Title: Flytraps and Their Operation [1921]

Author: F. C. Bishopp

Release date: September 18, 2020 [eBook #63226]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tom Cosmas from files generously made available

by USDA through The Internet Archive. All resultant

materials are placed in the Public Domain.

Entomologist, Investigations of Insects Affecting the

Health of Animals

FARMERS' BULLETIN 734

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

Contribution from the Bureau of Entomology

L. O. HOWARD, Chief

Washington, D. C. |

Issued June 10, 1916; second revision, March, 1921. |

Show this bulletin to a neighbor. Additional copies may be obtained free from the Division of Publications, United States Department of Agriculture

RESULTS obtained in experiments with the use of chemicals against fly larvæ in manure are presented in Bulletins Nos. 118, 245, and 408 of the Department of Agriculture. The biology of the house fly and the various methods of control are discussed in Farmers' Bulletin 851.

This bulletin is intended to give directions for the use of a supplementary means of controlling flies. It is adapted to all parts of the United States.

| Page. | |

| Uses and limitations of flytraps | 3 |

| Kinds of flies caught | 3 |

| Types of traps | 4 |

| Trapping the screw-worm fly | 13 |

| Baits for traps | 13 |

| Bait containers | 15 |

| Care and location of traps | 15 |

| Sticky fly papers | 16 |

| Poisoned baits | 16 |

| Caution | 16 |

FLYTRAPS have a distinct place in the control of the house fly and other noxious fly species. There is a general tendency, however, for those engaged in combating flies to put too much dependence on the flytrap as a method of abating the nuisance. It should be borne in mind that flytrapping is only supplementary to other methods of control, most notable of which is the prevention of breeding either by completely disposing of breeding places or by treating the breeding material with chemicals.

It may be said that there are two main ways in which flytraps are valuable: (1) By catching flies which come to clean premises from other places which are insanitary and (2) by capturing those flies which invariably escape in greater or less numbers the other means of destruction which may be practiced. Furthermore, the number of flies caught in traps serves as an index of the effectiveness of campaigns against breeding places.

Flytrapping should begin early in the spring if it is to be of greatest value. Although comparatively few flies are caught in the early spring, their destruction means the prevention of the development of myriads of flies by midsummer.

The various species of flies which are commonly annoying about habitations or where foodstuffs are being prepared may be divided roughly into two classes: (1) Those which breed in animal matter, consisting mainly of the so-called blowflies, including the screw-worm fly;[1] and (2) those which breed in vegetable as well as in animal matter. [ 4 ] In the latter group the house fly[2] is by far the most important. The stable fly is strictly a vegetable breeder, as are also certain other species which occasionally come into houses and in rare cases may contaminate foodstuffs. The stable fly,[3] which breeds in cow manure or decaying vegetable matter, and the horn fly,[4] which breeds in manure, are blood-sucking species, and can be caught in ordinary flytraps in comparatively small numbers only. The kind of flies caught depends to a considerable extent on the material used for bait. In general the house fly and other species which breed in vegetable matter are attracted to vegetable substances, while the blowflies will come most readily to animal matter. This rule, of course, is not absolute, as flies are less restricted in feeding than in breeding habits, and, as is well known, the house fly is attracted to a greater or less extent to any moist material, especially if it has an odor.

[1] Chrysomyia macellaria Pab.

[2] Musca domestica L.

[3] Stomoxys calcitrans L.

[4] Lyperosia irritans L.

The same general principle is involved in nearly all flytraps in use, though superficially they may appear quite different. The flies are attracted into a cage, as it were, by going through a passage the entrance of which is large and the exit small, so that there is little chance of the flies, once in, finding their way out again. This principle is modified to fit different conditions. For instance, the window trap, devised by Prof. C. F. Hodge, catches the flies as they endeavor to enter or leave a building; the garbage-can trap, for which Prof. Hodge is also to be credited, catches the flies that have entered garbage cans; and the manure-box trap retains the flies bred from infested manure put into the box.

The attractant used to induce flies to enter traps may consist of (1) food, as in baited traps; (2) odors, as in window traps placed in windows from which odors are emitted; and (3) light, as in traps on manure boxes. Of course, light is an important factor in the success of all traps, for, as is well known, flies have a marked tendency to go toward the light, and they usually enter the trap by flying toward the light after having been attracted beneath it by bait or after entering a room in search of food.

A number of traps of this general type are on the market, but most of these are of small size. Nearly all are constructed with a dome instead of a cone, and on this account the catching power is reduced about one-third. Moreover, the farmer, dairyman, or anyone with a few tools can construct traps at a small fraction of the sale price of ready-made ones.

A trap which appears from extensive tests made by Mr. E. W. Laake and the author to be best for effective trapping, durability, ease of construction and repair, and cheapness may be made as follows:

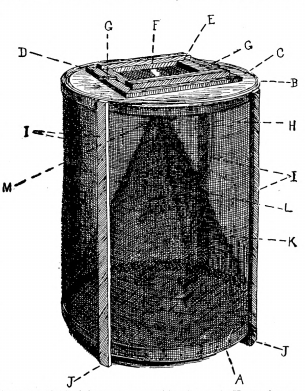

The trap consists essentially of a screen cylinder with a frame made of barrel hoops, in the bottom of which is inserted a screen cone. The height of the cylinder is 24 inches, the diameter 18 inches, and the cone is 22 inches high, and 18 inches in diameter at the base. Material necessary for this trap consists of four new or secondhand wooden barrel hoops, one barrel head, four laths, 10 feet of strips 1 to 1½ inches wide by one-half inch thick (portions of old boxes will suffice), 61 linear inches of 12 or 14 mesh galvanized screening 24 inches wide for the sides of the trap and 41 inches of screening 26 inches wide for the cone and door, an ounce of carpet tacks, and two turn-buttons, which may be made of wood. The total cost of the material for this trap, if all is bought new at retail prices, is about $1. In practically all cases, however, the barrel hoops, barrel head, lath, and strips can be obtained without expense. This would reduce the cost to that of the wire and tacks, which would be 80 cents. If a larger number of traps are constructed at one time, the cost is considerably reduced.

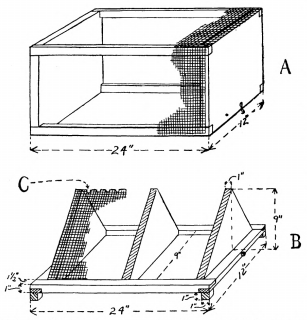

One of these traps is illustrated in figures 1 and 2. In constructing the trap two of the hoops are bent in a circle (18 inches in diameter on the inside), and nailed together, the ends being trimmed to give [ 6 ] a close fit. These form the bottom of the frame (A), and the other two, prepared in a similar way, the top (B). The top (C) of the trap is made of an ordinary barrel head with the bevel edge sawed off sufficiently to cause the head to fit closely in the hoops and allow secure nailing. A square, 10 inches on the side, is cut out of the center of the top to form a door. The portions of the top (barrel head) are held together by inch strips (D) placed around the opening one-half inch from the edge to form a jamb for the door. The door consists of a narrow frame (E) covered with screen (F) well fitted to the trap and held in place (not hinged) by buttons (G). The top is then nailed in the upper hoops and the sides (H) formed by closely tacking screen wire on the outside of the hoops. Four laths (I) (or light strips) are nailed to the hoops on the outside of the trap to act as supports between the hoops, and the ends are allowed to project 1 inch at the bottom to form legs (J). The cone (K) is cut from the screen and either sewed with fine wire or soldered where the edges meet at (L), or a narrow lath may be nailed along these edges. The apex of the cone is then cut off to give an aperture (M) 1 inch in diameter. It is then inserted in the trap and closely tacked to the hoop around the base.

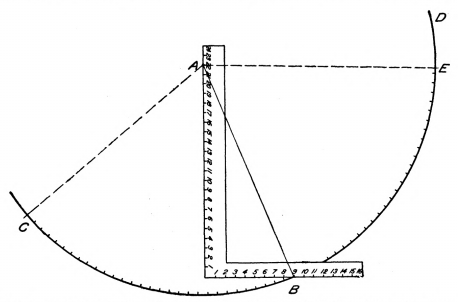

The construction of a cone of any given height or diameter is quite simple if the following method be observed. It is best to cut a pattern from a large piece of heavy paper, cardboard, or tin, Figure 3 illustrates the method of laying out a cone of the proper dimensions for the above trap. An ordinary square is placed on the material from which the pattern is to be cut; a distance (22 inches) equal to the height of the cone is laid off on one leg of the square at A, and a distance (9 inches) equal to one-half of the diameter of the base of the cone is laid off on the other leg at B, and a line is drawn between the points A and B. With the distance between these points as a radius and with the point A as a center, the portion of a circle, C D, is drawn. With a pair of dividers, the legs of which are set 1 inch apart, or with the square, lay off as many inches on the arc C D, starting at C, as there are inches around the base of the cone, which in this case is about 56½ inches, reaching nearly to the point E. Then add one-half inch for the lapping of the edges of the cone, and one-half inch which is taken up when the cone is tacked in, thus making a total distance from C to E of 57½ inches. Draw a line from A to C and another from A to E, and cut out the pattern on these lines and on the arc from C to as shown in figure 3. The edges AC and AE are then brought together, lapped one-half inch, and sewed with wire or soldered. After the aperture of the cone is formed by cutting off the apex, as previously described, it is ready for insertion in the trap.

In order to figure the distance around the base of a cone of any given diameter multiply the diameter by 3.1416 or 31⁄7.

The height of the legs of the trap, the height of the cone, and the size of the aperture in the top of the cone, each are of importance in securing the greatest efficiency.

A modification of the previously described trap has been made by Mr. D. C. Parman of the Bureau of Entomology. The principal point of advantage in this type is that it can be made more quickly and with fewer tools. The principles and dimensions are the same, the most striking difference being the absence of a wooden top. A single hoop with the thick edge down forms the upper frame of the cylinder and the entire top is made of screen. A circular piece of screen with a diameter about 3 inches greater than the diameter of the cylinder is cut; a hoop with a diameter equal to the inside of the top of the trap is then made of heavy wire and laid upon the disk of screen and the edges of the screen bent in over it. By folding in and crimping the edges of the wire over the wire hoop it will remain in position without difficulty and the edges of the screen disk are used to lift the top of the trap out for emptying flies. It is important to have the screen top fit the inside of the cylinder very snugly at all points. If there is any space left where flies can escape it is a good plan to bind the edge of the top with a strip of burlap. This not only helps to close the openings but keeps the hoop in place and aids in removing the top. Another difference is that the screen forming the sides of the cylinder is placed on the inside of the hoops and legs, the frame being built first and then the cylinder formed by tacking the wire on the inside of the hoops and nailing in along the upright strips and against the wire short pieces of laths with their upper ends against the lower edge of the hoop forming the top of [ 9 ] the trap and extending downward along the legs about two-thirds of their length. These strips hold the wire in place and give rigidity to the trap, and they are thick enough to project beyond the inner surface of the hoop and form a support upon which the edges of the screen top rest.

Conical traps with steel frames are satisfactory, but they are less easily rescreened. These, of course, can be constructed only by shops with considerable equipment. Traps constructed with a wooden disk about the base of the cone, and a similar disk around the top to serve as a frame, or those with a square wooden frame at the bottom and top, with strips up the corners, are fairly satisfactory. It should be borne in mind that the factor which determines the number of flies caught is the diameter of the base of the cone, if other things are equal. Therefore the space taken up by the wooden framework is largely wasted, and if it is too wide it will have a deterrent effect on the flies which come toward the bait. For this reason it is advisable that the wood around the base of the cone should be as narrow as consistent with strength—usually about 3 inches.

Under no condition should the sides or top of the trap be of solid material, as the elimination of light from the top or sides has been found to decrease the catch from 50 to 75 per cent.

The tent form of trap has been widely advocated in this country, but recent experiments indicate that it is much less efficient than the cone trap, and usually as difficult to construct and almost as expensive. The size of these traps may vary considerably, but one constructed according to the dimensions given in figure 4 will be found most convenient. The height of the tent should be about equal to the width of the base, and the holes (C) along the apex of the tent should be one-half to three-fourths of an inch in diameter and 1 inch apart. The box (A) should be provided with hooks to pass through the eyes on the base (B). Small blocks 1 inch thick are nailed beneath the corners of the tent frame to serve as legs.

As previously mentioned. Prof. Hodge has adapted the cone trap to use on the lids of garbage cans. It is not advisable to use this trap except where garbage cans are sufficiently open to admit flies. In such cases a hole may be cut in the lid of the can and one of the small balloon traps which are obtainable on the market attached over the hole. To make the trap effective the edges of this lid should extend well down over the top of the can. The lid should be held up slightly so as to allow the flies to pass under, but not high enough to admit direct light. Practically speaking, the garbage forms the bait for this trap, and when inside the can the flies are attracted to the light admitted through the trap. It is really advisable to have the garbage cans fly proof, so as to prevent danger of fly breeding within [ 10 ] them rather than to depend on traps on the lids, which necessarily allow odors to escape. A garbage can with a trap attached is illustrated in figure 5.

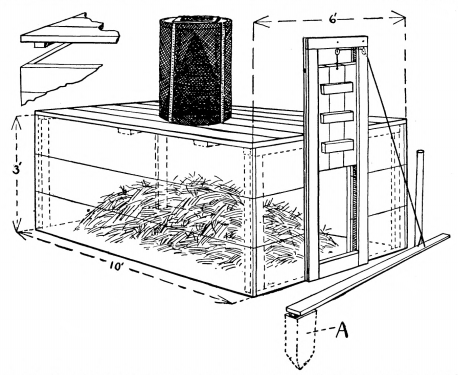

Manure pits or boxes are desirable for the temporary storage of manure, especially in towns and cities. These have been widely advocated, but the difficulty has been that manure often becomes infested before it is put into them, and flies frequently breed out before the boxes are emptied and often escape through the cracks. To obviate these difficulties a manure box or pit, with a modified tent trap or cone trap attached, is desirable. Mr. Arthur Swaim, of Florida, has devised a form of manure trap consisting of a series of screen tents with exit holes along the ridges of these, over which is a screen box. The latter retains the flies as they pass through the holes in the tents. The entire trap is removable.

In order to retain the fertilizing value of manure to the greatest extent it is advisable to exclude the air from it as much as possible and to protect it from the leaching action of rains. This being the case, there is really no necessity to cover a large portion of the top of the box with a trap, but merely to have holes large enough to attract flies to the light, and cover these holes with ordinary conical traps, with the legs cut off, so the bottom of the trap will fit closely to the box. The same arrangement can be made where manure is kept in a pit. In large bins two or more holes covered with traps should be provided for the escape of the flies.

Manure boxes should be used by all stock owners in towns and cities, and they are also adaptable to farms. The size of the manure bin should be governed by the individual needs, but for use on the farm it is desirable to make it large enough to hold all of the manure produced during the busiest season of the year. A box 14 feet long, 10 feet wide, and 4 feet deep will hold the manure produced by two horses during about five months. About 2 cubic feet of box space should be allowed for each horse per day. The bin should be made of concrete or heavy plank. When the latter is used the cracks should be battened to prevent the escape of flies. The bin may have a floor or it may be set in the ground several inches and the dirt closely [ 11 ] banked around the outside. For the admission of the manure a good-sized door should be provided in either end of a large bin. A portion of the top should be made easily removable for convenience in emptying the box, or one entire end of the box may be hinged. On account of the danger of the door being left open through carelessness, it is advisable to arrange a lift door which can be opened by placing the foot on a treadle as the manure is shoveled in. The door should be heavy enough to close automatically when the treadle is released. A manure bin with flytrap attached is shown in figure 6.

Attention is directed to a maggot trap devised by Mr. R. H. Hutchison, as described in Farmers' Bulletin 851 of the Department of Agriculture. Where large quantities of manure are produced on a farm this method of storing the manure on a platform and trapping the maggots which breed out may be more convenient than the manure bin.

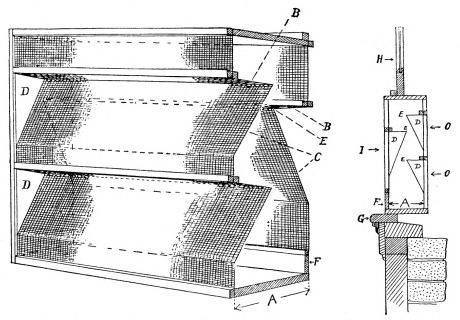

Prof. C. F. Hodge has designed a trap which is really a modified tent trap adapted to use in a window. This trap is constructed so as to catch the flies as they enter or leave through the window. It is adaptable to barns which are fairly free from cracks or other places where flies may enter. It may also be used on windows of buildings where foodstuffs are prepared and where flies endeavor to enter through the windows or escape after having gained entrance through [ 12 ] other passageways. All openings not provided with traps should be closely screened, and on large buildings traps may be installed in every third window.

This trap is essentially a screen box closely fitted to the frame of a window (see fig. 7). The thickness of the box at A should be about 12 inches. Instead of the screen running straight down over the box on either side it is folded inward nearly to the center of the frame in V-shaped folds running longitudinally across the window. One, two, or even more folds may be made in the screen on either side. The upper side of the fold B should extend toward the center almost at right angles with the side of the trap—that is, parallel with the top and bottom; and the lower side C should slant downward as shown in the drawing. The sides of the frame may be cut out at the proper angle and the pieces D returned after the screen has been tacked along the edges. Along the apex (inner edge) of each fold is punched a series of holes E about one-half inch in diameter and 1 inch apart. The apices of the folds on either side of the window should not be directly opposite. A narrow door F opening downward on hinges should be made on one side of the trap at the bottom for removal of the dead flies. The entire trap is fastened to the window by hooks so that it may be readily taken off. An additional trapping feature may be added by providing a tent trap fitted in the bottom of the box. A narrow slit is left along the base to allow the [ 13 ] flies to enter beneath the tent. Bait may be placed under the tent to attract the flies.

It has been found that the use of these window traps will aid in protecting animals in barns from stable flies and mosquitoes, and in some cases horseflies and other noxious species are caught. They tend to exclude the light, however, and are somewhat cumbersome, especially in thin-walled buildings.

[5] Chrysomyia macellaria Fab.

Recent efforts to reduce the loss to the live-stock industry of the Southwest resulting from the ravages of the screw-worm have directed attention to the employment of flytraps in this work.

Mention has been made of the importance of preventing the breeding of flies as a prerequisite to effective control. This is equally true of the screw-worm and other blowflies, which attack animals, and of the house fly. In the case of these blowflies main dependence must be placed on the complete and prompt burning of all carcasses and animal refuse.

Experiments conducted in the range sections of Texas indicate that traps properly baited and set are of material aid in preventing screw-worm injury to live stock. It is advised that at least one trap be maintained on each section of land. These should be located preferably near watering places and where cattle congregate, especially in the so-called "hospital traps," where the screw-worm-infested animals are kept for treatment.

The conical-type traps as described are advised. The traps should be set on a board platform about 2 feet square, securely fastened to a tree or on a post where the trap and bait will be the least disturbed by stock or wild animals.

During the latter half of one season over 100 gallons of flies, the vast majority of which were screw-worm flies, were captured in about 25 traps operated on a ranch in west Texas.

The question of the baits best adapted for this species and other points in regard to the operation of the traps are briefly discussed under subsequent headings.

The problem of selecting the best bait for flies is an important one. In choosing a bait it should be remembered that it is largely the fermentation which renders the material attractive, and that baits are most attractive during their most active period of fermentation. As has been indicated, the kind of bait used should be governed by the species of flies the destruction of which is desired. This is most often the house fly.

Experiments conducted indicate that a mixture of cheap cane molasses ("black-strap") and water is among the most economical and effective baits for the house fly. One part of molasses is mixed [ 14 ] with three parts of water. The attractiveness becomes marked on the second or third day.

Sugar-beet or "stock molasses," which is very cheap, especially in regions where produced, when mixed in the foregoing proportions, is fairly attractive.

On dairy farms, probably milk is the next choice as a bait to cane-molasses solution, considering its convenience. The curd from milk, with about one-half pound of brown sugar added to each pound and water to make it thoroughly moist, is a very good bait and continues to be attractive for 10 days or more if kept moist. A mash of bran made quite thin with a mixture of equal parts of water and milk and with a few tablespoonfuls of brown sugar and cornstarch and a yeast cake added makes an attractive and lasting bait. During hot weather stirring the old bait or adding fresh is a daily necessity if best results are to be secured.

Sirup made by dissolving 1 part of ordinary brown sugar in 4 parts of water and allowing the mixture to stand a day or two to induce fermentation is almost equal to the molasses and water as a fly bait. If it is desirable to use the sirup immediately after making it, a small amount of vinegar should be added. Honeybees are sometimes caught in large numbers at this bait. When this happens some of the other baits recommended should be used.

With the baits before mentioned comparatively few blowflies will be caught. For use about slaughterhouses, butcher shops, and other places where blowflies are troublesome, it has been determined that the mucous membranes which form the lining of the intestines of cattle or hogs are without equal as a bait. This material, which is commonly spoken of as "gut slime," can be obtained from packing houses where sausage casings are prepared. The offensive odor of this bait renders its use undesirable very near habitations or materials intended for human consumption.

For use under range conditions experiments are underway with dried gut slime. This material is giving satisfaction as a screw-worm fly attractant and is easily carried, being in a highly concentrated form. The flaky material is placed in the bait pans and water added at the rate of 1 part slime to 10 or 20 parts water, after which the mixture is thoroughly stirred.

Another packing-house product known as blood tankage is a good fly bait when used with molasses and water. This combination results in the capture of a large percentage of house flies. Where these materials are not obtainable fairly good catches will result from the use of fish scraps or meat scraps. With any of these baits the catches will be found not to be entirely meat-infesting flies, as actual counts have shown that the percentage of house flies in traps over such baits ranges from 45 to 75.

Overripe or fermenting fruit, such as watermelon rinds or crushed bananas, placed in the bait pans sometimes gives satisfactory results. [ 15 ] A combination of overripe bananas with milk is much more attractive than either one used separately. A considerable number of blowflies as well as house flies are attracted to such baits.

The size of the bait container in relation to the size of the trap is a very important consideration. It has been found that a small pan or deep pan of bait set in the center under a trap will catch only a small fraction of the number of flies secured by using larger, shallow containers. The best and most convenient pan for baits is a shallow circular tin, such as the cover of a lard bucket. Under range conditions it is advisable to use a more substantial bait pan and preferably one 1½ inches deep, so that a greater amount of bait may be used, thus preventing complete drying out between visits to the trap. Its diameter should be about 4 inches less than that of the base of the trap, thus bringing the edge within 2 inches of the outside edge of the trap. For liquid baits the catch can be increased slightly by placing a piece of sponge or a few chips in the center of the bait pan to provide additional surface upon which the flies may alight. The same kind of pans for bait may be used under tent traps. Two or more pans should be used, according to the length of the trap.

In many cases flytrapping has been rendered ineffectual by the fact that the traps were not properly cared for. In setting traps a location should be chosen where flies naturally congregate. This is usually on the sunny side of a building out of the wind. It is exceedingly important that the bait containers be kept well filled. This usually requires attention every other day. The bait pans should be washed out at rather frequent intervals. This gives a larger catch and avoids the danger of flies breeding in the material used for bait. Further, it should be borne in mind that traps can not be operated successfully throughout the season without emptying them. Where flies are abundant and the bait pans are properly attended to the traps should be emptied at weekly intervals. Where flies become piled high against the side of the cone the catching power of the trap is considerably reduced. The destruction of the flies is best accomplished by immersing the trap in hot water or, still better, where a tight barrel is at hand place a few live coals in a pan on the ground, scatter two tablespoonfuls of sulphur over them, place the trap over the coals, and turn the barrel over the trap. All of the flies will be rendered motionless in about five minutes. They may then be killed by using hot water, throwing them into a fire, or burying them. In the operation of flytraps in controlling the screw-worm it has not been found necessary, especially during hot weather, to kill the flies, as they die very rapidly within the traps. In order to empty a trap it may be inverted and the dead flies shaken down. As the living flies will naturally go upward, the door may [ 16 ] then be removed and the dead flies shaken out, the door replaced, and the trap set upright without loss of many of the living flies.

Sticky fly papers are of some value in destroying flies which have gained access to houses, but they have marked limitations and numerous objectionable features. For use out of doors traps are much more effective and economical.

Dr. Crumbine, of the Kansas State Board of Health, gives the following method for preparing fly paper:

"Take 2 pounds of rosin and 1 pint of castor oil, heat together until it looks like molasses. Take an ordinary paint brush and smear while hot on any kind of paper—an old newspaper is good—and place several about the room. A dozen of these may be made at a cost of 1 cent."

The question of destruction of flies with poisons is somewhat out of place here, but the close relationship of poisoned baits to trapping warrants a brief statement.

Probably the best poisoned bait for house flies is formaldehyde in milk used at the rate of about two teaspoonfuls of formaldehyde to a pint of a mixture of equal parts of milk and water. This is placed in flat dishes in places frequented by flies. A piece of bread or a sponge in the dish adds to the effectiveness. Brown sugar or molasses and water with 2½ per cent formaldehyde (commercial, 40 per cent solution) added will probably also give satisfactory results. As far as possible other liquids should be removed when poisoned baits are exposed.

The use of poison solutions, especially arsenical solution in tubs containing portions of animal carcasses, has been tried and advocated against the screw-worm by a number of stockmen. A comparatively weak poison solution—about 1 gallon of dip, diluted for use on cattle, to 7 gallons of water—is sufficient. Best results usually have been secured where a considerable portion of the animal matter was allowed to protrude from the poison solution, as there is a tendency for the solution to harden the bait and prevent its decomposition, thus reducing its attraction for flies.

It should be borne in mind that formaldehyde, 40 per cent, is poison about in the same proportion as wood alcohol, if taken internally. It should not be inhaled, nor should the eyes be unduly exposed to it. Special pains should be taken to prevent children from drinking poisoned baits and to prevent the poisoned flies from dropping into foods or drinks. Arsenical solutions, as is well known, are extremely poisonous to man and animals. Care should be taken to protect the poisoned baits from lire stock and it is not advisable to have the baits close to barnyards where fowls are kept, as they may be poisoned by eating the dead flies.

Transcriber Note

Minor typos have been corrected. Illustrations were moved to prevent splitting paragraphs. Produced from files generously made available by USDA through The Internet Archive. All resultant materials are placed in the Public Domain.