The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Problem of the Rupee, Its Origin and Its Solution

Title: The Problem of the Rupee, Its Origin and Its Solution

Creator: B. R. Ambedkar

Release date: September 5, 2020 [eBook #63132]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Joseph Koshy

THE PROBLEM OF THE RUPEE

ITS ORIGINS AND ITS SOLUTION

BY

B. R. AMBEDKAR

Sometime Professor of Political Economy at the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics, Bombay.

LONDON

P. S. KING & SON, LTD.

ORCHARD HOUSE, 2 & 4 GREAT SMITH STREET

WESTMINSTER

1923

DEDICATED

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY

FATHER AND MOTHER

Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd., Frome and London

PREFACE

In the following pages I have attempted an exposition of the events leading to the establishment of the exchange standard and an examination of its theoretical basis.

In endeavouring to treat the historical side of the matter I have carefully avoided repeating what has already been said by others. For instance, in treating of the actual working of the exchange standard I have contented myself with a general treatment just sufficiently detailed to enable the reader to follow the criticism I have offered. If more details are desired they are given in all their amplitude in other treatises. To have reproduced them would have been a work of supererogation; besides it would have only obscured the general trend of my argument. But in other respects I have been obliged to take a wider historical sweep than has been done by other writers. The existing treatises on Indian currency do not give any idea, at least an adequate idea, of the circumstances which led to the reforms of 1893. I think that a treatment of the early history is quite essential to furnish the reader with a perspective in order to enable him to judge for himself the issues involved in the currency crisis and also of the solutions offered. In view of this I have gone into that most neglected period of Indian currency extending from 1800 to [pg vi] 1893. Not only have other writers begun abruptly the story of the exchange standard, but they have popularised the notion that the exchange standard is the standard originally contemplated by the Government of India. I find that this is a gross error. Indeed the most interesting point about Indian currency is the way in which the gold standard came to be transformed into a gold exchange standard. Some old but by now forgotten facts had therefore to be recounted to expose this error.

On the theoretical side there is no book but that of Professor Keynes which makes any attempt to examine its scientific basis. But the conclusions he has arrived at are in sharp conflict with those of mine. Our differences extend to almost every proposition he has advanced in favour of the exchange standard. This difference proceeds from the fundamental fact, which seems to be quite overlooked by Professor Keynes, that nothing will stabilise the rupee unless we stabilise its general purchasing power. That the exchange standard does not do. That standard concerns itself only with symptoms and does not go to the disease: indeed, on my showing, if anything, it aggravates the disease.

When I come to the remedy I again find myself in conflict with the majority of those who like myself are opposed to the exchange standard. It is said that the best way to stabilise the rupee is to provide for effective convertibility into gold. I do not deny that this is one way of doing it. But I think a far better way would be to have an inconvertible rupee with a fixed limit of issue. Indeed, if I had any say in the matter I would propose that the Government of India should melt the rupees, sell them as [pg vii] bullion and use the proceeds for revenue purposes and fill the void by an inconvertible paper. But that may be too radical a proposal, and I do not therefore press for it, although I regard it as essentially sound. In any case the vital point is to close the Mints not merely to the public, as they have been, but to the Government as well. Once that is done I venture to say that the Indian currency, based on gold as legal tender with a rupee currency fixed in issue, will conform to the principles embodied in the English currency system.

It will be noticed that I do not propose to go back to the recommendations of the Fowler Committee. All those who have regretted the transformation of the Indian currency from a gold standard to a gold exchange standard have held that everything would have been all right if the Government had carried out in toto the recommendations of that Committee. I do not share that view. On the other hand, I find that the Indian currency underwent that transformation because the Government carried out those recommendations. While some people regard that Report as classical for its wisdom, I regard it as classical for its nonsense. For I find that it was this Committee which, while recommending a gold standard, also recommended and thereby perpetuated the folly of the Herschell Committee, that Government should coin rupees on its own account according to that most naïve of currency principles, the requirements of the public, without realising that the latter recommendation was destructive of the former. Indeed, as I argue, the principles of the Fowler Committee must be given up if we are to place the Indian currency on a stable basis. [pg viii]

I am conscious of the somewhat lengthy discussions on currency principles into which I have entered in treating the subject. My justification of this procedure is two-fold. First of all, as I have differed so widely from other writers on Indian currency, I have deemed it necessary to substantiate my view-point even at the cost of being charged with over-elaboration. But it is my second justification which affords me a greater excuse. It consists in the fact that I have written primarily for the benefit of the Indian public, and, as their grasp of currency principles does not seem to be as good as one would wish it to be, an over-statement, it will be agreed, is better than an understatement of the argument on which I have based my conclusions.

Up to 1913, the Gold Exchange Standard was not the avowed goal of the Government of India in the matter of Indian Currency, and although the Chamberlain Commission appointed in that year had reported in favour of its continuance, the Government of India had promised not to carry its recommendations into practice till the war was over and an opportunity had been given to the public to criticize them. When, however, the Exchange Standard was shaken to its foundations during the late war, the Government of India went back on its word and restricted, notwithstanding repeated protests, the terms of reference to the Smith Committee to recommending such measures as were calculated to ensure the stability of the Exchange Standard, as though that standard had been accepted as the last word in the matter of Indian Currency. Now that the measures of the Smith Committee have not ensured the stability of the Exchange Standard, it is given [pg ix] to understand that the Government, as well as the public, desire to place the Indian Currency System on a sounder footing. My object in publishing this study at this juncture is to suggest a basis for the consummation of this purpose.

I cannot conclude this preface without acknowledging my deep sense of gratitude to my teacher, Prof. Edwin Cannan, of the University of London (School of Economics). His sympathy towards me and his keen interest in my undertaking have placed me under obligations which I can never repay. I feel happy to be able to say that this work has undergone close supervision at his hands, and although he is in no way responsible for the views I have expressed, I can say that his severe examination of my theoretic discussions has saved me from many an error. To Professor Wadia, of Wilson College, I am thankful for cheerfully undertaking the dry task of correcting the proofs. [pg x]

[pg xi]

FOREWORD

By Professor Edwin Cannan

I am glad that Mr. Ambedkar has given me the opportunity of saying a few words about his book.

As he is aware, I disagree with a good deal of his criticism. In 1893 I was one of the few economists who believed that the rupee could be kept at a fixed ratio with gold by the method then proposed, and I did not fall away from the faith when some years elapsed without the desired fruit appearing (see Economic Review, July 1898, pp. 400—403). I do not share Mr. Ambedkar's hostility to the system, nor accept most of his arguments against it and its advocates. But he hits some nails very squarely on the head, and even when I have thought him quite wrong, I have found a stimulating freshness in his views and reasons. An old teacher like myself learns to tolerate the vagaries of originality, even when they resist “severe examination” such as that of which Mr. Ambedkar speaks.

In his practical conclusion I am inclined to think he is right. The single advantage offered to a country by the adoption of the gold-exchange system instead of the simple gold standard is that it is cheaper, in the sense of requiring a little less value in the shape of metallic currency than the gold standard. But all that can be saved in this way is a trifling amount, almost infinitesimal beside the advantage of having a currency more difficult for [pg xii] administrators and legislators to tamper with. The recent experience both of belligerents and neutrals certainly shows that the simple gold standard, as we understood it before the war, is not fool-proof, but it is far nearer being fool-proof and knave-proof than the gold-exchange standard. The percentage of administrators and legislators who understand the gold standard is painfully small, but it is and is likely to remain ten or twenty times as great as the percentage which understands the gold-exchange system. The possibility of a gold-exchange system being perverted to suit some corrupt purpose is very considerably greater than the possibility of the simple gold standard being so perverted.

The plan for the adoption of which Mr. Ambedkar pleads, namely that all further enlargement of the rupee issue should be permanently prohibited, and that the mints should be open at a fixed price to importers or other sellers of gold, so that in course of time India would have, in addition to the fixed stock of rupees, a currency of meltable and exportable gold coins, follows European precedents. In eighteenth-century England the gold standard introduced itself because the legislature allowed the ratio to remain unfavourable to the coinage of silver: in nineteenth-century France and other countries it came in because the legislatures definitely closed the mints to silver when the ratio was favourable to the coinage of silver. The continuance of a mass of full legal tender silver coins beside the gold would be nothing novel in principle, as the same thing, though on a somewhat smaller scale, took place in France, Germany, and the United States.

It is alleged sometimes that India does not want [pg xiii] gold coins. I feel considerable difficulty in believing that gold coins of suitable size would not be convenient in a country with the climate and other circumstances of India. The allegation is suspiciously like the old allegation that the “Englishman prefers gold coins to paper,” which had no other foundation than the fact that the law prohibited the issue of notes for less than £5 in England and Wales, while in Scotland, Ireland, and almost all other English-speaking countries notes for £1 or less were allowed and circulated freely. It seems much more likely that silver owes its position in India to the decision which the Company made before the system of standard gold and token silver was accidentally evolved in 1816 in England, and long before it was understood: and that the position has been maintained not because Indians dislike gold, but because Europeans like it so well that they cannot bear to part with any of it.

This reluctance to allow gold to go to the East is not only despicable from an ethical point of view. It is also contrary to the economic interest not only of the world at large, but even of the countries which had a gold standard before the war and have it still or expect soon to restore it. In the immediate future gold is not a commodity the use of which it is desirable for these countries either to restrict or to economize. From the closing years of last century it has been produced in quantities much too large to enable it to retain its purchasing power and thus be a stable standard of value unless it can constantly be finding existing holders willing to hold larger stocks, or fresh holders to hold new stocks of it. Before the war the accumulation of hoards by [pg xiv] various central banks in Europe took off a large part of the new supplies and prevented the actual rise of general prices being anything like what it would otherwise have been, though it was serious enough. Since the war the Federal Reserve Board, supported by all Americans who do not wish to see a rise of prices, has taken on the new “White Man's Burden” of absorbing the products of the gold mines, but just as the United States failed to keep up the value of silver by purchasing it, so she will eventually fail to keep up the value of gold. In spite of the opinion of some high authorities, it is not at all likely that a renewed demand for gold reserves by the central banks of Europe will come to her assistance. Experience must gradually be teaching even the densest of financiers that the value of paper currencies is not kept up by stories of “cover” or “backing” locked up in cellars, but by due limitation of the supply of the paper. With proper limitation enforced by absolute convertibility into gold coin which may be freely melted or exported, it has been proved by theory and experience that small holdings of gold are perfectly sufficient to meet all internal and international demands. There is really more chance of a great demand from individuals than from the banks. It is conceivable that the people of some of the countries which have reduced their paper currency to a laughing stock may refuse all paper and insist on having gold coins. But it seems more probable that they will be pleased enough to get better paper than they have recently been accustomed to, and will not ask for hard coin with sufficient insistence to get it. On the whole it seems fairly certain that the demand of Europe and [pg xv] European-colonised lands for gold will be less rather than greater than before the war, and that it will increase very slowly or not at all.

Thus on the whole there is reason to fear a fall in the value of gold and a rise of general prices rather than the contrary.

One obvious remedy would be to restrict the production of gold by international agreement, thus conserving the world's resources in mineral for future generations. Another is to set up an international commission to issue an international paper currency so regulated in amount as to preserve an approximately stable value. Excellent suggestions for the professor's classroom, but not, at present at any rate nor probably for some considerable period of time, practical politics.

A much more practical way out of the difficulty is to be found in the introduction of gold currency into the East. If the East will take a large part of the production of gold in the coming years it will tide us over the period which must elapse before the most prolific of the existing sources are worked out. After that we may be able to carry on without change or we may have reached the possibility of some better arrangement.

This argument will not appeal to those who can think of nothing but the extra profits which can be acquired during a rise of prices, but I hope it will to those who have some feeling for the great majority of the population, who suffer from these extra and wholly unearned profits being extracted from them. Stability is best in the long run for the community.

EDWIN CANNAN.

[pg xvii]

Contents

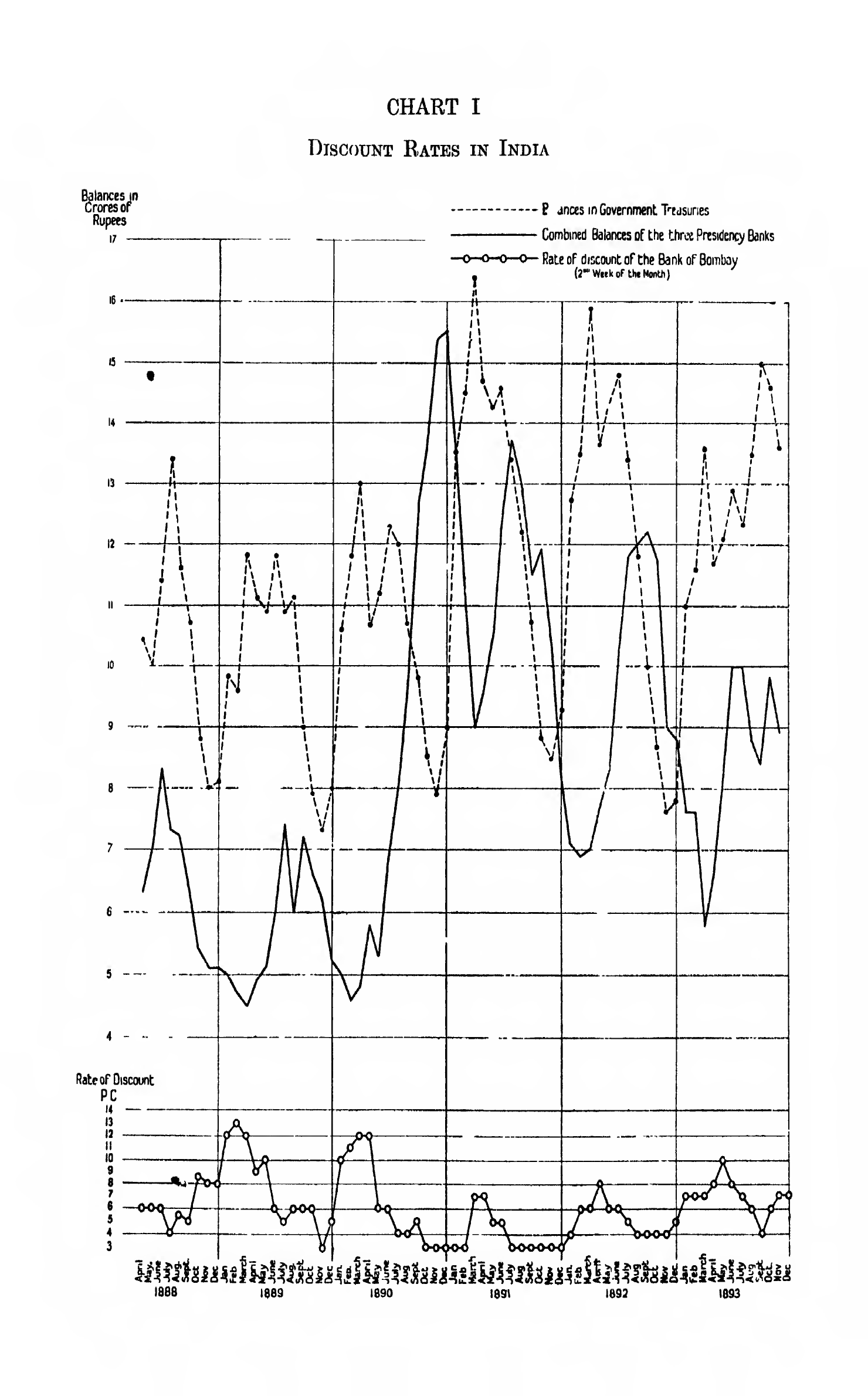

- CHART I: Discount Rates in India

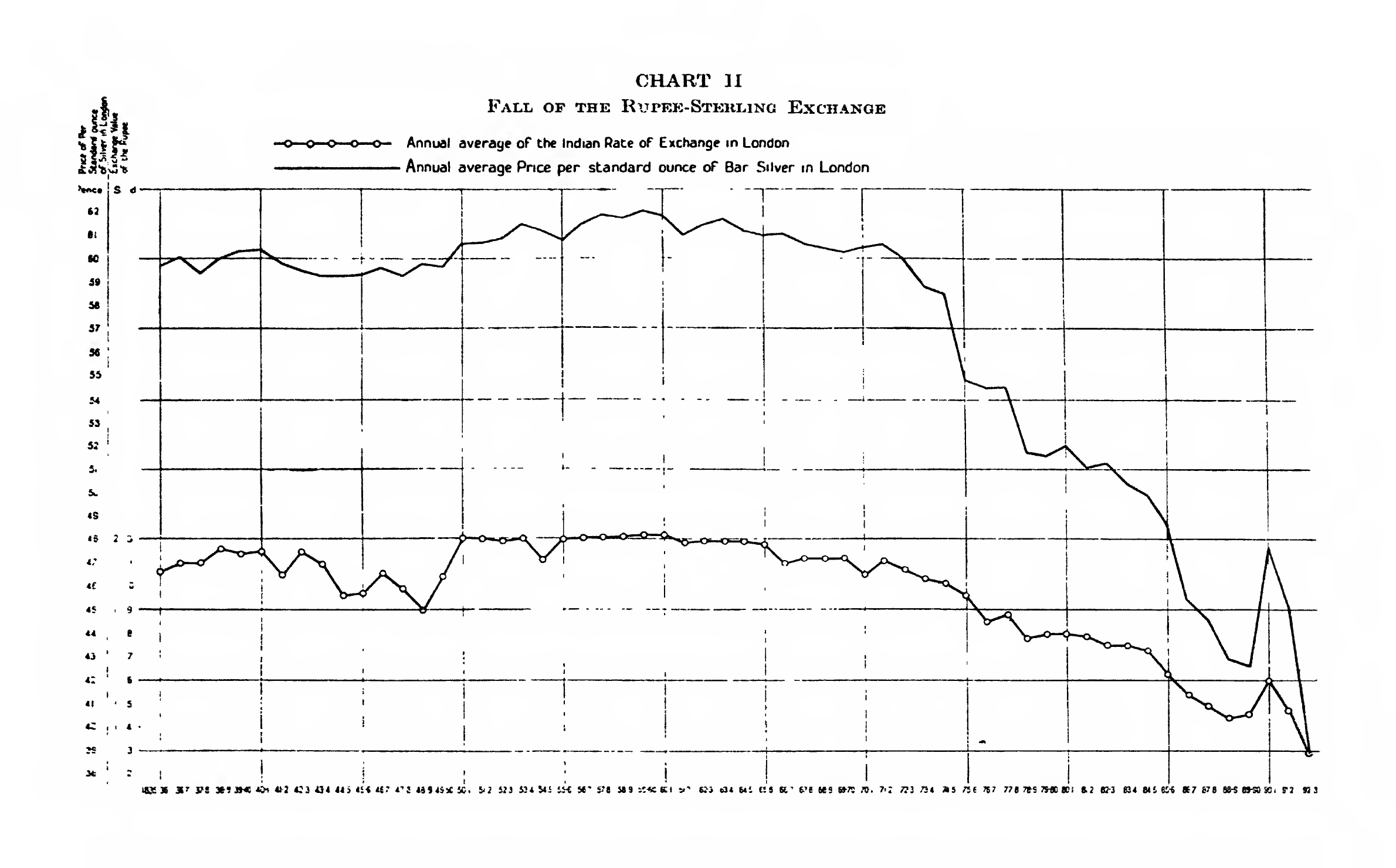

- CHART II: Fall of the Rupee-Sterling Exchange

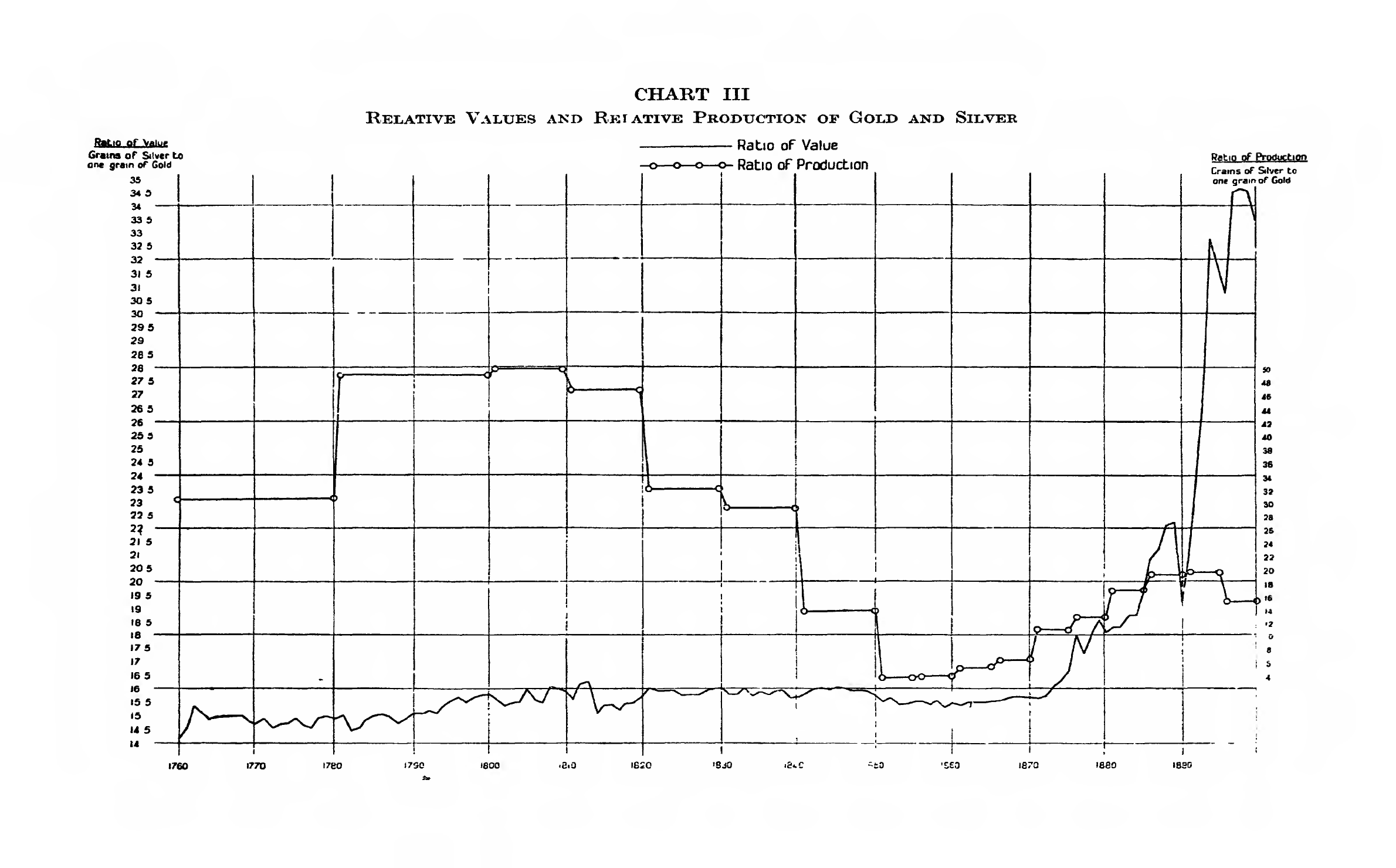

- CHART III: Relative Values and Relative Production of Gold and Silver

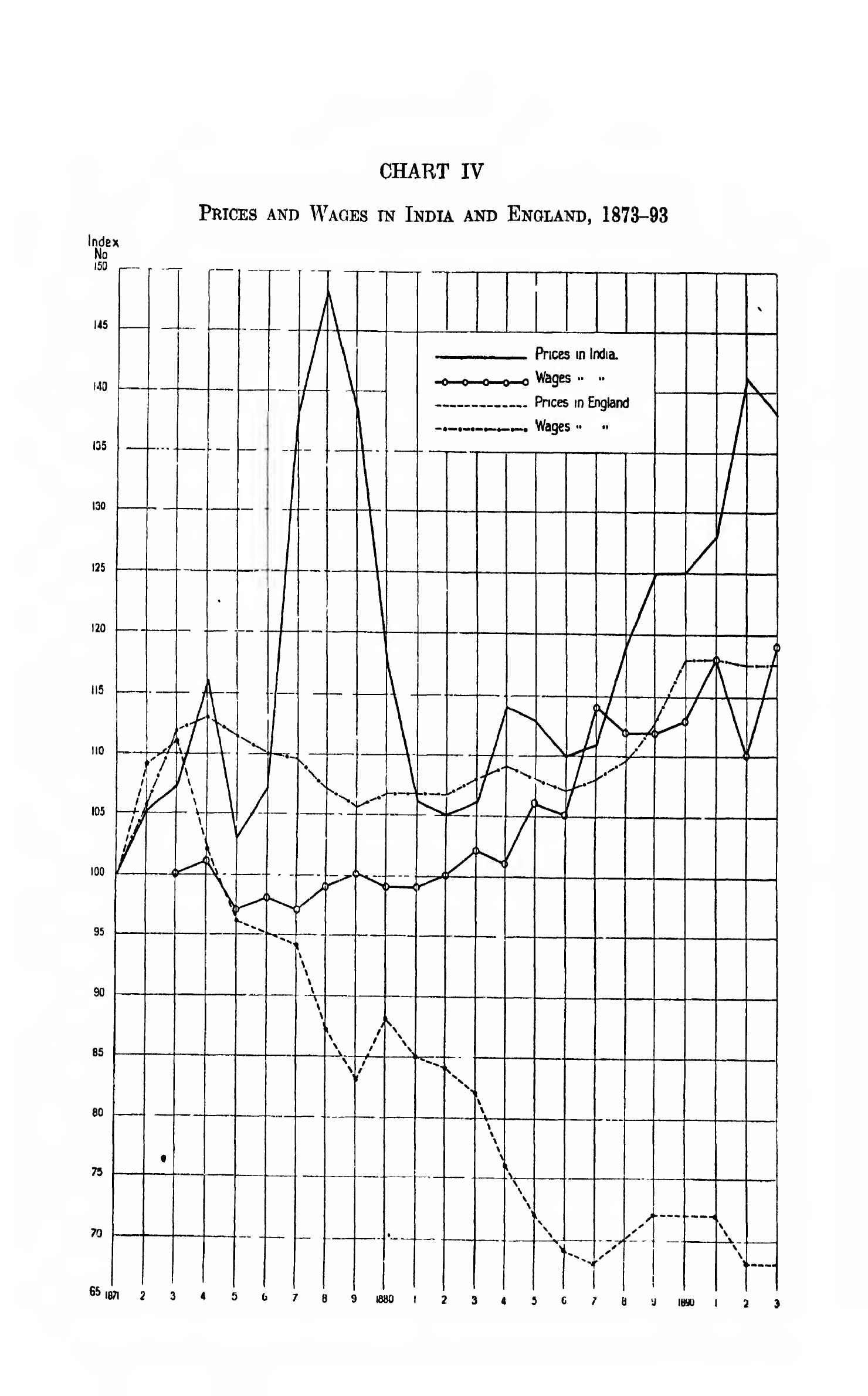

- CHART IV: Prices and Wages in India and England, 1873–93

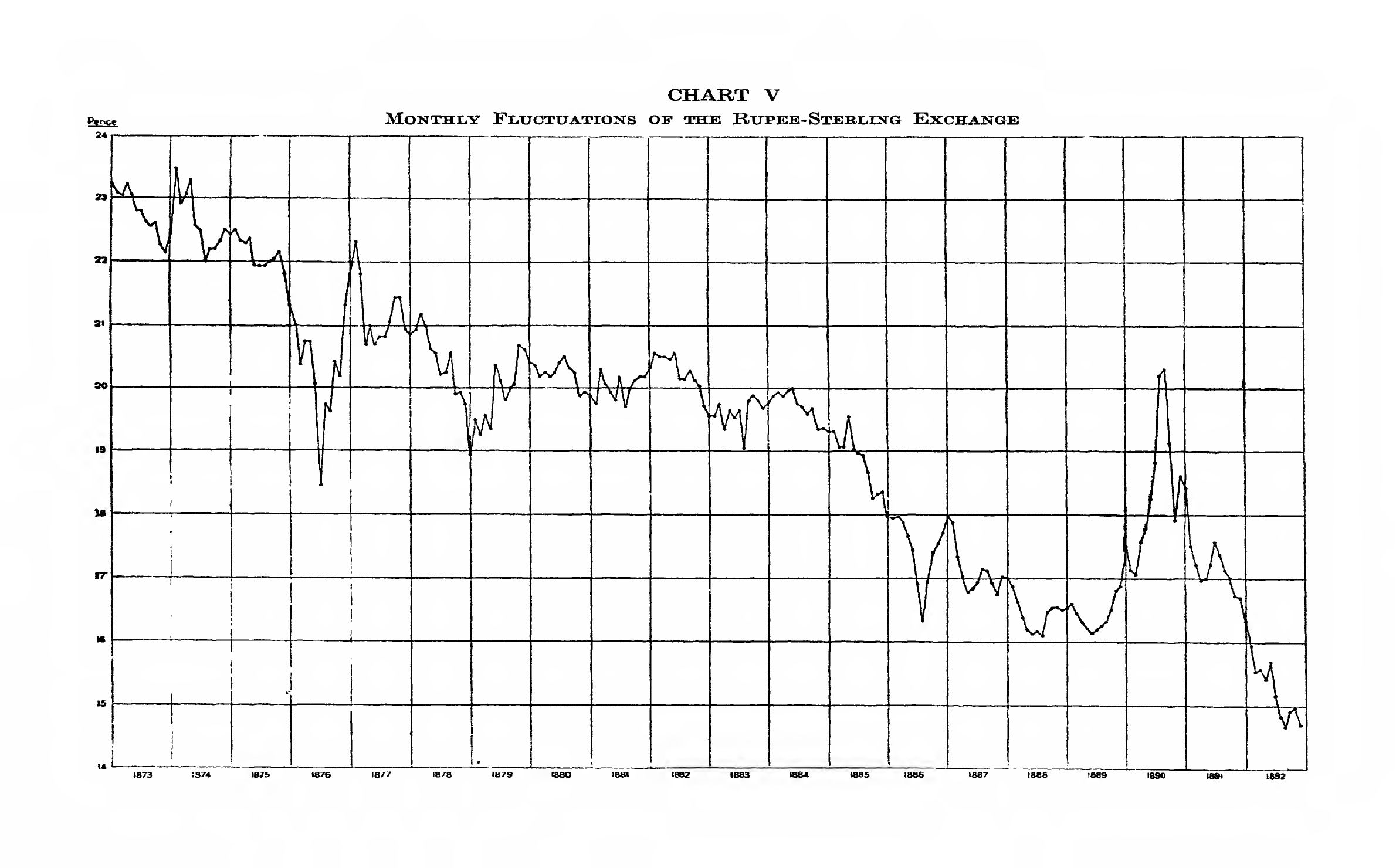

- CHART V: Monthly Fluctuations of The Rupee-Sterling Exchange

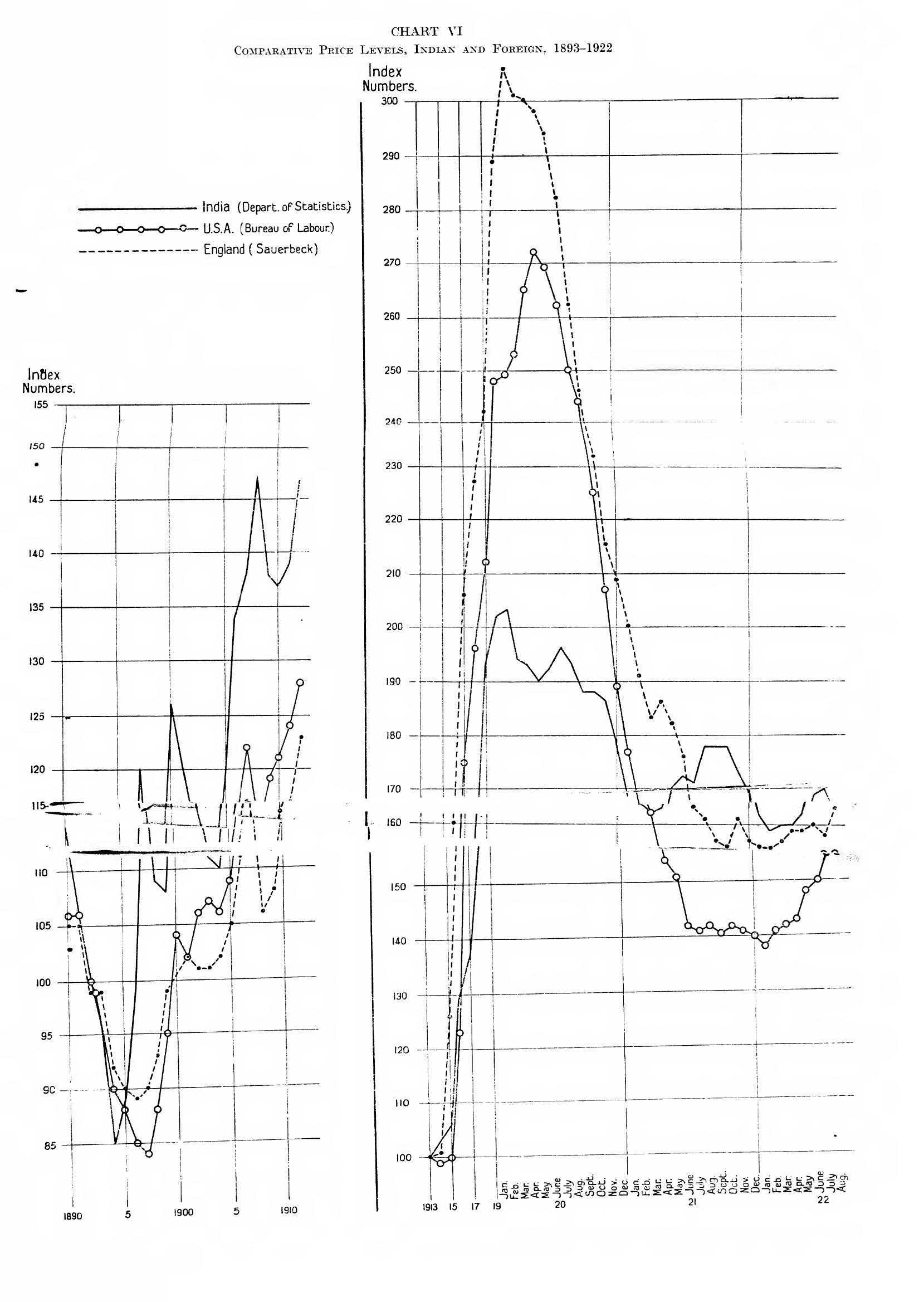

- CHART VI: Comparative Price Levels, Indian and Foreign, 1893–1922

[pg 1]

THE PROBLEM OF THE RUPEE

CHAPTER I

FROM A DOUBLE STANDARD TO A SILVER STANDARD

Trade is an important apparatus in a society based on private property and pursuit of individual gain; without it, it would be difficult for its members to distribute the specialised products of their labour. Surely a lottery or an administrative device would be incompatible with its nature. Indeed, if it is to preserve its character, the only mode for the necessary distribution of the products of separate industry is that of private trading. But a trading society is unavoidably a pecuniary society, a society which of necessity carries on its transactions in terms of money. In fact, the distribution is not primarily an exchange of products against products, but products against money. In such a society, money therefore necessarily becomes the pivot on which everything revolves. With money as the focusing-point of all human efforts, interests, desires and ambitions, a trading society is bound to function in a régime of price where successes and failures are results of nice calculations of price-outlay as against price-product.

Economists have no doubt insisted that “there cannot … be intrinsically a more significant thing than money,” which at best is only “a great wheel by means of which every individual in society has his subsistence, conveniences and amusements regularly distributed to him [pg 2] in their proper proportions.” Whether or not money values are the definitive terms of economic endeavour may well be open to discussion.1 But this much is certain, that without the use of money this “distribution of subsistence, conveniences and amusements,“ far from being a matter of course, will be distressingly hampered if not altogether suspended. How can this trading of products take place without money? The difficulties of barter have ever formed an unfailing theme with all economists, including those who have insisted that money is only a cloak. Money is not only necessary to facilitate trade by obviating the difficulties of barter, but is also necessary to sustain production by permitting specialisation. For who would care to specialise if he could not trade his products for those of others which he wanted? Trade is the handmaid of production, and where the former cannot flourish the latter must languish. It is therefore evident that if a trading society is not to be out of gear and is not to forego the measureless advantages of its automatic adjustments in the great give-and-take of specialised industry, it must provide itself with a sound system of money.2

At the close of the Moghul Empire, India, judged by the standards of the time, was economically an advanced country. Her trade was large, her banking institutions were well developed, and credit played an appreciable part in her transactions. But a medium of exchange and a common standard of value were among others the most supreme desiderata in the economy of the Indian people when they came, in the middle of the eighteenth century, under the sway of the British. Before the occurrence of this event, the money of India consisted of both gold and silver. Under the Hindu emperors the emphasis was laid on gold, while under the Mussalmans silver formed a large [pg 3] part of the circulating medium.3 Since the time of Akbar, the founder of the economic system of the Moghul Empire in India, the units of currency had been the gold mohur and the silver rupee. Both coins, the mohur and the rupee, were identical in weight, i.e. 175 grs. troy,4 and were “supposed to have been coined without any alloy, or at least intended to be so.”5 But whether they constituted a single standard of value or not is a matter of some doubt. It is believed that the mohur and the rupee, which at the time were the common measure of value, circulated without any fixed ratio of exchange between them. The standard, therefore, was more of the nature of what Jevons called a parallel standard6 than a double standard.7 That this want of ratio could not have worked without some detriment in practice is obvious. But it must be noted that there existed an alleviating circumstance in the curious contrivance by which the mohur and the rupee, though unrelated to each other, bore a fixed ratio to the dam, the copper coin of the Empire.8 So that it is permissible to hold that, as a consequence of being fixed to the same thing, the two, the mohur and the rupee, circulated at a fixed ratio.

In Southern India, to which part the influence of the [pg 4] Moghuls had not extended, silver as a part of the currency system was quite unknown. The pagoda, the gold coin of the ancient Hindu kings, was the standard of value and also the medium of exchange, and continued to be so till the time of the East India Company.

The right of coinage, which the Moghuls always held as inter jura Majestatis,9 be it said to their credit was exercised with due sense of responsibility. Never did the Moghul Emperors stoop to debase their coinage. Making allowance for the imperfect technology of coinage, the coins issued from the various Mints situated even in the most distant parts of their Empire10 did not materially deviate from the standard.

Name of the Rupee |

Weight in pure Grs. |

Name of the Rupee |

Weight in pure Grs. |

|---|---|---|---|

Akabari of Lahore |

175·0 |

Delhi Sonat |

175·0 |

Akabari of Agra |

174·0 |

Delhi Alamgir |

175·0 |

Jehangiri of Agra |

174·6 |

Old Surat |

174·0 |

Jehangiri of Allahabad |

173·6 |

Murshedabad |

175·9 |

Jehangiri of Kandahar |

173·9 |

Persian Rupee of 1745 |

174·5 |

Shehajehani of Agra |

175·0 |

Old Dacca |

173·3 |

Shehajehani of Ahamadabad |

174·2 |

Muhamadshai |

170·0 |

Shehajehani of Delhi |

174·2 |

Ahamadshai |

172·8 |

Shehajehani of Delhi |

175·0 |

Shaha Alam (1772) |

175·8 |

Shehajehani of Lahore |

174·0 |

||

[pg 5] The table on p. 4 of the assays of the Moghul rupees shows how the coinage throughout the period of the Empire adhered to the standard weight of 175 grs. pure.11

So long as the Empire retained unabated sway there was advantage rather than danger in the plurality of Mints, for they were so many branches of a single department governed by a single authority. But with the disruption of the Moghul Empire into separate kingdoms these branches of the Imperial Mint located at different centres became independent factories for purposes of coinage. In the general scramble for independence which followed the fall of the Empire, the right to coinage, as one of the most unmistakable insignia of sovereignty, became the right most cherished by the political adventurers of the time. It was the last privilege to which the falling dynasties clung, and was also the first to which the adventurers rising to power aspired. The result was that the right, which was at one time so religiously exercised, came to be most wantonly abused. Everywhere the Mints were kept in full swing, and soon the country was filled with diverse coins which, while they proclaimed the incessant rise and fall of dynasties, also presented bewildering media of exchange. If these money-mongering sovereigns had kept up their issues to the original standard of the Moghul Emperors the multiplicity of coins of the same denomination would not have been a matter of much concern. But they seemed to have held that as the money used by their subjects was made by them, they could do what they liked with their own, and proceeded to debase their coinage to the extent each chose without altering the denominations. Given the different degrees of debasement, the currency necessarily lost its primary quality of general and ready acceptability.

The evils consequent upon such a situation may well be imagined. When the contents of the coins belied the value indicated by their denomination they became mere merchandise and there was no more a currency by tale to act as a ready means of exchange. The bullion value of each coin had to be ascertained before it could be accepted as a final [pg 6] discharge of obligations.12 The opportunity for defrauding the poor and the ignorant thus provided could not have been less13 than that known to have obtained in England before the great re-coinage of 1696. This constant weighing, valuing, and assaying the bullion contents of coins was, however, only one aspect in which the evils of the situation made themselves felt. They also presented another formidable aspect. With the vanishing of the Empire there ceased to be such a thing as an Imperial legal tender current all through India. In its place there grew up local tenders current only within the different principalities into which the Empire was broken up. Under such circumstances exchange was not liquidated by obtaining in return for wares the requisite bullion value from the coins tendered in payment. Traders had to be certain that the coins were also legal tender of their domicile. The Preamble to the Bengal Currency Regulation XXXV, of 1793, is illuminating on this point. It says:—

“The principal districts in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, have each a distinct silver currency … which are the standard measure of value in all transactions in the districts in which they respectively circulate.

――――――――

“In consequence of the Ryots being required to pay their rent in a particular sort of rupee they of course demanded it from manufacturers in payment of their grain, or raw [pg 7] materials, whilst the manufacturers, actuated by similar principles with the Ryots, required the same species of rupee from the traders who came to purchase their cloth or their commodities.

“The various sorts of old rupees, accordingly, soon became the established currency of particular districts, and as a necessary consequence the value of each rupee was enhanced in the district in which it was current, for being in demand for all transactions. As a further consequence, every sort of rupee brought into the district was rejected from being a different measure of value from that by which the inhabitants had become accustomed to estimate their property, or, if it was received, a discount was exacted upon it, equal to what the receiver would have been obliged to pay upon exchanging it at the house of a shroff for the rupee current in the district, or to allow discount upon passing it in payment to any other individual.

――――――――

“From this rejection of the coin current in one district when tendered in payment in another, the merchants and traders, and the proprietors and cultivators of land in different parts of the country, are subjected in their commercial dealings with each other to the same losses by exchange, and all other inconveniences that would necessarily result were the several districts under separate and independent governments, each having a different coin.”

Here was a situation where trade was reduced to barter, whether one looks upon barter as characterised by the absence of a common medium of exchange or by the presence of a plurality of the media of exchange; for in any case, it is obvious that the want of a “double coincidence” must have been felt by people engaged in trade. One is likely to think that such could not have been the case as the medium was composed of metallic counters. But it is to be remembered that the circulating coins on India, by reason of the circumstance attendant upon the diversity in their fineness and legal tender, formed so many different species that an exchange against a particular species did not necessarily close the transaction; the coin must, in certain circumstances, have been only an intermediate to be further bartered against another, and so on till the one of the requisite species was [pg 8] obtained. This is sufficient indication that society had sunk into a state of barter. If this alone was the flaw in the situation, it would have been only as bad as that of international trade under diversity of coinages. But it was further complicated by the fact that although the denomination of the coins was the same, their metallic contents differed considerably. Owing to this, one coin bore a discount or a premium in relation to another of the same name. In the absence of knowledge as to the amount of premium or discount, every one cared to receive a coin of the species known to him and current in his territory. On the whole the obstacles to commerce arising from such a situation could not have been less than those emanating from the mandate of Lycurgus, who compelled the Lacedæmonians to use iron money in order that its weight might prevent them from overmuch trading. The situation, besides being irritating, was aggravated by the presence of an element of gall in it. Capital invested in providing a currency is a tax upon the productive resources of the community. Nevertheless, wrote James Wilson14 no one would question

“that the time and labour which are saved by the interposition of coin, as compared with a system of barter, form an ample remuneration for the portion of capital withdrawn from productive sources, to act as a single circulator of commodities, by rendering the remainder of the capital of the country so much the more productive.”

What is, then, to be said of a monetary system which did not obviate the evil consequences of barter, although enormous capital was withdrawn from productive sources, to act as a single circulator of commodities? Diseased money is worse than want of money. The latter at least saves the cost. But society must have money, and it must be good money, too. The task, therefore, of evolving good money out of bad money fell upon the shoulders of the English East India Company, who had in the meanwhile succeeded to the Empire of the Moghuls in India.

The lines of reform were first laid down by the Directors [pg 9] of the Company in their famous Despatch, dated April 25, 1806,15 to the authorities administering their territories in India. In this historic document they observed:—

“17. It is an opinion supported by the best authorities, and proved by experience, that coins of gold and silver cannot circulate as legal tenders of payment at fixed relative values … without loss; this loss is occasioned by the fluctuating value of the metals of which the coins are formed. A proportion between the gold and silver coin is fixed by law, according to the value of the metals, and it may be on the justest principles, but owing to the change of circumstances gold may become of greater value in relation to silver than at the time the proportion was fixed, it therefore becomes profitable to exchange silver or gold, so the coin of that metal is withdrawn from circulation; and if silver should increase in its value in relation to gold, the same circumstances would tend to reduce the quantity of silver coin in circulation. As it is impossible to prevent the fluctuation in the value of the metals, so it is also equally impracticable to prevent the consequences thereof on the coins made from these metals … To adjust the relative values of gold and silver coin according to the fluctuations in the values of the metals would create continual difficulties, and the establishment of such a principle would of itself tend to perpetuate inconvenience and loss.”

They therefore declared themselves in favour of monometallism as the ideal for the Indian currency of the future, and prescribed:—

“21. … that silver should be the universal money of account [in India], and that all … accounts should be kept in the same denominations of rupees, annas and pice …”

The rupee was not, however, to be the same as that of the Moghul Emperors in weight and fineness. They proposed that

“9. … the new rupee … be of the gross weight of—

Troy grains

180

Deduct one-twelfth alloy

15

――

An contain of fine silver troy grs.

165

[pg 10] Such were the proposals put forth by the Court of Directors for the reform of Indian currency.

The choice of a rupee weighing 180 grs. troy and containing 165 grs. pure silver as the unit for the future currency system of India was a well-reasoned choice.

The primary reason for selecting this particular weight for the rupee seems to have been the desire to make it as little of a departure as possible from the existing practice. In their attempts to reduce to some kind of order the disorderly currencies bequeathed to them by the Moghuls by placing them on a bimetallic basis, the Governments of the three Presidencies had already made a great advance by selecting out of the innumerable coins then circulating in the country a species of gold and silver coin as the exclusive media of exchange for their respective territories. The weights and fineness of the coins selected as the principal units of currency, with other particulars, may be noted from the summary table opposite.

To reduce these principal units of the different Presidencies to a single principal unit, the nearest and the least inconvenient magnitude of weight which would at the same time be an integral number was obviously 180 grs., for in no case did it differ from the weights of any of the prevailing units in any marked degree. Besides, it was believed that 180, or rather 179·5511, grs. was the standard weight of the rupee coin originally issued from the Moghul Mints, so that the adoption of it was really a restoration of the old unit and not the introduction of a new one.16 Another advantage claimed in favour of a unit of 180 grs. was that such a unit of currency would again become what it had ceased to be, the unit of weight also. It was agreed17 that the unit of weight in India had at all times previously been linked up with that of the principal coin, so that the seer and the manual weights were simply multiples of the rupee, which originally weighed 179·6 grs. troy. Now, if the weight of the [pg 11]

TABLE I

Issued by the Government of |

Territory in which it circulated |

Date and Authority of Issue. |

Silver Coins |

Gold Coins |

||||

Name |

Gross Weight Troy Grs. |

Pure Contents Troy Grs. |

Name |

Gross Weight Troy Grs. |

Pure Contents Troy Grs. |

|||

Bombay |

Presidency |

Surat Rupee |

179·0 |

164·740 |

Mohur |

179 |

164·740 |

|

Madras |

Presidency |

Arcot Rupee |

176·4 |

166·477 |

Star Pagoda |

52·40 |

42·55 |

|

Bengal |

Bengal, Bihar and Orissa |

Regulations XXXV of 1793 |

Sicca Rupee (19th Sun) |

179·66 |

175·927 |

Mohur |

190·804 |

189·40 |

Cuttock |

XII of 1805 |

|||||||

Ceded Provinces |

XLV of 1803 |

Furrakabad Rupee (Lucknow Sicca of the 45th Sun) |

173 |

166·135 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Conquered Provinces |

||||||||

Benares Provinces |

III of 1806 |

Benares Rupee (Muchleedar) |

175 |

168·875 |

— |

— |

— |

|

[pg 12] principal coin to be established was to be different from 180 grs. troy, it was believed there would be an unhappy deviation from the ancient practice which made the weight of the coin the basis of other weights and measures. Besides, a unit of 180 grs. weight was not only suitable from this point of view, but had also in its favour the added convenience of assimilating the Indian with the English units of weight.18

While these were the reasons in favour19 of fixing the weight of the principal unit of currency at 180 grs. troy, the project of making it 165 grs. fine was not without its justification. The ruling consideration in selecting 165 grs. as the standard of fineness was, as in the matter of selecting the standard weight, to cause the least possible disturbance in existing arrangements. That this standard of fineness was not very different from those of the silver coins recognised by the different Governments in India as the principal units of their currency, may be seen from the following comparative statement on p. 13.

It will thus be seen that, with the exception of the Sicca and the Benares rupees, the proposed standard of fineness agreed so closely with those of the other rupees that the interest of obtaining a complete uniformity without considerable dislocation overruled all possible objections to its adoption. Another consideration that seemed to have prevailed upon the Court of Directors in selecting 165 grs. [pg 13] as the standard of fineness was that, in conjunction with 180 grs. as the standard weight, the arrangement was calculated to make the rupee eleven-twelfths fine. To determine upon a particular fineness was too technical a matter for the Court of Directors. It was, however, the opinion of the British Committee on Mint and Coinage, appointed in 1803, that20 “one–twelfth alloy and eleven–twelfths fine is by a variety of extensive experiments proved to be the best proportion, or at least as good as any which could have been chosen.” This standard, so authoritatively upheld, the Court desired to incorporate in their new scheme of Indian currency. They therefore desired to make the rupee eleven–twelfths fine. But to do so was also to make the rupee 165 grs. pure—a content which they desired, from the point of view stated above, the rupee to possess.

TABLE II

Silver Coins recognized as Principal Units and their Fineness. |

Standard Fineness of the Proposed Rupee. |

More valuable than the Proposed Rupee. |

Less valuable than the proposed Rupee. |

|||

Name of the Coin. |

Its Pure Contents. Troy Grs. |

In Grs. |

By p.c. |

In Grs. |

By p.c. |

|

Surat Rupee |

164·74 |

165 |

— |

— |

·26 |

·157 |

Arcot Rupee |

166·477 |

165 |

1·477 |

·887 |

— |

— |

Sicca Rupee |

175·927 |

165 |

10·927 |

6·211 |

— |

— |

Furrukabad R. |

166·135 |

165 |

1·135 |

·683 |

— |

— |

Benares Rupee |

169·251 |

165 |

4·251 |

2·511 |

— |

— |

Reviewing the preference of the Court of Directors for monometallism from the vantage-ground of latter-day events, one might be inclined to look upon it as a little too short-sighted. At the time, however, the preference was well founded. One of the first measures the three Presidencies, into which the country was divided for [pg 14] purposes of administration, had adopted on their assuming the government of the country, was to change the parallel standard of the Moghuls into a double standard by establishing a legal ratio of exchange between the mohur, the pagoda, and the rupee. But in none of the Presidencies was the experiment a complete success.

In Bengal21 the Government, on June 2, 1766, determined upon the issue of a gold mohur weighing 179·66 grs. troy, and containing 149·92 grs. troy of pure metal, as legal tender at 14 Sicca rupees, to relieve the currency stringency caused largely by its own act of locking up the revenue collections in its treasuries, to the disadvantage of commerce. This was a legal ratio of 16·45 to 1, and as it widely deviated from the market ratio of 14·81 to 1, this attempt to secure a concurrent circulation of the two coins was foredoomed to failure. Owing to the drain of silver on Bengal from China, Madras, and Bombay, the currency stringency grew worse, so much so that another gold mohur was issued by the Government on March 20, 1769, weighing 190·773 grs. troy and containing 190·086 grs. pure gold with a value fixed at 16 Sicca rupees. This was a legal ratio of 14·81 to 1. But, as it was higher than the market ratio of the time both in India (14 to 1) and in Europe (14·61 to 1), this second effort to bring about a concurrent circulation fared no better than the first. So perplexing seemed to be the task of accurate rating that the Government reverted to monometallism by stopping the coinage of gold on December 3, 1788, and when the monetary stringency again compelled it to resume in 1790 the coinage of gold, it preferred to let the mohur and the rupee circulate at their market value without making any attempt to link them by a fixed ratio. It was not until 1793 that a third attempt was made to forge a double standard in Bengal. A new mohur was issued in that year, weighing 190·895 grs. troy and containing 189·4037 grs. of pure gold, and made legal tender at 16 Sicca rupees. This [pg 15] was a ratio of 14·86 to 1, but, as it did not conform to the ratio then prevalent in the market, this third attempt to establish bimetallism in Bengal failed as did those made in 1766 and 1769.

The like endeavours of the Government of Madras22 proved more futile than those of Bengal. The first attempt at bimetallism under the British in that Presidency was made in the year 1749, when 350 Arcot rupees were legally rated at 100 Star pagodas. As compared with the then market ratio this rating involved an under-valuation of the pagoda, the gold coin of the Presidency. The disappearance of the pagoda caused a monetary stringency, and the Government in December, 1750, was obliged to restore it to currency. This it did by adopting the twofold plan of causing an import of gold on Government account, so as to equalise the mint ratio to the market ratio, and of compelling the receipts and payments of Government treasuries to be exclusively in pagodas. The latter device proved of small value; but the former by its magnitude was efficacious enough to ease the situation. Unluckily the ease was only temporary. Between 1756 and 1771 the market ratio of the rupee and the pagoda again underwent a considerable change. In 1756 it was 364 to 100, and in 1768 it was 370 to 100. It was not till after 1768 that the market ratio became equal to the legal ratio fixed in 1749 and remained steady for about twelve years. But the increased imports of silver rendered necessary for the prosecution of the second Mysore war once more disturbed the ratio, which at the close of the war stood at 400 Arcot rupees to 100 Star pagodas. After the end of the war the Government of Madras made another attempt to bring about a concurrent circulation between the rupee and the pagoda. But instead of making the market ratio of 400 to 100 the legal ratio it was led by the then increasing imports of gold into the Presidency to hope that the market ratio would in time rise to that legally established in 1749. In an expectant mood so induced it decided, in 1790, to anticipate the event by fixing the ratio first at 365 to 100. [pg 16] The result was bound to be different from that desired, for it was an under-valuation of the pagoda. But instead of rectifying the error, the Government proceeded to aggravate it by raising the ratio still further to 350 to 100 in 1797, with the effect that the pagoda entirely went out of circulation, and the final attempt at bimetallism thus ended in a miserable failure.

The Government of Bombay seemed better instructed in the mechanics of bimetallism, although that did not help it to overcome the practical difficulties of the system. On the first occasion when bimetallism was introduced in the Presidency23 the mohur and the rupee were rated at the ratio of 15·70 to 1. But at this ratio the mohur was found to be over-rated, and accordingly, in August, 1774, the Mint Master was directed to coin gold mohur of the fineness of a Venetian and of the weight of the silver rupee. This change brought down the legal ratio to 14·83 to 1, very nearly, though not exactly, to the then prevailing market ratio of 15 to 1, and had nothing untoward happened, bimetallism would have had a greater success in Bombay than it actually had in the other two Presidencies. But this was not to be, for the situation was completely altered by the dishonesty of the Nawab of Surat, who allowed his rupees, which were of the same weight and fineness as the Bombay rupees, to be debased to the extent of 10, 12, and even 15 per cent. This act of debasement could not have had any disturbing effect on the bimetallic system prevalent in the Bombay Presidency had it not been for the fact that the Nawab's (or Surat) rupees were by agreement admitted to circulation in the Company's territories at par with the Bombay rupees. As a result of their being legal tender the Surat rupees, once they were debased, not only drove out the Bombay rupees from circulation, but also the mohur, for as rated to the debased Surat rupees the ratio became unfavourable to gold, and the one chance for a successful bimetallic system vanished away. The question of fixing up a bimetallic [pg 17] ratio between the mohur and the rupee again cropped up when the Government of Bombay permitted the coinage of Surat rupees at its Mint. To have continued the coinage of the gold mohur according to the Regulation of 1774 was out of the question. One Bombay mohur contained 177·38 grs. of pure gold, and 15 Surat rupees of the standard of 1800 contained 247,110 grs. of silver. By this Regulation the proportion of silver to gold would have been (247, 110)/(177·38) i.e. 13·9 to 1. Here the mohur would have under-valued. It was therefore resolved to alter the standard of the mohur to that of the Surat rupee, so as to give a ratio of 14·9 to 1. But as the market ratio was inclined towards 15·5 to 1, the experiment was not altogether a success.

In the light of this experience before them the Court of Directors of the East India Company did well in fixing upon a monometallic standard as the basis of the future currency system of India. The principal object of all currency regulations is that the different units of money should bear a fixed relation of value to one another. Without this fixity of value the currency would be in a state of confusion, and no precaution would be too great against even a temporary disturbance of that fixity. Fixity of value between the various components of the currency is so essential a requisite in a well-regulated monetary system that we need hardly be surprised if the Court of Directors attached special importance to it, as they may well have done, particularly when they were engaged in the task of placing the currency on a sound and permanent footing. Nor can it be said that their choice of monometallism was ill-advised, for it must be admitted that a single standard better guarantees this fixity than does the double standard. Under the former it is spontaneous; under the latter it is forced.

These recommendations of the Court of Directors were left to the different Governments in India to be carried into effect at their discretion as to the time and manner of doing it. But it was some time before steps were taken in consonance with these orders, and even then it was on the realisation of those parts of the program of the Court which pertained [pg 18] to the establishment of a uniform currency that the efforts of the different Governments were first concentrated.

The task of reducing the existing units of currency to that proposed by the Court was first accomplished in Madras. On January 7, 1818, the Government issued a Proclamation24 by which its old units of currency—the Arcot rupee and the Star pagoda—were superseded by new units, a gold rupee and a silver rupee, each weighing 180 grs. troy and containing 165 grs. of fine metal. Madras was followed by Bombay six years later by a Proclamation25 of October 6, 1824, which declared a gold rupee and a silver rupee of the new Madras standard to be the only units of currency in that Presidency. The Government of Bengal had a much bigger problem to handle. It had three different principal units of silver currency to be reduced to the standard proposed by the Court. It commenced its work of reorganisation by a system of elimination and alteration. In 1819, it discontinued26 the coinage of the Benares rupee and substituted in its place the Furrukabad rupee, the weight and fineness of which were altered to 180·234 and 135·215 grs. troy respectively. Apparently this was a step away from the right direction. But even here the purpose of uniformity, so far as fineness was concerned, was discernible, for it made the Furrukabad rupee like the new Madras and Bombay rupees, eleven-twelfths fine. Having got rid of the Benares rupee, the next step was to assimilate the standard of the Furrukabad rupee to that of Madras and Bombay, and this was done in 1833.27

Thus, without abrogating the bimetallic system, substantial steps were taken in realising the ideal unit proposed by the Court, as may be seen from the table on opposite page.

Taking stock of the position as it was at the end of 1833, we find that with the exception of the Sicca rupee and the gold mohur of Bengal, that part of the scheme of the Directors which pertained to the uniformity of coinage was an accomplished fact. Nothing more remained to carry it [pg 19]

TABLE III

Issued by the Government of |

Silver Coins. |

Gold Coins. |

Legal Ratio |

||||

Denomination. |

Weight. |

Fineness. |

Denomination. |

Weight. |

Fineness. |

||

Bengal |

Sicca Rupee |

192 |

176 or 11⁄12 |

Mohur |

204·710 |

187·651 |

1 to 15 |

Furrukabad Rupee |

180 |

165 or 11⁄12 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Bombay |

Silver Rupee |

180 |

165 or 11⁄12 |

Gold Rupee |

180 |

165 or 11⁄12 |

1 to 15 |

Madras |

Silver Rupee |

180 |

165 or 11⁄12 |

Gold Rupee |

180 |

165 or 11⁄12 |

1 to 15 |

to completion than to discontinue the Sicca rupee and to demonetise gold. At this point, however, arose a conflict between the Court of Directors and the three Governments in India. Considerable reluctance was shown to the demonetisation of gold. The Government of Madras, which was the first to undertake the reform of its currency according to the plan of the Court, not only insisted upon continuing the coinage of gold along with that of the rupee,28 but stoutly refused to deviate from the system of double legal tender at a fixed ratio prevalent in its territories,29 notwithstanding the repeated remonstrance's addressed by the Court.30 The Government of Bengal clung to the bimetallic standard with equal tenacity. Rather than demonetise the gold mohur it took steps to alter its standard31 by reducing its pure contents32 from 189·4037 to 187·651 troy [pg 20] grs., so as to re-establish a bimetallic system on the basis of the ratio adopted by Madras in 1818. So great was its adherence to the bimetallic standard that in 1833 it undertook to alter33 the weight and fineness of the Sicca rupee to 196 grs. troy and 176 grs. fine, probably to rectify a likely divergence between the legal and the market ratios of the mohur to the rupee34.

But in another direction the Government in India wanted to go further than the Court desired. The Court thought a uniform currency (i.e. a currency composed of like but independent units) was all that India needed. Indeed, they had given the Governments to understand that they did not wish for more in the matter of simplification of currency and were perfectly willing to allow the Sicca and the mohur to remain as they were, unassimilated.35 A uniform currency was no doubt a great advance on the order of things such as was left by the successors of the Moghuls. But that was not enough, and the needs of the situation demanded a common currency based on a single unit in place of a uniform currency. Under the system of uniform currency each Presidency coined its own money, and the money coined at the Mints of the other Presidencies was not legal tender in its territories except at the Mint. This monetary independence would not have been very harmful if there had existed also financial independence between the three Presidencies. As a matter of fact, although each Presidency had its own fiscal system, yet they depended upon one another for the finance of their deficits. There was a regular system of “supply” between them, and the surplus in one was being constantly drawn upon to meet the deficits in others. In the absence of a common currency this resource operation was considerably hampered. The difficulties caused by the absence of a common currency in the way of the “supply” operation made themselves felt in two different ways. Not being able to use as legal tender the money of other Presidencies, each was [pg 21] obliged to lock up, to the disadvantage of commerce, large working balances in order to be self-sufficient.36 The very system which imposed the necessity of large balances also rendered relief from other Presidencies less efficacious. For the supply was of necessity in the form of the currency of the Presidency which granted it, and before it could be utilised it had to be re-coined into the currency of the needy Presidency. Besides the loss on re-coinage, such a system obviously involved inconvenience to merchants and embarrassment to the Government.37

At the end of 1833, therefore, the position was that the Court desired to have a uniform currency with a single standard of silver, while the authorities in India wished for a common currency with a bimetallic standard. Notwithstanding these divergent views, the actual state of the currency might have continued as it was without any substantial alteration either way. But the year 1833 saw an important constitutional change in the administrative relations between the three Presidential Governments in India. In that year by an Act of Parliament38 there was set up an Imperial system of administration with a centralisation of all legislative and executive authority over the whole of India. This change in the administrative system, perforce, called forth a change in the prevailing monetary systems. [pg 22] It required local coinages to be replaced by Imperial coinage. In other words, it favoured the cause of a common currency as against that of a mere uniform currency. The authorities in India were not slow to realise the force of events. The Imperial Government set up by Parliament was not content to act the part of the Dewans or agents of the Moghuls, as the British had theretofore done, and did not like that coins should be issued in the name of the defunct Moghul emperors who had ceased to govern. It was anxious to throw off the false garb39 and issue an Imperial coinage in its own name, which being common to the whole of India would convey its common sway. Accordingly, an early opportunity was taken to give effect to this policy. By an Act of the Imperial Government (XVII of 1835) a common currency was introduced for the whole of India, as the sole legal tender. But the Imperial Government went beyond and, as if by way of concession to the Court—for the Court did most vehemently protest against this common currency in so far as it superseded the Sicca rupee40—legislated “that no gold coin shall henceforward be a legal tender of payment in any of the territories of the East India Company.”41

That an Imperial Administration should have been by force of necessity led to the establishment of a common currency for the whole of India is quite conceivable. But it is not clear why it should have abrogated the bimetallic system after having maintained it for so long. Indeed, when it is recalled how the authorities had previously set their faces against the destruction of the bimetallic system, and how careful they were not to allow their coinage reforms to disturb it any more violently than they could help, the provision of the Act demonetising gold was a grim surprise. However, for the sudden volte-face displayed therein, the Currency Act (XVII of 1835) will ever remain memorable in the annals of the Indian history. It marked [pg 23] the culminating-point of a long and arduous process of monetary reform and placed India on a silver monometallic basis with a rupee weighing 180 grs. troy and containing 165 grs. fine as the common currency and sole legal tender throughout the country.

No piece of British India legislation has led to a greater discontent in later years than this Act XVII of 1835. In so far as the Act abrogated the bimetallic system, it has been viewed with a surprising degree of equanimity. Not all its critics, however, are aware42 that what the Act primarily decreed was a substitution of bimetallism by monometallism. The commonly entertained view of the Act seems to be that it replaced a gold standard by a silver standard. But even if the truth were more generally known, it would not justify any hostile attitude towards the measure on that score. For what would have been the consequences to India of the gold discoveries of California and Australia in the middle of the nineteenth century if she had preserved her bimetallic system? It is well known how this increase in the production of gold relatively to that of silver led to a divergence in the mint and the market ratios of the two metals after the year 1850. The under-valuation of silver, though not very great, was great enough to confront the bimetallic countries with a serious situation in which the silver currency, including the small change, was rapidly passing out of circulation. The United States43 was obliged by the law of 1853 to reduce the standard of its small silver coins sufficiently to keep them dollar for dollar below their gold value in order to keep them in circulation. France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy, which had a uniform currency based on the bimetallic model of the French with reciprocal legal tender44 were faced with [pg 24] similar difficulties. Lest a separatist policy on the part of each nation,45 to protect their silver currency and particularly the small change, should disrupt the monetary harmony prevailing among them all, they were compelled to meet in a convention, dated November 20, 1865, which required the parties, since collectively called the Latin Union, to lower, in the order to maintain them in circulation, the silver pieces of 2 francs, 1 franc, 50 centimes and 20 centimes from a standard of 900 ⁄ 1000 fine to 835 ⁄ 1000 and to make them subsidiary coins.46 It is true that the Government of India also came in for trouble as a result of this disturbance in the relative [pg 25] value of gold and silver, but that trouble was due to its own silly act.47 The currency law of 1835 had not closed the Mints to the free coinage of gold, probably because the seignorage on the coinage of gold was a source of revenue which the Government did not like to forego. But as gold was not legal tender, no gold was brought to the Mint for coinage, and the Government revenue from seignorage fell off. To avoid this loss of revenue the Government began to take steps to encourage the coinage of gold. In the first place, it reduced the seignorage48 in 1837 from 2 per cent. to 1 per cent. But even this measure was not sufficient to induce people to bring gold to the Mint, and consequently the revenue from seignorage failed to increase. As a further step in the same direction the Government issued a Proclamation on January 13, 1841, authorising the officers in charge of public treasuries to receive the gold coins at the rate of 1 gold mohur equal to 15 silver rupees. For some time no gold was received, as at the rate prescribed by the Proclamation gold was undervalued.49 But the Australian and Californian gold discoveries altered the situation entirely. The gold mohur, which was undervalued at Rs. 15, became overvalued, and the Government, which was at one time eager to receive gold, was alarmed at its influx. By adopting the course it did of declaring gold no longer legal tender, and yet undertaking to receive it in liquidation of Government demands, it laid itself under the disadvantage of being open to be embarrassed with a coin which was of no use and must ordinarily have been paid for above its value. Realising its position, it left aside all considerations of augmenting revenue by increased coinage, and promptly issued on December 25, 1852, another Proclamation withdrawing that of 1841. Whether it would not have been better to have escaped the embarrassment by making gold general legal tender than depriving it of its partial legal-tender power is another matter. But, in so far as India was saved the trials and tribulations undergone by the bimetallic countries to preserve the silver part of their [pg 26] currency, the abrogation of bimetallism was by no means a small advantage. For the measure had the virtue of forearming the country against changes which, though not seen at the time, soon made themselves felt.

The abrogation of bimetallism in India accomplished by the Act of 1835, cannot therefore be made a ground for censure. But it is open to argument that a condemnation of bimetallism is not per se a justification of silver monometallism. If it was to be monometallism it might well have been gold monometallism. In fact, the preference for silver monometallism is not a little odd when it is recalled that Lord Liverpool, the advocate of monometallism,50 whose doctrines the Court had sought to apply to India, had prescribed gold monometallism for similar currency evils then prevalent in England. That the Court should have deviated from their guide in this particular has naturally excited a great deal of hostile comment as to the propriety of this grave departure.51 At the outset any appeal to ulterior motives must be baseless, for Lord Liverpool was not a “gold bug,” nor was the Court composed of “silver men.” As a matter of fact, neither of them at all considered the question from the standpoint as to which was a better standard of value, gold or silver. Indeed, in so far as that was at all a consideration worth attending to, the choice of the Court, according to the opinion of the time, was undoubtedly a better one than that of Lord Liverpool. Not only were all the theorists, such as Locke, Harris, and Petty, in favour of silver as the standard of value, but the practice of the whole world was also in favour of silver. No doubt England had placed herself on a gold basis in 1816. But that Act, far from closing the English Mint to the free coinage of silver, left it to be opened by a Royal Proclamation.52 The Proclamation, it is true, was never issued, but it is not to be supposed that therefore Englishmen [pg 27] of the time had regarded the question of the standard as a settled issue. The crisis of 1825 showed that the gold standard furnished too narrow a basis for the English currency system to work smoothly, and, in the expert opinion of the time,53 the gold standard, far from being the cause of England's commercial superiority, was rather a hindrance to her prosperity, as it cut her off from the rest of the world, which was mostly on a silver basis. Even the British statesmen of the time had no decided preference for the gold standard. In 1826 Huskisson actually proposed that Government should issue silver certificates of full legal tender.54 Even as late as 1844 the question of the standard was far from being settled, for we find Peel in his Memorandum55 to the Cabinet discussing the possibility of abandoning the gold standard in favour of the silver or a bimetallic standard without any compunction or predilection one way or the other. The difficulties of fiscal isolation were evidently not so insuperable as to compel a change of the standard, but they were great enough to force Peel to introduce his famous proviso embodying the Huskisson plan in part in the Bank Charter Act of 1844, permitting the issue of notes against silver to the extent of one-fourth of the total issues.56 Indeed, so great was the universal faith in the stability of silver that Holland changed in 1847 from what was practically a gold monometallism57 to silver monometallism because her statesmen believed that

“it had proved disastrous to the commercial and industrial interests of Holland to have a monetary system identical with that of England, whose financial revulsions, after its adoption [pg 28] of the gold standard, had been more frequent and more severe than in any other country, and whose injurious effects were felt in Holland scarcely less than in England. They maintained that the adoption of the silver standard would prevent England from disturbing the internal trade of Holland by draining off its money during such revulsions and would secure immunity from evils which did not originate in and for which Holland was not responsible.”58

But stability was not the ground on which either the Court or Lord Liverpool made their choice of a standard metal to rest. If that had been the case, both probably would have selected silver. As it was, the difference in the choice of the two parties was only superficial. Indeed, the Court differed from Lord Liverpool, not because of any ulterior motives, but because they were both agreed on a fundamental proposition that not stability but popular preference should be the deciding factor in the choice of a standard metal. Their differences proceeded logically from the agreement. For on analysing the composition of the currency it was found that in England it was largely composed of gold and in India it was largely composed of silver. Granting their common premise, it is easy to account why gold was selected for England by Lord Liverpool and silver for India by the Court. Whether the actual composition of the currency is an evidence of popular preference cannot, of course, be so dogmatically asserted as was done by the Court and Lord Liverpool. So far as England is concerned, the interpretation of Lord Liverpool has been questioned by the great economist David Ricardo. In his High Price of Bullion, Ricardo wrote:—

“For many reasons given by Lord Liverpool, it appears proved beyond dispute that gold coin has been for near a century the principal measure of value; but this is, I think, to be attributed to the inaccurate determination of the mint proportions. Gold has been valued too high; no silver can therefore remain in circulation which is of its standard weight. If a new regulation were to take place, and silver be valued too high … gold would then disappear, and silver become the standard money.”59 [pg 29]

And it is possible that mint proportions rather than popular preference60 could have equally well accounted for the preponderance of silver in India.61

Whether any other criterion besides popular preference could have led the Court to adopt gold monometallism is a moot question. Suffice it to say that the adoption of silver monometallism, though well supported at the time when the Act was passed, soon after proved to be a measure quite inadequate to the needs of the country. It is noteworthy that just about this time great changes were taking place in the economy of the Indian people. Such a one was a change from kind economy to cash economy. Among the chief causes contributory to this transformation the first place must be given to the British system of revenue and finance. Its effects in shifting Indian society on to a cash nexus have not been sufficiently realized,62 although they have been very real. Under the native rulers most payments were in kind. The standing military force kept and regularly paid by the Government was small. The bulk of the troops consisted of a kind of militia furnished by Jageerdars and other landlords, and the troops or retainers of these feudatories were in great measure maintained on the grain, forage, and other supplies furnished by the districts in which they were located. The hereditary revenue and police officers were generally paid by grants of land on tenure of service. Wages of farm servants and labourers were in their turn distributed in grain. Most of its officers being paid in kind, the State collected very little [pg 30] of its taxes in cash. The innovations made by the British in this rude revenue and fiscal system were of the most sweeping character. As territory after territory passed under the sway of the British, the first step taken was to substitute in place of the rural militia of the feudatories a regularly constituted and well-disciplined standing army located at different military stations, paid in cash; in civil employ, as in military, the former revenue and police officers with their followers, who paid themselves by perquisites and other indirect gains received in kind, were replaced by a host of revenue collectors and magistrates with their extensive staff, all paid in current coin. The payments to the army, police, and other officials were not the only payments which the British Government had placed on a money basis. Besides these charges, there were others which were quite unknown to native Governments, such as the “Home Charges” and “Interest on Public Debt,” all on a cash basis. The State, having undertaken to pay in cash, was compelled to realize all its taxes in cash, and as each citizen was bound to pay in cash he in his turn stipulated to receive nothing but cash, so that the entire structure of the society underwent a complete transformation.

Another important change that took place in the economy of the Indian people about this time was the enormous increase of trade. For a considerable period the British tariff policy and the navigation laws had put a virtual check on the expansion of Indian trade. England compelled India to receive her cotton and other manufactures at nearly nominal (2½ per cent.) duties, while at the same time she prohibited the entry of such Indian goods as competed with hers within her territories by prohibitory duties ranging from 50 to 500 per cent. Not only was no reciprocity shown by England to India, but she made a discrimination in favour of her colonies in the case of such goods as competed with theirs. A great agitation was carried on against this unfair treatment,63 and finally Sir Robert Peel admitted [pg 31] Indian produce to the low duties levied by the reformed tariff of 1842. The repeal of the navigation laws gave further impetus to the expansion of Indian commerce. Along with this the demand for Indian produce had also been growing. The Crimean War of 1854 cut off the Russian supplies, the place of which was taken by Indian produce, and the failure of the silk crop in 1853 throughout Europe led to the demand for Asiatic, including Indian, silks.

The effect of these two changes on the currency situation is obvious. Both called forth an increased demand for cash. But cash was the one thing most difficult to obtain. India does not produce precious metals in any considerable quantity. She has had to depend upon her trade for obtaining them. Since the advent of the European Powers, however, the country was not able to draw enough of the precious metals. Owing to the prohibitions on the export of precious metals then prevalent in Europe,64 one avenue for obtaining them was closed. But there was little chance of obtaining precious metals from Europe, even in the absence of such prohibition; indeed, precious metals did not flow to India when such prohibitions were withdrawn.65 The reason of the check to the inflow of precious metals was well pointed out by Mr. Petrie in his Minute of November, 1799, to the Madras Committee of Reform:66 until their territorial acquisitions the Europeans

“purchased the manufactures of India with the metals of Europe: but they were henceforward to make these purchases with gold and silver of India, the revenues supplied the place of foreign bullion and paid the native the price of his industry with his own money. At first this revolution in the principles of commerce was but little felt, but when [pg 32] opulent and extensive dominions were acquired by the English, when the success of war and commercial rivalship had given them so decided a superiority over the other European nations as to engross the whole of the commerce of the East, when a revenue amounting to millions per annum was to be remitted to Europe in the manufactures of the East, then were the effects of this revolution severely felt in every part of India. Deprived of so copious a stream, the river rapidly retired from its banks and ceased to fertilise the adjacent fields with overflowing water.”

The only way open when the prohibitions were withdrawn to obtain precious metals was to send more goods than this amount of tribute, so that the balance might bring them in. This became possible when Peel admitted Indian goods to low tariff, and the country was for the first time able to draw in a sufficient quantity of precious metals to sustain her growing needs. But this ease in the supply of precious metals to serve as currency was short-lived. The difficulties after 1850, however, were not due to any hindrance in the way of India's obtaining the precious metals. Far from being hindered, the export and import of precious metals was entirely free, and India's ability to procure them was equally great. Neither were the difficulties due to any want of precious metals, for, as a matter of fact, the increase in the precious metals after 1850 was far from being small. The difficulty was of India's own making, and was due to her not having based her currency on that precious metal, which it was easy to obtain. The Act of 1835 had placed India on an exclusive silver basis. But, unfortunately, it so happened that after 1850, though the total production of the precious metals had increased, that of silver had not kept pace with the needs of the world, a greater part of which was then on a silver basis, so that as a result of her currency law India found herself in an embarrassing position of an expanding trade with a contracting currency, as is shown on the opposite page.

On the face of it, it seems that there need have been no monetary stringency. The import of silver was large, and [pg 33]

TABLE IV

Years |

Merchandise. |

Treasure. Net Imports of |

Total Coinage of |

Excess (+) or Defect (―) of Coinage on Net Imports of |

Annual Production (in £, 00,000 omitted) of |

|||||

Imports. £ |

Exports. £ |

Silver. £ |

Gold. £ |

Silver. £ |

Gold. £ |

Silver. £ |

Gold. £ |

Gold. |

Silver. |

|

1850–51 |

11,558,789 |

18,164,150 |

2,117,225 |

1,153,294 |

3,557,906 |

123,717 |

+1,440,681 |

−1,029,577 |

8,9 |

7,8 |

1851–52 |

12,240,490 |

19,879,406 |

2,865,257 |

1,267,613 |

5,170,014 |

62,553 |

+2,304,657 |

−1,205,060 |

13,5 |

8,0 |

1852–53 |

10,070,863 |

20,464,633 |

3,605,024 |

1,172,301 |

5,902,648 |

Nil |

+2,297,624 |

−1,172,301 |

36,6 |

8,1 |

1853–54 |

11,122,659 |

19,295,139 |

2,305,744 |

1,061,443 |

5,888,217 |

145,679 |

+3,582,473 |

−915,764 |

31,1 |

8,1 |

1854–55 |

12,742,671 |

18,927,222 |

29,600 |

731,490 |

1,890,055 |

2,676 |

+1,860,455 |

−728,814 |

25,5 |

8,1 |

1855–56 |

13,943,494 |

23,038,259 |

8,194,375 |

2,506,245 |

7,322,871 |

167,863 |

+871,504 |

−2,338,382 |

27,0 |

8,1 |

1856–57 |

14,194,587 |

25,338,451 |

11,073,247 |

2,091,214 |

11,220,014 |

128,302 |

+146,767 |

−1,962,912 |

29,5 |

8,2 |

1857–58 |

15,277,629 |

27,456,036 |

12,218,948 |

2,783,073 |

12,655,308 |

43,783 |

+436,360 |

−2,739,290 |

26,7 |

8,1 |

1858–59 |

21,728,579 |

29,862,871 |

7,728,342 |

4,426,453 |

6,641,548 |

132,273 |

−1,086,794 |

−4,294,180 |

24,9 |

8,1 |

1859–60 |

24,265,140 |

27,960,203 |

11,147,563 |

4,284,234 |

10,753,068 |

64,307 |

−394,495 |

−4,219,927 |

25,0 |

8,2 |

[pg 34] so was the coinage of it. Why then should there have been any stringency at all? The answer to this question is not far to seek. If the amount of silver coined had been retained in circulation it is possible that the stringency could not have arisen. India has long been notoriously the sink of the precious metals. But in interpreting this phenomenon, it is necessary to bear in mind the caution given by Mr. Cassels that

“its silver coinage has not only had to satisfy the requirements of commerce as the medium of exchange, but it has to supply a sufficiency of material to the silversmith and the jeweller. The Mint has been pitted against the smelting-pot, and the coin produced by so much patience and skill by the one has been rapidly reduced into bangles by the other.”67

Now it will be seen from the figures given that all the import of silver was coined and used up for currency purposes. Very little or nothing was left over for the industrial and social consumption of the people. That being the case, it is obvious that a large part of the coined silver must have been abstracted from monetary to non-monetary purposes. The hidden source of this monetary stringency thus becomes evident. To men of the time it was as clear as daylight that it was the rate of absorption of currency from monetary to non-monetary purposes that was responsible as to why

“notwithstanding such large importations [to quote from the same authority], the demand for money has so far exceeded … that serious embarrassment has ensued, and business has almost come to a stand from the scarcity of circulating medium. As fast as rupees have been coined they have been taken into the interior and have there disappeared from circulation, either in the Indian substitute for stocking-foot or in the smelting-pot for conversion into bangles.”69

The one way open was to have caused such additional imports of silver as would have sufficed both for the monetary [pg 35] as well as the non-monetary needs of the country. But the imports of silver were probably already at their highest. For, as was argued by Mr. Cassels,