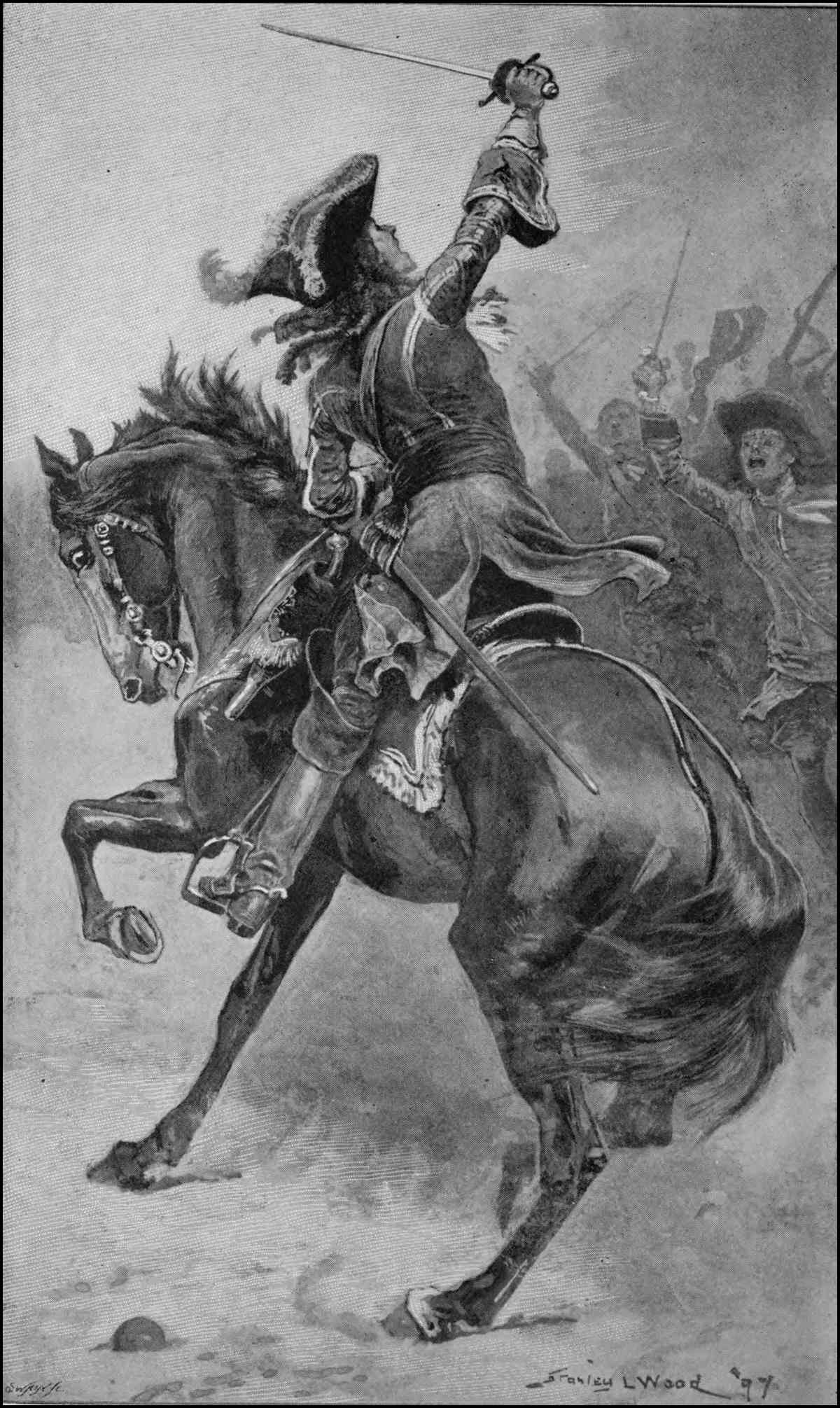

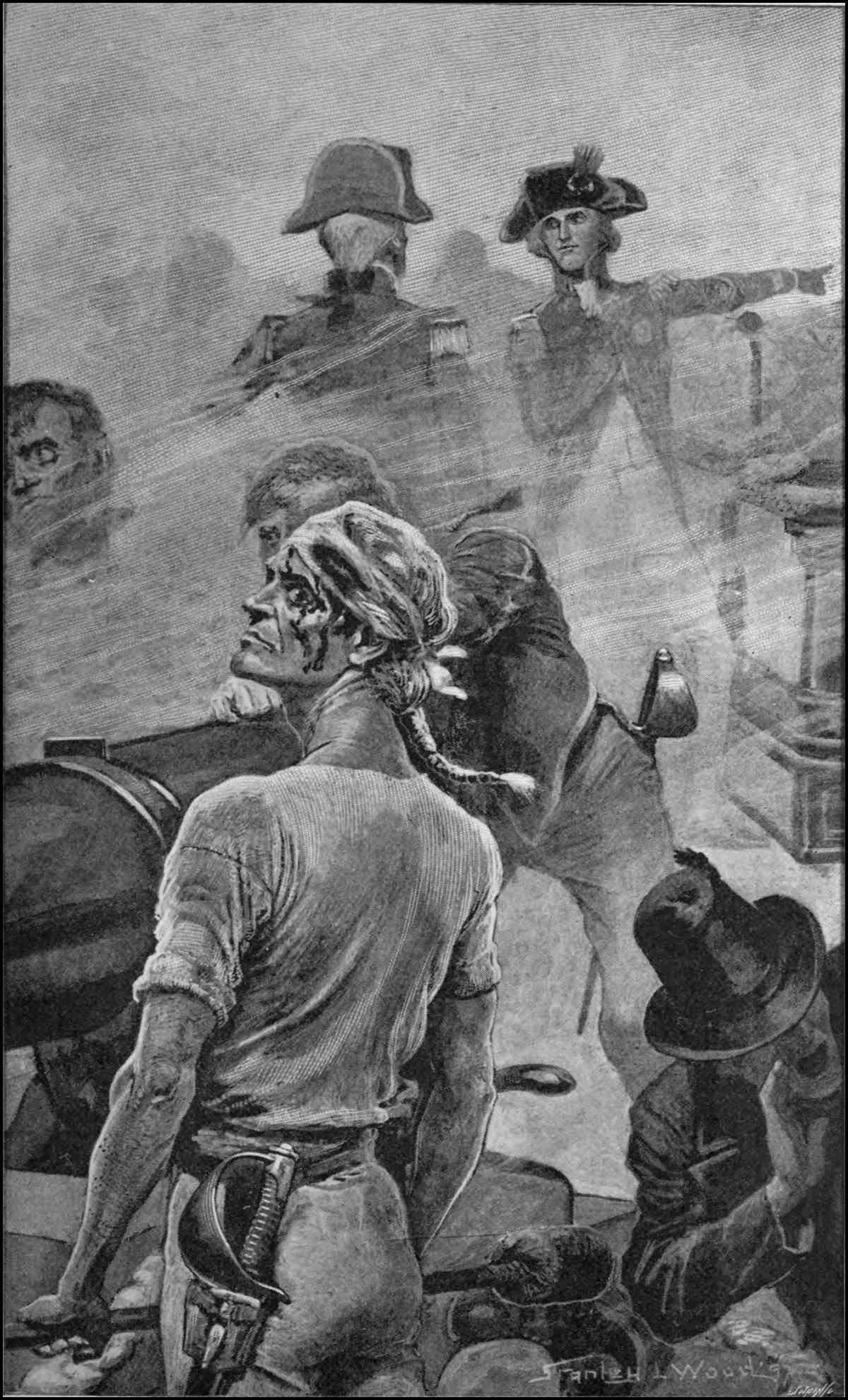

“ALMIGHTY GOD, OF THY GOODNESS, GIVE ME LIFE AND LEAVE ONCE TO SAIL AN ENGLISH SHIP ON YONDER SEA!”

(See page 54.)

Frontispiece.

Title: Men Who Have Made the Empire

Author: George Chetwynd Griffith

Illustrator: Stanley L. Wood

Release date: September 8, 2020 [eBook #63148]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Tim Lindell, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Men Who Have Made the Empire, by George Chetwynd Griffith, Illustrated by Stanley L. Wood

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/menwhohavemadeem00grifiala |

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

VALDAR, THE OFT-BORN. A Saga of Seven Ages. Imp. 16mo, cloth gilt. Illustrated by Harold Piffard. Price 6s.

THE VIRGIN OF THE SUN. A Tale of the Conquest of Peru. Crown 8vo, cloth. With Frontispiece by Stanley L. Wood. Price 6s.

KNAVES OF DIAMONDS. Being Tales of the Diamond Fields. Crown 8vo, cloth. Illustrated by E. F. Sherie. Price 3s. 6d.

London

C. ARTHUR PEARSON LIMITED

“ALMIGHTY GOD, OF THY GOODNESS, GIVE ME LIFE AND LEAVE ONCE TO SAIL AN ENGLISH SHIP ON YONDER SEA!”

(See page 54.)

Frontispiece.

Men who have

Made the Empire

BY

GEORGE GRIFFITH

THIRD EDITION

London

C. ARTHUR PEARSON LIMITED

HENRIETTA STREET, W.C.

1899

To

THE GLORIOUS MEMORY

OF

THE MIGHTY DEAD

AND TO

THE HONOUR OF THE LIVING

WHO ARE

CARRYING ON THEIR NOBLE WORK,

THE FOLLOWING PAGES

ARE INSCRIBED.

ix

| I. | |

| PAGE | |

| WILLIAM THE NORMAN | 1 |

| II. | |

| EDWARD OF THE LONG LEGS | 21 |

| III. | |

| THE QUEEN’S LITTLE PIRATE | 39 |

| IV. | |

| OLIVER CROMWELL | 71 |

| V. | |

| WILLIAM OF ORANGE | 97 |

| VI. | |

| JAMES COOK | 119 |

| VII. | |

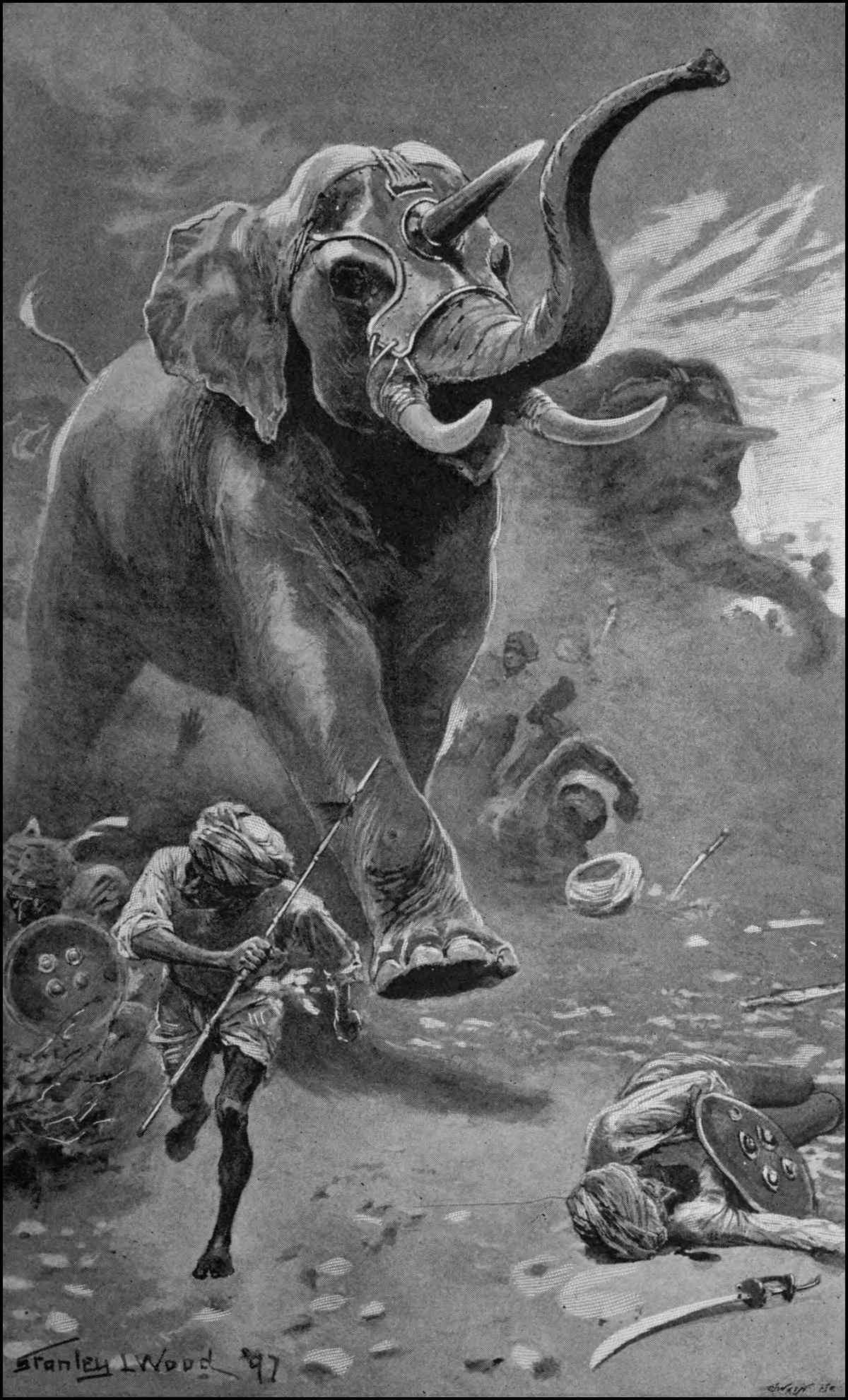

| LORD CLIVE | 143 |

| VIII. | |

| WARREN HASTINGS | 169 |

| IX.x | |

| NELSON | 193 |

| X. | |

| WELLINGTON | 223 |

| XI. | |

| “CHINESE GORDON” | 249 |

| XII. | |

| CECIL RHODES | 279 |

xi

By STANLEY L. WOOD

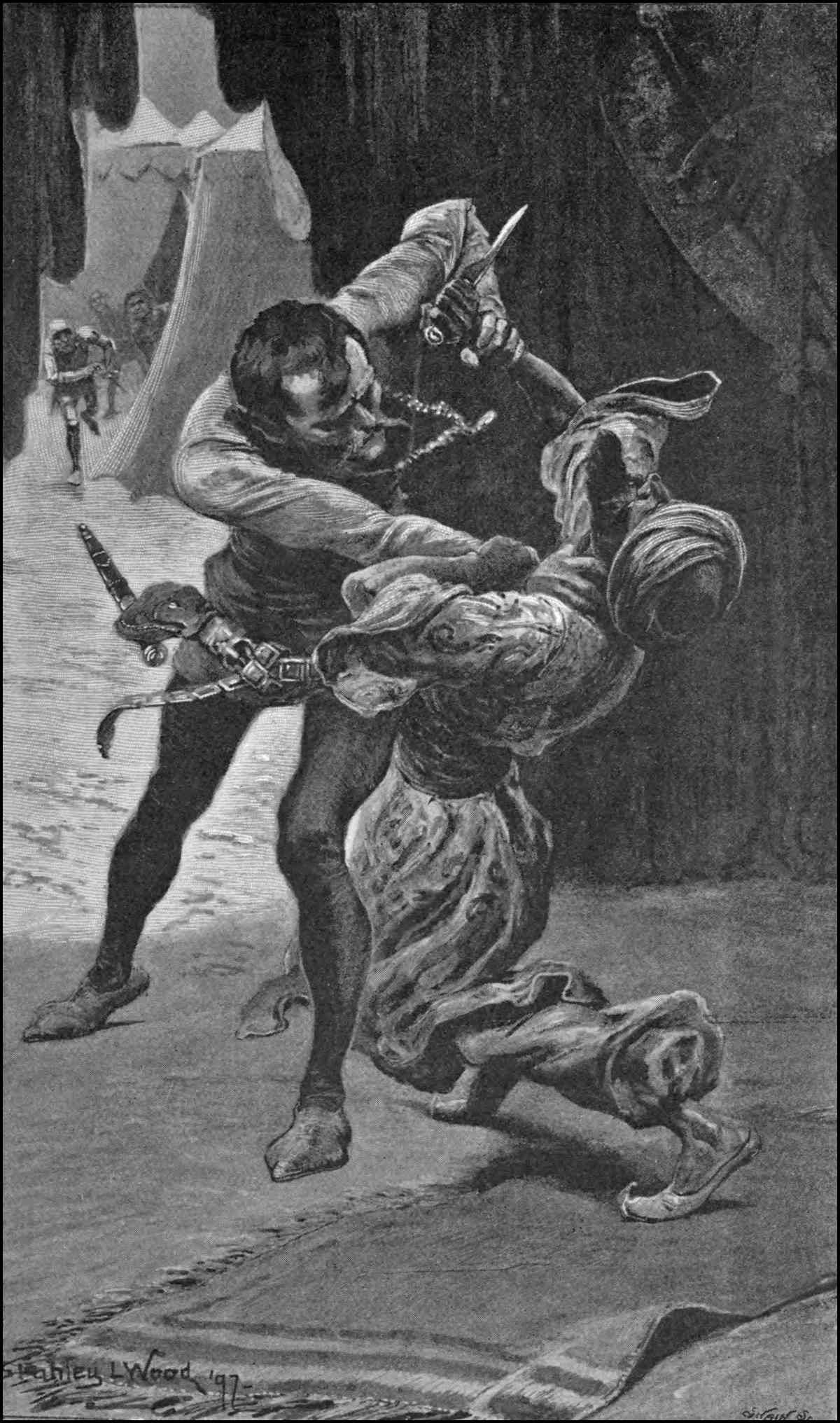

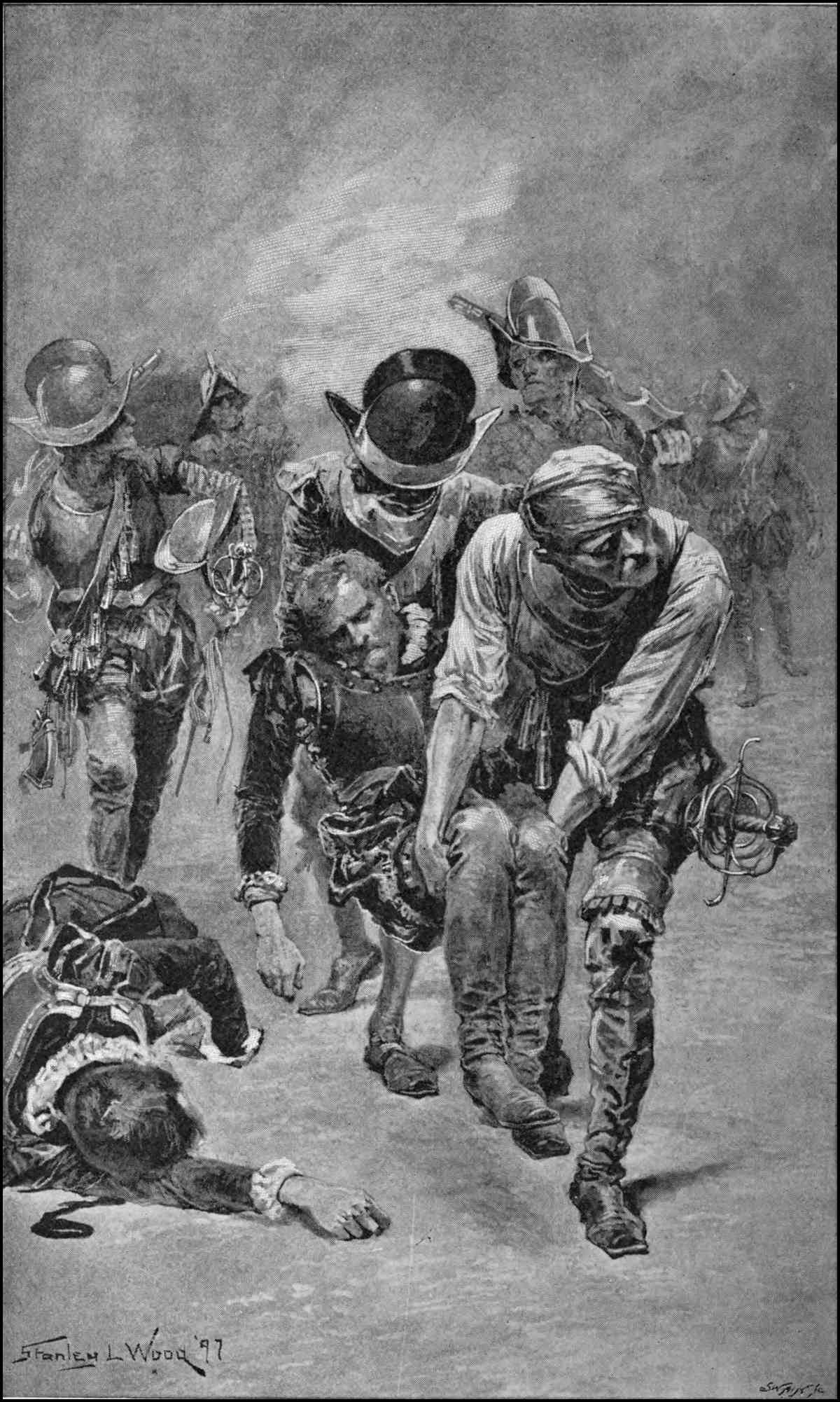

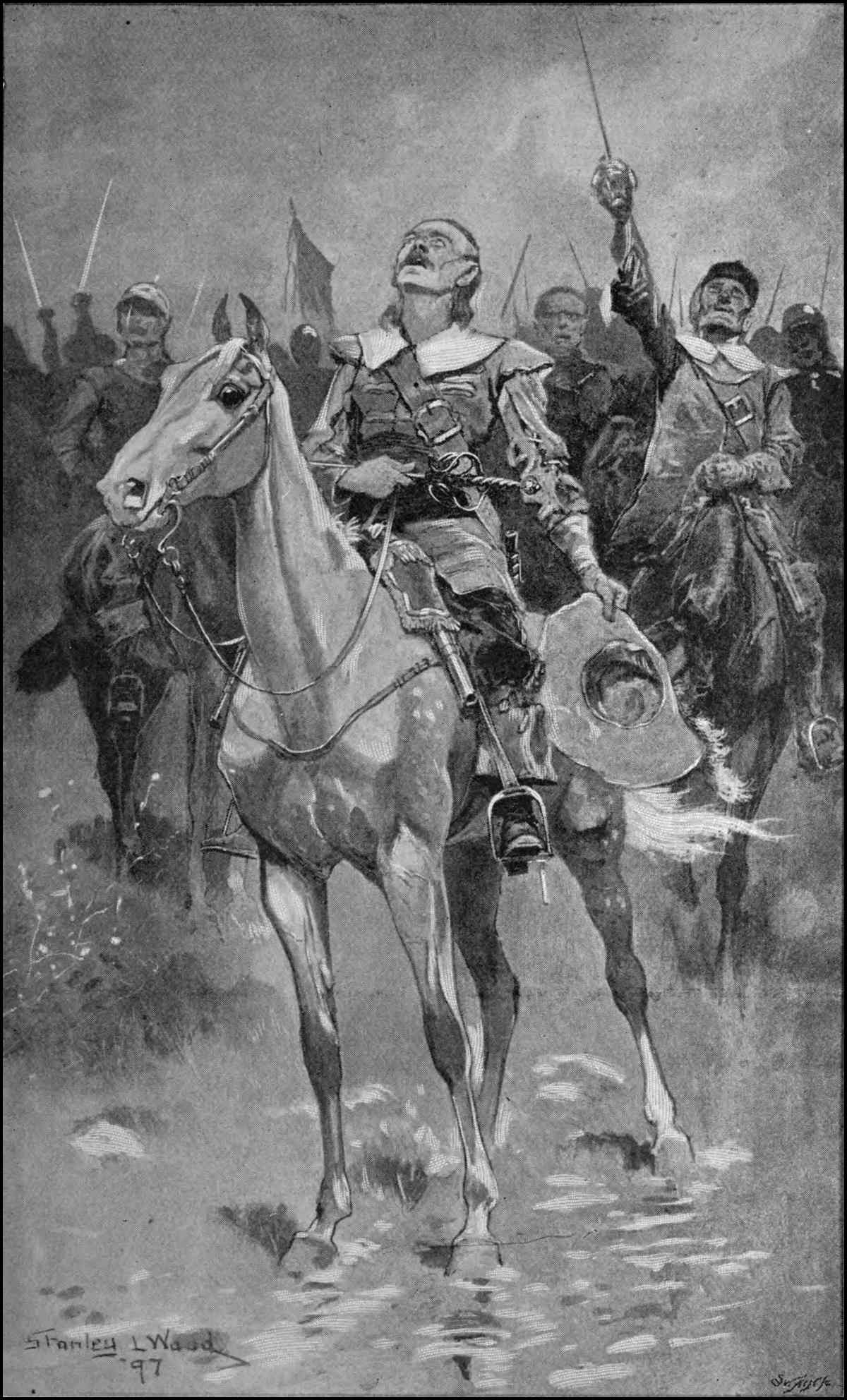

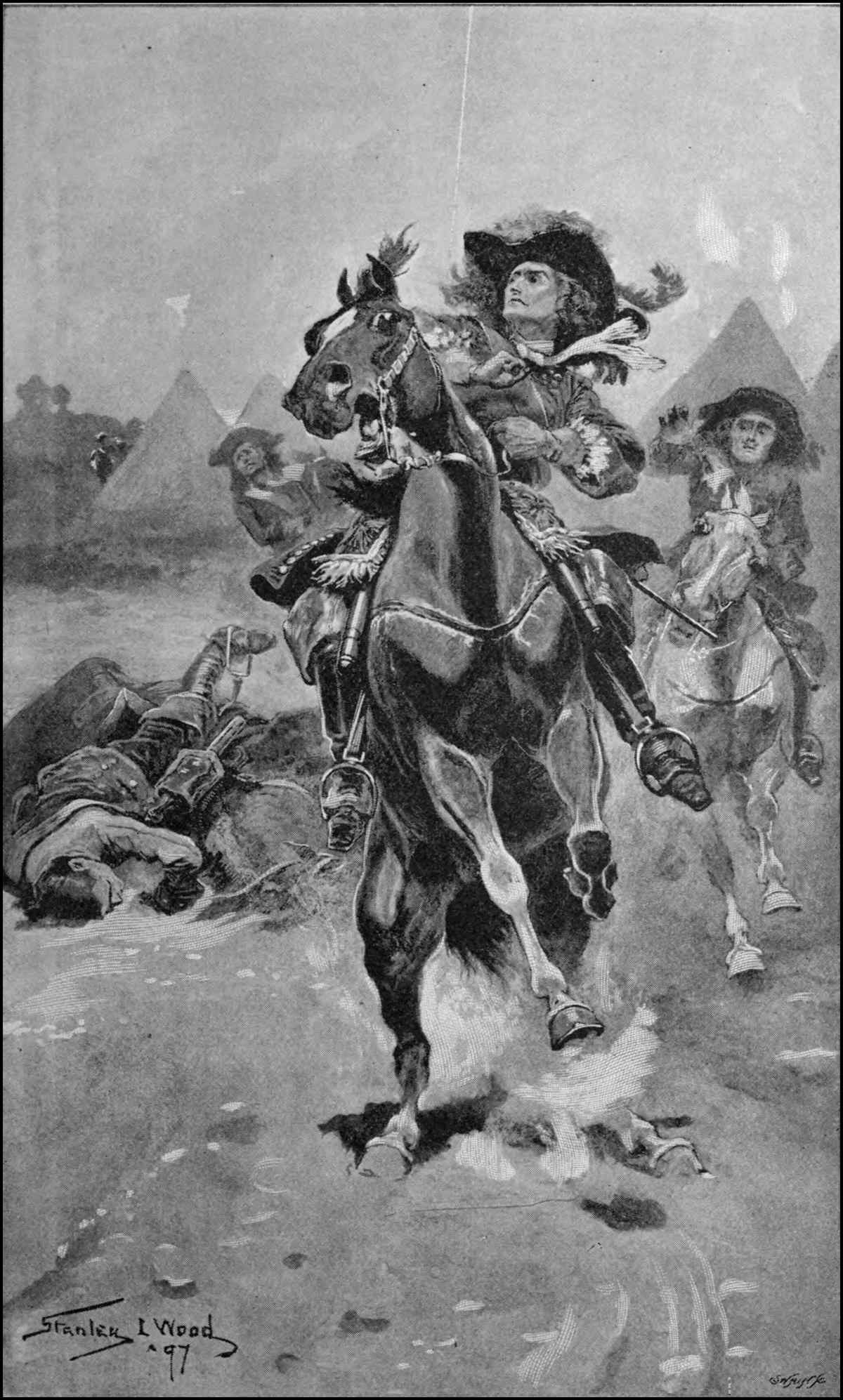

| “ALMIGHTY GOD, OF THY GOODNESS, GIVE ME LIFE AND LEAVE ONCE TO SAIL AN ENGLISH SHIP ON YONDER SEA!” | Frontispiece |

| Facing p. | |

| HE DROVE THE GOOD STEEL THROUGH MAIL AND FLESH AND BONE | 10 |

| DUKE WILLIAM ROARED OUT THAT HE WAS ALIVE | 17 |

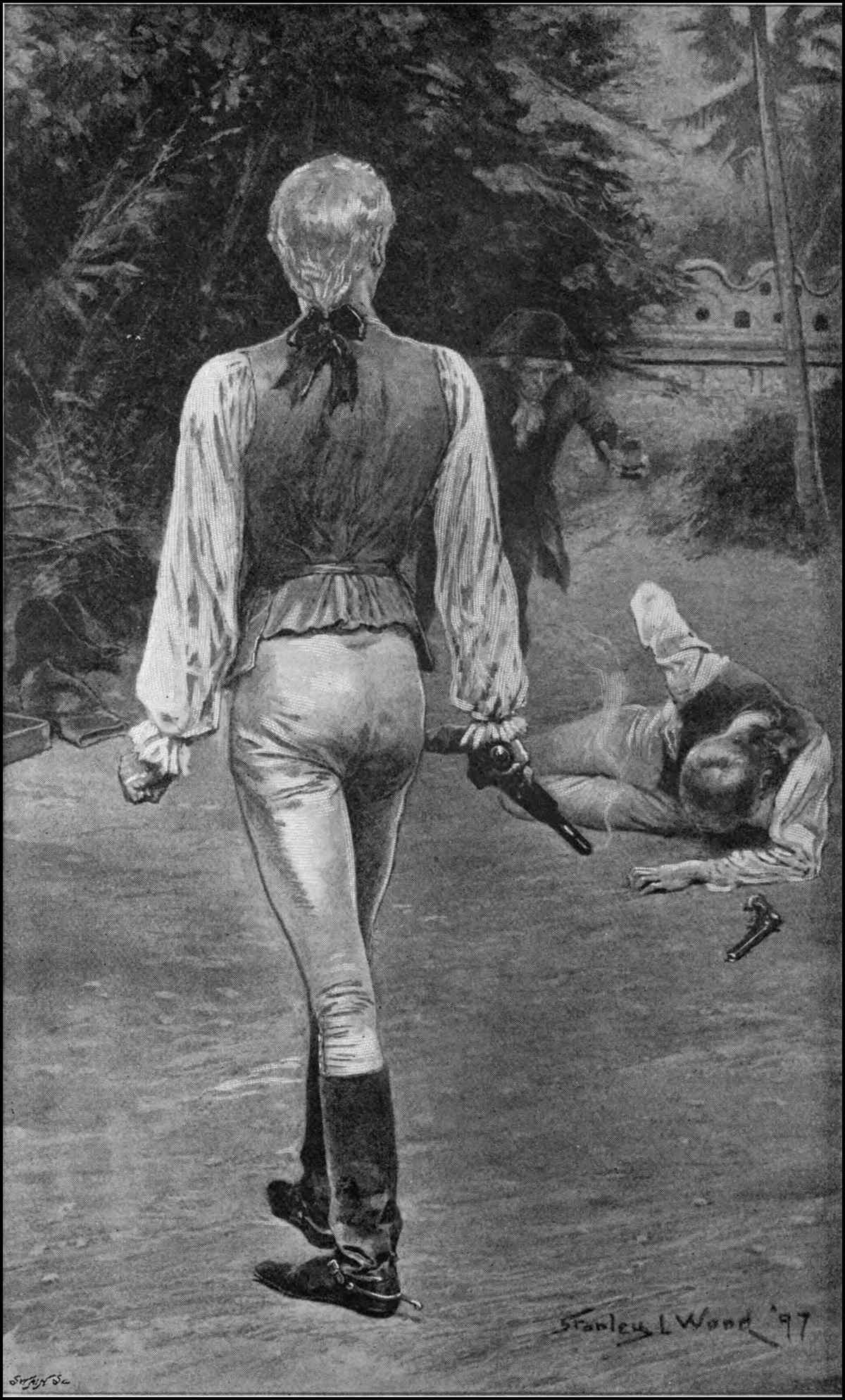

| EDWARD GRIPPED THE WOULD-BE MURDERER | 30 |

| THEY CARRIED HIM DOWN TO THE BOATS | 53 |

| HE SWOOPED WITH HIS CAVALRY ROUND THE REAR OF THE KING’S ARMY | 83 |

| HE HALTED HIS ARMY ... AND SANG THE HUNDRED AND SEVENTEENTH PSALM | 94 |

| MADE HIM REEL IN HIS SADDLE | 112 |

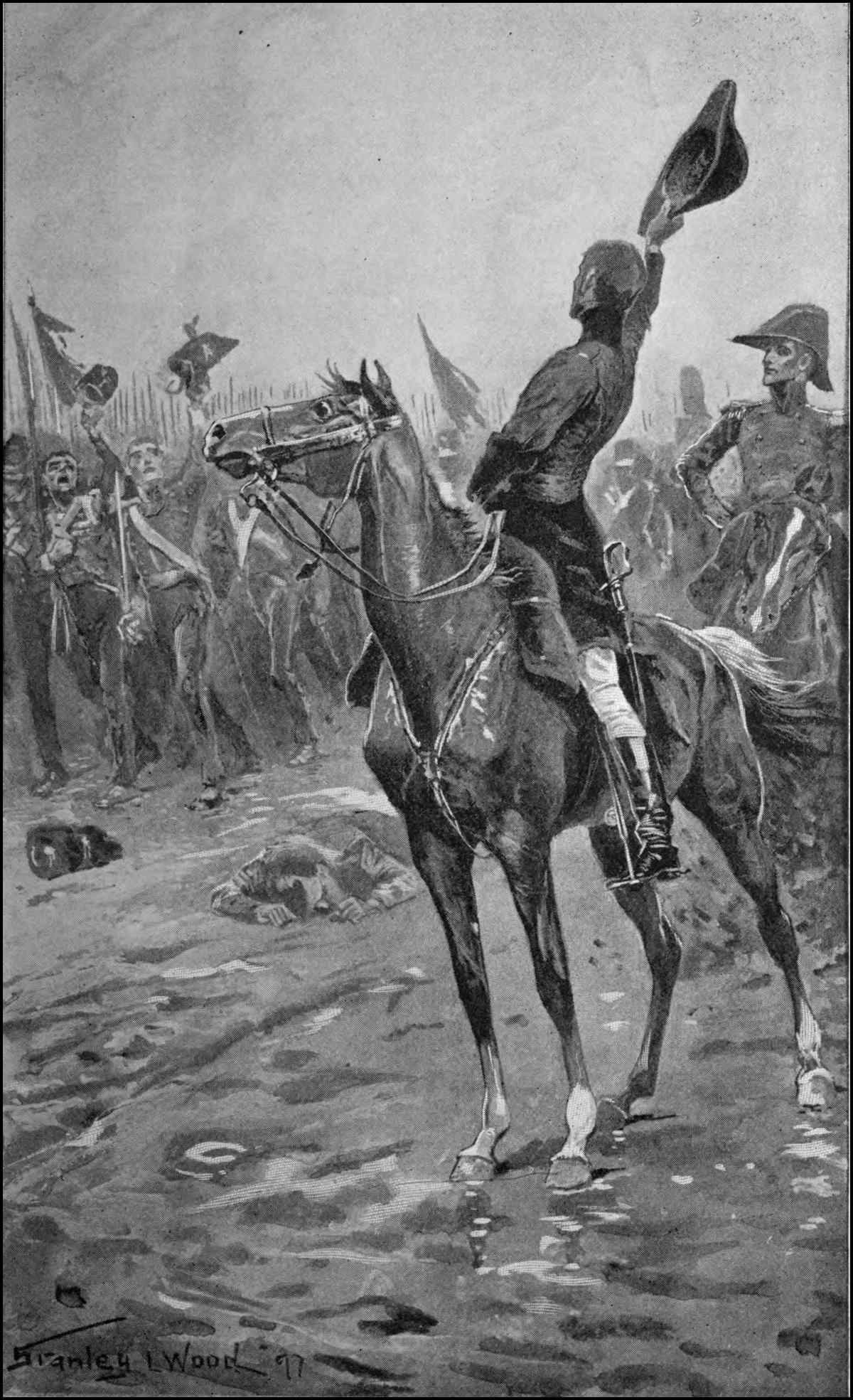

| “MEN OF ENNISKILLEN, WHAT WILL YOU DO FOR ME?”xii HE CRIED | 113 |

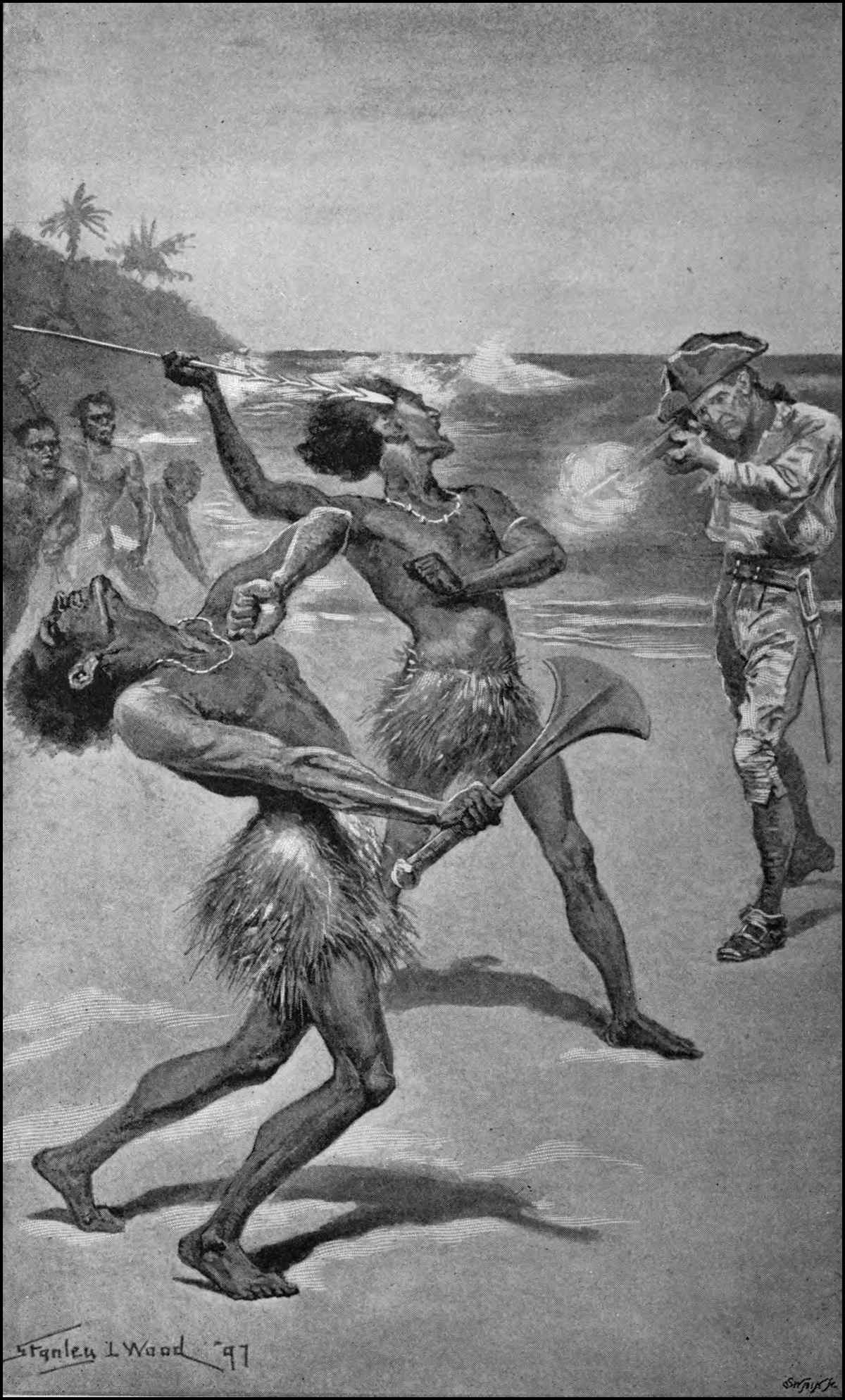

| MISSED HIM AND KILLED ANOTHER MAN BEHIND HIM | 141 |

| INSTEAD OF CHARGING THEY TURNED ROUND AND MADE LANES THROUGH THE ARMY BEHIND THEM | 158 |

| HIS ENEMY WENT DOWN WITH A BULLET IN THE RIGHT SIDE | 185 |

| NELSON AT COPENHAGEN | 214 |

| THE ORDER THAT SENT THE BRITISH LINE STREAMING DOWN FROM THE RISING GROUND | 246 |

| THE LONELY MAN WHO STOOD ON THE RAMPARTS OF KHARTOUM | 275 |

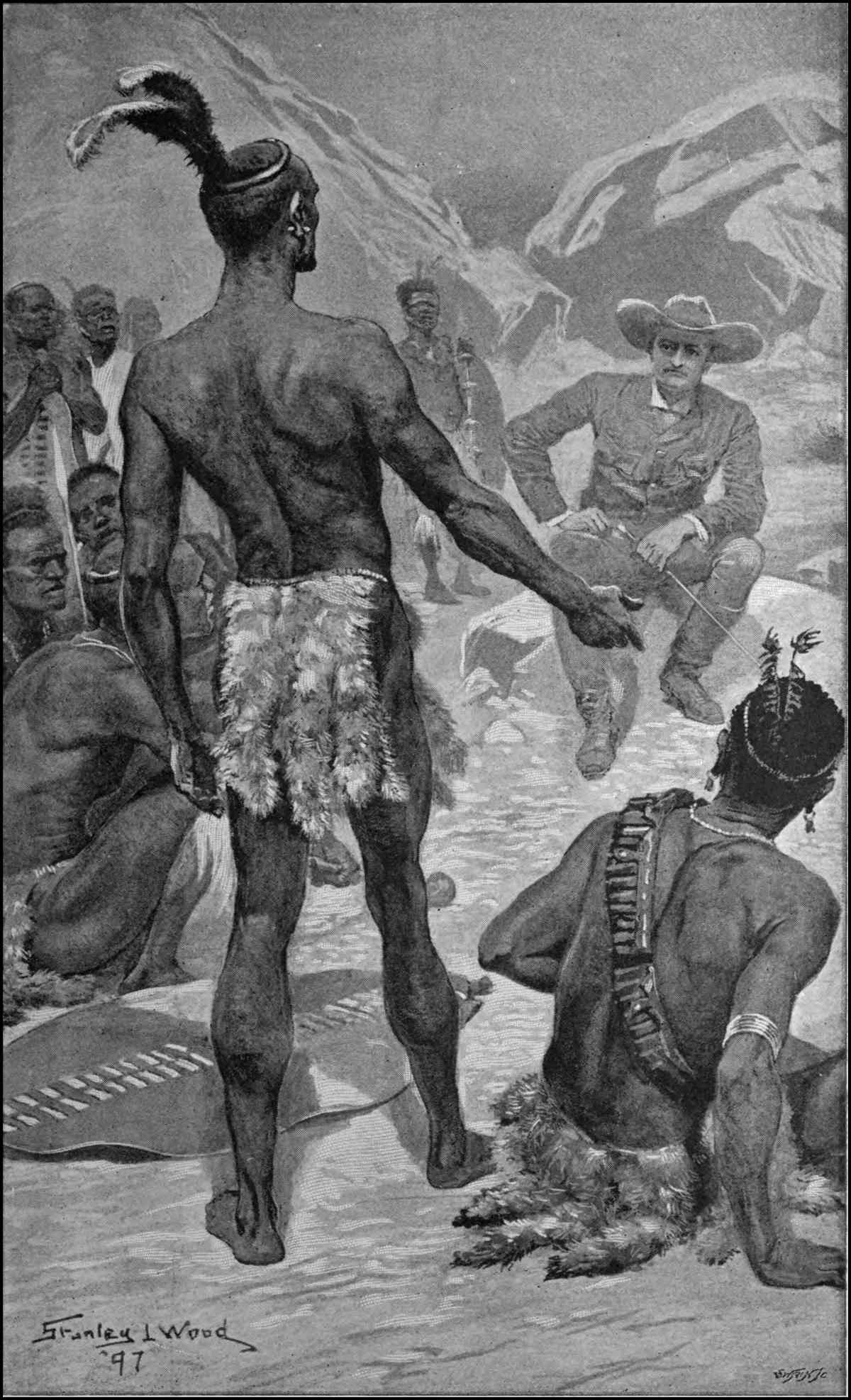

| THAT HISTORIC INDABA IN THE MATOPPOS | 300 |

xiii

The Epic of England has yet to be written. It may be that the fulness of time for writing it has not come yet, or it may be that Britain is still waiting for her Homer and her Virgil. Perhaps the matured genius of a Rudyard Kipling, that strong, sweet Singer of the Seven Seas, may some day address itself to the accomplishment of this most splendid of all possible tasks, and then, again, it may be that it is his only to sound the prelude. That is a matter for the gods to decide in their own good time, but this much is certain—that when this work has been worthily done the world will hear echoing through the ages such a thunder-song as has never stirred human hearts before.

It will begin, doubtless, with the battle-cries of the old Sea-Kings of the North, chanted to the music of their churning oars and the rush and roar of the foam swirling away under the bows of their longships, and from them it will go on ringing and thundering through the centuries, ever swelling in depth and volume as more and more of the races of men hear it rolling over the battle-fields of conxivquered lands, until at last—as every loyal man of English speech must truly hope—the roar of the Last Battle has rolled away into eternal silence, and north and south, east and west, the proclaiming of the Pax Britannica heralds the epoch of

“The Parliament of Man, the Federation of the World.”

But in the meantime, while we are waiting for the coming of the singer whose master-hand shall blend the song and story of Britain into an epic worthy of his magnificent theme, materials may be gathered together, old facts may be presented in new lights, and the great characters who have played their parts in the most tremendous drama that has ever occupied the Stage of Time may be re-grouped in such fashion as will make their subtler relationships more plain, and all this will make the great work readier to the hand of the Master when he comes.

It is a portion of this minor work that I have set myself here to do. The making of a nation and the building of nations up into empires is, humanly speaking, the greatest and noblest work that human hands and brains can find to do, for the making of an empire means, in its ultimate analysis, the substitution of order for anarchy, of commerce for plunder, of civilisation for savagery—in a word, of peace for strife.

Now, the British Empire as it stands to-day is unquestionably the greatest moral and material Fact in human history, and hence it is permissible toxv assume that the makers of it must, each in his own way, whether of peace or war, have been the greatest empire-builders the world has yet seen, and it is my purpose here to take the greatest of these and tell with such force and vividness as I may, the story of the man and his work. I am not going to write a series of biographies arranged in prim chronological ranks, nor am I going to confine myself to the narration of collated facts so dear to the hearts of educational inspectors and scholastic examiners. Such you will find already cut and dried for you in the school-books and in many ponderous tomes, from the reading of which may your good taste and good sense deliver you!

I shall seek rather to show you the living man doing the living work which his destiny called him to do. The man will not always be found of the best, nor the work, seemingly, of the noblest, but what I shall seek to show you is that the work had to be done in order that a certain end might be accomplished, and that the man who did it was, all things considered, the best and, it may be, the only man to do it. In so far as I do not do this I shall have failed in the doing of my own work.

One more word seems necessary in order to anticipate certain possible misconceptions. Our empire-making is not yet complete, even at home. The centuries of strife during which the hammering and welding together of the nations which now make up the United Kingdom has been progressingxvi have naturally and necessarily left certain national jealousies and antipathies behind them, and the last thing that I should desire would be to arouse any of these.

There are two kinds of patriotism, a smaller and a greater, a National and an Imperial. Both are equally good and noble, and it is necessary that the first should precede the second. But it is equally necessary that it should not supersede or obscure it, and it is to this later and greater, this Imperial patriotism that I shall appeal, and I would ask my readers, whatever their nationality, to remember that on the burning plains of India and the rolling prairies of Canada, in the vast expanses of the Australian Bush and the African Veld, there are neither Englishmen nor Scotsmen, Welshmen nor Irishmen; but only Citizens of the Empire, brothers in blood and speech, and fellow-workers in the building up of the noblest and stateliest fabric that human hands have ever reared or God’s sun has ever shone upon.

1

3

I

WILLIAM THE NORMAN

It may strike those of my readers who have only got their history from their school-books as somewhat strange that I should begin my record of British Empire-Makers with a man whom they have been taught to look upon as a foreigner, an invader, a conqueror, and a ruthless oppressor of the English.

The answer is simple, though manifold. The school-books are only filled with potted facts, and are therefore wrong and unreliable. It has been well said that England was made on the shores of the Baltic Sea and the German Ocean. The so-called Englishmen who occupied it at the time of the Conquest were not Englishmen at all, for the simple reason that the true English race had yet to be born, and, after it, the true British.

The England and Scotland of the eleventh century were peopled, not by nations, but by tribes mostly at bitter and constant war with each other. There were still Jutes and Angles, Picts4 and Scots, Danes and Swedes and Norwegians, each occupying their own little stretch of country, and governed, more or less effectually, by their chieftains, in proof of which it is enough to recall the fact that Harold’s last fight but one was against his own brother, who had come across the Narrow Seas at the head of a miscellaneous crowd of hungry pirates to steal as much as he could of the ownerless heritage that Edward the Confessor had left behind him.

A good deal of sentiment, more or less born of deftly-written romances, has glorified the memory of this same Harold. Whether it was deserved or not does not concern us now, any more than does his right or unright to the throne of England. It is enough here to grant him all honour as an able leader of armies, and a man who knew how to snatch victory from defeat, and glory from disaster by dying like a hero surrounded by the corpses of his foes.

The idle question whether he or William had the better right to the crown of England may be left to those who care for such quibbling. Let us, at the outset, in the words of the Sage of Chelsea, “clear our minds of cant.” There is no “right” or “wrong” in these things, saving only the eternal right of the strongest and wisest—the fittest or most suitable, in short, to wield power and dominion whether the less fit like it or not. The peoples are thrust headlong into the fiery5 crucible of War, and, on the adamantine anvil of Destiny, the Thor’s Hammer of Battle beats and crushes them into the shape that God has designed for them. It seems a rude method, but in many thousands of years we have found no other, so at least we may conclude that it is the best one known.

There is a very deep meaning in the seemingly flippant and almost impious saying of Napoleon: “God fights on the side of the biggest battalions.” He does—but you must reckon the bigness of the battalions, not only by their numbers, but by the value of their units, remembering always that one man with a stout heart and a cause he honestly believes in is worth a score who have neither heart nor faith.

Just such a man was William the Norman, son of Robert the Magnificent, otherwise styled the Devil, and Arlette the Fair, daughter of Fulbert the Tanner of Falaise. It is in this birth of his that we find the first clue to his real greatness. He was born of a union unhallowed by the sanction of the Church, among a people proud beyond all modern belief of their royal sea-king ancestry.

How did he come to achieve this almost miraculous triumph over a prejudice and hostility of which we can now form but a very dim idea?

We have to look no farther than his cradle to find the answer. Lying there, the little fellow used6 to grasp the straw in his baby fists with such a grip that it could not be pulled away from him. The straw broke first, and ever in his after life what William the Norman laid hold of he held on to; and that is why he became the first of our Empire-Makers.

No doubt it was the strain of the old pirate blood which ran so strongly in his veins that made him this. If we have successfully cleared our minds of cant, we shall see plainly that, since all nations begin in piracy of some sort, it is natural to expect that the best pirates will prove the best Empire-Makers. That old strain is, happily, not yet exhausted. When it is, Great and Greater Britain will be no more.

Few men have passed unscathed through such a stormy youth as his was. When he was seven years old his father, Duke Robert, having exacted an oath of unwilling fealty from his under-lords to his bonny but base-born heir, went away on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem from which he never returned, leaving him to the wardship of his friend, Alan of Brittany; and soon after Duke Robert’s death became known Alan was poisoned. After that for a dozen years the boy Duke was in constant peril of his life.

One night two lads were lying sleeping side by side in the castle of Vaudreuil, and in the silence and darkness of the night one of the Montgomeries, bitter enemies of the Lords of Falaise, to whose7 hate Alan of Brittany had already fallen a victim, crept up to the bedside with a naked dagger, and drove it blindly into the heart of one of the boys and fled.

Young Duke William—he was only a lad of twelve then—woke up to find himself wet with his playmate’s blood, but all unknowing then how nearly the history of the world had come to being changed by that foul and happily misdirected dagger-stroke. Had it found his heart instead there would have been no Norman Conquest, no blending of the two strains of blood from which has sprung the Imperial Race of earth, no British Empire, no United States of America—without all of which the world would surely have been very different.

Seven more years of plot and intrigue, of strife and turmoil, young Duke William lived through after this, growing ever keener in mind and stronger in body, and, as we may well believe, hardening into the incarnation of ruthless and yet wisely-directed Force which was so soon to make him a power among men. Before he was twenty he shot his arrows from a bow which no other man in his dukedom could bend, and he was already a finished knight, a pattern of the gentleman of his age, good horseman, good swordsman, gentle towards women and stern towards men, pure in his morals and moderate in his living; a good Christian according to his lights and the8 ideas of his day, and above all faithful to the ideals that he had set before himself.

Already at nineteen—that is to say in the year 1044—not only had he shaped his plans for reducing the disorder of his turbulent dukedom to discipline, but he had made his designs so manifest that the lawless lords and robber barons could see for themselves how stern a master he would make—as in good truth he did—and the deadly work of conspiracy started afresh. One night when he was sleeping in his favourite castle of Valognes, Golet, his court fool, came hammering at his bedroom door with his bauble, crying out that some traitor had let the assassins into the stronghold. He leapt out of bed, huddled on a few clothes as he ran to the stable, mounted his horse, and galloped away all through the night toward Falaise along a road which is called the Duke’s Road to this day. No sooner was he safe across the estuary of the Oune and Vire and in the Bayeux district than he pulled his dripping, panting horse up in front of the church of St. Clement, dismounted and knelt down to say his prayers and thank God for his merciful deliverance. Such was the youth who was father to the man justly styled William the Conqueror.

It was not long after this that the years of intrigue and plotting ended in armed revolt. Guy of Burgundy, William’s kinsman and once his playmate, looked with greedy eyes on the fair lands9 of Normandy. He was master of many provinces already, and among his hosts of friends there were not a few of William’s own under-lords, in whose breasts still rankled the shame of owning a bastard for their master. To his side came the Viscount of Coutance, Randolph of Bayeux, Hamon of Thorigny and Creuilly, and that Grimbald of Plessis whose hand was to have slain William that night in Valognes, and in the end this long-gathering storm burst on the grassy slopes of Val-ès-Dunes.

Master Wace the Chronicler, in his “Roman de Rou,” gives us a brilliant little picture of that long-past scene where the future Conqueror won his spurs—of many a brave and gallant gentleman clad cap-à-pie in shining mail, seated on mighty chargers impatiently pawing the ground, of long lances gay with fluttering ribbons tied on by dainty hands that morning, of waving plumes and flaunting pennons, and mild-eyed cattle grazing knee-deep in the long wet grass in peaceful ignorance of the bloody work that was about to be done.

But with all this we have little to do, and one episode must suffice. The starkest warrior among the rebels was Hardrez, Lord of Bayeux, and he, like many another, had sworn to slay William that day with his own hands. The oath had proved fatal to others before it did to him, but at length his turn came. Young Duke William saw him from afar, and with lance in rest made for him at10 a gallop. One of the knights who had followed Hardrez to battle charged at him in mid-course. The next moment horse and man went rolling in the grass, and William, dropping his splintered lance, drew his sword, and, the Lord of Bayeux coming up at the instant, he drove the good steel with one shrewd, strong thrust through mail and flesh and bone, and Hardrez never spoke again.

That stroke won William his dukedom, and the Chronicler, though a man of Bayeux himself, tells in stirring lines how the young lord and his faithful knights hunted the flying rebels off the field and rode them down like sheep.

This was not the last fight that William had for the mastery of his own land, but it left his hands free to begin the work that he had set himself to do, and he did it. To him unity was strength, and he was ready to go to any lengths to get it. His methods then, as afterwards in England, were severe—we should call them brutal nowadays, but these days are not those.

When the citizens of Alençon defied him they indulged in the pleasantry of hanging raw hides over the walls and beating them, shouting out the while that here there was plenty for the tanner’s son to do. He set his teeth and swore his favourite oath—by the Splendour of God—that they should have work enough ere he had done with them. When the city lay at his mercy he had two-and-thirty of the humourists sent out to him,11 and cut off their ears and noses and hands and feet, and had them tossed over the walls as a sort of hint that he was not quite the kind of person who could appreciate jokes about his ancestors. It was an inhuman deed, but history records no other public aspersions of the good name of Duke William’s mother.

Yet one more battle the young Duke had to fight before he crossed the Narrow Seas to the famous field of Senlac. Henry of France, his titular overlord, and Geoffrey of Anjou, jealous of the fast-growing power of Normandy, united their forces in an expedition which was half an invasion and half a plundering raid. Duke William, with infinite patience, and a quiet, marvellous self-restraint, held his own fiery temper and the angry ardour of his knights in check, watching the invaders burn town after town and village after village, and turning some of his fairest domains into a wilderness.

He never struck a blow until, one fatal afternoon, he swooped down from Falaise and caught the French army severed in two by the rising flood of the river Dive. Then he struck, and struck hard, and when the bloody work was over, Henry was glad to buy a truce and his liberty from his vassal with the strong castle of Tillièries and all its lands, and so heavy hearted was he at his defeat that, as the Chronicler tells us, “he never bore shield or spear again.”

Normandy had now become the most orderly12 and best governed country in Europe. Robbers, noble and otherwise, were ruthlessly suppressed, and the poorest possessed their goods in peace, while William himself had time to turn his thoughts to the gentler, and yet not less important, concerns of policy and love-making.

The old story of his courtship of the fair Matilda of Flanders with a riding whip is evidently a myth manufactured by some Saxon enemy, for Duke William was in the first place a gentleman, and, moreover, the lady and her parents were as anxious as he was for the marriage, seeing that he was now the most desirable of suitors. The truth is that the Church opposed their union on some shadowy grounds of consanguinity, and it did not take place until after a courtship of four years.

And now, having got our pirate Duke happily married and seen him undisputed lord of his own realm, we may go with him to St. Valery on the coast of Ponthieu and watch him working and praying and offering gifts at the old shrine, during those fifteen long days that he watched the weather-cocks and prayed for the south wind that was to waft his fleet and army over to the English shore.

It was on Wednesday, the 27th of September, that the wind at last veered round. The eager soldiery hailed the change as the granting of their prayers and the consent of Heaven to the beginning of their enterprise, and flung themselves into their ships like a great host of schoolboys setting out on13 a holiday. Soon the grey sea was covered with a swarm of craft, and it must have seemed as though the old Viking days had come back as the great square sails went up to the mast-heads, and the shining shields were hung along the bulwarks.

William himself, in his golden ship Mora, the present of his own dear Duchess, led the way with the sacred banner of the Pope at his mast-head, and the three Lions of Normandy floating astern. The Mora was lighter heeled or lighter loaded than the rest, for when morning dawned she was alone on the sea with the Sussex shore in plain sight. But presently a great forest of masts and clouds of gaily-coloured sails rose up out of the grey waters astern, and the whole vast fleet came on, urged by oar and wind, and by nine o’clock that morning the fore-foot of the Mora, close followed by her consorts, struck the English ground in Pevensey Bay.

It has often been told how William, as he landed, stumbled and fell on his hands and knees, and how those near him cried out that it was a fatal omen. The story may be myth or fact, but nothing could be more characteristic of the true man than his springing to his feet with both hands full of sand and laughing out in that great voice of his:

“Nay, by the Splendour of God, not so. See! Have I not taken seizin of my new kingdom and lawful heritage?”

But the army of the so-called English, that they14 had come to seek was nowhere to be found, and some days were spent in uncertainty and debate as to whether they should march on London or await battle on the shore with their sea communications open, and in the end they took the latter and the wiser course.

Meanwhile, as has been said, Harold was away in the North fighting and beating his brother Tostig and his fellow robbers, and the news of Duke William’s landing was flying northward to him. It must have been something of an anxious time for both—the Norman waiting day after day in that deadly inaction which is most fatal of all things to the courage and discipline of an army, and Harold hurrying southward at the head of his victorious troops, knowing that he was about to try conclusions with the best leader and the finest soldiery in Europe.

It is of little import here and to us now which of them had the best right, as the lawyer-quibble has it, to that which they were about to fight for. The point is that such claims as either had they were going to submit to the stern and final ordeal of battle—and in good truth a stern ordeal it proved to be.

As he came to the South the standard of Harold—the Fighting Man—was joined by troops of recruits attracted by the fame of his northern victory, and it was a great and really formidable army which at length assembled between London and15 the Sussex coast. Meanwhile the Normans, after the fashion of the pitiless warfare of those days, were dividing their time between the building of entrenched camps and ravaging, plundering, and burning throughout the pleasant Southern land.

Of course messages and parleyings passed between them. Harold from his royal house at Westminster bade Duke William come and fight him for his capital and his kingdom, to which Duke William warily replied: “Come and drive us into the sea if you can!” This at length King Harold was forced to attempt. And so it came to pass that, at length, on the 14th of October, the hosts of the Saxon and the Norman confronted each other on the field of Senlac by Hastings, on the morrow to strike blows whose echoes were to ring through many a long century, and to do deeds more mighty in their effect than either Harold or William dreamt of.

The Norman host has been called a horde of mailed robbers and cut-throats, eager only for plunder, and the Saxon army has been almost canonised as a band of heroes, gathered together to die in defence of their native land and their lawful king. Yet, strangely enough, the robbers and cut-throats spent the best part of the night confessing their sins and praying for victory, as well as in making the best dispositions to attain it. The patriots spent the same hours feasting and drinking, and swaggering to each other about16 the brave deeds they had done in the North and the greater things they were going to do on the morrow.

So the night passes, and the morning dawns grey and chill on the two now silent hosts. Then from the Norman ranks rises the solemn cadence of the Te Deum, and as this dies away the archers move out—forerunners of those stout yeomen whose clothyard shafts were one day to win Creçy and Agincourt. Then come the footmen with their long pikes, and after them the mailed and mounted knights, in front of whom rides Taillefer—Iron-Cutter and Minstrel—tossing his sword into the air and catching it, and singing the while the Song of Roland and Roncesvalles. As the archers and pikemen spread out in skirmishing order he sets spurs to his horse and charges at the Saxon line. He kills two men, and then goes down under the battle-axe of a third.

Then the arrows flew fast and thick, and charge after charge was made upon the palisades of stakes that fenced the Saxon position, high above which floated the Dragon Standard of Wessex and the banner of the Fighting Man.

But the double-bladed Saxon axes were no playthings, and they were swung by strong and strenuous arms, and every time the Norman front came up to the breastwork it was hewn down in swathes by the deep-biting blades. The arrows fell blunted and broken on the big Saxon shields and stout Saxon17 armour, and so Duke William, with that ever-ready resource of his, bade his archers shoot up into the air, and then down from the grey sky there fell a rain of whirring, steel-pointed shafts, one of which, winged by Fate, struck gallant Harold in the eye—doubtless as he was looking up wondering at this new manœuvre—and, piercing his brain, laid him lifeless in the midst of his champions.

Soon after this a cry went up that Duke William too was dead, and he, hearing this, tore off his helmet—a somewhat unsafe thing to do in such a fight—and roared out that he was alive, swearing—as usual by the Splendour of God—that the land of England should yet be his by nightfall.

So they laid on again. William’s horse went down under a pike-thrust. He clove the pike-man to the chin and asked one of his knights to lend him his horse. The knight refused, thinking more of his skin than his loyalty, whereupon William pitched him out of the saddle, swung himself up, and led another charge against the ever-dwindling ring of heroes who were still hammering away with their battle-axes—and this time the stout line wavers and breaks; the mail-clad warriors pour up the slope, shouting that the day is won; axe and sword ring loud and fast on helm and mail, the Saxons reel back, closing round the body of their king and the staff of his banner.

“Dex aide! Dex aide! Ha-Rou! Ha-Rou!” Duke William’s men yell and roar again as they18 scramble over heaps of mangled corpses filling the trenches and blocking the breaches in the palisades. Another moment or two of brief, bitter, and bloody struggle and the last Saxon ring breaks and melts away, and Hastings and England are won.

What followed is history so familiar that few words more from me will suffice. What Duke William had done in his own land he did after the same methods in the land that had been the Saxons’. Cruel, bloody, and savage they were beyond all doubt, but it is a question whether, even in the doing, they were more disastrous than the ferocious anarchy and the unceasing plunder and outrage and murder that had disgraced the weak and divided rule of the Saxon kings. In their effect they were a thousandfold better. Duke William believed that order was Heaven’s first law, and, by whatever means he had at hand, he was honestly determined to make it earth’s as well. And he succeeded, which after all is not an unsatisfactory test of honest merit. How well he did so let us ask, not one of his own chroniclers or troubadours, but the man who wrote the story of his own conquered people, and this is what he will tell us:

“Truly he was so stark a man and wroth that no man durst do anything against his will. Bishops he set off their bishoprics, and abbots off their abbacies, and thanes in prison. And at last he did not spare his brother Odo. Him he set in prison.19 Betwixt other things we must not forget the good peace that he made in this land, so that a man that was worth aught might travel over the kingdom unhurt with his bosom full of gold. And no man durst slay another though he had suffered never so mickle evil from the other.”

Such was this grim, stern, Thor’s-Hammer of a man, who by his strength and cunning hewed into shape that which in after days was to become the corner-stone of the glorious, world-shadowing fabric which we call the British Empire.

21

23

II

EDWARD OF THE LONG LEGS

Two centuries all but nine years have passed away since William the Conqueror, unwept, if not unhonoured, lost his life in avenging a paltry joke, and left his work for others to carry on. In the two centuries not much has been done, although no little show has been made meanwhile, and a great clash of arms has resounded through the world.

William the Red has died, as he lived, in a somewhat ignoble and futile manner. Henry I. has done one good thing, wedding, as it were, in his own person and that of the Lady Matilda, the two races which were afterwards to be one.

Stephen and Matilda have settled their differences and died, after the shedding of much wasted blood. Henry II., by the hand of Strongbow and his licensed pirates, has done a piece of good work badly in beginning that conquest of Ireland which is not to be completed until the Battle of the Boyne is lost and won.

Richard Lionheart has won much glory to very24 small profit in the magnificent madness of the Third Crusade. The barons, recognising, however dimly and clumsily, that they are, in good truth, citizens of the infant State whose lusty, turbulent youth already gives promise of its future strength and greatness, have become law-lords as well as landlords, and with mailed hands have guided that unwilling pen of John’s along the bottom of the parchment on which the Great Charter is written.

And, lastly, Simon of Montfort has taken a swift stride through several centuries and, arriving at the modern idea that the making of nations and the ordering of the world can be achieved by Talk, has, after not a little violence and the spilling of considerable blood that might have been better spent, got together that first Parliament or Talking-Machine, whose successors have so sorely hindered the progress of the world and balked the efforts of those appointed by God, and not by the counting of noses, to do its work.

So the two noisy and somewhat foolish centuries have rolled away into a blessed oblivion with a good deal of shouting and swaggering, of strife and bloodshed, but of little progress, saving that one Roger Bacon has lived and written a certain book and made himself a name for ever.

But all this time the work with which we are here most concerned, the making of an empire, has been waiting for the next God-sent man to come and do it, and this man was Edward Plantagenet,25 surnamed Longlegs, next in lineal succession, not as king, but as Empire-Maker, to him who won the fight at Senlac and got himself so well obeyed that “no man durst do anything against his will”—which was a great deal to say of any one in such days as those.

Edward of the Long Legs came on to the stage of History with long, swift, determined, and, in short, wholly characteristic strides. The Talking-Machine of the good Earl Simon had worked noisily, as is usual with such machines, and had produced little but sound and fury.

There was war all round, and the usual anarchy in Ireland and Wales. Llewelyn, Lord of Snowdon, for instance, had pitted himself gallantly against the logic of circumstances, and was seeking to reconstruct the ancient and now impossibly obsolete Celtic empire.

“Be of good courage in the slaughter, cling to thy work, destroy England and plunder its multitudes!” his bards had sung to him, and so he had honestly set himself to do, not recognising the fact that empires are neither made nor re-made by mere methods of miscellaneous blood-letting.

To the north, Scotland was divided by schisms and rent by the bitter jealousies of its nobles and clan-chieftains, savage, rude and poor, but gallant, strong, and very full of fight, as the English were to learn later on.

Over the Narrow Seas the wide domains which26 William the Norman had kept with his sword and which the second Henry had greatly increased by inheritance and marriage, were slipping piecemeal away from the throne to which they did not of right divine belong, and with which it was therefore impossible that they should remain.

Such, in briefest outline, was the scene into which Edward Longlegs strode, and of which he was to be for thirty-five years the central and dominating figure. His first look round, as it were, showed him the nature of the task which it was his destiny to forthwith set about.

With that clearness of vision without which no man has any chance of success in the business of empire-making, he instantly pierced the dust-storms of battle that were rising all about him, and the mist-clouds of debate which Earl Simon’s Talking-Machine had commenced to vomit forth, and behind and beyond these he saw a certain Fact, a prime necessity which had to be faced—in short a real Something of an infinitely greater importance than tribal warfare, the aspirations of bard-inspired princelings, or even parliamentary debates.

This was neither more nor less than the fact that, when the Maker of all things mapped out this part of the world, it pleased Him in His wisdom to put England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland into one little group of islands, and from this fact Edward Longlegs drew the deduction that the King of Kings had intended them to be under one lordship.

It seems a simple thing to say now, a fact so 27 patent that the mention of it seems superfluous. So does the larger fact that the world is round; but it was a very different matter in the times and circumstances of Edward Longlegs, and, indeed, his first and greatest claim to stand next in succession to William the Norman in the royal line of empire-makers consists in this: that he was capable of that master-stroke of genius which clearly demonstrated an imperial principle of which six hundred years of history have been the continuous and emphatic endorsement.

No sooner was the bloody fight of Evesham over and the good Earl Simon had breathed out his generous, if somewhat premature soul in that last cry of his: “It is God’s grace!” than Edward Longlegs seems to have set himself to prepare for the task that was to be his. He was not to be king in name for some seven years more, but as the historian of the English People with great pertinence remarked: “With the victory of Evesham, his character seemed to mould itself into nobler form.” In other words he was, perchance unconsciously, performing that indispensable preliminary to all really great and true public reforms, the reformation of himself.

Hitherto his life had been none of the best. He had been the leader of a retinue that had made itself something like infamous in the land. He had intrigued first with one party and then with another.28 He is accused of a faithlessness which, it is said, forced the good, though mistaken, Earl Simon into armed revolt against his liege lord—though this may, after all, only have been a stroke of wise and necessary policy, since he possibly saw even then that Chaos would not reform itself into Cosmos just for being talked at.

Then again, and with curious resemblance to William of Normandy, and later of Hastings and England, he had avenged an insult to his mother by the slaughter of some three thousand men in the rout of Lewes and a quite unjustifiable indulgence in pillage and slaughter when the Barons’ War was finally over.

“It was from Earl Simon,” says John Richard Green in one of those limpid sentences of his, “as the Earl owned with a proud bitterness ere his death, that Edward had learnt the skill in warfare which distinguished him among the princes of his time. But he had learnt from the Earl the far nobler lesson of a self-government which lifted him high above them as ruler among men.”

It seemed, indeed, as though, by this reformation of himself, he was to typify that reformation of England which it was his life-work to begin. The new Edward was to be the maker of the new England.

His first action after the war was characteristic of the man and the work that he was to do. The cessation of the fighting, as was usual in those days,29 had left an undesirable number of truculent warriors of various ranks wandering at large about the kingdom with their legitimate occupation gone. Edward, with that instinct of order characteristic of all true empire-makers, saw in these the possibilities of disorder, and with a happy combination of wisdom and adventure turned their swords and lances away from the bodies of their fellow-citizens by taking them to fight the Paynim in the Holy Land.

An incident of this excursion has been adorned by one of those pleasant fictions which, if the paradox may be pardoned, are none the less true for the fact that they are false. Edward, having sent certain hundreds of Moslems to Paradise with a perhaps unnecessarily ruthless dispatch, was considered by the sect of the Assassins to be a person who would be better dead than alive in Palestine, and so one of them, after several attempts, succeeded, as one may put it, in interviewing him privately with a poisoned dagger. The fiction has it that his consort, Eleanor of Castille, sucked the poison from the wound with her own sweet lips and so saved his life.

It is a pretty story, but, unfortunately for its authenticity, no one seems to have heard of it or thought it worth the telling until Ptolemy of Lucca told it a good half-century afterwards. But the truth underlying it remains, and this truth is that Edward Longlegs was blessed with that greatest of all earthly blessings, a loving and devoted wife.

The facts of the matter are few but eloquent. 30 Edward saw the dagger before it struck him, and gripped the would-be murderer with a grip worthy the muscles of Lionheart himself. There was a struggle, during which the dagger-point scratched his arm. A moment after it was buried in the assassin’s own heart. Then some of Edward’s retainers, hearing the scuffling, burst into the tent and satisfied themselves that the wretch had attempted his last murder by the somewhat superfluous method of knocking out his brains with a foot-stool.

Soon after this symptoms of poisoning showed themselves, and Edward, in his usual businesslike way, made his will and his peace with God and prepared to “salute the world” with becoming dignity. In the end not Eleanor’s lips but the surgeon’s knife removed the danger, and so once again a dagger-thrust which had come near to changing the history of Britain missed its mark.

It was during his return from this Crusade, as he was journeying through Calabria, that he met the messengers who told him that his father was dead and that he was King of England. Charles of Anjou, who was riding with him at the moment, wondered at the great grief he showed, and, being himself a man almost incapable of feeling, asked him why he should show more grief at his father’s death than he had done for the loss of his baby son who had died a short time before. The answer was to the point and worthy of the man.

“By the goodness of God,” he said, “the loss 31 of my boy may be made good to me, but not even God’s own mercy can give me a father again.”

It was on the same journey that there occurred that curious incident which is called the “Little Battle of Chalons,” and which is also instructive in giving us another view of the man who could use such wise and pious words as these. While he was travelling through Guienne, the Count of Chalons, one of the best and starkest knights of his age, sent a friendly message to request the favour of being allowed to break a lance with him. Edward, though he had been repeatedly warned of plots against his life by those who had designs on his French dominions, and though as a king he had a perfect right to decline the challenge of a vassal, was, as we should say nowadays, too good a sportsman to say no; but he took the precaution of going to the knightly trysting-place with an escort of a thousand men—in doing which he was well justified by the fact that the Count of Chalons was there waiting for him with about two thousand.

During the trouble which inevitably followed, the Count of Chalons did break a lance with Edward, but it was his own lance, and this failing, he gripped him round the neck in the most unknightly fashion and tried to drag him from the saddle. The Count was a strong man, but Edward was a little stronger,32 so he just sat still, and swinging his horse round, pulled him out of the saddle instead, after which, to put it into plain English, he gave him a sound thrashing, and when he at length cried for quarter, Edward, ever generous in the moment of victory, gave him the life that he had forfeited by his treachery, but, as a punishment, which the coroneted scoundrel justly deserved, he compelled him to take his sword back from the hands of a common soldier, and so disgraced him for ever in the eyes of his peers.

It may be added that the Little Battle of Chalons, in spite of the difference of numbers, ended in something like a picnic for the English, after which the king betook himself in leisurely fashion to the throne, and the work that was waiting for him.

No sooner was the crown upon his head, than he got to his task. The Prince of Snowdon, now calling himself Prince of Wales, had not only made himself master of his own country, but had pushed the war into England and reduced several English towns, the chief of which was Shrewsbury. Edward called upon him to restore the peace which he had broken, and to come and do homage for his lands. Llewelyn, in the plentitude of his pride, told him to come and fetch him.

Edward took a note of this, but waited two years while he replenished the royal treasury by more or less justifiable means. During this time, as it happened, the Prince’s promised bride, Eleanor,33 daughter of Earl Simon, fell into his hands. Again and again he summoned the Prince to perform the act of allegiance, holding his sweetheart meanwhile as a hostage in honourable captivity.

At length a fresh defiance from the Welshman roused him to action, and Longlegs strode swiftly across England and struck out hard and heavy. A single blow dissipated the dream of Celtic empire for ever. Llewelyn fled to his mountains and at length sued for peace. By rights his life was forfeit for rebellion, yet Edward not only forgave him but remitted the fine of £50,000 which he had imposed on the Welsh chieftains, and then invited Llewelyn to his court and married him with all due pomp and circumstance to the daughter of his old enemy—from which it will be seen that Edward Longlegs, like William the Norman, and indeed all good and capable empire-makers, was a gentleman.

Unhappily, Llewelyn repaid the kindness and courtesy by new rebellion, which ended, as it deserved, in disaster. Merlin had prophesied that, when money was made round, a Welsh prince should be crowned in London. During this last revolt Edward had caused round halfpence and farthings to be coined. When it was over the head of Llewelyn was sent to London and crowned with a garland of ivy on Tower Hill.

What Longlegs had thus done with Wales he sought by more devious and less effective means to do with Scotland. The dispute between Balliol34 and Bruce gave him the opportunity of intervention, and of this the dismal results are too well known to need detailed description at this time of day.

Here, again, we have nothing to do with personal right or wrong, or with the ethics of national independence. The business of empire-making is too urgent to wait for matters of this kind. It would perhaps have been better if Edward, after the sack and slaughter of Berwick, had hurled the whole weight of the English power against the object of his attack, as William the Norman would have done, and once and for all crushed the opposition into impotence.

It would have been bitter and bloody work, as the work of empire-making is apt to be, but the end might have justified the means. Certainly some centuries of bloodshed and bitterness would have been saved. The high ideal of a United Kingdom would have been realised nearly five hundred years earlier, and the progress of both realms in civilisation, wealth, and power might have been quickened immeasurably.

And after all, neither side in the long struggle would have lost anything worthy of being weighed against the greatness of the gain to both. There would have been no Stirling Bridge, but then there would have been no Falkirk; no Bannockburn, but also no Flodden Field. All this, as it happens, however, was not written in the Book of Destiny, and so it does not concern us here, since35 we have to consider how much of the work of empire-making Edward did, not what he failed to do or left undone.

The surrender of Stirling in 1305 apparently completed the conquest of Scotland, and Edward was for the time being the actual and undisputed sovereign of the whole country from the Pentland Firth to the English Channel, and it is probable that the conquest would have been a permanent one but for the entrance of another power into the field, and this was nothing less than the English Baronage itself. It was as though the chiefs of his own army had turned against him, and, in the fatal dispute which followed, Robert the Bruce saw his opportunity, and in the end re-won for Scotland that independence which has cost her so much and which, however precious as a matter of sentiment, was destined to prove of so little value to her.

All that is past and done with now, but still no one who holds that an empire is greater than a nation, even as the whole is greater than its part, can help looking back with regretful thoughts upon those pages of our history which would have been so much brighter and more glorious if those gallant Scots who fought through those long and bitter wars could have stood, as they have done since, side by side with their brothers of the South, and so made possible centuries ago the beginning of that great work in which they have borne so splendid a part.

Had that been so Edward Longlegs might have 36 been the founder instead of only one of the makers of the British Empire, and that last piteous scene by the sandy shores of the Solway Firth would never have been enacted.

But though in the end he neither conquered Scotland nor founded the United Kingdom, he did something else which, as the centuries went by, proved but little less important, for he began to make the British Constitution.

Gallant soldier and great general as he was, he was perhaps an even greater statesman. He saw far ahead of his times, too far indeed, for in his enlightened conviction that in the matter of taxation “what touched all should be allowed of all” we have the real reason for that revolt of the Baronage, which made a United Kingdom of the Fourteenth Century an impossibility.

Yet as law-maker he did work which lasted longer than that which he did on the battle-field. Like William the Norman, he was a stark man who knew how to get himself obeyed, and order, no matter how dearly bought, was the first thing to be got, and he got it. He could “make a wilderness and call it peace,” as he did over and over again with Wales and Scotland—and, indeed, to him a wilderness was better than a place where disorder dwelt—but he also made another peace within his own realms which was the first forerunner of that which we enjoy to-day. The laws37 which he made were for rich and poor, great and small, alike. The hand that was pitiless in destruction was also ready and strong to protect.

The manner of his death is as characteristic as any of the acts, good or bad, of his life. Old and weak and sick, he made the long journey from Westminster to the Solway to fulfil the oath which he had sworn at the knighting of his unworthy son to avenge Bruce’s murder of Comyns and to punish his rebellion.

Too feeble to keep the saddle, he was carried in a litter at the head of the hundred thousand men who were to be the instruments of his vengeance, but at length the news of victory after victory won by the Bruce stung him to a fury which for the time was stronger than his weakness, and at Carlisle the old warrior left his litter and once more mounted his charger. It is a pathetic sight even when looked at through the mists of the intervening centuries. We can picture the gallant struggle that he must have made to sit his horse upright and to bear without fainting the weight of the armour that was oppressing his disease-worn and weary limbs. The mailed hand which had struck the great Count of Chalons down could not now even draw the sword that hung useless at his side.

Only one thing remained strong in the man who had once been the very incarnation of strength. His inflexible will was still unbroken and unswerving in its devotion to the great ideal and master-project38 of his life. Had that will had its way, the flood of English strength and valour that was rolling slowly behind him would have burst in a torrent of death and desolation over the war-wasted fields of southern Scotland, and there can be but little doubt as to what the end would have been.

But it was not to be. The Spectre Horseman was already riding by his side, and, like the wine from a cracked goblet, the dregs of his once splendid strength ebbed away. At last the skeleton hand was outstretched, and he who had never been unhorsed by mortal foe was stricken from the saddle. Yet even then the proud spirit refused to yield. He took his place in the litter again. With almost dying lips he ordered the army forward; and, though the end was very near, he did not submit without a struggle, pathetic in its hopeless heroism, to conquer even Death itself and carry out his purpose in spite of the King of Terrors. Die he must, and that soon, but his spirit should live after him and he would still lead his army.

“Bury me not till you have conquered Scotland!” were almost the last words he spoke. Though they were disobeyed and Scotland was never conquered, yet they were well worthy of the iron-hearted man who said them.

39

41

III

THE QUEEN’S LITTLE PIRATE

Another couple of centuries with a few added years have slipped away, and the next scene of the slowly-unfolding drama opens on the sea instead of the land. The Idea which Edward of the Long Legs had so clearly conceived and so very nearly realised, the idea that the frontiers of the United Kingdom of which he had dreamt should be its sea-coasts has all the time been growing and deepening, for, like all ideas which faithfully reflect some fact in the universe, it could not die, and was bound some day to become a fact itself.

Politically, England and Scotland were still independent kingdoms, but many old differences had been forgotten and forgiven, and they had come a great deal closer, as it was fitting that they should do on the eve of their final union. Moreover, they were one in their dread and hatred of that cruel and implacable Colossus which, with one foot on the East and the other on the West, bestrode42 the world, drawing vast treasures from hidden El Dorados with which it built countless ships, and hired and armed innumerable men for the enslavement of mankind. For now we have reached those “spacious times of great Elizabeth,” when that lusty young giant of Liberty, recently born into the world, was girding on his armour, and making him ready to grapple with the powers of oppression and darkness which were just then most fitly incarnated in the shape of Spain.

It is almost impossible for us of the present day to understand clearly what the Spain of those days was. She was the first naval and military Power in the world, her ships and armies were everywhere, her wealth was honestly believed to be illimitable, and moreover she was the recognised champion of the Catholic Church, whose spiritual thunders mingled with the roar of her guns, and which supplemented the terror of her arms by all the diabolical enginry of torture and the awful powers of the Holy Office.

The world, in short, was on the eve of great and marvellous doings—on the one hand so terrible in their deadly earnestness and tremendous consequences, and on the other so fantastically splendid in their almost superhuman daring and undreamt-of rewards, that it looked as though the Fates were preparing some gigantic miracle wherewith to astound mankind. And so, in sober truth, they were, and the miracle about to be wrought was43 the making of what we now call the British Empire.

In the beginning of the latter half of the sixteenth century there was a yellow-haired, blue-eyed, round-faced and sturdily-built youngster sailing to and fro as ship’s boy in a tiny cockle-shell of a craft plying with the humbler kinds of merchandise between the Thames and the coasts of France and Flanders. Whether or not he had heard any of those wondrous stories which the western gales were wafting across the Atlantic from the golden Spanish Main we do not know, but probably he had, and, like many another sailor-lad of his day, he had dreamt wild dreams of blue seas and bright skies, of white-walled cities crammed with gold, and of stately galleons staggering across that mysterious sea stuffed to the deck with the treasures they were bringing to pour into the coffers of the King of Spain.

And yet, wild as these dreams may have been, they would have been commonplace in comparison with the bewildering exploits with which this same blue-eyed sailor-lad was one day to realise and excel them. For this was he whose name the mariners of Spain were soon to hear shrieked out by the voice of the tempest, booming in the roar of guns, and echoing through the crash of battle. This, in a word, was Francis Drake—El Draque, the Dragon, child and servant of the Devil himself, Scourge of the Church and Plunderer of the Faithful.

As I say, he may or may not have heard the 44 story of the Golden West, but it is quite certain that he did hear much of the black and terrible tales which the refugees and exiles from France and the Netherlands had to tell, for not a few of them crossed over in the little barque in which he served, and he could not fail to hear what they had to say of the murders and massacres, the torturing and outrage with which Spain was disgracing her knightly fame and her ancient faith. They are horrible enough for us to read even here in the security which that gallant struggle won for us, and now when we can only hear the shrieks of the tortured and the groans of the dying echoing faintly across the gulf of three centuries; but what must they have been to Francis Drake when he heard them told by those whose eyes had only just before looked upon the hideous reality—perhaps indeed by some of those racked and mutilated unfortunates who had managed to escape with their lives to seek the sheltering hospitality of Gloriana the Queen? Was it any wonder that deep down in his boyish heart there were planted those seeds of hate and horror which later on were to bear such terrible fruit?

The lad Francis seems to have performed his duties as ship’s boy as well as he did everything else, whether it was leading the Queen’s ships to harry the coast of Spain or raging and storming through one of his piratical raids among the45 Fortunate Isles of the West, for when his master died he made him his heir, and so Francis became a trader on his own account. For a few years he was just a peaceful shipmaster, making an honest and hard-won living; but all this time events were arranging themselves in more and more martial array, and the bursting of the storm was not very far off.

The actual fighting did not begin in the guise of recognised warfare for a very considerable time. Spain and England were at peace, each trying to humbug the other, but between Protestant and Catholic it was otherwise. Armed cruisers manned by angry Protestants made their appearance in the Narrow Seas, and whenever they got a chance fell upon Catholic ships and avenged the sufferings of their fellow-heretics in a fashion at once prompt and pitiless, and this at length so exasperated Philip that he closed his ports to English trade, and Drake’s occupation was gone. Better, in truth, had it been for Philip if he had left him undisturbed in his business!

He sold his little vessel, went to Plymouth, and entered the service of two kinsmen of his, one of whom was soon to prove somewhat of an empire-maker in his own line and whose name, with certain others soon to be mentioned, was destined to go down to everlasting fame indissolubly linked with that of Francis Drake. This was Captain John Hawkins, and when the young trader reached46 Plymouth he had just come back with a shipload of gold and other precious things from his first venture in slave-trading, and now at least Drake, who was still a lad in his teens, must have heard something of the wonders of El Dorado. Yet, curiously enough, when Captain Hawkins went back he did not go with him. He sailed instead, as a sort of supercargo, in another of Hawkins’ ships to Biscay, and there a momentous revelation awaited him, as though to guide him on the path of his destiny.

At San Sebastian about a score of English sailors, once strong and stalwart men of Devon, crept out of the dungeons of the Inquisition and took passage with him home. King Philip had taken off his embargo now, and these men were the remnant of the crew of a Plymouth ship which he had seized in port when the embargo was laid on. The others had rotted to death during the six months that he had bestowed his hospitality upon them. We can imagine what talks they had on the way home, and no doubt El Draque bore the stories of these forlorn mariners well in mind on that most memorable day when he “singed the King of Spain’s beard” at Cadiz.

John Hawkins came back from his second voyage richer than ever, and now all the mariners of the South Coast were beginning to dream golden dreams which were soon to become yet more golden deeds, and King Philip, to whom all such47 ventures were the flattest piracy, began to fear for his monopoly and instructed his ambassador in London to drop the hint that foreign trade with the Indies was forbidden, upon which, foolishly enough, or perhaps not knowing their own true strength, Queen Bess’s councillors backed down and forbade John Hawkins to start again.

He, obediently enough, stayed at home, but a certain George Lovell got together an expedition and slipped out to sea, westward bound. With him went Francis Drake, at length to see for the first time the blue waters and green shores of El Dorado. This time, however, it proved anything but golden for him or his companions, for they came back with shattered ships and still worse broken fortunes. They had drawn a blank in the great lottery which half Europe was wanting to gamble in.

Nothing daunted, he shipped again, this time with George Fenner, bound for Guiana. Again, financially speaking, the voyage ended in disaster, but there was one incident in it destined to bear good fruit. A big Portuguese galleasse, backed up by six gunboats, tried to enforce the prohibition against foreign trade. Fenner had one ship and a pinnace, and with these he fought the “Portugals” and thoroughly convinced them by the logic of shot and steel that he was not the sort of man to be prohibited from doing anything he wanted to do.

This forgotten action is really one of great importance.48 It was Francis Drake’s first taste of fighting, which in itself means a good deal, but it was also the beginning of that lordly and magnificent contempt which the English mariners of that day were soon to feel for all enemies, no matter how strong they might seem. It was this spirit which a few years later was to take Sir Richard Grenville

“With his hundred men on deck and his ninety sick below,”

into the midst of the fifty-three Spanish ships which he fought for an afternoon and a night before he surrendered so sorely against his will and fell dead of his wounds on the deck of the Spanish flagship. It was this, too, which, when that long seven days’ fight against the Armada was raging and roaring up the Channel, brought the flag of the Spanish Rear-Admiral down with a run just because the Little Pirate stamped his foot on the deck of that same Revenge and said that he was Francis Drake and had no time to parley.

Meanwhile the rumblings of the war-storm in Europe had been growing louder. The Netherlanders were at last turning on their torturers, Darnley had been murdered and Mary Queen of Scots put in prison, so Gloriana, feeling herself somewhat at leisure, took a hand in the next buccaneering expedition. It may be noted here, by the way, that there was no more ardent buccaneer and slave-trader in her dominions than49 Good Queen Bess herself. She lent ships though she withheld her commission, and her pirates did the rest. If disaster overtook them or if the Spanish Minister raged against their doings she promptly disowned them and felt sorry for her ships. But if they came back happily filled to the hatches with plundered treasure, she took her dividends and lent more ships.

It was thus with the expedition which sailed out of Plymouth on October 2, 1567, under the command of Admiral John Hawkins, whose second officer was Francis Drake. The diplomacy of the times called it the trading venture of Sir William Garrard and Co., but for all that there were two ships of the Royal Navy in it, the Jesus and the Minion, and the merchandise it carried consisted mainly of cannon and small arms, powder and shot, and cold steel.

The voyage began with a slave-raiding expedition down the Portuguese coast of Africa, whence with five hundred slaves they crossed to the Spanish Main. Here, after varying fortunes, they filled their ships with treasure, and Hawkins turned his prows northward for home. But while crossing the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico a furious hurricane burst upon them and drove his gold-and-pearl-laden vessels so far into it, that he came to the bold decision to put into the Spanish port of Vera Cruz to refit.

In the harbour he found twelve great galleons50 loaded with gold and silver, waiting for the convoy to escort them to Spain. They were utterly at the mercy of the English ships, but John Hawkins, pirate and slave-dealer, was still an English gentleman, so he made a solemn convention to leave the treasure-ships alone on condition of being allowed to refit in the harbour. Hawkins was already known in Spain as the “Enemy of God,” and Don Martin Enriquez, the new Governor of Mexico, had come out with special orders to abolish him by any means that might be found the readiest.

Don Martin seems to have thought that in this case treachery would suit best, so he signed the convention and gave his word of honour as a gentleman of Spain that the English ships should be allowed to come and go unmolested. So for three days the work of dismantling went on in peace, and on the fourth, half-disabled as they were, they were attacked. It was a fierce and bloody fight, and it ended in the sinking of four galleons, the wrecking of the Spanish flag-ship, and the killing of five or six hundred Spaniards.

But on the English side only the Jesus, the Minion, and the Judith got away and, shot-shattered and half-provisioned, began to stagger homeward across the wide Atlantic. On the way the Judith was lost, and took to the bottom with her all the proceeds of many months of trading and fighting and privation.

So the expedition came back poorer than it went,51 and Spain laughed aloud, but, as will be seen, somewhat too soon. Drake got home first, and no sooner did he land at Plymouth than he took horse for London. It so happened that a little while before Spanish ships carrying a huge amount of money to pay Alva’s army in the Netherlands, had been driven into the Thames by the Protestant rovers lately mentioned, and Gloriana, who never liked to let a good thing go, had held on to it on one pretext or another until Drake came hot-footed and angry-hearted to tell of the treachery of Vera Cruz.

Gloriana wanted nothing better. Her buccaneering venture had been a failure and here was a way of paying herself for the two ships she had risked, so she turned upon the Spanish Ambassador and told him point blank that until the injury done to her “honest merchants” was redressed she would hold the treasure in pledge. Naturally after that not a groat of it ever got to Alva or his soldiers.

That year, which was 1569, Drake went to Rochelle with Sir Thomas Wynter. The next summer he married Mary Newman, and a month or two later he was again steering to the westward in two little vessels, the Dragon and the Swan. The next year he went again, with the Swan alone, and this time he came back with a certain idea in his head which was magnificent to the point of absurdity. The adventures of the last two or three years had deepened his contempt for Spanish52 prowess, and now he laughingly proposed to go back, not to kill the goose that laid the King of Spain’s golden eggs, but to rifle the nest in which they were deposited. This was Nombre de Dios, the strongest city in the New World, and the richest to boot.

The means employed were, as was usual in this age of wonders, ridiculously inadequate to the end to which they were devoted. Of late years certain bold mariners have sought to win an ephemeral notoriety by crossing the Atlantic in open boats. Francis Drake set out on a serious and momentous expedition to the Spanish Main in the Pasha of 70 tons followed by the Swan of 25—that is to say in a couple of fishing-boats. These two cockle-shells were manned by seventy-three men all told, only one of whom had reached the age of thirty. It must have looked more like a parcel of lads going afloat on a holiday spree than an expedition with which all the world was soon to ring.

There is no space here to tell of all that befel these absurd adventurers on their devious and tedious way to Nombre de Dios, though no romancer ever imagined such a story as their adventures make. So it must suffice to say that on July 29th he started out across the Isthmus of Darien at the head of seventy-three men to attack a strong city as big as Plymouth, and with these he actually fought his way into the town, established himself in the centre of it and held it for some hours.

53

If his men had been the seasoned buccaneers of his later raids he would probably have taken it altogether, but they unhappily found in the Governor’s house a stack of silver bars twelve feet high, ten feet broad, and seventy feet long. This was a little too much for the nerves of the Devon boys, but Drake would not let them touch it, since the town was not yet theirs. Then a fearful rain-storm came on just about dawn and put out their matches and ruined their bow-strings, and then a terrible misfortune happened. Drake had been severely wounded in the leg, but he had concealed his hurt until the supreme moment came, and then, as he was leading his handful of heroes to the last attack, he went down with his boot full of blood. Something very like a panic now took his men, not for their own sakes but for his. In vain he stormed at them, and cried angrily:

“I have brought you to the door of the Treasure-house of the World! Will ye be fools enough to go away empty?”

“Your life is more precious to us and England than all the gold of the Indies!” they replied, and so by kindly force they carried him down to the boats and rowed away, having accomplished perhaps the most splendid failure in history.

The fame of this exploit instantly echoed through the whole Spanish Main and thence across the Atlantic to Europe. A few days later he avenged his failure at Nombre de Dios by cutting a big ship54 out from under the guns of Cartagena. Then he vanished, leaving no other trace behind him than the poor little abandoned Swan. For the next few months nothing was seen of him, though his hand was felt far and wide along the coast. Spanish store-ships disappeared, dispatch boats were intercepted, and coast-towns were raided with bewildering rapidity and effectiveness.

But all this time the deadly tropical fever was playing havoc with his little handful of men. His brother John died of it, and man after man was struck down till at last, out of the seventy-three who had sailed with him from Plymouth, he could only muster eighteen fighting men when he at length started to plunder the mule-train from Panama.

On the fourth day of the journey a very memorable thing happened, for that noon he reached the top of the dividing ridge of the Isthmus, and lo! there before him, only a few miles away, lay the smooth, shining expanse of the Pacific Ocean, that long-hidden, jealously-guarded sea on which his were the first English eyes that had ever gazed. He did just what such a man would have done in such circumstances. He fell on his knees and, raising his hands to heaven, cried aloud:

“Almighty God, of Thy goodness, give me life and leave once to sail an English ship on yonder sea!”

Years afterwards the prayer was granted, and not55 only did he sail on the Golden Sea, but crossed it while he was making the first voyage that an Englishman ever made round the world.

Were I writing a book instead of an essay I could tell of the plundering of the mule-trains, of the taking of Vera Cruz—where, to the astonishment of the Spaniards, he would not allow a single woman or an unarmed man to be hurt—and Nombre de Dios, which did not resist him so well the second time. It must, however, be enough to say that this time everything ended happily for the remnant that survived, and that on Sunday morning, August 9, 1573, while the good folks of Plymouth were in church, they heard a roar of artillery from the batteries followed by an answering salute from the sea and, straightway quitting their devotions, they ran out to learn the good news that Gloriana’s Little Pirate had come back safe at last and well loaded up with plunder.

His next venture was nothing less than that famous voyage of his round the world, with the fairy-story of which we have here nothing to do save to say that the fame of it, no less than the enormous treasure, the plunder of a hundred ships and a score of towns, with which the poor sea-worn, worm-eaten, wind-weary Golden Hind, staggered one Michaelmas morning into Plymouth Sound, at last convinced Queen Bess that in her dear Little Pirate—whom, by the way, she had never yet openly recognised—she had a champion56 who was worth a good many thousands of King Philip’s soldiers and sailors.

But now the first of Drake’s open rewards was to be his. The Golden Hind was hauled on to the slips at Deptford, and Gloriana and her court dined on board. When the dinner was over she bade her Little Pirate kneel before her, touched him on the shoulder with his own sword and bade him rise Sir Francis Drake. The Spaniards, by the way, had another title for him, no less honourable in his eyes, and this was “the Master-Thief of the New World.”

For some considerable time nothing happened beyond the failure of one or two trifling expeditions—which failure was Gloriana’s fault, and not Drake’s—and the setting of a price of £40,000 by favour of the King of Spain on the Little Pirate’s head—an investment of which Drake was soon to pay the dividend in the craft-crowded harbour of Cadiz.

Meanwhile, matters between England and Spain were going from bad to worse. For a few months unscrupulous intrigue, backed up by wholesale lying, hampered Drake most sorely in the preparation of that great work which was nothing less than the establishment of the sea-power of England. Everything that the fickleness of his mistress, the weathercock support of so-called friends at court, and the still more dangerous machinations of English statesmen in the pay of Spain could do,57 was done. The fleet, to his unutterable rage and disgust, was even placed on a peace-footing, despite the fact that the noise of the Armada’s preparations was still sounding across the Narrow Seas.

But at last, by some means or other, a certain Spanish spy had got himself suspected and stretched on the rack. Now the rack, as an aid to cross-examination, is not an ideal instrument, but it certainly served its purpose this time, for the spy in his torment gave away all the details of a vast scheme which embraced an alliance between France, Spain, and Scotland, together with a general Catholic uprising in England, which was to take place simultaneously with the Triple Invasion.

Never had England, and with her the cause of liberty, stood in such great and deadly peril. Gloriana at last flung diplomatic dalliance to the winds, stopped her lying and chicanery, kicked the Spanish Ambassador out of the country, and let her Little Pirate loose. Yet even now there was another lull before the storm, and this lull Philip took advantage of to invite a fleet of English corn-ships to his ports, where he seized them to feed that ever-growing sea-monster which he was going to pit against El Draque.

This settled the matter. Drake, only half ready for sea, put out with every ship that could move for fear more orders would come to stop him and, with an insolent assurance which augured well for the58 great things that he was about to do, actually ran his ships into Vigo Bay and forced the Spanish Governor to allow him to finish his preparations in Spanish waters. Then he turned his eager prows westward, stopping on the way at the Cape Verde Islands to lay waste Vera Cruz and make Santiago a heap of ashes.

Five years before young William Hawkins had been taken prisoner here and burnt alive with several of his crew, and this was El Draque’s way of wiping out the old score.

Then he sped on again, spent Christmas at Santa Dominica, refitted his ships and refreshed his men, and then fell like a thunderbolt on the famous city of Santo Domingo, the oldest in the Indies, founded by Columbus himself and ruled over by his brother. It was this that the Little Pirate had been preparing for during those other mysterious voyages of his. The blow was as crushing as it was unexpected, and the prestige of Spain in the West never recovered from it. The town was utterly stripped and dismantled by the victors. Fifty thousand pounds in cash, two hundred and forty guns of all calibres, and an immense amount of other spoil was brought away, and the whole fleet, after living at free quarters for a month, sailed southward, completely refitted and re-victualled, as usual, at the Spaniards’ expense.

When the news got to Europe, it was said that Philip had had “such a cooling as he had never59 had since he was King of Spain.” It is both interesting and instructive to learn that not the least part of the booty took the shape of a hundred English sailors who were found toiling as slaves in the Spanish galleys.

Reinforced by these, Gloriana’s Little Pirate crossed the Caribbean Sea and fell on Cartagena, the capital of the Spanish Main, and now the richest city in the Indies. Paralysed by the insolence of the attack, it soon fell under its fury and real strength. The booty was enormous, but the moral effect was still greater. The new-born sea-power of England had vindicated itself with triumphant suddenness, and Drake, having picked up the unfortunate remnants of Raleigh’s colony in Virginia—the time for colonising not having come yet—entered Plymouth Sound again in the Elizabeth Bonaventura at the head of his loot-laden fleet, and reported his arrival, piously regretting that on the way home he had missed the Spanish plate-fleet by twelve hours “for reasons best known to God.”