Title: Morristown National Historical Park, a Military Capital of the American Revolution

Author: Melvin J. Weig

Contributor: Vera B. Craig

Release date: July 15, 2020 [eBook #62651]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

by Melvin J. Weig, with assistance from Vera B. Craig

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 7

WASHINGTON 25, D. C., 1950

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Newton B. Drury, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER SEVEN

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 20¢.

“Washington Receiving a Salute on the Field of Trenton.” From the engraving by William Holl (1865), after the painting by John Faed.

During two critical winters of the Revolutionary War, 1777 and 1779-80, the rolling countryside in and around Morristown, N. J., sheltered the main encampments of the American Continental Army and served as the headquarters of its famed Commander in Chief, George Washington. Patriot troops were also quartered in this vicinity on many other occasions. Here Washington reorganized his weary and depleted forces almost within sight of strong British lines at New York. Here came Lafayette with welcome news of the second French expedition sent to aid the Americans. And here was developed, in the face of bitter cold, hunger, hardship, and disease, the Nation’s will to independence and freedom. Thus for a time this small New Jersey village became the military capital of the United States, the testing ground of a great people in its heroic fight for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Sir William Howe had been mistaken. Near the middle of December 1776, as Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s army in America, he believed the rebellion of Great Britain’s trans-Atlantic colonies crushed beyond hope of revival. “Mr.” Washington’s troops had been driven from New York, pursued through New Jersey, and forced at last to cross the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. The British had captured Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, the only American general they thought possessed real ability. Some mopping up might be necessary in the spring, but the arduous work of conquest was over. Howe could spend a comfortable winter in New York, and Lord Cornwallis, the British second in command, might sail for England and home.

Then suddenly, with whirlwind effect, these pleasant reveries were swept away in the roar of American gunfire at Trenton in the cold, gray dawn of December 26, and at Princeton on January 3. Outgeneraled, bewildered, and half in panic, the British forces pulled back to New Brunswick. Now they were 60 miles from their objective at Philadelphia, instead of 19. Worst of all, they had been maneuvered into this ignominious retreat by a “Tatterde-mallion” army one-sixth the size of their own, and they were on the defensive. “We have been boxed about in Jersey,” lamented one of Howe’s officers, “as if we had no feelings.” George Washington with his valiant comrades in arms had weathered the dark crisis. For the time being at least, the Revolution was saved.

Washington’s original plan at the beginning of this lightninglike campaign was to capture New Brunswick, where he might have destroyed all the British stores and magazines, “taken (as we have since learnt) their Military Chest containing 70,000 £ and put an end to the War.” But Cornwallis, in Trenton, had heard the cannon sounding at Princeton that morning of January 3, and, just as the Americans were leaving the town, the van of the British Army came in sight. By that time the patriot forces were nearly exhausted, many of the men having been without any rest for 2 nights and a day. The 600 or 800 fresh troops required for a successful assault on New Brunswick were not at hand. Washington held a hurried conference with his officers, who advised against attempting too much. Then, destroying the bridge over the Millstone River immediately east of Kingston, the Continentals turned north and marched to Somerset Court House (now Millstone), where they arrived between dusk and 11 o’clock that night.

Washington marched his men to Pluckemin the next day, rested them over Sunday, January 5, and on the Monday following continued on northward into Morristown. There the troops arrived, noted an American officer, “at 5 P. M. and encamped in the woods, the snow covering the ground.” Thus began the first main encampment of the Continental Army in Morris County.

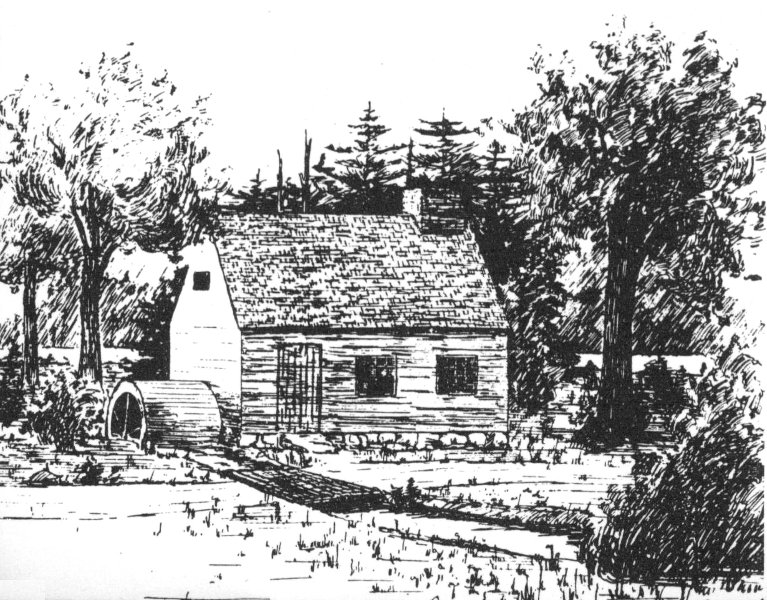

The Ford Powder Mill, built by Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., in 1776.

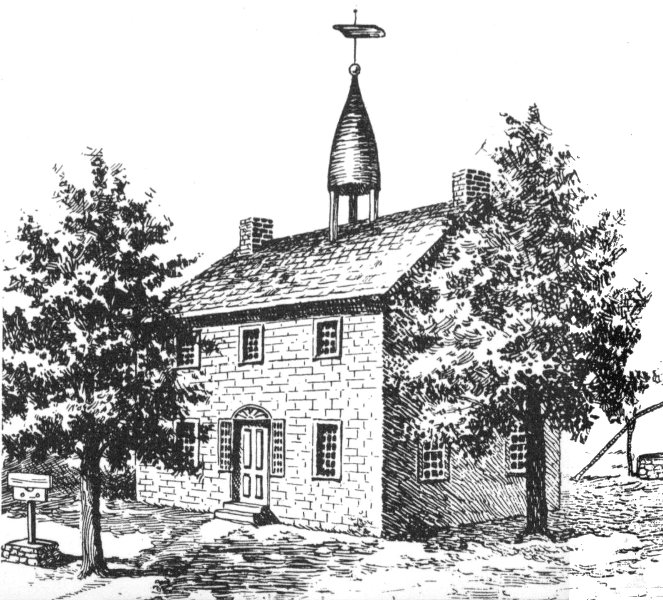

The Old Morris County Courthouse of Revolutionary War times.

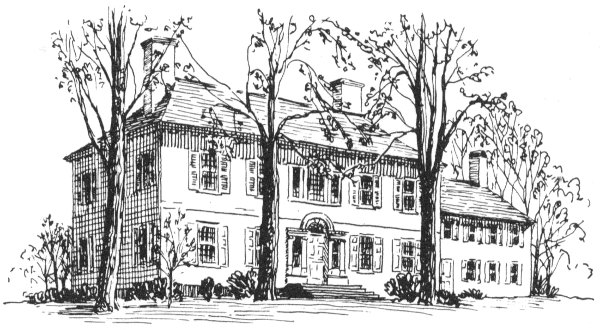

The Ford Mansion, shelter for Delaware troops in 1777 and occupied as Washington’s headquarters during the terrible winter of 1779-80.

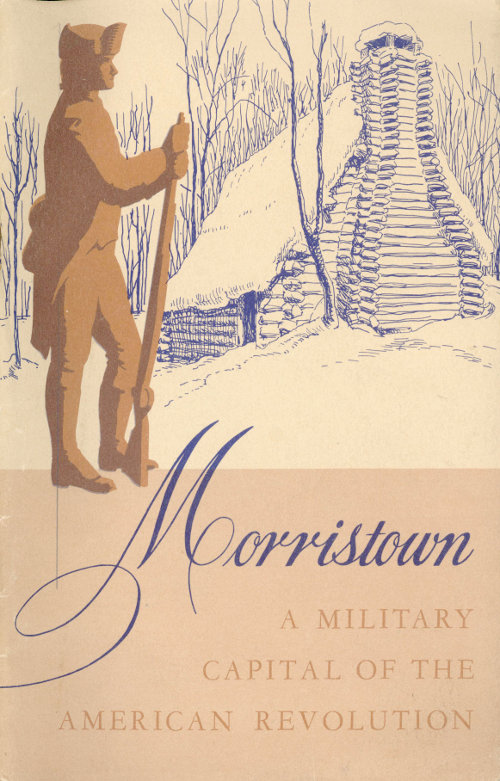

A letter dated May 12, 1777, described the Morristown of that day as “a very Clever little village, situated in a most beautiful vally at the foot of 5 mountains.” Farming was the mainstay of its people, some 250 in number and largely of New England stock, but nearby ironworks were already enriching a few families and employing more and more laborers. Among the 50 or 60 buildings in Morristown, the most important seem to have been the Arnold Tavern, the Presbyterian and Baptist Churches, and the Morris County Courthouse and Jail, all located on an open “Green” from which streets radiated in several directions. There were also a few sawmills, gristmills, and a powder mill, the last built on the Whippany River, in 1776, by Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., commander of the Eastern Battalion, Morris County Militia. Colonel Ford’s dwelling house, then only a few years old, was undoubtedly the handsomest in the village.

Washington’s immediate reasons for bringing his troops to Morristown were that it appeared to be the place “best calculated of any in this Quarter, to accomodate and refresh them,” and that he knew not how to obtain covering for the men elsewhere. He must have been impressed also with the demonstrated loyalty of Morris County to the patriot cause, even in those dreary, anxious weeks of late 1776 when its militia helped considerably to stave off attempted enemy incursions directly westward from the vicinity of New York. Finally, there were 4 already at Morristown three Continental regiments previously ordered down from Fort Ticonderoga, and union with these would strengthen the forces under his personal command.

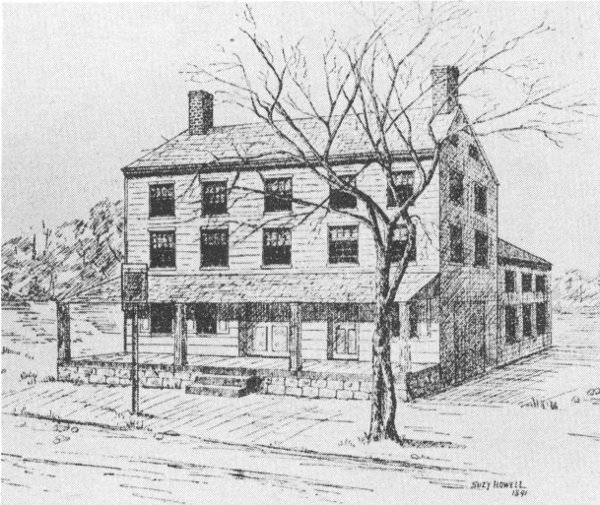

The Arnold Tavern, where Washington reputedly stayed in 1777.

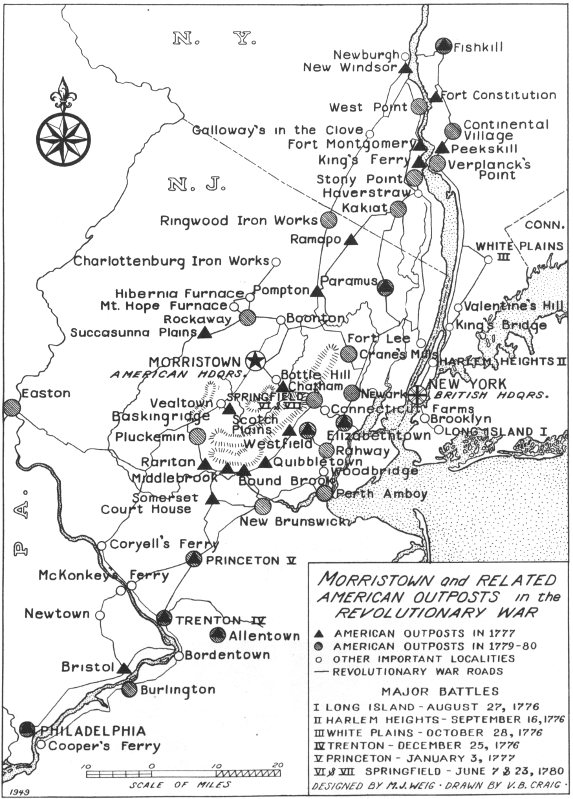

Even so, Washington hoped at first to move again before long, and it was only as circumstances forced him to remain in this small New Jersey community that its advantages as a base for American military operations became fully apparent. From here he could virtually control an extensive agricultural country, cutting off its produce from the British and using it instead to sustain the Continental Army. In the mountainous region northwest of Morristown were many forges and furnaces, such as those at Hibernia, Mount Hope, Ringwood, and Charlottenburg, from which needed iron supplies might be obtained. The position was also difficult for an enemy to attack. Directly eastward, on either side of the main road approach from Bottle Hill (now Madison), large swamp areas guarded the town. Still further east, almost midway between Morristown and the Jersey shore, lay the protecting barriers of Long Hill, and the First and Second Watchung Mountains. Their parallel ridges stretched out for more than 30 miles, like a huge earthwork, from the Raritan River on the south toward the northern boundary of the State, whence they were continued by the Ramapos to the Hudson Highlands. In addition to all this, the village was nearly equidistant from Newark, Perth Amboy, and New Brunswick, the main British posts in New Jersey, so that any enemy movement could be met by an American counterblow, either from Washington’s own outposts or from the center of his defensive-offensive web at Morristown itself. A position better suited to all the Commander in Chief’s purposes, either in that winter of 1777 or in the later 1779-80 encampment period, would have been hard to find.

Morristown and RELATED AMERICAN OUTPOSTS in the REVOLUTIONARY WAR

Local tradition has it that upon arriving in Morristown, on January 6, Washington went to the Arnold Tavern, and that his headquarters remained there all through the 1777 encampment period. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene lodged for a time “at Mr. Hoffman’s,—a very good-natured, doubtful gentleman.” Captain Rodney and his men were quartered at Colonel Ford’s “elegant” house until about mid-January, when they left for Delaware and home. 6 Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, on rejoining Washington in the spring of 1777, is said to have stayed at the homestead of Deacon Ephraim Sayre, in Bottle Hill. It has been stated that other officers, and a large number of private soldiers as well, were given shelter in Morristown or nearby villages by the Ely, Smith, Beach, Tuttle, Richards, Kitchell, and Thompson families.

According to the Reverend Samuel L. Tuttle, a local historian writing in 1871, there was also a campground for the troops about 3 miles southeast of Morristown on what were then the farms of John Easton and Isaac Pierson, in the valley of Loantaka Brook. Tuttle obtained his information from one Silas Brookfield and other eyewitnesses of the Revolutionary scene, who claimed that the troops built a village of log huts at that location. It is highly curious that not one of Washington’s published letters or orders refers to such buildings, nor are they mentioned in any other contemporary written records studied to date.

However the troops were sheltered, it was not long before the army which had fought at Trenton and Princeton began to melt away. Deplorable health conditions, lack of proper clothing, insufficient pay to meet rising living costs, and many other instances of neglect had discouraged the soldiery all through the 1776 campaign. The volunteer militiamen were particularly dissatisfied. Some troops were just plain homesick, and nearly all had already served beyond their original or emergency terms of enlistment. They had little desire for another round of hard military life.

Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene.

Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne.

Washington described his situation along this line in a letter of January 19 addressed to the President of Congress: “The fluctuating 7 state of an Army, composed Chiefly of Militia, bids fair to reduce us to the Situation in which we were some little time ago, that is, of scarce having any Army at all, except Reinforcements speedily arrive. One of the Battalions from the City of Philadelphia goes home to day, and the other two only remain a few days longer upon Courtesy. The time, for which a County Brigade under Genl. Mifflin came out, is expired, and they stay from day to day, by dint of Solicitation. Their Numbers much reduced by desertions. We have about Eight hundred of the Eastern Continental Troops remaining, of twelve or fourteen hundred who at first agreed to stay, part engaged to the last of this Month and part to the middle of next. The five Virginia Regts. are reduced to a handful of Men, as is Col Hand’s, Smallwood’s, and the German Battalion. A few days ago, Genl Warner arrived, with about seven hundred Massachusetts Militia engaged to the 15th [of] March. Thus, you have a Sketch of our present Army, with which we are obliged to keep up Appearances, before an Enemy already double to us in Numbers.”

Meanwhile, as the Commander in Chief noted in another letter of nearly the same date, his few remaining troops were “absolutely perishing” for want of clothing, “Marching over Frost and Snow, many without a Shoe, Stocking or Blanket.” Nor, due to certain inefficiencies in the supply services, was the food situation any better. “The Cry of want of Provisions come to me from every Quarter,” Washington stormed angrily on February 22 to Matthew Irwin, a Deputy Commissary of Issues: “Gen. Maxwell writes word that his People are starving; Gen. Johnston, of Maryland, yesterday inform’d me, that his People could draw none; this difficulty I understand prevails also at Chatham! What Sir is the meaning of this? and why were you so desirous of excluding others from this business when you are unable to accomplish it yourself? Consider, I beseech you, the consequences of this neglect, and exert yourself to remove the Evil.” Even in May, near the end of the 1777 encampment, there was an acute shortage of food.

In this situation, Washington wrought mightily to “new model” the American fighting forces. Late in 1776, heeding at last his pressing argument for longer enlistments, Congress had called upon the States to raise 88 Continental battalions, and had also authorized recruitment of 16 “additional battalions” of infantry, 3,000 light horse, three regiments of artillery, and a corps of engineers. A magnificent dream of an army 75,000 strong! Washington knew, however, that it was more than “to say Presto begone, and every thing is done.” Very early that winter he sent many of his general officers into their own States to hurry on the new levies. Night and day, too, he was in correspondence with anyone who might help in the cause, writing prodigiously. Still the business lagged painfully. “I have repeatedly 8 wrote to all the recruiting Officers, to forward on their Men, as fast as they could arm and cloath them,” the Commander in Chief advised Congress on January 26, “but they are so extremely averse to turning out of comfortable Quarters, that I cannot get a Man to come near me, tho’ I hear from all parts, that the recruiting Service goes on with great Success.” For nearly 3 months more, as events turned out, he had to depend for support on ephemeral militia units, “here to-day, gone to-morrow.” April 5 found him still wondering if he would ever get the new army assembled.

But the patriot cup of woe was not yet filled, and there was still another evil to fight. This was smallpox, which together with dysentery, rheumatism, and assorted “fevers” had victimized hundreds of American troops in 1776. Now the dread disease threatened to run like wildfire through the whole army, old and new recruits alike.

Medical knowledge of that day offered but one real hope of saving the Continental forces from this “greatest of all calamities,” namely, to communicate a mild form of smallpox by inoculation to every soldier who had not yet been touched by the contagion, thus immunizing him against its more virulent effects “when taken in the natural way.” Washington was convinced of this by the time he arrived at Morristown on January 6. He therefore ordered Dr. Nathaniel Bond to prepare at once for handling the business of mass inoculation in northern New Jersey, and instructed Dr. William Shippen, Jr., to inoculate without delay both the American troops then in Philadelphia and the recruits “that shall come in, as fast as they arrive.” During the next 3 months, similar instructions or suggestions were sent to officers and civil authorities connected with recruitment in New York, New Jersey, New England, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Undertaken secretly at first, the bold project was soon going full swing throughout Morristown and surrounding villages. Inoculation centers were set up in private houses, with guards placed over them to prevent “natural” spread of the infection. The troops went through the treatment in several “divisions,” at intervals of 5 or 6 days. Washington waxed enthusiastic as the experiment progressed. “Innoculation at Philadelphia and in this Neighbourhood has been attended with amazing Success,” he wrote to the Governor of Connecticut, “and I have not the least doubt but your Troops will meet the same.” As of March 14, however, about 1,000 soldiers and their attendants were still incapacitated in Morristown and vicinity, leaving but 2,000 others as the army’s total effective strength in New Jersey. A blow struck by Sir William Howe at that time might have been disastrous for the Americans. Fortunately, it never came.

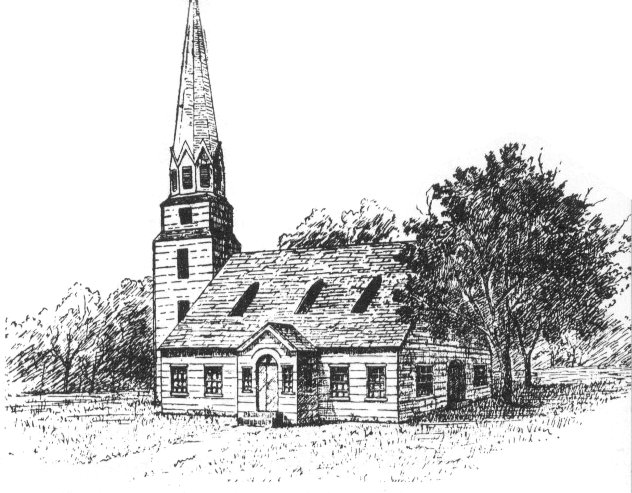

The episode was not without its tragic side, however. Since smallpox in any form was highly contagious, civilians in the whole countryside near the camp also had to be inoculated along with the army. Some 9 local people, and a small number of soldiers as well, contracted the disease naturally before the project got under way, or perhaps refused submission to the treatment. Isolation hospitals for these unfortunates were established in the Presbyterian and Baptist Churches at Morristown, and in the Presbyterian Church at Hanover. The patients died like flies. In the congregation of the Morristown Presbyterian Church alone, no less than 68 deaths from smallpox were recorded in 1777. Those who survived the ordeal were almost always pockmarked by it.

Sketches of the Baptist Church (above) and the Presbyterian Church (below) at Morristown, both used as smallpox hospitals in 1777.

Running the gauntlet of these and other problems, all at the same time, was discouraging for Washington, to say the least. Few generals have ever been more skilled, however, in ferreting out their opportunities, or in making better use of them. Nearly on a par with his remarkable victories at Trenton and Princeton was the way in which he reasserted patriot control over most of New Jersey during the winter and spring of 1777, excepting only the immediate neighborhood of New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. Even there, as time went on, the American pressure became more or less constant.

Stationing bodies of several hundred light troops at Princeton, Bound Brook, Elizabethtown, and other outlying posts, the Commander in Chief inaugurated from the beginning what might be termed a “scorched earth” policy. First came an order, on January 11, “to collect all the Beef, Pork, Flour, Spirituous Liquors, &c. &c. not necessary for the Subsistence of the Inhabitants, in all the parts of East Jersey, lying below the Road leading from Brunswick to Trenton.” This was followed, on February 3, by instructions for removing out of enemy reach “all the Horses, Waggons, and fat Cattle” his generals could lay their hands on. Payment for these items was to be guaranteed, but they might be taken by force from Tories and others who refused to sell. Washington likewise ordered the incessant hampering of all enemy attempts to obtain food and forage. 10 “I would not suffer a man to stir beyond their Lines,” he wrote to Col. Joseph Reed, “nor suffer them to have the least Intercourse with the Country.”

Conditions being what they were, the success with which these orders were carried into effect is astounding. Gradually, more provisions found their way to Morristown. On the other hand, hardly an enemy foraging party could leave its own camp without being set upon by the Americans. Newspapers, letters, and diaries of the period are filled with accounts of recurrent clashes between detachments of the two armies, some involving several thousand men. There were no great casualties on either side, but the Continentals seldom came off second-best. “Amboy and Brunswick,” wrote one historian, “were in a manner besieged.” Both enemy troops and horses grew sickly from want of fresh food, and many of them died before spring. In New York itself, where Sir William Howe kept headquarters, all kinds of provisions became “extremely dear” in price. Firewood was equally scarce in city and camp.

Thus, by enterprise and daring expedients, Washington greatly discomfited the British Army, reduced still further its waning influence in New Jersey, and simultaneously maintained his own small force in action, preventing the men’s minds from yielding to despondence.

As spring advanced and roads became more passable, the new Continental levies finally began to come in. “The thin trickle became a rivulet, then a clear stream, though never a flood.” By May 20, Washington had in New Jersey 38 regiments with a total of 8,188 men. Five additional regiments were listed, but showed no returns at that time. Moreover, this new army was on a fairly substantial footing, the enlistments being either for 3 years, or for the duration of the war. There was also an abundance of arms and ammunition, including 1,000 barrels of powder, 11,000 gunflints, and 22,000 muskets sent over from France. “From the present information,” wrote Maj. Gen. Henry Knox to his wife, “it appears that America will have much more reason to hope for a successful campaign the ensuing summer than she had the last.”

Now, with the prospects thus brightening, there might be something of a brief social season to relieve the strain of hard work. Martha Washington had arrived at headquarters on March 15, and other American officers looked forward to being joined by their wives. An intimate word picture of the Commander in Chief in his lighter moods was drawn by one such camp visitor, Mrs. Martha Daingerfield Bland, in a letter written to her sister-in-law from Morristown on May 12: “Now let me speak of our Noble & Agreeable Commander (for he Commands both sexes....) We visit them [the Washingtons] twice or three times a week by particular invitation—Ev’ry day frequently from Inclination, he is Generally busy in the fore noon—but from dinner til night he is free for all Company his Worthy Lady seemes to be in perfect felicity 11 while she is by the side of her old Man as she Calls him, We often make partys on Horse backe the Genl his Lady, Miss Livingstons & his aid de Camps ... at Which time General Washington throws of[f] the Hero—& takes up the chatty agreeable Companion—he can be down right impudent some times—such impudence, Fanny, as you & I like....”

General Howe had meanwhile determined, as early as April 2, to embark on another major attempt to capture Philadelphia, this time by sea approach. He apparently kept his own counsel, however, and up to the last minute neither the American nor the British Army knew his real intentions. The garrisons at Perth Amboy and New Brunswick left their cramped winter quarters for encampments in the open soon after the middle of May. This colored reports that Howe was about to attack Morristown, or that, while his main force advanced by land towards Philadelphia, a band of Loyalists would march from Bergen into Sussex County to aid a rising of the Tories there.

Made uneasy by these and other British movements, Washington decided that the time had come to leave Morristown. On May 28, therefore, leaving behind a small detachment to guard what military stores were still in the village, he accordingly moved the Continental Army to Middlebrook Valley, behind the first Watchung Mountain a short distance north of Bound Brook, and only 8 miles from New Brunswick. This was a natural position from which the Americans could both defy attack and threaten any overland expedition the enemy might make. Such was the relationship of the two armies as the curtain went up on the ensuing summer campaign. The encampment of 1777 at Morristown had drawn to a close.

Nearly two and a half years passed by before the main body of the Continental Army again returned to Morristown. During that interval the British both captured and abandoned Philadelphia, Burgoyne’s Army surrendered to the Americans at Saratoga, and France and Spain entered the conflict against Great Britain. Washington’s soldiers had stood up under fire on numerous occasions, besides weathering the winter encampment periods at Valley Forge in 1777-78, and at Middlebrook in 1778-79. On the other hand, the financial affairs of the young United States had gone from bad to worse. Hoped-for benefits from the French Alliance had not yet materialized, and the 3-year enlistments in the Continental Army had only 4 or 5 months more to run before their expiration. Moreover, while the military scales somewhat balanced in the North, the enemy held Savannah, and there were rumors that Sir Henry Clinton, Howe’s successor, would 12 soon leave New York by sea to attack Charleston. With the final issue still in doubt, America approached what was destined to be the hardest winter of the Revolutionary War.

Such was the general condition of affairs when, on November 30, Washington informed Nathanael Greene, then Quartermaster General, that he had finally decided “upon the position back of Mr. Kembles,” about 3 miles southwest of Morristown, for the next winter encampment of the Continental forces under his immediate command. As he later wrote to the President of Congress, this was the nearest place available “compatible with our security which could also supply water and wood for covering and fuel.”

The site thus chosen lay in a somewhat mountainous section of Morris County known as Jockey Hollow, and included portions of the “plantation” owned by Peter Kemble, Esq., and the farms of Henry Wick and Joshua Guerin. Some of the American brigades being already collected at nearby posts, Greene at once sent word to their commanders of Washington’s decision: “The ground I think will be pretty dry; I shall have the whole of it laid off this day; you will therefore order the troops to march immediately; or if you think it more convenient tomorrow morning. It will be well to send a small detachment from each Regiment to take possession of their ground. You will also order on your brigade quarter master to draw the tools for each brigade and to get a plan for hutting which they will find made out at my quarters.”

Simultaneously with this instruction, which was dated December 1, Washington himself arrived in Morristown, during a “very severe storm of hail & snow all day.” He promptly established his headquarters at the Ford Mansion, presumably at the invitation of Mrs. Theodosia Ford, widow of Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., who was then living in the house with her four children. Morristown had again become the American military capital.

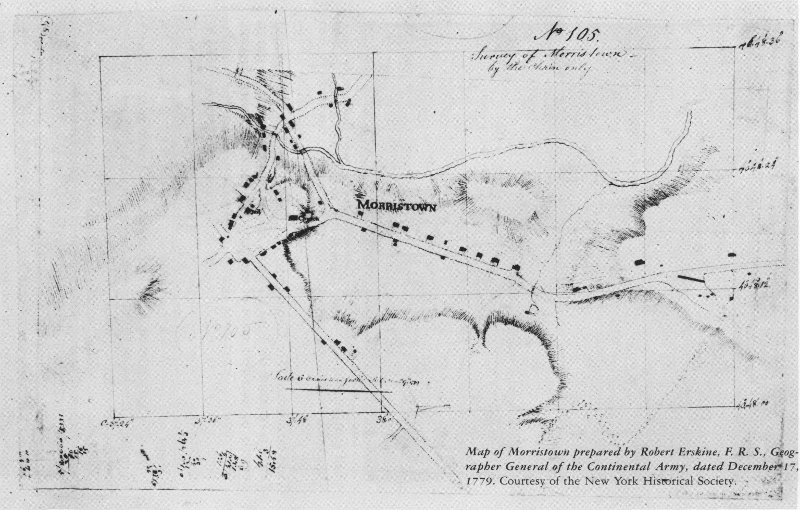

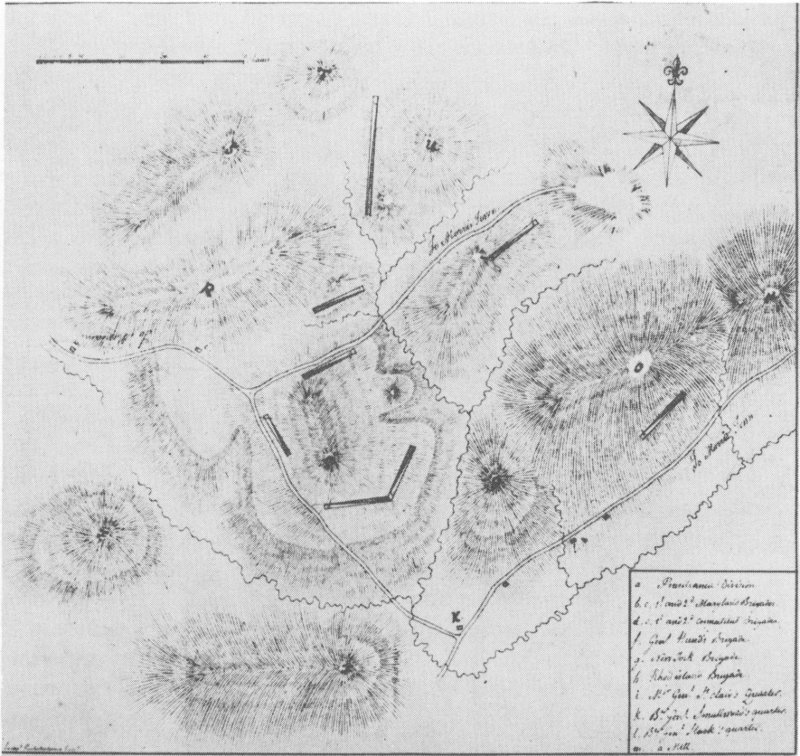

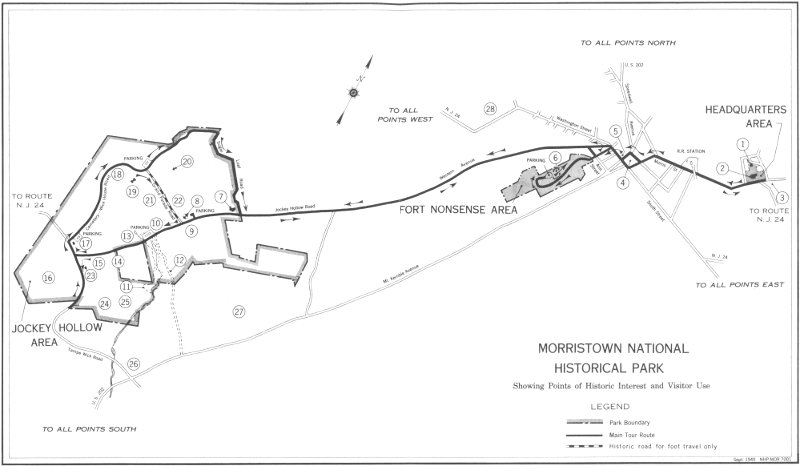

Events now moved swiftly. Many of the American troops reached Morristown during the first week of December, and the rest arrived before the end of that month. Estimates vary as to their total effective strength, but it was probably not under 10,000 men, nor over 12,000, at that particular time. Eight infantry brigades—Hand’s, New York, 1st and 2d Maryland, 1st and 2d Connecticut, and 1st and 2d Pennsylvania—took up compactly arranged positions in Jockey Hollow proper. Two additional brigades, also of infantry, were assigned to campgrounds nearby: Stark’s Brigade on the east slope of Mount Kemble, and the New Jersey Brigade at “Eyre’s Forge,” on the Passaic River, somewhat less than a mile further southwest. Knox’s Artillery Brigade took post about a mile west of Morristown, on the main road to Mendham, and there also the Artillery Park of the army was established. The Commander in Chief’s Guard occupied ground directly opposite the Ford Mansion. All the positions noted are shown exactly on excellent maps of the period prepared by Robert Erskine, Washington’s Geographer General, and by Capt. Bichet de Rochefontaine, a French engineer. A brigade of Virginia troops was included in original plans for the encampment, but it was ordered southward soon after arriving at Morristown, and played no major part in the story here related.

Map of Morristown prepared by Robert Erskine, F. R. S., Geographer General of the Continental Army, dated December 17, 1779. Courtesy of the New York Historical Society.

No 105.

Survey of Morristown—

by the chain only

Position of the Continental Army at Jockey Hollow in the winter of 1779-80. Drawn by Capt. Bichet de Rochefontaine, a French engineer.

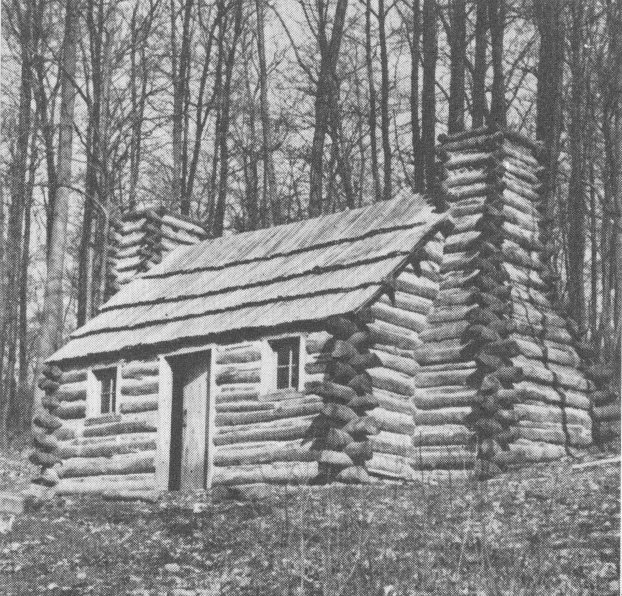

As they arrived in camp, the soldiers pitched their tents on the frozen ground. Then work was begun at once on building log huts for more secure shelter from the elements. This was a tremendous undertaking. There was oak, walnut, and chestnut timber at hand, but the winter had set in early with severe snowstorms and bitter cold. Dr. James Thacher, a surgeon in Stark’s Brigade, testified that “notwithstanding large fires, we can scarcely keep from freezing.” Maj. Ebenezer Huntington, of Webb’s Regiment, wrote that “the men have suffer’d much without shoes and stockings, and working half leg deep in snow.” In spite of 15 these handicaps, however, nearly all the private soldiers had moved into their huts around Christmastime, though some of the officers’ quarters, which were left till last, remained unfinished until mid-February. A young Connecticut schoolmaster who visited the camp near the end of December described it as a “Log-house city,” where his own troops and those of other States dwelt among the hills “in tabernacles like Israel of old.” About 600 acres of woodland were cut down in connection with the project.

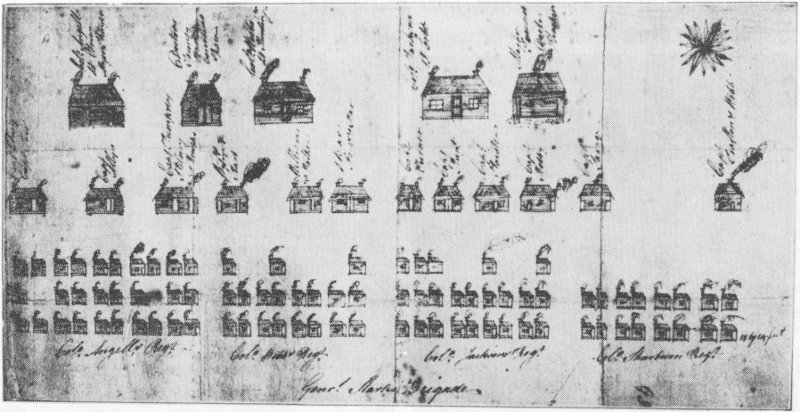

Each brigade camped in the Jockey Hollow neighborhood occupied a sloping, well-drained hillside area about 320 yards long and 100 yards in depth, including a parade ground 40 yards deep in front. Above the parade were the soldiers’ huts, eight in a row and three or four rows deep for each regiment; beyond those the huts occupied by the captains and subalterns; and higher still the field officers’ huts. Camp streets of varying widths separated the hut rows. This arrangement is clearly shown in a contemporary sketch of the Stark’s Brigade Camp.

The “hutting” arrangement for General Stark’s Brigade, 1779-80. From an original manuscript once owned by Erskine Hewitt, of Ringwood, N. J.

Logs notched together at the corners and chinked with clay formed the sides of the huts. Boards, slabs, or hand-split shingles were used to cover their simple gable roofs, the ridges of which ran parallel to the camp streets. All the soldiers’ huts, designed to accommodate 12 men each, were ordered built strictly according to a uniform plan: about 14 feet wide and 15 or 16 feet long in floor dimensions, and around 6½ feet high at the eaves, with wooden bunks, a fireplace and chimney at one end, and a door in the front side. Apparently, windows were not cut in these huts until spring. The officers’ cabins were generally larger in size, and individual variation was permitted in their design and construction. Usually accommodating only two to four officers, they had two fireplaces and chimneys each, and frequently two or more doors and 16 windows. Besides these two main types of huts, there were some others built for hospital, orderly room, and guardhouse purposes. The completed camp seems to have contained between 1,000 and 1,200 log buildings of all types combined.

Weather conditions when the army arrived at Morristown were but a foretaste of what was yet to come, and long before all the huts were up, the elements attacked Washington’s camp with terrible severity. As things turned out, 1779-80 proved to be the most bitter and prolonged winter, not only of the Revolutionary War, but of the whole eighteenth century.

One observer recorded 4 snows in November, 7 in December, 6 in January, 4 in February, 6 in March, and 1 in April—28 falls altogether, some of which lasted nearly all day and night. The great storm of January 2-4 was among the most memorable on record, with high winds which no man could endure many minutes without danger to his life. “Several marquees were torn asunder and blown down over the officers’ heads in the night,” wrote Dr. Thacher, “and some of the soldiers were actually covered while in their tents, and buried like sheep under the snow.” When this blizzard finally subsided, the snow lay full 4 feet deep on a level, drifted in places to 6 feet, filling up the roads, covering the tops of fences, and making it practically impossible to travel anywhere with heavy loads.

Reconstructions of typical log huts used by the officers (above) and by soldiers of the line (below) in the winter encampment of 1779-80.

What made things still worse was the intense, penetrating cold. General Greene noted that for 6 or 8 days early in January “there has been no living abroad.” Only on 1 day of that month, as far south as Philadelphia, did the mercury go above the freezing point. All the rivers froze solid, including both the Hudson and the Delaware, so that troops and even large cannon could pass over them. Ice in the Passaic River formed 3 feet thick, and, as late as February 26, the Hudson above New 17 York was “full of fixed ice on the banks, and floating ice in the channel.” The Delaware remained wholly impassable to navigation for 3 months. “The oldest people now living in this country,” wrote Washington on March 18, “do not remember so hard a Winter as the one we are now emerging from.”

The Pennsylvania Line campground in 1779-80, with a hospital hut in the foreground. From a recent painting in the park collection.

Not even good soldiers warmly clothed could be expected to endure this ordeal by weather without some complaint. How much more agonizing, then, was such a winter for Washington’s men in Jockey Hollow, who were again poorly clad! A regimental clothier in the Pennsylvania Line referred to some of the troops being “naked as Lazarus.” By the time their huts were completed, said an officer in Stark’s Brigade, not more than 50 men of his regiment could be returned fit for duty, and there was “many a good Lad with nothing to cover him from his hips to his toes save his Blanket.” As late as March, when “an immense body of snow” still remained on the ground, Dr. Thacher wrote that the soldiers were “in a wretched condition for the want of clothes, blankets and shoes.”

Still more critical was the lack of food for the men, and forage for the horses and oxen on which every kind of winter transportation depended. December 1779 found the troops subsisting on “miserable fresh beef, without bread, salt, or vegetables.” When the big snows of midwinter blocked the roads, making it 18 totally impossible for supplies to get through, the army’s suffering for lack of provisions alone became almost more than human flesh and blood could bear. Early in January 1780, said the Commander in Chief, his men sometimes went “5 or Six days together without bread, at other times as many days without meat, and once or twice two or three days without either ... at one time the Soldiers eat every kind of horse food but Hay.”

Thanks to the magistrates and civilian population of New Jersey, an appeal from Washington in this urgent crisis brought cheerful, generous relief. This alone saved the army from starvation, disbandment, or such desperate, wholesale plundering as must have eventually ruined all patriot morale. By the end of February, however, the food situation was once more acute. Wrote General Greene: “Our provisions are in a manner gone; we have not a ton of hay at command, nor magazines to draw from.” Periodic food shortages continued to plague the troops during the next few months. As late as May 9, there was only a 3-days’ supply of meat on hand, and it was estimated that the flour, if made into bread, could not last more than 15 or 16 days. Officers and men alike literally lived from hand to mouth all through the 1779-80 encampment period.

The cause of many difficulties faced by Washington that winter appears to have been the near chaotic state of American finances. Currency issued by Congress tumbled headlong in value, until in April-June 1780 it took $60 worth of “Continental” paper to equal $1 in coin. “Money is extreme scarce,” wrote General Greene on February 29, “and worth little when we get it. We have been so poor in camp for a fortnight that we could not forward the public dispatches for want of cash to support the expresses.” Civilians who had provisions and other necessaries to sell would no longer “trust” as they had done before; and without funds, teams could not be found to bring in supplies from distant magazines. Reenlistment of veteran troops and recruitment of new levies became doubly difficult. Even the depreciated money wages of the army were not punctually paid, being frequently 5 or 6 months in arrears. Dr. Thacher wailed at length about “the trash which is tendered to requite us for our sacrifices, for our sufferings and privations, while in the service of our country.” No wonder that desertions soon increased alarmingly, and that many officers, no longer able to support families at home, resigned their commissions in disgust! At the end of May an abortive mutiny of two Connecticut regiments in Jockey Hollow, though quickly suppressed, foreshadowed the far more serious outbursts fated to occur within a year.

Keeping the Continental Army intact under all these conditions was but part of Washington’s herculean task in 1779-80. Again, as at Morristown in the winter of 1777, and at Middlebrook in the winter of 1778-79, the threat of attack by an enemy superior in manpower 19 and equipment hung constantly over his head. Communications between Philadelphia and the Hudson Highlands had to be protected, and the northern British Army had to be prevented from extending its lines, now confined chiefly to New York and Staten Island, or from obtaining forage and provisions in the countryside beyond.

While the main body of American troops was quartered in Jockey Hollow, certain parts of it, varying in strength from about 200 men to as high as 2,000, were stationed at Princeton, New Brunswick, Perth Amboy, Rahway, Westfield, Springfield, Paramus, and similar outposts in New Jersey. Washington changed the most important of these detachments once a fortnight at first, but toward the spring of 1780 some units remained “on the Lines” for much longer periods. Thus Morristown served again as the vital center of a defensive-offensive web for the northern New Jersey and southern New York areas. The enemy damaged the outer margins of that web on several occasions, notably on June 7 and 23, when they penetrated to Connecticut Farms (now Union) and Springfield, but Washington’s defenses were never seriously broken, and through all that winter and spring his position in the Morris County hills remained relatively undisturbed.

Routine duty on the lines was interrupted on January 14-15 by what might be termed a “commando” raid on Staten Island. This daring expedition, planned by Washington and undertaken by Maj. Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling, was prepared with the utmost secrecy. Five hundred sleighs were obtained on pretence of going to the westward for provisions. On the night of the 14th, loaded with cannon and about 3,000 troops, these crossed over on the ice from Elizabethtown Point “with a determination,” to quote Q. M. Joseph Lewis, “to remove all Staten Island bagg and Baggage to Morris Town.”

Unfortunately for American hopes, the British learned about the scheme in time to retire into their posts, where they could defy attack. After lingering on the island for 24 hours without covering, with the snow 4 feet deep and the weather extremely cold, Stirling’s force could bring off only a handful of prisoners and some blankets and stores. What disturbed Washington most, however, was the disgraceful conduct displayed by large numbers of New Jersey civilians who joined the expedition in the guise of militiamen, and who, in spite of Stirling’s earnest efforts, looted and plundered the Staten Island farmers indiscriminately. All the stolen property that could be recovered was returned to the British authorities a few days later, but the harm had been done. On the night of January 25, the enemy retaliated by burning the academy at Newark and the courthouse and the meeting house at Elizabethtown. That exploit also marked the beginning of a new series of British raids in Essex and Bergen Counties which kept those districts in considerable uneasiness for several months to come.

MORRISTOWN NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

Showing Points of Historic Interest and Visitor Use

Except on rare occasions, such as participation in an occasional public celebration might afford, the average soldier found camp life at Morristown hard, unexciting, and often monotonous. Sometimes his whole existence seemed like an endless round of drill, guard duty, and “fatigue” assignments, the latter including such unpleasant chores as burying the “Dead carcases in and about camp.” What little recreation the line troops could find was largely unorganized and incidental. Washington proclaimed a holiday from work on St. Patrick’s Day 1780, which the Pennsylvania Division observed by sharing a hogshead of rum purchased for that purpose by Col. Francis Johnston, its then commander. Regulations prohibited gambling and drunkenness, however, and the prankster who strayed too far from military discipline “paid the piper” if caught. One soldier, convicted by court martial of “Quitting his Post, and riding Gen. Maxwell’s Horse,” received 150 lashes on his bare back. This war was a stern business; men who enlisted as privates in the Continental Army were not supposed to be looking for amusement.

The officers were somewhat more fortunate. Most of the generals obtained furloughs and went home to their families for part of the winter. Others could escape the tedium of camp life occasionally at least. Writes Lt. Erkuries Beatty, in a letter dated March 13, 1780: “I got leave of absence for three Days to go see Aunt Mills and Uncle Read who lives about 12 Miles from here ... that night Cousin Polly and me set off a Slaying with a number more young People and had a pretty Clever Kick-up, the next Day Polly and I went to Uncle Reads who lives about 4 Miles from Aunts, here I found Aunt Read and two great Bouncing female cousins and a house full of smaller ones, here we spent the Day very agreeably Romping with the girls who was exceeding Clever & Sociable.” Almost at the same time, “the lovely Maria and her amiable sister” were entertaining Capt. Samuel Shaw, of the 3d Artillery Regiment, at Mount Hope. “By heavens,” Shaw confidentially informed a fellow officer on February 29, “the more I know of that charming girl, the better I like her; every visit serves to confirm my attachment, and I feel myself gone past recovery.”

Dancing was another popular diversion among the officers that winter. At least two balls were held in Morristown by subscription, one on February 23 and the other on March 3. Lieutenant Beatty mentioned attending “two or three Dances in Morristown,” and also “a Couple of Dances at my Brother John’s Quarters at Battle [Bottle] Hill.” Many of these events were lively affairs patronized by a goodly proportion of the fair sex. Indeed, the energy displayed by “some of the dear creatures in this quarter” nearly exhausted Captain Shaw, who complained that “three nights going till after two o’clock have they made us keep it up.”

But for all such pleasurable excursions, the average Continental officer had adversities with which to deal. Frequently, he shared the greatest hardships of his men, and from day to day worked unremittingly to improve 23 their lot along with his own. Nor must it be forgotten that, unlike a private, an officer was expected to support and clothe himself largely from his pay or private means, and that he paid for recreation out of his own pocket. Sometimes officers were so deficient in clothing that they could not appear upon parade, much less enjoy visits with the ladies. Even Washington, at his headquarters in the Ford Mansion, often lacked necessities for his table, or experienced some other inconvenience. “I have been at my prest. quarters since the 1st day of Decr.,” he observed to General Greene on January 22, 1780, “and have not a Kitchen to Cook a Dinner in, altho’ the Logs have been put together some considerable time by my own Guard; nor is there a place at this moment in which a servant can lodge with the smallest degree of comfort. Eighteen belonging to my family and all Mrs. Fords are crouded together in her Kitchen and scarce one of them able to speak for the colds they have caught.”

Among the most interesting events which took place at Morristown in the spring of 1780 were those connected with the Chevalier de la Luzerne, Minister of France, and Don Juan de Miralles, a Spanish grandee who accompanied him, unofficially, on a visit to the American camp. These gentlemen arrived at headquarters on April 19, but Miralles became violently ill immediately afterwards, and it was only Washington’s distinguished French guest who could participate in the celebrations that followed during the next few days.

The highlight of Luzerne’s visit, which occurred on April 24, was eloquently described by Dr. Thacher: “A field of parade being prepared under the direction of the Baron Steuben, four battalions of our army were presented for review, by the French minister, attended by his Excellency and our general officers. Thirteen cannon, as usual, announced their arrival in the field.... A large stage was erected in the field, which was crowded by officers, ladies, and gentlemen of distinction from the country, among whom were Governor Livingston, of New Jersey, and his lady. Our troops exhibited a truly military appearance, and performed the manoeuvres and evolutions in a manner, which afforded much satisfaction to our Commander in Chief, and they were honored with the approbation of the French minister, and by all present.... In the evening, General Washington and the French minister, attended a ball, provided by our principal officers, at which were present a numerous collection of ladies and gentlemen, of distinguished character. Fireworks were also exhibited by the officers of the artillery.” Next day, amid the music of fifes and drums, and with another 13-cannon salute, Luzerne inspected the whole Continental Army encampment. Then he left for Philadelphia, escorted part-way on his journey by an honor guard which Washington provided.

Don Juan de Miralles saw nothing of these parades, entertainments, and reviews. The sickness which had seized him on his arrival at Morristown 24 was to prove fatal. His condition grew steadily worse as the days passed, and on April 28 he died. Final obsequies were held late the following afternoon, and again Dr. Thacher was on hand to describe events: “I accompanied Dr. Schuyler to head quarters, to attend the funeral of M. de Miralles.... The top of the coffin was removed, to display the pomp and grandeur with which the body was decorated. It was in a splendid full dress, consisting of a scarlet suit, embroidered with rich gold lace, a three cornered gold laced hat, and a genteel cued wig, white silk stockings, large diamond shoe and knee buckles, a profusion of diamond rings decorated the fingers, and from a superb gold watch set with diamonds, several rich seals were suspended. His Excellency General Washington, with several other general officers, and members of Congress, attended the funeral solemnities, and walked as chief mourners. The other officers of the army, and numerous respectable citizens, formed a splendid procession, extending about one mile ... the coffin was borne on the shoulders of four officers of the artillery in full uniform. Minute guns were fired during the procession, which greatly increased the solemnity of the occasion. A Spanish priest performed service at the grave, in the Roman Catholic form. The coffin was enclosed in a box of plank, and all the profusion of pomp and grandeur was deposited in the silent grave, in the common burying ground, near the church at Morristown. A guard is placed at the grave, lest our soldiers should be tempted to dig for hidden treasure. It is understood that the corpse is to be removed to Philadelphia.”

The “members of Congress” mentioned by Dr. Thacher as having attended Miralles’ funeral were undoubtedly Philip Schuyler, John Mathews, and Nathaniel Peabody, who had arrived in Morristown only the day before. These men had been appointed by their colleagues as a “committee at head-quarters” to examine into the state of the Continental Army, and to take such steps, in consultation with the Commander in Chief, as might improve its prospects of winning the war. The committee remained active until November 1, 1780, and during its life rendered valuable service as a liaison body between Congress, on the one hand, and headquarters on the other. Its very first report detailed at length “the almost inextricable difficulties” in which the committee found American military affairs involved. The report also stated, in unmistakeably plain words, what Washington had been saying all along, namely, that Congress itself would have to act quickly if the situation were to be saved.

Even as Schuyler and his co-workers penned their report, however, good news was arriving at headquarters. On May 10, 1780, following more than a year’s absence in his native France, the Marquis de Lafayette came to Morristown, fortified with word that King Louis XVI had determined to send a second major 25 armament of ships and men to aid the Americans. This assistance would prove more beneficial, it was hoped, than the first French expedition under the Count d’Estaing, which, after failing to take Newport in the late summer of 1778, had finally sailed away to the West Indies. Washington’s joy at seeing Lafayette again was doubled by this welcome information, and the army as a whole shared his feelings.

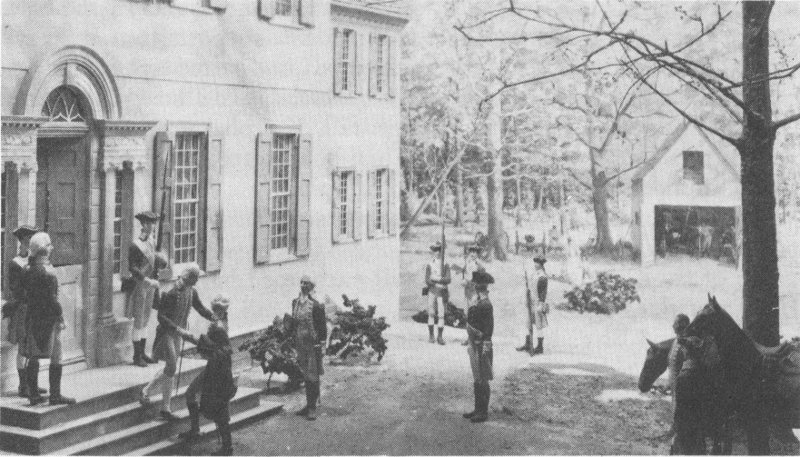

Washington greeting Lafayette on his arrival at headquarters, May 10, 1780. From a diorama in the historical museum.

The gallant young Frenchman remained a guest of his “beloved and respected friend and general” until May 14, when he left for Philadelphia, carrying with him letters from Washington and Hamilton informing members of Congress about his work in France. Approximately 6 days later he returned to Morristown, and from that time forth until the end of 1780 he continued with the Continental Army in New Jersey and New York State.

Early in June there was far less cheerful news. Reports reached camp that the enemy had taken Charleston, capturing General Lincoln with his entire army of 5,000 men. Worse still, the British forces under Sir Henry Clinton’s immediate command would now be released, in all probability, for military operations in the North.

This was the dark moment chosen by Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen, then commanding the enemy forces at New York, for an invasion of New Jersey, ostensibly to test persistent rumors that war-weariness among the Americans had reached a point where, suitably encouraged, they might abandon the struggle for independence. Five thousand British and German troops accordingly crossed over from Staten Island to Elizabethtown Point on June 6, and the next morning began advancing 26 toward Morristown. The first shock of their attack was met by the New Jersey Brigade, then guarding the American outposts; but as heavy fighting progressed, local militia came out in swarms to assist in opposing the invader. During the action, which lasted all day, the enemy burned Connecticut Farms. By nightfall, Knyphausen had come to within a half mile of Springfield. Then he retreated, in the midst of a terrific thunderstorm, to Elizabethtown Point.

Word of Knyphausen’s crossing from Staten Island reached Washington in the early morning hours of June 7. There were then but six brigades of the Continental Army still encamped in Jockey Hollow—Hand’s, Stark’s, 1st and 2d Connecticut, and 1st and 2d Pennsylvania—the two Maryland Brigades having left for the South on April 17, and the New York Brigade having marched for the Hudson Highlands between May 29 and 31. The troops at Morristown, ordered to “march immediately” at 7 a. m., reached the Short Hills above Springfield that same afternoon. There the Commander in Chief held them in reserve against any British attempt to advance further toward Morristown.

Except for occasional shifts in advanced outposts on both sides, there was no significant change in this situation for 2 weeks. Knyphausen’s troops continued at Elizabethtown Point, and the Americans remained at Springfield. On June 21, however, having learned positively that Sir Henry Clinton’s forces had reached New York 4 days earlier, Washington decided that the time had come to leave Morristown as his main base of operations. Steps were accordingly taken to remove military stores concentrated in the village to interior points less vulnerable to immediate attack. Stark’s and the New Jersey Brigades, Maj. Henry Lee’s Light Horse Troop, and the militia were left at Springfield, under command of General Greene. The balance of the Continental Army began moving slowly toward Pompton, but was encamped at Rockaway Bridge when Washington, having left his headquarters in the Ford Mansion, joined it on June 23. This dual disposition of the American forces was taken with a view to protecting the environs of both Morristown and West Point, either of which might be the next major British objective.

On June 23, the very day of Washington’s departure from Morristown, the enemy struck once more. This time, with one column headed by General Mathew and the other by Knyphausen, they succeeded in getting through Springfield, where the British burned every building but two. Greene’s command met the assault with such determination, however, that the attackers again retreated to their former position. That night they abandoned Elizabethtown Point and crossed over to Staten Island. Never again during the Revolutionary War was there to be another major invasion of New Jersey.

While this second Battle of Springfield was in progress, Washington moved the main body of the Continental Army “back towards Morris Town five or six miles,” where he would be in a better position to defend 27 the stores remaining there in case the British attack should carry that far. Then, on June 25, with definite assurance that the enemy had retired to Staten Island, he put all the troops under marching orders for the Hudson Highlands. The second encampment at Morristown was ended.

Early the next winter, which most of Washington’s forces spent at New Windsor, on the Hudson River just north of West Point, the New Jersey Line was assigned to quarters at Pompton. The Pennsylvania Line, consisting of 10 infantry regiments and one of artillery, repaired and occupied the log huts built by Hand’s and the 1st Connecticut Brigades at Jockey Hollow in 1779-80.

Morale was extremely low at this time among all the Continental troops stationed in New Jersey. Not only did the Pennsylvanians lack clothing and blankets, but they were without a drop of rum to fortify themselves against the piercing cold. Moreover, they had not seen even a paper dollar in pay for over 12 months. Many of the soldiers also claimed that their original enlistments “for three years or during the war” entitled them to discharge at the end of 3 years, or sooner in case the war terminated earlier, and that the officers, by interpreting their enlistments to run as long as the war should last, were unjustly holding them beyond the time agreed upon. Still another cause of irritation was that latecomers in the Continental Army, especially those from New England, had been given generous bounties for enlisting, whereas both the New Jersey and Pennsylvania veterans had already served 3 full years for a mere shadow of compensation.

Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne, then commanding the Pennsylvanians, had known for a long time that trouble was coming if these grievances were not soon remedied, and had repeatedly urged the authorities of his State to do something about them. His entreaties fell on deaf ears. Tired of pleading, the men at last resorted to mutiny. On the evening of New Year’s Day 1781, almost the whole Pennsylvania Line turned out by pre-arrangement, seized the artillery and ammunition, and prepared to leave the camp. Capt. Adam Bettin was killed, and two other officers wounded, in vain attempts to restore order. Wayne himself, popular though he was with both rank and file, could not persuade the mutineers to lay down their arms. At 11 o’clock that night they marched off toward Philadelphia with the announced intention of carrying their case direct to Congress.

The serious character of this revolt, especially the grave danger that it might spread rapidly to other parts of the Continental Army, was fully appreciated by Washington and his principal officers, including Wayne, who followed and caught up with the mutineers, then voluntarily accompanied them to Princeton. Meanwhile, the men preserved 28 their own order, declared they would turn and fight the British should an invasion of New Jersey be attempted in this crisis, and they handed over to Wayne two emissaries dispatched by Sir Henry Clinton to lure them into his lines with lavish promises. This display of loyalty, the firm stand taken by the mutineers, and at the same time the justness of their complaints, all had effect on representatives of Congress and the Pennsylvania State authorities who came to Princeton to negotiate the whole question. An agreement concluded on January 7 stipulated that enlistments for 3 years or the duration of the war would be considered as expiring at the end of the 3d year; that shoes, linen overalls, and shirts would be issued shortly to the men discharged; and that prompt action would be taken in the matter of back pay. Commissioners appointed by Congress went to work at once to settle the details. More than half the mutineers were released from the army, and the rest furloughed for several months, as a result of the final settlement. Their main grievances removed, many of the men later reenlisted for new bounties. The loss was thus not as great in actuality as had been feared at first.

Hardly had the Pennsylvania Mutiny subsided when, on January 20, the New Jersey troops at Pompton also rose in revolt. Although this second insurrection was a comparatively mild affair, Washington took no chances with it. Five hundred men under command of Maj. Gen. Robert Howe were sent to restore order, and early in the morning of January 27, these forces surrounded the camp at Pompton and forced the mutineers to parade without arms. Three ringleaders were condemned to be shot by 12 of their partners in the uprising, but when two had been executed, the third was pardoned. On February 7 following, Washington ordered the chastened New Jersey Brigade to Morristown, there to take up quarters “in the Huts, lately occupied by the Pennsylvanians.” The troops remained so posted until July 8, 1781, when the Brigade marched for Kingsbridge on the Hudson.

Gen. Anthony Wayne endeavoring to halt the Pennsylvania mutineers on New Year’s Night 1781. From a diorama in the historical museum.

The last major battles of the Revolutionary War were fought in the South, ending with the Virginia campaign which resulted in the surrender at Yorktown, on October 19, 1781, of the British Army commanded by Lord Cornwallis. Following this event, Washington ordered most of his forces to return northward. Plans were made to establish the main Continental Army encampment at Newburgh, N. Y., during the coming winter, but the New Jersey Brigade was directed to “take Post somewhere in the Vicinity of Morristown, to cover the Country adjacent, and to secure the communication between the Delaware and North [Hudson] River.”

Col. Elias Dayton, soon afterward promoted to brigadier general, was then in command of the New Jersey Brigade, which at that time consisted of two regiments with a combined strength of around 700 men. His troops had arrived at Morristown by December 7, 1781, and they immediately established themselves in its neighborhood, again using log huts for quarters. Local tradition gives the position of their encampment as being in Jockey Hollow, a short distance southeast of the Wick House. Wherever the exact location, the Brigade remained there until August 29, 1782, when Dayton had orders from Washington to march toward King’s Ferry. A few of the sick and some regimental baggage were left behind when the New Jersey troops began their march, but these also were forwarded in the next 2 weeks.

This was the last winter encampment of American forces in Morris County during the Revolutionary War. The period of Morristown’s significance as a base for Washington’s military operations in that conflict had come to a close.

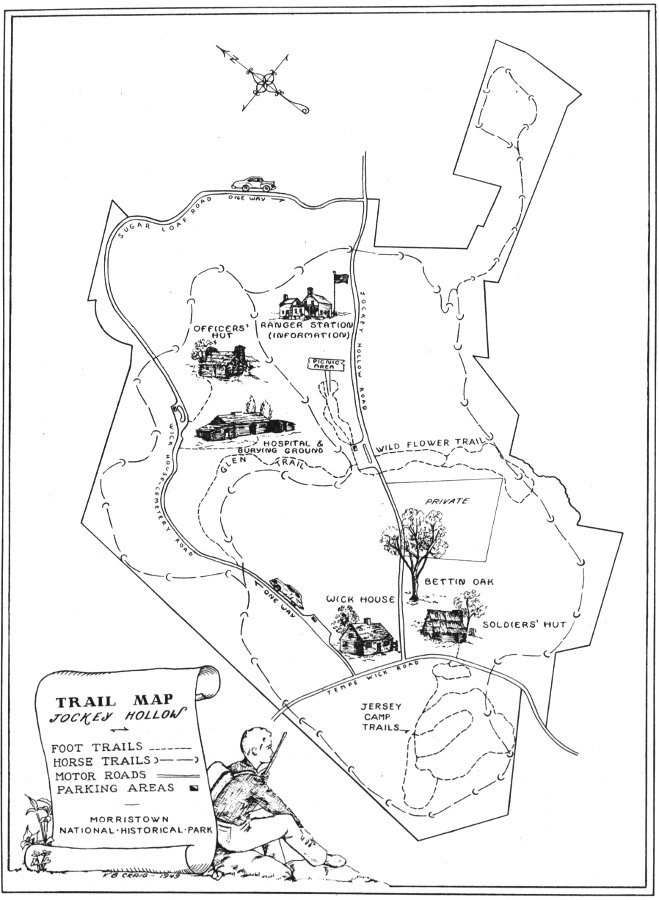

The following information, supplementing that contained in the narrative section of this handbook, is furnished as a convenient guide to points of special interest in and around Morristown National Historical Park. Numbers and titles in the text correspond to those shown on the Guide Map (pp. 20-21). Another map (p. 35) shows the bridle paths and foot trails in the jockey Hollow Area.

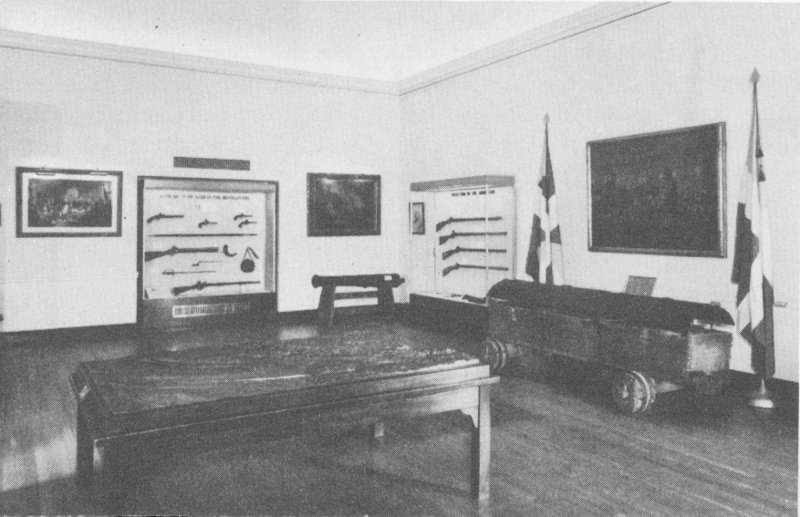

Located in the rear of the Ford Mansion (No. 2), at 230 Morris Street, Morristown, is the historical museum, a fireproof structure erected by the National Park Service in 1935. In the attractive entrance hall and four exhibition rooms of this building may be seen military arms and equipment, important relics of George and Martha Washington, and a large collection of other objects associated with the story of Morristown in Revolutionary War times. Here also 30 are located the park administrative offices, including those of the superintendent, chief clerk, historian, and museum staff.

The historical museum, focal point in telling the Morristown story.

Facing Morris Street where it joins Washington Avenue, is the Ford Mansion. This structure, a splendid example of late American colonial architecture, was built about 1772-74 by Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., an influential citizen, iron manufacturer, powder mill owner, and patriot soldier of Morristown. Colonel Ford died on January 10, 1777, from illness contracted during the “Mud Rounds” campaign of late 1776, in which he rendered valuable service to the American cause as commander of the Eastern Battalion, Morris County Militia. He was buried with military honors in the graveyard of the Presbyterian Church at Morristown.

The mansion itself served for a brief period in 1777 as quarters for the Delaware Light Infantry Regiment commanded by Capt. Thomas Rodney. During the Continental Army encampment of 1779-80, all but two rooms in the house were occupied by Washington’s official family, which, besides the Commander in Chief, included his devoted wife, Martha, his aides-de-camp, and some servants (p. 23). Mrs. Ford’s family consisted of herself and her four children: Timothy (aged 17), Gabriel (aged 15), Elizabeth (aged 13), and Jacob, III (aged 8).

Restoration of the Ford Mansion was begun by the National Park Service in 1939. Much of the beautiful old furniture now displayed in the building was there when Washington occupied it. The remaining furnishings 31 are mostly pieces dating from the Revolutionary War period or earlier, such as Mrs. Ford and her distinguished guests might have used.

Across Morris Street, slightly northeast of the Ford Mansion (No. 2), is the site occupied in 1779-80 by Washington’s Life Guard (officially, the Commander in Chief’s Guard). Erskine’s map of Morristown (p. 13) shows the exact position of some 13 or 14 log huts built by this unit for its winter quarters. Except for minor changes introduced at some uncertain date after March 1779, the Guard uniform consisted of a dark blue coat with buff collar and facings, red vest, fitted buckskin breeches, black shoes, white bayonet and body belts, black stock and tie for the hair, and a black cocked hat bound with white tape. The buttons were gilt.

Surrounded by the main business district of Morristown is a parklike area about 2½ acres in size. Here was the old Morristown Green of eighteenth century times. On the green itself, then crossed by roadways, stood the Morris County Courthouse and Jail, where both civil and military prisoners were confined during the Revolutionary War. About a dozen other buildings faced toward the green, among them the Arnold Tavern (No. 5), the Presbyterian and Baptist Churches (p. 9), and, in the winter of 1779-80, a large structure where Continental Army supplies were stored. Extending from the southwest side of the green was a broad, open space about 150 feet in depth and 250 feet long. This was often used for drill and parade purposes by both Continental troops and militia.

The Revolution Room in the historical museum, where weapons and military equipment of the Revolutionary War period are displayed.

Facing the northwest side of Morristown Green, about 100 to 150 feet from the present Washington Street corner, is the site of the Arnold 32 Tavern, which, according to local tradition, served as Washington’s headquarters in the winter of 1777 (p. 5). Built some years before the Revolutionary War, this structure was originally quite pretentious and handsomely furnished. During the nineteenth century it was converted into stores, and, in 1886, removed to another part of Morristown. Fire completed destruction of the building some 25 years later.

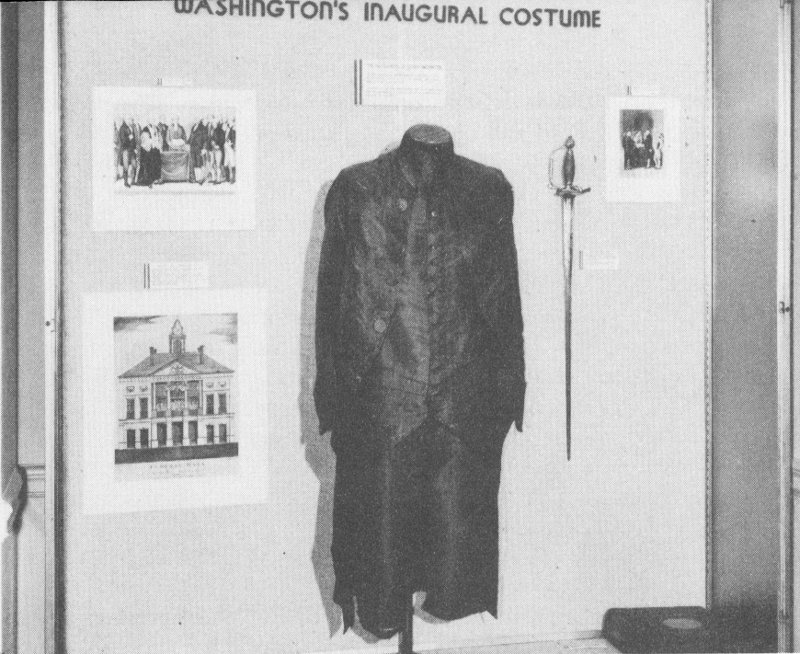

“Washington’s Inaugural Costume,” a typical exhibit in the historical museum.

Continuing from the south end of Court Street is a road leading upward into the Fort Nonsense Area of the park. There, at the top of a steep hill (the northern terminus of Mount Kemble), visitors may see a restored earthwork originally built at Washington’s order in 1777.

How the name “Fort Nonsense” came into being is unknown. It does not appear in any available written record before 1833, nor has anyone yet authenticated the oft-repeated story that the Commander in Chief’s reason for constructing this work was merely to keep the American troops occupied and out of mischief. Washington’s real intention is disclosed by an order of May 28, 1777, issued as the Continental Army moved to Middlebrook (p. 11). In this he directed Lt. Col. Jeremiah Olney to remain behind at Morristown, and with his detachment “and the Militia now here ... Guard the Stores of different kinds ... Strengthen the Works already begun upon the Hill near this place, and erect such others as are necessary for the better defending of it, that it may become a safe retreat in case of Necessity.” Other orders confirm the conclusion that Fort Nonsense was actually built to serve a very practical purpose.

Washington’s living and dining room in the Ford Mansion, showing the “secretary” desk once used by him as the American Commander in Chief.

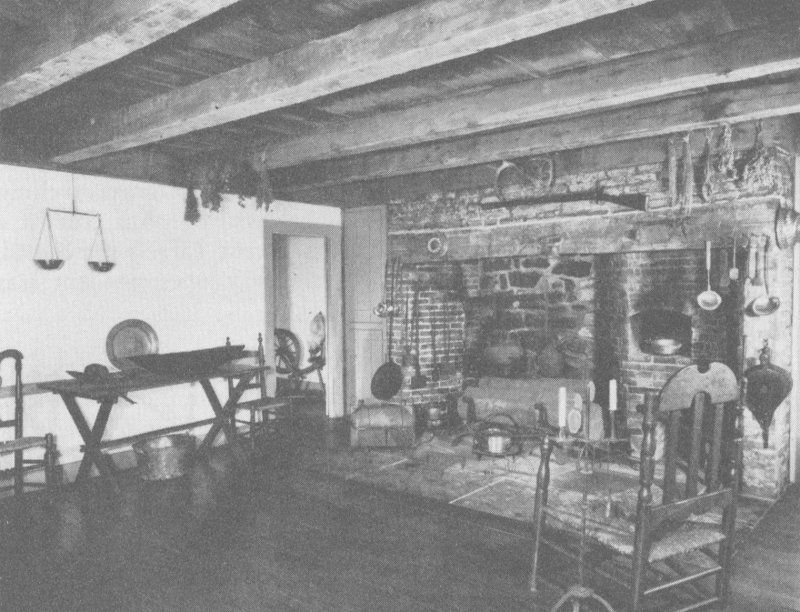

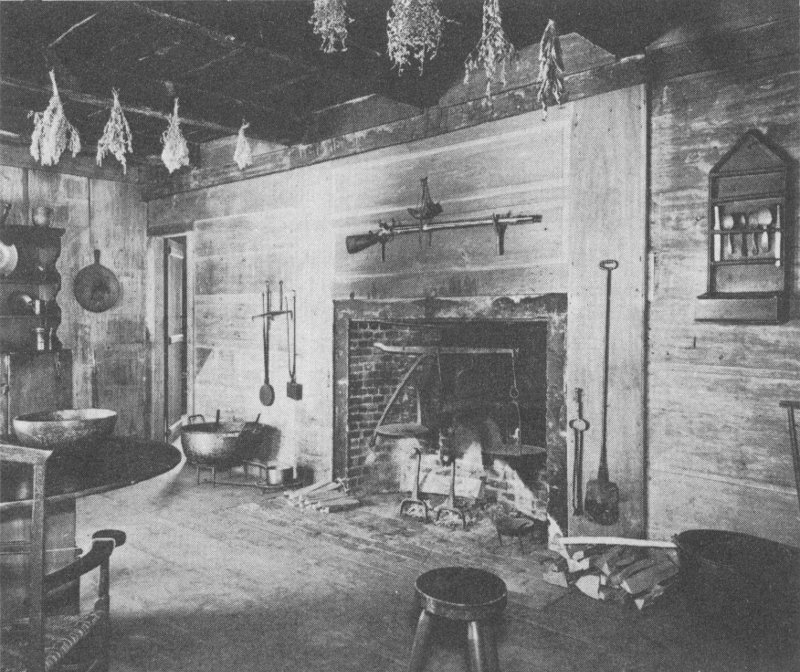

The kitchen in the Ford Mansion, where Washington’s official “family” and “all Mrs. Fords” tried to keep warm in January 1780.

“Fort Nonsense,” built in 1777 as a “retreat in case of Necessity” for troops assigned to guard American military stores at Morristown.

As years passed, the original lines of this earthwork gradually crumbled away. Their present appearance is the result of research and physical restoration work completed by the National Park Service in 1937.

At the southwest corner of the Jockey Hollow and Sugar Loaf Roads stands the Guerin House, in which is incorporated some of the original dwelling owned and occupied in Revolutionary War days by Joshua Guerin, a farmer and blacksmith of French Huguenot descent. Largely remodeled, the building now serves as a residence for the park superintendent. It is not open to visitors.

About one-quarter of a mile southwest of the Guerin House (No. 7), on the same side of the Jockey Hollow Road, is the ranger station. Here are located the office and quarters of the park ranger. Visitors may obtain free literature and other park information at this point.

About opposite the ranger station (No. 8), parallel to the east side of the Jockey Hollow Road, is the campsite occupied in 1779-80 by the New York Brigade under Brig. 35 Gen. James Clinton. In this brigade were the 2d, 3d, 4th, and 5th New York Regiments, with a combined total enlistment, in December 1779, of 1,267 men. The official uniform of these troops was blue, faced with buff; the buttons and linings, white.

TRAIL MAP

JOCKEY HOLLOW

Three-eighths of a mile southwest of the New York Brigade campsite (No. 9), on the west side of the Jockey Hollow Road, area picnic area and rest rooms. Parking facilities are provided close to the road. From that point a winding foot trail 36 (pp. 20, 35) leads to open places among the trees where tables and benches are placed for the convenience of visitors who wish to bring basket lunches. No fires are permitted, either here or elsewhere in the park.

More than 100 species of birds, some 20 species of mammals, and over 300 species of trees, shrubs, and wildflowers have been observed in Jockey Hollow at various times of the year. A walk over the Nature Trail (pp. 20, 35), which begins and ends at the Picnic Area (No. 10), affords opportunity to enjoy seeing many such elements of the park landscape. The area is a wildlife sanctuary, however, and visitors are reminded that disturbance of its natural features is prohibited by law (pp. 43-44).

Almost opposite the Picnic Area (No. 10), intersecting with the east side of the Jockey Hollow Road, is what has long been known as the Old Camp Road (p. 20). This leads across Mount Kemble to the old Basking Ridge Road, now Mount Kemble Avenue (U. S. Route 202), and to the site of Jacob Larzeleer’s Tavern, where Brig. Gen. John Stark made his quarters in 1779-80. Part of the road may have been built as the result of orders issued to Stark’s and the New York Brigades, on April 25, 1780, to “open a Road between the two encampments.”

About one-sixth of a mile southwest of the Picnic Area (No. 10), on the same side of the Jockey Hollow Road and parallel to it, is the campsite occupied in 1779-80 by the 1st Maryland Brigade under Brig. Gen. William Smallwood. In this brigade were the 1st, 3d, 5th, and 7th Maryland Regiments, with a combined total enlistment, in December 1779, of 1,416 men. The official uniform of these troops was blue, faced with red; the buttons and linings, white. About the middle of May 1780, following the departure of the 1st Maryland Brigade on April 17 preceding, soldiers of the Connecticut Line moved into the log huts erected on this site (p. 41).

About three-tenths of a mile southwest of the Picnic Area (No. 10), paralleling the opposite side of the Jockey Hollow Road, is the campsite occupied in 1779-80 by the 2d Maryland Brigade under Brig. Gen. Mordecai Gist. In this brigade were the 2d, 4th, and 6th Maryland Regiments, and Hall’s Delaware Regiment, with a combined total enlistment, in December 1779, of 1,497 men. The official uniform of these troops was the same as that of the 1st Maryland Brigade. About the middle of May 1780, following the departure of the 2d Maryland Brigade on April 17 preceding, soldiers of the Connecticut Line moved into the log huts erected on this site (p. 41).

Immediately southwest of the campsite occupied by the 2d Maryland Brigade in 1779-80 (No. 14), on the same side of the Jockey Hollow Road, stands the Bettin Oak. Near the base of this old tree is the traditional grave of Capt. Adam Bettin, who was killed on New Year’s Night 1781, during the mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line, then encamped nearby under command of Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne (pp. 27-28). Defensive works for the protection of Wayne’s camp were erected on Fort Hill, which rises to the eastward of this point. Nothing is left of these fortifications today.

About 1,200 feet southwest of the point where the Tempe Wick and Jockey Hollow Roads meet is the traditional campsite occupied in 1781-82 by the New Jersey Brigade under Brig. Gen. Elias Dayton (p. 29). In this brigade at that time were the 1st and 2d New Jersey Regiments, with a combined total enlistment, in April 1782, of around 700 men. The official uniform of these troops was blue, faced with buff; the buttons and linings, white.

The Wick House, built about 1750, and occupied as quarters by Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair in the winter of 1779-80.

On the north side of the Tempe Wick Road, about 325 feet west of its intersection with the Jockey Hollow Road, is the Wick House, which served in 1779-80 as quarters for Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair, then commander of the Pennsylvania Line encamped in Jockey Hollow (Nos. 20-21). The building was erected about 1750 by Henry Wick, a fairly prosperous farmer who had come to Morris County from Long Island a few years before. Tempe Wick, his youngest daughter, is said to have concealed her riding horse in a bedroom of the house, in January 1781, in order to prevent its seizure by the Pennsylvania mutineers (pp. 27-28). The interior of the building was furnished with period pieces following its restoration by the National Park Service in 1935. Efforts have also been made to recreate, as far as possible, the colonial atmosphere of the farm itself, as reflected in the nearby garden, barnyard, orchard, and open fields.

A corner of the kitchen in the Wick House.

The Wick House garden.

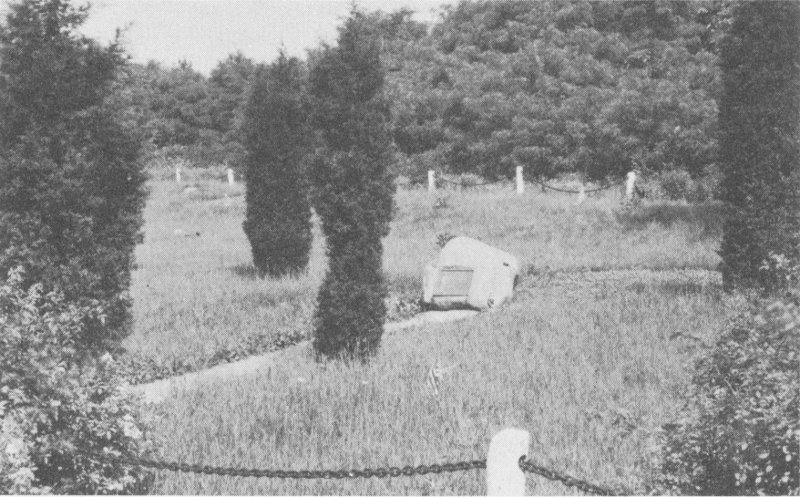

On the south side of the Cemetery-Wick House Road, at the point where it joins the Grand Parade Road, is the traditional site of the Continental Army Burying Ground in Jockey Hollow. Here are said to lie the remains of between 100 and 150 American soldiers who failed to survive the terrible winter of 1779-80.

Army Burying Ground in Jockey Hollow.

Immediately adjacent to the Army Burying Ground (No. 18), visitors may see a log structure of the type used for hospital purposes while the Continental Army lay encamped in Jockey Hollow. This building was reconstructed by the National Park Service from a description and plans prepared by Dr. James Tilton, Hospital Physician in 1779-80, and later Physician and Surgeon General, United States Army.

About 400 feet east of the reconstructed Army Hospital Hut (No. 19), on the west slope of Sugar Loaf Hill, and cutting diagonally across the Grand Parade Road, are the 40 campsites occupied in 1779-80 by the Pennsylvania Division commanded that winter by Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair. In this division were the 1st and 2d Pennsylvania Brigades. The former, under Brig. Gen. William Irvine, was composed of the 1st, 2d, 7th, and 10th Pennsylvania Regiments, with a combined total enlistment, in December 1779, of 1,253 men. In the latter, under Col. Francis Johnston, were the 3d, 5th, 6th, and 9th Pennsylvania Regiments, with a corresponding enlistment, at the same period, of 1,050 men. The official uniform of all these troops was blue, faced with red; the buttons and linings, white.

On the First Pennsylvania Brigade campsite may be seen a reconstruction, by the National Park Service, of the type of log hut used as quarters by officers of the Continental Army in 1779-80 (p. 16).

Reconstructed Army Hospital Hut.

North of the Grand Parade Road, below the east slope of Sugar Loaf Hill, is the level ground “between the Pensylvania & the York encampment” which served as the Grand Parade used by the Continental Army in 1779-80. Here the camp guards and detachments assigned to outpost duty usually reported for inspection, and the troops were sometimes paraded to witness military executions. The ground was also used for drill purposes. Near the Grand Parade was the “New Orderly Room” where courts martial were frequently held, and where Washington’s orders were communicated to the army.

Parallel to the north side of the Tempe Wick Road, about 300 feet southeast of where it joins the Jockey Hollow Road, is the 41 campsite occupied in 1779-80 by Hand’s Brigade, named for its commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Edward Hand. In this brigade were the 1st and 2d Canadian and the 4th and New 11th Pennsylvania Regiments, with a combined total enlistment, in December 1779, of 1,033 men. The official uniform of the Pennsylvania regiments was blue, faced with red; the buttons and linings, white. How all the Canadians were clothed is unknown, but some of them probably wore brown coats, faced with red, and white waistcoats and breeches.

This identical campsite was occupied by part of the Pennsylvania Line early in the winter of 1780-81, and from about February 7 to July 8, 1781, by the New Jersey Brigade of the Continental Army. Here occurred the great mutiny of the Pennsylvanians on New Year’s Night 1781 (pp. 27-28).

On the Hand’s Brigade campsite may be seen a reconstruction, by the National Park Service, of the type of log hut used by private soldiers of the Continental Army in 1779-80 (p. 16).

About 600 feet northeast of the Tempe Wick Road, along the south and east slopes of Fort Hill (No. 15), are the campsites occupied early in 1779-80 by the 1st and 2d Connecticut Brigades. The former, under Brig. Gen. Samuel Holden Parsons, was composed of the 3d, 4th, 6th, and 8th Connecticut Regiments, with a combined total enlistment, in December 1779, of 1,680 men. In the latter, under Brig. Gen. Jedediah Huntington, were the 1st, 2d, 5th, and 7th Connecticut Regiments, with a corresponding enlistment, at the same period, of 1,367 men. The official uniform of all these troops was blue, faced with white; the buttons and linings, white.

Both brigades left camp for detached duty “on the Lines” at Springfield and Westfield early in February 1780. On returning to camp, about the middle of May, they occupied the log huts vacated by the Maryland troops on April 17 preceding (Nos. 13-14). It was there that the 4th and 8th Connecticut Regiments rose in mutiny soon afterward (p. 18).

Some of the log huts built by the 1st Connecticut Brigade were occupied by Pennsylvania troops early in the following winter, previous to the mutiny which broke out on New Year’s Day 1781 (pp. 27-28).

At the northwest corner of Mount Kemble Avenue (U. S. Route 202) and the Tempe Wick Road is the site of Kemble Manor, built about 1765 as a residence for the Honorable Peter Kemble, one of the wealthiest and most influential men in the late colonial period of New Jersey history. Here were the quarters of Brig. Gen. William Smallwood, of the Maryland Line, in 1779-80; and of Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, of the Pennsylvania Line, in 1780-81. From “Mount Kemble,” early on the morning of January 2, 1781, Wayne wrote a hurried letter to Washington describing 42 the Pennsylvania Mutiny, which had taken place but a few hours before (pp. 27-28). In the nineteenth century the Kemble House was moved some distance north of its original location. It no longer bears much resemblance to the structure of Revolutionary War times.