Title: The Boy Travellers on the Congo

Author: Thomas Wallace Knox

Henry M. Stanley

Release date: September 19, 2019 [eBook #60328]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

AUTHOR OF

"THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN THE FAR EAST" "IN SOUTH AMERICA" AND "IN RUSSIA"

"THE YOUNG NIMRODS" "THE VOYAGE OF THE 'VIVIAN'" ETC.

THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN THE FAR EAST. Five Volumes. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00 each. The volumes sold separately. Each volume complete in itself.

| I. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Japan and China. |

| II. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Siam and Java. With Descriptions of Cochin China, Cambodia, Sumatra, and the Malay Archipelago. |

| III. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Ceylon and India. With Descriptions of Borneo, the Philippine Islands, and Burmah. |

| IV. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Egypt and Palestine. |

| V. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey through Africa. |

THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN SOUTH AMERICA. Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey through Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Argentine Republic, and Chili; with Descriptions of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, and Voyages upon the Amazon and La Plata Rivers. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00.

THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey in European and Asiatic Russia, with Accounts of a Tour across Siberia, Voyages on the Amoor, Volga, and other Rivers, a Visit to Central Asia, Travels Among the Exiles, and a Historical Sketch of the Empire from its Foundation to the Present Time. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00.

THE BOY TRAVELLERS ON THE CONGO. Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey with Henry M. Stanley "Through the Dark Continent." Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00.

THE VOYAGE OF THE "VIVIAN" TO THE NORTH POLE AND BEYOND. Adventures of Two Youths in the Open Polar Sea. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $2.50.

HUNTING ADVENTURES ON LAND AND SEA. Two Volumes. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $2.50 each. The volumes sold separately. Each volume complete in itself.

| I. | The Young Nimrods in North America. |

| II. | The Young Nimrods Around the World. |

☞ Any of the above volumes sent by mail, postage prepaid, to any part of the United States or Canada, on receipt of the price.

Copyright, 1887, by Harper & Brothers.—All rights reserved.

As indicated on the title-page, "The Boy Travellers on the Congo" is condensed from that remarkable narrative, "Through the Dark Continent," by one of the most famous explorers that the century has produced. The origin of the present volume is sufficiently explained in the following letter:

"Everett House, New York, December 1, 1886.

"My dear Colonel Knox,—It is a gift to be able to write to interest boys, and no one who has read your several volumes in the 'Boy Traveller' series can doubt that you possess this gift to an eminent degree. While reading those interesting and valuable books of yours, I have regretted that they were not issued in the time of my own youth, so that I might have enjoyed as a boy the treat of their perusal. Now, the Harpers desire a condensation of my two volumes, 'Through the Dark Continent,' to be made for young folks, but I have neither the time, nor the experience in juvenile writing, for performing the work. I suggest that you shall produce a volume for your series of 'Boy Travellers,' and assure you that it would delight me greatly to have you take your boys, who have followed you through so many lands, on the journey that I made from Zanzibar to the mouth of the Congo.

"There is too much in my work in its present form for their mental digestion; but, narrated in that chaste and forcible style which has proved so entertaining to them, they would certainly find the journey through Africa of exceeding interest when made in your company. By all means take Frank and Fred to the wilds of Africa; let them sail the equatorial lakes, travel through Uganda, Unyoro, and other countries ruled by dark-skinned monarchs, descend the magnificent and perilous Congo, see the strange tribes and people of that wonderful land, and repeat the adventures and discoveries that made my journey so eventful. You have my full permission, my dear friend, to use the material in any way you deem proper in adapting it to the requirements of the 'Boy Travellers.'

"Sincerely yours, as always,

Henry M. Stanley.

"To Colonel Thos. W. Knox."

The preparation of this book has been a double pleasure—first, to comply with the wishes of an old friend, and secondly, to carry the boys and girls of the present day to the wonderful region that, until very recently, was practically unknown. I have the fullest confidence that they will greatly enjoy the journey across equatorial Africa from the eastern to the western sea, and eagerly peruse every line of Mr. Stanley's narrative of discovery and adventure.

The portrait of Mr. Stanley is from a photograph taken early in 1886. The maps on the inside of the covers were specially drawn for this work, and the publishers, with their customary liberality, have allowed the use of wood-cuts selected from several volumes of African travel and exploration, in addition to those which originally appeared in "Through the Dark Continent."

In the hope that "The Boy Travellers on the Congo" will be as cordially received as were its predecessors in the series, the work is herewith submitted to press and public for perusal and comment.

T. W. K.

New York, May, 1887.

| CHAPTER I. | Crossing the Atlantic Ocean with Stanley.—"Through the Dark Continent."—An Impromptu Geographical Society.—Personal Appearance of Stanley.—Comments upon him by Frank and Fred.—How the Geographical Society was Organized.—Reading Stanley's Book.—Stanley's Departure from England for Zanzibar.—Joint Enterprise of Two Newspapers.—Preparations for the Expedition.—The "Lady Alice."—Barker and the Pococks.—Zanzibar.—Prince Barghash.—Inhabitants of Zanzibar.—The Wangwana. |

| CHAPTER II. | Transportation in Africa.—Men as Beasts of Burden.—Porters, and their Peculiarities.—Engaging Men for the Expedition.—A "Shauri."—Troubles with the "Lady Alice."—Agreement between Stanley and his Men.—Departure from Zanzibar.—Bagamoyo.—The Universities Mission.—Departure of the Expedition.—Difficulties with the Porters.—Sufferings on the March.—Native Suspension bridges.—Shooting a Zebra.—Losses by Desertion. |

| CHAPTER III. | Retarded by Rains and other Mishaps.—General Despondency.—Death of Edward Pocock.—A Change for the Better.—A Land of Plenty.—Arrival at Victoria Lake.—Native Song.—Afloat on the Great Lake.—Terrible Tales of the Inhabitants.—Encounters with the Natives.—The Victoria Nile.—Ripon Falls.—Speke's Explorations.—The Alexandra Nile.—Arrival at King Mtesa's Court.—A Magnificent Reception.—In the Monarch's Presence.—Stanley's First Opinions of Mtesa. |

| CHAPTER IV. | Personal Appearance of King Mtesa.—His Reception of Mr. Stanley.—A Naval Review.—Stanley's Marksmanship.—The King's Palace.—Rubaga, the King's Capital.—Reception at the Palace.—Meeting Colonel Linant de Bellefonds.—Converting Mtesa to Christianity.—Appeal for Missionaries to be sent to Mtesa.—Departure for Usukuma.—Fight with the Natives at Bumbireh Island.—Sufferings of Stanley and his Companions on Lake Victoria.—A Narrow Escape.—Return to Kagehyi.—Death of Fred Barker.—Embarking the Expedition.—King Lukongeh and his People. |

| CHAPTER V. | Departure for Refuge Island.—Arrival in Uganda.—Mtesa at War.—Stanley Joins him at Ripon Falls.—A Naval Battle on an African Lake.—The Waganda Repulsed.—Capture of a Wavuma Chief.—Stanley Saves the Chief's Life.—How Stanley brought the War to an End.—His Wonderful Machine for Destroying the Wavuma.—Retirement of the Army.—Stanley's Return to his Camp.—Expedition to Muta Nzege.—How it Failed.—The Expedition Marches Southward.—In King Rumanika's Country.—Arab Traders in Africa.—Hamed Ibrahim.—Kafurro and Lake Windermere.—Interviews with King Rumanika.—Exploring Lake Windermere.—An Unhappy Night.—Ihema Island. |

| CHAPTER VI. | Stanley tells about King Rumanika.—The Karagwé Geographical Society.—The King's Treasure-house.—Good-bye to his Majesty.—Hostility between Elephant and Rhinoceros.—Plundered in Usui.—The Sources of the Alexandra Nile.—Retrospection.—Questions of Topography.—Insolence of Mankorongo.—Death of "Bull."—Troubles with the Petty Kings.—Interview with the Famous Mirambo.—General Appearance of the Renowned African.—An Imposing Ceremony.—Blood-brotherhood.—How Grant's Caravan was Plundered.—Myonga's Threats.—A Compromise.—Among the Watuta.—In Sight of Lake Tanganika.—Arrival at Ujiji. |

| CHAPTER VII. | Mr. Stanley Takes the Chair.—Description of Ujiji.—The Arab and other Inhabitants.—Market Scenes.—Local Currency.—The Wajiji.—Lake Tanganika.—Stanley's Voyage on the Lake.—Rising of the Waters.—The Legend of the Well.—How the Lake was Formed.—Departure of the Expedition.—Scenery of the Coast.—Mountains where the Spirits Dwell.—Seeking the Outlet of the Lake.—The Lukuga River.—Experiments to find a Current.—Curious Head-dresses.—Return to Ujiji.—Length and Extent of Lake Tanganika. |

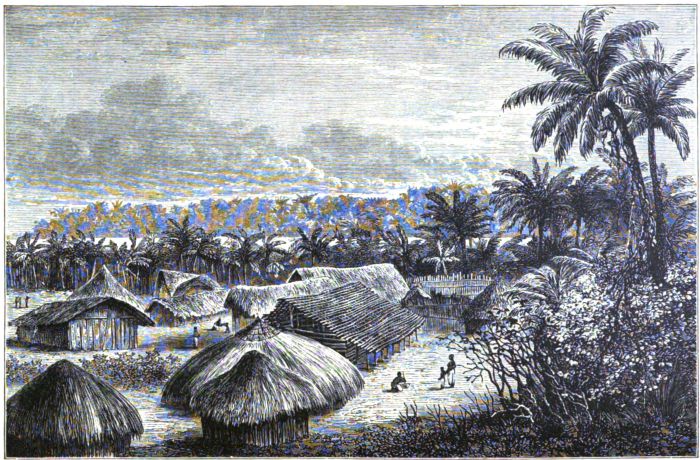

| CHAPTER VIII. | Stanley Continues the Reading.—Bad News at Ujiji.—Small-pox and its Ravages.—Desertions by Wholesale.—Departure of the Expedition.—Crossing Lake Tanganika.—Travellers' Troubles.—Terrifying Rumors.—People West of the Lake.—Singular Head-dresses—Cannibalism.—Description of an African Village.—Appearance of the Inhabitants.—In Manyema.—Story about Livingstone.—Manyema Houses.—Donkeys as Curiosities.—Kiteté and his Beard.—The Luama and the Lualaba.—On the Banks of the Livingstone. |

| CHAPTER IX. | Difficulties of Livingstone and Cameron with their Followers.—Personal Appearance of Tippu-Tib.—Negotiations for an Escort.—Tippu-Tib Arranges to go with Stanley.—The Wonders of Uregga.—Gorillas and Boa-constrictors.—Their Remarkable Performances.—A Nation of Dwarfs.—How Stanley Decided what Route to Follow.—Heads or Tails?—"Shall it be South or North?"—Signing the Contract with Tippu-Tib.—A Remarkable Accident.—Entering Nyangwé.—Location and Importance of the Place.—Its Arab Residents.—Market Scenes at Nyangwé.—Ready for the Start. |

| CHAPTER X. | Departure from Nyangwé.—The Dark Unknown.—In the Primeval Forest.—An African Wilderness.—Savage Furniture.—Tippu-Tib's Dependants.—A Toilsome March.—The Dense Jungle.—A Demoralized Column.—African Weapons.—A Village Blacksmith.—Skulls of Sokos.—Stanley's Last Pair of Shoes.—Snakes in the Way.—The Terrible Undergrowth.—Natives of Uregga and their Characteristics.—Skulls as Street Ornaments.—Among the Cannibals.—On the River's Bank.—A Sudden Inspiration.—The True Road to the Sea.—Tippu-Tib's Discouragements.—Encountering the Natives.—Successful Negotiations.—The Expedition Ferried over the River.—Camping in the Wenya. |

| CHAPTER XI. | How Stanley Obtained Canoes.—The People of Ukusu.—Their Hostility.—A Fight and Terms of Peace.—Separation from Tippu-Tib.—Departure "towards the Unknown."—A Sad Farewell.—Among the Vinya-Nara.—The Natives at Stanley Falls.—A Fierce Battle.—Defending a Stockade.—Boats Capsized in a Tempest and Men Drowned.—Beginning of the New Year.—A Battle on the Water.—Monster Canoes.—Among the Mwana Ntaba.—The Natives are Defeated.—First Cataract of Stanley Falls.—Camped in a Fortification. |

| CHAPTER XII. | Attacked by the Combined Forces of the Mwana Ntaba and Baswa Tribes.—They are Repulsed.—Exploring the First Cataract.—Carrying and Dragging the Boats through the Forest and around the Falls.—An Island Camp.—Native Weapons and Utensils.—Another Battle.—How Zaidi was Saved from a Perilous Position.—Caught in a Net.—How the Net was Broken.—Fishes in the Great River.—How the other Cataracts were Passed.—Afloat on Smooth Water.—A Hostile Village.—Another Battle.—Attacked by a Large Flotilla.—A Monster Boat.—A Temple of Ivory.—No Market for Elephants' Tusks.—Evidences of Cannibalism.—Friendly Natives of Rubunga.—Portuguese Muskets in the Hands of the Natives. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | In Urangi.—A Noisy Reception.—Wonderful Head-dresses.—A Treacherous Attack.—Animal Life along the River.—Birds and Beasts of the Great Stream.—A Battle with the Bangala.—Fire-arms in the Hands of the Natives.—The Savages, although in Superior Numbers, are Repulsed.—High Winds and Storms.—Effect of the Climate on Mr. Stanley's Health.—A Great Tributary River.—Friendly People of Ikengo.—Provisions in Abundance.—Islands in the River.—Death of Amina.—A Mournful Scene.—The Levy Hills.—Hippopotamus Creek.—Bolobo.—The King of Chumbiri.—A Crafty Potentate.—His Dress, Pipe, Wives, and Sons.—Inconvenient Collars.—Curious Customs. |

| CHAPTER XIV. | Treachery of the King's Sons.—The Greatest Rascal of Africa.—A Python in Camp.—Stanley Pool.—Dover Cliffs.—Mankoneh.—First Sound of the Falls.—Bargaining for Food.—Loss of the Big Goat.—Exchanging Charms.—Fall of the Congo from Nyangwé to Stanley Pool.—Going around the Great Fall.—Dragging the Boats Overland.—Gordon-Bennet River.—"The Caldron."—Loss of the "London Town."—Poor Kalulu.—His Death in the River.—Loss of Men by Drowning.—Sad Scenes in Camp. |

| CHAPTER XV. | The Friendly Bateké.—Great Snakes.—Soudi's Strange Adventures.—Captured by Hostile Natives.—Descending Rapids and Falls.—Loss of a Canoe.—"Whirlpool Rapids."—The "Lady Alice" in Peril.—Gavubu's Cove.—"Lady Alice" Rapids.—A Perilous Descent.—Alarm of Stanley's People.—Tributary Streams.—Panic among the Canoe-men.—Native Villages.—Inkisi Falls.—Tuckey's Cataract.—A Road over a Mountain.—Among the Babwendé.—African Markets.—Trading among the Tribes.—Shoeless Travellers.—Experiments in Cooking.—Limited Stock of Provisions.—Central African Ants.—"Jiggas."—Dangers of Unprotected Feet. |

| CHAPTER XVI. | A Disappointment.—Not Tuckey's Furthest.—Building New Canoes.—The "Livingstone," "Stanley," and "Jason."—Falls below Inkisi.—Frank Pocock Drowned.—Stanley's Grief.—"In Memoriam."—Mutiny in Camp.—How it was Quelled.—Loss of The "Livingstone."—The Chief Carpenter Drowned.—Isangila Cataract.—Tuckey's Second Sangalla.—Abandoning the Boats.—Overland to Boma.—The Expedition Starving.—A Letter Asking Help.—Volunteer Couriers.—Delays at Starting.—Vain Efforts to Buy Food.—A Dreary March.—Sufferings of Stanley's People.—The Leader's Anxiety. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | The Weary March Resumed.—Return of the Messengers.—Arrival of Relief.—Scene in Camp.—Distribution of Provisions.—The Song of Joy.—A Welcome Letter.—"Enough now: Fall to."—Personal Luxuries for the Leader.—"Pale Ale! Sherry! Port Wine! Champagne! Tea! Coffee! White Sugar! Wheaten Bread!"—Stanley's Reply to the Generous Strangers.—Summary Punishment for Theft.—Greeting Civilization.—Reception by White Men.—The Freedom of Boma.—Lifted into the Hammock.—Characteristics of Boma.—A Banquet and Farewell.—Ponta da Lenha.—Out on the Ocean.—Adieu to the Congo. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | Arrival at Kabinda.—West African Merchants.—Death among the Wangwana.—Illness among the People of the Expedition.—Stanley's Anxiety for his Followers.—Their Failing Health.—Encouraging them with Words and Kind Treatment.—The Bane of Idleness.—Leaving Kabinda.—San Paulo de Loanda.—Kindness of the Portuguese Officials.—H. B. Majesty's Ship "Industry."—Carried to the Cape of Good Hope.—The Wangwana See a "Fire-carriage."—To Natal and Zanzibar.—Reception.—Disbanding the Expedition.—Affecting Scenes.—Stanley's Tribute to his Followers. |

| CHAPTER XIX. | The Last Meeting on Board the "Eider."—Founding the Free State of Congo.—Mr. Stanley's Later Work on the Great River.—Building Roads and Establishing Stations.—Making Peace with the Natives.—Bula Matari.—Resources of the Congo Valley.—Stanley's Latest Book.—Steamers on the River.—The Congo Railway.—Stanley's Present Mission in Africa.—Emin Pasha and his Work.—How Stanley Proposes to Relieve him.—Dr. Schnitzler.—Bey or Pasha?—Mwanga, King of Uganda.—His Hostility to White Men.—Killing Bishop Hannington.—The Egyptian Equatorial Province.—Letter from Stanley.—His Plans for the Relief Expedition.—Tippu-Tib and his Men.—From Zanzibar to the Congo. |

| CHAPTER XX. | More African Studies.—Masai Land.—Early History of the Mombasa Coast.—Mount Kilimanjaro.—Its Discoverers and Explorers.—Rebmann's Umbrella.—Thomson's Expedition and its Object.—Frere Town and Mombasa.—Journey to Masai Land.—Hostility of the Natives.—Narrow Escapes.—Masai Warriors and their Occupations.—Manners and Customs of the People.—Thomson as a Magician.—Johnston's Kilimanjaro Expedition.—Height and Peculiarities of the Great Mountain.—Mandara and his Court.—Slave-trading.—Masai Women.—Surrounded by Lions.—Bishop Hannington.—Story of his Death in Uganda. |

| CHAPTER XXI. | Stanley's Hunting Adventures.—Africa the Field for the Sportsman.—Hunting in South Africa.—Night-shooting at Water-holes and Springs.—Abundance of Game.—Danger of this Kind of Sport.—Lions and Elephants.—Man-eating Lions.—In the Jaws of a Lion.—Dr. Livingstone's Narrow Escape.—The Hopo, or Game-trap on a Large Scale.—Du Chaillu and his Adventures.—Shooting the Gorilla.—Resemblance of the Gorilla to Man.—Prodigious Strength of the Gorilla.—How he is Hunted.—The End. |

At eight o'clock on the morning of December 15, 1886, the magnificent steamer Eider, of the North German Lloyds, left her dock in New York harbor for a voyage to Southampton and Bremen. Among the passengers that gathered on her deck to wave farewell to friends on shore was one whose name has become famous throughout the civilized world for the great work he has performed in exploring the African continent and opening it to commerce and Christianizing influences.

That man, it is hardly necessary to say, was HENRY M. STANLEY.

Near him stood a group of three individuals who will be recognized by many of our readers. They were Doctor Bronson and his nephews,[Pg 14] Frank Bassett and Fred Bronson, whose adventures have been recorded in previous volumes.[1]

Slowly the great steamer made her way among the ships at anchor in the harbor. She passed the Narrows, then entered the Lower Bay, and, winding through the channel between Sandy Hook and Coney Island, was soon upon the open ocean. Near the Sandy Hook light-ship she stopped her engines sufficiently long to discharge her pilot, and then, with her prow turned to the eastward, she dashed away on her course at full speed. Day by day and night by night the tireless engines throbbed and pulsated, but never for a moment ceased their toil till the Eider was off Southampton, more than three thousand miles from her starting-point.

Doctor Bronson was acquainted with Mr. Stanley, and soon after the steamer left the dock the two gentlemen were in conversation. After a little while the doctor introduced his nephews, who were warmly greeted by the great explorer; he had read of their journeys in the far East and in other lands, and expressed his pleasure at meeting them personally.

As for Frank and Fred, they were overjoyed at the introduction and the cordial manner in which they were received. They thanked Mr. Stanley for the kind words he had used in speaking of their travels, which had been of little consequence compared with his own. Frank added that he hoped some day to be able to cross the African continent; the way had been opened by Mr. Stanley, and, with the facilities which the latter had given to travellers, the journey would be far easier of accomplishment than it was twenty or even ten years ago.

Then followed a desultory conversation, of which no record has been preserved; other passengers came up to speak to Mr. Stanley, and the party separated. As the steamer passed into the open ocean most of the people on deck disappeared below for the double reason that there was a cold wind from the eastward and—breakfast was on the table.

"What a charming man Mr. Stanley is!" Fred remarked, as soon as they had withdrawn from the group.

"Yes," replied his cousin, "and so different from what I expected he would be. He is dignified without being haughty, and friendly without familiarity. Before the introduction I was afraid to meet him, but found myself quite at ease before we had been talking a minute. I'm[Pg 15] not surprised to hear how much those who know him are attached to him, nor at the influence he possesses over the people among whom his great work has been performed."

"Just think what a career he has had," continued Frank. "After various adventures as a newspaper correspondent in Spain, Abyssinia, Ashantee, and other countries, he was sent by the editor of the New York Herald to find Dr. Livingstone in the interior of Africa. He found the famous missionary; but when he came back, and told the story of what he had done, a great many people refused to believe him, because they considered the feat impossible for a newspaper correspondent. He came out of Africa at the same point where he entered it, and it was said by some that he had never ventured farther than a few miles from the coast. This made him angry, and the next time he went on a tour of exploration in Africa he made sure that the same criticism would be impossible."

"Yes, indeed!" responded Fred. "He went into the African wilderness at Bagomoya, on the east side of the continent, and came out at the mouth of the Congo, away over on the other side. He descended that[Pg 16] great river, which no white man had ever done before him, and passed through dangers and difficulties such as few travellers of modern times have known. And, besides—"

Before Fred could finish the sentence he had begun the Doctor joined them, and asked Frank where he had put the parcel of books that they had selected to read during the voyage.

"It is in our room," the youth replied, "and ready to be opened whenever we want any of the books. We will arrange our things this forenoon, and I will open the parcel at once."

"You selected Mr. Stanley's book, 'Through the Dark Continent,' I believe," Doctor Bronson continued, "and I think you had better bring that out first. Now that Mr. Stanley is with us, you will read it again with much greater interest than before."

The youths were pleased with the suggestion, which they accepted at once. Fred laughingly remarked that there might be danger of a quarrel between them as to who should have the first privilege of reading the book. Frank thought they could get over the difficulty by dividing the two volumes between them, but he admitted that the one who read the second volume in advance of the first would be likely to have his mind confused as to the exact course of the exploration which the book described.

Doctor Bronson said he was reminded of an anecdote he once heard[Pg 17] about a man who always read books with a mark, which he carefully inserted at the end of each reading. He was going through the "Life of Napoleon" at one time, and for three evenings in succession his room-mate slyly set back the mark to the starting-point. At the end of the third evening he asked the reader what he thought of Napoleon.

"He was a most wonderful man," was the reply; "in three days he crossed the Alps three times with his whole army, and went the same way every time."

While the party were laughing over the anecdote Mr. Stanley came up, and said he wished to have a share in the fun. The Doctor repeated the story, and explained how it had been called to his mind.

"Well," said Mr. Stanley, "it would be very unfortunate for Masters Frank and Fred to get the story of the Dark Continent doubled up in the manner you suggest. I propose that they shall study it together, one reading aloud to the other, and, as the entire book is too much for the limited time of this voyage, they will be obliged to omit portions of chapters here and there. The readings can take place daily during the afternoon and evening, and the youth who is to read can devote the forenoon to selecting the parts of the chapters he will suppress and those which are to be given to the listeners. I will assist him in his selections from time to time, and, with due diligence, the book will be finished before we reach Southampton."

It was unanimously voted that the plan was an excellent one, and the boys immediately proceeded to carry it out. The volumes were brought forth, and Frank retired to a corner of the saloon to make a selection for the first afternoon's reading. Mr. Stanley sat with him a short time, marking several pages and paragraphs, and then went on deck, where he joined Doctor Bronson in a brief promenade. Meantime Fred busied himself with an examination of several other books of African travel; he was evidently familiar with their contents, as he ran through the pages with great rapidity, and marked numerous passages, with the evident intention of referring to them in the course of the time devoted to what we may call the public readings.

There was an intermission of labor towards the middle of the day, and at this time Frank and Fred made the acquaintance of two or three other youths of about their age. When the latter learned of the proposed scheme, they asked permission to be allowed to hear how the Dark Continent was traversed, and their request was readily granted. Consequently the audience that assembled in the afternoon comprised some six or eight persons, including Mr. Stanley and Doctor Bronson. Neither[Pg 18] of the gentlemen remained there through the whole afternoon, partly for the reason that they were both familiar with the narrative and partly because they did not wish to seem otherwise than confident that the boys knew how to manage matters for themselves. This kind of work was not altogether new to Frank and Fred, as many of our readers are aware; and in all their previous experiences they had acquitted themselves admirably.

When everything was ready Frank began with the opening chapter of "Through the Dark Continent" and read as follows:

"While returning to England in April, 1874, from the Ashantee War, the news reached me that Livingstone was dead—that his body was on its way to England!

"Livingstone had then fallen! He was dead! He had died by the shores of Lake Bemba, on the threshold of the dark region he had wished to explore! The work he had promised me to perform was only begun when death overtook him!

"The effect which this news had upon me, after the first shock had passed away, was to fire me with a resolution to complete his work, to be, if God willed it, the next martyr to geographical science, or, if my life was to be spared, to clear[Pg 19] up not only the secrets of the Great River throughout its course, but also all that remained still problematic and incomplete of the discoveries of Burton and Speke, and Speke and Grant.

"The solemn day of the burial of the body of my great friend arrived. I was one of the pall-bearers in Westminster Abbey, and when I had seen the coffin lowered into the grave, and had heard the first handful of earth thrown over it, I walked away sorrowing over the fate of David Livingstone.

"Soon after this I was passing by an old book-shop, and observed a volume bearing the singular title of 'How to Observe.' Upon opening it, I perceived it contained tolerably clear instructions of 'how and what to observe.' It was very interesting, and it whetted my desire to know more; it led me to purchase quite an extensive library of books upon Africa, its geography, geology, botany, and ethnology. I thus became possessed of over one hundred and thirty books upon Africa, which I studied with the zeal of one who had a living interest in the subject, and with the understanding of one who had been already four times on that continent. I knew what had been accomplished by African explorers, and I knew how much of the dark interior was still unknown to the world. Until late hours I sat up, inventing and planning, sketching out routes, laying out lengthy lines of possible exploration, noting many suggestions which the continued study of my project created. I also drew up lists of instruments and other paraphernalia that would be required to map, lay out, and describe the new regions to be traversed.

"I had strolled over one day to the office of the Daily Telegraph, full of the subject. While I was discussing journalistic enterprise in general with one of the staff, the editor entered. We spoke of Livingstone and the unfinished task remaining behind him. In reply to an eager remark which I made, he asked:

"'Could you, and would you, complete the work? And what is there to do?'

"I answered:

"The outlet of Lake Tanganika is undiscovered. We know nothing scarcely—except what Speke has sketched out—of Lake Victoria; we do not even know whether it consists of one or many lakes, and therefore the sources of the Nile are still unknown. Moreover, the western half of the African continent is still a white blank.'

"'Do you think you can settle all this, if we commission you?'

"'While I live there will be something done. If I survive the time required to perform all the work, all shall be done.'

"The matter was for the moment suspended, because Mr. James Gordon Bennett, of the New York Herald, had prior claims on my services.

"A telegram was despatched to New[Pg 20] York to him: 'Would he join the Daily Telegraph in sending Stanley out to Africa, to complete the discoveries of Speke, Burton, and Livingstone?' and, within twenty-four hours, my 'new mission' to Africa was determined on as a joint expedition, by the laconic answer which the cable flashed under the Atlantic: 'Yes; Bennett.'

"A few days before I departed for Africa, the Daily Telegraph announced in a leading article that its proprietors had united with Mr. James Gordon Bennett in organizing an expedition of African discovery, under the command of Mr. Henry M. Stanley. 'The purpose of the enterprise,' it said, 'is to complete the work left unfinished by the lamented death of Dr. Livingstone; to solve, if possible, the remaining problems of the geography of Central Africa; and to investigate and report upon the haunts of the slave-traders.... He will represent the two nations whose common interest in the regeneration of Africa was so well illustrated when the lost English explorer was rediscovered by the energetic American correspondent. In that memorable journey, Mr. Stanley displayed the best qualities of an African traveller; and with no inconsiderable resources at his disposal to reinforce his own complete acquaintance with the conditions of African travel, it may be hoped that very important results will accrue from this undertaking to the advantage of science, humanity, and civilization.'

"Two weeks were allowed me for purchasing boats—a yawl, a gig, and a barge—for giving orders for pontoons, and purchasing equipment, guns, ammunition, rope, saddles, medical stores, and provisions; for making investments in gifts for native chiefs; for obtaining scientific instruments, stationery, etc., etc. The barge was an invention of my own.

"It was to be forty feet long, six feet beam, and thirty inches deep, of Spanish cedar three eighths of an inch thick. When finished, it was to be separated into five sections, each of which should be eight feet long. If the sections should be overweight, they were to be again divided into halves for greater facility of carriage. The construction of this novel boat was undertaken by Mr. James Messenger, boat-builder, of Teddington, near London. The pontoons were made by Cording, but though the workmanship was beautiful, they were not a success, because the superior efficiency of the boat for all purposes rendered them unnecessary. However, they were not wasted. Necessity compelled us, while in Africa, to employ them for far different purposes from those for which they had originally been designed.

"There lived a clerk at the Langham Hotel, of the name of Frederick Barker, who, smitten with a desire to go to Africa, was not to be dissuaded by reports of its unhealthy climate, its dangerous fevers, or the uncompromising views of exploring life given to him. 'He would go, he was determined to go,' he said.

"Mr. Edwin Arnold, of the Daily Telegraph, also suggested that I should be accompanied by one or more young English boatmen of good character, on the ground that their river knowledge would be extremely useful to me. He mentioned his wish to a most worthy fisherman, named Henry Pocock, of Lower Upnor, Kent, who had kept his yacht for him, and who had fine stalwart sons, who bore the reputation of being honest and trustworthy. Two of these young men volunteered at once. Both Mr. Arnold and myself warned the Pocock family repeatedly that Africa had a cruel character, that the sudden change from the daily comforts of English life to the rigorous one of an explorer would try the most perfect constitution; would most likely be fatal to the uninitiated and unacclimatized. But I permitted myself to be overborne by the eager courage and devotion of these adventurous lads, and Francis John Pocock and Edward Pocock, two very likely-looking young men, were accordingly engaged as my assistants.

"Soon after the announcement of the 'New Mission,' applications by the score poured into the offices of the Daily Telegraph and New York Herald for employment. Before I sailed from England, over twelve hundred letters were received from 'generals,' 'colonels,' 'captains,' 'lieutenants,' 'mid-shipmen,' 'engineers,' 'commissioners of hotels,' mechanics, waiters, cooks, servants, somebodies and nobodies, spiritual mediums and magnetizers, etc., etc. They all knew Africa, were perfectly acclimatized, were quite sure they would please me, would do important services, save me from any number of troubles by their ingenuity and resources, take me up in balloons or by flying carriages, make us all invisible by their magic arts, or by the 'science of magnetism' would cause all savages to fall asleep while we might pass anywhere without trouble. Indeed, I feel sure that, had enough money been at my disposal at that time, I might have led 5000 Englishmen, 5000 Americans, 2000 Frenchmen, 2000 Germans, 500 Italians, 250 Swiss, 200 Belgians, 50 Spaniards, and 5 Greeks, or 15,005 Europeans, to Africa. But the time had not arrived to depopulate Europe, and colonize Africa on such a scale, and I was compelled to respectfully decline accepting the valuable services of the applicants, and to content myself[Pg 22] with Francis John and Edward Pocock, and Frederick Barker—whose entreaties had been seconded by his mother.

"I was agreeably surprised also, before departure, at the great number of friends I possessed in England, who testified their friendship substantially by presenting me with useful 'tokens of their regard' in the shape of canteens, watches, water-bottles, pipes, pistols, knives, pocket-companions, manifold writers, cigars, packages of medicine, Bibles, prayer-books, English tracts for the dissemination of religious knowledge among the black pagans, poems, tiny silk banners, gold rings, etc., etc. A lady for whom I have a reverent respect presented me also with a magnificent prize mastiff named Castor, an English officer presented me with another, and at the Dogs' Home at Battersea I purchased a retriever, a bull-dog, and a bull-terrier, called respectively by the Pococks, Nero, Bull, and Jack.

"On the 15th of August, 1874, having shipped the Europeans, boats, dogs, and general property of the expedition, I left England for the east coast of Africa to begin my explorations."

Here Frank paused and informed his listeners that he would not read in full the chapter which followed, as they could not readily comprehend it without the aid of a map. "It contains," he said, "a summary of the history of the expeditions that have sought to find the sources of the Nile from the days of Herodotus to the present time, the accounts of the discoveries of the Central African lakes and of the Nile flowing from the northern end of Lake Victoria, together with a statement of the knowledge which Dr. Livingstone possessed concerning the Congo River and its course. At the end of the chapter Mr. Stanley repeats his proposal to solve the problems concerning the extent of Lakes Tanganika and Victoria, to find the outlet of the former, and determine whether the great river which Livingston saw was the Nile, the Niger, or the Congo. And now we will see," continued the youth, "how Mr. Stanley entered the African continent on his great exploration."

With these words he referred again to the book, and read as follows:

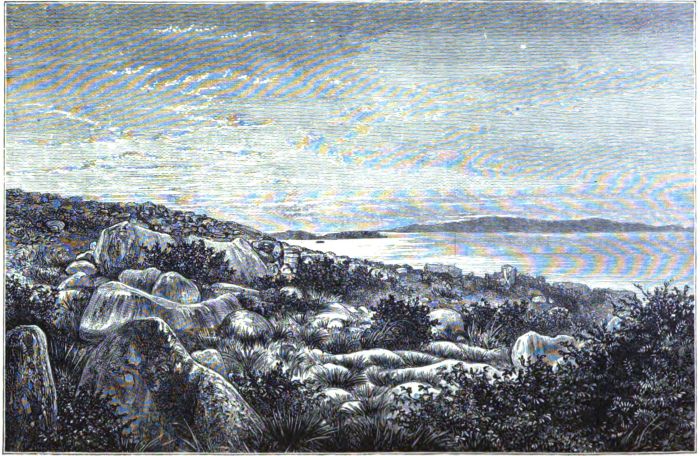

"Twenty-eight months had elapsed between my departure from Zanzibar after the discovery of Livingstone and my rearrival on that island, September 21, 1874.

"The well-remembered undulating ridges, and the gentle slopes clad with palms and mango-trees bathed in warm vapor, seemed in that tranquil, drowsy state which at all times any portion of tropical Africa presents at first appearance. A pale-blue sky covered the hazy land and sleeping sea as we steamed through the strait that separates Zanzibar from the continent. Every stranger, at first view of the shores, proclaims his pleasure. The gorgeous verdure, the distant purple ridges, the calm sea, the light gauzy atmosphere, the semi-mysterious silence which pervades all nature, evoke his admiration. For it is probable that he has sailed through the stifling Arabian Sea, with the grim, frowning mountains of Nubia on the one hand, and on the other the drear, ochreous-colored ridges of the Arab[Pg 23] peninsula; and perhaps the aspect of the thirsty volcanic rocks of Aden and the dry, brown bluffs of Guardafui is still fresh in his memory.

"The stranger, of course, is intensely interested in the life existing near the African equator, now first revealed to him, and all that he sees and hears of figures and faces and sounds is being freshly impressed on his memory. Figures and faces are picturesque enough. Happy, pleased-looking men of black, yellow, or tawny color, with long, white cotton shirts, move about with quick, active motion, and cry out, regardless of order, to their friends or mates in the Swahili or Arabic language, and their friends or mates respond with equally loud voice and lively gesture, until, with fresh arrivals, there appears to be a Babel created,[Pg 24] wherein English, French, Swahili, and Arabic accents mix with Hindi, and, perhaps, Persian.

"In the midst of such a scene I stepped into a boat to be rowed to the house of my old friend, Mr. Augustus Sparhawk, of the Bertram Agency. I was welcomed with all the friendliness and hospitality of my first visit, when, three years and a half previously, I arrived at Zanzibar to set out for the discovery of Livingstone.

"With Mr. Sparhawk's aid I soon succeeded in housing comfortably my three young Englishmen, Francis John and Edward Pocock and Frederick Barker, and my five dogs, and in stowing safely on shore the yawl Wave, the gig, and the tons of goods, provisions, and stores I had brought.

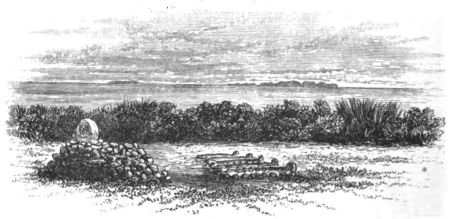

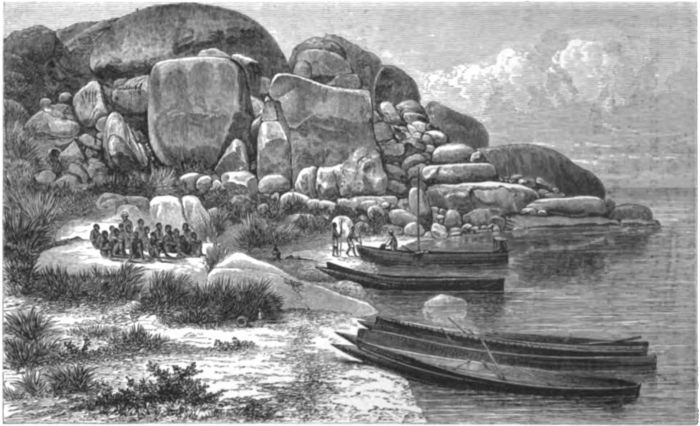

VIEW FROM THE ROOF OF MR. AUGUSTUS SPARHAWK'S HOUSE.

Frank Pocock. Frederick Barker. A Zanzibar boy. Edward Pocock. Kalula.

Bull-terrier "Jack." "Bull." Retriever "Nero." Mastiff "Captain." Prize Mastiff "Castor."

(From a Photograph by Mr. Stanley.)"Life at Zanzibar is a busy one to the intending explorer. Time flies rapidly, and each moment of daylight must be employed in the selection and purchase of the various kinds of cloth, beads, and wire in demand by the different tribes of the mainland through whose countries he purposes journeying. Strong, half-naked porters come in with great bales of unbleached cottons, striped and colored fabrics, handkerchiefs and red caps, bags of blue, green, red, white, and amber-colored beads, small and large, round and oval, and coils upon coils of thick brass wire. These have to be inspected, assorted, arranged, and numbered separately, have to be packed in portable bales, sacks, or packages, or boxed, according to their character and value. The house-floors are littered with cast-off wrappings and covers, box-lids, and a medley of rejected paper, cloth, zinc covers, and broken boards, sawdust, and other débris. Porters and servants and masters, employees and employers, pass backward and forward, to and fro, amid all this litter, roll bales over, or tumble about boxes; and a rending of cloth or paper, clattering of hammers, demands for the marking-pots, or the number of bale and box, with quick, hurried breathing and shouting, are heard from early morning until night.

"During the day the beach throughout its length is alive with the moving figures of porters, bearing clove and cinnamon bags, ivory, copal and other gums, and hides, to be shipped in the lighters waiting along the water's edge, with sailors from the shipping, and black boatmen discharging the various imports on the sand. In the evening the beach is crowded with the naked forms of workmen and boys from the 'go-downs,' preparing to bathe and wash the dust of copal and hides off their bodies in the surf. Some of the Arab merchants have ordered chairs on the piers, or bunders, to chat sociably until the sun sets, and prayer-time has come. Boats hurry by with their masters and sailors returning to their respective vessels. Dhows move sluggishly past, hoisting as they go the creaking yards of their lateen sails, bound for the mainland ports. Zanzibar canoes and 'matepes' are arriving with wood and produce, and others of the same native form and make are squaring their mat sails, outward bound. Sunset approaches, and after sunset silence follows soon. For as there are no wheeled carriages with the eternal rumble of their traffic in Zanzibar, with the early evening comes early peace and rest.

"Barghash bin Sayid, the Sultan of Zanzibar, heartily approved the objects of the expedition and gave it practical aid. It is impossible not to feel a kindly interest in Prince Barghash, and to wish him complete success in the reforms he is now striving to bring about in his country. Here we see an Arab prince, educated in the strictest school of Islam, and accustomed to regard the black natives of Africa as the lawful prey of conquest or lust, and fair objects of barter, suddenly[Pg 27] turning round at the request of European philanthropists and becoming one of the most active opponents of the slave-trade—and the spectacle must necessarily create for him many well-wishers and friends.

"The prince must be considered as an independent sovereign. His territories include, besides the Zanzibar, Pemba, and Mafia islands, nearly 1000 miles of coast, and extend probably over an area of 20,000 square miles, with a population of half a million. The products of Zanzibar have enriched many Europeans who traded in them. Cloves, cinnamon, tortoise-shell, pepper, copal gum, ivory, orchilla weed, india-rubber, and hides have been exported for years; but this catalogue does not indicate a tithe of what might be produced by the judicious investment of capital. Those intending to engage in commercial enterprises would do well to study works on Mauritius, Natal, and the Portuguese territories, if they wish to understand what these fine, fertile lands are capable of. The cocoa-nut palm flourishes at Zanzibar and on the mainland, the oil palm thrives luxuriantly in Pemba, and sugar-cane will grow everywhere. Caoutchouc remains undeveloped in the maritime belts of woodland, and the acacia forests, with their wealth of gums, are nearly untouched. Rice is sown on the Rufiji banks, and yields abundantly; cotton would thrive in any of the rich river bottoms; and then there are, besides, the grains, millet, Indian corn, and many others, the cultivation of which, though only in a languid way, the natives understand. The cattle, coffee, and goats of the interior await also the energetic man of capital and the commercial genius.

"Those whom we call the Arabs of Zanzibar are either natives of Muscat who have immigrated thither to seek their fortunes, or descendants of the conquerors of the Portuguese; many of them are descended from the Arab conquerors who accompanied Seyyid Sultan, the grandfather of the present Seyyid Barghash. While many of these descendants of the old settlers still cling to their homesteads, farms, and plantations, and acquire sufficient competence by the cultivation of cloves, cinnamon, oranges, cocoa-nut palms, sugar-cane, and other produce, a great number have emigrated into the interior to form new colonies. Hamed Ibrahim has been eighteen years in Karagwé, Muini Kheri has been thirty years[Pg 28] in Ujiji, Sultan bin Ali has been twenty-five years in Unyanyembé, Muini Dugumbi has been eight years in Nyangwé, Juma Merikani has been seven years in Rua, and a number of other prominent Arabs may be cited to prove that, though they themselves firmly believe that they will return to the coast some day, there are too many reasons for believing that they never will.

"The Arabs of Zanzibar, whether from more frequent intercourse with Europeans or from other causes, are undoubtedly the best of their race. More easily amenable to reason than those of Egypt, or the shy, reserved, and bigoted fanatics of Arabia, they offer no obstacles to the European traveller, but are sociable, frank, good-natured, and hospitable. In business they are keen traders, and of course will exact the highest percentage of profit out of the unsuspecting European if they are permitted. They are stanch friends and desperate haters. Blood is seldom satisfied without blood, unless extraordinary sacrifices are made. The conduct of an Arab gentleman is perfect. Impertinence is hushed instantly by the elders, and rudeness is never permitted.

"After the Arabs let us regard the Wangwana, or negro natives of Zanzibar, just as in Europe, after studying the condition and character of the middle-classes, we might turn to reflect upon that of the laboring population.

"After nearly seven years' acquaintance with the Wangwana, I have come to perceive that they represent in their character much of the disposition of a large portion of the negro tribes of the continent. I find them capable of great love and affection, and possessed of gratitude and other noble traits of human nature; I know, too, that they can be made good, obedient servants, that many are clever, honest, industrious, docile, enterprising, brave, and moral; that they are, in short, equal to any other race or color on the face of the globe, in all the attributes of manhood. But to be able to perceive their worth, the traveller must bring an unprejudiced judgment, a clear, fresh, and patient observation, and must forget that lofty standard of excellence upon which he and his race pride themselves, before he can fairly appreciate the capabilities of the Zanzibar negro. The traveller should not forget the origin of his own race, the condition of the Briton before St. Augustine visited his country, but should rather recall to mind the first state of the[Pg 29] 'wild Caledonian,' and the original circumstances and surroundings of primitive man.

"Being, I hope, free from prejudices of caste, color, race, or nationality, and endeavoring to pass what I believe to be a just judgment upon the negroes of Zanzibar, I find that they are a people just emerged into the Iron Epoch, and now thrust forcibly under the notice of nations who have left them behind by the improvements of over four thousand years. They possess beyond doubt all the vices of a people still fixed deeply in barbarism, but they understand to the full what and how low such a state is; it is, therefore, a duty imposed upon us by the religion we profess, and by the sacred command of the Son of God, to help them out of the deplorable state they are now in. At any rate, before we begin to hope for the improvement of races so long benighted, let us leave off this impotent bewailing of their vices, and endeavor to discover some of the virtues they possess as men, for it must be with the aid of their virtues, and not by their vices, that the missionary of civilization can ever hope to assist them.

"It is to the Wangwana that Livingstone, Burton, Speke, and Grant owe, in great part, the accomplishment of their objects, and while in the employ of those explorers, this race rendered great services to geography. From a considerable distance north of the equator down to the Zambezi and across Africa to Benguella and the mouth of the Congo, or Livingstone, they have made their names familiar to tribes who, but for the Wangwana, would have remained ignorant to this day of all things outside their own settlements. They possess, with many weaknesses, many fine qualities. While very superstitious, easily inclined to despair, and readily giving ear to vague, unreasonable fears, they may also, by judicious management, be induced to laugh at their own credulity and roused to a courageous attitude, to endure like stoics, and fight like heroes. It will depend altogether[Pg 30] upon the leader of a body of such men whether their worst or best qualities shall prevail.

"There is another class coming into notice from the interior of Africa, who, though of a sterner nature, will, I am convinced, as they are better known, become greater favorites than the Wangwana. I refer to the Wanyamwezi, or the natives of Unyamwezi, and the Wasukuma, or the people of Usukuma. Naturally, being a grade less advanced towards civilization than the Wangwana, they are not so amenable to discipline as the latter. While explorers would in the present state of acquaintance prefer the Wangwana as escort, the Wanyamwezi are far superior as porters. Their greater freedom from diseases, their greater strength and endurance, the pride they take in their profession of porters, prove them born travellers of incalculable use and benefit to Africa. If kindly treated, I do not know more docile and good-natured creatures. Their skill in war, tenacity of purpose, and determination to defend the rights of their elected chief against foreigners, have furnished themes for song to the bards of Central Africa. The English discoverer[Pg 31] of Lake Tanganika and, finally, I myself have been equally indebted to them, both on my first and last expeditions.

"From their numbers, and their many excellent qualities, I am led to think that the day will come when they will be regarded as something better than the 'best of pagazis;' that they will be esteemed as the good subjects of some enlightened power, who will train them up as the nucleus of a great African nation, as powerful for the good of the Dark Continent, as they threaten, under the present condition of things, to be for its evil."

Here Frank paused and announced an intermission of ten minutes, to enable the reader to rest a little. During the intermission the youths discussed what they had heard, and agreed unanimously that the description of Zanzibar and its people and their ruler was very interesting.

Before the reading was resumed, one of the youths asked if Zanzibar was the usual starting-point for expeditions for the exploration of Africa. Mr. Stanley was absent at the moment the question was asked, but the answer was readily given by Doctor Bronson.

"Zanzibar is the usual starting-point," said the Doctor, "but it is by no means the only one. Livingstone's expedition for exploring the Zambesi River set out from Zanzibar, and so did other expeditions of the great missionary. Burton and Speke started from there in 1856, when they discovered Lake Tanganika; and, four years later, Speke and Grant set out from the same place. Lieutenant Cameron, in his journey across Africa, made Zanzibar his starting point; and the expedition of Mr. Johnson to the Kilimandjaro Mountain was chiefly outfitted there, though it left the coast at Mombasa.

"Zanzibar," continued Doctor Bronson, "is the best point of departure for an inland expedition anywhere along the east coast of Africa, for the reason that it is the largest and most important place of trade. Its shops are well supplied with the goods that an explorer needs for his journey, and its merchants have a better reputation than those of other African ports. Everything in the interior of Africa must be carried on the backs of men, there being, as yet, no other system of transportation. Horses cannot live in certain parts of the interior of Africa, owing to the tsetse-fly, which kills them with its bites; and even were it not for this fly, it is likely that the heat of the climate would render them of little use. Occasionally, a traveller endeavors to use donkeys as beasts of burden, but these animals are scarce and dear, and of much less use than in other lands. Until Africa is provided with railways—and that will[Pg 33] not be for a long while yet—the transportation must be done by men. Every caravan that leaves the coast for the interior of the continent requires a large number of porters; and the difficulty of obtaining them is one of the greatest annoyances to merchants and travellers."

One of the youths said he supposed it was because the demand was so great that there was not a sufficient number of men.

"Not at all," replied the Doctor. "There are plenty of men in Africa, but they are not particularly anxious to work. Their wants are few, and they can live upon very little; consequently they are not over-desirous to go on a journey of several hundred miles and carry heavy burdens on their shoulders or heads. Added to their laziness is a lack of a feeling of responsibility or of honor. After engaging to go on a journey they fail to appear at the appointed time, and whenever they[Pg 34] are weary of their work they coolly drop their burdens at the side of the road and make off into the bushes. In the first few days of a journey a traveller is always deserted by many of his porters, and it is only when he gets far from the coast and has possibly entered an enemy's country that he can keep his men together. All travellers have the same story to tell, and they all agree that the Zanzibari porters are the most faithful of all in keeping their engagements, or, to say it better, the least unfaithful. For this reason, also, Zanzibar is a favorite starting-point for explorers. Frank will now read to us about the difficulties which Mr. Stanley encountered in outfitting his expedition."

Acting upon this hint, Frank opened the book and read as follows:

"It is a most sobering employment, the organizing of an African expedition. You are constantly engaged, mind and body; now in casting up accounts, and now travelling to and fro hurriedly to receive messengers, inspecting purchases, bargaining with keen-eyed, relentless Hindi merchants, writing memoranda, haggling over extortionate prices, packing up a multitude of small utilities, pondering upon your lists of articles, wanted, purchased, and unpurchased, groping about in the recesses of a highly exercised imagination for what you ought to purchase, and can not do without, superintending, arranging, assorting, and packing. And this under a temperature of 95° Fahr.

"In the midst of all this terrific, high-pressure exercise arrives the first batch of applicants for employment. For it has long ago been bruited abroad that I am ready to enlist all able-bodied human beings willing to carry a load. Ever since I arrived at Zanzibar I have had a very good reputation among Arabs and Wangwana. They have not forgotten that it was I who found the 'old white man'—Livingstone—in Ujiji, nor that liberality and kindness to my men were my special characteristics. They have also, with the true Oriental spirit of exaggeration, proclaimed that I was but a few months absent; and that, after this brief excursion, they returned to their homes to enjoy the liberal pay awarded them, feeling rather the better for the trip than otherwise. This unsought-for reputation brought on me the laborious task of selecting proper men out of an extraordinary number of applicants. Almost all the cripples, the palsied, the consumptive, and[Pg 35] the superannuated that Zanzibar could furnish applied to be enrolled on the muster-list, but these, subjected to a searching examination, were refused. Hard upon their heels came all the roughs, rowdies, and ruffians of the island, and these, schooled by their fellows, were not so easily detected. Slaves were also refused, as being too much under the influence and instruction of their masters, and yet many were engaged of whose character I had not the least conception, until, months afterwards, I learned from their quarrels in the camp how I had been misled by the clever rogues.

"All those who bore good characters on the Search Expedition, and had been despatched to the assistance of Livingstone in 1872, were employed without delay. Out of these the chiefs were selected: these were Manwa Sera, Chowpereh, Wadi Rehani, Kachéché, Zaidi, Chakanja, Farjalla, Wadi Safeni, Bukhet, Mabruki Manyapara, Mabruki Unyanyembé, Muini Pembé, Ferahan, Bwana Muri, Khamseen, Mabruki Speke, Simba, Gardner, Hamoidah, Zaidi Mganda, and Ulimengo.

"All great enterprises require a preliminary deliberative palaver, or, as the Wangwana call it, 'Shauri.' In East Africa, particularly, shauris are much in vogue. Precipitate, energetic action is dreaded. 'Poli, poli!' or 'Gently!' is the warning word of caution given.

"The chiefs arranged themselves in a semicircle on the day of the shauri, and[Pg 36] I sat à la Turque fronting them. 'What is it, my friends? Speak your minds.' They hummed and hawed, looked at one another, as if on their neighbor's faces they might discover the purport of their coming, but, all hesitating to begin, finally broke down in a loud laugh.

"Manwa Sera, always grave, unless hit dexterously with a joke, hereupon affected anger, and said, 'You speak, son of Safeni; verily we act like children! Will the master eat us?'

"Wadi, son of Safeni, thus encouraged to perform the spokesman's duty, hesitates exactly two seconds, and then ventures with diplomatic blandness and graciosity. 'We have come, master, with words. Listen. It is well we should know every step before we leap. A traveller journeys not without knowing whither he wanders. We have come to ascertain what lands you are bound for.'

"Imitating the son of Safeni's gracious blandness, and his low tone of voice, as though the information about to be imparted to the intensely interested and eagerly listening group were too important to speak it loud, I described in brief outline the prospective journey, in broken Kiswahili. As country after country was mentioned of which they had hitherto had but vague ideas, and river after river, lake after lake named, all of which I hoped with their trusty aid to explore carefully, various ejaculations expressive of wonder or joy, mixed with a little alarm, broke from their lips, but when I concluded, each of the group drew a long breath, and[Pg 37] almost simultaneously they uttered, admiringly, 'Ah, fellows, this is a journey worthy to be called a journey!'

"'But, master,' said they, after recovering themselves, 'this long journey will take years to travel—six, nine, or ten years.' 'Nonsense,' I replied. 'Six, nine, or ten years! What can you be thinking of? It takes the Arabs nearly three years to reach Ujiji, it is true, but, if you remember, I was but sixteen months from Zanzibar to Ujiji and back. Is it not so?' 'Ay, true,' they answered. 'Very well, and I assure you I have not come to live in Africa. I have come simply to see those rivers and lakes, and after I have seen them to return home. You remember while going to Ujiji I permitted the guide to show the way, but when we were returning who was it that led the way? Was it not I, by means of that little compass which could not lie like the guide?' 'Ay, true, master, true every word!' 'Very well, then, let us finish the shauri, and go. To-morrow we will make a proper agreement before the consul;' and, in Scriptural phrase, 'they forthwith arose and did as they were commanded.'

"Upon receiving information from the coast that there was a very large number of men waiting for me, I became still more fastidious in my choice. But with all my care and gift of selection, I was mortified to discover that many faces and characters had baffled the rigorous scrutiny to which I had subjected them, and[Pg 38] that some scores of the most abandoned and depraved characters on the island had been enlisted by me on the expedition. One man, named Msenna, imposed upon me by assuming such a contrite, penitent look, and weeping such copious tears, when I informed him that he had too bad a character to be employed, that my good-nature was prevailed upon to accept his services, upon the understanding that, if he indulged his murderous propensities in Africa, I should return him chained the entire distance to Zanzibar, to be dealt with by his prince. He delivered his appeal with impassioned accents and lively gestures, which produced a great effect upon the mixed audience who listened to him, and, gathering from their faces more than from my own convictions that he had been much abused and very much misunderstood, his services were accepted, and as he appeared to be an influential man, he was appointed a junior captain with prospects of promotion and higher pay.

"Subsequently, however, on the shores of Lake Victoria it was discovered—for in Africa people are uncommonly communicative—that Msenna had murdered eight people, that he was a ruffian of the worst sort, and that the merchants of Zanzibar had experienced great relief when they heard that the notorious Msenna was about to bid farewell for a season to the scene of so many of his wild exploits. Msenna was only one of many of his kind, but I have given in detail the manner of his enlistment that my position may be better understood.

"The weight of a porter's load should not exceed sixty pounds. On the arrival of the sectional exploring boat Lady Alice, great were my vexation and astonishment when I discovered that four of the sections weighed two hundred and eighty pounds each, and that one weighed three hundred and ten pounds! She was, it is true, a marvel of workmanship, and an exquisite model of a boat, such, indeed, as few builders in England or America could rival, but in her present condition her carriage through the jungles would necessitate a pioneer force a hundred strong to clear the impediments and obstacles on the road.

"I found an English carpenter named Ferris, to whom I showed the boat and explained that the narrowness of the path would make her portage absolutely impossible, for since the path was often only eighteen inches wide in Africa, and hemmed in on each side with dense jungle, any package six feet broad could by no means be conveyed along it. It was therefore necessary that each of the four sections should be subdivided, by which means I should obtain eight portable sections, each three feet wide. Mr. Ferris, perfectly comprehending his instructions, and with the aid given by the young Pococks, furnished me within two weeks with the newly modelled Lady Alice. Meantime I was busy purchasing cloth, beads, wire, and other African goods, the most of them coming from the establishment of Tarya Topan, one of the millionaire merchants of Zanzibar. I made Tarya's acquaintance in 1871, and the righteous manner in which he then dealt by me caused me now to proceed to him again for the same purpose as formerly.

"The total weight of goods, cloth, beads, wire, stores, medicine, bedding, clothes, tents, ammunition, boat, oars, rudders and thwarts, instruments and stationery, photographic apparatus, dry plates, and miscellaneous articles too numerous to mention, weighed a little over eighteen thousand pounds, or rather more than eight tons, divided as nearly as possible into loads weighing sixty pounds[Pg 39] each, and requiring therefore the carrying capacity of three hundred men. The loads were made more than usually light, in order that we might travel with celerity, and not fatigue the people.

"But still further to provide against sickness and weakness, a supernumerary force of forty men were recruited at Bagamoyo, Konduchi, and the Rufiji delta, who were required to assemble in the neighborhood of the first-mentioned place. Two hundred and thirty men, consisting of Wangwana, Wanyamwezi, and coast people from Mombasa, Tanga, and Saadani, affixed their marks opposite their names before the American consul, for wages varying from two to ten dollars per month and rations, according to their capacity, strength, and intelligence, with the understanding that they were to serve for two years, or until such time as their services should be no longer required in Africa, and were to perform their duties cheerfully and promptly.

"On the day of 'signing' the contract each adult received an advance of twenty dollars, or four months' pay, and each youth ten dollars, or four months' pay. Ration money was also paid them from the time of first enlistment, at the rate of one dollar per week, up to the day we left the coast. The entire amount disbursed in cash for advances of pay and rations at Zanzibar and Bagamoyo was $6260, or nearly thirteen hundred pounds.

"The obligations, however, were not all on one side. Besides the due payment to them of their wages, I was compelled to bind myself to them, on the word of an 'honorable white man,' to observe the following conditions as to conduct towards them:

"1st. That I should treat them kindly, and be patient with them.

"2d. That in cases of sickness, I should dose them with proper medicine, and see them nourished with the best the country afforded. That if patients were unable to proceed, they should be conveyed to such places as should be considered safe for their persons and their freedom, and convenient for their return, on convalescence, to their friends. That, with all patients thus left behind, I should leave sufficient cloth or beads to pay the native practitioner for his professional attendance, and for the support of the patient.

"3d. That in cases of disagreement between man and man, I should judge justly, honestly, and impartially. That I should do my utmost to prevent the ill-treatment of the weak by the strong, and never permit the oppression of those unable to resist.

"That I should act like a 'father and mother' to them, and to the best of my ability resist all violence offered to them by 'savage natives, and roving and lawless banditti.'

"They also promised, upon the above conditions being fulfilled, that they would do their duty like men, would honor and respect my instructions, giving me their united support, and endeavoring to the best of their ability to be faithful servants, and would never desert me in the hour of need. In short, that they would behave like good and loyal children, and 'may the blessing of God,' said they 'be upon us.'

"How we kept this bond of mutual trust and forbearance will be best seen in the following chapters, which record the strange and eventful story of our journeys.

"The fleet of six Arab vessels which were to bear us away to the west across the Zanzibar Sea were at last brought to anchor a few yards from the wharf of the American Consulate. The Wangwana, true to their promise that they would be ready, appeared with their bundles and mats, and proceeded to take their places in the vessels waiting for them. As fast as each dhow was reported to be filled, the nakhuda, or captain, was directed to anchor farther off shore to await the signal to sail. By 5 p.m., of the 12th of November, 224 men had responded to their names, and five of the Arab vessels, laden with the personnel, cattle, and matériel of the expedition, were impatiently waiting, with anchor heaved short, the word of command. One vessel still lay close ashore, to convey myself, and Frederick Barker—in charge of the personal servants—our baggage, and dogs. Turning round to my constant and well-tried friend, Mr. Augustus Sparhawk, I fervently clasped his hand, and with a full heart, though halting tongue, attempted to pour out my feelings of gratitude for his kindness and long-sustained hospitality, my keen regret at parting, and hopes of meeting again. But I was too agitated to be eloquent, and all my forced gayety could not carry me through the ordeal. So we parted in almost total silence, but I felt assured that he would judge my emotions by his own feelings.

"A wave of my hand, and the anchors were hove up and laid within ship, and then, hoisting our lateen sails, we bore away westward to launch ourselves into the arms of Fortune. Many wavings of kerchiefs and hats, parting signals from white hands, and last long looks at friendly white faces, final confused impressions of the grouped figures of our well-wishers, and then the evening breeze had swept us away into mid-sea, beyond reach of recognition.

"The parting is over! We have said our last words for years, perhaps forever, to kindly men! The sun sinks fast to the western horizon, and gloomy is the twilight that now deepens and darkens. Thick shadows fall upon the distant land and over the silent sea, and oppress our throbbing, regretful hearts, as we glide away through the dying light towards the Dark Continent.

"Upon landing at Bagamoyo, on the morning of the 13th of November, we marched to occupy the old house where we had stayed so long to prepare the first expedition. The goods were stored, the dogs chained up, the riding asses tethered, the rifles arrayed in the store-room, and the sectional boat laid under a roof close by, on rollers, to prevent injury from the white ants—a precaution which, I need hardly say, we had to observe throughout our journey. Then some more ration money, sufficient for ten days, had to be distributed among the men, the young Pococks were told off to various camp duties, to initiate them to exploring life in Africa, and then, after the first confusion of arrival had subsided, I began to muster the new engagés.

"There is an institution at Bagamoyo which ought not to be passed over without remark, but the subject cannot be properly dealt with until I have described the similar institution, of equal importance, at Zanzibar: viz., the Universities Mission. Besides, I have three pupils of the Universities Mission who are about[Pg 43] to accompany me into Africa—Robert Feruzi, Andrew, and Dallington. Robert is a stout lad of eighteen years old, formerly a servant to one of the members of Lieutenant Cameron's expedition. Andrew is a strong youth of nineteen years, rather reserved, and, I should say, not of a very bright disposition. Dallington is much younger, probably only fifteen, with a face strongly pitted with traces of a violent attack of small-pox, but as bright and intelligent as any boy of his age, white or black.

"The Universities Mission is the result of the sensation caused in England by Livingstone's discoveries on the Zambezi and of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa. It was despatched by the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in the year 1860, and consisted of Bishop Mackenzie, formerly Archdeacon of Natal, and the Rev. Messrs. Proctor, Scudamore, Burrup, and Rowley. It was established at first in the Zambesi country, but was moved, a few years later, to Zanzibar. Several of the reverend gentlemen connected with it have died at their post of duty, Bishop Mackenzie being the first to fall, but the work goes on. The mission at Bagamoyo is in charge of four French priests, eight brothers, and twelve sisters, with ten lay brothers employed in teaching agriculture. The French fathers superintend the tuition of two hundred and fifty children, and give employment to about eighty adults. One hundred and seventy freed slaves were furnished from the slave captures made by British cruisers. They are taught to earn their own living as soon as they arrive of age, and are furnished with comfortable lodgings, clothing, and household utensils.

"'Notre Dame de Bagamoyo' is situated about a mile and a half north of Bagamoyo, overlooking the sea, which washes the shores just at the base of the tolerably high ground on which the mission buildings stand. Thrift, order, and that peculiar style of neatness common to the French are its characteristics. The cocoa-nut palm, orange, and mango flourish in this pious settlement, while a variety[Pg 44] of garden vegetables and grain are cultivated in the fields; and broad roads, cleanly kept, traverse the estate. During the superior's late visit to France he obtained a considerable sum for the support of the mission, and he has lately established a branch mission at Kidudwe. It is evident that, if supported constantly by his friends in France, the superior will extend his work still farther into the interior, and it is therefore safe to predict that the road to Ujiji will in time possess a chain of mission stations affording the future European trader and traveller safe retreats with the conveniences of civilized life.[2]

"There are two other missions on the east coast of Africa: that of the Church Missionary Society, and the Methodist Free Church at Mombasa. The former has occupied this station for over thirty years, and has a branch establishment at Rabbai Mpia, the home of the Dutch missionaries, Krapf, Rebmann, and Erhardt. But these missions have not obtained the success which such long self-abnegation and devotion to the pious service deserved.

"On the morning of the 17th of November, 1874, the first bold step for the interior was taken. The bugle mustered the people to rank themselves before our quarters, and each man's load was given to him according as we judged his power of bearing burden. To the man of strong, sturdy make, with a large development of muscle, the cloth bale of sixty pounds was given, which would in a couple of months, by constant expenditure, be reduced to fifty pounds, in six months perhaps to forty pounds, and in a year to about thirty pounds, provided that all his comrades were faithful to their duties; to the short, compactly-formed man, the bead-sack, of fifty pounds' weight; to the light youth of eighteen or twenty years old, the box of forty pounds, containing stores, ammunition, and sundries. To the steady, respectable, grave-looking men of advanced years, the scientific instruments, thermometers, barometers, watches, sextant, mercury-bottles, compasses, pedometers, photographic apparatus, dry plates, stationery, and scientific books, all packed in forty-pound cases, were distributed; while the man most highly recommended for steadiness and cautious tread was intrusted with the carriage of the three chronometers, which were stowed in balls of cotton, in a light case weighing not more than twenty-five pounds. The twelve Kirangozis, or guides, tricked out this day in flowing robes of crimson blanket-cloth, demanded the privilege of conveying the several loads of brass-wire coils; and as they form the second advanced guard, and are active, bold youths—some of whom are to be hereafter known as the boat's crew, and to be distinguished by me above all others except the chiefs—they are armed with Snider rifles, with their respective accoutrements. The boat-carriers are herculean in figure and strength, for they are practised bearers of loads, having resigned their ignoble profession of hamal in Zanzibar to carry sections of the first Europe-made boat that ever floated on Lakes Victoria and Tanganika and the extreme sources of the Nile and the Livingstone. To each section of the boat there are four men, to relieve one another in couples. They get higher pay than even the chiefs, except the chief captain, Manwa Sera, and, besides receiving double rations, have the privilege of taking their wives along with them.[Pg 45] There are six riding asses also in the expedition, all saddled, one for each of the Europeans—the two Pococks, Barker, and myself—and two for the sick; for the latter there are also three of Seydel's net hammocks, with six men to act as a kind of ambulance party.

"At nine a.m. we file out of Bagamoyo in the following order: Four chiefs a few hundred yards in front; next the twelve guides, clad in red robes of Jobo, bearing the wire coils; then a long file of two hundred and seventy strong, bearing cloth, wire, beads, and sections of the Lady Alice; after them thirty-six women and ten boys, children of some of the chiefs and boat-bearers, following their mothers and assisting them with trifling loads of utensils, followed by the riding asses, Europeans, and gun-bearers; the long line closed by sixteen chiefs who act as rear-guard, and whose duties are to pick up stragglers, and act as supernumeraries until other men can be procured; in all, three hundred and fifty-six souls connected with the Anglo-American expedition. The lengthy line occupies nearly half a mile of the path which, at the present day, is the commercial and exploring highway into the lake regions.

"Edward Pocock acts as bugler, and he has familiarized Hamadi, the chief guide, with its notes, so that, in case of a halt being required, Hamadi may be informed immediately. The chief guide is also armed with a prodigiously long horn of ivory, his favorite instrument, and one that belongs to his profession, which he has permission to use only when approaching a suitable camping-place, or to notify to us danger in the front. Before Hamadi strides a chubby little boy with a native drum, which he is to beat only when in the neighborhood of villages, to warn them of the advance of a caravan, a caution most requisite, for many villages are situated in the midst of a dense jungle, and the sudden arrival of a large force of strangers before they had time to hide their little belongings might awaken jealousy and distrust.

"In this manner we begin our long journey, full of hopes. There is noise and laughter along the ranks, and a hum of gay voices murmuring through the fields, as we rise and descend with the waves of the land and wind with the sinuosities of the path. Motion had restored us all to a sense of satisfaction. We had an intensely bright and fervid sun shining above us, the path was dry, hard, and admirably fit for travel, and during the commencement of our first march nothing could be conceived in better order than the lengthy, thin column about to confront the wilderness.