Title: Further E. K. Means

Author: E. K. Means

Illustrator: E. W. Kemble

Release date: January 11, 2020 [eBook #61149]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by hekula03, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

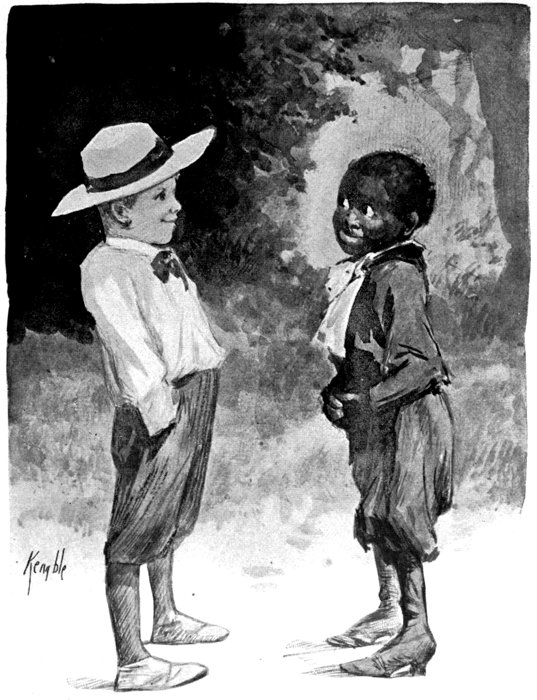

“Dey calls me Little Bit.”

Drawn by E. W. Kemble.

Is this a title? It is not. It is the name of a writer of negro stories, who has made himself so completely the writer of negro stories that this third book, like the first and second, needs no title.

The

Buscherbucher

Press

New York

| PAGE | |

| The Left Hind Foot | 1 |

| The ’Fraid-Cat | 136 |

| The Consolation Prize | 171 |

| The First High Janitor | 212 |

| Family Ties | 243 |

| The Ten-Share Horse | 263 |

| A Chariot of Fire | 286 |

He was the most innocent-looking chap you ever saw. He had the face of a cherub, eyes which inhabit the faces of angels, and a smile which every woman envied.

During her lifetime his mother had called him an angel. His sister composed a title for him from the initials of his name, and for short called him Org. The neighbors called him—if everything the neighbors called him should be recorded, this story would have to be fumigated at the very start.

He had just come to Tickfall from California. His mother and father did not miss him when he left, for they were dead. The neighbors missed him, but they did not mourn his loss. When Orren Randolph Gaitskill had gone, some predicted that he would be the loudest tick in Tickfall. They did not mean to flatter the youth or pay him a compliment. Everybody breathed easier, the cats came down out of the trees, the little girls walked the streets without the fear that their pig-tails of hair would be used for leading ropes, and the old inhabitants thankfully prophesied that there would be no more earthquakes in California.

As for Miss Virginia Harwick Gaitskill, his sister—bless her! the earth never shook when she was around, but the hearts of men were strangely agitated.

Everybody called Miss Virginia an angel except her angelic brother. He called her “Gince.”

Just now that young lady stood upon the portico of Colonel Tom Gaitskill’s home, calling in a clear, deep-toned voice:

“Org! Oh, Org! Come here!”

That youth, who had been playing “Indian” upon the Gaitskill lawn, promptly dropped upon his stomach at the sound of her voice, kept himself concealed behind some thick shrubbery, and began, as he expressed it, to “do a sneak.” His intended destination was the capacious stable in the rear of the premises. But he did not get far.

“Hurry up, Org! Come on here! I see you!” his sister called.

Her last remark was an absolute falsehood. She did not see him. But angels have a language of their own. It is not possible to command their attendance by ordinary earthly methods, and Virginia’s way succeeded.

“Aw, what you want, Gince? A feller can’t have no time to himself when you are around.”

“I want stamps, Org,” the girl said sweetly. “Take this fifty-cent piece and bring me back twenty-five twos.”

“What’s the name of that there woman in that post-office?”

“Miss Paunee,” she told him.

“It sounds like a mustang name to me,” Org remarked, pocketing the money ungraciously, and starting away with his hat pulled down over his eyes.

A moment later he assumed his former character, that of a prowling Indian, and his progress toward the street was from bush to bush and from tree to tree. He crept noiselessly down the street, looking from side to side with alert watchfulness, giving each bit of shrubbery and clump of weeds a careful inspection in anticipation of lurking enemies. When he came to the brow of the hill he ran downward at full speed. It was easier to run than to walk; slower speed would require the effort of holding back, and a genuine Indian hates work. At the foot of the hill he stopped like a clock with a broken spring.

There stood before him a little negro boy, almost exactly his size, and apparently his own age. Org’s first impression was that the stranger was certainly dark-complected, there being no variation in the color scheme except the whites of his eyes. Org’s next thought was that the darky was queerly dressed.

He was wearing a woman’s silk shirt-waist; his coat had originally belonged to some woman’s coat-suit, adjusted to the present wearer by bobbing its tail. His trousers had once belonged to some man who was much larger in the waist and much longer in the leg; but the present owner of the nether garments had made certain clumsy adjustments and the trousers made a sort of fit. The stranger’s legs were covered with a woman’s purple-silk stockings, and on his flat feet were a pair of high-heeled pumps.

“Hello!” Org said, his eyes glued to the ladylike clothes.

“Mawnin’, Marse, howdy?” the little negro responded timidly.

“My name ain’t Marse, it’s Org,” the white boy replied. “What’s your name? Who are you?”

“Dey calls me Little Bit. I’s Cap’n Kerley’s white nigger, an’ I sorter janitors aroun’ de Hen-Scratch.”

“White nigger?” Org remarked wonderingly, after a comprehensive survey of the negro boy. “The white of your eyes is white. That’s all the white I can see. Where you going?”

“Out to de Cooley bayou on de Nigger-Heel plantation.”

“Me, too,” Org remarked as he fell in step beside the negro boy.

Which is the reason why Miss Gaitskill waited impatiently the rest of the day for her stamps.

Without knowing it, Orren Randolph Gaitskill had found the greatest playmate in the world. Let every man born south of the Ohio River say “Amen!”

Little Bit was an angel, too. His mother called him “her angel chile.” His mother had fifteen other angelic children in her cabin, Little Bit being the youngest and the last. So his mother named him Peter, after his father, and Postscript to indicate his location in the annals of the family; thus Peter Postscript Chew took his place in the world.

But white folks never pay any attention to a negro’s name. They called him Little Bit.

In front of the Hen-Scratch saloon in the negro settlement known as Dirty-Six, Little Bit climbed into an empty farm-wagon to which two mules were harnessed.

“Dis here is Mustard Prophet’s team. He’s de overseer on Marse Tom’s Nigger-Heel plantation. I prefers to set down an’ travel. It ails my foots to walk. Mustard’ll let us ride.”

“I rode in a automobile in California,” Org remarked as he climbed into the wagon beside Little Bit.

“You’s fixin’ to ride in a aughter-be-a-mule now,” Little Bit snickered.

Mustard came out of the saloon and viewed the two boys with a great pretense of surprise.

“You two young gen’lemans gwine out wid me, too?” he asked.

“Yes, suh,” Little Bit told him.

“Gosh! I’ll shore hab a busy day wid de babies,” Mustard growled in a good-natured tone. “Dat ole Popsy Spout is in de secont imbecility of his secont childhood, an’ dis here white chile an’ dis cullud chile—lawdy!”

He climbed upon the wagon seat and clucked to his mules, driving slowly down the crooked, sandy road toward the Shin Bone eating-house.

“You boys watch dis team till I gits back,” he ordered. “Popsy’s gwine out wid us.”

About the time the boys had climbed into Mustard’s wagon in front of the saloon, Popsy Spout had entered the door of the eating-house and stood there with all the hesitancy of imbecility.

He was over six feet tall and as straight as an Indian. His face was as black as tar, and was seamed with a thousand tiny wrinkles. His long hair was as white as milk, and his two wrinkled and withered hands rested like an eagle’s talons upon a patriarchal staff nearly as tall as himself.

On his head was a stove-pipe hat, bell-shaped, the nap long since worn off and the top of the hat stained a brick-red by exposure to the weather. An old, faded, threadbare and patched sack coat swathed his emaciated form like a bobtailed bath-robe.

The greatest blight which old age had left upon his dignified form was in his eyes: the vacant, age-dimmed stare of second childhood, denoting that reason no longer sat regnant upon the crystal throne of the intellect.

There were many tables in the eating-house, but Popsy could not command his mind and his judgment to the point of deciding which table he would choose or in which chair he would seat himself.

Shin Bone, from the rear of his restaurant, looked up and gave a grunt of disgust.

“Dar’s dat ole fool come back agin,” he growled. “Ef you’d set him in one of dese here revolver chairs, he wouldn’t hab sense enough to turn around in it. I reckon I’ll hab to go an’ sell him a plate of soup.”

“Mawnin’, Popsy,” he said cordially, as he walked to the door where the old man stood. Shin reserved a private opinion of all his patrons, but outwardly he was very courteous to all of them, for very good business reasons.

“Mawnin’, Shinny,” Popsy said with a sighing respiration. “I wus jes’ tryin’ to reckoleck whut I come in dis place fur an’ whar must I set down at.”

“I reckin you better set down up close to de kitchen, whar you kin smell de vittles. Dat’ll git you more fer yo’ money,” Shin snickered. “I reckin you is hankerin’ atter a bowl of soup, ain’t you?”

“I b’lieve dat wuz whut I come in dis place fer. I’s gittin’ powerful fergitful as de days goes by.”

“You comes in here mighty nigh eve’y day fer a bowl of soup,” Shin told him. “Is you fergot dat fack?”

“Is dat possible?” Popsy exclaimed. “I muss be spendin’ my money too free.”

“You needn’t let dat worry yo’ mind,” Shin replied, as he motioned to a negro waitress to bring the soup. “You ain’t got nobody to suppote but yo’ own self.”

“Figger Bush lives wid me,” Popsy growled. “He oughter he’p suppote me some, but he won’t do it. He wuz always a most onreliable pickaninny, an’ all de good I ever got out of him I had to beat out wid a stick.”

“Figger’s wife oughter git some wuck out of him,” Shin laughed.

“She cain’t do it! Excusin’ dat, she ain’t home right now. Dat’s how come I’s got to eat wid you,” Popsy grumbled, digging the tine of his fork into the soft pine table to accentuate his remarks, and then flourishing the fork in the air for emphasis. “Figger is de lazies’ nigger in de worl’.”

Having uttered this remark, the old man leaned back in his chair and thrust the fork into his coat pocket while his aged eyes stared out of the window at nothing. Shin noted the disappearance of the fork, but did not mention it. The negro waitress appeared, placed the soup under the old man’s nose and went away. At last he glanced down.

“Fer de Lawd’s sake!” he exclaimed. “Whar did dis here soup come from?”

“You jes’ now ordered it,” Shin said sharply. “I had a cullud gal fotch it to you, an’ you got to pay fer it.”

“I won’t pay for it ontil atter I done et it,” Popsy growled.

He picked up a knife, started to dip it into the soup, found that this was the wrong tool, and thrust the knife into the pocket of his coat to keep company with the purloined fork.

Shin noted the disappearance of the knife, but said nothing. He handed Popsy a pewter spoon and remarked:

“You better lap it up quick, Popsy; she’ll be gittin’ cold in a minute.”

“Who’ll be gittin’ cold?” Popsy asked absently. “I didn’t hear tell of no she havin’ a cold. Is she got a rigger? Dese here spring days draws out all de p’ison in de blood.”

“Naw, suh. I says de soup will git cold.”

“Aw,” Popsy answered, as he dipped his spoon in the liquid and sipped it. “Dis soup am pretty tol’able good. Does you chaw yo’ vittles fawty times, Shinny?”

“Not de same vittles,” Shin said. “I chaws mo’ dan fawty times at a meal, I reckin.”

“Marse Tom Gaitskill says dat people oughter chaw deir vittles fawty times befo’ dey swallows it.”

“I’d hate to practise on a oystyer,” Shin giggled. “White folks is always talkin’ fool notions.”

Shin sat by and watched the old man as he consumed the remainder of his soup in silence. He also ate some crackers, drank a cup of coffee, to all appearances unconscious that Shin sat beside him. Finally, he looked up with a slightly surprised manner and asked:

“Whut did you say to me, Shinny?”

“I said I’d hate to practise on oystyers.”

“Practise whut on oystyers?”

“Chawin’ one fawty times,” Shin explained.

“My gawsh!” Popsy snorted. “Who ever heard tell of anybody in his real good sense chawin’ a raw oystyer fawty times? Is you gone crippled in yo’ head?”

“Naw, suh, I——”

The old man did not wait for the reply, but interrupted by rising to his feet with the intention of going out. The spoon he was holding he did not lay down upon the table, but carried it toward the door with him.

“De price is fifteen cents, Popsy,” Shin reminded him, as he followed him toward the front. “Let me hold yo’ spoon while you feels fer yo’ money.”

“I didn’t fotch no spoon wid me,” the old man whined, as he held it out to Shin. “Dis spoon is your’n.”

He paid the money to Shin, and started toward the door again, when he was once more intercepted.

“Lemme fix de collar of yo’ coat, brudder,” Shin suggested.

He seized the old man by the shoulders, shook the loose coat on his thin shoulders, and pretended to fit it around his wrinkled neck; at the same time, he thrust his hand into the coat pocket and extracted the purloined knife and fork.

Popsy never missed them. In fact, he did not know that he had them. Shin handed him his patriarchal staff and gave him a slight push toward the door.

At that moment Mustard Prophet stood at the entrance, “Is you ready to go out, Popsy?” Mustard asked cordially, as he shook hands.

“Dar now!” Popsy snorted. “I knowed I come in dis place fer some puppus, but I couldn’t think whut it wus. I promised to meet Mustard here. He’s gwine take me out to his house to dinner, an’ I’m done went an’ et!”

“Dat’s no diffunce, Popsy,” Mustard chuckled. “You’ll be hongry agin by de time you gits out to de Nigger-Heel.”

Popsy stopped beside the wagon and stared in pop-eyed amazement at the white boy who sat with his feet hanging out of the rear end.

“Befo’ Gawd!” the old man bawled. “Dar’s little Jimmy Gaitskill dat I ain’t seed fer sixty year’!”

“You’s gwine back too fur, Popsy,” Mustard laughed. “Dat’s Marse Jimmy Gaitskill’s grandchile.”

“Huh,” the old man grunted, as Mustard helped him to a seat in the wagon. “De Gaitskills look de same all over de worl’.”

“How does dey look, Popsy?” Mustard chuckled.

“Dey’s got de look of eagles,” Popsy replied.

Shin watched the wagon until it disappeared around a turn in the road. His eyes were on Popsy’s bent form as far as he could see it.

“Dat’s de biggest bat I ever knowed,” Shin remarked to the world as he turned back and entered his place of business.

Two hours later, Mustard Prophet stopped his wagon in the horse-lot of the Nigger-Heel plantation.

“Dis is whar you mounts down, Popsy,” he said.

“Whut does I git off here fer?” Popsy asked querulously.

“Gawd knows,” Mustard grinned. “I done fotch you out to de plantation as by per yo’ own request. Dis is it.”

He lifted the aged man down and walked with him to the house, making slow progress as the old man supported himself with his staff and insisted on stopping at frequent intervals to discuss some vagary of his mind, or to dispute something that Mustard had said.

At last Mustard assisted him to a chair on the porch and handed him a glass of water.

“Glad to hab you-alls out here wid me, Popsy,” he proclaimed. “Set down an’ rest yo’ hat and foots.”

“I ain’t seed de Nigger-Heel plantation fer nigh onto fifty year,” Popsy whined. “I used to wuck on dis plantation off an’ on when I wus a growin’ saplin’.”

“Dis place is changed some plenty since you used to potter aroun’ it,” Mustard said pridefully. “Marse Tom specify dat dis am one of de show-farms of all Louzanny. I made it jes’ whut it is now.”

“Dis ole house is ’bout all I reckernizes real good,” Popsy replied. “It ain’t changed much.”

“Naw, suh. I don’t let dis house git changed. Marse Tom lived here a long time, an’ when he moved to town I’s kinder kep’ de house like it wus when he lef’ it, only sorter made it like his’n in Tickfall. Marse Tom is gwine lemme live here till I dies. He tole me dat hisse’f.”

“It shore is nice to hab a good home,” Popsy said, looking vacantly toward the near-by woods, where he could hear the loud shouts of Little Bit and Orren Randolph Gaitskill.

“Would you wish to see de insides of de house?” Mustard asked. “I got eve’ything plain an’ simple, but it’s fine an’ dandy fer a nigger whose wife ain’t never out here to keep house. Hopey cooks fer Marse Tom, an’ I got to take keer of things by myse’f.”

“It’s real nice not to hab no lady folks snoopin’ aroun’ de place,” Popsy asserted. “Dey blim-blams you all de time about spittin’ on de flo’ an’ habin’ muddy foots.”

They walked about the house inspecting it. Popsy followed Mustard about, listening inattentively to Mustard’s talk, wondering what it was all about. He came to one room which attracted his attention because it looked as though it held the accumulated junk of years.

“Whut you keep all dis trash in dis room fer, Mustard?”

“Dis ain’t trash. Dese here is Marse Tom’s curiosities,” Mustard explained. “Dis is like a show—all kinds of funny things in here.”

The old man stepped within the room, and Mustard began to act as showman, displaying and expatiating upon all the interesting things of the place.

The room bore a remote resemblance to a museum. When Gaitskill had first moved on the plantation, nearly fifty years before, he had amused himself by making a collection of the things he found upon the farm and in the woods, which interested him or took his fancy. For instance, here was a vine which was twisted so that it resembled a snake. That was all there was to it. Because it looked like a snake, Gaitskill had picked it up and brought it to the house and added it to his collection.

Stuff of this sort had accumulated in that room for years. Mustard had no use for the room. Gaitskill had not needed it before him. When the overseer moved in, he had zealously guarded Marse Tom’s curiosities. As for Colonel Gaitskill, he did not even know the trash was in existence.

Mustard had added to the accumulation through the years. Now and then, in his work in the fields or woods, he would find something that reminded him of something that Marse Tom had “saved” in that room, so he would bring it in and add that to the pile.

So now Mustard had something to talk to Popsy about, and he talked Popsy to the verge of distraction, proclaiming all sorts of fanciful reasons for the preservation of each curious object. The old man was bored as he had never been bored in all his life. His feeble form began to droop with weariness, his mind failed to grasp the words which Mustard pronounced with such unction, but Mustard did not notice, and would not have minded if he had observed Popsy’s inattention. He intoned his words impressively and talked on and on.

At last Mustard opened a drawer and drew out a small, green-plush box. He opened this box with impressive gestures, as if it was some sacred object to be handled with extreme reverence. He held the opened box under Popsy Spout’s nose.

“Dat’s de greatest treasure we’s got in dis house, Popsy,” he announced.

“Whut am dat?” Popsy asked, rallying his scattered wits.

“Dat’s de royal rabbit-foot whut fotch all de luck to de Nigger-Heel plantation,” Mustard proclaimed. “Marse Tom gimme dat foot fifteen years ago. He said dat all his luck come from dat foot. He tole me to keep it an’ it would fotch good luck to me. It shore has done it.”

Popsy gazed down into the plush box. What he saw was a rabbit-foot with a silver cap on one end, and in the center of the cap was a small ring which might be used to hang the rabbit-foot on a watch-chain if one cared to possess such a watch-charm.

A few years ago the rabbit-foot novelty was for sale in any jewelry store in the South, and cost about one dollar. Because of the negro superstition regarding the luck of the rabbit’s foot, Gaitskill had bought one for his negro overseer.

The white man in the South in his dealings with the negroes is never skeptical of their favorite superstitions. In presenting the rabbit-foot to Mustard, Gaitskill had drawn upon his imagination and told a wonderful story of the efficacy of this particular luck-charm. He had been lost in the swamp, so Gaitskill said, and this foot had shown him the way out; he had fallen into the Gulf of Mexico, and this foot had saved his life; he had been poor, and now he was rich; he had been sick, and now he was well; he had been young, and now he was old—and all because of the luck of that particular rabbit-foot. All of this emphasized in Mustard’s mind the importance which Gaitskill attached to the possession of the foot, and made him believe that the white man only parted with it because he wanted his favorite negro overseer to share some of the good fortune which had come to him.

The tale had so impressed Mustard that he regarded that plush box with its sacred foot as being the most valuable thing upon the Nigger-Heel plantation. He guarded it constantly, and would have protected it from theft or injury with his life.

“Dat is puffeckly wonderful,” Mustard declared, gazing at the treasure with reverent eyes.

“Yes, suh, dat’s whut,” Popsy agreed dreamily “Le’s hunt some place to set down.”

In the meantime, Orren Randolph Gaitskill was out in the woods, getting acquainted with Little Bit. He asked many questions, and in a brief time he thought he knew all about his companion. Then he made a discovery, so unexpected, so overwhelming, that it terrified him and sent him through the woods and up to the house, squalling like a monkey.

“Dar’s a dandy swimmin’-hole over by dat cypress-tree, Marse Org,” Little Bit remarked.

“I ain’t been swimming since I left the Pacific Ocean,” was Org’s reply as he started in a run toward the designated spot.

As he ran, he began to shed his clothes. His hat dropped off first because that was easiest to remove, then his tie, after that his shirt was jerked off and cast aside. He could have been trailed from the starting point to the bayou by the clothes he left behind him. On the edge of the water he hopped out of his remaining garments and plunged head-first into the stream.

Ten seconds later, he rose to the surface shaking the water out of his eyes. It had taken Little Bit just that much longer to undress. At that moment, Little Bit leaped into the water, arms and legs outspread, his purpose being to make as much splash as possible.

He made a big splash, but he made a bigger sensation.

When Org saw that black object coming into the water after him, he got out of there. With a terrified shriek he splashed to the bank, scrambled up the muddy, slippery edge, and ran squalling across the woods toward the plantation-house.

Little Bit was mystified and terrified. He followed the shrieking white boy through the woods. Org ran into the open field, uttering a terrified wail at each jump. His fright became contagious, and while Little Bit did not have the least idea what it was all about, he added his wails to Org’s lamentations, and the woods echoed with the sounds of woe.

They scrambled over the fence and into the yard and ran screaming up the steps and into the house, just as Popsy had suggested that they hunt a place to sit down.

Mustard ran into the hall and confronted two boys, naked as the day they were born, both screaming at the top of their voices.

“Shut up, you idjit chillun!” Mustard howled. “Whut de debbil ails you? Whar is yo’-all’s clothes at?”

The terrified white boy ran to Mustard, threw both arms around his waist, and buried his face in Mustard’s coat-tail to shut out the awful sight. But he did not stop his screaming.

“Hey, you brats!” Mustard whooped. “Shut up yo’ heads! Whut you howlin’ about? Hush!”

Both boys suddenly stopped screaming, and there was a moment of silence. Mustard waited for them to get their breath and explain. All sorts of things had happened in Mustard’s variegated career, but this was new, to have two boys come prancing into his house without a stitch of clothes on their bodies, both screaming like maniacs. Little Bit was the first to catch his breath and speak.

“Whut ails you, Marse Org?” he asked in that soft, drawling, pathetic tone, whose minor note is the heritage of generations of servile ancestors. “Is a snake done bit you? Is you done fall straddle of a allergater when you jumped in de water? How come you ack dis-a-way?”

These questions served as a sufficient explanation to Mustard for their lack of clothes. Something had frightened them while they were swimming in the bayou.

Org opened his eyes and peeped around Mustard’s hip at Little Bit. Then he stepped aside and took a long look at the colored boy’s ebony body.

“Why, Little Bit,” Org exclaimed, “you are black all over your body!”

“Suttinly,” Little Bit agreed heartily. “I’s black as de bottom of a deep hole in de night-time. I’s a real cullud pusson, I is.”

“But—but—I thought you would be white under your clothes,” Org exclaimed.

“Naw, suh, I ain’t never been no color but black, inside an’ out, on top an’ down under,” Little Bit chuckled.

“But you said you were the cap’ns white nigger,” Org argued.

“Dat don’t mean white in color,” Little Bit explained. “De cap’n, he jes’ calls me dat because I remembers my raisin’ an’ does my manners an’ acks white.”

“It ’pears to me like you boys is bofe fergot yo’ raisin’ an’ yo’ manners,” Mustard snorted. “Whut you mean by comin’ up to my house as naked as a new-hatched jay-bird? ’Spose dey wus lady folks in dis house—whut dey ain’t, bless Gawd! Wouldn’t you two pickaninnies cut a caper runnin’ aroun’ here wid nothin’ on but yo’selfs an’ yo’ own skins?”

“I was so scared I left my clothes on the creek,” Org explained shamefacedly.

“I’ll go back wid you-alls. I don’t b’lieve you bofe got sense enough to find yo’ gyarments,” Mustard grumbled. “Whar wus you-all swimmin’ at?”

As the three walked out, Popsy Spout stood for a moment, his vacant eyes wandering over a room full of the most astounding accumulation of junk any collector ever assembled. It all meant nothing to Popsy. He was tired, awfully tired. The ride from town had wearied him, Mustard’s talk had wearied him, the pickaninnies on the plantation seemed to make a lot of noise. A long time ago he had asked Mustard to find him some place to sit down. He decided he would prefer to lie down. He needed rest and calm.

But Mustard was gone somewhere. He could hear his bawling voice getting farther away from the house all the time. He might be gone for a long time. He couldn’t sit down on that pile of junk. So Popsy walked feebly to the door and stood looking into the hall.

As he put his hand up to the door-jamb to support himself, he discovered that he was holding something. It was a green-plush box. He wondered what the box was. It was probably something, he could not remember what.

He put the box in the pocket of his coat, found a rocking chair, sat down and went to sleep.

Org walked back to the bayou under the escort of Mustard Prophet. He seemed unable to take his eyes off of Little Bit’s shiny black skin. He was slow to overcome his amazement at his discovery that a negro was black all over.

When they were riding home in big Mustard’s farm-wagon, he referred to it again.

“You’re a negro, ain’t you, Little Bit?” he asked, speaking in a softly apologetic tone, as if fearing to cause offense.

“Suttin!” Little Bit laughed. “I’s a black Affikin nigger. Anybody dat looks how dark complected I is kin see dat.”

“I never saw many colored persons in my life,” Org explained.

“You ain’t had no eyes ef you ain’t seed no niggers,” Little Bit chuckled. “Niggers is eve’ywhar. Gawd made ’em in de night, made ’em in a hurry an’ fergot to make ’em white. Dar’s niggers in heaven, an’ dars even plenty niggers in hell.”

At the Shin Bone eating-house, Mustard helped Popsy Spout down from the wagon and the two boys jumped to the ground. Popsy entered the restaurant, walked feebly over to a table and seated himself with a thankful sigh. He took out his pipe and placed it upon the table at his elbow, then spread a red bandana handkerchief over his head to keep the flies from disturbing him. Then he sank into a restful state of dreamy inanity, his mind just as near empty as it is possible for anything to be, considering the fact that nature abhors a vacuum.

In one corner of the room, the proprietor, Shin Bone, was engaged in some interesting experiments with loaded dice. He seemed never weary of his task as he rolled the cubes across the table, retrieved them again, and repeated. He tried to familiarize himself with their vagaries, to study their oddities and eccentricities, and in his imagination he planned many victories and great winnings through the aid of these pet bones.

The process was absorbing to him. His eyes popped out, the whites showing in a wide ring. His breathing was quick and husky as he shook the dice, and he muttered prayers and imprecations and incantations. Sometimes he threw the dice with one hand, sometimes with the other; he used certain luck charms, changing them from one pocket to the other, practising and experimenting with every sort of “conjure,” for he expected those little white cubes with the black spots to bring him the money with which to make a loud noise in Tickfall colored society.

Popsy roused himself from his dreamy vacuity and felt in his pocket for his tobacco-pouch. He would take a little smoke before dinner. He found the tobacco-pouch, also something else.

He brought forth a green-plush box and looked at it curiously. He opened it with hands which shook from senile palsy and examined its contents. It was a rabbit-foot surmounted with a silver cap on one end. He wondered where he had acquired the thing.

“Come here, Shinny!” he called. “Look whut I done found on myse’f.”

Shin Bone crossed the room, gazed at the treasure for a moment, and gave a surprised grunt.

“Whar did you git dis rabbit-foot?” he inquired suspiciously.

“I dunno, Shinny,” the old man replied in a complaining voice. “Whut is it fur?”

“Lots of folks has rabbit-foots,” Shin said. “I don’t b’lieve in ’em. I got four, an’ dey don’t fotch me no luck. Whar did you git dis’n?”

“I dunno.”

“Whar you been at to-day?” Shin asked.

“Well, suh, early dis mawnin’ I went to de Shoofly chu’ch an’ conversed de Revun Vinegar Atts a little; atter dat, I went out to de Nigger-Heel wid Mustard Prophet—ah—dat’s whar I got dis here foot. Mustard gib it to me. He esplained a whole lot about it an’ tole me dat Marse Tom gib it to him, an’ he passed it on.”

“Whut yo gwine do wid it?” Shin asked.

“’Tain’t no good to me,” Popsy whined, working at his tobacco-pouch and shaking some tobacco in his hand. “De only luck-charm I b’lieves in is de chu’ch. Ef de good Lawd is on yo’ side, who kin be agin you?”

Shin Bone knew better than to get Popsy started in a discussion of religion. His conversation on that theme was interminable. Besides, the plush box lying on the table between them had awakened several interesting trains of thought:

First, he knew Popsy had a trick of putting things into his pocket and walking off with them, forgetting where he acquired them, and even failing to remember what they were for. Second, he remembered that Mustard Prophet had often attributed much of his good fortune to the possession of a rabbit-foot. Thirdly, he knew that Colonel Gaitskill also had a rabbit-foot, for he had often heard him refer to it in his hearing and in the presence of the other negroes.

Now, did Popsy inadvertently take possession of Gaitskill’s rabbit-foot? Or did he absent-mindedly walk off with Mustard’s foot? Or did Mustard give his famous luck-charm away? Shin doubted this last supposition. If a luck-charm is good, it is very, very good. Or did Mustard steal Gaitskill’s rabbit-foot and Popsy take it from Mustard?

Popsy lighted his pipe and began to smoke. Shin Bone decided that he could make nothing of the mystery. A rabbit-foot was no good to him. He had tried them before. But loaded dice, now—he pulled the “bones” from his pocket and renewed his former operations.

In the kitchen a bell rang. A number of patrons who had been lingering outside came through the door and seated themselves at the table. Shin Bone arose to bring in the dinner. Popsy knocked the ashes from his pipe and got ready to eat.

As for Org and Little Bit, they did not get back to the Gaitskill home until the sun had sunk below the line of the tree-tops. And not until Orren Randolph Gaitskill beheld his sister sitting upon the porch did he think of the errand on which she had sent him ten hours before.

His small hand investigated his trouser-pocket, to see if he was still in possession of the fifty-cent piece. He might have lost it when he tossed aside his garments on the banks of the Cooley bayou.

“Org!” Virginia called sharply. “Where are those stamps?”

Org’s nervous fingers caressed the half-dollar in his pocket. His mind reached out like the tentacles of an octopus, grasping after an excuse.

“Where are my stamps?” she repeated.

“Er—ah—I went down-town,” Org began. “I went down-town—and—er—ah—Miss Paunee, that mustang woman in the post-office—she told me—she said——”

“Well?” Virginia’s tone was icy.

“Miss Paunee—she told me—ah—she said she didn’t have no two-cent stamps; she had sold out.”

If the glance of a sister’s eye could kill, most brothers would now be dead. Org survived the look she gave him, and sheepishly offered her the fifty-cent piece.

“You don’t need no stamps, Gince,” Org said soothingly. “Them guys you left behind ain’t worth writing letters to.”

“Please keep your opinions to yourself,” his sister advised. “Where have you spent the day?”

“I have been to the Nigger-Heel plantation with Little Bit. Little Bit is a colored person and a very good friend. A colored man named Mustard took me out in a wagon and brought me back,” Org informed her. Then eagerly: “Say, Gince, do you know that a negro is black all over his body, even under his clothes?”

“Where did you meet these blacks?” Virginia asked, avoiding Org’s question as to the color-line.

“I met Little Bit at the foot of the hill. He told me he was the captain’s white negro. I met Mustard Prophet in front of the Hen-Scratch saloon in Dirty-Six. We picked up Popsy Spout at Shin Bone’s hot-cat stand in Hell’s Half-Acre!”

Under this appalling summary of information, Miss Virginia reeled back in dismay.

“No doubt,” she said weakly.

“If you want to save stamps, Gince,” Org suggested eagerly, “you better write to Little Bit’s captain and let me carry the notes for you. I saw the captain when we were coming home. He’s got a’ automobile as big as a street-car. He was in the army and a German shot him——”

A slight flush appeared on Miss Virginia’s cheek. It spread slowly, like the unfurling of some flag—the star-spangled banner for instance.

“I don’t care to hear the personal history of the acquaintances you have made to-day,” Miss Virginia interrupted.

“His name is Captain Kerley Kerlerac, Gince,” Org persisted. “Little Bit told me. Little Bit, my colored friend, is the captain’s pet coon.”

In Tickfall, religion was reduced to the least common divisor. That is to say, there was one church for the white people and one for the black. The white children felt that they were imposed upon by the older and more dominating members of their families in that they were made to go to Sunday-school, whereas, the black children were permitted by their parents to grow up in that ignorance which is bliss.

Org had no particular love for religious instruction. All the time that he was trying to learn a sufficient portion of that day’s lesson to satisfy his teacher, he was thinking of a buzzard’s nest which Little Bit had told him about, a buzzard’s nest which contained two baby buzzards, both of them white as snow. If that buzzard’s nest had been concealed in some Sunday-school book—but Org never found anything interesting in a Sunday-school book. What little he knew of that day’s portion of the Scripture had been imparted to him by the laborious efforts of his sister, and he was now walking down the hill toward the church, mumbling his newly acquired information to himself.

“Whar you gwine, Marse Org?”

“Sunday-school. Come and go with me.”

“Ain’t fitten,” Little Bit giggled. “A little black coon like me ain’t got no place in a white chu’ch. Excusin’ dat, I janitors in a saloon, an’ Sunday-schools ain’t made fer such.”

“I’ll tell you all I know about the lesson,” Org urged. “Listen: Methusalem—oldest man ever was: nine hundred and sixty-nine years old—was not, for God took him—gathered to his fathers——”

“How ole you say he wus gwine on when he died?” Little Bit asked.

“Nine hundred and sixty-nine years.”

“Whoop-ee! Whut did de ole gizzard die of when he died?”

“I dunno,” Org replied. “He died of smoking cigarettes, I reckon. If you go with me, we’ll ask the teacher.”

“I mought stan’ outside behime de chu’ch while you axed,” Little Bit said doubtfully. “Who am dis here teacher?”

“Captain Kerley Kerlerac.”

“I ain’t gwine to no Sonday-school to ax my boss nothin’,” Little Bit said positively. “Dat white man don’t ’low no niggers to pesticate him wid ’terrogations. I knows!”

Org was not willing to part with his companion. He could have a great deal more fun with Little Bit than he could contemplating the career of a man who had lived nearly a thousand years and had been dead for several thousand more. Besides, he was a little skeptical of the alleged age of that old party. So when Org came to a corner where he should have turned to the right, he turned to the left, and from that time on there was a vacant chair in the Sunday-school.

The old cotton-shed on the edge of the Gaitskill sand pit was the first thing to attract the attention of the pair. In that storehouse, they found an old cotton-truck, and a door which had been torn off the hinges and was lying on the floor near the office.

They found amusement for a while by pulling each other around on the truck. Then they sat down in the door to cool off and gazed out over an expanse of water which formed a shallow pond in the sand pit.

“If we could get this old broken-down door over to that pond, we could have a raft to ride on,” Org remarked.

“’Tain’t no trouble,” Little Bit replied. “Jes’ load de door onto de cotton-truck an’ push de truck down to de pond.”

“You are certainly intell’gent, Little Bit,” Org exclaimed admiringly as he sprang to his feet.

“Pushin’ things an’ liftin’ things an’ loadin’ things—dat’s a cullud pusson’s nachel-bawn job,” Little Bit chuckled. “’Tain’t no trouble fer a nigger to think up dat.”

“Let’s get this door on the truck and move our raft,” Org urged.

It was not hard to do. The pine door was not very heavy, and from the time they got it out of the building, the route was down hill to the edge of the pond. They pushed the truck into the water, easily floated the door off, and then tugged mightily to drag the truck back to the empty storehouse again.

They found two long poles which would serve to steer with, and raced back to the edge of the pond and climbed aboard their raft.

The door sustained them just as long as most of their weight was on their poles, and they were trying to push off. At last they worked their raft out to about four feet of water and felt free to lift their steering-poles and ride.

Then that door slowly sank under their weight until the water was up to their knees, to their waists, to their shoulders. It stopped in its downward journey when it rested on the sandy bottom, and the two lads stood on it, looking at each other with the utmost astonishment, raising their chins to keep the water out of their mouths.

“You done got yo’ nice Sunday clothes all wet,” Little Bit sighed.

“Yours are wet, too,” Org retorted.

“Dis here is my eve’y-day suit. I ain’t got no all-Sonday gyarments. I wears dese ladylike clothes all de time.”

“I’m sorry you spoilt your only suit,” Org sympathized.

“’Tain’t spiled—it’s jes’ wet,” Little Bit replied. “Whut is us gwine do now?”

“We’re both wet. We might as well have a good time,” Org suggested philosophically.

“I likes good times an’ dis’n is started off real good,” Little Bit laughed. “You git offen dis ole door an’ le’s see ef it will hold me up.”

About four o’clock that afternoon somebody in the Gaitskill home asked where Orren Randolph Gaitskill was. He had not been seen since he left the house that morning to attend the Sunday-school.

Miss Virginia Gaitskill called Captain Kerley Kerlerac on the telephone and asked if Orren had been in his class that morning.

When a devilish boy happens to be the brother of an angelic girl, even a disillusioned war-veteran finds that lad possessed of qualities which he loves and admires for the boy’s sister’s sake.

Kerlerac informed her that he had missed Orren very much, that he was the brightest boy in his class, that all the others had made anxious inquiry about him, that he was about to call at the Gaitskill home to inquire if Orren was sick.

The answer which he heard to this panegyric was a giggle.

“Hello! Hello! What’s that?” he exclaimed.

The telephone clicked in his ear, indicating that she had hung up the receiver.

Kerley stood at the telephone scratching his head, a wry smile on his lips.

“I believe that giggle meant that she called me a liar,” he announced to his immortal soul. A reminiscent light beamed in his eyes. “She hasn’t changed in the past fifteen years—little spitfire!”

For half an hour Miss Virginia found something else to think about besides her wandering brother, but as the evening wore on, and he did not appear, she began to get uneasy again.

“That dang boy has played hookey and gone out in the woods with that pickaninny,” Colonel Gaitskill announced.

“Oh, maybe he’s lost in the swamp!” Virginia gasped.

“No danger of that,” Gaitskill said easily. “These little niggers around here can go across that swamp like a fox. They can’t get lost.”

But as the shadows lengthened across the Gaitskill lawn the women of the household were thrown into a panic. They insisted that it was not a natural or ordinary thing for Orren to miss his meals; that a hungry boy might be having a very good time at some amusement, but he would always be willing to postpone his play to eat, resuming his play after this meal.

“That’s so,” Gaitskill admitted. “When I was a boy nothing was ever more attractive to me than the consumption of food, and I enjoy being regular at my meals now. But, maybe he ate his lunch somewhere else?”

By telephone they made inquiry of every place where they thought Orren could have eaten. He had not been seen at any of those places.

Gaitskill saw that he was going to have to get out and hunt that boy. The prospect did not appeal to him. That boy was a nuisance. If he was lost, it was good riddance. He wasn’t worth finding—let him find himself. He went to the telephone and called up Captain Kerley Kerlerac.

“Say, Kerl, where’s that damn little pet nigger of yours?”

“Haven’t seen him to-day, Colonel.”

“He’s run off somewhere with Orren, and Orren hasn’t come home yet.”

“I’ll find him,” Kerley said eagerly.

“Oh, no! Don’t trouble yourself,” Gaitskill smiled. “I just wanted to know about Little Bit.”

Gaitskill sat down with a sly grin. He was getting old, he reflected, and the strenuous life was no longer attractive. If a searching party should have to be organized, he had now laid its foundation. It was a certainty that Kerlerac would organize the party and lead the search. Good old Kerl would see that Virginia’s brother was not lost.

It does not take a rumor long to spread over a little village. In a brief time, it was known to the remotest parts of Tickfall that Little Bit and Orren Gaitskill were lost.

Little Bit’s mother, in spite of the fact that she had fourteen others just like him in her cabin, aroused all the negro section of the town by her frantic wails. She announced in a voice like a calliope that she knew that her angel child had fallen into a well, had been eaten by an alligator, had been bitten by a snake, had been drowned in a bayou, had been stolen and carried away by white folks, had been lost in the swamp—and she howled like a banshee over each one of these possibilities, and others of the same general nature as she thought of them.

A great bellow of excitement went up from all the negroes, and a band of them hurried to the home of Captain Kerlerac to inquire the latest information about Little Bit. Their excitement was contagious, and the captain caught it, the white citizens of the town were inoculated, and in an incredibly short time the town was seething with an intense desire to organize a search-party and explore the woods for the lost boys.

“We’ll wait until night, men,” Kerlerac said. “If the boys don’t come in by dark, we will go out on the Little Moccasin Road and build fires on the highway for ten miles. Wherever they may be in the swamp, they will see that trail of fire and come to it.”

“That’s the way to do it,” several approving voices spoke.

“Don’t bother Colonel Gaitskill with it,” Kerley suggested. “He’s getting too old to be running around at night and exposing himself. If the boys don’t come in by dark, I will ring the court-house bell. Meet me there.”

It had not been very long since Kerlerac had been a boy himself. He knew every spot in that vicinity which was dear to boys, white and black. He listed each one in his mind and started on a lone search to each of these places.

His automobile carried him first to all the swimming-holes, then to the old picnic-grounds, then to the old tabernacle, where the negro camp-meetings were held, to the pool where the colored members of the Shoofly church conducted their baptizings, to the old stables and sheds around the fair-grounds. Finally, he left his machine beside the road and walked across the field to the old cotton-shed beside the sand pit.

The noise of shouting and laughter came to him before he arrived upon the scene. It was no trouble to locate the two boys as they splashed and paddled and fought with water and dived to the bottom to rise with a handful of sand to throw at each other.

Time had ceased to move for those two youngsters. Sunrise and sunset were just the same to them. A score of apple-cores strewn along the sandy shore indicated that they had lunched well and were not hungry.

“Hey, you!” Kerley called.

The two boys looked up with surprise.

“Come out of that water!” Kerley commanded. “Don’t you know it is nearly night?”

The astonishment on their faces when informed of the passage of time indicated that they had been completely engrossed with their amusement.

They climbed out of the water near Kerlerac and gave that gentleman a surprise.

“You’ve both got on your clothes!” he exclaimed. “Are you too lazy to strip when you take a Sunday swim?”

“Naw, suh. But our fust swim wus a mistake, Marse Cap’n,” Little Bit chattered, chilled by the wind after his day of activity in the water. “Us got on a raff an’ de raff wouldn’t hol’ us up.”

“Don’t report to me,” Kerley laughed. “March along home now! Right face! Forward!”

A little later Kerlerac marched the two wet youngsters upon the lawn and made them stand at attention in the presence of a dozen hysterical women.

“Here are your mud-cats, Colonel,” he smiled. “I found them paddling in the pond in the old sand pit.”

“I didn’t intend to get wet, Uncle Tom,” Org began, “but the raft was not large enough——”

“That’s enough for you,” Gaitskill cut him off. “Go around to the rear of the house.”

Miss Virginia Gaitskill stood upon the steps smiling.

“I think I knew you once, Miss Gaitskill,” Kerlerac said. “We were both younger then.”

“You were seven and I was five,” Virginia smiled, as she extended her hand.

“I remember,” Kerlerac answered. “You gave me a chocolate rat with a rubber tail. I could hold the tail and bounce the rat, or I could lay the rat down and watch it wiggle its tail very lifelike. I ate that rat, rubber-tail and all.”

“You gave me a rabbit-foot in a green-plush box,” Virginia laughed. “I did not eat the foot or the box. I have them both yet.”

“I have something that you did not give me,” Kerlerac said earnestly. “I stole it from you. I carried it through three battles across the sea. It is your picture as you were then.”

“Have I changed since then?” the girl asked, because she did not know what else to say.

“Yes. The photograph I have of you shows a little spitfire girl astride of a wabble-wheeled velocipede.”

“Oh—” that young lady gasped.

A moving-picture of the performances of Mustard Prophet when he discovered the loss of his rabbit-foot would be a valuable contribution to the silent drama. Alone in that big plantation-house, with no one to talk to, he spluttered with language like an erupting volcano, and cut as many capers as a cat having a fit.

After that he mounted the fastest horse on his plantation and rode to town, sweeping down upon his wife like a cyclone of wrath and fear and consternation.

“Dat ole bat stole dat rabbit-foot,” Mustard bellowed.

“I don’t b’lieve it,” Hopey replied, trying to soothe him. “Dat’s a good ole man.”

“He’s a good ole stealer,” Mustard howled. “He knows how to rob de hen-roost an’ hide de feathers. Lawd, when I think how heavy he sets in de amen cornder of de Shoofly meetin’-house, singin’ religion toons an’ foolin’ de people all de time—I tell you dat nigger ought to be churched!”

“But I don’t see what he wanted to take dat rabbit-foot fer,” Hopey declared. “He’s tole me plenty times dat he didn’t b’lieve in foots; he b’lieves in faith.”

“It’s wuth a thousan’ dollars—dat how come he took it!” Mustard bawled. “Mebbe it’s wuth a millyum; how does I know? Marse Tom, he’s got it all fixed up wid silver trimmin’s an’ in a plush box. Dat ain’t no cheap, common, nigger rabbit-foot. Dat’s a royal rabbit-foot, an’ it fotch Marse Tom all de luck he ever had. He tole me dat his own self.”

“Why don’t you go to Popsy an’ ax him fer it?”

“Dat ole lyin’ thief will say he ain’t got it, an’ ain’t never had it, an’ don’t know nothin’ about it,” Mustard wailed. “Atter dat, whar is I at?”

“Tell him dat it b’longs to Marse Tom, an’ you want it back,” Hopey urged.

“Yep. An’ dat ole gizzard will swell up an’ sw’ar he ain’t got nothin’ of Marse Tom’s an’ offer to go down to de bank an’ prove it befo’ Marse Tom’s own face. I don’t dast let Marse Tom know I done loss dat rabbit-foot. De kunnel would kill me dead!”

“I never thought of dat,” Hopey sighed.

“You don’t think about nothin’,” Mustard wailed. “Here I is in de wuss mess I’m ever got into, an’ you ain’t think about nothin’. Look at dis here jam. If Marse Tom finds out I loss de rabbit-foot, he’ll kill me; ef I ax dat ole Popsy-sneak to gib it back, mebbe he’ll blab dat it’s lost, an’ Marse Tom will hear about it, an’ I’ll git kilt jes’ de same. Anyhow, dat foot is plum’ gone an’——”

“Why don’t you git somebody to git it back fer you?” Hopey asked. “Ef Popsy stole it, it ’pears to me like somebody oughter be able to steal it back.”

“Suttinly, ef dey kin find it,” Mustard said, the light of new hope shining in his eyes. “I’d gib somebody one hundred dollars to steal it back fer me agin.”

“Dat’s plenty lib’ral,” Hopey said. “Mebbe ef you’ll hunt aroun’ you kin find somebody.”

Mustard quieted down and gave himself to deep meditation, trying to think of someone sufficiently bold to hold up Popsy and extract the treasure from his pocket.

Hopey took this opportunity to leave the room. She had heard a great deal from Mustard, and she did not care to be around when he began to mourn and lament again. She was a fat woman, and desired calm environments, and sought the ways of peace. Moreover, she did not attribute the same value to the rabbit-foot that Mustard did. It seemed to her that Gaitskill had given it to Mustard to keep for his own, and that he cared nothing for it, had forgotten all about it; he could not attach much importance to its possession when he had never made inquiry about it in all the time that Mustard had guarded it so zealously.

But Mustard was the best negro overseer in Louisiana for this reason as much as any other: he took care of things, regarded his employer’s property as more valuable even than his own, and everything belonging to Marse Tom was to be kept in order for the day when he should give an account of his stewardship.

After a while, Hopey thought of her friend, Dazzle Zenor. Dazzle had good sense, possessed the wisdom which comes from many varied experiences, and she would be able to help her now. She heard certain noises in the next room, which indicated that Mustard was getting ready to explode again, so she hastily left the house and went to town.

Dazzle lived in Ginny Babe Chew’s boardinghouse in Dirty-Six. So Hopey climbed pantingly to the second floor of this house and knocked on her door.

“Who’s dat?”

“Hopey Prophet is done come on bizzness. Open dis door!”

“Whut you come to see me fur?” Dazzle asked promptly, after she had admitted Hopey.

Dazzle was a woman who met all the exactions of Ethiopian beauty. Her skin as black as jet, her teeth like milk, her eyes so dark that they had a bluish tinge, slim and strong and graceful, an actress, a dancer, a singer, she was the dusky belle of Tickfall. Every negro man who had married anybody in the past four years had first proposed to and been rejected by Dazzle.

Many of Dazzle’s enterprises were highly adventurous, and she was always fearful and suspicious. So when Hopey hesitated to begin, Dazzle’s tone became sharp with anxiety:

“Whut you come to see me fur?” she repeated.

“I come to consult wid you about a little scrape our fambly is got into, Dazzle,” Hopey began. “Us is liable to hab plenty trouble onless somebody kin he’p us.”

“Whut’s done busted loose now?” Dazzle asked easily. Her mind was now at rest, for nothing that could happen to Hopey’s family could impinge on any of Dazzle’s previous escapades.

“Mustard is done loss his rabbit-foot!” Hopey exclaimed in tragic tones.

Dazzle laughed.

“I’ll gib Mustard a hatful of dem things. I’m got about twenty.”

“But dis here is a royal rabbit-foot,” Hopey said with emphasis.

“I never heerd of dat kind, but ’tain’t no ’count whutever it is,” Dazzle smiled. “I done tried all kinds, an’ I knows.”

“But dis rabbit-foot b’longed to Marse Tom Gaitskill,” Hopey informed her, “an’ Mustard lost it, an’ Marse Tom will kill Mustard ef he don’t git it back.”

“No doubts,” Dazzle chuckled. “White folks ain’t got no real good sense, an’ nobody cain’t tell whut dey will do.”

Then Dazzle listened while Hopey told the tale of the disappearance of the rabbit-foot. Dazzle was not much impressed with this story of another’s misfortune, but at the last one sentence stimulated her interest:

“Mustard says he will pay one hundred dollars to whoever gits his foot back.”

That was speaking in language which Dazzle could understand. She sprang to her feet.

“I’ll earn dat hundred dollars right now,” Dazzle proclaimed. “I’ll go out to Popsy’s cabin an’ pull his nose till he gibs up dat foot.”

“’Tain’t possible, Dazzle,” Hopey said. “We don’t want Marse Tom to know dat de foot is lost. Ef you go to pullin’ noses an’ skinnin’ shins, Popsy will beller, an’ Marse Tom will hear about dat.”

“He’d shore howl,” Dazzle agreed, reluctantly abandoning that plan. “Well, I’ll go out and make love to dat ole man, an’ sneak de rabbit-foot outen his pocket.”

“Any way will do dat will git de foot back ’thout makin’ too much of a rookus, Dazzle,” Hopey said. “We don’t want no row, no nigger scrape, no loud noise, and no white folks mixin’ in.”

“White folks is shore good mixers,” Dazzle said, wincing at the recollection of several plans of hers which had been rudely frustrated by the interference of the whites. “I’ll see whut I kin do.”

At the time that Hopey was in conversation with Dazzle Zenor, Mustard was in deep thought. At last a name came into his darkened and troubled mind which was like a blaze of light illuminating all his perplexities: “Skeeter Butts!”

Ten minutes later he entered the Hen-Scratch saloon and was told that the man he sought was in a little room in the rear.

“I’m shore glad to find you so easy, Skeeter,” Mustard said in a relieved tone. “Ef you had been out of town I would hab fotch’ my troubles to you jes’ the same, whar you wus.”

“Dis is whar you gits exputt advices on ev’ything,” Skeeter laughed as he sat down and lighted a cigarette.

Why is it that people make confidants of barkeeps?

And whom will we tell our troubles to when the world is made safe for prohibition?

Skeeter was a saddle-colored, dapper, petite negro, the dressiest man of any color who ever lived in Tickfall. His hair was always closely clipped, the part made in the middle of his head with a razor. His collars were so high that they made him look like a jackass, with his chin hanging over a whitewashed fence. His clothes were so loud that they invariably proclaimed the man a block away.

He was the “pet nigger” of all the well-to-do white people in the town, who invariably took him upon their hunting and fishing trips; his dancing, singing, gift of mimicry, and certain histrionic gifts had given him a place in many amateur theatrical exhibitions in Tickfall, among both whites and blacks; and with all his monkey trickery he, nevertheless, had the confidence of all the white people, and could walk in and out of more houses without a question being asked as to the reason for his presence there than any white or black in the little village.

Among the negroes he was Sir Oracle. He was matrimonial adjuster in courtship, marriage, and divorce; he was confidential adviser at baptisms and funerals; his expert advice was sought in all matters pertaining to lodge and church and social functions. In short, he represented in Tickfall colored society what Colonel Gaitskill did among the white people.

“Dis is whar you gits exputt advices on eve’ything,” Skeeter laughed, for he knew his standing among his people.

“I don’t want advices. I wants a hold-up man,” Mustard said gloomily.

“How come?”

“A feller stole somepin from me, an’ I wants somebody to steal it back,” Mustard explained.

“Bawl out wid it,” Skeeter snapped. “Don’t go beatin’ de bush aroun’ de debbil. Talk sense!”

Mustard hesitated for a long time, opened his mouth once or twice as if about to speak, shook his head, and seemed to think better of it.

“Well,” Skeeter snapped, “why don’t you tell it?”

“I don’t know how to begin,” Mustard sighed.

“Begin at de fust part an’ tell dat fust,” Skeeter ranted. “Is you been hittin’ Marse Tom’s bottle?”

Under this sort of prodding, continued for some time longer, Skeeter finally got Mustard started, and got the story. It is not necessary to repeat it, although Mustard’s way of telling what happened and what he thought of Popsy would be interesting.

“An’ now, Skeeter,” Mustard concluded, “de idear is dis: Popsy stole my rabbit-foot, an’ I want you to steal it back. Rob de ole man of my foot an’ fotch it back to me, an’ I’ll gib you one hundred dollars.”

“Pay in eggsvance?” Skeeter asked eagerly.

“No,” Mustard said.

“Bestow a little money in eggsvance to keep my mind int’rusted.”

“Suttinly. Ten dollars cash down—you got to pay it back ef you don’t do no good.”

“I’ll git de foot all right,” Skeeter said confidently.

“Don’t be too shore, Skeeter,” Mustard warned him. “You might git in jail, an’ ef you does, don’t ax me to he’p you.”

“You means to say ef I bust into ole Popsy’s cabin an’ steal de foot, an’ he gits me arrested, you won’t esplain nothin’ to de cote-house?”

“Nary a single esplain!” Mustard proclaimed solemnly. “Dat’s jes’ whut I means. I ain’t gwine git mixed up in dis no way an’ no how! Ef you gits in jail, I won’t open my mouth ef dey hangs you on a tree.”

Skeeter pulled out of his pocket the ten-dollar bill which Mustard had just given him and spread it out upon his knee, smoothing it with his yellow fingers.

“Gimme fo’ more ten-dollar bills to spread out on top of dis tenner,” Skeeter commanded.

Mustard promptly handed over the money.

“Dis here detecative stealin’ job is a risky bizzness,” Skeeter proclaimed. “I ain’t never got at nothin’ yit as dangersome.”

“I knows it, Skeeter,” Mustard agreed gloomily. “Ef you ain’t keerful, you’ll git a bullet in you; an’ ef dat sad misforchine happens to you I won’t even come to yo’ fun’ral. I ain’t gwine mix wid dis at all.”

Mustard arose, walked through the barroom, climbed upon his horse, and departed for the Nigger-Heel plantation.

Skeeter sat for a long time, considering all that Mustard had told him, the money still spread out upon his knee. Then he arose and pocketed the money, walked out to the rear, and sat down in a chair under his favorite china-berry tree.

Two boys up the street diverted his attention for a moment. They had a long, black bullwhip, and were taking turn-about trying to see who could “pop” it the loudest. The “cracker” on the whip was nearly worn off, and they decided to plait an entirely new cracker, one that would pop like a pistol. Neither had a pocket-knife, and they could find nothing with which to remove the old cracker. They tried to saw it off with a piece of sharp glass, abandoned that in favor of a piece of sharp-edged tin can, then took a sharp rock and tried to beat it off.

When they saw Skeeter Butts they swooped down on him.

“Lend us de loant of yo’ pocket-knife, Skeeter,” Little Bit asked.

Skeeter thrust his hand into his pocket, found nothing, and answered:

“I left it inside de barroom. I’m glad of it, because you’s be shore to cut yourselfs.”

Skeeter leaned his chair against the tree, sat down, and placed the heels of his shoes in the front rungs of the chair, tipped his hat down over his eyes until the bridge of his nose was invisible, and sat motionless. Except the tiny column of smoke that curled up from his cigarette, there was scarcely a sign of life.

The two boys wandered around to the front of the saloon. Then a bright idea came to Little Bit:

“Marse Org, less git a match an’ burn de cracker offen dis ole whup.”

“Where’s the match?”

Little Bit led him into the saloon and conducted him to the little room in the rear. There, upon a table, they found a box of matches, and Org struck one and applied it to the cracker, while Little Bit held the whip.

The cracker easily caught fire and burned freely. When it was near to the rawhide end of the lash Little Bit gave the whip a quick jerk and the flaming cracker flew off the end. The boys laughed at the success of their plan, picked up a handful of twine strings which lay around the floor, and walked out.

Boylike, they never looked to see where the flaming cracker went. They didn’t care where it went. They didn’t want it. They went out the way they had come, and ran up the street and far away.

Skeeter was undisturbed until Dazzle Zenor passed and roused him.

“I got a big job befo’ me,” she said.

“Me, too,” Skeeter replied.

“My job am a secret,” Dazzle offered.

“Mine, too,” Skeeter responded.

“I’s fixin’ to make a good bunch of money,” Dazzle boasted.

“I’ll either make money or git in jail,” Skeeter said. “I’m got a detecative job.”

“My job is harder,” Dazzle smiled. “I pick pockets.”

“I bet you is flirtin’ wid a jail, too,” Skeeter asserted.

“Mebbe so. I cain’t tell you no more——”

Suddenly she stopped and stared at the closed door in the rear of the saloon through which tiny spirals of smoke were issuing by way of the cracks.

“Is you fumigatin’, Skeeter?” she asked.

“Fumigatin’ whut?” Skeeter asked, then ran to the door and threw it open.

The room was filled with smoke and a pile of old trash and newspapers in one corner was ablaze.

With a loud whoop, Skeeter and Dazzle ran through the smoke to the fire; from the door which entered into the barroom, Figger Bush came in with a bucket of water, yelling like a wild man. It was all over in a minute.

“Good-by, Skeeter!” Dazzle laughed. “Mebbe us’ll meet in jail.”

“Dat fire is a bad sign for me, Dazzle,” Skeeter sighed. “Troubles is gittin’ ready to happen to me.”

“Things will shore happen whar a white boy an’ a pickaninny monkeys aroun’,” Dazzle told him.

When the inveterate smoker throws away a pipe, it may be safely presumed that the pipe has some potency. A briar-root sweetens with age, mellowing and ripening in its own nicotine, and then it becomes impossible. So it happened that Colonel Gaitskill was compelled to an act of abandonment. The pipe that had solaced him for years was hurled far over in a clump of weeds in the horse-pasture.

One pair of sharp eyes saw the act of abandonment and watched to see where the pipe fell. One pair of nimble feet carried their owner to the spot where the forsaken thing had fallen. A pair of eager hands laid hold upon it, and Orren Randolph Gaitskill found himself in proud possession of a real pipe.

If Orren’s Sunday-school teacher had arrived at that particular moment and had been disposed to instruct this youth upon the injurious effects of nicotine, he could have run a broom-straw down the stem of that pipe and brought it out all black and shiny with poison. Finding a cat who never had smoked, did not even “chaw,” he could have forced that straw between pussy’s teeth, drawing it lengthwise through the sides of her mouth, thus wiping off the nicotine upon her tongue. He could then have waited a few minutes and had a free show for himself and Orren Randolph Gaitskill: the exhibition of a suffering cat, dying miserably in a fit.

But, no! Orren had not the remotest idea of permitting a cat, or even a Sunday-school teacher, to share the delights of that pipe with him. He intended to smoke it in exclusive partnership with his colored friend, Little Bit.

Orren found Little Bit sitting on a curb-stone in front of the Hen-Scratch saloon, and exhibited the treasure.

“Dat’s a purty good pipe, but whar’s yo’ terbacker?” Little Bit asked.

“You ought to furnish that,” Org replied. “I’ve got the pipe and the matches.”

“I ain’t got none.”

“Don’t yo’ mammy smoke?”

“Naw. She dips.”

“Don’t your father smoke?”

“Ain’t got no paw. He’s daid.”

“Well, then: can’t you borrow a little tobacco from some of your friends?”

“Ain’t got no frien’s, excusin’ you.”

“What about Skeeter Butts?”

“He ain’t no frien’ of our’n. He’s mad at us because we sot his saloom on fire wid dat hot whup-cracker.”

“I never saw a colored person with as little as you have,” Orren said irascibly. “You haven’t got nothin’.”

“Dat’s a fack. Dat’s de nachel way niggers is. But I knows whar dar is plenty rabbit terbacker.”

“That’s as good as any, I’m sure,” Org said. “Lead me to it.”

A short distance on the edge of the town, Little Bit led Org into a wide pasture, along the edge of which there ran a little branch. He hunted a few minutes in search of a plant which is known in other places as “life everlasting,” but in Louisiana is called “rabbit tobacco.”

This can be said for it: the oldest pipe-user, dying for want of a smoke, will not smoke the weed called life everlasting. He lets rabbit tobacco alone. It has the flavor and the odor of tobacco. It also has an effect, when used, which invariably reminds every man of the time when he smoked his first cigar.

“Dar she is!” Little Bit exclaimed, pouncing upon a dry weed. “Dis here plant will gib us aplenty.”

He stripped off the dry leaves, crushed them in his hands and, assisted by Org, he packed the pipe-bowl. They walked to the edge of a little thicket and sat down upon a convenient log to enjoy their smoke. A long, level pasture stretched out before them, dotted here and there with grazing cattle, ending across the way with a rail fence, beside which grew a row of trees.

Org produced a box of matches, laid it upon the ground beside him, and reached out for the pipe.

“I’ll light up and smoke awhile, Little Bit. Then I’ll pass it to you.”

“Hit away, Marse Org. I ain’t really hankerin’ fer no pipe-smoke. I likes cigareets best. But I’ll go it a puff or two, ef you’ll puff fust.”

Org lighted the pipe and was charmed at the ease with which he could draw the smoke through the stem. The smoke was exceptionally sweet and cooling to the tongue, like the flavor of ether, although Org had never tasted that volatile fluid. He took four or five hearty puffs, and then felt that it was time to introduce his black friend to this charming and delightful accomplishment.

Little Bit had counted the number of times that Org had blown the smoke from his lips and he had too much regard for his “raisin’” to puff a single time more than his white companion. After four draws he handed back the pipe.

Org reached for it with a disinterested hand. He held the pipe listlessly and gazed out dreamily upon the level meadow with eyes which saw little and comprehended less and were not interested in that. Then the pipe dropped from his hands, and Org opened his eyes wide, as he suddenly beheld the entire pasture with all its grazing cattle, the fence with the trees at the far end—everything, in fact, rise up in the air and dance high above his head!

Org leaned back so far to behold the last of this phenomenon that he fell off the log and lay prone upon the ground.

“Whut ails you, Marse Org?” Little Bit asked solicitously. “Is de worl’ done turned down-side up fer you, too?”

Little Bit arose with the intention of helping his white companion, the entire earth tipped and rolled over on him and pushed him over the log, where he lay holding to the ground to keep from being pitched off.

One hour later the two boys crawled up on the log and sat down, trembling, weak, beyond any weakness they had ever experienced.

“I guess we got poisoned with something, Little Bit,” Org remarked. “I feel pretty bad.”

“Dar ain’t been many cullud folks as sick as I wus an’ lived through it,” Little Bit replied with weak boastfulness. “Niggers is like a mule: dey don’t git sick but one time an’ atter dat, dey die. I wus wuss off in de last hour dan I ever is been. It muss hab been somepin I et.”

“I been heap sicker than you were,” Org declared. “You lived through it—you say so yourself. But me, I’m dying now!”

“Dis ain’t no fitten place to die, Marse Org,” Little Bit protested. “De buzzards will eat us up out here all unbeknownst to nobody. Less mosey back to town whar people kin see us die an’ keep de buzzards off.”

“Less hurry. I ain’t got long to live,” Org declared.

“We moves now,” Little Bit sighed miserably. “Dis wus shore a narrer escapement fer us.”

Locomotion was a difficult task for both of them. They were glad when they came to the fence and could use a stick with one hand and cling to the fence with the other. When they reached the road, they made wild and desperate gestures and stopped a little automobile.

“Whar you fellers been at?” Skeeter Butts asked as he opened the door for them to climb in beside him. “You look all peeked up.”

“Me an’ Marse Org, we been smokin’ rabbit terbacker,” Little Bit told him.

“Ho! Ho! He! He!” Skeeter Butts howled. “I done dat trick once myself. You-alls gwine try it agin?”

“Naw, suh.”

“I reckin not,” Skeeter laughed. “I tried smokin’ dat stuff twenty year ago an’ right now whenever I sees a bush of dat rabbit terbacker, I grabs a tree an’ begins to heave!”

Skeeter turned his machine and started back to Tickfall.

“Whar you want me to take you?” he asked.

“Home, quick!” Org sighed.

“Drap me at de Hen-Scratch,” Little Bit begged. “I ain’t got de cornstitution to ride no furder.”

Skeeter drove to Gaitskill’s home, lifted Org out of the machine and carried him to the porch. Org promptly stretched out flat on his back on the porch floor and called:

“Gince! Oh, Gince! Come here and help me! I’m dying!”

Coming in answer to his call, Miss Virginia’s face at first assumed an expression of fright at the sight of Org, then, glancing at Skeeter’s grinning mug, her uneasiness vanished.

“What have you been doing?” she asked Org.

“Smoking,” Org confessed. “Smoking a pipe!”

“Where is that pipe?”

Org thrust a trembling hand into the pocket of his coat and produced the briar-root.

“The idea!” Miss Virginia snapped, looking at the pipe with loathsome repugnance. “What else have you in your pockets? Let me see!”

Org turned the pockets of his trousers wrong side out and a number of strange and nameless things rolled out, things which could have value only in the eyes of a boy.

“Turn out your coat pockets!” Virginia commanded.

Org thrust his hand into his coat and handed Virginia a green-plush box.

The eyes of Skeeter Butts nearly popped out of his head.

“For goodness’ sake!” Virginia exclaimed in an angry voice as she seized the box.

“I was carrying it for luck, Gince,” Org said apologetically. “Little Bit said it was lucky, but—oh, I feel so sick!”

Virginia opened the box and brought forth a rabbit-foot surmounted on one end with silver. Finding that it had not been injured, she spoke in a mollified tone:

“After this, you understand that this plush box is mine, young man! Don’t you ever touch it again!”

“I won’t. It ain’t no good.”

“Skeeter,” she said. “Carry Org up-stairs to my room. I’ll lead the way.”

Skeeter lifted the prostrate boy and carried him where his sister led. He lingered around the bed where he had placed Org until he saw Miss Virginia open the drawer of a dressing-table and place the green-plush box within it and shut the drawer.

“You wants me to git de dorctor, Miss Virginny?” Skeeter asked.

“No. That will be all for you, thank you.”

When Skeeter stepped out upon the road beside the house, he noticed Colonel Gaitskill out in the horse-pasture, walking around in a circle defined by a clump of grass, his eyes glued upon the ground as if he was hunting for something.

“Have you done loss somepin, Marse Tom?” Skeeter inquired as he walked to where he was.

“Yes. I had a pipe that I have smoked for twenty years. I threw it out in these weeds this morning and bought a new pipe. But the new pipe is an abomination. I’m looking for the old one.”

“I think young Marse Org is got dat ole one,” Skeeter laughed. “Miss Virginny jes’ now tuck it offen him an’ lef’ it on de front porch.”

Gaitskill stooped and broke off the stem of a weed. He stripped the leaves from the straight stem, crushed them, and sniffed at the peculiar, sweetish, tobacco odor.

Skeeter caught the scent, reeled backward, clutched at his throat, grabbed a convenient tree and began to heave!

When Skeeter Butts informed Mustard Prophet that his coveted rabbit-foot was in the Gaitskill home, Mustard nearly went into hysterics.

“My Gawd!” he wailed. “No tellin’ whut dem white chillun will do to dat foot—an’ mebbe I won’t never see it agin.”

“Dey ain’t gwine hurt it—Marse Tom’s house is safer dan a bank!” Skeeter protested.

“How’ll I ever git dat foot back outen dat house?” Mustard howled. “Of co’se de house is safer dan a bank. Us cain’t rob a white folk’s house.”

“How come you want it back ef it b’longs to Marse Tom?” Skeeter asked.

“It’s dis way, Skeeter,” Mustard said, trying to explain. “Eve’ything dat Marse Tom trusts to me, I keeps jes’ like it is when he gibs it to me. Ef he hands me a door-key, he needn’t ax me fer dat key fer ten year, but when he do, I’ll gib him dat key! Now, he gimme dat foot fifteen year ago, an’ he ain’t never mentioned dat foot since dat time nor seed it endurin’ all dem years; but ef he wuster come to de Nigger-Heel to-morrer an’ ax me, ‘Mustard, whar’s my rabbit-foot?’ my insides would bust open an’ be outsides onless I could say: ‘Here she am!’”

“I sees,” Skeeter Butts said. “You’s got a rep wid Marse Tom.”

“Dat’s right. I’s tryin’ not to ruin my rep.”

“I wish I’d ’a’ knowed dat little white boy had dat foot in his pocket,” Skeeter sighed. “I’d ’a’ picked his pocket or heldt him up or somepin’ like dat.”

“Too late fer dat now,” Mustard mourned. “Dat white boy found dat rabbit-foot down at ole Popsy’s cabin. Popsy lives back on de Gaitskill place in a cabin Marse Tom gib him, an’ dem pickaninnies wus playin’ aroun’ dar an’ swiped it. An’ ef Marse Tom ever ketches on dat I wus so keerless wid his royal foot dat I let a bat like ole Popsy git holt of it an’ run away wid it, an’ den let it git in de hands of dem chillun—Oh, Lawdy!”

Tears ran down the cheeks of Mustard Prophet. The loss of the luck-charm was a real tragedy to Mustard, for his life had been one of absolute fidelity in little things.

Every Southern man knows that the most unaccountable paradox in negro nature and character lies right here: you may choose the trickiest negro thief in Louisiana, give him the key to your money-chest, go to Europe and stay ten years, and when you return the negro will hand you the key, and the contents of the chest will be intact. Doubtless, he will open the chest a hundred times and investigate everything within it, but he will not betray his trust. Then, having surrendered the key and given an account of his stewardship, as he goes through the hall on the way out, he might pick up your gold-headed cane, stick it down his pants’ leg and hike!