Title: The Heart of Hyacinth

Author: Onoto Watanna

Illustrator: Kiyokichi Sano

Release date: November 7, 2020 [eBook #63653]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Mary Glenn Krause, Charlene Taylor, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Heart of Hyacinth, by Onoto Watanna, Illustrated by Kiyokichi Sano

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/heartofhyacinth00wata_0 |

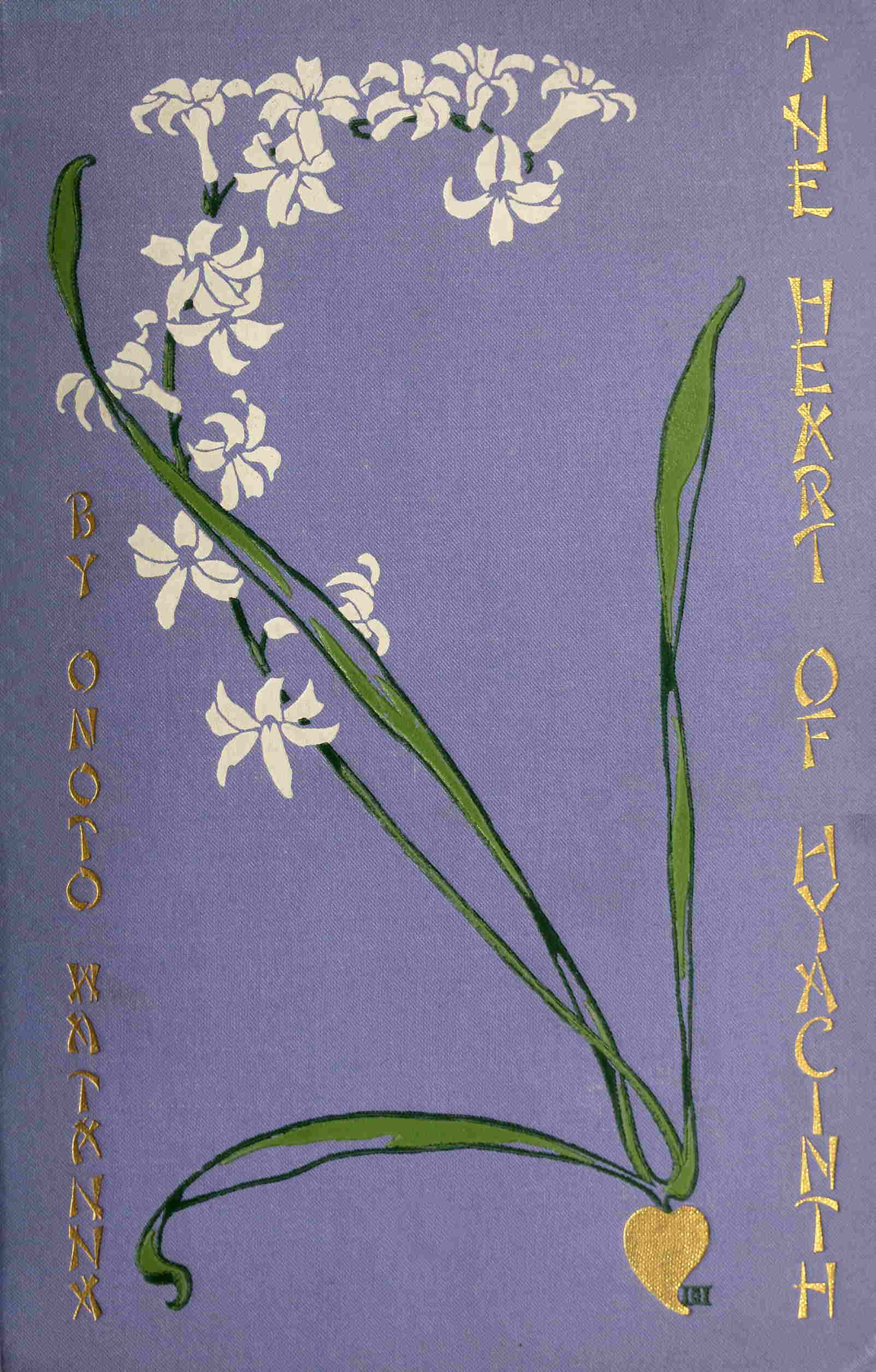

HYACINTH

| HYACINTH | Frontispiece |

| “KOMA LIFTED HER IN HIS ARMS” | 42 |

| “‘NOW, COME, LITTLE ONE: COME, GIVE ME THAT WELCOME HOME’” | 70 |

| “HE KNELT IN A RAPT SILENCE BESIDE HER” | 200 |

The City of Sendai, on the north-eastern coast of Japan, raises its head queenly-wise towards the sun, as though conscious of its own matchless beauty and that which envelops it on all sides. Here, where the waters flow into the Pacific, the surges are never heard. Neptune seems to have forgotten his anger in the presence of such peerless beauty.

Near to Sendai there is a bay called Matsushima. Here Nature has flung out her favors with more than lavish hand; for throughout the bay she has scattered jewel-like rocks, whose white sides rise above the waters, and whose surface gives nutrition to the graceful pine-trees which find their roots within the stone. Near to a thousand rocks they are said to number, and save for the one called Hadakajima, or Naked Island, all are crowned with pine-trees.

The historic temple Zuiganjii is situated at the base of a hill a few cho from the beach. About the temple are the tombs and sepulchres of the great Date family, once the feudal lords of Sendai. There is a huge image of Date Masamune, whose far-seeing mind sent an envoy to Rome early in the seventeenth century. The sepulchres are, for the most part, in the hollowed caves of the range of rocky hills behind the temples. Nameless flowers, large and brilliant in color, bloom about the tombs of these proud, slumbering lords. Mount Tomi bends its noble head in homage towards the glories of a past generation. The air is very still and cool. Silence enshrines and deifies all.

The inhabitants of Sendai and the little fishing village on the northern shore of the bay were simple, gentle folk. As though affected by the slumberous beauty of the hills and mountains hedging them in upon all sides, these let their life glide by with slow and sweetly sleepy tread. Not even the shock of the Restoration had brought this region’s people into that prophetic regard for the future which pervaded all other parts of the empire. The change-compelling progress which pressed in upon all sides seemed not as yet to have laid its withering finger upon fair Matsushima. Like their home, the inhabitants clung to their hermit existence.

When an English ship, having ploughed its way through the waters of the Pacific, sent out its men in boats to take the bay’s soundings, the people were not alarmed, but greatly mystified. The strange white men made their way in their smaller boats to the shore. A missionary and his wife were landed.

A little home, on a small hill situated only a short distance from the Temple Zuiganjii, they built for themselves. Afterwards, native artisans raised for them a larger structure, where for many years they patiently taught the gospel of Jesus Christ. The people gradually learned to love and reverence their pale teachers. There came a time when the little band, which had at first gone desultorily and curiously to the mission-house, began to see what the strangers termed “the light.” Then the Christian Church in far-away England enrolled a little list of converts to their religion.

The missionary grew old and white and bent. His gentle wife passed away. He lingered wistfully, a strangely isolated, though beloved, figure in the little community.

Then came a second visitation from an English vessel. Sailors and officers lolled about the town by day and rioted by night. Some of them wooed the dark-eyed daughters of the town but to leave them. One there was, however, who brought a girl, a shrinking, yet trustful girl, to the old missionary on the hill, and there, in the shabby old mission-house, the solemn and beautiful ceremony of the Christian marriage service was performed over their heads.

That was ten years before. At first the Englishman had seemingly settled in his adopted land, as he loved to call it. The place appealed to his artistic perceptions. The Mecca of all his hopes, he called it. Why should he return to the world of cold and strife? Here were peace, rest, and love unbounded. But before the close of the second year of their union an event occurred which shook the stranger suddenly into life’s vivid reality. A great duty thrust itself in his track. Not for himself, but for another, must he turn his back upon the land of love. A son had been born to him in the season of Little Heat.

So the Englishman crushed to his breast his foreign wife and child, and with reiterated promises of a speedy return he left them.

Letters in those days travelled slowly from England to Japan. Sometimes those addressed to the little town of Sendai remained for weeks in the offices at the open ports. Sometimes they travelled hither and thither from one port to another, the stupid indifference of officials scarcely troubling itself to send them to their proper destination. But finally, after many months, the little wife and mother in Sendai held between her trembling hands an English letter. It had come in a very large envelope, and there were several bulky inclosures—neatly folded documents they were—tied with red tape. There was also another letter, shorter than the one she held in her hand, and written in a different form. She could not even read her letter, though she did not doubt from whom it had come. Happy, she pressed her precious package to her lips and breast. She believed that the strangely printed papers within the envelopes, similar in her eyes to the many English papers he had always about him, were merely other forms of his epistle of love.

The woman waited with a divine patience for the return of the old missionary from a little journey inland. She watched for him, watched ceaselessly, constantly. And when he had returned she dressed the little Komazawa in fresh, sweet-smelling garments, and carried him with her papers to the mission-house.

Why detail the pain of that interview? The papers and one of the letters, it is true, were, indeed, from her lord, but they were sent by another, a stranger. The Englishman had died—died in what he termed a foreign country, since his home was by her side. In his last hours he had striven to write to her and instruct her in the course she must take in the years to come when he could not be by her as her loving guide.

Madame Aoi meekly followed the counsel of the aged missionary. Under his guidance, childlike and with unquestioning faith, she studied unceasingly the English language and the Christian faith.

If the old missionary had at first marvelled at the calm which settled upon her after that one wild outcry when first she had heard the dread tidings of her husband, he was not long in discovering that her passiveness was but an outer mask to veil the anguish of a broken heart, and to give her that strength which must overcome the weakness which would be the doom of her hopes. For Aoi was not left without some hope in life. Her lord, in departing, had set upon her an injunction, a duty. This it was her task to perform. Once that was accomplished, perhaps the strain might lessen. Meanwhile tirelessly, ceaselessly, she studied.

She had the natural gift of intelligence, and the advantage of having spent two full years with her husband. Hence it was not long before she mastered the language, and, if she spoke it brokenly and even haltingly, she wrote and read accurately.

To the little Komazawa she spoke only in English. She kept him jealously apart from the villagers, and taught his little tongue to shape and form the words of his father’s language.

“Some day, liddle one,” she would say, “you will become great big man. Then you will cross those seas. You will become great lord also at that England. So! It is the will of thy august father.”

It was the season of Seed Rain. The country was green and fragrant and the crops thirstily absorbed the rain. The villagers sat at their thresholds, some of them even indolently lounging in the open, unmindful or perhaps enjoying the seething rain, an antidote for the heat, which was somewhat sweltering for the season.

Children were playing in the street, nimbly jumping over the puddle ponds, or climbing, with the agility of monkeys, the trees that lined the streets, and about whose boughs they hung in various attitudes of daring delight.

One small boy had climbed to the very tip of a bamboo, and there he clung by his feet, swaying with the shakings of the slender tree, and the motion of those below him—far below him.

It was not often that the son of Madame Aoi was permitted such absolute freedom. Indeed, it was only upon those occasions when Komazawa, momentarily blind to the reproach of his mother’s sad eyes, literally thrust away the bonds which seemed to hold and chain him to their quiet household and burst out and beyond their reach. Surely, at the tip of this long, perilous bamboo he was quite beyond the reach of little Madame Aoi and her old servant, Mumè. But even in his present lofty position Komazawa had kept his eyes from the possible glimpse of his mother. His feet clung to the tree only because his hands were engaged in covering his ears.

Yet, even in the open, Komazawa was alone. The neighbors’ children played in little bodies and groups together, and Komazawa from his perch watched them with the same ardent wistfulness with which he was wont to regard them from the door of his little isolated home.

Old Mumè was angry. Her voice had become hoarse, and she was tired of her position in the rain, for the bamboo gave but scant shelter. She shook the tree angrily.

“Do not so,” entreated the gentle Aoi. “See how the tree bends. Take care lest it become angry with us and vent its vengeance upon my son. But, pray you, good Mumè, return to the home and give food and succor to our honorable guest.”

As Mumè shuffled off, her heavy clogs clicking against the pavement, Aoi called up, entreatingly, to the truant:

“Ah, Koma, Koma, son, do pray come down.”

But Komazawa, with head thrown backward, was whistling to the clouds. He was very well content, and it pleased him much to be wet through. How long he sat there, whistling softly strange airs and imagining wild and fanciful things, he could not have told, since the passage of time in these days of freedom was a thing which he noted little.

Gradually he became aware that the rain was becoming colder and the sky had darkened. Komazawa looked downward. There was nothing but darkness beneath him. He shivered and shook his little body and head, the hair of which was weighted with rain. Komazawa began to slide downward, feeling the way with his feet and hands. It was quite a journey down. In the darkness he had knocked his little shins against out-jutting broken boughs. He landed with both feet upon something palpitating and soft—something that caught its breath in a sigh, then inclosed him in its arms.

Komazawa guilty, but not altogether tamed, spoke no words to his mother. He stood stiffly and quietly still while she felt his wetness with her hands. But he threw off the cape in which she endeavored to wrap him. He was obliged to stand on tiptoe to put it back around his mother, and as this was an undignified position, his bravado broke down. Gradually he nestled up against her, and—strange marvel in Japan!—these two embraced and kissed each other.

After a while, as they trudged silently down the street homeward, Komazawa inquired, in a sharp little voice, as he looked up apprehensively at his mother:

“And the honorable stranger, mother?”

Aoi hesitated. The hand about her son trembled somewhat. His thin little fingers clutched it almost viciously. He flushed angrily.

“Why do you not answer me?” he asked, with peevishness.

“I have not seen the honorable one,” said Aoi, gently.

“Pah!” snapped the boy. “No, certainly, and we do not wish to see her. We do not like such bold intrusion.”

“Nay, son,” she reproved, “we must not so regard it. Let us remember the words of the good master, the august missionary.”

“What words?” inquired Koma, tartly. “Why, his excellency does not even know of the coming of the woman, since he is gone three days from Sendai now.”

“Ah, but my son, do you not remember that he taught us to treat with kindness the stranger within our gates?”

Koma made a sound of disapproval, his little, ill-tempered face puckered in a frown. After a moment he inquired again:

“But where is the woman, mother?”

Aoi regarded her small son almost apologetically.

“She is within our humble house,” she replied.

Koma pulled his hand from hers with a jerk. For a time he walked beside her in silence. He was strangely old for his years, and already he showed the inheritance of his father’s pride.

“Mother,” he said, “we do not wish the stranger to disturb our home. My father would not have permitted it. We are happy alone together. What do we want with this woman stranger?”

“But, my son, she is very ill.”

“She should have stayed at the honorable tavern. We do not keep a hostelry.”

Aoi sighed.

“Well,” she said, hopefully, “let us bear with her for a little while and afterwards—”

“We will turn her out,” quickly finished the boy.

“We will entreat her to remain,” said Aoi. “It would be proper for us to do so. But the stranger will not be lacking in all courtesy. She will not remain.”

They had reached their home. Now they paused on the threshold, the mother regarding the son somewhat appealingly, and he with his sulky head turned from her. Aoi pushed the sliding-doors apart. A gust of wind blew inward, flaring up the light of the dim andon and then extinguishing it. The house was in darkness.

Suddenly a voice, a piercing, shrill voice, rang out through the silent house.

“The light, the light!” it cried; “oh, it is gone, gone!”

Koma clutched his mother’s hand with a sudden, tense fear.

“The light!” he repeated. “Quickly, mother; the honorable one fears the darkness. Quickly, the light!”

Old Mumè was busily engaged in the kitchen. The milk over the fire had begun to bubble. With a large wooden stick she stirred it. Then she returned to her rice. As she pounded it into flat cakes, her old face, with its hundred wrinkles, was contorted, and she muttered and talked to herself as she worked. She was like some old witch, breathing incantations.

At the threshold of the room stood Koma. His eyes were very wide open and his cheeks were flushed. At his side his little hands were sharply clinched. His whole attitude betokened excitement and impatience. Suddenly he clapped his hands so loudly and sharply that the old woman started in fright; then catching sight of the little intruder, she hobbled towards him on her heels, her tongue in angry operation.

“Now, who but an evil one would frighten an old woman? Shame upon you, naughty one!”

“Oh, Mumè, you are so slow the evil one will catch you. Just see, the milk boils over. Still you do not hasten. Yet the illustrious ones are ill, very ill.”

“Tsh!” scolded the old woman, as she poured the steaming milk into a shallow bowl, and broke pieces of the rice-bread into it. “What, would you advise old Mumè about such matters? Would you have me burn the honorable babe?”

She cooled the preparation with her hand, fanning it back and forth across the bowl.

Koma watched her a moment with smouldering eyes. Suddenly he started, his little ears alert and attentive.

A cry, thin and piping at first, grew in volume. Was it possible that so small a thing could fill the house with its noise? Koma strode to the fire, seized the bowl with both hands, and, before the grumbling old servant could interfere, he was gone with it from the room, and speeding along the hall.

With his finger-tips on the closed shoji of the guest-chamber he tapped gently. It was softly pushed aside, and Aoi appeared in the opening. Stepping into the hall, she closed the sliding screens behind her.

The boy spoke in an eager whisper.

“Here is the milk the honorable one desired.”

“Where did you obtain it, son?”

“In the village. And see, we have warmed it, for it was quite cold. It is good goat’s milk.”

“Such a good son!” whispered Aoi, and stooped to kiss the upraised face ere she returned to the sick-chamber.

Koma crouched down on the floor by the door. He could hear within the soft glide of his mother’s feet across the floor. There was a murmuring of indistinguishable words. Then that voice, with its strange accent, which seemed to pierce and reach something in the boy.

The voice was weak now, but its exquisite clearness was not dulled. Then Koma heard the movement of the lifting of the babe; a little cry or two, then little gurgling, satisfied gasps. The babe was being fed with the milk he had procured. It gave Koma a strange satisfaction—a warm delight. He stretched out his little limbs across the floor. He, too, was satisfied. All was now well. Gradually his head drooped backward and Komazawa fell into a slumber.

Within, the stranger was imparting bits of her history to the sympathetic Aoi. She was hardly conscious of her words, which were spoken through her semi-delirium. Her feverish eyes, wide open, shone up into the bending face of Aoi, and held the Japanese woman with their piteous appeal. She seemed soothed under the gentle touch of Aoi’s hand on her brow.

“Pray thee to sleep,” gently the Japanese woman persuaded her.

She was quiet a moment, only to start up the next.

“Nay,” entreated Aoi, “sleep first—to-morrow speak. Rest, I pray you.”

“It was so long, so long!” cried the woman on the bed, clasping her thin hands across those on her head. “And, oh, the pain, the agony of it all! I was so tired—so—”

Her body palpitated and quivered with the sighing sobs that shook her. She sprang up suddenly, pushing away from her the hands of Aoi, which gently attempted to restrain her.

“It was all wrong—quite wrong from the first. But what did they care? They had their wedding. Ah, I tell you, they are bad, all bad! Ah, it was cruel, cruel!”

“Ah,” thought Aoi, sadly; “she, too, has been pierced with anguish. Truly, my heart breaks in sympathy with her.”

She bent above the quivering woman, her pitying face close to hers.

“Pray thee, dear one, take rest and comfort,” she said, smoothing softly her brow.

“Ah, you are so good, so good,” said the sick woman. “You are not like those others—those fearful people.” She covered her eyes with her thin hands as if to shut out a vision of some horror. “God will bless you, bless you for your goodness to me,” she said.

Exhausted, she lay back among the pillows, her eyes closed. How grateful to her must have felt that great English bed, with its soft coverlets! For how many days had she wandered, without sight or word of her own people! Her thin, fine lips quivered unceasingly, while her blue eyes held a constant mist, seemingly haunted by some troubled spectre that pursued her ceaselessly.

Once she raised her hands feebly, then plucked at the coverlet with long, white fingers.

“What a death! oh, what a death!” she whispered, faintly.

After a long silence her voice raised itself to the pitch of one delirious.

“If I could see—” Her words came slowly and with difficulty, and she repeated them ramblingly. “If I could only see—a white face—a white—one of my own people. Oh, so long, and, oh me!—mamma, mamma!”

“Ah, dear lady,” said Aoi, “if you will but deign to rest I will go forth and endeavor to find some of your people. There are white people in the next town. It is not far—not very far, and perhaps, ah, surely, they will come to you.”

“My people,” the woman repeated. “No, no.” Her voice became hoarse. She started up in her bed. “You do not understand. I must never, never see them again. I could not bear it. They are cruel, wicked. No! Ah, you shall promise me—promise me.”

She fell back, exhausted from her transport of passion. Aoi knelt beside her and took her hands within her own.

“I will promise you whatever you wish, dear lady. Only speak your desires to me. I will humbly try to carry them out.”

The sick woman’s voice was so weak that she scarce could raise it above a whisper, but her words were plain.

“Promise me that you will not give them my little one when I am gone. You are good, and will be kind to her. Oh, will you not? I would not be happy, I could not rest in peace if she were sent to—to him.” Her words rambled off again. “I left him,” she said, “ran away—far away, far away, and the country was all strange to me, and I could not find my way. Every one stared at me; it must have been because I had gone mad, you know, quite mad. All women do. I wanted to put a great distance between us, to get beyond his sight—beyond the sound of his voice, beyond—”

“Ah, do not speak more,” entreated Aoi, now in tears.

“Why, you are crying!” said the sick woman, looking wistfully into Aoi’s face. She began to weep, weakly, impotently, herself.

After a time she became quieter. She started once again, when Aoi had snuffed a few of the lights, seeming to dread the darkness, but when the Japanese woman’s hands reassured her, she was again silent. And as she slept she still clung spasmodically to the hands of Aoi.

Morning dawned with a haggard light. Ceaselessly the rain drizzled down. The torpid heat of the previous day had given place to a clammy chilliness. The weather oppressed the sick one. Her restlessness was gone, but passive quiet was more ominous. Her white face seemed to have shrunken through the night—so white and still it was that she seemed scarcely to breathe.

Too weak to bear the burden of her child against her, the mother permitted the little one to be cared for in an interior room lest its cries might disturb her. All through the day she spoke no word. Wearily, the heavy lids of her eyes were closed.

As the day began to wane, Aoi, thoroughly alarmed, summoned the village doctor; a very old and learned man he was considered. He felt the woman’s hands, listened to her breathing with his ear against her lips. Very cold her hands were, but her breathing was regular, though faint.

The doctor looked grave, solemn, and wise. He shook his bald head ominously.

“How long has the honorable one been thus?”

“Since early morn, sir doctor. She awoke from her night sleep only to fall into this condition.”

“The woman has but a short space of life left to her,” said the doctor, solemnly.

Aoi trembled.

“Her people—” she began, falteringly. “Oh, good sir doctor, it is very, very sad. So young! Ah, so beautiful!”

Seeming not to share or understand Aoi’s sympathy, the doctor gathered up his instruments and simples slowly, meanwhile glancing uneasily towards the face of the sick woman. He turned suddenly to Aoi.

“Madame,” he said, “the village sympathizes with you at the infliction placed upon you by this enforced guest, but—”

“You do not finish, sir doctor?”

“The woman became a nuisance at the tavern. The people there were not Kirishitans (Christians), and were moreover in ignorance of the woman’s speech. They could only comprehend that she wished to be taken to some one of her own people—so, madame, you—”

“I, being of her people,” said Aoi, with simple dignity, “she was brought to me. That was right. I thank my neighbors for their kindness. I am honored, indeed, with such a guest. She is welcome.”

The doctor moved towards the door.

“And the child? It is well, and will not accompany the mother on her last journey. What will become of it?”

Aoi did not reply.

“If it is desired by you, Madame Aoi,” said the doctor, endeavoring to be kind, “I will immediately despatch word to the city to send notification to the nearest open port. There, surely, must be some consul, or representative of the woman’s country. To them the child should go.”

Aoi spoke swiftly.

“The poor one’s people were unkind to her and cruel. How can we tell but that they might also abuse the child?”

“That is the affair of the child, Madame Aoi. Pray accept my counsel. Send the child—”

Interrupted by the sudden entrance of little Komazawa, he did not finish. The boy had evidently heard all, through the thin partition doors, against which he had leaned, listening intently. He thrust himself now before the doctor, with eyes purpled by excitement. His tense little body quivered.

“Sir doctor,” he said, in a voice new even to his mother, it was so strong and haughty, “you make mistake. The child is already among its own people. Here, in my father’s house, all people are Engleesh. So! The child belongs to us, since the mother did present it to us. It is a gift of the good God!”

Smiling and frowning together the little doctor bowed ironically to the little fellow facing him.

“And will the august one enlighten me as to whether he will make an effort to find the child’s legal guardians?”

“That is our affair, sir doctor, but I will answer. We will ask advice of the good excellency when he returns. He is in Sendai even now. He will be in our village to-night.”

The doctor bowed himself out, and Koma turned to his mother, a question in his eyes. Aoi nodded sadly. The poor white woman would die, had said the sir doctor.

Komazawa approached the bed softly, until he stood by the woman’s side, looking down fixedly upon her. How white was the still face, how beautiful the long lashes that swept the cheeks, how wonderful and sunlike the silken hair enveloping her head like a halo. Could she be real, this beautiful, still creature? Never had Komazawa seen anything like her. She seemed a spirit of the lingering twilight.

Suddenly he bent over her and softly touched the small hand that lay outside the coverlet. But soft as was his touch it acted like an electric shock upon the woman. She started and quivered, as her heavy lids lifted. At the little face bending above her she stared. A strange expression came into her face. Her voice was like that of one murmuring in a dream.

“A little white boy,” she said. “A little white—”

Her lips were stilled, but a breath, a sigh passed from her as Koma, with a sudden instinctive motion, put his face down to hers. When Aoi gently drew the boy up she found the still, white face softly smiling in the twilight, as though ere she slept she had seen a vision.

But Komazawa knelt by the bedside, weeping passionately.

Near the Temple Zuiganjii there is one huge rock, where the Date lords in the feudal days were wont to gather yearly, attended by musicians, and seeking recreation in gay amusements. It is of enormous size, and when the sun’s rays beat upon its white surface it shines like white, polished glass. Flat, embedded in the soil, there is, however, a part of the rock which rises many feet above the level, its out-jutting point resembling the head of some giant sea-monster. Under this jutting head a natural cave has been formed.

Here, on a summer day, two children were playing together. Far below them the Bay of Matsushima spread out its insistent beauty. Moored to the beach, a few cho below them, was their miniature raft-sampan, an old weather-beaten boat, in which they had made their pilgrimage from the village. Behind them were the tombs and the eastern hills. The sunlight slanting upon them was no less golden than these summer foot-hills of the mountains beyond.

Bareheaded and barelegged the children were, the sandals upon their feet wet, showing how they had paddled in the bay. The boy, a lad of possibly fifteen years, was stretched full length under the shadow of the rock, only his sandalled feet projecting into the sunlight, which he hoped would dry them. His elbows were in the sand, his chin resting upon one arm. He was reading from a very much worn and ragged book, the leaves of which he turned with the utmost care and tenderness.

The little girl had gradually come from the rock’s shadow, and now squatted at his feet. The sun fell upon her. She was a diminutive, odd little mite. Her hair, a dark shining brown, had been carefully knotted up into a little chignon at the top of her head, but, being wayward by nature, it had escaped the most persistent brushing and the severe pins which held it. It clung around her ears and little neck in soft, damp curls. Her face and hands were russet, sunburned and freckled. Her eyes were large and gray, shading towards blue. She wore but one garment, a little red, ragged kimono, very much frayed at the ends and soaked from her late paddling. Unlike the average Japanese child, the little girl was restless and lacked all sense of repose, an inherent instinct with Japanese children.

Though the boy had constituted her his audience and was reading aloud to her, she apparently had heard no word of what he had been reading. Having wriggled her way beyond the reach of his hand, she now looked about her for new means of engaging her active little mind. This she discovered in some stalks of grass. Having selected the stiffest blade she could find, she stealthily crept back to the feet of the boy, and first tickled, then pricked his feet with the grass. The natural result followed. The boy’s droning, monotonous voice in reading changed to a sudden, sharp grunt, and he threw up his heels, whereat the little girl burst into a wild, elfish peal of laughter. At the same time she renewed her jabs at the boy’s protesting feet.

Komazawa, still agitating his heels, closed the book with care, placed it in safety in the sleeve of his hakama, and swung upward, drawing his heels under him beyond the reach of his naughty tormentor.

With assumed gravity he regarded the small rogue before him.

“Something bitten you, yes?” she inquired, keeping her distance from him and hugging her knees up to her chin.

Koma nodded, silently.

“What?” she inquired. “What was that bitten you, Koma?”

“Gnat!” said the boy, briefly.

“Gnat?” She crept a few paces nearer to him, and peered up into his face.

“Yes—gnat,” he repeated, “bad devil gnat.”

The expression on the little girl’s face was involved. How was it possible for any one ever to know just what Komazawa meant when his face was so grave and smileless. She had an odd little trick of glancing up at one sideways under her eyelashes. She peeped up at Koma now for some time in this manner. Her mirth had changed to a matter of speculation. Did or did not Koma know what had bitten him? He had said it was a gnat. Her intelligence was not sufficiently developed to include the possibility that he might have meant her for the gnat. She ventured:

“Did you see that gnat bite you?”

“Yes, twice.”

Her eyes became wide.

“Where is it gone?” she inquired, breathlessly.

“Still there,” was his reply.

“Where?” She started, actually frightened. Koma’s voice and air of mystery began to work upon her active imagination. What was a gnat, anyway? And if one had actually bitten Komazawa, might it not also bite her? By this time she had entirely forgotten her own attacks with the grass blade. She was close to Koma now, her hands upon his arm, her upraised eyes searching his face.

“What is a gnat, Komazawa?”

“Bad little insect.”

“Oh! Does it bite?”

“Yes.”

“Did it also bite you?”

“Three times.”

“Oh!” A palpitating pause. Then:

“Will it bite me, too?”

“Maybe.”

She crept completely into his arms, shielding herself with his sleeves.

“Where is it—that bad gnat?”

“Here.” He pointed at her with an index-finger.

“Here!” She gave a little scream. “On my face!”

She was a small bundle of pricked nerves, frightened at a shadow of her own making. Komazawa relented, and pressed her little, fluttering face against his own.

“There—foolish one! No; there is nothing on your face. You are the gnat I meant.”

“Me!” She drew back a pace. “But I am not an insect!”

“Little bit like one,” said Koma, a smile of sunshine replacing his affected gravity a moment since.

His small companion sat up stiffly, half indignant, half curious.

“How’m I like unto an insect gnat?”

“Gnat jumps—this way, that, every way. So you do so. Can’t sit still, listen to beautiful stories.”

“I don’t like those kind stories. Like better stories about ghosts and—”

“Oh, you always get afraid of such stories, screaming like sea-gull.”

“Yes, but all same, I like to do that—like to hear such stories—like also get frightened and scream.”

“Gnat also bites—bites foot, same as you do.”

“That don’t hurt,” she said, her eyes askance. Then, repeating her words, questioningly, “That don’t hurt?”

“Oh yes, it does, certainly. What do you suppose I got to keep my feet under me now for?”

Her little bosom heaved.

“Let me see those foots, Komazawa.”

“Too sore.”

“Oh, Komazawa!”

Her eyes were beginning to fill. He thrust his two feet out quickly.

“No, no; they are all right.”

Her face was aglow again in an instant.

“Oh, I love you, my Koma,” she said. “I only pretend hurt your honorable foots.”

“That’s right. Now, you fix your hands so.” He illustrated, doubling his own hands into fists, then doubling hers also.

“That’s right. Make hand good and hard. So! Now you hit hard against those feet. So!”

He brought her little, closed fist down hard with his own hand on his offending foot. The little girl became pale. Her lips quivered. She began to sob.

Koma lifted her in his arms, jumped her on his shoulder, and carried her down to the beach, soothing her as he walked.

“That’s just little punishment for me; punishment for teasing little sister,” said Koma, laughing quietly. “That don’t hurt. You going to laugh soon? You just little gnat! That’s so? You bite just little bit. I am big dog. I bite big.”

He set her in the boat.

“Such a foolish little gnat,” he said, “always cry—always laugh. Like these waters—sometimes jump—sometimes lie still.”

“KOMA LIFTED HER IN HIS ARMS”

Standing in the boat he pushed it out into the bay with the large pole which served as a sort of paddling oar.

He smiled back over his shoulder at her. “Ah, the wind go blowing us home so quick. Now you smile once more. Good! Sun come up again!”

He had been speaking to her in English, idiomatic, but clear. Now he broke into Japanese song. His voice was round and large, full and sweet for one so young. It seemed to ring out across the bay, and float back to them from the echoing hills.

“Alas!” said Madame Aoi, as she brushed, with long hopeless strokes, the rippling hair of little Hyacinth. “Alas! no use try to keep you nice. Look at those hands—so brown like little boy’s—and that neck and face!”

Hyacinth sat upon the weekly chair of torture. Her little russet face had been scrubbed till it shone. Her hair was being brushed uncomfortably smooth with water, to prepare it for being twisted up in a pyramid on her head. Had she been a properly regulated Japanese child, one such hair-dressing a month would have sufficed. But, as a rule, she had scarcely escaped from under the painstaking hands of Aoi before she managed to shake down, or at least loosen, the beautiful glossy coiffure upon her head.

Cleaning-day, Hyacinth dreaded. Though Koma had taught her to swim in the bay like a veritable little duck, it is sad to relate that the little girl despised water which was thrown upon her for the purpose of removing that dirt, the inevitable portion of a child who plays continually in the open and burrows in beach sand.

So now, restless, rebellious, and miserable, anything but the usual passive little Japanese girl, she squirmed under the hands of Aoi.

The day was Sunday, a red-letter day for Aoi. The mission-house on the hill opened its doors to its tiny congregation upon this day. Hence Aoi prepared her little family against this weekly event, and poor Hyacinth was the chief subject of torture. Koma’s hair grew in a short, smooth mass, which required no brushing or twisting. Also, he had reached an age when he had wholly graduated from his mother’s hands and was competent to effect his own toilet. But he was forced to sit in the chamber of horrors during the time that his sister was undergoing the weekly operation, since, were his presence removed, it would have been impossible to manage or control the restless child.

“There!” exclaimed Aoi, as she placed the last pin in the child’s head. “Now, that is fine. Been good child to-day.”

Hyacinth slid down from the small stool, lingered in discontent on the floor a moment, then, with an expression of childish resignation, rose to her feet and stood silently awaiting further operations upon her.

Aoi lightly wafted a little powder towards her face and neck; then removed it with a soft cloth. The tanned skin appeared whitened and softened. Then she dressed her little charge in a fresh crêpe kimono—a red-flowered kimono it was—tied a purple obi about it with a huge bow behind, placed a flower ornament in the side of her hair, and Hyacinth’s toilet was completed.

Her appearance did credit to the labor of Aoi. She seemed such a bewitching, quaint little figure—her face, piquantly pretty, her hair shining, the red flower ornament matching her little red cheeks and lips. A moment later, too, the discontent and restlessness had quite fled from her face, for Koma had seized her the instant of her release and given her an enormous hug, to the palpitating anxiety of Aoi, who besought him to be careful not to disturb the elegance of her hair and gown.

“Now,” she told them, “go sit at the door like good children. Keep very still. Soon your mother will also be ready.”

Aoi expended less pains upon her own person. Her hair erection needed no re-dressing. She changed her cotton kimono for a very elegant silken one, powdered her face lightly in a trice, and a moment later was at the door, anxiously looking about for the children.

She was still a young woman, so pretty that it was hard to believe her the mother of a boy of sixteen. Her figure was slight and girlish, her face unmarked by any trace of age, save that the eyes were sad and anxious and the lips had a tendency to quiver pathetically. She fluttered down the little garden-path, looking right and left for the truants.

She discovered them bending over the great well in the garden.

“See,” said little Hyacinth. “There’s big cherry-tree in well, and little girl under it, also.”

Aoi looked at the reflection, lingered a moment, smiling pensively at the three faces in the water, then drew them away.

“Come,” she said. “Listen; those temple bells already are beginning to ring. We shall be late and disgrace his excellency.”

She opened a large paper parasol, and with Koma holding her sleeve on one side and Hyacinth on the other, they tripped up the hill to the little mission church.

They were late, as usual, to the extreme humiliation of Aoi, who shrank to the most obscure corner possible in the church. She gave one anxious, fluttering glance about her, shook her head at the restless Hyacinth, then very simply and naturally lifted her little, thin voice in singing with the rest of this strange congregation.

The old missionary at his stand, who had seen her entrance, beamed benignly upon her from over his spectacles. Though so old, his voice could be heard loud and clear, leading his little flock in their hymn of invocation.

The service was exceedingly simple. A reading from a Japanese translation of the Bible, a few announcements by the old pastor, then an address by a thin, curious-looking stranger, the new assistant of the missionary. After that followed the offerings, to which every one in the church contributed, even the children, then a sweet hymn, a solemn word of benediction, and church was over.

How strangely like the church in his own home in far-away England was this little mission-house to the old minister! These gentle people had labored to erect this house on the plan he had described to them. They lifted up the same voices in melodious hymns of praise to the same Creator. Their eyes looked up to their leader with the same profound devotion. Yes, surely, he had done right in the desertion of that small pastorate in England, which a hundred ministers could fill. Here lay his true work—the fruits of his labors. This had become his home.

So down the aisle he went, followed by his new assistant—with a word and a smile, and a hearty grip of the hand for each and all of his little band.

Aoi stood in the little pew, her face turned towards him, wistfully expectant. Even the restless Hyacinth peered at him with sombre, quieted gaze.

“Ah,” he said, “Mrs. Montrose and Koma. How is my little girl?” and he patted Hyacinth upon the head.

The new minister stared with some surprise at the two children, then looked questioningly at the old missionary. He was listening attentively and with old-fashioned courtesy to the words of the anxious Aoi.

“Is it not yet time, excellency? The boy is growing beyond me. What is to be done? I have taught him all the words I myself know of the English language, but, alas! I am very ignorant, and my tongue trips and halts.”

The missionary glanced gravely and thoughtfully at Koma, who was engaged in whispering to the inquisitive Hyacinth. The latter was intently engrossed in regarding the pale and anæmic face of the new minister.

“He seems such a boy—such a child,” said the old missionary, “I think you have done well by him, and it certainly was wise to keep him from the schools in Sendai.”

“Ah, excellency,” said Aoi, “he merely looks like a child. He is, indeed, much older than he appears. Was he not always old for his age? It is merely his constant association with the tiny one which causes him to appear so young.”

“Well,” said the missionary, “we must think about it. I will talk it over with Mr. Blount.” He indicated his assistant, who bowed quietly.

Aoi appeared troubled.

“Excellency,” she said, “it was the will of his august father that he should see something of the world when he should have attained to years of manhood.”

The missionary nodded thoughtfully.

“I will give you my opinion to-morrow—to-morrow evening,” he said. “The matter requires serious reflection.”

“Thank you,” she murmured, gratefully. “You are so good the gods will bless you.”

Thus, even within the house of the new religion, poor Aoi let slip from her lips that almost unconscious faith in the gods of her childhood.

Twilight falls slowly and tenderly in Matsushima. The trees, which spread out their arms over the waters, seem but to deepen their shadows and gradually become part of the creeping silver shadow of night. For night is scarcely dark here in the summer. The noon-rays are perpetual. The stars shine with an unusual lustre. Earth reflects the light of the moon and the stars upon its shimmering waters, its deep blue fields, its blossom-decked trees. The pebbles on the shore become whiter, and the whiteness of the sands deepens the green of the pines. Night is but one long twilight, slumberous and peaceful in fair Matsushima.

When the numerous candles are lighted in the temples on the hills, slanting out their glimmer upon the bewildered waters, one might almost wonder whether the stars have changed their place and descended like spirits to render more fairy-like this Princess of Bays.

An oddly assorted group of five people occupied a secluded spot on the shore. The influence of the night was upon them as they gazed out with seeing eyes that reflected the beauty of the scene and the emotions that tore at their hearts. A mother and two children—one, whose boy soul had only begun to open into a graver manhood, the other a child of seven. But seven years old was Hyacinth, yet in the child’s little face shone the restless, passionate nature of one old enough to feel an infinity of suffering. She it was who helplessly sobbed as they stood there by the bay—sobbed with an effort at strangulation, and who gazed not alone at the magic of the scene, but upward into the face of Komazawa.

One of the ministers broke the painful silence. An eager, odd, and somewhat nervous young man he appeared.

“Dear friend,” he said, addressing the boy Koma, “it will be much for the best. Our good friend here agrees with me in believing that it is your duty to follow the wishes of your father.”

Koma did not reply, but little Hyacinth raised a face of turbulent scorn towards the speaker. She did not speak, but contented herself with clasping the hand of Koma the tighter, pressing her face close against it.

“Possibly it might be as well to put off for a year—” began the elder missionary, hesitatingly. Aoi interrupted:

“Nay, excellency, the humble one agrees with the illustrious one. My lord’s son has come to manhood. It is time now that he should leave us,” her voice faltered—“for a season,” she added, softly.

The Reverend Mr. Blount bowed gravely.

“I am glad, madame,” he said, “to find that your views coincide with mine. Your son is—er—first of all more English than Japanese.”

Koma stirred uneasily. He opened his lips as though about to speak, then closed them and turned his face towards the speaker.

“He is, in fact, one of us,” continued the minister. “He has the physical appearance, somewhat of the training, and, let us hope, the natural instincts of the Caucasian. It would be not only ludicrous but wicked for him to continue here in this isolated spot, where he is, may we say, an alien, and particularly when it is his duty to follow the wishes of his father as regards his English estate. Certainly this is not where Komazawa belongs.”

“I do not agree with you, excellency,” said Koma, with a queer accent. “This is, indeed, my home. Do not, I beg you, be deceived in that matter. It is true that I am also Engleesh, but, ah, I am not so base to deny my other blood. Is it not so good, excellency? Could I despise this land of my birth, my honorable, dear home?”

“Nay, son,” interposed the agitated Aoi, “his excellency meant no reflection upon our Japan. But, oh, my son, you would not rebel against the will of your father?”

“No,” said Koma, clinching his hands at his side, “I would not.”

“Then you will go to this England, like a good son. The time has come.”

Koma remained plunged in gloomy thought.

After a moment he lifted his head and looked at the elder missionary.

“How do we know the time has come?”

“Because, my son, you have arrived at the years of manhood.”

“I am but sixteen years.”

The younger minister answered, quickly:

“It will require four or five years, at least, in England to learn the language and ways of your people thoroughly.”

“I already speak that language,” said Koma, flushing darkly. “Do I not, sir excellency?”

“No and yes. You have been brought up to speak the language. It is intelligible, but queer—wrong, somehow. You speak your father’s language like a foreigner.”

“Very well,” agreed Koma, bitterly. “Let us admit that. But may I inquire whether it will be necessary for me to go all the way to England to learn that language?”

“Well, yes. Four years in an English school will do much for you.”

“Four years; and when those four years are ended I still will lack one year from my majority.”

“That’s right,” said the missionary. “In England one attains one’s majority at twenty-one. So you would have a year in which to return, if you wish it, to Japan, previous to settling in England.”

“I do not know if I shall ever do that,” said the boy, sadly.

“It was the wish of your father,” said Aoi, pathetically.

“Yes, it was his wish,” repeated Koma. “Yet I will come back each year.”

“That is right,” said the old minister, patting him on the shoulder.

“Your father never came back,” said Aoi, sighing wistfully.

“It would be entirely out of the question for you to return each year. Be advised by me, Komazawa; I have your interest at heart,” said the young minister, earnestly. “Stay in England four years, then return and visit your mother and sister.”

“Let the good excellency decide for us,” said Aoi, glancing appealingly at her old friend. He drew his brows together.

“Wait till the time comes to decide that,” he concluded. “If the boy is old enough to leave home, he is of an age, also, to choose what he shall do. Let us not attempt to curb him.”

The new missionary assumed that Hyacinth was the sister of Komazawa. His interest in her was less than in Komazawa, since the boy was his father’s heir. Possibly, too, this might have been because of the natural antagonism with which the little girl had from the first met his overtures to her. From the moment when she became acutely aware that the new minister was practically responsible for the departure of her beloved Koma, the child conceived a violent dislike for him.

When the old minister, worn with his years of labor, quietly resigned his pastorate into the hands of his successor, and the new minister had taken up the management of the little church, Hyacinth refused henceforth even to enter the mission-house. All the entreaties and threats of Aoi were in vain, and, with Koma gone, she soon realized the fruitlessness of attempting to force her to do anything against her will. Comprehending the turbulent nature of the child, she knew that Hyacinth would only disgrace them both if she were forced into the church. So the departure of Komazawa meant at least the Sunday freedom of Hyacinth.

Nor was this the only result. The child, whose strange, independent nature had never been controlled by any one save by Koma, now that he was gone broke all restraints. She wandered at will about the bay, hiding in hollows in the rocks among the tombs when they sought to find her. Her little vagabond existence was not unlike that which Koma himself had led in his early childhood, save that she was not so easily restrained by the reproaches of Aoi. Like him, at this time, she scorned the companionship of other children. Like him she wandered away from her home in fits and starts, passive for an interval, and then bursting all bounds and disappearing sometimes for the space of an entire day or night, to return ragged and ravenously hungry.

But when the winter came, and the snow and icicles crested the trees and whitened the hills, poor Hyacinth was like a little, languishing, caged bird. Her face grew wistful and mournful. She would remain for hours with her face pressed against the street shoji, staring out into the white, cold world that bounded the horizon on all sides. If you had asked her what she was waiting for, she would have replied:

“I am waiting for the summer, for the summer brings Koma. He has promised.”

Yet when the summer came no Koma returned with the flowers and the sun.

Little Hyacinth grew accustomed to her solitude. The following year she came under the new edict of education, compulsory everywhere in Japan, and, in spite of her protests, was forced into school with a half-score of Japanese children of her own age.

At first she regarded with a fierce detestation the school and all connected with it. Did not the sensei (teacher), on the very first day, perch his spectacles upon his nose, and, drawing her by the sleeve to one side, examine her with the curiosity he would have bestowed upon some small animal. The children eyed her askance. One or two of the larger ones pointed at her hair, and, laughing shrilly, called her a strange name. If familiarity breeds contempt it also breeds toleration with the young. Hyacinth in the beginning had merely excited the curiosity, not the antipathy, of the Japanese teacher and his scholars. But as time passed they became accustomed to the difference between her and themselves. Gradually she slipped into being regarded and treated as one of them.

Then Hyacinth’s small, lonesome soul expanded to stretch out timid though passionate glad hands of comradeship to all the world. She became a favorite, the very life and soul of the school. Japanese children are painfully docile and passive. Never were such strange spirits infused into a Japanese class before.

So the years passed, not unhappily, for Hyacinth. Koma at the end of the second year was a mere memory, at the end of the third he was forgotten—wholly forgotten. Such is the fickle mind of a child of the nature of Hyacinth.

The fourth year brought him back to Matsushima. He had become very tall, taller than any of the inhabitants of Sendai he seemed, quite a head over them. He wore strange and unpleasant-looking clothes, such as those worn by the Reverend Mr. Blount, who was disliked as heartily as his predecessor had been beloved.

Koma was now an object of the greatest curiosity to Hyacinth. At first his strange appearance in the house frightened her into speechlessness. Never had she seen in all her minute experience such a strange-apparelled being, save, of course, the “abominable Blount.” In concert with the small children of the neighborhood, and in spite of the remonstrances of Aoi, Hyacinth would shout strange names whenever the gaunt figure of the white missionary appeared. “Forn debbil! Clistian!”—such were the names this little Caucasian bestowed upon the representative of her race.

She had become the most utter little backslider, if she could ever have been considered a member of the church. Respect and awe for the teachings of a careful and pious Shinto teacher, and association with a score of Shinto children, had had their due effect upon Hyacinth, and the influence of Aoi waned with the years. Little if anything of the ethics of the two religions did she understand, but to her the gods were bright, beauteous beings, whose temples were glittering gold, and whose priests kept them fragrant with incense and beaming lights by night. The mission-house was empty, ugly, dark, and damp—so it seemed to her—and an odious man, with terrible, long hairs falling from his chin, shouted and gesticulated to a congregation which often wept and groaned in unison.

The small children shouted derisively and often threw stones at the “abominable Blount” when in little groups together. But when one of their number met the minister alone, he would run from him in a sheer agony of fright.

So when Komazawa returned to Sendai, clad in the garments worn by the missionary, Hyacinth regarded him with mingled feelings of terror and fascination.

Though he made ceaseless efforts to speak to her, she could not be brought to utter one word in response. His every movement mystified her. She would sit on the floor through an entire meal watching him with wide eyes while he ate in a fashion she had never seen or heard of before.

Koma had discarded the chop-sticks, and now used, to the extreme joy and agitation of Aoi, great silver knives and forks, which she brought forth from a mysterious recess, which even the inquisitive Hyacinth had never discovered before.

Koma, distressed over the change in his little playmate, sought to win her friendship with presents purchased in England, boxes of strange sweetmeats—at least he told her they were sweetmeats. But they were coated with a black-brown covering which the little girl regarded suspiciously. She pushed almost fearfully from her the harmless chocolate drops. The sugar-coated biscuits tempted her to touch one with the tip of her tongue, but she retreated the next moment when she found the red coloring upon her fingers.

Koma regarded the girl with an expression half whimsical, half tragical, and, turning to his mother, said:

“Why, the little one is even more Japanese than I.”

Aoi nodded her head, smiling tenderly at the flushing face of Hyacinth.

“Will you not even speak to Komazawa?” she inquired, reproachfully. “Why, that is not kind. Do you not love your august brother?”

As Hyacinth made no response, Koma held out his hands to her.

“Come here, little one,” he said, bending to her till his face was quite close to hers.

Her fascinated eyes wandered from his strange apparel to his face. His eyes held hers with their strong, tender, reassuring expression. Half unconsciously she went closer to him.

“Do you not remember me, then?” he queried, in a soft voice, whose reproachful tones thrilled the girl.

Wistfully she approached him still closer, only to retreat in panic the next moment. She was like a little wild bird, shy and fearful, yet half anxious to make friends with a strange being.

Suddenly she began to cry, drawing her sleeve across her eyes and turning her face to the wall. She could not have told why she wept. Was it fear, childish conscience, or a slow recognition of her old, beloved Koma, whose name had become but a word to her?

If she remembered Koma at all, the memory bore no resemblance to this tall man-boy who had returned so suddenly to their home. To her he seemed a stranger, a fearful intruder.

Hurt to the quick, Madame Aoi whispered to her son. He arose without a word and disappeared into his room. Fifteen minutes later, Hyacinth, playing with a regiment of Japanese doll soldiers on the floor, having forgotten all her tears of a few minutes since, leaped to her feet suddenly, with a strange, little cry.

“‘NOW, COME, LITTLE ONE: COME, GIVE ME THAT WELCOME HOME’”

There in the middle of the room she stood, holding tightly in her hand her doll, and staring, as if fascinated by the smiling figure on the threshold. It was the same stranger surely, yet, ah, not the same. A few minutes had wrought such a change in his appearance. He had discarded the heavy, dark, mysterious clothes. He appeared like any other Japanese youth, save that he was much taller, and his face smiled down upon the little girl with an expression whose power she had been unable to resist even when he had worn those outlandish garments. He called to her, softly.

“Now, come, little one; come, give me that welcome home.”

Her hand unclinched, the doll dropped to the floor. With a sudden impulse she ran blindly towards him, and he caught her in his arms with a great hug, which was as familiar to her as life itself.

It was late in December, the time of Great Snow. Komazawa was still in Sendai, and Hyacinth had been taken from the school. She was now twelve years of age, still undeveloped in body and childish in mind.

Hyacinth, like most impressionable children, had quickly succumbed to the influence of the school-teacher. In his hands she had yielded like plaster to the sculptor. Out of crude, almost wild, material had been developed what seemed on the surface an admirable example of a Japanese child.

Komazawa, fresh from four years of training at an English school and intimate association with English students and professors, now set about the task of undermining all that the sensei had taught Hyacinth.

This was no light task. Hyacinth could not unlearn in a few months that which had practically become ingrained. Quite useless it was, therefore, for Komazawa to seek to turn the child’s mind to a new and alien point of view, when, too, this view-point was, in a measure, an acquired thing with Koma himself. Yet he was patient, and labored unceasingly.

No; the people in the West were not all savages and barbarians.

“Did they not look like the Reverend Blount?” would inquire his small pupil.

“Yes, somewhat like him.”

“Ah, then, they perhaps were not savages, but they certainly were monsters.”

“No; they are very fine people—high, great.”

“But only monsters and evil spirits have hair growing from the chin and awful, blue-glass eyes,” protested Hyacinth.

Whereupon Koma quietly brought a small mirror from his room, held it before her face, and bade her look within.

She stared curiously and somewhat timorously.

“What do you see?” he inquired, quietly.

“Little girl,” she said, in a faint voice.

“Yes, and what color are her eyes?”

The eyes within the glass became enlarged with excitement. The lips parted. Hyacinth put her face close to the glass.

“They are blue, also,” she said, shrinking.

“Very well, then. You, also, have blue eyes, Hyacinth.”

“Me!” She stared up at him, aghast.

“Certainly. Is not the little girl in the glass you?”

“No!” Her dilated eyes strained at the glass, then looked behind it and about her. She could see no other little girl in the room. There was only that face in the shining glass, with its blue, shiny eyes. With spasmodic working of features, she regarded it.

“This is you—certainly,” repeated Koma, pointing to the reflection.

An uncanny fear took possession of the little girl. Suddenly she raised her hand, knocking the glass from that of Koma.

“That’s not me. No! That’s lie. I am here—here! That’s not me.”

She burst into a passion of tears.

Raising the glass, Koma put it aside. He sought his mother immediately, and, with concern and perplexity in his face, told her of the incident of the mirror.

“Hyacinth was frightened—yes, actually afraid of the mirror. What can be the matter?”

“That is only natural,” said Aoi. “And I am much distressed that you should have frightened her with the glass.”

“But why should it affright her?”

“Because she has never seen one before.”

“Never seen a mirror before?”

“No. It is only of late years that they have come to Sendai, my son.”

“Why, the mirror is as old as the nation.”

“Oh, son, but not for general use. Until recent years they were regarded as things of mystery, and were very precious and priceless.”

“Yet as a child I had often seen my father’s mirror. Our house contains one, does it not?”

“True; but it is locked away in our secret panel.”

“But why?”

Aoi hesitated.

“It was, perhaps, a useless custom, my son. But in my younger days maidens were not permitted to see their own faces. The mirror was for the married woman only. Thus, a maiden was saved from being vain of her beauty.”

Koma frowned impatiently.

“A useless and foolish custom, truly. And now, here in these enlightened times, you put it into practice with Hyacinth. Why, you are prolonging the customs of the ancients here in this house, which should be an example of the new and enlightened age.”

Meekly Aoi bowed her head.

“You are honorably right, my son; yet there was another reason why the mirror was kept from the sight of the little one.”

“Yes?”

“How could I blast the little one’s life by letting her know of—of her peculiar physical misfortunes?”

“Physical misfortunes! What do you mean?”

“Why, the hair, eyes, skin—how strange, how unnatural!”

Koma threw back his head and laughed with an angry note.

“Oh, my mother, you are growing backward. You are seeing all things from a narrowing point of view. Because Hyacinth is not like other Japanese children, she is not ugly. Why, the little one is beautiful, quite so, in her own way.”

Aoi appeared troubled.

“You did not consider my father ugly, did you?”

“Ah no.”

“Well, but was he not fair of face?”

“It is true,” she admitted; then, sighing, added, “But I fear the little one would not agree with us in the matter. It might terrify her to see her own face—so different from that of her play-mates. In heart and nature she is all Japanese.”

“Nay; her natural parts have had no opportunities. She, like you, has seen only one side of life and the world. Now, is it not time to educate her real self?”

With an unconscious motion of distress, Aoi wrung her hands.

“The task is beyond me, my son. How can I effect it? Alas! as you say, I am in the same condition, for am I not all Japanese? My lord is gone these many years. I cannot keep step with the passage of time. Yes, son, I slip backward into the old mode of life and thought. When you were by my side, you were the prop that kept me awake, alive. But you were gone so long. Ah! it seemed as if time would never end.”

“Oh, my mother,” he cried, “I will never leave you again. It is I who am all wrong, wrong—I who am the renegade. But we will remain here together, and you, dear mother, will teach me all over again the precepts of my childhood. For these four years I have been studying, acquiring a new method of thought and life, yet I fell into it naturally. My father’s blood was strong in me. Yet, dear mother, now I feel I have been wrong in leaving you, and I will not return.”

“Oh, son,” she said, with trembling lips, “you are all Engleesh—all your father. And it is right. Do not speak of remaining here with us. A mother’s eyes can see deep beyond the shallows into her child’s soul. I know your restless heart cries for the other world. It is there, indeed, you belong. And you must return to this England and the college.”

“But I shall not remain,” he said, throwing his arm about her shoulder. “No; I shall come back when I am through college, for you and Hyacinth.”

Aoi did not speak. Her poor little hands trembled against his arms.

Fluttering to the door came Hyacinth. The tear-stains were gone from her face. In her hand she carried the small English mirror. Evidently she had overcome her repugnance and fear of it, and now regarded it as some strange and active possession.

Aoi looked up at her son with questioning eyes.

“The little one’s new education must commence at once,” he said, slowly.

He went to the child and took the mirror from her hand and again held it before her face.

“This is the beginning,” he said. “Let her become acquainted with herself as she is. This will force a new trend of thought.”

Then to the child:

“Who is this within?” he asked.

“It is I,” she said, simply.

She had discovered the secret of the mirror, and somehow it had lost all terror for her—nay, it held her with a strange delight and fascination.

“Little one,” said Komazawa, kneeling beside her, “look very often into the honorable mirror—every day. There you will see your own image. You will not be ignorant of yourself. You will learn much which the sensei cannot teach you. Also, go each day to the mission-house. No; do not shake your head so. But every day you must go to the school class. Then very soon, maybe in three years, I will return and complete the teaching.”

Hyacinth looked timidly up into his earnest face a moment. Then she suddenly smiled and dimpled.

“Very well,” she said, in English, in a tone whose note expressed as words could not her perplexed emotion.

A smile overspread Koma’s face.

“Ah,” he said, with a glance back at his mother, “the little one has not forgotten.”

“Yet,” said Aoi, “she has not spoken it, son, since you left Sendai five years ago.”

The Reverend Mr. Blount knocked sharply at the door of Madame Aoi’s house. There was no response at first to his summons, beyond a slight stir and bustle at the rear. After a pause the sliding-doors were pushed aside and the fat face of Mumè appeared for a moment, to disappear the next. She was heard chattering, in a grumbling voice, to some one within.

The visitor, grown impatient, rapped hard upon the panelling. A moment later there was the light patter of feet along the hall and Aoi appeared. She hastened towards the visitor with an apologetic expression.

Would the honorable one pardon her great discourtesy? She had been taking her noonday siesta and had not heard the visitor’s knock. She would immediately reprove her insignificantly rude and ignorant servant for not having shown the illustrious one welcome and hospitality.

“I want to see Hyacinth,” said the caller, entering the guest-room and slowly removing his kid gloves.

Hyacinth, Aoi informed her visitor, was also taking her noon sleep. Would the honorable one deign to excuse her, or should she disturb the little one?

“Asleep?” he repeated, disapprovingly. “How can that be, madame, since I only just saw her at the window?”

“She must have awakened, then,” said Aoi, simply.

The other nodded curtly. “No doubt,” he said. He seated himself stiffly in the only chair in the room, and when Aoi had quietly seated herself on a mat some distance from him, he clasped his hands together and leaned forward towards her.

“Madame Aoi,” he said, “I have just heard the most improbable, ridiculous tale about Hyacinth.”

Madame Aoi elevated her eyes in gentle question.

“That she is, in fact—er—engaged——that is, affianced—you know what I mean.”

Aoi smiled beamingly. Yes, she admitted, her daughter was, indeed, betrothed to Yamashiro Yoshida, “son of our most illustrious and respected and honorable friend in Sendai, Yamashiro Shawtaro.”

“But,” said the visitor, after a moment of speechless surprise, “this is the most preposterous, impossible of things. Why this—this Yamashiro Shawtaro, the father of the boy, is one of the most rabid Buddhists, and, besides, it is barbaric, an unheard-of thing, to think of marrying a girl of her age to any one.”

“The betrothal,” said Aoi, with a slight smile, “was all arranged by the Yamashiro family. The boy is the father’s salt of life. He cast eyes of desire upon the little one, and as he is the richest, noblest, and proudest youth in Sendai, we have accepted him. All the town envies us, excellency.”

“Does her brother know about this?” demanded Mr. Blount, severely.

“Oh yes, surely.”

“And what does he say? He is English enough to perceive the utter impossibility of such a marriage.”

“We have not heard from my son yet in the matter,” said Aoi, simply.

“Well,” said the other, “I can assure you that when he knows the truth he will refuse to countenance it.”

“But, illustrious master, how can he do so? He has not that right.”

“He has not the right! Why, even your Japanese law makes him her rightful guardian. He is still a citizen of Japan. A brother, in Japan, is his sister’s legal guardian. I know this to be a fact.”

“Ah, but, honored sir, you do not know everything.”

Mr. Blount looked over his gold-rimmed spectacles sharply, endeavoring to pierce beneath the softness of her tone. Japanese women were all guile was his inner comment.

“Well, now, suppose you explain to me why your son is not his sister’s guardian?”

“Because, august minister, he is not the little one’s actual brother.”

Mr. Blount started so that he actually bounded from his seat.

“What do you mean?” he jerked out to Aoi.

“The little one is only my adopted child,” said Aoi, smiling serenely.

The minister could scarcely believe he heard aright. The Japanese woman continued to smile in a manner whose guileless, impenetrable innocence of expression had the effect of irritating him excessively.

“If Hyacinth is not your child, Madame Aoi, who are her parents?”

“The gods forsaken little Hyacinth. She has no true parents.”

In his acute interest in the matter, the minister actually overlooked the slip of Aoi when she alluded to the “gods.” What he said, with his eyes fixed very sternly upon her face, was:

“You are deceiving me, Madame Aoi. You are hiding the truth from me.”

The slightest frown passed over Aoi’s face. Her color deepened, then faded, leaving her inscrutable and impassive once more.

The honorable one was augustly mistaken, for the humble one had nothing to hide. Since the affairs of her adopted child concerned only her foster-parent, it was impossible to deceive the honorable minister.

It was the visitor’s turn to flush, and he did so angrily. Plainly this Japanese woman was attempting to conceal, with the prevarication and guile of her people, some mystery concerning Hyacinth. If the girl was not the daughter of Aoi by her English husband, who then was she? She certainly was not pure Japanese. Could it be that she was not even in part Japanese? The possibility staggered the missionary.

“Madame Aoi, you are taking a most unusual attitude towards me to-day.”

Aoi inclined her head in a motion that might have meant either assent or negation.

“Hitherto,” continued the other, “you have not hesitated to accept my advice—”

“In matters concerning that religion, yes,” interposed Aoi, softly.

“Which surely concerns all other matters connected with your welfare and that of Hyacinth. No one knows better than you do that the lives of our parishioners, our children, are our particular care and charge. I take the interest of a parent in our little band. So you would not withhold your confidence from a parent?”

“What is it the honorable sir would know?”

“The history of Hyacinth—who she is, how you came by her, her people’s name—all information about her.”

“There is nothing to confide,” said Aoi, slowly, as though she chose her words carefully before replying. “The old excellency knew the history of the child. It was under his advice that the humble one adopted the little one.”

“Under Mr. Radcliffe’s advice!”

“Yes.”

“What did he know of Hyacinth?”

“The excellency deigned to make effort to discover the little one’s parents.”

“But you don’t mean to tell me that you did not know her parents?”

“Only the mother, and she lived but a day after the coming of the child.”

“Did Mr. Radcliffe fail to find her father?”

Nervously Aoi clasped her hands together. She did not answer.

“Did he find her father?” repeated Mr. Blount.

Aoi looked at him with a gleam of stubbornness in her glance.

“If the excellency did not make confidant of you before he died, why should I do so, also?”

“It is your duty, madame.”

She shook her head slowly.

“Certainly, it is your duty. It is perfectly plain that Hyacinth is a white—that she’s not pure Japanese, at all events.”

Aoi moved uneasily. Then she looked up very earnestly at her interlocutor.

“The little one knows nothing of her parentage, save that she is an orphan confided to my care. It would distress her to be told that—that she is not Japanese.”

“Then you admit that?”

“No; I do not so admit. I but begged the honorable one to put no such notion into her mind, so sorely would it distress her.”

“I wouldn’t think of keeping her in ignorance,” exclaimed the other, with some indignation. “She ought to have been told the truth long ago. I shall certainly tell her.”

“What can you tell her?”

Aoi had risen and was regarding the missionary with a strange expression.

“That I suspect she is not Japanese—not all Japanese.”

“She would not believe you,” said Aoi, thoughtfully.

“I will see her at once, if you will allow me,” said Mr. Blount, also rising. He was somewhat startled at the attitude and the reply of Aoi. She had placed herself before the door, as if to prevent the passage of any one desiring to enter.

“My daughter will not see visitors to-day,” she said. “You will excuse her.”

The next moment she had clapped her hands loudly. In answer to her summons, Mumè came shuffling into the room, hastily wiping her hands upon her sleeves, and looking inquiringly towards her mistress.

“The illustrious one,” said Aoi, with intense sweetness, “wishes to return home. Pray, conduct him to the street.”

She bowed with profound grace to the missionary, and stepped aside to permit him to pass.

He hesitated a moment, and then said, slowly and succinctly:

“Madame Aoi, I have only this to say. I shall immediately take it upon myself to unravel this mystery. I will communicate with the nearest open port at once, and find out whether my predecessor had correspondence with any one on this subject. Good-day.” He bowed stiffly.

Meanwhile Hyacinth lay stretched upon the matted floor of her chamber, her chin in one hand, the other holding an ancient oval mirror. She was studying her face closely, critically, and also wistfully.

The head was quaintly Japanese, yet the face was oddly at variance. For the hair was dressed in the prevailing mode of the Japanese maid of beauty and fashion in Sendai. It was a very elaborate coiffure, spread out on either side in the shape of the wings of a butterfly. Upon both sides of the little mountain at top projected long, dagger-like pins; gold they were and jewelled—the gift of Yoshida.

Hyacinth no longer fretted under the hands of a hair-dresser, since it was her pride and delight to have her hair dressed in this becoming and striking mode. If the hair-dresser, who came once a fortnight, puckered her face and shook her head when the beautiful, soft, brown locks twisted about her fingers, and did not follow the usual plastic methods used upon the hair of most Japanese maids, Hyacinth cared little. When the operation was completed, her hair, dark, shining, and smooth, appeared little different from that of other girls in the village.

It was the face beneath the coiffure that distressed the girl. The eyes were undoubtedly gray-blue. They were large, too, and wore an expression of wistful questioning which had only come there, perhaps, since the girl had begun to look into the mirror and to discover the secret of those strange, unnatural eyes.

The whiteness of her skin pleased her. What girl of her acquaintance would not be glad of such a complexion? She had small use for the powder-pot, into which her friends must dip so freely. Her mouth was rosy, the teeth within white and sparkling. Her chin was dimpled at the side and tipped with the same rose that dwelt in her rounded cheeks. The little nose was thin and delicate, piquant in shape and expression.