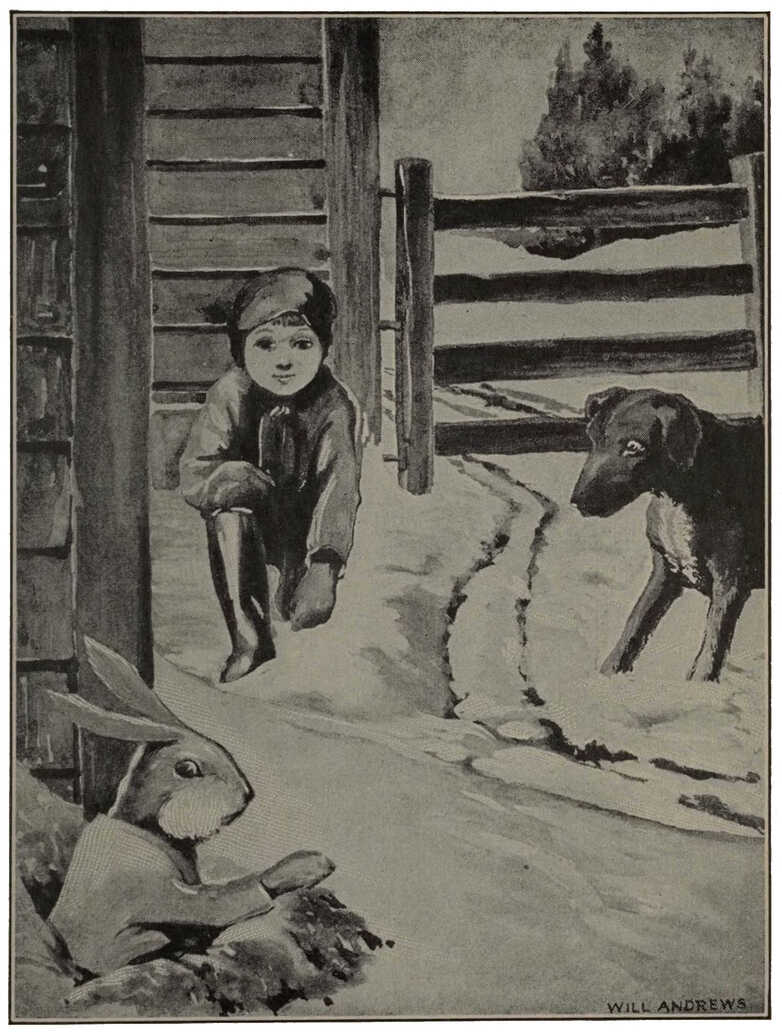

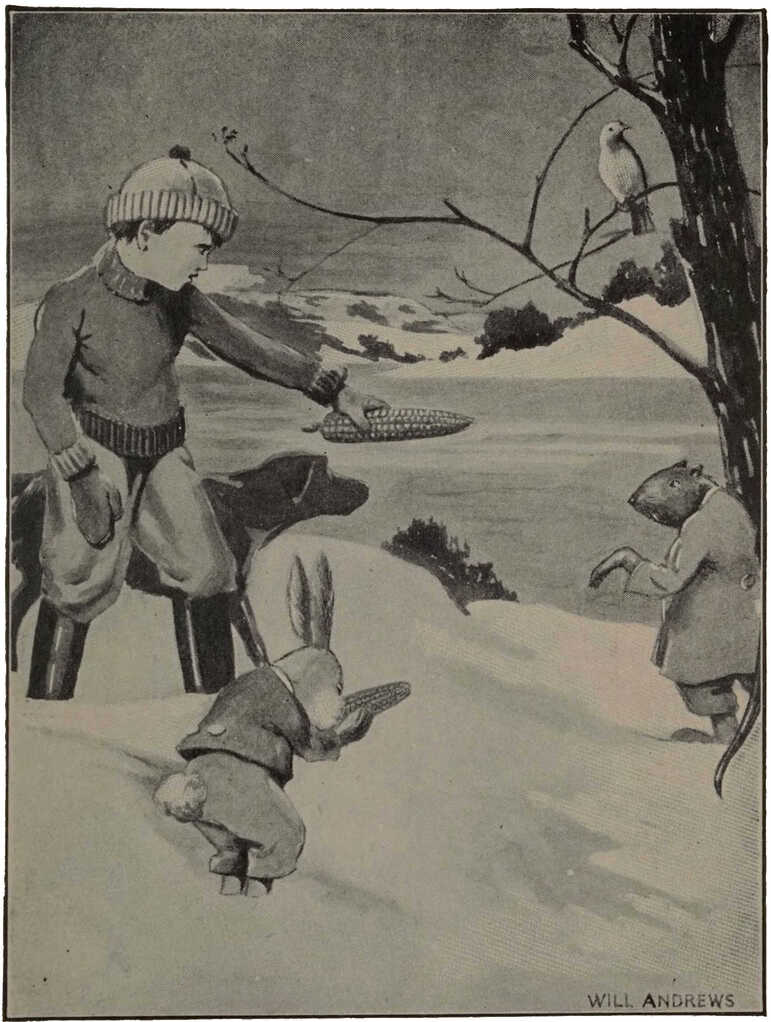

Watch makes friends with Nibble

Title: Nibble Rabbit Makes More Friends

Author: John Breck

Illustrator: William T. Andrews

Release date: December 18, 2020 [eBook #64078]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Roger Frank

Watch makes friends with Nibble

You remember all the funny things Nibble heard about Man from the guests who came to his Storm Party. That was the time the Big Hollow Oak blew down, and the brave little bunny who lived at Doctor Muskrat’s Pond rescued all the poor homeless folk who had been shaken out of it. He showed them the way to a fine little tent all made of cornstalks out in the Broad Field.

It was so nice and snug and comfortable, the minute they tucked their tails inside it, and caught their breaths, and sleeked down their fur and their feathers, they forgot all about how the Terrible Storm was having a tantrum outside. They had plenty of room to dance, and plenty of corn for refreshments—why, the party was as big a success as if they’d held it in a hired hall with engraved invitations.

But the most fun they had was talking about folks like you and me. And if you’d laid an ear to a crack before the wind tucked the snow blanket all around them, you wouldn’t have been very much flattered by what they said, either.

You might have overheard the bats insisting that Man looked like a frog. (You might say that about some folks, of course, but certainly not about you or me.) You’d prob’ly have heard the partridge say that Man was brown and wrinkly, like Grandpop Snapping-Turtle. (The man they saw certainly must have worn some funny clothes.) Chatter Squirrel said Man was pink and tan. (His pink was sunburn—the kind the fellows get down at the swimming-hole.)

Everyone just knew that everyone else was wrong. Then Gimlet Woodpecker insisted Man came as many shapes and sizes and colours as the flowers. And then they didn’t know what to think. There were just two things they all agreed on: he didn’t have a tail, and—he was dangerous. Nibble didn’t say anything, ’cause he’d never seen one.

But the first time he set eyes on Tommy Peele, he made up his mind they were all wrong—excepting about the tail. The little boy looked to him like a red-wing blackbird. (That was ’cause Tommy had on his new red mittens and his dark blue sweater and his shiny rubber boots.) But dangerous? He certainly didn’t look it. Still—when Silvertip the Fox only caught a glimpse of him, he turned tail and ran.

So Nibble made up his mind to copy the mouse motto: “Say nothing and stay cautious.” At least that’s what he thought he was—too cautious for anything. Wasn’t it perfectly safe and proper to dig into that queer lair where the mice were holding a party of their own? Wasn’t it nice and dark as his own hole? And nobody could possibly see him.

How was a bunny to know it was a soapbox? Or that it was part of a “figger-four” trap? Or that Tommy had set it ’specially for him?

You see he hadn’t been caught. He’d dug into it on purpose, because those nice little mice had invited him. And there the three of them were busy feasting when they heard the clump! clump! clump! of the clumsy hind paws of that little boy.

“Mice,” he said, “it’s that Man!”

Before he could twiddle a tail, Tommy’s red mitten was across the hole, and Tommy’s bare pink paw was closing on—the lady mouse. Then things began to fly!

Nibble was among them. He flew to the next little cornstalk tent, his heart thumping faster than his paws. “They were all of them right!” he gasped. “That Man is dangerous—dangerous as Silvertip himself. Poor Satin-skin! I s’pose that’s the end of her.”

He never thought of saying, “Poor Tommy Peele!” But Tommy was the right one to feel sorry for. Satin-skin had closed her little needle teeth on his finger. And before Nibble had taken a long breath he heard a voice squeaking, “Weeak! weeak! weeak!” which is mouse for, “I’m lost! Where are you?”

“Here!” he thumped with both hind feet. And who should come scuttling in but Satin-skin herself? He could feel her tremble all over as she tried to squirm right under him.

“My ears!” Nibble exclaimed. “I thought that Man had caught you!”

“No, I caught him!” wept the little lady mouse. “But he shook me so hard I was scared to let go again. And when I did, he sent me tail over ears. I tell you, it was awful! wee-eeak!”

“Shh! he’ll hear you,” Nibble warned. “There, your head will stop whirling pretty soon.” He knew just how she felt, ’cause he’d felt the same way himself—the time he tumbled off the back of that Red Cow he took for a log when Silvertip was chasing him.

But Tommy wasn’t even thinking about Satin-skin, let alone listening for her. He stamped his tall rubber boots and sucked his poor nipped finger. “Funniest thing!” he wondered to himself. “I just know there was a rabbit in that trap. I saw him go in there. I don’t guess it’s very much good. I’ll try the pitcher-wire.”

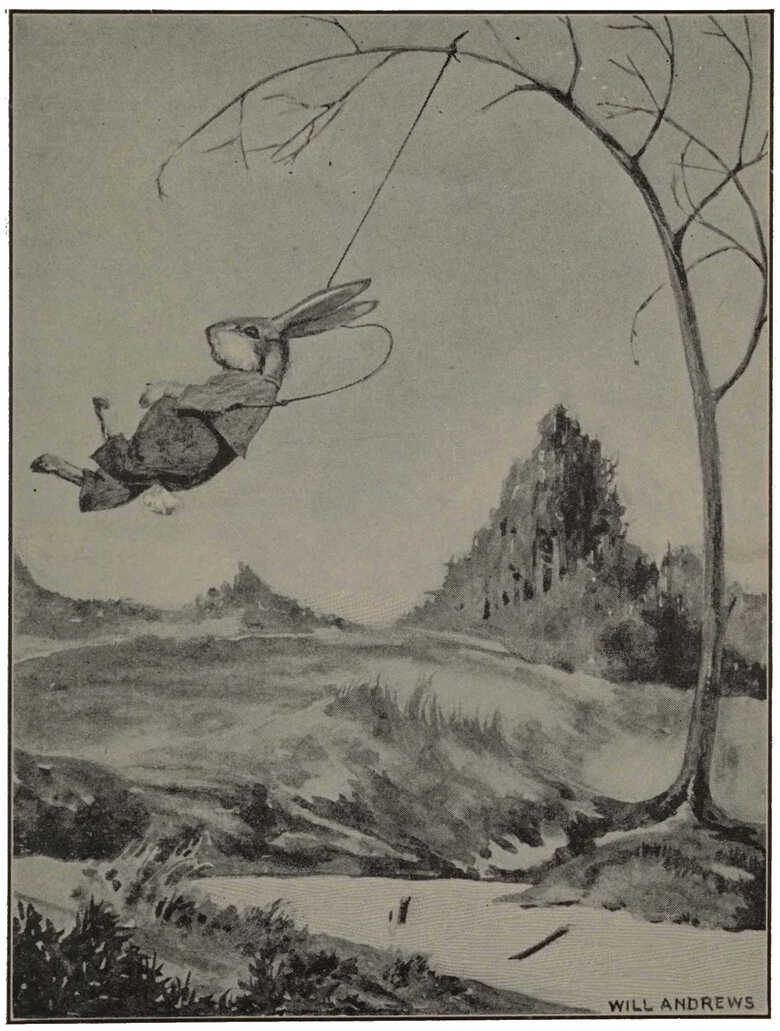

Nibble squirmed and flounced like a fish on the end of a line.

So he pulled on his red mitten and tramped off to the path in the bushes by the fence he’d seen Nibble slip through. This time he bent down a springy sapling and tied a loop of wire to the tip of it—the soft kind you use to hang pictures. And he pegged the lower edge of the loop across Nibble’s pathway.

Meanwhile, Nibble was busy comforting the lady mouse. “There, there! Don’t squeal any more. You’re not hurt a bit. But really, this gets more and more curiouser. Now Silvertip would certainly have eaten you. But I don’t see yet why folks are so scared of a Man, if that’s all he can do to you.”

“You’d know if he sh-sh-shook you!” sobbed the lady mouse.

But Nibble didn’t pay any attention. “I’m going to sneak up close to the Sparrows’ Tree and ask Chirp about it,” he announced.

Off went he, so fast he didn’t notice where he was putting his foot own.

He came to the fence—and the picture-wire. Zing! Now he knew what a trap was, for sure and certain. For the pegs let go, the sapling snapped back, and the wire caught him just behind his little fore legs and whipped him high up in the air.

He squirmed and flounced like a fish on the end of a line. He kicked harder and harder; and the wire pulled tighter and tighter, until he screamed.

From way up there in the air he could see Tommy Peele turn around and hurry toward him, swinging his red mittens as he ran. And he knew Tommy had something to do with it. “This,” thought he, “is why Man is dangerous. How awfully slow he flies. Now he’ll eat me!” And the wire was squeezing him so dreadful, he didn’t much care. But Tommy just cut that terrible loop, and took the rabbit gently into his arms.

“Poor little bunny! I didn’t know that was going to hurt you,” whispered the little boy. And he put a very sorry finger on the place where the picture wire had been.

But Nibble still kicked and struggled so hard that Tommy would have lost him if he hadn’t kept a tight hold of the bunny’s long ears. And Tommy did keep a tight hold, for the more he saw of Nibble the more he wanted him.

In ten minutes Nibble was locked in a cage. It really was a very nice one—for a rabbit who had been born there. But for Nibble it was as cramped as Ouphe the Rat’s narrow black tunnels under the haystack. It was only half a leap long and three creeps across. There was one dark corner in it where he could hide behind some hay when the humans came to look at him—and they did come, all sizes and colours and noises, just as Gimlet the Woodpecker had said. When they went away again he snubbed his nose trying to take the kinks out of his legs where he had been sitting on them.

And more than the humans came to call on him. For the minute they turned their backs a great big beast, much bigger than Silvertip, put his forepaws up on the front of the cage and sniffed at him. He was nearly the same colour as Silvertip, only his back was more grizzled and he had a white collar as well as a white shirtfront like most wild things wear. But this beast didn’t have a hungry look; he was only curious—like Nibble is himself when he isn’t scared. All the same, Nibble was afraid of him.

Just about sundown all these visitors went away. This was the chance Chirp Sparrow was looking for. He flew down and perched on the cage. Then he cheeped very softly, to make Nibble look at him.

Nibble pricked up an ear. Then he jumped so hard that he hit the front of the cage and bounced back again, but he picked himself up and thumped and wriggled his puffy tail trying to show Chirp how glad he was to see him. “Mr. Chirp, Mr. Chirp!” he exclaimed. “You’ll know how to help me. You know everything!”

“Well, not everything,” answered Chirp. But he preened the feathers on his shoulders and cocked his head on one side the way birds do when they’re pleased about anything. For he was immensely flattered. “I don’t know everything,” he repeated, “but I’ll call a sparrow council, and we’ll see what can be done about it.” And something’s pretty apt to happen when the sparrows put their minds to anything.

“Now you listen to me,” he went on. “You eat what they feed you and keep strong. You aren’t in any danger right away. And you try to make friends with that Dog.”

“What Dog?” asked Nibble. He was puzzled.

“He was here just a minute ago,” said Chirp. “That big foxy-looking beast. He’s a great friend of ours. He has a big dish by the back door that’s always full of delicious things. And he pretends to go to sleep while we pick up the crumbs. You be just as polite as you can to him. I’ll be back in the morning.” And Chirp flitted off to the sparrow roost, leaving Nibble almost cheerful again. He couldn’t help feeling that all this excitement was rather interesting.

Tommy Peele had tried to make his cage a comfortable one for Nibble to sleep in. But he didn’t know that a proper rabbit hole has fresh air blowing into it from above. The cage had only one dark, stuffy corner to hide in, or the open part behind a wire front. And there Nibble crouched in the hay Tommy had given him. But he kept cheerful. Chirp had said, “We’ll see what can be done about it,” and Nibble knew the clever Sparrow. So he just made a little song of the words until he sang himself to sleep with them.

Way ’long late toward the morning he woke up. His furry feet were tickling. So were his ears. And presently his shoulders tickled, too, where the fur stood straight up on them. Something was gnawing the floor of his cage.

“Who’s there?” he called softly. And oh, how he did pray it might be the field-mouse who had shown him the way through Ouphe’s tunnels! He could see the haystack where the wicked Rat lived, but it was so dark that that was all he could see.

“It’s I,” said the honey voice of Ouphe. “I’ve come to show you what can be done about it. I’m sorry to be late, but I had to attend to a little business with Chirp Sparrow.” The words were all right, but the way he said them was enough to make your skin crawl.

“What are you going to do?” demanded Nibble.

“I’m going to have breakfast with you,” said Ouphe. “I’m going to make a nice little door so I can come in and we’ll have a cozy time. I love little rabbits, I do.” And Nibble knew very well the way he loved them—like Slink the Weasel. For no wild beast needs to be warned against any one who has the horrid musky, flesh-eater’s smell about him. And Nibble smelled Ouphe.

“I’ll fasten my teeth right in your nose,” said Nibble, “the minute you poke it through my floor.”

“What good will that do?” sneered Ouphe. “You’ll hurt me almost as much as Chirp Sparrow. He pecked my ear, he did—the bold, bad bird! All the same, I ate him.”

“You didn’t!” sobbed Nibble. He just couldn’t believe it.

“Didn’t I just?” jeered Ouphe. “You can smell him on my whiskers when you bite me. Sparrow for supper and rabbit for breakfast. Mmn!” And he smacked his lips.

But Nibble almost forgot to be scared, he was so angry. He thumped his feet.

“Stop that!” snarled Ouphe. “Do you want the Dog to eat you?”

“Thump, Thump, THUMP!” went Nibble. He was bound to do whatever Ouphe didn’t want him to.

“Arrh!” cursed the bad Rat. Kerflip, kerflop, he jumped down and shuffled off to his haystack. Sure enough, there came the Dog, calling, “What’s the matter here?” And Nibble was too scared to answer.

“What’s the matter here?” repeated the Dog. He was standing in front of the cage wagging his long, plumy tail. But all Nibble could look at was the great teeth he showed when he smiled.

“Please,” said Nibble very faintly, “please, Mr. Dog, Ouphe the Rat ate Chirp Sparrow for supper to-night. I thought I ought to tell you because Chirp said you were friends.”

“He did, did he?” laughed the Dog. And he ran out his pink tongue, which scared Nibble more than ever. “And who brought you the news?”

“Ouphe did. He’s been trying to get into my cage.”

“You don’t say?” The Dog sniffed carefully. “Great Bones, Bunny!” he exclaimed, “Why didn’t you call me an hour ago. I’ll hate to show that to Tommy. He’ll think I wasn’t watching.”

“Ouphe said you’d eat me,” whispered Nibble.

“Eat you?” repeated the Dog. “Lies! All lies! And Ouphe knew it. I’ll tell you, Bunny, don’t believe a word that creature says. He never tells the truth, even by accident. And he’s always up to some devilment.”

Somehow Nibble knew he could believe the things the Dog said in his rough but friendly voice. All the same, he wanted to be pretty careful. “Why wouldn’t you want to eat me?” he asked.

“Why, because you belong to my Tommy. I’m not saying what I might do if you didn’t,” answered the Dog, wagging his tail harder than ever because he was so amused at Nibble. “Though I guess I’m too old and fat to catch you. But as long as you live in my Man’s barns and have my Man’s smell about you I’ll never touch you. My job is to take care of my Man’s things and see that nobody hurts them.”

Now it was queer, but just the way that nice, big, growl Dog said he might possibly try to catch him if he wasn’t Tommy Peele’s rabbit made Nibble feel better. He felt the Dog wasn’t pretending like Ouphe the Rat did after he’d been shouting horrid things at Chirp Sparrow. He gave a little laugh—a sniffly one, because he wasn’t quite over being afraid. “Please, Mr. Dog,” he murmured, “Chirp said I was to make friends with you.”

“Well, then, my name is Watch,” the Dog continued; “it’s my job to watch this farm and see that things don’t go wrong on it. And that’s why you should have called me the minute Ouphe put his ugly teeth into this.” He sniffed the gnawed spot on Nibble’s cage.

“Yes, sir.” Nibble apologized. “Chirp didn’t tell me that. He just said you were once a wolf, like Silvertip—only much more clever.”

“Urr!” remarked Watch, cocking an ear. “So Chirp’s been going into my family history? He’s a gossipy bundle of feathers.”

“No,” insisted Nibble honestly.

“Just about how the Wolves ate the Cows in the very First-Off Beginning.”

“All right,” answered Watch. “Then I’ll finish it for myself.”

“You know how the wolves ate the cows in the First-Off Beginning,” said Watch, after he had taken a sniff to make sure Ouphe was still in the haystack. “It was because the Plants just wouldn’t be eaten. And they were too clever to starve.” He settled himself down by Nibble’s cage.

“Yes,” answered Nibble, “and how the good stupid Cows did starve, so Mother Nature had to give them horns because they’d worn all their teeth off.” “Much good did that do them,” sniffed Watch. “Horns or no horns, you just ought to see me handle them.” He was very proud of his work, that nice dog.

“Well,” he went on, “some of us were terribly ashamed over the way we’d acted. But Mother Nature wouldn’t forgive us. She said if we ever were trusted we’d have to earn it ourselves. She’d never trust us. Her good Beasts wouldn’t have anything to do with us, and we wouldn’t have anything to do with the bad ones because we knew we weren’t as bad as they were. And we got lonely and unhappy—so, of course, we got sulky and snappy, too.

“Then the bad Beasts took to calling us ‘Dogs’—and that was a terrible insult in those days. And deep down inside we were very, very sorry—because we did so want to be trusted.

“One day a dog was walking all alone in the Forest and he saw the funniest little Creature playing there. It was so funny he sat down on his tail to watch it play. It hadn’t any teeth to speak of, and it hadn’t any hair, but it walked like a little cub bear. Just like one. It would stagger along a little ways and then it would sit down—plump! And then it would laugh. So that made the dog prick up his ears.

“He liked the sound it made when it laughed so much that he stayed there to listen to it. And pretty soon it saw him. But it didn’t run away. It just walked right up to him. And the queerest feeling came over that dog. He was happy, deep down inside him. Because it was trusting him.

“So he sat very still. And the little thing walked right up and felt of his teeth, and tried to find out how he winked his eyes. And the more it hurt him the better he loved it because then he was sure it was trusting him. And it had the sweetest smell. He put out his tongue and tickled it; and, of course, it laughed again. So he found out how to make it laugh whenever he wanted to. And they played out there in the sun and were very happy.

“By and by a Man came running up and behind him was a woman. So, of course, that dog knew that he had been playing with their Baby. And he got up and crept away because he knew that least of all they would have trusted him. But the Baby cried and held out its hands for him.

“All that night the dog was lonely because he’d lost the little soft thing that laughed and trusted him. And he told the Moon about it. Dogs always tell things to the Moon. And he was the most unhappy dog in the Forest because he’d only learned half of the secret about being trusted.”

Here Watch paused to rush at the haystack with a terrible bark because he thought Ouphe was sticking his nose out again. “Wurff!” he cleared his throat. “I’ll catch that fellow some day,” he remarked as he came back to Nibble Rabbit’s cage and sat down again.

Nibble was waiting for him with his little feet pressed close to the wires. He wasn’t afraid of any one while that dog was there to talk to him. “Go on, please,” he demanded. “You said its Father and Mother took away the little soft cub who had trusted him. And the poor dog felt lonely.”

“Cub? I didn’t say ‘cub,’ Bunny. It was a Baby. My, but you are a green little wild thing.” He smiled again, but this time Nibble wasn’t afraid of the long teeth he showed.

“You said it was like a little bear,” Nibble insisted, and he wrinkled up his own nose.

“Well, Cub or Puppy or Baby,” the dog went on. “That first dog wanted it the worst way. So he just trailed its people back to where they lived in a cave, and he hid up on top of the cave, where the gray smoke came creeping up through a crack. And sometimes he’d hear it laugh. And nobody thought of looking there for him.

“The dog would see the Man go out to hunt, and the Woman go down for water, and he could hear the Baby pattering around inside the cave. And then it would sit down, ‘plump!’ the way it did in the Forest. And then it would laugh again. And the dog’s tongue would just itch to tickle the Baby.

“So on the third day, when the Man went out to hunt and the Woman went down for water, he sneaked around to the cave door and first thing he knew he had his tickly tongue on the little soft thing. And his ears were so full of the noises it made that he didn’t hear its mother’s bare feet when she came back. And she threw the first thing that she had in her hand—which was the water—all over him.

“Of course that didn’t hurt him. He didn’t exactly like it any more than he liked the Baby’s fingers when they pulled his whiskers, but he never imagined she was fighting. He thought she was playing with him. So he trusted her—which is the whole secret about being trusted.

“And then wasn’t he glad. He just rolled around on the cave floor to dry himself—though the cave floor was never very clean. And he wriggled and giggled over it all. And he gave the Baby a lick with his tickly tongue so it laughed with him. But the Woman just stood there looking at him.

“Now, it’s a queer thing, Bunny, but Humans can’t stay angry if they laugh. There was the dog, all sprawly legs and waggly tail, not looking like a wolf at all, and the Baby laughing at him. And the Woman began to laugh, too. ‘You look so funny,’ she said, ‘you’ve got leaves in your whiskers.’ And so they were friends.”

“That was a lovely story.” Nibble chuckled, clear out to the tip of his tufty bunny tail. He chuckled so hard he forgot he was locked up in an uncomfortable cage, without a decent corner to snuggle in. “But you haven’t told me yet how the First Dog made friends with his Man. Go on. Please do.”

“N-no.” Watch answered thoughtfully, scratching his shoulder. “I’d rather not. I’m afraid you mightn’t understand.”

“Yes, I would,” teased Nibble. “Of course I would. In the very First-Off Beginning the dog made friends with the Baby and the Woman because he made them laugh. Did he make the Man laugh, too?”

“Why—yes. I expect he did,”

Watch answered. “You see, the Man wasn’t friendly when he came home. But the Woman and the Baby made him behave nicely. They always do. That is, they wouldn’t let him hit the dog with his stone hammer, or jab him with his spear. But he wouldn’t look at him. And the dog wanted that Man to trust him—wanted it most of all.

“So he began following the Man when he went out to hunt. But the Man threw stones at him as soon as they got where the Woman couldn’t see him do it, and told him to keep out of the way. The dog just crept off and hid.

“He saw the Man creep up on a band of wild cows that were grazing and sleeping in the sun. But just when he was almost close enough to kill one they all began to snort and run. And they ran right past where the dog was hiding from the Man.

“Of course he knew what that Man wanted. So he just bounded out and pinned a cow by the throat and sent her head over heels. And that did make the Man laugh. My, but he was happy! So then he trusted the dog, too, and they were the best of friends for ever and ever.” And Watch smiled as though he were right proud of the memory.

But Nibble was horrified. “Oh!” he gasped. “The poor cow! That was an awful thing to do. After the dogs pretended to be sorry that they had done it when they were starving. No wonder Mother Nature wouldn’t trust them.”

“There,” said Watch. “I knew you wouldn’t understand. He didn’t do it for himself. He did it for his Man.”

“The Wild Things warned me,” said Nibble. “Both of them are bad, Dog and Man.”

“Look here, Bunny,” Watch explained patiently. “They don’t either of them do that now. They take care of the cows—because now the cows belong to Man and have his smell about them. Just the way I won’t touch you because you’re my Man’s rabbit and have the smell of my Man. I don’t like to kill things—except Ouphe the Rat, and that’s because he doesn’t belong to my Man and my Man told me to. Mother Nature wouldn’t trust the dog, so he won’t obey her. Man did trust him, so he just everlastingly does obey his Man.”

“I’d believe that better if the cows told it to me,” said Nibble defiantly.

“All right! I’ll bring them up and let you talk to them as soon as they are milked and let out of the barn.” Watch was perfectly good-natured about it. “I’m going my rounds now, but you just tell me if Ouphe troubles you again.” And off he trotted, waving his plumy tail.

Nibble was terribly shocked. So any dog would do anything his Man told him to do, no matter what Mother Nature thought about it! Now just what did the cows think of that? Nibble wanted dreadfully to know, because he hadn’t the least chance in the world of asking Mother Nature or any of the wise Wild Things. How he did want good old Doctor Muskrat!

It was getting lighter and lighter, less and less scary every minute. Everything would be much more cheerful when the Sun peeked out over his shoulder from down South where he was busy with the other half of the Earth. Suddenly a voice shouted from somewhere right behind him,

It was just the Rooster calling himself by a high-toned name—the way he always does. But Nibble had never seen one. He was so s’prised he jumped and snubbed his nose against the cage. So he huddled up in the middle of it again.

Then all the voices of the farm-yard began calling, “Good morning! Good morning!” and he thought of course they were calling to the Sun. But pretty soon the pigs began their scary grunts and then one squealed, “Good morning. We want our breakfast.” Right off all the rest of them took it up. The horses whinnied and the cows mooed, and the sheep bleated, and the ducks and chickens and guinea-fowls and turkeys all shouted, “we want our breakfasts!”

Suddenly a new voice cheeped, right beside him, “I want my breakfast, too!” It was Chirp Sparrow!

“Oh, dear, I do wish they’d stop!” said Nibble. “Whoever are they calling? It isn’t the Sun!”

“’Course not. It’s their Man and Tommy Peele. I can hear them coming.”

Then Nibble remembered something. “Why, Chirp,” he said, in surprise, “Ouphe the Rat said he had eaten you! And he tried to eat me, too!”

“Ouphe is a liar,” said Chirp decidedly. “I hope he hears me say it. I wish that dog could catch him.”

“He never will,” Nibble answered sadly. “Silvertip could, but not that dog. He shouts every time and lets Ouphe know he’s coming. And when he does watch at one of Ouphe’s holes he keeps beating the haystack with his tail. That’s a tattle-tail for sure. Worse than the Mouse’s.”

“I’ll tell you what.” Chirp cocked his head on one side and looked thoughtful. “We’ll all have to put in and help the dog catch Ouphe. If we don’t, there’ll be a young dog on this farm and he’s sure to be a foolish one.”

“But how can I help while I’m in this cage?”

“You’ll be out before long!” said Chirp cheerfully. And so he was, though even Chirp didn’t know how it was going to happen.

And just then Tommy Peele came running up with some toothsome carrots and a whole armful of clover hay—for Nibble’s breakfast, though he hadn’t asked for it.

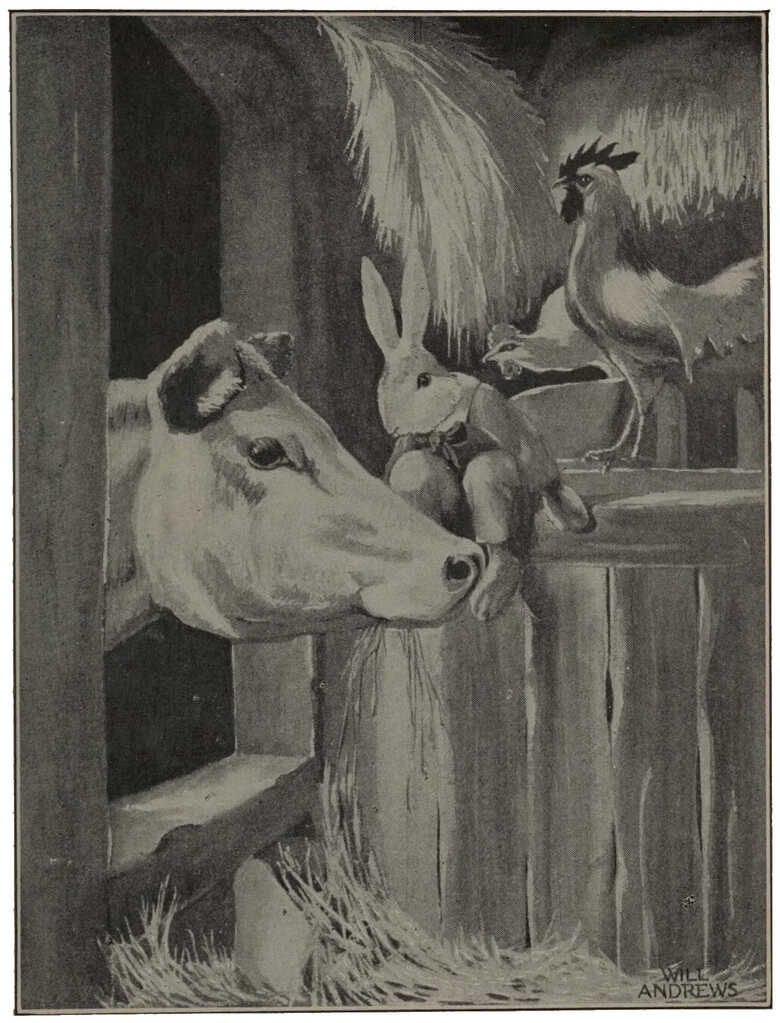

Watch must have kept his word about sending the cows to talk to Nibble Rabbit. For the first thing they did when the barn door was opened was to come trooping up to his cage. And an old White Cow put her big starey eye right up close to it, because she’s very near-sighted, and sniffed. Nibble’s fur blew as hard as it did the time of the terrible storm. But her breath was all warm and sweet with clover, so he wasn’t afraid, though she was three times as big as the dog.

The very first thing the White Cow said was: “Why don’t you eat your breakfast?”

“I can’t. I’m all cramped up in this cage,” answered Nibble.

The White Cow makes friends with Nibble.

“He’s too much afraid of being eaten,” laughed Chirp Sparrow, and he perched right on the White Cow’s horn.

“Why, there’s no one going to hurt him,” drawled the Cow in a surprised tone.

“There was Ouphe the Rat last night. Nibble felt pretty trembly about him.”

“Ouphe! The disgusting thing. He came in and messed up our feed and danced over us with his pricky feet so we couldn’t sleep. I just called Watch,” mooed the White Cow in her nice fluty voice. It reminded Nibble of the South Wind.

“Aren’t you afraid of Watch?” Nibble asked, for now he was truly going to find out whether Watch was bad. “He said he’d kill you if his Man told him to.”

“Watch? Why, Watch couldn’t kill any one. He’s too fat and sleepy and good-natured. And no man would ever tell him to.”

“Aren’t you afraid of Man?” Nibble asked next.

“Man!” The White Cow snorted again, and most of the others snorted, too. “Why, Tommy Peele’s all the man that ever milks me. And he’s only a little boy. He snuggles right in beside me as though he were my own Calf. I love Tommy Peele.”

“I don’t like Tommy Peele,” bellowed the Red Cow Nibble had taken for a log when Silvertip chased him. “I don’t like Tommy Peele. He threw stones at me when he drove me out of the cornfield.” She nudged the White Cow away and sniffed at Nibble’s carrot. “I’d like that,” said the greedy thing.

“You’d quarrel with any one,” drawled the White Cow. “You’re always doing something you’ve no business to do.” And she moved off.

Then Chirp Sparrow had a fine idea. “Look here,” he whispered in the Red Cow’s ear. “If you want to get even with Tommy Peele you just catch your horn in that wire and let out his rabbit.”

“Um-m, I dunno——” mumbled the Red Cow. She didn’t like stones the way Tommy could throw them.

“Then you can have the carrots—all the carrots. There are lots of them under the hay,” lied Chirp.

The Red Cow lurched her head awkwardly. Her horn caught on the wire. Then she got scared and tried to break loose again. But what she broke loose was the whole door. She bounced off with it dangling against her face. “Moo-oo-oo!” she bawled as she plunged about the barnyard. “Take it off! Take it off! It hurts my no-o-se!”

But Nibble didn’t care. He took a fine long jump that stretched his long legs. And then who ever said a rabbit couldn’t dance? He danced a proper hornpipe and he twiddled his puffy tail and flopped his ears—all at once—because it felt so good to be free. And Chirp Sparrow squawked and sat down on his tail feathers because he was laughing too hard to fly. Half at Nibble and half at the Red Cow.

Of course all the other sparrows came cheeping and chirping, and Chanticleer the Rooster crowed, though he didn’t know what he was crowing about. And the noise brought Watch the Dog on the run—and after him came Tommy Peele, not nearly so fast, for he still had his tall rubber boots on.

And Nibble took to the only hole he knew anything about—which was Ouphe’s—but he was so startled he didn’t stop to think of that. And the bad old rat woke up and started to come out of that very hole to see what all this noise was about.

Then wasn’t Nibble in a nice fix? Just wasn’t he?

In front of him Watch was sniffing and digging at the hay. Behind him Ouphe was murmuring in his sticky, trickly voice: “Come right in, little Friend Rabbit. Come right in.”

Just then Watch barked to Tommy Peele: “Here he is. I’ve got him.” And Tommy said in a very severe voice: “Go ’way, Watch. Don’t you hurt my bunny.”

“There,” barked Watch, “he says you’re still his bunny, even if you are wild again. Come along!” But Nibble didn’t move.

“Go away!” said Tommy again. “Go on, Watch; he’ll never come out until you do.”

But Watch didn’t move. He could hear Ouphe saying in a horrid voice: “Come in here, or I’ll take you by the tail and pull you in.” And he held his very breath—and his wagger with it!

Of course Ouphe thought he had gone away. And he wasn’t very scared of Tommy Peele. So he caught hold of Nibble’s tail. And then Nibble was so frightened he began to squeal and pull. And Ouphe held back.

“Come along, Nibble, come quick,” pleaded Chirp Sparrow. He meant that the dog was safer than the rat. But Ouphe thought he meant that the dog was gone. So he let Nibble pull him to the very edge of the hole.

“Aurgh!” sang Watch, very joyfully indeed. For he never touched Nibble at all, but nipped Ouphe the Rat right through the heart with those very long teeth he shows when he laughs.

Nibble sat right down there in the sunlight until he got his breath, and nobody tried to catch him.

Watch couldn’t. He had his mouth all full of Ouphe. And he was walking around on the tips of his toes, looking so vain that all the sparrows laughed at him. Even Tommy Peele joined in. But Watch didn’t care a bit. He just smiled as wide as he could let his mouth go and not lose Ouphe out of it.

And Nibble slipped over and ate his carrot. How good it tasted, now he was free!

Now don’t you forget that it was the greedy Red Cow who let Nibble out of his cage. She wanted his carrot so much that she pulled the wire door right off with her horn. And then she got scared and careered way down the Snowy Pasture with that door banging against her nose, getting madder and madder and madder.

Well, she finally scratched it off on to a prickly thorn bush that held up its arms to help her. And then she came back to the barnyard as fast as she could run. For she’d lost her temper entirely. And you know what happens when things do that. It happened to the Storm and to Mrs. Hooter, and to Silvertip the Fox, and to Chatter Squirrel, and Slyfoot the Mink, and Nature only knows how many more. It’s always something unpleasant.

Just then Watch barked to Tommy Peele, “Here he is. I’ve got him.”

But she hadn’t forgotten that carrot, because she was so terribly greedy. She galloped up and sclooped her tongue around beneath the pile of hay in Nibble’s cage. No, there weren’t any more carrots at all. So she rolled her eyes around and saw Nibble just finishing up the sweet inside of it. “Moo-oo-oo!” she roared. And it didn’t sound a bit like the White Cow’s fluty voice. Moo! She tried to catch Nibble on her sharp horns or trample him with her big hard toes. But he was too quick. He just made two jumps and ran under the haystack.

Then she shook her horns at Chirp Sparrow, who was perched on a fence post. “You lied!” she roared. “You said there were lots of carrots here!” But Chirp just squawked rudely and flew into a tree, and she only banged her sore nose on the fence wire.

So the next one she took after was Tommy Peele, who hadn’t done anything to her at all. And you remember Tommy had on his tall rubber boots, so he couldn’t run very fast. Not fast enough to run away from the Red Cow.

And suddenly Nibble found he was dreadfully afraid of what might happen to Tommy Peele. Besides, it was all his own fault—excepting that Chirp really oughtn’t to have lied to her. So he bounced out under her very nose, calling: “I took the carrot! I took the carrot!”

But the Red Cow wanted someone she could catch and hurt—because she had lost her temper. She wanted Tommy Peele. Only she never got him.

Because right then things did begin to happen. Watch dropped that rat and clamped his teeth right on her sore nose. “There!” he growled in his throat. “I’ll teach you to hurt my little boy!”

“I’ll hurt you!” bawled the Red Cow, trying to stamp in his ribs with her big horny feet.

“You will?” It was the White Cow’s voice—but it wasn’t fluty now. She was galloping, tail up and head down. “Whang!” she hit the Red Cow’s ribs. “Blam!” she hit her so hard in the shoulder that Watch lost his hold. And the Red Cow was all through hurting any one. She turned and ran, limping and licking her sore nose.

Maybe you think Nibble Rabbit wasn’t puzzled when he saw the Red Cow run bawling down the pasture with a limp that would keep her feeding in circles for a week. He had thought of course she was going to fight with Watch the Dog, and instead she had turned on Tommy Peele. Now that was wrong, so Watch had a perfect right to stop her. But, when the White Cow came charging up, Nibble never in the world expected to see her help Watch give the Bed Cow a terrible trouncing.

And here was Watch, all smiles and waggly tail, saying, “Much obliged, I’m sure, Mother Snowflake. I was finding that heifer quite a mouthful.”

And the White Cow was answering, “Oh, I’ve been waiting quite a while to drive a bit of sense into the wild little thing.” And she settled down to switching her tail and chewing her cud as calmly as ever.

But that made Nibble indignant. “She’s not a Wild Thing,” he said. “Wild Things have better manners than any of you or they’d be fighting all the time. I’m a Wild Thing myself, so I know.”

“Oh, it’s the Bunny,” drawled the White Cow, dragging her words the way she drags her toes, because she thinks as slowly as she walks. “Well, I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings. You’re perfectly right. Manners are to keep folks from fighting—to make them think before they pick a quarrel. That Red Cow just wouldn’t think until we made her. Now she’ll learn.”

“’Nother thing,” Nibble insisted, “we don’t help any one against our own kind.”

“That sort of talk is less use than a trampled cornstalk,” Mother Snowflake lowed sensibly. “All the kind we have here is Tommy Peele. His people take care of us, so we take care of him.”

“Yes,” Watch put in; “you saw how he trusted us.” And he waved his tail quite grandly.

“But he didn’t say ‘Thank you,’” Nibble looked about him in surprise, for Tommy had disappeared.

“He doesn’t keep it in his pocket, but he won’t forget it,” promised the Cow. And she wet her nostrils with her slaty tongue to sniff what it was going to be.

“He doesn’t talk our talk,” Watch explained, “but he does know the sign language of tails pretty well.”

“I told you,” she mooed triumphantly. For there came Tommy with his cap full of meal. He poured a big pile before her and a little one close to Nibble. But he gave Watch a great big hug.

“That little ‘thank you’ is for you,” smiled Watch over Tommy Peele’s shoulder. “Why, Bunny, do you think we didn’t see you trying to help us with the Red Cow?”

Nibble certainly had tried his best, for deep down inside him he began to know why the tame beasts all loved Tommy.

Still he hesitated. “I won’t come back to my cage,” he warned; “I’m wild, you know.”

“That’s all right,” Watch promised, “but wild or tame, you’re Tommy Peele’s, and some day you’ll be glad to know it. So go ahead and accept that ‘thank you’ like a sensible beast or you’ll be hurting Tommy’s feelings.”

Nibble really wanted to. My, but it smelled good! And the White Cow was heaving big sighs of happiness over her pile. But he didn’t want to be caught again, so he was very, very careful. Lip-it, lip-it, he tiptoed over and sniffed. Then he just couldn’t resist it. It WAS good! Quite as good as it smelled! Pretty soon he felt like sighing, too, because his little skin was tight.

And Tommy Peele never tried to catch him at all. Because now he knew what it felt like to be chased. He only took off his red mitten and twiddled his pinky fingers.

Nibble knew that those fingers were nice and gentle when they petted him, and that was all Tommy wanted to do. But he just couldn’t quite dare to let him. So he cleaned the last crumb off his whiskers with the little fur brushes he wears on his paws and said, “That was mighty nice, but I’m a Wild Thing still, and I’m going back to the woods, where I belong. Good-bye, Mr. Watch. Good-bye, Mother Snowflake” [for that’s what Watch had called the White Cow].

“Good-bye,” barked Watch. “You’ll find us here any time you want us.”

Mother Snowflake couldn’t stop to talk. She was too busy.

So Nibble signalled a very polite “Good-bye” to Tommy Peele with his little tufty tail, though it was still rather stiff where Ouphe the Rat had bitten it. But Tommy didn’t understand Nibble—not yet. He only knew the talk of the tame beasts. So he felt quite sad when he saw the Bunny go skipping, lipity, lipity, down the long lane.

Lipity, lipity, lipity, Nibble Rabbit hopped down the long lane from Tommy Peele’s red barn. He was in a dreadful hurry to get home to the Woods and Fields.

Out in the Snowy Pasture the wind blew cold. The Red Cow stood with her back to it, looking very sad and thoughtful, but she spoke to Nibble politely, for she’d found her temper again. Pretty soon he was passing the cornstalk tents in the Broad Field, but one of them smelled so foxy that he didn’t wait there for Silvertip to come back. Now he was in the Clover Patch. He stole past the oak that blew down in the Terrible Storm, and around the Brush Pile. Then he went straight for his own old hole.

How he had dreamed of it when Tommy had him in that cage! No one had been there since the Terrible Storm, for the doorway was drifted shut. So in he popped. And then he almost popped right out again, for there was someone in it.

Yes, someone was in his very own home, and he couldn’t tell who. But it was someone with a nice clovery breath, like White Cow’s, so Nibble thought he couldn’t be dangerous. “Here!” he called. “Whoever you are, wake up! This hole is mine!”

But Someone never answered.

He felt Someone’s warm fur, listened to Someone’s breathing. He touched Someone’s fat side with his paw. Then he tried to shake Someone by the scruff of his neck, but Someone was much too big for him. And Someone wouldn’t wake.

Nibble cocked his head on one side and thought about it. Then he tried a few experiments. At last he said: “Very well. There’s plenty of room for both of us in here. I don’t know but we’ll both be more comfortable. But you just remember when you do wake up that this hole is really mine.” Someone just slept on. But Nibble didn’t care, for he made a perfectly lovely foot-warmer.

The next morning Nibble brushed the sleep out of his eyes with his furry paws and nudged Someone. “Come along,” he urged. “We’ll hunt some breakfast.” For it was the dark of the moon when rabbits feed at early dawn and dusk. They prefer moonlight at other times. “I’ll get him out,” he thought, “and have a look at him.”

Someone only made a little sucking noise as though he were eating something perfectly delicious in his dream, and went on sleeping.

“You’re a funny beast,” said Nibble, right out loud. “I’m going to ask Doctor Muskrat about you.” Someone slept right on. So off Nibble set for the pond among the cattails. And all the breakfast he found along the way was some coarse grass, very dry and wind-whipped, and the dry brown seed heads of yarrow. And that wasn’t much after the wonderful breakfast Tommy had given him.

Everything was all changed. The cattails were drifted waist deep in snow, and the pond was all ice, so he could walk right up to Doctor Muskrat’s house in the middle of it. He thumped No answer. He thumped again, and then he danced as hard as he could on top of it. He was having a very busy time, all by himself, when he heard Doctor Muskrat’s gruff voice calling, “Who’s that? What do you think you’re trying to do, anyway?”

Nibble flashed about and saw the doctor’s tousled head poking from a hole among the cattails. “Good morning,” he said politely, “I was just looking for your front door.”

“Well, you’ll find it here, over this warm spring—the one spot in the pond that doesn’t freeze shut, so I always have a place to come for a breath of fresh air.” The old doctor was puffing as he made his way through the crusty hillocks between the bulrush stems. “Duck me, but it’s Nibble! Dear, dear! What did you want? You aren’t ill?” And he was all ready to dive back after one of his famous roots.

“No, indeed, but you know everything,” Nibble began confidently. “Won’t you please tell me who’s asleep in my home hole and won’t wake up?” And he told all about it.

“Hm!” Doctor Muskrat wriggled his nose thoughtfully, much as any nice old gentleman will when his spectacles are pulled too far down on it. “It sounds to me—it most certainly sounds to me like that fat old bluffer, Snoof Woodchuck.”

Nibble’s ears pricked. “Does he bite?” he asked anxiously.

“Oh, no,” Doctor Muskrat reassured him. “He’s a harmless old crank, and a strict vegetarian, though the garter snakes say he’s a snappish fellow before he completely wakes up in the spring. Who wouldn’t be, with their perpetual whispering and squirming? He lets it out that he’s a kind of hermit, and sits meditating in his hole, with his eye on the weather, but I’ve always suspected he was snoozing. On the day after the first February moon casts her shadow, he pretends to come out and deliver his opinion. Though I never knew any one who really saw him.”

Even People know the story. They call it Groundhog Day. And “Groundhog” is just a rude nickname for the woodchuck. Though how any one but the woodsfolk came to hear about it is a mystery.

“I’ll bet you a sassafras root,” went on the doctor contemptuously, “that lazy old skeezicks never wakes up a day before Tad Coon.”

“But if everybody thinks he does,” Nibble objected, “there must be something behind it.”

“There is,” Doctor Muskrat agreed. “There’s a lot of talk, and he’s the one who starts it, too. It would make you sick to hear him straddling around after the frost is out of the ground saying ‘I told you so. I told you it would be bad weather, or good weather,’ whichever it has happened to be. But I never saw any one who had heard him say it.”

The old doctor was puffing as he made his way through the bulrush stems.

“Well,” Nibble insisted, “why doesn’t someone keep watch and tell on him?”

Doctor Muskrat shook his head. “If you didn’t keep watch so that everyone would know they’d go right on believing him. And if you did that, and he did wake up, the joke would be on you. And that’s never any fun.”

Well, that certainly kept Nibble quiet for a little while. He was thinking. Pretty soon his nose began to wrinkle and his eyes hid like little pinpoints, deep in his fur. He was trying so hard not to laugh. “Doctor Muskrat,” said he, “how soon is that February moon?”

Doctor Muskrat waddled up the bank and took a nip of willow stem. “Grubs and clam shells!” he exclaimed in surprise. “Sap’s stirring. Why, it’s only the hatching of an egg away. [That’s two weeks as the woodsfolk count time.] Nibble,” he added curiously, “I believe you’re smelling something.”

“I am,” Nibble chuckled. “I’m smelling a wonderful joke. Half of it will be on that old snoozer in my hole and the other half will be—who’ll the other half be on?”

“There aren’t many folks out,” answered the doctor, telling them off on his paw. “There’s Chewee the Chickadee, Chaik the Jay, and Gimlet the Woodpecker—you couldn’t possibly fool him —and the fieldmice. The fieldmice! They do nothing but tattle and gossip and they’ll believe anything!”

And Nibble was delighted. “Well, the other half of this joke will be on the fieldmice. Doctor Muskrat, did you ever hear that the fur of a woodchuck woven into a mouse’s nest is a sure charm against an owl’s catching them? But it’s got to be plucked the day after the first February moon.”

Doctor Muskrat thought a minute, and then he laughed. He laughed so hard he slapped his tail on the ice, because he saw what Nibble Rabbit was thinking about.

Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat sat among the bulrushes on the Frozen Pond and laughed and chuckled over the joke they were planning on the old woodchuck in Nibble’s hole. He had everybody believing that he came out of his hole on the day we call Groundhog Day (though the woodsfolk never use a rude nickname like that even for a woodchuck) and predicted the weather. That is, everybody believed it except Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat.

This was their plan. They would get every fieldmouse in the woods and fields looking for the woodchuck on that particular day. Then if he did wake up the joke would be on the fieldmice. And if he didn’t—well, you just listen!

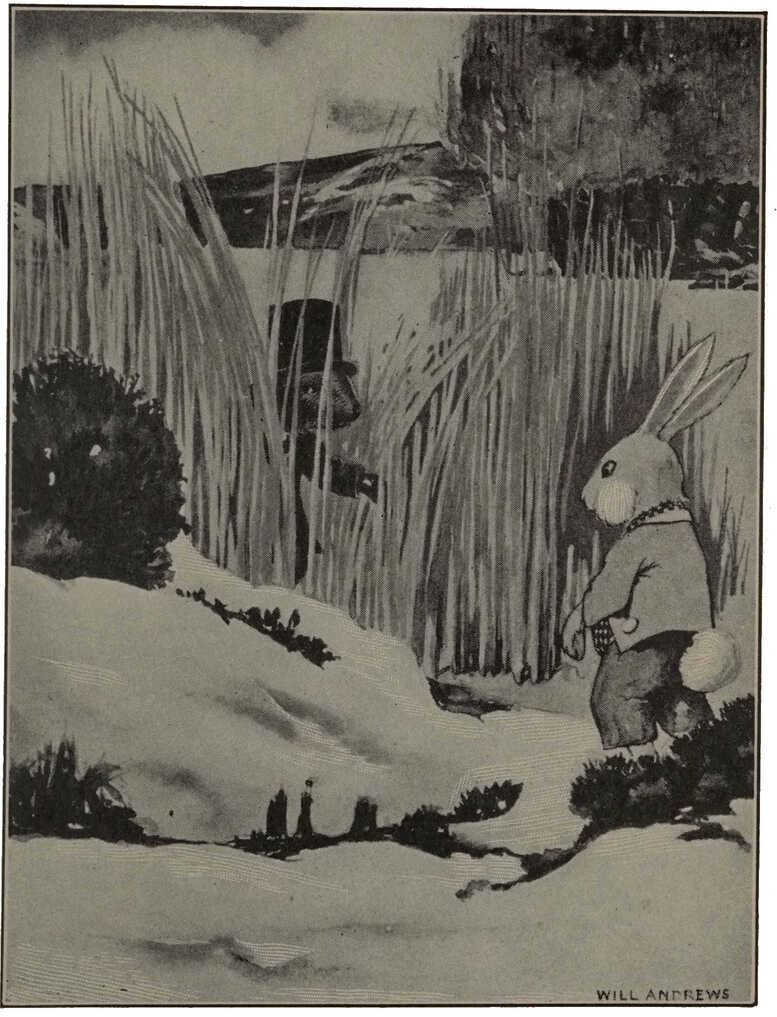

Nibble hopped all about, from the Frozen Pond to the little cornstalk tents in the Broad Field, looking for field-mice. And every time he found one he’d say, “What’s this story that’s going around? I hear that woodchuck fur plucked the day after the first February moon is a sure charm against owls. Just the littlest tuft woven into a nest will keep the young mice from being caught. Is there any truth in it?”

The mouse wouldn’t let on that any one knew more about mouse secrets than he did, so he’d say “Oh, that used to be an old mouse custom, but of late years it’s been hard to find a woodchuck.” And then he’d scuttle off to the holes and tunnels where the mice live and fuss and gossip and chatter about it.

Then they all ended up at the great hollow stump, where Great-grandfather Mouse has lived for so very many years that his ears are all crinkled, and set that agog. And poor old Great-grandfather Mouse got so bewildered that he dragged himself down to the Frozen Pond to talk with Doctor Muskrat. Which was exactly what Doctor Muskrat had been hoping for.

The Doctor was very polite and pleased to see him. “Certainly,” he said, “I’ve heard the story. Fact is, I might have heard it from you yourself when we were both very young. But, dear, dear, my memory isn’t very good any more. Only I’m perfectly sure it was the day after the first February moon!” He didn’t want any mistake about that.

“Yes, yes,” agreed Great-grandfather Mouse, “I remember. I remember it all, now you call it to mind. But where could I find a woodchuck?”

“Well, seeing we’re such old friends,” whispered Doctor Muskrat, “I’ll let you know. But it’s a secret. He’s down in Nibble Rabbit’s hole. I expect that sly young bunny means to be married in the spring, and won’t his hole be nicely lined with woodchuck fur, just won’t it?”

“Great grass seeds!” exploded Great-grandfather Mouse. “It’s a mouse charm. No rabbit has anything to do with it.” So he stumped off home, dragging his fat old tail and wagging his crinkled ears, and in half an hour more people knew about Doctor Muskrat’s secret than if Chatter Squirrel had shouted it from the treetops. They knew where the woodchuck was and they meant to get some fur off him, too.

And Nibble Rabbit was all but turning somersaults on his little paddy feet out behind the bulrushes because he was so amused over it.

The great day came at last—Groundhog Day—the day when the woodchuck ought to come out to foretell the weather for spring. And Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat weren’t the only ones who were watching for him.

For all the snow around the mouth of Nibble’s hole was tunnelled by the mice, and they were scuffling and squeaking beneath it; so it’s a wonderful thing Silvertip the Fox didn’t hear them. And Nibble thought what a wonderful joke it would be if that woodchuck did come walking out of the hole. So he shook him and jounced him and pulled his round, mousy ears and his long spiky whiskers. But, no! That woodchuck just wouldn’t wake up. So finally Nibble gave it up and crawled out of doors. And there at the mouth of the hole he met old Great-grandfather Fieldmouse, who was too fat and clumsy for any tunnel.

“Good morning,” said Nibble. “I see you’ve come to greet my friend Mr. Woodchuck when he comes out to foretell the weather.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Great-grandfather Fieldmouse very severely. “This is the day we come for our regular charm of woodchuck fur to keep our young safe from owls.” He spoke as solemnly as though he had done it every year of his life. “It’s strictly a mouse charm,” he went on, “and no rabbit is going to keep us from it!” He said that because Doctor Muskrat had given him the idea that Nibble meant to keep it all for himself. And Doctor Muskrat gave him that idea because he didn’t want Great-grandfather Mouse to suspect that Nibble had invented the whole story about the charm. Doctor Muskrat knew they’d never bother about coming after the woodchuck fur unless they thought that someone else wanted it as much as they did.

“Very well,” Nibble answered meekly; “but please leave a little for me.”

“We’ll see if there’s enough to go round,” replied the mouse. And with that he laid back his ears—he’s so old that they’re all crinkled—and marched down into Nibble’s own hole. And out he came with a mouthful of fur. And every fieldmouse from all the woods and fields solemnly marched in and did the very same thing as if they’d done it every year of their lives, too.

And maybe you think Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat didn’t laugh until their sides were fit to split—maybe you think they didn’t. Because they knew they were going to be able to prove to every one of the woodsfolk just where Mr. Woodchuck was and what he was doing on the next day after the first February moon.

After the last mouse had left his hole, Nibble went in to see what they had done. He came out again in a hurry. “Whew!” he said to Doctor Muskrat. “I’ll have to sleep in the Pickery Things to-night. It’s all mousy in there. But they’ve plucked that sleepy old woodchuck as bare as an egg.”

And Doctor Muskrat chuckled. “Just you wait until he wakes up in the spring!”

That wasn’t till a long way after St. Patrick’s Day, when the little gray pussies hung on all the willows. And he took three whole days to wake up in. For the first day he just grunted and groaned and made the noise that the woodsfolk take his name from. “Snoof, snoof!” he’d go as though he were trying to sneeze, but was too lazy to do it. And the minute he did that, Nibble hurried down to Doctor Muskrat in the marsh and told him about it.

“Very good,” said Doctor Muskrat. “Tell me how he behaves to-morrow.”

On the second day Snoof Woodchuck had turned over in the hole with his feet in the air and was acting as a dog does when he has a dream. Nibble told Doctor Muskrat.

“Very well,” said the Doctor. “He’ll stand on them to-morrow, and we’ll all be there to greet him.” Then he waddled off to the hollow stump where Great-grandfather Fieldmouse lives. And Great-grandfather Fieldmouse poked his head out.

“Well, well?” he demanded in his crotchety voice, because he’s very old— so old that his ears are all crinkled. “What do you want now?”

“I just wanted to let you know that to-morrow morning Snoof Woodchuck will take the air an hour after sun-up,” said Doctor Muskrat very politely.

“Well, what’s that got to do with me?” demanded Great-grandfather Fieldmouse.

“I let you know because we’re such old friends,” said Doctor Muskrat. “Surely you remember that as long as the mice kept up the good old custom of gathering to thank the woodchuck, the woodchuck stayed here and you always had your charm.”

“I suppose so, I suppose so,” grunted Great-grandfather Fieldmouse.

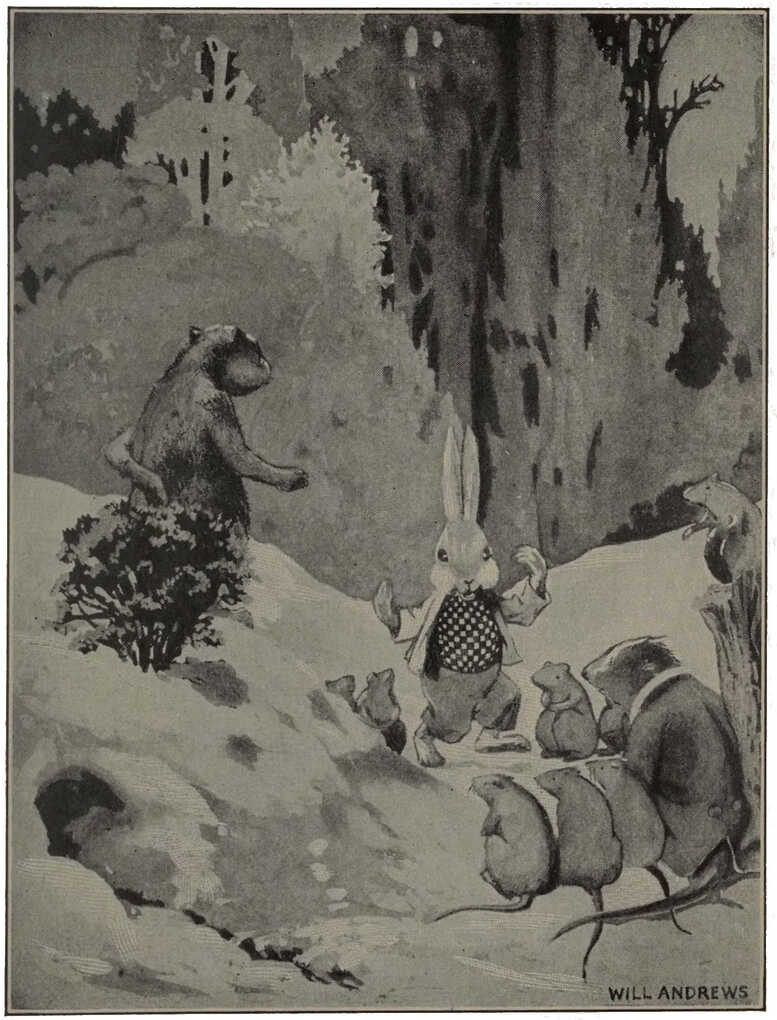

So on the third day, when Snoof Woodchuck climbed out into the air, all the fieldmice were assembled. He was very much complimented. He bowed pompously, this way and that—and oh, how funny he looked, as though the moths had been at him! “Hmm, hmm!” he began importantly. “As I told you when I predicted the weather on the next day after the first February moon——”

But he never got any further. For the mice simply squealed in surprise, “Why, that was the day we came for our charms of woodchuck fur. You were fast asleep!”

“You old bluffer,” jeered Doctor Muskrat, “we caught you napping this time!”

“Look at yourself!” squealed Nibble Rabbit, standing on his tallest toes to hop about. “See if you’re not mouse-eaten! You’re as naked as you were born—yah! I’m ashamed to look at you!” And the mice all echoed him.

And that woodchuck scuttled back into the very bottom of the hole and hid there until midnight. And then he went so far away that no one ever saw him again or even heard of him.

Quite a long while ago I promised to tell what Tommy Peele was doing in the Broad Field when he let Nibble Rabbit’s storm party out of the little cornstalk tent. Well, to begin with, he was looking for the tracks of the woodsfolk. But as long as the snow lay deep on the ground he didn’t find many.

For Doctor Muskrat and the fieldmice and Nibble Rabbit were about the only ones who stayed there. Doctor Muskrat was too clever to leave tracks where any one would see them. And the fieldmice had their tunnels far below the crust, so you never saw anything of them. And you’d have to creep around among the Pickery Things before you’d see many signs of Nibble Rabbit.

But the birds called very often to get a drink from the warm spring hidden among the bulrushes that was Doctor Muskrat’s front door. It was Chewee the Chickadee who brought news of the quail. “They have to go a long way in the deep woods every day to find enough seeds for so large a flock,” he said. “And they told me that I must leave every last weed head that pricked up above the snow in their thicket for Nibble Rabbit.”

Now that was very nice of the quail because there were very few seeds left, and Nibble was eating the dried grasses that the Pickery Things kept from him and the delicate bark from the sunny side of the willows.

Snoof Woodchuck comes out of his hole.

Chaik, the Jay, perked his crest thoughtfully. “It must be horrid to live in big flocks like that where you can never find a full crop for everyone at once. The partridge are perching in some evergreens. They say it’s safer than sleeping in the snow where they might be frozen in again. Only they can’t find anything to eat but birch and poplar buds, and they’re awfully hungry. But not so hungry as Hooter the Owl and his wife. I wonder why they flew away right in the middle of the terrible storm.”

“Silvertip the Fox left then, too,” said Gimlet the Woodpecker, who had been working in the orchard back of Tommy Peele’s barn. “There must be something in that.”

“There is,” said Nibble. “I was the game Mrs. Hooter chased into the cornstalk tent, but Silvertip was the one who came out of it. He mussed their feathers and they tweaked his ears, and now they’re afraid to meet each other!”

Chaik laughed. “The owls are still quarrelling,” he told Nibble.

“Well, Silvertip has learned to get into the chicken-coop,” Gimlet reported, “and Chirp Sparrow says that’s climbing into a peck of trouble.”

“Who cares?” Nibble rejoiced. “Now that Slyfoot’s gone to find a better hunting ground we have no one to look out for.”

But Doctor Muskrat spoke up very thoughtfully. “Yes, Nibble. Sooner or later we’ll have to look out for Man.”

“Shucks!” sniffed Nibble, carelessly flopping his ears. “No Man ever comes here unless it’s Tommy Peele. And he’s such a little one, who’s afraid of him?”

“I am.” And Doctor Muskrat stroked his whiskers with his paw. “You can’t judge the size of his jaw by the size of his trail, nor know how far he’ll reach out to bite you!”

But Nibble merely twiddled his tail to show how little he cared for a whole flock of Tommy Peeles. While Tommy had him in a cage up by the barn Tommy had been good to him. And none of the tame beasts were afraid of Tommy Peele. “He hasn’t any teeth to speak of,” Nibble protested, “and he hasn’t any claws. He couldn’t hurt any one. I’ve been right in his very paws, so I know.”

“Yes, you have,” agreed Doctor Muskrat. “And how did you get there? Didn’t he reach out and catch you when he was the whole length of the pasture away?”

And this time Nibble didn’t feel like twiddling his tail. It was perfectly true. He knew that somehow Tommy had been the one who made that dreadful wire snatch him into the air. And he hadn’t quite forgotten how it all but squeezed the life right out of him when he swung there. It hadn’t felt in the least like the soft touch of Tommy’s hand. So he asked with a little shiver, “What are those jaws like, Doctor Muskrat?”

“They’re harder than bone, and colder than stone. They never miss, and they never let go,” said the wise old Muskrat very earnestly. And that’s the truth about a muskrat trap. It’s just a pair of steel jaws, harder than bone and colder than stone, exactly as he said. And they’re worked by a terrible spring. They never miss because the spring won’t snap unless a beast steps right between them. And they won’t let go again until the Man opens the spring again. No beast can ever learn that. Because no beast has ever imagined that they weren’t a part of the Man.

“And a Man can have a whole pack of those jaws,” the old doctor went on. “They’ll hide out in the leaves where you can’t see or hear them; sometimes you just sniff the faintest chilly smell on them. They’re worse than a whole pack of Silvertips because you can see and hear and SMELL him.”

“How awful!” breathed Nibble. “It isn’t fair!”

“Well, Mother Nature wasn’t fair to Man in the First-Off Beginning,” argued the wise old beast. “The cows complained and got their horns, and so did a lot of others, but Man wouldn’t complain. It’s a law that when a beast invents anything for himself he has a right to use it. So you can’t blame Man for using anything.”

“Well,” said Nibble thankfully, “I’m glad Tommy Peele doesn’t use those jaws.”

But up behind the barn Tommy Peele had his first pair of the awful things. He wouldn’t have dreamed of using them on the chickens or Watch the Dog, or even on Nibble Rabbit, because they were friends of his. But he didn’t think any more of using them on a muskrat, that he didn’t know, than the muskrat would have thought of using his sharp teeth on Tommy Peele. And he wanted the muskrat’s skin. Which was perfectly natural because every man has had to use some other creature’s fur since the First-Off Beginning of things—until he got to be friends with them.

Don’t you ever believe that a small boy who grows up in the open air like Tommy Peele doesn’t know just as much about the ways of the wild things as any of the wild things know about the ways of men. Only he doesn’t know he knows it. Because he doesn’t have to hunt for every meal as he used to in the First-Off Beginning. And the only way you find out what you really do know, deep down inside you, is to use it. All the same, the very day Tommy Peele got out his trap was the day the muskrats began their spring running. He hadn’t seen their footprints, even yet, but that something deep down inside him told him it was time to expect them.

That trap wasn’t a very good one. He got it from Louis Thomson, who had a lot that he set out all through other people’s woods where he thought the other people wouldn’t catch him, because he wasn’t quite satisfied to hunt just on his own. And he knew this particular trap was slow because it was all rusty, and it hadn’t a good spring. But he made Tommy give him a two-bladed knife and his big glass shooter and twenty cents to boot. For the Red Cow wasn’t the only one who was greedy.

But Tommy oiled it and cleaned it and got it to work. And he specially showed it to Watch the Dog and told him to be very careful not to sniff around and get his nose in it. And Watch spread himself out beside Tommy while Tommy worked. Watch snoozed contentedly in the sun and flopped his tail whenever Tommy talked to him. For the weather was beginning to grow warmer. The thaw that the poor partridge had wanted so badly had come.

Down by the pond the ice was getting so soft that Nibble didn’t dare thump on it to call Doctor Muskrat. And he wanted to call him a great deal of the time. For he knew the wise old doctor was very careful about making tracks near his warm spring. But all sorts of careless young muskrats were wandering up and down the stream. They said it was mating time, and they were trying to find some lady muskrat who would be foolish enough to start housekeeping then. They ran in and out among the willows, gnawing and digging and making the plainest sort of trail, and then they would flop with their muddy feet right into the drinking hole.

I can tell you it made Nibble angry enough. He didn’t fancy drinking after them, but they didn’t pay any attention to him. And Chaik the Jay got into such a rage that he forgot he should have kept quiet there. He perched on the tallest bulrush and cursed and squalled at them. But when Doctor Muskrat heard the rumpus and lifted his head up through the ice, with his long teeth showing between his gray whiskers, they scuttled off as though Silvertip himself were after them.

And then the old doctor would fume. “The Mink take them and their love-making, the silly young things! What’s the sense of disturbing the whole marsh just because they want everyone to know they’re old enough to dig a nursery? Eh?” He forgot that he’d done the very same thing in his own first spring.

But Nibble thought they were having a mighty good time over it all. Only he wished they wouldn’t leave quite so many tracks for Tommy Peele to find.

And the very next day there came Tommy, splashing through the big puddles in his tall rubber boots, sloshing through the last of the snowdrifts, and whistling a lively tune. And Nibble pricked up his ears to listen. Because he thought that maybe Tommy was on a spring wandering of his own, and this was his mating song. For he never dreamed that whole generations of bunnies and muskrats and piping birds would grow old and die before Tommy even thought of such a thing.

Tommy had on his blue sweater, but he’d left his red mittens hanging back of the stove because he’d got them all wet snowballing. And Watch was dancing along in front of him singing “Aourgh! aorugh!” which is neither a mating song nor a proper hunting song. It was like Tommy’s whistle—it showed that he was perfectly happy.

But Nibble wasn’t. He was awfully uncomfortable. For all the footprints of those foolish young beasts led straight to the warm spring, which was still the only open water, though the ice was soft and melting all over the pond. And you remember this was the wise old doctor’s front door.

Of course Tommy followed them right there. And Nibble crouched into a clump of bulrushes close behind him—close enough to hear him working over something; close enough to hear Watch saying in an excited tone, “It’s all right! I can smell ’em—lots of ’em!”

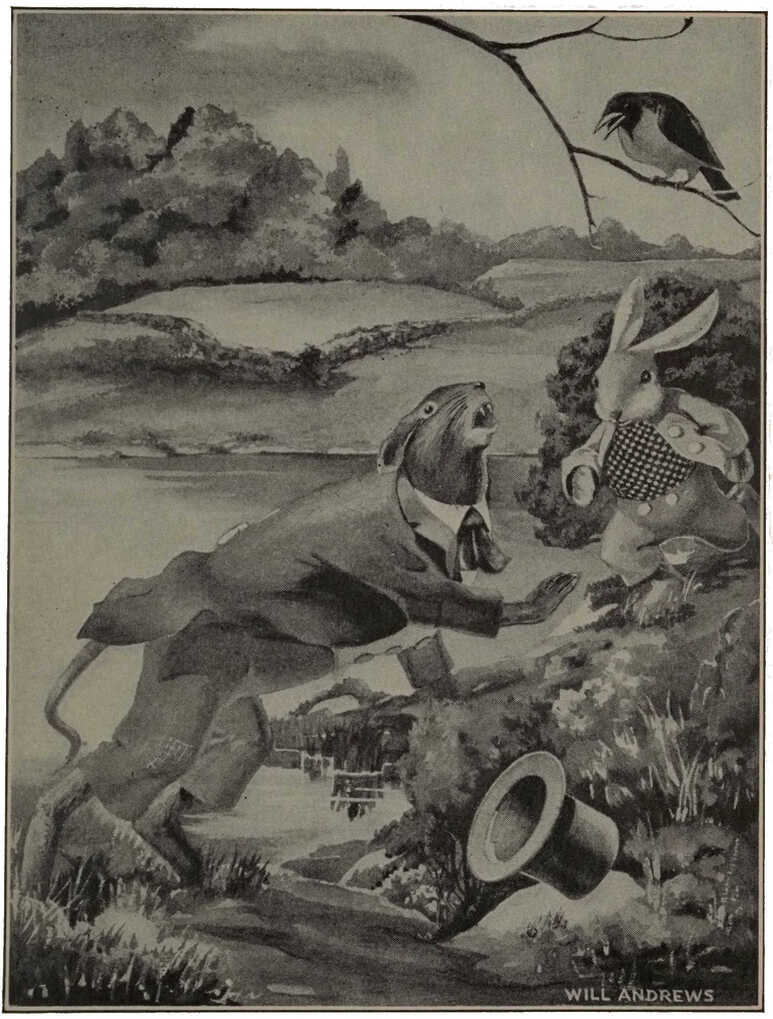

Nibble was so worried he nearly squirmed. He wanted to get out to the little round house in the middle of the pond and warn Doctor Muskrat. The minute Tommy’s back was turned he started to creep over the crumbly ice toward it. But Watch’s back wasn’t turned. He bounced out after Nibble. And he bounced right through the ice. And the minute Doctor Muskrat heard that splashing and thrashing right in his front pond, out he popped. “Clang!” That ugly trap had him by the paw!

“Oh-h-h! Oow-w-w!” screamed the poor old doctor. But he didn’t lose his head entirely. “Quick, Nibble,” he begged, “bite off my toes before that dog gets here! I can’t reach them.” His own poor old teeth were chattering with fear and pain.

And that’s exactly what Nibble was trying to do when Watch floundered out of the water. “Aourgh! I’ve got you!” he barked joyfully. Then he stopped short and wagged his tail in the friendliest way. “Why, you’re Tommy’s rabbit!” he said. And he tried to explain to Tommy Peele.

But Tommy wouldn’t listen. He couldn’t think of anything but that poor old beast, squealing over his hurt paw. It made Tommy’s own throat hurt to hear him. He wanted to help, but the doctor couldn’t understand. He just gnashed his teeth and snapped at Tommy. Then Tommy managed to touch the spring of the trap with his toe. He stepped, and it yawned open—just for an instant. Away went Doctor Muskrat.

But Nibble wasn’t looking. He had leaped back into his hiding place in the reeds and closed his eyes.

He wished he could close his long ears as well. He expected to hear his good old friend squeal when Tommy killed him. But all he heard was a splash.

Then Watch the Dog said, “I told you you’d be glad you were Tommy Peele’s rabbit!” He was standing close beside Nibble and he was looking over his shoulder to give an affectionate wag of his tail toward Tommy Peele. Nibble looked, too. And there was Tommy unfastening his trap from where he had tied it to a reed clump so it couldn’t be dragged away. But there was no sign of any muskrat.

“He’s gone,” Watch explained. “Tommy let him go. I expect that was because he was a friend of yours.” Of course there was still too much wolf in Watch for him to understand that Tommy had just been sorry for hunting the doctor. But Watch was sure anything that small boy did was wonderful, and reflected forever to his credit.

“But why did he bite him if he didn’t mean to eat him?” Nibble asked in a trembly voice. That was something he never did understand. And Watch didn’t try to. He was cocking his ears to see what next Tommy was going to do.

Tommy yanked the trap loose from the reed clump. And he wasn’t proud of owning it any more. He hated it— quite as much as Nibble or even Doctor Muskrat did. He swung it about his head and threw it splash into the hole Watch had made when he fell through the ice chasing Nibble.

Then he looked at a hole the doctor’s long teeth had slashed in his tall rubber boot. “I don’t care,” he said defiantly. “I don’t care a bit! I hurt him awfully. He had a perfect right to hurt me if he wanted to.”

The teeth hadn’t gone in deep enough really to bite Tommy’s toe, but of course neither Nibble nor Doctor Muskrat ever guessed that. Their hides belong to them and they couldn’t ever imagine that his tall rubber boots weren’t any more a part of Tommy than those steel jaws of his traps were. Watch could, because he sometimes wore a collar, and on very cold nights Tommy covered him up with a blanket, but he never thought of explaining it.

“Clang!” That ugly trap had Dr. Muskrat by the paw.

Then Tommy marched all the way up to the house and got his cap full of the same delicious meal he had given Nibble and the White Cow the day the Red Cow chased him. It was “Thank you” to them for helping him get away from her. He set out two little piles. Then he called: “Here Bunny, Bunny, Bunny!” And that showed Nibble that one of those piles was for him. So Watch was right. It was nice to be Tommy’s rabbit.

And Watch explained: “The other is for your friend the Muskrat. Don’t you eat it.”

As though Nibble would!

Of course Nibble Rabbit wouldn’t eat the pile of meal Tommy Peele left for Doctor Muskrat.

But he thought he was going to have a terrible time to keep all those foolish young muskrats, who were scuttling round in the marsh trying to start their spring love affairs, from doing it. He forgot that everything around the place where Tommy had set it still smelled of the little boy and his dog. So not another beast dared come near it.

Chaik the Jay and Chewee the Chickadee stole a few beakfuls, but Nibble knew Doctor Muskrat wouldn’t mind that. And he wanted company. So he told them all about how Tommy had caught the doctor and let him go again. And how Tommy had thrown away the trap.

Chaik raised and lowered his crest, just as we sometimes do our eyebrows, when we’re puzzled about anything. “He was lucky,” Chaik said. “I’ve seen beasts suffer in a trap for whole days before they died. And I never heard of any before that got out of one alive. I believe that human is queer. Sometimes I think he’s trying to think the way we woods folk do.”

“I know it,” chimed in Chewee. “When it was so terribly cold I was having an awful time. The ice had frozen over the cones so I couldn’t even pick a living among the pine trees. And do you know what he did? He tied a big lump of fat pork away out on the end of a springy branch, so that fat house cat couldn’t reach it. Just for me! Wasn’t that clever” And he began hopping about in the excited way he has whenever he gets to talking.

“Well, he most certainly is trying to make friends with us,” Nibble observed. “Only catching us in traps isn’t a very comfortable way of doing it. You fellows will have to help me convince Doctor Muskrat.”

Help! He needed it. It was two whole days before the doctor poked his head out of the hole where Watch had smashed the crumbly ice. The wise old beast wasn’t using his front door any more.

“Come on,” called Nibble cheerfully. “See what Tommy Peele left you to say he was sorry he bit you.”

“Not I,” growled the doctor. “I’ve had enough of his jaws.” He spread out his paddle paw. The good roots he stores in his medicine chest had nearly healed it, but his little toe was gone. “I’m going to move away as soon as I can travel.”

“Don’t do that,” pleaded Nibble. “If he bit your foot you certainly bit his. Now he doesn’t mean ever to use those jaws again. He threw them into that very hole.”

Pop! Down went the doctor to have a look. And his face was mighty surprised when it popped up again. “It’s the truth!” he said. “Those jaws are biting the mud. We needn’t worry so long as we can keep an eye on them. Nibble, I’ll just dip a whisker into that present Tommy Peele left for me!”

And he liked the meal quite as well as Nibble had—better, in fact. “I tell you what, Nibble,” he said as he stopped for breath, “this was mighty thoughtful of that Man. Now I wonder if he knew that I couldn’t dig or swim with my paw hurting me, because his paw was hurting him? I hope not.”

And that was very nice of him, because it was all Tommy’s fault in the beginning. Tommy had deliberately set that trap.

Chaik the Jay swallowed such a big beakful of meal that he had to crane his neck over it; then he blinked very seriously because Nibble was giggling at him. “Do you s’pose we could all trust Tommy the way Nibble can if we all were friends with him?” he demanded.

“Of course, of course!” chirped the enthusiastic Chickadee.

“Hm!” sniffed old Doctor Muskrat a bit gruffly, “that sounds very well from you birds. You have wings so you can fly away from him.”

“Certainly,” Chaik retorted, “but I’ve never seen him swim.”

“Hmm, hmm!” the doctor snorted again. And he hitched himself on his three sound legs over to a big stone that had grown warm in the sun and spread himself out flat like a small furry rug. He meant to think it over. But he felt so comfortable and full that he fell into a snooze.

Nibble was snoozing, too, snuggled up beside him, but he awoke when he heard Tommy’s tall rubber boots splattering through the slush. His father had put a patch on the hole, when he was mending an automobile tire, so it was as good as ever. Nibble nudged the doctor and then hurried over to greet Tommy, jumping the splashiest puddles and pattering right through the little ones because he didn’t want his friend to think Chaik and Chewee were the only ones who’d take the trouble. And Tommy took an ear of corn out of his pocket and shared it between them.

Then Tommy ordered Watch to stay back while he tried to speak to Doctor Muskrat. And the old doctor didn’t flash right into the water—as he really meant to. He sat up, holding his poor paw in front of him, and squinted his eyes to get a good look at the little boy. He didn’t even jump when Tommy laid down the other ear of corn, nor when Watch came sneaking disobediently up behind him because he wanted to poke his nose into what was going on. For Tommy caught him by the fur and pointed that inquisitive nose straight at the doctor. “There,” he ordered, “take a good smell so you’ll know him again. That’s my muskrat!”

And Nibble was so pleased he took a leap and kicked his furry heels so high that Tommy laughed at him. “You’re safe! You’re safe!” he rejoiced. “Isn’t it almost worth being caught for?”

Tommy’s tall rubber boots spattered through the slush.

And Doctor Muskrat considered his sore paw and then he considered the little boy. And he looked very thoughtful.

Neither Nibble Rabbit, nor Chaik Jay, nor Chewee the Chickadee, nor all of them together could make Doctor Muskrat say what he thought of Tommy Peele.

“No,” he insisted, “I haven’t made up my mind. It’s a safe rule for any beast to do as his kind have done before him, and I never knew any muskrats who made friends with a man.”

“Nor any man who wanted to be friends with a muskrat, either,” pleaded Nibble. “Tommy Peele’s different.”

“That’s the way with men,” said the doctor. “They’re always changing. Only the wild things stay the same.”

“What is Man, anyway?” Nibble asked. “He isn’t a bird and he isn’t a fish, and of course he isn’t a snake. But the bats, who came to my storm party in the cornstalk tent, said he couldn’t be a beast because he hadn’t any tail.”

“Nonsense!” snorted the doctor. “Tad Coon’s cousin, the bear, hasn’t any more tail than that. What did the bats think he was?”

“A kind of a frog,” said Nibble promptly. “But Chatter Squirrel didn’t agree with them.”

“A frog! A frog! Had those bats ever seen a man, then? Or a frog, either? Eh?” And the doctor made such a face of disdain that his whiskers bristled up like a lot of long darning needles on Granny’s fat pin cushion. “Why, a frog is less than a beast and a man—well, there used to be a tale going around when I wasn’t much bigger than Chewee there that Man was kin to Mother Nature herself in the very First-Off Beginning.” The old muskrat sank his head back between his shoulders and half closed his eyes.

“Go on,” said Nibble breathlessly.

“Eh? What?” The doctor came back with a start as though the shadow of an owl had passed near him. “I was just thinking about that winter. There was a big family of us the year I was born, for food was very plentiful. So were minks. And when my mother thought she heard one sniffing close by she’d tell us stories to keep us quiet. Otherwise we wriggled around in that dark old house like a lot of tadpoles, popping in and out of the water until you could almost swim on the very floor, it was so wet from our dripping. And when we got to romping we’d squeal more than a whole stump full of fieldmice.” Nibble couldn’t imagine the dignified, portly old fellow scuttling and squeaking. A rabbit hole is always very quiet. Because it’s on the ground and so many hunters might hear it if it weren’t.

“I just remember,” finished the doctor, “that one of our favourite tales was about how Man quarrelled with Mother Nature in the First-Off Beginning. She was used to the wild things. And most of them, excepting the ones who came up from under the earth, are very obedient. But Man just wouldn’t obey her. And she wouldn’t stand that, because it would be unfair to the rest of us, and because he was kin to her. So she said he could try getting along without her help and see how he liked that. And he certainly surprised her. He——”

But that’s as far as the wise old fellow ever got. For right then there came a most startling interruption. And so many brand-new happenings began that I’ll have to write a whole brand-new book to tell about them all.