Title: The Airship Boys in the Great War; or, The Rescue of Bob Russell

Author: De Lysle F. Cass

Illustrator: H. O. Kennedy

Release date: December 31, 2020 [eBook #64184]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University (http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

The Airship Boys in the Great War

OR

The Rescue of Bob Russell

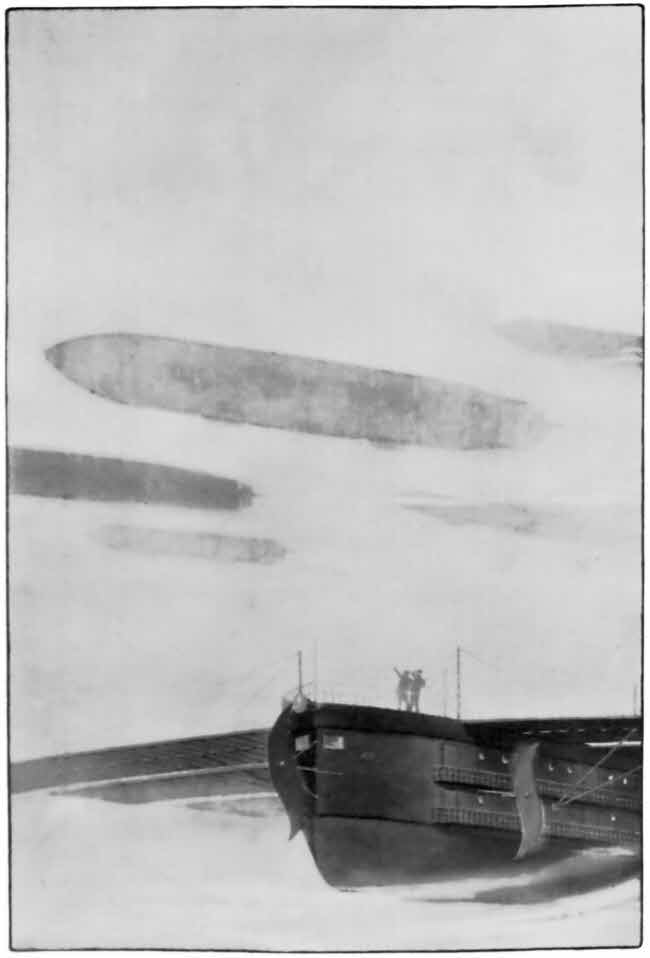

The “Ocean Flyer” Surrounded by Zeppelins.

or, The Rescue of

Bob Russell

BY

DE LYSLE F. CASS

Illustrated by Harry O. Kennedy

The Reilly & Britton Co.

Chicago

Copyright, 1915

by

The Reilly & Britton Co.

THE AIRSHIP BOYS IN THE GREAT WAR

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | What the Newspaper Told | 9 |

| II | In the Offices of the New York Herald | 17 |

| III | Someone Tries to Buy the “Flyer” | 27 |

| IV | Getting the “Flyer” Ready | 33 |

| V | Buck Stewart—and a Warning | 46 |

| VI | Escaping From Deadly Shadows | 54 |

| VII | What Happened to Ned | 62 |

| VIII | Six Miles Up in the Air | 70 |

| IX | Paris Proves Unfriendly | 78 |

| X | An Adventure in the Ardennes | 86 |

| XI | The Fight in the Forest | 95 |

| XII | Buck Takes His Life in His Hands | 100 |

| XIII | “To Be Shot at Sunrise” | 107 |

| XIV | The Rescue | 115 |

| XV | In Deadly Peril | 124 |

| XVI | Ned Saves the “Flyer’s” Crew | 129 |

| XVII | Bob Russell’s Story | 134 |

| XVIII | How Bob Was Captured as a Spy | 142 |

| XIX | A Strange Country | 149 |

| XX | A Fight With Wild Cossacks in Poland | 157 |

| XXI | Inside of Besieged Przemysl | 165 |

| XXII | The Boys Perform an Act of Mercy | 173 |

| XXIII | Strange Sights in Vienna | 182 |

| XXIV | On the Trail of the Conspirators | 191 |

| XXV | The Boys Get Worried Over Ned | 199 |

| XXVI | An Attempt to Assassinate the Emperor | 209 |

| XXVII | The Man in the Cloak Surprises Everybody | 216 |

| XXVIII | Surrounded by German Zeppelins | 225 |

| XXIX | The Battle Above the Clouds | 230 |

| XXX | The Most Terrible Accident of All | 236 |

| XXXI | The End of the “Ocean Flyer” | 244 |

| The “Ocean Flyer” Surrounded by Zeppelins | Frontispiece |

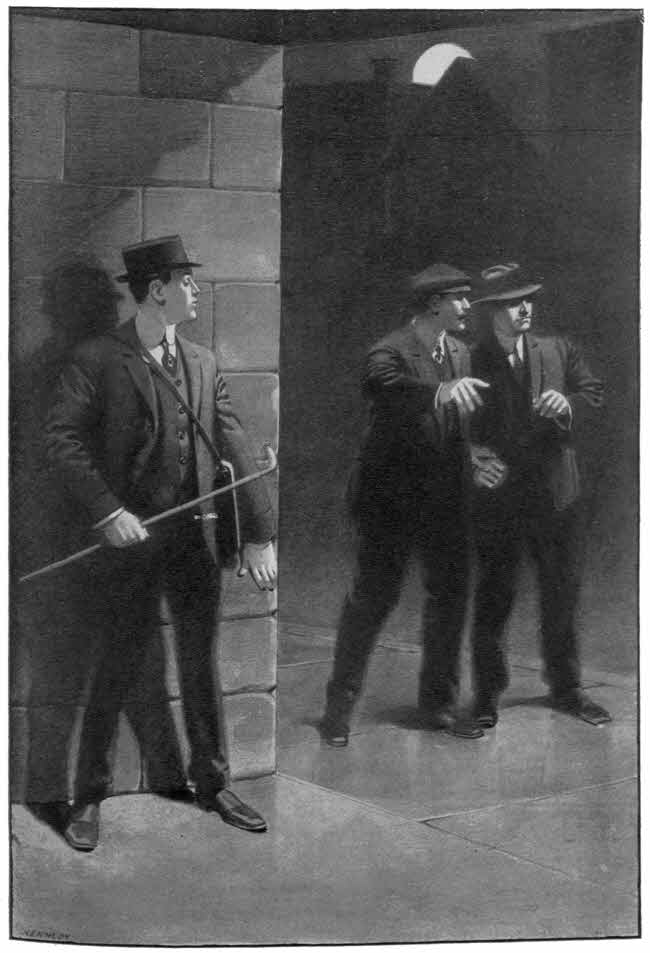

| A Narrow Escape | Page 60 |

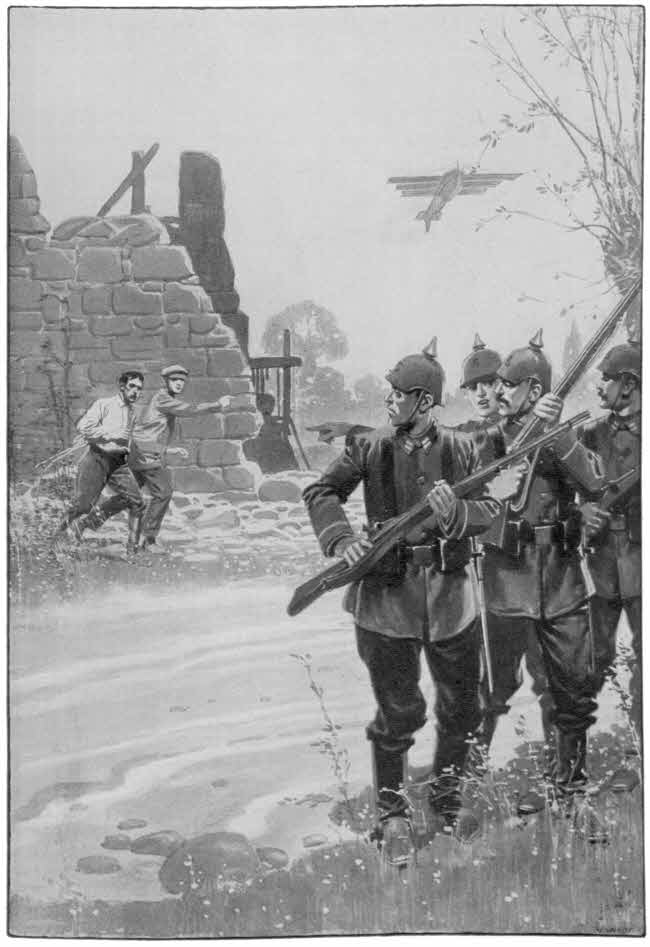

| The Rescue of Bob Russell | Page 118 |

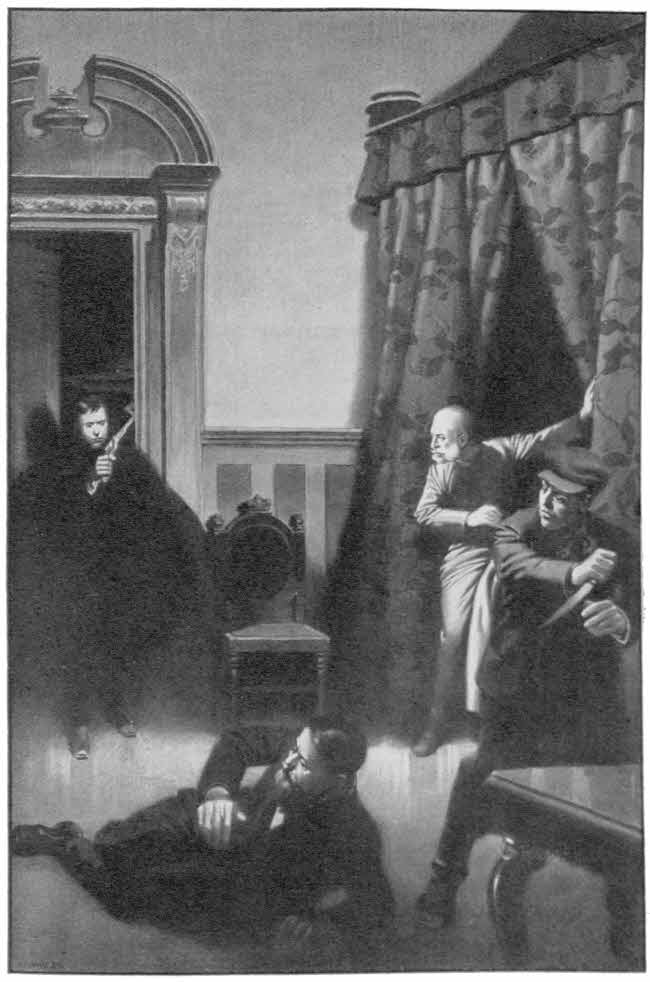

| The Mysterious Man in the Cloak | Page 220 |

[9]

The Airship Boys in the

Great War

“Great Guns!” exclaimed Alan Hope, bending down over the newspaper which he had spread out upon the table in front of him.

Ned Napier, who was deep in a pile of blue prints on his desk, glanced over at his chum.

“Great guns exactly describes it, if you’re reading those accounts of the war in Europe,” said he with a grin, “or maybe you’d better say the great-est guns, because that’s what they are using over there just now. But then, we shouldn’t worry as long as they aren’t shooting up the good old Stars and Stripes.”

“That’s just it, Ned; we should worry,” answered Alan, his face puckered into unaccustomed wrinkles, and his eyes still swiftly scanning the pages of the newspaper before him. “We ought to worry about this piece of[10] news, because it concerns a mighty good friend of ours.”

“Who! How’s that? Where is it?” cried Ned, swinging around in his swivel chair so as to face the other boy. Seeing that Alan was still staring as if bewildered at the paper, he arose and hurried over to the table. Leaning down over Alan’s shoulder, he at first could only see flaring headlines of three and four-inch black-faced type.

As Ned’s eye roved down the outspread sheet, however, it finally was caught by a smaller sub-head, sandwiched in between reports on the latest scandal on the Subway Investigation and alleged atrocities in Belgium. He gave a gasp of mingled astonishment and consternation as he read the following:

“AMERICAN WAR CORRESPONDENT IN PRISON

“Will Be Tried as a Spy!

“Associated Press Syndicate, Muhlbruck, via Brussels, November 13, (Delayed by censor).—Robert Russell, said to be an American newspaper man, has been arrested here and put under guard, pending trial as a spy by Gen. Haberkampf,[11] commanding the division of the West Battalion. The Germans are taking every precaution to safeguard the secrecy of their maneuvers, and this arrest is said to be only one of their determined efforts to discourage the presence of alien war correspondents. Russell is in grave danger of being shot unless he can satisfactorily explain certain papers found upon his person at the time of his arrest.”

No wonder that both Ned and Alan turned pale and looked at each other in a dazed, stupefied sort of way. Bob Russell was one of their oldest and dearest comrades, a lad only slightly older than themselves, who had gone through innumerable adventures with them. He had so often accompanied them in sensational exploits, that his name was often linked with theirs: The “Airship Boys.” He had accompanied them on the famous twelve-hour flight of the Ocean Flyer from London to New York; he had braved death with them in Mexico when the Airship Boys put a stop to the smuggling of Chinamen into this country; he had proved himself an intrepid comrade when they had dared wild Indian tribes in Navajo land in search of the hidden Aztec temple; he had risked death with them on their dash for the North Pole.

[12]

The Airship Boys and their adventures have been written up in newspapers and books and Bob Russell was no small factor in the success of his friends.

Bob Russell! As tried and true a comrade as ever a boy had—always cheerful, full of expedients, and “game” to the core. They could hardly realize that it was he who was now threatened by such frightful death, without a single friend near to aid him.

“Poor Bob!” exclaimed Alan, and was not at all ashamed of the unaccustomed lump that crowded further speech from his throat. “Poor Bob!” he repeated.

Ned had dropped his face into his hands and with closed eyes mentally pictured the crowded, ill-smelling prison where Bob sat unshaven and forlorn, surrounded by other wounded and miserable beings who felt no sympathy for him nor even spoke his language—who only shrank with wide, scared eyes from the suspicious glare of the armed Germans on guard. Maybe Bob was thinking of him too just then, wondering what the Airship Boys were doing, picturing them skimming luxuriously out over the sun-kissed ocean in careless forgetfulness of him, their devoted comrade of past days.

[13]

Alan interrupted Ned’s mournful imaginings again.

“Just think,” he cried, “of all the terrible barbarities which the newspapers say that the Germans have inflicted upon their captives. Think, they may perpetrate some similar awful atrocity upon poor old Bob!”

Ned shook his head impatiently.

“No, I don’t believe they would do anything like that,” said he. “Two-thirds of these torture and massacre stories we read about are hysterical exaggerations, prompted either by their enemies or newspaper writers with a lively imagination. The Germans are a kindly, civilized people, just as the English or French, and certainly more so than the Russians. If they shoot Bob it will be because they honestly believe him to be a spy.”

“But they mustn’t shoot him! It must be stopped some way!”

“Yes, but how? If all of the influence that Uncle Sam can exert won’t protect him, what can?”

“We can, Ned. There is no time to wait for diplomatic negotiations, which may accomplish nothing anyway. Remember that this newspaper says that certain incriminating papers[14] have been found on Bob’s person. If he is to be saved it must be done immediately and by us two alone. We can take the Ocean Flyer and reach Belgium in twenty or twenty-one hours, just as easily as we made that trip from New York to London in eighteen hours last year.”

“I admit that we can get there soon enough,” answered Ned, “but what about the third man whom we’ll need to help us manage the airship?”

“Why not ‘Buck’ Stewart, who went with us on the Flyer’s trip to London? We know that he is absolutely dependable, and is familiar with the workings of the ship besides. Then, too, the Herald will be more than glad of the chance to send one of its reporters with us to see the war at close range.”

Alan’s intense enthusiasm began to communicate itself to the slower-thinking, more practical Ned, but he was not ready to act without mature consideration of all the difficulties involved which might make a failure of their attempt.

“I don’t want you to think me lukewarm about doing anything in our power to save Bob,” said he, “but we’ve got to look carefully at all sides of this thing. Don’t you realize that the United States government wouldn’t sanction any high-handed breaking of[15] neutrality laws that might drag it into the war, just because an American citizen was held captive?”

“Then let’s go without the government’s permission! Who is there to stop us? We can get enough credentials from Mr. Latimer, managing editor of the Herald, to tide us over small passport difficulties, and further than those we certainly can depend upon ourselves. We won’t have to flaunt the Stars and Stripes under the nose of every foreigner we happen to meet over there anyway. Remember what Senator Bascom said in his speech on the Mexican war: ‘If the life of a single United States citizen is at stake, it is worth all of the millions of mere money that international war may cost us.’ We can’t desert good old Bob in an emergency like this, can we?”

“No!” shouted Ned, jumping to his feet and banging his fists on the desk in front of him. “You’re right, Alan. We’re going to show those chaps over there that it’s not such ‘a long, long way to Tipperary,’ after all, providing one can travel in the Airship Boys’ Ocean Flyer at the rate of two hundred miles an hour. Get on your hat and overcoat, Alan! We’re going over to the Herald office right now to see[16] what the editor of the Herald will do for us.”

“Hip, hip, hurrah!” shouted Alan, and grabbing Ned’s out-stretched hands they did a truly boyish war-dance around the sober, stately offices of the Universal Transportation Company, of which they were the heads.

[17]

The managing editor of the New York Herald received the engraved visiting cards of Alan Hope and Ned Napier with mingled pleasure and surprise.

“The Airship Boys! Send them right in,” said he to the young woman who had announced them from the outer office. Then the great newspaper man turned with an apologetic smile to the gentleman who still stood, hat in hand, beside his desk, as he had been about to leave just before the boys’ cards were brought in.

“Please excuse me, Mr. Geisthorn, for seeming to hurry you away in this manner, but I believe our little interview was about terminated anyway.”

“Yes, it is so,” replied the other, speaking with a strong German accent. “It is not for me yet to take too much of your precious time. As I have before said, I am myself a journalist, and know the value of even a minute’s time.”

The editor of the Herald arose to shake hands[18] in parting with his visitor. At the door the latter turned, hesitated momentarily, and then said:

“My excuses again, mein herr, but what was it that you called these gentlemen? The Aeroplane Children? What is that?”

The managing editor permitted a smile to edge his lips as he turned and pointed to a framed front page of the Herald, dated over two years ago. It was double headlined in heavy, black-letter type, and profusely illustrated with photographs of the coronation of King George V of England.

“I called them the Airship Boys,” said the editor. “That is a title they have won as a result of their astounding feats and innovations in aerial navigation. The page of the Herald which you see there on the wall represents a bit of newspaper history as well as the beginning of a new epoch in aeronautics. Those two young men, Ned Napier and Alan Hope, two years ago last June accomplished a flight from London to New York in twelve hours, bringing back with them photographs of the coronation ceremonies, and enabling us to publish them nearly a week earlier than any other American newspaper.”

[19]

“London to New York in twelve hours! Impossible!” ejaculated the visitor, gaping at the picture.

“I don’t wonder at your surprise,” responded the managing editor, “but that’s exactly what they accomplished in their Ocean Flyer—the largest and highest-powered aircraft ever devised—a vessel capable of carrying six or seven passengers at a consistent velocity of two hundred miles and more per hour; an airship which can be easily operated at a height of eight or ten miles, where the driver of any other machine would either freeze to death or die from lack of oxygen.”

“You are not what you call making funnies of me?” queried the astounded visitor, blinking at the editor fixedly through narrowed eyelids, as if to read his inmost thought. “All this that you tell me is true then?”

“Sir!” said the managing editor with a touch of temper.

“Pardon, mein herr; I do not mean to offend, but—”

“Mr. Napier and Mr. Hope,” announced the private secretary from the doorway.

Ned and Alan appeared, hat in hand, and were cordially greeted by their newspaper friend.[20] As they entered the room, the earlier visitor brushed past them on his way out, staring almost rudely in each boy’s face as he passed.

“Well,” said Alan, when the door clicked shut behind the man, “I hope whoever that is will know us the next time he sees us.”

The managing editor laughed as he waved his guests to seats and offered them cigars, which both boys refused with thanks.

“You’ll have to excuse Mr. Geisthorn, boys,” said he. “He is a newly appointed local correspondent for the Tageblatt, and I nearly floored him with an account of that London-to-New York flight of yours.”

“Oh, he was a German then,” said Ned, exchanging a significant glance with Alan.

“Why, yes, and seems to be a very nice fellow from what little I know of him. He arrived in this country only shortly after the war broke out and seems quiet and inoffensive,—never gets excited over the war news nor yells Bloody Murder when the ‘Vaterland’ is mentioned. He calls here every now and then to give me interesting bits of news which filter through to him but are cut out of the Herald’s regular Berlin cable service by the censor. Ever since our Mr. Russell got into difficulties over[21] there we haven’t been able to get anything like the exclusive copy we used to.”

“That’s just what we’re here to see you about, sir,” Ned remarked. “We read in this morning’s papers how Bob has been imprisoned as a spy and is liable to be shot at any minute. President Wilson naturally doesn’t want to embroil the United States unnecessarily in the war, and Bob may be backed up against a wall with the firing squad aiming at him before this ‘watchful waiting’ policy evolves any means of interceding in his behalf. Something must be done to help him right away.”

The lines of care around the great journalist’s mouth deepened with melancholy as he nodded.

“The Herald has of course registered a formal protest. We can do no more,” he said. “The life of a single individual doesn’t seem such a very big thing to war-crazed men who are blinded with cannon smoke and have been literally wading through human blood for three months past. We can get no satisfactory answer of any sort from the German field headquarters. The most that they will promise is that the affair will be investigated and rigid justice meted out.”

“But, hang it all—” broke in Alan, only to be silenced by the calmer, more practical[22] Ned. Pulling his chair closer to the editor’s desk and lowering his voice, he explained:

“Alan and I feel that for Bob’s sake we can’t afford to take chances on any such vague promises as have been given you. We propose to rescue him ourselves and without a moment’s unnecessary delay.”

“But how can—”

“Sh! In this case we must be careful that we aren’t overheard. There might be some German sympathizer about who would send word of our plans, or, on the other hand, even the federal government agents would interfere if they got wind of our scheme.”

“You are right,” answered the managing editor.

He pressed the electric button on the side of his desk, summoning the young lady secretary from the outer office.

“Miss Bloomfield, is there anyone out there waiting to see me?”

“No, sir.”

“Good! Kindly contrive to knock the big dictionary off your desk the moment anyone comes in, so that I may be warned of any visitors without their knowing it. That is all.” She closed the door.

[23]

“Now, boys.”

Ned resumed his explanation.

“The Ocean Flyer is still there in the hangar of the Newark plant of the Universal Transportation Company. Neither Mr. Osborne, president of the company, nor Major Honeywell, the secretary, have any financial interest in the airship. It belongs absolutely to Alan and me, and we intend to use it immediately for the trip to Muhlbruck, where we understand that Bob is awaiting trial.

“The Flyer is in the best of condition and almost ready for use at any moment. All that we need to do is to equip her with a few mechanical supplies, food, firearms, and so on. We can make the trip in less than twenty hours. To-day is Tuesday. If all goes well, we can have Bob back here ready to go out on a city assignment for you by next Monday.”

Wrinkles of deep thought lined the great newspaper man’s forehead as he listened attentively to the brief outline of the Airship Boys’ plan. He would have met such statements from any other boys not yet twenty-one years old with absolute ridicule, but he knew that, despite their youth, Ned Napier and Alan Hope were fully capable of carrying out their scheme.

[24]

“One thing more, though, boys,” said he, after a short period of silence. “Just how are you going to get Mr. Russell out of prison after you arrive in Muhlbruck? You won’t be able to overpower a whole German garrison, you know. Then, too, the chances are that when they see an airship of such unusual design as yours floating down upon them, they’ll recognize it as being of foreign construction and fire upon you.”

Alan answered him:

“We haven’t had time to plan that far ahead yet; we’re going to let that part of it take care of itself. We’ll have to be governed by circumstances after we get there anyway.”

“And in regard to their firing upon us as a hostile airship,” supplemented Ned. “I think the chances are that they may take us for one of their new types of dirigibles that Count Zeppelin is said to have almost ready for a big aerial raid upon England.”

The editor smiled a bit sadly at their shining eyes and enthusiastic faces. Then he shook his head.

“I don’t believe that even a German private could mistake the unusual build of the Ocean Flyer for the bologna-shaped gas bag of a Zeppelin,” said he. “Still, you are very brave boys,[25] and I want to compliment you sincerely upon your pluck in attempting this thing. All luck go with you. Now, what is it that you came here to have me do in your behalf?”

“Just this,” said Ned. “We would like to have you furnish us with full credentials as war-correspondents for the New York Herald to protect us from petty annoyances in case we should, for some unforeseen reason, have to abandon the Flyer and make our escape on foot. We promise you that the passports will not be used in any way that might implicate the paper in a breach of neutrality courtesies, and, anyway, we’re not going to do any actual fighting if we can help it.

“Also, we would like to have a personal letter to General Haberkampf, the German commandant at Muhlbruck, explaining that Bob Russell is an authorized and fully-accredited representative of the Herald, and the last person in the world to be concerned in secret service for the Allies.”

“Certainly you shall have all that you ask for,” cried the managing editor. “And here’s hoping that you make that bigoted old General Haberkampf come to his knees with—”

Crash!

Further utterance froze on the editor’s lips[26] and both boys sprang startled to their feet. Miss Bloomfield’s big dictionary had fallen to the floor with a bang in the outer office!

The editor strode to the private door just as it was pushed open by none other than Mr. Geisthorn, the new correspondent for the Berliner Tageblatt. Miss Bloomfield’s face showed angrily over his shoulder.

For a breathless moment all four of those in the private office stared quizzically at each other. The German was the first to recover his composure.

“Excuse, gentlemen,” said he, bowing low to each in turn, “I did not mean to interrupt, but did I not leave my gloves there on the desk?”

“I think not, sir,” replied the editor gravely. “Come in. You do not interrupt us. My conference with these gentlemen is already concluded. Mr. Napier, Mr. Hope, good day. I shall send you by boy this afternoon the copies from our files about which you inquired. Good-bye!”

As the Airship Boys passed out of the office, Mr. Geisthorn again bent upon them his peculiarly disconcerting stare. They remarked that his pale blue eyes were as hard and cold as steel.

[27]

“Well, young men, I’ve good news—truly surprising news for you,” said Major Baldwin Honeywell, as he shook hands with Ned and Alan the next morning when they returned to the offices of the Universal Transportation Company.

“We hope that you’re right, Major,” answered Ned. “What is the good news?”

“First let me ask you a question. How much did it cost you to build the Ocean Flyer and at what figure do you estimate the time you spent upon it, the only model of its kind yet completed? Your mechanism, parts, et cetera, are, of course, fully protected by international patents. The question is simply: For how much will you sell the Ocean Flyer just as she stands there in our Newark factory?”

“The machine itself cost us about twenty-five thousand dollars, Major. I should say that the market value of the craft itself, allowing compensation for our time and the fact that the[28] airship is absolutely unique, ought to make it worth at least a hundred and fifty or two hundred thousand dollars.”

Major Honeywell was rubbing his hands delightedly.

“Fine, fine! I knew that you would estimate it at about that amount. Boys, what do you say to a prospective purchaser who is willing to pay three hundred thousand dollars spot cash for this single model, leaving the company full patent and all further construction rights?”

“But the machine isn’t for sale at any price,” said Alan quietly. “We intend to use it ourselves immediately, and until we are finished with it, no consideration would tempt us to sell.”

“But, Alan—boys!—think of the sum you are offered: twelve times the actual cost, if the new owners are given immediate possession, and providing you agree not to dispose of another similar machine within a period of one year. You can build another airship just like the Flyer within two or three months at the longest, and you are at liberty to use it yourselves as you may please. To what immediate use can you put the vessel that will in any way compensate for the loss of three hundred thousand dollars in cold cash?”

[29]

“Major,” said Alan, “we are deeply grateful for your interest in the matter, but we feel that we can’t look at it as a mere matter of dollars and cents just now. Something a great deal more valuable to us is at stake—the life of Bob Russell, whom you know.”

Then Alan went on to tell Major Honeywell all about Bob’s predicament and how they proposed to save him. The old gentleman’s face grew more and more grave as he listened, and several times he shook his head disapprovingly.

“But, my dear boys,” he exclaimed, after Alan had concluded outlining their plans, “have you sufficiently considered the terrible dangers that you incur by this rash procedure? Quite aside from the momentary probability of aerial mishap, you must realize that the Germans would shoot you without scruple under the circumstances. Moreover, the entire United States government would be powerless to help you if once you were caught in a breach of neutrality laws, as your act certainly would be construed.”

“Thank you kindly for the well-meant word of caution, Major,” answered Alan, “but there is nothing you could say which would make us give up this chance of saving poor Bob’s life.”

“Then, if that is the case, here is my hand,[30] boys, and my heartiest well wishes go with you. While I cannot conscientiously endorse so dangerous a proceeding, I still can admire the pluck which prompts it.”

Both boys flushed under their kindly old friend’s praise, and Ned, who up to this time had played the part of a listener, said:

“Just who were these prospective purchasers of the Ocean Flyer? Why did they insist on taking immediate possession of it, and why the stipulation that we were to sell no other similar airship to anyone else within one year’s time?”

Major Honeywell shook his head.

“I am as much in the dark in that regard as you are, Ned. Just before you arrived this morning, I was visited by a Mr. Phillips, whose business it is to act as go-between and buyer for concerns which do not wish their own names to appear in a transaction. Mr. Phillips would not state for whom he was acting or for what purpose the Flyer was to be used, but said that he was authorized to pay spot cash for it. He seemed to be very much excited and anxious to close the deal at once.”

“Do you suppose that he could be representing one of the belligerent countries in Europe and wanted the Flyer for war?” asked Ned.

[31]

This was a new thought to Alan, who slapped his knee, exclaiming:

“I’ll bet that’s the whole secret. The war departments over there are all wild over this armored aeroplane idea anyway. England probably wants the Flyer to protect her from air invasion by Germany.”

“Or France wants it to use in dropping bombs along the western battle front in Belgium,” said Major Honeywell.

“Or maybe Germany wants it to supplement their rumored fleet of Zeppelins for the long-planned raid on England,” added Ned.

All three could not help but laugh heartily at the diversity of opinions thus expressed. In the midst of their merriment the telephone on Major Honeywell’s desk began suddenly to ring insistently.

“Hello,” called the Major, with the receiver to his ear. “Yes, yes. This is the offices of the Universal Transportation Company, Major Baldwin Honeywell, the treasurer, talking.... What?... Speak a little louder and more slowly, please; I can hardly understand you.... Yes.... Mr. Phillips approached me about the sale of the Ocean Flyer this morning.... Oh! you are speaking for him. I see.... No,[32] we have decided not to sell the airship.... No, not to sell it.... No, no, the price was quite gratifying, but the Flyer is not for sale.... Positively, sir!... You are wishing to give twenty-five thousand dollars more?... Hold the wire.”

Major Honeywell rolled a wild eye at the intently listening boys. Both shook their heads emphatically. The Major turned again to the telephone.

“I’m sorry, sir, but our decision is not to sell the Flyer at any price whatever.... No, I am sure that we shall not change our minds about it.... All right. To whom have I been speaking, please?”

As the Major asked this final question, Ned sprang to an adjacent extension of the telephone. He caught the distant guttural rumble of a heavy voice:

“My name, it is of no matter since you have not the airship for sale. Good-bye.”

The words were spoken with a marked German accent that in some way seemed peculiarly familiar to Ned. He had heard that voice before, and recently too. But where?

[33]

The rest of that day was a very busy one for the Airship Boys, even though Major Honeywell himself lent as much assistance as he could. There was a variety of miscellaneous supplies to be purchased, hurried letters to be written to Ned’s parents in Chicago and to Alan’s sister, Mary. Both boys agreed that it was best not to state the destination or object of their trip for fear that their beloved ones might suffer all sorts of anxieties until their safe return. So they wrote briefly that they were going off upon a little three or four days’ business trip in the Ocean Flyer and that it was the urgency of the business in hand that prevented their making the farewell visit they desired.

Their shopping for necessary supplies did not take the boys long, for they could estimate pretty closely what they would need. On account of the extremely high altitudes at which they would fly it was necessary for them to buy especially heavy underwear, felt boots, wool jackets, fleece-lined[34] fingered mittens and heavy caps for four persons—as Alan said: “The fourth outfit for Bob Russell, so that he won’t freeze coming back with us.”

Then there were food supplies (the Flyer was equipped with a regular cook’s galley) to be bought, a dozen hair-trigger automatic revolvers, half a dozen light-weight repeating rifles of the latest pattern, cartridge belts, rounds of ammunition, and a large American flag. Neither the firearms nor the flag were to be used except in case of absolute necessity.

Major Honeywell got the aeroplane works in Newark, where the Ocean Flyer was being kept in storage, on the telephone, and issued instructions to the manager there to run the big aircraft out of the hangar into the inclosed experimental field ready for inspection, and to lay in fresh supplies of the special grades of gasoline and ether needed for power.

All incidental shopping completed, Major Honeywell placed his big automobile at the disposal of Ned and Alan, and the trip between Greater New York and Newark was accomplished at a rate that turned the speedometer needle halfway around its circumference and raised angry protests from every traffic policeman as[35] the car whizzed by. This was not, of course, a wise thing to do, but the Major’s chauffeur was an especially good driver and the boys felt justified by the exceptional matter in hand.

An unusual stir was apparent inside the field of the aeroplane works as the Major’s automobile raced up to the high brick wall which insured privacy for the grounds. At the far end of the ground stretched the squatty brick buildings of the factory, with a wireless station and various other signaling devices on the parapeted roof. Extending out from the yard front and ending at the edge of the big experimental field, was the “setting-up room,” a drop of heavy canvas roofing, supported every hundred feet by rough, unpainted posts. Under this tent-like structure was to be seen almost every size and variety of flying craft made in America, to say nothing of several flying machines of obviously foreign design. Most of these were covered by heavy tarpaulins to protect them while not in use. A whole corps of mechanicians was just then pushing out into the aviation field another and very different type of flyer, the heroic proportions of which dwarfed all the other machines into insignificance.

The eyes of the Airship Boys lighted up.

[36]

“There she goes!” they cried in unison. “They are getting her all ready for us.”

They jumped out of the automobile and hurried across the field to where the peerless wonder of the world’s aircraft stood, a literal monument to their inventive genius.

The Ocean Flyer has been too fully commented upon and described in scientific journals, magazines and newspapers from coast to coast to require any very detailed account of it in this story.

Overlapping, dull glinting plates of the recently-discovered metal magnalium covered the entire body of the vessel like the scales of a fish. The planes and truss were likewise formed of this substance, which is a magnesium alloy with copper and standard vanadium, or chrome steel. The extreme lightness of magnalium, combined with a toughness found in no other metal or alloy, made possible the perfection of this largest of all airships.

The vessel was modeled after the general form of a sea gull, with wings outspread in full flight, its peculiarly ingenious construction insuring not only the maximum of speed, but also that hitherto elusive automatic stability of the planes which for years past has been the despair of aeroplane[37] builders on both sides of the “big pond.”

Braces extending from the bottom of the car body and metal cables from the top partly supported the vast expanse of magnalium steel sheets, but toward the outer ends, the wings, or planes, extended unsupported in apparent defiance of all mechanical laws. Three sets of “tandem” planes projected with slight dihedral angles for a distance decreasing from eighty, to sixty, to forty feet, on each side of the ship body, affording a wing-spread never before successfully attained, and giving the whole the exact resemblance of a gigantic metal bird.

Each of these planes was made of three distinct telescoping fore and aft sections, with a full spread of twenty-one feet. By means of the immense pressure gauges almost concealed under the curved front of the main plane, the rear sections were drawn in by cables on a spring drum until the width of each of the three planes was reduced to seven feet. The moment the air pressure was lessened by descent or lessening of speed, the narrow wing surfaces automatically spread. In rapid flight the reverse pressure on the gauges allowed the spring drums to reel in the extension surfaces, housing all extensions securely, either beneath or over the[38] main section of the wings. In this way the buoyancy of the airship remained always the same.

The body of the Ocean Flyer consisted of two decks or stories, with a pilot house, staterooms, fuel chambers, engineroom, bridges above and protective galleries. The completely enclosed hull, pierced with heavy, glass-protected ports, and doors, was twelve feet wide, thirteen feet high and thirty feet long, ending in a maze of metal trusswork at the rear, and a magnalium-braced tail, seventy-three feet more in length, exclusive of the twenty-foot rudder at the stern.

To drive this huge craft, a much higher percentage of motor power than ever before secured had to be transformed into propulsive energy. The ordinary aeroplane propeller permits the escape of much of the motive power, but the Ocean Flyer was equipped with the new French “moon” devices, which do away with the “slip,” and allow the full power of the engine to be applied to the greatest advantage. Viewed sidewise, this new form of propeller looks exactly like a crescent, its tips curving ahead of its shaft attachment. The massive eleven-foot propellers of the Ocean Flyer, with a section five feet broad at the center, gave ample “push.”[39] They were located just forward of and beneath the front edge of the long planes. Powerful magnalium chain drives connected these with the shaft inside the hull. Behind the chain drives, a light metal runway extended twelve feet from the car to the propeller bearings, so that the latter might be reached while the car was in transit, should adjustment or oiling be found necessary.

Within the hull of the vessel, four feet from the bottom, a shaft extended carrying a third or auxiliary “moon” propeller, differing from the exterior side propellers by being seven instead of eleven feet in length. This reserve propelling force was for use in case either of the other propellers became disabled.

The motive force of the Flyer was secured by a chemical engine, run by dehydrated sulphuric ether and gasoline. Magnalium cylinders sustained the shock of the tremendous “explosions” as the cylinders revolved past the exploding chamber and developed a power previously undreamed of.

Each of the two huge engines used was six feet in diameter, with four explosion chambers cooled by fans which fed liquid ammonia to the cylinder walls in a spray and then furnished[40] power for its re-liquefaction. In form, each engine resembled a great wheel, or turbine, on the rim of which appeared a series of conical cylinder pockets. These, when presented to the explosion chambers, received the impact of the explosion, and then, running through an expanding groove, allowed the charge to continue expanding and applying power until the groove terminated in an open slot which instantly cleansed the cylinders of the burnt gases. By this arrangement there was only a twentieth part of the engine wheel where no power was being simultaneously imparted, thus giving practically a continuous torque.

Weighing over five hundred pounds each, and with a velocity of one thousand five hundred revolutions per minute, those big turbines generated nine hundred and seventy-three horse power, natural brake test, and this could be raised to more than a thousand horse power without danger. Revolving in opposite directions, they eliminated all dangerous gyroscopic action. As has been said, power was applied to the propellers by special magnalium gearing.

The Ocean Flyer was equipped with the first enclosed car or cabin ever used on an aeroplane. The compartments of its two decks connected[41] with each other, but all could be made one air-tight whole. Even the engines were within an air-tight compartment. Attached to the bow of the hull was a large metal funnel with a wide flange. Tubes leading from the small end of this passed into each room on the vessel. Flying at sixty miles or more an hour caused the air to rush into this funnel with such force as soon to fill any or all of the compartments with compressed air. At a speed of two hundred miles per hour, this was likely to be so great that, instead of having too little air, there would be far too much were it not for regulating pressure gauges which shut off the flow from time to time. Thus the aeronauts were not only assured plenty of breathing air even in the highest altitudes, but the pressure gave sufficient heat to prevent frost bite from the intense cold which prevails beyond a certain height above the earth’s surface.

A supply of oxygen was of course carried for use in case of necessity, although the Airship Boys had in the past proved that their funnel device obviated all need of it.

The pilot room was located at the bow on the second deck. In appearance it largely resembled the wheel-house of the ordinary ocean liner. The[42] compass box, with its compensating magnetic mechanism beneath, stood just in front of the steering wheel, below and parallel with which, but not connected with it, was a wheel for elevating or depressing the planes. Both of these wheels operated indirectly, utilizing compressed air cylinders to move the big rudder and wing surfaces. At the right of these wheels was the engine control, consisting of a series of starting and stopping levers for each engine and the gear clutch for each wheel.

At the left, in compact, semicircular form, was the signal-board, the automatic indicator recording at all times the position of each plane, the set of the rudder and the speed of the engines. Below this was the chronometer and a speaking tube which kept the pilot always in communication with every other part of the vessel. Immediately behind the pilot’s wheel was a seeming confusion of indicators and gauges for the making of observations. There was the aerometer, the automatic barograph, the checking barometer, the equilibrium statoscope, a self-recording thermometer, the compressed air gauge for all compartments, chart racks, indicators to show the exact rate of consumption of fuel and lubricating oil and so on.

[43]

As may be surmised, the duties of the pilot were not merely to steer and keep a lookout ahead, but also to watch the machine and counteract the influence of unexpected air currents and those atmospheric obstructions like “pockets,” indistinguishable puffs of air, and the like, which are always very dangerous and will jolt an airship exactly as a rock or piece of wood will bounce an automobile into the air and maybe completely overturn it. Among experienced aeronauts, these air-ruts are recognized as being one of the chief perils in aviation.

Ned Napier and Alan Hope usually took turns acting as pilot on a three-hour shift, any longer interval of duty being too nerve-racking a strain. The third man whom they usually took with them on the Ocean Flyer was supposed to be stationed in the engine room. It was his duty to watch the automatic fuel and lubricator supply feed pipes, the compressed air gauges and pipe valves, the signal and illuminating light motor, the oxygen tanks and the plane valves, in addition to the wireless apparatus for communication with the outside world.

On long flights one of the three aviators slept while the others remained on duty. Thus one of them was always kept fresh and alert to meet[44] the demands of any unforeseen emergency.

Ned, Alan and Major Honeywell made a careful investigation of every detail of the Ocean Flyer, satisfying themselves that it was in all respects perfect for their hazardous trip. They found everything to be absolutely shipshape, and those additional supplies which had arrived, were already being stowed away on board.

“Well,” said Alan, “everything seems to be attended to properly, and there is no reason why we can’t start any time we like. The sooner the better, because there’s no telling what they may be going to do to Bob over there in Belgium any one of these days.”

“Right,” echoed Ned. “Let’s see. To-day is Wednesday. What do you say to starting off to-morrow morning early. Then we can arrive in Muhlbruck not later than some time early Friday morning. We will have darkness to cover our arrival there.”

“That’s a good idea,” supplemented Major Honeywell. “I don’t like to see you boys risking this thing, but if it must be done you should take every possible advantage. And now, if you’re through inspecting the Flyer, what do you say to riding back to New York with me in the automobile and taking dinner at my house?”

[45]

“The major is a man after my own heart,” cried Ned.

“My stomach cries out for him,” grinned Alan, as they made their way back to the waiting motor car.

[46]

It was not a particularly jolly meal at Major Honeywell’s that night. The major was oppressed by grave fears of what might happen to his young friends on their journey, and the Airship Boys felt the seriousness of the step they were about to take. However, youthful spirits are buoyant, and the good-smelling, appetizing dishes that were served them soon drove away dull gloom and revived the boys’ spirits. As Alan said:

“What’s the use of sitting here staring at each other across the table as if we were at a funeral? Nobody is going to die or even get hurt. It’s no use trying to be melancholy on a full stomach, and I, for one, am going to laugh right now.”

The dessert course was just being served when there came a ring at the doorbell, and a few minutes later the maid announced that a reporter from the Herald wanted to see either Mr. Napier or Mr. Hope.

[47]

“Show the gentleman right in here,” said Major Honeywell, after the boys had agreed to see him.

The young man who came in was slightly larger and older than either Ned or Alan. He was tall, wiry, and had the cool, assured bearing of one who has survived many rebuffs and still got what he wanted. As he entered the dining room door, both Ned and Alan sprang to their feet and rushed impulsively to meet him.

“Buck Stewart!” they shouted joyously, pumping his arms up and down. “Well, if this isn’t both the most unexpected and the luckiest thing! We’ve been wanting to have a talk with you for two days past, and meant to ask the managing editor about you Tuesday, only we were interrupted and got so flustered over it that we left before remembering that you were one of the main reasons for our call.”

“What good fairy brought you here to-night, Buck?” asked Ned, pulling the newcomer down into a chair at the table and shoving a piece of pie in front of him.

“I’d rather eat that pie than talk right now, but I suppose I’ve got to answer your question first,” said Buck. “We reporters always are in hard lines. You ask how I happen to be[48] here? Well, it was this way: The night city editor called me over about an hour ago and gave me an assignment on you two chaps.”

“Why, what news is there about us that the Herald could use?” asked Ned, exchanging a rapid glance with Alan and the major.

Buck removed a longing eye from the piece of pie to reply:

“We learned in some way that unknown parties had made you a cash offer of something like three hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars for the Ocean Flyer and that you turned them down cold. Is that true? Also, who were the people who wanted to buy the Flyer at such an astounding cash figure, and for what purpose did they want it? If you’ll give me full details I’ll be much obliged.” This as the reporter pulled a folded bundle of note paper and a pencil from his pocket. “These prospective buyers didn’t represent any one of the warring nations in Europe, did they?”

“That’s just what we don’t know and what we feared,” said Alan. “I’m afraid that we can’t give you much dope for a story, though, Buck, because we know as little about them as you do.”

Then he went on to tell about Mr. Phillips,[49] the go-between’s mysterious call, and the telephone conversation with the man with a strong German accent.

“I’m sure that I’ve heard his voice somewhere before and that not so very long ago, too,” added Ned. “I’ve racked my brains ever since trying to place him.”

“Huh, sounds funny,” commented the reporter musingly, “but you certainly haven’t given me much of a lead for the ‘story’ I was after. Well, I’ll be going and not interrupt your little party here any further.”

“Wait a minute, Buck,” said Ned. “We haven’t told you yet why we wanted to see the Herald’s managing editor about you.”

“That’s so,” said Buck, sitting down more comfortably in his chair. “Now if one of you gentlemen will hand me a fork, I’ll dispose of this mince pie while you’re spinning the yarn.”

So, while the reporter was busy making the pie disappear, Ned told him of Bob Russell’s predicament in Belgium and what they proposed to do towards a rescue.

“We want you to go with us, Buck,” said he, “just as you did the time we made the ‘twelve-hour’ London-to-New York flight two years ago with the coronation pictures for the[50] Herald. The managing editor will surely let you go for the two or three days needful when you ask him, especially as it will enable the paper to get a representative right at the front, with no bull-headed censor to edit his ‘copy.’”

“If the boss won’t let me off, I’ll throw up the job anyway,” shouted Buck, jumping up in great excitement. “Why, Bob Russell and I are old friends, just as you are, and I don’t want to leave him in the lurch any more than you do. It’s mighty good of you to give me this chance to make one of the rescue party. Count on Buck Stewart, boys—hair, tooth and nail!”

The reporter’s enthusiasm was contagious. All three sprang to their feet, and, with exclamations of mutual pleasure, were shaking hands to seal the compact when—

“Ting-a-ling-ling! Ting-a-ling-ling!” went the telephone bell.

“Ned,” called the major, who answered the call, “it’s somebody that wants to speak with you personally—a man with a marked German accent.”

The little company around the dining table stared curiously at each other as Ned Napier took up the receiver.

[51]

“Hello! This is Mr. Napier.... Yes, I’m one of the owners of the Ocean Flyer. Who is this speaking and what do you want?”

The voice at the other end of the line was harsh and guttural. The words were spoken in a truly menacing tone:

“You do not need to know who I am. It is sufficient that I warn you. We who are banded together in this country know this thing that you think of doing. We know that you intend a trip in your flying ship to the war zone. Take our advice and do not attempt it. You are being closely watched and we will not hold ourselves responsible for what may happen if you try to carry out your plan. You are young and life is dear to you. Beware!”

The telephone clicked abruptly at the other end of the line and the threatening voice was still. Ned sat as if petrified, his face a study of mingled amazement, indecision and indignation.

“What’s the matter, Ned? Who was it? Was it that same person who called up about the Flyer?” cried the others crowding around him.

“Yes,” replied Ned, “it was the same voice and I am sure that I have heard it before.”

Then he went on to tell them of the ominous[52] threats of the mysterious stranger. A chorus of exclamations followed his recital.

“The blackguard!” ejaculated Major Honeywell. “We ought to set detectives on his trail.”

“Small chance of ever catching him that way with the meagre clues we have,” said reporter Buck. “Besides, we haven’t time to monkey with anything like that,—unless, of course, you boys decide that it is better not to risk the enmity of these unknowns. They evidently mean business.”

Ned’s lips had fixed themselves into a grim, straight line, and Alan’s frown was no less determined.

“All he hopes to do is to frighten us into selling the airship to him,” said Alan, “and I don’t believe that his big threats were anything but sheer bluff. Why, they wouldn’t dare attack us right here in the heart of civilized New York.”

“Whoever they are, or whatever they may try to do, we’re not going to let a phone call scare us out of this effort to save Bob Russell,” said Ned. “We’re all ready to start now except for getting the Herald’s permission to let Buck here go with us. He can see the managing editor about that the first thing in the morning, and then we’ll be off immediately.

[53]

“But if this gang really has you boys spied upon, they will certainly make some attempt to stop you,” argued Major Honeywell.

“Nobody stands any chance of stopping us once we get up in the air,” answered Ned, “but, as you say, we may as well try to make our get-away as secretly as possible. I would suggest that instead of starting out by daylight to-morrow, as we planned, that we wait until midnight. Each of us can leave his house at a different time during the day and go about as if we have changed our minds and called the trip off. Then, just in time to reach the Newark factory, each one can start off alone. We should be able to disarm any suspicion in that way.”

Everybody approved heartily of Ned’s scheme and parted that night with a little more earnestness in their handshakes than usual. All of the road back home the Airship Boys cast furtive glances over their shoulders every now and then, but no sign of any followers was visible.

[54]

Alan Hope spent most of the next day at the offices of the Universal Transportation Company, and was inclined to scoff at the idea of his being watched. Nevertheless he had a loaded automatic revolver tucked away in his hip pocket, and, as night drew on, his assurance began to ooze gradually, and he felt more than once to make sure that his weapon was still there ready for defense.

Ned Napier was really impressed with the threats of the mysterious German, and, though he did not arm himself as Alan had, he kept a sharp lookout for suspicious characters about him. All day long he wandered with an air of affected carelessness through the downtown shopping district, made a couple of short business calls, ate leisurely at the Ritz, and seemed to have no thought of anything but home and bed for that evening.

Buck Stewart arose early that morning, ate a hearty breakfast, and when he started out took[55] with him what was apparently an ordinary cane, but which really was a rod of steel, encased in leather. Many reporters carry them when they are sent out on assignments into dangerous sections of the city.

Swinging his stick jauntily, he made his way first to the offices of the Herald, where a brief chat with the managing editor readily procured him permission to accompany the Airship Boys on their trip. The editor, in fact, made a regular assignment of it and cautioned Buck to take along with him plenty of pencils, notebooks and a small camera that could be swung over one shoulder with a strap.

Thus burdened, Buck again sought the street. Leaving “Newspaper Row” behind, he sauntered along, stopping now and then to look at articles in the shop windows, and finally decided to see the matinee at the Casino.

Broadway was thronged with the usual afternoon crowd of beautiful women and fashionably dressed idlers for which it is famous. The reporter shouldered his way through these, a little self-conscious of the bumping camera-box over his shoulder and the way his pockets bulged with surplus notebooks. Once a tall, plainly dressed man with a close-cropped beard bumped[56] into him. There was a mutual exchange of apologies and the crowd soon swallowed him. Later on Buck met a fellow newspaperman in front of the Astor and stopped to chat with him. An inadvertent side glance during this conversation discovered the same bearded stranger standing just to one side of the hotel entrance, as if hesitating whether to go in or not. There was no recognition in his cold eyes as Buck’s glance caught his, but the reporter’s heart gave a little jump.

“Pshaw!” growled Buck to himself, “I’m getting to be a regular old granny! Here I see the same passer-by twice in an afternoon on Broadway and am afraid that he’s a spy waiting to sandbag me.”

His uneasiness was not thus to be laughed off though, and spoiled his enjoyment of the performance at the theatre. He scanned the audience around him narrowly to see if the bearded man was among them, and was relieved at failing to find him.

After the show Buck again wandered aimlessly through the streets. He was keenly on the alert for spies, and found merely killing time to be harder than he had thought it would be. The strain was beginning to tell on his nerves. At[57] dusk a million lights flashed out in a dazzling array of figures and designs and the Great White Way made good its name. But Buck was tired of it by then. He strolled over to near-by Fifth Avenue, where there were fewer people to jostle him and the rattle of the streets was less distracting. He felt, for no apparent reason, increasingly sure that he was being followed.

To make sure of his suspicions Buck walked at times very slowly; at others rapidly; but he observed no suspicious “shadows.” True, there were a number of people walking behind him, but his inspection revealed nothing sinister about them.

Buck told himself that his fears were silly—that he was as bad as a girl in the dark. Still the vague dread oppressed him.

He ate in a small restaurant just off Fourth Avenue, entering the place at the same time as two other men whose dress indicated them to be shop clerks, or something of the kind. When he arose to pay his bill and leave, they did also. At the counter, one of them brushed as if accidentally against him, and Buck felt deft fingers pass swiftly over his pockets as if searching for something. Was the fellow feeling to see if Buck carried a revolver?

[58]

The reporter wondered, but said nothing to the strangers. Their faces were innocent enough and their eyes met his questioning glance candidly. Buck went on out into the night and they followed close on his heels. As he stood quietly in the doorway there, however, the men bade each other good night and parted—going in opposite directions along the street. Finally they disappeared in the darkness.

Buck was sorely perplexed. He felt absolutely certain that it was unsafe for him to be wandering about alone, yet it was several hours too early to start for Newark. Finally he decided to take in several moving picture shows as the safest way to keep out of danger. One of the men whom he had seen in the little restaurant was lounging outside of the first playhouse Buck visited. Before the films were fully run the reporter slipped out through one of the side exits into an alley.

It was so dark there that he hardly could see the ground under foot. Twenty assailants might be waiting in the gloom for aught he could tell. The reporter was not ashamed to take frankly to his heels and rush out onto the lighted street as fast as he could. He noticed that the lounger had disappeared from the theatre doorway.

[59]

Hoping now that he had thrown his unknown pursuers off the trail, Buck visited a second moving picture playhouse. There a drunken man plumped roughly down into the vacant seat next to him and tried to pick a quarrel without any excuse at all. The reporter would have taken this as rather a joke had it not been that there was no vile odor of intoxicants on this drunkard’s breath. Shoving the rough to one side, Buck hurried out of the theatre, walked quickly down the street to the next corner; crossed there to see if he was followed; turned the next corner; walked two blocks along an ill-lighted deserted side street and there jumped into a dark doorway to listen.

Yes! there was no mistake about it! He could hear the patter of running feet less than a quarter of a block behind. Ere Buck had time to flee, rubber heels on the pursuers’ shoes deadened their footfalls again and two shadowy figures appeared directly in front of his hiding place. They paused there, breathing hard, and holding a hasty conference.

“How ever did he get away from you, Hermann?” snarled the bigger of the two men to the other, whom Buck now recognized as the “drunken man” of the theatre.

[60]

“Why talk about that now that he has again eluded us?” he growled. “If only we had him here on this dark street, we could soon finish with him.”

“Yes, we must catch him at once. He must still be in the neighborhood and isn’t armed. I made sure of that in the restaurant a couple of hours ago. But anyway, he can’t go far without Otto, Wilhelm or some of the others seeing him. They are covering all of these three streets, you know.”

The man addressed as Hermann grunted his assent.

“I’m winded from that run after the fool,” said he. “Let’s sit down in this doorway and rest for a few moments.”

Buck’s heart began to beat faster. He knew that his discovery and assault were only a matter of a few seconds. The scoundrelly pair had now approached within arm’s reach of him, so without further delay the reporter swung aloft his loaded cane and brought it down in a smashing side blow on the head of the nearest man.

A Narrow Escape.

A bellow of rage and pain shocked the neighborhood into wakefulness. As the second man leaped savagely at him, Buck evaded a wicked[61] knife stab and struck him full between the eyes with his clenched fist. The fellow reeled, jerked a pistol from his pocket and emptied it blindly at the place where his combatant had stood an instant before.

But Buck was bounding down the street as fast as his legs could carry him, his camera bumping clumsily against his back. A cross-town trolley car was clanging the bell down the next street and the breathless reporter made a running jump to catch it. Just as he did so a third man with a closely-cropped beard sprang after him from the curb. He caught the camera and gave a mighty tug at it which broke the strap, and, with the box in his hands, sent him sprawling backwards in the street. The rushing trolley car did not stop, and Buck’s extraordinary agility was all that enabled him to swing aboard safely.

“It’s a fine night, mister,” said the conductor, as he rang up the fare.

Buck answered him with the sourest of stares.

[62]

Alan Hope reached the Newark factory of the Universal Transportation Company shortly before eleven o’clock that night, after an uneventful trip out via the suburban railroad service. He found the big plant gloomy and silent, without a light to show that activity was really going on within. In response to a prearranged code of rings on the bell at the great main gates, he was admitted.

The Ocean Flyer had been wheeled to the extreme end of the big aviation field where she might have plenty of room for her initial rise into the air, and the factory foreman informed Alan that all was now ready for departure at any minute.

Ned Napier arrived within ten minutes after his chum. Although he had sustained no actual mishap on the way out, it was by sheer luck only that he escaped the trap which had been laid for him. He had attended the performance at the Winter Garden, purposely leaving early. In[63] the foyer as he went out a stranger in full evening dress (apparently one of the spectators finishing his between-acts cigarette) accosted him with extreme politeness:

“Dear gentleman, your pardon,” said he, “but are you not Mr. Edward Napier, the aeronaut?”

“No,” Ned answered him coldly. “My name is Lloyd Jenkins. I am a traveling shoe salesman.”

“My mistake, then,” laughed the stranger lightly. “Just to show that there’s no hard feelings, won’t you join me in a little drink down at the bar?”

“No, thank you,” the boy answered, “I never use intoxicating liquors,” and then, being already suspicious, brushed on past the stranger and out into the street.

The usual line of taxicabs lined the whole curb on both sides of Broadway for a block or more. As soon as Ned appeared there was a hoarse-voiced chorus of shouts:

“Taxi! Taxicab, sir? This way, sir! Taxicab?”

Several of the chauffeurs crowded around Ned, trying to persuade him to patronize them rather than their fellows. One driver, muffled deep in[64] a fur-collared overcoat, even went so far as to lay his hand on the boy’s arm.

“I have a big, comfortable limousine car here,” he said. “Same price as those stuffy little taxis.”

Out of the corner of his eye Ned just then saw the persistent stranger of the theatre lobby coming out of the entrance towards him, and, not being anxious for any further acquaintance, the boy turned hastily to the chauffeur, saying:

“All right! Your limousine for me!”

“Where to, sir?”

Ned was properly cautious.

“The Grand Central Station,” he answered, intending then to change to another taxicab which could double on his tracks and take him on to the rendezvous in Newark.

The gentleman in evening clothes was hurrying towards Ned, signaling wildly for him to wait.

“Drive ahead!” called the boy to his chauffeur, and plunged into the black, cushioned depths of the big limousine. Ned kept right on going through, however, tore open the door on the opposite side, and was plunged headlong to the pavement by the sudden rush of the machine as it fairly leaped into high speed. There in the[65] gloom of the car he had vaguely observed the uneasy stir of a man hidden beneath the heaped-up rugs in the corner.

The boy raced across the street, dodging whizzing motors and heedless of angrily-honking horns, sprang inside the nearest taxicab and yelled to the driver:

“Give her all the juice you can! Five dollars extra if you can get me to Brooklyn Bridge within twenty-five minutes!”

“I’ll do my darnedest,” the chauffeur, a grizzled man of fifty, assured him.

They were off in a jiffy, amid a grating of gear-shifts and thunderous explosions of the opened exhaust. The motor began to whine as the gas was fed more and more rapidly; the white glare of Broadway slipped past the cab windows in a dull blur. Traffic policemen’s whistles were merely unheeded incidentals of the mad race.

Peering back through the little window in the rear of the machine, Ned saw at least two other automobiles join in the pursuit from the front of the theatre. The big limousine was one of them. The stranger in evening clothes and another man were craning their necks out of the other.

[66]

“Turn over onto Fifth Avenue and double up and down some of the side streets as fast as you can,” called Ned through the speaking tube to his chauffeur. “Never mind about Brooklyn Bridge. There are two machines behind that I want to shake off our trail.”

“All right, boss,” replied the chauffeur. “You just leave it to Barney O’Dorgan to lose any other chasing taxi in this old town.”

From then on it became a game of hide-and-go-seek. Finally away over on the East Side, it looked as if the pursuers had been shaken off. No sign of them had been apparent for at least half an hour, and Ned was just congratulating himself, when the car turned a corner, and right there, at a standstill under the arc-light, in the center of the otherwise deserted street, stood the big limousine, with the three men arguing violently beside it.

Chauffeur Barney O’Dorgan caught sight of it as soon as Ned did. Simultaneously the trio recognized their lost quarry and started towards it at a run. There was neither time nor space for Barney O’Dorgan to turn his car about, so, as cool as you please, he simply threw his gear lever as far as it would go, flooded the cylinders with gas, and the taxicab began to race backwards[67] at as furious a pace as it had previously gone forward.

Seeing their prey escaping, all three of the pursuers jerked revolvers from their coats and opened fire. Two bullets shattered the windshield in front of intrepid Barney’s face; another tore its vicious way through the wooden body of the cab and imbedded itself with a dull thud in the back wall not a foot from Ned’s head. All of the other shots went wild. Two blocks down this side street and the cursing pursuers were left more than half of that distance behind. Then chauffeur Barney reversed his gears, turned the machine about, and sped on his way, with Ned exulting behind him.

“Barney, you’re a peach, and you won’t ever regret the way you’ve stuck by me to-night,” Ned called gratefully.

“Oh, that’s all right,” the Irishman made answer. “I knew by your looks that you weren’t a crook, and certainly I wouldn’t let that gang of high-binders nab you. Where to now, sir?”

The driver certainly had proved himself trustworthy, so Ned decided to tell him his true destination.

[68]

“Have you gasoline enough left to drive me to the plant of the Universal Transportation Company in Newark?” he asked.

“Plenty of gas,” grinned Barney, “but I’m not so sure about the air in my tires. Wait until I look at them.”

The tires proved hard and sound, however. Once more Barney took the wheel, and from there on the ride to the rendezvous was uneventful. Ned presented the chauffeur with thirty dollars as a reward for his fidelity.

“That was a mighty close shave of yours, Ned,” said Alan, after he had heard the story, “but where can Buck Stewart be? It’s already past the time we agreed upon. Do you suppose they could have caught him?”

“Not yet, my boys,” cried a hearty voice behind them, and there stood the reporter, his clothes rumpled, his hat dented out of shape and with pockets a-bulge with notebooks. “There are only two parts of me missing—my camera and cane, and I had to leave them in other hands without stopping to argue about it.”

Then Buck told the story of his thrilling night’s experiences and mutual congratulations followed.

“Well, I guess that we’ve given them all the[69] slip at last,” said Alan, “and since it’s away past the hour we fixed for starting, let’s take our places aboard the Flyer and be off. We haven’t any too much time to lose, you know.”

“Right-o!” echoed Buck and Ned.

So the trio made their way to where the huge airship stood ready. They swung up the ladder into the main port. Ned took his position in the pilot room; Buck in the engine room. Alan made a hasty survey of the vessel, poking around here and there with a powerful hand-searchlight to see that all was as it should be. Their hearts beat high with excitement, which likewise agitated the little group of factory mechanics who had gathered to see them off. Just as Ned was about to signal Bob for their start, there came a tremendous battering upon the great barred doors of the factory.

“Open and admit us!” roared an authoritative, bull-like voice. “Let no man leave here before we enter—in the name of the United States of America!”

[70]

For an instant the hearts of all the boys stood still and each looked at the other in consternation.

“In the name of the United States of America!”

That meant that in some inexplicable way their project had leaked out and that the federal government had sent officers to prevent their going.

The heavy pounding on the great gate had resumed and now the same commanding voice shouted:

“Are you going to open to us, or is this intended as resistance of the law? I give you two minutes to open these doors before we smash them in!”

“That fellow means business,” whispered Alan. “Whatever can we do? We dare not oppose them, yet to let them in means the indefinite postponement of our flight.”

“We’ll go anyway,” said Ned, his eyes lighting with determination. “This is only another[71] scheme to delay us. Are you all ready there, Mr. Engineer?”

“Whenever you say the word,” answered Bob up through the tube.

“Then start your engines! We’ll be a mile up in the sky before they can break in those heavy doors.”

So saying, Ned jammed down hard on his starting lever, the whir of the big turbines swelled forth. But not a tremor shook the Ocean Flyer. It did not budge an inch.

Someone had been tampering with the pilot room apparatus.

With a groan of desperation, Ned bent over the complexity of gears. He located the trouble almost immediately and was relieved to note that it was merely superficial—a matter of minutes to repair. But too late! At that moment the big yard gates were burst open forcibly and in strode four burly federal plain-clothes men, displaying their badges of authority. One other man accompanied them. Alan, who went out on the lowest exposed gangway of the Flyer to meet them, recognized him in an instant. It was Mr. Geisthorn, the local correspondent of the Berliner Tageblatt.

“Is this Mr. Napier?” growled the leader.

[72]

“No, I am Mr. Hope. Mr. Napier will be here presently.”

The officer pulled an official looking document from his breast pocket and extended it towards Alan.

“We have a warrant for the arrest of both of you gentlemen. Also for that of one Stewart, said to be connected with the New York Herald.”

“Mr. Stewart will also be here presently,” said Alan. “Upon what charge are we to be detained?”

“Conspiracy—attempting to violate the federal neutrality by lending aid to one or another of the warring nations in Europe.”

“That is untrue.”

“I have nothing at all to do with that. My instructions are simply to place a man on guard over this vessel and to escort you gentlemen to the secretary of state at Washington.”

Alan’s wits were working fast. He was fighting to gain time, and the taffrail beneath his fingers was aquiver with subtle tremors; he could feel the premonitory hum of the engines as first one and then the other of the big turbines began moving. Ned had fixed the damage and things were going down in the engine room. The hum became a whir, a buzz and steady purr. The[73] Ocean Flyer trembled momentarily from stem to stern. The eleven-foot “moon” propellers began to whirl with rapidly increasing velocity. Then suddenly the streams of compressed air began to sing in a way that was like the terrifying moan of a cyclone near at hand. Then the tornado burst. Driven irresistibly forward by the most powerful propellers ever devised by man, that vast mass of steel surrendered and slid jolting forward for twenty yards or so, scattering the spectators wildly. With a bound the huge craft rose into the still air and plunged forward and upward on a forty-five degree angle at rapidly increasing speed.

“Stop, in the name of—” The official’s thunderous voice was lost in the distance. The factory buildings and the little group of detectives seemed to be dropping farther and farther down below, and, were it not for the rush of the wind, the Flyer might have seemed to be stationary. The figures on the aviation field already were dwarfed by distance and half obliterated in the darkness. A sudden flash of red light stabbed the shades far beneath, and the report of the officer’s revolver was faintly audible.

Already the airship was sailing out over[74] Greater New York. The lighted streets far below checked the area into rectangular figures like a gigantic chessboard. Broadway became a hazy blur of white, and the atmosphere took on a different quality—biting, hardy, more rarified. The stars which sparkled coldly down there on earth, became blazing, golden jewels in a setting of black velvet, which was the sky. The noise of the engines was now a low, steady drone.

The trip to Europe and the great war had begun.

There is nothing in particular to tell about the three-thousand mile air voyage across the Atlantic. To Alan, Ned and Buck, snugly encased within the automatically heated interior of the Ocean Flyer, the sense of aloofness from solid earth was lost, and it seemed much as if they were seated at their office desks back on Fifth Avenue.

The height of six miles from earth level at which they traveled, blotted out all sight of tangible objects, the comparative distance from which might have made the altitude terrifying to less experienced aviators than the Airship Boys. Sometimes the Flyer cut its way through clouds, but the main strata of these even lay far below[75] them. All that was visible through the heavily glassed portholes was a dull, grayish void. The terrific rate of speed at which they were traveling was not at all apparent.

The young aeronauts were kept too busy managing the ship to have spent much time star-gazing if there had been something of outside interest. Ned and Alan took turns in steering the course and taking hourly observations upon one or another of the exceedingly delicate instruments at their command. Buck stood to the engines in the hold, being relieved by one of the other boys when it came his turn to sleep or prepare meals.

Speaking of eating; those little repasts that Buck Stewart prepared in the cook’s galley were absolutely mouth-watering. Had he not been so able a newspaper reporter, he would have made a better chef. Oh! those luscious, thick, juicy steaks, oozing such odoriferous steam and a-swim in milk gravy from the same pan; hashed, golden-brown potatoes, one mouthful of which was to implant an insatiable craving for more; little green pickles with a real tang to them and flavored by the cinnamon, nutmeg and tasty spices in which they were bottled; flap-jacks, rich with molasses; sugar cakes and rich[76] coffee that warmed one down to the very toe tips; and fruits! Well, there were big, rosy-cheeked apples, that kind of oranges which can be smelled all over the room, nuts, raisins and what not. The larder was well stocked, and Buck Stewart certainly knew how to prepare it appetizingly if ever anyone did.

Fortunately the weather continued fair and no dangerous air-pockets or unexpected whirlpool wind currents were met with. The eighteenth hour of their flight found everything going as well as possibly could be wished. Their watches were still set to New York time; it was now six P. M. in America, but midnight in London. There was a full moon, and it was quite light.

“By this time,” observed Ned, “we ought to be pretty near the English coast, so I would suggest that we drop the Flyer down to an altitude where we can locate ourselves more definitely by actual landmarks.”

This was done. With the huge wing-like planes expanded to the full, the Ocean Flyer coasted aslant the air-waves. The cloud belt encircling the globe was penetrated and passed through, leaving small drops of moisture glistening all over the glass of the portholes. The moon’s rays made the metal body of the vessel[77] glitter like so much silver. As they dropped lower and lower, the world became dimly visible, seeming to be literally rising to meet the descending aviators. At an altitude of three thousand feet, the downward planing was discontinued and level flight again maintained.

To the one hand stretched the seemingly endless expanse of gray, breaker-crested ocean, but on the other, due ahead, lay the rock-bound, irregular coast of the British Isles. Not so very far away now, was poor Bob Russell on trial for his life.

All three boys were thinking about him. It was not necessary to mention his name.

“Not long now,” said Ned.

“No, not long,” agreed Alan and Buck.

[78]

The course of the Ocean Flyer was altered slightly so as to avoid passing over England and risking pot-shots from a people who were already in a semi-hysteria over the threatened invasion by German Zeppelins. The next land they saw was the coast of northern France. They followed the Norman coast for a short distance and then once more headed inland.

The flying speed had been reduced to thirty miles per hour, when the airship first sank to a three thousand foot level, and, traveling thus slowly, the boys had a pretty good chance to observe the country beneath them through their powerful binoculars.

Normandy, the district where the Airship Boys first began flying over France, had not yet been touched by hostile invasion, and, save for the absence of the usual fleets of fishing smacks along the coast, was to all appearances the same quaint, sleepy region as ever. Farther inland, however, the ravages the war had made were[79] more plainly visible. Few trains could be seen, and in many cases railway bridges or the tracks themselves had been torn up. Fields lay, for the most part, untilled; smoke no longer belched from the long, finger-like chimneys of busy factories. Nantes, Angiers, Le Mans and Chartres, all huge cities over which the Flyer passed, showed little activity save that even at this early hour crowds were congregated in the principal squares and in front of the government offices where daily returns from the battle front were posted.

The appearance of the Ocean Flyer was invariably the cause of intense excitement. People scurried frantically about, church bells rang the alarm and soldiers ran to their posts on the fortifications. Observed from the boys’ elevated position, the scene greatly resembled an ant-hill disturbed with a stick.