Title: The Shakespeare Garden

Author: Esther Singleton

Release date: February 5, 2020 [eBook #61325]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by ellinora, Alan and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

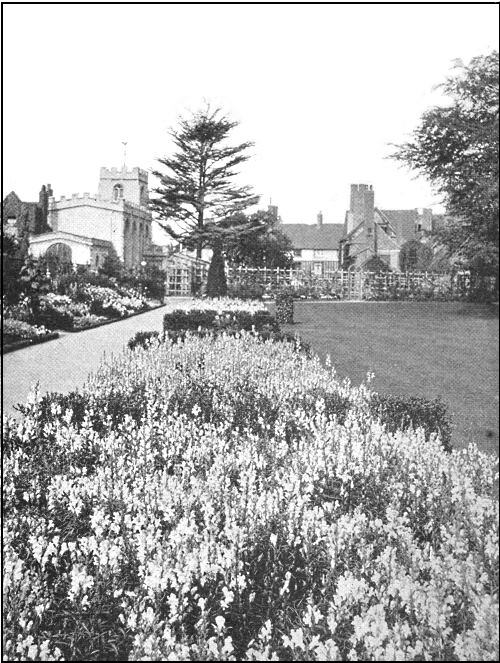

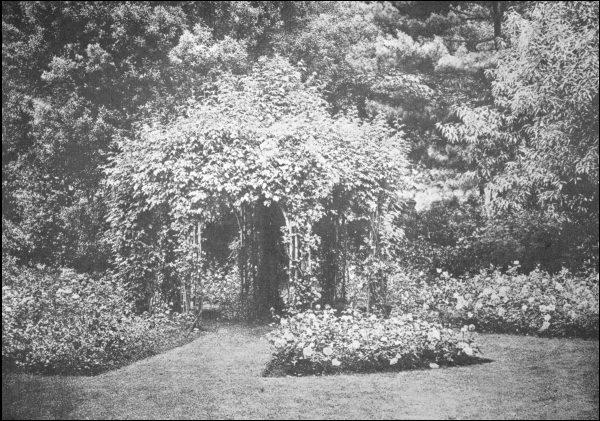

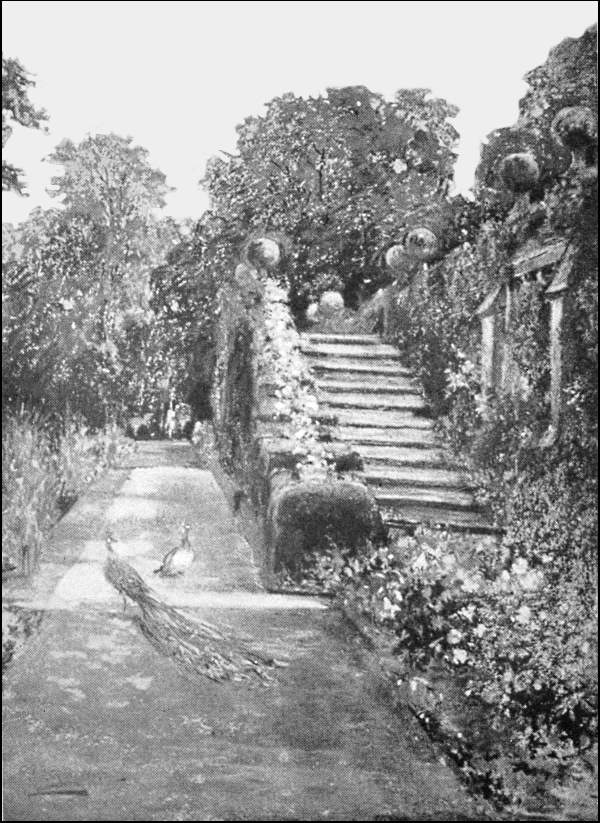

STRATFORD-UPON-AVON, NEW PLACE, BORDER OF ANNUALS

THE SHAKESPEARE GARDEN

BY ESTHER SINGLETON

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

AND REPRODUCTIONS OF

OLD WOOD CUTS

PUBLISHED BY THE CENTURY CO.

NEW YORK  M CM XX II

M CM XX II

Copyright, 1922, by

The Century Co.

Printed in U. S. A.

To the memory of

MY MOTHER

whose rare artistic tastes and whose cultured

intellect led me in early years to the appreciation

of shakespeare and all manifestations

of beauty in literature and art

PREFACE

In adding another book to the enormous number of works on Shakespeare, I beg indulgence for a few words of explanation.

Having been for many years an ardent and a devoted student of Shakespeare, I discovered long ago that there was no adequate book on the Elizabethan garden and the condition of horticulture in Shakespeare's time. Every Shakespeare student knows how frequently and with what subtle appreciation Shakespeare speaks of flowers. Shakespeare loved all the simple blossoms that "paint the meadows with delight": he loved the mossy banks in the forest carpeted with wild thyme and "nodding violets" and o'er-canopied with eglantine and honeysuckle; he loved the cowslips in their gold coats spotted with rubies, "the azured harebells" and the "daffodils that come before the swallow dares"; he loved the "winking mary-buds," or marigolds, that "ope their golden eyes" in the first beams of the morning sun; he loved the stately flowers of stately gardens—the delicious musk-rose, "lilies of all kinds," and the flower-de-luce; and he loved all the[Pg viii] new "outlandish" flowers, such as the crown-imperial just introduced from Constantinople and "lark's heels trim" from the West Indies.

Shakespeare no doubt visited Master Tuggie's garden at Westminster, in which Ralph Tuggie and later his widow, "Mistress Tuggie," specialized in carnations and gilliflowers, and the gardens of Gerard, Parkinson, Lord Zouche, and Lord Burleigh. In addition to these, he knew the gardens of the fine estates in Warwickshire and the simple cottage gardens, such as charm the American visitor in rural England. When Shakespeare calls for a garden scene, as he does in "Twelfth Night," "Romeo and Juliet," and "King Richard II," it is the "stately garden" that he has in his mind's eye, the finest type of a Tudor garden, with terraces, "knots," and arbors. In "Love's Labour's Lost" is mentioned the "curious knotted garden."

Realizing the importance of reproducing an accurate representation of the garden of Shakespeare's time the authorities at Stratford-upon-Avon have recently rearranged "the garden" of Shakespeare's birthplace; and the flowers of each season succeed each other in the proper "knots" and in the true Elizabethan atmosphere. Of recent years it has been a fad among American garden lovers to set[Pg ix] apart a little space for a "Shakespeare garden," where a few old-fashioned English flowers are planted in beds of somewhat formal arrangement. These gardens are not, however, by any means replicas of the simple garden of Shakespeare's time, or of the stately garden as worked out by the skilful Elizabethans.

It is my hope, therefore, that this book will help those who desire a perfect Shakespeare garden, besides giving Shakespeare lovers a new idea of the gardens and flowers of Shakespeare's time.

Part One is devoted to the history and evolution of the small enclosed garden within the walls of the medieval castle into the Garden of Delight which Parkinson describes; the Elizabethan garden, the herbalists and horticulturists; and the new "outlandish" flowers. Part Two describes the flowers mentioned by Shakespeare and much quaint flower lore. Part Three is devoted to technical hints, instruction and practical suggestions for making a correct Shakespeare garden.

Shakespeare does not mention all the flowers that were familiar in his day, and, therefore, I have described in detail only those spoken of in his plays. I have chosen only the varieties that were known to Shakespeare; and in a Shakespeare garden only[Pg x] such specimens should be planted. For example, it would be an anachronism to grow the superb modern pansies, for the "pansy freaked with jet," as Milton so beautifully calls it, is the tiny heartsease, or "johnny-jump-up."

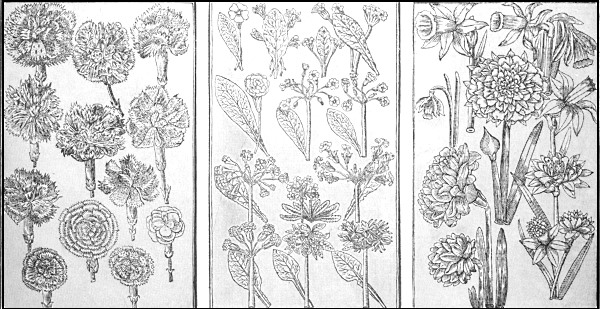

On the other hand, the carnations (or "sops-in-wine") and gilliflowers were highly developed in Shakespeare's day and existed in bewildering variety.

We read of such specimens as the Orange Tawny Gilliflower, the Grandpère, the Lustie Gallant or Westminster, the Queen's Gilliflower, the Dainty, the Fair Maid of Kent or Ruffling Robin, the Feathered Tawny, Master Bradshaw's Dainty Lady, and Master Tuggie's Princess, besides many other delightful names.

I have carefully read every word in Parkinson's huge volume, Paradisi in Sole; Paradisus Terrestris (London, 1629), to select from his practical instructions to gardeners and also his charming bits of description. I need not apologize for quoting so frequently his intimate and loving characterizations of those flowers that are "nourished up in gardens." Take, for example, the following description of the "Great Harwich":

I take [says Parkinson] this goodly, great old English Carnation as a precedent for the description of all the rest, which for his beauty and stateliness is worthy of a prime place. It riseth up with a great, thick, round stalk divided into several branches, somewhat thickly set with joints, and at every joint two long, green (rather than whitish) leaves turning or winding two or three times round. The flowers stand at the tops of the stalks in long, great and round green husks, which are divided into five points, out of which rise many long and broad pointed leaves deeply jagged at the ends, set in order, round and comely, making a gallant, great double Flower of a deep carnation color almost red, spotted with many bluish spots and streaks, some greater and some lesser, of an excellent soft, sweet scent, neither too quick, as many others of these kinds are, nor yet too dull, and with two whitish crooked threads like horns in the middle. This kind never beareth many flowers, but as it is slow in growing, so in bearing, not to be often handled, which showeth a kind of stateliness fit to preserve the opinion of magnificence.

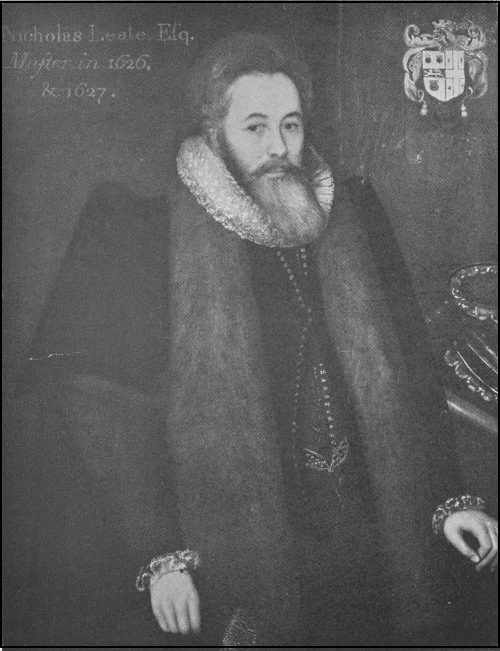

It will amaze the reader, perhaps, to learn that horticulture was in such a high state of development. Some wealthy London merchants and noblemen, Nicholas Leate, for example, actually kept agents traveling in the Orient and elsewhere to search for rare bulbs and plants. Explorers in the New World also brought home new plants and flowers. Sir Walter Raleigh imported the sweet potato and to[Pg xii]bacco (but neither is mentioned by Shakespeare) and from the West Indies came the Nasturtium Indicum—"Yellow Lark's Heels," as the Elizabethans called it.

Many persons will be interested to learn the quaint old flower names, such as "Sops-in-Wine," the "Frantic Foolish Cowslip," "Jack-an-Apes on Horseback," "Love in Idleness," "Dian's Bud," etc.

The Elizabethans enjoyed their gardens and used them more than we use ours to-day. They went to them for re-creation—a renewing of body and refreshment of mind and spirit. They loved their shady walks, their pleached alleys, their flower-wreathed arbors, their banks of thyme, rosemary, and woodbine, their intricate "knots" bordered with box or thrift and filled with bright blossoms, and their labyrinths, or mazes. Garden lovers were critical and careful about the arrangement and grouping of their flowers. To-day we try for masses of color; but the Elizabethans went farther than we do, for they blended their hues and even shaded colors from dark to light. The people of Shakespeare's day were also fastidious about perfume values—something we do not think about to-day. The planting of flowers with regard to the "perfume on the air," as Bacon describes it, was a part of ordinary garden[Pg xiii] lore. We have altogether lost this delicacy of gardening.

This book was the logical sequence of a talk I gave two years ago upon the "Gardens and Flowers of Shakespeare's Time" at the residence of Mrs. Charles H. Senff in New York, before the International Garden Club. This talk was very cordially received and was repeated by request at the home of Mrs. Ernest H. Fahnestock, also in New York.

I wish to express my thanks to Mr. Norman Taylor of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, for permission to reprint the first chapter, which appeared in the "Journal of the International Garden Club," of which he is the editor. I also wish to thank Mr. Taylor for his valued encouragement to me in the preparation of this book.

I wish to direct attention to the remarkable portrait of Nicholas Leate, one of the greatest flower collectors of his day, photographed especially for this book from the original portrait in oils, painted by Daniel Mytens for the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, of which Leate was master in 1616, 1626, and 1627.

The portrait of this English worthy has never been photographed before; and it is a great pleasure for me to bring before the public the features and[Pg xiv] personality of a man who was such a deep lover of horticulture and who held such a large place in the London world in Shakespeare's time. The dignity, refinement, distinction, and general atmosphere of Nicholas Leate—and evidently Mytens painted a direct portrait without flattery—bespeak the type of gentleman who sought re-creation in gardens and who could have held his own upon the subject with Sir Francis Bacon, Sir Thomas More, Sir Philip Sidney, Lord Burleigh, and Sir Henry Wotton—and, doubtless, he knew them all.

It was not an easy matter to have this portrait photographed, because when the Hall of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers was destroyed by a German bomb in 1917 the rescued portrait was stored in the National Gallery. Access to the portrait was very difficult, and it was only through the great kindness of officials and personal friends that a reproduction was made possible.

I wish, therefore, to thank the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers for the gracious permission to have the portrait photographed and to express my gratitude to Mr. Collins Baker, keeper of the National Gallery, and to Mr. Ambrose, chief clerk and secretary of the National Gallery, for their kind co-operation; to Mr. C. W. Carey, curator of the[Pg xv] Royal Holloway College Gallery, who spent two days in photographing the masterpiece; and also to Sir Evan Spicer of the Dulwich Gallery and to my sister, Mrs. Carrington, through whose joint efforts the arrangements were perfected.

I also wish to thank the Trustees and Guardians of Shakespeare's Birthplace, who, through their Secretary, Mr. F. C. Wellstood, have supplied me with several photographs of the Shakespeare Garden at Stratford-upon-Avon, especially taken for this book, with permission for their reproduction.

E. S.

[Pg xvi]

[Pg xvii]New York, September 4, 1922.

CONTENTS

PART ONE

THE GARDEN OF DELIGHT

| PAGE | ||

| Evolution of the Shakespeare Garden | 3 | |

| I. | The Medieval Pleasance | 3 |

| II. | Garden of Delight | 11 |

| III. | The Italian Renaissance Garden | 15 |

| IV. | Bagh-i-Vafa | 19 |

| V. | New Fad for Flowers | 21 |

| VI. | Tudor Gardens | 25 |

| VII. | Garden Pleasures | 29 |

| The Curious Knotted Garden | 31 | |

| I. | Flower Lovers and Herbalists | 31 |

| II. | The Elizabethan Garden | 40 |

| III. | Old Garden Authors | 68 |

| IV. | "Outlandish" and English Flowers | 78 |

PART TWO

THE FLOWERS OF SHAKESPEARE

| Spring: "The Sweet o' the Year" | 93 | |

| I. | Primroses, Cowslips, and Oxlips | 93 |

| II. | "Daffodils That Come Before the Swallow Dares" | 109 |

| III. | "Daisies Pied and Violets Blue" | 118 |

| IV. | "Lady-smocks All Silver White" and [Pg xviii]"Cuckoo-buds of Every Yellow Hue" |

130 |

| V. | Anemones and "Azured Harebells" | 133 |

| VI. | Columbine and Broom-flower | 137 |

| Summer: "Sweet Summer Buds" | 145 | |

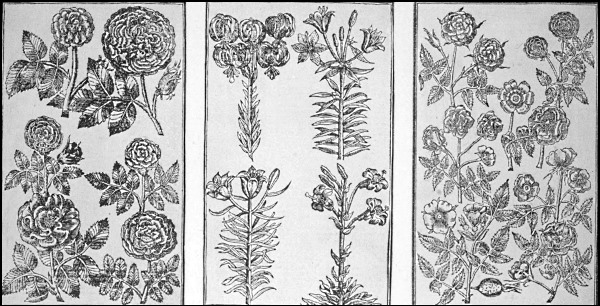

| I. | "Morning Roses Newly Washed with Dew" | 145 |

| II. | "Lilies of All Kinds" | 160 |

| III. | Crown-Imperial and Flower-de-Luce | 167 |

| IV. | Fern and Honeysuckle | 175 |

| V. | Carnations and Gilliflowers | 181 |

| VI. | Marigold and Larkspur | 189 |

| VII. | Pansies for Thoughts and Poppies for Dreams | 200 |

| VIII. | Crow-flowers and Long Purples | 207 |

| IX. | Saffron Crocus and Cuckoo-flowers | 210 |

| X. | Pomegranate and Myrtle | 215 |

| Autumn: "Herbs of Grace" and "Drams of Poison" | 224 | |

| I. | Rosemary and Rue | 224 |

| II. | Lavender, Mints, and Fennel | 231 |

| III. | Sweet Marjoram, Thyme, and Savory | 236 |

| IV. | Sweet Balm and Camomile | 243 |

| V. | Dian's Bud and Monk's-hood Blue | 246 |

| Winter: "When Icicles Hang by the Wall" | 253 | |

| I. | Holly and Ivy | 253 |

| II. | Mistletoe and Box | 261 |

PART THREE

PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS

| The Lay-out of Stately and Small Formal Gardens | 269 | |

| [Pg xix]I. | The Stately Garden | 271 |

| II. | The Small Garden | 276 |

| III. | Soil and Seed | 278 |

| IV. | The Gateway | 280 |

| V. | The Garden House | 281 |

| VI. | The Mount | 282 |

| VII. | Rustic Arches | 282 |

| VIII. | Seats | 284 |

| IX. | Vases, Jars, and Tubs | 284 |

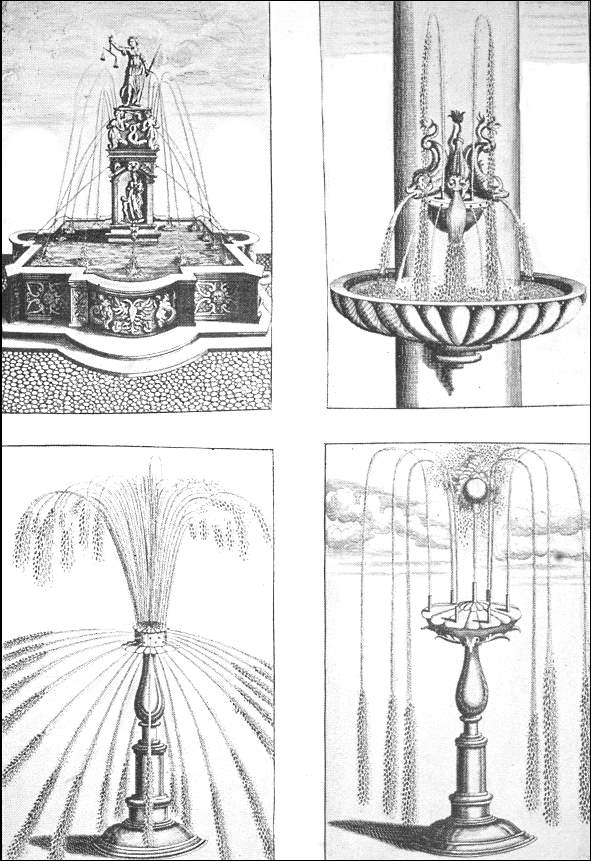

| X. | Fountains | 285 |

| XI. | The Dove-cote | 287 |

| XII. | The Sun-dial | 288 |

| XIII. | The Terrace | 289 |

| XIV. | The Pleached Alley | 292 |

| XV. | Hedges | 293 |

| XVI. | Paths | 294 |

| XVII. | Borders | 295 |

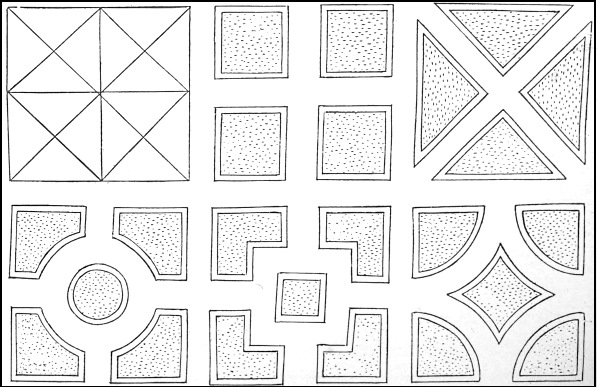

| XVIII. | Edgings | 297 |

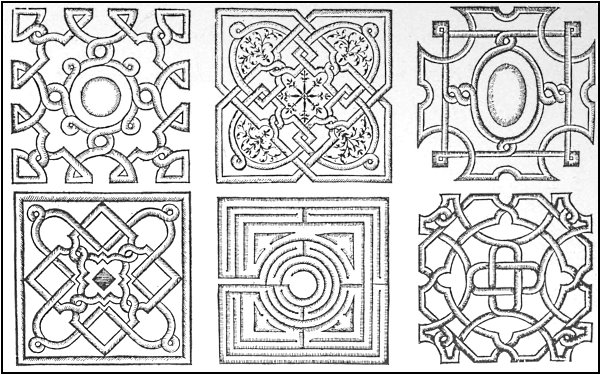

| XIX. | Knots | 298 |

| XX. | The Rock Garden | 302 |

| XXI. | Flowers | 302 |

| XXII. | Potpourri | 324 |

| A Maske of Flowers | 325 | |

| Complete List of Shakespearean Flowers with Botanical Identifications |

331 | |

| Appendix | 333 | |

| Elizabethan Gardens at Shakespeare's Birthplace | 333 | |

| Index | 347 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Stratford-upon-Avon, New Place, Border of Annuals | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

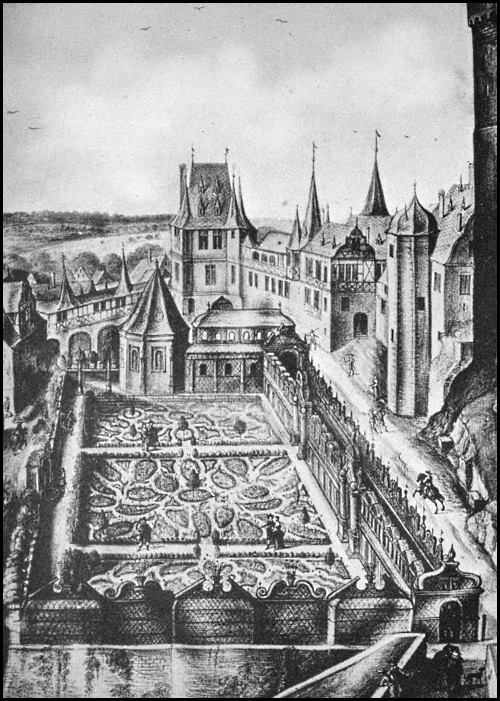

| Fifteenth Century Garden within Castle Walls, French | 8 |

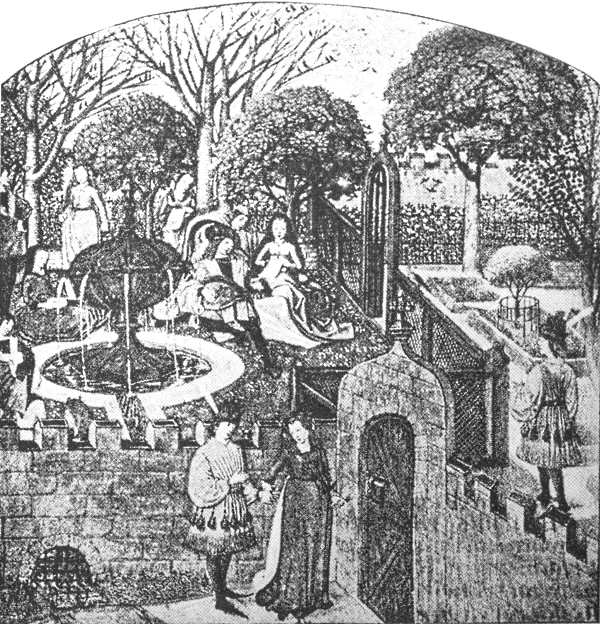

| Lovers in the Castle Garden, Fifteenth Century MS. | 17 |

| Garden of Delight, Romaunt of the Rose, Fifteenth Century | 17 |

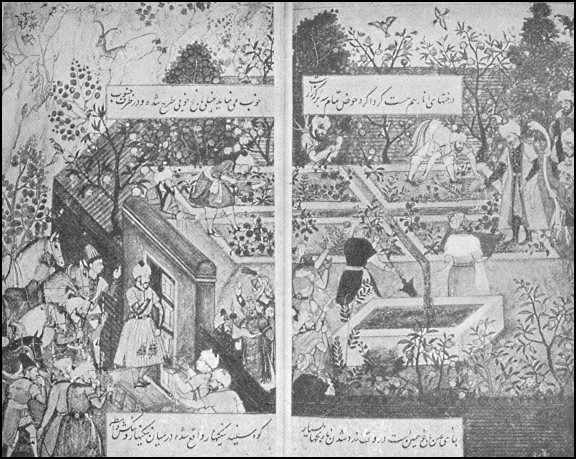

| Babar's Garden of Fidelity | 20 |

| Italian Renaissance Garden, Villa Giusti, Verona | 29 |

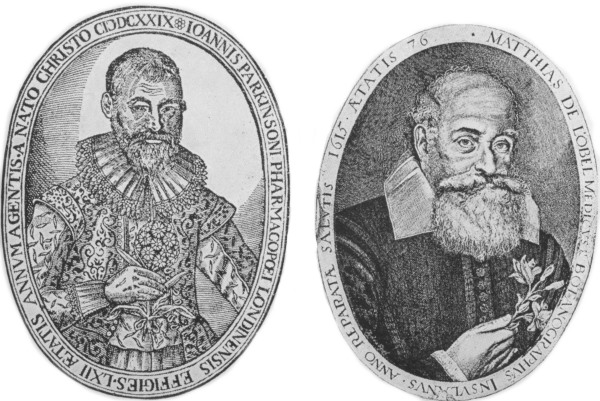

| John Gerard, Lobel and Parkinson | 32 |

| Nicholas Leate | 36 |

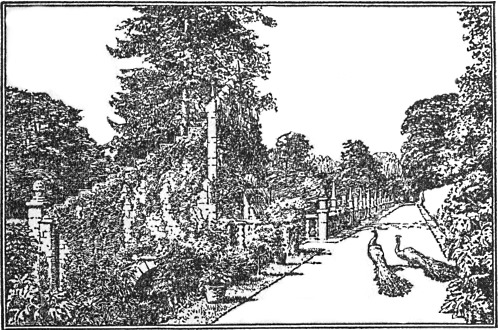

| The Knot-Garden, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon | 45 |

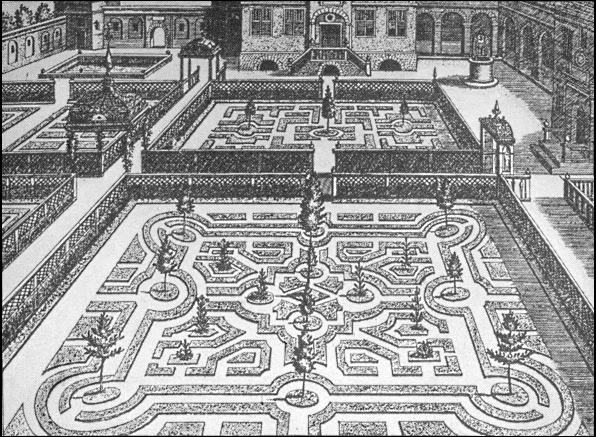

| Typical Garden of Shakespeare's Time, Crispin de Passe (1614) | 56 |

| Labyrinth, Vredeman de Vries | 64 |

| A Curious Knotted Garden, Crispin de Passe (1614) | 64 |

| The Knot-Garden, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon | 72 |

| Border, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon | 81 |

| Herbaceous Border, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon | 88 |

| Carnations and Gilliflowers; Primroses and Cowslips; and Daffodils: from Parkinson |

97 |

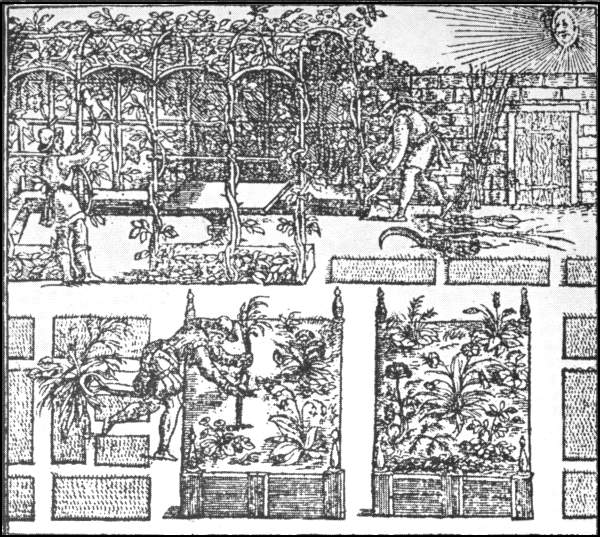

| Gardeners at Work, Sixteenth Century | 112 |

| Garden Pleasures, Sixteenth Century | 112 |

| Garden in Macbeth's Castle of Cawdor | 116 |

| Shakespeare's Birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon | 125 |

| [Pg xxii] Elizabethan Manor House, Haddon Hall | 136 |

| Rose Arbor, Warley, England | 145 |

| Red, White, Damask and Musk-Roses; Lilies and Eglantines and Dog-Roses: from Parkinson |

160 |

| Martagon Lilies, Warley, England | 168 |

| Wilton Gardens from de Caux | 176 |

| Wilton Gardens To-day | 176 |

| A Garden of Delight | 184 |

| Sir Thomas More's Gardens, Chelsea | 193 |

| Pleaching and Plashing, from The Gardener's Labyrinth | 209 |

| Small Enclosed Garden, from The Gardener's Labyrinth | 209 |

| A Curious Knotted Garden, Vredeman de Vries | 224 |

| Garden with Arbors, Vredeman de Vries | 224 |

| Shakespeare Garden, Van Cortlandt House Museum, Van Cortlandt Park, Colonial Dames of the State of New York |

241 |

| Tudor Manor House with Modern Arrangement of Gardens | 256 |

| Garden House in Old English Garden | 272 |

| Fountains, Sixteenth Century | 289 |

| Sunken Gardens, Sunderland Hall, with Unusual Treatment of Hedges |

304 |

| Knots from Markham | 321 |

| Simple Garden Beds | 321 |

PART ONE

THE GARDEN OF DELIGHT

EVOLUTION OF THE SHAKESPEARE

GARDEN

SHAKESPEARE was familiar with two kinds of gardens: the stately and magnificent garden that embellished the castles and manor-houses of the nobility and gentry; and the small and simple garden such as he had himself at Stratford-on-Avon and such as he walked through when he visited Ann Hathaway in her cottage at Shottery.

The latter is the kind that is now associated with Shakespeare's name; and when garden lovers devote a section of their grounds to a "Shakespeare garden" it is the small, enclosed garden, such as Perdita must have had, that they endeavor to reproduce.

The small garden of Shakespeare's day, which we so lovingly call by his name, was a little pleasure garden—a garden to stroll in and to sit in. The[Pg 4] garden, moreover, had another purpose: it was intended to supply flowers for "nosegays" and herbs for "strewings." The Shakespeare garden was a continuation, or development, of the Medieval "Pleasance," where quiet ladies retired with their embroidery frames to work and dream of their Crusader lovers, husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers lying in the trenches before Acre and Ascalon, or storming the walls of Jerusalem and Jericho; where lovers sat hand in hand listening to the songs of birds and to the still sweeter songs from their own palpitating hearts; where men of affairs frequently repaired for a quiet chat, or refreshment of spirit; and where gay groups of lords and ladies gathered to tell stories, to enjoy the recitation of a wandering trouvère, or to sing to their lutes and viols, while jesters in doublets and hose of bright colors and cap and bells lounged nonchalantly on the grass to mock at all things—even love!

In the illuminated manuscripts of old romans, such as "Huon of Bordeaux," the "Romaunt of the Rose," "Blonde of Oxford," "Flore et Blancheflore, Amadis de Gaul," etc., there are many charming miniatures to illustrate the word-pictures. From them we learn that the garden was actually within the castle walls and very small. The walls of the[Pg 5] garden were broken by turrets and pierced with a little door, usually opposite the chief entrance; the walks were paved with brick or stone, or they were sanded, or graveled; and at the intersection of these walks a graceful fountain usually tossed its spray upon the buds and blossoms. The little beds were laid out formally and were bright with flowers, growing singly and not in masses. Often, too, pots or vases were placed here and there at regular intervals, containing orange, lemon, bay, or cypress trees, their foliage beautifully trimmed in pyramids or globes that rose high above the tall stems. Not infrequently the garden rejoiced in a fruit-tree, or several fruit-trees. Stone or marble seats invitingly awaited visitors.

The note here was charming intimacy. It was a spot where gentleness and sweetness reigned, and where, perforce, every flower enjoyed the air it breathed. It was a Garden of Delight for flowers, birds, and men.

To trace the formal garden to its origin would take us far afield. We should have to go back to the ancient Egyptians, whose symmetrical and magnificent gardens were luxurious in the extreme; to Babylon, whose superb "Hanging Gardens" were among the Seven Wonders of the World; and to the[Pg 6] Romans, who are still our teachers in the matter of beautiful gardening. The Roman villas that made Albion beautiful, as the great estates of the nobility and gentry make her beautiful to-day, lacked nothing in the way of ornamental gardens. Doubtless Pliny's garden was repeated again and again in the outposts of the Roman Empire. From these splendid Roman gardens tradition has been handed down.

There never has been a time in the history of England where the cultivation of the garden held pause. There is every reason to believe that the Anglo-Saxons were devoted to flowers. A poem in the "Exeter Book" has the lines:

No one could write "blown-plants, honey-flowing" without a deep and sophisticated love of flowers.

Every Anglo-Saxon gentleman had a garth, or garden, for pleasure, and an ort-garth for vegetables.[Pg 7] In the garth the best loved flower was the lily, which blossomed beside the rose, sunflower, marigold, gilliflower, violet, periwinkle, honeysuckle, daisy, peony, and bay-tree.

Under the Norman kings, particularly Henry II, when the French and English courts were virtually the same, the citizens of London had gardens, "large, beautiful, and planted with various kinds of trees." Possibly even older scribes wrote accounts of some of these, but the earliest description of an English garden is contained in "De Naturis Rerum" by Alexander Neckan, who lived in the second half of the Twelfth Century. "A garden," he says, "should be adorned on this side with roses, lilies, the marigold, molis and mandrakes; on that side with parsley, cort, fennel, southernwood, coriander, sage, savory, hyssop, mint, rue, dittany, smallage, pellitory, lettuce, cresses, ortulano, and the peony. Let there also be beds enriched with onions, leeks, garlic, melons, and scallions. The garden is also enriched by the cucumber, which creeps on its belly, and by the soporiferous poppy, as well as by the daffodil and the acanthus. Nor let pot-herbs be wanting, if you can help it, such as beets, herb mercury, orache, and the mallow. It is useful also to the gardener to have anise, mustard, white pepper,[Pg 8] and wormwood." And then Neckan goes on to the fruit-trees and medicinal plants. The gardener's tools at this time were merely a knife for grafting, an ax, a pruning-hook, and a spade. A hundred years later the gardens of France and England were still about the same. When John de Garlande (an appropriate name for an amateur horticulturist) was studying at the University of Paris (Thirteenth Century) he had a garden, which he described in his "Dictionarus," quaintly speaking of himself in the third person: "In Master John's garden are these plants: sage, parsley, dittany, hyssop, celandine, fennel, pellitory, the rose, the lily, the violet; and at the side (in the hedge), the nettle, the thistle and foxgloves. His garden also contains medicinal herbs, namely, mercury and the mallows, agrimony with nightshade and the marigold." Master John had also a special garden for pot-herbs and "other herbs good for men's bodies," i.e., medicinal herbs, and a fruit garden, or orchard, of cherries, pears, nuts, apples, quinces, figs, plums, and grapes. About the same time Guillaume de Lorris wrote his "Roman de la Rose"; and in this famous work of the Thirteenth Century there is a most beautiful description of the garden of the period. L'Amant (the Lover) while strolling on the banks of a river discovered [Pg 9]this enchanting spot, "full long and broad behind high walls." It was the Garden of Delight, or Pleasure, whose wife was Liesse, or Joy; and here they dwelt with the sweetest of companions. L'Amant wandered about until he found a small wicket door in the wall, at which he knocked and gained admittance. When he entered he was charmed. Everything was so beautiful that it seemed to him a spiritual place, better even than Paradise could be. Now, walking down a little path, bordered with mint and fennel, he reached the spot where Delight and his companions were dancing a carol to the song of Joy. L'Amant was invited to join the dance; and after it was finished he made a tour of the garden to see it all. And through his eyes we see it, too.

FIFTEENTH CENTURY GARDEN WITHIN CASTLE WALLS, FRENCH

The Garden of Delight was even and square, "as long as it was large." It contained every known fruit-tree—peaches, plums, cherries, apples, and quinces, as well as figs, pomegranates, dates, almonds, chestnuts, and nutmegs. Tall pines, cypresses, and laurels formed screens and walls of greenery; and many a "pair" of elms, maples, ashes, oaks, aspens, yews, and poplars kept out the sun by their interwoven branches and protected the green grass. And here deer browsed fearlessly and squir[Pg 10]rels "in great plenty" were seen leaping from bough to bough. Conduits of water ran through the garden and the moisture made the grass as thick and rich as velvet and "the earth was as soft as a feather bed." And, moreover, the "earth was of such a grace" that it produced plenty of flowers, both winter and summer:

Myriads of birds were singing, too—larks, nightingales, finches, thrushes, doves, and canaries. L'Amant wandered on until he came to a marvelous fountain—the Fountain of Love—under a pine-tree.

Presently he was attracted to a beautiful rosebush, full of buds and full-blown roses. One bud, sweeter and fresher than all the rest and set so proudly on its spray, fascinated him. As he approached this flower, L'Amour discharged five arrows into his heart. The bud, of course, was the woman[Pg 11] he was destined to love and which, after many adventures and trials, he was eventually to pluck and cherish.

This fanciful old allegory made a strong appeal to the illustrators of the Thirteenth and later centuries; and many beautiful editions are prized by libraries and preserved in glass cases. The edition from which the illustration (Fifteenth Century) is taken is from the Harleian MS. owned by the British Museum.

The old trouvères did not hesitate to stop the flow of their stories to describe the delights and beauties of the gardens. Many romantic scenes are staged in the "Pleasance," to which lovers stole quietly through the tiny postern gate in the walls. When we remember what the feudal castle was, with its high, dark walls, its gloomy towers and loop-holes for windows, its cold floors, its secret hiding-places, and its general gloom, it is not surprising that the lords and ladies liked to escape into the garden. After the long, dreary winter what joy to see the trees burst into bloom and the tender[Pg 12] flowers push their way through the sweet grass! Like the birds, the poets broke out into rapturous song, as, for instance, in Richard Cœur de Lion:

[1] Pear.

[2] Birds.

In Chaucer's "Franklyn's Tale" Dorigen goes into her garden to try to divert herself in the absence of her husband:

In the "Roman de Berte" Charles Martel dines in the garden, when the rose is in bloom—que la rose est fleurie—and in "La Mort de Garin" a big dinner-party is given in the garden. Naturally the garden was the place of all places for lovers. In "Blonde of Oxford" Blonde and Jean meet in the garden under a blossoming pear-tree, silvery in the blue[Pg 13] moonlight, and in the "Roman of Maugis et la Belle Oriande" the hero and heroine "met in a garden to make merry and amuse themselves after they had dined; and it was the time for taking a little repose. It was in the month of May, the season when the birds sing and when all true lovers are thinking of their love."

In many of the illuminated manuscripts of these delightful romans there are pictures of ladies gathering flowers in the garden, sitting on the sward, or on stone seats, weaving chaplets and garlands; and these little pictures are drawn and painted with such skill and beauty that we have no difficulty in visualizing what life was like in a garden six hundred years ago.

So valued were these gardens—not only for their flowers but even more for the potential drugs, salves, unguents, perfumes, and ointments they held in leaf and petal, seed and root, in those days when every castle had to be its own apothecary storehouse—that the owner kept them locked and guarded the key. Song, story, and legend are full of incidents of the heroine's trouble in gaining possession of the key of the postern gate in order to meet at midnight her lover who adventurously scaled the high garden wall. The garden was indeed the happiest and the[Pg 14] most romantic spot in the precincts of the feudal castle and the baronial manor-house.

We do not have to depend entirely upon the trouvères and poets for a knowledge of Medieval flowers. A manuscript of the Fifteenth Century (British Museum) contains a list of plants considered necessary for a garden. Here it is: violets, mallows, dandelions, mint, sage, parsley, golds,[3] marjoram, fennel, caraway, red nettle, daisy, thyme, columbine, basil, rosemary, gyllofre,[4] rue, chives, endive, red rose, poppy, cowslips of Jerusalem, saffron, lilies, and Roman peony.

[3] Marigolds.

[4] Gilliflower.

Herbs and flowers were classed together. Many were valued for culinary purposes and for medicinal purposes. The ladies of the castle and manor-house were learned in cookery and in the preparation of "simples"; and they guarded, tended, and gathered the herbs with perhaps even more care than they gave to the flowers. Medieval pictures of ladies, in tall peaked head dresses, fluttering veils, and graceful, flowing robes, gathering herbs in their gardens, are abundant in the old illustrated manuscripts.

It is but a step from this Medieval "Pleasance" to the Shakespeare garden. But before we try to picture what the Tudor gardens were like it will be worth our while to pause for a moment to consider the Renaissance garden of Italy on which the gardens that Shakespeare knew and loved were modeled. No one is better qualified to speak of these than Vernon Lee:

"One great charm of Renaissance gardens was the skillful manner in which Nature and Art were blended together. The formal design of the Giardino segreto agreed with the straight lines of the house, and the walls with their clipped hedges led on to the wilder freer growth of woodland and meadow, while the dense shade of the bosco supplied an effective contrast to the sunny spaces of lawn and flower-bed. The ancient practice of cutting box-trees into fantastic shapes, known to the Romans as the topiary art, was largely restored in the Fifteenth Century and became an essential part of Italian gardens. In that strange romance printed at the Aldine Press in 1499, the Hypernotomachia[Pg 16] of Francesco Colonna, Polyphilus and his beloved are led through an enchanted garden where banquet-houses, temples and statues stand in the midst of myrtle groves and labyrinths on the banks of a shining stream. The pages of this curious book are adorned with a profusion of wood-cuts by some Venetian engraver, representing pergolas, fountains, sunk parterres, pillared loggie, clipped box and ilex-trees of every variety, which give a good idea of the garden artist then in vogue.

"Boccaccio and the Italians more usually employ the word orto, which has lost its Latin signification, and is a place, as we learn from the context, planted with fruit-trees and potherbs, the sage which brought misfortune on poor Simona and the sweet basil which Lisabetta watered, as it grew out of Lorenzo's head, only with rosewater, or that of orange-flowers, or with her own tears. A friend of mine has painted a picture of another of Boccaccio's ladies, Madonna Dianora, visiting the garden which the enamored Ansaldo has made to bloom in January by magic arts; a little picture full of the quaint lovely details of Dello's wedding-chests, the charm of roses and lilies, the flashing fountains and birds singing against a background of wintry trees, and snow-shrouded fields, dainty youths and damsels [Pg 17]treading their way among the flowers, looking like tulips and ranunculus themselves in their fur and brocade. But although in this story Boccaccio employs the word giardino instead of orto, I think we must imagine that magic flower garden rather as a corner of orchard connected with fields of wheat and olive below by the long tunnels of vine-trellis and dying away into them with the great tufts of lavender and rosemary and fennel on the grassy bank under the cherry trees. This piece of terraced ground along which the water spurted from the dolphin's mouth, or the Siren's breasts—runs through walled channels, refreshing impartially violets and salads, lilies and tall, flowering onions under the branches of the peach-tree and the pomegranate, to where, in the shade of the great pink Oleander tufts, it pours out below into the big tank for the maids to rinse their linen in the evening and the peasants to fill their cans to water the bedded out tomatoes and the potted clove-pinks in the shadow of the house.

LOVERS IN THE CASTLE GARDEN, FIFTEENTH CENTURY MS.

GARDEN OF DELIGHT, ROMAUNT OF THE ROSE, FIFTEENTH CENTURY

"The Blessed Virgin's garden is like that where, as she prays in the cool of the evening, the gracious Gabriel flutters on to one knee (hushing the sound of his wings lest he startle her) through the pale green sky, the deep blue-green valley; and you may[Pg 18] still see in the Tuscan fields clumps of cypress, clipped wheel shape, which might mark the very spot."

I may recall here that the early Italian and Flemish painters were fond of representing the Madonna and the Infant Jesus in a garden; and the garden that they pictured was always the familiar little enclosed garden of the period. The flowers that grew there were limited by the Church. Each flower had its significance: the rose and the pink both expressed divine love; the lily, purity; the violet, humility; the strawberry, fruit and blossom, for the fruit of the spirit and the good works of the righteous; the clover, or trefoil, for the Trinity; and the columbine for the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit, because of its dove-shaped petals.

The enclosed garden is ancient indeed.

So sang the esthetic Solomon.

A garden enclosed, a garden of living waters, a garden of perfumes—these are the motives of the Indian gardens of the luxurious Mogul emperors, whose reigns coincide with Tudor times.

Symbolism played an important part in Indian gardens. The beautiful garden of Babar (near Kabul) was called the Bagh-i-vafa—"The Garden of Fidelity." This has many points in common with the illustration of the "Romaunt of the Rose," particularly the high walls.

There is also great similarity with the gardens of Elizabethan days. The "pleached allies" and "knots" of the English gardens of Shakespeare's time find equivalents in the vine pergolas and geometrical parterres of the Mogul emperors; and the central platform of the Mogul gardens answered the same purpose as the banqueting-hall on the mound, which decorated nearly every English nobleman's garden.

Babar's "Garden of Fidelity" was made in the year 1508. We see Babar personally superintending the laying out of the "four-field plot." Two gardeners hold the measuring line and the architect stands by with his plan. The square enclosure at the bottom of the garden (right) is the tank. The whole is bordered with orange and pomegranate trees. An embassy knocks at the gate, but[Pg 20] Babar is too absorbed in his gardening to pay any attention to the guests.

Fifteen years later Babar stole three days away from his campaign against the Afghans and visited his beautiful garden. "Next morning," he wrote in his "Memoirs," "I reached Bagh-i-vafa. It was the season when the garden was in all its glory. Its grass-plots were all covered with clover; its pomegranate trees were entirely of a beautiful yellow color. It was then the pomegranate season and pomegranates were hanging red on the trees. The orange-trees were green and cheerful, loaded with innumerable oranges; but the best oranges were not yet ripe. I never was so much pleased with the 'Garden of Fidelity' as on this occasion."

BABAR'S "GARDEN OF FIDELITY"

Several new ideas were introduced into English gardens in the first quarter of the Sixteenth Century. About 1525 the geometrical beds called "knots" came into fashion, also rails for beds, also mounds, or "mounts," and also arbors. Cardinal Wolsey had all these novelties in his garden at Hampton Court Palace. It was a marvelous garden, as any one who will read Cavendish may see for himself; but Henry VIII was not satisfied with it when he seized the haughty Cardinal's home in 1529. So four years later the King had an entirely new garden made at [Pg 21]Hampton Court (the Privy Garden is on the site now) with gravel paths, beds cut in the grass, and railed and raised mounds decorated with sun-dials. Over the rails roses clambered and bloomed and the center of each bed was adorned with a yew, juniper, or cypress-tree. Along the walls fruit-trees were planted—apples, pears, and damsons—and beneath them blossomed violets, primroses, sweet williams, gilliflowers, and other old favorites.

Toward the end of his reign Henry VIII turned his attention to beautifying the grounds of Nonsuch Palace near Ewell in Surrey. These gardens were worthy of the magnificent buildings. A contemporary wrote: "The Palace itself is so encompassed with parks full of deer, delicious gardens, groves ornamented with trellis-work, cabinets of verdure and walks so embowered with trees that it seems to be a place pitched upon by Pleasure herself to dwell in along with health."

An example of a typical Tudor estate, Beaufort House, Chelsea, later Buckingham House, is said to have been built by Sir Thomas More in 1521 and re[Pg 22]built in 1586 by Sir Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, who died in 1615. The flowers at this period were the same for palace and cottage. Tudor gardens bloomed with acanthus, asphodel, auricula, anemone, amaranth, bachelor's buttons, cornflowers or "bottles," cowslips, daffodils, daisies, French broom (genista), gilliflowers (three varieties), hollyhock, iris, jasmine, lavender, lilies, lily-of-the-valley, marigold, narcissus (yellow and white), pansies or heartsease, peony, periwinkle, poppy, primrose, rocket, roses, rosemary, snapdragon, stock gilliflowers, sweet william, wallflowers, winter cherry, violet, mint, marjoram, and other sweet-smelling herbs.

During "the great and spacious time" of Queen Elizabeth there was an enormous development in gardens. The Queen was extremely fond of flowers and she loved to wear them. It must have pleased her hugely when Spenser celebrated her as "Eliza, Queen of the Shepherds," and painted her portrait in one of the pretty enclosed gardens, seated among the fruit-trees, where the grass was sprinkled with flowers:

So fond was the Queen of gardens that Sir Philip Sidney could think of no better way to please her than to arrange his masque of the "May Lady" so that it would surprise her when she was walking in the garden at Wanstead in Essex. Then, too, in 1591, when visiting Cowdry, Elizabeth expressed a desire to dine in the garden. A table forty-eight yards long was accordingly laid.

The Tudor mansions were constantly growing in beauty. Changes and additions were made to some of them and many new palaces and manor-houses were erected. Architects—among them John Thorpe—and landscape gardeners now planned the pleasure-grounds to enhance the beauty of the mansion they had created, adapting the ideas of the Italian Renaissance to the English taste. The Elizabethan garden in their hands became a setting for the house and it was laid out according to a plan that harmonized with the architecture and continued the lines of the building. The form of the garden and the lay-out of the beds and walks were[Pg 24] deemed of the greatest importance. Flowers, also, took a new place in general estimation. Adventurous mariners constantly brought home new plants and bulbs and seeds from the East and lately discovered America; merchants imported strange specimens from Turkey and Poland and far Cathay; and travelers on the Continent opened their eyes and secured unfamiliar curiosities and novelties. The cultivation of flowers became a regular fad. London merchants and wealthy noblemen considered it the proper thing to have a few "outlandish" flowers in their gardens; and they vied with one another to develop "sports" and new varieties and startling colors.

Listen to what an amateur gardener, William Harrison, wrote in 1593:

"If you look into our gardens annexed to our houses how wonderfully is their beauty increased, not only with flowers and variety of curious and costly workmanship, but also with rare and medicinable herbs sought up in the land within these forty years. How Art also helpeth Nature in the daily coloring, doubling and enlarging the proportion of one's flowers it is incredible to report, for so curious and cunning are our gardeners now in these days that they presume to do in manner what they list[Pg 25] with Nature and moderate her course in things as if they were her superiors. It is a world also to see how many strange herbs, plants and annual fruits are daily brought unto us from the Indies, Americas, Taprobane, Canary Isles and all parts of the world.

"For mine own part, good reader, let me boast a little of my garden, which is but small, and the whole area thereof little above 300 foot of ground, and yet, such hath been my good luck in purchase of the variety of simples, that, notwithstanding my small ability, there are very near 300 of one sort and another contained therein, no one of them being common or usually to be had. If, therefore, my little plat void of all cost of keeping be so well furnished, what shall we think of those of Hampton Court, Nonesuch, Theobald's, Cobham Garden and sundrie others appertaining to divers citizens of London whom I could particularly name?"

Several men of the New Learning, who, like Shakespeare, lived into the reign of James I, advanced many steps beyond the botanists of the early days of Queen Elizabeth. The old Herbals—the[Pg 26] "Great Herbal," from the French (1516) and the "Herbals" published by William Turner, Dean of Wells, who had a garden of his own at Kew, treat of flowers chiefly with regard to their properties and medical uses.

The Renaissance did indeed "paint the lily" and "throw a perfume on the violet"; for the New Age brought recognition of their esthetic qualities and taught scholastic minds that flowers had beauty and perfume and character as well as utilitarian qualities. Elizabeth as Queen had very different gardens to walk in than the little one in the Tower of London in which she took exercise as a young Princess in 1564.

Let us look at some of them. First, that of Richmond Palace. Here the garden was surrounded by a brick wall and in the center was "a round knot divided into four quarters," with a yew-tree in the center. Sixty-two fruit-trees were trained on the wall.

This seems to have been of the old type—the orchard-garden, where a few old favorite flowers bloomed under the trees and in the central "knot," or bed. In the Queen's locked garden at Havering-atte-Bower trees, grass, and sweet herbs seem to have been more conspicuous than the flowers. The[Pg 27] Queen's gardens seem to have been overshadowed by those of her subjects. One of the most celebrated belonged to Lord Burleigh, and was known as Theobald's. Paul Hentzner, a German traveler who visited England in 1598, went to see this garden the very day that Burleigh was buried.

He described it as follows:

"We left London in a coach in order to see the remarkable places in its neighborhood. The first was Theobald's, belonging to Lord Burleigh, the Treasurer. In the Gallery was painted the genealogy of the Kings of England. From this place one goes into the garden, encompassed with a moat full of water, large enough for one to have the pleasure of going in a boat and rowing between the shrubs. Here are great variety of trees and plants, labyrinths made with a great deal of labor, a jet d'eau with its basin of white marble and columns and pyramids of wood and other materials up and down the garden. After seeing these, we were led by the gardener into the summer-house, in the lower part of which, built semicircularly, are the twelve Roman Emperors in white marble and a table of touchstone. The upper part of it is set round with cisterns of lead into which the water is conveyed through pipes so that fish may be kept in them and[Pg 28] in summer time they are very convenient for bathing. In another room for entertainment near this, and joined to it by a little bridge, was an oval table of red marble."

Another and accurate picture of a stately Elizabethan garden is by a most competent authority, Sir Philip Sidney (1554-86), who had a superb garden of his own in Kent. In "Arcadia" we read:

"Kalander one afternoon led him abroad to a well-arrayed ground he had behind his house which he thought to show him before his going, as the place himself more than in any other, delighted in. The backside of the house was neither field, garden, nor orchard; or, rather, it was both field, garden and orchard: for as soon as the descending of the stairs had delivered they came into a place curiously set with trees of the most taste-pleasing fruits; but scarcely had they taken that into their consideration but that they were suddenly stept into a delicate green; on each side of the green a thicket, and behind the thickets again new beds of flowers which being under the trees, the trees were to them a pavilion, and they to the trees a mosaical floor, so that it seemed that Art therein would needs be delightful by counterfeiting his enemy, Error, and making order in confusion. In the midst of all the [Pg 29]place was a fair pond, whose shaking crystal was a perfect mirror to all the other beauties, so that it bare show of two gardens; one in deed and the other in shadows; and in one of the thickets was a fine fountain."

There were many such splendid gardens. Shakespeare was familiar, of course, with those of Warwickshire, including the superb examples at Kenilworth, and with those in the vicinity of London.

The Elizabethans used their gardens in many ways. They took recreation in them in winter and summer, and enjoyed the perfume and colors of their flowers with an intensity of delight and appreciation rarely found to-day. In their gardens the serious and the frivolous walked and talked, and here they were frequently served with refreshments.

It was also a fashion to use the garden as a setting for masques and surprises, such as those Leicester planned on a grand scale to please Queen Elizabeth at Kenilworth. Several of Ben Jonson's entertainments were arranged for performance on the terrace opening from house to garden.

By looking into that mirror of the period,[Pg 30] "Euphues and His England," by John Lyly (1554-1606), we can see two charming ladies in ruffs and farthingales and a gallant in rich doublet and plumed hat walking in a garden, and we gain an idea of the kind of "garden talk" that was comme il faut:

"One of the ladies, who delighted much in mirth, seeing Philautus behold Camilla so steadfastly, said unto him: 'Gentleman, what flower do you like best in all this border? Here be fair Roses, sweet Violets, fragrant Primroses; here be Gilliflowers, Carnations, Sops-in-Wine, Sweet Johns, and what may either please you for sight, or delight you with savor. Loth we are you should have a posie of all, yet willing to give you one, not that which shall look best but such a one as you shall like best.'"

What could Philautus do but bow gallantly and say: "Of all flowers, I love a fair woman."

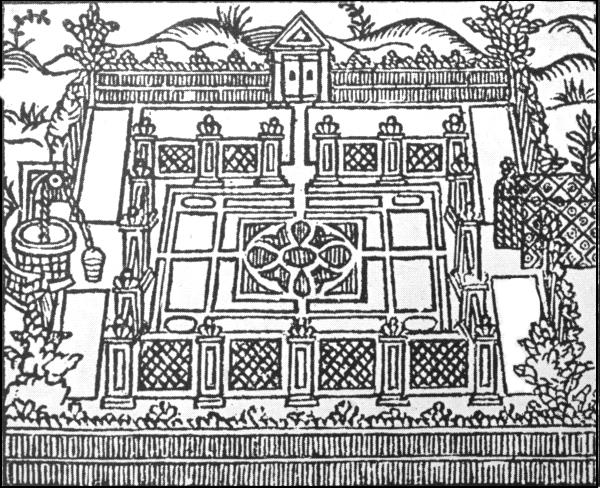

"THE CURIOUS KNOTTED GARDEN"

THE Elizabethan flower garden as an independent garden came into existence about 1595. It was largely the creation of John Parkinson (1567-1650), who seems to have been the first person to insist that flowers were worthy of cultivation for their beauty quite apart from their value as medicinal herbs. Parkinson was also the first to make of equal importance the four enclosures of the period: (1) the garden of pleasant flowers; (2) the kitchen garden (herbs and roots); (3) the simples (medicinal); and (4) the orchard.

One would hardly expect to find such esthetic appreciation of flowers from Parkinson, because he was an apothecary, with a professional attitude toward plants; and our ideas of an Elizabethan apothecary picture a dusty seller of narcotics and "drams of poison," like the old man to whom Romeo and Juliet repaired.

John Parkinson was of a different type. Our portrait illustration depicts him, wearing a stylish Genoa velvet doublet with lace ruff and cuffs, a man who could apparently hold his own in any company of courtiers and men of fashion. Parkinson knew a great many distinguished persons and entertained visitors at his nurseries, where he must have held them spellbound (if he talked as well as he wrote) while he explained the beauties of a new yellow gilliflower, the latest new scarlet martagon lily, or the flower that he so proudly holds in his hand—"the orange-color Nonesuch."

Parkinson's talents were recognized at court, for he was appointed "Apothecary to James I." He had a garden of his own at Long Acre, which he cultivated with enthusiasm, raising new varieties of well-known flowers and tending with care new specimens of foreign importations and exotics—"outlandish flowers" they were called in Shakespeare's day—and, finally, writing about his floral pets with great knowledge, keen observation, poetic insight, and quaint charm. His great book, "Paradisi in Sole; Paradisus Terrestris," appeared in London in 1629, the most original book of botany of the period and the most complete English treatise until Ray came.

JOHN GERARD

PARKINSON AND LOBEL

Although published thirteen years after Shakespeare's [Pg 33]death, Parkinson's book describes exactly the style of gardens and the variety of flowers that were familiar to Shakespeare; and to this book we may go with confidence to learn more intimately the aspect of what we may call the Shakespeare garden. In it we learn to our surprise that horticulture in the late Tudor and early Stuart days was not in the simple state that it is generally supposed to have been in. There were flower fanciers in and near London—and indeed throughout England—and there were expert gardeners and florists.

Parkinson was very friendly with the other London flower growers of whom he speaks cordially in his book and with never the least shadow of jealousy. He frequently mentions visiting the gardens of Gerard, Nicholas Leate, and Ralph Tuggy (or Tuggie).

Everybody has heard of Gerard's "Herbal or General Historie of Plants," published in 1597, for it is one of the most famous ancient books on flowers. A contemporary botanist said that "Gerard exceeded most, if not all of his time, in his care, industry and skill in raising, increasing, and preserving plants." For twenty years Gerard was superintendent of Lord Burleigh's famous gardens—one of which was in the Strand, London, and the other at Theobald's[Pg 34] in Hertfordshire. Gerard also had a garden of his own at Holborn (then a suburb of London), where he raised many rare specimens and tried many experiments. He employed a collector, William Marshall, to travel in the Levant for new plants. Gerard (1545-1607) was a physician, as well as a practical gardener; but, although he possessed great knowledge, he does not appear to have had the esthetic appreciation of flowers that Parkinson had in such great measure. His name is also written Gerade. Gerard's "Herbal" was not the first. Horticulturists could consult the "Grete Herbal," first printed by Peter Treveris in 1516; Fitzherbert, "Husbandry" (1523); Walter Cary, "Herbal" (1525); a translation of Macer's "Herbal" (1530); the "Herbal" by Dodoens, published in Antwerp in 1544; William Turner's "The Names of Herbs in Greke, Latin, Englishe, Duche and Frenche," etc. (1548), reprinted by the English Dialect Society (1881); Thomas Tusser's "Five Pointes of Good Husbandry," etc. (1573), reprinted by the English Dialect Society (1878); Didymus Mountain's (Thomas Hill) "A Most Brief and Pleasant Treatise Teaching How to Sow and Set a Garden" (1563), "The Proffitable Art of Gardening" (1568), and "The Gardener's Labyrinth" (1577);[Pg 35] Barnaby Googe's "Four Books of Husbandry," collected by M. Conradus Heresbachius, "Newly Englished and increased by Barnaby Googe" (1577); William Lawson's "A New Orchard and Garden" (1618); Francis Bacon's "Essay on Gardening" (1625); and John Parkinson's "Paradisi in Sole, Paradisus Terrestris" (1629).

Ralph Tuggie, or Tuggy, so often spoken of by Parkinson, had a fine show garden at Westminster, Where he specialized in carnations and gilliflowers. After his death his widow, "Mistress Tuggie," kept it up.

Another flower enthusiast was the Earl of Salisbury, who placed his splendid garden at Hatfield under the care of John Tradescant, the first of a noted family of horticulturists. John Tradescant also had a garden of his own in South Lambeth, "the finest in England" every one called it. Here Tradescant introduced the acacia; the lilac, called in those days the "Blue Pipe Flower"; and, if we may believe Parkinson, the pomegranate. Among other novelties that attracted visitors to this show garden he had the "Sable Flag," known also as the "Marvel of Peru."

Lord Zouche was another horticulturist of note. His fine garden at Hackney contained plants that[Pg 36] he himself collected on his travels in Austria, Italy, and Spain. Lord Zouche gave his garden into the keeping of the distinguished Mathias de Lobel, a famous physician and botanist of Antwerp and Delft. Lobel was made botanist to James I and had a great influence upon flower culture in England. For him the Lobelia was named—an early instance of naming plants for a person and breaking away from the quaint descriptive names for flowers.

Elizabethan gardens owed much to Nicholas Leate, or Lete, a London merchant who about 1590 became a member of the Levant Company. As a leading merchant in the trade with Turkey and discharging in connection with commercial enterprise the duties of a semi-political character, Leate became wealthy and was thus able to indulge his taste for flowers and anything else he pleased. He had a superb garden and employed collectors to hunt for specimens in Turkey and Syria. His "servant at Aleppo" sent many new flowers to London, such as tulips, certain kinds of lilies,—the martagon, or Turk's Cap, for instance,—irises, the Crown-Imperial, and many new anemones, or windflowers. The latter became the rage, foreshadowing the tulip-mania of later years. Nicholas Leate also imported the yellow Sops-in-Wine, a famous carnation from [Pg 37]Poland, which had never been heard of before in England, and the beautiful double yellow rose from Constantinople. Leate was a member of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, London, and Master of it in 1616, 1626, and 1627, and his portrait, given here, said to be by Daniel Mytens, hung in Ironmongers' Hall in London until this famous building was destroyed by a German bomb in 1917. Leate died in 1630.

NICHOLAS LEATE

Leate, being a most enthusiastic flower fancier and garden lover, not only imported rare specimens but tried many experiments. Indeed we are surprised in going through old garden manuals of Shakespearean days to see how many and how varied were the attempts to produce "sports" and novelties. We read of grafting a rosebush and placing musk in the cleft in an effort to produce musk-roses; recipes for changing the color of flowers; methods for producing double flowers; and instructions for grafting and pruning plants, sowing seeds, and plucking flowers during the increase, or waning, of the moon.

These professional florists and gentlemen amateurs valued their rare specimens from foreign countries as they valued their emeralds from Peru, Oriental pearls from Ceylon and rubies from India. Parkinson says very earnestly:

"Our English gardeners are all, or most of them, ignorant in the ordering of their outlandish[5] flowers, as not being trained to know them. And I do wish all gentlemen and gentlewomen whom it may concern for their own good, to be as careful whom they trust with the planting and replanting of their fine flowers as they would be with so many jewels; for the roots of many of them, being small and of great value, may soon be conveyed away and a clean, fair tale told that such a root is rotten, or perished in the ground, if none be seen where it should be; or else that the flower hath changed in color when it had been taken away, or a counterfeit one had been put in the place thereof; and thus many have been deceived of their daintiest flowers, without remedy or knowledge of the defect."

[5] Exotic.

The influence of the Italian Renaissance upon the Elizabethan garden has already been shown (see page 15), but the importance of this may be appropriately recalled here in the following extract from Bloom:

"The Wars of the Roses gave little time for gardening; and when matters were settled and the educational movements which marked the dawn of the Renaissance began, the gardens once again, after a[Pg 39] break of more than a thousand years, went back to classical models, as interpreted by the Italian school of the time. Thus the gardens of the Palace of Nonesuch (1529) and Theobald's (1560) showed all the new ideas: flower-beds edged with low trellises, topiary work of cut box and yew, whereby the natural growth of the trees was trained into figures of birds and animals and especially of peacocks; while here and there mounts were thrown up against the orchard or garden wall, ascended by flights of steps and crowned with arbors, while sometimes the view obtained in this manner was deemed insufficient and trellised galleries extended the whole length of the garden. In 1573 the gardens of Kenilworth, which Shakespeare almost certainly visited, had a terrace walk twelve feet in width and raised ten feet above the garden, terminating at either end in arbors redolent with sweetbrier and flowers. Beneath these again was a garden of an acre or more in size divided into four quarters by sanded walks and having in the center of each plot an obelisk of red porphyry with a ball at the top. These were planted with apple, pear and cherry while in the center was a fountain of white marble."

The Elizabethan garden was usually four-square, bordered all around by hedges and intersected by paths. There was an outer hedge that enclosed the entire garden and this was a tall and thick hedge made of privet, sweetbrier, and white thorn intermingled with roses. Sometimes, however, this outer hedge was of holly. Again some people preferred to enclose their garden by a wall of brick or stone. On the side facing the house the gate was placed. In stately gardens the gate was of elaborately wrought iron hung between stone or brick pillars on the top of which stone vases, or urns, held brightly blooming flowers and drooping vines. In simple gardens the entrance was a plain wooden door, painted and set into the wall or hedge like the quaint little doors we see in England to-day and represented in Kate Greenaway's pictures that show us how the style persists even to the present time.

Stately gardens were usually approached from a terrace running along the line of the house and commanding a view of the garden, to which broad flights of steps led. Thence extended the principal walks,[Pg 41] called "forthrights," in straight lines at right angles to the terrace and intersected by other walks parallel with the terrace. The lay-out of the garden, therefore, corresponded with the ground-plan of the mansion. The squares formed naturally by the intersection of the "forthrights" and other walks were filled with curious beds of geometrical patterns that were known as "knots"; mazes, or labyrinths; orchards; or plain grass-plots. Sometimes all of the spaces or squares were devoted to "knots." These ornamental flower-beds were edged with box, thrift, or thyme and were surrounded with tiny walks made of gravel or colored sand, walks arranged around the beds so that the garden lovers might view the flowers at close range and pick them easily.

It will be remembered that in "Love's Labour's Lost" Shakespeare speaks of "the curious knotted garden." There are innumerable designs for these "knots" in the old Elizabethan garden-books, representing the simple squares, triangles, and rhomboids as well as the most intricate scrolls, and complicated interlacings of Renaissance design that resemble the motives on carved furniture, designs for textiles and ornamental leather-work (known as strap-work, or cuirs). Yet these many hundreds of designs were not sufficient, for the amateur as well as the profes[Pg 42]sional gardener often invented his own garden "knots."

Where the inner paths intersected, a fountain or a statue or some other ornament was frequently placed. Sometimes, too, vases, or urns, of stone or lead, were arranged about the garden in formal style inspired by the taste of Italy. Sometimes, also, large Oriental or stone jars were placed in conspicuous spots, and these were not only intended for decoration but served as receptacles for water.

There were four principles that were observed in all stately Elizabethan gardens. The first was to lay out the garden in accordance with the architecture of the house in long terraces and paths of right lines, or "forthrights," to harmonize with the rectangular lines of the Tudor buildings, yet at the same time to break up the monotony of the straight lines with beds of intricate patterns, just as in the case of architecture bay-windows, clustered and twisted chimneys, intricate tracery, mullioned windows, and ornamental gables relieved the straight lines of the building.

The second principle was to plant the beds with mixed flowers and to let the colors intermingle and blend in such a way as to produce a mosaic of rich,[Pg 43] indeterminate color, ever new and ever varying as the flowers of the different seasons succeeded each other.

The third principle was to produce a garden of flowers and shrubs for all seasons, even winter, that would tempt the owner to take pleasure and exercise there, where he might find recreation, literally re-creation of mind and body, and become freshened in spirit and renewed in health.

The fourth principle was to produce a garden that would give delight to the sense of smell as well as to the sense of vision—an idea no longer sought for by gardeners.

Hence it was just as important, and infinitely more subtle, to mingle the perfumes of flowers while growing so that the air would be deliciously scented by a combination of harmonizing odors as to mingle the perfumes of flowers plucked for a nosegay, or Tussie-mussie, as the Elizabethans sometimes quaintly called it.

Like all cultivated Elizabethans, Shakespeare appreciated the delicious fragrance of flowers blooming in the garden when the soft breeze is stirring their leaves and petals. There was but one thing to which this subtle perfume might be compared and that was[Pg 44] ethereal and mysterious music. For example, the elegant Duke in "Twelfth Night," reclining on his divan and listening to music, commands:

Lord Bacon also associated the scent of delicate flowers with music. He writes: "And because the breath of flowers is far sweeter in the air (whence it comes and goes like the warbling of music) than in the hand, therefore nothing is more fit for delight than to know what be the flowers and plants that do best perfume the air. Roses, damask, and red, are fast flowers of their smells, so that you may walk by a whole row of them and find nothing of their sweetness, yea though it be in a morning's dew. Bays, likewise, yield no smell as they grow, rosemary little, nor sweet marjoram. That which above all others yields the sweetest smell in the air is the violet, especially the white double violet, which comes twice a year—about the middle of April and about Bartholomew-tide. Next to that is the musk-rose, then the strawberry leaves dying, which yield a most excellent cordial smell, then the flower of the vines, it is a little dust, like the dust of a bent, [Pg 45]which grows upon the cluster in the first coming forth; then sweetbrier, then wall-flowers, which are very delightful to be set under a parlor or lower chamber window; then pinks and gilliflowers; then the flowers of the lime-tree; then the honeysuckles, so they be somewhat afar off; of bean flowers, I speak not, because they are field flowers. But those which perfume the air most delightfully not passed by as the rest but being trodden upon and crushed are three: burnet, wild thyme and water-mints. Therefore, you are to set whole alleys of them to have the pleasure when you walk or tread."

Shakespeare very nearly follows Bacon's order of perfume values in his selection of flowers to adorn the beautiful spot in the wood where Titania sleeps. Oberon describes it:

Fairies were thought to be particularly fond of thyme; and it is for this reason that Shakespeare carpeted the bank with this sweet herb. Moreover, as we have just seen, Bacon tells us that thyme is[Pg 46] one of those plants which are particularly delightful if trodden upon and crushed. Shakespeare accordingly knew that the pressure of the Fairy Queen's little body upon the thyme would cause it to yield a delicious perfume.

The Elizabethans, much more sensitive to perfume than we are to-day, appreciated the scent of what we consider lowly flowers. They did not hesitate to place a sprig of rosemary in a nosegay of choice flowers. They loved thyme, lavender, marjoram, mints, balm, and camomile, thinking that these herbs refreshed the head, stimulated the memory, and were antidotes against the plague.

The flowers in the "knots" were perennials, planted so as to gain uniformity of height; and those that had affinity for one another were placed side by side. No attempt was made to group them; and no attempt was made to get masses of separate color, what Locker-Lampson calls "a mist of blue in the beds, a blaze of red in the celadon jars" and what we try for to-day. On the contrary, the Elizabethan gardener's idea was to mix and blend the flowers into a combination of varied hues that melted into one another as the hues of a rainbow blend and in such a way that at a distance no one could possibly tell what flowers produced this effect. This must[Pg 47] have required much study on the part of the gardeners, who kept pace with the seasons and always had their beds in bloom. Sir Henry Wotton, Ambassador to Venice in the reign of James I, and author of the "Elements of Architecture," but far better known by his lovely verse to Elizabeth of Bohemia beginning, "You meaner beauties of the night," was an ardent flower lover. He was greatly impressed by what he called "a delicate curiosity in the way of color":

"Namely in the Garden of Sir Henry Fanshaw at his seat in Ware Park, where I well remember he did so precisely examine the tinctures and seasons of his flowers that in their settings, the inwardest of which that were to come up at the same time, should be always a little darker than the outmost, and so serve them for a kind of gentle shadow, like a piece not of Nature but of Art."

Browne also gives a splendid idea of the color effect of the garden beds of this period:

By the side of the showy and stately flowers, as well as in kitchen gardens, were grown the "herbs of grace" for culinary purposes and the medicinal herbs for "drams of poison." Rosemary—"the cheerful Rosemary," Spenser calls it—was trained over arbors and permitted to run over mounds and banks as it pleased. Sir Thomas More allowed it to run all over his garden because the bees loved it and because it was the herb sacred to remembrance and friendship.

In every garden the arbor was conspicuous. Sometimes it was a handsome little pavilion or summer-house; sometimes it was set into the hedge; sometimes it was cut out of the hedge in fantastic topiary work; sometimes it was made of lattice work; and[Pg 49] sometimes it was formed of upright or horizontal poles, over which roses, honeysuckle, or clematis (named also Lady's Bower because of this use) were trained. Whatever the framework was, plain or ornate, mattered but little; it was the creeper that counted, the trailing vines that gave character to the arbor, that gave delight to those who sought the arbor to rest during their stroll through the gardens, or to indulge in a pleasant chat, or delightful flirtation. Shakespeare's arbor for Titania

was not unusual. Nor was that retreat where saucy Beatrice was lured to hear the whisperings of Hero regarding Benedick's interest in her. It was a pavilion

Luxuriant and delicious was this bower with the flowers hot and sweet in the bright sunshine.

Eglantine was, perhaps, the favorite climber for arbors and bowers. Browne speaks of

Barnfield, in "The Affectionate Shepherd," pleads:

And in Spenser's "Bower of Bliss":

A beautiful method of obtaining shady walks was to make a kind of continuous arbor or arcade of trees, trellises, and vines. This arcade was called poetically the "pleached alley."[6] For the trees, willows, limes (lindens), and maples were used, and the vines were eglantine and other roses, honeysuckle (woodbine), clematis, rosemary, and grapevines.

[6] Pleaching means trimming the small branches and foliage of trees, or bushes, to bring them to a regular shape. Certain trees only are submissive to this treatment—holly, box, yew privet, whitethorn, hornbeam, linden, etc., to make arbors, hedges, bowers, colonnades and all cut-work.

"Plashing is the half-cutting, or dividing of the quick growth almost to the outward bark and then laying it orderly in a slope manner as you see a cunning hedger lay a dead hedge and then with the smaller and more pliant branches to wreath and bind in the tops." Markham, "The County Farm" (London, 1616).

Another feature of the garden was the maze, or[Pg 51] labyrinth. It was a favorite diversion for a visitor to puzzle his way through the green walls, breast high, to the center; and the owner took delight in watching the mistakes of his friend and was always ready to give him the clue. When James I on his "Southern Progress" in 1603 visited the magnificent garden known as Theobald's and belonging to Lord Burleigh, where we have already seen[7] Gerard was the horticulturist, the King went into the labyrinth of the garden "where he re-created himself in the meanders compact of bays, rosemary and the like, overshadowing his walk."

The labyrinth, or maze, was a fad of the day. It still exists in many English gardens that date from Elizabethan times and is a feature of many more recent gardens. Perhaps of all mazes the one at Hampton Court Palace is the most famous.

The orchard was another feature of the Elizabethan garden. It was the custom for gentlemen to retire after dinner (which took place at eleven o'clock in the morning) to the garden arbor, or to the orchard, to partake of the "banquet" or dessert. Thus Shallow addressing Falstaff after dinner exclaims:

"Nay, you shall see mine orchard, where, in an[Pg 52] arbor, we will eat a last year's pippin of my own grafting with a dish of carraways and so forth."[8]

[8] "King Henry IV"; Part II, Act V, Scene III.

The uses of the Elizabethan garden were many: to walk in, to sit in, to dream in. Here the courtier, poet, merchant, or country squire found refreshment for his mind and recreation for his body. The garden was also intended to supply flowers for nosegays, house decoration, and the decoration of the church. Sweet-smelling herbs and rushes were strewn upon the floor as we know by Grumio's order for Petruchio's homecoming in "The Taming of the Shrew." One of Queen Elizabeth's Maids of Honor had a fixed salary for keeping fresh flowers always in readiness. The office of "herb-strewer to her Majesty the Queen" was continued as late as 1713, through the reign of Anne and almost into that of George I.

The houses were very fragrant with flowers in pots and vases as well as with the rushes on the floor. Flowers were therefore very important features in house decoration. A Dutch traveler, Dr. Leminius, who visited England in 1560, was much struck by this and wrote:

"Their chambers and parlors strewed over with sweet herbs refreshed me; their nosegays finely in[Pg 53]termingled with sundry sorts of fragrant flowers in their bed-chambers and private rooms with comfortable smell cheered me up and entirely delighted all my senses."

We have only to look at contemporary portraits to see how essential flowers were in daily life. For instance, Holbein's "George Gisze," a London merchant, painted in 1523, has a vase of choice carnations beside him on the table filled with scales, weights, and business paraphernalia.

The Elizabethan lady was just as learned in the medicinal properties of flowers and herbs as her Medieval ancestor. She regarded her garden as a place of delight and at the same time as of the greatest importance in the economic management of the household.

"The housewife was the great ally of the doctor: in her still-room the lady with the ruff and farthingale was ever busy with the preparation of cordials, cooling waters, conserves of roses, spirits of herbs and juleps for calentures and fevers. All the herbs and flowers of the field and garden passed through her fair white hands. Poppy-water was good for weak stomachs; mint and rue-water was efficacious for the head and brain; and even walnuts yielded a cordial. Then there was cinnamon water and the[Pg 54] essence of cloves, gilliflower and lemon water, sweet marjoram water and the spirit of ambergris.

"These were the Elizabethan lady's severer toils, besides acres of tapestry she had always on hand. Her more playful hours were devoted to the manufacture of casselettes, month pastilles, sweet waters, odoriferant balls and scented gums for her husband's pipe (God bless her!) and there were balsams and electuaries for him to take to camp, if he were a soldier fighting in Ireland or in the Low Countries, and wound-drinks if he was a companion of Frobisher and bound against the Spaniard, or the Indian pearl-diver of the Pacific. She had a specific which was of exceeding virtue in all swooning of the head, decaying of the spirits, also in all pains and numbness of joints and coming of cold.

"That wonderful still-room contains not only dried herbs and drugs, but gums, spices, ambergris, storax and cedar-bark, civet and dried flowers and roots. In that bowl angelica, carduus benedictus (Holy Thistle), betony, juniper-berries and wormwood are steeping to make a cordial-water for the young son about to travel; and yonder is oil of cloves, oil of nutmegs, oil of cinnamon, sugar, ambergris and musk, all mingling to form a quart of[Pg 55] liquor as sweet as hypocras. Those scents and spices are for perfumed balls to be worn round the ladies' necks, there to move up and down to the music of sighs and heart-beating, envied by lovers whose letters will perhaps be perfumed by their contact.

"What pleasant bright London gardens we dream of when we find that the remedy for a burning fever is honeysuckle leaves steeped in water, and that a cooling drink is composed of wood sorrel and Roman sorrel bruised and mixed with orange juice and barley-water. Mint is good for colic; conserves of roses for the tickling rheum; plaintain for flux; vervain for liver-complaint—all sound pleasanter than those strong biting minerals which now kill or cure and give nature no time to heal us in her own quiet way."[9]

[9] Thornbury.

Bacon's "Essay on Gardening" is very detailed and very practical, and it must be remembered that he was addressing highly cultivated and skilfully trained amateurs and professional gardeners when he wrote:

"God almighty first planted a garden; and indeed it is the purest of human pleasures; it is the greatest refreshment to the spirit of man. And a man shall[Pg 56] ever see that when ages grow to civility and elegancy men come to build stately sooner than to garden finely, as if gardening were the greater perfection."

The Elizabethan Age, with its superlatively cultivated men and women, was certainly one of those ages of civility and elegancy of which Bacon speaks. The houses were stately and the gardens perfection, affording appropriate setting for the brilliant courtiers and accomplished ladies of both Tudor and early Stuart times.

We sometimes hear it said that Francis Bacon's garden was his ideal of what a garden should be and that his garden was never realized. This, however, is not the case. Old prints are numerous of gardens of wealthy persons in the reign of Elizabeth and James I. Then, too, we have Sir William Temple's description of Moor Park, and "this garden," says Horace Walpole, "seems to have been made after the plan laid down by Lord Bacon in his Forty-sixth Essay."

Sir William's account is as follows:

"The perfectest figure of a garden I ever saw, either at home or abroad, was that of Moor Park in Hertfordshire, when I knew it about thirty years ago. It was made by the Countess of Bedford, esteemed among the perfectest wits of her time and [Pg 57]celebrated by Dr. Donne; and with very great care, excellent contrivance and much cost.

"Because I take the garden I have named to have been in all kinds the most beautiful and perfect, at least in the figure and disposition, that I have ever seen, I will describe it for a model to those that meet with such a situation and are above the regards of common expense.