Footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference. Full-page illustrations have been

moved to a paragraph break.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

The cover image, which had no text, has been provided with the basic

data from the title page.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

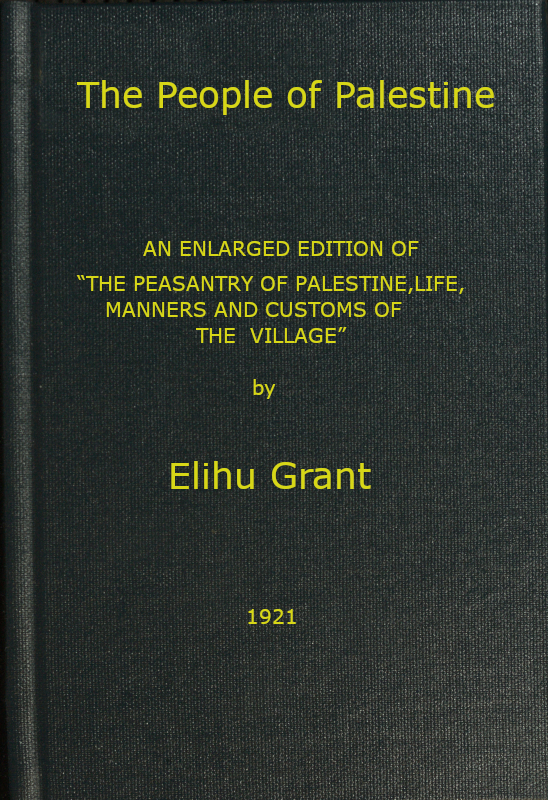

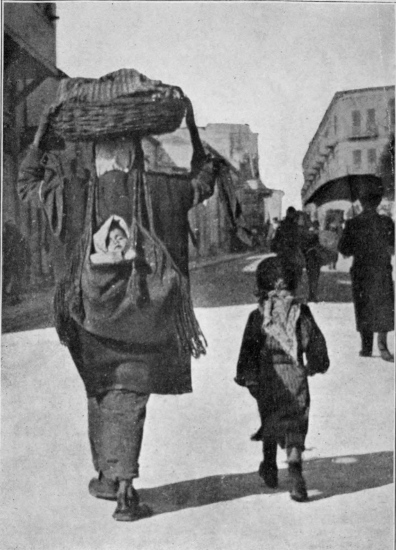

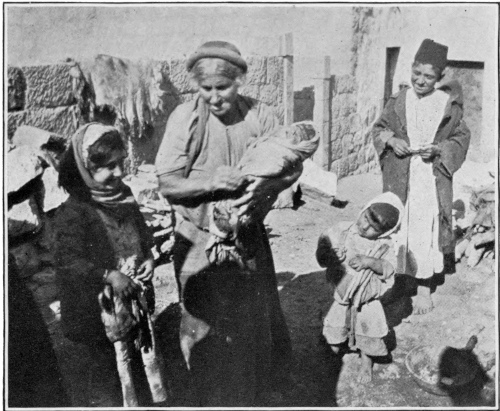

A SILOAM WOMAN, HER INFANT ON HER BACK AND PRODUCE ON HER HEAD

BIBLE LANDS AND PEOPLES—MODERN

BEING A COMPANION VOLUME TO “THE ORIENT IN BIBLE TIMES”

THE PEOPLE

OF PALESTINE

AN ENLARGED EDITION OF

“THE PEASANTRY OF PALESTINE, LIFE,

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS OF THE VILLAGE”

BY

ELIHU GRANT

PROFESSOR OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE IN HAVERFORD COLLEGE

PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1907, BY ELIHU GRANT

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

TO THE MEMORY OF

HINCKLEY GILBERT MITCHELL

PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION

We thought that Palestine had passed into ancient

history, but it has been a centre of modern events.

No country in the world has a more continuously

interesting and profitable story. Its present population

is made of sturdy and able people. Three great

religions call it Holy Land. It presents to view three

distinct types of human society, the desert nomad

who dwells in the tented encampment, the peasant

villager who reminds us in so many ways of the

people of the Bible, and the more foreign looking

and mingled folk of the large cities.

We have picked the village life as most suggestive

of the quaint customs of the past. It has been gratifying

to have those who know this life best, including

villagers themselves, praise the accuracy and sympathy

of the descriptions.

The volume has not been compiled from books,

but drawn from life. An additional chapter seeks

to sum present conditions.

Life has changed even in the East but much remained

in Palestine, especially under the Turkish

régime, that is suggestive of Bible Times. We trust

that we have provided here a cross-section of a most

interesting period. We hope for even more, that the

reader with dramatic imagination may be able to fill

the places and figures of the biblical past with life.

E. G.

Haverford, Pa.,

February 24, 1921.

A few words that are pretty well fixed in popular usage, as Beirut,

Jaffa, Jerusalem, etc., are not changed in spelling, but for most Arabic

words the following alphabet has been used in transliteration:

| — |

r |

gh |

y |

| b |

z |

f |

a |

| t |

s |

ḳ |

u |

| th |

sh |

k |

i |

| j |

ṣ |

l |

â |

| ḥ |

ḍ |

m |

û |

| kh |

ṭ |

n |

î |

| d |

ḍh or ẓ |

h |

|

| dh |

|

w |

|

The use of y final and of ô as aids to pronunciation will be of obvious

import. When a foreign word occurs in the book for the first time

it is put in italics.

7

CONTENTS

| Chapter I |

| |

| Introductory. Remarks on the country of Western Palestine: historical, topographical and geological; distances, levels, rock composition, hills, valleys, caves, soil, etc. The waters: rivers, lakes, the watershed, the Shephelah, ponds, springs, cisterns, reservoirs and pools. The seasons: wet and dry, the rainfall, sun, drought, the weather according to the months, effect on health and on food supply, harvest. The winds. Flora: trees and flowers. Fauna: wild animals, birds. Scenery: appearance of cities and villages in Palestine. Sites, buildings, gardens, roads, paths, wilderness, agricultural matters, ripening fruit, vineyards, care of the soil, walls, watch-towers, terraces, orchards, olives, figs, pomegranates, etc. |

Page 11. |

| |

| |

| Chapter II |

| |

| General characteristics of the population of Palestine. The Bedawîn or nomads. The village and its people. Moslems and Christians: their distribution, their mutual relations. Description of the peasant man and the peasant woman. |

Page 43. |

| |

| |

| Chapter III |

| |

| Village Life. Introductory. The tribe: how constituted, its fellowship and significance. The family within the tribe. Importance of a strong family. Marriage in family and tribe: marriage settlement, qualities of a good wife, customs and ceremonies preliminary to marriage, wedding festivities and the celebration. The status of the new wife. An anomalous state of affairs. A disappointed lover. Children: boyhood and girlhood, importance of sons, birth, announcing the newly-born, naming the child. The midwife, care of babies, attention to children in health and in sickness, clothing, growing up, play, amusements and work, training. Family and personal names. |

Page 51. |

| |

| |

| Chapter IV |

| |

| 8Village Life. The houses of the peasants: structure, arrangement, conveniences, utensils and furnishings. Foods: their preparation and storing, eating customs. Costumes; male attire, female attire. Household industry: division of labor between members, women’s work, house, oven, field and wilderness. Health data: poverty and superstition as foes to health, treatment of the sick, common ailments, diseases, hospitals and medical assistance. The dumb and the blind. Treatment of the insane, the leprous. Death, mourning, burial, graves. The cholera and its ravages in Palestine in 1902, attendant evils, famine and quarantines. |

Page 75. |

| |

| Chapter V |

| |

| Village Life. Religion. The religious basis of the peasant life. Country shrines venerated by the peasantry, saints, tombs, lamps, ruined churches, mosks, reverence for patriarchs and prophets, sacred trees. Superstitions concerning localities, minor superstitions, hair, doorways, food, evil eye. Prayer of women. Fatalism. Moslem prayer. Neby Mûsâ procession. Ramaḍân, Bairam. Eastern and Western Churches, organization, priesthood. Fasts, feasts, proselyting. The Samaritans and their Passover. |

Page 110. |

| |

| Chapter VI |

| |

| Village Life. Business. The Palestine peasant as a worker. Farming the first business of the village. The transition from the life of the nomad to the life of the peasant. Fellaḥîn. Land holdings and titles. Farming rights. Crops and sowing, work animals and their management, care of the standing crops, tares, mists, simultaneous reapings, harvest-time, threshing and cleaning. Grape season, vineyard districts, use of the fruit, raisins, export trade in raisins, care of vineyards, watch-towers in vineyards and orchards. The olive crop and its care. Flocks of sheep and goats, the young, varieties, the shepherd. The wool business and kindred industries, spinning and weaving. Undeveloped agricultural possibilities. The village market, shops, stores, bargaining and trade customs, measures and weights, currency, accounts, money-lending, village crier, the go-between, the shaykhs in business capacity. Transport and travel in the country, roads and vehicles. Stone and building trades, the materials and the tools. Miscellaneous trades, peasants in the city for business or for hire, dealers in antiquities and their ways. |

Page 130. |

| |

| |

| Chapter VII |

| |

| Village Life. Social privileges and customs. The elements that contribute to these, kinship, religious association, party traditions, proximity. Predominance of kinship as a factor. The influence of religion as a factor. Diversions of the peasant, conversation and the amenities, calling and calls. Greetings, salutations, colloquial address, business talk and discussion. Guest-house and its uses, coffee-making, food for guests. A roofing-bee. Play, games, celebrations. Hunting. Gipsies. Quarrels as an anti-social and social factor. Revenge, etc. |

Page 158. |

| |

| 9Chapter VIII |

| |

| Village Life. Intellectual matters. The state of learning, revival, services of the press in the Levant. Education, schools, missionary influence. Languages heard in the country, native and foreign. The peasant’s pride in his mother tongue. The Arabic language, its beauty and symmetry, literature, dialects, idioms, colloquialisms, exclamatory remarks, gestures, curses, proverbs. |

Page 170. |

| |

| |

| Chapter IX |

| |

| Village life in the concrete. Description of actual villages, Râm Allâh and el-Bîreh. |

Page 187. |

| |

| |

| Chapter X |

| |

| Village life in the concrete, continued, with some village environs. Eṭ-Ṭîreh, Khullet el-‛Adas, ‛Ayn ‛Arîk, Kefr Shiyân, ‛Ayn Ṣôba, Baytîn, Khurbet el-Moḳâtîr, Dayr Dîwân, eṭ-Ṭayyibeh, Jifnâ, ‛Ayn Sînyâ, Bîr ez-Zayt, ‛Âbûd, Mukhmâs. |

Page 213. |

| |

| |

| Chapter XI |

| |

| The village in its external relations. Attitude of villagers to the city and city people, now and formerly. Administration of the village from the city. The peasant and the government, taxes, private and official settlement of disputes. Postal service, native and foreign, telegraph. Passage of news and rumor. Travel, hindrances, quarantines, coastwise shipping, railway travel, peasant travel, pilgrimage travel, Russian pilgrims and the peasantry, other European pilgrim parties, tourists, traveling passes, transference of parcels, baggage, money, banking, consular service, the desire of the natives to emigrate. |

Page 225. |

| |

| |

| Chapter XII |

| |

| Recent events. Effects of the revolution. Syrians and the World War. Syrian ability. Schools and education. The new administration; certain functions and methods. Archæological interests. The Arabian problem. Arabia and its people, social customs, politics, poets, prophet and religion. |

Page 242. |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| |

PAGE |

| A Siloam Woman, Her Infant on Her Back and Produce on Her Head |

Frontispiece |

| River Auja of Jaffa |

20 |

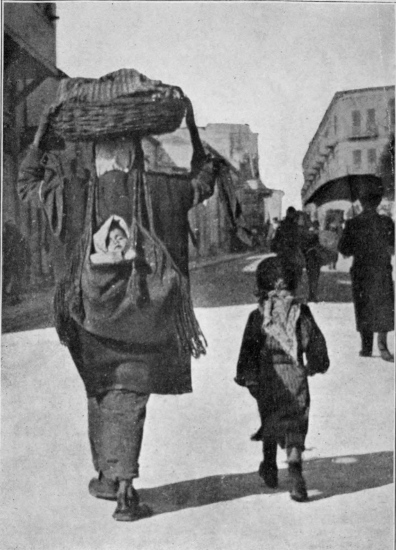

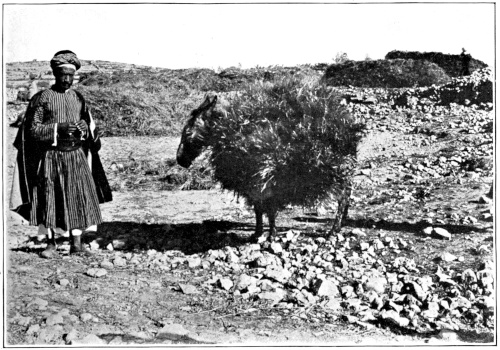

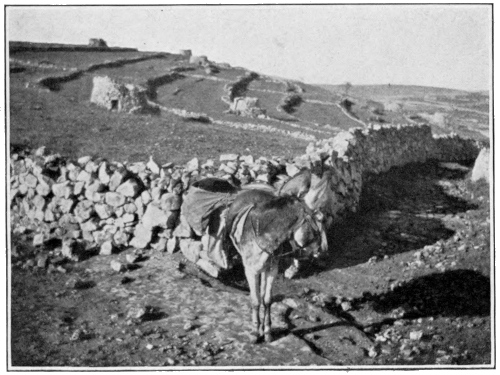

| Donkey at the Threshing Floor With a Load of Wheat |

28 |

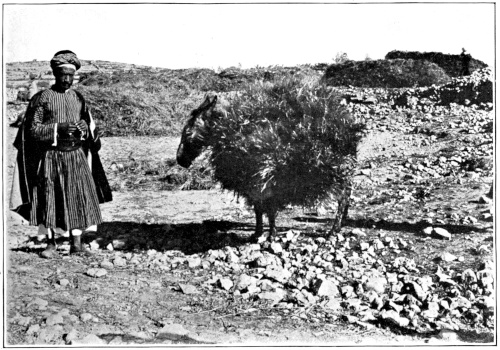

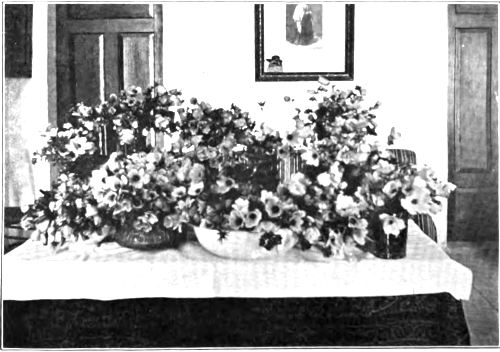

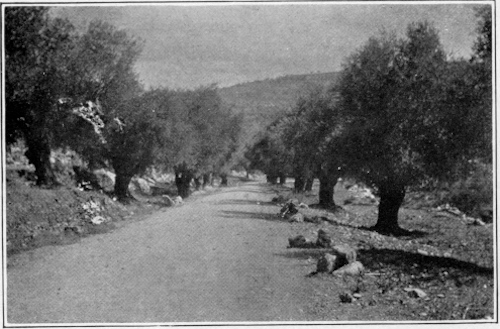

| Wild Anemones From Wady El-Kelb |

32 |

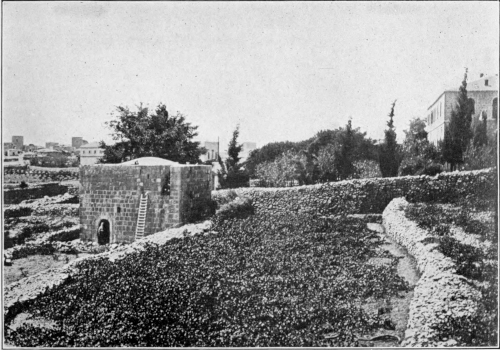

| A Vineyard at Râm Allâh |

36 |

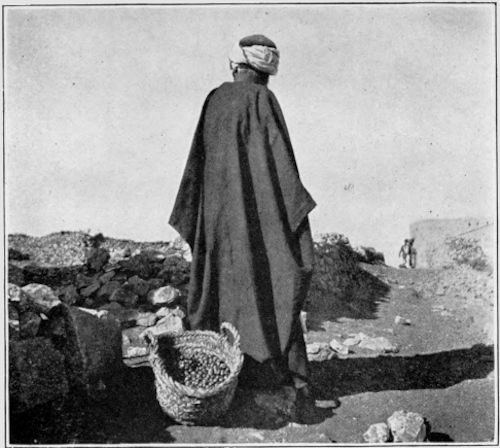

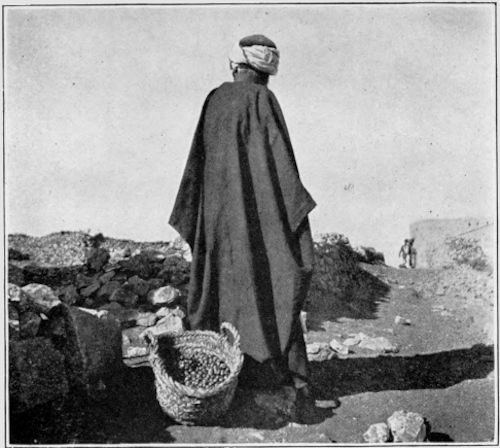

| Râm Allâh Man and a Basket of Olives |

38 |

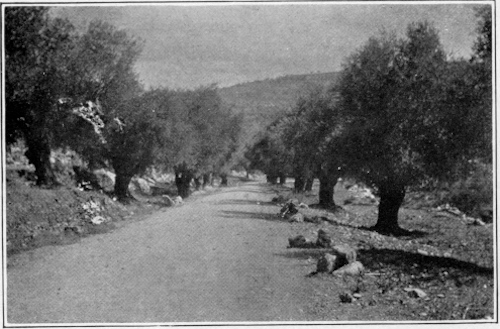

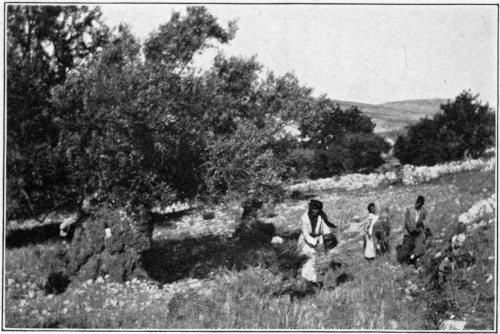

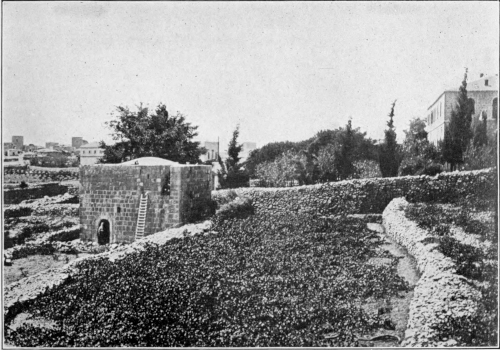

| Stretch of Olive Trees on Road to Ayn Sînyâ |

38 |

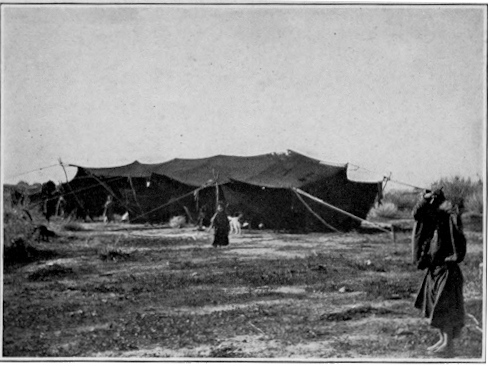

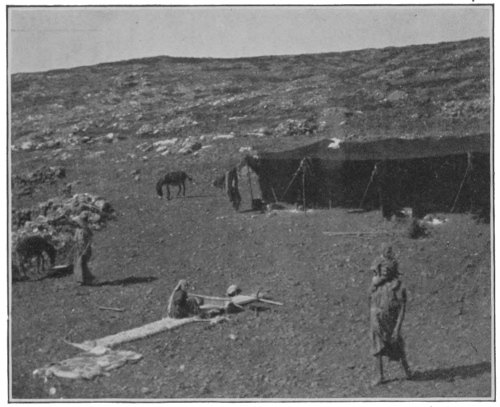

| A Bedawy House |

42 |

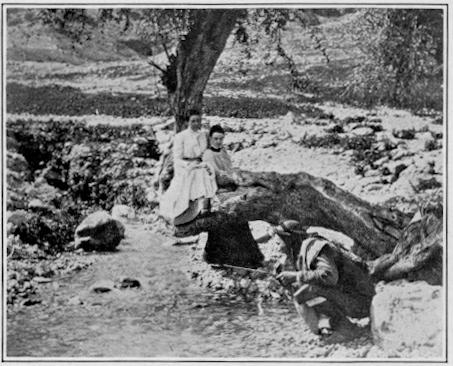

| Bedawy Drinking |

42 |

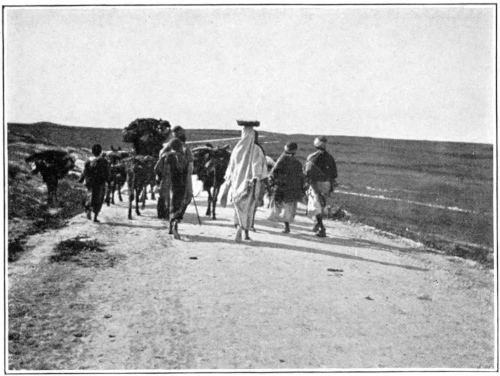

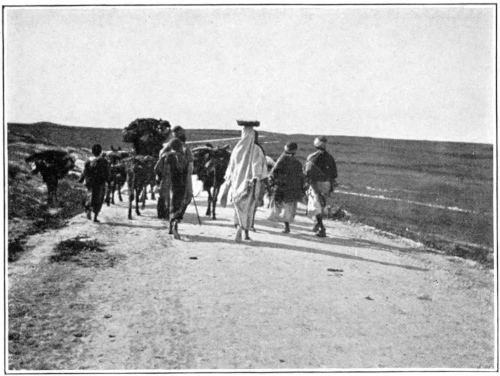

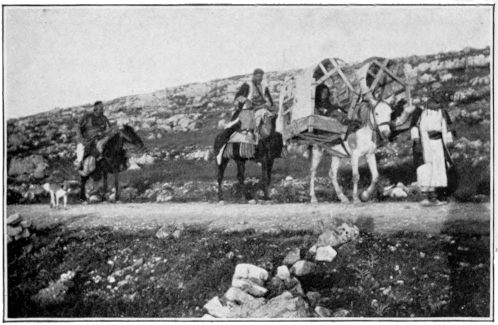

| Peasants on Way to Market With Produce |

44 |

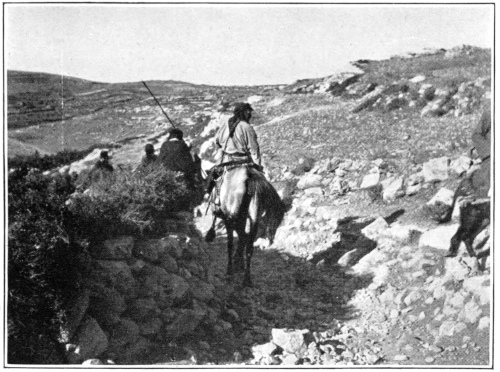

| Bedawin Horseman |

44 |

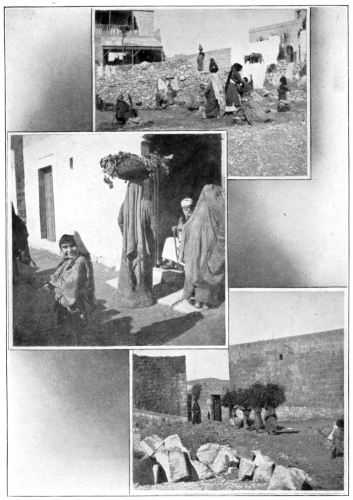

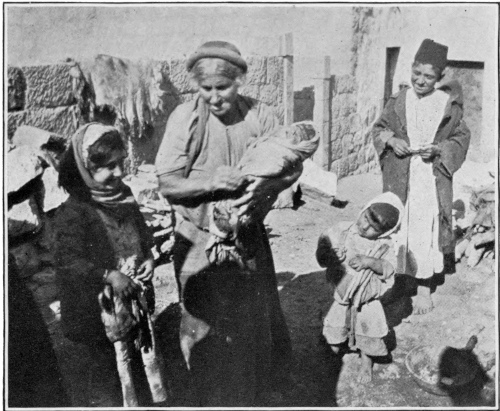

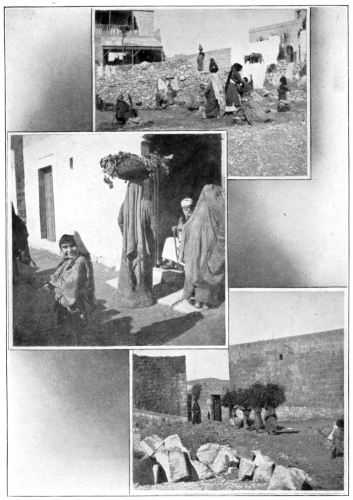

| Woman’s Work |

48 |

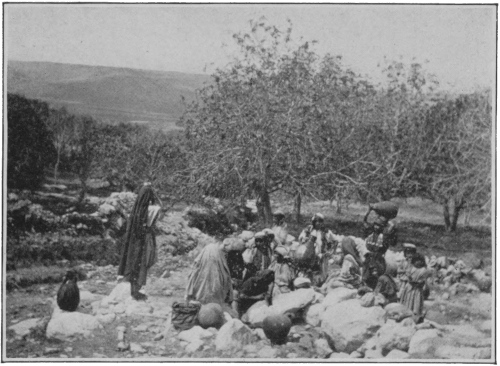

| Bringing Home the Bridal Trousseau |

54 |

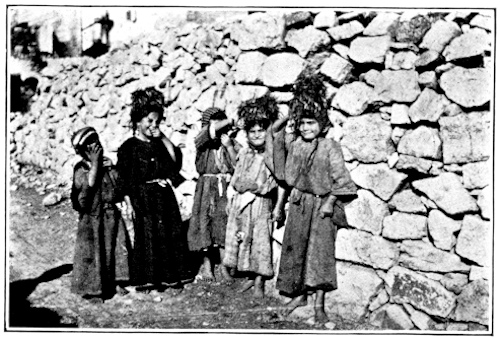

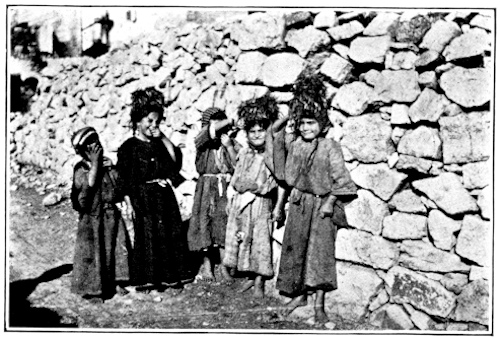

| Girls at Play Carrying Headloads of Grass in Imitation of the Women |

54 |

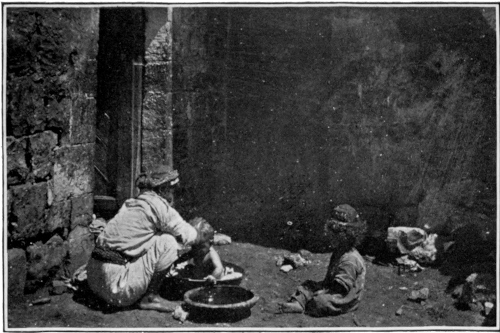

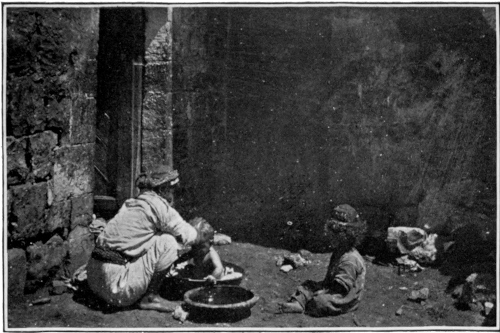

| Washing a Child |

58 |

| A Swaddled Infant |

58 |

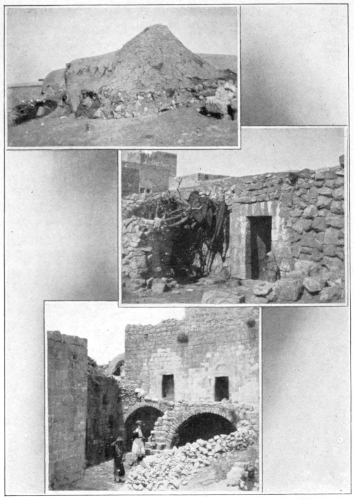

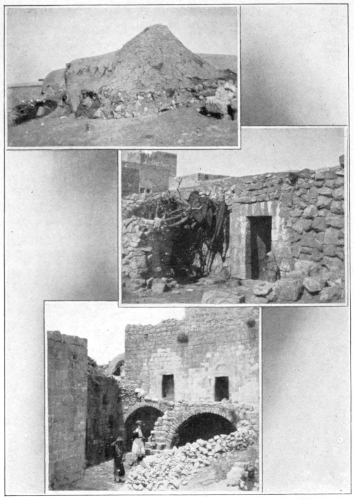

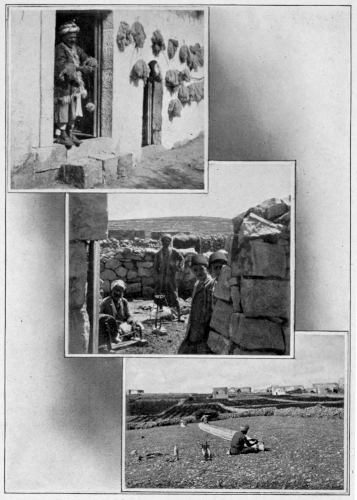

| Three Kinds of Houses—Mud, Dry-Stone, Stone-and-Mortar |

68 |

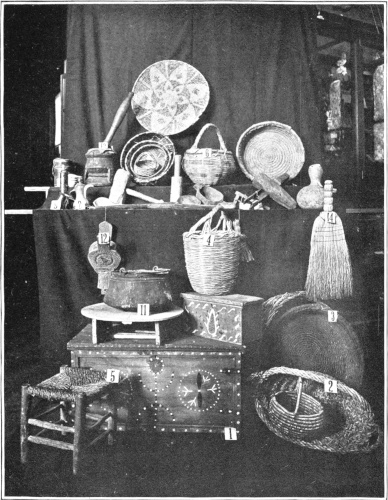

| Household Utensils |

76 |

| Bread-Making Utensils |

82 |

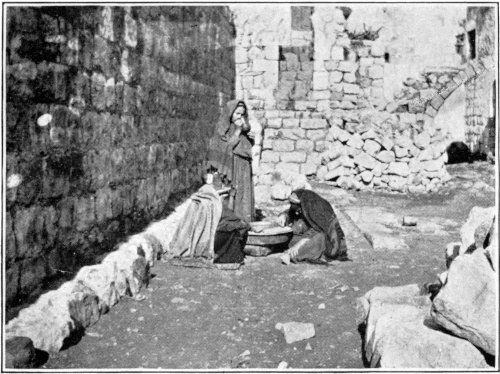

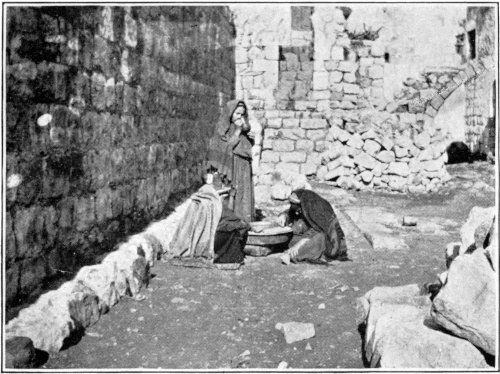

| In a Dooryard. Women Cleaning Wheat |

94 |

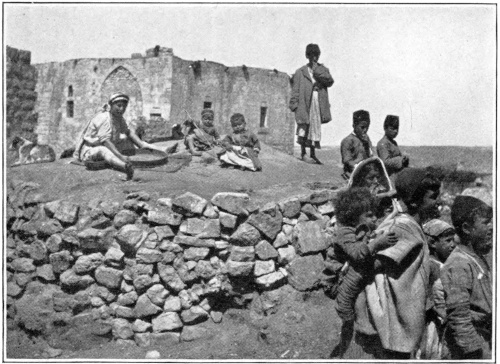

| On Top of an Oven. Women Sifting Wheat |

94 |

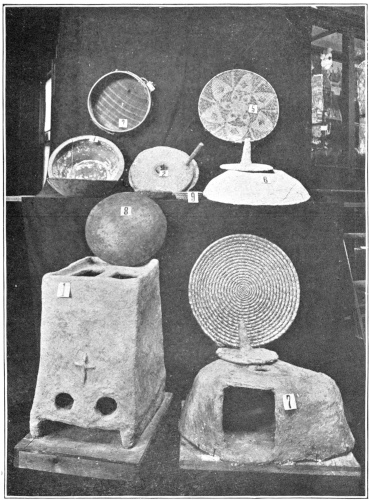

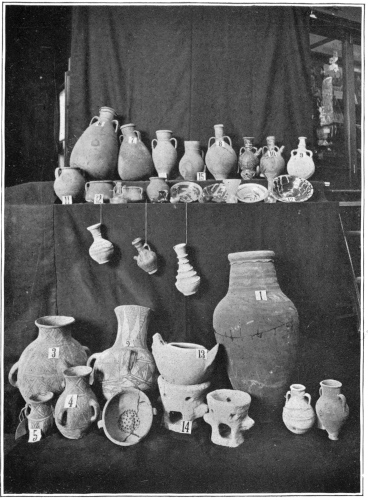

| Pottery |

114 |

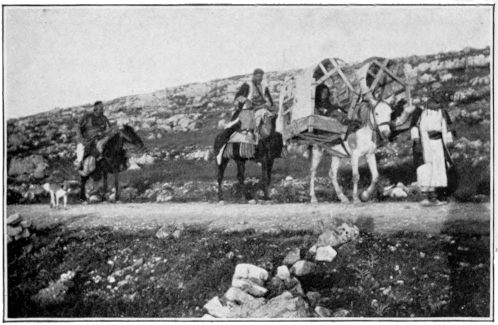

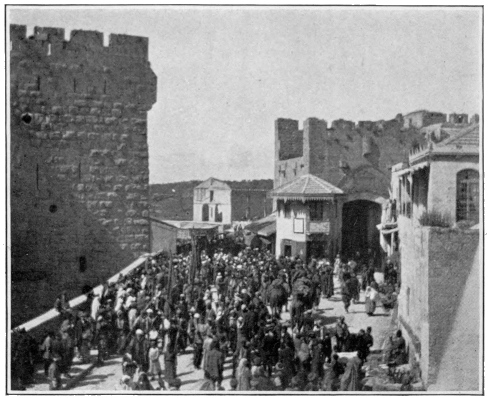

| On the Way to Jerusalem. For the Neby Musa Procession |

126 |

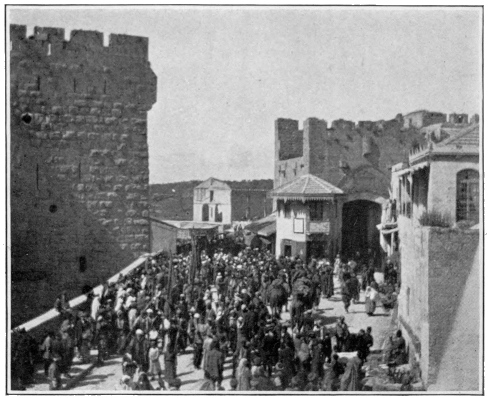

| A Neby Musa Contingent Arriving Within the Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem |

126 |

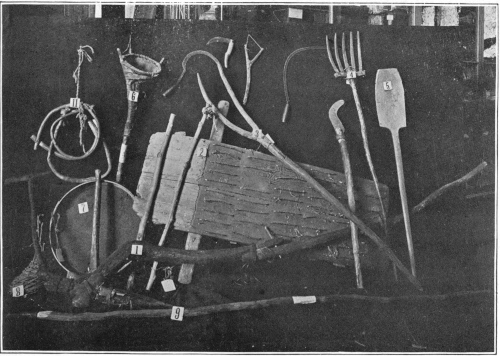

| Farming Implements |

130 |

| A Sower |

132 |

| Children Gleaning |

132 |

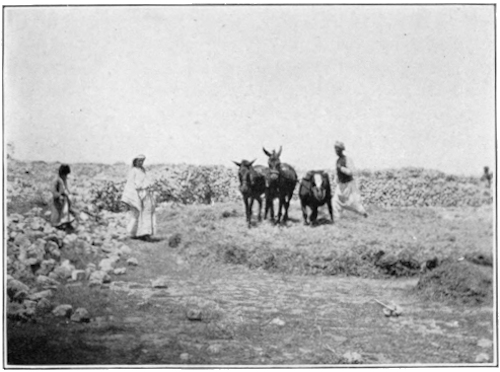

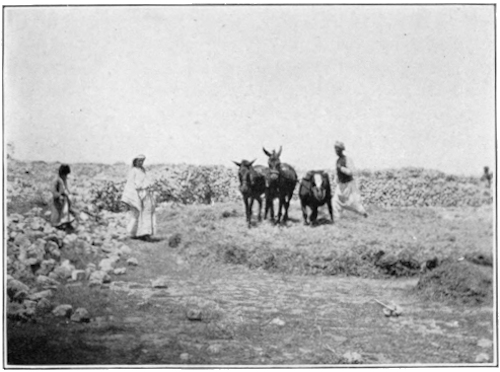

| Threshing |

140 |

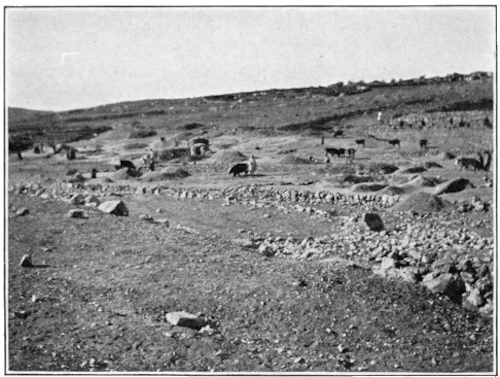

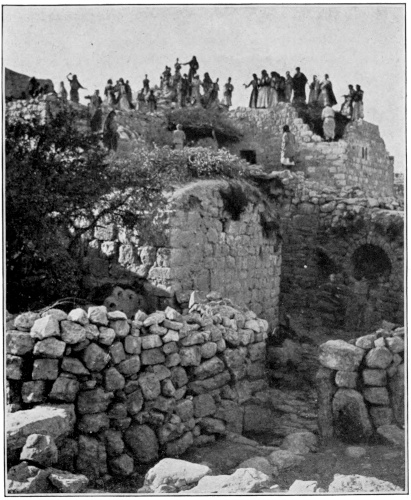

| A Threshing Scene in the Old Pool at Bethel |

140 |

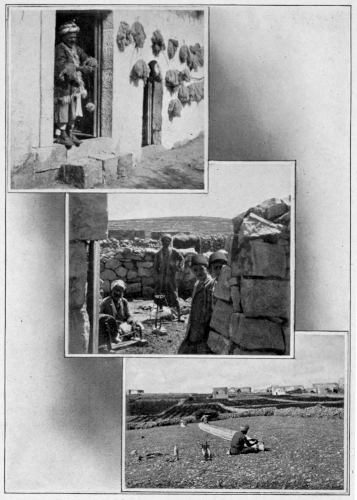

| 1. Hand Spinning 2. Reeling 3. Straightening Threads For Loom |

142 |

| Various Articles Made of Skin: Bottles, Bags, Pouches and Buckets |

150 |

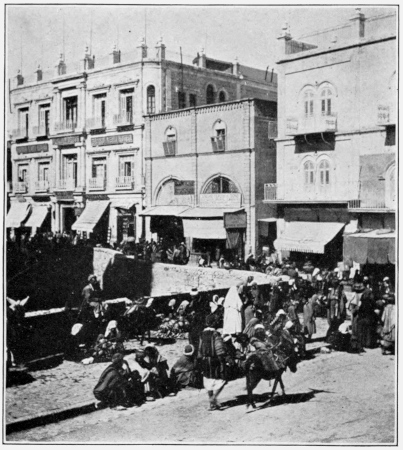

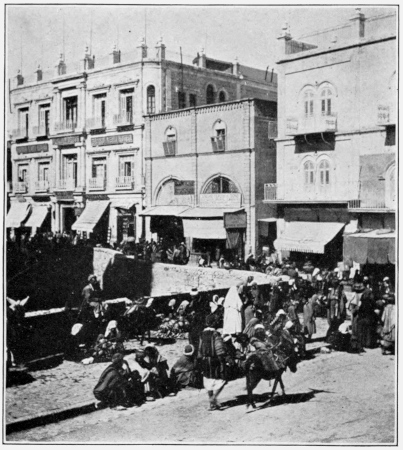

| A Market Scene: Peasantry Near David’s Tower, Jerusalem |

154 |

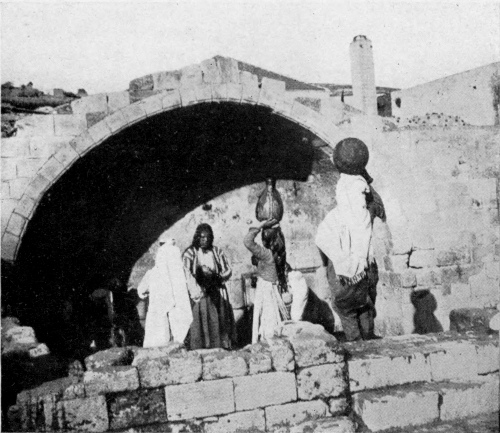

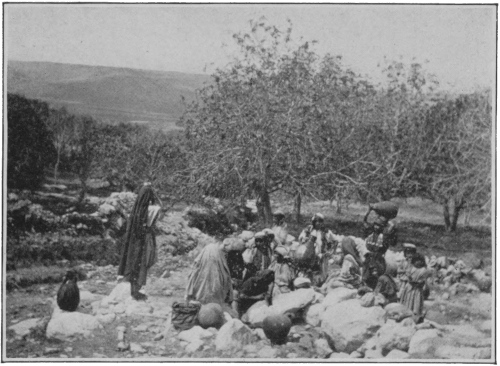

| Women at the Spring |

164 |

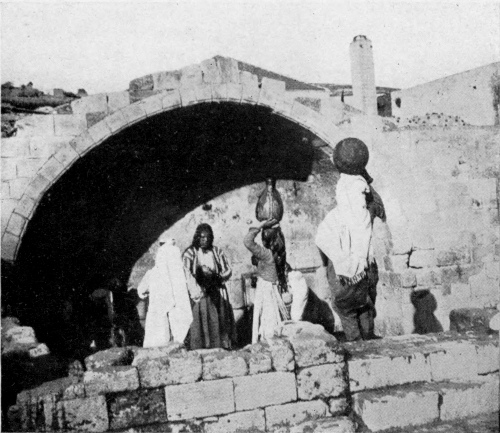

| Fountain at Nazareth |

164 |

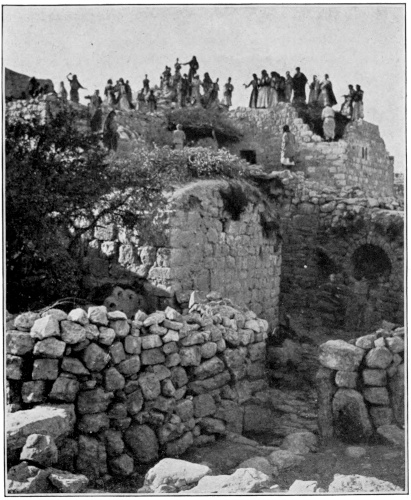

| A House-Roofing Bee (Et Tayyibeh) |

172 |

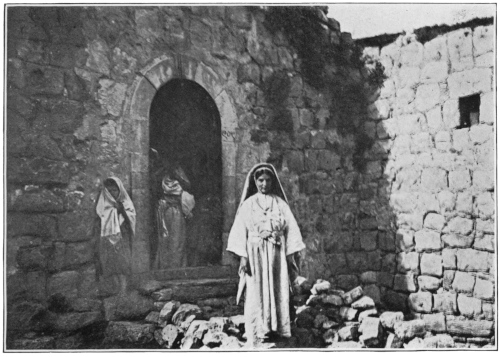

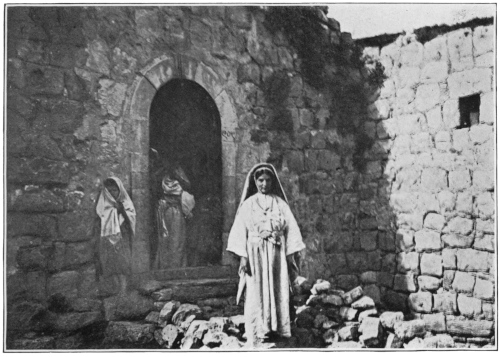

| A Râm Allâh Matron at Her own door |

187 |

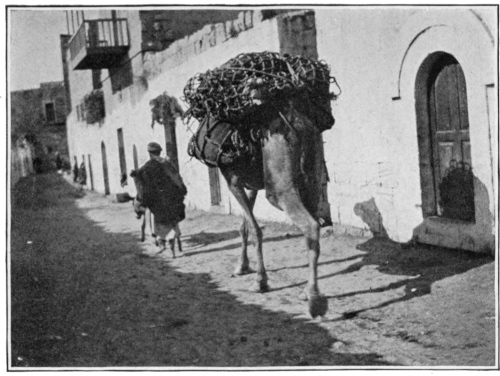

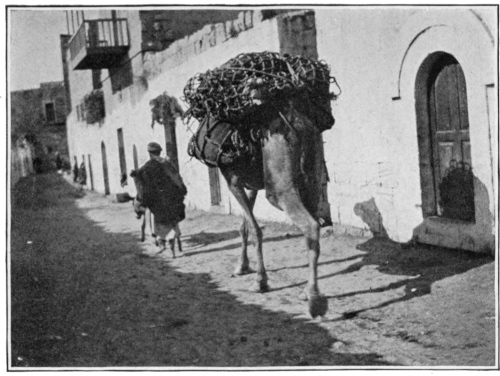

| Camel Carrying a Rope Net Filled With Clay Jars |

194 |

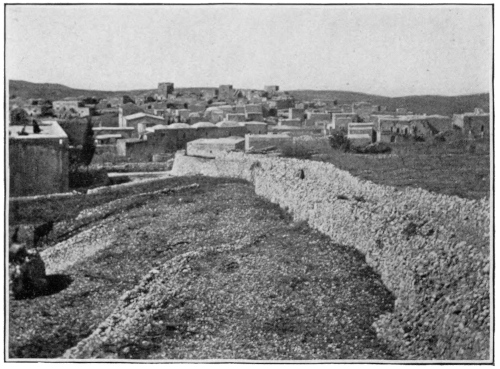

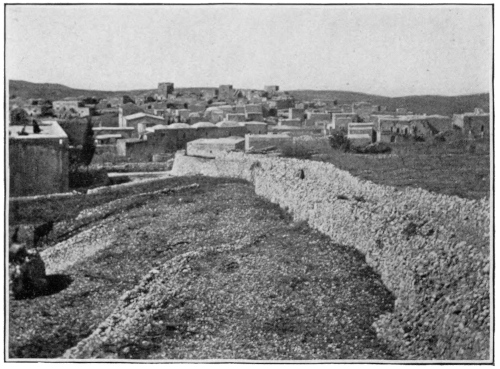

| Râm Allâh, as Entered by the Sinuous, Walled Lane From the East |

194 |

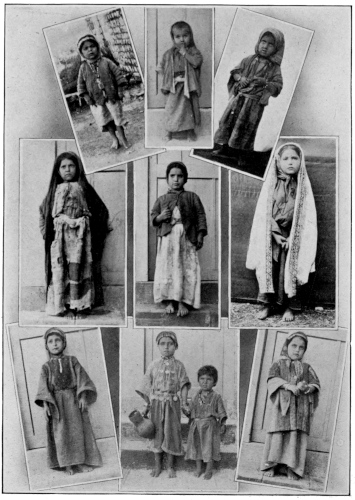

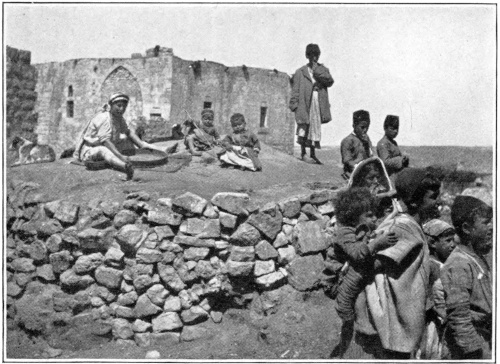

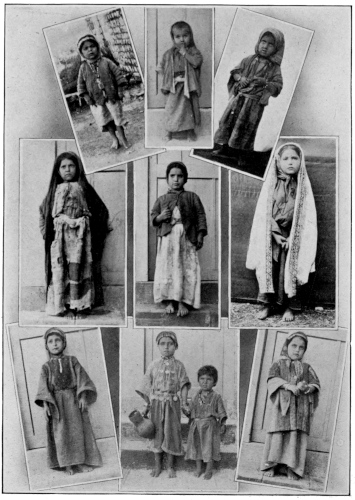

| Little Girls of the Village |

196 |

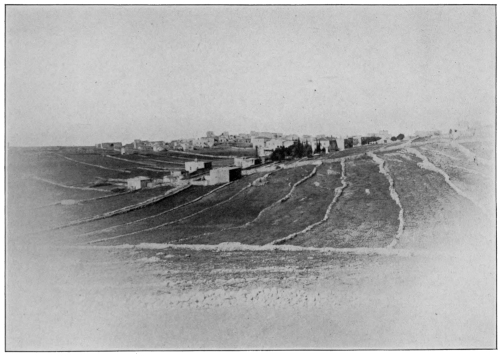

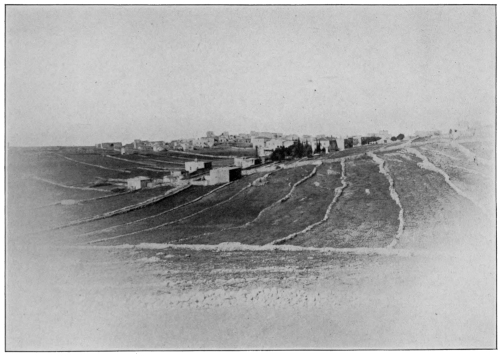

| The Village of Râm Allâh and Outlying Vineyards |

204 |

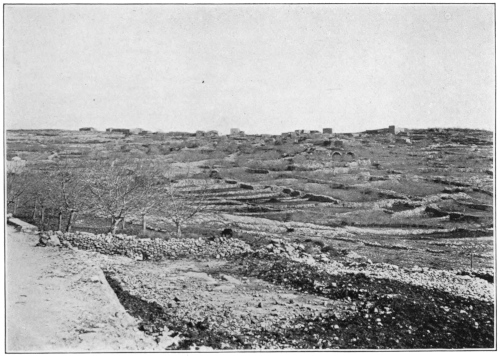

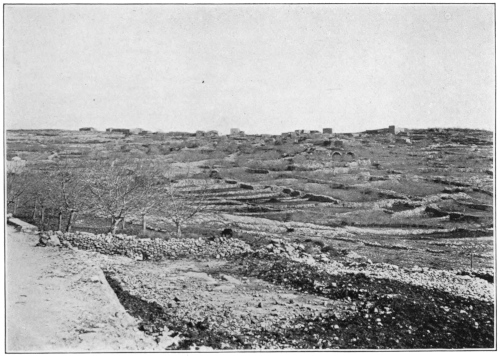

| El-Bireh (From the South) |

212 |

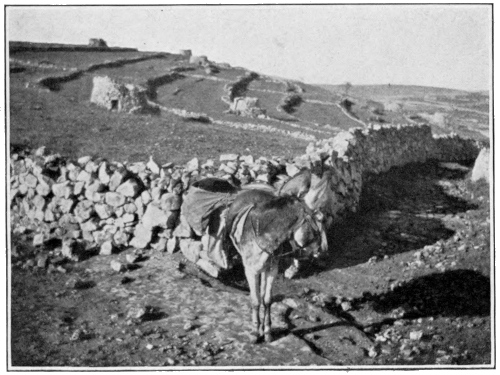

| Vineyards and Stone Watch Towers |

220 |

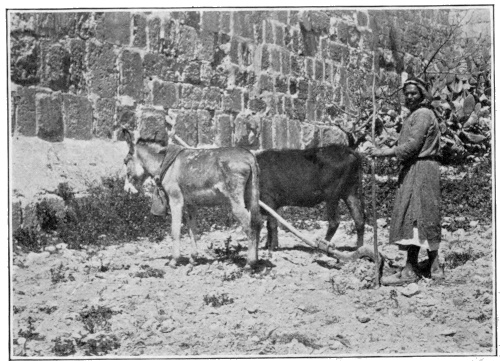

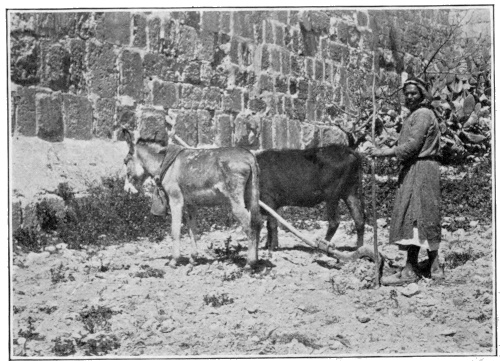

| Peasant Plowing |

220 |

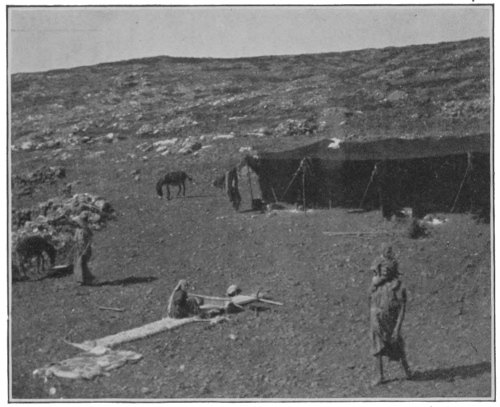

| Primitive Rug Weaving (Bedawin) |

230 |

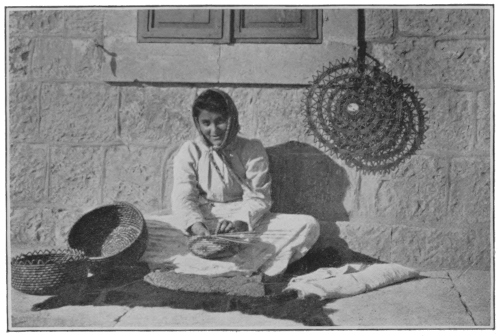

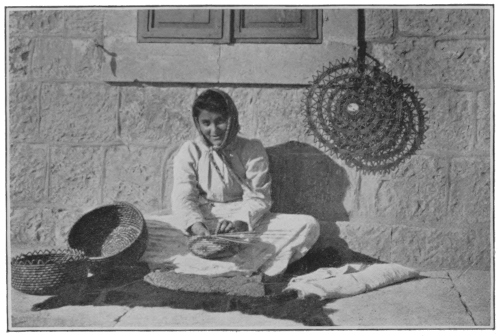

| Straw Mat and Basket Making: Jifna Woman |

230 |

11

The PEASANTRY of

PALESTINE

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY. THE COUNTRY OF WESTERN PALESTINE. GENERAL FEATURES

This little book will make no attempt to tell all

that could be said of its subject, but we hope that

its selection of things to tell will be gratifying to

you. Our wish is that not many of its pages may be

condemned as dry, but that most of them may have interest

and refreshment. If sometime when you are tired

you can sit down and be pleased with some of these

pages, here or there, you will know a little of how the

trudging peasant of the village feels as, going over hill

after hill, from each top he gazes off towards the west and

sees the evening mists thickening and looking like good,

cool mountains in the sea. It is pleasant to see the face of

the native light up as he catches sight of the clouds heavy

with blessings of moisture. Perhaps fierce sirocco days have

followed one another for some time, longer than usual. Such

days are usually looked for in trios at least, but often they

hold for a longer time. Their peculiarly enervating heat is

very trying, and when they have passed one welcomes

eagerly an evening that brings the heavy mist. This announces

that the succession of hot days is broken and that

some days of respite are coming. The welcome moisture

blesses the vineyards, the fig orchards, the tomatoes,

squashes and melons, and it is sure to bring out ejaculations

of blessing from the fervent peasant, praising the Father of

all, whose favoring mercy he feels.

12Look out on a morning early and you will see the mists[1]

scudding, drifting, veiling and dissevering like masses of

gauze, like streamers of truant hair. Perhaps some near

mountain may be cut off from the little hill half-way down

by a moat filled with billowing fog. Soon the sun cuts it

and scatters it away and the hot, dry day sets in. The roads

and rocks are powdered with lime dust, the somber morning

tones on the hills are touched with whitening brightness.

Here and there is the dusty gray of an olive-orchard or the

bright green of vineyards. Overhead, the brightest blue is

set with one yellow gem of fire that creeps up and up until

noon, and then the toiling peasantry, who have watched this

timepiece of the heavens, sit down in the nearest shade to

eat their food and chat. That done, they roll over for the

luxury of a nap and forget a hot, dry hour in a healthy doze.

The click of the chisel in the quarry ceases, the hoe is cast

aside, the driver is lying on his face, fast asleep, while the

donkey nibbles and rolls his load-sore back deliciously in

the dust. The camel sits like a salamander, apparently

minding no change of weather. Little birds pant for breath.

All is very still and hot.

But work-time comes again before the heat goes, and the

workmen half sit up, looking around, perhaps playfully

tossing a stick or clod on the head of a lazier comrade. The

work-saddles are roped on the backs of the animals. The

camel, long habituated to complaining, whether made to

kneel or rise again, utters grating gutturals from his long

throat. He is the Oriental striker, objecting, vocally, at least,

to every new demand upon him. Well waked, the countryside

begins to be busy again and work goes on until sundown.

As the afternoon slips into the evening you will see traveling

peasants hastening to make their villages. The hills are

touched with pinks and purples that shade into dark blue.

The gray owl calls, the foxes reconnoiter the fields, the village

13dogs bark, lights straggle out from the settlements. One

may hear the song of a watcher in a vineyard or the bang

of his musket as he shoots at a dog or fox meddling with

the vines. As we hastened one evening through a village

two hours distance from our own, the people, sitting about

the doors and in the alleys, seemed astonished and urged

us to stop overnight, not understanding our preference to

travel on in the growing dusk. But we went on, passing

possible sites for Ai, then Bethel and Beeroth, and so to

our own Râm Allâh. The way was precarious and stony,

with only the starlight to help us, and the evening was

chilly.

We might call Palestine, even the western part of it, which

is more familiar to us, a world in little, so much has been

packed into this little space between the Jordan and the

Mediterranean. Sometimes it has been a kingdom and sometimes

kingdoms. As a province or provinces it has acknowledged

masters on the south, east, north and west.

Far back in time the country was the range of numerous

unruly tribes. To-day it contains several districts within

the Asiatic holdings of the Turkish Empire. As one looks

inland from the Mediterranean on the Judean country, first

comes the straight unindented coast line of sand, then a

fertile strip of land parallel to it in which the orange and

the grains flourish. Next comes the secondary ridge of

Judean hills; then its primary ridge of mountains. These

latter are thirty-five miles from the sea and three fifths of a

mile above its level. Now, as we stand on the mountain

range, we have only twenty miles between us and the country

of the Dead Sea, but a rapid fall in levels which, in so short

a distance, makes the sand-hills seem to drop down and

away from us in a precipitous stairway to one of the lowest

spots on earth, the basin in which the Jordan River and the

Dead Sea lie, the so-called Ghôr. This depression is a

quarter of a mile below sea-level and hence three quarters

14of a mile below the high country in the neighborhood of

Jerusalem.

Western Palestine is a limestone country that is, geologically

speaking, new. Faulting, erosion and earthquake

as well have been hard at work in comparatively recent

geological times to make a most diversified surface in a land

of short distances. Its rocks are peppered with nodules of

flint. The weather wear on the country rocks of some

districts allows the flint nodules to drop out, thus leaving a

peculiar worm-eaten look in the stones and cliffs. In other

localities the cherty material runs in ribbon-like bands

within the limestone. The lime rock is often beautified by

geode-like recesses of lime crystal, and the slabs of lamellar

stone so much used for flooring, window-seats and roofing

are frequently penciled with exquisite dendritic markings.

Often the face of cleavage between blocks of building

material is glazed with a native pink. There are a few

houses in the villages whose external walls are constructed

of regular blocks so arranged as to alternate in a manner

resembling checkerwork of pink and white squares.

One thought that may occur to an American or European

as he looks at the numerous hills and mountains up and

down the middle and back of Western Palestine is that never

before has he had such a fine opportunity to see the shapes

of hills and valleys. For at home he seldom sees the whole,

real shape of a hill or a mountain, so covered is it with trees

or smaller growth. But here there is very little clothing

on the hills. Their knobs and shoulders, cliffs and ribs, are

almost as naked of trees as the blue skies above them. The

rock layers stand out at the worn edges very plainly. Some

hills are banded round and round horizontally with successive

layers of rock. Others are made up of layers slightly inclined,

and some look like giant clam-shells set down on the

land. In yet other hills the twistings and heavings have

given the sedimentary layers a vertical position up and

15down over the mountains, as if they had been tipped over.

These bands of rock are usually of limestone interspersed

with chunks of chert. Ordinarily the tops of the hills assume

a long, sloping, rounded shape because of the soft nature

of the rock and the wearing power of the deluging rains.

All around the highland country of Western Palestine are

mellow plains and fertile valleys. Up and down the western

border between the highlands and the Mediterranean is the

Maritime Plain, from eight to fifteen miles wide. Along the

eastern edge is the great depression of the Ghôr, the low

fertile basin that separates Western from Eastern Palestine

and provides a bed for the plunging current of the Jordan

and a sink for the Dead Sea. These two fertile strips are

barely connected toward the north by an arm of the Ghôr,

formerly called the Valley of Jezreel, that reaches to the

site of ancient Jezreel, and a succession of plains formerly

called the Plain of Esdraelon, that touch the Maritime Plain

around the nose of Carmel. The highland country is pierced

by many a cut called, in the language of the country, wâd,

or wâdy, the equivalent ordinarily of our valley, though the

climate of Palestine is such as to make it almost always the

case that a wâdy is a brook in the rainy weather of winter

and a dry gully during the rest of the year.[2] Some of these

wâdys are of considerable breadth and offer arable lands;

others are narrow, deep gorges. Into some of these gorges

the débris from the hillsides has tumbled so as to make it

impossible to use the valley bed as a road even in dry

weather.

Many of the passes mentioned in the literature of Palestine

are really highland paths. Valleys must often be avoided

as impassable during the winter rains and as stiflingly hot

in summer. Invading armies would seldom risk using narrow

valleys for their approach, as they would be easily

assailable from the hillsides.

16The limestone is full of holes and caves varying in size

from a pocket to a palace. The caves may be near the

surface or far in the secret places of the deep-chested

mountains. They make reservoirs for the catching of the

rain from the surface and hold it through the long dry

season, giving some of it in springs[3] and probably losing

floods of it in lower and lower caverns. Sometimes the

caves are like small rooms,[4] let into the sides of the cliffs,

as at ‛Ayn Fâra in the Wâdy Fâra, a few hours northeast

of Jerusalem, where there is a suite of four connecting rooms

in the side wall of the valley, thirty feet above the path.

In front of the rooms is a narrow ledge overhanging the

path, and up through this natural platform is a manhole

which offers the one way of access from below. All up and

down this wâdy are caves, some having been improved,

probably for purposes of hermit dwelling. In Wâdy es-Suwaynîṭ,

that is, the valley of Michmash, there are a good

many such cliff dwellings[5] which seem to be approachable

only by a rope let down from the top of the precipice

above. All through the wild gorges of the country one is apt

to come upon these caves with signs of use in some previous

age by troglodytes and hermits. When possible they are

now used as goat-pens, and thus offer unclean but dry

quarters to any one caught in a rain. At the cave near

Kharayṭûn the entrance is difficult to reach, up in the side

of a precipitous mountain. It is a narrow passage leading

to a large, high, vaulted room, a sort of natural cathedral,

with a large side chamber. Thence one may go through a

low, tortuous passage to other smaller rooms as far as most

of the adventurous care to go, the natives say to Hebron,

but the guide-books, something over five hundred feet.

About Jeba‛, east of er-Râm, the ground sounds hollow under

foot because of caves to which one may descend, in some

17cases by cut stairs, to find that the caves have been enlarged

and cemented. About two thirds of the way from el-Bîreh

to Baytîn, on the left of the path, is a cave which has been

made to do service as a catch-basin for the water from the

spring above. The mouth of the spring has been enlarged

artificially and connected by a rock-cut channel with the

cave. This channel has little grooves branching from it and

there seem to be here the conveniences of an ancient laundering

or fulling place. In the cave are two supporting columns

cut from the rock. The interior is well adorned to-day with

a pretty growth of delicate maidenhair ferns.

There are many caves in the hillsides of what is called the

Samson Country,[6] through which the railway from Jaffa to

Jerusalem passes. In and about Jerusalem are caves the

discussion of which does not belong here, though they can

hardly have failed, in their long association with the history

of that city, of having much significant connection with the

political and religious history of the people of the country.

Such are the caves about the Church of the Holy Sepulcher,

the little one under the great rock beneath the Dome

of the Rock, the artificially enlarged caves on the south

side of the Valley of Hinnom, the huge cave of Jeremiah,

north of the city, under the hill where the Moslems have

a cemetery, not to mention its counterpart across the road

and under the city, called Solomon’s Quarry or the Cotton

Grotto.

Near the village of Ḳubâb, but nearer the tiny village of

Abu Shûsheh, is a large cave now used as a sheep and goat

pen. It is called by the neighboring Moslems Noah’s Cave.

The top of it has evidently at some time fallen in, thus diminishing

its size, but giving it an immense mouth, quite conspicuous

all about the neighboring country to the north.

The peasantry, in their double desire to account for it and

also to say something against the Jews, tell this story about

18the cave. They say that Noah was making war against the

Jews who, being hard pressed, ran into this cave for shelter.

Thereupon Noah brought up his heavy guns and bombarded

the cave with such effect as to crush in the top, which fell

on the Jews, killing them all.

In connection with caves the peasants tell certain stories

of hyenas. To the peasant any story that has to do with

these creatures is gruesome. The hyena, they say, will

accost a lone pedestrian, rub up against him and cast a

spell over him until, in a dazed way, the man follows the

animal to its cave, where the hyena will despatch him. The

tale is continued to describe how the hyena is captured.

They say that a man strips himself naked and crawls into

the cave of the hyena, carrying one end of a rope which is

held by his companions outside. Once inside, his condition

deceives the hyena, as does also a cajoling tone which he

uses until the creature, quite unsuspecting, begins to fawn

and roll over. The man at once secures a leg of the hyena

with his rope, whereupon the men outside draw out the

beast and kill it with their clubs.

New graves are usually loaded with heavy stones and

watched at night to prevent the hyenas from exhuming the

dead bodies.

As the rock of the country is of a quickly dissolving kind,

the torrential force of the winter rains greatly facilitates

soil-making. The ground is strewn with loose stones, in

some places so thickly that the soil cannot be seen a few

rods away. Soil is carried rapidly about, so that where

there are no terraces or pockets to catch it the shelving rock

is soon denuded and the only deep earth is found in the

valleys or hollow plains.

The Jordan and the ‛Aujâ (Crooked) are the two largest

rivers of Palestine; Ḥûleh (Merom), Tiberias (Galilee) and

Baḥret Lût (the Dead Sea), its three lakes. There are many

streams, brooks and winter ponds that disappear with the

19rainy season. In a few deep-cut beds, where strong springs

supply the brooks, water flows in a current all the year.

The watershed of Western Palestine is considerably nearer

to the Jordan than to the Mediterranean, being about thirty-five

or forty miles from the Sea, but scarcely more than

twenty miles on the average from the river. The valley

courses of the streams generally take a southeasterly direction

from the watershed to the Jordan basin, and a northwesterly

direction towards the Mediterranean Sea. Those on the east

are narrower and more precipitous, since they have on that

side of the country the shorter distance and the more

remarkable fall in levels.

Fertility and population have generally favored the western

side of the watershed, with some notable exceptions.

This western slope is flanked by the low-lying hills of the

Shephelah and comes gradually down to the Maritime Plain.

The hills and plain on this side have very great historical

interest and have formed the bridge of the civilizations to

the north and to the south of Palestine. At the present

time, when travel comes by sea from the Western world,

this country is a threshold to the shrines and ancient sites

of Syria and the East.

The only ponds in the country are the winter ponds called

by the native name, balû‛a. These are formed by the winter

rains. They stand for about five months in low places, and

then disappear until the next rainy season.[7] Robinson, in

1838, passed by one of these on his way from el-Bîreh to

Jifnâ. As his journey that way was on June 13, the pond

was then dry. But this same pond may now be seen every

winter and spring full of water. The new carriage road cuts

the eastern end of it at a point a little over a mile north

of el-Bîreh. Another of these ponds may be seen just under

the village of Baytûnyeh, towards Râm Allâh. Were it not

for such short-lived ponds many of the country people would

20have little idea of any body of water larger than a rainwater

cistern. The Dead Sea may be seen from the high

hills to the east of these ponds and the Mediterranean from

those to the west, but only a small proportion of the peasantry

ever get to see either one of them. A distant view

gives the unexperienced no adequate notion of their size.

People living in Jaffa, on the sea, have been known to poke

fun at the upland folk and bewilder them with yarns about

the sea. One story that they impose on the credulous

countryman is that every night, at dark, a cover is put over

the sea, as one would cover over a jar of water, or a bowl of

dough. One man, on reaching Jaffa late in the afternoon

for his first visit, hastened down to the beach in order to see

the water before the cover should be put on for the night.

Perhaps the best known winter ponds are in the extensive

sunken meadows of the Plain of Esdraelon, athwart the way

from Jenîn to Nazareth.

The springs of Palestine are its eyes, as the Arabs put it,

and when they are sparkling with life the whole face of the

country lights up with a wholesome expression.[8] In places

where the springs are remote from the present settlements,

and now used only for the flocks or by travelers, there are

often to be seen remains of former buildings. Sometimes

villas or even villages may be traced; old aqueducts also, and

ruined reservoirs, showing how great pains were once taken

to utilize the water supply. At ‛Ayn Fâra is a copious supply

of water forming one of the few perennial brooks. In its

deeper pools the herdsmen water and wash their flocks.[9]

There is a very feeble attempt at gardening in the vicinity,

but for the most part the precious treasure flows away

unused. The valley sides show ancient masonry belonging

to more thrifty times. On the hill ‛Aṭâra, a mile south of

el-Bîreh, are ruined reservoirs to which the waters of the

spring now called ‛Ayn en-Nuṣbeh were carried by stone

21conduits, of which only small pieces remain. So may similar

indications be seen at ‛Ayn Ṣôba, at ‛Ayn Jeriyût, ‛Ayn

Kefrîyeh, all of which are west of Râm Allâh. Present-day

villages are often a considerable distance from the spring

on which they depend for drinking water. Many large

places are provided with but one spring. Nazareth and

Jerusalem are thus limited to one good spring each. Around

the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea are warm, even hot,

springs once much prized as watering-places. They are

generally sulphurous in character. Those at Tiberias, on the

Sea of Galilee, are used now as baths.

RIVER AUJA NORTH OF JAFFA

Of wells Palestine has but few. Some of those mentioned

in the Bible still remain, though not all are in use.[10] It

comes more naturally to the mind of an Oriental to devote

the labor and expense that it would take to dig a well to the

construction of something in which to catch a portion of the

rainfall. It is quite essential to the prosperity of Palestine

that its water resources be husbanded through the long dry

season.[11] As has been suggested, there is plenty of evidence

that formerly this was done in a very painstaking manner,

but at the present time far less care is given to this very

important matter. Numerous cisterns and reservoirs were

made to catch rain-water and the overflow of the fountains.

The large number of these ancient devices for saving water,

in contrast with the few made and used in these days, offers

one basis for a comparison of the condition of the country

in old and new Palestine. Rain-water was caught in

cemented pits not very unlike huge pear-shaped bottles.

Such water was used for all household purposes where

spring water failed; also for watering the animals. It was

drawn up as from a well. Occasionally these old cemented

cisterns are still in use. But all through the country there

are vast numbers of them that are no longer used. All

about Jerusalem, especially north of the city, among the

22olives, they may be seen; also about the district of Râm

Allâh, at Teḳû‛a and at Jânyeh.

The overflow of springs was provided for by more pretentious

structures,—the great rectangular box pools built

of solid masonry. The most noteworthy of these reservoirs

are the so-called Pools of Solomon, three in number, south

of Bethlehem, by the road that leads to Hebron. These

three immense reservoirs, each of which, when full, would

float a battleship, have a combined capacity of over forty

million gallons. Formerly stone aqueducts conveyed the

waters to Jerusalem. Remains of these are still to be seen.

The water is conveyed now through iron pipes, fully eight

miles, to the city. Jerusalem itself has the famous Pool of

Siloam,[12] the Sultan’s Pool and the Pool of Mâmilla. The

last one mentioned feeds a large reservoir within the city

walls, sometimes called the Patriarch’s Pool and sometimes

Hezekiah’s Pool.[13] At Bethel (Baytîn) the spring is surrounded

by an old reservoir larger than the Pool of Mâmilla.

It is now dry and its bottom is used as a threshing-floor.

And so all about the country are found the remains of

costly works designed for the saving and proper use of the

water supply. With such means of irrigation the productiveness

of the country must have been much greater than

at the present day.

Sometimes, in speaking of the seasons in Palestine, we say

summer and winter,[14] and sometimes we mention the four

seasons. Perhaps if we should say wet season and dry

season it would be less misleading, but even then one would

have to bear in mind that the wet season is not a time of

general downpour but simply the season in which the rains

of the year come.

The wet season, or winter,[15] as it is more generally called,

ought to provide, for the welfare of the country, from twenty-five

to thirty inches of rainfall in the highlands. Sometimes

23it is as low as sixteen inches, and it occasionally exceeds

thirty-five or even forty inches. Roughly speaking, the

wet season claims the five months, November to March.

In a very wet winter, perhaps, the rains will reach over a

period of nearly six months, but, on the other hand, the

rainy period may shrink to four. The most frequent and

heavy falls of rain in an ordinary season are looked for near

the beginning and at the close of the wet season. Many

pleasant days,[16] and even some entire weeks of rainless

weather, may be expected during this wet season. Now and

then there may be a winter during which the water will be

glazed over in the puddles a few times, or there may be

several falls of snow.[17] Driving, raw, chilling rains and

winds may prevail for a week at a time, or longer, and be

less easy to bear than the stronger cold of a more northerly

climate.[18]

The dry season is more in keeping with its name throughout

its control of nearly seven months, although rain in May has

been experienced and a slip in one of the summer months

is not unknown. At the end of September or at the beginning

of October a slight shower is expected. One scarcely

expects rain, however, until well into November. Despite

the very hot days in the dry summer season, the nights in

the Palestine highlands are generally cool. The Syrian sun

is a synonym for piercing, intense heat, and foreigners are

more apt to be thoughtless of its power than to overdo

caution. During the midsummer months it is hard to take

photographs except very early or very late, or with very

slow-acting lenses and plates. Then, too, the poorest light

for distant views may be in summer, when the intense heat

fills the air with a haze. Those who have seen the dead,

brown look that comes on a district of country which has

suffered an unusual period of drought may partly imagine

the appearance of Palestine after a six months’ absence of

24rain unrelieved except for the night-mists that may prevail

during some of that time.

After the drought the peasant, like the country, is pantingly

ready for the first rains of the autumn. He never

hesitates to choose between rain and sunshine. It is always

the former. Even if rain comes in destructive abundance

he has only to think of the terrors of a scanty rainfall to

repress all complaints. As we say in a complimentary way

to a guest, “You have brought pleasant weather,” so the

Syrian will say, “Your foot is green,” that is, “Your coming

is accompanied by the benedictions of rain.” Rains usually

begin with an appearance of reluctance,[19] but sometime in

November or December they ought to come down heavily

for most of a fortnight. Sometimes there are several weeks

of delightfully balmy weather between the drenching rains.

During an unusually dry winter, when the rainfall is below

twenty inches, much of the winter will be pleasant, at the

expense of the crops and of the general welfare. At such

times the price of wheat goes up and the scantily supplied

cisterns give no promise of holding out through the succeeding

summer. Springs dry down until the best of them offer

but a tiny stream, and hours must be spent at some of the

fountains to fill a few jars. Much of January is apt to be

rainy. February is strange and fickle, and because it is

especially trying to the vital forces of the aged and weak is

called Old Woman’s Month. We remember a very pleasant

February, but such are rare. Honest March is pretty much

its boisterous self even in Palestine. April is sunny and a

charming month for a journey. If the latter rains have been

delayed they may come even in April, though that is late.

But the needed rain has been known to come as late as

middle May, with unusually cold weather. Then the peasants

deemed such weather portentous.[20] The latter rains—how

familiar a phrase to the ears of many who may not

25know just why they are so called![21] The downpour of

November or December washed out the ground, made the

heat flee, brought back health to the succulent plants,

hastened the ripening of the oranges and did pretty well for

the cisterns, but this latter rain is the key of the situation.

If it does not come, wheat may sell at famine prices and all

the pains of a drought take hold of the land.[22] But if it

only will come, then wealth and comfort and a healthy

summer.[23]

Harvest begins in the springtime. May brings the yellow

heads on the grain, and it must be gathered or soon the

summer will be ended and the harvest past.[24] The grain on

the hills is a few weeks later than that in the valleys and

plains. A little donkey coming in from the hill terraces

with a back-load of sheaves looks very porcupiny. The

reaper grasps the stalks of wheat or barley with one hand

and cuts a long straw with the sickle in the other hand. If

he is hungry he starts a little fire and holds some of the

wheat heads over it until well parched, and then, rubbing

off the husks between his palms, he has a feast of the new

corn of the land. Thus treated, new wheat is called frîky

(rubbed).

During the time of ripening wheat one may see in the

fields, close to the ground, the heavy green leaves and yellow,

shiny apples of the mandrake.[25] The natives say that if one

eats the seeds of the fruit they will make him crazy. The

pulp has a pleasant, sweetish flavor and an agreeable smell.[26]

The only dreadful wind in Palestine is the east wind,[27]

because it blows from the inland desert and brings excessive

heat. The Arabic word for east is sherḳ, and so for east wind

26the Arab says Sherḳ-îyeh. From this we get, by corruption,

our word sirocco (or sherokkoh), which has come to mean

simply a hot, enervating blast from any direction. To the

Arab it is that wearing east wind whose coming can be felt

in the early morning before a breath of air seems stirring.

There is a certain chemical effect on the nervous system of

those who are particularly sensitive to the blighting touch of

the Sherḳîyeh. Sometimes this wind goes away suddenly

after a short day, but almost always its coming means that

it will run three days at least, and often more. There is a

similar wind in Egypt known to residents of Cairo as the

Khumsûn (fifty), from the likelihood that it will remain

fifty days. Such an unbroken period of hot winds must be

exceedingly rare in Palestine, though in the early autumn

of 1902 there was an almost continuous Sherḳîyeh for five

weeks. The east wind of winter is usually as disagreeably

cold as its relative in summer is hot and suffocating. The

only good thing that I ever knew the summer sirocco to do

was to cure quickly the raisin grapes spread on the ground

in September.

The west wind prevails a generous share of the time and

brings mists and coolness from the sea during the summer.

In the rainy season a northwest wind brings rain.[28] The

showers are often presaged by high winds from the west

and north.

September, with its trying siroccos, is often hotter than

May. The pomegranates ripen in this month. In the

country districts it is very hard to get goats’ milk from this

time onward for several months. The flocks are too far

distant, having been driven away to find pasture and water,

and a little later on the milk is all needed for the young.

During these days, too, it is not thought good to weaken the

goats by milking them any more than is quite necessary.

In the cities milk is always to be had.

27The Greek Feast of the Cross, about the end of September,

is looked forward to as marking the date for an early shower

which may be sufficiently strong to cleanse the roofs. After

that the rain may come in a month, or it may wait two.

The people notice a period of general unhealthiness just preceding

the autumn rains. Their advent usually puts an end

to it, bringing healthier conditions. Sometime along in the

autumn there is often noticed a warm spell of weather which

the natives call Ṣayf Ṣaghîr, or Ṣayf Rummân, that is, Little

Summer, or Pomegranate Summer.

The cement in the paved roofs cracks under the fierce heat

of summer and the early showers help to discover the bad

places which must be patched before the heavy winter rains.

In the case of earth-covered roofs the first shower ought to

be followed by a good rolling, the owners going over and over

them with stone rollers rigged with wooden handles that

creak out upon the clear air after the rain as they work

in the sockets. From the peculiar noise thus made the

Râm Allâh people have a local name of zukzâkeh for the

wooden handles of these stone rollers. In the northern part

of the country the name nâ‛uṣ is given to the roller handles

for a similar reason. The roofs of rolled earth can be kept

very tight. The covering of such roofs is made by mixing

sandy soil with clay and with the finest grade of chaff, called

mûṣ, from the threshing-floor. On old earth roofs patches

of grass[29] grow, and even grain has been seen springing up in

such places.

The Syrian peasant divides trees into classes by pairs.

There are those that are good to sit under and those that are

not. Then there are those that yield food and those that do

not. Finally there are those that are holy, and therefore

cannot be cut for charcoal or fuel, and those that are not

thus tabooed.

The fig-tree is a very useful food producer and is much

28cultivated. As elsewhere mentioned, the irritating effect of

the juices of the broken fig branch or leaf makes it less

desirable as a shade tree, but because of its dense shade it

must be resorted to in hot weather. The olive-tree gives

rather a thin shade. The carob-tree is a fine shade-giver.

The pine is a favorite in this respect, though few pines are

left. The needly cypress shades only its own central mast.

One might as well snuggle up to one’s own shadow for protection

as to expect it from a cypress. Pomegranate, lemon

and orange-trees, when large enough, afford shade, but they

are often in low, miasmatic places. The apple-tree does not

do well except in parts of northern Syria, as at Zebedâny,

near Damascus. Some fine pear-trees are to be seen above

Bîr ez-Zayt, though as a rule they are as difficult to cultivate

as apple-trees. At ‛Ayn Sînyâ are flourishing mulberry-trees

of great size. The opinion is held that the mulberry and the

silk culture usually associated with it would thrive peculiarly

well in Palestine. Mount Tabor is thinly studded with trees

except on the southeast side. Mount Carmel also has yet

some remains of its one-time forest. The oak is found in a

number of varieties, but is a great temptation to the charcoal

burner, as it affords the most desirable coal. The zinzilakt

is a favorite for shade. The best substitute for a shade tree

in the land is a large rock, the cool side of which helps one

to forget the burning glare of the noon sun.[30]

We shall have to call winter the season of rain, flowers and

travel. Rain ushers in the winter and also closes it. To

the middle and latter part of that season is due the bursting

of the blossoms and a push that sends flowers scattering into

the first months of the dry season.[31] Travel might find a

better time than much of the winter, but then it is cool and

if it rains, why, that is the way of the country, and this

explanation often suffices.

DONKEY AT THE THRESHING FLOOR WITH A LOAD OF WHEAT

On the flowers of the country Dr. Post’s book offers a

29mine of information for those skilled enough in the elements

of botany to make use of it. The little booklets of pressed

specimens offered for sale, when fresh, give an excellent idea

of the variety of wild-flower life in Palestine. Mrs. Hannah

Zeller, a daughter of former Bishop Gobat of Jerusalem, and

the wife of the late Rev. John Zeller of Nazareth and Jerusalem,

has been most successful in reproducing in color many

of the flowers of Palestine. Mrs. Zeller’s book of color plates,

published some years ago, is now hard to secure. She still

has the originals and an even larger collection which awaits

a publisher. Until some such publication in color is attempted

it will be difficult to describe in writing the unusual

splendor and variety of Palestine’s wild flowers.

The flower season really begins in what we should call

midautumn with the little lavender-colored crocus called by

the natives the serâj el-ghûleh or the lamp of the ghoul. A

better name for it would be serâj esh-shugâ‛ which would

mean the lamp of courage, as it thrusts its dainty head up

through the calcined earth, scarcely waiting for a drop of

moisture. After this brave little color-bearer of Flora’s

troop there follow the narcissus, heavily sweet, and the

cyclamen, clinging with its ample bulb in rocky cracks as

well as nestling in moist beds. But of all the flowers the

general favorite is the wild anemone, especially in its rarer

varieties, white, pink, salmon, blue and purple. The most

common is the red anemone, which is seen everywhere and

sometimes measures four or five inches across. Near Dayr

Dîwân we once rode through an orchard where the ground

was covered with a cloud of these red ones, so voluptuous, so

prodigally spread in a carpet of crimson beauty that one

almost held one’s breath at the charming scene. The red

ranunculus, which comes later, is almost as large, but it

looks thick and heavy in comparison, and the flaunting red

poppy, which comes still later, looks weak and characterless

beside the anemone. Even the wild red tulip suffers beside

30it. The colors of the anemone other than red are more rare,

but usually come earlier. About Jaffa they appear shortly

after Christmas. White ones and some of delicate shades

are found between there and the river ‛Aujâ. White ones

abound near Jifnâ, and are found east of Ḳubâb and east

of Sejed station. Purple, pink and blue ones are plentiful

in Wâdy el-Kelb and the Khullet el-‛Adas near Râm Allâh.

The large red ranunculus mentioned is found in large patches

between Jericho and the Dead Sea in early February. Considerably

later there is an acre-patch east of Dayr Dîwân

near the cliff descent towards eṭ-Ṭayyibeh. The red tulip is

rarer and follows soon. The red poppy is very abundant.

It has the delicacy of crêpe. It is scarcely welcome as it betokens

the close of the flower season. But one may for

some time yet gather flowers that blaze forth as brilliantly

in middle spring as do the autumn flowers in America: the

adonis, gorse, flax, mustard, bachelor’s button, anise, vetch,

everlasting, wild mignonette and geranium. In the vineyards,

about pruning time, the ground is covered with a rich

purple glow. The sweet-scented gorse abounds in the valleys

towards Ṭayyibeh. The vetches come in many colors, and

there are scores of other scarcely noticed little blossoms.

When the season has been especially rainy, as may occur

about every fifth or sixth year, the valleys such as ‛Ayn Fâra

will be knee-deep with the abundant flowering herbs and

weeds. The scented jasmine and the tall waving reeds over

the watercourse will add their charm to this favored spot.

Later, yellow thistles abound.

One of the oddities of the flower family is the black lily

of the calla order, which the natives call calf (leg) of the negro.

In the moist, shady caves, and sometimes in old cisterns,

masses of maidenhair fern grow in the cool shelter throughout

the year.

On the shores of Tiberias (Galilee) oleanders and blue

thistles are seen in May.

31In speaking of the wild animals of Palestine one is almost

led to include the dog and the cat. They are, however, on

the edge of domesticity and may fairly be omitted. Wolves,

hyenas, jackals and foxes are the troublesome wild beasts.

The last two are often about vineyards seeking to feed on

the grapes.[32] The jackal cry at night is very mournful and

sure to start up the barking of the dogs, who are themselves

often grape thieves.

The beautiful little gazels are started up in the wilderness

and go bounding off like thistle-down in a breeze, turning

every now and then, however, to look with wonder at the

traveler. Once, near eṭ-Ṭayyibeh we saw four together, and

once, east of Jeba‛, we saw a herd of nine gazels.

Among the smaller creatures met with are the mole-rat,

the big horny-headed lizard, called by the natives ḥirdhôn,

the ordinary lizard about the color of the gray-brown rocks

among which it speeds, the little green lizard that darts

about, and the pallid gecko, climbing on house-walls. The

beautiful and odd chameleon must also be mentioned.

Snakes are not commonly seen by the traveler. Scorpions,

black beetles, mosquitoes, fleas and a diabolical little sand-fly,

called by the natives ḥisḥis, are among the less agreeable

creatures noticed.

At Haifa, in the house of the Spanish vice-consul, we saw

the skin of a crocodile caught in the river Zerḳâ in 1902.

They spoke also of one which had been caught fourteen

years before in the same waters.

One of the showiest birds of Palestine is the stork, which

is mostly white, but has black wings, a red bill and red legs.

Its eyes, too, have a border of the latter color. The natives

call it abu sa‛d. Flocks of them may be seen frequently.

Now and then a solitary bird is seen in a wheat-field. Crows

with gray bodies and black wings are plentiful. Ravens,

vultures, hawks and sparrows are common. Twice I saw

32the capture of a sparrow by a hawk. Once, after having

started his victim from a flock, the hawk dashed after him

and caught him in a small tree but six feet from my head.

It was done with such terrific quickness as to surprise the

spectator out of all action. Gray owls (bûmeh), partridges

(shunnar), wild pigeons (ḥamâm) and quails (furri) are seen.

It seemed quite appropriate to see doves on the shores of

Galilee. On the surface of the same lake water-fowls were

observed. At Jericho we saw the robin redbreast; in the

gorge at Mâr Sâbâ, the grackle. Starlings in clouds haunt

the wheat-fields in harvest. Meadow-larks, crested, are very

common. Goldfinches, bulbuls, thrushes and wagtails are

also noticed.

WILD ANEMONES FROM WADY EL-KELB

The scenery of Western Palestine lacks the charm that

woods and water provide. Yet one grows to like it. The

early and late parts of the day are best for the most pleasing

effects. Then the views out across the vineyards and off on

the hills are very restful. The rolling coast plain backed by

the distant hills of the Judean highlands makes a pleasing

prospect, especially when decked with the herbage that

follows the rains. Quiet tastes are satisfied with such

pastoral scenes as those in the valley at Lubban or in the

plain of Makhna. Excellent distant views are afforded from

the hills near Nazareth, from which are seen the rich plains

of Esdraelon, Haifa, Mount Carmel and the Mediterranean.

The Sea of Galilee is delightfully satisfying. From Tabor

one gets a glorious sight of Hermon, snow-white, whence the

natives call it Jebel esh-Shaykh (Old Man Mountain). The

views from Mount Carmel of sea and coast-line and much

of the interior, the glimpse of the Mediterranean from the

hill of Samaria and the sweeping prospect from Gerizim are

all good. An easily attained and little known view-point

is Jebel Ṭawîl (Long Mountain) east of el-Bîreh. From here

of a late afternoon the country lies open in sharp, clear lines

throughout the central region. Jerusalem is seen lying due

33south in beautiful silhouette; the Mount of Olives is a little

east of it. The Dead Sea is southeast, eṭ-Ṭayyibeh north

of east, Bethel (Baytîn) northeast, Gibeon southwest, near

which is Neby Samwîl. Near at hand, to the south, are

el-Bîreh and Râm Allâh. Only one thing is lacking in this

view; that is the Mediterranean Sea. But this can be seen,

as well as Jaffa, Ramleh and Ludd from Râm Allâh. The

mountain east of the Jordan is plainly visible from all the

high points up and down the middle of the country. Other

good view-points are Neby Samwîl, Jeba‛, Mukhmâs, the hills

about Jerusalem, especially from the tower on the Mount of

Olives and from Herodium. Heroic scenery may be found in

the so-called Samson Country through which the railroad

from Jaffa to Jerusalem runs, in the Mukhmâs Valley, the

Wâdy Ḳelt and gorges around Mâr Sâbâ. Crag, ravine,

precipice and cave make such places memorable.

The approach to cities and villages is as characteristic as

any other aspect of them. There is a look from afar peculiar

to the settlements of different countries. As seen from a

distance American settlements are chiefly noticeable for the

chimneys, the sharp spires of churches, the long, monotonous

lines of factory buildings and mills and often the pointed

shape of house roofs. Add to these enormous bridges, miles

of railroad yards and cars, a nimbus of smoke and you have

the elements from which to make a view of any good-sized

town. For the smaller, sweeter, country places you must

subtract some of the above features and substitute some

woodsy and meadowy effects. In Syria the contrasts with

our more familiar scenes are plain to us in the distant view

of its cities and villages. Instead of the triangular shape is

the square look of the buildings. Instead of chimneys and

spires are the huge domes resting on square substructures,

and the pencil-like minarets rising up among them. The

distant view of Jerusalem is one of the most pleasing in the

entire country. It has been one of the standard charms of

34Palestine, delighting warrior, poet and pilgrim, and more

lately student, missionary and tourist. There she sits with

her feet in deep valleys, her royal waist girdled with the

crenelated wall and her head crowned with the altar sites of

ancient time. There are about her the things that charm

the poetic sense,—age, chivalry, religion. Not even eternal

Rome can be so rich in these and so equally possessed of

them all.

Though it is not always the case, yet the greater number

of Syrian cities and villages seek hilly sites.[33] The

ports cannot always do this, though Jaffa does. Damascus

spreads out over a low flat area. Ramleh and Ludd, being

plain dwellers, must live in lowlands. But defense is very

commonly sought by settling on the sides or top of a hill

and building the houses close together, if not one above

another, as if in steps.

Garden plots and vineyards are fenced in with hastily-constructed

walls of the loose stone picked up on the inside.[34]

Between these curving walls run sinuous lanes[35] into the villages

from the paths and roads outside.

It would be very easy to make a pocket-edition of a book

of all the roads in the country, no matter how small the

pocket. Some roads are planned for, taxed for and looked

for a great many years before the semblance of road-making

begins. But never mind that; Orientals enjoy a road in

prospect and in retrospect much longer than in fact. Where

the government does put through a road it is usually good

traveling. The highlands afford the best of road-making

materials and, if often enough repaired, no better roads

could be asked for. Many carriageways are over favoring

bits of country where the frequent passing has marked out

the only road. The Romans were the greatest road-makers

in Palestine. The remains of their work may even now be

seen in various places. Many of their old roads are indicated

35on the best maps. Roman roads at this day of decay do not,

as a rule, offer easy travel. The washings of a millennium or

two of rain have made them of the corduroy order.

Of paths one may make as many as one pleases in a country

where no barbed wire and few walls prevent. The permanency

of the old well-worn paths[36] is very noticeable, the

best one always leading to a village or to a spring. There is

such a thing as the tyranny of the path. It is very evident

where railroads rule, and even in a country where the travel

must be on the backs of animals, the little bridle-paths impose

on one and, taking advantage of the inertia of human

mentality, mark out one’s way with arbitrary exclusiveness.

When one’s time is limited to just a sufficient number of

days to allow one to see all the more notable places in the

country, it is scarcely to be expected that one will sacrifice

the surety of seeing a noted place for the chance of stumbling

on a place of less popular interest. The paths and time required

for seeing most places are almost as clearly indicated

as any schedule of trips in countries possessed of time-tables.

This accounts for the fact that, although thousands of

travelers pass over the beaten paths, and scores of students

go over the rarer paths, not one in the twenty or the thousand

is likely to get off the paths.

One of the bits of country thus scantily known to foreigners

is northern Judea, especially to the northwest of Jerusalem.

Most travelers passing through it on the way to Jerusalem

are in haste to reach the city, and once there, the fact that

any place is a few hours farther distant than a day’s trip

would allow forbids easy investigation.

One does not have to go far to reach the wilderness.[37] It

is any uncultivated place. It is the pasture for flocks,[38] the

wild of rocks and short, thorny bushes. The thorns[39] are

gathered every other year to build fires in the lime-kilns,

where the abundant lime-rock of the country is burned.

36When the men gather them for the lime-kilns the thorns are

piled in great heaps with heavy stones on them to hold them

down. When needed the heap is pierced with a long pole

and carried over the shoulder as on a huge pitchfork. During

the late winter and in spring only may one see green

fields in anything like a Western sense. The Plain of el-Makhna

presents a very lovely prospect from the height

above it. Something like a small prairie effect is had in the

Maritime and Esdraelon plains. Pasture privilege is commonly

had anywhere if the land be not under actual cultivation.

In the uplands the custom of leaving great tracts idle

in alternate years[40] in lieu of dressing the ground permits

wide pasturage. As the dry season advances the herdsmen

seek the deep valleys with their flocks. There is little opportunity

for new trees or shrubs to survive this universal

browsing. So it comes about that, except where orchards

are set out or scraps of ancient woods remain, trees are

seldom seen.

Summer is the time of fierce heat, and yet through it all

the grape-vines keep green and the luscious clusters grow

larger and ripen under their heavy armor-plate of leaves.

The peasants enjoy the tart taste of green fruit. Half-grown

grapes are sometimes eaten with salt on them. Green almonds

are eaten in the same way. Often it is hard to get

ripe peaches, melons and other fruits because of the tendency

of the peasants to pick them before they are ripe. But the

time of the ripe grapes is the glad time of the year. Instead

of saying “August” the peasants often use the expression

“In grapes.” It is a season by itself to them. The vineyard

owners build summer booths among the vines and sleep there

through the season. In large vineyards it is common to

employ a black man, perhaps a Moroccan, as a watcher.

The Syrian peasant stands in peculiar awe of the black

stranger. The watchers are provided with shotguns, for

37foxes and dogs like to eat grapes. All fruit must be guarded

against thievishly disposed neighbors. One who knows his

vineyard watches the progress of the choicest clusters, having

covered some of them early to keep them from drying and

to allow them to develop unplucked. Should any grapes be

stolen he quickly notices the loss. He sets a thin row of

fine stones along the top of his wall in such a way that a

night marauder must necessarily rattle them down and thus

awaken him. One of the heartless bits of meanness that a

hostile peasant can perpetrate in order to pay a grudge is to

cut the vine stocks of his enemy’s vineyard. Since it takes

three years for a new vineyard to bear, such an act is a

serious damage.

The finest grapes within reach of Jerusalem are those from

Hebron and Râm Allâh. Large white clusters similar to

the Malaga grapes are the favorites, though purple grapes

are also grown. At Râm Allâh the vines lie flat on the

ground. The vine is pruned back to leave three joints on

every small branch that is spared in the rigorous treatment.[41]

At Jifnâ the vines may be seen trained on stakes. At

Zaḥleh, in the Lebanon, the growers have a way of propping

up the main vine a few inches above the ground, so that a

vineyard has the look of waves of green. In Jerusalem some

of the grapes at the Greek Hospital and at the White Fathers’

near St. Stephen’s Gate are raised on arbors, and the clusters

are covered with little bags. Thus protected the grapes

ripen slowly and are enjoyed until late in the season. Vast

quantities of fresh grapes are consumed as an article of daily

food during August, September and October. The price,

when cheap, is a cent a pound, and it gradually creeps up

to the fancy price of six cents a pound late in the season.

Grapes have been provided from the country vineyards as

late as the first of December.

Trees need considerable soil, but the grape-vine will thrive

38with very little and will penetrate with its rootlets all the

fissures of the lime-rock for yards about. Then, too, the

luscious bunches lying on a pebbled ground do better than

those on clear soil. Most of the grass and wild, weedy

growth of the country is bulbous and clings in scanty soil,

gathering as in a reservoir all the available moisture.

When the crop demands clear ground the native farmer

piles the stones into walls, watch-towers or a huge heap in

a less fertile spot of the field.[42] It is often a problem to find

room for the waste stones. They may be tossed out into

the roads and paths. A stranger says, “I don’t see why

these people don’t clear these paths of stone; surely it would

pay.” But the farmers prefer stones in the paths to stones

in the garden patch. With their bare feet, or on their

donkeys, they are able by a lifetime of practise to pick their

way over such paths. Moreover, peasants are not nervous

in Palestine. Stones always furnish a handy weapon,[43] or

a reminder on the heels of a slow donkey. In going about

through the country one often sees piles of little stones set

up one on another. Sometimes these little piles are meant

for scarecrows; sometimes they are used to mark a boundary;

but there is a wider and more constant use for such loosely

built little columns. They are set up in sight of holy spots.

Apparently they are not only set up in the vicinity of shrines,

wilys, etc., but also in places whence a distant view may be

had of some holy place, as Jerusalem, which the natives call

“el-Ḳuds esh-Sharîf” (The Noble Holy) or, for short, el-Ḳuds,

which is practically equivalent to our expression

“The Holy City.”[44] These little columnar piles may also

be met in sight of the hill or mount called Neby Samwîl,

which we usually identify with the Mizpeh of Samuel.[45]

RÂM ALLÂH MAN AND A BASKET OF OLIVES

STRETCH OF OLIVE TREES ON ROAD TO AYN SÎNYÂ

The terrace is a thing of great utility to the hill farmer of

Palestine. To the traveler it is a thing of beauty as it climbs

39the hills with its artistically irregular breaks in what would

be otherwise a rather monotonous slope. But with terraces

and some water the earth is caught and filled with

many possibilities of fruit and vegetables. A hill well

terraced and well watered looks like a hanging garden.

Much of the farming in Judea is on the sides of hills. The

little iron-shod wooden plow is run scratching along the

terraces. Sometimes one of the oxen will be on a lower level

than the other. To go forward without slipping down the

hillside is not easy. What cannot be plowed is dug up

with the pickax, and wheat or barley will find lodgment in

every pocket of soil. As all the reaping is done by hand it

offers no especial difficulty, and the monotony of which

some people complain on prairie land is never experienced

on such a pitched-roof farm. Even where the made terrace

is allowed to decay there are many natural terraces where

the horizontal layers outcrop from the hillsides. Were the

country well kept up, all these terraces would be guarded

artificially, for in time a natural terrace loses its protecting

edge and the soil and rain come down cascading over the

hill stairs until the bed of the stream is reached.

Of food trees the olive is probably the most valuable. It

takes ten or fifteen years to bring it to the state of bearing

much fruit, but it may go on bearing heavy crops for a

century. The oil is freely used in cooking, for salads, for

lighting and for anointing. A hard-pressed peasant will

occasionally yield to the temptation to cut down some of

his olive-trees, selling the finest pieces of wood to the makers

of the olive-wood articles[46] which are prized by tourists,

and disposing of the rest as fire-wood.[47] A hundredweight

of such fire-wood sells for from twelve to twenty-five cents,

according to the season and the market, the city price being

considerably higher than the country price. A good olive-orchard

is a sure source of income, unless the taxes are too

40harshly and arbitrarily imposed. The cutting them down is

a real calamity to the country, but it is done only too frequently

in a poor year to avoid taxes. The trunk of an aged

olive-tree attains a great girth and a gnarled, knobby look.

Sometimes a large part of one of these huge trunks will be

quite hollowed out by decay, in which case the peasants

often fill up the cavities with a core of stones. The tree goes

on bearing with chief dependence on the state of the bark

for its healthy condition. The heavy crops and light crops

follow each other in somewhat the same relation as the

apple crops in our New England country. Women and

children gather up those olive berries that fall to the ground

early in the season. Whenever it is desired to gather the

crop of a tree or orchard the men beat the branches with

very long light poles and the women and the children pick

up the fallen fruit from the ground. Of course this is a poor

way to gather the best olives, but inasmuch as the chief

use of the olive in Palestine is to express the oil, it makes

less difference. The berries do not ordinarily grow to the

larger sizes so often seen in our markets. Perhaps one of

the very handsomest stretches of olive-orchards in the East

is at what is called the Ṣaḥrâ, near Beirut, between that city

and Shwayfât. Other smaller but excellent orchards are to

be seen between Bethlehem and Bayt Jâlâ, at Mâr Elyâs,

Bîr ez-Zayt and to the south of eṭ-Ṭayyibeh.

The fig in Judea ripens in August and its fruit may be

had for several months, as new fruit keeps maturing. There

are several varieties of this valuable tree. A few ripe figs

are often found as early as June and are luxuries.[48] The

natives sometimes hasten the ripening of a few early figs

by touching the ends with honey. The natives declare that

the fig-tree will not thrive near houses but will become

wormy. The action of the milk of fig branches and leaves

on the tissues of the eyes, lips and mouth is very disagreeable,

41sometimes making them very sore. The eyes of children in

the fig season are often very repulsive. For this reason the

people prefer other shade, if obtainable, than that of fig-trees.

Most fig-trees are small, about the size of an ordinary

plum-tree, but the large green varieties may grow to a considerable

size. When small fig-trees have sent up two

pliable trunk-shoots these are usually twisted together to

strengthen each other. They look like a suggestion of that

ugly taste in architecture that delighted in twisted columns.

The appearance of the branches of a leafless fig-tree is not

unlike that of the horse-chestnut in winter time. Large

quantities of the black figs and some of the white figs are

dried in the orchards, being spread out on the ground under

the strong sun-rays.

The pomegranate-tree looks more like an unkempt shrub.

The beautiful red bell-like blossoms are very attractive.

Lemons and oranges grown for profit are often small trees.

The sour marmalade orange grows into a larger, statelier tree.

At Urṭâs, near Solomon’s Pools, the largest and most

beautifully colored apricots grow. Peaches, plums, quinces

and almonds are plentiful, and the cherry, mulberry and

walnut thrive.

Concerning trees about the shrines and wilys and all the

so-called sacred trees there will be a more appropriate place

to speak later on.

In a land where fruit grows and flourishes one may have

far less fruit than in some fruitless city in a colder climate

but favored with ample facilities for transportation. Right

here within a few miles of the finest orange groves in the

land, near the vineyards, under the olive and fig-trees, with

peaches, pomegranates, apricots and plums, we probably find

shorter seasons for each than is the case in some Anglo-Saxon

city of the middle temperatures. Here fruit will be

much cheaper while it lasts, and some fruits, which must be

found near the trees, if enjoyed at all, such as the fig, will

42be available nowhere else as here. The peach, plum, orange,

apricot and grape go to the London, Liverpool, New York,

Chicago and Boston markets from the place producing the

earliest crops, and the trains and steamships continue bringing