Title: The Chronicles of Aunt Minervy Ann

Author: Joel Chandler Harris

Illustrator: A. B. Frost

Release date: March 9, 2021 [eBook #64770]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: This book contains outdated racial stereotypes and words that are now considered highly offensive.

THE CHRONICLES OF

AUNT MINERVY ANN

“I ain’t fergot dat ar ’possum.”

THE CHRONICLES OF

AUNT MINERVY ANN

BY

JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS

ILLUSTRATED BY

A. B. FROST

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

NEW YORK 1899

Copyright, 1899, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

| PAGE | ||

| I. | An Evening with the Ku-Klux | 1 |

| II. | “When Jess went a-fiddlin’” | 34 |

| III. | How Aunt Minervy Ann Ran Away and Ran Back Again | 70 |

| IV. | How She Joined the Georgia Legislature | 97 |

| V. | How She Went Into Business | 119 |

| VI. | How She and Major Perdue Frailed Out the Gossett Boys | 139 |

| VII. | Major Perdue’s Bargain | 157 |

| VIII. | The Case of Mary Ellen | 182 |

| “I ain’t fergot dat ar ’possum” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “Well, he can’t lead me” | 6 |

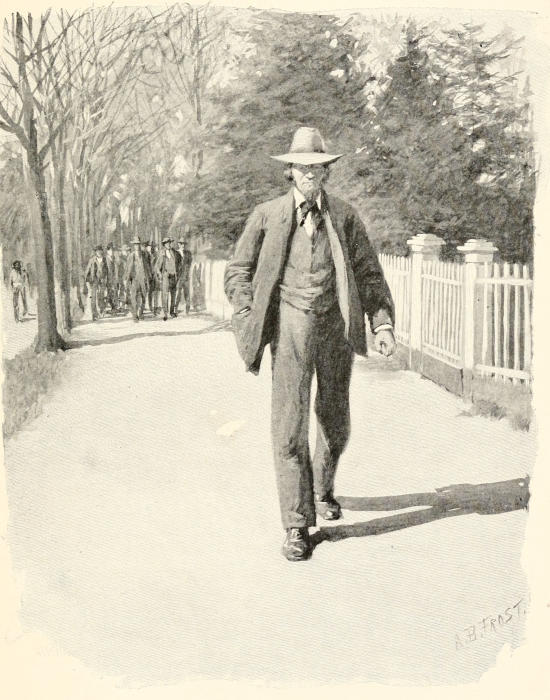

| He wore a blue army overcoat and a stove-pipe hat | 8 |

| “Sholy you-all ain’t gwine put dat in de paper, is you?” | 10 |

| Inquired what day the paper came out | 14 |

| “I was on the lookout,” the Major explained | 18 |

| In the third he placed only powder | 26 |

| We administered to his hurts the best we could | 30 |

| “I’d a heap rather you’d pull your shot-gun on me than your pen” | 32 |

| The Committee of Public Comfort | 72 |

| Buying cotton on his own account | 76 |

| “Miss Vallie!” | 78[viii] |

| “I saw him fling his hand to his shoulder and hold it there” | 80 |

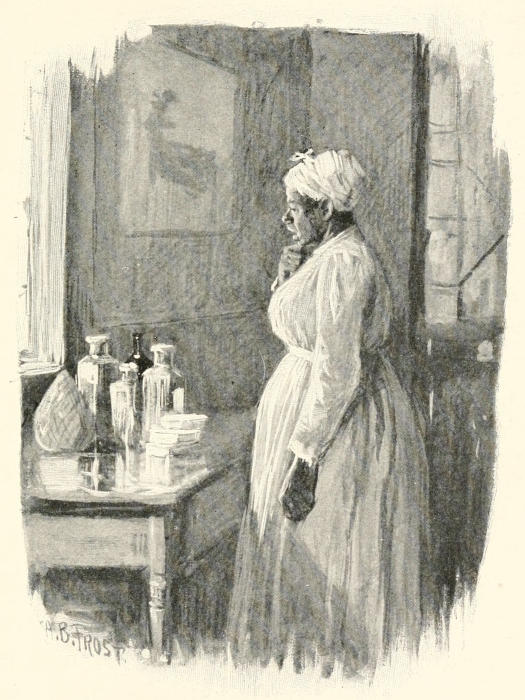

| “Dat ar grape jelly on de right han’ side” | 82 |

| “‘Conant!’ here and ‘Conant’ dar” | 84 |

| “Drapt down on de groun’ dar an’ holler an’ cry” | 90 |

| “Oh, my shoulder!” | 122 |

| “Marse Tumlin never did pass a nigger on de road” | 124 |

| “We made twelve pies ef we made one” | 126 |

| “I gi’ Miss Vallie de money” | 128 |

| “Ef here ain’t ol’ Minervy Ann wid pies!” | 130 |

| “You see dat nigger ’oman?” | 132 |

| “An’ he sot dar, suh, wid his haid ’twix’ his han’s fer I dunner how long” | 134 |

| “You’ll settle dis wid me” | 136 |

| “Dat money ain’t gwine ter las’ when you buy dat kin’ er doin’s” | 160 |

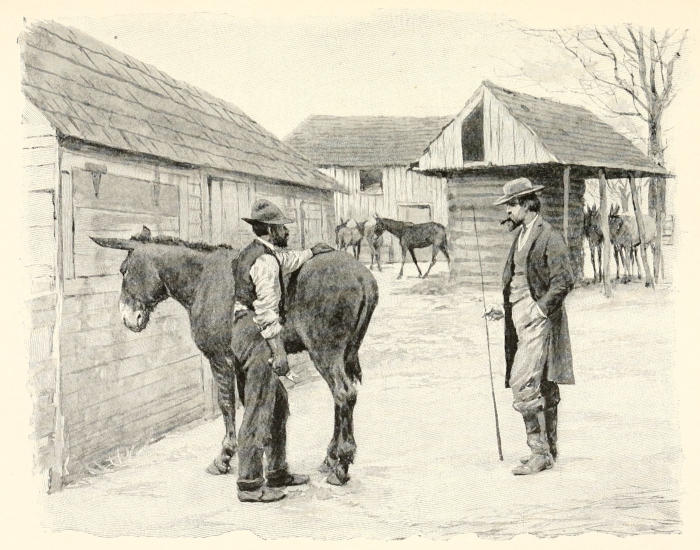

| Trimmin’ up de Ol’ Mules | 162 |

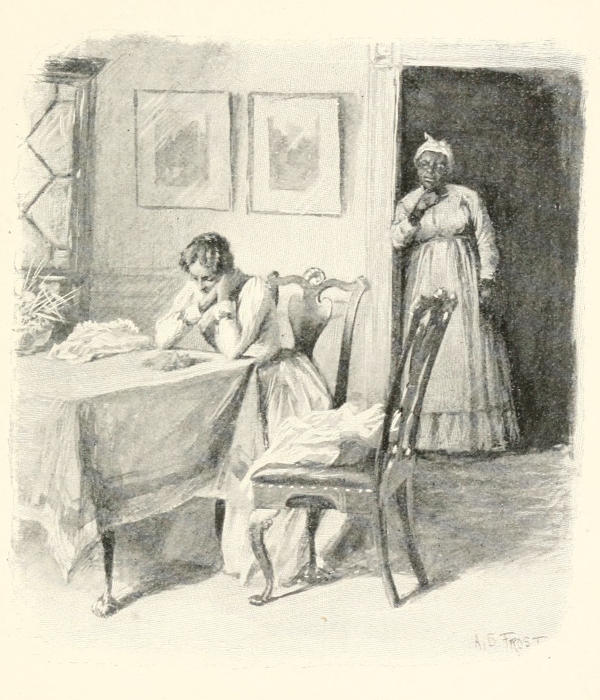

| “She wuz cryin’—settin’ dar cryin’” | 164 |

| “Here come a nigger boy leadin’ a bob-tail hoss” | 166[ix] |

| “He been axin’ me lots ’bout Miss Vallie” | 172 |

| “Marse Tumlin ’low he’ll take anything what he can chaw, sop, er drink” | 176 |

| “I hatter stop an’ pass de time er day” | 178 |

| “Hunt up an’ down fer dat ar Tom Perryman” | 180 |

The happiest, the most vivid, and certainly the most critical period of a man’s life is combined in the years that stretch between sixteen and twenty-two. His responsibilities do not sit heavily on him, he has hardly begun to realize them, and yet he has begun to see and feel, to observe and absorb; he is for once and for the last time an interested, and yet an irresponsible, spectator of the passing show.

This period I had passed very pleasantly, if not profitably, at Halcyondale in Middle Georgia, directly after the great war, and the town and the people there had a place apart, in my mind. When, therefore, some ten years after leaving there, I received a cordial invitation to attend the county fair, which had been organized by some of the enterprising spirits of the town and county, among whom[2] were Paul Conant and his father-in-law, Major Tumlin Perdue, it was natural that the fact should revive old memories.

The most persistent of these memories were those which clustered around Major Perdue, his daughter Vallie, and his brother-in-law, Colonel Bolivar Blasengame, and Aunt Minervy Ann Perdue. Curiously enough, my recollection of this negro woman was the most persistent of all. Her individuality seemed to stand out more vitally than the rest. She was what is called “a character,” and something more besides. The truth is, I should have missed a good deal if I had never known Aunt Minervy Ann Perdue, who, as she described herself, was “Affikin fum ’way back yander ’fo’ de flood, an’ fum de word go”—a fact which seriously interferes with the somewhat complacent theory that Ham, son of Noah, was the original negro.

It is a fact that Aunt Minervy Ann’s great-grandmother, who lived to be a hundred and twenty years old, had an eagle tattooed on her breast, the mark of royalty. The brother of this princess, Qua, who died in Augusta at the age of one hundred years, had two eagles tattooed on his breast. This, taken in connection with his name, which means The Eagle, shows that he was either the ruler of his tribe or[3] the heir apparent. The prince and princess were very small, compared with the average African, but the records kept by a member of the Clopton family show that during the Revolution Qua performed some wonderful feats, and went through some strange adventures in behalf of liberty. He was in his element when war was at its hottest—and it has never been hotter in any age or time, or in any part of the world, savage or civilized, than it was then in the section of Georgia now comprised in the counties of Burke, Columbia, Richmond, and Elbert.

However, that has nothing to do with Aunt Minervy Ann Perdue; but her relationship to Qua and to the royal family of his tribe, remote though it was, accounted for the most prominent traits of her character, and many contradictory elements of her strong and sharply defined individuality. She had a bad temper, and was both fierce and fearless when it was aroused; but it was accompanied by a heart as tender and a devotion as unselfish as any mortal ever possessed or displayed. Her temper was more widely advertised than her tenderness, and her independence more clearly in evidence than her unselfish devotion, except to those who knew her well or intimately.

And so it happened that Aunt Minervy Ann, after freedom gave her the privilege of showing her extraordinary qualities of self-sacrifice, walked about in the midst of the suspicion and distrust of her own race, and was followed by the misapprehensions and misconceptions of many of the whites. She knew the situation and laughed at it, and if she wasn’t proud of it her attitude belied her.

It was at the moment of transition from the old conditions to the new that I had known Aunt Minervy Ann and the persons in whom she was so profoundly interested, and she and they, as I have said, had a place apart in my memory and experience. I also remembered Hamp, Aunt Minervy Ann’s husband, and the queer contrast between the two. It was mainly on account of Hamp, perhaps, that Aunt Minervy Ann was led to take such a friendly interest in the somewhat lonely youth who was editor, compositor, and pressman of Halcyondale’s ambitious weekly newspaper in the days following the collapse of the confederacy.

When a slave, Hamp had belonged to an estate which was in the hands of the Court of Ordinary (or, as it was then called, the Inferior Court), to be administered in the interest of minor heirs. This was not a fortunate thing for the negroes, of which[5] there were above one hundred and fifty. Men, women, and children were hired out, some far and some near. They came back home at Christmastime, enjoyed a week’s frolic, and were then hired out again, perhaps to new employers. But whether to new or old, it is certain that hired hands in those days did not receive the consideration that men gave to their own negroes.

This experience told heavily on Hamp’s mind. It made him reserved, suspicious, and antagonistic. He had few pleasant memories to fall back on, and these were of the days of his early youth, when he used to trot around holding to his old master’s coat-tails—the kind old master who had finally been sent to the insane asylum. Hamp never got over the idea (he had heard some of the older negroes talking about it) that his old master had been judged to be crazy simply because he was unusually kind to his negroes, especially the little ones. Hamp’s after-experience seemed to prove this, for he received small share of kindness, as well as scrimped rations, from the majority of those who hired him.

It was a very good thing for Hamp that he married Aunt Minervy Ann, otherwise he would have become a wanderer and a vagabond when freedom came. It was a fate he didn’t miss a hair’s breadth;[6] he “broke loose,” as he described it, and went off, but finally came back and tried in vain to persuade Aunt Minervy Ann to leave Major Perdue. He finally settled down, but acquired no very friendly feelings toward the white race.

He joined the secret political societies, strangely called “Union Leagues,” and aided in disseminating the belief that the whites were only awaiting a favorable opportunity to re-enslave his race. He was only repeating what the carpet-baggers had told him. Perhaps he believed the statement, perhaps not. At any rate, he repeated it fervently and frequently, and soon came to be the recognized leader of the negroes in the county of which Halcyondale was the capital. That is to say, the leader of all except one. At church one Sunday night some of the brethren congratulated Aunt Minervy Ann on the fact that Hamp was now the leader of the colored people in that region.

“What colored people?” snapped Aunt Minervy Ann.

“We-all,” responded a deacon, emphatically.

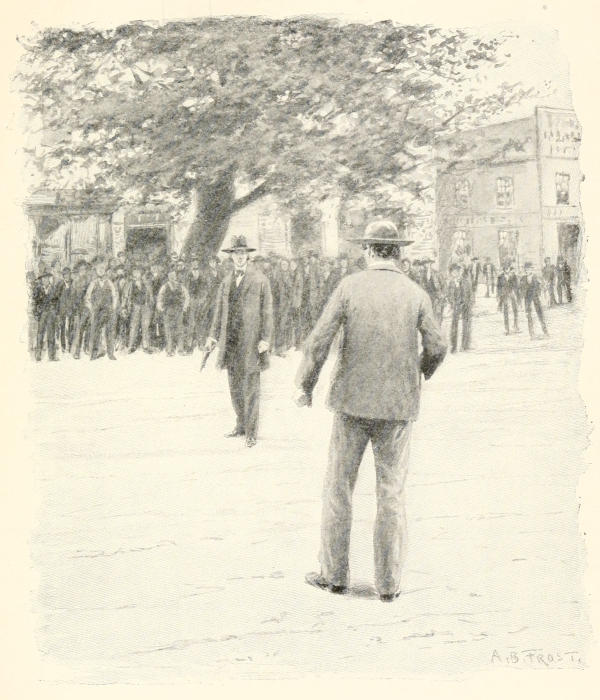

“Well, he can’t lead me, I’ll tell you dat right now!” exclaimed Aunt Minervy Ann.

“Well, he can’t lead me.”

Anyhow, when the time came to elect members of the Legislature (the constitutional convention[7] had already been held), Hamp was chosen to be the candidate of the negro Republicans. A white man wanted to run, but the negroes said they preferred their own color, and they had their way. They had their way at the polls, too, for, as nearly all the whites who would have voted had served in the Confederate army, they were at that time disfranchised.

So Hamp was elected overwhelmingly, “worl’ widout een’,” as he put it, and the effect it had on him was a perfect illustration of one aspect of human nature. Before and during the election (which lasted three days) Hamp had been going around puffed up with importance. He wore a blue army overcoat and a stove-pipe hat, and went about smoking a big cigar. When the election was over, and he was declared the choice of the county, he collapsed. His dignity all disappeared. His air of self-importance and confidence deserted him. His responsibilities seemed to weigh him down.

He had once “rolled” in the little printing-office where the machinery consisted of a No. 2 Washington hand-press, a wooden imposing-stone, three stands for the cases, a rickety table for “wetting down” the paper, and a tub in which to wash the forms. This office chanced to be my headquarters,[8] and the day after the election I was somewhat surprised to see Hamp saunter in. So was Major Tumlin Perdue, who was reading the exchanges.

“He’s come to demand a retraction,” remarked the Major, “and you’ll have to set him right. He’s no longer plain Hamp; he’s the Hon. Hamp—what’s your other name?” turning to the negro.

“Hamp Tumlin my fergiven name, suh. I thought ’Nervy Ann tol’ you dat.”

“Why, who named you after me?” inquired the Major, somewhat angrily.

“Me an’ ’Nervy Ann fix it up, suh. She say it’s about de purtiest name in town.”

The Major melted a little, but his bristles rose again, as it were.

“Look here, Hamp!” he exclaimed in a tone that nobody ever forgot or misinterpreted; “don’t you go and stick Perdue onto it. I won’t stand that!”

“No, suh!” responded Hamp. “I started ter do it, but ’Nervy Ann say she ain’t gwine ter have de Perdue name bandied about up dar whar de Legislature’s at.”

He wore a blue army overcoat and a stove-pipe hat.

Again the Major thawed, and though he looked long at Hamp it was with friendly eyes. He seemed to be studying the negro—“sizing him up,” as the[9] saying is. For a newly elected member of the Legislature, Hamp seemed to take a great deal of interest in the old duties he once performed about the office. He went first to the box in which the “roller” was kept, and felt of its surface carefully.

“You’ll hatter have a bran new roller ’fo’ de mont’s out,” he said, “an’ I won’t be here to he’p you make it.”

Then he went to the roller-frame, turned the handle, and looked at the wooden cylinders. “Dey don’t look atter it like I use ter, suh; an’ dish yer frame monst’us shackly.”

From there he passed to the forms where the advertisements remained standing. He passed his thumb over the type and looked at it critically. “Dey er mighty skeer’d dey’ll git all de ink off,” was his comment. Do what he would, Hamp couldn’t hide his embarrassment.

Meanwhile, Major Perdue scratched off a few lines in pencil. “I wish you’d get this in Tuesday’s paper,” he said. Then he read: “The Hon. Hampton Tumlin, recently elected a member of the Legislature, paid us a pop-call last Saturday. We are always pleased to meet our distinguished fellow-townsman and representative. We trust Hon. Hampton Tumlin will call again when the Ku-Klux are in.”

“Why, certainly,” said I, humoring the joke.

“Sholy you-all ain’t gwine put dat in de paper, is you?” inquired Hamp, in amazement.

“Of course,” replied the Major; “why not?”

“Kaze, ef you does, I’m a ruint nigger. Ef ’Nervy Ann hear talk ’bout my name an’ entitlements bein’ in de paper, she’ll quit me sho. Uh-uh! I’m gwine ’way fum here!” With that Hamp bowed and disappeared. The Major chuckled over his little joke, but soon returned to his newspaper. For a quarter of an hour there was absolute quiet in the room, and, as it seemed, in the entire building, which was a brick structure of two stories, the stairway being in the centre. The hallway was, perhaps, seventy-five feet long, and on each side, at regular intervals, there were four rooms, making eight in all, and, with one exception, variously occupied as lawyers’ offices or sleeping apartments, the exception being the printing-office in which Major Perdue and I were sitting. This was at the extreme rear of the hallway.

“Sholy you-all ain’t gwine put dat in de paper, is you?”

I had frequently been struck by the acoustic properties of this hallway. A conversation carried on in ordinary tones in the printing-office could hardly be heard in the adjoining room. Transferred to the front rooms, however, or even to the sidewalk facing[11] the entrance to the stairway, the lightest tone was magnified in volume. A German professor of music, who for a time occupied the apartment opposite the printing-office, was so harassed by the thunderous sounds of laughter and conversation rolling back upon him that he tried to remedy the matter by nailing two thicknesses of bagging along the floor from the stairway to the rear window. This was, indeed, something of a help, but when the German left, being of an economical turn of mind, he took his bagging away with him, and once more the hallway was torn and rent, as you may say, with the lightest whisper.

Thus it happened that, while the Major and I were sitting enjoying an extraordinary season of calm, suddenly there came a thundering sound from the stairway. A troop of horse could hardly have made a greater uproar, and yet I knew that fewer than half a dozen people were ascending the steps. Some one stumbled and caught himself, and the multiplied and magnified reverberations were as loud as if the roof had caved in, carrying the better part of the structure with it. Some one laughed at the misstep, and the sound came to our ears with the deafening effect of an explosion. The party filed with a dull roar into one of the front rooms, the[12] office of a harum-scarum young lawyer who had more empty bottles behind his door than he had ever had briefs on his desk.

“Well, the great Gemini!” exclaimed Major Perdue, “how do you manage to stand that sort of thing?”

I shrugged my shoulders and laughed, and was about to begin anew a very old tirade against caves and halls of thunder, when the Major raised a warning hand. Some one was saying——

“He hangs out right on ol’ Major Perdue’s lot. He’s got a wife there.”

“By jing!” exclaimed another voice; “is that so? Well, I don’t wanter git mixed up wi’ the Major. He may be wobbly on his legs, but I don’t wanter be the one to run up ag’in ’im.”

The Major pursed up his lips and looked at the ceiling, his attitude being one of rapt attention.

“Shucks!” cried another; “by the time the ol’ cock gits his bellyful of dram, thunder wouldn’t roust ’im.”

A shrewd, foxy, almost sinister expression came over the Major’s rosy face as he glanced at me. His left hand went to his goatee, an invariable signal of deep feeling, such as anger, grief, or serious trouble. Another voice broke in here, a voice that we both[13] knew to be that of Larry Pulliam, a big Kentuckian who had refugeed to Halcyondale during the war.

“Blast it all!” exclaimed Larry Pulliam, “I hope the Major will come out. Me an’ him hain’t never butted heads yit, an’ it’s gittin’ high time. Ef he comes out, you fellers jest go ahead with your rat-killin’. I’ll ’ten’ to him.”

“Why, you’d make two of him, Pulliam,” said the young lawyer.

“Oh, I’ll not hurt ’im; that is, not much—jest enough to let ’im know I’m livin’ in the same village,” replied Mr. Pulliam. The voice of the town bull could not have had a more terrifying sound.

Glancing at the Major, I saw that he had entirely recovered his equanimity. More than that, a smile of sweet satisfaction and contentment settled on his rosy face, and stayed there.

“I wouldn’t take a hundred dollars for that last remark,” whispered the Major. “That chap’s been a-raisin’ his hackle at me ever since he’s been here, and every time I try to get him to make a flutter he’s off and gone. Of course it wouldn’t do for me to push a row on him just dry so. But now——” The Major laughed softly, rubbed his hands together, and seemed to be as happy as a child with a new toy.

“My son,” said he after awhile, “ain’t there[14] some way of finding out who the other fellows are? Ain’t you got some word you want Seab Griffin”—this was the young lawyer—“to spell for you?”

Spelling was the Major’s weakness. He was a well-educated man, and could write vigorous English, but only a few days before he had asked me how many f’s there are in graphic.

“Let’s see,” he went on, rubbing the top of his head. “Do you spell Byzantium with two y’s, or with two i’s, or with one y and one i? It’ll make Seab feel right good to be asked that before company, and he certainly needs to feel good if he’s going with that crowd.”

So, with a manuscript copy in my hand, I went hurriedly down the hall and put the important question. Mr. Griffin was all politeness, but not quite sure of the facts in the case. But he searched in his books of reference, including the Geographical Gazette, until finally he was able to give me the information I was supposed to stand in need of.

While he was searching, Mr. Pulliam turned to me and inquired what day the paper came out. When told that the date was Tuesday, he smiled and nodded his head mysteriously.

“That’s good,” he declared; “you’ll be in time to ketch the news.”

Inquired what day the paper came out.

“What news?” I inquired.

“Well, ef you don’t hear about it before to-morrer night, jest inquire of Major Perdue. He’ll tell you all about it.”

Mr. Pulliam’s tone was so supercilious that I was afraid the Major would lose his temper and come raging down the hallway. But he did nothing of the kind. When I returned he was fairly beaming, and seemed to be perfectly happy. The Major took down the names in his note-book—I have forgotten all except those of Buck Sanford and Larry Pulliam; they were all from the country except Larry Pulliam and the young lawyer.

After my visit to the room, the men spoke in lower tones, but every word came back to us as distinctly as before.

“The feed of the horses won’t cost us a cent,” remarked young Sanford. “Tom Gresham said he’d ’ten’ to that. They’re in the stable right now. And we’re to have supper in Tom’s back room, have a little game of ante, and along about twelve or one we’ll sa’nter down and yank that darned nigger from betwixt his blankets, ef he’s got any, and leave him to cool off at the cross-roads. Won’t you go ’long, Seab, and see it well done?”

“I’ll go and see if the supper’s well done, and I’ll[16] take a shy at your ante,” replied Mr. Griffin. “But when it comes to the balance of the programme—well, I’m a lawyer, you know, and you couldn’t expect me to witness the affair. I might have to take your cases and prove an alibi, you know, and I couldn’t conscientiously do that if I was on hand at the time.”

“The Ku-Klux don’t have to have alibis,” suggested Larry Pulliam.

“Perhaps not, still—” Apparently Mr. Griffin disposed of the matter with a gesture.

When all the details of their plan had been carefully arranged, the amateur Ku-Klux went filing out, the noise they made dying away like the echoes of a storm.

Major Perdue leaned his head against the back of his chair, closed his eyes, and sat there so quietly that I thought he was asleep. But this was a mistake. Suddenly he began to laugh, and he laughed until the tears ran down his face. It was laughter that was contagious, and presently I found myself joining in without knowing why. This started the Major afresh, and we both laughed until exhaustion came to our aid.

“O Lord!” cried the Major, panting, “I haven’t had as much fun since the war, and a long time before.[17] That blamed Pulliam is going to walk into a trap of his own setting. Now you jest watch how he goes out ag’in.”

“But I’ll not be there,” I suggested.

“Oh, yes!” exclaimed the Major, “you can’t afford to miss it. It’ll be the finest piece of news your paper ever had. You’ll go to supper with me—” He paused. “No, I’ll go home, send Valentine to her Aunt Emmy’s, get Blasengame to come around, and we’ll have supper about nine. That’ll fix it. Some of them chaps might have an eye on my house, and I don’t want ’em to see anybody but me go in there. Now, if you don’t come at nine, I’ll send Blasengame after you.”

“I shall be glad to come, Major. I was simply fishing for an invitation.”

“That fish is always on your hook, and you know it,” the Major insisted.

As it was arranged, so it fell out. At nine, I lifted and dropped the knocker on the Major’s front door. It opened so promptly that I was somewhat taken by surprise, but in a moment the hand of my host was on my arm, and he pulled me inside unceremoniously.

“I was on the lookout,” the Major explained. “Minervy Ann has fixed to have waffles, and she’s[18] crazy about havin’ ’em just right. If she waits too long to make ’em, the batter’ll spoil; and if she puts ’em on before everybody’s ready, they won’t be good. That’s what she says. Here he is, you old Hessian!” the Major cried, as Minervy Ann peeped in from the dining-room. “Now slap that supper together and let’s get at it.”

“I’m mighty glad you come, suh,” said Aunt Minervy Ann, with a courtesy and a smile, and then she disappeared. In an incredibly short time supper was announced, and though Aunt Minervy has since informed me confidentially that the Perdues were having a hard time of it at that period, I’ll do her the justice to say that the supper she furnished forth was as good as any to be had in that town—waffles, beat biscuit, fried chicken, buttermilk, and coffee that could not be surpassed.

“How about the biscuit, Minervy Ann?” inquired Colonel Blasengame, who was the Major’s brother-in-law, and therefore one of the family.

“I turned de dough on de block twelve times, an’ hit it a hundred an forty-sev’m licks,” replied Aunt Minervy Ann.

“I’m afeard you hit it one lick too many,” said Colonel Blasengame, winking at me.

“I was on the lookout,” the Major explained.

“Well, suh, I been hittin’ dat away a mighty[19] long time,” Aunt Minervy Ann explained, “and I ain’t never hear no complaints.”

“Oh, I’m not complainin’, Minervy Ann.” Colonel Blasengame waved his hand. “I’m mighty glad you did hit the dough a lick too many. If you hadn’t, the biscuit would ’a’ melted in my mouth, and I believe I’d rather chew on ’em to get the taste.”

“He des runnin’ on, suh,” said Aunt Minervy Ann to me. “Marse Bolivar know mighty well dat he got ter go ’way fum de Nunited State fer ter git any better biscuits dan what I kin bake.”

Then there was a long pause, which was broken by an attempt on the part of Major Perdue to give Aunt Minervy Ann an inkling of the events likely to happen during the night. She seemed to be both hard of hearing and dull of understanding when the subject was broached; or she may have suspected the Major was joking or trying to “run a rig” on her. Her questions and comments, however, were very characteristic.

“I dunner what dey want wid Hamp,” she said. “Ef dey know’d how no-count he is, dey’d let ’im ’lone. What dey want wid ’im?”

“Well, two or three of the country boys and maybe some of the town chaps are going to call on him[20] between midnight and day. They want to take him out to the cross-roads. Hadn’t you better fix ’em up a little snack? Hamp won’t want anything, but the boys will feel a little hungry after the job is over.”

“Nobody ain’t never tell me dat de Legislatur’ wuz like de Free Masons, whar dey have ter ride a billy goat an’ go down in a dry well wid de chains a-clankin’. I done tol’ Hamp dat he better not fool wid white folks’ doin’s.”

“Only the colored members have to be initiated,” explained the Major, solemnly.

“What does dey do wid um?” inquired Aunt Minervy Ann.

“Well,” replied the Major, “they take ’em out to the nearest cross-roads, put ropes around their necks, run the ropes over limbs, and pull away as if they were drawing water from a well.”

“What dey do dat fer?” asked Aunt Minervy Ann, apparently still oblivious to the meaning of it all.

“They want to see which’ll break first, the ropes or the necks,” the Major explained.

“Ef dey takes Hamp out,” remarked Aunt Minervy Ann, tentatively—feeling her way, as it were—“what time will he come back?”

“You’ve heard about the Resurrection Morn,[21] haven’t you, Minervy Ann?” There was a pious twang in the Major’s voice as he pronounced the words.

“I hear de preacher say sump’n ’bout it,” replied Aunt Minervy Ann.

“Well,” said the Major, “along about that time Hamp will return. I hope his record is good enough to give him wings.”

“Shuh! Marse Tumlin! you-all des fool’in’ me. I don’t keer—Hamp ain’t gwine wid um. I tell you dat right now.”

“Oh, he may not want to go,” persisted the Major, “but he’ll go all the same if they get their hands on him.”

“My life er me!” exclaimed Aunt Minervy Ann, bristling up, “does you-all ’speck I’m gwine ter let um take Hamp out dat away? De fus’ man come ter my door, less’n it’s one er you-all, I’m gwine ter fling a pan er hot embers in his face ef de Lord’ll gi’ me de strenk. An’ ef dat don’t do no good, I’ll scald um wid b’ilin’ water. You hear dat, don’t you?”

“Minervy Ann,” said the Major, sweetly, “have you ever heard of the Ku-Klux?”

“Yasser, I is!” she exclaimed with startling emphasis. She stopped still and gazed hard at the Major. In response, he merely shrugged his shoulders[22] and raised his right hand with a swift gesture that told the whole story.

“Name er God! Marse Tumlin, is you an’ Marse Bolivar and dish yer young genterman gwine ter set down here flat-footed and let dem Kukluckers scarify Hamp?”

“Why should we do anything? You’ve got everything arranged. You’re going to singe ’em with hot embers, and you’re going to take their hides off with scalding water. What more do you want?” The Major spoke with an air of benign resignation.

Aunt Minervy Ann shook her head vigorously. “Ef dey er de Kukluckers, fire won’t do um no harm. Dey totes der haids in der han’s.”

“Their heads in their hands?” cried Colonel Blasengame, excitedly.

“Dat what dey say, suh,” replied Aunt Minervy Ann.

Colonel Blasengame looked at his watch. “Tumlin, I’ll have to ask you to excuse me to-night,” he said. “I—well, the fact is, I have a mighty important engagement up town. I’m obliged to fill it.” He turned to Aunt Minervy Ann: “Did I understand you to say the Ku-Klux carry their heads in their hands?”

“Dat what folks tell me. I hear my own color sesso,” replied Aunt Minervy Ann.

“I’d be glad to stay with you, Tumlin,” the Colonel declared; “but—well, under the circumstances, I think I’d better fill that engagement. Justice to my family demands it.”

“Well,” responded Major Perdue, “if you are going, I reckon we’d just as well go, too.”

“Huh!” exclaimed Aunt Minervy Ann, “ef gwine’s de word, dey can’t nobody beat me gittin’ way fum here. Dey may beat me comin’ back, I ain’t ’sputin’ dat; but dey can’t beat me gwine ’way. I’m ol’, but I got mighty nigh ez much go in me ez a quarter-hoss.”

Colonel Blasengame leaned back in his chair and studied the ceiling. “It seems to me, Tumlin, we might compromise on this. Suppose we get Hamp to come in here. Minervy Ann can stay out there in the kitchen and throw a rock against the back door when the Ku-Klux come.”

Aunt Minervy Ann fairly gasped. “Who? Me? I’ll die fust. I’ll t’ar dat do’ down; I’ll holler twel ev’ybody in de neighborhood come a-runnin’. Ef you don’t b’lieve me, you des try me. I’ll paw up dat back-yard.”

Major Perdue went to the back door and called[24] Hamp, but there was no answer. He called him a second time, with the same result.

“Well,” said the Major, “they’ve stolen a march on us. They’ve come and carried him off while we were talking.”

“No, suh, dey ain’t, needer. I know right whar he is, an’ I’m gwine atter ’im. He’s right ’cross de street dar, colloguin’ wid dat ol’ Ceely Ensign. Dat’s right whar he is.”

“Old! Why, Celia is young,” remarked the Major. “They say she’s the best cook in town.”

Aunt Minervy Ann whipped out of the room and was gone some little time. When she returned, she had Hamp with her, and I noticed that both were laboring under excitement which they strove in vain to suppress.

“Here I is, suh,” said Hamp. “’Nervy Ann say you call me.”

“How is Celia to-night?” Colonel Blasengame inquired, suavely.

This inquiry, so suddenly and unexpectedly put, seemed to disconcert Hamp. He shuffled his feet and put his hand to his face. I noticed a blue welt over his eye, which was not there when he visited me in the afternoon.

“Well, suh, I ’speck she’s tolerbul.”

“Is she? Is she? Ah-h-h!” cried Aunt Minervy Ann.

“She must be pretty well,” said the Major. “I see she’s hit you a clip over the left eye.”

“Dat’s some er ’Nervy Ann’s doin’s, suh,” replied Hamp, somewhat disconsolately.

“Den what you git in de way fer?” snapped Aunt Minervy Ann.

“Marse Tumlin, dat ar ’oman ain’t done nothin’ in de roun’ worl’. She say she want me to buy some hime books fer de church when I went to Atlanty, an’ I went over dar atter de money.”

“I himed ’er an’ I churched ’er!” exclaimed Aunt Minervy Ann.

“Here de money right here,” said Hamp, pulling a small roll of shinplasters out of his pocket; “an’ whiles we settin’ dar countin’ de money, ’Nervy Ann come in dar an’ frail dat ’oman out.”

“Ain’t you hear dat nigger holler, Marse Tumlin?” inquired Minervy Ann. She was in high good-humor now. “Look like ter me dey could a-heerd ’er blate in de nex’ county ef dey’d been a-lis’nin’. ’Twuz same ez a picnic, suh, an’ I’m gwine ’cross dar ’fo’ long an’ pay my party call.”

Then she began to laugh, and pretty soon went through the whole episode for our edification,[26] dwelling with unction on that part where the unfortunate victim of her jealousy had called her “Miss ’Nervy.” The more she laughed the more serious Hamp became.

At the proper time he was told of the visitation that was to be made by the Ku-Klux, and this information seemed to perplex and worry him no little. But his face lit up with genuine thankfulness when the programme for the occasion was announced to him. He and Minervy Ann were to remain in the house and not show their heads until the Major or the Colonel or their guest came to the back door and drummed on it lightly with the fingers.

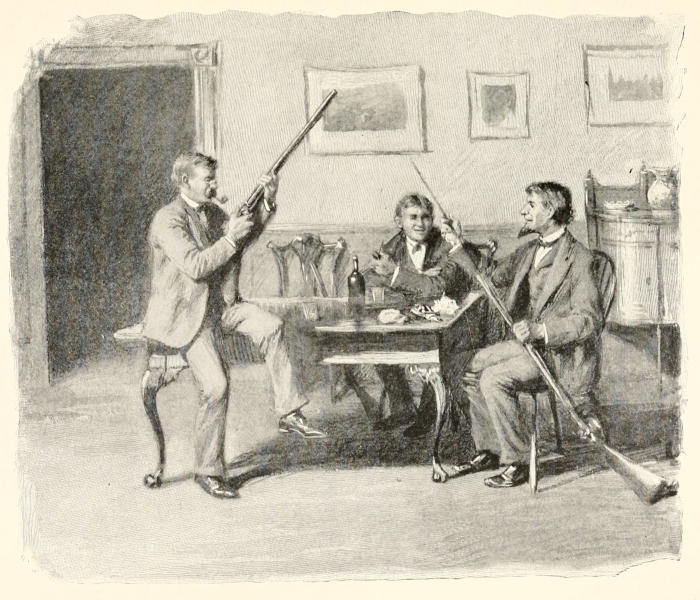

In the third he placed only powder.

Then the arms—three shot-guns—were brought out, and I noticed with some degree of surprise, that as the Major and the Colonel began to handle these, their spirits rose perceptibly. The Major hummed a tune and the Colonel whistled softly as they oiled the locks and tried the triggers. The Major, in coming home, had purchased four pounds of mustard-seed shot, and with this he proceeded to load two of the guns. In the third he placed only powder. This harmless weapon was intended for me, while the others were to be handled by Major Perdue and Colonel Blasengame. I learned afterward[27] that the arrangement was made solely for my benefit. The Major and the Colonel were afraid that a young hand might become excited and fire too high at close range, in which event mustard-seed shot would be as dangerous as the larger variety.

At twelve o’clock I noticed that both Hamp and Aunt Minervy were growing restless.

“You hear dat clock, don’t you, Marse Tumlin?” said Minervy as the chimes died away. “Ef you don’t min’, de Kukluckers’ll be a-stickin’ der haids in de back do’.”

But the Major and the Colonel were playing a rubber of seven-up (or high-low-Jack) and paid no attention. It was a quarter after twelve when the game was concluded and the players pushed their chairs back from the table.

“Ef you don’t fin’ um in de yard waitin’ fer you, I’ll be fooled might’ly,” remarked Aunt Minervy Ann.

“Go and see if they’re out there,” said the Major.

“Me, Marse Tumlin? Me? I wouldn’t go out dat do’ not for ham.”

The Major took out his watch. “They’ll eat and drink until twelve or a little after, and then they’ll get ready to start. Then they’ll have another drink all ’round, and finally they’ll take another.[28] It’ll be a quarter to one or after when they get in the grove in the far end of the lot. But we’ll go out now and see how the land lays. By the time they get here, our eyes will be used to the darkness.”

The light was carried to a front room, and we groped our way out at the back door the best we could. The night was dark, but the stars were shining. I noticed that the belt and sword of Orion had drifted above the tree-tops in the east, following the Pleiades. In a little while the darkness seemed to grow less dense, and I could make out the outlines of trees twenty feet away.

Behind one of these trees, near the outhouse in which Hamp and Aunt Minervy lived, I was to take my stand, while the Major and the Colonel were to go farther into the wood-lot so as to greet the would-be Ku-Klux as they made their retreat, of which Major Perdue had not the slightest doubt.

“You stand here,” said the Major in a whisper. “We’ll go to the far-end of the lot where they’re likely to come in. They’ll pass us all right enough, but as soon as you see one of ’em, up with the gun an’ lam aloose, an’ before they can get away give ’em the other barrel. Then you’ll hear from us.”

Major Perdue and Colonel Blasengame disappeared in the darkness, leaving me, as it were, on[29] the inner picket line. I found the situation somewhat ticklish, as the saying is. There was not the slightest danger, and I knew it, but if you ever have occasion to stand out in the dark, waiting for something to happen, you’ll find there’s a certain degree of suspense attached to it. And the loneliness and silence of the night will take a shape almost tangible. The stirring of the half-dead leaves, the chirping of a belated cricket, simply emphasized the loneliness and made the silence more profound. At intervals, all nature seemed to heave a deep sigh, and address itself to slumber again.

In the house I heard the muffled sound of the clock chime one, but whether it was striking the half-hour or the hour I could not tell. Then I heard the stealthy tread of feet. Someone stumbled over a stick of timber, and the noise was followed by a smothered exclamation and a confused murmur of voices. As the story-writers say, I knew that the hour had come. I could hear whisperings, and then I saw a tall shadow steal from behind Aunt Minervy’s house, and heard it rap gently on the door. I raised the gun, pulled the hammer back, and let drive. A stream of fire shot from the gun, accompanied by a report that tore the silence to atoms. I heard a sharp exclamation of surprise, then the noise[30] of running feet, and off went the other barrel. In a moment the Major and the Colonel opened on the fugitives. I heard a loud cry of pain from one, and, in the midst of it all, the mustard-seed shot rattled on the plank fence like hominy-snow on a tin roof.

The next instant I heard someone running back in my direction, as if for dear life. He knew the place apparently, for he tried to go through the orchard, but just before he reached the orchard fence, he uttered a half-strangled cry of terror, and then I heard him fall as heavily as if he had dropped from the top of the house.

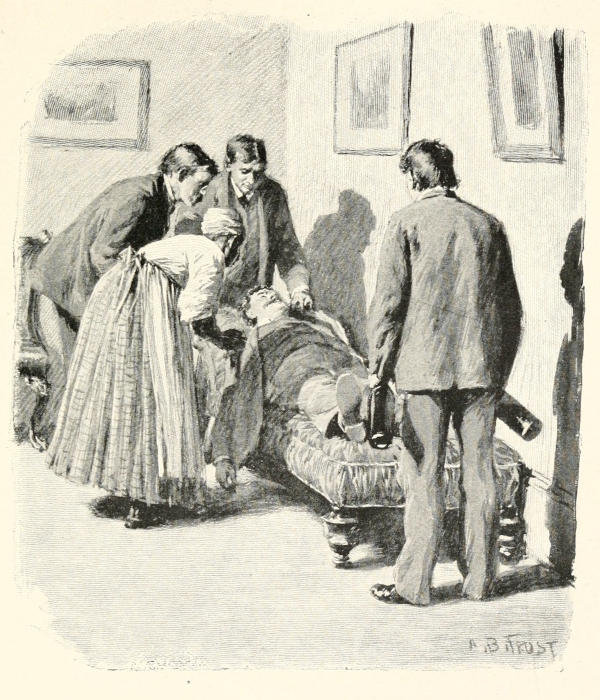

It was impossible to imagine what had happened, and it was not until we had investigated the matter that the cause of the trouble was discovered. A wire clothes-line, stretched across the yard, had caught the would-be Ku-Klux under the chin, his legs flew from under him, and he had a fall, from the effects of which he was long in recovering. He was a young man about town, very well connected, who had gone into the affair in a spirit of mischief. We carried him into the house, and administered to his hurts the best we could; Aunt Minervy Ann, be it said to her credit, being more active in this direction than any of us.

We administered to his hurts the best we could.

On the Tuesday following, the county paper contained[31] the news in a form that remains to this day unique. It is hardly necessary to say that it was from the pen of Major Tumlin Perdue.

“Last Saturday afternoon our local editor was informed by a prominent citizen that if he would apply to Major Perdue he would be put in possession of a very interesting piece of news. Acting upon this hint, ye local yesterday went to Major Perdue, who, being in high good-humor, wrote out the following with his own hand:

“‘Late Saturday night, while engaged with a party of friends in searching for a stray dog on my premises, I was surprised to see four or five men climb over my back fence and proceed toward my residence. As my most intimate friends do not visit me by climbing over my back fence, I immediately deployed my party in such a manner as to make the best of a threatening situation. The skirmish opened at my kitchen-door, with two rounds from a howitzer. This demoralized the enemy, who promptly retreated the way they came. One of them, the leader of the attacking party, carried away with him two loads of mustard-seed shot, delivered in the general neighborhood and region of the coat-tails, which, being on a level with the horizon, afforded as fair a target as could be had in the dark.[32] I understand on good authority that Mr. Larry Pulliam, one of our leading and deservedly popular citizens, has had as much as a quart of mustard-seed shot picked from his carcass. Though hit in a vulnerable spot, the wound is not mortal.—T. Perdue.’”

I did my best to have Mr. Pulliam’s name suppressed, but the Major would not have it so.

“No, sir,” he insisted; “the man has insulted me behind my back, and he’s got to cut wood or put down the axe.”

Naturally this free and easy card created quite a sensation in Halcyondale and the country round about. People knew what it would mean if Major Perdue’s name had been used in such an off-hand manner by Mr. Pulliam, and they naturally supposed that a fracas would be the outcome. Public expectation was on tiptoe, and yet the whole town seemed to take the Major’s card humorously. Some of the older citizens laughed until they could hardly sit up, and even Mr. Pulliam’s friends caught the infection. Indeed, it is said that Mr. Pulliam, himself, after the first shock of surprise was over, paid the Major’s audacious humor the tribute of a hearty laugh. When Mr. Pulliam appeared in public, among the first men he saw was Major Perdue. This[33] was natural, for the Major made it a point to be on hand. He was not a ruffler, but he thought it was his duty to give Mr. Pulliam a fair opportunity to wreak vengeance on him. If the boys about town imagined that a row was to be the result of this first meeting, they were mistaken. Mr. Pulliam looked at the Major and then began to laugh.

“I’d a heap rather you’d pull your shot-gun on me than your pen.”

“Major Perdue,” he said, “I’d a heap rather you’d pull your shot-gun on me than your pen.”

And that ended the matter.

The foregoing recital is unquestionably a long and tame preface to the statement that, after thinking the matter over I concluded to accept the official invitation to the fair—“The Middle Georgia Exposition” it was called—if nothing occurred to prevent. With this conclusion I dismissed the matter from my mind for the time being, and would probably have thought of it no more until the moment arrived to make a final decision, if the matter had not been called somewhat sharply to my attention.

Sitting on the veranda one day, ruminating over other people’s troubles, I heard an unfamiliar voice calling, “You-all got any bitin’ dogs here?” The voice failed to match the serenity of the suburban scene. Its tone was pitched a trifle too high for the surroundings.

But before I could make any reply the gate was flung open, and the new-comer, who was no other than Aunt Minervy Ann, flirted in and began to[35] climb the terraces. My recognition of her was not immediate, partly because it had been long since I saw her and partly because she wore her Sunday toggery, in which, following the oriental tastes of her race, the reds and yellows were emphasized with startling effect. She began to talk by the time she was half-way between the house and gate, and it was owing to this special and particular volubility that I was able to recognize her.

“Huh!” she exclaimed, “hit’s des like clim’in’ up sta’rs. Folks what live here bleeze ter b’long ter de Sons er Tempunce.” There was a relish about this reference to the difficulties of three terraces that at once identified Aunt Minervy Ann. More than that, one of the most conspicuous features of the country town where she lived was a large brick building, covering half a block, across the top of which stretched a sign—“Temperance Hall”—in letters that could be read half a mile away.

Aunt Minervy Ann received a greeting that seemed to please her, whereupon she explained that an excursion had come to Atlanta from her town, and she had seized the opportunity to pay me a visit. “I tol’ um,” said she, “dat dey could stay up in town dar an’ hang ’roun’ de kyar-shed ef dey wanter, but here’s what wuz gwine ter come out an’ see whar[36] you live at, an’ fin’ out fer Marse Tumlin ef you comin’ down ter de fa’r.”

She was informed that, though she was welcome, she would get small pleasure from her visit. The cook had failed to make her appearance, and the lady of the house was at that moment in the kitchen and in a very fretful state of mind, not because she had to cook, but because she had about reached the point where she could place no dependence in the sisterhood of colored cooks.

“Is she in de kitchen now?” Aunt Minervy’s tone was a curious mixture of amusement and indignation. “I started not ter come, but I had a call, I sho’ did; sump’n tol’ me dat you mought need me out here.” With that, she went into the house, slamming the screen-door after her, and untying her bonnet as she went.

Now, the lady of the house had heard of Aunt Minervy Ann, but had never met her, and I was afraid that the characteristics of my old-time friend would be misunderstood and misinterpreted. The lady in question knew nothing of the negro race until long after emancipation, and she had not been able to form a very favorable opinion of its representatives. Therefore, I hastened after Aunt Minervy Ann, hoping to tone down by explanation[37] whatever bad impression she might create. She paused at the screen-door that barred the entrance to the kitchen, and, for an instant, surveyed the scene within. Then she cried out:

“You des ez well ter come out’n dat kitchen! You ain’t got no mo’ bizness in dar dan a new-born baby.”

Aunt Minervy Ann’s voice was so loud and absolute that the lady gazed at her in mute astonishment. “You des es well ter come out!” she insisted.

“Are you crazy?” the lady asked, in all seriousness.

“I’m des ez crazy now ez I ever been; an’ I tell you you des ez well ter come out’n dar.”

“Who are you anyhow?”

“I’m Minervy Ann Perdue, at home an’ abroad, an’ in dish yer great town whar you can’t git niggers ter cook fer you.”

“Well, if you want me to come out of the kitchen, you will have to come in and do the cooking.”

“Dat ’zackly what I’m gwine ter do!” exclaimed Aunt Minervy Ann. She went into the kitchen, demanded an apron, and took entire charge. “I’m mighty glad I come ’fo’ you got started,” she said, “’kaze you got ’nuff fier in dis stove fer ter barbecue[38] a hoss; an’ you got it so hot in here dat it’s a wonder you ain’t bust a blood-vessel.”

She removed all the vessels from the range, and opened the door of the furnace so that the fire might die down. And when it was nearly out—as I was told afterward—she replaced the vessels and proceeded to cook a dinner which, in all its characteristics, marked a red letter day in the household.

“She’s the best cook in the country,” said the lady, “and she’s not very polite.”

“Not very hypocritical, you mean; well if she was a hypocrite, she wouldn’t be Aunt Minervy Ann.”

The cook failed to come in the afternoon, and so Aunt Minervy Ann felt it her duty to remain over night. “Hamp’ll vow I done run away wid somebody,” she said, laughing, “but I don’t keer what he think.”

After supper, which was as good as the dinner had been, Aunt Minervy Ann came out on the veranda and sat on the steps. After some conversation, she placed the lady of the house on the witness-stand.

“Mistiss, wharbouts in Georgy wuz you born at?”

“I wasn’t born in Georgia; I was born in Lansingburgh, New York.”

“I know’d it!” Aunt Minervy turned to me and nodded her head with energy. “I know’d it right pine blank!”

“You knew what?” the presiding genius of the household inquired with some curiosity.

“I know’d ’m dat you wuz a Northron lady.”

“I don’t see how you knew it,” I remarked.

“Well, suh, she talk like we-all do, an’ she got mighty much de same ways. But when I went out dar dis mornin’ an’ holler at ’er in de kitchen, I know’d by de way she turn ’roun’ on me dat she ain’t been brung up wid niggers. Ef she’d ’a’ been a Southron lady, she’d ’a’ laughed an’ said, ‘Come in here an’ cook dis dinner yo’se’f, you ole vilyun,’ er she’d ’a’ come out an’ crackt me over de head with dat i’on spoon what she had in her han’.”

I could perceive a vast amount of acuteness in the observation, but I said nothing, and, after a considerable pause, Aunt Minervy Ann remarked:

“Dey er lots er mighty good folks up dar”—indicating the North—“some I’ve seed wid my own eyes an’ de yuthers I’ve heern talk un. Mighty fine folks, an’ dey say dey mighty sorry fer de niggers. But I’ll tell um all anywhar, any day, dat I’d lots druther dey’d be good ter me dan ter be sorry fer me. You know dat ar white lady what Marse[40] Tom Chippendale married? Her pa come down here ter he’p de niggers, an’ he done it de best he kin, but Marse Tom’s wife can’t b’ar de sight un um. She won’t let um go in her kitchen, she won’t let um go in her house, an’ she don’t want um nowhars ’roun’. She’s mighty sorry fer ’m, but she don’t like um. I don’t blame ’er much myse’f, bekaze it look like dat de niggers what been growin’ up sence freedom is des tryin’ der han’ fer ter see how no ’count dey kin be. Dey’ll git better—dey er bleeze ter git better, ’kaze dey can’t git no wuss.”

Here came another pause, which continued until Aunt Minervy Ann, turning her head toward me, asked if I knew the lady that Jesse Towers married; and before I had time to reply with certainty, she went on:

“No, suh, you des can’t know ’er. She ain’t come dar twel sev’mty, an’ I mos’ know you ain’t see ’er dat time you went down home de las’ time, ’kaze she wa’n’t gwine out dat year. Well, she wuz a Northron lady. I come mighty nigh tellin’ you ’bout ’er when you wuz livin’ dar, but fus’ one thing an’ den anudder jumped in de way; er maybe ’Twuz too new ter be goshup’d ’roun’ right den. But de way she come ter be dar an’ de way it all turn out beats any er dem tales what de ol’ folks use ter[41] tell we childun. I may not know all de ins an’ outs, but what I does know I knows mighty well, ’kaze de young ’oman tol’ me herse’f right out ’er own mouf.

“Fus’ an’ fo’mus’, dar wuz ol’ Gabe Towers. He wuz dar whence you wuz dar, an’ long time ’fo’ dat. You know’d him, sho’, ’kaze he wuz one er dem kinder men what sticks out fum de res’ like a waggin’ tongue. Not dat he wuz any better’n anybody else, but he had dem kinder ways what make folks talk ’bout ’im an’ ’pen’ on ’im. I dunner ’zackly what de ways wuz, but I knows dat whatsomever ol’ Gabe Towers say an’ do, folks ’d nod der head an’ say an’ do de same. An’ me ’long er de res’. He had dem kinder ways ’bout ’im, an’ ’twa’n’t no use talkin’.”

In these few words, Aunt Minervy conjured up in my mind the memory of one of the most remarkable men I had ever known. He was tall, with iron-gray hair. His eyes were black and brilliant, his nose slightly curved, and his chin firm without heaviness. To this day Gabriel Towers stands out in my admiration foremost among all the men I have ever known. He might have been a great statesman; he would have been great in anything to which he turned his hand. But he contented[42] himself with instructing smaller men, who were merely politicians, and with sowing and reaping on his plantation. More than one senator went to him for ideas with which to make a reputation.

His will seemed to dominate everybody with whom he came in contact, not violently, but serenely and surely, and as a matter of course. Whether this was due to his age—he was sixty-eight when I knew him, having been born in the closing year of the eighteenth century—or to his moral power, or to his personal magnetism, it is hardly worth while to inquire. Major Perdue said that the secret of his influence was common-sense, and this is perhaps as good an explanation as any. The immortality of Socrates and Plato should be enough to convince us that common-sense is almost as inspiring as the gift of prophecy. To interpret Aunt Minervy Ann in this way is merely to give a correct report of what occurred on the veranda, for explanation of this kind was necessary to give the lady of the house something like a familiar interest in the recital.

“Yes, suh,” Aunt Minervy Ann went on, “he had dem kinder ways ’bout ’im, an’ whatsomever he say you can’t shoo it off like you would a hen on de gyarden fence. Dar ’twuz an’ dar it stayed.

“Well, de time come when ol’ Marse Gabe had[43] a gran’son, an’ he name ’im Jesse in ’cordance wid de Bible. Jesse grow’d an’ grow’d twel he got ter be a right smart chunk uv a boy, but he wa’n’t no mo’ like de Towerses dan he wuz like de Chippendales, which he wa’n’t no kin to. He tuck atter his ma, an’ who his ma tuck atter I’ll never tell you, ’kaze Bill Henry Towers married ’er way off yander somers. She wuz purty but puny, yit puny ez she wuz she could play de peanner by de hour, an’ play it mo’ samer de man what make it.

“Well, suh, Jesse tuck atter his ma in looks, but ’stidder playin’ de peanner, he l’arnt how ter play de fiddle, an’ by de time he wuz twelve year ol’, he could make it talk. Hit’s de fatal trufe, suh; he could make it talk. You hear folks playin’ de fiddle, an’ you know what dey doin’; you kin hear de strings a-plunkin’ an’ you kin hear de bow raspin’ on um on ’count de rozzum, but when Jesse Towers swiped de bow cross his fiddle, ’twa’n’t no fiddle—’twuz human; I ain’t tellin’ you no lie, suh, ’twuz human. Dat chile could make yo’ heart ache; he could fetch yo’ sins up befo’ you. Don’t tell me! many an’ many a night when I hear Jesse Towers playin’, I could shet my eyes an’ hear my childun cryin’, dem what been dead an’ buried long time ago. Don’t make no diffunce ’bout de chune, reel,[44] jig, er promenade, de human cryin’ wuz behime all un um.

“Bimeby, Jesse got so dat he didn’t keer nothin’ ’tall ’bout books. It uz fiddle, fiddle, all day long, an’ half de night ef dey’d let ’im. Den folks ’gun ter talk. No need ter tell you what all dey say. De worl’ over, fum what I kin hear, dey got de idee dat a fiddle is a free pass ter whar ole Scratch live at. Well, suh, Jesse got so he’d run away fum school an’ go off in de woods an’ play his fiddle. Hamp use ter come ’pon ’im when he haulin’ wood, an’ he say dat fiddle ain’t soun’ no mo’ like de fiddles what you hear in common dan a flute soun’ like a bass drum.

“Now you know yo’se’f, suh, dat dis kinder doin’s ain’t gwine ter suit Marse Gabe Towers. Time he hear un it, he put his foot down on fiddler, an’ fiddle, an’ fiddlin’. Ez you may say, he sot down on de fiddle an’ smash it. Dis happen when Jesse wuz sixteen year ol’, an’ by dat time he wuz mo’ in love wid de fiddle dan what he wuz wid his gran’daddy. An’ so dar ’twuz. He ain’t look like it, but Jesse wuz about ez high strung ez his fiddle wuz, an’ when his gran’daddy laid de law down, he sol’ out his pony an’ buggy an’ made his disappearance fum dem parts.

“Well, suh, ’twa’n’t so mighty often you’d hear[45] sassy talk ’bout Marse Gabe Towers, but you could hear it den. Folks is allers onreasonable wid dem dey like de bes’; you know dat yo’se’f, suh. Marse Gabe ain’t make no ’lowance fer Jesse, an’ folks ain’t make none fer Marse Gabe. Marse Tumlin wuz dat riled wid de man dat dey come mighty nigh havin’ a fallin’ out. Dey had a splutter ’bout de time when sump’n n’er had happen, an’ atter dey wrangle a little, Marse Tumlin sot de date by sayin’ dat ’twuz ‘a year ’fo’ de day when Jess went a-fiddlin’.’ Dat sayin’ kindled de fier, suh, an’ it spread fur an’ wide. Marse Tom Chippendale say dat folks what never is hear tell er de Towerses went ’roun’ talkin’ ’bout ‘de time when Jess went a-fiddlin’.’”

Aunt Minervy Ann chuckled over this, probably because she regarded it as a sort of victory for Major Tumlin Perdue. She went on:

“Yes, suh, ’twuz a by-word wid de childun. No matter what happen, er when it happen, er ef ’tain’t happen, ’twuz ’fo’ er atter ‘de day when Jess went a-fiddlin’.’ Hit look like dat Marse Gabe sorter drapt a notch or two in folks’ min’s. Yit he helt his head dez ez high. He bleeze ter hol’ it high, ’kaze he had in ’im de blood uv bofe de Tumlins an’ de Perdues; I dunner how much, but ’nuff fer ter keep his head up.

“I ain’t no almanac, suh, but I never is ter fergit de year when Jess went a-fiddlin. ’Twuz sixty, ’kaze de nex’ year de war ’gun ter bile, an’ ’twa’n’t long ’fo’ it biled over. Yes, suh! dar wuz de war come on an Jess done gone. Dey banged aloose, dey did, dem on der side, an’ we on our’n, an’ dey kep’ on a bangin’ twel we-all can’t bang no mo’. An’ den de war hushed up, an’ freedom come, an’ still nobody ain’t hear tell er Jesse. Den you come down dar, suh, an’ stay what time you did; still nobody ain’t hear tell er Jesse. He mought er writ ter his ma, but ef he did, she kep’ it mighty close. Marse Gabe ain’t los’ no flesh ’bout it, an’ ef he los’ any sleep on account er Jess, he ain’t never brag ’bout it.

“Well, suh, it went on dis away twel, ten year atter Jess went a-fiddlin’, his wife come home. Yes, suh! His wife! Well! I wuz stan’in’ right in de hall talkin’ wid Miss Fanny—dat’s Jesse’s ma—when she come, an’ when de news broke on me you could ’a’ knockt me down wid a permeter fan. De house-gal show’d ’er in de parler, an’ den come atter Miss Fanny. Miss Fanny she went in dar, an’ I stayed outside talkin’ wid de house-gal. De gal say, ‘Aunt Minervy Ann, dey sho’ is sump’n n’er de matter wid dat white lady. She white ez any er de dead, an’ she can’t git ’er breff good.’ ’Bout dat[47] time, I hear somebody cry out in de parler, an’ den I hear sump’n fall. De house-gal cotch holt er me an’ ’gun ter whimper. I shuck ’er off, I did, an’ went right straight in de parler, an’ dar wuz Miss Fanny layin’ face fo’mus’ on a sofy wid a letter in ’er han’ an’ de white lady sprawled out on de flo’.

“Well, suh, you can’t skeer me wid trouble ’kaze I done see too much; so I shuck Miss Fanny by de arm an’ ax ’er what de matter, an’ she cry out, ‘Jesse’s dead an’ his wife come home.’ She uz plum heart-broke, suh, an’ I ’speck I wuz blubberin’ some myse’f when Marse Gabe walkt in, but I wuz tryin’ ter work wid de white lady on de flo’. ’Twix’ Marse Gabe an’ Miss Fanny, ’twuz sho’ly a tryin’ time. When one er dem hard an’ uppity men lose der grip on deyse’f, dey turn loose ever’thing, an’ dat wuz de way wid Marse Gabe. When dat de case, sump’n n’er got ter be done, an’ it got ter be done mighty quick.”

Aunt Minervy Ann paused here and rubbed her hands together contemplatively, as if trying to restore the scene more completely to her memory.

“You know how loud I kin talk, suh, when I’m min’ ter. Well, I talk loud den an’ dar. I ’low, ‘What you-all doin’? Is you gwine ter let Marse Jesse’s wife lay here an’ die des ’kaze he dead? Ef[48] you is, I’ll des go whar I b’longs at!’ Dis kinder fotch um ’roun’, an’ ’twa’n’t no time ’fo’ we had de white lady in de bed whar Jesse use ter sleep at, an’ soon’s we got ’er cuddled down in it, she come ’roun’. But she wuz in a mighty bad fix. She wanter git up an’ go off, an’ ’twuz all I could do fer ter keep ’er in bed. She done like she wuz plum distracted. Dey wa’n’t skacely a minnit fer long hours, an’ dey wuz mighty long uns, suh, dat she wa’n’t moanin’ an’ sayin’ dat she wa’n’t gwine ter stay, an’ she hope de Lord’d fergive ’er. I tell you, suh, ’twuz tarryfyin’. I shuck nex’ day des like folks do when dey er honin’ atter dram.

“You may ax me how come I ter stay dar,” Aunt Minervy Ann suggested with a laugh. “Well, suh, ’twa’n’t none er my doin’s. I ’speck dey mus’ be sump’n wrong ’bout me, ’kaze no matter how rough I talk ner how ugly I look, sick folks an’ childun alters takes up wid me. When I go whar dey is, it’s mighty hard fer ter git ’way fum um. So, when I say ter Jesse’s wife, ‘Keep still, honey, an’ I’ll go home an’ not pester you,’ she sot up in bed an’ say ef I gwine she gwine too. I say, ‘Nummine ’bout me, honey, you lay down dar an’ don’t talk too much.’ She ’low, ‘Le’ me talk ter you an’ tell you all ’bout it.’ But I shuck my head an’ say dat ef[49] she don’t hush up an’ keep still I’m gwine right home.

“I had ter do ’er des like she wuz a baby, suh. She wa’n’t so mighty purty, but she had purty ways, ’stracted ez she wuz, an’ de biggest black eyes you mos’ ever seed, an’ black curly ha’r cut short kinder, like our folks use ter w’ar der’n. Den de house-gal fotched some tea an’ toas’, an’ dis holp ’er up mightly, an’ atter dat I sont ter Marse Gabe fer some dram, an’ de gal fotched de decanter fum de side-bode. Bein’, ez you may say, de nurse, I tuck an’ tas’e er de dram fer ter make sho’ dat nobody ain’t put nothin’ in it. An’, sho’ ’nuff, dey ain’t.”

Aunt Minervy Ann paused and smacked her lips. “Atter she got de vittles an’ de dram, she sorter drap off ter sleep, but ’twuz a mighty flighty kinder sleep. She’d wake wid a jump des ’zackly like babies does, an’ den she’d moan an’ worry twel she dozed off ag’in. I nodded, suh, bekaze you can’t set me down in a cheer, night er day, but what I’ll nod, but in betwix’ an’ betweens I kin hear Marse Gabe Towers walkin’ up an’ down in de liberry; walk, walk; walk, walk, up an’ down. I ’speck ef I’d ’a’ been one er de nervious an’ flighty kin’ dey’d ’a’ had to tote me out er dat house de nex’ day; but me! I des kep’ on a-noddin’.

“Bimeby, I hear sump’n come swishin’ ’long, an’ in walkt Miss Fanny. I tell you now, suh, ef I’d a met ’er comin’ down de road, I’d ’a’ made a break fer de bushes, she look so much like you know sperrets oughter look—an’ Marse Jesse’s wife wuz layin’ dar wid ’er eyes wide open. She sorter swunk back in de bed when she see Miss Fanny, an’ cry out, ‘Oh, I’m mighty sorry fer ter trouble you; I’m gwine ’way in de mornin’.’ Miss Fanny went ter de bed an’ knelt down ’side it, an’ ’low, ‘No, you ain’t gwine no whar but right in dis house. Yo’ place is here, wid his mudder an’ his gran’fadder.’ Wid dat, Marse Jesse’s wife put her face in de piller an’ moan an’ cry, twel I hatter ax Miss Fanny fer ter please, ma’m, go git some res’.

“Well, suh, I stayed dar dat night an’ part er de nex’ day, an’ by dat time all un um wuz kinder quieted down, but dey wuz mighty res’less in de min’, ’speshually Marse Jesse’s wife, which her name wuz Miss Sadie. It seem like dat Marse Jesse wuz livin’ at a town up dar in de fur North whar dey wuz a big lake, an’ he went out wid one er dem ’scursion parties, an’ a storm come up an’ shuck de boat ter pieces. Dat what make I say what I does. I don’t min’ gwine on ’scursions on de groun’, but when it come ter water—well, suh, I ain’t gwine ter[51] trus’ myse’f on water twel I kin walk on it an’ not wet my foots. Marse Jesse wuz de Captain uv a music-ban’ up dar, an’ de papers fum dar had some long pieces ’bout ’im, an’ de paper at home had a piece ’bout ’im. It say he wuz one er de mos’ renounced music-makers what yever had been, an’ dat when it come ter dat kinder doin’s he wuz a puffick prodigal. I ’member de words, suh, bekaze I made Hamp read de piece out loud mo’ dan once.

“Miss Sadie, she got mo’ calmer atter while, an’ ’twa’n’t long ’fo’ Marse Gabe an’ Miss Fanny wuz bofe mighty tuck up wid ’er. Dey much’d ’er up an’ made a heap un ’er, an’ she fa’rly hung on dem. I done tol’ you she ain’t purty, but dey wuz sump’n ’bout ’er better dan purtiness. It mought er been ’er eyes, en den ag’in mought er been de way er de gal; but whatsomever ’twuz, hit made you think ’bout ’er at odd times durin’ de day, an’ des ’fo’ you go ter sleep at night.

“Eve’ything went swimmin’ along des ez natchul ez a duck floatin’ on de mill-pon’. Dey wa’n’t skacely a day but what I seed Miss Sadie. Ef I ain’t go ter Marse Gabe’s house she’d be sho’ ter come ter mine. Dat uz atter Hamp wuz ’lected ter de legislatur, suh. He ’low dat a member er de ingener’l ensembly ain’t got no bizness livin’ in a kitchen, but[52] I say he ain’t a whit better den dan he wuz befo’. So be, I done been cross ’im so much dat I tell ’im ter git de house an’ I’d live in it ef ’twa’n’t too fur fum Miss Vallie an’ Marse Tumlin. Well, he had it built on de outskyirts, not a big jump fum Miss Vallie an’ betwix’ de town an’ Marse Gabe Towers’s. When you come down ter de fa’r, you mus’ come see me. Me an’ Hamp’ll treat you right; we sholy will.

“Well, suh, in dem days dey wa’n’t so many niggers willin’ ter do an’ be done by, an’ on account er dat, ef Miss Vallie wa’n’t hollin’ fer ’Nervy Ann, Miss Fanny er Miss Sadie wuz, an’ when I wa’n’t at one place, you might know I’d be at de yuther one. It went on dis away, an’ went on twel one day got so much like an’er dat you can’t tell Monday fum Friday. An’ it went on an’ went on twel bimeby I wuz bleeze ter say sump’n ter Hamp. You take notice, suh, an’ when you see de sun shinin’ nice an’ warm an’ de win’ blowin’ so saft an’ cool dat you wanter go in a-washin’ in it—when you see dis an’ feel dat away, Watch out! Watch out, I tell you! Dat des de time when de harrycane gwine ter come up out’n de middle er de swamp an’ t’ar things ter tatters. Same way when folks gitting on so nice dat dey don’t know dey er gittin’ on.

“De fus’ news I know’d Miss Sadie wuz bringin’ little bundles ter my house ’twix’ sundown an’ dark. She’d ’low, ‘Aunt Minervy Ann, I’ll des put dis in de cornder here; I may want it some time.’ Nex’ day it’d be de same doin’s over ag’in. ‘Aunt Minervy Ann, please take keer er dis; I may want it some time.’ Well, it went on dis away fum day ter day, but I ain’t pay no ’tention. Ef any ’spicion cross my min’ it wuz dat maybe Miss Sadie puttin’ dem things dar fer ter ’sprise me Chris’mus by tellin’ me dey wuz fer me. But one day she come ter my house, an’ sot down an’ put her han’s over her face like she got de headache er sump’n.

“Wellum”—Aunt Minervy Ann, with real tact, now began to address herself to the lady of the house—“Wellum, she sot dar so long dat bimeby I ax ’er what de matter is. She ain’t say nothin’; she ain’t make no motion. I ’low ter myse’f dat she don’t wanter be pestered, so I let ’er ’lone an’ went on ’bout my business. But, bless you! de nex’ time I look at ’er she wuz settin’ des dat away wid ’er han’s over her face. She sot so still dat it sorter make me feel quare, an’ I went, I did, an’ cotch holt er her han’s sorter playful-like. Wellum, de way dey felt made me flinch. All I could say wuz, ‘Lord ’a’ mercy!’ She tuck her han’s down, she did, an’ look[54] at me an’ smile kinder faint-like. She ’low, ‘Wuz my han’s col’, Aunt Minervy Ann?’ I look at ’er an’ grunt, ‘Huh! dey won’t be no colder when youer dead.’ She ain’t say nothin’, an’ terreckly I ’low, ‘What de name er goodness is de matter wid you, Miss Sadie?’ She say, ‘Nothin’ much. I’m gwine ter stay here ter-night, an’ ter-morrer mornin’ I’m gwine ’way.’ I ax ’er, ‘How come dat? What is dey done to you?’ She say, ‘Nothin’ ’tall.’ I ’low, ‘Does Marse Gabe an’ Miss Fanny know you gwine?’ She say, ‘No; I can’t tell um.’

“Wellum, I flopt down on a cheer; yessum, I sho’ did. My min’ wuz gwine like a whirligig an’ my head wuz swimmin’. I des sot dar an’ look at ’er. Bimeby she up an’ say, pickin’ all de time at her frock, ‘I know’d sump’n wuz gwine ter happen. Dat de reason I been bringin’ dem bundles here. In dem ar bundles you’ll fin’ all de things I fotch here. I ain’t got nothin’ dey give me ’cep’n dish yer black dress I got on. I’d ’a’ fotch my ol’ trunk, but I dunner what dey done wid it. Hamp’ll hatter buy me one an’ pay for it hisse’f, ’kaze I ain’t got a cent er money.’ Dem de ve’y words she say. I ’low, ‘Sump’n must ’a’ happen den.’ She nodded, an’ bimeby she say, ‘Mr. Towers comin’ home ter-night. Dey done got a telegraph fum ’im.’

“I stood up in de flo’, I did, an’ ax ’er, ‘Which Mr. Towers?’ She say, ‘Mr. Jesse Towers.’ I ’low, ‘He done dead.’ She say, ‘No, he ain’t; ef he wuz he done come ter life; dey done got a telegraph fum ’im, I tell you.’ ‘Is dat de reason you gwine ’way?’ I des holla’d it at ’er. She draw’d a long breff an’ say, ‘Yes, dat’s de reason.’

“I tell you right now, ma’m, I didn’t know ef I wuz stannin’ on my head er floatin’ in de a’r. I wuz plum outdone. But dar she sot des es cool ez a curcumber wid de dew on it. I went out de do’, I did, an’ walk ’roun’ de house once ter de right an’ twice ter de lef’ bekaze de ol’ folks use ter tell me dat ef you wuz bewitched, dat ’ud take de spell away. I ain’t tellin’ you no lie, ma’m—fer de longes’ kinder minnit I didn’t no mo’ b’lieve dat Miss Sadie wuz settin’ dar in my house tellin’ me dat kinder rigamarole, dan I b’lieve I’m flyin’ right now. Dat bein’ de case, I bleeze ter fall back on bewitchments, an’ so I walk ’roun’ de house. But when I went back in, dar she wuz, settin’ in a cheer an’ lookin’ up at de rafters.

“Wellum, I went in an’ drapt down in a cheer an’ lookt at ’er. Bimeby, I say, ‘Miss Sadie, does you mean ter set dar an’ tell me youer gwine ’way ’kaze yo’ husban’ comin’ home?’ She flung her[56] arms behime ’er head, she did, an’ say, ‘I ain’t none er his wife; I des been playin’ off!’ De way she look an’ de way she say it wuz ’nuff fer me. I wuz pairlized; yessum, I wuz dumfounder’d. Ef anybody had des but totch me wid de tip er der finger, I’d ’a’ fell off’n dat cheer an’ never stirred atter I hit de flo’. Ever’thing ’bout de house lookt quare. Miss Vallie had a lookin’-glass one time wid de pictur’ uv a church at de bottom. When de glass got broke, she gimme de pictur’, an’ I sot it up on de mantel-shelf. I never know’d ’fo’ dat night dat de steeple er der church wuz crooked. But dar ’twuz. Mo’ dan dat I cotch myse’f feelin’ er my fingers fer ter see ef ’twuz me an’ ef I wuz dar.

“Talk ’bout dreams! dey wa’n’t no dream could beat dat, I don’t keer how twisted it mought be. An’ den, ma’m, she sot back dar an’ tol’ me de whole tale ’bout how she come ter be dar. I’ll never tell it like she did; dey ain’t nobody in de wide worl’ kin do dat. But it seem like she an’ Marse Jesse wuz stayin’ in de same neighborhoods, er stayin’ at de same place, he a-fiddlin’ an’ she a-knockin’ on de peanner er de harp, I fergit which. Anyhow, dey seed a heap er one an’er. Bofe un um had come dar fum way off yan’, an’ ain’t got nobody but deyse’f fer ter ’pen’ on, an’ dat kinder flung um togedder.[57] I ’speck dey must er swapt talk ’bout love an’ marryin’—you know yo’se’f, ma’m, dat dat’s de way young folks is. Howsomever dat may be, Marse Jesse, des ter tease ’er, sot down one day an’ writ a long letter ter his wife. Tooby sho’ he ain’t got no wife, but he des make out he got one, an’ dat letter he lef’ layin’ ’roun’ whar Miss Sadie kin see it. ’Twa’n’t in no envelyup, ner nothin’, an’ you know mighty well, ma’m, dat when a ’oman, young er ol’, see dat kinder letter layin’ ’roun’ she’d die ef she don’t read it. Fum de way Miss Sadie talk, dat letter must ’a’ stirred up a coolness ’twix’ um, kaze de mornin’ when he wuz gwine on dat ’scursion, Marse Jesse pass by de place whar she wuz settin’ at an’ flung de letter in her lap an’ say, ‘What’s in dar wuz fer you.’

“Wellum, wid dat he wuz gone, an’ de fus’ news Miss Sadie know’d de papers wuz full er de names er dem what got drownded in de boat, an’ Marse Jesse head de roll, ’kaze he wuz de mos’ pop’lous music-maker in de whole settlement. Den dar wuz de gal an’ de letter. I wish I could tell dis part like she tol’ me settin’ dar in my house. You’ll never git it straight in yo’ head less’n you’d ’a’ been dar an’ hear de way she tol’ it. Nigger ez I is, I know mighty well dat a white ’oman ain’t got no business[58] parmin’ ’erse’f off ez a man’s wife. But de way she tol’ it tuck all de rough aidges off’n it. She wuz dar in dat big town, wuss’n a wilderness, ez you may say, by ’erse’f, nobody ’penin’ on ’er an’ nobody ter ’pen’ on, tired down an’ plum wo’ out, an’ wid all dem kinder longin’s what you know yo’se’f, ma’am, all wimmen bleeze ter have, ef dey er white er ef dey er black.

“Yit she ain’t never tol’ nobody dat she wuz Marse Jesse’s wife. She des han’ de letter what she’d kep’ ter Miss Fanny, an’ fell down on de flo’ in a dead faint, an’ she say dat ef it hadn’t but ’a’ been fer me, she’d a got out er de bed dat fust night an’ went ’way fum dar; an’ I know dat’s so, too, bekaze she wuz ranklin’ fer ter git up fum dar. But at de time I put all dat down ter de credit er de deleeriums, an’ made ’er stay in bed.

“Wellum, ef I know’d all de books in de worl’ by heart, I couldn’t tell you how I felt atter she done tol’ me dat tale. She sot back dar des ez calm ez a baby. Bimeby she say, ‘I’m glad I tol’ you; I feel better dan I felt in a mighty long time.’ It look like, ma’am, dat a load done been lift fum ’er min’. Now I know’d pine blank dat sump’n gotter be done, ’kaze de train’d be in at midnight, an’ den when Marse Jesse come dey’d be a tarrifyin’[59] time at Gabe Towers’s. Atter while I up an’ ax ’er, ‘Miss Sadie, did you reely love Marse Jesse?’ She say, ‘Yes, I did’—des so. I ax ’er, ‘Does you love ’im now?’ She say, ‘Yes, I does—an’ I love dem ar people up dar at de house; dat de reason I’m gwine ’way.’ She talk right out; she done come to de p’int whar she ain’t got nothin’ ter hide.

“I say, ‘Well, Miss Sadie, dem folks up at de house, dey loves you.’ She sorter flincht at dis. I ’low, ‘Dey been mighty good ter you. What you done, you done done, an’ dat can’t be holp, but what you ain’t gone an’ done, dat kin be holp; an’ what you oughter do, dat oughtn’t ter be holp.’ I see ’er clinch ’er han’s an’ den I riz fum de cheer.” Suiting the action to the word, Aunt Minervy Ann rose from the step where she had been sitting, and moved toward the lady of the house.

“I riz, I did, an’ tuck my stan’ befo’ ’er. I ’low, ‘You say you love Marse Jesse, an’ you say you love his folks. Well, den ef you got any blood in you, ef you got any heart in yo’ body, ef you got any feelin’ fer anybody in de roun’ worl’ ’cep’n’ yo’ naked se’f, you’ll go up dar ter dat house an’ tell Gabe Towers dat you want ter see ’im, an’ you’ll tell Fanny Towers dat you want ter see her, an’ you’ll[60] stan’ up befo’ um an’ tell um de tale you tol’ ter me, word fer word. Ef you’ll do dat, an’ you hatter come back here, come! come! Bless God! come! an’ me an’ Hamp’ll rake an’ scrape up ’nuff money fer ter kyar you whar you gwine. An’ don’t you be a’skeer’d er Gabe Towers. Me an’ Marse Tumlin ain’t a-skeer’d un ’im. I’m gwine wid you, an’ ef he say one word out de way, you des come ter de do’ an’ call me, an’ ef I don’t preach his funer’l, it’ll be bekaze de Lord’ll strike me dumb!’ An’ she went!”

Aunt Minervy paused. She had wrought the miracle of summoning to life one of the crises through which she had passed with others. It was not the words she used. There was nothing in them to stir the heart or quicken the pulse. Her power lay in the tones of her voice, whereby she was able to recall the passion of a moment that had long spent itself; in the fluent and responsive attitudes; in gesticulation that told far more than her words did. The light from the vestibule lamp shone full upon her and upon the lady whom she unconsciously selected to play the part of the young woman whose story she was telling. The illusion was perfect. We were in Aunt Minervy Ann’s house, Miss Sadie was sitting helpless and hopeless before her—the[61] whole scene was vivid and complete. She paused; her arm, which had been outstretched and rigid for an instant, slowly fell to her side, and—the illusion was gone; but while it lasted, it was as real as any sudden and extraordinary experience can be.

Aunt Minervy Ann resumed her seat, with a chuckle, apparently ashamed that she had been betrayed into such a display of energy and emotion, saying, “Yessum, she sho’ went.”

“I don’t wonder at it,” remarked the lady of the house, with a long-drawn sigh of relief.

Aunt Minervy Ann laughed again, rather sheepishly, and then, after rubbing her hands together, took up the thread of the narrative, this time directing her words to me: “All de way ter de house, suh, she ain’t say two words. She had holt er my han’, but she ain’t walk like she uz weak. She went along ez peart ez I did. When we got dar, some er de niggers wuz out in de flower gyarden an’ out in de big grove callin’ ’er; an’ dey call so loud dat I hatter put um down. ‘Hush up!’ I say, ‘an’ go on ’bout yo’ business! Can’t yo’ Miss Sadie take a walk widout a whole passel er you niggers a-hollerin’ yo’ heads off?’ One un um make answer, ‘Miss Fanny huntin’ fer ’er.’ She sorter grip my han’ at dat,[62] but I say, ‘She de one you wanter see—her an’ Gabe Towers.’

“We went up on de po’ch, an’ dar wuz Miss Fanny an’ likewise Marse Gabe. I know’d what dey wanted; dey wanted ter talk wid ’er ’bout Marse Jesse. She clum de steps fus’ an’ I clum atter her. She cotch ’er breff hard when she fus’ hit de steps, an’ den it come over me like a flash how deep an’ big her trouble wuz, an’ I tell you right now, ef dat had ’a’ been Miss Vallie gwine up dar, I b’lieve I’d ’a’ flew at ol’ Gabe Towers an’ to’ ’im lim’ fum lim’ ’fo’ anybody could ’a’ pull me off. Hit’s de trufe! You may laugh, but I sho’ would ’a’ done it. I had it in me. Miss Fanny seed sump’n wuz wrong, de minnit de light fell on de gal’s face. She say, ‘Why, Sadie, darlin’, what de matter wid you?’—des so—an’ made ez ef ter put ’er arms ’roun’ ’er; but Miss Sadie swunk back. Miss Fanny sorter swell up. She say, ‘Oh, ef I’ve hurt yo’ feelin’s ter-day—ter-day uv all de days—please, please fergi’ me!’ Well, suh, I dunner whar all dis gwine ter lead ter, an’ I put in, ‘She des wanter have a talk wid you an’ Marse Gabe, Miss Fanny; an’ ef ter-day is one er de days her feelin’s oughtn’ter be hurted, take keer dat you don’t do it. Kyar ’er in de parler dar, Miss[63] Fanny.’ I ’speck you’ll think I wuz takin’ a mighty heap on myse’f, fer a nigger ’oman,” remarked Aunt Minervy Ann, smoothing the wrinkles out of her lap, “but I wuz des ez much at home in dat house ez I wuz in my own, an’ des ez free wid um ez I wuz wid my own folks. Miss Fanny look skeer’d, an’ Marse Gabe foller’d atter, rubbin’ a little mole he had on de top er his head. When he wus worried er aggervated, he allers rub dat mole.