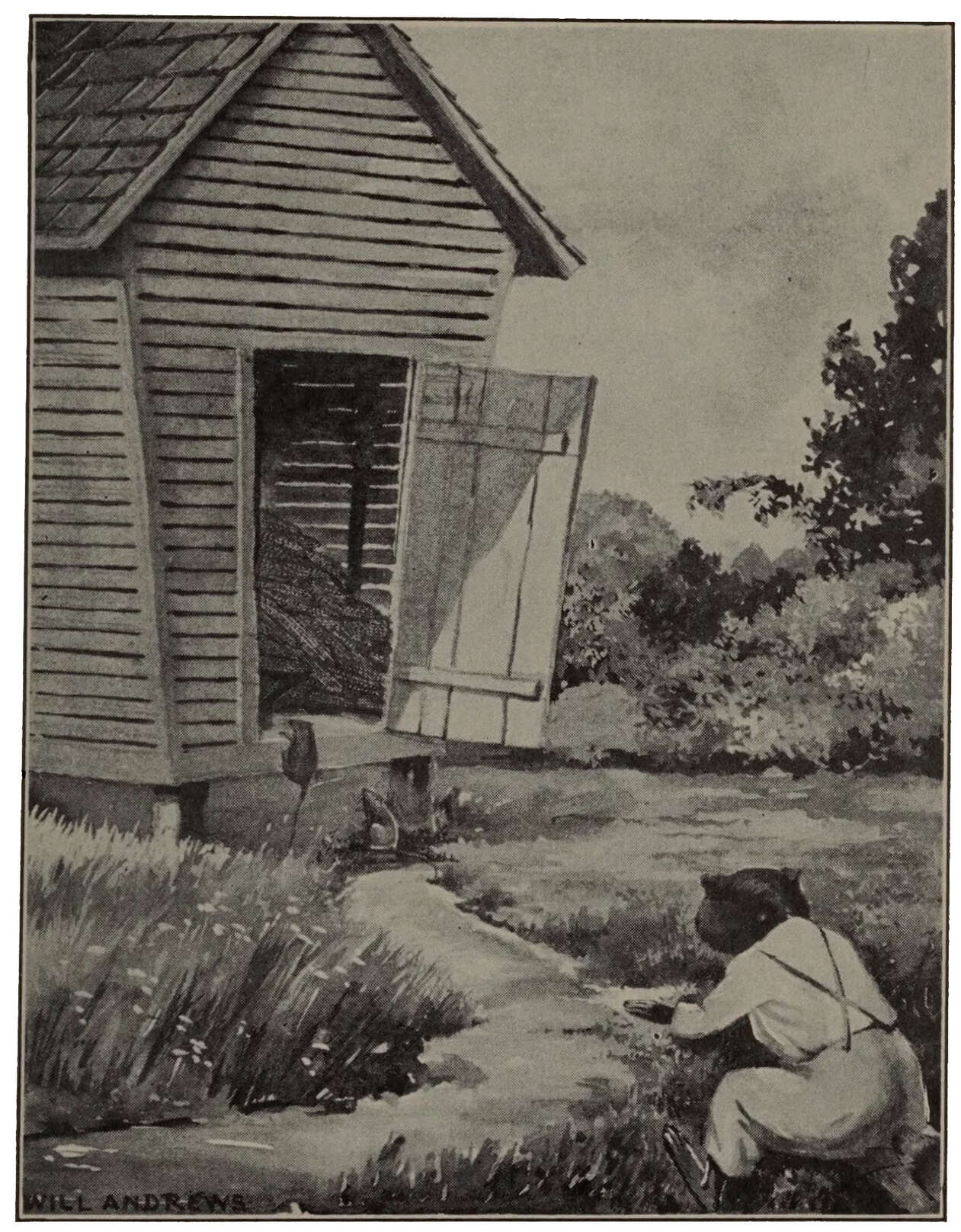

The hive had sent out a cloud of fighting bees to stand guard

Title: The Wavy Tailed Warrior

Author: John Breck

Illustrator: William T. Andrews

Release date: January 15, 2021 [eBook #64298]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Roger Frank

The hive had sent out a cloud of fighting bees to stand guard

“Scritch-scratch, scritch-scratch,” went a noise in the woods not very far away from the pond where Doctor Muskrat was telling a story to Nibble Rabbit and Stripes Skunk. Nibble’s ears flew up; the doctor got ready to dive; Stripes hunched himself up and peered anxiously over his shoulder because the sound came from the only direction where he knew of a hole to hide in. The willows, where he first lived, were over on the far side of the pond—and Stripes simply hates to swim. His tail gets all soggy, so it’s just as if you tried swimming with all your clothes on.

Scritch—r-r-rip! went the noise. Patter, patter, patter, came footsteps of somebody running. Then Nibble laughed. “Ho! It’s only old Tad Coon,” he said. “He’s in kind of a hurry.”

But when Tad Coon came out into the grassy space between the trees and the sand he was just strolling along as dignified as a duck in a puddle. “Morning, Doctor Muskrat,” he said politely. “Hello, Nibble. Who’s the visitor?” He knew all the time, but he was just pretending, to see what Stripes would do.

“This is Stripes Skunk,” said Nibble. “He wants to stay here and clean up the potato-bugs for Tommy Peele.”

“He does, does he?” Tad straddled his hind legs wide apart and sat back to stare at him in a most insulting way.

“Well, I hope you’ve warned all the birds. He’s the fellow who can keep their nests cleaned up for them.”

That made Stripes pretty angry. He turned half-way round and stamped his feet. “You’re mighty worried about them all of a sudden,” he snarled. “But I notice when the folks found those little dead chicks, they knew who to lay it to.”

“And I notice you were the one who killed them,” growled Tad with a crooked smile that showed all his teeth. He was getting ready to fight about it.

But wise old Doctor Muskrat just drawled in a sleepy, soothing voice, “As the grubby carp-fish said to the snapping-turtle, ‘My, but your nose is muddy!’”

That set Nibble Rabbit to giggling. “Hadn’t I better call the little owls?” he asked. “Then you can all throw mud at each other.”

“It’s mighty funny for you,” protested Tad Coon, “but as long as he stays here, that Skunk will be getting me into trouble.”

“No, I won’t. I did it in the first place because I was jealous. You could stay here and I couldn’t. But if I can stay, too, I won’t have anything to be jealous about, will I?” One thing about Stripes—he always tells the truth, you know.

“That’s so,” agreed Tad. “I’ll think about it.” Then he smiled the smile he has when he thinks about a joke. “Say, Stripes, do you like honey? I know where there is some.”

“Like honey?” You ought to have seen Stripes’ little pink tongue hang out at the very idea.

“Doctor Muskrat,” whispered Nibble when Tad and Stripes marched off, tail to tail, as companionable as though they’d never thought of fighting, “I’ve guessed Tad’s joke. He’s got those bees all angry—that was why he was running before he saw us. Now he’s going to set them on Stripes Skunk and have them chase him away, just as he set the striped buzzers with hot tails (paper-wasps he meant) on Trailer the Hound. Hadn’t I better warn him?”

“Now don’t you get to meddling, Nibble,” the doctor answered. “Those two will have to settle their own troubles. If Watch the Dog isn’t executioner of these woods and fields, neither are you their hen, to brood over them. You’re getting as bad as Jenny Wren in nesting season.” He said that because Jenny Wren is the fussiest thing in feathers, and she’s always scolding other people for not doing what she thinks is the proper way to do things. She nearly drives the meadowlarks wild by saying, “I told you so” every time someone finds their eggs that they hide in the long grass, just because she can’t make them take to nesting in her little squinchy dark knotholes.

“Just the same,” Nibble insisted, “I’m going to see what they’re doing,” And off he hopped.

But he didn’t hop so very far. For the bees had hung up their shelves upon shelves of little wax honey-bottles in the upper limb of the oak that was blown down in the Terrible Storm. Tad Coon had clawed off all the bark around their hole trying to reach his handy-paw into it. But he wasn’t going near it now—oh, no! He’d had one taste of their stings. And now the hive had sent out a swarm of fighting bees to stand guard. They were hanging in a noisy black cloud just above it.

Up went Stripes Skunk, balancing on the wide branch as nicely as you please, and he walked right into the middle of them. And then you should have heard them. They were fairly shrieking their sting song:

And bees always use it to work themselves up when they have a fight on so they’ll forget that as soon as they use their stings they’ll die.

“Oh!” cried Nibble. “He must be blinded. See what you’ve done with your jokes, you careless coon! This is worse than the one you played on Trailer.”

Even Tad Coon was shocked. He called, “Stripes, Stripes! come this way! Follow me! If you run through the brush they’ll leave you.”

But of course the bees were making such a noise Stripes Skunk couldn’t hear what he was saying. So he just called back, “I can’t reach in here—my paw’s too fat—but I have another idea.” Down he came. They could see him batting at the bees with his paddy paws until he popped into the big hollow in the oak’s trunk.

Tad Coon burst into tears when he saw the white tip-end of Stripes’ long wavy tail go into the hole. For a great big cloud of angry bees was pouring in after him. “He’s gone crazy. He’s gone crazy,” sobbed Tad. “This is the awfulest joke I ever played. Now he’ll be stung to death in that smelly black hole. It’s all my fault—why did I ever think of sending him up to meddle with their nest? Honest, I never meant to hurt him.”

Tad did truly feel so sorry for what he’d done that Nibble didn’t have the heart to scold him. “It isn’t entirely your fault,” he consoled. “Skunks do go crazy like quails and chickadees. Only he didn’t know what you did to Trailer the Hound, and I did. I ought to have warned him.”

“I—I just tho—thought it would be f—funny to see him run,” said poor Tad, gulping and choking.

But Tad Coon and Nibble Rabbit were wasting a lot of sympathy. For Stripes Skunk was perfectly happy. He just tucked his little pointy ears flat down against the sides of his head and took good care of his little black nose, and no bee could possibly hurt him. When Tad and Nibble saw him batting at the bees with his paws, as though he were trying to drive them away, he was only catching them. For Stripes knows more about the folks who wear two pairs of wings (that’s woods talk for most any kind of an insect) than any furry thing except the bats. Grab! He’d have a bee in his paddy paw that has a skin so thick her sting won’t go through it. Nip! and he’d munch the little bag of honey right out of her body. But the big luscious lumps of honeycomb were what he was really after.

And he knew right how he’d find them. You remember he was sleeping in that very hole in the bottom of the oak when he first met the little owls. But he hadn’t done any exploring. Now he said to himself, “If that limb is hollow way up to the hole where the bees come out I’ll go up inside and get the honey.” The tree was leaning because it had been blown down and was just raised a little on its branches, so he didn’t really have to climb—it was only walking up hill. Well——

The first thing Tad Coon knew, out walked Stripes Skunk, proud and pleased, with a great big comb of honey. And the bees were so busy inside, eating the drops he’d spilled, that they had forgotten all about him. Stripes dropped it down in front of Tad Coon. “Eat that,” he said. “There’s plenty more where it came from.”

Maybe you think Tad Coon didn’t? He just gorged on it and licked his whiskers.

All of a sudden Nibble thought of something. “Tad,” he chuckled, “this joke’s on you, too. Stripes asked you to be friends. Now he’s given you a present and you’ve eaten it. You’ve made a compact.”

“Did you think I wouldn’t make a compact with a nice smart beast like Stripes Skunk?” demanded Tad. “Of course we’re friends.”

“Tastes like more, doesn’t it?” grinned Stripes, watching him lick the last drops off his handy-paw. So he went in after another chunk of sweet, dripping honeycomb. And by this time their furry skins were feeling pretty tight. “There’s this about honey,” Stripes drawled, “you never know when you’ve had enough until you’ve had too much. Seems like we’d better stop off awhile.”

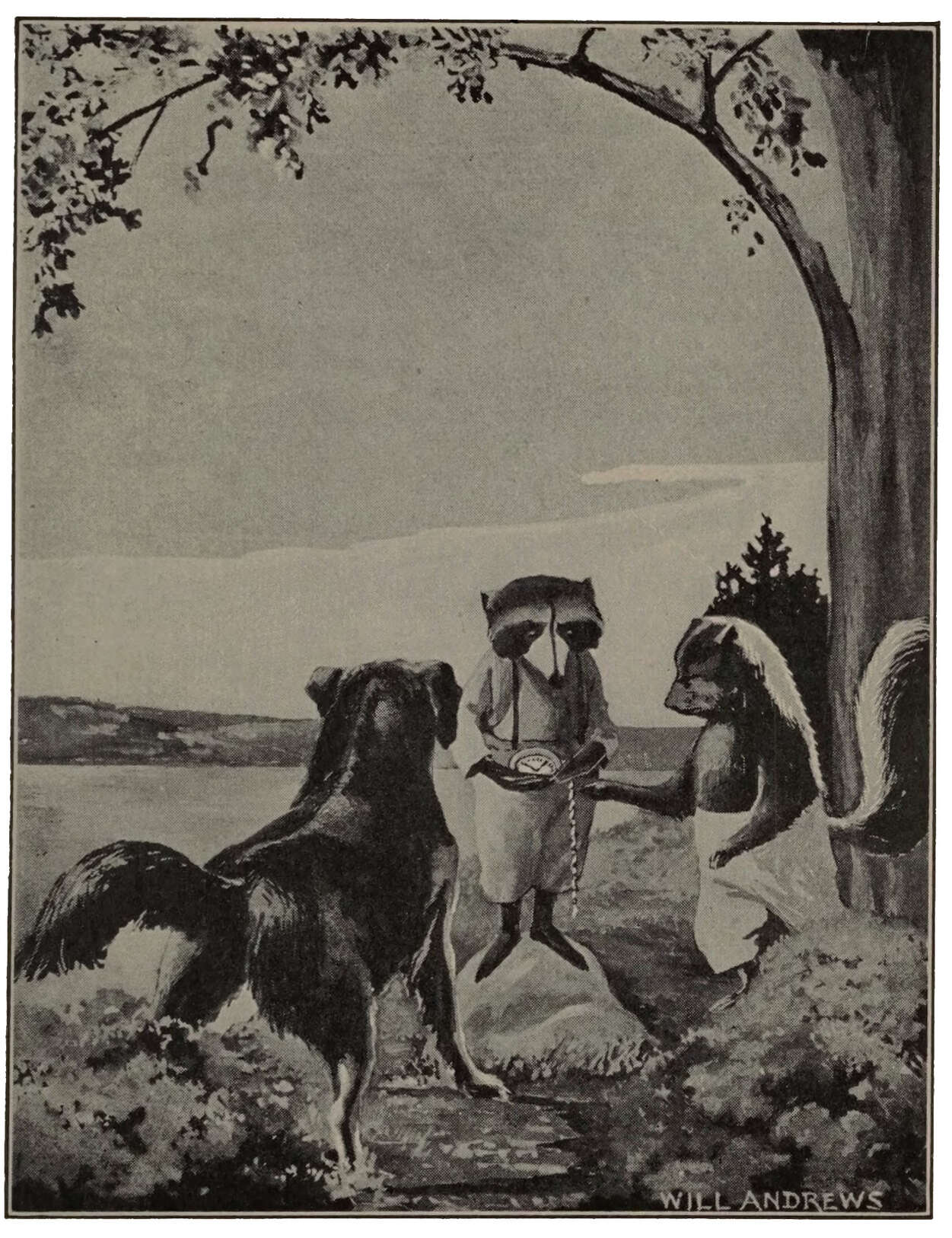

“Uh-huh,” mumbled Tad Coon, just a little bit doubtfully, because he’d never had enough to find out. The most he ever dares to do is to snoop out a mouthful and run. But he followed Stripes down to Doctor Muskrat’s pond, and they took a good drink and cleaned up their paws and their whiskers. Stripes sponged off his shiny black fur with his tongue, just as your cat does, but Tad splashed and splattered like a duck in a puddle.

First thing they knew, up popped Doctor Muskrat himself. “What do you think you’re doing?” he asked. Then he sniffed and tasted the water that was running off his nose. “What’s that funny smell?” he wanted to know. That’s how much honey was washing off Tad Coon.

“It’s honey,” Stripes explained. “Tad Coon showed me where it was and I got it for him, so now we’re friends. Wouldn’t you like some, too?”

“Me!” exclaimed the doctor. “Great Whiskered Catfish! Whatever would I do with it? Wash myself, like Tad Coon? Or give the mussels a treat so they’d keep their shelly mouths open? I wouldn’t eat it, you know; plants and fish are enough for me.”

“But this is plants,” Tad explained eagerly. He wanted an excuse to send Stripes Skunk back for some more. “The flowers make it and the bees suck it out of them and store it away to eat in the wintertime. Flowers are plants, you know.”

“Yes, I know,” grinned the doctor. “Every one of those big white waterlily flowers tells me that she has a perfectly delicious root down in the bottom of the pond. But I’ve never found any honey in them.”

Stripes looked over and saw the bees buzzing among the lilypads. “That’s just because you never looked,” he protested. “It’s down beneath their fuzzy yellow collars.” He meant their stamens, you know.

Plop went the old muskrat. Back he came, making the pool dance in the ripples behind his busy paddle-paws, and towing a waterlily. “Where’s the honey in that, Tad Coon?” he demanded. “You’re too much of a joker for me to believe any of your fairy tales.” And sure enough, there wasn’t a single drop.

Maybe you think Stripes and Tad weren’t puzzled! They’d always heard that the bees got their honey out of flowers.

“You needn’t think you can fool me like that, you smarty coon,” chuckled the wise old muskrat.

“But I’ve always believed it,” pleaded Tad. He thought it was because he was always playing jokes that when he tried to tell the truth no one would listen.

“Ho, ho! You did, did you?” teased the doctor. “Some bee must have been buzzing around your ears, then. They’ll tell you most any kind of a tale to keep you from learning the truth about their secret. They’re so afraid someone will listen that they never sing the words of their honey song. They only hum it. And half of the hives don’t even know them. They come to my waterlily patch for the same thing the wasps do. A wasp once told me that the yellow dust you got on your nose when you went to smell for the honey was the best food in the world for growing youngsters.”

“That’s so,” agreed Stripes Skunk with his funny little three-cornered ears pricked right straight up. “I find it on their legs most every time I catch them. Just the same, I do taste honey in most every bee I eat.”

“Eat bees!” sniffed Doctor Muskrat, turning up his whiskery nose. “Eat bees? You’re as poor a story teller as Tad Coon.”

Of course Stripes had to scramble around and catch one. Tad ate one, too, and he solemnly insisted he could taste the honey as plain as plain.

“What does that prove?” argued the doctor. “If it proves anything it goes to show that honey is a sort of milk from a well-fed bee.”

“That’s so!” agreed Tad. “It’s certainly much more sensible than that old fairy tale about the flowers. I believe we’ve guessed their secret. Let’s get some more, Stripes, and make sure.”

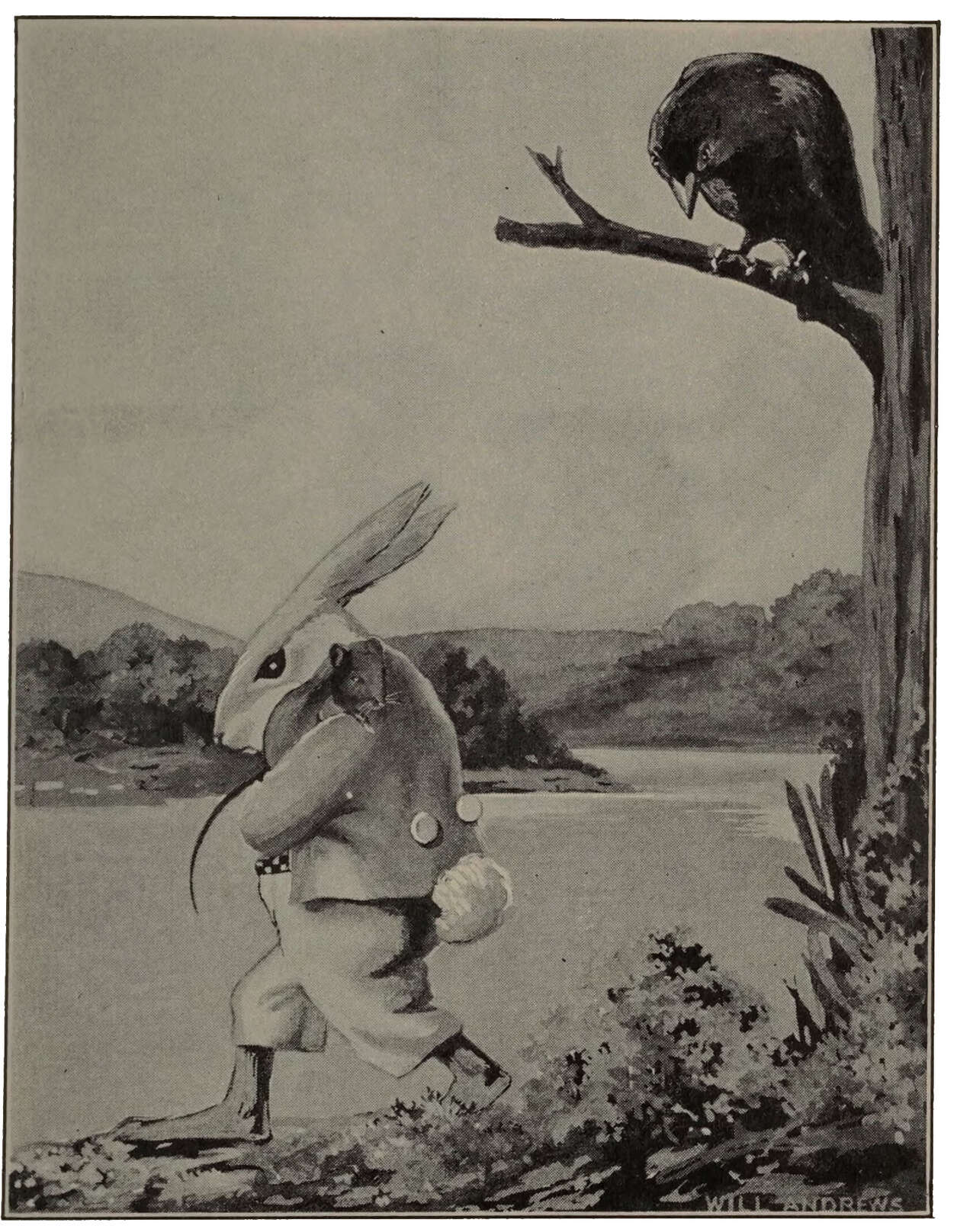

So off they went. And back they came. Stripes had such a mouthful of honeycomb he couldn’t run, and Tad’s piece was so luscious and crumbly he had to carry it in both of his handy-paws and walk on his hind feet like a little bear. They laid it down on Doctor Muskrat’s flat stone, and just as they were about to gorge on it again, along came Nibble Rabbit, lippity-lippity, all out of breath.

“Hello, Nibble. You’re just in time to eat,” said Tad Coon.

“No, thanks,” gasped Nibble, shaking his floppy ears. “I guess I’ll take mine straight out of the clover blossoms, the way I always do.”

“From clover blossoms?” squealed Tad. “Do they have honey? Waterlillies don’t. We looked to see.”

“Well, that’s the first flower ever I heard of that didn’t,” said Nibble, looking quite surprised, because he thought that was something everybody knew.

“Bees’ milk!” whooped Doctor Muskrat. And he let go that laugh he’d been holding in for so long. “Tad Coon believed honey was milk from a bee! O Tad Coon!”

I tell you what, Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat had a lot of fun teasing Tad Coon because he didn’t really know where honey came from.

All the woods and fields knew perfectly well that the little furry bat is the only thing in the world with both milk and wings. But Tad didn’t stop to think. He wouldn’t even stop to eat, he was so busy chasing Doctor Muskrat into the pond. And Doctor Muskrat laughed so hard he got water into his throat and had to climb out on his last winter’s house to cough. And when he couldn’t talk he kept splashing water at them with his scaly tail.

Well, they made so much noise that they didn’t hear who was coming. And Nibble Rabbit was so taken up with the joke on Tad Coon that he forgot to tell them. The first thing they knew, “Woof!” went a voice, and there was Watch the Dog and Tommy Peele.

You remember Tad Coon tried to get the bees after Stripes Skunk because he wanted to see him run? Well, Stripes certainly did run then. He’d been licking up little crumbs of tasty honeycomb and little trickles of honey from Doctor Muskrat’s flat stone, just getting ready for the time when he’d plunge his nose, sqush! right into the delicious middle of his piece. But he didn’t wait for that. He left it for Tommy Peele to find.

And Tommy found it. He found the crummy, broken piece that Tad Coon carried hugged against his furry body with his little handy-paws until it was all hairs, and he found the nice neat lump that belonged to Stripes Skunk lying right beside it. Of course that was the one he’d choose—Tommy liked honey quite as well as any one else. So he ate it—before Watch even thought to take a sniff.

Out of the bushes tiptoed Stripes Skunk, sort of timid, but hopeful.

The minute Watch saw him he knew something was wrong. “Yah! Get away, you, or I’ll chase you away!” he growled. You know he’d never made friends with Stripes and he didn’t intend to, either.

“But that Man took my honey,” said Stripes in his scary, whiney voice. “And Tad says that’s the way he makes friends.”

“Wah! What if he did? He didn’t know that.” Watch was snarling, snapping angry. “Do you ’spose for a minute I’d have let him if I’d known it was yours? We thought it was Tad Coon’s.”

Tommy fished and fished, but at first he did not get a single bite

Poor Stripes was shaking to the very end of his long wavy tail. He looked hopefully at Tommy Peele, but Tommy hadn’t even looked up. He was too busy digging for something. So there was nothing for Stripes to do but slink back into his bushes again and cock his eye through a little opening in the leaves to see what he was doing. And Watch didn’t try to follow because he had to dig, too.

Tommy was so interested in his digging, that all the beasts started to help him. Tommy grubbed a bit with his fingers and then he took a stick to get on faster. That’s because his hands aren’t any better for burrowing than Tad Coon’s handy-paws. Watch was making fine scratchy holes every here and there and snorting into them, trying to see what Tommy wanted to find.

Doctor Muskrat dug up a sweet flag root, and Nibble Rabbit unearthed a butterfly weed, but those weren’t what Tommy wanted. Tad Coon found a fine fat grub, but Tommy didn’t want that either, so Tad ate it himself. Then Tommy shook the earth off of a long, squirmy worm.

“Oh, oh,” laughed Nibble Rabbit. “Everybody’s here to help except the one we need. We must have Tommy make friends with Bobby Robin. He eats those all the time.”

But Tommy didn’t eat it. He put it on something on the end of a string and threw it into Doctor Muskrat’s pond. He was going to go fishing. He didn’t bother about a fishpole because he’d rather perch on the trunk of a tree that was leaning over the water and watch the fish come up to nibble. And the tree was right on the edge of the very bushes which were hiding Stripes Skunk.

Tommy fished and fished, but at first he didn’t get a single bite. By and by who should guess what he was trying to do but that smarty coon? “Watch,” he said to the dog, “he’s trying to snare something, isn’t he? Is it shellbacks or flicker-tails?” That’s woods slang for turtles or fish.

“Oh, yes,” squealed Nibble Rabbit, thumping his feet with excitement. “He’s going to catch them on that wire, like he caught me—like Bob White Quail.”

“Looks that way, doesn’t it?” commented Doctor Muskrat. “Which does he want to catch, then?”

“I don’t know,” answered Watch. “Does it make any difference?”

“Difference?” exclaimed Doctor Muskrat, who’s an expert at any kind of fishing. “It makes all the difference in the world. The shellbacks don’t care who’s above them so long as there’s water enough to swim in, but the finny folks won’t come where there’s a moving shadow until they know the meaning of it. Tell Tommy to move farther out so that branch reaches over him.”

This seemed so sensible that Watch nudged Tommy a little farther along on the tree trunk. And it wasn’t more than a minute before the fish came nosing around, peering up to be sure he had left them. First a school of little shiny minnows came nibbling. Suddenly they scattered. A big pickery back-fin had jogged by in the eel grass and it wasn’t quite hidden.

“Hssh!” breathed Doctor Muskrat, craning his neck. “It’s that big bass. Nibble Rabbit, if you dare to thump again, I’ll—I’ll——”

Everyone was fairly holding his breath. Tad Coon and Doctor Muskrat, who both fish for themselves, were mighty interested to see how Tommy was going to catch that bass. Doctor Muskrat was in the shadow of a cattail where he could see it. Tad was sitting up on his hind legs like Chatter Squirrel, trying to see without letting the fish see him. Watch didn’t even wag his tail and Nibble was trying to remember not to thump his feet or let his ears fly up, the way he always does when he’s excited. My, but his tickly nose was twitching! Even Stripes Skunk, hidden in the bushes, had his ears pricked, listening for what was going to happen.

“What’s he doing now?” breathed Nibble. “What’s he doing?”

“Hssh! He’s looking,” said Doctor Muskrat, putting up a paddle-paw to keep Nibble quiet. “The least little wiggle will scare him. He’s turning; he’s coming; he’s bit—Ow-w-w! Wonderful! Hold on! Hold on!” For that big bass nearly yanked Tommy Peele out of the tree when he found Tommy had caught him.

And then the noise did burst out. Everybody was bouncing and thumping and barking and squealing, getting into everybody’s way, trying to keep out of Tommy’s. And Tommy was trying to hold on to that fish line while he scrambled back to the ground where he could do some strong hauling. And the great big bass was jerking and jabbing and pulling and fighting, trying to get away from him.

And not a single one of them succeeded. Tad Coon got under Watch’s dancy paws; and Watch tripped Tommy Peele; and Tommy Peele went splash right into the pond; and that great big bass jumped, splash, right out of it. But he didn’t get away! Not with all those fellows after him!

For just as Tommy fell he threw up his hand to keep his fish line from being tangled. And that was just when the fish was jumping. You’d better believe he made a great big jump that time. He jumped in a great big half-circle right up into the bushes where Stripes Skunk was hiding. And then he began flouncing and bouncing to get back into the water again. And of course Stripes Skunk, who fishes a bit his own self, went to stop him.

Then there was a battle! The big bass snapped and flapped and put up all his pickery spines on his back fin. And Stripes Skunk slawed him and pawed him, trying to spear his toenails into those slippery, slidy scales to hold him. And Doctor Muskrat slapped his tail and fairly barked with excitement. “Bite him behind the eyes, Stripes! Bite him behind the eyes!” And at last Stripes got his teeth on the big roach of neck that begins just behind a fish’s eyes and bit. The bass gave one tremendous flap that sent the dust and sand and dead grass flying, and lay still.

But you ought to have seen Tommy Peele. He didn’t know what to do about it. Here was a strange beast he didn’t know at all, a small black beast that looked something like a pussy cat, only it had the most beautiful long, dark fur, with a wide white stripe parted behind its ears and running all the way down to the round white tip of its wonderful plumy tail. “Better let go that fish,” Tommy advised. “You certainly are a good fighter, but if you try to eat it you’ll get a fishhook in your own mouth, and there certainly will be trouble.”

Stripes battles with a big fish

Now of course Stripes didn’t know what Tommy meant. But he knew it was Tommy’s fish in the first place, and besides, Watch the Dog was just trembling on the tips of his toes because he wanted to snatch it back for Tommy. Only he didn’t have to. For Stripes was glad enough to put it down and stretch his tired neck and get the cramp out of his jaws that were stiff from gripping it. And when he yawned Tommy could see his pink throat and his pointy tongue—and some little hurty, bleedy spots where that pickery back-fin had stuck into him.

And there was Doctor Muskrat waddling up beside him to sniff the bass and say: “Well bitten, Stripes—very well bitten, indeed!” and Tad Coon was sort of chuckling in his throat: “By Tadpoles, Stripes, I’m glad you never tried to fight with me,” and Nibble was fairly purring, “I’m proud of you, Stripes. This is one more joke on Tad Coon. He said you didn’t know what teeth were for.” Even Watch wasn’t quite sure that he oughtn’t to be ashamed of himself for growling. He looked to see what Tommy Peele was going to do.

Tommy pulled in his line and took the hook out of the fish’s mouth—and then maybe you think they weren’t curious about it! “Aha!” said the wise old muskrat. “I thought it wasn’t just like the wire that caught you, Nibble. A fish is so slippy I couldn’t see how that would hold him. This is cold and smelly, like the cold jaws that caught me. Better not get too close to it.” And that’s just about what Tommy said when Tad Coon wanted to take the shiny thing in his handy-paws to look at it. And when Stripes Skunk saw that none of the others was afraid, he came closer, too, and crinkled up his nose at it.

That made Tommy laugh. “He’s friends,” shouted Nibble. “A man always makes friends when he laughs at you.” And Watch knew that, because it’s how the first dog made friends with the man and his wife and his baby in the First-Off Beginning.

Tommy looked at the bass and then he looked at Stripes Skunk again. He tossed it right beneath Stripes’ crinkly nose and said: “I believe you want this. Well, you can have it. There are lots more fish in Doctor Muskrat’s pond, and I just love fishing.” So Stripes knew Nibble Rabbit was right.

I guess you’d have liked to go fishing that sunny afternoon down by Doctor Muskrat’s pond your own self—I just believe you would! Tommy perched on the trunk of the tree again and did the fishing. Doctor Muskrat was cuddled down under the bulrushes most interested to see how Tommy did it. Nibble was nipping the tops of clovers, with an ear cocked so he wouldn’t miss any of the excitement when Tommy caught one—not that he cared for fish, but some other fellows did.

Tad and Stripes had eaten the great big bass, and now Tad was dozing, flat on his back in the sun, with his handy-paws folded over his fat tummy, and Stripes was curled up as tight as his fullness would let him, with his wavy tail over his shiny black nose, to keep the flies off it.

Even Watch was contented. He was napping, too. Sometimes he squirmed and growled to himself because he didn’t approve one little bit of having Tommy make friends with a bad Thing-from-Under-the-Earth like Stripes Skunk. It was plenty bad enough to have him make friends with mischievous Tad Coon! But Watch was happy all the same.

Pretty soon Stripes opened his shiny black eyes; he stretched himself and yawned. A leaf blew past and he pounced on it like a kitten. Then a grasshopper clicked up and he chased it. Next he took to playing with some leaves that were dancing in the wind, and then he took after his own plumy tail, whirling round and round in a mad little dance of his own, humming a little tune that was a happy, not a whiny, one.

Watch pricked up his ears because he was so surprised to think Stripes could sing—Bad Ones can’t, you know. And his own tail began to beat in time to Stripes’ patty little feet. So Stripes slyly pounced on it. Well, you know what happened then! Watch began to chase him. Only he couldn’t chase very fast because Stripes does look so funny when he’s running. His fur fluffs up and his hind feet are pigeon-toed, and his draggy, wavy tail goes flourishing in and out between them.

First Stripes got scared, but pretty soon he saw even Watch was laughing. And Watch tipped him right over on his back and snooted him in the ribs like he does the kittens. “You silly old thing,” he chuckled. “I won’t make any better compact with you than I did with Tad Coon, but I won’t hurt you while you behave yourself.”

“I’ll show you how I’ll behave,” said Stripes, and he deliberately boxed Watch’s big ear, just to show that he wasn’t afraid of him. And Tommy Peele ’most fell into the pond all over again, he was laughing so hard at them. They all made so much noise that the spotty blue kingfisher came over to cock his crest and see what they were doing. He and Doctor Muskrat gave Tommy a lot of good advice, only of course he didn’t understand it. But he did know they were very friendly, and that was the main thing.

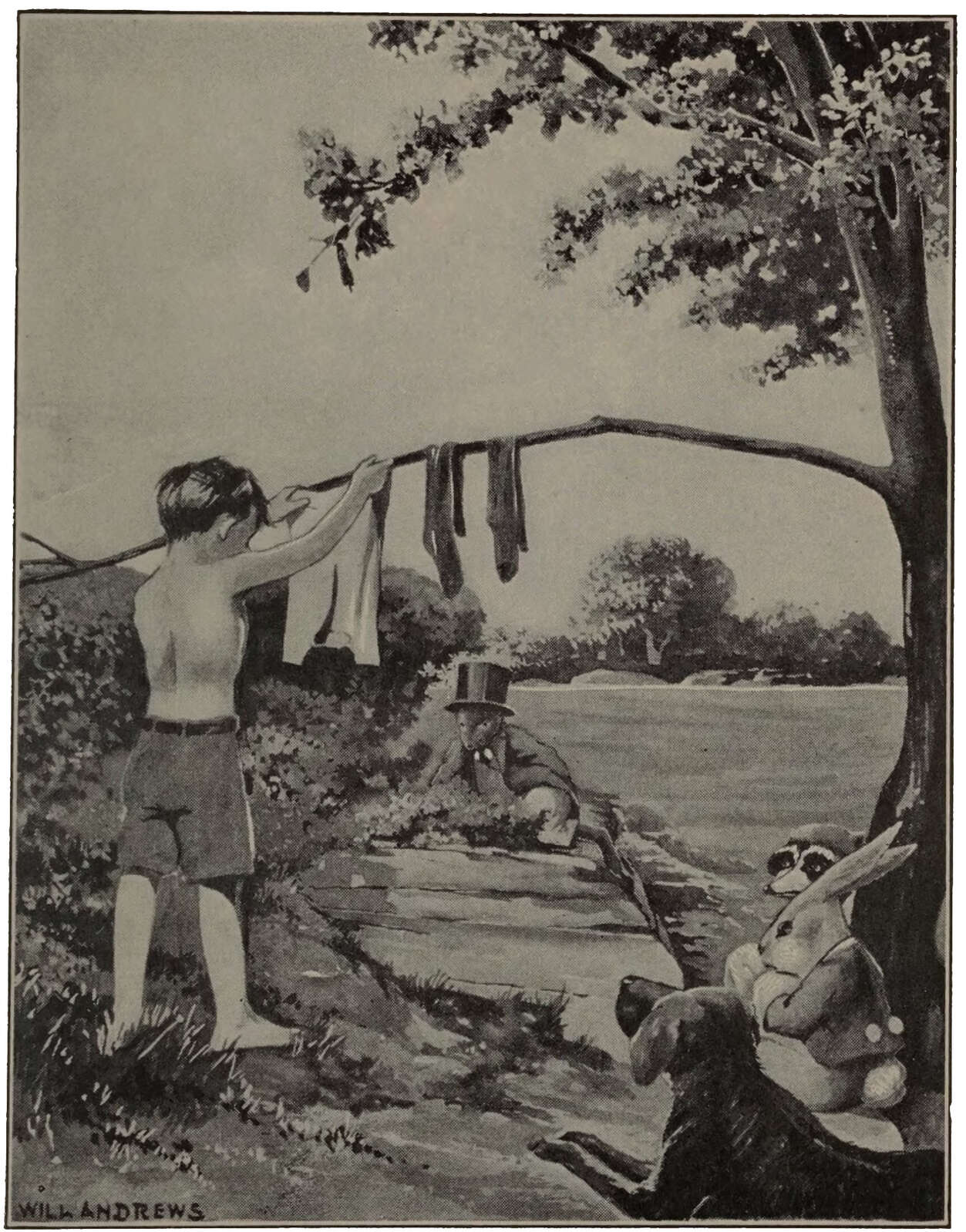

Somebody’s always falling into Doctor Muskrat’s pond. Nibble Rabbit did it the very first time he saw Doctor Muskrat. So did Tommy Peele, as I have just told you—but Tommy didn’t care a bit. Only he didn’t want to go home with his clothes all drippy, because his mother would make him drink some yarrow tea, to keep him from catching cold, you know. And it’s every bit as bad as the dose the old doctor gave Nibble. It doesn’t “taste like more”; it tastes like “never again!” So he took off his wettest things and hung them out in the sun to dry.

Tommy takes off his “skin” to dry

You ought to have seen Nibble Rabbit and Stripes Skunk and Tad Coon all stare at him. Even Doctor Muskrat was s’prised. “Here, Watch,” he said to Tommy’s dog, “don’t let him skin himself—he’ll die!”

“Ho, that isn’t his skin,” laughed Watch; “that’s just his fur. He does it every night. I know, because I sleep in his room—that’s a kind of a cage he sleeps in—so I see him.”

“Good gracious!” exclaimed Doctor Muskrat. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” put in Nibble Rabbit. “Chatter Squirrel said he’d seen men this way. He told me about them the night we were all in my little cornstalk tent, hiding from the terrible storm. He said they had skin like a frog, only tan, like my throat, or pink, like the inside of my mouth. Tommy’s a little of both.”

So he was. He was getting a fine spotty sunburn. But he wasn’t nearly as pink as he would have been if he’d gone swimming, like the boys Chatter Squirrel had seen. Only you can’t swim and catch fish at the same time. You scare them.

And Tommy was having such fun fishing, he wasn’t thinking about swimming or anything else. He even forgot all about the big shiny watch he had in his pants pocket. You know the kind—a big, cheap, noisy thing that took much more than a ducking to stop it. And it was fastened to them with a jingly chain.

Well, it was Nibble Rabbit’s long stick-up ears that heard it. My, but that was a funny sound! It was Tad Coon’s handy-paw that went after it. My, but that was a queer shaped, slippery-feeling thing! And it was Stripes Skunk who guessed what it really was.

“It’s a bug,” said Stripes after he’d sniffed his pointy nose against it and tried his teeth on it. “I never saw one just like it, but a bug it is. Lots of them make that sort of a ticky noise when they’re ready to bite open their hard cases and shake out their wings. This one must be just about ready by the noise he’s making.” And he scrooched down his ear to listen.

“I never heard them do that,” said Nibble Rabbit.

“Course not. They’re buried in the ground when they do it,” said Tad. “We dig ’em up and eat ’em.”

“Maybe Watch will remember where Tommy found it,” Nibble suggested.

“He wouldn’t pay any ’tention if he couldn’t eat it or chase it,” sniffed Tad. He was afraid Watch would take that shiny, noisy watch away from them and he wanted it to play with. “Tell you what, Stripes. Let’s bury it, and then when it comes out it’ll go right to laying its eggs, and we’ll have lots more just like it.”

“Sure,” agreed Stripes, and he went to digging. Nibble helped a little, too. He’d seen Tommy put a clam in his pocket—the one Tad Coon had given him, you know—so he didn’t think this was at all out of the way. Besides, if it was a bug and it did come out of its case in Tommy’s pocket it might bite him. And believe me, that watch was big enough to hold a mighty big bug.

They dug a nice hole and they buried Tommy Peele’s watch down in it and patted the earth smooth. Then Tad Coon lay down right on top of it so he’d be there when the thing that was making a noise inside of it came out.

By and by the fish stopped biting and the mosquitoes began. Tommy could hear Louie Thomson over in his own field calling his cows.

Well, Tommy thought he’d better look at his watch and see if it was time to go home. He’d left it in his pants pocket, tied to them with a jingly chain. His pants were on the ground beside Tad Coon, and Tad was asleep—he never opened his eyes, he just squinched them tighter shut than ever. When Tommy went to pick them up they wouldn’t come; because they were tied to his watch with that jingly chain. And the watch wasn’t in his pocket; it was buried right underneath Tad Coon.

When Tad saw Tommy was bound to have it he got up and looked around, as s’prised as could be. “’Scuse me,” said he; “was I in your way? Are you looking for something?” And when Tommy began to dig up the watch, Tad dug, too, quite politely, as though he were glad to help him find it.

But he didn’t fool Tommy’s dog. Watch said: “Tad Coon, what have you been doing?”

“I was just burying that bug. You can hear it making a noise inside the hard case Tommy’s dug up again,” owned Tad. “It would come out if he’d let me take care of it.”

By this time the dog could see the shiny, noisy watch ticking away on the end of its jingly chain. “You silly thing!” he barked. And he made so much noise that Louis Thomson let his cows go up to the barn alone and came to the fence to see what was happening. He didn’t come over it because Tommy Peele wouldn’t let him. But he climbed up on top of it, and saw Tad Coon grabbing at Tommy’s shiny watch.

“There is a bug inside,” Tad was saying. “Stripes says so, too, don’t you, Stripes?”

“It sounds like one,” answered Stripes, cocking his ears, and Nibble and Doctor Muskrat both agreed that it didn’t seem like anything else they had ever heard.

But Tommy’s dog just jeered. “Bug! It was doing that when the deep snow was all over the ground and there wasn’t a bug stirring.”

Tad Coon wouldn’t believe him. He turned it over in his handy-paws and sniffed and listened again. “It is, too, a bug,” he insisted. “And it’ll come out very soon. I can see the crack it’s making.” He meant the place where the back comes open.

By this time Tommy Peele could see what he wanted; so he opened his watch and showed Tad the little wheels that made all the ticking. And then wasn’t Tad Coon more puzzled than before. It certainly wasn’t a bug—but what was it?

Even Tommy’s very own dog didn’t know that. “It talks all the time,” he explained. “I can’t ever hear it say anything different, but it seems to tell Tommy to go and do something.”

Sure enough, Tommy Peele looked at his watch and whistled. “Hey,” said he, “I didn’t know it was so late. We ought to go up and do our milking.”

He was just slipping it back into his pocket when Louie Thomson called out, “Please, Tommy, let me come over and see your animals. Honest, I won’t hurt ’em.”

Splash went Doctor Muskrat into his pond. Flick went Nibble into the Pickery Things. Scratchy-scramble went Tad Coon up into a tree. Te-flap, te-flap went Stripes Skunk for his hollow oak, his pigeon-toed feet just slapping the ground and his long draggly tail trailing between them. Nobody stayed but Tommy’s dog, and he was bristling and growling.

“Aw, gee!” said the bad boy. “I only wanted a look at that cute one who was clawin’ at you. How’d you make ’em come to you?”

Tad Coon finds a new kind of bug

“I don’t,” said Tommy. “Maybe it’s because I feed them.” You see he didn’t know he’d made any compacts with them. Nobody could explain them to him. But it didn’t matter, because he really meant to keep them.

“What do you feed them?” said Louie. “I wish they’d be like that with me.”

“Gr-r-r!” growled Tommy’s dog. “It’s all sticks and no bones wherever you are. You’d have a better chance of making friends if you’d say, ‘Wisht I’d be like that with them.’” But even Tommy didn’t understand him.

You never saw any one so puzzled as Stripes Skunk and Tad Coon after Tommy had gone running back to the barn to milk his cows with that shiny watch ticking away in his pocket. “I didn’t hear it tell Tommy to do anything,” said Tad. “It was just saying the same thing over and over again all the time.” Because it made a noise Tad thought of course the watch was talking. He never knew the black marks on its face meant anything more to Tommy than Tommy would have known the black spots on a nice little orange-coloured ladybug meant anything to Tad Coon.

Stripes Skunk was squinting thoughtfully at one with his head on one side, and he knew what those spots meant; they meant that you mustn’t eat it. By and by he said, “It told me something. It told me that I must keep on the lookout for Tommy Peele’s potato bugs. They make just that kind of a noise when you squeeze ’em. And I’ll have to be mighty careful not to let ’em lay any eggs. They’re horrid things. I couldn’t eat very many of ’em.” So off he pattered to look at them.

Now a potato bug is a second cousin to the nice spotty ladybug—you know her all right enough. You sing that song, “Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home; your house is on fire and your children will burn.” And sure enough, she’ll lift her stiff black and orange skirts and shake out the wings she keeps tucked up under them so they won’t get draggled when she’s walking, and go off in a hurry.

But the potato bug isn’t pretty and he isn’t nice. He’s mustard-yellow, with three stripes, which mean that some folks can eat him, and a pair of dots which mean that most folks can’t. Just before the first frost in the fall he burrows down under the Earth-that-is common-to-all and makes himself a little house, snugly waterproofed with varnish against the rains. There he learns all sorts of tricks from the Bad Ones who are always making Mother Nature so much trouble.

When it comes time to creep out in the spring he knows she has guards out watching for him. Because his wife lays eggs that look like little clusters of yellow bananas and taste so good that she has to be mighty careful about hiding them. But there’s no end of trouble if they hatch, for nobody can eat his dirty little six-legged caterpillar children.

So he sends out spies to be sure the coast is clear and, when no one is looking, out marches a whole yellow-uniformed army that swarms all over the potato plant’s neat green leaves. And the army gnaws and nibbles and fights and scrambles to do all the harm and lay all the eggs it possibly can before Mother Nature’s fighters can come to rescue the poor potato plants.

Stripes had hunted a long time before he found a single spy just a few days before; now he was surrounded by a whole potato bug army. Tommy Peele’s potato patch was besieged! And there was no one to stop the enemy but a couple of meadowlarks. Even they gave up in despair when they saw Stripes march in, for the skunks are old foes of the meadowlarks. He was alone!

And he felt mighty discouraged, I can tell you. But he’d promised to fight them, so he set to work all alone, eating them as fast as ever he could lay a paw on them. That’s about the only way Mother Nature teaches her creatures to destroy such things.

My—they tasted strong! He felt sicker and sicker with every one. It grew dark and they hid so he could hardly find them—still he kept on eating. But at last they began to burn like fire inside him. He had just enough strength to stagger down to Doctor Muskrat’s pond—and the next thing he knew the sun was shining!

Stripes lay there in a sort of a daze, trying to think just what had happened to him. There was a queer, far-away sound in his poor little loppy, sick ears—but when he opened his eyes there was Bob White Quail standing right beside him. “What’s the matter, Stripes?” he was asking.

Suddenly Stripes could remember everything—those horrible hundreds and hundreds of potato bugs gnawing and squirming and swarming all around him. “I’m sick,” he moaned. “I promised to keep the bugs off Tommy Peele’s potatoes—but they’re too many for me. I’m beaten. Now I’ll have to go away and never come back here again.” And the tears began to trickle down his pointy nose and drip on his paddy-paws.

“You won’t, either,” snapped Bob White. “You saved me from dying in that wire snare. I haven’t forgotten that. Besides, those potato bugs are some of my own business. Get Doctor Muskrat to give you some medicine and then come and see what we quail-folk are doing.” He raised the covey-call, “Prr-whit! Prr-whit!” and off he flew to the Quail’s Thicket.

It didn’t take Bob White long to lay down the law to the quail-folk. In about the time it takes to swallow a seed they were whirring off in every direction. Bob White himself went to find those fly-away meadowlarks. “What do you mean by deserting like that in the face of the potato bug army?” he demanded. My, but his voice sounded pecky!

“We flew away because that terrible skunk came to help them,” fluttered the larks. “There was no use trying to fight him!”

“You didn’t have to fight him,” raged Bob White. “You only had to fight with him. You foolish, cowardly tip-tails! He’d come to help you!”

“To help us?” squawked the meadowlarks. “That beast! That beast who smashes our eggs and kills our mates and eats our young? We’d as soon expect help of Glider the Blacksnake.”

“You would, would you?” Bob White’s beak clicked dangerously.

“Well, it’s time you learned that skunk is a special one. He saved my life, and all the quail trust him. You get every meadowlark in all the woods and fields and the marsh beyond and go back to your fighting. Hear me?” And he looked so ruffly they didn’t even dare to answer him.

The next one to find poor sick after Bob White Quail had flown away, was Nibble Rabbit. “Hey, Stripes,” he said, “whatever is the matter?”

“I tried to eat all the potato bugs to keep my promise to help Tommy Peele—’deed and I did, Nibble. But I got too many inside of me all at once. They squirm and sting!”

Well, it didn’t take Nibble long to call Doctor Muskrat. And it didn’t take Doctor Muskrat long to stop the “squirming and stinging” Stripes thought was going on inside him. “You certainly prove that fighting those click-wings isn’t your regular job,” he said. “You can’t gorge on them. You must never eat more than three at a time without eating something else in between. Any meadowlark could tell you that.”

“They could, but they wouldn’t,” Stripes sniffed. He was feeling much better. “They flew away when they saw me coming.”

“They did?” cried Nibble. “Well, they’ve all come back again. You just ought to hear them. They’re——”

“Che-e-ep!” interrupted Bobby Robin, swooping down for a drink. “Ugh! I’m glad that’s over with!”

“What’s over with?” Doctor Muskrat was surprised to see how much he was drinking.

“Eating a potato bug!” chirped Bobby Robin. “I told that quail none of us thrushes could eat ’em, but he wouldn’t listen. He’s ruffling about like a kingbird, and he says he’ll peck the eyes out of any bird who refuses to try one. You just ought to see what’s going on and who he’s got to help him! But I must be flitting.”

“Where to?” asked Stripes. By now he was taking an interest in things.

“To send over everything I can find that has feathers in its wings,” said Bobby Robin. “Bob White needs ’em.”

And before he’d flown past Tad Coon’s tree, along came Miau the Catbird and told them exactly the same tale. And that cheered Stripes so much that he got up on his wobbly legs and staggered over to see what was going on.

He saw—oh, I can’t tell you everything he saw. For there were orange orioles and dark-red orioles and scarlet-red tanagers and blue-and-red bluebirds, and fawn-coloured cedarbirds, and black-and-white-and-tan bobolinks all eating and shouting, with the meadowlarks flying around as thick as gnats on a summer night, calling, “Catch ’em and e-e-eat ’em up!”

He saw Chewee the Chickadee leading a regiment of gorgeous black and white and blue and yellow and orange and green warblers in and out through the dark green leaves of the potato plants, urging them to “Pick! Peck! Pick all you see-ee-ee!” It was eggs Chewee was hunting. Every once in a while a whole cloud of birds would go winging off to feed in the woods and the grain-fields, and another cloud would come in and settle down to eating the potato-bug army again.

“Those good birds!” Stripes squealed joyfully, “I’ll never eat another egg!”

He was so grateful he just had to tell the first bird he met. That was Chaik the Bluejay, who was perched on a wild-apple tree in the fencerow. “Those nice, good birds,” he said. “I’m going right over to thank them.”

“Don’t you do it,” warned Chaik. “Don’t you say a word till they’re all finished, or they’ll fly away and never come back at all. They aren’t doing this for you; they’re doing it for Bob White Quail. If they thought for a minute it was because Bob White wanted you to stay here they’d say he was crazy.”

“I guess you’re right,” Stripes agreed sadly. “The meadowlarks flew away yesterday the very first minute they saw me. All the same I just wish they knew I hadn’t touched an egg since I came here—’cepting only Bob White’s and I paid up for those. And I never will again. What’s more, I won’t let any one else if I know anything about it. If they’d only let me bring my family to help I think we could even keep Slyfoot the Mink away.”

“Don’t mention it,” exclaimed Chaik. “I know birds. You can’t reason with them. They wouldn’t think of it. They wouldn’t even hear you.”

They’d been moving along as they talked, getting closer and closer to where the birds were busiest and noisiest.

“I can hear them all right enough,” Stripes had to shout. “Did you ever listen to such a racket? That little brown one is the loudest of all.”

“She’s Jenny Wren,” Chaik called back—you couldn’t talk low and hear even yourself. Besides, he thought no one was looking at anything but the fighting. He didn’t see the slim brown mate of Coquillicot the Thrasher slip out of the grass beside them. “Jenny left Johnny to watch her eggs while she got a drink—hours ago,” he went on. “She just loves to boss things. But poor Johnny thinks the hawk has got her.”

“It’s a wonder the hawk hasn’t caught someone, isn’t it?” Stripes said.

“No, it isn’t,” squawked Chaik. “Look up in that pickery pea-tree.” (He meant an acacia with long spiky thorns and blossoms like garden peas strung in tassels.)

Stripes squinted—he isn’t used to looking up—and finally shaded his eye under his paw. “What about it?” he asked in a puzzled way.

“Why, Bob White has it all filled with fighting kingbirds. They’d fly at an enemy and peck his eyes out. And if the hawk chased them they’d hide in the prickers where he couldn’t possibly catch them. The hawk knows—I say, Stripes, what do you suppose that Thrasher is telling them? They’re looking straight at us-”

But before Stripes could even think, Jenny Wren began to squawk, twice as loudly as before, “Murder! Help! Help!”

Jenny’s call gave Stripes a fine scare. Chaik had just finished warning him not to let the other birds know he was there. And they’d just begun to suspect that Coquillicot the Thrasher had seen them, because they’d seen Coquillicot fly up and tell something to the Kingbird Guard. All the kingbirds had begun peering down at them, and just then——

“Murder! Help!” went Jenny Wren.

Stripes hadn’t done a single thing to her, but there wasn’t going to be any time for explaining and arguing. Those kingbirds were ready to peck someone’s eyes out—there wasn’t any doubt of that! The red feathers on their heads stood straight on end as they came swooping down, whooping their war cry. They came like hailstones falling from a great black cloud—hailstones with beaks and claws! It was scary!

“Hide!” gasped Chaik and took to his wings. But poor Stripes could not fly; all he could do was to squirm a little closer under the thickest, shadiest branches. And right close beside him a birdy voice said, “Look out. Don’t wiggle so. You all but set your clumsy claws right on me.”

“Oh!” (Stripes was most too surprised to stay scared.) “I didn’t m-mean to,” he stammered, and he stood there on three legs, with a hind paw held up in the air, most awkward and ridiculous, craning his neck to see who it was.

It was a lovely bright brown bird with rose-red eyes and a long tail, cuddled down in her nest among the grasses. “I’m Coquillicot’s mate,” she explained. “I heard you tell Chaik the Blue jay that you’d never eat another egg, so of course I knew you were that friend Bob White spoke for at the ground-birds’ meeting.”

She was as nice and sociable as you please. Then she demanded anxiously: “Who was Jenny Wren calling the guard for?”

“Those kingbirds?” asked Stripes. “Why, I kind of thought they were after me.”

“No, they weren’t,” said the pretty bird. “I told Coquillicot to tell them who you were as soon as I heard you. But there’s a rumor that Glider the Blacksnake’s hawk-bitten son—the one with the crooked tail—has been seen here. It’s put us all in a flutter. Do find out!”

At that Stripes Skunk stood up stiff and straight. “If it’s a snake,” said he, “I’ll promise you that he’ll never eat another bird.” And with that he marched right out into all the pecking and scratching and flapping and screeching that was going on in the potato patch. Wheu-whirr-r-r! went a cloud of wings about his ears, but he just growled, “Where is he? I’ll take care of him.”

There had been more noise than enough before, but when Stripes Skunk marched out of the hedgerow, with his whiskers bristling and his long hairy tail arched up behind him-! No body could even imagine the noise of that! Wow!

Stripes marched right up to Jenny Wren, growling, “Show me that snake. I’ll take care of him. Where is he gone?” He was so busy thinking about what he had to do that he forgot to be scary. And not even a fighting kingbird took a single peck at him!

No. They all stopped still, as still, to listen. Only their wings whispered like leaves in the trees, as they wheeled and circled—and listened! “Where is that snake?” said Stripes again.

“It isn’t a snake!” cheeped Jenny Wren. “It’s a dreadful great big creepy crawly monster with a stinger sticking out of its tail. It’s spitting poison! It’s—it’s—there, it’s doing it now! Che-e-ep!” She began to flutter and wail all over again. The kingbirds squawked their war-cry, but they didn’t go any nearer.

Stripes did, though. He crept up, his long wavy tail sticking straight out behind him and the tip of it just trembling. He raised his paddy-paw. Scritch! Off came the leaves where the horrid thing was hiding. Down rolled——

A big green caterpillar! Jenny Wren screeched. The other birds fluttered with fear. But Stripes Skunk just sat down and laughed at it. This was too silly—to have all those foolish flyers making a fuss like that over what was just a nice juicy mouthful! He forgot that it really was a monster to Jenny—it was quite as big as she is and its mother, the moth, is bigger.

It lay on its back and wiggled all its sucker-feet in a most insulting way. It squirmed, and the eye-shaped stripes on its sides just squinted and made faces at Stripes Skunk. It even spat a mouthful of chewed leaves at him! A lot he cared. He swallowed it.

And all the birds watched him with their eyes just popping. Now was his time to make friends, when they were all listening. He began very politely: “Thank you for calling me, Mrs. Wren. Now, if——”

He was just going to add if they’d only believe he wasn’t eating eggs and give him a chance to show them he’d——

But right then a meadowlark began to shout, “My nest! He’s robbed it! Egg-eater! Egg-eater!” And if it hadn’t been for those fighting kingbirds there’s no knowing what would have happened. They gathered around and hustled Stripes back into the bushes, and kept him a prisoner.

Bob White Quail and the quail-folk were flying about like mad trying to make somebody listen, and Coquillicot was shouting at the top of his lungs from the highest tree he could find, and poor Chaik the Bluejay was shivering in a bush because he used to eat eggs himself—and the birds have not forgotten it.

“But I didn’t do it!” Stripes protested. “Honest, I didn’t.”

“We know you didn’t,” said the captain of the Kingbird Guard. “We’ve had a watch on you for a week and this has happened since you were talking with the mate of Coquillicot. That’s why we’re guarding you. When it gets dark those larks will go back home and you can run away.”

“But I don’t want to run away,” Stripes insisted. “I want to stay right here. I want to be friends—can’t you tell them so?”

But the kingbird captain didn’t even have time to answer him, for a cloud of screeching meadowlarks flew up and tried to get past the guard. And for a minute it even seemed as though they might succeed—though what they’d have done if they did we’ll never know. I have my doubts how brave they’d have been against a skunk after they were so afraid of a caterpillar. But that was the very moment when a cry of “Snake! Snake!” came from the pretty brown mate of Coquillicot.

Well, no amount of meadowlarks and kingbirds, both together, could have stopped Stripes Skunk. Coquillicot’s wife had been so friendly and kind to him! Now he dashed past the guards and down the hedgerow where her nest was hidden. And he got there just in time to see the crooked, hawk-bitten tail of the very blacksnake she had said she was afraid of. And maybe he didn’t pounce on it!

What followed was a battle. It was the battle the birds mean when you hear them singing about it—the Battle of Stripes Skunk and the Crook Tailed Snake! For Stripes doesn’t have the wide jaws of Silvertip the Fox to fight with. But he had the courage of three Silvertips. Time and again that snake got away from his teeth and coiled about his throat; time and again Stripes clawed away its hold and got his teeth in it! He had a dim notion that the trees were full of birds, anxiously watching, but not a feather fluttered, not a cheep sounded.

Not a cheep sounded—but far off from the top of the pickery acacia tree he heard the captain of the Kingbird Guard whistling like a policeman. “Whee-oo-wheet! Whee-oo-wheet!”

And at that the snake bit viciously right at his pink mouth. Snap! he closed his jaws, right on its ugly head. He felt his long tooth drive through it.

The coils that were wound about Stripes’ throat loosened. The snake dropped and lay still. Only its crooked tail kept wriggling.

“It’s dead,” thought Stripes. “It will never hurt another bird. But it’s bitten me. Now I’ll die, too.” And he licked his bite, wondering how soon that would happen.

He felt terribly hurt, because you know he didn’t fight on his own account; he was fighting for the kind little mate of Coquillicot, the Thrasher. You wouldn’t think the birds would forget a thing like that, would you? Well, they didn’t. Even the meadowlarks, who had been chasing him just a few minutes before, felt terribly ashamed of themselves. Still, nobody went to help him.

They had a reason. I told you that when the fight began the captain of the Kingbird Guard flew up into the very top of the tallest tree and began to whistle, “Whee-oo-wheet!” over and over again. It was a shrill, exciting noise, like fire engines make, or patrol wagons—a sort of clear-the-track-for-help whistle. He was calling the bird’s own Snake Guard, and he was calling her in the biggest sort of a hurry. And of course everyone else had to keep under cover so she’d see right off where she was wanted.

She was called in a hurry, and that’s the way she came. The kingbird captain saw a wee black speck, far up in the clouds, begin to drop. Down it flew. But before ever it reached Stripes Skunk that wee black speck was a big brown bird.

The bird was close behind him. Her wings were half closed, just wide enough to steer by. She had fallen, like a shooting star, out of the sky. When she spread out her wings and tail to stop herself, just as she reached the ground, the wind roared in her feathers.

Stripes raised his head. He saw the big hooked beak, the strong curved claws of a hawk reach down. “These birds are just bound to kill me,” he thought. “This one is big enough. Even Bob White won’t dare to stop it.” All the same, he wished Bob would try. He was tired of fighting all alone.

But the hawk was only reaching for the earth. She gave the snake a shake, cocked her eye knowingly at Stripes, and said, “Whee-ee! but that must have been a fight!”

Stripes lifted his nose from his paws. He couldn’t help feeling proud to be spoken to like that. “It certainly was,” he answered.

The hawk nodded. “I put that crook in his tail three years ago,” she explained. “He was a clawful then. He’s bigger now. I ought to have been here to help you. You’re feeling a little tired. Suppose I tear him up a bit and you eat some. How does that sound?”

“He’s bitten me. I’m just waiting to die,” said Stripes. “I don’t feel like eating.”

“Broken sticks and addled eggs!” exclaimed the hawk, grinning. “Didn’t you know he wasn’t that kind of a snake? He can only choke you. Do you mean to say that you’d fight a great big snake like that thinking it could kill you if it bit you?”

Stripes Skunk looked more proudly than ever at the long stretch of crook tailed snake that lay between them. “I didn’t fight it on purpose,” he explained. “It was bothering a bird. And I was trying to be friends with them. The bird it was bothering was the only one besides the quails who’d trust me. So of course I tried to kill it. I’ve killed lots of little ones, but I didn’t know how big this one was till I got hold of it. It did the queerest things.” Stripes craned his neck about. It felt pretty stiff where the snake had been choking him.

“Cac, cac!” chuckled the hawk. “I might have known you weren’t a regular snake killer by the size of your claws. Mine are twice as long. And much sharper, too. You spoil the edges of yours walking along the ground.”

“I know I do,” said Stripes. “A young bobcat showed me his once—he was afraid to eat me. They’re ’most as nice as yours. He has little slits in his paws where he hides them. But they’re no use for digging.”

“Who wants to dig?” teased the hawk. “You talk like a kingfisher. I chased one once and he hid in the end of a hole he was digging. Such a place for a bird!” Her red-brown eyes were sparkling.

“Well, I want to,” Stripes argued. “Digging is the quickest way in the world to catch a mess of fieldmice.”

“Do you eat them, too?” she exclaimed. “So do I. But that wasn’t what the kingfisher was after; he never touches fur.”

Stripes cocked his head, considering her. She was really very handsome. Her brown feathers gleamed with purple in the sun. They were beautifully marked with black and white when you saw them close by, and she had four narrow bands across her tail. Just now her face was pert and interested, but he knew it could look really wicked if she clicked that big curved beak at you. “Hm!” he answered, knowingly. “I think maybe that kingfisher was very sensible.”

This seemed to amuse her. She laughed again, in her noisy hawk way. Then she stepped over beside him. “I’ll tell you a joke,” she whispered. “They call me a hen hawk—and I don’t eat feathers! Very few of us wide-winged hawks who soar do it at all. It’s those sneaky round-winged fellows with tails too narrow for soaring who make a bad name for the family. They’re always hiding and pouncing out on some one. But birds are such fools, you know, lots of them never learn the difference.”

“Well, you wear such awful claws,” Stripes began.

“At your service,” said the hawk.

“Any time you need them. Just send word by a kingbird. But you don’t need me any longer just now.” And off she flew.

All the birds had been still as death while the hawk was talking to Stripes Skunk. Even the kingbirds and Coquillicot the Thrasher stayed hidden. But before the hawk was twenty wing-beats away, they came bursting from every bush and tree, calling and singing to him. And the meadowlarks, who had just been so sure he had robbed a nest of theirs, were so apologetic! But the voice he was listening for was that of Coquillicot’s slim little wife. Just wasn’t she grateful!

“I’m sorry I didn’t get here in time,” said Stripes sadly. “He had eggs in him. I felt them breaking when he choked me.”

“But they weren’t mine,” she cheeped joyfully. “Not a single one.”

“They were ours,” mourned the meadowlarks. “That’s why we’re so ashamed of ourselves for picking at you. But we’ll pay back. We’ll help you take care of Tommy Peele’s potato patch for ever and ever.”

Maybe that didn’t make Stripes happy! For if he could have their help to fight the potato bug army he was sure he could stay for ever and ever in Tommy Peele’s woods and fields.

Stripes was just going to dance a bit of the tickle out of his toes, the way he did when Tommy Peele made him happy, when Coquillicot the Thrasher flew out of the thorn tree. He’d been hiding away all by himself while he composed a triumph song—and that’s the biggest compliment any bird can pay you.

Coquillicot perched right over Stripes Skunk’s head, folded his tail straight up and down, tucked his wings under it, and began in a low, mysterious voice:

(He began to act out her terror as he sang.)

(Here his fluttering of fear changed to a ring of joy.)

He ended on a high ringing note that set every bird cheering at the very top of its voice. And the catbird, who can talk any bird tongue, began translating it to some of the summer visitors who couldn’t catch it at all. You can hear them still doing it, any time you listen to them.

When Stripes Skunk heard that triumph song he was completely overcome. You see he hadn’t known he was being brave. He just was thinking so hard about poor Coquillicot’s wife and what that awful snake was trying to do to her that he forgot to be afraid. He forgot to think about himself at all—and that’s the way most people get to be heroes.

Now he felt all choked up and sniffly. So the next thing he knew Doctor Muskrat came shuffling up and asked most sympathetically: “Poor Stripes, does it hurt you so very much? Where were you bitten? Those fool meadowlarks called out to me five minutes ago and then they flew right off without letting me know where to find you.”

“Right here,” said Stripes, opening his mouth. And he was just going to explain that it didn’t amount to anything at all—because it wasn’t that kind of a snake that had bitten him—when in Doctor Muskrat popped one of his perpetual root poultices. It wasn’t the kind he usually keeps on hand, but a special one, from the root of a spotted plantain, but it worked just the same in one way. Stripes couldn’t talk while he held it.

But he could laugh. He laughed until his sides hurt. For he wasn’t any hero to Doctor Muskrat; he was just fat furry Stripes Skunk, to be cuffed and coddled like any kitten. He felt like himself again. So he rolled and giggled until he got some of the laugh out of him, and then he bounced up and began his dancing. He chased his shadow and he chased the leaves and he chased his tail until he had all the birds chuckling. And when Miau the Catbird perched low down and tried to explain that hero notion to the doctor, he tweaked Miau’s tail, too. And Miau began to squawk and peck his ears for him.

No wonder Doctor Muskrat wasn’t impressed a bit. He just said: “Then you don’t vote against letting him stay here?”

“Of course not!” shrieked the birds.

“That’s good,” said the wise old beast. “We ’re going to have a meeting about it to-night, at moon-up, down by my pond. The mice have entered a protest.”

“The mice?” squawked the birds all together. “The mice? What have they to say about it? What can they do?”

“That remains to be seen,” said the doctor. “They’ve entered a protest, so all who fly by night must come and put in a good word for him.”

“Yah,” called somebody. “I’m going right away now to send the little owls with my vote.”

“No, you don’t,” said the doctor. “I’m guaranteeing that we’ll hear them and let them go home again in safety. There are two families who aren’t invited—the hawks and the owls.” With that he set off home, flapping his front paws and shuffling his hind ones, with his tail making a snake track between them, and Stripes went, too. But his tail had a sassy little quirk at the end.

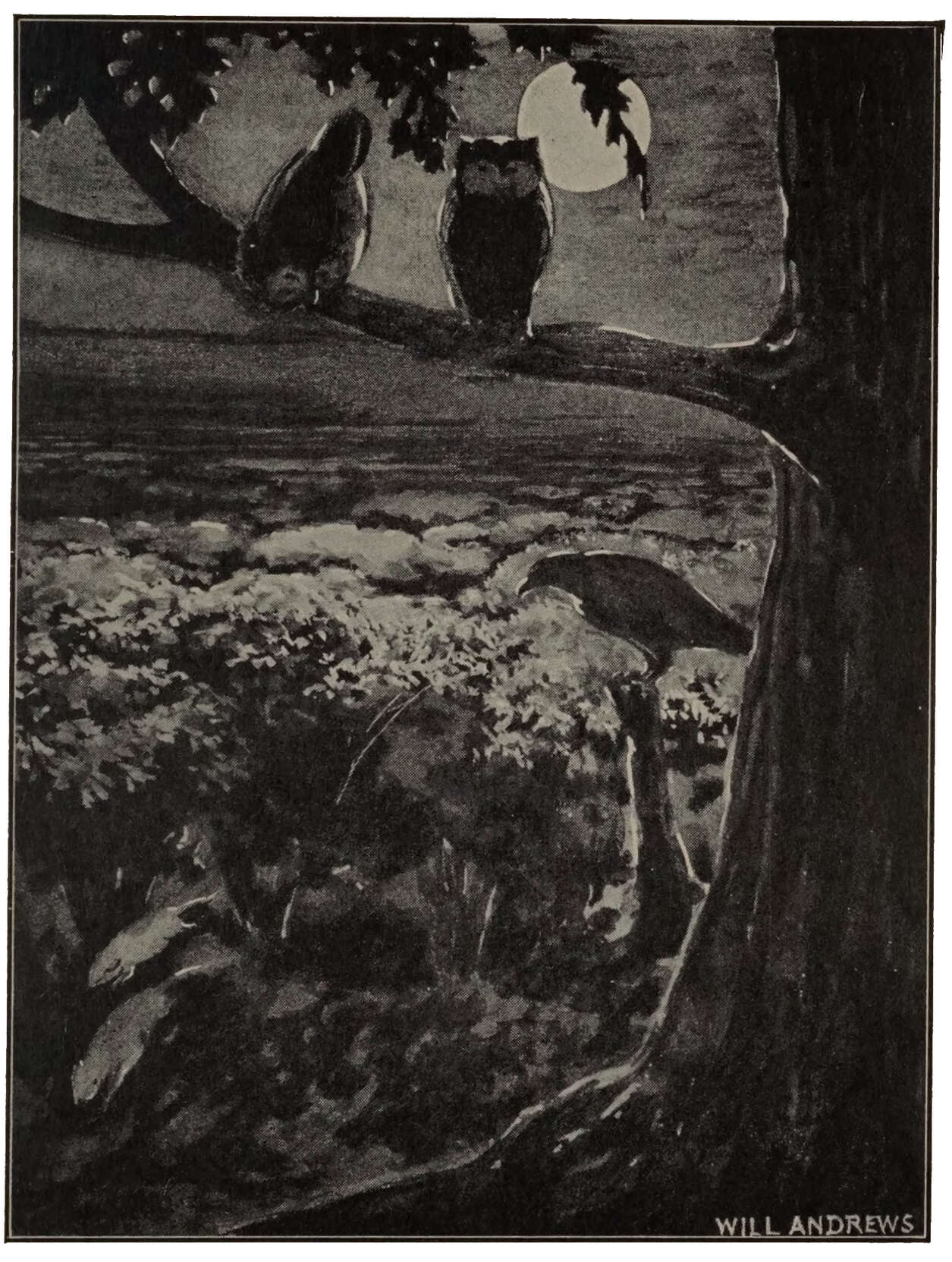

Promptly at moon-up the Woodsfolk began to gather at Doctor Muskrat’s Pond. Stripes was there already, and Tommy Peele’s dog Watch to represent Tommy because Tommy doesn’t talk the Woodsfolk tongue, and Chaik the Jay, and a whole company of small birds who can fly by moonlight, besides Bob White Quail and the whippoorwill Pretty soon Doctor Muskrat looked all around and asked: “Where are Tad Coon and Nibble Rabbit?”

“Nibble’s coming,” answered the whippoorwill. “I just saw him. He’s——” Here he interrupted himself. He remembered the old bird proverb, “A long tongue makes a ragged tail,” meaning that you’re apt to get pecked if you talk too much about other people ’s affairs. So he just finished, “He’s on the way.”

Both Stripes and Doctor Muskrat suddenly wondered why Nibble was away so much of the time lately. But before they could ask any questions, up hopped Nibble, as careless as you please, with a clover blossom sticking out of his mouth. He’d eaten it stem first, keeping the best till the last, just like you save the nice buttery middle of your bread for your last bite. But the doctor knew very well that he hadn’t picked it in the clover-patch over by the potatoes. He knew that because he’d just been there. Besides, the whippoorwill came out of the deep woods, and he was the only one who had seen Nibble.

“Hey, Bunny!” called the doctor. “Where’s Tad?”

“He hasn’t been with me,” Nibble called back. “I haven’t the least idea.”

“Well, where were you, then?” the doctor wanted to know.

“Studying scents,” said Nibble. But his whiskers bristled as though he were trying to keep from laughing. He had a secret all right.

“Well, you just study a scent or two over by Tad’s tree and see where he’s gone. We have to have him.”

Just then who should come crawling up but Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse. You remember him. He’s very fat and old; so fat that his tummy drags on the earth like Miner the Mole’s; so old that his ears are all crinkled. He makes as much fuss getting over the ground as a mud turtle and lots more noise with his grunting and sniffling. And of course he had a bodyguard of his family. He has a tremendous one, you know—a great big stump simply alive with them. Watch escorted him to the flat stone where Doctor Muskrat was sitting.

Doctor Muskrat greeted him. “We ’re all ready to listen,” he said, “except Tad Coon. We can’t find him.”

“Uff, uff!” panted Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse. “We’ll pass over the matter of Tad Coon, then. It’s unimportant. Then we can get down to business.”

“Crawling Crawfishes!” thought Doctor Muskrat. “He must know something about what’s happened to Tad.” He was puzzled.

When Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse said that he was willing to pass over the question of Tad Coon, that meant only one thing—he didn’t think there was any question. He must know that something had happened to Tad. But it’s no use asking anything of a fieldmouse. So Doctor Muskrat didn’t try.

“Mr. Fieldmouse,” he said, “we have been asked to meet and consider your reasons for barring Stripes Skunk from Tommy Peele’s woods and fields. Here we are, ready to listen.”

Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse’s crinkly ears began twitching. “We fieldmice have had many grievances in times past,” he sniffled in his high, squeaky voice. “But we have never spoken of them. As long as these woods and fields were run in the sensible way Mother Nature started them in the First-Off Beginning we took our chances like sensible mice. But things are changing. Some of you have made friends with Man—a thing we have never done. Man makes no difference to a fieldmouse, so even of that we will not complain. But when you make friends with the sworn enemy of the mice, a Thing-from-under-the-Earth, who has no proper place in the sun—I refer to this skunk,” he said as he waved his wriggly tail at Stripes—“it is high time we refused to let him remain. He must go!” And he sat back in a fat, shaking heap.

When the moon came up there wasn’t a single tail stirring

“Ah,” said Doctor Muskrat. “Then you mice will give up gnawing roots and spoiling plants and go back to the sensible way Mother Nature started you in the First-Off Beginning. In that case, I expect we will have to agree to your demand.”

“Give up eating roots? What do you mean?” gasped the fieldmouse.

“Yes, eat a nibble here and a nibble there, leaving the plants to be again as they were before. Are you willing to change?”

“Change! A fieldmouse never changes. Let me remind you, Doctor Muskrat, that we lived as we do to-day before any of you were made. This earth belongs to us fieldmice.”

“Perhaps,” said Nibble Rabbit, “but let me point out to you that if you fieldmice tried to run it there wouldn’t be a green thing left to grow out of the earth. We’d all starve, down to the very last mouse.”

“Impossible! Idiotic!” gasped the mice. “We will never change. Never!”

“If that is your answer, I shall put the matter to a vote. Does Stripes Skunk go or stay?” asked Doctor Muskrat.

“He stays! He stays!” shouted every one but the mice.

My, but the fieldmice were hopping mad—I mean it truthfully. They hopped up and down on Doctor Muskrat’s flat stone and lashed their tails and chattered. “That vote doesn’t mean anything,” shouted Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse. “We’ve all voted against him and there are more fieldmice here than all of you put together.”

“That isn’t the way we usually vote in the Woods and Fields,” said Doctor Muskrat. “We vote by families. Here are the night birds and the day birds (you know some of the birds can fly by moonlight and they liked Stripes well enough to come) and Nibble Rabbit and Watch the Dog who votes for Tommy Peele. If you want to vote by tails we’ll call a day meeting so all the birds can come.”

Well Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse knew that wouldn’t be any use. There are too many birds. So he said: “This is a fur vote. The birds haven’t anything to say.”

“Very well, then, shall I call a fur vote, at noon, a week from to-day?” asked Doctor Muskrat.

But Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse was afraid that all Stripes Skunk’s friends would use that chance to eat all the mice they could hold and reduce the vote. He turned to Watch. “This matter really only concerns Tommy Peele,” said he. “Can he afford to fight the fieldmice?”

“He can afford to stand by his friends,” Watch answered.

Then Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse spoke to Stripes himself. “Will you force us to fight?” he asked, “or will you go? Remember, Tad Coon has already vanished. Will you risk the same fate from the fieldmice? I warn you!”

“I will stay,” Stripes answered firmly.

“Then it is war! War to the tooth!” announced Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse. And off he humped, followed by all his family.

“Now what do you suppose those mice did to Tad Coon?” mused Doctor Muskrat.

Nibble takes the lady mouse to Doctor Muskrat

Stripes wasn’t a bit afraid, but he didn’t want every one else to suffer on his account. “I’ll go away willingly,” he told Doctor Muskrat, “if you think I ought to.”

“I don’t,” snapped the old doctor. “I think we might as well fight it out now. If we give in to them there’s no knowing what they’ll demand next. You’d think this world belonged to the fieldmice!” he snorted. (That’s one of the things Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse had said at the meeting, you know.) “A pretty place this world would be if they tried to run it. Next thing they’ll be saying they made it themselves, instead of Mother Nature.”

“But there are a great many fieldmice,” argued Stripes. “They may do a lot of harm.”

“They can’t do much more than they always have,” the angry old muskrat snorted harder than ever. “If they haven’t enough sense to see that, what more can you expect of them? The whole tail-and-whiskers of them, taken together, hasn’t the brains of a bullfrog.”

Nibble Rabbit didn’t say much. He had friends among them so, of course, they came to him. “I know they kill you,” he said, “but you treat the plants just the same. You ruin everything you set a tooth into. If you want them to know how important they are, all of you move away and let them see how it is to get along without you.”

Now that was sensible. But they wouldn’t listen. They said: “But if you fight us we’ll do away with you—just like we did with Tad Coon. You’ll be sorry.”

On the third day after Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse declared war, the mice began to fight. They felt sure they would have an easy victory. How do you suppose they meant to do it? They were going to spoil Tommy Peele’s potato patch!

This was really a bright idea. I don’t believe for a minute that they thought of it themselves—they must have heard it from somebody. I don’t mean that any one was a traitor to Stripes Skunk, but the fieldmice are always creeping about and listening to what people say when nobody imagines they’re near. They learned that Stripes was going to take care of the potato patch to pay back for those chickens he’d killed. If he didn’t, they thought of course Tommy Peele would send him away.

My, but Doctor Muskrat laughed when he heard the news! “It’s all over now,” said he. “We won’t even have to go out and fight them.” But he wouldn’t tell why.

So at dusk the fieldmice began to gather. If you think there were a lot of them out the day they went down into Nibble Rabbit’s hole to steal a mouthful of fur from the woodchuck for a charm against owls, you ought to have seen them now. For they’d all raised families since the spring had come. The grasses fairly shook with them; the earth was covered with them. At dark they began to scuttle into the potato patch.

“Ho, ho!” laughed the little owls. Those woodchuck charms didn’t bother them a bit. They feasted on fieldmice. But the angry mice wouldn’t pay any attention to them.

“Ca—caa,” chuckled the hawk.

“Just the minute the moon comes up so I can see to hunt, I’ll be with you.”

But when the moon did come up, there wasn’t a single tail stirring!

You see, those mice didn’t know about potatoes. They never ate them because they didn’t like the taste, but they never knew other people did. Now potato plants don’t intend to be eaten. They hide the potatoes that they make to feed themselves—the ones we steal from them—down under the ground. But they fill their green parts, that the mice saw above the ground, with a juice that makes folks mighty sorry if they try to eat them, excepting those bugs who never eat anything else. That’s why the bugs made Stripes sick. Any one can eat their eggs, or the bugs who hide under the ground, like the good potatoes, but the bugs and the green leaves above the ground—ugh! You know what Bobby Robin said about them.

Crunch, crunch, went the busy teeth of the cross little mice. Ow! In just seven whisks of a tail they turned and ran as fast as their scurry skippy feet could carry them. My, but they were sorry they’d tried to be so naughty!

You couldn’t very well blame Stripes for being delighted when he found out what they had done. They’d made themselves most awfully sick and sorry. And Stripes was one of the Things-from-under-the-Earth in the first place, you know; he couldn’t get so good and kind clear through to the bottom of him that he’d forgive the mean little things—not all of a sudden. The only reason he didn’t try to kill any of them right then was because he was afraid they’d disagree with him.

But Nibble Rabbit was sorry, so sorry. The mice had been kind to him—except old Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse who was pretty rude the day they marched into Nibble’s hole after woodchuck fur for a charm against owls. He couldn’t bear to hear them squeal and moan. He was just wishing with all his heart that his ears weren’t so very long when one of them called out from the shadow of a wide burdock-leaf: “Rabbit, oh, Rabbit! Bend down this leaf so I can get just a drop of dew on my tongue. I’m dying.”

Of course he hopped to help her. Yes, it was a lady mouse who had called. And wasn’t she s’prised to find he was the very same little bunny she had guided through the scary dark tunnels under the haystack! That was the time Ouphe the Rat was chasing him. And wasn’t he still more s’prised to find she was the same mouse. He’d been wanting to pay her back all that time. Now he had a chance.

“Drink?” said Nibble. “I’ll give you a drink. Hold up your toes and don’t wiggle.” With that he picked her up very gently by the loose fur on her collar and carried her down to Doctor Muskrat’s Pond. And maybe you think he didn’t thump and pound with his furry feet until the sleepy old doctor came out to prescribe for her.

“Water is right,” said the doctor. “Then she must eat all the sour wood-sorrel she can hold. There’s lots of it all about the Woods and Fields but I don’t suppose half of these silly mice know enough to use it.”

You know how kind Doctor Muskrat really is; he only pretends to be grumpy. Well, instead of crawling back into his nice warm bed he went flouncing around in the moonlight calling: “Water and wood-sorrel, you foolish mice, water and wood-sorrel!”

And this time you better believe they listened to him. It was wonderful how soon the squealing stopped after the crunching began—the crunching of mouse-teeth on wood-sorrel. And before very long they were scuttling back to their homes, whisking their tails behind them. But not a one except the lady mouse, who was Nibble Rabbit’s friend, ever thought to say “Thank you.” That’s mouse manners for you!

Doctor Muskrat didn’t give the twitch of a whisker about that. He just said: “Come on, Nibble. Now we’ll make them tell us what happened to Tad Coon.”

Thump-thump! went Doctor Muskrat’s paddle-paw on the hollow stump where Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse lives with all his children and his grandchildren and his great-grandchildren, and their children as well, until the stump is fairly swarming with them all.

Blam-blam! went Nibble Rabbit’s furry feet.

At least seven mouse mothers popped their heads out and hissed, “Hssh! You’ll wake the babies.” One of them added importantly, as though it were news, “There’s sickness in the house.”

Nibble Rabbit snickered. But Doctor Muskrat just growled: “I must speak with Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse!” And in another minute his crinkly old mousy ears showed in the doorway.

“Who’s there? What do you want?” he quavered. He was still feeling pretty shaky, I can tell you.

“It’s me,” said Doctor Muskrat. “I want to know what happened to Tad Coon.”

“I—I don’t know,” said Great-Grandfather Fieldmouse, and he coughed uncomfortably because he did know. So he was telling a lie when he said he didn’t—and he knew that, too.

So did Doctor Muskrat. “Hmp!” he snorted, “that isn’t what you said at the moonlight meeting. You asked Stripes Skunk if he dared to risk the same fate at your paws as happened to Tad Coon. What was it?”

“I won’t tell,” sniffed the old mouse. “A fieldmouse never changes. I said I wouldn’t tell you and I won’t. So there!”