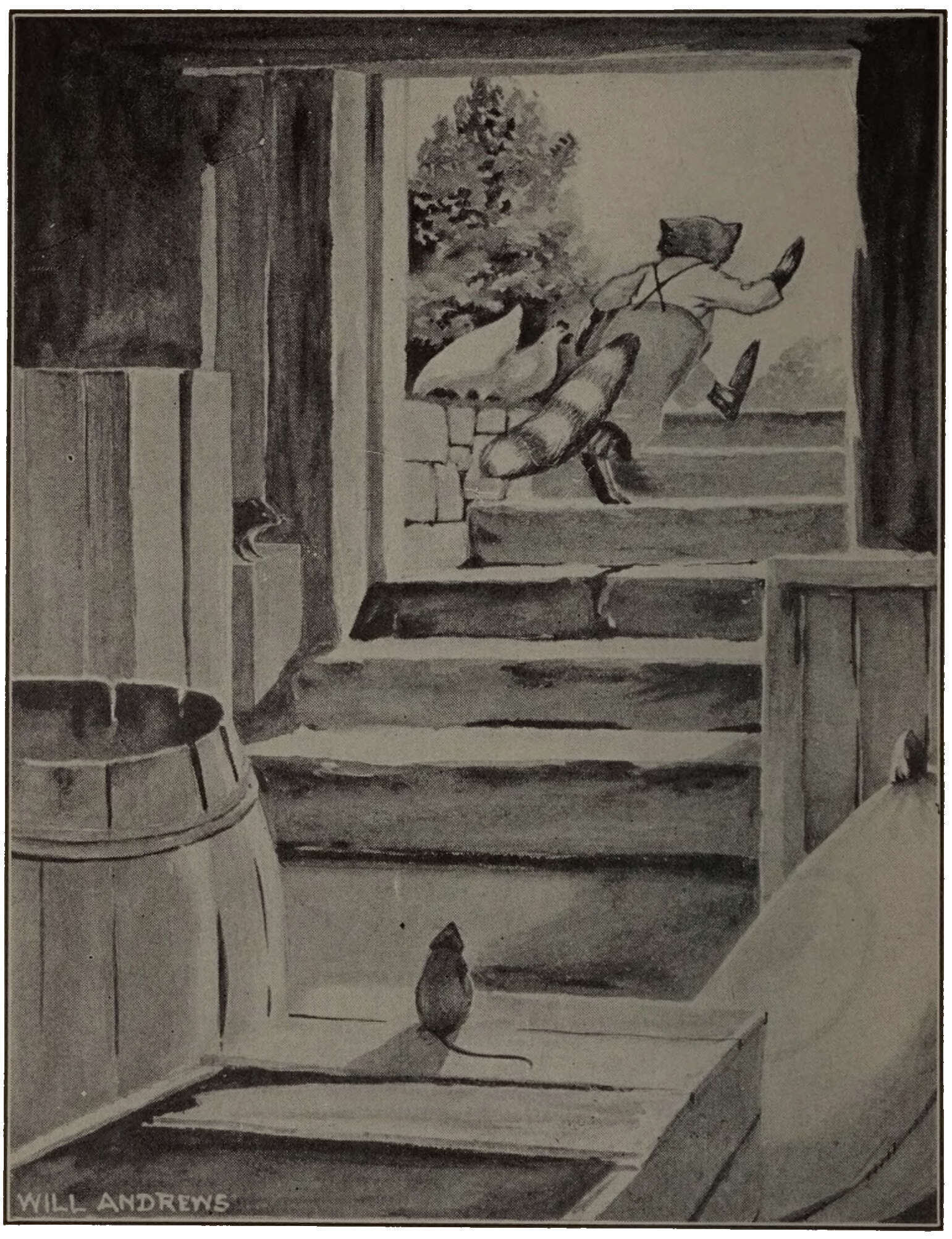

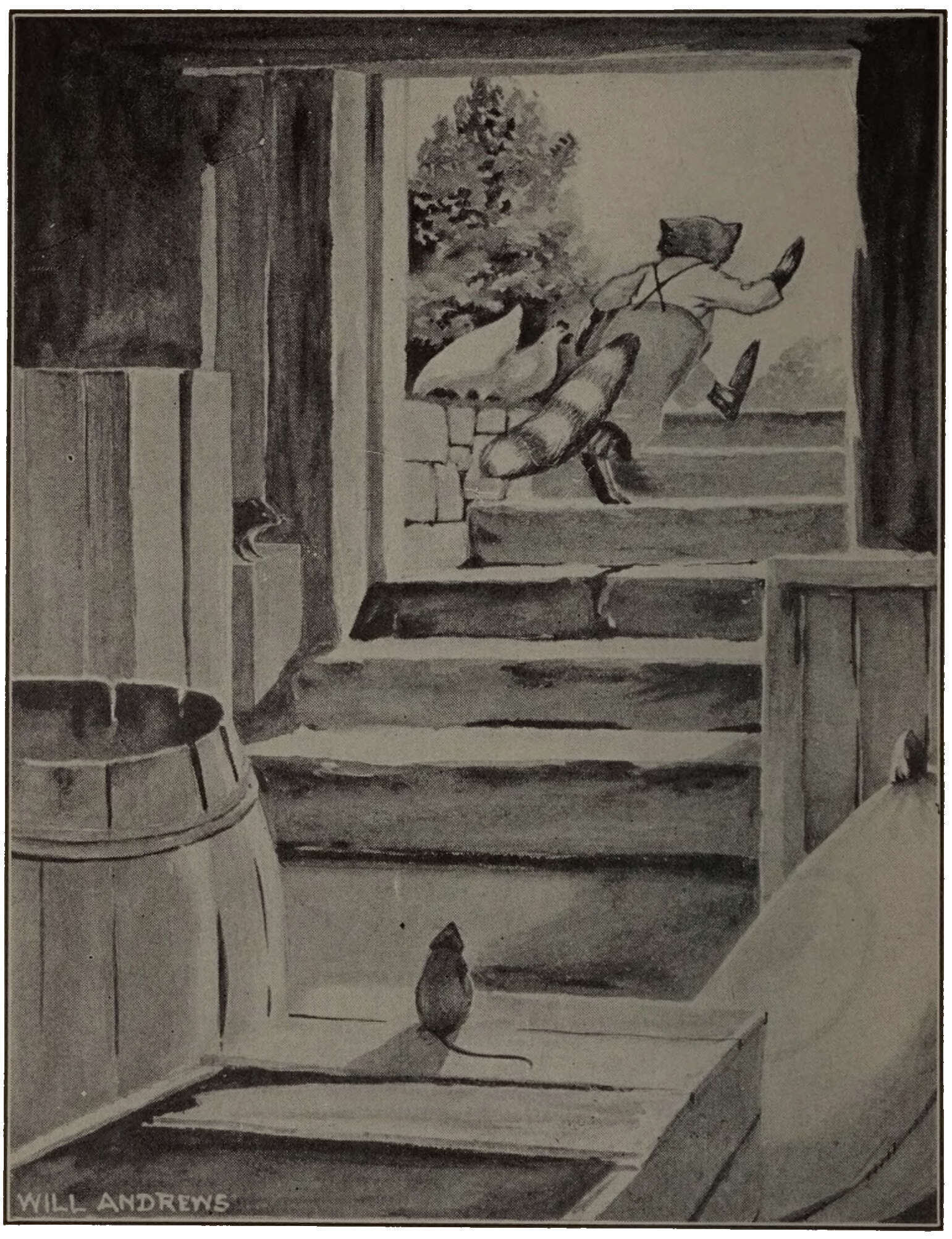

Maybe Tad Coon didn’t run! He hit the cellar steps just twice--blam! blam!

Title: Tad Coon's Great Adventure

Author: John Breck

Illustrator: William T. Andrews

Release date: January 26, 2021 [eBook #64397]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Roger Frank

Maybe Tad Coon didn’t run! He hit the cellar steps just twice--blam! blam!

Tad Coon was lost! And Doctor Muskrat and Nibble felt pretty discouraged over their chances of ever seeing him again. All the same they meant to try. They sent word of a meeting to the Woodsfolk by everyone they met. When they reached the pond, Stripes Skunk was sitting out on Doctor Muskrat’s flat stone, waiting for him.

“I’m leaving,” said he. “But I have to thank you for all you’ve done for me. Perhaps I’ll come back some time.” He seemed very sorry over it. His tail was droopy.

“You can’t go!” exclaimed the doctor. “You belong here in the Woods and Fields ever since you killed the crook-tailed snake for us. Now we’re counting on you to help us hunt for Tad.”

“But I must go,” said Stripes. “My mate wouldn’t leave the Deep Woods. She knew it was a dangerous place to live and she sent me hunting about to find a better one. Then she refused to come. I couldn’t think why she wouldn’t. But Chewee the Chickadee just came flying in with the news that the weasel has killed her. And she’s left three little kittens behind. I’ve got to do their hunting for them.”

“I see,” nodded the doctor. “But you send Chewee back here to-morrow at sunset. I’ll have a message for you.” He didn’t say a word about the meeting. So off went Stripes, with his ears drooped low and his tail most sorrowfully dragging.

When the Woodsfolk gathered by his pond the next afternoon Doctor Muskrat laid Tad Coon’s case before them. “We know what has happened to Tad Coon,” he said. “He chased some mice into a corn-crib and a man shut the door on him. What man, what corn-crib we do not know. One mouse escaped to tell the tale but the little owls ate him. If Tad is still alive the Woodsfolk must do their very best to find him.”

“We will, we will!” they squealed and yapped and chirped and whistled in all their different tongues. Even the little bats woke up inside their hollow tree and squeaked out that they, too, would keep an eye open for him.

“Another thing,” went on Doctor Muskrat. “Tad Coon is gone. Now Stripes Skunk has had to go into the Deep Woods to look after his kittens. The fieldmice are foolish but they are many and full of notions. We have only the hawks and owls to fight them. First thing we know the minks will be creeping in, unless Stripes brings his family to live with us.”

“Hooray! Hooray! for Stripes and his family! Bring ’em along!” shouted the Woodsfolk and that’s just the very message he wanted to send.

But just as the shouting was beginning to die down Chewee the Chickadee broke out in his shrill little voice: “And Nibble Rabbit’s mate said I was to tell him his bunnies were out of the ground and ready to travel.”

“Nibble Rabbit! Nibble Rabbit!” they hooted. “Oh, you sly one!” And Nibble dragged his ear down and licked it so he could hide his shyness behind it. There was more shouting and laughing than ever. But Doctor Muskrat was fairly flabbergasted. “Nibble!” he gasped. “You never told me!”

He was hurt because Nibble Rabbit had gone off and found himself a mate and raised a family without saying a word to him. He sat on his stone and almost sulked about it.

“But, Doctor Muskrat,” pleaded Nibble, “please let me explain----”

“What is there to explain?” retorted the doctor, “except that you never even told me.”

“There’s this much,” Nibble answered with a funny smile, “I didn’t know about them myself until just now.”

“What do you mean-‘didn’t know’?” snorted the old muskrat. “Is this some joke of Chewee’s? I don’t understand.”

“No,” said Nibble, and he looked very happy about it. “They’re mine all right enough, but this is the first I’ve heard from them.” Then he went on to tell about how it happened.

“You told me about scents. Of course I went off to find how everyone used them. My, it was fun! I could tell how folks lived, and what they ate, and when they were home, and where they went and who they saw while they were away. And I found that nearly everyone was making love to someone. I just couldn’t understand it.

“I couldn’t until I found a rabbit trail back in the Deep Woods. It was a lady rabbit’s trail. Of course I let her know I’d called before I came away. But next day I went back there. And I could see her bright eyes shining underneath the Pickery Things she hid in. By and by she came hopping out. Oh, Doctor Muskrat, she was the loveliest rabbit you’ve ever seen. She was just full of tricks and games and frolics. And run? she was swift as a fish, darting across your pond.

“She liked me, too. She didn’t even think I looked funny when I danced under the last full moon, even if the mice say I do. I kept telling her how nice it was here and she kept promising to come and meet you. Wouldn’t you have been s’prised?”

“No, I can’t really say I would,” chuckled the old muskrat.

That did surprise Nibble. “Then,” he went on, “she disappeared. Of course I thought Slyfoot the Mink had caught her. Why do you s’pose she hid away like that?”

“Ask her,” laughed Doctor Muskrat. “Run along, Bunny. Run along and ask her that yourself. They all do it.”

Everyone in the Woods and Fields insists that Chewee the Chickadee can’t keep his wings still or his tongue silent for a minute at a time. But they’re wrong. He sat perfectly quiet all the time Nibble Rabbit was telling Doctor Muskrat about his mate back in the Deep Woods. He had promised to let his mate know when Nibble was coming. He didn’t even let himself laugh when Nibble wanted to know why she had hidden away from him. That is, he didn’t until he saw Nibble hopping around the end of Doctor Muskrat’s pond to the place where Nibble jumps across the brook. Then Chewee took to his stubby wings and maybe you think he didn’t chuckle about it. He got the giggles so hard that he had to perch and hang on tight until he got over them.

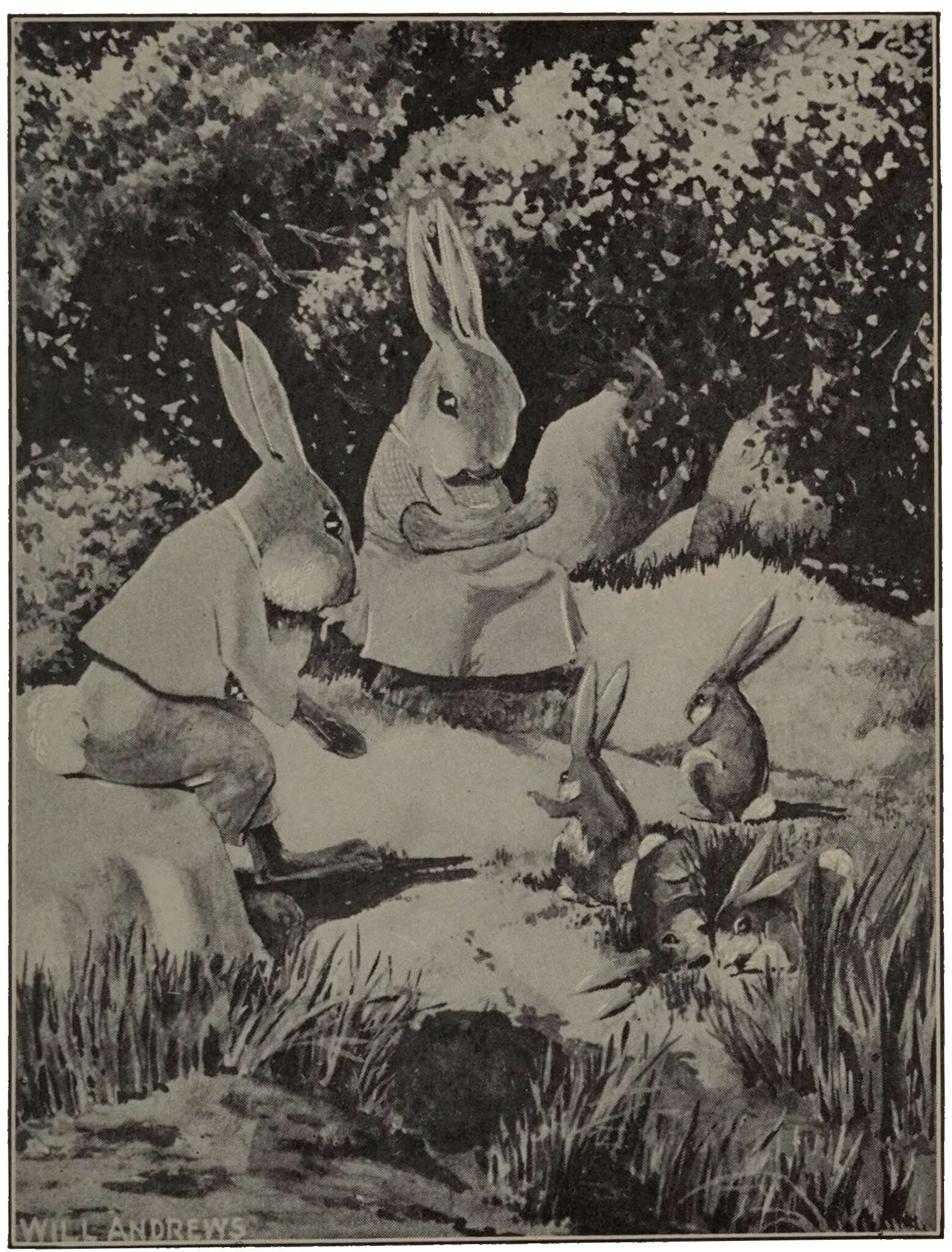

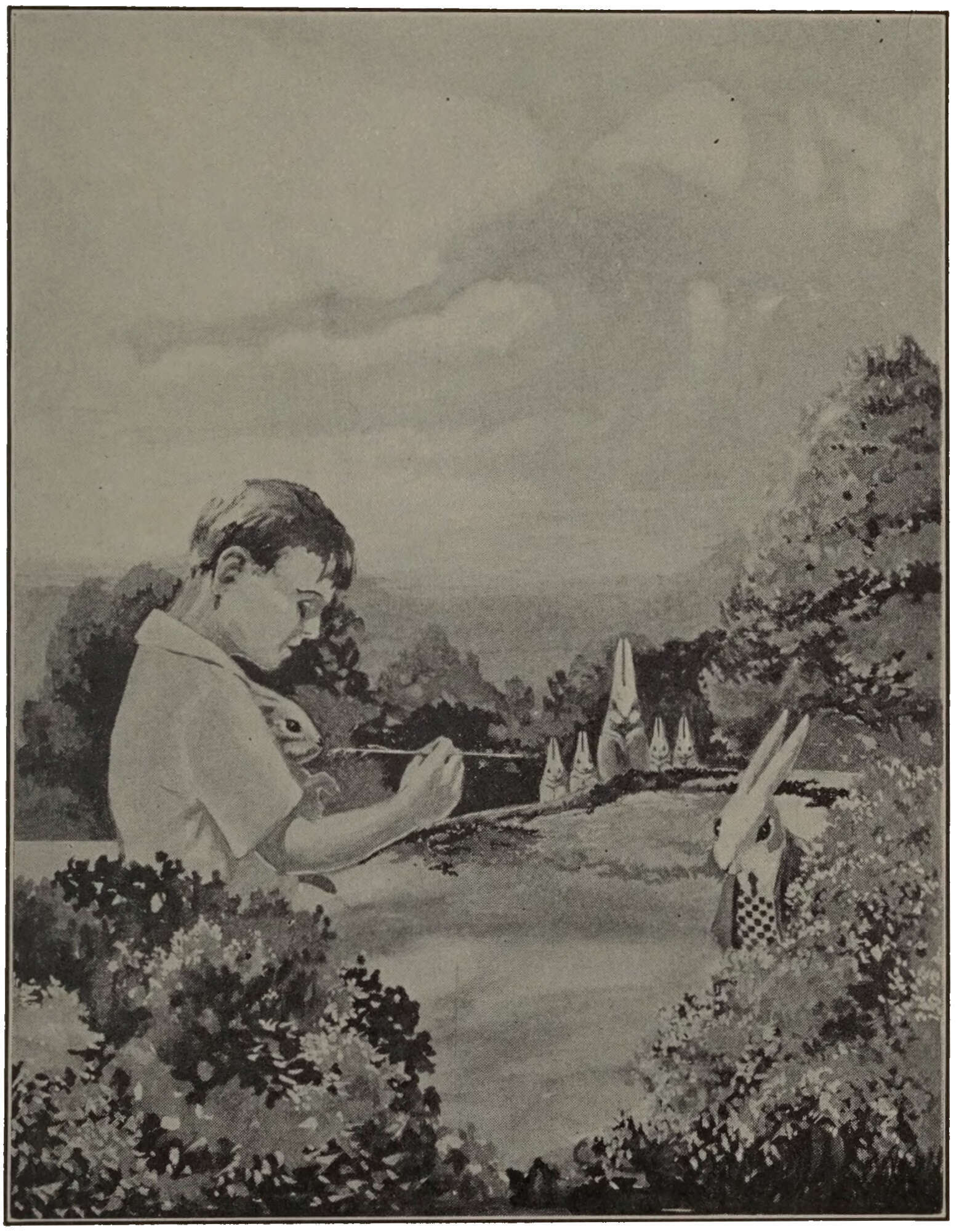

Lippity, lippity, lippity, went Nibble’s furry feet--my, but he was in a hurry to find his mate and his baby bunnies! Thump, thump, he went outside the Pickery Things she used to hide in while she waited for him. And out she came, with five of the cunningest, fattest, softest little balls of brown fur you ever saw. And they all twiddled their little tufty, cottony tails and pricked up their soft ears and opened their bright eyes wide at Nibble. But they wouldn’t let him come near them.

They all twiddled their little tufty, cottony tails.

That was because they thought he was angry. He thought he was, too. He said: “Why did you treat me like this, running away and hiding from me, and never even letting me know we had a family? You hurt my feelings dreadfully, Silk-ears.”

“Why, we always do it,” she protested. “Every mother rabbit makes her nest in some place where it’s hidden even from the father rabbit.”

“But you didn’t need to,” said Nibble. “We’re different. You didn’t think I’d hurt them, did you? Birds don’t do that. I’d have helped you take care of them.”

“That’s what father rabbits always say,” laughed Silk-ears, for that was the mother rabbit’s name.

“How many families have you raised, anyway?” Nibble wanted to know.

“This is the first,” smiled Silk-ears. “Aren’t they lovely bunnies for the first ones? But I’ve had a wise old mother rabbit, who’s raised ever and ever so many, to show me how. That was one reason I stayed here. And the other reason is that you couldn’t have helped me. We’re not like the birds. I don’t need your help to feed them and you leave a trail that’s ever so much plainer than mine. You’d have insisted on coming to see them and then Slyfoot the Mink would have followed you and found them. That’s why we mother rabbits always hide them away, even from you, until they’re big enough to run.”

Then wasn’t Nibble sorry he’d been cross! “I might have known you had a good reason,” he said. “You’re so clever.” He said it just as though she’d thought of it all by herself. And the minute those bunny babies heard he wasn’t angry any more they began to come closer and closer. One of them patted his white tail that was so much bigger than its own little puffy wisp, and another cuddled right up to him.

My, but Nibble was proud of his little bunnies! He wanted to take them back to the pond, right away quick, and show them to Doctor Muskrat. But Silk-ears, his mate, was quite stubborn about going. “No,” she said. “The old mother rabbit who told me how to raise them said that pond wasn’t a good place at all. She was there last year. Every one of her bunnies disappeared the minute they left the nest. Hooter the Owl got one, and Glider the Blacksnake got another, and Silvertip the Fox caught the third, and the last one just disappeared. She thinks Slyfoot the Mink found him while she was digging a new hole. She meant to leave him the old hole to live in. He was a very scary little bunny.”

Nibble pricked up his ears. “She went to dig a new hole, did she?” he asked. “Why was that?”

“Why, because she was going to raise a new family, of course, and she couldn’t have him tracking out and in.”

“How silly I was,” said Nibble. “Now I see why the stars said in my Fortune that Doctor Muskrat told me: ‘By dawn and by dusk you shall travel alone.’ I was plenty old enough to begin without any telling. And ‘All troubles are yours excepting your own.’ I was so busy getting rid of other people’s troubles that my own went with them. Now the Hooters have gone, and Silvertip, and Glider, and even Slyfoot doesn’t live there.” Nibble never thought that maybe wise old Doctor Muskrat had something to do with that fortune.

Of course his mate didn’t understand what he was talking about; she didn’t know any of the things he’d done. But she did know that he just insisted on talking to that wise old mother rabbit.

Of course you’ve guessed it before this--that wise old rabbit was Nibble’s own Mammy Bunny. He was down by the pond when she came back to see how he was getting along. She’d never think of going to ask Doctor Muskrat about him. He told her all the stories he hadn’t told Silk-ears and she shook her head when he told her that Tommy Peele was his special friend. She didn’t like boys a bit. I don’t think she really believed when he told her about Tommy’s dog, Watch, and Trailer the Hound. But then, mothers don’t know all about everything. They now what’s best for little bunnies, but you can’t expect them to know more than a great big grown-up rabbit like Nibble.

But Nibble didn’t care whether she believed him or not. “I’ve found you again,” he said, and he waggled his long ears, because he was so excited about it. “I’ve found you. Next thing you know we’ll have found Tad Coon.”

And maybe Mammy Rabbit wasn’t shocked at that! She didn’t think Tad Coon was a safe friend for any rabbit, even a big one. But that didn’t scare Silk-ears. It just made her prouder than ever of Nibble. So off they set for Tommy Peele’s Woods and Fields.

Maybe you think they didn’t have an exciting time getting their bunnies all the way over from their nest in the Deep Woods. It wasn’t because the little ones couldn’t run fast enough. It was mostly because they ran too fast. They scuttled all over and they wouldn’t pay the least attention to Nibble when he thumped his big furry feet at them. Of course they did keep watch of their mother’s white tail-tip--even tiny wee ones, as soon as their eyes are open at all, know that’s what it’s for--but they didn’t see any use in a father at all.

Just once one did. That was when the hawk swooped down. Silk-ears dodged into the Pickery Things, where no hawk could possibly reach her. Three bunnies tagged after her. Nibble just stepped under an elder bush, where the hawk couldn’t pounce from above, and one bunny squirmed right under him. Then it poked out its curious little nose from behind his elbow and blinked at the big bird.

One bunny poked out its curious little nose and blinked at the big bird.

She didn’t really mean them any harm. She was really hunting fieldmice though a hawk will pick up a wee rabbit now and again. But when she saw it was Nibble she just laughed. “Ca, ca! When did you take to hatching?” and flapped right on. She had a nest of her own not far from Nibble’s hole. Like a sensible bird she did her hunting away from home to keep out of neighbourhood quarrels. If she took one of Nibble’s babies she had a pretty good idea that someone would come after one of her own babies who as yet had only pin feathers.

But just as soon as the ungrateful little bunny saw his mother he ran to her. “Where’s the other one?” asked Silk-ears. “Wasn’t she with you?”

“I thought you had her,” said Nibble. And then the hunt for that fifth baby bunny began. They looked and looked until they were almost discouraged. Then, there she was! Where do you s’pose? In a deep footprint some horse had made. She thought she was pretty smart to have hidden so well that even her mother couldn’t find her.

“You bad little thing,” stamped Nibble. “That’s a regular hop-toad trick. We’ll call you ‘hop-toad’ if you ever do it again.”

But do you think he’d let Silk-ears shake her? Certainly not! And the baby didn’t know what a hop-toad was yet, so she didn’t care. Anyway, the Woodsfolk are very careless about naming their children. They just nickname them from some way they act or look and then call them that. And these were too little even to have nicknames yet.

The most exciting time was when they came to the brook that runs into Doctor Muskrat’s pond. The bunnies couldn’t jump, so Nibble had to pick them up by their furry collars, like he did the lady mouse, and carry them over, one by one, kicking and squirming. And Silk-ears jumped over beside him each time--as though she could do something if they did tumble in! Oh, she was glad to get them safe in Nibble’s home, I can tell you.

But if Nibble Rabbit had trouble with his naughty little bunnies you just ought to have seen Stripes Skunk. His kittens had a great idea of hunting things. When they hadn’t anything else to chase they chased each other or their own tails. They chased Nibble’s bunnies, and Nibble had to give one of them a kick that sent him tumbling. They chased Bob White’s stubby-tailed chicks until Bob gave them a smart pecking. They tried to chase the baby meadow-larks, but the little birds who nest on the ground are up and flying before most of the young furry things are out of their holes to bother them. That’s exactly why Mother Nature lets them grow up so much faster. They were very sweet-tempered kittens, anyway. They didn’t mean any harm, and they soon learned what they mustn’t do, and saved most of their chasing for the fieldmice.

Only they never learned not to tease Doctor Muskrat. He would no more get to sleep in the sun on his nice flat stone than somebody’s bad baby would pounce on him. Both Nibble and Stripes were afraid maybe he’d get cross about it. But that was before they caught him playing with those teasing little ones. He’d dive under the water and swim up underneath the stone. Then he’d pop up and snap at their paws when they tried to grab him. And they weren’t the only ones who thought it was fun.

But if Doctor Muskrat liked them, you just ought to have heard Tommy Peele the first time he saw them. He came out with his father to see if it was time to go after those potato-bugs. And of course neither of them could find a single one.

“That’s funny,” said Tommy’s father. “Those potato-bugs have been here. You can see holes where they’ve eaten the leaves. I wonder who cleaned them all up?”

Stripes Skunk sat up and saw what they were looking at. “It was the birds,” he explained, only of course Tommy didn’t understand him. Pretty soon Tommy saw something else. “This plant looks wilty,” he said. “It looks as though a mouse had been gnawing it.”

“It was a mouse,” smiled Nibble Rabbit, because he knew Stripes wouldn’t tell that he’d tried to stop them. He came hopping up close to Tommy. And Tommy didn’t know what he said, either, but his father must have understood a little.

“It’s queer about that stem,” he remarked. “I never knew mice to do anything like that before, but mice must be what your skunk friend is hunting here. That rabbit certainly isn’t afraid of him.”

“Those rabbits!” Tommy fairly squealed. For Silk-ears and all the babies were peeking at him with their long ears perked up among the potato stems. “And those skunks!” For Stripes Skunk’s three kittens were trying to squint at him from under the leaves, and the lower they put down their heads the higher they arched up their tails. But they didn’t know that. They thought they were beautifully hidden. And there were their three black plumes, with white tips squirming at the ends of them. No wonder Tommy laughed. No wonder he said: “Say, Dad. Let’s catch one!”

When Tommy tickled her nose with the tender end of a grass-blade she ate it.

You remember how scary wild Nibble Rabbit was when he was a baby. That was because his mother taught him that being scary is the very safest thing for a bunny to be. Most everything will eat him if it can catch him. But Nibble’s babies weren’t scary a bit. All they knew, so far, was making friends with folks. They made friends with their father, first of all. Then they’d made friends with Doctor Muskrat and with Stripes Skunk and his kittens, and Bob White Quail and his nice brown mate and all their little chicks. They hadn’t had a single thing to frighten them.

That’s why they weren’t very scared when Tommy Peele tried to catch them. They weren’t as scared as Stripes Skunk’s kittens. You know the kittens had seen their mother killed, so they knew dreadful things did happen. But they could see their father wasn’t afraid of Tommy, and he didn’t tell them to run. He just sat down to watch the fun.

Fun it was! Those bunnies and kittens played hide and seek with the little boy in and out of the potatoes until he didn’t have any wind left for running and laughing. The minute he’d stop they’d all come back as if they were teasing him to chase them again. They’d put up their little noses and sniff at him and they’d stamp their little feet at him. The skunks stamped their front feet and the bunnies stamped their hind ones. And Tommy Peele’s father, who had come to look over the potato patch, stamped the only feet he has and shouted: “Go it, Tommy! That’s the time you nearly got one!”

The only one who didn’t think it was funny was Nibble’s mate, Silk-ears. She was terribly frightened. And she was pretty cross with Nibble for laughing at her.

“Don’t worry,” Nibble chuckled. “That boy can’t catch them. And he wouldn’t hurt them if he could.”

But Nibble was only half right. You remember the baby who hid in a deep footprint, back in the Deep Woods? Nibble had called her a “hop-toad” for doing it. Well, she tried it again. And this time someone did see her--Tommy did. He scooped her up in his hand.

Poor Silk-ears was nearly distracted. She thumped hard and called: “Jump! Quick, bunny, jump!”

But that bad bunny didn’t jump at all. She just cuddled down and murmured: “It’s nice and warm in here. It’s comfortable.” And when Tommy tickled her nose with the tender end of a grass-blade she ate it. That most made the others envious.

But Tommy’s father had been watching Silk-ears. “The mother rabbit is so scared!” he said. “And she’s right. It’s nice to have them friendly, but suppose they trusted somebody else like that, maybe Louie Thomson. He might hurt them. And then it would be all your fault. Better let it go.” So Tommy did. And Silk-ears was mighty glad to get it back again.

Tommy’s father was perfectly right. The bunny didn’t mind a bit; she thought Tommy’s hand was a fine place to hide in, all soft and warm and comfortable. But somebody else mightn’t be so gentle with her. The only safety for wild things is to stay wild and be very, very careful. And yet, there are two sides to being scary; you’ll find that out when we come to it.

Silk-ears thought exactly the same way. She said: “It’s all right for you, Nibble, to be friendly with that Boy, because you’re a great big grown-up rabbit and you know just who you can trust and who you can’t, but something terrible will surely happen to that baby. If she wants to hide, she must learn to find herself a nice safe place in the grasses--she mustn’t just scrouch down into any little hollow and think if she keeps still nobody will see her. I wish Tommy Peele had given her a good shaking, I do! Then she’d have learned better.”

But you see, Tommy hadn’t. She wasn’t a bit scared; indeed, she was quite vain because she’d done something none of the others had dared to do. And she was all ready to do it again. She couldn’t see what her mother was making such a fuss about.

“That’s a regular hop-toad trick,” said Nibble. “I’m going to show her what one looks like. She won’t like that. And she won’t like being called Hop-toad, either. She’ll hurry up and get over acting like one.”

So he took the whole family around to the end of the Quail’s Thicket to where a great fat hop-toad lived under a big damp stone, and knocked, thump, thump! And from the dark, shady crack a pair of ruby eyes peeked out at them. Then a wrinkled hand came feeling out, a black hand with a yellow palm showing between its fingers, all spread out and grabby-looking. And then--out came the hop-toad’s nubbly head. My, but he was ugly!

But he’s very nice, you know. He never hurts anybody. Nibble never dreamed that even a silly baby would be afraid of him. “Good morning, Hop-toad,” said Nibble. “This is my family.”

The hop-toad blinked, because he’d been asleep for ever so long and he wasn’t all awake yet. “Oh-er-yes, your family. Quite a family.” He yawned; he opened his toothless mouth wide as wide, and he didn’t even put his hand up. And away went that bad bunny!

Away she went, past the woods-bridge, through the wire fence that goes around Tommy Peele’s Woods and Fields, out into a lane. She ran right into a boy who was walking down it. Then she did her hop-toad trick right over again--she scrouched down in a narrow wheel-rut. And the boy saw her. He reached down and scooped her up in his hand, just as Tommy Peele had done. But he wasn’t Tommy Peele, he was--Louie Thomson!

Louie Thomson! Yes, Louie Thomson was the boy who caught Nibble Rabbit’s runaway bunny baby. Just exactly what everyone was afraid of! For Louie Thomson wasn’t good and kind, like Tommy Peele. He did more awful things to the Wild Things than even Killer the Weasel, and they were terribly scared of him. Every last one of them was scared, excepting--excepting Nibble’s runaway bunny.

She didn’t know enough to be scared. She was just contrary. She wouldn’t believe that scrouching down in a little hollow like a hop-toad is the surest way to get caught. She would be afraid of a nice, toothless old hop-toad, who wouldn’t hurt anybody and she wouldn’t be afraid of cruel Louie Thomson, who hurt everybody excepting--excepting Nibble’s runaway bunny.

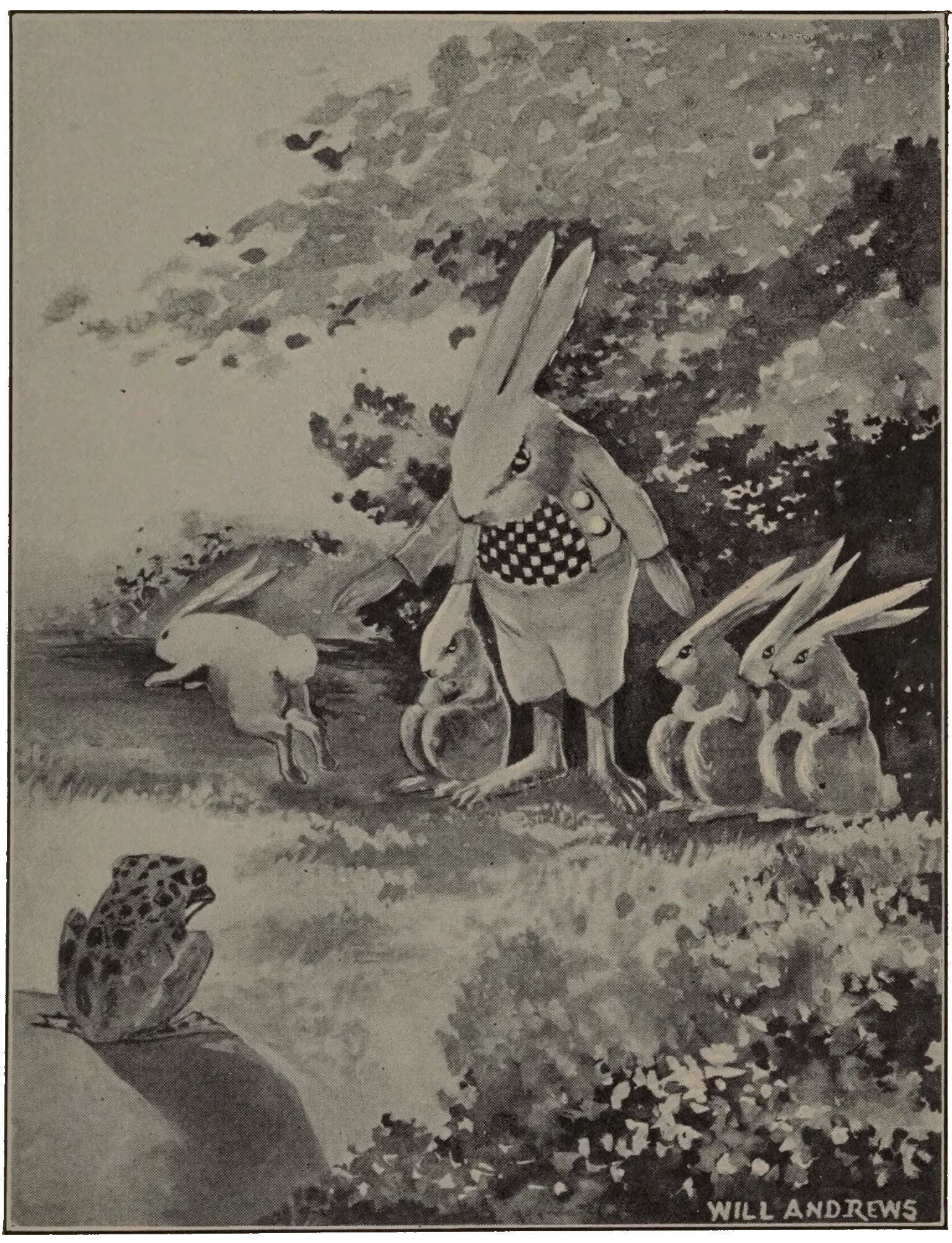

“Good morning, Hop-toad,” said Nibble. “This is my family.”

I told you the only way the Wild Things could be safe was to stay wild and be very careful. That’s because most of their wild enemies are the Things-from-under-the-Earth who came especially and particularly to eat them. But men are different. Deep down inside him every man knows that he’s just their big brother. He can half-remember the time when he used to live with them, before he quarrelled with Mother Nature.

Well, that wee bunny wasn’t a bit afraid of Louie Thomson; that’s just why she was safe with him. His hand was soft and warm, like Tommy Peele’s; when she cuddled down inside it he half-remembered what it was like in the First-Off Beginning of Things, when little boys and little bunnies played together. He didn’t want to hurt her. He said: “You cunning little thing, I’m going to take you home and show that smarty Tommy Peele he isn’t the only fellow who has pets. I guess I can tame you.” But he wasn’t any too sure. He had one pet already that he couldn’t tame.

Catching pets is one thing; taming them is another. You have to make them happy. And Louie hadn’t the least idea in the world how to do that. He took little bunny out of the clean, windy air and the warm sun and he put her in a smelly, dark cellar. He gave her some grass, but it was all tops and she was too little to eat anything but the tender white stems. He didn’t think to give her a drink of water. She was shivery cold and there wasn’t any mother to snuggle against. She was thirsty and there wasn’t any mother to give her a drink. She was lonely and there wasn’t any mother to comfort her. Poor bunny baby. She just sat in a miserable little heap and squalled, “Mammy, mammy, mammy!” exactly the way Nibble did when he lost his mother.

Suddenly a growly voice spoke up: “For sunlight’s sake, hush up, Bunny! She can’t possibly hear you. And I’m listening for something.”

That scared her quiet. Pretty soon the growly voice spoke up again, “Who are you, anyway?”

“I’m Nibble Rabbit’s bunny,” she sobbed.

“You are?” said the voice. “Did you ever hear him speak of Tad Coon?”

Now you know what happened to Tad Coon! It was Louie Thomson’s corn-crib he chased those mice in. It was Louie Thomson who shut the door on him. And it was Louie who put him in a cage in the dark, smelly cellar. No wonder none of the Woodsfolk could find him!

Now here was Nibble Rabbit’s baby, caged in an old box, right beside him. She told Tad all about Louie’s catching her when she was running away from the awful hop-toad.

“You are a silly bunny,” said Tad. “That hop-toad hasn’t a tooth in his head. He can’t hurt any one. And he’s wise. He’s most as wise as old Doctor Muskrat.”

“But he’s so scary ugly,” sniffed the bunny. “It must be horrid to be as ugly as that.”

“Ho!” snorted Tad. “He doesn’t think it’s horrid. He likes it. He doesn’t have to be careful about hiding like you bunnies.”

“I know,” sniffed the poor bunny. “I hid like a hop-toad. That’s why I was caught. My daddy told me not to. He called me ‘Hop-toad’ to make me stop doing it.” She began to cry again.

“That sounds like Nibble,” chuckled Tad. “Well, listen to me; you nice juicy little bunnies can’t hide too carefully. Everybody’ll eat you. But nobody wants to eat a hop-toad. I know I wouldn’t--not even now.”

“You wouldn’t eat me,” squealed the poor bunny.

“I might,” said Tad. “You see I’m so starvation hungry. Dry bread and carrots aren’t any food for a decent coon. Not even an ear of corn, by way of a change.”

“Oh, oh, oh!” cried the poor bunny. “Mammy! Mammy!”

“Now whist,” said Tad soothingly. “I can’t get you, so you’re perfectly safe. But if ever you get out of here you’ll be more careful about trusting folks, won’t you? You never can tell just how hungry they are, you know.”

“But I never will. I’ll die right here. I’ll never get out.”

“Yes, you will, too,” said Tad. “I’m going to get out. I don’t know when or how, but I will. And if ever I do it won’t take me a minute to open your cage with my handy-paws. And then I won’t want to eat you any more. This place is just alive with mice. If ever I get after them they’ll know it. Grr-r-r! I sit here and listen to them. I know all their holes. I’ll hunt ’em!” and he licked his whiskers at the very idea. “Now you cuddle down, little hop-toad, and I’ll tell you stories about Nibble Rabbit.”

And he did. He told her about the time he went fishing and splashed Nibble, and how Grandpop Snapping-turtle nipped the end of his tail. He forgot to be hungry and the bunny forgot to be scared until she fell fast asleep.

All night long Tad Coon kept still in his cage down in the dark, smelly cellar. He wasn’t waiting for a mouse to come and nibble his bread--they’d learned it wasn’t safe to do that. He was trying not to wake Nibble Rabbit’s poor little bunny.

All night he watched those mice scuttling about the floor with his mouth just watering. He was so dreadfully hungry. He didn’t have enough to eat, and it didn’t agree with him, and the damp air made his bones ache. It was worse yet when a rat came snooping in and caught one of the mice. He ate part of it and then left it lying right under Tad Coon’s hungry whiskers. But it was worst of all when that rat began to gnaw the bunny’s box. Tad shook his bars and chattered at him. “Go away! Go away, you brute, or I’ll trim your ugly whiskers!”

“Yah!” sneered the rat. “A lot you’ll do. You’ll die pretty soon. And when they throw you out on the rubbish-pile I’ll be the one who eats you!” Then he peered at the bunny. “I won’t bother to gnaw in and get her,” said he. “They’ll throw her out in the morning. She’s dead already!”

My, but Tad was sorry! But the rat was mistaken. The bunny wasn’t dead. She was just stretched out because she felt too weak to sit up any more. And Tad had waked up Louie Thomson with his snarling and shaking.

The little boy looked in at Tad. Tad glared back and growled at him. He gnashed his teeth when Louie tried the door to be sure it was locked. “You’re a horrid, hateful thing!” Louie snapped crossly. But he didn’t feel that way about the little rabbit.

He picked her out of the box, and she tried to curl up in his hand again, for it was the warmest thing she’d felt since she left her Mammy Silk-ears. That was too much for Louie. She was still trusting him; he felt a choke in his throat. “Don’t die, Bunny,” he almost sobbed. “Please don’t die. I didn’t know you were too little to leave your mother. If I take you home maybe she’ll find you.”

So he covered her up all warm and snug in his hands and began to run. He ran away down to the end of Doctor Muskrat’s pond, where it goes under the woods-bridge. He didn’t put her down in the road where he found her--even a boy knew that was no place for bunnies. He took her across the fence and laid her down where she could hide under the edge of the very same stone that belonged to the hop-toad. Then he went back to the fence to watch.

When she found herself all alone the poor baby began to call again in her weak voice: “Mammy, mammy!” Of course, the hop-toad heard. Out he came scrambling; he took just one look at Nibble Rabbit’s bad baby and then off he went in the biggest kind of a hop-toad hurry after Nibble.

Did you ever see a hop-toad in a hurry? He doesn’t hurry very often and he doesn’t hurry very fast, but he makes an awful fuss about it. He gulps a great big breath and then he shuts his mouth tight, tight, and flops along as hard as ever he can. Because when he’s used up that mouthful of breath he’ll have to stop and gulp another. That was the way the hop-toad hurried when he went to find Nibble.

But he didn’t have to hop so very far, because Bob White Quail was scratching about in his thicket. The hop-toad took two big gulps and then he had breath enough to gasp: “Fly quick! Tell Nibble Rabbit I’ve found his lost bunny.” And Bob White didn’t stop to ask any questions; he flew!

It seemed a long time to the poor, cold, hungry little bunny; she lay there under the edge of the hop-toad’s stone, calling her mammy, for she didn’t know where the hop-toad had gone. But I can tell you it seemed a lot longer to Louie Thomson. He was sitting on the fence feeling very sorry that he’d picked up that cunning little rabbit, and taken it home with him. And she wasn’t wishing her mother would come any harder than he was.

Then--ka-flick-it, ka-flick-it, ka-flick-it, came furry footsteps. Silk-ears came leaping over the tops of the grasses faster than Nibble ever ran, even when Glider the Blacksnake was after him. Faster than Bob White Quail can fly she came; as fast as a fish darting across Doctor Muskrat’s pond. And four other little bunnies came swishing through the grasses behind her. They couldn’t begin to follow her tail; they had to follow Nibble’s.

In just about two licks of a tongue Silk-ears had that lost bunny cuddled down beside her and was feeding her. My, how that hungry baby did eat! She ate and ate with her little eyes shut, too busy to pay any attention to her brothers and sisters, or to Nibble, or even to that very nice hop-toad. Her little sides grew fatter and fatter. By and by she felt so fat she had to roll over on her side, and the first thing anybody knew she was asleep. Right there in the sun--no place in the world for a sleepy bunny--but there she dozed. And nothing troubled her, not even a buzzy fly--because the hop-toad soon gulped him in. Tommy Peele’s Woods and Fields were all quiet and peaceful.

Even Louie Thomson tried not to wriggle for fear of disturbing them. But the top rail of that fence wasn’t any too comfortable, and the flies buzzed about his ears, because he hadn’t any hop-toad to gulp them, and at last a mosquito stabbed its stinger into his cheek. Slap! You ought to have seen those rabbits scuttle home--and the little lost bunny ran just about as fast as the rest. So Louie didn’t care. He put his hands into his pockets and went off home, whistling as gayly as a fiery-coloured oriole.

He whistled so loud that all the birds stopped to listen. He didn’t know just why he felt like whistling. He got to thinking about that coon he caught in his corn-crib. He’d had it in a cage for ever and ever so long, and it was crosser than ever. But he didn’t stop whistling. He went right down into his cellar, leaving the cellar door wide open behind him. Then he opened the door of the cage where he had Tad Coon. “Git along, you bitey old thing,” he said. “I don’t want any pets. They’re too much trouble.”

Tad Coon sat back in a corner, snarling. He didn’t believe Louie meant to be kind to anything. He just guessed that the minute he poked his nose out Louie’d hit him with something. Then he’d be thrown out on the rubbish-pile with Nibble Rabbit’s baby bunny, and the rats would eat him. He thought of course Louie had killed it because all the Woodsfolk knew he always killed things.

Sure enough, Louie picked up a stick and poked him in the ribs. “Hey, you!” he shouted crossly, “git out o’ there! Git a wiggle on!”

Tad grabbed that stick with his teeth and his handy-paws and snatched it right out of Louie’s hands. Then maybe he didn’t run! Bounce! He hit the cellar floor! He hit the cellar steps just twice--blam! blam! Louie came out and watched him gallop across the garden. When he disappeared into the cornfield he was still running. Pretty soon Louie saw him sneak under the fence into Tommy Peele’s potato patch. “Huh!” he grunted disgustedly, “Tommy can have his cranky old coon if he wants him.” He was just pretending he didn’t want Tad; he did, all the same. He felt so sorry he stopped whistling.

He just wanted him so much that he climbed up on the fence to see the last of him. And what do you s’pose Tad Coon was doing? He was lying on his back in the nice warm earth, wriggling and squirming. My, how good that felt! When he jumped up again he was actually smiling. He scrubbed his face and ears all neat and clean, and he fluffed out his tail, and he didn’t look a bit like the snarly beast who’d been living with Louie Thomson. He looked like the smarty one who had been playing with Tommy Peele’s watch and chain the day Tommy and Tad Coon and Stripes Skunk and Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat all went fishing.

And when Louie Thomson saw how happy he was, why, he just began whistling all over again louder than ever! But still he didn’t know why.

When Tad Coon got out of that damp, smelly cellar he was just about the happiest coon who ever hunted wood snails under a burdock leaf. He was happy until he’d eaten several snails and three fieldmice and one green frog. Then all of a sudden he remembered the bad news he had for Nibble Rabbit. You know he thought Louie had killed Nibble’s poor little bunny. My, how he hated to tell Nibble and Silk-ears!

So he lost his smile. His face got longer and longer as he dragged his feet toward Doctor Muskrat’s pond. It felt most as long as his tail. His eyes got all teary and his nose got all sniffy, just thinking how badly they were going to feel. But when he came around the end of the Quail’s Thicket who should he see but Nibble talking excitedly to Doctor Muskrat. Silk-ears and a lot of little bunnies were with him.

“It was Tad Coon, all right,” Doctor Muskrat was answering. “No one but Tad would have known all those stories he told the baby about you, Nibble. Now we’ll get Tommy Peele’s dog Watch to take Tommy after him. Tommy can undo that cage door. You’d better hurry right off and find him. We can’t leave Tad there another hour!”

How had that baby bunny come home? Tad couldn’t imagine. But here she was, and here were all his friends planning to rescue him. He felt so happy, all of a sudden, that he grinned until the tips of his prick-up ears most met. He just danced up, like a skittish butterfly in a breeze, squealing, “I’m here! I’m here!”

“However did you get away?” gasped Nibble and Doctor Muskrat in the same breath.

“That awful boy opened the cage door and I just ran,” chuckled Tad. “How did the baby get away from him?”

“She didn’t,” Nibble explained. “He brought her back to the hop-toad’s stone. And she says he isn’t awful a bit. She isn’t scared of him.” He looked around for the bunny, but she’d scuttled into the Pickery Things the second she saw Tad Coon. Nibble had to call and call.

By and by she squeaked: “I’m not scared of that boy, but I’m awfully scared of that coon. He said he’d eat me.”

“Yes, I did,” Tad owned up. “I told her little rabbits mustn’t trust us coons. But I won’t eat you now. I’m not a bit hungry.”

“There’s something queer about this,” said Doctor Muskrat. “That bad Louie Thomson wasn’t bad to the little bunny.”

But if the Woodsfolk were wondering about Louie Thomson that morning, they wondered a lot more that afternoon. And they weren’t the only ones who wondered. Tommy Peele came down for some more fishing. Of course Doctor Muskrat and Stripes Skunk were interested in that, and Stripes’s three kittens sat still as still, with their toes tucked in like a pussy-cat’s, and the white tips of their tails twitching, because every other fish belonged to them. The bunnies were snoozing in the Pickery Things, Chatter Squirrel and Chaik the Jay were having an argument, and Tommy’s dog, Watch, was barking at them, and Tad Coon was down at the lower end of the pond, happy as a frog on a lily pad, full of mussels to his very chin. Suddenly he looked up and saw Louie Thomson looking through the fence--right at him.

Wow! But you ought to have seen him go! He bounced past Tommy Peele, splattering water all over him. Everybody hid, even Chatter Squirrel; everybody but Watch, who began growling and barking.

This made Louie angry. He just leaned over the fence and squalled: “You can have your darned old coon! He’s just as mean as your darned old dog! I wisht I hadn’t let him go. I wisht I’d killed him when I had him--I do!”

“When did you ever have him?” jeered Tommy Peele.

“This morning. I had one of your rabbits, too--a little bitty one--but ’twasn’t big enough to keep, so I let it go again.”

“You broke your promise!” shouted Tommy. “You broke your promise. You said you’d never come over here and catch my wild things again!” My, but he was angry.

“I didn’t--so, there!” snapped Louie. “I caught that coon in our corn-crib. And I caught that little bunny right here where I’m standing now. But I don’t want any of your old pets, seeing you’re so selfish about them.”

“I am not selfish,” Tommy answered back. “You could have pets yourself, only you’re too lazy to feed them.”

“I’d like to know what I’d feed them with?” asked Louie. “I see my pa letting me go into his feed bins like your pa lets you. He wouldn’t even let me have some for my coon, but Ma gave me bread for him.” No wonder poor Tad was hungry!

Tommy most forgot to be angry. Maybe Louie Thomson wasn’t so very bad, after all. Maybe he did want to be friends. Every little boy didn’t have a father like his, who knew all about boys and wild things. “Say, Louie,” Tommy said in a different voice, “all these fellows love roasting ears. You can get some from our cornfield if you want--my dad won’t care.”

Did Louie want to? Did he? You just ought to have seen the feast he laid out, over by his fence, not by the flat stone where Tommy always put his feasts, so the Woodsfolk would guess it wasn’t from Tommy Peele.

Before long, “Munch, munch!” went Nibble Rabbit and Silk-ears, and all their little bunnies. “Crunch, crunch!” went Stripes Skunk and his kittens. “Scrunch, scrunch!” went Doctor Muskrat, and Chatter Squirrel, and Tad Coon. “Pick, peck, pick!” went Chaik the Jay, all busy on those sweet, juicy young ears of corn.

Tommy Peele and Louie Thomson were driving up Louie’s cows as friendly as though they’d never had a quarrel. But Tommy’s dog, Watch, pricked up both his ears as he listened to them. Then he galloped over to the feast and barked: “That’s Louie Thomson’s corn. He’s trying to make friends with you.”

“Yah! ’Tis not!” squawked Chaik. “He got it in Tommy Peele’s own field. I saw him!” You see, they didn’t know Tommy said he might because Louie’s father wouldn’t let him take any from his own cornfield, even if Louie did the hoeing.

“It’s in Tommy’s woods,” pointed out Doctor Muskrat. “We haven’t made any compact!”

But Tad Coon surprised them all. “Are you sure, Watch?” he asked. “’Cause if you’re certain sure I’m going back to his cellar again.”

“Back to that smelly, stuffy, dark cage!” exclaimed Nibble Rabbit. And his ears flicked straight up, he was so s’prised to be asking such a foolish question.

“Sure as mice is mice!” chuckled Tad. “That cellar’s just alive with them. And there’s that rat who bothered your bunny, Nibble. I’ve got a bone to pick with him--and he’s going to furnish the bone!”

“Don’t do it!” warned Stripes excitedly. “You’ll get caught again!”

“No, I won’t,” sniffed Tad. “I’m not going near that old trap.” Tad meant the corn-crib.

“But it’s all over traps!” Stripes insisted. “Traps and cages, for cows and horses and pigs and sheep--and men, even!” You see Stripes thought the houses and barns and sheds were all traps to catch the things who live in them and keep them from going wild again. And that’s half true, isn’t it?

“Traps for men?” squealed everybody. “Men don’t hunt men.”

“Don’t they, though?” asked Stripes. “Well, we skunks know something about that. There used to be wolves and bears and all sorts of wild things here, even wild men. They weren’t like these men. They were the colour of Chatter Squirrel, and they lived in little shady trees made of skin or in log piles, like the beavers.” He meant the tents and the winter houses of the Indians. “We skunks used to be good friends with them. But these men weren’t. They hunted them, just like they hunted the bears and the wolves and the beavers, too. The wild men were smarter than any of the other wild things, but these men who live here now just kept building more and more traps to catch them in. Now every last one of them is gone!”

“That’s so,” said Doctor Muskrat. And it is half true, too. The Indians did disappear when the white men built their houses, but of course it wasn’t because the white men trapped them the same as they trapped the wild things.

Everybody looked serious when Stripes Skunk explained that all the houses and barns and sheds on a farm were traps to catch the things who live in them. Even Doctor Muskrat didn’t know any better than to believe him, nor Chatter Squirrel, nor Chaik the Jay, nor Tad Coon.

But Nibble Rabbit pulled down his ear with his paw and licked the end of it very thoughtfully. “The cows aren’t trapped,” he said. “The White Cow said that cows lived in those barns because they made a compact with man. They give him milk, and he feeds them and keeps the wolves from killing them.”

“But there aren’t any more wolves!” argued Doctor Muskrat.

“The cows don’t know that,” said Nibble. “They thought Silvertip the Fox was a wolf. They were terribly excited about him.” My, but you ought to have seen Silk-ears. She began sitting up straight and putting her fur in order; she felt so vain because Nibble seemed to know all about everything.

And you ought to have seen Tad Coon’s eyes sparkle again. “Those big cages--barns, you call them, do you, Nibble?--can’t all be traps. The rats scuttle in and out of them.”

“But you’re bigger than the rats,” said Stripes. He still felt scary.

“But I’m not any bigger than Louie Thomson,” Tad argued. “I’m not nearly as big. I can use his hole.” Of course he meant the cellar door. “And I’ve just got to catch that mean old rat. He said he’d eat me, he did. Guess I’ll show him who’s going to do the eating.”

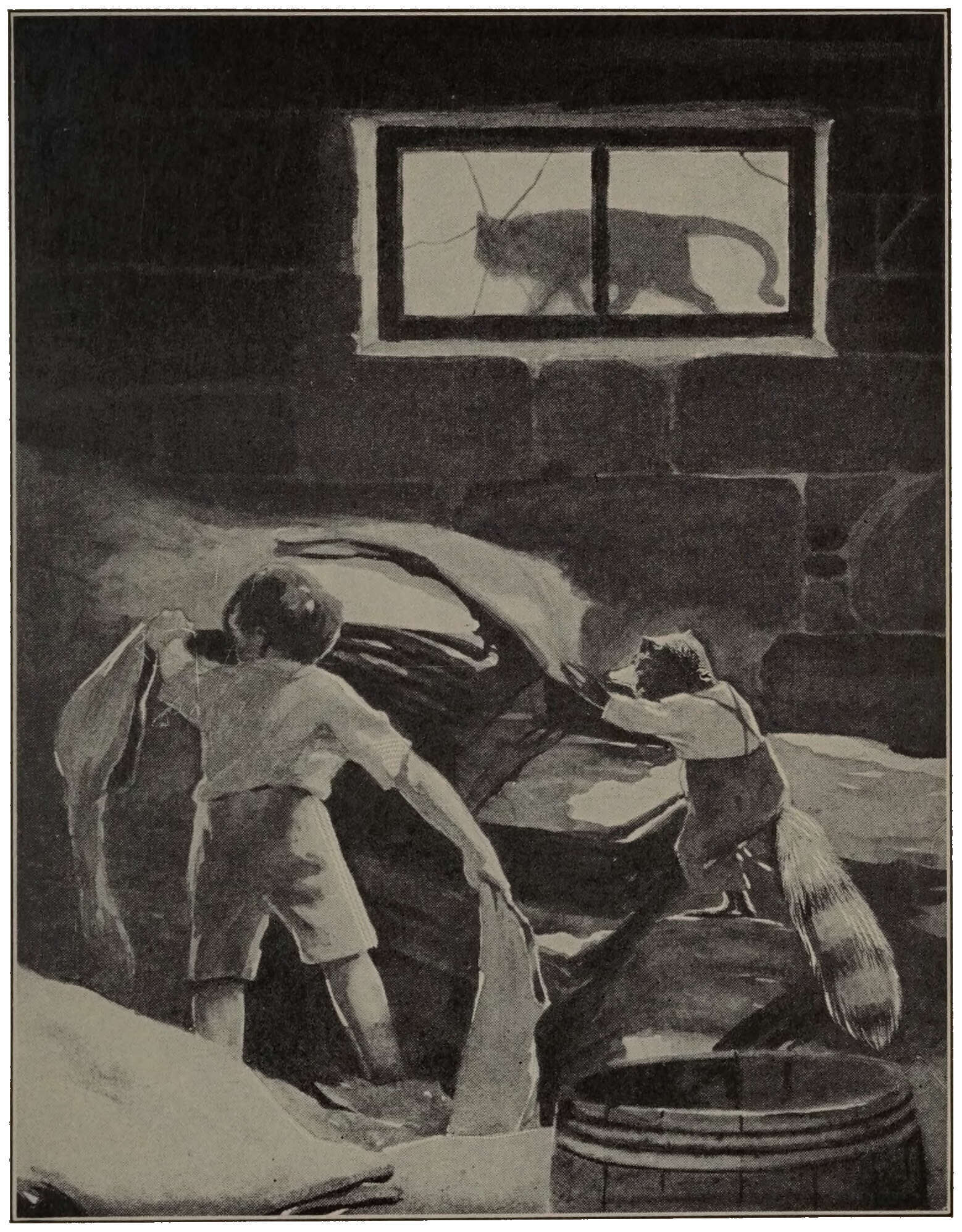

So off waddled that smarty coon. He sneaked round behind the woodpile and scuttled down into the cellar when nobody was looking. There was his cage, just the way he’d left it that morning. He climbed in and lay down.

It grew darker and darker. Pitter, pitter, sounded the feet of the scuttling mice. Then came the sound he was listening for--the scritchy-scratch of that rat’s claws on the cellar door. “Hey, you coon!” called the rat. He wanted to be sure Tad wasn’t out of that cage, hiding in some corner, ready to pounce on him. Tad didn’t answer. So the rat ran up a pipe and crept along until he could peek through the darkness. Tad could hear him sniffing. “Are you ready for the rubbish-pile already?” he asked. Still Tad didn’t say anything. Thump! He landed on the top of the cage. He felt the door was open. He crept in!

Bounce! Bite! Scree-ee-eech! That was the end of Mr. Rat! But--Bang! went the door! Tad was locked in again. Poor Tad Coon!

That’s what always happened to Tad. Every time he played a smarty trick on somebody it was sure to come back on him.

Tad Coon made some noise, I can tell you, when he caught that rat down in his jangly old cage. And the cage door made some more when it fell down and locked Tad in. And Tad made more yet, shaking the bars, trying to get out again.

Louie Thomson’s family was getting ready to go to bed. His father growled: “If that beast in the cellar makes any more noise I’ll go down there and kill him.”

Louie didn’t answer. He didn’t dare to argue. Besides, he didn’t believe it was really Tad. He’d let him go just that morning!

Louie’s mother asked: “Louie, did you remember to feed that coon?”

“No’m,” said Louie.

“Well, then, you can pick some scraps out of the pig’s pail to give him,” said she. She didn’t dare offer him anything else because his father was listening.

Do you think Louie would do that? I guess not. He’d learned something that afternoon. Tommy Peele showed him how nice sweet roasting ears of fresh corn were what you ought to feed a coon. He just pretended to pick up something, and then he sneaked down to listen. The coon was there all right enough; he could hear him. You just ought to have heard Louie then. His bare feet went pat-pat-patting over to his father’s cornfield. Then they came pat-pat-patting back again. Pat-pat they went on the cellar floor. And Tad could smell the nice sweet corn.

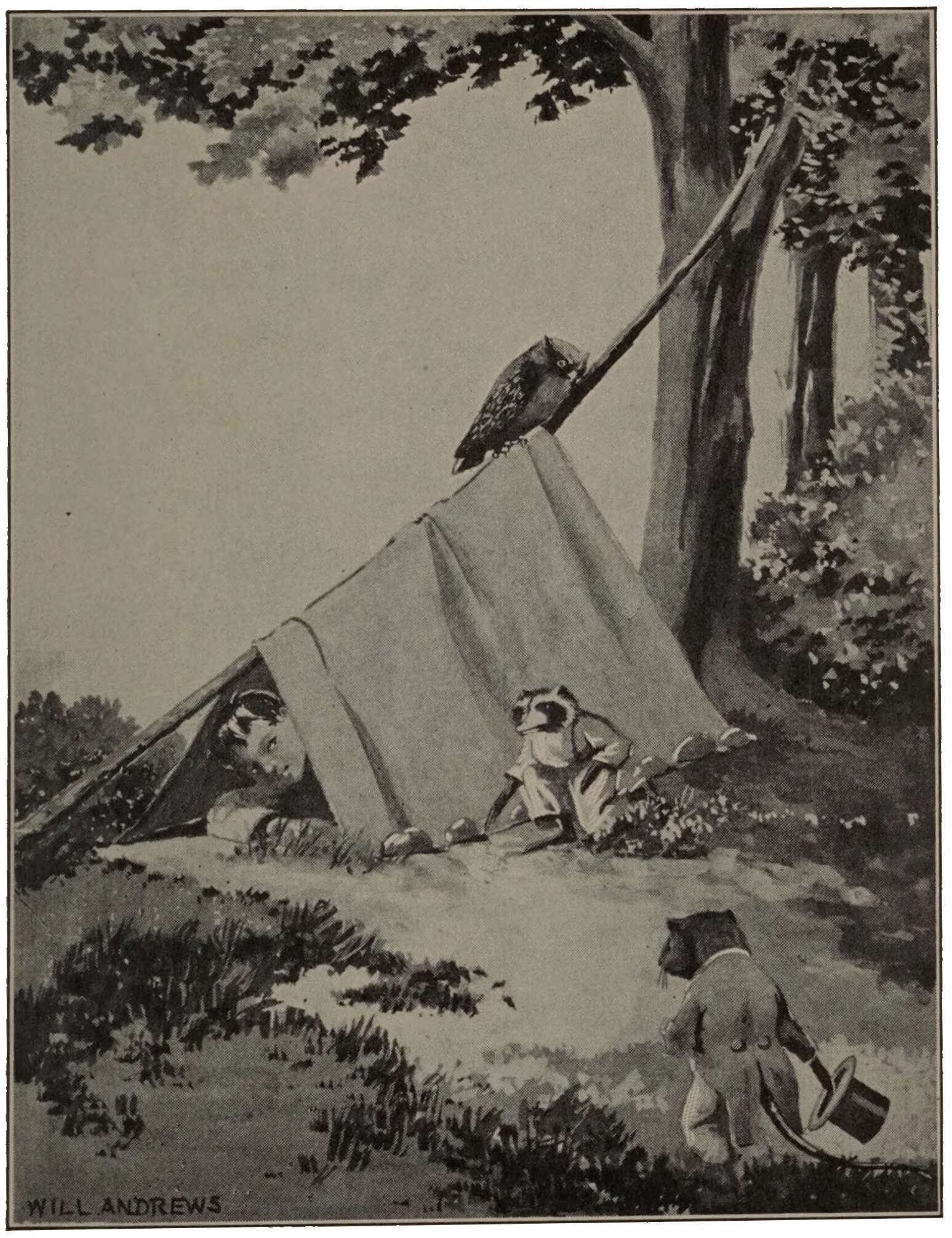

Tad and Louie had the grain sacks flying, to find the family of mice.

“There!” said Louie in a happy voice, “I guess you’ll be glad you came back again.” And he poked the corn into the cage. “Oh, I thought you hated me. I do want you to like me, you nice coon.”

Was this the cross little boy who’d snapped and snarled at him? Tad just couldn’t believe his ears. He stopped eating to listen.

“I will be good to you--’deed I will--if you’ll only be tame,” Louie was saying in this brand-new voice.

Tad poked his nose through his bars and sniffed at him. Then he took hold of his door in his handy-paws and shook it until the cellar echoed with its jangly noise.

“Don’t, don’t!” begged Louie. “My pa will hear you.” But Tad wanted to be let out. He went on shaking. “Aw, what’s the use of locking you up, you’ll come back to me, anyhow,” said Louie at last. He reached for the door and Tad’s little handy-paw caught hold of his finger. But he didn’t jerk it away, because this wasn’t a snappy, snarly coon. This cunning little fellow didn’t bite him any more than he’d bite Tommy Peele. He opened the door.

Thump went Tad on the floor. But this time he didn’t try to run--he was too busy examining Louie Thomson. He twitched Louie’s trousers and he felt of Louie’s toes, and his curious little handy-paws were so tickly they set Louie giggling.

Louie’s mother finished sweeping out her kitchen. She was all ready to go to bed now except for one thing. “It’s kind of funny,” she said to herself, “I haven’t seen Louie since I sent him down cellar to feed his coon.” So she took the lamp and started down the stairs, using the broom for a cane, because it came in so handy when she felt tired and stiff. On the fourth step she stopped to listen. That was a queer sound! There it was again. She smiled herself.

For what she heard was Louie giggling because Tad Coon’s handy-paws tickled him. Tad was examining him to see if he carried a bug in his pocket, like Tommy Peele. Nobody could convince Tad that Tommy’s noisy ticky watch wasn’t a bug.

The lamp cast a light on the cellar floor and Tad saw a mouse. He whisked around and caught it. There, now he could see a pile of grain sacks where he knew there was a whole family of them. He didn’t stop to think where the light was coming from. He’d got used to light and noises while Louie kept him locked up in that awful cage. He used to hate the cellar, too. Now that he was free he thought it was fun--the loveliest sort of a place to go hunting in. You’d better believe he and Louie had those grain sacks flying.

“Louie Thomson!” said his mother. “Whatever are you doing?”

“My coon’s catching a mouse,” laughed Louie. “Oh, Ma, he’s tame! I let him go this morning and he came right back again.” Of course Tad came back to get even with that mean old rat who plagued him while he was starving in his prison. But Louie didn’t guess that. “Shh, Ma!” he said. “Hold your light so’s he can see. Look! He’s caught another!”

“Good land!” exclaimed his mother again. “He’s smarter than a cat. I wish he’d come up and clean a few out o’ my kitchen.”

Just then, clump, clump, came Louie’s father down the stairs. Even Tad could tell he was angry by the way he was stamping--you know coons and skunks and bunnies, even, do it, too. He guessed it was time to be going.

“What does all this racket mean?” shouted Louie’s father. “I told you I’d kill that beast if I heard any more from him; now I’m going to do it.” And he snatched the broom from his wife’s hand. He wanted to use it for a club. Then he looked in the cage.

He didn’t see any coon, but he did see the corn Louie had brought for him! “What do you mean,” he roared, “breaking off my corn for your beast? I told you to leave my grain strictly alone. Now I’ll give you a licking you won’t forget. Where’s that brute gone?”

Tad was sneaking around behind him in the dark shadows. Whack! The broomstick just missed him as he bounced out the cellar door. Whack, whack, it came down on Louie Thomson’s shoulders. Out of the cellar door he bolted, too, and raced after Tad Coon.

Patty, patty, ka-flip, ka-flip, went Tad’s feet, running away from Louie Thomson’s house for the second time. Pad, pad, pad, pounded Louie Thomson’s feet, running after him. Louie was mad clear through, but he wasn’t mad at Tad Coon. He was angry at his father for trying to beat him with a broom.

All the same, he felt scary and lonely when he got out there in the darkness. He could hear Tad’s feet running down the alleyways between the corn. But the stalks were way up over his head. He couldn’t see where he was going. Pretty soon he couldn’t even hear the coon--he was all alone.

But was he? He stubbed his toe on something--something soft and furry and warm. It was Tad. For just as soon as Tad got over being scared about himself he began to wonder if that cross man with the big stick had done anything awful to poor Louie Thomson. He knew what it was like to be chased. Besides, Tad’s the most curious beast in all the woods and fields, and he had to know the meaning of those little, sad, sniffly noises Louie was making.

But Louie just knew Tad was sorry for him. The poor little boy threw himself on the ground and cried and cried. “It isn’t fair,” he sobbed. “I hoed that corn, I had a right to take just a little weeny bit of it for you. Besides, you earned it. You killed the mice in our cellar just as much as those old cats ever do. I wasn’t bad, and I just won’t take a licking for it.” All the same, he knew that’s what he’d get if he went back home.

Tad kept cocking his ears and touching Louie with his shy little handy-paws, trying to think what he was doing. Little coons cry, too, but they cry, “Wa-wa-wa,” more like a hungry little bird. By and by he got restless and started along.

“Wait for me! Wait for me!” called Louie, and he got up and followed Tad--all the way back to Doctor Muskrat’s pond.

The night was clear and warm. And it wasn’t so very dark, after all. Louie could see quite well. Now it was his turn to be curious about what Tad Coon was doing. A frog jumped in the long grass and Tad pounced on it, just the way he pounced on a mouse. But he didn’t eat it--not yet. He carried it over to the water. Then he began splashing.

“He’s washing it first,” thought Louie. “If that isn’t the beatin-est!”

Sure enough, when he had it washed all clean Tad gulped his frog. Then he paddled his paws and scrubbed his mouth and whiskers. Yes, and even reached up behind his ears.

“Washing looks kind of nice,” thought Louie to himself. So he tried it, too. He washed himself clean as clean--clean as that fat old coon, even. And then he felt so comfortable he curled up by Doctor Muskrat’s stone and fell fast asleep.

You wouldn’t think even the wild woodsfolk would be afraid of a tired little boy, fast asleep by the pond, but they were. They were most scared to death. The whippoorwill sounded a desperate warning as she circled about on her long pointed wings trying to make up her mind to scoop up a mouthful of water, and the little bats squeaked as though the big owl was after them.

They woke up a lot of the Woodsfolk who had eaten their late supper by moonlight and gone to bed. Stripes Skunk came over from the potato patch, and Nibble Rabbit loped out to the edge of the Pickery Things and stood there on tip-toe, even to his stick-up ears, he was so s’prised. Chatter Squirrel looked from the lowest branch of Tad Coon’s tree. Doctor Muskrat crawled up on his stone, and maybe you think he didn’t jump when he found who was sleeping beside it. But fat old Tad patted out of his nest in the cool bulrushes, where he’d been taking a little cat-nap with one ear open, and settled it.

“Needn’t anybody be afraid of Louie Thomson,” said Tad. “He’s my boy. And he’s most as nice as Tommy Peele, Nibble. He’s friends.”

“But we haven’t made any compact with him,” suggested Doctor Muskrat.

“Compact!” sniffed Tad. “The minute he found I was shut up in my cage he brought me the juiciest mouthful of corn you ever wet your whiskers in.”

“Yah!” jeered Stripes. “What did I tell you? Didn’t I say you’d get caught? It’s all over traps, wherever you find men.”

“You did,” admitted Tad. “It was the queerest thing. I could get into that cage, and so could that mean old rat--he thought I was dead, Mr. Scaly-tail did. You ought to have heard him squeal when I grabbed him. But then I couldn’t get out again!” Tad didn’t know it was his very own self who shook the cage door down. “It didn’t matter a bit,” he went on comfortably. “Louie came right down and turned me loose. But you’re right about another thing, Stripes, men do kill men.”

“What!” exclaimed all the woodsfolk.

Tad nodded solemnly. “Sure as tadpoles have tails! We were having the nicest mouse hunt, Louie and I, when that big man came stamping in. He tried to kill me with a stick, and he did hit Louie with it--twice.” Of course Louie’s father didn’t mean to kill him; he only meant to punish him for taking the corn. But Woodsfolk don’t beat their children, they only shake them.

“Louie could run, all the same,” Tad finished. “So he came with me; he’s going to go wild again and live with us.”

Doctor Muskrat looked at Louie in a very puzzled way. “I wonder if he can go wild?” said he. “It’s a long, long time since men were wild.” You ought to have seen the Woodsfolk prick up their ears over the idea.

It was early in the morning when Louie woke up and began to rub his eyes. Where was he? What were those little cheepy sounds all around him and that rustling and pattering--yes, and splashing? He remembered that splashing; it was the last thing he heard the night before. Tad Coon had been splattering and scrubbing in Doctor Muskrat’s pond.

That’s exactly where he was; down by Doctor Muskrat’s pond, with his head pillowed on the grass at the edge of Doctor Muskrat’s flat stone. The splashing wasn’t all Tad Coon’s; a little bit of it was the swish of Doctor Muskrat diving in head first when Louie stretched his arm. He dove in such a hurry that he left a nice newly dug sweetflag root behind him.

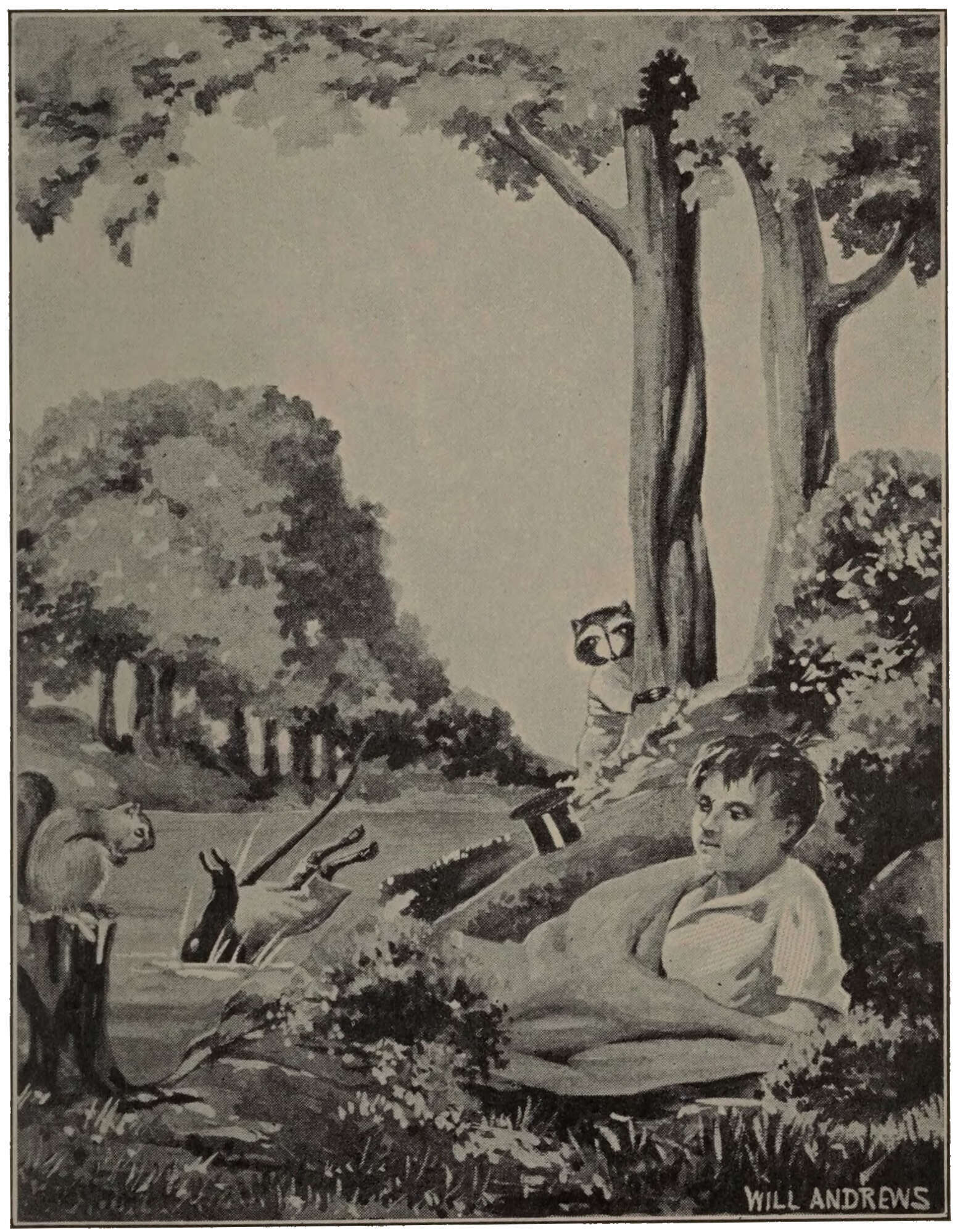

Louie opened his eyes, and then he lay very, very quiet. For all the Woodsfolk were out getting their breakfasts; they weren’t paying the least attention to him. He never knew there were so many of them. Chatter Squirrel ran down a tree and nibbled the edge of a mushroom. Three little mice ran down to drink; one gnawed the head of a bulrush Doctor Muskrat had cut down, and another shinned up a leaning grass stem and ate its seeds. Bob White Quail’s whole family came strolling by, dear little bright-eyed, striped brown puffballs, just beginning to have wing feathers. One of Stripes Skunk’s children jumped right over his feet; he was chasing a grasshopper. Nibble Rabbit’s bunnies were mostly chasing each other. They kicked up their furry heels and flicked their tufty little tails at each other, playing hide and seek in and out of some burdock leaves. Fat Tad Coon was making a happy whiny little song through his nose while he scrubbed another frog before eating it. And all the little birds would perk up their heads, give a touch or two to their feathers, and fly down to spatter in the pond and wet their whistles, maybe snatch a bug or a worm, before they began their morning song. By the time they were all wide awake Louie’s head was ringing with the racket. But he didn’t want them to stop--no, indeed, he just wanted to sing with them.

When Louie opened his eyes, all the woodsfolk were out getting their breakfasts.

He was very careful about getting up because he didn’t want to scare any of them. He sneaked down to wash, because everybody else was doing it, you know. First thing he knew he felt so happy he was whistling. Chaik the Jay shouted “Hey!” at him. And he just shouted back, “Hey yourself!” Because by then he knew Chaik was just making fun of him. Why, he was one of them; couldn’t he just make as much noise and have as much fun?

Yes, and have something to eat, too. He didn’t want a mushroom, like Chatter, because mushrooms sometimes give little boys worse pains inside them than the potato plants gave the foolish mice. He didn’t want a grasshopper, or a seed, like the quail, or a plantain leaf, like a bunny, or a frog or a bug or a worm. But there was that root of Doctor Muskrat’s. He smelled it--just like the wild things do. He tasted it. Then he ate it. Yum-m-m! It tasted like more.

The rest of the Woodsfolk didn’t pay any attention to Louie, but old Doctor Muskrat kept swimming round, wondering what had become of the root; he never dreamed that little boy would eat it.

Louie watched him for quite a while before he thought about it himself. Then he said: “You poor old rat. Never mind, I’ll pay you back.” And he waded right in among the cattails, scaring ’bout a dozen turtles who were sitting on a log, and grubbed up another root that had the same kind of leaves on it. He put that one on the stone where he’d found the one he ate.

Doctor Muskrat just blinked in surprise. He came out and sniffed it. He tasted it. “Why, that boy’s awfully clever. He’s found the right one first thing,” said he to himself. “Wonder if he could do it again?” So this time he went after another kind of a root.

Louie came up close and looked at it. Then he hunted and hunted until he found the kind of a plant it grew on. It was a big juicy mallow, the kind the doctor gave Nibble Rabbit that very first day when he found the little bunny in his cattails. You know how good that was! He laid it out on the flat stone and waited for Doctor Muskrat to taste it so he’d be sure it was the right one.

Wasn’t Doctor Muskrat pleased? Just wasn’t he! He called: “Tad, Tad Coon. This is the smartest boy I ever saw. He’s learning faster than any youngster I ever taught. If he doesn’t take to hunting us, these woods and fields will be just like Mother Nature made the world in the First-Off Beginning of Things.”

“O-ho!” said Tad, waddling over to see what was going on. “We’ll just have to show him what’s right and what isn’t--like we showed Stripes Skunk. I don’t believe he knows a bit more about it. I don’t guess he ever meant to be bad.”

“Yes,” agreed Doctor Muskrat, “but we mustn’t show him all our secrets right away; he might get caught again. I don’t want him carrying any tales back to that man he lived with. He knows enough already.”

Just then they pricked up their ears. Clump, clump, clump, came Louie’s father down the lane. Louie pricked up his ears, too. He knew his father would be angry because he had to drive up the cows himself. He knew what his father would do if he caught his little runaway son. Down he dropped on his hands and knees and crawled up the widest tunnel where Tad Coon creeps into Nibble Rabbit’s Pickery Things. He hid right in the very spot where Nibble hid the Red Cow’s bad baby. And his father couldn’t find hide nor hair of any one.

Tad chuckled to Doctor Muskrat: “He isn’t going to get caught again.”

And Louie didn’t, either. It was fun down by Doctor Muskrat’s pond, even if you were only a little boy instead of a furry wild thing--or a feathery one. When the sun grew warm, all the furry folk found themselves nice cool nests and went back to snooze again. Even the birds were quiet.

Louie wasn’t quite as comfortable as the rest because he didn’t have any fur--his legs were bare, and the mosquitoes bothered him--and he didn’t have any dark hole where he could crawl in and hide from them. But he was pretty smart, all the same. He didn’t try to hide in the bushes because all the little bugs who were taking their naps on the under side of the leaves woke up and buzzed around him. He lay out under Tad Coon’s tree, where the wind blew them right past, and covered himself with some nice flat branches after he’d shaken the bugs out of them. That certainly amused Tad Coon.

Miau the Catbird, who wears a gray coat and makes a noise like a week-old kitten, when he doesn’t sing, came and peeked at him. He raised that little black patch on his head, just as though he were lifting his hat to Louie. It looked as if he were a very polite little bird trying to say “Good morning.”

My, but didn’t he flutter when Louie answered, “Good morning, yourself, Mr. Bird!” But the little boy said it in such a nice voice Miau couldn’t stay scared, so he chirped back.

“Is that the way you say it?” giggled Louie, and he tried to talk exactly like him. He didn’t talk bird talk well at all. You ought to have heard Miau squawk, because he thought it was funny. And Louie squawked, too, so a couple of blackbirds with bright scarlet patches on their shoulders came over to see what was going on. So did Bobby Robin, and Chip Sparrow, who is one of Chirp Sparrow’s wild cousins, not nearly so big or dressed up, but with a lovely song, and a gorgeous black and orange oriole. A fine noise they were making.

But right in the middle of all their fun Louie heard another noise. It was his mother calling him. Her voice wasn’t happy, like those noisy birds, but very sad and lonely. Louie jumped up and ran as fast as ever he could to answer her.

“Oh, Louie, Louie! Your father said you weren’t here, but I sort of knew where I’d find you,” she cried when she had kissed him. “You mustn’t run away from me! I’ve been so afraid something would happen to you!”

“It did,” laughed Louie; “lots of things.” And he told her all about how nice all the Woodsfolk had been, and how the birds were teaching him bird talk. And where he got his breakfast--just everything. But she said, “Come home, and I’ll give you a better breakfast than that muskrat has in his whole pond.”

Do you know, Doctor Muskrat was really disappointed when he saw Louie Thomson go trotting up the lane beside his mother. “It’s too bad,” said he. “That boy of yours was learning very fast, Tad Coon. If he’d stayed down here by the pond just a little while longer he’d have been as wild as any of us.” You see the Woodsfolk wanted to have a nice wild boy to play with just as much as Louie ever wanted a nice tame coon.

Tad Coon’s own ears were drooping. “Maybe he was hungry,” Tad guessed. “Maybe we didn’t have the right things to feed him.” He knew what that was, because he’d been so hungry himself when he was shut up in Louie’s cage.

“Nonsense!” sniffed Doctor Muskrat. “If he’d only wait until Tommy Peele could teach him his way of fishing, he’d have had all he wanted.” You see, muskrats can eat their fish without taking the trouble to cook them.

Tad sighed. He was really just as disappointed as the doctor. A little boy was such fun; he did such queer things--he was as much fun for Tad Coon as Tad was for him. “That was his mother,” he said at last. “Maybe he was too little to leave her, like Nibble Rabbit’s bunny. He isn’t anywhere near full grown. All the same, I don’t think she takes very good care of him.” He was thinking that when Louie’s father struck him with the broom, his mother never did anything to stop him.

I guess Louie’s father would have been pretty s’prised to know Tad thought he was trying to kill his very own little son. He didn’t mean to hurt Louie--he just thought that Louie ought to obey him like Watch the Dog obeyed Tommy Peele. Watch wanted awfully to fight with Tad Coon because of what Tad did to Trailer the Hound, but Tommy just wouldn’t let him. Louie wanted to take some corn for his coon, and he just went ahead and took it anyway, even if his father forbade him. Watch knew you ought to obey, but even he couldn’t have explained to Tad Coon about it. Louie knew, deep down inside, but he didn’t want to believe it. He was still angry.

Tad Coon thought and thought. By and by he said, “Maybe our boy’s mother knows what’s best for him. They mostly do. Maybe he couldn’t go wild. He hasn’t a lick of fur to his skin. What would he do in the winter time? Bury himself in the mud like a frog? Eh?”

“Find himself one of those little trees of skin, like the red men Stripes Skunk told us about,” answered the doctor. “Stripes might remember where they got them.” He meant the skin tents the Indians used and he didn’t know that they had to kill great big buffaloes and tan their skins; he thought they just hunted for them like Tad hunts for a hollow tree to sleep in.

“I’m afraid they’re all gone, like those red men,” said Tad. “None of us have ever seen one.” And he was sort of lonesome till the middle of the afternoon, when who should come trotting back to the pond but Louie! And Tad was just as glad to see him as Louie had been to find Tad had come back to his old cage again.

No one in all the Woods and Fields could understand how Louie Thomson came to be back with them again. But here he was, and you ought to have seen what he brought with him! He brought some carrots out of his mother’s very own garden, and some corn bread out of her kitchen, and some sugar in a little bitty paper bag for the birds because he couldn’t bring them any grain, and he brought a blanket. His mother just must have given those things to him. Maybe Tad Coon was right when he said mothers know what is best for their little ones. Maybe his mother thought it was good for little boys to go wild if they wanted to in the summer-time--quite as good for them as hoeing corn in the hot sun.

Of course they had a feast. Doctor Muskrat was awfully taken up with that corn bread. He couldn’t imagine where it was grown. He kind of thought maybe housefolk made it out of pollen. You remember the wasps told him that the yellow dust you get on your nose when you smell a water lily was the bread they fed their little grubby young ones.

But didn’t Stripes Skunk just love that blanket! Louie knew it would be hot if he tried to sleep inside it. He didn’t want to be rolled up tight like a bug in a cocoon. A cocoon is the little silky blanket a caterpillar makes himself to go to sleep in. That may be nice for caterpillars, even in the summer time, but Louie made himself a tent instead. He slanted a long stick from the crotch of Tad Coon’s tree to the ground and hung the blanket over that. Then he spread out the corners and held them down with big flat stones. That was tent enough for him. But the woodsfolk just wouldn’t let it alone; they are so curious!

Stripes was perfectly delighted. He hadn’t ever seen a real skin tent like the Indians made, he’d only heard about them. This wasn’t much like any skin he knew about, but it smelled kind of furry, and he could see Louie meant to live in it. So he called his three kittens, because he wanted to explain the rule of tents to them. And of course curious old Tad Coon and Nibble Rabbit’s bunnies came, too, and sniffed and burrowed and poked their noses into all the wrinkly places and nibbled the fuzz till it set them sneezing.

“The rule of tents is that every night at sundown we skunks must look into every corner and see that there’s no one inside to disturb our man when he’s sleeping,” said Stripes. He meant snakes and mice and beetles--creepy-crawly things.

“Aye, aye,” squealed the kittens. They cleared out those bunnies in no time. Then they pounced on Tad Coon and pulled his fur until he was laughing so hard he couldn’t box their impudent little pricky ears. He tried to run out the wrong end. Down came the pole and off he walked, dragging the whole blanket after him, and the kittens couldn’t think where he was gone. And Louie most made himself sick laughing at them.

Louie put it up again, as soon as he got done laughing, and fastened it down with more stones all around. But Doctor Muskrat began to turn over the stones to see what they had under them. That was because the blanket smelled so queer. Then the mice came out to visit him and Stripes Skunk came out to hunt them. After that the little owls came and perched right over it. Louie could hear them talking.

“What’s that?” asked one. “It wasn’t here this morning.”

“It’s alive,” whispered the other, “I can hear it breathing.”

“It’s very queer,” said the first little owl. “It surely does breathe. But it hasn’t any head or any feet or any tail.” Of course the tent didn’t have any. Louie Thomson had a head and some feet, but the owls couldn’t see him.

“Maybe it’s got them all pulled in, like a turtle,” said her mate.

“Aw, you old squawk-sparrow!” she snapped. [That’s the same as calling a boy a “’fraid cat.”] “I’ll soon find out what it is.” And she lit right on Louie’s tent pole. “It’s all woolly,” she said. “I s’pose maybe it’s a buffalo.”

The woodsfolk were delighted with Louie’s tent.

“Buffaloes have horns,” insisted the little he-owl. “You just ask the cows. They know. They’re right over there in those woods. I dare you to ask ’em.”

“Are they?” said she. “That shows how much you know. They’re breaking into the cornfield this minute. Hear the fence--now!”

Sure enough there was the whine and snap of a wire when a cow leans into it, and a floundering and swishing as she tore at the leaves. Even Louie could hear it; he put out his head to listen.

“Whe-e-e-e!” yelled the little he-owl in the tree. “It is a turtle! It is!”

But as he spoke Louie gave the blankets a jerk, trying to climb out, and the rude little owl who was perched on it came tumbling and sliding down to the ground before she could catch herself. Didn’t she squawk? And didn’t they flap off as fast as their wings would go? They were too scared even to turn their heads as they flew.

If they had they’d have seen Louie Thomson running, too. And his feet were going most as fast as their wings--over to the cornfield.

My, but Louie was excited when he found the cows in his father’s corn. Of course it wasn’t his corn; his father told him so when he got angry with Louie for taking a little bit to feed Tad Coon. But Louie forgot all about that. Here were these bad old beasts biting and tearing and tramping it down after he’d had to hoe it so hard to start it growing.

“Get out of there!” he shouted. “Hi, boss! Move along!”

“Humph!” snorted the oldest cow. “It’s only that boy. We don’t have to pay any ’tention to him. It isn’t milking time.” And she snapped off another stalk.

“Get out of here, you cows!” said a new voice. “You don’t belong here, and you know it. Be reasonable now and go along.” Who do you think it was? It was Nibble Rabbit. He’d heard the noise, and he’d seen Louie run over to stop them, and he remembered the way the Red Cow took after Tommy Peele. He just knew it wasn’t safe for little boys to drive cows all alone when they didn’t want to be driven.

“I am reasonable,” said the cow stupidly. “The pasture’s all dried up. I can give a lot more milk if I eat this corn.” She knew well enough she was wrong.

“Maybe you can,” said Nibble, “but it doesn’t happen to be your corn. You walk right out of it and leave it alone, like Louie told you to.”

“I won’t!” said the cow. “We won’t!” they all mooed together. “We won’t, and you can’t make us. You go right back to the woods where you belong and mind your own business. You eat what you want without taking orders from any one.”

“Yes, but I only take a nibble here and a nibble there. I don’t destroy things,” Nibble Rabbit argued. “You’re worse than a whole woods full of fieldmice.”

That did make the cows cross. They hate mice. Mice make their grain taste musty, so the poor cows can’t eat it. They felt insulted. And just that very minute Louie hit one blam! right on her ribs with a stone.

“Moo-o-o-o!” she roared. “We’ll show you whether you can boss us!” And she put down her horns and began charging around in the corn. But the night was so dark and the corn was so tall she couldn’t find the little boy in it. He just scuttled for the fence and shinned over.

Slam! She hit the fence right behind him. But he was running up the lane as fast as he could go before the foolish thing could find the hole where she got into the cornfield, so she could get out again to chase him. He was going for help. Even if his father was mean, Louie just had to tell him what was happening.

Nibble Rabbit squeezed under the fence, but he didn’t run. Not yet! He stopped to shout at those foolish cows: “You made a mistake that time! Nobody can chase a little boy, not even if it is a great big cow without sense enough in her whole carcass to fill one of the slits in her clumsy hoofs. We Woodsfolk won’t stand it.” He gave an angry stamp and then his furry feet started twinkling. He was going for help, too. He knew whom he wanted and where to find him!

It didn’t take Louie Thomson very long to run up to his house and tell his father how the cows were in the corn. It didn’t take his father very long to get a hammer and some staples and a lantern. Or to hurry down the lane so fast that Louie had to run to keep up with him. But Nibble Rabbit beat them.

Nibble bounced into Tommy Peele’s barnyard next door and woke up Watch, the big shaggy, smiley dog who was his special friend. “It’s no work of mine,” said Watch when Nibble explained what he wanted. “They ought to have a dog of their own. But if Louie’s friends with all the Woodsfolk I s’pose we can’t let his cows think they can chase him if they want to and we won’t stop them.” So he took a good shake to get his coat feeling comfortable and galloped off after Nibble, smiling to himself because he thought it would be fun. And it was--for him!

But you never saw anybody so surprised as those cows! They went out of that cornfield a whole lot faster than they went in. Watch chased them way down to the very farthest corner of the fence and Nibble skipped along beside them, just kicking up his heels because he liked to see them run. Then Watch made them listen while he laid down the law to them. “How do you like being chased?” he barked. “Do you think it’s fun? Are you ever going to chase that boy again?”

“But he hit me with a stone!” moaned the cow. “He hit me with a stone.”

“Of course he did,” snapped Watch. “That’s because you didn’t obey him. You’re his cows, and that’s his corn. Are you going to do what he tells you or shall I teach you again?”

“Don’t!” they bellowed. “We’ll be good!” They meant it, too. They were so scared even Nibble Rabbit felt sure they did.

“All right,” Watch agreed. “You have to obey whoever feeds you, whether it’s Man or Mother Nature. You cows chose Man. Just remember that.” And off he trotted with Nibble hopping along beside him.

“I s’pose they can always go wild again, like the Red Cow’s mother did, and like Louie’s doing,” Nibble remarked. “I’d hate to belong to that man who was so cross to him and poor Tad Coon.” But right then they came on that very person, nailing up the fence, with Louie holding the lantern for him, friendly as anything. And he was saying, “I’ll throw all this corn they’ve broken down over the fence so the cows can finish it up in the morning, but you can take all you want for your coon.”

Louie looked up and saw Watch. “Why, that’s Tommy Peele’s dog!” he exclaimed. “He’s been helping us. That’s why the cows were gone.” And he ran right over to thank the furry old fellow who stood there proudly wagging his tail at them.