Title: An Englishwoman in Angora

Author: Grace Ellison

Illustrator: L. Raven-Hill

Release date: July 3, 2021 [eBook #65749]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer,, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

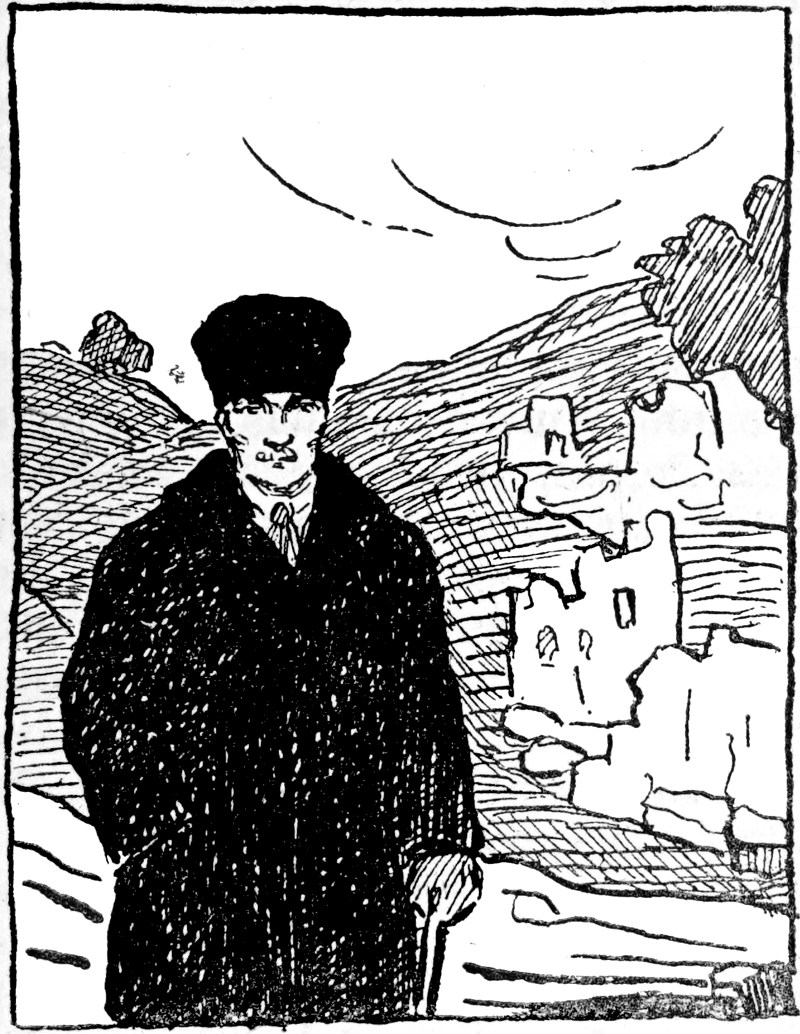

MISS GRACE ELLISON.

The first British woman to visit Angora since the beginning of the Nationalist Movement. She has always stood for Anglo-Turkish friendship.

Frontispiece

At the time of writing I am the only Englishwoman who has been in Angora since the Nationalist movement began.

Others, moved by curiosity, have sought permission to visit the country under its new régime, but Nationalist Turkey has bidden them wait—until she is sure that her guests will write, or speak, the truth about what they may see, and can be trusted to forget the prejudices with which they would almost certainly arrive.

For myself, I have three times been welcomed to Turkey with open arms on account of my nationality. On this occasion I was still welcome, but in spite of my nationality—an ugly truth that my mind almost refuses to accept.

To compare impressions from these visits one must first ask: “How could such a change of attitude come to pass?”

Formerly Great Britain was the country of all countries that “counted” in Turkey. To be a “gentleman”—(they used the English word)—was the Turks’ highest ambition. British stuffs were chosen in preference to French, not because they were finer or of greater value, but simply because they were British. Our ideals, our policy, and, I must add, our governesses, were almost regarded as sacred in Turkish eyes.

And now I am advised, for greater safety, to travel as an American! God forbid! I stand by the old flag.

I would smile, could the tears be hidden, when I xrecall the police officer who so solemnly enquired if I was sure I was not an American.

“Perfectly sure,” I replied.

“How then,” said he, “has that impossibility—an Englishwoman in Angora—become possible?”

“Your Government,” I answered, “has made it possible. As you have no one else here from my country, I have given myself this mission.... An old friend of the Turks, a woman who loves her own country! Can she not do something for that peace between us, which is a supreme necessity to both? That is why I am here.”

I do not forget that Turks were our “enemies” in the war. But they came back, beaten to the dust—and penitent. Then was the moment for us to have made our own terms. In that mood Turkey would have accepted—anything, but the one thing we imposed on her—the Greeks at Smyrna! That policy of sheer folly has transformed the veneration of her people into fear and distrust, if not hate.

Unjustly and unreasonably as we have behaved towards our old ally, we were not, indeed, alone in this mischievous exalting of Greek aggressions. Dare we not now own our mistake? We are great enough, and strong enough, to be generous, to mend our ways!

To-day, surely, it is the duty of English patriots to pour oil on the troubled waters, to explain to Turkey what can be explained, and to paint our countrymen, at least, less “black” than they have been made to seem by our rivals’ pen!

Lausanne Palace Hotel,

Lausanne,

January, 1923.

| PAGE | |

| An Englishwoman in Angora | ix |

| List of Illustrations | xv |

| On Board the Pierre Loti—Turkey’s Debt to Loti’s Magic Pen | 17 |

| Turkey and Tolerance—A Friendship Wasted | 22 |

| Malta: the Name I was to Hear Throughout Anatolia | 29 |

| Athens—“We Have Loved Helen; Must We Divorce Her?” | 36 |

| Smyrna: a Picture of Desolation | 43 |

| British Chivalry!—Brave Women a Nuisance! | 54 |

| Smyrna—God’s Work—The Exquisite Sunset—Man’s Work—War | 60 |

| Emotions and Impressions—“On the Way”—Nowhere to House the Poor People | 71 |

| More Impressions-“Sitting Amidst an Army of Supposed Savage Fanatics, Debating the Greatness of God” | 79 |

| A Journey on Foot—A Country Made by God, untouched by Man | 85 |

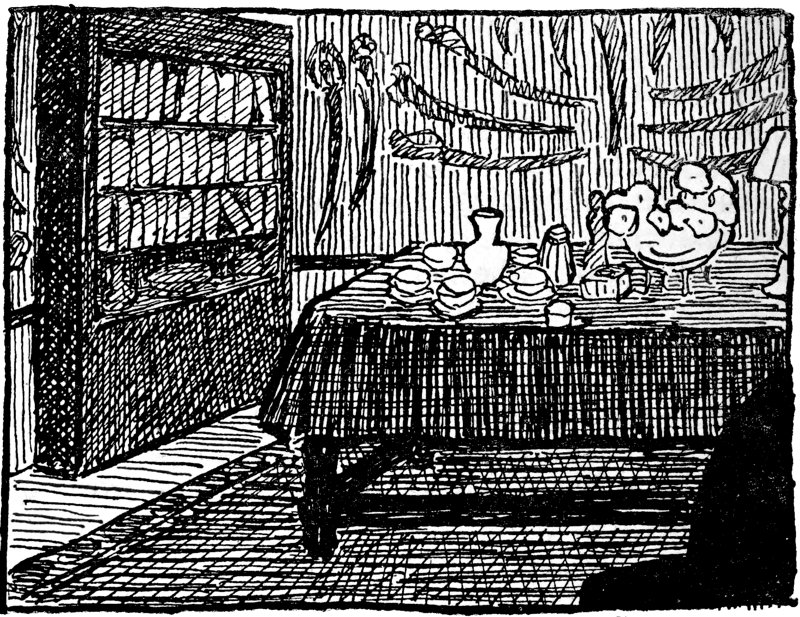

| A Public Meeting at Ouchak—Hospitality—A Sacred Rite | 94 |

| A Luggage Train—The Worst Stage of My Whole Journey | 104 |

| A Third-Class Compartment—A Frenchman Amongst the Ruins | 114 |

| In the “Train de Luxe”—The Supreme Good Fellowship of English Laughter—Journeying Towards the Cradle of New Turkey | 122 |

| Angora I.—Entering a “Brotherhood”—An Atmosphere of Camaraderie | 132 |

| Angora II.—At the Home of My Kind and Courteous Host | 141 |

| Angora III.—The Marvellous Atmosphere of a Great Birth | 147 |

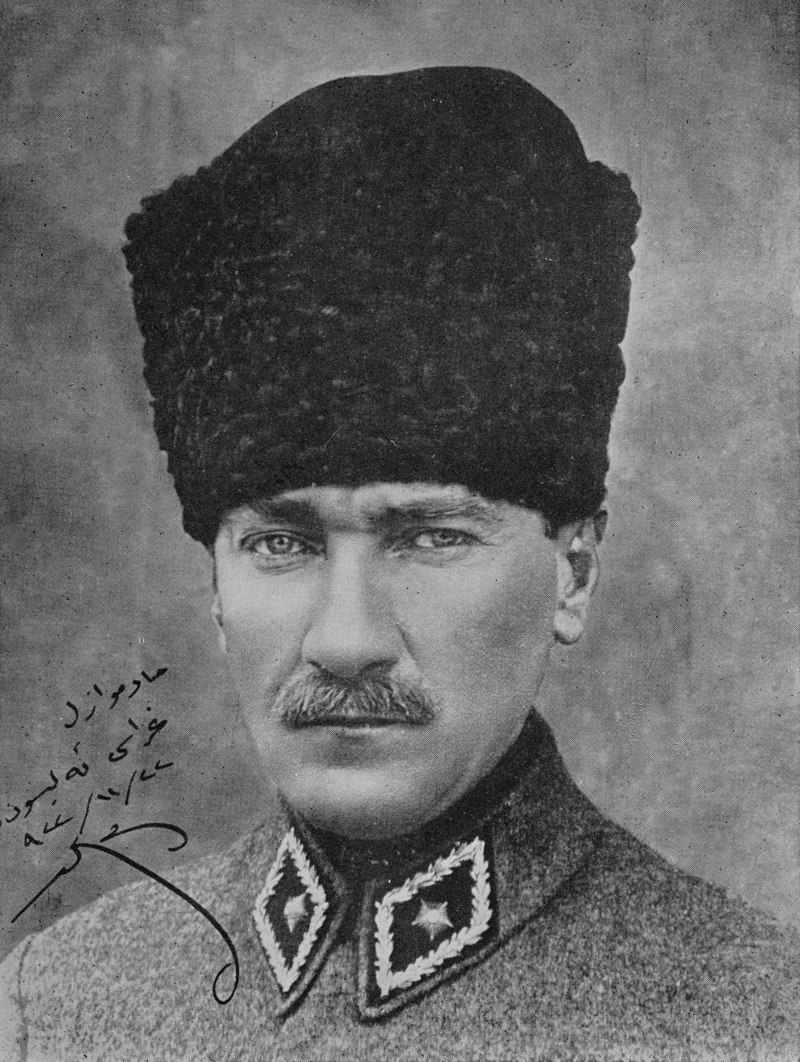

| The Ghazi Mustapha Kemal Pasha—The Greatest Man in Turkey To-day | 159 |

| An Interview with the Ghazi Mustapha Kemal Pasha | 174 |

| Mustapha Kemal Pasha—The Man Who is Master of His Fate | 179 |

| A Turkish Cabinet—The Three Best-Known Ministers—A Cabinet of Young Men | 192 |

| Turkish Cabinet—The Less-known Ministers of the Sovereign State | 198 |

| The Foreign Colony in Angora—A Group of Foreign Personalities | 202 |

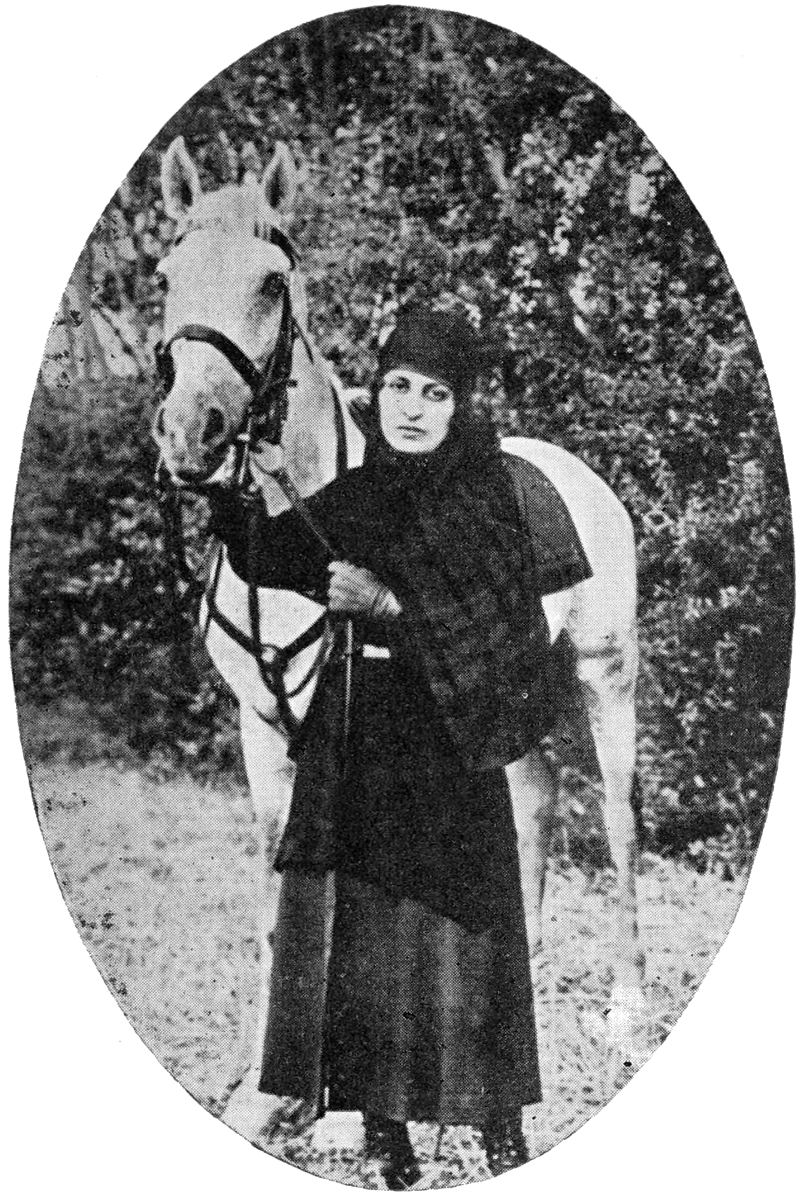

| Halidé Edib Hanoum, Author and Patriot—A Woman Dowered with the All-Conquering Gifts of the Truly Brave | 205 |

| Hospitals—Schools—Education and the Nationalist Writers—The Days Pass, but There is Still Much to Be Done and Seen | 215 |

| Last Days in Angora: Excursions, Conversations, Picnics—HAÏDAR Bey’s Party | 226 |

| Rome, the Eternal City—A Visit to the Catholics in Angora | 239 |

| Three Diplomats at Rome—The Guardianship of the Holy Tomb | 249 |

| En Route for Constantinople—A Night at Bilidjik Under the Frost-Laden Skies | 254 |

| From Bilidjik to Broussa by Yaili—After the day’s Roughening Experiences one can Sleep whatever the Accommodation | 259 |

| A Few Days in Broussa—The True Islam Atmosphere | 273 |

| Constantinople No Longer the Capital—The Heart and Spirit of Turkey are in Angora | 285 |

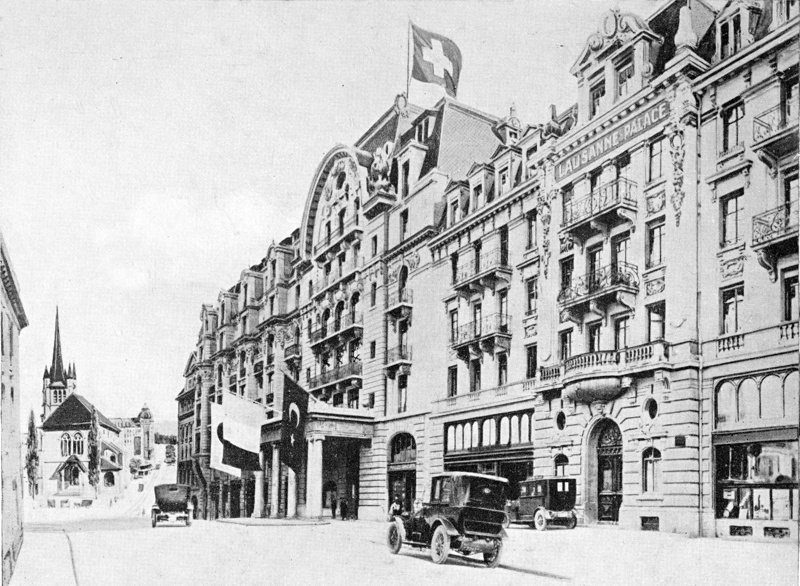

| Lausanne Palace Hotel—The Home of Turkey, France, and Japan—“Every Possible Phase of Complete Internationalism” | 298 |

| Turkey and the League of Nations—The Parliament of Nations Must Be Truly Impartial and International | 313 |

| The Future—Above All, a Lasting Peace | 318 |

| Index | 321 |

| Miss Grace Ellison | Frontispiece |

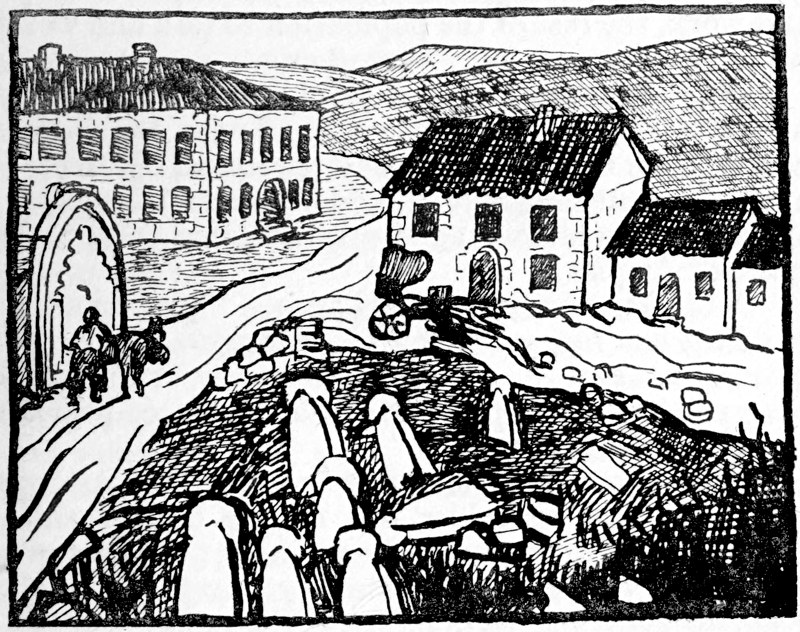

| Burnt Quarter in the French Part of Smyrna near the Quay | 48 |

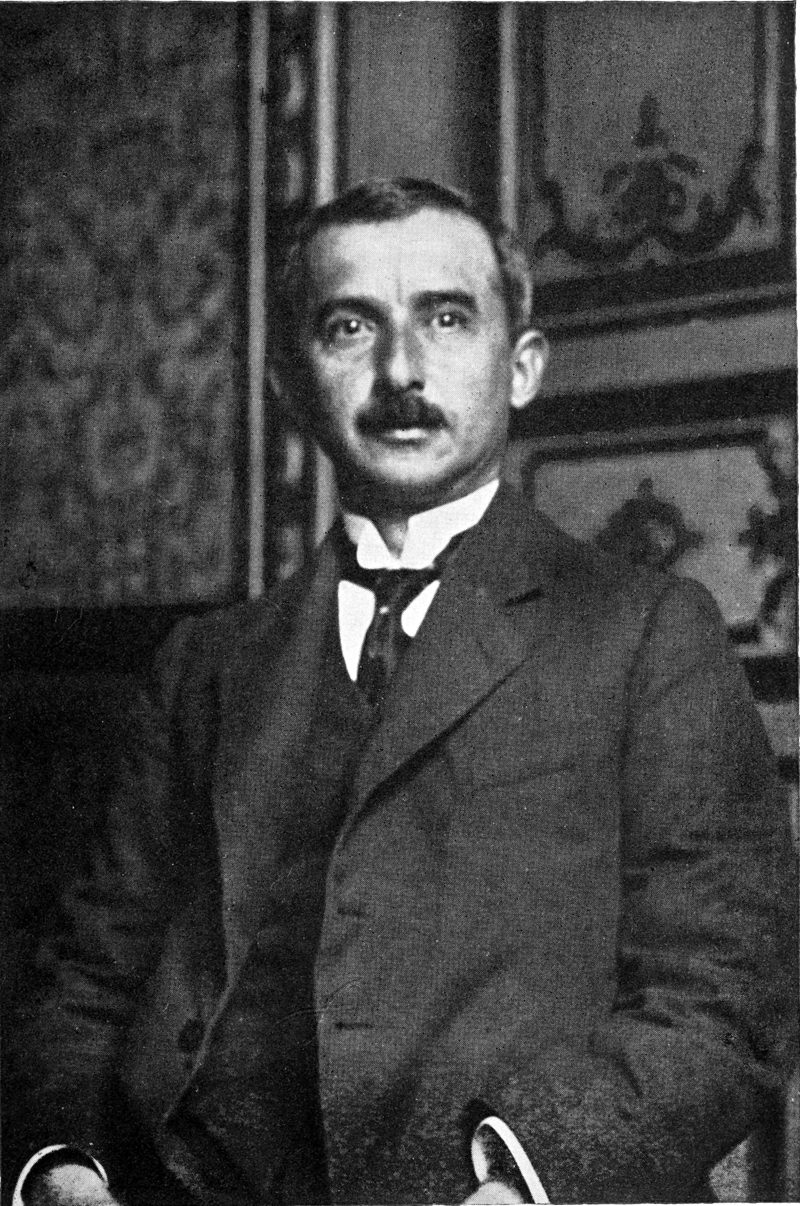

| Lord Curzon: “Turkey for the Turks, indeed!” | 64 |

| In an Ox Wagon | 89 |

| From a Turk’s Back | 104 |

| H.M. The Kaliph of Islam | 112 |

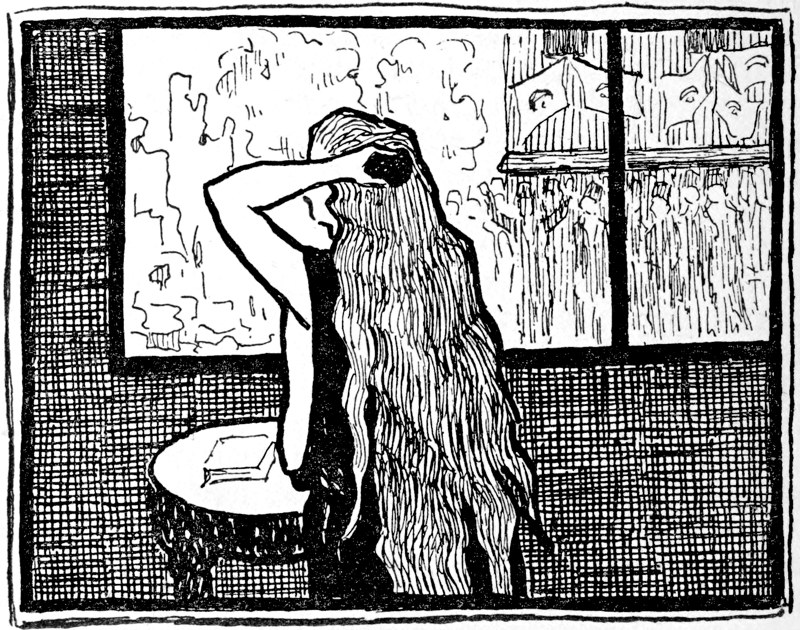

| A Battle Royal with my Tangled, Dusty Hair | 122 |

| A Bottle of Evian—Under the Table | 123 |

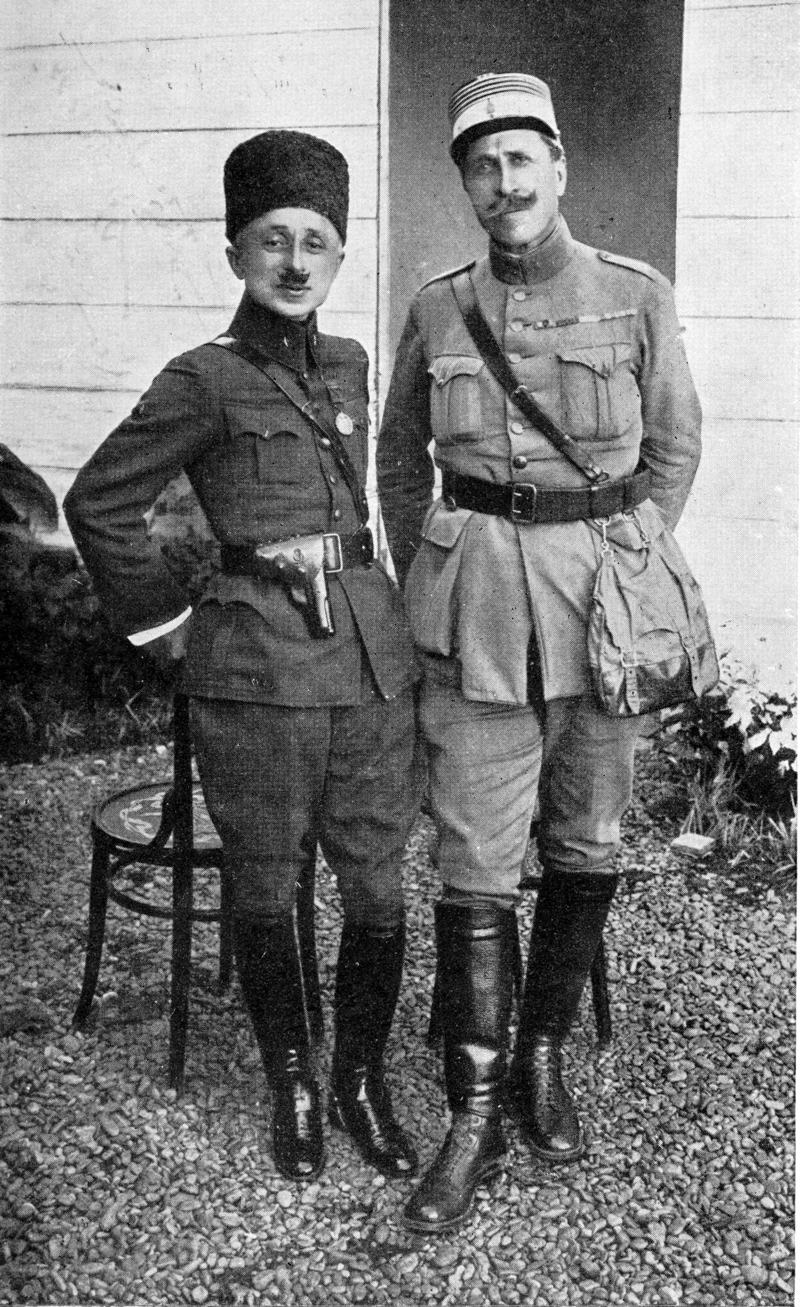

| General Moueddine Pasha, Military Instructor of Mustapha Kemal Pasha | 128 |

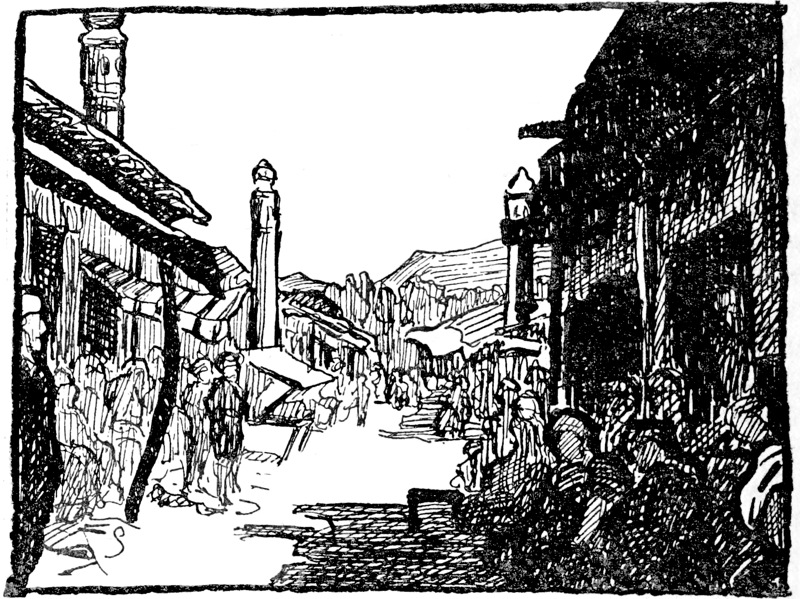

| The Market-place at Angora | 136 |

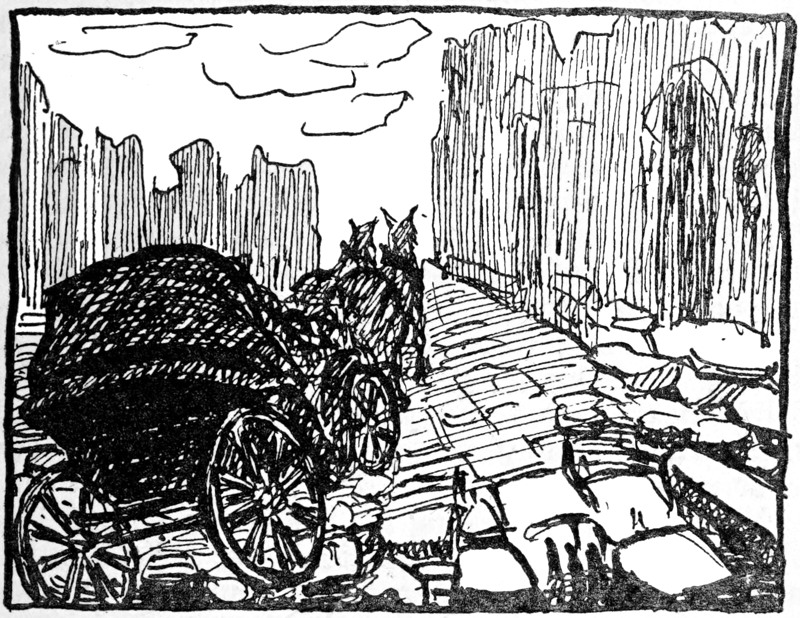

| “The carriages swing from angle to angle” | 137 |

| Grand National Assembly at Angora | 144 |

| “There is so much to sketch from our front door” | 145 |

| The Ghazi Mustapha Kemal Pasha, President of the Grand National Assembly, Angora | 160 |

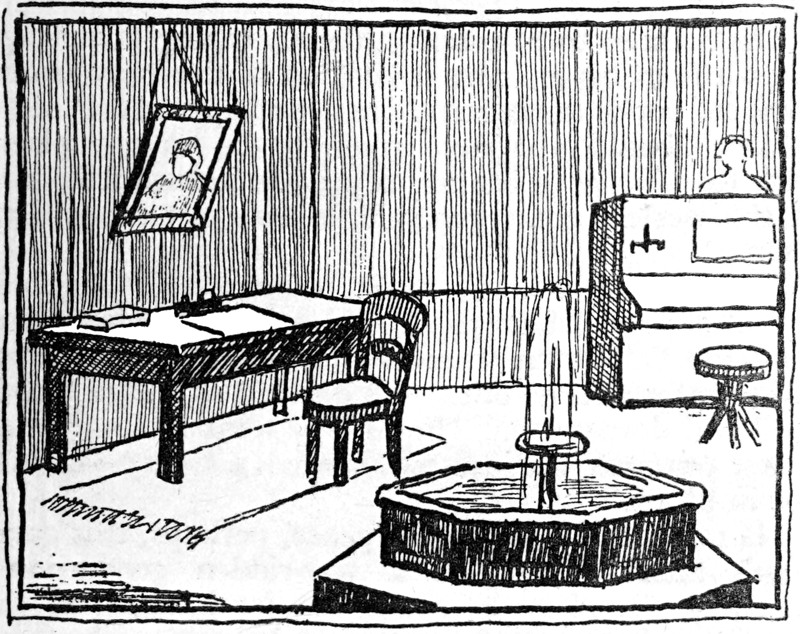

| On the wall of Mustapha Kemal Pasha’s study the Sultan Osman looks down on Mustapha Kemal Pasha | 164 |

| The Ante-room at Tchan-Kaya | 165 |

| Mustapha Kemal Pasha’s Sitting-room | 168 |

| Mustapha Kemal Pasha Walking in the Grounds of Tchan-Kaya | 171 |

| General Ismet Pasha, Minister for Foreign Affairs | 176 |

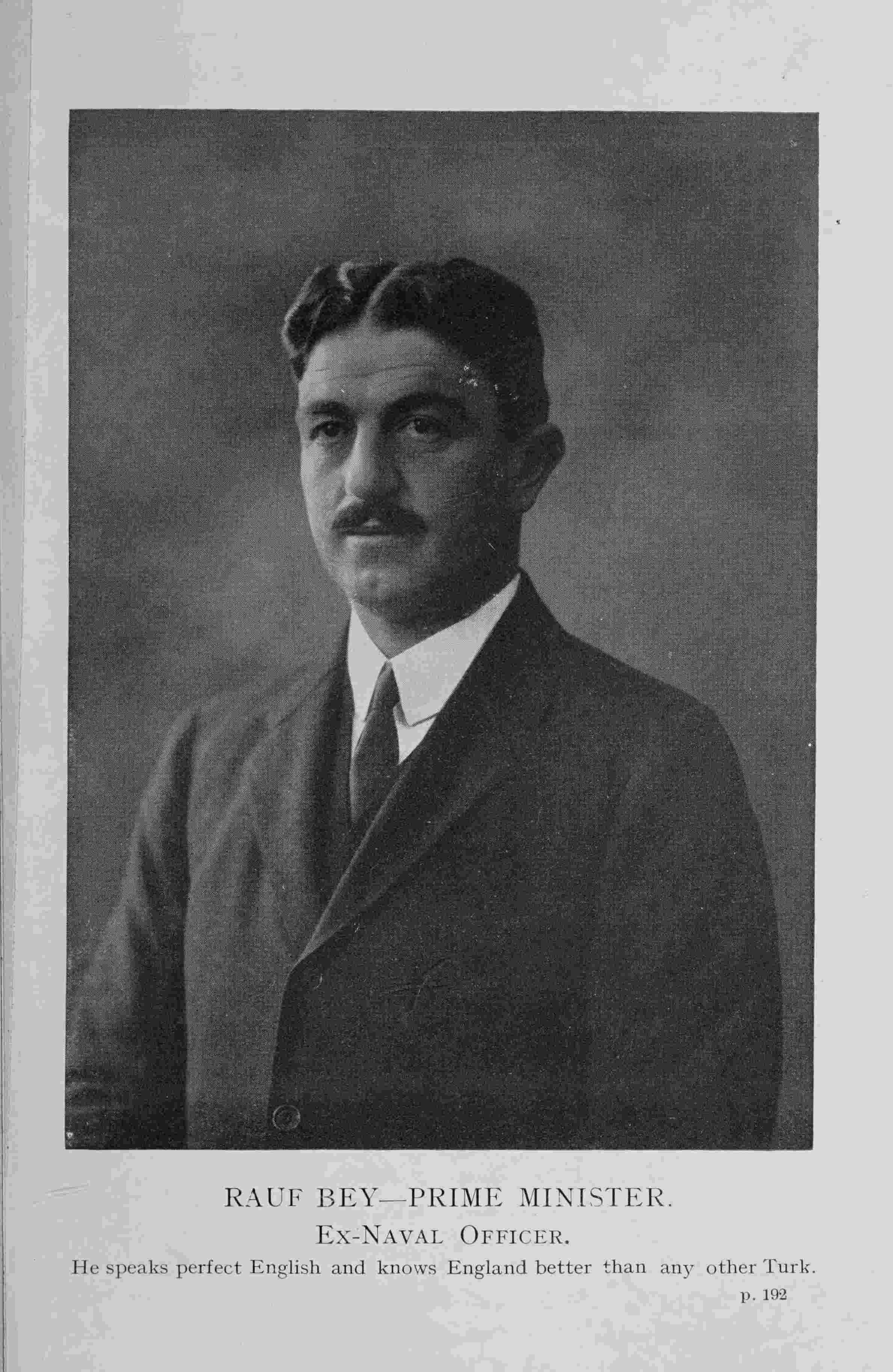

| Rauf Bey, Prime Minister | 192 |

| Halidé Hanoum, the well-known writer, patriot, and feminist leader | 208 |

| Dr. Adnan Bey, High Commissioner for Constantinople | 208 |

| Agha Aglou Ahmed Bey, Director of the Angora Press | 224 |

| A Luncheon Party at the Ottoman Bank, Angora | 240 |

| The Yaili with Drawn Curtains | 255 |

| Broussa | 256 |

| “He has the right to say, ‘Look at me’” | 261 |

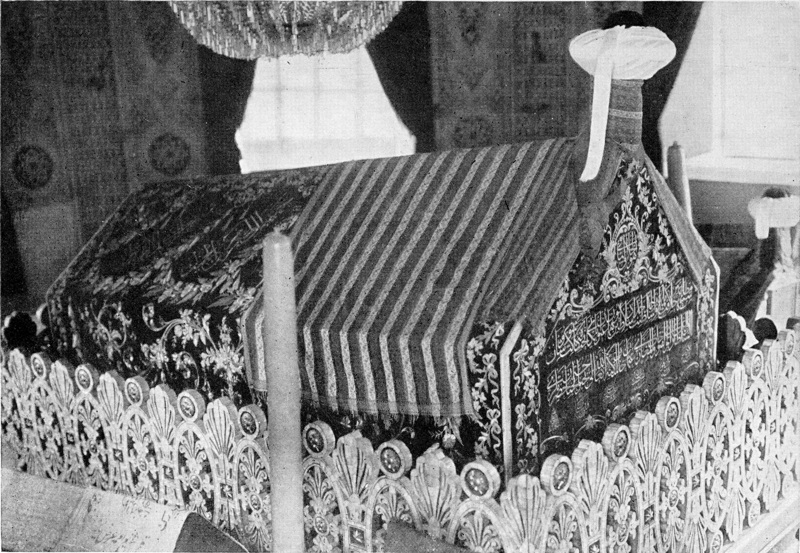

| The Tomb of the Sultan Osman at Broussa | 272 |

| General Refet Pasha and Colonel Mougin in Constantinople | 288 |

| Lausanne Palace Hotel | 304 |

Over a sea as smooth as ice, the sun shining brightly most of the way, the Messageries Maritimes steamer Pierre Loti is carrying us to Smyrna. Ten years ago, to a beaten Turkey (unable, it was supposed, to face an enemy for years to come), I had taken the same trip. And now, despite the prophets, I am returning to a victorious people; doubly victorious, since all the odds were against them.

“That is the kind of story I love,” I remarked to the sympathetic captain and his daughter, with whom I generally lunched as guest in their own cabin. They, indeed, were particularly interested in my adventure, for they knew the Near East well, and this was to be their last visit. Because he had just reached the age limit of those who ‘go down to the sea in ships,’ though it was only when you caught the word ‘papa’ upon his daughter’s lips that anyone would suspect the fact.

So they are blessed who marry young!

“It seems strange,” I told him one morning, “to be here—on board the Pierre Loti, and surely a presage of good luck, since his books have done so much to increase and widen my inborn sympathies with the East.”

Still more strange it proved; since the captain himself had named the ship for his admiration of the great French writer and in memory of personal friendship between them. A rare literary association for 18a steamer once in the service of the Czars. Wherefore, also, I found the master’s works in the ship’s library, and could renew acquaintance with many an old favourite: “Ramuntcho,” “Matelot,” “Ispahan,” “Les Pêcheurs d’Islande” and the “Désenchantées.”

The captain told me of his visit to Rochefort, and I told him how Antoine went to the same house for final instructions upon the staging of “Ramuntcho,” which, however, did not prove a success. How, indeed, could anyone think of dramatising Pierre Loti, whether in prose or verse? He gives us neither psychology nor dramatic incident. I can only suppose that Antoine permitted them to be produced—to show once for all that the thing could not be done; a hard lesson for the master!

“Among Loti’s collection of priceless treasures, rifled from every corner of the East, Antoine sought in vain for somewhere to place his hat! Finally, he hooked it on to an Eastern idol, and their talk began. In a few moments, however, there was a pause, for the astonished dramatist caught sight of the offending headgear suspended, as he supposed, in mid-air. However, a closer look revealed that it was resting upon a thin stream of water. The Eastern idol was a fountain!”

The captain expressed his surprise that I should not only be so familiar with Loti’s work, but that I could really know anything intimately of his private life, “seeing how the Frenchman disliked my own country.”

“My dear sir,” I replied, “if we are to find our friends to-day only among those who love England, we should be limited indeed. You and your charming daughter, par exemple, are you precisely admirers of the British Government?...

“To me, Art is first, and the rest—nowhere! I care not whether the genius first saw daylight in Paris, in New York, or in Timbuctoo. I have more friends out of England than in England. Like Kipling’s cat, ‘all places are alike to me.’ I only ask that your land be warm; and with all peoples who do not rob me I am ready and eager to be good friends. To 19‘guard the frontiers’ in Art would be to bring back the Dark Ages. The most sincere love of one’s own country should never teach one to be disdainful of les autres.”

“You are going to Nationalist Turkey,” he replied, “you will find yourself right up against Chauvinism all the time.”

“I don’t believe it. Forgive me, I really think you exaggerate. And besides—with my strong sympathies for the Turks!—I have always found Orientals the most broad-minded men.”

Then I brought back the talk to Pierre Loti. “Why do you say that he dislikes England so much?” I asked. “He does object to golf near the Pyramids; he is a little sarcastic about ‘Messrs. Thos. Cook & Co., Egypt, Ltd.,’ forgetting what it means to travel without them; he dislikes our Government for its pro-Greek policy and its injustice towards the Turks. As an Englishwoman I agree. And, like him, too, I regard New York as the nearest earthly approach to hell! We certainly do not hate America; only its noise, its materialism, and its advertising.

“I knew Pierre Loti best, perhaps, at his charming Basque home in Hendaye—thanks to my friendship with his heroines, Melek and Zeyneb. I know, at one time, he resented what seemed to him our Edward VII.’s ‘interference’ in French affairs. But that master of diplomats never gave his advice unasked; and, when he was told of the great Frenchman’s hostility, Pierre Loti was promptly invited to Windsor, and they became the best of friends. Would he were with us now, that he might but talk with the Ministers of both nations!

“After Windsor, Loti, I’m sure, would have spared his sarcasm. ‘There is one thing left now,’ he once declared. ‘We must appeal to H.M. Edward VII. He only can do what he likes in France!’ The French Admiralty had just refused him permission to carry away from one of their ships the table on which he had written the ‘Désenchantées.’”

The captain, it seemed, was ready to waive this point.

20“But I do not consider,” he resumed, “that Loti’s books are a true picture of Turkey as she is.”

“They would not, indeed, suit his arch-enemy Messrs. Cook,” I replied; “as Turner painted, he wrote, for those who have eyes to see. Tell him you never saw his Turkey, and he would reply: ‘Don’t you wish you could?’...

“Had Loti himself been English, he would, naturally, have reached a larger public among us. The warmth of his colouring is too often lost in translation. As a schoolgirl I learnt by heart the wonderful Preface to his “Ispahan”: ‘Qui vent venir avec moi voir les roses d’Ispahan,’ and I have dreamt of those roses ever since.”

The captain then spoke of the avenue at Constantinople which bears his name.

“A charming remembrance,” I replied, “but he needs no such ‘rosemary.’ Do we realise, I wonder, what French influence in the Near East owes to his supreme art. In England, except for a small minority, the word Turkey only means a vision of fair houris, veiled in the mysteries of the past, the great ‘Red’ Sultan, and massacres in Armenia. To France it means Aziadé, the Green Mosque at Brousse, Djénane, and the Fantômes d’Orient. Public opinion, to-day, can be ‘manufactured’ as easily as butter and cheese; but the imaginations once stirred by the magician’s pen will not yield so easily to the last Brew of Hate. France is not going to lose her dream of the East woven from Loti’s pen. A debt of gratitude neither she, nor Turkey itself, can ever pay.”

To travel by this steamer, bearing the name of a writer one loves so well, brings unceasing delight. Your menu-card, the life-belts on deck, even the towels, all bear a name to fill the mind with memory of beautiful things. As my eyes fell on the Pierre Loti’s lifeboat, swinging on its davits, I recalled the “Pêcheurs d’Islande,” with its tragic close: “and he never returned!” All the sorrow, the suffering, and the heart-ache; the useless watching, waiting, and longing—this, for the women, is War!

21Are we, indeed, to begin that all over again? For a “Greater Greece” than the Greeks themselves can sustain?

If all women who have suffered (and who has not?) would march to Westminster to protest, would any hear and pause? Can we fight a Press in the service of profiteers, bolstering up the Government, blocking the public view?

Are we not, after all, mere “pawns” of a Destiny that none can avert?

Pierre Loti’s long and interesting life is now very quickly drawing to its close. He has written his last words—a defence of his beloved Turks.

My supreme interest in Turkey among the Moslem nations, arose from influences, or instincts, I cannot now with any certainty determine. I suspect, however, it was in part reaction against the injustice of Gladstone—the idol of my father’s youth, until the betrayal of his hero Gordon—and in part indignation with those who called the Koran an “accursed book.” My religion is the universal tolerance I expect for my own, and I can feel only the most profound admiration for the Great Prophet of Islam, whose fine personality has left so benign an influence throughout the East, and for his “Bible,” with its noble study of our own Christ. Carlyle, you will remember, pays glowing tribute to this “Prophet Hero!”

So I devoured every book that I could lay hands on about these interesting peoples; fought for introductions to anyone who could talk of them, from book-knowledge or personal acquaintance; studied medicine—that their women might suffer less.

It was in 1906 that I first met Pierre Loti’s “disenchanted” heroines, Zeyneb and Melek; and we soon became the closest friends. The tale of their daring, but unpractical, flight had stirred my imagination. Their father was one of Abdul Hamid’s Ministers, and two or three times during my visit they were almost kidnapped by order of the Sultan. On one occasion it was, indeed, only a miracle which disclosed the plot that was to have carried them off (by motor from Nice to Marseilles, thence back by boat to Constantinople) to the punishment awaiting them.

23For hours they held me spellbound by their vivid descriptions of harem life, particularly the Sultan’s, and of the “Terror” under Abdul Hamid. With this clever monster at the helm, the Turks suffered a hundred times more than the Christians. Whole regiments of Albanians ceased to exist; whole companies went off to Yemen and were forgotten; Ministers died suddenly, and private families disappeared wholesale. Yet they must be thrown out of Europe, “bag and baggage,” because, in a minor degree, Christian Armenians, too, bled under Abdul Hamid!

After the departure of the two Hanoums (Turkish ladies), their father died suddenly. And though, when in Constantinople, I did my best to see and console their widowed mother, she persisted in regarding me as one of those giaours who had stolen away her daughters! And would listen to no defence or explanation.

It was then that I heard much of the coming Revolution: when and where “meetings” had taken place, who were members of the “secret societies,” which of their friends in prison would be liberated. In 1908, the Day of Deliverance suddenly came, to the astonishment of the whole world, and I, too, rejoiced, as though my own country were now set free!

I was, luckily, again in Constantinople for those great days. I saw the hideous tyrant of a few years ago driven through the streets of Pera; I was present at the opening of Parliament; introduced to the Sultan Abdul Hamid and his Grand Vizier Kiamil Pasha.

It was the Vizier’s charming daughter who soon became my dearest friend, and hostess for two subsequent visits. Once she spoke of me to Abdul Hamid’s successor, Mohammed V., as her “English sister” (her favourite term of endearment), and the Sultan replied: “I did not know Kiamil Pasha had any English children.” Poor man, he had a Turkish family of a score!

It was Hamid’s fall that first revealed to me how much Turkey loved England, what she was ready to 24give for British friendship. I had witnessed the arrival of our Ambassador, the late Sir G. Lowther, and his triumphant entry to Constantinople, when the horses were taken out of his carriage and he was drawn by Turks to the Embassy. As Abdul Hamid had compromised the nation by friendship with Germans, young Turkey threw herself at the feet of Great Britain.

Why could we not respond? Alas, our Ambassador and his French colleague, M. Constant, would openly express their preference for the despotic Abdul Hamid. And what was said, no doubt with no serious thought of offence, reached the ears of the young Turks and stung their pride: “People who visit Constantinople may be divided into two classes: those who like dirt and squalor” (of whom I was one), “and those who do not!”

It was inevitable that the Germans should make their profit from our discourtesy and blind contempt. We ought, from the first, to have known that she would send, as indeed she did, one of her finest diplomats to Constantinople. Marshall von Bieberstein, and his “retriever,” Dr. W—— of the Frankfurter Zeitung lost no opportunity of conciliating the young Turks, to what end we might, surely, have foreseen!

After the Balkan war, I paid a visit to vanquished Turkey; this time as a guest of my “Turkish sister” in Stamboul, whose father had been, meanwhile, banished to Cyprus, where he died. Under the circumstances I could not (for fear of further compromising my friends with the Government) see much of our Ambassador, Sir Louis Mallet, though I met him twice, and found him a charming man.

To all my appeals, at the Embassy and elsewhere, for British friendship and help to put Turkey on her feet again, I met the same foolish, “parrot” reply: “We cannot sacrifice Russia!” Nevertheless, when I returned to London, and published “An Englishwoman in a Turkish Harem” (the diary record of private friendships, widely circulated in the East), we, the friends of Turkey, determined to defy the Government, and formed an Ottoman Society for that purpose.

25When the war broke out I had just reached Berlin, once more en route for Turkey, Asia Minor, and afterwards Persia and India.

It is obvious that the world-tragedy had even a sharper sting for those of us who were bidden to hate our life-long “best friends” among the enemy peoples. Often enough, moreover, the individual “foe” (as was the case with my Turkish “sister”) could not throw off the heart’s allegiance to England merely because “it was war.”

Can we, indeed, honestly blame the young Turks? In the first place, they did not choose their own path. One man, Enver Pasha, joined Germany against the wishes of a whole nation. As one man, Mr. Lloyd George, would once have drawn the most constitutional of all peoples to fight the Turks, had not General Harington, luckily for them and us, disobeyed his command!

Besides, we did nothing to preserve our friendship with Turkey. Years of indifference, and most impolitic scoffings at real reforming enthusiasm, were followed, at the eleventh hour, by total neglect of any conciliating diplomacy, which could even then have kept Turkey out of the war, and shortened it by two years.

For instance, on the outbreak of war with Germany, “without notice, without the most banal of the forms of courtesy, on the very day when the Turkish flag should have been hoisted over the ships handed over to the Ottoman Commission, which had come to England to take charge of them, the dreadnoughts were seized by Great Britain and no offer was made by the British Government to refund, at least, the price of the two ships....” So wrote the late Grand Vizier Hakki Pasha; and one could mention many other, similar, senseless pin-pricks, which may inflame such people almost more than insults of greater import.

During the war my friendship for Turkey proved a serious handicap in hospital work. Anyone jealous of what privileges were by chance accorded to me would hand over a few choice tit-bits—that grew in passing—to the secret police. The French, unless in a fit of 26really inevitable war-depression, paid scant heed to such reports. The Americans, however, easily took alarm. One, I remember, actually spoke to me about the matter with a terror only equalled, in my experience, by that of the Cabinet Minister’s brother who once asked me: “How I could do anything so foolish as to live in a harem?”

It was a poor compliment to one of Turkey’s greatest statesmen, and to my hostess, his distinguished daughter.

But when I found that Roget’s “Thesaurus” gives as synonym for a harem, “a house of ill fame,” I understood!

Turkey, however, was crushed, defeated and, at Sèvres, humiliated. Were we not courting disaster by such unjust terms? If we remove the foot holding them down—but ever so slightly—will they rebound and strike?

“I cannot understand,” I said to one of their delegates, “how a Turk could be found to sign such a Treaty.” For always, with all their faults, I had known them proud.

“Had we not signed,” he answered, “the Greeks would have entered Constantinople, and God knows when we could have driven them out. What does it matter, the Treaty will not be ratified.”

To keep out the Greeks, to save bloodshed! Maybe he was right.

“At least, we are set free from Germany,” they said; and there is little we could not have asked then for such security.

They would have allowed Great Britain any privileges, any concessions, all sovereign rights, if only we had not permitted the occupation of Smyrna! When the Dutch pasteur, M. Lebouvier, sent the Times a full description of all the hideous bloodshed, the saturnalian orgies, and the riot with which the Greeks celebrated their triumphal entry, it was suppressed—and Englishmen do not know!

Consternation, despair, and anger were the order 27of the day. Those hitherto most apologetic for the part played by Turkey in the war, were now ready to glory in what they had done. A million and a half Turks enslaved by 300,000 “servant” Greeks! Can such things be?

In Constantinople a mass meeting of 250,000 people was held at the Byzantine Hippodrome, flags and banners were draped in black, women sobbed as at a funeral. They were mourning, indeed, for the city they were afterwards accused of having burned!

By what deplorable influence were we thus moved to attempt what would practically have meant the extermination of Turkey? The magic name of Venizelos is not enough! Again and again, the friends of Turkey have asked why? But we do not know whether British action was deliberate or the result of an incredibly big blunder!

M. Kemal Pasha’s great victory changed the face of affairs. Few in England had seemed to care what happened to this band of “rebels”; only a month before his victory, even our Intelligence Officers thought he would easily be beaten by the Greeks. Few had even heard of his three and a half years exile in the mountains!

Meanwhile, at home, we paid little heed, and scant courtesy, to the three Ambassadors from Angora, who came to negotiate peace. Békir Sami Bey’s confidential conversations with the ex-Prime Minister about the Soviet Government were handed on to M. Krassine. Youssouf Kemal Bey, indeed, obtained a hearing, but nothing was done. Fethi Bey (the Minister of the Interior, sent as a last resource) was told, and that was true, that Lord Curzon was seriously ill, but that no one “counted” in England except Mr. Lloyd George. Naturally, he asked the Premier for an audience, which was “promised,” but never given!

Incivility does not pay. It is too expensive a luxury for the greatest of nations. This level-headed Turk, accepting such treatment with all the dignity of his race, found many other things to praise in this country. “The English,” he said, “understand only 28one form of propaganda—the sword!” But of our institutions, our Parliament, our clubs, and the marvellous acting of Miss Sybil Thorndike in “Jane Clegg,” he said much, and nothing but praise, in Angora!

As a woman who has received the greatest kindness and courtesy from the Turks, my resentment, on behalf of Fethi Bey, was expressed with unmeasured indignation. His mission was not taken seriously; the Government dared to show him the cold shoulder!

For his part, most graciously he suggested that I should come over to Angora myself, to the cradle of the Nationalist movement, and see the hero of the Nationalists.

But for his ever-ready assistance it would have been useless to have made the attempt. When, in Angora, he renewed his apologies for all the discomfort I had endured, but I told him the journey itself had been a privilege, for it enabled me to see with my own eyes what his people had been driven to endure.

No, I could never have forgiven myself if, in a moment of weakness, I had been discouraged by the chivalry of the British officials and allowed them to persuade me to stay at home.

Our first stopping-place was Malta, the name I was destined to hear from one end of Anatolia to the other.

Was it not of Malta that Angora was born; and since “the trouble” in the East, Malta has been turned into a universal dumping-ground for officers’ wives and refugees. Whenever M. Kemal Pasha lifts his little finger, or Rauf Bey opens his mouth, the women and children are bundled off to Malta. They return, indeed, on any excuse, at the first opportunity (as why should they not?), until a panic-stricken Government again sends them to exile. One lady with us had done the trip in this way four times!

Constantinople, without our women, makes one wonder if it were so wise as it appears, thus to play for safety! After all, cannot the Englishwoman endure what the Russian, Greek and Armenian are left to put up with? If the husband is in danger, should not his wife be with him? “We want to ‘protect’ our women,” I had been told, and there is no finer ideal than chivalry. But, after Constantinople, I would suggest that we women also “want to protect our men!”

Softening, perhaps, the frankness for which my “French” education has been so often held responsible, I would only say: “There are alluring distractions!”

And in marriage I pin my faith upon the Italian proverb: “Keep to the women and cows of your own country.”

30The utter destitution of so many members of the old Russian aristocracy, has not deprived its women of their temperamental charm. It has provided them with an occasion (genuine enough, God knows) for tears no British youth can resist, unmoved as he will remain under the fiercest shell-fire.

Yet one Englishman told me his Russian wife had taken every penny he possessed, and vanished—he knew not where. Another “fears it is only a matter of time. His ‘noble’ wife cannot be expected to put up with Clapham, and when something better turns up, he will be discarded.” One married “a sweet, soft voice” out of sheer loneliness; and another, foolish and rich, clothed in priceless ermine the lady he met “at a bar!” There is no need to dwell on other, less honourable, “consequences” of such “casual” meetings.

At every corner in Constantinople the “bar” invites the busy and the brave to cocktails or a whisky, an example we have given the “despised” Turk, who had the wisdom to make Angora “dry.” Here, too, is the best of chances for pro-Greek propaganda, as our men meet no “Turkish” women, who are “really” safe in the bosom of their families. One is tempted, almost, to hope that for them the day of “freedom” may be postponed.

Facing this ugly side of what an “Army of Occupation” must always entail, does the Englishwoman who absolutely refused to “leave” need to stand on her defence? “Vanity Fair,” moreover, may serve to remind us that there were English women near Waterloo; and do our present generation require such careful wrapping in cotton-wool, while they are, nevertheless, too often left unprotected in the drab, hum-drum life of a modern “business” world.

It is remarkable, again, to reflect that every Turk one meets, who really “counts for something” in Angora, is a “Malta” man. If M. Kemal Pasha believed in decorations, surely a special medal would have been devised for those who had “visited” Malta.

31As a prison, it is agreeable enough, though the climate strikes one as enervating. The sun shines, even brightly, for the greater part of the year, and sunshine softens the captive’s lot! Had I never visited the island I should have soon learnt to know “the sights,” for in so many homes of Angora, Maltese picture postcards are displayed, almost like holy relics: Valetta, the “Chapel of Bones” (a barbaric idea), the Mahommedan cemetery, the cathedral, and the landing-stage. Everywhere, too, are the fair ladies of Malta, whose head-dresses closely resemble the Turkish tcharchaff.

The Angelus had sounded as I first entered the cathedral, to find myself amidst long rows of black-veiled women, reverently kneeling on the cold inlaid-marble floor, their heads bent in prayer, their fingers counting the beads as they recited their rosaries. The native type is dark-skinned, almost Mongolian, but they all speak English. For are they not British subjects, paid in British money, and entitled to our protection? There was talk, indeed, of extending the cover of “Nationalism” to them also; but, personally, I still felt everywhere, and all the time, that calming atmosphere of order, happiness, and prosperity that is brought by the British flag.

How is it, then, that we have so consistently failed to quiet the Turkish storms? Of course, every one of the “powers” has been involved, each playing for its own hand, striving to end or prolong the war in its own interests.

It is well known that the Turk himself has above all committed one crime—he has kept Constantinople!

Bent on a policy of peace (!) we undertook to disarm Turkey; but the mission despatched to Anatolia for this purpose could, or would, not accomplish its task. Then in May, 1919, despite the Mudros Armistice, we allowed the Greeks to occupy Smyrna! In March of the following year, came the English coup d’état!

The highest personalities—generals, important officials, anyone suspected of sympathy with the Nationalists—were arrested, placed in the hold of a 32man-of-war, for internment at Malta. All were taken on mere suspicion, thrust into prison without trial!

Yet the naïveté of the whole proceeding is almost more puzzling than its high-handed injustice! These dangerous men (!), supposed to be plotting against Great Britain, are all huddled together, and left to their own devices, for two years—and then released! Were we afraid? Did we repent? Will Government never pursue one policy to its logical conclusion?

I could but “wonder about” these things as I knelt in prayer. Clouds of incense have filled the cathedral, the Blessed Sacrament is safely returned to the tabernacle, the huge candles are extinguished, and the veiled ladies are reverently leaving the dimly-lighted church. Cannot faith bring peace?

“There must be peace.” I, who have faith in the spoken word, will declare it, everywhere and all the time, and will count him traitor who utters a word to the contrary. But I will tell them in Angora that “I am sorry for” Malta!

Fethi Bey, Minister of the Interior, carries his comfortable Turkish philosophy to the last extreme. Whatever happens, he will say that “It might have been worse.” In Malta, he acknowledged that he would have preferred greater comfort, but, then, “he might have been much more uncomfortable!” In any case, he seized upon the chance to learn English, and learnt it remarkably well. It is best, he believes, to understand an enemy; and, to that end, you must learn his language. Of Mr. Lloyd George, he declared that “Turkey owes him a debt of gratitude we can never repay.... But for the occupation of Smyrna, and the Malta coup d’état, there would have been no Nationalists. But for your Prime Minister we might all of us have been vassals. Indeed, we owe him a great deal.”

When I asked him what to expect in Angora, he warned me that “I must not look for the luxuries of the Savoy.”

33“Well, I can leave our jazz bands without one pang,” I replied.

“But you may find worse things in Angora than Jazz bands.”

Men like Fethi Bey, ready to meet all emergencies without complaint, make the right material to face the problem of Reconstruction, in a country ruined from end to end; and what a comfort it is to meet a man without a grievance!

When I attempted to sympathise with him for having to ride, because no motor could take these snow-blocked roads, he declared that “exercise would do him good.” When his horse stumbled, “it might have been worse.”

Yet, on my account, he apologised again and again for the condition of Angora; and I could only compare his humorous comparison with the Savoy, to Dr. Réchad’s strange attempt at consolation: “You certainly won’t need any evening dresses.”

It is, no doubt, the gift for always making the best of a bad bargain, that works for peace in the Turkish home. Your husband is not perfect, but “he might be worse”; the food is bad, but there might not be any; if the rooms are not clean, “we have known dirtier.” It is an “accommodating” point of view!

There is a story by Nasreddin Hodja, the great Turkish wit, which happily illustrates this racial characteristic. The Anatolian lived in constant terror of a vociferous wife, though no doubt he often reflected that there were worse women in the world. One day, however, someone told him that she had fallen into the river, and was being carried away by the tide. “Don’t worry,” said he, with a stoic’s calm, “she will go against it. She always does.”

On another occasion, this man of wit had carried a basket of figs to the lame Timur, on an official visit of respect. Timur amused himself by throwing the fruit in the Hodja’s face; but at each blow he cried out: “Allah is Great.” When asked why he so often praised God, he answered: “My wife wanted me to bring you apples.” Since Timur was privileged, if it pleased 34him, to strike the guest, he “thanked God” that he had chosen the smaller and lighter fruit.

As for my own mission in Malta, I had really come to buy a British flag!, as Messrs. Cook’s manager at Naples had supplied “everything” but just that.

For years I have never travelled without a Union Jack. The idea of undertaking so long and dangerous a journey without it, filled me with strange foreboding. Everywhere on the Front I had my “flag.” In a state of coma at the military hospital, the nuns were in great distress because I had expressed a wish to be buried in the flag, which, being under my pillow, was nowhere to be found! Naturally, in Paris I had foreseen my need. But the registered trunk, booked to Rome, had fallen on evil days, and there will be no luck for the “thief,” who is probably polishing his boots with my sacred relic!

At first, I seemed unable to escape the lace-makers of Malta; and when, following the direction of a naval officer, I found myself at last in a real “Harrod’s Store,” my luck, also, was still out. At the Army and Navy, the managing director declared they had “no sale for Union Jacks.”... Each man possessed his own. He dared not sell me the firm’s flag, for an order to hoist it might be given at any moment; and, if he failed to obey, he would very likely be driven out of the island!

As a last resource, I drove to a man said to have “flags for hire.” By this time I was too frenzied with disappointment to conceal my eagerness, and they promised me one for £7! Luckily enough, excitement prompted me to unfurl my treasure then and there, to find myself gazing, in mute astonishment, upon the Stars and Stripes! “Isn’t it the same thing?” cried the impostor, as I flung myself out of the shop.

But time and tide wait for no woman, and I must silence my superstitions, to join the Pierre Loti once more. Taking a last look on the fortifications of Malta, my thoughts turned to the imprisoned Turks, and my heart was filled with shame.

One day, perhaps, the Turks may hold Malta sacred, for assuredly the cream of her people were 35gathered there. One might almost have thought that such men as Prince Said Halim (late Grand Vizier), Rauf Bey, Fethi Bey, Hussein Djahid, and my admirable Angora guide,) Vely-Nedjdat, had been carefully selected to keep each other company.

Mrs. Stan-Harding once said of her eight and a half months in a Soviet prison: “At least I had this advantage, I met the best people in Russia.” As her hearers seemed puzzled by such a statement, she added, “They were all, naturally, in prison!”

I must tell them, in Angora, that England, at least, has always honestly tried to put right her own wrong-doings, and one day (may it be soon!) she will “redeem” herself to them also.

Mr. H. G. Wells somewhere describes the strange, great love we often feel for those we have deeply wronged—the wife, the friend, the enemy. May it not, at the long last, be so “after the war?”

Who knows if, indeed, this be not the dark hour before the dawn, of our nation’s friendships—with those we have been led to hate?

If only it were always calm, how delightful it would be to travel by sea!

From Malta to Athens, indeed, is not a long run; but when every moment you are tossed from side to side, at the mercy of all the winds in heaven, most things have a disagreeable look. As we approached the brown and arid coast of this historic peninsula, I thought how unjust it seems to have driven the Ottoman Greeks out of fertile Turkey to a fatherland that cannot feed them. You cannot obtain blood from a stone, nor fruitful crops from an unfertile soil. What is Greece to do for these poor people, who cannot all turn merchants or moneylenders?

Before landing at Piræus, with my Italian escort, I took the precaution to investigate the rate of exchange—250 drachmas to the £1 sterling.

“It is strange,” said I, “that we have none of this inconvenience in Turkey. There one always gets a fair ‘exchange,’ and no worry.”

The steamer slows down to anchor, and on all sides we are hustled by modern Shylocks. “Two hundred and fifty drachmas for a pound,” I asked, “how many for five shillings?” And the Greek answered: “Fifteen.” “Come and listen to this Greek arithmetic,” I called in Italian; but the man understood me, and let out a hearty laugh. Though I turned from him, without malice, he promptly raised his price from fifteen to forty-five (!), and in the end I 37bought drachmas enough to take us ashore, hoping for better terms on land.

I shall never forget that day at Piræus—heat and dust, flies and refugees. Could a more terrible combination be imagined? All along the quays lay these wretched folk, many of them fast asleep, with armies of flies crawling over them. If by chance one stumbled over a dusky body, which it was not easy to distinguish from the soil, a cloud of flies rose to smite you in the face—the most fatal of disease-carriers! The brown-faced women, dirtier even than the Neopolitans, now crowded round us, offering cakes and sweets from which they were every moment obliged to brush off thick coatings of flies, that once more struck one in the face or settled over my shoulders.

My Italian escort had, meanwhile, kindly procured a newspaper to act as fan, and now, hurriedly brushing away these horrible pests, he took a silk handkerchief out of his pocket to cover my neck. “What a magnificent husband you will make for someone,” I said, smiling with gratitude; and he blushed with all the charm of his twenty-one years.

In another moment my eye fell on the hard brown faces and big “Jewish” noses of the moneylenders, forcing a smile as they call on you to “buy.” They have very much the same expression as Southern Italians; keeping one eye, it would almost seem, to make a pleasant impression on possible purchasers, while the other betrays the keen and swift reckoning of profits to the uttermost farthing.

Seated behind little tables topped with boxes of glass, they are eagerly displaying their filthy paper money; haggling, arguing, smiling, and cheating you in one breath! Surely no type of humanity could carry us further from the heroes of our schoolday imaginings!

Wearied with fly-dodging, in fact, I had scant energy left for a “good bargain,” over this “paper filth” for honest English sterling.

Sympathy now prompted me to ask the Italian Whether his eyes were not in pain; and, by the power 38of auto-suggestion, the inquiry caused my own to ache as they had never ached before. Before we landed the captain had given me a solemn warning on no account to rub my eyes, however tormented by the continual glare of a bright sun on white houses, or I should be certain to “catch an incurable eye-disease and go on ‘weeping’ to the end of my days.”

“Never, never speak of disease again,” I had answered. “Misfortunes come quickly enough, without our going to fetch them.”

Fortunately even the flies could not make it a long journey from Piræus to Athens; and we could glance in passing at the quaint and not unattractive bookstalls, now showing large photographs of modern “Heroes”—the Greek generals! After all, they had done their best. They were no more responsible for the mistakes of their Government, than we are for ours.

Taking train for the last part of our route, we were packed like sardines among the ugliest possible types of human beings one could imagine; but, luckily, soon alighted at a station whose magic name should thrill the dullest heart.

We were in Athens! But the Italian could only exclaim: “What women!” I reminded him that they were, after all, descended from Helen of Troy, for whose beauty the world in its youth made war. Yet it seemed almost a heresy to name that name in such surroundings.

If only one could show all men what a tragedy is here.

“There is something I long to do,” I told my companion. “I would summon crowds of my countrymen and my countrywomen to the Albert Hall and borrow the magic tongue of Mr. Lloyd George, to draw their tears for our dear Christian brethren at the mercy of the brutal Turk! And then a deputation of these money-changing Greeks should be brought in to stand at the Welshman’s right hand and his left!”

How many, even then, would read, mark, and digest the grim comment?

But the Italian laughed again and again at the 39picture my words suggested. I could only murmur: “What is it, to be twenty-one!”

I believe we went into every church in Athens; for ever since I left home I have never passed a church or a mosque without sparing a moment to enter and pray for peace. “It will do no good,” said my companion, and I replied: “It will do no harm.”

We saw many women also at prayer, kneeling before their Ikons—not for victory, but in sad thoughts of their own dead, and for help and strength to bear their own terrible sorrows.

Once the Greek Pope came up and spoke to us, supposing, to my young Italian’s honest confusion, that we were man and wife. The spirit moved him to denounce, in very broken French, the treachery of England; and, whether or no it was from heat and fatigue, or from the sight of those broken-hearted women, something seemed to burst in my throat and bitter tears streamed from my tired eyes. I could not tell him I was English. I could not find words or strength, such as came to me later in Anatolia, to plead a little for England by putting some of the blame on M. Venizelos.

While the Italian discreetly left me—to kneel before an Ikon in silent prayer to the Man of Sorrows—I could but stand and suffer the attack upon my beloved country, choking with tears of humiliation.

Alas, the incident does not stand alone. When taking tea in an hotel, I asked my companion to make inquiries about the best place to buy a Union Jack, and the proprietor seized the opportunity to give us his opinion of British honour.

Now I never heard, throughout the whole of Anatolia, a single Turk speak of Britain or Mr. Lloyd George as these Greeks both spoke. It is a pity that some of our pro-Greek politicians were not with me—to learn the real value of all they have undertaken for their Christian brethren.

In that church, maybe, I was so cruelly overcome because the broken-hearted women had stirred in me a glowing vision of the great Pericles. “For me,” was 40his proud boast, “shall no man wear mourning. I have not shed one drop of human blood.” Could any ruler leave this earth with a nobler record? Could any conceive for himself so fine an epitaph?

Our rulers, and Venizelos, have wasted the precious blood of Europe to flatter their personal vanity and nurse an idle imperialism for Greece; and when everything goes wrong they have only to resign!

I had determined to ascend the Acropolis, whatever the effort to reach the top, and refused even to be discouraged when at the very entrance our driver pulled up and informed us that “it was forbidden” to drive within.

It did not occur to me to protest; but we had scarcely walked twenty yards up the steep ascent when a carriage (containing the captain and his daughter) and then another carriage (!) drove by. Naturally indignant, we returned to ask the man what he meant. To evade argument, he disingenuously explained: “It would need two horses to get up there, and I have only one.” The subterfuge only infuriated me the more, and when he had six times sturdily refused to obey orders, I simply seized the miserable little being by the shoulders and shook him like a rat. Violence proved the only way, and we had no more trouble with him!

It is horrible, in such hallowed surroundings, to be haggling about money; but, of course, we were cheated over our change!

“Never mind,” said the Italian, “let the creatures rob us. Gentlemen cannot fight with grooms.” And as I looked at the exquisite profile of this young Venetian against the Athenian skies, I could fancy myself accompanied by one of the old Patricians, amidst his degenerate, money-changing descendants.

Almost in silence we wandered over the ruins of a civilisation whence came the highest culture of the world. I felt, indeed, as if I had been born too late; for what have I in common with the century in which I live?

To-day nations are not judged by their lyrics that are the measure of their imagination, and without 41imagination the race must die. Our standards are skill in commerce!

Had I the art, whether of pen or brush, to pay fit homage to this immortal rock, who would look or listen? Could I invent yet one more machine to “save time”—for making more money—the world would be at my feet.

Where shall we look for a Pericles, who hand our laurels to the presiding genius of a “cash and carry” store?

There is no finer view of Athens than one can gain from the Acropolis, as the city lies at its feet, like some plain of brown paper dotted with green palms and the little white houses drawn in chalk.

“Here,” said I, “is the Greece of Oxford—of Homer and Plato, of Æschylus and of Sophocles! The magnificent traditions of an immortal past.

“It was in Oxford of classic memories, that I first heard the Tales of Greece, first listened to her great scholars telling of Andromache and Antigone in the exquisite language of the finest literature in the world.

“Here, too, is the Greece of Byron—of Childe Harold, and of the Maid of Athens!”

How the voice carries in this clear atmosphere! No wonder these ancient people would crowd under the blue skies to every play, tragic or comic, that their great dramatists could produce.

And now, as the sunset colours—gold, scarlet, violet, and purple—are glowing upon the immortal rock, over the marble ruins, I marvel at “tiny” Athens and her “vast” name.

Alas, for Hellas and modern Greece!

Had her own people been as faithful as Oxford to the traditions of ancient Greece, what would have been the Eastern Question to-day? And for some, no doubt, it is this very honouring of Hellas that has been responsible for our fatal pro-Greek enthusiasms. If we recognise the superiority of the modern Turk, loyalty to Plato, to Aristotle, and to Socrates must forbid speech; gratitude to the lyrcis of Hellas must tie the tongue. Orators and poets, artists and thinkers 42cannot forget. Hellas still lives and rules in the Republic of Letters and Art.

We understand Oxford; but for those who have been on the spot, facts tell another tale and speak with another voice. Where, in Greece to-day, are her men of intellect or imagination, even her aristocrats or her warriors? The millions spent in propaganda may serve to prolong the legend, they cannot alter facts. To visit, with glowing anticipations, this land of our dreams, means the awakening to bitter disillusion. Those only are still blind who will not see.

In Angora I could but plead for England: “We have loved Helen; must we divorce her?”

More than the eloquence of Venizelos, more than the gold of Zakaroff, more than any pity for Christian martyrs; it is our age-old loyalty to the civilisation to which we owe our visions and our ideals—that has led us so woefully and so wilfully astray. Is there not, after all, some “merit” in British “fair play” to a “lost cause?”

For Orientals, the sky is no less variable and uncertain than the political horizon. In the space of an hour the sea, calm as a lake, has been transformed to a roaring torrent.

Smyrna in the distance, and we are battling forward through one of the worst storms of the season. The steamer dances like a cork on the foam, while long sheets of rain drench the decks, huge waves washing into staterooms soak the carpet, thunder and lightning rage overhead; as in the grim battle of life, we can but hold on till the clouds pass.

Soon, indeed, are the waters about us again at rest, and the town rises to our view. A city burnt to the ground? Where are the ruins of which we have heard so much? Of a sudden the heavens answer.

As the lightning begins to play over the land, the “shells” of houses and their hollow interiors stand out clear before us—a picture of horror and desolation it would be hard to match. As we draw nearer it is no longer necessary for us to gaze upon the devastation; the blind could catch a strong smell of burning (not in itself disagreeable) and, in a few moments, we see that even the rains have not entirely quenched the clouds of smoke still rising from the tobacco factories.

Turkey considers herself at war, and red tape still prevails. But now one does not find many Turks who can speak English, though, strange to relate, there are quite a few English here still. We are not issuing passports to Turks!

Seeing my Turkish letters (better these than a 44British passport), the passport officer sent his secretary with me and my luggage to the Vali’s (i.e. governor’s) house. The Angora Ambassador in Rome, Djelalledine Arif Bey, had also telegraphed to the Vali that I was on my way, and requested that, as some acknowledgment of what I had done for Turkey, I should be given all possible facilities and a right royal welcome! The Vali, without doubt, did all he could.

I inquired of the officer what kind of man was the Vali, sure that the measure of his enthusiasm or his indifference would clearly reveal whether the master was liked by his men and thus provide me with a peep into the unknown. The man’s eyes positively lit up as he replied. It was clear that I should be well received by a good man. “He was sent to Malta, you know,” concluded the officer, as if that were enough. And, though I was English, I understood. I believe that the word “Malta” may soon be safely translated “patriot.”

I suppose it needed some courage to come to Turkey, braving the Custom house and passport officers even with special “protection”; but I met with no difficulties whatever. My companion only seemed puzzled by my name being the same as my father’s! A Turkish woman, of course, would be, e.g., Aïché Hanoun, wife of Rechid Pasha, or daughter of Zia Pasha. But have no foreign women, bearing their father’s name, been through the Smyrna customs, or am I not only the first British woman to visit Angora, but the first British spinster to enter Turkey?

Something of all I owed to the Vali for his “speeding up” of the customary formalities was forcibly impressed on me when I went back for my Turkish papers, to find one of my fellow-passengers, a Frenchman, still struggling with his passport and the custom duties.

The Vali’s konak (or palace) which I had long known from pictures, looks on to public gardens where the band plays every afternoon a strange mixture of Oriental and European music. It was delightful to 45hear Oriental tunes again, if indeed one can call Oriental music a tune. Anything in the major key seems out of focus with Turkey, its atmosphere, its scenery, and surroundings. The more one hears and understands the piercing melancholy of these refrains the more one loves them; and I am particularly grateful to all those Turks (M. Kemal Pasha included) who entertained me with the true native work.

In front of the marble steps of the palace Greek flags are used as mats—dishonoured and trampled with Turkish mud! Such a symbol of conquest struck me as neither generous nor happy; but I soon found that it had been adopted without the knowledge of the chivalrous Vali, who immediately put a stop to the custom.

His palace is lavishly supplied with fine carpets, always the chief item of furniture in the East, while there are many chairs and a handsome desk in the waiting room.

“Welcome to our shores, dear miss,” said the Vali.

And that he might at once disassociate me from English policy, I replied: “That is certainly a charming welcome from a Malta man.”

“Malta to me,” said my host, as he took my hand like an old friend, “is still incomprehensible. What can have happened to England?”

“I understand it, dear Excellency, no better than you can. The more I hear of what has taken place in Turkey during the last few years, the more often I repeat your own words. What, indeed? To an Englishwoman who loves her country, it means great sorrow; but this unreasoning hostility towards your people must stop. That is why I am going to Angora. After my visit, at any rate, the Turks shall see that one Englishwoman can stand out against injustice.”

“Thank you a thousand times, dear miss,” was his reply, as the attendant brought in coffee and cigarettes.

Like all the Nationalist leaders, the Vali is a young man. He looks, in fact, about forty, and comes from an Albanian family. Of medium height, slight and 46dark, good-looking despite his glasses, and intelligent; he is, above all, an honest and kindly gentleman. If all the “fanatics” of Angora are of this description, I shall have nothing to fear. Abdul Halik Bey is a great admirer of England.

Begging I should not hesitate to ask for anything, assuring me that no service possible to render will be neglected, he called up the head of the police and three of his officers to make my acquaintance. The Vali explains that as Smyrna is in ruins, I must go to the only existing hotel—a temporary establishment under the care of Naim Bey, who had been the proprietor of the two best hotels in Smyrna, now burnt to the ground. This “temporary establishment” was the town residence of the Spartallis and a very fine mansion indeed!

When I had said au revoir to the Vali, I paid my return visit to the chief of the police, Zia Bey—a handsome and very energetic young man of about thirty-two, who speaks only Turkish.

Again we drank coffee. He pointed to the picture of M. Kemal Pasha above his desk, and made a little speech about him, which, alas, I could not understand. As comment, however, I clapped my hands, adding: “M. Kemal Pasha Chok Guzel” (i.e., very beautiful), which evidently pleased him. He could see at least that my spirit was willing to pay tribute to his national hero although the Turkish words failed me. Throughout Anatolia, whenever at a loss for words, I adopted this phrase; never once did it fail to convey the meaning I intended—congratulations for his magnificent victory.

Zia Bey has published some detective novels—from his own personal experiences. Like the man himself, they seem to have secured wide applause.

He, too, like the Vali, is a stern enemy to delay, and often receives several people at once. He will listen to all you have to say, while the business of an earlier caller is still to be executed. Practical and courteous though such a custom may be, it obviously has its drawbacks. I wonder what would happen had 47I any advice to ask, or any suggestion to make, on what to me at least might seem private and confidential matters. Thanks to this system, however, it has been my privilege to meet at the Vali’s, or at Zia Bey’s, many notables of Smyrna, whom I might not have found time or occasion to visit.

One day when drinking my daily coffee with Zia Bey, he handed 20,000 Turkish pounds to a French merchant. A policeman, he explained, “found this in your rifled safe.” The merchant was so astonished that he spoke to me about it, adding: “Would they have been returned to me in any other land?”

Every day, after calling upon the Vali, I used to visit Zia Bey. To the Vali, of course, I could speak in French, but to Zia Bey I seldom went further than a repetition of praise for M. Kemal Pasha. It is not words that count when the heart is following the dictates of truth.

At the hotel I could only be accommodated by the dismissal of another guest. Men were sleeping everywhere—in the drawing-room, sitting-rooms, bedrooms, three, four, and six in a room, grateful to find anywhere to lay their heads. To my lot fell one of the best rooms in the house, containing a sofa as well as a bed large enough for four. I felt very guilty, but what could I do? I was the only woman!

To this improvised hotel everyone in Smyrna comes sooner or later, if not for accommodation, at least for meals and “light” refreshment. The country, of course, is dry, but the guests walk round the laws as cleverly as they do in the U.S.A. Americans are, perhaps, the chief offenders, and seem always able to bring in with them whatever they require. If they are caught Naim has to pay the damages! “Poor things,” he remarked by way of comment, “they are so far from their homes.”

Most unfortunately, the Turk’s kindness and consideration for his customers is not withheld from the flies. The Nationalist motto, “A free and independent Turkey,” has certainly been granted them—they go wherever they like, do whatever they like. 48They sit in thick layers on the table-cloth, they drown themselves in your glasses, you swallow them with your food; “and to think,” said a Danish merchant, “these creatures have been fattening on corpses!”

Whatever their nationality, all my neighbours made the most chivalrous endeavours to shield me from these pests. I was advised to sacrifice my bread as a cover to my glass when not drinking. I always refused water, and Naim Bey defied the law to give me German wine.

One day, exasperated beyond endurance, I procured what the French call a “guillotine,” and successfully slaughtered every fly that came within my reach. The “Italian” gently inquired whether the corpses were not more awful than the living insects.

“At least,” I said, “they cannot bite or carry microbes,” and I pursued the slaughter with a zeal that astonished even myself. I even aimed at those I saw walking over the South American’s arm, and hit his nose! Without a smile, he courteously declared that he did not mind what I might do to his nose, “but you will be careful of my glasses, won’t you?”

“Can’t you do something?” I asked Naim one day.

“They will go away when it is cold,” he replied with the philosophy of the true Turk.

“Cure or endure is also my motto,” I told him, smiling, “but I never endure before I’ve made a fine attempt to cure.”

On another occasion, my energies were not rewarded with true Christian gratitude or tact. I was busy as usual, when an orthodox lady who had given her nationality as “Catholic,” and was staying in Smyrna by special dispensation of the Turks, said to a Greek neighbour: “Look at this lady slaughtering flies, as her friends the Turks slaughter Christians.”

“Madame,” said I, “I have passed this morning among the ruins to which your ‘Christians’ have reduced this city.” I had yet to see the hideous devastation in Anatolia!

There were about two or three hundred business 49men in the hotel, waiting to learn their fate. They divided themselves into three distinct groups, in three different mess rooms. First, the silent, water-drinking, go-to-bed-at-nine Turks, in the library. Secondly, Americans, in the smoking-room, who left their allegiance to prohibition on the other side of the Atlantic; singing and dancing to the accompaniment of a banjo till the small hours of the morning. Thirdly, at a long table in the dining-room, sat the rest of us—principally business men—Italian, Spanish, Dutch, South American, Frenchmen, or Danes. My only fellow-countryman informed me that among other complications he had come to Smyrna to arrange, he has somehow to explain away the disappearance of 50,000 gallons of pure alcohol, sent from Cuba to Smyrna via New York. The officials in New York had helped themselves to the precious nectar, and sent the cargo on to Smyrna, refilled with water! Such are the trials of prohibition!

One and all, these men have but three topics of conversation: (1) the senseless policy of Mr. Lloyd George in sending the Greeks to Smyrna; (2) the criminal desire of the Turks to abolish capitulations; (3) the “probabilities” of likely successors to the deported Greeks and Armenians in the business world. It is assumed that Turkey cannot survive without the assistance of some European power. The Turk is a producer, not a merchant. The Italians affirm that trade would flourish in a happier world if they were given the vacancy. The Americans, however, dispute this honour, whilst the Dutchman, supported by a Dutch clergyman (born of French parents, but a British subject, in the service of Holland, speaking all three languages without an accent), declares the only power that is “going to count” in Turkey is Great Britain.

“In spite of her deplorable and ill-advised policy, her inexplicable treatment of the Turks, her protection of the Greeks (which has made them more arrogant and destestable than ever), there is something in the British national character which still commands respect and 50admiration. In six or eight months we shall see England back in Turkey, stronger than ever. England is not her government.”

I believe he is right. There was a more practical reason for his convictions than his deep affection for his English wife.

Holding no brief for Mr. Lloyd George, I still scorn these men of finance as cowards for their unmeasured abuse of the Premier.

“If you foresaw disaster so plainly,” I asked, “why did you not protest?”

“Every Chamber of Commerce sent a petition to Mr. Lloyd George,” was the reply, “which he put into his waste-basket.”

“Naturally. As practical men, is that your idea of a protest?”

“One of our biggest men, Mr. Patterson, went to the Paris Conference on our behalf.”

“Did he make himself heard? I assure you, if I had one hundred pounds invested in this country, instead of the hundreds of thousands your Scotsman holds, the world would have heard something of my visit to Paris!

“You saw financial disaster and ruin ahead, yet allowed yourselves to be talked into silence by M. Venizelos!”

Somehow, these men could not excite my pity. They were themselves more to blame than Mr. Lloyd George. With their huge financial backing, and vast interests in Smyrna, it was actually in their power, and theirs alone, to have kept out the Greeks.

It is a quaint result of my sense of justice that, in the French Secret Service, I am known as “a niece of Mr. Lloyd George.” When the brilliant one-time chef de Cabinet of Monsieur Briand published his violent attacks on Lord Robert Cecil and our late Premier, he also printed my replies. “He did not,” he kindly explained, “consider there was a word of truth in what I said, but he was unwilling to thwart an Englishwoman!”

Shortly after the appearance of my “defence,” the 51correspondent of a big newspaper in Chicago spoke of “my uncle,” Mr. Lloyd George. I protested, “not because I should not be proud of the relationship, but because I happen to have no such claim.”

“Dear lady,” he replied, “don’t think I shall ever want to spoil your little game.”

Such a remark did not merit a serious answer, and I allowed the matter to slide. I knew very well Mr. Lloyd George would never lift a finger to help “his niece,” for have I not four times appealed to him in vain on matters of the greatest national importance? Yet “his niece” will continue to defend him against “unjust” attacks, and criticise him also.

The Smyrna capitalists also did not love me because I wrote: “The day is past when financiers can obtain ‘concessions’ for 500 Turkish pounds backshish and then complain of the Turks for being amenable to bribes. The happy day will never return when the foreigner lived in Turkey without taxation, with next to nothing to pay in rent, was charged one and sixpence for a shooting licence, and had full control of money and trade.”

“Turkey is now for the Turks, and the Capitalists will have to recognise this or leave.

“Never again will Smyrna become the Aliens’ Paradise it once was. Would anyone, for example, have dared to offer the trams provided for Smyrna to any other nation but Turkey? Why were there not electric trams, instead of these wretched horse-boxes drawn by underfed ponies? And the compartment reserved for Turkish women was not even separated by a partition, but by a sheet that once perhaps was white!

“There are men in this town,” I wrote, “who would plunge Europe into war, to bring back the dear old lazy-going Turk who made so charming a background for our novels and plays. They would restore him for no higher purpose than to fill their purses at his expense.” At least, I said to these merchants: “If you cannot ‘love’ my whip, you know, in your heart of hearts, that I have spoken the truth. You should 52have a mighty respect for me, and I ask for nothing more.” The South American answered: “Every word you say is true, and we all admire you for it.”

Towards nightfall, however, my mind was occupied by certain more personal anxieties. The Italian had not yet even come to the hotel, and I could hear nothing of him. I began to reproach myself with not having attempted to extend the protection of my papers to him, although, like the gentleman he is, he had already refused my suggestion to that effect.

I could only apply, as a last resource, to the Vali’s secretary, who at once took me to the Caracol (i.e., the “lock-up”), where we found my friend in company with the Frenchman we had already been pitying for his struggles with passports. Neither of these young men were known in Smyrna; neither of them had secured permission from Angora to land; neither of them were personally known to their Consuls; neither of them were able to speak a word of Turkish. They could not explain themselves, and were, therefore, to be kept under arrest till further inquiries could be made.

“After all, in war-time did we not do worse things than this?” I asked the enraged Frenchman, who was declaring such treatment would make a casus belli.

“When I was serving your country and travelling to San Remo with a special letter of recommendation from the French Minister of War, I was detained for forty-eight hours at Mentone, because they considered my ‘Plato’s Republic’ a proof of sympathy with the Bolshevists.” I was able, however, with the secretary’s willing assistance, to liberate both my fellow-passengers without further delay.

Naim Bey gave me many special privileges, no doubt as the result of prompting from the same quarter. He sent me up breakfast in the mornings, though his servants were all “Catholics” (i.e., Armenians, under the Papal protection), and did not know their job. I never could understand how he contrived to supply me with milk, as the Greeks had killed most of the 53cows; but I was no less heartily grateful for his permission to use the Spartelli library, and for the reading-lamp which he borrowed for me from an American.

All these acts of kindness, however, were done with such an appearance of ease that I even ventured upon one more request.

“Could I use the piano to accompany my Italian friend?”

He did not hesitate to banish the six occupants of “mattresses” in the drawing-room from their domain until we finished “La Tosca” and “Madame Butterfly.” Then an American begged me to play the “Swannee River,” and nearly broke down before he had even got to the chorus.

“Did I not tell you,” said the sympathetic Naim, “Poor things, they are so far away from home!”

I suppose I should not be too severe upon these merchants among the ruins of their past glory, and, to do them justice, they are accepting defeat like good sportsmen. The Dutchman is as merry as a cricket, despite his £80,000 “gone west,” his thirty years’ work undone for ever, his fine farm burnt to cinders.

I wish he would make a book out of all he has seen and done in this land of romance. No one knows it better, and, if my own sympathies are apt to be with the brigands from whom he has twice suffered capture (because they only rob the rich), I have enjoyed few men’s tales of adventure more than his. Good and strong men are rare enough, and I know this one would never forget a friend. If danger threatened, it would only reach you over his dead body.

“Women are so absurdly brave,” said a charming British official, “that is why they are such a nuisance.”

He was seated at a small, improvised and over-crowded bureau in one of the few remaining houses on the Smyrna Quay. He had just sufficient of a Scotch accent to make one see that he would stand no nonsense—an asset, surely, in his position. Yet the obvious and zealous concern for his own countrywoman proved that, however carefully the calm exterior of the Scot may hide his feelings, his heart beats strong and true. He is no less proud, too, of his “women” than any citizen of the States!

But this able and active young man, master of any emergency at a crisis, could not accept my point of view about the Nationalist Turk. That, certainly, was not his fault, for who is there to interpret this “new” people to him? He only knows that, for the first time, Turks have dared to express themselves, and—like brave women—are becoming a great nuisance! Under the good Hamid, these lazy people were easy enough to manage. “Turkey for the Turks!” What a monstrous notion! Yet one feels, nay knows, that he has plenty of intelligence, will face facts, and learn to accept the inevitable.

Meanwhile, I, for my part, am throwing a most unwelcome additional weight upon his already over-burdened shoulders. He is clearly annoyed at my having come so far, and, in his place, who would not have felt the same?

But, unfortunately for him, he knows very well 55that a woman who, despite difficulties well-nigh insurmountable, has been able to reach Smyrna without a British viza, means to get her way and will not be lightly driven back.

If only the man had adopted the bullying and supercilious tone that becomes a uniform! One can so easily meet the “correct” officialism, counter its attacks, stand up to its incivility, and go one’s own way with a clear conscience. But it was not to be with my Scotch friend.

“I admire your courage immensely,” he said with a courteous grace, “but, pardon my asking, what is the sense of it all?”

“I want to study ‘the movement’ at Angora, and to see the national hero, M. Kemal Pasha.”

“Is it worth risking your life for that? Forgive me, it does seem rather a wicked waste.”

Outside his windows, on the calm waters of the bay, rode warships of many nations. The bright sun looked down, unkindly it almost seemed, upon the ruin and desolation around us. The arms of England, France and America were all there. Holland, he told me, had begged in terror for the protection of a warship.

“Terror of what?” I asked.

“Have you not heard, can you not see, we are on the brink of war? To-morrow you will be going home with the others. Our Government has given orders for the immediate evacuation of all our people. Later you will receive final instructions, and be told the meeting-place. This time it is war. There is no help for it. It has to come.”

He showed me a flashlight, well hidden in a corner of that dilapidated office, which would send out its news of “safety” when every Englishman had left the town, and he, my friend, had followed them in a boat with its oars muffled—if he were able to get away. If not, well, he had done his duty!

But I remained unmoved. “Do not worry about me. I have made all my plans, and shall start to-morrow for Angora. I know the risks, and I know, too, that all will be well for me.”

56At first, evidently, his official mind suspected that I was playing with his nerves, idly boasting of what no one would seriously attempt. When convinced, however, that I really meant what I said, he banged his fist on the table and just shouted:

“By Jove, if you belonged to me, you should not go.”

How I hoped he had lost his temper! But no, in another moment he was again all quiet concern, courteously persuasive.

“But,” said I, “I have reached here against long odds. I have come entirely on my own responsibility, and at my own expense. The Turks who met me here will take care of me, not my family nor my Government. Even war will not stop me.”

“And when there is war,” he replied, with a note of almost despairing entreaty, “for as there is a God above, it will come this time. Think of it! A woman absolutely alone among the Turks; not a European to help her. Six months, at least, in a concentration camp, illness, perhaps torture. God knows what will happen to you!”

“I shall not be put into a concentration camp, for there will be no war. I am going to stop it!”

I was smiling now, which only added to his distress.

“My dear young lady,” he cried, “keep your courage for some wiser, finer cause. Britain needs you.... Seriously, you are not going, are you?—And the war!”

“I shall nurse the British soldiers, or else return——”

“You speak of the Turks as if you trusted them. Is this wise?”

“Indeed, yes. I know them. The only way to treat a Turk is to trust him. He has never yet let me down. Why should he now? Even at this crisis you will find there is no other way but trust with the Moslem.”

Of course he was not convinced.

“Charming theories, but dangerous in practice; above all, dangerous for you. Go home. You can see your friends again when things are more settled. 57Don’t think I don’t admire your pluck; I do. In all my experience I never met a woman ready for greater risk; but we value you too much to let you go.”

It was a wearisome line of attack. I could so much more easily have dealt with violence from a would-be dictator. I tried again, hoping to silence a busy man.

“Please imagine you are an American,” I suggested, “and that time is money.”