THE

SEXUAL LIFE OF WOMAN

IN ITS

PHYSIOLOGICAL, PATHOLOGICAL AND HYGIENIC ASPECTS

Title: The sexual life of woman in its physiological, pathological and hygienic aspects

Author: E. Heinrich Kisch

Translator: Eden Paul

Release date: September 23, 2020 [eBook #63274]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Turgut Dincer, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The sexual life of woman—the appearance of the first indications of sexual activity, the development of that activity and its culmination in sexual maturity, the decline of that activity and its ultimate extinction in sexual death—the entire process of the most perfect work of natural creation—has throughout all ages kindled the inspiration of poets, aroused the enthusiasm of artists, and supplied thinkers with inexhaustible material for reflection.

In the following pages, this sexual life of woman will be considered both in relation to the female genital organs, and in relation to the feminine organism as a whole; in relation both to the physical and to the mental development of the individual; and in relation alike to the state of health and to the processes of disease. Thus from the standpoint of clinical investigation and of practical experience, the book will be a contribution towards the solution of the sexual problem, nowadays recognized as one of supreme importance.

It is thirty years since I published a work on the histological changes that occur in the ovaries during the climacteric period (Archiv. für Gynecologie, Vol. xii, Section 3); and ever since that time, the influence exerted upon the general health of women by the physiological and pathological processes occurring in their reproductive organs, has been to me a favourite subject for observation and experiment. The result of these studies is incorporated in my monographs, “The Climacteric Period in Women” (Erlangen, 1874), “Sterility in Women” (2nd Ed., Vienna, 1895), “The Uterus and the Heart” (Leipzig, 1898), and in various contributions to medical periodicals. I now have a welcome opportunity of drawing a general picture of sexual activity in women, and of illuminating this picture both by the light of my own experience and by numerous references to the works of other authors. In passing, I have devoted considerable attention to questions of education and personal hygiene, both of which are greatly influenced by the processes of the sexual life. Thus, I hope, the work will be rendered more interesting to the physician, and the general picture it is intended to convey will be more fully characterized by contemporary actuality.

Natural divisions of the subject are, I consider, furnished by the three great landmarks of the sexual life of woman: the onset of menstruation—the menarche: the culmination of sexual activity—the vimenacme; and the cessation of menstruation—the menopause. These several sexual epochs are differentiated by characteristic anatomical states of the reproductive organs, by the external configuration of the feminine body, by functional effects throughout the entire organism, and, finally, by pathological disturbances of the normal vital processes.

Thus in separate chapters a description is given of sexual processes, a detailed exposition of which will be vainly sought in the textbooks of gynecology, yet which are none the less of far-reaching importance in relation to the physical, mental, and social well-being of women, and in relation also to the development of human society; such topics are, the sexual impulse, copulation, fertility, sterility, the employment of means for the prevention of conception, the determination of sex, sexual hygiene. To the topics of pregnancy, parturition, lying-in, and lactation, since these are adequately discussed in works on midwifery, but little space has here been allotted.

It is my earnest hope that physicians and biologists may derive benefit from the book equal in amount to the pleasure I have gained in the work of writing it.

| PAGE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Sexual Life of Woman—Introduction | 1 | |||

| I. | The Sexual Epoch of the Menarche | 37 | ||

| First Appearance of Menstruation | 45 | |||

| Anatomical Changes in the Female Genital Organs at the Period of the Menarche | 50 | |||

| Menarche Praecox et Tardiva | 78 | |||

| Precocious and Retarded Menstrual Activity | 78 | |||

| Pathology of the Menarche | 82 | |||

| Anomalies of Menstruation | 83 | |||

| Inflammatory Processes | 87 | |||

| Disorders of Haematopoiesis | 89 | |||

| Cardiac Disorders | 94 | |||

| Diseases of the Nervous System | 99 | |||

| Masturbation | 104 | |||

| Disorders of Digestion | 107 | |||

| Diseases of the Respiratory Organs | 107 | |||

| Diseases of the Organs of the Senses | 108 | |||

| Hygiene during the Menarche | 111 | |||

| Menstruation | 128 | |||

| Pathology of Menstruation | 143 | |||

| Amenorrhœa, Menorrhagia, and Dysmenorrhœa | 160 | |||

| Vicarious Menstruation | 164 | |||

| The Sexual Impulse | 166 | |||

| Nymphomania, Anæsthesia and Psychopathia Sexualis | 184 | |||

| II. | The Sexual Epoch of the Menacme | 200 | ||

| Anatomical Changes in the Female Genital Organs in the Period of the Menacme | 209 | |||

| Pathology of the Menacme | 218 | |||

| Dyspepsia Uterina | 227 | |||

| Cardiopathia Uterina | 235 | |||

| Nervous Diseases Secondary to Diseases of the Genital Organs | 243 | |||

| Competence for Marriage of Women suffering from Disease | 250 | |||

| Hygiene during the Menacme | 261 | |||

| Copulation and Conception | 284 | |||

| Copulation | 284 | |||

| Conception | 304 | |||

| Pathology of Copulation | 323 | |||

| Vaginismus | 337 | |||

| Cardiac Troubles Due to Sexual Intercourse | 344 | |||

| Dyspareunia | 347 | |||

| Fertility in Women | 363 | |||

| The Restriction of Fertility and the Use of Means for the Prevention of Pregnancy | 388 | |||

| The Determination of Sex | 420 | |||

| I. Statistical Investigations | 422 | |||

| II. Anatomical Investigations | 446 | |||

| III. Experimental Investigations | 452 | |||

| Sterility in Women | 462 | |||

| Incapacity for Ovulation | 470 | |||

| Interference with Conjugation, Conditions Preventing Access of the Spermatozoa to the Ovum | 487 | |||

| Diseases of the Ovaries and the Fallopian Tubes | 489 | |||

| Diseases of the Uterus | 494 | |||

| Pathological Changes in the Cervix Uteri | 501 | |||

| viii | Displacements of the Uterus | 515 | ||

| Myoma of the Uterus | 523 | |||

| Diseases of the Vagina and the Vulva | 526 | |||

| Secretions of the Genital Organs | 528 | |||

| A. Absolute | 540 | |||

| B. Relative Sterility | 540 | |||

| Sexual Sensibility in Women | 542 | |||

| Incapacity for Incubation of the Ovum | 549 | |||

| Only-Child-Sterility | 561 | |||

| Operative Sterility | 563 | |||

| Table Showing the Causes of Sterility in Women | 569 | |||

| III. | The Sexual Epoch of the Menopause | 571 | ||

| The Menopause | 571 | |||

| Changes in the Female Reproductive Organs at the Menopause | 583 | |||

| The Time of the Menopause | 593 | |||

| The Age at which the Menopause occurs | 593 | |||

| 1. Race | 594 | |||

| 2. The Age at which the Menarche Occurred | 595 | |||

| 3. The Woman’s Sexual Activity | 597 | |||

| 4. The Social Circumstances of the Woman’s Life | 599 | |||

| 5. General Constitutional and Pathological Conditions | 599 | |||

| 6. Premature, Delayed, and Sudden Onset of the Menopause | 600 | |||

| Pathology of the Menopause | 608 | |||

| Diseases of the Genital Organs | 608 | |||

| Diseases of the Organs of Circulation | 620 | |||

| Diseases of the Digestive Organs | 630 | |||

| Diseases of the Skin | 632 | |||

| Disorders of Metabolism | 635 | |||

| Diseases of the Nervous System | 637 | |||

| Climacteric Psychoses | 643 | |||

| Hygiene during the Menopause | 653 | |||

| Fig. | Page | |

|---|---|---|

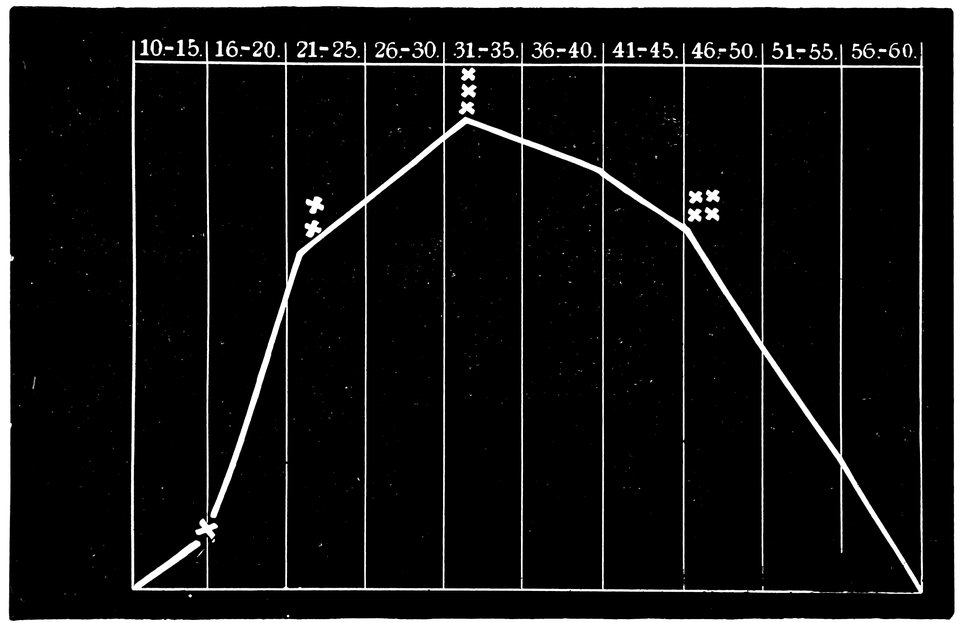

| 1. | Curve of the sexual life of woman from the tenth to the sixtieth year of life | 4 |

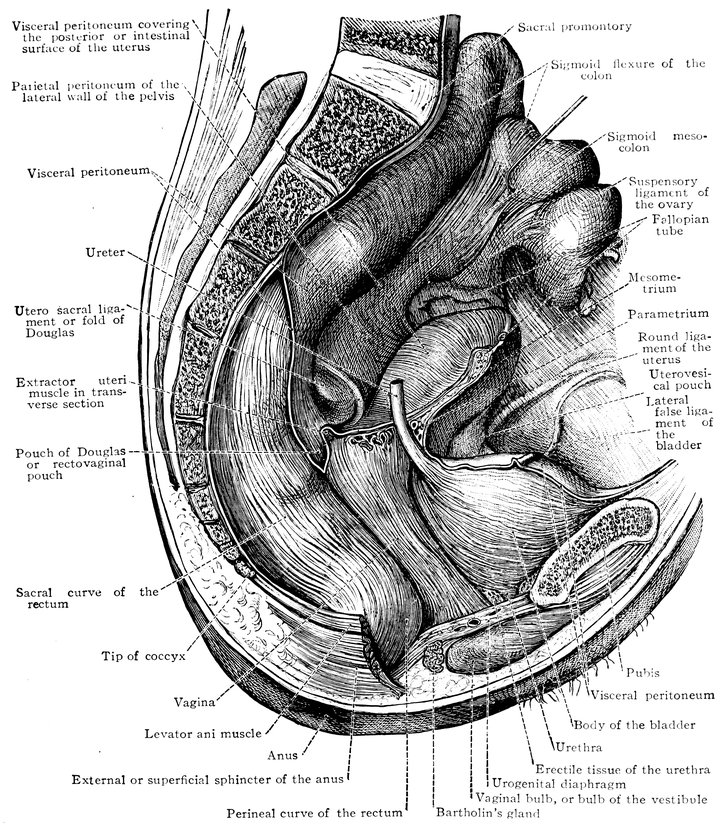

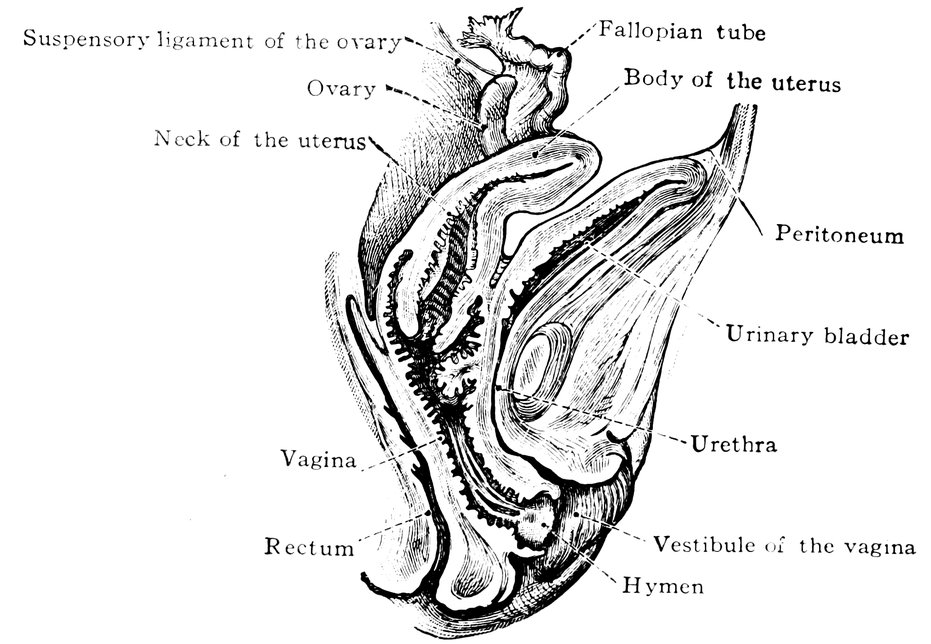

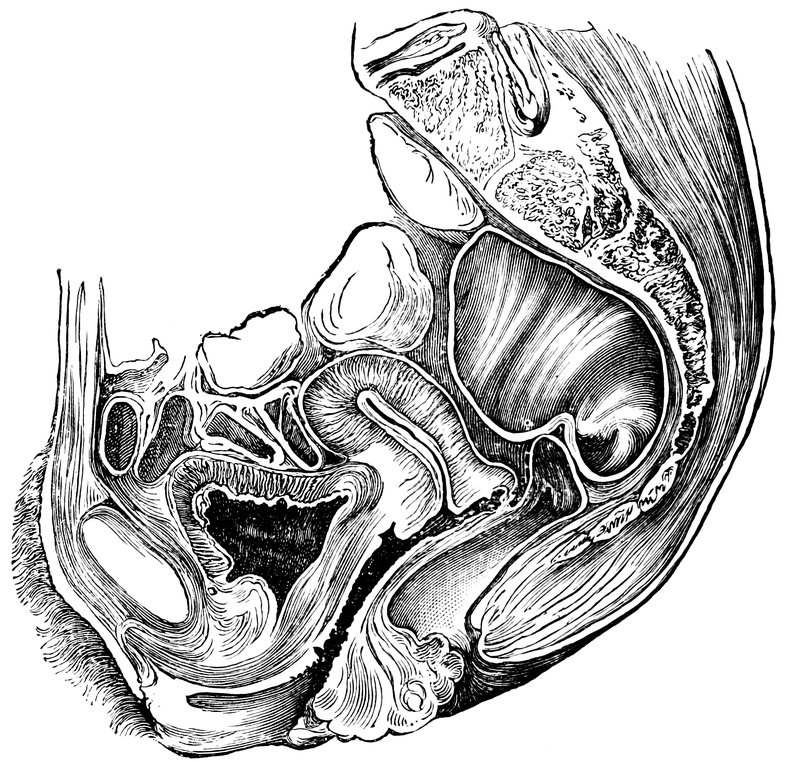

| 2. | Portion of the pelvic viscera in the female, etc. | 9 |

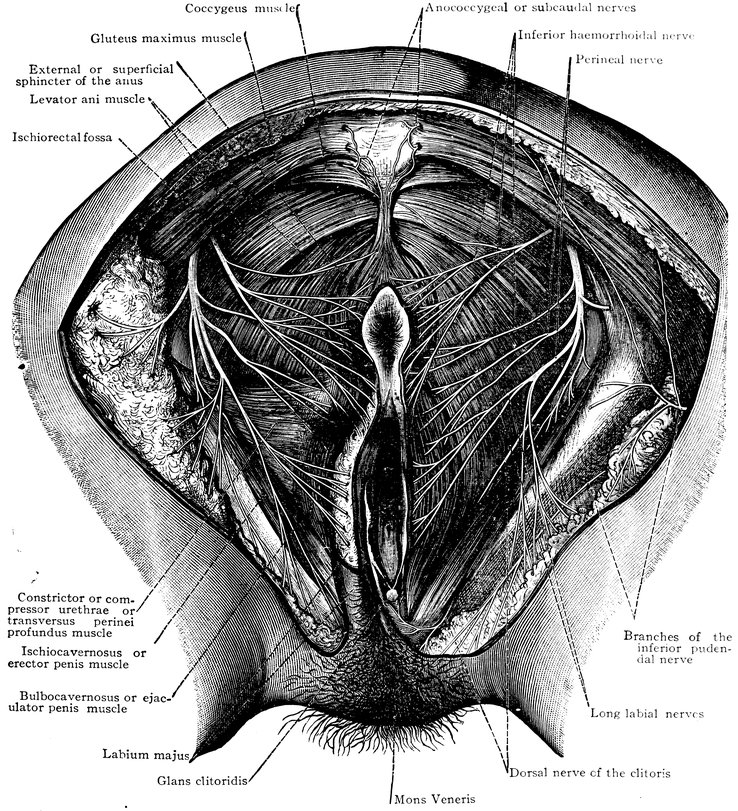

| 3. | The distribution of the pudic nerve in the female perineal and pubic regions | 11 |

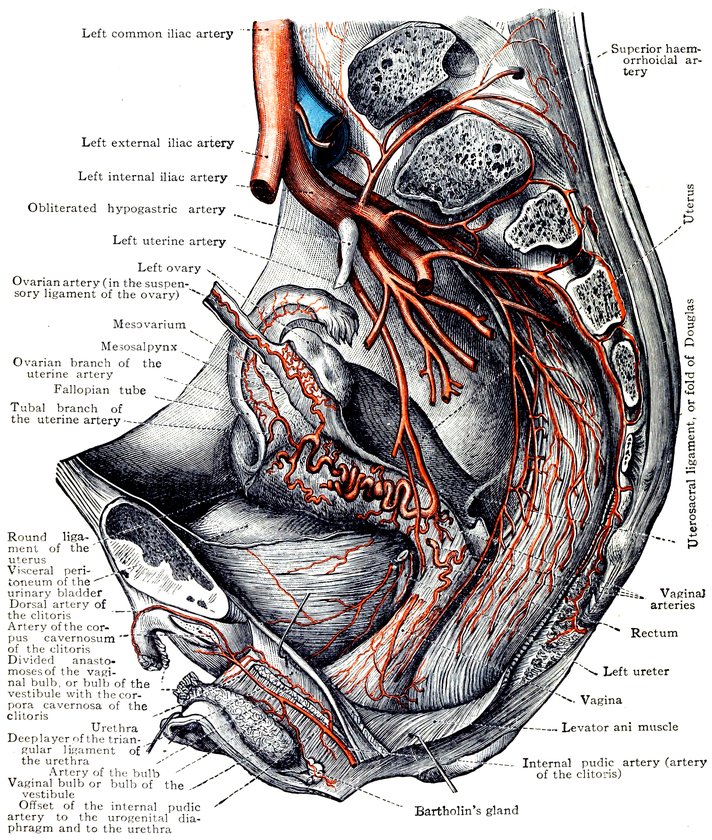

| 4. | The distribution of the lateral sacral arteries, etc. | 14 |

| 5. | Curve of menstrual cycle | 19 |

| 6. | Curve of rhythmical variations | 20 |

| 7. | Curve of beauty of woman. | 24 |

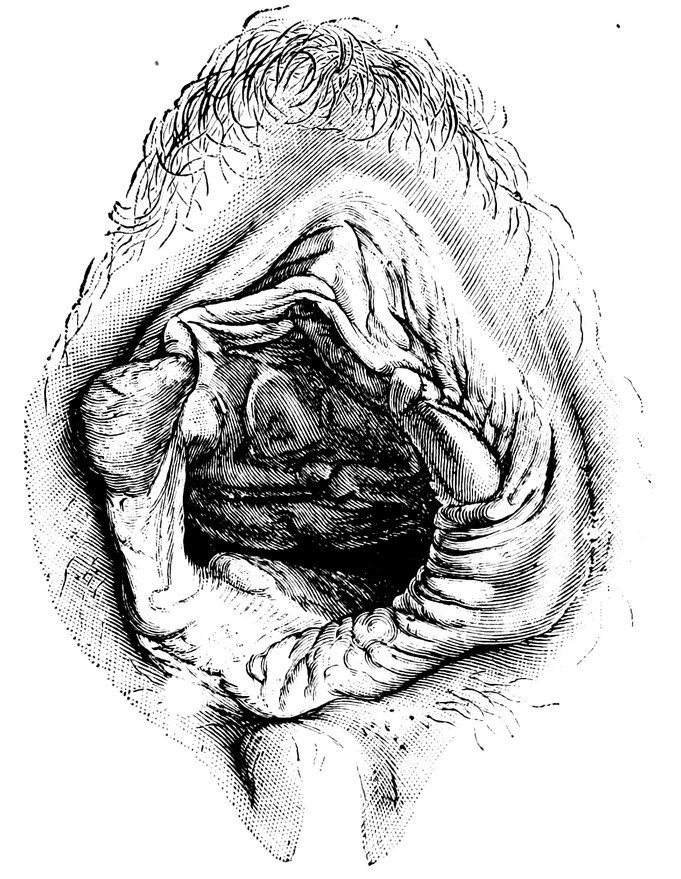

| 8. | Internal genital organs of new-born female infant | 51 |

| 9. | Reproductive organs of a new-born female infant | 52 |

| 10. | Internal genital organs of a girl aged eight years | 52 |

| 11. | Reproductive organs of a girl aged ten years | 53 |

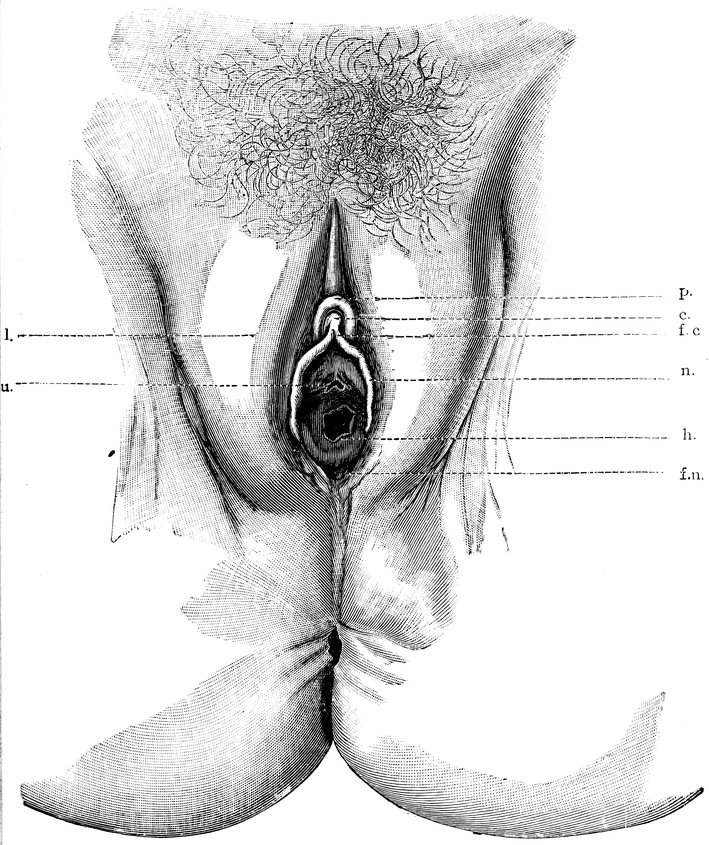

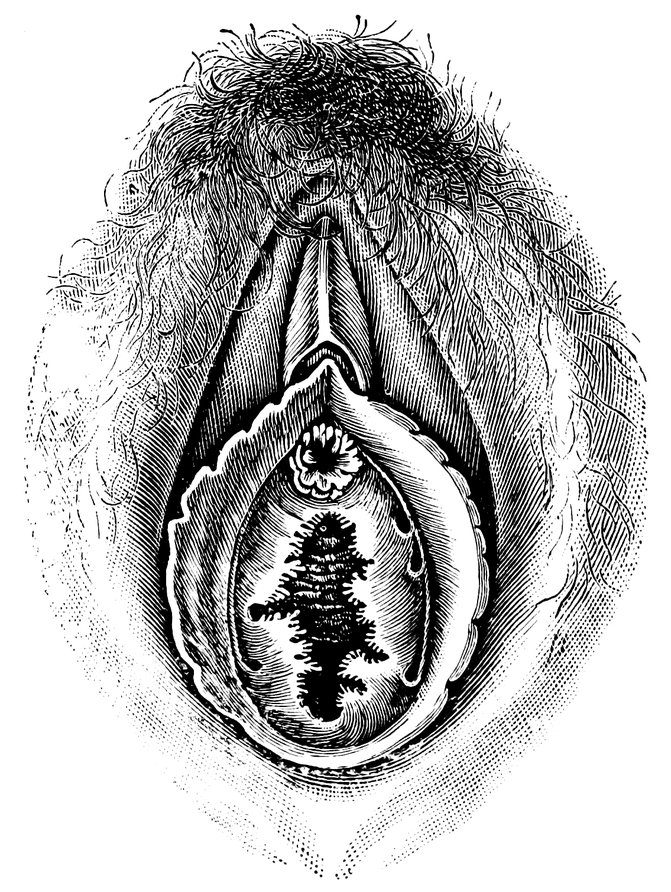

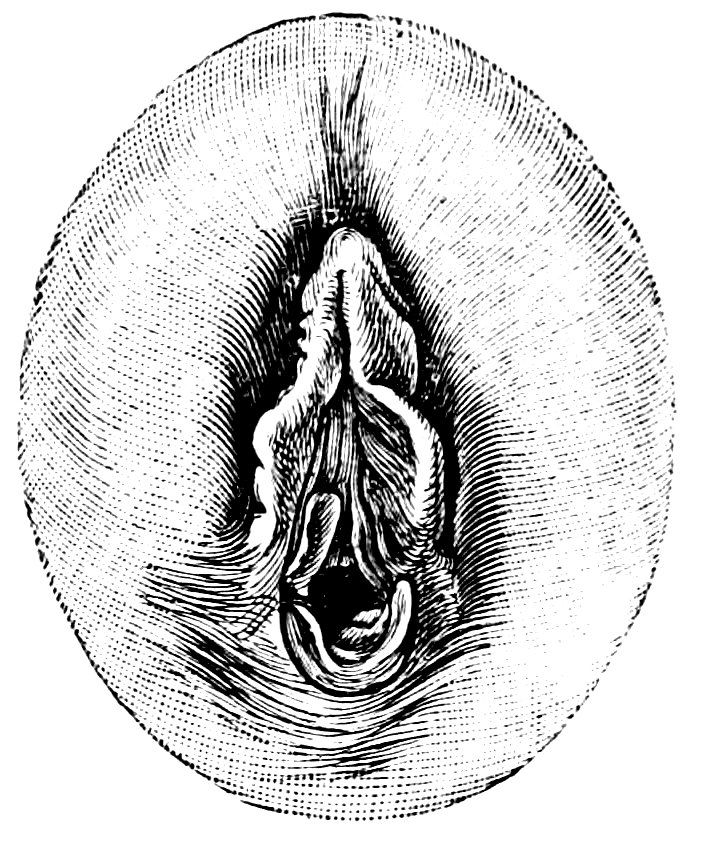

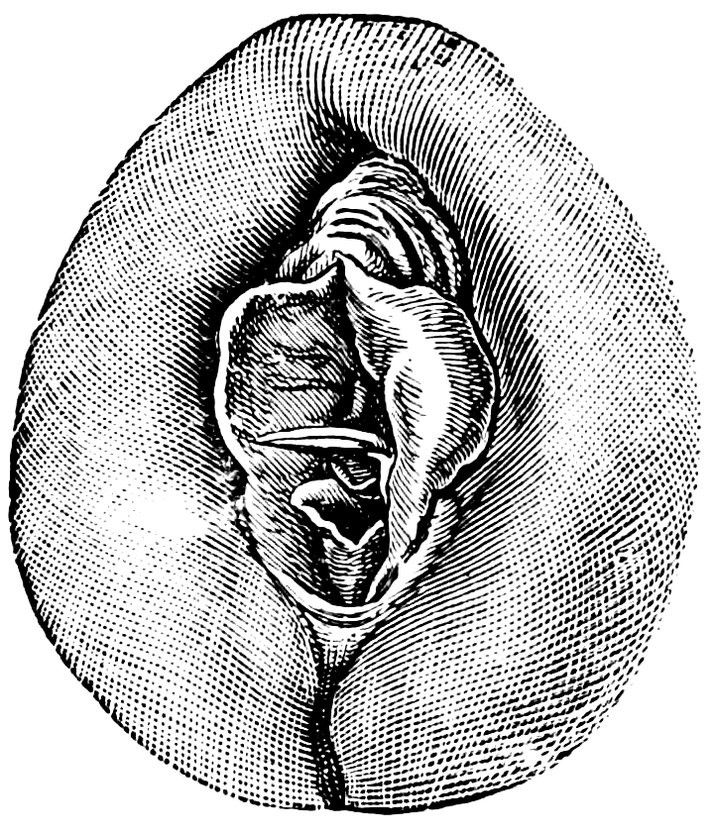

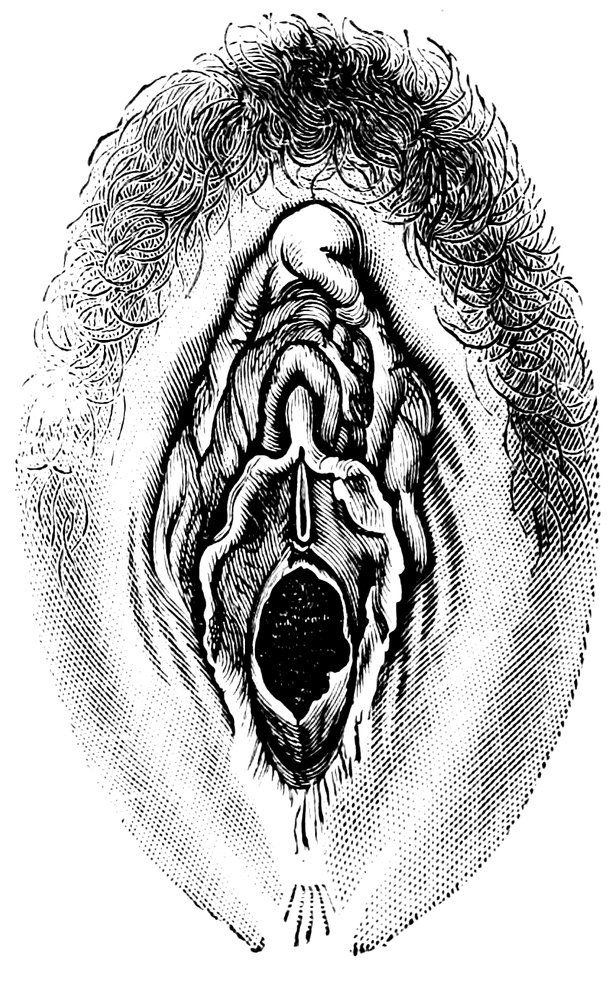

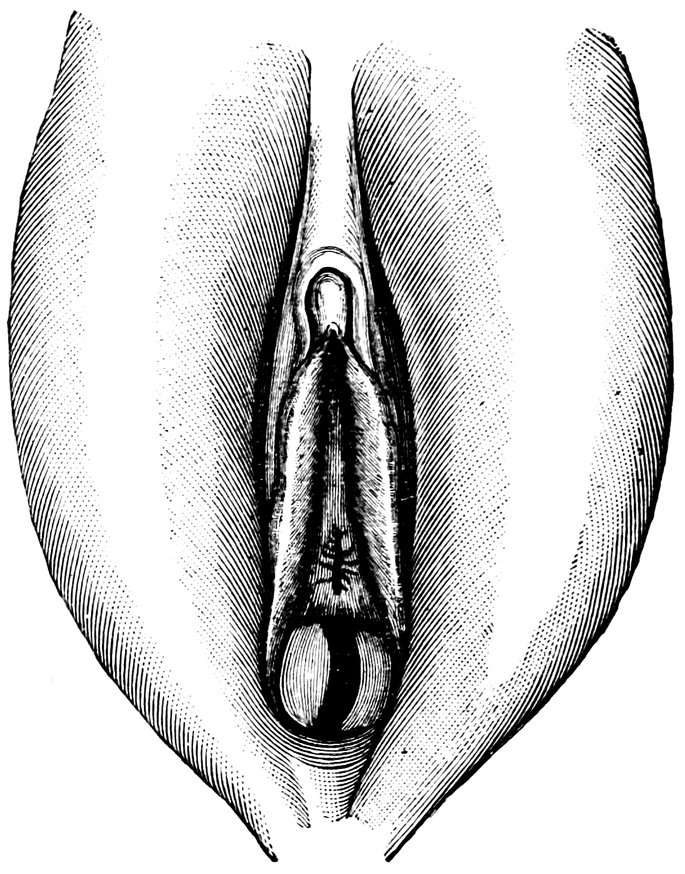

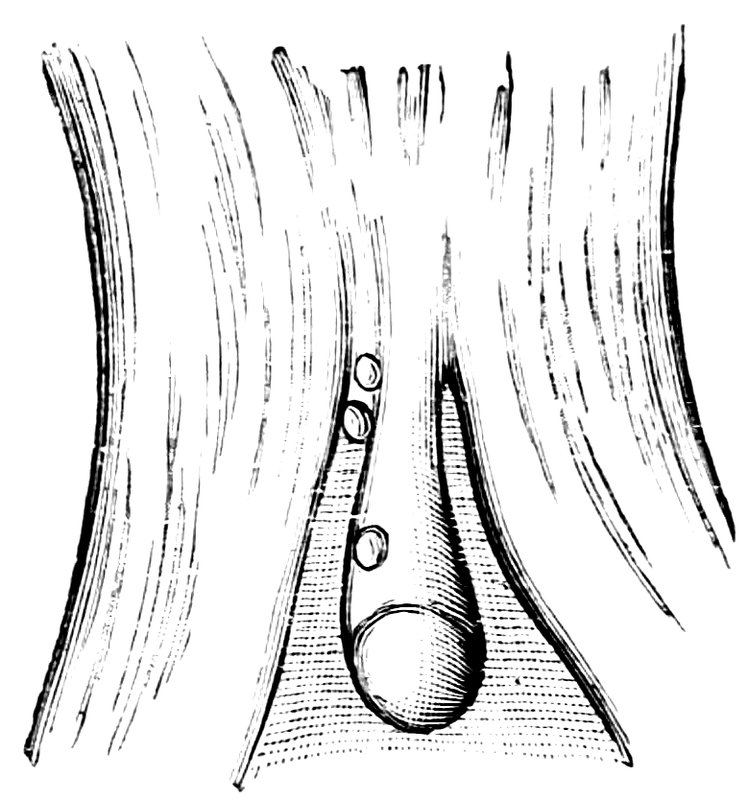

| 12. | Female external genital organs of a virgin | 54 |

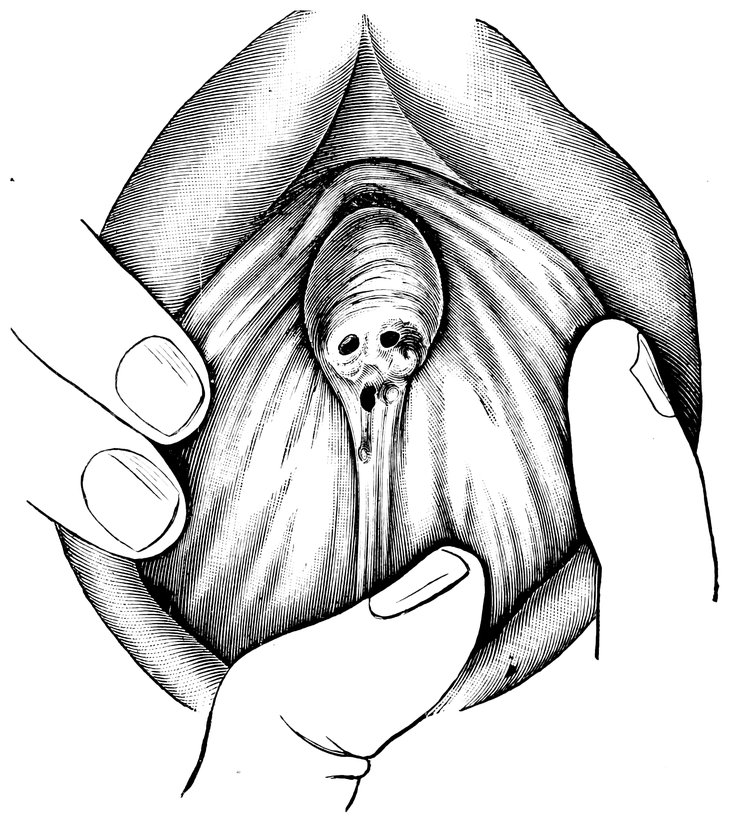

| 13. | The external genital organs of a virgin | 55 |

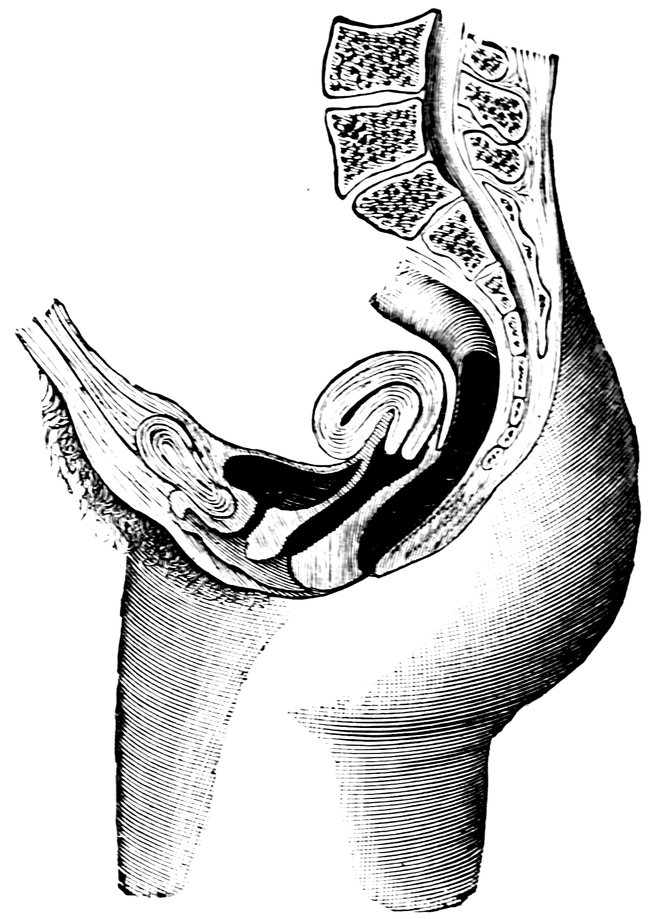

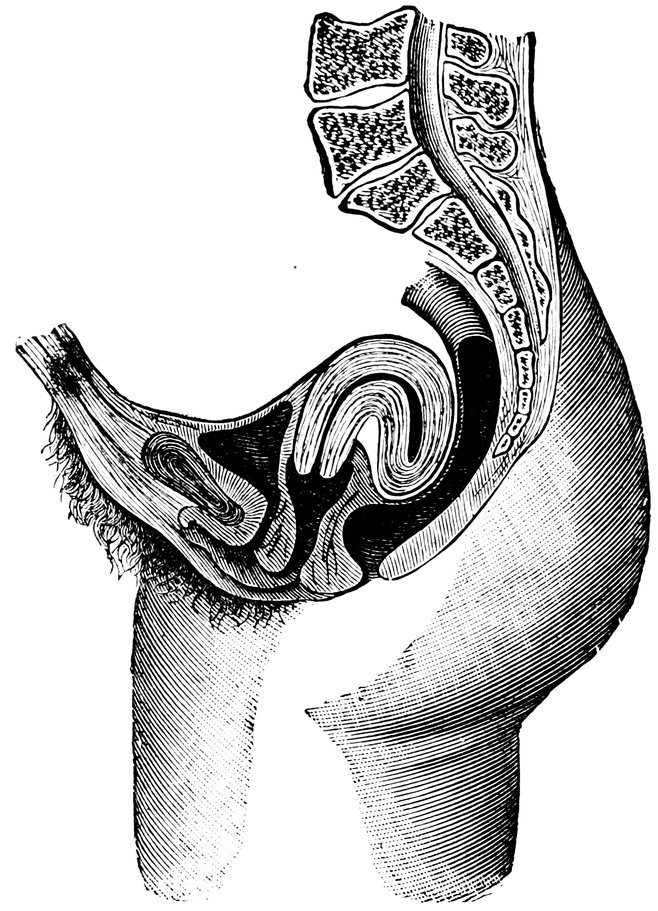

| 14. | Sagittal section of the female pelvis | 56 |

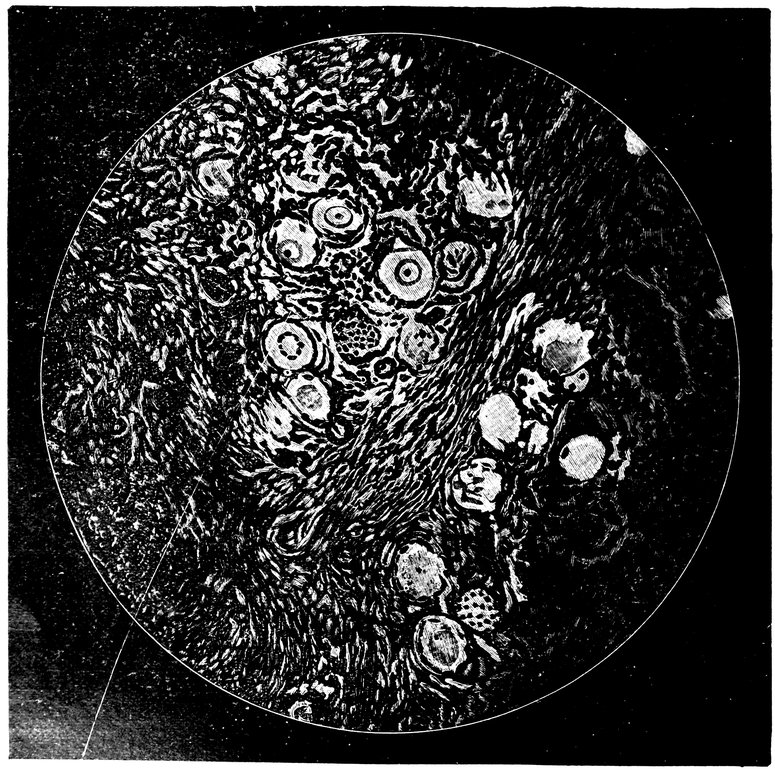

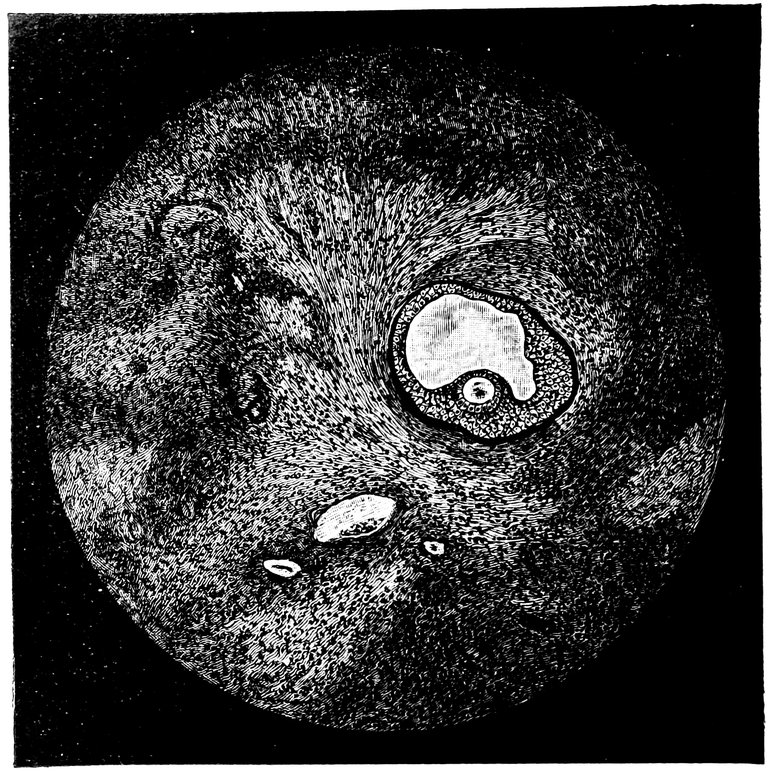

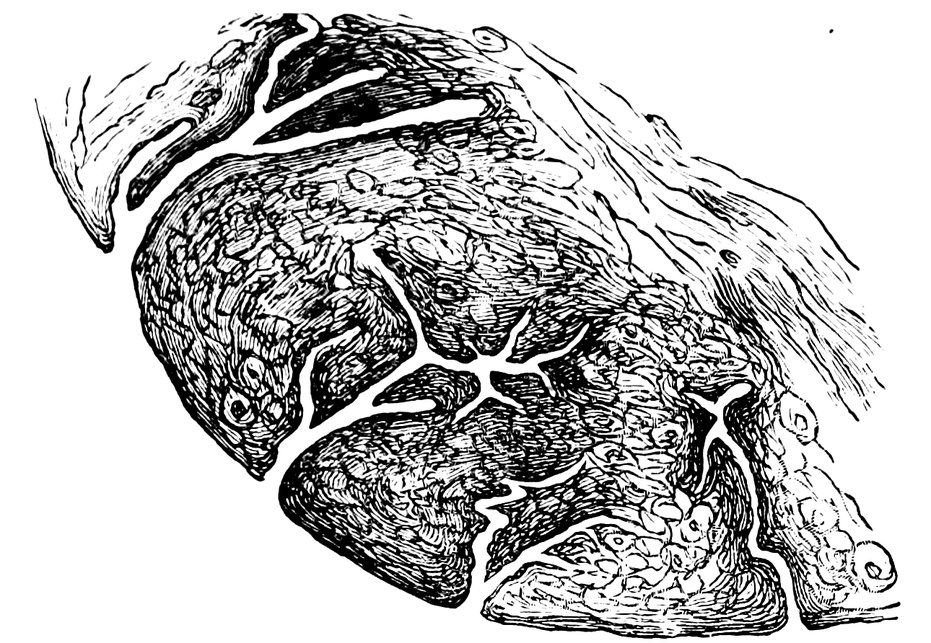

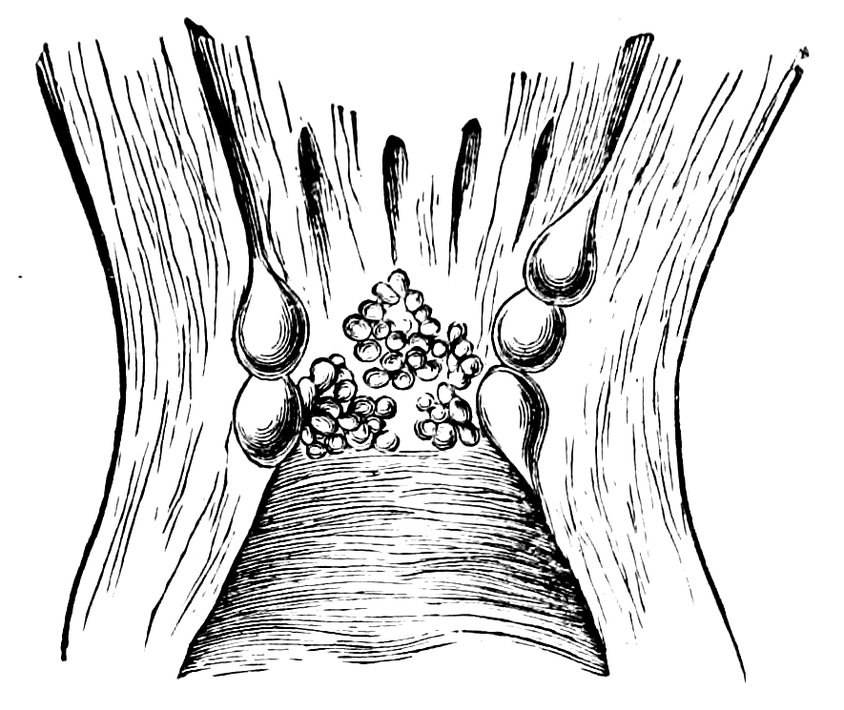

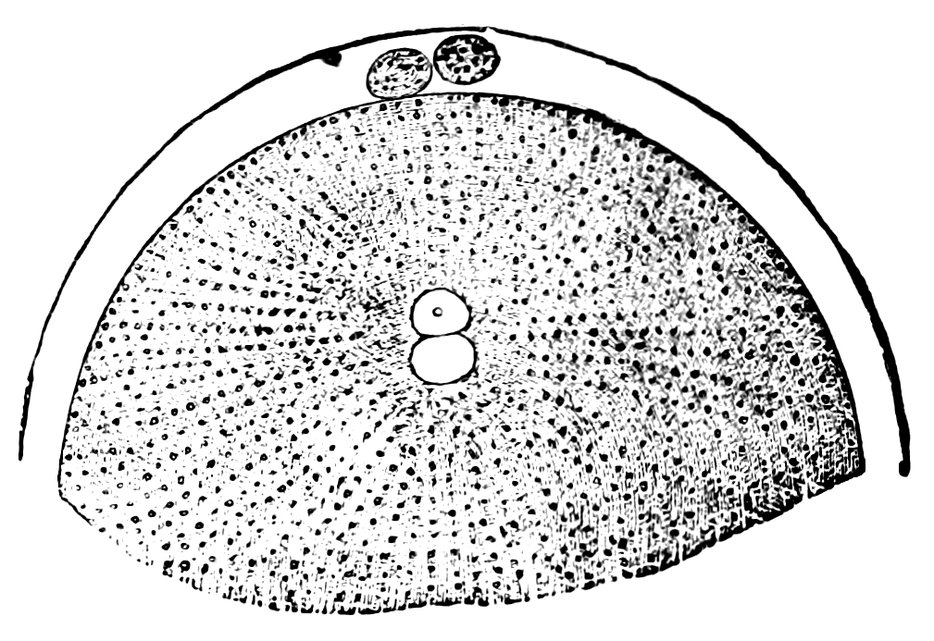

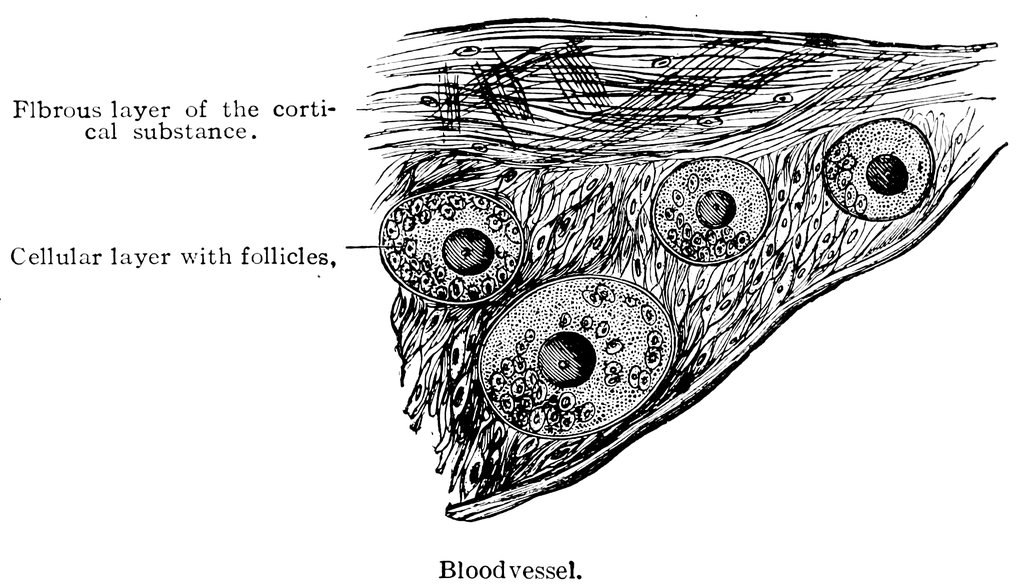

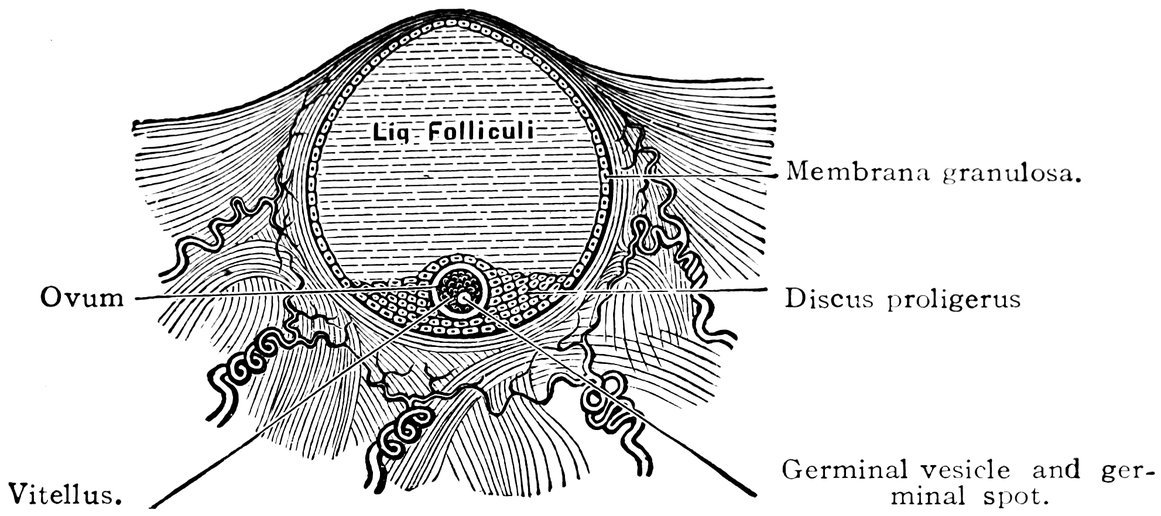

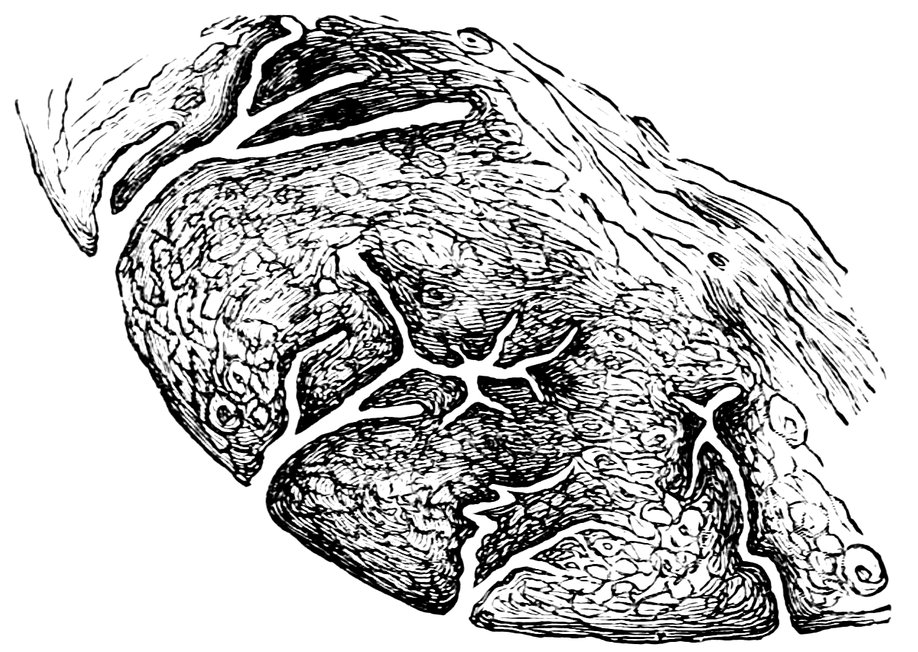

| 15. | Primitive follicles | 58 |

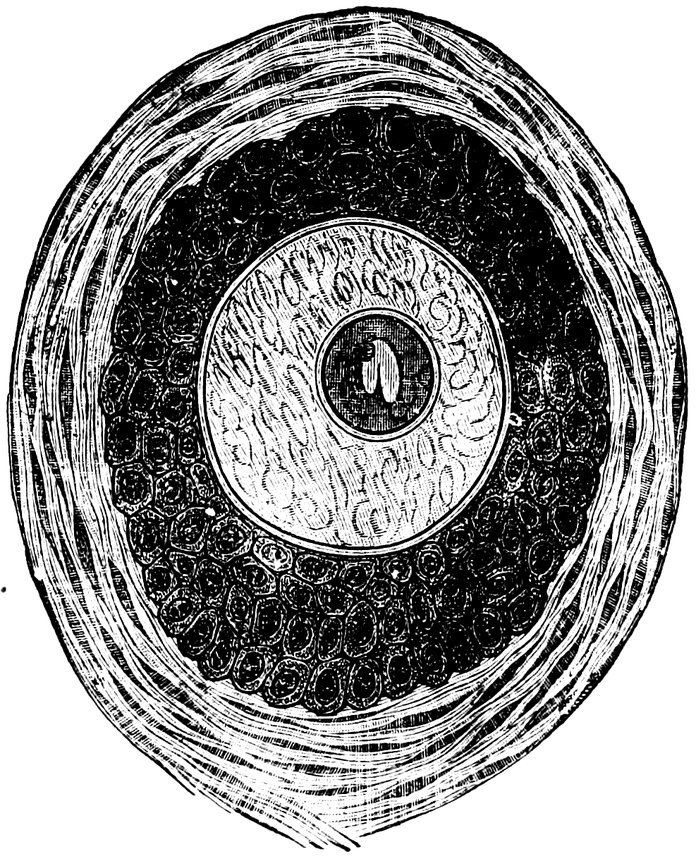

| 16. | Ripening follicles | 61 |

| 17. | Graafian follicles | 62 |

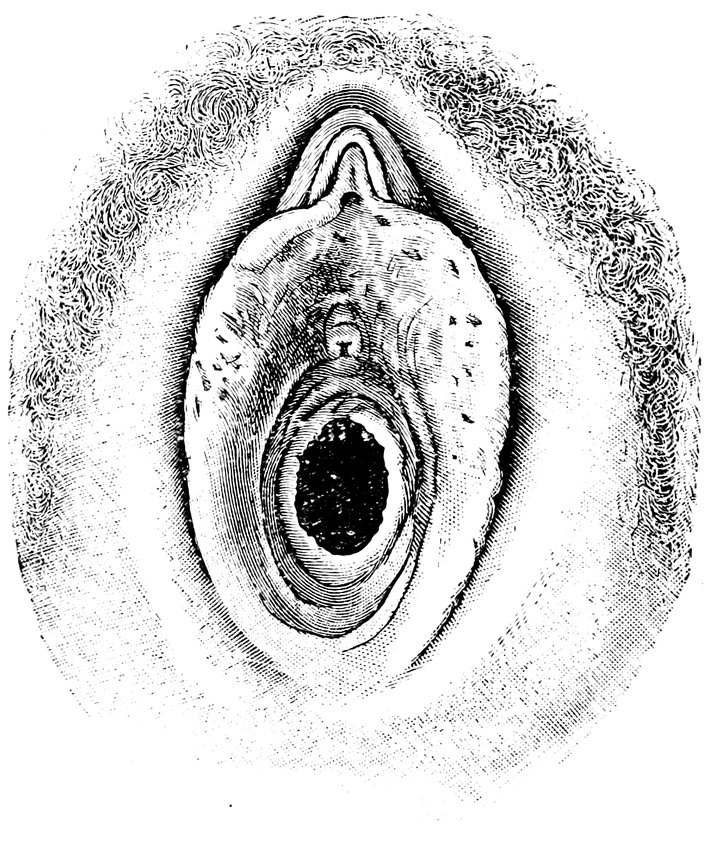

| 18. | Annular Hymen | 64 |

| 19. | Annular Hymen | 64 |

| 20. | Semilunar Hymen | 65 |

| 21. | Annular Hymen with Congenital Symmetrical Indentations | 65 |

| 22. | Fimbriate Hymen | 65 |

| 23. | Deflorated Fimbriate Hymen | 65 |

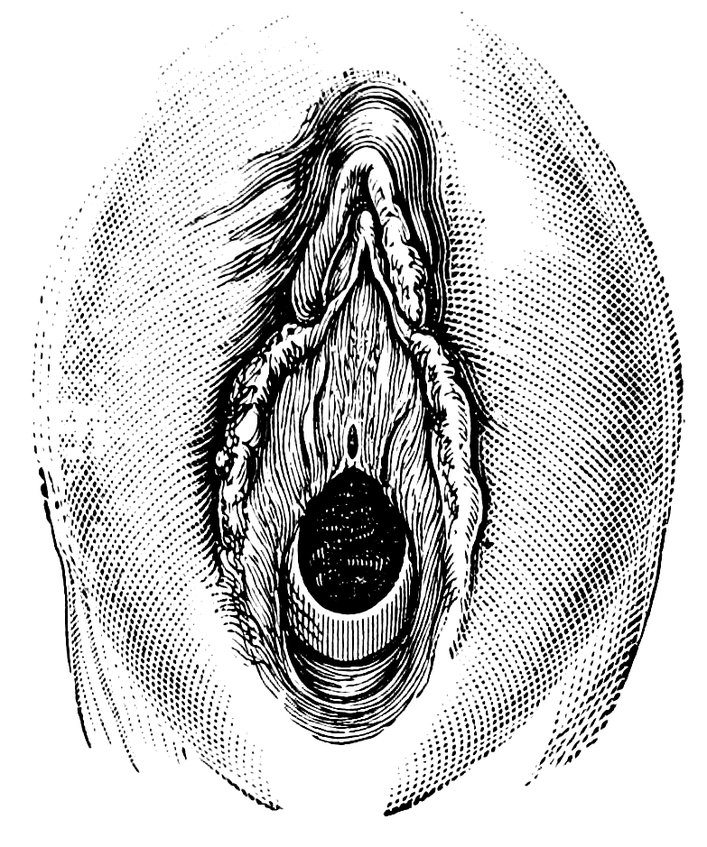

| 24. | Septate Annular Hymen | 67 |

| 25. | Septate Semilunar Hymen | 67 |

| 26. | Extremely tough Annular Hymen with an obliquely disposed Septum | 67 |

| 27. | Septate Hymen with Apertures of unequal Size | 67 |

| 28. | Septate Hymen with Apertures of unequal Size | 68 |

| 29. | Hymen with rudimentary Septum | 68 |

| 30. | Hymen with posterior rudimentary Septum | 68 |

| 31. | Labiate Hymen with posterior rudimentary Septum | 68 |

| 32. | Hymen with anterior rudimentary Septum | 69 |

| 33. | Hymen with anterior rudimentary Septum projecting in a opiniform Manner | 69 |

| 34. | Hymen with anterior and posterior rudimentary Septa | 69 |

| 35. | Hymen with filiform Process projecting from the anterior Margin | 69 |

| 36. | Hymen in which there are two symmetrically disposed thinned Areas. The left of these is perforated | 69 |

| 37. | Very unusual form of Hymen | 70 |

| 38. | Semilunar Hymen with cicatrized Lacerations in its Border | 70 |

| 39. | Deflorated Semilunar Hymen with laterally disposed symmetrical Lacerations | 70 |

| 40. | Deflorated Annular Hymen with several cicatrized Lacerations | 70 |

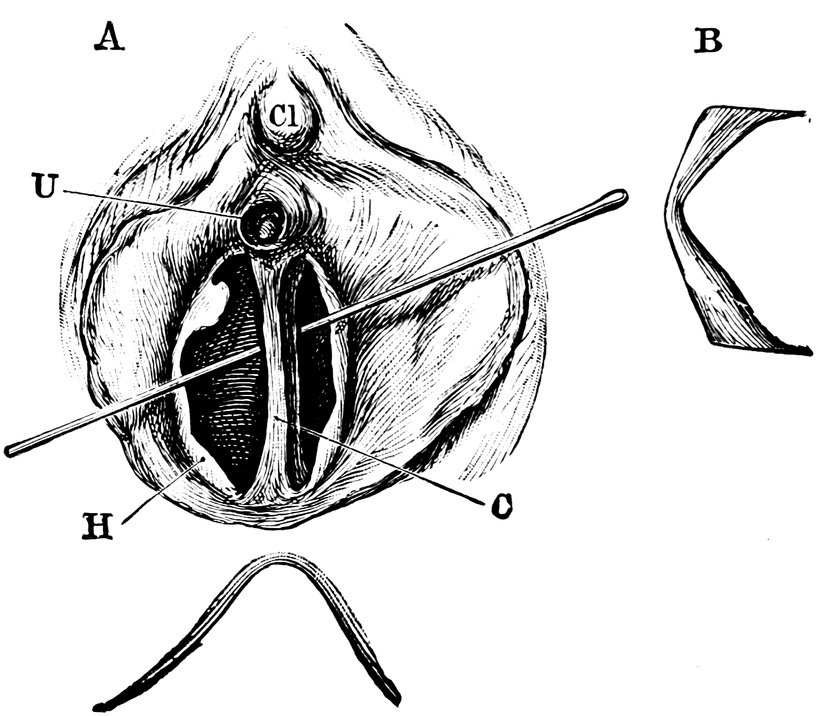

| 41. | A. Septate Hymen in which defloration has been effected through one of the Apertures. U. Urethra. Cl. Clitoris. H. Cicatrized Margin. C. Septum. B. Lateral view of Septum | 70 |

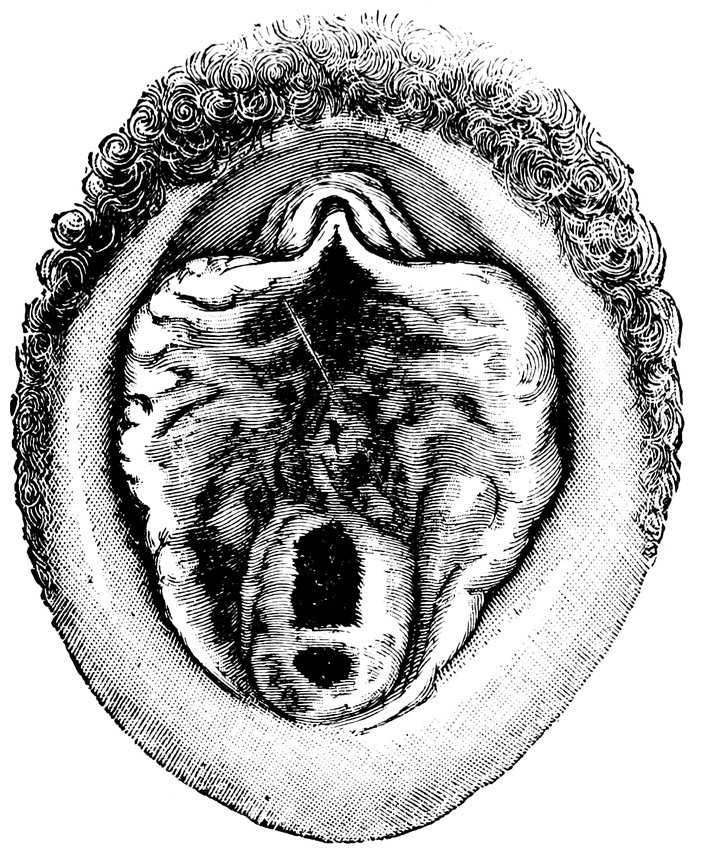

| 42. | Deflorated Septate Hymen | 71 |

| x43. | Hymen with larger anterior and smaller posterior Apertures | 71 |

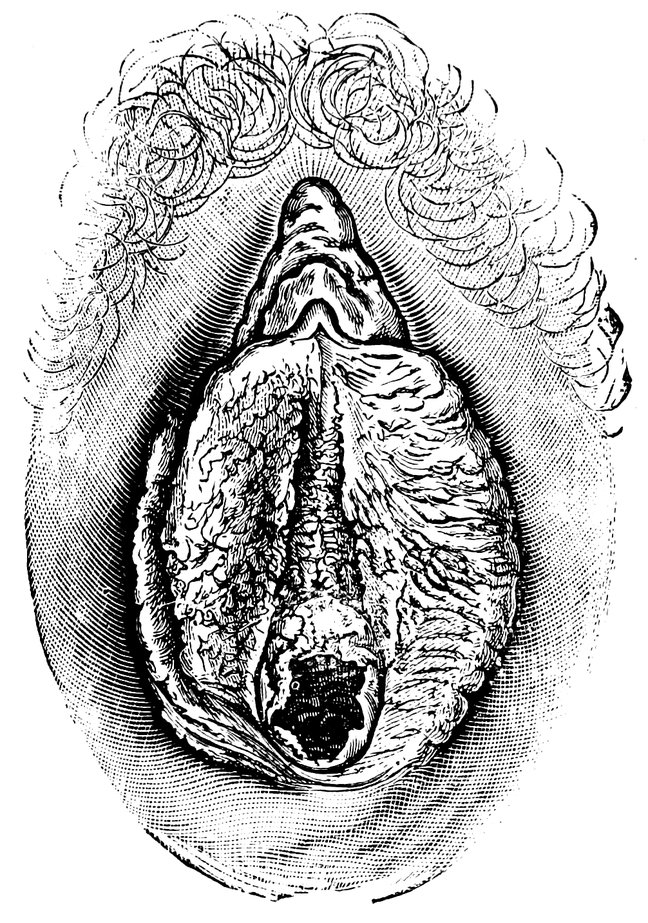

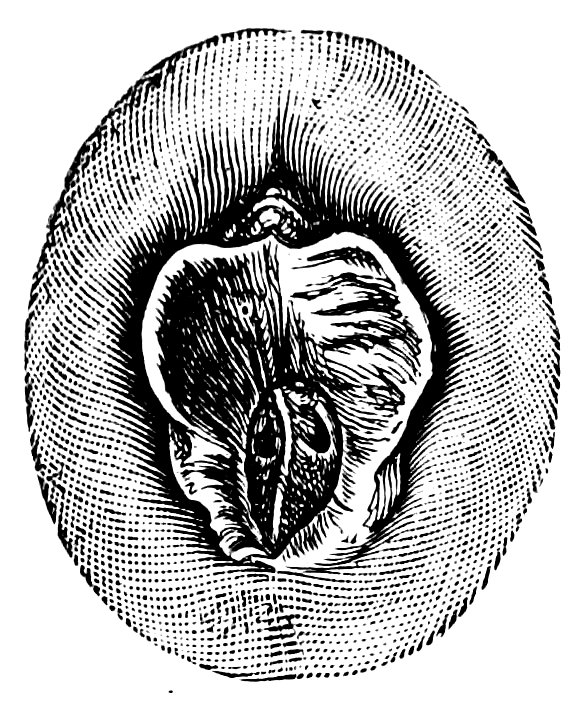

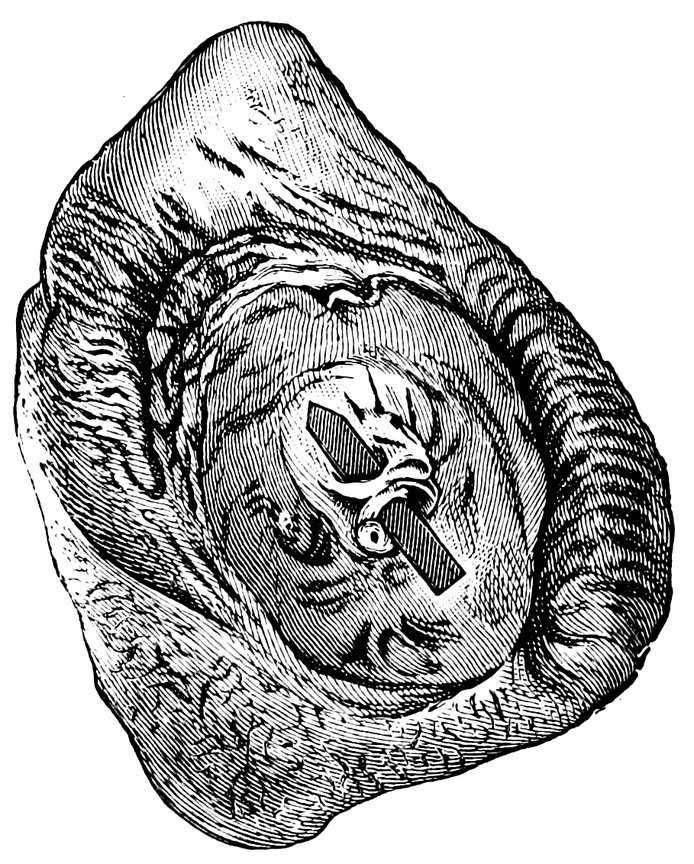

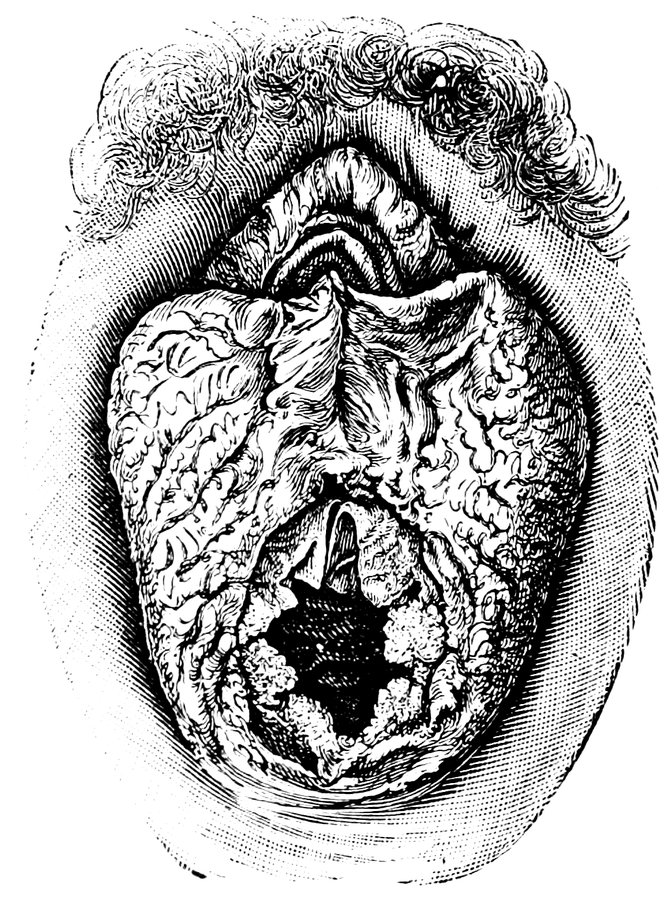

| 44. | Carunculæ Myrtiformes in a Primipara | 71 |

| 45. | Vaginal Inlet of a Multipara, without Carunculæ Myrtiformes. Slight Prolapse of Anterior and Posterior Vaginal Walls | 71 |

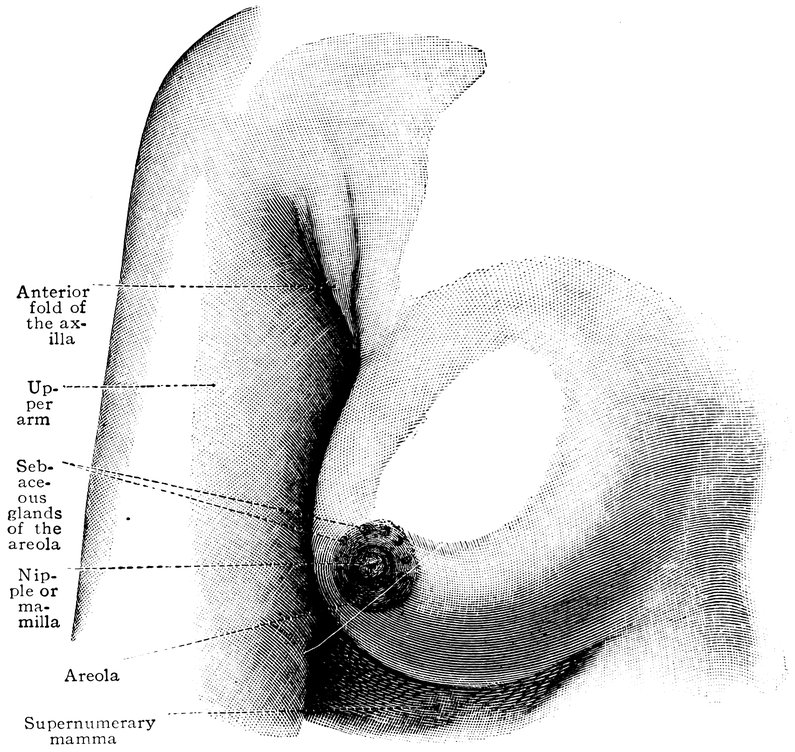

| 46. | The breast of a virgin aged eighteen years | 73 |

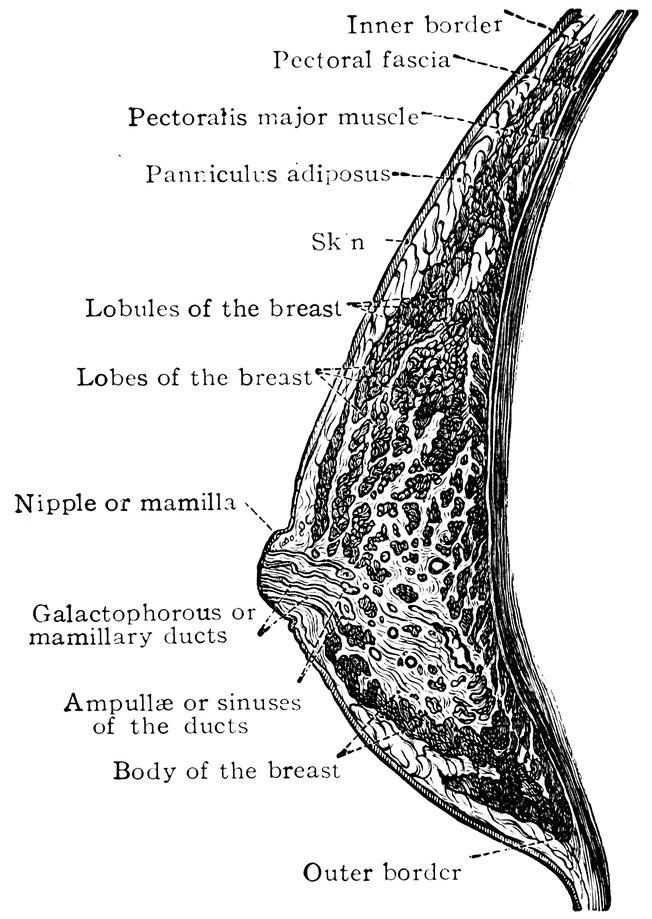

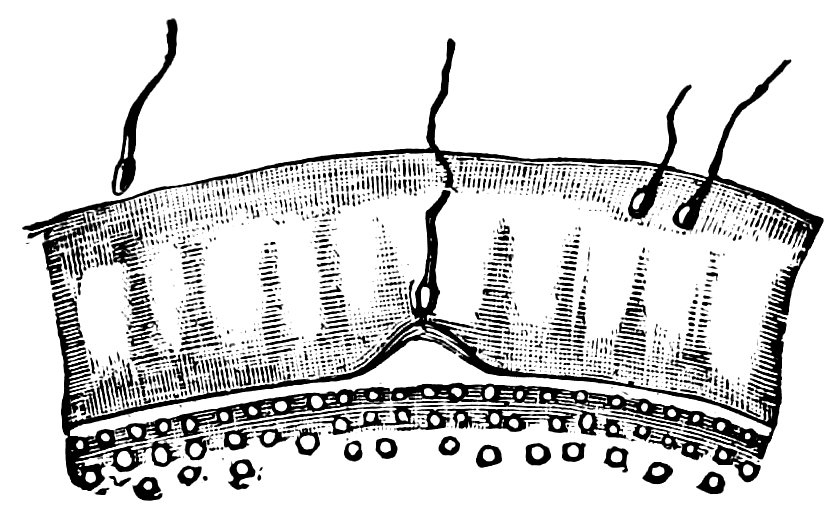

| 47. | Horizontal section through the female breast | 75 |

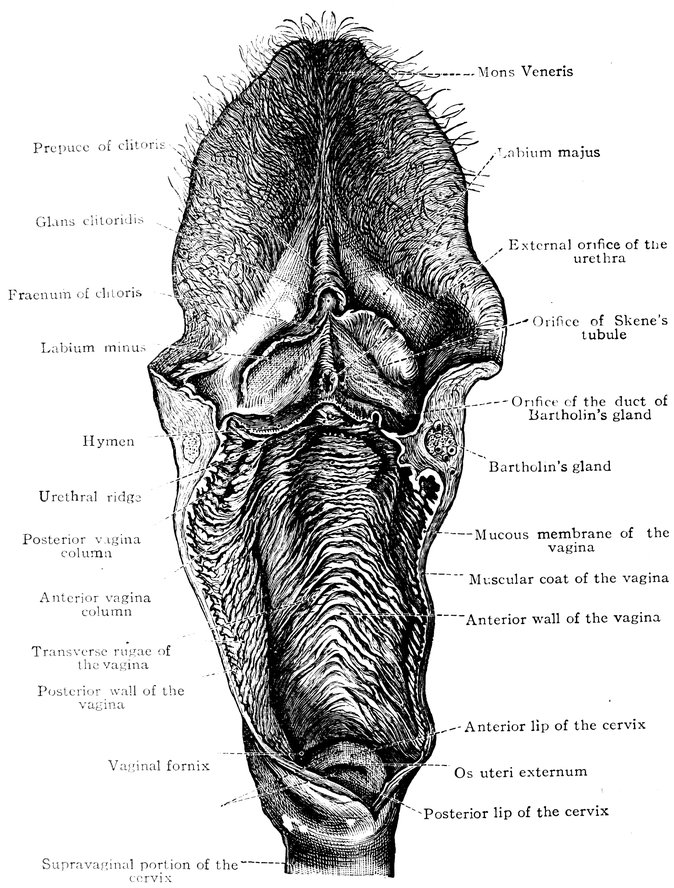

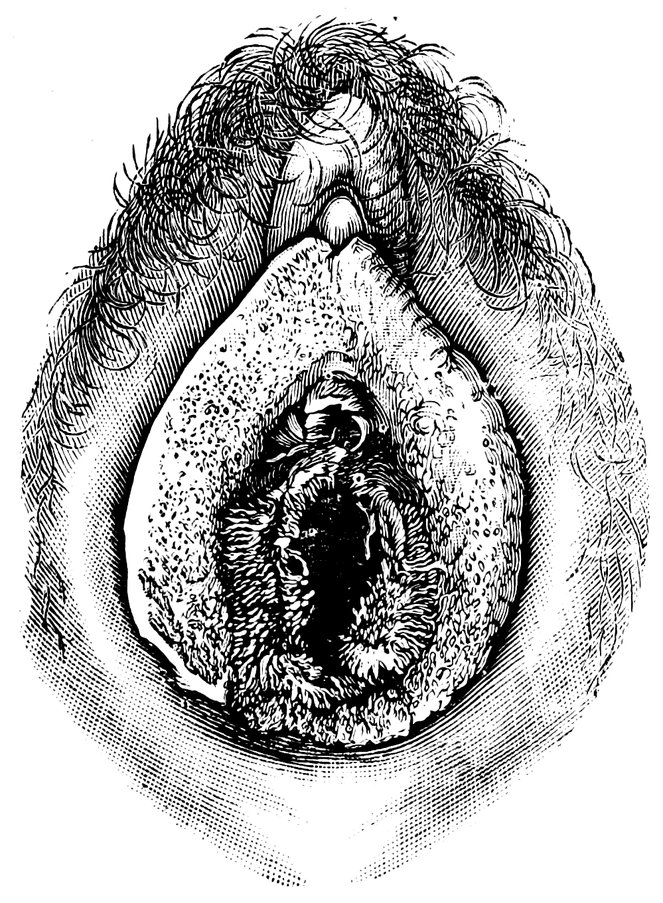

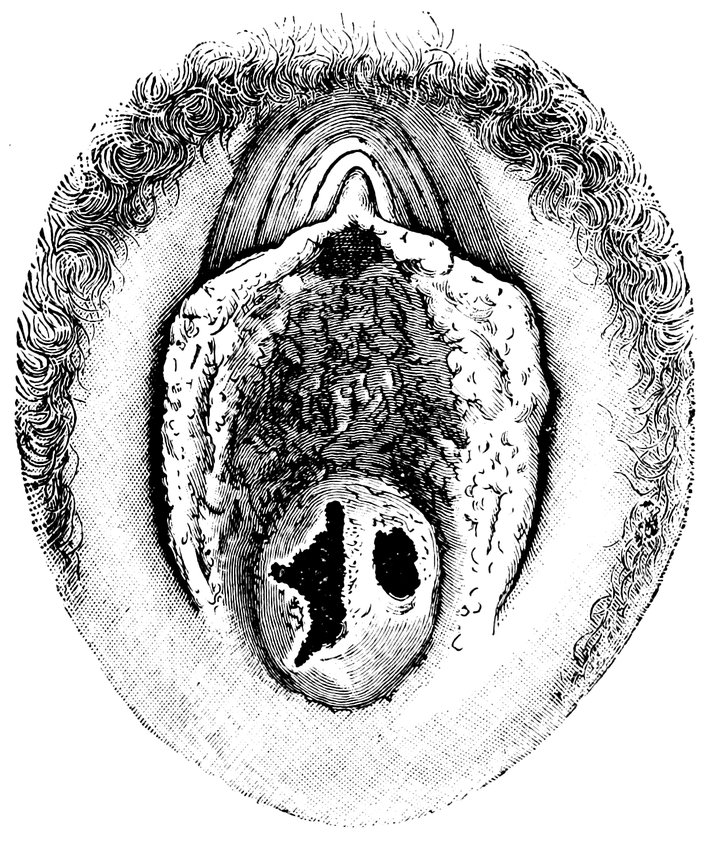

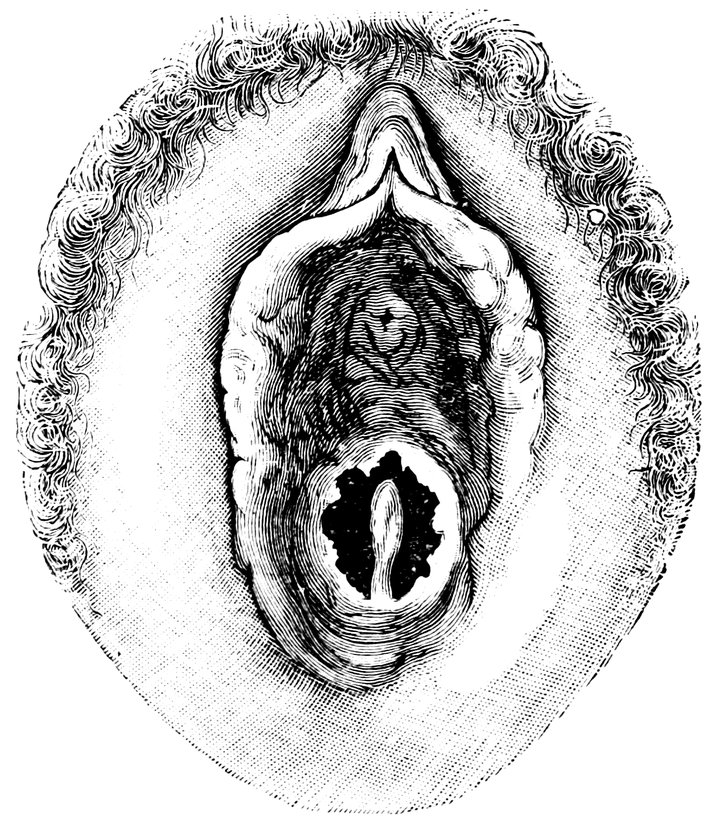

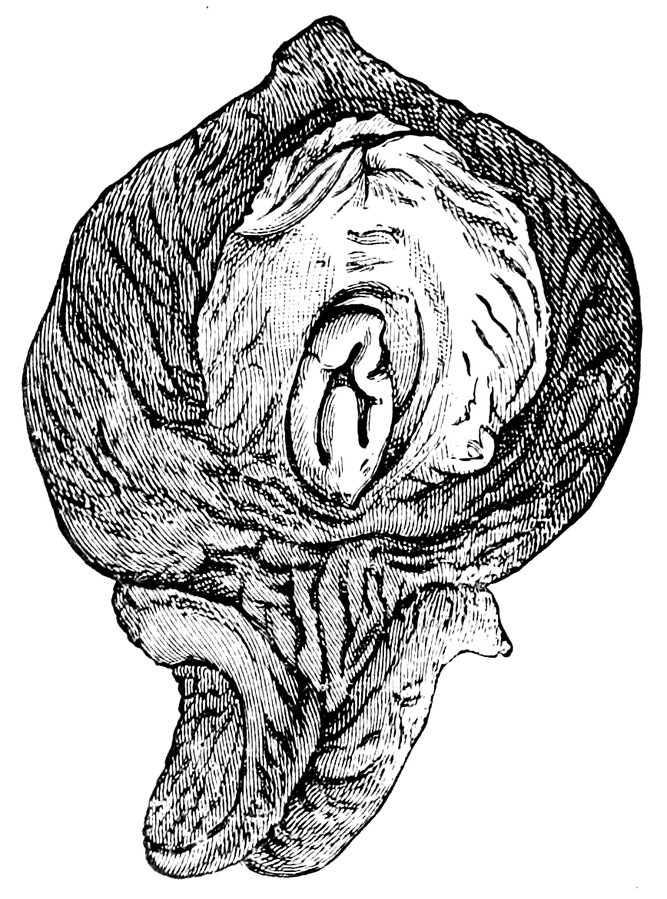

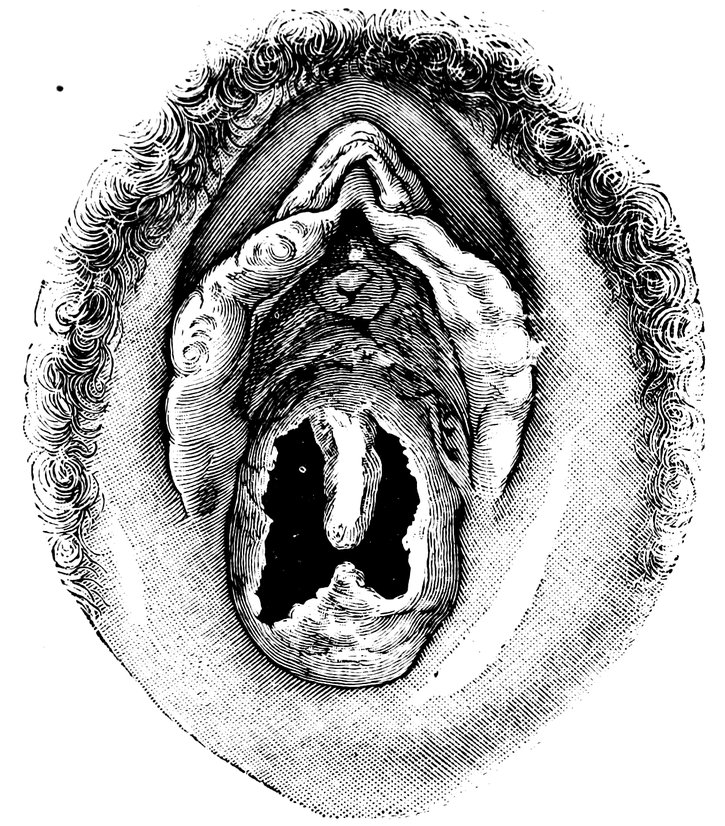

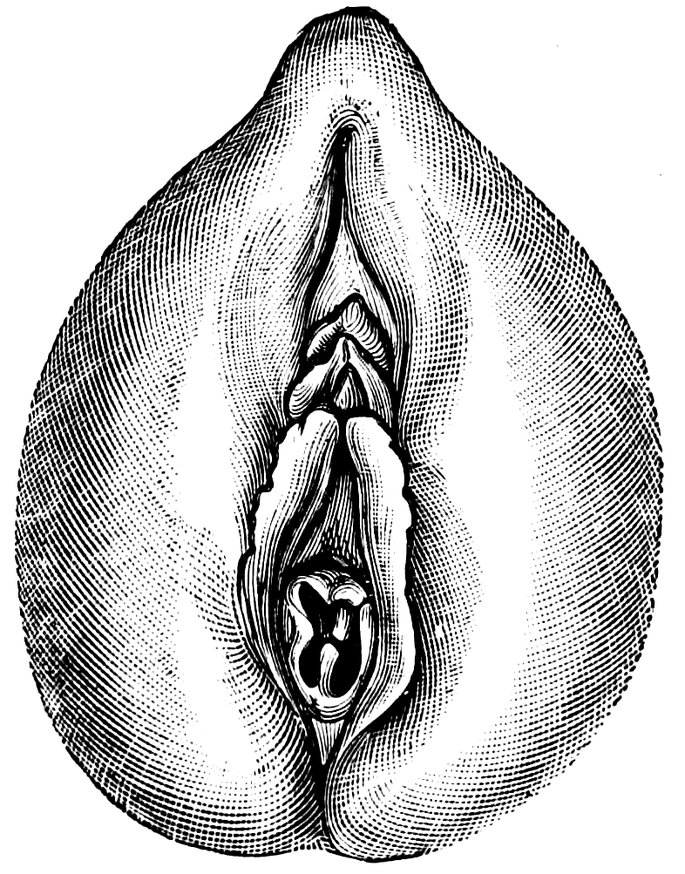

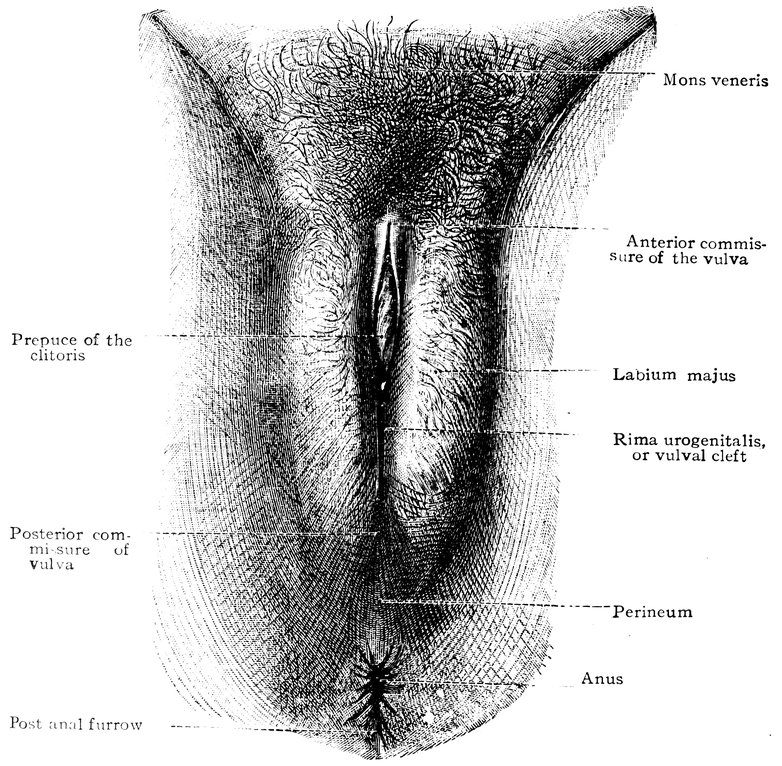

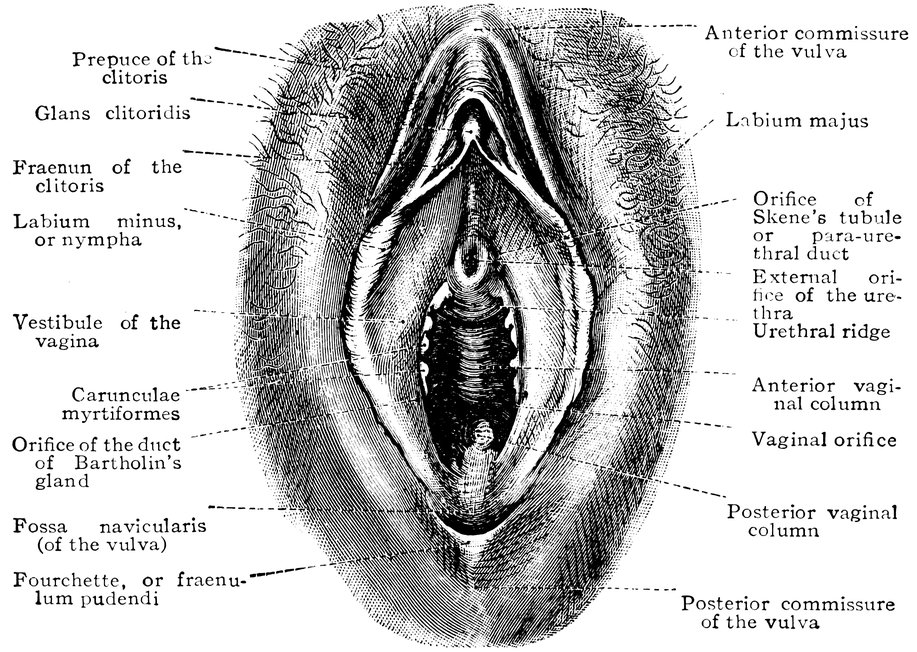

| 48. | The female pudendum, or vulva, with the labia majora | 204 |

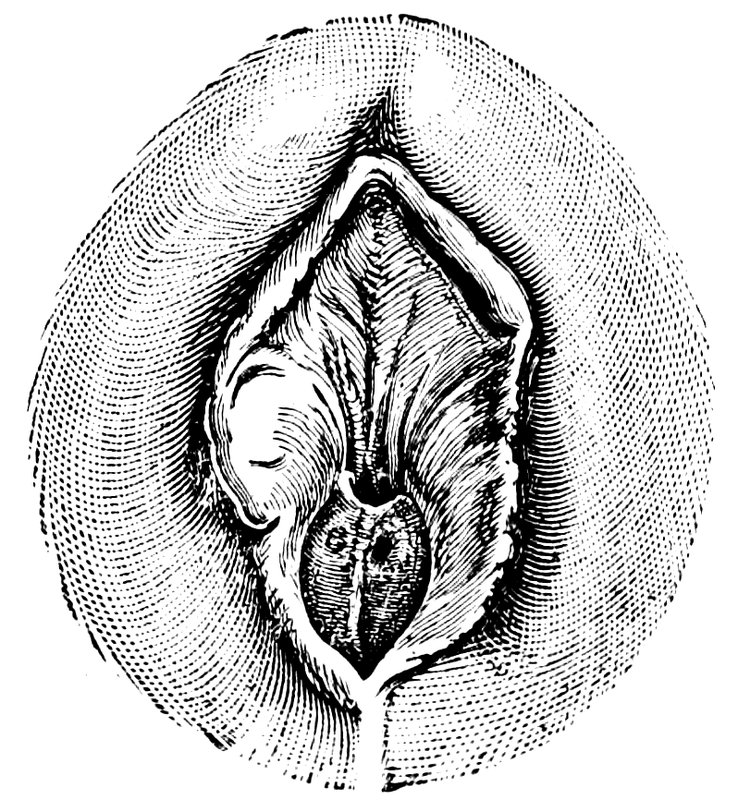

| 49. | Vestibule of the vagina, with the labia minora or nymphæ, etc | 205 |

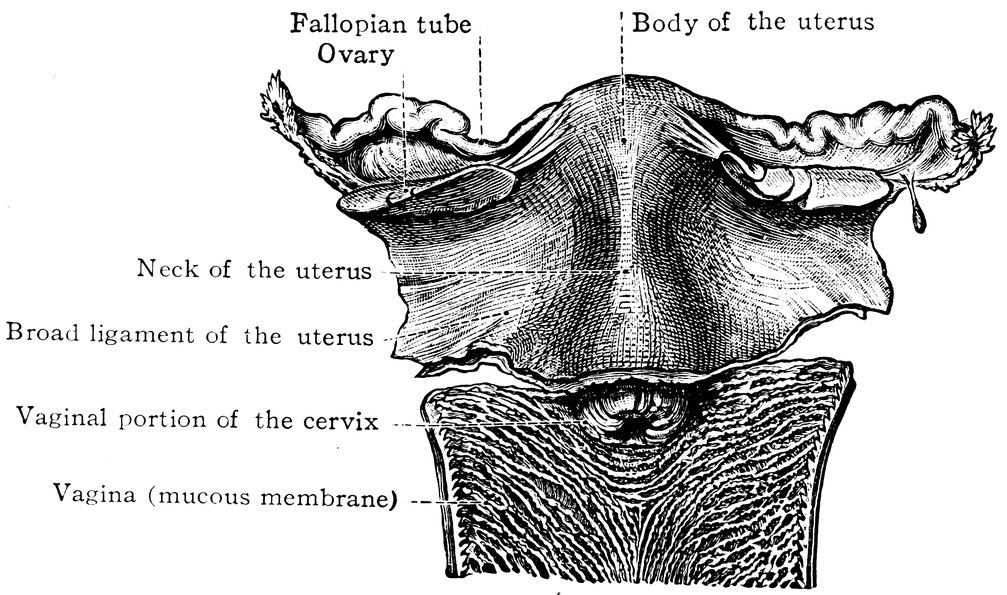

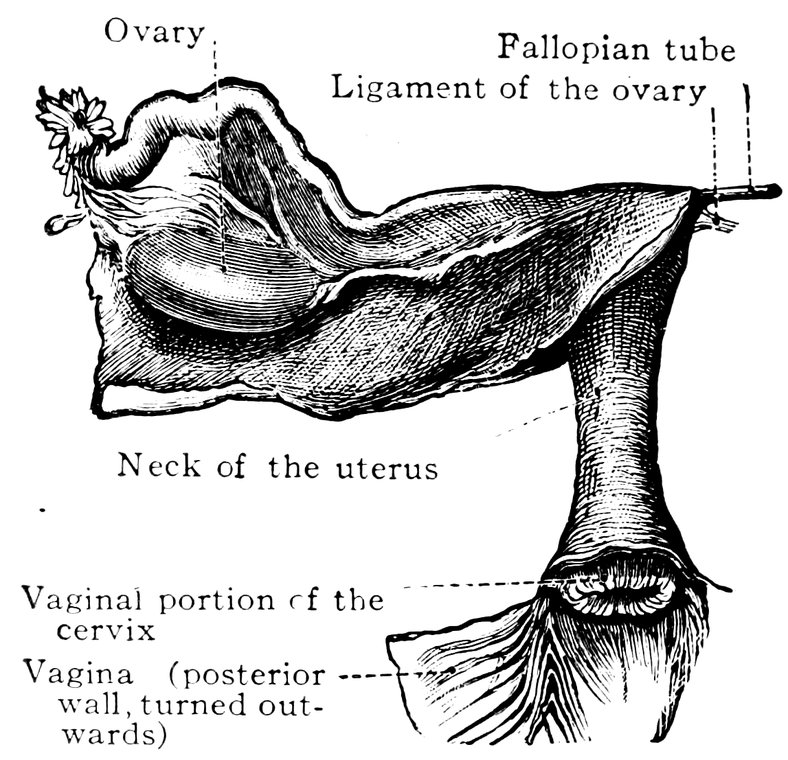

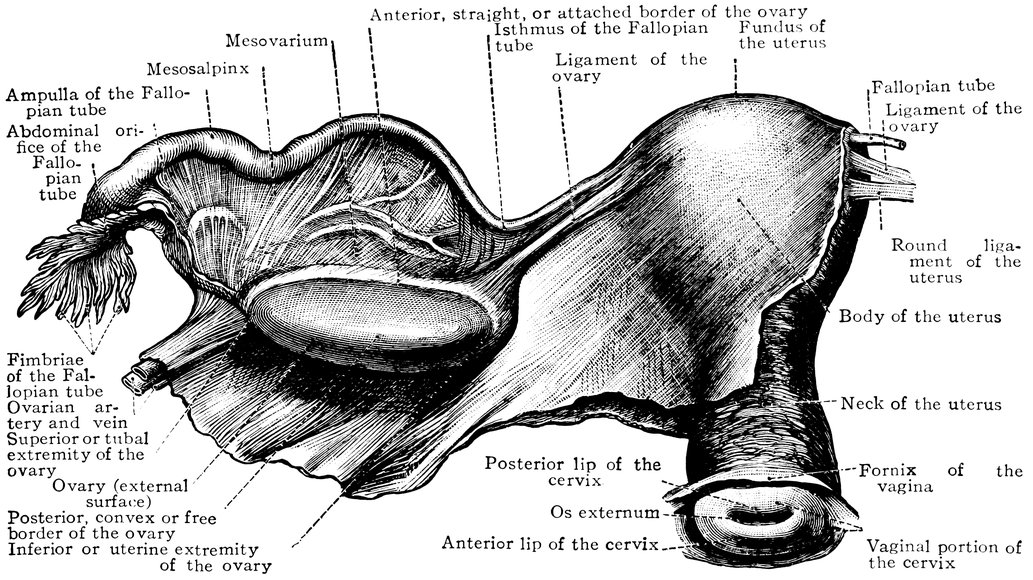

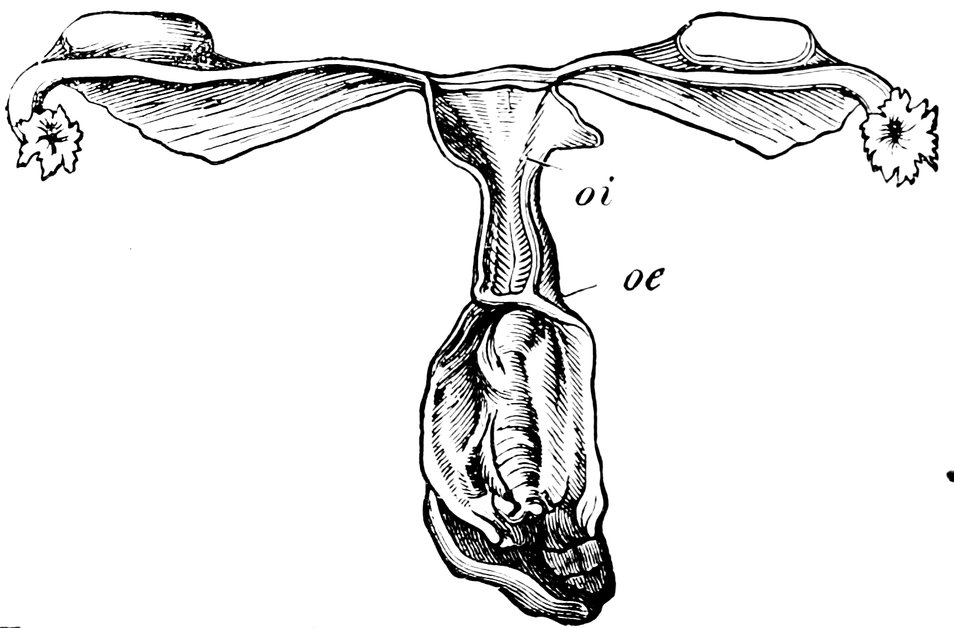

| 50. | The uterus, the left Fallopian tube and the left ovary, etc | 207 |

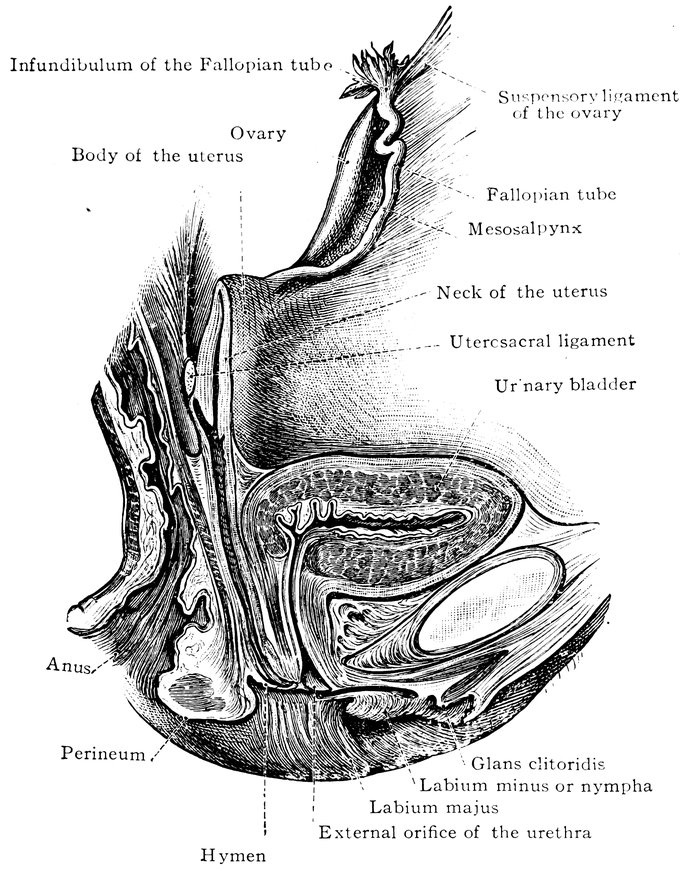

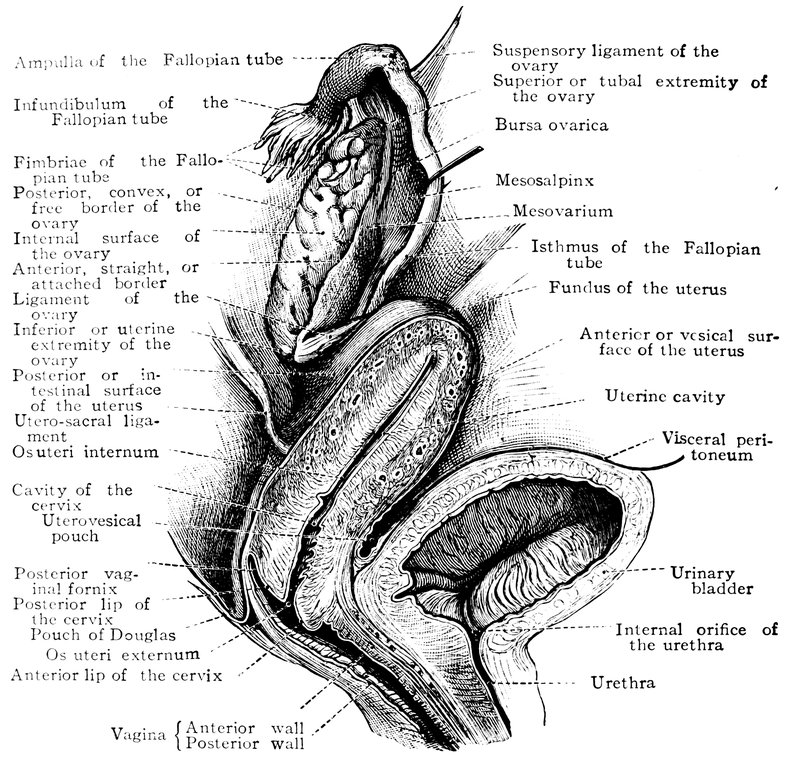

| 51. | Female internal genital organs in the fully developed state | 208 |

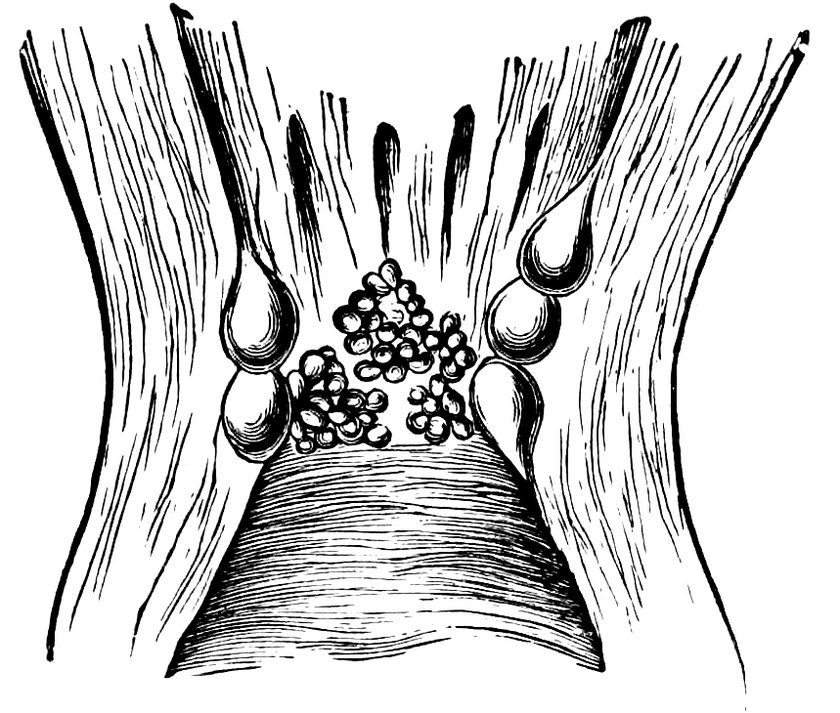

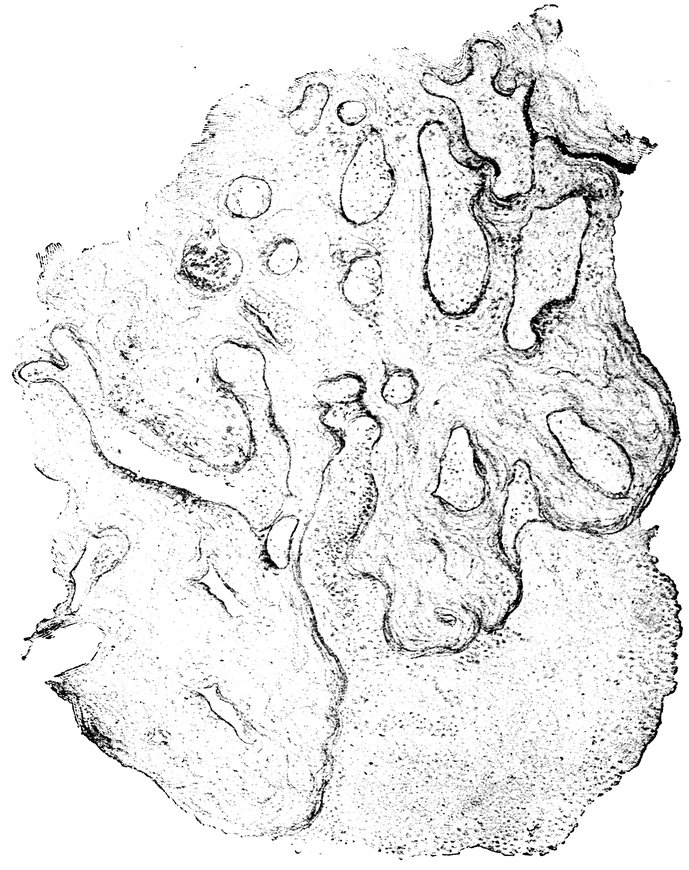

| 52. | Sagittal Section through the Cervix Uteri of a Woman twenty-six years of age. Dendriform branched glands | 217 |

| 53. | Cervix of a Woman seventy-two years of age, with glands that have undergone cystic degeneration | 217 |

| 54. | Sagittal Section through the Cervix Uteri of a Woman sixty-five years of age. The glands have undergone cystic degeneration | 217 |

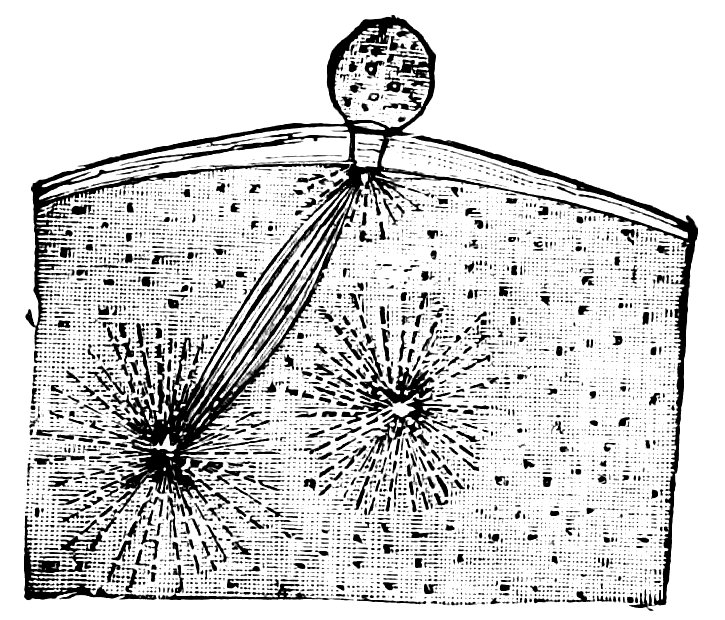

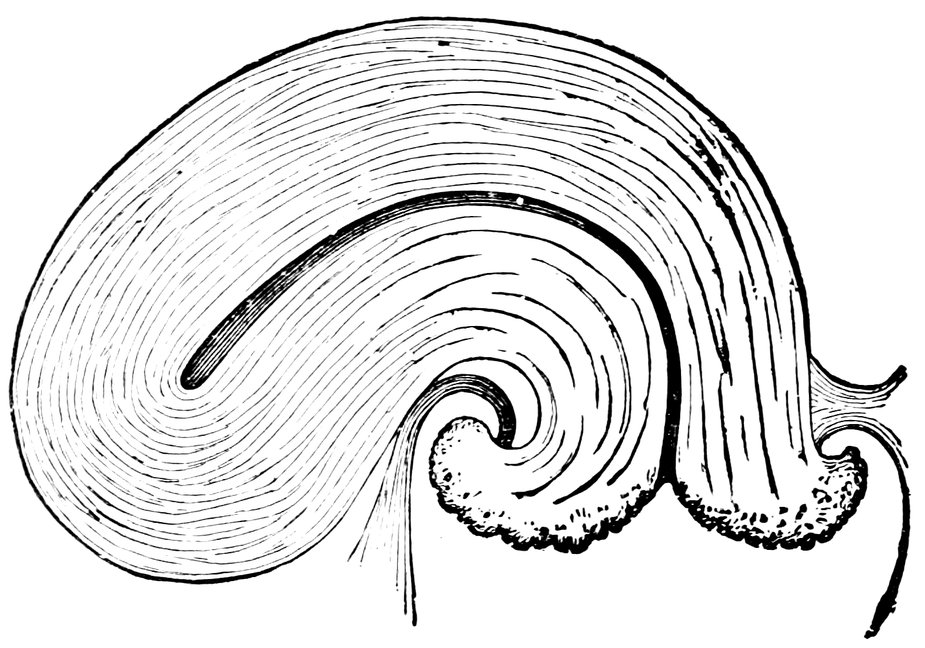

| 55. | First Stage. A. Entrance of a Spermatozoon into the Ovum of Ascaris Megalocephala. B. After preparations by M. Nussbaum. (Half of the ova only are depicted) | 306 |

| 56. | Ovum of Asterakanthion ten minutes after Fertilization | 306 |

| 57. | Fusion of Male Pro-nucleus and Female Pro-nucleus to form the Segmentation Nucleus of the Fertilized Ovum | 306 |

| 58. | Passage of Spermatozoon through the Zona Pellucida of the Ovum of Asterakanthion | 307 |

| 59. | Ovum of Scorpæna Scrofa Thirty-five Minutes after Fertilization | 307 |

| 60. | Male Pro-nucleus and Female Pro-nucleus in Fertilized Ovum of Frog, prior to the Formation of the Segmentation Nucleus | 307 |

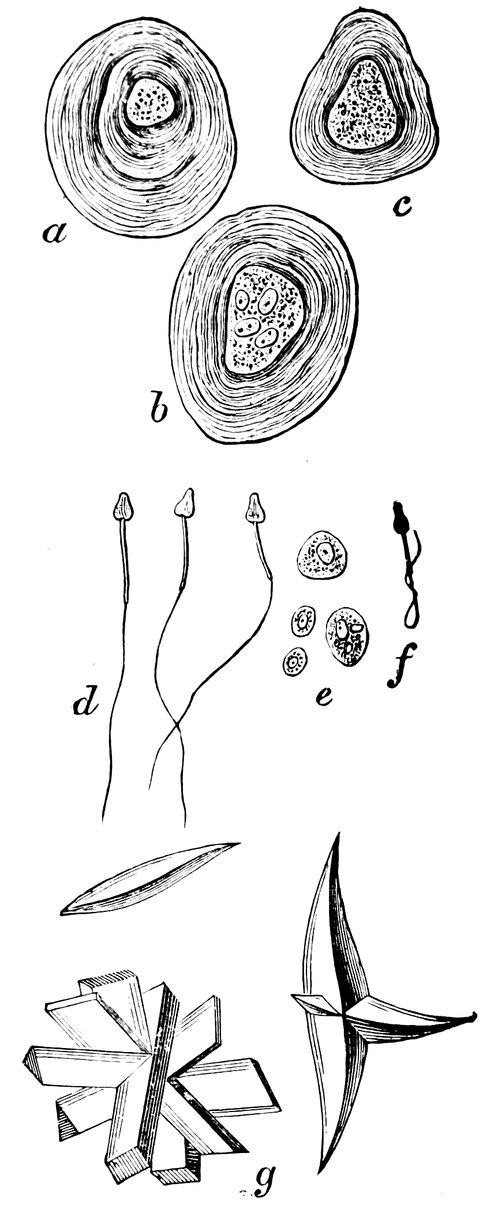

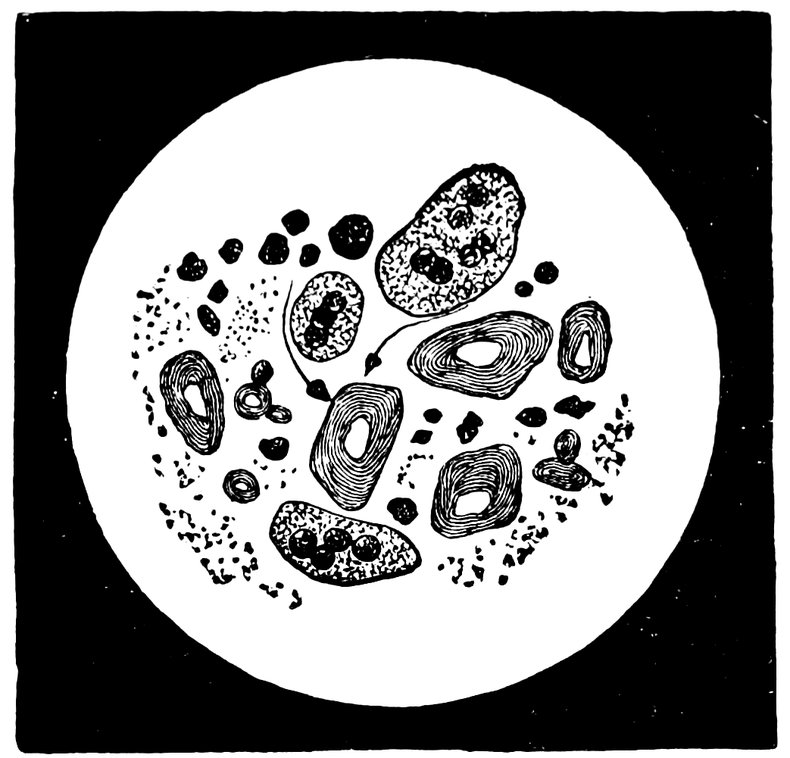

| 61. | a. b. c. Prostatic calculi from normal semen, d. Spermatozoa. e. Large and small cells, some containing granules, as morphological elements of semen. f. Spermatozoon distorted by imbibition of water. g. Crystals (after Bizzozero) | 311 |

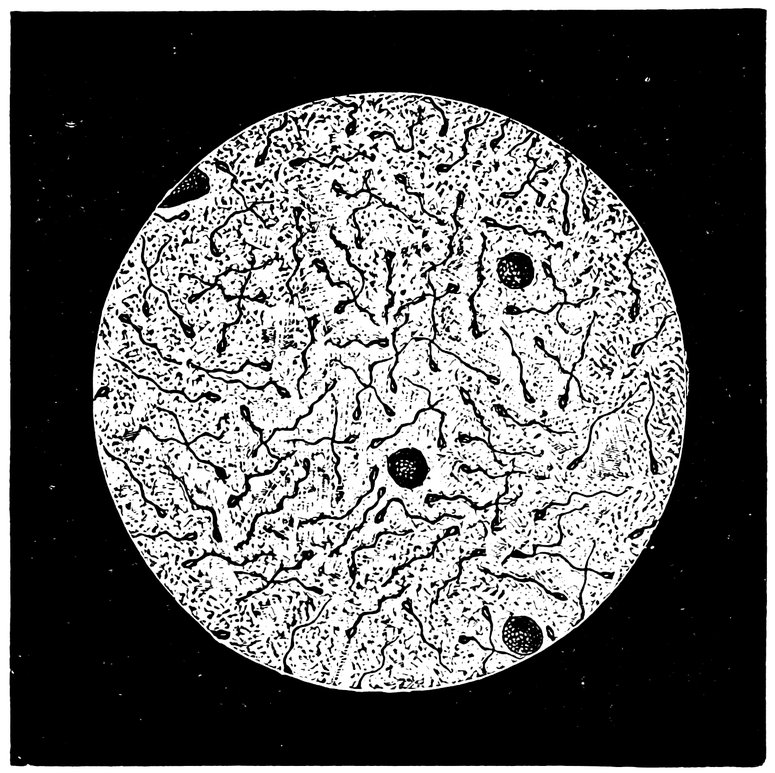

| 62. | Normal Semen | 311 |

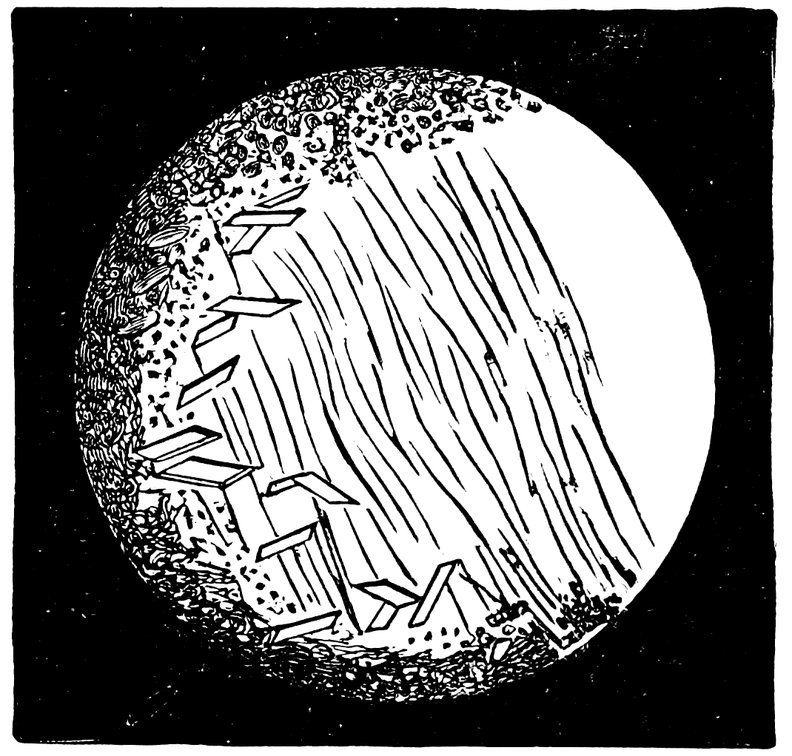

| 63. | Semen consisting chiefly of sperm-crystals, cylindrical epithelium, and small granules exhibiting molecular movement—but containing no spermatozoa | 315 |

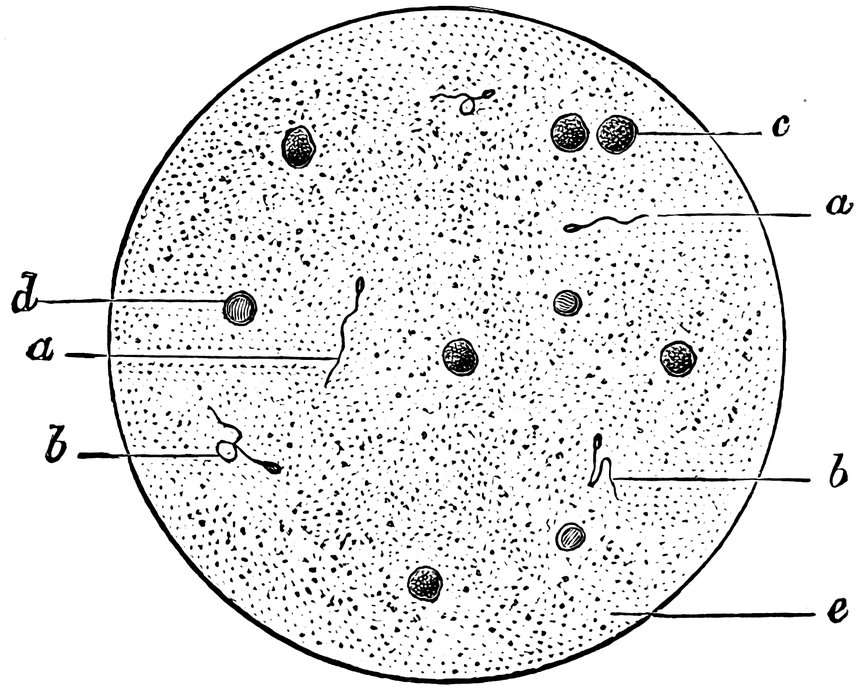

| 64. | Oligozoöspermia. a. Living Spermatozoa, b. Dead Spermatozoa, c. Pus Corpuscles, d. Erythrocyte, e. Seminal granules | 317 |

| 65. | Septate Hymen, the septum having a tendinous consistency | 324 |

| 66. | 326 | |

| 67. | Lipoma of the Right labium majus, including the Vaginal Inlet | 328 |

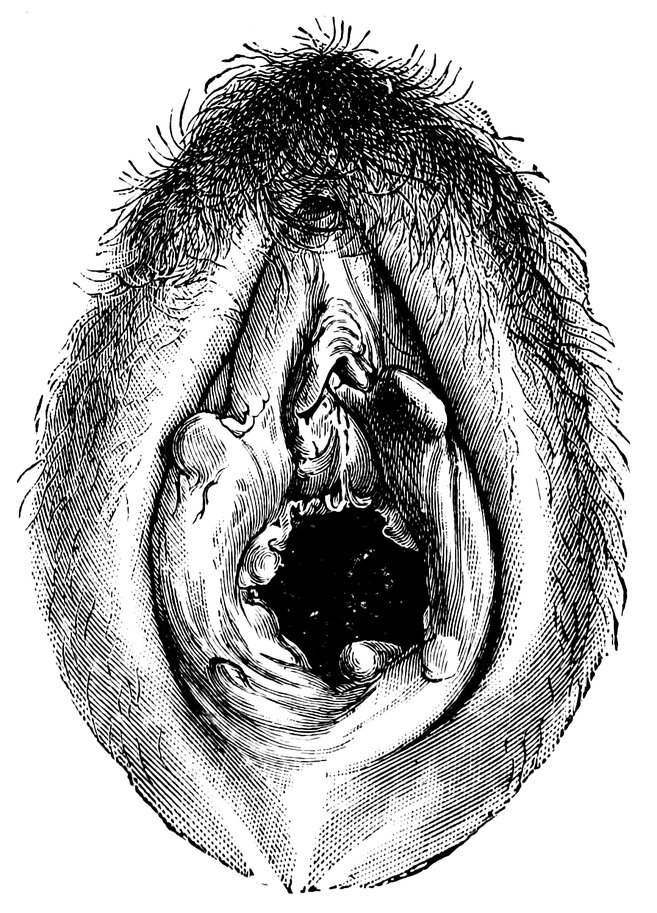

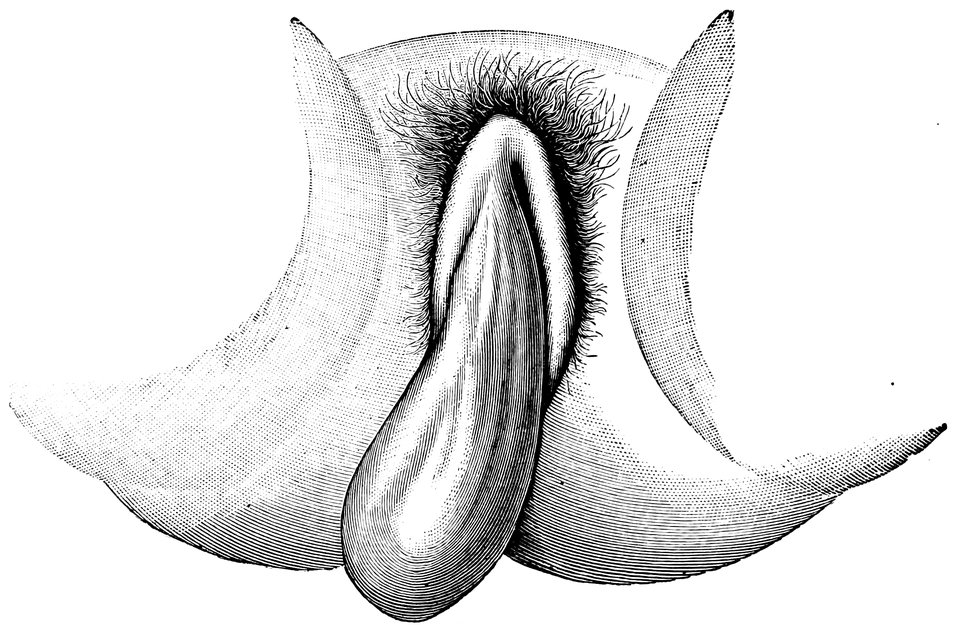

| 68. | “Hottentot Apron” in an adult Woman, hanging down between the thighs (after Zweifel) | 329 |

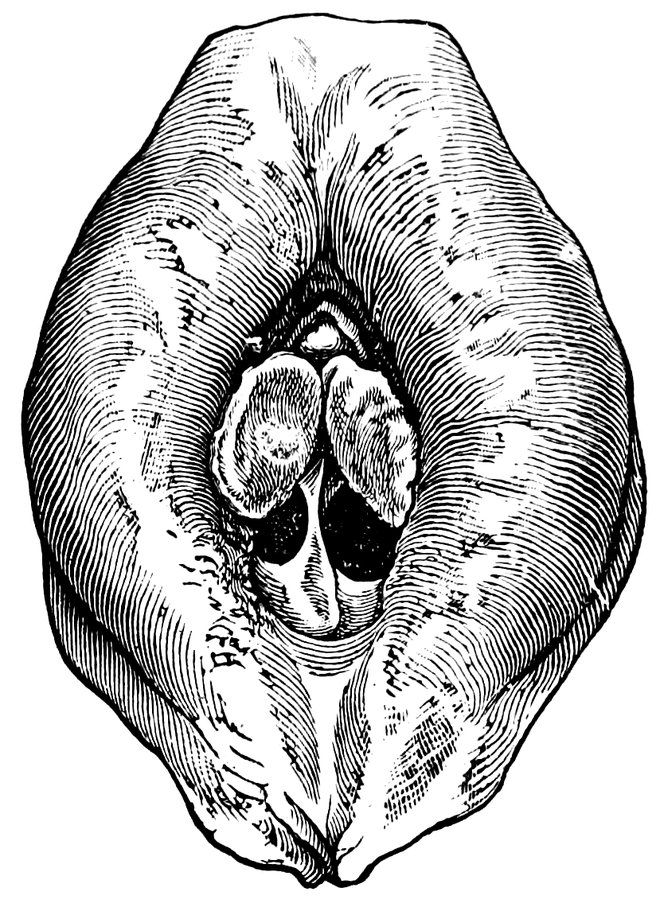

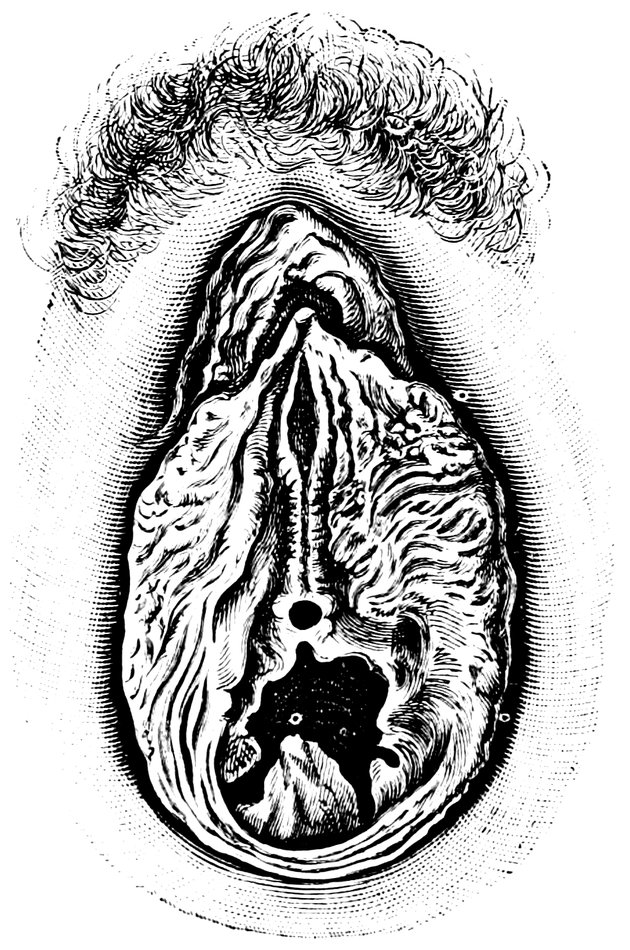

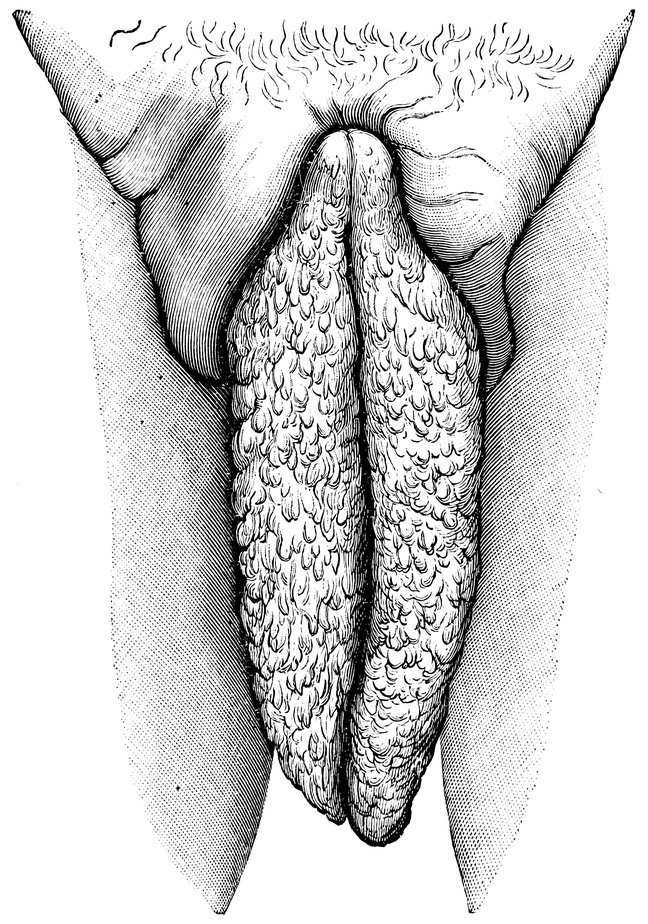

| 69. | Elephantiasis of the Labia Majora | 330 |

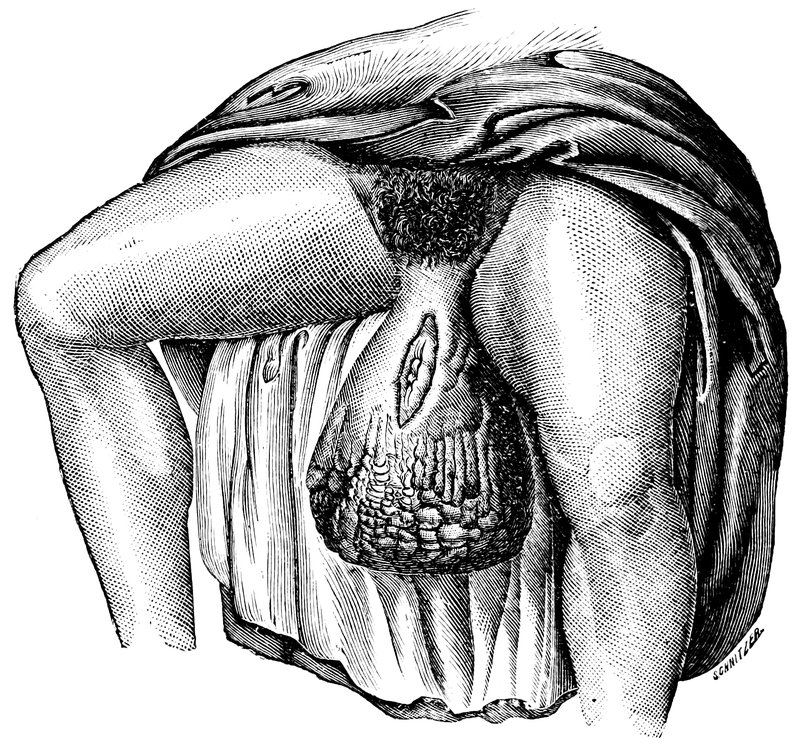

| 70. | Congenital Atrophy of the Uterus (after Virchow), oi, Ostium internum; oe, Ostium externum | 500 |

| 71. | 500 | |

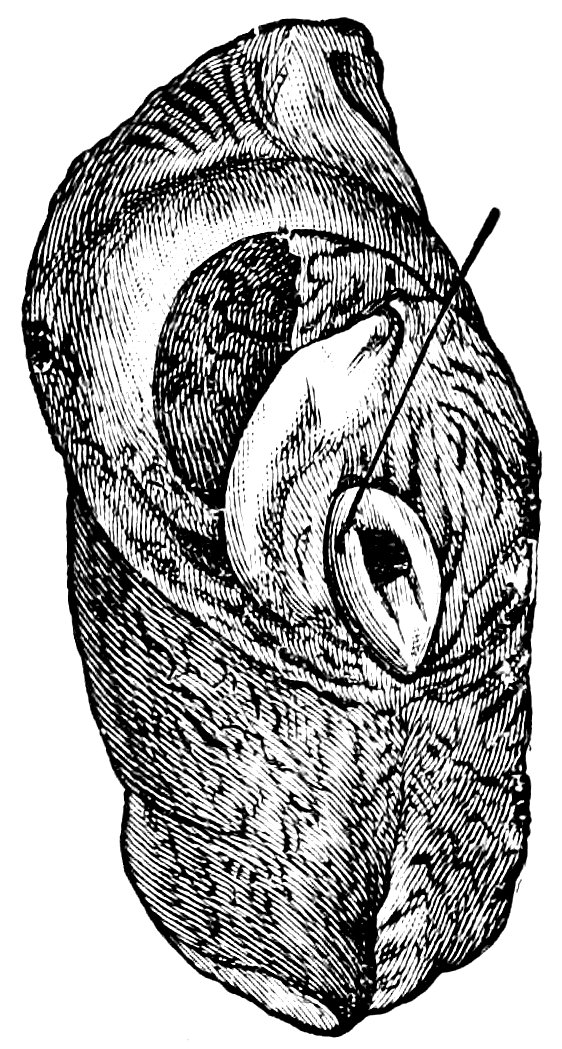

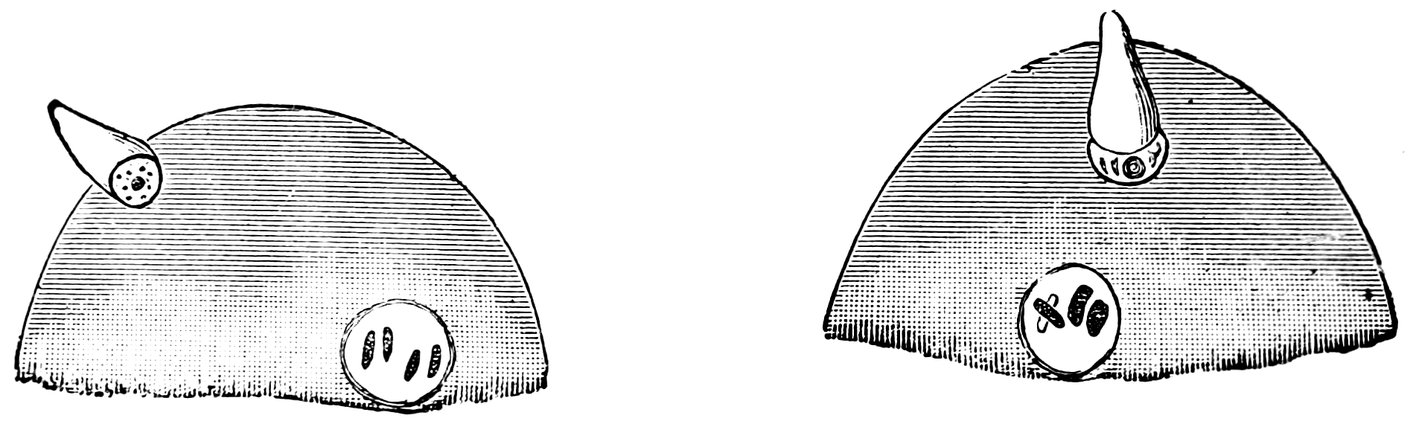

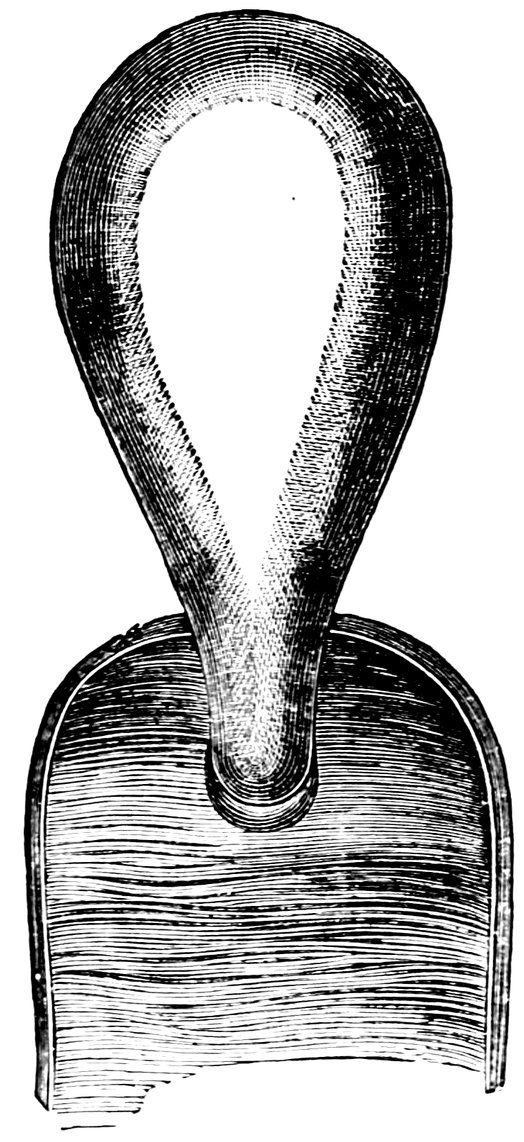

| 72. | Normal Shape of the Portio Vaginalis | 503 |

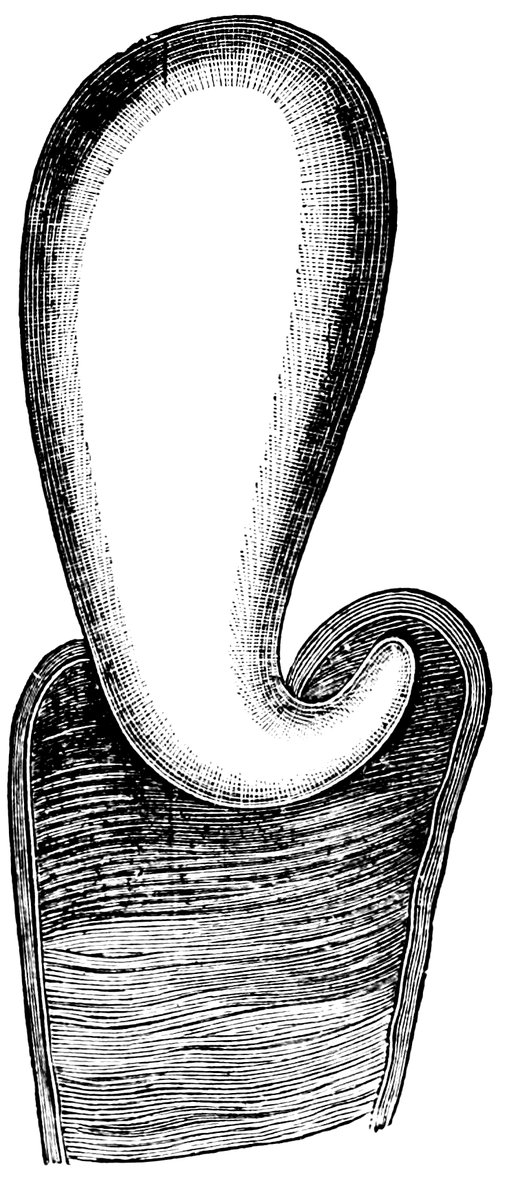

| 73. | Conoidal Shape of the Portio Vaginalis | 503 |

| 74. | “Apron-Shaped” Vaginal Portion, a. Greatly elongated anterior lip; b. Shorter posterior lip of the cervix | 504 |

| 75. | “Beak-Shaped” Vaginal Portion. Posterior aspect | 504 |

| 76. | Simple Hypertrophy of the Portio Vaginalis, which projected from the Vulva | 506 |

| 77. | Elongated Cervix, bent upwards | 506 |

| 78. | Cervical Polypus, originating from an Ovulum Nabothi | 510 |

| 79. | Ectropium in a Case of Bilateral Laceration of the Cervix (after A. Martin) | 514 |

| 80. | Anteflexio Uteri (after A. Martin) | 518 |

| 81. | Retroflexio Uteri (after A. Martin) | 520 |

| xi82. | Mucus from the Cervical Canal, taken one hour after sexual intercourse, from a woman suffering from chronic endometritis. Among the epithelial cells, pus cells, and finely granular masses, we see a few motionless, dead spermatozoa | 531 |

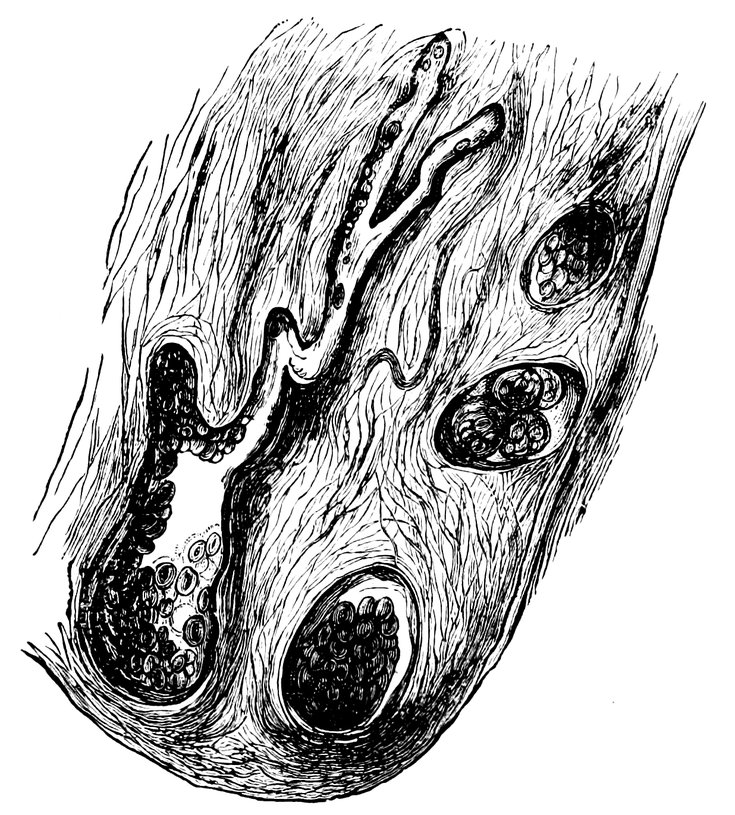

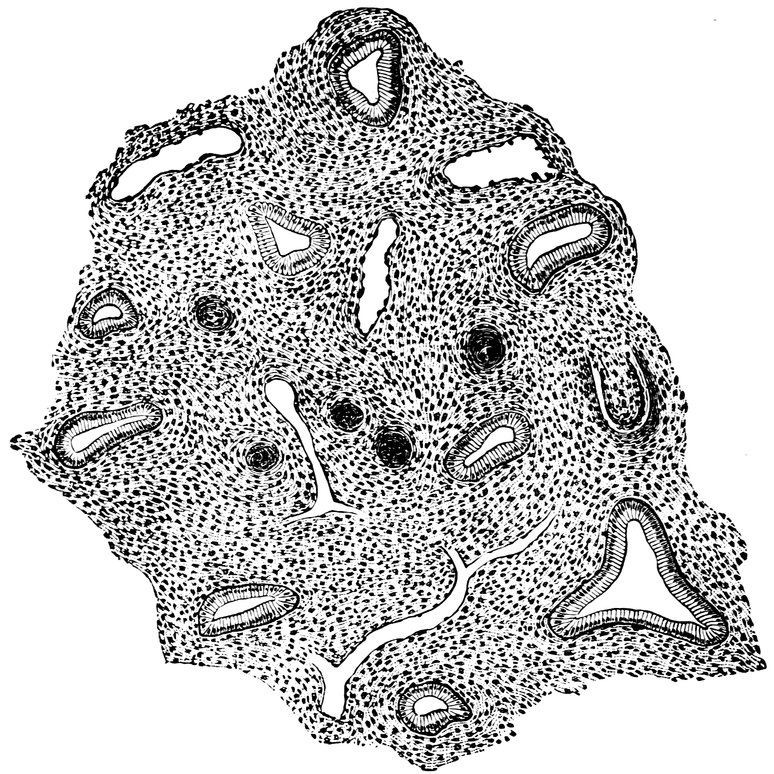

| 83. | Uterine Mucous Membrane in Endometritis (after A. Martin) | 554 |

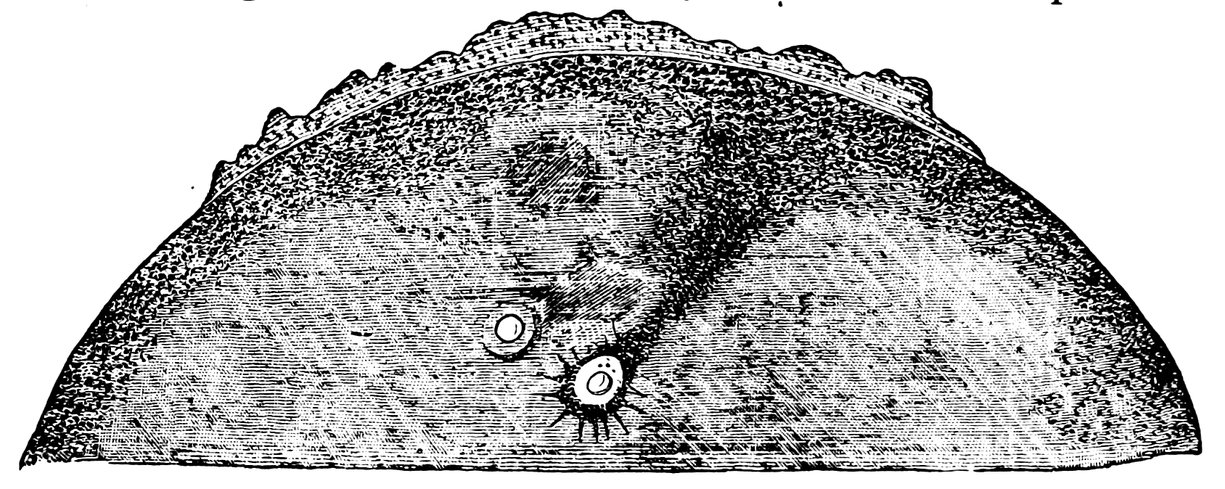

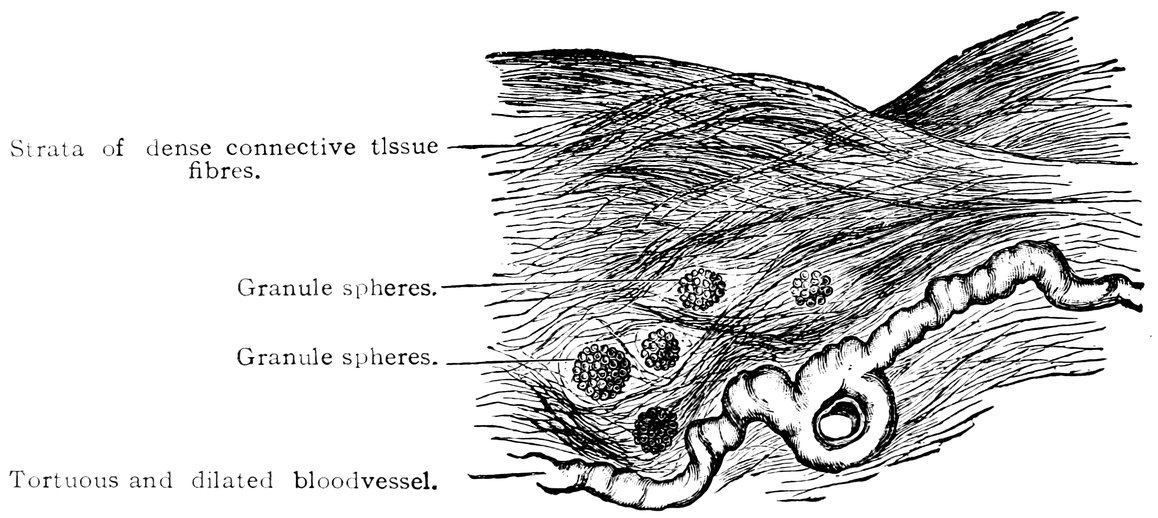

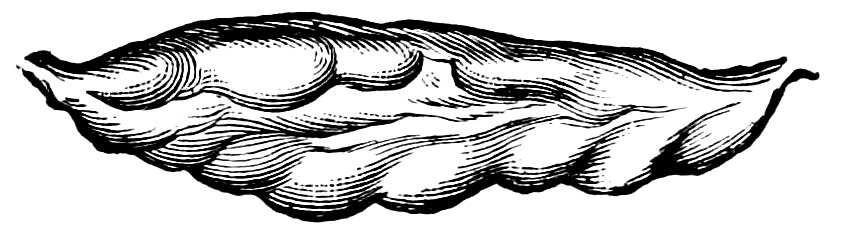

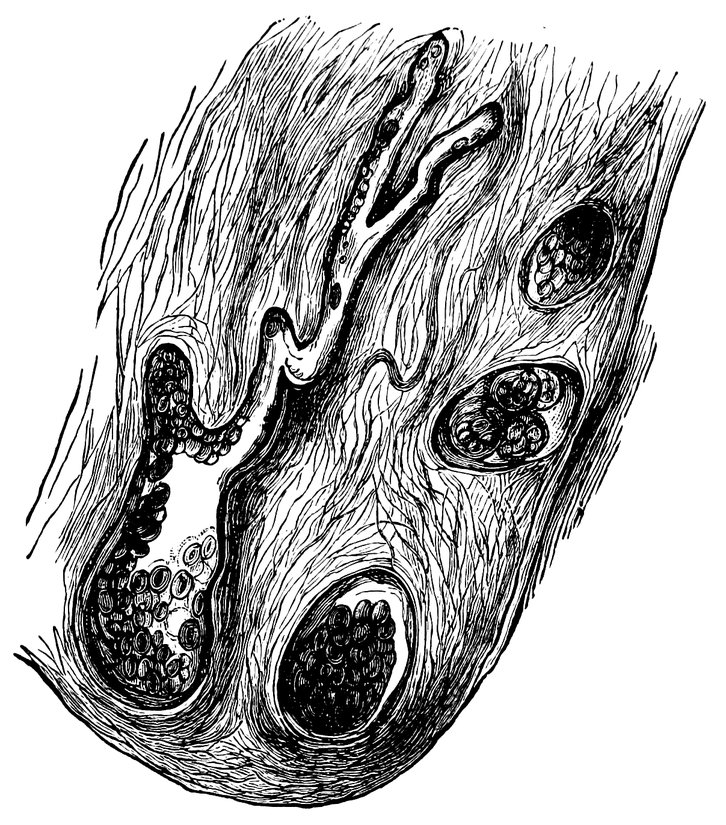

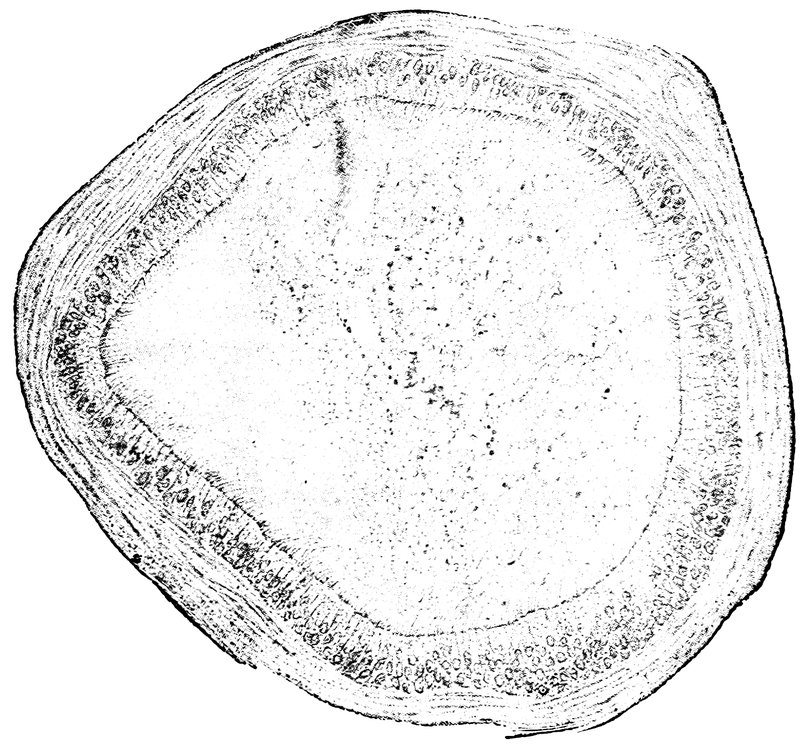

| 84. | Sagittal section through the ovary of a girl aged sixteen | 583 |

| 85. | Sagittal section through the ovary of a woman aged seventy-two years | 584 |

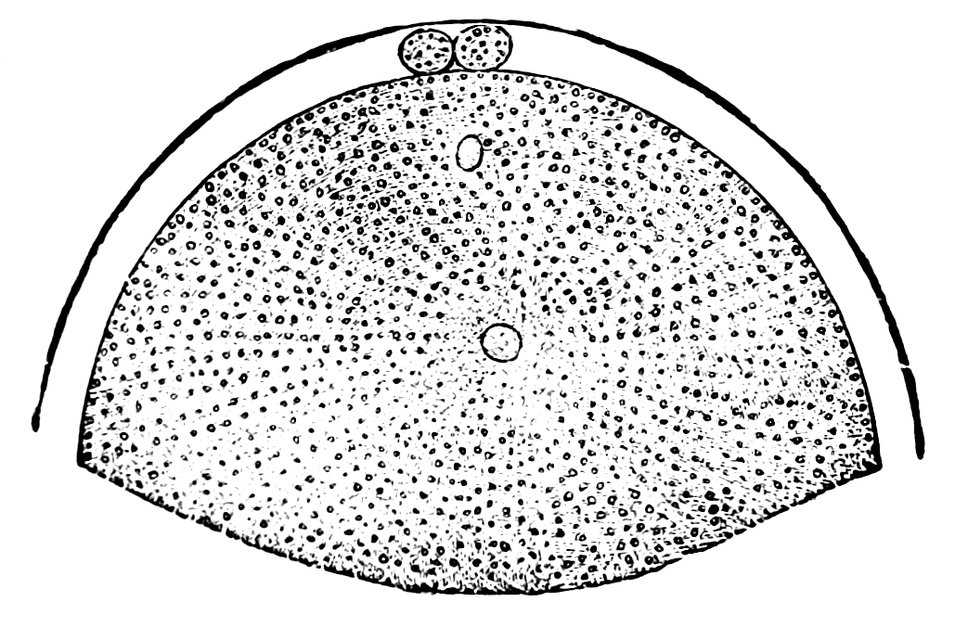

| 86. | Diagrammatic Representation of the Graafian Follicle | 585 |

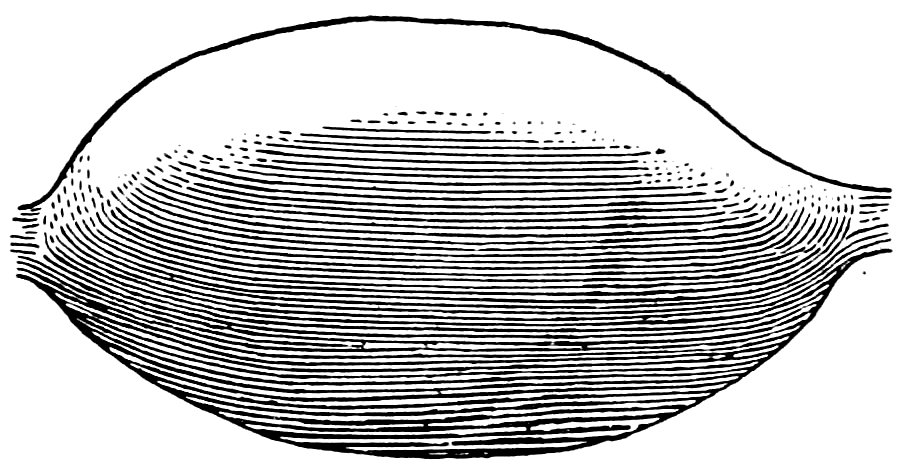

| 87. | Ovary of a Girl aged nineteen years (Normal Size) | 585 |

| 88. | Ovary of a Woman seventy-two years of age (Normal Size) | 585 |

| 89. | 586 | |

| 90. | 587 | |

| 91. | 588 | |

| 92. | Sagittal Section through the Cervix of a Woman twenty-six years of age. Dendriform branched glands | 588 |

| 93. | Sagittal Section through the Cervix of a Woman sixty-five years of age. Glands which have undergone Cystic Degeneration | 589 |

| 94. | Cervix of a Woman seventy years of age. The Cervical Glands have undergone Cystic Degeneration | 589 |

| 95. | Ovula Nabothi in the Portio Vaginalis | 590 |

| 96. | Vesicle (Ovula Nabothi) from the Uterine Mucous Membrane | 591 |

| 97. | Mucous Glands undergoing Cystic Degeneration | 592 |

By the sexual life of woman we understand the reciprocal action between the physiological functions and pathological states of the female genital organs on the one hand and the entire female organism in its physical and mental relations on the other; and the object of this book is to give a complete account of the influence exercised by the reproductive organs, during the time of their development, their maturity, and their involution, on the life history of woman.

From the earliest days of the medical art this sexual life of woman has aroused in the leaders of medical thought the highest interest, and for this reason great attention has been directed, not only to the anatomy of the genital organs and to the diseases of the reproductive system, but also to the individual manifestations of sexual activity and to the influence exercised by these on the female organism as a whole.

Several works by Hippocrates are extant on this subject, among which may be mentioned: περι Γυναικειης Φυσεος,[1] a treatise on the physiology and pathology of woman; περι Αφορων,[2] which discusses sterility in women; περι παρθενιων,[3] a treatise on the pathological states of virgins. These writings of Hippocrates contain some very remarkable observations on the influence exercised by disorders of the reproductive organs on the general health of women.

Aristotle wrote at some length on the functions of the female genital organs. In the writings of Aretæus and Galen on the diseases of women we find striking observations, as for instance, in Galen’s De Locis Affectis,[4] which contains a “Statement of the Similarity and Dissimilarity of Man and Woman.” Another notable work is that of Albertus Magnus, entitled De Secretis Mulierum.[5]

The numerous works on the diseases of women published in the sixteenth century consisted for the most part of a repetition of the observations of ancient writers. The gynecological treatises of the 2eighteenth century, however, bore witness to an increased knowledge of the anatomy of the female reproductive organs, and were illumined by Haller’s researches on the functions of these organs.

The subject with which we are especially concerned is discussed in a work by Boireau-Laffecteur, Essai sur les Maladies Physiques et Morales des femmes,[6] Paris, 1793; and also in Marie-Clement’s Considerations Physiologiques sur les Diverses Epoques de la Vie des Femmes,[7] Paris, 1803. the same connection we must mention von Humboldt’s treatise, Ueber den Geschlechtsunterschied und dessen Einfluss auf die organische Natur.[8] The first comprehensive work in which an exhaustive inquiry was made into the functional disorders of the female genital organs and the relation of these disorders to the female organism as a whole and to the physical and mental peculiarities of woman was Busch’s: Das Geschlechtsleben des Weibes,[9] Leipzig, 1839.

In the second half of the nineteenth century a very large number of monographs were published, investigating and describing the reflex disturbances produced alike in the individual organs and in the nervous system as a whole by changes in the uterus and its annexa. Many of these works will be mentioned more particularly in the course of this treatise.

The sexual life, based upon the purpose, so important to every creature, of the propagation of the species, possesses in the female sex a vital significance enormously greater than sexual activity possesses in the male. From the very beginning of sexuality, when the idea of a bisexual differentiation dawns for the first time in the brain of the little girl, down to the sexual death of the withered matron, who laments the loss of her sexual potency, physical and mental activity, work and thought, function and sensation, arise for the most part, wittingly or unwittingly, from that germinal energy which is the manifestation of the unalterable law that the existing organism endeavors to reproduce its kind.

Every phase of the sexual life of woman, from the threshold of puberty to the extinction of sexual activity, the first appearance of menstruation, the complete development of the sexual organs, the act of copulation, conception, pregnancy, parturition, and the puerperium, finally the involutionary process which accompanies the cessation of menstruation at the climacteric period—every one of 3these sexual phases entails consecutive physiological processes and pathological changes alike in the individual organs and in the nutritive condition of the entire organism, in the functions of the cardio-vascular apparatus, of the brain and the nerves, of the skin and the sense-organs, in the processes of digestion and general metabolism. Herein we see a striking illustration of the old saying of von Helmont, propter solum uterum mulier est quod est;[10] also of the similar aphorism of Hippocrates, uterus omnium causa morborum qui mulieres infestant;[11] a conception summed up by Goethe in the words of Mephistopheles:

Just as in a tree the process of growth is made manifest to the superficial observer by the pleasure he feels at the sight of the buds and blossoms, by the refreshment he obtains from the fruit, and by the sadness which the withering of the leaves causes him, so in the sexual life of woman there are landmarks which no one can possibly overlook, by means of which three great epochs are distinguished. These are: puberty (the menarche), recognized by the first appearance of menstruation and the awakening of the sexual impulse; sexual maturity (the menacme), in the fully developed woman, characterized by the functions of copulation and reproduction; and sexual involution (the menopause), in which we see the gradual decline and ultimate extinction of sexual power and all its manifestations. In all these three epochs the sexual life of woman not only affects the hidden domain of the genital organs, but controls also all the vegetative, physical, and mental processes of the body, and is clearly and incontestably apparent in all vital manifestations. What Madame de Staël said of love is indeed true of the entire sexual life of woman: l’amour n’est qu’unc épisode de la vie de l’homme; c’est l’histoire tout entière de la femme.[12].

The sexual life of woman is coextensive with the peculiar vital activity of the female sex, for it endures from the moment when 4individuality first begins to develop out of the indifferent stage of childhood until the decline into the dead-level of senility.

To illustrate this fact, I have drawn up a curve of the sexual life of woman, making use of the statistical data available in central Europe regarding the age at which menstruation first appears, the age at which maidens marry, the age at which the largest number of women give birth to a child, and the age at which menstruation ceases; and reducing the figures to averages. * denotes the fifteenth year of life, as the average age at the menarche; ** denotes the twenty-second year of life as the average age at marriage; *** denotes the thirty-second year of life, in which woman exhibits her maximum fecundity; **** denotes the forty-sixth year of life as the average age at the menopause. (Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.—Curve of the sexual life of woman from the tenth to the sixtieth year of life.

Not in this respect alone, however, is the sexual life of woman of paramount importance; it is, in addition, the mainspring of the well-being and progress of the family, of the nation, of the entire human race. In the evolution of man from the primitive state in which he existed merely for the performance of vegetative functions up to the highest stage of contemporary culture, in the history of all races and of all times, the sexual life has been a most 5potent determining factor. With that life, religion, philosophy, ethics, natural science, and hygiene, have been most intimately related; for that life, they have furnished precepts and laws. The history of the sexual life is identical with the history of human culture.

In a primitive condition of society, among people living in a state of nature and among the lower races of mankind, the sexual life of woman possesses no great general interest, the female being merely a chattel; the ownership of this chattel, moreover, being often temporary and transient. The investigations of anthropologists have shown that among primitive people this form of property is neither highly esteemed nor carefully safeguarded. In such societies no restraint is imposed on the sexual impulse, which is gratified without shame and without formality. No hindrance is offered to the mutual intercourse of the two sexes. Chastity in the females is not prized by the males, nor do the latter compete for the favors of the former. Procreation is no more than a gregarious impulse of the masses among whom the common ownership of all booty is a matter of tribal custom. The woman has no disposing power over that which every one desires and which every one has the right to demand. Very gradually, however, a change takes place in this respect, so that in every period of social life since the very earliest, the modesty of young girls, the high valuation put upon the preservation of virginity, the ethical approbation of chastity in the wife, respect for the duties and rights of the mother, the reverence felt for the matron—all these, throughout the sexual life of woman, have had a civilizing, ennobling, and elevating effect. Thus, as family life has become developed, and as love and marriage have been more highly esteemed, woman has become the much-prized embodiment of all that is beautiful and good, of all that is summed up in the idea of the “housewife,” and her sexual life has been more completely, more ideally admired. The danger is not remote, however, that the leveling tendencies of the present day, and an inclination to despise the sexual life of woman, far from resulting in a further elevation of the social status of womanhood, will result rather in its abasement.

The Bible, as we may expect from the patriarchal relationships of the women of that time, bears witness to the worth of woman, and, whilst esteeming child-bearing, refers to yet higher duties. Precise religious and social precepts are furnished for all the phases of sexual life.

6In classical antiquity, also, we see that woman rose to some extent above the low position she had previously occupied in the family circle and in society at large. Both among the Greeks and among the Romans, there was open to women a more intimate place in social life and a more influential rôle in the life of the family, than would have been their portion regarded merely in relation to their child-bearing activity. Amongst the Germans in the very earliest times, chastity gave rise to purer and more moral sexual relations; whereas among the Slavonic peoples the conception of woman as the childbearer continued to dominate these relations.

In consequence of the diffusion of Christianity, woman became man’s companion and equal, and her life, the sexual life included, acquired a deeper significance, owing to the stress which that religion laid on chastity as a virtue, and as a result of the educational influence of woman in the family circle.

With the progress of civilization the sexual life of woman comes to exhibit its activities only within the bounds of morality and law, which in human society have replaced the crude rule of nature, and have supplied regulations adapted to the changing phases of sexual vital manifestations. The wise adaptation of these regulations requires, however, a full understanding of the mental and physical processes, an exact recognition of the bodily states and intellectual sensibilities, of woman regarded as a sexual being.

Modern culture and the social organization of the present day, in association with the resulting sexual neuropathy of women, have exercised on their sexual life an influence as powerful as it is unfavorable, manifesting itself in the overpowering frequency of the diseases of women. In one of the most thoughtful books ever written on the subject of woman, Michelet’s L’Amour,[13] the author remarks that every century is characterized by the prevalence of certain diseases: thus, in the thirteenth century, leprosy was the dominant disease; the fourteenth century was devastated by bubonic plague, then known as the black death; the sixteenth century witnessed the appearance of syphilis; finally, as regards the nineteenth century, “se siècle sera nommé celui des maladies de la matrice”.[14] It is certain that the education and mode of life of the modern woman belonging to the so-called upper classes are, as far as sexual matters are concerned, in direct opposition to those that are agreeable to nature and those that the laws of health demand.

7Even before sexual development begins, before the physical ripening of the reproductive organs to functional activity, the imagination of young girls is often prematurely occupied with sexual ideas in consequence of unsuitable literature, owing to visits to theatres and exhibitions, or on account of social intercourse with young men who are not overscrupulous in the selection of topics for conversation. From the time of puberty up to the time of marriage the growing woman is under the influence of the now awakened sexual impulse, which experiences ever-renewed stimulation. A sedentary mode of life, unsuitable nutriment, and the early enjoyment of alcoholic beverages, exhibit their inevitable result in the frequency with which, in this epoch of the sexual life, chlorotic blood-changes, neurasthenic conditions, and diverse symptoms of irritation of the genital organs, make their appearance. Thus, when marriage, so often unduly postponed in consequence of the condition of modern society, does at length take place, it is apt to find the woman not only fully enlightened as regards sexual matters, but often in a state of nervous weakness from sexual stimulation, one of the type whose characteristics have been happily summed up by the French writer Prévost in the expression demi-vierge.[15] The conjunction of this state of affairs in the bride with the frequent partial impotence of the bridegroom, who has already dissipated the greater part of his virile power before entering upon marriage, leads often to the appearance of vaginismus and other sexual neuroses in young married women. Even more disastrous in its consequences as regards the future sexual life of the wife is the ever-increasing frequency of gonorrhœal infection in the first days of marital intercourse, with all the evil results of that infection. On the other hand, an ever-larger proportion of girls belonging to the “middle and upper classes,” abstaining alike from the good and the evil results of marriage, falls under the yoke of sexual impulses denied satisfaction or gratified by abnormal means, and suffers in consequence both physically and mentally. Further sources of injury arising from the conditions of modern social life are to be found in the neglect by women of the well-to-do classes of the duty of suckling their children, and in the ever-increasing frequency with which the women of these classes, after giving birth to one or two children, resort to the use of measures for the prevention of pregnancy, which result in serious consequences as regards both the nervous system and the genital organs of the women concerned. Thus there comes an accelerated ebb in the sexual life, leading to a premature appearance 8of the general phenomena of senility, with a cessation of the menstrual flow. The modern wife, who claims the right to lead the life that best pleases her, will be more rapidly overtaken by sexual death.

For the elucidation of the manifold reflex and other processes which are dependent upon or accompany the sexual phases of woman, we must in the first place consider the anatomical changes and physiological functions of the female reproductive organs characteristic of the several periods of sexual life which have already been distinguished. We must not fail also to take into consideration the mental states which accompany and characterize these respective phases.

The anatomical changes which occur in the female genital organs during these different phases of sexual life give rise to a number of manifold local stimuli, increasing and decreasing, varying greatly in intensity and area of distribution, upon which depend the reflex effects and remote manifestations in the sphere of the nervous and circulatory systems.

We must first consider the changes in the ovaries, which play an etiologically important part. At the onset of puberty, the follicular masses of the ovary exhibit a more active growth, the follicles increase in size, with their contained ova they approach the surface, and finally, by the bursting of the follicles, the ova are extruded. Then, in the life-phase in which conception occurs, and under the influence of the hyperæmia of all the pelvic viscera that accompanies this process, a notable development of the corpus luteum takes place, this latter body reaching its maximum size in the eleventh week of pregnancy, subsequently undergoing involution and leading to the formation of a considerable scar. Finally, in the critical period of life in which the menstrual flow ceases, a continually increasing growth and new formation of connective tissue-stroma takes place in the ovaries at the expense of their cellular constituents, and a regressive metamorphosis of the graafian follicles occurs.

In association with these sexual processes there ensues a series of striking changes in the shape and consistency of the ovaries, affecting both the surface and the parenchyma of these organs, and capable of stimulating the nervous ramifications in their tissue. In this connection it is worthy of note that the branches supplying the ovaries from the spermatic plexuses of the sympathetic contain a considerable proportion of sensory fibres.

Quite as significant, moreover, as the changes in the ovaries, are those which, in the course of the sexual life, the uterus undergoes, in shape and size, in its muscular substance and mucous lining, and in its vascular and nervous supply.

Fig. 2.—Portion of the pelvic viscera in the female, and their relation to the muscles of the pelvic outlet (or perineal muscles), shown in the left half of the pelvis, seen from the right side.—The parametrium. (From Toldt: Atlas of Human Anatomy.—Rebman Company, New York.)

10At the time of puberty the infantile uterus undergoes changes affecting both its external form and the shape of its interior cavity. The body of the uterus enlarges to the size characteristic of sexual maturity, and its mucous membrane becomes the seat of periodic changes. This waxing and waning growth and transformation of the uterine mucous membrane continues throughout the period of menstrual activity, the most superficial layers of the membrane being shed during menstruation, a process followed by regeneration, which is itself succeeded by the premenstrual thickening. When conception occurs, still more extensive changes ensue, the fertilized ovum becoming imbedded in the uterine mucous membrane, and the pregnant uterus, in shape and structure and in the respective relations of the body and neck of the organ, in the increasing distension of its veins and the increasing size of its nerves, becoming adapted to the important functions it has now to fulfil. When these have been fulfilled, and, parturition having taken place, the uterus is empty once more, the organ again adapts itself to altered circumstances by the process of involution. Later, in the climacteric period, a slow regressive process occurs, the outward manifestation of which is the cessation of the menstrual flow, characterized anatomically by atrophy of the muscular tissue of the uterus and of its vascular apparatus, by the dessication of its mucous membrane, by obliteration of the lumen of the uterine cavity, and ultimately by senile degeneration and atrophy of the now entirely functionless organ, so that it becomes an insignificant, cicatrized, solid body.

Next to the ovaries and the uterus, it is the pelvic fascia which in its entire architectonic structure as well as in its individual parts undergoes the most notable changes in consequence of the processes of generation.

A short account of the nerves and blood vessels of the female genital organs appears indispensable, to facilitate the comprehension of the manner in which sexual processes are influenced by the nervous system, and to demonstrate the intimate connection between the blood-supply of the genital apparatus and the general circulation.

The complex nervous network of the female sexual organs is supplied by spinal as well as by sympathetic fibres, the fibres from the two systems anastomosing in a very intimate manner.

Fig. 3.—The distribution of the pudic nerve, n. pudendus, in the female perineal and pubic regions. The trunk of the pubic nerve, n. pudendus, is covered by the gluteus maximus muscle. On the right side of the body the branches of the inferior pudendal nerve, rami perineales, nervi cutanei fermoris posterioris have been dissected out; but the branches of this nerve to the labium majus have been cut short. The formation of the anococcygeal or subcaudal nerves, nn. anococcygei, out of the posterior primary division of the coccygeal nerve and out of the perforating branches which arise from the anterior primary divisions of the fourth and fifth sacral nerves and the coccygeal nerve. (From Toldt: Atlas of Human Anatomy.—Rebman Company, New York.)

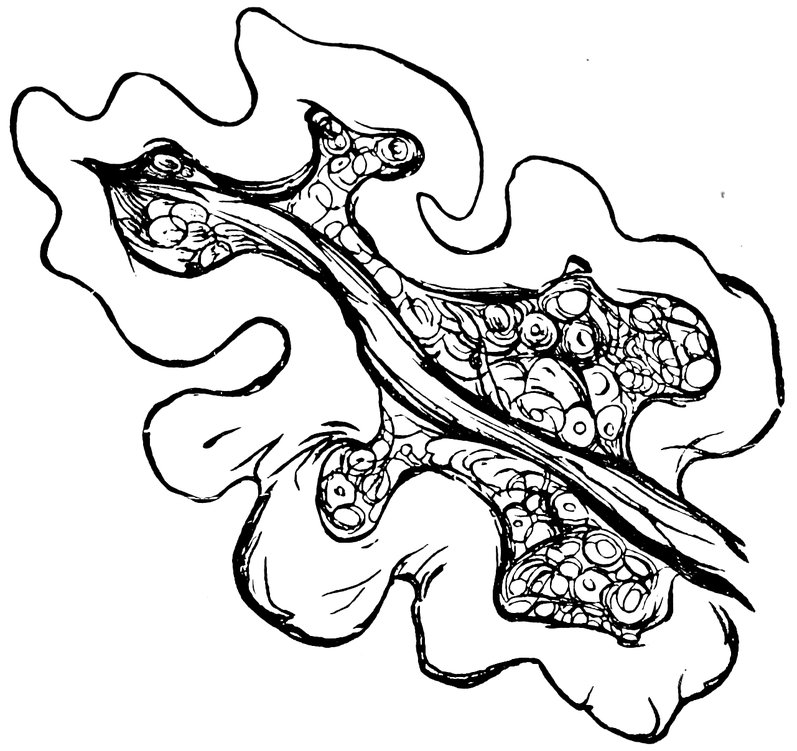

12The greater number of the spinal nerves distributed to the genital organs arise from the lumbar portion of the spinal cord, pass as rami communicantes to the first four lumbar ganglia of the great sympathetic cord, whence they proceed to the series of symmetrical (paired) and asymmetrical (azygos) sympathetic plexuses in front of, and adjacent to the abdominal aorta, which already contain afferent and efferent spinal fibres derived from the pneumogastric, phrenic, and splanchnic nerves. A small number only of coarse nerve-filaments, a larger number of fine nerve-filaments, derived from the sacral nerves, proceed direct to the internal genital organs; many of these fibres enter the lower extremity of the pelvic or inferior hypogastric pleans, some pass to the cervical ganglia of the uterus. Below the bifurcation of the aorta and in front of the sacral promontory, a large number of the uterine nerves, both of spinal and of sympathetic origin, unite to form an azygos plexus which has been shown by experiment to possess great functional importance. Anatomically this constitutes the upper undivided portion of the hypogastric plexus, which is the downward continuation of the abdominal aortic sympathetic plexus; but inasmuch as it is the principal channel of nervous impulses to the uterus it is often known at the present day as the great uterine plexus (plexus uterinus magnus). The nerves to the ovary and Fallopian tube (ovarian nerves) are derived from the spermatic (ovarian) plexus, an offshoot of the renal plexus; as the spermatic plexus descends, it is reinforced by branches from the abdominal aortic plexus, these branches often arising from a small ganglion (spermatic ganglion). The hypogastric or great uterine plexus, single and median above, divides below into the paired pelvic or inferior hypogastric plexuses, which pass downward and forward on either side of the rectum; these plexuses are reinforced by spinal elements derived from the sacral nerves. Before the terminal expansions of the pelvic or inferior hypogastric plexus enter the tissues of the internal genital organs, the bladder, and the rectum, small masses of ganglionic matter are interspersed among the nerve fibres.

To the above general sketch, which has been based on the synoptical description of Chrobak von Rosthorn, must be added a more detailed account of the innervation of the ovaries, this branch of the subject being of especial importance. The nerves of the ovary are derived from the sympathetic system, in part from the spermatic ganglion, in part from the second renal ganglion, and in part from the superior mesenteric plexus. The nerves of 13the ovary are for the most part vascular nerves, which unite before entering the ovary to form the ovarian plexus, and then pass into the hilum with the vessels, envelop the vessels of the medullary layer, and thence pass to the follicular region; exceedingly numerous, they form a close-meshed network, surrounding all the vessels up to the finest capillary ramifications; those fibres which terminate in the capillary walls and those also which reach the follicles are regarded by Riese as sensory. The great trunks of the uterine nerves are transversely disposed in relation to the great lateral vessels of the uterus, and passing inward toward the mucous membrane they break up into pencils of filaments; the uterine nerves proper are distributed for the most part to the muscular substance. In the Fallopian tubes, the nerves form arches around the lumen of the tube; some fibres also pass to the longitudinal folds of the mucous membrane.

This expansion of the nerves of the cerebrospinal and sympathetic systems in the female reproductive organs manifests the multiple interconnection of the two systems in this region, and proves beyond doubt that the sensory nerves of the genital organs have manifold connections with the motor tracts of the whole organism on the one hand and with the sensory ganglia of the central nervous system on the other, and in addition with the vasomotor centres and with efferent motor and secretory fibres.

As regards the vascular system of the female genital organs, the latter are supplied by the internal iliac artery. One of the two terminal branches of the common iliac, the internal iliac artery, descends into the pelvis over the sacro-iliac synchondrosis. Its branches may be arranged in four groups: anterior group, the hypogastric, iliolumbar, and obturator arteries; posterior group, the lateral sacral, gluteal, and sciatic arteries; internal group, the inferior vesical, uterine, and middle haemorrhoidal arteries; inferior group, comprising a single artery only, the internal pudic; the uterine artery supplies the uterus and the vaginal fornices; the ovarian artery supplies the ovary, the Fallopian tube, and the broad ligament of the uterus; the vaginal, cervicovaginal, or vesico-vaginal artery supplies the vagina; the internal pudic artery supplies the vestibule and the clitoris; the superior and inferior external pudic arteries (branches of the femoral artery) supply the labia majora. The veins of the female genital organs correspond in general to the arteries in their course and nomenclature, and empty their blood into the internal iliac vein.

Fig. 4.—The distribution of the lateral sacral arteries, the superior haemorrhoidal or superior rectal artery, the uterine artery, the ovarian artery and the distal portion of the internal pudic artery. (From Toldt: Atlas of Human Anatomy.—Rebman Company, New York.)

15Attention must also be paid to the extremely rich lymphatic vascular system of the female genital apparatus. The body of the uterus and the annexa of that organ, the neck of the uterus and the vaginal fornices, the middle segment of the vagina, the lower segment of the vagina, the vestibule and the external genital organs—each of these possesses an independent set of lymphatic vessels, leading moreover to independent groups of lymphatic glands. It may be said that the lymph from the vulva passes to the inguinal glands, that from the vagina and the neck of the uterus to the internal and the external iliac lympathic glands, that from the upper part of the uterus and also that from the ovaries and Fallopian tubes to the median group of lumbar lymphatic glands (also known, from their position in front of the aorta and the vena cava, as the aortic lymphatic glands) (Chrobak von Rosthorn).

The important influence which the genital processes exercise on the female organism as a whole is established not only by the anatomical relations just described but also by a number of physiological investigations and experiments and by the result of operations on the female genital organs.

Thermic and mechanical stimulation of the female genitals has, as my own experiments have shown, a notable influence on the heart and the general circulation. In these experiments, when uterine douches were given at temperatures of 4° C. (39° F.) and 45° C. (113° F.), the reflex nervous impulse which resulted from these manipulations had a two-fold influence on the circulation, manifesting itself first by an immediate and considerable augmentation in the functional activity of the heart, the frequency of which was increased in a degree proportional to the nervous sensibility of the individual, and secondly by a notable rise in blood pressure.

With a view to determining the influence of stimulation of the ovary on blood-pressure, Röhrig carried out some experiments on bitches, from which it appeared that electrical stimulation of the ovary invariably produced a remarkable increase in the general blood-pressure, an increase ranging from twelve to twenty-four millimeters of mercury. It further appeared in the course of these experiments that toward the end of the period of stimulation the rise in blood-pressure was always followed by a decline; to which, however, a renewed rise of blood-pressure succeeded after the stimulation was discontinued, provided the duration of this had not been excessive. Only after this second rise was the normal mean blood-pressure regained. Finally it was established that the pronounced 16phenomena of vagus-irritation exhibited by the curve during and immediately after the stimulation of the ovary were invariable concomitants of the rise of blood-pressure produced by such stimulation.

According to the observations of Federns, the blood-pressure undergoes a rhythmical change between one menstrual period and the next, the pressure curve being normally at its lowest at the time of the commencement of the flow, and at its highest at some time during the two days immediately preceding the flow. This rhythmical change of blood-pressure manifests itself also some time before the first onset of menstruation, when the approach of puberty is indicated only by the menstrual molimina.

Observations made by Kretschy in a patient with a gastric fistula have proved the influence exercised on gastric digestion by the physiological processes occurring in the female reproductive organs. In this patient, his attention was especially directed to determining at what period of digestion the secretion of acid by the stomach attains its maximum, and how that secretion increases and diminishes. He observed that the digestion of breakfast was completed in four and one-half hours, the acid-maximum occurring in the fourth hour, and the reaction of the gastric contents becoming neutral one and one-half hours later. This apparently constant acid-curve began, however, to become irregular as soon as the first symptoms of the approach of menstruation became apparent. When the flow had actually begun, he found that the reaction of the gastric contents remained acid throughout the entire day. As soon as the flow was over, the normal acid-curve was immediately reëstablished.

These observations have been confirmed by Fleischer. This investigator carried out his researches in menstruating women with normal stomachs, and found that with the appearance of the catamenia the process of digestion was almost always notably retarded, but that with the diminution and cessation of the flow digestion returned to the normal.

By stimulation of the central segment of the divided hypogastric or great uterine plexus, Cyon was able to provoke vomiting, a confirmation of the well-known physiological fact that irritative disturbances of the female reproductive organs have a reflex influence on the vomiting centre.

It is also clearly established that diverse stimulation of peripheral nerves, those for instance of the mammary gland, of the internal genitals, or of the epigastrium, is capable of affecting the motor centre of the uterus.

Worthy of note also are Strassmann’s experiments, showing that 17rise of pressure in the ovary causes swelling and structural changes in the uterine mucous membrane.

Striking also are Neusser’s discoveries that during menstruation there is an increase in the eosinophil cells of the blood, and that by the intermediation of the sympathetic nervous system the ovaries exercise an influence on the hæmatopoietic function of the red marrow of the bones. Most noteworthy is the connection between the functional activity of the ovaries and osteomalacia. In this disease of metabolism we have to do, according to Fehling’s now generally accepted assumption, with a trophoneurosis of the bones, a stimulation of the vasodilator nerves of the osteal vessels, dependent on a reflex impulse from the ovaries. The connecting path between the ovaries and the bones Neusser finds in this case also in the sympathetic nervous system.

The reflex influence exercised on the heart and the general circulation has been shown also by the results of operations on the female genital organs. In cases in which the ovaries have been removed, or in which these organs have been roughly handled, Hegar has noticed a great diminution in the frequency of the pulse, sometimes even cessation of the heart’s action. In similar circumstances Champonière also observed as a rule diminished frequency of the pulse, but in some cases increased frequency. Mariagalli and Negri have described tachycardia following laparotomy and the extirpation of double pyosalpinx. Bonvalot has published cases in which, in consequence of vaginal or intra-uterine injections, in consequence of simple examination, and in consequence of the performance of version, sudden death has resulted from cardiac syncope.

The psychical influences which proceed from the female genital organs in the different periods of sexual life have also great significance for the organism as a whole. Manifold impulses both stimulating and depressing arising in the reproductive organs affect the workings of the mind. The maiden at puberty is affected by the knowledge of sexuality; the sexually mature woman, by the desire for sexual satisfaction, and by the yearning for motherhood; the wife, by the processes of pregnancy, parturition, and suckling, or, on the other hand by the distressing consciousness of sterility; the woman at the climacteric period, by the knowledge of the disappearance of her sexual potency. The mind is further sympathetically influenced by the stimulation of the terminals of the sensory nerves in the genital organs. Through the increase of such stimulation, through its spread to adjacent nerves and nerve tracts and to the entire nervous system, the mind is affected, 18directly by irradiation, or indirectly by vasomotor processes and spinal hyperæsthesia.

Psychical manifestations and the nervous states associated with these are somewhat frequently, and even actual psychoses occasionally, encountered in the various phases of the sexual life of woman, sometimes taking the form of violent sexual storms, which may indeed, as ordinary menstrual reflexes, accompany every catamenial period.

Of great interest are the facts which have, in recent times especially, been scientifically established, pointing to a certain periodicity, to an undulatory movement of the general bodily functions of the female organism, dependent upon the sexual life. The observations of Goodman, Jacobi, von Ott, Rabuteau, Reinl and Schichareff, have shown that in woman the principal vital processes pursue a cycle made up of stages of increased and diminished intensity, and that this periodicity of the chief general processes of vital activity finds expression also in the functions of the reproductive organs. Goodman has compared this play of general vital functions to an undulatory movement. According to this writer, a woman’s life is passed in stages, each of which corresponds in duration with a single menstrual cycle. Each of these stages exhibits two distinct halves, in which the vital processes are respectively ebbing and flowing: in the latter we see an increase of all vital processes, a larger heat production, a rise in blood-pressure, and an increased excretion of urea; in the former we see, on the contrary, that all these vital processes display a diminished intensity. The moment when the period of increased vital activity is at an end, the moment when the ebb begins, corresponds, according to Goodman, to the commencement of the catamenial discharge.

Goodman sought for verification of this undulatory theory of the sexual life of woman in certain data regarding the bodily temperature and the blood-pressure. A more extensive research was undertaken by Jacobi, who, as the result of her observations, came to the following conclusions. In eight cases she noticed in the premenstrual epoch a rise of temperature ranging from 0.05° C. to 0.44° C. (0.09° F.–0.79° F.); and during the catamenial discharge a gradual fall of 0.039° C.–0.25° C. (0.072° F.–0.45° F.), never less, that is to say, than a quarter of a degree Centigrade; but in the majority of cases the temperature did not, while the catamenia lasted, regain the normal mean. She further observed in the generality of cases an increased excretion of urea during the premenstrual epoch; and a notable fall in blood-pressure during menstruation.

Reinl’s observations on healthy women, in whom menstruation ran a normal course, showed that in the great majority of cases in 19the premenstrual epoch the temperature was elevated as compared with that of the interval, that in eleven out of twelve cases the temperature gradually declined during menstruation, to fall in three-fourths of the cases below the mean temperature of the entire interval, and exhibiting in the post-menstrual epoch a still further depression, giving place, however, to a somewhat higher mean temperature during the first half of the interval. In the second half of the interval a higher mean temperature was observed than in the first half.

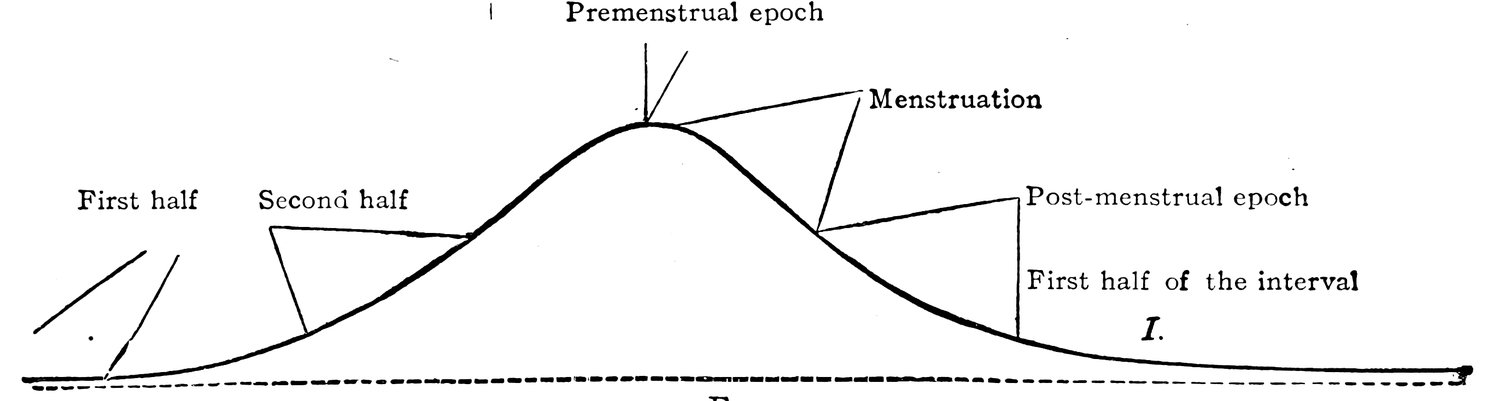

If we make a graphic representation of the mean differences in temperature commonly observed throughout the various stages of an entire menstrual cycle, we see that the curve does in fact take the form of a wave. That drawn by Reinl is shown in the following figure: (Fig. 5.)

Fig. 5.

The rising portion of the wave, the beginning of the tidal flow, corresponds to the second half of the interval; the height of the tidal flow, the crest of the wave, corresponds to the premenstrual epoch. As the flow gives place to the ebb, as the wave begins to decline, we come to the actual period of the catamenial discharge; later in the ebb is the post-menstrual epoch, and the lowest portion of the declining wave corresponds to the first half of the interval. Rhythmic changes corresponding to those observed in the temperature have been recorded—at least in isolated stages of the menstrual cycle—affecting the blood-pressure by Jacobi and by von Ott, affecting the excretion of urea by Jacobi and by Rabuteau, and affecting the pulse by Hennig. It is evident that the vital activity of the organism attains its maximum shortly before menstruation; and that with or immediately before the appearance of the catamenial discharge, a decline of that activity commences.

Schrader, through his researches on metabolism during menstruation in relation to the condition of the bodily functions during this process, has established that immediately before menstruation the elimination of nitrogen in the fæces and the urine is at its lowest, a fact which indicates that at this period of the menstrual cycle the disintegration of albumen in the body is notably diminished.

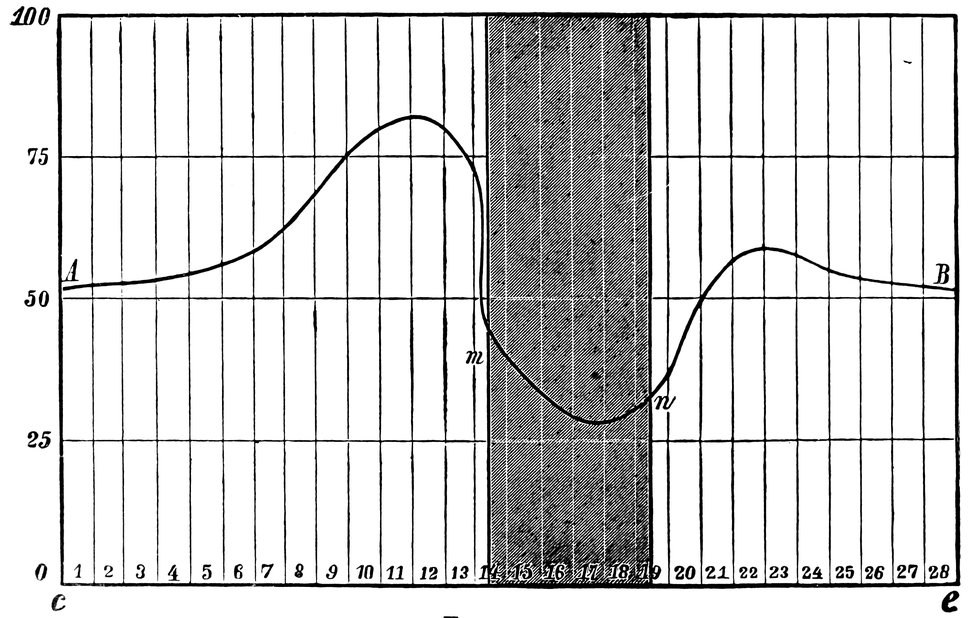

20Von Ott found in thirteen cases out of fourteen that at the beginning of the catamenial discharge or just before a considerable fall in blood-pressure occurred, and that throughout the flow the pressure almost always remained below the mean, no rise taking place till menstruation was finished; this fall in blood-pressure during menstruation was more considerable than could be accounted for by the moderate hæmorrhage. The same author, in conjunction with Schichareff, examined fifty-seven healthy women in respect of heat-radiation, muscular power, respiratory capacity, expiratory and inspiratory power, and tendon-reflexes. He found that the energy of the functions of the female body increased before the beginning of menstruation, but declined with or immediately before the appearance of the catamenial discharge. He exhibited this rhythmical variation in the vital processes by means of the following curve, in which the line A B represents these physiological variations, whilst on the abscissa line c e, the days of observation are recorded, and the interval m n represents the menstrual period. The degree of intensity of the united functions is indicated by the numbers 0–100 on the ordinate.

Fig. 6.

Still another point of view from which the influences affecting the female organism as a whole may be regarded has very recently become apparent in consequence of the doctrine of Brown-Séquard relating to the internal secretions of ductless glands. As regards the female reproductive glands, which in consequence of their structure must be referred to the group of ductless glands, and yet owing to 21their secretory function must be classed among secreting glands (so that the nature of the ovary is that of a secreting gland without an excretory duct), it would appear that these glands are not concerned only with the specific female reproductive functions of menstruation and ovulation, but that they also exercise a powerful influence on the nutritive processes, on metabolism and hæmatopoiesis, and on growth and development in their mental as well as their physical relations.

It is supposed that these glands under normal conditions enrich the blood with certain substances, which in part assist in hæmatopoiesis, and in part by regulating the vascular tone in the various organs are concerned in the normal processes of assimilation and general metabolism. According to Etienne and Demange, ovariin possesses an oxidising power similar to that possessed by spermin. Thus it becomes easy to understand how disturbances in the functions of the ovaries give rise to disturbances in the processes of general metabolism and of assimilation. Some go even further, though in doing so they leave the ground of assured fact, suggesting that the ovary in certain circumstances produces toxins, or that the normal ovary possesses an antitoxic function, and speaking of an occasional ovarian auto-intoxication of the body or of a menstrual intoxication. Thus, chlorosis is by some regarded as a disturbance of hæmatopoiesis, dependent on an abnormal condition of the female reproductive organs during the period of development, and referable to a disturbance of the internal secretion of the ovaries (Charrin, von Noorden, Salmon, Etienne, and Demange). And it is now generally assumed, the assumption being based on the observations recently made concerning the organo-therapeutic employment of the chemical constituents of the ovary, that many of the disorders, and especially those connected with the vasomotor system, common during the climacteric period, are dependent on the deficiency of the products of the internal secretion of the ovary that accompanies the cessation of the menses.

Recent experimental investigations on this subject have shown that the interconnection between the female genital organs and the organism as a whole, between the functions of the reproductive organs and the functions of other organs, does not depend on nervous influences only, but that in this interconnection the blood vascular system and the lymphatic vascular system also play their parts. Goltz has proved by actual experiment that the nervous influence on menstruation and ovulation is not the only determinant. In a bitch, he divided the spinal cord at the level of the first lumbar vertebra, and observed, as soon as the animal had recovered from the operation, the appearance of the usual signs of heat; the bitch was 22impregnated, and gave birth to one living and two dead puppies; lactation and sucking took place as in a normal animal. When the bitch was killed and the body examined it was found that no reunion had taken place in the severed spinal cord. The experiments of Halban gave similar results. He found that in apes, if the ovaries are removed from their normal situation and successfully transplanted to some region remote from the genital organs, the animals remain capable of menstruating. But if the ovaries, which have been transplanted beneath the skin or beneath the peritoneum, are subsequently entirely removed, menstruation, which has continued regularly after the first operation, ceases altogether after the second. It follows from these experiments that the cessation of the menstrual process may be considered to be brought about through the intermediation of the lymphatic or blood-vascular system, by the absence of a kind of internal secretion.

Loewy and Richter have further proved by experiment that in spayed bitches the consumption of nitrogen is less by about 20 per cent. and the entire gaseous interchange less by about 9 per cent., as compared with what takes place in normal animals, and that this change in respiratory metabolism lasts for a long time after the oöphorectomy, for as much as nine to twelve months. If dried ovaries are given to such animals in their food, the gaseous interchange rises to the former level and even higher.

The undulatory movement of the vital processes in woman is apparently in some way dependent on ovulation, though the nature of the connection has not hitherto been fully elucidated. This view is confirmed by the fact that no such rhythmic variation in the bodily functions can be detected either in girls under thirteen years of age, or in women from fifty-eight to eighty years of age in whom menstrual activity has entirely disappeared. The menstrual rhythm begins at puberty and ends when ovulation ceases.

A further contribution to the doctrine of the undulatory movement of the vital processes in woman is to be found in my own observations that pathological symptoms which have become manifest before and at the time of the first onset of menstruation, and have given but little trouble throughout the period of developed and regular sexual activity, are apt when menstruation ceases to recrudesce, and to become as prominent as they were at the commencement of the sexual life. Women who at the time of puberty suffered from cardiac troubles, from digestive disturbances, or from various forms of nervous irritation, and in whom as they grew up these disorders passed more or less into abeyance, are apt at the climacteric period to exhibit, as I have frequently been able to observe, a violent return of these symptoms, in the form, as the 23case may be, of tachycardia, of dyspeptic troubles, or of psychoneuroses. In this connection we may mention an observation of Potain’s, who distinguishes a peculiar form of chlorosis, occurring in individuals of delicate constitution, which, though apparently cured, reappears at the menopause.

Related to the sexual life of woman is another attribute, one intimately connected with the idea of the female sex, and one which since the primeval days of humanity has filled men with delight and poets with inspiration—the attribute of beauty.

The beauty of woman, a prominent secondary sexual character, makes its first appearance at puberty, when the girl’s form, hitherto undifferentiated in its external bodily configuration, begins to assume a soft and rounded appearance, when the features become regular, the breasts enlarge, and the pubic hair begins to grow—when, in short, to the primary sexual characters already existing, the secondary sexual characters are superadded.

Feminine beauty continues to increase until the attainment of sexual maturity. In her third decade woman arrives at the acme of her sexual life and at the same time attains the perfection of her beauty.

The ensuing sexual phases, pregnancy, parturition, and lactation, entail a decline in beauty, not rapid indeed, but advancing gradually, with the slow yet sure-footed pace of time. The organic revolutions accompanying these processes leave traces recorded upon the surface of the body in conspicuous and indelible characters. The illnesses, also, which so often accompany the fulfilment of sexual functions, in injuring health impair also beauty.

A woman who has given birth to and nursed an infant begins to lay on fat, and this tendency to obesity becomes more pronounced as the climacteric period approaches. The breasts become inelastic and pendent, the abdomen becomes ungracefully prominent; the tonicity of the entire organism gradually declines, and, in consequence of the loss of elasticity in the subcutaneous cellular tissue, the dreaded wrinkles make their appearance and the features become wizened. Beauty is a thing of the past. With the cessation of the sexual life the external secondary sexual characters disappear, and the old woman is even farther removed than the old man from our conception of beauty.

As Mantegazza insists, the beauties peculiar to women are one and all sexual; they depend, that is to say, upon the peculiar functions that nature has allotted to woman in the great mystery of procreation. One of the most vivid and poetical descriptions in ancient or modern literature of these secondary sexual characters on which feminine beauty depends is to be found in the Song of Solomon.

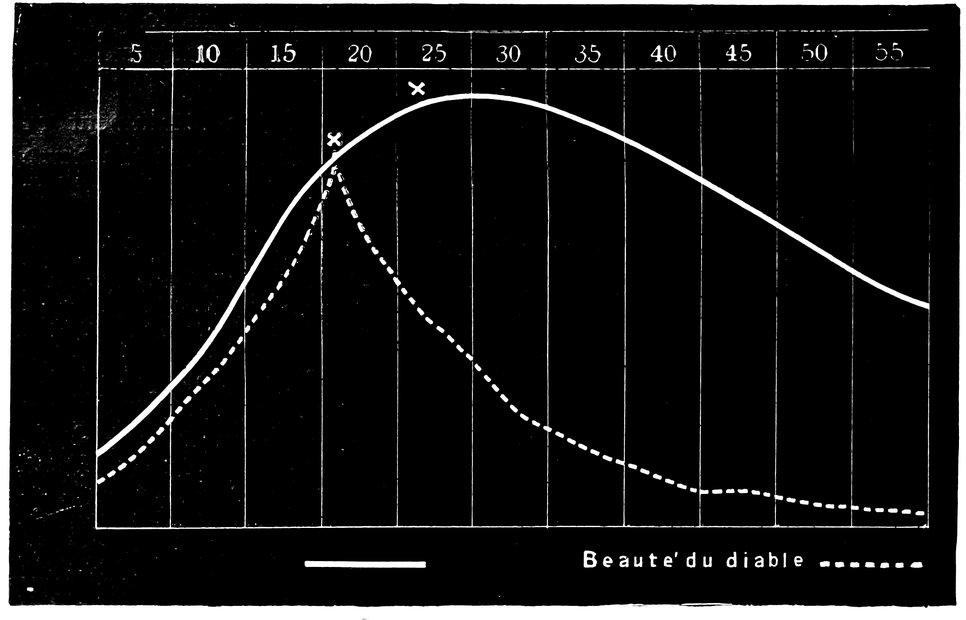

24In the following figure (Fig. 7) the curve of beauty of woman is given as drawn up by Stratz. In one case it may rise very quickly, to decline with equal quickness—the so-called beauté du diable;[16] in other cases, again, the curve rises very slowly, and declines also very slowly, the culmination of the curve being in this case attained later, and when attained being absolutely higher, than in the case of the steeper curve.

Fig. 7.

The age at which the maximum of beauty is attained is a very variable one. In the southern races this often occurs as early as the fourteenth or fifteenth year of life; but in the peoples of the Teutonic stock, Germans, Dutch, Scandinavians, and English, not as a rule before the twentieth year, and it may be even later. Stratz has known cases in which women did not attain the prime of their beauty until the thirtieth and even the thirty-third year. The same author, a most competent authority as regards the subject of feminine beauty, affirms that a beautiful woman is most beautiful when the period of maximum beauty coincides in her case with the first month of her first pregnancy. With the commencement of pregnancy the processes of nutrition are accelerated, all the tissues are tensely filled, the skin is more delicately and at the same time more brightly tinted owing to the greater activity of the circulation, the breasts become firmer and more elastic. Thus the attractive characteristics of beauty at its fullest maturity become 25enhanced, but for a short time only, since the enlargement of the abdomen in the further course of pregnancy impairs the harmony of the figure. Finally we must point out, before dismissing this subject, that women of the so-called better classes arrive as a rule at maturity later, and remain beautiful for a longer period, than women of the working classes.

The degree to which the female organism as a whole is influenced by the processes of the sexual life that occur in the genital organ depends upon many of the characteristics that combine to make up the individuality. Inherited characteristics, temperament, and race, play a great part in this connection; and not less important than these are the social conditions, the environment, in which the women under consideration pass their life. Thus, among women belonging to the poorer, labouring classes, the reflex manifestations in other organs dependent upon the processes of the genital organs are less frequent and less intense than among women belonging to the well-to-do strata of society and to the cultured classes; less also in the country than in large towns. In phlegmatic individuals, such manifestations exhibit less intensity than in those of an active, ardent temperament; they are less frequent in persons with a powerful constitution than in those endowed by inheritance with an unstable nervous system. Finally, they are less often encountered among families whose upbringing has aimed at hardening the constitution and at inculcating the control of instinctive impulses, than among those in whom from early childhood sensibility and impulsiveness have been given a loose rein.

Extremely variable also are the sympathetic disturbances and morbid states which depend on the processes of the sexual life of woman. “Le cri de l’organe souffrant ne vient pas de l’utérus, mais de tout l’organisme,”[17] says Courty. And a large number of isolated observations has shown how complex are the relations between the healthy and unhealthy female genital organs and the other organs of the body as well as the organism as a whole. Precise and incontestable proofs exist of such relations between the female genital organs and morbid changes in the eye and ear, the skin, the respiratory organs, and the vascular and nervous systems.

The influence exercised by the reproductive system on the general vital processes of woman is indicated also by the general statistics of mortality and the incidence of disease. Mortality in women, the earliest years of childhood being left out of consideration, 26is at its highest precisely during the great sexual epochs, namely at the time of puberty, during pregnancy, during the puerperium, and at the climacteric period. The complete performance of the reproductive functions entails a higher proportion of illnesses and death; and statistical records show that the mortality of married women between twenty and forty years of age, during the period, that is to say, in which in consequence of marriage they fulfil the duties of sexual intercourse and procreation, and are exposed to the dangers connected with these sexual acts, is much higher than the mortality of unmarried women of corresponding ages. Infection with the gonococcus and with the virus of syphilis, chronic salpingitis, metritis, and parametritis, the manifold diseases of pregnancy, the diseases of the puerperium, the various displacements of the uterus, osteomalacia—all these are pathological states the dependence of which upon the sexual life of the married or at any rate sexually active woman is indisputable. But the complete renunciation of sexual activity appears also to exercise an injurious influence on the health, and to give rise or at least predispose to morbid manifestations. Hysteria, for instance, chlorosis, uterine myomata, and various neuroses, have long been supposed to depend in part upon such renunciation, though the causal connection cannot be regarded as yet fully established.

Especially true as regards woman, indeed, is that which Ribbing says concerning the sexual life in general: “Since all human life and being has its origin in sexual relations, these sexual relations may be regarded as the heart of humanity. We may work day and night for the good of humanity, we may sacrifice for that good our time and our blood, but all this work and all this sacrifice appear to me to remain useless if we neglect and despise the sexual life, the eternally self-renewing elementary school of true altruism.”

From the vital phase in which, marked by the visible manifestations of puberty and by the first appearance of menstruation, ovulation is assumed to begin, the sexual life of woman continues to the period of life in which, marked by the climacteric cessation of menstruation, ovulation also ceases. The total duration of this sexual period in woman’s life is usually about thirty years; but it is subject to great variations, from six to forty-six years according to the available statistics, these variations depending upon climate, race, constitution, and the sexual activity of the person under consideration.

The duration and the intensity of the sexual life of woman depends upon a series of external conditions affecting the individual, but especially upon the inherited predispositions, upon the constitutional conditions, upon the varying vital power of the individual. 27My own observations have led me to formulate, as a general law, that the earlier a woman (climatic and social conditions being similar in the cases under comparison) arrives at puberty, the earlier, that is to say, that menstruation first makes its appearance, the greater will be the intensity and the longer the duration of sexual activity, the more will the woman in question be predisposed to bear many children, the more powerfully will the sexual impulse manifest itself in her, and the later will the menopause appear. It seems that in such women a more intense vitality animates the reproductive system, bringing about an earlier ripening of ova, a more favorable predisposition on the part of these ova to fertilization by the spermatozoa, a livelier manifestation of sexual sensibility, and a longer duration of ovarian functional activity.

My general views on this subject are embodied in the following propositions:

1. The duration of sexual activity is less in the women belonging to the countries of southern Europe than in those belonging to the countries of northern Europe. It would appear that in those climates in which ovulation begins sooner and menstruation first appears at an earlier age, the menopause also appears earlier; but that, on the contrary, in those climates in which puberty is late in its appearance, the decline of sexual activity is similarly postponed.

2. Women in our mid-European climates, in whom puberty appears at an early age, the first menstruation occurring between the ages of thirteen and sixteen, exhibit a more prolonged duration of the sexual life, of menstrual functional activity, than women in whom menstruation begins late, between the ages of seventeen and twenty. Extremely early appearance of the first menstruation—so early as to be altogether abnormal—has, however, the same significance as abnormally late onset of menstruation; both indicate that the sexual life will be of short duration.

3. Women whose reproductive organs have been the seat of a sufficient amount of functional activity, who have had frequent sexual intercourse, have given birth to several children, and have themselves suckled their children, have a sexual life of longer duration, as manifested by the continuance of menstruation, than women whose circumstances have been just the opposite of these, unmarried women, for instance, women early widowed, and barren women. Sexual intercourse at a very early age, however, accelerates the onset of the climacteric period and the termination of the sexual life. The same result follows severe or too frequent confinements.

4. The sexual life has a shorter duration in the women of the laboring classes and belonging to the lower strata of social life, as 28compared with upper class and well-to-do women. Bodily hardships, grief, and anxiety also hasten the onset of sexual death.

5. Women who are weakly and always ailing have a shorter sexual life than women who are powerfully built and always in good health. When irregularities and disorders have appeared in the various sexual phases, the decline of sexual activity occurs earlier than in women whose functions have in this respect been normal. Certain constitutional conditions, such as extreme obesity, certain acute diseases, such as typhoid fever, malaria, and cholera, and certain diseases of the uterus and its annexa, chronic inflammatory conditions for instance, bring about a notable shortening of the duration of the sexual life.

In 500 cases that have come under my own observation, the women concerned belonging to very various nationalities, the duration of the sexual life, as witnessed by the continuance of menstruation, was as follows:

Menstruation continued for:

| 6 years in | 1 woman. |

| 7 years in | 1 woman. |

| 9 years in | 2 women. |

| 11 years in | 4 women. |

| 15 years in | 6 women. |

| 16 years in | 8 women. |

| 17 years in | 12 women. |

| 18 years in | 15 women. |

| 19 years in | 9 women. |

| 20 years in | 6 women. |

| 21 years in | 18 women. |

| 22 years in | 20 women. |

| 23 years in | 24 women. |

| 24 years in | 18 women. |

| 25 years in | 16 women. |

| 26 years in | 25 women. |

| 27 years in | 26 women. |

| 28 years in | 29 women. |

| 29 years in | 36 women. |

| 30 years in | 22 women. |

| 31 years in | 32 women. |

| 32 years in | 49 women. |

| 33 years in | 31 women. |

| 34 years in | 26 women. |

| 35 years in | 12 women. |

| 36 years in | 12 women. |

| 37 years in | 10 women. |

| 38 years in | 8 women. |

| 39 years in | 6 women. |

| 40 years in | 2 women. |

| 43 years in | 2 women. |

| 45 years in | 1 woman. |

| 46 years in | 1 woman. |

Thus we see that the duration of the sexual life varies from 6 to 46 years. The most frequent duration is one of 32 years, next to this one of 29, next again, 31, 33, and 37 years, respectively. In 6 women only did the duration of the sexual life exceed 40 years, and in 4 only was it less than 11 years. In half of all my cases the duration of the sexual life was between 27 and 34 years, and from these figures we obtain an average duration of about 30 years.

For North Germany, Krieger gives data from which it appears that in this region the average duration of the sexual life is 30.49 years. In more than half of the 722 cases recorded by this writer the duration was between 31 and 37 years. In isolated cases the duration was very short, not exceeding 8, 9, or 10 years, or, on the other hand, as long as 47 years; whilst the number of cases increased fairly regularly up to the duration of 34 years, and thereafter again diminished.