arab, his brother, sat down upon the sand near his head. He covered himself with sackcloth. I heard him weeping. It was very silent, very cold and still on the shore in the early dawn.

A tall figure stepped forward, it was the Arab sheik, the leader of the boat. He laid his hand on the head of the weeping man and spoke to him calmly, eloquently, compassionately. I didn't understand Arabic, but I could understand what he was saying. The dead man had lived, had worked, had died. He had died working, without suffering, as men should desire to die. He had left a son behind him. The speech went on calmly, eloquently, I heard continually the word Khallas—all is over, finished. I watched the figures outlined against the grey sky—the long lean outline of the corpse with the toes sticking up so straight and stark, the crouching huddled figure of the weeping man and the tall upright sheik standing by his side. They were motionless, sombre, mysterious, part of the grey sea, of the grey sky.

Suddenly the dawn broke red in the sky. The sheik stopped, motioned silently to the four men. They lifted the dead man on to their shoulders. They moved away down the shore by the side of the sea which began to stir under the cold wind. By their side walked the sheik, his hand laid gently on the brother's arm. I watched them move away, silent, dignified. And over the shoulders of the men I saw the feet of the dead man with the toes sticking up straight and stark.

Then I moved away too, to make arrangements for White's burial: it had to be done at once.

* * * * *

There was silence in the smoking-room. I looked round. The Colonel had fallen asleep with his mouth open. The jobber tried to look bored, the Archdeacon was, apparently, rather put out.

"Its too late, I think," said the Archdeacon, "to—Dear me, dear me, past one o'clock". He got up. "Don't you think you've chosen rather exceptional circumstances, out of the ordinary case?"

The Commissioner was looking into the few red coals that were all that was left of the fire.

"There's another Tamil proverb," he said: "When the cat puts his head into a pot, he thinks all is darkness."

Yalpanam is a very large town in the north of Ceylon; but nobody who suddenly found himself in it would believe this. Only in two or three streets is there any bustle or stir of people. It is like a gigantic village that for centuries has slept and grown, and sleeps and grows, under a forest of cocoanut trees and the fierce sun. All the streets are the same, dazzling dusty roads between high fences made of the dried leaves of the cocoanut palms. Behind the fences, and completely hidden by them, are the compounds; and in the compounds still more hidden under the palms and orange and lime trees are the huts and houses of the Tamils who live there.

The north of the town lies, as it has lain for centuries, sleeping by the side of the blue lagoon, and there is a hut standing now in a compound by the the side of the lagoon, where it has stood for centuries. In this hut there lived a man called Chellaya who was by caste a Brahman, and in the compound next to Chellaya's lived another Brahman, called Chittampalam; and in all the other 50 or 60 compounds around them lived other Brahmans. They belonged to the highest of all castes in Yalpanam: and they could not eat food with or touch or marry into any other caste, nor could they carry earth on their heads or work at any trade, without being defiled or losing caste. Therefore all the Brahmans live together in this quarter of the town, so that they may not be defiled but may marry off their sons and daughters to daughters and sons of other Brahmans. Chellaya and Chittampalam and all the Brahmans knew that they and their fathers and their fathers' fathers had lived in the same way by the side of the blue lagoon under the palm trees for many thousands of years. They did no work, for there was no need to work. The dhobi or washer caste man, who washed the clothes of Brahmans and of no other caste, washed their white cloths and in return was given rice and allowed to be present at weddings and funerals. And there was the barber caste man who shaved the Brahmans and no other caste. And half a mile from their compounds were their Brahman rice fields in which Chellaya and each of the other Brahmans had shares; some shares had descended to them from their fathers and their grandfathers and great-grandfathers and so on from the first Brahmans, and other shares had been brought to them as dowry with their wives. These fields were sown twice a year, and the work of cultivation was done by Mukkuwa caste men. This is a custom, that Mukkuwa caste men cultivate the rice fields of Brahmans, and it had been a custom for many thousands of years.

Chellaya was forty five and Chittampalam was forty two, and they had lived, as all Brahmans lived, in the houses in which they had been born. There can be no doubt that quite suddenly one of the gods, or rather devils, laid a spell upon these two compounds. And this is how it happened.

Chellaya had married, when he was 14, a plump Brahman girl of 12 who had borne him three sons and two daughters. He had married off both his daughters without giving very large dowries and his sons had all married girls who had brought them large dowries. No man ought to have been happier, though his wife was too talkative and had a sharp tongue. And for 45 years Chellaya lived happily the life which all good Brahmans should live. Every morning he ate his rice cakes and took his bath at the well in his compound and went to the temple of Siva. There he talked until midday to his wife's brother and his daughter's husband's father about Nallatampi, their neighbour, who was on bad terms with them, about the price of rice, and about a piece of land which he had been thinking of buying for the last five years. After the midday meal of rice and curry, cooked by his wife, he dozed through the afternoon; and then, when the sun began to lose its power, he went down to the shore of the blue lagoon and sat there until nightfall.

This was Chellaya's passion, to sit by the side of the still, shining, blue waters and look over them at the far-off islands which flickered and quivered in the mirage of heat. The wind, dying down at evening, just murmured in the palms behind him. The heat lay like something tangible and soothing upon the earth. And Chellaya waited eagerly for the hour when the fishermen come out with their cast-nets and wade out into the shallow water after the fish. How eagerly he waited all day for that moment: even in the temple when talking about Nallatampi, whom he hated, the vision of those unruffled waters would continually rise up before him, and of the lean men lifting their feet so gently, first one and then the other, in order not to make a splash or a ripple, and bending forward with the nets in their hands ready to cast. And then the joy of the capture, the great leaping twisting silver fish in the net at last. He began to hate his compound and his fat wife and the interminable talk in the temple, and those long dreary evenings when he stood under his umbrella at the side of his rice field and watched the Mukkuwas ploughing or sowing or reaping.

As Chellaya grew older he became more and more convinced that the only pleasure in life was to be a fisher and to catch fish. This troubled him not a little, for the Fisher caste is a low caste and no Brahman had ever caught a fish. It would be utter pollution and losing of caste to him. One day however when he went down to sit in his accustomed place by the side of the lagoon, he found a fisherman sitting on the sand there mending his net.

"Fisher," said Chellaya, "could one who has never had a net in his hand and was no longer young learn how to cast it?"

Chellaya was a small round fat man, but he had spoken with great dignity. The fisher knew at once that he was a Brahman and salaamed, touching the ground with his forehead.

"Lord," he said, "the boy learns to cast the net when he is still at his mother's breast."

"O foolish dog of a fisher," said Chellaya pretending to be very angry, "can you not understand? Suppose one who was not a fisher and was well on in years wished to fish—for a vow or even for play—could such a one learn to cast the net?"

The old fisherman screwed up his wrinkled face and looked up at Chellaya doubtfully.

"Lord," he said, "I cannot tell. For how could such a thing be? To the fisher his net, as the saying is. Such things are learnt when one is young, as one learns to walk."

Chellaya looked out over the old man's head to the lagoon. Another fisherman was stealing along in the water ready for the cast. Ah, swish out flew the net. No, nothing—yes, O joy, a gleam of silver in the meshes. Chellaya made up his mind suddenly.

"Now, look here, fellow,—tell me this; could you teach me to cast a net?"

The old man covered his mouth with his hand, for it is not seemly that a fisher should smile in the presence of a Brahman.

"The lord is laughing at me," he said respectfully.

"I am not laughing, fellow. I have made a vow to Muniyappa that if he would take away the curse which he laid upon my son's child I would cast a net nightly in the lagoon. Now my son's child is well. Therefore if you will take me tomorrow night to a spot where no one will see us and bring me a net and teach me to cast it, I will give you five measures of rice. And if you speak a word of this to anyone, I will call down upon your head and your child's head ten thousand curses of Muniyappa."

It is dangerous to risk being cursed by a Brahman, so the fisherman agreed and next evening took Chellaya to a bay in the lagoon and showed him how to cast the net. For an hour Chellaya waded about in the shallow water experiencing a dreadful pleasure. Every moment he glanced over his shoulder to the land to make sure that nobody was in sight; every moment came the pang that he was the first Brahman to pollute his caste by fishing; and every moment came the keen joy of hope that this time the net would swish out and fall in a gentle circle upon a silver fish.

Chellaya caught nothing that night, but he had gone too far to turn back. He gave the fisherman two rupees for the net, and hid it under a rock, and every night he went away to the solitary creek, made a little pile of his white Brahman clothes on the sand, and stepped into the shallow water with his net. There he fished until the sun sank. And sometimes now he caught fish which very reluctantly he had to throw back into the water, for he was afraid to carry them back to his wife.

Very soon a strange rumour began to spread in the town that the Brahman Chellaya had polluted his caste by fishing. At first people would not believe it; such a thing could not happen, for it had never happened before. But at last so many people told the story,—and one man had seen Chellaya carrying a net and another had seen him wading in the lagoon—that everyone began to believe it, the lower castes with great pleasure and the Brahmans with great shame and anger.

Hardly had people begun to believe this rumour than an almost stranger thing began to be talked of. The Brahman Chittampalam, who was Chellaya's neighbour, had polluted his caste, it was said, by carrying earth on his head. And this rumour also was true and it happened in this way.

Chittampalam was a taciturn man and a miser. If his thin scraggy wife used three chillies, where she might have done with two for the curry, he beat her soundly. About the time that Chellaya began to fish in secret, the water in Chittampalam's well began to grow brackish. It became necessary to dig a new well in the compound, but to dig a well means paying a lower caste man to do the work; for the earth that is taken out has to be carried away on the head, and it is pollution for a Brahman to carry earth on his head. So Chittampalam sat in his compound thinking for many days how to avoid paying a man to dig a new well: and meanwhile the taste of the water from the old well became more and more unpleasant. At last it became impossible even for Chittampalam's wife to drink the water; there was only one way out of it; a new well must be dug and he could not bring himself to pay for the digging: he must dig the well himself. So every night for a week Chittampalam went down to the darkest corner of his compound and dug a well and carried earth on his head and thereby polluted his caste.

The other Brahmans were enraged with Chellaya and Chittampalam and, after abusing them and calling them pariahs, they cast them out for ever from the Brahman caste and refused to eat or drink with them or to talk to them; and they took an oath that their children's children should never marry with the grandsons and granddaughters of Chellaya and Chittampalam. But if people of other castes talked to them of the matter, they denied all knowledge of it and swore that no Brahman had ever caught fish or carried earth on his head. Chittampalam was not much concerned at the anger of the Brahmans, for he had saved the hire of a well-digger and he had never taken pleasure in the conversation of other Brahmans and, besides, he shortly after died.

Chellaya, being a small fat man and of a more pleasant and therefore more sensitive nature, felt his sin and the disapproval of his friends deeply. For some days he gave up his fishing, but they were weary days to him and he gained nothing, for the Brahmans still refused to talk to him. All day long in the temple and in his compound he sat and thought of his evenings when he waded in the blue waters of the lagoon, and of the little islands resting like plumes of smoke or feathers upon the sky, and of the line of pink flamingoes like thin posts at regular intervals set to mark a channel, and of the silver gleam of darting fish. In the evening, when he knew the fishermen were taking out their nets, his longing became intolerable: he dared not go down to the lagoon for he knew that his desire would master him. So for five nights he sat in his compound, and, as the saying is, his fat went off in desire. On the sixth night he could stand it no longer; once more he polluted his caste by catching fish.

After this Chellaya no longer tried to struggle against himself but continued to fish until at the age of fifty he died. Then, as time went on, the people who had known Chellaya and Chittampalam died too, and the story of how each had polluted his caste began to be forgotten. Only it was known in Yalpanam that no Brahman could marry into those two families, because there was something wrong with their caste. Some said that Chellaya had carried earth on his head and that Chittampalam had caught fish; in any case the descendants of Chellaya and Chittampalam had to go to distant villages to find Brahman wives and husbands for their sons and daughters.

Chellaya's hut and Chittampalam's hut still stand where they stood under the cocoanut trees by the side of the lagoon, and in one lives Chellaya, the great-great-great-grandson of Chellaya who caught fish, and in the other Chittampalam, the great-great-great-grandson of Chittampalam who carried earth on his head. Chittampalam has a very beautiful daughter and Chellaya has one son unmarried. Now this son saw Chittampalam's daughter by accident through the fence of the compound, and he went to his father and said:

"They say that our neighbour's daughter will have a big dowry; should we not make a proposal of marriage?"

The father had often thought of marrying his son to Chittampalam's daughter, not because he had seen her through the compound fence but because he had reason to believe that her dowry would be large. But he had never mentioned it to his wife or to his son, because he knew that it was said that an ancestor of Chittampalam had once dug a well and carried earth on his head. Now however that his son himself suggested the marriage, he approved of the idea, and, as the custom is, told his wife to go to Chittampalam's house and look at the girl. So his wife went formally to Chittampalam's house for the visit preparatory to an offer of marriage, and she came back and reported that the girl was beautiful and fit for even her son to marry.

Chittampalam had himself often thought of proposing to Chellaya that Chellaya's son should marry his daughter, but he had been ashamed to do this because he knew that Chellaya's ancestor had caught fish and thereby polluted his caste. Otherwise the match was desirable, for he would be saved from all the trouble of finding a husband for her in some distant village. However, if Chellaya himself proposed it, he made up his mind not to put any difficulties in the way. The next time that the two met, Chellaya made the proposal and Chittampalam accepted it and then they went back to Chellaya's compound to discuss the question of dowry. As is usual in such cases the father of the girl wants the dowry to be small and the father of the boy wants it to be large, and all sorts of reasons are given on both sides why it should be small or large, and the argument begins to grow warm. The argument became so warm that at last Chittampalam lost his temper and said:

"One thousand rupees! Is that what you want? Why, a fisher should take the girl with no dowry at all!"

"Fisher!" shouted Chellaya. "Who would marry into the pariah caste, that defiles itself by digging wells and carrying earth on its head? You had better give two thousand rupees to a pariah to take your daughter out of your house."

"Fisher! Low caste dog!" shouted Chittampalam.

"Pariah!" screamed Chellaya.

Chittampalam rushed from the compound and for many days the two Brahmans refused to talk a word to one another. At last Chellaya's son, who had again seen the daughter of Chittampalam through the fence of the compound, talked to his father and then to Chittampalam, and the quarrel was healed and they began to discuss again the question of dowry. But the old words rankled and they were still sore, and as soon as the discussion began to grow warm it ended once more by their calling each other "Fisher" and "Pariah." The same thing has happened now several times, and Chittampalam is beginning to think of going to distant villages to find a husband for his daughter. Chellaya's son is very unhappy; he goes down every evening and sits by the waters of the blue lagoon on the very spot where his great-great-great-grandfather Chellaya used to sit and watch the fishermen cast their nets.