England. I. [LHS]

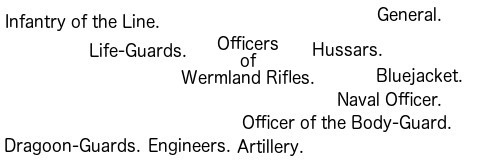

Title: The Armies of Europe

Author: Fedor von Köppen

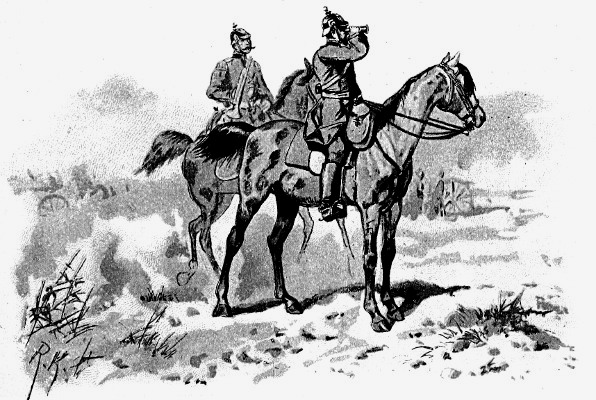

Illustrator: Richard Knötel

Translator: Lord Edward Gleichen

Release date: February 10, 2020 [eBook #61365]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Brian Coe, David Tipple, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924030725836 |

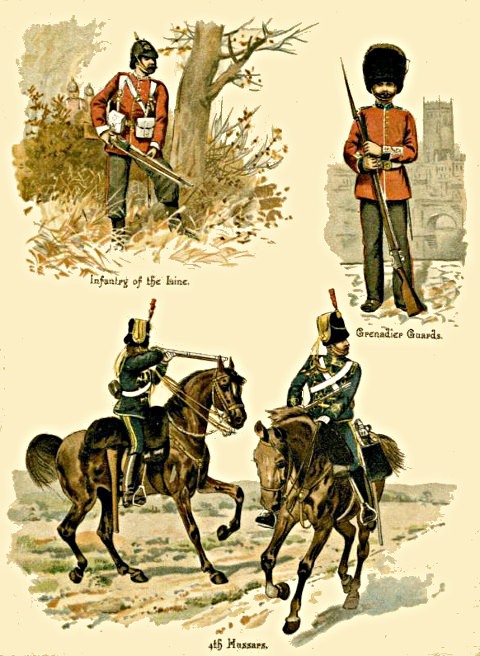

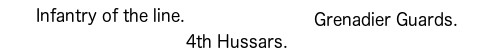

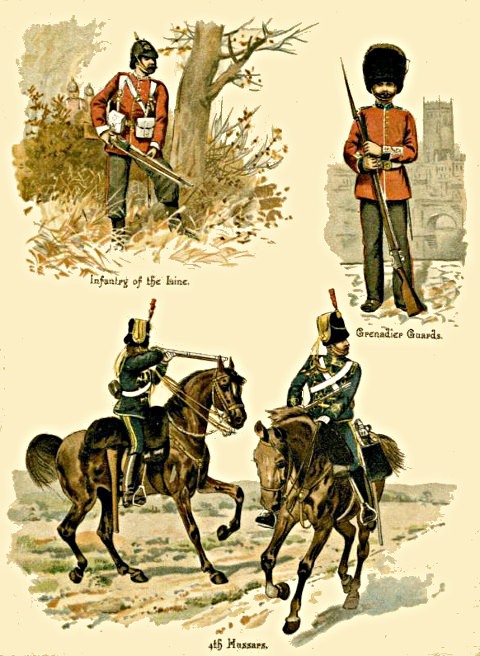

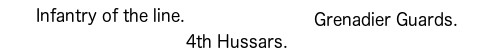

England. I. [LHS]

England. I. [RHS]

ILLUSTRATED.

TRANSLATED AND REVISED BY

COUNT GLEICHEN,

Grenadier Guards,

FROM THE GERMAN OF FEDOR VON KÖPPEN.

ILLUSTRATED BY RICHARD KNÖTEL.

LONDON:

WILLIAM CLOWES & SONS,

Limited,

13, CHARING CROSS, S.W.

1890.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

| PAGE | |

| Contents | iii |

| Preface | v |

| Translator’s Preface | vii |

| Army of the British Empire | 1 |

| The German Army | 20 |

| Austria-Hungary | 36 |

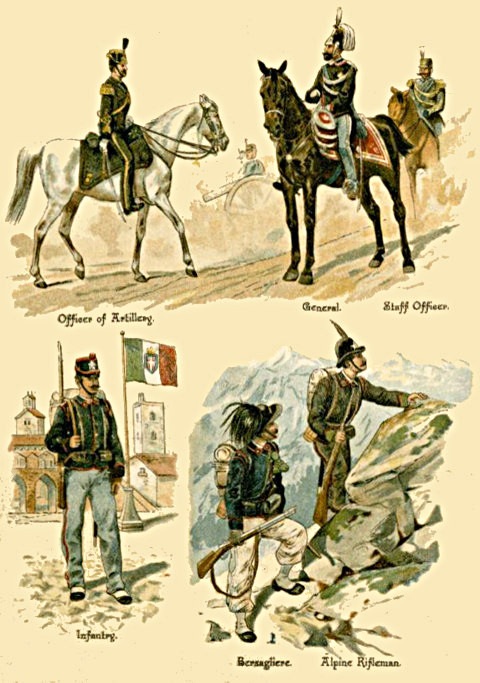

| Italy | 42 |

| France | 46 |

| Russia | 53 |

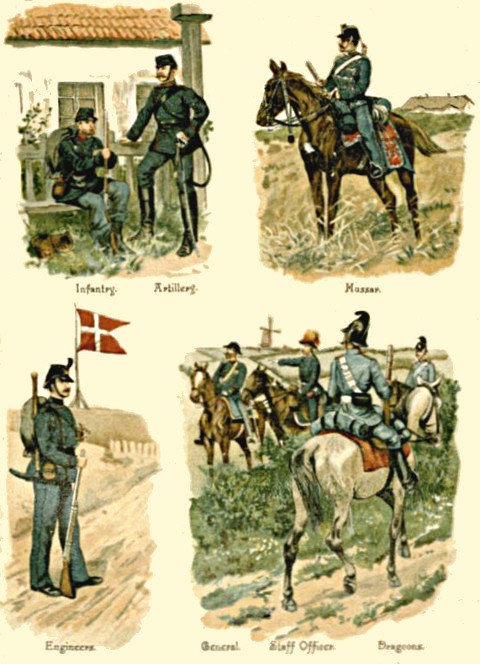

| Denmark | 59 |

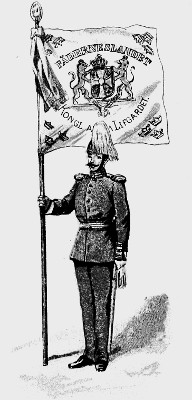

| Sweden and Norway | 61 |

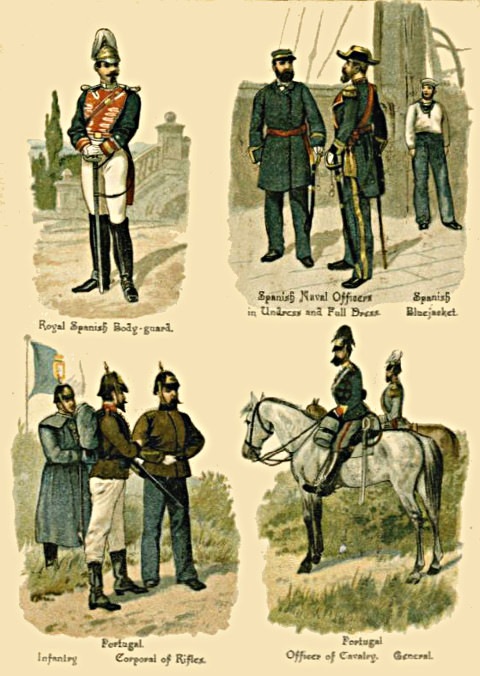

| Spain and Portugal | 64 |

| Switzerland | 67 |

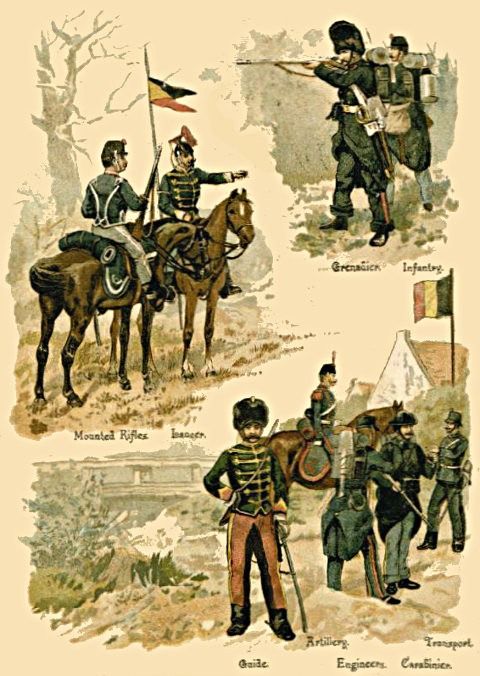

| Holland and Belgium | 69 |

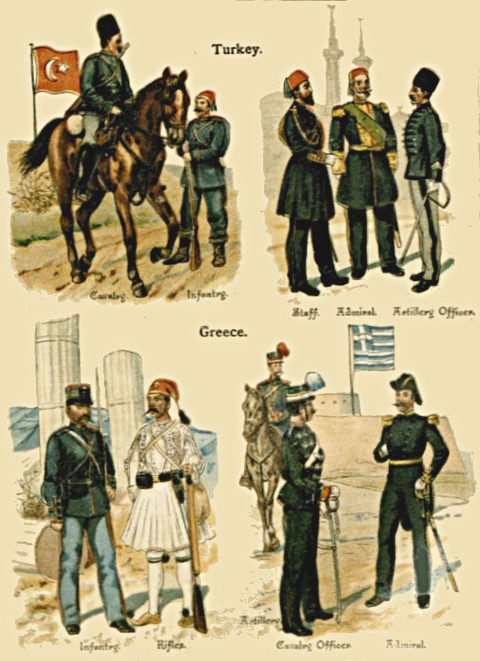

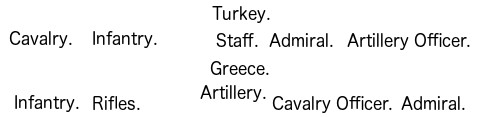

| Turkey and the States of the Balkan Peninsula | 73 |

| Appendix (Navies) | 79 |

A list of all the illustrations has been added to this ebook.

Here

is a link to it: Illustrations

“Si vis pacem, para bellum!”

“Let him who is desirous of peace prepare himself for war.” Thus runs the proverb which sums up the experiences and history of the most powerful Empire of old. If this maxim held good in the old Roman days, how much more applicable is it to the present time, when war-clouds are darkening the horizon, and threaten to burst in ruin and devastation on all nations who have not heeded the warning! There are, however, few who have not heeded it, and the governments of all nations have been for some time, and are still, reorganising their Armies and bringing them to a high state of efficiency in accordance with the experience taught them by the great wars of the last thirty years.

It is therefore necessary for all who take an interest in military matters, or in foreign politics, to become acquainted with the strength and organisation of the armed forces of the different European Powers, for it is only by a study of these Armies that we get to know the relative value of our own.

The matter contained in the following pages has been corrected up to date. The Corrigenda at the end of Germany, France, Italy, and Russia, refer to the alterations that have taken place during the progress of this work through the press.

A few words of the original text, such as “Landwehr” and “Ersatz,” have been retained in the translation, although applied to other than German countries. For their meaning, v. “The German Army,” p. 21, etc. There are no corresponding English words.

G.

November, 1890.

England. II. [LHS]

England. II. [RHS]

The British Army is constructed on a purely original system. It is like no other army in the world, and for this very good reason, that there is no empire in the world like the British Empire.

Great Britain and Ireland alone do not constitute the Empire. India, Australia, Canada, the Cape, and shoals of other colonies in every quarter of the globe, all help to build it up, and for its defence we must have an Imperial Army constructed to fit it. Let us see what we have got.

The first thing that strikes us about the Army is that, although of a decent size, it is not by any means too large—in fact, some people say that it is nothing like large enough. That, however, is a question which chiefly concerns the British taxpayer and his pocket, and with which we have nothing to do at this moment, so we will confine ourselves to contemplating its actual size.

The Empire contains, roughly, over 9,000,000 of square miles, and over 326,000,000 of inhabitants. To defend these we have an Army which numbers roughly as follows:—

| Regular Forces | 202,000 |

| 1st and 2nd Class Reserves | 57,000 |

| Militia and Militia Reserve | 134,000 |

| Yeomanry | 11,000 |

| Volunteers | 224,000 |

| Colonial Forces | 84,000 |

| Indian Native Army | 152,000 |

altogether, 864,000 men at the outside. This apparently large number, however, includes every single able-bodied man, British or Native, who has been trained to bear arms: the Regular Army forms not quite a quarter of it. Taken altogether, this gives an average of about 1 combatant to 350 non-combatants—not a large proportion. Germany’s proportion is 1 to 99. This is a large proportion, it is true, but then she is threatened by powerful enemies on her eastern and western frontiers, whereas we are an island, and look to our Navy as the first line of defence. This being so, we can do with a moderately small Army, and need not (yet) have recourse to the system of all other European countries—namely, universal conscription.

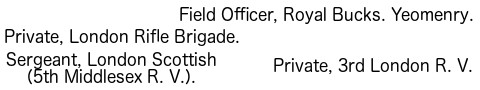

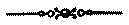

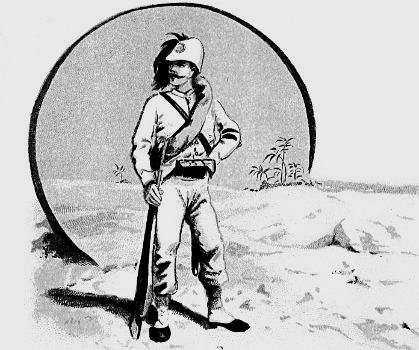

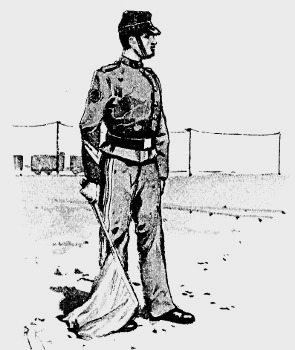

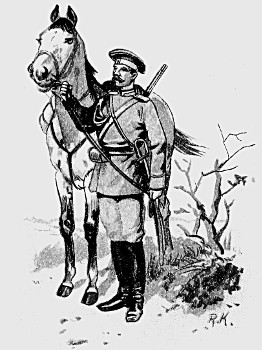

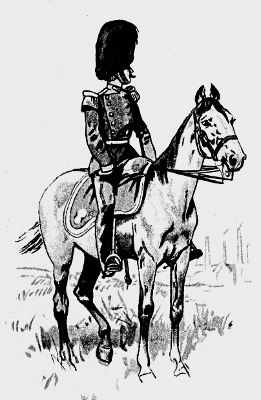

Mounted Infantry.

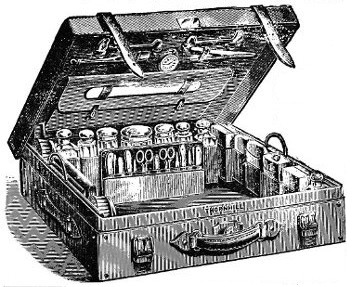

(Tropical Field Kit.)

It is absolutely necessary, however, that we should follow the principle which underlies the military systems of all countries, whether their armies are composed of conscripts or not. This principle is that of keeping a small number of troops under arms in peace-time, with a large reserve of [Pg 2] trained men ready to be called out in case of war. In our case, the small number under arms in peace-time is represented by the Active Army, both British, Indian, and Colonial,[2] and the large reserve by the 1st and 2nd Class Army Reserves, the Militia, the Militia Reserve, the Yeomanry, and the Volunteers.

Before starting on the details of these different forces, it would be as well to give the mode of enlistment and terms of service of the British soldier, with a slight sketch of his history.

The system of recruitment throughout the Army is that of voluntary enlistment. As mentioned above, we are the only country in Europe whose soldiers are thus enlisted. The subjects of all other European countries are liable to be enrolled in the army whether they like it or not, and, as a rule, they do not like it. This voluntary enlistment is a great advantage for us in one way, in that only those need be soldiers who want to be; but, on the other hand, the strength of our Army is chiefly dependent on the number of men who happen to fancy soldiering, and this is hardly a matter for congratulation. Up till now, the system has sufficed: let us hope we shall never have to change it.

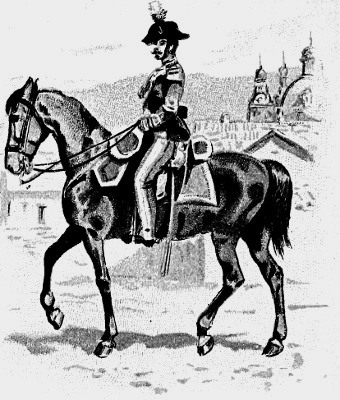

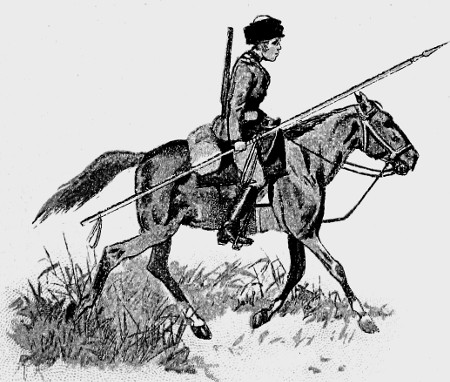

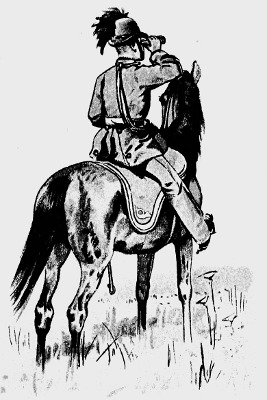

Cavalry.

(Tropical Field Kit.)

It is not generally known that there exists an Act[3] which has to be suspended annually by Parliament (or else it would now be in force), by which the Crown is empowered to raise by ballot as many men as may be necessary for the Army. In other words, the country is liable to conscription, as far as may be determined by the Crown’s advisers. This Act has, however, not been enforced since 1815. N.B.—This mode of raising troops must not be confounded with the “Embodiment of the Militia,” of which more hereafter.

Officers of Highland Light

Infantry and

Argyll and

Sutherland Highlanders.

Recruiting[Pg 3] is carried out by paid recruiters (non-commissioned officers) in the different districts. Formerly, the recruiting-sergeant used to clinch the bargain with the would-be recruit by presenting him with a shilling, on which the recruit usually got drunk. The “Queen’s Shilling” has, however, been done away with, and the recruit has now to get drunk at his own expense.

After going through certain formalities and answering certain questions before a magistrate, the recruit signs his “attestation-paper,” and is then considered as enlisted.

The terms of service are, as a rule, seven years with the colours and five years thereafter in the Reserve. There are a few exceptions to this; men joining the Household Cavalry, Colonial Corps,[4] and one or two other smaller branches of the Service, enlist for twelve years with the colours; men for the Royal Engineers or Foot Guards have the alternative of the usual term, or three years with the colours and nine years in the Reserve; whilst the Army Service Corps and Medical Staff Corps men and a few others serve for only three years with the colours and a varying term of years in the Reserve.

Recruits, at the date of their enlistment, must have the physical equivalent of 19 years of age, must be at least 5 ft. 4 in. high, and must have a minimum chest-measurement of 33 inches.[5]

Re-engagements up to seven or twelve years with the colours are permitted in most, and up to twenty-one years in special, cases.

At a very early period of English history every able-bodied man was bound to take up arms in the event of a civil war or invasion. He was, however, only liable to serve in his own county. This force thus formed was called the General Levy.

During the Middle Ages the feudal system was in force, i.e., the retainers, tenants, and vassals of every knight were required to attend their master if he went to fight abroad. The knights in their turn were bound to attend the king when he went to fight abroad, and thus a very respectable army was formed for the time being. This army, i.e., the knights and their followers, was called the Feudal Levy. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, members of the General Levy were told off for the service and defence of the Crown. They were trained and exercised in the profession of arms, and received the name of Trained Bands. The Honourable Artillery Company, a similar force, was raised about this time. The Sovereign could, if necessary, hire additional mercenary soldiers to assist him in war, and these were paid by Parliament. The Civil War, however, in Charles I.’s reign, upset the general military system, and for some time there was no National Army.

Officer, 5th (Northumberland)

Fusiliers.

On the Restoration, in 1660, considerable changes and improvements took place. The Feudal Levy was abolished, the General Levy became the Militia, and the foundations were laid of the present Standing Army.

It may be news to some people that the “raising or keeping a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace is against law,” but such is the fact. Parliament has every year to specially notify its consent to a standing army; otherwise the Army would cease to exist.

Since Charles II.’s time, the Standing Army has gradually been increasing and improving. Voluntary enlistment dates from his reign, but it apparently has not always been sufficiently productive of men, for we find in the last century that debtors and criminals were obliged to serve in the ranks, in order to keep the Army up to strength. The pressgang was also in force till 1780. It is hardly astonishing then that some, nay, a great many, ill-educated people have been taught, by means of traditions handed down from their great-grandfathers, to look upon the Army as a sink of iniquity, and that they still hold extraordinary and utterly unreasonable views on the subject. They need be under no apprehension about letting their sons and relations enlist. The Army is now composed of a very good class of men, drawn chiefly from the labouring and not from the criminal classes (as some people seem to imagine). The proportion of educated recruits is rapidly increasing, a better class of men is now enlisting, and the military crime of to-day is absurdly small as compared with that of twenty years ago, and is still decreasing.

The Active Army is divided into—

1. The Regular Army consists of Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, and Infantry; besides these are the non-combatant branches, [Pg 5] consisting of the Army Service Corps, the Ordnance Store Corps, the Medical Staff Corps, the Pay, Medical, Chaplains, and Veterinary Departments, and a few more.

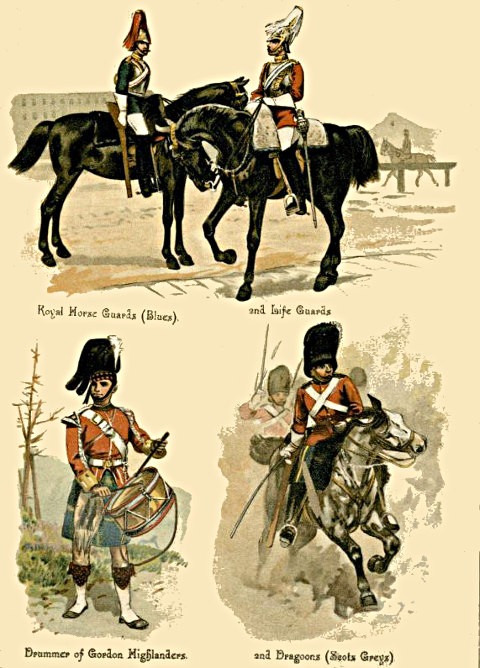

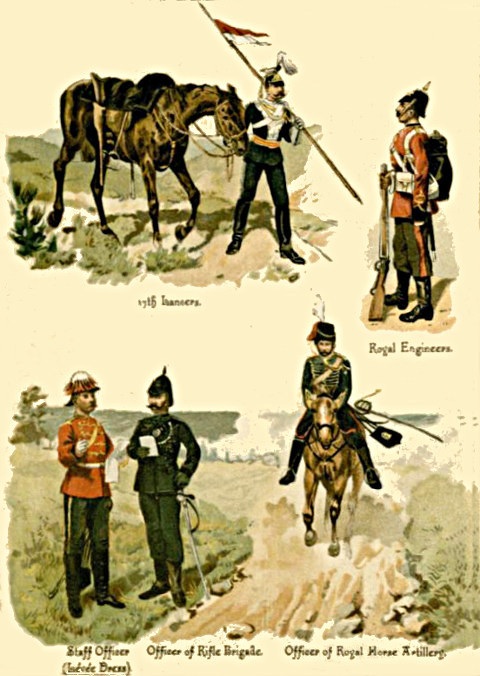

The Cavalry consists of 31 regiments, including—

| 2 | Regiments of Life Guards (Household Cavalry). |

| 1 | Regiment of Royal Horse Guards (Blues) (Household Cavalry). |

| 7 | Regiments of Dragoon Guards (1st to 7th). |

| 3 | Regiments of Dragoons (1st, 2nd, and 6th). |

| 5 | Regiments of Lancers (5th, 9th, 12th, 16th, and 17th). |

| 13 | Regiments of Hussars (3rd, 4th, 7th, 8th, 10th, 11th, 13th to 15th, and 18th to 21st inclusive). |

The British Cavalry is the smartest in the world. In the Cavalry of nearly all foreign armies, Germany for instance, and France, the horses are trained to a degree that is unheard of in the English arm; thus their men require but little skill in riding, and may be described as good soldiers on horseback. Ours, on the contrary, are born horsemen, and do not need to have their horses so thoroughly trained. The consequence is that when our men find themselves in a predicament not provided for by the Regulations, their natural qualities stand them in good stead, and by their brilliant riding and dash they turn to good account a situation which might otherwise offer serious difficulties. The British Cavalry is divided into Heavy, Medium, and Light, according to the size and weight of the men. The Household Cavalry, 1st and 2nd Dragoons, are heavy, and are never quartered abroad, the Hussars are light, and all the rest are medium Cavalry.

Sergeant-Drummer,

Coldstream Guards.

The Life Guards, Dragoon Guards (except the 6th), Dragoons, and 16th Lancers wear scarlet, the remainder of the Cavalry dark blue, tunics.

The Life Guards and Blues are the only regiments who wear cuirasses, and these they would probably leave behind on active service. They, the Dragoon Guards and the Dragoons (except the 2nd Scots Greys, who wear bearskins), wear steel or brass helmets, with plumes varying in colour according to the regiment. The Lancers wear the well-known Lancer cap, with the scarlet[6] “plastron” in front of their tunics. The Hussars wear the busby, with busby-bag and plume of different colours according to the regiment; and they have also six rows of yellow braid across the front of the tunic. All the Cavalry wear dark blue pantaloons[7] or overalls, with red, white, or yellow stripes, and the Household Cavalry has in addition white leather breeches and jackboots for full dress. The Cavalry forage-cap is a small round one, and always worn over the right ear.

Their arms are sword and carbine throughout; the Lancer regiments in addition carry the lance of male bamboo, and with a red and white pennon. The Cavalry carbine is of the Martini-Henry pattern, with a bore of ·450 in.; it is sighted up to 1,000 yds., and is a first-rate little weapon.

The establishment of a Cavalry Squadron (2 troops) in the field is:—

| 6 | officers, |

| 16 | non-commissioned officers, and |

| 122 | rank and file, of whom 26 are dismounted, and |

| 144 | horses, including draught-horses. |

A Regiment (4 squadrons) is composed of:—

| 1 | lieutenant-colonel, |

| 3 | majors, |

| 6 | captains, |

| 16 | subalterns, and 6 other officers, including adjutant, quartermaster, surgeon, paymaster, and 2 “vets.” |

| 75 | N. C. O.’s, |

| 666 | rank and file, and |

| 614 | horses. |

A Cavalry Brigade numbers 3 regiments, and details altogether 114 officers, 2,280 men, and 2,200 horses.

A Cavalry Division numbers 2 brigades (6 regiments), 2 batteries Horse Artillery, 1 battalion Mounted Infantry, and details altogether 325 officers, 6,600 men, and 6,500 horses.

The Artillery forms one “Royal Regiment,” consisting of:—

| 20 | Batteries of Royal Horse Artillery, |

| 80 | Batteries of Field Artillery, |

| 10 | Mountain Batteries, and |

| 96 | Garrison Batteries, |

with several depôts and 3 depôt batteries for their maintenance and supply. The Horse and Field Batteries are formed into groups of 2 or 3 batteries, chiefly for tactical reasons, called Brigade Divisions, each under a lieutenant-colonel.

A Horse Artillery Battery consists of 1 major, 1 captain, 3 subalterns, 21 N. C. O.’s, and 160 men (of which 73 are drivers), 193 horses, 6 guns, 6 ammunition wagons, and 7 other wagons.

A Field Artillery Battery of much the same, but with 9 men and 52 horses less.

The guns in use are at present of four different patterns:—

| Weight of Shell. | Calibre. | Sighted up to. | Are Armed with it. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 12 lbs. | 3 in. | 5,000 yds. | 14 R. H. A. and 29 F. A. batteries. |

| b | 13 lbs. | 3 in. | 4,800 yds. | 1 R. H. A. and 12 F. A. batteries. |

| c | 16 lbs. | 3.6 in. | 4,800 yds. | 2 F. A. batteries. |

| d | 9 lbs. | 3 in. | 3,500 yds. | 5 R. H. A. and 37 F. A. batteries. |

Of these patterns, the 12-pounder alone is a breech-loader; the others are muzzle-loaders.

The 12-pounder is being issued as fast as possible to all R. H. A. batteries. The F. A. will be divided into Light and Heavy Field Artillery, the former of which will receive the 12-pounder B.-L. gun, and the latter a new pattern 20-pounder B.-L. gun, with 8 horses to a team. When this is done, the R. H. A. will probably receive a new 10-pounder B.-L. gun.

2 guns and wagons together are called a Section; 1 gun and wagon, a Sub-division.

A Garrison Battery is variously constituted, according to its locality. The men of the battery have to work guns of all sorts and sizes in the different forts where they are quartered, and, as a rule, have no guns of their own.

Of the 96 Garrison Batteries, 4 are Siege-train batteries, quartered in the United Kingdom, and armed with heavy guns for battering purposes, and 4 more are “Heavy” batteries, quartered in India, the [Pg 7] guns of which are drawn by elephants and the wagons by bullocks.

The Garrison Artillery is grouped in 3 divisions: the Eastern (29 batteries), Southern (42), and Western (25). Although these divisions are by way of corresponding with the different points of the compass in Great Britain, the batteries composing them are scattered in every quarter of the globe, and the Militia Brigades attached are not necessarily Eastern, Southern, and Western ones.

The Mountain Artillery is armed with 2½-inch 7-pounder jointed guns, each gun and gun-carriage being carried in pieces on 5 mules. One battery is in England (Newport), one in South Africa, and the rest in India.

The Royal Malta Artillery is for the defence of that island, and is composed of Maltese officers and men.

Men of the Horse Artillery are dressed in dark-blue Hussar-like jackets, and busbies with a white plume and scarlet busby-bag; the remainder of the Artillery in dark-blue tunics with red facings, and black felt helmets with a brass ball instead of a spike. They are armed with Martini-Henry carbines, and either sword or sword-bayonet, according to their branch of the arm. The forage-cap is a small, round, brimless one, with a band of orange braid.

The corps of Royal Engineers is divided into a number of battalions, depôts, and other units, which are given below as far as possible. As will be seen, their duties, and especially those of the officers, are extremely various.

The officers are employed sometimes with their men and sometimes apart from them. A large number of R. E. officers (between 350 and 400) serve in India, in connection with Native Engineer troops; others are employed either at home or in a colony on staff work, public works, [Pg 8] Military Schools, the Ordnance Survey, military telegraphy and railways, Engineer Militia and Volunteers, and a host of other duties too numerous to mention. In fact, the Engineers form the Scientific Corps of the Army. The officers are trained in the R. M. Academy at Woolwich, and the rank and file are nearly all well-educated men, skilled mechanics and trained workmen forming the bulk of them. That their work does not interfere with their worth as soldiers has been shown on many a field, and individual instances of their gallantry are numerous.

Formerly the Corps was composed of a large number (about 40) of independent companies, split up and quartered throughout the Empire. Now they have been collated together and formed into different battalions and other units, according to their work.

The Corps is now composed as follows:—

(a.) A Bridging Battalion, consisting of 2 pontoon troops, each troop numbering 5 officers, 28 N. C. O.’s, and 183 men, with 20 pontoon- and 8 other wagons, and 190 horses. Each troop carries the material for 120 yards of pontoon-bridge.

(b.) 2 Field Battalions, each of 4 companies. The companies however still preserve their independence to a great extent, being quartered in widely divergent localities, according to requirements.

The 1st Battalion consists of the former Nos. 7, 11, 17, and 23 independent companies, and the 2nd of Nos. 12, 26, 37, and 38.

A Field Company consists of 7 officers, 26 N. C. O.’s, 184 sappers, etc., 70 horses, and 13 vehicles.

A proportion of the company, from one-fifth to one-third, is mounted.

These companies, as their name implies, are employed in digging, sapping, making field-works, and blowing up places, on active service.

(c.) A Telegraph Battalion of 2 divisions (in war, of 4 sections), the whole consisting of 6 officers, 15 N. C. O.’s, 224 men, 171 horses, and 22 vehicles. Their duties consist in laying lines of field telegraphs, and making themselves generally useful in their branch of science wherever they may happen to be.

(d.) A Submarine Mining Battalion, consisting of one depôt and 11 service companies (the old Nos. 4, 21, 22, 27, 28, 30, 33, 34, 35, 39, and 40), numbering about 760 of all ranks. Their strength varies according to the locality in which they are employed.

(e.) A Coast Battalion of 3 divisions, altogether about 240 of all ranks, employed in defensive works on the sea-coast.

(f.) 4 Survey Companies (Nos. 13, 14, 16, and 19), 330 men in all, engaged in the Ordnance and other official Surveys.

(g.) 17 Fortress Companies, of varying strengths (Nos. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 15, 18, 20, 24, 25, 29, 31, 32, 36, 41, and 42), which are employed in the repair and keeping up of fortresses. In war-time they would design and execute siege-batteries, parallels, and all work connected with either the attack or defence of fortresses. In peace-time they number altogether about 1600 men.

(h.) 8 Depôt Companies, which are employed in the training and drilling of recruits, and in work relating to the Corps. They number 820 men.

(i.) 2 Railway Companies (Nos. 8 and 10), which number 140 men together, and would be employed in the laying and repairing of railway lines on service.

(k.) A Supernumerary Staff of nearly 400 men, which is employed in a great variety of duties too numerous to mention.

420 more men are distributed in different parts of the world and in military schools of different sorts.

The grand total of Royal Engineers in peace-time is therefore about 7,300 men.

Officers and men are dressed, armed, and equipped very similarly to the Infantry of the Line (q. v.). They may, however, be readily distinguished by the broad red stripe on their trousers, and by the Royal Arms in front of the helmet. The forage-caps of the rank-and-file are small round ones with a broad yellow band and no brim, worn on the top of the head. Officers wear a black and gold pouch belt instead of a sash. The facings are of dark-blue velvet, with yellow edging.

The British Infantry is composed of—

Napoleon the Great said of the British Infantry: “It is the best infantry in the world; luckily, there is not much of it.” It has certainly not deteriorated since his day; but, unfortunately, it is not much more numerous now than it was then.

Two years ago a distinguished Russian general said to an English Guardsman: “Are your men as fine a lot as they were in ’54?” and on receiving an answer in the affirmative, said: “I am sorry for it, if we ever have to fight you again. I had more than enough of them in the Crimea.” And Moltke said of the late Nile Expedition in 1885: “No one but English soldiers could have done what they did.”

Such remarks speak for themselves.

The Brigade of Guards consists of three regiments—

These three regiments form the Sovereign’s Body-Guard, and do not usually serve out of Europe. The late campaigns in Egypt, however (1882 and 1885), and the prospective campaign in Canada in 1864, in all of which two or more battalions of Guards took part, go to prove that every rule has its exceptions.

At home, usually five battalions are quartered in London, and the other two in Windsor and Dublin respectively.

The uniform of the Guards differs from that of the Infantry of the Line chiefly in the shape of the facings and in the head-gear, the latter being the well-known bearskin, with white or red plumes for Grenadiers or Coldstream respectively. The forage-cap is round, with bands of red, white, and dice for the three regiments respectively. The armament and equipment is precisely that of the Infantry of the Line.

Of the 69 Regiments of the Line, one (Cameron Highlanders) consists of 1 battalion; two (60th King’s Royal Rifle Corps and Rifle Brigade) of 4 battalions; and the remainder of 2 battalions each. Total 141 battalions.

The regiments are now called after their “Territorial Districts,” which are the districts whence their recruits are drawn, and in which their depôt is situated. Up to 1881, the Infantry of the Line consisted of 109 regiments, mostly of 1 battalion each, and numbered up to 109. In that year, however, the system was changed, and a regiment is now known by the county or part of the country it recruits in, with occasionally the addition of a few other titles, such as “Borderers,” “King’s Own,” “Loyal,” etc., etc.

Of the 69 regiments we have—

| 9 | Regiments | of | Fusiliers. |

| 4 | ” | ” | Rifles. |

| 5 | ” | ” | Highlanders. |

| 7 | ” | ” | Regiments of Light Infantry. |

| 44 | ” | ” | Regiments of Infantry (pure and simple). |

The Infantry, with the exception of the four Rifle regiments, is, of course, clothed in scarlet tunics, with facings of dark blue, white, yellow, or green, according as whether the regiment is a “Royal,” English, Scottish, or Irish one.

The head-dress of the Fusiliers is a busby of rough sealskin, shaped similarly to the Guards’ bearskin, but much smaller. The (5th) Northumberland Fusiliers wear a red and white plume, the remainder none.

The Rifle regiments are clothed in a very dark green, almost black, uniform. The Rifle Brigade facings are black, those of the 60th K. R. R. red, and those of the other two, Scottish and Irish Rifles, dark and light green respectively. The first two mentioned are historically connected with Hussar regiments,[8] and consequently the officers wear round forage-caps, trailing swords, and a few other Cavalry-like details; and the late head-gear used to be a Hussar-like black busby. The helmet of all Rifle regiments is at present black, but it will shortly be exchanged for a black Astrakhan fatigue-cap, with plume for full dress.

The five Highland regiments are the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders), the Seaforth, the Gordon, the Cameron, and the Argyll-and-Sutherland Highlanders. They wear the feather-bonnet and well-known Highland dress—plaid, kilt, hose, white gaiters, and shoes. The tartan, sporran, hose, and a few other details differ in the various regiments.

Officer, 6th Dragoon Guards

(Carbineers).

The remainder of the Infantry, whether Light Infantry or not, wear[9] black felt helmets with brass spike and fixings, the scarlet tunic aforesaid, and blue-black trousers. Their forage-cap is the “Glengarry.”

The West India Regiment consists of two battalions of negroes, officered by Englishmen. The battalions are quartered, turn and turn about, in the West Indies and in our possessions on the West Coast of Africa. The men are dressed in white jackets, with a red vest over them, loose blue Zouave knickerbockers, and yellow gaiters. The head-dress is a turban.

The Infantry, whose weapon for the last seventeen years has been the Martini-Henry rifle, will very shortly be all armed with the new [Pg 11] magazine rifle, which has already been issued to a considerable number. The action is on the breech-loading bolt system; by it cartridges may be fired either singly or by means of the magazine, which is a black tin box, holding eight cartridges, and suspended immediately in front of the trigger-guard. The bore is extremely small, being only ·303 inches. The bullet is coated with a hard metal composition, for if it were of lead, it would “strip” in the grooves of the barrel, and by degrees choke it up. The powder is as yet not definitely fixed on, though numerous varieties have been tried with great success. It shoots point blank up to 300 yards, and is sighted on the back sight up to 2,000 yards. By a hanging foresight arrangement, it can be sighted up to 3,500 yards—nearly two miles! The cartridges are so small and light that more than twice the amount of ammunition can now be carried than was possible in the case of the late weapon.

The new bayonet is a much shorter implement than the late one, looking more like a large knife than a bayonet. The name of the new rifle is the Burton-Lee.

The equipment consists of a valise and canteen, suspended by leather braces to the belt, a havresack, wooden water-bottle, and bayonet-frog. Inside the valise is carried the great-coat (under the valise flap), and such articles as are necessary for the time being, such as boots, shirt, socks, hold-all, etc.

A new equipment, slightly different from the above, is now being issued.

Two pouches are attached to the belt in front, holding twenty rounds Martini-Henry ammunition each. Thirty more rounds are carried in the valise and havresack, making seventy in all. With the new rifle cartridges, however, and new pouches, it is expected that each man will be able to carry 150 rounds.

A battalion of Infantry is composed of 8 companies, each company numbering 3 officers, 10 N. C. O.’s, and 111 men on a field establishment. In peace-time, the company rarely numbers above 90 men all told, except in India. The battalion consists therefore of—

30 officers (1 lieut.-colonel, 4 majors, 5 captains, 16 subalterns, etc., etc.),

91 N. C. O.’s,

975 men,

70 horses,

16 carts.

These horses and carts belong for the most part to the Regimental Transport, which has been issued to each battalion forming part of the 1st Army Corps (of which more hereafter).

An Infantry Brigade consists of four battalions and details, and numbers in war-time 130 officers, 4,350 men, and 530 horses.

An Infantry Division consists of 2 brigades, 3 batteries Field Artillery, 1 squadron of Cavalry and details—total, 327 officers, 10,060 men, and 2000 horses.

An Army Corps is to consist of 3 Divisions of Infantry, 3 Horse Artillery, and 2 Field Artillery batteries, Royal Engineers, Cavalry squadron and details—total, 1,158 officers, 35,000 men, and 10,000 horses.

The Medical Staff Corps consists of 17 Divisions, distributed throughout Great Britain and Ireland, and numbering altogether about 400 medical officers and 2,000 N. C. O.’s and men. The depôt and training-school is at Aldershot, and the Army [Pg 12] Medical School at Netley. This Corps does not include the Indian Medical Staff Corps.

The Army Service Corps corresponds to the former Commissariat and Transport Corps, and deals with the issue of rations and general transport duty. It is divided into 37 companies, distributed throughout Great Britain and Ireland, and numbering 230 officers, 3,363 N.C.O.’s and men, and 1,300 horses and mules.

The Chaplains’ Department consists of about 80 chaplains, divided into four classes. There are four official denominations allowed, Church of England, Roman Catholic, Presbyterians, and Wesleyans. Men belonging to any other of the numerous sects of religion prevalent in England are officially entered as “Church of England.”

The organisation of the remaining departments, i.e., Ordnance Store, Veterinary, and Pay, is uninteresting, and need not be detailed here.

Of the Regular Forces, 21 regiments of Cavalry, 91 batteries of Artillery, most of the Engineers, and 73 battalions of Infantry are quartered in Great Britain and Ireland. Great Britain is divided into 11, Ireland into 3, and the Channel Islands into 2, Districts, each under the command of a major-general. These districts are sub-divided into Regimental Districts, each of these latter comprising the recruiting ground, depôt, and Volunteer battalions of a Territorial (i.e., Line Infantry) Regiment of two Regular and two or more Militia battalions. The Artillery and Engineers, both Regular, Militia, and Volunteer, are also apportioned to each district. The Regular Corps of all arms rarely remain more than two years in the same quarters, changing from station to station in accordance with different rosters and requirements.

The whole of the Regular Forces, with the exception of the five Heavy Cavalry regiments and Brigade of Guards, take their turn at foreign service in India and the Colonies. As a rule, one battalion of each regiment of the Line is abroad for sixteen years, and is “fed” with men from the other battalion at home. This system, by which all the best and soundest men of a regiment are sent abroad, can hardly be called a good one, but it is difficult to suggest another. For foreign service it is no use having the youngest and unmatured soldiers—they would probably only fall sick in a hot climate. It is, therefore, necessary to keep and train the men till they know their duty thoroughly, and then send them out as full-grown men. It is for this reason that complaints are so often seen in the newspapers that certain regiments are apparently composed of “beardless boys.” This may be so with the home battalion, but if the complaint-makers were to journey to the Colonies and see the other battalion, they would soon alter their opinion.

It sometimes occurs that both battalions are abroad together, in which case the depôt of the regiment is largely increased; in order to feed the two.

Cavalry regiments stay abroad from twelve to fifteen years, and are fed by their depôt.

This foreign service is one of the main impediments in the way of recruiting by conscription.

Of the Regular Forces abroad, 9 Cavalry regiments, 88 batteries of Artillery, 3 companies R. E., and 53 battalions of Infantry are in India; and 1 Cavalry regiment, 27 batteries Artillery, [Pg 13] 13 companies R. E., and 20 battalions of Infantry are in the Colonies.

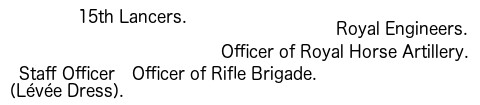

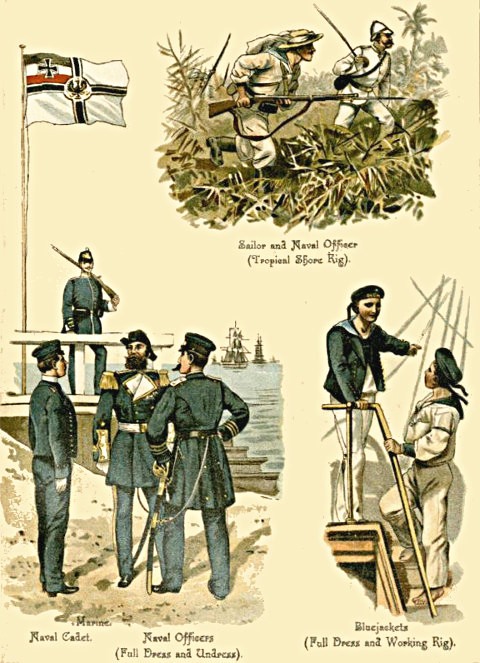

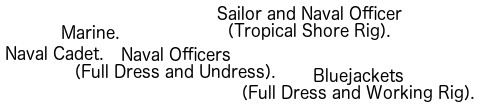

The Royal Marines, although not coming strictly under the head of the Army, are yet soldiers in the widest sense of the word, for they have been engaged by land and sea in every single campaign since their formation in 1755. They consist of two divisions, i.e. Artillery (16 companies) and Light Infantry (48 companies), in all nearly 14,000 men. They enlist for twelve years’ service, and may re-engage for nine years more. In garrison they perform the same duties as the Regular army, and on board ship work of a military character, such as guard mounting, working big guns, forming part of armed force on boat service, or fighting on shore under all sorts of conditions and in all climates. The latest development of the Marine is not a Horse-, but a Camel-Marine, a force of Marines having served up the Nile with the Camel Corps.

The Marines have done well wherever they have been, and still form, chiefly no doubt owing to their long service, some of our steadiest troops on service.

Their uniform and equipment is very similar to those of the corresponding branches of the Regular Army. A Marine may always be told from a Linesman by the badge on his helmet and shoulder-straps—a globe with the thoroughly apposite motto of “Per Mare, per Terram.”

The Native Indian Army is composed of Native Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, Infantry, Medical Corps, etc., etc., partly officered by Englishmen, and numbering altogether about 152,000 men, including 13,000 Volunteers.

It is divided into the Armies of the Bengal, Madras, and Bombay Presidencies. The English officers are drawn from the three Staff Corps of those Presidencies, which they have entered after serving for at least one year with their English regiments.

The Army of Bengal numbers—

19 Regiments of Bengal Cavalry, including 7 Lancer regiments.

4 Regiments Punjab Cavalry.

Central India Horse.

2 Bengal Mountain Batteries.

5 Punjab Mountain Batteries.

Corps of Bengal Sappers.

Corps of Guides, Cavalry (6 troops), and Infantry (8 companies).

45 Regiments Bengal Infantry.

5 Regiments Goorkha Light Infantry.

4 Regiments Sikh Infantry.

6 Regiments Punjab Infantry.

Hyderabad Contingent, 4 batteries F. Artillery, 4 regiments Cavalry, and 6 regiments Infantry.

Several Irregular Corps, and a Medical Department, chiefly Englishmen.

The Army of Madras numbers—

4 Regiments Cavalry, 2 of which are Lancer regiments.

Corps of Madras Sappers.

33 Regiments Madras Infantry, and a Madras Medical Department, etc.

The Army of Bombay numbers—

7 Regiments Cavalry, 2 of which are Lancer regiments.

2 Mountain Batteries.

Corps of Bombay Sappers.

30 Regiments Bombay Infantry, and a Bombay Medical Department, etc.

Natives enlist for any period of service, from three years to thirty. Most of the troops enlist for nine or fifteen years. They [Pg 14] must be physically fit and physically equivalent to a full-grown man. They are for the most part very keen soldiers, especially those that come from the North-West Provinces and Punjab. In many regiments the men have to find everything except firearms—even horses, accoutrements, and food, on their pay of about eighteenpence a day; and yet in some popular regiments there are several hundred candidates waiting for admission.

The Infantry is armed and equipped similarly to the British Infantry. Their rifle is of the Snider pattern, and is being exchanged for the Martini-Henry rifle. The uniforms of the Indian Army are very variegated, ranging from scarlet to yellow, and drab to green. The usual head-dress is the turban, but the other details of costume vary too much for description. The English officers wear in some regiments the native uniform, in others an English one.

A Native Cavalry regiment consists of 4 squadrons of 2 troops each, with an establishment of 10 English officers, Native officers, N. C. O.’s, and about 540 privates.

A Native Infantry Regiment consists of 1 battalion of 8 companies, with an establishment of 9 English officers, Native officers, N. C. O.’s, and about 820 privates. Each Infantry regiment is linked with two others, one of them supplying the other two with men, etc., in time of war.

The establishment of the Mountain Batteries varies according to locality.

A Native Reserve is being formed, but is not yet completely organised.

The Colonial Forces consist of those raised by each Colony of the British Empire for its own protection. With the exception of a few of the smaller islands in the West Indies and Pacific, it may be said that every one of our Colonies has trained a certain number of men for home defence.

The system of enlistment and service varies in almost every colony, according to requirements. In very few of them are there permanent forces under arms. They mostly correspond to our Militia, and are called out for an annual training only.

The native forces of Canada are—

| Cavalry, | 4 | regiments of Dragoons. | |

| 5 | regiments of Hussars. | ||

| 4 | Independent troops. | ||

| Artillery, | 19 | batteries Field Artillery. | |

| 5 | Brigades and 13 batteries Garrison Artillery. | ||

| ½ | battery Mountain Artillery. | ||

| Engineers, | 2 | companies. | |

| Infantry, | 74 | battalions of Infantry. | |

| 21 | battalions of Rifles. | ||

| 5 Independent companies. | |||

| Medical Staff Corps. | |||

| Total strength 38,500. | |||

Of the above troops, a very small number are permanent troops; the remainder consist of Militia, called out for about twelve days’ training in the year. There is universal liability to service in the Militia Reserve for all men between 18 and 60, so that in case of war the armed levy of the country would amount to over 600,000 men! Not more than 45,000 of these however are regularly trained. The country is divided into twelve Military Districts, and these again into Brigade and Regimental Divisions.

Besides this force, there is a Royal Military College, [Pg 15] and Royal Schools of Instruction for Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery.

Cape Colony has a force of about 4,500 men, consisting of Corps of—

Ceylon possesses a force of about 900 Volunteer Light Infantry.

Hong Kong possesses a force of Volunteer Artillery and Military Police (370).

Jamaica possesses a force of Volunteer Militia, Mounted Rifles, and Garrison Artillery (1,300).

Natal possesses a paid Volunteer Cavalry, Field Artillery, and Rifles, 1,500 altogether.

Singapore possesses a paid Volunteer Artillery and Military Police (1,000).

New Zealand possesses a Corps of paid Light Horse Volunteers, 13 batteries Volunteer Artillery, Engineer Corps, Force of Militia Infantry, and 7 or more Rifle battalions. A total of 7,400 men.

New South Wales has a force of 6,350 men, consisting of—

Reserve Force of Cavalry, Artillery, and Infantry, 2,700 of all ranks; besides a Naval Brigade and Naval Artillery Volunteers numbering nearly 500 men.

Queensland has a Defence Force of three classes, numbering altogether over 4,500 men.

South Australia has 2 troops of Lancers, 1 Field and 2 Garrison Batteries, 2 battalions Rifles, and numerous Mounted Rifle Corps, numbering altogether 2,700 men, including Volunteers.

Victoria has a force of several Cavalry and Artillery Corps, 4 battalions Rifles, Mounted Infantry, and numerous Rifle Volunteer Corps, besides a Reserve. Total 8,300 men.

Tasmania has a small force of Artillery and 2 regiments of Rifles, total 930 of all ranks.

Western Australia has a small force of Volunteer, Infantry, and Artillery—640 altogether.

Trinidad and other islands in the West Indies have raised small forces for their defence, about 1,000 altogether.

Total Colonial Forces, about 84,100 men.

Let us now turn to the Reserve Forces at home, composed of the two classes of Army Reserves, Militia, Militia Reserve, Yeomanry, and Volunteers. We will not take into account either the Native Indian Reserves, as they are not yet fully formed, or the Colonial Militia or Reserves, as they are inextricably mixed up with the Colonial Forces already described.

The 1st Class Army Reserve, created in 1877, consists of men who have served their three, seven, or eight years with [Pg 16] the Colours, and who then pass to this Reserve to complete their service to twelve years. They are liable to service at home and abroad when called out; this would happen only in case of war or national danger. The men would then either join their own regiments or be formed into separate corps, or, with their consent, be attached to a regiment or corps other than their old one. This class numbers over 54,000 men.

The 2nd Class Army Reserve, in which there are not quite 3,000 men, is composed of those men who have served twelve years with the Colours and then choose to enter this Reserve, and of a few other special classes of men. They do not serve out of Great Britain. Both classes are liable to be called out for an annual training, but have never yet been so called out.

The Militia consists of men voluntarily enlisted for six years, with power to re-engage for periods of four years up to forty-five years of age. The recruits are trained for six months or less at the depôt of the regimental district, and have subsequently to undergo only twenty-eight days’[10] training a year with their corps when called out. During these twenty-eight days the men receive regular pay, with a “bounty” of 10s. or upward at the end of the training. They are then dismissed till next year.

In cases of national emergency, the Militia may be called out, i.e. “embodied,” for active service. This has occurred four times already in this century; during the Crimean War, for instance, ten battalions of Militia were garrisoning our possessions in the Mediterranean, and no fewer than 32,000 entered the Regulars and fought before Sebastopol.

The Militia comprises Artillery, Engineers, and Infantry.

The Artillery consists of 34 brigades of Garrison Artillery, attached to the regular Garrison Artillery Divisions as follows:—4 to the Eastern, 21 to the Southern, and 9 to the Western Division. The Engineer Militia numbers 7 companies.

The Infantry consists of 131 battalions, attached to the different regiments of Infantry of the Line as their 3rd and 4th or other battalions, and belonging to the same regimental districts. Some regiments have only one Militia battalion attached, others as many as five.

The Militia is clothed, equipped, and armed identically with the Regular Army, the only distinction being that a Militia private wears the number of his battalion, and a Militia officer the letter M in addition on his shoulder-straps.

The Channel Islands have 4 regiments of Artillery, and 6 of Infantry Militia. Malta has 1 regiment of the latter.

The Militia numbers altogether 103,500 men.

The Militia Reserve consists of men enlisted from the Militia for six years or for the remainder of their Militia engagements. These are liable to an annual training, or to embodiment in case of national danger. The body was created in 1867 as a temporary expedient for an Army Reserve, the Austro-Prussian war of 1866 having caused extreme uneasiness to our authorities; for they discovered then that we had absolutely no reserves whatever, in case we went to war. The inducement to join is a pecuniary one, i.e. £1 bounty, paid in advance, for every year service in the Militia. It numbers altogether 30,160 men.

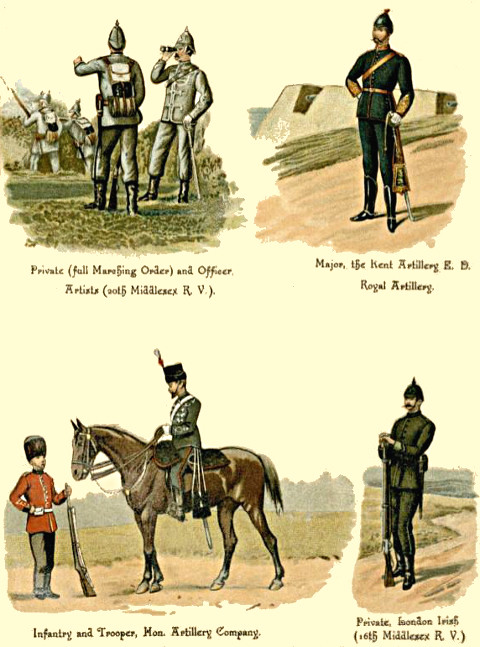

England. III. [LHS]

England. III. [RHS]

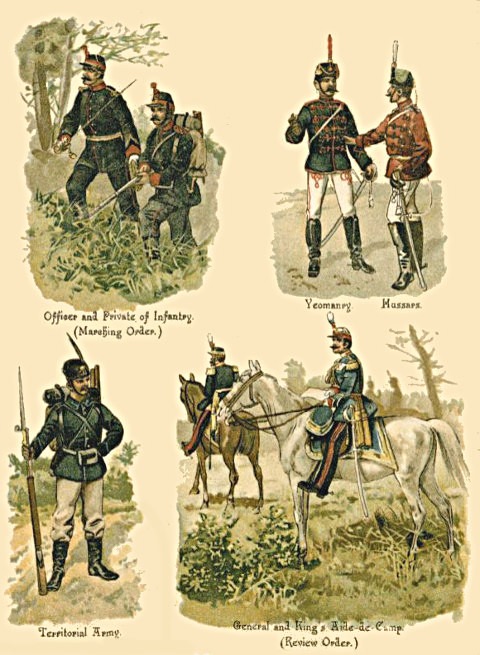

The Yeomanry is composed of 39 county regiments of Cavalry, and forms a species of Cavalry Militia or Volunteers. They are called out annually for only one week’s training. They are liable to be called out, in addition, for service in any part of Great Britain in case of threatened invasion, or to suppress a riot. They receive allowances and pay during their training, an allowance for clothing, and their arms, from the Government; but have to find their own horses. There is no Yeomanry in Ireland.

The Yeomanry numbered, in 1889, 10,739 men.

The Volunteers consist of a large number of Corps, both Artillery, Engineers, Infantry, and Medical Staff Corps, with 2 Corps of Light Horse and 1 of Mounted Rifles. The Honourable Artillery Company (composed of 1 battery Field Artillery, 6 troops Light Cavalry, and 8 companies Infantry), although not strictly Volunteers, may be considered as coming under this head.

The Artillery Volunteers are divided into 9 Divisions according to their locality, forming 62 Corps.

The Engineer Volunteers form 16 Corps of Engineers, 9 Divisions Submarine Miners, and 1 Railway Staff-Corps.

The Infantry comprises no less than 211 battalions, distributed throughout Great Britain, and attached to the different regular regimental districts. 31 Infantry Volunteer Brigades have now been formed, each consisting of five or more battalions, and each commanded by a colonel of Auxiliary Forces.

The number of Volunteers is unlimited, and has gone on steadily increasing, since their formation in 1859. The Corps were originally intended to be self-supporting, finding themselves in everything except arms. Now, however, the Government, having awoke to their importance as a great national reserve for home defence, gives a Capitation Grant of 35s. a year to the different Corps for every efficient Volunteer on their lists, and £2 10s. more for every officer and sergeant who obtains a certificate of proficiency.

Volunteers are liable to be called out for active military service in Great Britain, in case of a threatened invasion.

It is, however, a fact that, if they chose, the Volunteers might, on the eve of the invasion, all disappear within fourteen days by simply giving notice of their wish to retire! A little legislation on this point might not be out of place, though of course such a catastrophe is not to be dreamt of.

Volunteers are exempt from service in the Militia, and cannot be employed as a military body in aid of the Civil Power. They receive no pay, and have to attend a certain number of drills of different sorts every year, otherwise they are not considered efficient.

The Volunteers are not yet thoroughly equipped for service, but strenuous efforts are being made in this direction by private and public enterprise.

Their uniforms vary greatly in colour, from green or scarlet to drab or grey, and in appearance. It is, however, expected that all Corps will in time present a similar appearance to the Regular Forces, with the main distinction of silver or white-metal embroidery and buttons instead of the gold or brass of the Regulars.

The rifle of the Volunteers is either the Martini-Henry or the Snider.

The organisation of the Volunteer Corps [Pg 18] is identical with that of the corresponding Regular Forces.

There were on the 1st January, 1890, 216,999 efficient Volunteers, besides 7,022 non-efficients—total 224,021.

The mode of entrance of officers to the Regular Army is as follows:—The candidate, if wishing to enter the Cavalry or Infantry has two routes open to him. He may either pass a competitive “preliminary” and “further” examination for the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, remain there one year, and then enter his regiment direct (if successful in passing the “final” examination), or else he may be appointed as 2nd lieutenant to a Militia battalion, undergo two annual trainings, and then pass an examination equivalent to the Sandhurst “final.” Formerly this latter mode of entrance, i.e. through the Militia, was considered much the easiest, but now there is not much to choose between the two.

A candidate for the Artillery or Engineers has to pass two examinations in the R. M. Academy, Woolwich, and then spend two years there. The order of merit in which the cadets pass the “final” determines which branch they are to join. As a rule, those passing out high up join the Engineers, and the others the Artillery.

Other Military establishments are:—

(a.) The Staff College near Sandhurst, which an officer may enter by means of a competitive examination, after he has served five years at least with his regiment. Here he remains for two years, and is instructed in the various acquirements necessary for a good Staff officer, and in the higher branches of his profession. Having passed the final examination, the officer is attached for two months each to the two branches of the service other than that which he belongs to, and then rejoins his own regiment; he is then entitled to put p.s.c. after his name in the Army List.

(b.) School of Gunnery at Shoeburyness, where experiments are carried out and new inventions in gunnery tried, etc., etc.

(c.) Artillery College at Woolwich.—Instruction, etc., in the higher branches of gunnery.

(d.) School of Military Engineering at Chatham, where officers and N. C. O.’s of different Corps are put through a course, experiments in engineering tried, etc., etc.

(e.) School of Musketry at Hythe, for instruction of officers and N. C. O.’s in the use of, and in details and experiments concerning, small arms.

(f.) Schools of Gymnasium and Signalling at Aldershot, the Army Medical School at Netley, the Veterinary School at Aldershot, and the School of Music at Hounslow, whose titles sufficiently explain their raison d’être.

A glance at the latest accessories to the Army in the shape of Mounted Infantry, Machine-guns, and Cyclists, may not be out of place here.

The authorities consider that a force of Mounted Infantry (i.e., Infantry with rifles on horseback) will be of the greatest use to the Army in case of war. Accordingly, a force is being trained, little by little, which would be available to act as such on active service.

For the past two or three years 2 companies at Aldershot, formed of volunteers from the different Infantry battalions quartered there, and 1 company at the [Pg 19] Curragh, consisting of 150 men each, have been trained during the winter months to act as Mounted Infantry. On the conclusion of the course, the men are sent back to their regiments, and a fresh lot come on the following winter. These companies are intended to be formed into battalions when required. The duty of this force on service will be to act as Infantry, but with a rapidity of transport from one place to another unattainable by ordinary Infantry. Thus they may be pushed forward to attack a village, to hold a defensive position till supported by other Infantry, to assist the Cavalry, or to perform a hundred other duties of Infantry far in front of the real Infantry.

It is proposed that every battalion of Infantry and regiment of Cavalry should in future wars have a Machine-gun Detachment of 2 machine-guns, worked by 1 officer and 12 men, attached to it. A large number of men have been trained in this work, but there are at this moment but few complete detachments in existence.

Corps of Cyclists, chiefly Volunteer, have also lately been started, but it seems very questionable whether they would ever be of any use in a hostile country except to carry messages to and fro along good roads.

Finally, mention must be made of the recent apportioning of the British Regular Army into Army Corps. Serious difficulties have arisen in organising this matter, for, since regiments are always on the move from point to point at home, or between home, India, and the Colonies, it is a very difficult task indeed to arrange so that even one Army Corps should be ready to take the field at the shortest possible notice. It has, however, been done, and the 1st Army Corps is an accomplished fact. The 2nd is on the high road to completion, though as yet it is badly off for horses.

The above gives a tolerably fair idea of the strength and constitution of the Army of the British Empire. The Navy, it is true, is still our first line of defence, as it has been for hundreds of years; but although the best in the world, it is not yet large enough for our needs. Our Regular Army has also been shown to be barely large enough. It is, therefore, doubly necessary to keep the Army at a high pitch of efficiency, and fully supplied with everything needful, in order that if we ever come into collision with one of the colossal European powers detailed in the following pages, we shall not be found wanting.

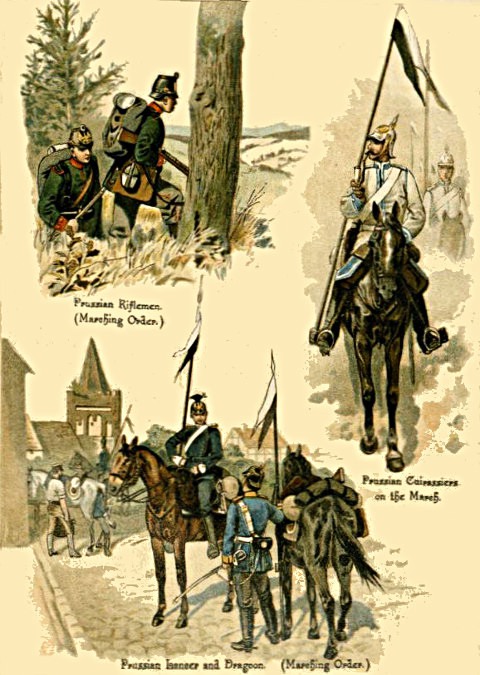

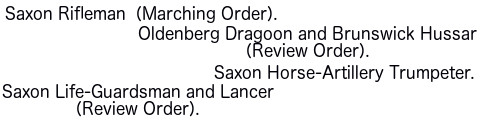

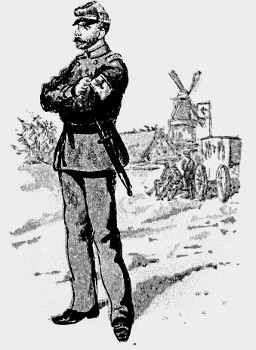

Prussian Hussar

of the Guard.

It was in the autumn of 1870, during the Franco-German War, that the preliminary arrangements were made for the forthcoming consolidation of the German Empire. Up to that time, Germany consisted of a multitude of States, each with its own Government and its own Army. The interests of these States, ranging as they did from kingdoms down to small principalities, were extremely conflicting, and internal hostility was frequently the result. The one great aim of King William of Prussia was to see them all united into one Empire, and defended by one Army. Aided by the genius of Bismarck, the negotiations were brought to a successful conclusion, and on the 18th January, 1871, William of Prussia was declared Emperor of Germany with the title of William I. At the same time the forces of the different States were combined, and the present German Army is the result.

In peace and war this United Army is under the command of the Emperor, and each man is bound by oath to render him faithful and loyal service.

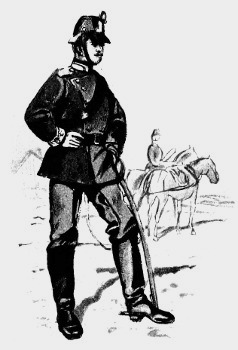

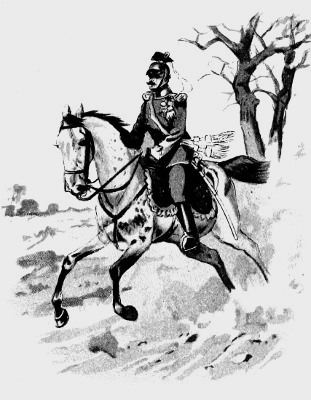

Several of the States, whilst keeping their own troops, have, by means of special military conventions, attached themselves and their forces still closer to the chief military power of the Empire, namely, [Pg 21] Prussia. On the other hand, a few of the larger States have reserved for themselves a certain independence in the management of their armies. The chief outward and visible sign thereof is seen in the variations of uniform from the strict Prussian pattern. Thus, the Bavarian Infantry has kept its light-blue tunic, the Saxons still have red piping round their skirts, and the Württembergers wear double-breasted tunics and grey greatcoats.

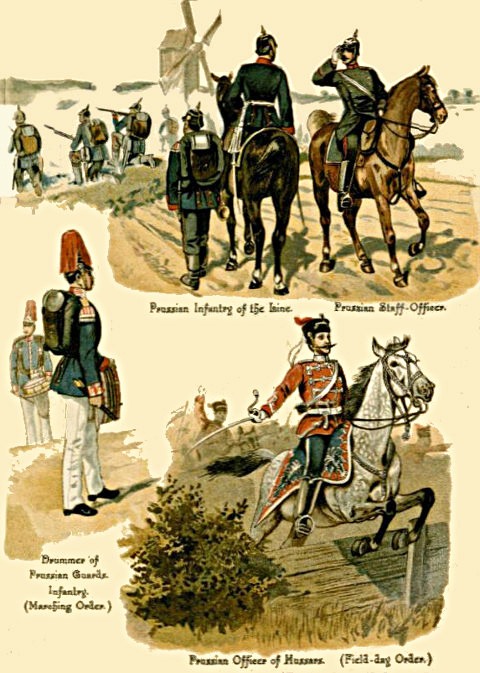

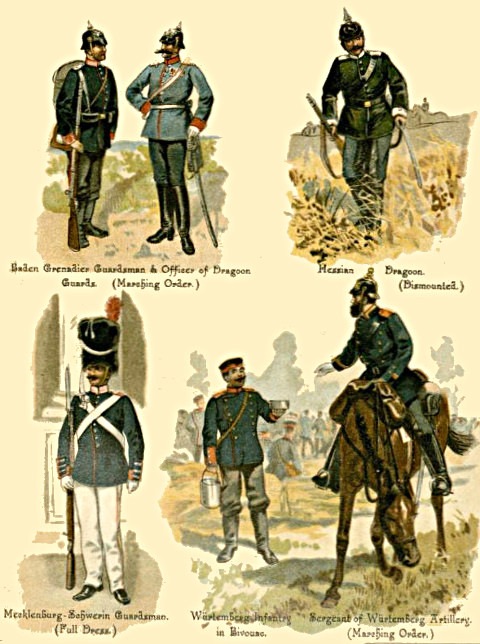

German Empire. I. [LHS]

German Empire. I. [RHS]

The Army may be roughly divided into four groups:

1. The combined forces of Prussia and the following States, which have concluded conventions with her: Saxe-Weimar, Saxe-Meiningen, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Saxe-Altenburg, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, the two principalities of Reuss, Oldenburg, Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Lippe, Schaumburg-Lippe, Lübeck, Bremen, Hamburg, Waldeck, Brunswick, Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Grand Duchy of Baden, and Grand Duchy of Hesse.

2. The Saxon Army Corps—(one).

3. The Bavarian Army Corps—(two).

4. The Württemberg Army Corps—(one).

Universal Conscription is the keystone of the Army. Introduced on September 3rd, 1814, first of all, it was amended by the law of the 16th April, 1871, and perfected by subsequent laws passed in 1874 and 1881. The recent edict of the 11th February, 1888, has put the finishing touches to it, so that it now holds sway throughout the whole Empire. According to this law, every German who is physically capable and who is in the enjoyment of civil rights, is bound to serve as a soldier.

A man is bound to commence his service, as a rule, with his 21st year.

The period of service is as follows:—

By this time the soldier is in his 45th year.

The 1st Class Landwehr is divided into complete units, and these are formed into Reserve Divisions for the Active Army. The 2nd Class Landwehr garrisons the interior and fortresses, and acts, if called out, as a reserve for the above-mentioned Landwehr Reserve divisions.

All men between the ages of 17 and 45 who are fit to bear arms and who are not serving in either the Active Army (including the Ersatz Reserve) or in the Landwehr, are enrolled in the 1st Class Landsturm. This body can only be called out in case of national invasion, or for garrison duty at home.

The Ersatz (i.e. Supply) Reserve consists of those men who are physically fit, but have, owing to surplus numbers or other causes, escaped being sent to serve in the Regular Army. Part of this Reserve undergoes a training of ten weeks in the first, six weeks in the second, and four weeks in the third year. These are considered as belonging to the so-called “Furlough Men”[12] class, and serve when required to complete the Army in the field. On the completion of their thirty-first year, the men are sent to the Landwehr and 2nd Class Landsturm, and there they remain till the termination of their [Pg 22] liability to service, i.e., their forty-fifth year. The men of the untrained portion of the Ersatz Reserve remain available for service up to their thirty-second year, and then pass over to the 1st and 2nd Classes of the Landsturm in due order.

Prussian Garde du Corps.

Court full-dress.

If every single able-bodied young man were to be taken for the Regular Army, two disadvantages would accrue to the State; on the one hand an immense amount of industrial labour would be lost to the country, and on the other, it would be impossible for the State to support such a huge Army. For this reason the law of the constitution has laid down that the peace Army is not to exceed one per cent. of the population. This gives the Army the respectable peace-strength of 468,409 men (not including officers and one-year volunteers). Of these numbers about 156,000 annually enter the ranks as recruits.

There is a supplementary clause to the law of universal conscription, and that is the one which allows of One-year Volunteers. It stands to reason that with a three-years’ bout of compulsory service, a large portion of the youth of the country are interrupted in the studies which are to prepare them for their particular professions, and that at a period when they can least afford to lose the time. For the labourer, who needs but little knowledge for his daily task, and for those handicraftsmen whose work demands but little brain capacity or culture of any sort, this interruption of business is of small moment. It is far otherwise, however, with the young man who requires to spend some time in the higher schools in order to fit himself for the profession he has chosen, be it industrial or scientific. This disadvantage of the conscription law makes itself felt in proportion to the progress in education and general culture made in the country. At the same time it is obvious that a man who has the assistance of a well-educated and well-trained mind does not require so long a period to master the intricacies of soldiering as one who is less intelligent.

For this reason the Government allows young men who have either received a certificate of educational efficiency from one of the higher schools or else passed an examination before a commission appointed for the purpose, to enter the service as volunteers on completing their seventeenth year. After one year with the Colours they are sent “on furlough” to the Active Reserve, and for this privilege they have to find themselves in uniform, equipment, and food during the period of their service. They may become officers in the following manner: If they have behaved well and have subsequently, during two trainings of several weeks each, whilst attached to a Corps, shown themselves professionally and socially qualified to become officers, they are balloted for by the officers of their district. If the ballot is favourable, they are commissioned by his Majesty and become full-blown officers of the Reserve. These have, in case of war, to complete the active establishment of officers to war-strength, or have to fill vacancies as officers in the Landwehr.

The German Army represents the people under arms, and their officers represent the cream of the Army. The road to the [Pg 23] higher, and even to the highest ranks, lies open to every educated man, without reference to social standing or birth, if he only have the necessary qualifications thereto.

Every candidate for an officer commission must possess—

1. A good general education, of which the candidate must give satisfactory proof, either by the possession of an “Abiturient” certificate,[13] or by passing an examination before a commission held in Berlin.

2. Physical qualifications for military service, including good eyes.

3. An honourable character.

Having satisfied the authorities on these subjects, the candidate now serves as a private for five months, generally with the regiment he intends to enter. At the end of this time, during which he is called an “avantageur,” he undergoes an examination in military duties, etc., and on receiving a certificate of satisfactory service from his superior officers, he becomes an ensign (“Porte-épée Fähnrich”) and is sent to a military college for a year. There he passes a final examination in military knowledge, and, if balloted for successfully by the officers of the regiment of his choice, he joins as second lieutenant.

Württemberg,

Sergeant of the Train.

As much as 40 to 45 per cent. of the officers are drawn from the Cadet Corps, which is distributed amongst establishments at Lichterfelde (near Berlin, head college), Kulm, Potsdam, Wahlstatt, Bensberg, Plön and Oranienstein, in Prussia; Dresden in Saxony, and Munich in Bavaria. A new college will shortly open in Karlsruhe. This Corps is chiefly composed of the sons of officers, who receive a cheap and excellent training and education. The proverb that “the apple falls close to the stem” is well exemplified here, for amongst the cadets are many who bear celebrated soldiers’ names, such as Roon, Steinmetz, Canstein, etc., etc.

Although the training in the Cadet Corps is chiefly a military one, yet on the whole the cadets receive an education equal to that of a first-class civilian college. Thus they are enabled in after-life, when they have left the Service, to pursue a civilian calling with greater ease than if their education had been purely military.

Mention may also be made here of the establishments in which the “Porte-épée Fähnrichs” (ensigns) are instructed: they are the military colleges of Potsdam, Engers, Neisse, Glogau, Hanover, Cassel, Anklam, Metz, and Munich. The higher branches of military science are pursued in the United Artillery and Engineer School, and the Staff College (Kriegsakademie), both in Berlin. The entire military education and training of the country are managed by an Inspection-General.

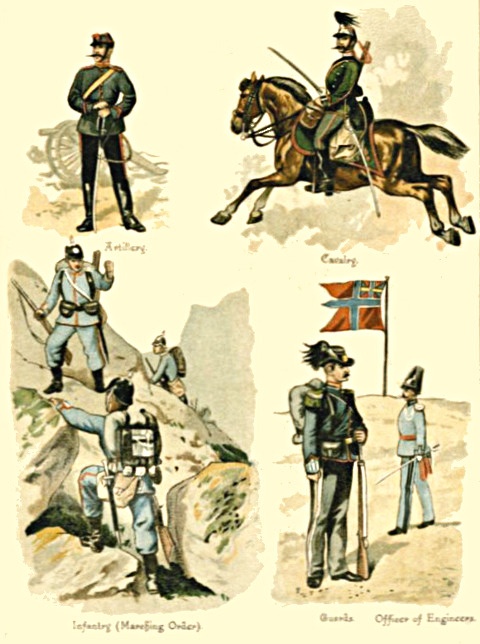

As in all large armies, the three great branches of the German service are Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery, besides the Engineers and Transport Corps, the latter of which is called the “Train.”

As everybody knows, Infantry is intended to go anywhere and fight anywhere. It is, therefore, equipped for all contingencies that may arise, and is armed with a weapon for use either at a long range or in close hand-to-hand fighting.

The German Infantry is[14] armed with a capital magazine-rifle, with a bore of ·315 inches, which, with a point-blank range of over 300 yards, will carry up to 2,400 yards. [Pg 24] The magazine is detachable, and holds 8 cartridges. The bayonet is a short sword-bayonet, very similar to the new English bayonet.

As a rule, the German foot-soldier has to carry his own equipment, both on the march and in action. The equipment consists of a knapsack with large mess-tin attached, great coat, bayonet and scabbard (to which latter is fastened a small spade), havresack, and water-bottle, and three pouches, two in front and one behind. These pouches hold, altogether, 150 rounds. The whole thing can be put on or taken off at a moment notice, by simply buckling or unbuckling the waist-belt and slipping the arms into, or out of, the knapsack braces. This new arrangement also obviates to a great extent the discomfort caused by the older pattern of equipment, which compressed the man chest considerably.

The old division of the Infantry into Grenadiers, Musketeers, and Fusiliers has now no significance, except from a historical point of view. Nowadays, the whole of the Infantry being identically equipped, they all receive exactly the same amount of instruction and training, with the sole exception that the Rifle battalions (Jäger) spend somewhat more time and pains on their musketry than the other troops.

Prussian Engineer.

“Grenadiers” first sprang into existence in the seventeenth century; as their name indicates, they were originally intended to throw hand-grenades amongst the enemy ranks. For this object, particularly powerful men were selected, and in France, under Louis XIV., four Grenadiers were at first attached to each company; subsequently, each battalion received a Grenadier company. Grenadiers were now introduced into every civilised army, but as there was seldom an opportunity for the employment of their special weapon, they were given muskets, and remained Grenadiers only in name, and thus the name came to be applied to particularly fine bodies of troops only. The Prussian Grenadier battalions of Frederick the Great were the flower of his Army, and in memory of these troops [Pg 25] the 1st Prussian Foot-Guard Regiment still wears the old sugar-loaf brass helmet on big review days and other special occasions. The title of “Grenadier Regiments,” which the first twelve Prussian Infantry regiments received in 1861, was only bestowed in order to keep green the memory of the old Grenadiers.

The names of “Musketeers” and “Fusiliers” come from the different firearms their predecessors bore, i.e., the musket and the rifle (fusil), first introduced into France in the seventeenth century. The Musketeers were at first the Heavy Infantry, in contradistinction to the Fusiliers, who represented the Light Infantry. Later, however, on each branch receiving the same firearm, the distinction ceased, and it is now only remembered through the old Fusilier songs, of which there exist several, and whose burden is the chaffing of the heavy Musketeer.

The peculiar qualities necessary for good Light Infantry have been developed par excellence in the Prussian Rifle battalions. These draw a very large proportion of their recruits from the gamekeepers and forester class of the country. Such men have of necessity been already trained in the attainments required for that branch of the Infantry. They are well acquainted with firearms and can shoot; they can put up with considerable hardships, they can find their way about a strange country, and they have studied in the school of nature—in short, they are the very men to make into skirmishers and marksmen, and are in their element on outpost or patrol duty. Frederick the Great was the first to train the Jäger as Light Infantry, and his influence is seen to this day. “Vive le roi et ses chasseurs” was the motto engraved on their “hirschfänger” (lit. “stag-sticker,” a large knife still worn by keepers for the purpose of giving the stag his coup de grâce) in his day, and it is still the watchword of the Prussian Riflemen of to-day. Frederick recognised that the true method of employing Riflemen was to extend them as skirmishers, and there is a story which tells how, when one day, in Potsdam, the Rifles were marching past him in close order, the old king shook his crutch-stick at them and shouted: “Get out of that, get out of that, you scoundrels!” and made them march past in extended order.

On the 1st of April, 1890, the German Infantry numbered 171 regiments of 3 battalions each, and 21 Rifle battalions—total 534 battalions.

The Guard and Grenadier Regiments are:—

| 4 | Regiments of Foot-Guards, |

| 4 | Regiments of Guard Grenadiers, |

| 12 | Prussian Grenadier regiments (Nos. 1–12), |

| 1 | Mecklenburg Grenadier regiment (No. 89), |

| 2 | Baden Grenadier regiments (Nos. 109 and 110), |

| 2 | Saxon Grenadier regiments (Nos. 100 and 101), |

| 2 | Württemberg Grenadier regiments (Nos. 119 and 123), |

| 1 | Bavarian Body-Guard regiment, |

| 1 | Hessian Body-Guard regiment (No. 115). |

The Fusilier and Rifle (Schützen) Regiments are:—

| 12 | Prussian Fusilier regiments (composed of 1 Guard Fusilier regiment, and Nos. 33–40, 73, 80, and 86 of the Line). |

| 1 | Mecklenburg Fusilier regiment (No. 90), and |

| 1 | Saxon Rifle (Schützen) regiment (No. 108). |

Of the remaining Line regiments, 81 are Prussian, i.e., Nos. 13–32, 41–72, 74–79, 81–85, 87–88, 97–99, 128–132, 135–138, and 140–143;

No. 91 is Oldenburg,

No. 92 is Brunswick,

No. 93 is Anhalt,

No. 94 is Saxe-Weimar,

No. 95 is Saxe-Meiningen and Saxe-Coburg-Gotha,

No. 96 is Saxe-Altenburg, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, and the two principalities of Reuss,

Nos. 111–114, and 144, are Baden, and

Nos. 116–118 are Hessian.

Total, 95 regiments of the first group.

Nine belong to the 2nd group, Saxony, i.e., Nos. 102–107, 133, 134, and 139.

Six belong to the 3rd group, Württemberg, i.e., Nos. 120–122 and 124–126.

The 4th group, Bavaria, has 18 regiments of the Line, which are numbered apart from the rest of the Army.

The Rifle (Jäger) battalions are thus divided:—

Prussia: 1 battalion Rifles of the Guard; 1 battalion Schützen of the Guard; 11 battalions Rifles of the Line (Nos. 1–11); 1 battalion Mecklenburg Rifles. Total, 14 battalions.

Saxony: 3 battalions Rifles of the Line (Nos. 12, 13, and 15).

Bavaria: 4 battalions Rifles (numbered apart).

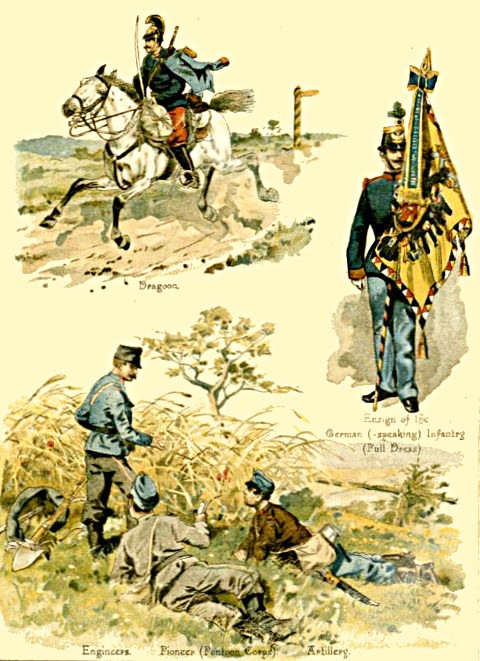

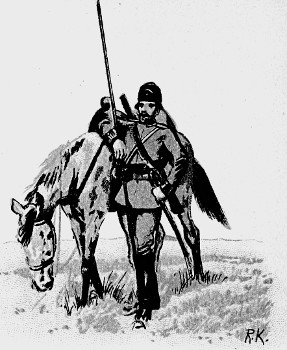

Württemberg. Dragoon.

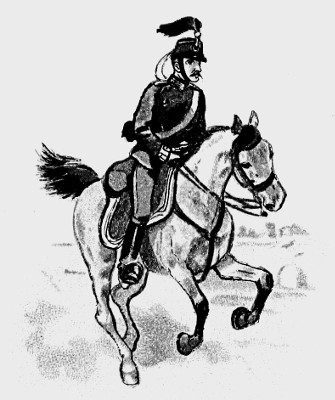

The Cavalry is intended for fighting chiefly at close quarters and on open ground. Their use on the battle-field is generally confined to the attack in close order.

Although both branches of the Cavalry, the Heavy and the Light, receive an identical training, yet the distinction between them has not yet entirely lost its old significance. The Cavalry of the German Army is divided into four groups, distinguished by different equipment and arms; they are the Cuirassiers, the Dragoons, the Lancers, and the Hussars. The chief weapon throughout is the sword, though the Cuirassiers differ from the others in being armed with a long straight sword, whilst that of the latter is slightly curved. Besides this weapon, the whole of the Cavalry is being armed with lances. As it may happen that the men may have to dismount and use firearms on foot, at present they are all armed with a useful carbine (Mauser, 1871 pattern); the non-commissioned officers and trumpeters wear a revolver instead.

The main point in a Cavalry fight is the shock, i.e., the moment when they come into contact with the enemy. This must be the result of gradually quickening the pace till at the supreme moment an irresistible mass is hurled with crushing force on the ranks of the enemy. The best powers of man and horse must therefore be reserved for this moment, and it is a fact that the turning-point of an action has often been decided by the mere impetus of the charge, and without any use whatever of cold steel.

German Empire. II. [LHS]

German Empire. II. [RHS]

Of the whole German Cavalry the Prussian arm has the best record. This dates from the time of Frederick the Great and his celebrated Cavalry leaders Zieten, Seydlitz, and others, who made use of bold and clever offensive tactics which led to [Pg 27] grand results at Rossbach, Leuthen, Zorndorf, and other actions. Prussian horses are powerful, fast, and capable of considerable endurance, so that they are particularly suited to military service. In addition, the Prussian soldier is a capital groom. These qualities, in conjunction with thorough discipline and tactical training, have brought the German Cavalry to a height of excellence that is surpassed by few.

The Cuirassiers are the troops who from their outward appearance most resemble the knights of the Middle Ages. Although the cuirass, from which they take their name, has lately been abolished for field service in consequence of its weight and inability to keep off the enemy bullets, yet with the lance, just introduced, a genuine knightly weapon has been brought in to take its place.

The Prussian Regiment of Gardes-du-Corps, whose chief is ex-officio the King of Prussia, is equipped and armed in the same way as the Cuirassiers. Although it forms a Royal body-guard, still the regiment has seen a considerable amount of service. History tells of a memorable saying of the Commander of the regiment, Colonel von Wacknitz, at the battle of Zorndorf (25th August, 1758), where the enemy, the Russians, were getting the best of the day; Frederick the Great was with his regiment, the Gardes-du-Corps, and said anxiously to Colonel von Wacknitz: “What do you think of it? My idea is that we shall get the worst of the action.” [Pg 28] Von Wacknitz lowered his sword and said: “Your Majesty, no battle is lost, in my opinion, where the Gardes-du-Corps have not charged.” “Very good,” said the king, “then charge.” And the fortune of the day was decided by the brilliant and successful attack made by this regiment. The battle was won, and the country saved.

In Bavaria the two regiments of Heavy Cavalry, and in Saxony the regiments of Horse Guards and Carbineers, correspond to the Prussian Cuirassiers.

The Dragoons were originally intended to combine the fire-action of Infantry with the rapidity of movement of Cavalry, and were therefore armed, on horseback, with a light musket and bayonet. The Brandenburg Dragoons of the great Elector Frederick William came greatly to the fore in this double capacity at the battles of Warsaw and Fehrbellin. The uncertainty, however, of the results of shooting when mounted, and the inconvenience of dismounting or mounting according as to whether the fight raged on foot or on horseback, showed plainly as time went on that the idea of an intermediate arm, a sort of mounted infantry, could not yet be brought to perfection. The Dragoons were therefore, during the eighteenth century, gradually formed into Cavalry pure and simple, and at the present time they are horse-soldiers, and horse-soldiers only. One of the most celebrated Cavalry attacks was that of the regiment of Anspach-Bayreuth Dragoons in the battle of Hohenfriedberg (4th June, 1745). In this action, the regiment rode down no fewer than 20 battalions of Infantry, took 2,500 prisoners and 66 standards, besides a large number of guns: as Frederick the Great said, “It is a feat unparalleled in history.” This regiment was, at a later period, turned into a Cuirassier regiment, and is now known as the Queen’s 2nd Cuirassiers (Pomeranians).

The Bavarian Chevau-légers correspond to the Prussian Dragoons, and many a record testifies to their gallantry in action.

The spirit of Zieten, the “Hussar-father,” and of old Blücher, “Field Marshal Forwards,” still lives in the Hussars of the German Empire. Activity, boldness, and cheeriness are the attributes which make a good Hussar, and many are the songs which record their successes in camp and field.

The Uhlans (Lancers) who spread such terror amongst the enemy in the war of 1870–71, hail, as far as their name goes, from Tartary.[15] For this reason, the French took them for a wild tribe, such as the Kirghiz of the Steppes, or the African Turcos. The name is, however, the only foreign element about them, for their mode of fighting is essentially German.

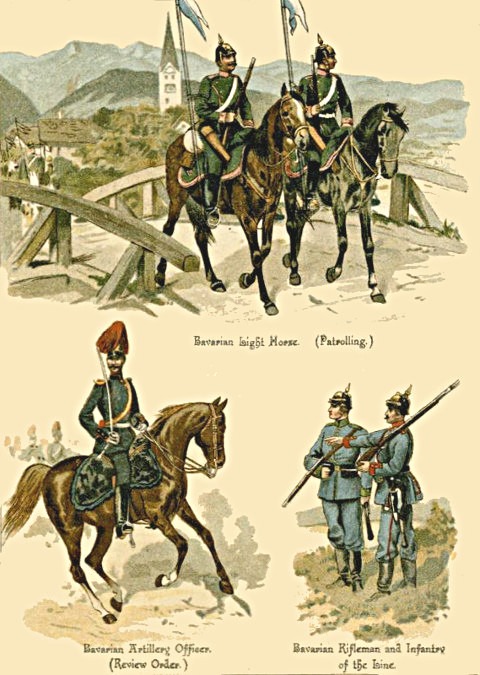

Bavarian

Halberdier.

(Full-dress.)